Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Teacher-student relationship quality effects on school students’ bullying victimization: A serial mediation model by student-student relationship and student engagement

1 School of Teacher Education, Heze University, Heze, 274015, China

2 School of Educational Science, Xinyang Normal University, Xinyang, 464000, China

* Corresponding Author: Yanfei Yang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(4), 541-548. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.069551

Received 20 December 2024; Accepted 26 June 2025; Issue published 17 August 2025

Abstract

This study examined the impact of teacher-student relationship quality on students’ risk of bullying victimization and the mediating roles of student-student relationships and student engagement in this relationship. A total of 656 Chinese junior high school students (females = 361, mean age = 13.75, SD = 0.98) completed validated measures of teacher-student relationship quality, student-student relationship quality, student engagement, and bullying victimization. Regression analysis results indicated that higher teacher-student relationship quality predicted a lower risk of student bullying victimization. Serial mediating effect testing of the student-student relationship quality and student engagement revealed that these factors fully mediated the relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization, resulting in a lower risk of bullying victimization. The results showed that student-student relationship quality had a more substantial mediating effect than student engagement. The findings support the Socio-Ecological Framework, suggesting that within the Microsystem, interactions between individuals and their immediate environments significantly impact their behavior. Specifically, these findings suggest that good teacher-student relationships can enhance the quality of student-student relationships and student engagement, thereby preventing and reducing the occurrence of bullying victimization.Keywords

Teachers and parents have expressed concern about the prevalence of bullies. Approximately 1 in 5 adolescents worldwide is bullied at school (Lessne & Yanez, 2016; Liu et al., 2022). Bullying victimization risk is an important risk factor for students’ development in school (Bradshaw et al., 2013) and could seriously impact students’ mental health, behavioral function, and academic performance (Kljakovic & Hunt, 2016; Huang, 2022). Bullying victimization is when individuals perceive themselves to be unable to defend themselves against intentional and repeated aggressive behavior in a school setting (Olweus, 1997). Much of this would depend on the student-to-student relationship and the student’s sense of engagement. However, the relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and students’ bullying victimization risk, with the mediation of student-student and student engagement in that relationship, remains unexplored. Therefore, this study aimed to address that gap in the evidence.

Teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization

The teacher-student relationship is defined as “the meaningful emotional and relational connection between the student and the teacher as a result of prolonged interaction” (Marengo et al., 2018, p.2012). Three key aspects—positive, negative, and conflictual—are often used to evaluate the quality of teacher-student relationships (Roorda et al., 2017). Positive interactions between teachers and students are generally defined by emotional warmth, mutual openness, and the provision of academic and emotional support, which foster a caring environment and the development of trust (Sulkowski & Simmons, 2018). Indifference, limited interaction, and insufficient support from teachers are key indicators of a negative teacher-student relationship, and these relationships are marked by alienation, emotional neglect, and a lack of trust (Pianta, 2013). Conflictual teacher-student relationships are typically marked by frequent arguments, confrontations, and non-cooperation, often resulting in disharmony and tension between the teacher and the student (Marengo et al., 2018).

Students who are bullied are more likely to experience classroom behavioral problems (Cook et al., 2010). This poor classroom behavior is associated with their overall lower school adjustment. Specifically, victims often have a more negative perception of the school and classroom climate (Jungert et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015). Moreover, bullied students have been found to report higher levels of emotional symptoms, such as anxiety and depression (Silberg et al., 2016). According to Voltmer and von Salisch (2017), negative emotions can have a detrimental impact on school adjustment and academic success. Therefore, the emotional difficulties of bullied students further undermine the quality of their classroom life.

Teachers play a dual role: they act as authority figures who promote proper behavior and address misconduct, and as facilitators who nurture students’ social skills, peer connections, and emotional well-being (Farmer et al., 2011; Quaglia et al., 2013). When teachers build positive relationships with students, their classroom authority is reinforced, and their capacity to guide students’ behavior and emotional control is improved, which in turn contributes to a better classroom atmosphere and overall classroom experience (Longobardi et al., 2017). Students with weak or negative relationships with their teachers tend to display externalizing problems, including aggressive acts and rule violations (Jungert et al., 2016), and are at higher risk of participating in bullying behaviors (Thornberg et al., 2018). Positive teacher-student relationships can enhance students’ sense of security and belonging, thereby reducing their feelings of isolation and alienation within the school environment. Good teacher-student relationships can help create a safer and more supportive environment, which may reduce the likelihood of students being bullied (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009).

Student-student relationship quality mediation

Student-student relationship quality refers to the quality of interaction between students (Yu et al., 2022). For instance, students in schools and classes where teachers care, respect, and support have higher levels of mental health (Sarkova et al., 2014), higher levels of peer acceptance (Hughes et al., 2014), and less involvement in antisocial behavior (Maldonado-Carreño & Votruba-Drzal, 2011), including bullying (Gregory et al., 2010; Richard et al., 2012). Teachers who demonstrate care and support can strengthen peer relationships and minimize student conflicts by fostering a stronger sense of classroom belonging. Teachers’ recognition of a student affects other students’ acceptance of them (Ten Bokkel et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2018). Praise or criticism also affects their image in the eyes of their peers.

A good student-student relationship has been identified as an important buffer that helps prevent bullying. Enhanced peer relationship quality is associated with increased prosocial engagement and a reduced risk of bullying and victimization (Johnson & Johnson, 2007, November). Negative student-student relationships may serve as an immediate risk factor for being victimized (Thornberg et al., 2018). Those who are victimized often report limited peer acceptance, lack of support, weak friendships, and little mutual interaction (Demaray & Malecki, 2003; Perren & Alsaker, 2006; Perren & Hornung, 2005). These factors collectively increase the likelihood of students being bullied.

Student engagement refers to the level of involvement of students in school-organized and learning-related activities, including cognitive-behavioral engagement and emotional engagement (Xie et al., 2019). Students’ engagement has a significant negative impact on bullying victimization (Xie & Mei, 2018).

Student-student relationship quality positively predicts student engagement (Yan et al., 2018) or more active participation in school learning and activities (Thornberg et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2018). Moreover, students with a high level of acceptance in their peer group are more actively involved in activities organized by the school and learning related. Support from peers motivates students and helps them recognize the importance of pursuing academic success (You, 2011).

Theoretical basis. Hughes et al. (2014) argued that within the Microsystem, interactions between individuals and their immediate environments significantly impact their behavior. Teachers have a considerable impact on peer ecology, with supportive and empathetic educators enhancing peer interactions and reducing peer conflict (Hughes et al., 2014). As managers of the classroom environment, teachers have a considerable impact on the classroom peer ecology (Hendrickx et al., 2016). Bullying, as a social phenomenon, is influenced by both personal and environmental factors (Swearer & Hymel, 2015; Thornberg et al., 2022b). Thus, teachers and students comprise an important Microsystem in the students’ school life.

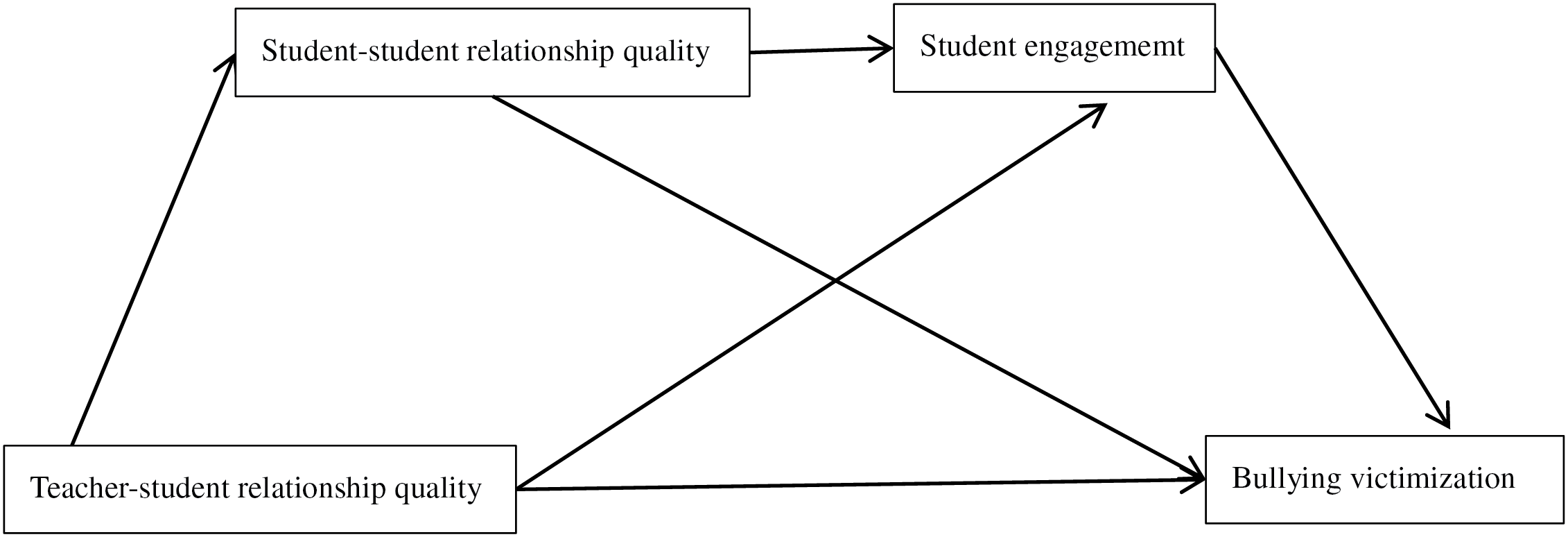

Goals of the study. This study examined the relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization among school students, as well as the mediating roles of student-student relationship quality and student engagement in this relationship. Figure 1 presents our conceptual model for testing the hypotheses.

Figure 1: Hypothetical model of the study

Hypothesis 1: The teacher-student relationship quality is negatively correlated with students’ bullying victimization risk.

Hypothesis 2: The quality of the student-student relationship significantly mediates the quality of the teacher-student relationship and the risk of students being bullied.

Hypothesis 3: Student engagement significantly mediates the relationship between teacher-student quality and students’ risk of bullying victimization.

Hypothesis 4: The student-student relationship quality and student engagement play a mediating role in the chain between teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization, strengthening this relationship more than either student-student relationship quality or student engagement alone.

A convenience sample of 656 Chinese junior high school students participated. By demographics, they comprised 295 boys (45%) and 361 girls (55%). They had an average age of 13.75 ± 0.98 years.

Teacher-student relationship quality and student-student relationship quality

The Dual School Climate and School Identification Measure-Student (SCASIM-St 15), developed by Yu et al. (2022), is a measure of teacher-student relationship quality. It comprises two subscales, each consisting of 3 items, assessing the quality of the teacher-student relationship and the student-student relationship. The items are rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Higher scores indicate better teacher-student or student-student relationships. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha values for the teacher-student relationship quality and student-student relationship quality scales were 0.89 and 0.93, respectively.

The Chinese Version of Delaware Bullying Victimization Scale-student (DBVS-S), revised by Xie et al. (2015), consists of 18 items on four dimensions: verbal bullying (e.g., “Students say hurtful things to me.”), physical bullying (e.g., “I have been pushed on purpose.”), social/relational bullying (e.g., “Students tell others to dislike me.”) and cyber bullying (e.g., “Classmates send negative messages about me to others privately through text messages, WeChat, QQ, etc.”). In this study, only the first three dimensions of the scale were used, with a total of 12 items. The items are rated on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (daily). Higher scores indicate greater victimization. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value of the bullying victimization scale was 0.88.

The Delaware Student Engagement Scale-Student (DSES-S), revised by Xie et al. (2019), comprises 11 items on cognitive-behavioral engagement (5 items, e.g., “I complete my homework on time.”), and emotional engagement (5 items, e.g., “I enjoy coming to school.”). The items are rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree). Higher scores indicate higher student engagement. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value of the student engagement scale was 0.93.

The Xinyang University ethics committee approved the study. Parents of the student consented to the study. The students assented to the study. They completed the surveys at school. Students were made aware of the study’s purpose, the voluntary nature of their participation, and the confidentiality of the data collection and analysis process.

The data analyses were conducted using SPSS 20.0 and the SPSS macro PROCESS (Hayes, 2013). First, descriptive data were obtained using SPSS 20.0, and then Pearson correlations were calculated to assess the correlations between the variables. Furthermore, the multi-mediation analyses were all conducted using the PROCESS macro in SPSS 20.0 (Hayes, 2013; Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The number of bootstrap samples for the bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals was 5000.

Test for common method variance

Since the data were student self-reports, and a Harman single-factor test was employed to assess common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003), five factors with eigenvalues greater than one were identified, which explained 63.71% of the variation. The variance explained by the first factor was 34.17%, less than the 40% threshold. Therefore, the common method deviation of the data in this study was not significant.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

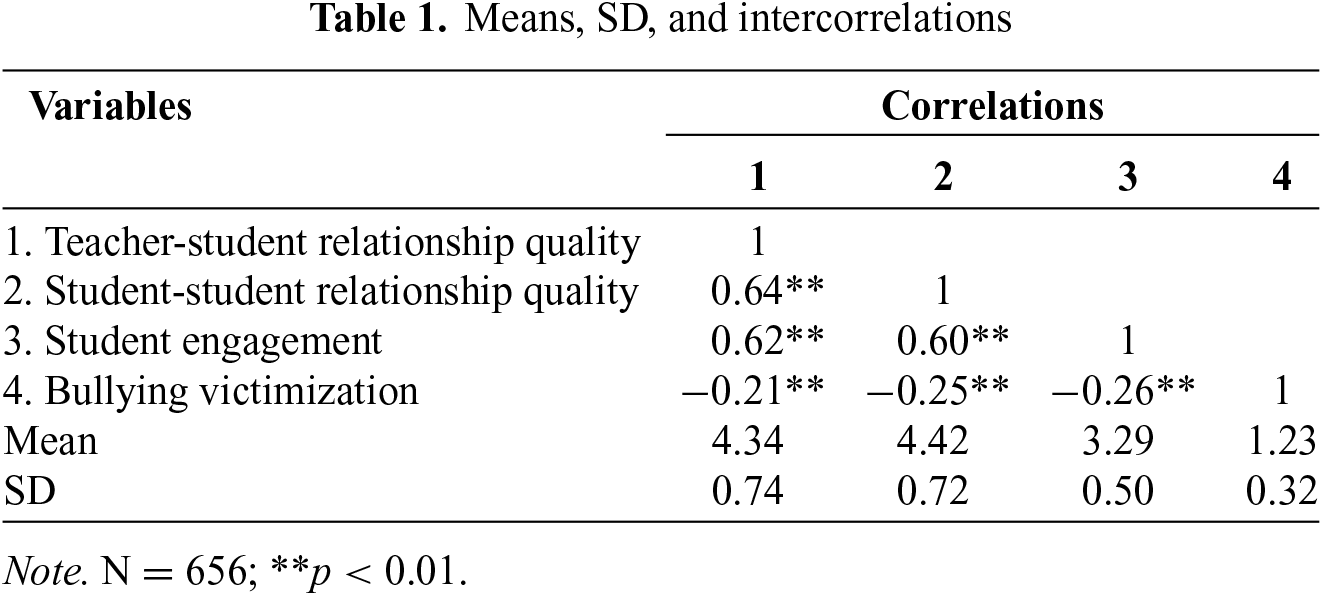

Table 1 presents the descriptive results of each variable and the correlation coefficients among the variables. The results show that teacher-student relationship quality was positively correlated with student-student relationship quality and student engagement, and negatively correlated with bullying victimization. Student-student relationship quality was positively correlated with student engagement and negatively correlated with bullying victimization. Student engagement was negatively correlated with bullying victimization. These were basically consistent with the results of previous studies.

Teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization risk

The results (see Table 1) show that teacher-student relationship quality was negatively correlated with bullying victimization (r = −0.21, p < 0.01). So, Hypothesis 1 was confirmed.

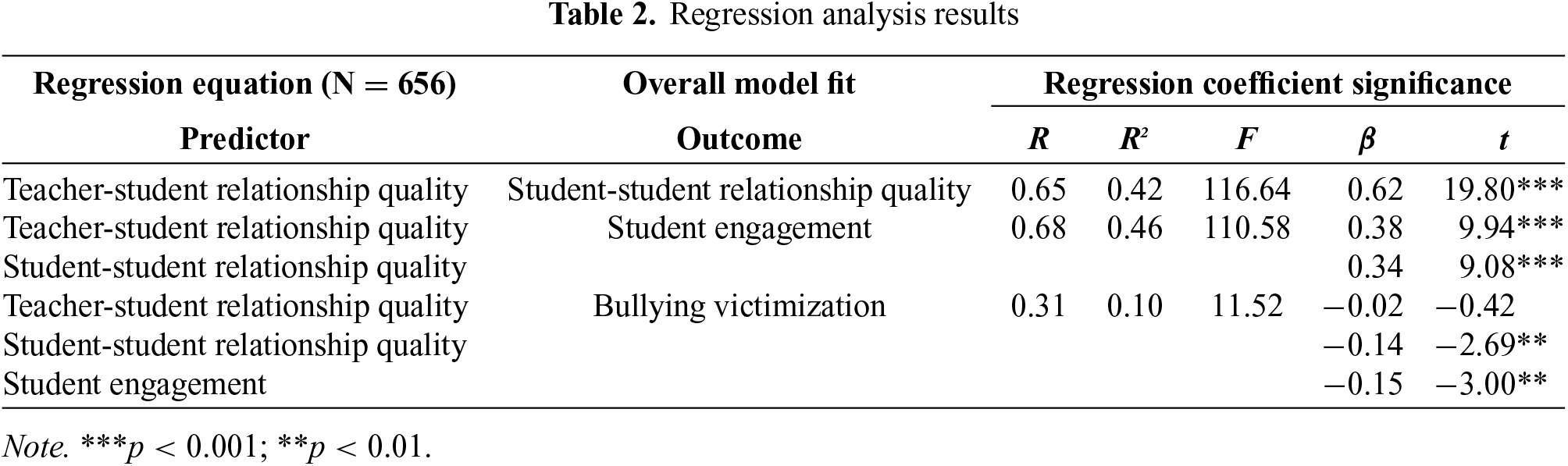

Test for mediation: Student-student relationship quality and student engagement

In this study, Model 6 in the PROCESS macro in SPSS 20.0, compiled by Hayes (2013), was used to test the mediating effect of student-student relationship quality and student engagement on the relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization, while controlling for gender, age, and grade. The results (see Table 2) show that teacher-student relationship quality positively predicted student-student relationship quality (β = 0.62, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.54, 0.65]) and bullying victimization was not significantly predicted (β = −0.02, p = 0.67, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.04]); Student-student relationship quality negatively predicted bullying victimization (β = −0.14, p < 0.01, 95% CI [−0.11, −0.02]). The results indicate that the quality of the student-student relationship significantly mediates the relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and students’ risk of bullying victimization. So, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

The results (see Table 2) indicate that teacher-student relationship quality positively predicts student engagement (β = 0.38, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.20, 0.56]). And student engagement negatively predicted bullying victimization (β = −0.15, p < 0.01, 95% CI [−0.17, −0.03]). So, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

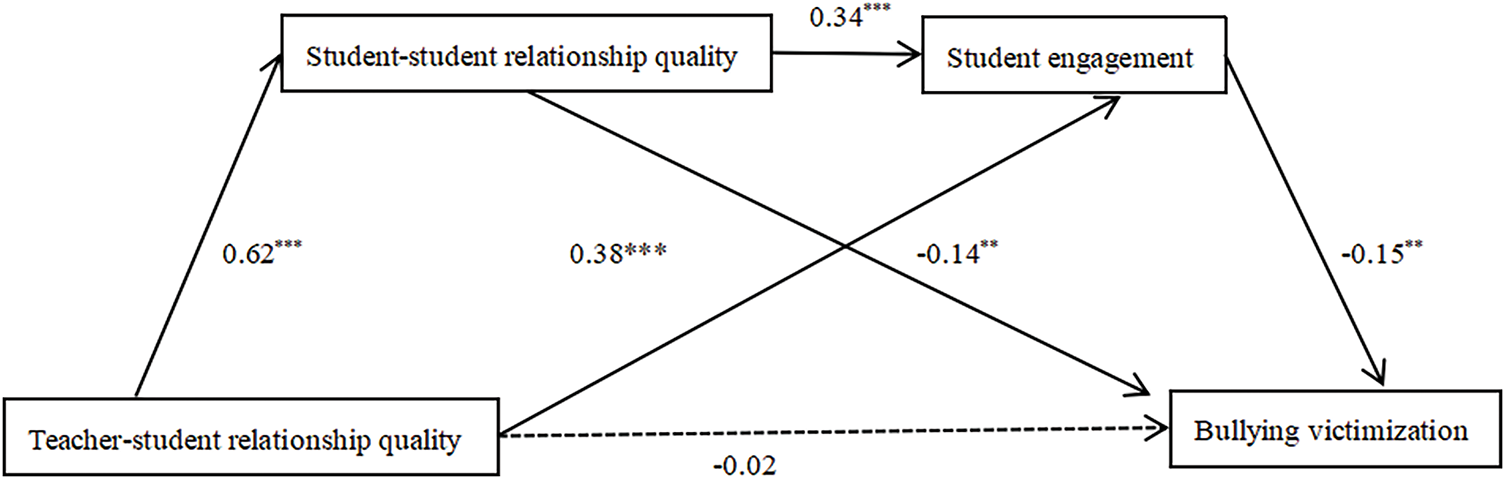

Student-student relationship quality positively predicted student engagement (β = 0.34, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.19, 0.29]) (see Table 2). Therefore, the single mediating effect of student-student relationship quality and student engagement was significant, and the chain mediating effect of student-student relationship quality and student engagement was also significant (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Figure 2: Full mediation model. Note. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01.

With the mediating effect of student-student relationship quality and student engagement, the effects of teacher-student relationship quality on bullying victimization became insignificant. Considering the above findings, the mediator variable, student-student relationship quality and student engagement, played a full mediating role in the relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization.

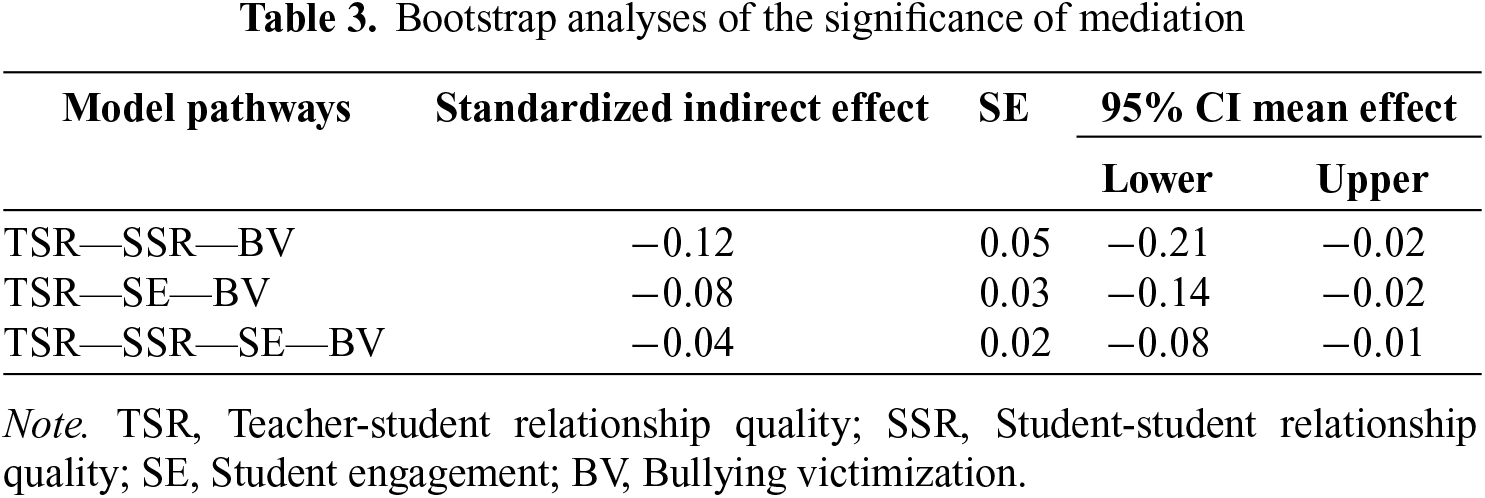

Then this study further tested the significance of the mediating effect in the model using the bootstrapping method (n = 5000 bootstrap samples). The significance of the indirect effects was determined at the level of 0.05 in this study; the indirect effect was considered statistically meaningful if the estimates of the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero. Table 3 shows the results of the bootstrap test for the significance of the mediating effect. As shown in Table 3, student-student relationship quality played a mediating role between teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization: the standardized estimated value of the mediating effect was −0.12 (SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.21, −0.02]). Student engagement also played a mediating role between teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization: the standardized estimated value of the mediating effect was −0.08 (SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.14, −0.02]). These findings further confirm Hypotheses 2 and 3.

Chain mediation effects. Student-student relationship quality and bullying victimization played a chain mediating role: the standardized estimated value of the mediating effect was −0.04 (SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.08, −0.01]). The estimates of the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero; the indirect effect of teacher-student relationship quality on bullying victimization was considered statistically meaningful. Figure 2 shows the specific path coefficients between variables. In conclusion, these results support Hypothesis 4.

The teacher-student relationship quality is negatively correlated with students’ bullying victimization risk, but it does not directly predict this risk significantly. This conclusion is consistent with previous research. Among longitudinal studies, some have found support for negative longitudinal associations between positive student–teacher relationships and bullying victimization (Demol et al., 2020). This finding is in line with the socio-ecological theory, which emphasizes that student-teacher relationships, as a crucial component of the Microsystem, directly influence students’ social behaviors (Hong & Espelage, 2012). Positive student-teacher relationships can enhance academic engagement (Roorda et al., 2017) and peer relationships (Endedijk et al., 2022), thereby reducing the likelihood of students being bullied (Forsberg et al., 2024).

The teacher-student relationship quality effects on students’ bullying victimization were more substantial through student-student relationship quality. These findings are explained by the fact that in schools and classes where teachers care, respect, and support students, students have a greater sense of class membership, less peer conflict, and better peer relationships (Hughes et al., 2014). In addition, teachers’ unconditional care and appreciation for students will help establish a good image of them among classmates, and also affect their recognition and acceptance by other students (Ten Bokkel et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2018). Moreover, the support of classmates can prevent or reduce bullying (Thornberg et al., 2018). Good student-student relationships are also seen as a key protective factor against bullying (Thornberg et al., 2018).

The student engagement mediated the quality of the teacher-student relationship and students’ bullying victimization. This finding was consistent with previous studies (Quin, 2017; Roorda et al., 2017). Teacher care and support for students is key to student engagement in learning activities and their sense of security in school (Thornberg et al., 2022a). Caring and supportive teacher-student relationships foster a trusting and safe class atmosphere, which helps students seek help from teachers and are more likely to interact with teachers during school and learning related activities (Quin, 2017; Roorda et al., 2017). Students are more involved in school and study-related activities, often develop emotional links with classmates, and are less likely to be bullied (He et al., 2022; Xie & Mei, 2018).

This study found that student-student relationship quality and student engagement serially mediated the teacher-student relationship and bullying victimization risk. This finding was consistent with previous research, which has shown that school classes with more caring, warm, and supportive teacher-student relationships tend to have similar student-student relationships (Thornberg et al., 2018). Teachers’ emotional support and acceptance of students are transmitted to students (Ten Bokkel et al., 2023). Students respect, understand, recognize, and accept other students, and recognition and acceptance are important indicators of the quality of student interaction (Zou et al., 1998). Accepted students have higher-quality interactions with class members. Whether it is a school-organized activity or a classroom learning task, their participation is higher (Thornberg et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2018; You, 2011), and they have a strong sense of belonging to the school (Weyns et al., 2018). When they are integrated into the school community, they develop stronger emotional connections with teachers and classmates and are less likely to be bullied (He et al., 2022; Xie & Mei, 2018).

This study examined the relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and junior high school students’ experiences of bullying victimization, as well as the mediating roles of student-student relationship quality and student engagement. Good teacher-student relationships can enhance student-student relationships, improve student engagement, and reduce students’ experiences of bullying victimization. Therefore, school teachers should foster a harmonious relationship with their students. As middle school students are in adolescence, bullying victimization hurts their academic development and mental health. The positive and harmonious teacher-student relationship is the key to preventing junior high school students from being bullied. Teachers should respect the diversity of students, treat each student fairly, and accept their behavior. In addition, teachers should offer more emotional support to students, pay attention to the problems and difficulties they encounter in school, and provide timely assistance. Moreover, teachers should also increase their degree of care for students and provide psychological counseling for those who are bullied.

Limitations and future directions

This study significantly contributed to the global discourse on bullying victimization in schools, emphasizing the challenges faced by junior high school students in China. It highlights the role of teacher-student relationship quality in influencing bullying victimization and provides a foundation for policy development and intervention strategies. Limitations of the study include its cross-sectional design, which prevents causal inferences, a sample restricted to a single geographical area that may not represent all Chinese junior high school students, and reliance on self-reported data that may introduce bias. Future research should conduct longitudinal studies, which could provide more insights into the long-term effects of teacher-student relationship quality on bullying victimization.

This study examined the relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and junior high school students’ experiences of bullying victimization, as well as the mediating effects of student-student relationship quality and student engagement in this relationship. The results showed that student-student relationship quality and student engagement played a full mediating role between teacher-student relationship quality and bullying victimization, respectively. Teacher-student relationship quality also indirectly predicted bullying victimization through the chain mediation of student-student relationship quality and student engagement.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the 2024 Henan Province Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (Youth Project) entitled “Research on the Mechanism and Intervention of Self-Regulated Learning in Promoting Children’s Chinese Reading Comprehension” (2024CJY070).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Yuan Yuan; data collection: Yuan Yuan; analysis and interpretation of results: Yanfei Yang; draft manuscript preparation: Yanfei Yang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data sets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the institution’s ethical standards and were by the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2013). A latent class approach to examining forms of peer victimization. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 839. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25, 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020149 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2003). Perceptions of the frequency and importance of social support by students classified as victims, bullies, and bully/victims in an urban middle school. School Psychology Review, 32(3), 471–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2003.12086213 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Demol, K., Lefot, G., Verschueren, K., & Colpin, H. (2020). Revealing the transactional associations among teacher-child relationships, peer rejection, and peer victimization in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(11), 2311–2326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01269-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Endedijk, H. M., Breeman, L. D., & van Lissa, C. J., (2022). The teacher’s invisible hand: A meta-analysis of the relevance of teacher-student relationship quality for peer relationships and the contribution of student behavior. Review of Educational Research, 92(3), 370–412. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211051428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Farmer, T. W., McAuliffe Lines, M., & Hamm, J. V. (2011). Revealing the invisible hand: The role of teachers in children’s peer experiences. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32, 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.04.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Forsberg, C., Sjögren, B., Thornberg, R., Hong, J. S., & Longobardi, C. (2024). Longitudinal reciprocal associations between student-teacher relationship quality and verbal and relational bullying victimization. Social Psychology of Education, 27(1), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09821-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gregory, A., Cornell, D., Fan, X., Sheras, P., Shih, T. H. et al. (2010). Authoritative school discipline: High school practices associated with lower bullying and victimization. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(2), 483. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018562 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Journal of Educational Measurement, 51(3), 335–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12050 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

He, E., Ye, X., & Mao, Y. (2022). The effect mechanism of school climate on school bullying among left-behind children. Journal of Educational Studies, 18(3), 144–158. [Google Scholar]

Hendrickx, M. M., Mainhard, M. T., Boor-Klip, H. J., Cillessen, A. H., & Brekelmans, M. (2016). Social dynamics in the classroom: Teacher support and conflict and the peer ecology. Teaching and Teacher Education, 53, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.10.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, L. (2022). Exploring the relationship between school bullying and academic performance: The mediating role of students’ sense of belonging at school. Educational Studies, 48(2), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1749032 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hughes, J. N., Im, M. H., & Wehrly, S. E. (2014). Effect of peer nominations of teacher-student support at individual and classroom levels on social and academic outcomes. Journal of School Psychology, 52(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2007, November). Preventing bullying: Developing and maintaining positive relationships among schoolmates. In: National Coalition against Bullying Conference (pp. 3–4Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

Jungert, T., Piroddi, B., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Early adolescents’ motivations to defend victims in school bullying and their perceptions of student-teacher relationships: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kljakovic, M., & Hunt, C. (2016). A meta-analysis of predictors of bullying and victimisation in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lessne, D., & Yanez, C. (2016). Student Reports of Bullying: Results from the 2015 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey. Web Tables. NCES 2017-015. USA: National Center for Education Statistics. [Google Scholar]

Liu, X., Liu, Q., Wu, F., Yang, Z., Luo, X., & et al. (2022). The co-occurrence of sibling and peer bullying and its association with depression and anxiety in high-school students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 30(2), 382–413. [Google Scholar]

Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2017). Violence in school: An investigation of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization reported by Italian adolescents. Journal of School Violence, 18(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2017.1387128 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maldonado-Carreño, C., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2011). Teacher-child relationships and the development of academic and behavioral skills during elementary school: A within-and between-child analysis. Child Development, 82(2), 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01533.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Marengo, D., Jungert, T., Iotti, N. O., Settanni, M., Thornberg, R., et al. (2018). Conflictual student-teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/victims. Educational Psychology, 38(9), 1201–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1481199 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12(4), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03172807 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Perren, S., & Alsaker, F. D. (2006). Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01445.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Perren, S., & Hornung, R. (2005). Bullying and delinquency in adolescence: Victims’ and perpetrators’ family and peer relations. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 64(1), 51–64. [Google Scholar]

Pianta, R. C. (2013). Classroom management and relationships between children and teachers: Implications for research and practice. In: Handbook of classroom management (pp. 695–720Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Quaglia, R., Gastaldi, F. G. M., Prino, L. E., Pasta, T., & Longobardi, C. (2013). The pupil-teacher relationship and gender differences in primary school. Open Psychology Journal, 6, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101306010069 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher-student relationships and student engagement: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 345–387. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316669434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Richard, J. F., Schneider, B. H., & Mallet, P. (2012). Revisiting the whole-school approach to bullying: Really looking at the whole school. School Psychology International, 33(3), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034311415906 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., & Koomen, H. M. (2017). Affective teacher-student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psychology Review, 46(3), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.17105/spr-2017-0035.v46-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sarkova, M., Bacikova-Sleskova, M., Madarasova Geckova, A., Katreniakova, Z., van den Heuvel, W. et al. (2014). Adolescents’ psychological well-being and self-esteem in the context of relationships at school. Educational Research, 56(4), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2014.965556 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Silberg, J. L., Copeland, W., Linker, J., Moore, A. A., Roberson-Nay, R. et al. (2016). Psychiatric outcomes of bullying victimization: A study of discordant monozygotic twins. Psychological Medicine, 46, 1875–1883. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716000362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sulkowski, M. L., & Simmons, J. (2018). The protective role of teacher-student relationships against peer victimization and psychosocial distress. Psychology in The Schools, 55(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22086 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Swearer, S. M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis-stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Ten Bokkel, I. M., Roorda, D. L., Maes, M., Verschueren, K., & Colpin, H. (2023). The role of affective teacher-student relationships in bullying and peer victimization: A multilevel meta-analysis. School Psychology Review, 52(2), 110–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2029218 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Thornberg, R., Forsberg, C., Hammar Chiriac, E., & Bjereld, Y. (2022a). Teacher-student relationship quality and student engagement: A sequential explanatory mixed-methods study. Research Papers in Education, 37(6), 840–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1864772 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Thornberg, R., Wegmann, B., Wänström, L., Bjereld, Y., & Hong, J. S. (2022b). Associations between student-teacher relationship quality, class climate, and bullying roles: A Bayesian multilevel multinomial logit analysis. Victims & Offenders, 17(8), 1196–1223. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2022.2051107 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2018). Victim prevalence in bullying and its association with teacher-student and student-student relationships and class moral disengagement: A class-level path analysis. Research Papers in Education, 33(3), 320–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1302499 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Voltmer, K., & von Salisch, M. (2017). Three meta-analyses of children’s emotion knowledge and their school success. Learning and Individual Differences, 59, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.08.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, C., Swearer, S. M., Lembeck, P., Collins, A., & Berry, B. (2015). Teachers matter: An examination of student-teacher relationships, attitudes toward bullying, and bullying behavior. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 31(3), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2015.1056923 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Weyns, T., Colpin, H., De Laet, S., Engels, M., & Verschueren, K. (2018). Teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement in the classroom: A three-wave longitudinal study in late childhood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 1139–1150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0774-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xie, J., Lv, Y., Bear, G. G., Yang, C., Marshall, S. J., & et al. (2015). Reliability and validity of the chinese version of delaware bullying victimization scale-student. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23(04), 594–596. [Google Scholar]

Xie, J., & Mei, L. (2018). School climate and bullying victimization: mediating effect of student engagement. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26(1), 113–117. [Google Scholar]

Xie, J., Qin, F., Bear, G. G., & Fu, Y. (2019). Reliability and Validity Of The Chinese Version Of Delaware Student Engagement Scale-student. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(2), 277–281. [Google Scholar]

Yan, L., Wang, X., Li, T., Zheng, H., & Xu, L. (2018). Impact of interpersonal relationships on the academic engagement of middle school students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26(1), 123–128. [Google Scholar]

You, S. (2011). Peer influence and adolescents’ school engagement. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29(2), 829–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.311 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yu, Y., Ng, J. H. Y., Wu, A. M., Chen, J. H., Wang, D. B. et al. (2022). Psychometric properties of the abbreviated version of the dual school climate and school identification measure-student (SCASIM-St15) among adolescents in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.576051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zou, H., Zhou, H., & Zhou, Y. (1998). The relationship between friendship, friendship quality and peer acceptance in middle school students. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Sciences), 145(1), 43–50. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools