Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The components of threat-related attentional biases among individuals with different levels of sense of control

1 College of Education Science, Jiaying University, Meizhou, 514015, China

2 School of Psychology, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, 330022, China

* Corresponding Authors: Shunying Zhao. Email: ; Baojuan Ye. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(4), 463-470. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.070060

Received 06 January 2025; Accepted 05 July 2025; Issue published 17 August 2025

Abstract

This study investigated how components of threat-related attentional biases are associated with levels of sense of control. Utilizing a using a spatial-cueing paradigm, 36 college students with a high sense of control (females = 22, Mage = 19.44, SD = 1.36) and 35 with a low sense of control (females = 15, Mage = 19.77, SD = 1.40) were assigned to task featuring different cue-target intervals (i.e., 50 and 800 ms). The student participants completed the Control Sense Scale, the GAD-7 Anxiety Scale, and the PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire. Data from employing spatial-cueing task procedure, would provide the evidence on any differences in attentional biases toward threat images between the two groups. A repeated measures ANOVA indicated that both groups to exhibit attentional avoidance under the 50 ms interval condition. However, individuals in the low sense of control group (i.e., LSC Group) demonstrated exacerbation of avoidance compared to those in the high sense of control group (i.e., HSC Group). The current study did not find any attentional bias components under the 800 ms interval condition. The findings provide preliminary evidence for a new vigilance-avoidance model for further study with a view to developing interventions targeting negative emotional disorders based on individuals’ sense of control.Keywords

How individuals respond to seemingly threatening events is of interst to protective interventions for their health wellbeing. Threat-related attentional bias refers to the individuals’ tendency to focus excessively on threatening stimuli in their environment. This bias helps human to improve the detection and handling of potential dangers (Cisler & Koster, 2010), which is crucial for survival. On the one hand, an excessive threat-related attentional bias may lead individuals to invest excessive cognitive resources in detecting and dealing with these threats to their current cognitive tasks and overall emotional regulation (Swick & Ashley, 2017). On the other hand, excessively threat-related attentional bias may result in maladaptive vigilance or distress, which contributes to more severe negative emotional disorders such as anxiety, fear, and depression (Armstrong et al., 2022; Bar-Haim et al., 2007). However, most previous studies focus on exploring the negative psychological consequences of threat-related attentional bias (Egan & Dennis-Tiwary, 2018; Mogg & Bradley, 2018), rather than the positives or gains from threat-related attentional bias. Few studies have investigated the antecedents of threat-related attentional bias, such as by sense of control.

Sense of control mediation. Sense of control is the belief that individuals have the ability to influence or shape the outcomes and environments in their lives, which is positively related to the individual’s perception of having the power to manage their surroundings and the outcomes of events (Wallston et al., 1987). A high sense of control is associated with a better sense of personal mastery or one’s sense of efficacy or effectiveness in carrying out goals. Sense of control also comes with ability to overcome perceived constraints obstacles that interfere with reaching goals. People with a strong sense of control have better mental and physical health, increased motivation, and greater psychological resilience during tough times (Infurna et al., 2011; Precht et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2023). On the one hand, a low sense of control may lead to feelings of helplessness or fatalism, which may contribute to emotional problems like stress, anxiety, and depression (Harrow et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2014). On the other hand, a strong sense of control enhances well-being by encouraging proactive coping strategies and boosting confidence in achieving personal goals (Infurna et al., 2011). Therefore, sense of control is vital for maintaining mental health and life satisfaction, which highlights a common target in many psychological intervention programs (Barlow et al., 2014; Koster et al., 2006).

As previously noted, sense of control may be linked to attentional biases towards threatening stimuli. Fenton-O’Creevy et al. (2012) propose that sense of control influences emotional experiences and subsequent reactions after seeing some threatening stimuli. Conceivably, a stronger sense of control may be more flexible at redirecting their attention away from threatening stimuli, which helps to maintain their attention on goal-oriented solutions. Those who could exert control over aversive stimuli exhibited less attentional bias towards such stimuli due to the power of top-down attention (Delchau et al., 2020; Maier & Seligman, 2016), assuming intact neurofuction.

Cognitive neuroscience. Cognitive neuroscience proposes a strong connection between sense of control and brain areas involved in processing threat-related information. Previous studies demonstrate that individuals with a higher sense of control are more effective in modulating the amygdala via the prefrontal cortex, suggesting a neurophysiological basis for the influence of control perception on threat-related attentional biases (Hartley et al., 2014; Owusu-Ansah, 2008; Sergerie et al., 2008). Thus, enhancing an individual’s sense of control over their environment and outcomes may help reduce attentional biases towards threats, thereby reducing the risk of emotional disorders by spacing cue effects.

Spacing cues. The spatial cueing paradigm (Hauschildt et al., 2013) not only uncovers the early (e.g., attentional vigilance) and late (e.g., difficulty disengaging attention) components of attentional biases, but also tracks attentional avoidance over time, thereby offering key advantages in exploring the causal link between sense of control and threat-related attentional biases. For instance, unlike the dot-probe paradigm, which presents different valence stimuli simultaneously, the spatial cueing paradigm presents only one image at a time, effectively avoiding the simultaneous influence of two different valence images on subsequent target tasks (Bar-Haim et al., 2007). By utilizing cues with different valences (e.g., Neutral versus Threatening) and employing both effective and ineffective target stimuli, the spatial cueing paradigm allows researchers to precisely manipulate and measure three distinct components of attentional bias-attentional vigilance, attentional avoidance, and attentional disengagement (Mogg & Bradley, 2016). Moreover, the spatial cueing task can assess how swiftly and accurately individuals redirect their attention away from or maintain it on threatening stimuli by varying the cue-target interval (Trost & Gibson, 2023). This paradigm also allows for an examination of how individuals with varying levels of sense of control respond to different cue stimuli and how this impacts subsequent target recognition. Such comparisons help researchers integrate individuals’ cognitive processes with emotional processes to understand attentional bias components (Pourtois & Vuilleumier, 2006), thus revealing how sense of control influences threat-related attentional biases (Gallagher et al., 2014). In summary, the spatial cueing paradigm is a valuable tool for investigating the interaction between sense of control and threat-related attentional biases, thereby providing a robust theoretical framework for developing effective intervention projects against negative emotional disorders.

Structure of the threat-related attentional bias. The components of threat-related attentional bias’ by temporality initial exhibit heightened vigilance toward threat stimuli, followed by avoidance behavior or difficulties in shifting attention away from these stimuli in later stages (Koster et al., 2006). The variations in cue duration and cue-target interval of dot-probe paradigm and spatial cueing paradigm could influence these attentional bias components, revealing a temporal dynamic of attentional vigilance, attentional avoidance, and attentional disengagement (Koster et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012). Attentional avoidance refers to the phenomenon where individuals automatically or strategically divert their attention away from the location of the threatening stimulus, even after it has disappeared (Cisler & Koster, 2010).

There is ongoing debate regarding whether specific attentional components occur at specific moments of cue duration and cue-target interval. Typically, attentional vigilance is observed around 100 ms, while attentional avoidance or attentional disengagement emerges between 300–500 ms. However, once the cue duration and cue-target interval are beyond 800 ms, the attentional bias components may diminish (Mogg et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2012). Nonetheless, some studies suggest that individuals with high trait anxiety continue to avoid threat images even at 1250 ms (Koster et al., 2007).

The present study. This study examine attentional bias components among different levels of sense of control, and to investigate whether attentional avoidance occurs in the mid-term or late phase of cue presentation. According to the vigilance-avoidance model, after individuals automatically detect threatening stimuli at an early stage, these stimuli immediately trigger negative emotional experiences such as anxiety and fear. To avoid these negative emotional experiences, individuals may adopt certain strategies to evade the threatening stimuli (Williams et al., 1996). Our specific research hypotheses were:

Hypothesis 1: Individuals with a low sense of control process information more slowly than those with a high sense of control under a 50 ms cue-target interval, as indicated by slower reaction times.

Hypothesis 2: Individuals with a high sense of control trust cues more under a 50 ms cue-target interval, as shown by higher accuracy in recognizing valid cues compared to invalid ones.

Hypothesis 3: Under a 50 ms cue-target interval, both high and low sense of control individuals show attention avoidance, with those low in control displaying a more pronounced tendency.

Hypothesis 4: Under an 800 ms cue-target interval, individuals with a low sense of control process information more slowly than those with a high sense of control, as indicated by slower reaction times.

Hypothesis 5: Under an 800 ms cue-target interval, neither individuals with a high nor low sense of control show significant attention bias.

A total of 71 participants, with 35 participants in the LSC Group (15 female, average age 19.77 ± 1.40 years, range 18–23) and 36 participants in the HSC Group (22 female, average age 19.44 ± 1.36 years, range 18–24). To investigate the effects of a threatening cue with a duration of 400 ms and cue-target intervals of 50 and 800 ms, this study adopted a mixed experimental design that combines both between-subjects and within-subjects elements.

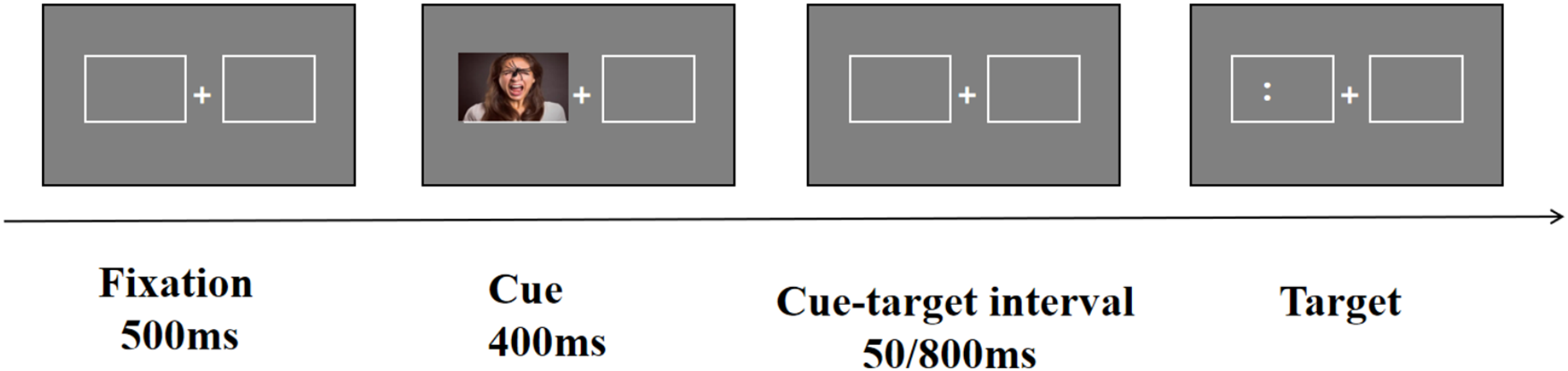

The experiment used a 2 (Group: High Sense of Control: HSC, Low Sense of Control: LSC) by 4 (Cue type: Threat-Valid, Threat-Invalid, Neutral-Valid, and Neutral-Invalid) mixed design. A spatial cueing task was employed, with the procedure outlined in Figure 1. Each trial began with a fixation point for 500 ms, followed by a cue presented for 400 ms within a rectangle on either the left or right side. The cue could be either a neutral image or a threat image. The cue could be either a neutral image or a threat image, with a 50% probability of being valid (the target appeared in the same rectangle as the cue) and a 50% probability of being invalid (the target appeared in the opposite rectangle). Following the cue presentation, a cue-target interval of either 50 or 800 ms was presented.

Figure 1: Spatial cueing task

At last, the target was presented, which disappeared after the participant pressed a key. Participants needed to respond quickly by pressing “F” for the left rectangle and “J” for the right rectangle. The main experiment consisted of 3 blocks, each with 80 trials, with 40 trials featuring a 50 ms cue-target interval and 40 trials featuring an 800 ms cue-target interval. Half of the participants experienced the sequence of 50 ms–800 ms–800 ms–50 ms, while the other half experienced 800 ms–50 ms–50 ms–800 ms. There was a 3-min break between blocks. To familiarize participants with the experimental procedure, a pre-training phase with 10 practice trials was conducted before the formal experiment. The images used in pre-training differed from those used in the formal experiment. All participants achieved 100% accuracy in 10 practice trials before the formal experiment.

Before the experiment, participants completed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, which were used to assess the severity of anxiety and depression. College students who scored over 10 points were not invited to participate in the formal ERP experiment.

The Research Ethics Committee of the first author’s institution approved the current study. Before the experiment, participants signed informed consent and were free to withdraw from this experiment at any time. Participants received compensation upon completion of the experiment.

To divide the participants into the high sense of control group and low sense of control group, participants completed the Chinese version (Li, 2012) of Sense of Control Scale (SCS, Lachman & Weaver, 1998). The SCS measures both personal self-efficacy and expectations regarding outcomes, providing a comprehensive assessment of an individual’s feelings and beliefs about control, which has been widely used in many studies and demonstrated good reliability and validity (Li, 2012). This scale comprises 12 items divided into two sub-scales: personal mastery (4 items, e.g., “When really want to do something, I usually find a way to succeed at it”), and perceived constraints (8 items, e.g., “What happens in my life is often beyond my control”). Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Totally disagree) to 7 (Totally agree), with higher scores indicating lower control sense. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for scores from the SCS total scale was 0.84, the Cronbach’s α of the personal mastery subscale was 0.76, and the Cronbach’s α of the perceived constraints subscale was 0.83.

Generalized anxiety disorder-7

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7, Spitzer et al., 2006), was originally developed by is a measure anxiety symptoms. The Chinese version of the GAD-7 was adapted and validated by He et al. (2010). The GAD-7 scale consists of 7 items, scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Almost every day), with higher scores indicating more anxiety symptoms. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for GAD-7 scores was 0.85.

Patient health questionnaire-9

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9, Kroenke et al., 2001) is a measure of depressive symptoms. Xu et al. (2007) revised and tested its reliability and validity in China. The PHQ-9 consists of 9 items, scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Almost every day), with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for PHQ-9 scores was 0.94, the present study.

Spatial cueing task and Stimuli

The spatial cueing task was administered using E-Prime 3.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Sharpsburg, MD, USA). Following the methodology established by Wang et al. (2012), 70 threat images and 70 neutral images were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang et al., 1997) and the Chinese Affective Picture System (CAPS; Bai et al., 2005). 56 university students (29 females, average age 19.63 ± 1.02) rated these 140 images on a 9-point scale for valence, arousal, and fear, with higher scores indicating increased valence, arousal, or fear. Participants also classified each image as either a threat image or not. 12 threat images and 12 neutral images were selected as cues based on scores, with a colon (i.e., :) as the target. t-tests showed that threat images had significantly higher scores (M = 6.14, SD = 0.55) than neutral images (M = 2.83, SD = 0.63) in fear, t (22) = −13.67, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 5.60. Threat images had significantly lower scores (M = 2.95, SD = 0.35) than neutral images (M = 4.53, SD = 0.34) in valence, t(22) = −11.29, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −4.58. Threat images had significantly higher scores (M = 5.75, SD = 0.42) than neutral images (M = 3.68, SD = 0.23) in arousal, t(22) = 14.92, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 6.11.

Trials with reaction times below 200 ms or above 1000 ms were excluded from the analysis. The avoidance-vigilance index and the avoidance-disengagement index were calculated using the formulas adopted by previous researchers (Yu, 2017). The avoidance-vigilance index is defined as follows: Under the valid cue condition, if RT Threat-RT Neutral > 0, it indicates attentional avoidance; conversely, if RT Threat-RT Neutral < 0, it indicates attentional vigilance. The avoidance-difficulty index is defined as follows: Under the invalid cue condition, if RT Threat-RT Neutral < 0, it indicates attentional avoidance; conversely, if RT Threat-RT Neutral > 0, it indicates difficulty in disengaging attention.

Repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze participants’ response times and accuracy rates. Subsequently, independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine whether there were group differences in the avoidance-vigilance and the avoidance-disengagement indices. Finally, one-sample t-tests were used to compare the two indices of each group against zero to determine whether attentional bias components were present in either group.

Response times- 50 ms cue-target interval

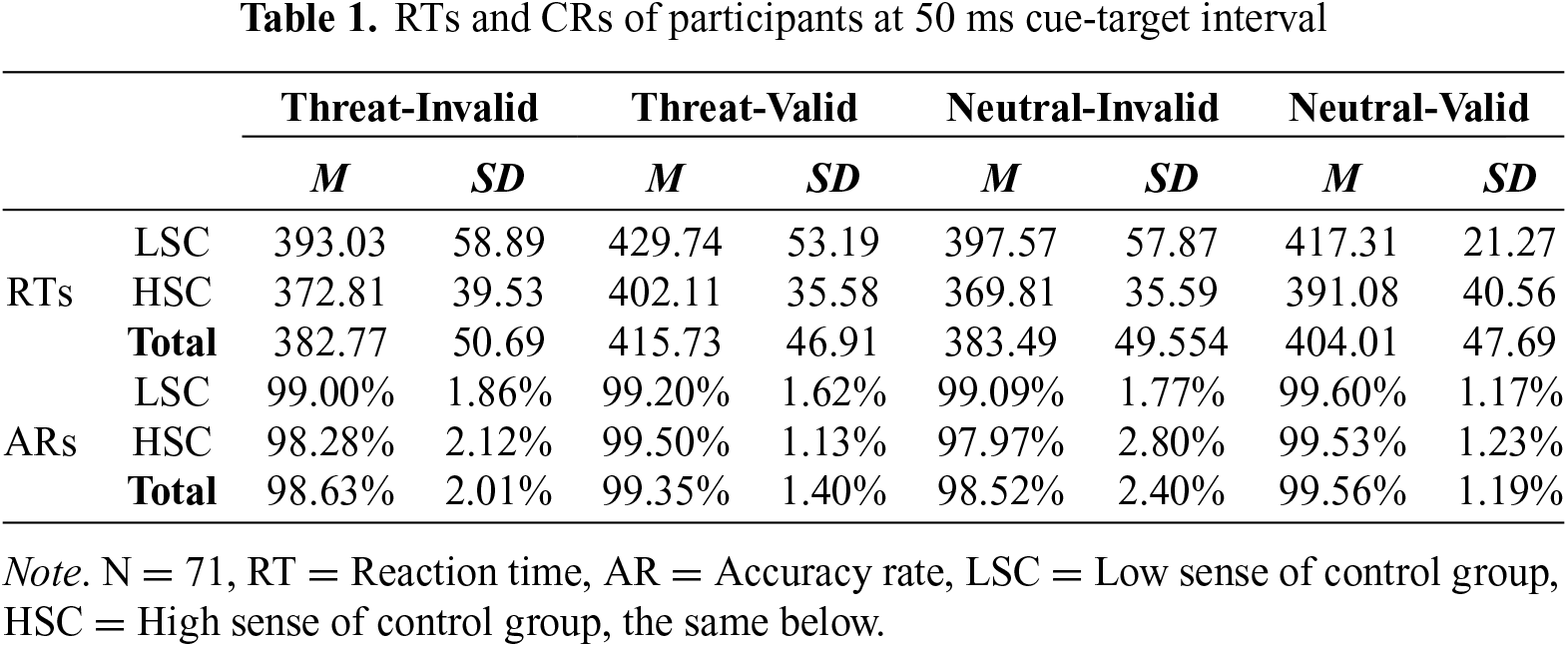

The means and standard deviations of response times are shown in Table 1.

The main effect of the group was significant (supporting Hypothesis 1), with the LSC (M = 409.41, SE = 9.89) showing significantly slower response times than the HSC (M = 383.95, SE = 9.89), [F (1, 69) = 5.72, p = 0.02,

The means and standard deviations of accuracy rates are shown in Table 1.

A repeated measures ANOVA on accuracy rates revealed a significant main effect of cue type, F (3, 207) = 7.79, p < 0.001,

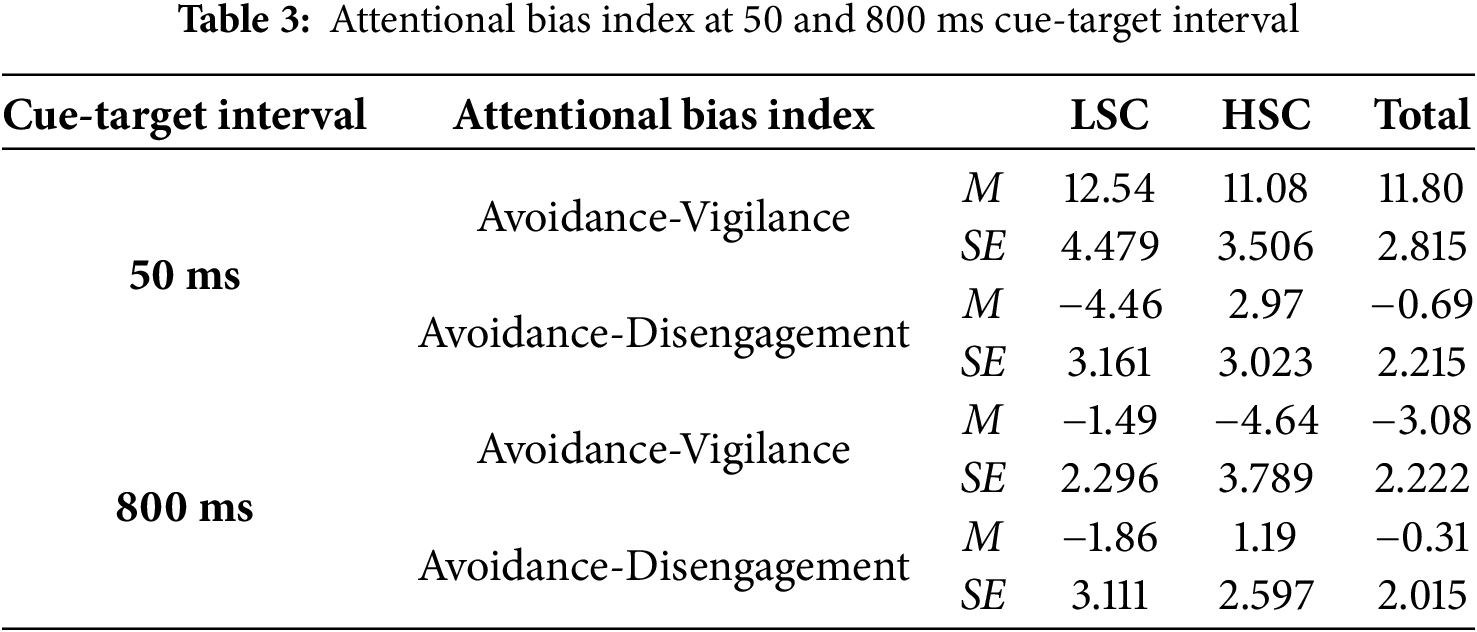

The means and standard deviations of the attentional bias index are shown in Table 3.

At the 50 ms cue-target interval, one-sample t-tests were conducted for the avoidance-vigilance index and avoidance-disengagement index both in the LSC and in the HSC, with a theoretical value of 0 (0 indicates no attentional bias). The results showed that the avoidance-vigilance index for the LSC (M = 12.54, SE = 4.48) was significantly higher than 0, t(34) = 2.80, p = 0.008, indicating significant attentional avoidance tendency. The avoidance-disengagement index for the LSC (M = −4.46, SE = 3.16) did not differ significantly from 0. The avoidance-vigilance index for the HSC (M = 11.08, SD = 21.03) was significantly higher than 0, t(35) = 3.16, p = 0.003, reflecting an attentional avoidance. The avoidance-disengagement index for the HSC did not differ significantly from 0. Independent samples t-tests showed no significant difference in the avoidance-vigilance index between the LSC and the HSC. However, a marginally significant effect was observed for the avoidance-disengagement index, with the LSC (M = −4.46, SE = 3.16) showing a higher tendency for attentional avoidance compared to the HSC (M = 2.97, SE = 3.02), t(34) = −1.70, p = 0.09. This results of attentional bias index supported Hypothesis 3.

Response times- 800 ms cue-target interval

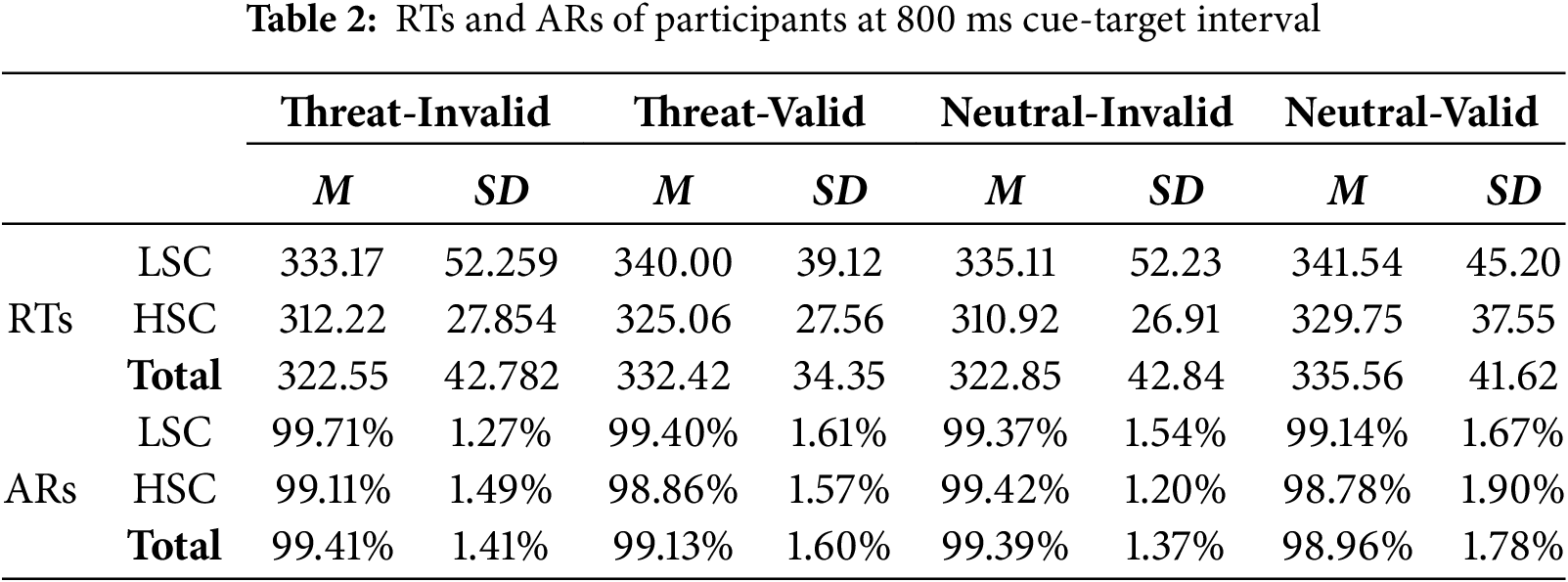

The means and standard deviations of response times are shown in Table 2.

Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of cue type [F (3, 207) = 14.81, p < 0.001,

The means and standard deviations of accuracy rates are shown in Table 2.

The group effect was not significant [F (1, 69) = 2.75, p = 0.102,

The means and standard deviations of the attentional bias index are shown in Table 3.

A one-sample t-test was conducted on the avoidance-vigilance index and the avoidance-disengagement index, revealing that the avoidance-vigilance index (M = −1.49, SE = 2.30) and avoidance-disengagement index (M = −1.86, SE = 3.11) in LSC group were not significant with 0. Similarly, the avoidance-vigilance index (M = −4.64, SE = 3.79) and avoidance-disengagement index in the HSC group (M = −1.19, SE = 2.60) were not significant with 0. Independent samples t-test results indicated that there were no significant differences in the avoidance-vigilance index and avoidance-disengagement index between the LSC group and the HSC group. The findings suggest that neither group exhibited attentional bias characteristics at an 800 ms interval, which supported Hypothesis 5.

This study found that in the cue-target paradigm, with a cue duration of 400 ms and a cue-target interval of 50 ms, both groups of participants exhibited avoidance of threatening stimuli, which is consistent with previous research (Wang et al., 2012; Yu, 2017). The results provide new evidence for the vigilance-avoidance model and further validate the argument that within the 300–500 ms interval of cue presentation, participants shift their attention from threat images to avoid negative emotional experiences (Mogg et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2012). In contrast, under 800 ms interval condition, neither the HSC nor the LSC group showed any attentional bias characteristics, which is also consistent with previous studies (Mogg et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2012).

From the perspective of the cue stimulus design, a 400 ms cue presentation time is sufficient for participants to fully perceive the threatening information in the images, which leads to avoidance tendencies to prevent further feelings of fear and anxiety. After the cue stimulus ends, with only a 50 ms interval before target recognition still reveals individuals’ motivational avoidance tendencies during the target recognition task. However, when the interval is extended to 800 ms, participants may have had enough time to regulate their emotions and adjust their attention to the target recognition task, resulting in the absence of threat-related attentional bias in that task. Both groups exhibited avoidance of threatening stimuli at the 50 ms interval, likely due to a general human tendency towards motivational avoidance of threatening stimuli (Cisler & Koster, 2010). On one hand, humans tend to avoid experiencing negative emotions like worry and fear, and on the other hand, this may stem from survival adaptation, as threatening stimuli often contain information that threatens human survival.

This study found that, whether at an interval of 50 or 800 ms, the reaction times of the low control group were significantly slower than those of the high control group. This indicates that the processing speed of the low control group is slower than that of the high control group, showing impaired information processing speed. This may be because a sense of control helps to regulate emotional responses after perceiving threatening information; individuals with a stronger sense of control can successfully shift their attention away from threatening stimuli and towards goal-directed solutions, thereby maintaining a faster target stimulus recognition speed (Brown et al., 2020; Fenton-O’Creevy et al., 2012). Furthermore, a sense of control can act as a buffering mechanism, helping individuals reduce attention and reaction to threatening stimuli (Maier & Seligman, 1976; Barlow, 2004). When individuals feel that they can control outcomes, they may pay less attention to potential threats or have less intense emotional reactions to these threatening images (Barlow, 2004). Those with a strong sense of control tend to believe they can cope with external threat information, thus reducing excessive attention to negative information.

The current study found that control beliefs lead to greater attention vigilance and avoidance of threat stimuli, possibly because individuals with higher control beliefs have more effective emotional regulation strategies (Brown et al., 2020). This finding implies that, by increasing sense of control over their circumstances and major life events, mental health practitioners can help individuals with mental health problems to reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other emotional issues effectively. In clinical practice, cognitive behavioral therapy often focuses on improving emotional reactions by boosting the individuals’ sense of control (Gallagher et al., 2014). Thus, enhancing the individuals’ sense of control may be a more practical approach than directly focusing on emotional disorders for practitioners in schools and related organizations. Furthermore, given the extensive literature supporting the link between threat-related attentional bias and emotional disorders like anxiety and depression (Armstrong et al., 2022; Bar-Haim et al., 2007), the current research suggests that individuals with a low sense of control may be at greater risk for developing depression and anxiety. Early intervention to help them rebuild a positive sense of control can effectively prevent the development of more severe emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, in the spatial cue-target paradigm, the emergence of attentional vigilance and attentional avoidance may appear incidentally (Mogg & Bradley, 1998). As a result, further research may need to be required to confirm the stability of the study’s conclusions. Secondly, the participants in this study were all university students and the homogeneity of the sample may limit the generalizability of the conclusions to different populations. Future research should aim to confirm the findings of this experiment across diverse populations. Specifically, childhood and adolescence are key and sensitive periods for the development of sense of control (Atherton et al., 2020). Studying these age groups could reveal how sense of control affects threat-related attentional biases, and highlight the value of interventions targeting sense of control for the prevention and treatment of mental health problems.

This study utilized a spatial cueing paradigm, manipulating participants’ mental preparation time in a target recognition task by setting two different intervals of 50 and 800 ms, to investigate whether individuals with different levels of control exhibit attentional bias toward various threat images. First, at the 50 ms interval, both groups of participants showed avoidance of threat images, with the low control group demonstrating a more pronounced tendency for attentional avoidance compared to the high control group. Second, when the stimulus interval was extended to 800 ms, the attentional avoidance phenomenon disappeared for both the low and high control groups, with no evidence of attentional disengagement difficulties or attentional vigilance. Third, regardless of whether the interval was 50 or 800 ms, the low control group showed a significant tendency for impaired information processing speed. The results help mental health professionals understand the relationship between sense of control and cognitive processing of threat-related information and provide insights for using sense of control to prevent and intervene in negative emotions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Philosophy and Social Science Fund for Young Scholars of Guangdong Province (GD23YXL06), Humanities and Social Sciences of Jiaying University (2023SKY01), General Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Fund of Guangdong Province (GD24XXL06), and Humanities and Social Sciences of Jiaying University (2023SKY02).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Baojuan Ye, Shunying Zhao; data collection: Shunying Zhao, Yulan Guo; analysis and interpretation of results: Shunying Zhao, Min Rao; draft manuscript preparation: Shunying Zhao, Min Rao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and material supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Approval: This experiment was approved by the Ethics Committee of the first author’s institution and in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent: All participants signed informed consent before the experiment, and were free to withdraw from this experiment at any time.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Armstrong, T., Engel, M., & Dalmaijer, E. S. (2022). Vigilance: A novel conditioned fear response that resists extinction. Biological Psychology, 174(10), 108401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2022.108401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Atherton, O. E., Lawson, K. M., & Robins, R. W. (2020). The development of effortful control from late childhood to young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(2), 417. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bai, L., Ma, H., Huang, Y., & Luo, Y. (2005). The development of native Chinese affective picture system—A pretest in 46 college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 19(11), 719–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcatb.2005.02.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Barlow, D. H. (2004). Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.147.8.1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Barlow, D. H., Sauer-Zavala, S., Carl, J. R., Bullis, J. R., & Ellard, K. K. (2014). The nature, diagnosis, and treatment of neuroticism: Back to the future. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(3), 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613505532 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brown, C. R., Berggren, N., & Forster, S. (2020). Not looking for any trouble? Purely affective attentional settings do not induce goal-driven attentional capture. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 82(3), 1150–1165. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-019-01895-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cisler, J. M., & Koster, E. H. W. (2010). Mechanisms of attentional biases towards threat in anxiety disorders: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Delchau, H. L., Christensen, B. K., O’Kearney, R., & Goodhew, S. C. (2020). What is top-down about seeing enemies? Social anxiety and attention to threat. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 82(4), 1779–1792. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-019-01920-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Egan, L. J., & Dennis-Tiwary, T. A. (2018). Dynamic measures of anxiety-related threat bias: Links to stress reactivity. Motivation and Emotion, 42, 546–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9674-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Lins, J. T., Vohra, S., Richards, D. W., Davies, G. et al. (2012). Emotion regulation and trader expertise: Heart rate variability on the trading floor. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 5(4), 227. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030364 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gallagher, M. W., Bentley, K. H., & Barlow, D. H. (2014). Perceived control and vulnerability to anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(6), 571–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9624-xv [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Harrow, M., Hansford, B. G., & Astrachan-Fletcher, E. B. (2009). Locus of control: Relation to schizophrenia, to recovery, and to depression and psychosis—A 15-year longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research, 168(3), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hartley, C. A., Gorun, A., Reddan, M. C., Ramirez, F., & Phelps, E. A. (2014). Stressor controllability modulates fear extinction in humans. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 113, 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2013.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hauschildt, M., Wittekind, C., Moritz, S., Kellner, M., & Jelinek, L. (2013). Attentional bias for affective visual stimuli in posttraumatic stress disorder and the role of depression. Psychiatry Research, 207(2), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

He, X., Li, C., Qian, J., Cui, H., & Wu, W. (2010). Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatients. Shanghai Arch Ives of Psychiatry, 22(4), 200–203. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2010.04.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Infurna, F. J., Gerstorf, D., Ram, N., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Long-term antecedents and outcomes of perceived control. Psychology and Aging, 26(3), 559. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Koster, E. H., Crombez, G., Verschuere, B., Van Damme, S., & Wiersema, J. R. (2006). Components of attentional bias to threat in high trait anxiety: Facilitated engagement, impaired disengagement, and attentional avoidance. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(12), 1757–1771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Koster, E. H. W., Crombez, G., Verschuere, B., Vanvolsem, P., & De Houwer, J. (2007). A time-course analysis of attentional cueing by threatening scenes. Experimental Psychology, 54(2), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169.54.2.161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lachman, M. E., & Weaver, S. L. (1998). The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 763. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (1997). International affective picture system (IAPS): Technical manual and affective ratings. NIMH Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, 1(39–58), 3. [Google Scholar]

Li, J. (2012). The study of attribution tendency in the rich-poor gap for different social classes [Doctoral Dissertation]. Wuhan, China: Central China Normal University. [Google Scholar]

Maier, S. F., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1976). Learned helplessness-theory and evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General, 105(1), 3–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.105.1.3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maier, S. F., & Seligman, M. E. (2016). Learned helplessness at fifty: Insights from neuroscience. Psychological Review, 123(4), 349. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mogg, K., & Bradley, B. P. (1998). A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(9), 809–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00063-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mogg, K., & Bradley, B. P. (2016). Anxiety and attention to threat: Cognitive mechanisms and treatment with attention bias modification. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 87(3), 76–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mogg, K., & Bradley, B. P. (2018). Anxiety and threat-related attention: Cognitive-motivational framework and treatment. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mogg, K., Bradley, B., Miles, F., & Dixon, R. (2004). Brief report time course of attentional bias for threat scenes: Testing the vigilance-avoidance hypothesis. Cognition and Emotion, 18(5), 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930341000158 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Owusu-Ansah, F. E. (2008). Control perceptions and control appraisal: Relation to measures of subjective well-being. Ghana Medical Journal, 42(2), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.4314/gmj.v42i2.43597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pourtois, G., & Vuilleumier, P. (2006). Dynamics of emotional effects on spatial attention in the human visual cortex. Progress in Brain Research, 156, 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(06)56004-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Precht, L. M., Margraf, J., Stirnberg, J., & Brailovskaia, J. (2023). It’s all about control: Sense of control mediates the relationship between physical activity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Current Psychology, 42(10), 8531–8539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02303-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sergerie, K., Chochol, C., & Armony, J. L. (2008). The role of the amygdala in emotional processing: A quantitative meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging. studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(4), 811–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.12.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Swick, D., & Ashley, V. (2017). Enhanced attentional bias variability in post-traumatic stress disorder and its relationship to more general impairments in cognitive control. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 14559. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15226-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Trost, J. M., & Gibson, B. S. (2023). Attention shifts in the spatial cueing paradigm reflect direct influences of experience and not top-down goals. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 31(4), 1536–1547. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-023-02429-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wallston, K. A., Wallston, B. S., Smith, S., & Dobbins, C. J. (1987). Perceived control and health. Current Psychology, 6(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686633 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, H., Huang, S., Huang, Y., Sun, X., & Zheng, X. (2012). The temporal course and habituation tendency of the attention bias to the threaten stimulus in the adolescents with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Psychological Development and Education, 28(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2012.03.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Williams, J. M. G., Mathews, A., & MacLeod, C. (1996). The emotional stroop task and psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin, 120(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xu, Y., Wu, H., & Xu, Y. (2007). The reliability and validity of patient health questionnaire depression module (PHQ-9) in Chinese elderly. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 19(5), 257–259. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2007.05.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yu, Y. (2017). Characteristics as well as cognitive and neural mechanisms of attentional bias and attentional control in trait anxiety [Doctoral Dissertation]. Chongqing, China: Army Medical University. [Google Scholar]

Zhang, W., Liu, H., Jiang, X., Wu, D., & Tian, Y. (2014). A longitudinal study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and its relationship with coping skill and locus of control in adolescents after an earthquake in China. PLoS One, 9(2), e88263. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhou, Y., Li, F., Wang, Q., & Gao, J. (2023). Sense of power and online trolling among college students: Mediating effects of self-esteem and moral disengagement. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 33(4), 378–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2023.2219527 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools