Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Parental autonomy support effects on children’s school adjustment: The longitudinal mediating effect of executive function

1 Beijing Key Laboratory of Learning and Cognition, Research Center for Child Development, School of Psychology, Capital Normal University, No. 105 Xisan Huan Beilu, Beijing, 100048, China

2 Beijing Petroleum Managers Training Institue, Dewai Xisanqidong, Beijing, 100096, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaopei Xing. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(4), 471-480. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.070062

Received 21 April 2025; Accepted 03 July 2025; Issue published 17 August 2025

Abstract

This longitudinal study examined the association between parental autonomy support and school-aged children’s adjustment across four major domains of school functioning, as well as the mediating role of children’s executive function. Participants were 476 school-aged children (girl: 49.2%, Mage = 10.49 years, SD = 1.32 years), who completed the Psychological Autonomy Support Scale, the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–2, and the Primary School Students’ Psychological Suzhi Scale at baseline and at two subsequent follow-up assessments. Results from unconditional latent growth curve models and structural equation modeling indicated that paternal autonomy support was a significant predictor of children’s adjustment across all four school domains. In contrast, maternal autonomy support was significantly associated only with interpersonal adjustment. Both the intercept (initial level) and slope (rate of change) of children’s executive function significantly predicted their adjustment in all four domains. Notably, the initial level of executive function fully mediated the association between paternal autonomy support and school adjustment, whereas the rate of change in executive function did not serve as a significant mediator. These findings underscore the importance of promoting parental autonomy-supportive behaviors-particularly among fathers-as a means to enhance children’s executive functioning and, consequently, their school adjustment.Keywords

Parental autonomy support plays an irreplaceable and positive role in children’s development. It refers to parenting behaviors that acknowledge children’s perspectives and opinions and encourage children to display independent and initiative-taking behaviors and make their own decisions (Chen et al., 2021; Ryan & Deci, 2009). As one of the core dimensions of positive parenting, autonomy support has beneficial effects in facilitating adaptive child functioning (Wang et al., 2024; Vasquez et al., 2016; Deci & Ryan 2002). Parents high in autonomy support tend to provide constructive guidance rather than control, which in turn fosters children’s internal motivation, self-determination, and goal-directed behavior socially desirable behaviors in children (Van Petegem et al., 2015). These qualities are critical for successful adjustment in school, a setting where children must regulate their own learning and navigate complex social environment. However, an open question is how and through what mechanisms parental autonomy support facilitates such adjustment. Specifically, we know relatively little about whether autonomy supportive parenting helps children develop the self-regulatory capacities-such as executive functions-that could underlie better academic and social adjustment.

Parental autonomy support and child development

Parental autonomy support contributes to children’s development by establishing a specific “developmental niche” that fosters autonomy and independence. The expression and effectiveness of autonomy support may vary across cultural contexts. For example, as China undergoes rapid economic development and social transformation, increasing emphasis is placed on cultivating children’s active exploration, initiative-taking, and autonomy, while social harmony and interdependence—shaped by enduring collectivist values—continue to be emphasized (Ho, 1986; Xu et al., 2024). Furthermore, the expression of autonomy support may differ by parent gender. Mothers often provide emotional support, whereas fathers are more likely to engage as playmates and encourage children to act bravely in unfamiliar situations. Through these complementary roles, parents foster an exploratory mindset and openness to new experiences, while also offering direct assistance when needed (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2008). Importantly, the effects of autonomy-supportive parenting are likely to extend beyond the home environment and into school contexts. Such parenting may support children’s ability to navigate the social and academic developmental tasks they encounter throughout their educational journey.

School adjustment and executive function

In school settings, children are required to adapt to daily learning demands by drawing on their individual cognitive and emotional resources. One key resource is executive function (EF), a set of psychological processes that enable individuals to exert conscious control over their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors (Li & Wang, 2004). EF is closely linked to children’s capacity to regulate emotions and behaviors, adjust to new environments, and take the perspectives of others (Moriguchi, 2014). According to Vygotsky’s (1987) theory of the Zone of Proximal Development—as extended in contemporary research on parenting by Valcan et al. (2018)—parents who provide high levels of autonomy support can offer children optimal opportunities to practice executive skills within their zones of proximal development. They do so by offering appropriate problem-solving strategies and scaffolding children’s ability to plan and carry out goal-directed activities. However, few studies have explicitly examined whether parental autonomy support fosters the development of cognitive regulatory abilities such as executive function. In addition, Executive function also facilitates school adjustment by enhancing children’s attention regulation and self-control and reducing distractions from irrelevant stimuli, thereby promoting the development of both academic and social skills (Passolunghi & Pazzaglia, 2005; Raver, 2012). Existing research has demonstrated that the growth trajectory of executive function is associated with improved problem-solving abilities, adaptability, literacy development, and reductions in internalizing problem behaviors (Hughes & Ensor, 2011; Swanson et al., 2008, 2017).

This study aims to examine the influence of parental autonomy support on later school adjustment from a developmental perspective, with a particular focus on the mediating role of executive function. School adjustment is conceptualized across four major domains: emotional, social, academic, and interpersonal functioning. The study tested the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Parental autonomy support predicts higher children’s school adjustment, and the effect may differ for fathers vs. mothers.

Hypothesis 2: Children’s executive function is associated with significant improvement over time.

Hypothesis 3: Both the initial level and the developmental rate of executive function mediate the relationship between parental autonomy support and children’s school adjustment to be stronger.

Participants were children recruited from an elementary school in Guangdong Province, China. Assessments were conducted at three time points in 2021: March (T1, n = 526), June (T2, n = 515), and September (T3, n = 500). The final sample consisted of 476 children (50.8% girls; 7.1% only children; Mage = 10.49 years, SD = 1.32). In addition, demographic information about the children’s parents was also collected. The mean age of fathers was 40.20 years (SD = 5.50), and that of mothers was 38.05 years (SD = 5.17). See Table 1 for more detailed demographic information.

The Psychological Autonomy Support Scale was employed to assess maternal and paternal autonomy support (Wang et al., 2007). The original 8-item scale was reported by children separately for their father and mother, yielding a total of 16 items. Sample items were provided in Appendix A. Responses are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“very often”). In the present study, separate mean scores were calculated for paternal and maternal autonomy support, with higher scores indicating greater perceived autonomy support from each parent. This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in Chinese populations (Wang et al., 2007). In the current sample, the internal consistency coefficient of scores from the scale was 0.91.

The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-2 (BRIEF-2, Gioia et al., 2015) was used to measure children’s executive function in daily life. The scale contains 55 items divided into nine subscales, such as inhibitory control and self-monitoring. The scale is scored on a three-point scale ranging from “1 = never” to “3 = often”, with higher scores indicating poorer executive function. Sample items were provided in Appendix A. For ease of understanding, all items of this scale were reverse scored, with higher scores indicating better levels of executive function. The internal consistency coefficients for children’s executive function scores were 0.94, 0.96, and 0.96 at the three time points in this study.

The Primary School Students’ Psychological Suzhi Scale (Zhang & Su, 2015) was used to measure children’s school adjustment. This subscale has 12 items divided into four dimensions: interpersonal adjustment, emotional adjustment, social adjustment and academic adjustment, and is scored on a five-point scale ranging from “1 = not at all like me” to “5 = exactly like me”. Sample items were provided in Appendix A. The total score for each dimension was calculated by reverse scoring some items, with higher scores indicating better adjustment. In this study, the internal consistency of children’s school adjustment scores was 0.80.

Demographic information about children and their parents was collected at T1, including the child’s gender, age and sibling. Parents’ education level, average monthly income and occupation scores were standardized and averaged to obtain an indicator of family socioeconomic status (SES), with higher scores reflecting higher family SES (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002).

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Psychology at Capital Normal University. Informed consent was obtained from parents prior to data collection. Data were collected at three time points, each spaced three months apart. Parental autonomy support and demographic information were collected at Time 1 (T1), children’s executive function was assessed across all three waves (T1–T3), and children’s school adjustment was measured at Time 3 (T3). With parental consent and child assent, trained research assistants administered the questionnaires to children either during regular classroom hours or immediately after school, and children completed the surveys independently.

The study used SPSS 21.0 for preliminary statistical analysis and Mplus 8.3 to construct latent growth curve model and mediation model.

Common Method Bias Test. Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to examine the presence of common method bias (Zhou & Long, 2004). An exploratory factor analysis was performed on all items from the study measures. The results indicated that the first unrotated factor accounted for 20.99% of the total variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. Therefore, common method bias was not a serious concern in this study.

Independent samples t-test indicated that there was no significant child gender difference (p > 0.05) for each study variable. The unconditional latent growth curve model was conducted to examine the developmental trajectory of children’s executive function, and the model fit well (χ2/df = 2.030, RMSEA = 0.047, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.996, SRMR = 0.011). Then, structural equation modeling was constructed to examine the total effect of parental autonomy support on children’s school adjustment. The model fit well after controlling for socioeconomic status, child age, and single-child status, χ2/df = 1.695, RMSEA = 0.038, CFI = 0.989, TLI = 0.953, SRMR = 0.024. Finally, executive function was added to the total effect model to examine whether its intercept and slope could play mediating roles in the relationship between parental autonomy support and school adjustment. The model fit well after controlling for the single-child status, father’s age, child’s age and socioeconomic status, χ2/df = 1.199, RMSEA = 0.020, CFI = 0.997, TLI = 0.992, SRMR = 0.032.

Independent samples t-test indicated that there was no significant child gender difference (p > 0.05) for each study variable (see Table 2). Table 3 presents the correlation coefficients among the main variables. Parental autonomy support was significantly positively correlated with T1–T3 children’s executive function and school adjustment, and children’s executive function was significantly correlated with school adjustment at all three time points; In addition, father’s age was significantly negatively correlated with T1 children’s executive function and social adjustment dimension, and was not significantly correlated with the other variables; Single-child status was positively correlated with children’s executive function and social adjustment at all three time points.

Unconditional latent growth curve modeling of executive function

Consistent with Hypothesis 3, the mean and variance of the intercept of children’s executive function were 127.80 and 228.32 (p < 0.001), indicating that there were significant individual differences in the level of children’s executive function at T1; the mean and variance of the slope were 2.58 and 37.58 (p < 0.001), indicating that children’s executive function showed a significant growth trend during the three measurements, and that there were significant individual differences in the rate of growth. The intercept and slope of executive function were significantly negatively correlated (r = −0.29, p < 0.001), suggesting that the higher the initial level of executive function, the slower its growth over time.

Executive function as a mediator between parental autonomy support and children’s school adjustment

Paternal autonomy support significantly and positively predicted all four dimensions of school adjustment (interpersonal adjustment: β = 0.18, p < 0.01; social adjustment: β = 0.22, p < 0.001; emotional adjustment: β = 0.14, p < 0.05; academic adjustment: β = 0.19, p < 0.01). In contrast, maternal autonomy support was significantly associated only with interpersonal adjustment, β = 0.14, p < 0.05. These findings support Hypothesis 1, which proposed that parental autonomy support would positively predict children’s school adjustment, but also suggest that the effects differ by parent gender.

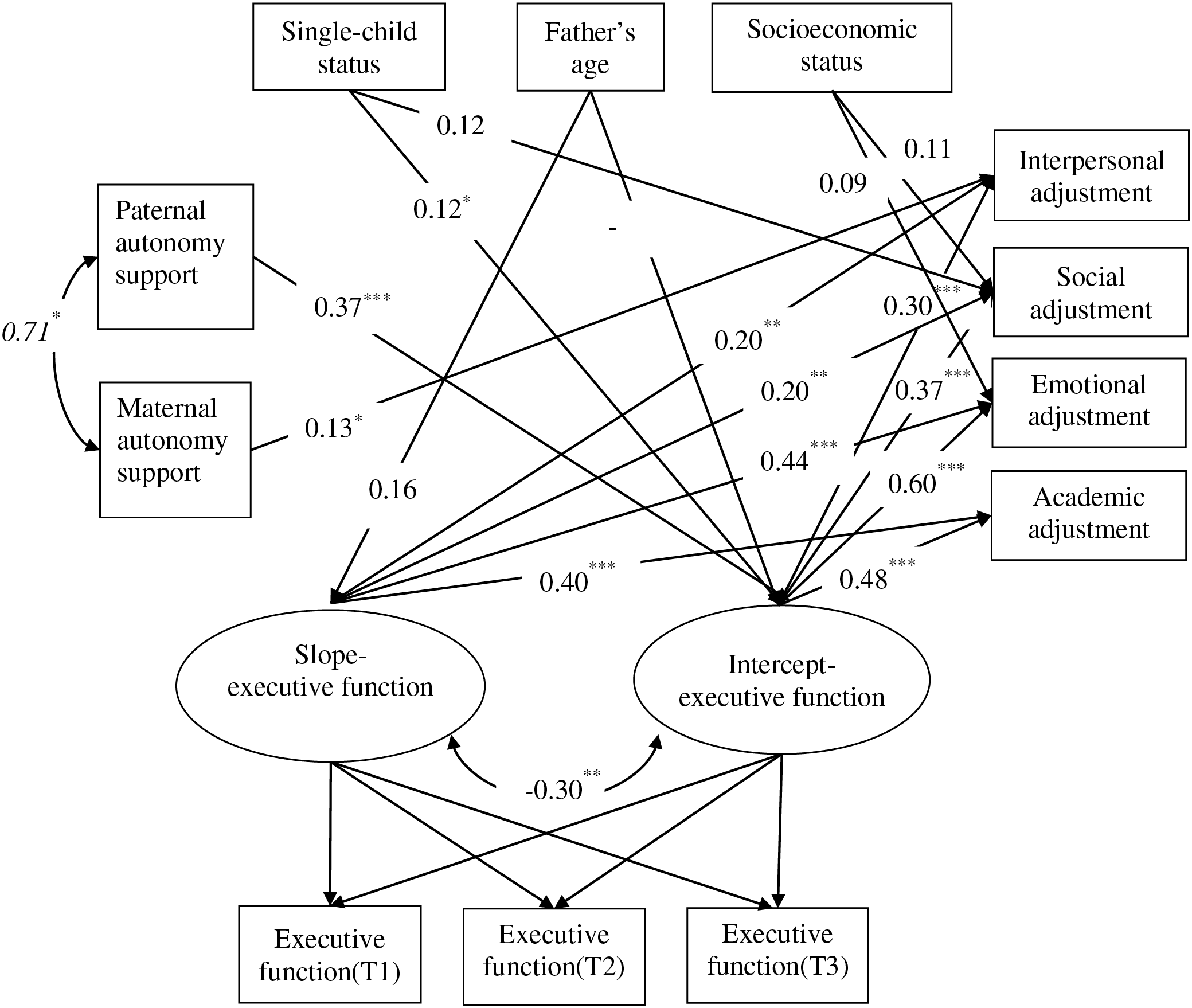

As shown in Figure 1, paternal autonomy support significantly predicted the intercept of executive function, β = 0.37, p < 0.001, and the intercept of executive function, in turn, significantly predicted all four dimensions of school adjustment, βs < 0.60, p < 0.001. Bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (CIs) indicated that the indirect effect of paternal autonomy support on children’s school adjustment through the intercept of executive function was significant across all dimensions (interpersonal adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.11, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.053, 0.196]; emotional adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.22, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.112, 0.343]; academic adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.18, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.089, 0.284]; social adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.14, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.067, 0.239]). Moreover, none of the direct paths from paternal autonomy support to the four dimensions of school adjustment were significant, indicating full mediation via the intercept of executive function. Although paternal autonomy support did not significantly predict the slope of executive function, β = −0.02, p > 0.05, the slope itself significantly predicted all four school adjustment outcomes, β < 0.44, p < 0.001, suggesting that children who exhibited faster development of executive function tended to show better school adjustment. However, the indirect effect of paternal autonomy support on school adjustment via the slope of executive function was non-significant (interpersonal adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = −0.003, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.060, 0.041]; emotional adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = −0.008, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.117, 0.095]; academic adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = −0.007, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.102, 0.093]; social adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = −0.004, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.057, 0.046]). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was only partially supported: the initial level of executive function fully mediated the relationship between paternal autonomy support and school adjustment, whereas the rate of executive function development did not serve as a significant mediator.

Figure 1: The mediating role of executive function between parental autonomy support and school adjustment. Note. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The direct effect of maternal autonomy support was significant only for children’s interpersonal adjustment, β = 0.13, p < 0.05. However, as shown in Table 4, maternal autonomy support was not a significant predictor of either the intercept, β = 0.02, p > 0.05, or the slope, β = 0.03, p > 0.05, of children’s executive function. Bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (CIs) further indicated that the indirect effects of maternal autonomy support on children’s school adjustment via the intercept of executive function were not significant across any of the four domains (interpersonal adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.004, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.051, 0.066]; emotional adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.009, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.096, 0.114]; academic adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.007, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.078, 0.092]; social adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.005, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.064, 0.076]). Similarly, the indirect effects via the slope of executive function were also non-significant (interpersonal adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.006, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.039, 0.059]; emotional adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.012, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.083, 0.119]; academic adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.011, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.079, 0.108]; social adjustment: standardized indirect estimate = 0.006, p > 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.041, 0.061]). The model-specific path estimates are presented in Table 3. Taken together, these results do not support Hypothesis 3 in the context of maternal autonomy support. That is, neither the initial level nor the developmental rate of executive function mediated the relationship between maternal autonomy support and children’s school adjustment.

First, the finding that paternal autonomy support significantly predicted children’s emotional, social, academic, and interpersonal adjustment aligns with the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), which posits that autonomy-supportive environments foster internal motivation, self-regulation, and goal-directed behavior-factors essential to successful school adaptation. From a cultural universal perspective, this result supports the notion that autonomy is a basic psychological need across cultures, and its satisfaction leads to positive developmental outcomes regardless of cultural context (Lansford et al., 2018). Although collectivistic cultures like China have traditionally emphasized social harmony and interdependence (Ho, 1986), with ongoing economic and societal development, parental autonomy support has become increasingly important for fostering children’s active exploration, initiative-taking, and self-reliance—capacities that are essential for adaptation and success in school environment (Xu et al., 2024). Moreover, the stronger effect of paternal autonomy support may reflect culturally specific gender roles, where fathers are often seen as facilitators of exploration and risk-taking—behaviors that promote adaptive functioning in unfamiliar school settings.

Second, the finding that the relationship between paternal autonomy support and school adjustment was fully mediated by children’s initial level of executive function aligns with existing developmental and cognitive theories. For example, the theory of Zone of Proximal Development posited that autonomy-supportive parents provide children with scaffolding that enhances their ability to practice executive skills in real-time problem-solving contexts (Vygotsky, 1987; Valcan et al., 2018). Fathers, in particular, are often more likely to promote autonomy through behaviors such as encouraging independent decision-making and self-expression. These cognitively stimulating yet supportive interactions may help foster early development of executive functions, including attentional control, goal setting, and working memory. As a self-regulatory system, executive function could help children to inhibit distractions, sustain attention, and regulate emotions, thereby facilitating successful adaptation to academic and social demands (Raver, 2012; Moriguchi, 2014). It also suggests that interventions aimed at improving children’s executive functioning (e.g., working memory training or self-regulation coaching) might amplify the benefits of paternal autonomy-supportive parenting.

Third, the finding that maternal autonomy support directly predicted only children’s interpersonal adjustment suggests a domain-specific influence of maternal behaviors. In collectivistic cultures such as China, mothers are typically viewed as primary emotional caregivers and often focus on fostering harmonious relationships and emotional attunement within the family (Ho, 1986). This cultural role may shape the ways in which maternal autonomy support is expressed—through emotion-related communication, perspective-taking, and social guidance—which may more directly promote children’s interpersonal functioning, independent of the child’s executive function level. Therefore, the impact of maternal autonomy support may be more pronounced in relational domains, such as interpersonal adjustment, than in cognitive or academic ones. Nevertheless, the absence of a broader or indirect effect for mothers in our study does not mean mothers are unimportant; rather, it suggests that mother’s autonomy support might operate through other mediators (such as emotional security) which were beyond the scope of our study. Future research could explore these alternative pathways, and examine whether this pattern holds in other cultures or if it is specific to the socio-cultural dynamics of urban China. Combined with the findings regarding fathers, these results highlight the importance of considering both parental roles and cultural context when evaluating the effects of autonomy support, and also underscore the need for a comprehensive and nuanced examination of the distinct domains of school adjustment, as well as a deeper understanding of their unique predictors.

Finally, our findings reveal meaningful gender differences in how parental autonomy support influences children’s school adjustment. Specifically, paternal autonomy support exerted its effects indirectly through children’s initial executive function, whereas maternal autonomy support had a direct effect on interpersonal adjustment. This divergence suggests that mothers and fathers may facilitate children’s development through distinct mechanisms, likely shaped by culturally defined parenting roles (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2008). Notably, this pattern to some extent lends further support to a growing body of research indicating that the association between autonomy-supportive parenting and children’s social competence may be stronger for fathers than for mothers (Leidy et al., 2011; Marsiglio et al., 2000; Paquette, 2004). These differential pathways underscore the need to consider parent-specific contributions in models of child development, particularly within the context of culturally grounded caregiving practices.

Implications for research and practice

Although only the initial level of executive function was found to mediate the relationship between paternal autonomy support and school adjustment, both the initial level (intercept) and growth rate (slope) of executive function significantly predicted children’s school adjustment outcomes. This supports the theoretical view that cognitive development supports social development. As a form of top-down cognitive regulation, executive function plays an important role in children’s ability to meet classroom demands, manage academic tasks across subjects, and interact effectively with peers and teachers (Blair & Razza, 2007). Children with strong executive function skills can shift attention between problems and strategies, inhibit impulsive responses, maintain task-related information in mind, participate actively in classroom activities, regulate emotions, establish positive relationships with teachers and classmates, and accurately analyze or comprehend complex information, all of which would contribute to successful school adjustment. Importantly, the findings extend previous research by highlighting that the growth rate of executive functions is also contribute to adaptive outcomes.

Children with more rapid development in executive function are better equipped to meet the increasing academic and behavioral demands during elementary school periods. During this period, rising expectations for autonomy, self-regulation, and academic independence make executive functioning especially salient for successful adjustment. Given that executive function remains highly malleable during school age, these findings suggest that optimizing children’s self-regulatory development—particularly within supportive parenting environments—may be an effective approach to enhancing school adjustment.

Implications for parent and student counseling and development

The school environment serves as one of the most critical micro-systems for children’s growth and socialization. School adjustment—commonly defined as children’s engagement with the school environment, participation in activities, and academic achievement (Ladd, 1996)—is widely recognized as a key indicator of psychological well-being and developmental competence. Successful adjustment entails more than academic performance; it also includes adhering to school norms and cultivating positive peer relationships, which are fundamental developmental tasks during the school-age period. In China, school maladjustment is a growing concern. Research indicates that approximately 20%–42% of school-aged children experience mild maladjustment, while 7%–12% suffer from more severe problems (Lu et al., 2018). Such maladjustment is not only associated with academic disengagement (e.g., truancy and dropout) but may also lead to long-term impairments in emotional regulation, interpersonal functioning, vocational decision-making, and even character development in adulthood (Liu, 2004).

Despite this, the current educational climate often overemphasizes cognitive outcomes and academic achievement, with insufficient attention paid to students’ socio-emotional development. In this context, our findings underscore the vital role of the family, particularly parental autonomy support, in promoting children’s adjustment in school. Integrated school-based mental health programs should actively involve parents, with a focus on promoting autonomy-supportive parenting. Providing targeted guidance—especially for fathers—on how to support autonomy in daily interactions may be particularly effective in improving children’s school adjustment and long-term development.

Limitations and future directions

The present study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, a short-term longitudinal design limited our ability to capture developmental changes in executive function over the course of childhood. Second, our study focused exclusively on one positive parenting dimension—autonomy support—without accounting for the potential influence of other parenting behaviors. Future research should adopt a broader family systems perspective to examine additional environmental factors that may contribute to children’s school adjustment. Third, executive function was assessed solely through child self-reports. It is important to note that different assessment methods—such as parent/teacher ratings or laboratory-based tasks—may capture distinct facets of executive function and reflect varying levels of cognitive analysis. For instance, self-report measures typically assess children’s goal-directed behavior in unstructured, everyday contexts, whereas laboratory tasks assess processing efficiency under optimal and controlled conditions (Toplak et al., 2013). Fourth, the study relied on a single-informant design, which may introduce bias. Future research would benefit from incorporating multi-informant approaches to obtain more reliable and comprehensive data. Finally, the sample was drawn primarily from primary school children in low- to middle-income families in Guangdong Province, China. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or other culture. Replicating the study with more diverse and representative samples is recommended to enhance external validity.

The present study underscores the distinct pathways through which paternal and maternal autonomy support contribute to school adjustment among Chinese school-aged children. Specifically, paternal autonomy support promotes children’s multidimensional school adjustment indirectly by enhancing their initial executive function, whereas maternal autonomy support directly facilitates interpersonal adaptation. Moreover, the accelerated development of executive function in higher grade levels further supports children’s ability to adjust to school demands. These findings suggest that by leveraging the complementary strengths of each parent—fathers providing cognitive scaffolding for executive function, and mothers offering relational and emotional support—families and educators can more effectively promote school adjustment. The study highlights the need for culturally sensitive interventions that optimize both autonomy-supportive parenting practices and children’s self-regulation within educational settings.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the children and their parents for participating in this survey.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (CN) (Grant No. 32071074).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xia Hu, Xiaopei Xing; data collection: Xiaopei Xing; analysis and interpretation of results: Zhu Li, Yawen Shi; draft manuscript preparation: Xia Hu, Zhu Li, Yawen Shi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data for this study are available by emailing the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Psychology at the Capital Normal University.

Informed Consent: Consent for participation in this study was provided by all participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Blair, C., & Razza, R. P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78(2), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 21(3), 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chen, X., Chen, X., Zhao, S., Way, N., Yoshikawa, H. et al. (2021). Autonomy- and connectedness-oriented behaviors of toddlers and mothers at different historical times in urban China. Developmental Psychology, 57(8), 1254–1260. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of Self-Determination Research: Theoretical and Applied Issues. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. [Google Scholar]

Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S. C., & Kenworthy, L. (2015). Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function®. Second Edition (BRIEF®2). Lutz, FL, USA: PAR Inc. [Google Scholar]

Ho, D. Y. F. (1986). Chinese pattern of socialization: A critical review. In: M. H. Bond (Ed.The psychology of the Chinese people (pp. 1–37). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Hughes, C., & Ensor, R. (2011). Individual differences in growth in executive function across the transition to school predict externalizing and internalizing behaviors and self-perceived academic success at 6 years of age. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 108(3), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2010.06.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ladd, G. W. (1996). Shifting ecologies during the 5 to 7 year period: Predicting children’s adjustment during the transition to grade school. In: A. J. Sameroff, & M. M. Haith (Eds.The five to seven year shift: The age of reason and responsibility (pp. 363–386). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

Lansford, J. E., Godwin, J., Al-Hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., Bornstein, M. H. et al. (2018). Longitudinal associations between parenting and youth adjustment in twelve cultural groups: Cultural normativeness of parenting as a moderator. Developmental Psychology, 54(2), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Leidy, M. S., Schofield, T. J., Miller, M. A., Parke, R. D., Coltrane, S. et al. (2011). Fathering and adolescent adjustment: Variations by family structure and ethnic background. Fathering, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.0901.44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, H., & Wang, N. Y. (2004). On the developmental researches of executive function. Psychological Science, 27(2), 426–430. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-6981.2004.02.053 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, W. L. (2004). An investigation of the developmental characteristics of school adjustment among elementary and middle school students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, (2), 113–114. [Google Scholar]

Lu, F. R., Liu, D. D., Li, D. F., & Yun, W. (2018). The relationship between parental style and school adjustment among primary school student: Cross-legged regression analysis. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 16(2), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2018.02.010 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Marsiglio, W., Amato, P., Day, R. D., & Lamb, M. E. (2000). Scholarship on fatherhood in the, 1990s, and beyond. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1173–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01173.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moriguchi, Y. (2014). The early development of executive function and its relation to social interaction: A brief review. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(867), 388. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (2008). Mothers’ and fathers’ support for child autonomy and early school achievement. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 895–907. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Paquette, D. (2004). Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development, 47(4), 193–219. https://doi.org/10.1159/000078723 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Passolunghi, M. C., & Pazzaglia, F. (2005). A comparison of updating processes in children good or poor in arithmetic word problem-solving. Learning and Individual Differences, 15(4), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2005.03.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Raver, C. C. (2012). Low-income children’s self-regulation in the classroom: Scientific inquiry for social change. American Psychologist, 67(8), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2009). Promoting self-determined school engagement: Motivation, learning, and well-being. In: K. R. Wenzel, & A. Wigfield (Eds.Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 171–195). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203879498 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Swanson, H. L., Jerman, O., & Zheng, X. (2008). Growth in working memory and mathematical problem solving in children at risk and not at risk for serious math difficulties. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 343–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.343 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Swanson, H. L., Orosco, M. J., & Kudo, M. (2017). Does growth in the executive system of working memory underlie growth in literacy for bilingual children with and without reading disabilities? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 50(4), 386–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219415618499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Toplak, M. E., West, R. F., & Stanovich, K. E. (2013). Practitioner review: Do performance-based measures and ratings of executive function assess the same construct? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(2), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Valcan, D. S., Davis, H., & Pino-Pasternak, D. (2018). Parental behaviours predicting early childhood executive functions: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 607–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9411-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Petegem, S., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Beyers, W. (2015). Rebels with a cause? Adolescent defiance from the perspective of reactance theory and self-determination theory. Child Development, 86(3), 903–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Vasquez, A. C., Patall, E. A., Fong, C. J., Corrigan, A. S., & Pine, L. (2016). Parent autonomy support, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning: A meta-analysis of research. Educational Psychology Review, 28(3), 605–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9329-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In: R. Rieber, & A. Carton (Eds.The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky (vol. 1, pp. 39–285). New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

Wang J., Kaufman T., Mastrotheodoros S., Branje S. (2024). The longitudinal associations between parental autonomy support, autonomy and peer resistance. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(4), 1015–1027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01915-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, Q., Pomerantz, E. M., & Chen, H. (2007). The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Development, 78(5), 1592–1610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xu, J., Chen, X., Liu, S., Weng, X., Zhang, H. et al. (2024). Parental autonomy support and psychological control and children’s biobehavioral functioning: Historical cohort differences in urban China. Child Development, 95(6), 2166–2177. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.14145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhang, D. J., & Su, Z. Q. (2015). Development of psychological suzhi measure for primary school student. Journal of Southwest University (Social Sciences Edition), 41(3), 89–95+19. [Google Scholar]

Zhou, H., & Long, L. R. (2004). Statistical remedies for common method biases. Advances in Psychological Science, 12(6), 942–950. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-3710.2004.06.018 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools