Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Does problematic mobile phone use affect facial emotion recognition?

Department of Psychology, School of Educational Science, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, 225009, China

* Corresponding Author: Xianli An. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(4), 523-533. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.070123

Received 31 October 2024; Accepted 20 May 2025; Issue published 17 August 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the impact of problematic mobile phone use (PMPU) on emotion recognition. The PMPU levels of 150 participants were measured using the standardized SAS-SV scale. Based on the SAS-SV cutoff scores, participants were divided into PMPU and Control groups. These participants completed two emotion recognition experiments involving facial emotion stimuli that had been manipulated to varying emotional intensities using Morph software. Experiment 1 (n = 75) assessed differences in facial emotion detection accuracy. Experiment 2 (n = 75), based on signal detection theory, examined differences in hit and false alarm rates across emotional expressions. The results showed that PMPU users demonstrated higher recognition accuracy rates for disgust faces but lower accuracy for happy faces. This indicates a tendency among PMPU users to prioritize specific negative emotions and may have impaired perception of positive emotions. Practically, incorporating diverse emotional stimuli into PMPU intervention may help alleviate the negative emotional focus bias associated with excessive mobile devices use.Keywords

Technological advancements have facilitated the widespread use of mobile phones in people’s daily lives, but this prevalence has also brought a risk of dependency. Problematic mobile phone use (PMPU) or smartphone addiction (SA) have grown increasingly prevalent in recent years (Olson et al., 2022; Glumbić et al., 2020). Mobile phone use is replacing in-person interactions at a phenomenal rate. On one hand, online social interaction is taking the place of face-to-face interaction; on the other hand, PMPU leads people to spend more time on their phones, significantly reducing opportunities for in-person social engagement. This shift carries a high risk for behavioral disorders (Bianchi & Phillips, 2005; Leung, 2008). Facial emotion recognition is essential for human social interaction. However it remains unclear whether and how PMPU impacts facial emotion perception. This study seeks to address this question.

PMPU refers to excessive and uncontrollable mobile phone use in individuals, and it is associated with emotional issues such as anxiety and depression (Rozgonjuk et al., 2018; Busch & McCarthy, 2021), Not surprisingly, intense mobile phone usage may hinder interpersonal relationships due to social anxiety and poor recognition of facial expressions (Adolphs, 2002).

The emotional face processing theory posits that proficiency at emotion recognition is important for emotional regulation (Calvo & Lundqvist, 2008), as it allows individuals to accurately perceive others’ intentions and emotional states, thereby facilitating appropriate responses. In contrast, poor recognition abilities may lead to interpersonal conflicts and emotional issues. Thus, emotion recognition and processing are critical to emotional health and social relationships. While the evidence suggests that individuals who are overly dependent on mobile phones tend to show a stronger inclination toward negative emotions (Hou et al., 2021), this behavioral pattern requires to be validated through controlled experimental studies, particularly among those with PMPU. Such research is critical, as individuals with PMPU may exhibit heightened focus on negative emotions (Arrivillaga et al., 2023; Elhai et al., 2016; Rozgonjuk & Elhai, 2019; Squires et al., 2020) and impaired emotional connectivity (Gao et al., 2023).

In the field of emotion recognition research, existing experimental paradigms that use facial stimuli exposure are relatively well-developed (Cassidy et al., 2019; Jaeger et al., 2020). These paradigms typically present facial expressions with varying emotional intensities to examine how emotional faces are recognized, both with and without interference.

Emotion recognition tasks generally follow relatively standardized protocols, in which facial expression images are often presented as stimuli, and participants are asked to identify or evaluate the emotions expressed in these images. This approach has been widely used in behavioral research on emotion recognition (Zebrowitz et al., 2013). While methodological variations exist across studies, emotion recognition task designs share common features: They usually use facial expression images as primary stimuli, focus on identifying or evaluating the emotions conveyed by the stimuli, and employ systematic control over stimulus presentation (e.g., duration, intensity) and response recording to measure how well individuals recognize emotions. Typically, such experimental procedures involve several phases: presenting standardized emotional stimuli, collecting behavioral response data, and calculating quantitative results through statistical analysis.

Human facial expressions are rich and varied, with such variations manifesting not only in the types of emotions they convey (e.g., happy, anger) but also in emotion intensity (e.g., mild, intense). Given this complexity, it is essential to include facial expression images that vary in both emotion type and intensity in emotion recognition tasks. This helps to more careful examination of participants’ emotion perception abilities. In the present study, we did this by using software to manipulate the intensity of standard facial expression images across different emotion types.

People with PMPU are known to have higher rates of comorbid psychological disorders, such as depression and anxiety (Whitton et al., 2015). Notably, individuals with these affective disorders consistently show heightened sensitivity and specificity when processing negative emotional stimuli (Van Kleef et al., 2022). Against this background, the present study aims to investigate how PMPU impacts the recognition of specific facial emotions under controlled conditions of emotion type and intensity. We hypothesize that compared to the control group, individuals with PMPU will demonstrate higher accuracy in recognizing specific negative emotions.

Clarifying this issue will contribute to understanding the mechanisms through which PMPU impacts the recognition of specific emotions, thereby informing psychological interventions related to mobile phone dependence.

We designed two experiments to investigate the impact of PMPU on the recognition of facial emotions. Experiment 1 assessed participants’ emotion recognition performance through systematic manipulation of stimulus types and intensity levels. Outcomes primarily measure the accuracy rates in recognizing specific facial emotions. Experiment 2 examined participants’ capacity to discriminate target emotion under conditions of interference. This was achieved by introducing competing emotional distractors (e.g., presenting happy faces as targets alongside neutral and surprise faces as distractors), with performance measured by participants’ capacity to correctly identify the target emotion despite the presence of distractors.

Experiment 1 employed a 2 (Group: PMPU Group, Control Group) × 6 (Emotion Type: happy, sad, anger, fear, surprise, disgust) × 5 (Emotion Intensity: 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%) mixed factorial design. Stimuli for this experiment were created using morphing software to generate gradient sequences for each emotion type, with intensity levels ranging from 0% (neutral) to 100% (full intensity) in 20% increments. The experiment was conducted in a quiet, isolated room and lasted approximately 25 min. Experiment 2 used stimuli derived from the same gradient sequences as Experiment 1 but with two key adjustments: emotions were presented at a fixed 60% intensity level, and all images were converted to grayscale using Photoshop to standardize brightness, retaining only facial cues. The underlying principle of the two experimental designs is identical (see Figure 1) but differed in specific details, including processing and presentation of stimulus materials, experimental procedures, and response requirements. These nuances are not fully captured in a single diagram. The details regarding the design for each experiment are provided in the subsequent experimental section.

Figure 1: Principle of the two experimental designs

This study has obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of the College of Education Science of the Yangzhou University (JKY-2021030401). All participants provided written informed consent.

The Short Version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS-SV, Kwon et al., 2013) was used to assess participants’ level of PMPU. The SAS-SV comprises 10 items, each rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater levels of mobile phone dependency. According to the proposed cutoff scores (Kwon et al., 2013), females scoring above 33 and males scoring above 31 could be classified as PMPU users with mobile phone addictive tendency. The Cronbach’s α for SAS-SV scores was 0.855 in the present study.

While the SAS-SV includes “addiction” in its name, we adopted PMPU as our primary term for theoretical and methodological rigor. Currently, most researchers remain cautious about the concept of smartphone addiction (SA) due to insufficient physiological and behavioral evidence. Specifically, addiction is typically defined as a disorder that causes physical and mental impairment, but many argue that excessive smartphone use does not universally meet this standard. Therefore, when investigating psychological and behavioral issues related to smartphone use, PMPU should be adopted as the term rather than SA (Panova & Carbonell, 2018). This choice helps avoid overpathologizing everyday mobile phone use behavior and sidestep unnecessary ethical or academic controversies, aligning with current research trends that emphasize careful terminology. This study uses SAS-SV cutoff scores solely to divide participants into the PMPU group and the Control group rather than labeling individuals as “addicted”.

Experiment 1: Effects of PMPU on Emotional Face Recognition under Different Intensity Conditions

This experiment aims to assess the impact of PMPU on the recognition of facial emotion at varying intensities (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%). It investigated how the PMPU and Control groups perceived specific emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, disgust) under each intensity condition.

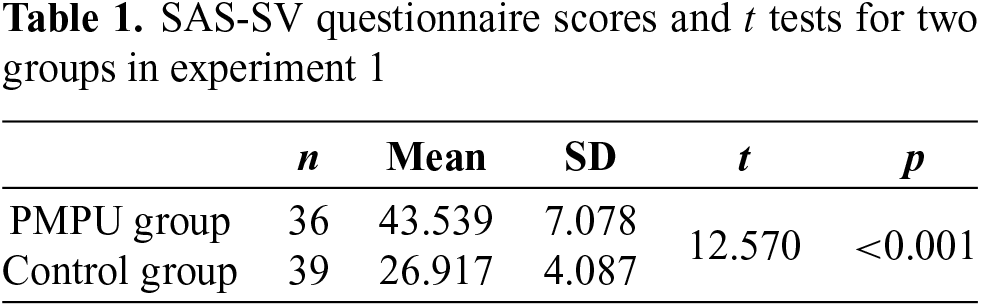

In Experiment 1, a total of 75 participants were included, with 36 classified into the PMPU group and 39 into the control group based on their SAS-SV scores. Among them, 19 were male and 56 were female, with a mean age of 21.93 ± 2.18 years. Table 1 presents the statistical comparison of SAS-SV scores between the two groups. Participants voluntarily enrolled in the study, provided informed consent prior to the experiment onset, and were free to withdraw at any time. Fixed monetary compensation was provided upon completion of the experiment.

The facial stimuli in this study were selected from the validated NimStim facial expression set (Tottenham et al., 2009). To mitigate potential effects of racial and gender differences on face perception (Lipp et al., 2015), we selected only Asian-looking female models. This approach ensured consistency and isolated demographic variables, allowing us to attribute recognition differences primarily to PMPU rather than participant characteristics.

Using Morph software, we generated emotion intensity gradients (20%–100%) for each of the six basic emotions (happy, sad, anger, fear, surprise, disgust) from these models. Each emotion was systematically manipulated across a progressive intensity continuum (Figure 2), resulting in a total of 150 emotional expressions. Additionally, one neutral face was included per model, with a total of five neutral faces across the five models, yielding a final stimulus set comprising 155 facial stimuli.

Figure 2: Disgust emotion face sequence, with the vertical axis representing model species and the horizontal axis representing emotion intensity processed by Morph

E-Prime 2.0 was used to present stimuli. Each model included six basic emotions, with five intensity levels per emotion; this resulted in 25 presentations per basic emotion, totaling 150 emotional stimulus trials. Combined with five neutral faces (one per model), the formal experiment comprised 155 trials. Facial images were presented in a randomized order across participants.

In each trial (as depicted in Figure 3), participants were directed to focus on the center of the screen. Each trial began with a central fixation cross (“+”) displayed for 500 ms, followed by the presentation of a facial stimulus for 500 ms. After the stimulus disappeared, emotion category options (happy, sad, angry, fear, surprise, disgust) appeared on the screen, with no time constraints for participants to respond. Participants selected, using a mouse, the option corresponding to the emotion they perceived, with options randomized across trials to minimize response bias. The next trial commenced after a random inter-trial interval of 900–1300 ms. Prior to the formal experiment, participants completed six practice trials.

Figure 3: Flow chart for a single trial in experiment 1

Data were extracted from E-data and sorted by intensity (20%–100%) and emotion type (happy, sad, angry, fearful, surprised, disgusted). Average recognition accuracy was calculated for each intensity level (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100%) within each emotion type. Separate 2 (Group: PMPU vs. Control) × 5 (Intensity) repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to examine group differences in recognition accuracy across intensity levels for each emotion type. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0.

For happiness, the 2 (Group) × 5 (Intensity) repeated measures ANOVA type revealed significant main effects of Intensity (F(4,288) = 56.622, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.440) and Group (F(1,72) = 4.578, p = 0.036, η2 = 0.060), indicating recognition accuracy varied across intensity levels and differed between groups. The interaction between Group and Intensity was not significant. Simple effect analysis indicated that the PMPU group exhibited significantly lower recognition accuracy at 60% intensity compared to the Control group (MPMPU = 0.953 ± 0.011, MControl = 0.989 ± 0.012, p = 0.029).

For disgust, the main effects of Group (F(1,72) = 4.116, p = 0.046, η2 = 0.054) and Intensity (F(4,288) = 24.126, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.251) were also significant, with no significant interaction effect between Group and Intensity. At 80% intensity, the PMPU group showed marginally higher recognition accuracy than Control group (MPMPU = 0.726 ± 0.046, MControl = 0.6 ± 0.047, p = 0.058).

For the remaining emotion types (anger, fear, sad, surprise), only the main effect of Intensity was significant; neither the main effect of Group nor the Group × Intensity interaction reached significance (all p > 0.05). Results for both groups’ recognition accuracy of each emotion type across intensity levels are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Recognition accuracy of the six types of emotions in both PMPU and Control groups under different intensity conditions. The horizontal axis represents emotion intensity, while the vertical axis represents recognition accuracy. SP, surprise; FE, fear; HA, happy; AN, anger; SA, sad; DI, disgust. “*” indicates significant differences between the two groups (p < 0.05)

Results of Experiment 1 showed that the PMPU group exhibited significantly lower recognition accuracy for happy faces, particularly at moderate intensity (60%), and a trend toward higher accuracy for disgust faces. These findings suggest that PMPU may be associated with impaired recognition of positive emotions and enhanced recognition of negative emotions, shedding light on the specificity of emotional processing biases in this population. The significant group main effect at 60% intensity further indicates that between-group differences in emotion recognition are most pronounced under moderate-intensity conditions.

The reduced accuracy in recognizing happy facial expressions is consistent with prior research, which found that mobile phone use does not substantially enhance positive emotional experiences (Mcelroy & Young, 2024) and that excessive reliance on mobile phones can impair the experience of happiness (Arzu et al., 2021). Together, these findings support the idea that PMPU may reshape affective processing systems, leading to diminished sensitivity to positive emotional cues like happy faces.

The observed group differences in emotion recognition suggest potential alterations in emotional perception among individuals with PMPU, which could contribute to challenges in experiencing happiness and maintaining well-being. Specifically, under moderate-intensity conditions, the PMPU group exhibited heightened accuracy for disgust and diminished accuracy for happiness relative to controls, aligning with broader patterns of biased emotional processing. This intensity-specific effect, emerging primarily at medium intensities, is consistent with prior research demonstrating that fluctuations in emotional expression intensity modulate ERP components (Recio et al., 2014) as recognition mechanisms dynamically adapt to changing stimulus salience. Notably, our data revealed no significant group differences in response times, leaving unresolved whether these effects arise from inherent deficits in emotional processing or attentional biases.

The recognition accuracy patterns observed in the current study could be interpreted as reflecting selective recognition tendencies for specific emotions, but this interpretation requires further validation, for example, through interference paradigms that incorporate hit and false alarm rates. Accordingly, Experiment 2 was designed to address these issues.

Experiment 2: Effects of PMPU on Facial Emotion Recognition under Interference Condition

Facial emotion recognition requires two key abilities: accurate identification of target emotions and effective filtering of distracting emotions. These dual capacities involve distinguishing between similar emotions (e.g., sadness vs. disgust) to correctly interpret others’ emotional states and respond appropriately. In experimental contexts, interference stimuli, such as task-irrelevant emotional cues that resemble the target emotion (e.g., a background face expressing surprise when the target face shows happiness), are specifically incorporated to assess how well individuals can distinguish between two or more similar emotions. This design directly tests the capacity to filter irrelevant information while maintaining precision in identifying the target emotion. This experiment investigated emotional recognition biases in individuals with PMPU under interference conditions. Specifically, it used hit and false alarm rates derived from signal detection theory to validate the existence of recognition biases.

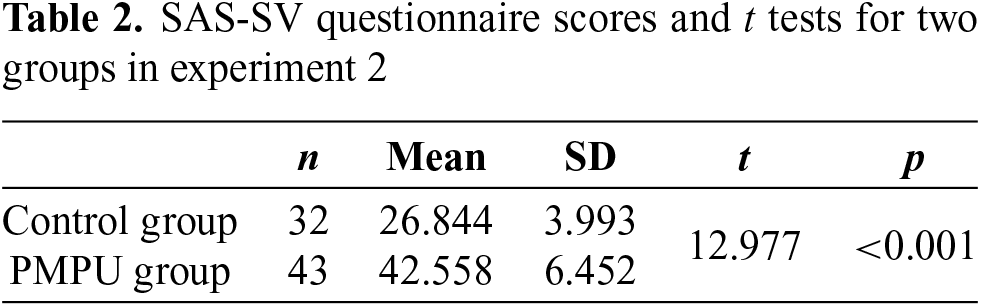

In Experiment 2, participant recruitment followed the same procedure as in Experiment 1. The SAS-SV questionnaire was administered to college students, with 43 classified into the PMPU group and 32 into the control group based on their scores. The final sample included 15 males and 60 females, with a mean age of 21.48 ± 1.99 years. Table 2 presents the statistical comparison of SAS-SV scores between the two groups. Participants voluntarily enrolled in the study, provided informed consent prior to the offline experiment onset, and were free to withdraw at any time during the process. Fixed monetary compensation was provided upon completion of the experiment.

Based on the finding that the differences in emotion recognition responses between the PMPU and control groups in Experiment 1 were primarily evident under the medium-intensity condition, emotion recognition disparities between the two groups likely manifest most clearly under moderate intensity conditions. Thus, in Experiment 2, emotional intensity was fixed at a 60% level. Photoshop was used to convert these stimuli to black and white, with brightness standardized and only facial cues retained.

For the experimental materials, given that the distinction between neutral expressions and 60%-intensity emotional features is highly salient. Using only neutral faces as noise (N) would risk inducing a ceiling effect in hit rates. Thus, emotionally ambiguous faces were included alongside neutral faces as noise stimuli to create effective interference. Consistent with previous study (Killgore et al., 2017), noise stimuli were selected to be morphologically similar to target emotions and frequently confused with them. Three types of facial stimuli were used: emotional signals (SN), neutral noise (N1), and emotional noise (N2).

The experiment was programmed using E-Prime 2.0 and consisted of 6 stimulus blocks, with each participant completing all blocks. Prior to the formal experiment, participants received instructions and completed 5 practice trials. A mandatory 1-min break was provided between blocks, resulting in a total of 180 trials across all 6 blocks. In each block, signals and noise were presented 15 times each, totaling 30 presentations. Among the 15 noise stimuli, 10 were emotional faces and 5 were neutral faces. The presentation order within each block was randomized, while the emotion types of signals and noise in adjacent blocks were counterbalanced to avoid sequence effects.

Participants were not informed of the probability of signal vs. noise presentations and responded via keyboard as instructed. Prior to the experiment, stickers labeled “YES” and “NO” were affixed to the “D” and “K” keys, respectively, to guide participants in indicating the presence or absence of a signal. Each trial began with a 500-ms fixation cross (“+”), followed by a 300-ms presentation of either a signal (SN) or noise (N) face. Participants were then prompted to respond swiftly and accurately by pressing “D” for signals or “K” for noise. A 2000-ms inter-trial interval followed each response before the next trial commenced. The flowchart for a single trial is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Flow chart for a single trial in experiment 2

E-data files were converted to Excel format to calculate hit rates (Phit) and false alarm rates (Pfalse alarm) using standard formulas. Phit represents the probability of correctly identifying a target emotion when present, while Pfalse alarm indicates the probability of incorrectly reporting a target emotion when absent. A 2 (Group: PMPU vs. Control) × 6 (Emotion Type: happy, sad, angry, fear, surprise, disgust) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine group differences in Phit and Pfalse alarm across emotion types.

For Phit, the ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Emotion Type (p < 0.001), while the main effect of Group was not statistically significant. The interaction between group and emotion type was marginally significant (F(5,350) = 2.362, p = 0.050, η2 = 0.033). Simple effects analysis indicated that the Phit for disgust in the PMPU group was significantly higher than in the Control group (MPMPU = 0.875 ± 0.019, MControl = 0.811 ± 0.022, p = 0.034), and the Phit for sadness in the PMPU group was higher than in the Control group (MPMPU = 0.722 ± 0.028, Mcontrol = 0.642 ± 0.034, p = 0.074) though this effect did not reach conventional significance.

For Pfalse alarm, the same 2 (Group) × 6 (Emotion Type) repeated measures ANOVA revealed only a significant main effect of Emotion Type. The main effect of Group and the Group × Emotion Type interaction failed to reach statistical significance, indicating no overall group differences in false alarm rates. The results for Phit and Pfalse alarm across all six emotions by both groups are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: False alarm and hit rate of the PMPU and Control groups for the types of emotions. The horizontal axis represents the emotion type. SP, surprise; FE, fear; HA, happy; AN, anger; SA, sad; DI, disgust. “*” indicates significant differences between the two groups (p < 0.05)

The results of Experiment 2 indicate that the PMPU group demonstrated higher hit rates for disgust recognition. This further suggests that specific emotion recognition biases shape how individuals with high PMPU recognize emotions. Although emotional recognition bias has been identified as a manifestation of psychological disorders and behavioral addictions (Dondaine et al., 2014; Freeman et al., 2018), these biased outcomes cannot definitively diagnose addiction. This limitation exists because emotional sensitivity and bias are often influenced by multiple psychological factors, where both an individual’s current emotional state and the presentation format of target emotions may affect recognition tendencies (Uribe & Meuret, 2024; Wang & Li., 2023).

When similar emotions served as a source of interference, the PMPU group achieved a significantly higher hit rate in recognizing disgust compared to the control group. This difference in hit rates may reflect a stronger propensity for recognizing disgust among individuals in the PMPU group. Notably, disgust is a unique emotion. Previous physiological research has shown that observing and recognizing disgust activates specific neural pathways, which can induce a similar disgust response in the observer (Wicker et al., 2003). The elevated hit rate for disgust in the PMPU group suggests that those with problematic mobile phone use may experience disgust responses more frequently than the general population.

Taken together, the findings from Experiments 1 and 2 indicate that both PMPU and the diversity of emotional stimuli shape recognition biases toward happiness and disgust, thereby influencing recognition outcomes.

Implications for Theory and Research

Experiment 1 assessed emotion recognition accuracy for six basic emotions in both the PMPU and control groups using emotional images varying in type and intensity. Specifically, it examined how PMPU influences recognition outcomes under specific conditions and identified that individuals with PMPU showed heightened sensitivity to disgust, evidenced by higher recognition accuracy, particularly for moderate-intensity expressions. Experiment 2 further explored this phenomenon by measuring hit and false alarm rates for basic emotions under interference conditions, with results confirming the presence and impact of such heightened sensitivity to disgust. Together, both experiments revealed that individuals with PMPU exhibit heightened sensitivity to moderate-intensity disgust facial expressions. While such heightened sensitivity to disgust may impair intimate relationships and emotional experiences (Collisson et al., 2025), disgust itself can also facilitate the avoidance of potential harm and disease (Oaten et al., 2009). Thus, the heightened sensitivity to disgust observed in individuals with PMPU merits attention.

Notably, this heightened sensitivity primarily affected recognition outcomes under moderate-intensity conditions. Across varying emotional intensities, differences in emotion recognition between the two groups were confined to a specific intensity range, suggesting that PMPU may influence both relative and absolute thresholds of emotional perception (Lee et al., 2014). However, this remains a tentative inference drawn from the results, highlighting the need for further research to clarify whether PMPU impacts individuals’ perceptual thresholds for emotions.

In the experiments, the PMPU group also demonstrated significantly lower accuracy than the control group in recognizing happy expressions at 60% intensity. As happiness is the only inherently positive basic emotion, the heightened sensitivity to negative emotions (particularly toward disgust) observed in individuals with PMPU could impair their ability to recognize happiness among multiple emotional stimuli. Perception of happiness is directly linked to the attainment of well-being, with effective awareness and experience of happiness being critical for mental and physical health (Smith et al., 2023). The reduced accuracy in recognizing happiness among individuals with PMPU suggests that excessive phone use may not yield the anticipated positive emotional benefits. This sensitivity-driven difference at moderate intensities resulted in diminished recognition of medium-intensity happiness, a pattern that may reflect the typicality effect: extreme-intensity stimuli obscure meaningful differences in decoding (Juslin & Laukka, 2001). Thus, moderate emotional intensities appear most effective in revealing the role of PMPU in emotion recognition through measurable data.

In Experiment 1, participants were required to identify facial expressions varying in intensity. Under these conditions, the difference in disgust recognition between the two groups was only marginally significant. In Experiment 2, where facial intensity was fixed, only core facial features were retained, and interference was limited to a single stimulus, significant differences in disgust recognition emerged. Comparing the two experiments, this discrepancy may stem from the diverse emotional materials presented within each block in Experiment 1, which created overly rich stimuli. This richness likely attenuated the influence of their heightened sensitivity to disgust when judging such expressions, contributing to the marginal significance in that experiment. The diversity of emotional stimuli not only enhances neuronal responses in specific brain regions (Kuraoka & Nakamura, 2006) but also promotes the development of empathic abilities (Cardini et al., 2012). In contrast, monotonous or impoverished stimuli tend to produce opposing effects. This aligns with consensus in cognitive neuroscience, which holds that enriched external stimuli generally facilitate the development of specialized brain functions, including emotion recognition. Thus, the diversity of emotional stimuli may mitigate the heightened sensitivity to specific negative emotions (such as disgust) observed in individuals with PMPU.

Experiment 2 further revealed a higher hit rate for disgust faces among the PMPU group, indicating that under interference conditions, their heightened sensitivity to disgust persisted, leading to more accurate recognition. This result reinforces the presence of heightened sensitivity to disgust in this population, as evidenced by elevated hit rates. When combined with the findings from Experiment 1 of reduced accuracy in recognizing happiness among individuals with PMPU, these results suggest that an excessive focus on negative emotions may hinder the perception of positive emotions, potentially contributing to various emotional and psychological issues in this group. Such a propensity toward negative emotions may indeed be a contributing factor to physical and mental health problems. Mindfulness and mental training, which promote positive emotional experiences to counteract such tendencies, have been shown to effectively address these issues (Garland et al., 2010).

Analyses across both experiments support the existence of emotion-specific recognition sensitivities and confirm their role in processing specific emotions. Individuals with PMPU exhibit stronger heightened sensitivity to disgust, most pronounced at moderate emotional intensities, and this sensitivity likely impairs their recognition of medium-intensity happiness. However, when processing multiple emotional stimuli, the influence of this sensitivity on judgments appears to weaken.

Importantly, the experiments provide no evidence that individuals with PMPU have globally impaired emotion recognition abilities or general deficits in emotional processing. Such emotion-specific sensitivities are not inherently positive or negative; rather, their implications depend on context. That said, they may increase vulnerability to emotional confusion, for example, the frequent confusion of fear with surprise (Roy-Charland et al., 2015) or disgust with anger (Hendel et al., 2023). These measures did not differ significantly between groups, however, suggesting that PMPU may not substantially affect the differentiation of commonly confused emotions. Interpretation of these findings should be cautious, however, given potential cross-cultural influences.

In discussing findings related to emotion recognition, it is critical to acknowledge the complexity of the factors that shape such recognition. Individual differences exert a significant influence: research indicates that certain personality traits facilitate the recognition of negative emotions (Meehan et al., 2017). Physiological and psychological disorders also significantly impact emotion recognition, often contributing to specific recognition deficits (Keating et al., 2022). Additionally, substance addiction or dependence has been associated with reduced cognitive ability to recognize specific emotions (Meyers et al., 2015).

Beyond individual factors, environmental and contextual cues play a significant role in emotion recognition, with situational factors exerting variable effects through their combined influence (Reschke et al., 2017). This complexity suggests that the effects of PMPU on emotion recognition (such as the heightened sensitivity to disgust observed here) may be mediated by other factors, and that PMPU likely impacts emotional recognition differently across individuals, indicating substantial individual variability. For instance, individuals from affluent backgrounds with higher education and stable relationships may experience different effects of problematic phone use compared to those from disadvantaged backgrounds with lower education and unstable relationships. This underscores the need for comprehensive examinations of multifactorial interactions in PMPU research, careful control of covariates, and the inclusion of diverse samples.

Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

While various behavioral addictions impair emotional cognition (Arafat & Thoma, 2024; Estévez et al., 2017), the present study found no evidence that individuals with PMPU exhibit poorer emotion recognition abilities than controls. This indirectly supports the validity of PMPU as a research construct, yet evidence remains insufficient to conclusively categorize mobile phone addiction as a form of behavioral addiction.

Experimental results indicate that differences in emotion recognition between the two groups primarily occur at specific intensity levels of facial emotions. We cannot infer that individuals with PMPU consistently perform worse than controls in real-world emotion recognition, nor can we draw conclusions from individual metrics alone to claim that they are inferior in emotion recognition or that their recognition patterns are inferior to those of controls. For example, in real-world emotional interactions, bodily cues are sometimes even more crucial than facial expressions (Aviezer et al., 2012). Given that bodily and contextual cues may more accurately convey genuine emotional information than deliberately suppressed facial expressions under specific conditions, further research is warranted into the emotion recognition and expression capabilities of individuals with PMPU in real-life contexts.

The results demonstrate variability in emotion recognition associated with PMPU, which shapes recognition tendencies. However, these differences in recognition do not necessarily indicate better or worse performance. Given ongoing debates around the conceptualization of PMPU, discussions about its impact on emotion recognition should be interpreted cautiously.

This study also has several limitations. First, we focused exclusively on the role of PMPU in emotion recognition, without assessing participants’ levels of anxiety, depression, or other factors that may influence PMPU (Ran et al., 2022). As noted earlier, the factors affecting emotion recognition are highly complex, and the emotion recognition characteristics of individuals with PMPU may also stem from multiple psychological and social factors. Therefore, we cannot directly conclude that PMPU causes specific emotion recognition deficits. This is why, when discussing the results of this study, we emphasize interpreting the associations of PMPU with individual outcomes rather than making causal claims.

This highlights the need to incorporate more psychological and sociological variables that influence emotions into models, or to strictly control them as covariates, when exploring individual differences in emotional processing or recognition. Moreover, emotion recognition involves not only the identification of diverse emotional stimuli but also implicit and explicit processing mechanisms (Ikeda, 2023). Our study only assessed final explicit recognition outcomes and did not examine implicit recognition processes. Future research should therefore investigate implicit emotion recognition mechanisms in individuals with PMPU. Employing ERP or fMRI to explore their brain activity patterns during emotion recognition would provide a more comprehensive understanding of these recognition processes.

Empirical results indicate that individuals with PMPU exhibit distinct tendencies in emotion recognition. Specifically, PMPU exerts a significant influence on the perception of facial emotions, particularly at moderate intensity levels. Individuals with PMPU demonstrate heightened accuracy in recognizing specific negative emotions, with a notable enhancement in sensitivity to disgust expressions. This heightened focus on negative emotional stimuli may interfere with their perception of positive emotions. Overemphasis on negative emotional cues could impair the ability to perceive positive emotions, thereby emerging as a noteworthy contributor to emotional and psychological difficulties in this population. Notably, presenting a diverse range of emotional stimuli may help mitigate the impact of these recognition tendencies on emotion processing.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant Number: 20BSH134).

Author Contributions: The author Bowei Go made contributions to this study, including experiment design, software programming, participant recruitment, experiment and questionnaire administration, data collection and organization, data analysis, paper writing, and paper revision. The author Xianli An made contributions to this study, including proposing research concepts, providing questionnaire materials, offering software and equipment resources, obtaining funding, guiding data analysis, revising the paper, and approving the final version. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data will be made available upon request.

Ethics Approval: This study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Educational Science at Yangzhou University (JKY-2021030401). Following all guidelines, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time and assured that personal information would remain confidential as requested.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Adolphs, R. (2002). Recognizing emotion from facial expressions: Psychological and neurological mechanisms. Behavior Cognitive Neuroscience Review, 1(1), 21–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582302001001003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Arafat, D., & Thoma, P. (2024). Impairments of sociocognitive functions in individuals with behavioral addictions: A review article. Journal of Gambling Studies, 40(2), 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-023-10227-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Arrivillaga, C., Elhai, J. D., Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2023). Depressive symptomatology is associated with problematic smartphone use severity in adolescents: The mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 17(3), 1802–7962. https://doi.org/10.5817/cp2023-3-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arzu, K. U., Neslihan, L., & Sefa, L. (2021). The relationship between happiness and smart phone addiction in regular physical exercises. Gymnasium: Scientific Journal of Education, Sports & Health, 22(2), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.29081/gsjesh.2021.22.2.05 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Aviezer, H., Trope, Y., & Todorov, A. (2012). Body cues, not facial expressions, discriminate between intense positive and negative emotions. Science, 338(6111), 1225. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1224313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bianchi, A., & Phillips, J. G. (2005). Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 8(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2005.8.39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Busch, P. A., & McCarthy, S. (2021). Antecedents and consequences of problematic smartphone use: A systematic literature review of an emerging research area. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 106414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106414 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Calvo, M. G., & Lundqvist, D. (2008). Facial expressions of emotion (KDEF): Identification under different display-duration conditions. Behavior Research Methods, 40(1), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.1.109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cardini, F., Tajadura-Jiménez, A., Serino, A., & Tsakiris, M. (2012). It feels like it’s me: Interpersonal multisensory stimulation enhances visual remapping of touch from other to self. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception & Performance, 39(3), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1163/187847612x648422 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cassidy, B. S., Boucher, K. L., Laniebs, S. T., & Krendl, A. C. (2019). Age effects on trustworthiness activation and trust biases in face perception. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Collisson, B., Saunders, E., & Yin, C. (2025). The ick: Disgust sensitivity, narcissism, and perfectionism in mate choice thresholds. Personality and Individual Differences, 238, 113086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2025.113086 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dondaine, T., Robert, G., Péron, J., Grandjean, D., Vérin, M. et al. (2014). Biases in facial and vocal emotion recognition in chronic schizophrenia. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 900. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00900. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Elhai J. D., Levine J. C., Dvorak R. D., & Hall B. J. (2016). Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.079 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Estévez A., Jáuregui P., Sánchez-Marcos I., López-González H., & Griffiths M. D. (2017). Attachment and emotion regulation in substance addictions and behavioral addictions. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 534–544. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Freeman, C. R., Wiers, C. E., Sloan, M. E., Amna, Z., Veronica, R. et al. (2018). Emotion recognition biases in alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism Clinical & Experimental Research, 42(8), 1541–1547. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gao, L., Zhang, Y., Chen, H., Li, X., Li, W. et al. (2023). Problematic mobile phone use inhibits aesthetic emotion with nature: The roles of presence and openness. Current Psychology, 42(24), 21085–21096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03175-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S. et al. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 849–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Glumbić, N., Brojčin, B., Žunić-Pavlović, V., & Đorđević, M. (2020). Problematic mobile phone use among adolescents with mild intellectual disability. Psihologija, 53(4), 359–376. https://doi.org/10.2298/psi190729014g [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hendel E., Gallant A., Mazerolle M-P., Cyr S-I., Roy-Charland A. (2023). Exploration of visual factors in the disgust-anger confusion: The importance of the mouth. Cognition and Emotion, 37(4), 835–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2023.2212892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hou, J., Zhu, Y., & Fang, X. (2021). Mobile phone addiction and depression: Multiple mediating effects of social anxiety and attentional bias to negative emotional information. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 53(4), 362–373. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1041.2021.00362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ikeda, S. (2023). Emotion recognition from ambiguous facial expressions and utterances: Relationship between implicit and explicit processing. Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 27(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.24193/cbb.2023.27.01 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jaeger, B., Todorov, A. T., Evans, A. M., & Beest, I. V. (2020). Can we reduce facial biases? Persistent effects of facial trustworthiness on sentencing decisions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 90, 104004. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/a8w2d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Juslin, P. N., & Laukka, P. (2001). Impact of intended emotion intensity on cue utilization and decoding accuracy in vocal expression of emotion. Emotion, 1(4), 381–412. https://doi.org/10.1037//1528-3542.1.4.381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Keating, C. T., Sowden, S., & Cook, J. L. (2022). Comparing internal representations of facial expression kinematics between autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism Research, 15(3), 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Killgore, W. D. S., Balkin, T. J., Yarnell, A. M., & Capaldi, V. F. (2017). Sleep deprivation impairs recognition of specific emotions. Neurobiology of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms, 3, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbscr.2017.01.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kuraoka, K., & Nakamura, K. (2006). Impacts of facial identity and type of emotion on responses of amygdala neurons. Neuroreport, 17(1), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wnr.0000194383.02999.c5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kwon, M., Kim, D. J., Cho, H., & Yang, S. (2013). The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS One, 8(12), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lee, T. H., Baek, J., Lu, Z. L., & Mather, M. (2014). How arousal modulates the visual contrast sensitivity function. Emotion, 14(5), 978. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Leung, L. (2008). Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Children & Media, 2(2), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482790802078565 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lipp, O. V., Craig, B. M., & Dat, M. C. (2015). A happy face advantage with male caucasian faces: It depends on the company you keep. Social Psychological & Personality Science, 6(1), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614546047 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mcelroy, T., & Young, W. (2024). Is having your cell phone the key to happiness, or does it really matter? Evidence from a randomized double-blind study. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01595-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Meehan, K. B., Panfilis, C. D., Cain, N. M., Antonucci, C., & Sambataro, F. (2017). Facial emotion recognition and borderline personality pathology. Psychiatry Research, 255, 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Meyers, K. K., Crane, N. A., O'Day, R., Zubieta, J. K., Giordani, B., Pomerleau, C. S. et al. (2015). Smoking history, and not depression, is related to deficits in detection of happy and sad faces. Addictive Behaviors, 41(1), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Oaten, M., Stevenson, R. J., & Case, T. I. (2009). Disgust as a disease-avoidance mechanism. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Olson, J. A., Sandra, D. A., Colucci, L. S., Albikaii, A., & Veissière, S. P. L. (2022). Smartphone addiction is increasing across the world: A meta-analysis of 24 countries. Computers in Human Behavior, 129, 107138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107138 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Panova T., & Carbonell X. (2018). Is smartphone addiction really an addiction? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ran, G., Li, J., Zhang, Q., & Niu, X. (2022). The association between social anxiety and mobile phone addiction: A three-level meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 130, 107198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107198 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Recio G., Schacht A., & Sommer W. (2014). Recognizing dynamic facial expressions of emotion: Specificity and intensity effects in event-related brain potentials. Biological Psychology, 96(1), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Reschke, P. J., Knothe, J. M., Lopez, L. D., & Walle, E. A. (2017). Putting “Context” in context: The effects of body posture and emotion scene on adult categorizations of disgust facial expressions. Emotion, 18(1), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Roy-Charland, A., Perron, M., Young, C., Boulard, J., & Chamberland, J. A. (2015). The confusion of fear and surprise: A developmental study of the perceptual-attentional limitation hypothesis using eye movements. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 176(5), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2015.1066301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rozgonjuk, D., & Elhai, J. D. (2019). Emotion regulation in relation to smartphone use: Process smartphone use mediates the association between expressive suppression and problematic smartphone use. Current Psychology, 40, 3246–3255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00271-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rozgonjuk, D., Levine, J. C., Hall, B. J., & Elhai, J. D. (2018). The association between problematic smartphone use, depression and anxiety symptom severity, and objectively measured smartphone use over one week. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.019 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Smith, B. W., Decruz-Dixon, N., Erickson, K., Guzman, A., Phan, A. et al. (2023). The effects of an online positive psychology course on happiness, health, and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24(3), 1145–1167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00577-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Squires, L. R., Hollett, K. B., Hesson, J., & Harris, N. (2020). Psychological distress, emotion dysregulation, and coping behaviour: A theoretical perspective of problematic smartphone use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 1284–1299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00224-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tottenham, N., Tanaka, J. W., Leon, A. C., Mccarry, T., Nurse, M. et al. (2009). The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Research, 168(3), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Uribe, S., & Meuret, A. E. (2024). Examining the influence of social anxiety biases on emotion recognition for masked versus unmasked facial expressions. Journal of Experimential Psychopathology, 15(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438087241277573 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Kleef, R. S., Marsman, J. B. C., van Valen, E., Bockting, C. L., Aleman, A. et al. (2022). Neural basis of positive and negative emotion regulation in remitted depression. NeuroImage: Clinical, 34, 102988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2022.102988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, J., & Li, H. (2023). Emotional processing deficits in individuals with problematic pornography use: Unpleasant bias and pleasant blunting. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 12(4), 1046–1060. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2023.00058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Whitton, A. E., Proudfoot, J., Clarke, J., Birch, M. R., Parker, G. et al. (2015). Breaking open the black box: Isolating the most potent features of a web and mobile phone-based intervention for depression, anxiety, and stress. JMIR Mental Health, 2(1), e3573. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.357 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wicker, B., Keysers, C., Plailly, J., Royet, J. P., Gallese, V. et al. (2003). Both of us disgusted in my insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron, 40(3), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00679-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zebrowitz, L. A., Franklin, R. G., Hillman, S., & Boc, H. (2013). Older and younger adults’ first impressions from faces: Similar in agreement but different in positivity. Psychology & Aging, 28(1), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools