Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Monetary reward and punishment effects on behavioral inhibition in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder tendencies

1 Department of Psychology, School of Education Sciences, Guangdong Polytechnic Normal University, Guangzhou, 510665, China

2 Heyuan Dapugang Primary School of Guangdong Province, Heyuan, 517000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Huifang Yang. Email: ,

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(4), 535-540. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.070124

Received 11 February 2025; Accepted 26 May 2025; Issue published 17 August 2025

Abstract

The study investigated the effects of monetary rewards and punishments on the behavioral inhibition in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) tendencies. The present study adopted the signal stopping task paradigm, with 66 children with ADHD tendencies as the research subjects. A mixed design of 2 (reward and punishment type: reward, punishment) × 2 (stimulus type: monetary stimulus, social stimulus) was used. The analysis applied a between intervention group (with reward and punishment type variables) and within type of reward approach (by stimulus type as intra subject variables). The results showed that monetary punishment better promotes behavioral inhibition in children with an ADHD tendency than does reward. In addition, this study showed that monetary punishment and social rewards affected the speed–accuracy trade-off of inhibited behavior in children with an ADHD tendency. These findings suggest that withdrawal of a material token resulted in more behavioural compliance in children with an ADHD tendency.Keywords

Behavioural regulation in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is primary to their management in school settings. ADHD is a chronic neurodevelopmental and behavioral disorder that occurs often in childhood and adolescence, with a current global prevalence of approximately 5% (Khamzina et al., 2024). However, a seemingly larger number of children present with ADHD tendencies. These are children with a tendency for ADHD, who exhibit behavioral problems and characteristics similar to those of children with ADHD but do not fully meet the diagnostic criteria therefor (Veenman et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2016). Improving behavioral inhibition in children with ADHD and those with an ADHD tendency is important to improve their core deficits. Children with ADHD tendencies are an understudied population their behavioural regulation, hence this study.

Children with ADHA Tendencies. Children with ADHD tendency learn with normal children, but their behaviors, such as wandering, impulsivity, and hyperactivity, tend to disrupt the classroom. Educators often use rewards and punishments as a means of encouraging individuals to inhibit task-irrelevant or inappropriate behaviors to achieve goals, and to reduce problematic behaviors by promoting the development of behavioral inhibition and improving participation in classroom activities (Li et al., 2019; Janina & Claudia, 2021). Therefore, exploring the relationship among rewards, punishments, and behavioral inhibition in children with ADHD plays an important role in education and intervention.

There is evidence to suggest ADHD tendency behavioral problems can be significantly improved through early intervention in this group (Ou et al., 2022). The limited research evidence on behavioural inhibition among children with ADHD tendency is a hinderance to intervention design for their improved education outcomes.

Behavioral inhibition: nature and theory. Barkley (1997) proposed a behavioral response inhibition model of ADHD and argued that response inhibition deficits are at the core of ADHD. Response inhibition, also known as behavioral inhibition, is a process that regulates an individual’s cognition and behavior; certain habitual or dominant behaviors can be inhibited to prevent inappropriate responses, where the brain must control behavior to achieve better performance (Li et al., 2019; Miyasaka & Nomura, 2023). For example.

Gray’s (2000) reinforcement sensitivity theory (RST) explains the relationship among rewards, punishments, and behavioral inhibition. According to RST, when an individual is exposed to a certain stimulus, it activates a specific neural system, and their behaviors, emotions, and motives change. The theory suggests that there are two types of neural systems: the behavioral approach system, which is sensitive to rewarding stimuli and promotes behavior, and the behavioral inhibition system (BIS), which is sensitive to punishing stimuli and inhibits behavior.

Logan’s (1994) stop-signal task (SST) is widely used reinforcement sensitivity theory inhibit behavioural dysregulation. The SST requires subjects to recognize a single stimulus quickly and accurately and to rapidly switch between a reactive state and an inhibited state after a specific time interval regardless of the presence or absence of a stop signal. Response speed and the ability to inhibit behaviors can be effectively assessed using the SST (Shao, 2017).

Rewards and punishment. Children with ADHD are usually more sensitive to rewarding stimuli than the average child, of which there is less evidence regarding children with ADHD tendencies. Moreover, while rewards are effective in improving inhibited movement in children with ADHD, but no conclusion has been drawn about their sensitivity to punishing stimuli (Furukawa et al., 2019; Xiao, et al., 2020; Jiang & Yan, 2022). Therefore, more research is needed on punishment sensitivity in children with ADHD tendencies.

Extrinsic feedback rewards and punishments promote behavioral inhibition, but many factors influence the effectiveness of rewards and punishments, including the magnitude (Herrera et al., 2014), frequency (Lan & Li, 2015), and type of reward or punishment (Furukawa et al., 2019). The type of reward or punishment affects reward processing in individuals with ADHD, and social and monetary rewards are processed by different neural networks (Baumann et al., 2022). Some studies show that patients with ADHD are more sensitive to monetary feedback than social feedback and that monetary feedback is more inhibitory (Miyasaka & Nomura, 2019; Sutcubasi et al., 2018), but money is not the only way to encourage learning and performance, and the effects of verbal feedback continue to play a role in the development of children with ADHD (Miyasaka & Nomura, 2019, 2023). Therefore, the effects of implementing different types of rewards and punishments should be considered when designing reward and punishment tests.

Informed by SST propositions, we aimed to explore the effects of four types of rewards and punishments, namely monetary rewards, social rewards, monetary punishments, and social punishments, on the behavioral inhibition ability of children with ADHD tendencies. We hypothesized the following regarding behavioural inhibition in children with ADHD tendencies by reward/punishment and stimulus types:

(1) The behavior inhibition rate of the punishment group is higher than that of the reward group;

(2) The behavioral inhibition rate of children with ADHD tendency under social stimuli is higher than that under monetary stimuli;

(3) The effects of monetary rewards, social rewards, monetary punishments, and social punishments on inhibitory behavior in children with ADHD tendencies vary.

Increasingly, education systems are adopting inclusive education practices. Inclusive education is an educational philosophy in which all students are embraced and provided with opportunities to learn and operate within the mainstream schooling framework, guaranteeing that children with special needs enjoy quality education (Miao, 2022; Hornby & Kauffman, 2024; Khamzina et al., 2024).

Research design and ethics approval

The Institutional Review Board of Department of Psychology at Guangdong Polytechnic Normal University approved the study. Parenst of the children consented to the study and the children assented to the study in writing. The SST was programmed in E-Prime 3.0. The SST was presented on a computer screen, and the experiment was conducted in the activity rooms of the elementary schools. Two conditions, one with the stop signal and the other without, were presented randomly in the SST, accounting for 25% and 75% of the trials, respectively. Considering the short attention span of children with an ADHD tendency, the experiment was designed to last 10 min.

The experiment was divided into a practice phase and a formal experimental phase. Eight trials were completed during the practice phase, and feedback was provided in the form of the neutral words “correct” and “incorrect” to familiarize subjects with the rules. In the formal experiment, 80 trials were divided into two phases, each comprising 40 trials, with a 1-min rest period between phases. Feedback was provided in the form of different reward and punishment pictures (gold coins as monetary stimuli and emotions as social stimuli) (Li et al., 2015). The groups received different instructions.

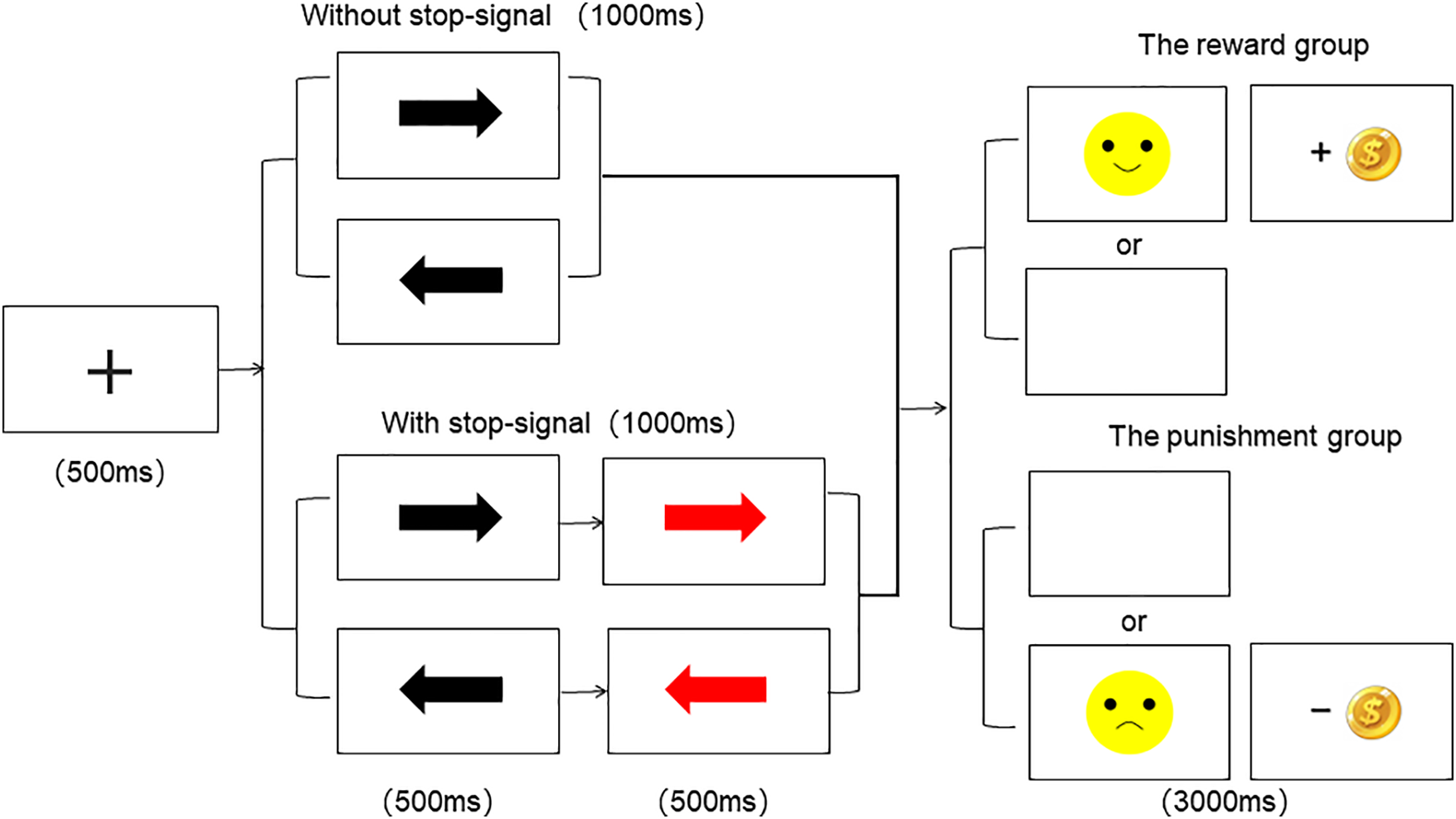

The experiment used a 2 (reward and punishment) × 2 (monetary stimuli and social stimuli) mixed design (see Figure 1). The between-subjects factor was group, and the within-subjects factor was stimulus type. The dependent variables were the response times (RTs) and accuracy rates on the SST. The SST has both variable and constant stop-signal delays (SSDs), which have similar behavioral inhibition effects (Sinopoli et al., 2011). In the constant SSD condition, the stop signal appeared 500 ms after the target stimulus. For the condition without the stop signal, delayed RTs were included, so the RTs in this condition were used as an indirect indicator of behavioral inhibition. As the stop-signal response was terminated before completion in the constant SSD condition, RT could not be measured directly, so the RT for the condition without the stop signal and the accuracy rate for the condition with the stop signal were used as objective metrics of behavioral inhibition (Eagle & Baunez, 2010; Li et al., 2015).

Figure 1: The SST experimental process

A total of 245 children with an ADHD tendency were identified. Among them, 66 children (46 boys and 20 girls; mean age, 10 ± 1.02 years) were randomly selected to complete the SST. According to the results, the rate of ADHD was higher in boys than girls. The male-to-female ratio in the literature ranges from 1.9:1 to 3.2:1 (Salari et al., 2023), and the sex ratio was not controlled in this study. All participants were screened and completed the questionnaires. The participants had no other psychiatric disorders or any history of medication use within the last 6 months, and were not enrolled in other interventions. The participants had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity, were right-handed, and were not color blind or color deficient.

The sample size was calculated using G* Power 3.1 software. For a medium effect size (f = 0.25), the sample size required for each group was ≥33 to achieve 80% power at a significance level of 0.05. The criteria and selection procedures for children with an ADHD tendency were as follows by parent and teacher rating as described next

Parents and teachers of students in grades 3–5 from five elementary schools completed the Chinese versions of Conner’s Parent Symptom Questionnaire (PSQ) and the Teacher Rating Scale (TRS), adapted by Fan and Du (2004).

The Conner’s Parent Symptom Questionnaire (PSQ). This PSQ consists of 48 items on six behavioural factors of Conduct Problems, Learning Problems, Psychosomatic, Impulsive-Hyperactive, Anxiety, and the Hyperactivity Index. The questionnaire is scored on a 4-point scale with answer options of “none”, “a little more”, “quite a bit”, and “a lot”. The Z score was obtained by summing the scores for each question and dividing the total by the number of items. A Hyperactivity Index Z score ≥ 1.5 is considered indicative of ADHD. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the PSQ is 0.92, representing good validity (Su et al., 2001a). The PSQ has good reliability and validity with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.93 for the total questionnaire (Fan & Du, 2004). In this study, the internal consistency reliability coefficient of the PSQ was 0.974.

Teacher Rating Scale (TRS). The teachers completed the TRS on the children, The TRS comprises 28 questions. The TRS Cronbach’s α coefficient a previous study was 0.95, indicating good validity (Su et al., 2001b). The TRS scores had good reliability and validity with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.91, and the internal consistency reliability coefficient of the TRS was 0.95 in this study.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

In this study, 66 children with an ADHD tendency were screened for ADHD according to a Z-score on the Hyperactivity Index ≥ 1.5 and the results on the Chinese versions of the PSQ and TRS, and they were randomly divided into reward and punishment groups.

In the SST condition without the stop signal, participants were required to make a quick keystroke response based on the direction of the black arrow (“Q” key for leftward and “P” key for rightward). Participants were prohibited from responding when the black arrow turned red after 500 ms. The left and right arrows had the same probability of appearing and turning red. The screen presented stimuli according to the participant’s response. The “reward group” saw a gold coin or a smiley face after each correct response (up to a maximum of 40 gold coins), while no feedback was given for incorrect responses. The “punishment group” was deducted one gold coin for each incorrect response, while no feedback was given for correct responses (Figure 1). The time between each trial was 1000 ms.

Data were processed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), all outliers (±3 standard deviations relative to the mean) were excluded. Repeated-measures ANOVA was employed to determine main effect of group on the accuracy rate by condition.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics.

Repeated-measures ANOVA showed that the main effect of group on the accuracy rate on the SST was borderline significant F (1, 64) = 3.99, p = 0.05, ηp2 = 0.06). The punishment group had a higher accuracy rate than the reward group, suggesting that punishment promotes behavioral inhibition in children with an ADHD tendency. Hypothesis 1 was supported. The interaction between group and stimulant was not significant, F (1, 64) = 0.22, p = 0.64. The main effect of stimulant was also nonsignificant, F (1, 64) = 0.67, p = 0.42. The group × stimulant interaction effect on RT was not significant for the condition without the stop signal, F (1, 64) = 0.66, p = 0.42. Hypothesis 3 was not supported. he main effect of group was also nonsignificant, F (1, 64) = 0.23, p = 0.64. Hypothesis 1 was not supported.

Pearson’s correlation analyses were conducted on the RT and accuracy rates in the SST condition without the stop signal, separately for each group (Li et al., 2015). The results showed the RT and accuracy rate of the reward group under social stimuli were positively correlated at the 0.01 level (r = 0.59), indicating that social reward drove subjects to improve their RT and accuracy, while no significant correlation was detected under the monetary stimuli. Hypothesis 2 was supported in some parts. The RT and accuracy rate under the monetary stimuli were significantly and positively correlated at the 0.05 level (r = 0.37) in the punishment group, suggesting that monetary punishment drives subjects to improve accuracy and RTs to avoid punishment. Hypothesis 3 was supported. No significant correlation was detected under the social stimuli. Hypothesis 2 was not supported.

To explore whether rewards and punishments affect behavioral inhibition in children with an ADHD tendency, as in children with ADHD, the present study assessed the performance of children with an ADHD tendency using the SST with monetary reward, social reward, monetary punishment, and social punishment conditions.

First, punishment promoted behavioral inhibition more than reward in children with an ADHD tendency. Consistent with the results of a previous study on children with ADHD (Furukawa et al., 2019), this may be related to the reinforcement sensitivity of children with ADHD, who are more sensitive to punishment. Children with an ADHD tendency are more averse to punishment; they are prone to avoidance, withdrawal, and anxiety in the face of punishment (Furukawa et al., 2017). Gray’s RST states that behavior is inhibited when the BIS system is activated. Participants are required to inhibit their dominant responses in tasks with a stop signal, and these inhibitory processes create conflict and activate the BIS system, which accelerates behavioral inhibition (Amiri, 2018).

Previous research has shown that reinforcement improves inhibitory control in children and adolescents with ADHD (Ili et al., 2016), but the relationship among rewards, punishments, and inhibitory control may be moderated by other factors, and rewards and punishments may affect children with ADHD differently depending on their developmental stage, the task requirements, and the reward or punishment method (Miyasaka & Nomura, 2023).

Second, there was a nonsignificant effect of the type of stimuli on behavioral inhibition in children with an ADHD tendency. Demurie et al. (2011, 2016) reported that children with ADHD are more sensitive to monetary stimuli than social stimuli, yet no other studies have reported that behavioral inhibition in children with ADHD is differentially affected by different reward and punishment stimuli (Miyasaka & Nomura, 2023). However, they found an age effect, suggesting that verbal feedback plays a role as children with ADHD develop. Thus, this study considered both changes in behavioral inhibition according to the developmental stage of the individual as well as children’s processing of monetary and social rewards.

Children with ADHD must inhibit impulsivity/hyperactivity and inattentive behaviors if they want to learn in the classroom. Moreover, behavioral inhibition deficits are predictive of ADHD, and behavioral inhibition in children with ADHD is significantly weaker than in normal children (Puiu et al., 2018). However, children with ADHD are more sensitive to punishment than controls (Furukawa et al., 2017), which could be the case with those with ADHD tendencies.

The present study showed that monetary punishment and social rewards affect the speed–accuracy trade-off as it relates to inhibitory behavior in children with an ADHD tendency. As the relationship among rewards, punishments, and inhibitory control may be moderated by other factors, there may be variability in the mechanisms by which rewards and punishments occur.

Study limitations and suggestions for further research

The present study had some limitations. The nonsignificant results in this study may relate to the ecological validity of the experiment. The monetary rewards used by Demurie et al. (2016) were actual amounts, such as “you earned 5 euros”, and the social rewards were pictograms of interactions between two people, in which one person gave a “thumbs up” and praised the other’s performance. In contrast, we used picture stimuli with one-way feedback. The monetary stimuli were pictures of gold coins, and the social stimuli were pictures of facial expressions. Pictograms are considered to be valid ecological rewards, and future research should consider using experimental materials with higher ecological validity.

Future research should continue to explore the effects of different rewards and punishments on the inhibition of behavior in children with an ADHD tendency, including through multivariate analyses and the use of different frequencies, types, and timings of rewards and punishments. Personality traits, such as reinforcement sensitivity, should also be considered, as well as developmental changes. Finally, it is necessary to design experimental materials closer to the real-world situation and combine them with a variety of quantitative indicators, such as cerebral, cardiac, or skin electrical activity, among other physiological indicators, to increase the accuracy of the results.

In conclusion, different reward and punishment stimuli can affect behavioral inhibition in children with an ADHD tendency. The academic community has not yet elucidated the mechanisms underlying reward and punishment in children with ADHD (Le et al., 2019). More research is needed on this group, as well as in children with an ADHD tendency, to provide practical and theoretical guidance on teaching and interventions in the context of integrated education.

Acknowledgement: We thank the participants who participated in this study.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National General Projects in 2020 of the 13th Five Year Plan of National Education Science in China: A Study on Attention Training Interventions for ADHD Children in Regular Classes from the Perspective of Educational Neuroscience (BHA200123).

Author Contributions: The investigation, formal data analysis, and first drafting was completed by Peixuan Kuang. Huifang Yang was the corresponding author who contributed to the entirety of the conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and review. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted after obtaining Institutional Review Board approval from the Department of Psychology at Guangdong Polytechnic Normal University. We received the consent of all participants before survey began. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Amiri, S. (2018). Study of retrospective, prospective memory and cognitive ability according to the reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality: behavior approach and behavioral inhibition. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 5(4), 51–60. [Google Scholar]

Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Baumann, S., Hartz, A., Scharke, W., De Brito, S. A., Fairchild, G. et al. (2022). Differentiating brain function of punishment versus reward processing in conduct disorder with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 23(5), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2021.1995809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Demurie, E., Roeyers, H., Baeyens, D., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2011). Common alterations in sensitivity to type but not amount of reward in ADHD and autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(11), 1164–1173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02374.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Demurie, E., Roeyers, H., Wiersema, J. R., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2016). No evidence for inhibitory deficits or altered reward processing in ADHD: Data from a new integrated monetary incentive delay go/no-go task. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(4), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054712473179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Eagle, D. M., & Baunez, C. (2010). Is there an inhibitoryresponse-control system in the rat? Evidence from anatomical and pharmacological studies of behavioral inhibition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(1), 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fan, J. & Du, Y. S. (2004). Research on the norms and reliability of the Conners Teacher Evaluation Scale in Chinese cities. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 16(2), 67–71. [Google Scholar]

Furukawa, E., Alsop, B., Shimabukuro, S., & Tripp, G. (2019). Is increased sensitivity to punishment a common characteristic of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder? An experimental study of response allocation in Japanese children. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11(4), 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-019-00307-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Furukawa, E., Alsop, B., Sowerby, P., Jensen, S., & Tripp, G. (2017). Evidence for increased behavioral control by punishment in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 58(3), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gray, J. A. & McNaughton, N. (2000). The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Gu, L., Bai, X. J., & Wang, Q. (2014). Timeliness of impact of reward/punishment stimulations on behavioral inhibition ability and automatic physiological responses. Psychological Journal, 46(10), 1476–1485. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1041.2014.01476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Herrera, P. M., Mario, S., Adam, H., & Bekinschtein, T. A. (2014). Monetary rewards modulate inhibitory control. Frontiers in Human Neuroence, 8, 257. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hornby, G., & Kauffman, J. (2024). Inclusive education, intellectual disabilities and the demise of full inclusion. Journal of Intelligence, 12(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12020020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ili, M., Anna, V. D., & Anouk, S. (2016). The interaction between reinforcement and inhibitory control in ADHD: A review and research guidelines. Clinical Psychology Review, 44, 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.01.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Janina, R. M., & Claudia, P. (2021). The influence of associative reward learning on motor inhibition. Psychological Research, 86(1), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-021-01485-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jiang, D. ei, & Yan, H. H. (2022). Effects of rewards and punishments on filtering novel distracting stimuli in children with ADHD. Psychology Letters, 5(1), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.12100/j.issn.2096-5494.222008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Khamzina, K., Stanczak, A., Brasselet, C., Desombre, C., Legrain, C. et al. (2024). Designing effective pre-service teacher training in inclusive education: A narrative review of the effects of duration and content delivery mode on teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education. Educational Psychology Review, 36(1), 13–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09851-8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lan, J. J., & Li, Q. (2015). The effects of reward and punishment on inhibitory control functioning in children with mild intellectual disabilities. Contemporary Educational Theory and Practice, 7(3), 147–149. [Google Scholar]

Le, T. M., Wang, W., Zhornitsky, S., Dhingra, I., & Li, C. S. R. (2019). Interdependent neural correlates of reward and punishment sensitivity during rewarded action and inhibition of action. Cerebral Cortex, 30(3), 1662–1676. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhz194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, G., Bai, X. J., & Wang, Q. (2015). Effects of reward and punishment on behavioral inhibition and autonomic physiological responses in the procedural phase. Psychological Journal, 47(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2015.00039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, W., Zheng, C., Jiang, T., & Chen, Y. (2019). A study of gender differences in individual behavioral inhibition under conditions of monetary, social rewards and punishments. In: Abstracts Collection of the 22nd National Academic Conference on Psychology. (pp. 1119–1120). [Google Scholar]

Logan, G. D. (1994). On the ability to inhibit thought and action: A users’ guide to the stop signal paradigm. In: Inhibitory processes in attention memory & language (pp. 189–239). San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

Ma, H. X., Gong, R., Yang, Q., Zhu, Y. L., & Liu, R. N. (2016). Effects of emotion on time-distance estimation and aversion latency in Children with ADHD tendency. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24(3), 389–394. [Google Scholar]

Miao, X. Y. (2022). Analysis of hotspots in Chinese study of classroom-based education. Chinese Journal of Special Education, (12), 16–22. [Google Scholar]

Miyasaka, M., & Nomura, M. (2019). Asymmetric developmental change regarding the effect of reward and punishment on response inhibition. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 12882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49037-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Miyasaka, M., & Nomura, M. (2023). Effect of financial and non-financial reward and punishment for inhibitory control in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 134(1), 104438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2023.104438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ou, Z. X., Yang, C. Y., Fu, T., Yang, L. T., Peng, J. Y. et al. (2022). Effects of core symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder on behavioral problems in Children with ADHD tendency. Sichuan Mental Health, 35(6), 518–523. [Google Scholar]

Puiu, A. A., Wudarczyk, O., Goerlich, K. S., Votinov, M., Konrad, K. et al. (2018). Impulsive aggression and response inhibition in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Disruptive Behavioral Disorders: Findings from a systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 90(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Salari, N., Ghasemi, H., Abdoli, N., Rahmani, A., Shiri, M. H. et al. (2023). The global prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 49(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

Sinopoli, K. J., Schachar, R., & Dennis, M. (2011). Reward improves cancellation and restraint inhibition across childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1479–1489. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Shao, H. H. (2017). The effects of reward and punishment cues, attentional load on inhibitory control of impulsive individuals [Master’s thesis]. Xi'an, China: Shaanxi Normal University. [Google Scholar]

Su, L. Y., Li, X. R., Huang, C. X., Luo, X. R., & Zhang, J. S. (2001a). The national collaborative group for the child behavior rating scale. The conners parent symptom questionnaire for urban Chinese norms. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 9(4), 4. [Google Scholar]

Su, L. Y., Xie, G. R., Luo, X. R., Zhang, J. S., & Li, X. R. (2001b). Conners Teacher Rating Scale for urban China norms. Chinese Journal of Practical Pediatrics, 16(12), 4. [Google Scholar]

Sutcubasi, B., Metin, B., Tas, C., Krzan, F. K., Sarı, B. A. et al. (2018). The relationship between responsiveness to social and monetary rewards and ADHD symptoms. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 18, 857–868. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-018-0609-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Veenman, B., Luman, M., Hoeksma, J., Pieterse, K., & Oosterlaan, J. (2019). A randomized effectiveness trial of a behavioral teacher program targeting ADHD symptoms. J Atten Disord, 23(3), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716658124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xiao, H., Liu, B., & Cao, A. (2020). Research progress on reinforcement sensitivity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Chinese Journal of Child Health, 28(7), 769–773. https://doi.org/10.11852/zgetbjzz2019-1401 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools