Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Transformational leadership effects on employee bootleg innovation in the context of digital transformation: Creative self-efficacy mediation and leader-member exchange moderation

1 School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China, Beijing, 100872, China

2 State Administration for Market Regulation Development Research Center, Beijing, 100820, China

3 Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation, Beijing, 100710, China

* Corresponding Author: Feng Hu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(4), 513-521. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.070126

Received 18 February 2025; Accepted 25 May 2025; Issue published 17 August 2025

Abstract

This study examined the relationship between transformational leadership and employee bootleg innovation through the mediating role of creative self-efficacy and the moderating role of leader-member exchange (LMX). Data were collected from 279 employees and 56 matched supervisors within a large Chinese digital transformation group. A moderated mediation model analysis found that transformational leadership predicts higher employee bootleg innovation. Creative self-efficacy mediated the positive relationship between transformational leadership and employee bootleg. Additionally, leader-member exchange significantly moderated the relationship between transformational leadership and creative self-efficacy, for a further enhancement of bootleg innovation. These findings underscore the importance of transformative leadership in fostering digital employee innovation. This study provides further evidence of the relevance of self-determination theory in explaining the leadership and employee innovation, relationship within the context of digital transformation. By implication, creative self-efficacy and leader-member exchange are modifiable factors by digital transformation entities seeking a competitive advantage.Keywords

Leadership type is pivotal for digital transformation when it supports employee motivation and innovation (Imran et al., 2021). Digital transformation is for embracing new technologies to maintain competitiveness in a dynamic environment (Zhang & Chen, 2024) and capitalizing on continuous improvement (Zhao et al., 2022; Zimmer et al., 2023). The transformational leadership style appears to have high prospects to inspire employee creativity through providing a visionary and inspirational environment that encourages innovative thinking (Gong et al., 2023). Bootleg innovation is a trending, competitive practice. Bootleg innovation is characterized by unsanctioned and self-directed employee innovation activities (Criscuolo et al., 2014), employing informal methods to overcome organizational constraints and address complex challenges (Huang et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2022). Logically, digital transformation with bootleg innovation requires employees with creative self-efficacy, or belief in their creative abilities. Important, employees would likely exhibit creative self-efficacy if they have high-quality leader-member exchange (LMX) relationships. These relationships, marked by trust, respect, and open communication, can foster bootleg innovation (Buch, 2015). We aimed to investigate these relationships in a digital transformation context to identity leads that would promote managerial practices for organizational competitiveness

Transformational leadership and bootleg innovation

Transformational leadership is a style where leaders inspire and influence their followers by encouraging innovation, challenging norms, and fostering a shared vision (MacKie & Kaiser, 2014). Known for its visionary, charismatic, and supportive qualities, transformational leadership motivates employees to think creatively and take ownership of their work (Jun & Lee, 2023). Research consistently demonstrates a positive relationship between transformational leadership and innovation (Gad David et al., 2023; Gong et al., 2023).

In this study, we posit that transformational leadership positively influences employee bootleg innovation, a form of unsanctioned, self-directed innovative behavior aimed at benefiting the organization (Augsdorfer, 2012). Unlike negative deviant behaviors, bootleg innovation challenges the status quo constructively, driven primarily by intrinsic motivation (Vadera et al., 2013). Leadership plays a pivotal role in fostering environments where employees feel encouraged to pursue such innovative ideas outside formal organizational channels (Lin et al., 2024).

Transformational leadership promotes bootleg innovation through three core components: inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration (Bass & Riggio, 2005). Inspirational motivation involves articulating a compelling vision that empowers employees to strive for excellence and explore innovative solutions autonomously (Augsdorfer, 2012). Intellectual stimulation encourages employees to challenge the status quo and think critically, fostering a psychologically safe environment for risk-taking and creative exploration (Criscuolo et al., 2014). Individualized consideration provides personalized support and recognizes employees’ unique strengths, making them feel valued and motivated to pursue their creative endeavors (Awan & Jehanzeb, 2022). This personalized attention helps employees trust their leader’s support for autonomy and innovation. Together, these components create a culture of empowerment and ownership, essential for driving bootleg innovation in organizational settings (Gad David et al., 2023; Gong et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023a).

Mediating role of creative self-efficacy

Creative self-efficacy or the belief in one’s capacity to generate creative outcomes, is central to understanding innovative behaviors such as bootleg innovation (Tierney & Farmer, 2002). Employees with high creative self-efficacy are more likely to take risks, explore unconventional solutions, and pursue innovative projects independently, even without formal organizational approval (Shalley et al., 2004). This psychological confidence enables them to overcome challenges and engage in self-directed, proactive behaviors necessary for bootleg innovation.

Transformational leadership fosters creative self-efficacy through individualized consideration and intellectual stimulation (Bass, 1985). Individualized consideration involves personalized support and encouragement, helping employees recognize their creative potential and feel valued in their contributions (Criscuolo et al., 2014). Intellectual stimulation challenges employees to think critically, question assumptions, and explore new possibilities, building their confidence in generating innovative solutions (Shin & Zhou, 2003). By promoting these behaviors, transformational leadership creates an environment where employees feel empowered to take creative risks, strengthening their creative self-efficacy.

As a mediator, creative self-efficacy would bridge the gap between transformational leadership and bootleg innovation. For instance, employees who believe in their creative abilities are more likely to engage in unsanctioned innovation, even when formal support is absent (Gong et al., 2009). Also, stronger social networks are associated with higher bootleg innovation (Cao & Xue, 2023). These findings suggest creative self-efficacy’s critical role as a psychological mechanism linking leadership to innovative behaviors.

Moderating role of leader-member exchange

Leader-member exchange (LMX) plays a critical moderating role in the relationship between transformational leadership and creative self-efficacy, as suggested by social-exchange theory (Martin et al., 2016). High-quality LMX relationships, characterized by trust, mutual respect, and open communication, enhance employees’ intrinsic motivation, making them more receptive to transformational leadership behaviors (Hackett et al., 2018). Employees in such relationships feel valued and supported, which amplifies the influence of transformational leadership on their belief in their creative abilities (Buch, 2015; Wang et al., 2005).

Transformational leaders inspire confidence in employees through individualized consideration and intellectual stimulation. When coupled with strong LMX, this encouragement leads employees to internalize their leader’s support and believe in their creative potential. This, in turn, fosters creative self-efficacy, a critical driver of innovative behaviors like bootleg innovation (Shin & Zhou, 2003). In contrast, employees in low-quality LMX relationships may not fully benefit from transformational leadership, as the absence of trust and support weakens their confidence in pursuing innovation (Hackett et al., 2018; Tierney & Farmer, 2002).

Furthermore, high-quality LMX provides employees with greater autonomy and resources, enabling them to take proactive, self-directed actions toward innovation (Stewart & Johnson, 2009) These interactions highlight LMX’s role in bridging transformational leadership and creative self-efficacy, thereby strengthening the motivational processes necessary for bootleg innovation (Buch, 2015; Stewart & Johnson, 2009; Van Dyne et al., 2002). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Research has shown that individual-level variables, such as self-efficacy, are key predictors of idea generation, while managerial support serves as a significant predictor of innovative endeavors (Hughes et al., 2018; Magadley & Birdi, 2012). Building on these insights, this study establishes a comprehensive framework to promote bootleg innovation by integrating intrinsic motivation (creative self-efficacy), external contextual stimuli (transformational leadership), and the interplay between internal and external factors (leader-member exchange). Given this theoretical foundation, Hypothesis 4 synthesizes these relationships within a moderated mediation framework. Specifically, it suggests that creative self-efficacy mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and bootleg innovation, while LMX moderates this mediation process.

Self-termination theory mechanisms of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are likely drive creativity and innovation at individual, team, and organizational levels (Hughes et al., 2018). For instance, intrinsic motivation would be a core driver of workplace creativity crucial for bootleg innovation, which requires higher levels of proactive involvement (Amabile, 1996; Liu et al., 2024). Intrinsic motivation presumes a transformational leadership style for innovative behaviors (Rank et al., 2009). Leadership type would be an extrinsic motivation factor that creates the environment for innovation potential to become a reality (Lin et al., 2024). For instance, transformational leadership stimulates intrinsic motivation, enhancing creative self-efficacy and encouraging bootleg innovation (Kim et al., 2023). While prior research emphasizes intrinsic motivation innovation behavior, the interaction between intrinsic and extrinsic factors remain underexplored. This study addresses this gap by focusing on leader-member exchange (LMX), which bridges intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

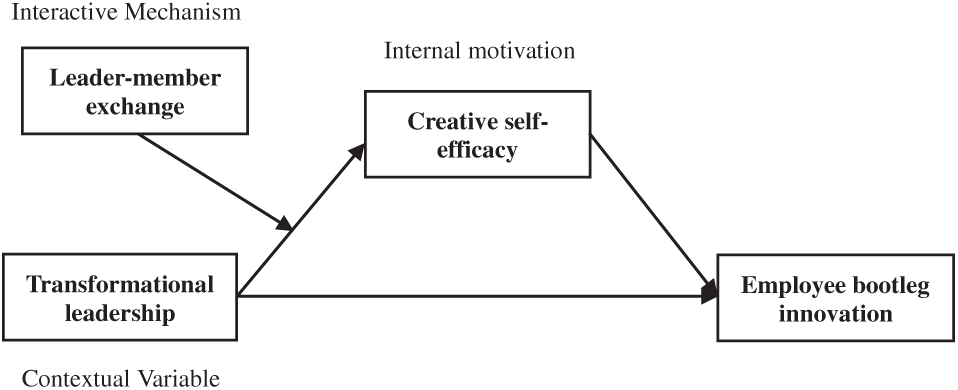

In summary, Figure 1 presents our conceptual combining these internal and external factors to explore how transformational leadership promotes bootleg innovation behavior in the context of digital transformation leveraging employee creative self-efficacy and LMX.

Figure 1: Study conceptual model

Goals of the study. Based on our theoretical research model, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Transformational leadership positively influences employee bootleg innovation.

H2: Creative self-efficacy plays the mediating role of transformational leadership on employee bootleg innovation.

H3: Leader-member exchange plays the moderating role of transformational leadership on creative self-efficacy.

H4: Creative self-efficacy and leader-member exchange jointly play a moderated mediating role in the relationship of transformational leadership on employee bootleg innovation.

By integrating intrinsic motivation (creative self-efficacy), contextual leadership (transformational leadership), and interactive mechanisms (LMX), this study has prospects to significantly contribute to the knowledge base on bootleg innovation in the digital industry context.

Participants and data collection

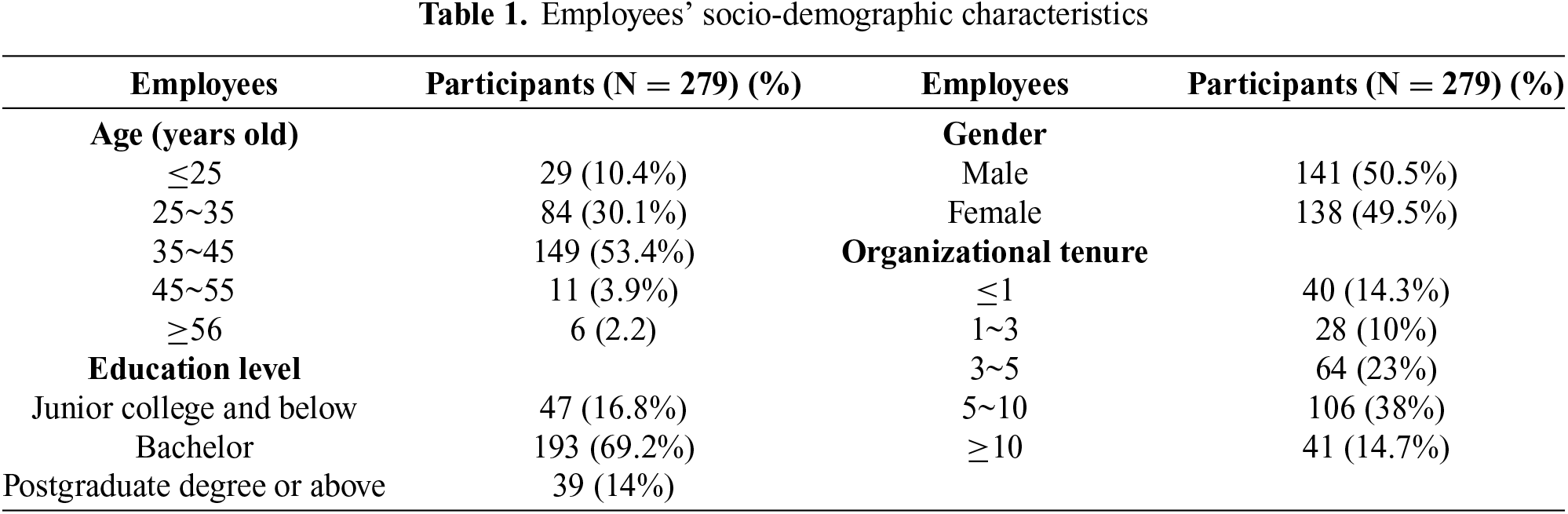

Data were collected from 279 employees and marched 56 supervising leaders. The questionnaire gathered demographic information from 279 employees (see Table 1), and their perceptions of transformational leadership and creative self-efficacy, while data on leader-member exchange and employee bootleg innovation were provided by their 56 supervising leaders.

Validated measures were employed and with back translation from the original English versions into Chinese by responses were scores on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Transformational Leadership. We employed a modified version of the 8-item Transformational Leadership Scale, originally adapted by Chinese scholars (Chen et al., 2006), which incorporated key research insights from previous studies (Bass, 1985; Waldman et al., 2001). A sample item is “My leader shows determination in accomplishing the goal.” The Transformational Leadership Scale scores yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.886, a CR value of 0.911, and an AVE value of 0.562, indicating high internal consistency reliability and good convergent validity. To justify aggregation, we assessed intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) due to the multilevel data structure. The results showed an ICC (1) value of 0.36 and an ICC (2) value of 0.74, suggesting high within-group agreement and reliability of group means.

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX). To assess the quality of the leader-member relationship, we used a 7-item scale developed (Scandura & Graen, 1984). The original LMX questionnaire was answered by employees. In our study, it was completed by leaders, so we modified the wording accordingly. Sample items include: “My subordinates know how satisfied I am with what they do,” and “I have enough confidence in my subordinates that they would defend and justify my decisions if I were not present to do so”. Leader-Member Exchange has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.870, a CR value of 0.902, and an AVE value of 0.569, demonstrating strong reliability and acceptable convergent validity.

Creative Self-Efficacy. We adopted the 8-item Creative Self-Efficacy Scale (Carmeli & Schaubroeck, 2007), that assess employees’ belief in their ability to generate creative solutions. Sample items include: “When facing difficult tasks, I am certain that I will accomplish them creatively.” and “I will be able to successfully overcome many creative challenges.” Creative Self-Efficacy scores achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.876, a CR value of 0.903, and an AVE value of 0.539 the present study, reflecting reliable internal consistency and satisfactory convergent validity.

Employee Bootleg Innovation. To measure employee bootleg innovation, we used the 5-item Employee Bootleg Innovation Scale developed (Criscuolo et al., 2014). An example item is: “My subordinate has the flexibility to work his/her way around official work plans, digging into new potentially valuable business opportunities.” Employee Bootleg Innovation scores achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.838, a CR value of 0.887, and an AVE value of 0.612 in the present study, suggesting high internal consistency and good convergent validity.

Control Variables. Previous research has shown that demographic factors such as gender, age, education level, organizational tenure, and position within the organization may influence employee behaviors (Jiang & Lin, 2021; Zhao, 2024, 2022; Zhao & Luan, 2022). We accounted for these factors in our analyses.

Ethical approval was granted by Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation. All participants were explicitly informed that their participation was voluntary and that their data would be kept confidential. All procedures followed were under the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

We employed hierarchical linear model analysis in SPSS 27 for the hypotheses testing (Hypothesis 1–3). To test Hypothesis 4, we employed the bootstrap method to assess the moderated mediation model while controlling for relevant variables.

Given that the data was collected from the same respondents at the same time, we examined the potential influence of common method bias. To assess this, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted. The results indicated that the single-factor model had a very poor fit, and the four-factor model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (χ² [344] = 547.88, χ²/df = 1.59, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04), as presented in Table 2. The variance extracted by the common factor was 0.376, which is below the recommended threshold of 0.50 (Fornell & Laecker, 1981).

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables. Transformational leadership (TL) was found to be significantly correlated with leader-member exchange (LMX) (r = 0.62, p < 0.01), creative self-efficacy (CSE) (r = 0.54, p < 0.01), and employee bootleg innovation (EBI) (r = 0.47, p < 0.01). Similarly, LMX showed significant correlations with both CSE (r = 0.53, p < 0.01) and EBI (r = 0.53, p < 0.01). Additionally, CSE was significantly correlated with EBI (r = 0.56, p < 0.01).

Transformational leadership (TL) and employee bootleg innovation (EBI). Hypothesis 1 predicted that transformational leadership (TL) is positively related to employee bootleg innovation (EBI). As shown in Model 5 of Table 4, the standardized coefficient for TL is 0.39 (p < 0.01), indicating a significant positive relationship between TL and EBI, thus providing strong support for Hypothesis 1.

Creative self-efficacy mediation. Hypothesis 2 proposed that creative self-efficacy (CSE) mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and employee bootleg innovation. The first step in testing this mediation was to examine the relationship between TL and CSE. As displayed in Model 2 of Table 4, the standardized coefficient for TL is 0.446 (p < 0.01), demonstrating that TL positively influences CSE. The second step was to assess the effect of CSE on EBI. Model 6 in Table 4 shows that the standardized coefficient for CSE is 0.55 (p < 0.01), indicating a strong positive influence of CSE on EBI. Together, these results suggest that CSE partially mediates the relationship between TL and EBI, thus providing preliminary support for Hypothesis 2. To further validate this mediation effect, the bootstrapping procedure was applied using SPSS (Hayes, 2009). The indirect effect of TL on EBI through CSE was estimated at 0.199 (β = 0.05), and the 95% confidence interval (CI) for this indirect effect was [0.12, 0.31], which does not include zero, confirming the mediation effect. Hence, Hypothesis 2 is fully supported.

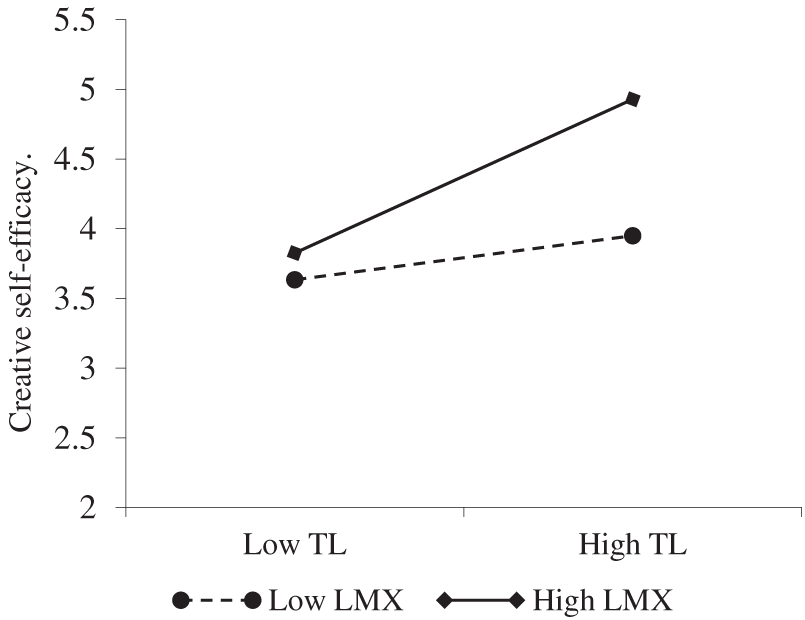

Leader-member exchange moderation. Hypothesis 3 proposed that leader-member exchange (LMX) moderates the relationship between transformational leadership (TL) and creative self-efficacy (CSE). As shown in Model 3 of Table 4, the standardized coefficient for the interaction between TL and LMX is 0.20 (p < 0.01), providing strong evidence in support of Hypothesis 3. To further explore and clarify the nature of this moderating effect, a simple slopes analysis was conducted (see also Zhao, 2024). The results indicate that at high levels of LMX (+1 SD), the indirect effect of TL on CSE is 0.5517, whereas at low levels of LMX (−1 SD), the indirect effect drops to 0.1579. These findings demonstrate that the relationship between TL and CSE strengthens significantly as LMX increases. The Figure 2 shows that the positive relationship between transformational leadership and creative self-efficacy is significantly stronger when leader-member exchange is high. Thus, these findings fully support Hypothesis 3.

Figure 2: Moderating effect of LMX on the relationship between TL and CSE.

Note. TL, transformational leadership; LMX, leader-member exchange; CSE, creative self-efficacy; EBI, employee bootleg innovation.

As shown in Table 5, the results indicate that the moderated mediation effect is significant (index = 0.084, boot SE = 0.031, boot CI: [0.016, 0.139]), with the confidence interval not including zero, confirming the robustness of the effect. More specifically, the analysis revealed that when leader-member exchange (LMX) is high, the mediating effect of transformational leadership (TL) on employee bootleg innovation (EBI) through creative self-efficacy (CSE) is stronger (effect = 0.209, boot SE = 0.061, boot CI: [0.083, 0.322]). Therefore, these findings provide strong support for Hypothesis 4, demonstrating that LMX moderates the mediation effect, such that the impact of transformational leadership on employee bootleg innovation through creative self-efficacy is more pronounced when LMX is high.

First, this study revealed a positive effect of transformational leadership on employee bootleg innovation, consistent with prior research (Cao & Xue, 2023; Fang, 2024; Zou et al., 2023). Transformational leadership achieve this by fostering intrinsic motivation, building employees’ confidence in their creative abilities, and providing the necessary support and resources to pursue novel ideas.

Second, creative self-efficacy mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and employee bootleg innovation. Previous studies have demonstrated that self-efficacy or proactive motivation plays a pivotal role in stimulating employee creativity and innovation (Hughes et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2024; Parker et al., 2010). Bootleg innovation requires a higher level of self-efficacy or proactive compared to general innovation. Creative self-efficacy enables employees to believe in their capacity to generate and implement new ideas, thereby bridging the gap between leadership influence and actual creative performance (Du et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2024; Lu et al., 2023; Newman et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2012).

Third, leader-member exchange moderates the relationship between transformational leadership and creative self-efficacy. Research has shown that LMX plays a crucial role in shaping the effectiveness of leadership behaviors in influencing employees’ self-efficacy and innovative behaviors (Buch, 2015; Hackett et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2005). When LMX is high, employees are more likely to perceive their leaders’ transformational behaviors as supportive and motivating, which in turn enhances their creative self-efficacy. This aligns with the findings of previous studies indicating that positive leader-member relationships can strengthen the impact of transformational leadership on employees’ innovative outcomes (Lin et al., 2024; Martin et al., 2016).

Implications for theory and practice

This study makes a meaningful contribution to this ongoing dialogue by integrating transformational leadership theory with leader-member exchange (LMX) theory, offering a more nuanced understanding of how intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors interact to promote innovation, particularly in the form of bootleg innovation. This study offers two significant theoretical contributions. First, it emphasizes the crucial role of motivational mechanisms (Hughes et al., 2018) in the context of digital transformation. In the process of digital transformation, intrinsic motivation remains a key factor in fostering employee innovation. Despite the focus on new leadership styles (Huang et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023b; Zheng et al., 2022) or emerging impact mechanisms (Liu et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2023) in the literatures, this study suggests that the core underlying mechanisms of motivation—such as intrinsic motivation—may continue to play a pivotal role in driving innovation in the context of digital transformation. This perspective offers a more nuanced understanding of how traditional mechanisms, such as intrinsic motivation, continue to be relevant and effective in stimulating innovation in organizations undergoing digital change.

The second contribution of this study is its integration of internal mechanisms (self-efficacy), external contextual stimuli (transformational leadership), and the interaction between these internal and external factors (leader-member exchange) to propose a comprehensive motivational mechanisms framework for understanding bootleg innovation behavior. Previous research has often focused either on internal or external factors (Lu et al., 2023; Qu et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023a) in isolation, with limited studies effectively combining these elements. By proposing a framework that links intrinsic motivation with the influence of transformational leadership and the moderating role of leader-member exchange, this study offers a more holistic view of the factors influencing employee innovation behavior, especially in the context of bootleg innovation. This integrative framework allows for a deeper exploration of the complex interactions between individual motivations, leadership behaviors, and organizational contexts, providing new insights into how these factors collectively foster innovative behavior in organizations.

In the digital transformation era, organizations must prioritize effective leadership that fosters motivation, creativity, and innovation, rather than pursuing trendy leadership styles. First, transformational leadership is vital in promoting bootleg innovation by inspiring employees to embrace change and innovate. Its focus on creating a compelling vision, intellectual stimulation, and individualized support empowers employees to respond proactively to the challenges of digital transformation (Kraus et al., 2022; Zhang & Chen, 2024). Second, creative self-efficacy plays a key role in driving innovation (Parker et al., 2010). Employees who believe in their ability to innovate are more likely to engage in proactive behaviors like bootleg innovation (Gong et al., 2009). Managers can enhance creative self-efficacy by providing resources, encouragement, and a safe environment for experimentation without fear of failure (Zimmer et al., 2023). Third, leader-member exchange (LMX) significantly amplifies transformational leadership’s impact on bootleg innovation in the context of digital transformation. High-quality LMX, built on trust, respect, and open communication, fosters a supportive environment where employees feel valued and empowered to take creative risks (Buch, 2015; Hughes et al., 2018). Organizations should encourage leaders to strengthen relationships with employees through transparent communication, personalized support, and regular engagement to ensure leadership enables bootleg innovation effectively.

Limitations and future directions

First, this study’s findings are based on data from a single large Chinese enterprise undergoing digital transformation, which may limit generalizability. Future research should explore a broader range of industries and countries to validate these results. Second, while LMX is a key moderator, other contextual factors may also influence the relationship between transformational leadership and creative self-efficacy. The study’s control variables, guided by prior research, could be expanded to include meta-analysis (Lin et al., 2024; Martin et al., 2016) validated variables in future studies, providing a more comprehensive framework. Third, although the matched survey design mitigates common method variance (CMV) to some extent (Zhao et al., 2022), future research should incorporate diverse methods, such as objective performance data or longitudinal studies, to further enhance reliability. Additionally, future research should not necessarily focus on developing novel leadership approaches or exploring new mechanisms, but rather, it should investigate the relevance and impact of established motivational mechanisms in the context of digital transformation.

Previous research has extensively demonstrated the significant relationship between leadership and both creativity and innovation, emphasizing the central role of motivational mechanisms as core drivers in this dynamic (Hughes et al., 2018; Magadley & Birdi, 2012). This study responds to previous research findings, and as hypothesized, all of the proposed hypotheses received support from the research data. This study highlights the critical role of transformational leadership in fostering bootleg innovation, with creative self-efficacy as a key mediator and leader-member exchange (LMX) as a vital moderator. Transformational leadership enhances employees’ creative confidence, encouraging proactive bootleg innovation. High-quality LMX, characterized by trust and open communication, amplifies this effect by creating a supportive environment for creative risks. The findings emphasize the importance of combining transformational leadership and strong leader-member relationships to drive bootleg innovation, particularly in the context of digital transformation, where cultivating motivation, creativity, and trust is essential for organizational success.

Acknowledgement: There are no funds for the current study. The authors are grateful to the employees who participated in this study.

Funding Statement: This study is supported by the China Association of Trade in Services (CATIS-PR-250225).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhiying Sun, Feng Hu; data collection: Zhiying Sun, Guolong Zhao; analysis and interpretation of results: Feng Hu, Zhiying Sun. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval was granted by Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Participation for this study is voluntary.

Availability of Data and Materials: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context. Boulder, CO, USA: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

Augsdorfer, P. (2012). A diagnostic personality test to identify likely corporate bootleg researchers. International Journal of Innovation Management, 16(1), 1250003. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919611003532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Awan, M. A. A., & Jehanzeb, K. (2022). How CEO transformational leadership impacts organizational and individual innovative behavior: Collaborative HRM as mediator. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 43(8), 1271–1286. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-05-2021-0197 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2005). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.New York: Psychology Press, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410617095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Buch, R. (2015). Leader-member exchange as a moderator of the relationship between employee-organization exchange and affective commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.934897 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cao, P., & Xue, S. (2023). Research on the social network to bootleg innovation—Based on the bootstrap method. In: The 2023 4th International Conference on Education, Knowledge and Information Management (ICEKIM 2023Nanjing, China. [Google Scholar]

Carmeli, A., & Schaubroeck, J. (2007). The influence of leaders’ and other referents’ normative expectations on individual involvement in creative work. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.11.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, Y., Jia, L., Li, C., Song, J., & Zhang, J. (2006). Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and employee organizational commitment: An empirical study in the Chinese context. Journal of Management World, 22(1), 96–105. [Google Scholar]

Criscuolo, P., Salter, A., & Ter Wal, A. L. J. (2014). Going underground: Bootlegging and individual innovative performance. Organization Science, 25(5), 1287–1305. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Du, Y., Li, P., & Zhang, L. (2018). Linking job control to employee creativity: The roles of creative self-efficacy and regulatory focus. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 21(3), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12219 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fang, S. (2024). Relationship between transformational leadership and employee creativity in China. International Journal of Leadership and Governance, 14(3), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.47604/ijlg.2857 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fornell, C., & Laecker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gad David, K., Yang, W., Pei, C., & Moosa, A. (2023). Effect of transformational leadership on open innovation through innovation culture: Exploring the moderating role of absorptive capacity. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 35(5), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2021.1979214 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gong, Y., Huang, J., & Farh, J. (2009). Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.43670890 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gong, T., Nanu, L., Le, L. H., & Ali, F. (2023). Translating transformational leadership and organizational innovativeness into creative customer behavior: Underlying processes and boundary conditions. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 64(4), 436–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/19389655231182091 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hackett, R. D., Wang, A. C., Chen, Z., Cheng, B. S., & Farh, J. L. (2018). Transformational leadership and organisational citizenship behaviour: A moderated mediation model of leader-member-exchange and subordinates’ gender. Applied Psychology, 67(4), 617–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12146 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, D., Sun, T., Zhu, T., & You, X. (2024). The impact of platform leadership on employee bootleg innovation: A verification of a moderated dual path model. Current Psychology, 43(40), 31372–31385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06693-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, D., Zhu, T., Wu, Y., & Sun, T. (2022). A study on paradoxical leadership and multiple path mechanisms of employees’ bootleg innovation. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 3391–3407. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S383155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hughes, D. J., Lee, A., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2018). Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.03.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Imran, F., Shahzad, K., Butt, A., & Kantola, J. (2021). Digital transformation of industrial organizations: Toward an integrated framework. Journal of Change Management, 21(4), 451–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2021.1929406 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jiang, R., & Lin, X. (2021). Trickle-down effect of moral leadership on unethical employee behavior: A cross-level moderated mediation model. Personnel Review, 51(4), 1362–1385. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2020-0257 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jun, K., & Lee, J. (2023). Transformational leadership and followers’ innovative behavior: Roles of commitment to change and organizational support for creativity. Behavioral Sciences, 13(4), 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kim, J., Yang, J., & Lee, Y. (2023). The impact of transformational leadership on service employees in the hotel industry. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 731. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kraus, S., Durst, S., Ferreira, J. J., Veiga, P., Kailer, N. et al. (2022). Digital transformation in business and management research: An overview of the current status quo. International Journal of Information Management, 63(4), 102466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102466 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, L., Huang, G., & Yan, Y. (2022). Coaching leadership and employees’ deviant innovation behavior: Mediation and chain mediation of interactional justice and organizational identification. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 3861–3874. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S381968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lin, X., Luan, Y., Zhao, K., & Zhao, G. (2024). A meta-analysis of the relationship between leadership styles and employee creative performance: A self-determination perspective. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 18(4), 319–355. https://doi.org/10.3868/s070-009-024-0016-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, L., Long, J., Liu, R., & Wan, W. (2024). Influencing mechanism of the combination of creative self-efficacy and psychological safety on employees’ bootleg innovation. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 18(4), 441–464. https://doi.org/10.3868/s070-009-024-0021-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu, L., Luo, T., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Perceived overqualification and deviant innovation behavior: The roles of creative self-efficacy and perceived organizational support. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 967052. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.967052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

MacKie, D., & Kaiser, R. B. (2014). The effectiveness of strength-based executive coaching in enhancing full range leadership development: A controlled study. Consulting Psychology Journal, 66(2), 118–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Magadley, W., & Birdi, K. (2012). Two sides of the innovation coin? An empirical investigation of the relative correlates of idea generation and idea implementation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 16(1), 1250002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919611003386 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Martin, R., Guillaume, Y., Thomas, G., Lee, A., & Epitropaki, O. (2016). Leader-member exchange (LMX) and performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 67–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12100 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Newman, A., Tse, H. H. M., Schwarz, G., & Nielsen, I. (2018). The effects of employees’ creative self-efficacy on innovative behavior: The role of entrepreneurial leadership. Journal of Business Research, 89, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310363732 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Qu, J., Khapova, S. N., Xu, S., Cai, W., Zhang, Y. et al. (2023). Does leader humility foster employee bootlegging? Examining the mediating role of relational energy and the moderating role of work unit structure. Journal of Business and Psychology, 38(6), 1287–1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-023-09884-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rank, J., Nelson, N. E., Allen, T. D., & Xu, X. (2009). Leadership predictors of innovation and task performance: Subordinates’ self-esteem and self-presentation as moderators. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(3), 465–489. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X371547 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Richter, A. W., Hirst, G., van Knippenberg, D., & Baer, M. (2012). Creative self-efficacy and individual creativity in team contexts: Cross-level interactions with team informational resources. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1282–1290. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Scandura, T. A., & Graen, G. B. (1984). Moderating effects of initial leader-member exchange status on the effects of a leadership intervention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(3), 428–436. [Google Scholar]

Shalley, C. E., Zhou, J., & Oldham, G. R. (2004). The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? Journal of Management, 30(6), 933–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shin, S. J., & Zhou, J. (2003). Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040662 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stewart, M. M., & Johnson, O. E. (2009). Leader—member exchange as a moderator of the relationship between work group diversity and team performance. Group & Organization Management, 34(5), 507–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601108331220 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

Vadera, A. K., Pratt, M. G., & Mishra, P. (2013). Constructive deviance in organizations: Integrating and moving forward. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1221–1276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313475816 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Dyne, L., Jehn, K. A., & Cummings, A. (2002). Differential effects of strain on two forms of work performance: Individual employee sales and creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.127 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Waldman, D. A., Ramirez, G. G., House, R. J., & Puranam, P. (2001). Does leadership matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069341 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, H., Law, K. S., Hacket, R. D., Wan, D., & Chen, Z. X. (2005). Leader-member exchange as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and followers’ performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.17407908 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xiao, H., Su, A., & Teng, L. (2023). The effect of time pressure on deviant innovation behavior: The mediating role of innovation self-efficacy and job crafting. In: Proceedings of the 5th Management Science Informatization and Economic Innovation Development Conference, Guangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

Zhang, J., & Chen, Z. (2024). Exploring human resource management digital transformation in the digital age. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(1), 1482–1498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01214-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhang, C., Li, S., Liu, X., & Wang, X. (2023a). Transformational leadership and supply chain innovativeness: Mediating role of knowledge sharing climate and moderating role of supply base rationalization. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 35(9), 2164–2180. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-06-2022-0550 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, L., Qin, G., Yang, F., & Jiang, P. (2023b). Linking leader humor to employee bootlegging: A resource-based perspective. Journal of Business and Psychology, 38(6), 1233–1244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-023-09881-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhao, G. (2024). Emotional exhaustion weakens the relationship between social media use and knowledge sharing behavior. Acta Psychologica, 250(2), 104496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhao, G., & Luan, Y. (2022). Could transformational leadership predict employee voice behaviour? Evidence from a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2022.2028070 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhao, G., Luan, Y., Ding, H., & Zhou, Z. (2022). Job control and employee innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.720654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zheng, X., Mai, S., Zhou, C., Ma, L., & Sun, X. (2022). As above, so below? The influence of leader humor on bootleg innovation: The mechanism of psychological empowerment and affective trust in leaders. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 274. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.956782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zimmer, M. P., Baiyere, A., & Salmela, H. (2023). Digital workplace transformation: Subtraction logic as deinstitutionalising the taken-for-granted. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 32(1), 101757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2023.101757 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zou, B., Yu, S., & Zou, Y. (2023). Exploring the influence of millennial ‘social butterflies’ on bootleg innovation: A study of moderated mediation effects. Journal of Logistics, Informatics and Service Science, 10(4), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.33168/JLISS.2023.0409 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools