Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The effect of technostress on professional identity among online international language teachers: Growth mindset mediation and technical support moderation

1 University International College, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, 999078, China

2 Institute for Research on Portuguese-Speaking Countries, City University of Macau, Macau, 999078, China

* Corresponding Author: Bo Hu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 587-597. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.066359

Received 06 April 2025; Accepted 23 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

Grounded in the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, this study investigates the relationship between technostress and professional identity among 313 online international language teachers (82.11% female; 77.64% aged 24 and above; 63.87% with postgraduate education). It further examines the mediating role of growth mindset and the moderating effect of technical support. The results indicate that higher levels of technostress are associated with lower levels of professional identity. Growth mindset partially mediates this relationship: elevated technostress not only directly weakens teachers’ professional identity but also indirectly reduces it by undermining their growth mindset. Moreover, technical support significantly moderates the mediating effect of growth mindset. Specifically, under conditions of high technical support, the negative impact of technostress on professional identity is attenuated, allowing teachers to better maintain or enhance their sense of professional identity. This study extends the application of the JD-R model to the context of digital education and underscores the importance of enhancing technical support and psychological empowerment for online international language teachers to help them manage technostress and sustain professional identity and teaching effectiveness.Keywords

Amid the rapid advancement of digital education, online international language teaching has become an integral component of global education systems. In particular, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a sharp surge in demand for online language instruction, prompting many language teachers to transition to or adopt online teaching modalities (Moorhouse & Kohnke, 2021). However, this shift has introduced considerable technostress, which can exert profound effects on teachers’ professional identity and career development (Khlaif et al., 2023).

Technostress refers to the stress individuals experience when interacting with information and communication technologies (Tarafdar et al., 2019). Professional identity, defined as teachers’ self-perception and commitment to their professional role, is a core element of professional development (Beijaard et al., 2004). For online language teachers, technostress may undermine professional identity by reducing self-efficacy and subjective well-being (Truţa et al., 2023; Khlaif et al., 2023). Nevertheless, growth mindset, a key psychological resource, may serve as a mediator in this relationship (Dweck & Yeager, 2019). Teachers with a growth mindset are more likely to perceive technological challenges as opportunities for learning, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of stress (Bardach et al., 2024). Additionally, organizational support has been shown to reduce the negative impact of stress on professional identity (Zhu et al., 2025). Adequate support not only enhances teachers’ confidence in coping with stress but also helps prevent emotional exhaustion and maintain identity stability (Pogere et al., 2019).

While previous studies have examined these variables independently, there is a lack of empirical research integrating them within a unified framework. Therefore, this study, grounded in the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), aims to investigate the impact of technostress on the professional identity of online international language teachers. It further examines the mediating role of growth mindset and the moderating effect of technical support, providing theoretical insights to inform efforts aimed at supporting teachers’ professional development in digital contexts.

Technostress and professional identity

The rapid advancement of digital technologies has brought unprecedented convenience to education, particularly in enhancing the flexibility and accessibility of online teaching (Gabbiadini et al., 2023). However, this trend has also imposed greater adaptive demands on online language teachers, requiring them to invest considerable time and effort in coping with frequent technological updates (Jena, 2015). Such sustained demands can lead to chronic stress (Chesley, 2014), adversely affecting their physical and mental well-being, job satisfaction, and professional performance (Yang et al., 2025).

According to the JD-R model, excessive job demands deplete individuals’ psychological resources, resulting in burnout and identity crises (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Empirical studies have shown that technostress consumes both cognitive and emotional resources among teachers (Salanova et al., 2013). When teachers devote substantial energy to troubleshooting technological issues, their attention to the core pedagogical mission and educational values may diminish, weakening their identification with the teaching role (Khlaif et al., 2023). Moreover, recurrent difficulties in using technology can lead teachers to question their professional competence, reducing their sense of self-efficacy (Chou & Chou, 2021) and triggering self-doubt about their suitability for the profession (Wang et al., 2024). This self-doubt can erode professional confidence and destabilize their sense of identity as teachers (Ballantyne, 2022).

Compared to local teachers, online international language teachers face more complex forms of technostress. In addition to technological challenges, they often encounter pressures arising from intercultural conflicts (Ulla et al., 2024). When such stress hampers the effective delivery of language instruction and intercultural engagement, teachers may experience a sense of failure in fulfilling their core responsibilities, which can culminate in a professional identity crisis (Gong & Gao, 2024).

The mediating effects of growth mindset

The growth mindset refers to the belief that one’s abilities and intelligence can be developed through effort and guidance (Dweck, 2006). As a crucial psychological resource, it is both shaped by job demands and influential in determining work-related outcomes (Dweck & Yeager, 2019). Previous research has shown that a growth mindset enhances individuals’ adaptability and motivation for professional development when faced with challenges, thereby mitigating the negative impact of external stressors (Bardach et al., 2024). For teachers experiencing technostress, those with a growth mindset are more capable of mobilizing internal and external resources to alleviate burnout and self-doubt (Zarrinabadi et al., 2023). Embracing a growth mindset enables teachers to perceive professional challenges as opportunities for growth and to reinforce their professional identity through continuous learning (Barkhuizen, 2023).

Furthermore, a growth mindset not only supports effective coping with technostress but also fosters a sense of self-efficacy and innovation in the face of a rapidly changing educational environment (Maximilian et al., 2024). Specifically, it encourages teachers to view technological challenges as opportunities to enhance their pedagogical skills and instructional quality, rather than as threats, thereby strengthening their identification with the teaching profession (Lopes et al., 2023). In the context of online international language teaching, teachers are frequently required to adapt to a wide array of digital tools and platforms—a process often accompanied by technology-induced anxiety and self-doubt (Khlaif et al., 2023). However, teachers with a growth mindset are more likely to take initiative in problem-solving, continuously improve their technological competencies, and derive a sense of accomplishment and professional fulfillment from overcoming difficulties (Apple & Mills, 2022). Such proactive learning behaviors not only help to alleviate technostress but also reinforce teachers’ identification with the value and societal significance of their profession (Barkhuizen, 2023).

The moderating effects of technical support

According to organizational support theory, various forms of support that individuals receive at work, such as emotional, informational, and instrumental support, can effectively alleviate job stress and enhance job satisfaction and professional identity (Kurtessis et al., 2017). With the widespread integration of digital technologies in education, technical support has become a critical component of organizational support (Gabbiadini et al., 2023), particularly in the context of online international language teaching (Ertmer & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010). For online language teachers, the timeliness and effectiveness of technical support directly influence their instructional efficiency and psychological well-being (Zinukova & Korobeinikova, 2024). Research indicates that teachers who receive adequate technical support are better able to adapt to new technologies, experience reduced technology-related anxiety, and demonstrate enhanced self-efficacy (Dong et al., 2020). As such, technical support, functioning as a specialized form of organizational support, plays a pivotal role in helping teachers manage technostress and foster professional growth (Li & Wang, 2021).

Within the framework of the JD-R model, technical support is conceptualized as a key job resource that mitigates the adverse effects of excessive job demands, such as technostress, while simultaneously enhancing psychological resources and adaptive capacities (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). In online teaching environments, technical support—delivered through structured training, real-time troubleshooting, and continuous platform optimization—not only reduces technostress directly but also bolsters teachers’ positive psychological responses to technological challenges (Khlaif et al., 2023). Furthermore, prior research suggests that sufficient technical support facilitates the transformation of technostress into opportunities for growth and learning, thereby reinforcing a growth mindset and promoting stronger professional identity (Avidov-Ungar & Forkosh-Baruch, 2018). In contrast, when technical support is lacking, even teachers with a growth mindset may struggle to perceive technostress as a developmental opportunity due to resource constraints (Yang et al., 2025), which may undermine the beneficial impact of growth mindset on professional development (Patrick & Joshi, 2019). In sum, technical support, as a crucial job resource, moderates the mediating role of growth mindset by enabling teachers under high-support conditions to more effectively convert technostress into enhanced professional identity and growth.

This study adopts the JD-R model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017) as its theoretical framework to examine the mechanism by which technostress influences professional identity among online international language teachers. The JD-R model posits that various job demands deplete individuals’ physiological and psychological resources; without sufficient resources to compensate, this depletion may result in psychological exhaustion, loss of motivation, and role withdrawal (Demerouti et al., 2001). Technostress is manifested in the form of stress caused by technological malfunctions, platform adaptation challenges, and information overload in remote teaching. It can be categorized as a hindrance demand, which hinders goal attainment and is difficult to reframe as an opportunity for growth (Crawford et al., 2010).

In contrast, growth mindset, as a form of personal resource, enables individuals to cognitively reframe technological challenges in a constructive manner, thereby mitigating the negative effects of stress (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007; Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). At the same time, technical support provided by the organization serves as a critical job resource that can both directly buffer perceived stress and enhance teachers’ sense of self-efficacy (Granziera et al., 2021), thus contributing to the stability of their professional identity. Drawing on the dual-pathway mechanism of demands and resources outlined in the JD-R model, this study further explores the mediating role of growth mindset in the relationship between technostress and professional identity, as well as the moderating role of technical support. A moderated mediation model is thus constructed to uncover the underlying psychological processes involved in the formation and maintenance of professional identity among online international language teachers.

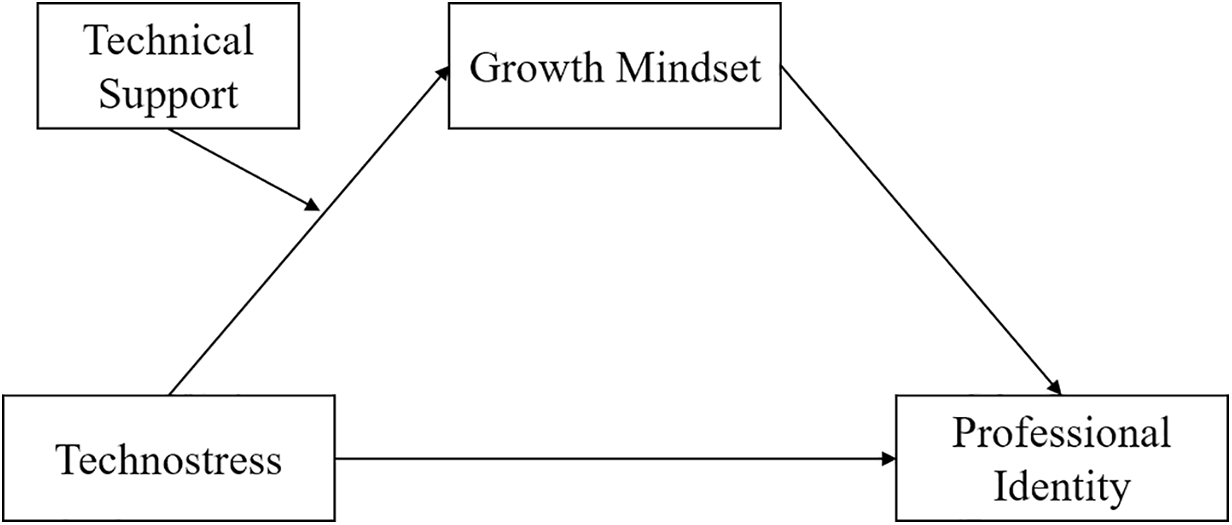

The primary aim of this study is to examine how technostress influences the professional identity of international language teachers and to investigate the roles of growth mindset and technical support within this relationship. To address this objective, we propose a moderated mediation model, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Proposed moderated mediation model

Based on this model, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H1: Technostress predicts lower professional identity.

H2: Growth mindset mediates the technostress and professional identity for higher professional identity.

H3: Technical support moderates the negative relationship between technostress and growth mindset.

H4: Technical support moderates the mediating effect of growth mindset between technostress and professional identity for higher professional identity.

The participants in this study consisted of 313 online international Chinese language teachers, including 56 males (17.89%) and 257 females (82.11%). In terms of age, 25 participants (7.99%) were between 18 and 23 years old, 147 (46.97%) were between 24 and 27, 96 (30.67%) were between 28 and 35, and 45 (14.38%) were aged 35 or above. Regarding educational background, 48 participants (15.34%) held a bachelor’s degree, 214 (68.37%) held a master’s degree, and 51 (16.29%) held a doctoral degree.

Although the sample was predominantly female (82.11%), this distribution aligns with the actual gender composition of the teaching profession in China. Previous studies have consistently shown that women represent the majority of the teaching workforce in China (Wang & Li, 2025; Li et al., 2025), which is reflected in the gender profile of the present sample.

All instruments used in this study were previously published and empirically validated. To ensure their applicability to the population of online international Chinese language teachers, five experts in relevant fields were invited to assess the content validity and linguistic suitability of the items prior to formal implementation. For example, the item “receiving help from colleagues” was revised to “receiving help from colleagues or technical support teams” to better reflect the online teaching context. All instruments were presented using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Technostress was measured using the Emotions in Technology Use Scale developed by Shen and Guo (2024), which was further validated in the study by Li et al. (2025). The scale includes 3 items designed to assess the level of stress teachers experience due to technology use in teaching. A sample item is: “The additional preparation required to use technology in teaching makes me feel stressed.” Higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived technostress. In the current study, the Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.807.

Professional identity was assessed using the Teacher Professional Identity Scale developed by Wei (2008), which has demonstrated strong reliability and validity in subsequent studies, including Bai and Li (2025). Based on Zhu et al. (2025), 4 items were selected from the original scale based on high factor loadings and strong relevance to the international teaching context. A sample item is: “When introducing myself, I am happy to mention that I am an international Chinese language teacher.” The Cronbach’s α for this scale in the present study was 0.890.

Growth mindset was measured using the Growth Mindset Scale developed by Sigmundsson and Haga (2024), which includes 8 items assessing individuals’ beliefs about the developability of abilities and intelligence through effort and learning. In this study, 4 items with factor loadings below 0.5 were removed. The remaining 4 items, such as “I know that with effort I can improve my skills and knowledge,” were retained to measure growth mindset among international Chinese language teachers. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.835.

Perceived technical support was assessed using a revised scale adapted from Eisenberger et al.’s (2020) Perceived Organizational Support Scale and the Technical Support Scale developed by Gabbiadini et al. (2023) for remote teaching contexts. The items were further refined based on expert consultation to align with the realities of online international Chinese language teaching. The final scale included 4 items, such as: “I can receive timely technical help to solve problems in my teaching.” The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.917.

Gender, age, and educational background were included as control variables in the analysis.

This study, deemed minimal risk, was approved by the Ethics Committee at the first author’s affiliated institution (Ref No. UIC/L/25/218) prior to data collection. A snowball sampling method was employed. Initial participants were recruited through professional development groups for Chinese language teachers, and they were invited to refer eligible peers to participate in the survey in order to expand the sample size.

All participants provided informed consent, with clear notification that their participation was entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without penalty. Participants were also assured that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential, and that all collected data would be used solely for academic research purposes.

The survey was administered anonymously via the online platform SoJump (www.wjx.cn). Upon completion of the questionnaire, participants received a small token of appreciation for their time and participation.

Data were analyzed using AMOS 28.0, SPSS 27.0, and PROCESS v4.1. Given that all data were self-reported by participants, common method bias (CMB) was assessed using Harman’s single-factor test. The results showed that the first unrotated factor accounted for 38.912% of the total variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40% (Podsakoff et al., 2003), indicating that there was no significant threat of CMB in this study.

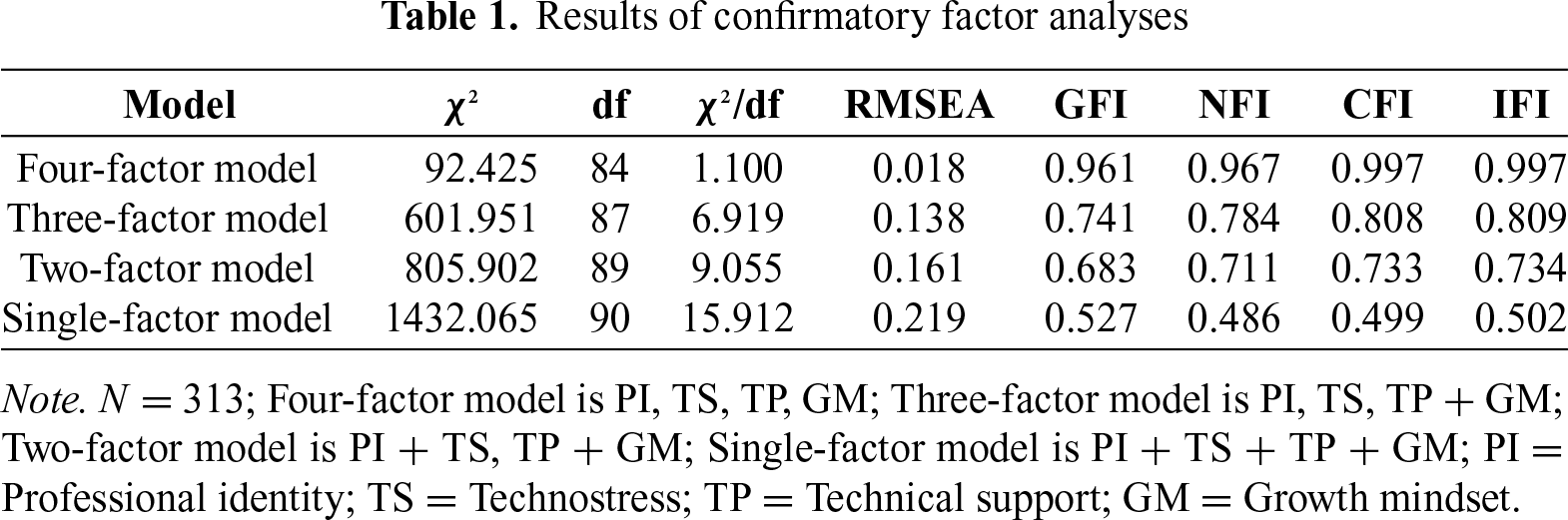

Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation analysis, and reliability testing (Cronbach’s α) were conducted using SPSS. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed in AMOS to examine the measurement model. As shown in Table 1, the four-factor model—including technostress, professional identity, growth mindset, and technical support—demonstrated the best fit (χ²/df = 1.100, RMSEA = 0.018, GFI = 0.961, NFI = 0.967, CFI = 0.997, IFI = 0.997), indicating satisfactory structural validity.

Subsequently, SPSS was used to conduct regression analyses to test the main effects. Mediation and moderation analyses were carried out using the models in PROCESS macro for SPSS. To further assess the significance of the mediating and moderating pathways, the bias-corrected bootstrap method was employed with 5000 resamples to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI). An effect was considered statistically significant if the confidence interval did not include zero.

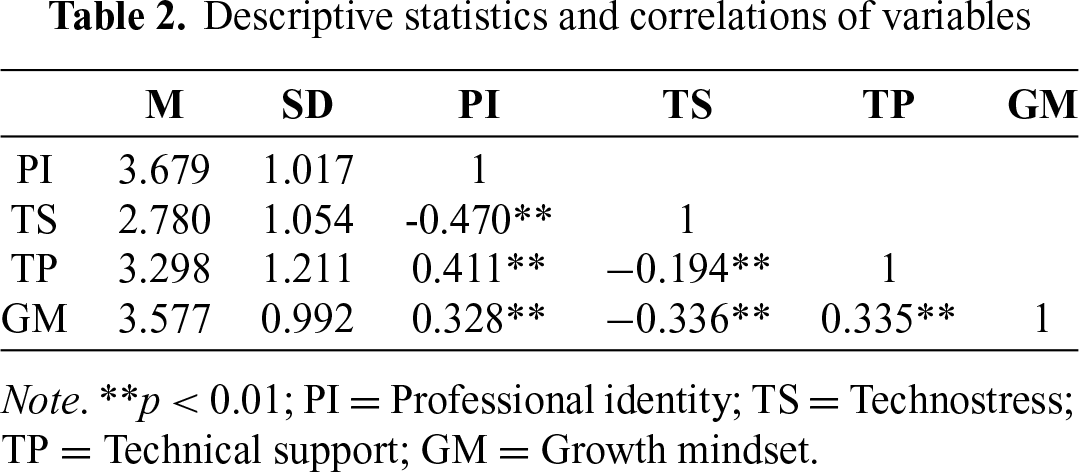

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among the key variables. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, are presented in Table 2. The results revealed a significant negative correlation between professional identity and technostress (r = –0.470, p < 0.01), and significant positive correlations between professional identity and both technical support (r = 0.229, p < 0.01) and growth mindset (r = 0.322, p < 0.01). In addition, technostress was negatively correlated with technical support (r = –0.171, p < 0.01) and growth mindset (r = –0.344, p < 0.01). Technical support was also positively correlated with growth mindset (r = 0.427, p < 0.01). These findings are consistent with theoretical expectations and provide empirical support for further testing of the causal relationships among the variables.

Main effect analysis of technostress on professional identity

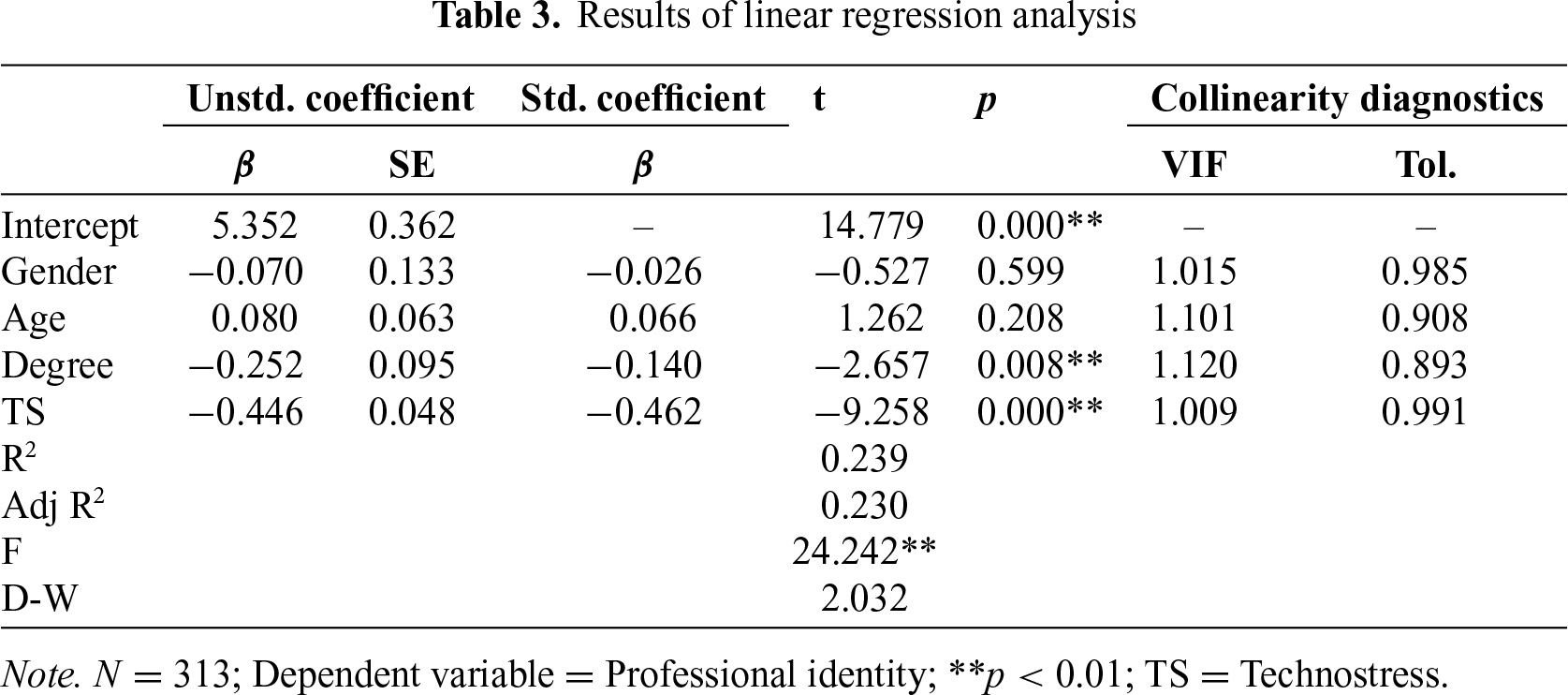

A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted with gender, age, and educational background as control variables, technostress as the independent variable, and professional identity as the dependent variable. As shown in Table 3, the regression model yielded a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.239, indicating that the set of predictors (i.e., gender, age, education, and technostress) jointly explained 23.9% of the variance in professional identity.

The F-test revealed that the overall model was statistically significant (F = 24.242, p = 0.000 < 0.05), suggesting that at least one independent variable significantly predicts professional identity. Furthermore, the results of multicollinearity diagnostics showed that all variance inflation factor (VIF) values were below 5, indicating no serious multicollinearity issues.

An examination of the standardized regression coefficients indicated that technostress significantly and negatively predicted professional identity (β = –0.446, t = –9.258, p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

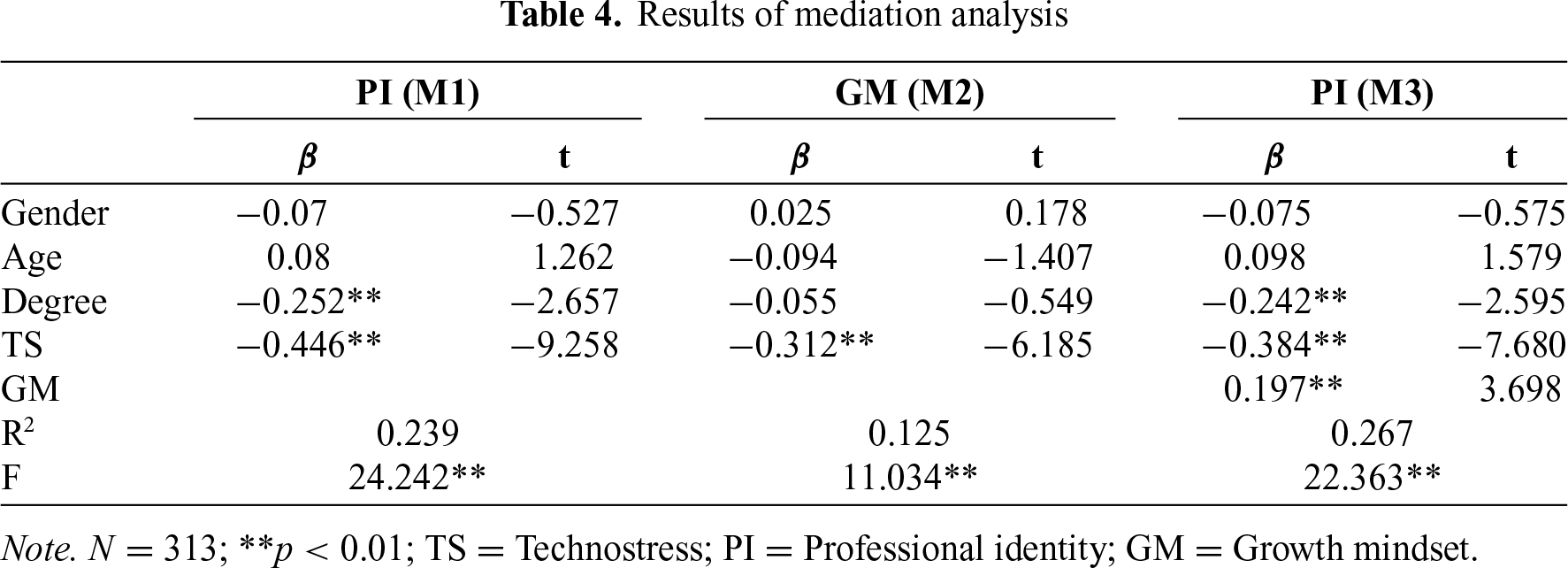

Mediating effects analysis of growth mindset

The mediation effect was tested using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro for SPSS. As shown in Table 4, the results indicate that in Model 1, technostress had a significant negative effect on professional identity (β = –0.446, p < 0.05). In Model 2, technostress also had a significant negative effect on growth mindset (β = –0.312, p < 0.05). In Model 3, the effect of technostress on professional identity remained significantly negative (β = –0.384, p < 0.05), and growth mindset positively predicted professional identity (β = 0.197, p < 0.05).

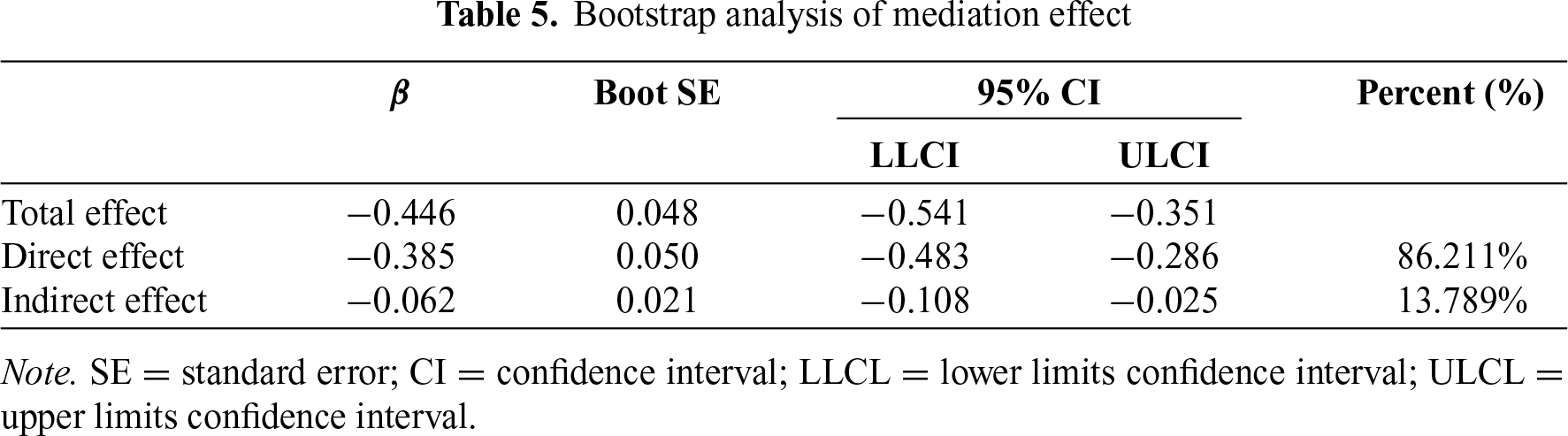

To further examine the significance of the mediation effect, a bootstrap method with 5000 resamples and 95% CI was employed. As shown in Table 5, the total effect of technostress on professional identity was –0.446, indicating a significant total effect (95% CI = [–0.541, –0.351], excluding 0). The direct effect of technostress on professional identity was –0.385, accounting for 86.211% of the total effect, suggesting a significant direct effect (95% CI = [–0.483, –0.286], excluding 0).

The indirect effect of technostress on professional identity through growth mindset was –0.062, indicating the mediation effect is statistically significant (95% CI = [–0.108, –0.025], excluding 0). As the direct effect remained significant, this suggests a partial mediation, with the indirect effect accounting for 13.789% of the total effect. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Examination of moderation effect and moderated mediation effect

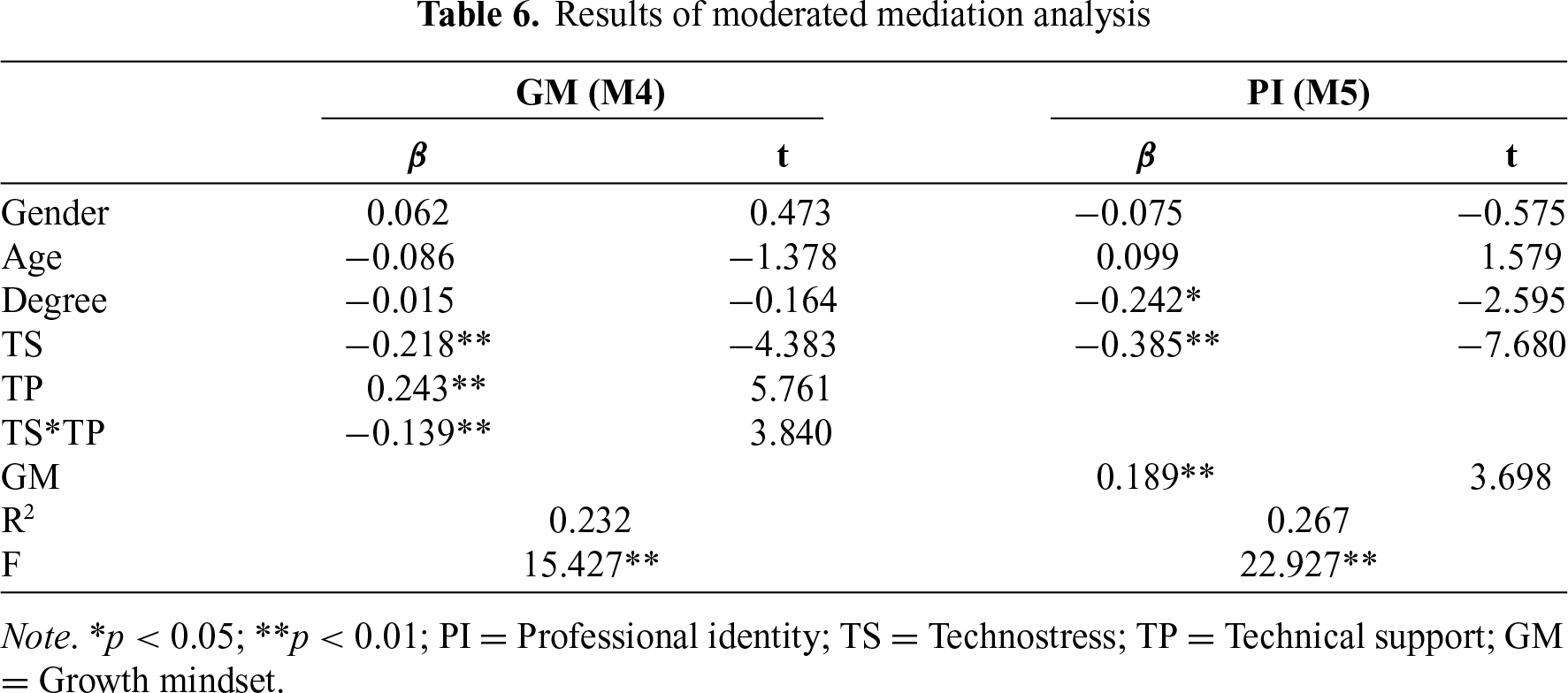

A moderated mediation analysis was conducted using Model 7 of the PROCESS macro for SPSS. The bootstrap method was applied with 5000 resamples and a 95% CI. The results are presented in Table 6.

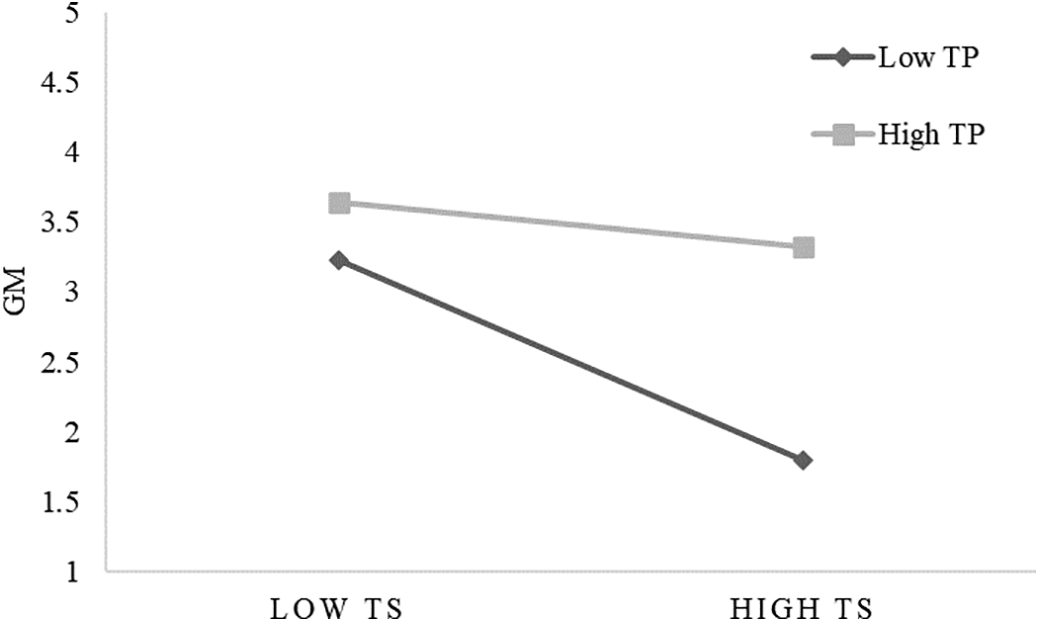

In Model 4, technostress was found to have a significant negative effect on growth mindset (β = –0.218, p < 0.01), while technical support had a significant positive effect on growth mindset (β = 0.243, p < 0.01). Furthermore, the interaction term between technostress and technical support also showed a significant negative effect on growth mindset (β = –0.139, p < 0.01). These findings indicate that technical support negatively moderates the relationship between technostress and growth mindset, such that the negative effect of technostress on growth mindset is stronger when technical support is low.

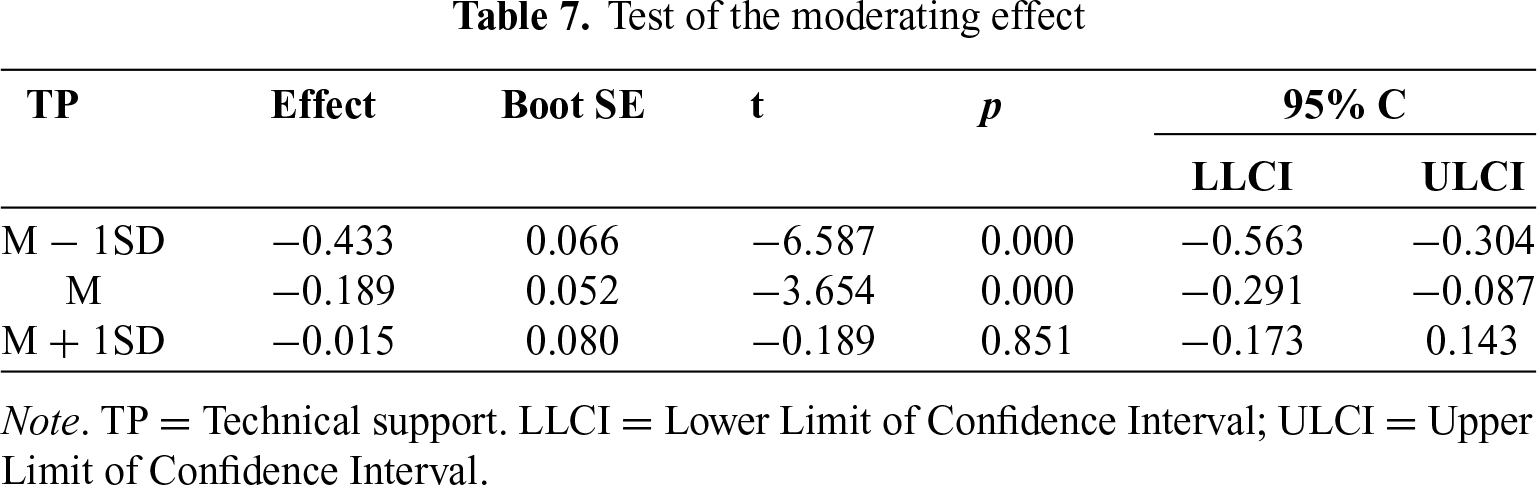

To further examine the moderating effect of technical support, a simple slope analysis was conducted. As illustrated in Figure 2 and detailed in Table 7, when the level of technical support was low (Mean − 1 SD), technostress had a significant negative effect on growth mindset (β = –0.433, p < 0.01). When technical support was at the mean level, the negative effect weakened (β = –0.189, p < 0.01). However, when technical support was high (Mean + 1 SD), the effect of technostress on growth mindset was no longer significant (β = –0.015, p > 0.05).

Figure 2: Simple slopes of the interaction between technostress (TS) and technical support (TP) on growth mindset (GM)

These findings suggest that technical support effectively buffers the negative impact of technostress on growth mindset, confirming a significant moderating effect. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

In Model 5, technostress had a significant negative effect on professional identity (β = –0.385, p < 0.01), while growth mindset had a significant positive effect on professional identity (β = 0.197, p < 0.01), indicating that growth mindset serves as a mediator in the relationship between technostress and professional identity.

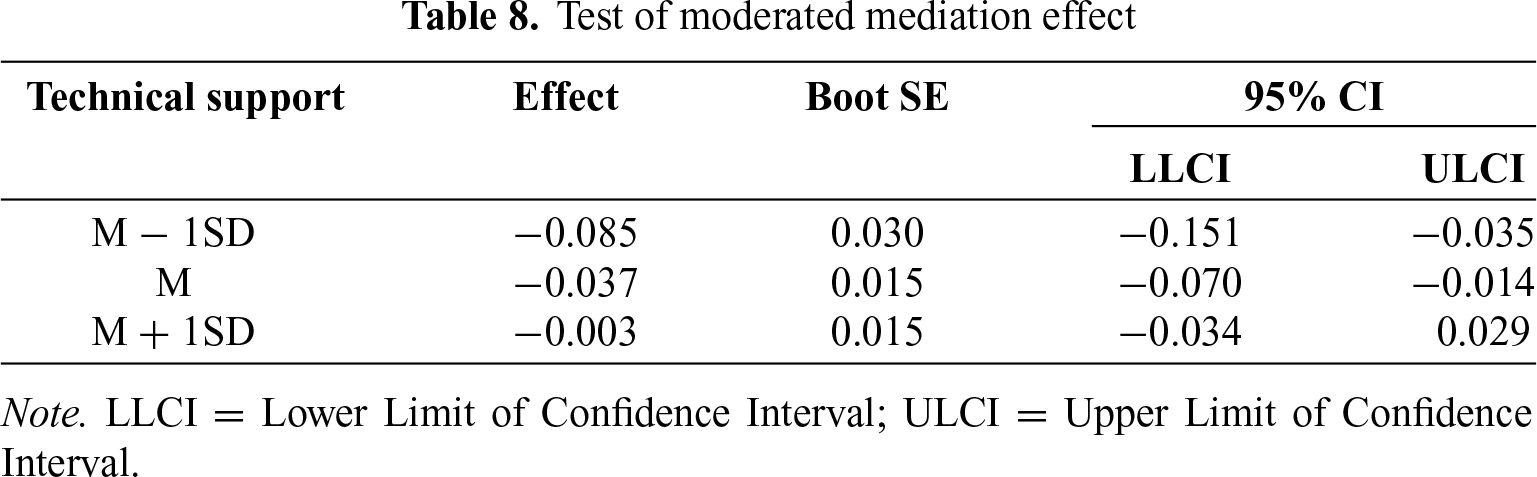

Regarding the moderated mediation effect, the bootstrap results (see Table 8) showed that when the level of technical support was low (Mean − 1 SD), the indirect effect of technostress on professional identity via growth mindset was –0.085, indicating a statistically significant mediation effect (95% CI = [–0.151, –0.035], excluding 0). However, when technical support was high (Mean + 1 SD), the indirect effect decreased to –0.003, indicating that the mediation effect was not significant (95% CI = [–0.034, 0.029], including 0).

As the level of technical support increased, the mediating effect of growth mindset became weaker and eventually non-significant, suggesting that technical support attenuates the indirect effect of technostress on professional identity via growth mindset. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Firstly, the findings of this study indicate that technostress significantly and negatively predicts professional identity among online international language teachers, a result consistent with previous research (Khlaif et al., 2023). This suggests that when teachers experience excessive technological stress, their sense of professional identity tends to decline. Such a negative relationship may stem from the anxiety and frustration induced by technostress (Li et al., 2025), which can impair teachers’ evaluations of their own competence and value (Yang et al., 2025), ultimately weakening their professional identity. According to the JD-R model, prolonged exposure to high-stress environments depletes cognitive and emotional resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), which may further undermine teachers’ well-being and long-term career development (Lu et al., 2024). Therefore, to ensure the stability of professional identity, educational institutions should focus on effectively reducing technostress in online teaching contexts (Joo et al., 2016) by providing timely and efficient technical support and training, thereby alleviating psychological burdens and fostering more proactive attitudes toward technological challenges (Graham et al., 2009).

Secondly, this study revealed a partial mediating role of growth mindset in the relationship between technostress and professional identity. This finding suggests that although technostress directly undermines teachers’ professional identity, those with a strong growth mindset are more capable of reframing technostress as an opportunity for self-improvement and professional growth, thus buffering its negative impact. Specifically, a growth mindset enables teachers to reconceptualize challenges, find meaning in adversity (Barkhuizen, 2023), and activate intrinsic motivation to seek solutions, thereby reducing the psychological depletion caused by technostress (Dweck & Yeager, 2019). Compared to teachers who focus solely on the burdens of lacking skills, those with a growth mindset are more likely to view technological challenges as opportunities to enhance their capabilities (Saka & Celik, 2024). This cognitive reappraisal not only facilitates emotional regulation but also strengthens their sense of agency and professional identity (Heyder et al., 2023). Therefore, it is recommended that educational institutions systematically integrate growth mindset training into teacher development programs, making it a key pathway for mitigating technostress and reinforcing professional identity.

Finally, the study further revealed the moderating effect of technical support on the mediating role of growth mindset in the relationship between technostress and professional identity. Specifically, the mediating effect of growth mindset was more pronounced when technical support was perceived to be high. This finding highlights a critical theoretical mechanism: technical support, as an external resource, works synergistically with growth mindset, an internal psychological resource. From the perspective of the JD-R model, when teachers encounter technostress as a threat to their resources, technical support offers external compensation, while growth mindset enables them to better utilize and transform those resources (Crawford et al., 2010; Al-Fudail & Mellar, 2008; Dong & Mertala, 2021). Notably, this synergy appears to be nonlinear—technical support not only directly alleviates stress but also amplifies the protective function of growth mindset, resulting in a “1 + 1 > 2” effect. This interaction confirms the dynamic interplay between contextual organizational factors and individual psychological traits (Rockstuhl et al., 2020; Hobfoll et al., 2018). As a situational resource at the organizational level, the effectiveness of technical support depends not only on its quality but also on how individuals perceive and engage with it (Gabbiadini et al., 2023; Kırmızı & Gülbak, 2025). Therefore, this study highlights that the core value of providing systematic technical support lies not only in reducing technostress itself but also in activating teachers’ positive psychological resources. This interaction at the organization–individual interface fosters a virtuous cycle that strengthens and enhances their professional identity.

Implication for theory and practice

This study extends the applicability of the JD-R model on a theoretical level. First, by validating the JD-R framework within the context of digital education, the study confirms its explanatory power in capturing the work experiences of online international language teachers, thereby broadening the model’s theoretical boundaries in emerging work environments. Second, the findings strengthen the theoretical role of personal resources within the JD-R model. By demonstrating the mediating role of growth mindset, the study affirms that personal resources function not merely as buffering factors but also as critical transmission mechanisms linking work conditions and outcomes, thus enriching the conceptualization of personal resource pathways within the model. Most importantly, the study reveals an interaction effect between job resources and personal resources, namely, that technical support moderates the mediating effect of growth mindset. This finding contributes to the evolution of the JD-R model from a dual-pathway framework toward a more integrated structure that emphasizes synergistic resource interactions.

Practically, this study provides concrete recommendations for enhancing the professional identity of online international language teachers. First, educational institutions should proactively identify and alleviate technostress, for example, by establishing reliable technical support systems, optimizing online teaching platforms, and offering regular technology training programs to reduce the depletion of teachers’ psychological resources. Second, the cultivation of a growth mindset should be systematically embedded in professional development initiatives. This could involve workshops, reflective coaching, and peer support activities aimed at helping teachers develop a positive cognitive framework for coping with challenges. Lastly, institutions should recognize that the value of technical support extends beyond solving technical problems—it also serves as a catalyst for activating psychological resources, thereby enhancing teachers’ adaptability and reinforcing their professional identity.

Limitations and future direction

Despite the theoretical and empirical contributions of this study to understanding the relationships among technostress, growth mindset, and professional identity, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample was predominantly female, resulting in a gender imbalance that may limit the generalizability of the findings, particularly when interpreting gender-based differences in perceptions of technostress and the construction of professional identity. Future research should aim to recruit more gender-balanced samples and further explore the psychological coping mechanisms and identity development pathways associated with technostress across different gender groups. Second, the use of a cross-sectional design restricts the ability to draw causal inferences between variables. Longitudinal studies are recommended to examine the dynamic processes through which growth mindset and technical support influence professional identity over time. Furthermore, the measurement of professional identity in this study, while aligned with prior research, adopts a simplified four-item scale that may not fully capture its multidimensional nature. This limitation should be addressed in future studies through the use of more comprehensive instruments or mixed-method approaches to ensure greater content validity. Finally, the scope of this study was limited to a specific demographic and cultural context. Future research should expand the sample to include international language teachers from diverse countries and cultural backgrounds, thereby enhancing the external validity and cross-cultural applicability of the findings.

Grounded in the JD-R model, this study systematically examined the impact of technostress on the professional identity of online international language teachers, highlighting the partial mediating role of growth mindset and the moderating effect of technical support. The findings reveal that technostress significantly undermines teachers’ professional identity. However, teachers with a strong growth mindset demonstrate greater adaptability and positivity when facing technological challenges, thereby mitigating the negative effects of technostress. Moreover, technical support not only directly reduces technological difficulties but also strengthens the protective function of growth mindset, reflecting a synergistic effect between organizational and personal resources. These results contribute to extending the JD-R model within the context of digital education and offer practical implications for educational administrators in developing teacher support strategies and optimizing technical training systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhiyong Zhu, Jinhao Li, Bo Hu, Hong Chen; data collection: Zhiyong Zhu, Jinhao Li; analysis and interpretation of results: Zhiyong Zhu, Jinhao Li; draft manuscript preparation: Zhiyong Zhu, Jinhao Li, Bo Hu, Hong Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, [Bo Hu], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University International College, Macau University of Science and Technology (Approval No.: UIC/L/25/218).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Al-Fudail, M., & Mellar, H. (2008). Investigating teacher stress when using technology. Computers & Education, 51(3), 1103–1110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.11.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Apple, M. T., & Mills, D. J. (2022). Online teaching satisfaction and technostress at Japanese universities during emergency remote teaching. In: Transferring language learning and teaching from face-to-face to online settings (pp. 1–25). Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-8717-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Avidov-Ungar, O., & Forkosh-Baruch, A. (2018). Professional identity of teacher educators in the digital era in light of demands of pedagogical innovation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.017 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bai, B., & Li, J. (2025). Preschool teachers’ professional well-being, emotion regulation, and professional identity: A multi-level latent profile approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 157, 104965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2025.104965 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ballantyne, C. A. (2022). A kaleidoscope of I-positions: Chinese volunteers’ enactment of teacher identity in Australian classrooms. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 23(6), 809–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2022.2057991 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bardach, L., Bostwick, K. C. P., Fütterer, T., Kopatz, M., Hobbi, D. M., et al. (2024). A meta-analysis on teachers’ growth mindset. Educational Psychology Review, 36(3), 84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09925-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Barkhuizen, G. (2023). Language teacher mindset and teacher identity. The Language Teacher, 47(5), 8–9. https://doi.org/10.37546/jalttlt47.5-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chesley, N. (2014). Information and communication technology use, work intensification and employee strain and distress. Work, Employment and Society, 28(4), 589–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017013500112 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chou, H.-L., & Chou, C. (2021). A multigroup analysis of factors underlying teachers’ technostress and their continuance intention toward online teaching. Computers & Education, 175, 104335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dong, C., & Mertala, P. (2021). Two worlds collide? The role of Chinese traditions and Western influences in Chinese preservice teachers’ perceptions of appropriate technology use. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(1), 288–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12990 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dong, Y., Xu, C., Chai, C. S., & Zhai, X. (2020). Exploring the structural relationship among teachers’ technostress, technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACKcomputer self-efficacy and school support. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 29, 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00461-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY, USA: Random House. [Google Scholar]

Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Eisenberger, R., Shanock, L. R., & Wen, X. (2020). Perceived organizational support: Why caring about employees counts. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7(1), 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044917 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ertmer, P. A., & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T. (2010). Teacher technology change: How knowledge, confidence, beliefs, and culture intersect. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42(3), 255–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2010.10782551 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gabbiadini, A., Paganin, G., & Simbula, S. (2023). Teaching after the pandemic: The role of technostress and organizational support on intentions to adopt remote teaching technologies. Acta Psychologica, 236, 103936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.103936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gong, Y., & Gao, X. (2024). Language teachers’ identity tensions and professional practice in intercultural teaching. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688241241125 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Graham, C. R., Tripp, T., & Wentworth, N. (2009). Assessing and improving technology integration skills for preservice teachers using the teacher work sample. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 41(1), 39–62. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.41.1.b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Granziera, H., Collie, R., & Martin, A. (2021). Understanding teacher wellbeing through job demands-resources theory. In: Cultivating teacher resilience (pp. 229–244). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5963-1_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Heyder, A., Steinmayr, R., & Cimpian, A. (2023). Reflecting on their mission increases preservice teachers’ growth mindsets. Learning and Instruction, 86(3), 101770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2023.101770 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jena, R. K. (2015). Technostress in ICT enabled collaborative learning environment: An empirical study among Indian academicians. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 1116–1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.020 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Joo, Y. J., Lim, K. Y., & Kim, N. H. (2016). The effects of secondary teachers’ technostress on the intention to use technology in South Korea. Computers & Education, 95, 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.12.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Khlaif, Z. N., Sanmugam, M., Joma, A. I., Odeh, A., & Barham, K. (2023). Factors influencing teacher’s technostress experienced in using emerging technology: A qualitative study. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 28(2), 865–899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-022-09607-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kırmızı, Ö., & Gülbak, G. M. (2025). An analysis of pre-service EFL teachers’ development of adaptive expertise in relation to their mindsets: A guided reflection approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 162, 105063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2025.105063 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., et al. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, J., Bai, B., & Liu, H. (2025). When technology meets emotions: Exploring preschool teachers’ emotion profiles in technology use. Computers & Education, 236(1), 105355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2025.105355 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, L., & Wang, X. (2021). Technostress inhibitors and creators and their impacts on university teachers’ work performance in higher education. Cognition, Technology & Work, 23, 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10111-020-00625-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lopes, A., Thomas Dotta, L., & Pereira, F. (2023). Factors influencing teachers’ uses of new technologies: Mindsets and professional identities as crucial variables. International Journal of Instruction, 16(4), 521–542. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2023.16430a [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu, J., Chen, J., Li, Z., & Li, X. (2024). A systematic review of teacher resilience: A perspective of the job demands and resources model. Teaching and Teacher Education, 151, 104742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104742 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maximilian, V., Yannick, H., & Christian, M. (2024). Fostering the digital mindset to mitigate technostress: An empirical study of empowering individuals for using digital technologies. Internet Research, 34(6), 2341–2369. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-09-2022-0766 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moorhouse, B. L., & Kohnke, L. (2021). Thriving or surviving emergency remote teaching necessitated by COVID-19: University teachers’ perspectives. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30, 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00567-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Patrick, S. K., & Joshi, E. (2019). Set in stone or willing to grow? Teacher sensemaking during a growth mindset initiative. Teaching and Teacher Education, 83, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.04.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pogere, E. F., López-Sangil, M. C., García-Señorán, M. M., & González, A. (2019). Teachers’ job stressors and coping strategies: Their structural relationships with emotional exhaustion and autonomy support. Teaching and Teacher Education, 85, 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.07.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rockstuhl, T., Eisenberger, R., Shore, L., Kurtessis, J. N., Ford, M. T., et al. (2020). Perceived organizational support (POS) across 54 nations: A cross-cultural meta-analysis of POS effects. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(6), 933–962. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00311-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Saka, D., & Celik, S. (2024). The inclusive mindset transformation needs of teachers working in challenging conditions: An examination from the perspective of Activity and Attribution Theory. Teaching and Teacher Education, 152, 104793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104793 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Salanova, M., Llorens, S., & Cifre, E. (2013). The dark side of technologies: Technostress among users of information and communication technologies. International Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.680460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Shen, Y., & Guo, H. (2024). I feel AI is neither too good nor too bad: Unveiling Chinese EFL teachers’ perceived emotions in generative AI-mediated L2 classes. Computers in Human Behavior, 161, 108429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108429 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sigmundsson, H., & Haga, M. (2024). Growth Mindset Scale: Aspects of reliability and validity of a new 8-item scale assessing growth mindset. New Ideas in Psychology, 75, 101111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2024.101111 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tarafdar, M., Cooper, C. L., & Stich, J. F. (2019). The technostress trifecta—techno eustress, techno distress and design: Theoretical directions and an agenda for research. Information Systems Journal, 29(1), 6–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12169 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Truţa, C., Maican, C. I., Cazan, A.-M., Lixăndroiu, R. C., Dovleac, L., et al. (2023). Always connected @ work: Technostress and well-being with academics. Computers in Human Behavior, 143, 107675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107675 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ulla, M. B., Perales, W. F., & Tarrayo, V. N. (2024). Becoming and being online EFL teachers’: Teachers’ professional identity in online pedagogy. Heliyon, 10(17), e37131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, J., & Li, P. (2025). Basic psychological needs satisfaction mediation of the relationship between kindergarten error management climate and creative teaching. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 35(2), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065788 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Q., Zhao, G., & Yao, N. (2024). Understanding the impact of technostress on university teachers’ online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic with the Transactional Theory of Stress (TTS). Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 33, 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00718-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wei, S. (2008). A Research on Teachers’ Professional Identity [Doctoral dissertation], Chongqing, China: Southwest University. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.7666/d.y1422969 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, D., Liu, J., Wang, H., Chen, P., Wang, C., et al. (2025). Technostress among teachers: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Computers in Human Behavior, 168, 108619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2025.108619 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zarrinabadi, N., Jamalvandi, B., & Rezazadeh, M. (2023). Investigating fixed and growth teaching mindsets and self-efficacy as predictors of language teachers’ burnout and professional identity. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688231151787 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhu, Z., Li, J., & Hu, B. (2025). Professional identity construction in transnational language teacher: Integrating conservation of resources and identity theories in a cross-cultural context. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 4(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2025.2530730 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zinukova, N., & Korobeinikova, T. (2024). The role of digital technologies in maintaining the mental health of foreign language teachers. Educological Discourse, 1(44), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.28925/2312-5829.2024.16 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools