Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

How exploitative leadership undermines employees’ proactive behaviors: Evidence for the roles of self-control depletion and distributive justice

Department of Business Administration, Hoseo University, Cheonan, 31066, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Fei Xu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 609-618. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.066587

Received 11 April 2025; Accepted 15 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This research sought to examine whether employees’ views of distributive justice within the organization moderate the influence of exploitative leadership on the depletion of their self-control resources, and whether self-control depletion serves as a mechanism linking exploitative leadership to employees’ taking charge behavior. Data were obtained from 299 employees in China (51.8% male; average age = 27.67 years, SD = 3.83) using a two-wave survey design with a two-week interval. Hierarchical regression analyses revealed that distributive justice did not significantly buffer the impact of exploitative leadership on self-control depletion. Furthermore, exploitative leadership was found to undermine employees’ taking charge behavior indirectly by increasing their self-control depletion. These findings extend ego depletion theory by clarifying how exploitative leadership drains employees’ self-control resources and thereby hampers proactive behavior. Practically, the results highlight the need for organizations to limit exploitative leadership practices and support employees in conserving their self-control resources to encourage proactive workplace behaviors.Keywords

Research indicates that organizations demonstrating fairness in human resource management practices tend to have employees who are more engaged and productive (Hassan, 2002; Imran et al., 2015; Jang et al., 2021; Sadeghi et al., 2013; Rahman et al., 2016). When employees perceive organizational justice, they are often more inclined to display discretionary behaviors that benefit the workplace, such as organizational citizenship behavior (Jehanzeb & Mohanty, 2020). Such perceptions of fairness can also foster a sense of empowerment and mitigate the risk of self-control depletion (Kamalian et al., 2010; Singh & Singh, 2019). Prior research further suggests that when employees perceive a high level of organizational justice, distributive justice exerts a stronger effect on work-related outcomes compared with other justice dimensions (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009; Colquitt et al., 2001; Kashif et al., 2017). Nevertheless, leadership plays a pivotal role in influencing and shaping these dynamics. Little is known about how exploitative leadership (EL) shapes employees’ readiness to take charge when their perceptions of distributive justice differ. Existing studies have predominantly highlighted the role of constructive leadership approaches, including empowering (Li et al., 2017) and inclusive leadership (Wang et al., 2020), in encouraging proactive behavior among employees; relatively few studies have investigated the detrimental role of destructive leadership styles (e.g., abusive supervision) in this regard (Sun et al., 2023a). As a distinct type of destructive leadership, EL reflects certain harmful leadership practices (Schmid et al., 2019). It requires more scholarly attention to reveal its constraining influence on employees’ taking charge behavior. Moreover, leadership processes are strongly shaped by cultural context, yet limited research has examined these relationships within collectivist settings such as China.

Ego depletion theory (Baumeister et al., 1998) suggests that EL, through manipulative or unjust behaviors, may drain employees’ self-control resources. As a consequence, employees’ resources may be exhausted, limiting their capacity to perform proactive actions like taking charge. Within this theoretical framework, we propose that in contexts where distributive justice is perceived to be high, employees’ sense of organizational support can buffer the negative emotional impact of the work environment (Akram et al., 2022; Kashif et al., 2017). In other words, the detrimental effect of EL on employees’ self-control may be attenuated, enabling employees to remain engaged and retain the energy and willpower necessary to undertake the challenges associated with taking charge behavior. Building on this framework, the present study aims to assess whether self-control depletion serves as a mechanism through which EL influences employees’ taking charge behavior, and whether perceived organizational distributive justice (PODJ) alters this process.

Exploitative leadership and employee taking charge

Exploitive leadership, a form of destructive leadership, is characterized by leaders engaging in behaviors that serve their personal interests while neglecting or harming the well-being of their subordinates (Schmid et al., 2019). Such leadership can suppress employees’ innovative initiatives (Wang et al., 2023a) as well as their willingness to share knowledge (Wang et al., 2023b). Due to the inherent power imbalance, employees subjected to EL may feel unable to confront their leaders directly and may instead engage in subtle retaliatory actions (Ye et al., 2022). For example, they might withhold behaviors that could benefit the organization, such as proactive taking charge behaviors examined in this study (Bajaba et al., 2023; Cropanzano et al., 2017).

Self-control depletion as a mediator

As noted by Baumeister et al. (1998) and later by Muraven and Baumeister (2000), the phenomenon of self-control depletion emerges when previous acts of volition temporarily reduce the self’s capacity or willingness to engage in goal-directed actions, including self-regulation, decision-making, and initiating behavior. Emotional exhaustion, in comparison, reflects a long-lasting state of emotional and physical depletion (Cropanzano et al., 2003). Although both concepts involve the depletion of resources, self-control depletion primarily reflects a short-term decline in willpower and self-regulatory capacity, whereas emotional exhaustion pertains to sustained exhaustion of emotional and physical resources.

Ego depletion theory proposes that a decrease in the self-regulatory resources required for successful task performance may impair employees’ productivity (Belschak & Den Hartog, 2010). This type of depletion is especially pronounced under EL, where employees are subjected to excessive demands while receiving insufficient resources (Baumeister et al., 1998; Joosten et al., 2014; Nie & Wang, 2025; Schmid et al., 2019). As self-control resources become exhausted, employees’ likelihood of engaging in proactive behaviors like taking charge diminishes, since they lack the necessary regulatory strength and determination to perform their daily responsibilities effectively (Cangiano et al., 2021; Ouyang et al., 2019). Essentially, high levels of self-control depletion markedly diminish individuals’ cognitive and self-regulatory capacities (Baumeister et al., 1998; Joosten et al., 2014; Nie & Wang, 2025), leaving them with limited energy and motivation to engage proactively. This mechanism differs from the longer-term effects of emotional exhaustion on employees’ emotional and physical well-being, underscoring the unique theoretical contribution of the present study.

Perceived organizational distributive justice as a moderator

Under EL, employees often perceive their work environment as unfair and oppressive, which can gradually drain their self-regulatory resources. It is important to note that employees’ perceptions of the organization’s policies and practices may differ from their perceptions of the leader’s behavior (Wang et al., 2023b).

Employees’ assessment of the fairness in reward allocation, considering the effort, resources, or contributions they provide, is known as distributive justice (Colquitt, 2001). For example, when organizations allocate resources and rewards equitably, employees tend to invest more effort in their work (Xu et al., 2024) and enhance their performance through diligent work (Colquitt et al., 2001). In settings characterized by low distributive justice, employees may feel not only exploited by their leaders but also disadvantaged by the organization in terms of fair reward distribution, which can exacerbate the depletion of their self-regulatory resources. Conversely, in contexts where distributive justice is high, meaning that career development opportunities and chances to enhance work-related skills are allocated fairly and meet employees’ expectations (Hicks-Clarke & Iles, 2000; Kim et al., 2017), employees may be better able to cope with EL. Even if they expend significant effort to deal with such leaders, the perception of fair treatment by the organization can help replenish the resources consumed, thereby reducing the overall depletion of self-regulatory capacity (Kim et al., 2017). In light of this reasoning, we posit that the presence of distributive justice within the organization can protect employees’ self-control resources from being eroded by the effects of exploitative leadership.

EL is relatively prevalent in Chinese workplaces (Sun et al., 2023a) and can lead to considerable depletion of employees’ self-control resources. At the same time, how employees perceive the fairness of organizational resource distribution may influence the extent to which EL depletes their self-control resources. In a cultural environment characterized by high power distance, such as China, employees’ sense of organizational justice affects not only their compliance with leadership behaviors but also the level of depletion of their self-regulatory resources (Lian et al., 2012). Therefore, exploring the moderating effect of employees’ perceptions of distributive justice on the interplay between EL, self-control depletion, and proactive behavior provides valuable insights into leadership mechanisms in the Chinese context and carries significant theoretical and practical implications.

Goal of the Study

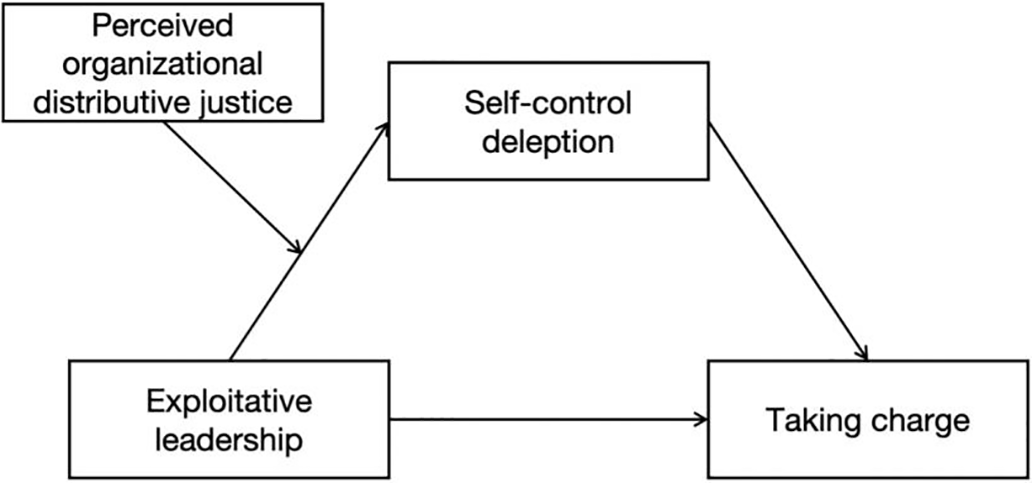

This study examines the mediating role of self-control depletion and the moderating effect of perceived organizational distributive justice in the relationship between EL and employees’ taking charge behavior. Specifically, we tested a moderated mediation model in which perceived organizational distributive justice influences the indirect effect of EL on taking charge behavior through self-control depletion (see the conceptual framework presented in Figure 1). This study tested the hypotheses outlined below:

Figure 1: The conceptual model

H1: Higher EL predicts lower employee taking charge.

H2: EL indirectly lowers employee taking charge through self-control depletion.

H3: PODJ moderates the influence of EL on employees’ self-control depletion, with higher levels of perceived fairness reducing the resource depletion caused by EL.

H4: PODJ diminishes the indirect influence of EL on employees’ taking charge behavior through self-control depletion, weakening this mediated relationship when distributive justice is high.

This study included 299 full-time employees representing a range of industries and occupations in China. The sample consisted of 51.8% men and 48.2% women, with an average age of 27.67 years (SD = 3.83) and an average organizational tenure of 3.86 years (SD = 2.28); 83.6% had a bachelor’s degree.

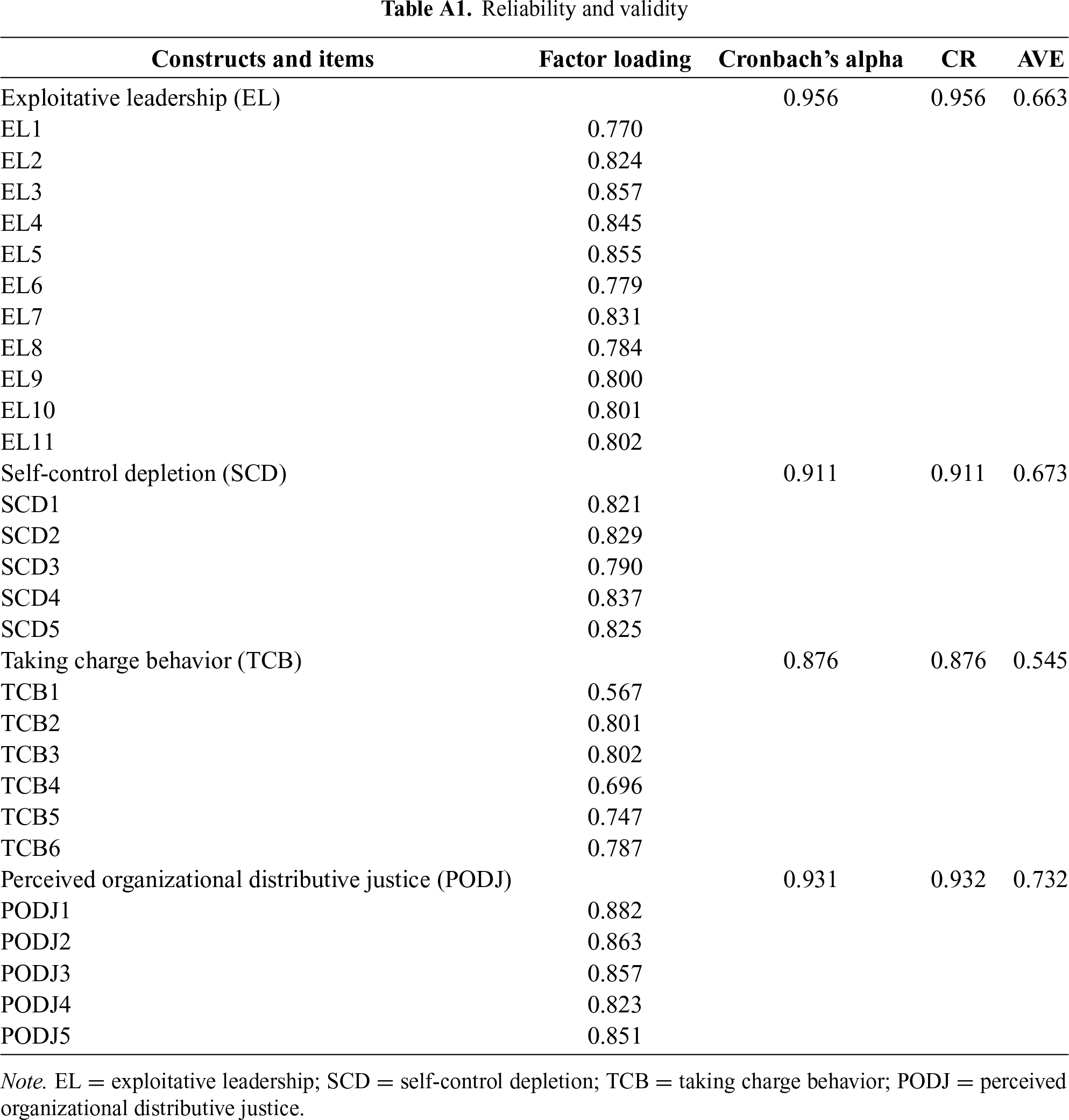

We measured EL, self-control depletion, taking charge behavior, and perceived organizational distributive justice using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The widely used English scales were translated into Chinese following Brislin’s (1970) translation and back-translation procedure. The factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) for all study variables are reported in Appendix A, Table A1.

The exploitative leadership scale, developed by Schmid et al. (2019), comprises 15 items. One illustrative item reads: “Takes it for granted that my work can be used for his or her personal benefit.” Analysis of reliability showed that the measures used in this study were highly consistent internally, with a Cronbach’s alpha value reaching 0.956.

We measured self-control depletion with a 5-item scale developed by Lanaj et al. (2014). One representative item is: “I feel like my willpower is gone.” The scale demonstrated strong internal reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.911 in the present sample, indicating satisfactory consistency.

The taking charge behavior scale, adapted from Morrison and Phelps’ (1999) original 10-item scale, consists of six items (Li et al., 2016). In order to measure the construct reliably within the Chinese organizational context, six items exhibiting the highest factor loadings were chosen. A representative item reads: “I often try to institute new work methods that are more effective for the company.” Internal consistency was found to be satisfactory, as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.876 in the present study.

Perceived organizational distributive justice

We assessed perceived organizational distributive justice with the Chinese adaptation of a 5-item scale by Wang (2009), which was derived from the original scale created by Niehoff and Moorman (1993). A representative item reads: “I consider my workload to be quite fair.” A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.931 indicated that the scale had excellent internal consistency in the current sample.

Following previous research (Nie & Wang, 2025; Wang et al., 2024), we controlled for demographic characteristics that may affect key variables in our model. Participants provided demographic details, including their gender, age, length of tenure in the current organization, and highest level of education.

Completion of the questionnaire served as participants’ informed consent, with assurances that participation was voluntary and that confidentiality would be maintained. To mitigate the risk of common method bias, the study employed a two-wave survey design with a two-week gap between waves. In the initial wave, participants provided data on their demographics, EL, and perceived organizational distributive justice. In the follow-up wave, they reported on self-control depletion and taking charge behavior. Data were collected through the survey platform wenjuanxing, which is a popular survey platform for online data collection in China and has been used by many academic studies (Li et al., 2023; Zhang & Liu, 2023).

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to evaluate the discriminant validity of the multi-item measures used in the survey. Subsequently, Hypothesis 1 was tested using hierarchical regression analysis in SPSS 27.0. Furthermore, Hypotheses 2 through 4 were examined with the SPSS PROCESS macro. We used bootstrapping analysis based on 5000 bootstrap samples with 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals to determine whether the mediation and moderation effects were significant.

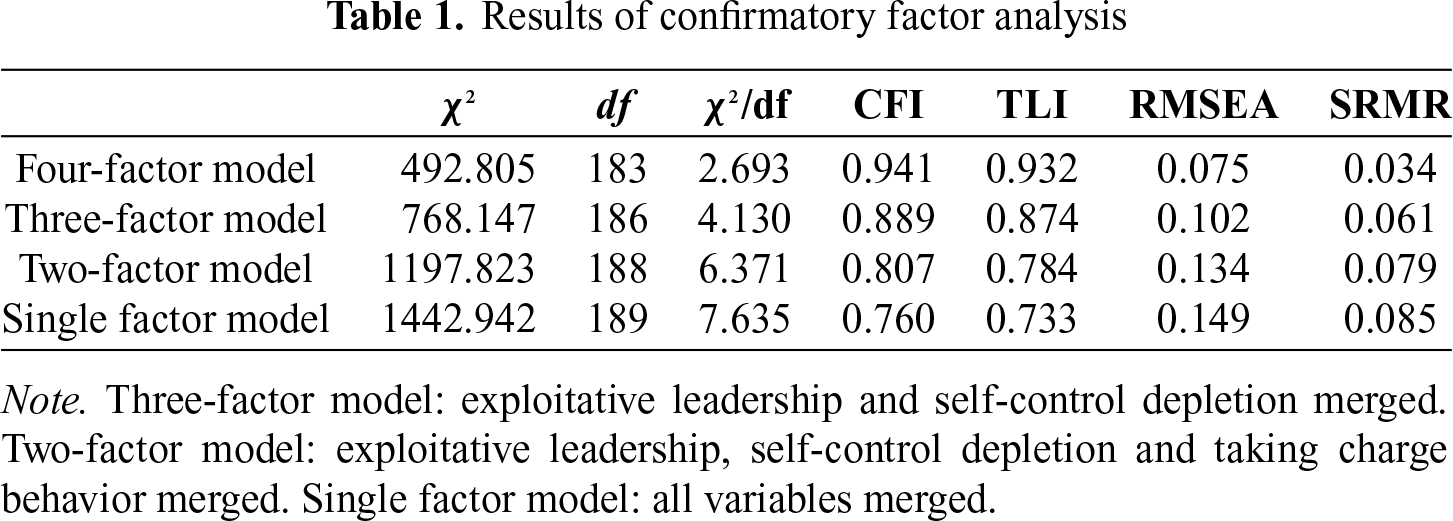

As presented in Table 1, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results demonstrated that the proposed research model exhibited an acceptable fit (

Since all variables were collected via employee self-report, the resulting dataset primarily reflects a single-source perspective. To assess the presence of common method bias, we incorporated a latent common method factor into the analysis based on the suggestions made by Podsakoff et al. (2003) in their study. The results indicated that the five-factor measurement model, which included a common method factor along with the four key variables (

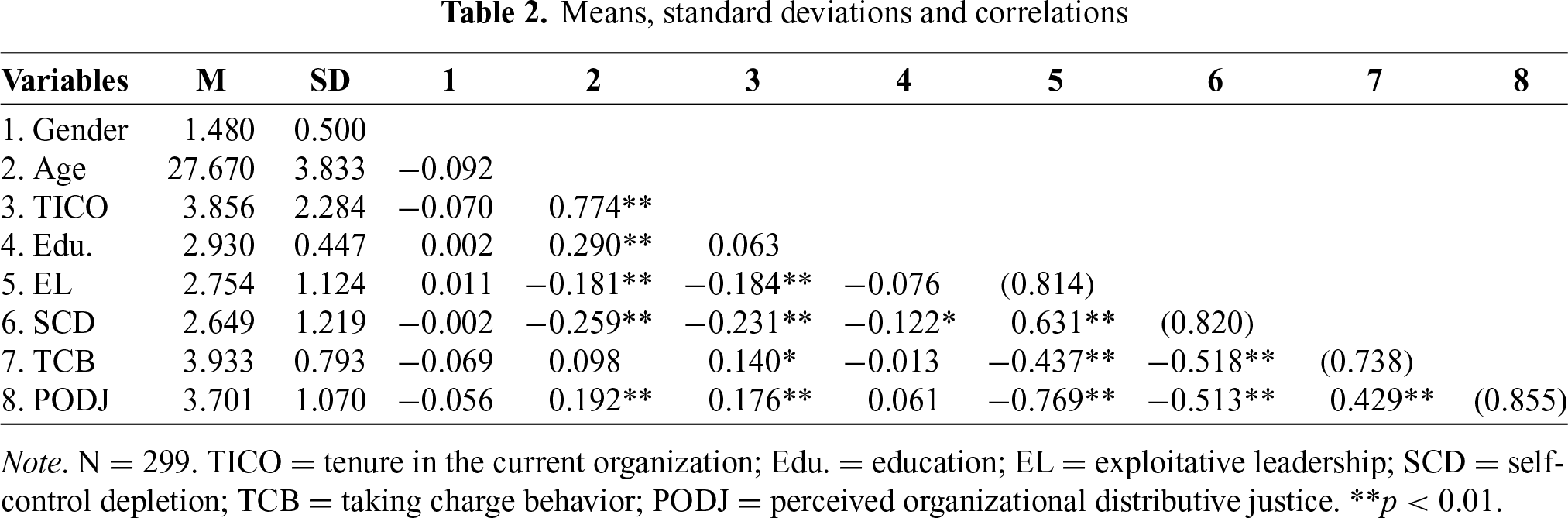

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, as well as the correlation coefficients for both the demographic characteristics and the main variables examined in this study. Correlation analysis indicated that EL was strongly and negatively correlated with perceived organizational distributive justice (r = −0.769, p < 0.01) and moderately negatively correlated with employees’ taking charge behavior (r = −0.437, p < 0.01), while showing a substantial positive correlation with self-control depletion (r = 0.631, p < 0.01).

The analysis revealed that perceived organizational distributive justice was inversely related to self-control depletion (r = −0.513, p < 0.01) and positively associated with taking charge behavior (r = 0.429, p < 0.01). Additionally, a significant negative correlation was observed between self-control depletion and taking charge behavior (r = −0.518, p < 0.01). These outcomes serve as a preliminary basis for the forthcoming hypothesis testing.

Exploitative leadership and employee taking charge

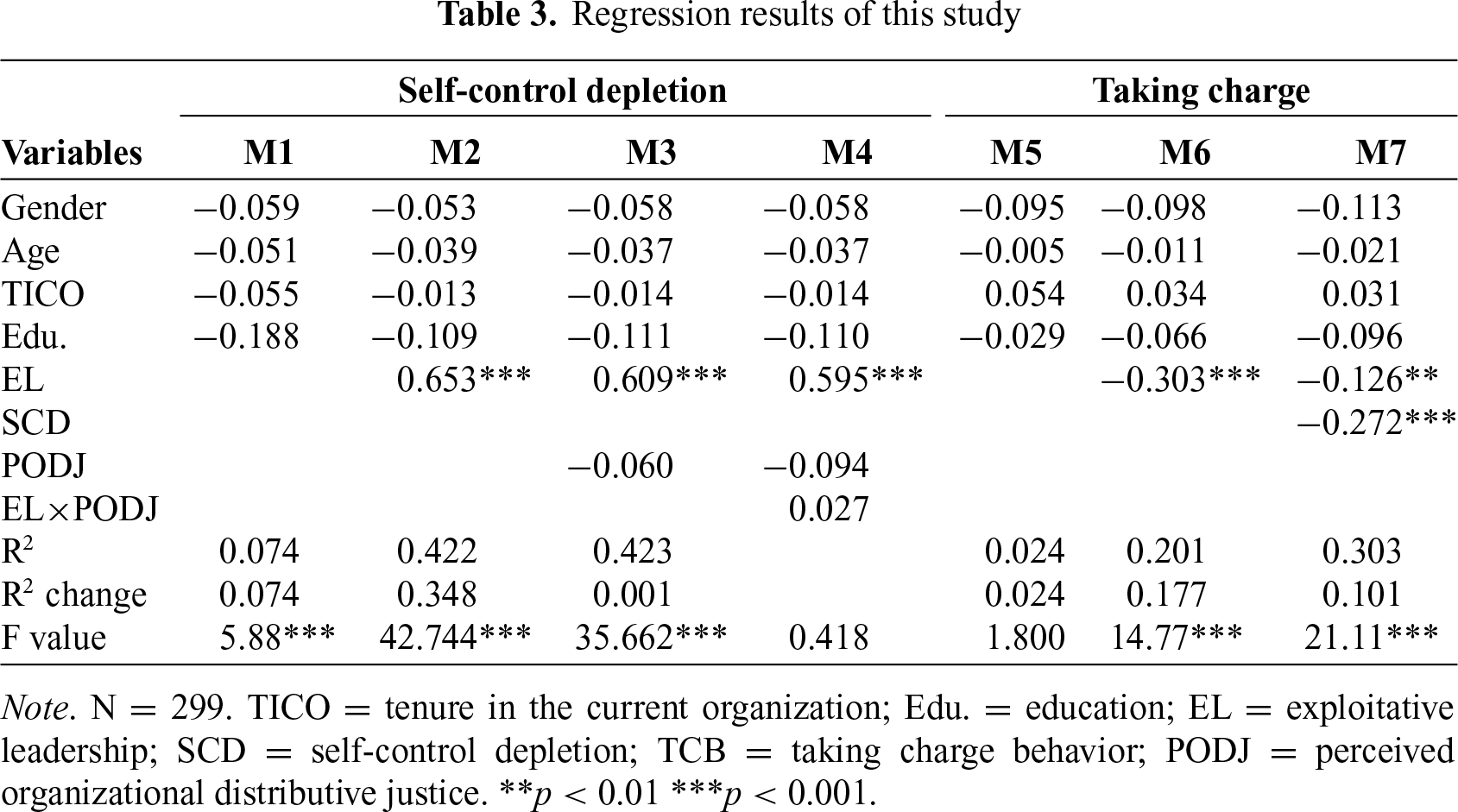

Hierarchical regression analysis was employed to systematically evaluate the validity of Hypothesis 1. After controlling for demographic characteristic variables, the results were shown in Model 6 of Table 3. The results showed that EL was negatively correlated with taking charge behavior (estimate = −0.303, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Self-control depletion as a mediator

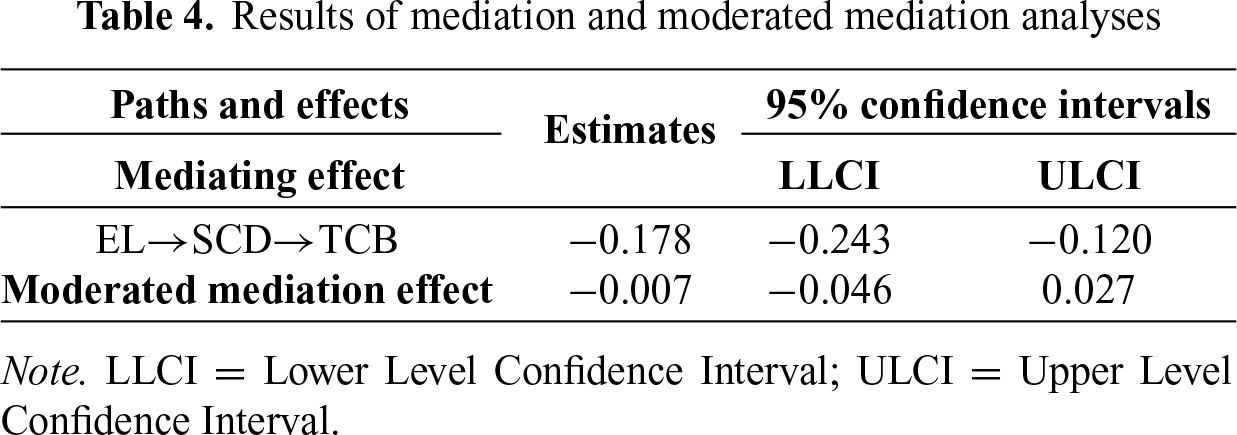

To rigorously test Hypothesis 2, which posits that self-control depletion serves as a mediating mechanism through which EL undermines employees’ proactive engagement in taking charge, we used 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (bootstrapping = 5000) to assess its mediating effect. As shown in Table 4, EL significantly undermines employees’ proactive engagement in taking charge indirectly through the mediating mechanism of self-control depletion (indirect effect = −0.178, 95% CI [−0.243, −0.120], excluding 0), thereby providing robust empirical support for Hypothesis 2. Additionally, after accounting for self-control depletion as a mediator, the direct influence of EL on employees’ proactive engagement in taking charge remained robust and statistically significant (estimate = −0.126, 95% CI [−0.213, −0.038], p < 0.01), indicating partial mediation.

Perceived organizational distributive justice as a moderator

The moderation effect analysis, as summarized in Table 3, did not confirm Hypothesis 3. The results showed that the interaction of EL and perceived organizational distributive justice on employee self-control depletion did not reach significance (estimate = 0.027, 95% CI [−0.108, 0.162], p = 0.696).

Moderated mediation of perceived organizational distributive justice

The findings from moderated mediation analyses indicated that the overall moderated mediation was not significant (estimate = −0.007, 95% CI [−0.046, 0.027]). Notably, the indirect effect of EL on employees’ proactive engagement in taking charge through self-control depletion was significant under both high (estimate = −0.170, 95% CI [−0.242, −0.109]) and low levels of perceived organizational distributive justice (estimate = −0.154, 95% CI [−0.246, −0.072]), and the difference between these effects did not reach significance (difference estimate = −0.016, 95% CI [-0.099, 0.059]). As such, Hypothesis 4 was not supported.

Our findings indicate that EL is associated with reduced employee taking charge behavior, which aligns with previous research (Kong et al., 2025). Nevertheless, the high-power-distance characteristic of Chinese culture may partially mitigate this negative effect, as employees are more likely to accept authority and tolerate exploitative behaviors (De Luque & Sommer, 2000). Furthermore, many Chinese industries rely heavily on top-down management practices (Sun et al., 2023a; Wu et al., 2021), which can suppress proactive employee behaviors due to the fear of challenging hierarchical authority. In addition, the pressures arising from China’s rapid economic growth and highly competitive work environment can further deplete the personal resources necessary for engaging in proactive behaviors (Obrenovic et al., 2020). Consequently, the interplay of cultural and industrial factors in China creates a complex context in which EL influences employees’ taking charge behavior.

The present study advances prior research by providing compelling evidence that EL affects employees’ taking charge behavior indirectly through self-control depletion, thereby corroborating earlier findings (Nie & Wang, 2025). Exploitative leaders often pursue their objectives by taking advantage of employees (Schmid et al., 2019), requiring employees to continuously exert self-regulation to meet excessive demands. This persistent effort can exhaust their self-regulatory resources, leading to a decline in proactive behaviors. From the standpoint of ego depletion theory (Baumeister et al., 1998), self-control depletion explains the mechanism linking EL to employees’ taking charge behavior.

Notably, the hypothesized moderation by perceived organizational distributive justice was not confirmed in our analyses. This outcome may be influenced by China’s strong hierarchical and authoritarian culture, in which employees’ obedience to authority can limit the buffering effect of justice perceptions (Sun et al., 2023a; Wu et al., 2021). Even when employees perceive resource allocation as fair, EL can still drain their self-regulatory capacity. Thus, fair distribution alone may be insufficient to counteract the negative consequences of EL. For example, Sahibzada et al. (2024) demonstrated that when employees perceive a higher level of organizational support, the emotional exhaustion triggered by exploitative leadership can be mitigated. Based on this, we suggest that broader forms of organizational support or comprehensive justice, including procedural, interpersonal, and distributive justice, may be more effective in mitigating the impact of EL on employees’ self-control depletion.

Implications for managerial practice

Our study offers several practical insights. First, the findings indicate that EL depletes employees’ self-control resources and suppresses their willingness to take charge. Considering the critical role of taking charge behavior in contemporary organizations (Kim et al., 2015), it is essential for organizations to minimize the occurrence and persistence of EL in order to foster employees’ proactive engagement.

Second, the mediating effect of self-control depletion highlights the importance of alleviating employees’ resource exhaustion in the workplace as a means to encourage proactive behaviors. Accordingly, managers should closely monitor employees’ psychological states and behavioral cues in daily work settings, and take action to limit individual or contextual factors that drain employees’ self-control resources (Lyddy et al., 2021). Finally, since taking charge behavior is a voluntary and resource-intensive form of proactivity (Strauss et al., 2017), organizations need to ensure that employees have sufficient support and access to diverse resources. Providing enriched job resources and multi-dimensional organizational support can create a more favorable environment for employees to engage in and sustain proactive change-oriented behaviors.

Strengths, limitations and future research directions

Extensive literature underscores the significance of leadership in facilitating employees’ proactive initiatives, notably taking charge (Liu et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022). Despite this focus on positive leadership, the effects of destructive leadership styles on employees’ proactive behaviors remain relatively underexplored (Sun et al., 2023b). Although scholarship on EL has expanded in recent years (Elsaied, 2022), its potential implications for employees’ willingness to take charge remain insufficiently examined. By revealing that exploitative leadership diminishes employees’ proactive efforts to take charge, this research advances existing knowledge on destructive leadership and reinforces evidence of its harmful outcomes.

Nevertheless, several limitations of this study should be noted. First, all variables were measured using self-reported data. We implemented a three-wave survey design and carried out statistical assessments to control for common method bias, and the results implied that any bias present was unlikely to significantly distort the findings. Even so, future research should consider incorporating multisource data, such as supervisor assessments of proactive behavior, or implementing field experiments to further reduce potential method-related bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

Second, the data were obtained exclusively from Chinese employees. Because cultural norms may shape both leadership dynamics and proactive work behaviors, future studies should replicate and validate these findings in diverse cultural and organizational contexts to strengthen their generalizability.

Finally, the moderating role of perceived organizational distributive justice was not supported in this study. This indicates that other contextual or organizational factors may be more relevant in shaping how EL affects employees’ taking charge behavior. Subsequent research could investigate alternative moderators and examine how broader organizational support systems might buffer or intensify the negative influence of EL on proactive work behaviors.

Our findings suggest that exploitative leadership leads to heightened self-control depletion among employees, thereby reducing their engagement in taking charge behavior. We further tested whether perceived organizational distributive justice could moderate this effect. Contrary to expectations, the findings indicated that distributive justice did not moderate the association between exploitative leadership and self-control depletion, nor did it significantly influence the indirect path from exploitative leadership to taking charge behavior. By clarifying the distinct role of EL in shaping employees’ resource depletion and proactive conduct, this study enriches both theoretical insight and practical implications.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely thank all participants for their contribution to this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xueqin Zhang, Fei Xu, Zerui Wang; data collection: Xueqin Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Xueqin Zhang, Fei Xu; draft manuscript preparation: Xueqin Zhang, Fei Xu, Zerui Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Fei Xu], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study collected data through anonymous questionnaires and did not involve any sensitive personal information. Participation was entirely voluntary, and respondents could withdraw at any time without any negative consequences. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), and completion of the questionnaire was considered as providing informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Akram, Z., Ahmad, S., Akram, U., Asghar, M., & Jiang, T. (2022). Is abusive supervision always harmful toward creativity? Managing workplace stressors by promoting distributive and procedural justice. International Journal of Conflict Management, 33(3), 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijcma-03-2021-0036 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ambrose, M. L., & Schminke, M. (2009). The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: A test of mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 491–500. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bajaba, A., Bajaba, S., & Alsabban, A. (2023). Exploitative leadership and constructive voice: The role of employee adaptive personality and organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness-People and Performance, 10(4), 601–623. https://doi.org/10.1108/joepp-07-2022-0218 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Belschak, F. D., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2010). Pro-self, prosocial, and pro-organizational foci of proactive behaviour: Differential antecedents and consequences. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2), 475–498. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909x439208 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cangiano, F., Parker, S. K., & Ouyang, K. (2021). Too proactive to switch off: When taking charge drains resources and impairs detachment. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(2), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386–400. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research [Review]. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E. L., Daniels, S. R., & Hall, A. V. (2017). Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 479–516. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D. E., & Byrne, Z. S. (2003). The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

De Luque, M. F. S., & Sommer, S. M. (2000). The impact of culture on feedback-seeking behavior: An integrated model and propositions. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 829–849. https://doi.org/10.2307/259209 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Elsaied, M. (2022). Exploitative leadership and organizational cynicism: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 43(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-02-2021-0069 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hassan, A. (2002). Organizational justice as a determinant of organizational commitment and intention to leave. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 7(2), 55–66. [Google Scholar]

Hicks-Clarke, D., & Iles, P. (2000). Climate for diversity and its effects on career and organisational attitudes and perceptions. Personnel Review, 29(3), 324–345. [Google Scholar]

Imran, R., Majeed, M., & Ayub, A. (2015). Impact of organizational justice, job security and job satisfaction on organizational productivity. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 3(9), 840–845. [Google Scholar]

Jang, J., Lee, D. W., & Kwon, G. (2021). An analysis of the influence of organizational justice on organizational commitment. International Journal of Public Administration, 44(2), 146–154. [Google Scholar]

Jehanzeb, K., & Mohanty, J. (2020). The mediating role of organizational commitment between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: Power distance as moderator. Personnel Review, 49(2), 445–468. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-09-2018-0327 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Joosten, A., Van Dijke, M., Van Hiel, A., & De Cremer, D. (2014). Being “in control” may make you lose control: The role of self-regulation in unethical leadership behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1686-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kamalian, A. R., Yaghoubi, N.-M., & Moloudi, J. (2010). Survey of relationship between organizational justice and empowerment (A case study). European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 24(2), 165–171. [Google Scholar]

Kashif, M., Zarkada, A., & Thurasamy, R. (2017). Customer aggression and organizational turnover among service employees the moderating role of distributive justice and organizational pride. Personnel Review, 46(8), 1672–1688. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-06-2016-0145 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim, S. H., Laffranchini, G., Wagstaff, M. F., & Jeung, W. (2017). Psychological contract congruence, distributive justice, and commitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 32(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-05-2015-0182 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim, T.-Y., Liu, Z., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2015). Leader-member exchange and job performance: The effects of taking charge and organizational tenure. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(2), 216–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1971 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kong, L. N., Liu, S., Liu, L., & Yu, S. K. (2025). How exploitative leadership undermines subordinates’ taking charge behavior? A moderated mediation model. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 479. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02791-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lanaj, K., Johnson, R. E., & Barnes, C. M. (2014). Beginning the workday yet already depleted? Consequences of late-night smartphone use and sleep. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 124(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.01.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, N., Chiaburu, D. S., & Kirkman, B. L. (2017). Cross-level influences of empowering leadership on citizenship behavior: Organizational support climate as a double-edged sword. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1076–1102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314546193 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, R., Zhang, Z.-Y., & Tian, X.-M. (2016). Can self-sacrificial leadership promote subordinate taking charge? The mediating role of organizational identification and the moderating role of risk aversion. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(5), 758–781. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2068 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, G., Zheng, Q., & Xia, M. (2023). How do human resource practices help employees alleviate stress in enforced remote work during lockdown? International Journal of Manpower, 44(2), 354–369. [Google Scholar]

Lian, H. W., Ferris, D. L., & Brown, D. J. (2012). Does power distance exacerbate or mitigate the effects of abusive supervision? It depends on the outcome. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Liu, M., Zhang, P., Zhu, Y., & Li, Y. (2022). How and when does visionary leadership promote followers’ taking charge? The roles of inclusion of leader in self and future orientation. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1917–1929. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S366939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lyddy, C. J., Good, D. J., Bolino, M. C., Thompson, P. S., & Stephens, J. P. (2021). The costs of mindfulness at work: The moderating role of mindfulness in surface acting, self-control depletion, and performance outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(12), 1921–1938. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Morrison, E. W., & Phelps, C. C. (1999). Taking charge at work: Extrarole efforts to initiate workplace change. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.2307/257011 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Nie, Q., & Wang, M. (2025). Exploitative leadership and employees’ unethical behavior from the perspective of ego depletion theory: The moderating effect of microbreaks. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 32(2), 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/15480518241305683 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Niehoff, B. P., & Moorman, R. H. (1993). Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 527–556. https://doi.org/10.5465/256591 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Obrenovic, B., Du, J. G., Khudaykulov, A., & Khan, M. A. S. (2020). Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: A job performance model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 475. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ouyang, K., Cheng, B. H., Lam, W., & Parker, S. K. (2019). Enjoy your evening, be proactive tomorrow: How off-job experiences shape daily proactivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(8), 1003–1019. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rahman, A., Shahzad, N., Mustafa, K., Khan, M. F., & Qurashi, F. (2016). Effects of organizational justice on organizational commitment. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(3), 188–196. [Google Scholar]

Sadeghi, M., Musavi, M., Samiie, S., & Behrooz, A. (2013). Developing human resource productivity through organizational justice. Public Administration and Governance, 3(2), 173–190. [Google Scholar]

Sahibzada, Y. A., Ali, M., Toru, N., Jan, M. F., & Ellahi, A. (2024). Exploitative leadership and green innovative behavior of hospitality employees: Mediation of emotional exhaustion and moderation of perceived organization support. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 8(5), 1847–1866. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhti-02-2024-0161 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schmid, E. A., Verdorfer, A. P., & Peus, C. (2019). Shedding light on leaders’ self-interest: Theory and measurement of exploitative leadership. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1401–1433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317707810 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Singh, S. K., & Singh, A. P. (2019). Interplay of organizational justice, psychological empowerment, organizational citizenship behavior, and job satisfaction in the context of circular economy. Management Decision, 57(4), 937–952. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-09-2018-0966 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Strauss, K., Parker, S. K., & O’Shea, D. (2017). When does proactivity have a cost? Motivation at work moderates the effects of proactive work behavior on employee job strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 100, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.02.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun, Z. Z., Wu, L. Z., Ye, Y. J., & Kwan, H. W. (2023a). The impact of exploitative leadership on hospitality employees’ proactive customer service performance: A self-determination perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(1), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijchm-11-2021-1417 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun, U. Y., Xu, H., Kluemper, D. H., Lu, X., & Yun, S. (2023b). What does leaders’ abuse mean to me? Psychological empowerment as the key mechanism explaining the relationship between abusive supervision and taking charge. Group & Organization Management, 15, 47. https://doi.org/10.1177/10596011231204387 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, X. (2009). An empirical study on the structure and reality of organizational justice in China. Management Review, 21(9), 39–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Wang, Z., Chen, Y., Ren, S., Collins, N., Cai, S., & Rowley, C. (2023a). Exploitative leadership and employee innovative behaviour in China: A moderated mediation framework. Asia Pacific Business Review, 29(3), 570–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2021.1990588 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Z., Ren, S., Chadee, D., & Chen, Y. (2024). Employee ethical silence under exploitative leadership: The roles of work meaningfulness and moral potency. Journal of Business Ethics, 190(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05405-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Q., Wang, J., Zhou, X., Li, F., & Wang, M. (2020). How inclusive leadership enhances follower taking charge: The mediating role of affective commitment and the moderating role of traditionality. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Wang, C., Zhang, Y., & Feng, J. (2023b). Is it fair? How and when exploitative leadership impacts employees’ knowledge sharing. Management Decision, 61(11), 3295–3315. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-09-2022-1289 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu, L. Z., Sun, Z. Z., Ye, Y. J., Kwan, H. K., & Yang, M. Q. (2021). The impact of exploitative leadership on frontline hospitality employees’ service performance: A social exchange perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 96, 102954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102954 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xu, X.-M., Cropanzano, R., McWha-Hermann, I., & Lu, C.-Q. (2024). Multiple salary comparisons, distributive justice, and employee withdrawal. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(10), 1533–1554. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xu, A. J., Loi, R., & Chow, C. W. C. (2022). Why and when proactive employees take charge at work: The role of servant leadership and prosocial motivation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2021.1934449 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ye, Y., Lyu, Y., Wu, L.-Z., & Kwan, H. K. (2022). Exploitative leadership and service sabotage. Annals of Tourism Research, 95, 103444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103444 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, C., & Liu, L. (2023). Exploring the role of employability: The relationship between health-promoting leadership, workplace relational civility and employee engagement. Management Decision, 61(9), 2582–2602. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-05-2022-0717 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools