Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

When friendship meets love: A short-term prospective study of opposite-sex friends need fulfillment effects on romantic relationship quality

1 School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

2 Conservatory of Music, Shaanxi Vocational Academy of Art, Xi’an, 710001, China

3 School of Education Science, Anhui Normal University, Wuhu, 241000, China

* Corresponding Author: Baoyan Yang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 701-711. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.067155

Received 26 April 2025; Accepted 14 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This study explored the relationship between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and romantic relationship quality, as well as the potential underlying mechanisms, including perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships, need fulfillment given by romantic partners and romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends. A total of 98 unmarried Chinese young adults in romantic relationships were participants (females = 45.9%; M = 22.71, SD = 2.81). The findings from regression, mediation, and moderation analyses indicated need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends was associated with lower romantic relationship quality. Perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships mediated the relationship between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and romantic relationship quality to be higher. The association between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and both romantic relationship quality and perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships was moderated by need fulfillment given by romantic partners to be lower as need fulfillment given by romantic partners increased. Romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends moderated the association between perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships and romantic relationship quality to be lower as individuals’ romantic desire for opposite-sex friends decreased. These findings suggest that higher need fulfillment by romantic partners in opposite-sex friend relationships may lower romantic relationship quality. Based on these findings, there is need to balance opposite-sex friendships for safety in romantic relationships.Keywords

Research suggests that close friendships with individuals of the opposite sex can trigger feelings of jealousy in romantic partners, particularly as the relationship advances towards commitment (Vanderdrift et al., 2012). About 68% of adults had previously been friends before entering a romantic relationship (Stinson et al., 2022), suggesting that opposite-sex friendships often evolve into romantic partnerships, with these friends serving as potential alternatives to romantic partners (Reczek, 2020; Bleske-Rechek & Buss, 2001; Pearce et al., 2021). Moreover, individuals may dislike their romantic partner’s friends of the opposite sex (Gilchrist-Petty & Bennett, 2019; Sucrese et al., 2023). Regardless, individuals may seek support from family, friends, and other sources, leading to reduced dependence on their romantic partner (Machia & Proulx, 2020; Belu & O’Sullivan, 2020; Schmitt & Buss, 2001). Previous studies have primarily examined how need fulfillment from romantic partners and family members affects romantic relationships. However, there has been limited exploration of the impact of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on romantic relationships (Machia & Proulx, 2020; Belu & O’Sullivan, 2020; Schmitt & Buss, 2001). Therefore, this study investigated how opposite-sex friends need fulfillment explained romantic relationship quality.

Need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and romantic relationship quality

According to the interdependence theory (Rusbult & Arriaga, 1997), if an individual’s important needs for companionship and self-expansion can be met outside of a romantic relationship, this can reduce dependence on the romantic partner and affect romantic relationship quality (Brady & Baker, 2022; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003; Carswell et al., 2021). Opposite-sex friends play a significant role in providing information about mate choice, boosting self-esteem, and confidence (Fulmer, 2023; Lemay & Wolf, 2016). Individuals tend to form friendships with the opposite sex based on various criteria such as physical attractiveness, economic resources, and physical prowess. However, the selection criteria may be gendered with men prioritizinge physical attractiveness in their opposite-sex friends, while women prioritizing economic resources and physical prowess (Sassler, 2010; Buss & Schmitt, 2019)

When individuals are dissatisfied with their romantic relationships or fail to find an ideal partner, opposite-sex friends can serve as an alternative to fulfill mate selection needs, potentially decreasing romantic relationship quality (Buss et al., 2017; Graham & Leri, 2019). Romantic relationship development encompasses the journey from initial acquaintance to establishing a committed partnership (Joel & MacDonald, 2021), and attraction and romantic desire between individuals of the opposite sex are significant factors in this progression. The study suggests that in addition to a romantic partner, individuals can have their needs fulfilled by friends, family, work, and recreation (Machia & Proulx, 2020).

Perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships mediation

Some studies have found that external need fulfillment in romantic relationships indirectly predicts romantic relationship decline by enhancing perceptions of alternative quality (Machia & Proulx, 2020). Familiarity between individuals can enhance attraction (Li et al., 2025; Reis et al., 2011). Similarly, with the more need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends, the higher perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships (Yang et al., 2023). If an individual’s perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships surpasses that of their romantic relationship, individuals may choose to end the romantic partnership and pursue an opposite-sex friend with better perceived quality. Therefore, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends may influence romantic relationship quality by impacting individuals’ perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships.

Need fulfillment given by romantic partners moderation

Studies have shown that individuals in satisfying romantic relationships tend to develop cognitive biases towards opposite-sex friends, including motivation biases and perception biases (Sels et al., 2021; Vanderdrift et al., 2009). Motivation bias involves devaluing attractive alternatives to maintain self-consistency, while perception bias can either lead to perceiving alternatives as poor quality or completely ignoring their existence (Auger et al., 2025). Need fulfillment given by romantic partners reinforces these cognitive biases by enhancing satisfaction in the romantic relationship.

However, if a romantic partner fails to meet an individual’s needs for new resources, ideas, or other requirements, the assessment biases favoring alternative choices will weaken, leading the individual to become more interested in exploring other options (Johnson & Rusbult, 1989; VanderDrift et al., 2009). Consequently, individuals with high need fulfillment given by romantic partners may become less concerned about need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends. Conversely, they may be interested in need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends, and may gradually reduce their reliance on their romantic partners.

Romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends moderation

Opposite-sex friendships with elevated levels of romantic desire are prone to engaging in more interactions (Aron et al., 2022). For instance, when individuals possess intense romantic desire for their opposite-sex friends, they are inclined to escalate their interactions, possibly resulting in the neglect of existing romantic partners and a heightened probability of entering into romantic relationships with these opposite-sex friends (Lemay & Wolf, 2016). Conversely, if the level of romantic desire for opposite-sex friends is low, individuals are unlikely to transition the friendship into a romantic relationship, even if they perceive the opposite-sex friends as a better alternative. Additionally, individuals’ platonic friendships with opposite-sex friends are often accepted by their romantic partners, making these friends a common socialization object for the partners (Worley & Samp, 2014). Therefore, the impact of perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships on romantic relationship quality may vary based on an individual’s level of romantic desire for opposite-sex friends. Hence, we propose specifically, lower perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships on romantic relationship quality, would diminish as individuals’ romantic desire for opposite-sex friends decreased.

According to interdependence theory (Rusbult & Arriaga, 1997), higher levels of external need fulfillment are linked to increased recognition of alternative options. This realization may prompt individuals to acknowledge that their needs could be satisfied beyond their current romantic relationships, potentially reducing dependence on their partners and leading them to contemplate the possibility of ending the relationship (Liu et al., 2015; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). By the interdependence theory (Rusbult & Arriaga, 1997), need fulfillment given by romantic partners can reduce the substitutability of need satisfaction provided by others (see also Van Lange & Balliet, 2015; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003; Columbus et al., 2021).

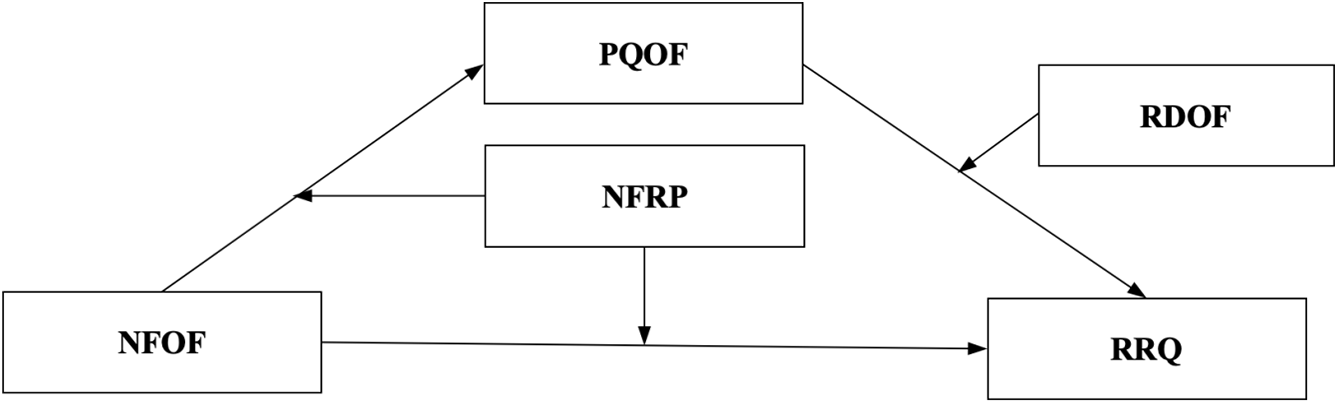

The current study tested a moderated mediation model (Figure 1) to examine the relationship between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and romantic relationship quality, with perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships mediation, and need fulfillment given by romantic partners and romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends moderation. Our specific hypotheses were:

Figure 1: Conceptual model of current study. Note. NFOF (need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends); NFRP (need fulfillment given by romantic partners); PQOF (perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships); RDOF (romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends); RRQ (romantic relationship quality).

H1: Need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends predicts lower romantic relationship quality.

H2: Perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships mediates the relationship between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and romantic relationship quality for lower romantic relationship quality.

H3: Need fulfillment given by romantic partners moderates the effect between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and romantic relationship quality and perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships so that predictive effect of on romantic relationship quality, are diminished as need fulfillment given by romantic partners increases.

H4: The association between perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships and romantic relationship quality is moderated by romantic desire so that the effect of perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships on romantic relationship quality is diminished as individuals’ romantic desire for opposite-sex friends decreases.

A convenience of 98 unmarried individuals in romantic relationships from Northwest China were participants, 53 were male (54.1%) and 45 were female (45.9%). The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 29 years (M = 22.71, SD = 2.81), while the duration of their relationships spanned from 0.5 to 120 months (M = 25.76, SD = 23.25).

We utilized the Need Fulfillment Scale (Machia & Proulx, 2020) to assess need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and need fulfillment given by romantic partners, across 7 dimensions of independence, self-improvement, self-expansion, caregiving, security, sexual contact, and companionship (6 items each). Items were on a nine-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 9 (completely agree). Two sample items were “My relationship with my current partner fulfills my need for independence” and “My relationship with my current opposite-sex friend fulfills my need for independence”. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for the Need Fulfillment Scale (T1 to T4) provided by opposite-sex friends were 0.90, 0.90, 0.91, and 0.92, respectively. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the Need Fulfillment Scale scores (T1 to T4) provided by romantic partners were 0.92, 0.94, 0.96, and 0.96.

Romantic relationship quality based on factors including love commitment and breakup considerations (Belu & O’Sullivan, 2025). Relationship quality as love commitment was assessed using the Chinese version of the Investment Model Scale (IMS-CR), a scale developed by Rusbult and revised by Liu (Rusbult et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2015). The love commitment subscale, comprising seven items, was utilized to measure love commitment. For example, “I aspire for our relationship to endure over an extended period”. Participants responded to each item on a nine-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (completely agree). Higher scores indicated higher levels of love commitment and romantic relationship quality. Cronbach’s α coefficients for scores at T1 to T4 were 0.87, 0.88, 0.88, and 0.86, respectively. Relationship breakup considerations was utilized the Breakup Consideration Scale to assess breakup considerations (VanderDrift et al., 2009). It consists of five items, on a nine-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (completely agree). For example, “I almost told my romantic partner that I wanted to break up with him/her.” Higher scores indicated higher levels of breakup considerations and lower levels of romantic relationship quality. In this study, the Chinese version of the scale was used, which was translated and revised by several experts to ensure its alignment with the Chinese background and context. Cronbach’s α coefficients for scores at T1 to T4 were 0.94, 0.94, 0.95, and 0.94, respectively.

Perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships

The Investment Model Scale (Rusbult et al., 1998) subscale consisting of five items was the measure. Each item is on a nine-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (completely agree), with higher scores indicating greater perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships (Liu et al., 2015). The original scale is a general scale that assesses the quality of alternatives. We adapted it for our research by substituting “other people” with “opposite-sex friends” to evaluate perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships. One example item was “My relationship with my opposite-sex friends is almost ideal”. To ensure cultural relevance, the Chinese version of the scale, translated and revised by multiple experts, was employed. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for scores at T1 to T4 were 0.90, 0.94, 0.96, and 0.94, respectively.

Romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends

The study utilized the Romantic Desire Scale (Lemay & Wolf, 2016), which comprises four items scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely). Higher scores indicate a stronger romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends. One sample item was “To what extent are you interested in dating your opposite-sex friends?” To ensure cultural relevance, the Chinese version of the scale, translated and revised by multiple experts, was used. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for T1 to T4 were 0.86, 0.89, 0.87, and 0.91.

We employed the Chinese version of the Investment Size Subscale from the Investment Model Scale (Rusbult et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2015) to assess the investment size in love. Participants rated their investment size in love by responding to five items. Each item was assessed on a nine-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 9 (completely agree). One example item was “My partner and I share a lot of memories”. Cronbach’s α coefficients for scores at T1 to T4 were 0.77, 0.82, 0.84, and 0.87, respectively.

All data used in this study were collected by the authors. No external, third-party, or publicly available datasets were employed. The Northwest Nnormal University ethics committee approved the study. Participants granted consent to the study to implement at four different time points, approximately one week apart. Throughout the study, participants had the option to discontinue at any point based on their personal preferences. The tasks and procedures were explained and demonstrated by the researcher, and participants received financial compensation upon completion of the study.

Analysis implemented using SPSS 26.0. Four steps were involved in the data analysis. First, following the data processing methods used in previous research (Gilchrist-Petty & Bennett, 2019; Machia & Proulx, 2020), this study generated lagged variables for need fulfillment from opposite-sex friends and romantic partners at each time point. The data from Ti were duplicated to Ti+1 to create lagged variables. Specifically, a new variable Xt−1 was created by copying the data of X (need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends) from T1 to T2, then from T2 to T3, and from T3 to T4. Similarly, a new variable Wt−1 was created by copying the data of W (need fulfillment given by romantic partners) from T1 to T2, then from T2 to T3, and from T3 to T4. Ultimately, each subject had three sets of available data. Need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends (Xt−1) and need fulfillment given by romantic partners (Wt−1) utilized data from three time points, ranging from T1 to T3, while the other variables used data from three time points, ranging from T2 to T4, for the same subjects. Second, we conducted a regression analysis to verify H1, and we examined the mediation effect proposed in H2 using the SPSS Process macro (Model 4). Finally, to examine the moderation effect proposed by H3 and H4, the Process macro (Model 22) developed by Hayes was adopted (Hayes, 2012).

Descriptive analysis and correlation analysis

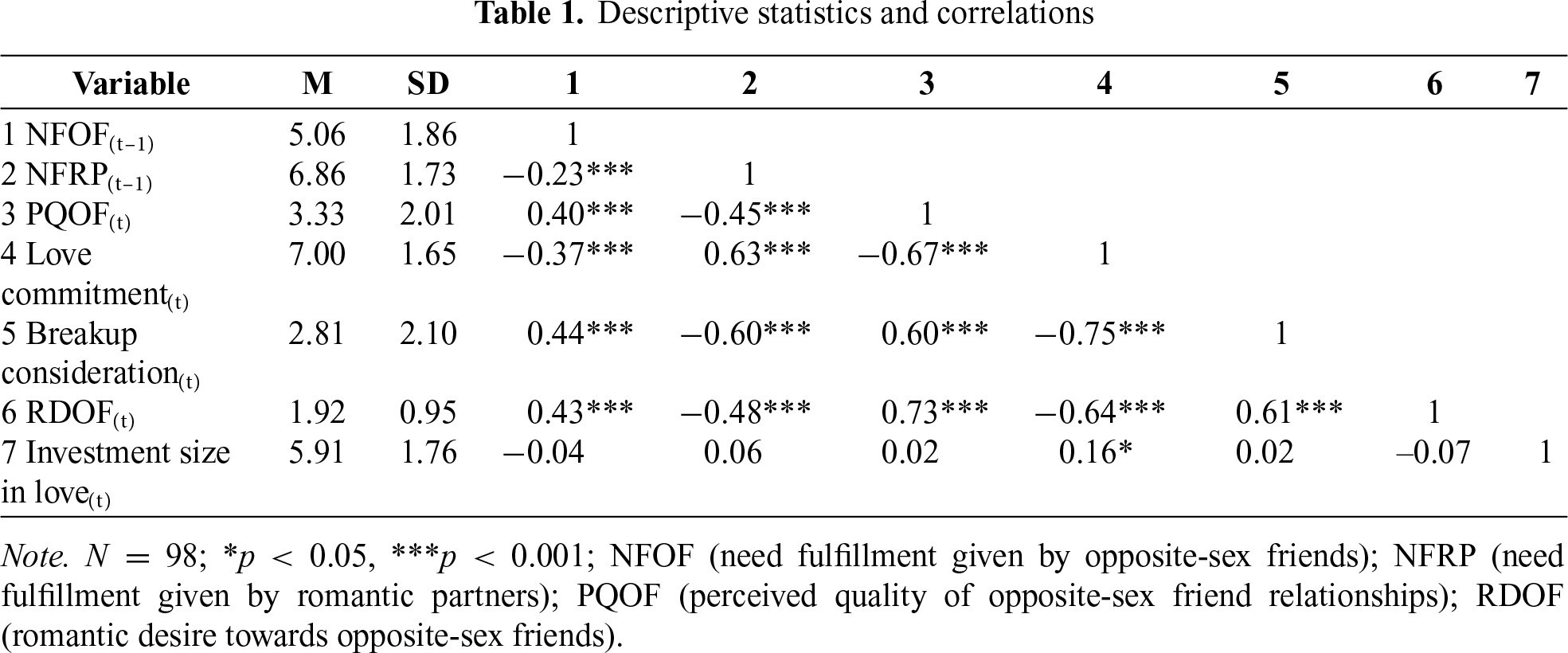

Table 1 provided the descriptive statistics and correlations summaries of the study variables. Need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends showed a positive correlation with perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships (r = 0.40, p < 0.001) and breakup consideration (r = 0.44, p < 0.001) one week later, while displaying a negative correlation with love commitment (r = –0.37, p < 0.001) one week later. Need fulfillment given by romantic partners was significantly negatively related to perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships (r = –0.45, p < 0.001) and breakup consideration (r = –0.60, p < 0.001) one week later, and significantly positively related to love commitment (r = 0.63, p < 0.001) one week later. Perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships was significantly negatively related to love commitment (r = –0.67, p < 0.001), romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends was significantly negatively related to love commitment (r = –0.64, p < 0.001) and positively related to breakup consideration (r = 0.61, p < 0.001), thus supporting H1.

Main effect of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on romantic relationship quality

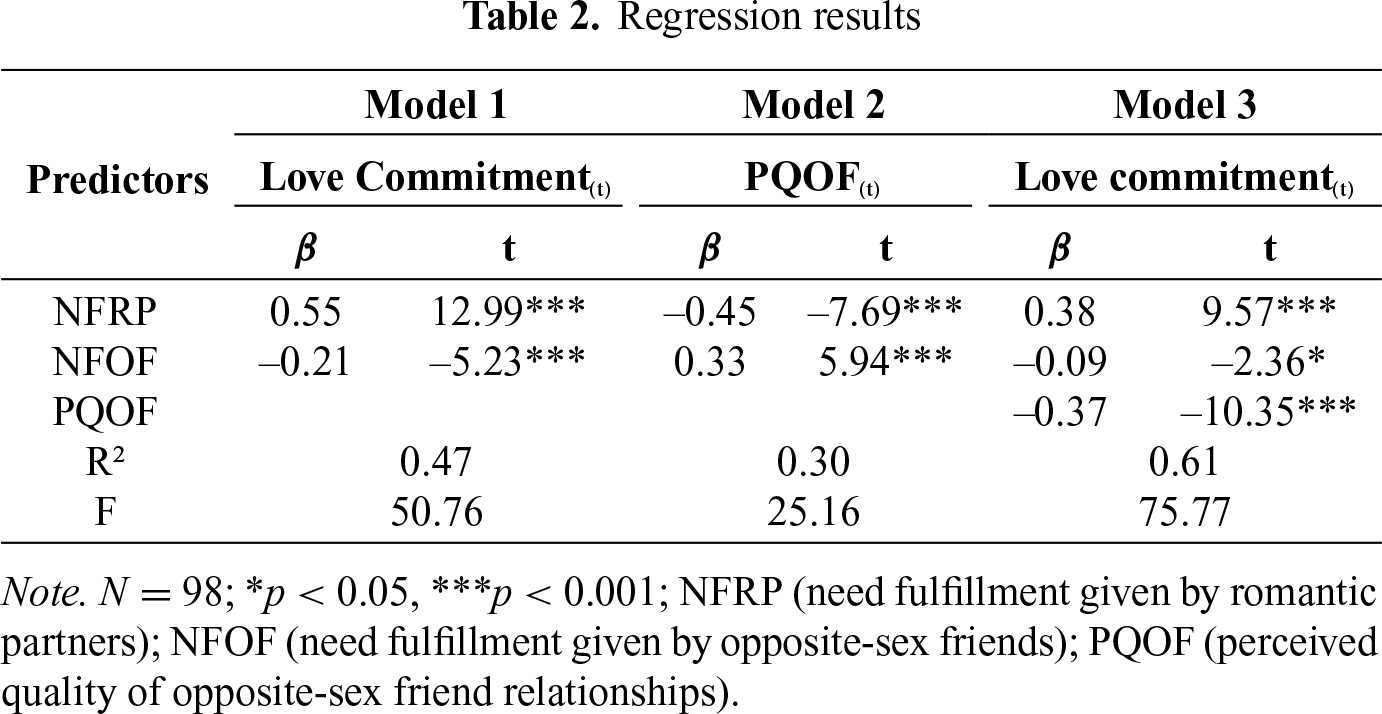

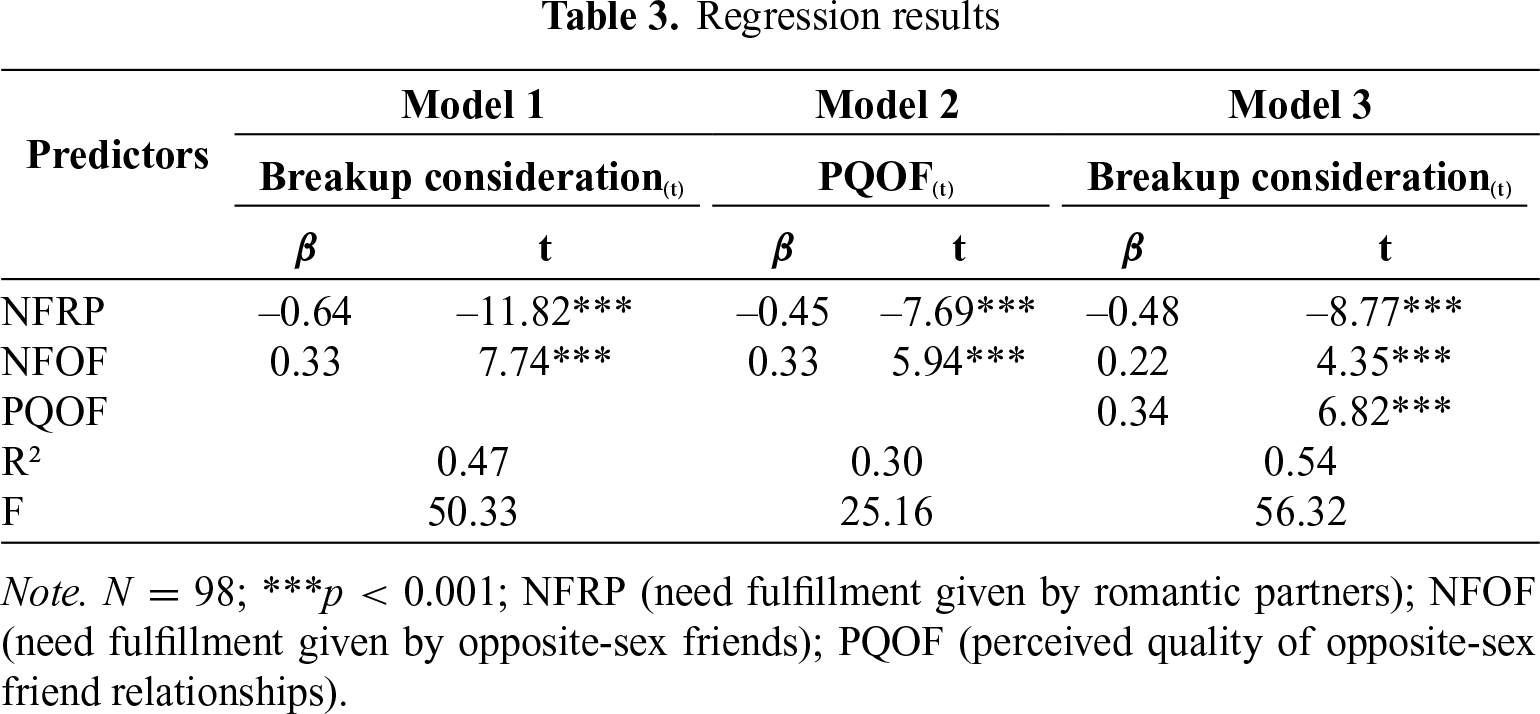

As presented in Table 2, when love commitment was used as the dependent variable, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends significantly negatively predicted love commitment (β = –0.21, p < 0.001) one week later. As presented in Table 3, when breakup considerations were used as the dependent variable, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends significantly positively predicted breakup considerations (β = 0.33, p < 0.001) one week later. Therefore, H1 was further confirmed.

Perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships mediation

As presented in Table 2, when love commitment was used as the dependent variable, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends significantly positively predicted the perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships (β = 0.33, p < 0.001) and negatively predicted love commitment (β = –0.21, p < 0.001) one week later. After adding perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships one week later, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends still significantly negatively predicted love commitment one week later (β = –0.09, p < 0.05), and perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships significantly negatively predicted love commitment one week later (β = –0.37, p < 0.001). Therefore, perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and love commitment. Bootstrapping results showed an indirect effect, such that need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends decreased love commitment through perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships (b = –0.12, 95% CI [–0.18, –0.07]). Thus, perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships mediated the effect of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on love commitment, thus supporting H2.

As presented in Table 3, when breakup considerations were used as the dependent variable, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends significantly positively predicted the perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships (β = 0.33, p < 0.001) and breakup considerations (β = 0.33, p < 0.001) one week later. After adding perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships one week later, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends still significantly positively predicted breakup considerations one week later (β = 0.22, p < 0.001), and perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships significantly positively predicted breakup considerations one week later (β = 0.34, p < 0.001). Therefore, perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and breakup considerations. Bootstrapping results showed an indirect effect, such that need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends increased breakup considerations through perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships (b = 0.11, 95% CI [0.05, 0.19]). Thus, perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships mediated the effect of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on breakup considerations, thus supporting H2.

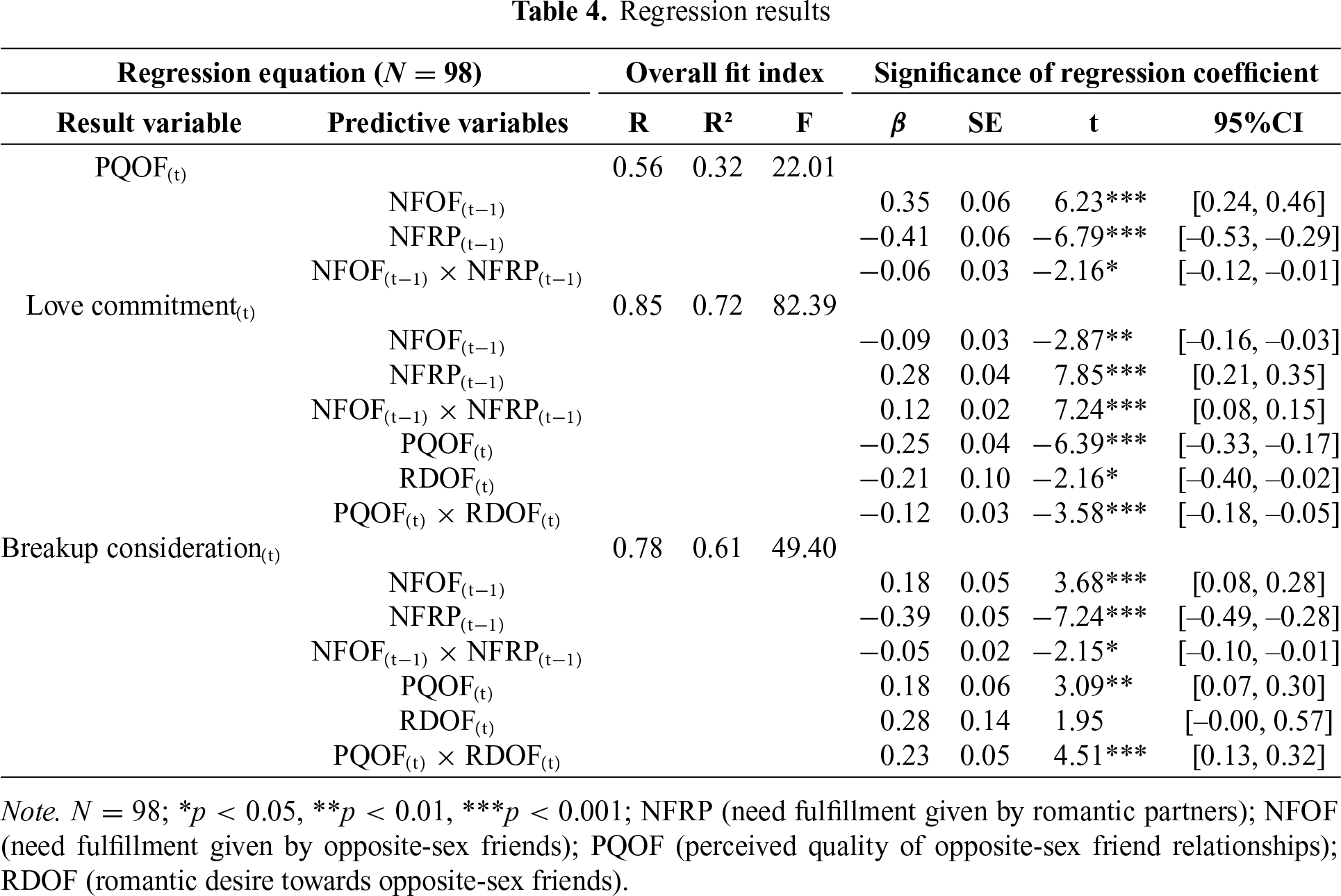

Need fulfillment given by romantic partners and romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends as moderators

Utilizing love commitment, measured one week later, as an indicator of romantic relationship quality, as shown in Table 4, the interaction between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and need fulfillment given by romantic partners has a significantly predictive influence on perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships one week later (β = –0.06, p = 0.032). This suggests that need fulfillment given by romantic partners acts as a moderator in the initial stages of the mediation model, supporting H3. Furthermore, the interaction between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and need fulfillment given by romantic partners significantly predicts love commitment one week later (β = 0.12, p < 0.001), highlighting the moderating role of need fulfillment given by romantic partners in the relationship between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and love commitment. In addition, the interaction term involving perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships one week later and romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends significantly predicts love commitment (β = –0.12, p < 0.001), indicating that romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends plays a moderating role in the latter stages of the mediation model, supporting H4.

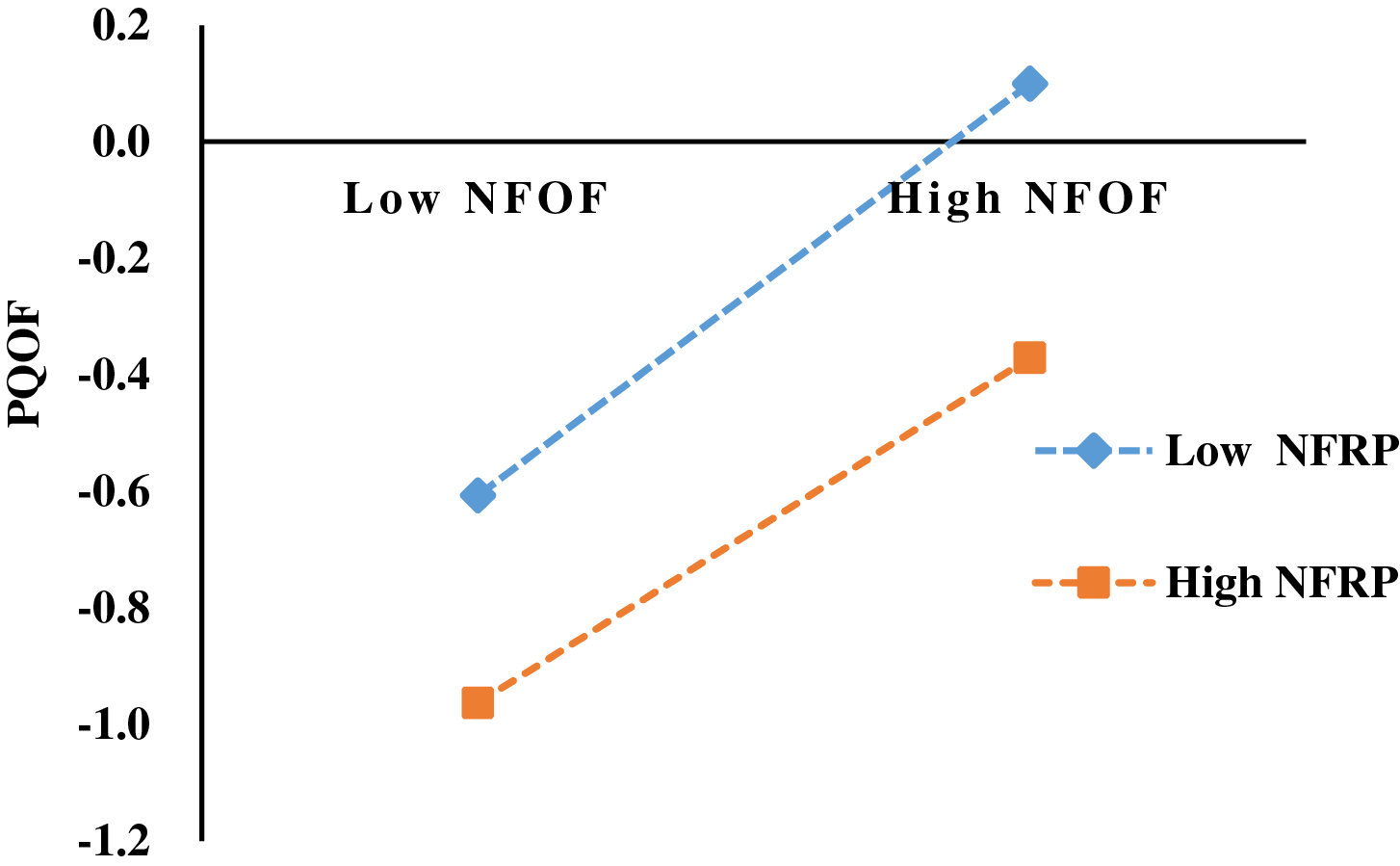

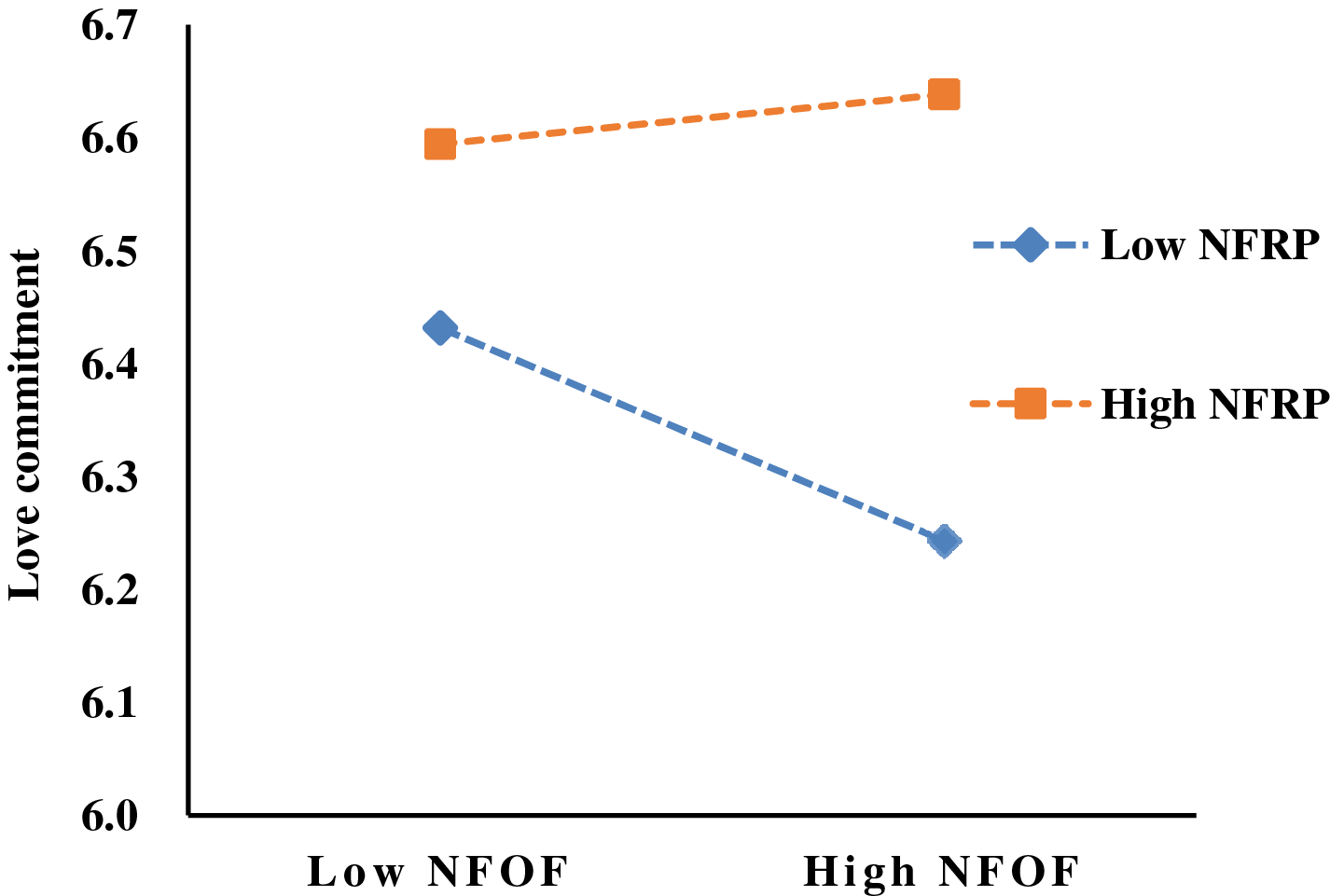

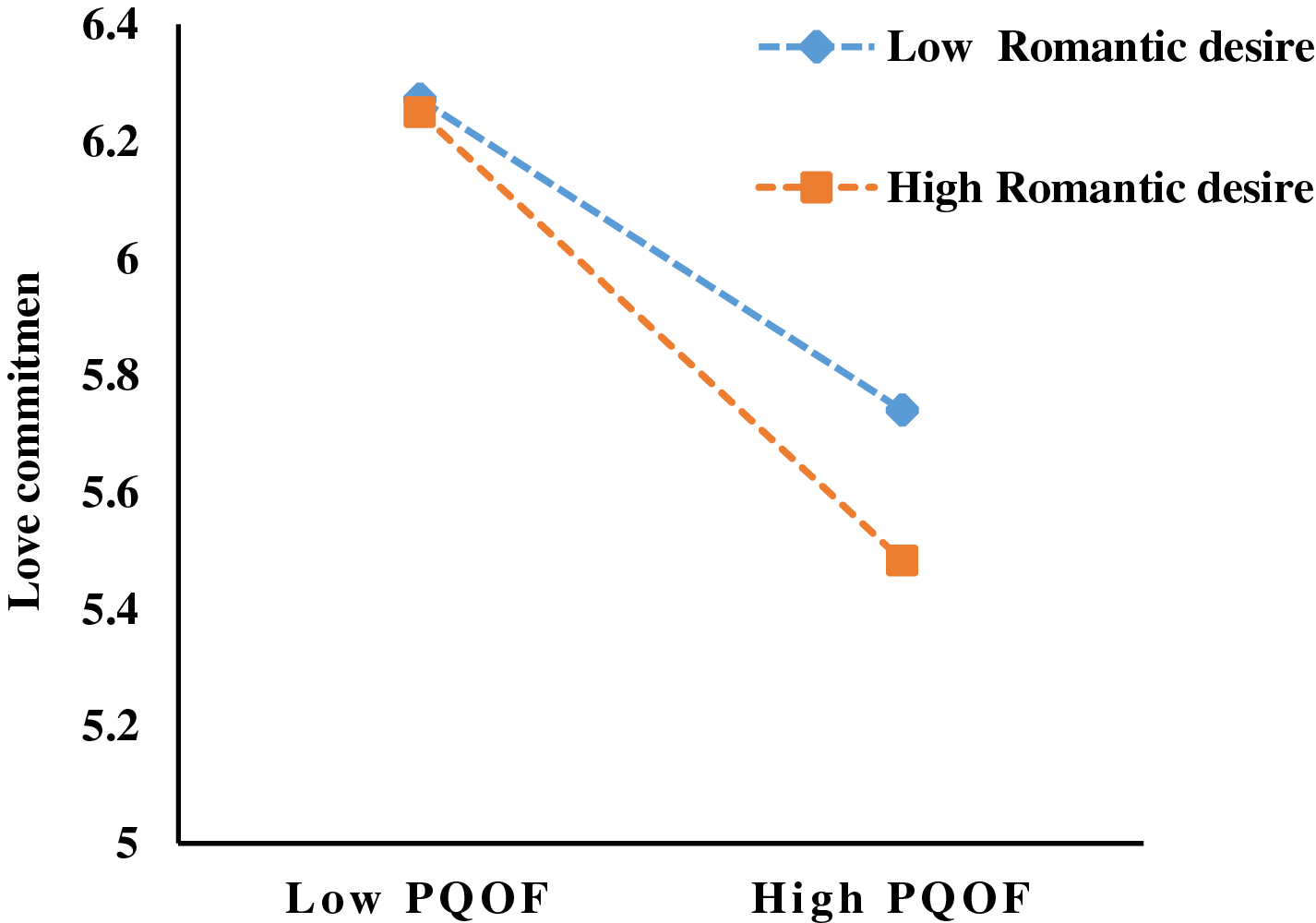

In order to elucidate this moderating effect, we categorized need fulfillment given by romantic partners and romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends into high and low groups based on one standard deviation above and below the mean, and then conducted a simple slope analysis. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate that when need fulfillment given by romantic partners was low, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends significantly positively predicted perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships one week later (β = 0.46, p < 0.001), and also significantly negatively predicted love commitment one week later (β = –0.30, p < 0.001). On the other hand, when need fulfillment given by romantic partners was high, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends still positively predicted perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships one week later, but with a smaller effect size (β = 0.24, p < 0.001), and also positively predicted love commitment one week later (β = 0.11, p < 0.01). This suggests that as the level of need fulfillment given by romantic partners increases, the predictive impact of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships and love commitment one week later gradually diminishes. Additionally, Figure 4 demonstrates that when romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends was low, perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships significantly negatively predicted love commitment (β = –0.14, p < 0.01). Conversely, when romantic desire was high, perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships exhibited a stronger negative predictive effect on love commitment (β = –0.37, p < 0.001). This implies that as romantic desire levels increase, the adverse predictive effect of perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships on love commitment gradually intensifies.

Figure 2: Moderating effect of NFRP on the link between NFOF and PQOF. Note. NFRP (need fulfillment given by romantic partners); NFOF (need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends); PQOF (perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships).

Figure 3: Moderating effect of NFRP on the link between NFOF and love commitment. Note. NFRP (need fulfillment given by romantic partners); NFOF (need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends).

Figure 4: Moderating effect of RDOF on the link between PQOF and love commitment. Note. RDOF (romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends); PQOF (perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships).

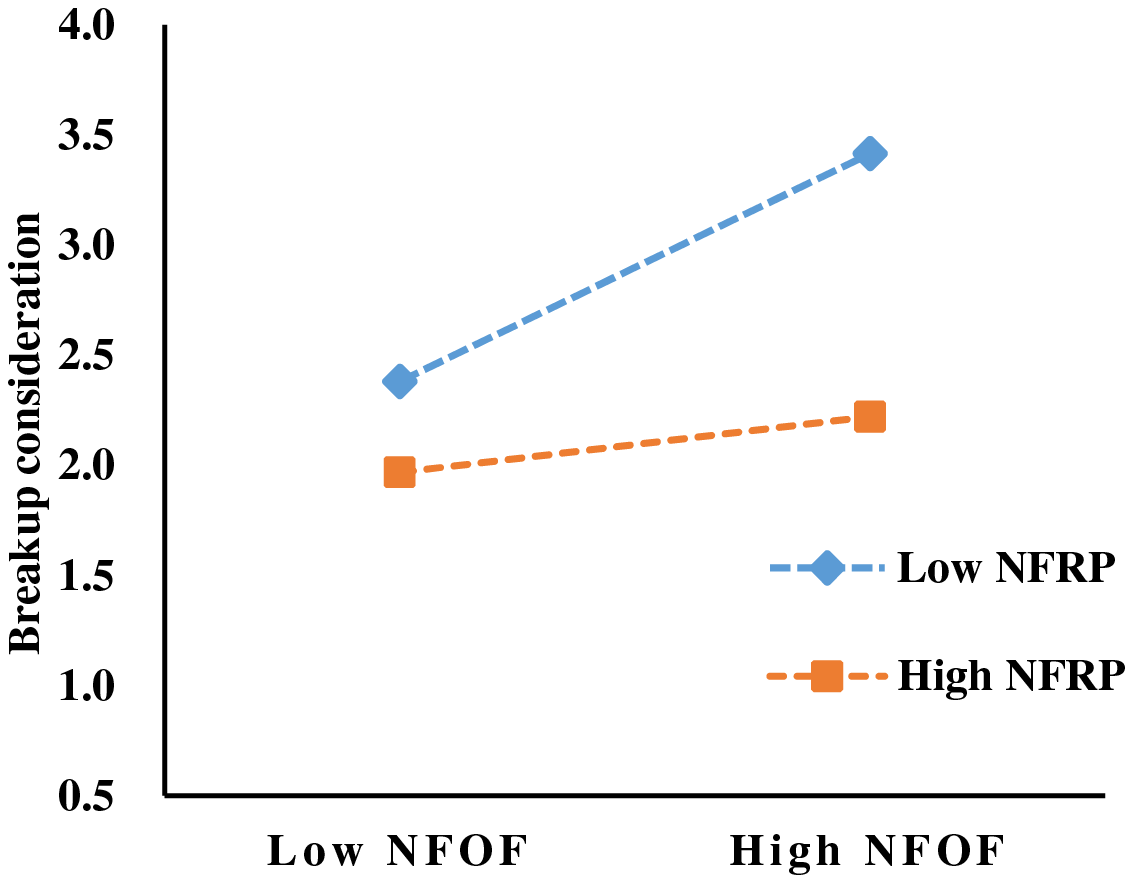

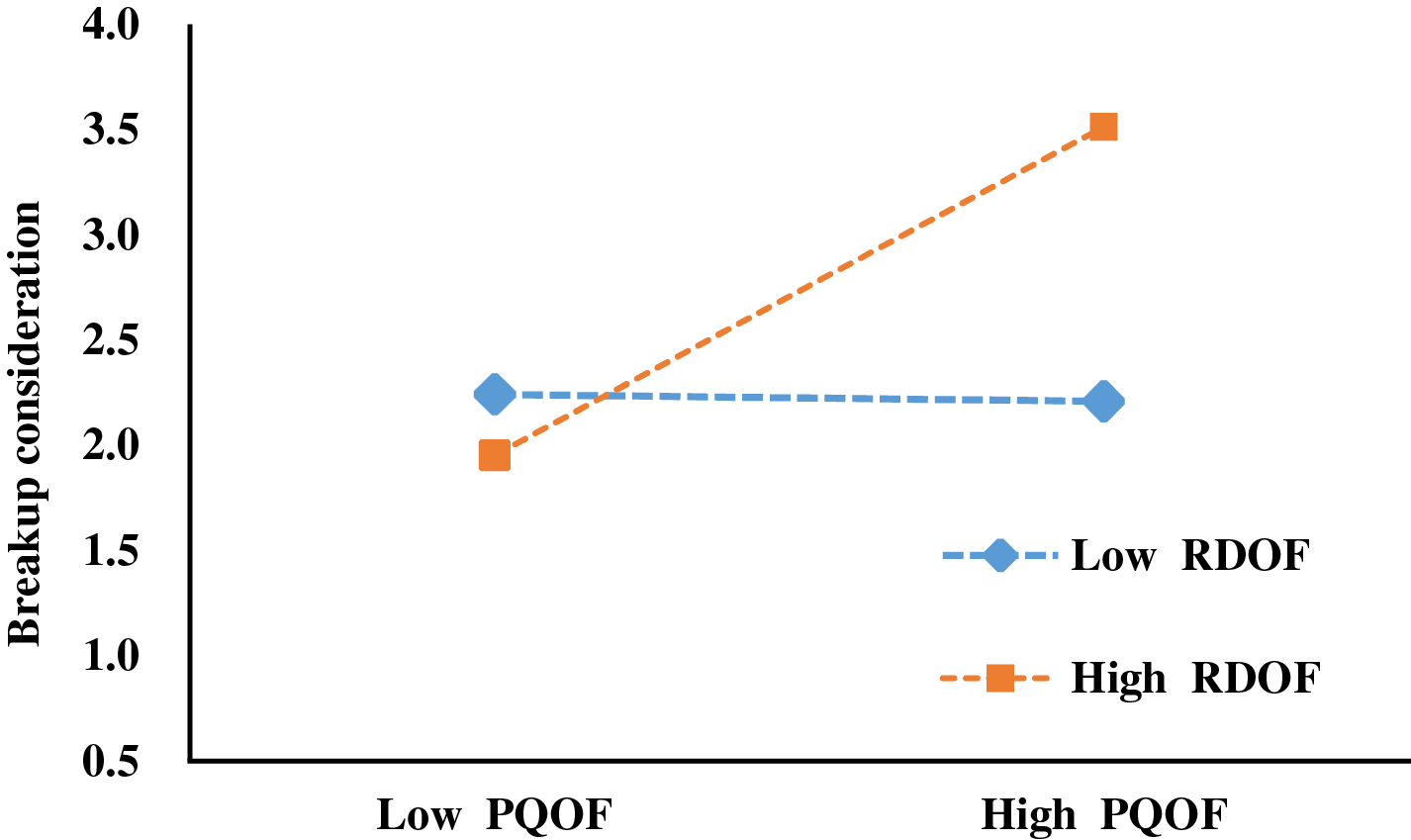

Utilizing breakup considerations, measured one week later, as an indicator of romantic relationship quality, the moderating effect of need fulfillment given by romantic partners on the first half path of the mediation model remained consistent, as shown in Table 4. The interaction between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and need fulfillment given by romantic partners negatively predicted breakup considerations one week later (β = –0.05, p < 0.05), indicating that need fulfillment given by romantic partners moderated the relationship between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and breakup considerations, supporting H3. Additionally, the interaction terms involving perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships and romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends positively predicted breakup considerations (β = 0.23, p < 0.001), showing that romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends played a moderating role in the latter half of the mediation model, supporting H4.

In order to elucidate this moderating effect, we categorized need fulfillment given by romantic partners and romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends into high and low groups based on one standard deviation above and below the mean, and then conducted a simple slope analysis. Figure 5 illustrate that when need fulfillment given by romantic partners was low, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends significantly positively predicted breakup considerations one week later (β = 0.27, p < 0.001). When need fulfillment given by romantic partners was high, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends was not significant in predicting breakup considerations one week later (β = 0.09, p = 0.11). This suggests that as the level of need fulfillment given by romantic partners increases, the predictive impact of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on breakup considerations one week later gradually diminishes. Additionally, Figure 6 demonstrates that when romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends was low, perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships did not significantly predict breakup considerations (β = –0.02, p = 0.753). Conversely, when romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends was high, perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships exhibited a stronger positive predictive effect on breakup considerations (β = 0.40, p < 0.001). This implies that as romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends increases, the positive predictive effect of perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships on breakup considerations gradually intensifies. Meanwhile, the mediating effect of perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships is moderated by romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends. Specifically, individuals with high romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends show a significant mediating effect of perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships, whereas individuals with low romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends do not exhibit a significant mediating effect. Need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends directly influences breakup considerations.

Figure 5: Moderating effect of NFRP on the link between NFOF and breakup consideration. Note. NFRP (need fulfillment given by romantic partners); NFOF (needfulfillment given by opposite-sex friends).

Figure 6: Moderating effect of RDOF on the link between PQOF and breakup consideration. Note. RDOF (romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends); PQOF (perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships).

This study found that need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends significantly and negatively impacts romantic relationship quality. Specifically, individuals who receive more need satisfaction from their opposite-sex friends tend to have lower romantic relationship quality. Previous studies have found that when individuals receive greater emotional support, intimacy, or value recognition from sources outside the romantic relationship (e.g., family or friends), the perceived irreplaceability of their romantic partner and the functional uniqueness of the romantic relationship are directly eroded, thereby reducing their satisfaction and commitment to the existing romantic relationship (VanderDrift et al., 2012). Furthermore, previous studies also found that an individual’s need satisfaction from alternative choices, such as family and friends, can influence their romantic relationship quality and even lead to the belief that their original romantic relationship is replaceable (Tran et al., 2019). These thoughts not only diminish the individual’s initial expectations of the romantic relationship and decrease satisfaction, but also decrease dependence on the romantic relationship and undermine its quality (Machia & Proulx, 2020; Tran et al., 2019). According to the interdependence theory, when individuals have their important needs met by opposite-sex friends, their satisfaction with these friends and their perception of alternatives to their current romantic partner increase, resulting in decreased romantic relationship quality (Van Lange & Balliet, 2015). This study confirms and elaborates on the idea that high-quality opposite-sex friendships can pose a threat to stable and lasting romantic relationships, with need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends playing a crucial role in reducing romantic relationship quality.

This study found that perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships mediated the relationship between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and romantic relationship quality. In other words, higher need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends was associated with a higher perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships, which in turn played a key role in reducing the level of love commitment and fostering breakup considerations (Yang et al., 2023). The interdependence theory highlights the interconnected nature of relationships, suggesting that an individual’s dependence on their current romantic relationship is closely linked to relationship satisfaction and potential alternative choices (Sels et al., 2021; Van Lange & Balliet, 2015). The more need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends, the lower satisfaction with the current romantic relationship, while the perceived quality of an opposite-sex friend as a potential alternative increases, ultimately leading to greater breakup considerations and reduced love commitment (Brady & Baker, 2022). A higher level of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends is associated with lower commitment to the current romantic relationship, and lower love commitment levels are often linked to a decline in romantic relationship quality and breakup considerations (Yang et al., 2023).

This study found that when an individual’s romantic partner fails to meet their needs adequately, the cognitive biases (motivation bias and perception bias) towards opposite-sex friends identified in prior research may become ineffective (Lydon et al., 2024; Johnson & Rusbult, 1989), and this loss of cognitive bias leads the individual to show greater interest in alternative choices; they may also potentially re-evaluate their opposite-sex friendships. Moreover, the study found that under these conditions of low need fulfillment given by romantic partners, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends had a significant negative impact on love commitment after a week. Conversely, when need fulfillment given by romantic partners was high, the negative impact on love commitment was weakened (eventually becoming non-significant). In fact, need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends actually exerted a significant positive influence on love commitment a week later. This finding aligns with previous research (Machia & Proulx, 2020; Yang et al., 2023), suggesting that when romantic partners adequately fulfill each other’s needs, opposite-sex friendships can benefit, rather than threaten, romantic relationships. Furthermore, the study illuminated the role of spontaneous romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends. Heightened romantic desire towards these friends was found to diminish the negative predictive effect of perceived friendship quality on romantic relationship quality, indicating that individuals with strong romantic desire may be more prone to consider leaving their partner for the friend (Lemay & Wolf, 2016). Critically, however, low romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends acts as a protective factor; even if these friends meet many needs, the individual is unlikely to seek a romantic transition, thereby helping to preserve the quality of the primary romantic relationship. In summary, these findings collectively offer a nuanced and fresh perspective for individuals navigating opposite-sex friendships within romantic relationships, highlighting the critical moderating roles of both partner need fulfillment and self-directed romantic desire towards friends in determining the impact of those friendships on the romantic bond.

Implications for research and practice

This study offers insightful theoretical direction and actionable strategies for individuals within romantic partnerships who harbor concerns that their partner’s opposite-sex friends could potentially undermine the stability of their current relationship. There are a number of surprising negative effects of romantic relationship breakups due to reduced romantic relationship quality. As an important part of need fulfillment, the impact of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on romantic relationships cannot be ignored. Based on the interdependence theory (Rusbult & Arriaga, 1997), this study reveals the internal mechanisms and potential boundary conditions under which need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends influences romantic relationship quality, and provides richer literature support and practical guidance for the study of need fulfillment and romantic relationships.

This study’s findings suggest that closer relationships between individuals in a romantic relationship and their opposite-sex friends can have a detrimental effect on their romantic relationship. Perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships serves as a key mechanism through which need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends negatively impacts romantic relationship quality. As individuals receive more need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends, their perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships also increases, with high-quality opposite-sex friendships being a significant factor in the decrease of romantic relationship quality.

In addition, romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends can be seen as a spontaneous perception. When an individual experiences romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends, they may mistakenly believe that their friends reciprocate these desires, leading to increased efforts to maintain the relationship, such as staying in touch. This study revealed that as the level of romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends, the negative predictive impact of perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships on romantic relationship quality also decreases gradually. This suggests that individuals in romantic relationships who have strong romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends may be more likely to consider leaving their current partners in favor of pursuing romantic relationships with these friends (Lemay & Wolf, 2016). However, if an individual has low romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends, even if these opposite-sex friends can meet their many needs, the individual may not be willing to transition their friendship into a romantic relationship. This reluctance can help prevent the deterioration of romantic relationship quality, thus acting as a protective factor in romantic relationships.

Limitations of the study and future directions

This research also has the following limitations, which need to be further improved in future studies. (1) This study ruled out same-sex relationships; future research could strengthen the design by including those couples, thereby increasing representativeness. (2) This study focused solely on unmarried young men and women, which limits its scope. Future studies could encompass both unmarried and married individuals to provide a more comprehensive analysis. (3) This study used convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the findings and may introduce reporting bias. Future research should employ stratified random sampling across multiple regions and age groups, and integrate multiple data sources to improve sample representativeness and measurement accuracy. (4) This study employs a short-term prospective design, providing compelling evidence for the causal relationships among variables. However, it encounters several challenges in contacting participants weekly over four weeks, including time conflicts, participant fatigue, and dropout rates. Future research should refine the study design and allocate adequate resources and time for long-term follow-ups to more clearly and reliably elucidate the causal relationships among the variables.

The study’s results showed that: (1) Need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends had a significant negative effect on romantic relationship quality. (2) Perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships mediated the effect of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on romantic relationship quality. (3) Need fulfillment given by romantic partners moderates the association between need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends and romantic relationship quality and perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships, the positive effect of Need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships and the negative predictive effect of need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on romantic relationship quality, were diminished as need fulfillment given by romantic partners increased. (4) Romantic desire towards opposite-sex friends moderates the association between perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships and romantic relationship quality, the negative effect of perceived quality of opposite-sex friend relationships on romantic relationship quality, was diminished as individuals’ romantic desire for opposite-sex friends decreased.

Acknowledgement: We thank the participants who volunteered their time and information for this study, as well as the field team for their assistance with data collection, quality control, and secure handling. We are also grateful to our colleagues for their constructive feedback and support during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Xiaoyue Zhao: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Proofreading. Ting Wang: Investigation, Data curation. Baoyan Yang: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Hongyu Zang, Qifeng Gao, Zhongyuan Zhang and Birong Xing: Writing—review & editing, Proofreading. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data used in this study were collected by the authors. No external, third-party, or publicly available datasets were employed. Data and materials will be made available on request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou (Approval No.: 2022100906). The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all procedures of this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or national research committee.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Aron, A., Lewandowski, G., Branand, B., Mashek, D., & Aron, E. (2022). Self-expansion motivation and inclusion of others in self: An updated review. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(12), 3821–3852. [Google Scholar]

Auger, E., Thai, S., Birnie-Porter, C., & Lydon, J. E. (2025). On creating deeper relationship bonds: Felt understanding enhances relationship identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 51(11), 2248–2265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Belu, C. F., & O’Sullivan, L. F. (2020). Once a poacher always a poacher? Mate poaching history and its association with relationship quality. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(4), 508–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1610150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Belu, C. F., & O’Sullivan, L. F. (2025). It’s just a little crush: Attraction to an alternative and romantic relationship quality, breakups and infidelity. The Journal of Sex Research, 62(4), 515–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2024.2310702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bleske-Rechek, A. L., & Buss, D. M. (2001). Opposite-sex friendship: Sex differences and similarities in initiation, selection, and dissolution. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(10), 1310–1323. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672012710007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brady, A., & Baker, L. R. (2022). The changing tides of attractive alternatives in romantic relationships: Recent societal changes compel new directions for future research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12650 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Buss, D. M., Goetz, C., Duntley, J. D., Asao, K., & Conroy-Beam, D. (2017). The mate switching hypothesis. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (2019). Mate preferences and their behavioral manifestations. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 77–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Carswell, K. L., Muise, A., Harasymchuk, C., Horne, R. M., Visserman, M. L., et al. (2021). Growing desire or growing apart? Consequences of personal self-expansion for romantic passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(2), 354. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Columbus, S., Molho, C., Righetti, F., & Balliet, D. (2021). Interdependence and cooperation in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(3), 626–650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Fulmer, J. (2023). Self-esteem and the motivation to establish romantic relationships: Advancements in sociometer theory [Master’s thesis]. Fresno, CA, USA: California State University. [Google Scholar]

Gilchrist-Petty, E., & Bennett, L. K. (2019). Cross-sex best friendships and the experience and expression of jealousy within romantic relationships. Journal of Relationships Research, 10(18), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/jrr.2019.16 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Graham, Z. A., & Leri, J. D. (2019). Selection, initiation, and dissolution of opposite-sex friendships revisited. The Journal of Psychology and The Behavioral Sciences, 26, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [white paper]. Retrieved from: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Joel, S., & MacDonald, G. (2021). We’re not that choosy: Emerging evidence of a progression bias in romantic relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 25(4), 317–343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Johnson, D. J., & Rusbult, C. E. (1989). Resisting temptation: Devaluation of alternative partners as a means of maintaining commitment in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 967–980. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.967 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lemay, E. P., & Wolf, N. R. (2016). Projection of romantic and sexual desire in opposite-sex friendships: How wishful thinking creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(7), 864–878. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216646077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, J., Li, Y., Wang, J., Chen, L., & Ouyang, Y. (2025). Are people more attractive to people they are familiar with than those people they don’t? Journal of Humanities, Arts and Social Science, 9(2), 398–404. [Google Scholar]

Liu, X. C., Zhao, L., Zhang, L. L., & Yang, L. (2015). Reliability and validity of the Investment Model Scale in Chinese dating couples. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23(6), 1020–1023. [Google Scholar]

Lydon, J. E., Tissera, H., Auger, E., & Nishioka, M. (2024). Devaluation of attractive alternatives: How those with poor inhibitory ability preemptively resist temptation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 01461672241259194. [Google Scholar]

Machia, L. V., & Proulx, M. L. (2020). The diverging effects of need fulfillment obtained from within and outside of a romantic relationship. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(5), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

Pearce, E., Machin, A., & Dunbar, R. I. (2021). Sex differences in intimacy levels in best friendships and romantic partnerships. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 7(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

Reczek, C. (2020). Sexual-and gender-minority families: A 2010 to 2020 decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 300–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Reis, H. T., Maniaci, M. R., Caprariello, P. A., Eastwick, P. W., & Finkel, E. J. (2011). Familiarity does indeed promote attraction in live interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(3), 557–570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Rusbult, C. E., & Arriaga, X. B. (1997). Interdependence theory. In: S. Duck (Ed.Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, research and interventions (2nd ed.) (pp. 221–250Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

Rusbult, C. E., Martz, J. M., & Agnew, C. R. (1998). The investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships, 5(4), 357–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00177.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rusbult, C. E., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2003). Interdependence, interaction, and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 351–375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Sassler, S. (2010). Partnering across the life course: Sex, relationships, and mate selection. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00718.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Schmitt, D. P., & Buss, D. M. (2001). Human mate poaching: Tactics and temptations for infiltrating existing mateships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(6), 894–917. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.6.894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sels, L., Reis, H. T., Randall, A. K., & Verhofstadt, L. (2021). Emotion dynamics in intimate relationships: the roles of interdependence and perceived partner responsiveness. In: Affect dynamics (pp. 155–179Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82965-0_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stinson, D. A., Cameron, J. J., & Hoplock, L. B. (2022). The friends-to-lovers pathway to romance: Prevalent, preferred, and overlooked by science. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(2), 562–571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Sucrese, A. M., Burley, E. E., Perilloux, C., Woods, S. J., & Bencal, Z. (2023). Just friends? Jealousy of extramarital friendships. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 17(3), 333. [Google Scholar]

Tran, P., Judge, M., & Kashima, Y. (2019). Commitment in relationships: An updated meta-analysis of the investment model. Personal Relationships, 26(1), 158–180. [Google Scholar]

Van Lange, P. A. M., & Balliet, D. (2015). Interdependence theory. In: Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., Simpson, J. A., Dovidio, J. F. (Eds.APA handbook of personality and social psychology (vol. 3, pp. 65–92Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

VanderDrift, L. E., Agnew, C. R., & Wilson, J. E. (2009). Nonmarital romantic relationship commitment and leave behavior: The mediating role of dissolution consideration. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(9), 1220–1232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209337543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Vanderdrift, L. E., Lehmiller, J. J., & Kelly, J. R. (2012). Commitment in friends with benefits relationships: Implications for relational and safe-sex outcomes. Personal Relationships, 19(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

Worley, T. R., & Samp, J. (2014). Friendship characteristics, threat appraisals, and varieties of jealousy about romantic partners’friendships. Interpersona, 8(2), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.5964/ijpr.v8i2.169 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, B., Zhao, X., Wang, T., Zhong, Z., Zhang, Y., et al. (2023). Effects of the need fulfillment given by opposite-sex friends on breakup considerations: A moderated mediation model. Acta Psychologica, 241, 104091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.104091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools