Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Fathers’ overprotective parenting and young children’s problem behaviors: Mediating by mothers’ overprotective attitudes and parenting stress

1 Department of Early Childhood Education, School of Education and Psychology, Shaoxing University, Shaoxing, 312000, China

2 Department of Early Childhood Education, College of Teacher Education, Huzhou University, Huzhou, 313000, China

* Corresponding Author: Ruiqian Li. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 681-688. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.069421

Received 23 June 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This study examined the relationship between paternal overprotective parenting and problem behaviors of preschool children, and maternal overprotective attitudes and parenting stress mediation of that relationship. Data were collected from 265 families, including parents and preschool children (ages 3–6). The results revealed that paternal overprotective attitudes significantly influenced maternal overprotective attitudes and maternal parenting stress. Maternal overprotective attitudes, in turn, increased maternal parenting stress, exacerbated children’s problem behaviors. Paternal overprotective attitudes indirectly contributed to these behaviors through both maternal overprotective attitudes and parenting stress. The effect was more pronounced on boy than girl younger than older preschoolers. These findings are explained by the family systems theory through the mechanism of interconnected parental subsystems, wherein paternal overprotection triggers maternal stress and overprotective attitudes, ultimately affecting child behaviors. Healthy parenting would entail psychologically safe paternal overprotection, lower maternal stress, and promoting autonomy-supportive parenting practices to reduce the risk of problem behaviors in preschool children.Keywords

Paternal overprotection manifests through excessive worry, safety concerns, and restriction of autonomy which could hamper, child psychological-behavioral development (Derlan et al., 2019). Problem behaviors in young children that deviate from age-appropriate norms negatively affect their social adaptability and psychological well-being (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1978). Such behaviors are categorized as hostile-aggressive (e.g., hitting, biting, lying), anxious-worried (e.g., excessive worry, loneliness, fear), and hyperactive-distractible behaviors (e.g., impulsivity, restlessness; Achenbach et al., 2016). Parenting behaviours by gender could may manifest in mothers being more overprotective their parenting practices overall (Lanjekar et al., 2022), while fathers may be into safety concerns (Lanjekar et al., 2022). Inadvertently, the interplay between paternal and maternal behaviors may further restrict children’s autonomy and exploratory abilities, thereby increasing the risk of problem behaviors (Tavassolie et al., 2016). These parenting dynamics well researched and documented in individualistic western culture than in collectivistic cultures. Moreover, existing studies have uncovered gender-specific associations among parental overprotective attitudes, parenting stress, and children’s problem behaviors, with these associations exhibiting significant cultural-context dependency (Bornstein, 2015).

Parental overprotective attitudes on children’s problem behaviors

Parental overprotective attitudes refer to excessive worry, intervention, and control exhibited by parents during the upbringing of young children (Thomasgard et al., 1995). Previous research has delineated parental overprotective attitudes into three core dimensions: intrusion, indulgence & permission, and worry & protection (Soenens et al., 2005). “intrusion” refers to parenting that limits the child’s opportunities to do theirown tasks independently, assists, and intervenes (Diemer et al., 2021; Spada et al., 2012, p. 289). “indulgence & permission” reflects parenting that does not discipline the child in situationswhere behavioral guidance is necessary (Hasbani et al., 2023, p. 2; Mak et al., 2020, p. 2995). “worry & protection” stems from parenting with high expectations for the child, such thatthe child avoids negative experiences and only haspositive experiences (Clarke et al., 2013, p. 621).

Maternal overprotective attitudes and parenting stress mediation

Maternal overprotective attitudes, rooted in safety concerns or parenting self-doubt, typically elevate parenting stress and create feelings of being overwhelmed (Hubert & Aujoulat, 2018). Existing research has shown that when mothers attempt to shield young children from experiencing any form of adversity, they may need to invest more time and energy in meeting their children’s needs, thereby experiencing heightened parenting stress (Lim & Shim, 2021).

Maternal parenting stress refers to the psychological burden and emotional pressure experienced by mothers during the parenting process due to factors such as role demands, responsibilities, environmental challenges, and the child’s characteristics (Deater-Deckard, 2008). This stress affects maternal mental health and has profound implications for children’s behavioral development. Maternal parenting stress can be categorized into parent-domain stress and child-domain stress. Parent-domain stress primarily arises from role conflicts, sense of responsibility, life disruptions, and changes in spousal relationships experienced during the parenting process (Crnic & Low, 2002; Fang et al., 2024). Child-domain stress refers to the pressure that parents feel due to their children’s behavior, developmental status, or personality traits (Deater-Deckard, 2008).

High levels of parenting stress, often associated with maternal anxiety, depression, and irritability, are significantly correlated with young children’s problem behaviors and may lead to harsh parenting practices (Silinskas et al., 2020). This can result in children feeling insecure and unsupported and may contribute to problem behaviors (Tsotsi et al., 2019). In the absence of stable emotional support, children may exhibit amplified emotional reactions to setbacks, thereby impeding their social adaptation, which, in turn, can adversely affect peer relationships and compromise both academic learning and overall developmental trajectories (Mak et al., 2020). Prolonged exposure to high parenting stress may foster negative self-perceptions and worsen behavioral problems (Tsotsi et al., 2019). Therefore, maternal parenting stress is a critical factor influencing the well-being of the entire family and the development of young children.

Theoretical foundations. Family systems theory (FST), as formalized by Cox and Paley (2021), proposes that families function as interconnected units where behaviors, emotions, and stressors dynamically transmit across subsystems (e.g., father-mother-child). Central to FST is the principle of bidirectional influence, wherein paternal parenting attitudes directly shape maternal practices and psychological states, as observed in the transmission of overprotective behaviors (Tavassolie et al., 2016). Specifically, fathers’ actions (e.g., excessive control rooted in safety concerns) may inadvertently elevate maternal stress by creating role conflicts or undermining maternal autonomy—a process termed cross-generational stress propagation (Cox & Paley, 2021, p. 590). This stress transmission is critical, as heightened maternal parenting stress has been consistently linked to increased problem behaviors in children, including hostility-aggression and anxiety-worry, due to disrupted emotional support and inconsistent caregiving (Silinskas et al., 2020; Tsotsi et al., 2019). FST further emphasizes cultural contextualization, noting that parental roles and stress responses vary across societies; for instance, in collectivistic cultures like China, paternal authority may intensify maternal stress through societal pressures such as “face” preservation (Bornstein, 2015, p. 68). Within this framework, maternal overprotective attitudes and parenting stress act as pivotal mediators, explaining how paternal behaviors indirectly affect child outcomes without direct paternal-child pathways (Derlan et al., 2019). Thus, FST provides a lens to interpret the chain mediation identified in this study: paternal overprotection → maternal overprotection → maternal stress → child problem behaviors, highlighting subsystem interdependencies. By integrating FST, this study’s findings on gender and age differences (e.g., boys experiencing higher stress transmission) can be contextualized as manifestations of systemic family dynamics rather than isolated parental effects.

The China parenting context. These three dimensions are prominent in Chinese parenting and are tied to “face” and societal pressures, shaping overprotective behaviors and impacting children through stress transmission. Overprotection, although motivated by safety concerns, can transmit parental anxiety to children and hinder autonomy, problem solving, and emotional regulation, leading to difficulties in adaptation and anxiety (Bögels & Brechman-Toussaint, 2006).

Within the specific sociocultural context of China, traditional gender role beliefs, such as “son preference,” may reinforce gender differentiation through two pathways. Parents tend to have higher expectations of boys’ social achievements, leading to more intensive overprotective strategies (Chen et al., 2000; Lansford, 2022). However, gender differences in children’s behavioral manifestations, such as boys’ aggressive behaviors vs. girls’ anxiety tendencies, may further widen the gender gap in parenting stress and behavioral problems through interactive mechanisms (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008). Notably, parenting behaviors are not static but, rather, constitute a dynamic, adaptive process that evolves with children’s developmental stages (Peng et al., 2021). Existing evidence indicates that younger children in nursery classes (aged 3–4 years), owing to their limited self-care abilities and social adaptability, are more likely to elicit high-intensity protective behaviors from their parents (Smetana, 2017). Moreover, peak levels of maternal parenting stress during this stage are often directly associated with the ongoing demands of daily caregiving and responsibility of guiding social adaptation (Crnic & Low, 2002).

Building on the latest advancements in family systems theory and fathering research, this study constructs a chain mediation model aimed at achieving two breakthroughs: 1) uncovering the intergenerational transmission mechanism through which paternal overprotective attitudes influence young children’s problematic behaviors via maternal parenting practices in Chinese families and 2) examining the moderating role of maternal parenting stress in this transmission pathway, thereby providing cross-cultural empirical evidence for child behavior interventions under a dual-parenting framework.

Based on the aforementioned research objectives, this study proposes the following research questions:

(RQ1) What are the characteristics of paternal and maternal overprotective attitudes, maternal parenting stress, and young children’s problem behaviors?

(RQ2) Do paternal overprotective attitudes indirectly influence young children’s problem behaviors through maternal overprotective attitudes and parenting stress?

Significance. Existing research has preliminarily revealed a dynamic associative network connecting paternal and maternal overprotective attitudes, maternal parenting stress, and young children’s problem behaviors (Norman & Elliot, 2015). However, critical research gaps persist regarding the mechanisms of transmission across the paternal, maternal, and child subsystems, and current empirical evidence primarily suffers from three limitations. First, most studies examining multivariate interactions rely on cross-sectional data, making it difficult to clarify the longitudinal pathways through which paternal parenting attitudes influence children’s behavior via maternal parenting practices as mediators (Cabrera et al., 2018). Second, over 78% of related studies focus on mother-child dyads, overlooking the unique role of fathers as “moderators” in family parenting dynamics (Palm, 2014). Third, there is a lack of mechanistic explanations for the “father→mother→child” chain effects of parenting stress transmission within the family system, particularly the unexplored potential pathway whereby paternal overprotective attitudes may exacerbate maternal parenting stress by intensifying maternal controlling behaviors (Li et al., 2024).

This study sample comprised parents of preschool children (N = 265) from a Chinese region. Regarding paternal age, 53 fathers (20.0%) were under 30 years old, 115 fathers (43.4%) were aged 31–35 years, and 97 fathers (36.6%) were 36 years old or older. For maternal age, 85 mothers (32.1%) were under 30 years old, 113 mothers (42.6%) were aged 31–35 years, and 67 mothers (25.3%) were 36 years old or older. The parents reported on 137 boys (51.7%) and 128 girls (48.3%).

Parental overprotective attitudes

This study utilized the 18 items Overprotective Parenting Scale (OPS) developed by Jung (2020). The OPS comprises three-dimensions: intrusion (8 items, e.g., Does not scold the child even if they act badly or impolitely), worry & protection (6 items, e.g., Just leaves the child be even if they disturb other adults), and indulgence & permission (4 items, e.g., Protects the child from being criticized for their mistakes). The OPS employs a five-point Likert scale scoring system (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”)

The present study, the fathers’ overprotective attitudes scores yielded an overall Cronbach’s α of 0.903, with sub dimension reliabilities as follows: intrusion (fathers of young children) = 0.848, worry & protection (fathers of young children) = 0.817, and indulgence & permission = 0.816. For mothers’ overprotective attitudes scores, the overall Cronbach’s α was 0.901, with subdimension reliabilities as follows: intrusion (mothers of young children) = 0.807, worry & protection (mothers of young children) = 0.818, and indulgence & permission (mothers of young children) = 0.800.

This study utilized the 30 items Parenting Stress Index (PSI) developed by Abidin (1990) and validated by Yeo (2016) to assess parenting stress in East Asian cultural contexts. The PSI comprises two dimensions: Parent Domain Stress (19 items, e.g., I often feel swamped by the trivialities of daily life), which measures internal pressures related to parental role identity and caregiving self-efficacy, and Child Domain Stress (11 items, e.g., My child is more prone to throwing tantrums than their peers), which evaluates the challenges associated with children’s behavioral characteristics and parent-child interaction quality. All items are rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all applicable” to 5 = “completely applicable”). For maternal parenting stress, the PSI scores demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.890), with subdimensional reliabilities of 0.797 for the Parent Domain and 0.843 for the Child Domain.

This study adopted the 30 item Preschooler Behavior Questionnaire (PBQ) developed by Behar and Stringfield (1974), a parent-report instrument validated by Kang (2018), to assess children’s behavior in East Asian family contexts. The PBQ assesses children’s behavioral manifestations over the past month through three core dimensions (10 items per dimension): (a) Hostility–Aggression (e.g., physical aggression, verbal conflicts), (b) Worry–Anxiety (e.g., separation anxiety, social withdrawal), and (c) Hyperactivity–Distractibility (e.g., restlessness, task persistence difficulties). The items are on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all applicable” to 5 = “completely applicable”). For children’s problematic behaviors, the overall Cronbach’s α for PBQ scores was 0.914, demonstrating high internal consistency, with subscale reliabilities of 0.833 for Hostility–Aggression, 0.822 for Worry–Anxiety, and 0.809 for Hyperactivity–Distractibility.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shaoxing University, and research authorization was granted by the relevant educational authorities. The children’s parents and teachers provided informed consent. Child-related questionnaires were completed by school teachers. The parents and teachers completed the surveys online.

We used SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 23.0 for the data analysis. The AMOS 23.0, to structural equation modeling fit test demonstrated that the ratio of degrees of freedom (2.203 < 3.000) was within the ideal standard interval. Other indicators included the root mean square error of approximation = 0.068 (ideal range < 0.08), adjusted goodness-of-fit index = 0.909 (ideal range > 0.08), nonnormed fit index = 0.947 (ideal range > 0.9), goodness-of-fit index, comparative fit index, incremental fit index = 0.948, 0.970, 0.970 (all ideal criteria were greater than 0.90; Franke & Byrne, 1995). The indices in this study were all within the recommended range of values, and the data suggest that the hypothesized theoretical model fits the actual data to some extent and that the findings of the model are convincing.

Correlation analysis of the mediation model

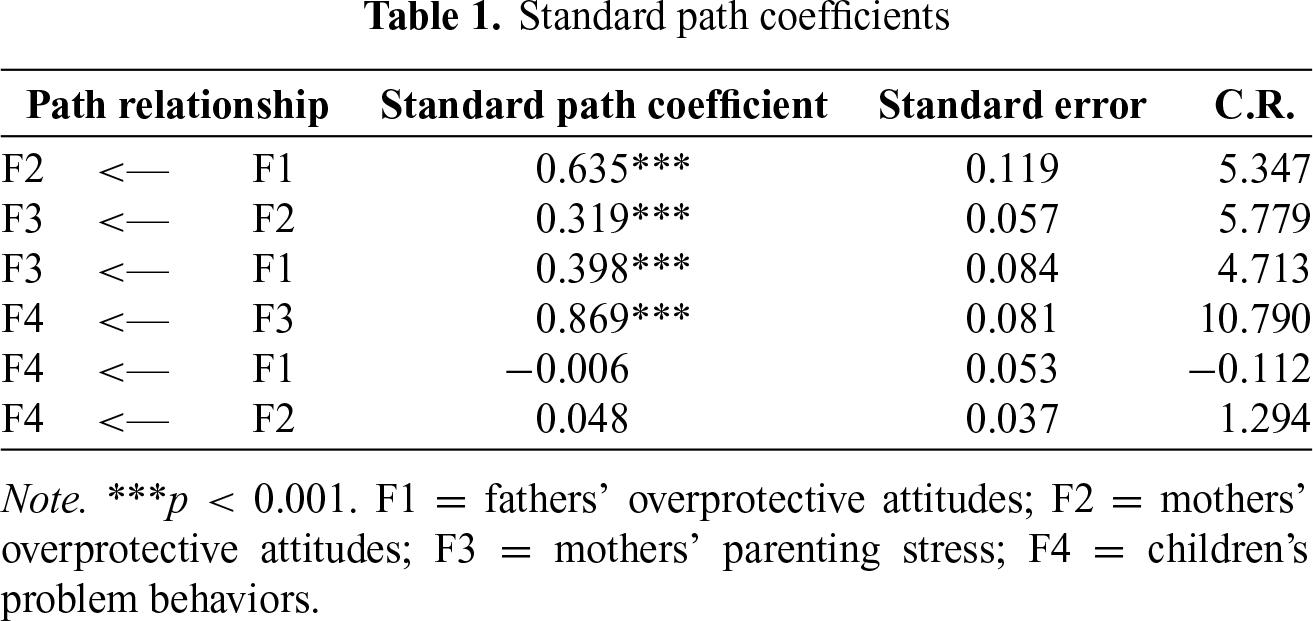

Table 1 presents the main findings. Fathers’ overprotective attitudes had a significant positive impact on mothers’ overprotective attitudes (standardized path coefficient = 0.635). Similarly, mothers’ overprotective attitudes significantly increased their parenting stress (standardized path coefficient = 0.319), which, in turn, had a strong positive effect on their children’s problem behaviors (standardized path coefficient = 0.869). Furthermore, fathers’ overprotective attitudes directly influenced mothers’ parenting stress (standardized path coefficient = 0.398). However, neither fathers’ nor mothers’ overprotective attitudes had a significant direct effect on children’s problem behaviors. Instead, fathers’ overprotective attitudes indirectly influenced children’s problem behaviors through two mediating pathways. The first pathway operated via mothers’ overprotective attitudes and parenting stress, with a mediating effect of 0.635 × 0.319 × 0.869 = 0.176, accounting for 33.7% of the total indirect effect (0.176/0.522). The second pathway operated through the mother’s parenting stress alone, resulting in a mediating effect of 0.398 × 0.869 = 0.346, accounting for 66.3% of the total indirect effect (0.346/0.522). Figure 1 is used to illustrate the influences between variables.

Figure 1: Variable model diagram

Collateral findings. Significant gender-based differences were identified in fathers’ and mothers’ overprotective attitudes, mothers’ parenting stress, and children’s problem behaviors (see Table 2). Specifically, fathers exhibited significantly higher overprotective attitudes toward boys (M = 2.06, SD = 0.486) than girls (M = 1.88, SD = 0.359), whereas mothers showed elevated overprotective attitudes toward boys (M = 2.43, SD = 0.670) than girls (M = 2.18, SD = 0.519). Furthermore, mothers reported greater parenting stress for boys (M = 1.73, SD = 0.547) than girls (M = 1.48, SD = 0.478), and children’s problem behaviors were more pronounced in boys (M = 1.85, SD = 0.581) than in girls (M = 1.62, SD = 0.491).

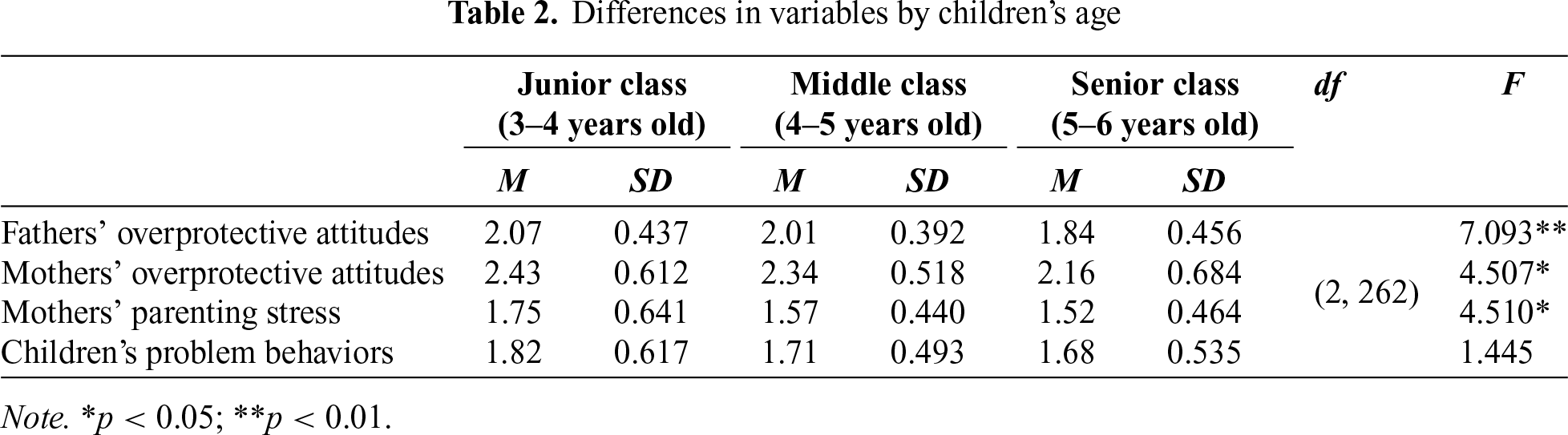

Significant age-based differences were observed in fathers’ overprotective attitudes (p < 0.01), mothers’ overprotective attitudes (p < 0.05), and mothers’ parenting stress (p < 0.05); no significant age-related differences were found in children’s problem behaviors. Specifically, fathers of older preschoolers (senior class) exhibited significantly lower overprotective attitudes (M = 1.84, SD = 0.456) than those of younger preschoolers (junior class; M = 2.07, SD = 0.437). Similarly, mothers of older preschoolers demonstrated less overprotective attitudes (M = 2.16, SD = 0.684) than did mothers of younger preschoolers (M = 2.43, SD = 0.612). Additionally, mothers of older preschoolers reported significantly lower parenting stress (M = 1.52, SD = 0.464) than did mothers of younger preschoolers (M = 1.75, SD = 0.641).

This study found that paternal overprotection was associated with higher maternal overprotection and parenting stress, as well as the behavioral development of young children (Derlan et al., 2019). In Chinese culture, fathers’ high expectations and excessive intervention in relation to their children are particularly prominent. Such behaviors may lead to role conflicts or ambiguity in mothers’ responsibilities during parenting. Particularly, when parenting philosophies diverge, mothers may feel undermined or interfered with, thereby increasing their psychological burden (Crnic & Low, 2002). Furthermore, paternal overprotection may undermine maternal parenting autonomy and exacerbate maternal stress through its negative impact on children’s behaviors, such as dependency and behavioral problems (Tavassolie et al., 2016).

Maternal overprotection parenting was associated with higher stress, supporting the notion that overprotection may increase the psychological burden on mothers during parenting. For example, previous research has found that mothers who exhibit overprotective behaviors, particularly when confronted with their children’s behavioral problems or developmental challenges, often experience heightened feelings of responsibility and psychological pressure (Hubert & Aujoulat, 2018). Relevant studies also indicate that maternal overprotective behaviors aim to shield their children from adversity as much as possible, and which could also be burden on mothers (Lim & Shim, 2021). Under such circumstances, overprotective mothers are more likely to experience anxiety, helplessness, and emotional states that can significantly increase parenting stress.

This study found maternal parenting stress exacerbated problem behaviors in young children. Parenting stress leads mothers to exhibit emotional, punitive, or neglectful behaviors during child-rearing, which directly affects young children’s behavioral development and increases their risk of problem behaviors (Mak et al., 2020). Research indicates that mothers with high stress levels are more likely to exhibit negative emotions and inconsistent parenting behaviors, which may lead to an increase in problem behaviors among young children (Tsotsi et al., 2019).

This study found that paternal and maternal overprotection did not have a significant direct impact on problem behaviors in young children. However, paternal overprotection can indirectly influence children’s problem behaviors through maternal overprotective attitudes and parenting stress as well as independently through maternal parenting stress. This result is both consistent and inconsistent with those of previous research (Lanjekar et al., 2022; Bögels & Brechman-Toussaint, 2006). In terms of consistency, existing studies have indicated that parental overprotection does not directly lead to problem behaviors in young children but exerts its influence indirectly through complex family interaction mechanisms (Lanjekar et al., 2022). For example, previous research has indicated that paternal overprotection may indirectly influence children’s behavioral development by affecting maternal parenting practices and psychological states (Derlan et al., 2019). The inconsistency lies in the fact that some studies suggest parental overprotection has a direct impact on problem behaviors in young children, particularly when parents exhibit excessively controlling behaviors toward their children (Bögels & Brechman-Toussaint, 2006). Additionally, cultural context may be a significant factor contributing to these differences. In Chinese families, mothers typically assume primary caregiving responsibilities, and paternal overprotection tends to indirectly influence children by affecting maternal parenting attitudes, parenting stress, and caregiving authority (Zhang et al., 2023).

Paternal overprotective behaviors may indirectly influence problem behaviors in young children by increasing maternal parenting stress, a conclusion supported by family systems theory and related empirical research over the past decade (Cox & Paley, 2021). Research indicates that paternal overprotective behaviors often manifest as excessive intervention and control over young children, which may lead mothers to experience role conflict or feelings of inadequacy during the parenting process, thereby increasing their psychological burden (Derlan et al., 2019). Furthermore, Maternal parenting stress is significantly associated with both internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors in young children (Tsotsi et al., 2019). Therefore, paternal overprotective behaviors indirectly influence problem behaviors in young children through maternal parenting stress, a mechanism that is particularly pronounced in cases in which parents lack effective communication or in which mothers have limited psychological resources.

The study revealed significant gender differences, with boys scoring higher than girls for paternal and maternal overprotective attitudes, maternal parenting stress, and problem behaviors. Parents’ overprotection of boys may reflect traditional cultural expectations, such as ‘son preference,’ and higher success expectations (Chen et al., 2009). Maternal stress is greater for boys, likely because of their externalizing behaviors (e.g., aggression, impulsivity) and the societal pressures on mothers. Boys also exhibit more problem behaviors than girls, potentially due to biological factors (e.g., hormones) and socialization practices that encourage risk taking but neglect emotional regulation (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008).

The study showed significant age-related differences in paternal and maternal overprotective attitudes and maternal parenting stress but not in children’s problem behaviors. Parents of senior kindergarten children (ages 5–6) exhibit lower overprotection and stress than those of junior kindergarten children (ages 3–4), likely due to younger children’s greater dependency and care needs (Crnic & Low, 2002). As children age, improved independence reduces overprotection and maternal stress, which aligns with developmental parenting adjustments (Smetana, 2017). Problem behaviors, although differing in form (e.g., emotional dependency in younger children vs. impulsivity in older children), show no significant age-related variations (Yeo, 2016).

Based on the findings related to children’s gender, this study recommends enhancing boys’ family education environments through multidimensional strategies. First, parenting organizations should address paternal overprotection by promoting autonomy support (McBride et al., 2020). Second, a tiered stress reduction system is recommended to alleviate maternal stress and encourage shared childcare responsibilities (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020). Additionally, targeted interventions for boys’ problem behaviors can enhance behavior and emotional regulation, kindergarten parent education programs should promote gender-equitable parenting to mitigate the negative effects of traditional gender stereotypes (Cochran & Niego, 2018).

Given the age-related differences in children’s variables, parents and educators should adapt parenting approaches to foster autonomous exploration. Additionally, efforts to alleviate stress for mothers of younger children—through family support, parenting training, and peer networks (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020)—are crucial for effective parenting. Although problem behaviors show no significant age-related differences, consistent behavioral guidance and home-kindergarten collaboration remain essential for supporting children’s healthy development (Cochran & Niego, 2018).

Based on the findings regarding variable relationships, a multifaceted approach involving families, kindergartens, and society is recommended to enhance family education and support children’s development (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020). Key strategies include improving parental awareness, addressing paternal overprotection (McBride et al., 2020), and reducing maternal stress through support groups and consultations (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020). Kindergartens should strengthen home–kindergarten collaboration and provide parental education and teacher training (Cochran & Niego, 2018). Community support networks, including family education centers and multidisciplinary systems, are essential (Cochran & Niego, 2018). Policy-level efforts should enhance funding, evaluation, and intervention mechanisms for overprotective families (Bornstein & Bradley, 2014).

Limitations and future directions

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample of children and parents is regionally specific, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings across China. Second, regional differences in cultural and economic contexts may lead to variations in parental attitudes, stress, and children’s problem behaviors. Finally, factors such as the kindergarten environment and peer relationships, which have not been fully addressed, may also influence children’s behavior. Future research should expand the sample to include more regions, offering a broader exploration of parental attitudes and children’s behaviors across diverse contexts.

This study reveals a significant chain mediation pathway within family systems: paternal overprotective attitudes indirectly contribute to young children’s problem behaviors through maternal overprotective attitudes and parenting stress. Specifically, fathers’ overprotection directly influences mothers’ overprotective tendencies and maternal parenting stress, while maternal overprotection further elevates maternal stress, which strongly predicts children’s problem behaviors. Notably, neither paternal nor maternal overprotection directly affects children’s behaviors, underscoring the critical mediating role of maternal psychological states.

The indirect effects account for all observed influences on child outcomes. The first mediation pathway—via maternal overprotective attitudes and parenting stress—explains 33.7% of the total indirect effect. The second pathway, operating solely through maternal parenting stress, explains 66.3%. This indicates that paternal behaviors primarily impact children by exacerbating maternal stress, rather than through direct parent-child interactions, aligning with family systems theory’s emphasis on interconnected subsystems.

Significant gender disparities emerged, with boys experiencing higher levels of overprotection, maternal stress, and problem behaviors compared to girls. Fathers exhibited stronger overprotective attitudes toward boys than girls, while mothers reported greater stress for boys than girls. Boys also displayed more pronounced problem behaviors, suggesting sociocultural factors like traditional gender expectations amplify these dynamics.

Age-based variations were evident, with younger preschoolers (ages 3–4) facing higher parental overprotection and maternal stress than older children (ages 5–6). Fathers of junior-class children showed greater overprotection than those of senior-class children, and mothers of younger children reported elevated stress. These differences likely stem from younger children’s greater dependency and care demands, highlighting developmental shifts in parenting practices.

These findings underscore the need for parenting programs for promoting autonomy-supportive practices and shared caregiving responsibilities to reduce maternal stress. Educationally, kindergartens must integrate gender-equitable parenting workshops and strengthen home-school collaboration, particularly for families with younger children.

Policy-wise, governments should establish community support networks (e.g., family education centers) and allocate funding for stress-reduction initiatives, ensuring culturally responsive approaches in collectivistic contexts like China. Ultimately, fostering psychologically safe parenting environments will enhance children’s social adaptation and long-term well-being.

Acknowledgement: We extend our sincere gratitude to all kindergarten teachers who facilitated our research on overprotective parenting and children’s problem behaviors. We are especially thankful to the participating families, both mothers and fathers, who shared their parenting experiences and allowed us to assess the relationship of parental overprotection, parenting stress, and children’s behavioral development.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Shaoxing Educational Science Planning Project under Grant/Award No. SGJ2022011 and the 2023 Zhejiang Provincial “14th Five-Year Plan” Family Education Research Project under Grant/Award No. 1452Z013.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the article. Ruiqian Li led the conceptualisation of the research, organisation and drafting of the paper. Peibing Zheng and Mengxin Yan directed the data analyses. Xinyi Zhou and Ziyu Wu led the draft questionnaire protocol. Yiting Wang led the conceptualisation of the research and the draft questionnaire protocol. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shaoxing University, and research authorization was granted by the relevant educational authorities.

Informed Consent: The directors of the selected kindergartens provided formal approval for this study on parental overprotection and children’s problem behaviors. Both the kindergartens and participating parents (mothers and fathers) provided written informed consent before data collection regarding overprotective parenting practices, parenting stress, and children’s behavioral assessments.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1990). Parenting Stress Index (PSIProfessional manual (3rd ed.). Lutz, FL, USA: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1978). The classification of child psychopathology: A review and analysis of empirical efforts. Psychological Bulletin, 85(6), 1275–1301. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.85.6.1275 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Achenbach, T. M., Ivanova, M. Y., Rescorla, L. A., Turner, L. V., & Althoff, R. R. (2016). Internalizing/externalizing problems: Review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. Journal of The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(8), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Behar, L., & Stringfield, S. (1974). A behavior rating scale for the preschool child. Developmental Psychology, 10(5), 601. https://doi.org/10.1037/H0037058 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bögels, S. M., & Brechman-Toussaint, M. L. (2006). Family issues in child anxiety: Attachment, family functioning, parental rearing and beliefs. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(7), 834–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bornstein, M. H. (2015). Children’s parents. In: R. M. Lerner (Ed.Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (7th ed) (pp. 55–132Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy403 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bornstein, M. H., & Bradley, R. H.(Eds.) (2014). Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Cabrera, N. J., Volling, B. L., & Barr, R. (2018). Fathers are parents, too! Widening the lens on parenting for children’s development. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12275 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, X., Liu, M., & Li, D. (2000). Parental warmth, control, and indulgence and their relations to adjustment in Chinese children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(3), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chen, X., Wang, L., & Wang, Z. (2009). Shyness-sensitivity and social, school, and psychological adjustment in rural migrant and urban children in China. Child Development, 80(5), 1499–1513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01347.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Clarke, K., Cooper, P., & Creswell, C. (2013). The parental overprotection scale: Associations with child and parental anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(2), 618–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cochran, M., & Niego, S. (2018). Parenting and social networks. In: M. H. Bornstein (Eds.Handbook of parenting (3rd ed) (vol. 4, pp. 123–148London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2021). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 585–607. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-051920-110133 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Crnic, K. A., & Low, C. (2002). Everyday stresses and parenting. In: M. H. Bornstein (Ed.Handbook of parenting: Practical issues in parenting (2nd ed.) (vol. 5, pp. 243–267Mahwah, NJ, USA: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

Deater-Deckard, K. (2008). Parenting stress, London, UK: Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.15347/wjm/2022.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Derlan, C. L., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Updegraff, K. A., Jahromi, L. B., & Fuentes, S. (2019). A prospective test of the family stress model with Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 7(2), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Diemer, M. C., Treviño, M. S., & Gerstein, E. D. (2021). Contextualizing the role of intrusive parenting in toddler behavior problems and emotion regulation: Is more always worse? Developmental Psychology, 57(8), 1242. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fang, Y., Luo, J., Boele, M., Windhorst, D., van Grieken, A., et al. (2024). Parent, child, and situational factors associated with parenting stress: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(6), 1687–1705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02027-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Franke, G. R., & Byrne, B. M. (1995). Structural equation modelling with eqs and eqs/windows. Journal of Marketing Research, 32(3), 378. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151989 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hasbani, E. C., Félix, P. V., Sauan, P. K., Maximino, P., Machado, R. H. V., et al. (2023). How parents’ feeding styles, attitudes, and multifactorial aspects are associated with feeding difficulties in children. BMC Pediatrics, 23(1), 543. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-04369-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hubert, S., & Aujoulat, I. (2018). Parental burnout: When exhausted mothers open up. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jung, Y. S. (2020). Development of an overprotective parenting scale for mothers with young children [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Yonsei University. [Google Scholar]

Kang, S. H. (2018). Effects of mothers’ parenting attitudes, parenting efficacy, and preschoolers’ self-regulation ability on preschoolers’ problem behaviors [Master’s thesis]. Incheon, Republic of Korea: Incheon National University Graduate School of Education, Early Childhood Education. [Google Scholar]

Lanjekar, P. D., Joshi, S. H., Lanjekar, P. D., Wagh, V., & Wagh, V. (2022). The effect of parenting and the parent-child relationship on a child’s cognitive development: A literature review. Cureus, 14(10), e30574. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lansford, J. E. (2022). Annual research review: Cross-cultural similarities and differences in parenting. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(4), 466–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, X., Zhang, C., Yang, R., Fong, V. L., Way, N., et al. (2024). Father knows best? Chinese parents’ perceptions of their influence on child development. Journal of Family Studies, 30(6), 947–967. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2024.2356600 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lim, S. A., & Shim, S. Y. (2021). Effects of parenting stress and depressive symptoms on children’s internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(4), 989–1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01929-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mak, M. C. K., Yin, L., Li, M., Cheung, R. Y. H., & Oon, P. T. (2020). The relation between parenting stress and child behavior problems: Negative parenting styles as mediator. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(11), 2993–3003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01785-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

McBride, B. A., Dyer, W. J., Liu, Y., Brown, G. L., & Hong, S. (2020). The differential effects of maternal and paternal involvement on child behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(6), 716–726. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nomaguchi, K., & Milkie, M. A. (2020). Parenthood and well-being: A decade in Review. Journal of Marriage and The Family, 82(1), 198–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Norman, H., & Elliot, M. (2015). Measuring paternal involvement in childcare and housework. Sociological Research Online, 20(2), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3590 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Palm, G. (2014). Father involvement in early childhood programs. St Paul, MN, USA: Redleaf Press. [Google Scholar]

Peng, B., Hu, N., Yu, H., Xiao, H., & Luo, J. (2021). Parenting style and adolescent mental health: The chain mediating effects of self-esteem and psychological inflexibility. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 738170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.738170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Silinskas, G., Kiuru, N., Aunola, K., Metsäpelto, R. L., Lerkkanen, M. K., et al. (2020). Maternal affection moderates the associations between parenting stress and early adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing behavior. Journal of Early Adolescence, 40(2), 221–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431619833490 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Smetana, J. G. (2017). Current research on parenting styles, dimensions, and beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Soenens B., Vansteenkiste M., Luyten P., Duriez B., & Goossens L. (2005). Maladaptive self-representations in parenting. Journal of Personality, 73(1), 225–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Spada, M. M., Caselli, G., Manfredi, C., Rebecchi, D., Rovetto, F., et al. (2012). Parental overprotection and metacognitions as predictors of worry and anxiety. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 40(3), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246581100021X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tavassolie, T., Dudding, S., Madigan, A. L., Thorvardarson, E., & Winsler, A. (2016). Differences in perceived parenting style between mothers and fathers: Implications for child outcomes and marital conflict. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(6), 2055–2068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0376-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Thomasgard, M., Metz, W. P., Edelbrock, C., & Shonkoff, J. P. (1995). Parent-child relationship disorders. Part I. Parental overprotection and the development of the Parent Protection Scale. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 16(4), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-199508000-00006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tsotsi, S., Broekman, B. F. P., Shek, L. P., Tan, K. H., Chong, Y. S., et al. (2019). Maternal parenting stress, child exuberance, and preschoolers’ behavior problems. Child Development, 90(1), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Yeo, Y. J. (2016). The relationship between parenting stress, parenting attitude, and children’s problem behaviors in mothers with preschoolaged children: Focusing on the mediating effects of spirituality and mindfulness [Master’s thesis]. Anyang-si, Republic of Korea: Korea Counseling Graduate University. [Google Scholar]

Zahn-Waxler, C., Shirtcliff, E. A., & Marceau, K. (2008). Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4(1), 275–303. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhang, L., Guo, F., Chen, Z., & Yuan, T. (2023). Father’s co-parenting and children’s externalizing problem behaviors: The chain mediating role of maternal parenting stress and parenting efficacy. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(4), 928–933. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s451878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools