Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Operational police members’ empathy during engagements with survivors of trauma: A rural community perspective

Department of Psychology, University of South Africa, Pretoria, 0002, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Masefako Andronica Gumani. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 807-814. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065776

Received 01 October 2024; Accepted 11 February 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

This study explored law enforcement members’ empathetic engagements with primary survivors of trauma. Informants were 15 South African Police Service members from a rural district of the Limpopo (females = 26.6%; constables = 13.3%). Unstructured open-ended and follow-up telephone interviews, field notes, and diaries were used as data-collection methods. Data were analysed following the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis guidelines. Emergent themes indicated that law enforcement members engage in three types of empathy, namely affective, cognitive, and cognitive-affective empathy when called upon to help survivors of trauma. Their affective empathy involved police members’ emotional connection with the survivors. The cognitive empathy entailed an understanding of the survivors’ circumstances and trauma. The cognitive-affective empathy combines elements of cognitive (understanding) and affective (emotional connection) empathy. These findings are significant in informing the nature of police–survivor engagements with traumatic cases for survivor empowerment.Keywords

Police work may entail exposure to victims’ unpredictable critical incidents, which requires mental strength, balance and flexibility to manage without being affected (Bloksgaard & Prieur, 2021). In many ways, police engagement with victims of trauma is an occupational hazard, which could result in vicarious trauma (VT) (Gumani, 2017, 2022; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995b; Sinclair & Hamill, 2007; Tabor, 2011). Important police competencies in engaging trauma victims (hereafter survivors) would require empathy expression towards the trauma survivors (Bober & Regehr, 2006)—an element of care that is embedded in their work (Figley, 1995). Empathy is other-help oriented to relieve others of distressing situations. Sympathy is self-help oriented, aimed at relieving personal distress and leads to trauma reactions, including VT (Hojat et al., 2009). However, it is unclear how police working with trauma survivors employ empathy to assist trauma survivors’ recovery. This study aimed to explore how South African police engaged in empathy in their work with trauma survivors.

Police empathetic engagements with trauma survivors

Types of empathy include affective, somatic, cognitive and cognitive-affective empathy. Affective empathy involves emotional connections with trauma survivors (Hojat et al., 2009; Inzunza et al., 2022). Somatic empathy is with observable, physical manifestations and physiological reactions (Rothschild, 2006). Cognitive empathy is an understanding of trauma survivors’ situations in a helping role (Hojat et al., 2009; Inzunza, 2015), while cognitive-affective empathy combines cognitive and affective empathy through fusing understanding and emotional connection (Hojat et al., 2009). Police members’ community custodian roles require expression of empathy through positivity, respect, dialogue, trust and justice during engagements with community members. This is unlike the warrior type of policing propagated by the public media, focused on crime reduction without trustful engagements with community members (Bloksgaard & Prieur, 2021; Giles et al., 2024; McCaffery & Richardson, 2022).

By definition, police members’ daily operations involve interpersonal relations (Inzunza, 2015; Matthias et al., 2024), calling on empathic understanding and emotional support in their first responders’ roles (Wassermann et al., 2019). To the extent that the police have empathic skills, they are better able to handle difficult situations and prevent conflicts with professionalism and a sense of humanity (Bloksgaard & Prieur, 2021; Inzunza, 2015; Inzunza et al., 2022; Jakobsen, 2021). Empathy requires perceiving survivors as human beings who need assistance (Lorei & Balaneskovic, 2023), requiring the police to make responsible decisions (Inzunza, 2015).

Their cognitive and empathic ability to notice pain in another person may lead to being sympathetic and having emotional contagion (Figley, 1995; Inzunza et al., 2022). Without marginal empathy competences, police would fail in their role in trauma survivor empowerment and support (Fedina et al., 2018; Gezinski, 2020; Govender & Pillay, 2022; Keys, 2024; Matthias et al., 2024; Noray, In press; Rono, 2022; Saxton et al., 2021; Serrano-Montilla et al., 2021; Ulo, 2021).

The context of work matters to the empathic engagement of police with trauma survivors, showing that those in rural settings may be less well served. Rural areas have a lower police presence (Matthias et al., 2024), and there presently is little research interest in rural crime and policing (Clack & Minnaar, 2018).

Theoretical foundations. The theory of mind (ToM) is relevant to explaining how police may perceive and understand trauma survivor situations through empathy (Inzunza et al., 2022). The constructivist self-development theory (CSDT) denotes that police should have competencies to constructively engage trauma survivors; otherwise, VT may result as they stand in the shoes of the survivors (Basu et al., 2020; Moulden & Firestone, 2007; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995a, 1995b). That way, the police members would experience the emotional trauma reactions observed in the survivors, as they view themselves as the “saviours” of the survivors (Figley, 1995; Sabin-Farrell & Turpin, 2003). Therefore, they recall survivors’ trauma materials as their own (Moulden & Firestone, 2007), thus experiencing compassion fatigue (Figley, 1995; Jenkins & Baird, 2002). These result in trauma survivor-helper identification (identifying with and feeling sympathy for the survivors, thus having a sense of responsibility towards the survivors by adjusting own behaviour and lifestyle to accommodate the survivors) (Figley, 1995; Sabin-Farrell & Turpin, 2003), thus showing more empathy towards the survivors (Pross, 2006; Rodrigo, 2005). However, police members' intrapersonal outcomes with trauma survivors (how the service provider responds to circumstances emotionally and cognitively) and interpersonal outcomes (verbal and non-verbal behaviours towards the survivor aimed at helping) (Jakobsen, 2021) are less well known in developing country rural communities.

South Africa’s policing agency, South African Police Service (SAPS), was changed from a military force during the apartheid regime to a civil community resource (Govender & Pillay, 2022). Its focus is operational policing (working with and assisting survivors during critical incidents) (Rees & Smith, 2008; South African Police Service Annual Report, 2010/11; Sekwena et al., 2007). The police role is thus community policing and victim support (SAPS Act No. 68 of 1995; SAPS Amendment Act No. 83 of 1998; SAPS Amendment Act No. 57 of 2008), which is enhanced through visible policing (proactive, accessible policing in communities) (SAPS Annual Report, 2010/11). The SAPS, therefore, operates within the victim empowerment programme (VEP), a victim-friendly criminal justice system aimed at providing a range of intersectoral, multidisciplinary, and comprehensive services to empower trauma survivors to deal with traumatic incidents (Department of Social Development, 2009). The South African Service Charter for Victims of Crime also underscores the police role in improving service delivery and upholding survivors’ rights (Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, 2007). These roles require the police to have empathy capabilities for handling stressful situations when engaging with trauma survivors (Beagley et al., 2018; Inzunza, 2015; Montealegre-Cerrato, 2022). Unfortunately, community members’ confidence in the police, including SAPS members, is decreasing due to a lack of empathy (Matthias et al., 2024). This hinders community policing, as research globally and in Africa, including South Africa, reports of non-empathetic police–survivor engagements like police brutality, corruption, and secondary victimisation (Inzunza, 2015; Inzunza et al., 2022; Lorei & Balaneskovic, 2023).

The study aimed to explore empathy among operational SAPS members in their trauma survivor services in a rural South African community. The study was guided by the following questions: (i) What are the ways in which empathy is expressed when police members engage with trauma survivors? and (ii) What impact does empathy have on police members?

The study employed Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2014). IPA is appropriate for exploratory studies aimed to understand the subjective, lived experiences and personal meanings of people, and in this case, the empathy competencies among operational SAPS members when engaging with and assisting trauma survivors of rape, domestic violence, murder and road accidents.

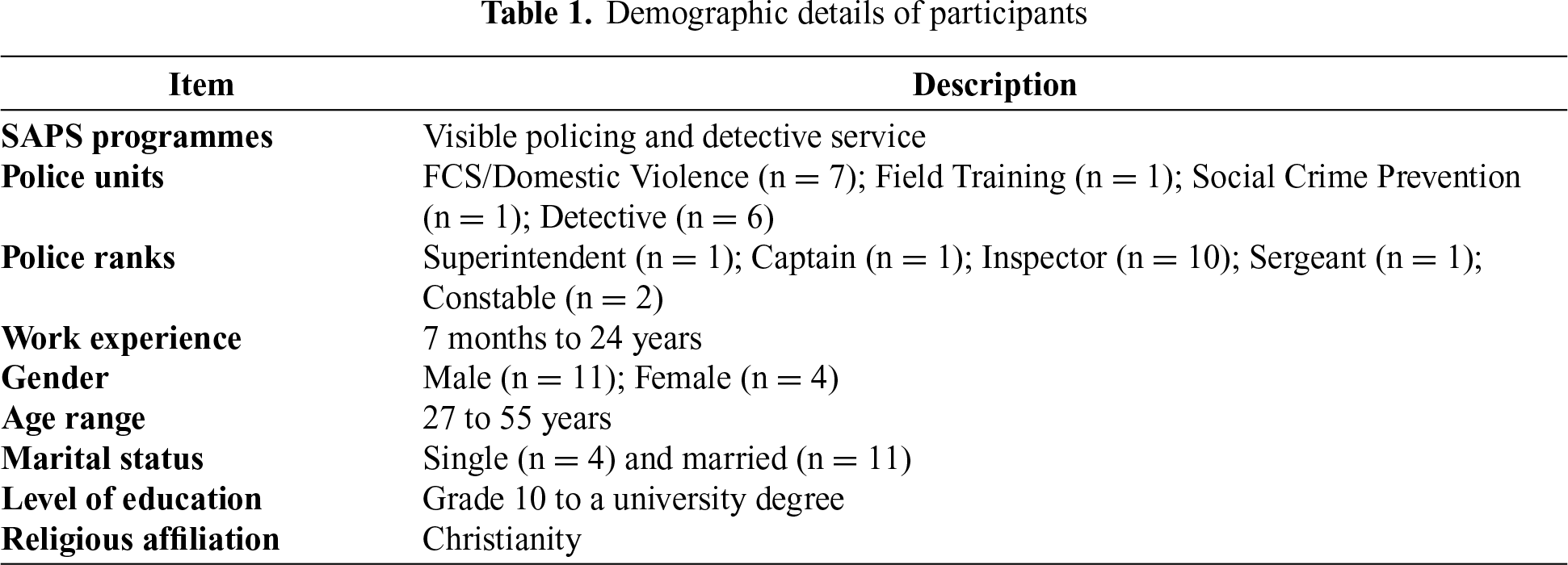

Purposive sampling was used to select 15 operational police members in the rural district in the northernmost part of Limpopo province. The police members worked in various trauma survivor units, including Family Violence, Child Abuse and Sexual Offences (FCS), and Domestic Violence, Field Training, Social Crime Prevention and Detective Service. By socio-demographics, their age range was 27 to 55 years, of which four were females and seven were males. Table 1 provides an overview of the participants’ demographic information.

Data collection and trustworthiness

The police completed unstructured individual interviews. The main interview question was: What are your experiences of working with survivors of trauma? This was supplemented by follow-up questions on empathy and diaries for additional data. For credibility and trustworthiness of the data, member checking through telephone follow-up interviews was used to verify the completeness and representativeness of the findings. Data, methods, and theoretical triangulation; checking of themes by other researchers; and thick descriptions of the phenomenon under study were used (Bryman, 2008). Data collected in participants’ languages were back-translated to retain the original meaning. The interviews lasted for 45 to 60+ min (Franchuck, 2004).

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the University of South Africa (Reference Number: PERC-2008R). The SAPS granted permission to collect data from the identified police stations (Reference Number: 2/1/2/1). Participants consented to the study in writing with assurances of anonymity and confidentiality. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage without reprisal. The interviews were conducted at the workplaces of the participants in their languages and in English, in accordance with their preferences, to ensure that the participants were comfortable and free to express their views. Data were transcribed verbatim.

Data were analysed according to the following IPA guidelines of Pietkiewicz & Smith (2014) to reflect the participants’ realities: (i) analysing the content, language, context, relationships and time by reading each transcript several times; thus, generating interpretation notes and analytical memos; (ii) coding these into meaning units for conceptual understanding; (iii) comparing and clustering incidents in the data to form superordinate and subordinate themes to show similarities and differences concerning individual experiences; and (iv) interpreting and contextualising themes in literature.

The following themes characterise how police members express empathy when engaging with trauma survivors during critical incidents: Affective empathy with trauma survivors, cognitive empathy with trauma survivors, and cognitive-affective empathy with trauma survivors. The following sections elaborate on the themes with discussion.

Theme 1. Affective empathy with trauma survivors

The police members spoke of emotional connection to trauma survivors, recognising similar trauma from previous other cases and in their own lives. Under this broad theme, the police members’ responses comprised the following three sub-themes: Experiencing the same emotion as the survivors, experiencing independent negative emotions, and experiencing sympathy for the survivors.

Experiencing the same emotion as the survivors

Some members found themselves experiencing the same emotions as the trauma survivors they were helping in cases of domestic violence, particularly physical assault of women, and gang rape of a child. This is what some of the police members expressed:

…having domestic problems… After making the protection order application, I took her… for… medical treatment… I felt the same pain that the woman felt. I put myself in her position… I felt that if it were me, I would not know what to do with the pain… when I saw it… I took that pain from her and applied it to myself (Female, FCS/domestic violence inspector)

My heart was hurt when I thought of the girl being raped by eight boys… I asked her… “How many times do you think each of these boys raped you?” and she said, ‘Each boy raped me twice.’ When I work on a case, I put myself in the victim’s position. This then helps me to work on the case with vigour… to make follow-ups on the case… I feel the same pain that the victim feels as I would be feeling as though the perpetrator did something to me… (Male, detective inspector)

Two of the members highlighted having the trauma that they have experienced in their own lives being reawakened, in the form of pain, when observing and hearing trauma survivors sharing experiences. The following were their reflections:

I used to preach to the people [colleagues] saying “You guys do the correct thing… repeating to my second-in-command… I know what pain is. Pain cannot be understood unless someone has experienced it. I was a victim before… a victim in many types of crime… (Male, FCS/domestic violence superintendent)

…by helping the victim to calm down… It affects my mind because when the victim tells me her problem of domestic violence, I start to recall that I have also gone through the same problem. The experience comes back to my mind while I am helping the victim… I have also come across this and it is painful (Female, field training sergeant)

Experiencing independent negative emotions

While an understanding of the survivors’ circumstances was reported, emotional distress and various other forms of pain, being hurt and affected and experiencing intrusions were experienced when handling cases of physical and sexual assault as well as murder of women and children. The following are the police members’ accounts:

…when she asked the husband to use a condom during sexual intercourse he agreed, but when he used it, he pierced the condom underneath… this was not pleasing to her… It was painful to me… This man… drove him and the wife hastily to death… It was for the first for me hearing of such a story… We… go to community meetings… to address the people… (Female, FCS/domestic violence inspector)

…we took her to hospital, opened a docket and she received proper treatment… beaten with a fist… there is a month that we dedicate to educating men about abusing women… When I see a woman injured to that point… It did not feel good… it is painful… (Male, FCS/domestic violence inspector)

…such as the domestic violence cases, affect and hurt us… when a victim tells you what happened and is crying at the same time. I must start by helping the victim to calm down and sit down (Female, field training sergeant)

…you are serving the community. The community puts all its trust in you… case involved the murder of a young child… she was firstly raped and then murdered… When I saw this… I felt severe pain because of the way the child was murdered… I felt like I was dreaming… see a picture of the things that I saw at the crime scene while seated (Male, detective captain)

Experiencing sympathy for the survivors

The members expressed pity and their focus on helping the survivors to recover from the aftereffects of domestic violence after observing the survivors’ conditions and listening to their stories. Examples of their reflections include the following:

When I listened to their story… the wife was… injured as the husband had beaten her up… badly injured that I felt pity for her… I… showed the woman her rights… to open a case… a protection order… If it were me, I would have opened a case and applied for a protection order… I felt pain at that time when I saw it; I turned the situation around and applied it to myself... if a person has bruises or is swollen then it means that she felt a lot of things… (Female, FCS/domestic violence inspector)

…a fight between a husband and wife… I felt that… we should learn that a person should be faithful in marriage, including myself… This did not treat me well at all… When a person says that ‘I felt pain’… ‘I was afraid’. I also feel the pain. I also feel sympathy for her… (Male, social crime prevention inspector)

From these accounts, it was apparent that exposure to the survivors’ familiar circumstances fitted with the police members’ meanings (assimilation) (MacEachern et al., 2019), while anticipation of unfamiliar circumstances of domestic violence and gang rape (Pienaar et al., 2007) led to the police members’ negative revision of their assumptions (and thus negative accommodation) (Basu et al., 2020; Payne et al., 2007). High levels of empathy among some police members, as is the case here, are linked to high posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms (Beagley et al., 2018) while low levels of empathy may lead to burnout thus affecting performance (Turgoose et al., 2017). The association between work responsibilities and personal lives has also been reported in other police studies, including the SAPS (Foley & Massey, 2021; Middleton et al., 2022; Tehrani, 2007; Van Lelyveld, 2008), which resembles empathic ability (Inzunza et al., 2022).

Theme 2. Cognitive empathy with trauma survivors

In this case, the police members reported empathy that included voluntarily performing cognitive tasks of trying to understand the survivors’ situations and engaging in actions that were based on that understanding. This is explained through the sub-theme below.

Voluntary cognitive tasks

Police members believed to exercise control over the circumstances of domestic violence and sexual assault and neglect of children. They perceived cognitive empathy critical to their job description and accountability, which included interviewing and taking survivors’ and witnesses’ statements, advising, counselling, referring, releasing protection orders against and arresting perpetrators, et cetera. The following are some of the examples that were narrated:

…after realising the escalating crimes where women were victims of abuse… most police members did not have interest in working in this unit. I then said who is supposed to police that type of a crime? …I volunteered as a single member… carrying plus or minus 200 cases… working by myself… recruiting more members to… join the unit… a police inspector who was also involved in committing… sexual abuse… involving his own children… my undertaking was “I am a member of the police service” … I was there to assist those who needed help… I don’t remember saying that ‘I am now leaving the child protection unit.’ (Male, FCS/domestic violence superintendent)

…all sexual offences and child neglect… investigating, taking statements and interviewing victims and witnesses as well as all other people involved… linked to domestic violence… a young man… beating up his family members, expelled his mother from home and threatening to kill his siblings by hacking them with an axe. A protection order was released against him… went to arrest him… an abduction case of young people… The father was… admitted to hospital... I must make sure that the suspect is dealt with… the girl who was supposedly raped by the father… her father told her and her siblings to leave their home… I also threatened to arrest him… I told her that death was not a solution… I referred her to a particular counsellor… social workers… psychologists… (Female, FCS/domestic violence constable)

I have to switch over to the person’s situation in order to assist… In some instances… we find that there was no rape committed… When I work on a case… I put myself in the victim’s position… to be able to make follow-ups on the case because if I do not do so then I will feel as though the victim’s situation is not a problem (Male, detective inspector)

…we are compelled to go in there and check where the wounds are. If I am questioned in court, then I should not have evidence without reasons… I should have seen everything to report… (Male, detective inspector)

As should be apparent from the interview evidence, the police members displayed cognitive empathy by their judgements at the crime scenes for a deeper understanding of the trauma causing circumstances (perspective-taking) (see also Hojat et al., 2009; Inzunza, 2015; Inzunza et al., 2022; Jakobsen, 2021). In their cognitive empathy expression, the police members prioritised resolving the survivors’ situations without being overwhelmed by the trauma materials they were exposed to (MacEachern et al., 2019). Therefore, they cognitively assimilated the survivors’ circumstances and trauma per case by allowing information about and meaning of the survivors’ trauma into their pre-existing cognitive beliefs and efficiently finding ways of intervening (Basu et al., 2020; Payne et al., 2007). In summary, police cognitive empathy entails being aware of oneself during police–survivor engagements and gaining understanding of a survivor’s experience without judging whether the experience is positive or negative for oneself and thus not being distressed by it (Cao & Chen, 2020; Lorei & Balaneskovic, 2023).

Theme 3. Cognitive-affective empathy with trauma survivors

In some cases of domestic violence, road accidents, murder and child neglect, police members expressed a sense of combined sympathy and empathy, which symbolised being conflated by survivors’ circumstances and trauma, and complicated their work. These included the following: Overwhelming cognitive tasks and sympathy vs. empathy.

Overwhelming cognitive tasks

The police members expressed a sense of overwhelm when performing cognitive tasks for gaining an understanding of the survivors’ situations of domestic violence, road accidents, and murder and performing aligned actions. They reported emotional distress and a flooding of intrusions for days to weeks in the forms of constant thoughts, having mental pictures of what they perceived and being in a dream-like state. Some reported to avoid certain foods, sexual intercourse and similar actions, which served as trauma cues or being “part of it”. This is what they shared:

When I arrive at a scene and there is an odour, I will inhale it all… It takes time for me to function normally… compared to before I faced the corpse… it lasts for about three to four days… I join it. I must be part of it for me to work… I turn to be like the corpse... I will not be able to eat porridge with meat for the rest of the day (Male, detective inspector)

I spent about two to three weeks constantly thinking about those things… I felt like I was dreaming… could see a picture of the things that I saw at the crime scene while seated… everything that I see with my eyes comes to the mind… they can make the mind not to function properly… (Male, detective captain)

When I ate, I recalled those things as though I could smell that body. It was as though I still had the smell on me… (Male, detective inspector)

There is usually blood all over the place… this disturbs the mind. The picture of the child will also remain in the mind for several weeks. When I see meat put in front of me, the mind will recall that, hey! It is better to be given green vegetables… I will not be able to have sexual intercourse with my wife because… that picture will come back… During the post-mortem... I will spend the whole week without having the desire for sexual intercourse… as it appears like what I saw at the scene… looking after a corpse… I do not want to face it… go around the corpse and mention anything that is missing and that is there (Male, detective inspector)

…a woman was murdered by her husband by hacking her on the head with an axe… This is what makes me feel pain… also frightening to me… I wonder if such a thing can be done to a human being. I cannot even concentrate on my family when I am home after knocking off… I wonder what is happening in this world and how a person can do such a painful thing to another person… I experience mental fatigue. We see things that we are not supposed to see… unusual and frightening… (Male, detective inspector)

…one case I found overwhelmingly frightening. A man drove over about four pedestrians on a road and their legs and arms were cut off… gather parts of their bodies… to match each part with its body… Such… affect us as we are also human… (Male, detective inspector)

I sometimes become afraid of attending to these murders… I must transport the body… be with the doctor in the post-mortem room… due to that fear I sometimes ignore some of the most important things at the scene of crime… (Male, detective inspector)

…when the person has been hacked… I must check whether the private part is there… give a full report of what I saw at the scene… I can look after the corpse the whole day… This is what affected me… (Male, detective inspector)

Some reported mutually shared feelings with the trauma survivors having the potential for negative occurrences in their own (members’) lives. This is what one member said:

…because I believed that they were advised to use condoms to avoid the rapid spread of the virus [HIV] in their bodies. This man thus made the spread of the virus to be rapid... I felt like this man wanted to kill me. It felt painful… like he was doing this to me and that he wanted to have sexual intercourse with me without using a condom… It was the first time for me hearing such a story. I concluded that a person could kill you without physically assaulting you… (Female, FCS/domestic violence inspector)

Sympathy vs. empathy

Several members expressed observing bizarre and intolerable occurrences, including domestic violence and child neglect, drawing a sense of sympathy for and with the survivors. These were some of their reflections:

This person becomes my responsibility… the victim phoning me at 10 o’clock at night… This will also cost me my rest. I will start to think that if the situation is traumatising the victim in this manner, then it means that she is really affected by the situation… my day’s activities are centred around this matter… This is the case that made me to leave only five days after my leave started… I drove the whole night as the victim would phone me even around 01h00 at night… (Female, FCS/domestic violence constable)

These cases [child neglect cases] mostly affect my mind as I never stop thinking about them. Even when I am home, I will be thinking about those children and what would have happened had I not known about the situation… Sometimes I use money out of my own pocket as I feel that the victim’s situation is unbearable (Male, FCS/domestic violence inspector)

…I work on cases as though they are mine, as I do this for the community. This causes me to have stress... (Male, FCS/domestic violence inspector)

I felt tempted and even used personal resources to assist the child… These are real experiences. It is not like a book that you can just close. You carry these things with you… The other case… involved a woman who was hacked by her husband. I was not supposed to be sympathetic towards her but be empathetic. This case affected me. It made me to feel pain. I was also traumatised… frightens me. Therefore, seeing the blood affected me. I also felt angry due to what happened… (Male, social crime prevention inspector)

Hojat et al. (2009) acknowledge that empathy and sympathy often co-occur thus making a distinction between cognitive and affective empathy difficult, which is the case here. Dealing with unusual circumstances led to the negative revision of the members’ assumptions about people and the world in which they were serving (negative accommodation) (Basu et al., 2020; Payne et al., 2007). Complications in the forms of various VT-related reactions resulted.

Understanding of the survivors’ experiences of domestic violence and neglect was accompanied by feeling the same way that the survivors felt, which then tainted their interventions (Hojat et al., 2009). Again, a sense of responsibility towards the survivors as well as empathic ability and empathic concern led to empathic responses (executing compassionate acts like handling cases outside working hours and using personal resources to care for the survivors) (see also Figley, 1995), also known as “the cost of caring” (Foley & Massey, 2021; Tehrani, 2007).

Implications for the police members’ empathy practices

The expression of the three types of empathy depended on the following antecedents: the nature of the cases that were handled (see Clack & Minnaar, 2018), importantly, police members being engaged in personal and situational experiences of trauma (see also Inzunza, et al., 2022; Richards et al., 2021), and risking VT-related reactions (Sabin-Farrell & Turpin, 2003; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995a; Tabor, 2011). By implication, helping the police with empathy skills for the proper handling of trauma cases with understanding of the survivors’ circumstances, and engaging with them with the required degree of emotional and situational control would lead to improved police–survivor engagements (see also Bloksgaard & Prieur, 2021; Lorei & Balaneskovic, 2023).

Regulations of empathic ability, concern and responses as well as varying degrees of trauma assimilation and positive accommodation would be helpful to responsive police-survivor engagements (Basu et al., 2020; Pienaar et al., 2007). Police members’ actions for survivor empowerment would be particularly important all the way from case investigations, protection orders facilitation, survivors counselling, referrals and consciousness-raising (Department of Social Development, 2009). These align with guardian policing and victim safety (Giles et al., 2024; McCaffery & Richardson, 2022; Richards et al., 2021).

Police vetting that considers empathy for efficient operational policing is important (Bloksgaard & Prieur, 2021; Inzunza, 2015; Inzunza et al., 2022; McCaffery & Richardson, 2022; Montealegre-Cerrato, 2022). Retraining of operational police members for empathy upskilling in various police units and within cultural backgrounds (Bloksgaard & Prieur, 2021; Gracia et al., 2014; Inzunza, 2015; Inzunza et al., 2022; McCaffery & Richardson, 2022; Rauch et al., 1994), as the CSDT alludes (Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995a), is necessary.

Limitations and future directions

The study’s small participant sample limited generalisations that could be considered in future quantitative studies with bigger and more representative samples in the rural districts in South Africa. Conducting the interviews at participants’ workplaces could have also led to giving socially desirable answers at some point.

Future studies could explore guardian policing, levels of trauma assimilation and accommodation and work engagement in enhancing the VEP agenda.

The study’s goal was achieved, namely, to highlight police members’ empathetic engagements with trauma survivors in a rural context. The study findings indicate that despite all the negative reports about police (including SAPS) members’ conduct, not all is lost! The members are still committed to meeting the SAPS VEP’s objectives through empathetic engagements despite encountering VT-related reactions.

Acknowledgement: The author thanks all the police members who participated in the study.

Funding Statement: This paper is an extract from the project funded by the University of Venda Research and Publications Committee.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the University of South Africa (Reference Number: PERC-2008R) and permission granted by the SAPS (Reference Number: 2/1/2/1). Consent forms were signed before commencing with the study and participants were assured of anonymity, confidentiality and withdrawal without reprisal.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Basu, N., Schuler, K. R., Marie, L., Taylor, S. E., Fadoir, N. A. et al. (2020). Moderating effect of meanings-made on the relationship between exposure to potentially traumatic life events and suicidal ideation. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 30(2), 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054137319898333 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beagley, M. C., Peterson, Z. D., Strasshofer, D. R., & Galovski, T. E. (2018). Sex differences in posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms in police officers following exposure to violence in Ferguson: The moderating effect of empathy. Policing: an International Journal, 41(5), 623–635. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-01-2017-0007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bloksgaard, L., & Prieur, A. (2021). Policing by social skills: The importance of empathy and appropriate emotional expressions in the recruitment, selection and education of Danish police officers. Policing and Society, 31(10), 1232–1247. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2021.1881518 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bober, T., & Regehr, C. (2006). Strategies for reducing secondary or vicarious trauma: Do they work? Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/mhj001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Cao, X., & Chen, L. (2020). The impact of empathy on work engagement in hemodialysis nurses: The mediating role of resilience. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 17(1), e12284. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Clack, W., & Minnaar, A. (2018). Rural crime in South Africa: An exploratory review of ‘farm attacks’ and stocktheft as the primary crimes in rural areas. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, 31(1), 103–135. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338573120. [Google Scholar]

Department of Social Development (2009). National policy guidelines for victim empowerment. Pretoria: Department of Social Development. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.za/documents/other/national-policy-guidelines-victim-empowerment-13-jul-2009. [Google Scholar]

Fedina, L., Backes, B. L., Jun, H., Shah, R., Nam, B. et al. (2018). Police violence among women in four U.S. cities. Prevention Medicine, 106(16), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.10.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In: C. R. Figley (Ed.Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (pp. 1–20Levittown, PA, USA: Brunner/Mazel Publishers. [Google Scholar]

Foley, J., & Massey, K. L. D. (2021). The ‘cost’ of caring in policing: From burnout to PTSD in police officers in England and Wales. The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles, 94(3), 298–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X20917442 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Franchuck, J. E. (2004). Phenomenology vs grounded theory: The appropriate approach to use to study the perspectives of instructional librarians on their roles in information literacy education for undergraduates. Paper written for Interdisciplinary Studies 560, Qualitative Methods. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: http://www.slis.ualberta.ca/cap04/judy/paper.htm. [Google Scholar]

Gezinski, L. B. (2020). It’s kind of hit and miss with them’: A qualitative investigation of police response to intimate partner violence in a mandatory arrest state. Journal of Family Violence, 37(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00227-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Giles, H., Maguire, E. R., & Hill, S. L. (2024). Policing at the crossroads: An intergroup communication accommodation perspective. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302241245639 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Govender, D., & Pillay, K. (2022). Policing in South Africa: A critical evaluation. Insight on Africa, 14(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/09750878211048169 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gracia, E., Gracia, F., & Lila, M. (2014). Male police officers’ law enforcement preferences in cases of intimate partner violence versus non-intimate interpersonal violence: Do sexist attitudes and empathy matter? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(10), 1195–1213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854814541655 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gumani, M. A. (2017). Vicarious traumatisation experiences among South African Police Service members in a rural setting: An exploratory study. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 27(5), 433–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2017.1375207 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gumani, M. A. (2022). Work stressors and vicarious trauma among South African Police Service members. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(3), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2022.2031630 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hojat, M., Vergare, M. J., Maxwell, K., Brainard, G., Herrine, S. K. et al. (2009). The devil is in the third year: A longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical students. Academic Medicine: Journal of The Association of American Medical Colleges, 84(9), 1182–1191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17e55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Inzunza, M. (2015). Empathy from a police work perspective. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 16(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/14043858.2014.987518 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Inzunza, M., Brown, G. T. L., Stenlund, T., & Wikström, C. (2022). The relationship between subconstructs of empathy and general cognitive ability in the context of policing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(907610), 239. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.907610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jakobsen, K. K. (2021). Empathy in investigative interviews of victims: How to understand it, how to measure it, and how to do it? Police Practice and Research, 22(2), 1155–1170. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2019.1668789 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jenkins, S. R., & Baird, S. (2002). Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma: A validation study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(5), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020193526843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Keys, D. (2024). Reckless brutality to womankind: Police violence against black women in Colonial Nigeria. Journal of Gender Studies, 33(1), 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2023.2206638 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lorei, C., & Balaneskovic, K. (2023). De-escalation in everyday police operation. Salus Journal, 11(2), 101–119. https://search.informit.org/doi/pdf/10.3316/informit.354555456318471. [Google Scholar]

MacEachern, A. D., Dennis, A. A., Jackson, S., & Jindal-Snape, D. (2019). Secondary traumatic stress: Prevalence and symptomology amongst detective officers investigating child protection cases. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 34(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9277-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Matthias, K., Thomas, I., & Makanga, R. K. (2024). Law enforcers or law breakers: Beyond corruption—Africans cite brutality and lack of professionalism among police failings. Afro Barometer Policy Paper No. 90: Let the people have a say—Pan African profiles. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/PP90-PAP6-Africans-cite-corruption-and-lack-of-professionalism-among-police-failings -Afrobarometer-26jan24.pdf. [Google Scholar]

McCaffery, P., & Richardson, L. (2022). Trauma-informed police resources for human trafficking cases. Department of Justice, Canada. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372498291_Trauma-informed_police_resources_for_human_trafficking_cases. [Google Scholar]

Middleton, J., Harris, L. M., Matera Bassett, D., & Nicotera, N. (2022). Your soul feels a little bruised: Forensic interviewers’ experiences of vicarious trauma. Traumatology, 28(1), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000297 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Montealegre-Cerrato, H. (2022). Compassion and empathy: Comparing police officers with and without military experience [Doctoral thesis]. Minneapolis, MN, USA: Walden University. [Google Scholar]

Moulden, H. M., & Firestone, P. (2007). Vicarious traumatisation: The impact on therapists who work with sexual offenders. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 8(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838006297729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Noray, K. (2024). Police brutality, law enforcement, and crime: Evidence from Chicago. Journal of Urban Economics, 141, 103630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2023.103630 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Payne, A. J., Joseph, S., & Tudway, J. (2007). Assimilation and accommodation processes following traumatic experiences. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 12(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020600788206 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K. W. (1995a). Trauma and the therapist: Countertransference and vicarious traumatisation in psychotherapy with incest survivors. New York, NY, USA: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K. W. (1995b). Treating therapists with vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress disorder. In: C. R. Figley, (Ed.Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatised (pp. 150–177Levittown, PA, USA: Brunner/Mazel Publishers. [Google Scholar]

Pienaar, J., Rothmann, S., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R., (2007). Occupational stress, personality traits, coping strategies and suicide ideation in the South African Police Service. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(2), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854806288708 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2014). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychological Journal, 20(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.14691/CPPJ.20.1.7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pross, C. (2006). Burnout, vicarious traumatization and its prevention: What is burnout, what is vicarious traumatization? Torture, 16(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Rauch, J., Levin, N., Lue, M., Ngubeni, K. (1994). Creating a new South African Police Service: Priorities in the post-election period [Research report written for the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation]. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: https://www.csvr.org.za/wp-content/uploads/1994/07/Creating-a-New-South-African-Police-Service.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Rees, B., & Smith, J. S. (2008). Breaking the silence: The traumatic circle of policing. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 10(3), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2008.10.3.83 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Richards, J., Smithson, J., Moberly, N. J., & Smith, A. (2021). If it goes horribly wrong the whole world descends on you: The influence of fear, vulnerability, and powerlessness on police officers’ response to victims of head injury in domestic violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 7070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rodrigo, W. D. (2005). Conceptual dimensions of compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma [Master’s dissertation]. Burnaby, BC, Canada: Simon Fraser University. [Google Scholar]

Rono, J. K. (2022). A critical evaluation of police reforms in Kenya [Abstract]. In: O. M. Akinlabi, (Ed.Policing and the rule of law in Sub-Saharan Africa. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003148395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rothschild, B. (2006). Help for the helper: Self-care strategies for managing burnout and stress. New York, NY, USA: W. W. Norton and Company. [Google Scholar]

Sabin-Farrell, R., & Turpin, G. (2003). Vicarious traumatisation: Implications for the mental health of health workers. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(3), 449–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00030-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

SAPS Act No. 68 of 1995, South African Police Service Act No. 68 of 1995. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: http://www.info.gov.za/view/DownloadFileAction?id=70987. [Google Scholar]

SAPS Amendment Act No. 57 of 2008, South African Police Service Amendment Act No. 57 of 2008. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/3185784.pdf. [Google Scholar]

SAPS Amendment Act No. 83 of 1998, South African Police Service Amendment Act No. 83 of 1998. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: http://www.info.gov.za/view/DownloadFileAction?id=70741. [Google Scholar]

Saxton, M. D., Olszowy, L., MacGregor, J. C. D., MacQuarrie, B. J., & Wathen, C. N. (2021). Experiences of intimate partner violence victims with police and the justice system in Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518758330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sekwena, E., Mostert, K., & Wentzel, L. (2007). Interaction between work and personal life: Experiences of police officers in the North-West Province. Acta Criminologica, 20(4), 37–54. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC28955. [Google Scholar]

Serrano-Montilla, C., Lozano, L. M., Alonso-Ferres, M., Valor-Segura, I., & Padilla, J. (2021). Understanding the components and determinants of police attitudes toward intervention in intimate partner violence against women: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 24(1), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211029398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sinclair, H. A. H., & Hamill, C. (2007). Does vicarious traumatisation affect oncology nurses? A literature review. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 11(4), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2007.02.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

South African Police Service Annual Report (2010/11). SAPS together squeezing crime to zero. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: http://www.info.gov.za/view/DownloadFileAction?id=152417. [Google Scholar]

Tabor, P. D. (2011). Vicarious traumatization: Concept analysis. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 7(4), 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-3938.2011.01115.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tehrani, N. (2007). The cost of caring: The impact of secondary trauma on assumptions, values and beliefs. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 20(4), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070701690069 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Turgoose, D., Glover, N., Barker, C., & Maddox, L. (2017). Empathy, compassion fatigue, and burnout in police officers working with rape victims [Abstract]. Traumatology, 23(2), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000118 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ulo, E. (2021). Police brutality and human rights abuse: A study of the end SARS Protest in Nigeria. International Journal of Management, Social Sciences, Peace and Conflict Studies, 4(2), 179–193. [Google Scholar]

Van Lelyveld, C. R. (2008). The experience of vicarious trauma by the police officers within the South African Police Service in the Limpopo province [Master’s dissertation]. Polokwane, South Africa: University of Limpopo. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Retrieved from: http://ulspace.ul.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10386/759/VanLelyveldcr.pdf;sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

Wassermann, A., Meiring, D., & Becker, J. R. (2019). Stress and coping of police officers in the South African Police Service. South African Journal of Psychology, 49(1), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318763059 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools