Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Adolescent psychological resilience and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis

Psychology Department, Education College, Jianghan University, Wuhan, 430056, China

* Corresponding Author: Xianglian Yu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 771-790. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.067273

Received 29 April 2025; Accepted 19 November 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

A meta-analysis was conducted to systematically examine the relationship between adolescent psychological resilience and subjective well-being, including its tripartite components and potential moderators. Relevant literature was systematically searched across domestic and international databases, yielding 112 eligible studies comprising 115 independent samples (N = 78,018 adolescents). Significant positive correlations were identified between psychological resilience and both subjective well-being (r = 0.508, p < 0.001) and its components: life satisfaction (r = 0.470, p < 0.001) and positive affect (r = 0.465, p < 0.001). A weak negative correlation emerged with negative affect (r = −0.253, p < 0.001). Heterogeneity analysis revealed substantial between-study variance, suggesting significant moderator effects. Moderator analysis demonstrated significant cultural influences with Western cultural contexts showing stronger associations (r = 0.641, p < 0.001) than Eastern counterparts (r = 0.499, p < 0.001). Psychological resilience measurement instruments also served as significant moderators, particularly for the associations with positive and negative affect. Specifically, the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) demonstrated stronger correlations with positive affect, while the Resilience Trait Scale for Chinese Adolescents (RTSCA) showed stronger inverse correlations with negative affect. These findings elucidate the complex interplay between psychological resilience and subjective well-being while informing targeted intervention strategies.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe advent of positive psychology has positioned subjective well-being (SWB) as a pivotal metric in mental health assessment (Seligman et al., 2005). Subjective well-being (SWB) comprises three components: life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect (Buecker et al., 2023; Busseri & Sadava, 2011; Şimşek, 2009; Vladisavljević & Mentus, 2019). Elevated SWB correlates with enhanced psychophysiological functioning, reduced maladaptive behavioral patterns, and greater occupational commitment (Diener et al., 1999; Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002; Gan & Cheng, 2021). Over decades, SWB research has demonstrated robust positive associations with occupational performance and social relational quality (Diener et al., 2018).

Emerging evidence identifies psychological resilience as a significant predictor of SWB variance across populations (Chuning et al., 2024). Resilience functions as a protective factor mitigating negative emotional impacts while enhancing SWB (Israelashvili, 2021). As a multidimensional adaptive capacity, resilience enables successful navigation through adversity and stressogenic environments (Masten, 2018; Masten et al., 2021; Troy et al., 2023).

While a general positive association between resilience and SWB is established, the magnitude and consistency of this relationship remain unclear, particularly among adolescents. While existing meta-analytic work has focused on elderly populations (Ye & Zhang, 2021), documented age-specific variations in resilience trajectories (Blanco-García et al., 2021) necessitate targeted investigation of adolescent resilience-SWB dynamics. Crucially, Previous individual studies have reported inconsistent findings, with effects ranging from negligible to exceptionally strong, highlighting significant heterogeneity that remains unexplained.

Despite extensive empirical attention, the resilience-SWB relationship exhibits substantial heterogeneity across studies. While predominant findings report positive correlations (Ma, 2023; Sorrenti et al., 2022; Wan et al., 2023), null associations (Jiang & Chen, 2020) and inverse relationships (Akintunde et al., 2023) have also been documented. Reported effect sizes demonstrate remarkable variability, ranging from negligible (r = 0.001) to exceptionally strong (r = 0.940) across studies (Eldeleklioğlu & Yıldız, 2020; Jiang & Chen, 2020). The potential moderating effects of participant characteristics (e.g., cultural background) and methodological factors (e.g., assessment instruments) remain insufficiently elucidated. To address these knowledge gaps, this meta-analysis employs threefold objectives: (1) quantifying the population-level correlation between adolescent resilience and SWB, (2) identifying salient moderators of this association, and (3) providing empirical foundations for targeted intervention development.

Psychological resilience and subjective well-being

Empirical findings regarding the resilience-SWB association in adolescents are marked by substantial inconsistency, creating a critical need for systematic synthesis and explanation.

As a core construct in positive psychology, psychological resilience has been demonstrated to exert substantial influence on mental health outcomes (Ungar & Theron, 2020). While a general positive association is often reported (Moreira et al., 2021; Sorrenti et al., 2022), the literature reveals dramatic variability, with effects ranging from negligible (e.g., r = 0.001; Jiang & Chen, 2020) to exceptionally strong (e.g., r = 0.94; Eldeleklioğlu & Yıldız, 2020). Such divergent findings suggest that the relationship is not monolithic but is likely contingent upon a range of methodological, developmental, and cultural factors. This pronounced variability underscores the complexity of the association and indicates the presence of unidentified moderating factors. Notwithstanding these discrepancies, resilience is widely recognized as a critical determinant of SWB variations. Based on this empirical foundation, Hypothesis 1 (H1) is formulated: Psychological resilience is positively associated with subjective well-being.

Moderating variables influencing the relationship between psychological resilience and subjective well-being

The inconsistencies could be by moderators yet to be examined. We propose that the variability in effect sizes is systematically influenced by cultural, methodological, and developmental factors, which form the theoretical basis for our moderator analyses.

Cultural context may systematically influence resilience-SWB dynamics by shaping the very expression and function of these constructs. Cross-cultural studies demonstrate divergent resilience manifestations, with Spanish populations showing heightened stress sensitivity yet elevated resilience capacities (Palomera et al., 2022; Topçu & Dinç, 2024). SWB exhibits substantial cross-national variability, as evidenced by 30-nation comparisons revealing significant intercountry differences (Moreta-Herrera et al., 2023; Rajkumar, 2023; Suh et al., 1998). Critically, cultural values (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism) may alter how resilience resources translate into well-being outcomes. For instance, in collectivistic cultures, resilience might be more tightly linked to relational harmony and familial support, whereas in individualistic cultures, it may correlate more strongly with personal achievement and autonomy. These fundamental differences provide a compelling theoretical rationale for why the resilience-SWB correlation might vary significantly across cultural contexts. Hypothesis 2 (H2): Cultural typology moderates the resilience-SWB relationship.

Measurement heterogeneity constitutes a critical methodological consideration that may influence observed resilience-SWB associations. Various instruments operationalize psychological resilience through distinct conceptual frameworks and dimensional structures (Table 1). For instance, the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC; Connor & Davidson, 2003) assesses domains such as personal competence and stress tolerance, while its Chinese adaptation emphasizes tenacity, strength, and optimism (Yu & Zhang, 2007). The Resilience Scale for Chinese Adolescents (RSCA; Hu & Gan, 2008) focuses on contextually relevant adaptive capacities including goal planning and family support. Comparatively, the Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA; Friborg et al., 2003) measures factors including personal competence and social resources. These instrument-specific conceptualizations are not merely technical differences; they reflect fundamentally different emphases on what constitutes resilience. Consequently, a scale focusing on positive traits (e.g., CD-RISC) might show a stronger correlation with positive affect, while a scale emphasizing coping with distress (e.g., RSCA) might correlate more strongly with negative affect. Furthermore, conceptual overlap between certain resilience dimensions (e.g., optimism) and well-being components can artificially inflate correlations. This theoretical framework directly predicts that the choice of measurement instrument will systematically moderate the observed effect size. These instrument-specific conceptualizations may differentially capture resilience constructs, potentially moderating the observed relationships with SWB components. Hypothesis 3 (H3): Resilience measurement instruments moderate the resilience-SWB relationship.

Developmental stages may moderate adolescent resilience-SWB associations due to normative changes in psychological capacities and social demands. Enhanced social-cognitive maturation in older adolescents may strengthen these correlations (Wo, 2019). Positive age-resilience gradients have been documented, with older cohorts demonstrating superior resilience (Lim et al., 2025). Comparative studies reveal higher SWB levels in junior high students vs. university populations (Wu et al., 2020). Theoretically, the link between resilience and SWB might strengthen with age as adolescents develop more sophisticated emotion regulation and cognitive reframing skills. Conversely, the specific developmental challenges faced at different stages (e.g., identity formation in late adolescence vs. academic pressure in mid-adolescence) might alter how resilience manifests and connects to well-being. These developmental differences provide a clear rationale for expecting the strength of the association to vary across educational stages. SWB trajectories exhibit distinct developmental patterns across the lifespan (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2008). Hypothesis 4 (H4): Adolescent developmental stage moderates the resilience-SWB relationship.

Literature search and selection

Meta-analysis represents a quantitative approach that systematically combines results from multiple independent studies to derive more precise estimates of effects and examine sources of heterogeneity. This study adhered to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines throughout the research process (Page et al., 2021).

First, a systematic literature search was conducted across eight English databases (Web of Science, Elsevier SD, Medline, EBSCO-ERIC, SAGE Online Journals, PsycINFO, PsycArticles, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses) using title/abstract keywords related to psychological resilience and subjective well-being. The search strategy employed the following Boolean operators: (“resilience” or “psychological resilience” or “mental toughness”) for psychological resilience concepts, and (“subjective well-being” or “well-being” or “happiness” or “positive emotions” or “negative emotions”) for subjective well-being components. Subsequently, complementary searches were performed in three Chinese databases: China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Data, and VIP Chinese Journal Database, encompassing both journal articles and dissertation repositories. A combined search matrix was created by systematically pairing resilience-related terms with well-being indicators across all databases. The search encompassed publications up to October 2024, yielding an initial pool of 30,683 records after duplicate removal.

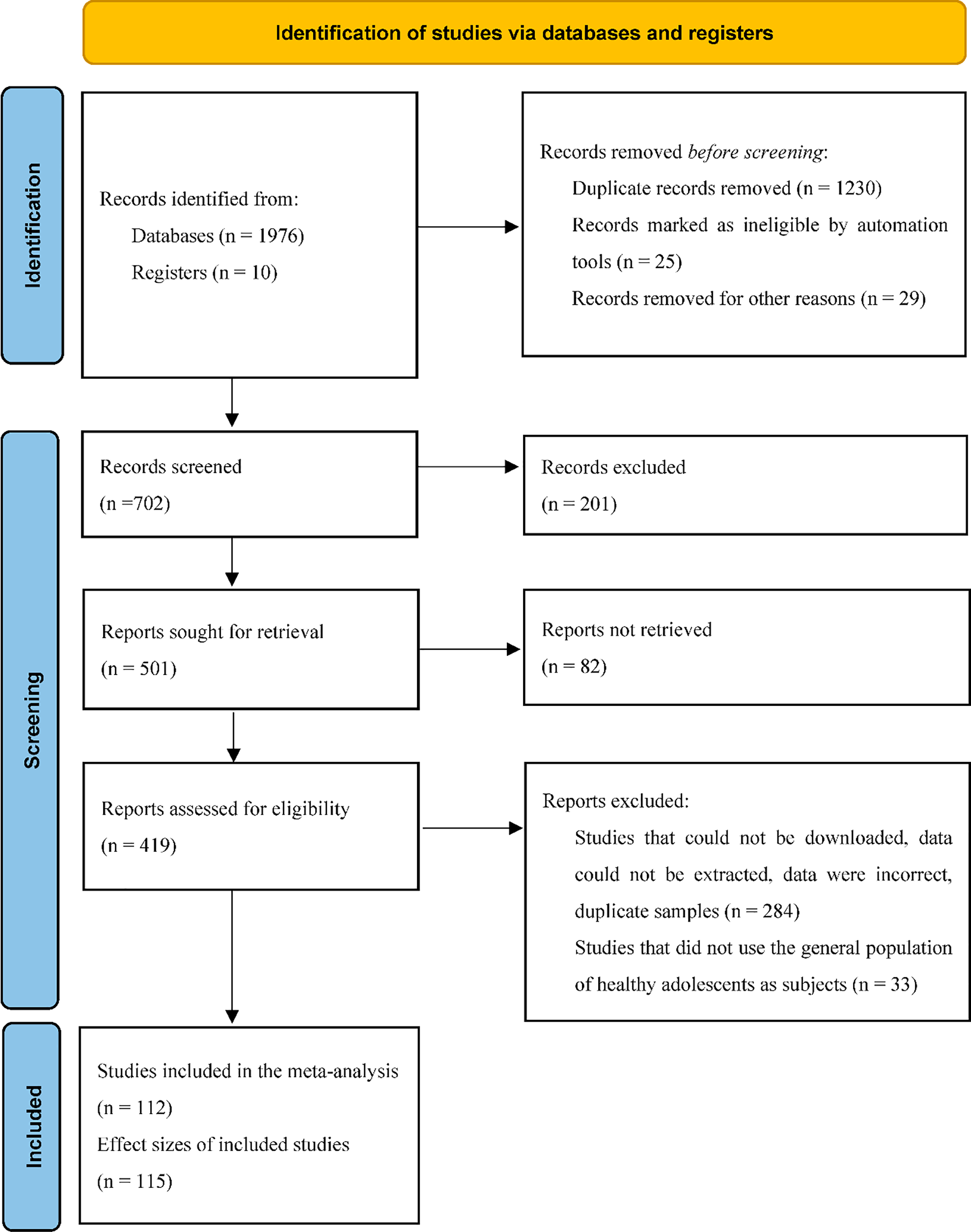

All records were imported into Zotero reference management software and screened against eight inclusion criteria: (1) empirical studies excluding theoretical/review papers; (2) quantitative measurement of both constructs with reportable correlation coefficients (r-values) or convertible statistics; (3) exclusion of non-questionnaire methodologies; (4) explicit sample size reporting; (5) inclusion of multiple publication types; (6) removal of duplicate datasets; (7) adolescent samples (≥12 years) without clinical conditions; (8) exclusion of alternative well-being constructs. The final meta-analysis incorporated 112 qualified publications containing 115 independent studies, with a combined sample size of 78,018 participants meeting all inclusion criteria (see Figure 1 for PRISMA flow diagram).

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of literature search and inclusion process

Literature quality assessment and coding

Study quality was assessed using an adapted Jadad scale (Zhang et al., 2019), which was selected for its comprehensive coverage of methodological rigor domains relevant to observational studies in psychological research. The Jadad scale was preferred over other quality assessment tools because it provides a balanced evaluation across multiple dimensions including sampling methodology, psychometric properties, and publication standards, making it particularly suitable for assessing the quality of correlation studies included in this meta-analysis.

Quality assessment was conducted across four domains: (1) Participant selection: Randomized sampling (2 points), non-randomized (1 point), unreported (0 points); (2) Data validity ratio: ≥0.90 (2 points), 0.80–0.89 (1 point), <0.80/unreported (0 points); (3) Instrument reliability: Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.80 (2 points), 0.70–0.79 (1 point), <0.70/unreported (0 points); (4) Publication tier: CSSCI/SSCI journals (2 points), Peking University core journals (1 point), non-peer-reviewed publications (0 points). Total scores ranged 0–10, with higher scores indicating superior methodological rigor.

Systematic coding was performed for: authorship, publication year, cultural context, correlation coefficients, sample size, female proportion, study quality scores, and resilience instrumentation (see Table 1). Pearson’s r served as the effect size metric, extracted under five protocols: (1) Independent samples from multi-sample studies were coded separately; (2) Subgroup analyses (e.g., gender-specific) were extracted individually; (3) Baseline data prioritized for longitudinal designs; (4) Dimension-level correlations were aggregated via Fisher’s z-transformation; (5) Alternative statistics (t, χ2, F, β) were converted to r values using established formulae (Peterson & Brown, 2005).

When studies reported multiple effect sizes for different SWB components (life satisfaction, positive affect, negative affect) or multiple independent samples, we employed the following approach:

(1) For studies reporting correlations between resilience and different SWB components, each correlation was treated as an independent effect size to preserve the specificity of relationships with distinct well-being dimensions.

(2) For studies with multiple independent samples (e.g., different participant groups), each sample was coded separately.

(3) For studies reporting both overall SWB scores and component scores, we prioritized the component scores to maintain analytical precision, while the overall scores were included in supplementary analyses to ensure comprehensive coverage.

This approach allowed us to examine the nuanced relationships between resilience and specific well-being components while maintaining statistical independence of effect sizes. The random-effects model used in our analyses inherently accommodates some degree of dependence through its variance components structure.

A dual independent coding procedure was implemented for study characteristics (participant demographics, female ratio, etc.). Intercoder reliability was high (Cohen’s κ = 0.92), and inter-coder discrepancies were resolved through consensus-based reconciliation with source materials, with final coded data presented in Table 2.

Publication bias control and testing

Publication bias, characterized by the preferential publication of studies with statistically significant results, poses a significant threat to the validity of meta-analytic findings due to the systematic exclusion of non-significant outcomes. To address this bias, the current study incorporated both peer-reviewed publications (journal articles and conference proceedings) and gray literature, including unpublished dissertations, to broaden the scope of included research. A multi-method approach was employed to assess publication bias: funnel plot symmetry analysis (Light & Pillemer, 1984), where visual inspection of plot asymmetry provides preliminary evidence of bias; the fail-safe N coefficient (Rosenthal, 1995), which quantifies the number of additional null studies required to overturn the observed effect (with a threshold of 5k + 10, where k represents the number of included studies); Egger’s regression test (Egger et al., 1997), where a non-significant intercept (p > 0.05) indicates minimal bias; and the trim-and-fill method (Liu et al., 2023), an iterative algorithm that estimates the potential impact of missing studies by imputing hypothetical effect sizes and recalculating adjusted estimates. These complementary techniques collectively evaluate the robustness of the meta-analytic conclusions against publication bias.

The choice between fixed-effect and random-effects models hinges on assumptions about the underlying distribution of effect sizes. The fixed-effect model presumes homogeneity across studies, attributing observed variations solely to sampling error, while the random-effects model acknowledges heterogeneity in true effect sizes due to systematic differences in study characteristics such as participant selection and measurement tools (Schmidt et al., 2009). Given the substantial variability in measurement instruments (e.g., CD-RISC, RSA) and demographic characteristics (e.g., cultural backgrounds, educational stages) observed across the included studies, the random-effects model was selected to account for both within-study and between-study variance, thereby providing more conservative and generalizable estimates of the population effect size.

Heterogeneity testing was conducted to determine the suitability of the chosen analytic model. Two primary metrics were utilized: the Q-statistic, which evaluates total variance across studies under a chi-square distribution (with p < 0.05 indicating significant heterogeneity), and the I2 index, quantifying the proportion of true heterogeneity relative to total observed variance, classified as low (25%), moderate (50%), or high (75%) (Higgins et al., 2002). These analyses not only informed model selection but also guided the interpretation of variability in effect sizes. Consistent with contemporary meta-analytic practices, the random-effects model was retained regardless of heterogeneity levels to ensure methodological rigor and accommodate potential unobserved moderators.

Analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.0 software. The primary analysis computed weighted mean effect sizes (Pearson’s r) under the random-effects framework. Moderator analyses were conducted through subgroup analyses for categorical variables (cultural context, resilience measurement instruments, population type). Statistical significance was assessed using maximum likelihood estimation with Knapp-Hartung adjustments to mitigate type I error inflation. Three moderators were systematically evaluated: cultural background (Eastern/Western), resilience measurement tools (e.g., CD-RISC, RSA) and population characteristics (adolescents vs. university students).

This integrated methodological framework adheres to PRISMA guidelines while preserving the original study’s theoretical intent, ensuring both statistical robustness and clinical interpretability. Full reproducibility is facilitated through transparent reporting of analytic decisions and effect size conversion protocols (Peterson & Brown, 2005).

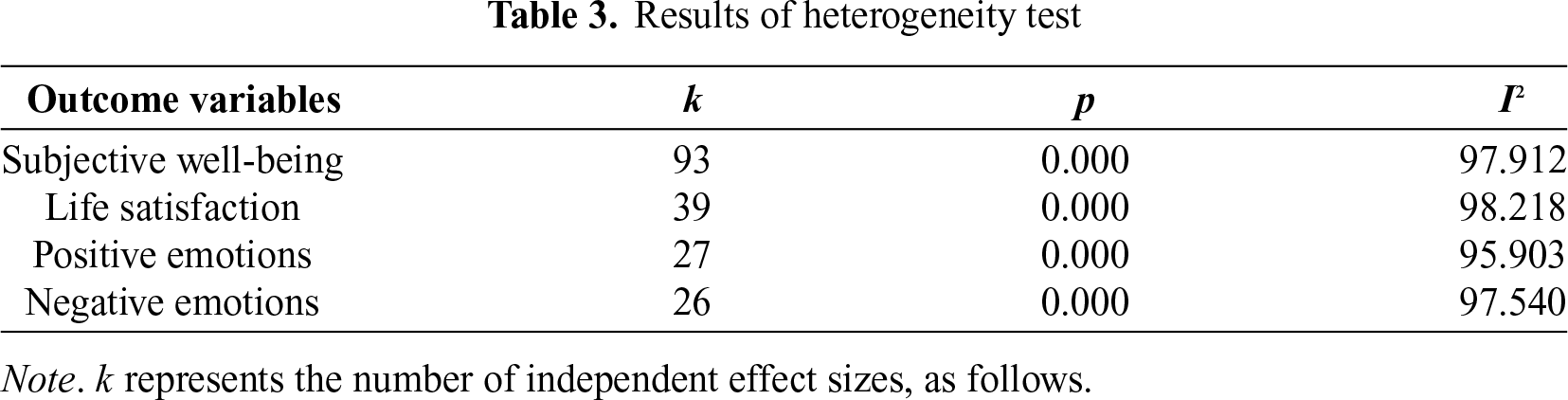

A heterogeneity test was conducted on the included effect sizes to validate the use of a random-effects model. As summarized in Table 3, the Q statistics for psychological resilience and its associations with subjective well-being, life satisfaction, positive emotions, and negative emotions were 4406.274, 2132.129, 634.646, and 1016.136, respectively. All Q values reached statistical significance (p < 0.001), confirming substantial heterogeneity among effect sizes. Furthermore, the I2 values for these associations exceeded 75% (97.912, 98.218, 95.903, and 97.540), indicating exceptionally high heterogeneity according to conventional benchmarks (Higgins et al., 2002). These I2 values signify that over 95% of the observed variance in effect sizes reflects genuine differences in study-level effects rather than sampling error. These findings necessitated the adoption of a random-effects model for analysis. The observed heterogeneity suggests that variations in effect estimates across studies may arise from methodological or contextual factors beyond those examined in the current moderator analyses, underscoring the presence of substantial unexplained variance and cautioning against over-interpretation of the pooled effect sizes. Complete heterogeneity statistics (Q, df, T2) are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

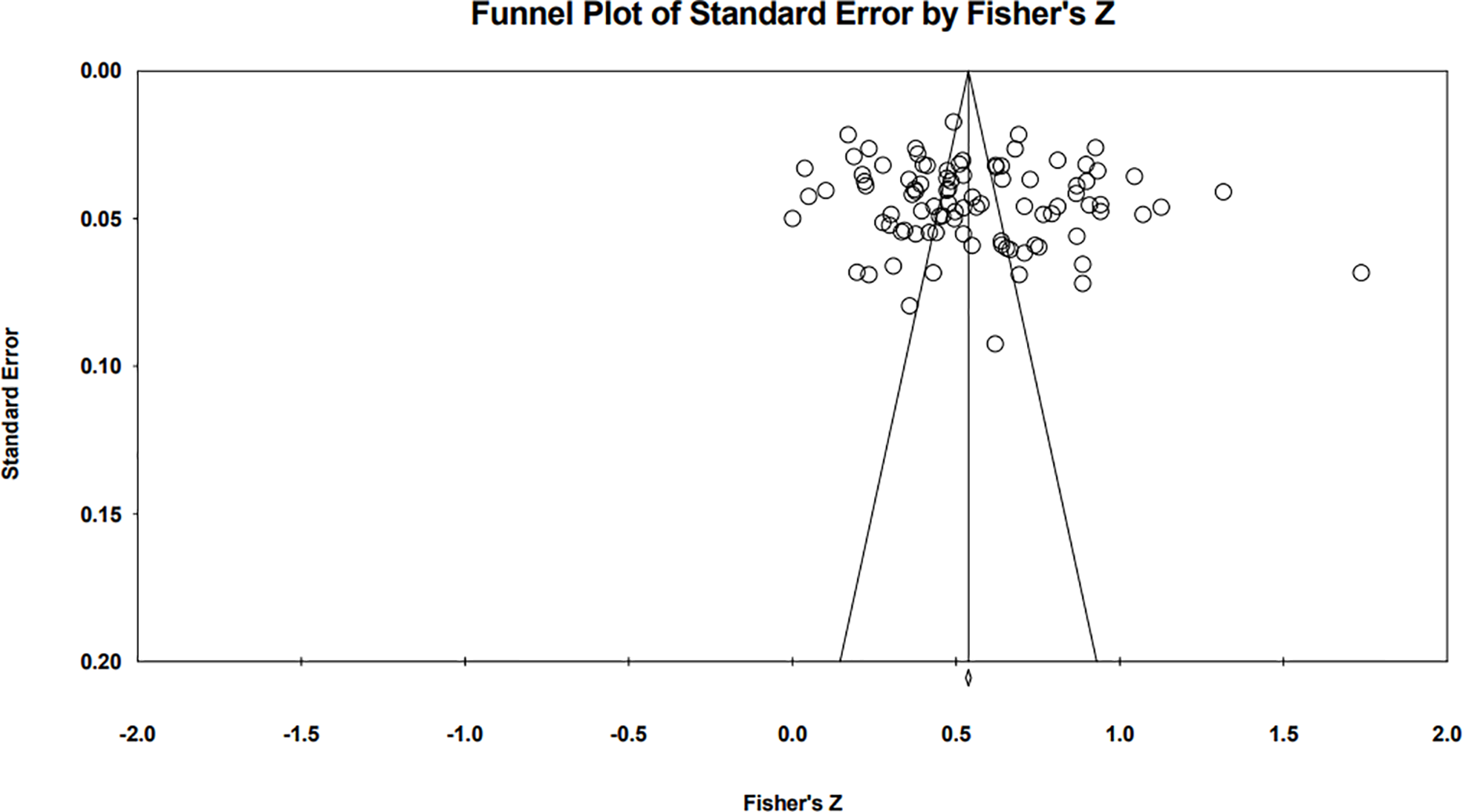

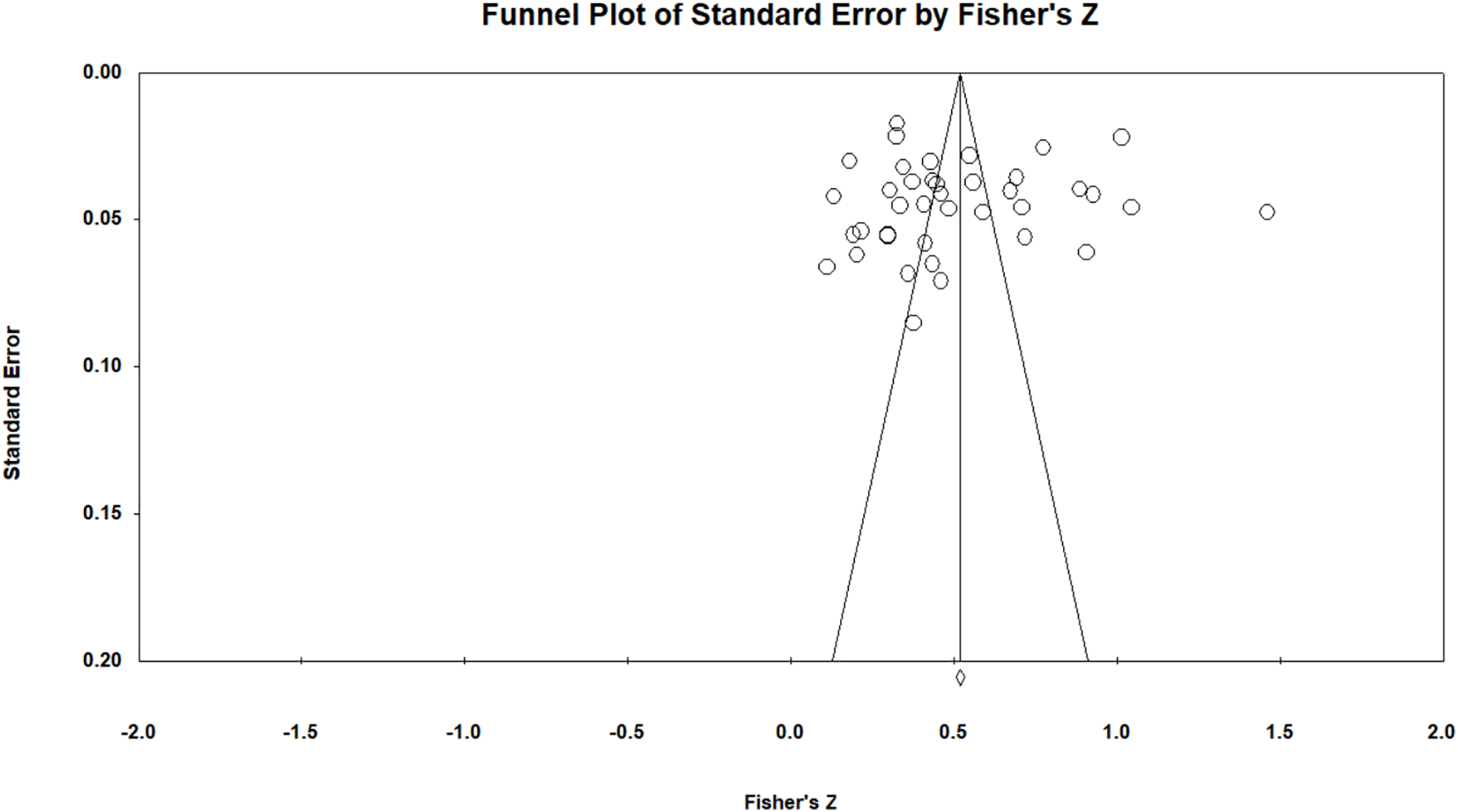

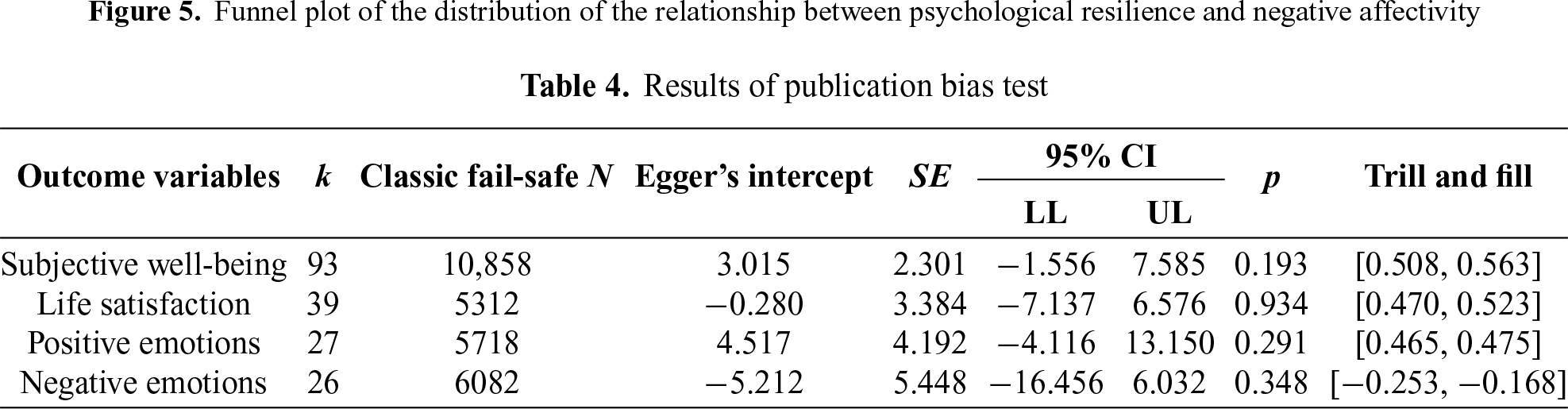

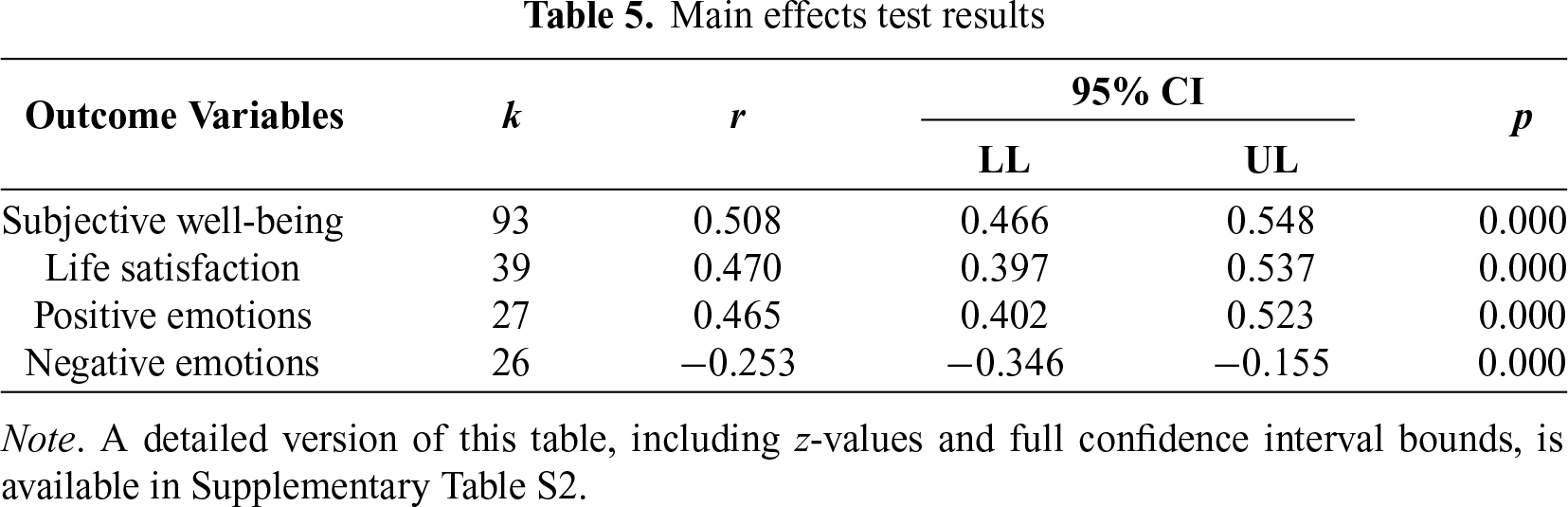

Publication bias was assessed through four methods: funnel plots, the fail-safe N statistic, Egger’s regression, and the Trim and Fill method (Figures 2–5; Table 4). First, funnel plot symmetry for all examined relationships—psychological resilience with subjective well-being and its components—suggested minimal publication bias, as effect sizes clustered evenly around the mean. Second, the fail-safe N values for these associations (10,858; 5312; 5718; 6082) substantially exceeded the critical threshold of 5k + 10 (k = number of studies), further supporting the robustness of the findings. Third, non-significant Egger’s regression results (p = 0.193, 0.934, 0.291, 0.348) provided additional evidence against publication bias. Finally, Trim and Fill adjustments revealed no meaningful changes in overall effect magnitudes. Collectively, these analyses confirm that publication bias is unlikely to distort the reported relationships.

Figure 2: Funnel plot of the distribution of the relationship between psychological resilience and subjective well-being

Figure 3: Funnel plot of the distribution of the relationship between psychological resilience and life satisfaction

Figure 4: Funnel plot of the distribution of the relationship between psychological resilience and positive emotions

Figure 5: Funnel plot of the distribution of the relationship between psychological resilience and negative affectivity

The results of the main effects analysis examining the relationship between psychological resilience and subjective well-being (SWB), including its three components, are presented in Table 5. According to the criteria proposed by Cohen (1988), correlation coefficients (r) are interpreted as follows: negligible (r = 0.00–0.09), weak (r = 0.10–0.29), moderate (r = 0.30–0.49), and strong (r = 0.50–1.00). The results indicate a statistically significant strong positive correlation between psychological resilience and overall SWB (r = 0.508, p < 0.001). Moderate correlations were observed between psychological resilience and life satisfaction (r = 0.470, p < 0.001) as well as positive emotions (r = 0.465, p < 0.001). In contrast, psychological resilience showed a weak but significant negative correlation with negative emotions (r = −0.253, p < 0.001). These findings collectively demonstrate that psychological resilience is robustly associated with subjective well-being and its constituent dimensions, with varying magnitudes of correlation across components.

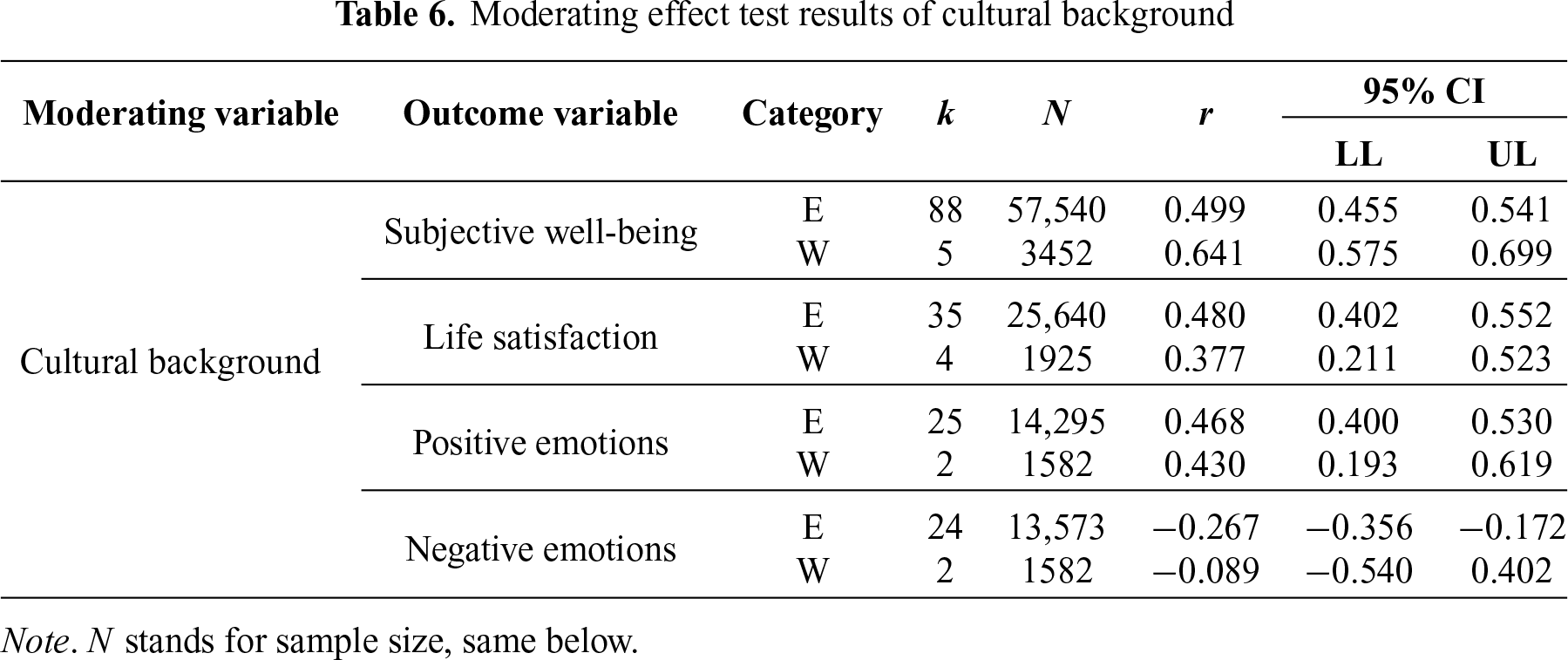

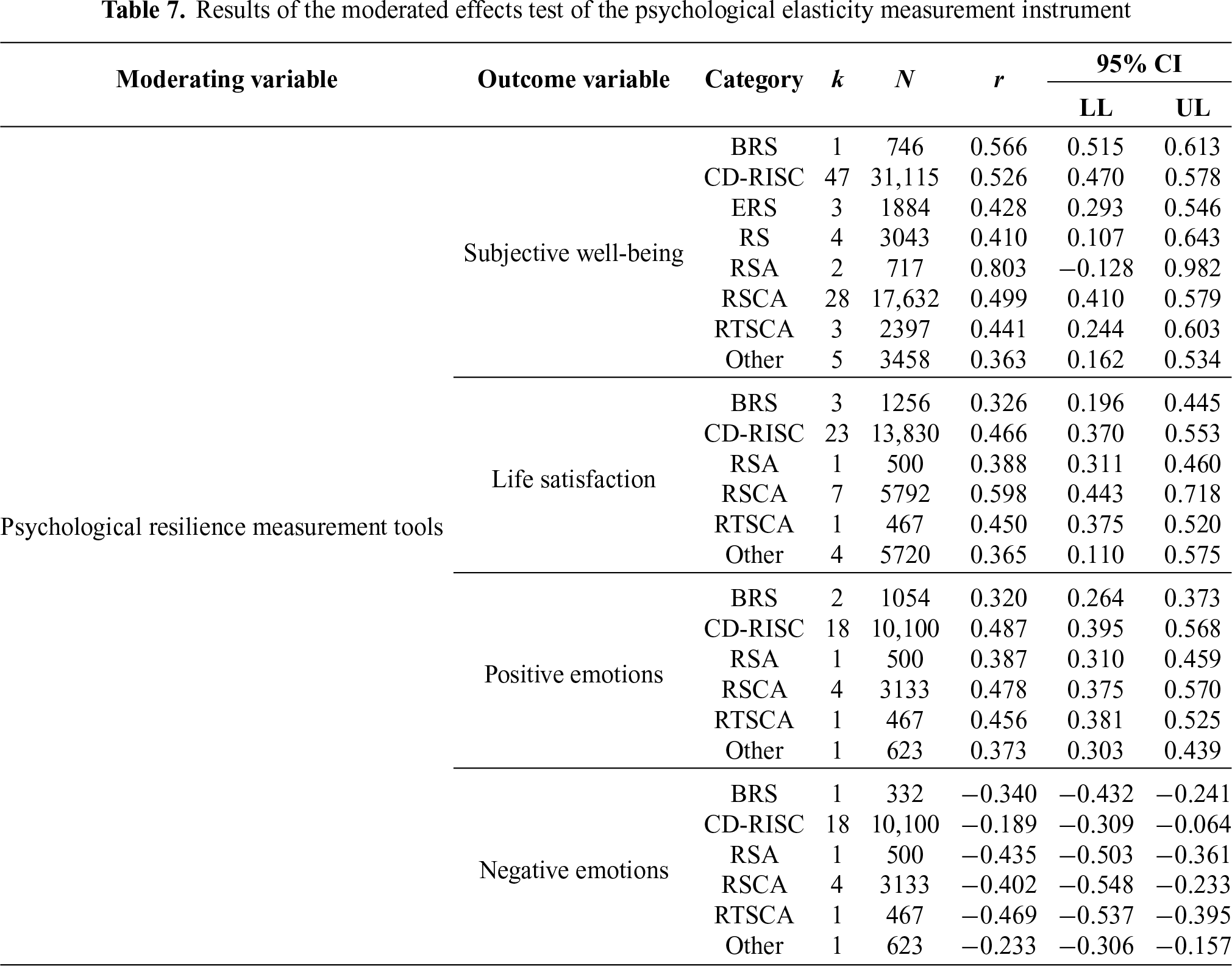

The heterogeneity test results revealed substantial heterogeneity among the included studies, necessitating further exploration of potential moderating factors. Subgroup analyses were conducted for categorical moderators (cultural background, psychological resilience measurement instruments, and adolescent participant groups; Tables 6–8). Comprehensive results for all moderators, including full heterogeneity statistics and subgroup details, are provided in Supplementary Tables S3–S5.

Cultural Background (Table 6). Cultural background significantly moderated the relationship between psychological resilience and subjective well-being (QB = 11.905, p < 0.01). Specifically, the correlation coefficient was stronger in Western contexts (r = 0.641, p < 0.001) compared to Eastern contexts (r = 0.499, p < 0.001). No moderating effects were observed for life satisfaction (QB = 1.424, p > 0.05), positive emotions (QB = 0.113, p > 0.05), or negative emotions (QB = 0.473, p > 0.05).

Measurement Instruments (Table 7). Psychological resilience measurement tools significantly moderated the associations with positive emotions (QB = 17.202, p < 0.01) and negative emotions (QB = 32.329, p < 0.001). The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) demonstrated the strongest correlation between psychological resilience and positive emotions (r = 0.487, p < 0.001), surpassing results from the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) and Resilience Scale for Chinese Adolescents (RSCA). Conversely, the Resilience Trait Scale for Chinese Adolescents (RTSCA) exhibited the strongest inverse correlation with negative emotions (r = −0.409, p < 0.001), outperforming BRS and CD-RISC. No moderation was detected for subjective well-being (QB = 11.110, p > 0.05) or life satisfaction (QB = 9.693, p > 0.05).

Participant Groups (Table 8). Participant type (e.g., age, educational stage) did not moderate the relationships between psychological resilience and subjective well-being (QB = 3.321, p > 0.05), life satisfaction (QB = 2.404, p > 0.05), positive emotions (QB = 0.087, p > 0.05), or negative emotions (QB = 0.010, p > 0.05).

The relationship between psychological resilience and subjective well-being

A systematic review of 112 domestic and international studies was conducted to investigate the internal mechanisms through which psychological resilience influences is associated with subjective well-being (SWB) and its three components, along with potential moderating variables affecting these relationships. The results revealed significant associations between psychological resilience and all SWB dimensions in adolescents: strong positive correlations with overall SWB (r = 0.508, p < 0.001), moderate correlations with life satisfaction (r = 0.470, p < 0.001) and positive emotions (r = 0.465, p < 0.001), and a weak negative correlation with negative emotions (r = −0.253, p < 0.001), consistent with prior findings (Asanjarani et al., 2023; Satici, 2016), thereby confirming Hypothesis 1. From an emotional regulation perspective, resilience is linked to enhanced stress management capabilities, associated with reduced negative emotional responses while amplified positive affective experiences (Etherton et al., 2022; Kong et al., 2021). Individuals with higher resilience demonstrate emotional stability during adversity, which may mitigate the detrimental impact of emotional volatility on SWB (Chuning et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2016). Cognitively, resilience is associated with adaptive appraisal patterns that may enhance SWB. Optimistic cognitive reappraisal of life events is facilitated by associated with resilience, and may promote life satisfaction and well-being (Jiang & Chen, 2020; Liu et al., 2015). Intrinsic psychological mechanisms of resilience involve the accumulation of psychological resources, which may sustain positivity during adversity and stress (Zhou & Zhou, 2022). Resilience is associated with enhanced adaptive capacity, which may facilitate effective responses to life challenges and transitions (Ye et al., 2018). Higher resilience is associated with greater psychological resources, and the maintenance of positive affect during difficulties (Liang et al., 2018). The stress-buffering model posits that resilience may reduce stress-induced emotional distress through proactive coping strategies (Miranda & Cruz, 2022). For instance, under sleep deprivation or academic stress, highly resilient individuals tend to reframe challenges as growth opportunities rather than threats, which is associated with reduced negative affect and heightened positive emotional experiences (An et al., 2023). Neurobiological evidence has linked resilience to optimized dopaminergic functioning, which may enhance reward sensitivity and positive emotional processing (An et al., 2023). Experience-sampling studies demonstrate that high-resilience university students exhibit more frequent and intense positive emotions, often expressed through overt affective displays that reinforce well-being; conversely, low-resilience individuals engage in maladaptive cognitive rumination, exacerbating negative emotional states (Lv et al., 2017).

These findings support specific, actionable steps for enhancing adolescent well-being. In schools, this includes implementing resilience training programs that teach cognitive reappraisal and emotion regulation skills. For practitioners, integrating brief resilience assessments into well-being screenings can help identify at-risk youth for targeted counseling. At a broader level, embedding resilience-building principles into curricula and teacher training can serve as a universal prevention strategy.

Moderating factors affecting the relationship between psychological resilience and subjective well-being

The moderating effect of cultural type

Meta-analytic results indicated that cultural background significantly moderated the relationship between psychological resilience and subjective well-being (SWB), partially validating Hypothesis 2. Specifically, the correlation coefficient between psychological resilience and SWB was significantly higher in Western cultural contexts than in Eastern contexts. This divergence may stem from culturally embedded value orientations. A cross-national survey across 19 countries demonstrated stronger associations between hedonic pursuits and well-being in individualistic cultures (Joshanloo & Jarden, 2016). Western cultures, emphasizing individualism and personal autonomy (Cohen et al., 2016), may promote resilience through self-regulation and self-efficacy, thereby amplifying resilience’s positive association with SWB (Krys et al., 2019). In contrast, Eastern cultures prioritize collectivism and relational harmony, where resilience is shaped not only by intrapersonal factors but also by external systems––social support (Huang et al., 2016), familial bonds (Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020), and community cohesion (Hall & Zautra, 2010)––as theorized in ecological resilience frameworks (Ungar, 2008). Within these cultural contexts, the mechanisms linking resilience to SWB enhancement are comparatively multifaceted. Furthermore, Western studies frequently employ scales incorporating dimensions such as “spiritual faith” or “perceived control” (e.g., CD-RISC), which align more closely with individualistic conceptualizations of resilience, potentially amplifying observed resilience-SWB associations. However, cultural background did not significantly moderate life satisfaction, positive affect, or negative affect, likely because affective components (positive/negative emotions) and cognitive components (life satisfaction) of SWB operate through distinct pathways (Campbell, 1976; Garcia et al., 2017; Lazić et al., 2021). Cultural influences may thus manifest more prominently in global SWB evaluations rather than specific subcomponents.

The moderating effect of psychological resilience measurement tools

Meta-analytic results revealed that psychological resilience measurement instruments significantly moderated the relationships between resilience and both positive and negative affect. This heterogeneity underscores the conceptual and operational diversity inherent in resilience assessment, as detailed in Table 1.

Notably, resilience measured by the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) demonstrated significantly stronger correlations with positive affect compared to other instruments, whereas the Resilience Trait Scale for Chinese Adolescents (RTSCA) showed stronger inverse correlations with negative affect. These differential associations can be understood by examining the core dimensions emphasized by each scale (see Table 1).

The CD-RISC’s stronger linkage with positive affect aligns with its comprehensive focus on positive adaptive traits, including personal competence, tenacity, and optimism (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Conversely, the RTSCA’s pronounced role in negative affect regulation corresponds to its conceptual grounding in stress-coping mechanisms, internal locus of control, and problem-solving orientation (Liang & Cheng, 2012). These instrument-specific conceptual foci provide a compelling explanation for the observed differential associations with SWB components.

Beyond conceptual differences, methodological characteristics of the instruments also contribute to the observed heterogeneity. Variations in instrument reliability and validity may systematically influence observed resilience-SWB relationships, as instruments with superior psychometric properties more accurately capture the true construct (Lau, 2022). The tabular overview (Table 1) illustrates the multidimensional nature of resilience, explaining why scales with differing dimensional emphases (e.g., the RSA’s focus on social resources vs. the RS’s emphasis on existential meaningfulness) demonstrate varying predictive validity for specific well-being components. The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS), while practical for large-scale surveys due to its brevity, has limited capacity to assess the full spectrum of this complex construct (Smith et al., 2008).

A critical methodological consideration is the stability of these moderator findings. It must be noted that estimates for certain scales were derived from a limited number of studies (e.g., k = 2 for the Resilience Scale for Adults, RSA). While these results contribute to the pattern of measurement heterogeneity, their precision is limited, and they should be interpreted as preliminary evidence requiring confirmation through future research with larger samples.

The moderating role of participant groups

Subgroup analyses indicated no significant moderating effect of participant group on the resilience-SWB association, contradicting Hypothesis 4. Despite greater social experience among older adolescents, no significant differences in resilience-SWB correlation strength were observed between groups. This null finding may reflect developmental continuity during adolescence, as both middle school and university students occupy critical periods of identity formation, face comparable academic-social stressors, and exhibit minimal age-related divergence. Methodological convergence in measurement instruments and study designs across groups may have attenuated observable differences, thus limiting divergence in association magnitudes. Future investigations should stratify adolescent subgroups (e.g., junior high, senior high, vocational students) to examine stage-specific mechanisms linking resilience to SWB.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the predominantly cross-sectional nature of included studies precludes causal inferences about the resilience-SWB relationship. Future research should employ longitudinal or experimental designs to establish temporal precedence and causality.

Second, the dichotomous East-West cultural classification may overlook important within-culture variations and sociopolitical differences. Future research should incorporate more nuanced cultural indicators such as individualism-collectivism dimensions.

Third, while measurement heterogeneity for resilience constructs was identified as a significant moderator, a parallel concern involves the operationalization and measurement of subjective well-being. The construct of SWB was measured using various instruments across studies, with differing emphases on its cognitive (life satisfaction) and affective (positive and negative affect) components, as well as the use of composite scores vs. separate dimensions. This methodological heterogeneity may contribute to variance in the observed effects, and future meta-analyses would benefit from conducting sensitivity analyses based on SWB measurement instruments.

Fourth, the high heterogeneity (I2 > 95%), while addressed through moderator analyses, remains largely unexplained and may affect the precision of aggregate estimates. The exceptionally high heterogeneity suggests that the pooled correlation should be interpreted as a summary of a highly diverse literature rather than a precise estimate of a single, stable population parameter, which consequently lowers the confidence in the accuracy of the aggregate effect size. Future work should explore additional moderators (e.g., socioeconomic status, specific life stressors) to account for this variance.

Fifth, reliance on self-report measures introduces potential common method variance. Future research should incorporate objective or multi-informant measures of well-being.

Sixth, and relatedly, there is potential conceptual and operational overlap between measures of psychological resilience and subjective well-being. Some dimensions of resilience scales (e.g., optimism, emotional regulation) may conceptually overlap with components of well-being scales (e.g., positive affect, life satisfaction). This shared methodological variance might inflate the observed correlations beyond the true underlying relationship between the distinct constructs.

Seventh, as noted in the discussion of moderator effects, several subgroup analyses were conducted with a limited number of studies, particularly for specific resilience measurement instruments (e.g., RSA, RTSCA) and Western cultural samples. The effect size estimates for these subgroups, while informative, may lack stability and require replication in future meta-analyses with a broader evidence base.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the findings have clear practical implications. Evidence-based resilience programs such as the Penn Resilience Program (PRP) and the Resilience Doughnut model, which incorporate cognitive-behavioral techniques, emotion regulation skills, and social support building, are strongly recommended for implementation in school settings. The cultural differences identified suggest that interventions should be adapted, with Western approaches emphasizing individual strengths and Eastern approaches incorporating familial and community resources. The growing association between resilience and well-being over time, potentially amplified by contemporary challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic and increased digitalization, underscores the urgent relevance of embedding these resilience-focused interventions in educational and mental health frameworks.

This meta-analysis provides the first large-scale synthesis specifically examining the relationship between psychological resilience and subjective well-being in adolescent populations while comprehensively investigating cultural, methodological, and developmental moderators. The results revealed significant correlations between psychological resilience and SWB across its core components—life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect. Critically, cultural context and measurement instruments were identified as significant moderators of these associations, providing crucial insights into the boundary conditions of the resilience-SWB relationship.

Acknowledgement: We thank all the participants who helped collect and select the literature.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Hubei Provincial Department of Education 2024 Annual Provincial Education Science Planning Project (Grant No. 2024ZX021), and the Provincial Teaching and Research Project of Hubei Province Colleges and Universities (No. 2023298).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Jie Wu and Zijian Zhang; methodology, Jie Wu and Tingye Chai; software, Jie Wu; data curation, Jie Wu, Zijian Zhang and Yunbo Shen; writing—original draft preparation, Jie Wu and Zijian Zhang; writing—review and editing, Jie Wu, Zijian Zhang, Tingye Chai, Yunbo Shen and Xianglian Yu; funding acquisition, Xianglian Yu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data will be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Registration and Protocol: The systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD420251161399). The full protocol can be accessed at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251161399 (accessed on 01 January 2025). No amendments were made to the information provided at registration.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jpa.2025.067273/s1.

References

Akintunde, T. Y., Isangha, S. O., Iwuagwu, A. O., & Adedeji, A. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and subjective well-being of migrants: Exploring the role of resilience and gender differences. Global Social Welfare, 11(3), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-023-00310-w [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

An, Y., Ji, X., Zhou, L., & Liu, J. (2023). Sleep and subjective well-being among chinese adolescents: Resilience as a mediator. Asian Journal of Social Health and Behavior, 6(3), 112. https://doi.org/10.4103/shb.shb_238_23 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Asanjarani, F., Kumar, A., & Kalani, S. (2023). Student subjective wellbeing amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran: Role of loneliness, resilience and parental involvement. Child Indicators Research, 16(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09963-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science & Medicine, 66(8), 1733–1749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Blanco-García, C., Acebes-Sánchez, J., Rodriguez-Romo, G., & Mon-López, D. (2021). Resilience in sports: Sport type, gender, age and sport level differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Buecker, S., Luhmann, M., Haehner, P., Bühler, J. L., Dapp, L. C. et al. (2023). The development of subjective well-being across the life span: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 149(7–8), 418–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000401 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Busseri, M. A., & Sadava, S. W. (2011). A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 290–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310391271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Campbell, A. (1976). Subjective measures of well-being. American Psychologist, 31(2), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.31.2.117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chuning, A. E., Durham, M. R., Killgore, W. D. S., & Smith, R. (2024). Psychological resilience and hardiness as protective factors in the relationship between depression/anxiety and well-being: Exploratory and confirmatory evidence. Personality and Individual Differences, 225, 112664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL, USA: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Cohen, A. B., Wu, M. S., & Miller, J. (2016). Religion and culture: Individualism and collectivism in the East and West. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47(9), 1236–1249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116667895 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Eldeleklioğlu, J., & Yıldız, M. (2020). Expressing emotions, resilience and subjective well-being: An investigation with structural equation modeling. International Education Studies, 13(6), 48. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v13n6p48 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Etherton, K., Steele-Johnson, D., Salvano, K., & Kovacs, N. (2022). Resilience effects on student performance and well-being: The role of self-efficacy, self-set goals, and anxiety. The Journal of General Psychology, 149(3), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2020.1835800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Friborg, O., Hjemdal, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Martinussen, M. (2003). A new rating scale for adult resilience: What are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 12(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gan, Y., & Cheng, L. (2021). Psychological capital and career commitment among Chinese urban preschool teachers: The mediating and moderating effects of subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 509107. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.509107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Garcia, D., Sagone, E., De Caroli, M. E., & Al Nima, A. (2017). Italian and Swedish adolescents: Differences and associations in subjective well-being and psychological well-being. PeerJ, 5, e2868. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hall, J. S., & Zautra, A. J. (2010). Indicators of community resilience: What are they, why bother?. In: Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 350–371). New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Higgins, J., Thompson, S., Deeks, J., & Altman, D. (2002). Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: A critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 7(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1258/1355819021927674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hu, Y., & Gan, Y. (2008). Development and psychometric validity of the resilience scale for Chinese adolescents. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 8, 902–912. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Huang, S., Wen, Z., Zeng, Y., Li, Y., & Yang, Y. (2016). The mediating role of psychological resilience and self-efficacy in emotional regulation between social support and subjective well-being in college students. Chinese Journal of School Health, 37(10), 1559–1561. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2016.10.037 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Israelashvili, J. (2021). More positive emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with better resilience, especially for those experiencing more negative emotions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648112. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jiang, Y., & Chen, Y. (2020). A correlation study of the psychological resilience and subjective well-being of postgraduates—a comparative study on the differences between postgraduates and undergraduates. Education Research Monthly, 6, 76–81. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.16477/j.cnki.issn1674-2311.2020.06.011 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Joshanloo, M., & Jarden, A. (2016). Individualism as the moderator of the relationship between hedonism and happiness: A study in 19 nations. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.025 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kong, F., Yang, K., Yan, W., & Li, X. (2021). How does trait gratitude relate to subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents? The mediating role of resilience and social support. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(4), 1611–1622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00286-w [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Krys, K., Uchida, Y., Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2019). Open society fosters satisfaction: Explanation to why individualism associates with country level measures of satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(6), 768–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1557243 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lau, W. (2022). The role of resilience in depression and anxiety symptoms: A three-wave cross-lagged study. Stress and Health, 38(4), 804–812. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lazić, M., Jovanović, V., Gavrilov-Jerković, V., & Boyda, D. (2021). A person-centered evaluation of subjective well-being using a latent profile analysis: Associations with negative life events, distress, and emotion regulation strategies. Stress and Health, 37(5), 962–972. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Liang, B., & Cheng, C. (2012). Psychological health diathesis assessment system: The development of resilient trait scale for Chinese adults. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 10(4), 269–277. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Liang, J., Cui, X., Zuo, C., Wang, Y., & Yue, S. (2018). Social support on subjective well-being among vocational college students: Mediation effect of general self-efficacy and resilience. Modern Preventive Medicine, 45(13), 2383–2386. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Light, R. J., & Pillemer, D. B. (1984). Summing up: The science of reviewing research. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvk12px9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lim, S. S. M., Brooker, A., Giampiccolo, A., Klidis, S., Lim, H. S. et al. (2025). Resilience and its associated factors in optometry students from eight institutions across six countries. Clinical & Experimental Optometry, 108(3), 310–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164622.2025.2454532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Liu, J., Li, S., & Xie, Y. (2023). Research on influencing factors of user information avoidance behavior in social network environment based on meta-analysis. Information and Documentation Services, 44(1), 92–102. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Liu, S., Liu, K., Li, T., & Lu, L. (2015). The impact of mindfulness on subjective well-being of college students: The mediating effects of emotion regulation and resilience. Journal of Psychological Science, 38(4), 889–895. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2015.04.017 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lv, M., Xi, J., & Luo, Y. (2017). Daily emotional characteristics in individuals with different resilience levels: Supplementary evidence from experience-sampling method (ESM). Acta Psychologica Sinica, 49(7), 928–940. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1041.2017.00928 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ma, L. (2023). The relationship and intervention of mental resilience and subjective well-being of junior high school students [master’s thesis]. Yan’an, China: Yan’an University. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.27438/d.cnki.gyadu.2023.000592 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Masten, A. S. (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 12–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12255 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Masten, A. S., Lucke, C. M., Nelson, K. M., & Stallworthy, I. C. (2021). Resilience in development and psychopathology: Multisystem perspectives. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 521–549. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-120307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Masten, A. S., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2020). Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: Reflections in the context of COVID-19. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-020-00010-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Miranda, J. O., & Cruz, R. N. C. (2022). Resilience mediates the relationship between optimism and well-being among Filipino university students. Current Psychology, 41(5), 3185–3194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00806-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moreira, A. L., Yunes, M.Â.M., Nascimento, C. R. R., & Bedin, L. M. (2021). Children’s subjective well-being, peer relationships and resilience: An integrative literature review. Child Indicators Research, 14(5), 1723–1742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09843-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moreta-Herrera, R., Oriol-Granado, X., González-Carrasco, M., & Vaca-Quintana, D. (2023). Examining the relationship between subjective well-being and psychological well-being among 12-year-old-children from 30 countries. Child Indicators Research, 16(5), 1851–1870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-023-10042-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C. et al. (2021). The PRISMA, 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Palomera, R., Gonzalez-Yubero, S., Mojsa-Kaja, J., & Szklarczyk-Smolana, K. (2022). Differences in psychological distress, resilience and cognitive emotional regulation strategies in adults during the Coronavirus pandemic: A cross-cultural study of Poland and Spain. Anales De Psicología, 38(2), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.462421 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rajkumar, R. P. (2023). Cultural values and changes in happiness in 78 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of data from the World Happiness Reports. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1090340. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1090340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rosenthal, R. (1995). Writing meta-analytic reviews. Psychological Bulletin, 118(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.2.183 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Satici, S. A. (2016). Psychological vulnerability, resilience, and subjective well-being: The mediating role of hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 102(1), 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.057 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schmidt, F. L., Oh, I., & Hayes, T. L. (2009). Fixed- versus random-effects models in meta-analysis: Model properties and an empirical comparison of differences in results. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 62(1), 97–128. https://doi.org/10.1348/000711007X255327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. The American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Şimşek, Ö. F. (2009). Happiness revisited: Ontological well-being as a theory-based construct of subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(5), 505–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9105-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P. et al. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sorrenti, L., Caparello, C., & Filippello, P. (2022). The mediating role of optimism and resilience in the association between COVID-19-related stress, subjective well-being, hopelessness, and academic achievement in Italian university students. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(6), 5496–5515. Retrieved from: https://journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/8447. [Google Scholar]

Suh, E., Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Triandis, H. C. (1998). The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgments across cultures: Emotions versus norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.482 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Topçu, F., & Dinç, M. (2024). Psychological resilience and valued living in difficult times: Mixed method research in cultural context. Current Psychology, 43(39), 30595–30612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06552-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Troy, A. S., Willroth, E. C., Shallcross, A. J., Giuliani, N. R., Gross, J. J. et al. (2023). Psychological resilience: An affect-regulation framework. Annual Review of Psychology, 74(1), 547–576. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020122-041854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ungar, M. (2008). Resilience across cultures. British Journal of Social Work, 38(2), 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl343 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ungar, M., & Theron, L. (2020). Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(5), 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30434-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Vladisavljević, M., & Mentus, V. (2019). The structure of subjective well-being and its relation to objective well-being indicators: Evidence from EU-SILC for Serbia. Psychological Reports, 122(1), 36–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118756335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1(2), 165–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Wan, X., Huang, H., Zhang, Y., Peng, Q., Guo, X. et al. (2023). The effect of prosocial behaviours on Chinese undergraduate nursing students’ subjective well-being: The mediating role of psychological resilience and coping styles. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 32(1), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Windle, G., Markland, D. A., & Woods, R. T. (2008). Examination of a theoretical model of psychological resilience in older age. Aging & Mental Health, 12(3), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802120763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wo, C. (2019). College students’ psychological resilience and subjective well-being: The mediating role of emotional self-efficacy [master’s thesis]. Shenyang, China: Shenyang Normal University. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Wu, X., Gai, X., Wang, W., Xie, X., Wang, H., & et al. (2020). Establishing national norms for the adolescents’ well-being scale for Chinese middle school and college students. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 18(4), 530–536. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Ye, F., Xie, M., Wang, L., Wang, S., & Li, L. (2018). Studying on the relationship between work hoped-for selves and subjective well-being mediated by resilience of college students. Chinese Health Service Management, 35(12), 938–941. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Ye, J., & Zhang, X. (2021). Relationship between resilience and well-being in elders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 29(2), 202–217. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2021.00202 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yu, X., & Zhang, J. (2007). Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) with Chinese people. Social Behavior and Personality, 35(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2007.35.1.19 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, Y., Li, S., & Yu, G. (2019). The relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety: A meta-analysis with Chinese students. Advances in Psychological Science, 27(6), 1005–1018. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2019.01005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhou, H., & Zhou, Q. (2022). Effect of physical exercise on subjective well-being of college students: Chain mediation effect of cognitive reappraisal and resilience. Journal of Shandong Sport University, 38(1), 105–111. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.14104/j.cnki.1006-2076.2022.01.013 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools