Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Core self-evaluations (CSE) and career success: Task performance and leader-member exchange (LMX) mediation effects

School of Economics and Management, Jinzhong University, Jinzhong, 030619, China

* Corresponding Author: Xin Guo. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 825-832. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.069822

Received 01 July 2025; Accepted 17 November 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Core Self-Evaluations are linked to career success, yet the person-environment factor mechanisms underlying this relationship remain unclear. This meta-analysis (N = 135,809) synthesized the evidence on whether person task performance and LMX environment mediate the effects of CSE on career success both objective (salary) and subjective (job satisfaction) indicators. This study employed meta-analytic structural equation modeling (MASEM) to test direct and indirect pathways. Results integrating tournament theory and LMX theory show that CSE positively relates to task performance and LMX, both of which in turn relate to salary and job satisfaction. A significant sequential mediation pathway was also supported (CSE → LMX → task performance → career success). These findings highlight the dual importance of individual performance and social exchange with leaders in achieving career success and advance theory by linking tournament and LMX perspectives.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FilePeople want to succeed in their career endeavors, and by the actions they take, assume productive workplace exchanges with team members. Workplace leaders are critical to career success for good or bad. They may influence how employees view themselves and the job actions they engage in (Carasco-Saul et al., 2015). The career success ladder is by how people self-evaluate and whether they engage in mutually productive relationships with workplace leaders, assuming supportive leadership (Judge & Bono, 2001; Kuvaas et al., 2012). Career success refers to individuals’ cumulative work achievements and is strongly associated with CSE—a person’s appraisal of self-worth and competence (Judge et al., 1998). While previous research confirms that CSE relates to both objective (salary) and subjective (job satisfaction) career success (Chang et al., 2011), how CSE leads to these career success outcomes remains unclear. Yet, there is a sizable amount of research evidence on these relationships to be synthesized.

Core self-evaluations and career success

CSE, as a higher-order trait encompassing self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, emotional stability, and locus of control (Judge et al., 2003), equips employees with psychological resources that facilitate constructive leader–member interactions. For example, individuals high in CSE tend to approach challenges with confidence and composure, exhibit resilience under stress, and convey reliability—all qualities that leaders interpret as signals of competence and trustworthiness. These attributes could make high-CSE employees more attractive exchange partners and increase the likelihood that leaders will reciprocate with support and resources, thereby fostering the development of high-quality LMX relationships.

Task performance and leader-member exchange (LMX) mediation

The CSE → performance link has been well-established (Judge et al., 2003). To further justify the CSE → LMX link, prior meta-analytic evidence shows that employee individual differences are among the strongest antecedents of LMX quality (Dulebohn et al., 2012). In particular, member personality traits and self-evaluations may influence how leaders perceive and respond to them during the exchange process.

Although prior research generally finds that CSE relates positively to career success and performance, results are not fully consistent. Some studies report strong direct effects (e.g., Judge & Bono, 2001; Chang et al., 2011), whereas others reveal weaker or nonsignificant relationships (e.g., He et al., 2023). One likely reason is that the mechanisms through which CSE influences career success remain insufficiently understood. These inconsistencies warrant a meta-analytic investigation to clarify the overall magnitude of effects and to illuminate the processes by which CSE contributes to employee outcomes.

Tournament theory highlights performance as the basis for advancement (Lazear & Rosen, 1981), while LMX theory emphasizes the benefits of supportive leader relationships (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Specifically, tournament theory suggests that high performance leads to greater career rewards, while LMX theory posits that strong leader relationships provide access to valuable resources and opportunities. These theories thus imply that task performance and LMX can serve as key mediators between CSE and career success.

Focusing on only one of these perspectives would provide an incomplete view of career success: performance alone overlooks the relational context of leader support, while relationships alone overlook the competitive reality of advancement. Considering them together offers a more comprehensive framework, as tournament and LMX theories capture complementary aspects of how CSE translates into career success. We selected task performance and LMX because they directly reflect the two theoretical perspectives we integrate. Tournament theory emphasizes performance as the basis for rewards (Lazear & Rosen, 1981), whereas LMX theory highlights relational access to resources and support (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). These mechanisms are theory-proximal, complementary, and consistently represented in the available evidence. In contrast, other candidates are less suitable: proactive personality is highly correlated with CSE (e.g., Valls et al., 2020), OCB is not directly captured in organizational reporting systems and its link to career success is weaker than that of job performance (Organ, 2018), and networking represents another relational pathway that overlaps with LMX. Integrating both perspectives, this meta-analysis employed MASEM to test mediating pathways using a large, cross-national sample, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the CSE–career success relationship.

The goal of this study is to clarify how CSE contributes to career success by testing the mediating roles of task performance and LMX. Drawing on tournament theory (Lazear & Rosen, 1981) and LMX theory (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995), the author proposes that CSE fosters career success by enhancing task performance and building high-quality relationships with leaders.

We hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1. Task performance mediates the positive relationship between CSE and both objective career success (salary; Hypothesis 1a) and subjective career success (job satisfaction; Hypothesis 1b).

Hypothesis 2. Leader-member exchange (LMX) mediates the effects of CSE on salary (Hypothesis 2a) and job satisfaction (Hypothesis 2b).

Hypothesis 3. CSE influences career success through a sequential pathway involving LMX and task performance, affecting both salary (Hypothesis 3a) and job satisfaction (Hypothesis 3b).

MASEM includes two steps (Bergh et al., 2016; Viswesvaran & Ones, 1995). The first one is to build a full meta-analytic correlation matrix. The second step is to conduct an Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis drawing on the established meta-analytic correlation matrix (Ogunfowora et al., 2021; Young et al., 2021). This methodology is widely used in recently published meta-analyses.

To construct a comprehensive meta-analytic correlation matrix, the author reviewed both primary studies and existing meta-analyses. In line with previous work (Lee et al., 2020; Young et al., 2021), the author directly used true score correlations (ρ) provided by earlier meta-analyses. For correlations not available, the author conducted an original meta-analysis to estimate them. Literature was searched using Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar with keywords such as core self-evaluations, task performance, leader-member exchange, salary, career success, job satisfaction, and career satisfaction. This search yielded several relevant ρ values. However, the author could not find a ρ for CSE and LMX, so the author performed an original meta-analysis using the keywords “LMX”, “leader-member exchange”, and “CSE” to evaluate the correlation between CSE and LMX.

To be included in the current study, the following inclusion criteria were made: First, for ρ values of interest in the correlation matrix, they should be estimated utilizing the random-effect model. Second, ρ values should be located at the individual level rather than the group or team level. Third, for r values between CSE and LMX, they should (a) include effect sizes, (b) be located at an individual level rather than a group or team level, and (c) be sampled from the workplace rather than school or physical context. Studies were excluded if they did not meet these criteria, lacked usable effect sizes, were not reported in English, or fell outside the publication year range covered by our search.

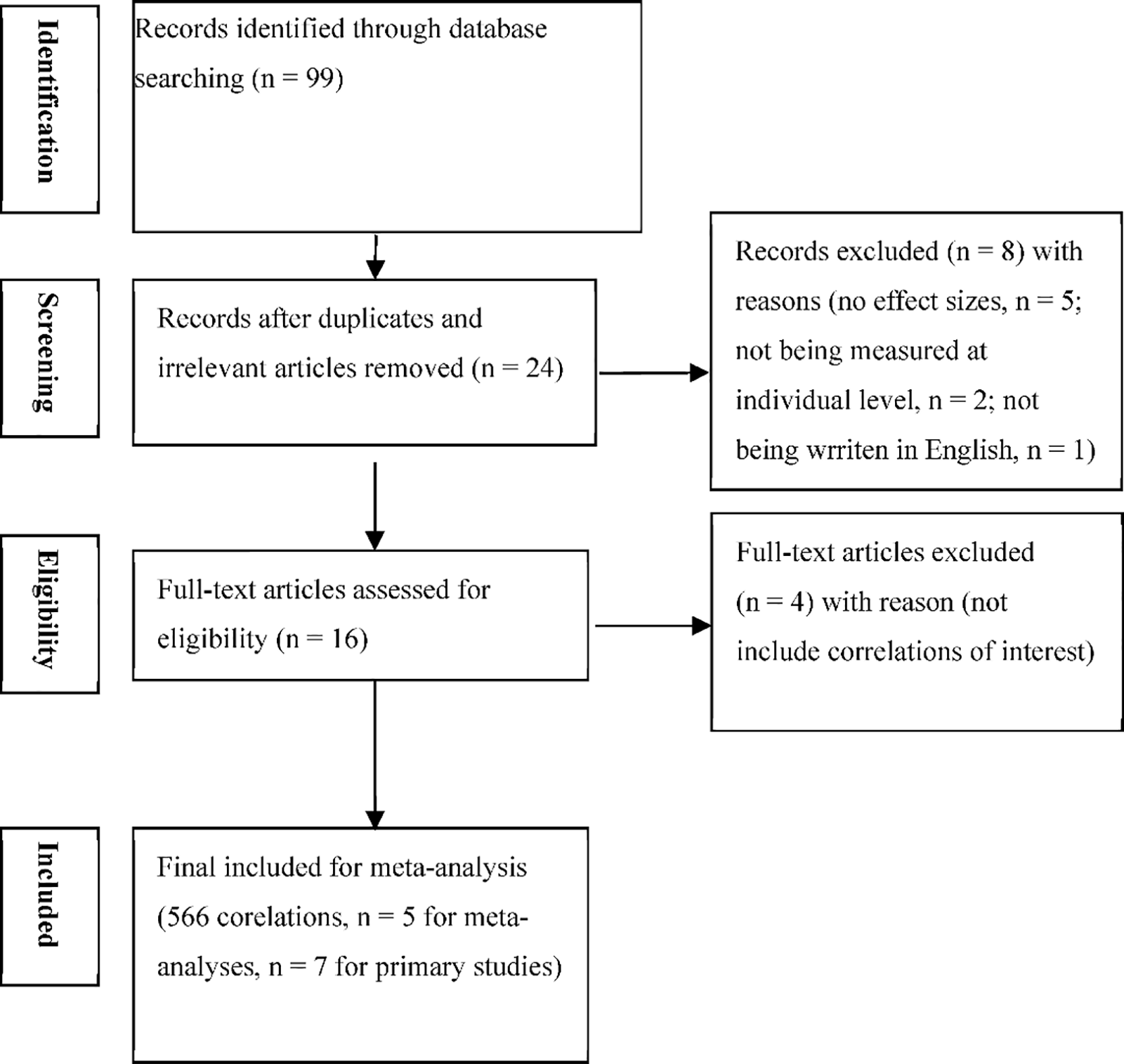

To ensure coding accuracy, each ρ or r was coded by two persons (Greco et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2020; Ogunfowora et al., 2021; Young et al., 2021). The author invited a research assistant to assist with this process. Any coding discrepancies were discussed and resolved collaboratively. This studyadhered to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines throughout the research process (Page et al., 2021). The procedures for literature search, inclusion, and coding are illustrated in Figure 1. In our sample, for the CSE–LMX relationship, 43% were conducted in non-Western contexts, indicating cross-cultural coverage; for other relationships drawn from prior meta-analyses, cultural information was not consistently available. See Supplementary Materials for details.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart

To start, this study employed the random-effect meta-analysis to evaluate the true score correlation between LMX and CSE. In particular, this analysis is conducted utilizing the psychmeta (Dahlke & Wiernik, 2019) package in R. Measurement error is corrected utilizing reliabilities (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015). The overall correlations used in the mediation analysis are provided in Table 1. Heterogeneity indices (e.g., I²) were not reported because many correlations were drawn from prior meta-analyses (see Table 1). Given the large cumulative sample sizes and the use of random-effects models, the influence of heterogeneity on the results is likely to be minimal.

Then, to test our model examining task performance and LMX as mediators of the CSE–career success linkage, this study applied MASEM analysis (Bergh et al., 2016; Viswesvaran & Ones, 1995) using Mplus version 8.03 software (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Specifically, a meta-analytic correlation matrix was input into the MPLUS software. Then, the maximum likelihood method is applied to conduct path analysis. This study utilized the harmonic mean as the sample size for the model. We used the harmonic mean, rather than the total sample size or a simple arithmetic mean, because it provides a balanced estimate when combining correlations based on different sample sizes across paths, although it may underestimate the effective sample size and should therefore be interpreted with caution. The results of the path analysis are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

For relationships where meta-analytic results were drawn from previous studies, publication bias had already been assessed and found to be low. For relationships estimated in our own meta-analyses, we conducted Egger’s test and found a low risk of publication bias (p ≥ 0.050). We also performed trim-and-fill analyses, which provide a more powerful check, and these similarly suggested that publication bias was unlikely to affect the results.

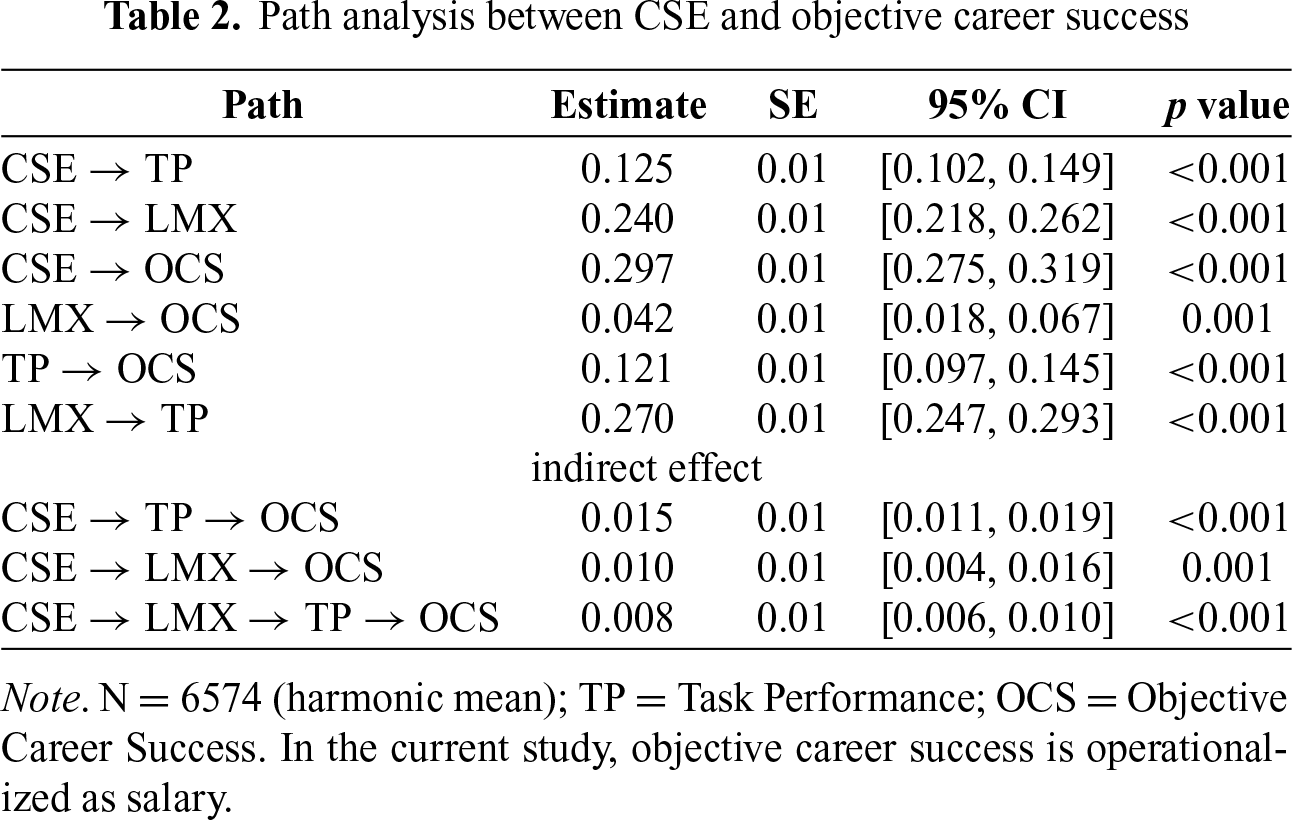

As shown in Table 2, the model fit is excellent: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 1, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 1, Chi-Square = 2012.71, Degrees of Freedom (df) = 6. The model is just identified, so this study retained all paths to avoid altering the fit index.

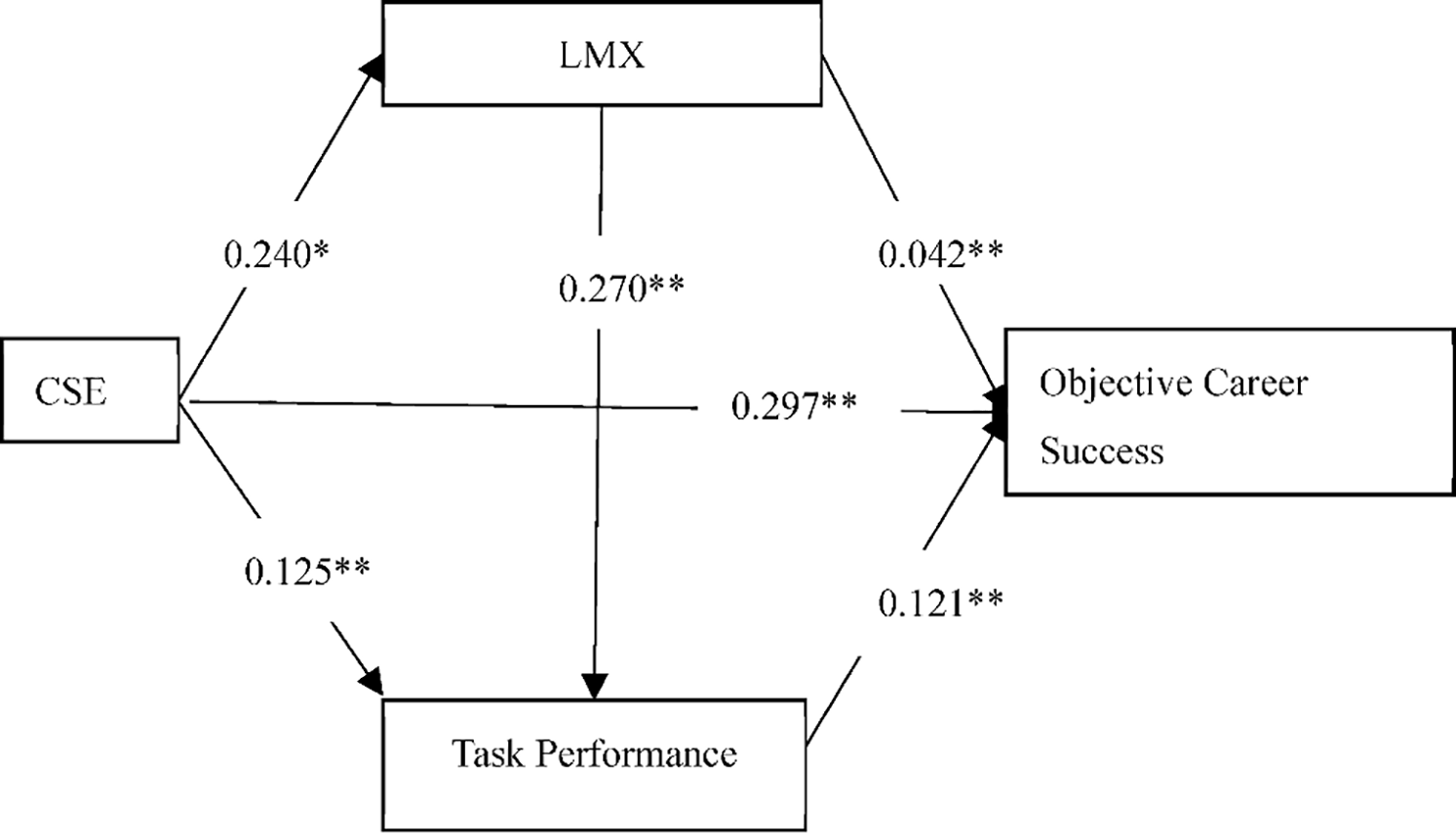

Task performance medication. H1(a) tested the mediation of task performance in the CSE-salary relationship. Results show significant path coefficients: (a) CSE → task performance (β = 0.125, p < 0.001), (b) task performance → salary (β = 0.121, p < 0.001), and (c) the indirect path CSE → task performance → salary (β = 0.015, p < 0.001), supporting H1(a). This suggests that CSE contributes to salary partly by enhancing employees’ performance, consistent with tournament theory’s emphasis on performance as a basis for advancement.

LMX mediation. H2(a) tested LMX as a mediator in the CSE-salary relation. Significant results were found: (a) CSE → LMX (β = 0.240, p < 0.001), (b) LMX → salary (β = 0.042, p = 0.001), and (c) the indirect path CSE → LMX → salary (β = 0.010, p = 0.001), supporting H2(a). This indicates that CSE also translates into salary gains through stronger leader relationships, consistent with LMX theory.

Task performance-LMX chain mediation. H3(a) proposed a sequential mediation (CSE → LMX → task performance → salary). The indirect path was significant (β = 0.008, p < 0.001), confirming H3(a). Figure 2 illustrates the CSE-salary linkage. This sequential pathway highlights how leader support can facilitate performance improvements, which then drive career advancement.

Figure 2: Results of path analysis between CSE and salary. Note. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

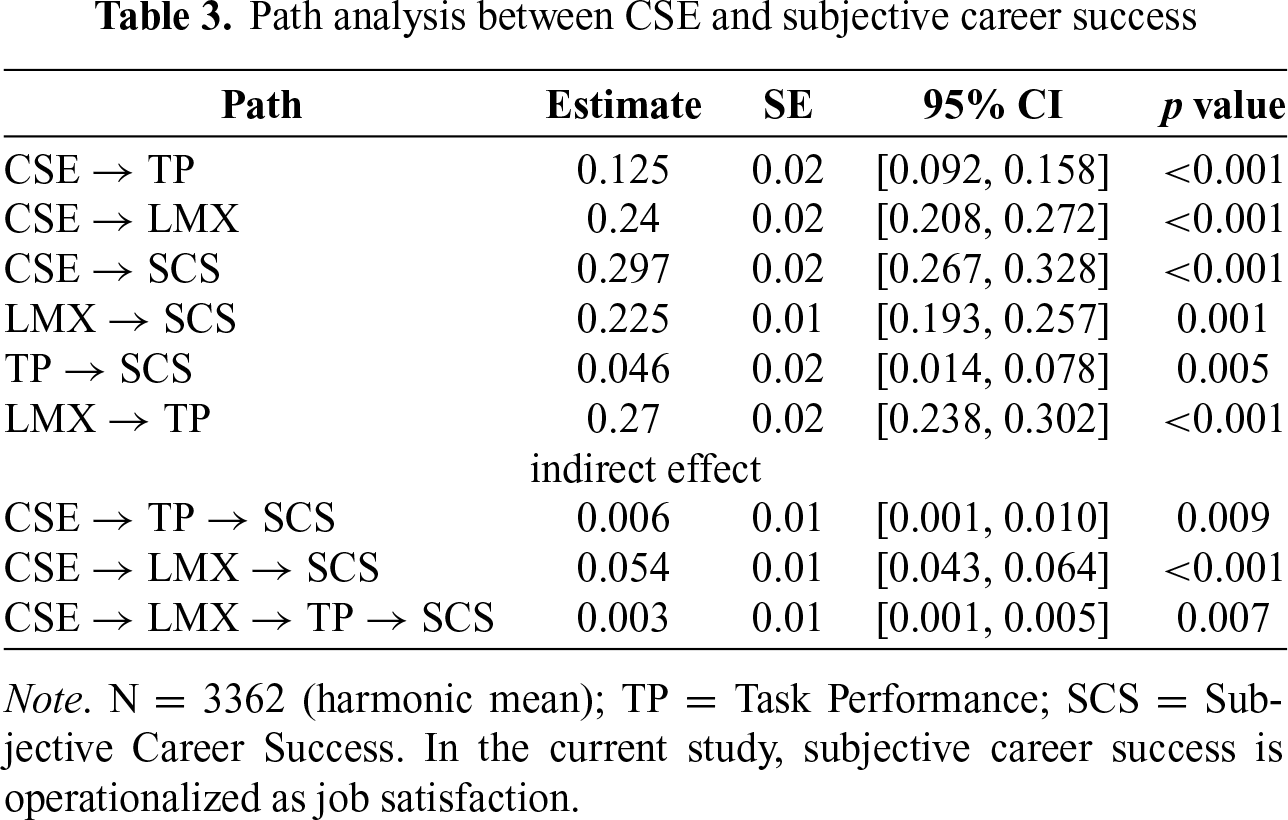

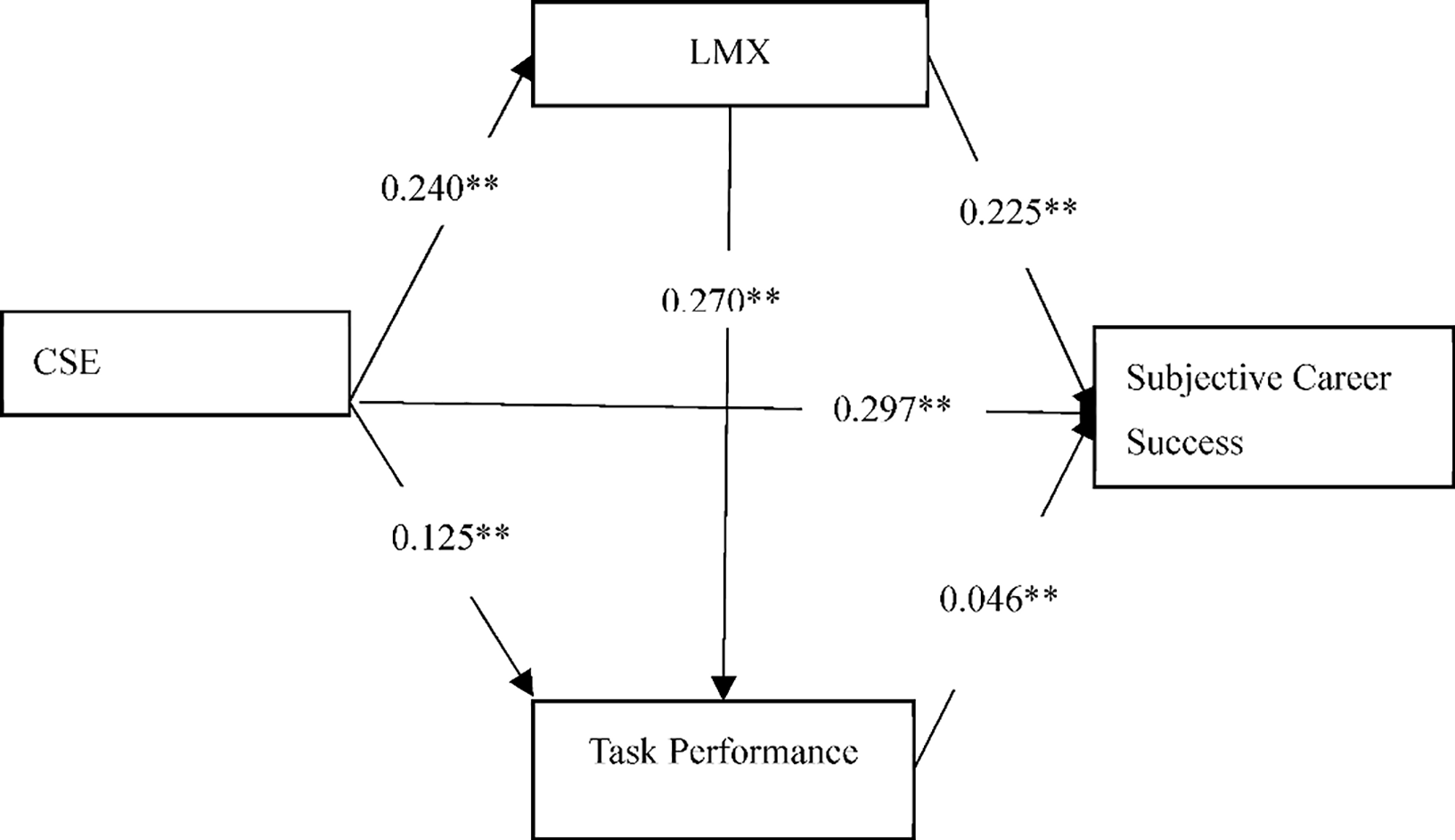

H1(b) tested the mediation of task performance in the CSE-subjective career success relationship. As shown in Table 3, significant path coefficients were found: (a) CSE → task performance (β = 0.125, p < 0.001), (b) task performance → subjective career success (β = 0.046, p = 0.005), and (c) the indirect path CSE → task performance → subjective career success (β = 0.006, p = 0.009), supporting H1(b). This implies that CSE enhances job satisfaction partly by enabling higher performance.

H2(b) tested LMX as a mediator in the CSE-subjective career success linkage. Significant results were: (a) CSE → LMX (β = 0.240, p < 0.001), (b) LMX → subjective career success (β = 0.225, p = 0.001), and (c) the indirect path CSE → LMX → subjective career success (β = 0.054, p < 0.001), supporting H2(b). This shows that CSE improves job satisfaction mainly through building stronger leader relationships, consistent with the relational perspective.

H3(b) proposed a sequential mediation (CSE → LMX → task performance → subjective career success). The indirect path was significant (β = 0.003, p = 0.007), confirming H3(b). Figure 3 illustrates the CSE-subjective career success linkage. This sequential effect underscores the interplay of relationships and performance in shaping subjective career success.

Figure 3: Results of path analysis between CSE and subjective career success. Note. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

The results of this meta-analysis confirm that CSE is a robust predictor of both salary and job satisfaction, consistent with prior evidence that a positive self-concept fosters long-term career outcomes (Judge & Hurst, 2008; Chang et al., 2011). By identifying task performance and LMX as key mediators, this study extends earlier work that emphasized human capital (Ng & Feldman, 2010) as pathways to career success. Notably, the stronger mediating role of LMX in predicting subjective career success underscores the centrality of relational resources in shaping employees’ satisfaction and well-being at work (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Furthermore, the indirect effect of LMX on job satisfaction is substantially larger than that of task performance, highlighting the unique value of high-quality workplace relationships (Liden & Maslyn, 1998). Finally, this meta-analysis reveals a sequential pathway in which CSE enhances LMX, which subsequently boosts task performance and ultimately career success—a mechanism largely overlooked in earlier research. Together, these findings illuminate the dynamic interplay between personality, leader relationships, and individual performance, offering a more integrated understanding of how career success unfolds over time.

Implications for theory, research, and practice

This study makes three main contributions to the literature on CSE and career success. First, it shows that task performance mediates the CSE–career success link, extending human capital theory by clarifying how personality resources translate into outcomes. Second, it highlights LMX as a stronger mediator, advancing social exchange theory by underscoring the value of leader–member relationships for subjective career success. Third, it identifies a sequential pathway from CSE to LMX to task performance and career success, integrating human capital and social exchange perspectives to offer a more comprehensive view of how career success unfolds.

A research implication is that while our model specified the pathway CSE → LMX → task performance → career success, we acknowledge that the reverse ordering (CSE → task performance → LMX → career success) is also theoretically plausible. CSE may enhance task performance, which then facilitates the development of high-quality leader–member relationships, consistent with tournament theory and performance-based views of LMX development. Moreover, signaling theory (Spence, 1978) suggests that leaders may interpret strong performance as a reliable signal of competence, attribute it to enduring personal qualities, and reciprocate by investing in higher-quality exchanges.

Practice implications of the findings include the fact that individuals should recognize the importance of both CSE and LMX in pursuing career success. While CSE may be relatively stable, self-confidence can be enhanced through targeted interventions (Selmi et al., 2018). Employees are also advised to proactively cultivate constructive relationships with supervisors, as high-quality exchanges provide greater access to resources, support, and developmental opportunities (Liden & Maslyn, 1998; Gerstner & Day, 1997).

For organizations, these findings highlight the value of considering CSE in recruitment and selection, given its long-term implications for performance and satisfaction (Judge & Hurst, 2008). Beyond selection, organizations can design interventions that bolster self-efficacy and resilience, while also training leaders to build and maintain high-quality LMX relationships (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Such practices not only foster employee career success but also benefit organizations through enhanced engagement, retention, and overall performance.

Limitations and future directions

First, as the underlying primary studies mostly relied on self-report measures, common method bias may be present (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Future research could use objective measures, such as expert observations to reduce this bias. Second, this study relied on job satisfaction as the sole indicator of subjective career success due to data limitations. Although job satisfaction is a well-established proxy (Judge & Hurst, 2008), other indicators such as career satisfaction (Greenhaus et al., 1990) may also be important, and future studies should consider them to provide a fuller picture. Third, the study relied mainly on cross-sectional data, which limits our ability to make strong causal inferences, and the outcome measures were restricted in scope. Future research could employ longitudinal designs and include a broader range of indicators of career success. Future longitudinal and cross-lagged studies are needed to directly compare these competing sequences and establish the most likely causal ordering. Finally, because part of our data was drawn from prior meta-analyses that did not distinguish cultural contexts, we were unable to examine cultural contingencies of LMX in our integrative analysis. Future research could test whether cultural values (e.g., individualism–collectivism) moderate the relative importance of performance- vs. relationship-based pathways.

Career success is crucial for every employee, and much research has focused on identifying its antecedents. This study applied MASEM to synthesize evidence from 135,809 employees and clarify how CSE translates into career success. We found that task performance and LMX act as complementary and sequential mediators, linking CSE to both salary and job satisfaction. These results advance theory by integrating tournament and LMX perspectives, showing that career success is achieved not only through performance but also through leader relationships. Practically, the findings highlight the importance of fostering both self-confidence and supportive leader exchanges to promote sustainable career success.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Major Research Project on High-Quality Development of Lifelong Education in Shanxi Province for 2025: Research on the Construction and Incentive Mechanism of Lifelong Education Teaching Staff Team (SXZSJY25108).

Availability of Data and Materials: The data analyzed in this study are available in the online Supplementary Materials accompanying the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: This meta-analysis is based on publicly available data extracted from previously published studies that adhered to ethical research standards. As no human participants were directly involved, additional ethical approval was not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jpa.2025.069822/s1. *Coding information, the meta-analysis paper list, and the PRISMA checklist are provided in the Supplementary Material.

References

Bergh, D. D., Aguinis, H., Heavey, C., Ketchen, D. J., Boyd, B. K. et al. (2016). Using meta-analytic structural equation modeling to advance strategic management research: Guidelines and an empirical illustration via the strategic leadership-performance relationship. Strategic Management Journal, 37(3), 477–497. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2338 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Carasco-Saul, M., Kim, W., & Kim, T. (2015). Leadership and employee engagement: Proposing research agendas through a review of literature. Human Resource Development Review, 14(1), 38–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484314560406 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chang, C.-H., Ferris, D. L., Johnson, R. E., Rosen, C. C., & Tan, J. A. (2011). Core self-evaluations: A review and evaluation of the literature. Journal of Management, 38(1), 81–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063114196 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dahlke, J. A., & Wiernik, B. M. (2019). psychmeta: An R package for psychometric meta-analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement, 43(5), 415–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621618795933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1715–1759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311415280 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Erez, A., & Judge, T. A. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations to goal setting, motivation, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1270. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1997). Meta-Analytic review of leader-member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 827–844. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.82.6.827 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Greco, L. M., Porck, J. P., Walter, S. L., Scrimpshire, A. J., & Zabinski, A. M. (2022). A meta-analytic review of identification at work: Relative contribution of team, organizational, and professional identification. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107, 795–830. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/256352 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

He, Y., Kunaviktikul, W., & Sirakamon, S. (2023). Core self-evaluation and subjective career success of nurses in the People’s Hospitals of Dali, the People’s Republic of China. Nursing Journal CMU, 50(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar]

Iaffaldano, M. T., & Muchinsky, P. M. (1985). Job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 97(2), 251–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.97.2.251 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., & Bono, J. E. (1998). The power of being positive: The relation between positive self-concept and job performance. Human Performance, 11(2–3), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.1998.9668030 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2003). The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 303–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00152.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Judge, T. A., & Hurst, C. (2008). How the rich (and happy) get richer (and happierRelationship of core self-evaluations to trajectories in attaining work success. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 849–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kuvaas, B., Buch, R., Dysvik, A., & Haerem, T. (2012). Economic and social leader-member exchange relationships and follower performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(5), 756–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.12.013 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lazear, E. P., & Rosen, S. (1981). Rank-order tournaments as optimum labor contracts. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 841–864. [Google Scholar]

Lee, A., Lyubovnikova, J., Tian, A. W., & Knight, C. (2020). Servant leadership: A meta-analytic examination of incremental contribution, moderation, and mediation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12265 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liao, E. Y., & Hui, C. (2019). A resource-based perspective on leader-member exchange: An updated meta-analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 38(1), 317–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9594-8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M. (1998). Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. Journal of Management, 24(1), 43–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(99)80053-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. (2017). Mplus. In: Handbook of item response theory (pp. 507–518). Boca Raton, FL, USA: Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2010). Human capital and objective indicators of career success: The mediating effects of cognitive ability and conscientiousness. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 207–235. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909x414584 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ogunfowora, B. T., Nguyen, V. Q., Steel, P., & Hwang, C. C. (2021). A meta-analytic investigation of the antecedents, theoretical correlates, and consequences of moral disengagement at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, Advance Online Publication, 107(5), 746. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Organ, D. W. (2018). Organizational citizenship behavior: Recent trends and developments. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 295–306. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104536 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C. et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (2015). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings (3rd Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483398105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Selmi, W., Rebai, H., Chtara, M., Naceur, A., & Sahli, S. (2018). Self-confidence and affect responses to short-term sprint interval training. Physiology & Behavior, 188, 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.01.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Spence, M. (1978). Job market signaling. In: Uncertainty in economics (pp. 281–306). Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

Valls, V., González-Romá, V., Hernandez, A., & Rocabert, E. (2020). Proactive personality and early employment outcomes: The mediating role of career planning and the moderator role of core self-evaluations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2025.104113 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Viswesvaran, C., & Ones, D. S. (1995). Theory testing: Combining psychometric meta-analysis and structural equations modeling. Personnel Psychology, 48(4), 865–885. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01784.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Young, H. R., Glerum, D. R., Joseph, D. L., & McCord, M. A. (2021). A meta-analysis of transactional leadership and follower performance: Double-edged effects of LMX and empowerment. Journal of Management, 47(5), 1255–1280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320908646 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools