Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Leader workaholism and employee work fatigue: The role of emotional exhaustion and family support

1 School of Entrepreneurship, Yiwu Industrial and Commercial College, Jinhua, 321000, China

2 School of Business Administration, Keimyung University, Daegu, 42601, Republic of Korea

3 Business School, Xianda College of Economics and Humanities, Shanghai International Studies University, Shanghai, 200089, China

* Corresponding Author: Zheng Zhang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 815-823. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.070151

Received 09 July 2025; Accepted 03 November 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

This study examined emotional exhaustion and family support in the relationship between leader workaholism and employee work fatigue. The participants were 408 employed adults (74% female, age range 25 to 27 years) across five industries: sales (31.65%), finance (25.32%), education (20.25%), public administration (12.66%), and technology (10.13%), from 79 work teams in China. Survey data were collected at three time points over a three-month period. The results from structural equation modeling indicated that leader workaholism was associated with higher employee work fatigue. Emotional exhaustion mediated the relationship, contributing to higher levels of employee fatigue. Furthermore, family support moderated the relationship between emotional exhaustion and work fatigue. These findings align with the conservation of resources theory and the social support buffering model, both of which propose that resources, such as family support, can help buffer the negative effects of stressors like workaholism. The implications of these findings highlight the significance of family support as a valuable resource in reducing work fatigue and emotional exhaustion among employees, particularly in environments where leader workaholism is prevalent.Keywords

In today’s fast-paced work environment, the phenomenon of “workaholic leadership” has become increasingly prevalent due to high-intensity tasks and demanding workloads (She et al., 2024; Zeng and Liu, 2022). Many leaders work overtime with few days off, sacrificing essential family life and social activities (Mullens & Glorieux, 2024; Roberts, 2007; Suleiman et al., 2021). Workaholic leaders exhibit a compulsive and excessive dedication to their work (Mullens & Glorieux, 2024; Roberts, 2007; Suleiman et al., 2021). This workaholism is exacerbated by the global shift to hybrid work models and the rise of digitization, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic (Spagnoli et al., 2020; Zapata et al., 2024). Employees may bear the brunt of their leaders’ compulsive work demands, risking both work fatigue and emotional exhaustion as excessive demands blur the boundaries between work and personal life (e.g., Andersen et al., 2023; Balducci et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2022; Frone & Tidwell, 2015).

Leader workaholism on employee work fatigue

Workaholic leaders often demonstrate work addiction, cultivating an organizational culture that prioritizes long hours and constant engagement (Ng et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2024). The “996 work culture” (working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week) creates a significant risk of overwork for both leaders and employees (Chen et al., 2023); Employees may feel compelled to emulate these behaviors to align with. their leaders’ expectations, leading to increased workloads and elevated stress levels (Wang et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2025). The cognitive aspect of workaholism, marked by obsessive thoughts about work, can spill over into employees’ experiences (Huyghebaert et al., 2018). As a result, employees may struggle to disengage from work, even during personal time, which can contribute to feelings of fatigue and overwhelm (Allen & Finkelstein, 2014).

In summary, previous studies have established a clear link between leadership styles and employee well-being (Huyghebaert et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2024). Specifically, workaholic leadership has been associated with higher levels of employee stress and burnout (Chen et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024).

Mediator of emotional exhaustion

A state of energy depletion resulting from prolonged and excessive stress was defined emotional exhaustion (Wright & Cropanzano, 1998). Workaholic leaders often demonstrate an extreme commitment to their work, which fosters a demanding environment that pressures employees to extend their work hours and intensify their dedication (Chang et al., 2023; Schaufeli et al., 2008). This pressure can elevate stress levels among employees, thereby increasing the likelihood of emotional exhaustion (Huyghebaert et al., 2018). Emotional exhaustion can then lead to work fatigue, which encompasses feelings of being overwhelmed and lacking the energy to perform tasks effectively (Grandey, 2000; Janssen et al., 2010). When employees experience emotional exhaustion, their capacity to engage with their work diminishes, contributing to increased fatigue and a decline in job performance (Clark et al., 2016; Clark et al., 2020). Additionally, the demands placed on employees by workaholic leaders can create an unsustainable work pace (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). As employees struggle to meet these demands, they may experience emotional exhaustion, which further exacerbates their feelings of work fatigue (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

Moreover, studies have shown that leader behaviors, particularly workaholism, are associated with increased employee stress and emotional exhaustion (e.g., Balducci et al., 2021; Clark et al., 2016). For example, workaholic leadership styles have been found to correlate with elevated levels of employee burnout (Chen et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024). This evidence supports the idea that emotional exhaustion may mediate the relationship between leader workaholism and employee work fatigue.

Family support refers to the emotional and spiritual comfort provided by an individual’s family (Atkin et al., 2022). As an important component of social support, family support plays a crucial role in alleviating stress and promoting mental health (Clark et al., 2020; Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). According to the social support buffering model (Aneshensel & Stone, 1982), family support can significantly reduce the negative effects of stressors. It acts as a protective factor against the harmful impacts of emotional exhaustion, helping employees become more resilient and less fatigued (Cohen & Wills, 1985). When employees experience emotional exhaustion, a supportive family environment can offer comfort and understanding, alleviating the intensity of the link with emotional exhaustion and work fatigue.

Second, employees with strong family support are often better equipped to cope with stress (Holahan & Moos, 1985). Family members help individuals reframe their experiences, offer emotional reassurance, and provide practical assistance (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). Consequently, when faced with emotional exhaustion, these employees are more likely to manage their fatigue effectively, reducing the risk of it escalating into work fatigue (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000).

Finally, family support can help reduce overall stress levels (Holahan & Moos, 1985; Ganster et al., 1986), which aligns with the social support buffering model’s claim that support networks can mitigate stress. When employees receive emotional and practical assistance from family members, it can alleviate the cumulative stress they experience (e.g., Liu et al., 2015; Pluut et al., 2018), making them less likely to suffer from work fatigue, even in the face of emotional exhaustion.

Our study integrates Conservation of Resources theory with the Social Support Buffering Model to offer a dual-lens perspective on how family support mitigates the negative effects of workaholic leadership. According to COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001), stress arises not only from acute resource loss but also from the cumulative depletion of resources without adequate recovery—a key mechanism that underscores the role of emotional exhaustion as a mediator (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Under this framework, when leaders exhibit excessive work focus (i.e., work addiction), they create a high-pressure environment that depletes employees’ emotional and physical resources, ultimately increasing work fatigue (Huyghebaert et al., 2018). Moreover, workaholic leaders often establish behavioral norms through their own work habits (Spence & Robbins, 1992). Employees may feel compelled to emulate these behaviors to meet leader expectations or preserve a professional image (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Wang et al., 2024). Such modeling can intensify employees’ workloads, further contributing to work fatigue (Chen et al., 2023). While COR theory emphasizes that stress stems from resource loss and that recovery requires resource replenishment (Hobfoll, 2001), the Social Support Buffering Model highlights that social support mitigates the impact of stressors by influencing cognitive appraisal and coping strategies (Cohen & Wills, 1985). In our integrated model, family support functions both as a resource reservoir (consistent with COR) and a psychological buffer (consistent with the Buffering Model). By examining how leaders’ workaholic behaviors deplete employee resources and how family support alleviates these effects, we provide a comprehensive framework for understanding work-related stress dynamics.

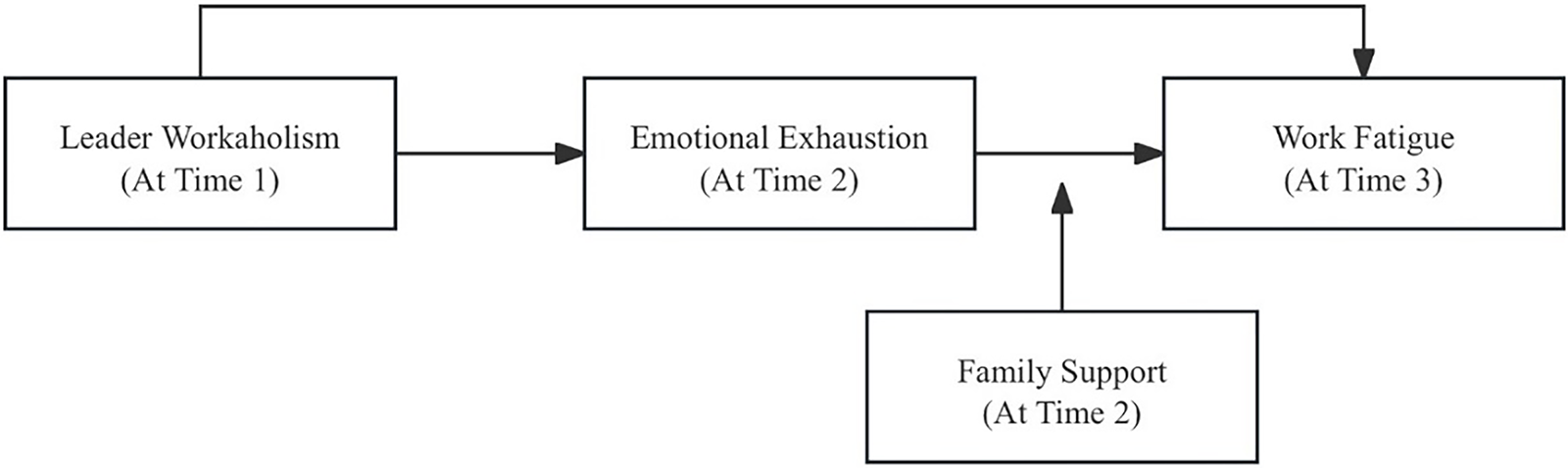

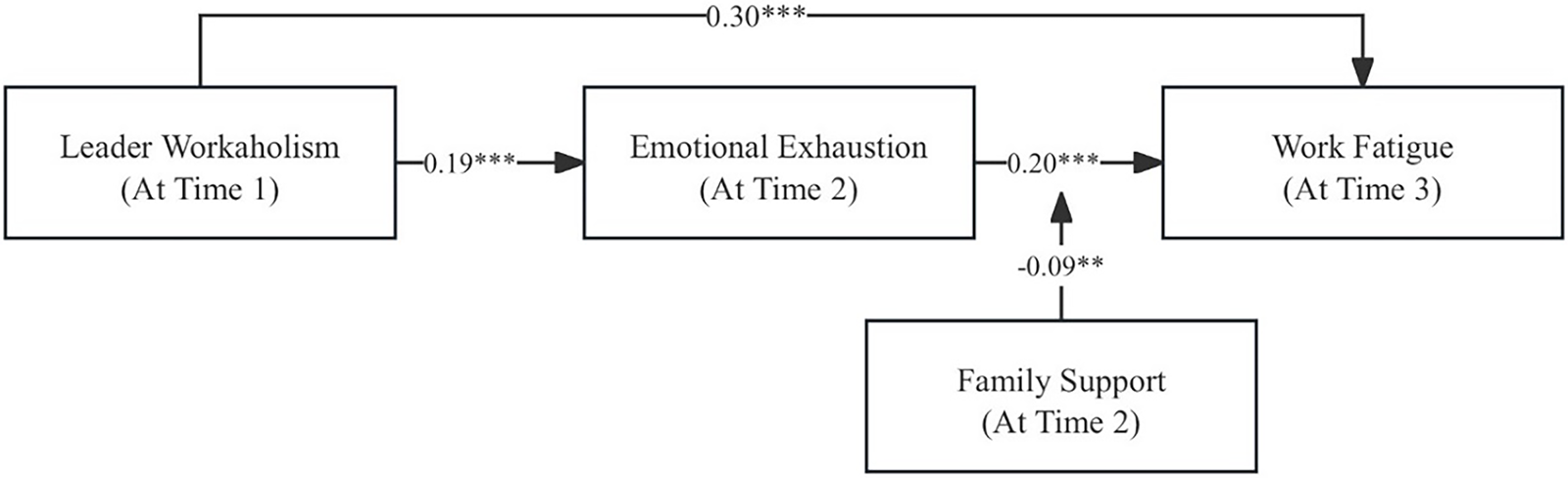

Goals of the Study. This study examines the relationship between leader workaholism and employee work fatigue, and also analyzed the roles of emotional exhaustion and family support in this relationship. Figure 1 presents our theoretical model. Based on this model, we propose the following hypotheses for testing.

Figure 1: Emotional exhaustion, family support and work fatigue = rated by employee; Workaholism = rated by leaders

Hypothesis 1: Leader workaholism is associated with higher employee work fatigue

Hypothesis 2: Employee emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between leader workaholism and employee work fatigue.

Hypothesis 3: Family support moderates the emotional exhaustion and work fatigue relationship for lower employee work fatigue.

Hypothesis 4: Family support moderates the indirect effect of leader workaholism on employee work fatigue via emotional exhaustion for lower employee work fatigue.

The findings contribute to the evidence on how family support can mitigate the effects of employee overwork among employees and the related phenomena of work stress. Moreover, these findings also offer relevant insights for the well-being of workers and the effectiveness of the organization through demand-driven leadership approaches.

Participants included 408 employees from 79 work teams (N = 79 leaders, one per team). These 79 teams were distributed across five industries: sales, finance, education, public administration, and technology. Among the employees, 74% were female (mean age = 26.18 years, SD = 0.39 years). Among the team leaders (N = 79), 43% were female, with the average age of 34.7 years (SD = 5.56), and 95% were married. For the team leaders, 77.2% of the people have a university degree or above, and the average tenure of each supervisor’s position is 8.92 years (SD = 5.13). Among the employees, 82.8% held a college degree or higher, and the average weekly work hours were 44.87 h (SD = 8.23).

The measurement method adopted by this research institute (as described below) was adapted from the English version. The translation process involved the use of the back-translation procedure proposed by Brislin (1986) for the translation of the survey items. All measurement indicators were scored using a five-point Likert scale.

Workaholism. At Time 1, leaders reported their workaholism using the 10-item scale developed by Schaufeli et al. (2009). A sample item is, “It is important to me to work hard even when I do not enjoy what I am doing.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

Emotional exhaustion. At Time 2, employees self-assessed their emotional exhaustion using the 3-item measure from Boswell et al. (2004), this scale was based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach & Jackson, 1986). A sample item is, “I feel burned out from my work.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75.

Family support. At Time 2, the employees used a scale developed by Zimet et al. (1988) which consisted of 4 items to self-assess the level of family support they perceived. A sample item is, “My family really tries to help me.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Work fatigue. At Time 3, employees self-assessed their work fatigue using the 18-item scale from Frone and Tidwell (2015). Sample items include, “Do you feel physically tired after work?”, “Do you feel mentally tired after work?”, and “I feel very depressed after work.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Control variables. Our study has imposed a limit on employees’ weekly working hours that working hours are related to work fatigue (e.g., Yang & Lu, 2023). In addition, we controlled for age, gender, education level, and team size, as prior studies have demonstrated that these variables influence work fatigue (e.g., Chu et al., 2022; Frone et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2024).

All participants provided informed consent. Each participant was assigned a unique identification code to ensure confidentiality. Committee of Yiwu Industrial and Commercial College approved the study (ID: ZP2025-01-002). Permission was granted by the participating organizations. Data were collected through WeChat.

Data analysis

We employed the Mplus 8.4 version and combined the bootstrap sampling method (Cheung et al., 2021) to apply the structural equation model (SEM) to test the proposed hypotheses. Each independent variable was represented by the average score of its associated measurement items (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2011). To assess the hypothesized mediating effect and moderating mediating effect, we conducted 10,000 iterations of Monte Carlo simulation in Mplus software to generate a 95% confidence interval (CI).

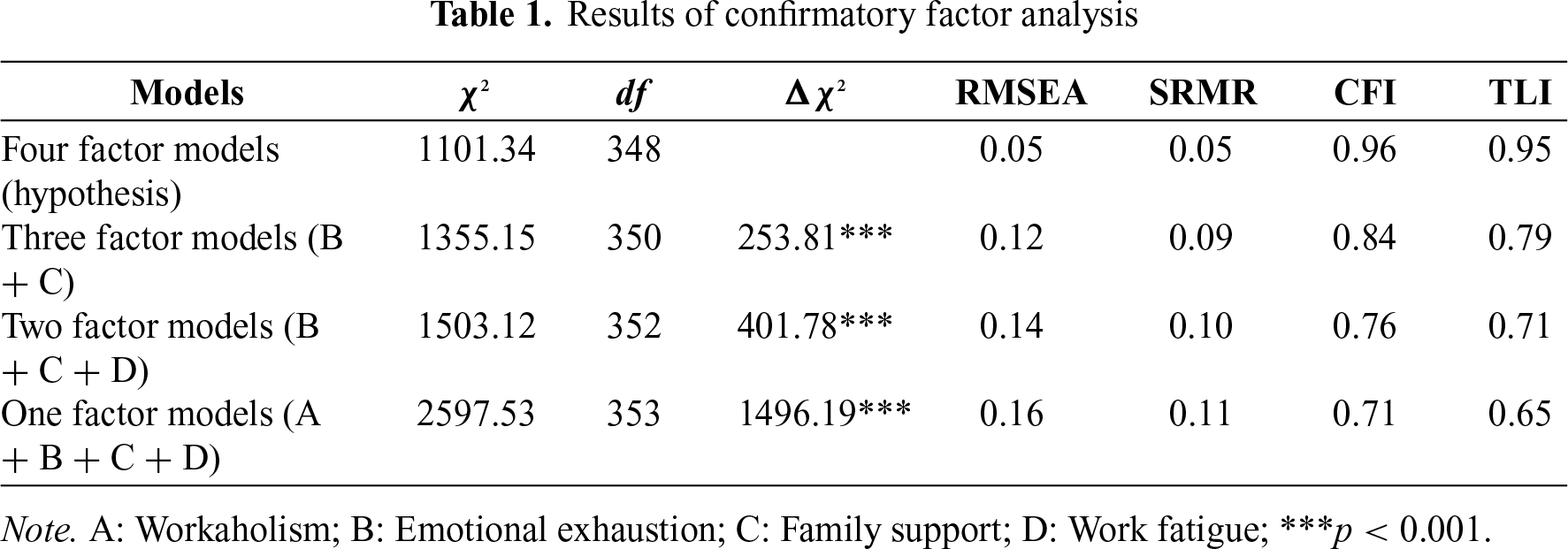

To assess potential multicollinearity bias, we conducted a Harman single-factor test, and the results showed that the variance explained by the first factor was 29.53%, which was below the 40% threshold. Furthermore, as shown in Table 1, the fit indices of the confirmatory factor analysis of the single-factor model did not reach the standard values (χ2 = 2597.53, df = 353, RMSEA = 0.16, SRMR = 0.11, CFI = 0.71, TLI = 0.65). Therefore, the variables in this study do not exhibit significant common method bias.

As Table 1, the proposed four-factor model exhibits excellent fit indices (χ²/df = 3.16, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.05, with all factor loadings exceeding 0.70). Based on these results, we conclude that all study variables are sufficiently distinguishable. These findings validate the chosen model and lay a strong foundation for subsequent analysis.

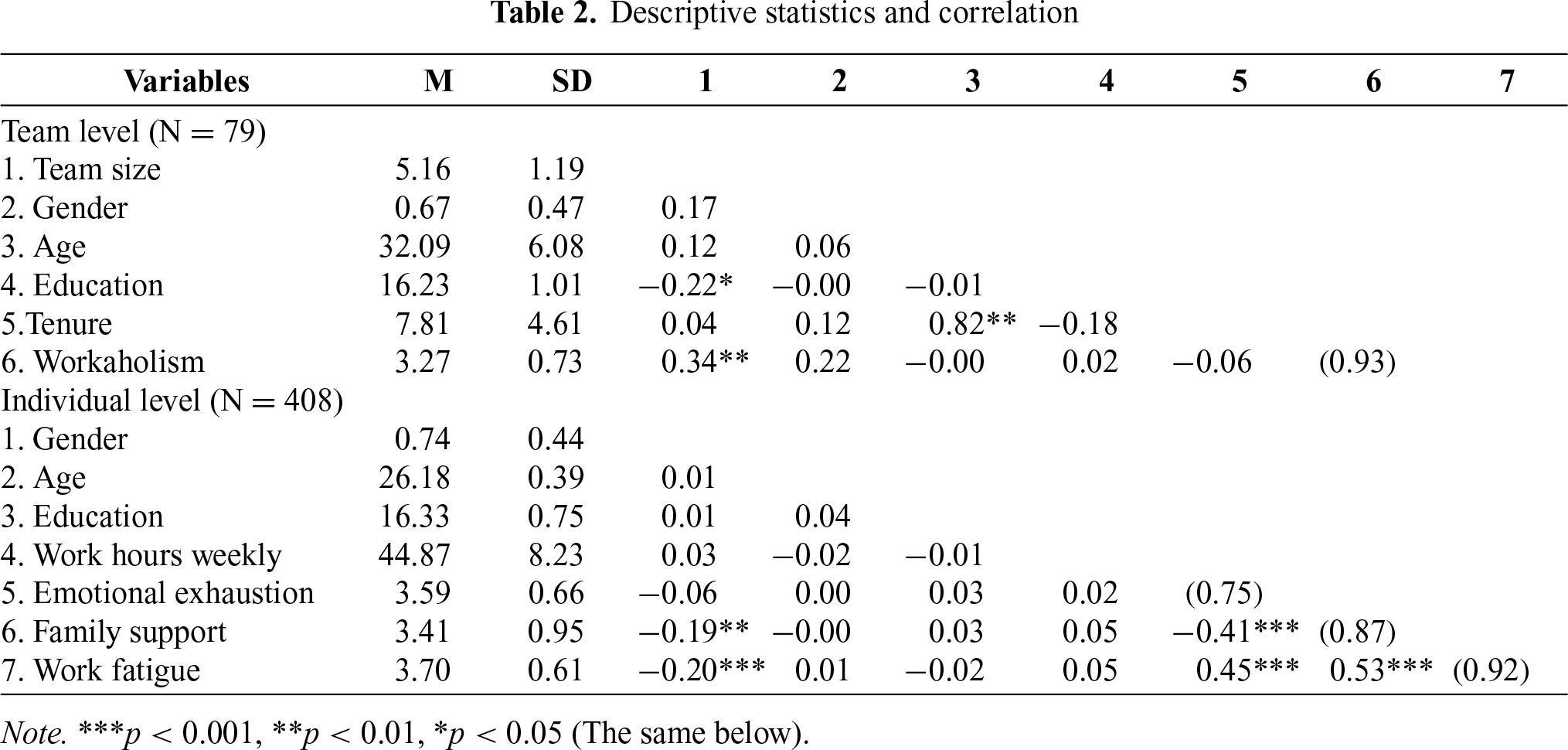

As shown in Table 2, family support is negatively correlated with emotional exhaustion (r = −0.41, p < 0.001), while emotional exhaustion is significantly correlated with work fatigue (r = 0.45, p < 0.001), which is consistent with the hypothesis. Additionally, we used the SEM to test all the hypotheses, and this model was able to simultaneously estimate all the proposed paths.

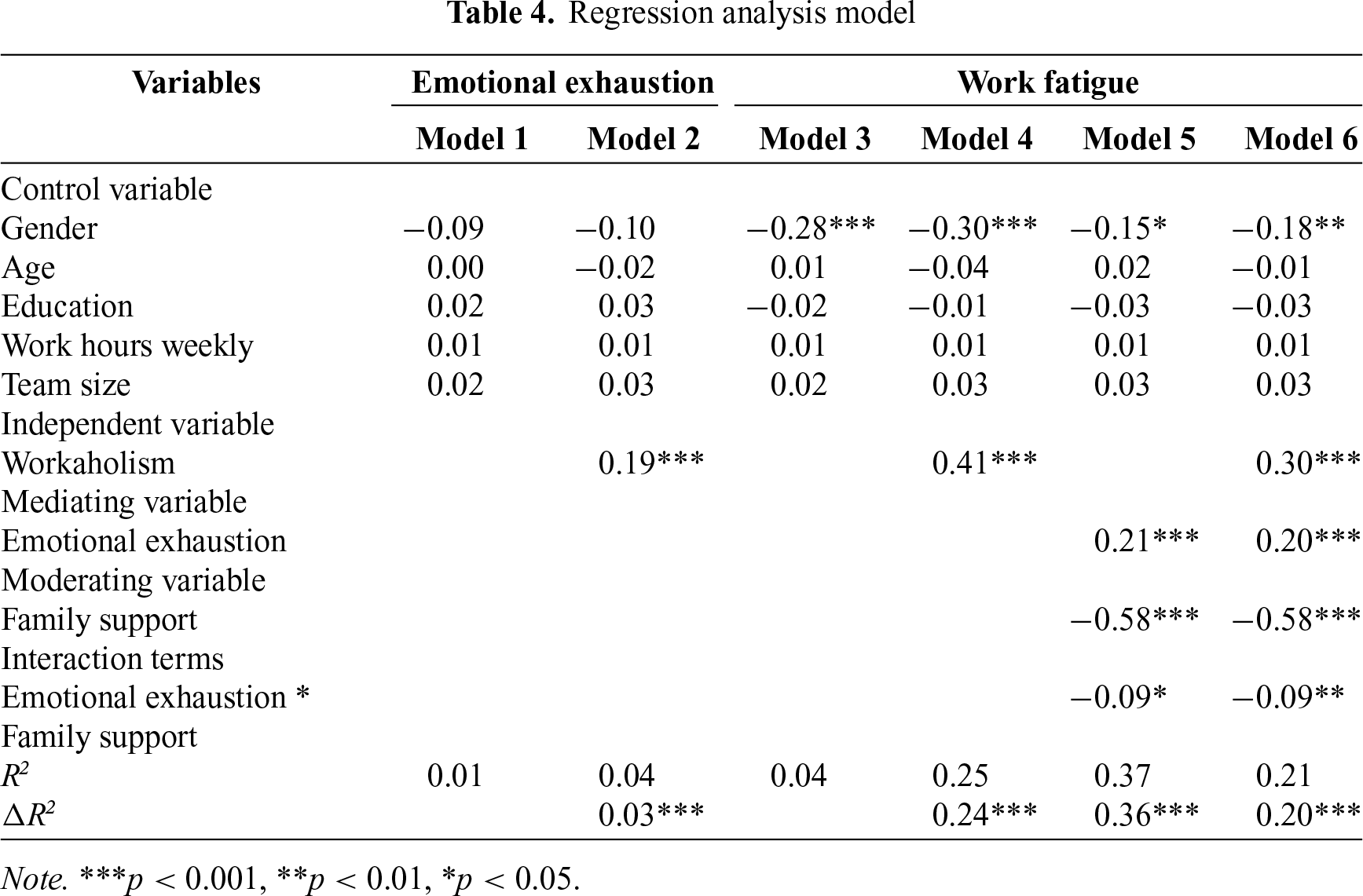

Leader Workaholism effects on employee fatigue. Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate a significant link between the leaders’ workaholism and employee work fatigue (B = 0.30, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval [0.23, 0.37]). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

Figure 2 illustrates a significant correlation between leader workaholism and employee emotional exhaustion (B = 0.19, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval [0.10, 0.29]), as is the relationship between employee emotional exhaustion and work fatigue (B = 0.20, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval [0.14, 0.27]). Furthermore, Tables 3 and 4 present the path from leader workaholism to employee work fatigue via emotional exhaustion (B = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% confidence interval [0.02, 0.07]). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

Figure 2: Model path coefficient diagram of study. Note. The test results are obtained while controlling for the influence of the control variables. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01.

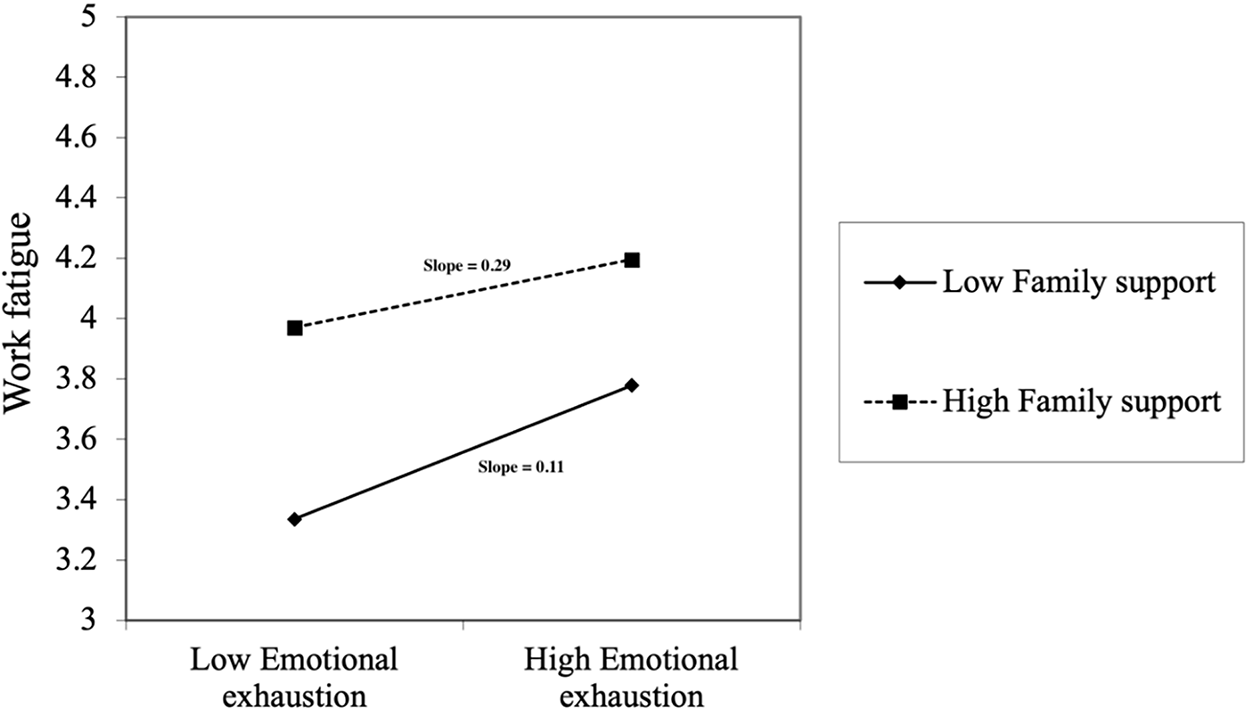

Figure 2 also indicates that family support can moderate the positive relationship between employee emotional exhaustion and work fatigue (B = −0.09, SE = 0.05, p < 0.01). To better illustrate this interaction, we followed the procedure proposed by Aiken and West, 1991 and plotted the interaction graph based on the average level of family support plus or minus one standard deviation (see Figure 3). Additionally, Tables 3 and 4 show that when the level of family support is higher, the positive correlation between emotional exhaustion and job fatigue is weaker than when the level is lower (B = 0.11, SE = 0.05, 95% confidence interval [0.02, 0.21]); while when the level is lower, this positive correlation is stronger (B = 0.29, SE = 0.05, 95% confidence interval [0.20, 0.38]). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Figure 3: Moderating effect of family support

We calculated the indirect mediation effect of emotional exhaustion under different levels of family support. Tables 3 and 4 show that leader workaholism on employee work fatigue via emotional exhaustion is significant at both low and high levels of family support (at low levels, B = 0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% confidence interval [0.02, 0.11]; at high levels, B = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% confidence interval). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

This study indicates that there is a significant positive correlation between leader workaholism and employee work fatigue. This result aligns with Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001), which suggests that individuals strive to protect their limited resources—such as emotional energy—and experience stress and fatigue when these resources are depleted (Park et al., 2014; Sun & Pan, 2008). In the present context, leaders’ workaholic behaviors appear to drain employees’ psychological resources, thereby inducing emotional exhaustion and ultimately contributing to work fatigue.

Furthermore, emotional exhaustion was identified as a mediator in the relationship between leader workaholism and employee work fatigue. Our finding resonates with prior research (e.g., Allen & Finkelstein, 2014; Liu et al., 2015; Li & Peng, 2022) and can be understood from the perspective of the COR theory. Specifically, working under a workaholic leader gradually consumes employees’ emotional and cognitive resources, thereby increasing their susceptibility to fatigue. This mediation mechanism helps to elucidate the underlying process—often referred to as the “black box”—by which leaders’ excessive work engagement impairs employee well-being, as informed by both COR theory and the Social Support Buffering Model (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Hobfoll, 2001).

Additionally, family support was found to buffer the negative effect of emotional exhaustion on work fatigue. Consistent with the social support buffering perspective (Aneshensel & Stone, 1982; Cohen & Wills, 1985), familial support appears to mitigate the translation of emotional exhaustion into work fatigue (Liu et al., 2015). This result highlights the vital role of non-work support systems in enhancing employee resilience (Bardoel et al., 2014; Meacham et al., 2025), illustrating how external resources can alleviate the adverse impacts of workplace stressors.

Implications for research and practice

This research offers practical implications for organizations seeking to proactively prevent workaholism and its negative consequences. First, organizations should cultivate a healthy work culture by promoting the value of balancing work and life, reducing excessive overtime, and implementing flexible working arrangements (Kahn, 1990; Parkes & Langford, 2008). Such initiatives can help establish normative boundaries around work intensity and availability.

Second, for each organization, establishing open communication channels is of utmost importance, as it enables employees can express their concerns regarding workload, stressors, and support needs (Edmondson, 1999). Complementary to this, organizations should integrate soft skill development into training programs to strengthen employees’ resilience and stress management capabilities (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011). Regular check-ins and constructive feedback sessions can help leaders identify challenges faced by team members and provide timely support. Furthermore, systematic monitoring of employee workload and stress levels can assist in detecting potential risks before they escalate (Sonnentag & Frese, 2002).

Third, given that family support can play a role in alleviating emotional exhaustion and work fatigue, organizations are encouraged to develop initiatives that foster family involvement in the work environment. Examples include organizing family days, offering workshops to help families understand common workplace stressors (Hammer et al., 2011), and providing resources to help employees strengthen their family support systems (Allen, 2001; Fox et al., 2022; Odle-Dusseau et al., 2016).

Limitations and future research directions

Our research has several limitations that warrant attention in future research. First, although the three-wave time-lagged design strengthens temporal inference, it does not establish definitive causality among workaholism, emotional exhaustion, family support, and work fatigue. While path analysis provides valuable insights into these relationships, future studies could employ experimental approaches—such as randomized controlled trials—or adopt longer-term longitudinal designs (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Lu et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the universality of the research results may be limited by the characteristics of the sample, including a high proportion of female participants (74%) and a relatively narrow age distribution (SD = 0.39). Future research should attempt to replicate these results in more diverse and representative samples in order to enhance their external validity.

Second, although this study explains the mediator emotional exhaustion based on the Conservation of Resources theory and the Social Support Buffering Model (Aneshensel & Stone, 1982; Hobfoll, 1989, 2001), other theoretical frameworks may offer complementary insights. For example, incorporating the Job Demands-Resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Bakker et al., 2023) could further the specific mechanism by which leader workaholism affect employee fatigue.

Finally, the use of self-reporting measurement methods may introduce common method bias (Cooper et al., 2020; Podsakoff et al., 2024). To improve methodological rigor, future studies are recommended to incorporate multiple sources of data—such as supervisor evaluations or objective indicators of work behavior and fatigue.

This study proposed a moderated mediation model to provide an understanding of leader workaholism and employee work fatigue, with emotional exhaustion serving as a mediator and family support as a moderator. Our results indicate that leader workaholism significantly contributes to employee work fatigue, with emotional exhaustion playing a key mediating role. Moreover, family support functions as a buffer that mitigates the adverse effects of emotional exhaustion and weakens the association between leader workaholism and employee fatigue. A major strength of our research lies in its focus on the detrimental consequences of workaholic leader, including increased emotional exhaustion and fatigue among employees. Our findings underscore the urgent need for organizations to recognize and address leader workaholism, offering valuable insights for developing interventions that foster healthier and more sustainable work environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research has been supported by the Zhejiang Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences (26NDJC089YBM).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization and study design: Wenjie Qiu; data collection: Zheng Zhang; data analysis: Jiyuan Wang; draft preparation: Wenjie Qiu; review and editing: Jiyuan Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Zheng Zhang, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved and supervised by the Research Ethics Committee of Yiwu Industrial and Commercial College (ID: ZP2025-01-002). All participants provided informed consent before participation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

Allen, T. D. (2001). Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(3), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1774 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Allen, T. D., & Finkelstein, L. M. (2014). Work-family conflict among members of full-time dual-earner couples: An examination of family life stage, gender, and age. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(3), 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Andersen, F. B., Djugum, M. E. T., Sjåstad, V. S., & Pallesen, S. (2023). The prevalence of workaholism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1252373. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1252373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Aneshensel, C. S., & Stone, J. D. (1982). Stress and depression: A test of the buffering model of social support. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39(12), 1392–1396. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290120028005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Atkin, A. L., Christophe, N. K., Yoo, H. C., Gabriel, A. K., Wu, C. S., & et al. (2022). The development and validation of the familial support of multiracial experiences scale. The Counseling Psychologist, 50(1), 40–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/00110000211046354 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands-resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-053933 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Balducci, C., Spagnoli, P., Avanzi, L., & Clark, M. (2021). A daily diary investigation on the job-related affective experiences fueled by work addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(4), 967–977. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bardoel, E. A., Pettit, T. M., De Cieri, H., & McMillan, L. (2014). Employee resilience: An emerging challenge for HRM. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 52(3), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12033 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Boswell, W. R., Olson-Buchanan, J. B., & LePine, M. A. (2004). Relations between stress and work outcomes: The role of felt challenge, job control, and psychological strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-8791(03)00049-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner & J. W. Berry (Eds.Field methods in cross-cultural research, (pp. 137–164). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

Chang, P. C., Gao, X., Wu, T., & Lin, Y. Y. (2023). Workaholism and work-family conflict: A moderated mediation model of psychological detachment from work and family-supportive supervisor behavior. Chinese Management Studies, 17(4), 770–786. https://doi.org/10.1108/cms-09-2021-0380 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, X., Masukujjaman, M., Al Mamun, A., Gao, J., & Makhbul, Z. K. M. (2023). Modeling the significance of work culture on burnout, satisfaction, and psychological distress among the Gen-Z workforce in an emerging country. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02371-w [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2021). Testing moderation in business and psychological studies with latent moderated structural equations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36, 1009–1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09717-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chu, X., Zhang, L., & Li, M. (2022). Humble leadership and work fatigue: The roles of self-efficacy and perceived team autonomy-support. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(4), 340–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2022.2031623 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Clark, M. A., Michel, J. S., Zhdanova, L., Pui, S. Y., & Baltes, B. B. (2016). All work and no play? A meta-analytic examination of the correlates and outcomes of workaholism. Journal of Management, 42(7), 1836–1873. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063145223 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Clark, M. A., Smith, R. W., & Haynes, N. J. (2020). The multidimensional workaholism scale: Linking the conceptualization and measurement of workaholism. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1281–1307. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 558–577. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.112.4.558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cooper, B., Eva, N., Fazlelahi, F. Z., Newman, A., Lee, A. et al. (2020). Addressing common method variance and endogeneity in vocational behavior research: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dong, M., Zhang, T., Li, Y., & Ren, Z. (2022). The effect of work connectivity behavior after-hours on employee psychological distress: The role of leader workaholism and work-to-family conflict. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 722679. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.722679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fox, K. E., Johnson, S. T., Berkman, L. F., Sianoja, M., Soh, Y., & et al. (2022). Organisational-and group-level workplace interventions and their effect on multiple domains of worker well-being: A systematic review. Work & Stress, 36(1), 30–59. [Google Scholar]

Frone, M. R., Reis, D., & Ottenstein, C. (2018). A German version of the three-dimensional work fatigue inventory (3 D-WFIFactor structure, internal consistency, and correlates. Stress and Health, 34(5), 674–680. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Frone, M. R., & Tidwell, M. C. O. (2015). The meaning and measurement of work fatigue: Development and evaluation of the three-dimensional work fatigue inventory (3D-WFI). Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ganster, D. C., Fusilier, M. R., & Mayes, B. T. (1986). Role of social support in the experience of stress at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.1.102 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Family, work, work-family spillover, and problem drinking during midlife. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(2), 336–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00336.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Anger, W. K., Bodner, T., & Zimmerman, K. L. (2011). Clarifying work-family intervention processes: The roles of work-family conflict and family-supportive supervisor behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual review of organizational psychology and organizational behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Holahan, C. J., & Moos, R. H. (1985). Life stress and health: Personality, coping, and family support in stress resistance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(3), 739–747. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.3.739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Huyghebaert, T., Fouquereau, E., Lahiani, F. J., Beltou, N., Gimenes, G., & et al. (2018). Examining the longitudinal effects of workload on ill-being through each dimension of workaholism. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(2), 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000055 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Janssen, O., Lam, C. K., & Huang, X. U. (2010). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The moderating roles of distributive justice and positive affect. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(6), 787–809. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.614 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Beck, T. E., & Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 21(3), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.07.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, X., & Peng, P. (2022). How does inclusive leadership curb workers’ emotional exhaustion? The mediation of caring ethical climate and psychological safety. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 877725. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.877725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Liu, Y., Wang, M., Chang, C. H., Shi, J., Zhou, L., & et al. (2015). Work-family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and displaced aggression toward others: The moderating roles of workplace interpersonal conflict and perceived managerial family support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lu, L., Megahed, F. M., & Cavuoto, L. A. (2021). Interventions to mitigate fatigue induced by physical work: A systematic review of research quality and levels of evidence for intervention efficacy. Human Factors, 63(1), 151–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720819876141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1986). The Maslach Burnout Inventory. Palo Alto, CA, USA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

Meacham, H., Holland, P., Pariona-Cabrera, P., Kang, H., Tham, T. L., & et al. (2025). The role of family support on the effects of paramedic role overload on resilience, intention to leave and promotive voice. Personnel Review, 54(1), 236–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-08-2023-0685 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mullens, F., & Glorieux, I. (2024). Dreams versus reality: Wishes, expectations and perceived reality for the use of extra non-work time in a 30-hour work week experiment. Community, Work & Family, 27(2), 225–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2022.2092452 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ng, T. W., Sorensen, K. L., & Feldman, D. C. (2007). Dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of workaholism: A conceptual integration and extension. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28(1), 111–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.424 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Odle-Dusseau, H. N., Hammer, L. B., Crain, T. L., & Bodner, T. E. (2016). The influence of family-supportive supervisor training on employee job performance and attitudes: An organizational work-family intervention. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(3), 296–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Park, H. I., O’Rourke, E., & O’Brien, K. E. (2014). Extending conservation of resources theory: The interaction between emotional labor and interpersonal influence. International Journal of Stress Management, 21(4), 384–405. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038109 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Parkes, L. P., & Langford, P. H. (2008). Work-life balance or work-life alignment? A test of the importance of work-life balance for employee engagement and intention to stay in organisations. Journal of Management & Organization, 14(3), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.837.14.3.267 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pluut, H., Ilies, R., Curşeu, P. L., & Liu, Y. (2018). Social support at work and at home: Dual-buffering effects in the work-family conflict process. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 146, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.02.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11(1), 17–61. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-110721-040030 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2011). Introduction to Psychometric Theory. New York, NY, USA: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Roberts, K. (2007). Work-life balance—The sources of the contemporary problem and the probable outcomes: A review and interpretation of the evidence. Employee Relations, 29(4), 334–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450710759181 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., & Taris, T. W. (2009). Being driven to work excessively hard: The evaluation of a two-factor measure of workaholism in the Netherlands and Japan. Cross-Cultural Research, 43(4), 320–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397109337239 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Applied Psychology, 57(2), 173–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00285.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

She, Z., Ma, L., Li, Q., & Jiang, P. (2024). Help or hindrance? The effects of leader workaholism on employee creativity. Journal of Business Research, 182, 114767. [Google Scholar]

Sonnentag, S., & Frese, M. (2002). Performance concepts and performance theory. Psychological Management of Individual Performance, 23(1), 3–25. [Google Scholar]

Spagnoli, P., Molino, M., Molinaro, D., Giancaspro, M. L., Manuti, A., & et al. (2020). Workaholism and technostress during the COVID-19 emergency: The crucial role of the leaders on remote working. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 620310. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.620310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Spence, J. T., & Robbins, A. S. (1992). Workaholism: Definition, measurement, and preliminary results. Journal of Personality Assessment, 58(1), 160–178. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5801_15 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Suleiman, A. O., Decker, R. E., Garza, J. L., Laguerre, R. A., Dugan, A. G., & et al. (2021). Worker perspectives on the impact of non-standard workdays on worker and family well-being: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12265-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sun, L. Y., & Pan, W. (2008). HR practices perceptions, emotional exhaustion, and work outcomes: A conservation-of-resources theory in the Chinese context. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1225 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, B., Wang, Z., Zhang, W., Sheng, Z., Zhang, L., & et al. (2025). Time after time: The influence of perceived coworker overtime, affect and workaholism on daily withdrawal responses. Applied Psychology, 74(1), e12580. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12580 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, F., Wu, M., Ding, H., & Wang, L. (2024). How and why strengths-based leadership relates to nurses’ turnover intention: The roles of job crafting and work fatigue. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 45(4), 702–718. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-03-2023-0143 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wright, T. A., & Cropanzano, R. (1998). Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(3), 486–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Yang, Y. J., & Lu, L. (2023). Influence mechanism and impacting boundary of workplace isolation on the employee’s negative behaviors. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1077739. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1077739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zapata, L., Ibarra, G., & Blancher, P. H. (2024). Engaging new ways of work: The relevance of flexibility and digital tools in a post-COVID-19 era. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 11(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/joepp-04-2022-0079 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zeng, Q., & Liu, X. (2022). How workaholic leadership affects employee self-presentation: The role of workplace anxiety and segmentation supplies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 889270. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.889270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools