Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

National Common Language Proficiency (NCLP) and social adaptation among high school students: The chain mediating role of prosocial tendency and language communication strategies

1 Research Center for the Development of Education for Northwest Minorities, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

2 School of Marxism, Lanzhou Jiaotong University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

3 School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

* Corresponding Author: Baobao Dang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 749-759. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.071932

Received 15 August 2025; Accepted 20 November 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between NCLP and social adaptation among high school students, as mediated by prosocial tendency and language communication strategies. The sample comprised 547 Tibetan high school students aged 15–18 years (female = 69.5%, mean age = 16.67 years, SD = 0.95) from the Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, China. They completed questionnaires surveys on NCLP, social adaptation, prosocial tendency, and language communication strategies. The mediation analysis results indicated that NCLP significantly predicted social adaptation. Prosocial tendency and language communication strategies independently and significantly mediated the relationship between NCLP and social adaptation. Prosocial tendency and language communication strategies played a chain-mediating role between NCLP and social adaptation. Moreover, no significant gender differences were found in this mediating mechanism. These findings align with Language Socialization Theory, indicating that NCLP shows significant associations with the development of prosocial tendencies and the selection of language communication strategies, which in turn are linked to social adaptation.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileAcross the globe, actively adapting to mainstream society and achieving effective integration has become a crucial foundation for ethnic minority groups to safeguard their rights, promote cultural exchange and achieve social mobility. Effective social integration enables minority group members to overcome structural barriers and transform their ethnic cultural capital into human capital recognized by the wider society, thereby gaining fairer access to development opportunities (Pikulytska, 2022). At the same time, their integration into mainstream society enriches sociocultural diversity, fosters mutual understanding and empathy among different groups, and contributes to more stable and harmonious social development (Ergashev & Farxodjonova, 2020).

However, in reality, many ethnic minority members remain disadvantaged in accessing education, pursuing career development, and engaging in cross-cultural interactions, making it difficult to achieve genuine social adaptation (Mirza & Warwick, 2024). For example, the Tibetan ethnic group in China faces numerous challenges in adapting to modern society due to differences in language, culture and living environments. To achieve genuine integration into mainstream society and successfully adapt, the national common language plays an irreplaceable role. Not only does it serve as a tool for conveying information, it is also a crucial medium for accessing employment opportunities, acquiring modern scientific and cultural knowledge, and achieving social adaptation (Fox et al., 2019). The term ‘national common language’ usually refers to a language that is legally established in a multi-ethnic nation as the shared means of communication for all ethnic groups nationwide (Kamusella, 2018). Examples include Mandarin Chinese in China, English in the United States, and Russian in Russia.

Tibetan high school students study both Tibetan and the national common language simultaneously (Zhang et al., 2024). The systematic differences in phonology, grammar and pragmatic rules between the two languages often leave them with inadequate proficiency in acquiring and applying the national common language (Zhang, 2021). This limits their social competitiveness and undermines their adaptability in education, career development, and social participation. Therefore, conducting an in-depth analysis of the underlying mechanisms by which NCLP influences social adaptation holds significant theoretical value and practical implications for understanding the social integration process of ethnic minority groups.

Social adaptation refers to the process by which individuals interact with their social environment, achieving equilibrium between themselves and their surroundings through self-adjustment or environmental modification (Liu et al., 2022; Walker et al., 2004). Language Socialization Theory(LST) conceptualizes language, culture, and social behavior as an integrated continuum, with language learning and social adaptation occurring in tandem. Social and cultural elements embedded in language—such as values, culture, and ideology—are internalized during language acquisition, thereby shaping social behavior (Schieffelin & Ochs, 1986; Ou & Gu, 2021). Some research indicates that NCLP is often a prerequisite for effective social adaptation in multi-ethnic societies (Lou, 2021; Taguchi, 2015). Wilczewski and Alon (2023) conducted a literature review on the social adaptation of international students and found that second-language proficiency positively predicts adaptation to mainstream society, the higher second language proficiency correlates with the better social adaptation. Conversely, individuals with poor second language proficiency are more likely to be ignored or excluded by peers, potentially leading to challenges in educational participation and career development, resulting in significantly reduced social adaptation (Khanal & Gaulee, 2019). However, Tibetan high school students are immersed in a predominantly Tibetan-language home environment for extended periods. Their school education relies on the national common language. Frequently navigating these disparate language contexts, they often find it difficult to communicate fluently with members of other ethnic groups (Zhang, 2021), which can lead to challenges in social adaptation. In this process, in addition to the fundamental role of language, the internal psychological mechanisms and external behaviors of ethnic minorities also play significant roles. Specifically, whether they can actively engage in social interactions to cultivate prosocial tendencies and effectively employ diverse language communication strategies may serve as a crucial pathway for overcoming language barriers and achieving successful social adaptation.

The mediating role of prosocial tendency

Prosocial tendency refers to an individual’s inclination to engage in behaviors that benefit others or society in interpersonal interactions, thereby facilitating adaptation to social environments and alignment with societal expectations (Laguna et al., 2022). A study of Spanish adolescents found that they enhanced their acceptance by peers through positive prosocial tendency and behaviors, which in turn provided emotional support for smooth group adaptation (Schoeps et al., 2020). Similarly, a survey of adolescents in Yunnan Province, China, revealed that prosocial tendency positively predicts their social adaptation and contribute to the development of peer relationships (Lin et al., 2006). These findings suggest a close link between prosocial tendency and social adaptation. LST emphasizes that in the process of language communication, people not only establish social relationships but also develop emotional attachments to others and society, prompting them to exhibit more prosocial tendencies and behaviors, thereby helping individuals integrate into the group and achieve the goal of social adaptation (Hu et al., 2021). As the shared medium of communication among ethnic minorities, the national common language can impact prosocial tendency toward community members. This prosocial tendency, constructed based on the common language, holds significant implications for individuals’ social adaptation (Meier & Smala, 2021). Therefore, prosocial tendencies may function as a mediating factor between NCLP and social adaptation.

The mediating role of language communication strategies

Language communication strategies are deliberate plans or techniques used by language users to achieve communicative goals when encountering difficulties (such as insufficient language knowledge or communication barriers (Faerch & Kasper, 1983)). Research shows that learners with lower language proficiency tend to adopt avoidance or non-language strategies due to a lack of language confidence. In contrast, those with higher proficiency are more likely to use achievement-oriented strategies, such as target language and cooperative strategies, to improve communication effectiveness (Yang et al., 2022). When communicating, individuals often employ appropriate language communication strategies to convey information, enhance their participation in interactions, and achieve social adaptation (Dobao, 2002). According to cross-cultural adaptation theory, mastering the target language or utilising target language strategies helps language learners to establish supportive social relationships, thereby promoting intercultural communication and sociocultural adaptation. Using language communication strategies can also make interactions smoother, reduce communication anxiety and pressure, boost confidence in language use and foster a sense of belonging in new social environments, thereby influencing social adaptation (Ahmad et al., 2022; Alshammari et al., 2023). Evidently, for language learners, choosing appropriate communicative strategies facilitates better social adaptation (Zhang, 2021). Therefore, language communication strategies may function as a mediating factor between NCLP and social adaptation.

Chain mediation effect of prosocial tendency and language communication strategies

Based on the communicative adaptation theory proposed by American psychologist Giles and Beebe (1984), linguistic communication is essentially a dynamic process of adjustment. In this process, NCLP forms the foundation for individuals to engage in effective social interaction. Higher language competence provides the necessary tools for cross-cultural communication, bolsters individuals’ communicative confidence, and thereby increases their willingness to initiate and sustain social interactions. Research suggests that when individuals can fluently use the national common language, their anxiety in cross-group interactions is significantly reduced. This positive emotional experience serves as a crucial psychological foundation for stimulating prosocial tendencies (Thielmann & Pfattheicher, 2022). Conversely, insufficient language proficiency tends to induce feelings of frustration and withdrawal in social settings, thereby inhibiting the expression of prosocial tendencies. Building upon the foundation of language proficiency, prosocial tendency serves as a key intrinsic motivator that significantly influences an individual’s choice of language strategies. Individuals with higher prosocial tendency often exhibit stronger empathy and a greater desire for social connection. In interactions, they proactively employ positive language strategies to achieve communicative goals and promote group integration (Fu et al., 2022; Saleem et al., 2021). Empirical research further indicates that such individuals can more accurately discern others’ communicative intentions and emotional states (Pang et al., 2022). They also flexibly adapt language strategies according to different interlocutors, contexts, and situations to maintain effective communication and build positive social relationships (Laguna et al., 2020), thereby creating favorable conditions for ultimately achieving social adaptation. Thus, prosocial tendency and language communication strategies may serve as chain mediators between NCLP and social adaptation.

The Language Socialization Theory (LST) proposed by American linguists Schieffelin and Ochs (1986) posits that language learning is not merely the acquisition of language skills but also a process of individual socialization. The theory encompasses two interrelated mechanisms. Firstly, socialization achieved through language—as a vehicle for culture, language enables individuals to internalize its embedded social norms and values during acquisition, thereby helping them to understand and adhere to societal rules. Second, language practice through socialization, wherein individuals must learn context-appropriate speech acts to effectively engage in social interactions and establish social connections. This process, in turn, further develops their language abilities (Wang, 2023). Within the context of China’s multi-ethnic nation-state, this theory holds significant explanatory value. For minority group members, learning the national common language enables them to integrate into broader societal communities, internalize shared values and behavioral norms, and develop more inclusive group identities. thereby impacting their adaptation to the mainstream social environment (Ou & Gu, 2021).

According to the latest census data from China, the Tibetan population on the mainland has reached 7.0607 million, making Tibetans one of the country’s largest ethnic minorities (Zhang et al., 2024). Tibetan students learn both Tibetan and the national common language, creating a unique bilingual learning environment. In this context, whether NCLP affects the social adaptation of Tibetan high school students remains an issue that urgently requires exploration. Existing research on NCLP in China has largely focused on language planning and proficiency status, with no studies examining its impact on high school students’ social adaptation. Furthermore, prior work has not explored the mediating roles of prosocial tendency and language communication strategies in the relationship between NCLP and social adaptation, which is precisely the breakthrough point of this study.

This study adopts a language socialization theory perspective to explore the impact of high school students’ NCLP on social adaptation, and to analyze the mediating role of prosocial tendencies and language communication strategies. To achieve our aim, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: NCLP predicts higher social adaptation.

H2: Prosocial tendencies mediate the relationship between NCLP and social adaption for higher social adaptation.

H3: Language communication strategies mediate the relationship between NCLP and social adaptation for higher social adaptation.

H4: Prosocial tendencies and language communication strategies play a chain mediating role between NCLP and social adaptation.

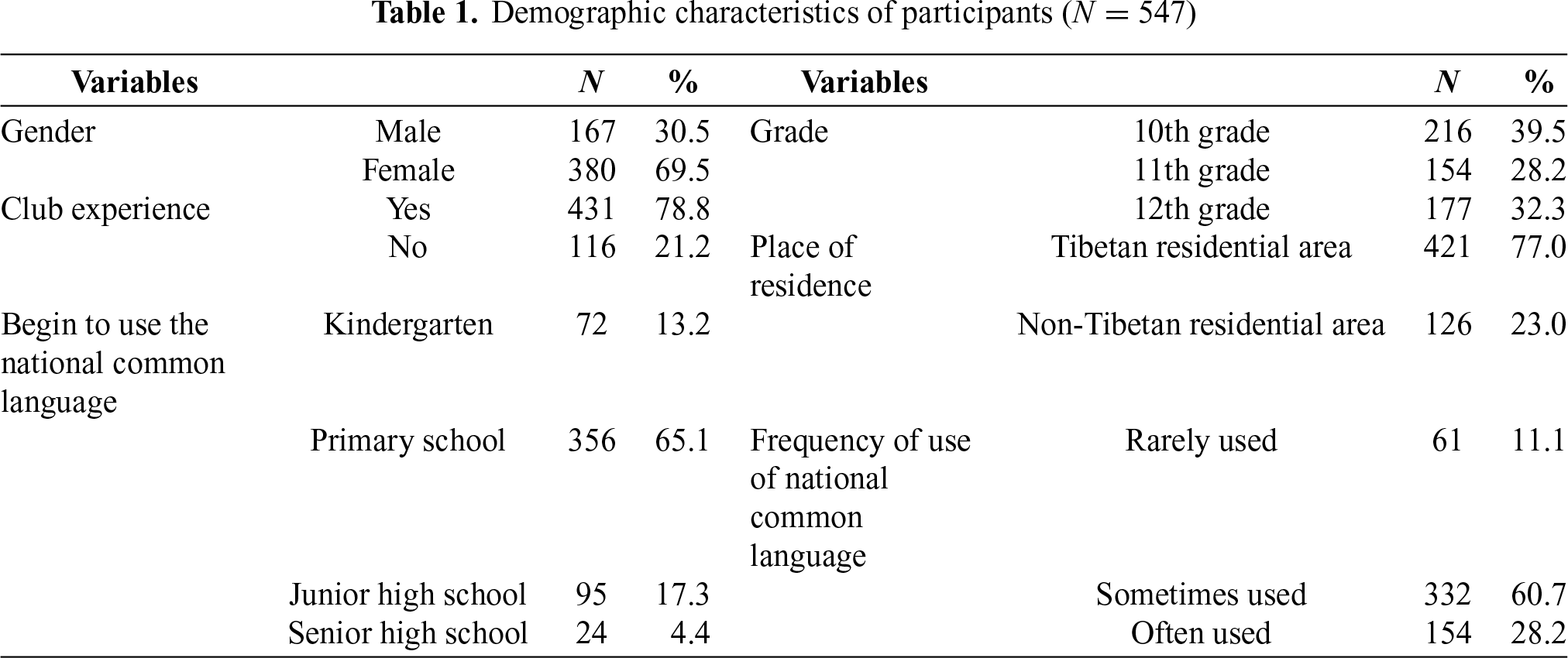

This study employed a convenience sampling method to recruit participants from a representative public high school in the Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Northwest China. The school’s multicultural environment authentically reflects the typical social context of Tibetan communities in the region, thereby providing a representative setting for investigating social adaptation processes among Tibetan students. The sample consisted of Tibetan high school students aged 15 to 18 (M = 16.67, SD = 0.95). Of the 640 questionnaires distributed, 547 valid responses were returned, yielding an effective response rate of 85.5%. The final sample included 167 males (30.5%) and 380 females (69.5%), with grade distribution as follows: 216 (39.5%) in 10th grade, 154 (28.2%) in 11th grade, and 177 (32.3%) in 12th grade. Detailed demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Data were collected using the following scales. All scales employed a 5-point Likert format (ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”), and were piloted prior to formal administration.

The NCLP scale (Ayshamu, 2020) was adapted for high school students through review by two experts, evaluation by two local teachers from the participating school, and a pilot study (N = 80), which confirmed its suitability for this population. The final version consists of 18 items across four dimensions: listening comprehension ability (3 items; e.g., “I can understand humor expressed in the National Common Language”), oral expression ability (3 items; e.g., “I feel nervous or anxious when answering questions in the National Common Language during class”), written expression ability (7 items; e.g., “I can write well-structured essays using a rich vocabulary in the National Common Language”), and self-evaluation (5 items; e.g., “I believe my proficiency in the National Common Language influences my daily communication”). In this study, scores from the NCLP scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. Confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the scale had good structural validity (

The 30-item Adolescent Social Adaptation Scale (ASDS; Liu et al., 2022), consisting of five dimensions: perception (7 items; e.g., “I am aware of my true inner feelings”), tolerance (4 items; e.g., “I work harder when facing pressure”), coping ability (7 items; e.g., “I try to identify possible ways to improve unfavorable situations”), resilience (5 items; e.g., “I can find someone to talk to when I’m upset”), and reflexivity (7 items; e.g., “I reflect on my ways of dealing with problems”). In this study, the ASDS scores yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90. The scale’s structural validity was indicated as good by confirmatory factor analysis (

The 26-item Prosocial Tendency Scale (PTS; Kou et al., 2007) was employed, comprising six dimensions: openness (4 items; e.g., “I will try my best to help others when someone is present”), anonymity (5 items; e.g., “I prefer to donate anonymously”), altruism (4 items; e.g., “I don’t donate money or goods to benefit from it”), compliance (5 items; e.g., “I rarely refuse when others ask me for help”), emotional (5 items; e.g., “I often help others when they are feeling upset”), and urgency (3 items; e.g., “I tend to help those who are seriously injured or ill”). In this study, the scale demonstrated good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89. Confirmatory factor analysis supported its construct validity (

Language communication strategies scale

The revised version of the Language Communication Strategies Scale (LCSS), developed by Li (2016) and Faerch & Kasper (1983), comprises 20 items. This scale includes six dimensions: reduction strategies (4 items; e.g., “During conversations, I abandon difficult topics and shift to simpler ones”), cooperation strategies (2 items; e.g., “When I don’t understand what someone is saying, I ask them to repeat it”), native language strategies (3 items; e.g., “If I don’t know how to say something in the National Common Language, I use my native language instead”), target language strategies (5 items; e.g., “When others don’t understand what I say in the National Common Language, I rephrase it to help them understand”), nonverbal strategies (3 items; e.g., “I use gestures or facial expressions to convey my meaning”), and retrieval strategies (3 items; e.g., “When conversing in the National Common Language, I use contextual cues to guess what the speaker intends to express”). In this study, the LCSS scores achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81, and the structural validity indicators are good (

This Ethics Committee of Northwest Normal University approved the study (ERB No. 2023093) in June 2024. The student’s parents or guardians provided study consent and the students provided study assent. The students completed the surveys during normal school hours. The entire test process lasted about 20 min.

This study utilized IBM SPSS version 28.0 for correlation analysis and regression analysis, and employed Mplus 8.3 to examine the mediating effects of prosocial tendencies (M1) and language communication strategies (M2) between NCLP (X) and social adaptation (Y). The significance of the mediation effect was tested using the bootstrap method, with a 95% confidence interval; if the interval did not contain 0, it indicated a statistically significant mediation effect (Erceg-Hurn & Mirosevich, 2008). The result of Harman’s one-factor test on the sample data showed that the variance explained by the first common factor was 30.16%, which is below the threshold of 40% (Podsakoff et al., 2003), suggesting that there is no common method bias in the study.

Descriptive and correlation statistics

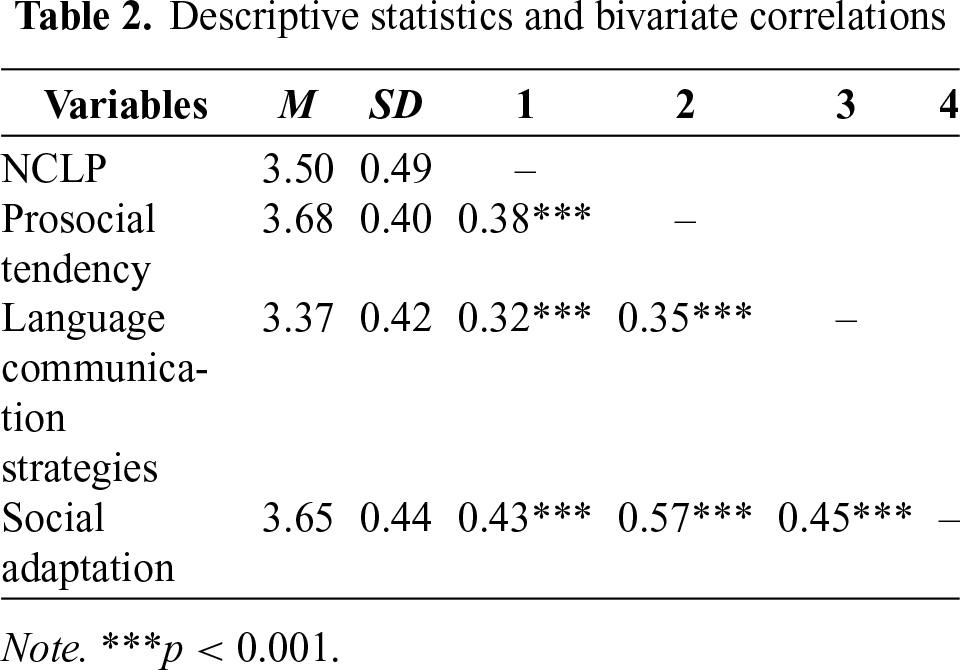

Table 2 presents the results of the descriptive analysis and correlation analysis of NCLP, prosocial tendency, language communication strategies, and social adaptation. As shown in the table, the mean scores for high school students’ NCLP (M = 3.50, SD = 0.49), prosocial tendency (M = 3.68, SD = 0.40), language communication strategies (M = 3.37, SD = 0.42), and social adaptation (M = 3.65, SD = 0.44) are all higher than the median of 3. Pearson correlation results indicate that NCLP is significantly positively correlated with prosocial tendency (r = 0.38, p < 0.001), language communication strategies (r = 0.32, p < 0.001), and social adaptation (r = 0.43, p < 0.001); Secondly, prosocial tendency were significantly positively correlated with language communication strategies (r = 0.35, p < 0.001) and social adaptation (r = 0.57, p < 0.001); Additionally, language communication strategies were also significantly positively correlated with social adaptation (r = 0.45, p < 0.001).

Predictive role of NCLP in social adaptation

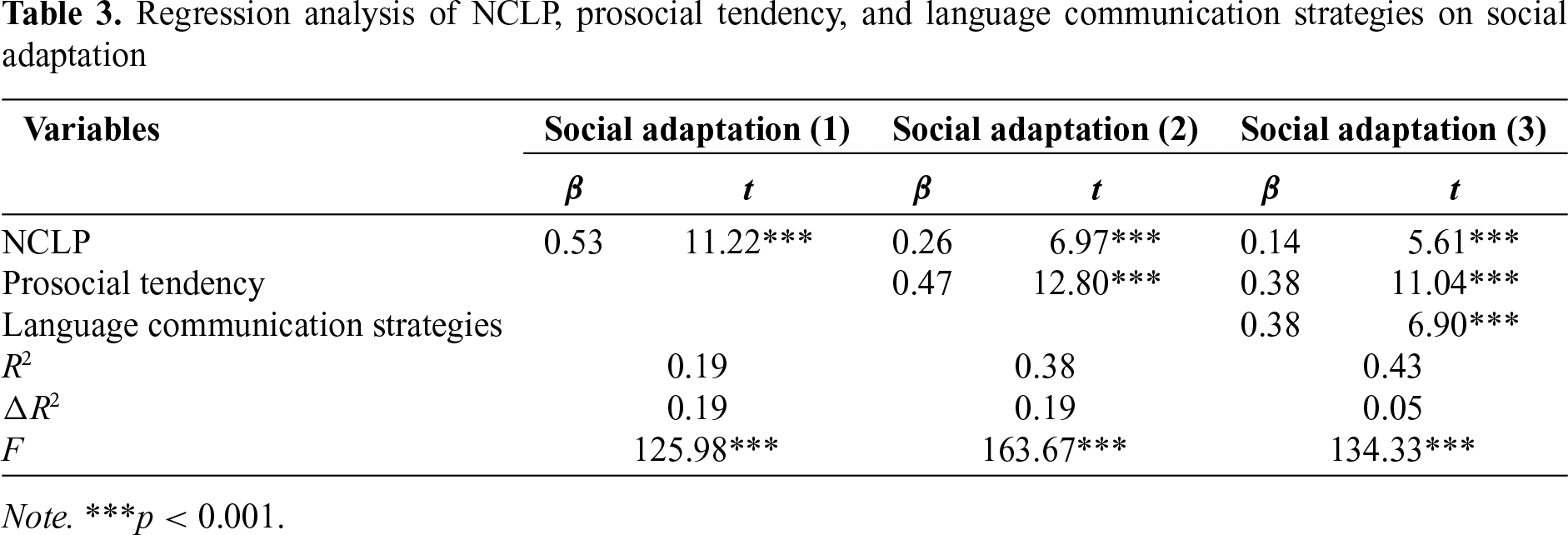

Through stepwise regression analysis, we analyze the predictive effects of NCLP, prosocial tendency, and language communication strategies on social adaptation, with results shown in Table 3. In Social Adaption (1), NCLP was entered as the sole predictor and significantly and positively predicted social adaptation (β = 0.53, p < 0.001), with an explanatory power of 19%. In Social Adaption (2), both NCLP and prosocial tendency were added as predictors. NCLP (β = 0.26, p < 0.001) and prosocial tendency (β = 0.47, p < 0.001) both significantly predicted social adaptation, with a combined explanatory power of 38%, of which prosocial tendency contributed an additional 19% (p < 0.001). In Social Adaption (3), language communication strategies were also added to the regression model. The results showed that NCLP (β = 0.14, p < 0.001), prosocial tendency (β = 0.38, p < 0.001), and language communication strategies (β = 0.38, p < 0.001) all remained significant positive predictors, with the model explaining 43% of the variance; language communication strategies contributed an additional 5% (p < 0.001). The results of the regression analysis indicate that NCLP to predict social adaptation through the indirect effects of prosocial tendency and language communication strategies.

NCLP effects on social adaptation

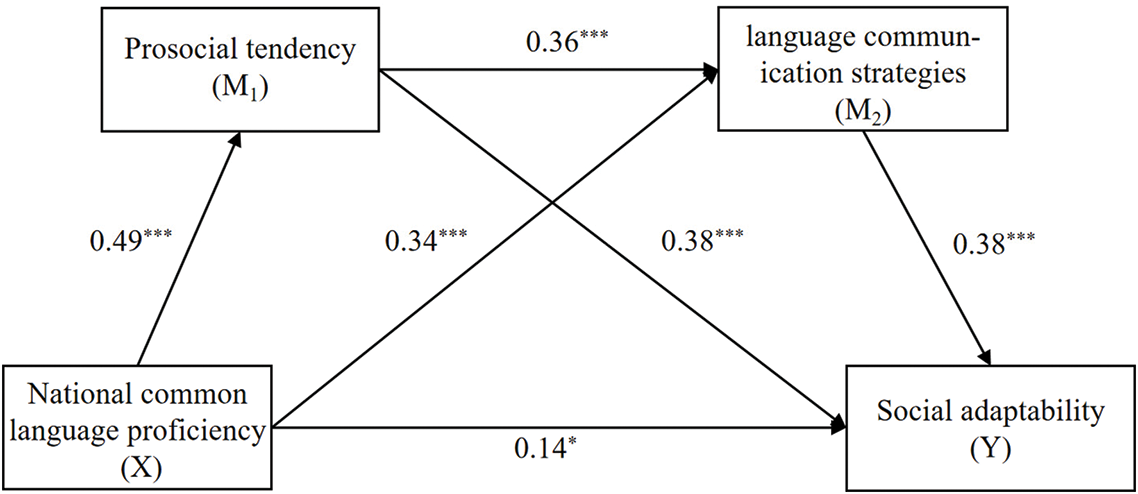

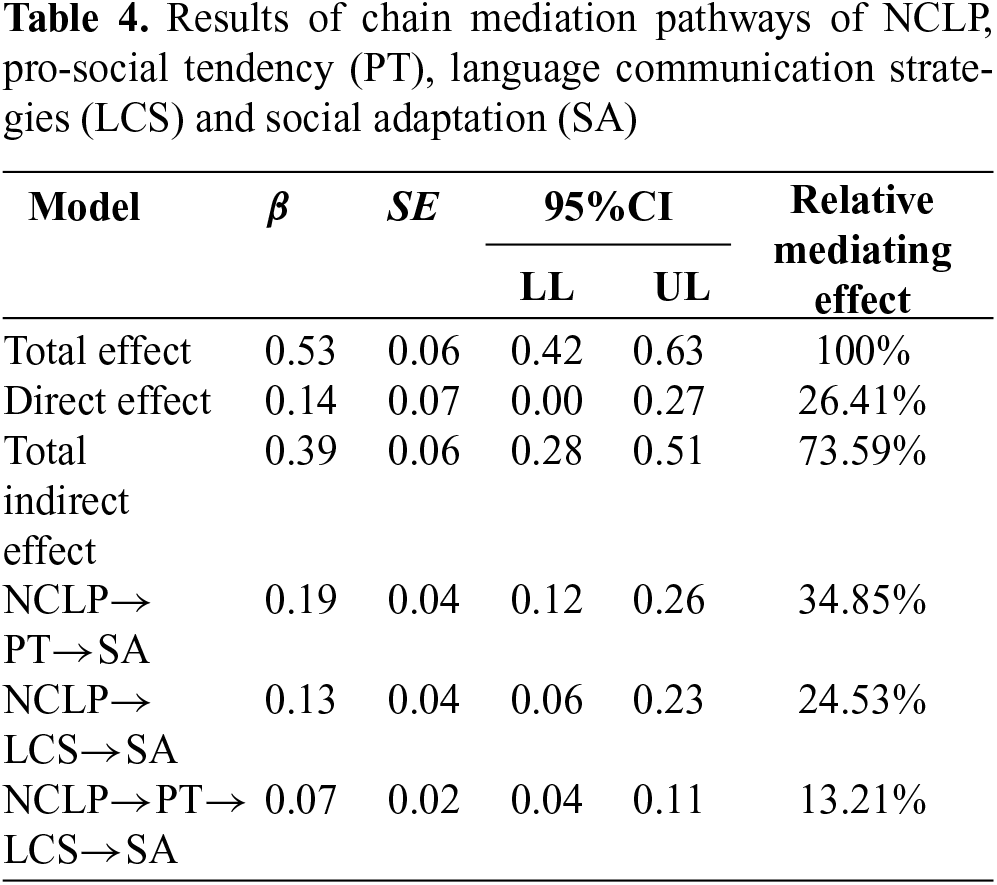

Using the bias-corrected non-parametric percentile bootstrap method for mediation testing. NCLP (X) was specified as the independent variable, social adaptation (Y) as the dependent variable, prosocial tendency (M1) and language communication strategies (M2) as mediators. The results of the difference analysis indicated that students with club participation experience exhibited significantly higher prosocial tendency (t(545) = 2.43, p < 0.01) and social adaptation (t(545) = 3.84, p < 0.001) compared to those without such experience. The earlier the acquisition of the national common language, the stronger the proficiency (F(3, 543) = 9.67, p < 0.001), prosocial tendency (F(3, 543) = 3.79, p < 0.05) and social adaptation (F(3, 543) = 3.86, p < 0.01). Furthermore, more frequent daily use of the national common language was associated with greater language proficiency (F(2, 544) = 40.59, p < 0.001), stronger prosocial tendency (F(2, 544) = 11.51, p < 0.001), and more frequent use of language communication strategies (F(2, 544) = 4.39, p < 0.001). (See Table S1 in the Supplementary File). Therefore, it is necessary to control for club participation, time since beginning to use the national common language, and frequency of language use as variables when examining the mediating effects. The model was constructed in Mplus, and the results are presented in Figure 1. The model in the present study remains within the acceptable range (

Figure 1: A chain mediation model for NCLP, pro-social tendency, language communication strategies and social adaptation. Note. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05

NCLP exerted a significant indirect effect on social adaptation through prosocial tendency (β = 0.19, 95% CI = [0.12, 0.26]), accounting for 34.85% of the total effect (Table 4). This suggests that high school students with higher NCLP tends to impact stronger prosocial tendency, which in turn enhances their social adaptation, supporting Hypothesis 2.

Language communication strategies mediation

NCLP can also influenced social adaptation through language communication strategies (β = 0.13, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.23]), accounting for 24.53% of the total effect (Table 4). This indicates that students with better NCLP are more adept at employing language communication strategies, which subsequently promote social adaptation. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Prosocial tendency and Language communication strategies chain mediation

This study also investigated whether prosocial tendency and language communication strategies work through chain mediation effects between NCLP and social adaptation. The results show that NCLP influences social adaptation through the chain mediation of prosocial tendency and language communication strategies (β = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.11]), with the effect size accounting for 13.21% of the total effect (Table 4), confirming the existence of chain mediation effects. The results support Hypothesis 4.

To examine whether gender differences exist in the relationship model between national common language proficiency and social adaptation, this study employed AMOS 24.0 to conduct a multi-group structural equation modeling analysis. First, the Unconstrained model (Model 1) demonstrated acceptable model fit (χ2/d = 1.92, CFI = 0.91, IFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.04), indicating the model’s applicability across gender groups. Subsequently, we conducted measurement invariance testing via nested model comparisons and found no significant difference between the measurement weights model (Model 2) and the unconstrained model (Model 1) (∆χ2(6) = 14.11, p = 0.25), confirming measurement model identity. The structural weights model (Model 3) also showed no significant difference from Model 2 (∆χ2(1) = 0.20, p = 0.29). (See Table S2 in the Supplementary File). This confirms that cross-group equality constraints hold from the measurement section to the structural relationships section. Furthermore, the critical ratios (CR values) for cross-group parameter comparisons were all below the critical threshold of 1.96 (Rong, 2009). Therefore, the structural relationship between NCLP and social adaptation shows no significant gender differences, demonstrating cross-gender stability (See Tables S3 and S4, and Figures S1 and S2 in the Supplementary File).

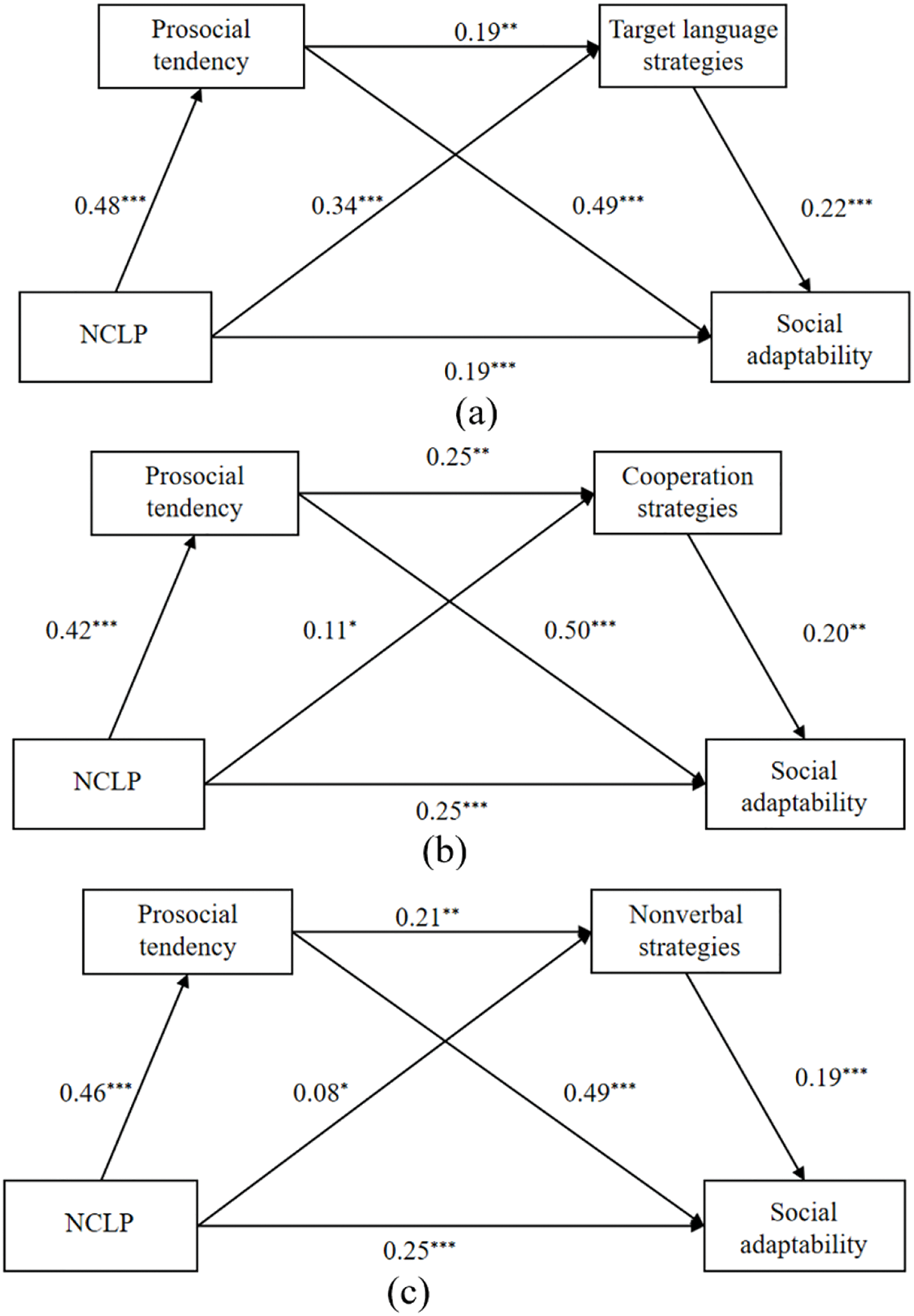

Mediation effect results of different language communication strategies

We performed mediation analysis on different language communication strategies, with the following results: the target language strategy demonstrated a significant mediating effect in the NCLP→LCS→SA pathway (β = 0.08, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.13]), accounting for 16% of the total effect. It also showed a significant chain mediation effect in the NCLP→PT→LCS→SA pathway (β = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.04]), explaining 4% of the total effect. Similarly, the cooperation strategy exhibited significant mediation in the NCLP→LCS→SA pathway (β = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.07]), representing 8% of the total effect, and also reached significance in the chain mediation pathway (β = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.04]), contributing 6% to the total effect. The nonverbal strategy showed significant mediation in the NCLP→LCS→SA pathway (β = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.04]), accounting for 4% of the total effect, and also demonstrated a significant mediating effect in the chain pathway (β = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.03]), explaining 4% of the total effect. In contrast, native language, reduction, and retrieval strategies showed no significant mediating effects (See Table S5 and Figures S3–S5 in the Supplementary File). The complete path diagrams are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Path diagram of the chain mediation model for different language strategies. (a) Path diagram of the target language strategies; (b) Path diagram of the cooperation strategies; (c) Path diagram of the nonverbal strategies. Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

The present study found that NCLP significantly and positively predicts social adaptation, with no significant differences observed between genders. This finding provides important support and extension to previous findings. In previous research, Zhomar (2018) conducted case studies on four Tibetan university students and found that an individual’s language proficiency, as a form of sociocultural capital, is closely associated with personal development and social adaptation. Our study reinforces this conclusion through a larger sample survey. This relationship can be explained from three perspectives. First, socialization is achieved through language acquisition. As a shared medium among ethnic minorities, the national common language shows consistent correlations with reduced psychological distance in cross-group communication across genders (Harwood et al., 2005). Its use correlates with enhanced familiarity and trust, and individuals with higher language proficiency tend to experience greater emotional acceptance as “in-group members” in cross-ethnic interactions. These observed patterns are subsequently linked to reported confidence in social adaptation (Wang, 2023). Second, higher NCLP is associated with improved self-identity, self-esteem, and positive interpersonal relationships, as well as reduced feelings of loneliness and stress. Furthermore, NCLP correlates with enhanced coping abilities and resilience—all factors that demonstrate significant relationships with social adaptation (Gong et al., 2021). Third, NCLP is essential for high school students to access educational resources and prepare for future life. NCLP facilitates textbook comprehension, participation in academic discussions, and utilization of online learning materials. These linguistic advantages are associated with improved academic performance, a stronger language foundation for career development, and enhanced responsiveness and coping skills when confronting challenges (Jang & Brutt-Griffler, 2019). Therefore, enhancing NCLP among Tibetan high school students is crucial for their social adaptation.

Prosocial tendency functions as a mediating mechanism between NCLP and social adaptation. According to in-group communication theory, language learning shows consistent associations with learners’ identification with the mainstream society, correlating with their sense of in-group belonging in multicultural environments. These observed relationships are linked to reduced feelings of alienation related to language barriers, higher levels of self-efficacy in linguistic communication, and improved environmental coping abilities (Wu et al., 2025; Armstrong-Carter et al., 2023). Some researches also suggest that as adolescents’ language abilities improve, their social cognition and emotional capacities continue to develop, enabling them to more deeply understand and embrace multiculturalism (Conte et al., 2018). These cognitive and emotional shifts influence the development of prosocial tendency. Concurrently, adolescents with stronger prosocial tendencies are more likely to establish positive relationships with peers from other ethnic backgrounds in school settings (Li et al., 2023). For Tibetan high school students, higher NCLP is associated with more active participation in peer-group social activities and encourages prosocial behaviors such as cooperation, sharing, and helping. Through these behaviors, they accumulate social experiences and interpersonal skills, fostering greater initiative and enthusiasm in adapting to social life (Laguna et al., 2022). Therefore, stronger NCLP correlates with more successful integration into group life, more frequent demonstration of prosocial tendencies, and greater willingness to engage in social interactions. These interrelated factors collectively form an important foundation for social adaptation.

Moreover, language communication strategies mediate the relationship between NCLP and social adaptation. When language learners can proficiently use the national common language and adjust their communication strategies according to specific contexts, they can convey information more accurately and gain a deeper understanding of others. This enables them to build more stable and harmonious interpersonal relationships, thereby achieving the goal of social adaptation (Pratama & Zainil, 2020). Research on second language acquisition has also revealed that individuals at different proficiency levels employ distinct communicative strategies, including target language strategies, cooperative strategies, and nonverbal strategies, all of which enhance their ability to interact with others, and adapt to societal life (Ting & Phan, 2008). For instance, in school settings, Tibetan high school students engage in classroom interactions with teachers and peers using the national common language. They flexibly combine target language strategies (such as word substitution, self-correction), cooperation strategies (e.g., seeking clarification, co-constructing meaning), and nonverbal strategies (e.g., using gestures and facial expressions). This not only enhances the quality of their classroom participation but also lays the foundation for interpersonal interactions in their future studies and careers (Burdelski & Howard, 2020; Sultanova, 2025). Therefore, for students with insufficient NCLP, developing their capacity to flexibly select and deploy communication strategies according to specific contexts and interlocutors is essential for promoting successful social adaptation.

The important finding of this study is that prosocial tendency and language communication strategies function as a chain mediator between NCLP and social adaptation. According to Communicative Adaptation Theory, when individuals with limited language proficiency demonstrate prosocial tendencies, such as offering help in public settings or expressing goodwill toward others, they tend to actively employ various language communication strategies, including adjusting speaking speed or using simple, easily understandable vocabulary, to ensure their intentions are understood and their messages are conveyed effectively (Yaraghi & Shafiee, 2018). This demonstrates that prosocial tendencies can stimulate individuals’ willingness to engage in communication, prompting them to employ diverse linguistic strategies. As Tibetan high school students continuously enhance their NCLP, they progressively transcend geographical and cultural boundaries, aspiring to connect with broader communities and manifest their prosocial tendencies (Gong et al., 2021). To achieve smooth social interactions, they flexibly select appropriate language communication strategies to effectively convey their goodwill and willingness to cooperate to others. This approach enables them to receive positive feedback in social exchanges and better integrate into modern society (Grueneisen & Warneken, 2022; Pang et al., 2022). Therefore, as a typical internal psychological trait, prosocial tendency influences language learners to pay greater attention to the needs and emotions of others during interactions, demonstrating empathy and a cooperative spirit. This provides both the prerequisite and motivation for the application of language communication strategies. The use of these strategies enables them to communicate more smoothly with others, establish more stable and harmonious interpersonal relationships, and thereby achieve better social adaptation (Tiu et al., 2023).

The differential mediation effects observed among communication strategies reveal a meaningful pattern in their social adaptation functions. Specifically, the target language strategy represents the most direct behavioral manifestation of NCLP, enabling active engagement in mainstream social contexts (Pratama & Zainil, 2020). The cooperation strategy exemplifies the behavioral externalization of prosocial tendency (Laguna et al., 2022). Meanwhile, the nonverbal strategy serves as a crucial supplement to verbal communication, providing compensatory means to maintain interaction flow.

Theoretical and practical implications

In the Chinese cultural context, this study investigated the impact of NCLP on social adaptation. It innovatively revealed a chain mediation mechanism, in which prosocial tendency and language communication strategies sequentially mediate the relationship between NCLP and social adaptation. The study further extends the application scope of LST by demonstrating that NCLP serves not merely as a communicative tool but as a pivotal factor influencing the social adaptation of ethnic minorities. The findings indicate no significant gender differences in this mechanism, while simultaneously verifying the specific mediating pathways of various dimensions of target language strategy, cooperation strategy, and nonverbal strategy. By integrating the process of language socialization with group psychological mechanisms, the findings of this study not only enhance the explanatory power of LST within the cultural context of Chinese ethnic minorities, but also provide a culturally appropriate theoretical model for understanding the social adaptation process of Tibetan high school students, thereby laying a crucial foundation for subsequent research.

Based on the research results, this study recommends taking proactive measures to enhance both the NCLP and social adaptation of ethnic minority high school students. First, it is essential to transcend traditional classroom language instruction and integrate the learning of the national common language into authentic life contexts. By organizing students’ participation in campus cultural activities, social practices, and cross-community exchanges, learners can consolidate their language knowledge and enhance pragmatic competence through practical application. This approach enables deeper integration of language learning with life experience and social adaptation (Qasserras, 2023). Second, cultivate students’ prosocial awareness and skills. Initiatives such as incorporating prosocial behavior education such as participation in volunteer services and cooperative learning through campus culture and moral education classes building would enhance social adaptation (McDougle & Li, 2023). Third, offering targeted language communication strategy training. With group discussions and situational tasks would encourage students to apply these strategies in authentic communication scenarios (Sultanova, 2025; Dos Santos, 2020). Finally, collaboration among schools, families, and communities to create extracurricular language-use platforms, such as book clubs, debate societies, and community volunteer programs would expand students’ opportunities for using the national language and engaging in social interaction (Eden et al., 2024).

Limitations and future research directions

Although this study reveals NCLP effects on social adaptation, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study adopted a cross-sectional design and relied solely on participants’ self-reported data, which may introduce certain limitations in terms of objectivity. Future research could implement a multi-informant evaluation mechanism involving teachers, parents, and students. Furthermore, employing longitudinal tracking designs to develop latent growth models would help better elucidate the dynamic relationship between national common language proficiency and social adaptation. Second, this study focuses solely on Tibetan high school students, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should include a broader range of cultural and ethnic groups to allow for comparative analyses of the mechanisms linking language learning and social adaptation across different cultural contexts. Third, the study does not differentiate between direct and indirect language communication strategies. Future research should investigate the distinct effects of these strategy types on the social adaptation of high school students to provide a more nuanced understanding of their roles. Fourth, while this study relied on quantitative methods to reveal relationships between variables, future research could integrate field observations and in-depth interviews to explore the underlying mechanisms and contextual factors more comprehensively.

This study examined the impact of NCLP on social adaptation among Tibetan high school students in China. Using a mediation model, we found that prosocial tendencies and language communication strategies sequentially mediate the relationship between NCLP and social adaptation. These findings not only enhance our understanding of the complex interplay between language learning and social adaptation in Tibetan high school students but also highlight the critical role of NCLP in individual social adaptation. Consequently, actively improving NCLP among ethnic minorities is essential for their social adaptation.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the Ministry of Education of China’s Youth Fund for Humanities and Social Sciences Research (Grant: 25XJC880001) and the Gansu Provincial Ethnic Affairs Commission’s 2025 Research Project on Fostering a Strong Sense of Community for the Chinese Nation (Grant: 2025-YJXM-16).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Baobao Dang, Wenjing Li, Shifeng Li; data collection: Baobao Dang, Wenjing Li; analysis and interpretation of results: Baobao Dang, Wenjing Li, Haiyan Zhao; draft manuscript preparation: Baobao Dang, Wenjing Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwest Normal University approved the study (ERB No. 2023093).

Informed Consent: All participants provided appropriate informed consent to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jpa.2025.071932/s1.

References

Ahmad, S. N., Rahmat, N. H., & Shahabani, N. S. (2022). Exploring communication strategies and fear of oral presentation among undergraduates. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 12(8), 1810–1832. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v12-i8/14642 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Alshammari, M. K., Othman, M. H., Mydin, Y. O., & Mohammed, B. A. (2023). Exploring how cultural identity and sense of belonging influence the psychological adjustment of international students. Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences, C Physiology & Molecular Biology, 15(1), 251–257. https://doi.org/10.21608/eajbsc.2023.290566 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Armstrong-Carter, E., Do, K. T., Duell, N., Kwon, S. J., Lindquist, K. A. et al. (2023). Adolescents’ perceptions of social risk and prosocial tendencies: Developmental change and individual differences. Social Development, 32(1), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ayshamu, R. (2020). National common language proficiency of Uyghur college students and its impact on learning experiences [master’s thesis]. Nanjing, China: Nanjing University. p. 62–63. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Burdelski, M. J., & Howard, K. M. (2020). Language socializationin classrooms: Culture, interaction, and anguage development, (pp. 112–132). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Conte, E., Grazzani, I., & Pepe, A. (2018). Social cognition, language, and prosocial behaviors: A multitrait mixed-methods study in early childhood. Early Education and Development, 29(6), 814–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2018.1475820 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dobao, A. M. F. (2002). The effect of language proficiency on communication strategy use: A case study of Galician learners of English. Miscelánea: A Journal of English and American Studies, 25, 53–75. https://doi.org/10.26754/ojs_misc/mj.200210524 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dos Santos, L. M. (2020). The discussion of communicative language teaching approach in language classrooms. Journal of Education and E-learning Research, 7(2), 104–109. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2020.72.104.109 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Eden, C. A., Chisom, O. N., & Adeniyi, I. S. (2024). Parent and community involvement in education: Strengthening partnerships for social improvement. International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, 6(3), 372–382. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijarss.v6i3.894 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Erceg-Hurn, D. M., & Mirosevich, V. M. (2008). Modern robust statistical methods: An easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. American Psychologist, 63(7), 591–601. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ergashev, I., & Farxodjonova, N. (2020). Integration of national culture in the process of globalization. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(2), 477–479. [Google Scholar]

Faerch, C., & Kasper, G. (1983). Strategies in interlanguage communication. London, UK: Longman Pub Group. [Google Scholar]

Fox, R., Corretjer, O., & Webb, K. (2019). Benefits of foreign language learning and bilingualism: An analysis of published empirical research 2012–2019. Foreign Language Annals, 52(4), 699–726. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12424 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fu, W., Wang, C., Chai, H., & Xue, R. (2022). Examining the relationship of empathy, social support, and prosocial behavior of adolescents in China: A structural equation modeling approach. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01296-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Giles, H., & Beebe, L. M. (1984). Speech-accommodation theories: A discussion in terms of second-language acquisition. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 1984(46), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.1984.46.5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gong, Y., Gao, X., Li, M., & Lai, C. (2021). Cultural adaptation challenges and strategies during study abroad: New Zealand students in China. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 34(4), 417–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2020.1856129 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Grueneisen, S., & Warneken, F. (2022). The development of prosocial behavior—from sympathy to strategy. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43(Suppl C), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Harwood, J., Giles, H., & Palomares, N. A. (2005). Intergroup theory and communication processes. Intergroup Communication: Multiple Perspectives, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

Hu, H., You, Y., Ling, Y., Yuan, H., & Huebner, E. S. (2021). The development of prosocial behavior among adolescents: A positive psychology perspective. Current Psychology, 42, 9734–9742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02255-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jang, E., & Brutt-Griffler, J. (2019). Language as a bridge to higher education: A large-scale empirical study of heritage language proficiency on language minority students’ academic success. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 40(4), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2018.1518451 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kamusella, T. (2018). Nationalism and national languages. In J. Tollefson & M. Pérez-Milans (Eds.The Oxford handbook of language policy and planning (pp. 163–182). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Khanal, J., & Gaulee, U. (2019). Challenges of international students from pre-departure to post-study: A literature review. Journal of International Students, 9(2), 560–581. https://doi.org/10.32674/iis.v9i2.673 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, pp. 191–192. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

Kou, Y., Hong, H. F., Tan, C., & Li, L. (2007). Revision of the adolescent prosocial tendencies scale. Psychological Development and Education, 23(1), 112–117. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Laguna, M., De Longis, E., Mazur-Socha, Z., & Alessandri, G. (2022). Explaining prosocial behavior from the inter-and within-individual perspectives: A role of positive orientation and positive affect. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00464-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Laguna, M., Mazur, Z., Kędra, M., & Ostrowski, K. (2020). Interventions stimulating prosocial helping behavior: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 50(11), 676–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12704 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, F. Y. (2016). Research on factors affecting communicative strategies [master’s thesis]. Ürümqi, China: Xinjiang University. pp. 63–64. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Li, B., Hu, X., Chen, L., & Wu, C. (2023). Longitudinal relations between school climate and prosocial behavior: The mediating role of gratitude. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 419–430. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S395162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lin, X. Y., Fang, X. Y., Li, H., Liu,C. Y., Yang, Z. W. (2006). Trends of pro-social tendency and prediction of school adjustment among students in Yunnan Province. Psychological Development and Education, 22(4), 44–51. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Liu, L., Guo, C., Shi, M. X., Wang, J. X., Li, Q. et al. (2022). Development and application of a social adjustment questionnaire for children and adolescents. Journal of Southwest University, 44(8), 2–12. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.13718/j.cnki.xdzk.2022.08.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lou, N. M. (2021). Acculturation in a postcolonial context: Language, identity, cultural adaptation, and academic achievement of Macao students in Mainland China. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 85, 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.10.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

McDougle, L. M., & Li, H. (2023). Service-learning in higher education and prosocial identity formation. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 52(3), 611–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640221108140 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Meier, G., & Smala, S. (2021). Languages and social cohesion: A transdisciplinary literature review (pp. 8–30). London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Mirza, H. S., & Warwick, R. (2024). Race and ethnic inequalities. Oxford Open Economics, 3(Suppl 1), i365–i452. https://doi.org/10.1093/ooec/odad026 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ou, W. A., & Gu, M. M. (2021). Language socialization and identity in intercultural communication: Experience of Chinese students in a transnational university in China. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(3), 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1472207 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pang, Y., Song, C., & Ma, C. (2022). Effect of different types of empathy on prosocial behavior: Gratitude as mediator. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 768–827. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.768827. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pikulytska, L. (2022). The impact of international students’ social adaptation on the training process in higher education. Educational Challenges, 27(1), 92–107. https://doi.org/10.34142/2709-7986.2022.27.1.08 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pratama, V. M., & Zainil, Y. (2020). EFL learners’ communication strategy on speaking performance of interpersonal conversation in classroom discussion presentation. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on English Language and Teaching (ICOELT 2019pp. 29–36. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200306.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Qasserras, L. (2023). Systematic review of communicative language teaching (CLT) in language education: A balanced perspective. European Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 4(6), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejedu.2023.4.6.763 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rong, T. S. (2009). AMOS and research methods (pp. 151–162). Chongqing, China: Chongqing University Press. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Saleem, S., Zahra, S. T., Subhan, S., & Mahmood, Z. (2021). Family communication, prosocial behavior and emotional/behavioral problems in a sample of Pakistani adolescents. The Family Journal, 29, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807211023929 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schieffelin, B. B., & Ochs, E. (1986). Language socialization. Annual Review of Anthropology, 15(1), 163–191. [Google Scholar]

Schoeps, K., Mónaco, E., Cotolí, A., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2020). The impact of peer attachment on prosocial behavior, emotional difficulties and conduct problems in adolescence: The mediating role of empathy. PLoS One, 15(1), e0227627. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sultanova, D. (2025). A model of communicative strategies in teaching English to non-linguistic students. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence, 1(2), 1165–1168. [Google Scholar]

Taguchi, N. (2015). Cross-cultural adaptability and development of speech act production in study abroad. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 25, 343–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12073 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Thielmann, I., & Pfattheicher, S. (2022). Editorial overview: Current and new directions in the study of prosociality. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47(Suppl C), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ting, S. H., & Phan, G. Y. (2008). Adjusting communication strategies to language proficiency. The Modern Language Journal, 23(1), 55–74. [Google Scholar]

Tiu, J., Groenewald, E., Kilag, O. K., Balicoco, R., Wenceslao, S. et al. (2023). Enhancing oral proficiency: Effective strategies for teaching speaking skills in communication classrooms. Excellencia: International Multi-Disciplinary Journal of Education, 1(6), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10408499 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Walker, B. H., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R., & Kinzig, A. P. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

Wang, L. (2023). Language socialization and language transmission among the new urban generation (pp. 12–14). Nanjing, China: Nanjing University Press. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Wen, Z., & Liu, H. (2020). Mediating and moderating effects (pp. 56–62). Beijing, China: Educational Science Press. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Wilczewski, M., & Alon, I. (2023). Language and communication in international students’ adaptation: A bibliometric and content analysis review. Higher Education, 85(6), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00888-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wu, X. I., Occhipinti, S., & Watson, B. (2025). Mainland Chinese students’ psychological adaptation to Hong Kong: An intergroup communication perspective. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 46(8), 2342–2357. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2287045 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, H., Tsung, L., & Cao, L. (2022). The use of communication strategies by second language learners of Chinese in a virtual reality learning environment. Sage Open, 12(4), 21582440221141877. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221141877 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yaraghi, E., & Shafiee, S. (2018). Roles of learner autonomy and willingness to communicate in communication strategy use of EFL learners. International Journal of English Language and Literature Studies, 7(3), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.18488/JOURNAL.23.2018.73.55.74 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, J. (2021). Practice and experience of national common language education in Tibet Autonomous Region. National Languages, 43(6), 3–14. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Zhang, H. K., Ma, Q. F., & Qiu, S. H. (2024). A study on the trend of population change of Tibetans in China: 2000–2020. Chinese Tibetology, 37(4), 163–174. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Zhomar, Y. (2018). A case study on the relationship between language proficiency and personal development of Tibetan students in Qinghai Tibetan area. Chinese Journal of Language Policy and Planning, 3(5), 40–45. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.19689/j.cnki.cn10-1361/h.20180504 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools