Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Sports participation and academic engagement: The chain mediating role of positive affect and life satisfaction

1 The Department of Psychological Health Education Center, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, 410004, China

2 Department of Psychology, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410081, China

3 Key Laboratory for Cognition and Human Behavior, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410081, China

4 Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29208, USA

* Corresponding Author: Siting Li. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 723-730. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.073368

Received 16 September 2025; Accepted 17 October 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Academic engagement is a key factor in students’ academic success, yet its psychological pathways remain underexplored in the context of physical activity. This study investigated the relationship between sports participation and academic engagement, with a focus on the sequential mediating roles of positive affect and life satisfaction. A total of 1365 Chinese secondary school students (females = 55.09%; mean age = 15.95 years, SD = 1.65) participated in the study. Participants completed the Physical Activity Rating Scale, the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale, the Satisfaction with Life Scale, and the Academic Engagement Scale. Correlation and mediation analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 23.0 and Hayes’ (2017) PROCESS macro. The results showed that sports participation positively predicted academic engagement, and this relationship was sequentially mediated by positive affect and life satisfaction. These findings suggest that physical activity not only benefits students’ emotional well-being but also promotes their academic involvement. Schools should consider integrating physical activity into educational strategies to foster both psychological and academic development in adolescents.Keywords

Increasing evidence suggests that sports participation as voluntary involvement in physical (Ling et al., 2022) is not only beneficial to students’ physical health (Warburton et al., 2006; Janssen & LeBlanc, 2010) but also contributes positively to their academic lives (Owen et al., 2022). Academic engagement, defined as a sustained and positive involvement in learning activities (Ling et al., 2022), is a key predictor of academic achievement among children and adolescents. While sports participation has long been recognized as beneficial to students’ physical and mental health (Malm et al., 2019), how it translates into better academic engagement remains underexplored, especially in developing countries. It is plausible that this effect operates through emotional and psychological pathways. Accordingly, the present study investigates the association between sports participation and academic engagement among school children from disadvantaged backgrounds, with particular attention to the mediating roles of positive affect and life satisfaction.

Sports participation and academic engagement

Sports participation may serve as a protective factor that enhances students’ academic engagement by promoting self-discipline, teamwork, emotional regulation, and a sense of achievement, all of which are associated with positive youth development outcomes (Bailey et al., 2013; Fraser-Thomas et al., 2005; Eime et al., 2013). Specifically, students who regularly participate in sports are more likely to display higher levels of academic motivation, persistence, and emotional involvement in learning (Trudeau & Shephard, 2008; Eime et al., 2013).

Previous research indicates that academic engagement is affected by multiple variables such as grit (Liu, 2020), family economic status (Aiyu, 2019), parenting styles (Wang et al., 2018), and teachers’ caring behaviors (Wang & Min, 2020). Additionally, positive affect (PA), life satisfaction (LS), and sports participation have all been shown to contribute positively to academic engagement (Ling et al., 2022). Grounded in the framework of positive psychology, this study aims to explore the positive psychological mechanisms—specifically PA and LS—that may mediate the relationship between sports participation and academic engagement among LBC.

Mediating role of positive affect

Positive affect refers to the experience of pleasurable emotions such as joy, enthusiasm, and contentment, which reflect an individual’s tendency to experience the world in an optimistic and energetic way (Watson et al., 1988). In-school physical activity, would enhance adolescents’ positive affect by promoting feelings of enjoyment, accomplishment and social connectedness (Eime et al., 2013; Lubans et al., 2016). For instance, participation in structured school sports programs provides opportunities for peer interaction, goal achievement, and physical mastery, all of which contribute to heightened emotional states such as happiness and excitement (Bailey et al., 2009). These positive emotional experiences not only enhance students’ overall well-being (Willms, 2003) but also serve as a motivational resource that supports better learning outcomes.

Empirical studies have shown that positive affect plays a facilitative role in academic engagement by enhancing students’ intrinsic motivation, resilience, and willingness to invest cognitive effort (Ouweneel et al., 2011; Pekrun et al., 2002). When students feel emotionally uplifted, they are more likely to approach learning with enthusiasm (vigor), persistence, and enjoyment (absorption), which are core elements of academic engagement (Fredricks et al., 2004). Therefore, positive affect may function as a key psychological mechanism linking sports participation with higher levels of academic engagement among adolescents.

Mediating role of life satisfaction

Life satisfaction (LS) is defined as a cognitive evaluation of one’s overall quality of life according to self-determined criteria (Pavot & Diener, 1993). Unlike transient emotional states, LS reflects a stable and global judgment about life circumstances and is considered a core component of subjective well-being, alongside positive affect (PA) and negative affect (Lucas et al., 1996; Diener, 1984). While these components are interrelated, they represent distinct dimensions of psychological functioning (Pavot & Diener, 2008).

Sports participation enhances LS through multiple psychological and social pathways (Bae et al., 2024; Gao et al., 2025). For instance, regular involvement in physical activity provides opportunities for achieving personal goals, experiencing competence, building social relationships, and developing a sense of belonging—all of which contribute to greater life satisfaction (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013; Eime et al., 2013). Aslo, school-based sports offer adolescents structured contexts for peer interaction, emotional support, and identity development, which are key predictors of LS in youth populations (Holder et al., 2009).

In turn, higher life satisfaction is associated with greater academic engagement (Datu & King, 2018). For instance, students with high LS are more likely to report stronger intrinsic motivation, sustained attention, and positive attitudes toward learning (Tian et al., 2014). LS may facilitate engagement by promoting a sense of personal meaning, reducing stress, and enhancing self-efficacy in academic contexts (Suldo & Huebner, 2006). Therefore, LS may function as a psychological mechanism through which sports participation contributes to students’ increased involvement and persistence in academic tasks.

The chain mediation effect of positive affect and life satisfaction

Positive emotions are not only indicators of individual happiness but also key psychological resources that facilitate personal growth, broaden cognitive repertoires (Fredrickson, 2004; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005). They also strengthen social connections, thereby supporting long-term development (Fredrickson, 2001). Within the domain of school-based sports participation, such positive emotions often arise from experiences of enjoyment, accomplishment, and social interaction (Eime et al., 2013), which in turn foster a greater sense of life satisfaction (Holder et al., 2009).

As two core components of subjective well-being (SWB), positive affect (PA) and life satisfaction (LS) would exert complementary and sequential influences on academic engagement. Specifically, positive emotions can broaden students’ attention and thinking (Fredrickson, 2001), enhance their motivation and self-efficacy (Ouweneel et al., 2011). These effects would improve their cognitive evaluation of life circumstances or life satisfaction. In turn, greater life satisfaction fosters more persistent and meaningful involvement in academic activities (Tian et al., 2014). Thus, PA and LS may operate in a chain mediation model, wherein PA enhances LS, which in turn promotes academic engagement. These psychological outcomes, in turn, contribute to greater motivation and engagement in other life domains, including academics (Standage et al., 2003). Therefore, school-based sports may initiate a sequence from PA to LS to academic engagement through the fulfillment of basic psychological needs.

China’s rapid economic growth and urbanization have led to large-scale rural-to-urban migration, with an estimated 286 million rural workers moving to cities in 2020 (Zhuang & Wu, 2024). Many migrant workers move individually rather than with their families, resulting in physical separation from their children (Lu, 2014). The household registration system (hukou) restricts rural migrants’ access to public services in cities, forcing many parents to leave their children behind in rural areas to attend local schools (Zhou & Cheung, 2017). Rural left-behind children (LBC), defined as those under 17 left behind by one or both parents for at least six months in their registered rural villages, numbered 41.8 million according to the 2020 national census (Zhuang & Wu, 2024). These children often experience emotional neglect, insufficient parental care, and limited access to educational and social resources, making them a vulnerable population in need of focused support and intervention. Compared to their peers, LBC experience greater emotional and behavioral difficulties, such as lower academic achievement, poorer peer relationships, and higher levels of depression and anxiety (Wang & Mesman, 2015).

LBC’s opportunities for sports participation are primarily limited to school physical education classes and informal activities such as rope skipping, running, or group games. However, due to the absence of parental care and emotional support, they are more likely to suffer from lower levels of life satisfaction and academic engagement (Wen et al., 2019; Song et al., 2018). Among these challenges, their academic disengagement is particularly concerning (Deng & Tian, 2021). Thus, exploring how sports participation might indirectly enhance their academic engagement via psychological mechanisms like PA and LS is of great practical significance.

Goals of the study

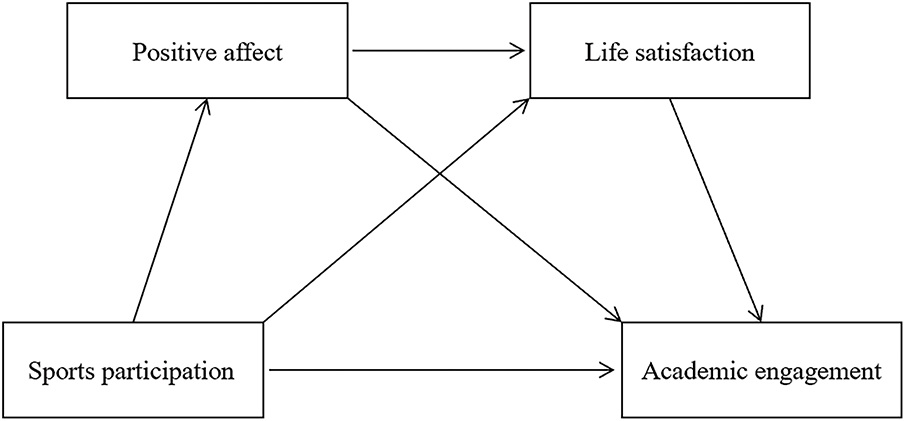

The present study explored the effect of sports participation on Chinese left-behind children (LBC) and how it relates to their academic engagement, taking into account the roles of Positive Affect and Life Satisfaction individually and in combination. Figure 1 outlines the study’s conceptual framework. This conceptual model is grounded in Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), which posits that environments supporting autonomy, competence, and relatedness—such as sports contexts—can satisfy basic psychological needs, leading to both positive affect and a more satisfied life. We formulated the following hypotheses:

Figure 1: Theoretical framework of the research

Hypothesis 1: Sports participation is associated with higher academic engagement.

Hypothesis 2: Positive affect plays a mediating role in the relationship between sports participation and academic engagement.

Hypothesis 3: Life satisfaction plays a mediating role in the relationship between sports participation and academic engagement.

Hypothesis 4: Positive affect and life satisfaction have a chain mediating role in the link between sports participation and academic engagement.

A random sample of 1365 of 2203 students were identified as left-behind children (LBC) based on their response to a screening item indicating that one or both parents had been working outside the home for at least six consecutive months. Of this subsample, 613 (44.91%) were boys and 752 (55.09%) were girls, with an average age of 15.95 ± 1.65 years.

Sports participation was assessed using the revised Physical Activity Rating Scale (PARS-3) developed by Liang (1994). This scale included three items (e.g., What forms of physical activity do you regularly participate in?) that examine the intensity, duration, and frequency of physical activity. Participants were asked to rate the three items from 1 to 5. The total amount of physical activity was calculated by intensity x (time-1) x frequency, with higher scores indicating greater levels of physical activity. This scale has demonstrated good applicability among Chinese junior high school students (Yan Jun et al., 2020). In the current study, the internal consistency of PARS-3 scores α = 0.70).

The Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) was used to assess individuals’ frequencies of positive and negative affect. The Positive Affect subscale (PA) consists of 10 adjectives (e.g., enthusiastic) describing PA; the Negative Affect subscale (NA) consists of 10 adjectives (e.g., upset) describing negative affect. Each adjective is followed by five options: almost none, relatively little, moderately, relatively much and extremely much, rated from 1 to 5, respectively. Each subscale is calculated separately, with higher total scores on PA indicating a higher frequency of PA and higher total scores on NA indicating a higher frequency of negative affect. Evidence of the applicability of the scale to Chinese adolescents has been provided (Huang Li & Zhongmin, 2003). The coefficient α for PANAS scores this study were 0.90 for PA and 0.91 for NA, respectively.

LS was measured using the Brief Multidimensional Students’ LS Scale (BMSLSS, Seligson et al., 2003), which comprises six items addressing, one for each of six domains of LS: family, school, living environment, friends, self, and overall. Each item was scored from “1 = very dissatisfied” to “7 = very satisfied”. A higher score indicated a higher level of LS. Previous research has shown that the scale has good reliability and validity among Chinese secondary school students (Ye et al., 2014). The internal consistency coefficient α of the scale in this study was 0.90.

Academic engagement was measured using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-Student (UWES-S). The questionnaire was developed by Schaufeli et al. (2002) and translated and revised by Li and Huang (2010). The UWES-S contains 17 items, encompassing three dimensions: motivation (e.g., “I am willing to study as soon as I get up in the morning”), vigor (e.g., “I can keep studying for a long time and don’t need a break in between”) and absorption (e.g., “I was immersed in my studies”). Each item was scored from “1 = hardly ever” to “7 = always”. The items were summed to create a total score. A higher total score represented more engagement in learning. Previous studies have shown that this scale has good reliability when used with LBC (Xiong et al., 2020). The internal consistency coefficient α of UWES-S scores the was 0.96 in this study.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University, and the study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent individually, with assurances of anonymity and confidentiality. To protect participants’ privacy, all data were deidentified, and analyses were conducted on aggregated data.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). First, the internal consistency of each scale was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Descriptive statistics, including the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD), were calculated for the continuous variables. Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among sports participation, positive affect (PA), life satisfaction (LS), and academic engagement.

To test the hypothesized mediation and chain mediation models, we used the PROCESS macro for SPSS developed by Hayes (2017). Specifically, Model 6 was adopted to examine the separate mediating effects of PA and LS as well as their sequential mediating role in the relationship between sports participation and academic engagement. The significance of the mediating effects was assessed using the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method with 5000 resamples and a 95% confidence interval (CI). A mediating effect was considered significant if the CI did not include zero (Fang et al., 2012; Mao & Ye, 2021).

As this study relied entirely on self-reported data, there was a potential risk of common method bias (CMB). To assess the extent of CMB, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted before the formal data analysis. The results showed that five factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor accounted for 36.944% of the total variance, which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 40%. These findings suggest that common method bias was not a serious concern in this study.

Descriptive findings and correlation analysis

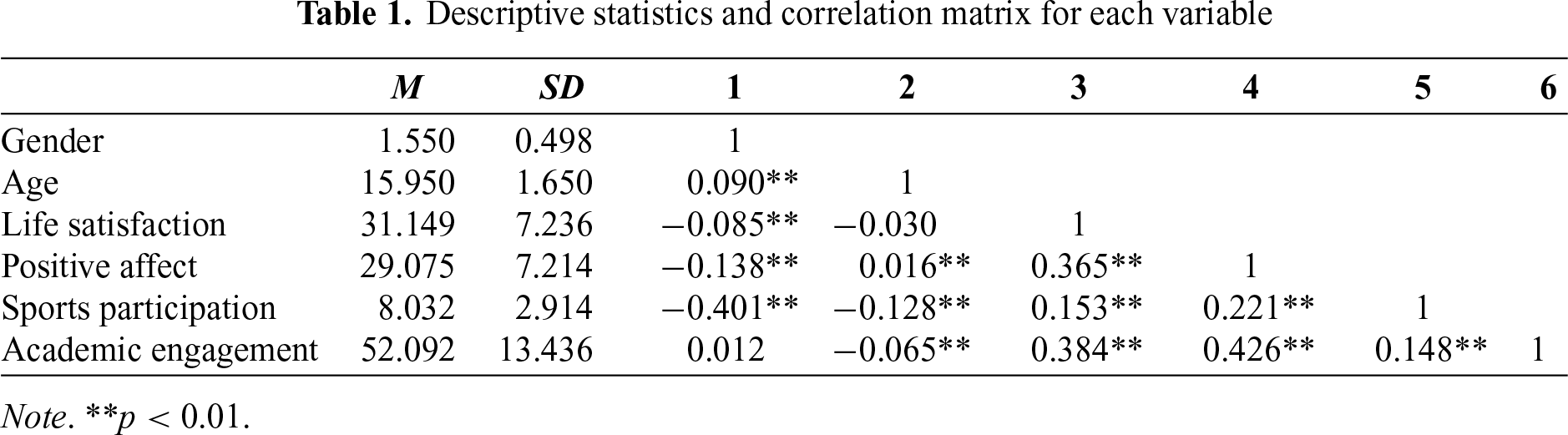

As shown in Table 1, there were significant positive correlations among the measures of LS, PA, sports participation and academic engagement (p < 0.01). These relations thus supported subsequent hypothesis testing.

The predictor variables in each equation were standardized (converted to Z-scores) to ensure comparability across variables, facilitate interpretation of coefficients, and improve numerical stability during model estimation. Collinearity diagnostics were evaluated given that all variables were significantly correlated with each other and could suffer from collinearity problems, causing instability in the results. The results showed that the variance inflation factor VIF (1.0–1.192) was less than 3 or 5 for all predictor variables and the tolerance (0.861–1.0) was greater than 0.1, therefore the data did not reflect serious collinearity problems and could be further tested for chain mediating effects.

Mediation effects of positive affect and life satisfaction

Controlling for the demographic variables of sex and age, the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (2017) was used to examine the mediating effects of positive affect (PA) and life satisfaction (LS) in the relationship between sports participation and academic engagement among left-behind children (LBC).

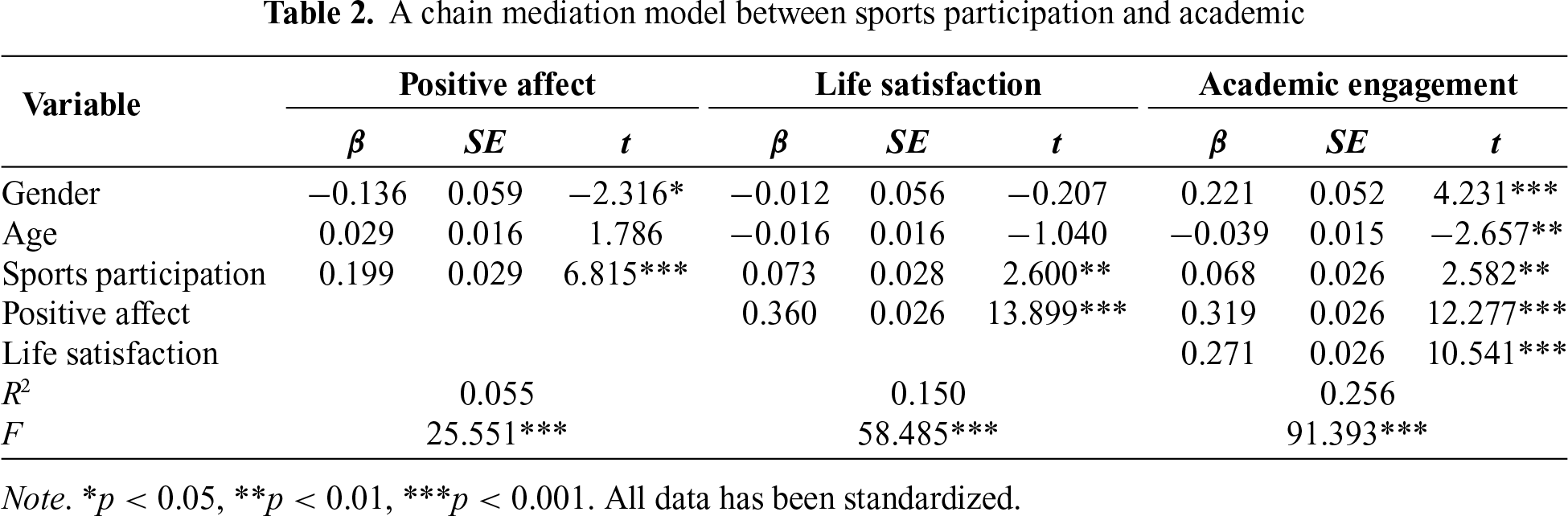

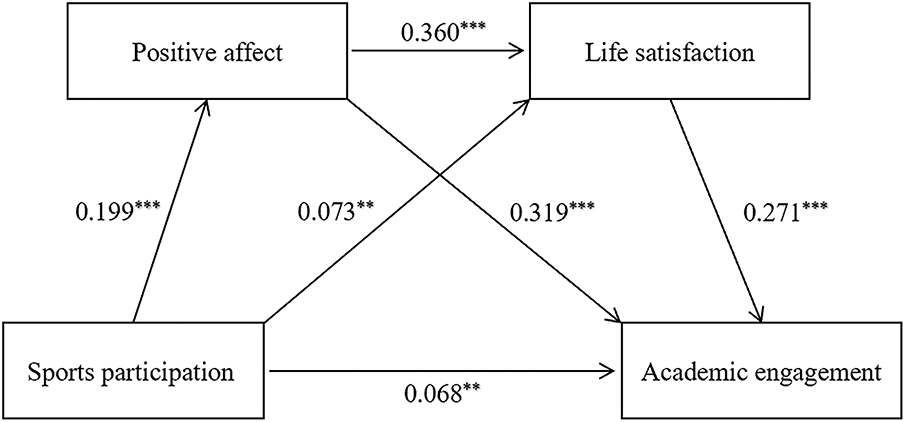

As shown in Table 2, sports participation significantly and positively predicted academic engagement (β = 0.068, t = 2.582, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. It also positively predicted PA (β = 0.199, t = 6.815, p < 0.001) and LS (β = 0.073, t = 2.600, p < 0.01). In turn, PA significantly predicted LS (β = 0.360, t = 13.899, p < 0.001) and academic engagement (β = 0.319, t = 12.277, p < 0.001), while LS also positively predicted academic engagement (β = 0.271, t = 10.541, p < 0.001).

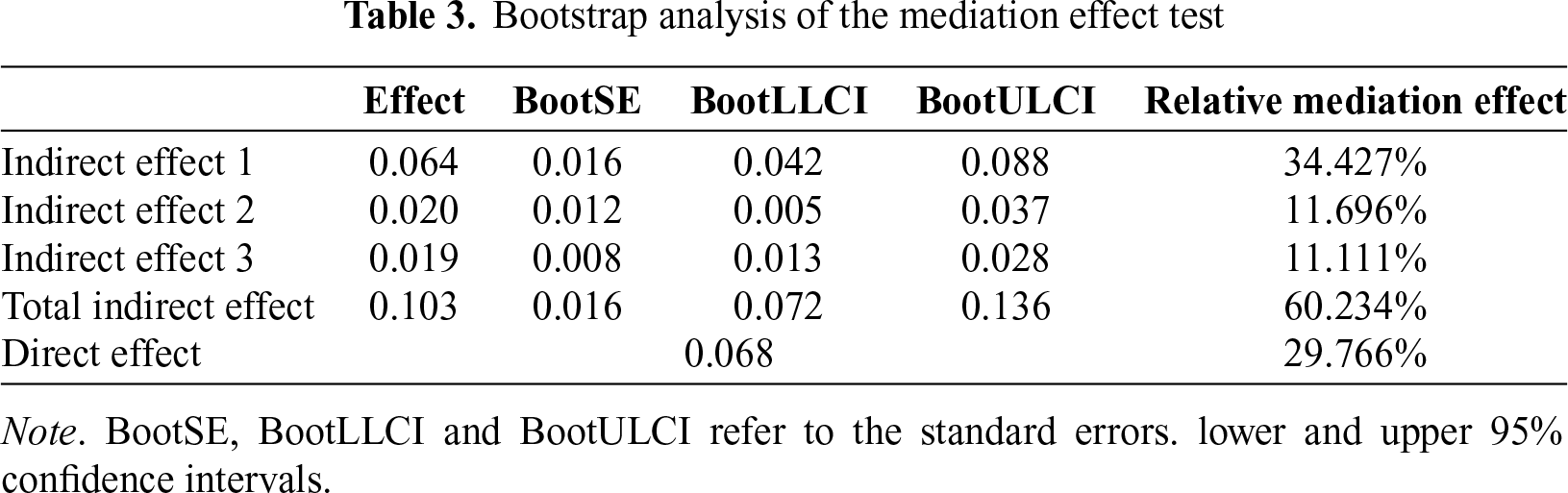

The significance of the mediating effects was tested using the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method with 5000 resamples. As presented in Table 3, the mediating effect of PA was significant (β = 0.064), with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of (0.042, 0.088), accounting for 34.427% of the total effect. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. The mediating effect of LS was also significant (β = 0.020), with a 95% CI of (0.005, 0.037), accounting for 11.696% of the total effect. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Chain mediation effects As shown in Figure 2, the chain mediating effect of PA and LS between sports participation and academic engagement was significant (β = 0.019), with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of (0.013, 0.028), accounting for 11.111% of the total effect. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Figure 2: The chain mediation model. Note. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

This study examined the effects of sports participation on academic engagement and explored the mediating roles of positive affect (PA) and life satisfaction (LS) among Chinese left-behind children (LBC). The findings revealed a positive association between sports participation and academic engagement, consistent with previous research (Owen et al., 2018). These results align with the Eco-developmental theory (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999), which suggests that micro-level settings such as sports participation can promote learning engagement by mitigating the adverse effects of parental absence. Sports participation may help LBC reduce negative emotions, develop regular exercise habits and grit, and improve cognitive functioning, thus facilitating their academic engagement (Xiaoju, 2014). Furthermore, the cultural emphasis on perseverance in Chinese society reinforces the positive link between sports participation and academic engagement.

The mediating roles of positive affect (PA) and life satisfaction (LS) were supported in this study. PA was found to partially mediate the relation between sports participation and academic engagement, consistent with the Positive Activity Model (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013). According to the Broaden-and-Build Theory (Fredrickson, 2001), PA broadens individuals’ cognitive and behavioral repertoires, helping them build lasting psychological resources that promote greater life satisfaction. Additionally, LS also served as a significant mediator. Sports participation may enhance LS by reducing stress and improving overall well-being, which further encourages proactive learning behaviors. Drawing on Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), sports participation satisfies basic psychological needs such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness, fostering both PA and LS. The confirmed chain mediation effect indicates that PA contributes to increased LS, which in turn facilitates academic engagement. This finding aligns with positive psychology’s emphasis on the role of positive experiences in promoting life satisfaction and adaptive outcomes (Seligman et al., 2005), highlighting an integrated psychological mechanism whereby sports participation enhances academic engagement through sequential improvements in PA and LS.

Together, these results suggest that sports participation enriches LBC’s psychological resources through enhanced positive emotions and life satisfaction, thereby increasing their engagement in academic learning. These insights underscore the value of fostering sports activities as a practical intervention to support the academic development of LBC.

When designing school-based interventions to enhance academic engagement among left-behind children (LBC), it is important to recognize the mediating roles of positive affect (PA) and life satisfaction (LS) as key psychological pathways. Interventions that aim to promote PA can help broaden students’ emotional and cognitive repertoires (e.g., play, exploration, study) and build valuable psychological resources such as resilience and motivation, which are essential for sustained learning (Denovan et al., 2019). Our findings support the view that PA significantly predicts academic engagement and contributes to greater life satisfaction, both of which facilitate more active and meaningful involvement in school.

Given these findings, sports participation can serve as a promising avenue for improving PA, LS, and academic engagement among LBC. Schools are encouraged to create more accessible and engaging physical activity opportunities that foster positive emotional experiences and a sense of competence and belonging. At the same time, primary caregivers should be supported and guided to encourage children’s regular participation in physical activity and help them establish healthy lifestyle habits that contribute to both emotional well-being and academic success.

Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Further Research

This study sheds light on the psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between sports participation and academic engagement among left-behind children (LBC), offering practical insights for enhancing student engagement through emotion- and well-being-based interventions. Given these findings, sports participation appears to be a promising avenue for improving positive affect (PA), life satisfaction (LS), and academic engagement in LBC. Schools are encouraged to create more accessible and enjoyable opportunities for physical activity that foster positive emotional experiences, a sense of competence, and social connectedness. Likewise, primary caregivers should be supported and guided to encourage regular participation in physical activities at home, helping children to cultivate healthy routines that support both emotional well-being and learning outcomes.

Despite these contributions, the present study has several limitations. First, all data were collected via self-report questionnaires, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Future studies should consider incorporating multi-informant approaches (e.g., reports from teachers or caregivers) to improve data validity. Second, the sample consisted exclusively of LBC in China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other cultural or social contexts. Cross-cultural studies or research involving other vulnerable populations would help to test the robustness of these findings. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the design restricts conclusions about causality. Longitudinal or experimental designs are recommended to better understand the temporal dynamics and causal pathways involved. Finally, this study focused only on PA and LS as mediators. Future research may explore additional psychological or contextual factors (e.g., self-efficacy, peer support, school climate) to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how sports participation affects academic engagement.

We explored the effects of sports participation on academic engagement among left-behind children (LBC), as well as the independent and chain-mediating roles of positive affect (PA) and life satisfaction (LS). The results indicate that sports participation significantly predicts academic engagement. Positive affect and life satisfaction both play significant mediating roles in this relationship. Moreover, PA and LS jointly form a chain mediating pathway linking sports participation and academic engagement. These findings underscore the importance of promoting physical activity and psychological well-being to enhance academic engagement in LBC.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the 2024 “Furong Plan”—Excellent Ideological and Political Worker Program in Higher Education, Master Teacher Studio Project (FRJH2402), awarded to Dr. Hongmei Yuan.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hongmei Yuan, Yu Zhang; Methodology, Siting Li, Yu Zhang, Yunheng Zhao; Software, Siting Li, Yu Zhang; Validation, Hongmei Yuan, Siting Li, Yu Zhang, Yunheng Zhao, Dan Shen; Formal analysis, Siting Li, Yu Zhang, Yunheng Zhao; Investigation, Hongmei Yuan, Siting Li, Yu Zhang, Yunheng Zhao, Dan Shen; Resources, Hongmei Yuan, Yu Zhang, Yunheng Zhao, Dan Shen; Data curation, Siting Li; Writing—original draft preparation, Hongmei Yuan, Siting Li; Writing—review and editing, Hongmei Yuan, Siting Li, Yu Zhang, Yunheng Zhao, Dan Shen, E. Scott Huebner; Visualization, Siting Li, Yunheng Zhao; Supervision, Hongmei Yuan, Dan Shen, E. Scott Huebner; Project administration, Hongmei Yuan; Funding acquisition, Hongmei Yuan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author without undue reservation.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University Biomedical Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided informed consent individually, with assurances of anonymity and confidentiality. To protect participants’ privacy, all data were deidentified, and analyses were conducted on aggregated data.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aiyu, L. S. L. (2019). A study on the mechanism of the role of family background on academic performance-using parent-child educational expectation bias as an explanatory mediator. Education Exploration, (6) , 1–8. [Google Scholar]

Bae, M. H., Zhang, X., & Lee, J. S. (2024). Exercise, grit, and life satisfaction among Korean adolescents: A latent growth modeling analysis. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1392. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18899-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bailey, R., Armour, K., Kirk, D., Jess, M., Pickup, I. et al. (2009). The educational benefits claimed for physical education and school sport: An academic review. Research Papers in Education, 24(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar]

Bailey, R., Hillman, C., Arent, S., & Petitpas, A. (2013). Physical activity: An underestimated investment in human capital? Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 10(3), 289–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Datu, J. A. D., & King, R. B. (2018). Subjective well-being is reciprocally associated with academic engagement: A two-wave longitudinal study. Journal of School Psychology, 69, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.05.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar]

Deng, Y., & Tian, L. (2021). The main learning psychological problems of rural left-behind children and their educational countermeasures. Survey of Education, 47, 17–19+61. https://doi.org/10.16070/j.cnki.cn45-1388/g4s.2021.47.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Denovan, A., Dagnall, N., Macaskill, A., & Papageorgiou, K. (2019). Future time perspective, positive emotions and student engagement: A longitudinal study. Studies in Higher Education, 45(7), 1533–1546. [Google Scholar]

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Fang, J., Zhang, M. Q., & Ch, H. J. (2012). Mediation analysis and effect size measurement: Retrospect and prospect. Psychological Development and Education, 28(1), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2012.01.015 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fraser-Thomas, J. L., Côté, J., & Deakin, J. (2005). Youth sport programs: An avenue to foster positive youth development. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 10(1), 19–40. [Google Scholar]

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. [Google Scholar]

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1O37//0OO3-O66X.56.3.218 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1377. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion, 19(3), 313–332. [Google Scholar]

Gao, J., Nie, Y., Guo, M., Tang, W., Qu, G. et al. (2025). Analysis of the association between adolescent physical activity and life satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 738. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02847-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

Holder, M. D., Coleman, B., & Sehn, Z. L. (2009). The contribution of active and passive leisure to children’s well-being. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(3), 378–386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Huang, L., Yang, T., & Li, Z. (2003). Applicability of the positive and negative affect scale Chinese. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 17(1), 54–56. [Google Scholar]

Janssen, I., & LeBlanc, A. G. (2010). Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 7(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Li, X., & Huang, R. (2010). Report on the revision of the University-Wide Engagement in Learning Scale (UWES-S). Psychological Research, 3(1), 84–88. [Google Scholar]

Liang, D. Q. (1994). Stress levels of college students and their relationship with physical exercise. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 1, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

Ling, Y., Hu, X. J., Jiang, Y. D., You, J. J., & Chen, Y. (2022). Features of sports participation in left-behind children and the impact on their positive development: A latent profile analysis. China Journal of Health Psychology, 30(8), 1256–1260. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2022.08.027 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, Y. M. (2020). Grit and learning engagement: A chain mediation ananlysis. Shanghai Educational Research, 9, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.16194/j.cnki.31-1059/g4.2020.09.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu, Y. (2014). Parental migration and education of left-behind children: A comparison of two settings. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 76(5), 1082–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lubans, D., Richards, J., Hillman, C., Faulkner, G., Beauchamp, M. et al. (2016). Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics, 138(3), e20161642. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social, 71, 616–628. [Google Scholar]

Lyubomirsky, S., & Layous, K. (2013). How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412469809 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Malm, C., Jakobsson, J., & Isaksson, A. (2019). Physical activity and sports—Real health benefits: A review with insight into the public health of Sweden. Sports, 7(5), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7050127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mao, Y., & Ye, Y. H. (2021). Specific antecedents of entrepreneurial intention among newly returned Chinese international students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 622276. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.622276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ouweneel, E., Le Blanc, P. M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2011). Flourishing students: A longitudinal study on positive emotions, personal resources, and study engagement. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(2), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.558847 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Owen, K. B., Foley, B. C., Wilhite, K., Booker, B., Lonsdale, C. et al. (2022). Sport participation and academic performance in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 54(2), 299–306. [Google Scholar]

Owen, K. B., Parker, P. D., Astell-Burt, T., & Lonsdale, C. (2018). Effects of physical activity and breaks on mathematics engagement in adolescents. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 21(1), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.07.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). The review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–172. [Google Scholar]

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105. [Google Scholar]

Standage, M., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2003). A model of contextual motivation in physical education: Using constructs from self-determination and achievement goal theories to predict physical activity intentions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 97. [Google Scholar]

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Roma, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two-sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar]

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.60.5.410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Seligson, J. L., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2003). Preliminary validation of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Social Indicators Research, 61(2), 121–145. [Google Scholar]

Song, S., Chen, C., & Zhang, A. (2018). Effects of parental migration on life satisfaction and academic achievement of left-behind children in rural China—A case study in Hubei Province. Children, 5(7), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5070087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2006). Is extremely high life satisfaction during adolescence advantageous? Social Indicators Research, 78(2), 179–203. [Google Scholar]

Szapocznik, J., & Coatsworth, J. D. (1999). An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Drug abuse: Origins & interventions (pp. 331–366Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10341-014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tian, L., Han, M., & Huebner, E. S. (2014). Preliminary development of the adolescent students’ basic psychological needs at school scale. Journal of Adolescence, 37(3), 257–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Trudeau, F., & Shephard, R. J. (2008). Physical education, school physical activity, school sports and academic performance. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Wang, L., & Mesman, J. (2015). Child development in the face of rural-to-urban migration in China: A meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci, 10(6), 813–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615600145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, H. R., & Shui, M. (2020). A study on influence of teachers' caring behavior on learning engagement of rural junior high school students. Occupation and Health, (9) , 1263–1266+1271. https://doi.org/10.13329/j.cnki.zyyjk.2020.0336 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, L. X., Zhang, L. A., & Chang, S. M. (2018). The relationship between secondary school candidates’ family socioeconomic status and learning engagement: The multiple mediating roles of parental educational expectations and parenting behaviors. Chinese Journal of Special Educaton, 12, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

Warburton, D. E., Nicol, C. W., & Bredin, S. S. (2006). Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(6), 801–809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Wen, Y. J., Li, X. B., Zhao, X. X., Wang, X. Q., Hou, W. P. et al. (2019). The effect of left-behind phenomenon and physical neglect on behavioral problems of children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Willms, J. D. (2003). Student engagement at school: A sense of belonging and participation. Results from PISA 2000. Paris, France: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. [Google Scholar]

Xiaoju, Z. (2014). An analysis of the significance of young students’ participation in extracurricular physical exercise. Curriculum Teaching Materials Teaching Research, 2, 70. [Google Scholar]

Xiong, H., Liu, K., & Zhang, J. (2020). The effect of teacher-student relationship on left-behind children’s school adjustment: The chain mediating role of mental health and school engagement. Psychology Techniques and Applications, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

Yan Jun, T. B., Lu, S., Hu, L., Huanyu, L., & Min, L. (2020). The relationship between extracurricular physical exercise and school adaptation of adolescents: A chain mediating model and gender difference. China Sport Science and Technology, 10, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.16470/j.csst.2020161 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ye, M., Li, L., Li, Y., Shen, R., Wen, S. et al. (2014). Life satisfaction of adolescents in hunan, China: Reliability and validity of Chinese brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Social Indicators Research, 118(2), 515–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0438-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhou, S., & Cheung, M. (2017). Hukou system effects on migrant children’s education in China: Learning from past disparities. International Social Work, 60(6), 1327–1342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872817725134 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhuang, J., & Wu, Q. (2024). Interventions for left-behind children in Mainland China: A scoping review. Children and Youth Services Review, 166, 107933. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools