Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Social anxiety and non-suicidal self-injury in college students: Loneliness mediation and positive coping moderation

1 School of Psychology, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, 200234, China

2 Psychology Section, Secondary Sanatorium of Air Force Healthcare Center for Special Services, Hangzhou, 310007, China

3 Mental Health Education Center, Yiyang Normal College, Yiyang, 413000, China

4 Center of Student Mental Health Education, Yangtze University, Wuhan, 430100, China

5 Xi’an Changli Oil & Gas Engineering & Technical Services Co., Xi’an, 714000, China

6 School of Education, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, 200234, China

7 Teacher Education College, Hunan City University, Yiyang, 413000, China

8 Department of Geriatric Psychiatry, Suzhou Mental Health Center, Suzhou Guangji Hospital, The Affiliated Guangji Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, 415100, China

* Corresponding Authors: Wenqin Chen. Email: ; Dong Wang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 731-738. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.074914

Received 29 January 2025; Accepted 31 October 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

We examined positive coping styles and loneliness effects on the relationship between social anxiety and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) behaviors among young adults. A sample of 1129 Chinese college students (females = 42.52%; mean age = 20.00 years, SD = 1.61 years; 53.32% from rural areas) completed the Chinese Revised Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A), the UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-6), the Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ), and the Adolescent Non-suicidal Self-injury Assessment Questionnaire (ANSSIAQ). Controlling for gender, age, onlychild status, and residence, regression analysis revealed that social anxiety is associated with higher levels of NSSI behaviors. Loneliness mediated this relationship, making it more pronounced. Positive coping styles moderated the effect of social anxiety on loneliness. Specifically, high levels of positive coping attenuated the social anxiety effect on loneliness. This study affirms Nock’s integrated theoretical model of NSSI, demonstrating that social anxiety (an interpersonal vulnerability factor) and limited positive coping (an intrapersonal vulnerability factor) are significant predictors of NSSI. By implication, college student counselors should provide developmental activities for reducing social anxiety in students, thereby lowering their risk for loneliness and NSSI.Keywords

Social anxiety is a prevalent emotion in interpersonal scenarios and has been shown to be associated with an increased risk for self-injury (Morrison & Heimberg, 2013; Wang et al., 2023), particularly with a sense of loneliness (McClelland et al., 2021). However, the outcomes can vary depending on how stress is managed through coping behaviors (Taylor et al., 2018).

College students are vulnerable partly due to the stressors associated with emerging adulthood, including the transition from high school to university and from adolescence to adulthood (Aldiabat et al., 2014). Some may engage in self-injury as a way of negative coping. Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) refers to the direct and deliberate destruction of one’s own body tissue without lethal intent (Nock, 2010). NSSI has been listed in the DSM-5 and is known to predict future psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts (Kiekens et al., 2023a). It is a growing public health concern, especially among individuals aged 20–24, who have the second-highest prevalence after adolescents (Gandhi et al., 2018). A survey of first-year students from nine countries reported a 17.7% lifetime prevalence of NSSI (Kiekens et al., 2023b). However, how and which social anxiety characteristics predict self-injury may depend on the cultural context, and few studies have been conducted in collectivist cultures. This study aimed to examine the relationship between social anxiety and self-injury risk within collectivistic Chinese culture.

Social anxiety is the uneasiness, nervousness, or fear experienced in the presence of others (Schlenker & Leary, 1982). It is a common human experience that exists on a continuum (McNeil, 2001), with severe impairment of social functioning developing into social anxiety disorder (Morrison & Heimberg, 2013). Social anxiety can lead to serious consequences, such as suicide and self-injury (Buckner et al., 2017; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). For example, a large-scale survey of 20,130 adults found that individuals with generalized anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder are more likely to engage in NSSI and suicide attempts compared to those with other anxiety disorders (Chartrand et al., 2012). Moreover, research by Zou et al. (2024) indicates that social anxiety among college students is linked to NSSI, and a study by Tatnell et al. (2024) shows that reductions in social anxiety are associated with decreases in NSSI.

Loneliness is an emotional state in which individuals feel disconnected from others due to unmet personal needs (Copel, 1988). Loneliness is different from social isolation. Loneliness refers to the subjective perception of lacking a desired social network or companionship, whereas social isolation is the objective lack or paucity of social contacts and interactions with other persons (Valtorta & Hanratty, 2012). Loneliness is strongly associated with social anxiety (Maes et al., 2019). The experience of loneliness is unpleasant and painful (Younger, 1995), and it is linked to an increased risk of depression, anxiety, suicide, and even mortality (Moeller & Seehuus, 2019; McClelland et al., 2020; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). Interestingly, a recent five-year longitudinal study found that while social anxiety predicts loneliness, loneliness does not significantly predict social anxiety (Reinwarth et al., 2024), suggesting a need for further studies. Loneliness has also been identified as a potential risk factor for NSSI (Costa et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2018). Social anxiety represents an interpersonal vulnerability factor, while loneliness is a highly aversive intrapersonal emotion. However, how these two factors jointly influence NSSI among college students remains unclear.

The moderating role of positive coping

Coping styles refer to the actions individuals take to manage stressful events and maintain well-being (Folkman & Lazarus, 1986). Positive coping can effectively reduce social anxiety (Li, 2020) and lessen feelings of loneliness (Dong et al., 2023), which may, in turn, reduce the risk of NSSI (Castro & Kirchner, 2018; Wu & Liu, 2019).

However, the role of positive coping in relation to NSSI remains inconclusive. One study of Chinese college students suggested that positive coping acts as a protective factor against NSSI (Wu & Liu, 2019). In contrast, another study found no significant difference in the use of positive coping between adolescents with and without a history of NSSI, although those with a history of NSSI were more likely to use negative coping (Giordano et al., 2022). Surprisingly, a study of American college students found that those who engaged in NSSI reported using more positive coping than those who did not (Trepal et al., 2015). However, little is known about whether positive coping can buffer the effects of social anxiety (an interpersonal vulnerability factor) and loneliness (an intrapersonal aversive emotion) on NSSI among college students.

According to Nock’s integrated theoretical model of NSSI (Nock, 2009), interpersonal vulnerability factors—such as poor communication skills and inadequate social problem-solving—can lead to NSSI. Social anxiety falls within this category of interpersonal vulnerability factors. The integrated theoretical model of NSSI (Nock, 2009) would lead to the expectation that high aversive emotions and interpersonal vulnerabilities, combined with an inability to cope or the use of poor coping styles, may lead individuals to engage in NSSI as a temporary means of stress regulation. These theoretical propositions warrant examination in collectivist cultural contexts.

Chinese society is characterized by collectivist values and Confucian principles that emphasize interpersonal harmony (Huang, 2024). However, rapid modernization has prompted a shift toward individualization, creating a context of cultural dissonance for contemporary college students (Yan, 2010). This unique socio-cultural context is associated with heightened psychological challenges. Research indicates that collectivist orientations may intensify the impact of loneliness on adverse health outcomes (Lee et al., 2021), while cultural dimensions also moderate the relationship between loneliness and social anxiety among adolescents (Wang et al., 2024).

Structural factors such as the urban-rural divide and the legacy of the One-Child Policy (OCP) further compound these challenges. Urban areas have a significantly higher proportion of only-child families (64.95%) compared to rural regions (9.80%) (Lee, 2012). While only children often receive more familial support, they may lack opportunities to develop coping skills for social adversity, increasing their vulnerability to social anxiety and NSSI (Cameron et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2022). Conversely, rural students often experience social defeat and struggle to adapt to urban college life, potentially exacerbating loneliness.

When facing these combined socio-cultural and psychological pressures—namely, social anxiety and loneliness—individual coping styles become crucial. However, the role of positive coping within the Chinese context appears complex and, at times, paradoxical. Although typically associated with better mental health (Meng et al., 2011) and reduced loneliness (Zhang et al., 2021), positive coping has paradoxically been linked to elevated NSSI risk among rural adolescents (Zhou et al., 2022), underscoring the need for context-specific investigations.

Given the high prevalence of NSSI among Chinese college students (11.8%; Qu et al., 2023), it is essential to examine, within the Chinese context, how social anxiety and loneliness influence NSSI and how positive coping may moderate these relationships.

Grounded in Nock’s (2009) integrated theoretical model of NSSI, this study seeks to develop a moderated mediation model to explore the impact and mechanisms of social anxiety on NSSI among college students. Based on this conceptual framework, the following hypotheses were tested (see Figure 1 for the conceptual model):

Figure 1: A simple mediation model showing the effects of social anxiety on NSSI via loneliness. Note. ***p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 1: College students with elevated social anxiety are at an increased risk of engaging in NSSI.

Hypothesis 2: Loneliness mediates the relationship between social anxiety and NSSI, such that higher social anxiety increases loneliness, which in turn increases NSSI risk.

Hypothesis 3: Positive coping moderates the mediating pathway from social anxiety to NSSI through loneliness, such that the indirect effect is weaker among students with higher levels of positive coping.

A total of 1129 college students from three universities in China participated in the study. The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 25 years (M = 20.00, SD = 1.61). Of the participants, 480 were female (42.52%); 414 were only children (36.67%), and 715 had siblings (63.33%). Regarding residence, 602 students were from rural areas (53.32%), and 527 were from urban areas (46.68%).

Social anxiety was assessed using the 12-item Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A; Benner & Graham, 2009; Sun et al., 2017). An example item is: “I worry about what others think of me.” The scale uses a 5-point Likert rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all the time), with higher scores indicating greater social anxiety. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for SAS-A was 0.96.

Loneliness was measured using the 6-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-6; Hudiyana et al., 2022; Xiao & Du, 2023). An example item is: “I lack companionship.” The scale uses a 4-point Likert rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always), with higher scores indicating stronger feelings of loneliness. In this study, the UCLA scale scores achieved a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.95.

The Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ; Xie, 1998) consists of 20 items, including a Positive Coping subscale (12 items) and a Negative Coping subscale (8 items). Only the Positive Coping subscale was used in this study to measure positive coping styles among college students. An example item is: “Escape through work, study, or other activities.” The scale uses a 4-point Likert rating scale ranging from 0 (never use) to 4 (always use), with higher scores reflecting a greater tendency to use positive coping when dealing with stress. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the Positive Coping subscale was 0.93.

Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI)

The Adolescent Non-suicidal Self-injury Assessment Questionnaire (ANSSIAQ; Wan et al., 2018) consists of 12 items, each representing a different type of NSSI behavior. An example item is: “Deliberately pinched yourself.” Each item is rated on a five-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always), with higher scores indicating more frequent engagement in NSSI. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the ANSSIAQ was 0.86.

Prior research suggests that sex, age, only-child status, and type of residence may influence NNSI (Han et al., 2017). Therefore, these variables were included as controls. Variables were coded as follows: sex (1 = male, 2 = female), only-child status (1 = only child, 2 = has siblings), and residence (1 = rural, 2 = urban).

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Normal University (Approval No. 2025-005). All participants provided informed consent, and confidentiality was strictly maintained. Participation was voluntary, and data were collected anonymously through an online survey platform (wjx.cn).

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0. First, Harman’s one-factor test was conducted to assess common method bias. The results revealed six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor accounted for 34.20% of the total variance, below the 40% threshold, indicating no serious common method bias. Next, multicollinearity was assessed. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values for all predictor variables ranged from 1.19 to 1.50, well below the threshold of 5, and tolerance values ranged from 0.67 to 0.85, above the 0.20 threshold, indicating no multicollinearity concerns.

Following Hayes (2013), the SPSS macro PROCESS (Model 4) was used to test the mediating role of loneliness in the relationship between social anxiety and NSSI, controlling for gender, age, only-child status, and residence. The mediation effect of loneliness was examined using a non-parametric percentile bootstrap method (N = 5000, 95% CI) and Model 4 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013). Also, using the SPSS macro program PROCESS (Model 7), the moderated mediating role of positive coping and loneliness was tested while controlling for gender, age, only-child status, and residence (Hayes, 2013).

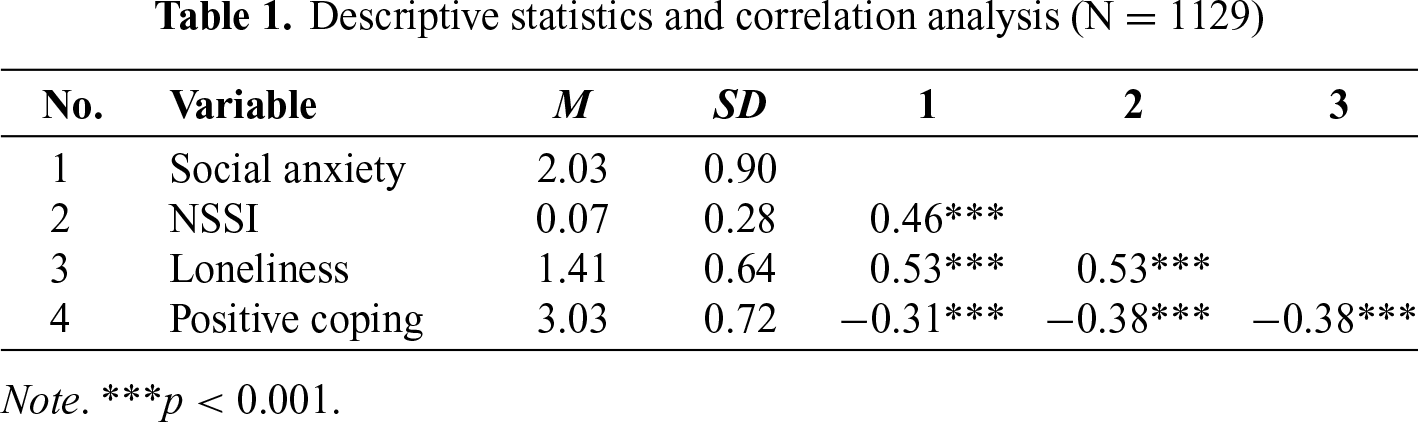

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 1 presents the statistical measures of the study’s correlated variables, including the means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients. The results showed that social anxiety was significantly and positively correlated with NSSI (r = 0.46, p < 0.001) and loneliness (r = 0.53, p < 0.001), but significantly and negatively correlated with positive coping (r = −0.31, p < 0.001). Loneliness was also significantly and positively correlated with NSSI (r = 0.53, p < 0.001). Furthermore, positive coping was significantly and negatively correlated with both NSSI (r = −0.38, p < 0.001) and loneliness (r = −0.38, p < 0.001).

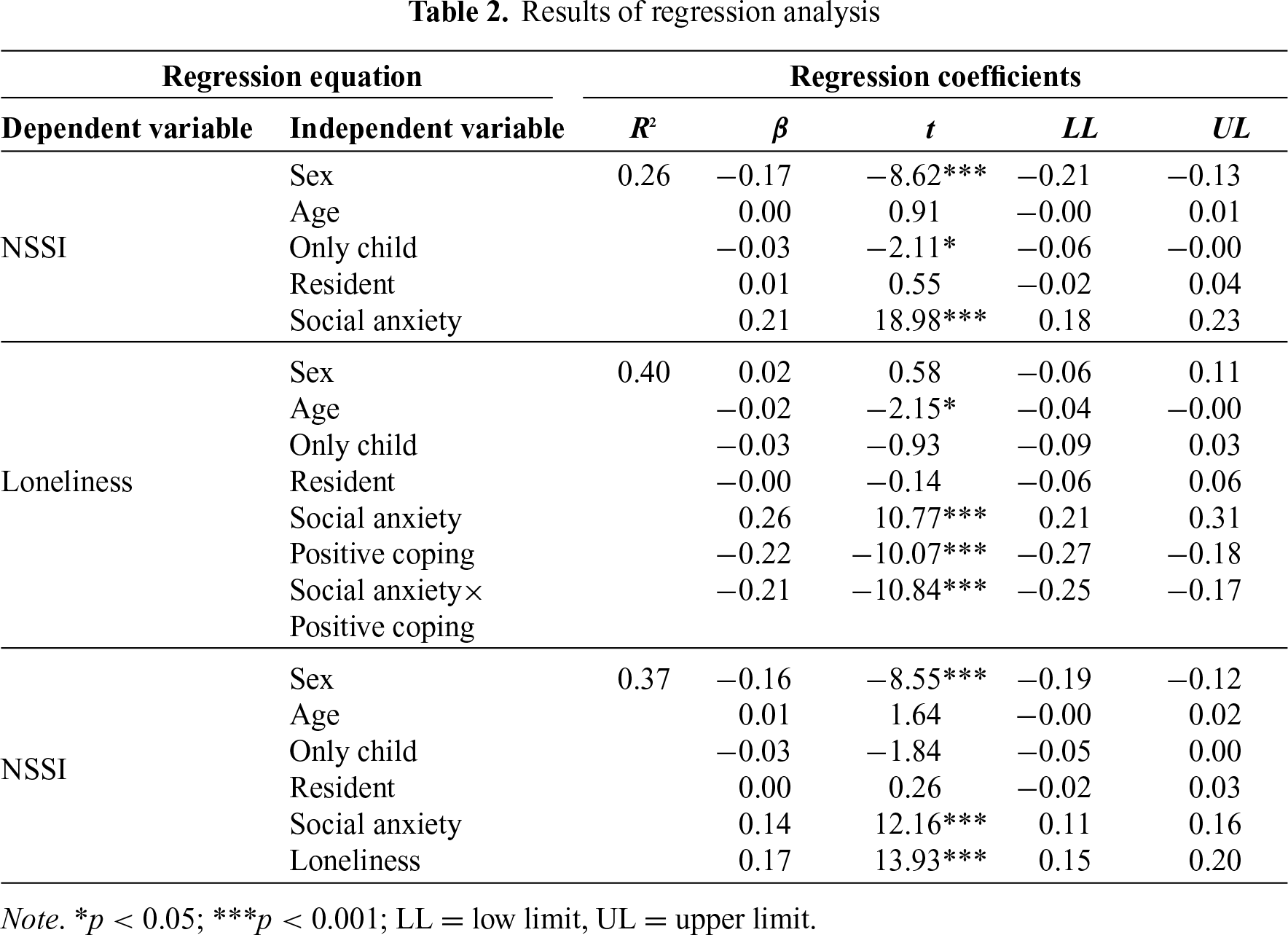

Social anxiety effects on NSSI

The regression analysis results are shown in Table 2. After controlling for gender, age, only-child status, and residence, social anxiety significantly and positively predicted NSSI (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1.

Mediation effect of loneliness

The results revealed that social anxiety significantly and positively predicted loneliness (β = 0.41, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.36, 0.45]). When both social anxiety and loneliness were entered into the regression equation, loneliness significantly and positively predicted NSSI (β = 0.17, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.15, 0.20]), and social anxiety remained a significant predictor (β = 0.14, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.11, 0.16]). These findings indicate a partial mediating effect. The indirect effect of social anxiety on NSSI through loneliness was β = 0.07, 95% CI [0.00, 0.11], accounting for 33.87% of the total effect. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

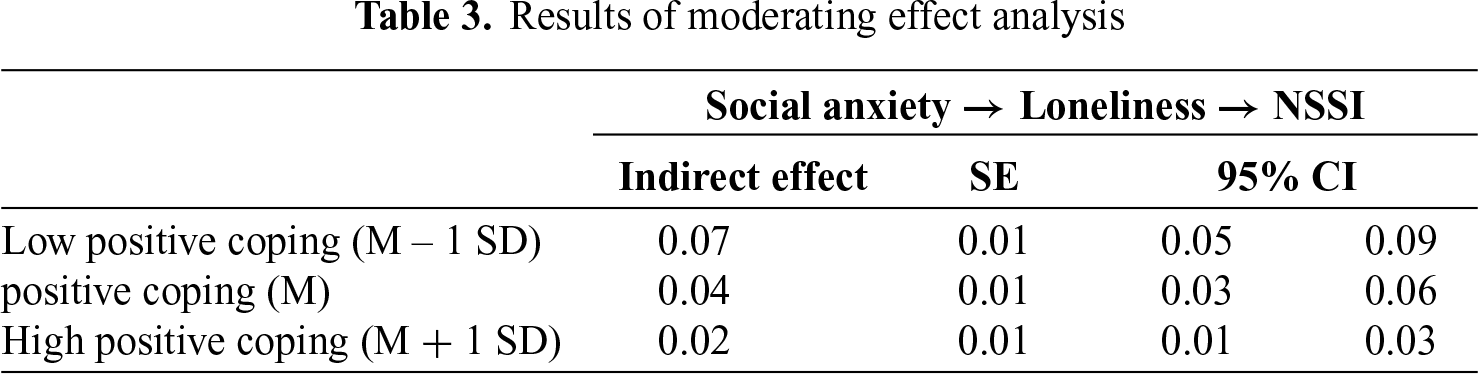

Moderated mediation effect of positive coping

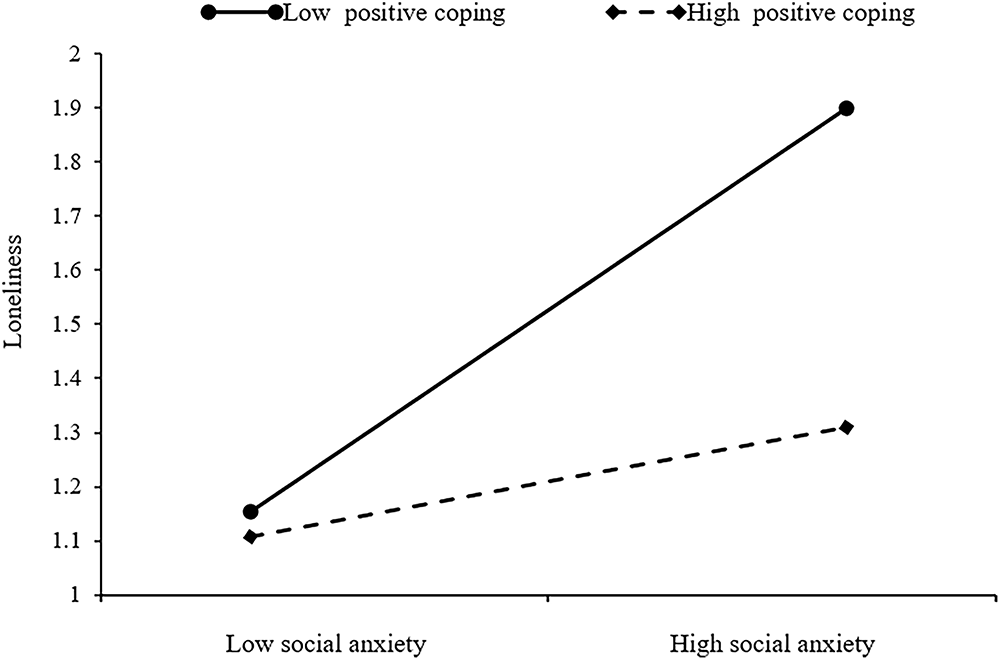

The results showed that social anxiety positively predicted loneliness (β = 0.26, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.21, 0.31]), and the interaction between positive coping and social anxiety was significant (β = −0.21, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.25, −0.17]). The main effect of loneliness on NSSI remained significant when all variables were included in the regression equation (β = 0.17, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.15, 0.20]). These results suggest that positive coping moderates the first stage of the mediation pathway, influencing the strength of the relationship between social anxiety and loneliness. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

To further examine the moderating effect, a simple slopes analysis was conducted by dividing participants into high and low positive coping groups based on their positive coping scores. As shown in Figure 2, social anxiety significantly predicted loneliness among participants with low positive coping (β = 0.41, t = 17.18, p < 0.001). In contrast, for participants with high positive coping, this relationship was weaker but remained significant (β = 0.11, t = 3.56, p < 0.01).

Figure 2: Analysis of the moderating effect of positive cope

As shown in Table 3, for the low positive coping group, social anxiety significantly influenced NSSI through loneliness (β = 0.07, 95% CI [0.05, 0.09]). For the high positive coping group, the indirect effect was smaller (β = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.03]). The difference in the indirect effects between the two groups was significant, with a difference coefficient of −0.04 (95% CI [−0.05, −0.02]), confirming the moderated mediation effect and further supporting Hypothesis 3.

This study found social anxiety to significantly and positively predict NSSI in college students. Both the direct and indirect effects were highly significant. Findings are consistent with Nock’s (2009) integrated theoretical model of NSSI and previous research (Nock, 2009; Wang et al., 2023; Zou et al., 2024). For instance, a large-scale survey of 2717 Chinese university students confirmed the positive correlation between social anxiety and NSSI (Zou et al., 2024). In college environments, where students are constantly surrounded by peers, negative societal biases against NSSI can make those who engage in NSSI more self-conscious and hypervigilant during social interactions (Burke et al., 2019). This heightened awareness, both physical and emotional, can exacerbate social anxiety, thereby strengthening the link between social anxiety and NSSI.

This study found loneliness to mediate the relationship between social anxiety and NSSI among college students. This finding supports Nock’s integrated theoretical model of NSSI and aligns with previous research (Nock, 2009; Reinwarth et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023; Costa et al., 2021; McClelland et al., 2021). For instance, loneliness is associated with a sense of being physically and psychologically “helpless,” which further increases the likelihood of NSSI. College students are particularly susceptible to feelings of loneliness (Qualter et al., 2015). Within Chinese culture, which emphasizes harmony, interdependence, and collective belonging (Huang, 2024), loneliness is not merely an emotional experience but may also be perceived as a failure in social adaptation and an absence of identity integration, thereby amplifying its detrimental effects and association with NSSI (Beller & Wagner, 2020). For individuals with pre-existing social anxiety, who are already fearful of negative evaluation (Villarosa-Hurlocker et al., 2018), the collective cultural expectation to conform may lead them to be viewed as incompetent if they fail to meet the core cultural ideal of sociability (Hu et al., 2024). Such experiences can intensify feelings of frustration and worthlessness, prompting avoidance behaviors that worsen loneliness. This cycle reinforces both interpersonal (social anxiety) and intrapersonal (loneliness) vulnerabilities as outlined in Nock’s (2009) model, ultimately elevating NSSI risk.

The results also revealed that positive coping moderated the first stage of the mediating pathway (social anxiety → loneliness → NSSI). Specifically, students with high levels of positive coping experience a weaker effect of social anxiety on loneliness compared to those with low levels of positive coping. This finding suggests that positive coping buffers the impact of social anxiety on loneliness among college students, a finding consistent with previous research (Zhang et al., 2021; Li, 2020; Dong et al., 2023). Without positive coping, discrepancies between social relationship expectations and lived experiences can widen, contributing to chronic loneliness (Van Buskirk & Duke, 1991). When individuals adopt positive coping strategies, such as proactive problem-solving or seeking support, collectivist cultures can provide a robust social support environment for such strategies. In collectivist contexts like China, stress coping is often viewed as a shared responsibility, and family and social networks are expected to provide emotional and instrumental support (Taylor et al., 2004). However, collectivist norms emphasizing restraint and indirect communication can sometimes inhibit help-seeking behaviors (Kim et al., 2008). Nevertheless, against the backdrop of increasing individualization and the growing prominence of the one-child generation, more Chinese college students are beginning to actively express psychological needs or seek support (Zhu et al., 2015). Positive coping may therefore enable students to mobilize collective resources, such as family and peer support, to alleviate the helplessness and loneliness triggered by social anxiety.

Implications for students’ counseling and development practice

Our study findings suggest a need for college mental health professionals to prioritize teaching positive coping to help alleviate the impact of negative emotions on NSSI. Specifically, College mental health education programs could focus on enhancing interpersonal skills as a starting point, enabling students to better manage social anxiety, reduce loneliness, and ultimately decrease NSSI. Moreover, college students should be recognized as a high-risk population for NSSI. NSSI serves both intrapersonal functions (e.g., emotion regulation, avoidance of aversive emotions, self-punishment) and interpersonal functions (e.g., communication pain, influencing others, or seeking support) (Nock & Prinstein, 2005; Klonsky & Glenn, 2009).

For students experiencing social anxiety, consciously increasing the use of positive coping can help reduce the loneliness associated with social anxiety, thereby weakening its impact on NSSI.

Limitations and future recommendations

Social anxiety, loneliness, and NSSI exhibit dynamic changes over time. The cross-sectional design employed in this study limits the ability to assess these variables dynamically. Future research should employ longitudinal or diary study designs to assess these variables more dynamically and clarify their temporal relationships. Second, positive coping is multidimensional, and state social anxiety often varies across situations. While this study examined the overall effect, future research should differentiate between coping types (e.g., problem-focused vs. emotion-focused) to identify the most effective forms of intervention. Finally, although this study focused on loneliness as a highly aversive emotion, other emotional and interpersonal factors—such as depression or social self-efficacy—should be explored in future studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of NSSI mechanisms among college students.

In conclusion, social anxiety emerged as a significant predictor of NSSI among college students. Loneliness mediates the relationship between social anxiety and NSSI. Positive coping moderates the first stage of the mediation pathway (social anxiety → loneliness → NSSI). Specifically, students with high levels of positive coping show a weaker predictive effect of social anxiety on loneliness compared to those with lower levels of positive coping, indicating a buffering effect of positive coping.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to acknowledge all participants.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Yiyang Federation of Social Science Circles [Grant Number J0416232].

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Yang He and Tao Xu; methodology, Wenqin Chen and Jian Yang; software, Tao Xu; validation, Jian Yang and Shuang Li; formal analysis, Jian Yang; investigation, Jian Yang and Shuang Li; resources, Dong Wang and Wenqin Chen; data curation, Tao Xu; writing—original draft preparation, Yang He and Tao Xu; writing—review and editing, Jian Yang, Yang He and Yiqian Xie; visualization, Shuang Li; supervision, Dong Wang and Wenqin Chen; project administration, Dong Wang and Wenqin Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Wenqin Chen, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Normal University (Approval No. 2025-005), and was conducted in strict accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Aldiabat, K., Matani, N., & Navenec, C. L. (2014). Mental health among undergraduate university students: A background paper for administrators, educators and healthcare providers. Universal Journal of Public Health, 2, 209–214. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujph.2014.020801 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beller, J., & Wagner, A. (2020). Loneliness and Health: The moderating effect of cross-cultural individualism/collectivism. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(10), 1516–1527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264320943336 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Benner, A. D., & Graham, S. (2009). The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Development, 80(2), 356–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01265.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Buckner, J. D., Lemke, A. W., Jeffries, E. R., & Shah, S. M. (2017). Social anxiety and suicidal ideation: Test of the utility of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 45, 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.11.010 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Burke, T. A., Piccirillo, M. L., Moore-Berg, S. L., Alloy, L. B., & Heimberg, R. G. (2019). The stigmatization of nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(3), 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22713 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cameron, L., Erkal, N., Gangadharan, L., & Meng, X. (2013). Little emperors: Behavioral impacts of China’s one-child policy. Science, 339(6122), 953–957. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1230221 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Castro, K., & Kirchner, T. (2018). Coping and psychopathological profile in nonsuicidal self-injurious Chilean adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22493 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chartrand, H., Sareen, J., Toews, M., & Bolton, J. M. (2012). Suicide attempts versus nonsuicidal self-injury among individuals with anxiety disorders in a nationally representative sample. Depression and Anxiety, 29(3), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20882 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Copel, L. C. (1988). Loneliness. A conceptual model. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 26(1), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.3928/0279-3695-19880101-08 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Costa, R. P. O., Peixoto, A. L. R. P., Lucas, C. C. A., Falcão, D. N., Farias, J. T. D. S., et al. (2021). Profile of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: Interface with impulsiveness and loneliness. Jornal De Pediatria, 97(2), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2020.01.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dong, W. L., Li, Y. Y., Zhang, Y. M., Peng, Q. W., Lu, G. L., et al. (2023). Influence of childhood trauma on adolescent internet addiction: The mediating roles of loneliness and negative coping styles. World Journal of Psychiatry, 13(12), 1133–1144. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v13.i12.1133 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1986). Stress-processes and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(2), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.95.2.107 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gandhi, A., Luyckx, K., Baetens, I., Kiekens, G., Sleuwaegen, E., et al. (2018). Age of onset of non-suicidal self-injury in Dutch-speaking adolescents and emerging adults: An event history analysis of pooled data. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 80, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.10.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Giordano, A. L., Prosek, E. A., Schmit, E. L., & Schmit, M. K. (2022). Examining coping and nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents: A profile analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 101(2), 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12459 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Han, A., Xu, G., & Su, P. (2017). A Meta-analysis of characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury among middle school students in mainland China. Chinese Journal of School Health, 38(11), 1665–1670. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2017.11.019 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hu, N., Zhang, W., Haidabieke, A., Wang, J., Zhou, N., et al. (2024). Associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070590 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, M. (2024). Confucian culture and democratic values: An empirical comparative study in East Asia. Journal of East Asian Studies, 24(1), 71–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2023.23 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, W., Zhou, Y. J., Zou, H. Y., Yang, X., Xu, H., et al. (2022). Differences in non-suicidal self-injury behaviors between only-child and non-only-child adolescents with mood disorders: A cross-sectional study. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics, 24(7), 806–811. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2201106 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hudiyana, J., Lincoln, T. M., Hartanto, S., Shadiqi, M. A., Milla, M. N., et al. (2022). How universal is a construct of loneliness? Measurement invariance of the UCLA loneliness scale in Indonesia, Germany, and the United States. Assessment, 29(8), 1795–1805. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911211034564 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kiekens, G., Claes, L., Hasking, P., Mortier, P., Bootsma, E., et al. (2023a). A longitudinal investigation of non-suicidal self-injury persistence patterns, risk factors, and clinical outcomes during the college period. Psychological Medicine, 53(13), 6011–6026. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722003178 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kiekens, G., Hasking, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Auerbach, R. P., et al. (2023b). Non-suicidal self-injury among first-year college students and its association with mental disorders: Results from the World Mental Health International College Student (WMH-ICS) initiative. Psychological Medicine, 53(3), 875–886. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721002245 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., & Taylor, S. E. (2008). Culture and social support. The American Psychologist, 63(6), 518–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Klonsky, E. D., & Glenn, C. R. (2009). Assessing the functions of non-suicidal self-injury: Psychometric properties of the inventory of statements about self-injury (ISAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31(3), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-008-9107-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, M. H. (2012). The one-child policy and gender equality in education in China: Evidence from household data. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9277-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, S. H., Cole, S. W., Park, J., & Choi, I. (2021). Loneliness and immune gene expression in Korean adults: The moderating effect of social orientation. Health Psychology: Official Journal of The Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 40(10), 686–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001133 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, D. (2020). Influence of the youth’s psychological capital on social anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: The mediating role of coping style. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 49(11), 2060–2068. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v49i11.4721 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maes, M., Nelemans, S. A., Danneel, S., Fernández-Castilla, B., Van den Noortgate, W., et al. (2019). Loneliness and social anxiety across childhood and adolescence: Multilevel meta-analyses of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Developmental Psychology, 55(7), 1548–1565. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000719 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

McClelland, H., Evans, J. J., Nowland, R., Ferguson, E., & O’Connor, R. C. (2020). Loneliness as a predictor of suicidal ideation and behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 880–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

McClelland, H., Evans, J. J., & O’Connor, R. C. (2021). Exploring the role of loneliness in relation to self-injurious thoughts and behaviour in the context of the integrated motivational-volitional model. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 141, 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.07.020 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

McNeil, D. W. (2001). Terminology and evolution of constructs in social anxiety and social phobia. In: S. G. Hofmann, P. M. DiBartolo (Eds.From social anxiety to social phobia: Multiple perspectives (pp. 8–19). Boston, MA, USA: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

Meng, X. H., Tao, F. B., Wan, Y. H., Hu, Y., & Wang, R. X. (2011). Coping as a mechanism linking stressful life events and mental health problems in adolescents. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences: BES, 24(6), 649–655. https://doi.org/10.3967/0895-3988.2011.06.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moeller, R. W., & Seehuus, M. (2019). Loneliness as a mediator for college students’ social skills and experiences of depression and anxiety. Journal of Adolescence, 73, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.03.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Morrison, A. S., & Heimberg, R. G. (2013). Social anxiety and social anxiety disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 249–274. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185631 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nock, M. K. (2009). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nock, M. K. (2010). Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2005). Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.140 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Qu, D., Wen, X., Liu, B., Zhang, X., He, Y., et al. (2023). Non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese population: A scoping review of prevalence, method, risk factors and preventive interventions. The Lancet Regional Health. Western Pacific, 37, 100794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100794 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., et al. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615568999 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Reinwarth, A. C., Beutel, M. E., Schmidt, P., Wild, P. S., Münzel, T., et al. (2024). Loneliness and social anxiety in the general population over time—Results of a cross-lagged panel analysis. Psychological Medicine, 54(16), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724001818 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schlenker, B. R., & Leary, M. R. (1982). Social anxiety and self-presentation: A conceptualization model. Psychological Bulletin, 92(3), 641–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.92.3.641 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun, M., Liu, K., Liu, L., Meng, L., & Huang, L. (2017). Validity and reliability evaluation of Social Anxiety Scale of simplified version among junior middle school students. Modern Preventive Medicine, 44(23), 4310–4313. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Tang, J., Li, G., Chen, B., Huang, Z., Zhang, Y., et al. (2018). Prevalence of and risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury in rural China: Results from a nationwide survey in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 226, 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.051 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tatnell, R., Terhaag, S., & Melvin, G. (2024). COVID19 lockdown and non-suicidal self-injury: A mixed methods analysis of NSSI during Australia’s national lockdown. Archives of Suicide Research: Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 28(1), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2022.2155279 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Taylor, P. J., Jomar, K., Dhingra, K., Forrester, R., Shahmalak, U., et al. (2018). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.073 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Taylor, S. E., Sherman, D. K., Kim, H. S., Jarcho, J., Takagi, K., et al. (2004). Culture and social support: Who seeks it and why? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Trepal, H. C., Wester, K. L., & Merchant, E. (2015). A cross-sectional matched sample study of nonsuicidal self-injury among young adults: Support for interpersonal and intrapersonal factors, with implications for coping strategies. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0070-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Valtorta, N., & Hanratty, B. (2012). Loneliness, isolation and the health of older adults: Do we need a new research agenda? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 105(12), 518–522. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2012.120128 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Buskirk, A. M., & Duke, M. P. (1991). The relationship between coping style and loneliness in adolescents: Can sad passivity be adaptive? The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 152(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1991.9914662 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Villarosa-Hurlocker, M. C., Whitley, R. B., Capron, D. W., & Madson, M. B. (2018). Thinking while drinking: Fear of negative evaluation predicts drinking behaviors of students with social anxiety. Addictive Behaviors, 78, 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.10.021 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wan, Y., Liu, W., Hao, J., & Tao, F. (2018). Development and evaluation on reliability and validity of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury assessment questionnaire. Chinese Journal of School Health, 39(2), 170–173. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2018.02.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Y., Liu, Y., & Zhou, J. (2023). Cyberbullying victimization and nonsuicidal self-injury in early adolescents: A moderated mediation model of social anxiety and emotion reactivity. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 26(6), 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2022.0346 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, J. A., Wang, H. F., Cao, B., Lei, X., & Long, C. (2024). Cultural dimensions moderate the association between loneliness and mental health during adolescence and younger adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(8), 1774–1819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-024-01977-w [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu, J., & Liu, H. (2019). Features of nonsuicidal self-injury and relationships with coping methods among college students. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 48(2), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v48i2.825 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xiao, R., & Du, J. (2023). Reliability and validity of the 6-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-6) for application in adults. Journal of Southern Medical University, 43(6), 900–905. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2023.06.04 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xie, Y. (1998). Reliability and validity of simple coping style scale. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 2(1), 53–54. [Google Scholar]

Yan, Y. (2010). The Chinese path to individualization. The British Journal of Sociology, 61(3), 489–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2010.01323.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Younger, J. B. (1995). The alienation of the sufferer. Advances in Nursing Science, 17(4), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-199506000-00006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, Y., Huang, L., Luo, Y., & Ai, H. (2021). The relationship between state loneliness and depression among youths during COVID-19 lockdown: Coping style as mediator. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 701514. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.701514 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhou, J., Zhang, J., Huang, Y., Zhao, J., Xiao, Y., et al. (2022). Associations between coping styles, gender, their interaction and non-suicidal self-injury among middle school students in rural west China: A multicentre cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 861917. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.861917 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhu, T., Nie, D., Yan, Z., & Zhao, N. (2015). A pilot study of comparing social network behaviors between onlies and others. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning, 5(3), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.5555/3002119.3002124 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zou, H., Tang, D., Chen, Z., Wang, E. C., & Zhang, W. (2024). The effect of social anxiety, impulsiveness, self-esteem on non-suicidal self-injury among college students: A conditional process model. International Journal of Psychology, 59(6), 1225–1233. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.13248 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools