Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The longitudinal relationship between active use of social network sites and loneliness: Examining the mediating effects of positive feedback and social support

1 College of Education, Ludong University, Yantai, 264025, China

2 Department of Psychology, Shaoxing University, Shaoxing, 312000, China

3 School of Mathematics Information, Shaoxing University, Shaoxing, 312000, China

* Corresponding Author: Jing Wu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 871-876. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.075981

Received 10 June 2024; Accepted 07 November 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

This study employed a longitudinal approach to investigate how positive feedback and social support mediate the connection between active social network use and feelings of loneliness. A total of 811 college students (females = 58.20%, Mage = 19.15, SD = 0.99) participated in this research study. At T1 time point, students completed the Active SNS Questionnaire. At T2 time point, students completed the online versions of the Positive Feedback Scale, Perceived Social Support Multidimensional Scale, and UCLA Loneliness Scale. T2 online positive feedback influences how T1 actively uses their social network, which relates to T2 loneliness, especially when loneliness levels are low. T2 perceived social support also partly mediates how T1 active social network use influences T2 loneliness, especially when loneliness levels are low. T2 online positive feedback and T2 perceived social support serve a mediating role sequentially in the relationship between T1 active social network use and T2 loneliness. The results of this study indicate that active social network site use can consistently help students receive more positive feedback, perceive more social support, and thus reduce loneliness.Keywords

Social networking sites (SNS) are increasingly vital in people’s everyday lives. Previous studies have examined various aspects of SNS use and the psychological behaviors of users, such as the relationship between SNS engagement and loneliness (Berryman et al., 2018), well-being (Verduyn et al., 2017), depression (Tandoc et al., 2015), and so on. Nevertheless, few studies have considered the social interaction qualities of active vs. passive SNS use (Burke et al., 2011, May; Frison & Eggermont, 2016) and how positive feedback and social support may help mitigate the risk of loneliness. Active SNS includes behaviors such as updating statuses, posting photos, commenting on others’ statuses, and so on. In contrast, passive SNS use refers to behaviors in which users browse others’ statuses and messages, do not participate in posting comments, and do not engage in communication or interaction with others (Cheung et al., 2011).

Assuming that people’s primary goal in using SNS is to maintain or grow their social interactions (Cheung et al., 2011). Feedback qualities and social support can reduce the risk of loneliness among individuals with vulnerabilities, such as young college students. Our study aimed to explore these relationships in the Chinese college context.

Active social network sites use and loneliness

Loneliness is an unpleasant and painful psychological experience when the emotional needs of individuals in interpersonal relationships cannot be fully satisfied (Rokach, 2019). People who feel lonely often report lower life satisfaction and less clarity about their self-concept (Çivitci & Çivitci, 2009), and a higher risk for depression, suicide, and many other psychobehavioral problems (Chang et al., 2015). On the one hand, active SNS use can expand the scope of an individual’s interpersonal network, help individuals maintain good emotional connections (Basilisco & Jin, 2015), and alleviate their sense of loneliness. SNS can provide users with a positive interpersonal experience (Frison & Eggermont, 2016). On the other hand, passive SNS use can increase the risk of loneliness (Teppers et al., 2014), while active SNS use can reduce loneliness (Al-Saggaf & Nielsen, 2014; Lee et al., 2013). Few studies have utilized a longitudinal design to study these relationships

The mediating roles of positive feedback and social support

In the process of socializing through SNS, people pay special attention to the feedback they receive from others (Shin et al., 2017), which can be supportive or problematic. Supportive or positive feedback can be from friends on online platforms, suggesting a kind of value recognition as in social support (Basalingappa et al., 2016). Positive feedback can help reduce individuals’ sense of isolation, which has a positive impact on mental health over time (Deters & Mehl, 2013).

SNS provides opportunities for social support through connections with others (Jung & Sundar, 2016; Park et al., 2009). Perceived social support is especially vital for college students in reducing stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms (Price et al., 2006), as well as preventing mental health problems (Li et al., 2015; Trepte et al., 2015). There is evidence indicating that active SNS use might decrease loneliness (Lin et al., 2021), and a longitudinal study is still needed to explore how social support influences the connection between active SNS use and loneliness across time.

Existing research examining how active SNS use correlates with loneliness is more based on Facebook, but Chinese netizens are more likely to use SNS such as WeChat (China Internet Network Information Center, 2021), Weibo, and QQ. Facebook and WeChat have similar functions in terms of publicizing personal statuses and posting comments, but they are quite different in terms of the groups they target. Facebook is geared towards all users of the network platform, while WeChat, Weibo, and QQ are geared towards only familiar friends and are relatively more private. There are fewer studies on the relationship between active SNS, such as WeChat, Weibo, and QQ, and loneliness, and a lack of longitudinal studies. Therefore, based on the use of WeChat, Weibo, and QQ, this study examines the long-term effects of active SNS use on college students’ loneliness and its underlying mechanisms.

The present study and hypotheses

This study employed a longitudinal research design to investigate the contribution of active SNS use to reducing risk for loneliness in college students and the role of positive feedback and social support over time. We examined the following three hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1. Positive feedback might mediate the link between active SNS use and loneliness over time.

Hypothesis 2. Active SNS use may contribute to a lower risk for loneliness over time through social support.

Hypothesis 3. Positive feedback and social support sequentially mediate the link between active SNS use and the risk of loneliness over time.

The study sample comprised 811 Chinese college students (58.2% = female, Mean_age = 19.15, SD = 0.99). Participants all had more than 3 months of experience in using Social networks. Their majors include Chinese language and literature, English, mathematics, and chemistry.

The 5-item Intensity of Active SNS (Frison & Eggermont, 2016) includes items like “I post content or update my status while using social network sites.” and “I upload photos when I use social network sites.” Items are on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = “never” to 7 = “several times per day”. Higher scale scores indicate higher levels of active SNS use. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the active SNS scale scores was 0.86.

The Positive Feedback Scale comprises 5 items assessing the degree of receiving positive feedback on SNS (Liu & Brown, 2014). Sample items include “How often do you get positive feedback or responses when updating your status on SNS?” and “How often do you get positive feedback or responses when you post a photo on SNS?” Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree.” Higher scores indicate a greater amount of positive feedback received on SNS. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for SES scores was 0.93.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988; Chou, 2000) is a 12-item instrument that assesses the level of social support received via SNS from family, friends, and significant others. Sample items include “I can receive emotional help and support from my family when needed” and “my friends can truly assist me”. Participants rate the items on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = “Very strongly disagree” to 7 = “Very strongly agree.” Higher scores indicate a greater perceived level of social support. In our study, the MSPSS scores had a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.95.

The UCLA-8 Loneliness Scale demonstrates strong validity and reliability among Chinese populations (Chen et al., 2021; Hays & DiMatteo, 1987). Sample items include: “I feel isolated from others,” and “I felt left out.” Respondents evaluate each statement on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 = “Never” to 4 = “Always.” Higher scores reflect greater loneliness. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the UCLA Loneliness Scale was 0.82.

According to Al-Yagon (2008), gender and age are significant factors that influence loneliness. As a result, the study incorporated these factors as control variables in the regression analysis.

The Shaoxing College Ethics Committee approved the study. Participants provided their consent to the study, with assurances of confidentiality of their data and its use for study purposes only. At the end of the survey, a small gift was given to the subjects as a reward. The initial survey took place in February 2022, and the second one was conducted in July 2022.

SPSS 25.0 and Mplus 8.3 were utilized for the analyses. A two-step approach was employed to investigate the mediating effects in the latent variable structural model. First, the goodness of fit of the measurement model was tested. Secondly, if the measurement model’s goodness of fit was satisfactory, the structural model was evaluated through maximum likelihood estimation.

Multiple items measuring a unidimensional latent variable can cause significant measurement errors. To address this, we employed a packing method procedure to combine items and create clear indicators for each unidimensional construct. Three-item parcels were created for the T1 active SNS use and T2 loneliness factors. We consult a series of standard fit indices to assess both the measurement and structural models’ fit: relative chi-square statistic (χ2/df), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR). Measurements are generally considered acceptable at values of χ2/df ≤ 5, ≤0.08 for the RMSEA, ≥0.90 for the CFI and TLI, and ≤0.08 for SRMR (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Since bootstrap estimation is among the most accurate methods for evaluating confidence intervals of indirect effects, it was employed in this study to determine their significance. In this study, 2000 bootstrap samples were randomly drawn from the original data to compute confidence intervals (CI). The indirect effect will be considered significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) for it does not include 0.

This study used Harman’s single-factor approach to evaluate common method bias. All items from the four questionnaires were subjected to exploratory factor analysis using SPSS 25.0. The analysis revealed seven factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1. The first factor accounted for 36.61% of the total variance, which is below the 40% cutoff. Therefore, the findings indicate that significant common method bias is probably not present in this study.

Measurement model for evaluating mediated relationships

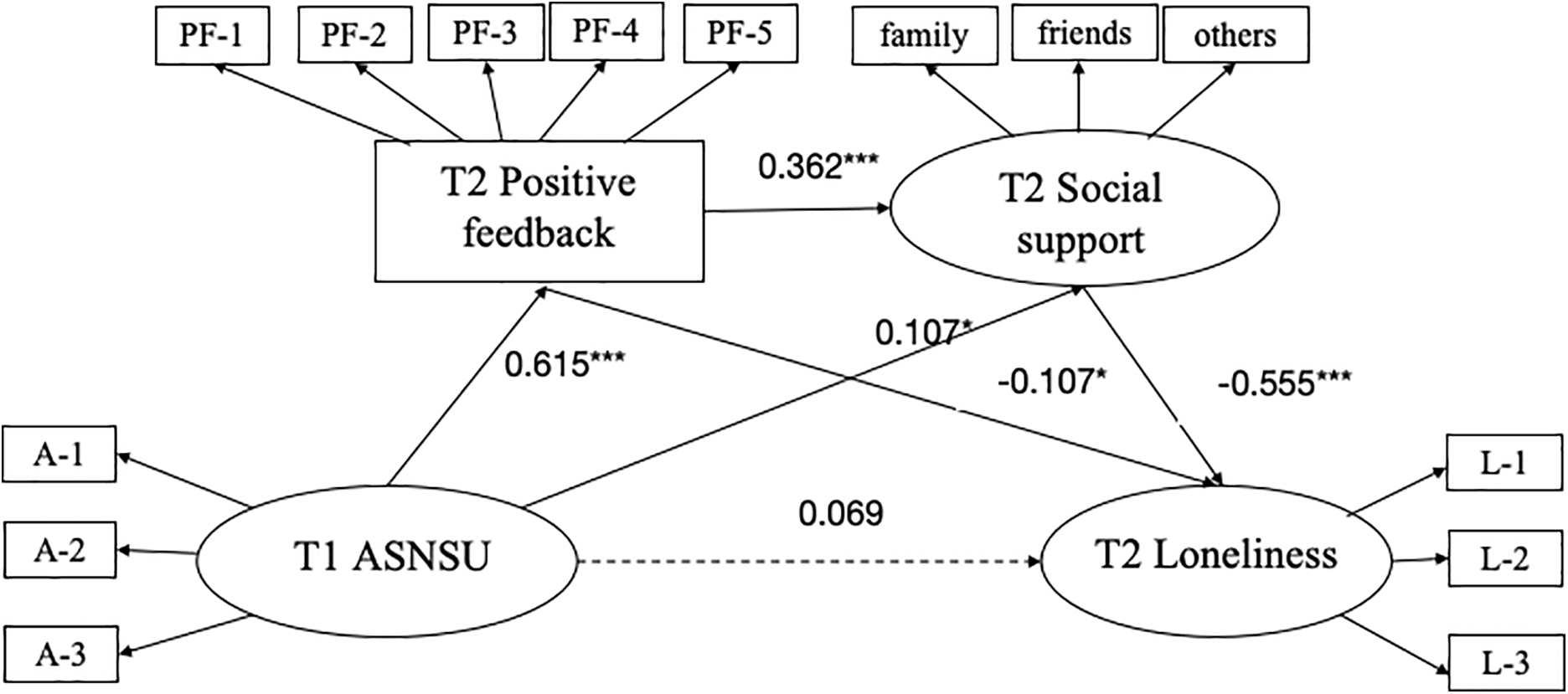

The items were randomly assigned in this study to reduce measurement error and enhance model fit. The measurement model includes four latent variables (i.e., T1 active SNS use, T2 positive feedback, T2 social support, and T2 loneliness) and 14 observed variables. The model showed a good fit with the data: χ2/df = 4.38, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.06. Since the loadings of each indicator on the latent factors are significant, it suggests that each latent variable is well-represented by its respective indicator (p < 0.001, see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The finalized model (N = 811). All factor loadings have been standardized. A-1, A-2, and A-3 represent three parcels of active SNS use; PF1 to PF5 are five parcels of self-concept clarity; L-1 to L-3 represent three parcels of loneliness. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001

Descriptive analysis and correlations

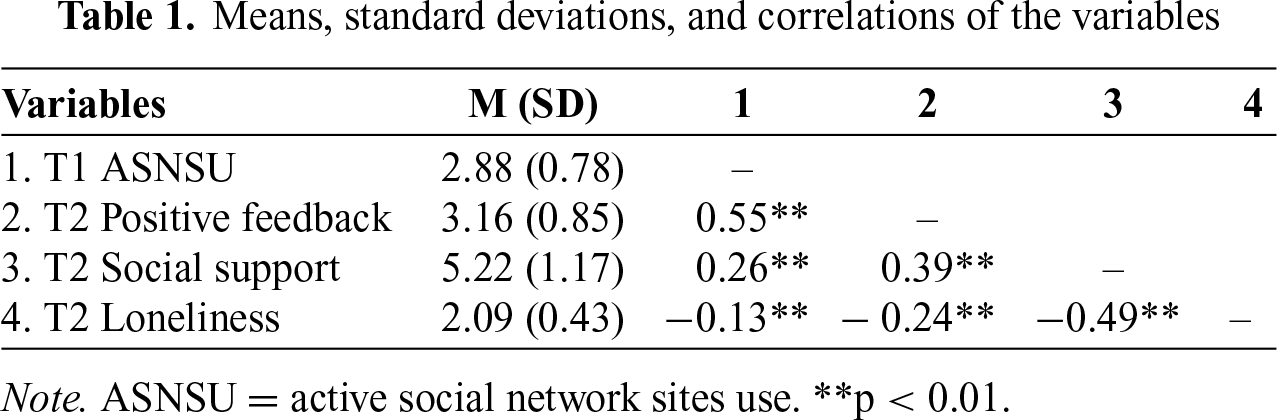

The results of the descriptive statistics analysis for all variables are presented in Table 1. Active SNS use at T1 showed a positive correlation with positive feedback at T2 (r = 0.55, p < 0.01) and with social support at T2 (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), while it was negatively correlated with loneliness at T2 (r = −0.13, p < 0.01). Likewise, T2 positive feedback was positively associated with T2 social support (r = 0.39, p < 0.00) and inversely related to T2 loneliness (r = −0.24, p < 0.01). Additionally, T2 social support was negatively correlated with T2 loneliness (r = −0.49, p < 0.01).

Structural model for the direct and indirect paths

Active use of SNS at T1 directly decreases loneliness at T2 (β = −0.16, p < 0.001). However, when mediating factors are taken into account, T1 active SNS use no longer significantly affects T2 loneliness (β = −0.07, p > 0.01). Additionally, T1 active SNS use significantly boosts T2 positive feedback (β = 0.62, p < 0.001), and in turn, T2 positive feedback significantly decreases T2 loneliness (β = −0.11, p < 0.05). These findings support Hypothesis 1.

T1 active SNS use significantly increased T2 social support (β = 0.11, p < 0.05), and T2 social support significantly reduced T2 loneliness (β = −0.56, p < 0.001). This result supports Hypothesis 2. Meanwhile, T2 social support significantly increased T2 positive feedback (β = 0.36, p < 0.001). This suggests that T2 positive feedback and T2 social support sequentially mediate the relationship between T1 active SNS use and T2 loneliness. This supports Hypothesis 3.

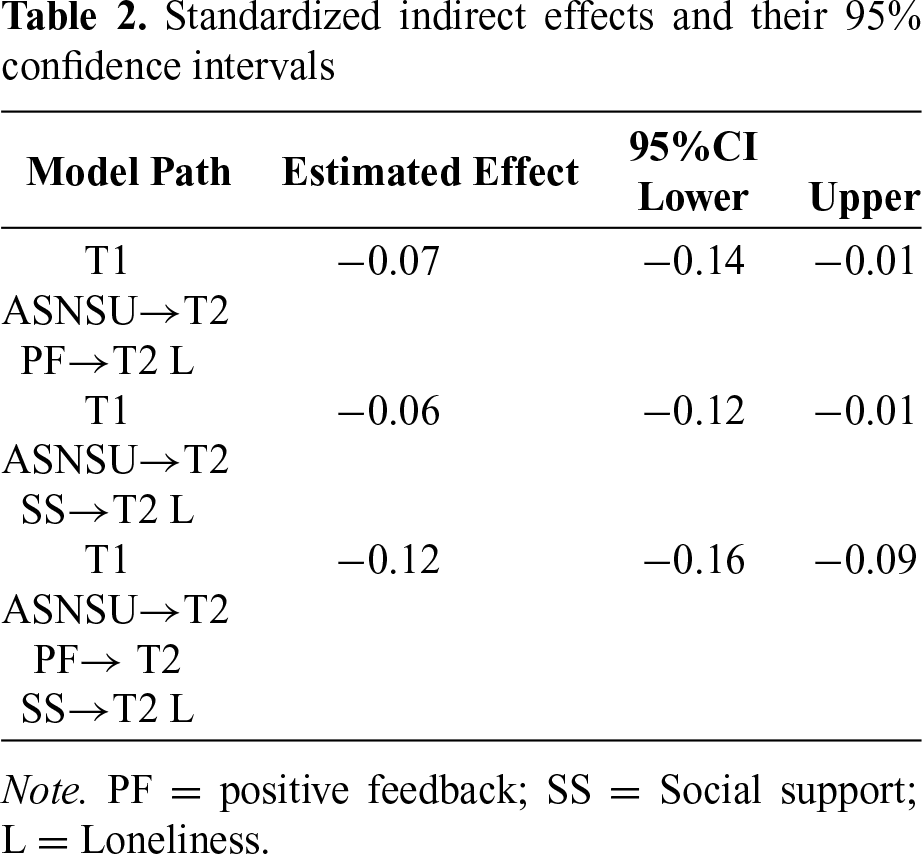

We use the bootstrap procedure to estimate indirect effects (see Figure 1). The indirect effect of T1 active SNS use → T2 positive feedback → T2 loneliness was −0.07 (95% CI: −0.14~−0.01). The indirect effect of T1 active SNS use → T2 social support → T2 loneliness was −0.06 (95% CI: −0.12~−0.01). The indirect effect of T1 active SNS → T2 positive feedback → T2 social support → T2 loneliness was −0.12 (95% CI: −0.16~−0.09) (see Table 2). The results indicated that the 95% CI did not include 0, demonstrating that all indirect effects in the sequential mediation model were statistically significant.

In this study, we used the tracking research paradigm to explore how college students’ active SNS use impacts loneliness and its underlying mechanisms by constructing a structural equation model. We found that the baseline level of active SNS use negatively predicted college students’ loneliness levels. Behaviors such as posting statuses, uploading photos, and commenting on friends’ statuses can help reduce loneliness and support mental health among adolescents. The results confirm the three hypothesized effects proposed earlier.

This study discovered that active use of SNS can decrease the personal risk of loneliness over time, mediated by positive feedback. These findings align with those from earlier cross-sectional research (Lin et al., 2021). One of the main motivations for individuals to use SNS is to gain recognition and attention from others (Basalingappa et al., 2016). Receiving a higher frequency of positive feedback online increases adolescents’ positive emotional experiences (Bevan et al., 2012), which, in turn, leads to an increase in psychological well-being.

Perceived social support through active SNS use mediated a decrease in loneliness over time. This may be because active SNS engagement enables individuals to access greater social support, which in turn further alleviates loneliness (Lin et al., 2021). Social support serves as a crucial psychological resource for managing stressful situations and is key in predicting mental health outcomes (George et al., 1989; Brissette et al., 2002).

Over time, positive feedback and social support mediated the link between active SNS use and loneliness risk. Active SNS use increases the frequency of positive feedback received by individuals, which further increases social support and ultimately decreases loneliness. This finding can be attributed to the fact that a higher frequency of positive feedback often indicates a strong level of social support (Liu & Brown, 2014). Additionally, a supportive social environment fosters the development of an individual’s psychological well-being.

Implications for theory and practice

As society continues to develop, SNS has become a key platform for communication among youth, significantly affecting their psychological health. How to scientifically manage SNS use and safeguard adolescents’ mental well-being is now a major concern for researchers.

The present study’s findings shed light on how active SNS use influences loneliness and show how this effect changes over time. Hence, the present study is an important addition to research in the area of SNS use. Colleges can build an online communication platform to facilitate students’ online communication. Parents and teachers can encourage students to actively use social networks to express their thoughts and emotions, and communicate more with friends through social networks. By actively using social networks, students can receive more feedback and social support, which helps alleviate their feelings of loneliness.

Limitations and future directions. While this study has its strengths, it also faces certain limitations. A major limitation is that the study involved only Chinese undergraduate students, which raises questions about the generalizability of the findings to other age groups and cultural contexts. Only two follow-up surveys were conducted in this study, and future studies can further verify the results of this study through more surveys. Future research can expand the sample size and select students from different cultural backgrounds to conduct surveys. Additionally, various mediators (e.g., self-clarity) and moderators (e.g., gender) might influence this relationship.

This study found that positive feedback and social support serve as mediators in the relationship between college students’ active SNS use and their risk of loneliness over time, which would reduce their risk for loneliness. Findings improve insight into how active SNS use affects loneliness risk over time. They also suggest that acknowledging the key links between active SNS use, positive feedback, social support, and loneliness could inform interventions aimed at reducing loneliness among college students. Boosting positive feedback and social support through various psychological programs might effectively decrease loneliness in the long run.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Educational Science Planning Project in Zhejiang Province [2025SCG138] and National Social Science Fund Later-stage Funding Project [24FZXB026].

Author Contributions: Conceptualization and writing—original draft preparation, Jing Wu; investigation and methodology, Yuan Gao; data curation, Quanlu Hao; visualization and supervision, Zhun Liu, Weijie Meng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration. Ethics approval for the study was granted by the ethics committee of Shaoxing University.

Informed Consent: All participants in the study were fully informed of the content and purpose of the research and obtained informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Al-Saggaf, Y., & Nielsen, S. (2014). Self-disclosure on Facebook among female users and its relationship to feelings of loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 36(1), 460–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.014 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Al-Yagon, M. (2008). On the links between aggressive behavior, loneliness, and patterns of close relationships among non-clinical school-age boys. Research in Education, 80(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.7227/rie.80.7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Basalingappa, A., Subhas, M. S., & Tapariya, R. (2016). Understanding likes on Facebook: An exploratory study. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 6(3), 234. https://doi.org/10.29333/ojcmt/2566 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Basilisco, R., & Jin, K. (2015). Uses and gratification motivation for using Facebook and the impact of Facebook usage on social capital and life satisfaction among Filipino users. International Journal of Software Engineering & Its Applications, 9(4), 181–194. [Google Scholar]

Berryman, C., Ferguson, C. J., & Negy, C. (2018). Social media use and mental health among young adults. Psychiatric Quarterly, 89(2), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-017-9535-6 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bevan, J. L., Pfyl, J., & Barclay, B. (2012). Negative emotional and cognitive responses to being unfriended on Facebook: An exploratory study. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(4), 1458–1464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.03.008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brissette, I., Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2002). The role of optimism in social network development, co**, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.102 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Burke, M., Kraut, R., & Marlow, C. (2011, May). Social capital on facebook: Differentiating uses and users. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA: ACM, pp. 571–580. [Google Scholar]

Burke, M., Marlow, C., & Lento, T. (2010, April). Social network activity and social well-being. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference On Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA: ACM, pp. 1909–1912. [Google Scholar]

Chang, E. C., Muyan, M., & Hirsch, J. K. (2015). Loneliness, positive life events, and psychological maladjustment: When good things happen, even lonely people feel better!. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.016 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, W., Meng, Q.-F., Tian, X., Zhang, G.-Y., & Wang, L. (2021). Validity and reliability of the Short-form of the University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale among middle school students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 35, 583–589. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Cheung, C. M., Chiu, P. Y., & Lee, M. K. (2011). Online social networks: Why do students use Facebook? Computers in Human Behavior, 27(4), 1337–1343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.028 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

China Internet Network Information Center (2021). 2021 Research report on user behavior of social applications in China. [cited 2025 Nov 1]. http://www.cnnic.net.cn/. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Chou, K. L. (2000). Assessing Chinese adolescents’ social support: The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(2), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(99)00098-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Deters, F. G., & Mehl, M. R. (2013). Does posting Facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(5), 579–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612469233 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review, 34(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314567449 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

George, L. K., Blazer, D. G., Hughes, D. C., & Fowler, N. (1989). Social support and the outcome of major depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 154(4), 478–485. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.154.4.478 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hays, RD, DiMatteo, MR (1987). A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of personality assessment, 51(1), 69–81 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Jung, E. H., & Sundar, S. S. (2016). Senior citizens on Facebook: How do they interact and why? Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.080 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, K. T., Noh, M. J., & Koo, D. M. (2013). Lonely people are no longer lonely on social networking sites: The mediating role of self-disclosure and social support. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(6), 413–418. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0553 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, X., Chen, W., & Popiel, P. (2015). What happens on Facebook stays on Facebook? The implications of Facebook interaction for perceived, receiving, and giving social support. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.066 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, S., Liu, D., Liu, W., Hui, Q., Cortina, K. S., & You, X. (2021). Mediating effects of self-concept clarity on the relationship between passive social network sites use and subjective well-being. Current Psychology, 40, 1348–1355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0066-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, D., & Brown, B. B. (2014). Self-disclosure on social networking sites, positive feedback, and social capital among Chinese college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Park, N., Kee, K. F., & Valenzuela, S. (2009). Being immersed in a social networking environment: Facebook groups, uses and gratifications, and social outcomes. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(6), 729–733. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2009.0003 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Price, E. L., McLeod, P. J., Gleich, S. S., & Hand, D. (2006). One-year prevalence rates of major depressive disorder in first-year university students. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 40(2), 68–81. [Google Scholar]

Rokach, A. (2019). The psychological journey to and from loneliness: Development, causes, and effects of social and emotional isolation. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

Shin, Y., Kim, M., Im, C., & Chong, S. C. (2017). Selfie and self: The effect of selfies on self-esteem and social sensitivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tandoc, E. C., Ferrucci, P., & Duffy, M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is Facebooking depressing? Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.053 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Teppers, E., Luyckx, K., Klimstra, T. A., & Goossens, L. (2014). Loneliness and Facebook motives in adolescence: A longitudinal inquiry into directionality of effect. Journal of Adolescence, 37(5), 691–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.003 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Trepte, S., Dienlin, T., & Reinecke, L. (2015). Influence of social support received in online and offline contexts on satisfaction with social support and satisfaction with life: A longitudinal study. Media Psychology, 18(1), 74–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.838904 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2017). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11, 274–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12033 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar]

Çivitci, N., & Çivitci, A. (2009). Self-esteem as mediator and moderator of the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 954–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.022 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools