Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Review of the Research on the Impact Resistance Mechanical Performance of Prestressed Segmental Precast and Assembled Piers

1 Department of Civil Engineering, Hangzhou City University, Hangzhou, 310015, China

2 Zhejiang Engineering Research Center of Intelligent Urban Infrastructure, Hangzhou, 310015, China

3 Department of Civil Engineering, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China

* Corresponding Author: Xinquan Wang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Construction Failures and Prevention under Unforeseen Circumstances)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(4), 819-850. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.060580

Received 05 November 2024; Accepted 25 December 2024; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This article provides an overview of the current development status of prestressed segmental precast and assembled piers, Emphasis was placed on analyzing the stress characteristics of bridge piers under impact. The concept of recoverable functional design and its application prospects were elaborated, and finally, the research on the impact resistance performance of prestressed segmental precast and assembled piers was discussed. Research has shown that optimizing design and material selection can effectively enhance the impact resistance and structural durability of bridge piers. At the same time, the introduction of the concept of recoverable functionality provides new ideas for the rapid repair and functional recovery of bridge piers, which helps to improve the recovery efficiency of bridges after extreme events. Future research should focus on the evaluation methods of impact resistance performance, new connection technologies, in-depth application of recoverable functional design, a combination of impact simulation experiments and numerical analysis, and exploration of comprehensive disaster prevention and reduction strategies. These research results will also promote the further development and innovation of prefabricated assembly technology in bridge engineering, bringing new ideas and methods to the field of engineering construction.Keywords

With the support and investment from national policies, there has been a significant increase in transportation routes, leading to a rise in the number of elevated bridges and river-crossing beam bridges. The bridge piers are a critical component of bridge structures, as they may be subject to collisions with vehicles, vessels, and other modes of transportation during their operation. Such collisions can exert impact forces on the piers, resulting in structural damage, cracks, and other forms of deterioration. Over time, these issues can affect the overall performance and lifespan of the bridge. 2 Current status of prefabricated bridge pier technology development.

As of March 2021, the elevated bridge piers of Chongqing’s urban rail transit system had suffered a cumulative total of 69 vehicle collisions, with 11 of these incidents occurring in 2019 [1]. Between 2000 and 2009, out of the 85 major bridge accidents reported, 15% were directly or indirectly caused by vehicle collisions [2].

According to statistics from the U.S. Department of Transportation, among the many large bridges in service, approximately one in ten bridges have been decommissioned due to collapse caused by collisions with off-course vessels [3,4]. According to international data, between 1960 and 2002—a span of 42 years—globally, 32 major bridges were damaged or destroyed by ship collisions. Of these, 15 bridges in the United States alone were struck, resulting in 321 fatalities. Based on incomplete domestic statistics, there have been over 300 ship-bridge collision incidents on the main channels of the Yangtze River, Pearl River, and Heilongjiang River basins, with the number of such accidents remaining consistently high year after year [5]. A specific case occurred on 22 February 2024, in Nansha District, Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province, where an empty container ship collided with a pier of the Lixinsha Bridge, causing the bridge deck to break and resulting in five deaths. These data and cases highlight the severe threat that ship-bridge collisions pose to bridge safety and human life.

Bridge accidents triggered by flood disasters are also increasing. For instance, during the flood disaster in 1994, bridges were washed away, resulting in the disruption of major railway trunk lines in China for more than 200 times, with over 300 locations damaged and transportation halted for more than 3600 h. Additionally, incidents such as the collapse of the Xi’an Bahe Bridge on the Longhai Railway in Shaanxi in 2002, the collapse of the Panjin Bridge in Liaoning in 2004, the collapse of the Nanzamu Bridge in Xinbin Manchu Autonomous County, Liaoning, in 2007, and the collapse of the Tangying Bridge over the Yi River in Henan in 2010, have all had tremendous impacts on China’s transportation and economic development [6].

In the southwestern region of China, rockslide disasters typically manifest as sudden and unpredictable hazards. Given that numerous roads and bridges are constructed in mountainous terrains, rock collision accidents occur frequently, leading to severe consequences and subsequently affecting the normal performance of bridge piers. As of 2021, rockslide disasters have been reported in the southwestern region for eight consecutive years. The collapse of bridges due to rock impacts has disrupted traffic flow, posing a substantial threat to both the national economy and the safety of people’s lives and property [7,8].

Therefore, research on the impact resistance of bridge piers holds significant importance in the field of bridge engineering. By conducting in-depth studies and discussions on the impact resistance performance of bridge piers, we can continuously improve the theoretical framework and technical proficiency of bridge engineering, elevate the overall standard of bridge construction, and contribute to the sustainable development of the transportation industry.

Prefabricated bridge piers represent a novel construction method for bridges, characterized primarily by dividing tall piers vertically and horizontally into several components according to a certain modulus. These components are cast in prefabrication yards surrounding the bridge site, transported to the site via watercraft or vehicles, and then lifted and assembled. The advantages of this construction method lie in the prefabrication of components in prefabrication yards, which minimizes external interference, and offers standardized component production, convenient and efficient construction, energy conservation, and environmental protection. The main steps in the construction of prefabricated bridge piers include prefabrication of components, installation and connection, and concrete joint filling. Among these, the assembly joint is a critical process, requiring both firmness and safety, as well as a simple structure to facilitate construction.

This article will commence with an overview of the development of prefabricated bridge pier technology, analyze the application prospects of prefabricated bridge piers in the field of impact resistance, and integrate the concept of restorable functionality design. Furthermore, it will provide an outlook on research into the impact resistance of prefabricated bridge piers.

2 The Current State of Precast Prestressed Bridge Piers Technology

As the demand for transportation infrastructure continues to increase, the construction of bridge infrastructure is trending towards higher quality, efficiency, and safety. Efforts are being made to minimize the impact on the surrounding environment and reduce environmental pollution during the construction process [9]. Against this backdrop, scholars such as D’Amato have employed nonlinear analysis methods to assess the seismic performance of existing bridge structures, including conventional reinforced concrete bridges [10] and historic stone masonry arch bridges [11], as well as their sensitivity to the assumed mechanical properties of masonry materials. This research aims to explore effective protection and reinforcement strategies to extend the service life of these structures.

For new bridge constructions, traditional methods struggle to meet the high standards required by modern bridge engineering. In response, Accelerated Bridge Construction (ABC) technology has emerged as a viable solution. ABC technology involves the use of prefabricated components for rapid assembly, thereby reducing on-site traffic disruptions, ensuring construction quality, enhancing construction safety, and lowering lifecycle costs. This integrated technology has demonstrated significant maturity and broad application in the superstructure of bridges, with successful fabrication of prestressed concrete beams exceeding 61 m in span [12].

The application of ABC technology in substructures primarily manifests as prefabricated segmental bridge piers, which were first implemented in the Pontchartrain Bridge in New Orleans, United States, in 1955. Over the past six decades, this technology has gradually been extended to non-seismic and low-seismicity regions [13]. Two types of connections—socket-type connections and grouted corrugated pipe connections—have been successfully applied in the Jiamin Elevated Road Bridge project in Shanghai, China [14].

Although prefabricated segmental bridge piers have been applied in low-seismicity regions, their use in impact-resistant applications still faces skepticism and challenges. A key technical issue for the prefabricated segmental bridge pier system is ensuring effective connections between prefabricated components under various loading conditions. Different assembly node connection methods can have varying impacts on the mechanical performance of the bridge piers.

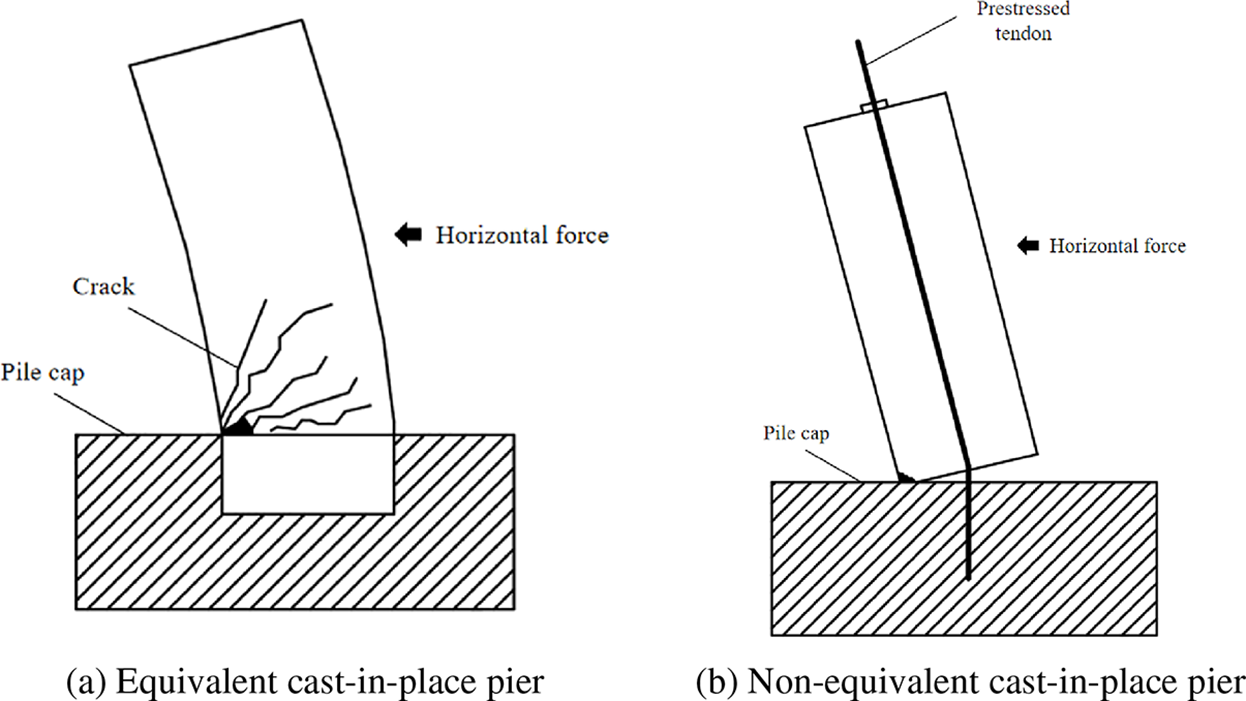

According to Fig. 1, the connection configurations of prefabricated segmental bridge piers can be categorized into two main types based on their mechanical behavior: one type is the “equivalent cast-in-place” (ECP) type, which matches or closely resembles the performance of conventional cast-in-place piers (see Fig. 1a); the other type is the “non-equivalent cast-in-place” (NECP) type, which exhibits distinct mechanical characteristics (see Fig. 1b). The “equivalent cast-in-place” (ECP) structure is designed to ensure that the load-bearing performance of the prefabricated pier is consistent with that of a traditionally cast-in-place pier. In contrast, the “non-equivalent cast-in-place” (NECP) design incorporates prestressing technology, specifically post-tensioning, to apply prestressing tendons. This design allows for nonlinear rotation to primarily occur at designated swinging nodes during an earthquake, thereby maintaining the elastic state of the main body of the prefabricated components and reducing the impact of seismic forces on the structure.

Figure 1: Two basic structures of precast assembled piers

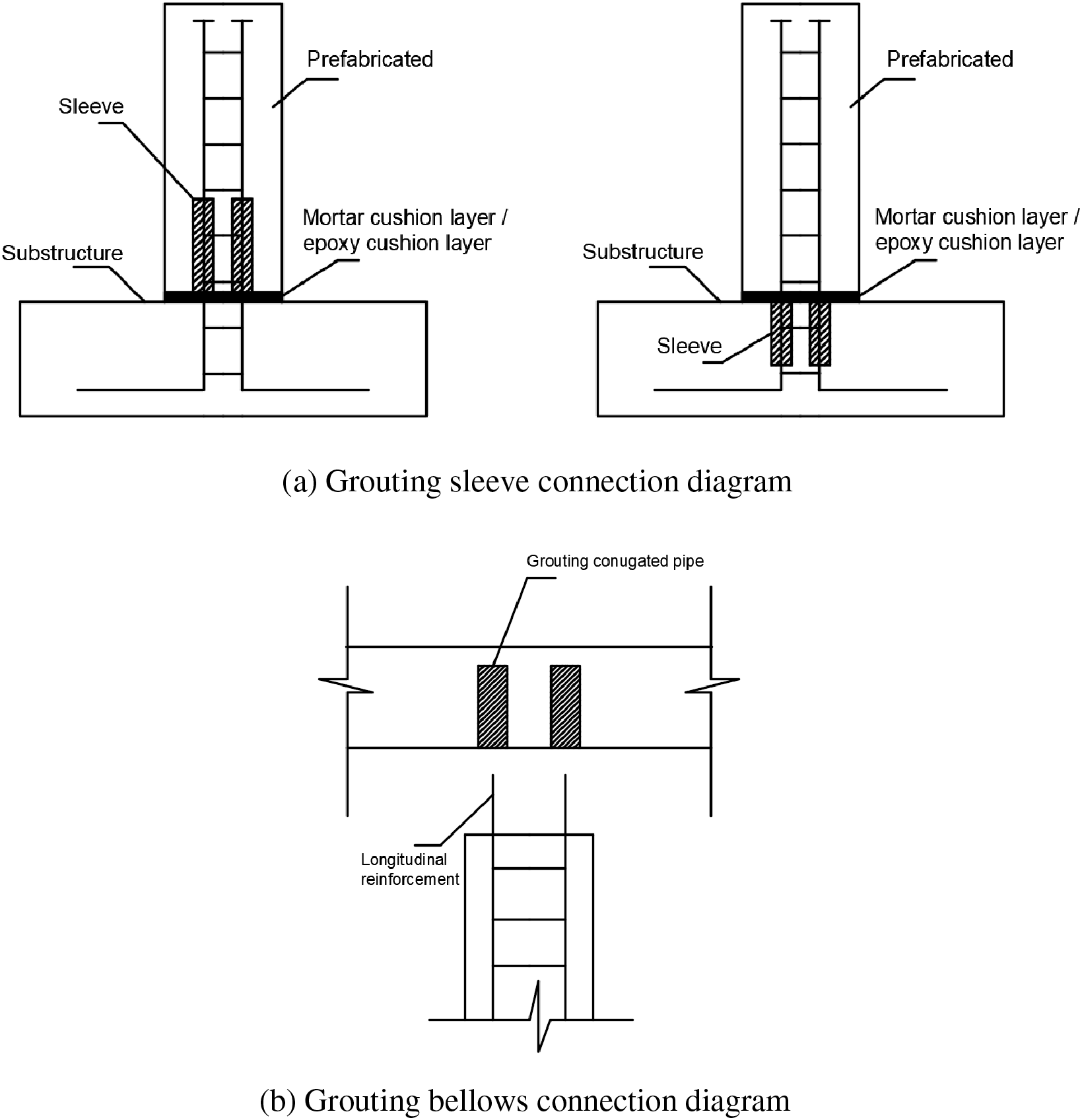

The “equivalent cast-in-place” (ECP) prefabricated bridge piers are the most widely used connection type in current engineering practice. They can be further subdivided into ductile connections and high-strength connections. The design philosophy of ductile connections is to allow the reinforcement to yield first during an earthquake, ultimately forming a plastic hinge zone within the connection region. This design ensures that the ECP prefabricated bridge pier has sufficient ductility, requiring the connection area to withstand significant plastic deformation without losing stability. In contrast, high-strength connections are based on the principle of capacity design. By increasing the load-carrying capacity of the connection region, these connections ensure that the ECP prefabricated bridge pier remains within the elastic range during seismic events, avoiding any plastic deformation. This allows plastic hinges to develop fully within the prefabricated sections of the pier, thereby absorbing seismic energy. The primary connection methods used for constructing “equivalent cast-in-place” prefabricated bridge piers include grouted sleeve connections (see Fig. 2a), grouted corrugated pipe connections (see Fig. 2b), socket-type connections (see Fig. 2c), and splice connections (see Fig. 2d). Common connection forms for “non-equivalent cast-in-place” bridge piers involve prestressing tendon connections (see Fig. 2e) [15,16].

Figure 2: Common types of connection structures for prefabricated bridge pier systems

Given the unique nature of the connection joints in prefabricated segmental bridge piers, the discontinuity at the joints results in inferior mechanical performance, particularly in shear resistance, compared to traditional concrete bridge piers. To systematically investigate the mechanical behavior of prefabricated segmental bridge pier joints under combined loading conditions (axial force, shear force, and bending moment), Li et al. [17] conducted monotonic loading tests on four prestressed prefabricated bridge piers with epoxy-splice (ES) joints and three prefabricated bridge piers with grouted sleeve splice (GSS) joints. The test results showed that as the slenderness ratio increased from 1.3 to 5.3 for the ES joint piers and from 3.3 to 5.3 for the GSS joint piers, the ultimate shear capacity of the joint plane decreased significantly by 71% and 34%, respectively, while the ultimate bending moment increased by 20% and 9%, respectively. This finding reveals that the failure mechanisms of these two types of joints (ES and GSS) in prefabricated bridge piers are the result of multiple force fields acting together, leading to failure modes that differ significantly from the pure shear and pure bending modes observed in traditional cast-in-place joints. Therefore, the shear resistance of the joints in prefabricated segmental bridge piers is a critical factor that cannot be overlooked in the overall assessment of their mechanical performance.

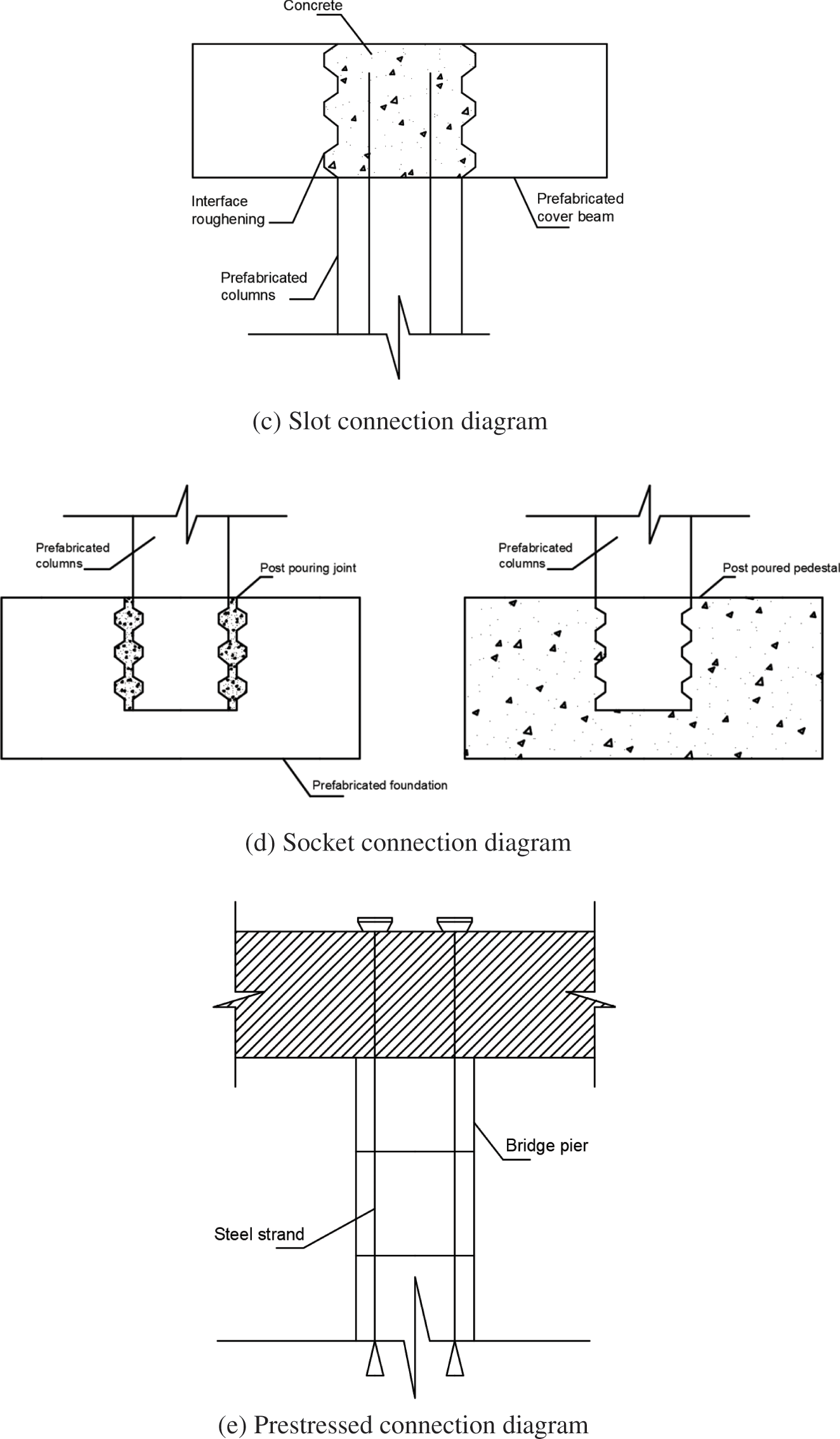

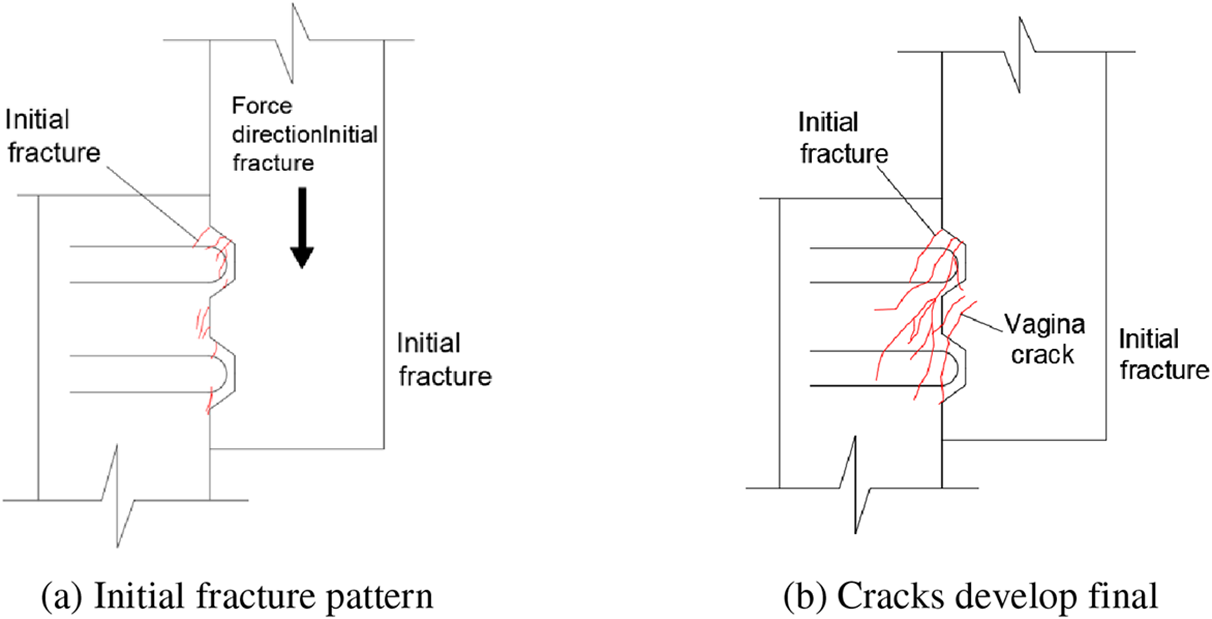

The shear load-carrying capacity of the joints in prefabricated segmental bridge piers primarily stems from the friction between the concrete interfaces at the joints, the pin effect of shear keys, and the bonding performance of the adhesive materials used at the joints. These contributing factors are closely related to parameters such as concrete strength and the configuration of shear keys [18,19]. Yuan et al. [20] conducted direct shear tests on shear key specimens with epoxy-splice joints, comprehensively considering three key factors: the number of shear keys, the reinforcement of key teeth, and the presence or absence of internal prestressing tendons. As shown in Figs. 3 and 4, the crack development paths did not follow the typical failure mode of unreinforced shear key teeth, which typically propagate along the root of the key teeth. Instead, cracks primarily occurred by spalling along the concrete cover of the reinforced key teeth. This phenomenon is significantly different from the overall detachment of unreinforced key teeth under shear forces, highlighting the substantial impact of reinforcement on the failure mode of shear key teeth. Further comparative analysis revealed that three-tooth shear key specimens exhibited a significant improvement in plastic deformation capacity compared to two-tooth shear key specimens. The study results further confirmed that through reasonable reinforcement design of the key teeth and optimized configuration of internal prestressing tendons, the ductility of shear keys during the failure process can be effectively enhanced, while the ratio between cracking load and ultimate load can be significantly reduced. Additionally, these structural optimization measures altered the final failure mode of the specimens, avoiding the common brittle failure at the root of plain concrete key teeth, thereby improving the overall performance and durability of the structure.

Figure 3: Development sequence of cracks in reinforced triple key tooth adhesive joints

Figure 4: Development sequence of cracks in reinforced double key tooth shear key adhesive joints

Liu et al. [21] conducted direct shear tests on ultrahigh-performance concrete (UHPC) prefabricated nodes with dry joints and found that the increase in constraint stress, the improvement in concrete matrix strength, and the incorporation of steel fibers can effectively improve the shear bearing capacity of UHPC prefabricated nodes.

Zhang et al. [22] addressed the insufficient self-centering capability of traditional three-column prefabricated segmental bridge piers by designing a new type of bridge pier. In this design, the central pier uses grouted corrugated pipe connections, while the side piers employ prestressing tendon connections to achieve swaying behavior. Research findings indicate that, compared to traditional bridge piers, the new bridge pier configuration with energy-dissipating reinforcement exhibits excellent performance in both energy dissipation and residual displacement control while maintaining good ductility. Consequently, the seismic performance of the new bridge pier is significantly improved.

Zhang [23] studied the seismic shear behavior of grouted sleeve connections in prefabricated bridge pier joints using 1:4 scale models with shear span ratios of 2.50 and 1.75. The results showed that failure occurred due to grout compression followed by longitudinal reinforcement fracture, with higher shear span ratios exacerbating concrete damage at the pier base. Comparisons of energy dissipation, stiffness degradation, and ductility confirmed the specimens’ excellent seismic performance.

Wang et al. [24] proposed a new connection method, which used lapped large-diameter steel bars and ultra-high performance concrete grouting to achieve connection. Studies have shown that when the length of the deformed steel bars in UHPC reaches 5 times the diameter of the steel bars when the steel bar diameter does not exceed 32 mm, it can meet the seismic requirements. At the same time, the use of a larger steel bar diameter can further enhance the deformation capacity of the bridge pier.

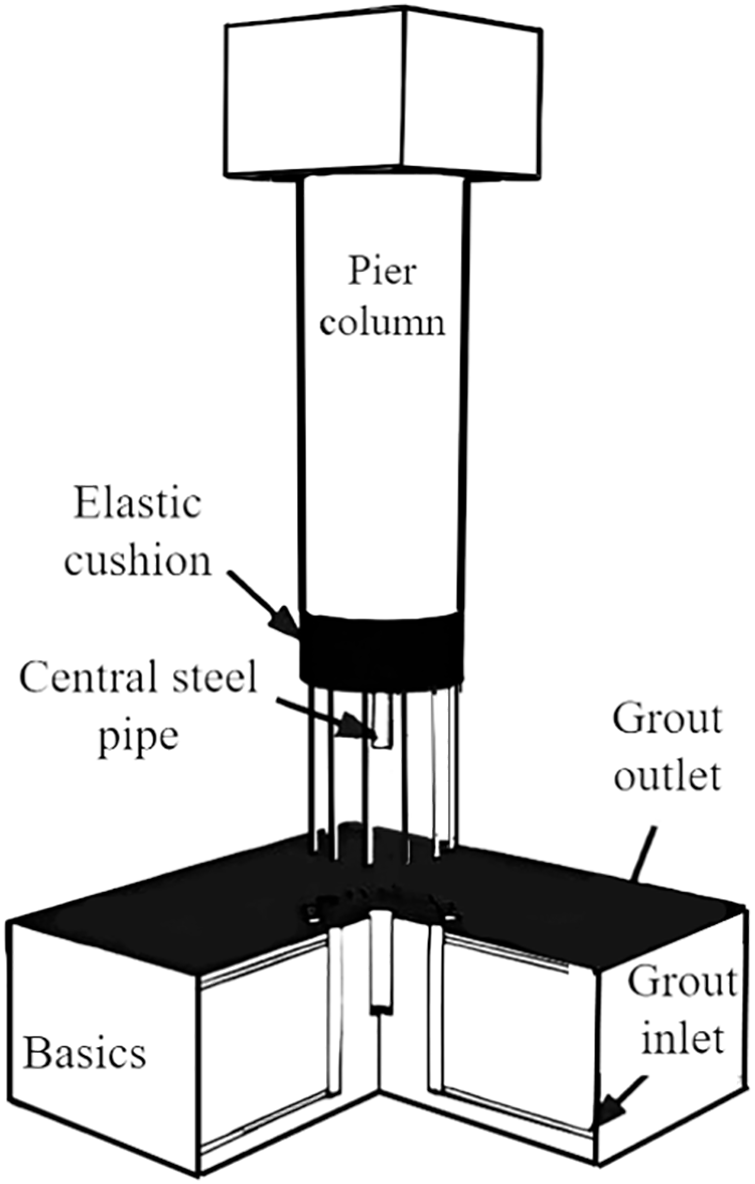

Jia et al. [25] by adding elastic gaskets in the plastic hinge area of the pier column, as shown in Fig. 5, the seismic resistance of the pier column is significantly improved. Studies have shown that the main seismic response indicators of precast concrete bridge piers connected by grouting metal bellows are equivalent to those of cast-in-place bridge piers.

Figure 5: Prefabricated prestressed segmental precast and assembled piers with elastic cushion blocks

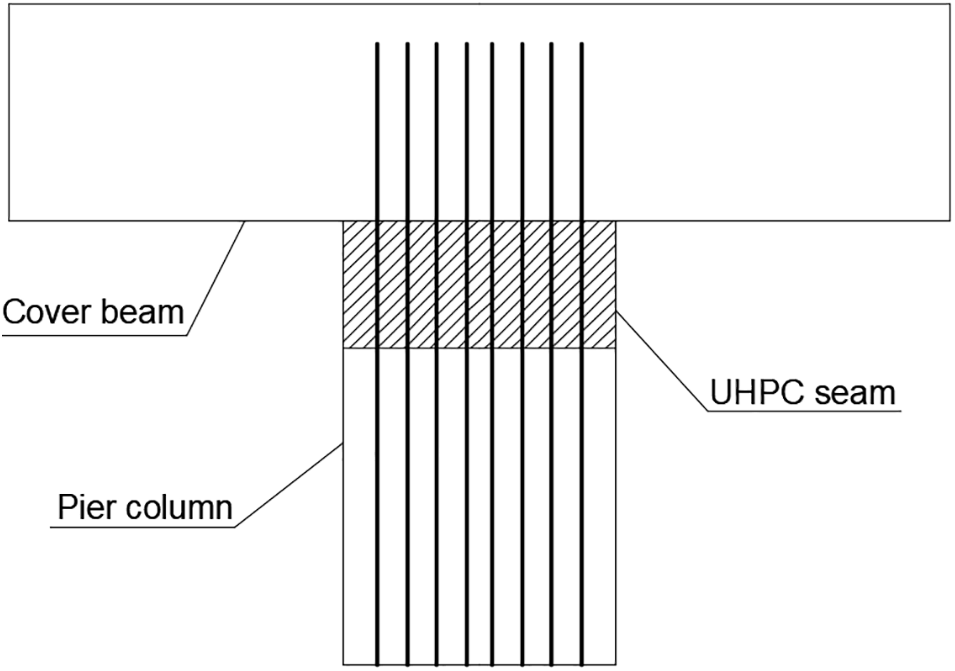

Shafieifar et al. [26] a new connection method for prefabricated cap beams and pier columns is proposed, as shown in Fig. 6. This method overlaps the steel columns of the cap beams and pier columns and uses ultra-high performance concrete to seal the joints. After experimental verification, this connection method shows good structural performance and is suitable not only for earthquake-prone areas but also for non-seismic areas, while achieving sufficient ductility.

Figure 6: Prefabricated cap beam and pier column connection method

Fan et al. [27] investigated the application of grouted corrugated pipes with large-diameter reinforcement bars and compared their mechanical performance to that of cast-in-place bridge piers through pseudo-static tests. The results showed that the prefabricated piers exhibited comparable lateral strength to cast-in-place piers but had relatively lower ductility. Analyzing existing research, the shear bearing capacity of precast pier joints primarily depends on the friction between the concrete interfaces, the pinning effect of the shear key, and the bonding performance of the adhesive material at the joints. The ductility and bearing capacity of the shear key can be significantly enhanced through effective design and material selection. Furthermore, exploring new connection methods—such as the use of overlapping large-diameter steel bars, ultra-high-performance concrete grouting, and the incorporation of elastic gaskets in the plastic hinge area of the pier column—can greatly improve the seismic resistance and deformation capacity of precast piers.

Analysis of Existing Research, the shear load-carrying capacity of joints in prefabricated segmental bridge piers primarily depends on the friction between concrete interfaces at the joints, the pin effect of shear keys, and the bonding performance of the adhesive materials. Through proper design and material selection, the ductility and load-carrying capacity of shear keys can be significantly enhanced. Additionally, research into new connection methods, such as lap splicing of large-diameter reinforcement bars with Ultra-High-Performance Concrete (UHPC) grouting, and the addition of elastic pads in the plastic hinge regions of pier columns, can improve the seismic and deformation capabilities of prefabricated bridge piers.

However, experimental studies on the local shear performance and shear failure mechanisms of prefabricated segmental bridge pier joints are insufficient, and the influence of key tooth parameters on joint shear performance remains unclear. Most existing studies on the shear capacity of prefabricated joints are based on segmental beams, and there is a lack of theoretical calculation methods for typical joints and design specifications for shear capacity in China. Furthermore, research on the mechanical behavior of prefabricated joints under coupled loading conditions is still in its exploratory stage [16].

3 Current Status of Research on Impact Resistance Performance of Traditional Bridge Piers

Current research hotspots in pier impact resistance performance focus on several key areas: the development of new anti-collision facilities, optimization of pier structures, effects of various factors on pier impact resistance performance, and intelligent detection and early warning systems. The main research content centers on the dynamic response of different pier structures under various impact forces. Research methods are primarily divided into experimental research, numerical analysis, and dynamic analysis methods.

Li et al. [28] investigated the dynamic performance of concrete beam-column joints under various impact loading conditions using a pendulum testing system. The study systematically analyzed how impact location and loading mode affect joint safety, highlighting that distributed impacts cause more significant damage than concentrated impacts. This provides a new perspective for evaluating concrete structures under impact loads. Additionally, Li revealed that interface damage between Precast Concrete (PC) beams and joints negatively affects node integrity and examined the performance of wet joint configurations at different impact locations [29]. The results showed that shear keys and interface reinforcement excel in resisting shear-controlled failure but are less effective against flexure-controlled failure. These findings offer a scientific basis for designing wet joints in PC nodes to better withstand specific impact loads.

Given the high costs and challenges associated with bridge pier impact experiments, many researchers utilize finite element simulation to investigate the impact resistance performance of bridge piers.

Mohammed et al. [30] conducted a finite element analysis (FEA) of bridge piers subjected to impact loads, validating the reliability and accuracy of the FEA method. Chen et al. [31] used the LS-DYNA software with MAT159 for concrete and MAT3 for reinforcement to model the behavior of concrete bridge piers under impact loading, successfully capturing the dynamic response and further validating the accuracy and reliability of FEA. As a result, many researchers now employ FEA to study vehicle-bridge pier collisions, with the methodology becoming increasingly mature.

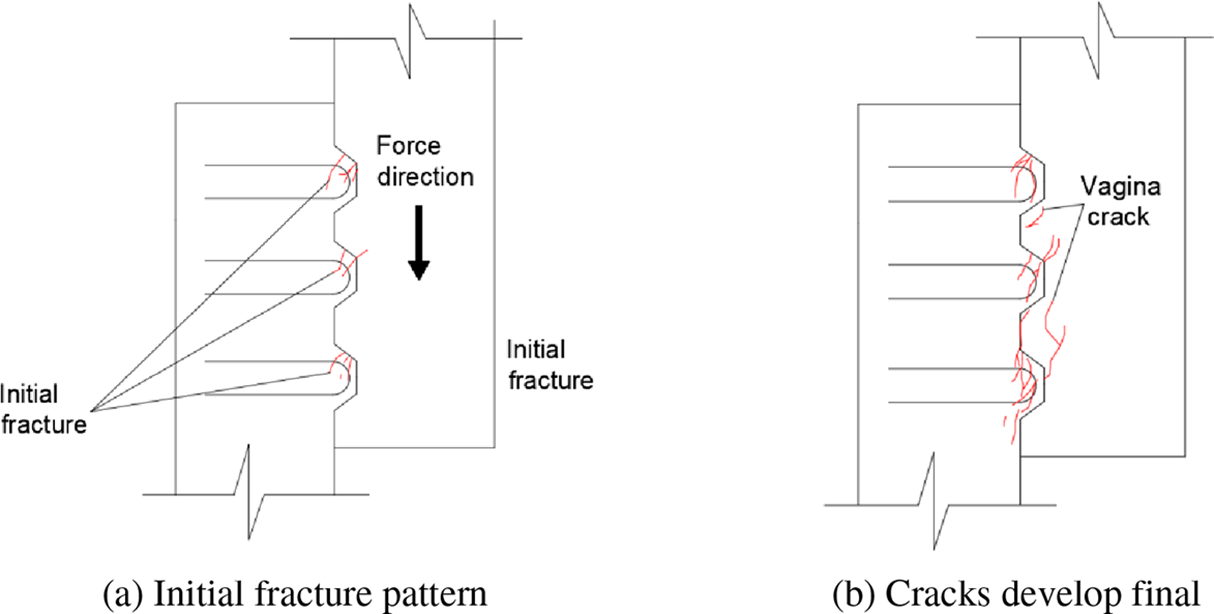

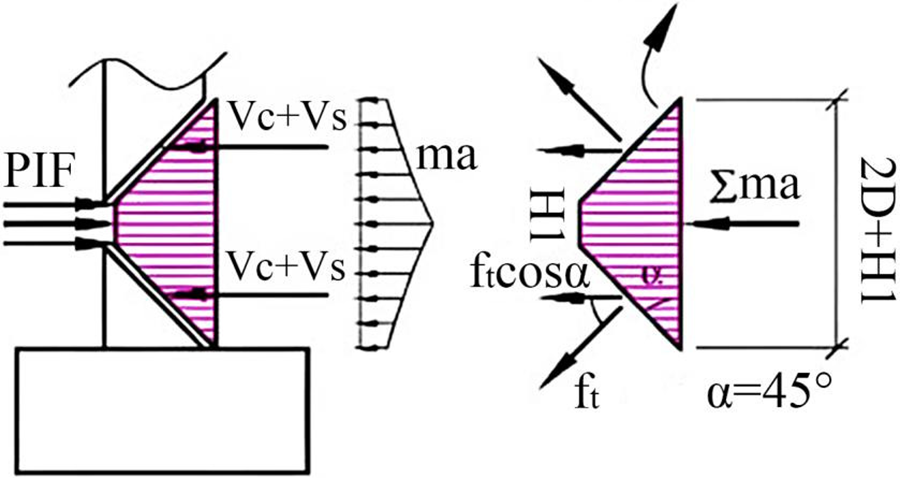

Do et al. [32] proposed an analytical model to predict the load-time curve for rectangular Reinforced Concrete (RC) columns subjected to vehicle impacts. The model considers four consecutive impact stages: bumper, engine, truck bed, and cargo. The study found that the impact force varies over time depending on the specific parameters and initial conditions of the vehicle model. The model’s predictions were in high agreement with numerical simulation results. The failure mode of the column is determined by its maximum dynamic shear capacity and the Punching Shear Force (PIF) generated during the collision. Specifically, bending failure occurs when the PIF is less than 0.5 times the maximum dynamic shear capacity, while shear failure occurs when the PIF is greater than or equal to 0.5 times the maximum dynamic shear capacity. For example, when the PIF reaches 30,000 kN, the impacted region of the RC column experiences punching shear failure, exceeding the shear capacity of the column section due to engine impact. According to the shear failure mode of concrete structures under impact loads, the crack patterns associated with punching shear failure are illustrated in Fig. 7. The dynamic shear force of the column can be expressed as:

where DIFc and DIFs are the dynamic increase factors of the strength of concrete and steel in the diagonal section, respectively; Vc and Vs are the contributions of concrete and steel to resisting shear, respectively; m and a are the mass and acceleration of the shear plug, respectively; ft is the tensile strength of concrete; and α is the inclination angle of the diagonal crack (α = 45°).

Figure 7: Simplified punching shear model of the RCBC

Additionally, the results of this study indicate that the peak impact force is associated with the vehicle engine impact, while the maximum impulse may be influenced by either the engine impact or the cargo impact.

Sharma et al. [33] categorized the performance of bridge piers under vehicle impact into three typical levels: (P1) fully operational with no damage, (P2) operational with damage, and (P3) complete structural collapse. However, these definitions are primarily qualitative and have limited applicability to affected bridge piers. Heng et al. [34], in studying the performance of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete (UHPC) bridge piers under heavy truck impacts, quantified these three performance levels based on numerical simulation results and applied them broadly to the entire bridge structure. Heng K proposed a bridge performance evaluation method based on the residual lateral displacement of the pier, which allows for comparing the damage states of piers with different diameters. The expression for this method is as follows:

In the above equation,

Li et al. [35] established the finite element model of four typical double-pier reinforced concrete Bridges Pier (RCBP), and systematically conducted numerical simulation of 108 collision scenarios of piers. The results show that the impact resistance of the pier is closely related to the seismic resistance, that is, the RCBP with stronger seismic resistance can resist the larger vehicle impact force. In addition, RCBP exhibits five potential failure modes under vehicle impact, namely spalling of concrete cover, internal plastic hinge formation, pier fracture, longitudinal and transverse pier reinforcement rupture, and complete bridge collapse, which are greatly affected by seismic tolerance. Finally, the study also analyzes and assesses the impact of seismic capabilities on the dynamic response and damage levels of vehicular impact RCBP. It is found that the dominant factor that determines whether RCBP fails under vehicle collision is the peak dynamic shear demand at the bottom of the pier. The comprehensive damage evaluation method and evaluation index

In the above formula,

Gholipour et al. [36] studied the numerical study on the dynamic behavior of UHPFRC reinforced rocking concrete piers with different configurations, including rocking integral pier (RMono), four-stage rocking segment pier (RSeg4), and eight-stage rocking segment pier (RSeg8). To compare the performance of a monolithic pier (Mono) in case of vehicle collision. It is found that compared with Mono and RMono, segmental pier (RSeg8) (RSeg4) has higher recovery, lower peak impact force, and internal force. Still, the concrete spalling at corners and edges is more serious due to inter-segment slip. However, the use of UHPFRC cladding at the column foot, cap, and beam joints, as well as at the edge of the column segment, can significantly reduce the concrete spalling damage and improve the recovery of the pier. The research shows that the segmental-type swinging pier has a good reference prospect and provides a direction for improvement.

Heng et al. [37] studied the dynamic response and damage failure of bridge substructure under heavy truck impact, and the study showed that the whole impact process of heavy truck can be divided into four stages: head impact stage, engine impact stage, cab crushing stage, and trailer impact stage. The first and third stages are characterized by hard shocks, while the second and fourth stages can be seen as soft shocks. During the impact process, the impact of the bumper, engine, and cargo successively produces three peak impact forces. The peak of engine impact is much larger than other peaks, and the final failure of bridge pier is mainly caused by cargo impact.

Fang et al. [38] studied the dynamic response and failure mode of concrete pier under the combined impact of collision and explosion, and the research showed that concrete failure and damage were usually manifested as spalling and crushing of concrete in the collision area. Direct shear failure is the main failure mode that controls the performance of reinforced concrete bridge columns under collision and explosion loads.

Malek et al. ’s [39] research shows that with the increase of pier column size, its peak displacement decreases, and the load transferred to the column during the collision can be effectively reduced. As shown in Fig. 8, the peak displacement decreases with the increase in pier size. At the top of the pillar of the minimum size C100 (the pillar with a cross-sectional area of 100 cm in diameter), the maximum displacement is about 6.3 mm; The C150 is 3.9 mm; The C200 is 3.2 mm; The C250 is 2.2 mm. Larger cross-sectional columns have less displacement under impact. However, the displacement pattern of the C250 is different, with slight displacement at the bottom and significant displacement at the top, possibly due to Linear Variable Differential Transformer (LVDT) errors. In addition, the displacement change between C100 and C150 (38.1%) is greater than that between C150 and C200 (about 18%) or between C200 and C250, indicating that smaller piers respond more strongly to impact. This further indicates that increasing the pier size helps to reduce displacement and damage caused by impact.

Figure 8: Peak lateral displacement along column height

Li et al. [40] deeply explored the response characteristics of prefabricated mortise and tenon joint (fusion mortise and tenon joint with cast-in-place wet joint technology) under vehicle impact, focusing on analyzing the influence of joint depth, lap reinforcement, and grouting effect. The results show that although the peak impact of prefabricated piers is similar to that of monolithic piers, the prefabricated piers show less bending deformation. Especially, when the joint depth reaches or exceeds 0.4 times (0.4 d) of the pier diameter, its impact resistance and energy absorption capacity are significantly improved, which effectively reduces pier damage. In addition, when the length of the lap steel bar is 10 times or more (10 d) than the diameter of the steel bar, the risk of connection failure is significantly reduced, reducing damage to piers, joints, and pier cap beams. At the same time, properly increasing the diameter of the lap steel bar can also improve the local stiffness near the joint and effectively prevent the occurrence of excessive damage.

Chen et al. [41] conducted a nonlinear finite element simulation of vehicle collisions with typical reinforced concrete bridge piers, performing an in-depth analysis of the characteristic failure modes of these piers. The study revealed that shear failure was predominant in the piers. When the fixed constraint position at the bottom of the pier was lowered by 1 m from ground level, the primary damage zone expanded from 1.2 m above ground to 2.5 m, indicating that the location of the fixed point significantly influences the extent of pier damage. Additionally, it was found that increasing the diameter of the stirrups from 8 to 24 mm resulted in an average reduction of 71.3% in the maximum horizontal displacement of the pier, demonstrating that a larger stirrup diameter substantially enhances the pier’s impact resistance and effectively reduces structural deformation.

Cao et al. [42] analyzed the damage characteristics of piers impacted by vehicles through the finite element method, indicating that the reinforced concrete pier column may suffer brittle shear failure under the action of high-speed vehicle collision, and the damage has a nonlinear relationship with the initial collision velocity. Severe shear failure occurs suddenly when the speed reaches 70 km/h. In addition, the paper also studies the impact resistance of the pier and proposes that the outer steel pipe can effectively improve the impact resistance of the pier and significantly reduce the damage of the pier.

Sun et al. [43] conducted a series of static and impact loading tests on the grout sleeve, revealed the direct shear failure mode of the grout sleeve, and developed and verified a finite element modeling method. Further, truck-bridge collision simulations using the model show that increasing the number of column segments increases pier stiffness, while appropriate joint surface friction effectively controls reinforcement shear stress and provides additional shock resistance support.

Li et al. [44] evaluated the influence of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) shear reinforcement on the lateral continuous impact resistance of Double-column Reinforced Concrete Pier (DCBP) through lateral continuous impact tests and numerical simulation of three scaled vehicles. It is found that CFRP shear reinforcement changes the failure mode of the pier: from shear failure of the bare pier, to shear failure of the slightly damaged pier, and then to bending failure of the intact pier. In addition, the reinforced piers exhibit higher damage and deformation capabilities, increasing ductility and energy dissipation. Specifically, the cumulative energy dissipation of slightly damaged and intact CFRP-reinforced piers is 3.6 times and 3.9 times that of unreinforced piers, respectively.

Xiang et al. [45] used ANSYS/LS-DYNA finite element software to build collision models of deep beams under different impact velocities and quantitatively calculated the damage degree of deep beams. The impact resistance and damage degree of reinforced concrete deep beams under different boundary conditions and different impact positions are further analyzed. The results show that, under the impact load, the damage of the deep beam first forms in the local area, and then expands to the whole area. The vertical deformation of the deep beam reaches the extreme value when t = 10 ms, and then the deep beam begins to have rebound deformation. In the rebound deformation stage, the local damage increases twice near the impact position. The impact velocity mainly affects the damage distribution and damage degree of the section near the impact location, and has little influence on the section far away from the impact location.

Wang [46] conducted a drop hammer impact scale test on a square reinforced concrete column to simulate vehicle and column collision, analyzed and compared the impact resistance of concrete columns under different impact masses and bending stiffness of sections, and compared the dynamic and static load tests. The maximum value of impact force Pd, max, and impact action time Δt are mainly affected by impact velocity v and impact mass m, both of which increase with the increase of v and m, which is consistent with the research conclusion of scholar Wang et al. [47]. Further analysis shows that the peak value of impact force Pd, max has no obvious correlation with Δt and flexion stiffness K. These findings provide important insights into the dynamic response of concrete columns in vehicle-column collisions.

Xie [48] used the gravity drop hammer impact system to conduct lateral impact tests on T-shaped steel reinforced concrete columns and conducted numerical simulation studies with ABAQUS finite element software. The results show that this type of concrete column exhibits excellent impact resistance, thanks to the strong support of the built-in steel bone. The main damage was concentrated in the mid-span area, showing the characteristics of flexural shear failure. In addition, the level of axial pressure has a significant effect on the development of concrete cracks: although the increase in axial pressure ratio inhibits the expansion of curved cracks to a certain extent, it also intensifies the development of oblique cracks. Although the peak value and duration of the impact force change little in the platform stage, the maximum displacement and residual deformation in the span increase with the increase of the axial compression ratio.

Yang et al. [49], through the pendulum impact test, showed that the damage modes of bridge piers under horizontal impact were mainly the cracking of concrete at the bottom of the front impact surface and the crushing of concrete at the bottom of the back impact surface. In addition, the axial compression ratio is in the range of (0~0.2), and an appropriate increase is helpful to enhance the impact resistance of the pier. These results provide an important reference for bridge design and help to optimize the seismic and shock-resistant design of structures.

He et al. [50] conducted an in-depth study on the behavior of precast pier with grouting sleeve connection under horizontal low-speed impact load and systematically compared and analyzed cast-in-place and precast specimens in terms of failure mode, reinforcement strain, impact force, displacement, and energy dissipation capacity. The results show that the peak impact force is 3 to 7 times higher than the peak static load due to the inertial effect caused by the impact load. Compared with cast-in-situ specimens, the grouting layer of prefabricated specimens is more likely to produce transverse cracks, and the self-loading point of inclined cracks extends to the bottom of the pier after impact. It is worth noting that when the filling degree is between 30% and 100%, the impact force time curve of pier specimens is not significantly different from that of cast-in-place specimens. However, the decrease of grouting fullness will increase the maximum displacement of pier specimens and weaken the transfer efficiency of shock waves between reinforcement bars.

After falling hammer impact test, Lu [51] explored the failure mechanism of RC columns under lateral impact load, and investigated the influences of axial compression ratio and slenderness ratio on the failure situation. In this paper, polyurethane coating and carbon fiber cloth are used to protect RC columns, and the impact test shows that these two materials can effectively improve the impact resistance of RC columns.

By designing and analyzing 48 vehicle-bridge collision scenarios, Li et al. [52] evaluated the effectiveness of Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) strengthening technology in improving the vehicle impact resistance of built bridge piers. The results show that FRP cladding can significantly enhance the ability of bridge piers to resist vehicle impact, and reduce the damage and deformation degree of bridge piers affected by impact. The best reinforcement scheme is proposed, which is the fiber orientation of 0 degrees to the circumference, the reinforcement height of 3 m and four layers of carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) encapsulation.

Han et al. [53] conducted an in-depth study on the differences in dynamic response and failure modes of prefabricated segment columns reinforced with or without Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) through numerical simulation. The results show that when the vehicle is struck at a speed of 100 km/h, the bending moment and shear value at the damaged section of the prefabricated section column with steel bars and the prefabricated section column without steel bars differ by 7.6% and 7.1%, respectively. At this impact velocity, the peak impact force increases by 15.8% due to the local stiffness of the precast segment column strengthened by CFRP. It is worth noting that the bottom of the precast segment column reinforced with CFRP was crushed, while the entire precast segment column showed shear failure under vehicle impact.

Xia et al. [54] proposed and tested the composite structure of Ultra-High Performance Concrete-Bioinspired Honeycomb Column Thin-wall structure (UHPC-BHTS). The structure combines the shock resistance properties of UHPC with the buffering capabilities of BHTS to improve the Energy Absorption (EA) efficiency of the structure during collision events. Studies have shown that under low energy shock conditions, UHPC panels can effectively absorb most of the internal energy, maintain structural integrity, and cooperate with BHTS but not fully activate their energy absorption potential. However, when the UHPC panel breaks under high energy impact, BHTS plays a major role in energy absorption, and the entire composite structure can absorb up to 97.19% of the impact internal energy, which is significantly better than the 2.39% of the traditional RC column specimen. The results of this study confirm that UHPC-BHTS composite structure has superior energy dissipation capacity in the anti-collision design of bridge piers, and provide a reference for the further study of impact energy dissipation structure.

This section provides an overview of the latest advancements in the study of pier impact resistance, highlighting the following critical areas:

(1) Development of Novel Crash Barriers and Structural Optimization:

Researchers have actively developed new types of crash barriers and optimized structural designs to enhance the impact resistance of bridge piers. Innovations such as reinforcing sway concrete piers with ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete (UHPFRC) and employing carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) for shear strengthening have significantly improved the energy absorption capacity and damage recovery of piers.

(2) Analysis of Influencing Factors:

Multiple studies have shown that factors such as pier dimensions, axial compression ratio, and slenderness ratio significantly influence the impact resistance of bridge piers. Larger piers can effectively reduce displacement and damage caused by collisions; moderately increasing the axial compression ratio can help suppress the propagation of bending cracks but may exacerbate diagonal cracking; the slenderness ratio directly affects the failure mechanism of piers under lateral impact loads. Environmental conditions, including seismic forces, also substantially impact the dynamic response and extent of damage to piers.

(3) Intelligent Monitoring and Early Warning Systems:

The development of intelligent monitoring and early warning systems has garnered significant attention for the timely identification of potential safety hazards. Utilizing sensor networks to monitor real-time changes in pier condition, combined with data analysis algorithms, enables online assessment of pier health, providing a scientific basis for maintenance decisions.

(4) Numerical Simulation Methods:

Given the high cost and technical challenges associated with actual impact experiments, finite element analysis has become the primary tool for studying the impact resistance of bridge piers. Material models such as MAT159 and MAT3 are widely used for simulating concrete and reinforcement, accurately capturing the behavior of piers under impact loading. Software like LS-DYNA and ABAQUS allows researchers to more precisely predict dynamic responses under various conditions and validate the effectiveness of different reinforcement measures.

(5) Failure Modes and Damage Assessment:

Experimental and simulation results indicate that piers primarily exhibit shear or bending failures when subjected to impacts. Based on metrics such as force-time curves, displacement, and energy dissipation, a quantitative damage assessment system has been established to guide design and repair practices in engineering. Specifically, the application of mortise-and-tenon joint prefabricated connection technology in prefabricated piers has enhanced local stiffness at joints and improved overall structural impact resistance.

(6) Comprehensive Protection Strategies:

In light of increasingly complex usage environments and technical requirements, single protective measures are insufficient. Therefore, composite structures integrating multiple materials and technologies have become a research focus. For example, ultra-high-performance concrete-biologically inspired honeycomb tubular thin-walled structures (UHPC-BHTS) have demonstrated excellent energy absorption performance under both low- and high-energy impact conditions, offering new insights for future crash barrier design.

Many scholars have studied the impact resistance of pier, fully demonstrated the dynamic response and damage mechanism of traditional pier under impact, and put forward a series of impact resistance measures and methods. It is not difficult to find from the study of the impact resistance of the traditional pier that the performance of the pier under the impact condition is obviously different from that of the traditional static system. Although the Equivalent Static Force (ESF) method is still an important means to evaluate the impact performance of bridge piers, the traditional static analysis method and theory are not fully applicable to the study of the impact performance of bridge piers.

4 Restorable Function Design Concept and Its Application Scenarios

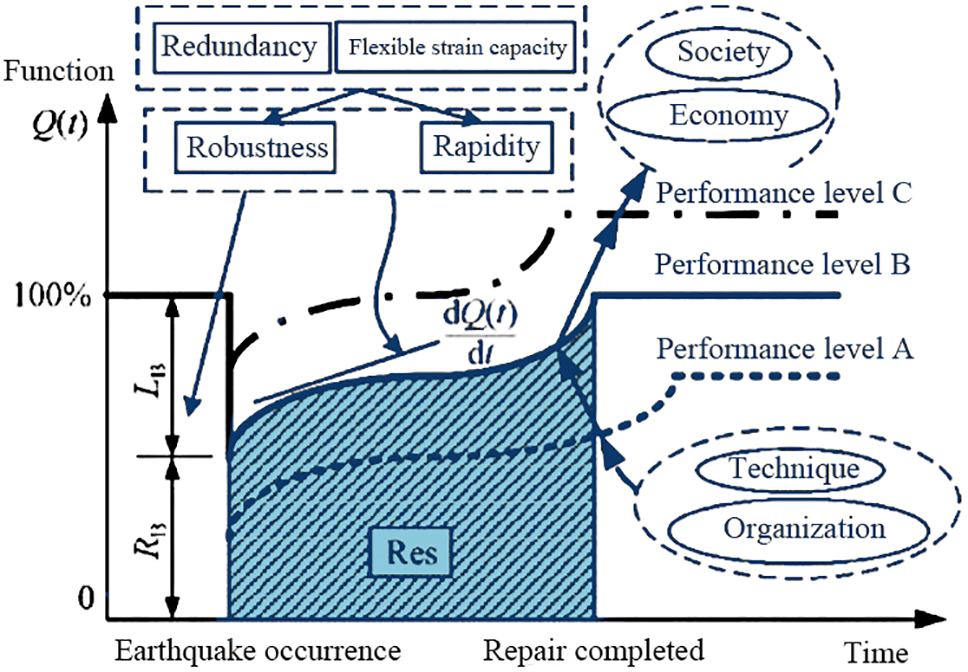

The concept of recoverable function is mainly applied to the seismic field, and according to the realization of its functions, it can be divided into recoverable function city, recoverable function structure, and recoverable function system [55]. The research object of the concept of recoverable function is not limited to the single structure but considers the influence of the surrounding environment on the structure-function. This concept focuses on the performance of structures under earthquake action and focuses on the performance of their recovery after earthquakes. The traditional aseismic structure (as shown in Fig. 9-Performance level A) has significantly reduced functions after an earthquake, which is difficult to repair and takes a long time. Indirect losses are serious, and it is difficult to restore the original performance. In contrast, the recoverable function concept (Fig. 9-Performance level B) focuses on maintaining and quickly recovering function after an earthquake and may even improve performance through repair (Fig. 9-Performance level C). Moreover, the robustness and rapidity of the system can be increased by increasing redundancy and resourcefulness [56]. This new concept is of great value in reducing indirect earthquake losses and improving post-earthquake recovery ability.

Figure 9: Schematic diagram of earthquake restorable functions

The concept of restorable function earthquake resistance not only ensures life safety but also emphasizes maintaining structural functionality while comprehensively considering the factors that impact this. Its spatial scope extends beyond individual buildings to include surrounding structures and essential service facilities. In terms of time span, it encompasses the entire process from the onset of an earthquake to the full restoration of structural functions, with dynamic evaluation of performance throughout. Therefore, an ideal restorable function earthquake-resistant structure should remain intact during minor earthquakes and recover quickly from rare, severe earthquakes. Additionally, its evaluation system should accurately reflect this rapid recovery capability.

This concept is currently widely used in the field of structural earthquake resistance, such as restorable function connecting beams, restorable frame structures, and restorable function columns. Among them, restorable function columns are structural columns that only need simple repairs after being damaged by an earthquake without affecting normal use, or can quickly restore their use functions after repeated repairs after multiple earthquakes [57]. This is also a special bridge pier system formed by integrating the concept of restorable function into bridge pier research.

At present, the restorable column technology can be divided into four categories: a rocking column, a column with low-bond ultra-high-strength steel bar transverse constraint reinforcement, a column with Shape Memory Alloy (SMA) material longitudinal reinforcement at the bottom of the column, and a pre-plastic hinged section column segment replaceable column. Due to the unique characteristics of the rocking column, this subsection mainly describes the rocking column. The design feature of the rocking column is that when an earthquake occurs, the earthquake force on the structure is reduced by rocking action. Secondly, the column with low-bond ultra-high-strength steel bar transverse constraint reinforcement can achieve self-reset function after an earthquake by using the elastic recovery force of ultra-high-strength steel bar. The column with material longitudinal reinforcement at the bottom of the column can achieve self-reset by using the superelastic property of shape memory alloy. Finally, the pre-plastic hinged section column segment replaceable column, this type of column design allows the damaged column segment to be assembled and replaced after an earthquake, thereby effectively improving the functional recovery efficiency of the structure.

By releasing column end constraints, the rocking column forms tensioning connections, allowing the column to sway during earthquakes, effectively reducing the effect of earthquakes on the structure and reducing the demand for ductility, which is an effective strategy in seismic design and enhancing the seismic performance of building structures [58]. The rocking column is divided into the prestressed column and the un-prestressed column.

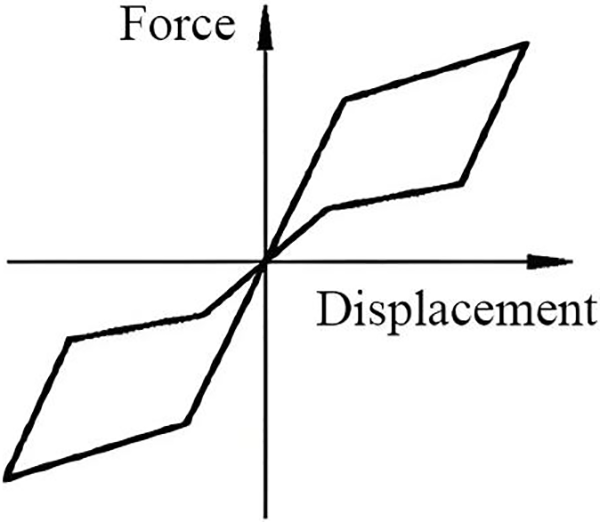

The swaying column with prestressed tendons alone cannot effectively cope with the influence of strong earthquakes, so energy-consuming components are usually configured at the end of the column to achieve the adjustable stiffness of the column end [59]. This design allows the columns to remain resilient in the event of small earthquakes, while in moderate to large earthquakes, the columns will wobble, and the energy-consuming components can effectively dissipate seismic energy. After the earthquake, the residual displacement can be significantly reduced by the self-weight and resetting mechanism of the prestressed tendons. Therefore, the hysteretic curve of such columns under low cyclic loading usually takes on a “flag” shape, as shown in Fig. 10. This design strategy has significant advantages in improving the seismic performance of building structures.

Figure 10: Flag shaped hysteresis curve

Jia et al. [60] systematically studied the nonlinear mechanical properties of axially post-tension-prestressed segmental Concrete Filled Steel Tube (CFST) pier under horizontal and reciprocating loading through quasi-static tests, including hysteresis, skeleton curve, prestress loss, energy dissipation, joint performance, and plastic joint development. The results show that the pier has excellent lateral force resistance and self-resetting ability. The residual deviation rate is as low as 0.2% when the pier fails, but the prestress loss reaches 15% when the maximum displacement deviation rate is 5.8%. It is pointed out that the energy dissipation of piers without additional energy dissipation devices is limited, and it is suggested to add joint energy dissipation devices to enhance the seismic performance.

The Shape memory alloy Restrained Rocking pier (SRR) is a low-damage precast concrete member connected to the substructure by Shape Memory Alloy (SMA) and Energy Dissipation (ED) unbonded connectors. Among them, the superelastic Nitinol prestressed SMA linkage provides a self-centering function and dissipates energy, which is enhanced by the replaceable ED linkage made of low-carbon steel. Steel sheathing and end steel plate together protect the joint from concrete damage. Akbarnezhad et al. [61] conducted a numerical evaluation of the response of the column under lateral load, and the results showed that the SRR column could effectively achieve the target performance: avoid damage under conventional seismic displacement, and show significant self-centering effect and hysteretic damping ability.

Fang et al. [62] designed a self-centering swing (SCR) system with shape memory alloy (SMA) washer springs that not only maintains the benefits of traditional swing blocks but also incorporates several innovative features. In particular, the built-in “safety locking device” can effectively control the swing amplitude of the pier and ensure the stability of the structure. During the deformation process, the SMA washer spring can not only dissipate the energy moderately but also absorb the drift energy further through the bending of the pier itself after the deformation limit. In addition, SMA washers are reusable due to their material properties and require no maintenance or replacement. Its stacking mode is flexible and adaptable to diverse design needs.

With the development of prefabricated assembly technology in recent years, the special structure and connection form of prefabricated assembled bridge piers provide a good application scenario for the concept of restorable function. The following is a review of the development status of the combination of the restorable function concept and prefabricated assembly technology.

The precast segmental pier is effective in shortening the construction period and reducing the cost. Self-centering capability can be introduced by combining the post-tensioned steel bar bundle, but it may be accompanied by the problems of energy dissipation reduction and damage concentration. In response to this problem, Li et al. [63] proposed an innovative design concept that aims to achieve better energy dissipation and damage dispersion by promoting multi-joint openings, while maintaining self-centering ability. The concept is realized by introducing Damage Control Rubber Joints (DCRJs) with varying stiffness under each segment. To validate the design, a quasi-static test was performed on four scaled samples using this method, focusing on the evaluation of damage conditions, failure modes, energy dissipation capacity, rebound index, and damage dispersion. The results show that the PSP under this design exhibits decentralized joint openings, enhanced displacement ductility, and damage mitigation, resulting in excellent seismic and resilient performance.

Unbonded steel beams are used in Partially Prestressed Concrete (PPC) to reduce residual displacement and achieve restorability. Tong et al. [64] adopted the composite reinforcement of unbonded steel bundles and High-strength Energy-Dissipating (H-ED) rebar, carried out cyclic load tests on PPC piers, and quantitatively evaluated its seismic performance, compared with the traditional Polymer Cement Composite (PCC) piers using Low-strength Energy-Dissipating (L-ED) rebar. The test results show that H-ED rebar has significant improvement in bearing capacity, ductility and self-centering ability. In PPC piers of key Bridges, H-ED rebar can be used to replace L-ED rebar.

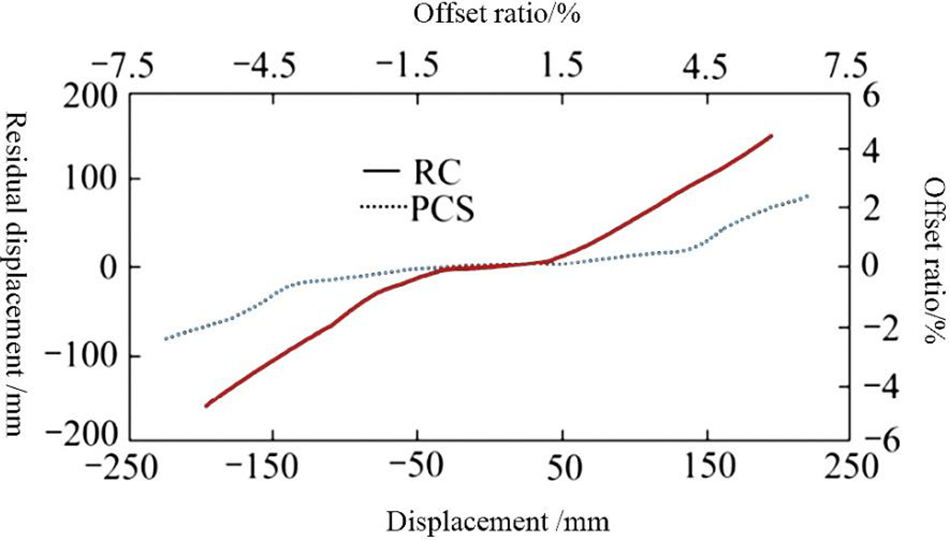

Ge et al. [65] compared the performance of the two-stage prestressed prefabricated pier with the cast-in-place pier with the scale down to 1/3 through quasi-static test. As shown in Fig. 11, the results show that the residual displacement of PCS of the pier segment specimens under the same maximum displacement class (migration rate of 6%) is only 44% of that of the monolithic cast-in-place specimens. Under the same maximum displacement class (6% deviation rate), the energy dissipation capacity of PCS specimen is only 1/3 of that of RC specimen. The cumulative energy dissipation capacity of PCS specimen is 40% of that of RC specimen. The results show that the bonded full-prestressed segmental piers have excellent self-resetting ability and minimal residual deformation, and have good post-earthquake recovery function.

Figure 11: Comparison of residual displacement between assembled specimens and integral cast-in-place specimens

White et al. [66] proposed a new prestressed prefabricated bridge design, which combines an external steel dissipator and an internal energy-dissipating steel bar at the bottom of the column. Both energy-dissipating elements are mechanically connected to the column body. The experimental results show that the new precast pier not only has self-resetting ability but also has excellent hysteretic performance, which can be repaired quickly and economically after sustaining limited damage.

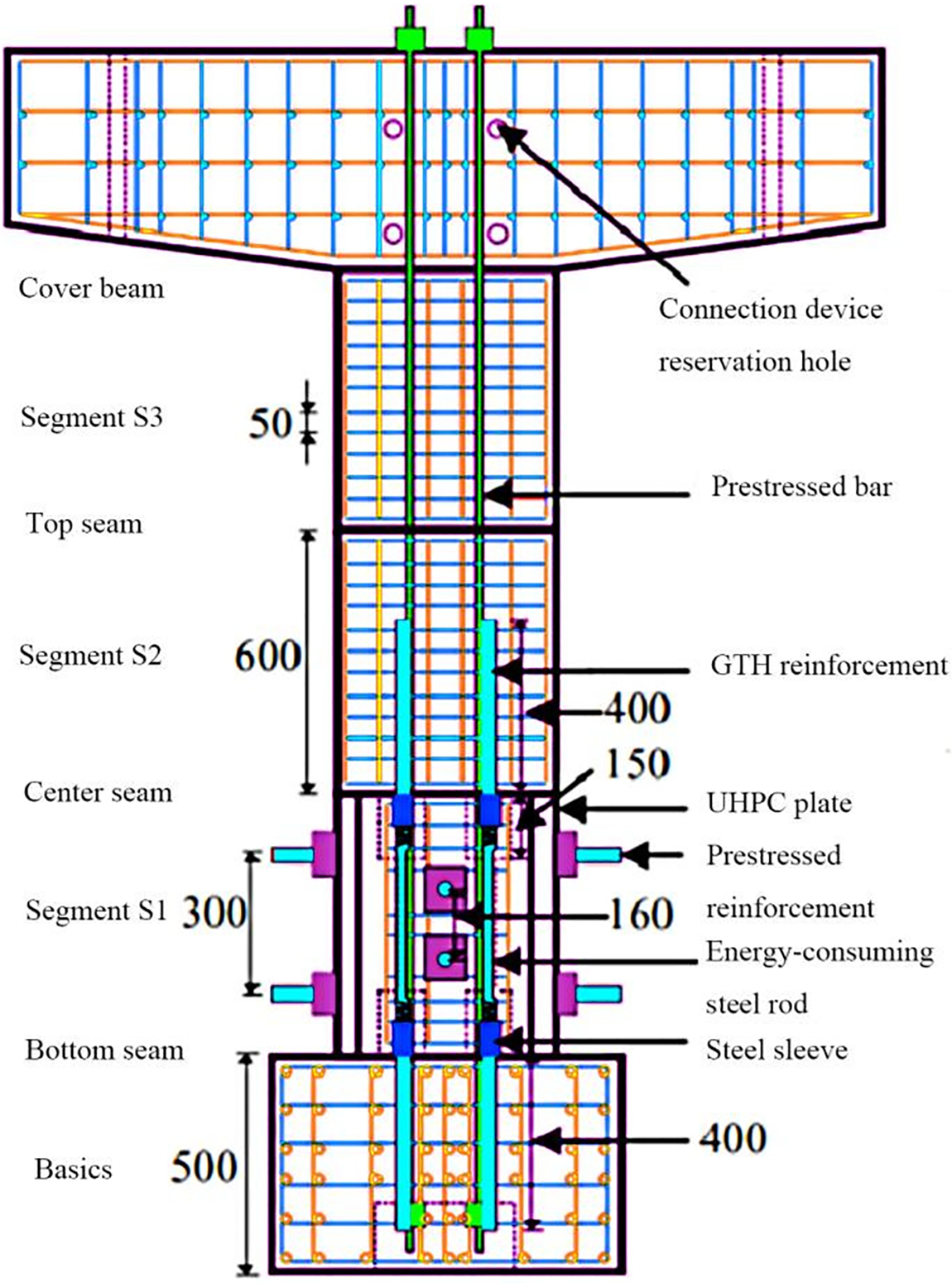

Wang et al. [15,67,68] proposed an innovative prestressed precast assembled ultra-high performance concrete pier, the design of which is shown in Fig. 12. The pier base consists of a core area and four replaceable UHPC plates connected by prestressed steel bars with energy-dissipating bars in the middle for quick replacement after an earthquake. The team carried out low-cycle reciprocating loading tests on the specimens and repaired parts to verify their excellent seismic performance. In the test, the damage of energy dissipation bar and UHPC cover plate is significant, and the reinforcement of cover plate can prevent the failure and the decrease of bearing capacity. Although the core concrete damage is less, the bearing capacity of the repaired specimens is similar to that of the original specimens, but the initial stiffness is reduced.

Figure 12: Prestressed assembly of UHPC bridge piers

Mao et al. [69] proposed a new type of prefabricated pre-stressed rocking column, which features energy-dissipating angle steel externally attached at the base and unbonded prestressed strand cables arranged in the middle section. Through bidirectional low-cycle reversed loading tests, when loaded to a displacement angle of 1/15 around the strong axis, only the angle steel yielded, with minimal damage to the column body and low residual displacement. Additionally, in the weak axis direction, the column demonstrated moderate energy dissipation and self-centering capabilities, though these were slightly less pronounced compared to those in the strong axis direction.

Shi et al. [70] used lead squeeze dampers (LEDs) as replaceable energy-consuming components, as shown in Fig. 13, and established a wobble-self-resetting double-pillar pier system (RSC-LEDs) with the assembled LEDs, and studied its seismic performance. The results show that the overall force-displacement relationship can be approximately bilinear, the hysteretic curve is “flag”, the mechanical properties are very little affected by the cover beam, and the LEDs added will not significantly change the equivalent yield displacement and post-yield stiffness of the double-column pier system, which is a more controllable mechanical property of the pier system.

Figure 13: RSC LEDs double column pier construction form

Wang et al. [71] proposed Precast Concrete Filled Steel Tube (PSCFST) pier with an external energy dissipation ring. The research shows that the lateral bearing capacity and energy dissipation capacity of piers with energy dissipation rings are increased by 60% and 20% times, and the damage is controllable, which is convenient for quick repair after an earthquake. In addition, it is found that the initial prestress does not affect the energy consumption; The increase of energy dissipation ring strength improves stiffness and energy dissipation ability; When the width is reduced, the equivalent stiffness and unloading stiffness are reduced, and the energy dissipation ability is significantly weakened.

Wang et al. [72] proposed a prestressed assembled hollow pier with Angle steel at its bottom. The experiment shows that the hysteretic curve of the prestressed hollow pier has an obvious pinching phenomenon. After adding energy-consuming steel bars, the stiffness and energy-consuming capacity of the pier have been significantly improved. However, when the axial compression ratio is too large, the protective layer concrete will fall off, resulting in shear failure.

Li [73] explored the application of superelastic Shape Memory Alloy (SMA), external energy dissipation device, and concretion-filled double-layer steel pipe (CFDST) segment in seismic precast columns. The results show that although the integral CFDST column has high energy dissipation capacity, the strength degradation is significant and the residual displacement is large due to the buckling and plastic deformation of the steel pipe. The addition of internal steel energy dissipation (ED) rebar at the joint of the prefabricated segment increases the energy dissipation but the residual displacement. By replacing ED bar with SMA bar, energy dissipation is reduced. However, the SMA rod works in conjunction with the external ED device to create a hybrid energy dissipation system that significantly enhances energy absorption, increasing cumulative dissipation by 43.0% and reducing residual displacement by 42.6%.

Haber et al. [74] proposed an innovative connection method in which the steel bars in the prefabricated pier column were mechanically connected to the reserved joints in the cap, and concrete was poured outside the plastic hinge to ensure a stable connection between the prefabricated pier column and the cap. This design facilitates the replacement of damaged rebar after the plastic hinge area protective layer is removed.

Tazarv et al. [75] proposed to use SMA bars instead of ordinary steel bars in the plastic hinge area for bellows grouting to connect prefabricated piers, while ordinary steel bars were maintained in other areas. The SMA bar is mechanically connected to the ordinary steel bar. The test results show that compared with prefabricated piers with the same parameters, prefabricated piers with SMA rods exhibit better energy dissipation capacity while maintaining lower residual deformation.

Chou et al. [76] used full-length round steel pipes to constrain concrete segments, which were connected by post-tensioned bonded prestressed tendons, and a mild steel damper was set at the bottom of the pier. The test results show that the design of a mild steel damper can make the pier have good energy dissipation capacity.

Marriott et al. [77] designed a replaceable anti-buckling fusion-type mild steel damper, and the test results show that this damper can significantly improve the energy dissipation performance of prefabricated piers.

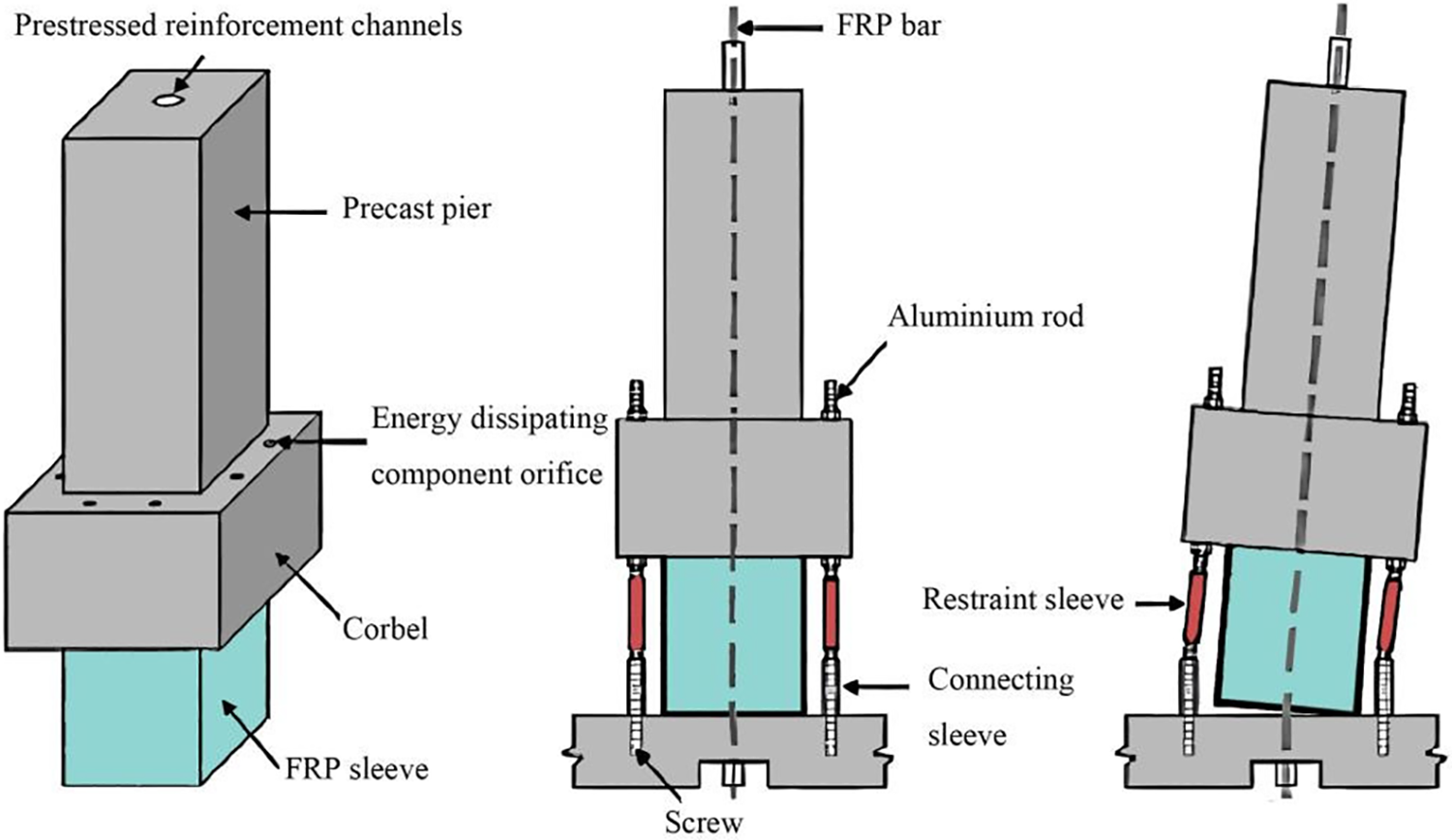

Guo et al. [78] proposed a new type of external bracket self-centering pier (as shown in Fig. 14), which significantly reduced the problem of spalling or crushing concrete by using glass fiber composite material to wrap concrete at the bottom of the pier column. The pier design has epoxy-clad aluminum rods on the outside as replaceable energy-consuming devices. The test results show that the load-displacement curve of the specimen presents a flag shape, showing small residual displacement and excellent recoverability.

Figure 14: External cow leg self resetting prefabricated bridge pier

Bao et al. [79] designed three sets of prefabricated frame concrete pier models in order to study the seismic characteristics of bridge piers under different prestressed levels: UPT-0.5 and UPT-0.7 samples with 0.5 and 0.7 prestressed unbonded post-tensioned reinforcement bundles combined with grouting splicing sleeve, and reference sample PC-S connected only with grouting splicing sleeve. The quasi-static test shows that all piers have bending failure, and the UPT-0.5 specimen has the most serious damage. With the increase of prestress, the area of the hysteretic curve of the UPT-0.7 specimen expands, and the yield and peak load of the UPT specimen increase by more than 18%, and the initial and failure stiffness increase by more than 10%. However, prestress has limited influence on ductility, residual and column displacement. Compared with PC-S, the cumulative energy dissipation value of UPT-0.5 and UPT-0.7 specimens is reduced by 76% and 53%, respectively. The combination of grout splice sleeve and unbonded post-tensioned prestressed reinforcement not only speeds up the construction speed of the precast segmental frame pier, but also significantly improves its self-centering ability.

Gao [80] installed a bi-directional energy-consuming viscoelastic damper on the outside of the precast pier (as shown in Fig. 15). The test results show that this improvement measure can improve the bearing capacity and energy dissipation capacity of prefabricated pier, and effectively reduce the deformation of pier top and shear at pier bottom. However, the damper has a weak effect on acceleration response control.

Figure 15: Schematic diagram of the position of bidirectional energy dissipation viscoelastic dampers

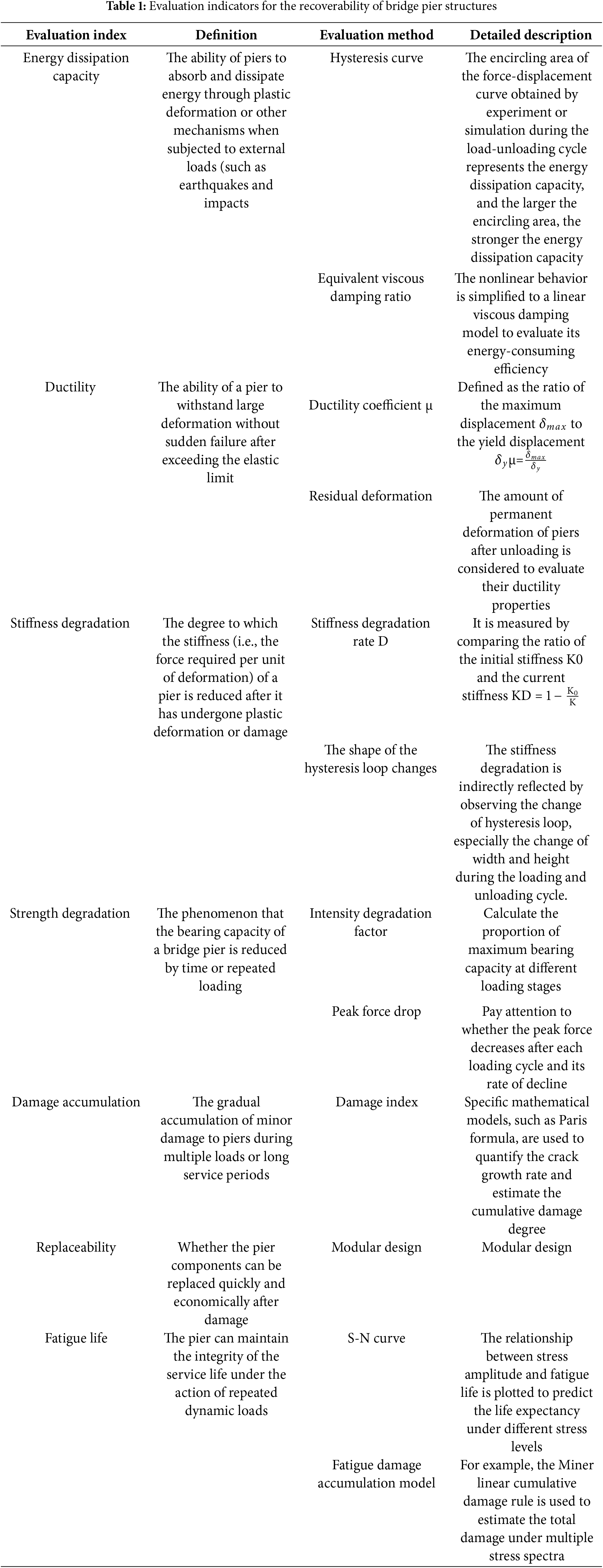

According to the above research, many domestic and foreign scholars have adopted the concept of recoverable function for structural design and verified the remarkable progress of new structural systems through experiments and numerical simulation. In this process, a set of comprehensive evaluation systems and an evaluation index of recoverable functions are gradually constructed. The evaluation of the recoverable function of structures after damage is a key step in advancing the concept and also provides valuable guidance for structural design. For the restorable function of the pier structure, the performance evaluation indexes directly related to it are shown in Table 1.

Based on the above research contents, prefabricated bridge piers significantly reflect the applicable advantages of the concept of recoverable function. Through the built-in mechanical energy-consuming steel bars and external replaceable energy-consuming devices, it can efficiently realize the rapid replacement and functional recovery of damaged components, indicating that this field will become the focus and mainstream trend of future research on bridge piers, and open up an important research path for the study of impact resistance of prefabricated bridge piers. In addition, this section systematically summarizes the evaluation system and evaluation index of the recoverable function, in order to provide some reference and inspiration for the related structural design.

5 Prospects of Research on Impact Resistance Performance of Prestressed Segmental Precast and Assembled Piers

As an innovative bridge construction technology, prefabricated pier is gradually emerging in the field of bridge engineering with its advantages of high construction efficiency, quality control and environmental friendliness. Especially in the aspect of impact resistance, this technology has become the focus of the academic and engineering circles. Based on the previous in-depth discussion on the development status of prefabricated pier technology and its impact resistance, this chapter will look forward to the future research direction in this field.

(1) The research of impact resistance evaluation and design method needs to be strengthened. In order to accurately predict the response of prefabricated piers to different impacts and formulate corresponding design criteria and specifications, we need to develop more advanced evaluation methods. This includes, but is not limited to, the in-depth study of the dynamic response of bridge piers to emergencies such as vehicle impact and ship collision, as well as the establishment of more accurate numerical analysis models. Through these efforts, we can ensure that the piers maintain their structural integrity and functionality in the event of impact, thus guaranteeing the safe operation of the bridge.

(2) The application of new connection technologies and materials is also an important direction of future research. With the continuous progress of science and technology, new materials such as high-performance concrete and fiber-reinforced composite materials continue to emerge, which provide new possibilities for improving the impact resistance of bridge piers. At the same time, new connection technologies such as mechanical connections and prestressed connections are also being developed, which are expected to further improve the overall performance and durability of piers. Therefore, we need to conduct in-depth research on the application effect of these new materials and new technologies in prefabricated piers to explore the best application scheme.

(3) A critical direction for future research on the impact resistance of prefabricated segmental bridge piers will be the thorough investigation of resilient design concepts. Integrating this philosophy into pier design can facilitate the development of self-resetting structures and rapid replacement of damaged components, thereby significantly enhancing the recovery capability of piers after an impact event. This approach not only mitigates economic losses and social impacts but also extends the service life of bridges, improving their economic efficiency. By incorporating resilient design, a harmonious balance between the safety and economy of bridge structures can be achieved, offering new insights and methods for the sustainable development of bridge engineering.

(4) The combination of impact simulation experiments with numerical analysis will be a key approach in future research. This integrated method not only provides a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamic response and failure mechanisms of prefabricated segmental bridge piers under complex impact loads but also offers more accurate data support for impact resistance studies. Such a holistic research strategy enhances our comprehension of pier behavior and provides reliable references for optimizing structural design. Through this approach, researchers can better assess and predict the performance of piers in practical applications, leading to the formulation of more scientifically sound and reasonable engineering strategies to ensure the safety and reliability of bridge structures.

(5) The study of comprehensive disaster prevention and reduction strategy is also an indispensable part of the future. The impact resistance of pier not only depends on its own design and material selection, but also is affected by many factors such as the surrounding environment and the overall layout of the bridge. Therefore, we need to explore comprehensive disaster prevention and reduction strategies to improve the overall disaster resistance of the bridge system.

To sum up, the study of impact resistance of prefabricated pier is a complex and important subject. By strengthening the research of evaluation and design methods, exploring the application of new connection technologies and materials, in-depth research on the design concept of recoverable functions, combined with impact simulation test and numerical analysis, we can continuously improve the impact resistance of prefabricated piers, and provide solid technical support for the safe operation and sustainable development of Bridges.

This review systematically examines the current development status, advancements in impact resistance mechanical performance studies, and the application prospects of resilient design philosophy for prefabricated segmental bridge piers. Through a detailed analysis of existing research findings, this paper elucidates the dynamic response, failure characteristics, and repair capabilities of prefabricated segmental bridge piers under various impact scenarios, and discusses key directions for future research.

(1) Prefabricated segmental bridge piers represent an innovative construction technology offering advantages such as efficient construction, quality control, and environmental friendliness. This method significantly shortens construction schedules and minimizes impacts on the surrounding environment. However, their impact resistance is critical in addressing emergencies such as vehicle collisions and ship strikes. Studies indicate that impact resistance is influenced by factors including joint connection methods, material properties, and structural design. Optimizing design and material selection can enhance the impact resistance and durability of bridge piers.

(2) Research into the impact resistance of bridge piers primarily focuses on the development of new crash barriers, optimization of pier structures, analysis of influencing factors, and intelligent monitoring and early warning systems. The research methodologies encompass experimental studies, numerical analysis, and dynamic analysis. The application of finite element simulation techniques enables researchers to more accurately predict the dynamic response of piers under different conditions and validate the effectiveness of various reinforcement measures. Additionally, a quantitative damage assessment system has been established based on metrics such as force-time curves, displacement, and energy dissipation, providing scientific support for design and repair practices in engineering.

(3) Initially applied in seismic engineering, the concept of resilient design has gradually expanded into bridge engineering. This philosophy emphasizes the rapid recovery of structural functionality after an impact, reducing economic losses and social impacts. Integrating this concept into pier design facilitates the development of self-resetting structures and rapid replacement of damaged components, significantly improving recovery efficiency following extreme events. Research shows that incorporating internal mechanical energy-dissipating rebars and external replaceable energy-dissipation devices allows prefabricated segmental bridge piers to achieve efficient rapid replacement of damaged components and functional restoration, indicating that this area will become a focal point and mainstream trend in future research.

(4) Future research should systematically address the following key areas to advance the impact resistance of prefabricated bridge piers: developing advanced evaluation and design methods for accurately predicting pier responses and formulating robust design guidelines; investigating the optimal application of new materials such as high-performance concrete, fiber-reinforced composites, and technologies like mechanical and prestressed connections to enhance performance and durability; deepening the study of resilient design philosophy to develop self-resetting structures and rapid replacement mechanisms for damaged components; integrating impact simulation tests with numerical analysis to fully reveal dynamic responses and failure mechanisms, providing data support for performance optimization; and exploring comprehensive disaster prevention and mitigation strategies from a systems perspective to improve the overall disaster resilience of bridge systems. These research directions will pave new pathways for enhancing the impact resistance of prefabricated bridge piers and drive continuous progress and innovation in bridge engineering technology.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Tutor Yifang Huang at the Training Platform of Construction Engineering at the Polytechnic Institute of Zhejiang University for their help in the bridge pier test. The author sincerely thanks Xi Wu for her invaluable support and assistance during the literature research process.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LTGG23E080001, Scientific Research Foundation of Hangzhou City University under Grant Nos. X-202107 and X-202109, Zhejiang Engineering Research Center of Intelligent Urban Infrastructure under Grant No. IUI2023-ZD-14.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing, Project administration: Chengquan Wang; Writing—original draft preparation: Rongyang Liu; Supervision: Xinquan Wang; Investigation: Boyan Ping, Haimin Qian; Validation: Xinquan Wang, Xiao Li; Project administration: Yuhan Liang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, C. Q. W., upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lu SL. Research on the evaluation method of car crash safety of existing urban rail bridges [master’s thesis]. Chongqing, China: Chongqing Jiaotong University; 2023. [Google Scholar]

2. Zhang YQ. Impact analysis and damage assessment of vehicleImpacting pier based on LS-DYNA [master’s thesis]. Chongqing, China: Nanjing University of Science and Technology; 2022. [Google Scholar]

3. Du XS. Lessons to be learned from the June 15 accident involving a ship collided with the Jiujiang Bridge. China Maritime Saf. 2007;(9):32–5 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

4. Tang GD, Yang DJ. Events involving foreign ship collisions and bridge damage and the precautions taken. J China Foreign High. 1983;(5):16–21 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

5. Liu X. Study on dynamic response and riskassessment of cable-stayed bridge under shipcollision [master’s thesis]. Chongqing, China: Chongqing Jiaotong University; 2023. [Google Scholar]

6. Liang X. Research on risk management of flood control in cross river bridge project [master’s thesis]. Hefei, China: Anhui Jianzhu University; 2021. [Google Scholar]

7. Tan LB. Study on the damage mechanism of rolling stone impact pier and the stress characteristics of pier [master’s thesis]. Mianyang, China: Southwest University of Science and Technology; 2022. [Google Scholar]

8. Lu XF, Mou TM, Liu ZY. Flood disasters and preventative measures for bridges in mountainous areas of Sichuan. Urban Roads Bridges Flood Control. 2020;(7):135–7 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

9. Xiang YQ, Zhu S, Zhao Y. Research and development on accelerated bridge construction technology. China J Highw Transp. 2018;31(12):1–27 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]