Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Investigation on Shear Performance of Concrete T-Beam Bridge Strengthened Using UHPC

1 Guangdong Communication Planning & Design Institute Group Co., Ltd., No. 146 Huangbianbei Road, Baiyun District, Guangzhou, 510440, China

2 Guangdong Province Construction Engineering Machinery Construction Co., Ltd., No. 7 Cuiyu Road, Nansha District, Guangzhou, 511455, China

3 School of Civil and Transportation Engineering, Guangdong University of Technology, No. 100 Waihuangxi Road, Panyu District, Guangzhou, 510006, China

* Corresponding Author: Shaohua He. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative and Sustainable Materials for Reinforced Concrete Structures)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(5), 1327-1341. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.065177

Received 05 March 2025; Accepted 27 June 2025; Issue published 05 September 2025

Abstract

This investigation examines the shear performance of concrete T-beams reinforced with thin layers of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) through an approach that integrates experimental evaluation, numerical simulation, and practical project verification. The research is based on a real bridge, and in accordance with the similarity principle, three reduced-scale T-beams with varying UHPC thicknesses were fabricated and tested to examine their failure modes and shear behaviors. A finite element model was created to enhance understanding of how UHPC reinforces these structures, while also considering the effects of material strength and arrangement. In addition to the laboratory tests, the actual bridge was analyzed to assess the effectiveness of the proposed strengthening technique. Results indicated that concrete T-beams strengthened with 30 mm-thick layers of UHPC had significant improvements, including a 491% increase in shear stiffness, a 23.15% rise in ultimate resistance, and a 155% enhancement in deformability compared to unreinforced T-beams. Furthermore, these improvements continued to increase with the application of thicker UHPC layers. Using 120 MPa-grade UHPC with a thickness of 50 mm and an A-type arrangement ensured that the dynamic and static performance of the T-beam bridge met established code requirements. This research highlights the potential of UHPC thin layers in effectively reinforcing concrete beams for enhanced shear performance.Keywords

The growing traffic demands and widespread overload have significantly accelerated the degradation of concrete bridges, raising concerns about their long-term durability [1]. Various strengthening techniques have been applied to address these challenges, including section augmentation with normal concrete (NC), external steel plate bonding, external prestressing, the application of carbon fiber-reinforced polymer composites (CFRP) and strain-hardening cementitious composites (SHCC) concrete [2]. Although these methods improve load-bearing capacity, they often face limitations such as complex construction, high costs, and long-term material deterioration [3–6]. Therefore, there is a pressing demand for a reinforcement method that combines effectiveness, durability, cost-efficiency, and simplicity to address the practical challenges in modern engineering.

Ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) has gained increasing attention in recent years as an effective solution for strengthening structurally deficient concrete bridges [7–9]. This is primarily attributed to its outstanding mechanical properties [10,11], including exceptional compressive and tensile strength [12,13], enhanced toughness [14], and superior durability characteristics [15,16]. Extensive research has validated UHPC’s effectiveness in bridge rehabilitation applications [17,18]. Significant research efforts have been devoted to investigating UHPC’s potential for improving the structural performance of concrete beams. For instance, Bahraq et al. [19] reinforced rectangular concrete beams with UHPC, demonstrating a shift in failure mode from brittle shear failure in unreinforced beams to ductile failure in reinforced beams. Similarly, Wang et al. [20] strengthened rectangular beams using precast UHPC slabs, reporting a 25.1% increase in shear capacity compared to benchmark beams. Zhang et al. [21] employed cast-in-place UHPC layers for reinforcing concrete beams, achieving a 17.84% improvement in shear capacity by varying the UHPC layer thickness from 20 to 40 mm. Furthermore, studies by Liu and Charron [22] investigated the UHPC reinforcement of T-beams in various configurations, revealing that U-shaped sectional UHPC reinforcement significantly enhanced both elastic shear stiffness and ultimate shear capacity, with improvements ranging from 35.5% to 111.9% for elastic shear stiffness and 85.2% to 132.8% for ultimate shear capacity. Although these results provide valuable insights, the development of UHPC-based strengthening methodologies for T-beam members is still in its nascent stage.

The present investigation aims to elucidate the shear performance characteristics of T-beams reinforced with UHPC, utilizing empirical data from bridge rehabilitation projects in China. The study focused on the design and fabrication of three scaled T-beams reinforced with UHPC. A comprehensive analysis of failure modes and load-displacement relationships was conducted. Additionally, seven finite element models were developed and analyzed to investigate the influence of UHPC layer thickness, material strength, and reinforcement configurations on T-beam shear behavior. The derived results were successfully implemented in the structural rehabilitation of an actual bridge project. This study provides valuable insights and guidance for strengthening T-beam bridges using UHPC.

2 Prototype Bridge Description

The Shawei Bridge, located in Guangdong Province, China, was constructed in 2007. As shown in Fig. 1a, the bridge encompasses a total span of 176 m, comprising 11 spans of 16 m each, with four T-beams allocated per span. The bridge deck exhibits a width of 7.5 m, while the T-beams have a sectional depth of 1.3 m, featuring a web thickness of 20 cm at mid-span and 30 cm at the supports. Comprehensive inspections have identified approximately 689 cracks throughout the bridge, with widths varying from 0.04 to 0.24 mm, as presented in Fig. 1b. The presence of these cracks significantly undermines the durability and shear capacity of the structure, resulting in non-compliance with established Chinese codes [23]. An urgent strengthening measure is being implemented to ensure the safety and functionality of the bridge.

Figure 1: Background bridge composition and web cracks (Unit: mm): (a) Configuration of the Shawei Bridge; (b) Crack distribution of the Shawei Bridge

3.1 Test Specimens and Fabrications

Based on the configuration and arrangement of the prototype bridge, three scaled concrete T-beams were designed using a 1:2.5 scale ratio by the similarity principle [24].

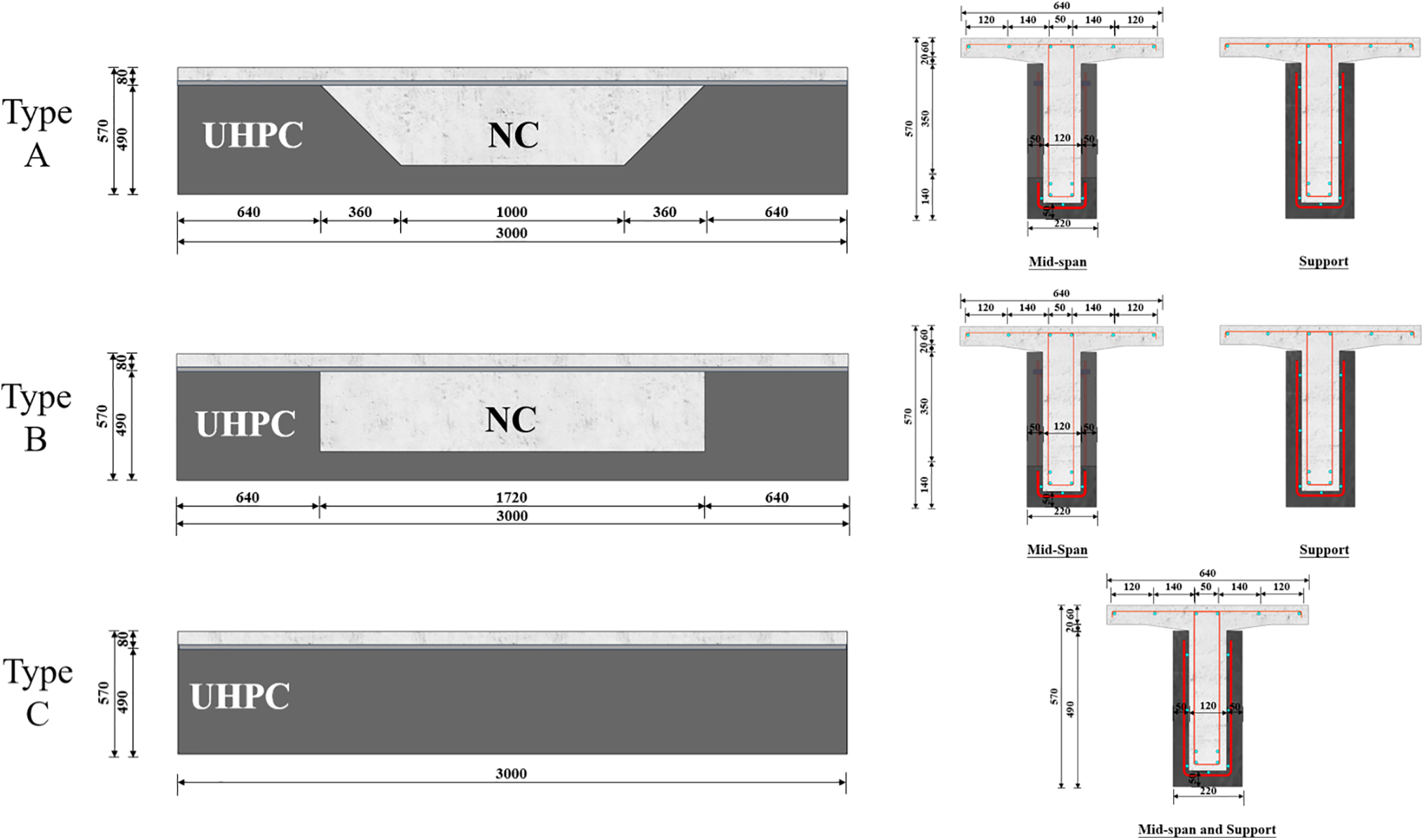

The goal of this study is to examine the shear reinforcement performance of reinforced concrete T-beams with insufficient shear capacity. To this end, the shear span section was reinforced with full cross-section height, while the midspan section was reinforced with partial height. This form of reinforcement also mitigates the effect of UHPC weight on the midspan. As illustrated in Fig. 2, two of the beams were reinforced with thin UHPC layers, featuring the beam web fully reinforced in the shear span and partially reinforced at mid-span, which is referred to as Type A arrangement in the present study. The interface of the UHPC reinforcement was roughened and inserted using Φ8 steel bars with a 30 mm embedment length. The 30 mm UHPC layer was further strengthened with high-strength steel wire mesh, while the 50 mm UHPC layer incorporated a Φ8 steel rebar mesh.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of T beam (Unit: mm)

Table 1 presents detailed information about the T-beam specimens. The specimen nomenclature follows this convention: “UN” denotes UHPC-strengthened beams, “T” corresponds to UHPC layer thickness (in mm), “A” identifies the UHPC configuration type, and the numerical value “120” indicates the UHPC’s compressive strength (in MPa). To illustrate, the nomenclature UN-T30-A-120 corresponds to a 30-mm-thick UHPC-strengthened T-beam configured in Type A arrangement, demonstrating a compressive strength of 120 MPa. Additionally, the code UN-T0 refers to the unreinforced T-beam. Fig. 3 shows the specific operational procedures for each interface treatment method.

Figure 3: Interface treatment

The NC used in the T-beam specimens is of C55 grade, consistent with that of the prototype bridge. The strengthening material is RPC120, which contains a steel fiber content of 2%. The mechanical characteristics of normal concrete (NC) and ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) were evaluated in compliance with the Chinese national standards [25,26]. Test results indicated that NC exhibited a compressive strength of 66.0 MPa (cube specimens), 57.0 MPa (prism specimens), and an elastic modulus of 36.8 GPa. The ultra-high-performance concrete exhibited compressive strengths of 129.0 MPa (cubic specimens) and 111.0 MPa (prismatic specimens), while its Young’s modulus was determined to be 39.5 GPa. The yield strength and elastic modulus of the HRB400-grade steel rebar were determined to be 455 MPa and 200 GPa, respectively.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the main steps in specimen fabrication were as follows: Fig. 4a setting the formwork; Fig. 4b casting and standard-curing the NC; Fig. 4c roughing and inserting steel rebars; and Fig. 4d casting and standard-curing the UHPC.

Figure 4: Fabrication of test specimens: (a) Formwork setting; (b) Pouring and curing NC; (c) Surface treatment; (d) Pouring and curing UHPC

3.2 Test Setup and Instrumentation

All T-beams were tested using a 10,000 kN servo-controlled hydraulic machine, with the load applied through two sets of transverse steel roller supports, creating a 1500 mm pure bending section and 675 mm shear spans on each side, resulting in a shear span-to-depth ratio (λ) of 1.33. Fixed and sliding hinge supports were positioned at both ends of the T-beam, spanning a center-to-center distance of 2900 mm, while the bottom of the T-beam was leveled with gypsum for horizontal alignment, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. During the preload phase, the load was gradually increased to 10 kN to ensure complete contact between the T-beam and the supports, eliminating any initial imperfections in the test setup. Loading commenced in force-controlled mode with 50 kN increments until crack observation triggered the transition to displacement control (1 mm/min). Testing continued until either significant failure or 20% load drop from maximum, with 1-min dwell periods at each load stage for system stabilization. Fig. 5b shows the sensor arrangement, with an LVDT mounted beneath the mid-span of T-beams to measure deflection.

Figure 5: Test setup and Instruments: (a) Test setup; (b) Arrangement of sensor (Unit: mm)

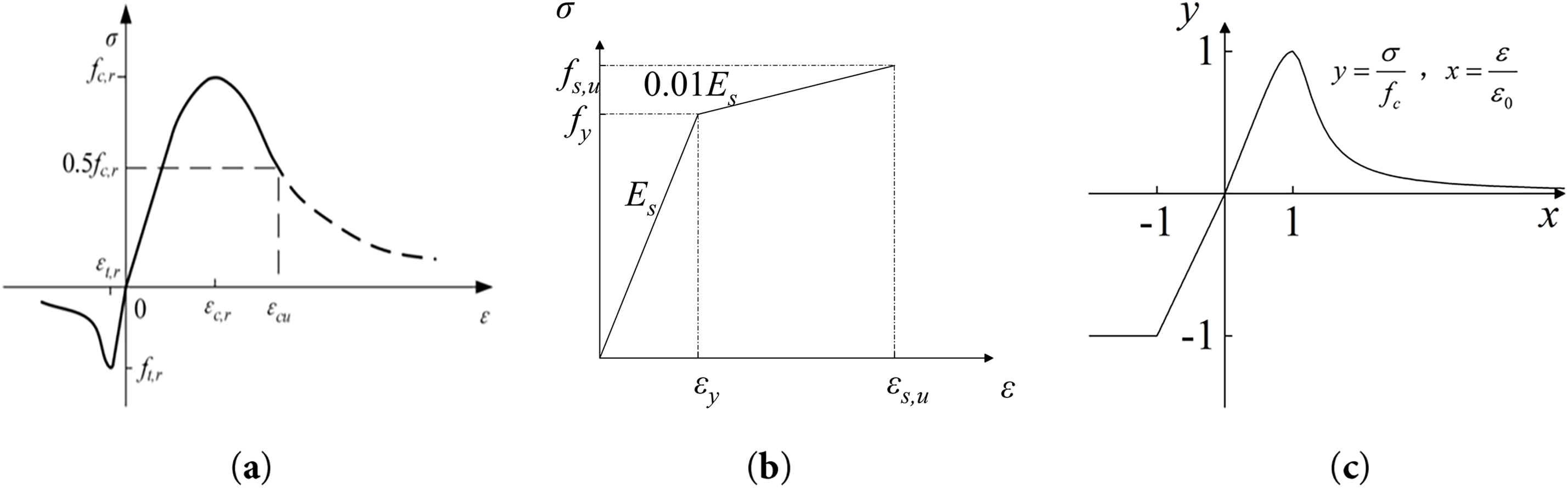

The numerical simulation was conducted using ANSYS APDL to perform parametric studies on T-beams reinforced with UHPC. Fig. 6 shows the constitutive models of the materials involved. The constitutive model for NC follows the uniaxial stress-strain relationship in the Chinese code (GB/T 50010-2010) [27]. The axial tension and compression constitutive models for UHPC follow those proposed by Naeimi and Moustafa [28] and Savino et al. [29], where ε0 represents the peak strain corresponding to fc. For steel rebars, the uniaxial tension model uses the double oblique line model [30].

Figure 6: Constitutive Model: (a) Concrete, (b) Steel, (c) UHPC

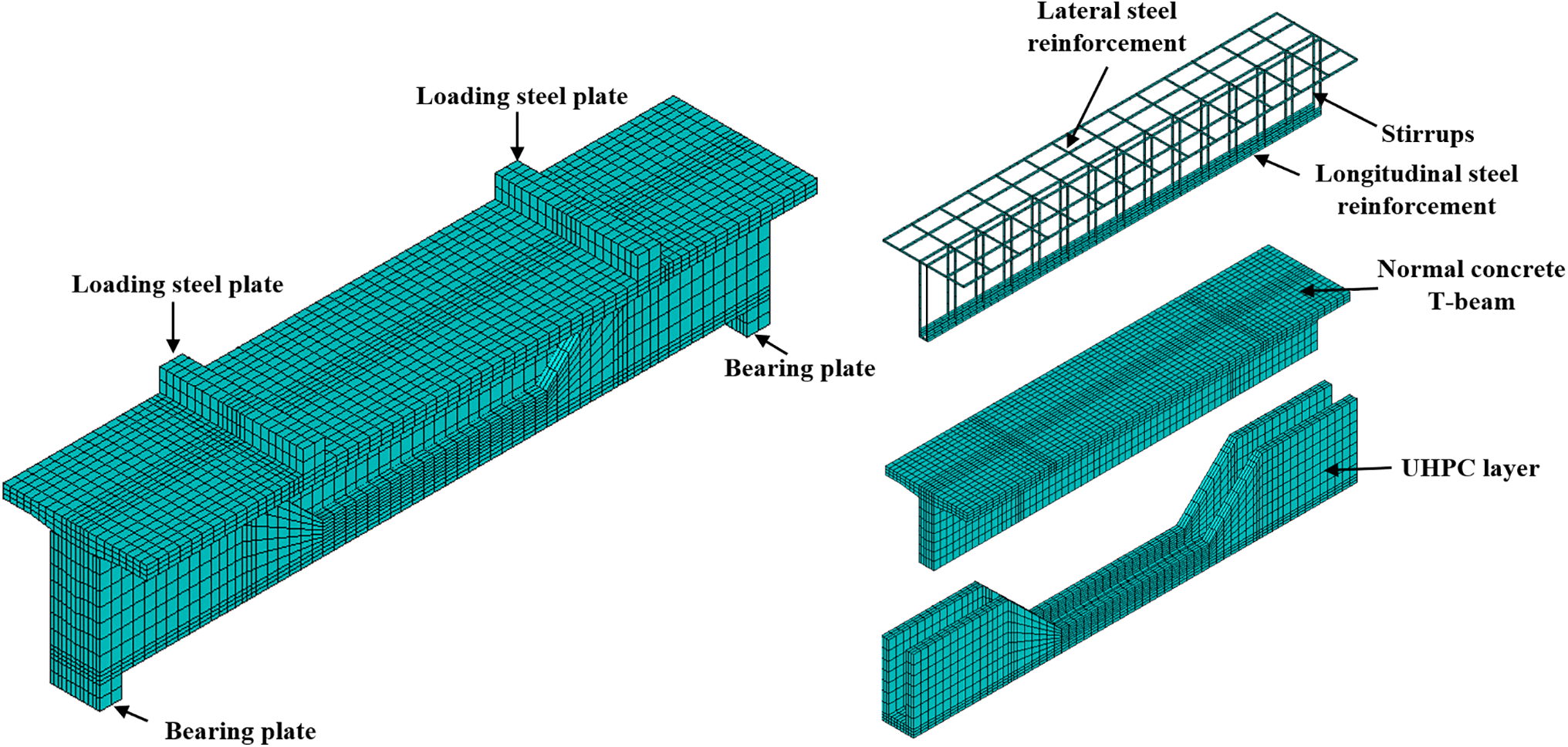

4.2 Element Selection and Meshing

The finite element model composition and mesh division are presented in Fig. 7. The numerical simulation employed the following element types: Solid65 for concrete components, Solid45 for loading pads and supports, and Link8 for steel reinforcement. The concrete-UHPC interface was modeled using contact pairs (Contact173 and Target170 elements). Since no delamination was observed at the UHPC-NC interface in the experiments, the KEYOPT (12) parameter was set to 2 to allow sliding while keeping the interface intact. Interfacial friction was modeled by assigning a friction coefficient via the material constant MU using the MP command. The concrete-steel rebar interaction was simulated through nodal coupling. An optimized mesh configuration was adopted, with element dimensions of 20 × 60 × 50 mm and 30 × 60 × 30 mm, achieving an effective balance between computational cost and numerical accuracy.

Figure 7: Finite element model

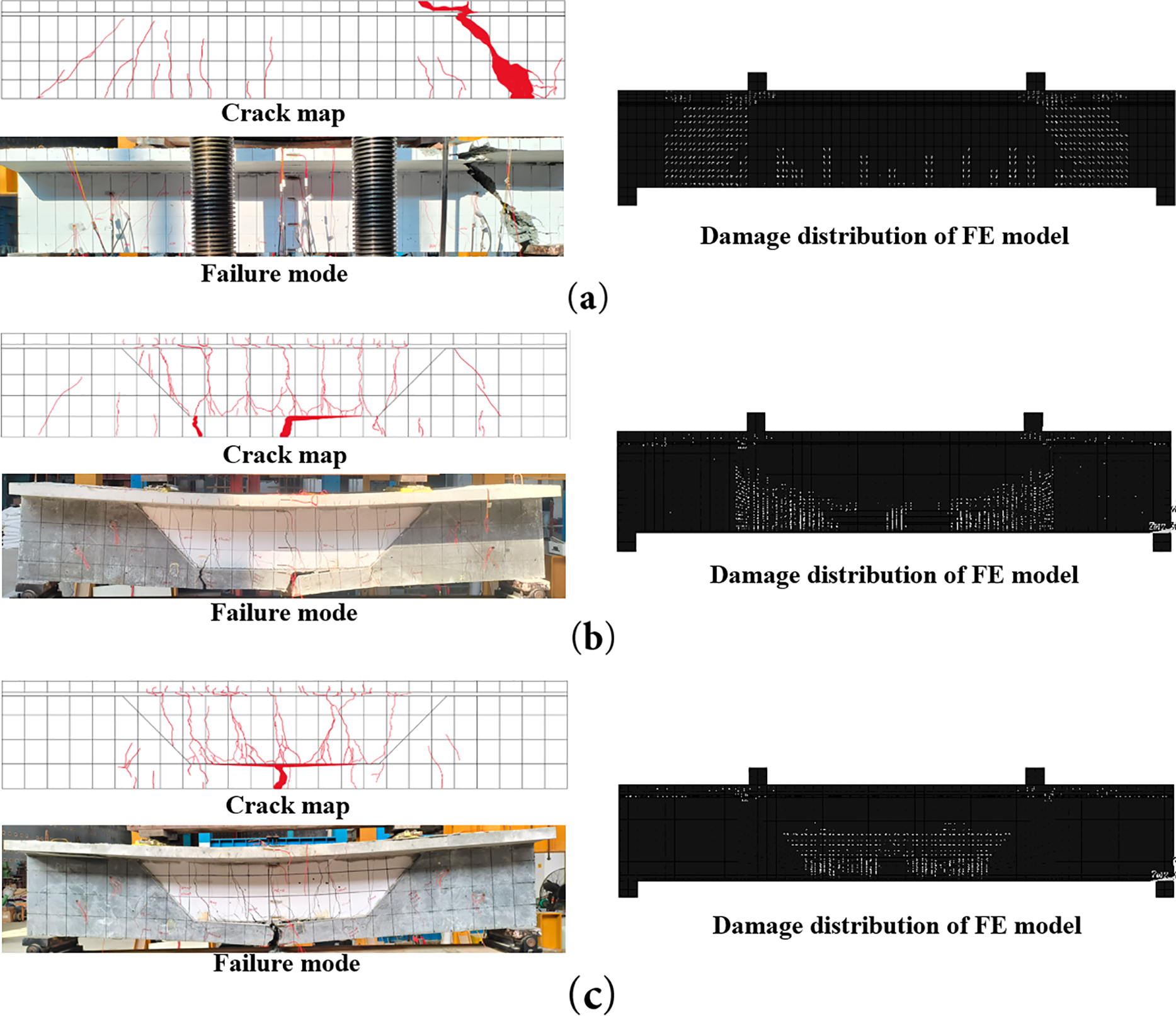

Fig. 8 presents a comparative visualization of the experimental failure patterns observed in the T-beam specimens and the corresponding damage distribution predicted by the finite element simulations. Cracks in the unreinforced T-beam (UN-T0) primarily concentrate in the shear span, with the main crack following a diagonal path from the loading points to the supports, resulting in a typical shear failure. In contrast, the T-beams reinforced with UHPC in UN-T30-A-120 and UN-T50-A-120 exhibit a significant shift to ductile flexural failure, with crack propagation significantly reduced near the shear span and primarily developing in the pure bending region. This behavioral transition stems from UHPC’s superior strength and ductility characteristics, which are substantially improved by the steel fibers’ crack-arresting capability, effectively inhibiting the development of diagonal shear cracks. Additionally, stress redistributions caused by the formation of plastic hinges in the relatively weak pure bending region contribute to the shift in failure mode from brittle shear to ductile flexural failure. The FE models also produced failure characteristics similar to those observed in the experiments, indicating that the models reliably replicated the experimental results.

Figure 8: Failure pattern of test specimens: (a) UN-T0; (b) UN-T30A-120; (c) UN-T50A-120

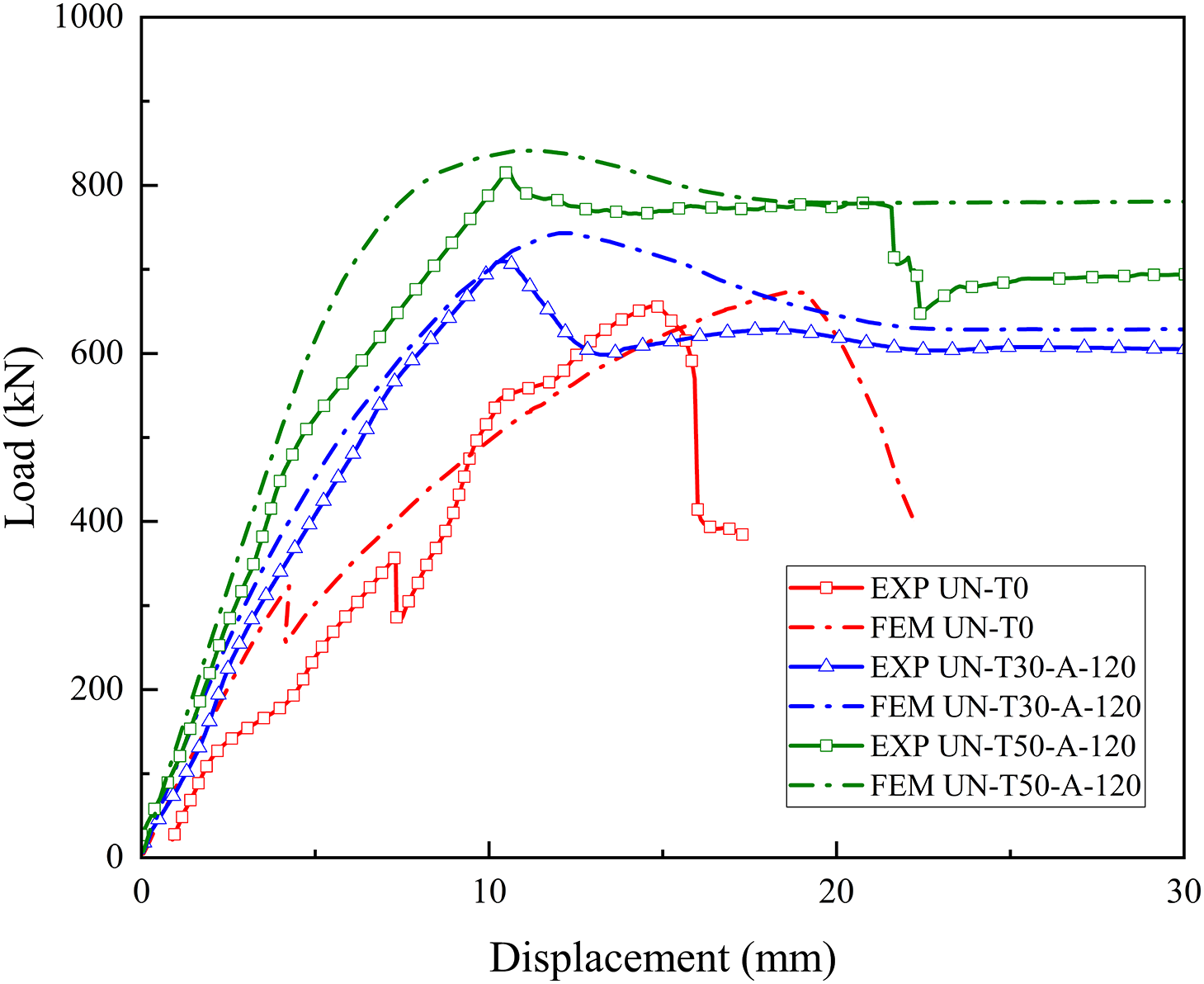

Fig. 9 plots the load-displacement curves of the T-beams reinforced with UHPC, showing that the use of UHPC enhances post-failure ductility and load-bearing capacity, which aligns with the experimentally observed failure modes. Incorporating UHPC layers improves deformability, reduces crack propagation, and shifts the brittle shear failure seen in UN-T0 to a ductile flexural mode in its counterparts (e.g., UN-T30-A-120 and UN-T50-A-120), resulting in a prolonged descending curve for the UHPC-reinforced beams. In particular, the load-deflection curve for UN-T0 exhibits a sharp decline after reaching its peak load, consistent with experimental observations. A sharp stepwise change occurs at approximately 357 kN in this curve, attributed to the formation of shear cracks resulting from the tensile rupture of the shear stirrups.

Figure 9: Load-deflection curve of test specimens

The load-deflection responses of specimens UN-T30-A-120 and UN-T50-A-120 demonstrate sustained deformation capacity beyond peak load attainment, evidencing enhanced post-failure shear performance and structural ductility. This behavior corresponds well with the observed ductile failure mechanisms in UHPC-strengthened T-beams. The load-deflection response of specimens UN-T30-A-120 and UN-T50-A-120 exhibits three characteristic regimes: (1) an initial linear elastic phase with proportional load-deflection behavior; (2) a nonlinear elastoplastic phase marked by crack propagation and reduced stiffness; and (3) a post-failure phase demonstrating residual load-bearing capacity despite progressive displacement accumulation and strength degradation.

Table 2 presents a summary of the shear performance indicators, which are characterized by the experimental load-deflection curves. In this table, the term Pcr denotes the initial cracking load, while Pu indicates the ultimate load. The variable K represents the elastic shear stiffness. The key deformation parameters are defined as follows: Δy represents the yield-point deflection at mid-span, Δu denotes the ultimate-load deflection, and Δf corresponds to the final recorded deflection at test termination. The deformation capacity index, μΔf, is calculated as Δf/Δy, and the ductility index, μΔu, is calculated as Δu/Δy [31,32].

As shown in Table 2, the K values for the UN-T30-A-120 and UN-T50-A-120 increase by 303% and 491%, respectively, compared to the UN-T0 beam. Consequently, the μΔu (deformation) values for the UN-T30 and UN-T50 are reduced by 11.65% and 14.03%, respectively, relative to UN-T0. The Pcr for the UN-T30-A-120 and UN-T50-A-120 displays markable increases of 193% and 223% over UN-T0, while the Pu for these beams also shows enhancement, with increases of 8.42% and 23.15% compared to UN-T0. The μΔf for the UN-T30-A-120 and UN-T50-A-120 demonstrate increases of 310.8% and 334.7%, respectively, in comparison to UN-T0. It is noted that the μΔf and μΔu values for the UN-T50-A-120 and UN-T30-A-120 are relatively similar, suggesting that variations in UHPC thickness have a minimal impact on ductility. However, the results demonstrate that increasing the UHPC thickness from 30 mm to 50 mm leads to significant performance enhancements: stiffness (K) increases by 46.5%, cracking load (Pcr) improves by 10.41%, and ultimate load capacity (Pu) rises by 12.78% This indicates that increasing the UHPC thickness further enhances the crack resistance, shear capacity, deformation, and shear stiffness of the T-beams.

A parametric analysis based on the above FE models was performed to evaluate further the influence of critical factors on the T-beams reinforced with UHPC. The parameters include the UHPC strength and types of UHPC arrangements. Table 3 and Fig. 10 provide a summary of the details of the parametric analysis.

Figure 10: Arrangement of UHPC layer (Unit: mm)

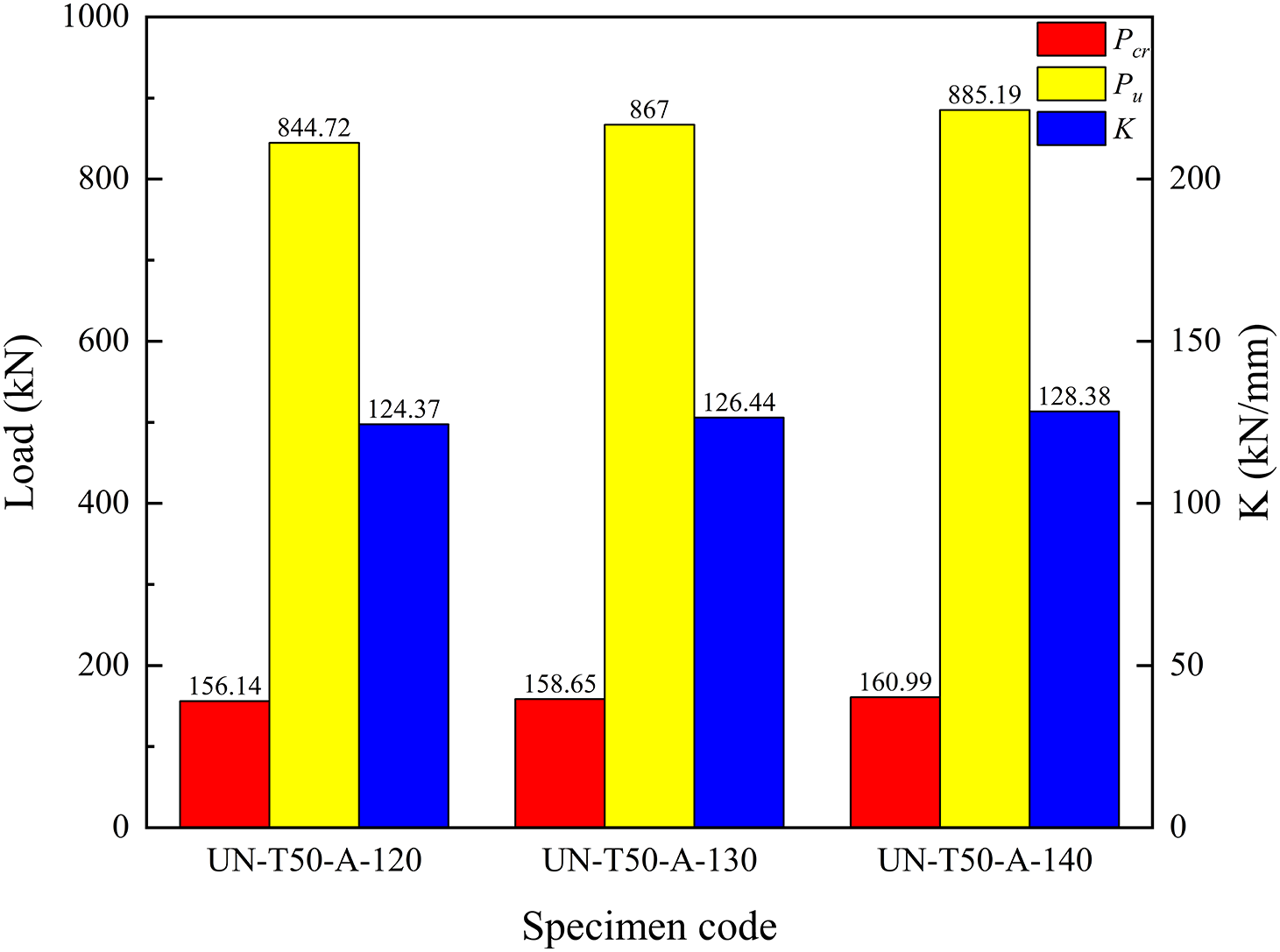

5.4.1 Influence of UHPC Strength

Fig. 11 demonstrates the influence of UHPC compressive strength on the shear behavior of T-beam specimens. Analysis results demonstrate that enhancing UHPC compressive strength from 120 MPa to 130 MPa and 140 MPa yields progressive stiffness improvements, with specimens UN-T50-A-130 and UN-T50-A-140 exhibiting 1.67% and 3.23% higher K values, respectively, compared to the baseline UN-T50-A-120. Similarly, the Pcr demonstrates improvements of 1.61% and 3.11% for these beams relative to UN-T50-A-120. Furthermore, the enhancement in UHPC strength from 120 MPa to 130 MPa and 140 MPa results in an elevation of the Pu for UN-T50-A-130 and UN-T50-A-140 by 2.64% and 4.79%, respectively. These findings suggest that while the application of higher UHPC strength can yield slight improvements in shear stiffness, crack resistance, and ultimate load-bearing capacity of T-beams, the overall enhancements are marginal. Therefore, considering the associated construction costs, a UHPC strength grade of 120 MPa is recommended for practical engineering applications.

Figure 11: Influence of UHPC strength on T-beams

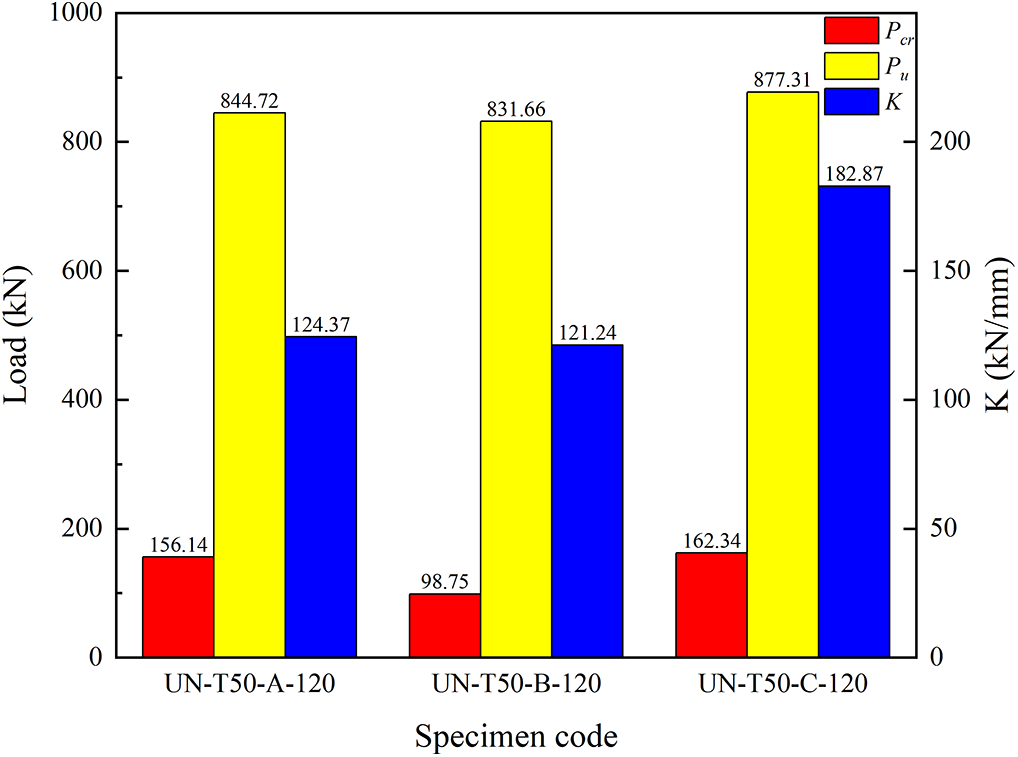

5.4.2 Influence of UHPC Arrangement

Fig. 12 demonstrates the influence of UHPC arrangement on the shear performance of T-beams, indicating that shear performance varies with different layer configurations. A comparison reveals that the Pcr and Pu of UN-T50-C-120 are 3.97% and 3.86% greater, respectively, than those of UN-T50-A-120. In contrast, the Pcr and Pu of UN-T50-B-120 are 36.75% and 1.54% lower, respectively, when compared to UN-T50-A-120. The UHPC layer in the type A arrangement, characterized by a variable height of UHPC within the shear zone, exhibits shear resistance comparable to that of the type C arrangement, which employs a full-height UHPC jacket. However, the stiffness (K) of UN-T50-C-120 surpasses that of UN-T50-A-120 and UN-T50-B-120, which may compromise the structural ductility of T-beam bridges under shear loads, as supported by experimental findings. Consequently, for practical engineering applications involving the rehabilitation of T-beam bridges, the UHPC layer in the type A arrangement is recommended.

Figure 12: Influence of UHPC arrangement on T-beams

6.1 Engineering Strengthening Solutions

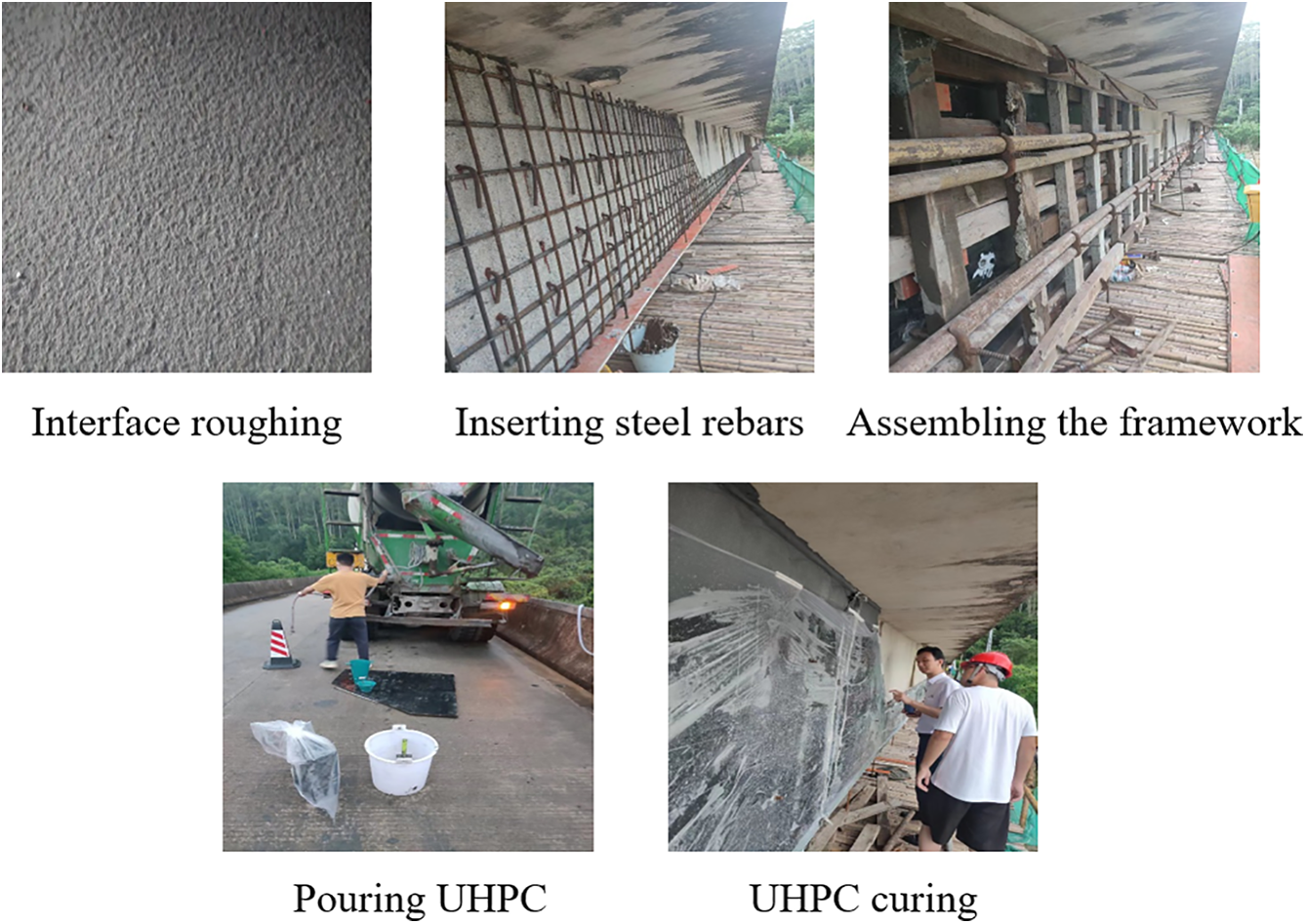

Based on the conclusions drawn from the above laboratory tests and FE simulations, a UHPC reinforcement system with 120 MPa compressive strength was selected and implemented for the retrofit of the prototype Shawei Bridge. The UHPC layer is 50 mm thick and arranged in a Type A configuration. The embedded steel rebars within the UHPC layer have a diameter of 12 mm. Additionally, short interfacial steel rebars, measuring 8 mm in diameter, are implanted into the original T-beam and spaced 400 mm apart. The material properties of both the steel and concrete are consistent with those used in the earlier model tests. Fig. 13 illustrates the repair process at the Shawei Bridge construction site, which consists of the following steps: (a) Roughening the web surface of the original T-beams; (b) Inserting short steel rebars into the roughened interface; (c) Assembling the wooden formwork after completing both longitudinal and vertical steel reinforcements; (d) Pouring UHPC and covering it with a plastic membrane to maintain humidity; and (e) Demolding the structure after it has naturally cured for 28 days.

Figure 13: Construction site of Shawei Bridge

6.2 Dynamic and Static Load Tests

Dynamic and static tests were conducted on the UHPC-reinforced prototype bridge to assess the effectiveness of the proposed strengthening solution. The field test included deflection monitoring, strain verification coefficients, crack width closure assessments, dynamic amplification factors, and frequency evaluations of the T-beams. These parameters were systematically compared with the permissible limits specified in the Chinese design code [33]. The findings indicated that the deflection check coefficient for the UHPC-reinforced T-beams ranged from 0.5 to 0.88, falling within the acceptable range of 0.5 to 0.9, while the strain check coefficient ranged from 0.4 to 0.79, aligning with the expected standards of 0.4 to 0.8. The relative residual deformation for the T-beams varied from 2.1% to 16.7%, remaining below the 20% threshold. Additionally, the crack closure width for the bridge was less than one-third of the original crack width, and the first-order frequency measured was 10.74 Hz, exceeding the minimum requirement of 1 Hz. The maximum dynamic amplification factor was recorded at 0.144, indicating that the bridge deck provided a smooth experience with no significant jolts or bumps as vehicles passed over. Overall, the prototype bridge was successfully reinforced using the proposed retrofitting approach, meeting all code requirements and confirming the effectiveness and safety of the scheme.

This paper presents an experimental study and numerical simulation on the shear performance of T-beams reinforced with UHPC. The study examined the influence of varying UHPC reinforcement layer thicknesses on the shear performance of T-beams. Additionally, it examined the influence of UHPC strength and reinforcement form on the shear performance through numerical simulation methods. The results were then applied to the repairing of an actual bridge. The main conclusions are as follows:

1. Incorporating a UHPC thin layer in T-beams significantly improves their shear performance, resulting in a transition from brittle shear failure to ductile flexural failure under shear loads. The UHPC layer significantly improves the crack resistance, shear capacity, and shear stiffness of T-beams, with shear capacity increasing by up to 23.15%. Increasing the thickness of the UHPC layer from 30 to 50 mm further enhances shear capacity by an additional 12.78%.

2. The shear capacity of reinforced T-beams is influenced by both the compressive strength of UHPC and the configuration of the UHPC layer. Notably, the Type A arrangement, featuring a partial-height UHPC layer within the shear-critical region, exhibits similar shear resistance to the Type C arrangement employing a full-height UHPC jacket.

3. The structural rehabilitation of the prototype bridge, employing 120 MPa UHPC in Type A configuration, satisfactorily complied with all stipulated code provisions for static and dynamic performance requirements.

4. The FE models discussed in this paper did not account for the differences in creep and shrinkage between the newly cast UHPC layer and the existing NC substrates. The time-dependent properties of the concrete may influence the bond at the interface between UHPC and NC. Therefore, it is recommended that future research further investigate the effects of concrete shrinkage and creep on the UHPC-NC interface.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank all the anonymous referees for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Funding Statement: The Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou (Grant # 2024A04J9888), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant # 52278161), and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant # 2023A1515010535).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Data Curation, Conceptualization, Zhiyong Wan; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Investigation, Guozhang Luo; Methodology, Validation, Resources, Pailin Fang; Conceptualization, Validation, Menghui Ji; Data Curation, Zhizhao Ou; Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Visualization Preparation, Writing—Review & Editing, Shaohua He. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Shao XD. Bridge engineering. 4th ed. Beijing, China: China Communications Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

2. Hamoda A, Ghalla M, Yehia SA, Ahmed M, Abadel AA, Baktheer A, et al. Experimental and numerical investigations of the shear performance of reinforced concrete deep beams strengthened with hybrid SHCC-mesh. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2024;21(1):e03495. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Schranz B, Michels J, Czaderski C, Motavalli M, Vogel T, Shahverdi M. Strengthening and prestressing of bridge decks with ribbed iron-based shape memory alloy bars. Eng Struct. 2021;241(2):112467. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.112467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Switek-Rey A, Denarié E, Brühwiler E. Early age creep and relaxation of UHPFRC under low to high tensile stresses. Cem Concr Res. 2016;83(3):57–69. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2016.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. He SH, Zhong HQ, Huang X, Xu YM, Mosallam AS. Experimental investigation on shear fatigue behavior of perfobond strip connectors made of high strength steel and ultra-high performance concrete. Eng Struct. 2025;322(1):119181. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.119181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. He SH, Zhou DF, Bai BS, Liu CX, Dong Y. Experimental study on shear performance of prefabricated HSS-UHPC composite beam with perfobond strip connectors. Eng Struct. 2025;324(7):119318. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.119318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Jin W, Yang Q, Peng X, Xu B. A review on mechanism and influencing factors of shear performance of UHPC beams. Buildings. 2024;14(11):3351. doi:10.3390/buildings14113351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xiao G, Chen X, Xu L, Kuang F, He S. Flexural performance of UHPC-reinforced concrete T-beams: experimental and numerical investigations. Struct Durab Health Monit. 2025;1–15. doi:10.32604/sdhm.2025.064450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhong H, Chen Z, Liu C, He S, Wan Z, Yu Z. Fatigue shear failure mechanism and prediction method for UHPC-NC bond interfaces. Eng Struct. 2025;336(3):120455. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2025.120455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. He SH, Huang X, Huang JL, Zhang YY, Wan ZY, Yu ZT. Shear bond performance of UHPC-to-NC interfaces with varying sizes: experimental and numerical evaluations. Buildings. 2024;14(11):3684. doi:10.3390/buildings14113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. He SH, Huang X, Zhong HQ, Wan ZY, Liu G, Xin HH, et al. Experimental study on bond performance of UHPC-to-NC interfaces: constitutive model and size effect. Eng Struct. 2024;317(S1):118681. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.118681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Cheng XL, Mu R, Liu XY. Review on preparation and mechanical properties of ultra-high performance concrete. Bull Chin Ceram Soc. 2024;43(12):4295–312. doi:10.16552/j.cnki.issn1001-1625.20240816.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kravanja G, Mumtaz AR, Kravanja S. A comprehensive review of the advances, manufacturing, properties, innovations, environmental impact and applications of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Buildings. 2024;14(2):382. doi:10.3390/buildings14020382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xu R, Li J, Li W, Zhang W. Experimental and numerical study of bonding capacity of interface between ultra-high performance concrete and steel tube. Struct Durab Health Monit. 2025;19(2):285–305. doi:10.32604/sdhm.2024.057513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Peng G, Wu J, Shi C, Hu X, Niu D. Effect of thermal curing regimes on the mechanical properties, and durability of UHPC: a state-of-the-art review. Structures. 2025;74(3):108667. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2025.108667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Redžić N, Grgić N, Baloević G. A review on the behavior of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) under long-term loads. Buildings. 2025;15(4):571. doi:10.3390/buildings15040571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Cao JH, Zhang Y, Shao XD, Huang SL, Cai WY, Zhang XP. Review on UHPC bridge research 2024. J Munic Technol. 2025;43(3):1–17. doi:10.19922/j.1009-7767.2025.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Editorial Department of China Journal of Highway and Transport, Han Q, Wang JQ, Wang L, Ye XW, Qi JN. Review on China’s bridge engineering research: 2024. China J Highw Transp. 2024;37(12):1–160. doi:10.19721/j.cnki.1001-7372.2024.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bahraq AA, Ali Al-Osta M, Ahmad S, Al-Zahrani MM, Al-Dulaijan SO, Rahman MK. Experimental and numerical investigation of shear behavior of RC beams strengthened by ultra-high performance concrete. Int J Concr Struct Mater. 2019;13(1):6. doi:10.1186/s40069-018-0330-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang GL, Zhang YX, Yang JL, Ding WS, Yang JK, Shao JC, et al. Shear behavior of full-scale reinforced concrete beams strengthened with ultra-high performance concrete plates. Sci Technol Eng. 2024;24(5):2007–14. doi:10.21838/uhpc.16659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang JR, Cao JL, Wang YP, Ma KZ. Shear behavior of reinforced concrete beams strengthened by ultra-high performance concrete. Sci Technol Eng. 2022;22(19):8421–30. [Google Scholar]

22. Liu T, Charron JP. Experimental study on the shear behavior of UHPC-strengthened concrete T-beams. J Bridge Eng. 2023;28(9):04023064. doi:10.1061/JBENF2.BEENG-6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. JTG 3362-2018. Design specification for highway reinforced concrete and prestressed concrete bridges and culverts. Beijing, China: People’s Communications Press; 2018 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/jigou/glj/202006/P020230330561291441977.pdf. [Google Scholar]

24. Nam JS, Park YJ, Kim JK, Han JW, Nam YY, Lee GH. Application of similarity theory to load capacity of gearboxes. J Mech Sci Technol. 2014;28(8):3033–40. doi:10.1007/s12206-014-0710-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. GB 50081-2019. Standard for test methods of concrete physical and mechanical properties. Beijing, China: China Architecture & Building Press; 2019 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zc/wjk/art/2019/art_17339_242198.html. [Google Scholar]

26. GB/T 31387-2015. Reactive powder concrete. Beijing, China: Standards Press of China; 2015 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=9CACB7D137463D0F9428AEA8CCBE9DFB. [Google Scholar]

27. GB50010-2010 (2015). Code for design of concrete structures (2024). Beijing, China: China Architecture & Building Press; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.ccsn.org.cn/Zbbz/Show.aspx?Guid=dc81f287-9b5e-400f-ac14-6893a273ae1c. [Google Scholar]

28. Naeimi N, Moustafa MA. Compressive behavior and stress-strain relationships of confined and unconfined UHPC. Constr Build Mater. 2021;272(9):121844. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Savino V, Lanzoni L, Tarantino AM, Viviani M. Tensile constitutive behavior of high and ultra-high performance fibre-reinforced-concretes. Constr Build Mater. 2018;186(8):525–36. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Perdahcıoğlu ES, Geijselaers HJM, Huétink J. Constitutive modeling of metastable austenitic stainless steel. Int J Mater Form. 2009;2(1):419. doi:10.1007/s12289-009-0478-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li Y, Zhou H, Zhang Z, Yang J, Wang X, Wang X, et al. Macro-micro investigation on the coefficient of friction on the interface between steel and cast-in-place UHPC. Eng Struct. 2024;318:118769. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.118769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Obaydullah M, Jumaat MZ, Alengaram UJ, ud Darain KM, Huda MN, Hosen MA. Prestressing of NSM steel strands to enhance the structural performance of prestressed concrete beams. Constr Build Mater. 2016;129(3):289–301. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.10.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. JTG/T J21-01-2015. Load test methods for highway bridge. Beijing, China: People’s Communications Press; 2015 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: http://www.huaxiajianyan.com/ueditor/php/upload/file/20200416/1587021523953880.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools