Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Strengthening Efficacy of External FRP Laminates on Aged Prestressed Beams with Unbonded Strands

Faculty of Civil Engineering, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, No. 35–37, Ho Hao Hon Street, Cau Ong Lanh Ward, Ho Chi Minh City, 700000, Vietnam

* Corresponding Author: Phuong Phan-Vu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Smart Sensors and Smart CFRP Components for Structural Health Monitoring of Aerospace, Energy and Transportation Structures)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(5), 1111-1125. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.070179

Received 10 July 2025; Accepted 13 August 2025; Issue published 05 September 2025

Abstract

As prestressed concrete (PC) structures age, long-term effects, e.g., creep, shrinkage, and prestress losses, compromise their structural performance. Strengthening these aged PC beams has become a crucial matter. One effective solution is to use externally bonded fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) sheets; however, limited research has been done on aged PC beams using the FRP, especially for beams with unbonded prestressing strands (UPC beams). Therefore, this research investigates the flexural strengthening efficacy of external FRP sheets on aged UPC beams with unbonded tendons. Aging minimally affected the failure modes of UPC beams, with nonstrengthened beams showing flexural failure via rebar yielding and concrete crushing, and FRP-strengthened beams failing due to FRP debonding and tensile reinforcement yielding, though tendons in the aged beams did not yield due to prestress losses, unlike the new beams. The U-wrap anchor curbed widespread debonding, leading to tensile reinforcement yielding and FRP rupture. Aging hastened crack growth and stiffness loss, increasing deflections and reducing load resistance, but FRP reinforcement mitigated these effects, enhancing cracking resistance by 14% over the unstrengthened aged beams and 7% over the new beams while boosting ultimate resistance by 9% above the non-strengthened new beams. Compared to the new FRP-strengthened beams, the aged counterparts had lower cracking resistance, stiffness and capacity—showing 20% higher deflections, 7–9% lower serviceability loads, 7%–17% reduced ultimate strength and 17% less deformability—due to prestress losses and premature FRP debonding.Keywords

Prestressed concrete structures with unbonded tendons are a cornerstone of modern civil infrastructure [1,2], including bridges, parking structures, and industrial buildings, due to their ability to efficiently manage tensile stresses through pre-compression, fast construction, and simple maintenance. However, as these structures age, long-term phenomena, such as creep, shrinkage, and prestress losses, compromise their material properties and structural performance [3,4]. With the increasing demand to extend the service life of existing infrastructure and accommodate higher loading requirements, strengthening of these aged prestressed concrete beams has become a critical matter. A promising technique involves the use of externally bonded fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) sheets, which offer a lightweight, corrosion resistant, and high-strength solution for flexural strengthening [5,6].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of externally bonded FRP sheets in enhancing the structural performance of prestressed concrete beams [7,8], including the loading capacity, deflection, and cracking performances. Reed and Peterman [9] demonstrated that carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) laminates enhanced the flexural and shear resistances of old bonded prestressed concrete (BPC) girders. Nguyen-Minh et al. [10] investigated the flexural behavior of unbonded prestressed concrete (UPC) T beams reinforced with CFRP sheets. Their results showed that the use of CFRP sheets and U-wrapped anchors significantly affected tendon strain and governed the flexural capacity, crack width, mid-span displacement, and ductility of the beams. Murphy et al. [11] conducted experimental studies on the shear strengthening of prestressed concrete I-girders using externally bonded FRP sheets. They found that FRP strengthening was effective in increasing the load carrying capacity of the girders. Tran et al. [12] have shown that FRP strengthening is effective in eliminating the detrimental effects of fatigue loading, i.e., creep and degradation of material properties, on prestressed concrete beams. External FRP reinforcement has also been proven to be effective in enhancing the stiffness and flexural resistance of corroded beams [13]. External strengthening of FRP can also restore the structural integrity of damaged UPC beams and even increase their loading resistance beyond that of undamaged UPC beams.

Despite this progress, the literature on FRP strengthening of aged prestressed beams is sparse [14,15]. Most studies focus on new beams, where material properties are well defined and long-term effects are absent. As a result, current standards and guidelines for strengthening structures with FRP composites are largely based on new or minimally aged concrete. Some studies have touched on ageing effects tangentially, for example, Shen et al. [16] examined the retrofitting effect of basalt FRP sheets on deteriorated RC beams, but none has systematically addressed prestressed beams subjected to long-term effects of creep, shrinkage, and prestress losses. This gap is significant, as aging alters the structural behaviour in ways that directly impact FRP performance, necessitating targeted research.

The effectiveness of FRP strengthening on aged prestressed beams with unbonded tendons differs from that of new beams due to several interrelated factors tied to long-term degradation [17,18]. First, the creep and shrinkage in aged concrete magnify the camber (upward deflection) induced by prestressing on uncracked PC beams [19]. It is noted that PC beams are typically designed to remain uncracked under service loads, relying on the prestressing force to offset the effects of dead and live loads. In new PC beams, the soffit remains relatively flat, ensuring uniform contact with FRP sheets and maximizing bond efficiency. In contrast, aged PC beams (uncracked) develop a curved soffit with time, reducing the effective bonding area and introducing geometric imperfections that hinder FRP adhesion [20,21]. This curvature can cause stress concentrations at the FRP-concrete interface, increasing the likelihood of premature debonding [22,23]—a failure mode less prevalent in new beams with planar surfaces. Second, prestress losses are significantly higher in aged beams due to the cumulative effects of tendon relaxation, concrete creep, and shrinkage. Unlike bonded tendons, unbonded tendons do not develop localized bonds with the surrounding concrete, resulting in a more uniform stress distribution throughout the tendon length but also greater sensitivity to prestress losses over time [24]. The reduced prestressing due to these losses decreases the contribution of the prestressing reinforcement, and thus places greater demand on the FRP reinforcement, altering its effectiveness compared to new beams. Third, the material properties of the aged concrete differ markedly from those of the new concrete [25,26]. Over time, concrete undergoes microcracking, surface deterioration, increased brittleness, and a reduction in tensile strength. These changes weaken the bond between the FRP and the concrete, since the strength of the interfacial shear depends heavily on the substrate’s condition. In addition, the accumulation of creep-induced strain in aged beams alters the stress state at the time of application of the FRP, potentially reducing the composite between the FRP and concrete compared to new beams, where strains are minimal prior to strengthening.

Prior studies [10,27] provided important insights into the flexural behavior of unbonded prestressed concrete beams strengthened with CFRP, showing how tendon strain, crack control, and ductility are affected. However, these studies were conducted on new beams, without the consideration of long-term aging effects. In contrast, our study evaluates beams after 6.5 years of natural aging—a duration during which over 98% of creep and shrinkage effects accumulate. In addition, unlike the recommendations of ACI 440.2R-17 [20,28], which are largely calibrated for newer concrete members, our research addresses bond behavior and performance degradation specific to aged unbonded systems, an area currently lacking in design guidance. Furthermore, Eshwar et al. [22] and Al-Ghrery et al. [23] reported that soffit curvature can compromise CFRP bonding, but did not experimentally quantify its long-term implications or mitigation strategies such as U-wrap anchorage, which is one of the central contributions of this paper. From a broader perspective, the structural resilience of aging infrastructure is critical in light of increasing service demands and environmental deterioration. Resilience encompasses not only the ability to withstand loads but also to recover or sustain performance after degradation. Recent frameworks—such as those proposed by Xu et al. [29], Mata et al. [30], and Oz et al. [31]—highlight the importance of post-damage recoverability and adaptive strengthening in resilient buildings. Our study contributes to this direction by demonstrating how FRP retrofitting can restore or exceed baseline capacity in aged beams, hence improving the structural resilience of prestressed concrete systems throughout their lifecycle.

From the aforementioned knowledge gap, this paper is aimed at filling this gap by evaluating the effectiveness of external FRP sheets on aged prestressed beams with unbonded prestressing strands. Through experimental comparisons with identical new beams from the previous work of the authors, the research quantifies the impact of aging on structural performance. The studied factors comprises the layer number of FRP sheets and the use of FRP anchorage (e.g., U-wraps), which are expected to influence both the capacity and the failure mode. The findings are intended to inform the retrofitting of olsder infrastructure, offering actionable insights for engineers tasked with ensuring structural safety and longevity. The novelty of this work lies in (1) experimentally evaluating FRP strengthening efficacy on naturally aged, unbonded prestressed concrete (UPC) beams, (2) analyzing bond behavior and curvature-induced debonding mechanisms not addressed in prior works, and (3) comparing aged vs. new beam performance in terms of cracking, stiffness, ultimate load, and deformability. To our knowledge, this is the first study that integrates 6.5 years of real-time aging, FRP retrofitting, and U-wrap anchorage effectiveness on UPC beams.

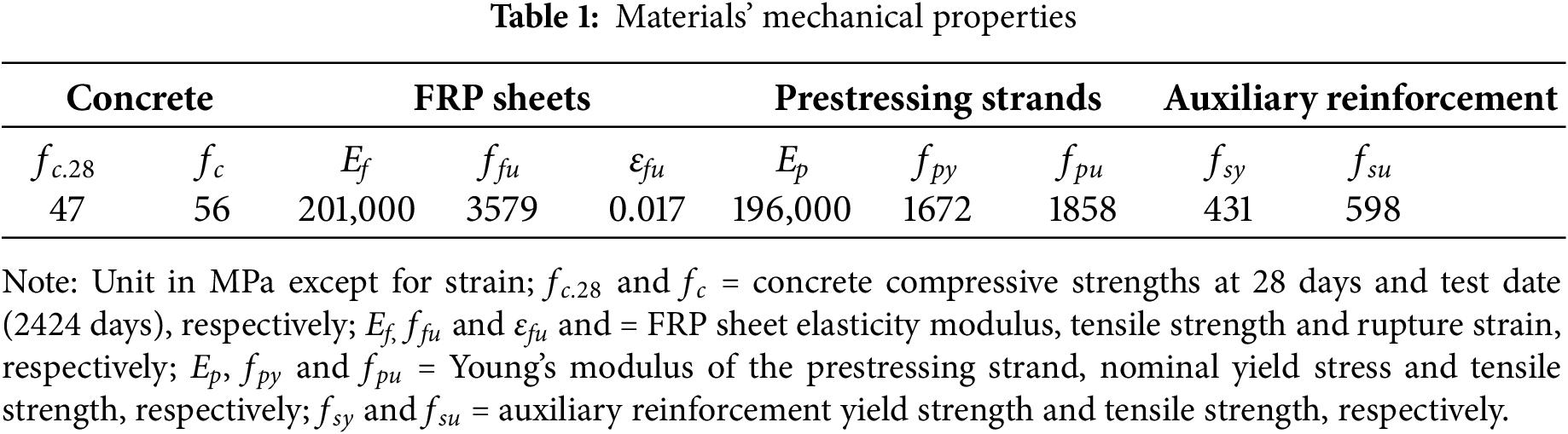

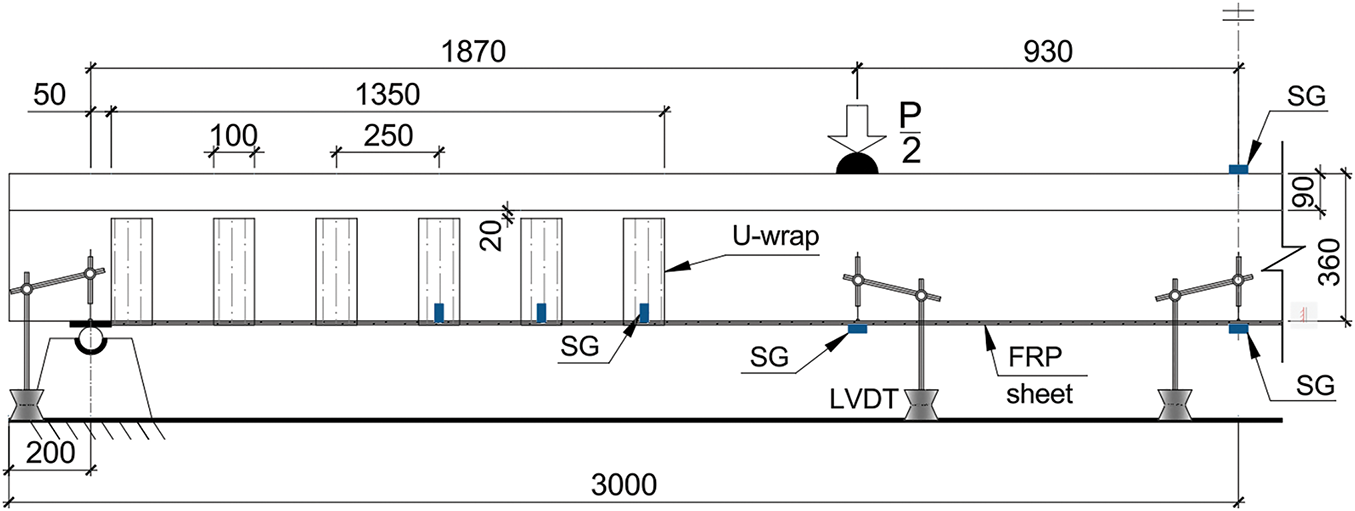

The beam samples were cast using ready-mix concrete, with mix proportions based on designs reported in previous work [12,32]. Concrete exhibited a drop of 120 ± 20 mm, a value commonly accepted for the construction of structural elements [33,34]. The compressive strength was evaluated using a standardized testing protocol [35] on six 150 × 150 × 150 mm3 cubes. The concrete strengths at 28 days and the testing date of the beam specimen (2424 days) were presented in Table 1. To enhance the strength of the beam specimens, external carbon-FRP sheets were adopted. The mechanical characteristics of these FRP materials, which had a nominal thickness of 0.167 mm, were evaluated following ASTM D3039 [36] and are listed in Table 1. The epoxy adhesive, as specified by the manufacturer, possessed a modulus of elasticity ranging from 3 to 3.5 Gpa and a tensile strength of 60 MPa. Prestressing was achieved using low relaxation 7-wire strands with a nominal diameter of 12.7 mm, meeting the requirements of ASTM A416 [37] requirements, with their properties also provided in Table 1. Additional reinforcement properties are similarly documented in Table 1.

The beams had an effective span of 5600 mm, as depicted in Fig. 1. With a span-to-effective depth ratio of roughly 18.4, typical designs for PC beams, the beams were expected to exhibit a predominantly flexural behavior. Posttensioning was applied using two unbonded tendons, each initially stressed to 128 kN. Based on ACI 318-19 [38] and aligned with various studies, the beams were categorized as Class U (uncracked). Supplemental reinforcement included two Ø12-mm steel bars at the bottom, four Ø10-mm steel bars at the top, and two-legged Ø6-mm stirrups at 175 mm spacing (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Test beam (unit in mm)

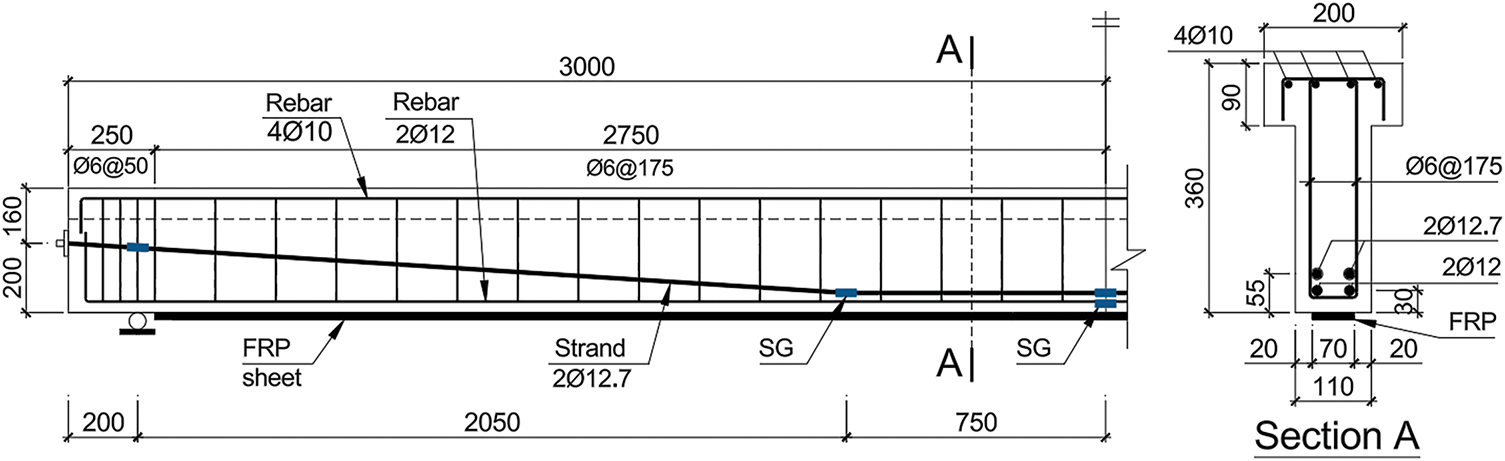

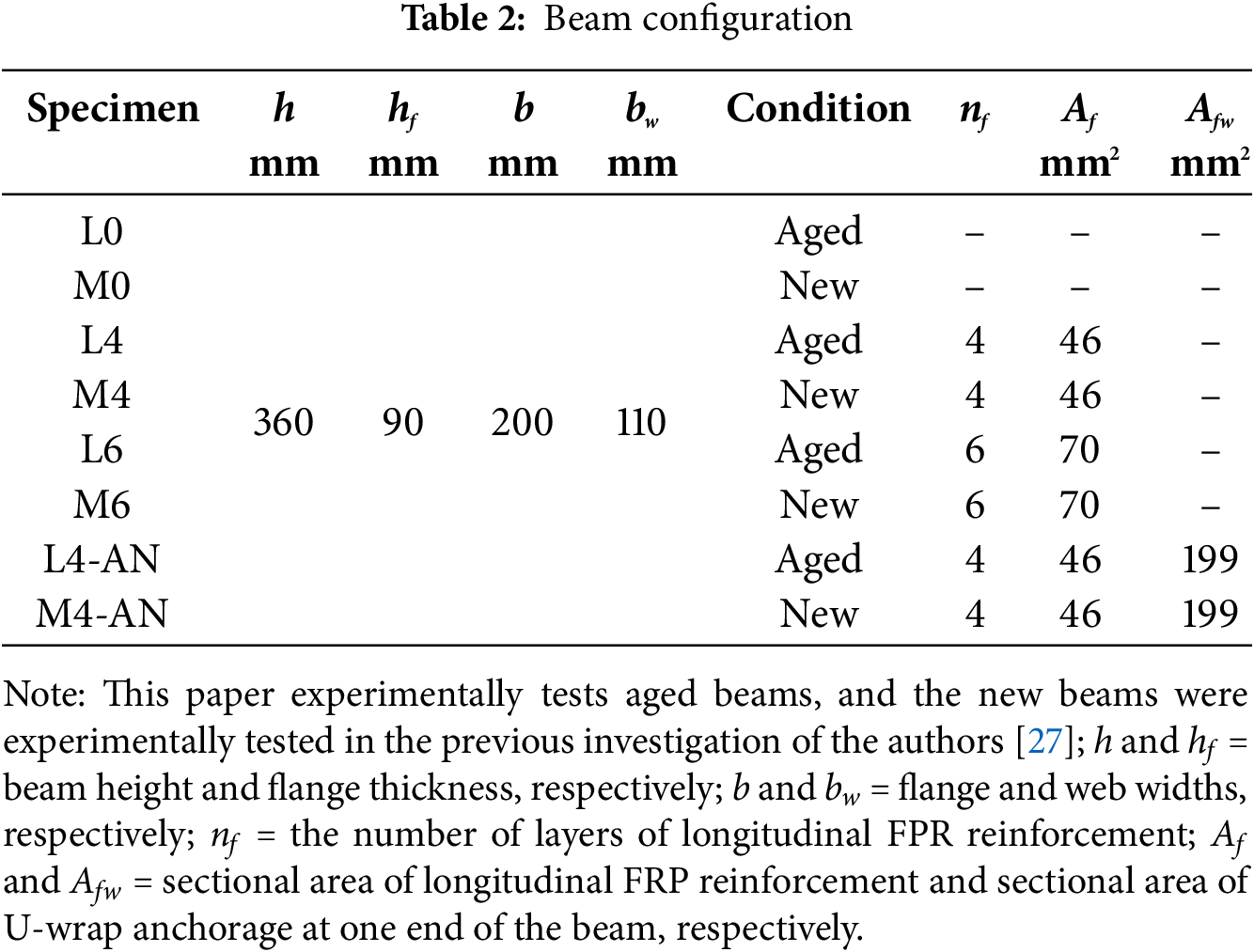

The experimental program involved four T-beams with the dimensions presented in Fig. 1. These comprised a control beam without FRP reinforcement (L0), two beams reinforced with four (beam L4) and six (beam L4) layers of FRP sheets, and one beam reinforced with four FRP layers and a U-wrap anchorage system (L4-AN), shown in Fig. 2, to mitigate premature debonding of longitudinal FRP sheets. Premature debonding and loss of composite action are known to reduce the efficacy of externally bonded FRP systems [32,34], and U-wrap anchorages have been shown to address this issue effectively [12,20,28].

Figure 2: Testing setup and U-wrap (unit in mm)

After a concrete curing period of 28 days, the beam was left for 6.5 years (2424 days) under a simply supported condition shown in Fig. 2 subjected to its self-weight. It should be noted that shrinkage and creep effects after 6.5 years account for 98% of those effects after a typical design period, that is, 30 years, according to AS 3600:2018 [39]. During the 6.5-year aging period, the beams were stored in an outdoor shelter under natural environmental conditions without direct rainfall. The exposure took place in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, which features a tropical monsoon climate with annual temperature fluctuations between 24°C and 35°C, and relative humidity ranging from 70% to 85%. Although direct carbonation depth was not measured, the environmental exposure was conducive to natural carbonation, drying shrinkage, and creep accumulation. The beams were protected from mechanical disturbance and maintained in a simply supported state, sustaining only their self-weight. While this natural aging approach allows realistic simulation of long-term prestress loss, one limitation is the absence of continuous monitoring of ambient CO2 levels and internal humidity. Future studies may consider controlled environmental chambers to isolate specific effects such as carbonation or moisture transport. Moreover, as the purpose is to simulate the scenario where the prestressed beam is still uncracked under service loads (typical design of PC beams), the beam was left to carry only its self-weight to magnify the effects of creep and shrinkage on the upward curvature as discussed in the introduction. The effective prestressing force of the tendon was determined according to the procedure in [40] and the effective prestressing strain of the tendon at the time of the test was 4.21‰ (18.4% reduction due to long-term prestress losses). After this period, the test beams were retrofitted with the FRP system. The effective prestressing strain of the tendon at the time of testing (4.21‰) was estimated based on the analytical approach by Rosenboom et al. [40], which accounts for long-term prestress losses due to creep, shrinkage, relaxation, and elastic shortening. Creep and shrinkage losses were estimated using the age-adjusted effective modulus method and AS 3600:2018 creep-shrinkage functions. Tendon relaxation loss was based on the manufacturer’s specifications for low-relaxation strands. The resulting strain values were validated by direct strain measurements using pre-installed foil strain gauges at the mid-span of each beam. Furthermore, to quantify the ageing effect, four new beams from a previous investigation by the authors [27]—labelled M0, M4, M6, and M4-AN—were included for comparison, mirroring the designs of L0, L4, L6, and L4-AN, respectively. The test matrix is described in Table 2.

Before FRP installation, the soffit curvature of each aged beam was measured using a string-line method in conjunction with laser leveling to assess creep-induced camber. The curvature was found to range between 4 and 6 mm across the 5.6 m span, consistent with long-term prestressed beam behavior. To enhance the bond under such conditions, mechanical grinding was employed to remove surface laitance and expose aggregates, followed by air-blasting to clean the surface and ensure adequate dryness. During FRP application, flexible rollers and spatulas were used to ensure proper adaptation of the sheets to the slightly curved soffit and to promote epoxy penetration. Despite these measures, the residual curvature of the soffit may have introduced non-uniform bond stresses, contributing to premature debonding in aged beams without anchorage, as supported by localized strain drops and failure observations.

2.2 Instrumentation and Testing Scheme

Following a seven-day cure period for the FRP composites, the beams were subjected to monotonic loading until failure using a four-point loading setup (Fig. 2) under a load-controlled approach. Strain measurements were obtained using foil strain gauges (SG): 5-mm gauge length SGs were used for prestressing tendons, longitudinal bars, FRP sheets, and U-wraps, while 60-mm gauge length SGs were applied to concrete. Five SGs monitored strain on the prestressing strands, and one SG measured strain in the steel rebar, with their positions indicated in Fig. 1. The strain of the FRP sheets was recorded at midspan and loading points using SGs (Fig. 2), while additional SGs tracked concrete strain and strain in the FRP anchorage (Fig. 2). The deflections of the test beam were measured at the mid-span, two loading points, and supports using linear variable differential transducers (LVDT), as illustrated in Fig. 2. A load cell was used to record the applied load, applied using a hydraulic jack. The loading rate of 15 kN/min was adopted. The crack widths were manually gauged with microscopes. The test data, including deflection, load, and strain, were recorded automatically through a data acquisition system. All deflection, load, and strain data were recorded using a National Instruments USB-6212 16-channel data acquisition (DAQ) system, sampling at 10 Hz. Strain gauges, LVDTs, and the load cell were connected through signal conditioners. The system was controlled and monitored using LabVIEW software, which enabled real-time data acquisition and ensured synchronized measurement across all sensors. Data were automatically logged in digital format for post-processing and analysis.

3 Experimental Findings and Discussions

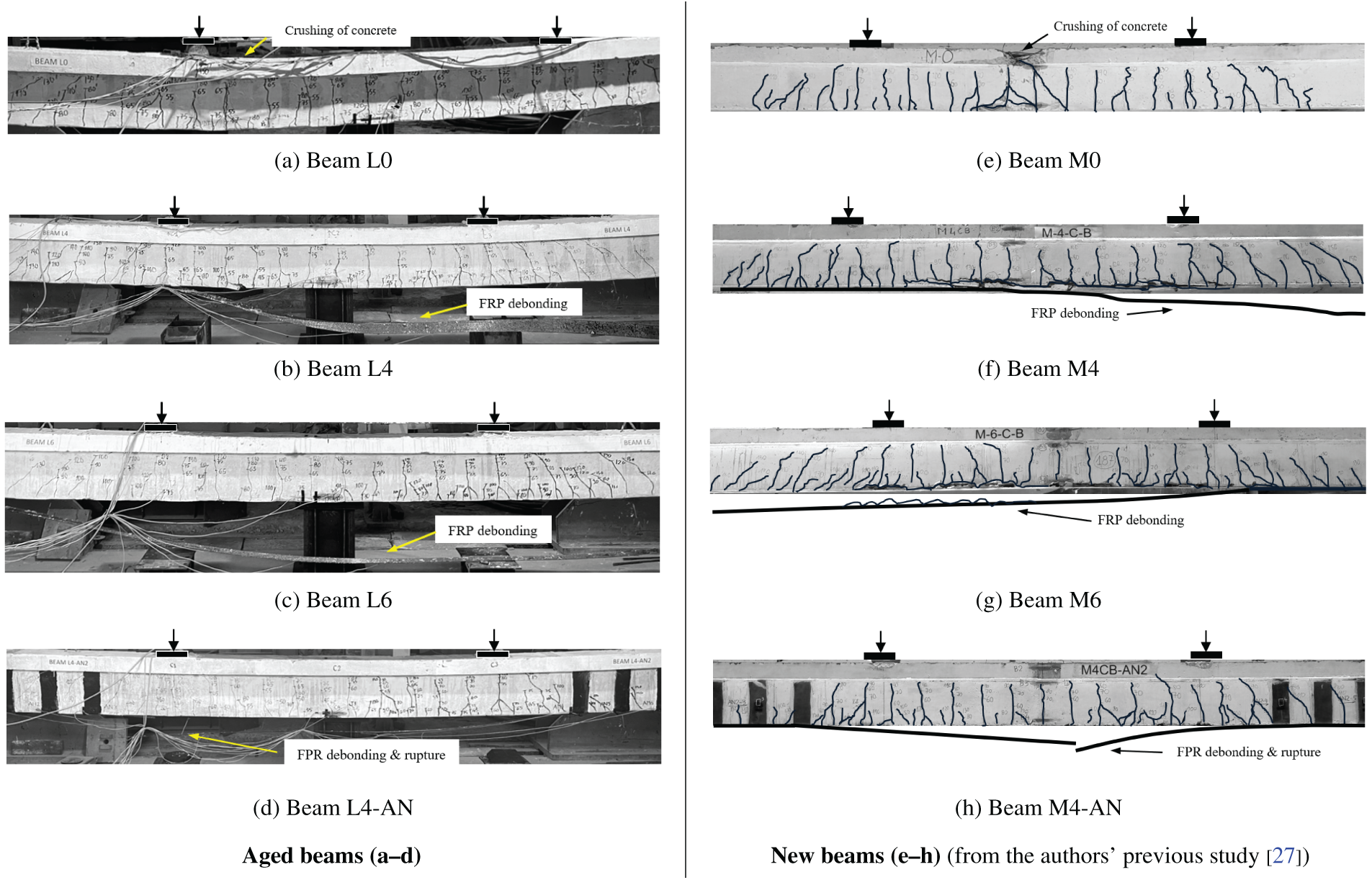

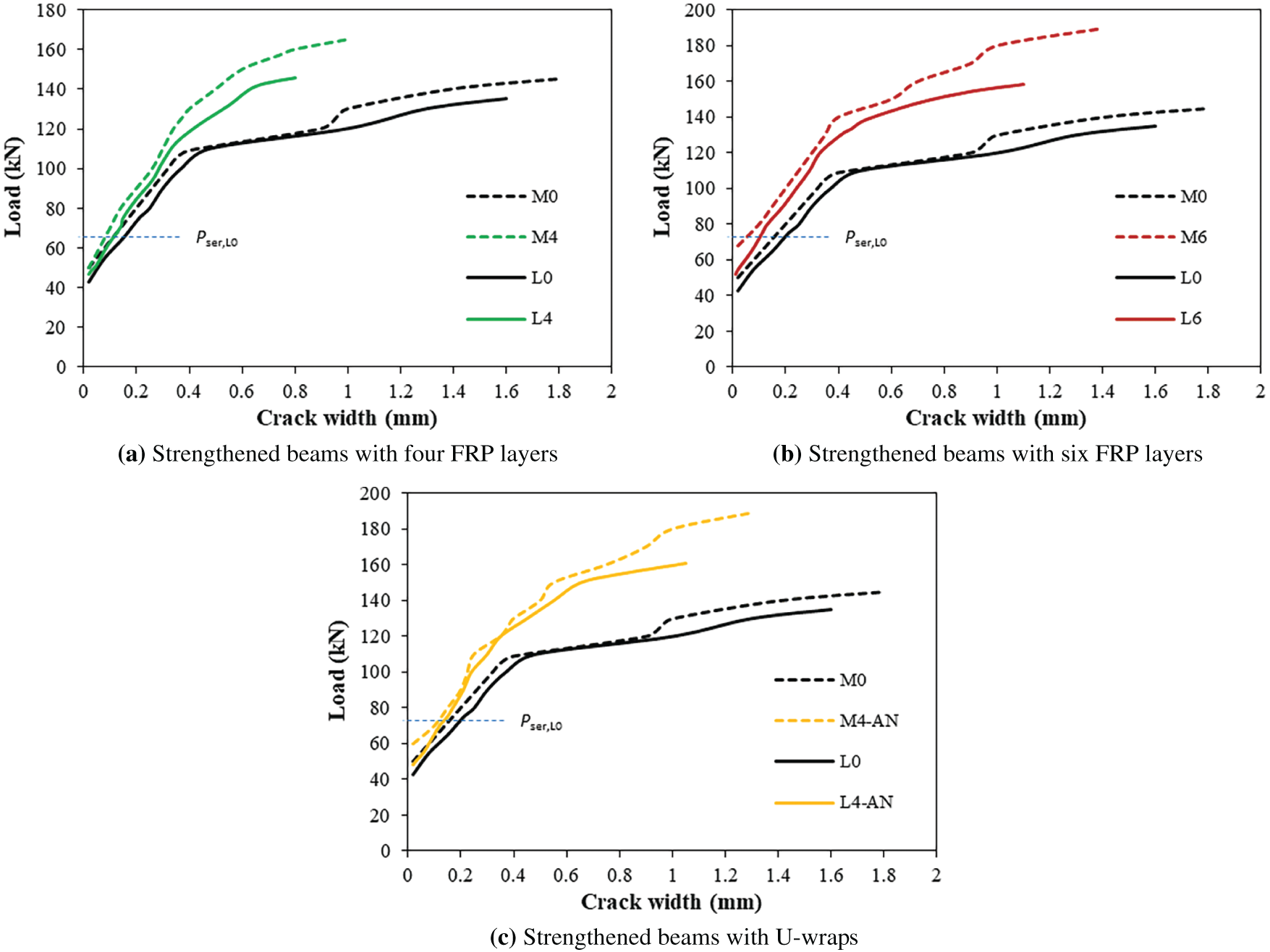

The failure characteristics and crack development of the aged and new unbonded prestressed concrete (UPC) beams are presented in Fig. 3. The results of the experiments are compiled in Table 3. In general, aging affected the beams’ deflection, serviceability and ultimate load-bearing capacities, although it had little impact on the general failure mode. The deflection behavior and load resistances are elaborated in a subsequent section. The aged (beam L0) and new (beam M0) beams without retrofitting exhibited similar flexural failure mechanisms, characterized by yielding of the tensile reinforcement, followed by crushing of the concrete at the top, as depicted in Fig. 3a and e and detailed in Table 3. However, the prestressing tendon did not produce in the aged beam while it yielded in the new beam, as shown in Table 3 (the yield strain of the prestressing tendon yield was 8.5%). This observation can be explained by the reduction in the effective stress of the prestress in the aged beam due to long-term stress losses, resulting in its smaller total final stress. This finding is in line with Rosenboom et al. [40], who reported that aged girders exhibited reduced tendon stress and did not reach yielding after FRP strengthening. Similarly, Shen et al. [16] observed tendon underperformance in 60-year-old RC beams, reinforcing that prestress loss in aged members significantly impairs the tendon’s contribution to flexural strength.

Figure 3: Failure pattern of test specimens (e–h) from the authors’ previous study [27]

The UPC beams strengthened with FRP sheets had a different failure behavior from their unstrengthened beams; nonetheless, similar to the latter, aging did not substantially change the failure pattern of the FRP-FRP-strengthened UPC beams. As shown in Fig. 3b,c and f,g, the beams with 4 or 6 layers of FRP without U-wraps failed due to the yield of the tensile reinforcement and the complete debonding of the external FRP sheets, whereas the upper concrete was undamaged. In the aged beams (beams L4 and L6), the prestressing tendons did not reach yielding, whereas yielding occurred in the new counterparts (beams M4 and M6) (Table 3). The debonding of FRP reflects a breakdown in the composite between the FRP and concrete, causing the strengthening to be ineffective. This debonding began in the flexural region, driven by wide cracks, and progressed toward the supports, as shown in Fig. 3b,c and f,g.

To ensure effective bonding, the concrete surface was prepared by mechanical grinding to remove surface laitance and expose the coarse aggregate, followed by thorough cleaning and drying prior to adhesive application. This process aimed to maximize the mechanical interlock and improve epoxy penetration into the aged substrate. Despite these measures, aged beams exhibited premature FRP debonding, likely due to microcracks and reduced tensile strength inherent to long-term degradation. Strain gauges affixed at multiple locations along the FRP length captured strain discontinuities, with a pronounced strain drop observed near the flexural span prior to debonding. These profiles highlight a loss of composite action, indicating failure at the FRP–concrete interface. In contrast, beams with U-wrap anchors showed more uniform strain distribution and delayed debonding initiation, suggesting the anchorage system effectively restrained interfacial peeling and distributed shear stresses over a wider area. This finding is consistent with earlier studies on bond performance over curved or aged substrates [23,30], reinforcing the necessity of anchorage systems in aging retrofitting scenarios.

The inclusion of a U-wrap anchor mitigated widespread debonding and confined it to a smaller zone, i.e., flexural span. This is evident in the failure mode of the beams with the U-wrap system, which involved the yielding of tensile reinforcement, along with the debonding and rupture as shown in Fig. 3d,h. The prestressing strands in the aged beam (beam L4-AN) with the U wraps also did not yield while they yielded in the new counterpart (beam M4-AN). Despite this difference, the general failure behaviors of the aged and new UPC beams with the U-wrap anchorage were comparable, suggesting that aging had minimal influence on the failure pattern.

Although both L4-AN and M4-AN incorporated identical FRP configurations and U-wrap anchorages, the aged beam (L4-AN) exhibited lower ultimate strength and deformability than the new beam (M4-AN). Notably, the failure in both cases occurred in the flexural span via FRP rupture and bar yielding, without any signs of anchorage peeling or delamination, confirming that the U-wraps effectively prevented end debonding. The underperformance of L4-AN is mainly attributed to long-term degradation effects in the aged beam: (1) a significant 18.4% prestress loss reduced the internal pre-compression, (2) the aged concrete had compromised bond quality despite surface preparation, and (3) material embrittlement limited strain development in both FRP and reinforcement. These factors collectively reduced the strain energy capacity of the composite system and led to lower overall load resistance and ductility, even though the failure pattern remained similar.

3.2 Flexural Response and Resistance

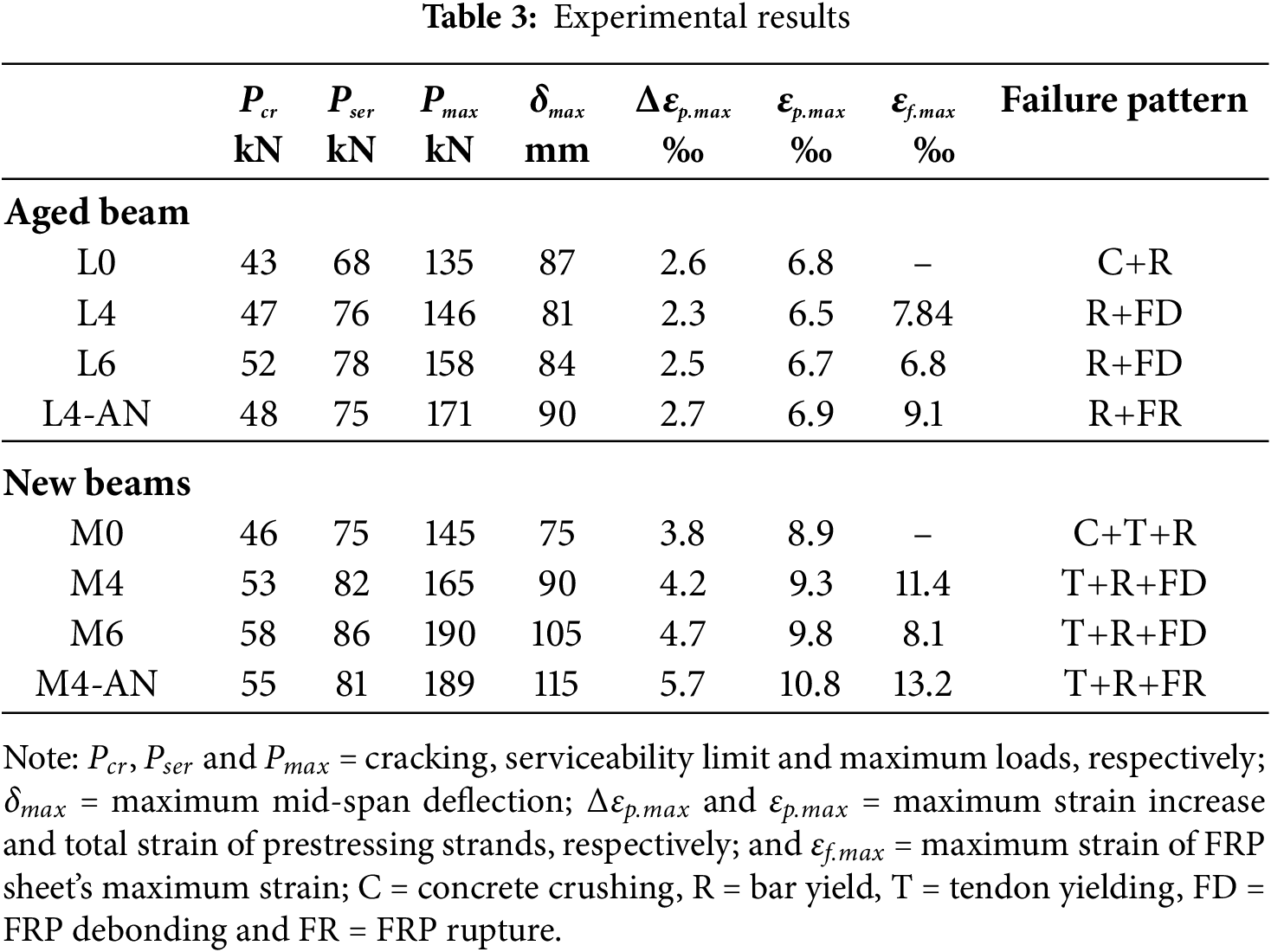

The bending characteristics of the UPC beams are depicted through plots of beam deflection vs. applied load, as presented in Fig. 4. The response can be regarded as linear elastic up to the cracking load, Pcr, marking the point at which cracks begin to appear. At this phase, the UPC beams exhibited fairly consistent behavior irrespective of their condition (whether aged or new, and with or without FRP reinforcement). However, the cracking resistance of the aged beams was lower than that of the new beams. For example, the Pcr of the unreinforced aged beam (L0) was 7% smaller than the Pcr of the new counterpart (beam M0) (Table 3). The lower crack resistance of the aged beam was mainly due to the long-term prestress losses, which reduced the pre-compression level of the beam. The lower crack resistance of the aged beam was mainly due to the long-term prestress losses, which reduced the pre-compression level of the beam [10,19,27], thereby accelerating crack initiation under service load. The application of FRP sheets improved the crack resistance of the aged beams, increasing their Pcr by an average of 14% and 7% compared to non-strengthened aged (L0) and new (M0) beams, respectively (Table 3). Nevertheless, the Pcr of the FRP-strengthened aged beams retrofitted with FRP was still lower than that of the new counterpart, at an average of 11% (Table 3).

Figure 4: Load-displacement behavior. Note: Pcr,L0 = beam cracking load L0; Pser, L0 = beam L0; Pser,L0 = serviceability limit load L0; and Pu,L0 = maximum load of beam L0

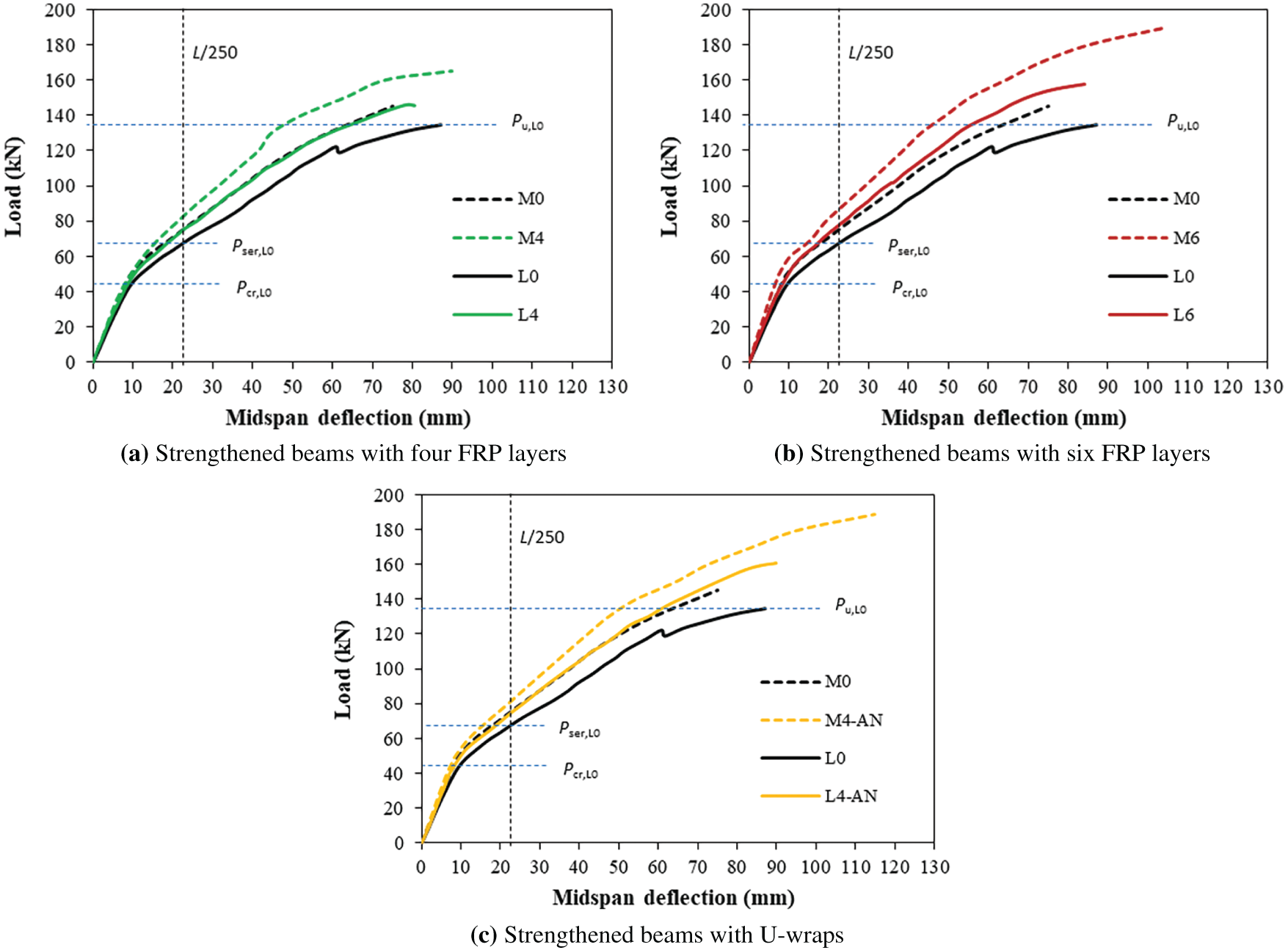

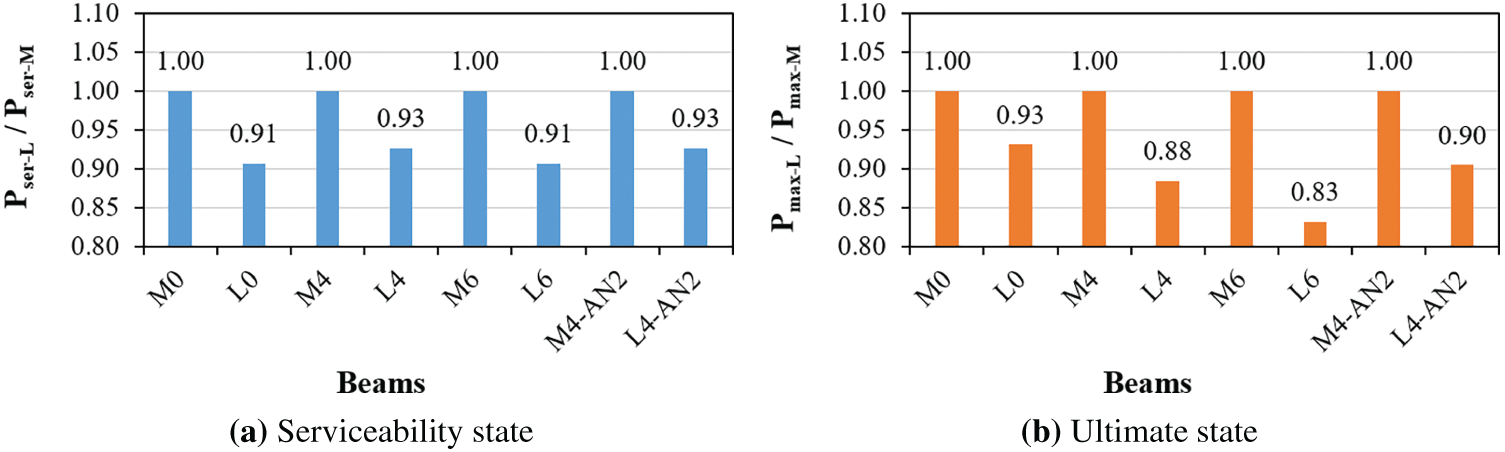

After exceeding the cracking load, the bending stiffness of the UPC beams was reduced considerably, and their behavior shifted to a more inelastic pattern as shown in Fig. 4. Aging reduced cracking resistance and resulted in faster crack growth (Fig. 5), and thus triggered an earlier decline in stiffness in the aged beams, leading to greater deflections compared to their new counterparts. More specifically, at the serviceability limit state of the new beam M0 (the loading level where the beam deflection reaches the maximum allowed value of span/250 as per AS 3600:2018 [39]), the deflection of the aged beam L0 was 17% higher than that of the new beam M0 (Fig. 4). For consistency, the serviceability load (Pser) for all beam specimens—regardless of aging condition or strengthening configuration—was defined as the load corresponding to a mid-span deflection of L/250 (i.e., 22.4 mm for a 5600 mm span), in accordance with AS 3600:2018 [39]. This uniform definition enables direct comparison across all cases for evaluating stiffness degradation and strengthening efficacy. This reduction in stiffness became even more pronounced at the final stage. For example, at the maximum load of the aged beam L0, the deflection of the aged beam was around 34% higher than that of the new counterpart (Fig. 4). Furthermore, ageing diminished the beams’ load-carrying resistances of the beams. The serviceability (Pser) and ultimate (Pu) resistances of the aged beam L0 were reduced by 9% and 7%, respectively, compared to those of the new beam M0, as illustrated in Fig. 6a and b.

Figure 5: Cracking response

Figure 6: Serviceability and ultimate resistances of old vs. new beams. Note: Pser-L and Pser-M = serviceability resistance of aged and new beams, respectively; Pmax-L and Pmax-M = ultimate resistance of aged and new beams, respectively

The application of FRP sheets to the aged UPC beams greatly mitigated the adverse impacts of aging, enhancing overall performance. FRP reinforcement curtailed crack progression and narrowed crack widths in the strengthened beams compared to the non-strengthened counterpart (Fig. 5). Consequently, the stiffness of the aged beams reinforced with FRP sheets was enhanced, resulting in better performances in terms of deflection and serviceability resistance (Pser) than those of the non-strengthened new beam M0 (Fig. 4 and Table 3). Neither the number of FRP layers nor the presence of U-wrap anchorage appeared to significantly affect the behavior during the serviceability phase. Furthermore, the external FRP sheets proved to be more impactful during the final stage. While the ultimate resistances of the aged beams exceeded that of the new unstrengthened beam M0 by 1%, 9%, and 18% for the configurations with 4 layers, 6 layers, and U-wrap anchorage, respectively, these findings should be interpreted in context. The gains reflect the effectiveness of external FRP in partially restoring flexural capacity in aged structures. However, compared to unstrengthened aged beams (L0), the improvements were even more significant (up to 26%). The increase is also influenced by factors such as FRP rupture strain, bonding effectiveness, and anchorage confinement. Nonetheless, premature debonding and limited composite action in aged beams reduced the efficiency of FRP compared to its full potential observed in new beams, consistent with observations by Al-Ghrery et al. [23] on curved soffit debonding. The ultimate resistances of the aged beams exceeded that of the new beam M0 by 1%, 9% and 18% for the configurations with 4 layers, 6 layers, and U-wrap anchorage, respectively. Additionally, the deformability of these aged beams surpassed that of beam M0, as evidenced by their maximum deflections, which were 8%, 12%, and 20% higher for the beams with 4 layers, 6 layers, and U-wrap anchorage, respectively (Table 3).

However, compared to their new counterparts, the FRP-strengthened aged beams exhibited reduced cracking resistance, bending stiffness, and load-carrying resistance. These aged beams showed wider cracks (Fig. 5), larger deflections (Fig. 4), and reduced loading resistances (Fig. 6) relative to the new beams with the same strengthening configuration. For instance, at the serviceability resistance of beam M0 (Pser,M0), the deflection of the aged beams was, on average, 20% higher than that of the new counterparts (Fig. 4). Because of their smaller flexural stiffness, the serviceability resistance of the aged beams was 7%–9% smaller compared to that of the new counterparts, as indicated in Fig. 6a. The decrease in loading resistance was more pronounced in the final stage, as evident via the ultimate resistance of the aged beams, which was 7% to 17% lower than that of the new counterparts (Fig. 6b). The deterioration in the loading resistance of the aged UPC beams was mainly attributed to their smaller prestressing force due to the higher prestress losses and the premature FRP debonding, which reduced their contributions to the load resistance. This is demonstrated by the maximum tendon strain and FRP strain of the aged beams being 33% and 26% smaller than those of the new beams, as indicated in Table 3. As explained in the introduction, creep and shrinkage in older concrete can amplify camber (upward deflection) in uncracked PC beams. It should be noted that PC beams are typically engineered to remain uncracked under service loads. In new PC beams, the underside remains fairly level, promoting consistent contact with FRP sheets and optimizing bonding effectiveness. However, in aged uncracked PC beams, the soffit gradually becomes curved due to prolonged creep and shrinkage. This decreases the contact area available for bonding and introduces irregularities, impairing the bonding of FRP and causing more premature debonding of FRP [22,23]. Furthermore, aging effects also reduced the deformability of the aged beams, evident via their maximum deflection being 17%, on average, smaller than that of the new counterparts (Table 3).

A key limitation of this study lies in the use of a single specimen per test configuration, which restricts the statistical robustness of the results. Consequently, the observed performance differences (e.g., 7%–14% increase in cracking or ultimate resistance) should be interpreted as indicative rather than definitive. This constraint is primarily due to the significant time, cost, and logistical effort required to age large-scale specimens over 6.5 years while preserving structural integrity. To strengthen the findings, future research should incorporate multiple replicates per configuration to support statistical confidence. Furthermore, numerical simulations using finite element modeling (FEM) can be developed to complement the experimental data. These models can explore variability in material properties, aging parameters, and bond behavior, thereby allowing sensitivity analysis and virtual parametric studies to generalize the observed trends and assess the reliability of FRP strengthening under aging effects.

This study experimentally evaluated the flexural performance of aged unbonded prestressed concrete (UPC) beams strengthened with externally bonded fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) sheets after 6.5 years of natural aging. The behavior of these aged beams was benchmarked against both unstrengthened and FRP-strengthened new beams to assess the effects of aging and the efficacy of FRP retrofitting. The results showed that aging did not fundamentally alter the failure modes of UPC beams. While unstrengthened beams failed due to bar yielding and concrete crushing, FRP-strengthened beams failed predominantly through FRP debonding and bar yielding. Notably, prestressing tendons in aged beams did not yield due to significant long-term prestress losses, unlike in new beams, whereas the use of U-wrap anchorages effectively delayed debonding and led to failure by FRP rupture and bar yielding.

Aging accelerated crack development and reduced flexural stiffness, resulting in lower service and ultimate capacities. However, the FRP sheets improved the cracking resistance of the aged beams by 14% compared to the unstrengthened aged beams (L0), demonstrating effective mitigation of aging-induced deterioration. While their ultimate strength exceeded that of the unstrengthened new beams (M0) by up to 9%, this should be interpreted as a secondary benchmark. The primary efficacy of strengthening is better represented by the up to 26% increase in ultimate resistance when comparing strengthened vs. unstrengthened aged beams (e.g., L0 vs. L4-AN). Despite this improvement, strengthened aged beams still underperformed their newly strengthened counterparts in terms of cracking resistance, stiffness, and load-carrying capacity. On average, the aged strengthened beams exhibited 20% greater deflection, 7%–9% lower serviceability load, and 7%–17% lower ultimate strength compared to new strengthened beams, primarily due to increased prestress loss and inferior bond conditions caused by aging. Their deformability was also reduced by approximately 17%.

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Only one specimen per configuration was tested, which restricts the statistical generalizability of the findings. The natural aging process was conducted in uncontrolled environmental conditions without monitoring parameters such as carbonation depth, moisture profile, or microcrack development. Furthermore, the estimation of prestress losses relied on analytical models rather than direct long-term instrumentation. Future work should involve replicate testing to establish statistical robustness, incorporate accelerated or controlled environmental aging (e.g., temperature and humidity cycles), and utilize finite element modeling to perform parametric studies that assess the influence of varying bond, curvature, and aging conditions on FRP performance. Additional exploration of hybrid strengthening systems—such as combining FRP with near-surface mounted reinforcement—would also be beneficial.

From a practical standpoint, the findings support the use of externally bonded FRP systems, particularly when coupled with U-wrap anchorages, as a viable retrofitting strategy for deteriorated prestressed infrastructure. This technique is especially promising for enhancing the structural resilience and service life of bridges and buildings exposed to aggressive environments, such as those in tropical and high-humidity regions. The study contributes to resilience-based design and retrofit approaches by demonstrating that even naturally aged, unbonded prestressed beams can recover or exceed baseline performance through targeted FRP strengthening.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the Ministry of Education and Training of Vietnam for this research, under grant no. B2023-MBS-02.

Funding Statement: No funding was received for this study.

Author Contributions: Phuong Phan-Vu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Supervision. Thanh Q. Nguyen: Investigation, Data Curation, Validation, Visualization. Phuoc Trong Nguyen: Formal Analysis, Writing—Review & Editing, Project Administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. Additional data can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study does not involve human participants or animals.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ghaemdoust MR, Yang J, Wang F, Li S, Jamhiri B. Performance assessment of post-tensioned concrete-filled steel tube beams using unbonded tendons with uncertainty quantification. Adv Stru Eng. 2023;26(16):3065–88. doi:10.1177/13694332231207431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Rafieizonooz M, Jang H, Kim J, Kim C-S, Kim T, Wi S, et al. Performances and properties of steel and composite prestressed tendons—a review. Heliyon. 2024;10(11):e31720. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Atmajayanti AT, Haryanto Y, Hsiao F-P, Hu H-T, Nugroho L. Effective flexural strengthening of reinforced concrete T-beams using bonded fiber-core steel wire ropes. Fibers. 2025;13(5):53. doi:10.3390/fib13050053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gebre A, Gedu M, Gebre Y. Carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) laminates: flexural strengthening method for prestressed concrete beams with anchorage loss. Funct Compos Stru. 2024;6(4):045010. doi:10.1088/2631-6331/ad8f8e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mansour W, Li W, Wang P, Fame CM, Tam L, Lu Y, et al. Improving the flexural response of timber beams using externally bonded carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) sheets. Materials. 2024;17(2):321. doi:10.3390/ma17020321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Najafgholipour MA, Kouhbanani SSK, Peykari K. Experimental study on debonding and buckling of externally bonded carbon fiber reinforced polymer sheets in compression. Eng Fail Anal. 2024;163(1):108550. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Qiang X, Liu Q, Chen L, Jiang X, Dong H. Experimental study on flexural performance of prestressed concrete beams strengthened by Fe-SMA plates. Constr Build Mater. 2024;422(3):135797. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang J, Wang M, Han K, Wang J. Fatigue performance and damage of partially prestressed concrete beam with fiber reinforcement. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2024;21(8):e03665. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Reed CE, Peterman RJ. Evaluation of prestressed concrete girders strengthened with carbon fiber reinforced polymer sheets. J Bridge Eng. 2004;9(2):185–92. doi:10.1061/(asce)1084-0702(2004)9:2(185). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Nguyen-Minh L, Vo-Le D, Tran-Thanh D, Pham TM, Ho-Huu C, Rovňák M. Shear capacity of unbonded post-tensioned concrete T-beams strengthened with CFRP and GFRP U-wraps. Com Stru. 2018;184(11):1011–29. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.10.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Murphy M, Belarbi A, Bae S-W. Behavior of prestressed concrete I-girders strengthened in shear with externally bonded fiber-reinforced-polymer sheets. PCI J. 2012;57(3):63–82. doi:10.14359/10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tran DT, Phan-Vu P, Pham TM, Dang TD, Nguyen-Minh L. Repeated and post-repeated flexural behavior of unbonded post-tensioned concrete T-beams strengthened with CFRP sheets. J Compos Constr. 2020;24(2):04019064. doi:10.1061/(asce)cc.1943-5614.0000996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Do-Dai T, Chu-Van T, Tran DT, Nassif AY, Nguyen-Minh L. Efficacy of CFRP/BFRP laminates in flexurally strengthening of concrete beams with corroded reinforcement. J Build Eng. 2022;53(6):104606. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Edan AS, Abdulsahib WS. The impact of using prestressed CFRP bars on the development of flexural strength. Open Eng. 2024;14(1):20240059. doi:10.1515/eng-2024-0059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Nugroho L, Haryanto Y, Hu H-T, Hsiao F-P, Pamudji G, Setiadji BH, et al. Prestressed concrete T-beams strengthened with near-surface mounted carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer rods under monotonic loading: a finite element analysis. Eng. 2025;6(2):36. doi:10.3390/eng6020036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shen D, Jiao Y, Li M, Liu C, Wang W. Behavior of a 60-year-old reinforced concrete box beam strengthened with basalt fiber-reinforced polymers using steel plate anchorage. J Adv Concr Technol. 2021;19(11):1100–19. doi:10.3151/jact.19.1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zu K, Luo B, Raftery GM, Lim JB, Liu K, Ding G, et al. A novel clamping anchor for prestressing CFRP plate strengthening of steel tube. J Constr Steel Res. 2025;227(6):109366. doi:10.1016/j.jcsr.2025.109366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Fava G, Colombi P. Fatigue life of steel components strengthened with FRP composites. In: Rehabilitation of metallic structural systems using fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) composites. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2025. p. 197–224. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-22084-5.00015-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Naaman AE. Prestressed concrete analysis and design: fundamentals. 2nd ed. Michigan, MI, USA: Techno Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

20. ACI 440.2R-17. Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for Strengthening Concrete Structures. Farmington Hills, MI, USA: American Concrete Institute (ACI); 2017. [Google Scholar]

21. CEB-FIP. Externally bonded FRP reinforcement for RC structures (fib Bulletin 14). Lausanne, Switzerland: CEB-FIP; 2001. [Google Scholar]

22. Eshwar N, Ibell TJ, Nanni A. Effectiveness of CFRP strengthening on curved soffit RC beams. Adv Str Eng. 2005;8(1):55–68. doi:10.1260/1369433053749607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Al-Ghrery K, Al-Mahaidi R, Kalfat R, Oukaili N, Al-Mosawe A. Experimental investigation of curved-soffit RC bridge girders strengthened in flexure using CFRP composites. J Bridge Eng. 2021;26(4):04021009. doi:10.1061/(asce)be.1943-5592.0001691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Naaman AE, Alkhairi FM. Stress at ultimate in unbonded post-tensioning tendons: part 2—proposed methodology. ACI Str J. 1992;88(6):683–92. doi:10.14359/1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chang X, Wang X, Liu C, Wu Z, Noori M. Anchoring and stressing methods for prestressed FRP plates: state-of-the-art review. J Reinforced Plast Compos. 2024;2(4):45. doi:10.1177/07316844241258864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kim T-K, Park J-S. Flexural behavior evaluation for seismic, durability and structure performance improvement of aged bridge according to reinforcement methods. Int J Concr Struct Mater. 2024;18(1):51. doi:10.1186/s40069-024-00693-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Nguyen-Minh L, Phan-Vu P, Tran-Thanh D, Phuong Thi Truong Q, Pham TM, Ngo-Huu C, et al. Flexural-strengthening efficiency of CFRP sheets for unbonded post-tensioned concrete T-beams. Eng Struct. 2018;166:1–15. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.03.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. CNR-DT 200 R1/2013. Guide for the design and construction of externally bonded frp systems for strengthening existing structures-materials, RC and PC structures, masonry structures. Rome, Italy: National Research Council (CNR); 2013. [Google Scholar]

29. Xu G, Guo T, Li A, Zhang H, Wang K, Xu J, et al. Seismic resilience enhancement for building structures: a comprehensive review and outlook. Structures. 2024;59(2):105738. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Mata R, Nuñez E, Forcellini D. Seismic resilience of composite moment frames buildings with slender built-up columns. J Build Eng. 2025;111(1):113532. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2025.113532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Oz I, Raheem SEA, Turan C. Mitigation measure using tuned mass dampers for torsional irregularity impact on seismic response of L-shaped RC structures with soil-structure interaction. Structures. 2025;79(22):109449. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2025.109449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Phan-Vu P, Tran DT, Pham TM, Dang TD, Ngo-Huu C, Nguyen-Minh L. Distinguished bond behaviour of CFRP sheets in unbonded post-tensioned reinforced concrete beams versus single-lap shear tests. Eng Struct. 2021;234(1):111794. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.111794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Truong QPT, Phan-Vu P, Tran-Thanh D, Dang TD, Nguyen-Minh L. Flexural behavior of unbonded post-tensioned concrete T-beams externally bonded with CFRP sheets under static loading. In: International Conference on Advances in Computational Mechanics 2017 (ACOME 2017) Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; 2018; Phu Quoc, Vietnam: Springer. [Google Scholar]

34. Tran DT, Phan-Vu P, Nguyen-Minh L, Nguyen PT, Pham TM. Effects of pre-cracking on effectiveness of external fibre-reinforced polymer strengthening in unbonded prestressed beams. Eng Struct. 2025;328(2):119719. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2025.119719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. TCVN 10303:2014. Control and assessment of compressive strength. Ha Noi, Vietnam: Viet Nam Standards and Quality Institute (VSQI); 2014. [Google Scholar]

36. ASTM D3039/3039M-17. Standard test method for tensile properties of polymer matrix composite materials. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2017. [Google Scholar]

37. ASTM A416/A416M-18. Standard specification for low-relaxation, seven-wire steel strand for prestressed concrete. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2018. [Google Scholar]

38. ACI 319-19. Building code requirements for structural concrete and commentary. Farmington Hills, MI, USA: American Concrete Institute (ACI); 2019. [Google Scholar]

39. AS 3600:2018. Concrete structures. Sydney, NSW, Australia: Standards Australia; 2018. [Google Scholar]

40. Rosenboom O, Hassan TK, Rizkalla S. Flexural behavior of aged prestressed concrete girders strengthened with various FRP systems. Const Build Mater. 2007;21(4):764–76. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools