Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Structural Health Monitoring Using Image Processing and Advanced Technologies for the Identification of Deterioration of Building Structure: A Review

1 Department of Computer Engineering, Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute, Mumbai, 400019, India

2 Department of Structural Engineering, Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute, Mumbai, 400019, India

* Corresponding Author: Kavita Bodke. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning Approaches for Real-Time Damage Detection and Structural Monitoring in Civil Structures)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(6), 1547-1562. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.069239

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 17 November 2025

Abstract

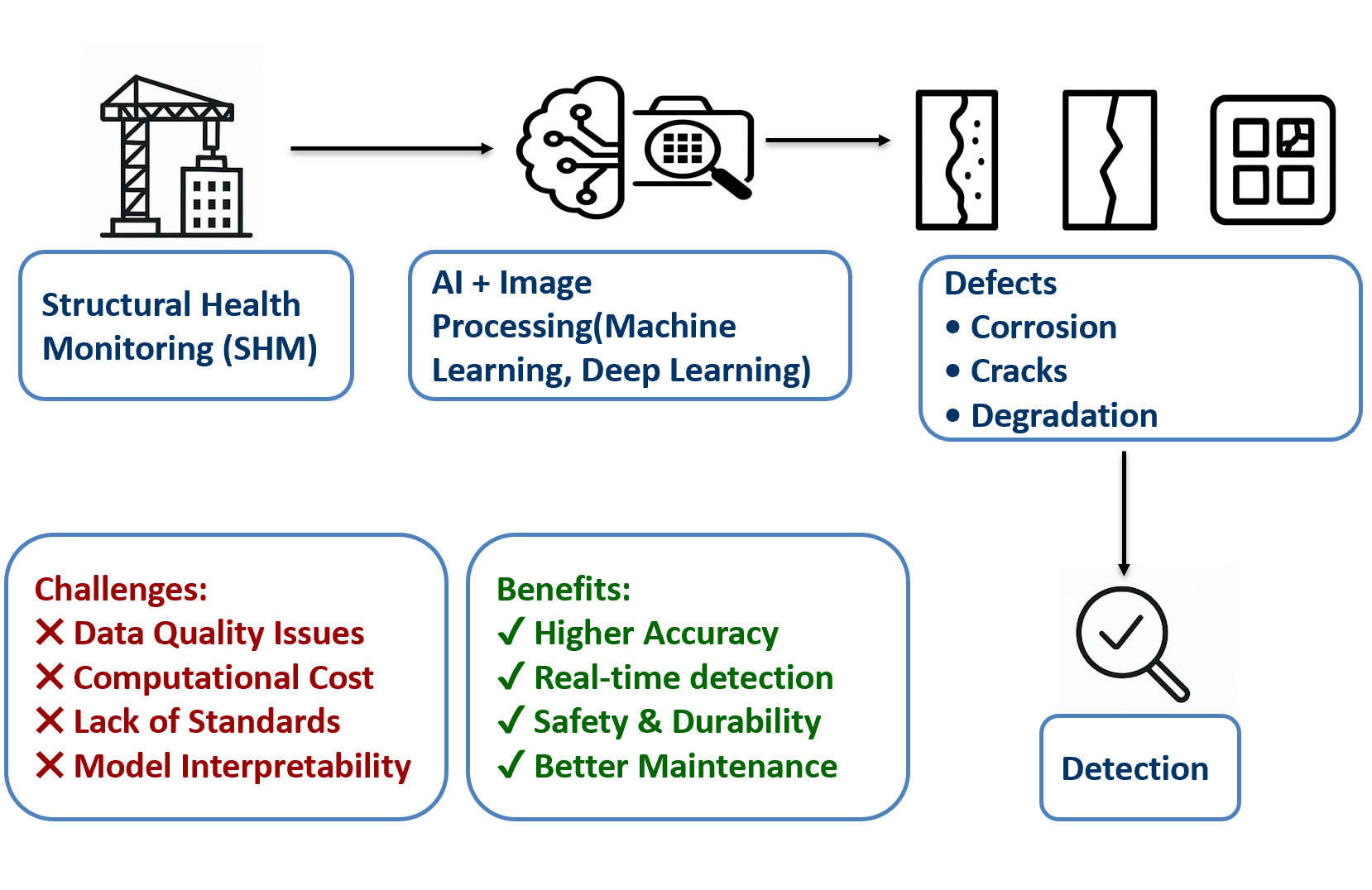

Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) systems play a key role in managing buildings and infrastructure by delivering vital insights into their strength and structural integrity. There is a need for more efficient techniques to detect defects, as traditional methods are often prone to human error, and this issue is also addressed through image processing (IP). In addition to IP, automated, accurate, and real- time detection of structural defects, such as cracks, corrosion, and material degradation that conventional inspection techniques may miss, is made possible by Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies like Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL). This review examines the integration of computer vision and AI techniques in Structural Health Monitoring (SHM), investigating their effectiveness in detecting various forms of structural deterioration. Also, it evaluates ML and DL models in SHM for their accuracy in identifying and assessing structural damage, ultimately enhancing safety, durability, and maintenance practices in the field. Key findings reveal that AI-powered approaches, especially those utilizing IP and DL models like CNNs, significantly improve detection efficiency and accuracy, with reported accuracies in various SHM tasks. However, significant research gaps remain, including challenges with the consistency, quality, and environmental resilience of image data, a notable lack of standardized models and datasets for training across diverse structures, and concerns regarding computational costs, model interpretability, and seamless integration with existing systems. Future work should focus on developing more robust models through data augmentation, transfer learning, and hybrid approaches, standardizing protocols, and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration to overcome these limitations and achieve more reliable, scalable, and affordable SHM systems.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

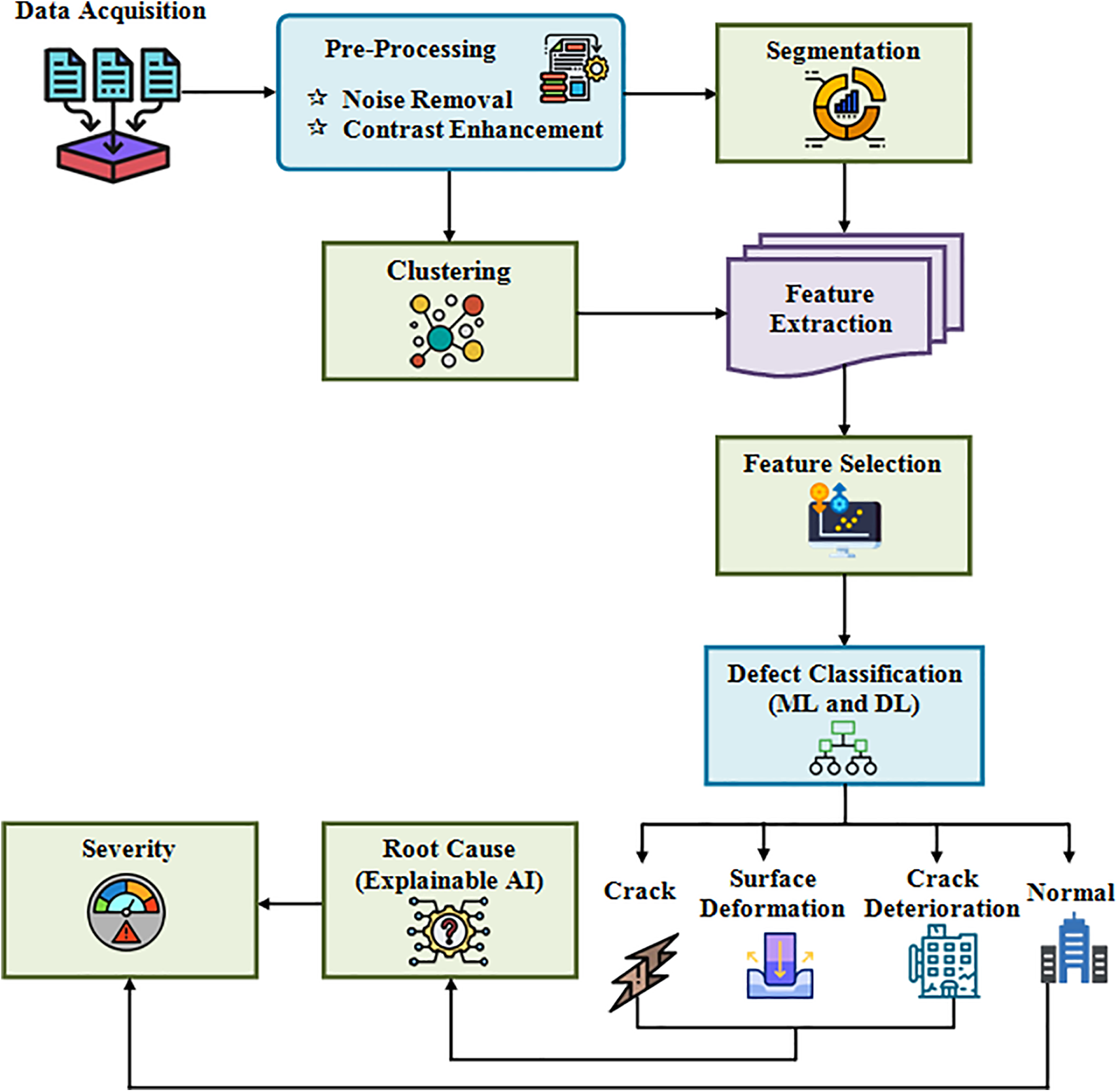

Recently, in the computer science field, big data technologies have been developed that have transformed all facets of society [1]. In SHM, Information technologies play an important role by enabling the real-time collection, analysis, together with visualization of data from various sensors. Thereby allowing the early recognition of potential issues and confirming the safety and durability of infrastructure [2]. SHM is defined as the continuous monitoring of structures like buildings and bridges to assess their integrity, detect damage, along with ensure safety via the deployment of sensors as well as data analysis [3]. SHM involves the use of numerous techniques to monitor structures’ condition over time, enabling early detection of deterioration and mitigating the risks associated with structural failures. Globally, owing to the aging of infrastructure and enhanced exposure to harsh environmental conditions, the deterioration of structures is a significant problem [4]. Common forms of damage that can weaken the safety and functionality of buildings are the deterioration of structures, such as cracks in concrete, corrosion of steel reinforcements, and dampness [5]. Early identification of these deteriorations is important for planning preventive maintenance and ensuring the structural integrity of buildings [6]. Thus, it is essential to have techniques for identifying deteriorations, as traditional methods for SHM often fail to accurately detect deteriorations and typically rely on manual inspections, visual assessments, and physical testing, which can be time-consuming, expensive, and often subjective [7]. Therefore, the emergence of advanced technologies, such as image processing (IP), artificial intelligence (AI), and its subsets, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has revolutionized the field of SHM, allowing more efficient, accurate, and automated assessment of structural health and providing more precise identification of deteriorations [8,9]. However, the effectiveness and reliability of these advanced models are highly dependent on the availability of large, diverse, and high-quality datasets for training and validation. Fig. 1 elucidates an example framework for defect classification in SHM using advanced AI. While this framework outlines a typical flow, it is important to note that various AI network architectures exist, and not all visual defect detection systems may adhere to this precise schematic.

Figure 1: Illustrating a common workflow from data acquisition to defect classification and root cause analysis

To diagnose, analyze, and categorize different forms of structural damage, IP methods use high- resolution images, thermal imaging, and other advanced visual data. These methods can vary from normal techniques like edge detection and thresholding to more difficult techniques like pattern recognition and feature extraction [10]. The other advanced techniques, like ML techniques, enable systems to learn as of data along with upgraded performance over time. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), one type of DL approach, are specifically made to work with visual data and can identify intricate patterns in images. ML algorithms can automatically identify and categorize different kinds of structural deterioration by being trained on massive photo datasets with identified damage instances [11]. Also, SHM using IP and advanced technologies has seen significant trends, including the integration of AI techniques like ML as well as DL for automated, precise, and real-time detection of structural defects. Yet, data quality, model interpretability, and the smooth integration of these technologies with current monitoring systems are still lacking. Potential solutions include standardizing protocols, strengthening interdisciplinary collaboration, and creating robust algorithms to increase the effectiveness and dependability of SHM systems. These developments look to confirm the longevity, safety, and resilience of building structures by facilitating rapid interventions and preventive maintenance.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a comprehensive analysis of contemporary SHM approaches, with a focus on image processing, machine learning, and deep learning applications. Section 3 addresses important research gaps and issues in the subject. Finally, Section 4 ends the review by suggesting future research and development directions in AI-driven SHM.

SHM has evolved significantly with the integration of IP and advanced technologies like ML and DL. While conventional Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) encompasses a diverse range of robust non- destructive testing (NDT) methods—including those based on vibration analysis, acoustic emission, and strain gauging for comprehensive structural performance evaluation—the visual inspection component of traditional SHM often relies heavily on manual assessments. These manual visual inspections can be resource-intensive, time-consuming, and prone to human error. This review, however, primarily focuses on the transformative role of image processing and artificial intelligence in enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of visual detection of structural deterioration within the broader SHM landscape. By enabling automated, precise, and real-time detection of structural defects, recent advancements in IP have revolutionized SHM. Studies have shown that computer vision algorithms can effectively identify and classify various forms of structural deterioration, including cracks, corrosion, and material fatigue. In SHM, the ML and DL applications have enhanced the accuracy along efficiency of these systems. For predicting potential future deterioration, ML algorithms can learn from historical data, while DL models can analyze complex patterns in large datasets to detect subtle signs of damage that may be missed by traditional methods. Nevertheless, the advent of IP, ML, and DL has revolutionized this field, offering more efficient and non-invasive methods for identifying structural deterioration. DL, specifically CNNs, has shown promising results in automating SHM tasks. CNNs, with their ability to learn hierarchical features from raw images, have been successfully employed in detecting cracks, corrosion, and other deterioration in building materials. The robustness of CNN models in SHM applications is augmented by recent advancements, thus improving accuracy and reducing the need for extensive labeled datasets. Thus, integrating IP with ML and DL offers a transformative approach for SHM, thereby providing rapid, scalable, and accurate deterioration detection methods, reducing costs and human error, and ensuring timely interventions for building safety. Nevertheless, challenges remain in improving model generalization across different environments and materials.

2.1 The Role and Advancements of Image Processing and AI in SHM

An important process, which encompasses the utilization of various technologies along with techniques to evaluate a structure’s condition over time, is termed SHM [12]. Ensuring the safety, longevity, and performance of infrastructure like buildings, bridges, dams, and other critical structures by detecting and monitoring any form of damage, degradation, or deterioration is the SHM’s primary objective [13]. SHM typically involves continuous or periodic monitoring, which helps in identifying issues at early stages before they lead to catastrophic failure. This proactive approach could reduce maintenance costs along with extending the lifespan of the infrastructure [14]. Primarily, real-time analysis and interpretation of continuous data from SHM systems have been explored in the research study of [15]. For vibration-based SHM systems, an algorithm and MATLAB-based software were presented, comprising modules for damage detection, modal identification, real-time data processing, and stakeholder warnings. The overall output for each running window was calculated by averaging the sequential analysis results after the data in each equal-length segment was examined independently. This kind of averaging reduced the impact of noise on the final invention. Then, in the research of [16], the investigation was done on the nonlinear modeling of a bridge as a case study-centric damage evaluation along with the proposal of the SHM system. A suitable SHM system, which increased the bridge’s lifespan with lower maintenance costs and a lower chance of failure, was implemented. The 3D non-linear analysis produced more refined results with values that were more in accord with the in-situ study. Thus, it was strongly advised to use a 3D non-linear analysis meant for the assessment together with the evaluation of bridge damage. Also, Jiangyin Bridge was taken as anexample of the integration of SHM with bridge maintenance in the research study of [17]. A suspension bridge was used as an example to demonstrate how its SHM system aided in administration and maintenance. The findings showed good consistency when compared to the study of the finite-element method (FEM). Thus, it was confirmed that the bridge was in good shape in terms of its capacity in July 2014. Moreover, in the study of [18], SHM value in bridges’ seismic emergency management was analyzed. For estimating such benefits, the Value of Information (VoI), which came as of Bayesian decision theory, was a useful tool. The findings revealed that the VoI was significant when the estimated costs of decision alternatives, like “keeping the bridge open” or “closing the bridge,” assessed devoid of SHM data, were similar. SHM system analyses on bridges were separately done in the study of [19]. The system along with sensors was built for covering the parameters for the most significant deterioration mechanisms. Bridge monitoring made it possible to determine when the bridge’s deformation state exceeded the allowable value as well as reached a critical level of alert, either as a result of traffic activity or following the occurrence of a catastrophic event (earthquake, floods that caused the substructures to erode, terrorist attacks, and so on). Finally, the study in [20,21] explored the automation of a bridge SHM system employing the BIMification approach, along with the development of a BIM- based finite element model and a life-cycle cost analysis for transportation bridges integrated with seismic SHM systems. By using the BIM model, the SHM system’s sensory components were controlled and monitored [20]. The percentage difference in results was analyzed about the European Community (EC) findings, while the outcomes of static together with dynamic measurements were evaluated against numerical computations. Implementing such systems allows bridge authorities to save time and money by automating bridge monitoring, data recording, processing, as well as results evaluation while also enabling real-time bridge Health Monitoring (HM). The model was used to estimate the overall costs and advantages of these monitoring systems for post-seismic evaluations in the study of [21]. By implementing the technique in the particular case study, it was demonstrated that traffic deviation only happened across a small portion of the road when indirect costs were minimal. The analysis employed a probabilistic technique that made it possible to attain weighted measures of the system’s financial gain from a life-cycle viewpoint. This helped bridge managers and operators determine whether installing a seismic SHM monitoring system was truly worthwhile.

2.2 Visual Manifestations of Structural Deterioration by Image Processing and for AI-Based SHM

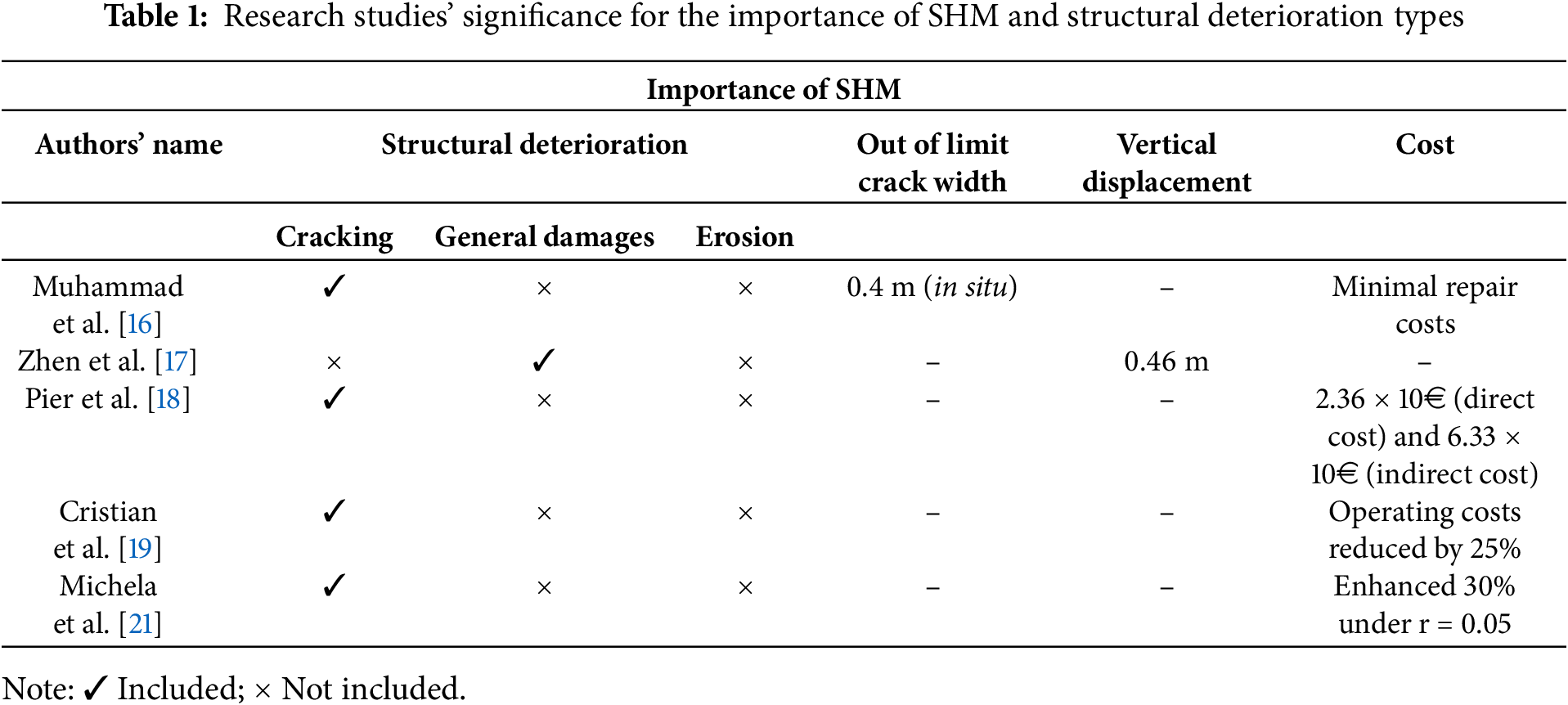

To ensure infrastructure longevity along with safety, SHM is important for detecting and assessing several sorts of structural deterioration, like corrosion, fatigue, and material degradation [22]. The detection and monitoring of various types of structural deterioration, including cracks, corrosion, dampness, moisture, and other structural failures, are involved in SHM [23,24]. The detection and monitoring of cracks are paramount among the various forms of deterioration as they can signal underlying weaknesses or stresses within the structure [25]. Visually, cracks appear as linear disruptions on surfaces, making them highly amenable to analysis through image processing (IP) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques. Advanced IP tools can identify and analyze these cracks from digital images, assessing their potential impact on overall stability by quantifying their dimensions and patterns [26]. Corrosion, another critical form of deterioration, often manifests visually through rust stains, discoloration, and material spalling, particularly in concrete structures due to rebar expansion. Image processing techniques combined with AI models are increasingly being utilized to detect these visual indicators in real-time, offering efficient monitoring solutions. Similarly, other structural failures, like material fatigue, can result in surface deformations or micro-cracks that are detectable through advanced image analysis. The integration of IP and AI in SHM offers a powerful non-contact method to identify and assess these diverse forms of visual deterioration. The results demonstrated that corrosion health management (CHM) systems, when implemented in aircraft, could enhance diagnostic and prognostic processes, contributing to better prevention of structural failures and ensuring the safety of passengers and crew. Also, it is essential to explain the research studies’ significance for the importance of SHM, which are detailed in Table 1.

To ensure infrastructure’s safety as well as longevity, Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) is vital. SHM systems use various sensing technologies to detect, monitor, and assess structures’ conditions in real time. The importance of SHM is reflected in its ability to prevent catastrophic failures, extend the lifespan of structures, and reduce maintenance costs.

The review highlights various structural deterioration factors, such as cracking, general damages, and erosion. For instance, Muhammad et al. [16] noted the importance of monitoring vertical displacement, with a measured crack width of 0.4 m, and emphasized minimal repair costs associated with timely SHM intervention. Zhen et al. [17] reported significant vertical displacement (0.46 m) due to general damages, underlining the need for continuous monitoring. Pier et al. [18] discussed the direct and indirect costs associated with structural deterioration, amounting to 2.36

2.3 Significance of Image Processing in SHM

The importance of incorporating image-processing (IP) methods into SHM is to overcome the inherent difficulties of traditional monitoring methods [27]. These methods surpass the limitations of traditional sensors, especially when it comes to identifying localized or subtle damage that could go undetected otherwise [28]. By utilizing sophisticated IP techniques, such as edge detection, thresholding, and segmentation, the system can automatically identify faults without the need for manual inspection. This lowers worker costs and human error. By offering automated, non-invasive, real-time, and economical methods for identifying, evaluating, and tracking structural damage or degradation, IP expands the potential of SHM, ultimately increasing safety and lowering maintenance expenses [29]. Several studies highlight the practical applications and challenges of IP in SHM:

• UAV-Integrated IP Systems: The study by [30] explored the health monitoring (HM) of civil structures with incorporated Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) and IP systems. A multi-rotor UAV model was created to conduct a thorough field inspection of civil structures, with real-time testing conducted on a university campus. The successfully validated outcomes demonstrated that this strategy served as a time-efficient and cost-effective solution for monitoring large civil constructions.

• Pitfalls of Image-Based SHM: The detailed study of [31] investigated the pitfalls of image- based SHM in terms of (i) false positives, (ii) false negatives, and (iii) base rate bias. Combining frequentist methodology with Bayesian analysis to assess damage detection system accuracy, the results found that even very precise models might produce false positives when damage was uncommon. The analysis also revealed a small chance that a positive result actually indicated damage, even with highly precise models.

• Subsurface Damage Detection and Crack Identification: Research by [32,33] analyzed subsurface damage detection and SHM through digital image correlation and topology optimization. They also benchmarked IP algorithms for UAV-aided crack detection in concrete structures using SHM.

– The initial finite element model of the structure was first developed to divide members into elements, treating their constitutive properties as unknowns in the optimization problem.

– According to the results, the applied approach could be employed as a promising subsurface damage detection method, successfully extracting fine-grained subsurface damage information.

• Filter-Based Crack Identification: In the research study of [34], six filters were used to detect edges in the frequency (Butterworth and Gaussian) and spatial (Roberts, Prewitt, Sobel, and Laplacian of Gaussian) domains. The investigation found that the Gaussian filter Laplacian was accurate, exact, and the fastest technique for crack identification in the spatial domain, also producing the finest detectable fracture width.

2.4 Significance of Machine Learning in SHM

Using Machine Learning (ML) in SHM offers significant advantages, such as enabling real-time data analysis, improving the accuracy of damage detection, and facilitating the early identification of potential structural issues. In practical terms, AI algorithms, leveraging the power of ML, have demonstrated an unparalleled ability to process colossal datasets derived from various sensors [35]. ML allows for more accurate and timely assessments of structural integrity, leading to improved maintenance and safety [36]. ML applications in SHM include vibration-centric monitoring, image-centric analysis, and multi-state classification of structural conditions [37]. In SHM, ML models like Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest (RF), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Gradient Boost, Naive Bayes, and Linear Regression play a pivotal role by leveraging their unique capabilities to analyze massive amounts of data and identify patterns indicative of structural integrity.

2.4.1 Specific ML Model Applications and Performance

• Support Vector Machines (SVM):

– SVMs are ideal for classification tasks and well-suited for SHM applications where clear boundaries between damaged and undamaged states need to be established, even with complex, high-dimensional data, as demonstrated by the Vibration-Based SVM for SHM which effectively mapped damaged features for data categorization [38].

– A limitation noted for SVMs is the need for large datasets to effectively train the models, which might not always be available in practical SHM scenarios [38].

– The research in [39] explained the SVM for automated modeling of nonlinear structures employing health monitoring (HM) results. Stiffness characteristics were taken from hysteresis loop analysis (HLA) for training the SVM model with restrictions. A proof-of- concept case study confirmed the suggested approach’s capacity to precisely identify more model parameters with an average error for a nonlinear numerical structure in the presence of 10% RMS measurement noise. Overall outcomes indicated the developed predictive model could correctly represent fundamental dynamics and structural deterioration, as well as forecast potential future reactions and risks.

• K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN):

– The study of [40] analyzed the enhancement of the SHM framework on beams based on the KNN algorithm. KNN’s non-parametric nature makes it highly effective for pattern recognition and damage detection, particularly in scenarios where data distributions are not well-defined. This capability significantly improves the overall performance of damage detection models.

– The findings demonstrated that the presented SHM model improved the overall performance of damage detection in beams, decreased modeling time, and provided higher precision. However, the scalability of the algorithm for larger and more complex structures was difficult to consider as a concern.

• Random Forest (RF):

– Leveraging ensemble learning, the Random Forest (RF) technique offers robust performance against overfitting and efficiently handles high-dimensional data with good accuracy, making it particularly suitable for assessing regional seismic damage states in complex structures like concrete beam bridges, as analyzed in the research of [41].

– These performance metrics for bridge systems and components showed that RF has significant potential for assessing regional beam bridges’ seismic damage states. A limitation is the need for extensive training data to effectively train the RF model, particularly in scenarios where such data is difficult to obtain.

• XGBoost:

– XGBoost, a gradient-boosting framework, is noted for its high efficiency and flexibility, excelling in predictive tasks such as accurately forecasting concrete electrical resistivity in SHM, as analyzed in the research of [42]. An expanded dataset with a greater variety of experimental data could enhance the applied model’s predictive power. The impact of cracks and reinforcing on electrical resistivity measurement (ERM) will be examined in the following phase of this study.

– Furthermore, the research of [43] explored the explainable ML model for load-deformation correlation in long-span suspension bridges employing XGBoost-SHAP. Training and testing of the dataset for the XGBoost model were made using the SHM system for a suspension bridge. Midspan deflections and expansion joint displacements were considered output factors, while temperature, wind, and vehicle loads were utilized as input factors. The data showed that the highest prediction accuracy was attained by XGBoost. In contrast to vehicle and wind loads, temperature had a major impact on long-span suspension bridges’ deformation during normal operation.

• Other ML Models and Feature Combinations:

– The SHM utilizing ML and cumulative absolute velocity features was investigated in [44]. Five ML models, such as SVM, Logistic Regression (LR), Ordinal Logistic Regression (OLR), and artificial neural networks (ANN10 and ANN100), were compared. Two test sets were employed: Set-1 originating from the training set’s distribution and Set-2 from a separate one. Findings showed that the combination of CAV and relative CAV (RCAV) for linear response performed better out of all feature combinations.

2.4.2 Deep Learning (DL) Models Utilization in SHM

As mentioned earlier, Deep Learning (DL) is a subset of Machine Learning (ML) and has played an important role in damage detection and identifying damage (including cracks) in Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) [45]. DL algorithms have revolutionized different fields by enabling automated and highly accurate analysis of enormous data collected from sensors and imaging devices [46]. These algorithms can efficiently process complex patterns and features in the data, permitting the early detection of structural anomalies and cracks that are unnoticed using traditional methods [47].

Furthermore, the capabilities of SHM systems are augmented by the integration of DL with other advanced technologies like image processing (IP) and data fusion, enabling more comprehensive and precise assessments of structural health [48]. Some of the DL models are (1) CNNs, (2) Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), (3) Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs), (4) Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), (5) Autoencoders, and (6) Deep Belief Networks (DBNs).

Specific DL Model Applications and Studies

• Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs):

– CNNs are exceptionally well-suited for image-based SHM tasks. Their intrinsic ability to automatically learn hierarchical features directly from raw images makes them highly effective for detecting and classifying visual damage like cracks and corrosion [45,46,47,49].

– The research of [49] explained the application of CNNs and impedance-centric SHM for damage detection. This study demonstrated that the applied methodology was able to classify damages and pristine signatures considering three diverse structures for three temperature levels, achieving a damage detection probability greater than the expected level.

• Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs):

– RNNs are crucial for analyzing sequential and time-series data common in continuous SHM.

– The study of [50] explained large-scale SHM using composite RNNs and grid environments. Their RNN framework, based on a spatiotemporal composite autoencoder network and a 5D, time-dependent grid environment, tested damage diagnosis capabilities on a numerical 10-story, 10-bay structure. Results confirmed the grid-oriented damage detection method as a useful approach to large-scale SHM.

– The SCAN architecture effectively utilized DL, LSTM units, and multi-objective training to produce powerful damage-sensitive features that precisely detected and localized damage in the absence of existing damaged condition data.

– The advanced predictive SHM in high-rise buildings using RNNs was analyzed in [51]. The created model showed excellent accuracy when used for forecasting time series of vertical, lateral (X), and lateral (Y) displacements, showcasing strong accuracy and generalization capability.

• Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs):

– The study by [52,53] analyzed the unsupervised structural damage detection centered on a deep Convolutional AutoEncoder (CAE) along with lost data reconstruction for SHM employing deep convolutional GANs.

– The implemented GAN model was essential for interpreting the full signal content and generating realistic hypotheses for missing signals [53]. It successfully reconstructed data even when the data loss ratio reached 83.33.

– A primary limitation of the implemented GAN model was its training on a dataset obtained from the intact structure, leading it to learn only the structural baseline dynamic features.

• Autoencoders:

– Autoencoders are effective for unsupervised anomaly detection. The primary goal of the applied method in [52] was to use a CAE network that utilized the structure’s raw vibration data to detect and measure structural degradation.

– Results obtained were in line with the bridge’s projected overall state, demonstrating the technique’s effectiveness in quantifying damage to real-world structures as damage spread across them [52].

Hybrid Deep Learning Frameworks

• The structural damage identification technique employing a hybrid DL framework was explored in the research of [54]. Three components—a CNN, Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC), and Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD)—were used to identify structural deterioration. Experimental findings showed that the implemented EEMD-PCC-CNN approach had notable performance advantages in damage recognition compared to existing classical methods like SVM, KNN, RF. This hybrid framework could prevent feature selection in conventional identification approaches and greatly increase structural damage identification accuracy by thoroughly mining building structure features.

• Lastly, damage detection in SHM using a hybrid CNN and RNN model was investigated. This model combined spatial and temporal feature types to improve discrimination capacity compared to strategies that solely used deep features. The Z24-bridge (Switzerland) benchmark dataset was used to test the approach’s correctness, demonstrating high precision in identifying the tested structure’s deterioration.

Performance Outcomes and Comparative Analysis

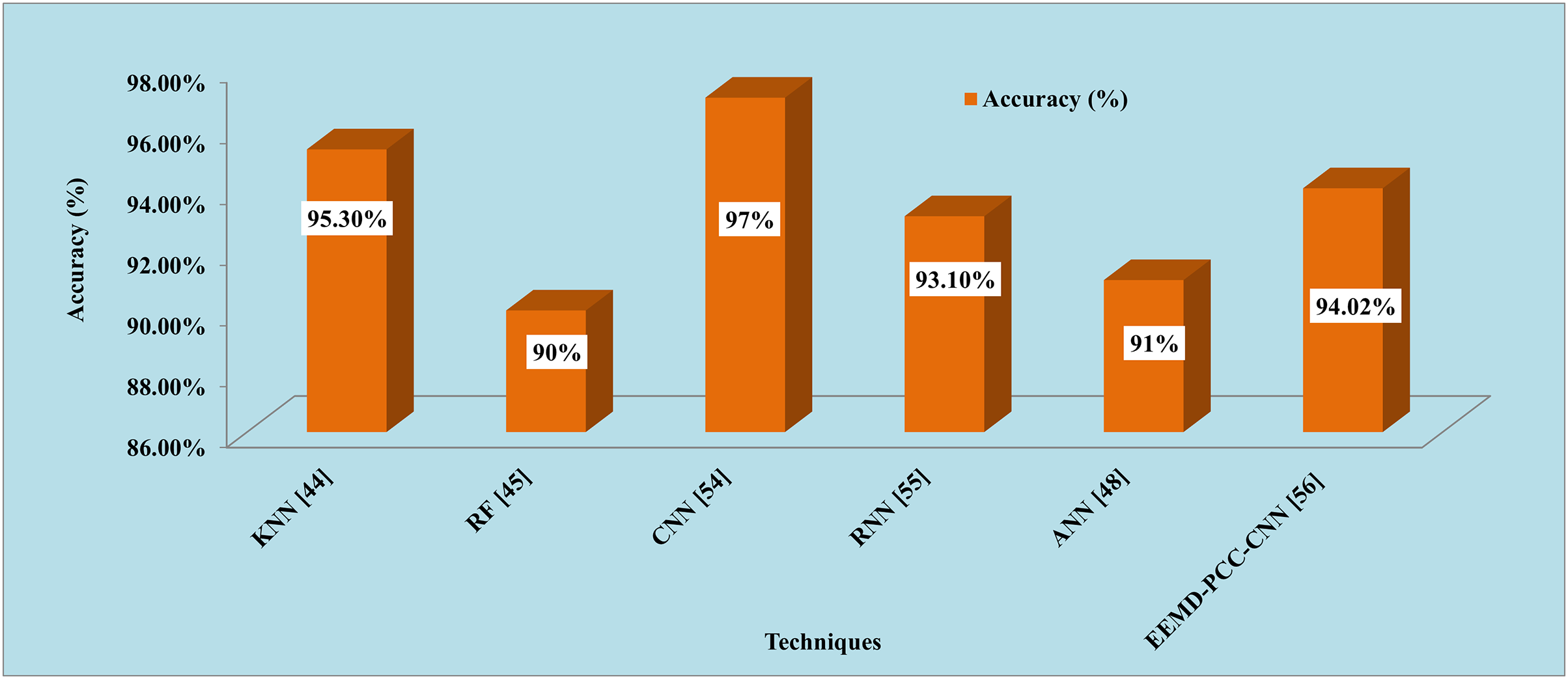

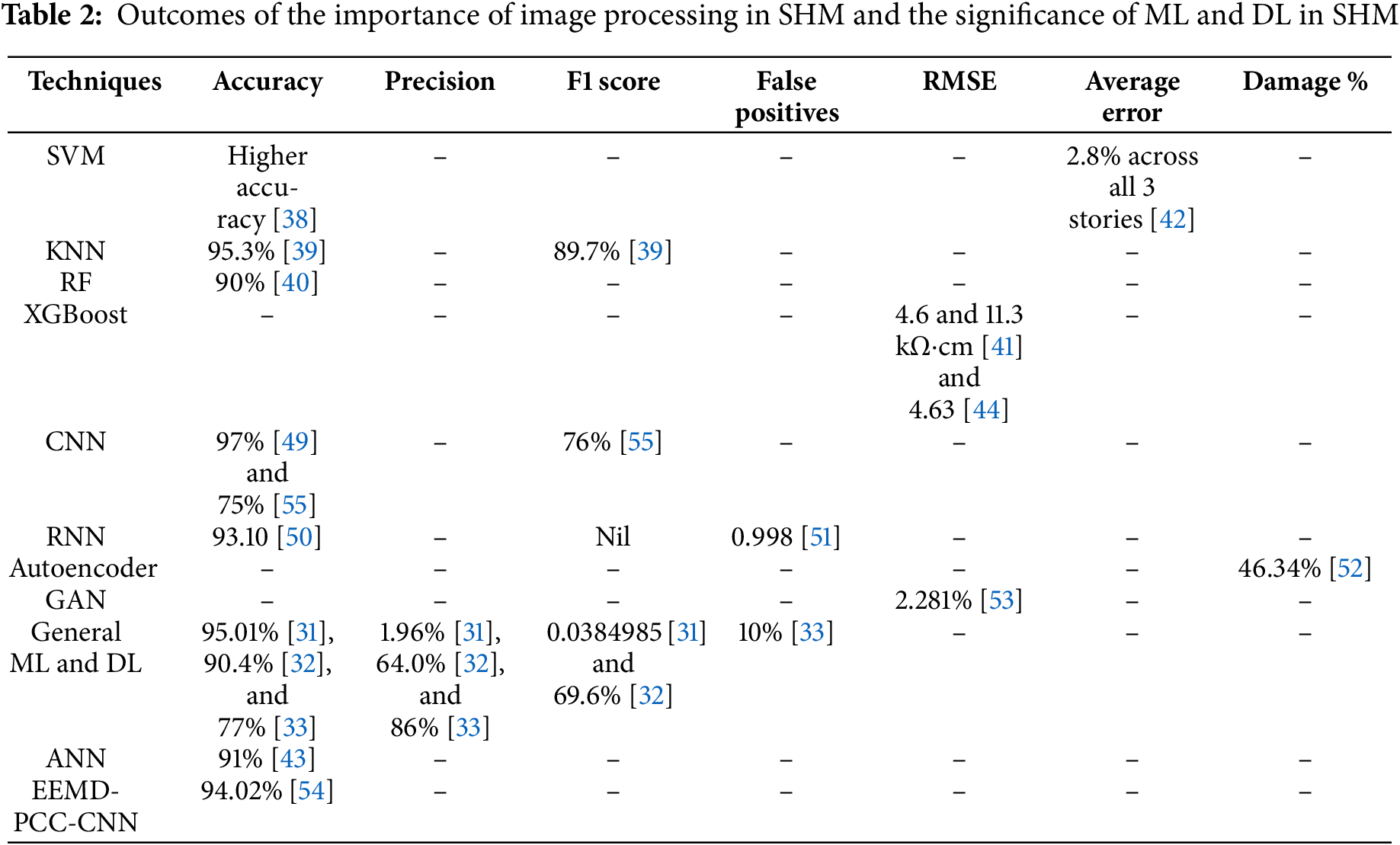

It is essential to characterize the outcomes of the importance of IP in SHM and the significance of ML and DL in SHM. These outcomes are tabulated in Table 2 based on general ML, DL, and their techniques. Fig. 2 explains the datasets utilized in the references for the importance of IP in SHM and the significance of ML and DL in SHM.

Figure 2: Importance of ML and DL in SHM and the comparison of the techniques about accuracy metrics

IP plays a crucial role in SHM by enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of damage detection, enabling automated and precise analysis of structural integrity, as depicted in Table 2. Techniques such as SVM and KNN have demonstrated significant efficacy, with accuracy rates reaching 95.3% and 89.7%. Advanced ML and DL approaches, including CNN and RNN, further elevate SHM capabilities, achieving accuracy rates as high as 97% and 93.1%, respectively. These methods contribute to reducing false positives and improving metrics like precision, F1 score, and RMSE, thereby making them essential for accurate SHM. Research shows that RF achieves an accuracy of 90%, while techniques like XGBoost and GAN have also been employed with promising results, such as a 2.281% damage detection rate. The integration of autoencoders and ensemble methods like EEMD-PCC-CNN further underscores the importance of ML and DL in achieving high precision and reliability in SHM, with studies reporting an average accuracy of around 95.01%, a precision of 90.4%, and F1 scores highlighting the effectiveness of these techniques in maintaining structural health.

It is important to note that the performance metrics presented in Fig. 2 and Table 2 are compiled from various independent research studies, each applying algorithms to different datasets, structural types, and damage scenarios. Therefore, these values should be interpreted as reported efficacy within specific contexts, illustrating the broad potential and versatility of ML and DL in SHM, rather than serving as direct, standardized comparative benchmarks. While these figures showcase impressive accuracy rates and other metrics, readers should be mindful that these results are derived from heterogeneous experimental setups. Direct comparison between algorithms across different studies is inherently limited due to variations in dataset size, damage types, sensor modalities (though our focus is on visual), and evaluation methodologies. The purpose here is to highlight the significant capabilities and advancements demonstrated by these techniques in diverse SHM applications and to provide a comprehensive overview of the state-of-the-art and the general trends in performance. Future work on standardized benchmarks will be crucial for more rigorous head-to-head comparisons.

Comparing various algorithms’ performance with regard to accuracy metrics for the significance of ML and DL in SHM is essential. As detailed in Fig. 2, various ML and DL models showcase their prowess in identifying and analyzing structural anomalies in SHM.

• A notable accuracy rate of 95.3% was exhibited by the KNN algorithm, making it highly effective in pattern recognition and damage detection.

• The RF method followed with an impressive 90% accuracy, leveraging its ensemble learning approach to enhance prediction reliability.

• CNN stood out with a remarkable 97% accuracy, excelling in IP tasks critical to SHM.

• Likewise, a strong accuracy rate of 93.1% was attained by the RNNs, showcasing their capability in handling sequential data and time-series analysis.

• Solid 91% accuracy was demonstrated by ANNs, providing a versatile approach to modeling complex relationships within data.

• Lastly, the EEMD-PCC-CNN technique, combining Empirical Mode Decomposition, Partial Correlation Coefficient, and CNN, achieved a commendable 94.02% accuracy, highlighting the effectiveness of hybrid models in enhancing SHM outcomes.

The field of Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) is essential to guarantee the safety, lifespan, and usefulness of structures, especially in the background of deterioration brought on by aging, environmental stresses, or natural disasters. While the combination of SHM with advanced technologies like Image Processing (IP), Machine Learning (ML), and Deep Learning (DL) has shown significant promise for automating the detection and tracking of structural deterioration, several challenges and research gaps still need to be addressed for their widespread and reli able implementation. The following are some of the significant research gaps:

3.1 Technical Challenges in Model Development

• Robustness to Environmental Variations: Although visual information (images, videos) can offer valuable data about structural health, issues persist with the consistency, quality, and resolution of the obtained images, particularly in difficult-to-reach or complex places. Furthermore, existing image preprocessing techniques (like noise removal, enhancement, and normalization), which are essential for improving the quality of data input to ML/DL models, are not necessarily resilient to changes in environmental factors like weather or lighting. This limits the reliability of automated systems in real-world, dynamic conditions.

• Model Explainability and Interpretability: Advanced ML/DL models often act as “black boxes,” making it challenging to understand their decision-making processes. This lack of interpretability can be a significant hurdle in safety-critical SHM applications, where engineers and stakeholders need to trust and understand the reasoning behind a damage detection or prognosis. Further research is required to develop more explainable AI models for SHM.

3.2 Data and Standardization Gaps

• Lack of Standardized Models and Datasets: Even though ML and DL models have demonstrated substantial potential in categorizing damage types and forecasting the future health of structures, there is a significant lack of standardized models or comprehensive datasets for training and validation across various building kinds and materials. This absence hinders direct comparison of different algorithms, slows down model development, and limits the generalizability of developed solutions. Without diverse, standardized benchmark datasets, models trained on specific structures may not perform reliably on others, necessitating extensive re-training and validation.

• Data Collection and Labeling Challenges: The process of collecting large volumes of high-quality, annotated data for training ML/DL models is often time-consuming, expensive, and requires expert knowledge for accurate labeling of defects. This scarcity of robust, real-world datasets is a major impediment to developing highly accurate and generalizable SHM systems.

3.3 Practical and Resource Limitations

• High Computational Cost: The significant computational power needed for training and deploying advanced ML/DL models can restrict the accessibility and broad use of these technologies, particularly for smaller organizations or in remote areas. Optimizing model architectures and developing more efficient algorithms are crucial for practical deployment.

• Cost of High-Quality Imaging Equipment: The initial investment in high-quality imaging equipment can be substantial, posing a barrier to widespread adoption, especially for continuous monitoring of large-scale infrastructure. Research into more affordable and accessible sensing technologies is needed.

• Real-time Capabilities and Integration: While advancements have been made, achieving true real- time processing and decision-making, especially for large volumes of data from multiple sensors, remains a challenge. Seamless integration of these advanced technologies with existing SHM infrastructure and workflows is also complex.

To detect, analyze, and monitor various forms of building deterioration, such as cracks, corrosion, dampness, and other structural issues, SHM using IP has introduced a revolutionary and highly

efficient method. This technology also provides significant advantages over traditional inspection methods, enabling non-destructive testing, real-time monitoring, and automation, thereby offering enhanced cost-effectiveness. By using IP techniques like computer vision, ML, and DL, it has become possible to accurately identify and quantify structural damage at an early stage, preventing costly repairs and ensuring the building’s safety. High-resolution images captured by cameras, drones, or thermal imaging devices are utilized by SHM systems to constantly monitor the structural integrity of buildings and detect issues that may have gone unnoticed previously. Compared to traditional manual inspection, the integration of ML and DL techniques significantly enhances the accuracy and efficiency of defect identification. Despite these advantages, the effect of ambient factors on image quality remains a significant drawback noted in research publications. Changes in lighting, shadows, and occlusions can adversely affect image quality and lower model accuracy. To overcome these challenges and fully harness the potential of AI in SHM, future research and technological advancements are essential. Researchers should concentrate on enhancing the models’ resilience using advanced methods, including data augmentation, transfer learning, and hybrid approaches that blend DL with traditional IP techniques. Furthermore, key areas for future work include:

• Development of Standardized Datasets and Benchmarks: Establishing universally accepted datasets and performance metrics will facilitate more rigorous comparisons between different models and accelerate collective progress.

• Multi-Modal Data Integration: Exploring the fusion of IP data with other sensor modalities (e.g., vibration, acoustic, strain) could provide a more comprehensive understanding of structural health.

• Real-Time Processing and Edge Computing: Advancements in real-time processing capabilities and deployment on edge devices are crucial for immediate damage detection and practical field implementation.

• Explainable AI for SHM: Developing more interpretable AI models will build trust among engineers and stakeholders, allowing for better understanding of diagnostic and prognostic outcomes.

• Predictive Maintenance and Lifecycle Management: Moving beyond mere detection to robust prediction of remaining useful life and integrating SHM insights into comprehensive asset management strategies will maximize the long-term benefits for infrastructure owners and operators.

• Cost-Effectiveness and Accessibility: Continued efforts are needed to reduce the overall cost of high-quality imaging equipment and computational resources, making these advanced SHM solutions more accessible globally. By improving the models’ resistance to environmental changes, refining IP methods, and addressing these broader research avenues, the effectiveness of SHM systems in preserving building safety and prolonging their lifespan can be significantly increased.

Acknowledgement: We would like to acknowledge MAHAJYOTI, an Autonomous Institute of the OBC Bahujan Welfare Department, Government of Maharashtra, for providing a fellowship for the said research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, Kavita Bodke; validation, Keshav Kashinath Sangle; supervision, Sunil Bhirud. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bibri SE, Krogstie J. On the social shaping dimensions of smart sustainable cities: ICT of the new wave of computing for urban sustainability. Sustain Cities Soc. 2017;29(7491):219–46. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2016.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Palma P, Steiger R. Structural health monitoring of timber structures-Review of available methods and case studies. Constr Build Mater. 2020;248:118528. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Plevris V, Papazafeiropoulos G. AI in structural health monitoring for infrastructure maintenance and safety. Infrastructures. 2024;9(12):225. doi:10.3390/infrastructures9120225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Angst UM. Challenges and opportunities in corrosion of steel in concrete. Mater Struct. 2018;51(1):4. doi:10.1617/s11527-017-1131-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chemrouk M. The deteriorations of reinforced concrete and the option of high performances reinforced concrete. Procedia Eng. 2015;125:713–24. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2015.11.112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Barrelas J, Ren Q, Pereira C. Implications of climate change in the implementation of maintenance planning and use of building inspection systems. J Build Eng. 2021;40(4):102777. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Niezrecki C, Baqersad J, Sabato A. Digital image correlation techniques for NDE and SHM. In: Handbook of advanced non-destructive evaluation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 1–46. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-30050-4_47-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Muralitharan S, Nelson W, Di S, McGillion M, Devereaux PJ, Barr NG, et al. Machine learning-based early warning systems for clinical deterioration: systematic scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e25187. doi:10.2196/25187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Azimi M, Eslamlou A, Pekcan G. Data-driven structural health monitoring and damage detection through deep learning: state-of-the-art review. Sensors. 2020;20(10):2778. doi:10.3390/s20102778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Valença J, Puente I, Júlio E, González-Jorge H, Arias-Sánchez P. Assessment of cracks on concrete bridges using image processing supported by laser scanning survey. Constr Build Mater. 2017;146(12):668–78. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.04.096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Rodrigues F, Cotella V, Rodrigues H, Rocha E, Freitas F, Matos R. Application of deep learning approach for the classification of buildings’ degradation state in a BIM methodology. Appl Sci. 2022;12(15):7403. doi:10.3390/app12157403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lynch JP, Farrar CR, Michaels JE. Structural health monitoring: technological advances to practical implementations [scanning the issue]. Proc IEEE. 2016;104(8):1508–12. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2016.2588818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Preethichandra DMG, Suntharavadivel TG, Kalutara P, Piyathilaka L, Izhar U. Influence of smart sensors on structural health monitoring systems and future asset management practices. Sensors. 2023;23(19):8279. doi:10.3390/s23198279.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. de Oliveira VP, Reis A, Alves Salvador Filho JA. Assessing the evolution of structural health monitoring through smart sensor integration. Procedia Struct Integr. 2024;64(5):653–60. doi:10.1016/j.prostr.2024.09.323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kaya Y, Safak E. Real-time analysis and interpretation of continuous data from structural health monitoring (SHM) systems. Bull Earthq Eng. 2015;13(3):917–34. doi:10.1007/s10518-014-9642-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Fawad M, Koris K, Salamak M, Gerges M, Bednarski L, Sienko R. Nonlinear modelling of a bridge: a case study-based damage evaluation and proposal of Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) system. Arch Civil Eng. 2022;68(3):569–84. doi:10.24425/ace.2022.141903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sun Z, Sun H. Jiangyin bridge: an example of integrating structural health monitoring with bridge maintenance. Struct Eng Int. 2018;28(3):353–6. doi:10.1080/10168664.2018.1462671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Giordano PF, Limongelli MP. The value of structural health monitoring in seismic emergency management of bridges. Struct Infrastruct Eng. 2022;18(4):537–53. doi:10.1080/15732479.2020.1862251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Comisu CC, Taranu N, Boaca G, Scutaru MC. Structural health monitoring system of bridges. Procedia Eng. 2017;199(2):2054–9. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.09.472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Fawad M, Salamak M, Poprawa G, Koris K, Jasinski M, Lazinski P, et al. Author Correction: automation of structural health monitoring (SHM) system of a bridge using BIMification approach and BIM-based finite element model development. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):17638. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-40355-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Torti M, Venanzi I, Laflamme S, Ubertini F. Life-cycle management cost analysis of transportation bridges equipped with seismic structural health monitoring systems. Struct Health Monit. 2022;21(1):100–17. doi:10.1177/1475921721996624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gharehbaghi VR, Noroozinejad Farsangi E, Noori M, Yang TY, Li S, Nguyen A, et al. A critical review on structural health monitoring: definitions, methods, and perspectives. Arch Computat Methods Eng. 2022;29(4):2209–35. doi:10.1007/s11831-021-09665-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Monavari B. SHM-based structural deterioration assessment [dissertation]. Brisbane, QLD, Austrilia: Queensland University of Technology; 2019. doi:10.5204/thesis.eprints.132660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Annamdas VGM, Bhalla S, Soh CK. Applications of structural health monitoring technology in Asia. Struct Health Monit. 2017;16(3):324–46. doi:10.1177/1475921716653278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Gkoumas K, Galassi MC, Allaix D, Anthoine A, Argyroudis S, Baldini G, et al. Indirect structural health monitoring (iSHM) of transport infrastructure in the digital age. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2023. doi:10.2760/364830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mutlib NK, Baharom SB, El-Shafie A, Nuawi MZ. Ultrasonic health monitoring in structural engineering: buildings and bridges. Struct Cont Health Monitor. 2016;23(3):409–22. doi:10.1002/stc.1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Raksha M. A review on–structural health monitoring and image processing. Int J Sci Res Eng Dev. 2010. [cited 2025 Jul 18]. Available from: https://ijsred.com/volume2/issue5/IJSRED-V2I5P8.pdf. [Google Scholar]

28. Rabi RR, Vailati M, Monti G. Effectiveness of vibration-based techniques for damage localization and lifetime prediction in structural health monitoring of bridges: a comprehensive review. Buildings. 2024;14(4):1183. doi:10.3390/buildings14041183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Shilar FA, Ganachari SV, Patil VB, Yunus Khan TM, Saddique Shaik A, Azam Ali M. Exploring the potential of promising sensor technologies for concrete structural health monitoring. Materials. 2024;17(10):2410. doi:10.3390/ma17102410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Sankarasrinivasan S, Balasubramanian E, Karthik K, Chandrasekar U, Gupta R. Health monitoring of civil structures with integrated UAV and image processing system. Procedia Comput Sci. 2015;54(3):508–15. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2015.06.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Plevris V. Addressing the pitfalls of image-based structural health monitoring: a focus on false positives, false negatives, and base rate bias. arXiv:2410.20384. 2024. [Google Scholar]

32. Dizaji MS, Alipour M, Harris DK. Subsurface damage detection and structural health monitoring using digital image correlation and topology optimization. Eng Struct. 2021;230(6):111712. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.111712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Dorafshan S, Thomas RJ, Maguire M. Benchmarking image processing algorithms for unmanned aerial system-assisted crack detection in concrete structures. Infrastructures. 2019;4(2):19. doi:10.3390/infrastructures4020019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhao S, Kang F, Li J, Ma C. Structural health monitoring and inspection of dams based on UAV photogrammetry with image 3D reconstruction. Autom Constr. 2021;130(1):103832. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2021.103832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Shibu M, Kumar KP, Pillai VJ, Murthy H, Chandra S. Structural health monitoring using AI and ML based multimodal sensors data. Meas Sens. 2023;27(19):100762. doi:10.1016/j.measen.2023.100762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ghiasi R, Torkzadeh P, Noori M. A machine-learning approach for structural damage detection using least square support vector machine based on a new combinational kernel function. Struct Health Monit. 2016;15(3):302–16. doi:10.1177/1475921716639587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Smarsly K, Dragos K, Wiggenbrock J. Machine learning techniques for structural health monitoring. In: Proceedings of the 8th European Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring (EWSHM 2016); 2016 Jul 5–8; Bilbao, Spain. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

38. Pan H, Azimi M, Gui G, Yan F, Lin Z. Vibration-based support vector machine for structural health monitoring. In: Experimental vibration analysis for civil structures. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 167–78. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-67443-8_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhou C, Chase JG, Rodgers GW. Support vector machines for automated modelling of nonlinear structures using health monitoring results. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2021;149(2):107201. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Altabey WA, Noori M, Wu Z, Silik A, Sarhosis V. Enhancement of structural health monitoring framework on beams based on k-nearest neighbor algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 14th International Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring. Lancaster, PA, USA: Destech Publications, Inc.; 2023. p. 1–9. doi:10.12783/shm2023/37068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lei X, Sun L, Xia Y, He T. Vibration-based seismic damage states evaluation for regional concrete beam bridges using random forest method. Sustainability. 2020;12(12):5106. doi:10.3390/su12125106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Dong W, Huang Y, Lehane B, Ma G. XGBoost algorithm-based prediction of concrete electrical resistivity for structural health monitoring. Autom Constr. 2020;114(8):103155. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Chen M, Xin J, Tang Q, Hu T, Zhou Y, Zhou J. Explainable machine learning model for load-deformation correlation in long-span suspension bridges using XGBoost-SHAP. Dev Built Environ. 2024;20:100569. doi:10.1016/j.dibe.2024.100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Muin S, Mosalam KM. Structural health monitoring using machine learning and cumulative absolute velocity features. Appl Sci. 2021;11(12):5727. doi:10.3390/app11125727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Malekloo A, Ozer E, AlHamaydeh M, Girolami M. Machine learning and structural health monitoring overview with emerging technology and high-dimensional data source highlights. Struct Health Monit. 2022;21(4):1906–55. doi:10.1177/14759217211036880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Cha YJ, Ali R, Lewis J, Buyukozturk O. Deep learning-based structural health monitoring. Autom Constr. 2024;161(3):105328. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Neves C. Structural Health Monitoring of Bridges Model-free damage detection method using machine learning. [dissertation]. Stockholm, Sweden: KTH Royal Institute of Technology; 2017. [Google Scholar]

48. Wang YW, Ni YQ, Wang SM. Structural health monitoring of railway bridges using innovative sensing technologies and machine learning algorithms: a concise review. Intell Transp Infrastruct. 2022;1:liac009. doi:10.1093/iti/liac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. de Rezende SWF, dos Reis Vieira de Moura JJr, Neto RMF, Gallo CA, Steffen VJr. Convolutional neural network and impedance-based SHM applied to damage detection. Eng Res Express. 2020;2(3):035031. doi:10.1088/2631-8695/abb568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Eltouny KA, Liang X. Large-scale structural health monitoring using composite recurrent neural networks and grid environments. Comput Aided Civ Infrastruct Eng. 2023;38(3):271–87. doi:10.1111/mice.12845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Ghaffari A, Shahbazi Y, Mokhtari Kashavar M, Fotouhi M, Pedrammehr S. Advanced predictive structural health monitoring in high-rise buildings using recurrent neural networks. Buildings. 2024;14(10):3261. doi:10.3390/buildings14103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. He Y, Huang Z, Liu D, Zhang L, Liu Y. A novel structural damage identification method using a hybrid deep learning framework. Buildings. 2022;12(12):2130. doi:10.3390/buildings12122130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Rastin Z, Ghodrati Amiri G, Darvishan E. Unsupervised structural damage detection technique based on a deep convolutional autoencoder. Shock Vib. 2021;2021(1):6658575. doi:10.1155/2021/6658575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Lei X, Sun L, Xia Y. Lost data reconstruction for structural health monitoring using deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. Struct Health Monit. 2021;20(4):2069–87. doi:10.1177/1475921720959226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Bui-Tien T, Bui-Ngoc D, Nguyen-Tran H, Nguyen-Ngoc L, Tran-Ngoc H, Tran-Viet H. Damage detection in structural health monitoring using hybrid convolution neural network and recurrent neural network. Frat Ed Integrità Strutturale. 2022;16(59):461–70. doi:10.3221/igf-esis.59.30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools