Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Automatic Potential Safety Hazard Detection for High-Speed Railroad Surrounding Environment Using Lightweight Hybrid Dual Tasks Architecture

The Faculty of Transportation Engineering, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, 650031, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yunpeng Wu. Email: ; Fengxiang Guo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Enhanced Low-Altitude Technology Applications in Structural Integrity Evaluation and Safety Management of Transportation Infrastructure Systems)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(6), 1457-1472. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.069611

Received 26 June 2025; Accepted 13 August 2025; Issue published 17 November 2025

Abstract

Utilizing unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photography to timely detect and evaluate potential safety hazards (PSHs) around high-speed rail has great potential to complement and reform the existing manual inspections by providing better overhead views and mitigating safety issues. However, UAV inspections based on manual interpretation, which heavily rely on the experience, attention, and judgment of human inspectors, still inevitably suffer from subjectivity and inaccuracy. To address this issue, this study proposes a lightweight hybrid learning algorithm named HDTA (hybrid dual tasks architecture) to automatically and efficiently detect the PSHs of UAV imagery. First, this HDTA architecture seamlessly integrates both detection and segmentation branches within a unified framework. This design enables the model to simultaneously perform PSH detection and railroad parsing, thereby providing comprehensive scene understanding. Such joint learning also lays the foundation for PSH assessment tasks. Second, an innovative lightweight backbone based on the shuffle selective state space model (S4M) is incorporated into HDTA. The state space model approach allows for global contextual information extraction while maintaining linear computational complexity. Furthermore, the incorporation of shuffle operation facilitates more efficient information flow across feature dimensions, enhancing both feature representation and fusion capabilities. Finally, extensive experiments conducted on a railroad environment dataset constructed from UAV imagery demonstrate that the proposed method achieves high detection accuracy while maintaining efficiency and practicality.Keywords

With the rapid expansion of high-speed railways, potential safety hazards (PSHs) along the tracks—such as foreign objects—can be blown or displaced onto the railway due to adverse weather conditions or strong winds, posing serious threats to safe railway operations. For instance, in 2021, over ten incidents involving foreign objects like plastic tarps and covered nets entering high-speed rail tracks led to numerous train delays and cancellations in China, causing significant economic losses [1]. Therefore, the timely and accurate detection of the surrounding environment of high-speed railways is essential for ensuring the safe operation of railway systems. At present, PSH detection primarily relies on manual inspection, which is labor-intensive and inefficient. Fortunately, aerial inspection using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has emerged as a promising solution. However, manually interpreting UAV imagery to identify PSH near railway tracks remains time-consuming and subjectivity. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop an automated visual inspection (VI) method capable of accurately detecting PSH and interpreting both tracks and surrounding infrastructure in UAV imagery.

In recent years, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), known for their ability to extract deep features, have been extensively utilized across a range of vision tasks. Representative object detection frameworks include two stage models such as RCNN series [2,3], as well as prominent one stage detectors like SSD [4], YOLOv4 [5], YOLOv5 [6], YOLOv7 [7], YOLOv8 [8]. Compared to two-stage approaches, the YOLO series incorporates more sophisticated designs in terms of network structure, anchor strategies, loss formulations, and data augmentation techniques, leading to superior detection accuracy and real-time performance. Notably, YOLOv10 integrates an NMS-free (Non-Maximum Suppression) and end-to-end processing mechanism, achieving competitive performance and high inference speed. With regard to saliency detection, classical networks include DeepLabv3+ [9], MobileNetv3 [10], GCnet [11], SegFormer [12], Mask2former [13] and other methods [14–16]. Although the aforementioned models perform well in individual detection or segmentation tasks, their specialized design for single tasks and lack of distance information make them unsuitable for distance-based evaluation of PSHs in high-speed railroad environments.

To date, numerous CNN-based approaches have been proposed for railroad safety and infrastructure monitoring. Reference [17] proposed a defect detection method called ELA-YOLO based on YOLOv8, which integrates linear attention for better representation with lower complexity, a selective feature pyramid network for improved multi-level feature fusion, and a lightweight detection head for efficient output. Reference [18] developed a spatial–temporal neural network model based on ResNet-Transformer architecture to predict the occurrence of broken rails one year in advance. Furthermore, research on engineering applications based on UAV imagery has also been widely developed, reference [19] presented a UAV and Mixed Reality (MR)-based inspection method to enhance efficiency and personnel involvement. It builds an MR digital environment for semi-automatic UAV control, defect data collection, and visual management. Experiments show the method effectively supports exterior wall defect inspection and provides a foundation for advancing MMESE. Reference [20] proposed CDCR-ISeg, an interactive segmentation model supported by a new 1500-image dataset (UAV-CrackX4, X8, X16) covering diverse zoom levels and domains. The model integrates super-resolution and domain adaptation to boost generalization and reduce annotation effort, and uses a vector map with reversed directions to enhance boundary detection. Reference [21] proposed PDIS-Net, an instance segmentation framework for UAV-based pavement distress detection. It uses dynamic convolution by predicting kernel positions and weights, refines them through metric learning and fusion, and applies them to feature maps to generate accurate instance masks.

In the field of PSH detection around railways, reference [22] developed an automatic real-time instance segmentation framework called YOLARC (You Only Look at Railroad Coefficients), which utilizes UAV imagery for high-speed railway monitoring. Building upon [22], reference [23] proposed the YOLARC++ framework for PSH detection in UAV images. This framework incorporates a Large Selective Kernel (LSK) module that adaptively adjusts the receptive field and mitigates the impact of scale variation. However, applying instance segmentation to object detection introduces unnecessary computational overhead. To address this issue, reference [24] proposed an all-in-one YOLO (AOYOLO) framework for multi-task railway component detection. AOYOLO employs a ConvNeXt-based backbone to extract super features and integrates a U-shaped salient object segmentation branch to enhance railway surface defect (RSD) segmentation and component detection. Furthermore, reference [25] introduced YOLORS, a hybrid learning architecture designed to segment railroad from drone images and assess PSHs along the railway. It features a stripe-pooling-based segment branch for pixel-level tasks and introduces a novel object-guided mosaic data augmentation method to improve small-object detection performance. However, these models generally require a large number of parameters and incur high computational costs for railway environment detection, which limits their usability and practical deployment.

Specifically, applying deep learning techniques for the timely and accurate detection of potential safety hazards (PSH) surrounding high-speed railways presents the following challenges: 1) Balancing computational cost and accuracy. Existing models often require substantial computational resources to achieve high detection accuracy. However, their large parameter sizes and high computational complexity significantly hinder deployment on edge devices, limiting their practical engineering utility. 2) Lack of global modeling capability. Traditional CNN-based methods struggle to capture long-range contextual dependencies. While Transformer-based approaches offer improved global modeling, their inherent quadratic computational complexity severely reduces efficiency and practical applicability.

To address these limitations, we propose a novel hybrid learning framework named HDTA (Hybrid Dual-Task Architecture), designed for accurate parsing of UAV imagery to detect railway lanes and tracks, while simultaneously identifying PSH through a unified architecture that integrates a pixel-level sparse segmentation branch and an object detection branch. Specifically, HDTA is equipped with a lightweight backbone built upon S4M (Shuffled Selective State Space Module) blocks. The S4M module first leverages the global modeling capability of the Selective State Space Model (SSM) to extract long-range contextual features from UAV images, and then applies a channel-wise shuffle operation to reduce computational complexity and enhance multi-source feature fusion. This design enables the S4M-Backbone to achieve an optimal trade-off between robust global feature extraction and computational efficiency.

Extensive experiments demonstrate that HDTA delivers outstanding performance in both pixel-level parsing and object detection tasks. The primary contributions of this research are as follows:

1) This study introduces a hybrid learning architecture, named HDTA (Hybrid Dual Tasks Architecture), to simultaneously segment railroad and detect PSHs along high-speed railways in UAV imagery, laying the foundation for PSH evaluation task.

2) An innovative lightweight backbone network based on the shuffle selective state space model(S4M) has been integrated into HDTA to achieve efficient and high-accuracy PSH detection and track segmentation.

3) Extensive experiments on the railroad environment dataset created using drone images demonstrate that the proposed system achieves high detection rates while maintaining efficiency and convenience.

The remaining content of the article is organized as follows: The proposed method is elaborated in Section 2. The related experiments and results are presented in Section 3. The conclusion is described at the end of the paper.

Recently, networks based on selective state spaces [26–28] have emerged as strong competitors to conventional CNN and Transformer architectures, owing to their ability to model long-range dependencies with linear computational complexity inherent to the state space model (SSM). Inspired by these advances, this study introduces a PSH detection system built upon a novel “SSM-with-shuffle” framework, which enables simultaneous detection of PSHs along railroad tracks and parsing of both tracks and roads.

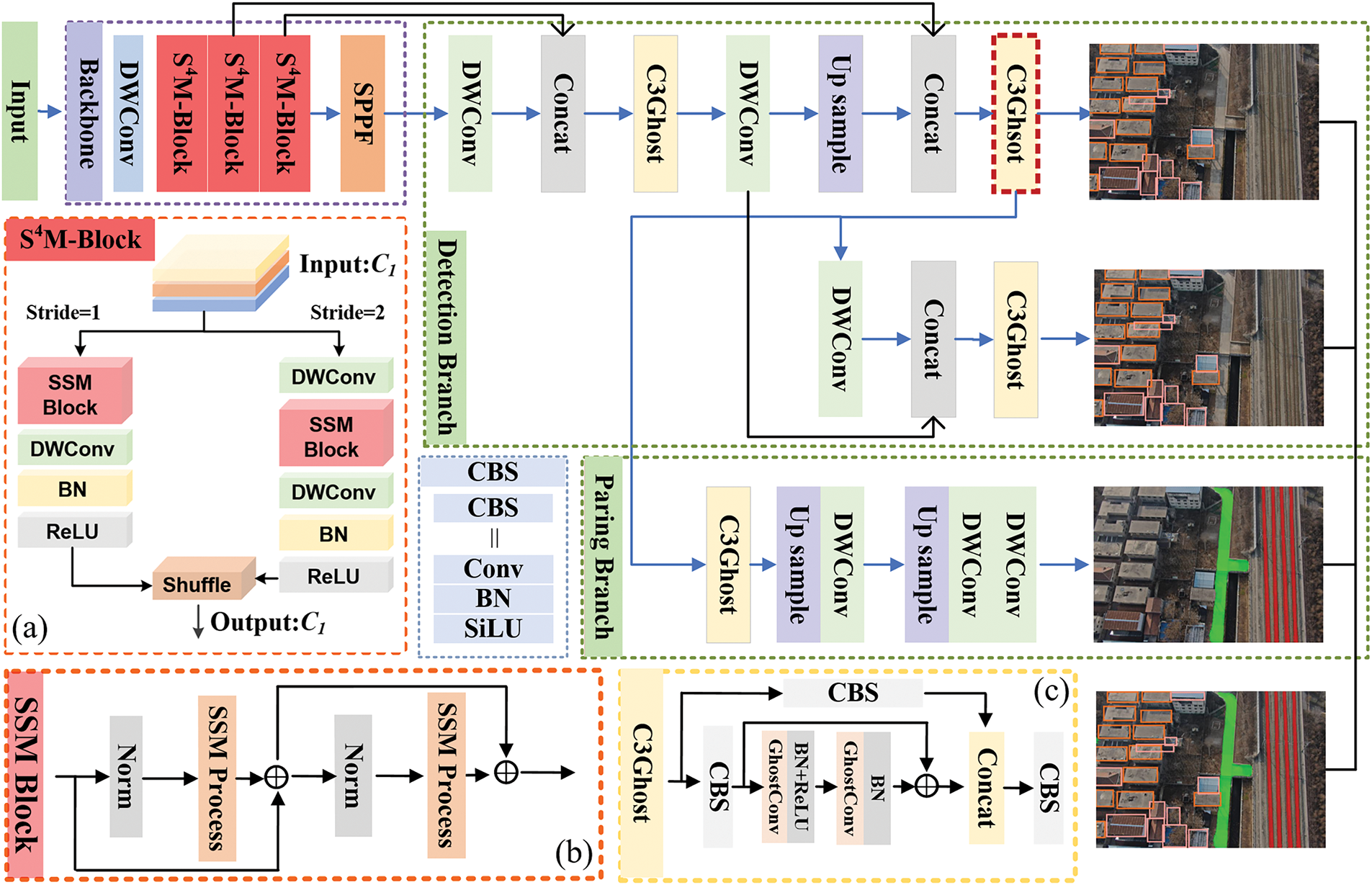

Fig. 1 illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed HDTA. HDTA integrates a backbone network built upon Shuffle Selective State Space Model (S4M) blocks with detection and segmentation branches based on the C3Ghost module. This design enables the extraction of two-scale high-level features for object detection and facilitates pixel-level segmentation of railroad.

Figure 1: The architecture of HDTA. Note the C3Ghost enclosed by the dashed line serves as the starting point of parsing branch. (a) The Shuffle Selective State Space Model (S4M) block. (b) SSM block. (c) C3Ghost block

2.2 Backbone Using Shuffle Selective State Space Model (S4M)

The backbone section in Fig. 1 presents the detailed composition of the S4M-based backbone network. This backbone consists of one downsampling layer followed by three S4M blocks, each of which incorporates a built-in downsampling function. The input image is progressively downsampled through the backbone network. Fig. 1a illustrates the overall structure of the S4M (Shuffle Selective State Space Model)-block. Each S4M-block consists of a SSM block, DWConv, Batch Normalization layer, and an activation function. The information flow within the S4M-block is determined by the downsampling ratio. The extracted feature space is then processed with a shuffle operation to promote feature fusion and enable lightweight computation. Specifically, for the S4M block (stride = 2), given an input

where

where the number of groups for the shuffle operation is set to 4.

The SSM process module adopts 2D Selective Scanning [28] to bridge the gap between the sequential na-ture of 1D selective scanning and the non-sequential structure of 2D visual data.

The SPPF module can also be incorporated into backbone to enhance the network’s representational capacity by aggregating multi-scale pooled features. This module has been validated in various versions of YOLO (v8–v12), where it is integrated into the backbone to collect such features. In summary, the proposed lightweight backbone leverages selective state spaces, offering strong feature extraction capabilities and effective long-range contextual modeling.

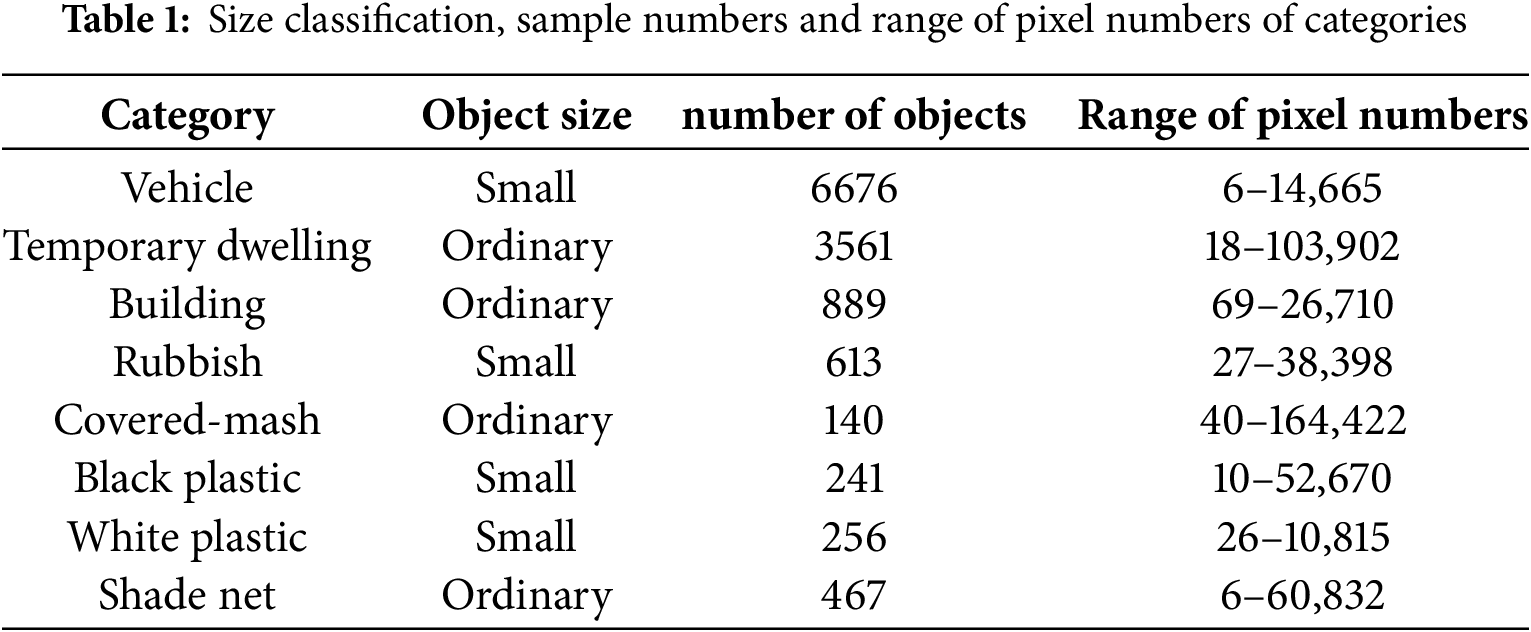

Two detection heads of different scales were used in the detection branch to detect objects in receptive fields of varying sizes, thereby improving detection accuracy. To reduce the computational cost of the model, DWConv and C3Ghost were also utilized in the detection branch. PSH in the railroad environment primarily include garbage, plastic protective sheets, sunshades, covering nets, and temporary shelters. According to the Median Relative Area (MRA) [25], the detection categories in the dataset are categorized into small objects and ordinary objects based on the typical size of the majority of samples in each category, as shown in Table 1. Table 1 also lists the number of samples and the range of pixel numbers about each category, the pixel count for each category is calculated within images of size 640 × 640. During the training process of HDTA, the input images are first resized to 640 × 640 to improve inference efficiency, and then fed into the model, followed by four downsampling operations. Accordingly, inputting a 640 × 640 image yields dual prediction grids at resolutions of 80 × 80 and 40 × 40.

To perform fine-grained analysis of tracks and roads in UAV imagery with minimal extra computational burden, DWConv and C3Ghost were also applied in the segmentation branch of HDTA. This approach maintains the model’s lightweight nature and accuracy. Attributed to the feature fusion in multi scale and long-distance modeling capabilities provided by the S4M-Backbone, the performance of track analysis is further enhanced. As shown in Fig. 1, the 14th-layer of HDTA is selected as the starting point for image reconstruction in semantic parsing tasks.

2.5 Hybrid Multi-Task Loss Function

Since HDTA performs both detection and segmentation tasks, a hybrid loss function is proposed for both tasks and simultaneously constrains the ESH detection and railroad pixel-level parsing tasks. The hybrid loss can be expressed as:

where

where

In this section, ablation experiments are performed with backbone of various models(EfficientNet [29], StarNet [30] and Swin-TransFormer [31]), including the newly introduced S4M-Backbone within the same HDTA framework, to assess the impact of backbone choice on the architecture’s effectiveness. Experiments between HDTA and other SOTA models were also conducted. These included detection comparisons with (DINO [32], Faster RCNN [2], YOLOv8 [33], YOLOv11 [34] and YOLOv12 [35]) and segmentation comparisons with (MoblieNetv3, GCnet, SegFormer, Mask2Former and other models) to validate the superiority of the proposed HDTA.

3.1 Dataset Description and Training Settings

The railroad environment drone images are taken using the DJI Mavic 3 Pro, which captures images with a focal length range from 24 to 166 mm and the maximum resolution of captured images is 8064 × 6048. A cruising velocity of 10–15 m/s is maintained during drone operation. More than 3000 images are taken for the railroad environment dataset. To enable clearer visualization of object classification, Fig. 2 presents a visual representation of PSH categories classification. Experiments are conducted on a Linux server configured with a CPU: i7-13700, GPU: RTX 4070, and 32 GB of RAM. The training process spans 300 epochs, starting with an initial learning rate of 3.84 × 10−3, which is reduced by a factor of 10 after 243 epochs. The dataset is randomly split into training, validation, and testing sets in a 7:2:1 ratio. Mosaic methods are used to data augmentation. The hyperparameters η1–η3 are set to 0.06, 0.3, 0.95, respectively. The PR curve, mIoU, mAP0.5, mAP0.5−0.95 and recall are the performance indicators used in the experiments.

Figure 2: Visualization of PSH for each category

The PR curves and mAP50 reflects hazard detection performance are employed to validate the effectiveness of the S4M-Backbone in HDTA. Additionally, the mIoU is also used to reflect the accuracy of pixel-level parsing tasks. Ablation experiments are performed with a backbone of various models (EfficientNet, StarNet and Swin-TransFormer). The computational complexity of different backbones was kept within a similar range.

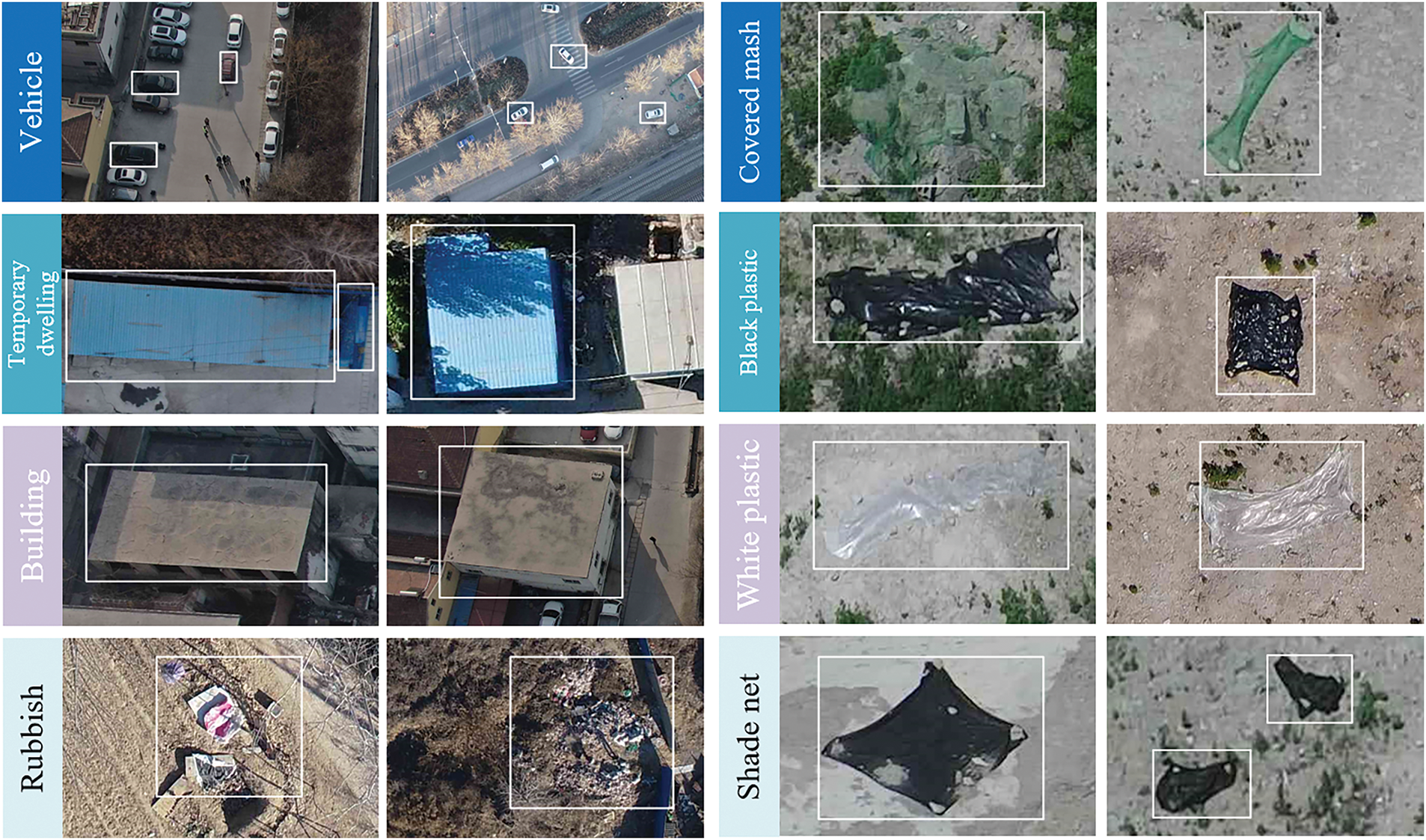

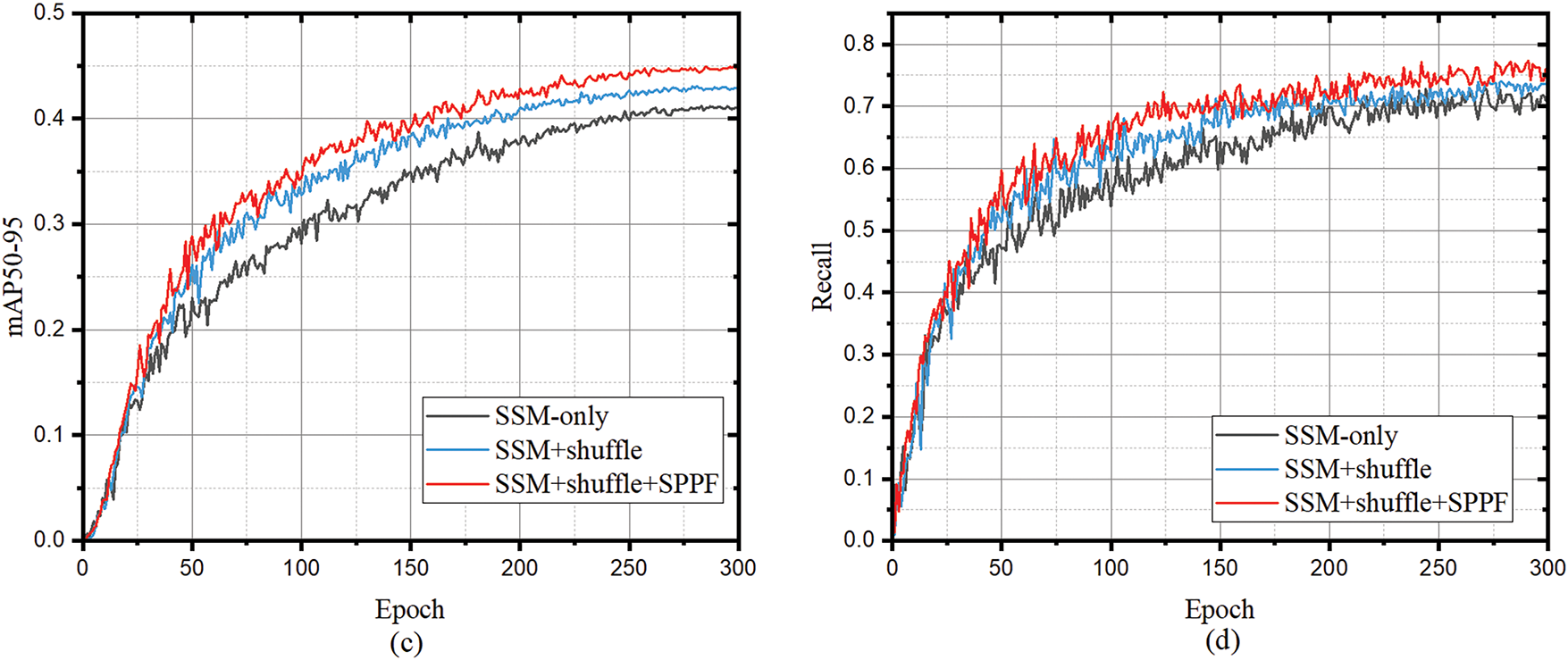

Ablation study on key modules: The ablation study uses the performance of HDTA with a backbone composed of SSM blocks only as the baseline. Fig. 3 illustrates the impact of key modules—namely the shuffle operation and the SPPF module—on the performance of the S4M-based backbone. It can be observed that as the shuffle operation and SPPF module are progressively added, HDTA demonstrates consistent improvements across various performance metrics. In terms of mIoU, the inclusion of the shuffle operation and SPPF brings segmentation performance gains of 0.53% and 0.34%, respectively. For mAP50, the progressive addition of the shuffle operation and SPPF results in detection performance improvements of 1.86% and 2.22%, respectively. The shuffle operation facilitates more effective inter-channel information exchange, while the SPPF module enhances the model’s ability to capture multi-scale contextual information. These advantages strengthen the backbone’s feature extraction and fusion capabilities, thereby improving the overall recognition performance of HDTA.

Figure 3: MIoU, mAP50, mAP50–95 and recall of HDTA gradually integrates base blocks on S4M backbone. (a) The impact of progressively adding basic blocks on mIoU performance for railroad segmentation. (b–d) Effects of progressively adding basic blocks on detection performance in terms of mAP50, mAP50–95, and Recall, respectively

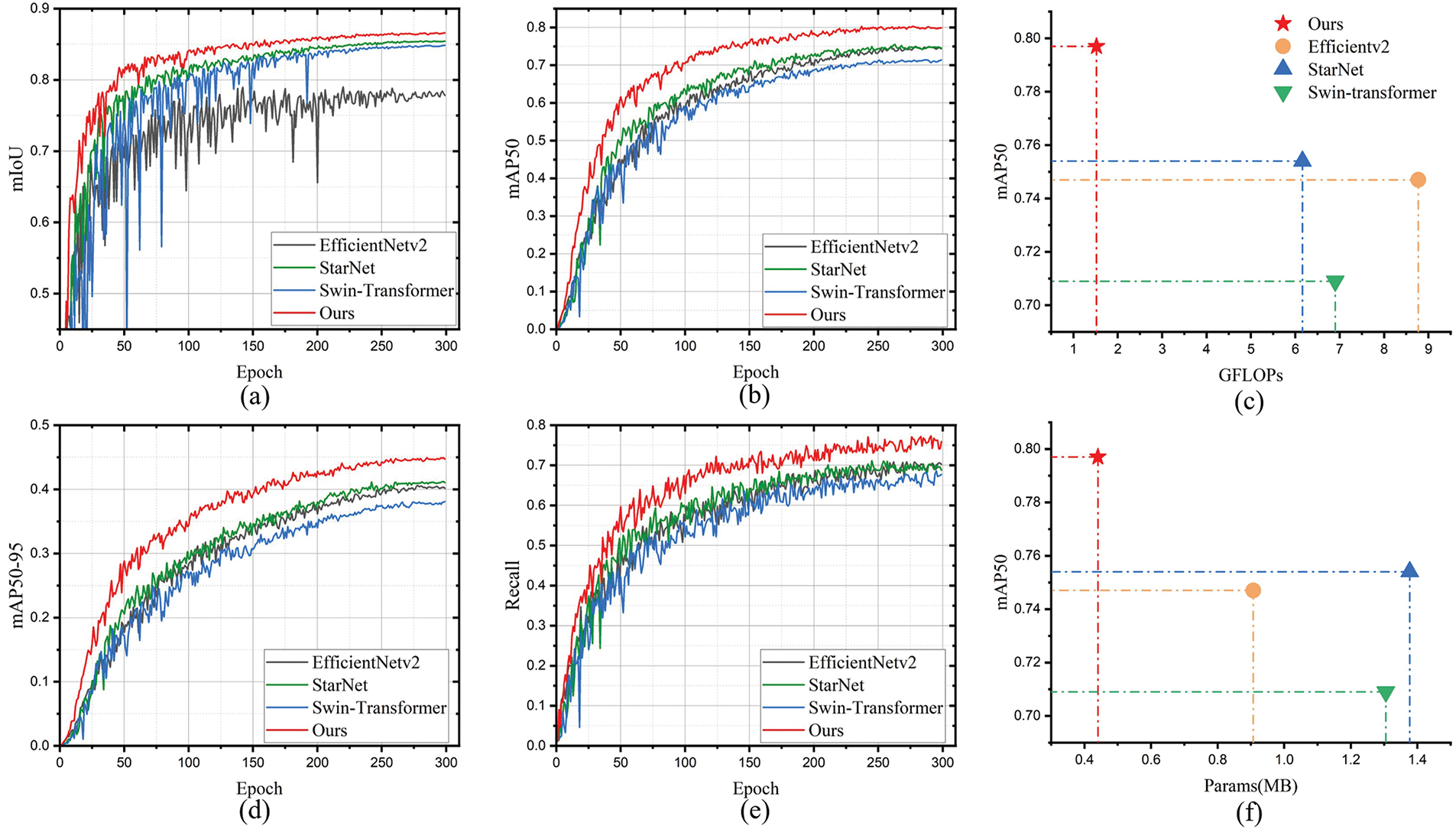

Ablation study on backbone: Ablation experiments were conducted using various backbone networks (EfficientNet, StarNet and Swin Transformer), particularly focusing on the S4M backbone network proposed in HDTA. All backbone variants are trained and validated within the same HDTA framework, with all other training parameters kept identical to ensure consistency. As shown in Fig. 4a, HDTA with the S4M backbone achieved the best parsing performance in railroad and road segmentation, with an mIoU of 86.5%, surpassing the EfficientNetv2, StarNet, and Swin-Transformer backbone networks by 8.38%, 1.11%, and 1.79%, respectively. Thanks to the long-sequence contextual modeling capability empowered by the SSM theory, the proposed S4M backbone network demonstrated significant advantages in pixel-level parsing tasks on image scales. In PSH detection, as shown in Fig. 4b,d, the proposed S4M backbone still achieved the best detection performance compared to other backbone methods within the same HDTA framework. In terms of mAP@0.5, S4M reached the highest accuracy of 79.7%, surpassing the EfficientNetv2, StarNet, and Swin-Transformer backbone by 5.0%, 4.3%, and 8.8%, respectively. In terms of mAP@0.5:0.95, S4M showed an even greater performance advantage, achieving an accuracy of 44.9%, which is higher by 4.6%, 3.72%, and 6.82% compared to the EfficientNetv2, StarNet, and Swin-Transformer backbone networks. Fig. 4e presents the detection recall performance of different backbone networks. As indicated by the red line in the figure, S4M also achieved the best recall performance.

Figure 4: Comparison of different backbones in terms of performance, number of parameters, and computational cost. (a) Railroad and road parsing performance comparisons on mIoU. (b,d,e) PSH detect performance comparisons on mAP0.5, mAP0.5:0.95 and recall. (c,f) Comparison of computational cost, number of parameters, and performance

Fig. 4c,f illustrates the mAP@0.5 performance of different backbone networks under varying parameter counts and computational loads. As shown in Fig. 4c, S4M achieves the highest performance (79.7% mAP@0.5) with only 1.52 GFLOPs of computational cost, while the best-performing alternative, StarNet, requires 6.16 GFLOPs to reach a lower mAP@0.5 of 75.4%. In terms of parameter count, S4M delivers the best performance among all backbone networks with only 0.44 MB of parameters, achieving the highest energy efficiency across all evaluated backbones.

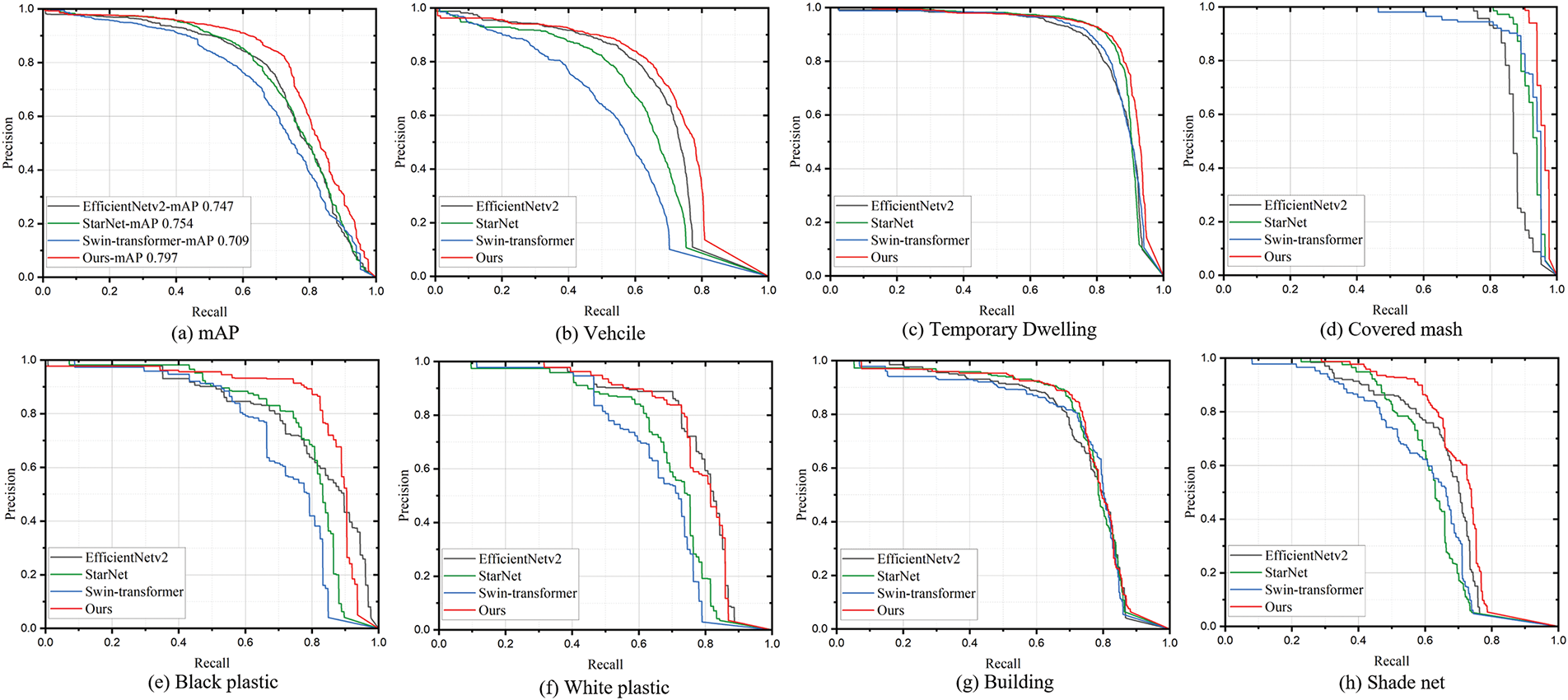

Furthermore, Fig. 5 highlights the advantages of HDTA equipped with the S4M backbone in terms of mAP@50 and AP@50. As shown in Fig. 5a, HDTA with the S4M backbone achieves the highest mAP of 79.7% across all categories, outperforming HDTA variants using EfficientNetV2, StarNet, and Swin Transformer backbones by 5.0%, 4.3%, and 8.8%, respectively. Additionally, as shown by the red curves in Fig. 5b–h, HDTA based on the S4M backbone consistently achieves the best precision-recall (PR) performance across nearly all categories when compared to other backbone methods. Moreover, HDTA with the S4M backbone shows notable performance advantages in detecting small objects such as vehicles, exceeding the performance of backbones based on EfficientNetV2, StarNet, and Swin Transformer by 3.2%, 9%, and 17%, respectively. This demonstrates that the global feature extraction capabilities enabled by state space model remain highly effective for small object detection. Furthermore, supported by state space model, HDTA also slightly outperforms other backbone networks in dense object categories such as temporary stops and buildings.

Figure 5: Comparison of different backbones in terms of mAP and AP. (a) The mAP across all categories. (b-h) are APs of vehicle, temporary dwelling, covered mash, black plastic, white plastic, building, shade net

3.3 Comparative Experiments between HDTA and SOTA Models

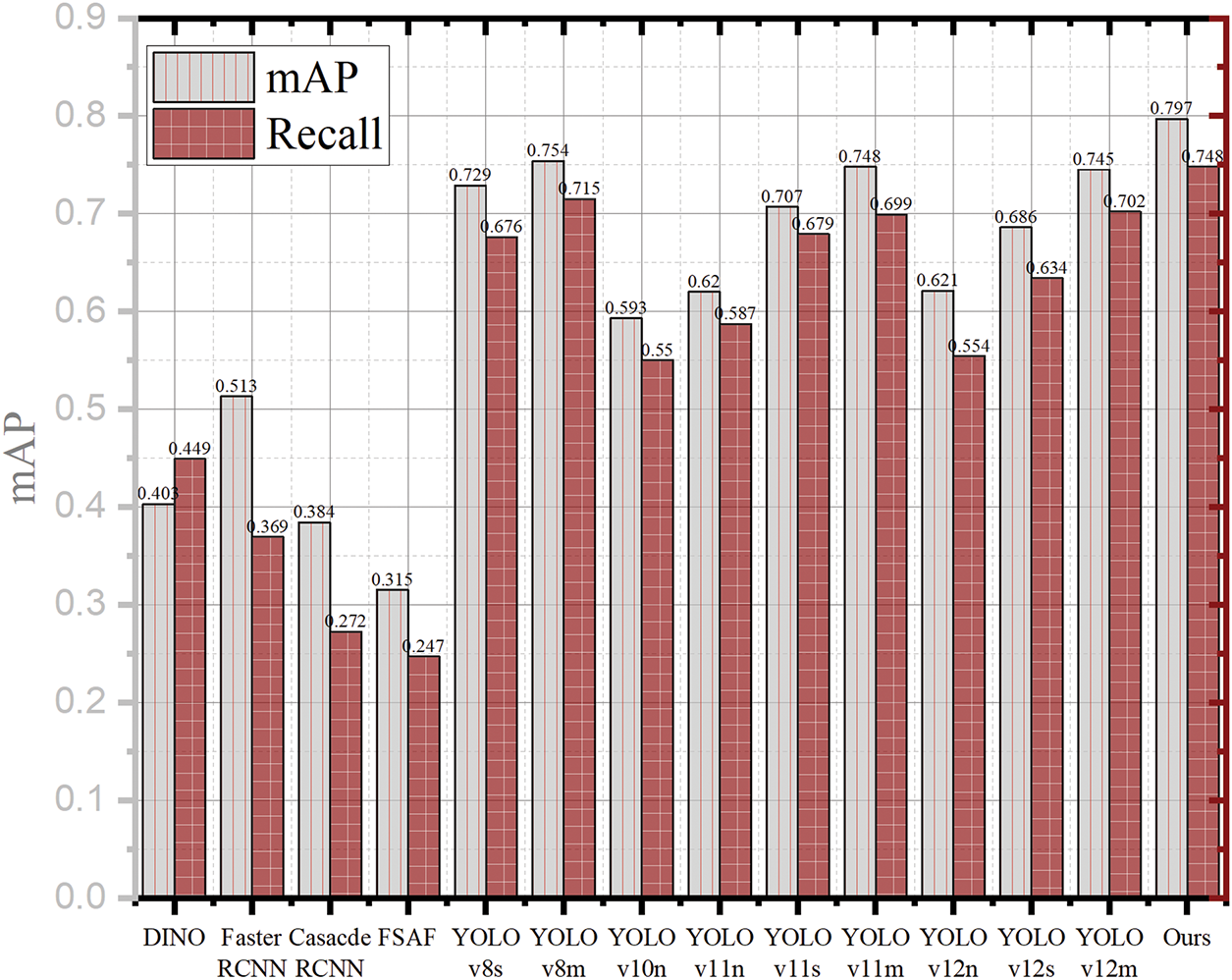

Comparisons on object detection: Fig. 6 presents the experimental results of various models on the PSH detection task, including mAP and recall. As shown in Fig. 6, DINO, Faster R-CNN, Cascade R-CNN, and FSAF generally underperform compared to the YOLO series in terms of accuracy. However, HDTA remains the best-performing model among all, achieving approximately 80% mAP and 75% recall. Specifically, the mAP of HDTA surpasses that of YOLOv8s, YOLOv8m, YOLOv11s, YOLOv11m, YOLOv12s, and YOLOv12m by 6.8%, 4.3%, 9%, 4.9%, 11.1%, and 5.2%, respectively. In terms of recall, HDTA exceeds these models by 7.2%, 3.3%, 6.9%, 4.9%, 11.4%, and 4.6%, respectively.

Figure 6: Comparison of PSH detection performance in terms of mAP and recall

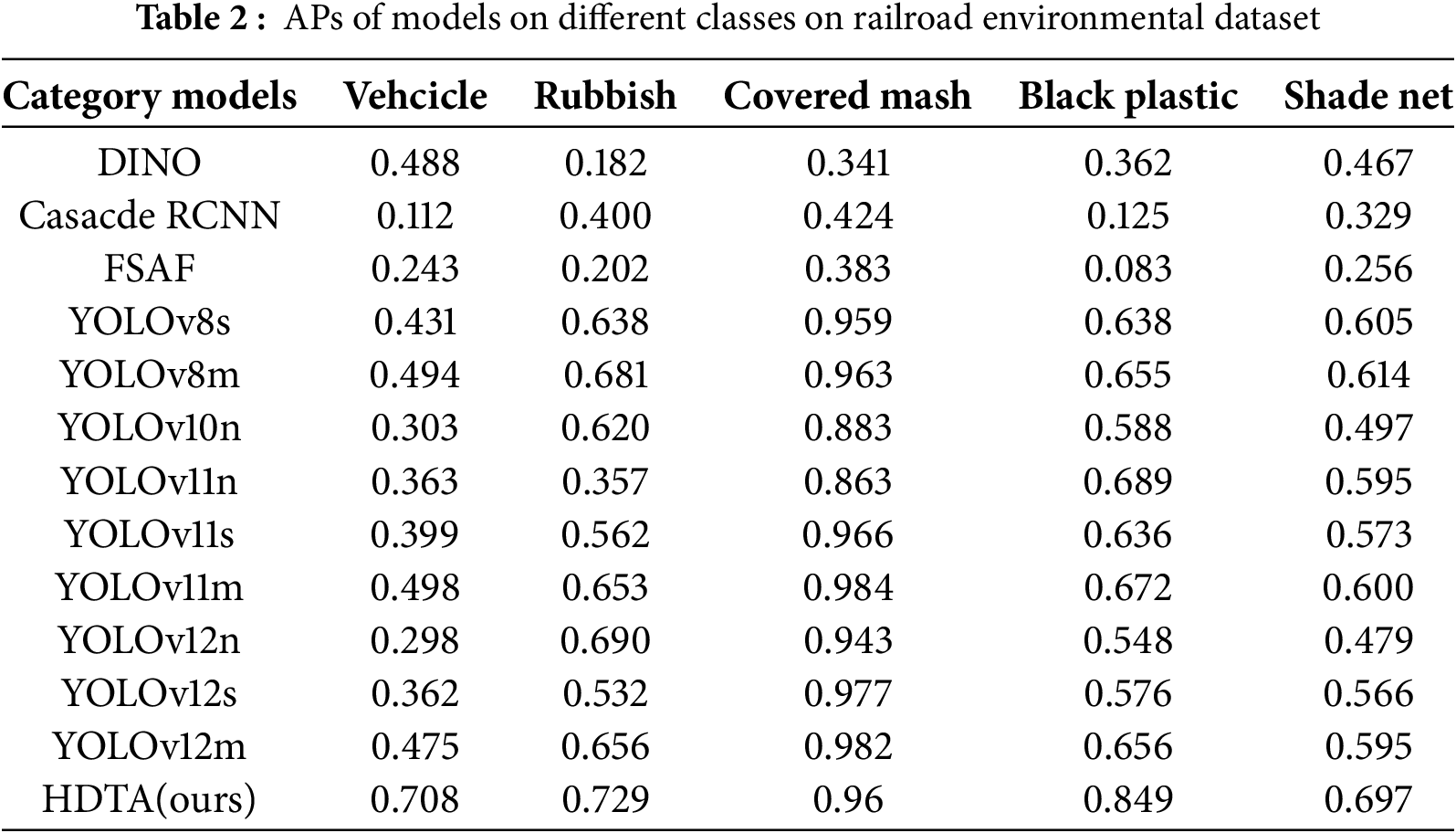

Table 2 presents a performance comparison between HDTA and other models on specific categories within the environmental dataset. As shown in the table, DINO, Cascade R-CNN, and FSAF perform worse than the YOLO series across all categories. However, our proposed HDTA demonstrates significant performance advantages over the YOLO series in categories such as Vehicle, Rubbish, Black Plastic, and Shade Net. For instance, in the vehicle category, HDTA achieves AP50 scores that are 27.7%, 21.4%, 40.1%, 34.5%, 30.9%, 21%, 41%, 34.6%, and 23.3% higher than those of YOLOv8s, YOLOv8m, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n, YOLOv11s, YOLOv11m, YOLOv12n, YOLOv12s, and YOLOv12m, respectively. This demonstrates that even small categories such as Vehicle can be accurately detected by HDTA, which may be attributed to HDTA’s long-sequence global modeling capability, allowing it to effectively extract features of the Vehicle category across vast regions. HDTA also shows strong competitiveness in the remaining categories. In summary, the advanced network architecture and the S4M backbone empower HDTA with highly effective PSH target detection capabilities in high-speed railroad scenarios.

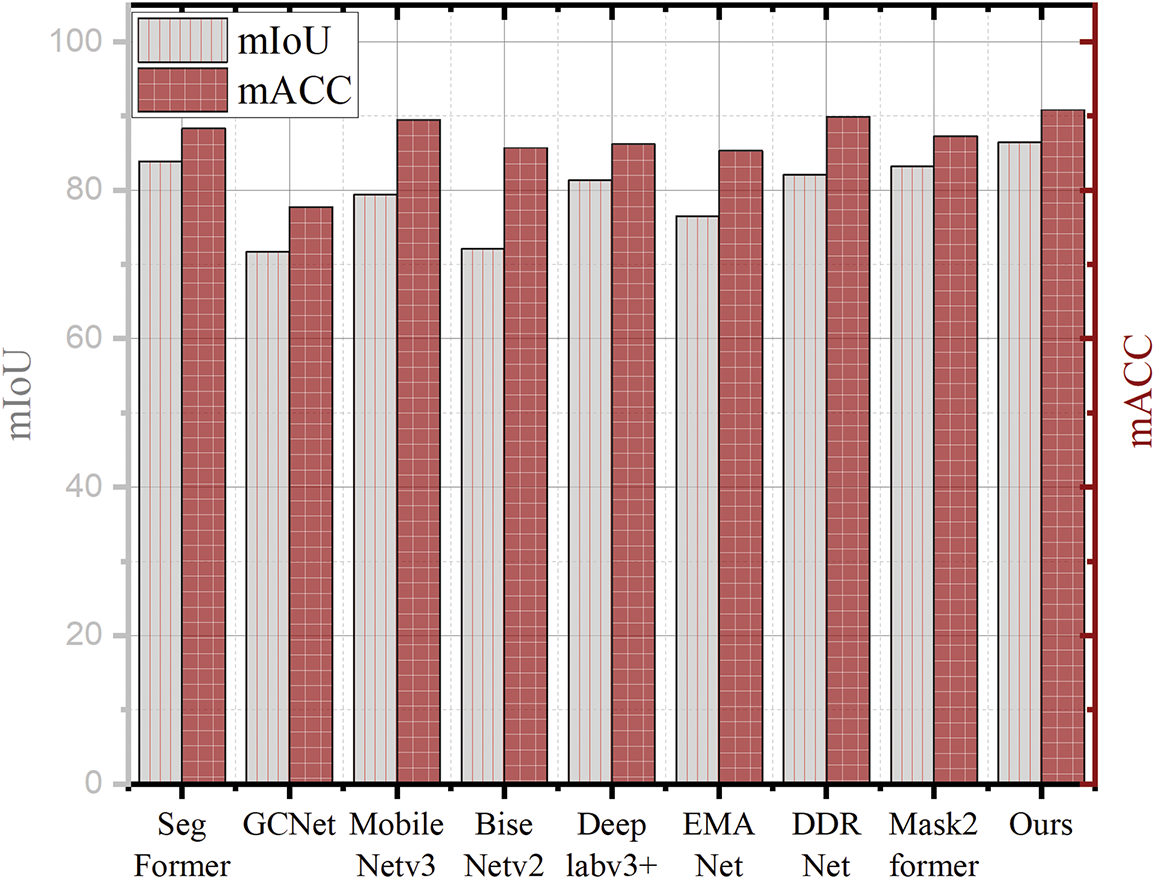

Comparisons on segmentation: Fig. 7 illustrates the experimental results of various models on railroad and roadway parsing tasks in terms of mean Accuracy (mACC) and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU). As shown in Fig. 7, the proposed HDTA ranks first in mACC, outperforming SegFormer, GCNet, MobileNetv3, BiSeNetv2, DeepLabv3+, EMANet, DDRNet, and Mask2Former by 2.5%, 13.7%, 1.3%, 5.1%, 4.6%, 5.5%, 0.9%, and 3.5%, respectively. In terms of mIoU, HDTA also achieves the highest value of 86.5%, exceeding the performance of SegFormer, GCNet, MobileNetv3, BiSeNetv2, DeepLabv3+, EMANet, DDRNet, and Mask2Former by 2.6%, 14.8%, 7.1%, 14.4%, 5.1%, 10%, 4.4%, and 3.3%, respectively. These results convincingly demonstrate the superior capability of HDTA in pixel-level parsing. Notably, unlike conventional models that focus solely on semantic segmentation, the HDTA architecture integrates both object detection and parsing branches, enabling not only precise segmentation of railroad and road regions but also effective PSH detection.

Figure 7: Comparison of parsing performance in terms of mIoU and mACC

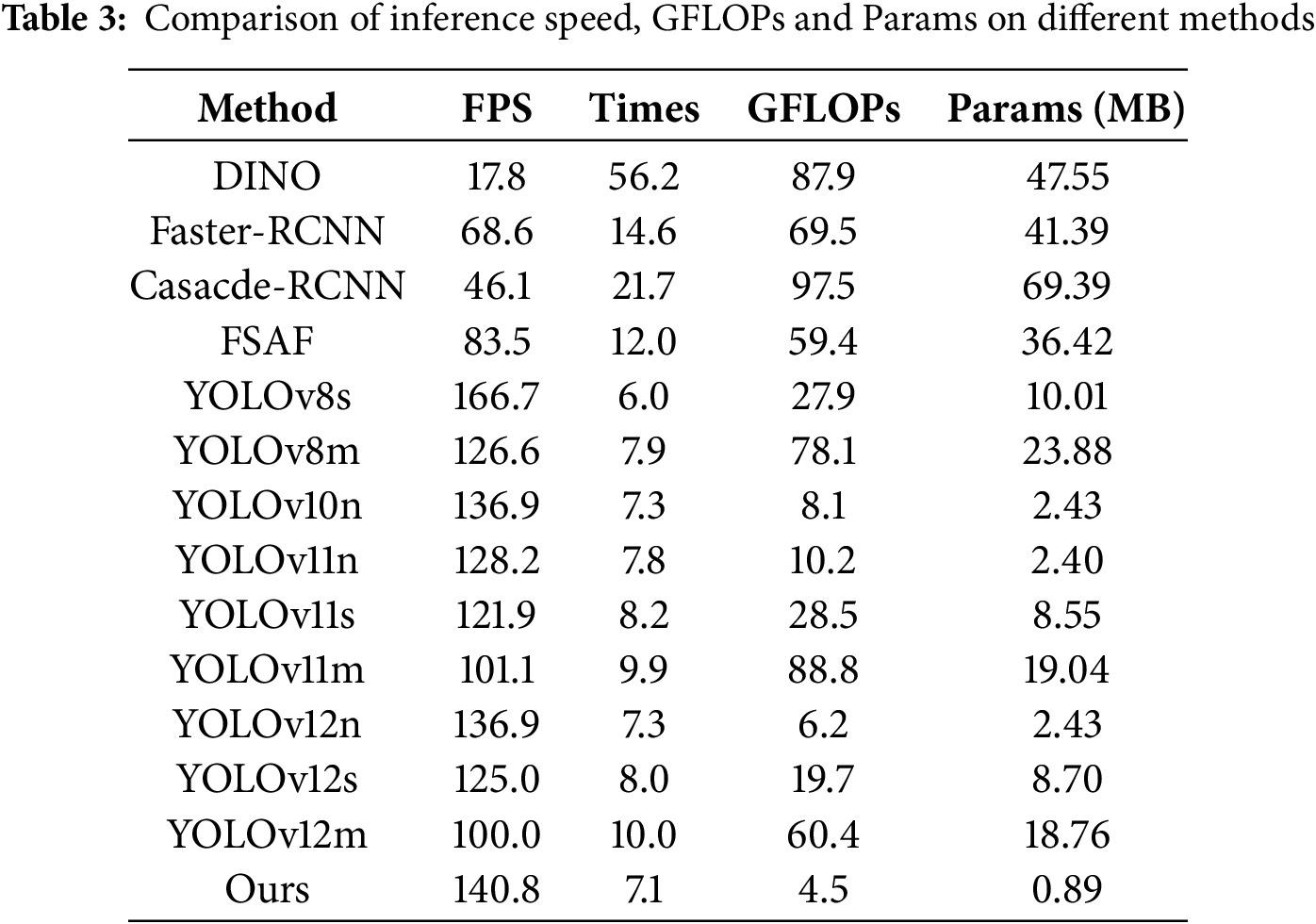

Comparisons on inference speed, GFLOPs and params: Table 3 presents a comparison of inference speed, GFLOPs, and parameter counts, with all models evaluated on an RTX 4070. It can be observed that DINO, Faster R-CNN, Cascade R-CNN, and FSAF are inferior to the YOLO series in terms of inference speed. Compared to the YOLO series, our proposed HDTA achieves the lowest GFLOPs and parameter count—4.5 GFLOPs and 0.89 MB, respectively. In terms of inference speed, HDTA outperforms most YOLO models, reaching 140.8 FPS. While maintaining a lightweight design and high inference speed, HDTA also demonstrates superior detection accuracy over all compared methods Therefore, we believe that HDTA possesses the capability for fast detection of PSH in the high-speed railway surrounding environment.

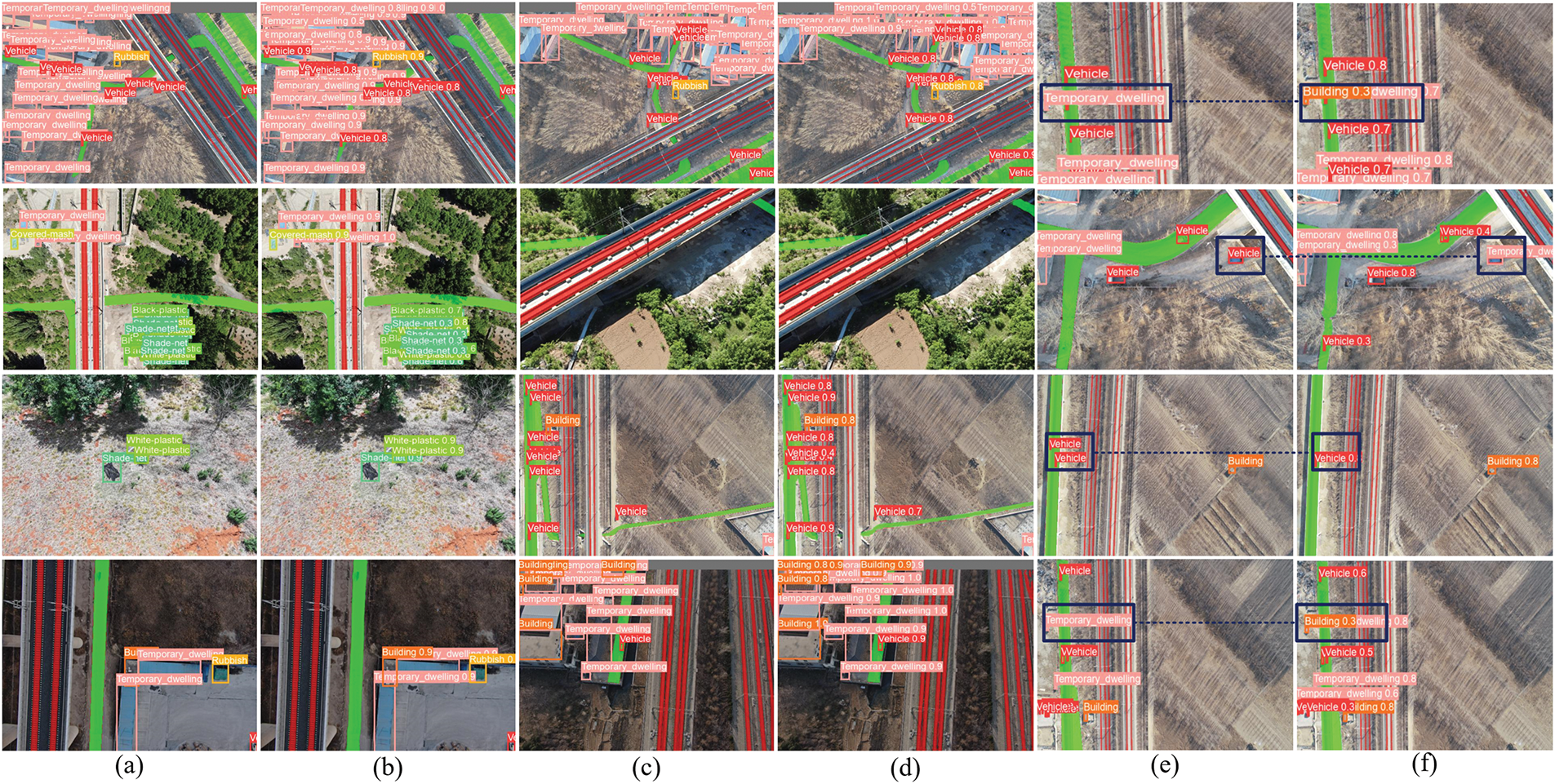

Visualization: As shown in Fig. 8, the proposed system is capable of accurately parsing high-speed railroad tracks and roads, while successfully detecting all PSHs along the railroad. Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 8b and d, the system effectively detects small object categories such as vehicles and rubbish, as well as dense object categories like building and temporary dwelling. These results demonstrate that the proposed HDTA maintains strong adaptability and robustness, even in complex high-speed railroad environments. However, some limitations still exist in current methods, for example, there are misclassification issues between buildings and temporary dwellings, as seen in the first and fourth rows of column (f); and cases of vehicles being misclassified as temporary dwellings or entirely missed, as shown in the third and fourth rows of column (f). To address these issues, future work can focus on increasing the quantity and diversity of samples from easily confused categories such as Temporary Dwelling and vehicle to enhance the model’s discriminative ability. Additionally, incorporating more powerful context-aware mechanisms could further strengthen the model’s feature extraction and classification capabilities.

Figure 8: Visualization examples of the prediction results by HDTA using the railroad environment dataset. (a,c,e) are ground truth, (b,d,f) are corresponding predicted results. (e,f) display examples of false positives and false negatives

To better parse tracks in drone images, detect potential safety hazards (PSHs) along the tracks, and leverage the advantages of drone imagery, this paper proposes a hybrid learning architecture called HDTA (Hybrid Dual Tasks Architecture). HDTA is designed for parsing railroad and road in drone images while detecting PSHs around the tracks simultaneously. The HDTA assembles a newly lightweight backbone based on the S4M-block. The S4M-block could facilitate feature fusion and extract global contextual information while maintaining linear complexity. This design enables the S4M-Backbone to achieve both strong global feature extraction capability and low computational cost. Compared to advanced segmentation models like MaskFormer and SegFormer, the proposed HDTA achieves superior performance with 90.8% mACC and 86.5% mIoU. It also outperforms leading object detection models, including the YOLO series, with a recall of 74.8% and a mAP of 79.7%. Additionally, among all the compared models, HDTA has the smallest computational cost of 4.5 GFLOPs and the smallest parameters of only 0.89MB. However, there is still room for improvement in HDTA in the following aspects:

(1) The algorithm currently lacks sufficient capability for edge deployment. A UAV-based onboard inspection system with high accuracy and low equipment requirement is wait for development.

(2) Adverse weather conditions present major obstacles for UAV-based PSH detection in railway settings. Elements like rain, snow, or thick fog can impair visibility, leading UAVs to capture images that are blurred, distorted, or poorly lit, ultimately reducing the effectiveness and accuracy of exist models.

Accordingly, this research outlines the insights and development directions for future work:

(1) Designing an integrated onboard inspection system with tailored software, optimized for real-time UAV-based PSH inspection. The system aims to achieve high accuracy while maintaining low computational load, cost, and power consumption.

(2) Expanding on existing research, create a robust and efficient PSH detection algorithm that can perform reliably in harsh weather conditions, thereby improving the model’s resilience and adaptability to challenging environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 52362048), and in part by Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (grant No. 202301BE070001-042 and grant No. 202401AT070409).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Zheda Zhao, Tao Xu, Yunpeng Wu; methodology, Zheda Zhao, Tao Xu; software, Zheda Zhao, Tao Xu, Tong Yang; validation, Zheda Zhao, Tao Xu, Tong Yang, Yunpeng Wu; formal analysis, Zheda Zhao, Tao Xu, Tong Yang; investigation, Yunpeng Wu, Fengxiang Guo; resources, Yunpeng Wu, Fengxiang Guo; data curation, Yunpeng Wu, Fengxiang Guo; writing—original draft preparation, Zheda Zhao, Tao Xu, Tong Yang; writing—review and editing, Zheda Zhao, Tao Xu, Yunpeng Wu; visualization, Zheda Zhao; supervision, Yunpeng Wu, Fengxiang Guo; project administration, Yunpeng Wu, Fengxiang Guo; funding acquisition, Yunpeng Wu, Fengxiang Guo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Yunpeng Wu], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhao Z, Qin Y, Qian Y, Wu Y, Qin W, Zhang H, et al. Automatic potential safety hazard evaluation system for environment around high-speed railroad using hybrid u-shape learning architecture; 2025;26(1):1071–87. doi:10.1109/TITS.2024.3487592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster r-cnn: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Cai Z, Vasconcelos N, editors. Cascade r-cnn: delving into high quality object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA: IEEE. p. 6154–62. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu C-Y, et al. Ssd: single shot multibox detector. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Springer. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1512.02325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bochkovskiy A, Wang C-Y, Liao H-YM. Yolov4: optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv:2004.10934. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jocher G, Mineeva T, Vilariño R. YOLOv5 [Online]. [cited 2025 Aug 12]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5. [Google Scholar]

7. Wang C-Y, Bochkovskiy A, Liao H-YM,editors. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2023. p. 7464–75. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jocher G. YOLOv8 [Online]. [cited 2025 Aug 12]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

9. Chen L-C, Zhu Y, Papandreou G, Schroff F, Adam H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV). Munich, Germany; 2018. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1802.02611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Howard A, Sandler M, Chu G, Chen L-C, Chen B, Tan M, et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2019. p. 1314–24. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1905.02244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cao Y, Xu J, Lin S, Wei F, Hu H. Gcnet: non-local networks meet squeeze-excitation networks and beyond. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops. Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2019. p. 1971–80. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1904.11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xie E, Wang W, Yu Z, Anandkumar A, Alvarez JM, Luo PJ. SegFormer: simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. 2021;34:12077–90. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2105.15203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cheng B, Misra I, Schwing AG, Kirillov A, Girdhar R. Masked-attention mask transformer for universal image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. New Orleans, LA, USA; 2022. p. 1280–9. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2112.01527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yu C, Gao C, Wang J, Yu G, Shen C, Sang N. Bisenet v2: bilateral network with guided aggregation for real-time semantic segmentation. Int J Comput Vis. 2021;129(11):3051–68. doi:10.1007/s11263-021-01515-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li X, Zhong Z, Wu J, Yang Y, Lin Z, Liu H. Expectation-maximization attention networks for semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1907.13426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hong Y, Pan H, Sun W, Jia Y. Deep dual-resolution networks for real-time and accurate semantic segmentation of road scenes. arXiv:2101.06085. 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2101.06085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ma R, Chen J, Feng Y, Zhou Z, Xie J. ELA-YOLO: an efficient method with linear attention for steel surface defect detection during manufacturing. Adv Eng Inform. 2025;65(2):103377. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2025.103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang X, Dai J, Liu X. A spatial-temporal neural network based on ResNet-Transformer for predicting railroad broken rails. Adv Eng Inform. 2025;65:103126. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2025.103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tan Y, Zheng Y, Yi W, Li S, Chen P, Cai R, et al. Intelligent inspection of building exterior walls using UAV and mixed reality based on man-machine-environment system engineering. Autom Constr. 2025;177(3):106344. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2025.106344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shan J, Jiang W, Feng X. Bridging cross-domain and cross-resolution gaps for UAV-based pavement crack segmentation. Autom Constr. 2025;174:106141. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2025.106141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhou J, Wang Y, Zhou W. Efficient instance segmentation framework for UAV-based pavement distress detection. Autom Constr. 2025;175(1):106195. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2025.106195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wu Y, Meng F, Qin Y, Qian Y, Xu F, Jia L. UAV imagery based potential safety hazard evaluation for high-speed railroad using Real-time instance segmentation. Adv Eng Inform. 2023;55(6):101819. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2022.101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Meng F, Qin Y, Wu Y, Shao C, Yang H, Jia L. Automatic risk level evaluation system for potential environmental hazards along high-speed railroad using UAV aerial photograph. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;277(5):127257. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.127257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wu Y, Chen P, Qin Y, Qian Y, Xu F, Jia L. Automatic railroad track components inspection using hybrid deep learning framework. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2023;72:5011415–15. doi:10.1109/tim.2023.3265636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wu Y, Zhao Z, Chen P, Guo F, Qin Y, Long S, et al. Hybrid learning architecture for high-speed railroad scene parsing and potential safety hazard evaluation of UAV images. Measurement. 2025;239:115504. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhu L, Liao B, Zhang Q, Wang X, Liu W, Wang X. Vision mamba: efficient visual representation learning with bidirectional state space model. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2401.09417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ma J, Li F, B Wang. U-mamba: enhancing long-range dependency for biomedical image segmentation. arXiv:2401.09417. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2401.04722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu Y, Tian Y, Zhao Y, Yu H, Xie L, Wang Y, et al. Vmamba: visual state space model. arXiv:2401.10166. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2401.10166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tan M, Le Q. Efficientnet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2019. Vol. 67, p. 6105–14. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1905.11946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ma X, Dai X, Bai Y, Wang Y, Fu Y. Rewrite the Stars. arXiv:2403.19967. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2403.19967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 10012–22. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2103.14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Caron M, Touvron H, Misra I, Jégou H, Mairal J, Bojanowski P, et al. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. Montreal, QC, Canada; 2021. p. 9630–40. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2104.14294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Varghese R, Sambath M. Yolov8: A novel object detection algorithm with enhanced performance and robustness. In: International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS); 2024 Apr 18–19. Chennai, India: IEEE. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ADICS58448.2024.10533619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Khanam R, Hussain M. Yolov11: an overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv:2410.17725. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tian Y, Ye Q, Doermann D. Yolov12: attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv:2502.12524. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2502.12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools