Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hybrid Attention-Driven Transfer Learning with DSCNN for Cross-Domain Bearing Fault Diagnosis under Variable Operating Conditions

1 School of Mechanical and Equipment Engineering, Hebei University of Engineering, Handan, 056038, China

2 Key Laboratory of Intelligent Industrial Equipment Technology of Hebei Province, Hebei University of Engineering, Handan, 056038, China

3 Department of Mechanics, Tianjin University, Tianjin, 300354, China

4 National Demonstration Center for Experimental Mechanics Education, Tianjin University, Tianjin, 300354, China

* Corresponding Author: Kai Yang. Email:

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(6), 1607-1634. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.069876

Received 02 July 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 17 November 2025

Abstract

Effective fault identification is crucial for bearings, which are critical components of mechanical systems and play a pivotal role in ensuring overall safety and operational efficiency. Bearings operate under variable service conditions, and their diagnostic environments are complex and dynamic. In the process of bearing diagnosis, fault datasets are relatively scarce compared with datasets representing normal operating conditions. These challenges frequently cause the practicality of fault detection to decline, the extraction of fault features to be incomplete, and the diagnostic accuracy of many existing models to decrease. In this work, a transfer-learning framework, designated DSCNN-HA-TL, is introduced to address the enduring challenge of cross-condition diagnosis in rolling-bearing fault detection. The framework integrates a window global mixed attention mechanism with a deep separable convolutional network, thereby enabling adaptation to fault detection tasks under diverse operating conditions. First, a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is employed as the foundational architecture, where the original convolutional layers are enhanced through the incorporation of depthwise separable convolutions, resulting in a Depthwise Separable Convolutional Neural Network (DSCNN) architecture. Subsequently, the extraction of fault characteristics is further refined through a dual-branch network that integrates hybrid attention mechanisms, specifically windowed and global attention mechanisms. This approach enables the acquisition of multi-level feature fusion information, thereby enhancing the accuracy of fault classification. The integration of these features not only optimizes the characteristic extraction process but also yields improvements in accuracy, representational capacity, and robustness in fault feature recognition. In conclusion, the proposed method achieved average precisions of 99.93% and 99.55% in transfer learning tasks, as demonstrated by the experimental results obtained from the CWRU public dataset and the bearing fault detection platform dataset. The experimental findings further provided a detailed comparison between the diagnostic models before and after the enhancement, thereby substantiating the pronounced advantages of the DSCNN-HA-TL approach in accurately identifying faults in critical mechanical components under diverse operating conditions.Keywords

The operating condition of rolling bearings, as critical rotating components in mining machinery systems, has a significant influence on the performance and reliability of the equipment [1,2]. With prolonged operating hours, wear inevitably develops in rolling bearings, leading to the degradation of characteristic parameters and adaptability—a phenomenon commonly referred to as bearing failure. If operators do not identify faults in a timely and accurate manner during operation, the system may become paralyzed, leading to severe economic losses or even personnel injury [3–5]. The above review clearly highlights the critical role of rolling bearing fault diagnosis in practical industrial applications. References [3–5] through systematic reviews and representative empirical cases have profoundly elucidated the indispensable role of fault diagnosis technology in preventing sudden equipment failures, reducing downtime, and enhancing both production safety and operational efficiency. Ultimately, from multiple dimensions, including methodology, application scenarios, and engineering implementation pathways, the key role of fault diagnosis technology in preventing equipment failures, reducing maintenance costs, ensuring production safety, and enhancing system reliability is revealed. In recent years, the concept of “system resilience” introduced in the field of disaster engineering has offered a novel perspective for fault diagnosis [6]. The health management of bearing systems requires not only assurance of accuracy in fault detection (robustness) but also the consideration of buffering capacity during performance degradation throughout fault evolution (redundancy), together with the rapid responsiveness of maintenance strategies (recovery capability), analogous to seismic structures. Therefore, the development of efficient and durable rolling bearing fault detection systems is critical for ensuring the operational health of rotating equipment and machinery, particularly within an intelligent laboratory for mining equipment.

In recent years, researchers have proposed numerous efficient strategies for bearing fault diagnosis, which can be broadly categorized into signal-processing and intelligent-diagnosis paradigms. Among them, signal-processing methods such as Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) [7] and Wavelet Decomposition (WD) [8] have been extensively applied to feature extraction, yielding favorable results. Nevertheless, such signal-processing schemes are highly contingent on expert experience and pre-existing domain knowledge [9]. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence diagnostic approaches, owing to their superior nonlinear mapping capabilities, have been recognized as highly suitable for addressing mechanical fault diagnosis problems that require intricate signal processing techniques and extensive expert knowledge [10]. The diagnostic model based on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) has rapidly developed and is widely used in various bearing fault diagnosis environments. Several scholars have contributed advanced research ideas, such as Zhao et al. [11], who developed a CNN model with adaptive intra- and inter-stage mechanisms, which can accurately detect gear faults even when speed conditions change. Jiang et al. [12] introduced a lightweight feature distillation network leveraging depthwise separable convolution to overcome the computational bottleneck in industrial bearing health monitoring. Chen et al. [13] proposed a diagnostic approach that integrates a convolutional neural network with the discrete wavelet transform for intelligent fault identification in turbine gearboxes. Although CNN frameworks have been extensively developed, bearing fault diagnosis in real industrial environments still encounters several complex challenges [14,15]: (1) The scarcity of labeled fault data renders the adaptation of various deep learning models difficult. (2) Under cross-condition and cross-device environments, significant variations in the distribution of vibration signals are observed, while traditional models exhibit poor generalization, leading to diagnostic outcomes that frequently deviate from expectations. The reviews conducted by the scholars above have highlighted the critical challenges faced by current bearing fault diagnosis technologies in practical industrial applications, particularly the issues of data scarcity and cross-domain generalization. These investigations have not only substantiated the limitations of deep learning in complex industrial scenarios but have also indicated the directions for subsequent improvements in the present study. Consequently, transfer learning approaches have been progressively incorporated into deep learning models to address the challenges mentioned above.

In response to the challenge of data scarcity in mechanical fault diagnosis under complex and non-stationary operating conditions, transfer learning is introduced in this study. Robust identification of cross-working-condition bearing faults has been under limited target sample conditions through dynamic weight adaptation between the source and the target domains [16]. This method trains deep models on source-domain data and, through transfer learning, acquires knowledge analogous to, yet distinct from, that of the target domain. Subsequently, the learned knowledge is applied to the target fault diagnosis task to address concrete challenges in the target domain, including insufficient training samples and distributional shifts [17,18]. Transfer learning has been validated as effective for bearing fault diagnosis, as reported in [17,18]. When confronted with practical issues, including limited data and distributional drift, the strategy has been validated to enhance generalization and diagnostic performance markedly. Consequently, transfer learning has seen broad advancement and intensive study in intelligent fault diagnosis. Zhuang et al. [19] performed a longitudinal study of transfer learning techniques, systematically categorizing 42 homogeneous methods into evolutionary clusters that map technical advancements across decades. Zhong et al. [20] proposed a computationally efficient CNN architecture that integrates cross-domain adaptation and attention-aware feature fusion, empirically demonstrating the potential of transfer learning to alleviate accuracy degradation in bearing diagnostics under data-limited conditions. Astutkar and Tallur [21] developed a transferable parameter optimization framework, which demonstrated cross-condition generalization capability in fault detection for rotating machinery. Compared with traditional methods, the Astutkar and Tallur enhanced the fine-tuning efficiency of the target domain diagnostic model by 37.2%. Although the transfer above and deep learning methods have achieved excellent performance in rolling bearing fault identification under fixed operating conditions, three critical challenges remain unresolved when deep transfer models are deployed for diagnosis under variable operating regimes. First, during fault diagnosis, the extracted fault features tend to be excessively dispersed, thereby diminishing diagnostic efficiency. Second, when data collected under disparate operating conditions exhibit pronounced discrepancies, conventional weighting schemes fail to yield satisfactory performance in bearing fault diagnosis. Third, reliance on a single operating condition as the source domain is inadequate for addressing the issue of shifting data distributions under varying operating conditions. Therefore, practical enhancements to the fault diagnosis network architecture are warranted.

At present, the advent of attention mechanisms (AM) has provided a flexible and effective solution to this challenge. The distinctive properties of AM have been shown to enhance the precision and efficacy of fault diagnosis network models substantially [22]. AM enables associations among disparate positions within a sequence to compute a unified representation, thereby promoting efficient allocation of computational resources within the model. In addition, the mechanism can leverage the advantages of active learning, achieving comparable outcomes with a reduced number of composite samples. Liu et al. [23] proposed a novel LMFEMD model based on the local-global strategy. By means of a newly devised lightweight self-attention mechanism, the LMFEMD model achieved differentiated learning of feature mappings across sub-domains. Zhang et al. [24] developed an optional nuclear convolution deep residual network method for equipment failure analysis, grounded in channel-space AM and feature fusion. This approach addressed the issues of inconspicuous fault feature details and data excess within the system. Liao et al. [25] proposed the QCNN model, which integrates secondary neurons and attention mechanisms, enabling the model to separate the features of secondary neurons through attention and enhancing its ability to recognize fault features. Ma et al. [26] proposed a joint attentional feature fusion method to improve target detection performance by mining dependencies across different scales through the sequential integration of channel and positional attention modules. Li et al. [27] proposed an attention-enhanced neural network approach for fault diagnosis. In this manner, the model’s ability to highlight fault features and gather comprehensive information has been enhanced. Yu et al. [28] proposed an improved integration of the Swin Transformer and the GADF method for bearing fault detection. The hybrid attention mechanism of the improved Swin Transformer is leveraged, and when combined with a global attention module, this approach enables the accurate classification of a broader range of fault types, even under simulated complex operating conditions. Xu et al. [29] developed a multi-branch heterogeneous convolutional architecture (SSG-Net). Through a feature recalibration strategy based on a mixed attention mechanism, SSG-Net significantly improved the cross-domain recognition accuracy of fault features, and its robustness to perturbations in operating parameters was enhanced considerably.

Although prior studies have verified the efficacy of hybrid attention mechanisms for fault diagnosis, several issues persist, as noted by the aforementioned scholars. Nevertheless, in practical bearing diagnosis, numerous challenges persist: Firstly, the operating conditions are generally intricate and variable. Moreover, when compared with the standard dataset, the fault dataset is relatively diminutive. Second, complex and variable operating conditions induce pronounced shifts in feature distribution and signal non-stationarity, and several existing diagnostic models fail to achieve satisfactory diagnostic accuracy. Third, within existing methodologies, few studies have integrated hybrid attention mechanisms with transfer learning to address bearing fault diagnosis under variable operating conditions in small-sample regimes. In response to the aforementioned issues, a novel bearing fault diagnosis model, DSCNN-SwinGAM, which integrates transfer learning, is proposed. Through three key components, it targets explicitly diagnosis under variable operating conditions with limited samples. Firstly, the traditional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is optimized by substituting the standard convolutional layers with Depthwise Separable Convolution (DSC) layers. In this way, both computational efficiency and fault identification accuracy are enhanced. Second, a window-global hybrid AM is integrated into the key convolutional layers. This strategy utilizes dual-channel processing to enhance the extraction of salient fault features, eliminating the need for elaborate feature engineering. Finally, the constructed model is deployed within a transfer-learning framework to address fault diagnosis under small-sample conditions. The key contributions of this research are as follows:

(1) In view of the weak fault-feature information under varying operating conditions, a hybrid attention module was constructed in this study. By combining windowed attention with global attention mechanisms, the module jointly processes and accentuates critical features, thereby strengthening the model’s capacity to focus on fault characteristics.

(2) By enhancing the convolutional layers of the CNN and substituting traditional convolutions with depthwise separable convolutions (DSC), the overall computational cost of the model is reduced, thereby improving diagnostic efficiency and increasing the precision of fault detection.

(3) By integrating the proposed model with transfer learning, the method effectively tackles the challenges of fault diagnosis across heterogeneous operating conditions. The experimental results further substantiate the feasibility of deploying the model for bearing diagnosis under variable regimes.

This study is structured as follows: The second part systematically explains the basic theoretical system of this work. The third chapter focuses on analyzing the implementation framework of the diagnostic model integrating the transfer learning mechanism. The fourth chapter presents a 2D verification scheme, which is theoretically based on the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) bearing database and empirically researched on an independently built bearing fault diagnosis experimental platform to assess the viability of the methodology. The final chapter summarizes the research results and proposes extended thinking directions for later engineering applications.

2.1 Depthwise Separable Convolution

The concept of depthwise separable convolution did not arise instantaneously; rather, its fundamental principle lies in decomposing a conventional convolution into two independent operations: depthwise convolution and pointwise convolution. The idea of DSCNN was initially explored in the Inception network family and was later formalized and popularized by Howard et al. in the MobileNet architecture in 2017 [30]. Concurrently, Chollet corroborated the effectiveness of depthwise separable convolution from a complementary perspective in the Xception architecture [31]. In that design, the standard inception modules were replaced with depthwise separable convolutions. Empirical results demonstrated that Xception outperformed contemporary models on large-scale datasets such as ImageNet, indicating that its convolutional design is not only lightweight but also endowed with strong representational capacity, thereby constituting an efficient and broadly applicable convolutional paradigm. Since then, the superior efficiency-performance trade-off of depthwise separable convolution has motivated its adoption as a foundational architecture for constructing new diagnostic models in recent years. For instance, Xu et al. [32] proposed a diagnostic model that integrates the residual mixed channel attention mechanism with DSCNN (RMCA-DSCNN). This integration effectively combines the advantages of both components, significantly reducing the overall computational load while enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Jiang et al. [33] introduced an optimized deep separable convolutional neural network, in which multiple layers are vertically stacked and a residual structure is incorporated. This type of design equips the model with the ability to incorporate more convolutional layers while minimizing the loss of efficiency during convolutional operations. Zhao et al. [34] proposed a novel bearing fault diagnosis scheme that combines a dual-scale convolutional neural network with a bidirectional gated recurrent unit (DSCNN-BiGRU). This integrated architecture enhances the model’s ability to characterize multi-scale information and optimizes the extraction of hierarchical features from vibration signals. Geng et al. [35] developed a lightweight bearing fault diagnosis architecture incorporating depthwise separable convolution with a sparse attention mechanism. This combination achieves a favorable balance between model performance and computational complexity, demonstrating strong diagnostic performance in experimental evaluations. The aforementioned pioneering studies established the theoretical underpinnings of depthwise separable convolution and substantiated its efficacy in bearing fault diagnosis. Inspired by these advances, the present research refrains from a naïve adoption of DSCNN. Instead, it integrates it with the proposed hybrid attention mechanism to address the degradation in diagnostic accuracy induced by excessive model parameters during computation. Consequently, the synergy between DSCNN and the hybrid attention mechanism not only preserves the lightweight and high-throughput advantages of DSCNN but also remedies its limitation in capturing global correlations among local features, thereby delivering concurrent gains in both accuracy and speed.

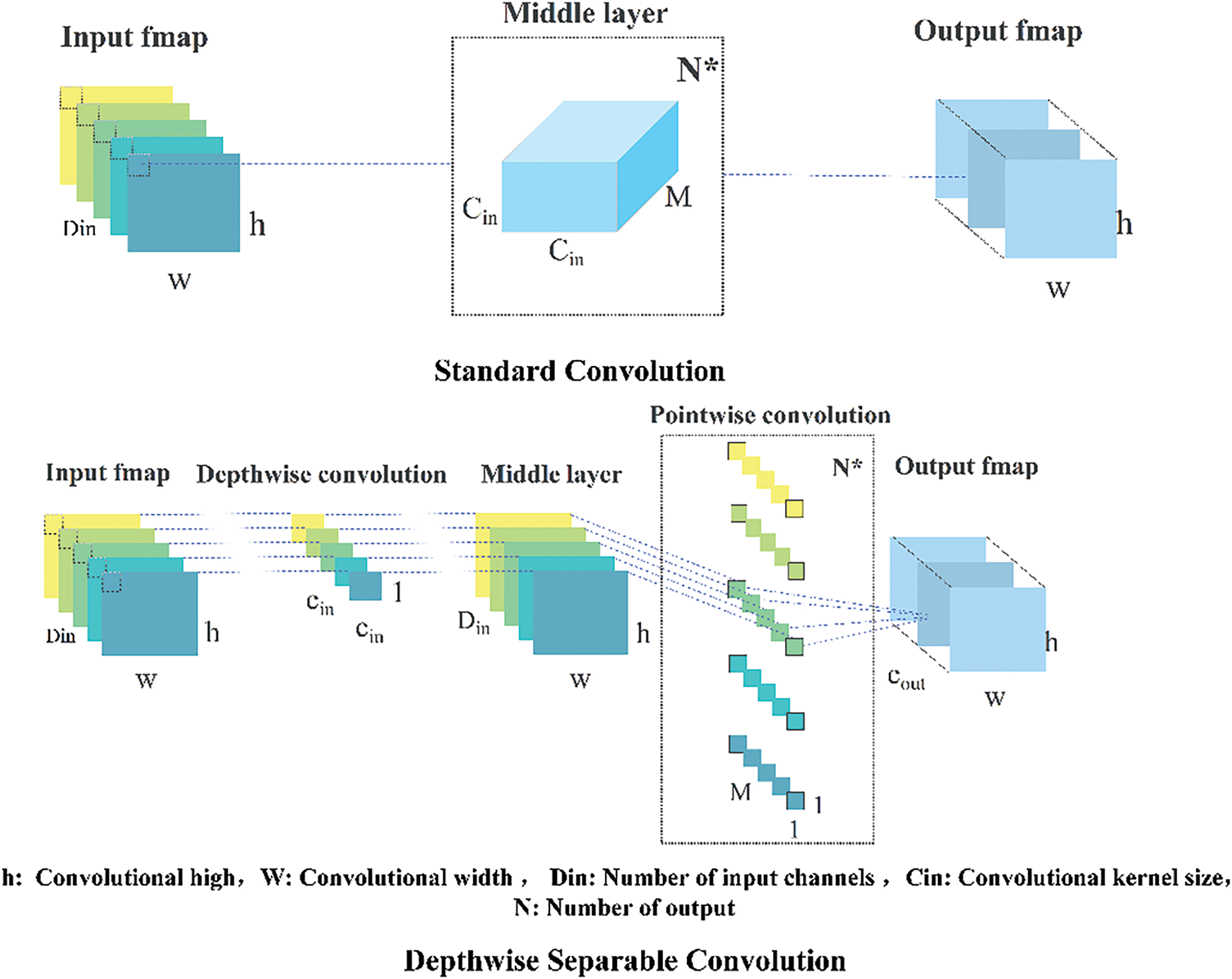

In this research, depthwise separable convolution is utilized to substitute the traditional convolutional layer. Depthwise separable convolution is realized by decomposing the conventional convolution into two independent processes. At the depthwise stage, each input channel is convolved with its respective kernel, allowing for the effective extraction of spatial features for individual channels [30]. Subsequently, a 1 × 1 pointwise convolution conducts a linear combination of the depthwise outputs, integrating information across channels. In contrast to traditional convolutions that handle spatial and channel dimensions simultaneously, this architecture explicitly decouples the modeling of spatial and channel features. It has been demonstrated that this structure enhances computational efficiency and accuracy while maintaining competitive model performance [32–35]. A schematic of the depthwise separable convolution is presented in Fig. 1. The formula principles are referenced in Formulas (1)–(6). The formal definition of conventional convolution is as follows:

Figure 1: Different convolutional computation processes

Where,

We know that the input data size is

Furthermore, the number of parameters and the amount of computation required to generate a deeply separable convolution with the same size output are:

The parametric and computational ratios of the standard convolution and the DSC can be calculated as follows:

Formulas (5) and (6) indicate that the computational cost of depthwise separable convolution is much lower than that of standard convolution, and this difference can also be reflected in complex models.

In this research, the hybrid attention mechanism is primarily composed of a window-based attention mechanism (Swin) and a global attention mechanism (GAM), with fault features extracted through a dual-channel branch. The underlying principles of these two attention mechanisms are introduced in the following section.

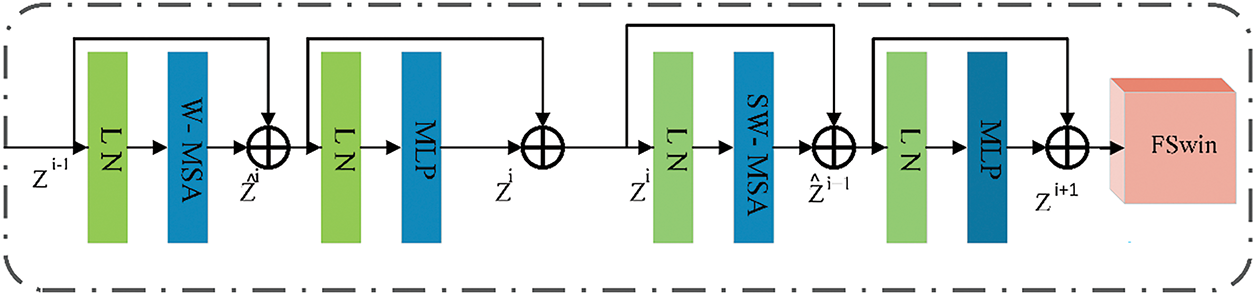

The Swin Transformer framework incorporates a window attention mechanism module from the Transformer model to minimize the number of model parameters and processing complexity while enhancing the capability to handle large-sized images [36]. Fig. 2 shows the Swin Block architecture. This module inherits the core algorithm of the Swin Transformer and conducts feature engineering optimization. It is primarily composed of the layer normalization unit (LN), the windowed multi-head self-attention mechanism (W-MSA), the shifted window multi-head self-attention mechanism (SW-MSA), and the multi-layer perceptron (MLP), which together form the feature calculation flow. The system achieves the multi-scale collaborative capture of dynamic features through the cascade design of W-MSA and SW-MSA. After the feature transfer in the backbone network, the mathematical representations of the outputs at each level can be described entirely by Formulas (7)–(10):

Figure 2: Swin module structure

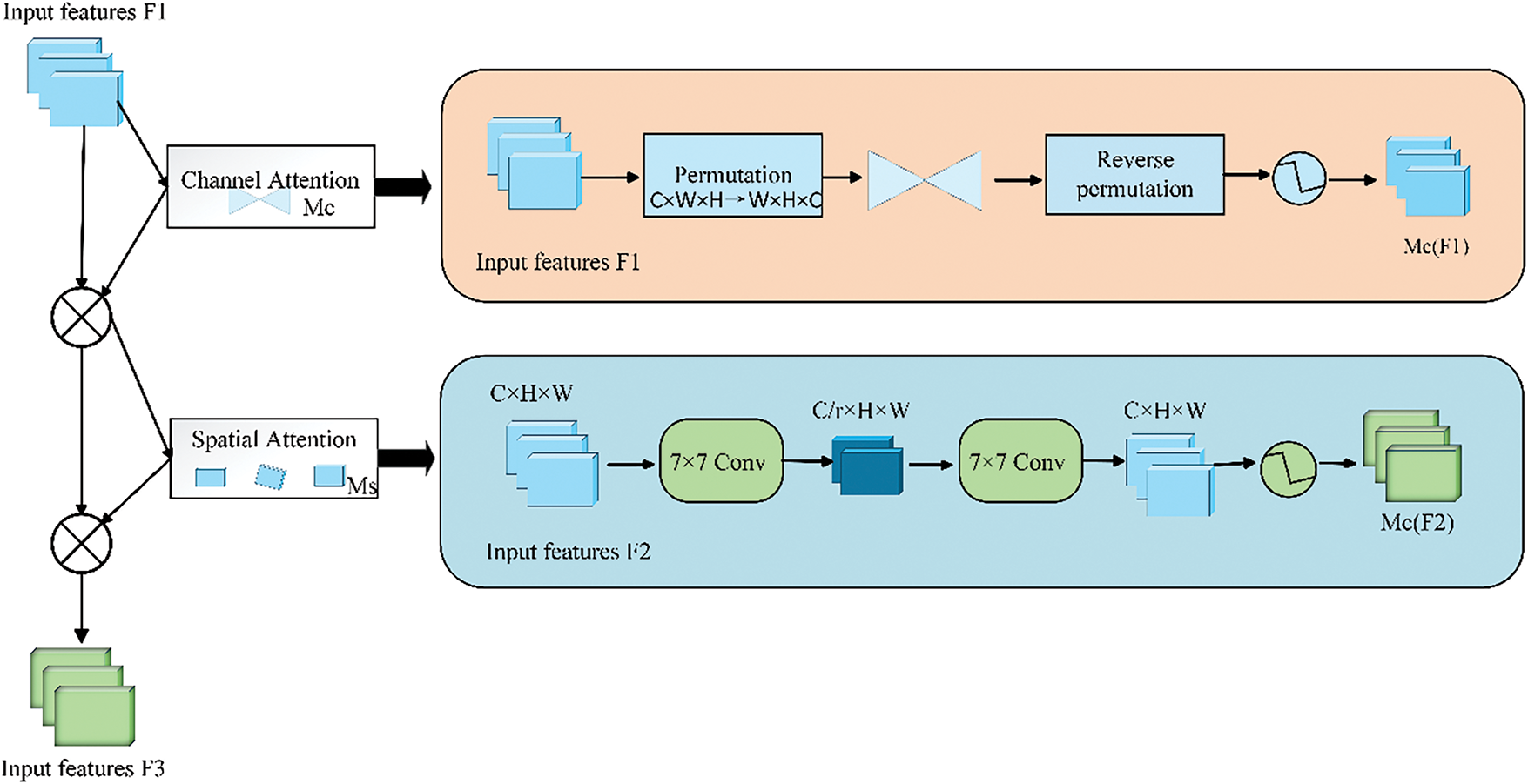

In the realm of deep learning, when dealing with alterations in image scaling and irregular data input, the CNN is found to be inefficient under certain circumstances. This situation may affect the overall training efficiency of the model. To address this issue, the Global Attention Mechanism (GAM) model is employed to enhance detection accuracy by strengthening the interaction between spatial and channel dimensions. Additionally, critical feature information in these dimensions is effectively captured, and information loss is minimized by the model [37]. Fig. 3 demonstrates the architecture of the GAM component. GAM incorporates both the Channel Attention Mechanism (CAM) and the Spatial Attention Mechanism (SAM). The architectural diagrams of CAM and SAM are presented in the rightmost module of Fig. 3.

Figure 3: GAM module structure

3.1 DSCNN-HA-TL Diagnostic Framework

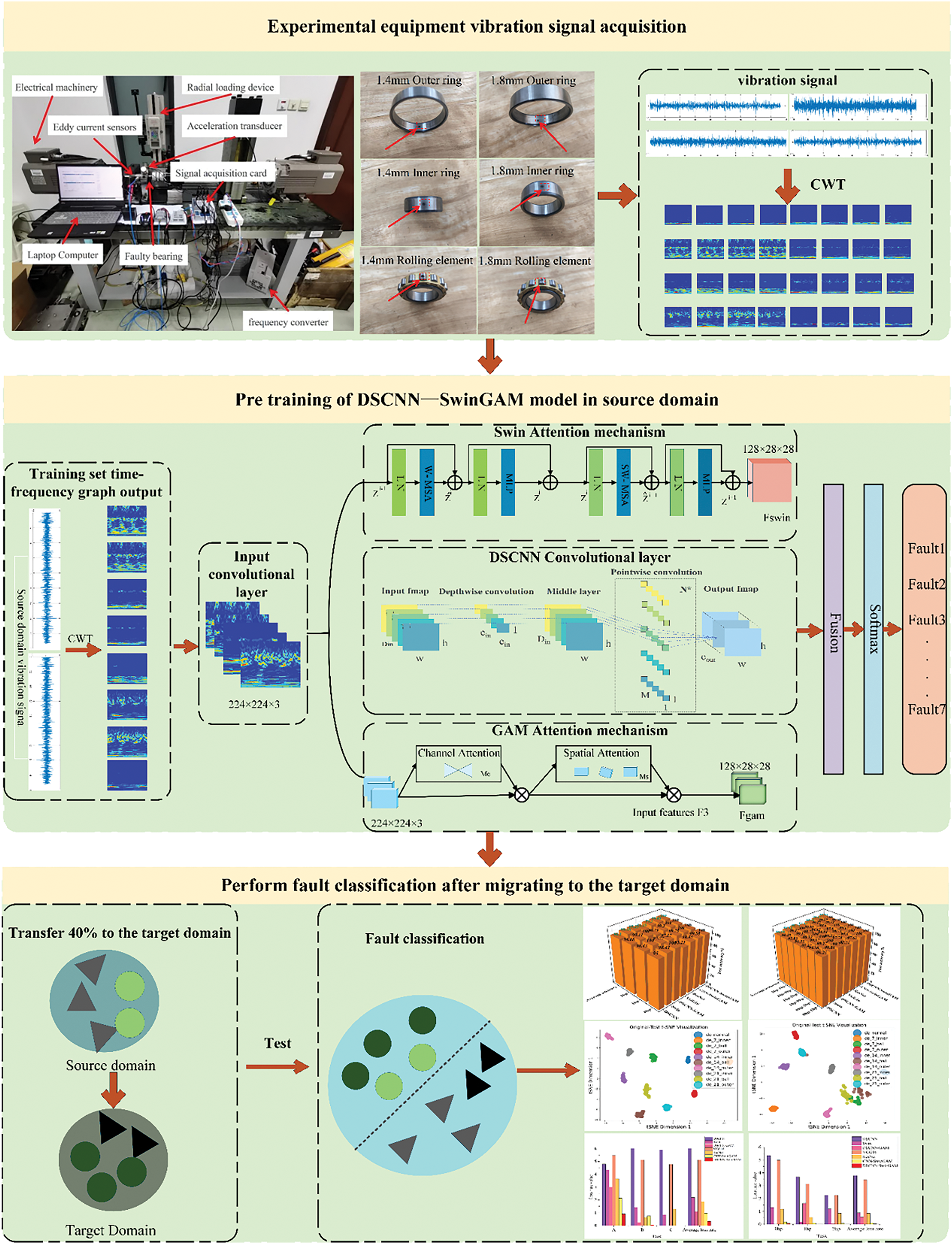

In response to the challenge of fault detection for rolling bearings under fluctuating operating conditions in practical applications, a transfer-learning diagnostic paradigm is proposed that integrates a window-global hybrid attention mechanism with an enhanced convolutional layer network. The DSCNN-HA-TL diagnostic framework primarily comprises raw signal preprocessing; transformation of signals into two-dimensional image representations via the continuous wavelet transform (CWT); feature extraction and categorization by the DSCNN-SwinGAM model, and the subsequent application of transfer learning.

The operation of the DSCNN-SwinGAM fault diagnosis scheme applied to transfer learning is introduced in the following four steps, and the overall process is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Flow chart of DSCNN-HA-TL diagnosis framework

Firstly, the time-frequency processing is carried out on the vibration signals collected from the experimental platform. The time-frequency representation is obtained via the CWT, using the complex Morlet wavelet as the mother wavelet (with a bandwidth of 100 and a center frequency of 1). A total of 128 wavelet scales were employed, corresponding to frequencies ranging from 46.875 to 6000 Hz, under a sampling rate of 12 kHz. The resulting time-frequency map is rendered at 224 × 224 pixels, meeting the input requirements of the deep learning model. The model receives the two-dimensional time-frequency representations generated by Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) as inputs for the feature recognition module. The features are first filtered through a 3 × 3 convolutional blocks built on a CNN backbone. This convolutional block is composed of a convolutional layer and a max-pooling layer. The conventional convolutional layer is substituted with a depthwise separable convolution (DSC), thereby reducing the overall parameter count of the model and enhancing the accuracy of fault identification.

In the second stage, the preprocessed image features are exploited to extract local descriptors from the fault images via the Swin window attention mechanism. Concurrently, global representations are derived by the CNN equipped with the Global Attention Module (GAM). The two components collaborate to refine and classify fault features. After the DSC produces the initial feature map, the map is processed by the GAM and then sequentially propagated through the channel attention submodule (CAM) and the spatial attention submodule (SAM). The input characteristic map undergoes dimension conversion, passes through a two-layer MLP to enhance the interaction between cross-dimensional channels and spatial dependencies, and is output via Sigmoid activation. In the spatial-focus component, spatial information is fused by a two-layer convolutional network, thereby enhancing the efficacy of spatial feature extraction. Initially, the channel dimensionality is reduced through a 7 × 7 convolution, followed by another 7 × 7 convolution that restores the number of channels to their original scale, after which a Sigmoid activation function is applied. Meanwhile, a primary feature map is generated following the DSC process, and local features are extracted from the fault image via Swin’s sliding window attention mechanism. By computing attention scores within each sliding window, inter-feature relationships are effectively captured, allowing the model to represent dependency structures in the time-frequency domain and to extract salient signal information with high efficiency.

In the third stage, the global and local feature tensors extracted via GAM and Swin are first projected to a common spatial resolution and then concatenated and fused. Thereafter, the aligned global and local feature tensors are concatenated along the channel dimension. Subsequently, the fused tensor is compressed to a 1 × 1 spatial dimension by adaptive average pooling to yield a fixed-length global feature vector. Adaptive averaging and aggregation of the fused features enable effective integration of representations across levels. Consequently, both performance and generalization are improved, allowing the model to accomplish classification more effectively.

In the fourth stage, the constructed model is first pre-trained on data from a single operating condition and subsequently fine-tuned with a limited dataset from another condition. Thereafter, the fine-tuned diagnostic model is employed to identify faults in bearing vibration data, thereby enabling the analysis of limited-data error in bearings across various job environments.

In this study, several key issues must be addressed when processing the CWRU public dataset and the bearing fault diagnosis testing platform data: data quality assessment, data cleaning, fault feature extraction, and adaptive model selection. These issues can be effectively addressed through reasonable processing and analysis strategies, improving the precision and dependability of error identification and analysis. The obtained 1D vibration signal was transformed into 2D image data using the CWT. During dataset segmentation and processing, a segmentation function was introduced, with an overlap rate set to 0.3 to achieve a 30% overlap between each pair of adjacent subsequences. The complex Morlet wavelet was utilized as the mother wavelet, with a bandwidth of 100 and a central frequency of 1. The number of scales was set to 128, spanning a frequency range from 46.875 to 6000 Hz, while the sampling rate was configured at 12 kHz. Consequently, the time-frequency representation was generated with a resolution of 224 × 224 pixels, thereby fulfilling the input specifications of the deep learning model.

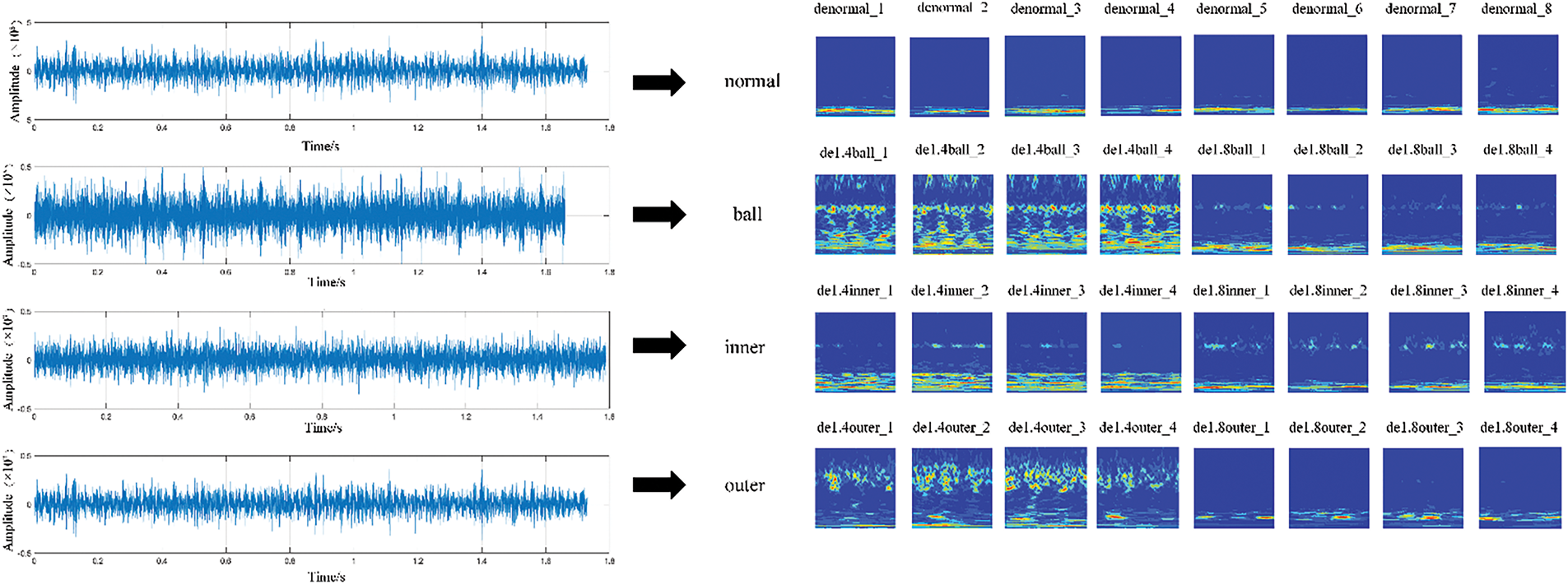

The one-dimensional vibration signals acquired from the CWRU dataset were processed using CWT. For the 0 hp operating condition, four fault categories—normal state, rotating component defect, inner ring fault, and outer ring fault—were examined. At each fault site, three fault diameters (0.007, 0.014, and 0.021 inches) were selected for systematic analysis.

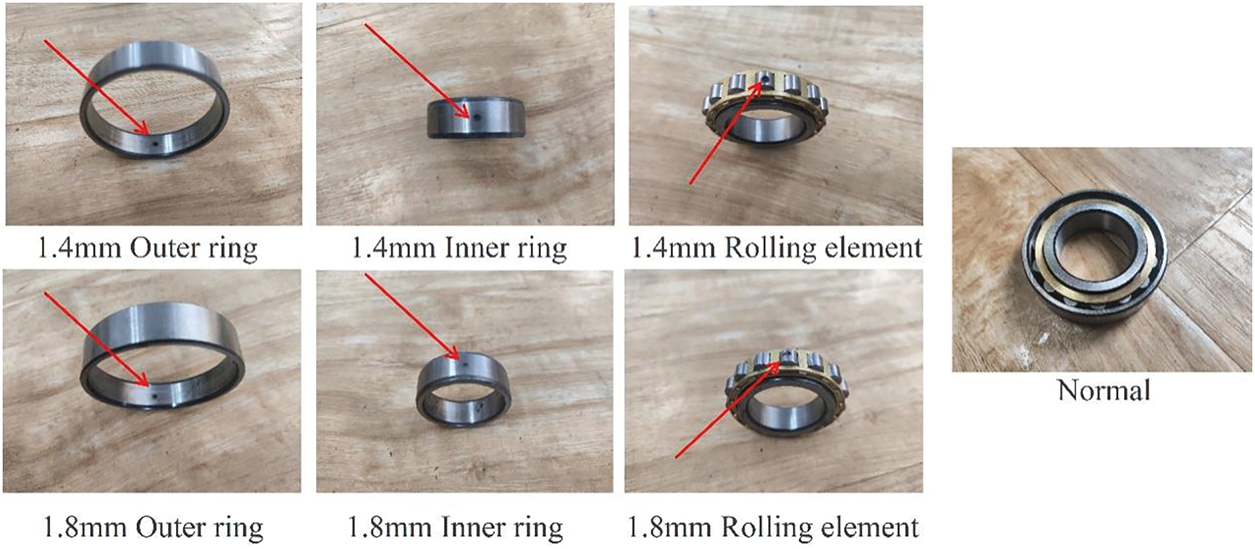

Furthermore, one-dimensional vibration signals acquired from the bearing fault diagnosis experimental platform were processed utilizing CWT. Pitting damage configurations of 1.4 and 1.8 mm were investigated at the previously specified fault locations under a load condition of 0.25 MPa. Subsequently, the acquired one-dimensional vibration signals were converted into time-frequency representations through CWT processing, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Visualization example of fault signal CWT of the bearing experimental platform

4 Experimental Results and Analysis

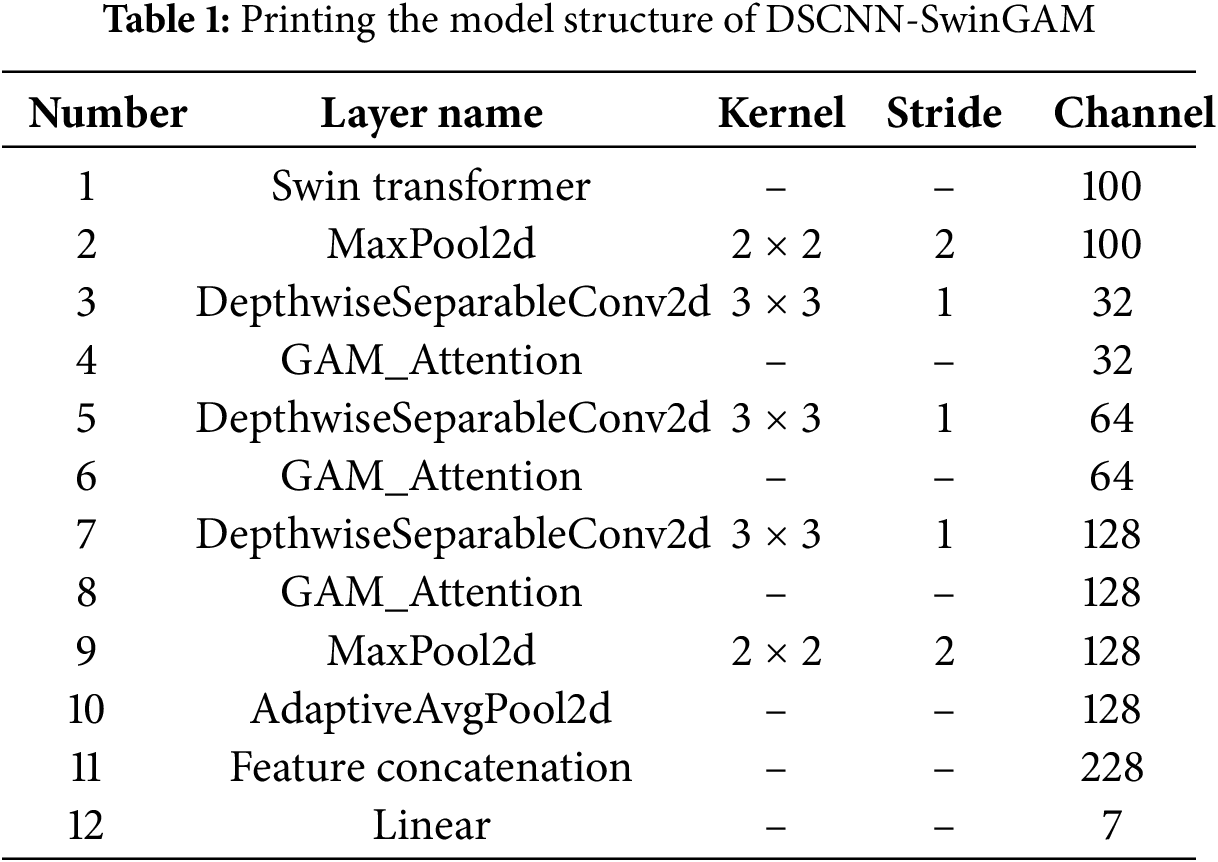

The DSCNN-SwinGAM network model was applied in a transfer learning-based diagnostic approach and evaluated through two experimental scenarios. The effectiveness of this method in bearing fault diagnosis was confirmed by comparing it with several leading data-driven techniques. The model proposed in this study is a hybrid architecture that integrates three primary approaches: Swin Transformer, GAM, and DSCNN. The input to the entire model is a batch size of 32, with an input image size of 224 × 224 and three channels. The output is the classification result of 7 categories. First, the input data are processed through a Swin Transformer layer, where the number of output channels is fixed at 100. Thereafter, a MaxPool2d layer with a 2 × 2 kernel and a stride of 2 is employed to reduce the spatial resolution. Thereafter, multiple DepthwiseSeparableConv2d layers with a 3 × 3 kernel and a stride of 1 are employed, with the channel count progressively increased from 32 to 128. After each convolution, a GAM attention layer is incorporated to accentuate salient features. Pooling layers are then reapplied to reduce dimensionality further, and an AdaptiveAvgPool2d layer is used to aggregate the output to a fixed size adaptively. Next, feature concatenation is performed to integrate information across channels, yielding a richer representation. A flattening layer is then applied to prepare the feature maps for the fully connected layer. The ultimate predictions are generated by a fully-connected layer featuring seven output units. The model structure is printed as shown in Table 1.

To assess the efficacy of the presented DSCNN-SwinGAM model in diagnosing bearing faults, DSCNN-SwinGAM was compared with six other models: (1) The DSCNN (Deeply Separable Convolutional Neural Network), constructed by replacing standard convolutions with depthwise separable convolutions, is regarded as a cornerstone of lightweight modeling. However, its principal limitation lies in the potential attenuation of representational capacity. Although the decomposed architecture markedly reduces computational cost and parameter count, this factorization compromises the immediate and comprehensive fusion of information across channels. The literature [38] has widely noted that this leads to a reduction in the richness of feature representations. (2) The Swin (which only employs the attention mechanism of the Swin Transformer and omits the DSCNN and GAM components), as a representative of the new generation of visual architectures, according to literature [39], its limitations mainly lie in the fact that it needs to be pre-trained on large-scale datasets to demonstrate good diagnostic performance. (3) The DSCNN-GAM model (which employs depthwise separable convolution but pairs it with an independent, non-hybrid attention mechanism GAM) has a limitation in that its structure mainly re-weights local features in previous studies, lacking an explicit part for modeling long-range global relationships [40]. (4) The VGG16 (a 16-layer deep model with small convolutional kernels stacked) achieves depth through stacking convolutions. Its large number of parameters and high computational cost make it difficult to deploy on modern mobile devices [41]. (5) The ResNet, a residual network with 18 layers, mitigates the vanishing gradient issue in deep architectures through the incorporation of residual connections; its core module still contains a large number of computationally intensive standard convolution operations, and model efficiency was not the primary design goal [42]. (6) The CNN-SwinGAM retains the hybrid attention mechanism of SwinGAM; it replaces the depthwise separable convolution at the bottom layer with standard convolution. Despite this, its computational cost is still significantly higher compared to the DSCNN architecture, and it is more prone to overfitting [32]. The core design of our model, DSCNN-SwinGAM, is predicated on the lightweight DSCNN architecture and efficiently integrates the long-range dependency modeling of the Swin Transformer with the global channel enhancement afforded by GAM, thereby achieving an optimal balance between efficiency and diagnostic performance.

The hyperparameters for all models were configured as follows: the objective function was set to cross-entropy loss, the optimization algorithm used was Adam, and the initial learning rate was set to 0.001. The batch size was determined to be 32, and the total number of iterations was set at 130. The mean value of 10 replicated trials was computed to minimize the stochastic influences on the experimental outcomes.

This study utilizes five primary evaluation metrics for comparison to comprehensively assess the proposed method: fault recognition accuracy, loss rate, changes in the model training loss curve, confusion matrix, and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) feature visualization.

4.1 Experiment 1: CWRU Dataset

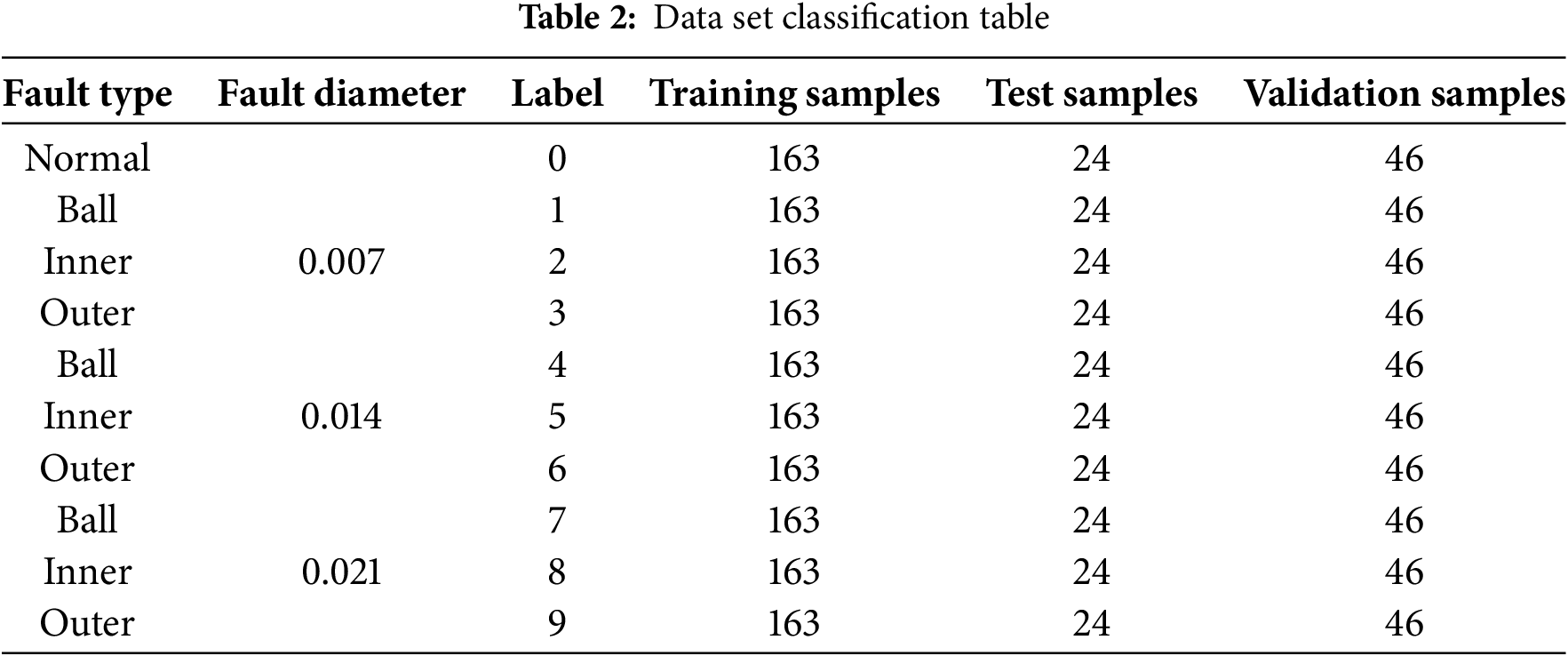

The diagnostic benchmark test exploited the bearing dataset from CWRU [43] within the experimental verification framework. The test bench utilized SKF6205 deep groove ball bearings, and the fault states included local pitting at various positions (inner/outer raceways, rolling elements) with size defects ranging from 0.007 inches to 0.021 inches, as well as 10 standard types. The detailed parameter specifications are presented in Table 2.

Model Validation

This study aims to validate the effectiveness of the proposed DSCNN-SwinGAM detection model in transfer learning applications and to conduct a comparative analysis with alternative transfer learning approaches. The model was initially pre-trained on the complete source-domain dataset encompassing three operating conditions (0, 1, and 2 hp). Thereafter, 40% of the samples from each fault category in the target domain were randomly selected as training instances to fine-tune the pre-trained model. In comparison, the remaining 60% were utilized as a validation set to evaluate the effectiveness of the transferred model.

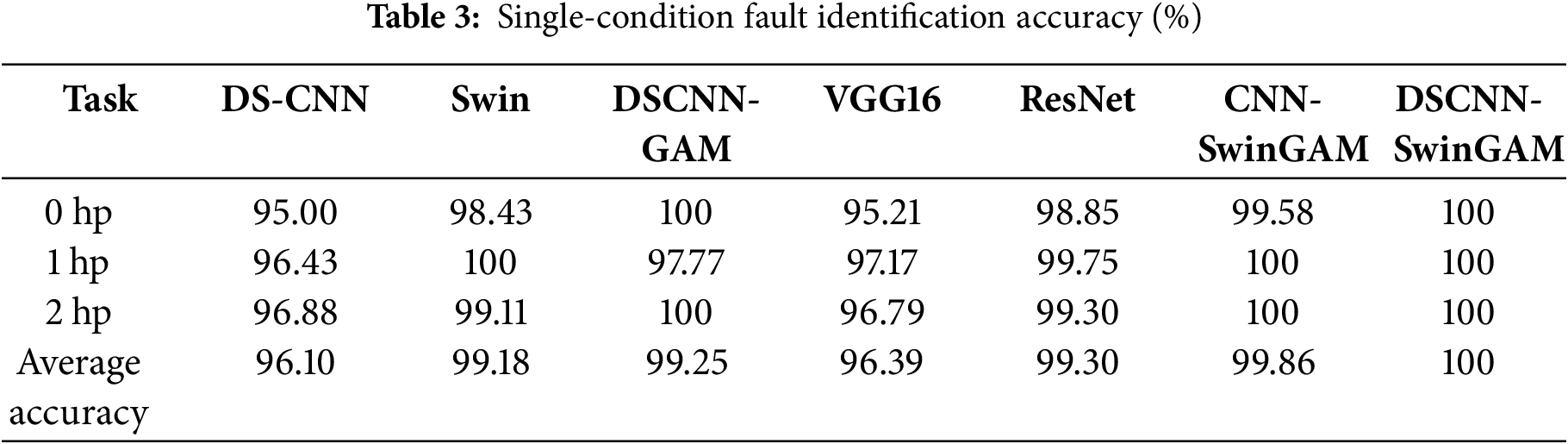

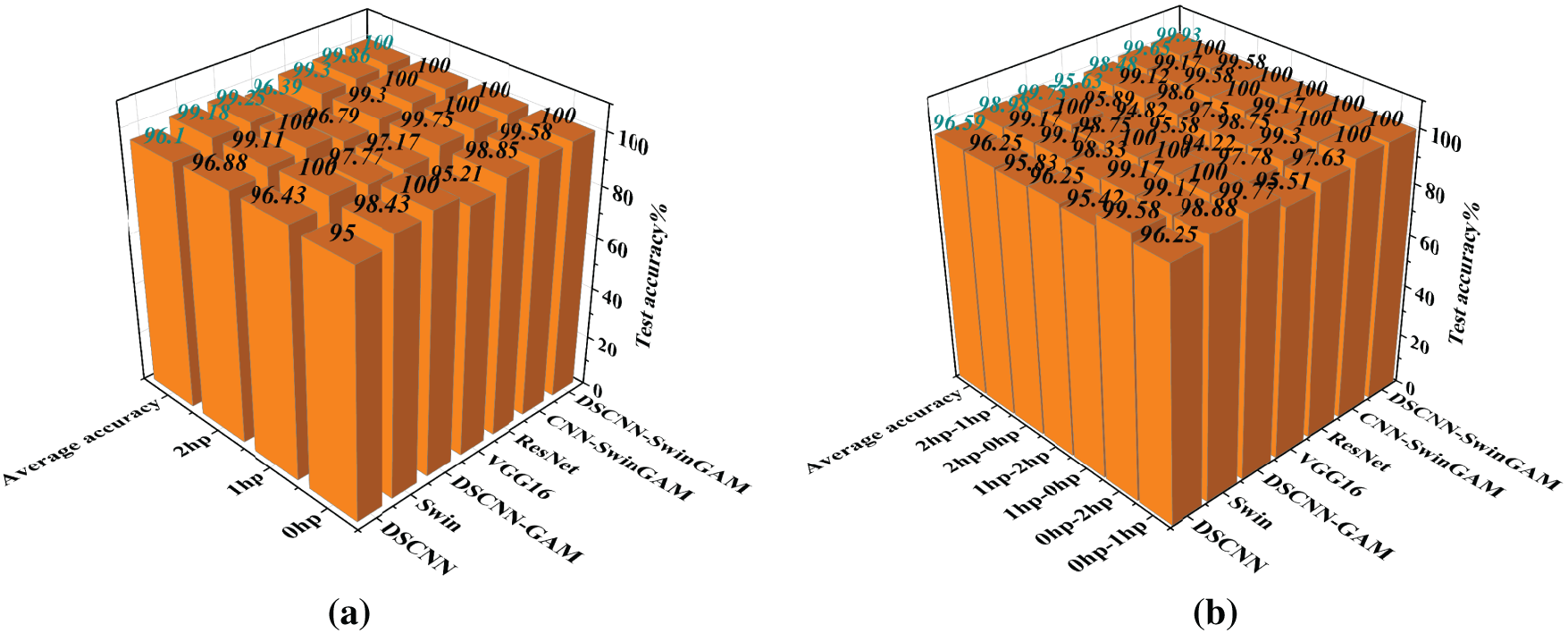

First, rigorous diagnostic tests and evaluations were conducted for all models on three single-condition tasks (0, 1, and 2 hp) in the CWRU dataset. The following average accuracies denote the mean fault-identification precision on the validation set following ten separate pre-training sessions for each model. By comparison, the DSCNN-SwinGAM model attained an average fault-classification precision of 100% on the test dataset, indicating superiority over the competing models. Specifically, its accuracy exceeded those of DSCNN (96.10%), Swin (99.18%), DSCNN-GAM (99.25%), VGG16 (96.39%), ResNet (99.30%), and CNN-SwinGAM (99.86%) by 3.90, 0.82, 0.75, 3.61, 0.70, and 0.14 percentage points, respectively. The results showed that DSCNN-SwinGAM achieves higher fault identification accuracy than other comparable models in the single-condition tasks of the CWRU dataset, confirming its diagnostic superiority. The final test accuracy of each model is presented in Table 3 and Fig. 6a.

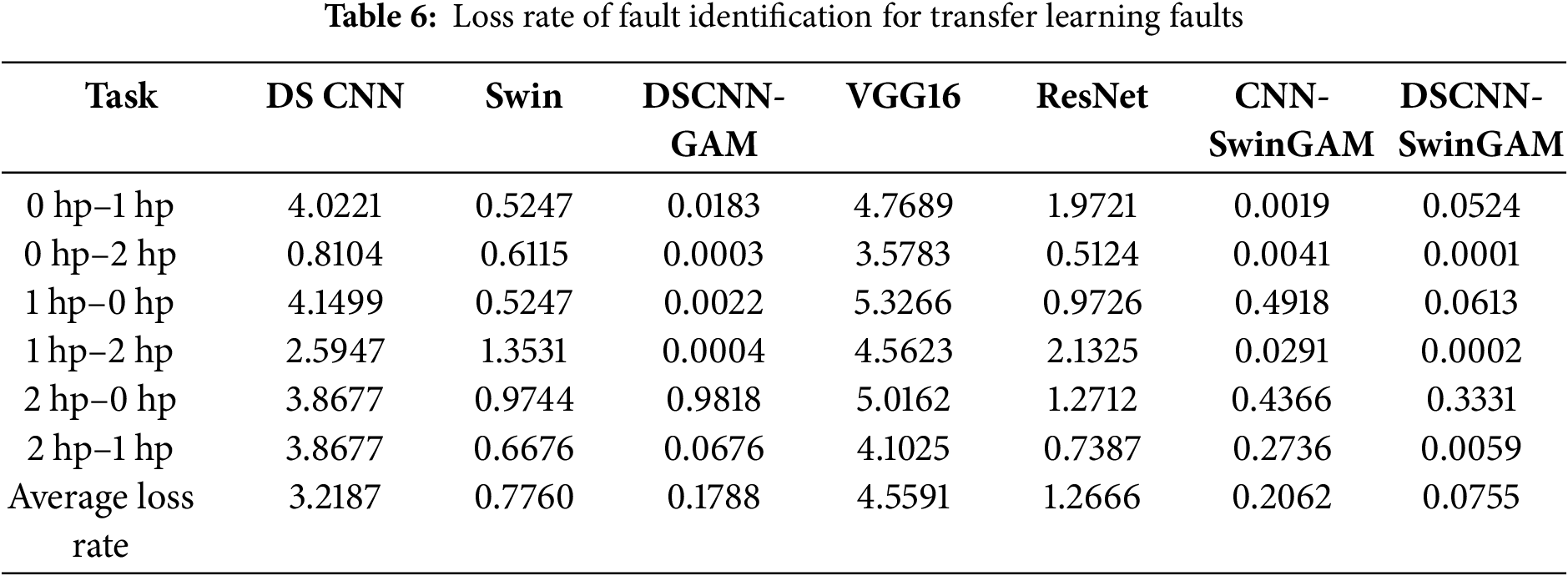

Figure 6: Visualization of fault recognition accuracy for each model: (a) Fault recognition accuracy under three single operating conditions, (b) Fault recognition accuracy for six migration tasks

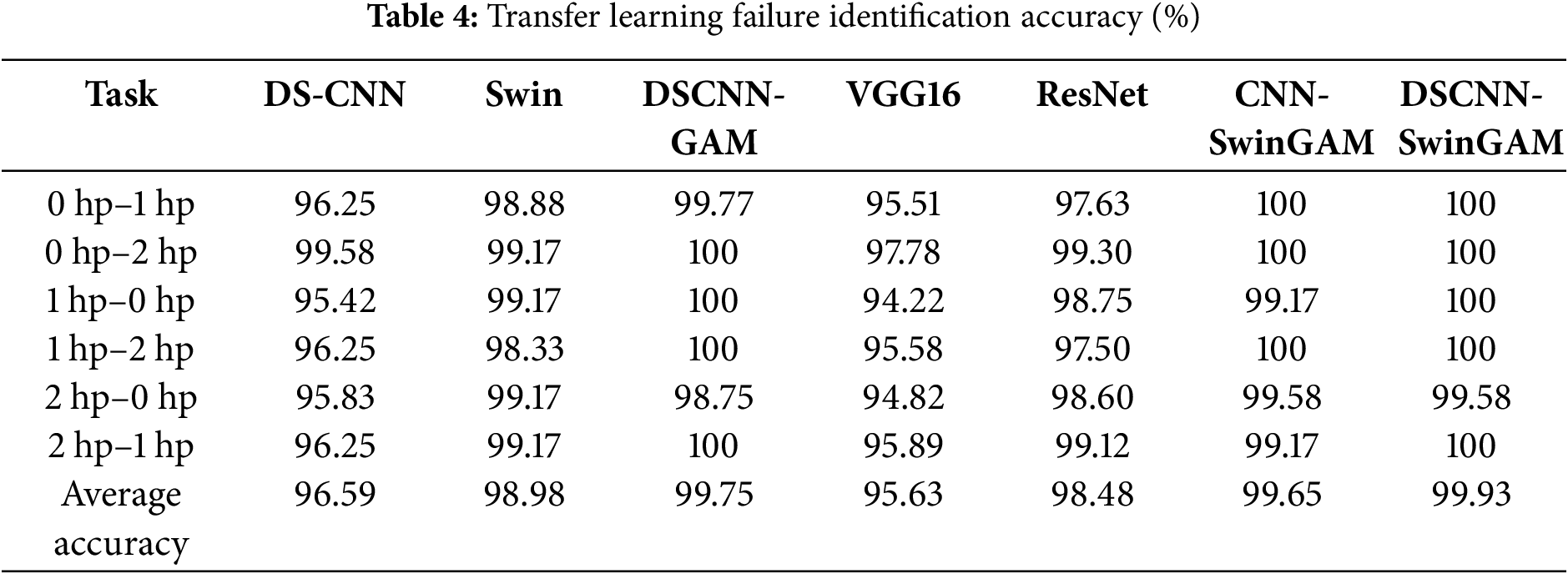

The accuracy rates of the transfer learning diagnosis are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 6b. Across six distinct transfer tasks in the CWRU dataset, the DSCNN-SwinGAM model yielded a higher mean fault-classification accuracy over ten transfers than all comparator methods (Table 4). The mean transfer diagnostic accuracy of DSCNN-SwinGAM reached 99.93%, representing a marked improvement over the comparison models. Specifically, its performance exceeded those of DSCNN (96.59%), Swin (98.98%), DSCNN-GAM (99.75%), VGG16 (95.63%), ResNet (98.48%), and CNN-SwinGAM (99.65%) by 3.34, 0.95, 0.18, 4.30, 1.45, and 0.28 percentage points, respectively. The results indicate that the fault identification accuracy of DSCNN-SwinGAM is superior to that of the other comparison models under the transfer tasks of the CWRU dataset, confirming its superiority in the variable operating condition bearing fault diagnosis task under small sample conditions.

In the comparative analysis of fault identification accuracy across the models above, DSCNN-SwinGAM demonstrates superior performance in fault diagnosis under individual working condition tasks and six different migration tasks.

Secondly, the stability of the model is assessed in DSCNN-SwinGAM through the analysis of the loss rate and the validation loss curve. Specifically: (1) A lower loss rate indicates that the model’s predictions are closer to the ground truth, thereby evidencing superior model performance. (2) The trajectory of the loss curve was examined to ascertain convergence and to mitigate overfitting.

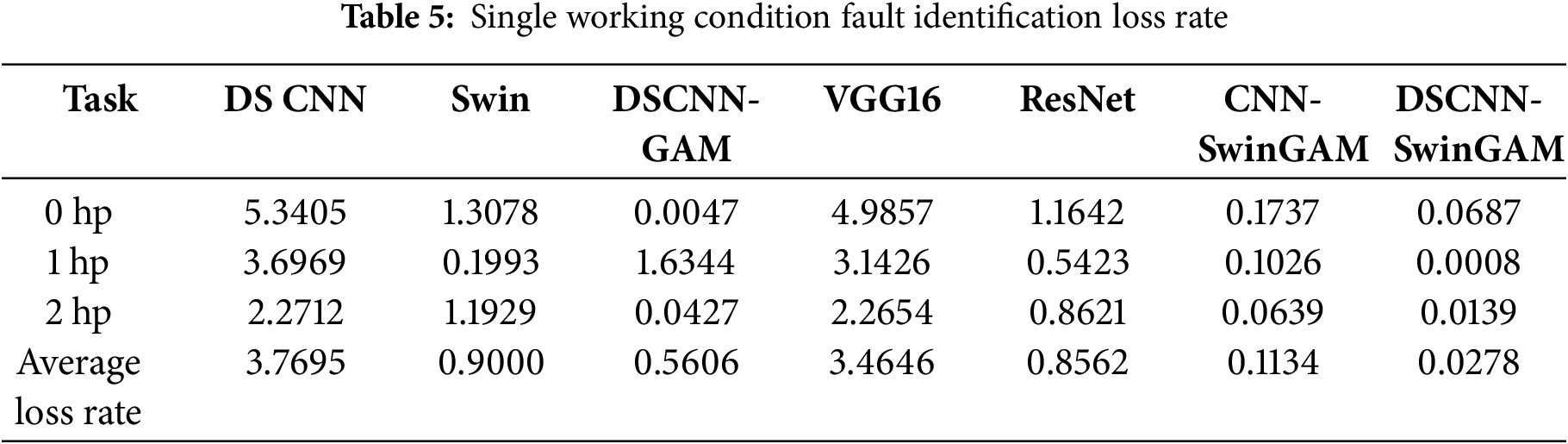

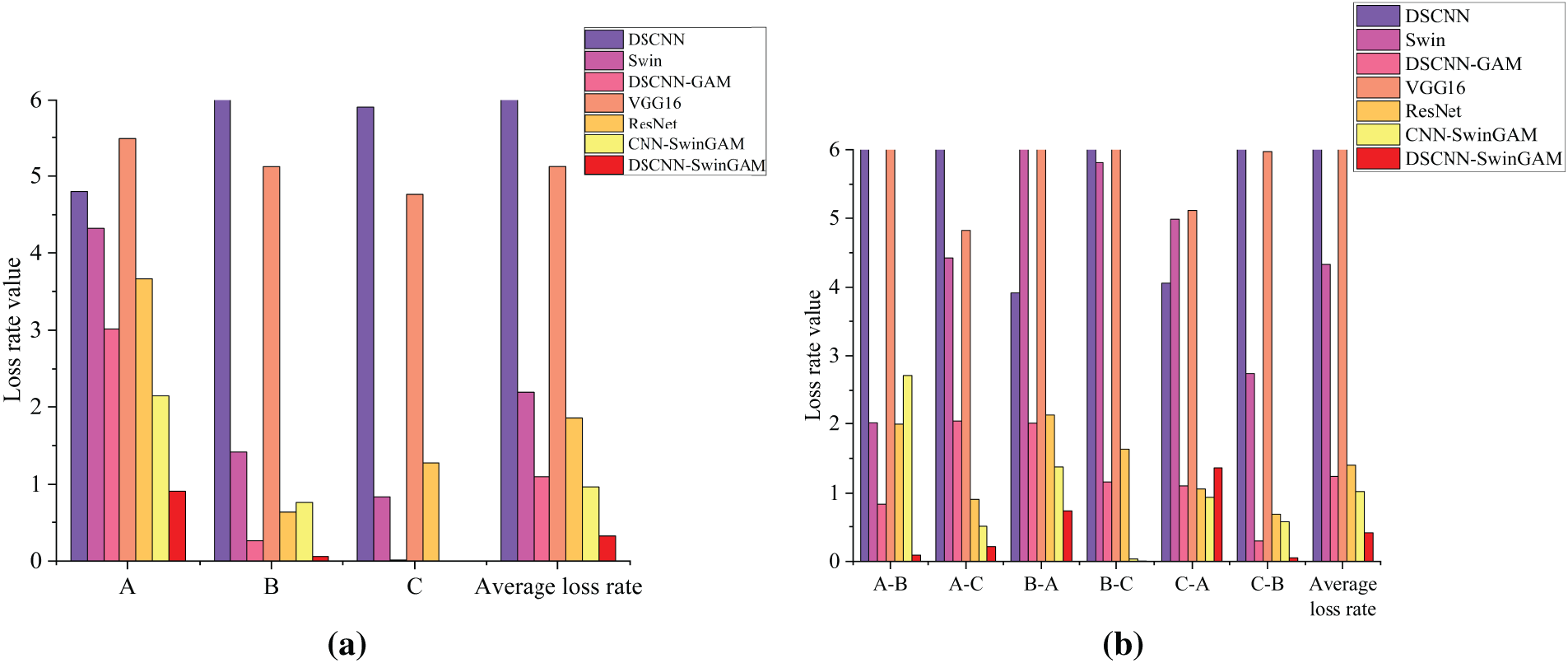

The experimental results show that the average loss rate of the DSCNN-SwinGAM model after testing under three different working conditions is 0.0278, which is significantly lower than that of other models. Specifically, DSCNN-SwinGAM was lower by 3.7417, 0.8722, 0.5328, 3.4368, 0.8284, and 0.0856 than DSCNN (3.7695), Swin (0.9000), DSCNN-GAM (0.5606), VGG16 (3.4646), ResNet (0.8562), and CNN-SwinGAM (0.1134), respectively. The results indicate that the average loss rate of DSCNN-SwinGAM is lower than that of other comparison models under the single-condition task of the CWRU dataset, confirming that its model is more stable in the fault diagnosis identification task than other comparison models. The experimental results of the test loss rate for each model are presented in Table 5 and Fig. 7a.

Figure 7: Visualization of fault recognition loss rate during pre-training of each model: (a) Loss rate of fault recognition under three single operating conditions, (b) Loss rate of fault recognition for six transmission tasks

The experimental results show that the average loss rate of the DSCNN-SwinGAM model in the transfer learning task is 0.0755 after evaluation, significantly lower than that of other models. Specifically, DSCNN-SwinGAM was lower by 0.0755, 0.0755, 0.0755, 4.4836, 1.1911, and 0.0755 than DSCNN (3.2187), Swin (0.9260), DSCNN-GAM (0.1788), VGG16 (4.5591), ResNet (1.2666), and CNN-SwinGAM (0.2062), respectively. The results indicate that the average loss rate of DSCNN-SwinGAM is lower than that of other comparison models in the transfer task of the CWRU dataset, confirming its superior stability in the fault diagnosis identification task. The transfer test loss rates of each model are shown in Table 6 and Fig. 7b.

Analysis of the loss rates indicates that, across three distinct operating conditions and transfer-learning tasks, DSCNN-SwinGAM attains a lower average loss rate than the models above. This finding implies that the model’s predictions on the test set are substantially closer to the ground-truth labels, thereby evidencing superior fitting capacity.

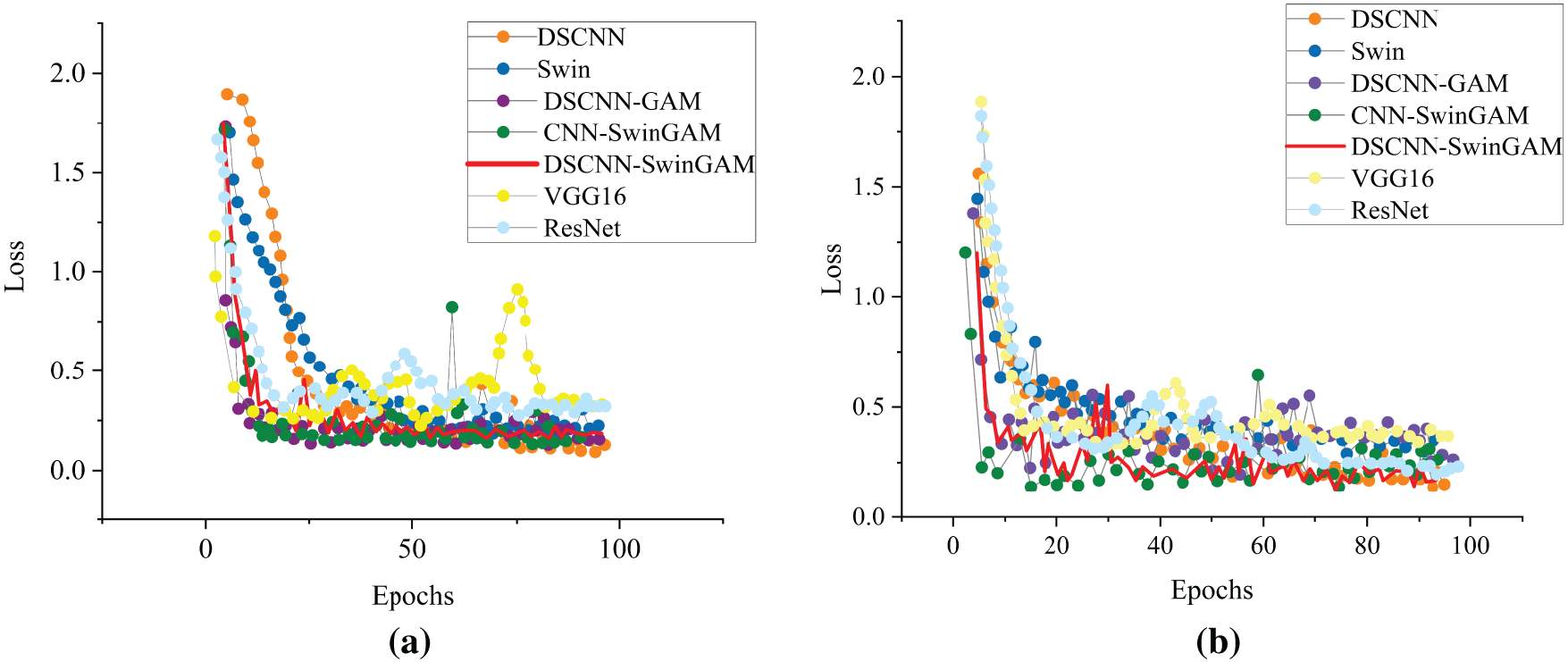

The evolution of the loss curves during pre-training indicates that, across both tasks, DSCNN-SwinGAM achieves the most rapid convergence relative to the other models. Fig. 8a,b illustrates the loss-curve trajectories during training under the 0 hp operating condition and the 0–1 hp transfer task, respectively.

Figure 8: Changes in loss curves during pre-training of each model: (a) Changes in training loss curves of each model under 0 hp operating conditions, (b) Changes in training loss curves of each model under 0 –1 hp transfer tasks

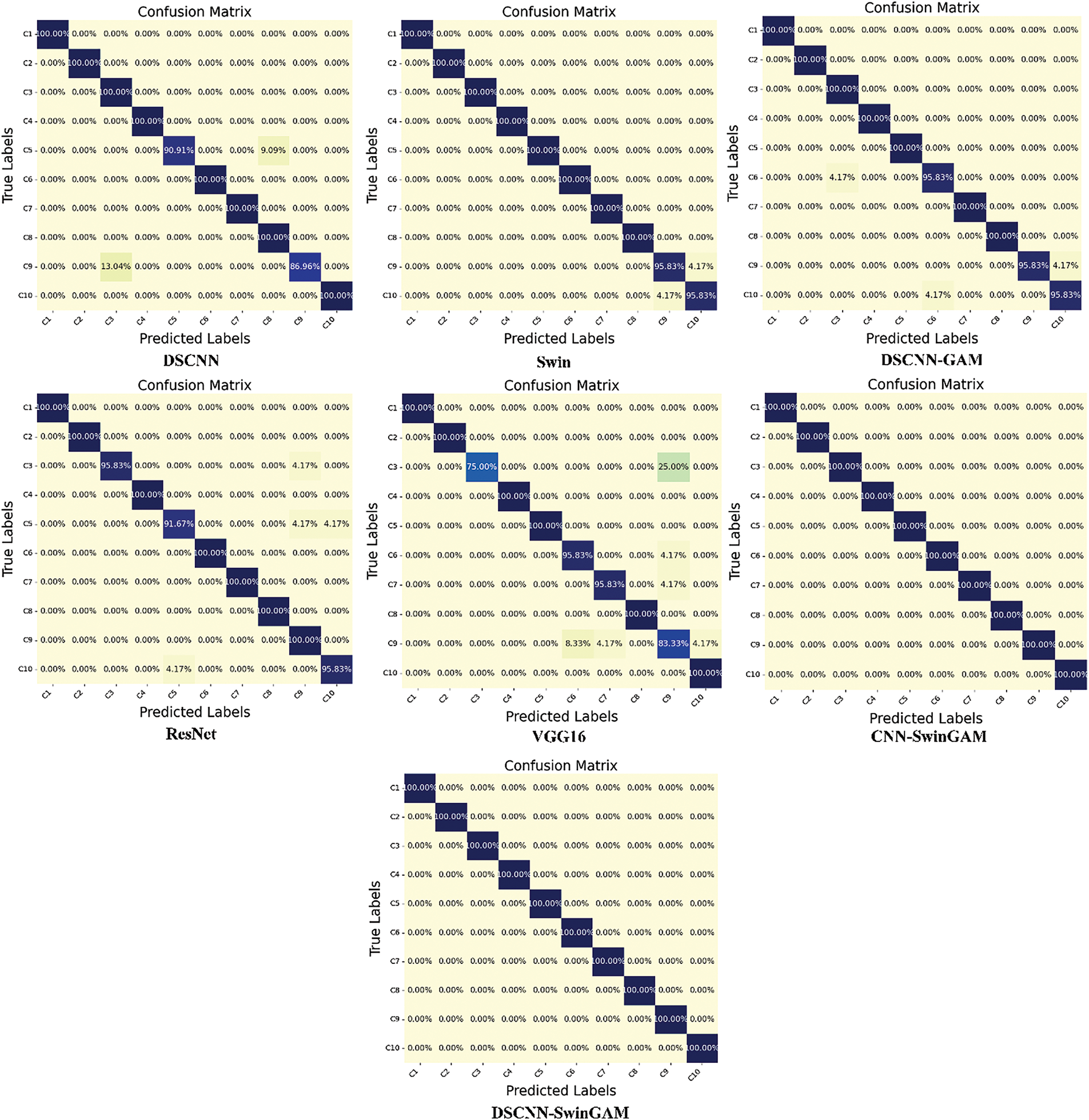

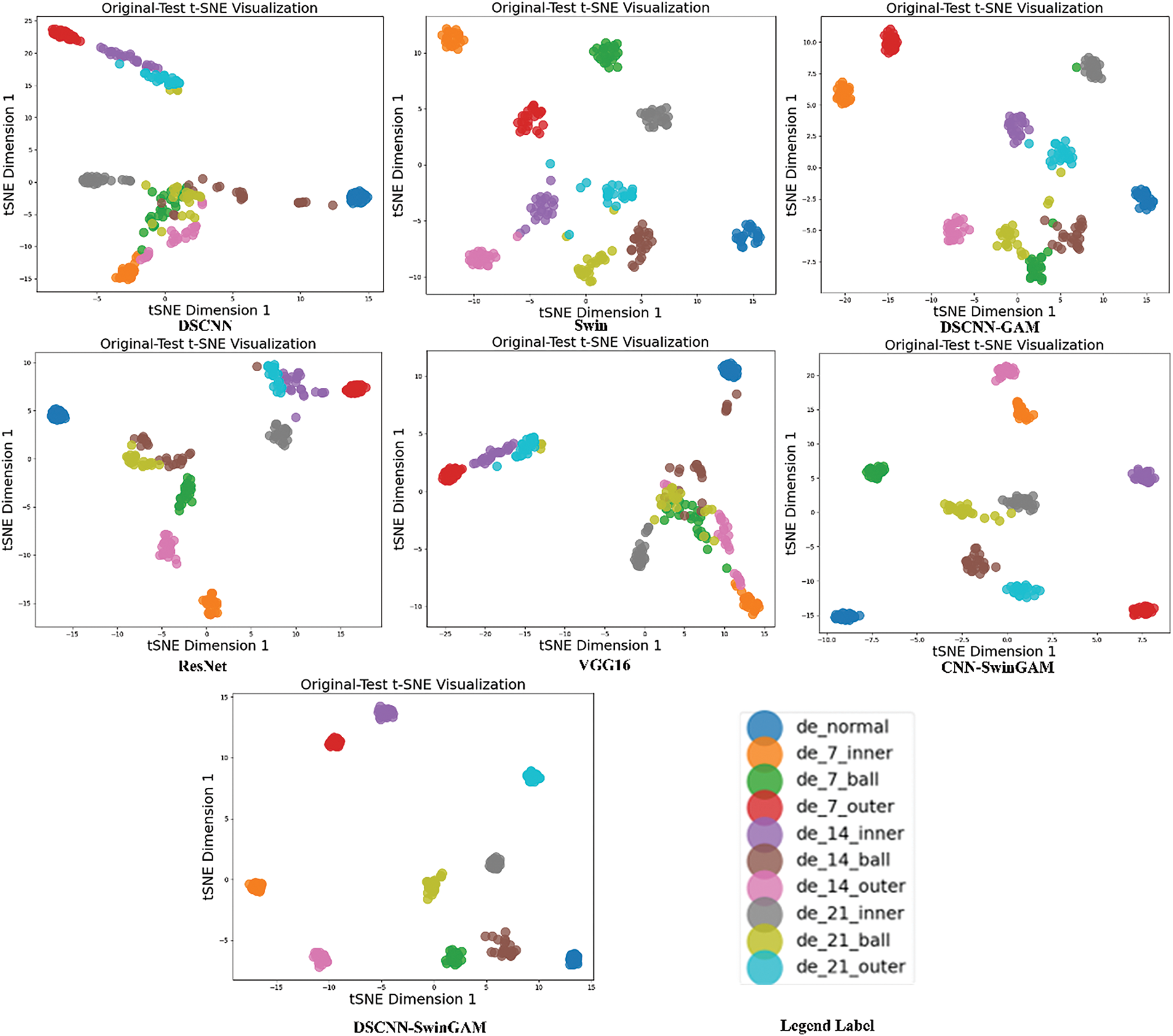

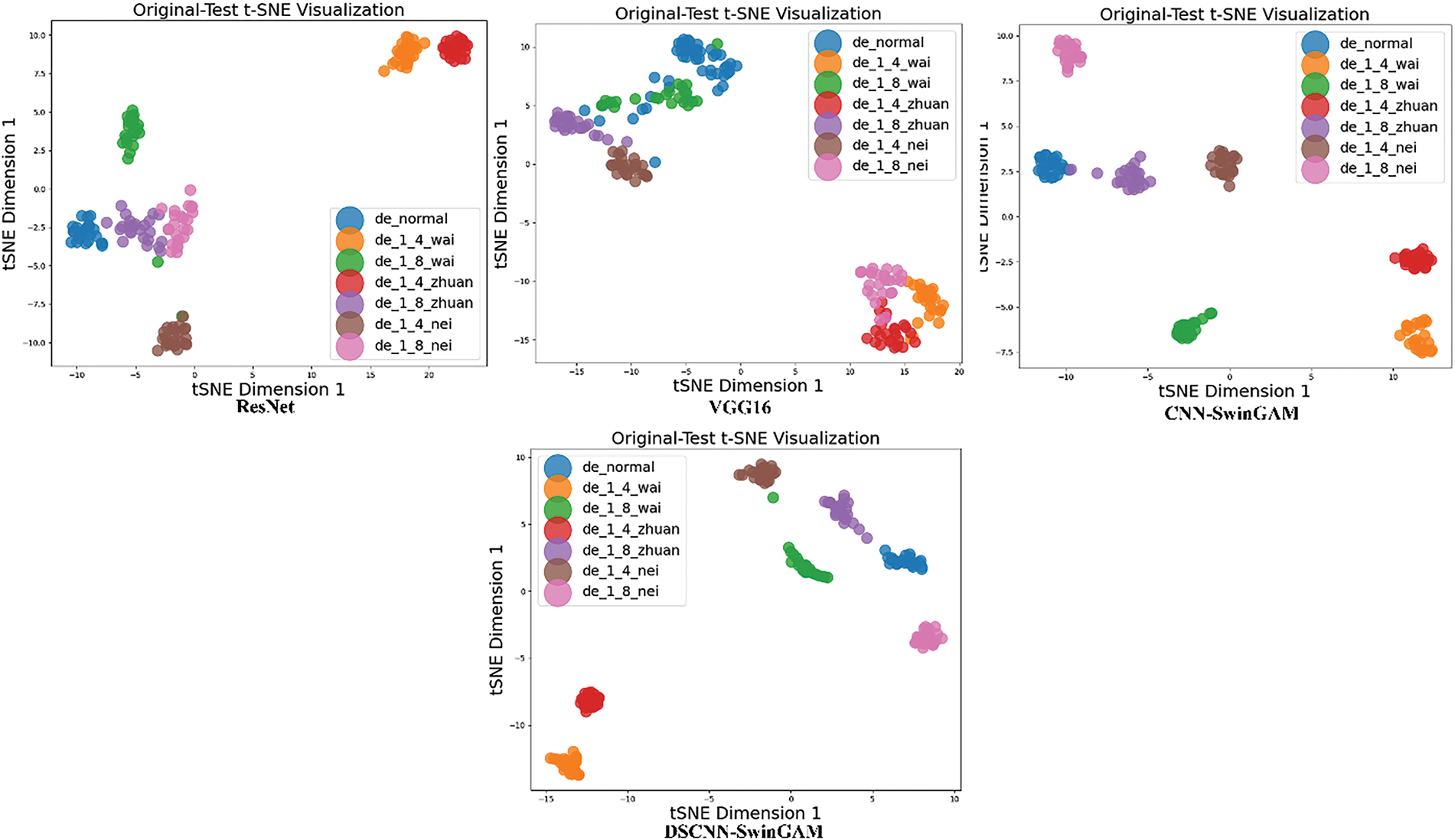

Fig. 9 illustrates the confusion matrices of the identification outcomes for seven models on the CWRU dataset, with the 0–1 hp transfer task employed as an illustrative example. The non-dark green region is utilized to represent the quantity or proportion of samples corresponding to various category combinations, thereby enhancing the intuitiveness and comprehensibility of the information. A visualization of the t-SNE features under the transfer task is provided in Fig. 10.

Figure 9: Confusion matrix for each model under the migration task

Figure 10: t-SNE visualization of each model of the migration task

4.2 Experiment 2: Bearing Fault Diagnosis Experimental Platform Data Set

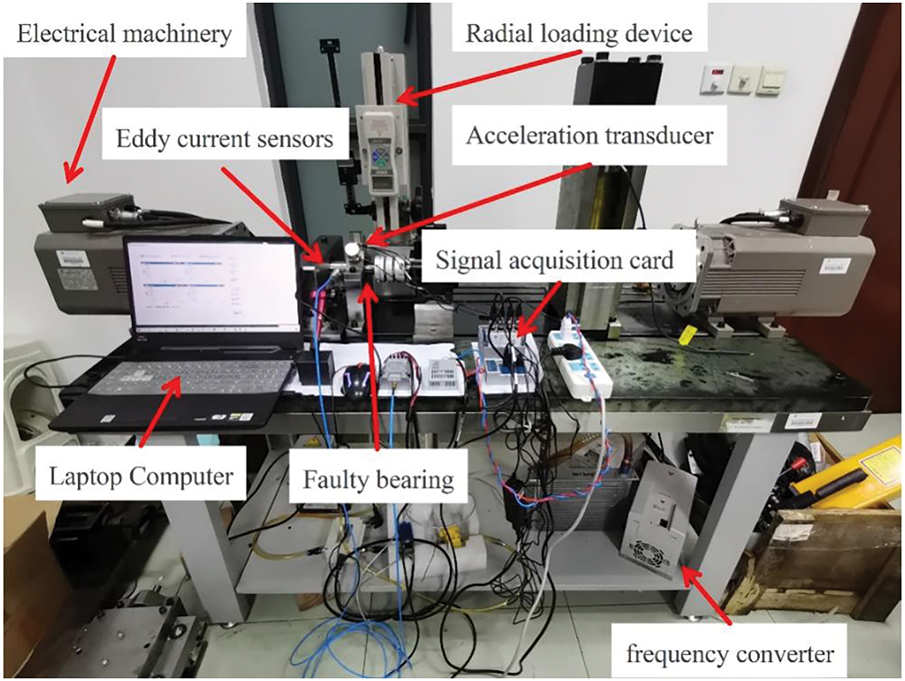

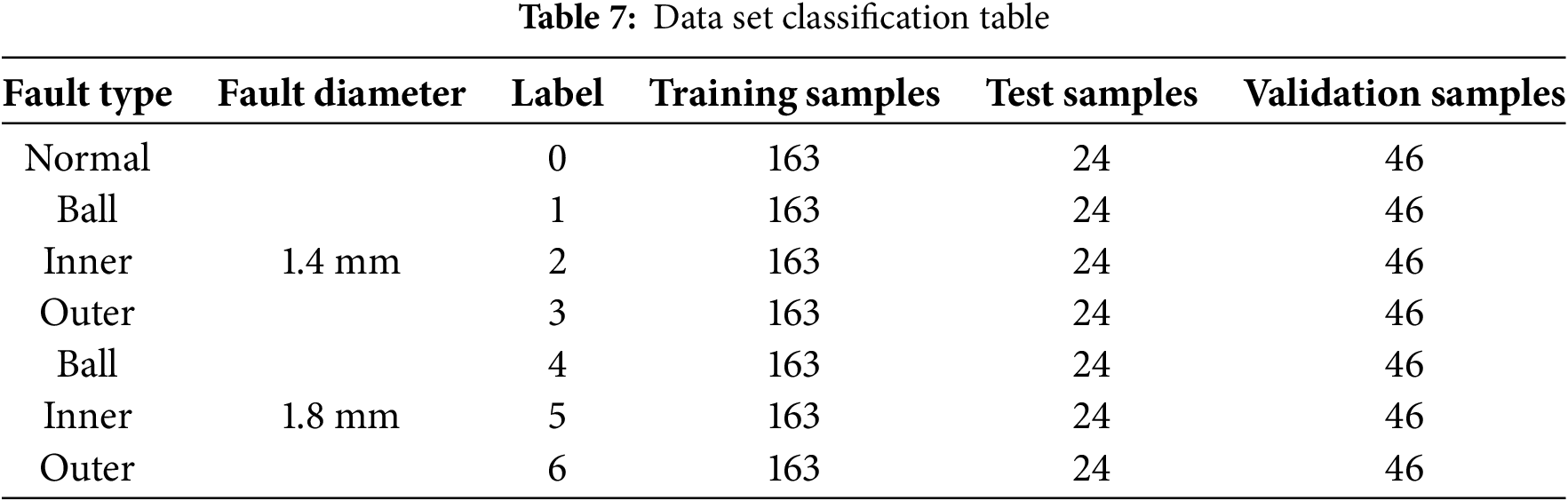

The experimental dataset collected on the bearing fault diagnosis platform is used to validate the proposed error identification framework. The bearing fault diagnosis testbed is designed to acquire fault data under constant rotational speed and to emulate the dynamics of a bearing-rotor system. The testbed primarily comprises a motor, a radial loading device, a faulted bearing, an accelerometer, a laptop computer, an eddy-current sensor, a frequency converter, and an NI9234 data-acquisition card, among other components (Fig. 11). The motor’s sampling speed is 2700 revolutions per minute, corresponding to a frequency of 45 Hz. In the fault diagnosis experiments, we used SKF NU 1006 cylindrical roller bearings manufactured by SKF as a case study. The vibration acceleration signals are collected using sensors installed on the upper portion of the bearing housing and at locations adjacent to both sides of the bearing. Thereafter, three distinct loads (0, 0.25, and 0.5 MPa) are applied to the bearing via the radial loader. These loads are categorized into three working conditions: A, B, and C. Finally, the pitting damages of 1.4 and 1.8 mm on the standard rolling bearing, inner ring, outer ring, and rolling elements are classified into seven failure states (considering no failure as a special type of failure). A set of seven category labels is provided, and the dataset is stratified as summarized in Table 7. A schematic of rolling-bearing pitting damage is shown in Fig. 12.

Figure 11: Experimental platform for bearing fault diagnosis

Figure 12: Example of rolling bearing pitting damage

Model Validation

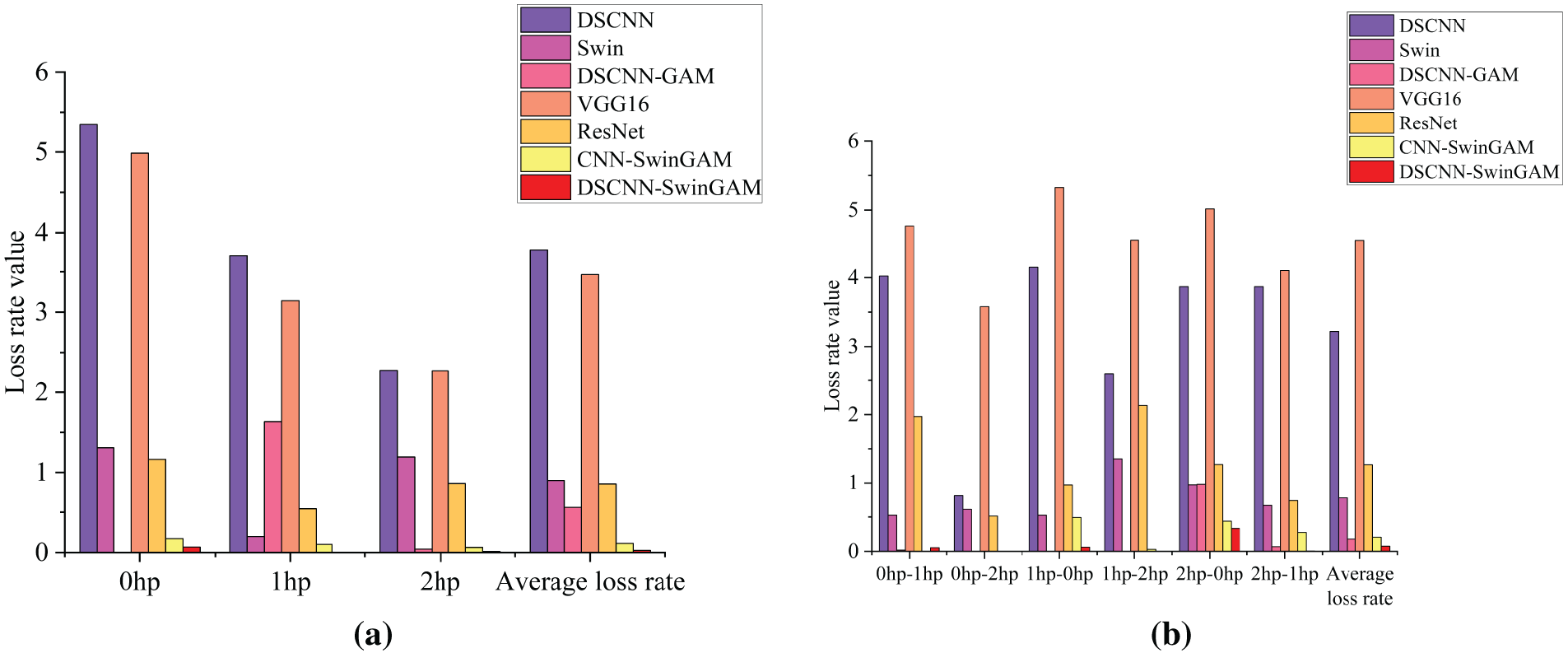

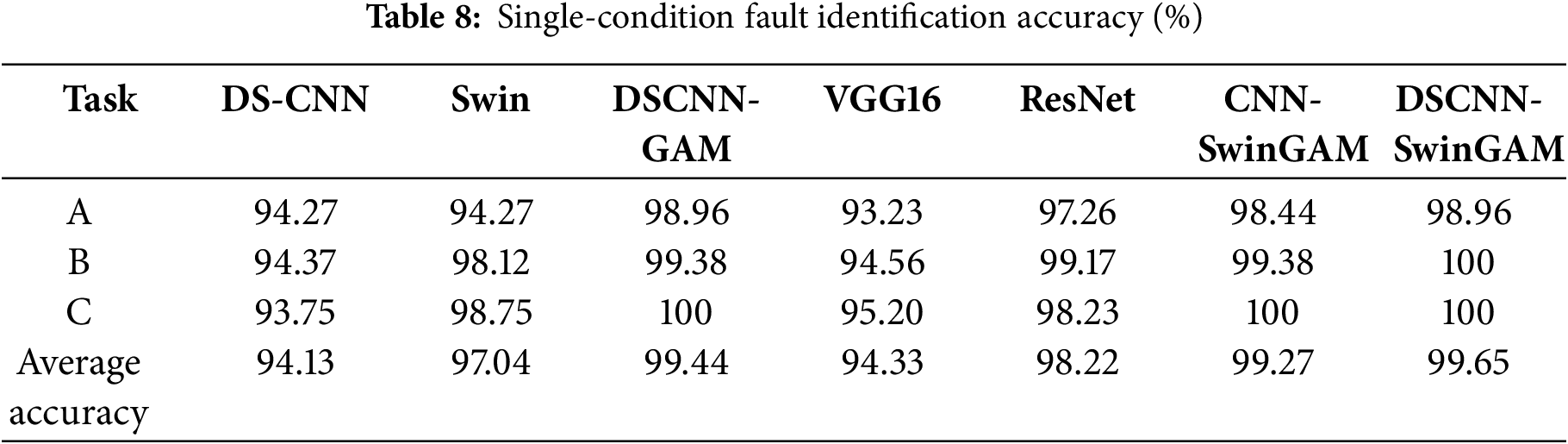

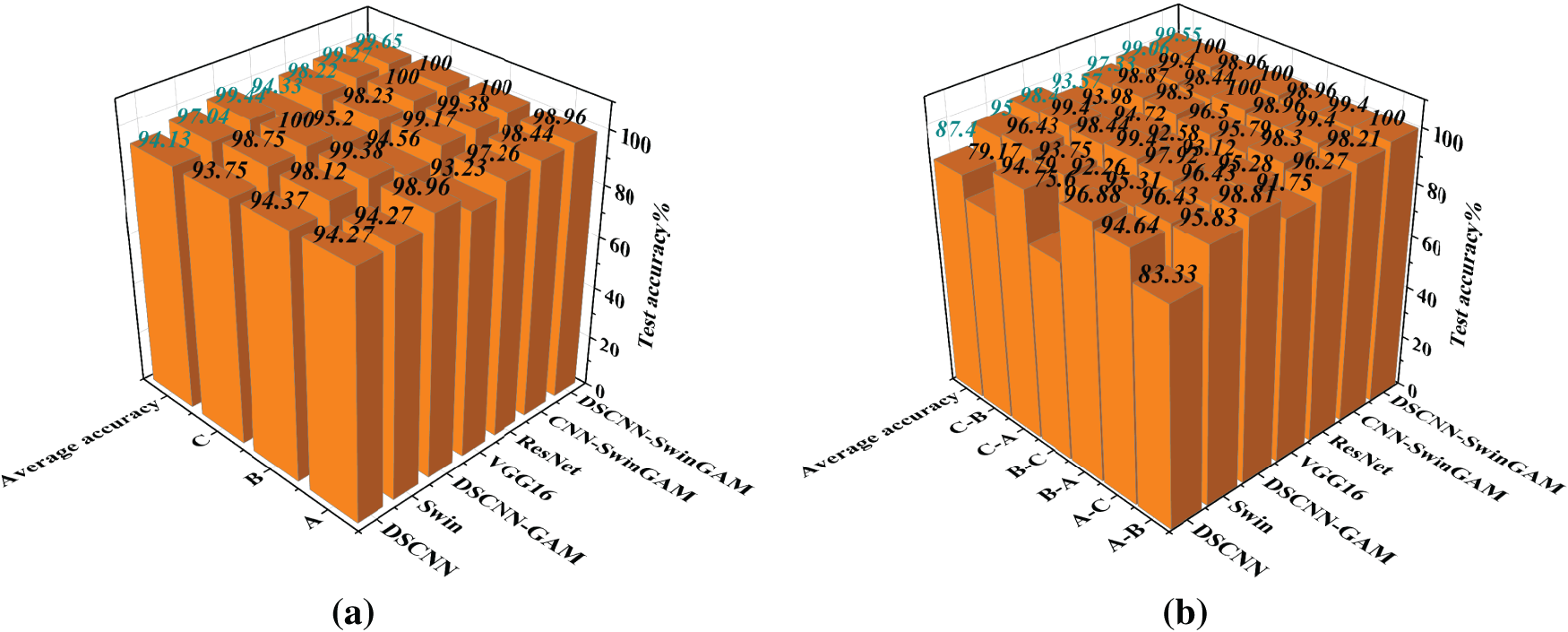

On the diagnostic experimental platform dataset, this study tested different models under three different working conditions (A, B, and C). The DSCNN-SwinGAM model achieved an average fault-classification precision of 99.65% on the test dataset, significantly outperforming other architectures. Specifically, the accuracy of DSCNN-SwinGAM exceeded that of DSCNN (94.13%), Swin (97.04%), DSCNN-GAM (99.44%), VGG16 (94.33%), ResNet (98.22%), and CNN-SwinGAM (99.27%) by 5.52, 2.61, 0.21, 5.32, 1.43, and 0.38 percentage points, respectively. Table 8 and Fig. 13a demonstrate the final evaluation accuracy of each algorithm framework.

Figure 13: Visualization of fault recognition accuracy for each model: (a) Fault recognition accuracy under three single operating conditions, (b) Fault recognition accuracy for six migration tasks

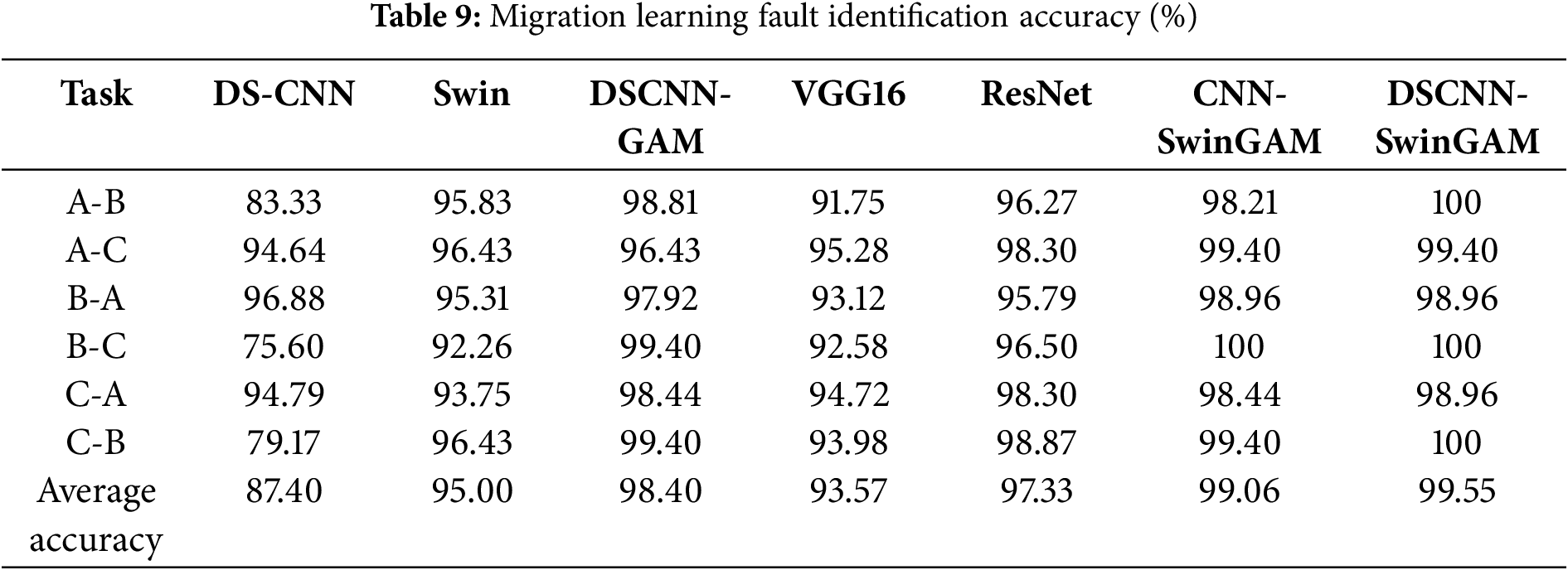

The accuracy rates of the migration task diagnosis are shown in Table 9 and Fig. 13b. Across six distinct transfer tasks, DSCNN-SwinGAM achieved the highest fault-classification accuracy, yielding an average transfer diagnostic accuracy of 99.55%, which was significantly superior to that of the comparator models (Table 8). Specifically, compared with DSCNN (87.40%), Swin (95.00%), DSCNN-GAM (98.40%), VGG16 (93.57%), ResNet (97.33%), and CNN-SwinGAM (99.06%), DSCNN-SwinGAM achieved relative gains of 12.15, 4.55, 1.15, 5.98, 2.22, and 0.49 percentage points, respectively. The results show that, under the transfer task of the bearing fault diagnosis experimental platform dataset, the fault identification accuracy of DSCNN-SwinGAM is superior to other comparison models, confirming its superiority in the variable-condition bearing fault diagnosis task under small sample conditions.

Second, the stability of the model is assessed by analyzing the loss rate and the validation loss trajectory. Specifically: (1) A lower loss rate indicates that the predictions are closer to the ground truth, thereby evidencing superior model performance. (2) The trend of the loss curve is examined to ascertain convergence and to mitigate overfitting.

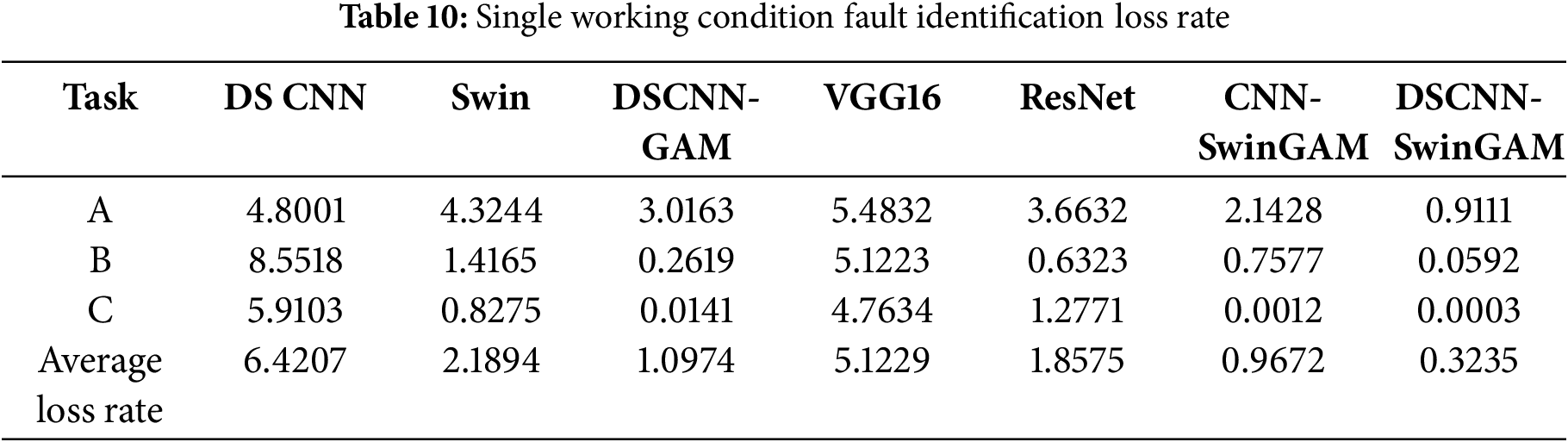

The evaluation results of the three individual case tasks demonstrate that the average loss rate of the DSCNN-SwinGAM architecture is approximately 0.3235, which is significantly lower than that of other reference architectures. Specifically, the test loss of DSCNN-SwinGAM was lower by 6.0972 than DSCNN (6.4207), by 1.8659 than Swin (2.1894), by 0.7739 than DSCNN-GAM (1.0974), by 4.7994 than VGG16 (5.1229), by 1.534 than ResNet (1.8575), and by 0.6437 than CNN-SwinGAM (0.9672). The test-loss results for each model are provided in Table 10 and Fig. 14a. The results show that the average loss rate of DSCNN-SwinGAM under the single-condition task of the experimental diagnostic platform is lower than that of other comparison models. Thus, this model is more stable in the fault diagnosis identification task compared with other comparison models.

Figure 14: Visualization of fault recognition loss rate during pre-training of each model: (a) Loss rate of fault recognition under three single operating conditions, (b) Loss rate of fault recognition for six transmission tasks

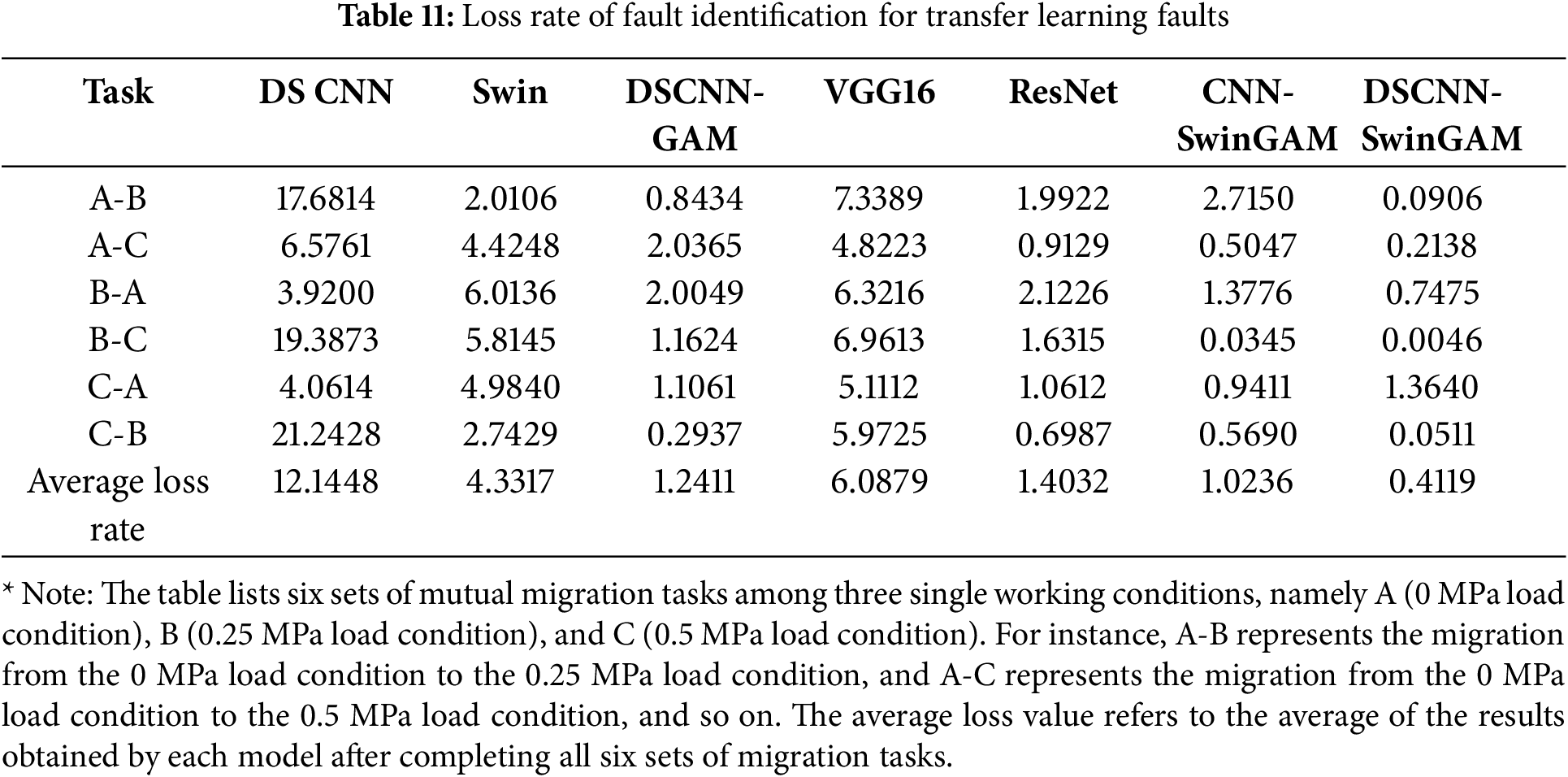

The experimental results indicate that, in the dataset transfer learning task on the experimental diagnostic platform, the DSCNNSwinGAM model achieves an average loss rate of 0.4119, which is markedly lower than that of the comparator models. Specifically, it is lower by 11.7329 relative to DSCNN, by 3.9198 relative to Swin, by 0.8292 relative to DSCNN-GAM, by 5.676 relative to VGG16, by 0.9913 relative to ResNet, and by 0.6117 relative to CNNSwinGAM. These findings substantiate the effectiveness of the stepwise enhancements applied to the DSCNN backbone, thereby supporting several conclusions. The DSCNN demonstrated a relatively high loss value, further verifying the significant role of the hybrid attention mechanism it introduced in enhancing the stability of the model’s operation in diagnostic tasks. Both Swin and DSCNN-GAM also showed high loss values, fully indicating that a single attention mechanism struggles to effectively focus on the limited fault features in small sample tasks, thereby affecting the stability of diagnostic results. The loss values of VGG16 and ResNet were higher than those of the proposed model, suggesting that their stability in the variable operating condition fault diagnosis task under small sample conditions is lower than that of the model proposed in this study. Furthermore, the loss value of CNNSwinGAM exceeds that of the model proposed herein, thereby providing additional evidence that the DSCNN-based design not only reduces the overall parameter count but also enhances stability and robustness in the diagnostic recognition task. In summary, through ablation experiments and comparative evaluations, each design decision incorporated into the proposed model has been explicitly validated. It has also been confirmed that, under small-sample conditions, the stability of DSCNN-SwinGAM in variable-operating-condition fault diagnosis and recognition is significantly superior to that of the comparator models. The test loss rates of the transfer tasks for each model, along with the comparison bar charts, are shown in Table 11 and Fig. 14b.

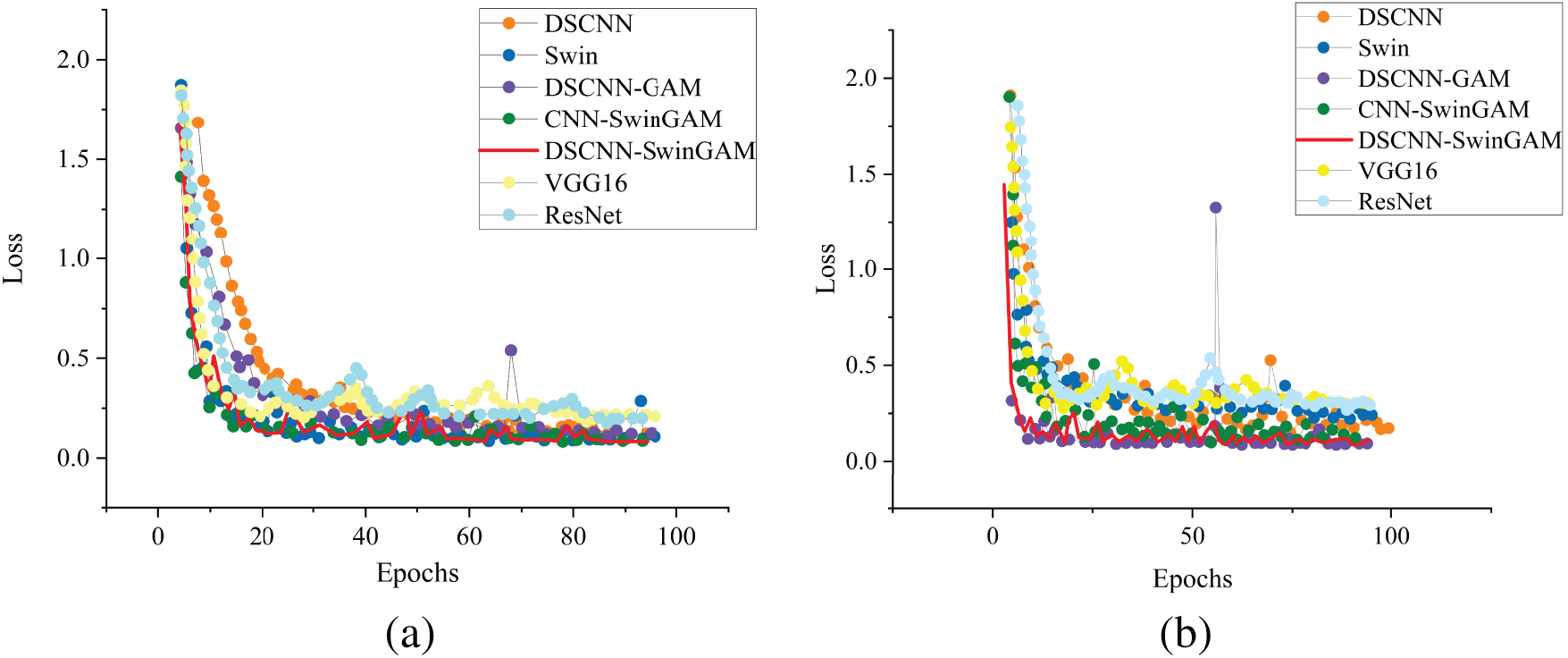

From the variations in the loss curves during pre-training, it can be observed that in both experiments, the DSCNN-SwinGAM model demonstrates the fastest convergence. For example, the changes in the training process loss curves under working condition A and the A-B migration task are illustrated in Fig. 15a,b, respectively.

Figure 15: Changes in loss curves during pre-training of each model: (a) Changes in training loss curves of each model under A operating conditions, (b) Changes in training loss curves of each model under A-B transfer tasks

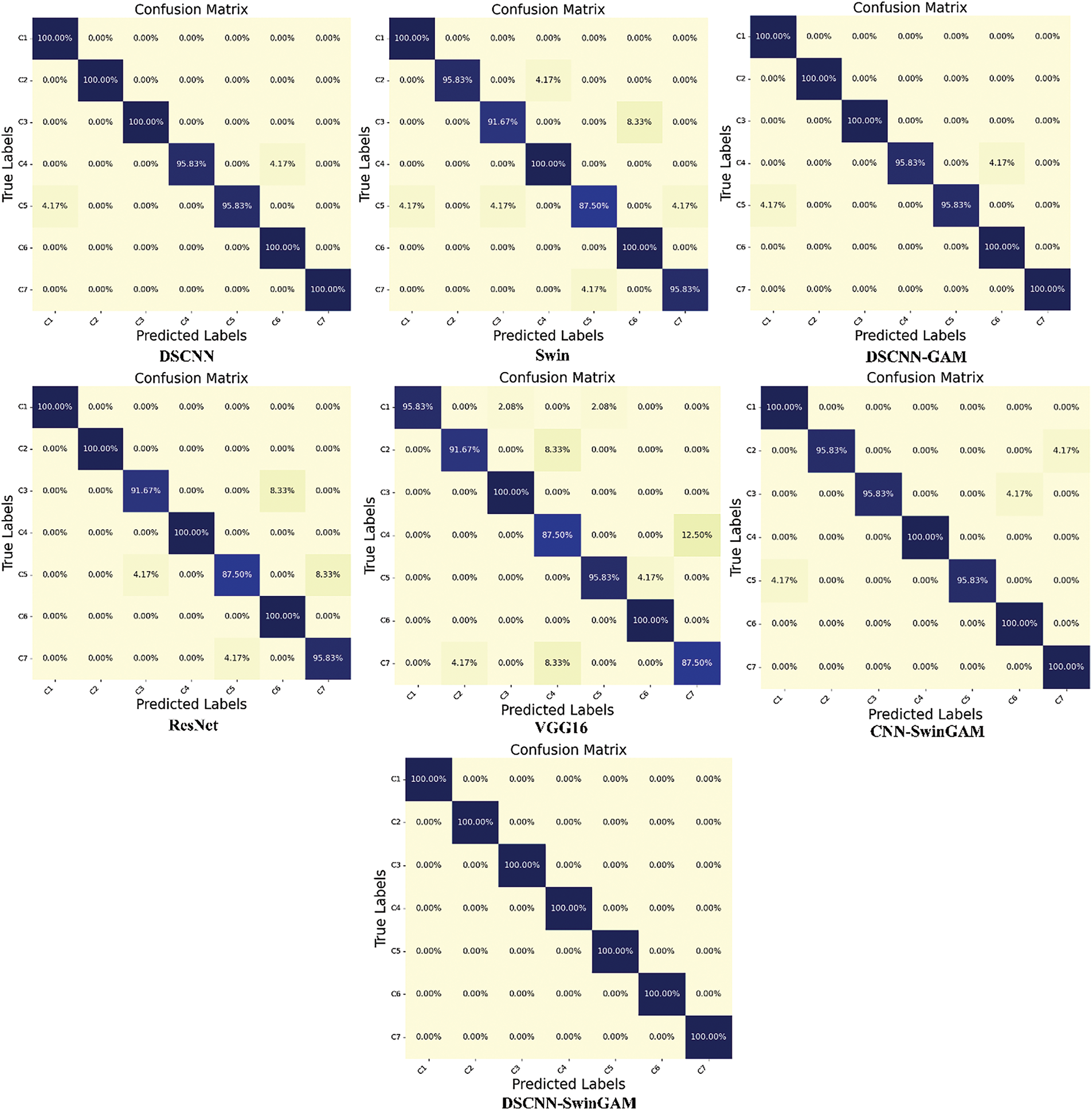

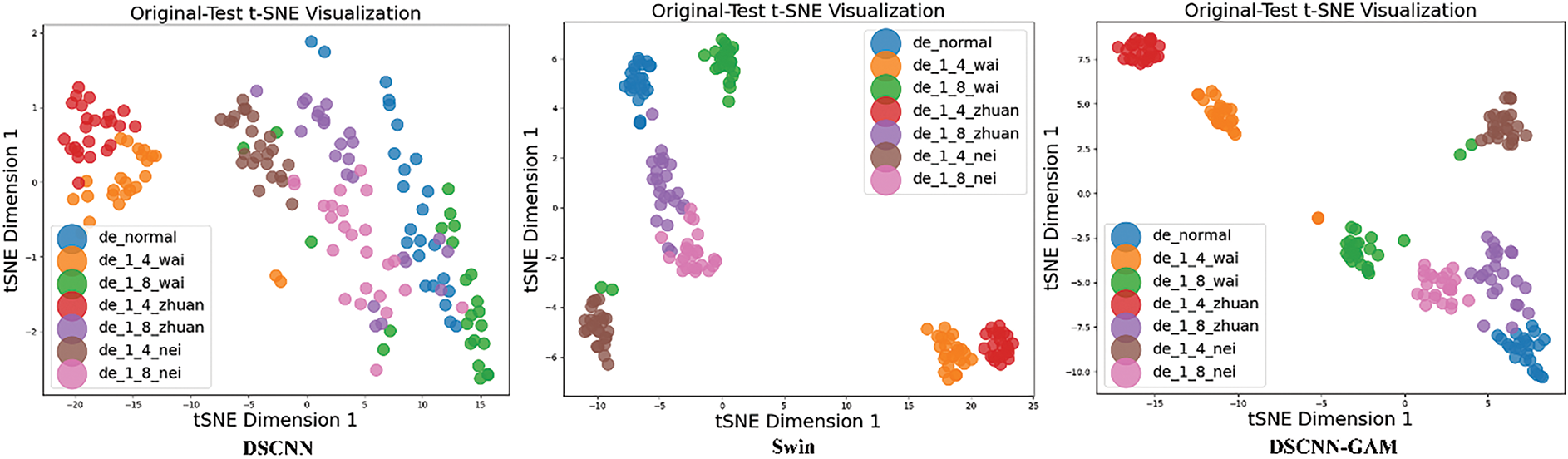

To further substantiate the experimental findings, the confusion matrix and t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) visualization of the detection outcomes was employed. Fig. 16 displays the confusion matrices for the detection results of the seven models on the dataset collected by the experimental platform using the example of the A-B transfer task. The visualization diagram of t-SNE features under the migration task is shown in Fig. 17.

Figure 16: Confusion matrix for each model under the migration task

Figure 17: t-SNE visualization of each model of the migration task

This study proposes an advanced DSCNN-SwinGAM architecture and, within a transfer-learning paradigm, establishes the DSCNN-HA-TL diagnostic framework. The objective is to address the complexity inherent in bearing fault diagnosis under variable operating conditions with limited samples. First, the network model (DSCNN-SwinGAM) integrates CWT, DSCNN, the Swin window attention mechanism, and GAM. Through the coherent integration of these components, a DSCNN backbone is utilized to construct an enhanced convolutional layer in the CNN. Moreover, the model leverages the multi-scale feature extraction of the Swin Transformer and introduces global attention through the GAM. These augmentations enable effective capture of time-frequency and local spatial features, thereby markedly improving fault-signal recognition while reducing the computational parameter footprint. Second, under a transfer-learning setting, fault identification across disparate operating conditions can be accomplished via fine-tuning. Finally, the proposed diagnostic approach is evaluated through multiple lines of verification, including results from numerous transfer-learning diagnosis tasks conducted on public datasets and bearing testbed datasets, loss-rate assessments, visualization analyses, confusion matrix inspections, ablation studies, and comparative experiments against peer models. The results demonstrate that, under small-sample regimes, the DSCNN-HA-TL method delivers strong performance on bearing fault diagnosis under variable operating conditions.

Although the proposed method has yielded satisfactory results for condition-variable bearing fault diagnosis under small-sample regimes, several issues warrant further investigation. For example, training efficiency could be further improved, enabling deployment in additional industrial scenarios, such as time-varying rotational speeds, variable temperatures, cross-device conditions and facilitating the development of online fault diagnosis pipelines. If these challenges are addressed, then this diagnostic method could serve as a practical approach for managing equipment maintenance and handling faults in complex industrial environments.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12272259) and the Key Research and Development Fund of Universities in Hebei Province (2510800601A).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Qiang Ma, Zepeng Li and Kai Yang; data collection: Qiang Ma and Kai Yang; analysis and interpretation of results: Zepeng Li and Kai Yang; draft manuscript preparation: Zepeng Li, Shaofeng Zhang and Zhuopei Wei. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cui W, Meng G, Wang A, Zhang X, Ding J. Application of rotating machinery fault diagnosis based on deep learning. Shock Vib. 2021;2021(1):3083190. doi:10.1155/2021/3083190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sun H, Cao X, Wang C, Gao S. An interpretable anti-noise network for rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on FSWT. Measurement. 2022;190(04):110698. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.110698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hoang DT, Kang HJ. A survey on deep learning based bearing fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing. 2019;335(7):327–35. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2018.06.078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ju Y, Tian X, Liu H, Ma L. Fault detection of networked dynamical systems: a survey of trends and techniques. Int J Syst Sci. 2021;52(16):3390–409. doi:10.1080/00207721.2021.1998722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Rai A, Upadhyay SH. A review on signal processing techniques utilized in the fault diagnosis of rolling element bearings. Tribol Int. 2016;96(4):289–306. doi:10.1016/j.triboint.2015.12.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Alsehaimi A, Houda M, Waqar A, Hayat S, Ahmed Waris F, Benjeddou O. Internet of Things (IoT) driven structural health monitoring for enhanced seismic resilience: a rigorous functional analysis and implementation framework. Results Eng. 2024;22(2):102340. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sun Y, Li S, Wang X. Bearing fault diagnosis based on EMD and improved Chebyshev distance in SDP image. Measurement. 2021;176(17):109100. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2021.109100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kankar PK, Sharma SC, Harsha SP. Fault diagnosis of ball bearings using continuous wavelet transform. Appl Soft Comput. 2011;11(2):2300–12. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2010.08.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wu J, Zhao Z, Sun C, Yan R, Chen X. Learning from class-imbalanced data with a model-agnostic framework for machine intelligent diagnosis. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2021;216:107934. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2021.107934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Janssens O, Slavkovikj V, Vervisch B, Stockman K, Loccufier M, Verstockt S, et al. Convolutional neural network based fault detection for rotating machinery. J Sound Vib. 2016;377(6):331–45. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2016.05.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhao X, Yao J, Deng W, Ding P, Ding Y, Jia M, et al. Intelligent fault diagnosis of gearbox under variable working conditions with adaptive intraclass and interclass convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(9):6339–53. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3135877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Jiang L, Shi C, Sheng H, Li X, Yang T. Lightweight CNN architecture design for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Meas Sci Technol. 2024;35(12):126142. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad7a1a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chen R, Huang X, Yang L, Xu X, Zhang X, Zhang Y. Intelligent fault diagnosis method of planetary gearboxes based on convolution neural network and discrete wavelet transform. Comput Ind. 2019;106(3):48–59. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2018.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yu X, Wang Y, Liang Z, Shao H, Yu K, Yu W. An adaptive domain adaptation method for rolling bearings’ fault diagnosis fusing deep convolution and self-attention networks. IEEE Trans Instrument Measure. 2023;72(1):3509814. doi:10.1109/TIM.2023.3246494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao S, Wang G, Li X, Chen J, Jiang L. Fault diagnosis of rolling bearing based on cross-domain divergence alignment and intra-domain distribution alienation. J Vibroeng. 2023;25(6):1124–40. doi:10.21595/jve.2023.23210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yin Z, Zhang F, Xu G, Han G, Bi Y. Multi-scale rolling bearing fault diagnosis method based on transfer learning. Appl Sci. 2024;14(3):1198. doi:10.3390/app14031198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Huo C, Jiang Q, Shen Y, Zhu Q, Zhang Q. Enhanced transfer learning method for rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on linear superposition network. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;121(10):105970. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li W, Huang R, Li J, Liao Y, Chen Z, He G, et al. A perspective survey on deep transfer learning for fault diagnosis in industrial scenarios: theories, applications and challenges. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2022;167(12):108487. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2021.108487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhuang F, Qi Z, Duan K, Xi D, Zhu Y, Zhu H, et al. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proc IEEE. 2021;109(1):43–76. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2020.3004555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhong H, Lv Y, Yuan R, Yang D. Bearing fault diagnosis using transfer learning and self-attention ensemble lightweight convolutional neural network. Neurocomputing. 2022;501(1):765–77. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.06.066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Asutkar S, Tallur S. Deep transfer learning strategy for efficient domain generalisation in machine fault diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6607. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-33887-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Lv H, Chen J, Pan T, Zhang T, Feng Y, Liu S. Attention mechanism in intelligent fault diagnosis of machinery: a review of technique and application. Measurement. 2022;199(2):111594. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu B, Yan C, Liu Y, Lv M, Huang Y, Wu L. ISEANet: an interpretable subdomain enhanced adaptive network for unsupervised cross-domain fault diagnosis of rolling bearing. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;62:102610. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang S, Liu Z, Chen Y, Jin Y, Bai G. Selective kernel convolution deep residual network based on channel-spatial attention mechanism and feature fusion for mechanical fault diagnosis. ISA Trans. 2023;133:369–83. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2022.06.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Liao JX, Dong HC, Sun ZQ, Sun J, Zhang S, Fan FL. Attention-embedded quadratic network (qttention) for effective and interpretable bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2023;72(11):3511113. doi:10.1109/TIM.2023.3259031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ma W, Zhou T, Qin J, Zhou Q, Cai Z. Joint-attention feature fusion network and dual-adaptive NMS for object detection. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;241(2):108213. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.108213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li X, Xiao S, Zhang F, Huang J, Xie Z, Kong X. A fault diagnosis method with AT-ICNN based on a hybrid attention mechanism and improved convolutional layers. Appl Acoust. 2024;225(3):110191. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2024.110191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yu L, Du X, Yang D, Liu Y. Improved swin transformer integrated with GADF method for bearing fault detection. Eng Res Express. 2025;7(3):035420. doi:10.1088/2631-8695/adf8bc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Xu Z, Liu T, Xia Z, Fan Y, Yan M, Dang X. SSG-net: a multi-branch fault diagnosis method for scroll compressors using swin transformer sliding window, shallow ResNet, and global attention mechanism (GAM). Sensors. 2024;24(19). doi:10.3390/s24196237.doi:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. MobileNets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. [Google Scholar]

31. Chollet F. Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1800–7. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xu H, Xiao Y, Sun K, Cui L. Improved depthwise separable convolution for transfer learning in fault diagnosis. IEEE Sens J. 2024;24(20):33606–13. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2024.3432921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Jiang R, Wu C, Zhong C. A depthwise separable convolution-based neural network for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. J Comput Methods Sci Eng. 2024;24(6):4153–70. doi:10.1177/14727978241293233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhao M, Sun H, Li X. DSCNN-BiGRU: a novel deep learning model for bearing fault diagnosis under noisy conditions. J Fail Anal Prev. 2025;24(12):424. doi:10.1007/s11668-025-02238-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Geng Z, Zhou S, Ren Z, Yu T, Zhang P. DSC-SparseFormer: a lightweight framework for bearing fault diagnosis based on depthwise separable convolution and sparse attention mechanism. Nondestruct Test Eval. 2025;2025:1–27. doi:10.1080/10589759.2025.2517694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, Hu H, Wei Y, Zhang Z, et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 9992–10002. doi:10.1109/iccv48922.2021.00986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu Y, Shao Z, Hoffmann N. Global attention mechanism: retain information to enhance channel-spatial interactions. arXiv:2112.05561. 2021. [Google Scholar]

38. Tang T, Hu T, Chen M, Lin R, Chen G. A deep convolutional neural network approach with information fusion for bearing fault diagnosis under different working conditions. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part C J Mech Eng Sci. 2021;235(8):1389–400. doi:10.1177/0954406220902181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Lv L, Yasenjiang J, Wang D, Xu L. Fault diagnosis method for rolling bearings with small samples based on DCGAN and improved swin transformer. J Phys Conf Ser. 2025;2954(1):012113. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2954/1/012113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang Q, Wu B, Zhu P, Li P, Zuo W, Hu Q. ECA-net: efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 11531–9. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.01155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2014. [Google Scholar]

42. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA, pp. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Case Western Reserve University. [cited 2024 Oct 12]. Available from: http://www.eecs.cwru.edu/laboratory/bearings/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools