Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Experimental Study on Abrasion Resistance of Self-Compacting Concrete

1 Hubei Key Laboratory of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, China Three Gorges University, Yichang, 443002, China

2 Huaneng Lancang River Hydropower Inc., Kunming, 650214, China

3 College of Water Conservancy and Environment, China Three Gorges University, Yichang, 443002, China

* Corresponding Author: Yongdong Meng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Sustainable and Durable Construction Materials)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(6), 1733-1744. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.070098

Received 08 July 2025; Accepted 06 August 2025; Issue published 17 November 2025

Abstract

To mitigate the severe abrasion damage caused by high-velocity water flow in hydraulic engineering applications in Xizang, China, this study systematically optimized key mix design parameters, including aggregate gradation, sand ratio, fly ash content, and superplasticizer dosage. Based on the optimized mix, the combined effects of an abrasion-resistance enhancement admixture (AEA) and silica fume (SF) on the abrasion resistance of self-compacting concrete (SCC) were examined. The results demonstrated that the appropriate incorporation of AEA and SF significantly improved the abrasion resistance of SCC without compromising its workability. The proposed mix design not only achieves superior abrasion resistance but also provides practical guidance for the material design and engineering application of durable hydraulic concrete in harsh environments. Future research will focus on comprehensive durability assessments by simulating extreme hydraulic conditions, including sustained exposure to high-velocity sediment-laden flows, repeated freeze-thaw cycles, and corrosive salt spray environments, to thoroughly evaluate the long-term performance evolution of abrasion-resistant self-compacting concrete. Meanwhile, advanced microstructural analytical methods should be applied toelaborate the synergistic mechanisms of abrasion-resistance enhancement admixture (AEA), silica fume (SF), and steel fibers in altering the hydration product formation, optimizing the distribution of pore structure, and strengthening interfacial transition zones, to establish a solid scientific foundation for the development of high-performance composite materials.Keywords

In the high-altitude regions of western China, hydraulic engineering structures are subjected to complex environmental effects, including intense ultraviolet radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations, alternating dry-wet cycles, and high-sediment-laden flows. Overflow surfaces of hydraulic structures, such as spillway dams, flood discharge tunnels, and baffle piers, are particularly vulnerable to cracking, leakage, freeze-thaw damage, and erosion due to abrasion. These issues lead to concrete spalling and steel reinforcement exposure, significantly compromising the operational safety and service life of the infrastructure. Erosion, abrasion, and cavitation caused by high-velocity sediment-laden flows present persistent technical challenges that undermine the safety of overflow structures. Such damage can result in localized instability and failure of the energy dissipation structures in dams, posing a severe threat to the overall stability and safety of hydraulic systems. Current solutions to mitigate abrasion and erosion problems in hydraulic structures primarily focus on two approaches. First, abrasion-resistant materials are applied as protective coatings to concrete surface. Second, concrete mix designs are optimized to improve abrasion resistance, incorporating polymer fibers [1–4], abrasion-resistant aggregates [5–7], and anti-abrasion admixtures [8,9]. In parallel, advancing the sustainability of concrete has become a critical research priority, with a focus on identifying high-performance materials with minimal environmental impact. Numerous studies on the sustainability and performance optimization of construction materials have examined the effects of alternative materials, admixtures, and adjustments in key parameters on the physical-mechanical properties, durability, and service life of concrete [10–12]. These efforts are crucial for supporting low-carbon applications and promoting sustainable development [13–15].

Research has demonstrated that incorporating alternative materials can effectively enhance the wear resistance of self-compacting concrete (SCC). Meena et al. [16] found that SCC mixtures with up to 60% waste ceramic tiles exhibited superior mechanical properties compared to conventional mixtures. Zhu et al. [17] investigated the fracture behavior of SCC with varying rubber contents (0%, 10%, 20%, 30%) and revealed that rubber particles, with their flexible structure and improved deformation capacity compared to natural river sand, enhanced the bridging effect within the matrix and reduced stress concentration at crack tips. Sosa et al. [18] reported that steel fiber-reinforced concrete exhibited better carbonation resistance, freeze-thaw durability, and abrasion resistance than conventional concrete. Esquinas et al. [19] conducted comparative tests on three types of fly ash-based concrete mixtures, demonstrating that substituting siliceous filler with non-standard fly ash resulted in SCC with improved durability, corrosion resistance, and favorable shrinkage properties. Li et al. [20] compared the microstructure, mechanical properties, and durability of three concrete types: 100% Portland cement concrete, low-content fly ash concrete, and high-fly ash concrete. The results indicated that while the mechanical properties of high-fly ash concrete were relatively poor at early ages, they improved at later ages, providing good workability, impermeability, and abrasion resistance. Abed et al. [21] developed high-performance SCC using recycled aggregates and reclaimed fly ash, showing that an optimal mix with 50% recycled aggregates and 15% waste fly ash provided the best abrasion resistance. Boğa and Şenol [22] found that replacing gravel with basalt or recyclable marble aggregates at a ratio of 25% to 100% resulted in high-strength and durable SCC. Collectively, these studies confirm that the incorporation of supplementary materials can significantly improve the abrasion resistance of concrete [23,24].

This study focuses on developing SCC with enhanced abrasion resistance to mitigate erosion damage induced by high-velocity water flow under dry and low-humidity conditions. Initially, the effects of sand ratio and fly ash content on the compressive strength of concrete at various curing ages were investigated, and the fundamental mix proportions for SCC were determined. Subsequently, the influence of abrasion-resistance enhancement admixture (AEA) on the mechanical properties of SCC was systematically examined. The effects of varying AEA content on the workability, strength development, and durability of concrete were comprehensively evaluated. Finally, the impact of silica fume and steel fiber dosage on the abrasion resistance of concrete was quantitatively analyzed. The findings provide not only an effective strategy to enhance the abrasion resistance of SCC but also an experimental foundation for further related studies.

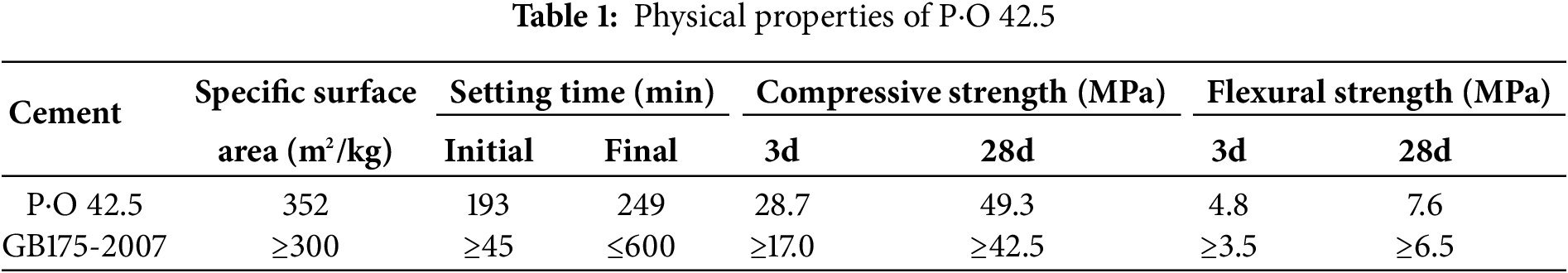

Portland cement (P·O 42.5) was used in this study, with its physical properties listed in Table 1. To improve the concrete performance, Class II fly ash (FA) was incorporated as a supplementary cementitious material. The sand and gravel aggregates were mechanically crushed, with the sand exhibiting a fineness modulus of 2.7. The gravel aggregates had a maximum particle size of 20 mm and an apparent density of 2700 kg/m3, with all properties conforming to standard specifications. A polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer (PCE) and an abrasion-resistance enhancement admixture (AEA) were used. Steel fibers, with a diameter ranging from 0.18 to 0.22 mm and a length between 12 and 14 mm, demonstrated excellent flexural performance and high purity. All raw materials underwent thorough physical testing and met the relevant standards.

The mechanical properties of concrete were evaluated using a digital compression testing machine (Model: HCT-206B), which ensured compliance with stiffness and surface flatness requirements for both compressive and splitting tensile tests. Abrasion resistance was assessed using an abrasion testing machine (Model: HKCM-2). All mechanical tests were conducted in accordance with the “Test Code for Hydraulic Concrete” (SL/T 352-2020) [25].

2.2 Experimental Design and Methods

To ensure that the experimental concrete satisfied the performance requirements in terms of workability, strength, and durability, a series of trial mix tests were conducted based on a reference mix proportion. These tests were carried out in accordance with the “Design Specification for Hydraulic Concrete Mix Proportions” (DL/T 5330-2015) [26] and the “Technical Specification for Application of Self-compacting Concrete” (CECS203-2021) [27]. The primary aim was to optimize aggregate gradation, sand-to-aggregate ratio, fly ash content, and superplasticizer dosage. The compressive strength was calculated using Eq. (1), while the abrasion resistance strength was determined using Eq. (2).

where:

where:

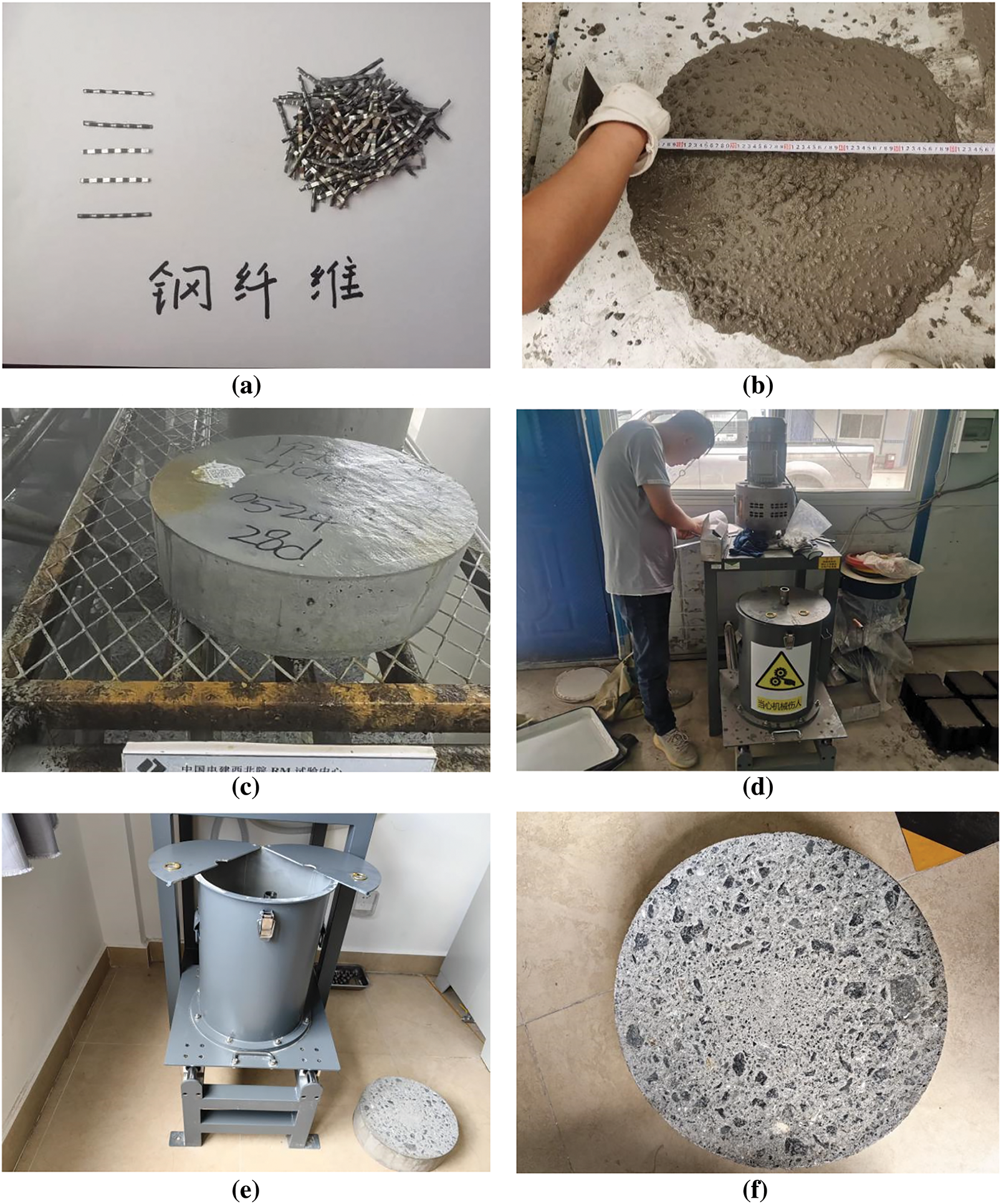

To ensure that the prepared concrete meets the mechanical performance requirements of SCC while facilitating comprehensive abrasion-resistance testing, a W/B ratio of 0.35 was adopted for the preliminary mix design. Five and content levels were selected: 42%, 44%, 45%, 47%, and 49%, along with eight fly ash replacement levels: 0%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 35%, and 40%. The preliminary mix test examined the influence of sand content on the compressive strength of concrete at curing ages of 3d, 7d, 28d, and 90d. A total of 156 standard cubic specimens (150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm) were prepared. Based on the results, a reference mix proportion was established for the subsequent abrasion resistance tests of SCC. The test design included five levels of AEA content: 0%, 0.5%, 0.8%, 1.0%, and 1.3%. Among these, the mix with 0% AEA served as the control group, and was tested for slump-flow, compressive strength at 7d and 28d, and abrasion resistance at 28d. Considering the multiple experimental factors, three SCC mixes with appropriate AEA contents were selected based on preliminary test outcomes. These were further modified by incorporating silica fume (SF) at dosages of 0.3%, 0.5%, 0.7%, and 0.9% to assess the effects of both AEA and SF on the self-compacting and abrasion-resistant properties of SCC. A total of 180 specimens were used in this phase. The experimental procedure for SCC is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Testing process of SCC. (a) Steel fiber (Length: 0.18~0.22 mm); (b) After blending slump-flow test; (c) Standard curing of specimens; (d) Abrasion resistance testing machine; (e) Abrasion resistance test; (f) Test specimen of abrasion resistance

3.1 Selection of Sand Ratio and Content of FA for Pre-Testing

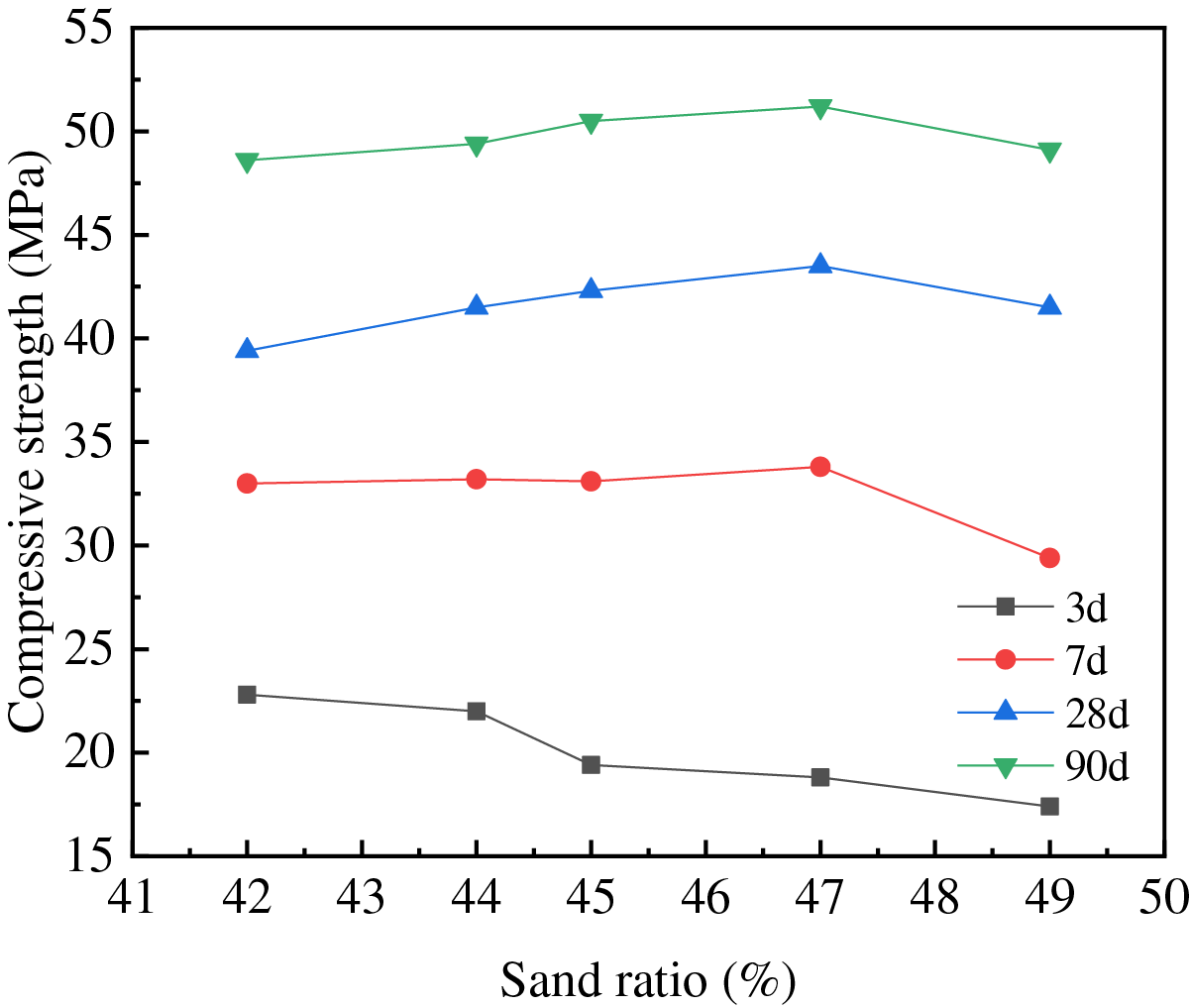

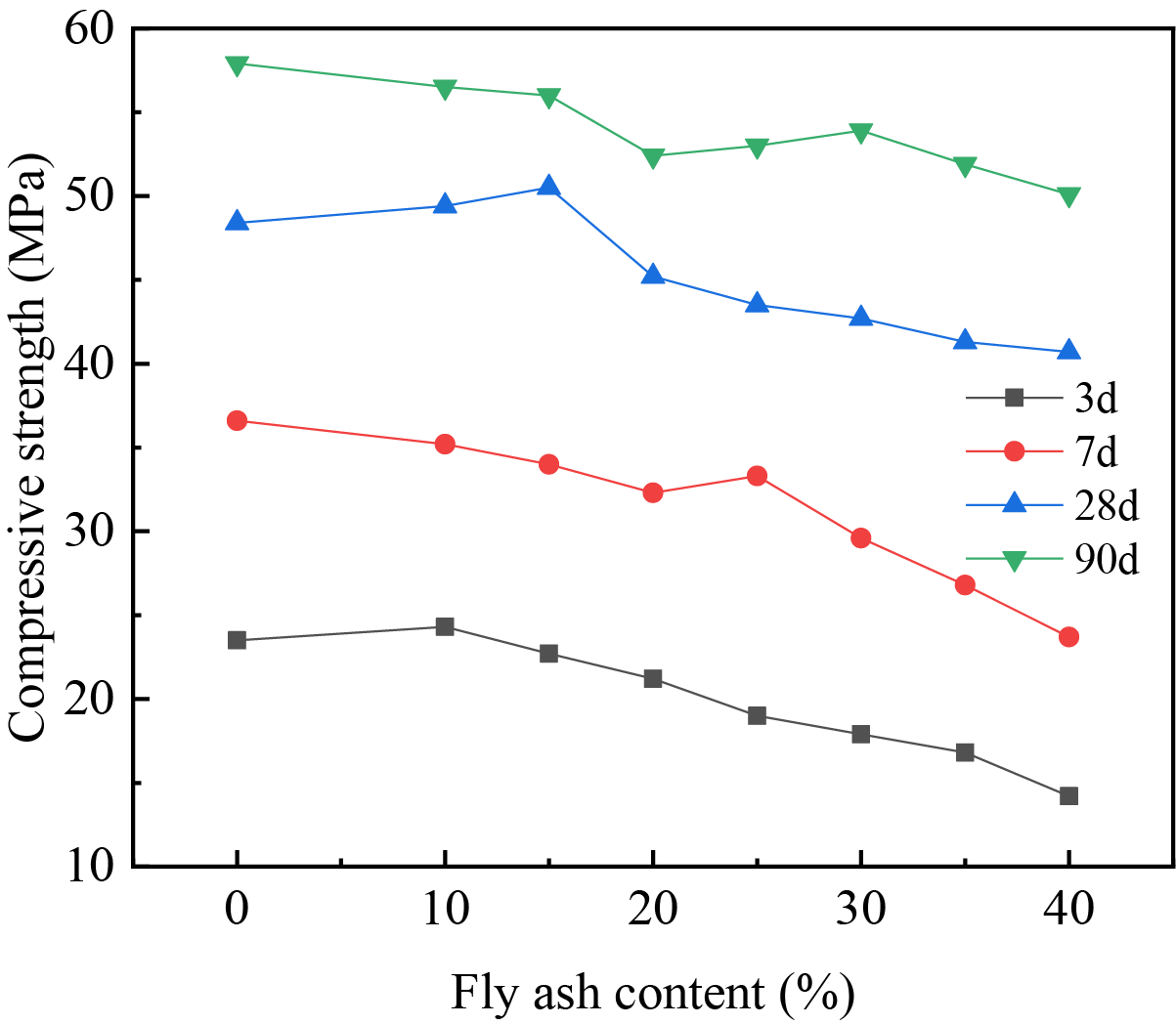

Figs. 2 and 3 illustrate the correlation sand ratio and concrete compressive strength at different curing ages, along with the variation in FA content.

Figure 2: Compressive strength under different sand ratios

Figure 3: Compressive strength under different content of FA

As illustrated in Fig. 2, no clear correlation is observed between the fluctuation of the sand ratio and the compressive strength of concrete. For mixtures with identical W/B ratios, variations in sand volume within a certain range exert minimal influence on compressive strength. While changes in sand content may affect the workability of the mixture, the compressive strength generally remains stable. It has been reported that the incorporation of FA can potentially reduce compressive strength; however, the addition of an appropriate amount of FA has been shown to significantly enhance it. The influence of varying FA contents on the compressive strength of SCC is evaluated in this study, as presented in Fig. 3. A notable reduction in early-age compressive strength is observed with increasing FA content. After 28d, the compressive strength continues to decline with higher FA dosage, though the rate of decrease slows. When the FA content exceeds a certain threshold, a continuous reduction in cement consumption is observed. Additionally, FA suppresses the early hydration rate of cement, lowers the heat of hydration, reduces the formation of early hydration products, and consequently decreases compressive strength.

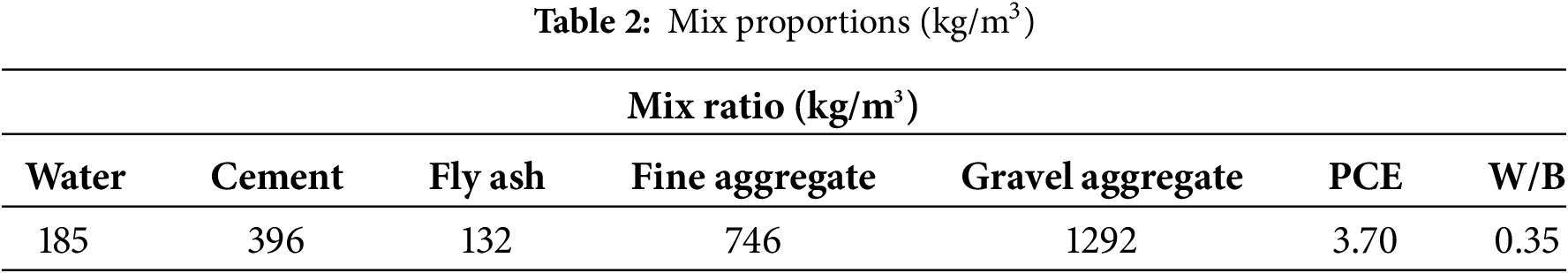

Based on the comprehensive preliminary test data and the observed slump flow and workability characteristics during the testing process, a sand ratio of 47% and an FA content of 25% were selected as the standard mix proportions for the SCC abrasion resistance test. The detailed mix proportions are listed in Table 2.

3.2 The Influence of Impact Resistant and Wear-Resistant Agents

3.2.1 The Relationship between Content of AEA and Slump-Flow

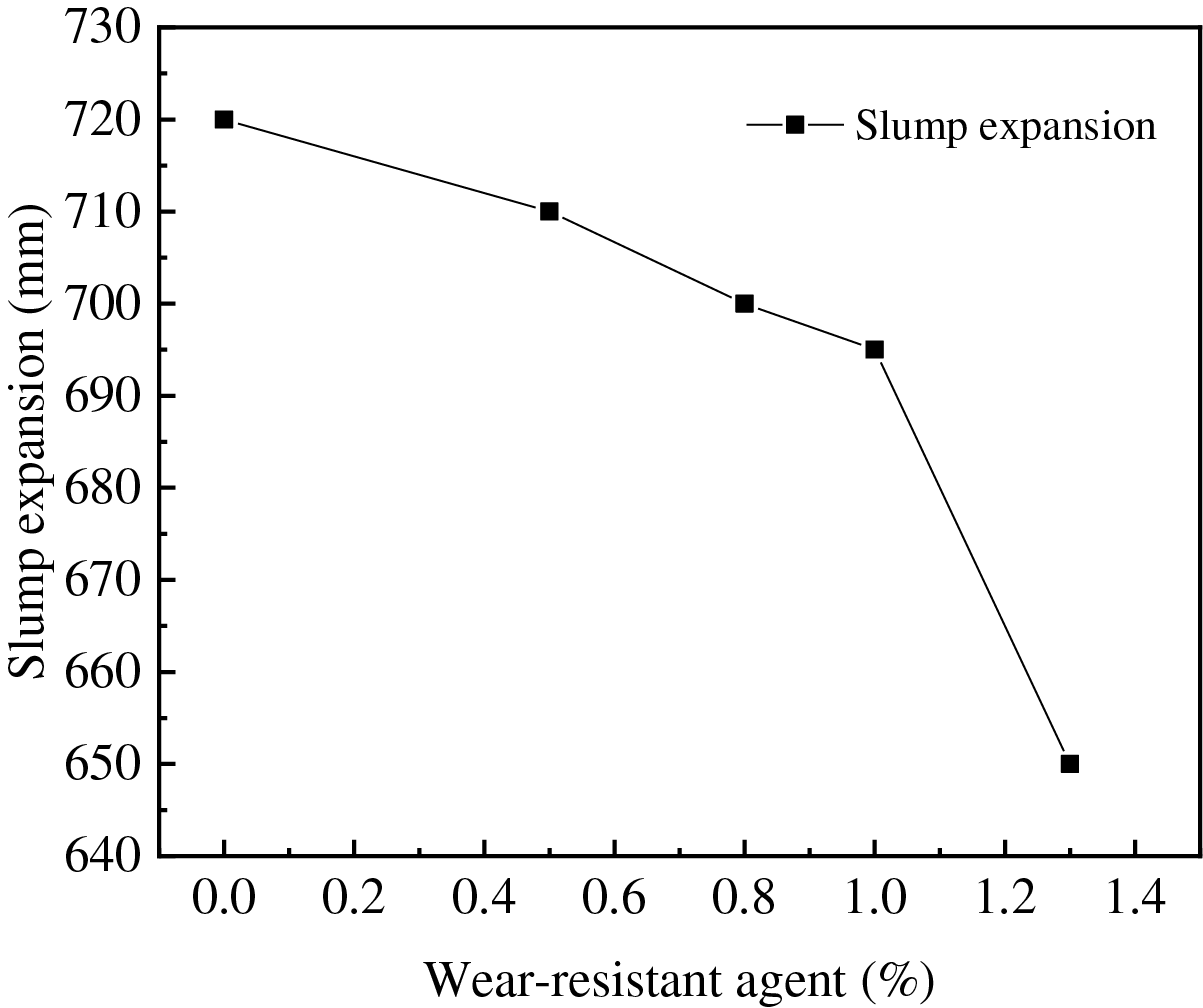

Fig. 4 illustrates the relationship between concrete slump-flow and varying AEA dosages.

Figure 4: Slump-flow under different content of AEA

As shown in Fig. 4, the slump-flow of concrete gradually decreases with increasing AEA content. When the AEA content is below 1%, the reduction in slump-flow is relatively minor. However, when the content exceeds 1%, a more pronounced decline in slum-flow is observed. After the addition of AEA, the slump-flow remains within the range of 650 mm to 710 mm. The incorporation of AEA enhances the workability of concrete to a certain extent. Nevertheless, when the AEA content surpasses 1%, the slump-flow exhibits a significant decrease followed by a subsequent increase.

3.2.2 The Correlation between the Content of AEA and Abrasion Resistance Strength

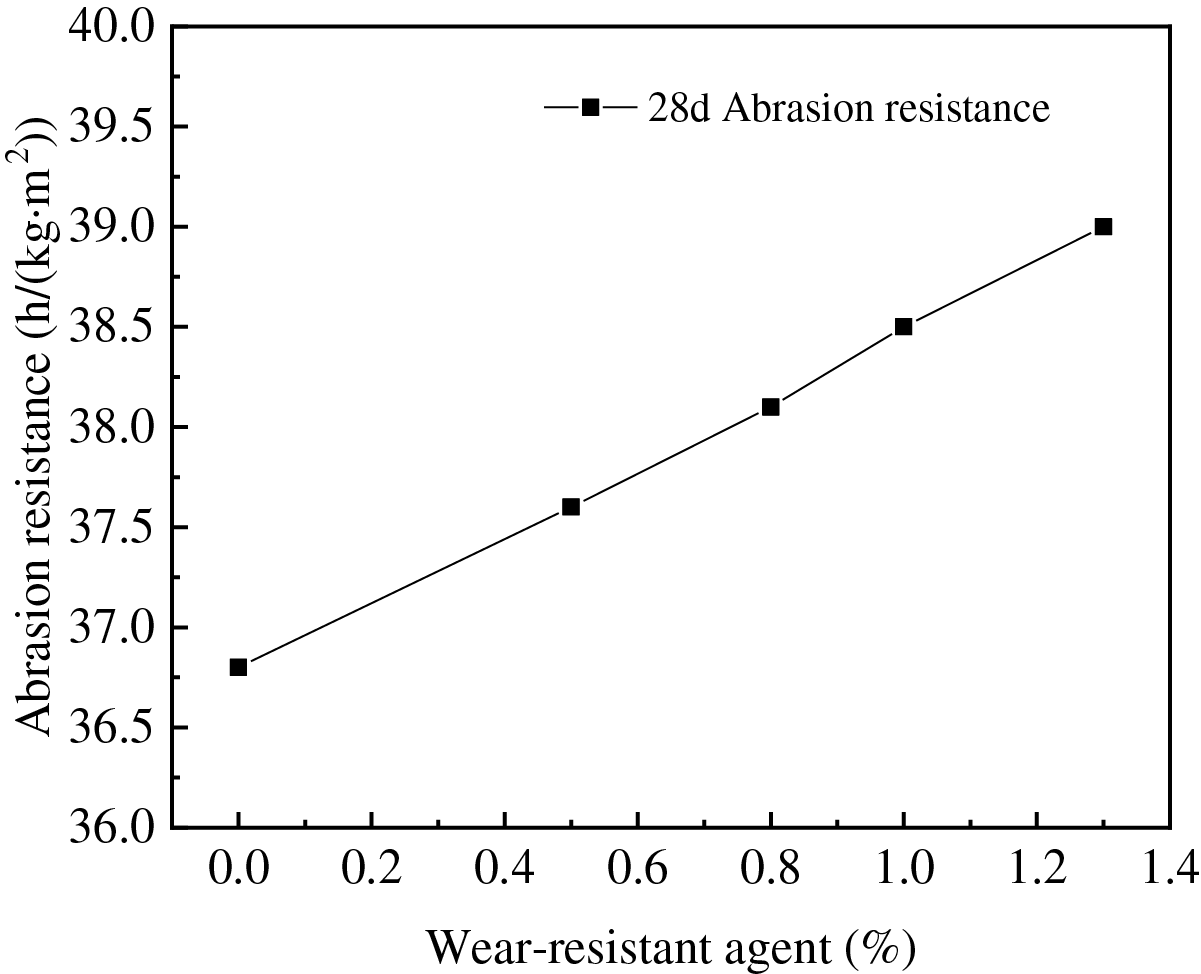

Fig. 5 illustrates the correlation between the 28d concrete abrasion resistance and varying quantities of AEA.

Figure 5: Abrasion resistance under different content of AEA

As shown in Fig. 5, a positive correlation is observed between the AEA content and the 28d abrasion resistance strength. The enhancement in abrasion resistance significantly improves the concrete’s strength against impact and abrasion. The AEA modifies the concrete’s pore structure by reducing the volume of large pores in the binder while increasing the number of small and micro-pores. These pores are isolated from one another, leading to improved water and air tightness, which reduces the potential for corrosion damage and contributes to a substantial improvement in impact and wear resistance.

3.2.3 The Correlation between the Content of AEA and the Compressive Strength

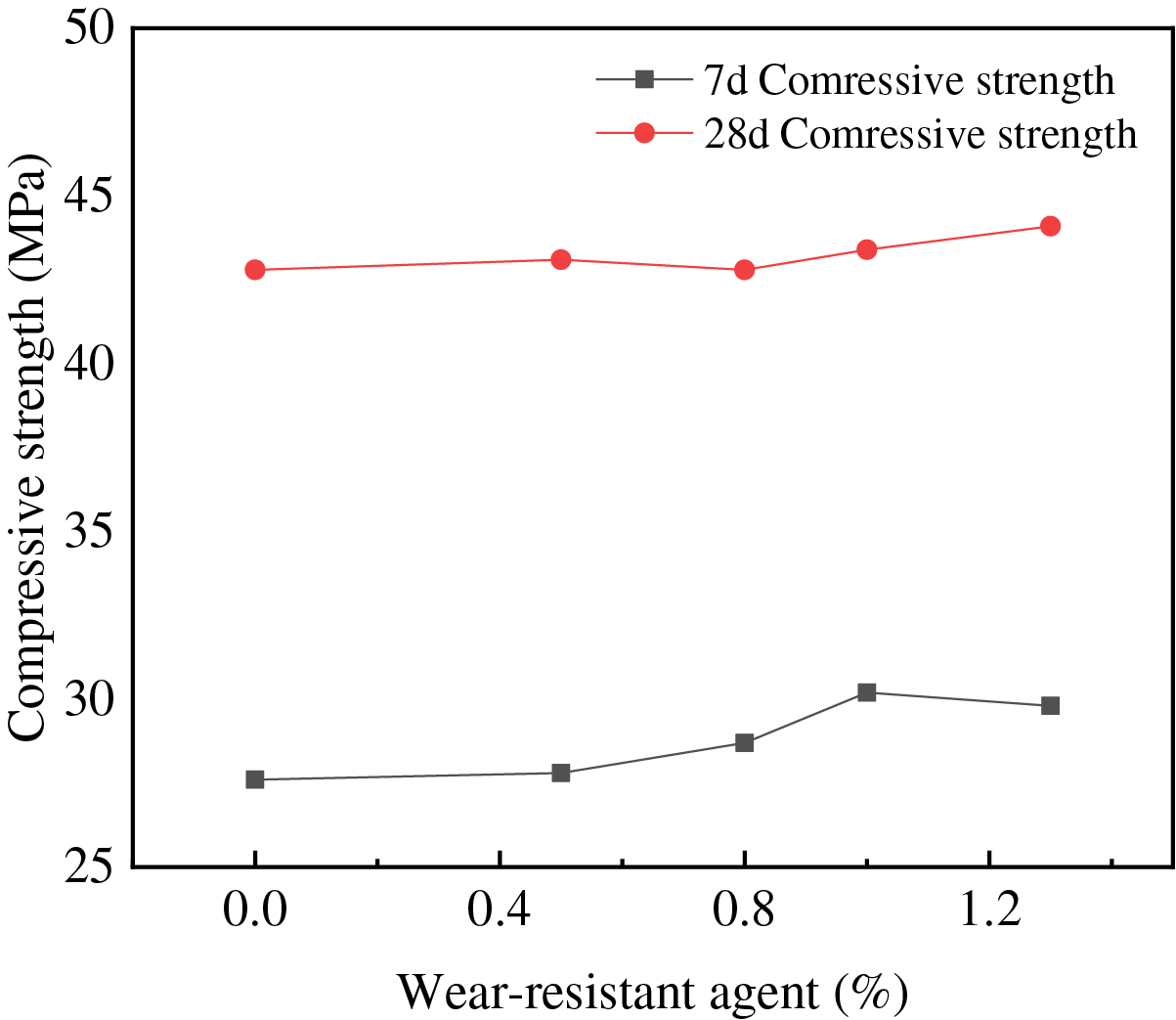

Fig. 6 illustrates the correlation between the compressive strength of concrete at 7d and 28d and the varying dosages of AEA.

Figure 6: Compressive strength under different content of AEA at 7d and 28d ages

Fig. 6 shows that the compressive strength of concrete at both 7d and 28d increases overall with the addition of AEA, although the growth is relatively modest. At 7 days, the highest compressive strength of concrete is achieved with 1.0% AEA, reaching 30.2 MPa. Compared to the reference concrete without AEA at the same age, the compressive strength increases by 2.6 MPa, corresponding to a 9.4% increase. At 28 days, the maximum compressive strength is observed at 1.3% AEA, reaching 44.1 MPa. In contrast, the reference concrete without AEA shows an increase of 1.3 MPa at the same age, representing a 3% increase. AEA exhibits excellent water-reducing effects, improving the workability of the concrete. Additionally, it activates the activity of fly ash, promoting the formation of dense and hard hydration products of cementitious materials, improving the interface between the cementitious materials and aggregates, and significantly enhancing the overall compressive strength of the concrete. In conclusion, AEA positively influences the compressive strength of concrete at different ages, although the extent of improvement may be limited.

3.3 The Effect of Silica Fume on the Concrete Properties

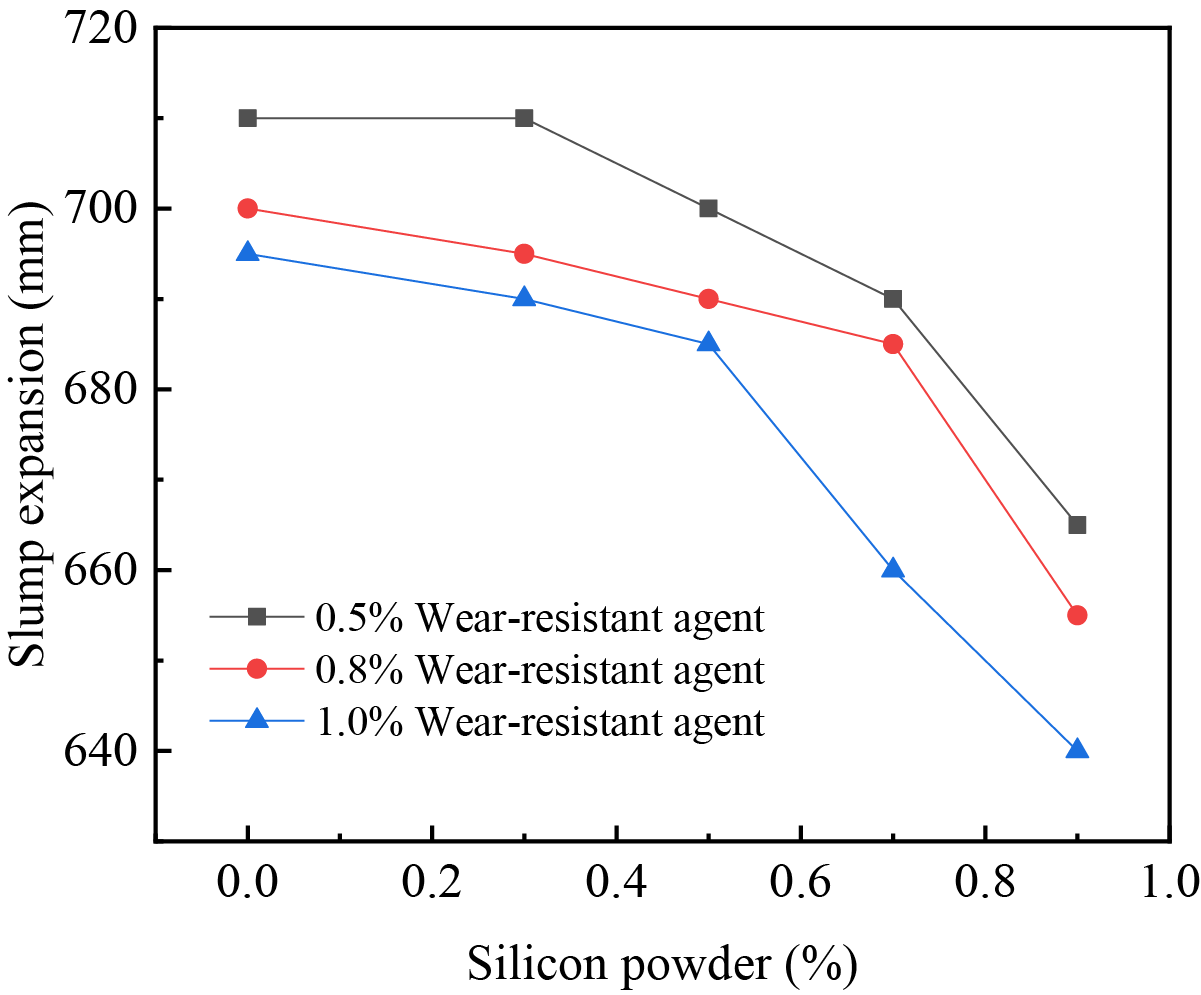

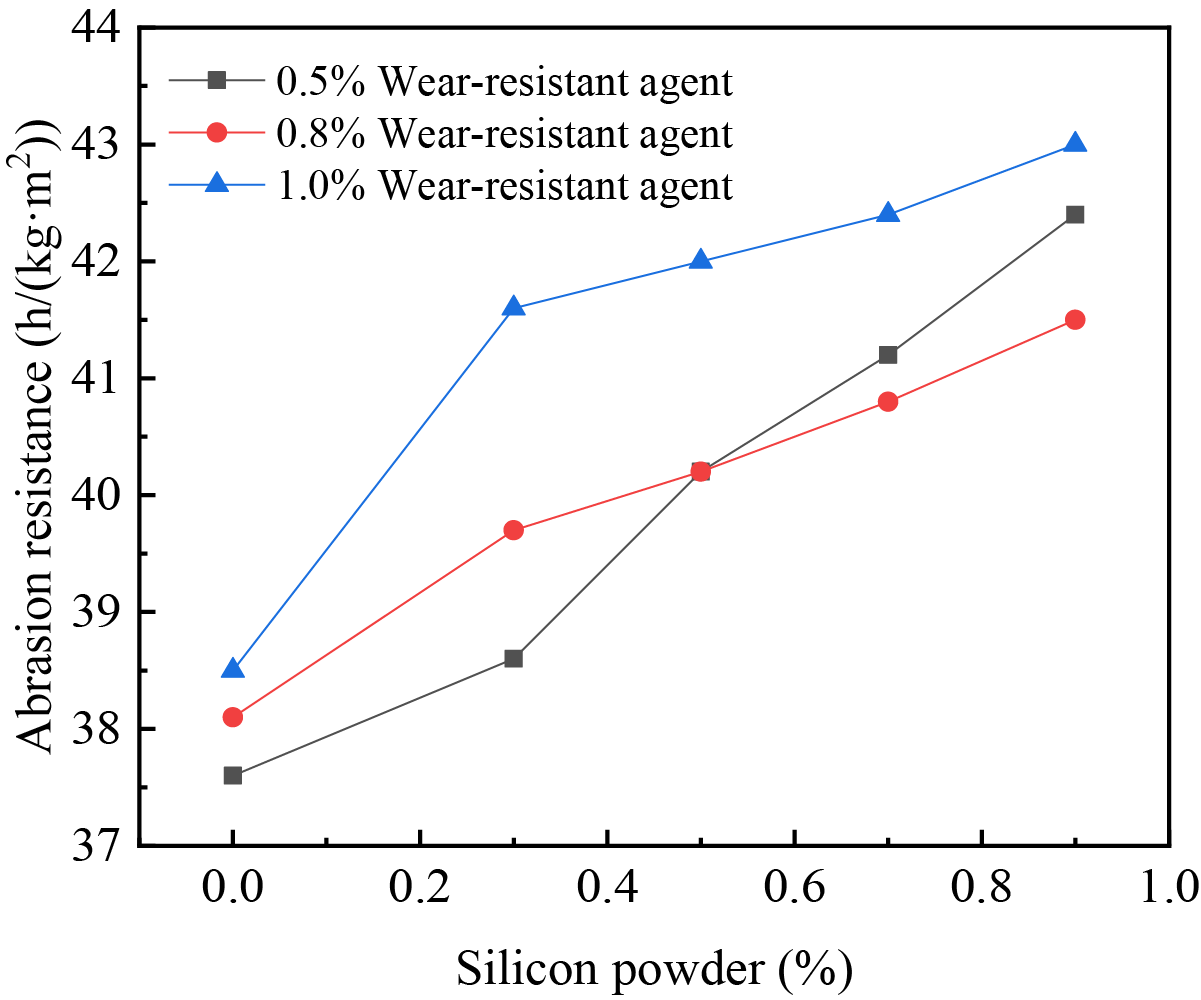

Based on the experimental results of SCC with added AEA, representative self-compacting concrete mixtures containing 0.5%, 0.8%, and 1.0% AEA were selected as baseline samples to improve the abrasion resistance of the concrete. Subsequently, silica fume was incorporated at concentrations of 0.3%, 0.5%, 0.7%, and 0.9% to further investigate the self-compacting properties and abrasion resistance of the concrete. The relationship between silica fume content and the slump-flow is shown in Fig. 7, while the effect of varying silica fume content on the abrasion resistance strength at 28d is presented in Fig. 8.

Figure 7: Slump-flow under different content of silica fume

Figure 8: Abrasion resistance of concrete with silica fume

As shown in Fig. 7, under the conditions of 0.5%, 0.8%, and 1.0% AEA, the slump-flow of concrete decreases with increasing silica fume content. When the silica fume content exceeds 0.5%, the rate of slump-flow reduction accelerates in all three concrete groups, leading to a gradual decline in the self-compacting performance of the concrete. Additionally, for the same silica fume content, the AEA content required for the slump-flow of concrete decreases in the following order: 0.5%, 0.8%, and 1.0%. Fig. 8 illustrates that, under varying AEA dosages, the abrasion resistance strength of concrete increases with higher silica fume content. Compared to the three concrete groups, the abrasion resistance strength shows notable improvement. When the AEA content is 0.5%, the abrasion resistance strength increases from 37.6 to 42.4 h/(kg·m2), representing a 12.8% increase. At 0.8% AEA content, the abrasion resistance strength rises from 38.1 to 43.6 h/(kg·m2), a 14.4% increase. When the AEA content is 1.0%, the strength increases from 38.5 to 43.0 h/(kg·m2), showing an 11.7% improvement. This significant increase enhances the abrasion resistance of the concrete to a certain extent. The analysis indicates that the activator in the anti-abrasion agent has significantly increased the reactivity of silica fume in the concrete, promoting its reaction with calcium hydroxide (a hydration product of cement) to form S-C-H gel. This process improves the overall strength of the concrete, making its gel products denser, harder, and more abrasion-resistant. It also enhances the interface between the cement paste and aggregates, resulting in a more uniform concrete structure. Consequently, this improves the concrete’s crack resistance and its ability to withstand cavitation erosion and pulsating pressure from high-speed sediment-laden water flow, thereby achieving the goal of enhancing the concrete’s abrasion resistance performance.

3.4 The Effect of Steel Fiber on the Concrete Properties

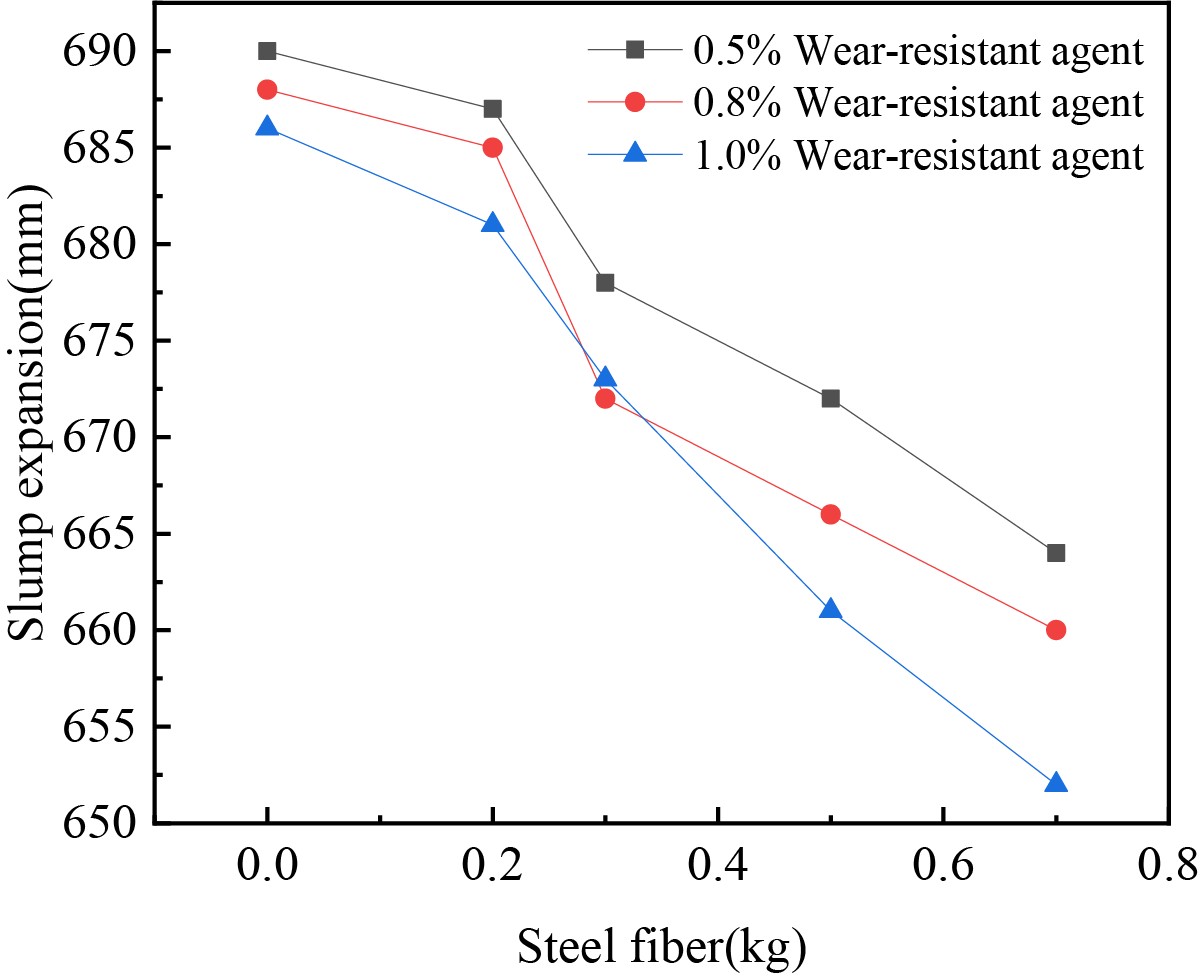

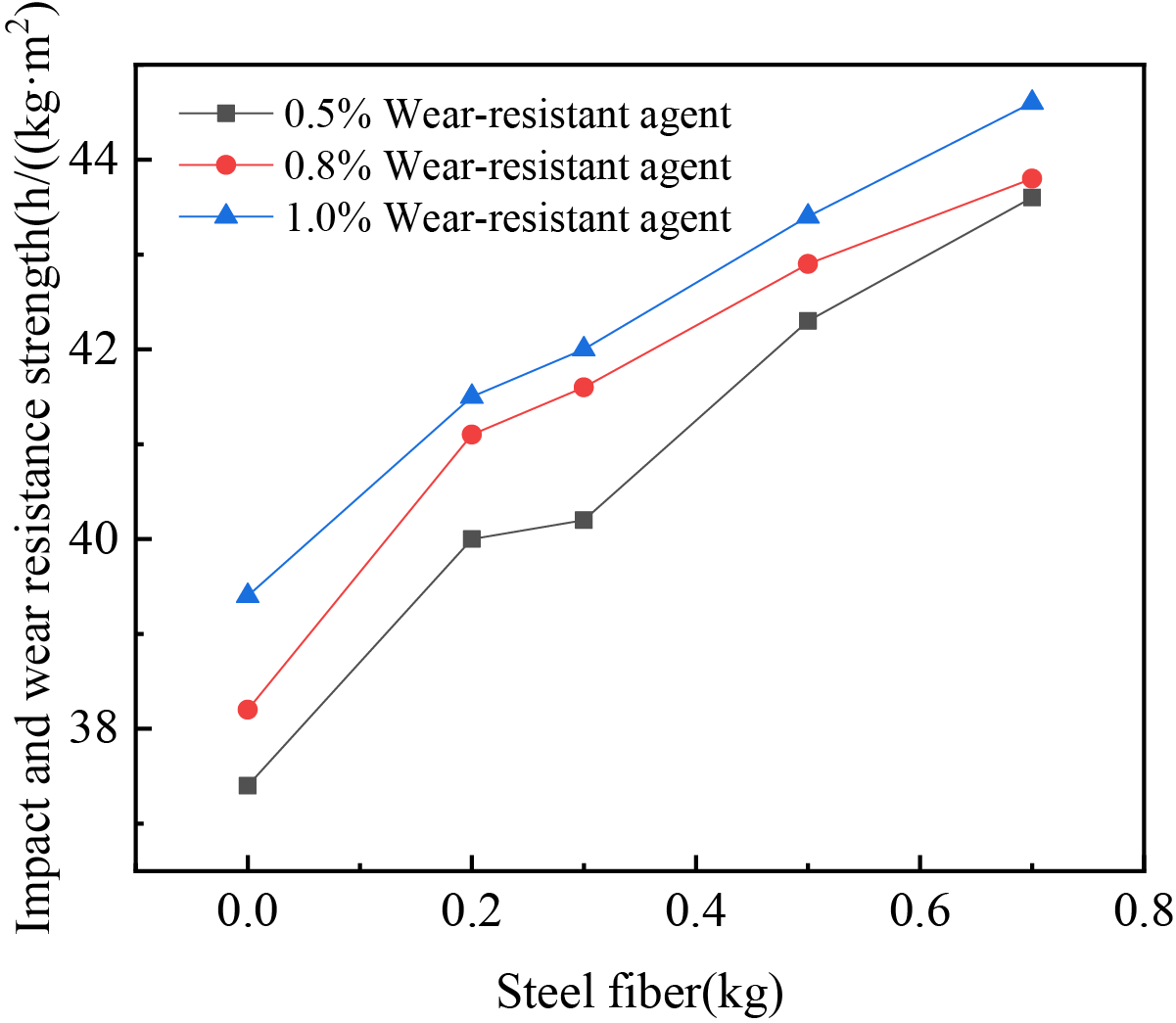

Due to the excessive use of cementitious materials in self-compacting concrete and the significant heat generated during hydration, concrete is susceptible to cracking even in the absence of vibration. To enhance its durability and improve resistance to cracking, especially in thin-walled structures, the incorporation of steel fibers is beneficial. In this study, self-compacting concrete mixes with AEA at concentrations of 0.5%, 0.8%, and 1.0% were selected. Steel fibres were added at dosages of 0, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 kg to investigate their effects on the slump-flow and abrasion resistant strength of the concrete. The relationship between varying steel fiber contents and the slump-flow of self-compacting concrete is shown in Fig. 9. Additionally, Fig. 10 illustrates the relationship between steel fiber content and the abrasion resistance strength at 28d.

Figure 9: Slump-flow concrete with steel fiber

Figure 10: Abrasion resistance of concrete with steel fiber

From Fig. 9, it is evident that as the steel fiber content increases, the slump-flow of concrete decreases under AEA conditions of 0.5%, 0.8%, and 1.0%. When the steel fiber content exceeds 0.2 kg, the reduction in slump-flow becomes more pronounced across all three concrete mixes, leading to a gradual decline in self-compacting performance. Furthermore, for the same steel fiber content, the corresponding AEA contents required for the slump-flow to range from high to low are 0.5%, 0.8%, and 1.0%, respectively. Varying volumes of steel fiber are incorporated into the self-compacting and abrasion-resistant concrete mixes, ensuring that the slump-flow meets the required range of 700 ± 50 mm. As shown in Fig. 10, the abrasion resistance of the concrete increases with higher steel fiber content under varying AEA dosages. Notably, compared to the three concrete groups, there is a significant enhancement in both impact and abrasion resistance strength. At an AEA content of 0.5%, the abrasion resistance increases from 37.4 to 43.6 h/(kg·m2), a 16.58% increase. Similarly, at 0.8% AEA content, the strength rises from 38.2 to 43.8 h/(kg·m2), reflecting a 14.66% increase. At 1.0% AEA, the strength increases from 39.4 to 44.6 h/(kg·m2), corresponding to a 13.20% increase. This substantial improvement notably enhances the abrasion resistance of the concrete. While the inclusion of steel fiber may reduce the workability of self-compacting concrete, an optimized experimental mix ratio and appropriate mixing methods can improve the internal structure of fiber-reinforced concrete. Such approaches help mitigate the formation of detrimental pore defects and maximize the reinforcing and toughening effects of the fiber. Consequently, this facilitates the preparation of self-compacting concrete with steel fibers that meet the required construction standards.

Variations in sand ratio notably influence the workability of concrete mixtures, whereas their effect on compressive strength is minimal. Conversely, increasing fly ash content leads to a reduction in compressive strength, although the rate of decline diminishes with prolonged curing. Self-compacting concrete incorporating 47% sand and 25% fly ash exhibits comparatively favorable mechanical performance.

As the dosage of AEA increases, the slump-flow of concrete gradually decreases, with a more pronounced reduction observed when the dosage exceeds 1%. While AEA significantly improves abrasion resistance, its contribution to compressive strength enhancement at various curing ages is relatively limited. At AEA dosages of 0.5%, 0.8%, and 1.0%, slump-flow declines with increasing silica fume content, and this reduction becomes substantial when the silica fume content exceeds 0.5%. Moreover, slump-flow decreases markedly when the steel fiber content exceeds 0.2 kg/m3.

The combined use of abrasion-resistant admixtures, silica fume, and steel fiber enhances the overall mechanical strength of concrete, promotes matrix densification, and significantly improves abrasion resistance.

Given the harsh service conditions encountered by hydraulic concrete structures, future research should emphasize long-term durability monitoring. By replicating hydraulic environments—such as high-velocity water flow, freeze-thaw cycling, and salt spray exposure—systematic investigations can be carried out on the evolution of mechanical properties in self-compacting, abrasion-resistant concrete. Furthermore, advanced microstructural characterization techniques should be employed to examine the effects of abrasion-resistant agents, silica fume, and steel fibers on hydration products, pore structure, and the interfacial transition zone, thereby supporting the optimized design of composite materials.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledged the invaluable support and assistance provided by all technical and laboratory staff who contributed to the experimental work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52179137).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Yongdong Meng, Zhenglong Cai; Investigation: Yongdong Meng, Jindong Xie, Zhenglong Cai, Xiaowei Xu; Methodology: Yongdong Meng, Zhenglong Cai, Yu Lyu; Data curation: Zhenglong Cai; Writing—original draft: Yongdong Meng, Zhenglong Cai; Writing—review & editing: Weixi Zhu, Yongdong Meng; Resources: Weixi Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data and materials will be made available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Felekoğlu B, Türkel S, Altuntaş Y. Effects of steel fiber reinforcement on surface wear resistance of self-compacting repair mortars. Cem Concr Compos. 2007;29(5):391–6. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.12.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Haigh R. The mechanical behaviour of waste plastic milk bottle fibres with surface modification using silica fume to supplement 10% cement in concrete materials. Constr Build Mater. 2024;416(22):135215. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Gopinath M, Abimaniu P, Dharsan Rishi C, Pravinkumar K, Tejeshwar PG. Experimental investigation on waste plastic fibre concrete with partial replacement of coarse aggregate by recycled coarse aggregate. Mater Today Proc Forthcoming. 2023;126(4):4690. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.04.573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Huynh TP, Ho Minh Le T, Vo Chau Ngan N. An experimental evaluation of the performance of concrete reinforced with recycled fibers made from waste plastic bottles. Results Eng. 2023;18:101205. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sherwani AFH, Faraj R, Younis KH, Daraei A. Strength, abrasion resistance and permeability of artificial fly-ash aggregate pervious concrete. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2021;14:e00502. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang C, Wang Z, Liu S, Luo H, Fan W, Liu Z, et al. Anti-corrosion and wear-resistant coating of waterborne epoxy resin by concrete-like three-dimensional functionalized framework fillers. Chem Eng Sci. 2021;242:116748. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2021.116748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li T, Liu X, Wei Z, Zhao Y, Yan D. Study on the wear-resistant mechanism of concrete based on wear theory. Constr Build Mater. 2021;271(3):121594. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yön MŞ, Arslan F, Karatas M, Benli A. High-temperature and abrasion resistance of self-compacting mortars incorporating binary and ternary blends of silica fume and slag. Constr Build Mater. 2022;355(2):129244. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Witzke FB, Beltrame NAM, Angulski da Luz C, Medeiros-Junior RA. Abrasion resistance of metakaolin-based geopolymers through accelerated testing and natural wear. Wear. 2023;530-531(4):204996. doi:10.1016/j.wear.2023.204996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Adegbemileke SA, Osuji SO, Ogirigbo OR. An assessment of the pozzolanic potential and mechanical properties of Nigerian calcined clays for sustainable ternary cement blends. Sustain Struct. 2024;4(3):000057. doi:10.54113/j.sust.2024.000057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mohamed OA, Zuaiter HA, Jawa MM. Carbonation and chloride penetration resistance of sustainable structural concrete with alkali-activated and ordinary Portland cement binders: a critical review. Sustain Struct. 2025;5(2):000075. doi:10.54113/j.sust.2025.000075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sathiparan N, Subramaniam DN. Optimizing fly ash and rice husk ash as cement replacements on the mechanical characteristics of pervious concrete. Sustain Struct. 2025;5(1):1000065. doi:10.54113/j.sust.2025.000065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chowdhury JA, Islam MS, Islam MA, Al Bari MA, Debnath AK. Analysis of mechanical properties of fly ash and boiler slag integrated geopolymer composites. Sustain Struct. 2025;5(2):000073. doi:10.54113/j.sust.2025.000073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rosti F, Iselobhor VI, Hossienpour F, Gopu V, Cooper S. Experimental study on the strength behavior of concrete reinforced with cornhusk fiber. Steps Civ Constr Environ Eng. 2025;3(1):1–12. doi:10.61706/sccee1201124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sukkari A, Al-Khateeb G, Wajeeh M, Ezzat H, Zeiada W. Impact of sasobit on asphalt binder’s performance under UAE local conditions. Steps Civ Constr Environ Eng. 2024;2(3):1–8. doi:10.61706/sccee1201120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Meena RV, Jain JK, Chouhan HS, Mandolia R, Beniwal AS. Impact of waste ceramic tile on resistance to fire and abrasion of self-compacting concrete. Mater Today Proc. 2022;60:167–72. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.12.287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhu X, Chen X, Tian H, Ning Y. Experimental and numerical investigation on fracture characteristics of self-compacting concrete mixed with waste rubber particles. J Clean Prod. 2023;412(5):137386. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sosa I, Thomas C, Polanco JA, Setién J, Sainz-Aja JA, Tamayo P. Durability of high-performance self-compacted concrete using electric arc furnace slag aggregate and cupola slag powder. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;127:104399. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Esquinas AR, Álvarez JI, Jiménez JR, Fernández JM. Durability of self-compacting concrete made from non-conforming fly ash from coal-fired power plants. Constr Build Mater. 2018;189:993–1006. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li Y, Wu B, Wang R. Critical review and gap analysis on the use of high-volume fly ash as a substitute constituent in concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2022;341(3):127889. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Abed M, Rashid K, Rehman MU, Ju M. Performance keys on self-compacting concrete using recycled aggregate with fly ash by multi-criteria analysis. J Clean Prod. 2022;378:134398. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Boğa AR, Şenol AF. The effect of waste marble and basalt aggregates on the fresh and hardened properties of high strength self-compacting concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2023;363(10–11):129715. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yao Q, Qi S, Wu F, Yang X, Li H. Abrasion-resistant and temperature control of lining concrete for large-sized spillway tunnels. Appl Sci. 2020;10(21):7614. doi:10.3390/app10217614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wu S, Jiang SF, Shen S, Wu Z. The mix ratio study of self-stressed anti-washout underwater concrete used in nondrainage strengthening. Materials. 2019;12(2):324. doi:10.3390/ma12020324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. SL/T352-2020. Test code for hydraulic concrete. Beijing, China: China Water Resources Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

26. DL/T5330-2015. Code for mix design of hydraulic concrete. Beijing, China: China Electric Power Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

27. CECS203-2021. Technical specification for application of self-compacting concrete. Beijing, China: The National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China; 2021. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools