Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Recent Efforts on the Compressive and Tensile Strength Behavior of Thermoplastic-Based Recycled Aggregate Concrete toward Sustainability in Construction Materials

1 Department of Civil Engineering, Cyprus International University, Nicosia, 99628, North Cyprus via Mersin 10, Türkiye

2 Department of Civil Engineering, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, 99628, Cyprus

3 Department of Architecture, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, 99628, Cyprus

4 Departement of Civil Engineering, İstanbul Kültür Üniversitesi, Istanbul, 34156, Türkiye

5 Research Institute of Sciences and Engineering, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, 27272, United Arab Emirates

6 Faculty of Civil Engineering, Damascus University, Damascus, Syria

* Corresponding Author: Ahed Habib. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Sustainable and Durable Construction Materials)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2026, 20(1), . https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.070194

Received 10 July 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 08 January 2026

Abstract

Concrete production often relies on natural aggregates, which can lead to resource depletion and environmental harm. In addition, improper disposal of thermoplastic waste exacerbates ecological problems. Although significant attention has recently been given to recycling various waste materials into concrete, studies specifically addressing thermoplastic recycled aggregates are still trending. This underscores the need to comprehensively review existing literature, identify research trends, and recognize gaps in understanding the mechanical performance of thermoplastic-based recycled aggregate concrete. Accordingly, this review summarizes recent investigations focused on the mechanical properties of thermoplastic-based recycled aggregate concrete, emphasizing aspects such as compressive strength, tensile behavior, modulus of elasticity, and durability characteristics. The primary aim is to consolidate scattered research findings, identify key parameters influencing mechanical behavior, and propose future research directions. Understanding the influence of recycled thermoplastic aggregates on concrete performance significantly supports sustainable construction practices by reducing dependency on virgin aggregates and mitigating environmental impacts associated with waste disposal. In addition, assessing mechanical performance contributes to confidence in the practical application, encouraging the broader adoption of thermoplastic-based recycled aggregate concrete in construction projects. Through this critical synthesis, the review guides researchers and industry practitioners toward informed decisions on the feasibility and reliability of integrating thermoplastic waste into concrete, thereby promoting sustainable infrastructure development.Keywords

Thermoplastic wastes, from road-marking residues, industrial coatings and flaking architectural paints, are rich in polymeric binders (ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), polyamide, polypropylene (PP), polystyrene) that impart hydrophobicity and flexibility but inhibit cement bonding [1–3]. Proper valorization begins with thorough contaminant removal (adhesive films, pigments) and precise size grading to yield coarse and fine recycled aggregates [4–8]. Gámez-García et al. [9] classified and cleaned thermoplastic-based coarse aggregates before replacing 5%–20% of natural stone in pedestrian-scale concrete mixes, demonstrating feasibility for sidewalks and curbs. Mohammadian and Haghi [10] extended this approach to thermosetting wastes, crushing cured resin scraps into lightweight fine aggregates, while Surendranath and Ramana [11] showed that Bakelite particles up to 15% could substitute fine aggregate in fly-ash-based concrete. Surface-treatment strategies further enhance matrix-aggregate cohesion. Various studies [12–17] pioneered coatings of low-dose EVA and nanosilica on recycled plastic particles, tailoring interfacial transition zones to mitigate porosity and water sorptivity. Such hybrids have been applied in both mortar systems and sand-replacement concrete, consistently improving bond integrity without forfeiting lightweight benefits. Fiber reinforcement broadens the performance envelope of plastic-aggregate concretes [18–21]. For instance, Meng et al. [22] investigated steel vs. polypropylene fibers at 50% replacement, Hong et al. [23] and Gao et al. [24,25] compared single and hybrid fiber geometries, and Gayake and Desai [26] demonstrated multifunctional PET fibers that simultaneously boost flexural capacity and reduce thermal conductivity. Beyond conventional mixes, thermoplastic wastes have appeared in polymer concrete [27], masonry blocks with granulated polystyrene plus polypropylene fibers [28,29], and 3D-printed cementitious composites using ETM microspheres alongside recycled glass [30]. In bituminous paving, Sambaturu et al. [31] blended low density polythene (LDPE) and demolition plastics with mineral aggregates, Khoury et al. [32] created permeable “geoplastics” by mixing PET bottle strips with soil, other studies have also investigated this application [33–39]. Durability-focused work includes freeze-thaw modeling of PP-fiber mixes with water-reducing agents [40], comparative freeze-thaw trials against virgin-aggregate concrete [41], sulfur polymer concretes using recycled aggregates [42], and chloride-ingress modeling via Fick’s second law [43]. Collectively, these studies underscore the importance of standardized aggregate characterization, life-cycle assessment and long-term, multi-hazard performance data to transition thermoplastic-based aggregates from laboratory demonstrations to mainstream, sustainable construction materials [6,44–47]. On the other hand, this review isolates thermoplastic-based recycled aggregates from broader recycled aggregate concrete streams and summarizes their compressive and tensile strength behavior. The contribution herein aims to provide important information to support the production of green construction materials.

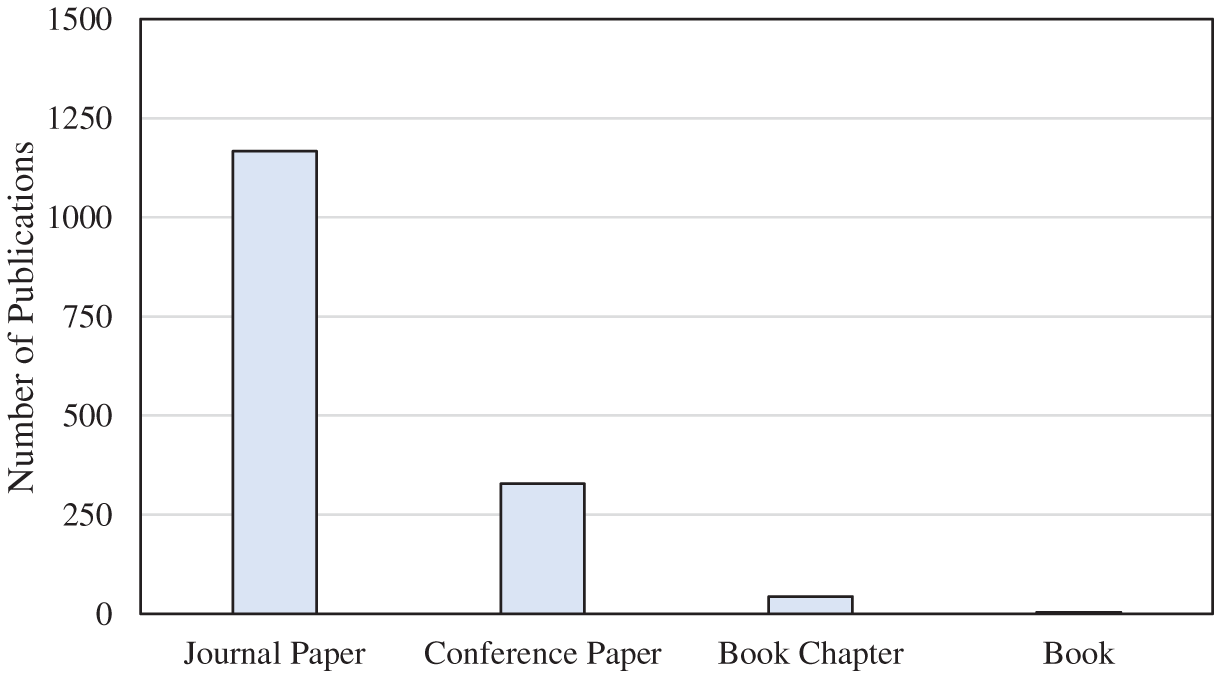

This section reports the findings of a bibliometric study aimed at outlining how research has progressed around concrete mixtures that include recycled plastic aggregates. As part of this analysis, a search in Scopus targeting records with the terms “recycled aggregate concrete” and “plastics” in titles, abstracts, or keywords was conducted. This search yielded 1543 publications spanning from the year 2000 to the beginning of 2025. The data herein were annual English language publication output related to thermoplastic-based recycled aggregates retrieved from Scopus in June 2025 without any filters other than the keyword search, making our results inclusive of articles published in multidisciplinary as well as field-specific journals. Of these, 1167 were journal articles. Conference papers contributed 328 entries, followed by 44 book chapters and four books, as shown in Fig. 1. This distribution points to a strong preference for journal outlets in publishing research on this subject.

Figure 1: Types of Scopus-indexed studies on concrete mixtures with recycled aggregates from plastics

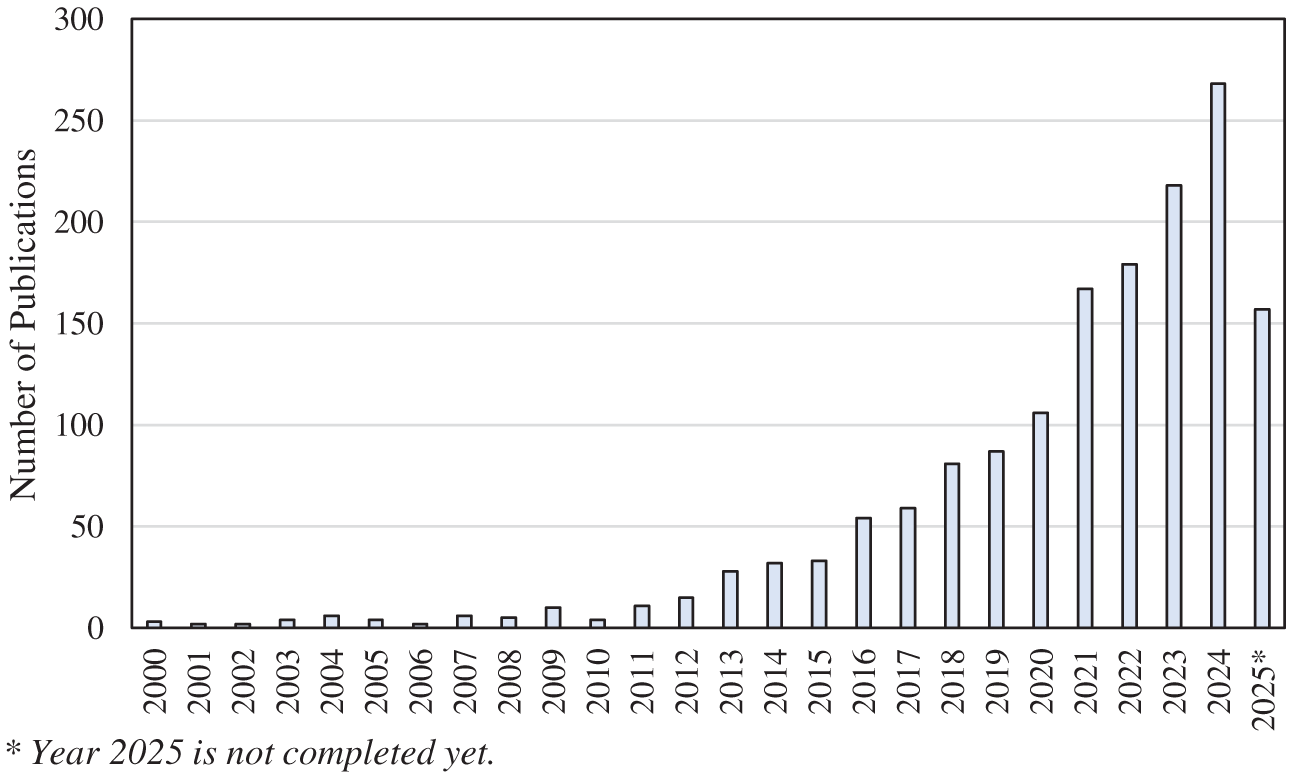

During the first decade, the annual publication count remained low, staying below ten entries per year until 2009. After that, the numbers began to climb. In 2015, the output reached 33 publications, increasing to 54 the following year. From there, the rise continued steadily, reaching 218 in 2023. In 2024, the total peaked at 268. Preliminary data for 2025 already show 157 entries, although the year is still in progress (Fig. 2). The upward trend suggests a growing focus on research into waste-based materials for construction.

Figure 2: Number of yearly publications on concrete mixtures with recycled aggregates from plastics in the Scopus database

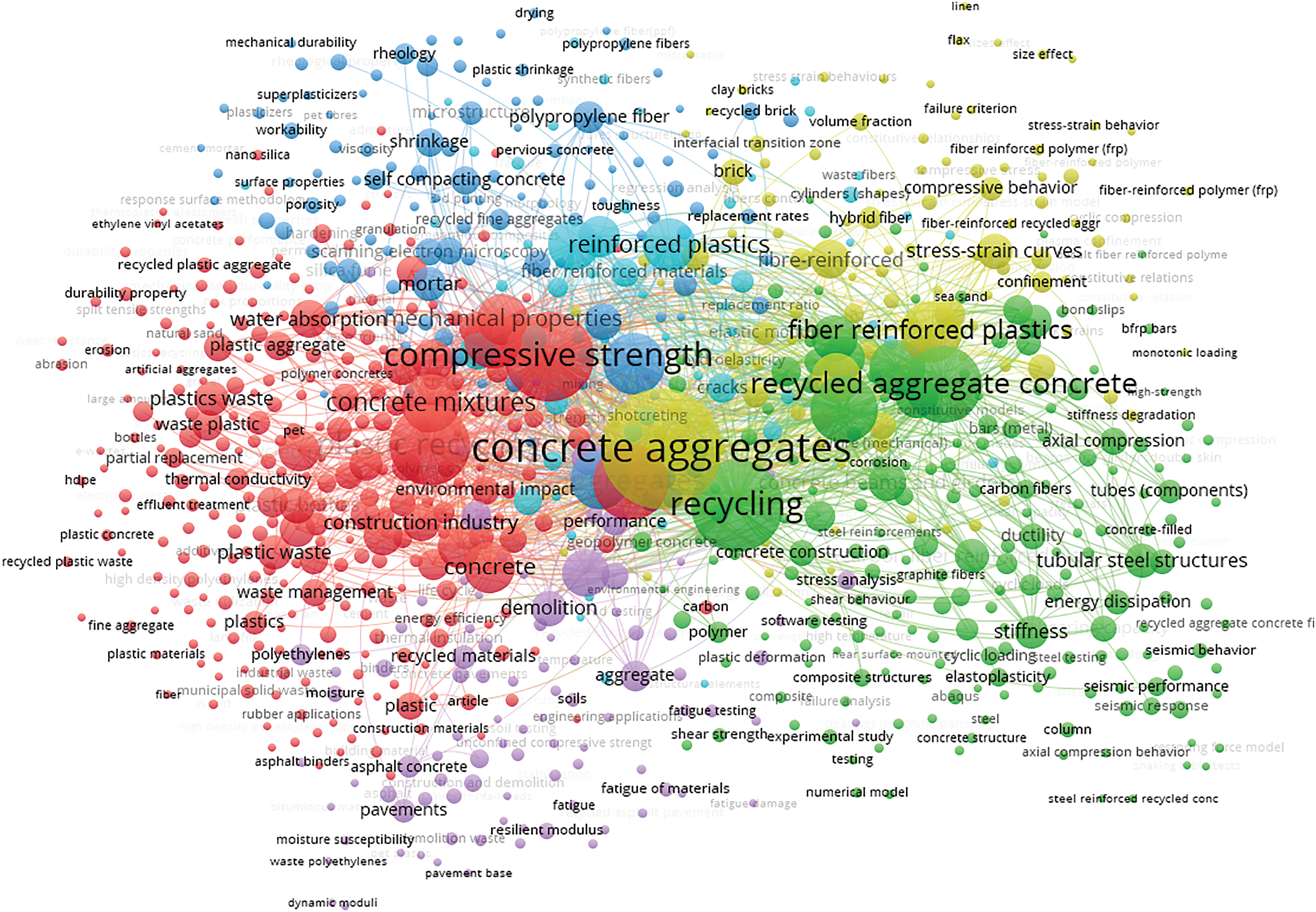

Keyword co-occurrence maps were created using VOSViewer, highlighting the main research areas and groupings (Fig. 3). The largest group of studies focuses on concrete strength, aggregate types, and mechanical testing, showing the technical nature of much of the work. A separate group centers on recycling, material reuse, and environmental considerations. These studies often examine life-cycle outcomes (energy, emissions, waste diversion) and durability performance. Other groupings bring together studies involving polymer-modified concrete, fiber-based mixes, and issues like shrinkage. One group includes papers that examine applications in roads and pavements, where recycled plastic concrete is tested under load and environmental exposure.

Figure 3: Co-occurrence of keywords in previous research on concrete mixtures with recycled aggregates from plastics in the Scopus database

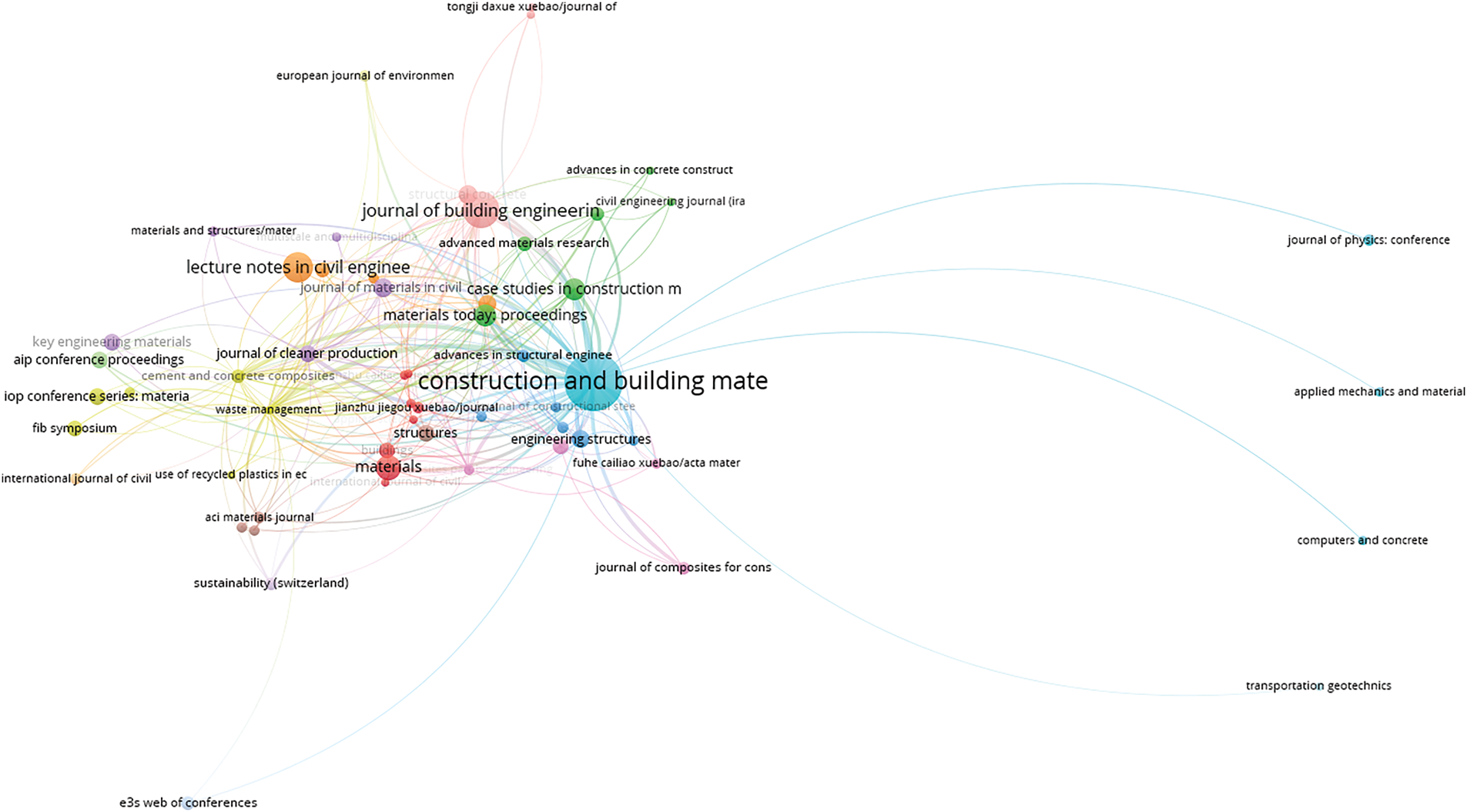

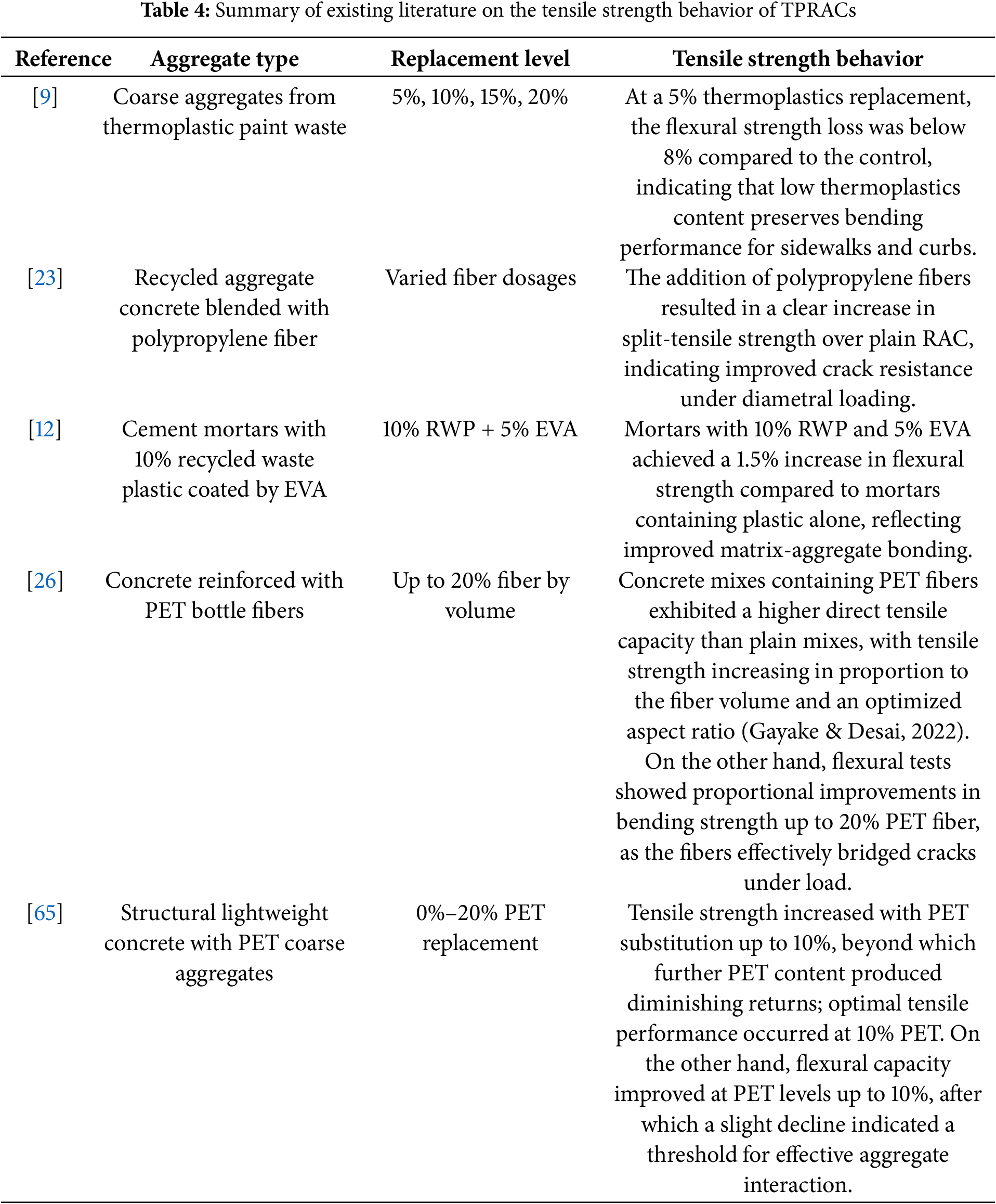

Citation networks show that Construction and Building Materials functions as the most prominent journal in this field. It shares strong links with Journal of Building Engineering and Materials and Structures (Fig. 4). Other closely connected journals include those focusing on waste use and composite materials, showing where different research subjects overlap. A few journals such as Applied Mechanics and Materials and Transportation Geotechnics are positioned further out in the network, likely reflecting more focused or newer areas of work. Author affiliation data indicate that China has produced the highest number of publications. Researchers in the United Kingdom, India, and the United States also make up a large part of the dataset (Fig. 5). European countries show dense cross-national collaborations, while research ties between North American and Asian institutions are also strong. There is added input from Brazil, Saudi Arabia, and Malaysia, pointing to growing international interest in adapting cement-based materials to accept plastic waste.

Figure 4: Citation analysis of influential journals in the area of concrete with recycled aggregates from plastics in the Scopus database

Figure 5: Citation analysis of contributing countries in the area of concrete with recycled aggregates from plastics in Scopus database

Taken together, the bibliometric data present a clear picture of how the field has shifted over time. Initial efforts concentrated on whether plastic materials could physically function within cement systems. More recent studies have combined technical testing with attention to environmental concerns and reuse goals. The growth in collaborations and the appearance of broader topics suggest that researchers are building a larger, more coordinated base of knowledge around recycled plastic concrete.

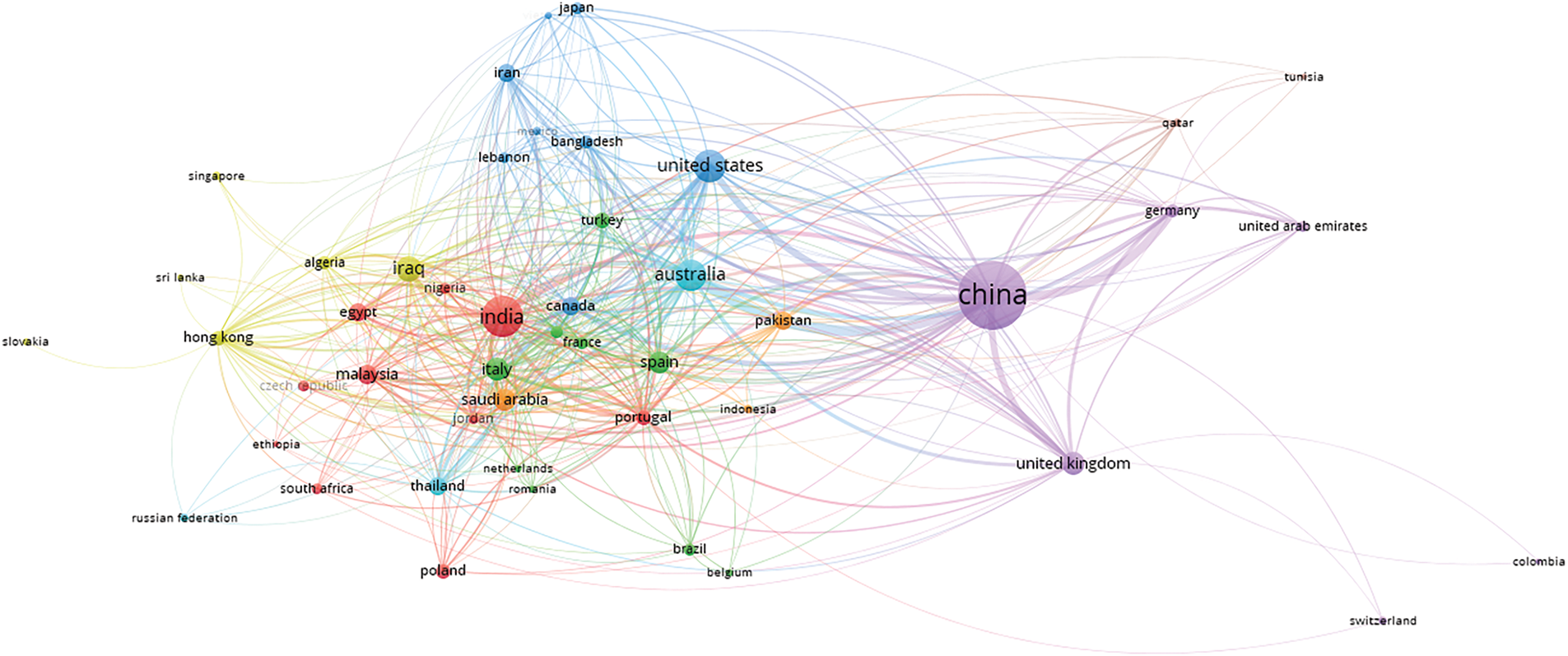

3 Thermoplastics Wastes as Recycled Aggregates

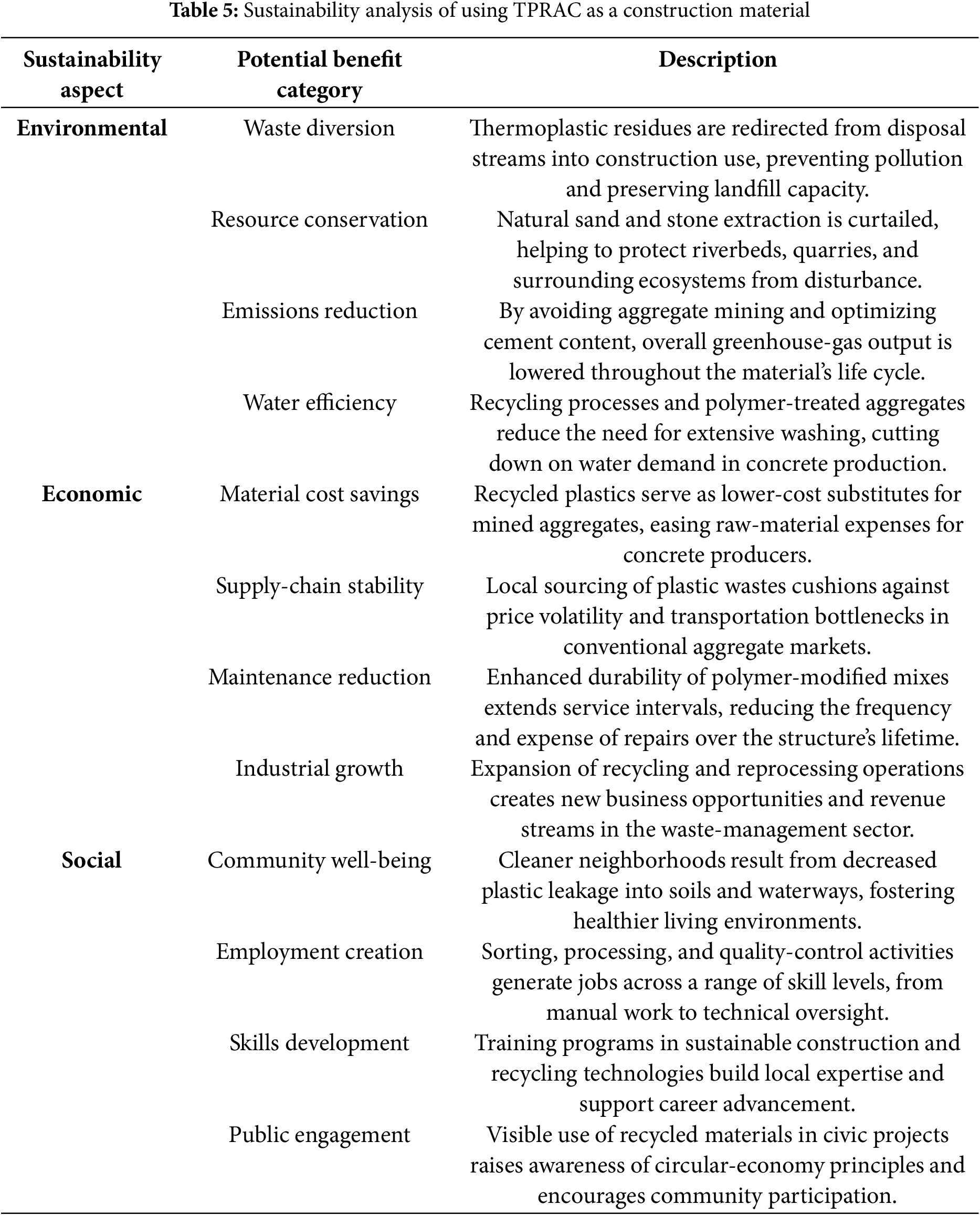

Thermoplastic wastes, Table 1, represent a growing environmental challenge and an untapped resource for sustainable construction materials [48–51]. Derived from road-marking residues, industrial coatings, and flaking architectural paints, these thermoplastics, Table 2, contain polymeric binders, commonly ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), polyamide, polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene, that confer hydrophobicity and flexibility but impede bond formation with traditional cement matrices. Transforming thermoplastic wastes into thermoplastic-based recycled aggregates seeks to valorize this waste stream, reduce dependence on virgin aggregates, and minimize landfill disposal. Gámez-García et al. [9] evaluated four concrete mixes incorporating thermoplastic-based coarse aggregates at 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% replacement levels, reporting that at 5% substitution compressive and flexural strength losses did not exceed 8%, while density, absorption, and porosity remained within acceptable limits for active-mobility applications (sidewalks and curbs). Preparation and characterization of these recycled aggregates require careful size grading and cleaning to remove adhered contaminants [4,6,52]. Surendranath and Ramana [11] similarly showed that Bakelite plastic waste, a rigid thermosetting polymer, can replace natural fine aggregate in fly-ash–based concrete up to 15%, with optimum strength at a 7.5% replacement. Mohammadian and Haghi [10] demonstrated that thermosetting plastic wastes, though chemically distinct from thermoplastics, can be cleaned, crushed, and incorporated as lightweight fine aggregates. These findings indicate that diverse polymeric wastes, when processed into thermoplastic-based aggregates, can confer both density reduction and satisfactory mechanical performance. The compressive strength of thermoplastic-based aggregate concrete typically declines with increasing plastic content due to poor matrix-aggregate adhesion and the low stiffness of plastic particles. However, several modification strategies mitigate these effects. Al-Mansour et al. [15] incorporated 2%–4% EVA and nanosilica into cement mortars containing 10% and 15% recycled plastic aggregates, achieving up to a 5.5% strength improvement and a 50% reduction in carbonation depth; the EVA formed polymer films around the aggregates to enhance cohesion, while nanosilica filled micro-pores and densified the matrix.

Al-Mansour et al. [13] examined waterproof cementitious composites with EVA–nanosilica hybrids and found that although EVA alone increased porosity and slightly depressed compressive strength, the organic-inorganic hybrids fully mitigated strength loss while halving water sorptivity. Building on these advances, Al-Mansour et al. [14] replaced 10% and 15% of sand with recycled plastic aggregates treated with EVA–nanosilica, reporting 15%–18% density reduction, retention of mechanical strength, ductility improvements up to 107%, roughly 50% better waterproofing, and over 70% enhanced carbonation resistance; they further estimated that a 10% global sand replacement by these aggregates could cut annual sand consumption by 0.56–1 billion tons and CO2 emissions by 2.8–13.9 million tons. Polymeric stabilization and fiber reinforcement have also proven effective in bolstering thermoplastic-based aggregate concrete performance. Ma et al. [27] investigated polyurethane-based composites prepared with remolded Pisha sandstone (a polymer concrete aggregate) and observed compressive strength reductions due to residual polyurethane on the aggregate surfaces; adding EVA improved bond strength and both unconfined and triaxial compressive behavior, while EVA-modified composites exhibited superior freeze-thaw and wet-dry durability. Meng et al. [22] studied steel and polypropylene fibers in recycled coarse-aggregate concrete (50% replacement) and found that both fiber types increased compressive strength relative to non-reinforced mixes. Impact and tensile performance benefit markedly from fiber addition: Hong et al. [23] mixed polypropylene fiber into recycled aggregate concrete, reporting improvements in both compressive and split-tensile strength; Gao et al. [24,25] showed that hybrid fibers deliver the greatest impact resistance and that hooked steel fibers outperform straight and crimped alternatives. Gayake and Desai [26] synthesized findings on PET bottle fibers, reporting that PET inclusion improves tensile, bending, and impact strengths but reduces thermal conductivity, indicating multifunctional benefits when fibrous residues are judiciously employed. Modulus of elasticity and deformation capacity are likewise influenced by thermoplastic-aggregate incorporation and subsequent modifications [53]. Al-Mansour et al. [12] demonstrated that in EVA-coated recycled-plastic mortars (10% aggregate + 5% EVA), deformation energy absorption doubled, attributed to enhanced interfacial transition zones that improve matrix-aggregate coordination. Domínguez-Santos and Guerra [28] assessed concrete blocks with granulated polystyrene and polypropylene fibers, showing that these additives enhance block stiffness and ductility and, in low- to medium-height frames (2–8 stories), improve overall structural performance. Consideration of the effect of long-term durability under environmental cycling was also a vital topic considered in previous research for adopting thermoplastic-based aggregate concrete. Chen et al. [40] applied a damage-mechanics model to 40% recycled-coarse-aggregate concrete under freeze-thaw cycles; mixes with polypropylene fiber and a gas-lifting water-reducing agent achieved F200 frost resistance, with the agent most effective at slowing damage. Richardson et al. [41] compared freeze-thaw durability of recycled demolition-aggregate concrete to virgin-aggregate concrete and found parity when aggregates were carefully selected and pre-treated, indicating no durability penalty. Mohamed et al. [42] explored sulfur polymer concrete (SPC), a thermoplastic binder system using modified sulfur and recycled aggregates, and reported that SPC reached 76% of its ultimate compressive strength within one day, matching Portland-cement concrete at 80˚C–100˚C, thus affirming its thermal-cycling resilience. Beyond mechanical performance, resistance to moisture, carbonation, and chloride ingress underpins service life. Chen et al. [43] applied Fick’s second law to model chloride penetration in recycled-aggregate concretes, identifying air-entraining and water-reducing admixtures as primary durability enhancers, followed by recycled-aggregate quality and polypropylene fiber; predicted service lives ranged from 30 to 40 years in chloride environments. Choi et al. [54] produced mortar and concrete with fine aggregate from recycled PET bottles, observing increased flow, decreased compressive strength at 25%–75% PET-aggregate content, and higher water absorption for mortars with 40%–60% PET aggregates, though the strength-to-density ratio peaked at 25% in concrete. Cuevas et al. [30] examined 3D-printed cementitious composites with recycled glass and ETM microspheres, showing that the printing process impacts porosity and capillary transport more than recycled additives, parallels that inform additive-manufacturing of thermoplastic-aggregate concretes. Thermoplastic wastes also find application in bituminous systems and geotechnical materials. Sambaturu et al. [31] reviewed replacing conventional pavement materials with LDPE and demolished concrete, highlighting moisture resistance, low cost, and thermoplastic processing versatility. In geotechnical applications, Khoury et al. [32] combined recycled plastic bottles with soil to create a geoplastic material with unconfined compressive and indirect tensile strengths comparable to ordinary concrete, providing a stable, permeable pavement base. These studies confirm that thermoplastic-based aggregates, with proper mix-design adjustments, EVA–nanosilica hybrids, fiber reinforcement, admixture optimization, and thermoplastic binder systems, yield concrete composites with competitive mechanical properties, enhanced durability, and reduced environmental footprints. However, standardization of aggregate characterization, comprehensive life-cycle assessments, long-term multi-hazard performance data, and economic feasibility analyses remain critical research gaps. Future investigations should focus on scale-up validation, structural demonstration projects, combined environmental loading scenarios, and integration into circular-economy frameworks to realize the promise of thermoplastic-based aggregates in sustainable infrastructure.

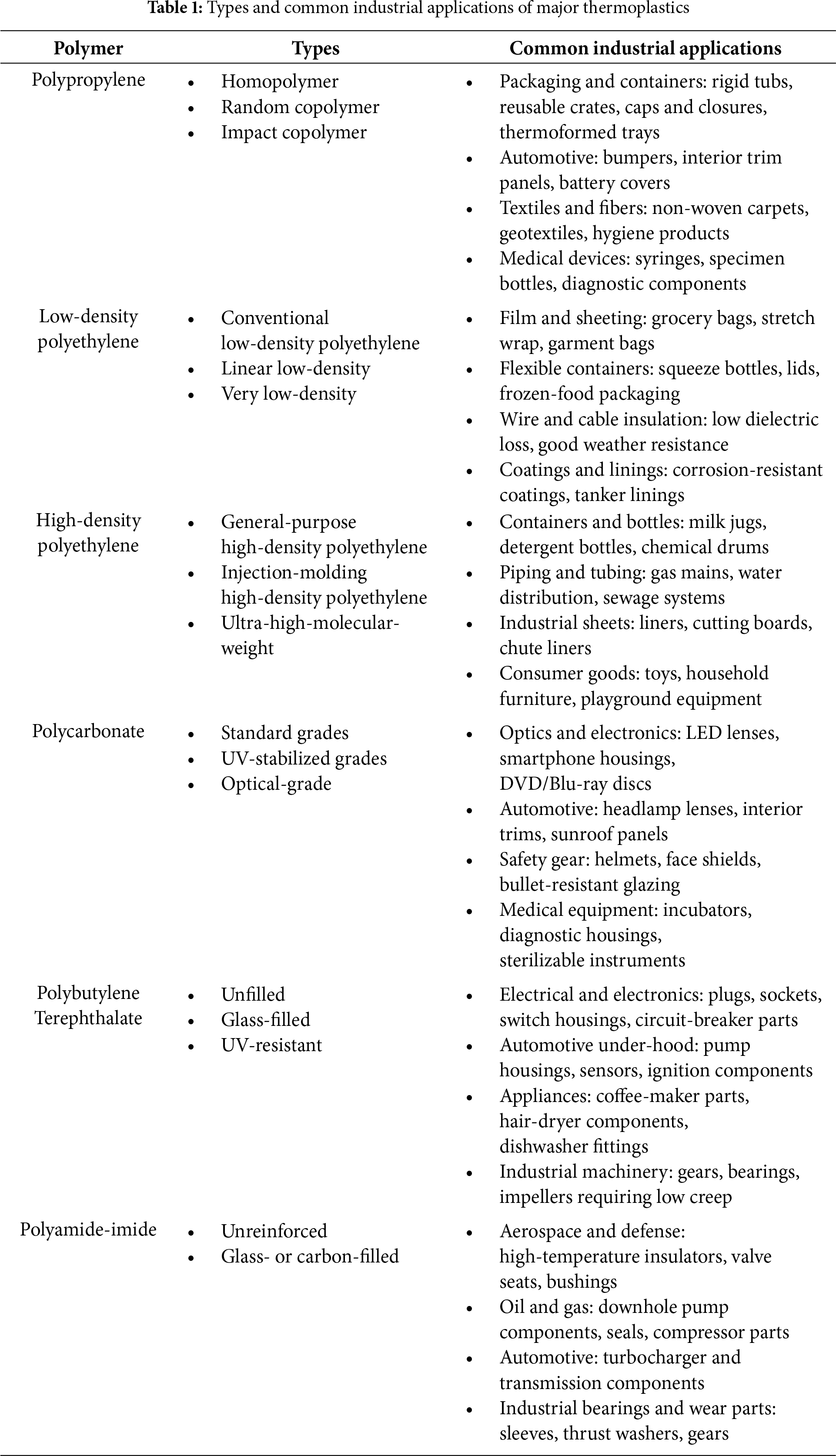

The compressive strength is a fundamental indicator of its load-bearing capacity and long-term performance [56–62]. When natural aggregates are partially or wholly replaced by thermoplastic-based aggregates or other polymeric wastes, compressive strength becomes the critical metric by which viability is judged. Early investigations on thermoplastic-based recycled aggregate concrete (TPRAC) revealed strength reductions attributable to poor interfacial bonding and the inherent flexibility of plastic particles [63,64]. Table 3 summarizes some of the research efforts on the compressive strength of TPRAC. However, subsequent studies have demonstrated that careful mix design, including controlled replacement ratios, polymer coatings, fiber additions, and hybrid binder systems, can arrest or even reverse these reductions. A synthesis of the literature shows that compressive strength trends span from modest declines at low substitution levels to enhancements when waste plastics are modified or combined with reinforcing agents. Understanding these trends is crucial for determining practical replacement thresholds and designing thermoplastic-based recycled aggregate concrete (TPRAC) mixes that meet structural and durability requirements under real-world conditions. The replacement of natural aggregates with thermoplastic-based recycled aggregates has a pronounced influence on compressive strength, with the magnitude of reduction generally increasing with higher plastic content. Surendranath and Ramana [11] evaluated Bakelite plastic waste (a thermosetting polymer) as a fine aggregate replacement, ranging from 0% to 15%, in fly-ash–based concrete and identified an optimal compressive strength at 7.5% substitution, beyond which strength diminished due to the polymer’s low stiffness. Similarly, Gámez-García et al. [9] investigated thermoplastic-based coarse aggregates from paving waste at 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% replacement levels, finding that at 5% substitution compressive strength losses did not exceed 8%, a threshold acceptable for active-mobility infrastructure. In lightweight concretes utilizing waste PET aggregates, Choi et al. [54] reported 28-day compressive strength decreases of 5%, 15%, and 30% for PET-aggregate contents of 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively, though the strength-to-density ratio at 25% replacement surpassed that of control mixtures. A meta-analysis by Uche et al. [65] of twenty studies confirmed that PET aggregate substitution up to 20% generally maintains or slightly enhances compressive strength, with inter-study variability linked to aggregate processing and mix proportions. Although unmodified plastic aggregates tend to decrease compressive strength, polymer coatings and nano-additives can mitigate these losses by enhancing aggregate-matrix interactions. Al-Mansour et al. [15] introduced EVA and nanosilica into cement mortars with 10% and 15% recycled plastic aggregates, recording up to a 5.5% strength improvement and a 50% reduction in carbonation depth; EVA formed polymer films around the aggregates to enhance cohesion, while nanosilica filled micro-voids and densified the matrix. In a related study, Al-Mansour et al. [13] observed that EVA alone slightly decreased compressive strength due to increased porosity; however, EVA–nanosilica hybrids fully mitigated the strength reduction while halving water sorptivity. Extending these findings to practical sand replacement, Al-Mansour et al. [14] substituted 10% and 15% of natural sand with recycled plastic aggregates treated with EVA–nanosilica, demonstrating near-reference compressive strength retention, 15%–18% density reduction, and up to 107% improvement in ductility. In sustainable cement mortars, the dual incorporation of 10% recycled plastic aggregates and 5% EVA preserved density while mitigating strength loss [12]. Beyond concrete, Ma et al. [27] applied EVA to polyurethane-stabilized Pisha sandstone aggregates, recovering a significant portion of compressive strength lost due to residual polymer and enhancing both unconfined and triaxial performance. Fiber reinforcement has also proven effective: Gao et al. [25] noted that steel–polypropylene hybrid fibers increased toughness without sacrificing compressive strength, while Hong et al. [23] reported improvements in both compressive and split-tensile strength with polypropylene fibers. Thermoplastic binder systems offer a complementary strategy: Mohamed et al. [42] developed sulfur polymer concrete that achieved 76% of its ultimate compressive strength within one day and exhibited strengths ~20% higher than Portland cement concrete at temperatures below 60˚C. Khoury et al. [32] produced a plastic-soil geoplastic material with compressive strengths comparable to ordinary concrete, demonstrating viability as a pavement base. The ability of recycled-aggregate concretes to retain compressive strength under environmental stressors is critical for long-term durability. Chen et al. [40] subjected C30 TPRAC containing 40% recycled coarse aggregates to freeze-thaw cycles; mixes with polypropylene fiber and a gas-lifting water-reducing agent achieved an F200 frost resistance rating, with the agent particularly effective at slowing damage. Richardson et al. [41] compared freeze-thaw durability of recycled-aggregate and virgin-aggregate concretes, finding compressive strength retention parity after 56 cycles. Emerging composite formulations, such as EVA–cable–polystyrene mixtures and thermosetting wastes as lightweight aggregates, further expand the potential for TPRAC [16,48,49,66]. Collectively, these studies indicate that unmodified plastic aggregate replacement up to 5%–10% typically incurs strength losses below 10%, while polymer coatings, fiber reinforcement, and innovative binders can generate 5%–20% strength improvements. Future research should focus on long-term field assessments, standardized aggregate characterization, and life-cycle analyses to optimize compressive strength alongside sustainability and economic benefits in thermoplastic-based recycled aggregate concrete applications.

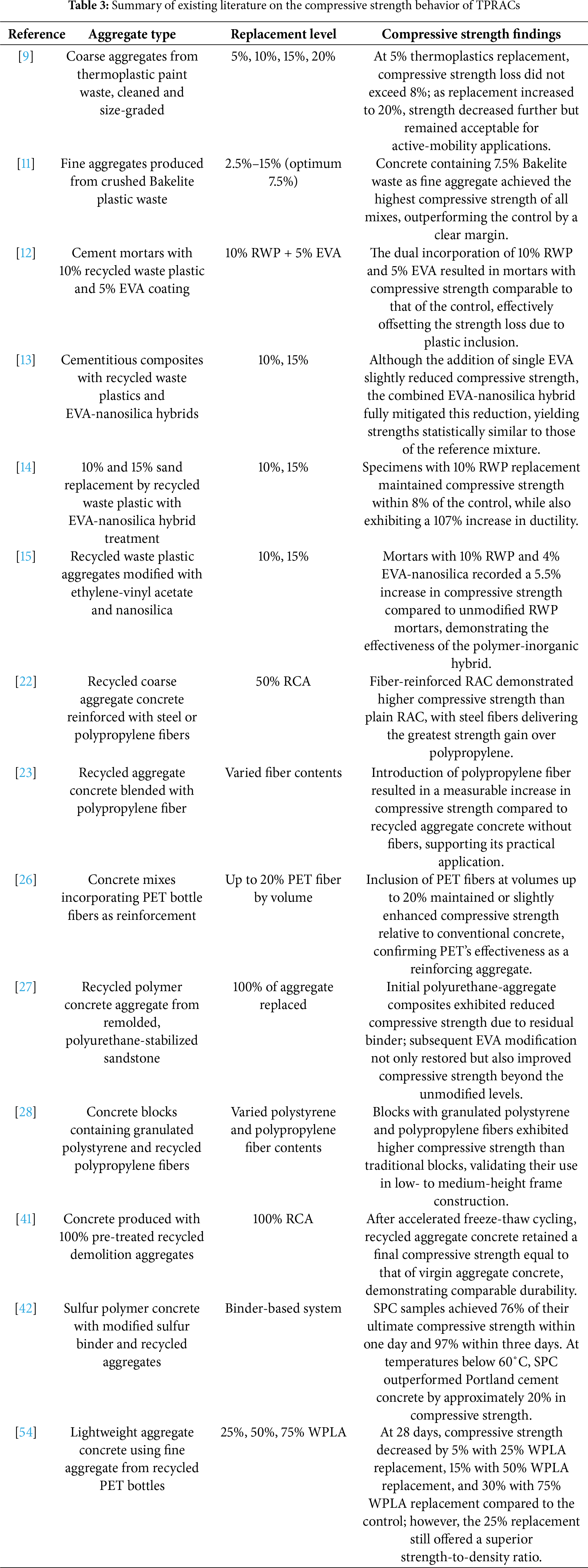

Tensile strength is a critical indicator of concrete’s ability to resist crack initiation and propagation under service loads, particularly in structural and pavement applications where bending stresses and tensile forces govern performance [67–71]. When natural aggregates are partially substituted with recycled thermoplastic-based aggregates or other polymeric wastes, the inherently low stiffness and smooth surfaces of plastic particles tend to weaken the cementitious matrix under tensile and flexural loading. Nonetheless, a growing body of research has demonstrated that, through judicious selection of replacement levels, incorporation of fibers, and modification of the matrix–aggregate interface via polymer coatings or nano-additives, it is possible not only to mitigate strength losses but, in some cases, to achieve tensile and flexural strengths comparable to or exceeding those of conventional mixes. Baseline investigations into unmodified plastic-aggregate concretes reveal that tensile and flexural strength declines accompany increasing plastic content. Table 4 summarizes some of the research efforts on the tensile strength of TPRAC. Uche et al. [65]’s meta-analysis of twenty studies on PET-aggregate concretes further quantified these trends, showing that tensile and flexural strengths typically remain within 90%–100% of control values up to 10% PET aggregate substitution but decline markedly beyond this level. Collectively, these baseline studies establish an upper limit of about 5%–10% unmodified plastic aggregates for tension- and bending-critical applications. Gámez-García et al. [9] extended these observations to thermoplastic-based coarse aggregates derived from paving waste, incorporating them at replacement levels of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%. Flexural strength losses did not exceed 8% at a 5% substitution rate, a threshold within acceptable limits for active-mobility infrastructure such as sidewalks and curbs. Enhancement of tensile and flexural performance through fiber reinforcement has been widely explored. Hong et al. [23] investigated concretes mixed with varying dosages of polypropylene fiber: split-tensile strength increased by up to 20% relative to non-fiber mixes at optimum fiber content, while flexural toughness improved dramatically due to fiber bridging across microcracks. Gayake and Desai [26] reviewed applications of waste PET bottle fibers in concrete, noting consistent improvements in tensile, bending, and impact strengths across multiple studies. They highlighted that PET fibers, with aspect ratios between 30 and 60, fiber volumes of 0.5%–1.0%, and suitable surface treatments, enhanced crack resistance and post-cracking ductility without substantially compromising workability. These findings underscore that fiber reinforcement can compensate for the tensile and flexural weaknesses introduced by plastic aggregates, enabling more resilient TPRAC designs. Another effective strategy involves modifying the matrix-aggregate interface with polymer coatings and nano-additives. Al-Mansour et al. [13,15] demonstrated that a dual mix of 10% recycled waste plastic aggregates and 5% EVA, combined with nanosilica, preserved matrix density, decreased strength losses only marginally, and doubled deformation energy absorption under flexural loading. The organic-inorganic interfacial transition zones engineered by EVA coatings enabled coordinated deformation, enhancing both tensile crack resistance and flexural ductility. Beyond concrete, geoplastic materials incorporating thermoplastic wastes have shown promising tensile performance. Choi et al. [54] indicated that even 25% PET aggregates result in significant strength losses. Therefore, in practical terms, designers targeting post-cracking ductility and crack control can opt for 10% recycled plastic aggregates with 0.5% polypropylene fiber or 5% EVA-nanosilica admixture, depending on performance priorities and environmental considerations. Mechanistically, tensile and flexural enhancements derive from improved load transfer across cracks and more cohesive interfacial zones: fibers bridge microcracks and arrest propagation, while EVA coatings and nanosilica densify the interface, reducing stress concentrations at aggregate surfaces. Despite these advances, gaps remain. The long-term durability of tensile and flexural properties under environmental cycling, such as freeze-thaw and wet-dry regimes, has been less extensively studied for TPRAC than for compressive behavior. Although Chen et al. [40] and Richardson et al. [41] established that freeze-thaw durability can match that of virgin-aggregate concretes in compression, analogous assessments for tensile and flexural performance in TPRAC are lacking. Standardized protocols for measuring flexural toughness and indirect tensile strength in polymer-modified recycled concretes are also needed to facilitate inter-study comparisons. Field trials and structural-scale demonstrations will further validate laboratory findings and support code development. In conclusion, tensile and flexural strength behavior in TPRAC and related composites exhibits clear trends: unmodified plastic aggregates depress bending strengths with increasing content; fiber reinforcement and matrix modifications can fully recover or improve tensile and flexural capacities; and conservative substitution levels of 5%–10% plastic aggregates strike a balance between sustainability and mechanical performance. Future research should focus on multifactorial optimization, integrating fibers, polymer coatings, nano-additives, and aggregate surface treatments, as well as durability protocols, to ensure that TPRAC meets the tensile and flexural demands of sustainable infrastructure.

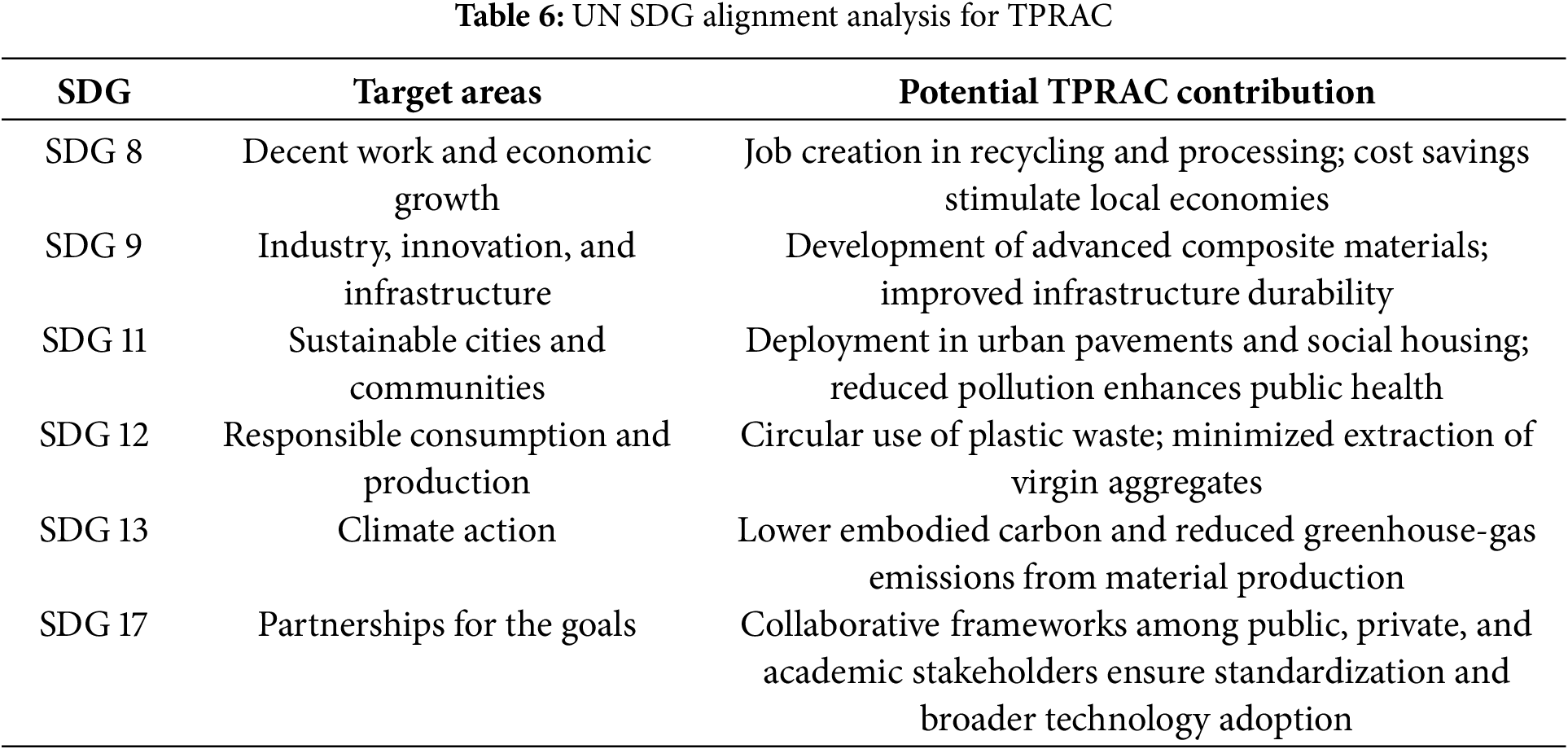

This section discusses sustainability claims that recur across the literature into environmental, economic, and social dimensions, with attempts to tie them to realistic deployment contexts (e.g., sidewalks, low-traffic pavements, masonry units). The emphasis herein is on outcomes most directly influenced by aggregate substitution (waste diversion, quarrying avoidance, moisture/carbonation behavior) rather than system-level factors outside mix design. Table 5 aggregates these outcomes in a structured way. It lists the sustainability aspect, groups them into specific benefit categories (e.g., waste diversion, maintenance reduction), and describes the mechanism or evidence typically reported in TPRA studies. Accordingly, it allows readers to trace a claimed benefit to a mechanism that can be verified or scoped in project specifications.

6.1 Potential Environmental Benefits

Thermoplastic-based recycled aggregate concrete offers a practical way to reduce environmental strain by redirecting plastic waste away from landfills and incinerators. When recycled thermoplastics are used in place of part of the natural aggregates, the need to extract fresh materials such as crushed stone and river sand drops noticeably. This drop not only slows the pace of resource depletion but also lessens the ecological damage tied to quarrying and mining, including noise disturbances, energy-intensive transport, and disruption of natural habitats. In concrete mixes where plastic particles are carefully matched with binders, the amount of cement can sometimes be slightly reduced without weakening the structure. Polymers tend to improve the bond at the microscopic level between the cement paste and the aggregates, which helps maintain overall strength despite the softer nature of the plastic itself [1,12,13,17,19,53,72]. This adjustment contributes further to emissions reduction, as cement production remains one of the highest carbon emitters in the construction industry. Water use during production also sees a modest benefit, since recycled plastic aggregates usually need less washing than raw minerals. In addition, the surface of thermoplastic particles tends to absorb less water, which helps control the total amount of water required in the mix. Taken together, these material characteristics allow TPRAC to limit the environmental strain caused by both waste accumulation and the high resource demand typical of conventional concrete.

6.2 Potential Economic Benefits

Replacing a portion of natural aggregates in concrete with thermoplastic materials offers immediate savings, particularly in areas, like the Saudi Arabia, where sand and gravel are costly due to transport and extraction fees. In such regions, reprocessing local plastic waste into usable aggregate becomes an affordable alternative and add efforts to help them achieve their sustainability goals. Over time, these savings extend beyond initial construction. Concrete made with polymer-infused aggregates and plastic-based reinforcements tends to resist damage from repeated freezing and thawing, salt exposure, and environmental carbon dioxide. As a result, structures built with this material typically last longer and require fewer repairs. There’s also potential for small-scale manufacturers and recycling operators to enter the market by tailoring their equipment to meet the demands of this kind of concrete. Where such businesses succeed, they not only supply a functional building material but also support economic activity at the local level. When all these savings, lower upfront costs, reduced upkeep, and the reuse of discarded plastics, are taken together, the case for integrating thermoplastic aggregates into everyday building practices become.

Redirecting plastic waste into construction materials through TPRAC has shown noticeable benefits for local communities. Streets and neighborhoods that once bore the brunt of scattered dumping grounds now see cleaner spaces and fewer signs of plastic fragments in the soil and nearby streams. This shift is not just about environmental repair, it also marks a change in how people think and act. Communities involved in these efforts often experience a stronger sense of responsibility among residents, who begin taking part in waste collection efforts and support local recycling drives without being asked. Recycling processes linked to TPRAC have also opened work opportunities for people who have long been left out of formal employment. Jobs in sorting, processing, and monitoring the quality of recycled materials help support families and offer a foothold for those looking to rejoin the workforce. It’s not uncommon for residents to take pride in seeing a street or public bench built from recycled plastic, especially when they know their neighbors helped make it happen. Public feedback reflects this growing approval. Projects that incorporate recycled materials tend to gain stronger support, especially from younger generations who see them as a signal of smarter, future-conscious development. Sidewalks, low-traffic road surfaces, and seating areas made from TPRAC are often met with satisfaction not only for their durability but also because they feel like visible proof of a smarter way of building. In some cities, local governments, universities, and construction firms have teamed up to offer training programs focused on the technical skills needed to work with TPRAC. These programs introduce young people and career changers to a field where both recycling and construction know-how come together. As a result, a new kind of workforce is taking shape, one that understands both the material and the mission behind it. The combined effects, from cleaner spaces to new job paths, show that putting thermoplastics into roads and infrastructure doesn’t only solve a waste problem. It becomes a way to knit stronger, more aware communities with a sense of shared progress.

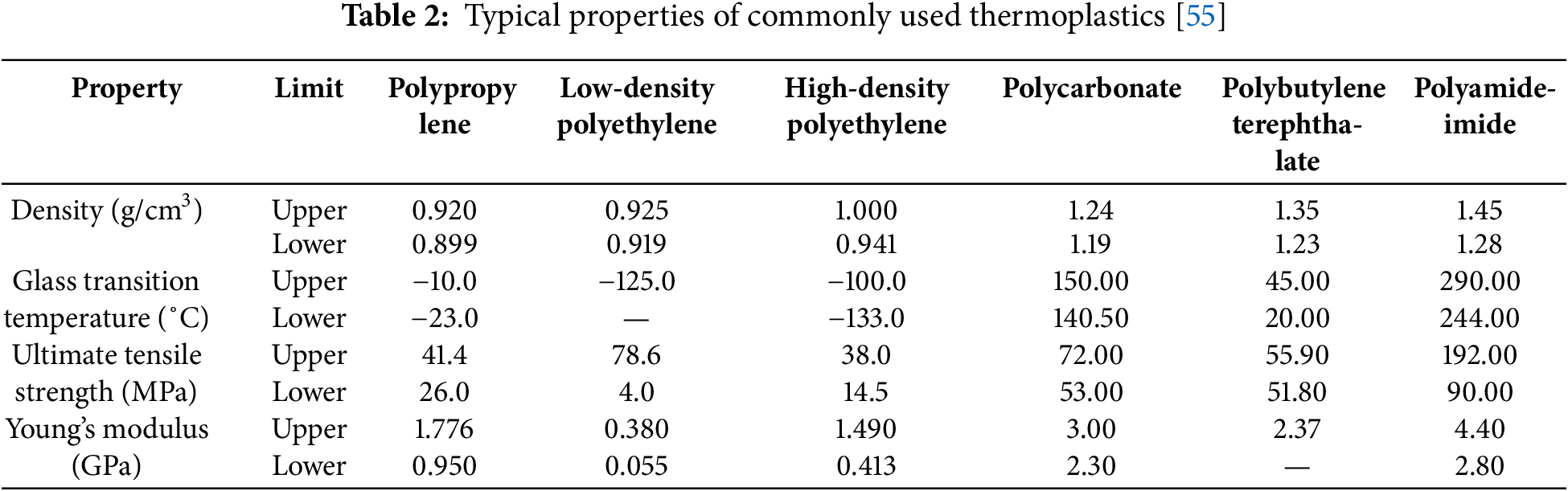

Thermoplastic-based recycled aggregate concrete offers a direct and practical contribution to several of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly those related to responsible industry, environmental protection, and community well-being, as mentioned in Table 6. Its development draws together recycled plastics and traditional cement-based materials, resulting in durable, innovative mixtures that support Goal 9, which prioritizes infrastructure built on more efficient and future-oriented methods. These materials are not experimental curiosities—they are being adapted for real-world use in public walkways, community parks, and affordable housing, where they help reduce the overall environmental strain tied to construction, aligning with the spirit of Goal 11. The reuse of discarded plastics in concrete mixes reflects a shift in how waste is handled, aligning with Goal 12’s push for sustainable consumption and production. Instead of sending thermoplastic waste to landfills or incinerators, the process redirects it into long-lasting structures, changing how we think about materials and their life cycles. This shift also carries weight under Goal 13, since TPRAC can significantly lower emissions linked to mining virgin aggregates and producing cement. In practice, this means buildings and roads made with these composites carry a smaller carbon load throughout their lifetimes. There are economic dimensions as well. As demand for such materials increases, so does the need for skilled workers to handle recycling processes, run production lines, and manage on-site implementation. This supports Goal 8, which focuses on sustainable economic growth and fair employment. The rise of local recycling initiatives and specialized manufacturing facilities can offer long-term opportunities for workers and communities alike. What makes broader adoption possible is the growing cooperation among researchers, municipalities, waste processors, and builders. These partnerships, tied to Goal 17, do more than share technical knowledge. They help align standards, refine policies, and bring production up to scale without losing track of quality or safety. When different sectors work in rhythm, the rollout of new technologies like TPRAC becomes more grounded and more responsive to the needs of both cities and rural areas. In all, TPRAC is not just a technical solution, but part of a broader shift in how materials are sourced and used in construction, guided by principles of responsibility, efficiency, and long-term environmental care.

7 Discussions and Future Directions

Recent investigations have revealed that the partial replacement of natural aggregates with thermoplastic-based aggregate residues can sustain or even improve mechanical performance when mixtures include polymer coatings, fibers, or nanoparticles. Compressive strength declines under unmodified conditions emerge at high substitution rates; however, the adaptation of ethylene-vinyl acetate treatments and nanosilica fillers has countered these losses and improved carbonation resistance. Tensile and flexural tests confirm that low doses of waste plastics maintain bending capacity, especially when paired with polypropylene or PET fibers. Durability trials under freeze-thaw cycles demonstrate that appropriately selected admixtures preserve strength after repeated temperature fluctuations. These outcomes confirm that TPRAC holds potential for pedestrian pathways and non-structural elements. Despite these encouraging results, research methods vary widely and testing conditions remain inconsistent. Aggregate preparation protocols range from simple washing and crushing to complex thermal treatments, making cross-study comparisons difficult. Characterization techniques for particle size, surface roughness, and chemical composition often rely on different standards, and mechanical tests differ in loading rates and curing regimes. These inconsistencies hinder the identification of best practices for mixture design and aggregate processing. Important gaps remain in life-cycle evaluation and real-world validation: environmental assessments often overlook the energy consumed during aggregate grinding and cleaning, and few studies quantify net reductions in greenhouse-gas emissions or landfill volumes. Economic analyses are scarce, and cost models for large-scale production of thermoplastic-based aggregates are missing. Multi-factor tests on chloride penetration, carbonation, and chemical exposure under field conditions are rare, especially for infrastructure exposed to deicing salts or coastal environments. Future studies should adopt standardized test protocols for aggregate characterization, unified metrics for particle grading, residual binder quantification, and interfacial transition-zone properties. Experimental programs can integrate controlled surface treatments and fiber dosages to identify optimal combinations across compressive, tensile, and durability metrics. Long-term trials on full-scale panels or pilot sidewalks will reveal performance under real traffic, moisture, and temperature fluctuations. Researchers can also utilize digital image correlation and acoustic emission monitoring to track damage progression under cyclic loading. Computational methods, finite element analysis, machine learning models, and digital-twin simulations, can predict mechanical responses and accelerate mixture optimization. Development of cost-benefit frameworks will help practitioners weigh material savings against processing expenses. Collaboration among civil engineers, materials scientists, and waste-management professionals will support scalable recycling workflows and regulatory approvals. Implementation guides for municipal agencies can outline procedures for sorting, cleaning, quality control, and mixing, while training modules and certification programs can strengthen workforce readiness. Advancing these directions will pave the way for greener concrete alternatives that reduce reliance on virgin aggregates and mitigate the impacts of plastic waste. With coordinated efforts and robust data, TPRAC can transition from laboratory curiosity to mainstream construction material for sustainable infrastructure.

This study focused on assessing the mechanical performance of concrete that includes thermoplastic-based recycled aggregates, addressing a gap in the current research where thermoplastic waste remains relatively untested compared to other recycled materials. Despite the widespread availability of plastic residues, their application in concrete mixes has been uneven, particularly with regard to compressive and tensile strength. By examining existing studies, this work consolidates technical findings related to strength behavior, surface treatments, and durability, aiming to guide future material use in construction that reduces environmental strain without sacrificing performance. Based on the aforementioned statements, the following conclusions are drawn:

• Unmodified thermoplastic aggregates can replace up to 5%–10% of natural aggregates without causing unacceptable losses in compressive or tensile strength. These levels are suitable for non-structural or lightly loaded applications, such as pedestrian surfaces and curbs.

• EVA coatings and nanosilica additives significantly improve matrix-aggregate bonding. EVA-nanosilica hybrids counteract the strength reductions typically seen with plastic inclusion, preserving or enhancing compressive strength and reducing carbonation depth.

• The addition of polypropylene or PET fibers restores and often enhances tensile and flexural strength, offsetting the weaknesses introduced by low-stiffness plastic particles. Optimized fiber volume and geometry are key to maximizing crack resistance and ductility.

• TPRAC mixes incorporating admixtures, surface treatments, and fibers have demonstrated comparable freeze-thaw and chloride ingress resistance to virgin-aggregate concrete. These findings support its potential use in exposure-prone environments.

• Beyond mechanical performance, TPRAC offers substantial environmental and economic advantages, including reductions in landfill use, virgin aggregate extraction, and greenhouse-gas emissions. Its alignment with several UN Sustainable Development Goals underlines its broader social value.

Although this review consolidates encouraging evidence regarding the mechanical and sustainability performance of thermoplastic-based recycled aggregate concrete, the field is still evolving, and several review and research opportunities remain to cover other properties of TPRAC, such as durability and other long-term aspects. Further investigations into long-term durability under realistic service conditions, as well as structural-scale applications, are essential to validate laboratory findings and encourage practical adoption. In parallel, more comprehensive environmental and economic assessments will strengthen the case for large-scale use by clarifying the overall benefits relative to conventional materials. Advancing these directions will help bridge the gap between experimental research and real-world implementation, supporting the broader integration of thermoplastic-based recycled aggregates into sustainable construction practices.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mahmoud Alhashash, Abdullah Alariyan, Ameen Mokhles Youns, Favzi Ghreivati, Ahed Habib, and Maan Habib; analysis and interpretation of results: Mahmoud Alhashash, Abdullah Alariyan, Ameen Mokhles Youns, Favzi Ghreivati, Ahed Habib, and Maan Habib; draft manuscript preparation: Mahmoud Alhashash, Abdullah Alariyan, and Ameen Mokhles Youns; manuscript review & editing: Favzi Ghreivati, Ahed Habib, and Maan Habib. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hannawi K, Prince W, Kamali-Bernard S. Effect of thermoplastic aggregates incorporation on physical, mechanical and transfer behaviour of cementitious materials. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2010;1(2):251–9. doi:10.1007/s12649-010-9021-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kazemi M, Faisal Kabir S, Fini EH. State of the art in recycling waste thermoplastics and thermosets and their applications in construction. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021;174(3–4):105776. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Almeshal I, Tayeh BA, Alyousef R, Alabduljabbar H, Mustafa Mohamed A, Alaskar A. Use of recycled plastic as fine aggregate in cementitious composites: a review. Constr Build Mater. 2020;253(7):119146. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang B, Yan L, Fu Q, Kasal B. A comprehensive review on recycled aggregate and recycled aggregate concrete. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021;171(5):105565. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang D, Lu C, Zhu Z, Zhang Z, Liu S, Ji Y, et al. Mechanical performance of recycled aggregate concrete in green civil engineering: review. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2023;19(2):e02384. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Habibi A, Ramezanianpour AM, Mahdikhani M. RSM-based optimized mix design of recycled aggregate concrete containing supplementary cementitious materials based on waste generation and global warming potential. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021;167(4):105420. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang H, Xiao J, Tang Y, Duan Z, Poon CS. Long-term shrinkage and mechanical properties of fully recycled aggregate concrete: testing and modelling. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;130(3):104527. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang P, Sun X, Wang F, Wang J. Mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete: a review. Polymers. 2023;15(3):615. doi:10.3390/polym15030615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Gámez-García DC, Vargas-Leal AJ, Serrania-Guerra DA, González-Borrego JG, Saldaña-Márquez H. Sustainable concrete with recycled aggregate from plastic waste: physical-mechanical behavior. Appl Sci. 2025;15(7):3468. doi:10.3390/app15073468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mohammadian M, Haghi A. A study on application of recycled thermosetting plastic in concrete [Studiu privind aplicarea materialelor plastice termorigide în beton]. Revue Roumaine De Matériaux/Romanian J Mater. 2013;43(3):276–84. [Google Scholar]

11. Surendranath A, Ramana PV. Valorization of bakelite plastic waste aimed at auxiliary comprehensive concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2022;325(4):126851. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Al-Mansour A, Chen S, Xu C, Peng Y, Wang J, Ruan S, et al. Sustainable cement mortar with recycled plastics enabled by the matrix-aggregate compatibility improvement. Constr Build Mater. 2022;318(11):125994. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Al-Mansour A, Yang R, Xu C, Dai Y, Peng Y, Wang J, et al. Enhanced recyclability of waste plastics for waterproof cementitious composites with polymer-nanosilica hybrids. Mater Des. 2022;224(17):111338. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2022.111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Al-Mansour A, Dai Y, Xu C, Yang R, Lu J, Peng Y, et al. Upcycling waste plastics to fabricate lightweight, waterproof, and carbonation resistant cementitious materials with polymer-nano silica hybrids. Mater Today Sustain. 2023;21(11):100325. doi:10.1016/j.mtsust.2023.100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Al-Mansour A, Yang R, Xu C, Chen S, Peng Y, Zeng Q. Carbonation resistance enhancement of cement mortars with recycled plastics using ethylene-vinyl acetate and nanosilica [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icdcs/2022/parti/4/. [Google Scholar]

16. Gregorova V, Ledererova M, Stefunkova Z. Investigation of influence of recycled plastics from cable, ethylene vinyl acetate and polystyrene waste on lightweight concrete properties. Procedia Eng. 2017;195:127–33. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.04.534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liang Z, Hu Z, Zhou Y, Wu Y, Zhou X, Hu B, et al. Improving recycled aggregate concrete by compression casting and nano-silica. Nanotechnol Rev. 2022;11(1):1273–90. doi:10.1515/ntrev-2022-0065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yao X, Pei Z, Zheng H, Guan Q, Wang F, Wang S, et al. Review of mechanical and temperature properties of fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete. Buildings. 2022;12(8):1224. doi:10.3390/buildings12081224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ahmed TI, Tobbala DE. Rubbered light concrete containing recycled PET fiber compared to macro-polypropylene fiber in terms of SEM, mechanical, thermal conductivity and electrochemical resistance. Constr Build Mater. 2024;415(7):135010. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yan ZW, Bai YL, Zhang Q, Zeng JJ. Experimental study on dynamic properties of flax fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete. J Build Eng. 2023;80(9):108135. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2023.108135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shen MY, Guo ZH, Feng WT. A study on the characteristics and thermal properties of modified regenerated carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastic composite recycled from waste wind turbine blade spar. Compos Part B Eng. 2023;264(11):110878. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Meng XH, He C, Feng XF. Research on mechanical properties of fiber recycled concrete. Appl Mech Mater. 2011;94–96:909–12. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.94-96.909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hong SU, Lee YT, Kim SH, Baek SK, Cho YS. Strength properties of recycled aggregate concrete mixed with polypropylene fiber. Appl Mech Mater. 2012;147:28–31. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.147.28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Gao L, Shi Y, Liu YC. Influence study of reinforced fiber on the impact resistance performance of recycled aggregate concrete. Adv Mater Res. 2011;418–420:250–3. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.418-420.250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Gao L, Shi Y, Xu GQ, Sun H, Ma HB. Influence study of steel fiber shape on the impact resistance performance of recycled aggregate concrete. Appl Mech Mater. 2012;174–177:1512–5. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.174-177.1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Gayake SB, Desai AK. A literature review identifying the scope for utilization of waste polyethylene terephthalate bottle fibers in concrete for enhancing structural properties. In: Sustainable building materials and construction. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 365–70. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-8496-8_45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ma W, Zhao Z, Guo S, Zhao Y, Wu Z, Yang C. Performance evaluation of the polyurethane-based composites prepared with recycled polymer concrete aggregate. Materials. 2020;13(3):616. doi:10.3390/ma13030616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Dominguez-Santos D, Guerra MCG. Mechanical and structural behavior of concrete blocks with granulated polystyrene (PS) and recycled polypropylene (PP) fibres and their use in low and medium height frames. J Earthq Eng. 2024;28(7):2000–26. doi:10.1080/13632469.2023.2271074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Habib A, Yildirim U. Simplified modeling of rubberized concrete properties using multivariable regression analysis. Mater Constr. 2022;72(347):e289. doi:10.3989/mc.2022.13621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Cuevas K, Chung SY, Sikora P, Stephan D. Performance of normal-weight and lightweight 3D printed cementitious composites with recycled glass: sorption and microstructural perspective. J Build Eng. 2024;97(6):110880. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sambaturu SB, Surendra Y, Nagaseshu Babu T, Hemantha Raja P, Reddy KR. Usage of waste materials in pavement construction with replacement of conventional materials. J Civil Eng Technol. 2017;8(4):1305–12. [Google Scholar]

32. Khoury N, Khoury C, Abousleiman Y. Soil fused with recycled plastic bottles for various geo-engineering applications. In: GeoCongress 2008. New Orleans, LA, USA: American Society of Civil Engineers; 2008. p. 336–43. doi:10.1061/40970(309)42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Jitsangiam P, Nusit K, Teeratitayangkul P, Ping Ong G, Thienchai C. Development of a modified Marshall mix design for Hot-mix asphalt concrete mixed with recycled plastic based on dry mixing processes. Constr Build Mater. 2023;404(4):133127. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lee SY, Le THM. Feasibility of sustainable asphalt concrete materials utilizing waste plastic aggregate, epoxy resin, and magnesium-based additive. Polymers. 2023;15(15):3293. doi:10.3390/polym15153293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Lim SM, He M, Hao G, Ng TCA, Ong GP. Recyclability potential of waste plastic-modified asphalt concrete with consideration to its environmental impact. Constr Build Mater. 2024;439(2):137299. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xiao R, Polaczyk P, Huang B. Mitigating stripping in asphalt mixtures: pretreatment of aggregate by thermoplastic polyethylene powder coating. Transp Res Rec J Transp Res Board. 2024;2678(4):776–87. doi:10.1177/03611981231186598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ameri M, Mohammadi R, Mousavinezhad M, Ameri A, Shaker H, Fasihpour A. Evaluating properties of asphalt mixtures containing polymers of styrene butadiene rubber (SBR) and recycled polyethylene terephthalate (rPET) against failures caused by rutting, moisture and fatigue. Frat Integrità Strut. 2020;14(53):177–86. doi:10.3221/igf-esis.53.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Song S, Li Q, Wang J, Wang N, Shang J, Zhang S. Utilization of thermoplastic resin as foamed asphalt modifier in cold recycled mixtures. J Clean Prod. 2024;478(8):143973. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Xiao R, Zhang M, Zhong J, Baumgardner GL, Huang B. Waste plastic powder coating on acidic aggregates: a new hydrophobic coating technology to build moisture-resistant asphalt mixtures. Transp Res Rec J Transp Res Board. 2025;2679(1):992–1005. doi:10.1177/03611981231193413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen AJ, Zhang Q, Wang J, Gai ZF. Freez-thaw cycle test and a damage mechanics model for recycled concrete. Eng Mech. 2009;26(11):102–7. [Google Scholar]

41. Richardson A, Coventry K, Bacon J. Freeze/thaw durability of concrete with recycled demolition aggregate compared to virgin aggregate concrete. J Clean Prod. 2011;19(2–3):272–7. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.09.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Mohamed AMO, El Gamal MM, El Saiy AK. Thermo-mechanical behavior of newly developed sulfur polymer concrete. In: Proceedings of the GCC Environment and Water Resources Conference; 2006 Mar 1–6; Manama, Bahrain. p. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

43. Chen AJ, Wang J, Ge ZF, Wu M. The durability life prediction of recycled concrete under chlorate environment. Adv Mater Res. 2011;314–316:849–52. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.314-316.849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Xing W, Tam VW, Le KN, Hao JL, Wang J. Life cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete on its environmental impacts: a critical review. Constr Build Mater. 2022;317(11):125950. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Müller A. Energieeinsparungen durch das Recycling von Bauabfällen? Bautechnik. 2022;99(12):916–23. doi:10.1002/bate.202200098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Bhagat GV, Savoikar PP. Durability related properties of cement composites containing thermoplastic aggregates—a review. J Build Eng. 2022;53(7):104565. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Esmaeili-Falak M, Sarkhani Benemaran R. Application of optimization-based regression analysis for evaluation of frost durability of recycled aggregate concrete. Struct Concr. 2024;25(1):716–37. doi:10.1002/suco.202300566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Jo BW, Park SK, Park JC. Mechanical properties of polymer concrete made with recycled PET and recycled concrete aggregates. Constr Build Mater. 2008;22(12):2281–91. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.10.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Książek M. The analysis of thermoplastic characteristics of special polymer sulfur composite. Continuum Mech Thermodyn. 2017;29(1):11–29. doi:10.1007/s00161-016-0516-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Mondal MK, Bose BP, Bansal P. Recycling waste thermoplastic for energy efficient construction materials: an experimental investigation. J Environ Manage. 2019;240(3):119–25. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.03.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Singh P, Singh DN, Debbarma S. Macro- and micro- mechanisms associated with valorization of waste rubber in cement-based concrete and thermoplastic polymer composites: a critical review. Constr Build Mater. 2023;371(4):130807. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Nguyen TD, Cherif R, Mahieux PY, Lux J, Aït-Mokhtar A, Bastidas-Arteaga E. Artificial intelligence algorithms for prediction and sensitivity analysis of mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete: a review. J Build Eng. 2023;66:105929. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2023.105929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Liang C, Bao J, Gu F, Lu J, Ma Z, Hou S, et al. Determining the importance of recycled aggregate characteristics affecting the elastic modulus of concrete by modeled recycled aggregate concrete: experiment and numerical simulation. Cem Concr Compos. 2025;162(3):106118. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2025.106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Choi YW, Moon DJ, Kim YJ, Lachemi M. Characteristics of mortar and concrete containing fine aggregate manufactured from recycled waste polyethylene terephthalate bottles. Constr Build Mater. 2009;23(8):2829–35. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.02.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Grigore M. Methods of recycling, properties and applications of recycled thermoplastic polymers. Recycling. 2017;2(4):24. doi:10.3390/recycling2040024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Xu G, Guo T, Li A, Zhang H, Wang K, Xu J, et al. Seismic resilience enhancement for building structures: a comprehensive review and outlook. Structures. 2024;59(2):105738. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Mata R, Nuñez E, Forcellini D. Seismic resilience of composite moment frames buildings with slender built-up columns. J Build Eng. 2025;111(1):113532. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2025.113532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Wei H, Jing H, Sang L. The technological innovation pathway for green, low-carbon, and durable pavement construction and maintenance. Sci China Technol Sci. 2024;67(12):3959–61. doi:10.1007/s11431-024-2733-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Jiang X, Huang W, Luo S, Kong W, Du K. Investigation of the performance evolution mechanism of epoxy asphalt binder and mixture: influence of curing agent and epoxy content. Constr Build Mater. 2025;472(3):140779. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Shrif M, Al-Sadoon ZA, Barakat S, Habib A, Mostafa O. Optimizing gene expression programming to predict shear capacity in corrugated web steel beams. Civ Eng J. 2024;10(5):1370–85. doi:10.28991/cej-2024-010-05-02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Habib A, Barakat S, Al-Toubat S, Junaid MT, Maalej M. Developing machine learning models for identifying the failure potential of fire-exposed FRP-strengthened concrete beams. Arab J Sci Eng. 2025;50(11):8475–90. doi:10.1007/s13369-024-09497-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Habib A, Junaid MT, Dirar S, Barakat S, Al-Sadoon ZA. Machine learning-based estimation of reinforced concrete columns stiffness modifiers for improved accuracy in linear response history analysis. J Earthq Eng. 2025;29(1):130–55. doi:10.1080/13632469.2024.2409865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Ganiron TU. Effect of thermoplastic as fine aggregate to concrete mixture. Int J Adv Sci Technol. 2014;62:31–42. doi:10.14257/ijast.2014.62.03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Gavela S, Rakanta E, Ntziouni A, Kasselouri-Rigopoulou V. Eleven-year follow-up on the effect of thermoplastic aggregates’ addition to reinforced concrete. Buildings. 2022;12(11):1779. doi:10.3390/buildings12111779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Uche CKA, Abubakar SA, Nnamchi SN, Ukagwu KJ. Polyethylene terephthalate aggregates in structural lightweight concrete: a meta-analysis and review. Discov Mater. 2023;3(1):24. doi:10.1007/s43939-023-00060-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Chen Y, Chen C, Cai Z, Zhu P, Liu R, Liu H. Effect of strength of parent concrete on utilization of recycled aggregate concrete: a review. J Build Eng. 2025;103:112187. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2025.112187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Habib A, Yildirim U. Influence of isolator properties and earthquake characteristics on the seismic behavior of RC structure equipped with quintuple friction pendulum bearings. Int J Str Stab Dyn. 2023;23(6):2350060. doi:10.1142/s0219455423500608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Xiao J, Tang Y, Chen H, Zhang H, Xia B. Effects of recycled aggregate combinations and recycled powder contents on fracture behavior of fully recycled aggregate concrete. J Clean Prod. 2022;366(9):132895. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Siyahi A, Kavussi A, MIRZA BA. Enhancing skid resistance of two-component road marking paint using mineral and recycled materials [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.ijte.ir/article_14773_7132939d5ed2b9df310d1f4fc177b587.pdf. [Google Scholar]

70. Habib A, Yildirim U. Distribution of strong input energy in base-isolated structures with complex nonlinearity: a parametric assessment. Multidiscip Model Mater Struct. 2023;19(2):324–40. doi:10.1108/mmms-08-2022-0158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Habib A, AL Houri A, Junaid MT, Barakat S. A systematic and bibliometric review on physics-based neural networks applications as a solution for structural engineering partial differential equations. Structures. 2024;69(6):107361. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2024.107361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Borayek AG, Faried AS, Osman KM, Sofi WH. Influence of polyester and acrylic polymer coatings on the mechanical, physical and microstructural characteristics of recycled aggregate concrete. Egypt J Chem. 2025;68(6):477–92. doi:10.21608/ejchem.2024.320216.10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools