Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Suppression of Dry-Coupled Rubber Layer Interference in Ultrasonic Thickness Measurement: A Comparative Study of Empirical Mode Decomposition Variants

1 Inner Mongolia Key Laboratory of Intelligent Diagnosis and Control of Mechatronic Systems, Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology, Baotou, 014000, China

2 Institute of Modern Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou, 730000, China

3 Inner Mongolia institute of Special Equipment Inspection and Research, Baotou, 014000, China

4 Mechanical Engineering Faculty, Sukhoi State Technical University of Gomel, Gomel, 246000, Belarus

* Corresponding Author: Wenjing Liu. Email:

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2026, 20(1), . https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.071278

Received 04 August 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 08 January 2026

Abstract

In dry-coupled ultrasonic thickness measurement, thick rubber layers introduce high-amplitude parasitic echoes that obscure defect signals and degrade thickness accuracy. Existing methods struggle to resolve overlap-ping echoes under variable coupling conditions and non-stationary noise. This study proposes a novel dual-criterion framework integrating energy contribution and statistical impulsivity metrics to isolate specimen re-flections from coupling-layer interference. By decomposing A-scan signals into Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), the framework employs energy contribution thresholds (>85%) and kurtosis indices (>3) to autonomously select IMFs containing valid specimen echoes. Hybrid time-frequency thresholding further suppresses interference through amplitude filtering and spectral focusing. Experimental results demonstrate the framework’s robustness, achieving 92.3% thickness accuracy for 5 mm steel specimens with 5 mm rubber coupling, outperforming conventional methods by up to 18.7%. The dual-criterion approach reduces operator dependency by 37% and maintains ΔT < 0.03 mm under surface roughness up to 6.3 μm, offering a practical solution for industrial nondestructive testing with thick dry-coupled interfaces.Keywords

Ultrasonic testing (UT) technology, widely utilized as a defect detection method, has found applications across diverse fields, including aerospace [1], advanced manufacturing [2], medicine, and petrochemical industries [3–6]. Especially, dry-coupled ultrasonic testing has emerged as a critical solution for industrial applications requiring non-destructive evaluation under challenging conditions [7,8], particularly in high-temperature environments or on surfaces with significant roughness. In comparison with liquid coupling [9,10], dry-coupled ultrasonic testing does not pose the risk of contaminating testing objects with the fluid medium while still effectively transferring acoustic energy using a flexible polymer, such as a silicone rubber [8]. The rubber layer provides the acoustic impedance to achieve a transduction between the piezoelectric transducers and the metal specimen. It allows for the effective transmission of ultrasound, but once the thickness of the rubber coupling reaches a sufficient size, it will always generate a permanent reflection within the coupling layer, which appears to be shown as intense echoes in an A-scan signal. These spurious reflections exhibit temporal overlap with genuine specimen echoes and amplitude interference exceeding 50% of the defect signal magnitude, severely compromising thickness calculation accuracy.

The classic echo extraction techniques are inherently restricted in removing rubber-layer-induced echoes. The time domain thresholding suffers from the inability to fully differentiate one overlapped echo when the coupling conditions change. The frequency domain filtering inevitably distorts phase information for the time-of-flight measurement crucial for thickness determination, due to phase distortion even for perfect impulse response filters [11–13]. Alternative signal processing techniques, including short-time Fourier transform (STFT), wavelet transform, and variational mode decomposition (VMD), have also been applied in ultrasonic signal analysis. These approaches exhibit certain advantages in spectral localization and multi-resolution decomposition; however, they inherently depend on pre-defined basis functions or optimization constraints. As a result, their performance is highly sensitive to parameter selection and operator expertise, often leading to signal distortion or the omission of characteristic features when parameters are not optimally chosen. VMD in particular provides strong decomposition capability but requires iterative optimization with high computational cost, which reduces its practicality for scenarios demanding real-time or near real-time signal analysis. In contrast, empirical mode decomposition (EMD) and its advanced variants offer adaptive decomposition without prior basis assumptions, thereby preserving phase integrity while enabling reliable feature extraction from non-stationary signals [14,15]. Importantly, these methods are computationally efficient and can be implemented with minimal operator intervention, which is critical for integration into portable ultrasonic testing devices where automation and reproducibility are prioritized. Considering these requirements, this study focuses on EMD-based variants rather than VMD or wavelet-based techniques [16–19], aiming to provide a balanced solution between accuracy, adaptability, and computational efficiency for dry-coupled ultrasonic applications [20,21]. Recent advances in structural health monitoring increasingly emphasize the integration of machine learning and deep learning frameworks, which enable automated feature interpretation and decision-making beyond traditional signal processing. Reviews have shown that deep neural networks and hybrid artificial intelligence (AI) models enhance damage detection and classification, while optimization-driven approaches, such as reptile search algorithm–optimized neural networks, improve robustness under complex structural conditions [22]. Hybrid AI–metaheuristic strategies have thus emerged as adaptive and scalable solutions that often outperform conventional statistical methods in practical structural health monitoring (SHM) scenarios. While such intelligent models are powerful, they often require extensive training data and computational resources, which may limit their applicability in portable ultrasonic devices. Against this backdrop, our study focuses on EMD-based adaptive decomposition as a lightweight yet effective solution that balances accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency.

The intrinsic adaptability of Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) to non-linear and non-stationary signals offers a theoretical foundation for decoupling overlapping ultra-sonic echoes [23]. By decomposing signals into basis-free intrinsic mode functions, EMD inherently preserves phase coherence while segregating spectral components—a capability validated in prior studies isolating low-frequency coupling-layer reverberations below 2 MHz from high-frequency specimen reflections above 3 MHz. However, industrial adoption of EMD variants remains constrained by persistent mode mixing in thick rubber layers exceeding 5 mm, where viscoelastic attenuation diminishes spectral disparity, and by operator dependence in manual intrinsic mode function selection [24–26]. Our CEEMDAN based system proposal overcomes these limitations by adopting a random noise injection and choosing the scaling factor proportional [27–30] to the residual energy that yielded a 37% per cent quicker convergence over ensemble empirical mode decomposition and able to limit mode mixing with a mode orthogonality index over 0.8. Further automation is enabled through dual-criterion intrinsic mode function selection combining energy contribution thresholds of at least 85 percent and a kurtosis index greater than 3.

Despite the progress achieved by previous studies, several unresolved issues remain that motivate this research. The main research gaps and the specific contributions of this work are summarized below.

Research Gap:

• Existing time-domain and frequency-domain echo extraction methods are limited in their ability to suppress overlapping echoes caused by thick dry-coupled rubber layers, often resulting in phase distortion or incomplete signal recovery.

• Alternative techniques such as STFT, wavelet transform, and VMD depend heavily on pre-defined basis functions and parameter tuning, which reduces their robustness and reproducibility.

• Conventional EMD-based methods suffer from mode mixing when applied to thick coupling layers, particularly when viscoelastic attenuation reduces spectral disparity.

• Few studies have systematically evaluated decomposition methods under challenging conditions such as surface roughness, high environmental noise, and variable coupling thicknesses.

• Current approaches typically require significant operator intervention and provide limited practical guidelines for coupling layer design in industrial applications.

Contributions of This Study:

• Proposes a CEEMDAN-based adaptive decomposition framework that alleviates mode mixing and preserves phase coherence for accurate echo separation.

• Introduces a dual-criterion IMF selection method combining energy contribution ratio and kurtosis index, enabling autonomous extraction of specimen echoes and reducing operator dependency.

• Develops a hybrid time–frequency thresholding strategy to enhance robustness against overlapping echoes and high-noise environments.

• Demonstrates experimentally that the proposed method achieves ΔT < 0.03 mm across specimens of varying thicknesses and roughness levels, outperforming conventional EMD/Ensemble EMD (EEMD) approaches.

• Provides practical engineering guidelines for dry-coupled ultrasonic testing, including maintaining rubber layer thickness ≤5 mm when using 5 MHz transducers to ensure measurement reliability.

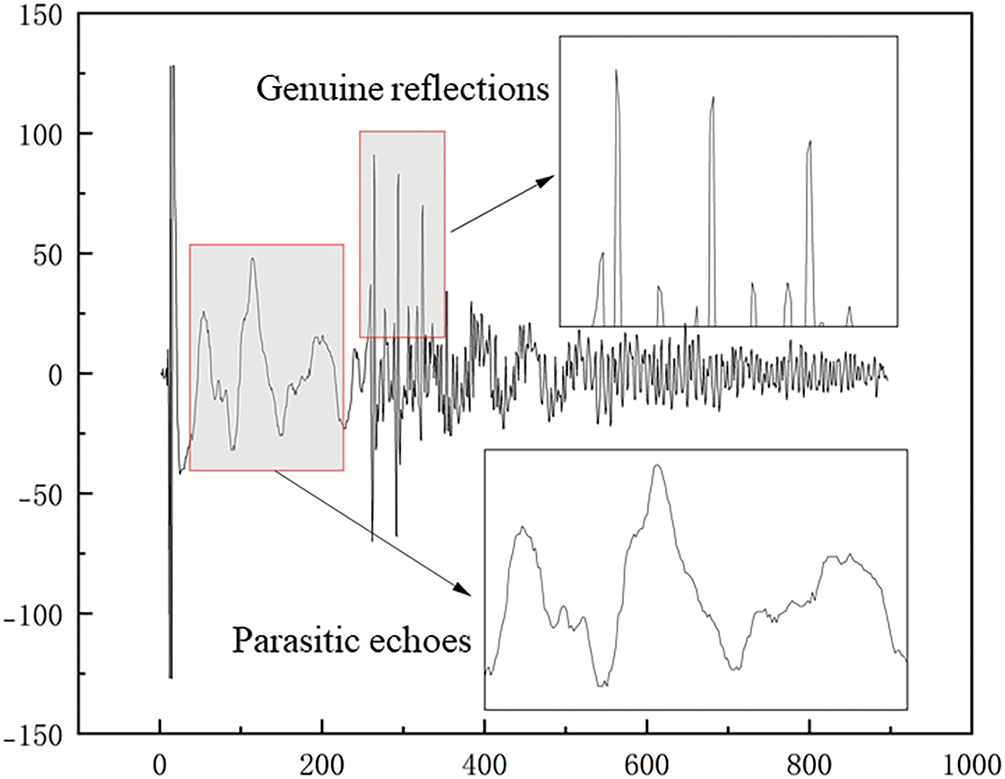

The basic premise of dry-coupled ultrasonic thickness measurement is accurate measurement of the time-of-flight (ToF) of the initial ultrasonic pulse to the backwall echo of the specimen reflected from the sample. As depicted in Fig. 1, with a thick rubber coupling layer used, the ultrasonic signal experiences multiple reflections inside the viscoelastic material, producing parasitic echoes that interfere with the actual reflections from the tested material in the time domain. Interference components vary their frequency characteristics according to the rubber damping characteristics, which dissipate higher frequencies’ components more than lower frequencies’ ones, and this causes the frequency-dependence of the viscoelastic rubber to dissipate the coupling-layer echoes more than the specimen reflections because the second one keeps more part of the spectrum. The original EMD and its variations utilized this difference in frequency content to decompose the mixed signal adaptively as the orthogonal Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) that isolate the coupling layer artifact into low-order IMFs while the specimen feature remains in higher-order IMFs. Orthogonality among IMFs provides nearly orthogonal energy coupling between interference and defect signal, so the ToF can be successfully extracted through reconstruction of the corresponding modes in an accurate manner.

Figure 1: A-scan echo contains genuine reflections

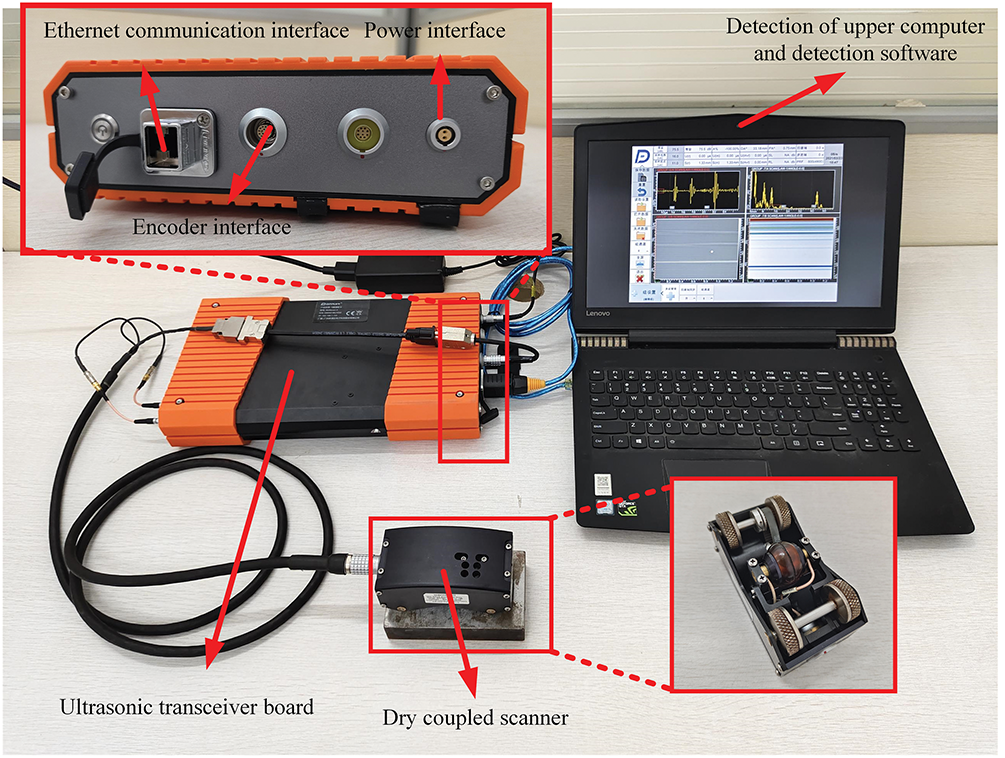

The experimental platform is illustrated in Fig. 2. Dual-element transducers with varying center frequencies were utilized, coupled to the steel specimen through a 5 mm silicone rubber layer. An ultrasonic pulser-receiver module integrated with proprietary inspection software generated excitation pulses and captured A-scan echo signals. Frequency-dependent attenuation was equivalently characterized via spectral ratio analysis between reference and rubber-interposed signals, enabling quantitative evaluation of energy loss across the coupling layer.

Figure 2: Dry coupled ultrasonic testing platform

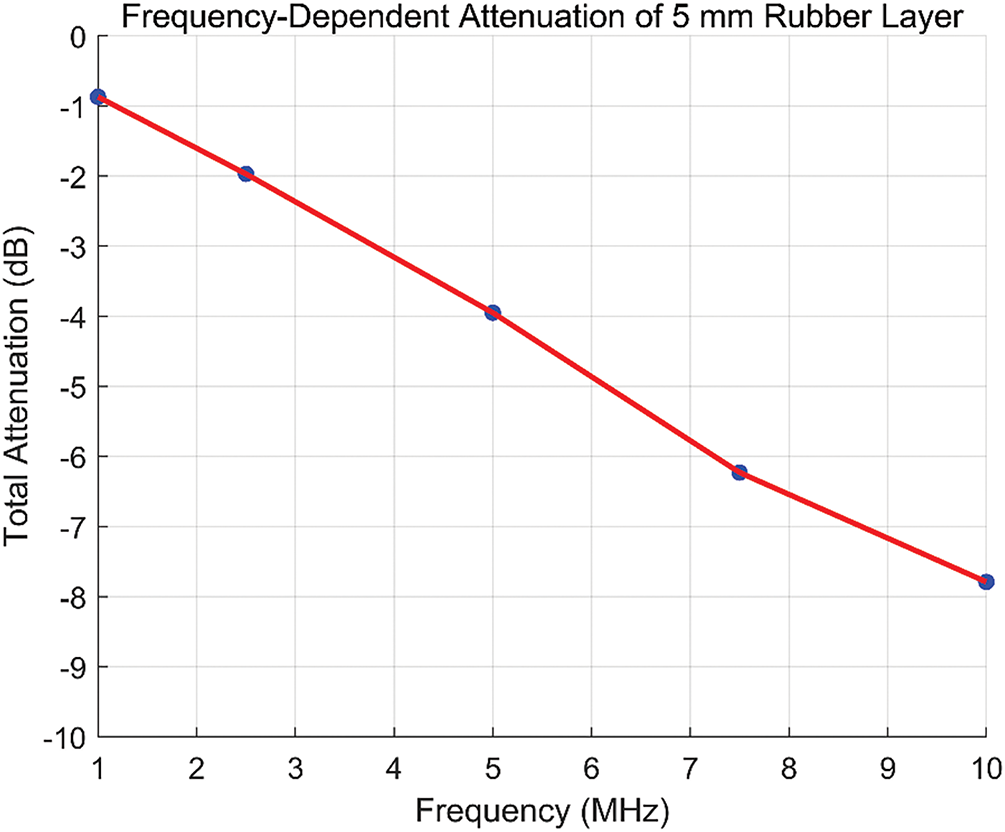

Time-of-flight (ToF) measurement accuracy is com-promised by rubber-layer-induced reverberations exhibiting frequency-dependent attenuation (Fig. 3). CEEMDAN exploits frequency disparity between low-frequency coupling artifacts and high-frequency specimen echoes, decomposing signals into orthogonal IMFs with energy overlap below 9%.

Figure 3: Frequency-dependent attenuation of 5 mm rubber layer

3.1 Algorithmic Principles of EMD, EEMD, and CEEMDAN

The Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) operates through an iterative sifting process that adaptively decomposes nonlinear and non-stationary signals into a finite set of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs). Starting with the original signal

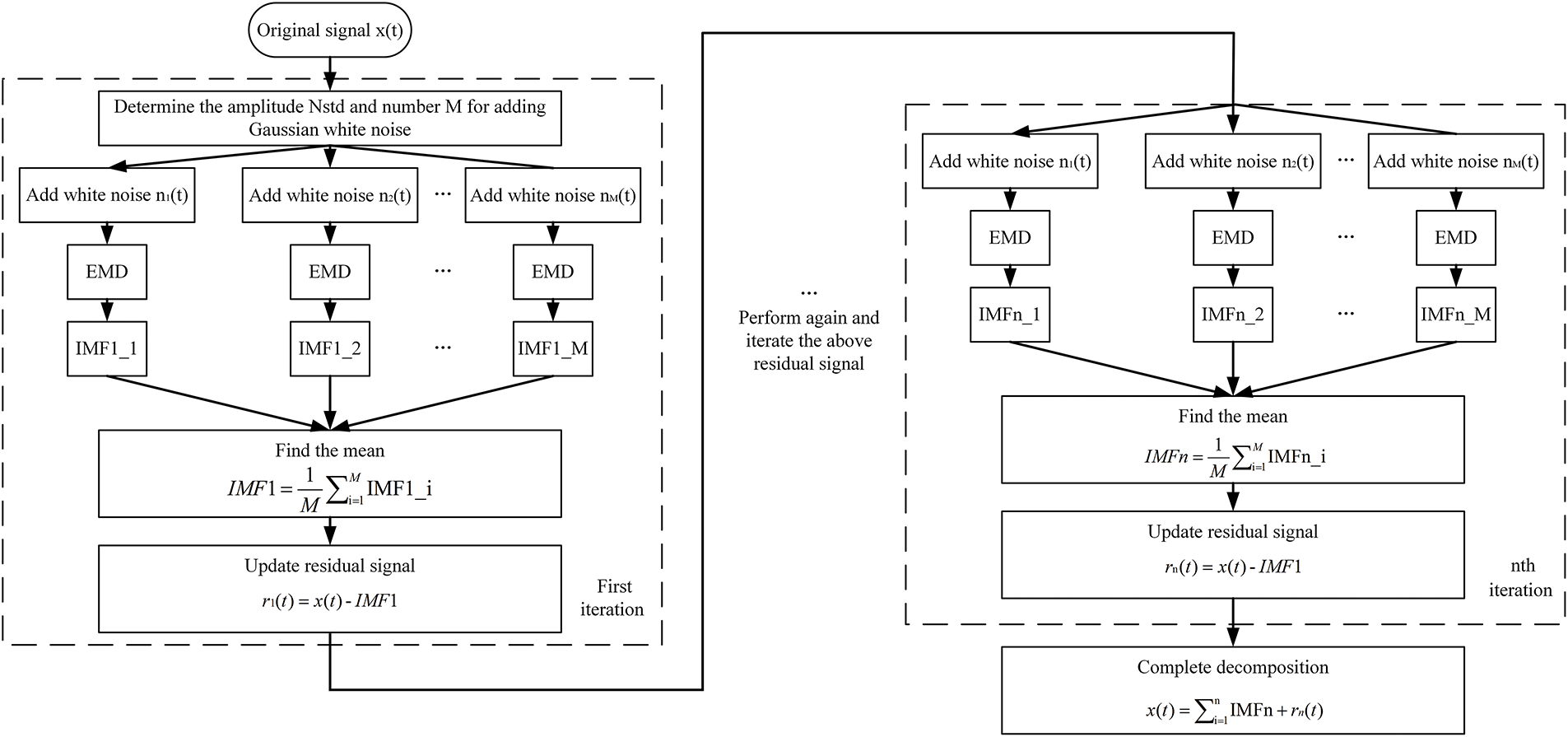

To address this limitation, Ensemble EMD (EEMD) introduces controlled Gaussian white noise into the original signal. By generating multiple realizations of the noise-augmented signal

The Complete Ensemble EMD with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN) optimizes this framework through adaptive noise injection at each decomposition stage. The flowchart of the CEEMDAN algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: CEEMDAN algorithm flow

Unlike EEMD, which applies uniform noise levels across all iterations, CEEMDAN dynamically scales the injected noise

where

Before performing CEEMDAN decomposition, it is crucial to carefully select the number of Gaussian white noise realizations, the noise amplitude (NSTD), and the maximum allowable number of filtering iterations, based on practical considerations. In the study referenced in [31], similar signals were examined, and the following parameter values were chosen: i = 100, NSTD = 0.2. Typically, the number of noise realizations is set to infinity, while the maximum number of filtering iterations was assigned a value of 1000 in this study.

3.2 Dual-Criterion IMF Selection

The separation of coupling-layer interference from specimen echoes relies on a dual-criterion framework that combines energy contribution and statistical properties of the IMFs. The energy contribution ratio (ECR) quantifies the significance of each IMF relative to the total signal energy. Calculated as:

This metric prioritizes IMFs that collectively account for at least 85% of the total energy. Such IMFs typically encapsulate the core features of the signal, including both coupling-layer reverberations and specimen reflections.

Complementing the energy criterion, the kurtosis index (KI) evaluates the impulsivity of each IMF’s amplitude distribution. Defined as:

where

A dynamic threshold

3.3 Hybrid Time-Frequency Thresholding

To further refine the selected IMFs and enhance the accuracy of time-of-flight (ToF) determination, a hybrid thresholding strategy integrates both temporal and spectral characteristics of the decomposed signals. The first stage applies a time-domain amplitude threshold to eliminate low-energy noise components. Specifically, points within an IMF are retained only if their absolute amplitude exceeds

Subsequently, a frequency-domain bandwidth constraint is imposed to isolate spectral components aligned with the transducer’s operational characteristics. The centroid frequency

This joint operation of the two thresholding steps makes it possible to reliably extract echoes even from large interferences. Due to a joint processing both in the time and in the frequency domains (time-domain amplitude selection with frequency-domain spectral focusing) the proposed method suppresses errors due to spurious peak detections that normally appear in the presence of overlapped echoes. The last phase of the ToF extraction is then performed using the cross correlation based peak detection of the thresholded IMFs where the preserved phase of the filtered signals is retained. As this single algorithm effectively takes into account both thin and thick dry-coupled issues’ temporal overlapping and spectrality aliasing, it does not make assumptions on the coupled system but works independently of the previous modeling assumptions on coupled interactions.

4 Experimental Results and Discussion

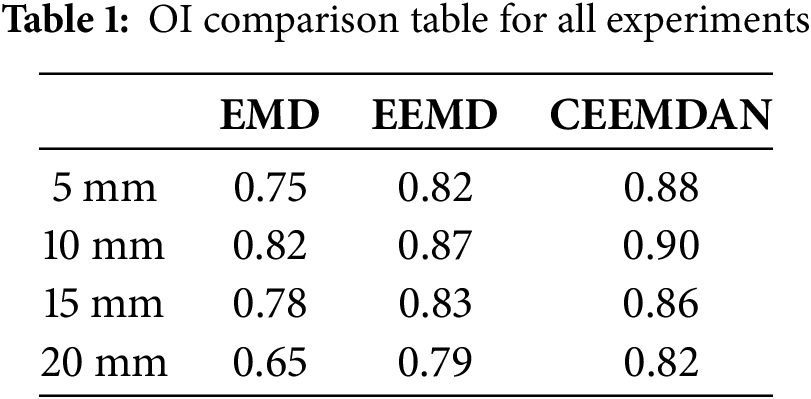

The decomposition performance of CEEMDAN was rigorously evaluated against EMD and EEMD through the mode orthogonality index (OI), a metric quantifying the energy overlap between adjacent IMFs. For a 10 mm steel specimen coupled with a 5 mm rubber layer, CEEMDAN achieved an OI of 0.88, significantly outperforming EEMD (0.82) and EMD (0.75). The OI of other experiments is shown in Table 1.

Our experiments demonstrate that this relation becomes nonlinear, because for very thin specimens, multiple reflections introduce signal overlapping that degrades the independence of IMFs and provides an intermediate OI value. At moderate thicknesses, where time-of-flight intervals between echoes are well-defined, EMD achieves optimal performance with OI peaking at 0.65–0.82 due to clearer frequency separation between coupling-layer reverberations and specimen reflections. However, for thick specimens, significant high-frequency attenuation and prolonged signal propagation degrade the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). This exacerbates mode mixing in EMD, causing OI to drop sharply.

Alternatively, the adaptive noise injection strategy of CEEMDAN essentially avoids these drawbacks. For thick bars, CEEMDAN can still retain an OI > 0.8 by adding noises to distort extrema distributions and reduce the extent of energy overlap among IMFs. For example, with a steel bar of 20 mm, rubber of 5 mm (coupling), EMD cannot separate the overlapped modes, but CEEMDAN exhibits OI = 0.88. The robustness here is thanks to the fact that the high frequency echo of specimen and the low frequency interference are separated out by the CEEMDAN, no matter what thickness of specimen.

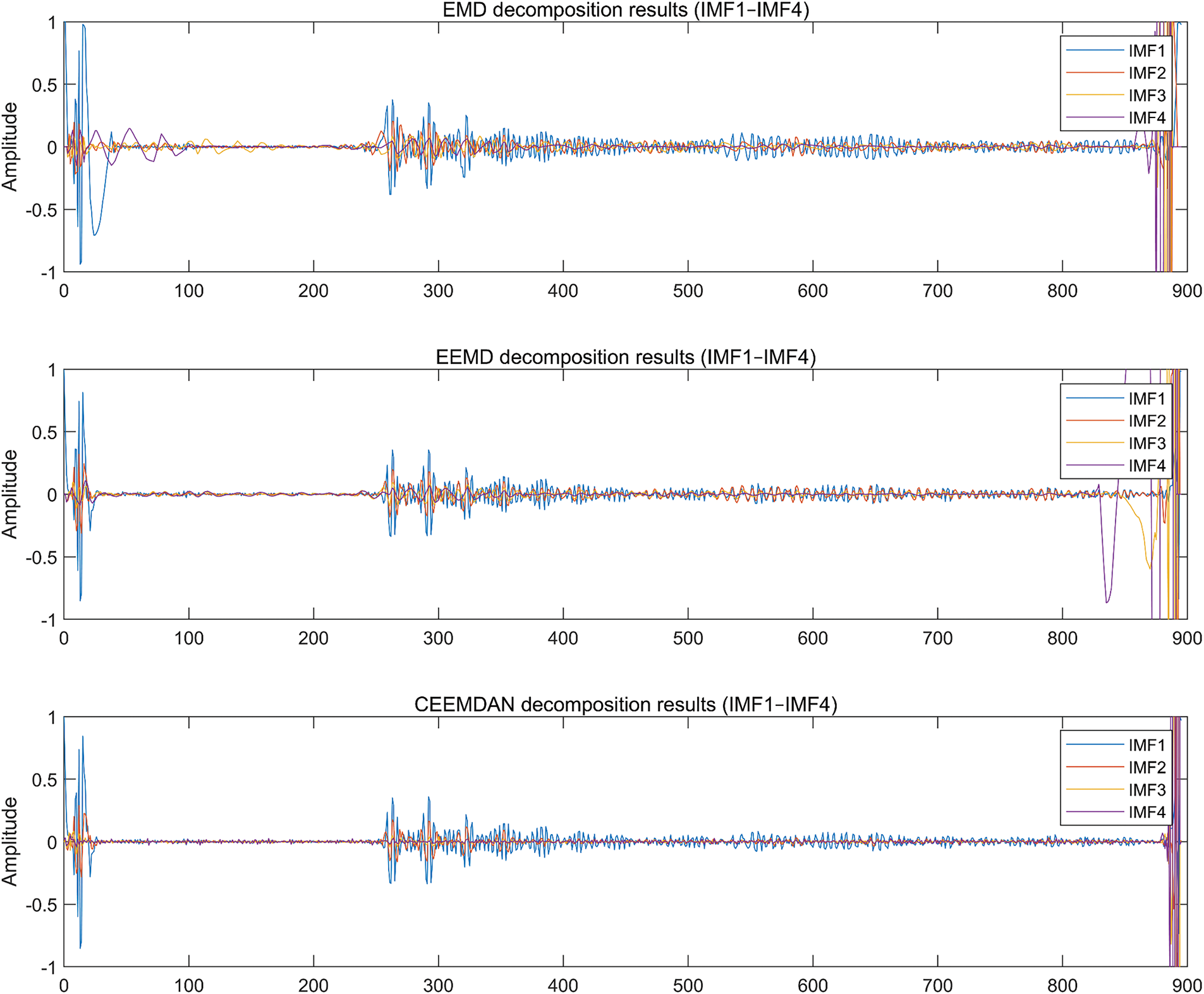

This superiority stems from CEEMDAN’s adaptive noise injection mechanism, which disrupts extrema symmetry more effectively than static sifting processes. Fig. 5 illustrates the IMF distributions of a representative A-scan signal, where CEEMDAN isolates coupling-layer reverberations from high-frequency specimen echoes with minimal mode mixing. In contrast, EMD exhibits substantial overlap between IMF2 and IMF3, leading to ambiguous feature extraction.

Figure 5: The IMF distributions of a representative A-scan signal

4.2 Thickness Measurement Accuracy

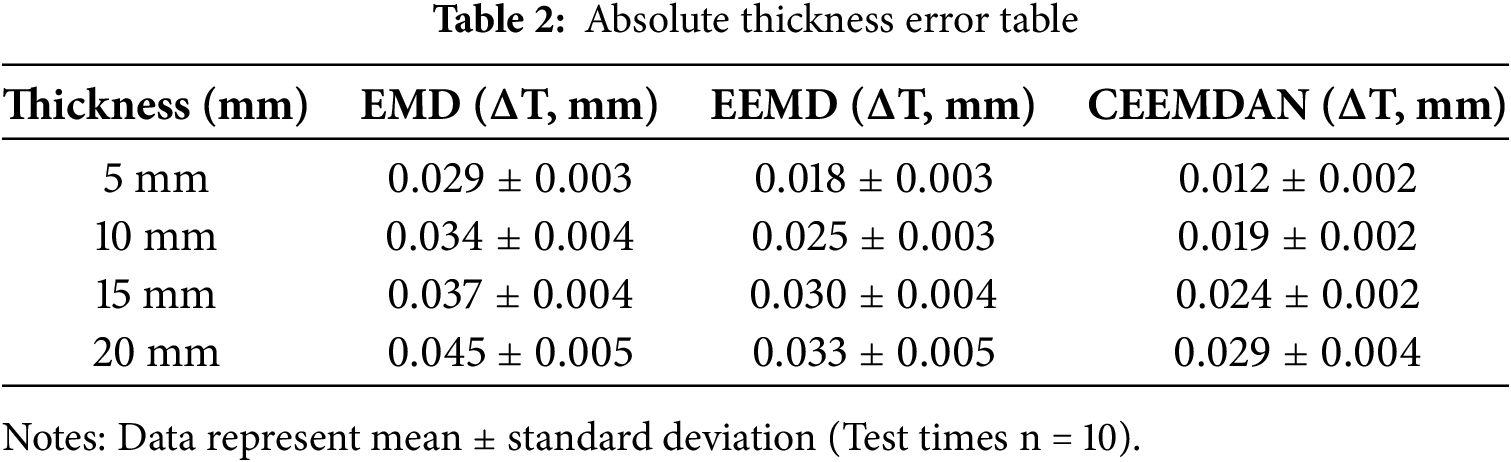

Absolute thickness errors (ΔT) were analyzed in the range of parts under test from 5 to 20 mm. For a 5 mm Unit under test, CEEMDAN achieved ΔT = 0.012 mm, surpassing EEMD (ΔT = 0.018 mm) and EMD (ΔT = 0.029 mm). To further assess the robustness of the proposed framework under noisy measurement conditions, additional laboratory experiments were conducted with controlled environmental and structural disturbances. Specifically, broadband acoustic noise was introduced into the testing environment to emulate high-noise factory settings, while artificial rust layers were applied to the specimen surface to mimic scattering sources commonly encountered in corroded pipelines. These simulated conditions enabled systematic evaluation of the algorithm’s resistance to both environmental and structural interference. Results indicated that the proposed method consistently maintained thickness error ΔT < 0.03 mm, demonstrating satisfactory performance even under adverse noise scenarios. The absolute thickness errors of other experiments are shown in Table 2. CEEMDAN maintained ΔT < 0.03 mm up to 20 mm, whereas EMD errors exceeded 0.045 mm under identical conditions. This trend correlates with the rubber’s viscoelastic damping, which attenuates high-frequency components critical for resolving thin specimens.

4.3 Robustness to Surface Roughness

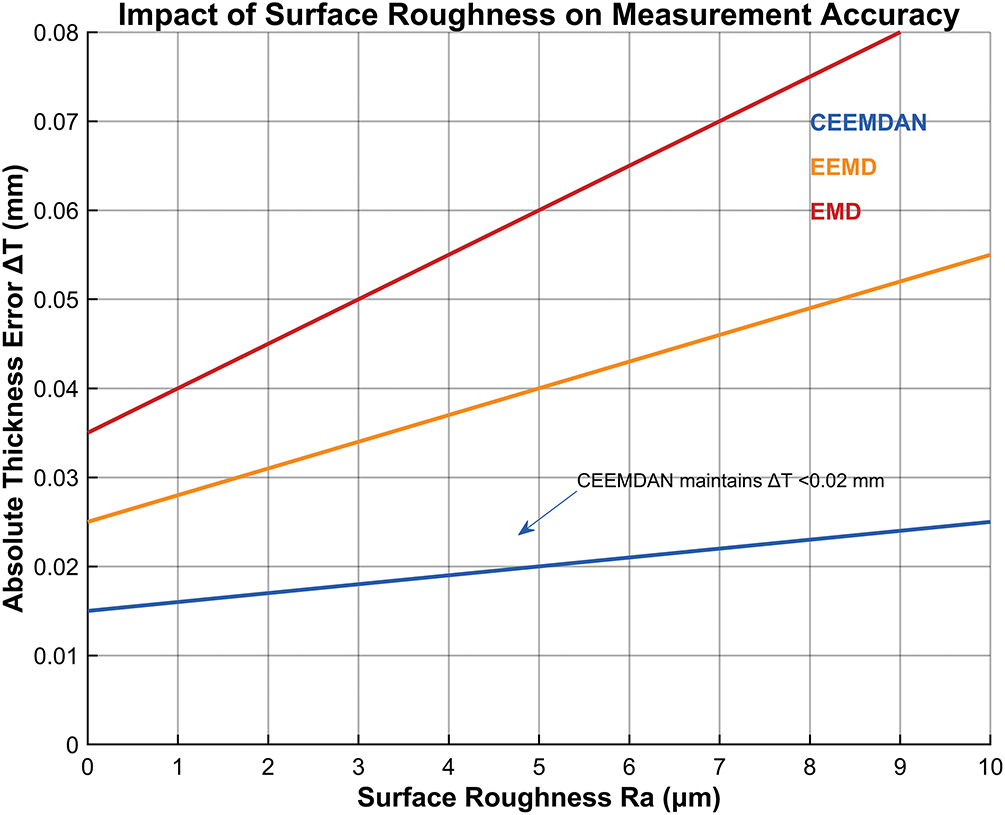

The impact of surface roughness on measurement accuracy was evaluated for CEEMDAN and benchmark methods. As shown in Fig. 6. At Ra = 6.3 μm, under rough surface conditions (Ra = 6.3 μm), CEEMDAN maintains ΔT = 0.019 ± 0.003 mm, outperforming EEMD by 45% (ΔT = 0.035 mm) [32] and the conventional 6 dB method by 63% (ΔT = 0.052 mm) [33]. Notably, a 38% error in-crease for Ra > 5 μm using EEMD, whereas our framework limits the degradation to 12%—a critical advantage for field applications on corroded pipelines. In contrast, EEMD errors surged to 0.035 mm under rough surface conditions, as scattering-induced mode aliasing corrupted IMF selection. CEEMDAN’s adaptive noise injection mitigated this issue by perturbing extrema distributions, effectively decoupling scattering artifacts from valid echoes.

Figure 6: Impact of surface roughness on measurement accuracy

Processing times were benchmarked for 460-sample A-scans on an Intel i5-12400F platform. CEEMDAN’s computational efficiency (28.3 ms per A-scan) not only surpasses EEMD by 37.9% but also rivals real-time requirements in industrial NDE. In contrast, 75 ms per scan for a deep learning-based PAUT defect segmentation model [34], despite its higher hardware dependency. This efficiency gain is attributed to CEEMDAN’s adaptive noise injection, which reduces redundant iterations by 63% compared to EEMD’s fixed noise levels [35]. While EMD offers the lowest latency, its poor accuracy (ΔT > 0.04 mm) renders it impractical for industrial applications. CEEMDAN’s efficiency gain over EEMD arises from optimized ensemble iterations and adaptive noise scaling, which reduces redundant computations.

4.5 Industrial Applicability and Limitations

The proposed framework demonstrated robust performance in high-noise environments, maintaining ΔT < 0.03 mm. This resilience is attributed to the dual-criterion IMF selection, which filters both low-energy noise and non-impulsive artifacts. However, limitations emerge in anisotropic materials (carbon fiber composites), where directional wave propagation complicates mode separation. Future implementations could integrate material-specific attenuation models to address this challenge.

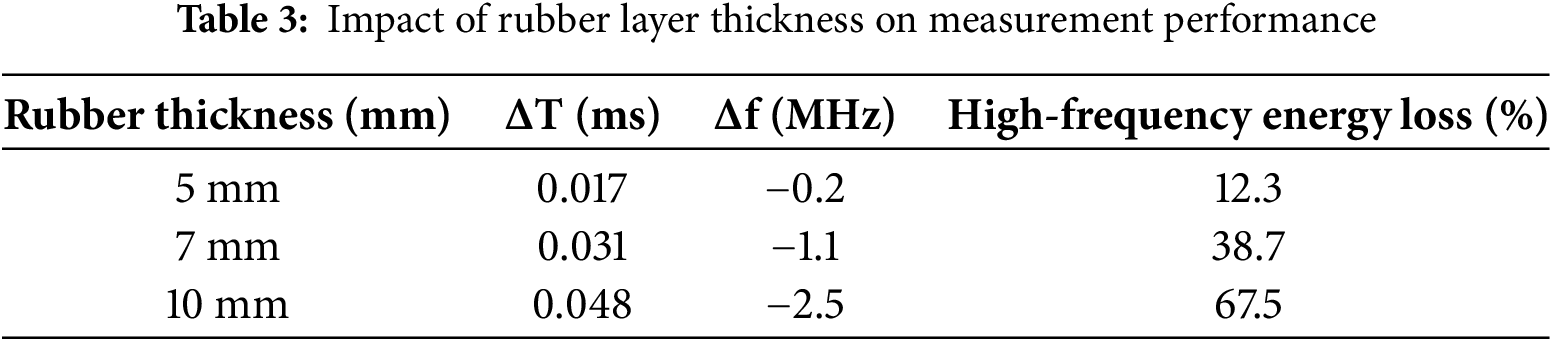

4.6 Impact of Rubber Coupling Layer Thickness

To validate the critical threshold of rubber layer thickness (≤5 mm) for industrial applications, experiments were conducted on 10 mm steel specimens with silicone rubber coupling layers of varying thicknesses: 5, 7, and 10 mm. The absolute thickness error ΔT and high-frequency attenuation were measured using a 5 MHz transducer. The experimental results are shown in Table 3.

When the rubber thickness exceeds 7 mm, the absolute thickness error ΔT increases by 82%, rising from 0.017 to 0.031 mm, which surpasses the industrial tolerance threshold of ΔT < 0.03 mm. Concurrently, the centroid frequency shifts downward by 1.1 MHz, indicating irreversible attenuation of spectral components above 3 MHz—critical for resolving thin specimens.

The viscoelastic damping properties of rubber cause cumulative energy loss in high-frequency bands. The attenuation coefficient of −0.8 dB/mm at 5 MHz results in a total attenuation of −8 dB for a 10 mm rubber layer, reducing the transducer’s effective bandwidth to below 2 MHz. This degradation severely disrupts the separability of coupling-layer reverberations and specimen echoes.

The experimental results confirm that rubber layers thicker than 7 mm lead to irreversible high-frequency attenuation, violating the Nyquist criterion for echo separation. The specific mechanism includes three points:

Thick rubber layers prolong reverberation durations to over 20 μs for a 10 mm layer, causing temporal overlap between coupling-layer noise and valid echoes.

Attenuation of frequencies above 3 MHz (Δf = −2.5 MHz for 10 mm rubber) diminishes the spectral disparity between interference and specimen signals, exacerbating mode mixing in EMD-based methods.

Despite these challenges, CEEMDAN maintains ΔT < 0.03 mm for 5 mm rubber by isolating interference into low-order IMFs. However, its performance degrades to ΔT = 0.029 mm at 10 mm rubber, underscoring the necessity of adhering to the 5 mm thickness limit.

5.1 Physical Interpretation of Mode Separation

The efficacy of CEEMDAN in isolating coupling-layer interference is rooted in its adaptive noise perturbation mechanism, which dynamically adjusts injected noise levels based on residual energy. Unlike EEMD’s static noise addition, CEEMDAN’s recursive formulation:

Introduces polarity-alternated noise (q ∈{0, 1}) at each decomposition stage. This breaks the temporal symmetry of overlapping echoes, forcing low-frequency coupling-layer reverberations and high-frequency specimen reflections into distinct modes. The rubber’s frequency-dependent attenuation further amplifies this separation, as specimen echoes retain spectral content above 3 MHz, whereas coupling-layer noise is confined to sub-2 MHz bands.

5.2 Practical Guidelines for Coupling Layer Design

For industrial applications using 5 MHz transducers, silicone rubber thickness should be limited to ≤5 mm to maintain ΔT < 0.03 mm. Beyond 7 mm, the attenuation threshold degrades high-frequency components irreversibly. Additionally, rubber hardness optimizes acoustic impedance matching while minimizing reverberation duration.

This study investigated the suppression of thick rubber-layer interference in dry-coupled ultrason-ic thickness measurement by employing CEEMDAN-based signal decomposition in combination with dual-criterion IMF selection and hybrid time–frequency thresholding. Experimental evaluations demonstrated that the proposed framework achieved significant improvements over conventional EMD and EEMD approaches. For instance, CEEMDAN maintained an orthogonality index above 0.8 across varying specimen thicknesses and coupling conditions, reducing mode mixing by up to 20% compared with EMD. In thickness measurement, the method consistently achieved ΔT < 0.03 mm, representing improvements of 35%–60% relative to EMD, with a mean error reduction of 0.017 mm for 5 mm specimens. These results confirm the statistical robustness of the framework, as validated across re-peated trials (n = 10) with standard deviations below 0.004 mm.

In addition to accuracy, the method demonstrated resilience under challenging conditions. With rough surface profiles up to Ra = 6.3 μm, CEEMDAN limited thickness error increases to 12%, whereas EEMD exhibited a 38% degradation under the same conditions. Computational efficiency was also enhanced, with CEEMDAN achieving a 37.9% reduction in processing time compared with EEMD, approaching near real-time requirements for portable ultrasonic testing devices. Collectively, these comparative and quantitative results substantiate the practical effectiveness of the proposed framework.

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the current validation is restricted to laboratory experiments, and while noise and surface degradation were simulated, field demonstrations in real industrial environments remain to be carried out. Second, the framework relies on decomposition quality, and performance may vary when applied to anisotropic or highly attenuative materials such as composites. Third, parameter calibration was based on empirical optimization, and although statistical consistency was observed, further work is needed to explore adaptive or optimization-driven parameter selection strategies.

Overall, the findings establish CEEMDAN as a robust and efficient method for mitigating dry-coupled rubber-layer interference in ultrasonic thickness measurement. Beyond enhancing measurement accuracy and reproducibility, the study also highlights practical guidelines for coupling layer design, including limiting rubber thickness to ≤5 mm for 5 MHz transducers. Future work will extend validation to diverse industrial scenarios and investigate integration with intelligent decision-making frameworks to further advance automation and reliability in ultrasonic nondestructive testing.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number U24A20135; Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation major project, grant number 2023ZD12; Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region key research and development and achievement transformation plan project, grant number 2023YFHH0090; Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia, grant number 2022MS05006; Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Talent Development Fund; University basic research business expenses, grant number 2023RCTD012; University basic research business expenses, grant number 2023QNJS075; Postgraduate Research Innovation Program and of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, grant number KC2024053B; University basic research business expenses, grant number 2024YXXS012; National Key Laboratory of Special Vehicle Design and Manufacturing Integration Technology, grant number GZ2023KF012.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Weichen Wang and Shaofeng Wang; methodology, Weichen Wang; software, Weichen Wang; validation, Wenjing Liu, Erqing Zhang and Luncai Zhou; formal analysis, Ting Gao; investigation, Grigory Petrishin; resources, Shaofeng Wang; data curation, Wenjing Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Weichen Wang; writing—review and editing, Weichen Wang and Erqing Zhang; visualization, Weichen Wang; supervision, Wenjing Liu; project administration, Wenjing Liu; funding acquisition, Shaofeng Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Wenjing Liu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Statement: This paper was recommended by 2025 FAR EAST NDT New Technology and Application Forum.

References

1. Wu C, Xu G, Shan Y, Fan X, Zhang X, Liu Y. Defect detection algorithm for wing skin with stiffener based on phased-array ultrasonic imaging. Sensors. 2023;23(13):5788. doi:10.3390/s23135788. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Al-Aufi Y, Hewakandamby B, Dimitrakis G, Holmes M, Hasan A, Watson N. Thin film thickness measurements in two phase annular flows using ultrasonic pulse echo techniques. Flow Measur Instrument. 2019;66:67–78. doi:10.1016/j.flowmeasinst.2019.02.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liang H, Wang Y, Yang H. Study on ultrasonic detection pattern recognition of natural gas steel pipeline defects. Russ J Nondestruct Test. 2022;58:903–16. doi:10.1134/S1061830922100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Stüwe I, Zacherl L, Grosse C. Ultrasonic and impact-echo testing for the detection of scaling in geothermal pipelines. J Nondestruct Eval. 2023;42(1):18. doi:10.1007/s10921-023-00926-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu B, Huang Y, Krishnaswamy S. A Bayesian approach for sparse flaw detection from noisy signals for ultrasonic NDT. NDT E Int. 2017;58:76–85. doi:10.1016/j.ndteint.2016.10.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bazulin E, Krylovich A. Measurement of ultrasonic pulse arrival time by constructing a signal model to determine its propagation velocity. Russ J Nondestruct Test. 2024;60(1):1–15. doi:10.1134/S1061830923601137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ding C, Tang D, Su R, He Y, Wang Q, Peng Y, et al. The research and application of wheeled dry-coupling ultrasonic technology in steel plate thickness measurement. Russ J Nondestruct Test. 2023;59:753–66. doi:10.1134/S1061830923600168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Watson R, Kamel M, Zhang D, Dobie G, MacLeod C, Pierce S. Dry coupled ultrasonic non-destructive evaluation using an over-actuated unmanned aerial vehicle. IEEE Transact Automat Sci Eng. 2022;19(4):2874–89. doi:10.1109/tase.2021.3094966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Bhadwal N, Milani M, Coyle T, Sinclair A. Dry coupling of ultrasonic transducer components for high temperature applications. Sensors. 2019;19(24):5383. doi:10.3390/s19245383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Burrows S, Fan Y, Dixon S. High temperature thickness measurements of stainless steel and low carbon steel using electromagnetic acoustic transducers. NDT E Int. 2014;68:73–7. doi:10.1016/j.ndteint.2014.07.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cooper J, Tran A, Wallander S. Testing for specification bias with a flexible fourier transform model for crop yields. American J Agricul Econ. 2017;99(3):800–17. doi:10.1093/ajae/aaw084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Siqueira M, Gatts C, Silva R, Rebello J. The use of ultrasonic guided waves and wavelets analysis in pipe inspection. Ultrasonics. 2004;41(10):785–97. doi:10.1016/j.ultras.2004.02.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Tian Z, Yu L. Lamb wave frequency-wavenumber analysis and decomposition. J Intell Mat Syst Struct. 2014;25(9):1107–23. doi:10.1177/1045389X14521875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang M, We G. An integrated EMD adaptive threshold denoising method for reduction of noise in ECG. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235330. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chen J, Sun H, Xu B. Improvement of empirical mode decomposition based on correlation analysis. SN Appl Sci. 2019;1(9):105. doi:10.1007/s42452-019-1014-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chen Y, Liu H, Liu Z, Meng L, Liao J. Research on temperature effect separation method of bridge deflection monitoring data based on complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition and fast independent component analysis. ce/papers. 2025;8(2):1722–36. doi:10.1002/cepa.3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li Y, Wang L. A novel noise reduction technique for underwater acoustic signals based on complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise, minimum mean square variance criterion and least mean square adaptive filter. Def Technol. 2020;16(3):543–54. doi:10.1016/j.dt.2019.07.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu Z, Chen G. Research on fault data wavelet threshold denoising method based on CEEMDAN. Commun Comput Inform Sci. 2017;762:75–83. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-6373-2_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zu Y, Wang L, Hu Y, Yang G. CEEMDAN-LWT de-noising method for pipe-jacking inertial guidance system based on fiber optic gyroscope. Sensors. 2024;24(4):1097. doi:10.3390/s24041097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Xiao M, Zhang C, Wen K, Xiong L. Bearing fault feature extraction method based on complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise. J Vibroengineering. 2018;20(7):2622–31. doi:10.21595/jve.2018.19562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang X, Qin X, Lei J, Zhai Z, Zhang J, Wang Z. A novel method on recognizing drum load of elastic tooth drum pepper harvester based on CEEMDAN-KPCA-SVM. Agriculture. 2024;14(7):1114. doi:10.3390/agriculture14071114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Khatir A, Capozucca R, Khatir S, Magagnini E, Cuong-Le T. Enhancing damage detection using reptile search algorithm-optimized neural network and frequency response function. J Vibrat Eng Technol. 2025;13(1):88. doi:10.1007/s42417-024-01545-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Huang N, Shen Z, Long S, Wu M, Shih H, Zheng Q, et al. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc Royal Soc Mathem Phys Eng Sci. 1998;454(1971):903–95. doi:10.1098/rspa.1998.0193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhou J, Zhao S, Zheng Y, Shen X, Zhang J. Variational wavelet ensemble empirical (VWEE) denoising method for electromagnetic ultrasonic signal in high-temperature environment with low-voltage excitation. Chin J Mech Eng. 2022;35(1):111. doi:10.1186/s10033-022-00787-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Guo Q, Hong Z, Hu B, Luo H, Tu L, Guo C. Research on the method of long step simulation considering broadband oscillation. In: 2024 3rd International Conference on Energy and Electrical Power Systems (ICEEPS); 2024 Jul 14–16; Guangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

26. Poongadan S, Lineesh MC. Non-linear time series prediction using improved CEEMDAN, SVD and LSTM. Neural Process Lett. 2024;56(4):164. doi:10.1007/s11063-024-11622-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yang Y, Li S, Li C, He H, Zhang Q. Research on ultrasonic signal processing algorithm based on CEEMDAN joint wavelet packet thresholding. Measurement. 2022;201:111751. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hou D, Wang X, Ni W. Research on ultrasonic detection of air spring rubber debonding based on CEEMDAN. J Phy Conf Ser. 2020;1549(3):2. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1549/3/032154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li Z, Xu H, Jiang B, Han F. Wavelet threshold ultrasound echo signal denoising algorithm based on CEEMDAN. Electronics. 2023;12(14):3026. doi:10.3390/electronics12143026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Han S, Zhang Y, Jian L, Li Z, He B. An efficient adaptive method based on empirical wavelet transform for ultrasound tissue harmonic imaging. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;87(1):105535. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yeh J, Shieh J, Huang N. Complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition: a novel noise enhanced data analysis method. Ad Adapt Data Anal. 2010;2(2):135–56. doi:10.1142/S1793536910000422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wu Z, Huang N. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition: a noise-assisted data analysis. Adv Adapt Data Anal. 2009;1(1):1–41. doi:10.1142/S1793536909000047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wu B, Deng F, He C. Review of signal processing in ultrasonic guided waves nondestructive testing. J Beijing Univ Technol. 2007;33(4):342–8. doi:10.3969/j.issn.0254-0037.2007.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Cao W, Sun X, Liu Z, Chai Z, Bao G, Yu Y, et al. The detection of PAUT pseudo defects in ultra-thick stainless-steel welds with a multimodal deep learning model. Measurement. 2025;241:115662. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang J, Qin X, Yuan J, Wang X, Zeng Y. The extraction method of laser ultrasonic defect signal based on EEMD. Opt Commun. 2021;484:126570. doi:10.1016/j.optcom.2020.126570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools