Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Diffusion-Driven Generation of Synthetic Complex Concrete Crack Images for Segmentation Tasks

1 Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Delft University of Technology, Delft, 2628 CN, Netherlands

2 College of Water Conservancy and Hydropower Engineering, Hohai University, Nanjing, 210098, China

3 The National Key Laboratory of Water Disaster Prevention, Nanjing, 210098, China

4 Department of Civil, Environmental and Ocean Engineering, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

* Corresponding Author: Xiao Tan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-driven Monitoring, Condition Assessment, and Data Analytics for Enhancing Infrastructure Resilience)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2026, 20(1), . https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.071317

Received 05 August 2025; Accepted 23 September 2025; Issue published 08 January 2026

Abstract

Crack detection accuracy in computer vision is often constrained by limited annotated datasets. Although Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have been applied for data augmentation, they frequently introduce blurs and artifacts. To address this challenge, this study leverages Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) to generate high-quality synthetic crack images, enriching the training set with diverse and structurally consistent samples that enhance the crack segmentation. The proposed framework involves a two-stage pipeline: first, DDPMs are used to synthesize high-fidelity crack images that capture fine structural details. Second, these generated samples are combined with real data to train segmentation networks, thereby improving accuracy and robustness in crack detection. Compared with GAN-based approaches, DDPM achieved the best fidelity, with the highest Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) (0.302) and lowest Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) (0.461), producing artifact-free images that preserve fine crack details. To validate its effectiveness, six segmentation models were tested, among which LinkNet consistently achieved the best performance, excelling in both region-level accuracy and structural continuity. Incorporating DDPM-augmented data further enhanced segmentation outcomes, increasing F1 scores by up to 1.1% and IoU by 1.7%, while also improving boundary alignment and skeleton continuity compared with models trained on real images alone. Experiments with varying augmentation ratios showed consistent improvements, with F1 rising from 0.946 (no augmentation) to 0.957 and IoU from 0.897 to 0.913 at the highest ratio. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of diffusion-based augmentation for complex crack detection in structural health monitoring.Keywords

Digital Image Correlation (DIC) is a noncontact optical measurement technique that computes full-field displacement and strain by comparing greyscale or color feature patterns on a surface before and after loading [1]. When applied to crack analysis, a random speckle pattern is first sprayed onto the surface of specimens [2], and a high-speed camera captures a sequence of speckle images at different load levels during testing [3]. Subset-matching algorithms (e.g., cross-correlation) are then utilized to compare gray-value patterns between successive frames (or against a reference frame) to produce a displacement vector at each pixel [4]. Based on that, the displacement field is differentiated by finite difference to obtain the local strain field [5]. Regions with pronounced strain concentration indicate crack initiation sites, and the crack propagation path and opening displacement are accurately recorded as loading continues [6]. The accuracy of DIC measurements depends on uniformly distributed and high-contrast speckled patterns. Irregularities, detachment, or blurring during loading degrade matching quality. Besides, DIC also produces large volumes of high-resolution, high-frame-rate images, which require not only computationally intensive subset matching but also robust Central Processing Unit/Graphics Processing Unit (CPU/GPU) resources, substantial memory, and extensive storage. As a result, DIC demands significant resources and time for data acquisition, transferring, and post-processing.

Deep learning methods make it possible to perform crack segmentation directly from standard camera images by inputting raw RGB (Red, Green, Blue) frames into a convolutional segmentation network (e.g., U-Net, DeepLab, etc.) or a lightweight variant, which produces pixel-precise crack masks in a short time [7–9]. Instead of relying on speckle-patterned specimens, deep learning models are trained on annotated images. Data augmentation and specialized loss functions are applied to address class imbalance (e.g., a combination of cross-entropy and Dice loss) and accommodate varying lighting, textures, and background colors [10–12]. For example, a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) was employed to segment cracks in various concrete structures, enabling precise pixel-level crack identification. It achieved an Intersection over Union (IoU) score of 85.9% in crack segmentation, with a processing time of less than 0.1 s [13]. Concrete cracks are also segmented using the SegCrack model, which employs a hierarchically structured transformer encoder to extract multiscale features. Experimental results showed that SegCrack achieved an IoU score of 92.63% [14]. In addition, the Semantic Transformer Representation Network (STRN) is an attention-based encoder–decoder model designed for accurate, real-time pixel-level crack segmentation [15]. These segmentation models were able to convert RGB images into binary crack maps. Based on binary images, further research has focused on quantifying crack characteristics (e.g., width) using pixel measurements [16]. After that, zooming effect is applied to translate pixel-based crack maps into actual real-world geometric dimensions [17]. Compared with DIC methods, deep learning models significantly reduce the need for costly hardware or surface preparation, and they also improve processing speed. In addition, they provide direct pixel-level damage mapping rather than indirect strain-based inference, making them more practical and scalable for real-time crack monitoring in different structural conditions.

A major challenge of deep learning methods is the limited availability of annotated crack images, especially for complex cracks [18]. The quality and quantity of training samples directly affect segmentation accuracy [19]. To address this challenge, Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN)-based data augmentation has been adopted to expand training datasets with complex crack patterns [20]. For example, in reference [21], GAN was used to expand a pavement defect dataset from 4160 to 9600 images across five categories. Using the augmented data, the classification accuracy of VGG16 network improved from 88.6% to 91.4%, highlighting the effectiveness of generated images in boosting model performance. However, the synthetic images produced by these GAN-based generative models often suffer from visible artifacts, unrealistic textures, and insufficient diversity, which limit their effectiveness. In some cases, GAN-based methods even degrade the performance of crack-segmentation networks [22]. In addition, GAN-based generative models struggle to generate high-resolution images, and the resolution is typically limited to 64 × 64 or 128 × 128 pixels due to architectural constraints [23]. As a result, the augmented dataset may still lack the diversity and fidelity required to train robust crack-segmentation networks.

To address these challenges, Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) offer a robust alternative for data augmentation in crack analysis. Unlike GANs, DDPMs adopt a likelihood-based training approach that gradually adds and removes Gaussian noise over multiple timesteps, enabling stable learning of complex data distributions [24]. This denoising process allows DDPMs to generate high-fidelity, artifact-free images that preserve fine crack details and realistic textures. More importantly, DDPMs can generate detailed images that overcome the resolution limitations, which are typically observed in traditional GANs (e.g., Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network). These advantages make DDPMs particularly suitable for tasks requiring detailed structural representation, such as automated detection and segmentation of complex cracking conditions. However, existing literature on generating high quality images for complex concrete cracks using DDPMs remains limited. Recent studies applied diffusion-based models for crack segmentation, with diffusion models outperforming conventional deep learning in complex backgrounds and discontinuous annotations by capturing long-range dependencies and global crack continuity. Diffusion-based models achieved the best crack segmentation performance, with CrackDiff (84.1%) slightly surpassing DeepLabV3+ (83.4%) and transformer-based SegFormer (83.3%) [25]. Similarly, RoadPainter (71.8%) outperformed convolutional neural network (CNN)-based methods such as LinkNet (59.5%) and PSPNet (55.5%) [26]. However, diffusion-based crack segmentation methods remain supervised approaches that rely on high-quality datasets with labeled crack images.

This study presents a novel two-stage crack segmentation framework that incorporates DDPM to generate higher resolution and structurally accurate images of complex concrete cracks, which effectively overcomes the limitations associated with GAN-based approaches. Specifically, the contributions of this research are summarized as follows: (1) This research explores the potential of DDPMs as an alternative to traditional GAN-based approaches. The proposed method focuses on synthesizing realistic and diverse images of complex cracks through a progressive denoising process, enhancing the quality and variability of training data. (2) This research also aims to evaluate the impact of DDPM-augmented datasets on the performance of different semantic segmentation models in achieving accurate pixel-level crack detection. This work contributes to a scalable and effective augmentation strategy tailored for material characterizations and structural health monitoring applications.

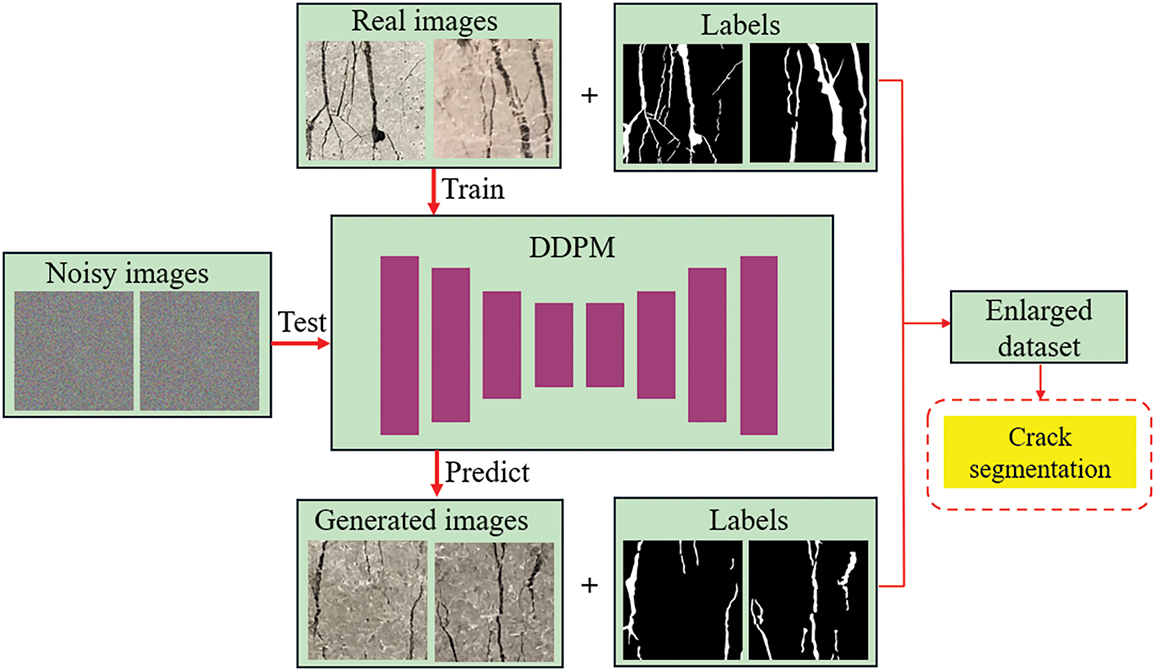

This study proposes a two-stage crack segmentation framework, which is designed to enhance the detection of complex cracks in concrete structures by leveraging the generative capabilities of DDPM:

(1) Stage I: A DDPM is trained on a limited set of real crack images and then used to generate a diverse set of synthetic and high-quality images that preserve fine structural details and realistic textures. The generated images are combined with the original dataset to synthetically create an enriched training set, addressing the challenge of insufficient annotated data and improving the performance of segmentation models.

(2) Stage II: A semantic segmentation model is trained using the augmented dataset to learn pixel-level crack features. The segmentation network benefits from the increased variability and fidelity of the training samples, leading to improved performance in identifying cracks with irregular shapes, varying widths, and diverse surface backgrounds.

The overall framework integrates data generation and segmentation in a cohesive pipeline, with the goal of improving robustness and accuracy in real-world crack monitoring scenarios. The illustration of diffusion-augmented image segmentation framework is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Illustration of the diffusion-augmented image segmentation framework

2.1 Data Augmentation via Diffusion Models

GANs have been widely adopted as a class of generative models capable of image synthesis [27]. A standard GAN framework comprises two adversarial networks: a generator that creates data similar to the real distribution, and a discriminator that distinguishes between real and synthetic samples [28]. Through the adversarial training process, the generator gradually learns to produce increasingly realistic data. Despite their impressive performance, GAN-based models suffer from several well-known limitations. GANs often suffer from training instability, which can lead to non-convergence and visual artifacts [29]. They are also prone to mode collapse, producing limited output variations regardless of input diversity, thus failing to capture the full data distribution. GANs are further constrained by limited image resolution in generation. As resolution increases, training becomes more unstable and resource-intensive, making it less suitable for tasks requiring fine structural details. Instead, DDPM offers an effective solution for generating higher resolution images without artifacts, making it well-suited for capturing complex crack patterns in structural testing scenarios [30]. DDPMs are a class of latent-variable generative models that synthesize data by progressively denoising samples initialized as pure Gaussian noise. The framework consists of two sequential processes: a forward diffusion process and a reverse denoising process [26]. The forward process incrementally corrupts the original data by adding Gaussian noise over a series of timesteps, transforming structured data into random noise. This process is defined as a fixed Markov chain. In contrast, the reverse process is a learnable Markov chain where a neural network such as a U-Net predicts the parameters of a Gaussian distribution at each step to gradually remove noise and reconstruct the data. Training involves minimizing the difference between the actual noise and the noise predicted by the model at each timestep. After training, the model generates high-quality data by reversing the noise process, beginning with random Gaussian inputs.

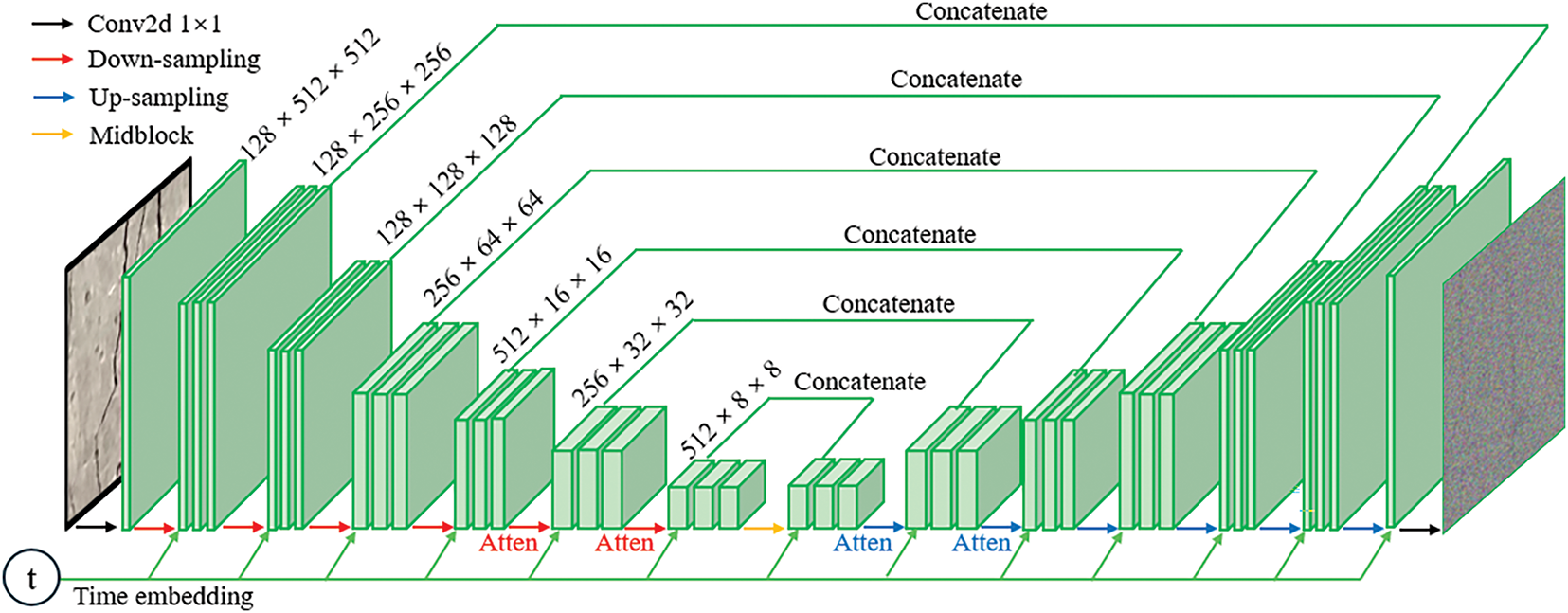

Fig. 2 presents the architecture of the DDPM implemented in this study. The network adopts a U-Net-like design tailored for diffusion-based image synthesis. A key feature is the inclusion of a time embedding module, which encodes the current diffusion timestep using sinusoidal positional encoding followed by fully connected layers. This temporal information is injected into both the down-sampling and up-sampling blocks, allowing the model to learn how noise evolves over time. The input image is first processed by a 1 × 1 convolutional layer (Conv2d) to extract low-level features.

Figure 2: Model architecture of U-Net used in DDPM

The resulting feature map is then passed through six sequential down-sampling blocks. These blocks progressively reduce spatial resolution while increasing feature depth. A mid-block is placed between the down-sampling and up-sampling stages to further process the compressed features. The up-sampling path mirrors the encoder, with transposed convolutions used to gradually restore the original resolution. Each up-sampling block receives skip connections from its corresponding down-sampling block, which provide high quality spatial features to improve detail recovery. These skip connections are essential for preserving edge and texture information, particularly in fine-grained regions such as cracks. Throughout the network, the model learns to predict the noise component added to the image at each step. This noise prediction is used during the reverse diffusion process to iteratively denoise the input and generate realistic images.

2.2 Semantic Segmentation Models

Six representative semantic segmentation models are employed to evaluate the impact of the augmented dataset on crack segmentation performance. These models were carefully selected based on their architectural diversity and varying levels of model complexity, enabling a comprehensive evaluation across different network designs. The six architectures are:

(1) U-Net: A widely adopted encoder-decoder architecture initially designed for biomedical image segmentation. U-Net has demonstrated robust performance in structural damage detection due to its symmetric skip connections that help recover spatial resolution lost during down-sampling [31].

(2) LinkNet: This model introduces additive skip connections between the encoder and decoder, which efficiently preserve spatial information while reducing computational complexity. LinkNet is particularly suitable for real-time applications such as on-site inspection or drone-based structural monitoring [32].

(3) FPN: FPN enhances feature learning at multiple scales by constructing a top-down pyramid of features with lateral connections. This design is especially beneficial for detecting cracks of varying widths and orientations, making it effective in scenes with both fine and coarse structural details [33].

(4) DeepLabV3+: This model leverages atrous convolutions through the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling module to capture multi-scale contextual information. The decoder module then refines the segmentation outputs. DeepLabV3+ is known for its high accuracy on complex datasets and performs well in tasks involving irregular crack patterns [34].

(5) MaNet: An improved version of U-Net, MaNet incorporates multi-scale attention mechanisms and a position-aware attention module. These features enhance the ability of the model to focus on relevant regions while suppressing noise, which is crucial for distinguishing cracks from background textures or surface noise [35].

(6) SegFormer: A transformer-based segmentation model that combines hierarchical transformer encoders with lightweight decoders. SegFormer provides state-of-the-art accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. It excels in learning global dependencies, which benefits the detection of long, continuous cracks across large structural areas [36].

To ensure a fair comparison, all models were trained using the same training and validation splits, data augmentation strategies, hyperparameter settings, image resolution, and batch size. These models represent a broad spectrum of complexity, ranging from lightweight architectures like U-Net and FPN to more advanced and resource-intensive models such as MaNet and SegFormer. By evaluating a diverse set of models, the study aims to demonstrate the performance of the DDPM-augmented dataset across different network families, from CNN-based encoders to transformer-based backbones.

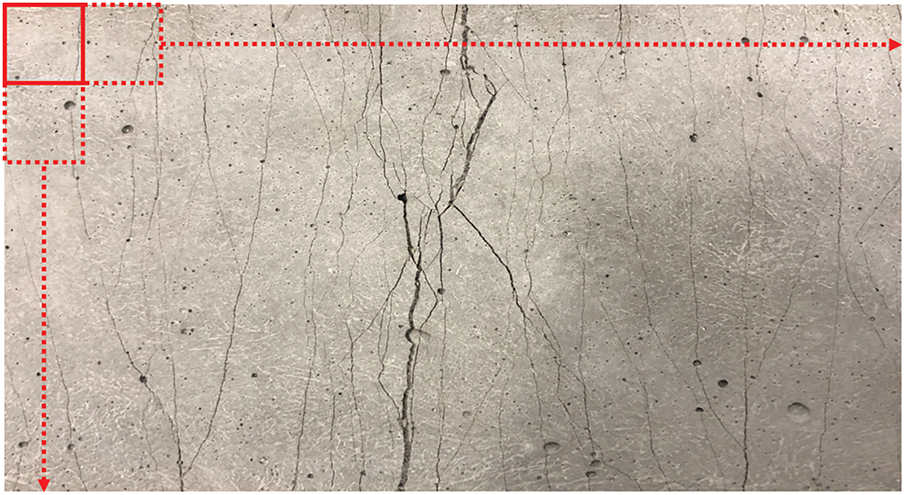

Representative images were collected to train the DDPM model, comprising a total of 600 high quality images. The images were obtained from laboratory-scale concrete bending tests under varying loading conditions and cropped from 18 full-specimen images (resolution: 4032 × 3024 pixels), as illustrated in Fig. 3. A sliding window approach was applied to crop the high-resolution images into fixed-size sub-regions of 512 × 512 pixels. The dataset exhibits diverse crack patterns, including hairline, branching, and wide-open fractures, ensuring variability for training. Crack widths range from a few pixels to moderate sizes, with both short, localized cracks and long continuous ones traversing the surface. Many cracks intersect and branch, forming complex skeletons. Background textures with pores and surface roughness introduce natural variation. Some samples contain dense crack networks, while others show only a few. Overall image quality is sufficient to capture fine cracks, with mostly uniform illumination and adequate contrast, though variations in sharpness and brightness are present across samples. Subsequently, the trained DDPM model synthesized an additional 600 high-fidelity images, preserving structural textures and fine crack details. Both the original and generated images were annotated using the LabelMe toolbox to produce pixel-level segmentation masks with fine-grained crack labels. This process involved outlining the exact boundaries of visible cracks using polygonal tools, enabling the creation of fine-grained labels that capture subtle variations in crack width, orientation, and shape. The corresponding binary masks precisely delineate crack regions, with white pixels indicating cracks and black pixels representing the background. They preserve the geometry of the original cracks, ranging from thin hairline lines to wide-open fractures, and capture branching, intersections, and continuity along the crack skeleton. Some masks contain sparse cracks, while others show dense crack networks, reflecting the variability of the dataset. By removing background noise such as pores and stains, the masks provide clean pixel-level annotations that enable reliable supervision for segmentation models.

Figure 3: Illustration of data collection method

A total of 600 images were used to train the generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) model. For training and evaluating the segmentation model, the dataset was randomly split into three subsets: 80% for training to learn feature representations, 10% for validation to monitor performance and tune hyperparameters, and 10% for testing to provide an unbiased assessment of model generalization. A fixed random seed was employed during the dataset division to ensure reproducibility. To assess the impact of data augmentation, two datasets were prepared and tested: (1) the dataset with 600 real images and (2) a combined dataset of 1200 images, integrating 600 DDPM-generated synthetic images with 600 real images. To ensure that the testing set was entirely unseen by the generative model, 10% of the real images were replaced with new samples, which were designated as the testing set and excluded from the generative AI training process.

To enhance the diversity of the training dataset and improve model generalization, data augmentation based on geometric transformations is applied. These transformations include horizontal and vertical flips and perspective distortion, which help simulate variations in real-world scenarios. By artificially expanding the training dataset, the model becomes more robust to different orientations and perspectives of the input data. However, to ensure an unbiased evaluation of model performance, no data augmentation is applied to the testing and validation datasets. These datasets remain unaltered to reflect real-world conditions accurately, allowing for a fair assessment of the model’s generalization capability on unseen data. This approach ensures that performance metrics, such as accuracy and precision, are measured under realistic conditions without artificial modifications.

The deep learning approaches were implemented using Python 3.11.13, PyTorch 2.7.1, and HuggingFace diffusers 0.34.0. The models were implemented on an NVIDIA RTX-5090 Mobile GPU (24 GB, laptop version) with CUDA 12.8. The DDPM employed a U-Net2D backbone consisting of six levels with block output channels of 128, 128, 256, 256, 512, and 512, with two residual layers per block and attention applied in the last two down-sampling and up-sampling stages. The diffusion process followed a standard DDPM scheduler configuration without the use of Exponential Moving Average (EMA). Both the noise schedule steps, and the inference steps were initially set to 1000. Images were resized to 512 × 512, normalized to (−1, 1), and randomly flipped horizontally for augmentation. The model was trained for 50 epochs with a batch size of 2, a learning rate of 1 × 10−5, and AdamW optimizer (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999, no weight decay). A cosine learning rate scheduler without warm-up was applied, and mixed-precision (fp16) training was enabled via Accelerate. The DDPM was trained using a mean squared error (MSE) loss to predict Gaussian noise at each timestep, and the final trained model was used in the reverse diffusion process to generate high-fidelity synthetic crack images. For segmentation, six models were trained for 200 epochs using a batch size of 8, an image resolution of 512 × 512, and a learning rate of 1 × 10−3. The Adam optimizer was also used with standard hyperparameters (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999). Model checkpoints were saved every 10 epochs, and the model with the best validation IoU was selected for final evaluation. Because the background region of concrete surfaces occupies a much larger proportion than cracks, resulting in severe class imbalance, all segmentation tasks were trained with a combined loss function of Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) and Dice loss, as shown in Eq. (1). BCE provided stable pixel-level optimization, while Dice loss enhanced sensitivity to small and thin crack structures.

where N is the total number of pixels; yi ∈ {0, 1} denotes the ground-truth label of the i-th pixel; pi ∈ {0, 1} is the predicted probability of the i-th pixel being a crack, obtained after the sigmoid activation to the network output; ∈ is a small constant (10−7) introduced for numerical stability to prevent division by zero; LBCE, LDice, and L correspond to the Binary Cross-Entropy loss, Dice loss, and the combined loss, respectively.

The performance of data generation is evaluated using the Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) metric, a perceptual measure that quantifies the similarity between synthetic and real images based on deep feature representations [37]. LPIPS computes the distance between normalized feature activations extracted from a pretrained network. Lower LPIPS values indicate that the generated images are more perceptually similar to real ones, capturing human visual judgments more effectively. The definition of LPIPS is shown in Eq. (2).

where x and y are the input and generated images being compared; Fl is the feature map extracted from the l-th layer of a pretrained deep network, and

The Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) between real image x and generated image y is defined as the product of a luminance term, a contrast term, and a structure term [38]. For SSIM (0–1), higher values indicate better similarity between the generated and reference images. The SSIM is defined in Eq. (3).

where x is the matrix data from a window in the target image; y is the matrix data from a window in the reference image; C1 and C2 are small constants introduced to avoid division by zero, with C1 = 0.0001 and C2 = 0.0009; μx and μy are the mean values of x and y, respectively; σx and σy are the variances of x and y, respectively; and σxy is the covariance between x and y.

To assess the accuracy of crack segmentation, two performance metrics were used, which are the IoU and the dice coefficient (F1), as defined in Eqs. (4) and (5) [39]:

The Dice coefficient is calculated based on four parameters: true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN). TP refers to correctly identified cracks, while TN refers to correctly identified uncracked regions. FP occurs when uncracked concrete is incorrectly classified as cracked, and FN occurs when cracks are mistakenly labeled as uncracked. IoU measures the overlap between the predicted segmentation and the ground truth, defined as the ratio of the area of their intersection to the area of their union. Both the IoU and F1 range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better segmentation performance [18].

In addition to conventional evaluation metrics, Eqs. (6)–(8) introduce three structure-aware measures: Boundary-IoU evaluates the alignment between predicted and ground-truth boundaries [40], Skeleton Continuity assesses the connectivity of the predicted crack skeleton, and Centerline Recall quantifies the fraction of ground-truth centerlines captured by the prediction. All three metrics, Boundary-IoU, skeleton continuity, and centerline recall, range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better performance.

where B(P) denotes the set of boundary pixels in the predicted mask, and B(G) denotes the set of boundary pixels in the ground-truth mask.

where Llongest is the length of the longest connected crack skeleton, and Ltotal is the total length of all predicted skeleton pixels.

where C(G) represents the centerline pixels of the ground-truth crack mask obtained by skeletonization, and P represents the set of pixels predicted as crack. This metric quantifies the fraction of ground-truth crack centerlines correctly detected by the prediction.

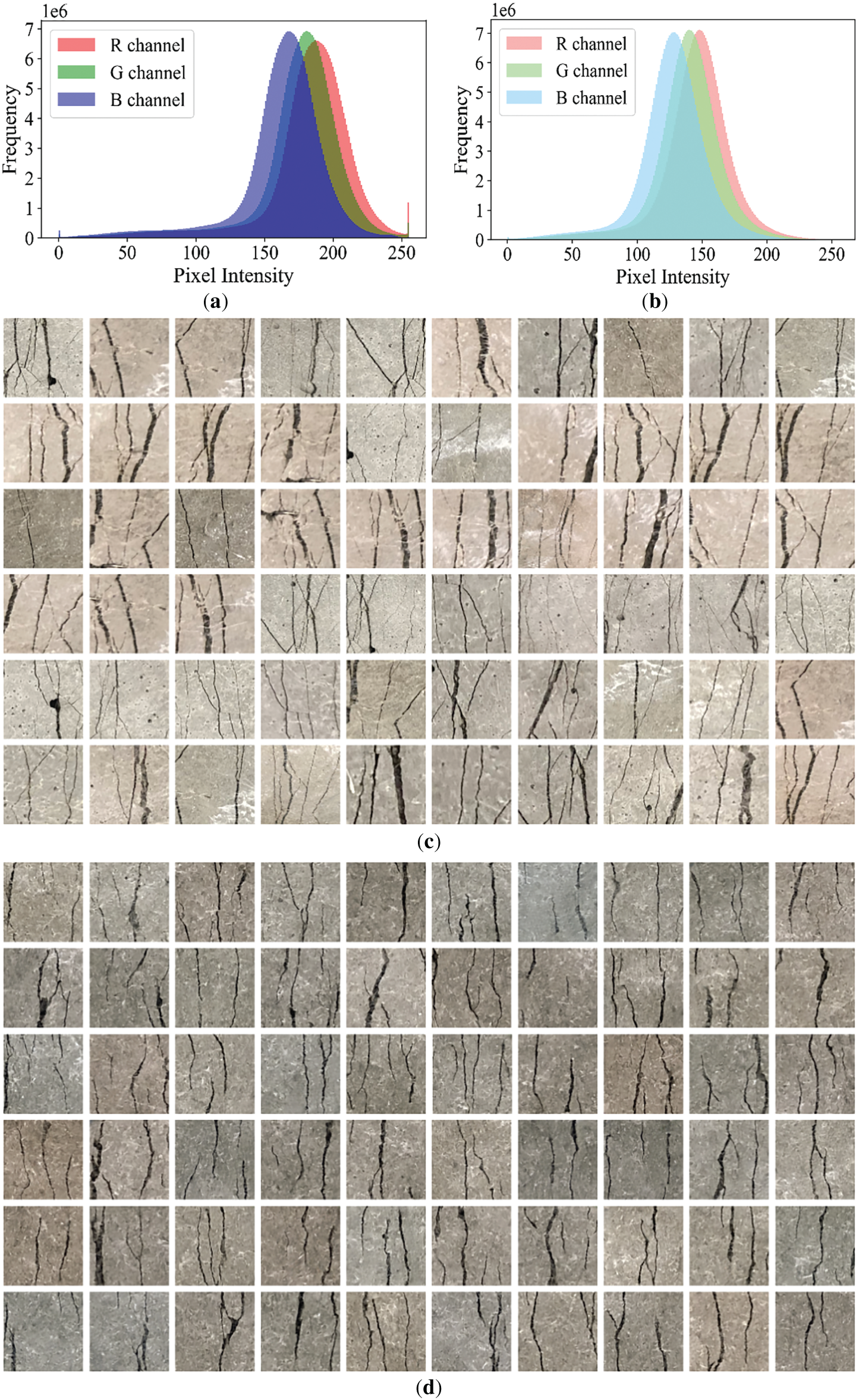

Fig. 4a illustrates the pixel intensity distributions for the RGB channels in the original dataset. The histograms reveal that the red, green, and blue channels follow similar distributions, with most pixel intensities falling in the mid-to-high range (approximately 100 to 250). This pattern indicates that the dataset primarily consists of well-exposed images with balanced illumination and sufficient contrast, which are crucial for effective feature extraction during model training. The smooth curves and overlapping distributions across the three channels also reflect a consistent color balance, reducing the likelihood of bias and supporting the generalizability. In contrast, the pixel intensity histogram of the DDPM-generated images, shown in Fig. 4b, reveals a shift in distribution toward a more concentrated range between 50 and 200. This band suggests that the synthetic images tend to exhibit more uniform lighting conditions, softer textures, and slightly lower brightness levels. Such characteristics may be attributed to the nature of the denoising diffusion process, which tends to regularize local variations and suppress high-frequency noise during image generation. While this may slightly reduce contrast, it helps reduce background noise and potentially improve model robustness by providing a smoother data distribution. The complementary nature of these distributions suggests that incorporating DDPM-generated images into the training set can increase the diversity of pixel-level features, thereby enriching the learning space of the segmentation models. Moreover, this variation may help improve the model’s ability to generalize across different lighting and texture conditions in real applications.

Figure 4: Illustration of: (a) pixel intensity distribution of original images; (b) pixel intensity distribution of augmented images; (c) representative examples of original images; and (d) representative examples of augmented images

A qualitative comparison between Fig. 4c and d further confirms the visual similarity between real and synthetic images. Despite the observed differences in pixel distribution, the generated images replicate key visual features of the original dataset, including fine crack patterns, edge sharpness, and surface texture. There is no noticeable degradation in image quality or unnatural artifacts. This resemblance confirms the effectiveness of DDPM in synthesizing structurally consistent images, which not only enhances training diversity but also maintains label fidelity. Collectively, these findings highlight the value of DDPM-generated images as a meaningful complement to real data for semantic segmentation tasks in structural crack detection.

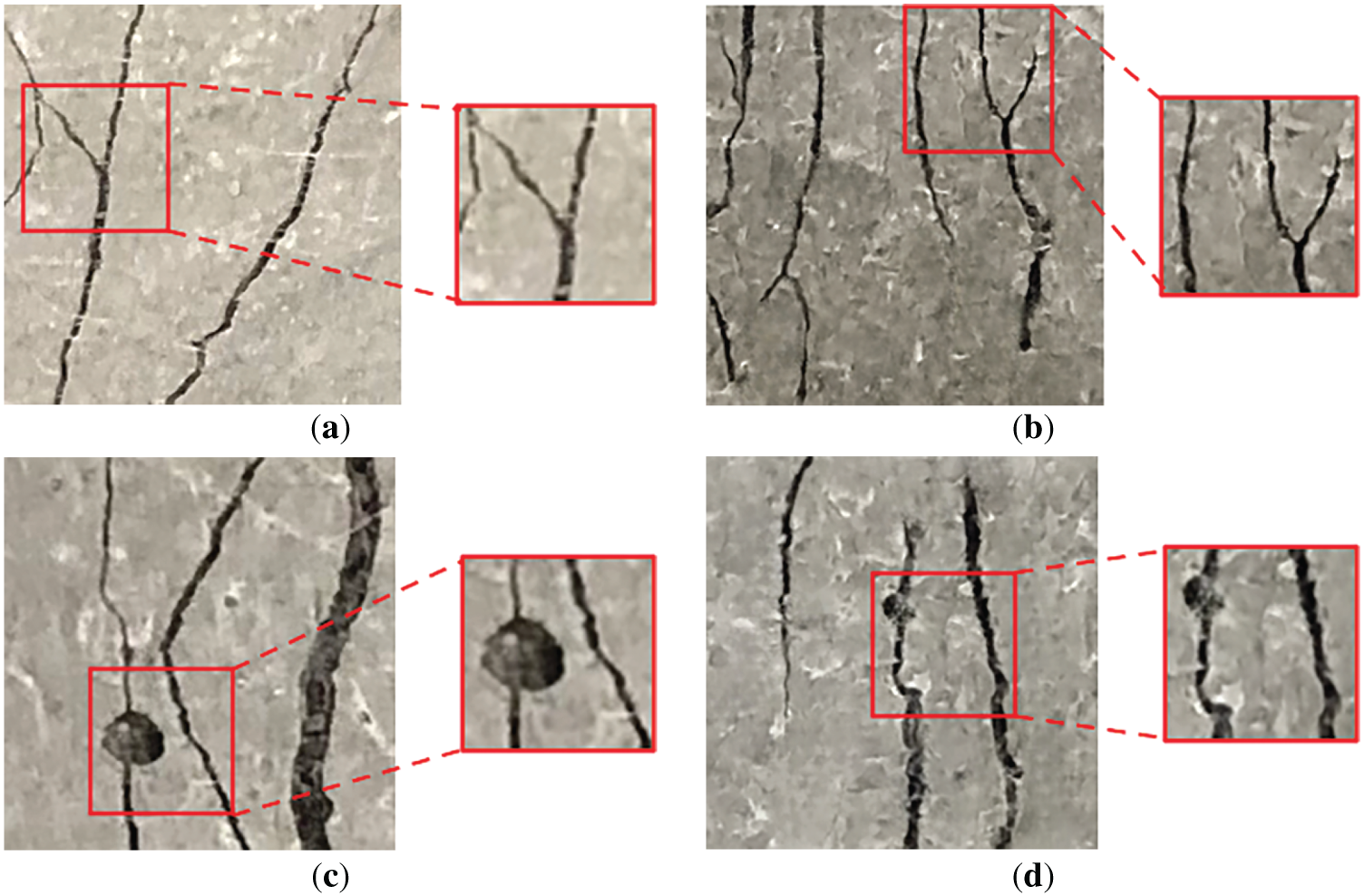

To further assess the fidelity of the generated images, zoomed-in panels were incorporated in the figures for both the original and the generated images to enable direct comparison. These magnified regions highlight fine crack details such as width, branching, and edge sharpness, as shown in Fig. A1. In comparison to the real images, the generated cracks demonstrate a faithful preservation of crack color, edge sharpness, and width, while also maintaining the overall texture continuity of the surrounding surface (e.g., white dots). By conducting local-scale comparisons between real and synthetic images, the generative model is shown to preserve essential crack features, thereby supporting the reliable use of synthetic data in crack-related computer vision tasks. Moreover, the realism of the generated images was independently verified by a domain expert in concrete materials.

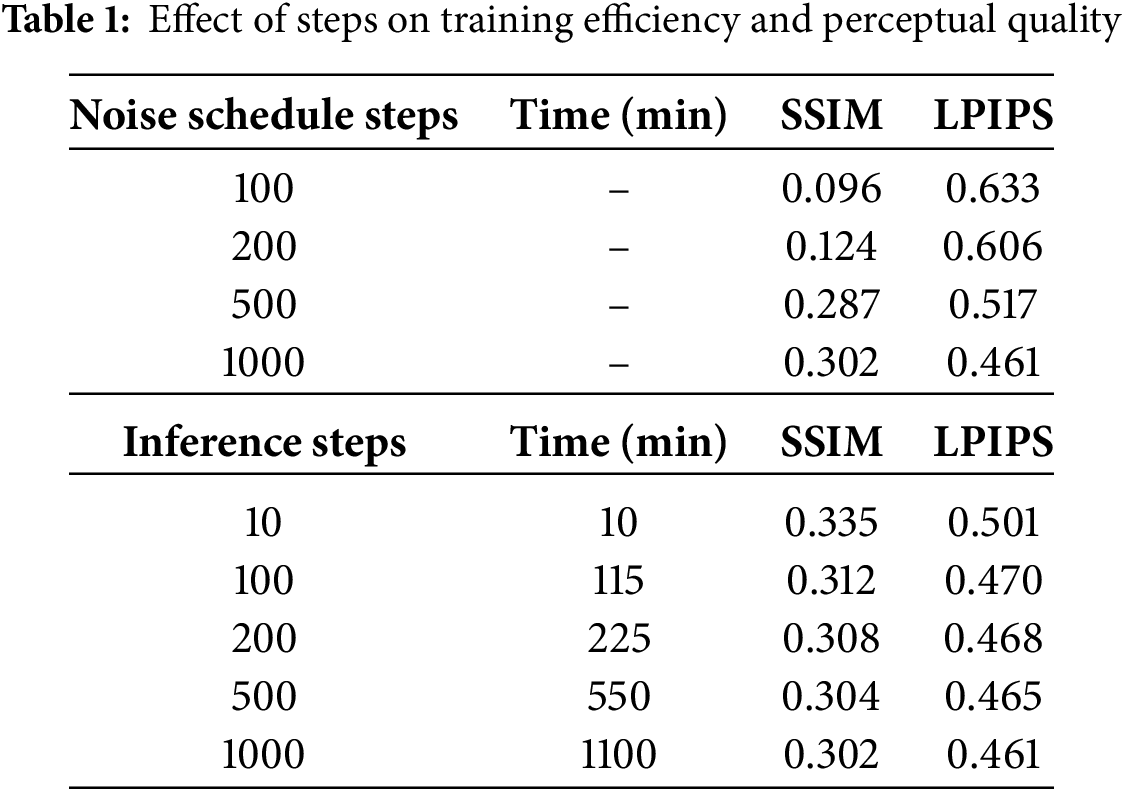

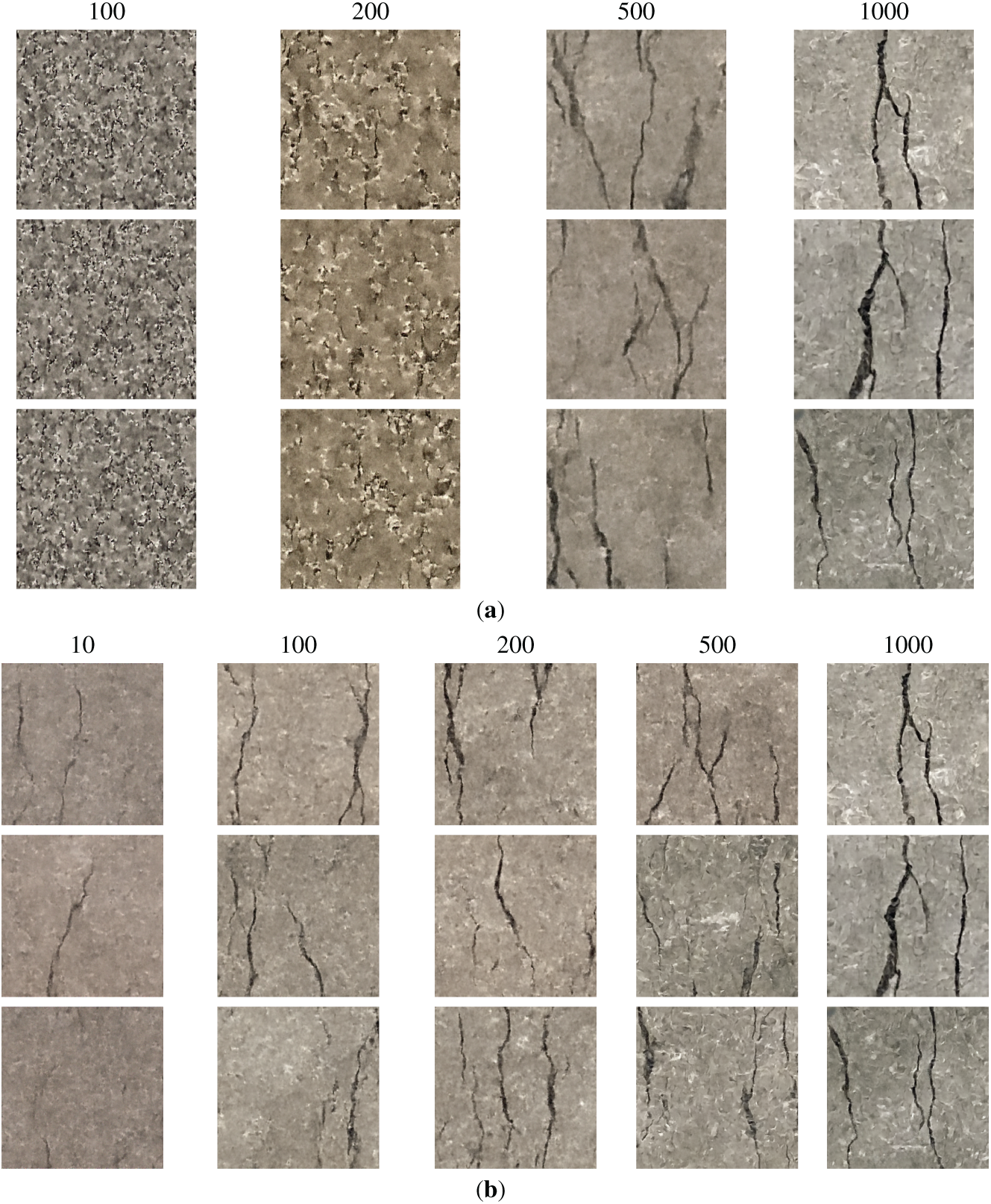

The ablation study was conducted by varying both the noise steps (100, 200, 500, and 1000 forward timesteps) and the inference steps (10, 100, 200, 500, and 1000). In diffusion models, noise steps refer to the number of forward timesteps used during the training. In this process, clean images are gradually corrupted with noise. A larger number of noise steps (e.g., 1000) provides a smoother noise schedule and typically leads to more stable training. Inference steps, on the other hand, denote the number of reverse denoising steps during sampling. As illustrated in Table 1, the effect of step configurations on perceptual quality (SSIM and LPIPS) was evaluated, considering both noise schedule steps and inference steps. To note, the variation in noise schedule steps does not influence the training time.

The results indicate that increasing the number of noise schedule steps leads to a clear improvement in image quality. With only 100 steps, the SSIM was 0.096 and the LPIPS reached 0.633, reflecting poor structural similarity and perceptual quality. When the steps increased to 200, SSIM rose to 0.124 and LPIPS dropped to 0.606. A more significant enhancement appeared at 500 steps, where SSIM reached 0.287 and LPIPS dropped to 0.517. The best results were obtained with 1000 steps, yielding the highest SSIM of 0.302 and the lowest LPIPS of 0.461. This shows that a larger noise schedule provides more stable diffusion and higher quality generation. This result is further illustrated in Fig. 5a, where 100 and 200 steps fail to reveal clear crack patterns, whereas 1000 steps produce visibly distinct cracks.

Figure 5: Examples of generated images with varying: (a) noise schedule steps and (b) inference steps

With the noise steps fixed at 1000, using only 10 inference steps required 10 min for sampling. It produced the highest SSIM value of 0.335, although the LPIPS value remained relatively high at 0.501. As the number of inference steps increased, the generation time grew almost linearly, reaching about 1100 min at 1000 steps. During this process, SSIM gradually declined from 0.335 at 10 steps to 0.302 at 1000 steps, while LPIPS steadily improved from 0.501 to 0.461, reflecting enhanced perceptual similarity at the cost of reduced structural similarity and substantially longer inference time. Although SSIM decreased, the realism of the generated images improved, as shown in Fig. 5b. Overall, inference speed remains a major challenge in applying DDPM to image generation, while using 1000 inference steps also impacts the image generation speed in real applications.

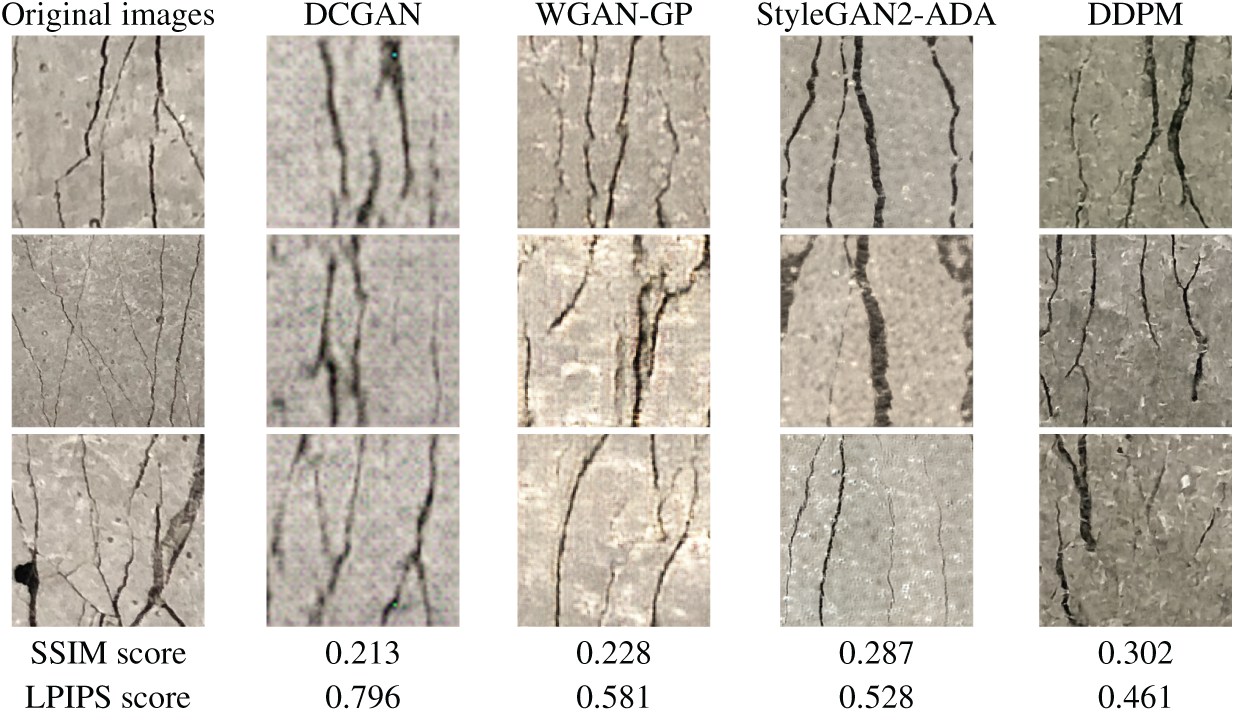

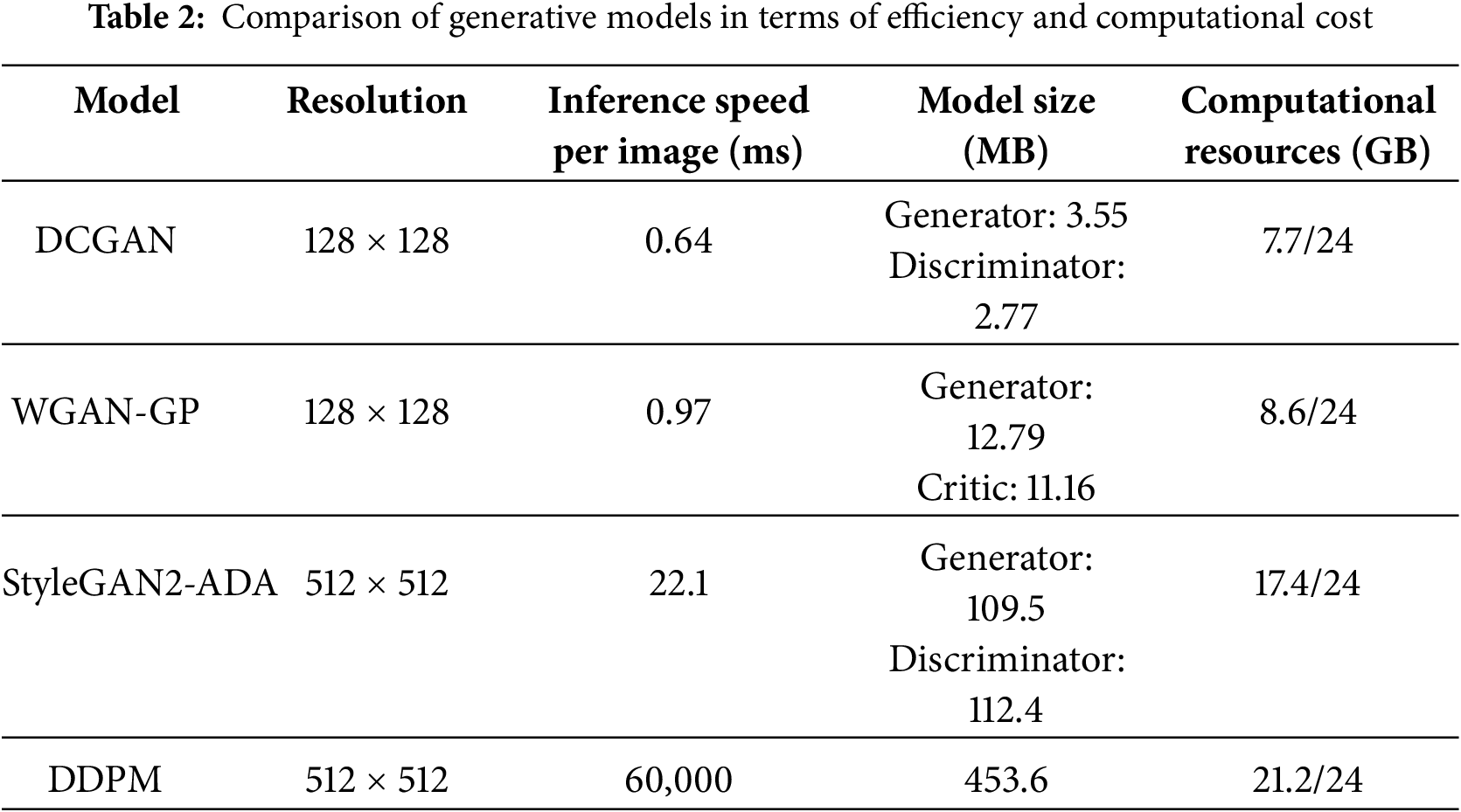

3.2 Comparison of GANs with DDPM

The images generated by DCGAN, WGAN-GP, StyleGAN2-ADA, and DDPM are compared in Fig. 6. The outputs from DCGAN appear blurry and exhibit numerous artificial artifacts, a consequence of unstable training and limited representational capacity in capturing complex crack patterns. In contrast, WGAN-GP produces sharper and more realistic images with fewer visual distortions. This improvement is attributed to the use of a gradient penalty, which stabilizes the training process and mitigates mode collapse, thereby enabling the generator to produce images with more natural textures and coherent structures. However, despite these enhancements, WGAN-GP still struggles with synthesizing fine structural details, particularly in images with dense or irregular crack formations. DDPM, on the other hand, demonstrates a significant improvement in image generation quality. StyleGAN2-ADA can generate higher resolution images with sharp crack details, but it has limited capability in reproducing the background surface due to its tendency to focus on prominent structural patterns rather than subtle texture variations. By employing a likelihood-based training mechanism and a sequential denoising process, DDPM achieves high-quality image synthesis with exceptional fidelity. The generated images closely resemble real crack samples, preserving both micro-level boundaries and overall spatial distribution. This fidelity is critical for crack segmentation, where minor geometric discrepancies can lead to significant segmentation errors.

Figure 6: Comparison of images generated by different generative AI models

Quantitatively, the improvement in generative quality is evident in the SSIM and LPIPS scores. The SSIM scores increased from 0.213 with DCGAN to 0.228 with WGAN-GP, then to 0.287 with StyleGAN2-ADA, and further increased to 0.302 with DDPM. The LPIPS scores decreased from 0.796 with DCGAN to 0.581 with WGAN-GP, 0.528 with StyleGAN2-ADA, and further to 0.461 with DDPM. The consistent improvement in SSIM and reduction in LPIPS indicate that the synthetic images are becoming increasingly similar to real ones in both structural integrity and perceptual quality. In particular, DDPM achieves higher SSIM and lower LPIPS compared to GAN-based models, demonstrating superior ability to capture both global consistency and fine-grained crack characteristics. These improvements yield high-quality synthetic data that are especially beneficial in data-scarce scenarios, as they enhance the training of downstream crack detection and segmentation models. By enriching datasets with realistic variations, DDPM-generated images improve model performance, mitigate overfitting, and increase robustness to unseen defect patterns during deployment. Based on the comparison results, DDPM was identified as the most suitable model for image augmentation and was therefore adopted in subsequent experiments.

The image generation using DCGAN and WGAN-GP was conducted at a lower resolution of 128 × 128, constrained by the model architecture. StyleGAN2-ADA and DDPM were trained on higher-resolution images (512 × 512). Table 2 summarizes the comparison of generative models in terms of efficiency and computational cost. DCGAN at 128 × 128 resolution with a batch size of 8 achieves the fastest inference speed of 0.64 ms, with a generator size of 3.55 MB and a discriminator size of 2.77 MB, requiring 7.7 GB of GPU memory out of 24 GB. WGAN-GP at the same resolution and batch size of 8 runs slightly slower at 0.97 ms, with larger model sizes of 12.79 MB for the generator and 11.16 MB for the critic and requires 8.6 GB of memory. WGAN-GP has larger model sizes than DCGAN because its generator and critic require higher capacity to support Wasserstein distance estimation and gradient penalty regularization. StyleGAN2-ADA at 512 × 512 resolution with a batch size of 8 requires 22.1 ms per inference, with a generator size of 109.5 MB and a discriminator size of 112.4 MB, consuming 17.4 GB of GPU memory. In comparison, DDPM at 512 × 512 resolution with a batch size of 2 is the slowest, requiring 60,000 ms (1 min) per inference (1000 inference steps), with a model size of 453.6 MB and a memory usage of 21.2 GB. Overall, DDPM remains much slower than GANs despite its superior image quality.

3.3 Comparison of Segmentation Models

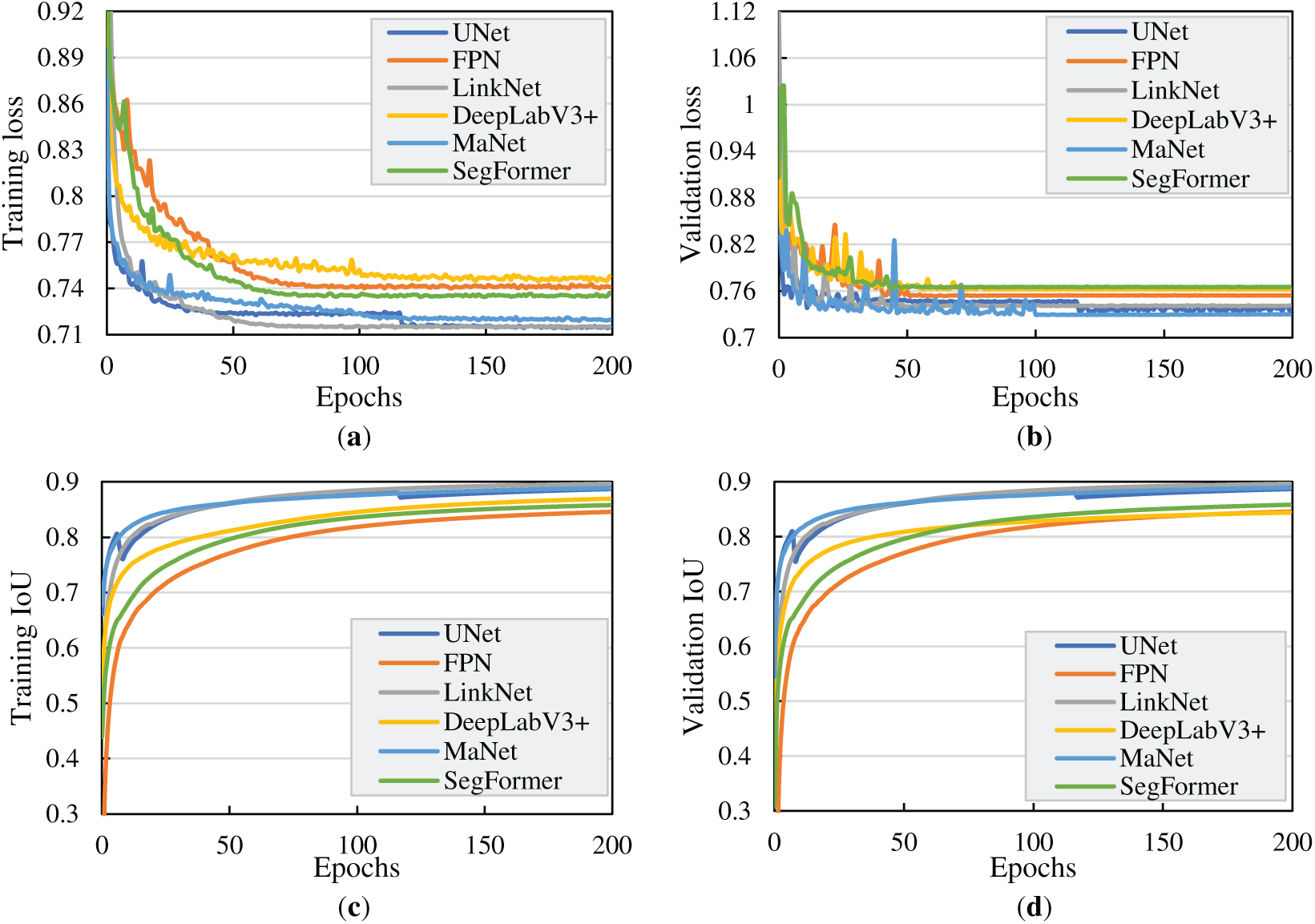

Fig. 7 shows the changes in training and validation loss, as well as IoU, across different epochs. Over the course of 200 training epochs, the comparative evaluation of six segmentation models revealed clear differences in both convergence behavior and final performance. In the loss-based evaluation, DeepLabV3+ consistently achieved the lowest and most stable values, ranging from 0.762 to 0.766, indicating superior optimization efficiency. SegFormer followed closely, converging to a similar but slightly less optimal range, while UNet, FPN, and LinkNet demonstrated comparable convergence, stabilizing around 0.74–0.75. MaNet exhibited relatively weaker performance, with its loss stabilizing at approximately 0.73–0.74, suggesting that it was less effective in minimizing error compared with the other architectures. In the validation IoU analysis, all six models demonstrated smooth and stable convergence. LinkNet, UNet, and MaNet achieved the strongest performance, converging to the highest IoU values in the range of 0.887–0.897. DeepLabV3+ and SegFormer achieved slightly lower but still competitive IoU values, stabilizing between 0.845 and 0.858. FPN converged reliably but attained the lowest IoU of 0.846, highlighting its relative limitations compared with the other architectures.

Figure 7: Training and validation loss and IoU performance over epochs: (a) training loss; (b) validation loss; (c) training IoU; and (d) validation IoU

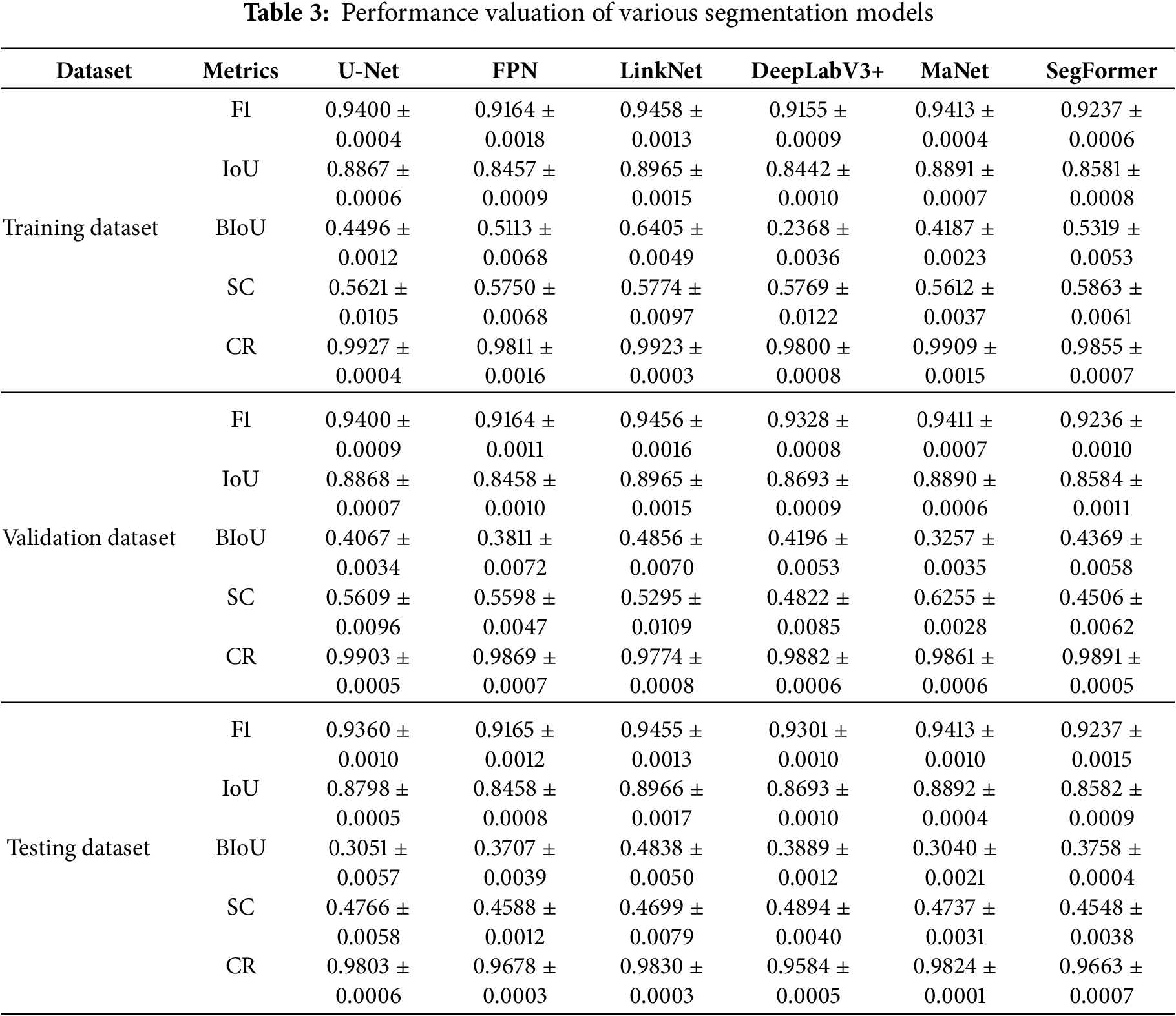

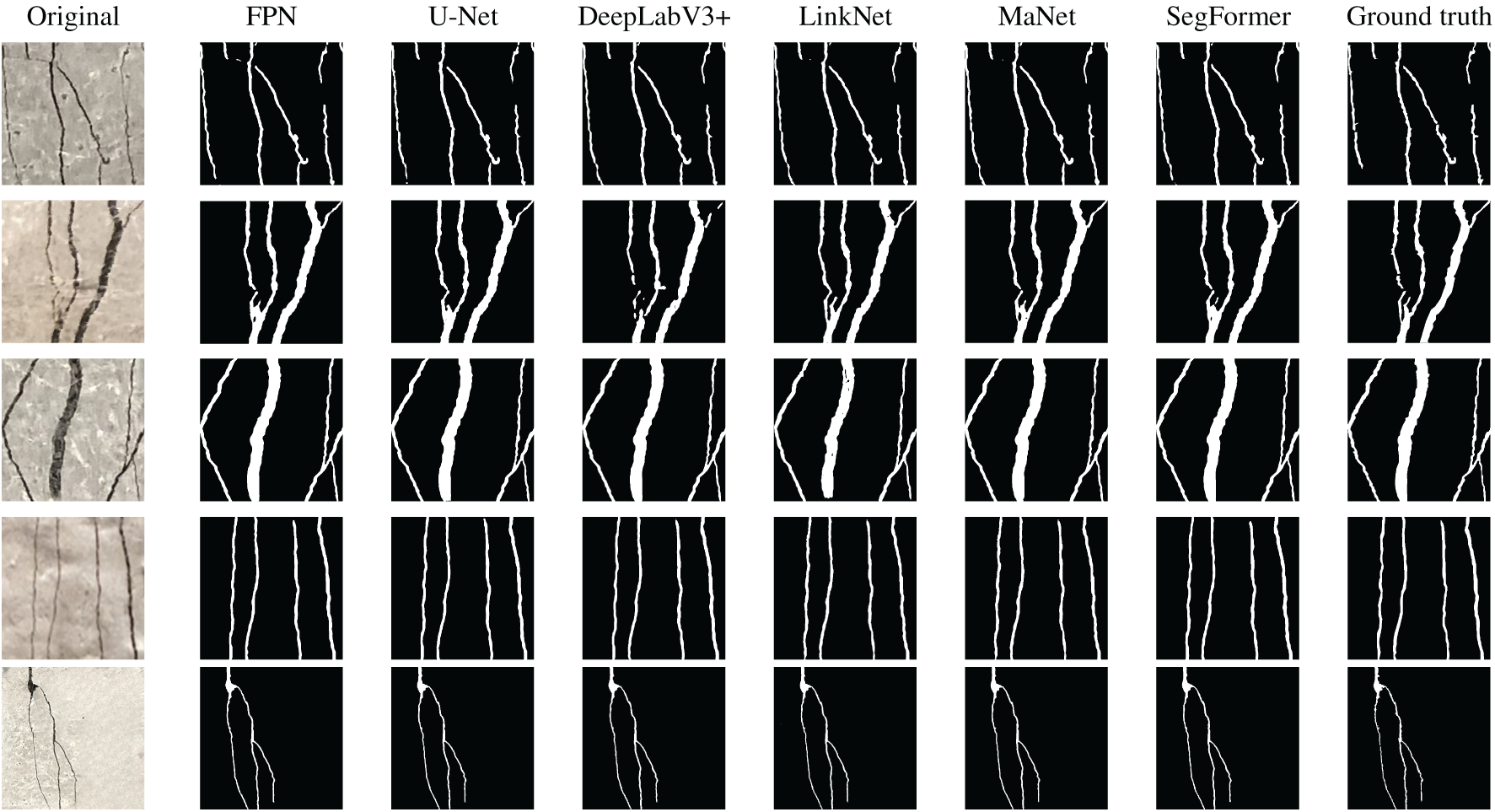

To evaluate the effectiveness of the models, six semantic segmentation architectures were tested: U-Net, FPN, LinkNet, DeepLabV3+, MaNet, and SegFormer. Their performance on the training, validation, and testing datasets is summarized in Table 3, using F1 score, IoU, Boundary IoU (BIoU), Skeleton Continuity (SC), and Centerline Recall (CR). Among these models, LinkNet achieved the highest F1 and IoU scores across all datasets. On the training set, it reached an F1 of 0.8965 and an IoU of 0.9455. On the validation set, the values were 0.9455 and 0.8965, respectively. On the testing set, it achieved an F1 of 0.9455 and an IoU of 0.8966, demonstrating robustness and strong feature extraction ability. In addition, LinkNet obtained the highest BIoU, suggesting that it captures object boundaries more accurately, while also achieving competitive SC and CR values. These highlight its ability to preserve structural continuity and align well with the ground-truth centerlines. Collectively, these results demonstrate that LinkNet not only achieves accurate region-level segmentation but also maintains fine-grained geometric details that are critical for crack and defect analysis. U-Net and MaNet followed closely with competitive F1 and IoU values. MaNet stood out by achieving the highest SC score of 0.6255 on the validation dataset, indicating stronger capability in preserving fine structural details. In contrast, DeepLabV3+ delivered relatively balanced results, but its BIoU on the training set was only 0.2368, indicating difficulties in capturing precise boundary alignment. SegFormer showed mid-range performance across most metrics, reflecting moderate generalization ability. FPN generally lagged in F1 and IoU despite achieving reasonable BIoU scores. Overall, these results indicate that convolutional models such as LinkNet and U-Net remain highly competitive, particularly for achieving high segmentation accuracy, while MaNet provides advantages in preserving continuity of thin structures. Transformer-based SegFormer demonstrates stable but less dominant performance, and DeepLabV3+ shows trade-offs between overall accuracy and boundary precision. The consistency of results across training, validation, and testing suggests that all models trained stably with moderate overfitting. Representative segmentation results from various semantic segmentation models are shown in Fig. 8. FPN and DeepLabV3+ exhibited higher error rates, particularly when processing images with complex crack patterns. These models often struggled to capture fine structural details, resulting in incomplete or fragmented segmentations.

Figure 8: Representative examples of predicted results from various segmentation models

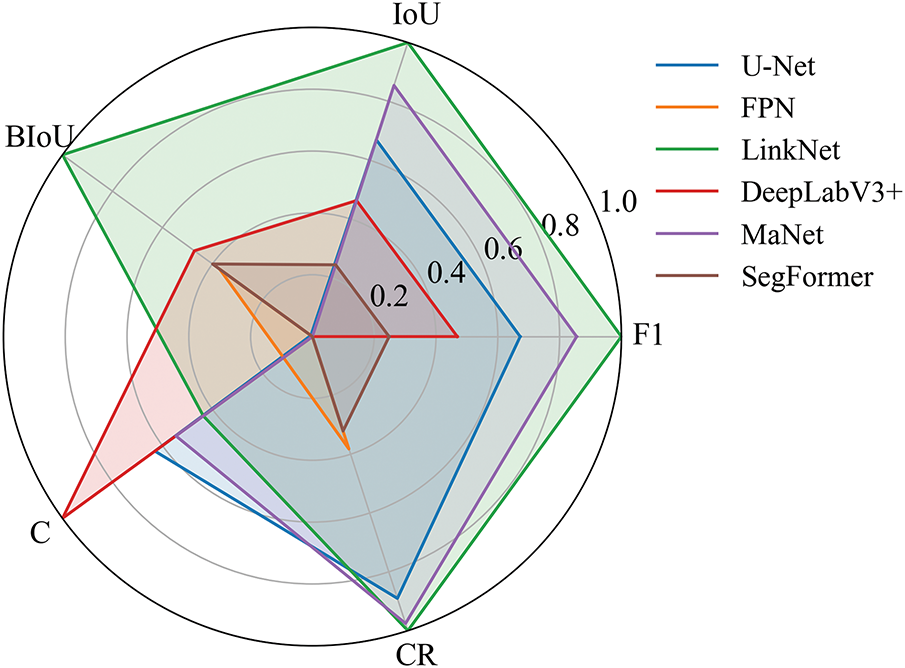

To provide a holistic comparison across multiple metrics, a radar chart (Fig. 9) was constructed by first applying min–max normalization to each metric so that their values were scaled to the range of 0 to 1, thereby eliminating the influence of differing numerical ranges (e.g., BIoU ≈ 0.3–0.5 vs. CR ≈ 0.97–0.98). Each axis of the radar chart corresponds to one performance metric, and the normalized performance of each model is plotted and enclosed to form a polygon. A larger enclosed area represents superior overall performance. From the visualization, LinkNet forms the most extensive polygon across most metrics, confirming it as the optimal model in terms of both region-level accuracy and structural detail preservation.

Figure 9: Radar chart comparing the performance of six segmentation models across five evaluation metrics

3.4 Effects of Data Augmentation

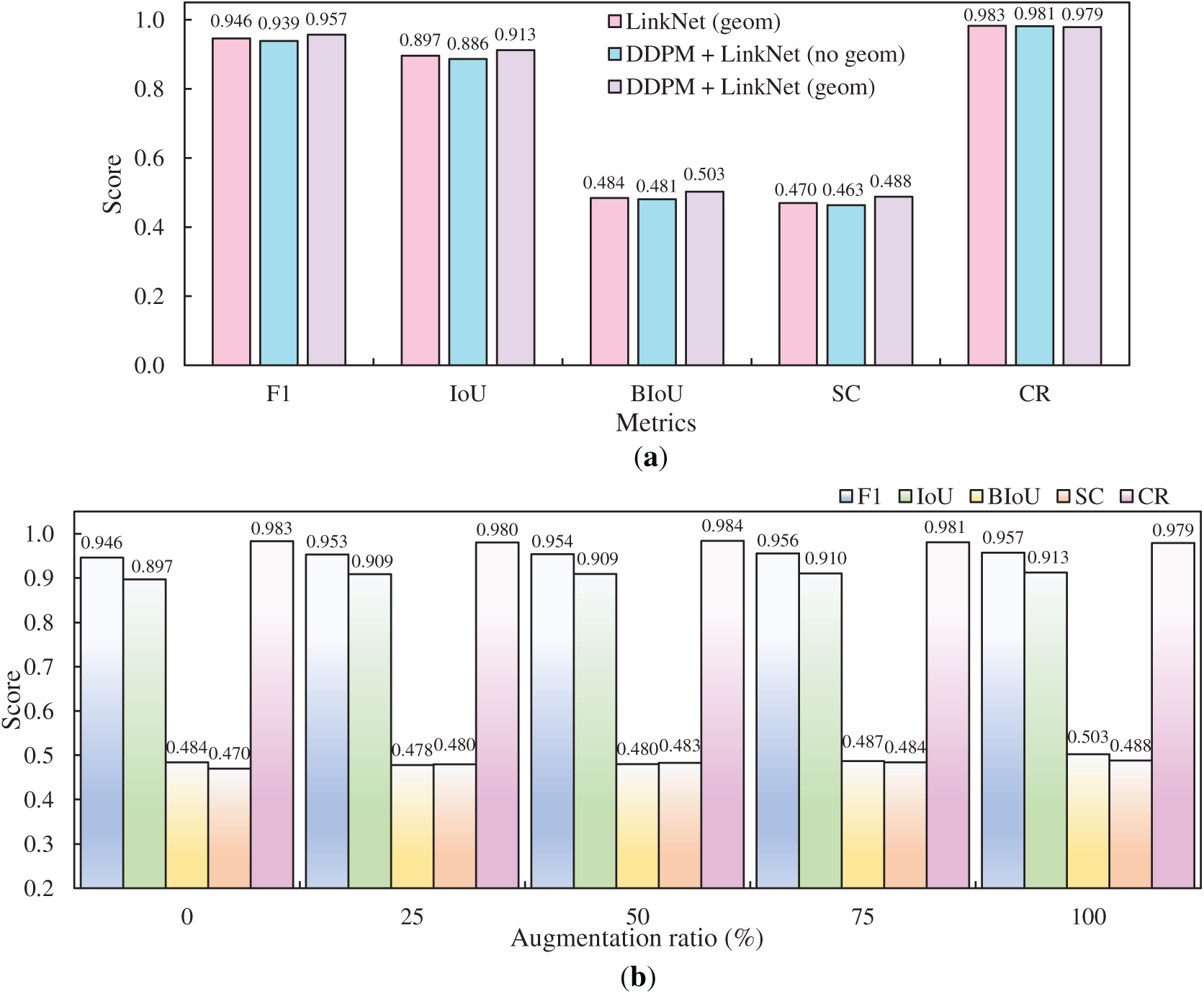

With LinkNet identified as the optimal model in Section 3.3, further evaluation is conducted to investigate data augmentation strategies. Fig. 10a illustrates the comparison between geometric augmentation and generated images. The DDPM + LinkNet with geometric augmentation (geom) achieved the highest F1 score of 0.957 and an IoU of 0.913, confirming its superior region-level segmentation accuracy. It also outperformed the other configurations in BIoU with 0.503 and SC with 0.488, demonstrating a stronger ability to delineate boundaries and preserve fine structural continuity. Although its CR score reached 0.979, slightly below the 0.983 obtained by LinkNet with geometric augmentation alone, the model still performed competitively. The overall improvements across the other metrics indicate that integrating synthetic data with geometric transformations provides the most effective strategy for enhancing segmentation performance. Fig. 10b shows that increasing the augmentation ratio from 0 to 100 consistently improves segmentation performance. The F1 score rises from 0.946 without augmentation to 0.957 at the highest augmentation ratio, while IoU improves from 0.897 to 0.913, confirming better overlap between predictions and ground truth. BIoU and SC also increase, from 0.484 to 0.503 and from 0.470 to 0.488, respectively, indicating enhanced precision in boundary alignment and improved continuity in structural details. CR remains relatively stable, fluctuating around 0.980, which suggests that augmentation primarily strengthens region- and boundary-level accuracy without significantly affecting the coverage of crack centerlines. Collectively, these results highlight that higher augmentation ratios, particularly when combined with diffusion-generated data, contribute to steady gains in segmentation accuracy and structural consistency.

Figure 10: Effects of data augmentation strategies: (a) comparison between geometric augmentation and generated images and (b) impact of augmentation ratio

3.5 Challenges and Future Studies

Generative models such as GANs and DDPMs can synthesize images but face trade-offs between controllability and diversity. Achieving fine-grained control over attributes like texture, color, and surface conditions is especially important in domains such as concrete damage simulation, where visual fidelity and variation are critical for building robust datasets. Controllable image generation allows users to guide the output by conditioning on specific features, such as crack patterns, making it ideal for generating diverse samples of particular damage types. Techniques like style transfer can further enhance this by applying domain-specific aesthetics to generic structural forms. In this context, conditional GANs represent an early but effective attempt to incorporate controllability into generative modeling by conditioning the generation process on class labels or auxiliary information. Although conditional GANs can guide the synthesis toward specific crack categories, they still suffer from instability and resolution limitations. By contrast, modern image generation systems, including conditional diffusion models, Stable Diffusion, and DALL·E, incorporate multi-modal conditioning mechanisms. These models take structured inputs such as text prompts, segmentation maps, or sketches to steer the generation process toward desired outcomes.

Although the proposed DDPM framework demonstrates strong capability in generating high quality crack images, the training data used in this study were mostly collected under relatively consistent lighting conditions. In real-world structural monitoring scenarios, however, illumination may vary significantly due to natural light, shadows, or artificial sources. Such variation could affect both the fidelity of DDPM-generated outputs and the robustness of segmentation models trained with augmented datasets. Future research should therefore examine how lighting variation influences the quality and realism of DDPM outputs, and whether incorporating illumination-augmented training data (e.g., synthetic lighting transformations or conditional diffusion models) can improve the generalization of downstream crack detection tasks.

Another promising direction is the edge deployment of diffusion models. The computational overhead and inference latency of DDPM remain high, as discussed in Section 3.2. For real-time crack monitoring in field environments, deploying DDPMs on edge devices such as embedded GPUs or mobile accelerators is essential. Future research could therefore explore lightweight diffusion variants (e.g., distilled or accelerated DDPMs) to achieve efficient generation under limited hardware resources. Such developments would enable on-site crack analysis without reliance on cloud infrastructure, facilitating real-time and scalable structural health monitoring.

Generative augmentation enhances data diversity by synthesizing realistic samples but still relies on manual labeling, especially for tasks requiring precise annotations. Since generated images lack ground-truth labels, manual or semi-automated annotation remains necessary. Current methods may introduce label noise, limiting their effectiveness. Thus, reducing labeling effort remains an open challenge. Future research should focus on developing generative models that can produce both realistic images and reliable annotations simultaneously. Promising directions include mask-conditioned generation, label transfer techniques, weakly supervised learning, and self-supervised methods to reduce manual labeling effort and mitigate annotation noise.

Future research should aim to develop controllable generative models for crack monitoring tasks using conditional diffusion models. Additionally, optimizing models for deployment on edge devices or low-power hardware would allow real-time generation in field conditions. With high-quality segmentation models, future research can enable real-time crack quantification during bending tests. This advancement would allow for continuous monitoring of crack initiation and propagation, providing deeper insights into material behavior under stress. It could also improve the accuracy of failure prediction, support the development of more robust structural health monitoring systems, and reduce the need for post-test analysis. Beyond crack analysis, machine learning has also been applied to predict concrete properties from mixture proportions, with deterministic and robust optimization enhancing reliability under varying conditions [41]. Building on this, machine learning models can be trained using identified crack widths and crack counts to predict properties such as tensile strength and tensile strain capacity.

This study introduced a diffusion-based framework for generating high quality, artifact-free images of complex concrete cracks and demonstrated its effectiveness as a data augmentation strategy for improving crack segmentation performance. Based on the above investigation, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) Compared with conventional GAN-based methods, DDPM generated visually more realistic and structurally detailed crack images, achieving the highest SSIM score of 0.302 and the lowest LPIPS score of 0.461, significantly outperforming DCGAN (SSIM 0.213, LPIPS 0.796), WGAN-GP (0.228, 0.581), and StyleGAN2-ADA (0.287, 0.528).

(2) Ablation on DDPM step configurations showed that increasing the noise schedule steps improved image quality, with SSIM rising from 0.096 at 100 steps to 0.302 at 1000 steps and LPIPS decreasing from 0.633 to 0.461. Therefore, small step counts cannot be used for training DDPM effectively. For inference process, fewer steps such as 10 achieved the highest SSIM of 0.335 but slower reduction in LPIPS, whereas larger step counts improved perceptual similarity at the cost of longer generation times.

(3) Among the six segmentation models evaluated, LinkNet achieved the best overall performance, with F1 reaching 0.9455 and IoU 0.8966 on the testing dataset. It also obtained the highest BIoU of 0.4838, competitive SC of 0.4699, and a strong CR of 0.9830, confirming its robustness in capturing both region-level accuracy and fine structural details. Incorporating DDPM-generated images with geometric augmentation further improved accuracy, with F1 increasing to 0.957 and IoU to 0.913, along with enhanced boundary alignment and skeleton continuity.

(4) Despite the advantages of DDPMs, several challenges remain. First, generative models face a trade-off between controllability and diversity, and future research should explore conditional diffusion frameworks for fine-grained control over crack attributes. Second, the dataset used in this study was collected under relatively uniform illumination, whereas real-world monitoring involves varying lighting conditions; extending training with illumination-augmented data would improve generalization. Third, the computational overhead of DDPMs limits real-time deployment, highlighting the need for lightweight or distilled variants suitable for edge devices. Finally, generative augmentation still depends on manual labeling, and future work should develop approaches that jointly produce images and reliable annotations to reduce labeling burden.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 52508343) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No.: B250201004).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Pengwei Guo; methodology, Pengwei Guo; software, Pengwei Guo; validation, Xiao Tan and Yiming Liu; formal analysis, Pengwei Guo; investigation, Pengwei Guo; resources, Xiao Tan; data curation, Pengwei Guo; writing—original draft preparation, Pengwei Guo; writing—review and editing, Xiao Tan and Yiming Liu; visualization, Pengwei Guo; supervision, Xiao Tan and Yiming Liu; project administration, Xiao Tan and Yiming Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

Figure A1: Representative examples of real and synthetic crack images: (a) and (c) show real images, while (b) and (d) present the generated images. Red boxes indicate selected regions of interest, with the corresponding zoom-in panels displayed on the right

References

1. Mousa MA, Yussof MM, Hussein TS, Assi LN, Ghahari S. A digital image correlation technique for laboratory structural tests and applications: a systematic literature review. Sensors. 2023;23(23):9362. doi:10.3390/s23239362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Golewski GL. An extensive investigations on fracture parameters of concretes based on quaternary binders (QBC) by means of the DIC technique. Constr Build Mater. 2022;351:128823. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Etchepareborda P, Moulet MH, Melon M. Random laser speckle pattern projection for non-contact vibration measurements using a single high-speed camera. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2021;158:107719. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2021.107719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xavier J, Sousa AM, Morais JJ, Filipe VM, Vaz M. Measuring displacement fields by cross-correlation and a differential technique: experimental validation. Opt Eng. 2012;51(4):043602. doi:10.1117/1.OE.51.4.043602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhu H, Guo Y, Tan X. Self-adaptive moving least squares measurement based on digital image correlation. Optics. 2024;5(4):566–80. doi:10.3390/opt5040042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xu Y, Chen H, Liang Y, Shen J, Yang H. Study on fracture characteristics and fracture mechanism of fully recycled aggregate concrete using AE and DIC techniques. Constr Build Mater. 2024;419:135540. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dong J, Wang N, Fang H, Guo W, Li B, Zhai K. MFAFNet: an innovative crack intelligent segmentation method based on multi-layer feature association fusion network. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;62:102584. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Laxman K, Tabassum N, Ai L, Cole C, Ziehl P. Automated crack detection and crack depth prediction for reinforced concrete structures using deep learning. Constr Build Mater. 2023;370:130709. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Qiu S, Zaheer Q, Ehsan H, Hassan Shah SMA, Ai C, Wang J, et al. Multimodal fusion network for crack segmentation with modified U-net and transfer learning-based MobileNetV2. J Infrastruct Syst. 2024;30(4):04024029. doi:10.1061/JITSE4.ISENG-249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chu H, Chen W, Deng L. Cascade operation-enhanced high-resolution representation learning for meticulous segmentation of bridge cracks. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;61:102508. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Xiang C, Wang W, Deng L, Shi P, Kong X. Crack detection algorithm for concrete structures based on super-resolution reconstruction and segmentation network. Autom Constr. 2022;140:104346. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Guo P, Meng X, Meng W, Bao Y. Automatic assessment of concrete cracks in low-light, overexposed, and blurred images restored using a generative AI approach. Autom Constr. 2024;168:105787. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Liu Y, Yao J, Lu X, Xie R, Li L. DeepCrack: a deep hierarchical feature learning architecture for crack segmentation. Neurocomputing. 2019;338:139–53. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.01.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang W, Su C. Automatic concrete crack segmentation model based on transformer. Autom Constr. 2022;139:104275. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sarkar K, Shiuly A, Dhal KG. Revolutionizing concrete analysis: an in-depth survey of AI-powered insights with image-centric approaches on comprehensive quality control, advanced crack detection and concrete property exploration. Constr Build Mater. 2024;411:134212. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Guo P, Meng W, Bao Y. Automatic identification and quantification of dense microcracks in high-performance fiber-reinforced cementitious composites through deep learning-based computer vision. Cem Concr Res. 2021;148:106532. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Guo P, Meng X, Meng W, Bao Y. Monitoring and automatic characterization of cracks in strain-hardening cementitious composite (SHCC) through intelligent interpretation of photos. Compos Part B Eng. 2022;242:110096. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jin T, Gu S, Shou Z, Shi H, Zhang M. Investigation of attention mechanism-enhanced method for the detection of pavement cracks. Struct Durab Health Monit. 2025;19(4):903. doi:10.32604/sdhm.2025.063887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jin T, Ye XW, Li Z. Establishment and evaluation of conditional GAN-based image dataset for semantic segmentation of structural cracks. Eng Struct. 2023;285:116058. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2023.116058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Pan Z, Lau SL, Yang X, Guo N, Wang X. Automatic pavement crack segmentation using a generative adversarial network (GAN)-based convolutional neural network. Results Eng. 2023;19:101267. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Que Y, Dai Y, Ji X, Leung AK, Chen Z, Jiang Z, et al. Automatic classification of asphalt pavement cracks using a novel integrated generative adversarial networks and improved VGG model. Eng Struct. 2023;277:115406. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Guo P, Meng W, Bao Y. Intelligent characterization of complex cracks in strain-hardening cementitious composites based on generative computer vision. Constr Build Mater. 2024;411:134812. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Han C, Ma T, Huyan J, Tong Z, Yang H, Yang Y. Multi-stage generative adversarial networks for generating pavement crack images. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;131:107767. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nichol AQ, Dhariwal P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. arXiv:2102.09672. 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2102.09672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Cano-Ortiz S, Sainz-Ortiz E, Iglesias LL, del Árbol PMR, Castro-Fresno D. Enhancing pavement crack segmentation via semantic diffusion synthesis model for strategic road assessment. Results Eng. 2024;23:102745. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang H, Chen N, Li M, Mao S. The crack diffusion model: an innovative diffusion-based method for pavement crack detection. Remote Sens. 2024;16(6):986. doi:10.3390/rs16060986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Shin H, Ahn Y, Tae S, Gil H, Song M, Lee S. Enhancement of multi-class structural defect recognition using generative adversarial network. Sustainability. 2021;13(22):12682. doi:10.3390/su132212682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu P, Qi H, Liu J, Feng L, Li D, Guo J. Automated clash resolution for reinforcement steel design in precast concrete wall panels via generative adversarial network and reinforcement learning. Adv Eng Inform. 2023;58:102131. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhou X, Li M, Liu Y, Yu W, Elchalakani M. Cross-domain damage identification of bridge based on generative adversarial and deep adaptation networks. Structures. 2024;64:106540. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lugmayr A, Danelljan M, Romero A, Yu F, Timofte R, Van Gool L. Repaint: inpainting using denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 11461–71. [Google Scholar]

31. Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; 2015 Oct 5–9; Munich, Germany. p. 234–41. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chaurasia A, Culurciello E. Linknet: exploiting encoder representations for efficient semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Visual Communications and Image Processing; 2017 Dec 10–13; St. Petersburg, FL, USA. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/VCIP.2017.8305148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lin TY, Dollár P, Girshick R, He K, Hariharan B, Belongie S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2117–25. [Google Scholar]

34. Chen LC, Zhu Y, Papandreou G, Schroff F, Adam H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 801–18. [Google Scholar]

35. Fan T, Wang G, Li Y, Wang H. Ma-Net: a multi-scale attention network for liver and tumor segmentation. IEEE Access. 2020;8:179656–65. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3025372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xie E, Wang W, Yu Z, Anandkumar A, Alvarez JM, Luo P. SegFormer: simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:12077–90. [Google Scholar]

37. Lightning A. Learned perceptual image patch similarity (LPIPS); 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://lightning.ai/docs/torchmetrics/latest/image/learned_perceptual_image_patch_similarity.html. [Google Scholar]

38. Hore A, Ziou D. Image quality metrics: PSNR vs. SSIM. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition; 2010 Aug 23–26; Istanbul, Turkey. p. 2366–9. [Google Scholar]

39. Duan S, Tan X, Guo P, Guo Y, Bao Y. The transformative roles of generative artificial intelligence in vision techniques for structural health monitoring: a state-of-the-art review. Adv Eng Inform. 2025;68:103719. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2025.103719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cheng B, Girshick R, Dollár P, Berg AC, Kirillov A. Boundary IoU: improving object-centric image segmentation evaluation. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 19–25; Online. p. 15334–42. [Google Scholar]

41. Mandal S, Shiuly A, Sau D, Mondal AK, Sarkar K. Study on the use of different machine learning techniques for prediction of concrete properties from their mixture proportions with their deterministic and robust optimisation. AI Civ Eng. 2024;3(1):7. doi:10.1007/s43503-024-00024-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools