Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Ab initio Investigation of Structural Units and Raman Vibrational Characteristics in Ge-Se-Te Glasses

Faculty of Information Science and Technology, Wenhua College, Wuhan, 430074, China

* Corresponding Author: Kan Yu. Email:

Chalcogenide Letters 2026, 23(1), 1 https://doi.org/10.32604/cl.2026.075604

Received 04 November 2025; Accepted 24 December 2025; Issue published 26 January 2026

Abstract

Chalcogenide glasses in the Ge-Se-Te system possess wide infrared transparency and strong optical nonlinearity, yet the microscopic origin of their vibrational behavior remains unclear. Using ab initio calculations, we analyzed Raman-active modes in GeSexTe4−x (x = 0–4) tetrahedra, edge-sharing tetrahedra, and ethane-like Ge2Se2xTe6−2x (x = 0–3) clusters. For GeSexTe4−x (x = 0–4) tetrahedra, the symmetric stretching vibrations exhibit two families: Ge-Se-dominated and Ge-Te-dominated modes, both showing monotonic redshifts as the number of same-type bonds increases. In edge-sharing tetrahedra, the Ge-Ch-Ge-Ch (Ch = Se or Te) four-membered-ring breathing frequency decreases with higher Te content, and a comparable softening is observed in the A1g and Eg modes of ethane-like Ge2Se2xTe6−2x units, where Te substitution lowers the breathing and antisymmetric stretching frequencies. These systematic redshifts are well explained by harmonic vibrational theory and bond polarizability models, indicating that Te substitution increases effective mass, softens local force constants, and redistributes bond-polarizability contributions, collectively leading to weaker Ge–Ch bonding and reduced structural rigidity. The results provide microscopic insight into the compositional evolution of Raman features in Ge-Se-Te chalcogenide glasses.Keywords

Chalcogenide glasses in the Ge-Se-Te system represent an important class of amorphous semiconductors with exceptional infrared transmission, large optical nonlinearities, and high refractive indices [1,2,3]. Their compositional flexibility allows continuous tuning of structural and optical properties, which makes them attractive for infrared photonics, sensing, and information storage applications. Among these systems, the substitution of selenium by tellurium plays a pivotal role in modifying both the bonding character and network connectivity, thereby influencing vibrational and electronic behaviors [4,5]. At the atomic scale, Ge-Se-Te glasses consist of diverse structural motifs, including Ge-centered tetrahedra, edge-sharing tetrahedral units, and Ge–Ge–linked ethane-like units (Ge2Ch6, Ch = Se, Te). Substituting Se with the heavier Te atom not only alters bond lengths and bond angles but also changes the force constants and local symmetry of these units. These structural modifications have a pronounced impact on the Raman-active vibrational modes, often manifested as systematic redshifts in the stretching and breathing frequencies. Experimental studies have observed such spectral trends [6,7,8], but the detailed evolution of specific local vibrational modes with Te→Se substitution still requires more quantitative clarification.

To address this issue, this study employs ab initio calculations to analyze the structural and vibrational evolution of representative Ge-Se-Te building blocks. The investigation focuses on three fundamental units: mixed GeSexTe4−x (x = 0–4) tetrahedra, edge-sharing tetrahedral pairs, and Ge–Ge–bonded ethane-like structures to explore how the gradual substitution of Se by Te affects local geometry and characteristic vibrational modes. While cluster-level models have inherent limitations in capturing medium-range glass disorder, they are widely used in chalcogenide research to probe local coordination environments and allow a controllable way to isolate substitution effects [9,10,11,12,13]. Through this approach, this work aims to provide complementary microscopic insight into how local structural changes influence Raman-active vibrational modes in Ge-Se-Te units. The resulting analysis supports more reliable Raman spectral assignments and helps improve understanding of the composition-dependent vibrational behavior of Ge-Se-Te glasses.

Geometry optimizations and vibrational frequency analyses were carried out using density functional theory (DFT) with the B3LYP hybrid functional and LANL2DZ effective core potentials augmented with polarization functions (d) without any scaling factor. The maximum deviation of 7 cm−1 (≈5.19%) between our computed and literature experimental Raman modesconfirms that this level of theory already reproduces the literature experimental frequencies within their intrinsic uncertainty. The structural models included three representative types of Ge-Se-Te units: (i) mixed GeSexTe4−x (x = 0–4) tetrahedra, (ii) edge-sharing tetrahedral pairs containing Ge-Se-Ge-Se, Ge-Se-Ge-Te, and Ge-Te-Ge-Te four-membered rings, and (iii) ethane-like units with systematically varied Se/Te substitution. All cluster models were terminated with hydrogen atoms to saturate dangling bonds, maintain charge neutrality, and preserve realistic local coordination environments of Ge and chalcogen atoms, consistent with established cluster-based approaches for chalcogenide glasses [10,14]. The optimized structures were verified by the absence of imaginary frequencies. Raman activities were obtained from analytical frequency calculations normalizing the intensity of each Raman vibrational mode simultaneously.

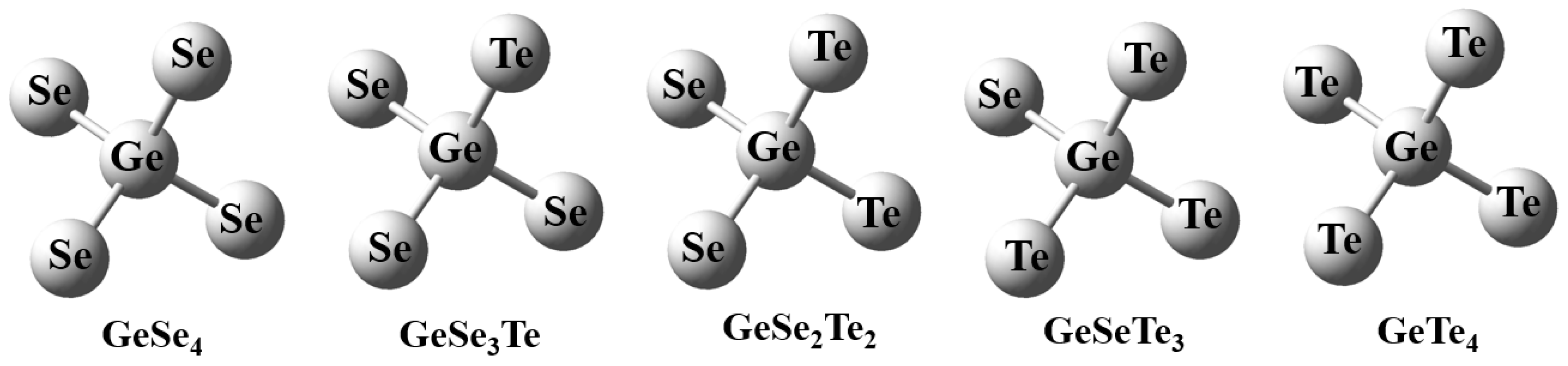

The optimized geometries of the GeSexTe4−x (x = 0–4) tetrahedral units obtained in this work show strong consistency with structural parameters reported in previous experimental and theoretical studies, confirming the reliability of the present computational results. The calculated Ge-Se bond lengths range from 2.40 Å to 2.43 Å, while the Ge-Te bond lengths lie between 2.62 Å and 2.67 Å, which are showed in Table 1. These values are in close agreement with the reported averages of ~2.40 Å for Ge-Se and ~2.60 Å for Ge-Te bonds in amorphous Ge-Se and Ge-Te systems, respectively [15,16]. The slight overestimation observed here may be attributed to the use of hybrid functional and effective core potential basis sets, which tend to marginally elongate heavy-atom bonds due to relativistic and polarization effects. Meanwhile, the internal bond angles within the tetrahedra deviate slightly from the ideal 109.5°. The bond lengths and angles of the overall structure are within acceptable ranges. In addition, the isolated tetrahedral unit structure of the GeSexTe4−x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4) clusters are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1: Optimized structural parameters (averaged values) of the GeSexTe4−x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4) clusters with bond distance (Å) and bond angle (degree).

| Cluster | Bond Distance (Å) | Bond Angle (Degree) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ge-Se | Ge-Te | Se-Ge-Se | Se-Ge-Te | Te-Ge-Te | |

| GeSe4 | 2.40 | -- | 109.5 | -- | -- |

| GeSe3Te | 2.43 | 2.62 | 108.9 | 110.3 | -- |

| GeSe2Te2 | 2.43 | 2.63 | 99.2 | 113.8 | 103.2 |

| GeSeTe3 | 2.41 | 2.62 | -- | 108.9 | 110.2 |

| GeTe4 | -- | 2.67 | -- | -- | 109.5 |

Figure 1: The isolated tetrahedral unit structure of the GeSexTe4−x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4) clusters.

The number and types of vibrational modes in the GeSexTe4−x tetrahedral units can be further rationalized based on molecular symmetry and the general 3N − 6 rule [17,18], where N represents the number of atoms in a nonlinear molecule. For a tetrahedral cluster such as GeSe4 (five atoms), this leads to 3 × 5 − 6 = 9 fundamental vibrational degrees of freedom. Group theoretical analysis within the Td point group predicts that these nine modes transform as A1 + E + 2F2, all of which are Raman active, while only the F2 modes are also infrared active. The A1 mode corresponds to the symmetric stretching of the four Ge-Se (Ge-Te) bonds, whereas the triply degenerate F2 modes involve asymmetric stretching and bending motions of the tetrahedron. As Te atoms are introduced, the molecular symmetry is progressively reduced (to C3v, C2v), leading to the splitting and mixing of degenerate F2 modes. This symmetry lowering results in additional Raman-active components and a noticeable redistribution of vibrational intensities. All the Raman vibrational modes of GeSexTe4−x clusters are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: The calculated Raman vibrational frequencies of GeSexTe4−x clusters with different point group (Td, C3v, C2v).

| Point Group | Td | ||||||||||||

| Cluster | GeSe4/GeTe4 | ||||||||||||

| Vib. Mode | ν1(A1) | ν2(E) | ν3(F2) | ν4(F2) | |||||||||

| Freq./cm−1 | 194/123 | 89/48 | 283/227 | 94/65 | |||||||||

| Point Group | C3v | ||||||||||||

| Cluster | GeSe3Te/GeSeTe3 | ||||||||||||

| Vib. Mode | ν1(A1) | ν2(A1) | ν3(A1) | ν4(E) | ν5(E) | ν6(E) | |||||||

| Freq./cm−1 | 251/146 | 167/271 | 86/75 | 269/232 | 83/69 | 64/52 | |||||||

| Point Group | C2v | ||||||||||||

| Cluster | GeSe2Te2 | ||||||||||||

| Vib. Mode | ν1(A1) | ν2(A1) | ν3(A1) | ν4(A1) | ν5(A2) | ν6(B1) | ν7(B1) | ν8(B2) | ν9(B2) | ||||

| Freq./cm−1 | 266 | 153 | 81 | 41 | 55 | 268 | 80 | 222 | 79 | ||||

The calculated Raman-active vibrational frequencies of the GeSe4 and GeTe4 tetrahedral units exhibit excellent consistency with experimental observations reported for GeSe2 and GeTe2 glasses. For the GeSe4 tetrahedron, the computed A1 symmetric stretching mode (ν1) appears at 194 cm−1, which closely matches the experimentally observed Raman band centered around 201 cm−1 attributed to the breathing vibration of corner-sharing GeSe4/2 tetrahedra in Ge-Se glasses [19,20]. For the GeTe4 tetrahedron, the computed A1 mode appears at 123 cm−1, which is in excellent agreement with the main Raman peak of GeTe2 glasses observed between 127 cm−1, corresponding to the symmetric stretching of Ge-Te bonds [21,22,23]. The consistency between the main vibrational frequencies of the GeSe4 and GeTe4 tetrahedral units and the corresponding literature values verifies the reliability of the calculations. On this basis, we further investigated the Raman vibrational frequencies of the GeSexTe4−x mixed tetrahedra and their gradual evolution behavior.

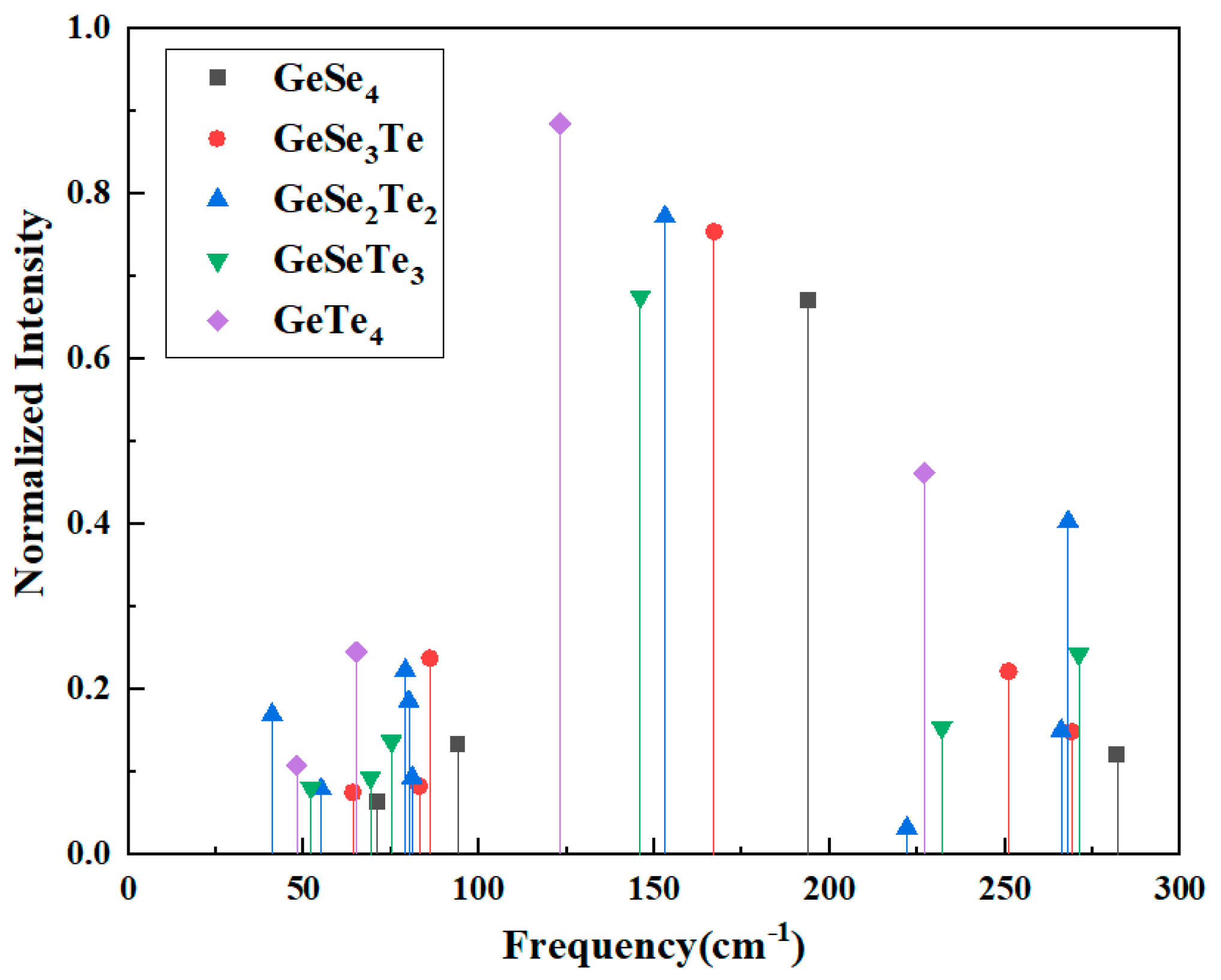

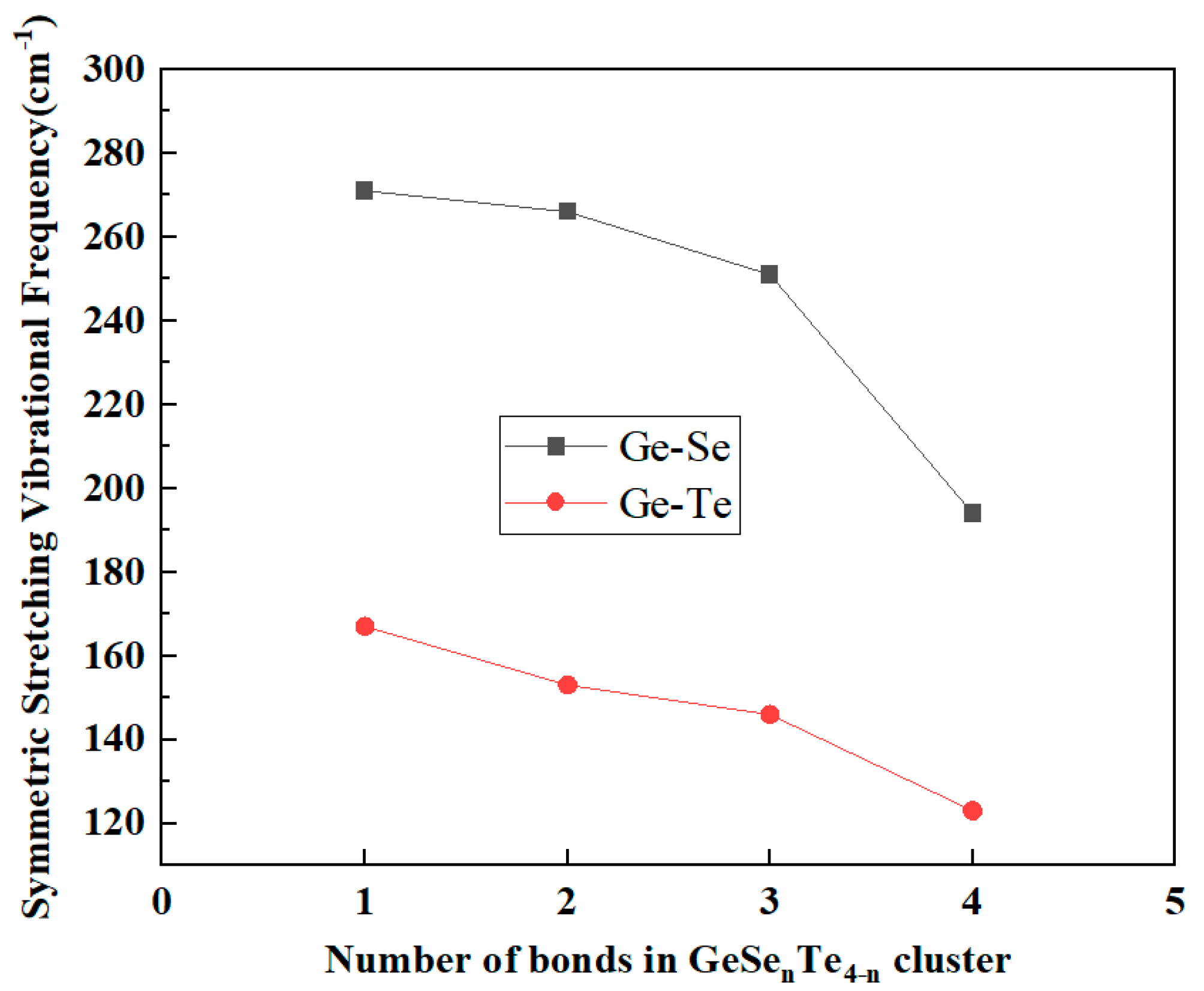

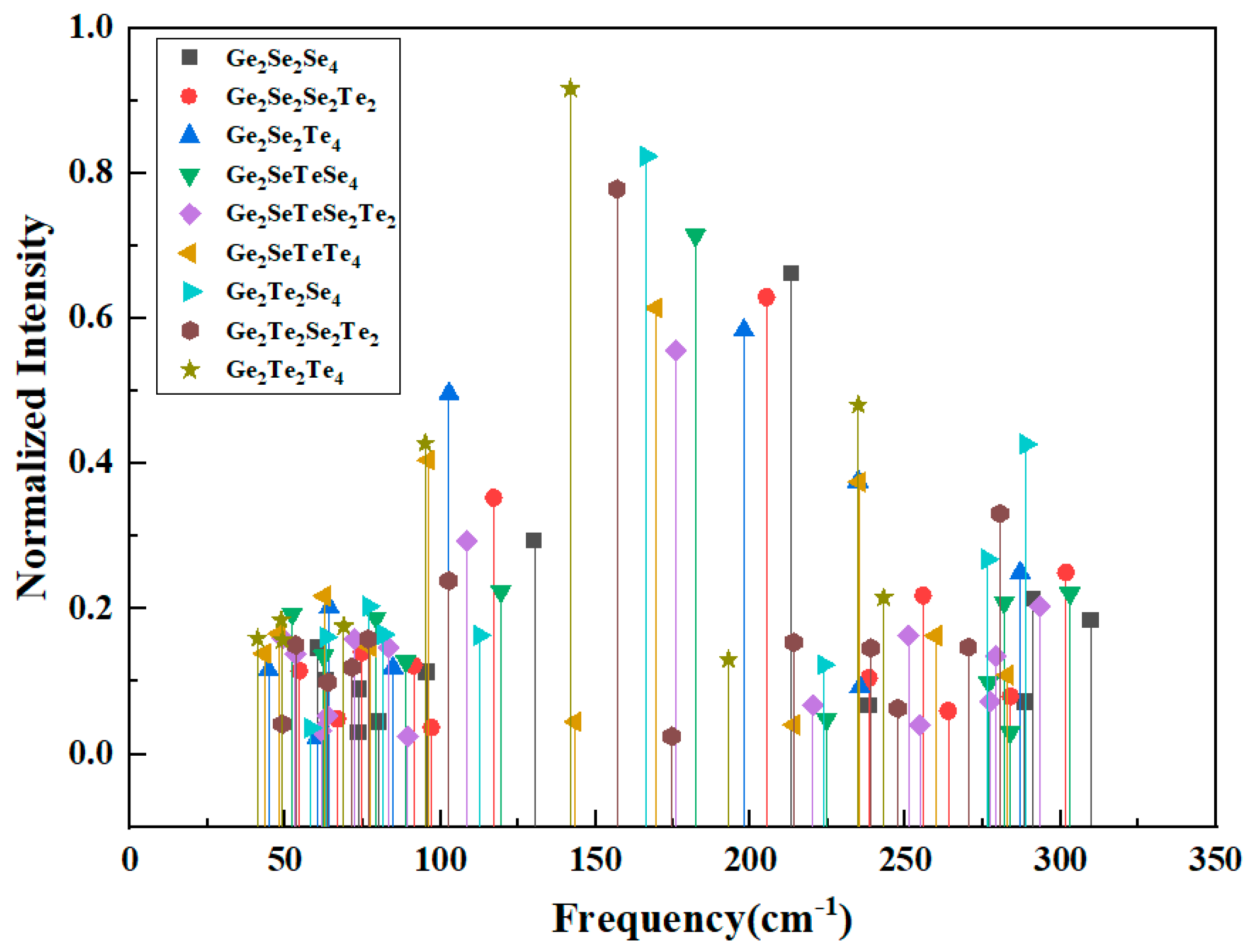

The calculated Raman vibrational modes of the GeSexTe4−x tetrahedra exhibit distinct frequency distributions with normalized intensity in Fig. 2, which reflect the local bonding environment around the Ge center. The symmetric stretching vibrations extracted from all GeSexTe4−x mixed tetrahedra, as illustrated in Fig. 3, can be clearly categorized into two groups: (i) modes primarily associated with Ge-Se bonds and (ii) modes dominated by Ge-Te bonds. A systematic trend is observed in both categories, indicating that the vibrational frequency of the symmetric stretching mode strongly depends on the number of equivalent bonds of a given type within the tetrahedral unit. For the Ge-Se related symmetric stretching modes, the frequency gradually decreases as the number of Ge-Se bonds in the tetrahedron increases. Specifically, the mode involving a single Ge-Se bond (in GeSeTe3) exhibits the highest frequency at 271 cm−1, followed by 266 cm−1 for two Ge-Se bonds (GeSe2Te2), 251 cm−1 for three Ge-Se bonds (GeSe3Te), and 194 cm−1 for four Ge-Se bonds (GeSe4). A similar frequency-decreasing trend is also observed for Ge-Te related symmetric stretching modes, which shift from 167 cm−1 for a single Ge-Te bond (in GeSe3Te) to 123 cm−1 for four Ge-Te bonds (GeTe4).

Figure 2: The vibrational mode frequencies of GeSexTe4−x clusters with normalized intensity.

Figure 3: The symmetric stretching vibrational mode frequency shift with Ge-Se and Ge-Te bands related.

3.2 Edge-Sharing Tetrahedral Unit

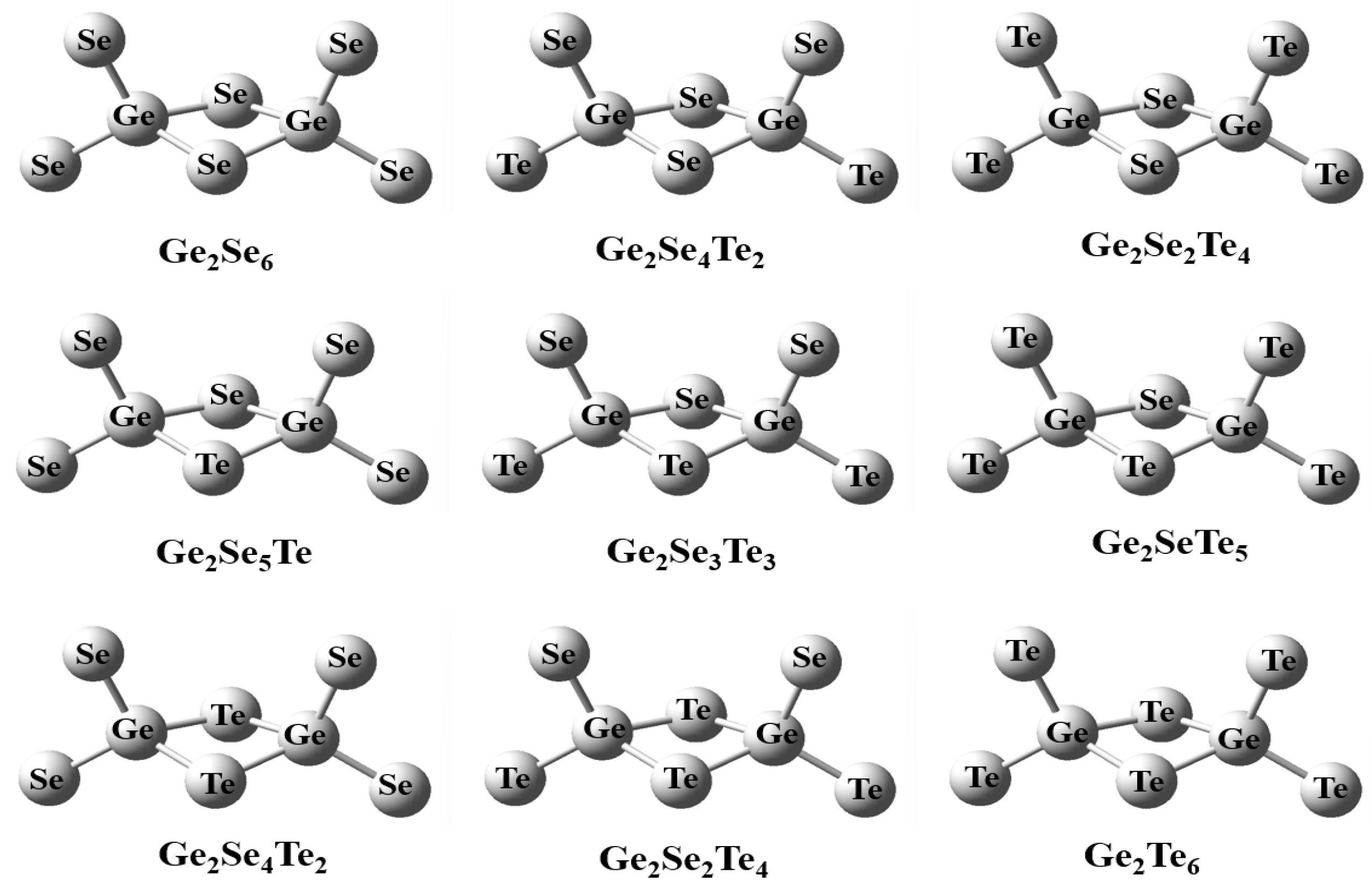

In addition to the isolated tetrahedral units, edge-sharing tetrahedral (EST) structures in the Ge-Se-Te system were also investigated. Owing to the different proportions of Se and Te atoms, a variety of mixed edge-sharing configurations can be formed. To ensure a systematic and comparable analysis, this study adopted a symmetric substitution approach. Specifically, substitutions were introduced in pairs at equivalent atomic sites within the symmetric edge-sharing tetrahedral framework, thereby maintaining the overall structural symmetry and allowing a clear observation of compositional evolution. Following this substitution scheme, nine distinct symmetric configurations were constructed, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The optimized structural parameters, including Ge-Ch (Ch = Se, Te) bond lengths and inter-tetrahedral bond angles, are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 4: The edge-shared structure of the Se2−xTex-Ge2SenTe2−n-Se2−xTex (n = 0, 1, 2; x = 0, 1, 2) cluster.

Table 3: Optimized structural parameters (averaged values) of the edge-shared Se2−xTex-Ge2SenTe2−n-Se2−xTex (n = 0, 1, 2; x = 0, 1, 2) clusters with bond distance (Å) and bond angle (degree).

| Cluster | Bond Distance (Å) | Bond Angle (Degree) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ge-Se | Ge-Te | Se-Ge-Se | Se-Ge-Te | Te-Ge-Te | Ge-Se-Ge | Ge-Te-Ge | |

| Se2GeSe2GeSe2 | 2.40 | -- | 101.8 | -- | -- | 82.1 | -- |

| SeTeGeSe2GeSeTe | 2.41 | 2.60 | 108.3 | 110.9 | -- | 83.2 | -- |

| Te2GeSe2GeTe2 | 2.42 | 2.61 | 96.6 | 114.2 | 103.9 | 83.4 | -- |

| Se2GeSeTeGeSe2 | 2.41 | 2.63 | 109.5 | 109.7 | -- | 86.3 | 77.9 |

| SeTeGeSeTeGeSeTe | 2.41 | 2.61 | 111.1 | 108.1 | 114.4 | 86.4 | 78.4 |

| Te2GeSeTeTe2 | 2.42 | 2.62 | -- | 108.1 | 111.1 | 86.6 | 78.6 |

| Se2GeTe2GeSe2 | 2.40 | 2.62 | 100.4 | 114.7 | 98.3 | -- | 81.7 |

| SeTeGeTe2SeTe | 2.41 | 2.62 | -- | 109.8 | 109.4 | -- | 81.8 |

| Te2GeTe2GeTe2 | -- | 2.64 | -- | -- | 104.6 | -- | 82.5 |

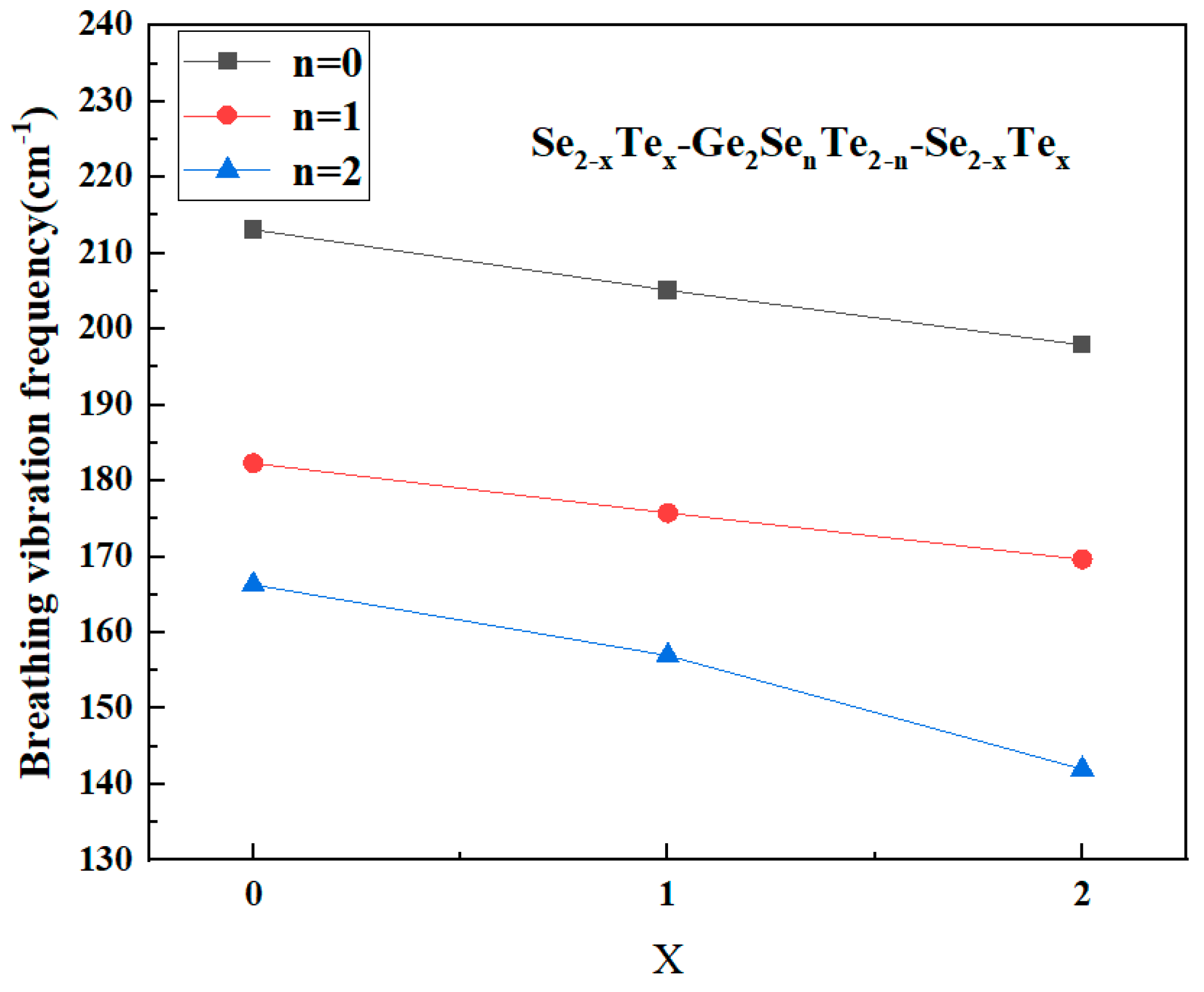

Fig. 5 presents the normalized-intensity vibrational-mode frequencies of the edge-sharing clusters. Given the complexity and the large number of vibrational modes in edge-sharing tetrahedral (EST) structures, the present study focuses on the breathing vibration of the four-membered rings as the primary subject of analysis, which considered as the most intense Raman active mode of the edge-sharing Ge2Ch6 (Ch = Se, Te) structure arises from the in-phase symmetric stretching (breathing) vibration ν(A1) of the two GeCh4 tetrahedra. Table 4 collects the computed symmetric breathing frequencies ν(A1) of the four-membered rings formed in edge-sharing clusters. Three distinct ring types occur in the dataset: (i) Ge-Se-Ge-Se, (ii) Ge-Se-Ge-Te, and (iii) Ge-Te-Ge-Te. For each ring type the calculations were performed for a series of clusters in which Se atoms occupying the ring-corner (top-corner) positions are progressively replaced by Te.

Figure 5: The vibrational mode frequencies of Edge-Sharing Se2−xTex-Ge2SenTe2−n-Se2−xTex (n = 0, 1, 2; x = 0, 1, 2) clusters with normalized intensity.

Table 4: The main vibrational modes and frequency of Edge-Sharing clusters.

| Cluster | Breathing Vibration Mode (Four-Membered Ring) | Vibration Frequency/cm−1 |

|---|---|---|

| Se2GeSe2GeSe2 | ν(A1) (Ge-Se-Ge-Se) | 213 |

| SeTeGeSe2GeSeTe | ν(A1) (Ge-Se-Ge-Se) | 205 |

| Te2GeSe2GeTe2 | ν(A1) (Ge-Se-Ge-Se) | 198 |

| Se2GeSeTeGeSe2 | ν(A1) (Ge-Se-Ge-Te) | 182 |

| SeTeGeSeTeGeSeTe | ν(A1) (Ge-Se-Ge-Te) | 176 |

| Te2GeSeTeTe2 | ν(A1) (Ge-Se-Ge-Te) | 170 |

| Se2GeTe2GeSe2 | ν(A1) (Ge-Te-Ge-Te) | 166 |

| SeTeGeTe2SeTe | ν(A1) (Ge-Te-Ge-Te) | 157 |

| Te2GeTe2GeTe2 | ν(A1) (Ge-Te-Ge-Te) | 142 |

The results show two clear and mutually consistent trends in Fig. 6. First, comparing the three ring chemistries at equivalent degrees of substitution demonstrates that the ring breathing frequency systematically decreases as the average chalcogen changes from Se, mixed Se/Te to Te. The pure Ge-Se-Ge-Se rings give the vibrational mode frequencies from 213, 205 to 198 cm−1 for 0, 1 and 2 Te substitutions at the specified corner sites, respectively, the mixed Ge-Se-Ge-Te rings occupy an frequency shift from 182, 176 to 170 cm−1, and the pure Ge-Te-Ge-Te rings present the frequencies decreasing from 166, 157 to 142 cm−1, which can be seen that the ring breathing frequency decrease with the increasing of Te substitutions at the specified corner sites. Second, within each ring class ((i) Ge-Se-Ge-Se, (ii) Ge-Se-Ge-Te, and (iii) Ge-Te-Ge-Te.) the breathing frequency decreases monotonically as the number of Te atoms in the ring local environment increases. the breathing frequency is highest for Ge-Se-Ge-Se rings, the middle for Ge-Se-Ge-Te rings and lowest for Ge-Te-Ge-Te rings.

Figure 6: The Breathing vibrational mode frequency of Edge-Sharing Se2−xTex-Ge2SenTe2−n-Se2−xTex (n = 0, 1, 2; x = 0, 1, 2) clusters.

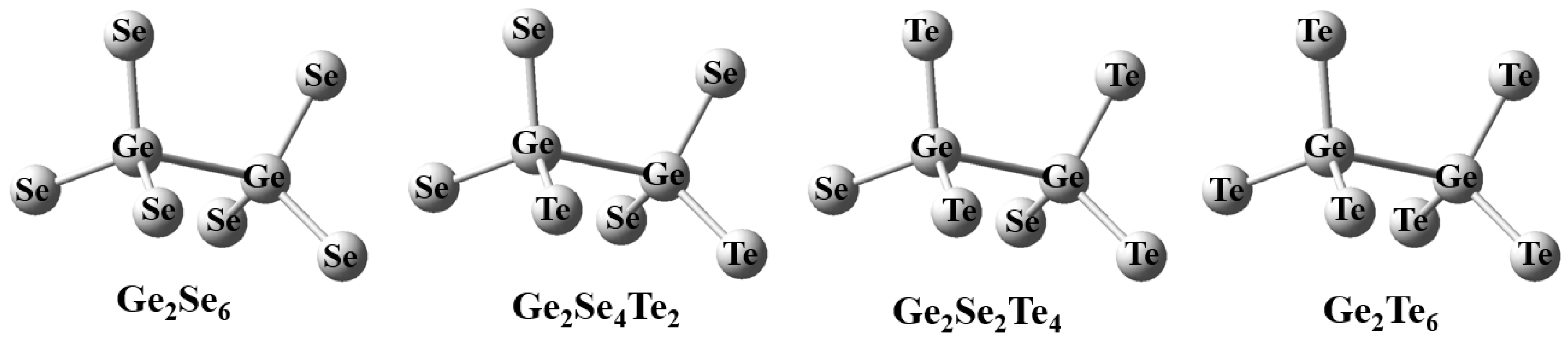

For the ethane-like “Ch3Ge-GeCh3” structural motifs with a central Ge-Ge bond and six terminal Ch atoms (Ch = Se or Te).in the Ge-Se-Te system, the analysis primarily focused on the stretching vibration modesand their dependence on the Se/Te ratio at the terminal sites. To ensure structural symmetry and to systematically reveal the compositional evolution, a symmetric even-substitution scheme was adopted, in which two equivalent terminal atoms were simultaneously replaced in each step. This approach yielded four representative configurations, as illustrated in Fig. 7, and the optimized bond lengths and bond angles for these structures are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5: Optimized structural parameters of the Ethane-like Ge2Se2xTe6−2x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3) clusters with bond distance (Å) and bond angle (degree).

| Cluster | Bond Distance (Å) | Bond Angle (Degree) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ge-Se | Ge-Te | Ge-Ge | Se-Ge-Se | Se-Ge-Te | Te-Ge-Te | |

| Se3Ge-GeSe3 | 2.41 | -- | 2.50 | 112.3 | -- | -- |

| Se2TeGe-GeSe2Te | 2.41 | 2.62 | 2.50 | 111.9 | 112.7 | -- |

| SeTe2Ge-GeSeTe2 | 2.42 | 2.62 | 2.50 | -- | 111.8 | 112.2 |

| Te3Ge-GeTe3 | -- | 2.62 | 2.51 | -- | -- | 112.6 |

Figure 7: The Ethane-like structure of Ge2Se2xTe6−2x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3) clusters.

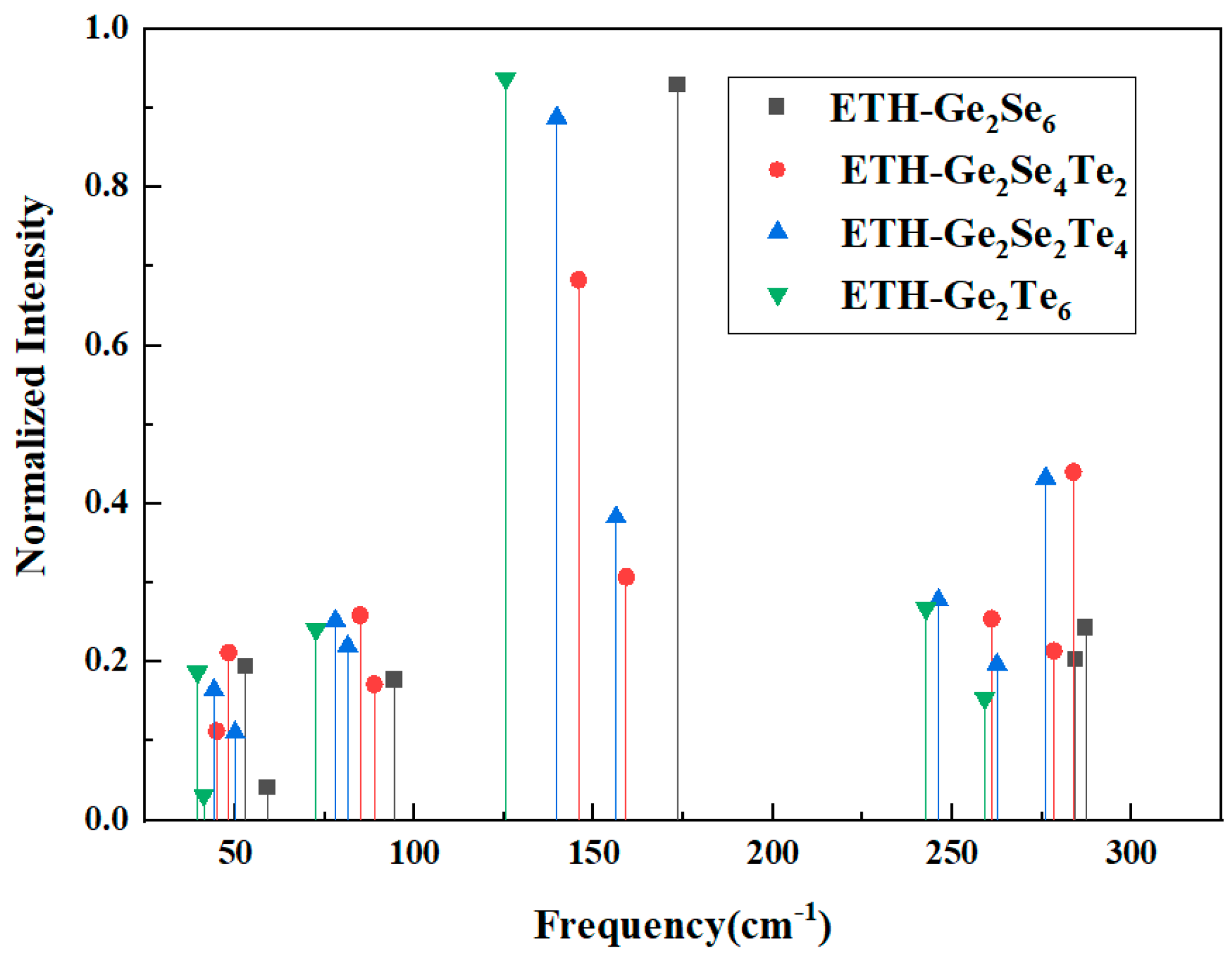

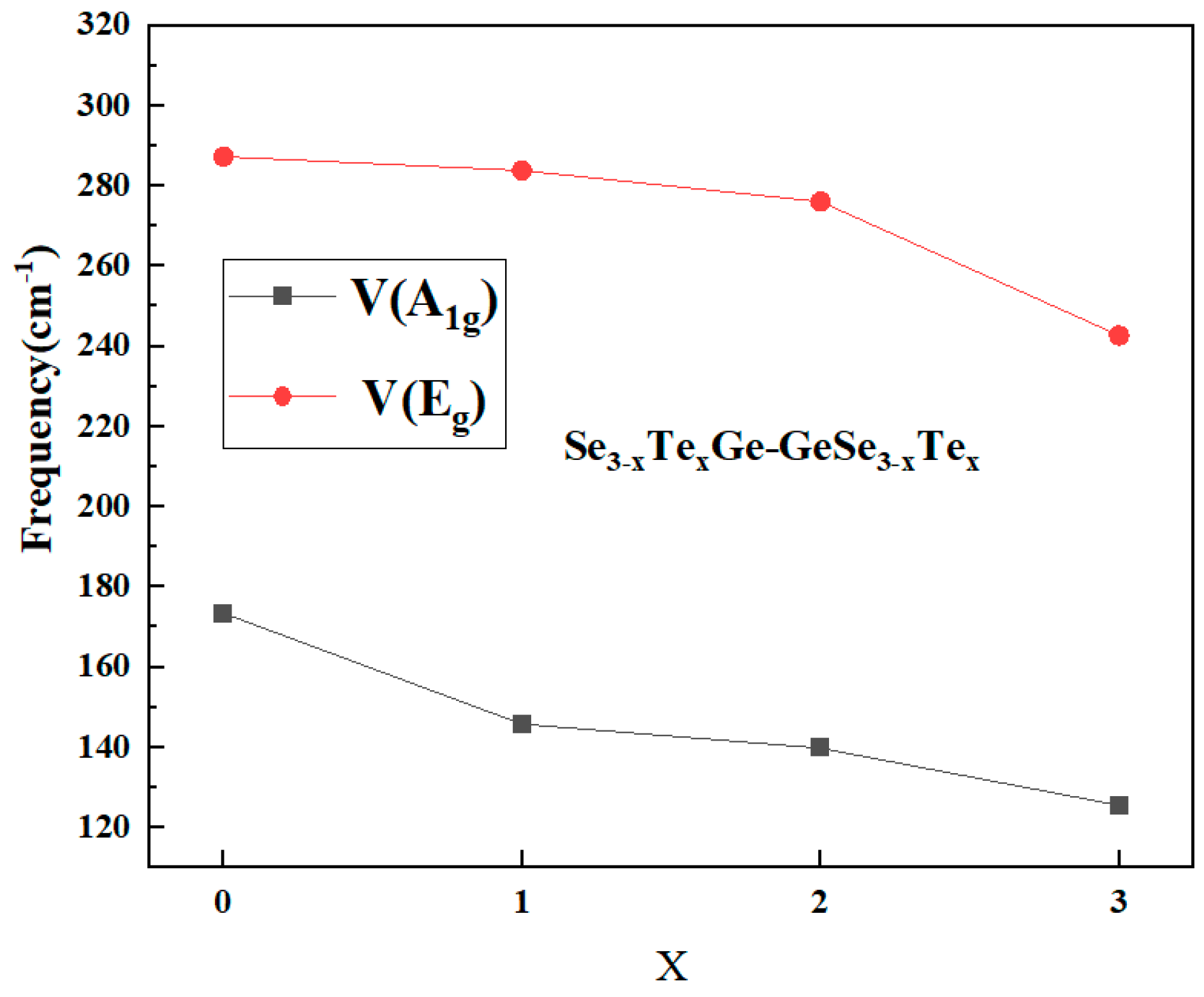

Fig. 8 shows the frequencies of vibrational modes in ethane-like Ge2Se2xTe6−2x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3) clusters with intensity normalization. From all the vibrational modes of the above structure, the main two vibrational modes in terms of intensity are selected based on their D3d symmetry classification using point-group analysis, as shown in Table 6. The strongest feature arises from the A1g breathing mode, in which all six Ge-Ch (Ch = Se or Te) bonds extend and contract in unison while the two GeCh3 fragments remain collinear; this in-phase motion produces the largest change in molecular polarizability and therefore dominates the spectrum. The second-stronging contribution is the Eg antisymmetric stretch, where the two GeCh3 units oscillate out of phase: as one Ge-Ch bond lengthens, its counterpart across the Ge–Ge axis shortens. According to literature [24], the ethane-like Se3Ge-GeSe3 structural unit is characterized by the peak at 175 cm−1, which is well matched with the calculated vibration frequency of Se3Ge-GeSe3 cluster attributed to ν(A1g) mode (173 cm−1)—in Table 6. The close agreement between the calculated results and the literature data validates the scientific rationality of the computational approach.

Figure 8: The vibrational mode frequencies of Ethane-like Ge2Se2xTe6−2x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3) clusters with normalized intensity.

Table 6: The main vibrational modes and vibration frequency of ethane-like Ge2Se2xTe6−2x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3) clusters.

| Cluster | Main Vibration Mode | Vibration Frequency/cm−1 | Main Vibration Mode | Vibration Frequency/cm−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Se3Ge-GeSe3 | ν(Eg) | 287 | ν (A1g) | 173 |

| Se2TeGe-GeSe2Te | ν(Eg) | 283 | ν (A1g) | 146 |

| SeTe2Ge-GeSeTe2 | ν(Eg) | 276 | ν (A1g) | 140 |

| Te3Ge-GeTe3 | ν(Eg) | 242 | ν (A1g) | 125 |

A comparative analysis of the main stretching modes with ν(A1g) and ν(Eg) in Fig. 9 revealed a clear and consistent trend: the stretching vibration frequency decreases progressively with increasing Te content in the terminal positions. These results further demonstrate that the substitution of Se by Te significantly alters the local bonding environment and vibrational response of ethane-like clusters in chalcogenide glass networks.

Figure 9: The main vibrational mode frequency in Ethane-like Ge2Se2xTe6−2x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3) clusters.

Table 7 summarises the deviations between our calculated values and the literature frequencies for the principal symmetric-stretching modes of Ge-Se and Ge-Te clusters. Overall, the calculated wavenumbers track the experimental ones within ±7 cm−1, corresponding to relative errors of −3.48% to +5.19%. The largest discrepancy (+7 cm−1, 5.19%) is observed for edge-sharing Ge2Te6. In addition, no experimental data is listed for the ethane-like Ge2Te6 unit in Table 7, To the best of our knowledge, experimental Raman measurements specifically identifying the ETH-Ge2Te6 structural motif have not been reported in the literature, which is consistent with previous structural studies reporting a low fraction of Ge-Ge homopolar bonds in Ge-Te glasses [25,26].

Table 7: Experimental and calculated vibrational frequencies of main symmetric stretching modes for Ge-Se and Ge-Te clusters with deviation analysis.

| Cluster Type | Vibrational Mode (Symmetry) | ν Exp/cm−1 | ν Calc/cm−1 | Error (cm−1) | Error Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GeSe4 | A1 symmetric stretch | 201 [19,20] | 194 | −7 | −3.48% |

| Ge2Se6 (edge-sharing) | A1 breathing stretch | 218 [9] | 213 | −5 | −2.29% |

| Ge2Se6 (ethane-like) | A1g symmetric stretch | 175 [24] | 173 | −2 | −1.14% |

| GeTe4 | A1 symmetric stretch | 127 [21] | 123 | −4 | −3.15% |

| Ge2Te6 (edge-sharing) | A1 breathing stretch | 135 [27] | 142 | +7 | 5.19% |

| Ge2Te6 (ethane-like) | A1g symmetric stretch | -- | 125 | -- | -- |

The compositional evolution of vibrational features in Ge-Se-Te systems can be reasonablyinterpreted based on vibrational spectroscopy theory and bond polarizability models [28,29,30], which together indicate that frequency shifts typically involve contributions from changes in bond force constants, atomic masses, and bond-polarizability effects. The systematic redshift of the main Raman-active symmetric stretching modes in Ge-Se-Te clusters (GeSexTe4−x tetrahedra, edge-sharing tetrahedra, and ethane-like units) is are therefore better understood as the collective outcome of these three contributions. Under the harmonic approximation, the frequency (ν) of a stretching vibration is shown in Eq. (1):

In GeSexTe4−x tetrahedra, all symmetric stretching vibrations can be grouped into two main types: Ge-Se related and Ge-Te related modes. The frequency of each group systematically decreases as the number of identical bonds within a tetrahedron increases. This trend primarily reflects the redistribution of vibrational energy among equivalent oscillators, leading to a smaller effective restoring force constant (keff). Additionally, our calculated bond-angle variations (e.g., Se-Ge-Se decreasing from ≈109.5° to ≈99.2° in mixed Se/Te tetrahedra) and bond-distance variations from ~2.4 Å(Ge-Se) to ~2.6 Å(Ge-Te) further reduce keff by enabling softer angular restoring forces, consistent with established central-force models. Consequently, tetrahedra with more identical bonds exhibit lower symmetric stretching frequencies than those containing fewer.

For edge-sharing tetrahedra, the vibrational behavior is dominated by the breathing modes of the four-membered rings (Ge-Se-Ge-Se, Ge-Se-Ge-Te and Ge-Te-Ge-Te).

νring(GeSeGeSe) > νring(GeSeGeTe) > νring(GeTeGeTe)The frequency hierarchy indicates a gradual softening of the breathing motion as Te atoms replace Se at the bridging sites. This can be attributed to the smaller bond-bending force constant (kθ) and lower ring strain in Te-rich configurations, which facilitate angular relaxation and mode coupling across the shared edge. Our calculated breathing frequencies follow this hierarchy with typical decreases of ~4–15 cm−1 for each symmetric 2Te-for-2Se substitution step in Table 4, supporting the interpretation that both mass and angular-force reductions are operative.

In the ethane-like structures, the focus is placed on the stretching modes with ν(A1g) and ν(Eg). The substitution of terminal Se atoms by heavier and less electronegative Te atoms monotonically red-shifts both the A1g and Eg vibrational modes. This effect can be described by the local mode-coupling model, in which heavy-atom substitution enhances mass loading and redistributes energy between stretching and bending coordinates.

This work provides a systematic DFT analysis of how Te → Se substitution affects the vibrational behavior of representative Ge-Se-Te structural units. By examining a complete series of GeSexTe4–x (x = 0–4) tetrahedra together with edge-sharing and ethane-like motifs, the study establishes a coherent microscopic picture linking bond-length/angle variations to the observed Te-induced redshifts of Raman-active modes. The results clarify how reduced mass, Ge-Ch (Ch = Se or Te) bond weakening, and local geometric relaxation collectively shape the compositional evolution of vibrational frequencies. These trends offer a unified reference for interpreting Raman features in Ge-Se-Te glasses and provide a structural basis for subsequent experimental or computational investigations.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research in the paper has been carried out with the support as follows: Wenhua College General Research Project (Grant No. 2023Y06), and Wen Hua College Doctoral Fund (Grant No.2022Y14).

Author Contributions: Xuecai Han—Conceptualization, methodology, writing, original draft; Yilin Tong—Data curation, validation, investigation; Jiaqi Bao—Formal analysis, visualization; Kan Yu—Writing, review & editing, supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Yang L, Zhou GJ, Lin CG. Composition-dependent properties and network structure of Ge-Se-Te chalcogenide glasses. Chalcogenide Lett. 2023;20(1):1–9. doi:10.15251/CL.2023.201.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu K, Kang Y, Tao H, Zhang X, Xu Y. Effect of Se on structure and electrical properties of Ge-As-Te glass. Materials. 2022;15(5):1797. doi:10.3390/ma15051797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xia D, Huang Y, Zhang B, Yang Z, Zeng P, Shang H, et al. On-chip broadband mid-infrared supercontinuum generation based on highly nonlinear chalcogenide glass waveguides. Front Phys. 2021;9:598091. doi:10.3389/fphy.2021.598091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Micoulaut M, Piarristeguy A, Masson O, Escalier R, Flores-Ruiz H, Pradel A. Alteration of structural, electronic, and vibrational properties of amorphous GeTe by selenium substitution: an experimentally constrained density functional study. Phys Rev B. 2021;104(14):144204. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.104.144204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pethes I, Chahal R, Nazabal V, Prestipino C, Trapananti A, Michalik S, et al. Chemical short-range order in selenide and telluride glasses. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120(34):9204–14. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b05996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sharma T, Sharma R, Kanhere DG. A DFT study of SenTen clusters. Nanoscale Adv. 2022;4(5):1464–82. doi:10.1039/D1NA00321F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kotsalas IP, Raptis C. Structural raman studies of GexS1−x chalcogenide glasses. J Optoelectron Adv Mater. 2001;3(3):675–84. [Google Scholar]

8. Gao Y, Jiang Y, Lu X, Yang Z. Structural engineering of glass for regulating chemical surroundings of dopants. J Mater Chem C. 2025;13(2):561–7. doi:10.1039/D4TC03864A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jackson K, Briley A, Grossman S, Porezag DV, Pederson MR. Raman-active modes of a–GeSe2 and a–GeS2: a first-principles study. Phys Rev B. 1999;60(22):R14985–9. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.60.R14985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Holomb R, Mitsa V, Akalin E, Akyuz S, Sichka M. Ab initio and Raman study of medium range ordering in GeSe2 glass. J Non Cryst Solids. 2013;373–374:51–6. doi:10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2013.04.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Popescu M, Sava F, Lőrinczi A. A new model for the structure of chalcogenide glasses: the closed cluster model. J Non Cryst Solids. 2009;355(37–42):1815–9. doi:10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2009.05.066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gholipour-Ranjbar H, Fang H, Guan J, Peters D, Seifert A, Jena P, et al. Designing new metal chalcogenide nanoclusters through atom-by-atom substitution. Small. 2021;17(27):2002927. doi:10.1002/smll.202002927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Galeener FL. Band limits and the vibrational spectra of tetrahedral glasses. Phys Rev B. 1979;19(8):4292–7. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.19.4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mitsa V, Feher A, Petretskyi S, Holomb R, Tkac V, Ihnatolia P, et al. Hysteresis of low-temperature thermal conductivity and Bos on peak in glassy (g) As2S3: nanocluster contribution. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2017;12:345. doi:10.1186/s11671-017-2125-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Jóvári P, Kaban I, Steiner J, Beuneu B, Schöps A, Webb MA. Local order in amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5 and GeSb2Te4. Phys Rev B. 2008;77(3):035202. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.77.035202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yildirim C, Micoulaut M, Boolchand P, Kantor I, Mathon O, Gaspard JP, et al. Universal amorphous-amorphous transition in GexSe100–x glasses under pressure. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27317. doi:10.1038/srep27317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mellor TM, Yurchenko SN, Jensen P. Artificial symmetries for calculating vibrational energies of linear molecules. Symmetry. 2021;13(4):548. doi:10.3390/sym13040548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Han X, Tao H, Gong L, Wang X, Zhao X, Yue Y. Origin of the frequency shift of Raman scattering in chalcogenide glasses. J Non Cryst Solids. 2014;391:117–9. doi:10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2014.03.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Dwivedi PK, Tripathi SK, Pradhan A, Kulkarni VN, Agarwal SC. Raman study of ion irradiated GeSe films. J Non Cryst Solids. 2000;266:924–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-3093(99)00867-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yuan B, Chen H, Sen S. Aging-induced structural evolution of a GeSe2 glass network: the role of homopolar bonds. J Phys Chem B. 2022;126(4):946–52. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c08836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chahal S, Prabhudessai AG, Shekhawat R, Vinoth S, Ramesh K. Structure–property relationships in critically connected (GeTe4)100–x(As2Se3)x glasses. Dalton Trans. 2022;51(32):12100–13. doi:10.1039/D2DT01969H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gonçalves C, Mereau R, Nazabal V, Boussard-Pledel C, Roiland C, Furet E, et al. Study of the Ge20Te80-xSex glassy structures by combining solid state NMR, vibrational spectroscopies and DFT modelling. J Solid State Chem. 2021;297:122062. doi:10.1016/j.jssc.2021.122062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bayko DP, Lucas P. Structural analysis and chemical stability of Ge and as telluride glasses by Raman spectroscopy. J Non Cryst Solids X. 2023;18:100186. doi:10.1016/j.nocx.2023.100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xu SW, Wang RP, Yang ZY, Wang L, Barry LD. Homopolar bonds in Se-rich Ge‒As‒Se chalcogenide glasses. Chin Phys B. 2016;25(5):057105. doi:10.1088/1674-1056/25/5/057105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Andrikopoulos KS, Yannopoulos SN, Kolobov AV, Fons P, Tominaga J. Raman scattering study of GeTe and Ge2Sb2Te5 phase-change materials. J Phys Chem Solids. 2007;68(5–6):1074–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2007.02.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Tverjanovich A, Khomenko M, Benmore CJ, Bokova M, Sokolov A, Fontanari D, et al. Bulk glassy GeTe2: a missing member of the tetrahedral GeX2 family and a precursor for the next generation of phase-change materials. Chem Mater. 2021;33:1031–45. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c04409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Stronski AV, Shportko KV, Kochubei HK, Popovych MV, Lotnyk AA. X-ray diffraction and Raman spectroscopy studies of Ga-Ge-Te alloys. Semicond Phys Quantum Electron Optoelectron. 2024;27(4):404–11. doi:10.15407/spqeo27.04.404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wirtz L, Lazzeri M, Mauri F, Rubio A. Raman spectra of BN nanotubes: Ab initio and bond-polarizability model calculations. Phys Rev B. 2005;71(24):241402. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.71.241402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Berger E, Komsa HP. Polarizability models for simulations of finite temperature Raman spectra from machine learning molecular dynamics. Phys Rev Materials. 2024;8(4):043802. doi:10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.8.043802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lazzeri M, Mauri F. First-principles calculation of vibrational Raman spectra in large systems: signature of small rings in crystalline SiO2. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90(3):036401. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.036401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools