Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Photothermal Methane-to-Ethanol Conversion over Cu Single-Atom–Cu9S5 Coupled Crystalline Carbon Nitride

1 Basic Education Department, Heze Vocational College, Heze, 274000, China

2 Department of Food Science and Chemical Engineering, Heze Vocational College, Heze, 274000, China

3 Research and Technology Service Center, Heze Vocational College, Heze, 274000, China

* Corresponding Author: Han Song. Email:

Chalcogenide Letters 2026, 23(1), 5 https://doi.org/10.32604/cl.2026.076594

Received 11 October 2025; Accepted 23 November 2025; Issue published 26 January 2026

Abstract

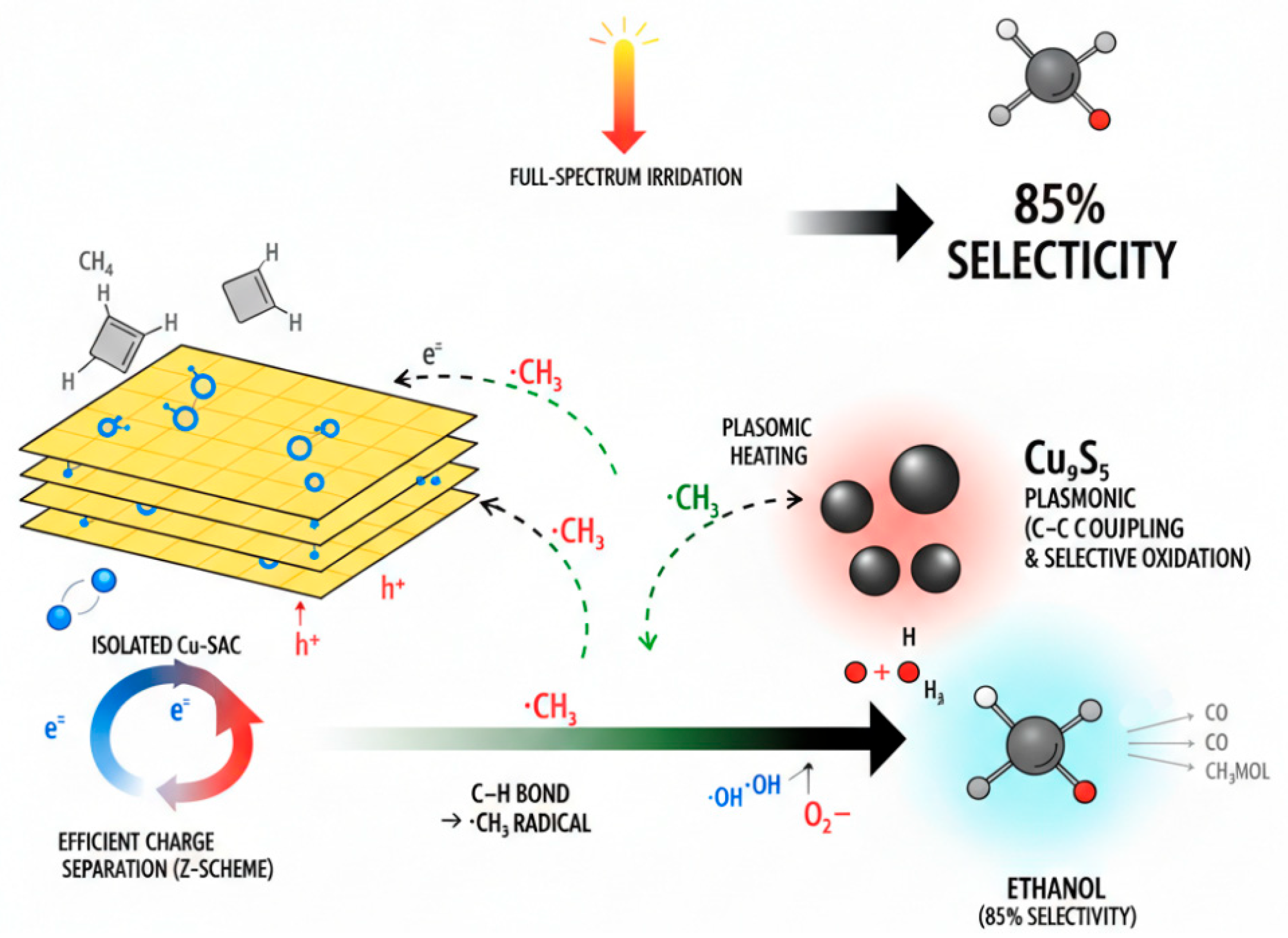

We report the rational design and synthesis of a novel trifunctional catalyst comprising atomically dispersed copper single-atom (Cu-SAC) sites and Cu9S5 nanoparticles co-loaded onto a highly crystalline carbon nitride (CCN) support for the photothermal conversion of methane to ethanol. The distinct active sites operate in synergy: the Cu-SAC sites, coordinated to the nitrogen-rich CCN framework, serve as highly efficient centers for the initial activation of methane’s C-H bond to form methyl radicals, while the plasmonic Cu9S5 nanoparticles act as dedicated sites for the subsequent C-C coupling and partial oxidation steps, driven by a combination of photochemical and photothermal effects. Under mild conditions (200°C, full-spectrum light), the optimized Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst achieves an exceptional ethanol production rate of 385 μmol g−1 h−1 with a selectivity of 85% at a methane conversion of 5.2%. Mechanistic studies reveal that a Z-scheme heterojunction between CCN and Cu9S5 facilitates efficient charge separation, while the spatial decoupling of C-H activation and C-C coupling functions is crucial for suppressing the formation of CO2. This work presents a powerful catalyst design strategy that integrates atomically precise active sites with plasmonic co-catalysts for tackling challenging chemical transformations.Keywords

The rising levels of methane in the atmosphere pose a critical environmental concern, as this greenhouse gas exhibits a global warming potential exceeding that of carbon dioxide by more than twenty-five times [1]. At the same time, methane constitutes the dominant fraction of natural gas and shale gas reserves, offering an immense yet largely untapped carbon resource. Conventional industrial routes for methane conversion, such as the two-step Fischer-Tropsch process, are predicated on the initial reforming of methane to syngas (CO + H2). This indirect pathway is notoriously energy-intensive, requiring harsh reaction conditions (temperatures > 700°C and high pressures) that lead to significant energy consumption, rapid catalyst deactivation through coking and sintering, and substantial capital investment [2]. As a result, converting methane through direct partial oxidation into oxygenated compounds has gained attention as a more attractive and cost-effective pathway. However, this direct route is kinetically hindered by the formidable dissociation energy of the C-H bond and thermodynamically plagued by the propensity for over-oxidation of the desired products to thermodynamically stable carbon dioxide.

To overcome these kinetic and thermodynamic barriers under milder conditions, photocatalysis has been explored as a promising green technology [3]. By utilizing photons as the primary energy input, photocatalysis can generate energetic charge carriers (electron-hole pairs) that effectively lower the activation energy. Although photocatalysis holds significant promise, traditional systems generally exhibit poor solar-to-chemical conversion efficiency. This drawback arises mainly from the swift recombination, coupled with the restricted utilization of sunlight, since wide-bandgap semiconductors typically absorb only within the ultraviolet region of the spectrum. Photothermal catalysis has recently emerged as a superior strategy that harnesses the full solar spectrum by synergistically combining photochemical and thermochemical pathways. In a photothermal system, absorbed photons not only generate charge carriers for photocatalytic reactions but also induce localized heating through non-radiative relaxation processes. This localized photothermal effect can significantly accelerate reaction kinetics, enhance product selectivity, and mitigate catalyst deactivation, offering a pathway to bridge the efficiency gap between laboratory-scale research and industrial application [4].

While significant progress has been made in the direct conversion of methane to C1 oxygenates like methanol and formaldehyde, the selective synthesis of C2+ products, particularly ethanol, remains a formidable challenge often described as a “holy grail” in C1 chemistry [5]. The formation of ethanol requires not only the efficient activation of the initial C-H bond but also precise control over the subsequent C-C coupling step, a process that is kinetically demanding and must compete with facile oxidation pathways. The fundamental difficulty lies in the fact that the active sites responsible for methane activation are often even more reactive toward the desired alcohol products, leading to an intractable trade-off between conversion and selectivity [6]. A successful catalyst must therefore possess distinct, spatially or electronically decoupled sites to manage these sequential reaction steps independently.

In this work, we propose and demonstrate a novel trifunctional catalyst architecture meticulously designed to address these challenges. The catalyst features atomically dispersed copper single-atom (Cu-SAC) sites and digenite (Cu9S5) nanoparticles co-loaded onto a highly crystalline carbon nitride (CCN) support. The rationale for this design is multifold. First, crystalline carbon nitride, synthesized via a molten salt method, provides a defect-minimized, ordered semiconductor framework with an extended π-conjugated system, which is superior to amorphous g-C3N4 for promoting efficient charge carrier transport and separation [7]. Second, single-atom catalysts (SACs) offer the ultimate in atomic efficiency and provide well-defined, uniform active sites that can mimic the precision of homogeneous catalysts. We hypothesize that Cu single atoms, stabilized by coordination with the nitrogen atoms of the CCN framework, will serve as ideal sites for the selective activation of methane’s C-H bond [8]. Third, Cu9S5, a p-type chalcogenide semiconductor with a narrow bandgap, acts as a potent photosensitizer, extending light absorption across the visible and near-infrared regions, and as a plasmonic nanostructure capable of generating significant localized heat—a critical component for the photothermal effect [9]. Furthermore, the mixed-valence Cu(I)/Cu(0) surface states inherent to copper sulfides are known to be highly effective for facilitating C-C coupling reactions [10].

We hypothesize that a powerful synergistic effect will arise from the functional and spatial separation of these distinct active sites. The Cu-SAC sites will selectively generate methyl radicals (·CH3) via C-H activation, which will then migrate to the photothermally-activated Cu9S5 nanoparticles for the subsequent C-C coupling and controlled oxidation to ethanol. This division of labor on a highly conductive CCN support is designed to suppress over-oxidation pathways and achieve unprecedented selectivity and efficiency for direct methane-to-ethanol conversion. This study details the synthesis, comprehensive characterization, and photothermal catalytic performance of this novel Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst, alongside relevant control samples, to elucidate the underlying structure-activity relationships and reaction mechanism.

Crystalline carbon nitride was synthesized using a molten salt-assisted thermal polymerization method adapted from previous reports [7]. Atomically dispersed copper was loaded onto the CCN support via a wet impregnation-annealing strategy [11]. A measured quantity of 1.0 g of the prepared CCN powder was introduced into 50 mL of anhydrous ethanol, after which the mixture was subjected to ultrasonic treatment for 30 min to obtain a well-dispersed and homogeneous suspension. An aqueous solution of CuCl2·2H2O (containing 10 mg of Cu, to achieve a theoretical loading of 1.0 wt%) was added dropwise to the CCN suspension under vigorous stirring. The mixture was stirred for 12 h to facilitate ion exchange and adsorption. The solvent was subsequently removed by rotary evaporation at 60°C. The obtained light-blue powder was dried and then subjected to a reductive annealing treatment.

The final dual-site catalyst was prepared by growing Cu9S5 nanoparticles onto the Cu-SAC/CCN support using a solvothermal method [12]. 100 mg of Cu-SAC/CCN was dispersed in 40 mL of ethylene glycol in a 100 mL beaker and sonicated for 1 h. Subsequently, 10.5 mg of CuCl2·2H2O (to achieve a final Cu9S5 loading of approximately 5 wt%) and 12.7 mg of L-cysteine (molar ratio of Cu:S ≈ 1.8:1) were added to the suspension. The mixture was transferred into an autoclave. This catalyst was denoted as Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN.

For comparative purposes, several control catalysts were synthesized. Cu9S5/CCN was prepared using the same solvothermal method described above, but using 100 mg of bare CCN as the support instead of Cu-SAC/CCN. Cu Nanoparticles on CCN (Cu-NP/CCN) were prepared by a similar impregnation method as Cu-SAC/CCN, but with a higher theoretical Cu loading of 5 wt% and a milder annealing temperature of 350°C under an Ar atmosphere to promote the formation of nanoparticles rather than single atoms.

The photothermal conversion of methane was carried out in a continuous-flow fixed-bed reactor system. 50 mg of the catalyst powder was packed into the center of a quartz tube reactor. The reactor was placed inside a programmable horizontal tube furnace for temperature control. A 300 W Xe lamp (Newport, full spectrum) served as the light source, positioned to illuminate the catalyst bed through a quartz window. The light intensity at the catalyst surface was measured to be 150 mW cm−2. For a typical reaction, the catalyst was first pre-treated in Ar at 200°C for 1 h. The reaction was then initiated by introducing a gas mixture of CH4 (20 mL/min), O2 (2 mL/min), and water vapor. Water vapor was introduced by bubbling an Ar stream (5 mL/min) through a DI water saturator maintained at 50°C.

The successful synthesis of the dual-site Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst and its corresponding control materials was confirmed through a suite of comprehensive characterization techniques, which elucidated their crystal structure, morphology, chemical states, and optical properties. Fig. 1 presents a schematic representation of the synthesis route. The approach begins with the preparation of a carbon nitride support possessing high crystallinity, after which Cu single atoms are anchored onto the framework, followed by the successive formation of Cu9S5 nanoparticles.

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of the synthesis procedure for the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst.

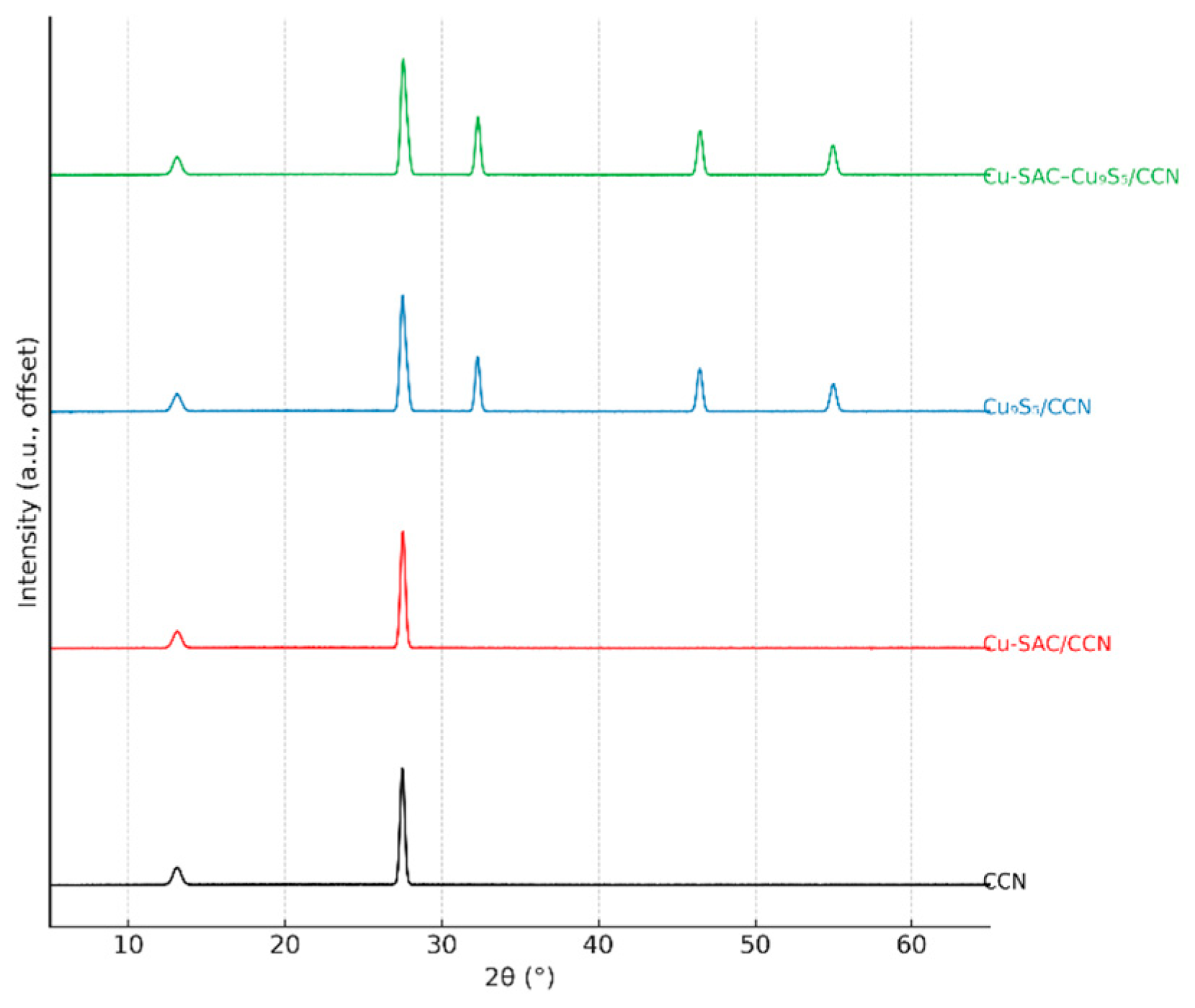

The crystalline characteristics of the synthesized catalysts were examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD), as presented in Fig. 2. For the pristine CCN support, two well-defined diffraction peaks can be observed. The weaker reflection at 2θ = 13.1° is attributed to the (100) plane, which corresponds to the in-plane packing arrangement of the tri-s-triazine units. In contrast, the intense and sharp peak located at 2θ = 27.5° is assigned to the (002) plane, indicative of the typical interlayer stacking structure associated with graphitic layers [13]. The high intensity and narrow full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the (002) peak confirm the high degree of crystallinity achieved through the molten salt synthesis method, in stark contrast to the typically broad peak observed for amorphous g-C3N4 prepared by direct melamine pyrolysis [7]. For the Cu-SAC/CCN sample, the XRD pattern is nearly identical to that of bare CCN, with no detectable peaks corresponding to copper or copper oxide phases. This absence of diffraction signals for Cu species provides initial, albeit indirect, evidence for the atomic dispersion of copper on the support [14]. Upon loading Cu9S5, both the Cu9S5/CCN and Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN samples display additional diffraction peaks at 2θ = 27.8°, 32.3°, 46.5°, and 55.0°. These peaks can be indexed to the (104), (107), (110), and (119) crystal planes of the rhombohedral phase of digenite (Cu9S5, JCPDS No. 47-1748), confirming the successful formation of the copper sulfide component [12].

Figure 2: XRD patterns of CCN, Cu-SAC/CCN, Cu9S5/CCN, and Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN.

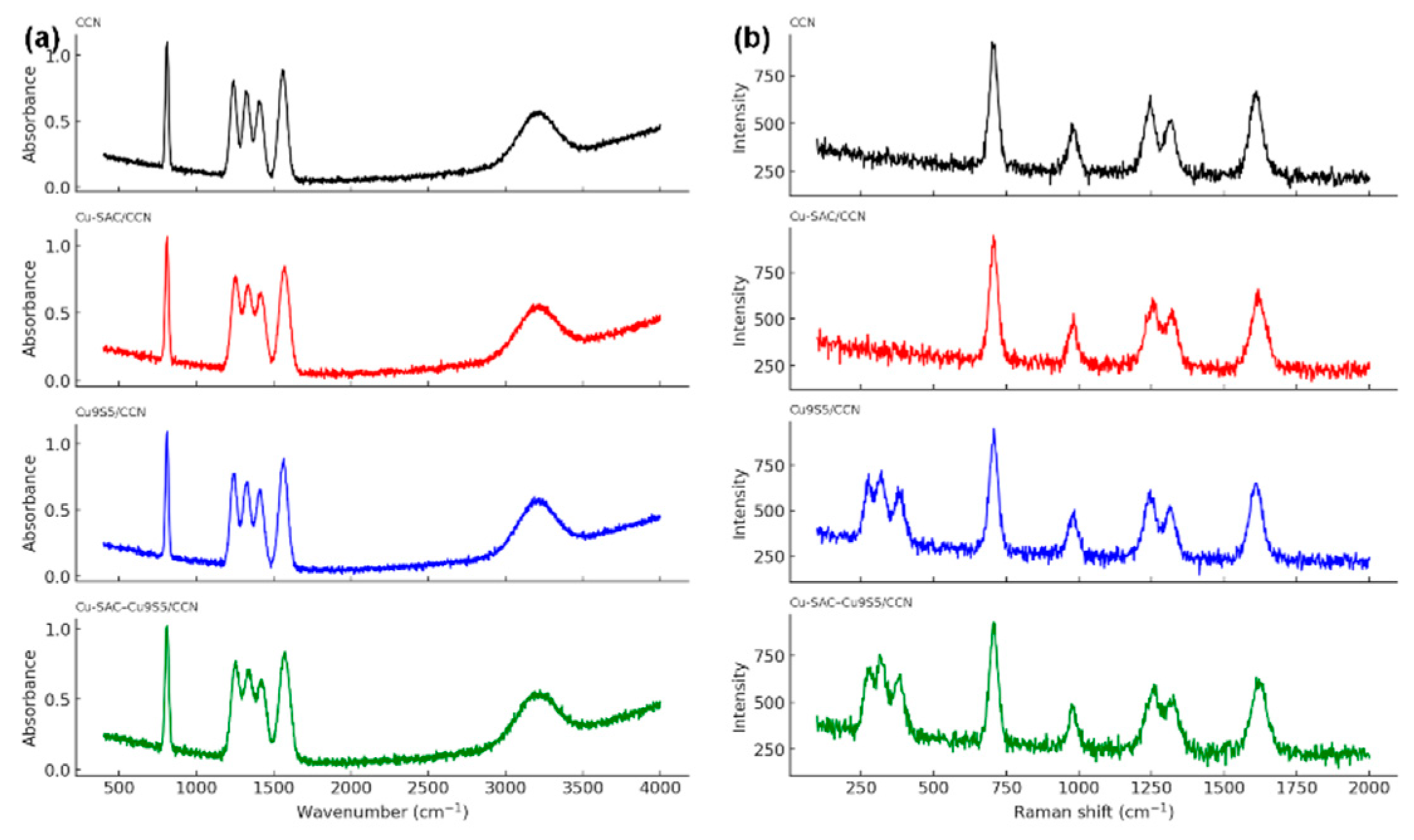

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy were employed to probe the chemical bonding and vibrational structures of the materials. The FTIR spectra of all synthesized samples (Fig. 3a) display the characteristic absorption bands of the carbon nitride framework. The broad absorption feature observed within the 3000–3400 cm−1 range is associated with the stretching vibrations of residual N–H functionalities as well as adsorbed water molecules. In addition, a set of intense bands appearing between 1200 and 1650 cm−1 can be ascribed to the characteristic stretching vibrations of aromatic C–N heterocycles. A distinct and sharp signal near 810 cm−1 is further identified, corresponding to the breathing vibration of the tri-s-triazine structural units [15]. Notably, in the Cu-SAC/CCN and Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN samples, a slight blueshift and broadening of the C-N stretching bands are observed, suggesting a perturbation of the electronic environment of the C-N heterocycles due to the coordination of Cu single atoms with the nitrogen atoms in the framework.34 The Raman spectra (Fig. 3b) further corroborate the successful synthesis, showing characteristic vibrational modes for the g-C3N4 structure and additional low-frequency modes below 500 cm−1 in the Cu9S5-containing samples, which are attributable to Cu-S lattice vibrations.

Figure 3: (a) FTIR spectra and (b) Raman spectra of the synthesized catalysts.

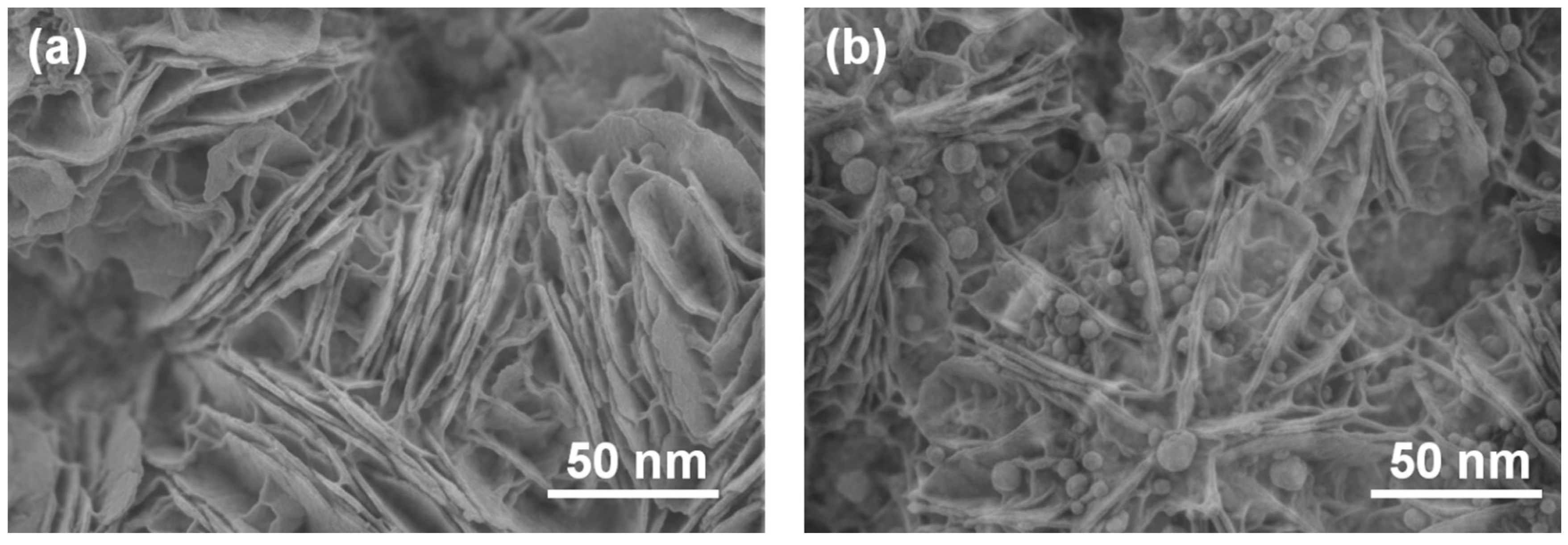

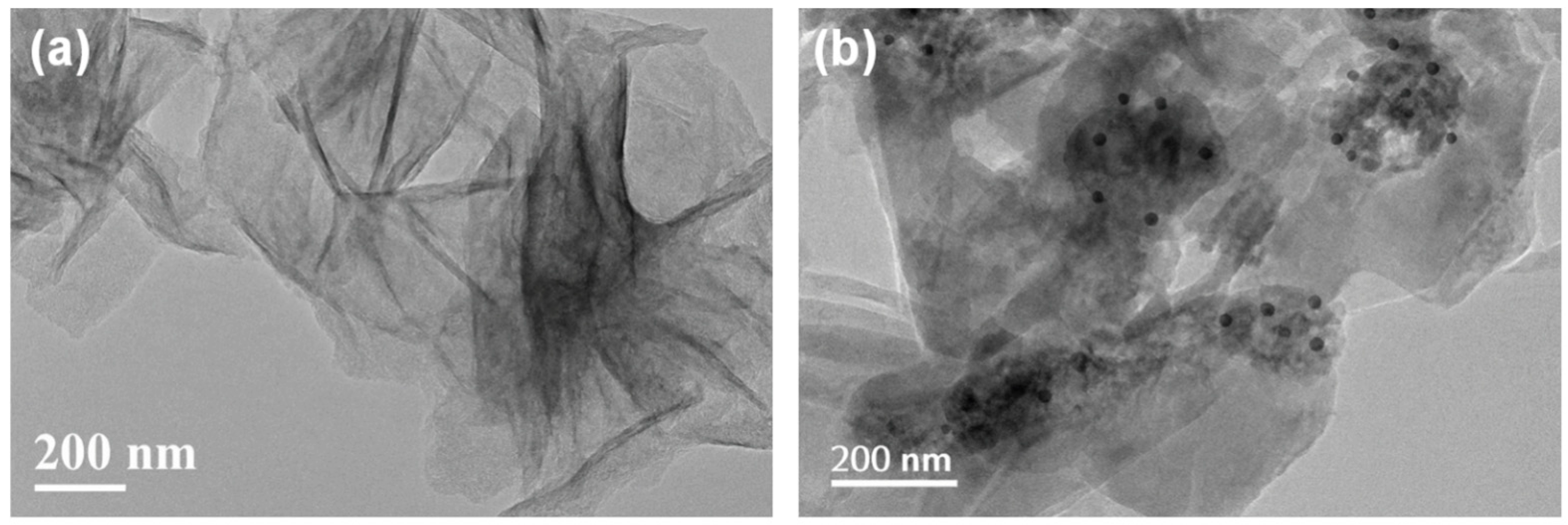

FESEM images (Fig. 4) reveal that the CCN support possesses a stacked, lamellar structure composed of thin nanosheets, a typical morphology for graphitic carbon nitride. Low-magnification TEM images (Fig. 5) of the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN composite show that dark nanoparticles are uniformly dispersed on the surface of the translucent CCN nanosheets. These nanoparticles, identified as Cu9S5, have a quasi-spherical shape with an average diameter of 18 ± 2 nm.

Figure 4: FESEM images of (a) CCN and (b) Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN.

Figure 5: Low-magnification TEM images of (a) Cu-SAC/CCN and (b) Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN.

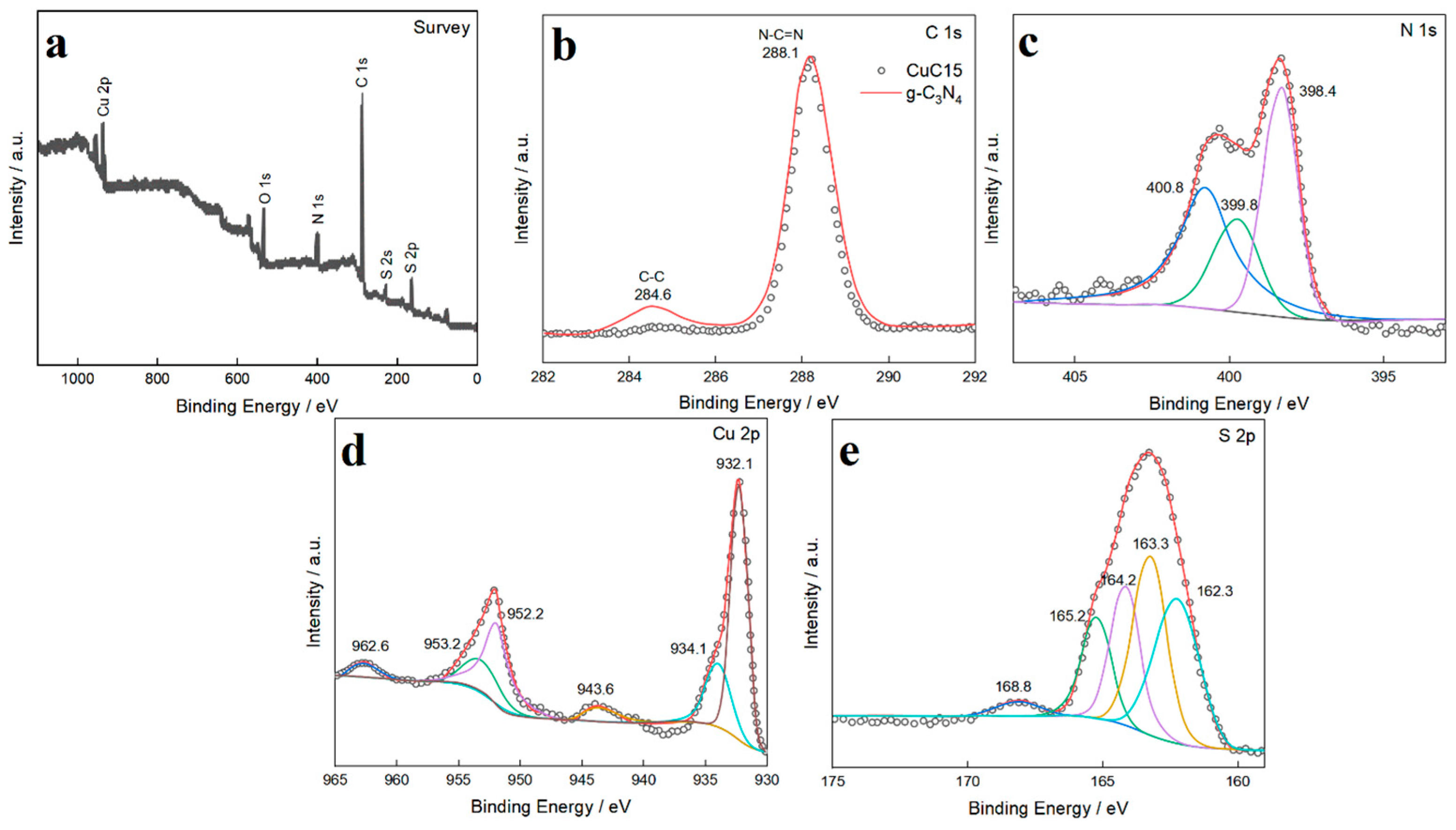

XPS analysis was conducted to investigate the surface elemental composition and chemical valence states of the catalysts. The survey spectra (Fig. 6a) confirm the presence of C, N, Cu, and S in the final composite. The high-resolution C 1s spectrum (Fig. 6b) can be deconvoluted into two main peaks at 284.8 eV (adventitious carbon, C-C) and 288.2 eV, the latter being characteristic of the sp2-hybridized carbon in the N-C=N coordination of the triazine rings [16]. The N 1s spectrum (Fig. 6c) is fitted with three peaks at 398.7 eV, 400.0 eV, and 401.1 eV, corresponding to pyridinic N (C-N=C), pyrrolic N (N-(C)3), and graphitic N, respectively. The high-resolution Cu 2p spectrum provides critical insight into the distinct copper species (Fig. 6d). For Cu-SAC/CCN, the Cu 2p3/2 peak is located at 932.7 eV, with weak satellite peaks, indicating a valence state between Cu+ and Cu2+, which is characteristic of Cu single atoms coordinated with nitrogen atoms (Cu-Nx) [17]. For the dual-site Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst, the Cu 2p3/2 peak is broader and can be deconvoluted into two components. The peak at 932.7 eV corresponds to the Cu-Nx single-atom sites, while a new, more intense peak emerges at a lower binding energy of 932.2 eV, which is attributed to Cu(I) species in the Cu-S bonding environment of Cu9S5 [9]. This deconvolution provides compelling evidence for the coexistence of two distinct copper chemical environments on the catalyst surface. The S 2p spectrum for Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN (Fig. 6e) shows a doublet with peaks at 161.9 eV (S 2p3/2) and 163.1 eV (S 2p1/2), confirming the presence of S2− in a metal sulfide lattice.

Figure 6: High-resolution XPS spectra of the catalysts: (a) Survey, (b) C 1s, (c) N 1s, (d) Cu 2p, and (e) S 2p.

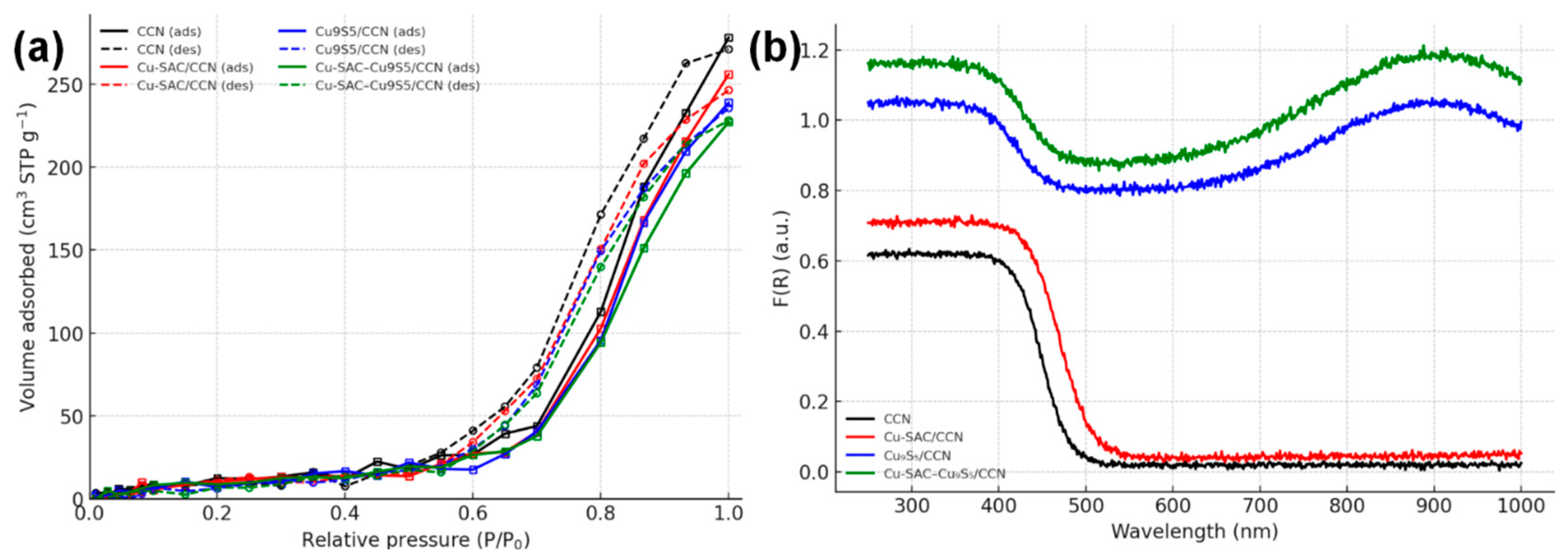

The textural properties of the catalysts were evaluated by N2 adsorption-desorption measurements (Fig. 7a). All samples exhibit Type IV isotherms with distinct H3 hysteresis loops [18]. The physicochemical properties are summarized in Table 1. The pristine CCN support possesses a high BET specific surface area of 152.4 m2 g−1. After loading the co-catalysts, the surface area slightly decreases to 141.8 m2 g−1 for Cu-SAC/CCN and 126.5 m2 g−1 for Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN, likely due to partial pore blockage. Nevertheless, the high surface area is maintained, which is beneficial for exposing a large number of active sites and facilitating reactant adsorption [19]. The optical properties were investigated by UV-vis DRS (Fig. 7b). Bare CCN shows a characteristic semiconductor absorption edge at approximately 450 nm, corresponding to a bandgap of 2.75 eV, calculated from the Tauc plot. The introduction of Cu single atoms in Cu-SAC/CCN results in a slight redshift of the absorption edge. Strikingly, the Cu9S5-containing samples (Cu9S5/CCN and Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN) exhibit strong and broad absorption across the entire visible and near-infrared (NIR) regions. This significantly enhanced light-harvesting capability is attributed to the narrow bandgap of Cu9S5 (~1.55 eV) [20].

Figure 7: (a) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms. (b) UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra.

Table 1: Physicochemical Properties of Synthesized Catalysts.

| Catalyst | BET Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Cu Loading (wt%) | S Loading (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCN | 152.4 | 0.45 | - | - |

| Cu-SAC/CCN | 141.8 | 0.41 | 0.95 | - |

| Cu9S5/CCN | 128.9 | 0.38 | 4.12 | 1.15 |

| Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN | 126.5 | 0.37 | 5.03 | 1.13 |

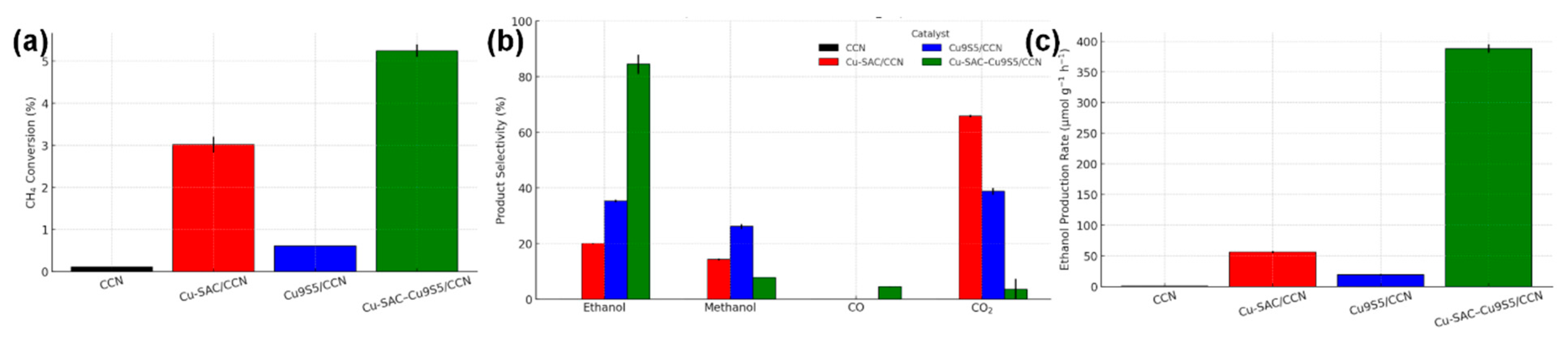

The photothermal catalytic activity of the prepared materials toward the direct transformation of methane into ethanol was assessed using a continuous-flow fixed-bed reactor system. The results, summarized in Fig. 8 and Table 2, unequivocally demonstrate the superior activity and selectivity of the dual-site Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst and highlight the profound synergistic effect between its components. Under optimized conditions (200°C, 150 mW cm−2 full-spectrum light), the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst achieved a remarkable ethanol production rate of 385.1 μmol g−1 h−1, coupled with a high ethanol selectivity of 85.3% and a methane conversion of 5.2%. The main byproducts were methanol (8.1%), CO (4.5%), and CO2 (2.1%).

Figure 8: (a) Methane conversion and (b) product selectivity over different catalysts under optimized photothermal conditions (200°C, light). (c) Ethanol production rates.

The performance of the control catalysts starkly underscores the necessity of the dual-site architecture. The bare CCN support showed negligible activity, confirming it is not catalytically active on its own. The Cu-SAC/CCN catalyst exhibited a moderate methane conversion of 3.1% but suffered from poor selectivity; the primary product was CO2 (65.4%), with only minor amounts of methanol (14.5%) and ethanol (20.1%). This suggests that while Cu single atoms are effective for C-H bond activation, they are not selective for C-C coupling and tend to promote deep oxidation. Conversely, the Cu9S5/CCN catalyst showed very low methane conversion (0.6%), indicating its inefficiency in activating the C-H bond, although the selectivity towards ethanol among the products was slightly better than for Cu-SAC/CCN. The Cu-NP/CCN catalyst also showed inferior performance compared to the dual-site catalyst, with lower conversion (2.5%) and ethanol selectivity (45.2%), highlighting the unique role of the atomically dispersed sites. The combination of Cu single atoms and Cu9S5 nanoparticles in the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst leads to a performance that far exceeds the sum of its individual components, providing clear evidence of a powerful synergistic effect [21].

Table 2: Catalytic performance of various catalysts for methane-to-ethanol conversion.

| Catalyst | Temp (°C) | Light | CH4 Conv. (%) | Selectivity (%) C2H5OH/CH3OH/CO/CO2 | Ethanol Rate (μmol g−1 h−1) | AQE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN | 200 | Yes | 5.2 | 85.3/8.1/4.5/2.1 | 385.1 | 9.8 |

| Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN | 200 | No | 0.4 | 60.1/15.2/10.5/14.2 | 20.9 | - |

| Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN | 120 | Yes | 2.1 | 80.5/10.3/5.2/4.0 | 147.3 | - |

| Cu-SAC/CCN | 200 | Yes | 3.1 | 20.1/14.5/-/65.4 | 54.3 | - |

| Cu9S5/CCN | 200 | Yes | 0.6 | 35.2/25.8/-/39.0 | 18.4 | - |

| Cu-NP/CCN | 200 | Yes | 2.5 | 45.2/20.1/-/34.7 | 98.6 | - |

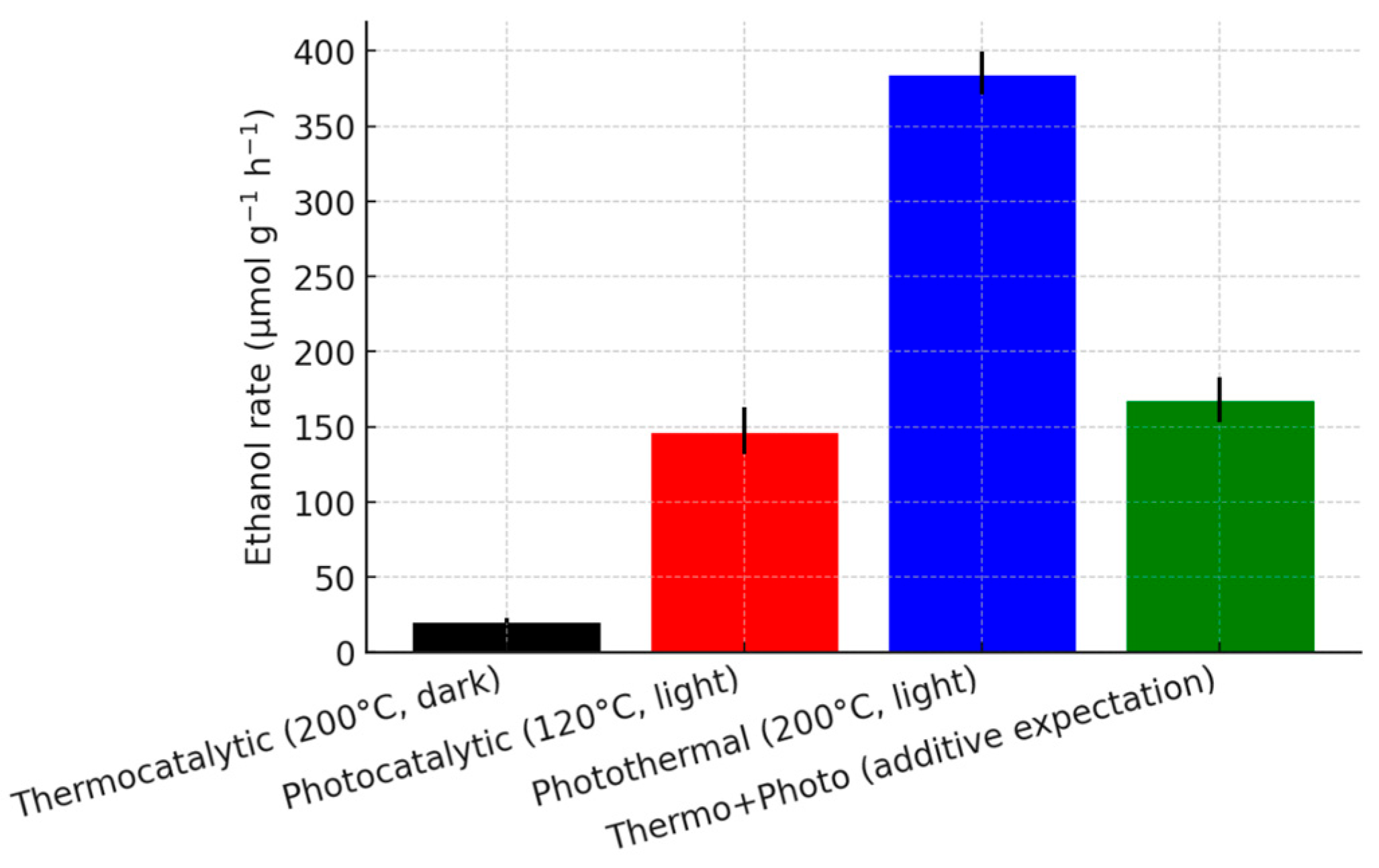

To further dissect the interplay between light and heat, the reaction was performed under different conditions (Fig. 9). In the dark at 200°C (purely thermocatalytic), the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst yielded a very low ethanol rate of 20.9 μmol g−1 h−1. Under illumination at a lower temperature of 120°C (predominantly photocatalytic), the rate was 147.3 μmol g−1 h−1. The rate achieved under photothermal conditions (385.1 μmol g−1 h−1) is significantly greater than the simple sum of the thermocatalytic and photocatalytic rates (20.9 + 147.3 = 168.2 μmol g−1 h−1). This non-additive behavior confirms a strong photothermal synergy, where light and heat work in concert to enhance the catalytic process beyond their individual contributions. The localized heating generated by the plasmonic Cu9S5 nanoparticles likely provides the necessary thermal energy to overcome the activation barrier for the kinetically challenging C-C coupling step, a process that is inefficient under purely photocatalytic or thermocatalytic conditions.

Figure 9: Comparison of ethanol production rates over Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN under thermocatalytic, photocatalytic, and photothermal conditions, demonstrating the synergistic effect.

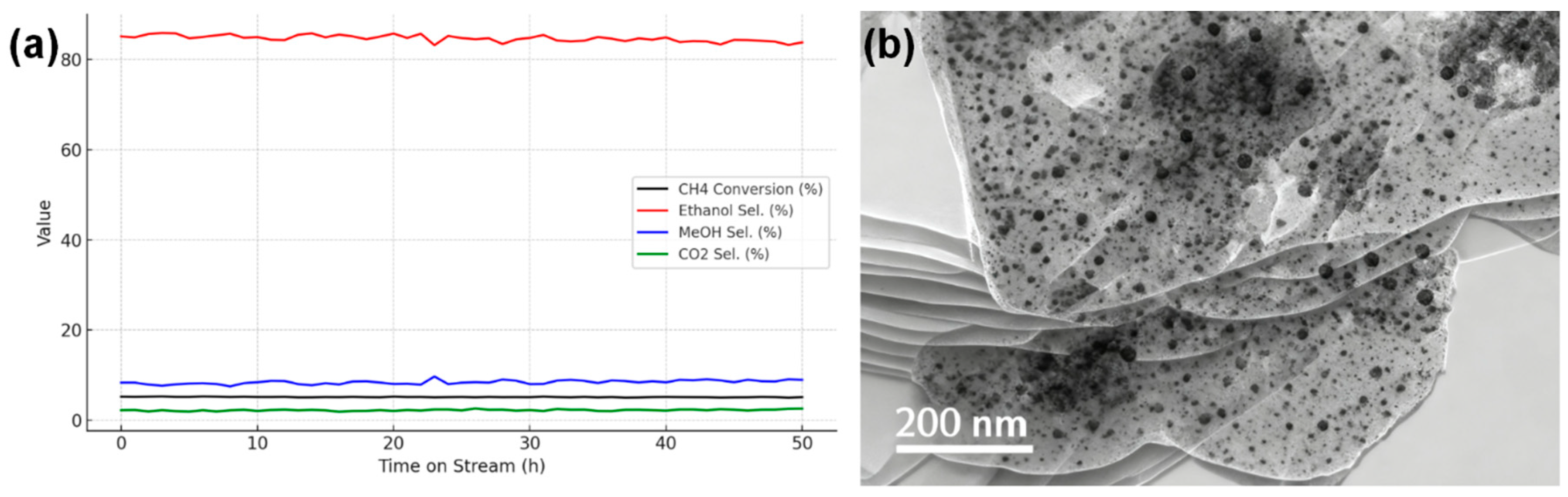

The stability of the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst, a critical parameter for practical applications, was evaluated in a 50-h continuous test under optimized photothermal conditions. As shown in Fig. 10a, the catalyst exhibited excellent durability, maintaining over 95% of its initial methane conversion and ethanol selectivity throughout the entire run. This indicates high resistance to deactivation processes such as coking or active site sintering [22]. To verify the structural integrity, the spent catalyst was characterized by TEM. The post-reaction TEM images (Fig. 10b) show that the Cu9S5 nanoparticles retain their morphology and dispersion. The exceptional stability can be ascribed to the pronounced interaction between the Cu species and the highly ordered, crystalline CCN framework, which provides a durable metal–support interface.

Figure 10: (a) Long-term stability test of the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst over 50 h of continuous operation. (b) TEM image of post-reaction characterization of the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst.

To unravel the origin of the superior performance of the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst, a series of spectroscopic and electrochemical experiments were conducted to probe the charge carrier dynamics and identify key reactive intermediates. The results support a synergistic mechanism involving a Z-scheme heterojunction and functionally decoupled active sites.

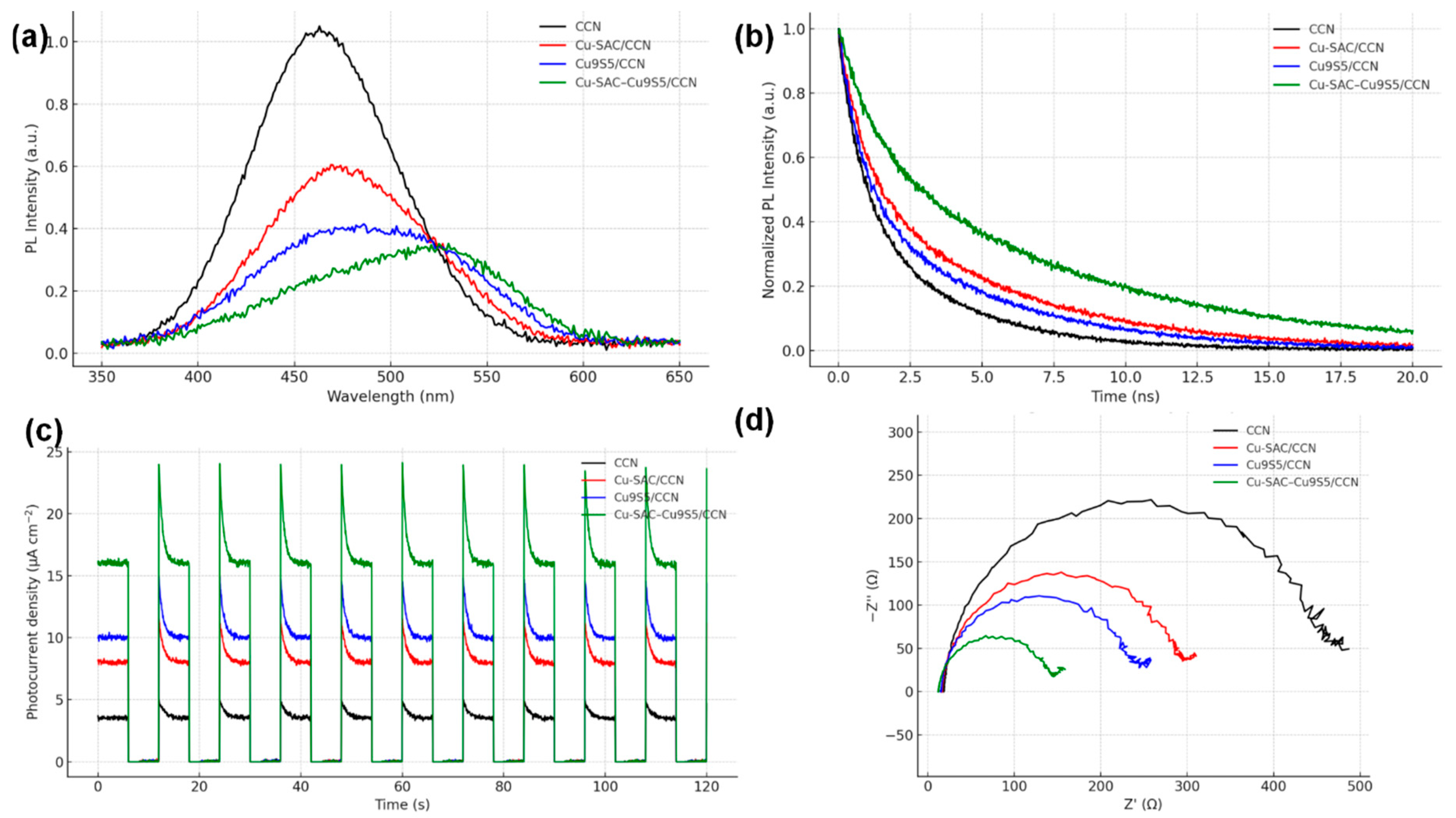

The efficiency of charge separation and transfer is a key determinant of photocatalytic activity. Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy (Fig. 11a) reveals that pristine CCN exhibits a strong emission peak, indicative of a high rate of electron-hole recombination. The PL intensity is significantly quenched in all modified samples, with Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN showing the most pronounced quenching effect, signifying the most efficient suppression of charge carrier recombination [16]. This is further supported by time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) decay spectra (Fig. 11b), where the average carrier lifetime for Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN (τ = 5.8 ns) is substantially longer than that of CCN (τ = 2.1 ns). Electrochemical measurements provide further evidence. The transient photocurrent response (Fig. 11c) of Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN is the highest among all samples, indicating the most efficient generation and separation of photo-induced charges. Furthermore, the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Nyquist plot (Fig. 11d) shows that Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN possesses the smallest arc radius, which corresponds to the lowest charge transfer resistance at the catalyst-electrolyte interface [19]. These results collectively demonstrate that the construction of the heterojunction between CCN, Cu-SAC, and Cu9S5 dramatically improves the separation and transport of charge carriers.

Figure 11: (a) PL spectra, (b) TRPL decay curves, (c) transient photocurrent responses, and (d) EIS Nyquist plots of the synthesized catalysts.

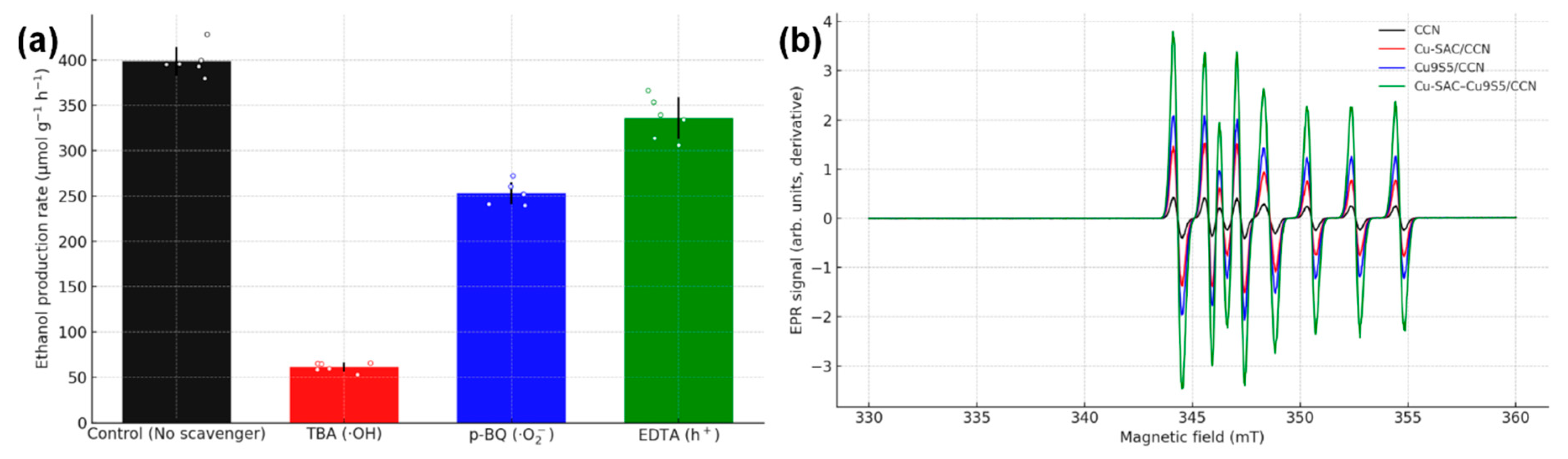

Radical scavenging experiments were conducted to determine the dominant reactive species involved in the activation of methane. As shown in Fig. 12a, the addition of TBA, a scavenger led to a dramatic decrease in the ethanol production rate by over 80%, indicating that ·OH radicals are the main species responsible for the initial C-H bond cleavage [2]. In-situ EPR spectroscopy with DMPO as a spin-trapping agent was used to directly detect the radical intermediates. Under reaction conditions (Fig. 12b), characteristic quartet signals for both DMPO-OH and sextet signals for DMPO-·CH3 adducts were clearly observed, providing direct evidence for the generation of hydroxyl and methyl radicals during the photothermal reaction [23].

Figure 12: (a) Effect of different radical scavengers on the ethanol production rate. (b) In-situ EPR spectra showing signals of DMPO-OH and DMPO-CH3 adducts.

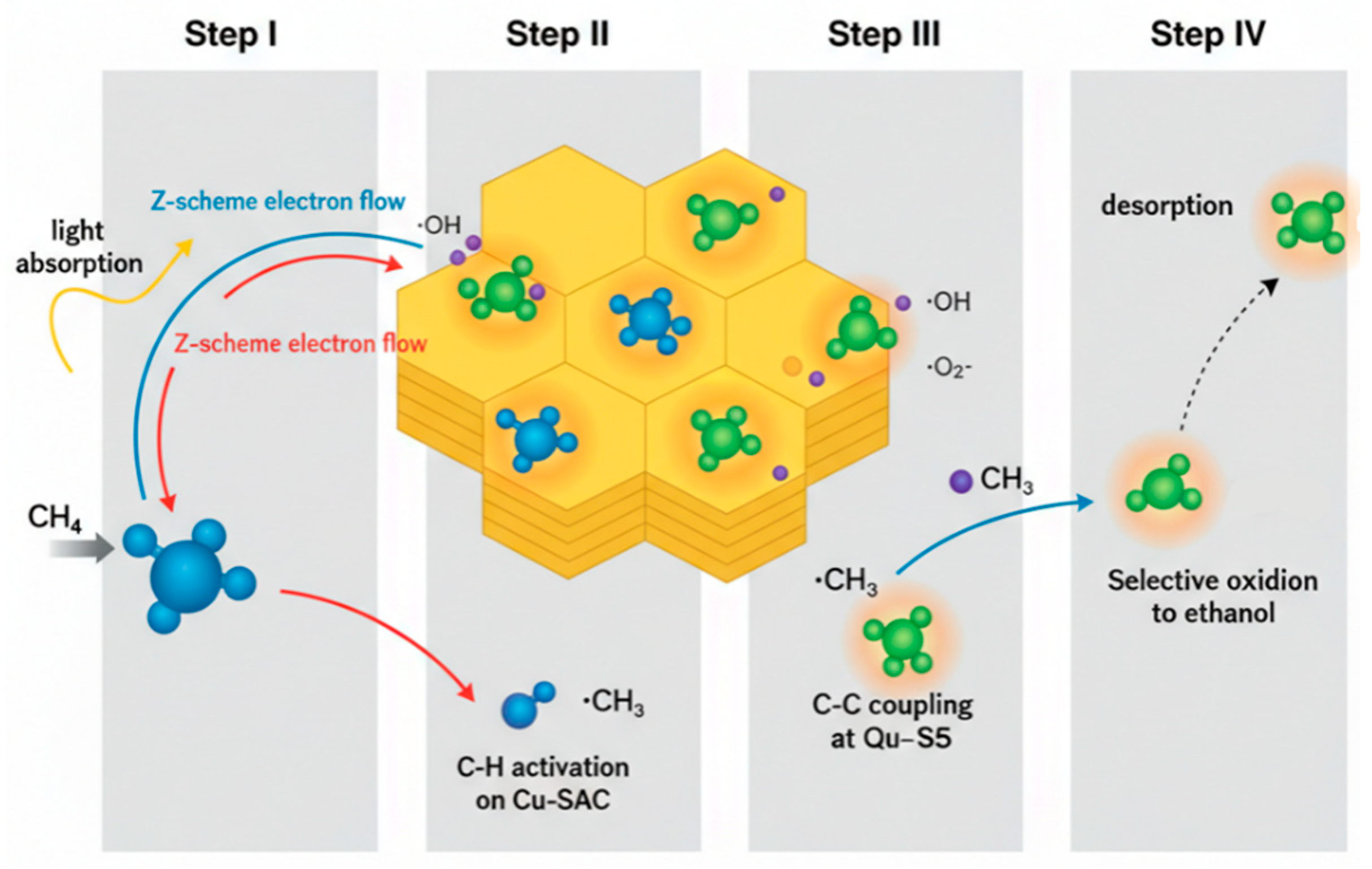

Based on the collective experimental and characterization results, a plausible photothermal reaction mechanism over the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst is proposed and illustrated in Fig. 13. The mechanism relies on a Z-scheme charge transfer pathway and the synergistic interplay of the distinct active sites.

- Step I: Light Harvesting and Charge Separation. Upon full-spectrum light irradiation, both the CCN support (Eg ≈ 2.75 eV) and the Cu9S5 nanoparticles (Eg ≈ 1.55 eV) are excited, generating electron-hole pairs. Due to the well-matched band alignment, a Z-scheme charge transfer pathway is established. The photogenerated electrons in the conduction band (CB) of CCN migrate to combine with the holes in the valence band (VB) of Cu9S5. This process effectively separates the charge carriers, leaving highly oxidative holes in the VB of CCN and highly reductive electrons in the CB of Cu9S5. This Z-scheme mechanism preserves the charge carriers with the strongest redox potentials, which is essential for driving the challenging oxidation and reduction reactions. Simultaneously, the LSPR effect of the plasmonic Cu9S5 nanoparticles generates high-energy “hot” electrons and significant localized heat, contributing to the photothermal effect.

- Step II: C-H Bond Activation at Cu-SAC Sites. The highly oxidative holes accumulated in the VB of CCN (+1.55 V vs. NHE) are powerful enough to oxidize adsorbed water molecules, generating highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH) (E0(OH/H2O) = 2.38 V vs. NHE). Methane molecules preferentially adsorb near the atomically dispersed Cu-Nx sites, which act as Lewis acid centers, polarizing and weakening the C-H bonds [24]. The proximate ·OH radicals then attack the adsorbed methane, leading to homolytic cleavage of a C-H bond to form a methyl radical (CH3) and a water molecule. The spatial confinement of this step to the Cu-SAC sites ensures high efficiency for the initial activation.

- Step III: C-C Coupling at Cu9S5 Sites. The newly formed, mobile ·CH3 radicals migrate across the catalyst surface to the adjacent Cu9S5 nanoparticles. These nanoparticles serve as dedicated C-C coupling centers. The localized heat generated from the photothermal effect provides the necessary activation energy for the kinetically challenging dimerization of two ·CH3 radicals to form ethane (C2H6), or for the coupling of a ·CH3 radical with a ·CH2OH intermediate (formed from partial oxidation of another methyl radical). The unique electronic structure of the mixed-valence Cu(I)/Cu(0) sites on the Cu9S5 surface is believed to be critical in stabilizing the transition state for C-C bond formation [10].

- Step IV: Selective Oxidation to Ethanol. The C2H6 intermediate is then selectively oxidized to ethanol by ·OH radicals or other reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide radicals (·O2−) generated from the reduction of O2 by the electrons in the CB of Cu9S5. The final ethanol product has a relatively weak adsorption energy on the surface and readily desorbs, preventing further oxidation to CO or CO2. This functional and spatial decoupling of C-H activation (at Cu-SACs) from C-C coupling and product formation (at Cu9S5) is the key to overcoming the selectivity-conversion trade-off that plagues conventional catalysts.

Figure 13: Proposed Z-scheme photothermal reaction mechanism for methane-to-ethanol conversion over the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst.

The performance of the Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst represents a significant advancement in the direct conversion of methane to C2+ oxygenates. As shown in Table 3, its ethanol production rate and selectivity under mild photothermal conditions are highly competitive with, and in many cases superior to, other state-of-the-art systems reported in the literature, which often require UV light, precious metal co-catalysts, or more complex reactor setups. The success of this work underscores the power of designing catalysts with multifunctional, spatially segregated active sites to control complex reaction networks.

Table 3: Comparison with state-of-the-art catalysts for direct methane to C2+ oxygenates.

| Catalyst System | Reaction | Conditions (T, Oxidant, Light) | Ethanol/C2+ Oxy. Rate (μmol g−1 h−1) | Selectivity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN | Methane to Ethanol | 200°C, O2/H2O, Full Spectrum | 385.1 | 85.3 (Ethanol) | This Work |

| CTF-1-Pt | Methane to Ethanol | RT, O2/H2O, 365 nm LED | ~300 (estimated) | ~80 (Ethanol) | [25] |

| Zn-O-Fe(MS) | Methane to Ethanol | RT, H2O, 300 W Xe | 372 | ~75 (Ethanol) | [23] |

| q-BiVO4 | Methane to Methanol | RT, O2, 300 W Xe | 1100 (Methanol) | 96.1 (Methanol) | [3] |

| NiO/CZ | Methane to Alcohols | 450°C, O2/H2O, Dark | 150 (Methanol + Ethanol) | N/A | [26] |

| Au-Pd/TiO2 | Methane to Methanol | 50°C, O2, Dark | 51.1 (Methanol) | 33.6 (Methanol) | [27] |

This study successfully demonstrates the design and synthesis of a novel, highly efficient trifunctional photothermal catalyst, Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN. The catalyst architecture, featuring atomically dispersed copper sites and Cu9S5 nanoparticles synergistically coupled with a crystalline carbon nitride support, was rigorously confirmed through extensive material characterization. Techniques such as HAADF-STEM and XPS provided direct evidence for the coexistence of distinct Cu-Nx single-atom sites and phase-pure Cu9S5 nanoparticles, validating the intended dual-site structure. The rationally designed Cu-SAC–Cu9S5/CCN catalyst exhibited outstanding performance under mild photothermal conditions (200°C, full-spectrum irradiation). It achieved a high ethanol production rate of 385.1 μmol g−1 h−1, an exceptional selectivity of 85.3%, and a notable apparent quantum efficiency of 9.8% at 420 nm. Mechanistic investigations revealed that the catalyst’s superior performance stems from a profound synergistic effect governed by a Z-scheme charge transfer mechanism and the functional decoupling of active sites. The highly crystalline CCN support facilitates efficient charge separation, generating potent oxidative holes that produce ·OH radicals. These radicals, in concert with the Cu-SAC sites, trigger the initial C-H bond activation of methane to form methyl radicals. Subsequently, the photothermally activated Cu9S5 nanoparticles, benefiting from enhanced light absorption and localized heating, serve as dedicated centers for the kinetically demanding C-C coupling step. This spatial separation of reaction steps is crucial for steering the reaction pathway towards ethanol while effectively suppressing the over-oxidation to CO2. This work not only provides a highly effective catalyst for the challenging valorization of methane but also presents a powerful and generalizable design strategy for creating advanced catalytic materials. By integrating atomically precise sites for bond activation with plasmonic, multifunctional co-catalysts for subsequent bond formation, this approach opens new avenues for tackling other complex chemical transformations. The fundamental insights gained into the synergistic interplay of photochemistry, thermochemistry, and spatially segregated active sites offer a clear roadmap for the future development of next-generation catalysts for a sustainable energy and chemical industry.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiaohan Zhang, Han Song; data collection: Xiaohan Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Xiaohan Zhang, Han Song, Maoyuan Yin; draft manuscript preparation: Han Song and Xiaoli Rong. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Han Song, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Lei Y, Sala X, García-Antón J, Muñoz J. A review on photocatalytic methane conversion systems: from fundamental mechanisms to the emerging role of ferroelectric materials. J Mater Chem A. 2025;13(18):12712–45. doi:10.1039/D4TA08554J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jiang Y, Fan Y, Li S, Tang Z. Photocatalytic methane conversion: insight into the mechanism of C(sp3)–H bond activation. CCS Chem. 2022;5(1):30–54. doi:10.31635/ccschem.022.202201991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xiong Y, Liu J, Wang Y. Insight on reaction pathways of photocatalytic methane conversion. Chem Synth. 2025;5(3):50. doi:10.20517/cs.2024.118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Varotto A, Pasqual Laverdura U, Feroci M, Grilli ML. Photo-thermal dry reforming of methane with PGM-free and PGM-based catalysts: a review. Materials. 2024;17(15):3809. doi:10.3390/ma17153809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Park MB, Park ED, Ahn WS. Recent progress in direct conversion of methane to methanol over copper-exchanged zeolites. Front Chem. 2019;7:514. doi:10.3389/fchem.2019.00514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Latimer AA, Kakekhani A, Kulkarni AR, Nørskov JK. Direct methane to methanol: the selectivity–conversion limit and design strategies. ACS Catal. 2018;8(8):6894–907. doi:10.1021/acscatal.8b00220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li H, Cheng B, Xu J, Yu J, Cao S. Crystalline carbon nitrides for photocatalysis. EES Catal. 2024;2(2):411–47. doi:10.1039/D3EY00302G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Solomon EI, Heppner DE, Johnston EM, Ginsbach JW, Cirera J, Qayyum M, et al. Copper active sites in biology. Chem Rev. 2014;114(7):3659–853. doi:10.1021/cr400327t. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Olatunde OC, Onwudiwe DC. Temperature controlled evolution of pure phase Cu9S5 nanoparticles by solvothermal process. Front Mater. 2021;8:687562. doi:10.3389/fmats.2021.687562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sun L, Han J, Ge Q, Zhu X, Wang H. Understanding the role of Cu+/CuO sites at Cu2O based catalysts in ethanol production from CO2 electroreduction—a DFT study. RSC Adv. 2022;12(30):19394–401. doi:10.1039/D2RA02753D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Suja P, Rahul P, Bhasin V, Bhattacharya D, Seo JW, Pulinthanathu Sree S, et al. Atomically Dispersed Cu on Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheets as Catalysts for the Synthesis of Disubstituted Triazoles. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2025;8(2):1214–24. doi:10.1021/acsanm.4c06206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Senthilkumar M, Babu SM. Crystal structure controlled synthesis and characterization of copper sulfide nanoparticles. AIP Conf Proc. 2016;1731(1):050131. doi:10.1063/1.4947785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Alizadeh T, Nayeri S, Hamidi N. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)/graphite nanocomposite as an extraordinarily sensitive sensor for sub-micromolar detection of oxalic acid in biological samples. RSC Adv. 2019;9(23):13096–103. doi:10.1039/C9RA00982E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nandi D, Taher A, Ul Islam R, Siwal S, Choudhary M, Mallick K. Carbon nitride supported copper nanoparticles: light-induced electronic effect of the support for triazole synthesis. R Soc Open Sci. 2016;3(11):160580. doi:10.1098/rsos.160580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liu D, Lu C, Wu J. CuO/g-C3N4 nanocomposite for elemental mercury capture at low temperature. J Nanoparticle Res. 2018;20(10):277. doi:10.1007/s11051-018-4374-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chen S, Yang S, Sun X, He K, Ng YH, Cai X, et al. Carbon-coated Cu nanoparticles as a cocatalyst of g-C3N4 for enhanced photocatalytic H2 evolution activity under visible-light irradiation. Energy Technol. 2019;7(8):1800846. doi:10.1002/ente.201800846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang T, Nie X, Yu W, Guo X, Song C, Si R, et al. Single atomic Cu-N2 catalytic sites for highly active and selective hydroxylation of benzene to phenol. iScience. 2019;22:97–108. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2019.11.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Champati A, Sahu PK, Rath A, Naik B, Pradhan A. Enhanced photodegradation of antibiotics and antimicrobial activity by a g-C3N4/g-C3N5 nanosheet heterojunction photocatalyst. ACS Omega. 2025;10(38):43871–90. doi:10.1021/acsomega.5c04579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lin TH, Chang YH, Chiang KP, Wang JC, Wu MC. Nanoscale multidimensional Pd/TiO2/g-C3N4 catalyst for efficient solar-driven photocatalytic hydrogen production. Catalysts. 2021;11(1):59. doi:10.3390/catal11010059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Dong J, Zhang Y, Hussain MI, Zhou W, Chen Y, Wang LN. g-C3N4: properties, pore modifications, and photocatalytic applications. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(1):121. doi:10.3390/nano12010121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cui Z, Song S, Liu H, Zhang Y, Gao F, Ding T, et al. Synergistic effect of Cu+ single atoms and Cu nanoparticles supported on alumina boosting water-gas shift reaction. Appl Catal B Environ. 2022;313:121468. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.121468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yuan B, Zhu T, Han Y, Zhang X, Wang M, Li C. Deactivation mechanism and anti-deactivation measures of metal catalyst in the dry reforming of methane: a review. Atmosphere. 2023;14(5):770. doi:10.3390/atmos14050770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hao S, Wang M, Zhang L, Lv X, Peng C, Huang Y, et al. Switching photocatalytic methane oxidation toward ethanol by tuning spin states. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2025;64(34):e202510241. doi:10.1002/anie.202510241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rezabal E, Ruipérez F, Ugalde JM. Quantum chemical study of the catalytic activation of methane by copper oxide and copper hydroxide cations. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;15(4):1148–53. doi:10.1039/C2CP43544F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zheng LL, Li X, Wang D, Chen Y, Fu Q, Wu DS, et al. Selective anchoring of Pt NPs on covalent triazine-based frameworks via in situ derived bridging ligands for boosting photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nanoscale. 2024;16(12):6010–6. doi:10.1039/D4NR00289J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Okolie C, Belhseine YF, Lyu Y, Yung MM, Engelhard MH, Kovarik L, et al. Conversion of methane into methanol and ethanol over nickel oxide on ceria–zirconia catalysts in a single reactor. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(44):13876–81. doi:10.1002/anie.201704704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xu Y, Chen E, Tang J. Photocatalytic methane conversion to high-value chemicals. Carbon Future. 2024;1(1):9200004–20. doi:10.26599/CF.2023.9200004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools