Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deep Learning and Heuristic Optimization for Secure and Efficient Energy Management in Smart Communities

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Kuwait College of Science and Technology, Doha District, Kuwait City, P.O. Box 35001, Kuwait

2 Computer Sciences Program, Department of Mathematics, Turabah University College, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif, 21944, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Computing & Games, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, TS1 3BX, UK

* Corresponding Author: Murad Khan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Technologies in Information Security )

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 143(2), 2027-2052. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.063764

Received 23 January 2025; Accepted 08 April 2025; Issue published 30 May 2025

Abstract

The rapid advancements in distributed generation technologies, the widespread adoption of distributed energy resources, and the integration of 5G technology have spurred sharing economy businesses within the electricity sector. Revolutionary technologies such as blockchain, 5G connectivity, and Internet of Things (IoT) devices have facilitated peer-to-peer distribution and real-time response to fluctuations in supply and demand. Nevertheless, sharing electricity within a smart community presents numerous challenges, including intricate design considerations, equitable allocation, and accurate forecasting due to the lack of well-organized temporal parameters. To address these challenges, this proposed system is focused on sharing extra electricity within the smart community. The working of the proposed system is composed of five main phases. In phase 1, we develop a model to forecast the energy consumption of the appliances using the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) integrated with the attention module. In phase 2, based on the predicted energy consumption, we designed a smart scheduler with attention-induced Genetic Algorithm (GA) to schedule the appliances to reduce energy consumption. In phase 3, a dynamic Feed-in Tariff (dFIT) algorithm makes real-time tariff adjustments using LSTM for demand prediction and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values to improve model transparency. In phase 4, the energy saved from solar systems and smart scheduling is shared with the community grid. Finally, in phase 5, SDP security ensures the integrity and confidentiality of shared energy data. To evaluate the performance of energy sharing and scheduling for houses with and without solar support, we simulated the above phases using data obtained from the energy consumption of 17 household appliances in our IoT laboratory. Finally, the simulation results show that the proposed scheme reduces energy consumption and ensures secure and efficient distribution with peers, promoting a more sustainable energy management and resilient smart community.Keywords

Technological and social innovations in the electric energy sector have empowered consumers to actively participate in both producing and managing their electricity, leading to a shift in decision-making and control away from traditional utilities [1]. Similarly, energy management in smart homes has become a critical area of research due to the increasing demand for energy efficiency, cost savings, and sustainability. Smart homes, equipped with interconnected IoT devices and intelligent systems, generate vast amounts of real-time data that can be leveraged for optimized energy consumption and scheduling. In addition, the advent of prosumers and energy-sharing mechanisms has introduced new paradigms for strategic decision-making, ensuring that prosumers benefit equitably while collectively approaching a socially optimal energy-sharing strategy [2,3].

Deep learning techniques have demonstrated exceptional capabilities in modeling complex energy consumption patterns and improving prediction accuracy. By accurately forecasting energy demand, these techniques enable smarter appliance scheduling and real-time load management, reducing energy costs while enhancing efficiency. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, in particular, are well-suited for time-series forecasting due to their ability to retain long-term dependencies. Recent research has demonstrated that LSTM-based models outperform traditional methods, such as AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs), in predicting household energy consumption [4]. Furthermore, community power grids are playing an increasingly significant role in modern power systems. These grids, consisting of interconnected microgrids (MGs), facilitate peer-to-peer energy trading and efficient power distribution [5]. The energy trading among MGs and with the main grid is managed through a community market structure. In this structure, individual MGs operate autonomously in the local layer while an independent third party coordinates energy transactions in the market layer. The concept of adjustable power sharing allows for more flexible and cost-effective utilization of controllable energy resources within microgrids. In this context, optimizing the scheduling and control of household appliances using deep learning models, such as attention-based LSTMs and heuristic algorithms like Genetic Algorithms (GA), is crucial for maximizing energy efficiency [6].

Moreover, integrating attention mechanisms with deep learning models has further enhanced appliance scheduling. In addition, attention mechanisms allow the model to focus on relevant time steps, improving predictions’ accuracy and optimization’s effectiveness. In a recent study, the authors demonstrated an attention-based LSTM model for appliance scheduling, resulting in improved energy efficiency and reduced operational costs [7]. According to the authors, this research introduces a novel Non-instructive Load Monitoring (NILM) approach using Bidirectional Attention LSTM Networks. Further, the method enhances traditional NILM accuracy by incorporating bidirectional and attention mechanisms into LSTM models and kernel density estimation. Consequently, in recent literature, the attention-deep LSTM model incorporates a novel sandwich structure and an improved attention mechanism that has demonstrated superior performance in predicting electric energy consumption by focusing on different features in each time unit and optimizing parameters using particle swarm optimization (PSO) [8]. Further, the attention-LSTM model has improved short-term load prediction by considering price fluctuations and generating weight vectors that enhance prediction accuracy [9]. In non-intrusive load monitoring (NILM), attention-enhanced bidirectional LSTM models have been used to decompose total energy consumption into individual appliance usage, achieving high accuracy through kernel density estimation to fit training data and modify model outputs. Furthermore, in the context of Integrated Energy Microgrids (IEMs), a CNN-Attention-LSTM model combined with federated learning has been proposed to forecast multi-energy loads while protecting data privacy. This approach allows for distributed training without sharing local data, achieving accuracy comparable to central models and higher precision than individual models, even under false data injection attacks [10]. Overall, applying attention-based LSTM networks in energy management enhances prediction accuracy and supports the development of more efficient and resilient energy systems.

Optimization of smart home energy management has become essential in enhancing the efficiency and sustainability of modern living spaces. These techniques leverage advanced technologies to reduce energy consumption, minimize costs, and lower environmental impact. One of the fundamental approaches is integrating smart meters and energy management systems, which provide real-time data on energy usage. Further, the data obtained from the smart meters enables homeowners to monitor and control their energy consumption more effectively, making informed decisions to reduce wastage [11,12]. In addition, the transition from traditional electricity meters to smart meters has enabled the collection of more detailed datasets, which include physical, demographic, and socioeconomic variables. This has allowed for the application of unsupervised machine learning algorithms, such as feature selection and cluster analysis, to better understand consumption behaviors and environmental attitudes among different user clusters [13]. Similarly, this data is used to optimize the working mechanism of smart home appliances so that they consume as little energy as possible. For instance, heuristic optimization techniques like GA, binary particle swarm optimization (BPSO), and wind-driven optimization (WDO) are also utilized to schedule home appliances efficiently. These techniques, integrated into a Home Energy Management Controller (HEMC), optimize energy consumption patterns based on Time of Use (ToU) pricing schemes, thereby reducing electricity bills and peak demand [14,15]. Additionally, multi-objective optimization approaches consider both energy cost minimization and occupant comfort. For instance, a time average stochastic optimization formulation, simplified to Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) using Lyapunov optimization, manages home loads in real-time while accounting for rooftop solar power generation variations and grid energy prices. This IoT-based controller optimizes energy use and alerts occupants to potential malfunctions, ensuring both efficiency and safety [15].

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) report 2023, the energy consumption in the residential sector reaches approximately 21 quadrillion British Thermal Unit (BTU) [16]. The distribution of the energy consumption of data is shown in Fig. 1. Therefore, it is essential to address this enormous increase with substantial solutions. In this regard, we proposed an energy-sharing system among smart communities to enhance and optimize smart home energy management systems by lowering electrical energy consumption. This paper introduced an attention module that enhances LSTM by enabling the model to focus on specific input parts and assigning weights to prioritize relevant information for more accurate predictions. To predict smart home energy consumption using LSTM with attention, we collect time series data from various appliances, preprocess it, and normalize it using min-max scaling. Further, we add another approach to optimize appliance usage and reduce energy costs by shifting high-energy tasks to off-peak times. Additionally, a GA with an attention module is proposed to optimize appliance scheduling, minimizing energy consumption during peak hours. This hybrid approach combines GA’s heuristic search capabilities with the attention mechanism’s focus on critical time intervals, resulting in efficient scheduling and reduced energy costs. Finally, the surplus energy from solar generation is calculated as the difference between generation and consumption, with any excess stored in batteries or shared with the grid. The proposed dFIT algorithm adjusts tariffs based on real-time data, using LSTM for demand prediction and SHAP values for model transparency. The proposed dynamic approach ensures fair tariff rates, optimizes renewable energy adoption and promotes efficient energy use.

Figure 1: US residential energy consumption of various households [18]

The rest of the article is organized as follows. Section 2 gives an overview and literature on predicting and optimizing smart home energy. The problem statement section presented in Section 3 highlights the current challenges and issues. Further, the proposed energy-sharing system is elaborately described in Section 4. The experimentation and results are critically discussed in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 outlines the conclusions.

Optimized energy consumption in smart homes can be achieved through advanced deep learning techniques and edge computing for intelligent energy management [17]. Deep learning-based approaches enable efficient pattern recognition, trend analysis, and automation, significantly improving energy forecasting and demand-side management [18–20]. Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have demonstrated their capability in predicting electricity load variations based on multiple influencing factors such as weather conditions, time of day, and historical usage patterns [19]. To ensure the smart and efficient utilization of electricity within a smart community, demand response (DR) systems have gained prominence [21–23]. These systems allow consumers to adjust their energy usage dynamically based on signals from grid operators or market fluctuations. For instance, an intelligent DR-based system has been designed to optimize energy consumption in smart grids, effectively reducing electricity costs, peak-to-average ratios (PAR), and carbon emissions (CE) while maintaining user comfort [24]. Further, the schemes discussed above use a smart appliances scheduler and energy management controller (ASEMC), and they utilize heuristic algorithms such as GA, WDO, PSO, etc. Finally, the simulation results show that the proposed algorithms significantly reduce electricity bill costs, PAR, and CE, improving user comfort regarding delay, air freshness quality, and thermal and visual comfort. However, the authors do not discuss the potential trade-offs between reducing electricity bill costs, PAR, CE, and improving user comfort and whether any conflicting objectives need to be considered in the optimization process. Consequently, by participating in DR programs, consumers can reduce their energy consumption during peak demand periods or shift it to when electricity is cheaper or more readily available [25].

Energy forecasting for appliance scheduling has also been extensively explored in recent research [26,27]. By predicting optimal operation times for home appliances, smart energy systems can schedule energy-intensive tasks during non-peak hours, thereby reducing overall costs. For example, a deep learning-based methodology has been developed for intelligent load forecasting in smart cities, leveraging spatiotemporal transformers for energy prediction [28]. While this methodology enhances computational efficiency, it does not fully address the trade-off between computational complexity and real-time processing in IoT-enabled environments. Similar studies propose NB-IoT-based communication frameworks for smart home appliances, ensuring real-time coordination between energy systems and cloud platforms [29]. However, these frameworks often lack security measures, leaving energy-sharing networks vulnerable to cyber threats [30]. The test results demonstrate that the verification system can successfully communicate between the NB-IoT device and the cloud platform, meeting the design requirements. However, the paper does not provide detailed information about the specific design and implementation of the smart household appliance system based on NB-IoT and the Ocean Connect cloud platform. It also lacks in-depth technical analysis and evaluation of the system’s performance.

In community-centric energy-sharing systems, surplus energy from distributed energy resources (DERs) is shared among members, either through peer-to-peer trading platforms or community-managed microgrids [31–33]. It involves the exchange of surplus energy between households or businesses within a local community. This sharing can be facilitated through various means, such as peer-to-peer energy trading platforms or community-based microgrids. Further, in a sustainable power distribution system, a community’s efficient and equitable power distribution is processed to minimize the environmental impact. It ensures that energy resources are allocated to meet the community’s needs while promoting renewable energy sources and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Further, implementing community real-time pricing as a tariff structure can benefit flexible households financially. Recent studies propose game-theoretic models for energy trading, where households strategically interact to maximize individual and collective benefits [34]. It presents a bottom-up community energy system model and uses a game-theoretic approach to derive a community real-time pricing structure. However, the analysis is based on a bottom-up community energy system model and a game-theoretic approach, which may have certain simplifications and assumptions that may not fully capture the complexity of real-world scenarios. The same problem is addressed in [35], where the authors introduce a model for community microgrids wherein members can trade energy and services. Further, the distribution of revenues and costs among the members ensures that no individual within the community faces penalties when compared to acting independently. Further, in a recent research weighted Information Gap Decision Theory (IGDT)-based robust model is proposed to handle uncertainties, validated on the IEEE 24-bus system [36]. Furthermore, the proposed system explores how Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES), Dynamic Line Rating (DLR), and Dynamic Transformer Rating (DTR) enhance power grid flexibility, reduce wind spillage and load shedding, and minimize operational costs and emissions. In addition, bi-level optimization model are used to determine the optimal location and sizing of Flexible Renewable Virtual Power Plant (FRVPP) in active distribution networks (ADNs). Using unscented transformation (UT) for uncertainty modeling and the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) approach for problem conversion, the study optimizes economic and technical performance, reducing costs and improving grid resilience.

Despite advancements in energy prediction, optimization, and community sharing, significant challenges remain. Many existing approaches fail to integrate multiple key components, such as:

• Dynamic demand forecasting using deep learning models with attention mechanisms.

• Appliance scheduling optimized through hybrid heuristic algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms (GA).

• Real-time pricing strategies, including dynamic Feed-in Tariff (dFIT) mechanisms.

• Security measures to ensure safe energy transactions and data integrity in smart energy-sharing systems.

We also present the summary of some of the important schemes closely similar to the domain of this research in the literature review in the following Table 1.

To address these gaps, this study proposes a holistic energy management system that integrates energy prediction, scheduling, tariff optimization, and cybersecurity within a unified framework. The following sections elaborate on our methodology and experimental validation.

The advancements in distributed generation technologies and the embrace of distributed energy resources have led to the growth of sharing economy businesses in the electricity sector. These technologies, such as blockchain and IoT devices, enable peer-to-peer distribution and real-time response to changes in supply and demand. The sharing economy model, which promotes collaborative effort among participating actors, is argued to lead to more efficient, sustainable, and resilient outcomes than utilities’ centralized decision-making. However, sharing electricity among consumers in a smart community may pose several challenges. For instance, several complex design considerations will be taken into account when designing a digital system to mediate among households. The need for one home in a centralized community may be changed from another. The consequence of this phenomenon manifests itself as a proliferation of challenges regarding the equitable allocation and apportionment of electrical energy within these domestic homes. Furthermore, many constraints, such as the inadequate organization of temporal parameters, may be linked to faulty forecasting. In addition, net metering is a billing arrangement that allows individuals or businesses with solar panels (or other distributed energy systems) to receive credit for excess electricity they generate and feed back into the grid. However, the exclusion of net metering may reduce profitability. Apart from the above problems and limitations in the current community-centric energy-sharing system, we also list some important problems.

• The upfront costs for installing renewable energy systems (like solar panels or wind turbines) can be high. This financial barrier can limit the ability of some community members to participate.

• Managing and maintaining renewable energy systems requires technical knowledge. Communities might need to rely on external experts, which can increase costs and reduce self-sufficiency.

• Renewable energy sources like solar and wind are intermittent and depend on weather conditions. Conserving the community’s energy demands can be problematic without efficient energy storage solutions (like batteries).

• Energy-sharing models must navigate complex regulatory environments, which vary by region. Issues like grid interconnection policies, electricity tariffs, and subsidies for renewable energy can significantly impact the viability of community-centric energy projects.

• The existing electrical grid may not be equipped to handle decentralized energy production and distribution. Upgrading grid infrastructure to accommodate local energy sharing can be costly and complex.

• Community-centric models are typically designed for small-scale operations. They may not be easily scalable to larger populations or geographically dispersed communities.

• There’s a risk of creating energy inequity within the community. Those who can afford to invest in renewable technologies might benefit more than those who cannot, potentially widening socio-economic gaps.

• These models often depend on external factors like government incentives, technological advancements, and energy market prices, which can be unpredictable.

The proposed system is divided into two phases. In phase 1, an appliance scheduling system is designed to reduce the energy consumption of homes with and without solar support. Similarly, in phase 2, a demand response strategy is devised for homes without solar support to fulfill their energy requirements from the community grid.

The proposed system empowers smart homes within a solar-powered community to share surplus electricity with homes lacking solar power. The plan incorporates a scheduling mechanism for smart homes featuring multiple appliances to curtail energy consumption. The community grid, furnished with substantial electrical storage devices, stores the energy generated by these smart homes for later use. LSTM networks, a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), handle sequential data well but can lose details in long sequences. Enhancing LSTM with an attention module allows the model to focus on specific input parts, improving prediction accuracy. Time series data from various appliances is collected, preprocessed, and normalized to predict smart home energy consumption. The LSTM network then processes these sequences, capturing temporal dependencies. The attention mechanism assigns weights to significant time steps, enhancing predictions and optimizing appliance usage to reduce energy costs. Further, a GA with an attention module optimizes appliance scheduling, minimizing energy consumption during peak hours. This approach combines GA’s search capabilities with the attention mechanism’s focus on critical intervals, leading to efficient scheduling. Finally, excess energy is stored or shared with the grid for surplus energy from solar generation. The dFIT algorithm adjusts tariffs based on real-time data, ensuring fair rates and promoting efficient energy use. A systematic description of the proposed model is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: A birdseye overview of the proposed system

Fig. 3 shows the working of each module in the following flowchart.

Figure 3: Flowchart of the proposed system

4.2 Community-Centric Energy Management System (CEMS)

In the proposed scheme, we are considering two types of users: (1) users with solar support represented with

where

Each house of

However, to participate in the sharing energy program, the

To enhance solar energy systems, households use forecasting devices and smart meters to predict production and manage appliance schedules based on energy prices. This data is shared with community grid management to assess additional power needs and set electricity tariffs. Different feed-in tariff structures are applied based on households’ production capacities, with uniform charges for imported community grid power. We propose an enhanced Feed-In Tariff (eFIT) algorithm using the LSTM model to dynamically adjust in real-time, optimizing incentives for renewable energy producers while ensuring grid stability.

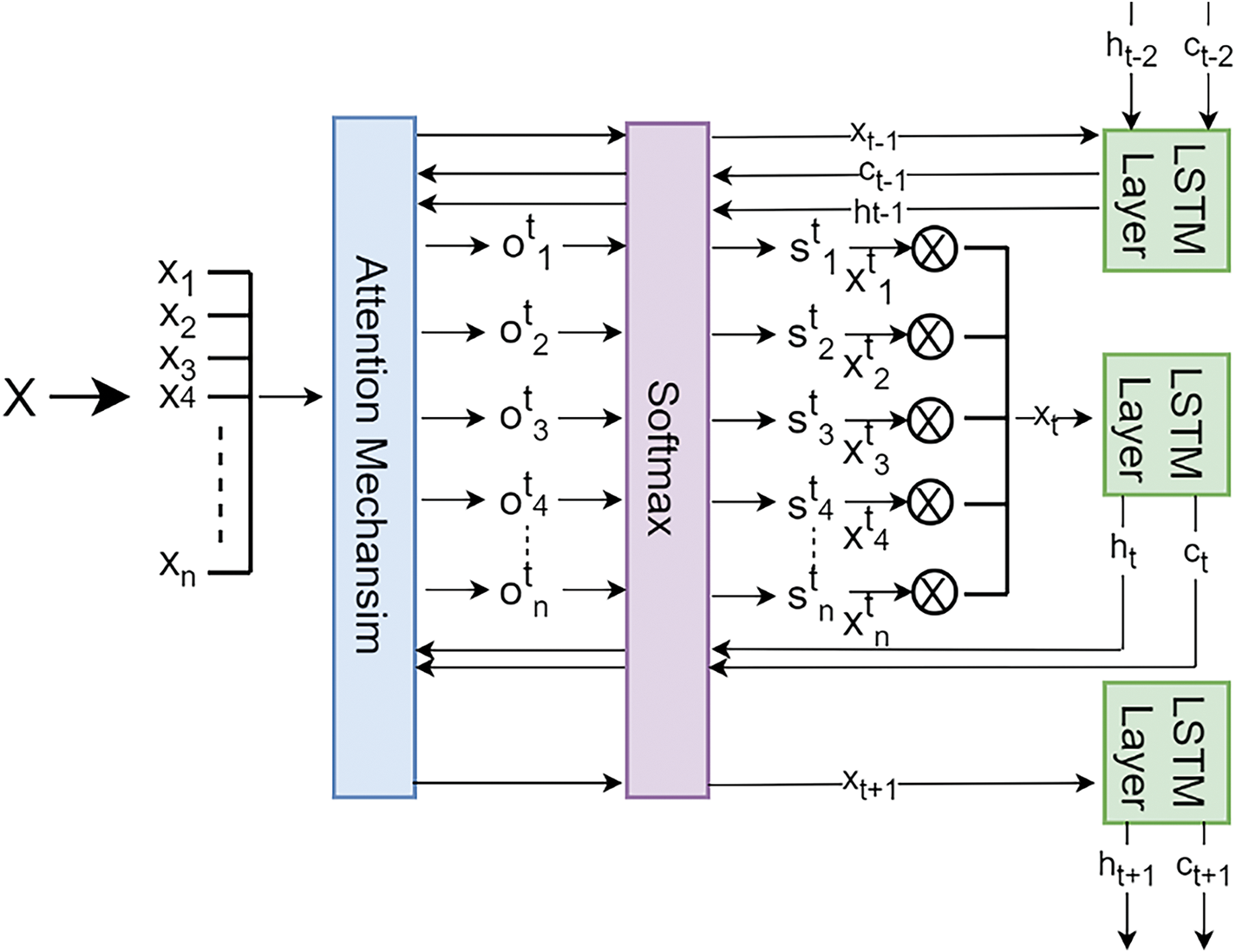

4.2.3 Energy Consumption Predication Based on LSTM with Attention Module

LSTM networks, a type of RNN, excel in processing sequential data like time series. They effectively capture long-term dependencies, aiding in future value predictions based on historical data. However, traditional LSTMs may forget key details in lengthy sequences. The attention module addresses this by enabling the model to focus on relevant input parts, assigning weights to filter important information. This results in more accurate predictions by emphasizing critical data points.

Predicting energy consumption in smart homes using LSTM with an attention module requires collecting time series data from home appliances, including hourly or minute-by-minute records for devices such as refrigerators, air conditioners, and lights. We then preprocess this data for the model. The following section outlines the data processing steps and the underlying mathematical model for LSTM with an attention mechanism.

where xt represents the energy consumption at time step t.

After collecting the data, we normalize it to ensure that all values are on a similar scale, which helps faster convergence during training. We use a min-max scaling approach.

where

The next is to create input sequences

This means using the past n time steps to predict the value at the next step.

After preparing the data for training and validation, the LSTM network processes the input sequence and captures temporal dependencies. At each time step t, the LSTM computes the following gates and states:

where σ denotes the sigmoid function,

We applied the attention mechanism to enhance model focus on relevant parts of the input sequence, improving prediction accuracy and prioritizing significant time steps. Attention weights reveal the most influential time steps, clarifying the model’s decision-making process. The goal is accurate predictions for optimal appliance scheduling, reducing energy costs by shifting high-energy tasks to off-peak times. The attention mechanism uses a linear layer to produce weights, which are used to weight LSTM outputs, assigning importance to each hidden state by computing attention scores.

where

Furthermore, the LSTM uses the context vector c to make the final prediction.

where

Finally, the working mechanism of the LSTM with the attention module is shown in the following Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Deep LSTM module with an attention mechanism

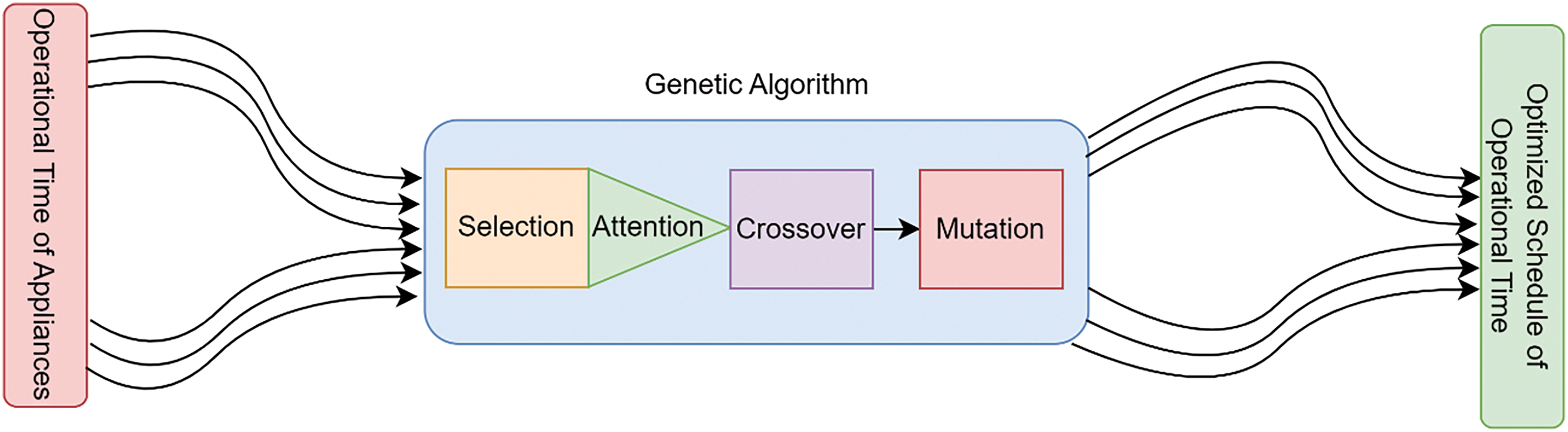

4.3 Smart Scheduler Based on Genetic Algorithm with Attention Module

The energy consumption is predicted to rise over the next 24 h. To address this, we propose a genetic algorithm (GA) with an attention module for optimizing appliance scheduling to reduce energy use, especially during peak hours. This advanced GA leverages natural selection principles and integrates an attention mechanism to prioritize key elements in the scheduling process. It selects the fittest individuals based on a fitness function that evaluates energy consumption minimization while meeting constraints. The function also incorporates the importance of various time intervals. Let xi,t represent whether appliance i operates at time t, with energy consumption indicated by Pi,t. The fitness function F is defined as:

where T is the set of all time intervals, i is the set of all appliances, ct is a cost weight for time (higher during peak hours), Ti is the required operation time for appliance i, and λ is a penalty coefficient.

The attention weights αt are calculated to emphasize specific time intervals based on their impact on energy consumption:

where At is an activation score for time t. The fitness function then incorporates these attention weights:

Finally, combining GA and the attention mechanism offers a robust approach to optimizing appliance scheduling as shown in Fig. 5. In the proposed scheme, the GA explores various scheduling possibilities, while the attention mechanism ensures the model focuses on critical time intervals, leading to more efficient and feasible schedules. The proposed hybrid approach significantly reduces energy consumption and costs, especially during peak demand periods, and can be adapted to various household or industrial settings with multiple appliances and complex scheduling requirements.

Figure 5: An overview of the GA-based smart scheduler

4.4 Surplus Energy Calculation and Distribution

We saved energy in two ways: (1) solar generation and (2) scheduling home appliances. We propose a method to compute surplus energy from solar systems and sell it to the community grid. Surplus energy is the difference between solar generation and household consumption at each time slot t, calculated when solar generation exceeds household needs.

If

Furthermore, using the GA, determine the optimized appliance schedule and compute the energy saved Esaved(t) at each time slot t. Similarly, the battery level is updated to store any surplus energy calculated in the previous step. The following relation gives the updated battery level at a time t + 1 with the efficiency factor

This ensures that the battery is not overcharged beyond its maximum capacity

The total surplus energy

The actual surplus energy

If the battery has enough capacity to store all the surplus energy, then

Finally, we compute the total revenue

The above addition gives the total revenue from selling the surplus energy over 24 h.

4.5 Dynamic Feed in Tariff (dFIT)

We propose the dFIT algorithm to collect real-time data on energy production (Et), consumption (Ct), market prices (Pt), weather (Wt), and grid status (Gt) at each time step t. The collected data is normalized for LSTM model training, and then structured into time-series sequences. Each sequence Xt consists of N previous time steps, with the target Yt being the next time step’s energy demand (yt+1). The LSTM processes Xt to predict future energy demand (Ŷt+1) using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) for loss quantification. SHAP values are employed for model transparency, providing insights into feature contributions to predictions. Once trained, the model is deployed in a community cloud for real-time predictions, dynamically calculating the tariff rate based on predicted demand. A peak rate (Rpeak) applies if demand exceeds a threshold; otherwise, an off-peak rate (Roff-peak) is used. This dynamic system includes a feedback loop for continual performance monitoring and model retraining with new data. Additionally, smart contracts automate payments based on tariff rates, optimizing financial incentives for renewable energy and promoting grid stability. The working of the Algorithm 1 is given below.

4.6 Integration of Software Defined Perimeter (SDP) Security

The SDP framework has been adopted to address cybersecurity challenges in the proposed energy management system. This dynamic, identity-driven security architecture offers a zero-trust model that effectively secures the energy-sharing network by authenticating and authorizing entities before any interaction with the system. SDP enhances IoT security by isolating devices, encrypting communication, and monitoring network activity.

4.6.1 Key Components of the SDP Implementation

• SDP Controller: This unit acts as the central management unit, controlling resource access. The controller enforces access policies and manages secure connections between authenticated devices and the energy-sharing system.

• Identity Provider (IdP): Verifies devices and users using digital certificates and multi-factor authentication (MFA) credentials. This ensures that only authorized participants access the energy management resources.

• Policy Engine: Implements fine-grained access controls based on contextual attributes such as device role, user identity, location, and behavioral data. This guarantees minimal exposure of critical system components.

• Encrypted Overlay Network: Data communication is safeguarded through encrypted tunnels (AES-256/TLS) between authenticated nodes, ensuring the confidentiality of shared energy data.

• Dynamic Threat Detection: This feature monitors the network in real-time for anomalies, such as unusual access attempts or data transfer spikes, and triggers isolation of affected components when threats are detected.

4.6.2 SDP Deployment in Energy Management

In the proposed energy model, the following entities are secured when transmitting energy data to each other.

• Community Grid: The integration of SDP ensures that only validated energy data is shared within the grid, preventing malicious energy injections.

• Smart Homes: SDP isolates home devices, including IoT-enabled smart meters and appliances, minimizing their exposure to network-wide vulnerabilities.

• Centralized Modules: Critical modules, such as the LSTM-based prediction engine and GA optimization scheduler, process encrypted data, preserving system integrity.

5 Performance Evaluation and Discussion

We evaluated the performance of energy sharing and scheduling of 17 household appliances in homes with and without solar support. Data was collected by connecting the appliances in our IoT lab, using the energy pricing detailed in Section 4.5. The study involved two houses: one with an 8 kW solar support and one without. Peak hours were set from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., during which solar energy met the entire demand, and surplus energy was sent to the community grid. Appliances were classified as shiftable or non-shiftable, as noted in Table 2. Shiftable appliances typically operated during non-peak hours, but users could manually adjust their operation to avoid dissatisfaction. Houses needing energy from the grid were charged under the proposed model, while solar-supported houses sold surplus energy to the community grid at a fixed rate of $0.16 per kWh. The following Table 3 combines the simulation parameters and their description used in all experiments. The computer used for the simulation consists of a Corei7 processor with Intel Iris Xe graphics support. To utilize the Intel Iris Xe graphics functionality, we used the OpenVINO Intel tool kit. However, we also added code to use a GPU instead.

This section evaluates the proposed system’s performance through several experiments, divided into: (1) deep LSTM with attention module performance, (2) GA with attention module for optimal appliance scheduling, and (3) surplus energy calculations.

5.2.1 Performance Evaluation of the Proposed Deep LSTM with Attention Module

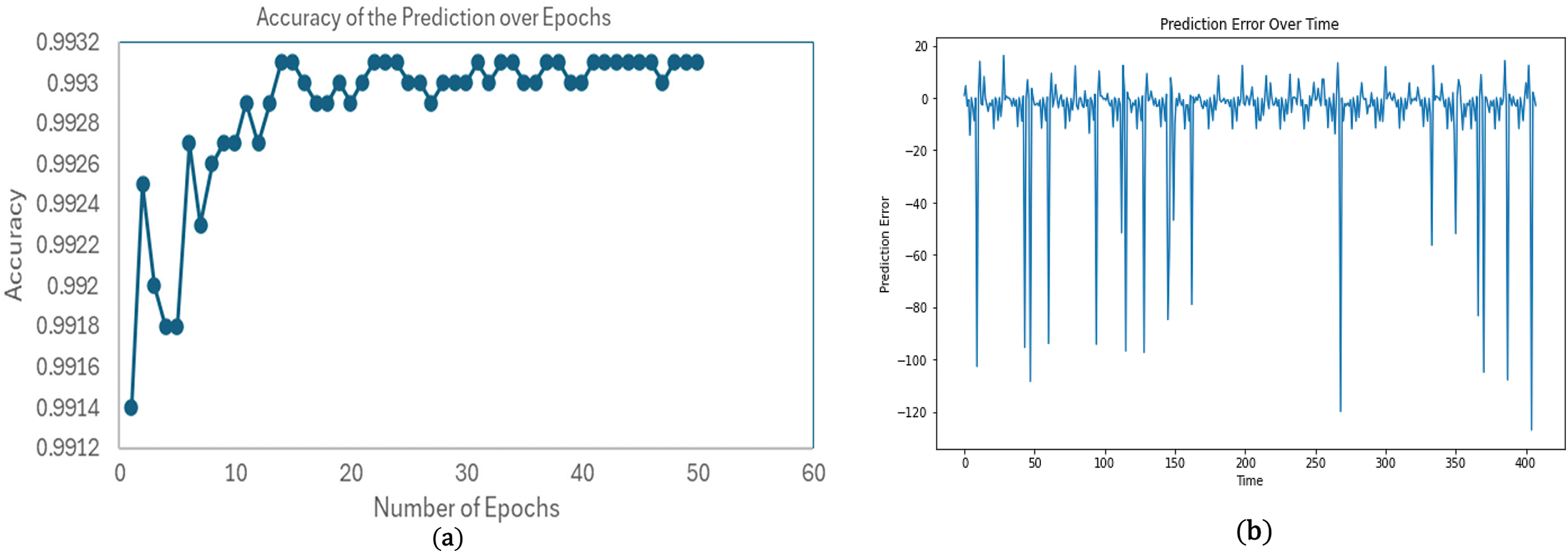

Fig. 6a shows the training and validation loss over 50 epochs for the LSTM model with an attention module, indicating effective learning with rapid convergence and minimal loss gap. Fig. 6b depicts the training and validation accuracy, stabilizing around 99.35% after an initial rapid increase, demonstrating good generalization and minimal overfitting. The attention mechanism enhances the model’s ability to focus on relevant time steps, improving predictive performance.

Figure 6: (a) Training and validation loss, (b) Training and validation accuracy of deep LSTM with attention module over epochs

Similarly, the following Fig. 7a displays the prediction accuracy of an LSTM model with an attention module over 50 epochs. The accuracy initially fluctuates but rapidly improves, stabilizing around 99.32%. This indicates that the model effectively learns from the data with minimal overfitting. Like Fig. 6, the attention mechanism enhances the LSTM’s ability to focus on important time steps, contributing to high and consistent accuracy. Similarly, Fig. 7b illustrates the prediction error over time for an energy consumption model. As we can see in the Fig. 7b, most errors are clustered around zero, indicating accurate predictions. However, there are significant negative spikes, suggesting occasional large underestimations. While the overall error distribution shows good model performance, the frequent significant negative errors highlight a need for improvement. Consistently minor prediction errors and minimal outliers are desirable for a robust model. In the future, we will work on reducing these spikes, further enhancing the model’s reliability and accuracy.

Figure 7: (a) Prediction accuracy over epochs and (b) Predication error over time

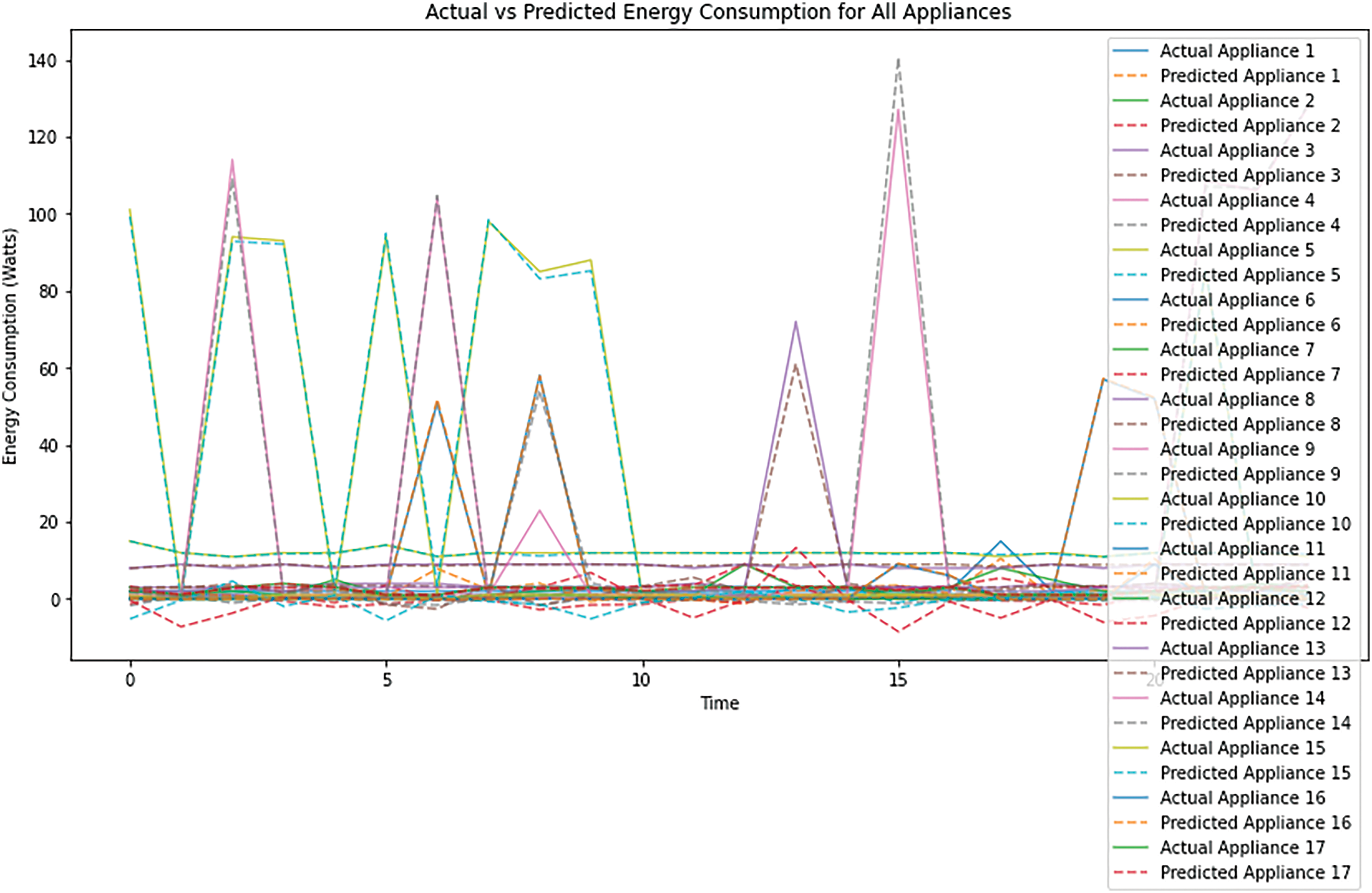

Fig. 8 shows the actual vs. predicted energy consumption for all 17 appliances over a specified period. Each appliance has two lines: one solid line for actual consumption and one dashed line for predicted consumption. A high correlation between actual and predicted lines indicates effective model performance. Similarly, peaks represent high energy usage periods, and the model accurately captures these fluctuations. Further, discrepancies between the actual and predicted values highlight areas for model improvement. Overall, the model demonstrates strong predictive capability with some variations in accuracy across different appliances due to the appropriate scheduling of the appliances.

Figure 8: The actual vs. Prediction energy consumption for all the appliances

The correlation matrix of attention weights displays the correlation between attention weights across different time steps in the LSTM with an attention module for predicting energy consumption, as shown in Fig. 9. As we can see, the matrix shows strong correlations along the diagonal, indicating that attention weights are highly focused on the same time step. The off-diagonal values are lower, suggesting less correlation between different time steps. Further, the figure shows that the attention mechanism effectively focuses on relevant time steps for prediction. The attention mechanism enhances the LSTM’s ability to capture important temporal dependencies, leading to more accurate energy consumption predictions. Similarly, accurate predictions allow for better scheduling of appliance usage, shifting loads to non-peak times, and leveraging cheaper or renewable energy sources. The system can dynamically adjust energy consumption based on real-time predictions, improving demand response and reducing peak loads. In addition, by focusing on relevant time steps, the system can identify patterns in energy usage, enabling users to implement strategies that minimize unnecessary energy consumption. Finally, better predictions and attention-driven insights lead to more efficient use of energy resources, reducing waste, lowering overall energy costs, and increasing user satisfaction.

Figure 9: Correlation matrix of attention weights

5.2.2 Performance Evaluation of Smart Scheduler with GA-Attention Module

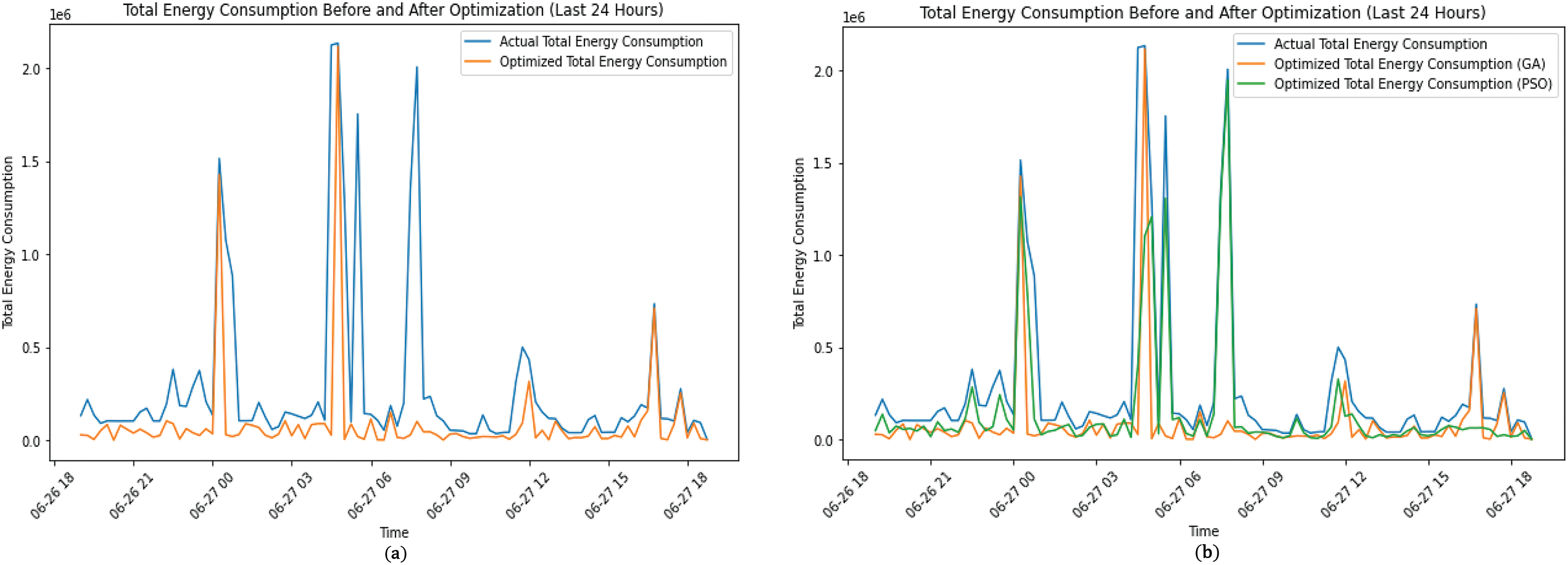

Fig. 10a compares total energy consumption before and after optimization over 24 h. Optimized consumption significantly reduces peaks, indicating effective load shifting and better energy resource utilization. The smoother optimized line with fewer spikes suggests a consistent energy usage pattern, demonstrating the effectiveness of the GA with an attention module in minimizing energy use. This highlights the system’s capability to reduce overall consumption and savings. The attention mechanism enhances the GA by focusing on relevant time intervals, leading to accurate predictions and better results, effectively managing energy demand, and optimizing appliance scheduling.

Figure 10: (a) Actual vs. Optimized energy consumption for the last 24 h and (b) Comparison of energy consumption optimization with GA and PSO

Fig. 10b compares total energy consumption before and after optimization using GA with an attention module and PSO. Both methods reduce peak energy consumption compared to actual use, proving effective in energy management. The GA with an attention module offers smoother and more consistent reductions, flattening peaks more effectively than PSO. While PSO reduces consumption, its variability indicates that GA with attention achieves more stable optimization. Overall, GA, with an attention module, excels in minimizing consumption, optimizing scheduling, and enhancing sustainable energy management in smart homes.

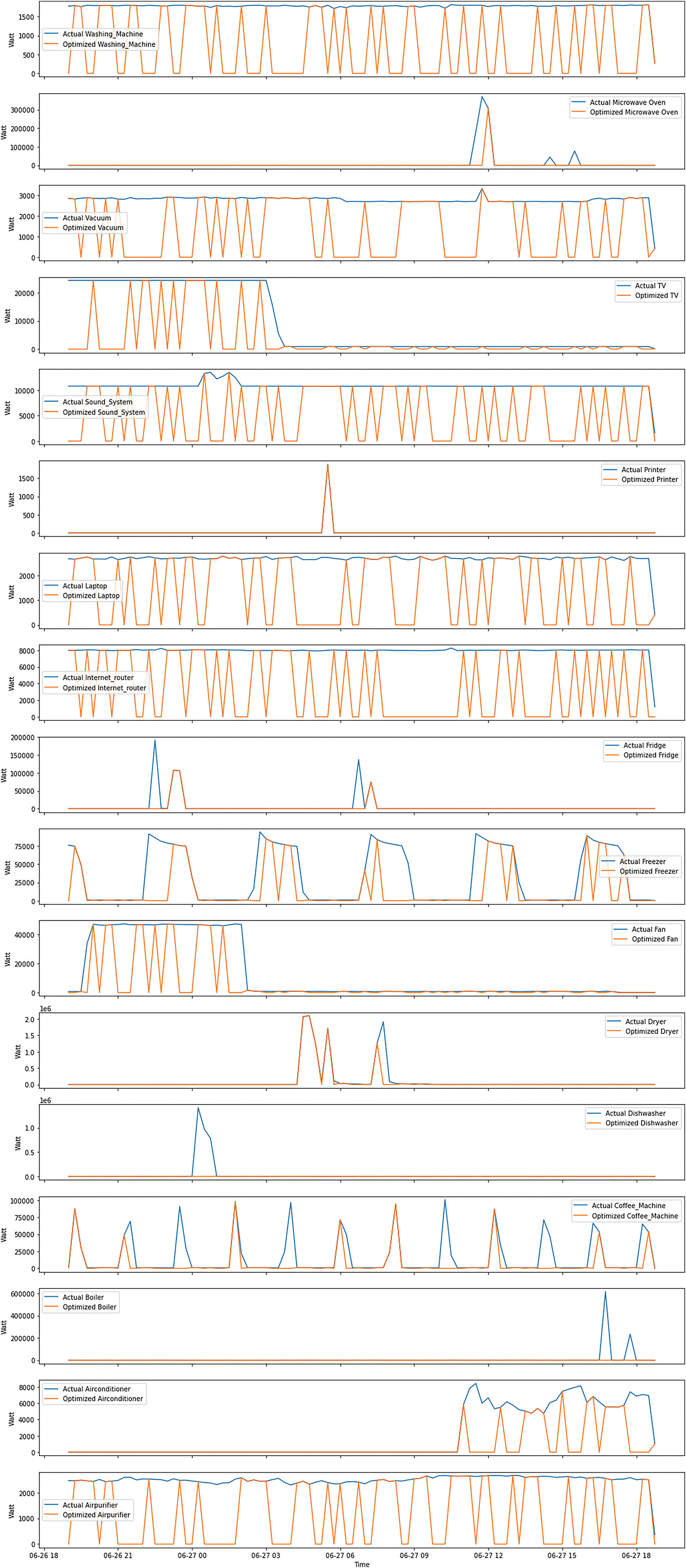

Finally, Fig. 11 displays the actual vs. optimized energy consumption for individual appliances over the last 24 h. Each subplot corresponds to a different appliance, such as the washing machine, microwave oven, vacuum, TV, etc. The optimized energy consumption lines are consistently smoother and lower than the actual consumption lines, indicating significant energy savings. Also, the optimization shifts energy usage to non-peak times and ensures more efficient operation of each appliance.

Figure 11: Actual and optimized energy consumption for each appliance

5.2.3 Surplus Energy Calculation

Fig. 12a illustrates the battery levels in a home utilizing renewable energy sources over time. Initially, the battery charges rapidly as solar energy generation exceeds household consumption. After reaching its maximum capacity (10 kWh), it fluctuates slightly due to discharges during low solar generation and high demand periods, especially at night. This reflects efficient renewable energy use, with the battery storing excess solar energy and discharging during high demand, thus minimizing grid dependence and enhancing energy independence.

Figure 12: (a) Battery level over time and (b) Surplus energy sent to the grid

The proposed smart scheduler further reduces energy costs using stored energy during peak times. Surplus energy can also be sent back to the grid, benefiting community resources and potentially generating revenue. Fig. 12b shows this surplus energy over time, with spikes indicating excess solar generation surpassing consumption. Lower surplus during some periods indicates effective battery use to meet household needs before exporting excess energy, emphasizing reduced external energy reliance. This system promotes renewable energy use, contributes to grid stability, and optimizes energy generation, storage, and consumption.

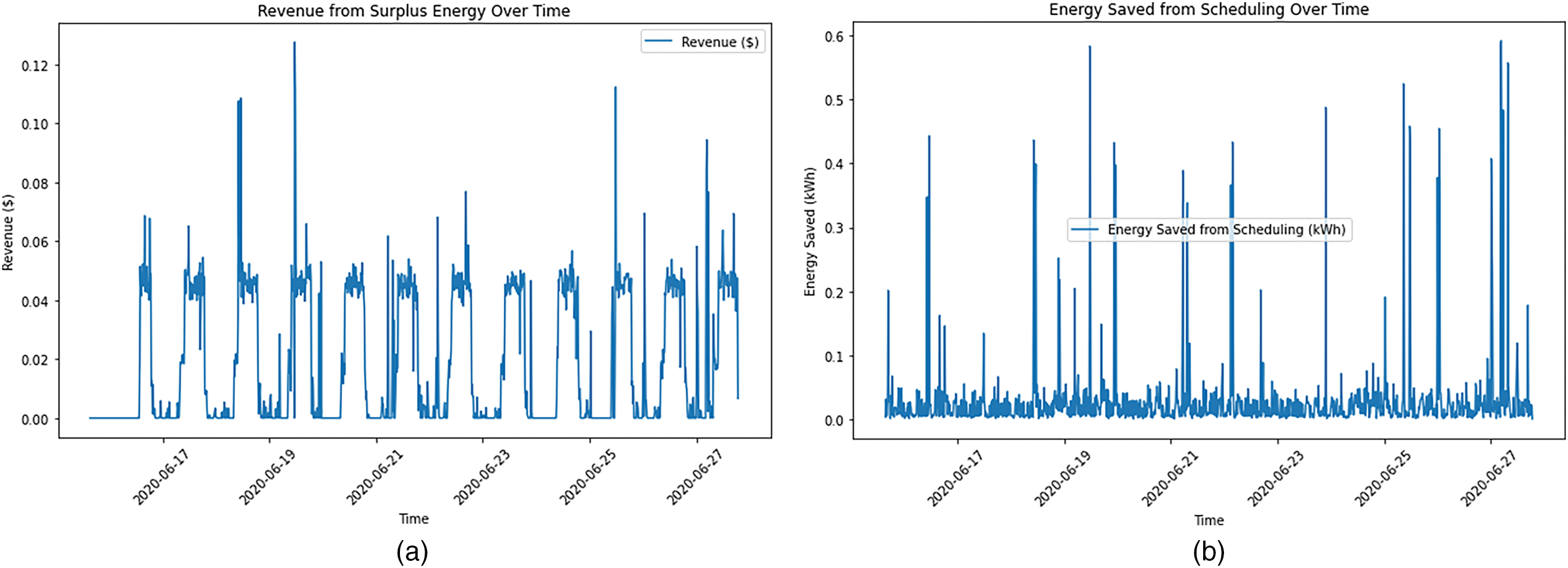

Fig. 13a shows the revenue generated from surplus energy sold to the grid over time. Spikes indicate when surplus energy was sold, with higher spikes reflecting periods of more significant solar generation. Revenue fluctuates, peaking around mid-June, suggesting effective monetization of solar energy, primarily during daylight hours. This revenue stream highlights the economic viability of renewable energy systems and their role in grid stability. Similarly, Fig. 13b depicts energy savings achieved through optimal scheduling of appliance use, showing spikes when appliances were shifted to non-peak times or aligned with solar generation. Consistent energy savings indicate the effectiveness of scheduling, with peaks at 0.6 kWh due to efficient demand management.

Figure 13: (a) Revenue generated from surplus energy trade over time and (b) Energy saved from scheduling of appliances during peak hours

Lower savings persist due to ongoing optimization, underscoring intelligent scheduling’s role in enhancing energy efficiency and sustainability. The energy saved from solar generation reflects consistent savings during daylight, peaking at 0.25 kWh. The cyclical pattern shows reliance on solar power during the day and zero savings at night, demonstrating the system’s capacity to reduce grid dependency and promote sustainability. Overall, these figures illustrate the significant impact of solar generation on energy savings in smart homes.

5.2.4 Securing the Proposal System with SDP

The following Fig. 14a illustrates the impact of SDP on unauthorized access attempts, showing a consistent prevention of all unauthorized attempts throughout the simulation period. This highlights the efficiency of the SDP framework in blocking unauthorized access via pre-authentication mechanisms. The Fig. 14b presents the computational overhead introduced by SDP, demonstrating a minimal increase in response time (~2.8 ms) compared to the baseline. This slight overhead confirms that the security enhancements provided by SDP do not significantly affect the system’s operational efficiency. These results validate SDP as a secure and performance-conscious solution for the proposed energy management system.

Figure 14: (a) Impact of SDP on unauthorized access attempts and (b) Computational overhead introduced by SDP

This research presents a novel approach to optimizing household energy management through intelligent scheduling and renewable energy integration. Our system utilizes advanced machine learning and real-time data analysis to improve energy efficiency, cut costs, and promote sustainable practices in smart homes. We found that a hybrid LSTM and attention model significantly enhance prediction accuracy for energy demand and solar generation. By forecasting these variables, our system employs an attention-induced-GA algorithm for optimal appliance scheduling aligned with high solar output and low demand periods. Additionally, we introduce a dFIT mechanism that adapts to real-time changes in energy dynamics, ensuring an economically viable solution for energy trading. To address cybersecurity challenges in smart energy-sharing networks, we integrated an SDP framework into the proposed system. SDP’s zero-trust architecture ensures secure communication, access control, and anomaly detection across the network. Finally, the simulations show that our system achieves notable energy savings by shifting appliance usage to non-peak hours, aligning energy consumption with high solar generation. The results highlight the potential of solar energy in minimizing grid reliance and promoting sustainability. Furthermore, the integration of SDP reinforces the security of energy transactions, addressing a critical challenge in IoT-enabled energy systems. Future work will refine prediction models, explore advanced security mechanisms, and expand the system’s applicability to larger communities and diverse energy environments.

Acknowledgement: We deeply acknowledge Kuwait College of Science and Technology for supporting and providing a research environment to conduct this study.

Funding Statement: The Project was Funded by Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS) under project code: PN23-15EM-1901.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Murad Khan and Mohammed Faisal; methodology, Murad Khan and Fahad R. Albogamy; software, Murad Khan, Mohammed Faisal, and Muhammad Diyan; validation, Murad Khan, Mohammed Faisal, Fahad R. Albogamy, and Muhammad Diyan; formal analysis, Murad Khan, Mohammed Faisal, Fahad R. Albogamy, and Muhammad Diyan; resources, Murad Khan; data curation, Murad Khan, Mohammed Faisal, Fahad R. Albogamy, and Muhammad Diyan; writing—original draft preparation, Murad Khan, Mohammed Faisal, Fahad R. Albogamy, and Muhammad Diyan; writing—review and editing, Murad Khan, Mohammed Faisal, Fahad R. Albogamy, and Muhammad Diyan; visualization, Murad Khan and Fahad R. Albogamy; supervision, Murad Khan; project administration, Murad Khan; funding acquisition, Murad Khan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and simulation code of the paper is available on the following link to our GitHub repository (https://github.com/mmohmand/Smart_Home_Simulation.git, accessed on 27 March 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chen Y, Zhao C, Low S, Mei S. Approaching prosumer social optimum via energy sharing with proof of convergence. In: 2022 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM); 2022 Jul 17–21; Denver, CO, USA. doi:10.1109/PESGM48719.2022.9917028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Morgan J, Canfield C. Comparing behavioral theories to predict consumer interest to participate in energy sharing. Sustainability. 2021;13(14):7693. doi:10.3390/su13147693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen L, Liu N, Liu L, Yu X, Xue Y. Data-driven stochastic game with social attributes for peer-to-peer energy sharing. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2021;12(6):5158–71. doi:10.1109/TSG.2021.3093587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kong W, Dong ZY, Jia Y, Hill DJ, Xu Y, Zhang Y. Short-term residential load forecasting based on LSTM recurrent neural network. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2019;10(1):841–51. doi:10.1109/tsg.2017.2753802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Fan S, Xu G, Ai Q, Gao Y. Community market based energy trading among interconnected microgrids with adjustable power. IEEE Trans Ind Appl. 2023;59(1):148–59. doi:10.1109/TIA.2022.3212992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. El Makroum R, Khallaayoun A, Lghoul R, Mehta K, Zörner W. Home energy management system based on genetic algorithm for load scheduling: a case study based on real life consumption data. Energies. 2023;16(6):2698. doi:10.3390/en16062698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Fan Y, Liu C, Guo T, Jiang D. Bidirectional attention LSTM networks for non-instructive load monitoring. In: 2022 Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM-2022 London); 2022 May 27–29; London, UK. p. 399–404. doi:10.1109/PHM2022-London52454.2022.00076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. He YL, Chen L, Gao Y, Ma JH, Xu Y, Zhu QX. Novel double-layer bidirectional LSTM network with improved attention mechanism for predicting energy consumption. ISA Trans. 2022;127(5):350–60. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2021.08.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sheng Y, Feng R, Lu H. LSTM short-term load-prediction model for IES including electricity price and attention mechanism. In: Ma Y, editor. Advanced theory and applications of engineering systems under the framework of Industry 4.0. Singapore: Springer; 2023. p. 169–86. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-9825-6_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang G, Zhu S, Bai X. Federated learning-based multi-energy load forecasting method using CNN-attention-LSTM model. Sustainability. 2022;14(19):12843. doi:10.3390/su141912843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Rajesh P, Cherala V, Yemula PK. Smart meter data analytics for building monitoring system: a case study. In: 2023 IEEE PES Conference on Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Middle East (ISGT Middle East); Mar 12–15, 2023; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; 2023. doi:10.1109/ISGTMiddleEast56437.2023.10078592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Emrouznejad A, Panchmatia V, Gholami R, Rigsbee C, Kartal HB. Analysis of smart meter data with machine learning for implications targeted towards residents. Int J Urban Plan Smart Cities. 2023;4(1):1–22. doi:10.4018/ijupsc.318337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Parath JC, Saha AK. Smart meter data analytics-load identification and abnormality detection using computational algorithms: a case study. In: 2022 IEEE 6th International Conference on Condition Assessment Techniques in Electrical Systems (CATCON); 2022 Dec 17–19; Durgapur, India. p. 41–5. doi:10.1109/CATCON56237.2022.10077617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mahmood Z, Cheng B, Butt NA, Rehman GU, Zubair M, Badshah A, et al. Efficient scheduling of home energy management controller (HEMC) using heuristic optimization techniques. Sustainability. 2023;15(2):1378. doi:10.3390/su15021378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sarapan W, Boonrakchat N, Paudel A, Boonraksa T, Boonraksa P, Marungsri B. Optimal energy management in smart house using metaheuristic optimization techniques. In: 2022 International Conference on Power, Energy and Innovations (ICPEI); 2022 Oct 19–21; Pattaya Chonburi, Thailand. doi:10.1109/ICPEI55293.2022.9986889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chatterjee A, Paul S, Ganguly B. Multi-objective energy management of a smart home in real time environment. IEEE Trans Ind Appl. 2023;59(1):138–47. doi:10.1109/TIA.2022.3209170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Abdoulabbas TE, Mahmoud SM. Power consumption and energy management for edge computing: state of the art. Telecommun Comput Electron Control. 2023;21(4):836. doi:10.12928/telkomnika.v21i4.24350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Syamala M, Komala CR, Pramila PV, Dash S, Meenakshi S, Boopathi S. Machine learning-integrated IoT-based smart home energy management system. In: Swarnalatha P, Prabu S, editors. Handbook of research on deep learning techniques for cloud-based industrial IoT. New York, NY, USA: IGI Global. 2023. p. 219–35. doi:10.4018/978-1-6684-8098-4.ch013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Saber SM, Sabah Hassan G, Sameer Jabbar M, Fadhil Tawfeq J, Dheyaa Radhi A, Soon JosephNg P. Enhancing smart home energy efficiency through accurate load prediction using deep convolutional neural networks. Period Eng Nat Sci. 2023;11(3):139. doi:10.21533/pen.v11i3.3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wei G, Chi M, Liu ZW, Ge M, Li C, Liu X. Deep reinforcement learning for real-time energy management in smart home. IEEE Syst J. 2023;17(2):2489–99. doi:10.1109/jsyst.2023.3247592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chen C. Demand response: an enabling technology to achieve energy efficiency in a smart grid. In: Lamont LA, Sayigh A, editors. Application of smart grid technologies. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press. 2018. p. 143–71. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-803128-5.00004-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Desai SK, Dua A, Kumar N, Das AK, Rodrigues JJPC. Demand response management using lattice-based cryptography in smart grids. In: 2018 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM); 2018 Dec 9–13; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. doi:10.1109/GLOCOM.2018.8647560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ahmed S, Bouffard F. An online framework for integration of demand response in residential load management. In: 2017 IEEE Electrical Power and Energy Conference (EPEC); 2017 Oct 22–25; Saskatoon, SK, Canada. doi:10.1109/EPEC.2017.8286202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Daniel-George D, Mihaela C, Bogdan M, Radu T. Implementing demand response using smart home IoT devices. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Automation, Quality and Testing, Robotics (AQTR); 2020 May 21–23; Cluj-Napoca, Romania. doi:10.1109/aqtr49680.2020.9129991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mohagheghi S, Raji N. Dynamic demand response: a solution for improved energy efficiency for industrial customers. IEEE Ind Appl Mag. 2015;21(2):54–62. doi:10.1109/MIAS.2014.2345799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Azzam SM, Elshabrawy T, Ashour M. Energy management of smart homes considering appliance scheduling flexibility. In: 2019 Ninth International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Information Systems (ICICIS); 2019 Dec 8–10; Cairo, Egypt. p. 259–64. doi:10.1109/icicis46948.2019.9014687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Al-Adaileh A, Khaddaj S. Machine learning prediction based integrated smart energy management system to improve home energy efficiency. In: 2022 21st International Symposium on Distributed Computing and Applications for Business Engineering and Science (DCABES); 2022 Oct 14–18; Chizhou, China. doi:10.1109/DCABES57229.2022.00042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Babuji R, Pious AE, Vinu AT, Devi V, Thiripurasundari D, Kumar SS. A deep learning approach for intelligent IoT based energy management system. In: 2022 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS); 2022 Apr 7–9; Erode, India. p. 1037–41. doi:10.1109/ICSCDS53736.2022.9760925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Jiang Z, Wang Z, Hu J, Song T, Cao Z. Research on smart household appliance system based on NB-IoT and cloud platform. In: 2018 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC); 2018 Dec 7–10; Chengdu, China. p. 875–9. doi:10.1109/CompComm.2018.8780875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang X, Xue F, Wu Q, Lu S, Han B, Piao L. Vulnerability assessment for power grids based on inverse-community structure. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT); 2022 Aug 22–25; Shanghai, China. doi:10.1109/ICIT48603.2022.10002772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Vespermann N, Hamacher T, Kazempour J. Access economy for storage in energy communities. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2021;36(3):2234–50. doi:10.1109/tpwrs.2020.3033999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Crespo-Vazquez JL, AlSkaif T, González-Rueda ÁM, Gibescu M. A community-based energy market design using decentralized decision-making under uncertainty. IEEE Trans Smart Grid. 2021;12(2):1782–93. doi:10.1109/TSG.2020.3036915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Khorasany M, Mishra Y, Ledwich G. Market framework for local energy trading: a review of potential designs and market clearing approaches. IET Gener Trans Dist. 2018;12(22):5899–908. doi:10.1049/iet-gtd.2018.5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sarfarazi S, Deissenroth-Uhrig M, Bertsch V. Aggregation of households in community energy systems: an analysis from actors’ and market perspectives. Energies. 2020;13(19):5154. doi:10.3390/en13195154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Savelli I, Cornelusse B, Paoletti S, Giannitrapani A, Vicino A. A local market model for community microgrids. In: 2019 IEEE 58th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC); 2019 Dec 11–13; Nice, France. p. 2982–7. doi:10.1109/cdc40024.2019.9029414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Aghdam EA, Moslemi S, Nakisaee MS, Fakhrooeian M, Al-Hassanawy AJK, Masali MH, et al. A new IGDT-based robust model for day-ahead scheduling of smart power system integrated with compressed air energy storage and dynamic rating of transformers and lines. J Energy Storage. 2025;105(2):114695. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.114695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools