Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multi-Objective Optimization of Marine Winch Based on Surrogate Model and MOGA

1 College of Marine Engineering Equipment, Zhejiang Ocean University, Zhoushan, 316022, China

2 Jiesheng Marine Equipment Co., Ltd., Ningbo, 315806, China

3 Innovation Centre of Excellence for Marine New Quality Productivity, Zhejiang Ocean University, Zhoushan, 316022, China

* Corresponding Author: Quanliang Liu. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 143(2), 1689-1711. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.063850

Received 25 January 2025; Accepted 21 April 2025; Issue published 30 May 2025

Abstract

This study proposes a multi-objective optimization framework for electric winches in fiber-reinforced plastic (FRP) fishing vessels to address critical limitations of conventional designs, including excessive weight, material inefficiency, and performance redundancy. By integrating surrogate modeling techniques with a multi-objective genetic algorithm (MOGA), we have developed a systematic approach that encompasses parametric modeling, finite element analysis under extreme operational conditions, and multi-fidelity performance evaluation. Through a 10-t electric winch case study, the methodology’s effectiveness is demonstrated via parametric characterization of structural integrity, stiffness behavior, and mass distribution. The comparative analysis identified optimal surrogate models for predicting key performance metrics, which enabled the construction of a robust multi-objective optimization model. The MOGA-derived Pareto solutions produced a design configuration achieving 7.86% mass reduction, 2.01% safety factor improvement, and 23.97% deformation mitigation. Verification analysis confirmed the optimization scheme’s reliability in balancing conflicting design requirements. This research establishes a generalized framework for marine deck machinery modernization, particularly addressing the structural compatibility challenges in FRP vessel retrofitting. The proposed methodology demonstrates significant potential for facilitating sustainable upgrades of fishing vessel equipment through systematic performance optimization.Keywords

Fiber-reinforced plastic (FRP) fishing boats have experienced significant growth in recent years due to their notable advantages of lightweight and high strength. However, compared to steel fishing boats, FRP fishing boats have lower stiffness, resulting in a more compact structure and limited space during construction. This poses higher demands on the deck machinery of fishing boats, which were originally relatively bulky [1]. Upgrading and transforming traditional deck machinery can facilitate the upgrading and replacement of fishing boat deck machinery, as well as address the issue of technological innovation in FRP fishing boat deck machinery [2]. Additionally, this aligns with the requirements of energy conservation, emission reduction, “dual carbon,” and the concept of sustainable development [3].

As the most prevalent and standard deck machinery on fishing boats, developing scientifically-based multi-objective optimization schemes for fishing boat winch systems to achieve their upgrading has emerged as a crucial issue that requires immediate attention. Lightweight vessels have the potential to substantially enhance the loading capacity or sailing speed per unit weight, thereby effectively achieving energy conservation, reduced consumption, and decreased emissions.

Over the years, numerous scholars have conducted extensive research on deck machinery, such as winches, and their optimization in terms of performance. Solovyov and Cherniavsky [4] analyzed the impact of various factors, including barrel size, material properties, rope characteristics, and load levels, on the rate of strain accumulation. Their objective was to provide barrel designs for new winches and establish load constraints for existing winches. To achieve this, they developed new ropes and specialized software to assist trawl fishing boats in predicting situations that may result in the plastic deformation of the winch components. Wu et al. [5] introduced the concept of modular design and combined it with fuzzy clustering artificial intelligence to determine different module divisions. They applied this approach to calculate the parameters of each stage during the operation of a ship anchor winch, thereby facilitating the overall structural design. Finally, the amount of outfitting is 1600; the anchoring depth is h < 82.5 m, and the coaxial bedroom single-side double drum design is adopted. Ye et al. [6] introduced a full-scale testing device to evaluate the stress exerted on winches by multi-layer wound fiber ropes, using high-modulus polyethylene ropes. This paper concludes by conducting the spooling experiment on the full ocean depth oceanographic multiple-layer winch with fiber rope with a length of 13,000 m. The experimental result indicated that it could be considered a promising tool for estimating and analyzing the deformation of rope under various tensions and the rope winding application in engineering. Sarca et al. [7] conducted a strength analysis on the ultimate load borne by the main shaft of shipborne winches. They accomplished the redesign and optimization of the main shaft structure through the optimization of wall thickness size and the implementation of a hollow shaft structure. Through the processes of optimization, redesign, and simulation using finite element analysis, the achieved results show a 45% reduction in the weight of the shaft. From the economical point of view, by using a tube instead of a bar, it is possible to achieve a reduction of almost 6000 USD for a batch of 1000 shafts. Jia and Li [8] proposed a design method for strengthening the tank wall of trimaran based on topology optimization. Under the premise of ensuring that the bulkhead has sufficient structural strength, seven structural strength check conditions were designed. Finally, under the condition that the stress distribution and maximum stress of the bulkhead and reinforcement do not change, the mass of the bulkhead and reinforcement is reduced. Huda and Mursid [9] performed topology optimization on a mooring winch bracket, aiming to remove material from the bottom of the bracket and achieve a weight reduction ratio of 13%.

Many practical engineering optimization problems, often involving simultaneous optimization of multiple conflicting objectives, can be referred to as multiple objective optimization problems (MOP). For multi-objective optimization, a widely accepted and applied approach is to obtain a Pareto solution set through a multi-objective optimization algorithm based on the Pareto mechanism, including NSGA-II [10], MOPSO [11], NSGA-III [12], and other classic algorithms and newly developed DC-NSGA-III [13] and other derivative algorithms. However, as the number of targets increases and the number of non-dominant solutions increases exponentially, Pareto-based EA does not provide sufficient pressure for the solution set to converge to the true Pareto Front (PF) with a limited number of evaluations. Using the surrogate model to construct a global performance prediction model to replace expensive experiments and simulations is an effective auxiliary means. Khishe et al. [14] developed the Multi-Objective Chimp Optimization Algorithm (MOChOA), a multi-objective variation of ChOA, to solve multi-objective optimization problems in engineering. MOChOA, which uses a memory structure, leader selection strategy, and grid mechanism, outperforms well-known intelligent algorithms in tests and can be applied in various fields with competing objectives due to its good performance and fast execution. Xiong et al. [15] used a surrogate model-based strategy to perform multi-objective optimization on the front-end structure of the vehicle body. The results show that the automobile body is lightweight and designed with a mass reduction of 4.12 kg while other mechanical performance is well guaranteed. Zhang et al. [16] proposed an optimization framework based on Kriging, which applies a method to determine fluid dynamics parameters. By dynamically filling sample points and updating the Kriging model with gradient information of geometric constraints, the optimization efficiency is further improved. Aljaidi et al. [17] proposed a multi-objective RIME optimization framework (MORIME). By Combining with the multi-objective optimization technology, engineers can optimize multiple objectives (such as weight, strength, cost, etc.) simultaneously in the truss design. Jangir et al. [18] proposed a new multi-objective non-sorting Harris Eagle optimizer (NSHHO). The NSHHO algorithm has advantages in solving unconstrained, constrained, and realistic problems with different linear, nonlinear, continuous, and discrete characteristics based on the Pareto frontier, and provides a new solution for the optimization of complex engineering problems. Li et al. [19] utilized the Moving Least Squares (MLS) absorption method, Kriging model, Marine Predator Algorithm (MPA), Vector surrogate modeling method, and Hybrid Collaborative Sampling technique and proposed a vectorial surrogate modeling method based on the moving Kriging (MK-VSMM) model. By comparing with alternative methods, it is demonstrated that the developed MK-VSMM exhibits exceptional modeling and simulation performance. Liu et al. [20] proposed a vector surrogate modeling method based on the Moving Kriging Method (MK-VSMM) model to establish a multi-fidelity Co Kriging surrogate model for ship hydrodynamic performance optimization. The results showed that the optimal ship obtained had a better resistance optimization effect. Kyprioti et al. [21] proposed a new adaptive experimental design framework that combines predicted variance and LOOCV error as weight factors for Kriging element modeling. Engineers can explore and develop by adjusting coefficient balance, and optimize weight estimation using nearest neighbor interpolation. The results show that the proposed method performs better in six examples, is suitable for local nonlinear functions, and has lower computational costs. Mehmani et al. [22] introduced an automated surrogate model selection framework named COSMOS, which aims to meet the modeling demands of complex system design problems. Zhang and Taflanidis [23] proposed an efficient optimization method based on the surrogate model to solve design problems with multiple random objectives. It extends the MODU-AIM algorithm previously used for dual objective problems by introducing a Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm (MOEA) to handle situations with more than two objectives. Currently, the optimization of fishing boat winches faces several key issues. Firstly, the optimization is primarily focused on the individual components, lacking a comprehensive approach to optimize the entire equipment. This study blanking in the multi-objective optimization research of fishing boat winches has resulted in the absence of a reliable system multi-objective optimization framework.

While the traditional design adopts empirical formulas, there are the following problems: (1) The design based on the empirical formula of specific materials (such as steel), it cannot directly adapt to the nonlinear mechanical behavior of new materials (such as FRP), resulting in falsely high safety factor or failure risk; (2) The design compensates for uncertainty through amplification of safety factor, resulting in material redundancy and weight out of limits; (3) The design paradigm with single index as the core cannot quantify the conflict relation among lightweight, rigidity and cost, resulting in the imbalance of comprehensive performance.

Traditional optimization methods such as single surrogate models have the following problems: (1) Poor adaptability of model assumptions: Kriging: Based on the spatial correlation assumption, the interpolation error of non-uniform sampling data is significant. Polynomial response surface (PRS): The dragging phenomenon is likely to occur in high-order nonlinear problems, such as dynamic tension fitting failure of winch wire rope; (2) High-dimensional disaster and over-fitting: when the design variable exceeds 5 dimensions, the prediction accuracy of single-surrogate model drops sharply. Under the small sample training, the support vector regression (SVR) is likely to over-fit the noise data, and the generalization ability is poor; (3) Inefficiency of multi-objective optimization: multiple calls are required to calculate Pareto frontier, and the calculation time of single-surrogate model increases exponentially. In case of target conflict, it is difficult for a single model to capture a non-convex solution set, resulting in a local optimal trap.

Furthermore, various methods have been employed by researchers to optimize the design of wind turbines, wheels, and bodies. These methods include radial basis function neural networks, Kriging, surrogate models, and multi-objective genetic algorithms. Implementing these methods has led to improved performance, decreased weight, and enhanced stability of the subjects under investigation. Consequently, this article proposes the use of a surrogate model and multi-objective genetic algorithms to optimize fishing boat winches and presents a multi-objective optimization framework that encompasses the entire equipment as the object of study. It solves the problems of poor material adaptability, multi-objective conflict, and inaccurate dynamic response prediction in the design of new fishing winches. Its advantages are reflected not only in the improvement of performance indicators but also in providing a scalable and adaptive optimization model for complex engineering systems. Furthermore, they provide a key technical path for the upgrading of fishery equipment and the design of green ships.

The innovations in this paper are summarized as follows:

(1) Theoretical innovation: We have compared different surrogate models by error analysis, selected an optimal model to replace the original complex model, and proposed an expensive multi-objective optimization framework based on the combined surrogate model and mixed error indicators;

(2) Application and innovation: The proposed method is applied to the multi-objective lightweight problem of FRP fishing boat winches, filling the current research gap of multi-objective winch systems at home and abroad, and promoting the transformation and upgrading of ship equipment.

The subsequent sections of this article are organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the overall framework and relevant theories of the proposed method, while Section 3 performs pre-processing for the multi-objective optimization of winches. In Section 4, the proposed method is employed to undertake a multi-objective optimization design for an engineering case to validate its effectiveness. Finally, the main conclusions are drawn.

2 Optimization Framework and Related Theories

2.1 Proposed Overall Optimization Framework

Since this study concentrates on the multi-objective lightweight design of structures, it is necessary to first define the multi-objective optimization problem, including the parameters comprising the design variables, objective function, and constraint function. Subsequently, a finite element model (FEM) must be constructed to define the stiffness DM, safety factor SF, and mass GM performance indicators. Following this, the design variables and their upper and lower limits should be determined, and a parameterized FEM should be created. Three kinds of surrogate models, namely Kriging, genetic aggregation (GA), and RBFNN, are constructed. Then the optimal surrogate model with the optimal performance prediction effect of each target is selected through the error size. Based on the determined surrogate model, a multi-objective optimization model is constructed. Then, the Pareto solution set is obtained through the multi-objective genetic algorithm (MOGA) algorithm, and the selected design point is verified and analyzed. Finally, the multi-objective optimization design can be finalized.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, the overall multi-objective optimization framework for the entire system is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Multi-objective optimization design scheme

The surrogate model, also known as the approximate model, refers to the construction of efficient mathematical models through a series of mathematical formulas to replace actual analytical models. In practical engineering problems, the relationship between input and output is often a black-box function that cannot be directly obtained. Evaluating the target response under multiple different parameters requires a large number of simulation calculations as the basis. Using surrogate models instead of large-scale simulation calculations can greatly reduce computational costs and optimization cycles.

Nowadays, the commonly used single surrogate models include Polynomial Response Surface (PRS) [24], Kriging [25–27], Multivariate Adaptive Regression Spline (MARS) [28,29], Artificial Neural Network (ANN) [30–33], and Support Vector Regression (SVR) [34,35].

Ensemble surrogate models integrate multiple single surrogate models, improving predictive capabilities through weighted averaging, dynamic selection, or stacking strategies. By using model complementation, the deviation is reduced, and the precision is improved significantly in high-dimensional/nonlinear problems, which makes the ensemble surrogate models applicable to complex problems under multiple working conditions. The performance comparison analysis of the single surrogate model and combined surrogate model is shown in Table 1 below:

The Kriging model was first proposed by Krige [26] as an interpolation method, and Matheron [27] systematically and theoretically analyzed its results, thus obtaining a mathematical expression. Subsequently, Lophaven et al. [36] proposed an auxiliary design analysis method based on the DoE method and Kriging technique. This model is an interpolation model suitable for approximating deterministic computer simulations, which can represent multiple characteristic functions and provide estimates of uncertainty [37–39]. The relevant expressions for the Kriging model are as follows:

in the formula:

Radial basis function neural network (RBFNN) is a commonly used artificial neural network model, widely used in fields such as mechanical product optimization design, pattern recognition, prediction, and control. Its core is the radial basis function (RBF), which is a local function whose output is only related to the distance from each point in the input space to the center of the network. This property gives RBFNN advantages such as fast convergence, high-precision approximation, and good robustness. The structure of RBFNN consists of three layers: the input layer, the hidden layer, and the output layer. Among them, the hidden layer is composed of several radial basis functions, each of which has a center and a bias, while the output layer is linear. The training process of the network includes two steps: first, to use a clustering algorithm to determine the center of each radial basis function, and then to use the least squares method to determine the weights [40].

In the RBFNN model, the mathematical relationship between the output layer nodes and the hidden layer nodes is expressed as follows:

where

Due to the error between the response surface model and the real model, this error affects the accuracy and reliability of the optimized design results. If the error exceeds the allowable range, the model must be redesigned with experimental samples. So before optimizing, it is necessary to conduct error analysis on the approximate response surface model to determine its accuracy. The accuracy of the response surface is determined by the coefficient of determination

(1)

in the formula:

(2) RMAE:

in the formula:

(3) RAAE:

where:

The range of values for

The closer RMAE and RAAE are to 0, the smaller the prediction error of the proxy model and the higher the accuracy of the surrogate model.

MOGA is a typical Pareto method that was the first to explicitly use Pareto sorting and niche techniques to search for the Pareto optimal frontier. This approach aims to improve population diversity and prevent premature convergence of the solution population [41].

The MOGA algorithm ranks all individuals in the population using the concept of “Pareto optimal individuals” and performs selection operations based on this ranking order during the evolutionary process. This ensures that the top Pareto optimal individuals have a higher chance of being inherited into the next generation population. After a certain number of iterations, the MOGA algorithm can ultimately search for the Pareto optimal solution for multi-objective optimization problems [42].

The MOGA flowchart, shown in Fig. 2, consists of the following steps:

1. Population initialization: Randomly generate a set of individuals, each representing a potential solution.

2. Fitness calculation: Calculate the fitness value for each individual using multiple objective functions and obtain a fitness vector.

3. Pareto front sorting: Sort individuals based on their fitness vectors and divide them into different Pareto fronts. A solution is considered Pareto optimal if it is not dominated by other solutions.

4. Crowding distance calculation: Calculate the distance between each individual and its neighboring individuals within each Pareto front to maintain population diversity.

5. Selection operation: Select a group of individuals from the population to generate the next generation of individuals. The selection strategy is typically based on Pareto front and crowding distance.

6. Crossover and mutation operations: Perform crossover and mutation operations on the selected individuals to generate new individuals and add them to the next generation population.

7. Population update: Replace the existing individuals with the new ones to form the next generation population.

8. Termination condition: Stop the algorithm if the predetermined number of iterations is reached or a satisfactory solution is found.

Figure 2: Genetic algorithm flow chart

3 Multi-Objective Optimization Pre-Processing for Winches

This article selects a 10 t electric winch from a specific enterprise as the research object and conducts multi-objective optimization on the electric winch to achieve the goals of reducing weight, increasing safety factor, and minimizing deformation during operation without making significant adjustments to the manufacturing process. The 3D model of the electric winch is shown in Fig. 3 and consists primarily of a rope guide, drum, reducer, brake device, motor, and wall frame. The technical parameters are provided in Table 2.

Figure 3: Engineering model of electric winch. 1—Rope guide; 2—Drum; 3—Reducer; 4—Brake device; 5—Motor; 6—Wall frame

3.2 Initial Performance Analysis under Multiple Operating Conditions

During the actual operation of the electric winch, the position of the rope guide changes according to the direction of the wire rope. When the rope guide is located at both ends, the force on the drum is at its maximum. At this time, the flange plates on both sides of the drum experience the highest level of extrusion stress. In addition to the extrusion stress on the flange plate, the drum also experiences the effects of gravity, torque, and extrusion stress from the steel wire rope on the drum, as well as the braking torque from the brake.

The drum and rope guide are the main components of the winch, and the load they bear can be divided into six parts: the gravity of the wire rope on the drum, the torque of the wire rope on the drum, the extrusion stress caused by the wire rope on the drum, the extrusion stress on the flange plate of the drum, the torque of the brake on the drum, and the torque of the wire rope on the drum.

(1) The gravity of the wire rope on the drum:

where:

(2) Torque of the wire rope on the drum:

where:

(3) The extrusion stress of the steel wire rope on the drum, pointing to the axis:

where:

(4) The rope extrusion stress on the drum flange plate:

where:

(5) Torque of the brake on the drum:

where:

(6) The extrusion force of the steel wire rope on the drum:

In the case of an electric winch used on a fishing boat, the maximum lateral force occurs when the rope is at the left and right limit positions. One position is when the rope is close to the wall frame (referred to as condition 1), and the other position is when the rope is close to the reducer (referred to as condition 2). The remaining stress is analyzed based on the calculations mentioned above. Therefore, this paper conducts a performance analysis of a fishing boat electric winch under extreme working conditions, focusing on these two working conditions.

By solving and analyzing the winch with an added load, the maximum deformation, minimum safety factor, and position can be determined. The result is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Analysis of cloud chart

According to the analysis results of condition 1, it can be observed that under the current working condition, the maximum deformation of the electric winch occurs at the brake side plate. However, the maximum deformation is very small and does not affect the normal operation. In terms of safety factor, the minimum equivalent stress safety factor is 1.94, which is located at the drum.

According to the analysis results of condition 2, it can be observed that condition 2 bears some resemblance to condition 1. Under condition 2, the side plate of the gearbox is where the maximum deformation of the electric winch is located. However, this maximum deformation is very small and does not impact the normal operation of the winch. In terms of safety factor, the minimum equivalent stress safety factor is 2.01.

Based on the analysis results, it is evident that the drum serves as the primary load-bearing component. The significant deformation and low safety factor are mainly concentrated in the drum, while there is considerable potential for multi-objective optimization in other parts.

3.3 Establishment of an Optimization Model

When conducting multi-objective optimization of the electric winch, it is essential to establish the fundamental principles of the design. These principles include:

(1) Minimize the weight of the electric winch, maximize the safety factor, and minimize the maximum deformation without influencing the performance requirements of the winch. It is recommended to select the design variables that have a high probability of influencing the weight, safety factor, and maximum deformation of the winch based on enterprise experience.

(2) Determine the trade-off relationship. Since there are multiple optimization objectives, there may be conflicts or competition between different objectives. In such cases, it is crucial to consider the trade-off relationship between them and determine the priority of the results. The significance of this paper lies in improving the winch structure and reducing its weight. Under the condition of significant weight reduction, the requirements for the minimum safety factor and maximum deformation of the winch can be appropriately relaxed as long as they remain within a reasonable range of application.

(3) Ensuring the manufacturability of the electric winch after optimization is crucial. The Pareto solution obtained through the multi-objective optimization algorithm must meet the manufacturability requirements of the enterprise. This includes ensuring that the plate thickness parameter is an integer and is available for use by the enterprise. Furthermore, the manufacturing process of the winch should not be adjusted, and the manufacturing cost should be minimized as much as possible.

After considering the optimized components, sizes, and the aforementioned finite element analysis results, a total of 20 parameters have been selected as design variables, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Electric winch and parameter model

According to the characteristics of the model’s structure size, it can be observed that excessive changes in the equivalent up and down will not cause automatic modeling errors that affect the generation of the model. The upper limit parameter size of the design variable is set at 135% of the initial size, while the lower limit is set at 65% of the initial size. To avoid model reconstruction errors during subsequent optimization, the upper limit size of parameter X7 is defined as 130% of the initial size, while the lower limit is set at 70% of the initial size. The upper and lower limits of the dimensional variables of the electric winch are presented in Table 3.

When establishing the multi-objective optimization model, it is essential to confirm the design variables, constraints, and objective functions of the components. In this optimization, the aforementioned 20 parameters are chosen as the design variables. At the same time, we need to minimize the mass and deformation coefficient and increase the safety coefficient. Following enterprise requirements and considering actual working conditions, the equivalent stress safety factor should not be less than 1.3, and the maximum deformation must be limited to 2 mm. Based on these criteria, the multi-objective optimization model is formulated as follows:

4 Multi Objective Optimization Design of Winch

Once the multi-objective optimization model is established, a design of experiments (DoE) is conducted for the winch. A total of 200 sample points is selected for this test, and 200 sets of sample points are obtained through finite element analysis, as shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: DoE sample points of electric winch

4.2 Surrogate Model Construction

The response surface function is constructed using GA, RBFNN, and Kriging. RMAE, RAAE, and R2 are used to judge the accuracy of the response surface after the construction of the response surface function. The results of the error analysis are presented in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Result error and judgment result of response surface model. (a)

It can be observed that when the Kriging method is used to fit the response surface of the model, the determination coefficient

Based on the data in the figure, the RAAE and RMAE error metrics are scaled to a range of 0–1 (the smaller the value, the better) and combined with the

E is the original error,

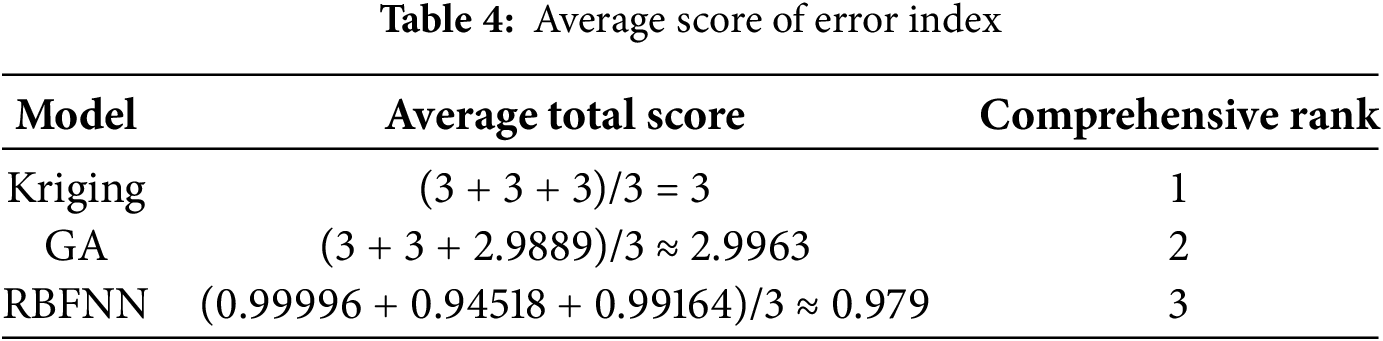

The smaller the error is, the higher the score is. The score obtained is shown in Table 4:

It can be seen that for all target parameters, Kriging’s error index has RAAE = 0, RMAE = 0, and R2 = 1. As a result, the comprehensive score is full (3.0), and the performance is perfect. Therefore, Kriging will be selected as the approximate function of GM subsequently.

The sensitivity analysis results of design variables to SF, DM and GM of optimization target are shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Sensitivity analysis diagram of optimization target

According to the sensitivity analysis chart, it can be observed that design variables X17 and X19 have the highest sensitivity to the optimization target results, making the greatest contribution to the maximum safety factor and showing a positive effect. On the other hand, X16 and X19 have the most impact on the maximum deformation, exhibiting a negative effect. Regarding quality, X16 and X18 make the highest contribution and have a positive effect. Thus, the two design variables that have the greatest impact on the target are selected to generate response maps for X17 and X19 to SF, X16 and X19 to DM, and X16 and X18 to GM. The three-dimensional response surface characteristics are shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Three-dimensional response surface characteristics. (a) Response diagram of X17 and X19 to SF; (b) Response diagram of X16 and X19 to DM; (c) Response diagram of X16 and X18 to GM

Before solving the approximate response surface function, the first step is to select a more suitable optimization algorithm. In this optimization, a multi-objective genetic algorithm is chosen to solve problems with multiple objectives. Through a multi-objective genetic algorithm, multiple sets of solutions can be found, and the global optimal solution can be found in a relatively short time through parallel search capability, which is suitable for complex nonlinear problems.

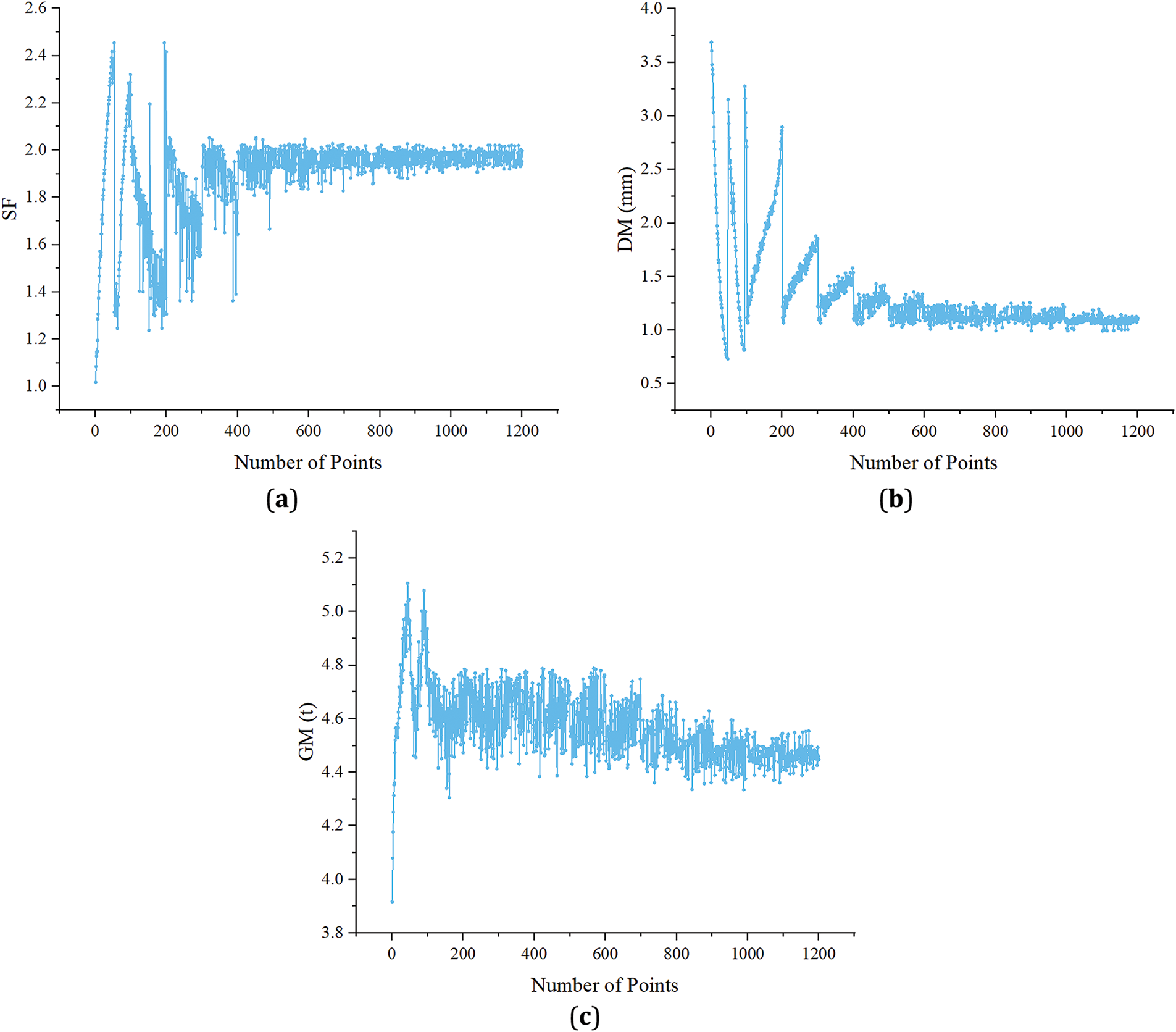

When solving, the mass of the optimized object is set to be minimized, the constraint objective safety factor is maximized, and the maximum deformation is minimized. The initial sample points are set to 100, and the maximum number of iterations is set to 1000. Each time, 100 samples are generated, resulting in an expected number of evaluations of 1E+5. The iteration diagram is shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Iteration diagram. (a) Iteration diagram of safety factor; (b) Iterative graph of maximum deformation; (c) Iterative graph of quality

After a large number of iterative calculations, some candidate points were selected from the generated 100,000 sample points, and the resulting Pareto solution set is shown in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Pareto solution set

Analysis of the above chart shows that in the non-dominated solutions, solution B has the best weight optimization effect, but its safety factor has decreased. Although the maximum deformation of solution A has slightly increased, the weight optimization is obvious, and the safety factor is also above the initial safety factor. Therefore, it is proposed to use solution A for subsequent optimization and verification analysis.

Based on the determination of solution A and performance prediction using a surrogate model, the performance prediction data shown in Table 5 were obtained. According to the results, the optimized electric winch weighs 4426 kg, which is about 7.6% lower than the previous 4791 kg. The optimization effect is significant.

Due to errors in the solutions obtained based on the surrogate model, it is necessary to reintroduce the optimized design variables into the model for performance analysis. The design variables in the solution A obtained through solving have a significant impact on machining accuracy, which does not meet the processing requirements of real-world enterprises. For instance, the board’s thickness accuracy is designed to be 0.01 mm, while enterprises typically purchase boards with integer thickness for processing. Therefore, it is necessary to round the design variable data and incorporate it into the model for scheme validation analysis. The results of the comparative analysis of the adopted design variables are shown in Table 6.

The results obtained from the validation analysis of the adopted design points are presented in Table 7. The results indicate that the maximum prediction error of DM, SF, and GM was −2.70%, while the prediction error of the other two targets was less than 1%. Based on the results, it can be observed that the proposed multi-standard optimization scheme for the electric winch system yields a 7.86% reduction in weight, a 2.01% increase in safety factor, and a 23.97% reduction in maximum deformation, demonstrating a significant overall optimization effect.

In order to meet the processing requirements of the enterprise, the structural parameters according to the requirements of the quality processing technology need to be rounded. Through the production of the optimized physical prototype, the prototype indeed achieves a weight reduction of 376 kg. As the strength and rigidity are not easy to test on-site, the simulation model is used to simulate the ultimate working condition on the ship for design and production, and enterprises generally verify the relevant performance based on this method.

In terms of the actual effect, according to the material price of the electric winch and the data, the price of the marine winch with a tension of 10 t is generally about 30,000 yuan, while the price of the winch can be reduced by about 2400 yuan by reducing 7.86% of the mass. Taking 100 series winches produced by the enterprise per year as an example, the accumulated annual material cost can be reduced by 240,000 yuan, with high economic benefits and market competitiveness. The 2.01% safety factor increases the wind and wave resistance of the winch during operation, prolongs the service life of the equipment, and reduces the accident rate. The maximum deformation reduction of 23.97% can reduce the accuracy error of the steel wire rope, avoid the tearing of the fishing net or the escape of the fish, and also enhance the durability of the equipment structure.

On the whole, the optimized electric winch can better adapt to the FRP fishing vessels, conforming to the trend of replacing traditional fishing vessels with FRP fishing vessels. It can not only reduce the use of manufacturing materials and reduce the waste of resources, but also reduce the overall load of FRP fishing vessels, thus reducing fuel consumption, prolonging the endurance time, and reducing carbon emissions, which conform to the national call for “double carbon (carbon peak, carbon neutralization)”. For shipboard operators, mass reduction allows for more flexible positioning of electric winches, improving both accuracy and efficiency for fishing operations.

A method has been proposed for optimizing the parameters of marine winches by combining a surrogate model with MOGA. This method effectively reduces complexity and improves the efficiency of the optimization process by using experimental design to select sample points and replacing the original model with a surrogate model. Additionally, the performance of the winch has been significantly improved through a multi-objective genetic algorithm. The effectiveness of the proposed optimization strategy was verified through a comparative analysis of predicted and calculated values. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) An optimization framework has been proposed to solve a series of optimization problems for expensive mechanical products, providing a better path for the optimization design of three-dimensional engineering structures.

(2) The proposed optimization framework was applied to the fishing winch. After optimization, the values of some parts with high stress, such as X14 (wall frame length), X19, and X20 (drum flange reinforcement thickness), were increased. On the other hand, the values of some parts with low stress, such as X1, X2 (upper box thickness), and X7 (rope rack support width), were reduced. Ultimately, the weight of the winch was reduced by 7.86%, the safety factor was increased by 2.01%, and the maximum deformation was reduced by 23.97%. This verifies the effectiveness of the proposed scheme.

This research has made good progress in the multi-objective optimization design of the fishing boat’s electric winch. The proposed series of optimization methods has a certain guiding significance for the optimization and upgrading of the fishing boat’s electric winch and other series of products. The proposed framework and series of methods can be considered for the popularization and application of the fishing boat’s electric winch and other equipment. However, this study only considers the optimization of the structural parameters of the electric winch. In the future, a multi-objective optimization study will be carried out on the electric winch of the fishing vessel from the material, process, control, and other aspects. Meanwhile, the model will be extended to different winch types or other deck machinery for research.

Acknowledgement: The first author is pleased to acknowledge the helps of the China Fishery Equipment Technology Innovation Alliance and Jiesheng Marine Equipment Company.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Basic Public Welfare Research Program of Zhejiang Province (No. LGN22E050005).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization and methodology, Ji Lin; formal analysis, writing—review and editing and writing—original draft preparation, Chunhuan Jin; supervision and project administration, Quanliang Liu; funding acquisition, Linsen Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of his study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Coronil-Huertas DJ, Rodriguez-García C, Pavón-Quintana S, Vidal-Pérez JM, Sarmiento-Carbajal J, Cabrera-Castro R. Optimization of the stowage of fishing discards: innovations in trawlers in the gulf of Cadiz (SW Iberian Peninsula). Reg Stud Mar Sci. 2024;76(1):103593. doi:10.1016/j.rsma.2024.103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lee TH, Lee NU, Lee DJ, Jung BK. Analysis of ship noise characteristics generated according to sailing conditions of the G/T 1000-ton stern fishing trawler. J Mar Sci Eng. 2021;9(8):914. doi:10.3390/jmse9080914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wei S, Zhang Y. Research on the coupling and coordinated development of digital economy and green innovation efficiency. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Internet Finance and Digital Economy; 2022 Aug 19–21; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. doi:10.1142/9789811267505_0035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Solovyov V, Cherniavsky A. Computational and experimental analysis of trawl winches barrels deformations. Eng Fail Anal. 2013;28:160–5. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2012.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wu C, Wang S, Long J, Liu Q. Research on modular design and manufacturing of ship anchor winch structure under artificial intelligence optimisation. Int J Wirel Mob Comput. 2022;22(2):148. doi:10.1504/ijwmc.2022.123315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ye H, Li W, Lin S, Ge Y, Han F, Sun Y. Experimental investigation of spooling test on the multilayer oceanographic winch with high-performance synthetic fibre rope. Ocean Eng. 2021;241:110037. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.110037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sarca A, Leordean D, Vilău C. Studies regarding redesign and optimization of the main shaft of a naval winch. Appl Mech Mater. 2015;808:271–9. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.808.271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Jia D, Li F. Design of bulkhead reinforcement of trimaran based on topological optimization. Ocean Eng. 2019;191(12):106498. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2019.106498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Huda N, Mursid O. Finite element analysis and topology optimization design of anchor mooring winch support bracket. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2022;972(1):012078. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/972/1/012078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Putra GL, Kitamura M. Study on optimal design of hatch cover via a three-stage optimization method involving material selection, size, and plate layout arrangement. Ocean Eng. 2021;219(3):108284. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2020.108284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Coello Coello CA, Lechuga MS. MOPSO: a proposal for multiple objective particle swarm optimization. In: Proceedings of the 2002 Congress on Evolutionary Computation; 2002 May 12–17; Honolulu, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/CEC.2002.1004388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Deb K, Jain H. An evolutionary many-objective optimization algorithm using reference-point-based nondominated sorting approach, part I: solving problems with box constraints. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2014;18(4):577–601. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2013.2281535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jiao R, Zeng S, Li C, Yang S, Ong YS. Handling constrained many-objective optimization problems via problem transformation. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2021;51(10):4834–47. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2020.3031642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Khishe M, Orouji N, Mosavi MR. Multi-objective chimp optimizer: an innovative algorithm for multi-objective problems. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;211(7):118734. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Xiong F, Wang D, Ma Z, Chen S, Lv T, Lu F. Structure-material integrated multi-objective lightweight design of the front end structure of automobile body. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2018;57(2):829–47. doi:10.1007/s00158-017-1778-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang D, Wang Z, Ling H, Zhu X. Kriging-based shape optimization framework for blended-wing-body underwater glider with NURBS-based parametrization. Ocean Eng. 2021;219(58):108212. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2020.108212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Aljaidi M, Mashru N, Patel P, Adalja D, Jangir P, Arpita, et al. MORIME: a multi-objective RIME optimization framework for efficient truss design. Results Eng. 2025;25(5):103933. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jangir P, Heidari AA, Chen H. Elitist non-dominated sorting Harris Hawks optimization: framework and developments for multi-objective problems. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;186(2):115747. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li ZA, Dong XW, Zhu CY, Chen CH, Zhang H. Vectorial surrogate modeling method based on moving Kriging model for system reliability analysis. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2024;432(1):117409. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2024.117409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu X, Zhao W, Wan D. Multi-fidelity Co-Kriging surrogate model for ship hull form optimization. Ocean Eng. 2022;243(1):110239. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.110239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kyprioti AP, Zhang J, Taflanidis AA. Adaptive design of experiments for global Kriging metamodeling through cross-validation information. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2020;62(3):1135–57. doi:10.1007/s00158-020-02543-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mehmani A, Chowdhury S, Meinrenken C, Messac A. Concurrent surrogate model selection (COSMOSoptimizing model type, kernel function, and hyper-parameters. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2018;57(3):1093–114. doi:10.1007/s00158-017-1797-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang J, Taflanidis AA. Evolutionary multi-objective optimization under uncertainty through adaptive Kriging in augmented input space. J Mech Des. 2020;142(1):011404. doi:10.1115/1.4044005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Schmit LAJr., Farshi B. Some approximation concepts for structural synthesis. AIAA J. 1974;12(5):692–9. doi:10.2514/3.49321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mastrippolito F, Aubert S, Ducros F. Kriging metamodels-based multi-objective shape optimization applied to a multi-scale heat exchanger. Comput Fluids. 2021;221(5):104899. doi:10.1016/j.compfluid.2021.104899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Krige DG. A statistical approach to some basic mine valuation problems on the Witwatersrand. J S Afr Inst Min Metall. 1952;4:201–15. [Google Scholar]

27. Matheron G. Principles of geostatistics. Econ Geol. 1963;58(8):1246–66. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.58.8.1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Dey P, Das AK. Application of multivariate adaptive regression spline-assisted objective function on optimization of heat transfer rate around a cylinder. Nucl Eng Technol. 2016;48(6):1315–20. doi:10.1016/j.net.2016.06.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Friedman JH. Multivariate adaptive regression splines. Ann Statist. 1991;19(1):1–67. doi:10.1214/aos/1176347963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Buhmann M. Radial basis functions: theory and implementations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. 272 p. [Google Scholar]

31. Buhmann MD, Levesley J. Radial basis functions: theory and implementations. Math Comput. 2004;73:1578–81. [Google Scholar]

32. Park DC, El-Sharkawi MA, Marks RJ, Atlas LE, Damborg MJ. Electric load forecasting using an artificial neural network. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 1991;6(2):442–9. doi:10.1109/59.76685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liu X, Liu X, Zhou Z, Hu L. An efficient multi-objective optimization method based on the adaptive approximation model of the radial basis function. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2021;63(3):1385–403. doi:10.1007/s00158-020-02766-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Xiang H, Li Y, Liao H, Li C. An adaptive surrogate model based on support vector regression and its application to the optimization of railway wind barriers. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2017;55(2):701–13. doi:10.1007/s00158-016-1528-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Smola AJ, Schölkopf B. A tutorial on support vector regression. Stat Comput. 2004;14(3):199–222. doi:10.1023/B:STCO.0000035301.49549.88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Lophaven SN, Nielsen HB, Søndergaard J. DACE—a matlab kriging toolbox [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 20]. Available from: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=faa5c71aeea78dd50c6c85e2a087307d292170b7. [Google Scholar]

37. Zhang Y, Yao W, Ye S, Chen X. A regularization method for constructing trend function in Kriging model. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2019;59(4):1221–39. doi:10.1007/s00158-018-2127-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhou Q, Wu J, Xue T, Jin P. A two-stage adaptive multi-fidelity surrogate model-assisted multi-objective genetic algorithm for computationally expensive problems. Eng Comput. 2021;37(1):623–39. doi:10.1007/s00366-019-00844-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Fu C, Wang P, Zhao L, Wang X. A distance correlation-based Kriging modeling method for high-dimensional problems. Knowl Based Syst. 2020;206:106356. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2020.106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen Q, Zhang J, Zhang C, Zhou H, Jiang X, Yang F, et al. CFD analysis and RBFNN-based optimization of spraying system for a six-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) sprayer. Crop Prot. 2023;174(5):106433. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2023.106433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Tian Y, Cheng R, Zhang X, Cheng F, Jin Y. An indicator-based multiobjective evolutionary algorithm with reference point adaptation for better versatility. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2018;22(4):609–22. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2017.2749619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ma H, Fei M, Jiang Z, Li L, Zhou H, Crookes D. A multipopulation-based multiobjective evolutionary algorithm. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2020;50(2):689–702. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2018.2871473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools