Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Modeling and Simulation of Epidemics Using q-Diffusion-Based SEIR Framework with Stochastic Perturbations

1 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, College of Science, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, 11623, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Mathematics and Sciences, College of Humanities and Sciences, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, 11586, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Mathematics, Air University, PAF Complex E-9, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Muhammad Shoaib Arif. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Mathematical Modeling: Numerical Approaches and Simulation for Computational Biology)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 143(3), 3463-3489. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.066299

Received 04 April 2025; Accepted 12 May 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

The numerical approximation of stochastic partial differential equations (SPDEs), particularly those including q-diffusion, poses considerable challenges due to the requirements for high-order precision, stability amongst random perturbations, and processing efficiency. Because of their simplicity, conventional numerical techniques like the Euler-Maruyama method are frequently employed to solve stochastic differential equations; nonetheless, they may have low-order accuracy and lower stability in stiff or high-resolution situations. This study proposes a novel computational scheme for solving SPDEs arising from a stochastic SEIR model with q-diffusion and a general incidence rate function. A proposed computational scheme can be used to solve stochastic partial differential equations. For spatial discretization, a compact scheme is chosen. The compact scheme can provide a sixth-order accurate solution. The proposed scheme can be considered an extension of the Euler Maruyama method. Stability and consistency in the mean square sense are also provided. For application purposes, the stochastic SEIR model is considered using q-diffusion effects. The scheme is used to solve the stochastic model and compared with the Euler-Maruyama method. The scheme is also compared with nonstandard finite difference method for solving deterministic models. In both cases, it performs better than existing schemes. Incorporating q-diffusion further enhanced the model’s ability to represent realistic spatial-temporal disease dynamics, especially in scenarios where classical diffusion is insufficient.Keywords

Epidemic modelling has historically been fundamental in comprehending and managing infectious diseases. The SEIR (Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Recovered) model is significant among many models due to its capacity to represent the dynamics of diseases with a latent period, like measles, influenza, and the new coronavirus. This model categorizes the population into four separate compartments, offering a framework to examine the transmission and potential control techniques for infectious illnesses.

The conventional SEIR model has been thoroughly examined; however, real-world situations frequently require adaptations to address more intricate dynamics, including spatial dispersion and atypical incidence rates. Incorporating diffusion factors in epidemic models facilitates the simulation of spatial dissemination, an essential element in comprehending small outbreaks and their potential progression into extensive epidemics. Conventional diffusion models presume uniform distribution; however, the emergence of q-diffusion provides a more generalized and adaptable methodology. Using non-linear diffusion processes as its foundation, q-diffusion is a parameterized diffusion model that accurately shows different spreading rates and changes in population density and movement patterns.

Advantages of the SEIR Framework:

1. The SEIR model has an exposed (E) compartment that specifically reflects those infected but not yet contagious. Diseases with a notable incubation time and a lag between exposure and infectiousness are especially well-suited for the SEIR model.

2. The SIR model (Susceptible-Infected-Recovered) presumes no latent period; people immediately become infectious following exposure. Though less accurate for diseases like COVID-19, measles, tuberculosis, or influenza when a delay between infection and infectiousness exists, it is appropriate for diseases with very short or insignificant incubation periods.

3. COVID-19, measles, tuberculosis, and influenza show important transmission dynamics during incubation. Simpler models (like SIR) can produce false forecasts about outbreak time and control actions without explicitly incorporating this delay.

4. Including the exposed class lets one more realistically model intervention tactics like contact tracing and quarantine that aim at people in the latent (exposed) stage before they become contagious.

5. Additionally, the SEIR model framework improves the ability to estimate the basic reproduction number

Thus, the SEIR model forms a natural foundation for studying the spatial-temporal spread of infectious diseases, especially when combined with modern extensions like stochastic perturbations and generalized diffusion effects, as considered in this study.

Stochastic effects: Because actual disease transmission is naturally unpredictable owing to differences in human behavior, environmental variables, and intervention programs, stochastic effects are quite important. Deterministic models can miss the variety and uncertainty in case counts, especially in the early phases of outbreaks or small populations. Including stochasticity helps to more accurately portray epidemic dynamics, including the likelihood of disease extinction, outbreak variability, and random deviations around mean paths.

Spatial diffusion: Spatial diffusion explains why infectious diseases do not spread consistently. Transmission, on the other hand, is affected by local clustering, mobility patterns, and regional variation in contact rates. Spatially explicit models, particularly those including generalized diffusion such as q-diffusion, can mimic events like the wave-like spread of diseases or the generation of localized hotspots.

Studying infectious diseases and their transmission among populations is crucial in epidemiology for reducing outbreaks and developing efficient control techniques. Contagious diseases have consistently posed a significant issue for public health experts, academics, and policymakers globally. Understanding the evolution of epidemics is essential for formulating effective control methods and comprehending the complex interplay between human behaviour, environmental factors, and disease transmission.

The groundbreaking SIR (Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered) model, first presented in 1927 by pioneers Kermack and McKendrick [1], is the ancestor of the SEIR model. In their innovative study, they set out to investigate the mechanisms that control the spread of infectious diseases. An expansion of the SIR model, the SEIR model takes into account a crucial component of infectious diseases: the latent or incubation period. This better represents the real progression of numerous infectious diseases, including Ebola, HIV/AIDS, and COVID-19, wherein a person may be infected but not yet contagious. You can estimate an extra parameter using the supplied data when you include the “Exposed” compartment. As a result, key epidemiological factors such as the disease’s transmission rate and incubation period can be more precisely estimated. In recent years, extensive research has been conducted on the SEIR epidemic model, as evidenced by sources [2–5].

A vital component of contemporary epidemic modelling is the depiction of the incidence rate. Classical models frequently utilize a bilinear or mass-action incidence function, which may inadequately represent the intricacies of disease transmission dynamics. Integrating a generalized incidence rate considering behavioural modifications, and saturation effects improves the model’s precision and relevance [6].

The increasing complexity of these advanced models needs strong numerical methods that can accurately and stably capture their intricate dynamics. Analytical solutions for these models are frequently inaccessible because of the non-linear and stochastic characteristics of the governing equations, requiring the creation of effective computational methods [7]. A computational framework designed for the SEIR model incorporating q-diffusion and a generalized incidence rate can yield significant insights into disease dynamics, serving as a robust tool for decision-making for policymakers and healthcare professionals [8].

Not all populations experience the same rate of epidemic spread. An important factor in the spread of diseases is geographical heterogeneity, including human movement, age, population density, place, and physical obstacles. Epidemic models rely on diffusion, which considers the geographical spread of infectious diseases [9]. Policymakers can make educated judgments regarding resource allocation and intervention tactics using diffusion models, which incorporate geographical features, human mobility patterns, and contact networks. Since diseases might spread from one place to another, these models help determine which areas should receive vaccinations first, increasing the effectiveness of these programs in disease management.

Diffusion models can be broadly classified into two categories: local and non-local. In local diffusion, as described by the Laplacian operator, the primary factor influencing the spread of a phenomenon (in this case, a disease) is the degree to which it interacts with and is connected to nearby or neighbouring areas. Capone et al. [10] examine a reaction-diffusion SEIR model for infectious diseases, examining the non-linear asymptotic stability of the endemic equilibrium, studying long-term solution behaviour, and locating absorbing sets in phase space. In their analysis of a diffusive SEIR model with non-linear incidence, Han and Lei [11] highlighted the importance of the parameter in the persistence and extinction of diseases by concentrating on the global stability of the equilibria.

In contrast, the idea of non-local diffusion suggests that a phenomenon might extend over greater distances than just its immediate surroundings. Due to its mathematical attractiveness and large epidemiological insights, the non-local diffusion epidemic model has recently become a focal point of academics. Coville and Dupaigne [12] investigate a one-dimensional non-local variant of Fisher’s equation to understand better how genetic mutations spread across populations. The non-local diffusion pattern, which is thought to control the distribution of hereditary characteristics, is shown using a convolution operator.

The non-local diffusion equation and the classical heat equation with the Neumann boundary condition share many commonalities, as shown in studies by Cortazar et al. [13,14]. These include the following: the solutions to both equations exhibit similar asymptotic behaviour as

Much recent research has investigated SIR, SIS, and SVIR, among others, as epidemic models in the context of non-local spread. A basic SIR model with non-local diffusion was the subject of recent work by Kuniya and Wang [15], who sought to prove that its equilibrium was stable on a global scale. In their investigation of an epidemic model involving free boundaries and non-local diffusion, Zhao et al. [16] detail the spread of infectious organisms through such a model and the lack of diffusion in the case of sick humans. In contrast to local diffusion models, their results show distinct solutions and a binary between spreading and vanishing; picking a non-local diffusion kernel function might speed up the spreading process. Disease management, primarily through increased vaccination rates, is emphasized in [17], presenting a qualitative analysis of an SVIR epidemic model incorporating non-local dissemination. New insights into non-local diffusion epidemic models, including several infected compartments, were provided by Zhang and Zhao [18], who investigated travelling wave solutions in a non-local diffusive Zika transmission model using bilinear incidence. In their discussion of treat-age effects in a non-local dispersal SIR epidemic model, Bentout and Djilali [19] examine the asymptotic profiles. According to their research, the disease can only be contained if more people are treated more quickly. Djilali et al. [20] thoroughly examine a SIR epidemic model in a heterogeneous environment with non-local diffusion and non-linear incidence, focusing on studying the global stability of equilibrium states.

Measles, tuberculosis, and influenza are just a few infectious diseases that have prompted the development and analysis of several epidemic models in recent years [21,22]. Bilinear incidence rate

Treatment is a crucial and successful strategy for preventing and controlling the dissemination of infectious diseases. Classical epidemic models posit that the treatment rate of infection is proportional to the number of infected individuals; however, the recovery rate is generally contingent upon medical resources, including pharmaceuticals, vaccinations, hospital capacity, isolation facilities, and treatment efficacy. Recognizing that each community or nation possesses finite resources for illness management, it is imperative to implement an appropriate treatment strategy. Wang and Ruan [26] presented a continual intervention within a SIR model as follows:

which replicated a constrained capacity for therapy. Additionally, Wang [27] examined the subsequent piecewise linear treatment function:

where

Furthermore, the efficacy of treatment will be significantly compromised if infected persons experience delays in receiving care. In [29], Zhang and Liu employed a continuous and differentiable saturation therapy function

Despite the widespread use of SIR or SIS epidemic models with a saturated incidence rate in numerous literatures [30–32], the saturated treatment function in SEIR epidemic models has received surprisingly little attention.

Many scientists are now focusing on finding solutions to non-linear differential equations that describe many events. Current society is primarily focused on c-calculus and partial differential equations. Euler and Jacobi formulated the history of c-calculus in the seventeenth century. Jackson [33] was a trailblazer in the 20th century who built on the work of Euler and Jacobi. Several mathematical and analytical subfields discovered broad uses for c-calculus in the mid-twentieth century, leading to a dramatic upsurge in its study. In recent times, c-calculus has been relevant to mathematical modelling in quantum computing. Read [34,35] for more information.

Recent developments in epidemic modelling have revealed an increasing intersection between classical compartmental models (e.g., SIR, SEIR) and data-driven methods like machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL). While conventional models give interpretability and control over biological assumptions, ML/DL methods offer great prediction power, particularly when real-time data are plentiful. Many papers have suggested hybrid models combining the mathematical framework of SEIR models with the learning ability of neural networks to forecast future case trends or estimate parameters more precisely. The work of Chumachenko et al. [36], for example, reveals the use of deep learning for real-time epidemic forecasting, indicating that such models can better capture non-linear dynamics and data anomalies than purely theoretical approaches. Recent studies have likewise used convolutional and recurrent neural networks to model spatial-range diffusion processes. Our present work emphasizes a high-order deterministic and stochastic numerical framework. However, it supports data-driven approaches by offering a theoretically strong basis that might be improved with ML for real-time relevance.

A new subfield of mathematics, the q-calculus, investigates the connection between the two fields. The field of q-calculus is regarded as a main resource for research in various branches of mathematics, including number theory, combinatorics, basic hypergeometric functions, quantum theory, and orthogonal polynomials. This area has developed a novel approach to differential transform methods appropriate for numerically solving ordinary and partial differential equations.

The q-differential equation originated in this subject, which accounts for several physical processes in quantum dynamics, discrete dynamical systems, and discrete stochastic processes. Please note that q-differential equations are defined on a time scale denoted as

Particularly in epidemiological systems with variable spatial interactions, the adoption of q-diffusion in this work is driven by its capacity to generalize classical diffusion while maintaining local behavior. Unlike classical diffusion, which assumes consistent spatial spreading, and fractional diffusion, which simulates long-range memory effects, q-diffusion offers a non-linear generalization that captures unusual yet localizable transport dynamics. Modeling scenarios where non-uniform interaction structures, spatial clustering, or intervention actions change movement patterns in non-classical ways that influence disease transmission is especially beneficial.

This work presents a new computational method for addressing the SEIR epidemic model enhanced by q-diffusion and a generalized incidence rate. The scheme employs a high-order spatial discretization method to handle the q-diffusion term and a time-stepping algorithm for stability and accuracy. The suggested scheme’s stability and convergence are thoroughly examined, and its performance is compared to existing approaches.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

1. Formulation of an SEIR epidemic model incorporating q-diffusion and a generalized incidence rate.

2. Development of a computational scheme that achieves high accuracy in both temporal and spatial domains.

3. Stability and convergence analysis to ensure reliability in simulations.

4. Application of the proposed model to a case study, demonstrating its capability to simulate realistic epidemic scenarios.

This study intends to close the gap between recent theoretical developments in epidemic modelling and their actual use in practice using computational methods. This research adds to the growing body of practical and adaptable epidemic analysis methods by enhancing the SEIR framework with q-diffusion and generalized incidence rates.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the suggested numerical scheme and the stability and consistency studies in Section 3. With q-diffusion, Section 4 shows the development of the stochastic SEIR model. Section 5 offers a comparative study with current techniques and numerical experiments. Finally, Section 6 wraps up the paper and suggests possible avenues for future investigation.

2 Proposed Computational Scheme

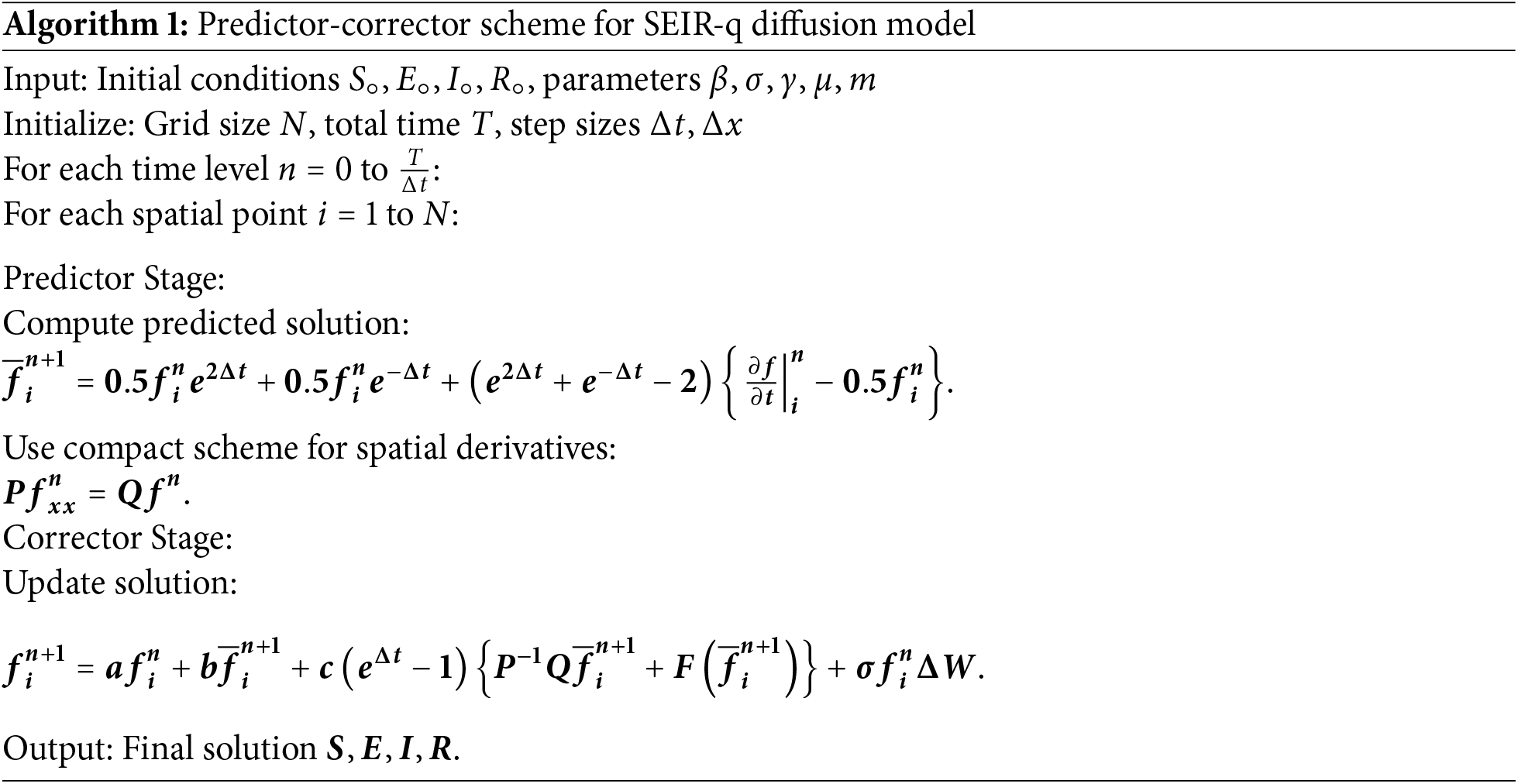

This scheme is a predictor-corrector method for SPDEs with q-diffusion effects applied to an SEIR epidemic model. Using high-order accuracy and stability, the goal is to numerically simulate how an infectious disease spreads spatially and stochastically in a population. A numerical scheme will be presented that will solve stochastic time-dependent partial differential equations. A numerical scheme for the deterministic model is proposed before proposing a numerical scheme for stochastic partial differential equations. The proposed numerical scheme is a predictor-corrector scheme that requires a solution calculated on

This is a reaction-diffusion equation, where

2.1 Predictor Stage (Exponential Integrator)

The first stage of the proposed scheme is constructed as

where

The first stage of the scheme (2) can be considered a modified exponential integrator that can be used separately to find the first-order accurate solution of time-dependent partial differential equations. However, a predictor stage finds the solution at some arbitrary time level in this condition.

The second stage of the proposed scheme is presented as

where

2.3 Solve for Coefficients via Taylor Expansion

To find these parameters, substitute the first stage of the proposed scheme (2) with the second stage (3).

By using the Taylor series expansion

By substituting Eq. (5) into Eq. (4) it is obtained

Now, equating the coefficients of

This will ensure the scheme’s time accuracy and stability by matching terms order by order. There are no arbitrary coefficients, and everything is mathematically consistent.

By solving linear Eq. (7), the values in the form of expression can be obtained.

So, the time discretization scheme for the deterministic model (1) can be expressed as

2.4 Space Discretization Using Compact Scheme

Space discretization is performed by employing a compact scheme. The compact scheme for this can be written as

where

where

This compact scheme will give sixth-order accuracy in space and capture fine-scale spatial disease variations (e.g., infections clustered in a city).

Now consider the stochastic differential equation as

where

The first stage of the proposed scheme for Eq. (13) is the same for the deterministic model, i.e., Eq. (10). While the second stage of the proposed scheme considered is expressed as

where

We developed a predictor-corrector type computational method in our work that efficiently resolves stochastic partial differential equations essential to epidemic modelling. Using a modified exponential integrator, which is well-suited for capturing fast changes in disease dynamics, the system starts with a predictor stage, offering an initial approximation of the solution. In the corrector stage, this predicted value is adjusted using a mix of current and projected values and their rates of change. The time discretization parameters are carefully selected using Taylor series expansion to guarantee accuracy and stability. A sixth-order compact technique is used for spatial discretization, enabling us to precisely capture fine-scale changes in disease transmission. A stochastic factor is included to reflect natural unpredictability in the transmission of illnesses, such as changes in contact rates or external influences like policy changes, making the model more realistic. This approach provides a consistent, precise, and effective instrument for simulating how an infectious illness spreads over time and location in a population, which is pertinent for public health forecasting and control policies.

Fourier series analysis or Von Neumann stability analysis is one of the existing criteria for checking the stability conditions of existing finite difference schemes. The criterion provides conditions for temporal and spatial step sizes of the schemes. The analysis gives the exact stability conditions of the numerical scheme of linear partial differential equations and estimates the numerical scheme of non-linear partial differential equations. However, the non-linear partial differential equation must be linearized before applying this analysis. To apply this analysis in this contribution, transformations must be considered

where

By applying transformations (15), (16) for the first stage of the scheme (10) gives with

where

where

By applying the transformations (15), (16) into the second stage of the proposed scheme (14) using

Using Eq. (18) in Eq. (19) can be written as

where

The amplification factor for this case is written as

The following equation can be obtained from Eq. (21).

If

Theorem 1: The proposed numerical scheme for time and compact spatial discretization is consistent in a mean square sense with

Proof 1: Let

where

The expected value of the square of difference Eqs. (24) and (25) gives

Eq. (26) can be expressed as

By using the inequality

By using inequality (28) into inequality (27) it yields

By applying the

Thus, it is proven that the proposed scheme in time and compact space is consistent in the mean square sense. □

A mathematical model of SEIR is expressed with a bilinear incident rate. The model is comprised of four compartments: susceptible, exposed, infected, and recovered. Let

Susceptible Class Eq. (31):

Exposed Class Eq. (32):

Infectious Class Eq. (33):

Recovered Class Eq. (34):

Subject to the initial conditions

These are the initial distributions of each class over space. It reflects the geographical spread of the disease at the beginning (e.g., urban vs. rural infections).

And boundary conditions are expressed as

represents the No-flux boundary conditions, no movement in/out at domain boundaries, this means the region is closed (like an isolated city or quarantined area)

Choice of Functional Form: The interaction function used in this study is a saturated incidence rate given by

Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE) Eqs. (37)–(41):

The disease-free equilibrium (steady state without disease) for ordinary differential equations can be found by setting

By solving Eqs. (37)–(40) the disease-free equilibrium points can be found as

This means everyone is susceptible, with no current infections or recoveries.

Derivation of

Using the Next Generation Matrix (NGM) approach,

Dependence of

Implications of

Theorem 2: The system of ordinary differential equations by putting

Proof 2: The Jacobian system of ordinary differential equations corresponding to Eqs. (33)–(36) is expressed as

The Jacobian at disease-free equilibrium points

The eigenvalues of the matrix (48) are expressed as

For the real part of all eigenvalues to be negative, the expression under the square root must not overcome the negative term in

The future work will address the stability and bifurcation analysis of the endemic equilibrium, potentially using numerical continuation and Lyapunov-based approaches. □

The suggested technique is designed to address both deterministic and stochastic scenarios. The approach can be seen as an enlarged version of the Euler-Maruyama method. The Euler-Maruyama method incorporates a singular component for stochastic models, while the remainder is the Euler method. The Euler approach offers first-order temporal precision. The suggested system extends the first-order Euler method for deterministic models. It addresses the Wiener process term in stochastic differential equations in a manner analogous to the Euler method. The Euler technique is formulated as a single-stage process, whereas the proposed scheme is developed as a two-stage process. The Von Neumann stability analysis indicates that the method is conditionally stable, imposing limits on step sizes and associated parameters. A stable solution can be achieved if the scheme meets the stability criteria. Thus, the fulfillment of stability is essential for obtaining a convergent solution.

For simulation, we take the birth/death rate

To determine the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix at the disease-free equilibrium (DFE)

Then, solving the characteristic equation

we obtain the eigenvalues,

Since all eigenvalues are real and negative, the disease-free equilibrium

Numerical Implementations details: All numerical simulations presented in this paper are based on a discrete scheme combining a high-order compact spatial discretization with a modified exponential integrator for time evolution. All simulations are conducted using uniform grids in space and time. Zero-flux (Neumann) boundary conditions are applied. The initial conditions are discretized based on predefined spatial profiles. Stochastic terms are implemented via independently generated Gaussian noise at each time step and spatial location. The method is implemented in MATLAB, and step sizes are chosen to ensure numerical stability. This numerical framework has been consistently applied to all simulations and figures this study presents. The simulations were performed on a standard personal computer with an Intel Core i7 processor (2.6 GHz) and 16 GB RAM. No parallel processing or GPU acceleration was used. The proposed scheme involves two stages per time step and utilizes a sixth-order compact spatial discretization. The time complexity per time step is

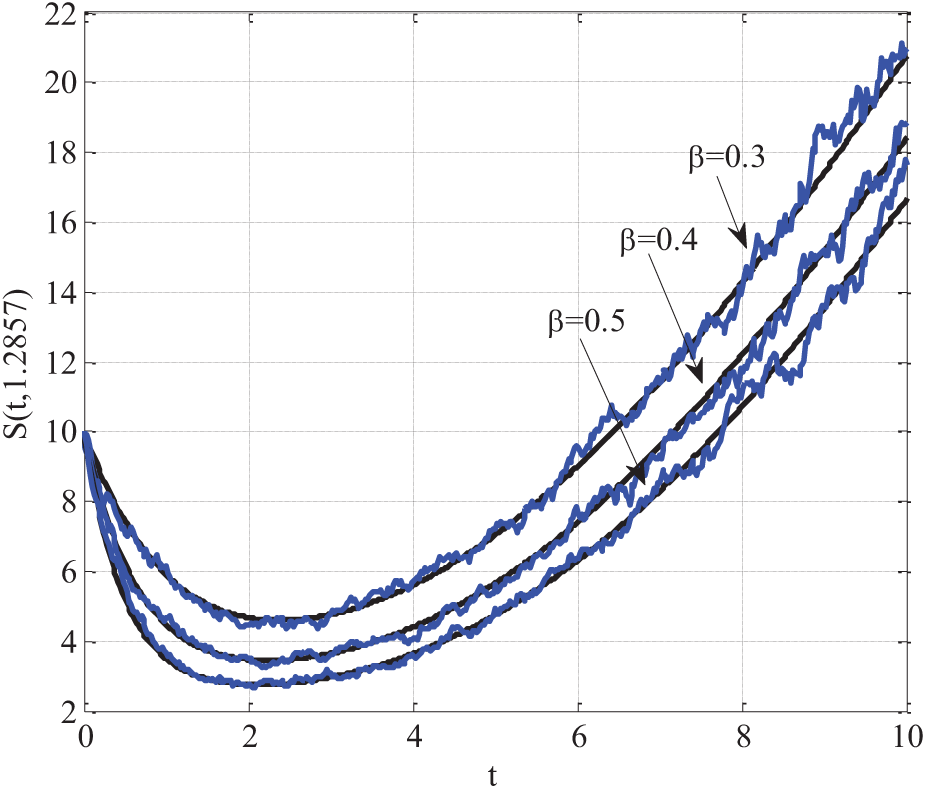

5.1 Effect of Transmission Rate

Fig. 1 shows the variation in the susceptible population over time for different values of the transmission rate

Figure 1: Variation of

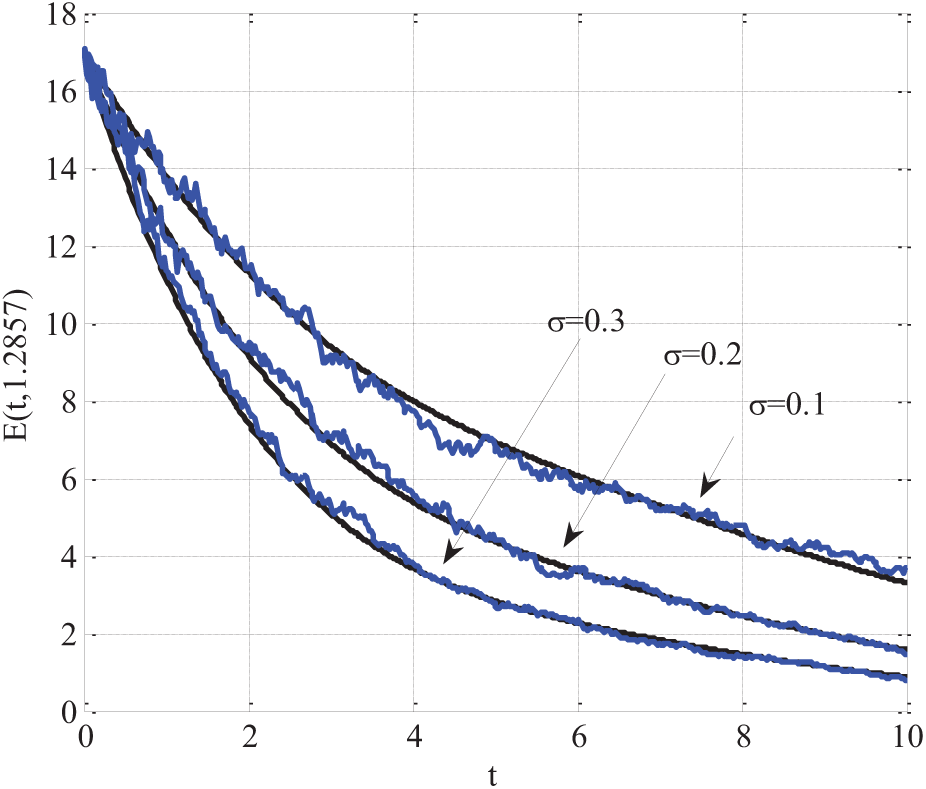

5.2 Effect of Progression Rate

Fig. 2 demonstrates the effect of varying the progression rate

Figure 2: Variation of

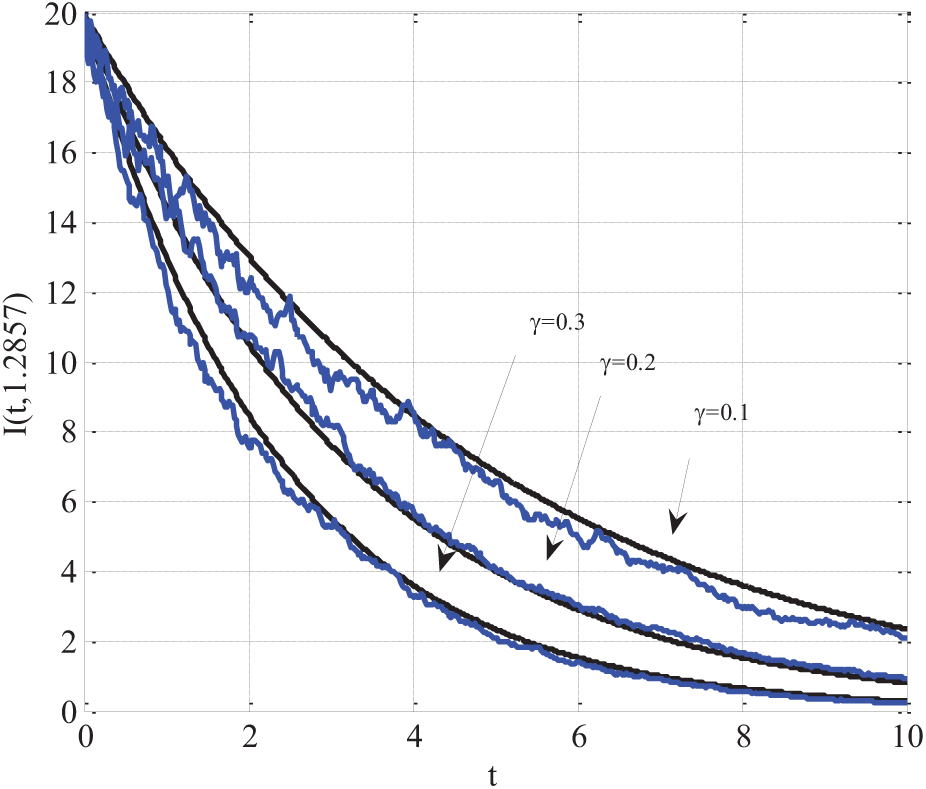

5.3 Effect of Recovery Rate

Fig. 3 illustrates how the infected population evolves over time for varying values of the recovery rate

Figure 3: Variation of

5.4 Effect of Saturation Parameter

Fig. 4 presents the variation in the susceptible (left plot) and exposed (right plot) populations over time for different values of the saturation parameter

Figure 4: Variation of parameter

5.5 Comparison of Proposed and Numerical Scheme and the Existing Nonstandard Finite Difference (NSFD) Schemes for Susceptible Population (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5 presents a comparative analysis of the relative error in the susceptible population between the proposed numerical scheme and the existing nonstandard finite difference (NSFD) method. The simulation is performed using the following parameter values:

Figure 5: Comparison of proposed and existing NSFD schemes for susceptible people using

5.6 Comparison of Proposed Scheme and Existing NSFD Scheme (Figs. 6–8)

Figs. 6 to 8 compare the performance of the proposed numerical scheme with an existing nonstandard finite difference (NSFD) scheme. The reference solution obtained using MATLAB’s pdepe solver is the benchmark since the exact analytical solution is unavailable. The figures demonstrate that the proposed scheme consistently provides results closer to the reference solution than the NSFD method. It is worth noting that the NSFD method, as reported in [42], may exhibit inconsistency for specific choices of time and space step sizes. The improved accuracy and stability of the proposed scheme validate its effectiveness in capturing the dynamics of the SEIR model with q-diffusion.

Figure 6: Comparison of proposed and existing NSFD schemes for exposed people using

Figure 7: Comparison of proposed and existing NSFD schemes for infected people using

Figure 8: Comparison of proposed and existing NSFD schemes for recovered people using

5.7 Comparison of Proposed Scheme and Euler-Maruyama Method for Stochastic SEIR Model (Fig. 9)

Fig. 9 compares the solution profiles of the stochastic SEIR model using the proposed computational scheme (right panel) and the Euler-Maruyama method (left panel). The simulation was conducted using the following parameters:

Figure 9: Comparison of proposed and Euler Maruyama method for solving deterministic model using

Fig. 10 shows the sensitivity analysis plot of how variations in the parameters

Figure 10: Sensitivity analysis using

5.9 Comparison of Simulation and Real Data Validation

In Fig. 11, the SEIR model incorporating q-diffusion and stochastic effects was validated by comparing its simulated results with real-world epidemic data. The comparison focused on all four compartments: Susceptible, Exposed, Infectious, and Recovered. The following model parameters were used:

Figure 11: Comparing of simulation results with real-world epidemic data using

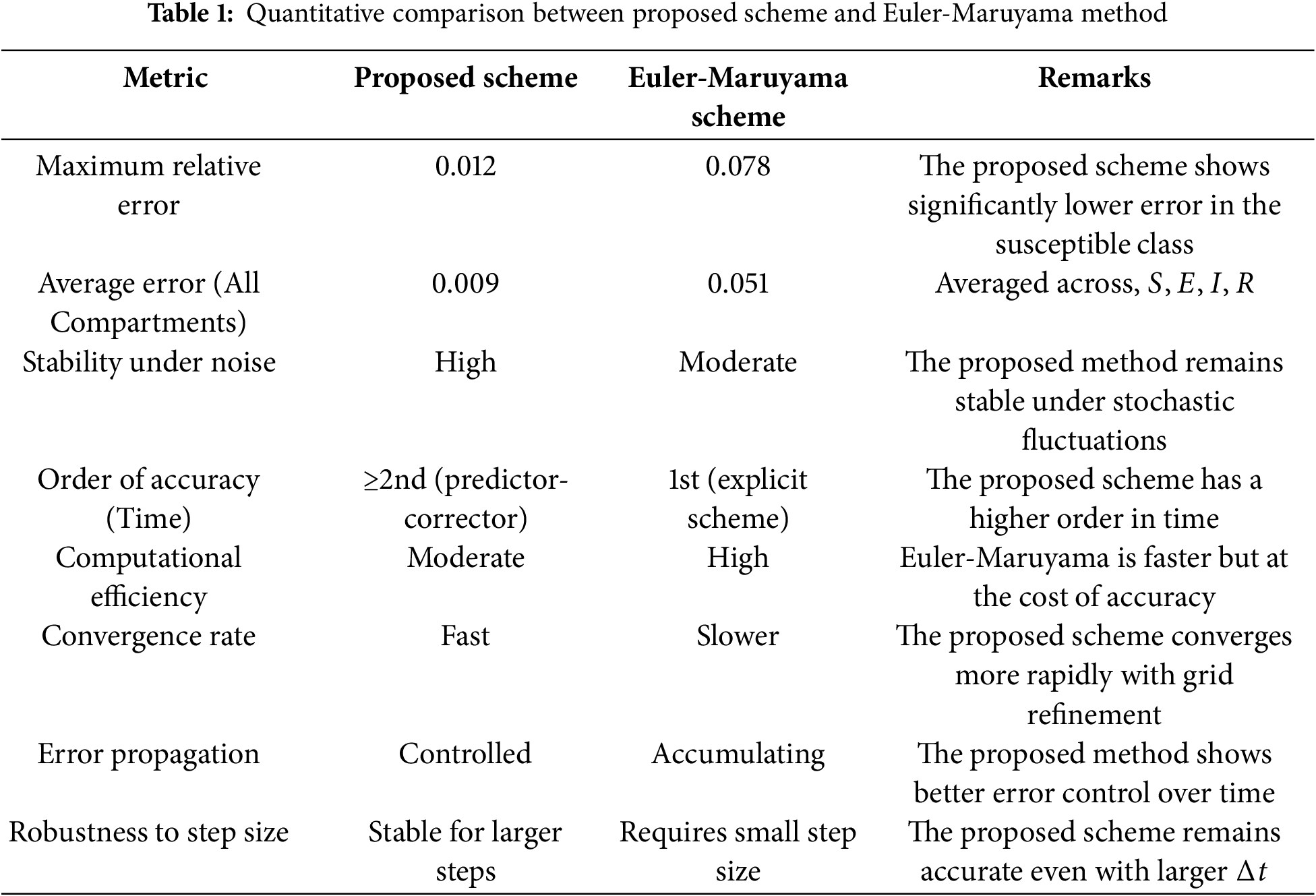

A quantitative comparison Table 1 compares the proposed scheme and the Euler-Maruyama method based on key performance metrics.

The proposed scheme outperforms the Euler-Maruyama method regarding accuracy, stability, and error control. While Euler-Maruyama is more straightforward and computationally lighter, it is more prone to instability and cumulative error, especially for stiff or noisy SEIR systems.

5.10 Pseudo-Code of the Proposed Scheme

A step-by-step pseudo-code for the predictor-corrector scheme (Algorithm 1) is given as follows:

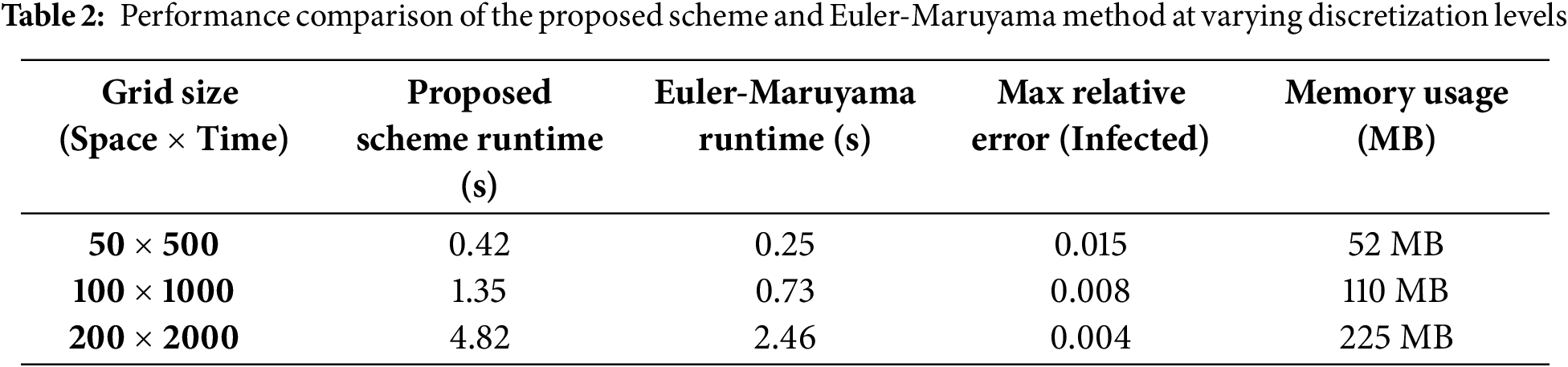

5.11 Computational Cost Analysis

The proposed scheme has Time complexity:

5.12 Runtime and Resource Benchmark (Table 2)

We conducted performance tests on a standard machine (Intel Core i7 2.6 GHz, 16 GB RAM) using MATLAB. Below is a summary of runtimes for different discretization levels.

A high-order computational scheme for solving stochastic SEIR epidemic models, including q-diffusion and a general incidence rate, has been developed in this work. Spatial discretization is done using a sixth-order compact finite difference approach, and the classical Euler-Maruyama method is extended to improve accuracy and stability in the stochastic framework. A finite difference scheme for handling deterministic and stochastic partial differential equations has been proposed. The scheme was explicit, and the solution of the SEIR model was found in two stages. The scheme can be called a predictor-corrector scheme. It does not need any iterative scheme to find the solution. The local stability analysis of the model was also presented. The approach has been exhaustively examined for stability and consistency in the mean square sense, guaranteeing its dependability for resolving stochastic partial differential equations. Numerical studies were run to show how well the system captured the dynamics of epidemic spread. The outcomes were contrasted with those from the Euler-Maruyama approach for the stochastic case and the nonstandard finite difference (NSFD) method for the deterministic counterpart. The suggested method outperformed in terms of accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency in both evaluations. Especially in cases where classical diffusion is inadequate, including q-diffusion improved the model’s capacity to depict realistic spatial-temporal illness dynamics. The concluding points can be expressed as

• The proposed scheme performed better than the Euler-Maruyama method in solving the stochastic model.

• The proposed approach yielded a lower error than the current nonstandard finite difference method in addressing the deterministic model.

• Susceptible people were grown, and exposed people were declined by enhancing the parameter of incidence rate.

The suggested computational approach offers a strong and adaptable tool for examining complex stochastic epidemic models. Future research could concentrate on expanding the approach to other kinds of epidemic models, including more complicated boundary conditions, or creating adaptive algorithms for mesh refinement and time-step control to increase computational efficiency even more.

Future Work: We want to expand the current study in numerous significant ways in future work. Although this article emphasizes the local stability of the disease-free equilibrium, other studies will investigate the presence and stability of endemic equilibria utilizing analytical techniques, including Lyapunov methods and numerical bifurcation analysis. Including the derivation and implications of the basic reproduction number under q-diffusion and stochastic effects, we also intend to look at the global dynamical characteristics of the model. Including actual epidemiological data for parameter estimate and model, validation will increase the practical relevance of the system. We also plan to expand the model to multi-region or network-based epidemic systems, where q-diffusion can seize geographic diversity in disease dissemination. We will investigate parallelization methods and adaptive time-stepping to increase computing efficiency. At last, future extensions will implement the SEIR model with classical diffusion (based on the standard Laplacian operator) and fractional diffusion (using Caputo or Riesz derivatives).

As part of our future study, we intend to investigate hybrid modelling strategies combining the suggested q-diffusion-based SEIR framework with machine learning tools. One such path is using ML algorithms for real-time parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, or residual correction in the numerical solution. Especially under time-varying and region-specific circumstances, deep learning models like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and attention-based architecture could also be included to enhance the forecast accuracy of the system. Including spatially detailed epidemic data also lets us assess the interaction between q-diffusion and spatiotemporal learning models, promoting theoretical and practical points of view on epidemic spread forecasting.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Saudi Arabia. The 2nd and 4th authors would like to acknowledge Prince Sultan University.

Funding Statement: This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, methodology, and analysis, writing—review and editing, Amani Baazeem; funding acquisition, Kamaleldin Abodayeh; investigation, Yasir Nawaz; methodology, Muhammad Shoaib Arif; project administration, Kamaleldin Abodayeh; resources, Kamaleldin Abodayeh; supervision, Muhammad Shoaib Arif; visualization, Yasir Nawaz; writing—review and editing, Amani Baazeem; proofreading and editing, Muhammad Shoaib Arif. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kermack WO, McKendrick AG. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc R Soc Lond A Math Phys Sci. 1927;115(772):700–21. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Keeling MJ, Rohani P. Modeling infectious diseases in humans and animals. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

3. d’Onofrio A. Stability properties of pulse vaccination strategy in SEIR epidemic model. Math Biosci. 2002;179(1):57–72. doi:10.1016/S0025-5564(02)00095-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. He S, Peng Y, Sun K. SEIR modeling of the COVID-19 and its dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020;101:1667–80. doi:10.1007/s11071-020-05743-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Korobeinikov A. Lyapunov functions and global properties for SEIR and SEIS epidemic models. Math Med Biol. 2004;21(2):75–83. doi:10.1093/imammb/21.2.75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Li MY, Smith HL, Wang L. Global dynamics of an SEIR epidemic model with vertical transmission. SIAM J Appl Math. 2001;62(1):58–69. doi:10.1137/S0036139999359860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Özalp N, Demirci E. A fractional order SEIR model with vertical transmission. Math Comput Modelling. 2011;54(1–2):1–6. doi:10.1016/j.mcm.2010.12.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yan P, Liu S. SEIR epidemic model with delay. ANZIAM J. 2006;48(1):119–34. doi:10.1017/S144618110000345X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang J, Ma Z. Global dynamics of an SEIR epidemic model with saturating contact rate. Math Biosci. 2003;185(1):15–32. doi:10.1016/S0025-5564(03)00087-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Capone F, De Cataldis V, De Luca R. On the non-linear stability of an epidemic SEIR reaction-diffusion model. Ric Mat. 2013;62:161–81. doi:10.1007/s11587-013-0151-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Han S, Lei C. Global stability of equilibria of a diffusive SEIR epidemic model with non-linear incidence. Appl Math Lett. 2019;98:114–20. doi:10.1016/j.aml.2019.05.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Coville J, Dupaigne L. On a non-local equation arising in population dynamics. Proc R Soc Edinb A Math Phys Sci. 2007;137(4):727–55. doi:10.1017/S0308210504000721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cortazar C, Elgueta M, Rossi JD, Wolanski N. Boundary fluxes for non-local diffusion. J Differ Eq. 2007;234(2):360–90. doi:10.1016/j.jde.2006.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cortazar C, Elgueta M, Rossi JD, Wolanski N. How to approximate the heat equation with Neumann boundary conditions by non-local diffusion problems. Arch Ration Mech Anal. 2008;187:137–56. doi:10.1007/s00205-007-0062-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kuniya T, Wang J. Global dynamics of an SIR epidemic model with non-local diffusion. Nonlinear Anal Real World Appl. 2018;43:262–82. doi:10.1016/j.nonrwa.2018.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhao M, Zhang Y, Li WT, Du Y. The dynamics of a degenerate epidemic model with non-local diffusion and free boundaries. J Differ Eq. 2020;269(4):3347–86. doi:10.1016/j.jde.2020.02.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bentout S, Djilali S, Kuniya T, Wang J. Mathematical analysis of a vaccination epidemic model with non-local diffusion. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2023;46(9):10970–10994. doi:10.1002/mma.9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang R, Zhao H. Traveling wave solutions for Zika transmission model with non-local diffusion. J Math Anal Appl. 2022;513(1):126201. doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2022.126201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bentout S, Djilali S. Asymptotic profiles of a non-local dispersal SIR epidemic model with treat-age in a heterogeneous environment. Math Comput Simul. 2023;203:926–56. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2022.07.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Djilali S, Chen Y, Bentout S. Asymptotic analysis of SIR epidemic model with non-local diffusion and generalized non-linear incidence functional. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2023;46(5):6279–6301. doi:10.1002/mma.8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ahmed S, Jahan S, Shah K, Abdeljawad T. On mathematical modelling of measles disease via collocation approach. AIMS Public Health. 2024;11(2):628. doi:10.3934/publichealth.2024032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ullah I, Ahmad S, Al-Mdallal Q, Khan ZA, Khan H, Khan A. Stability analysis of a dynamical model of tuberculosis with incomplete treatment. Adv Differ Eq. 2020;2020(1):499. doi:10.1186/s13662-020-02950-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Acedo L, Gonzalez-Parra G, Arenas A. An exact global solution for the classical epidemic model. Nonlinear Anal Real World Appl. 2010;11(3):1819–25. doi:10.1016/j.nonrwa.2009.04.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Esteva L, Matias M. A model for vector transmitted diseases with saturation incidence. J Biol Syst. 2001;9(4):235–45. doi:10.1142/S0218339001000414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sun CJ, Lin YP, Tang SP. Global stability for a special SEIR epidemic model with non-linear incidence rates. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2007;33(1):290–7. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2005.12.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang W, Ruan S. Bifurcation in an epidemic model with constant removal rate of the infectives. J Math Anal Appl. 2004;291(2):775–93. doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2003.11.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang WD. Backward bifurcation of an epidemic model with treatment. Math Biosci. 2006;201(1–2):58–71. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2005.12.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Eckalbar JC, Eckalbar WL. Dynamics of an epidemic model with quadratic treatment. Nonlinear Anal Real World Appl. 2011;12(1):320–32. doi:10.1016/j.nonrwa.2010.06.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang X, Liu XN. Backward bifurcation of an epidemic model with saturated treatment function. J Math Anal Appl. 2008;348(1):433–43. doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2008.07.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhou T, Zhang W, Lu Q. Bifurcation analysis of an SIS epidemic model with saturated incidence rate and saturated treatment function. Appl Math Comput. 2014;226:288–305. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2013.10.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Arif MS. A novel explicit scheme for stochastic diffusive SIS models with treatment effects. Partial Diff Equ Appl Math. 2025;14:101215. doi:10.1016/j.padiff.2025.101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhou L, Fan M. Dynamics of an SIR epidemic model with limited medical resources revisited. Nonlinear Anal Real World Appl. 2012;13(1):312–24. doi:10.1016/j.nonrwa.2011.07.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Jackson FH. On q-functions and a certain difference operator. Trans R Soc Edinb. 1909;46:253–81. doi:10.1017/S0080456800002751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ernst T. The history of q-calculus and a new method [licentiate thesis]. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

35. Khan A, Shah K, Abdeljawad T, Amacha I. Fractal fractional model for tuberculosis: existence and numerical solutions. Sci Rep. 2024;14:12211. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-62386-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Chumachenko D, Dudkina T, Chumachenko T. Assessing the impact of the Russian war in Ukraine on COVID-19 transmission in Spain: a machine learning-based study. Model Digitalization. 2023. doi:10.32620/reks.2023.1.01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Agarwal RP. Certain fractional q-integrals and q-derivatives. Math Proc Camb Philos Soc. 1969;66:365–70. [Google Scholar]

38. Aral A, Gupta V, Agarwal RP. Applications of q-calculus in operator theory. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

39. Nawaz Y, Arif MS, Abodayeh K, Bibi M. Finite difference schemes for time-dependent convection q-diffusion problem. AIMS Math. 2022;7(9):16407–16421. doi:10.3934/math.2022897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Abdi WH. Application of q-Laplace transform to the solution of certain q-integral equations. Rend Circ Mat Palermo. 1962;11:245–57. doi:10.1007/BF02843870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Annaby MH, Mansour ZS. q-Taylor and interpolation series for Jackson q-difference operators. J Math Anal Appl. 2008;334:472–83. doi:10.1016/j.jmaa.2008.02.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Pasha SA, Nawaz Y, Arif MS. On the nonstandard finite difference method for reaction-diffusion models. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2023;166:112929. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Alharthi NH, Jeelani MB. Analyzing a SEIR-Type mathematical model of SARS-COVID-19 using piecewise fractional order operators. AIMS Math. 2023;8(11):27009–27032. doi:10.3934/math.20231382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools