Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Innovative Aczel Alsina Group Overlap Functions for AI-Based Criminal Justice Policy Selection under Intuitionistic Fuzzy Set

1 Department of Mathematics, Abbottabad University of Science and Technology, Abbottabad, 22500, Pakistan

2 Department of Mathematics, Khushal Khan Khattak University, Karak, 27200, Pakistan

3 Department of Mathematics, COMSATS University Islamabad, Abbottabad Campus, Abbottabad, 22060, Pakistan

4 Department of Mathematics, Islamia College Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa, Peshawar, 25120, Pakistan

5 Department of Computing, Mathematics and Electronics, “1 Decembrie 1918” University of Alba Iulia, Alba Iulia, 510009, Romania

6 Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, Transilvania University of Brasov, Iuliu Maniu Street 50, Brasov, 500091, Romania

* Corresponding Authors: Kamran. Email: ; Ioan-Lucian Popa. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Algorithms, Models, and Applications of Fuzzy Optimization and Decision Making)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 2123-2164. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.064832

Received 25 February 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) is essential for handling complex decision problems under uncertainty, especially in fields such as criminal justice, healthcare, and environmental management. Traditional fuzzy MCDM techniques have failed to deal with problems where uncertainty or vagueness is involved. To address this issue, we propose a novel framework that integrates group and overlap functions with Aczel-Alsina (AA) operational laws in the intuitionistic fuzzy set (IFS) environment. Overlap functions capture the degree to which two inputs share common features and are used to find how closely two values or criteria match in uncertain environments, while the Group functions are used to combine different expert opinions into a single collective result. This study introduces four new aggregation operators: Group Overlap function-based intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel-Alsina (GOF-IFAA) Weighted Averaging (GOF-IFAAWA) operator, intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel-Alsina (GOF-IFAA) Weighted Geometric (GOF-IFAAWG), intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel-Alsina (GOF-IFAA) Ordered Weighted Averaging (GOF-IFAAOWA), and intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel-Alsina (GOF-IFAA) Ordered Weighted Geometric (GOF-IFAAOWG), which are rigorously defined and mathematically analyzed and offer improved flexibility in managing overlapping, uncertain, and hesitant information. The properties of these operators are discussed in detail. Further, the effectiveness, validity, activeness, and ability to capture the uncertain information, the developed operators are applied to the AI-based Criminal Justice Policy Selection problem. At last, the comparison analysis between prior and proposed studies has been displayed, and then followed by the conclusion of the result.Keywords

Decision-making is a vital process in almost every field, from business and healthcare to engineering and artificial intelligence. However, real-world decision-making often involves complex problems with conflicting goals and an abundance of uncertainty. To address such challenges, MCDM has become a widely used approach. MCDM helps evaluate different options based on multiple criteria, even when these criteria may conflict with each other. While classical MCDM methods require exact numerical data, real-world scenarios are rarely so precise, as they are influenced by vagueness, ambiguity, and incomplete information. To handle this uncertainty, Zadeh’s fuzzy set (FSs) [1] was introduced as a groundbreaking concept. Klir and Yuan [2] discussed the fundamental principles of FS theory and its application in uncertainty modeling. The FS theory has been widely applied in various areas, such as Yang et al. [3] applied fuzzy logic in control systems, and [4] extended its application in environmental management.

Extension of Fuzzy Sets

Building on Zadeh’s FSs, in 1986, Atanassov introduced Intuitionistic FSs (IFS) [5], which take uncertainty modeling a step further. IFS incorporates not only a membership degree (MD) (

The inclusion of both MD and NMD allows IFS to represent hesitation or uncertainty more effectively, making it highly applicable in fields like risk assessment, healthcare [6], and supply chain management [7]. For example, in healthcare decision-making, a patient’s symptoms might partially match multiple diagnoses, and IFS can capture this ambiguity better than traditional methods. Moreover, IFS-based aggregation operators, such as weighted averaging and geometric operators, provide tools for combining information from multiple criteria or experts. Wan et al. [8] extended the idea of IFS by developing intuitionistic fuzzy (IF) preference relations that improve decision reliability by incorporating expert opinions and weighting mechanisms. Khan et al. [9] introduced the Daimond IFs and explored the role of aggregation operators in MCDM making and demonstrated their effectiveness in fusing uncertain information.

Recognizing the limitations of IFS, in 2013, Yager introduced Pythagorean FSs (PFS) [10] as a generalization. PFS relaxes the strict condition of IFS by ensuring that the square sum of MD and NMD is less than or equal to 1:

This relaxation allows PFS to handle more complex scenarios with higher levels of uncertainty. Adak et al. [11] introduced some new operations on PFS as an extension of IFS, demonstrating their ability to better capture uncertainty in decision-making. The authors of [12] applied PFS to MCDM, highlighting their effectiveness in handling imprecise information. Thakur et al. [13] conducted a comprehensive study on various Pythagorean fuzzy set distance metrics and demonstrated their effectiveness in improving decision-making accuracy across different application scenarios. PFS applications were further discussed by the author of [14], who demonstrated their benefits in sustainability modelling, where environmental and economic requirements frequently coincide.

Further expanding the capabilities of fuzzy set theory, in 2016, Yager introduced q-Rung Orthopair FSs (q-ROFS) [15]. These sets generalize PFS by allowing the

This generalization enables q-ROFS to manage even higher levels of uncertainty and hesitation. Darko and Liang [16] highlighted that q-ROFS enhance decision-making flexibility by accommodating a wider range of uncertainty. Saha et al. [17] demonstrated their effectiveness in transportation systems, particularly in optimizing routes under unpredictable traffic conditions. Liu and Wang [18] explored their role in collaborative decision-making, showing that they improve consensus-building in group evaluations. Wang et al. [19] applied q-ROFS to financial risk assessment, proving their superiority over IFS and PFS in handling volatile market conditions.

Aggregation Operators in Fuzzy Environments

Triangular norms (T-N) and triangular conorms (T-CN) [20] have long served as essential tools in FSs and aggregation processes, offering mathematical frameworks for modeling “and” and “or” operations, respectively. Over time, numerous types of T-N and T-CNs have been developed, each with unique properties tailored to different applications. Algebraic T-Ns and T-CNs, among the most basic forms, were defined by simple multiplication and addition operations adjusted for the FS range [0, 1] by Beliakov et al. [21]. Tomasa Calvo et al. [22] highlighted that algebraic T-Ns and T-CNs serve as foundational tools in fuzzy aggregation, thanks to their mathematical simplicity and interpretability within the [0, 1] interval.

The Aczel-Alsina (AA) aggregation operator [23] has gained prominence in MCDM due to its ability to flexibly model relationships between inputs using additive generators. This operator is particularly effective in handling nonlinear interactions and is adaptable to various fuzzy set extensions, such as IFSs, PFSs, Hesitant fuzzy set (HFS), and their higher-order extensions. These extensions have broadened the applicability of AA operators, making them suitable for complex decision-making scenarios under uncertainty, including medical diagnosis [24], environmental impact assessment [25], risk management [26], and supply chain optimization [27]. Researchers have extensively explored these operators to address challenges like evaluating hospital service quality and managing uncertain data in large-scale decision-making [28]. Son et al. applied AA aggregation operators to IF MCDM, demonstrating their effectiveness in complex decision scenarios [29]. Thus, the choice of AA operators in this study is motivated by their enhanced adaptability and efficacy in modeling uncertainty within IF environments, aligning with our objective of improving decision-making processes under uncertainty.

In 1982, Dombi [30] defined Dombi T-Ns and Dombi T-CNs operations, which offer the advantage of variability through the operation of parameters. Liu et al. [31] leveraged Dombi operations in IFSs to develop an MCDM problem using a Dombi Bonferroni mean operator under IF information. Chen and Ye [32] proposed an MCDM problem utilizing Dombi aggregation operators in single-valued neutrosophic information. Shi and Ye [33] extended Dombi operations to neutrosophic cubic sets for travel decision-making problems. Lu and Ye [34] first defined a Dombi aggregation operator for linguistic cubic variables, developing an MCDM method in a linguistic cubic setting. He [35] introduced Typhoon disaster assessment based on Dombi hesitant fuzzy information aggregation operators. Dombi aggregation operators have been widely applied in MCDM due to their flexibility in handling nonlinear interactions. Qiyas et al. [36] introduced intuitionistic fuzzy credibility-based Dombi aggregation operators and successfully applied them to a real-world MCDM problem involving railway train selection. Similarly, Dombi operators have been integrated with power operators [37] for IFSs, and Akram et al. demonstrated the applicability of PF Dombi aggregation operators in complex decision-making scenarios [38].

The choice of AA aggregation operators over other types, such as Dombi, Frank [39], and Archimedean [40], is justified by their unique mathematical properties and superior adaptability to the research objectives of this study. AA operators offer a high degree of parameterization, enabling the modeling of different decision-maker attitudes (e.g., optimism, pessimism) and information fusion behaviors. Their logarithmic-exponential formulation allows for a smooth transition between various standard T-Ns and T-CNs, making them highly adaptable to different fuzzy set extensions. Furthermore, AA operators are capable of handling both weak and strong interactions among input arguments, which is crucial for complex decision-making environments involving uncertainty, hesitation, or partial truth. While Dombi, Frank, and Archimedean operators have their own merits, the AA operators were specifically chosen in this work to exploit their flexibility and adaptability in modeling uncertainty within IF environments. For instance, Chen et al. developed AA-based aggregation operators for IFSs, highlighting their advantages in handling imprecise and indeterminate data [41]. Li et al. applied AA aggregation operators to IF MCDM, demonstrating their effectiveness in complex decision scenarios [42]. Thus, the AA operators are particularly well-suited to the goals of our research, which seeks to enhance decision-making processes under uncertainty.

Group and Overlap Functions

Overlap and Grouping functions have become essential tools in fuzzy decision-making, especially when dealing with complex MCDM problems. Overlap functions were introduced by Bustince et al. [43] to measure the degree of similarity or commonality between two fuzzy sets. These functions assess how much the MDs of two fuzzy values overlap. Unlike traditional T-norms, which focus on strict intersection rules, overlap functions allow for a more flexible comparison, especially when data is partially matching or uncertain.

Overlap functions have been widely used in different fields. For instance, Xu [44] applied them in clustering analysis to compare data similarity. Tapia et al. [45] explored their use in image processing, particularly in edge detection and segmentation tasks. Cabrerizo et al. [46] highlighted their usefulness in classification problems and data fusion, where overlapping or conflicting data needs to be handled effectively. Qiao et al. [47] and [48] further studied the mathematical structure of overlap functions and showed how they improve decision-making by better handling uncertainty and ambiguity. More recently, Zhang et al. [49] and Dai [50] emphasized their importance in uncertainty modeling and pattern recognition.

On the other hand, Group functions were introduced by Sola et al. [51] to aggregate multiple expert opinions into a single, collective decision. These functions are designed to ensure fairness, inclusivity, and consistency in group-based decision scenarios. Group functions [52] are especially useful in policy-making, collaborative design, and resource planning, where different stakeholders contribute diverse assessments. For example, Bedregal et al. [53] highlighted their application in policy formation, while Ahamdani et al. [54] demonstrated their effectiveness in environmental assessments where multiple uncertain factors must be considered. Gonçalves-Coelho and Mourão [55] also developed robust MCDM algorithms under IF environments using these functions.

When Overlap and Group functions are combined with IFS, the decision-making process becomes even more powerful. IFS allows for separate membership and non-membership degrees, which gives a more detailed view of uncertainty. Overlap functions help evaluate how much different IFS values agree or conflict, while group functions help merge expert opinions under the IFS framework. Together, they address the limitations of traditional T-norms and T-conorms, which often fail to handle overlapping, uncertain, or hesitant information.

A good example of their combined use is in criminal justice policy selection, where criteria like public safety, rehabilitation, and cost often overlap or contradict. In such scenarios, traditional fuzzy methods may not be flexible enough to capture the real complexity. However, by using overlap and group functions within an IFS-based framework, it becomes possible to balance all factors more effectively, leading to better, fairer decisions under uncertainty.

Motivation

Current studies have predominantly relied on traditional T-Ns and T-CNs-based aggregation operators to address MCDM problems within the IF environment. Although these operators are mathematically consistent and widely accepted, they often impose rigid logical structures that may not adequately capture the nuances of real-world uncertainty, which frequently involves overlapping information and hesitation. To overcome these limitations, we propose a novel framework that integrates group and overlap functions with AA operational laws in the IFS environment. This study introduces four innovative aggregation operators: Group Overlap Function-Based IF AA Weighted Averaging (GOF-IFAAWA), IF AA Weighted Geometric (GOF-IFAAWG), IF AA Ordered Weighted Averaging (GOF-IFAAOWA), and IF AA Ordered Weighted Geometric (GOF-IFAAOWG). These operators not only handle averaging and geometric aggregation but also incorporate ordered and priority-based considerations. This comprehensive approach allows for a more nuanced management of overlapping and hesitant information, particularly in complex decision-making scenarios where criteria may interact in non-linear ways. For instance, in the context of criminal justice policy selection, these operators can effectively balance the uncertain and overlapping criteria related to public safety, rehabilitation, and cost-efficiency. Furthermore, the adoption of AA operational laws within this framework offers an added advantage due to their non-linear and parametric structure, which enhances adaptability in uncertain environments. The synergy of AA laws with group and overlap functions in the IF context allows for more interpretable, accurate, and robust aggregation of criteria, particularly in decision scenarios characterized by vagueness, expert hesitation, and overlapping information. This methodological shift not only advances the theoretical foundations of fuzzy decision-making but also opens new avenues for practical applications in areas such as healthcare, environmental sustainability, public policy, and intelligent systems.

Major Contributions

The major contributions in this research as:

• We have developed a novel decision-making framework by integrating group and overlap functions with AA operational laws under the IFS environment. This integration significantly enhances the flexibility and adaptability of aggregation processes in complex decision-making scenarios. The framework allows for a more nuanced representation of uncertainty and hesitation, making it highly suitable for real-world applications where decision criteria are often overlapping and imprecise.

• We introduce four new aggregation operators, including Group Overlap Function-Based IF AA Weighted Averaging (GOF-IFAAWA), IF AA Weighted Geometric (GOF-IFAAWG), IF AA Ordered Weighted Averaging (GOF-IFAAOWA), and IF AA Ordered Weighted Geometric (GOF-IFAAOWG). These operators are designed to handle averaging, geometric, ordered, and priority-based aggregation under uncertainty. They provide a more comprehensive approach to information fusion, enabling decision-makers to consider various aspects of complex problems in a structured and systematic manner.

• We have applied the proposed framework to a real-world problem involving AI-based criminal justice policy selection. This application demonstrates the practical utility and effectiveness of our proposed methods in identifying optimal policy alternatives. The results show that our framework can effectively balance the uncertain and overlapping criteria related to public safety, rehabilitation, and cost-efficiency, providing decision-makers with valuable insights and support.

• Through a comparative analysis with existing methods, including IF weighted Average, IF weighted geometric, IF Aczel Alsina, IF Aczel Alsina Power, IF Einstein, and IF Einstein Power aggregation operators, we have demonstrated the superiority of our proposed operators in managing overlapping and hesitant information. The analysis underscores the enhanced performance and reliability of our approach in complex decision-making environments, highlighting its potential for broader application across various domains.

Paper Structure

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 explains the basic ideas such as Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets (IFS), t-norms, t-conorms, and Aczel-Alsina (AA) operational laws. In Section 3, we introduce new operational laws using Group and Overlap Functions (GOF) with IFS and AA. Section 4 defines the GOF-based IFAA Weighted Average and Ordered Weighted Average aggregation operators and discusses their properties. Section 5 presents the GOF-based IFAA Weighted Geometric and Ordered Weighted Geometric aggregation operators with a detailed explanation of their behavior. Section 6 describes a step-by-step MCDM algorithm to solve decision-making problems using the proposed operators. Section 7 gives numerical examples to show how the method works in real situations. Section 8 covers the implementation steps of the method. Section 9 studies how changing the parameter

The fundamental ideas of IFSs are examined in this section, with particular attention paid to the functions and characteristics of T-Ns and T-CNs as well as the operational processes of Intuitionistic fuzzy numbers (IFNs). Additionally, we examine group functions, overlap functions, and their associated properties, including the AA T-N and AA T-CN, highlighting their distinctive characteristics and applications.

Definition 1. [5] An IFS

here

Definition 2. [43] Let

•

•

•

•

•

Example 1. Here are some commonly used

1. Continuous T-N and positive T-CN is are examples of

2. The function

where

3. The function

4. The function

5. The function

6. The function

Definition 3. [43] Let

•

•

•

•

•

Example 2. Here are some commonly used overlap functions

1. Continuous t-norm and positive t-norm are examples of

2. The function

where

3. The function

4. The function

5. The function

6. The function

Definition 4. [23] The Aczel Alsina T-norm is defined as:

where

Definition 5. [23] The AAT-CN

where

3 Group Overlap Function Based IF Aczel Alsina Operational Laws

Since Aszel-Alsina t-norm and t-conorm are more flexible in the decision making environment. Also, overlap and grouping functions have emerged as a focal point of research in the field of aggregation functions. In this section, we define some novel operational laws based on overlap and grouping functions with Aczel-Alsina norms underthe IFS environment. It can be defined as:

Definition 6. See Appendix A

Theorem 1. Assume that

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

Proof. See Appendix B ◼

4 Group and Overlap IF AA Weighted Averaging Operator

In this section, we present the Aczel Alsina averaging operator based on the overlap and grouping function under the IF environment. The Aczel-Alsina operator is a type of triangular norm and conorm that’s highly flexible due to its variable parameters. It has been applied to various types of fuzzy to MCDM problems. Overlap and grouping functions are fundamental concepts in fuzzy logic and set theory. They are used to model the intersection and union of fuzzy sets in a way that captures the degree of overlapping or grouping between sets. These functions are crucial for handling uncertainty and vagueness in data, providing a more nuanced approach than traditional binary set operations. It can be defined as:

Definition 7. See Appendix C

Theorem 2. Assume that

Proof. See Appendix D◼

Based on Theorem 1, we have some properties of the

Proposition 1. Let

[1. Idempotency:] If all

Proof. See Appendix E ◼

[2. Boundary:] If

where

Proof. See Appendix F ◼

[3. Monotonicity:] Let

Proof. See Appendix G ◼

[3. Monotonicity:] Let

Proof. See Appendix H ◼

Group and Overlap IF AA Ordered Weighted Averaging Operator (GOF-IFAAOWA)

In this section, we propose the Aczel Alsina order weighted average operator based on overlap and grouping function under the IFS setting. The mathematical formulation for GOF-IFAAOWA:

Definition 8. See Appendix I

Theorem 3. Assume that

Proof. See Appendix J ◼

Proposition 2. Let

[1. Idempotency:] If all

Proof. See Appendix K ◼

[2. Boundary:] Let

where

Proof. See Appendix L ◼

[3. Monotonicity:] Let

Proof. See Appendix M ◼

5 Group and Overlap Based IF-AA Weighted Geometric Operator

In this section, we present the Aczel Alsina geometric operator based on the overlap and grouping function under the IF environment. The Aczel-Alsina operator is a type of triangular norm and conorm that’s highly flexible due to its variable parameters. It has been applied to various types of fuzzy to MCDM problems. Overlap and grouping functions are fundamental concepts in fuzzy logic and set theory. They are used to model the intersection and union of fuzzy sets in a way that captures the degree of overlapping or grouping between sets. These functions are crucial for handling uncertainty and vagueness in data, providing a more nuanced approach than traditional binary set operations. It can be defined as:

Definition 9. See Appendix N

Theorem 4. Assume that

Proof. See Appendix O ◼

Based on Theorem 1, we have some properties of the

Proposition 3. Let

[1. Idempotency:] If all

Proof. See Appendix P ◼

[2. Boundary:] If

where

Proof. See Appendix Q ◼

[3. Monotonicity:] Let

Proof. See Appendix R ◼

5.1 Group and Overlap Based IF-AA Ordered Weighted Geometric Operator

In this section, we propose the Aczel-Alsina order weighted geometric operator based on the overlap and grouping function under the IFS setting. The mathematical formulation for GOF-IFAAOWA:

Definition 10. See Appendix S ◼

Theorem 5. Assume that

Proof. See Appendix T ◼

Proposition 4. Let

[1. Idempotency:] If all

Proof. See Appendix U ◼

[2. Boundary:] Let

where

Proof. See Appendix V ◼

[3. Monotonicity:] Let

Proof. See Appendix W ◼

6 Optimising Multiple Attributes Decision Making by Applying the GOF-IFAA Weighted Aggregation Operator

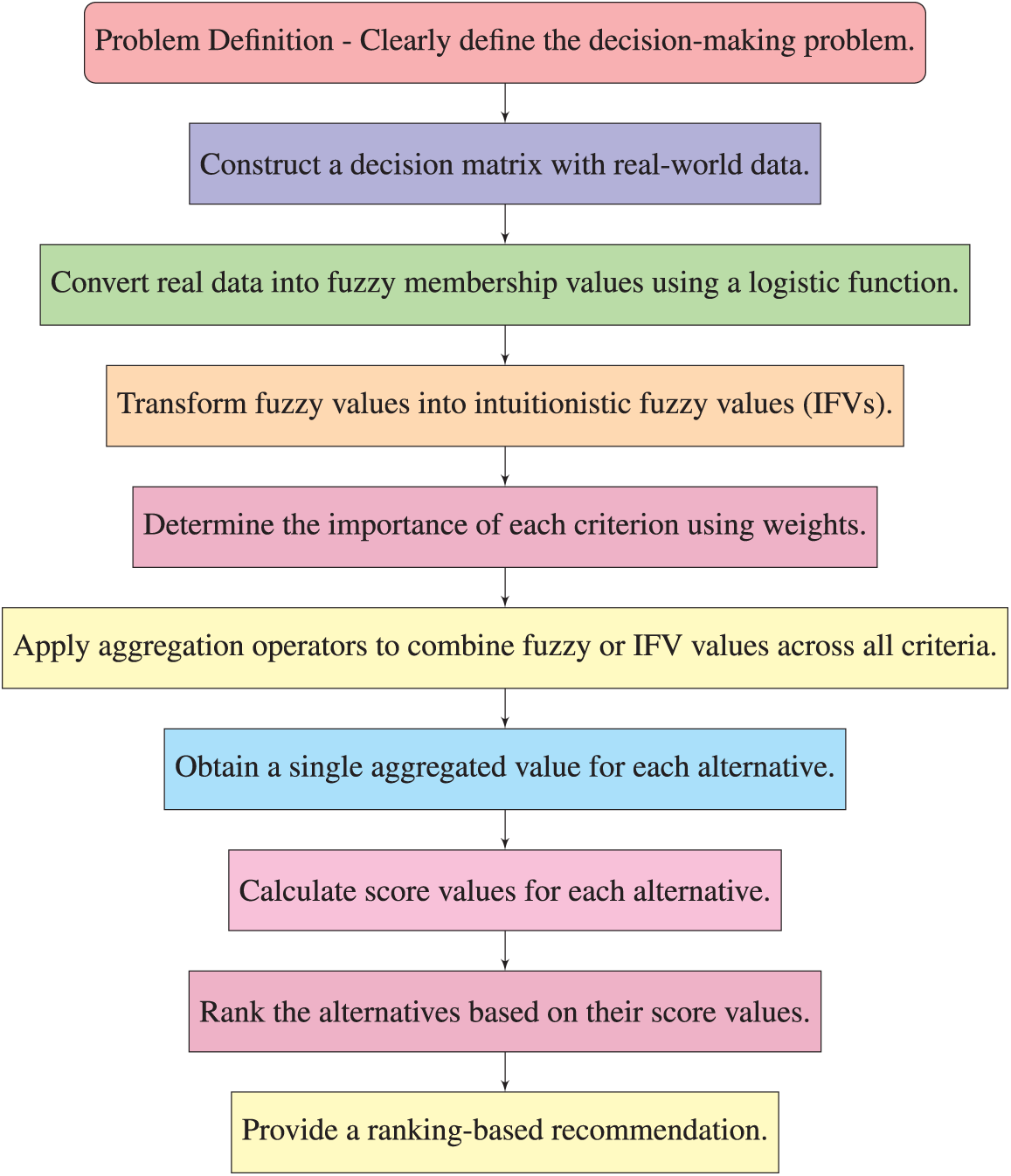

In this section, we will discuss the MCGDM problem based on the proposed methodology to demonstrate its accuracy and effectiveness. To solve the MCDM problem, the above steps are followed:

Step-1: Let

Step-2: To model ambiguity in decision-making, we convert discrete numerical values from Table 1 (e.g., scores like 92, 45, 90) into fuzzy membership values (

Example: For

Step-3: To change the fuzzy values or numbers into intuitionistic fuzzy values or numbers, we use

Step-4: Normalize D, if required, into

where

Step-5: When making a choice, weights indicate how important one criterion is in relation to the others. Subjective weighting relies on the views of experts, whereas quantitative weighting makes use of a variety of methods. In this case, the weight criterion is determined using entropy techniques.

The entropy for the j-th criterion is given by:

and the weights formula as:

Step-6: Utilize the GOF-IFAAWA operator to aggregate all

or the GOF-IFAAWG operators

Step-7:Evaluate the score value of the accumulated matrix of step 3 by using (8).

In cases where score values are equal, apply an accuracy function a to the aggregated results to resolve ties and finalize the ranking. The accuracy function provides a secondary measure of performance, ensuring a clear distinction between alternatives with equal score values. This ensures the robustness and reliability of the decision-making process. The mathematical formulation of the accuracy function is given below:

Step-8: Rank the alternatives

7 A Case Study: AI-Based Criminal Justice Policy Selection

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being used to support policy decisions in the criminal justice system. Choosing the most appropriate AI-based solution requires evaluating different alternatives across multiple criteria. In this example, we consider five policy alternatives: predictive policing systems, AI-assisted sentencing tools, rehabilitation-focused AI applications, public safety monitoring systems, and AI-supported social service systems. These are evaluated based on criteria such as accuracy, ethical implications, cost-effectiveness, privacy, and overall societal impact.

Alternatives

Predictive Policing Systems (

AI-Assisted Sentencing Tools (

Rehabilitation-Focused AI Applications (

Public Safety Monitoring Systems (

AI-Based Social Service Systems (

Evaluation Criteria

Accuracy (

Ethical Implications (

Cost-Effectiveness (

Privacy (

Societal Impact (

In our study on AI-based criminal justice policy selection, we evaluated four policy alternatives against five key criteria. The dataset was built using expert opinions, official policy reports, and historical criminal justice data. Experts assessed each policy’s performance per criterion using linguistic terms, which were converted into fuzzy values to manage uncertainty and subjectivity. After normalizing and preprocessing the data for consistency, we applied fuzzy aggregation operators to evaluate the policies effectively.

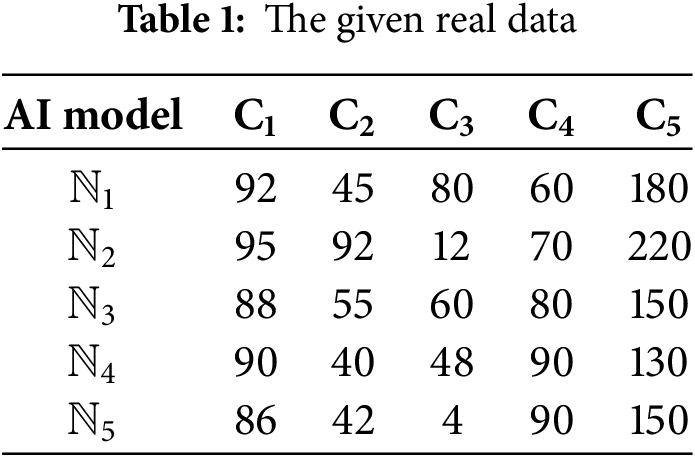

Step 1: Table 1 presents the raw performance data for each AI model across all criteria.

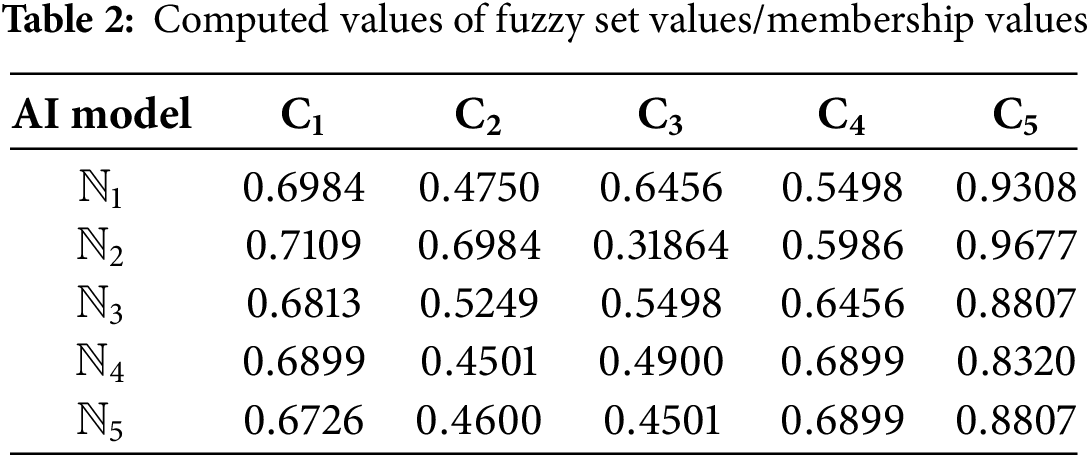

Step 2: Real data was transformed into fuzzy sets (FS) using Eq. (22), with results shown in Table 2. For example, for

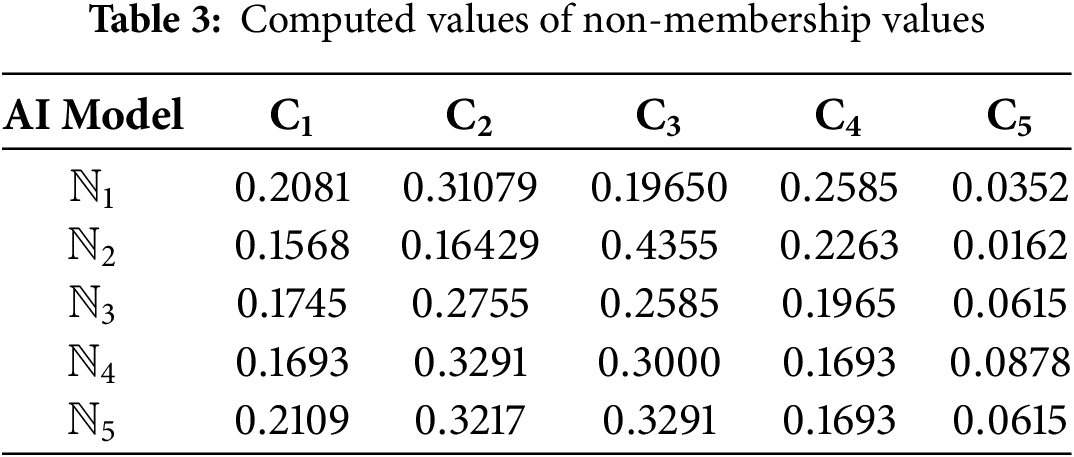

Step 3: Non-membership degrees (NMD) were calculated using Eq. (23) and are displayed in Table 3. For instance, with

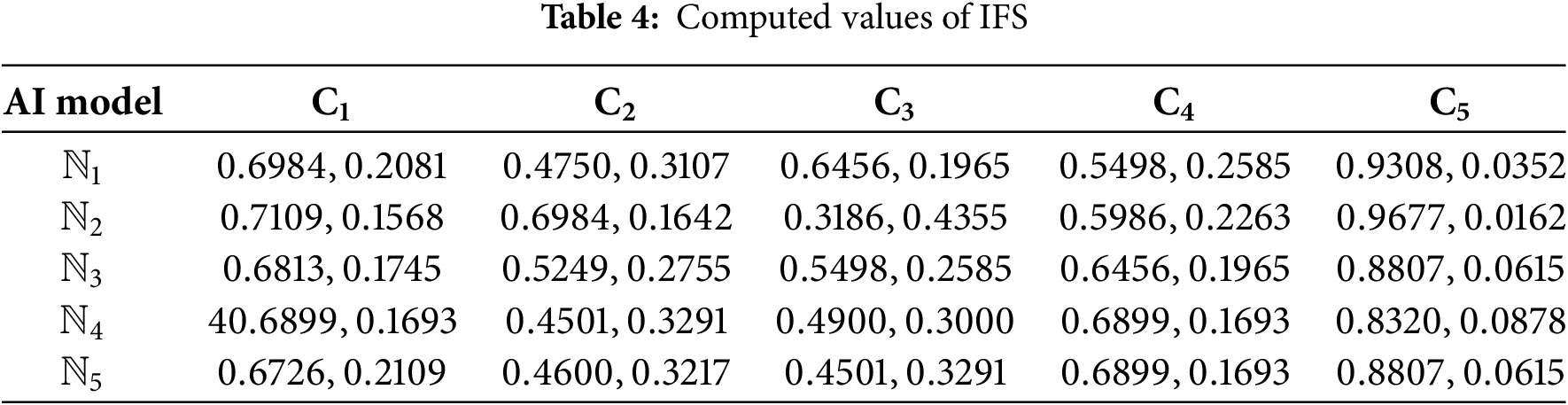

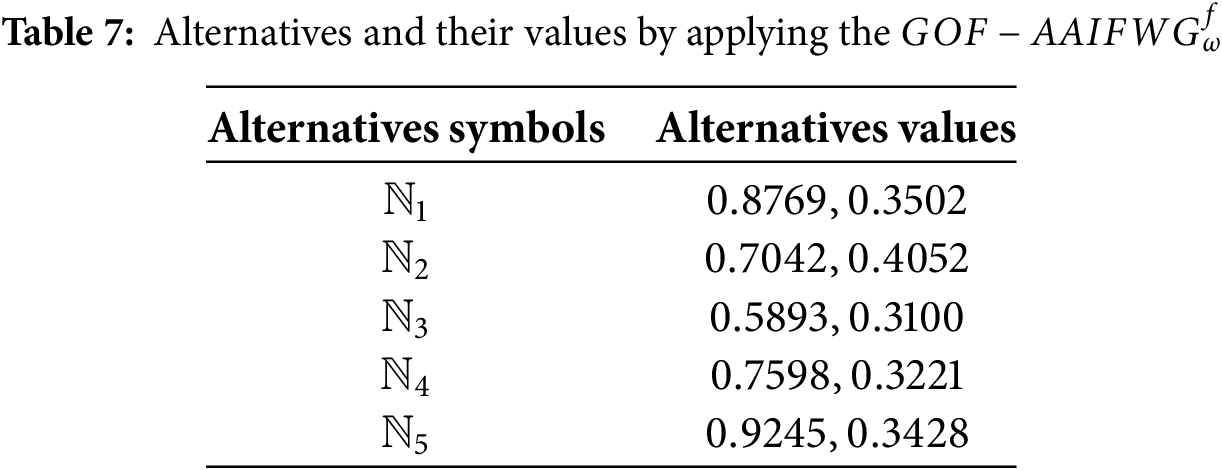

Step 4: Fuzzy set values were converted into intuitionistic fuzzy values (IFVs) as shown in Table 4.

Step 5: Criteria weights, derived from Eq. (20), are exhibited in Table 5.

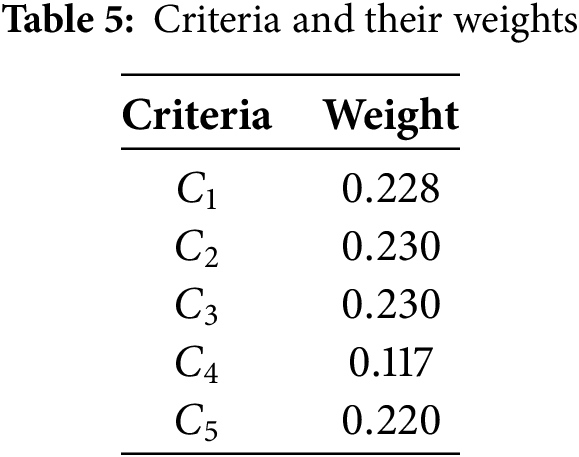

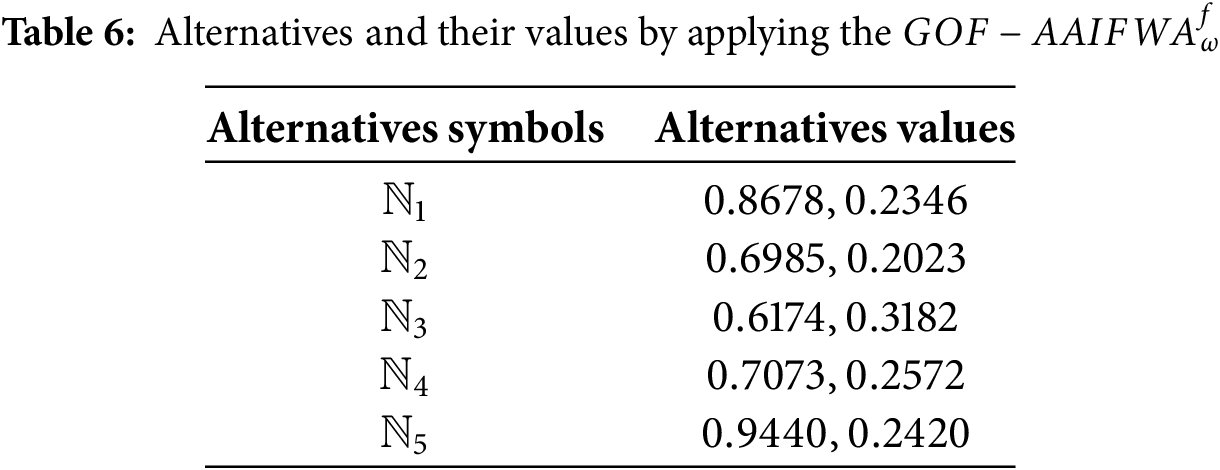

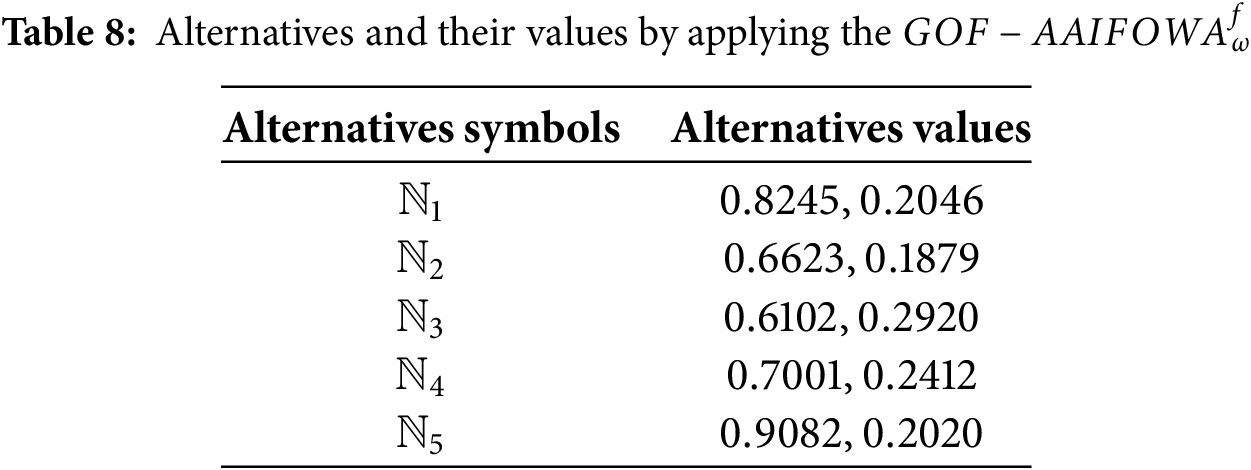

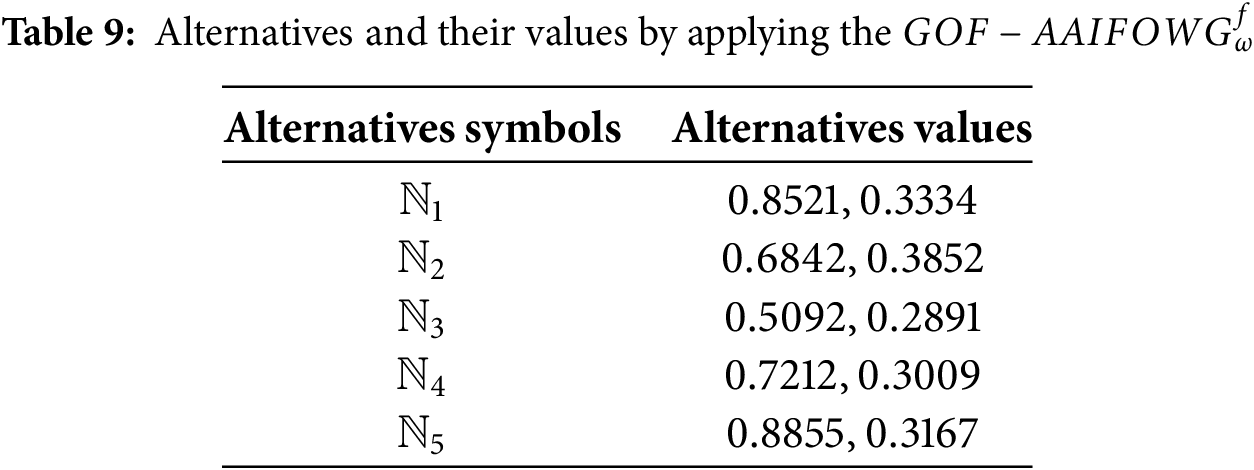

Step 6: Aggregate values from the

Step 7: Total values from the

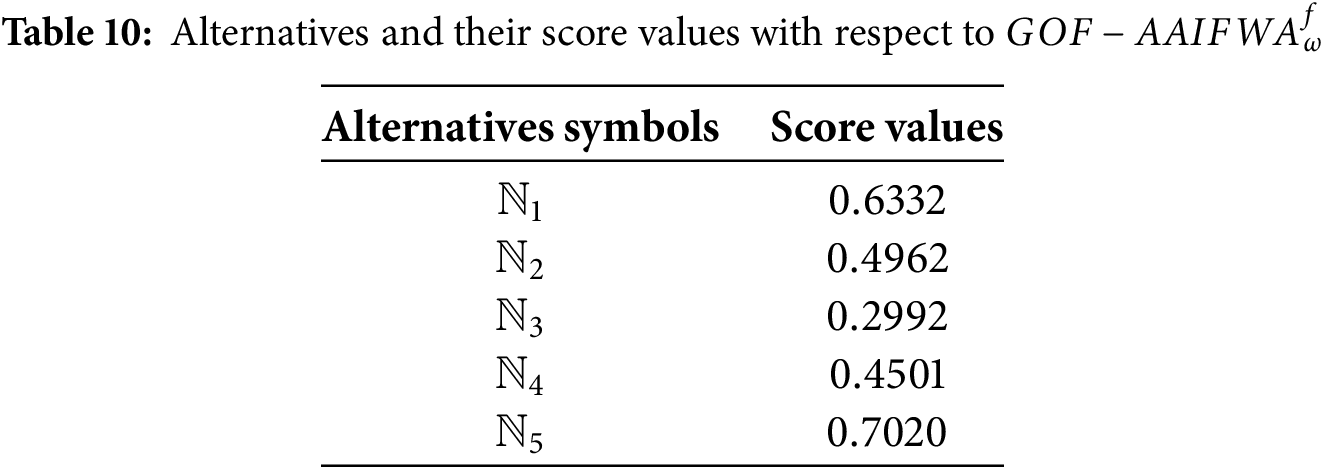

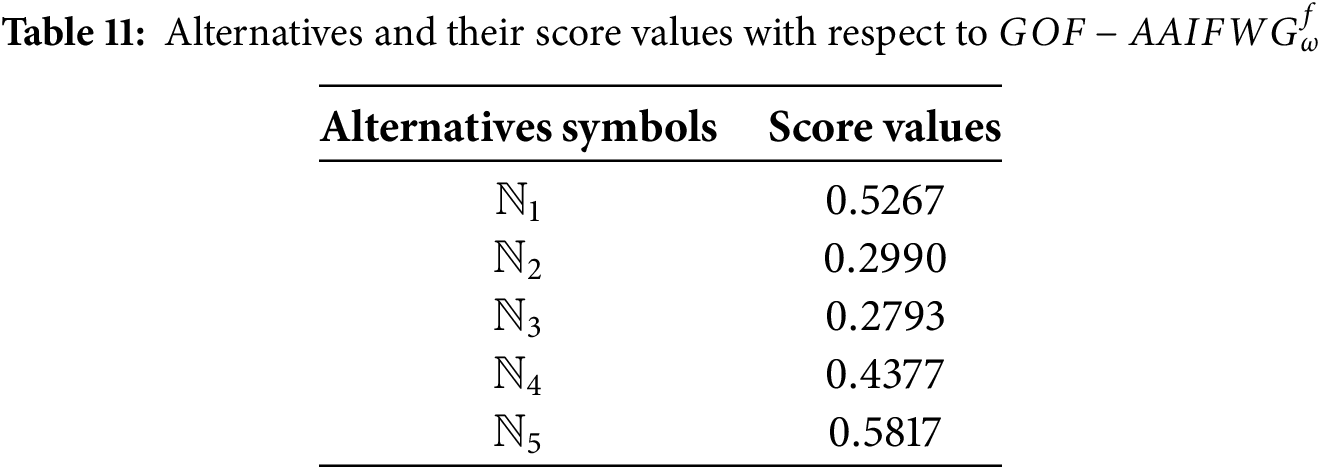

Step 8: Eq. (18) aggregated total values for the

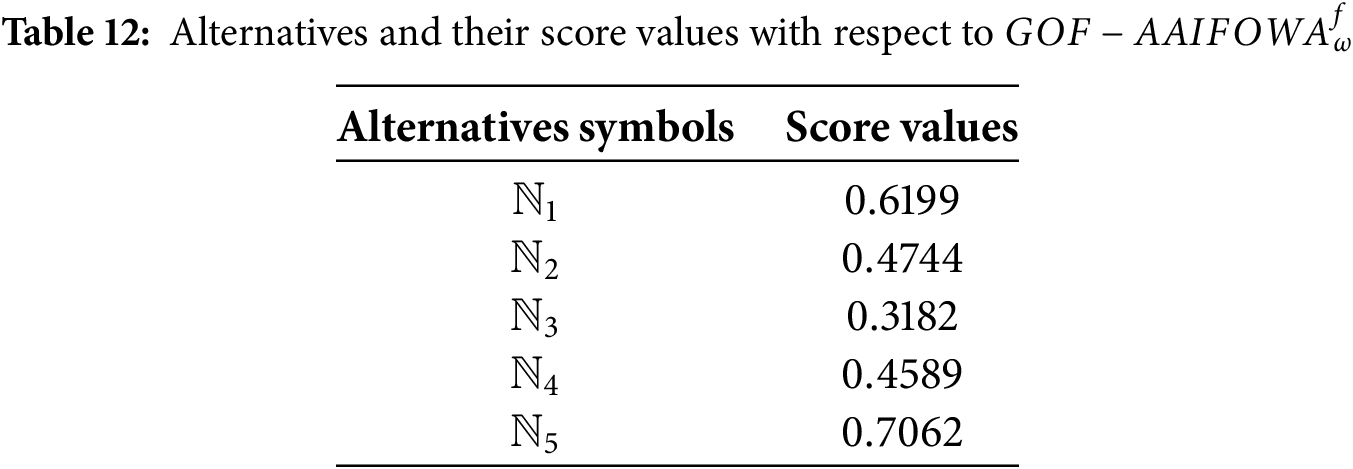

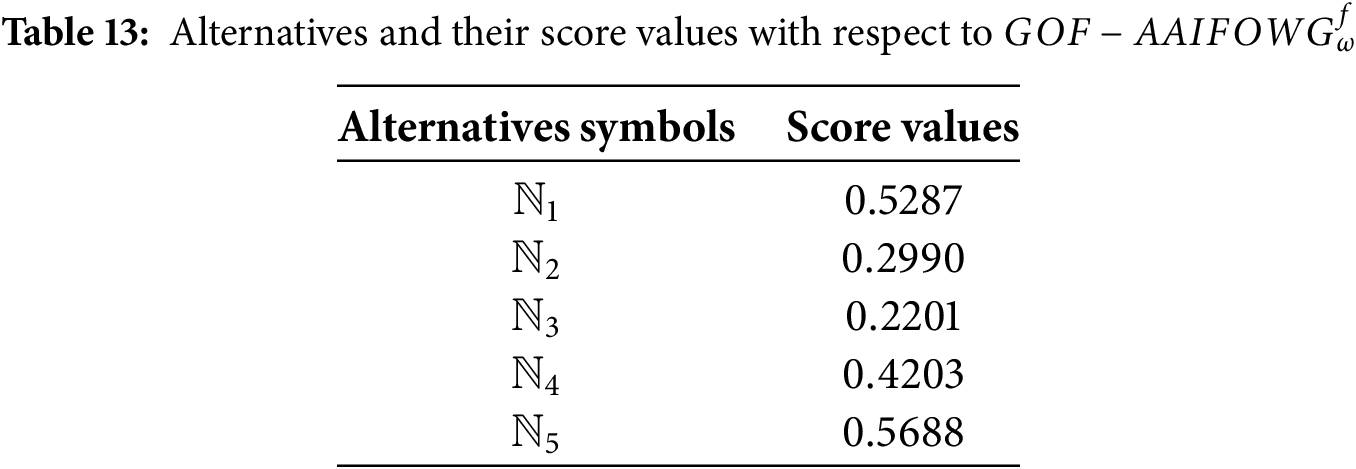

Step 9: Score values for the

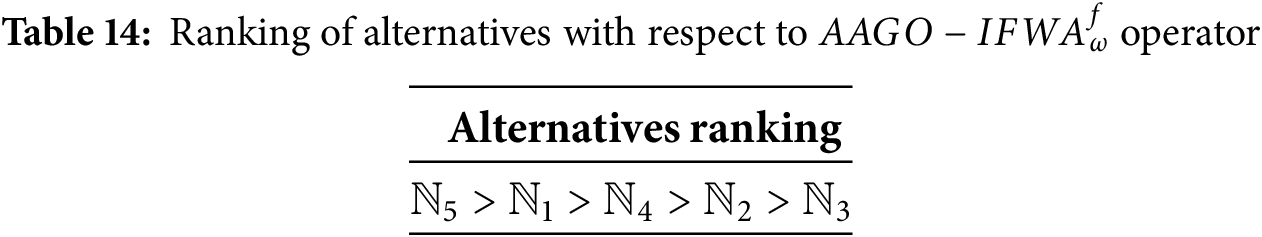

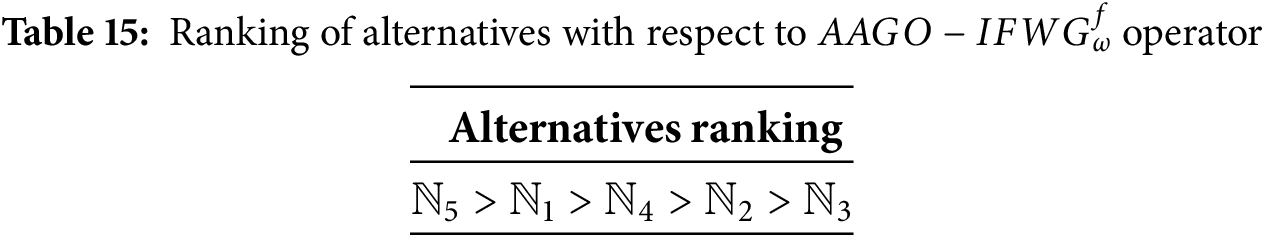

Step 10: Tables 14 to 17 rank the alternatives based on the

9 Influence of Parameter

The operator

The parameter p plays a critical role in the aggregation process of the proposed operators (GOF-IFAAWA and GOF-IFAAWG), as it controls how individual criteria and their interdependencies contribute to the final decision. A higher value of p emphasizes more dominant criteria, whereas a lower value tends to equalize the influence across all criteria. The sensitivity of the proposed operators to p means that their selection can significantly influence the decision outcomes. For example, in contexts where specific criteria are more important, such as treatment effectiveness in healthcare, a higher p may be more suitable. Conversely, when criteria hold similar importance, a lower or moderate value may provide a more balanced outcome. Choosing an appropriate value for p poses practical challenges, as it often requires domain-specific knowledge or trial-and-error experimentation. In practice, three main strategies are used: (1) leveraging expert opinions to reflect the relative importance of criteria; (2) analyzing historical or empirical data to test different p values; and (3) aligning the selection of p with the context of the decision-making problem. For instance, a balanced business decision might call for a moderate p, while a high-stakes public policy issue might necessitate a more skewed weighting favoring critical criteria. To guide the selection process, sensitivity analysis can be a valuable tool. By varying p over a defined range (e.g., 0 to 1), decision-makers can observe how rankings and criteria weights shift, thereby identifying values of p that produce stable and consistent outcomes. This analysis reveals the robustness of the aggregation operators and helps fine-tune them for specific applications. Ultimately, whether through expert input, empirical validation, or automated optimization techniques, selecting the optimal value of p is essential to ensure reliable and accurate decision-making results.

Impact of Parameter

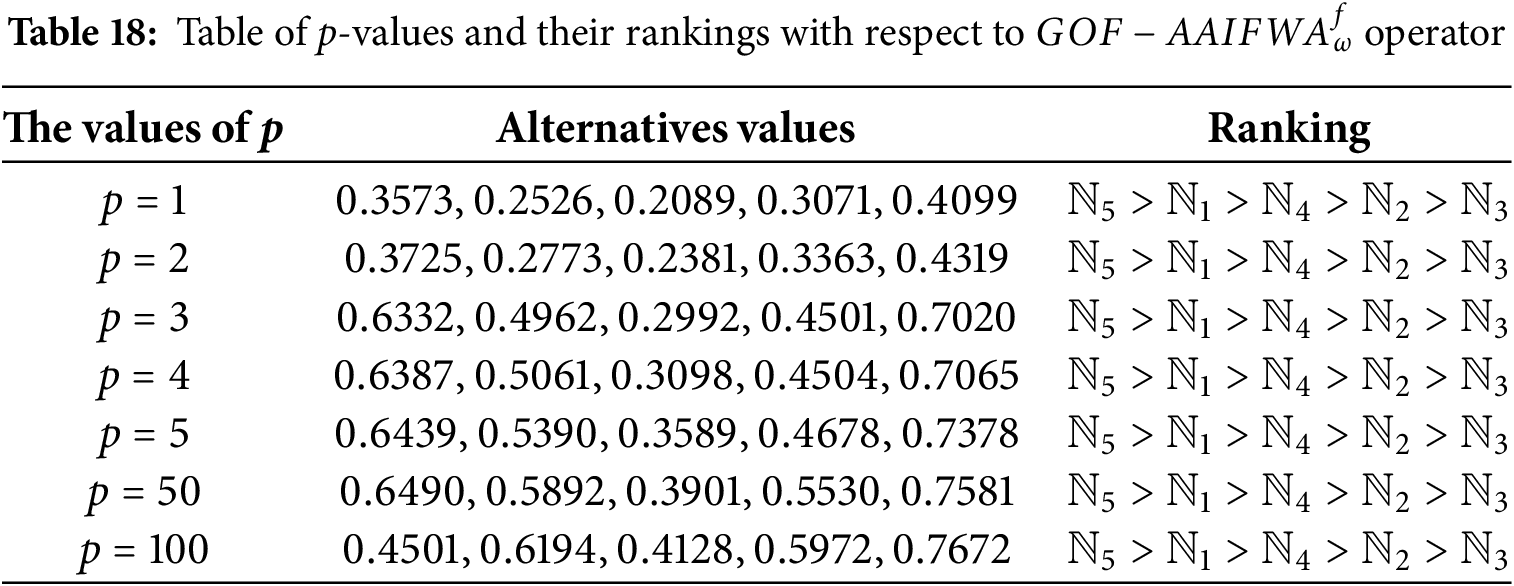

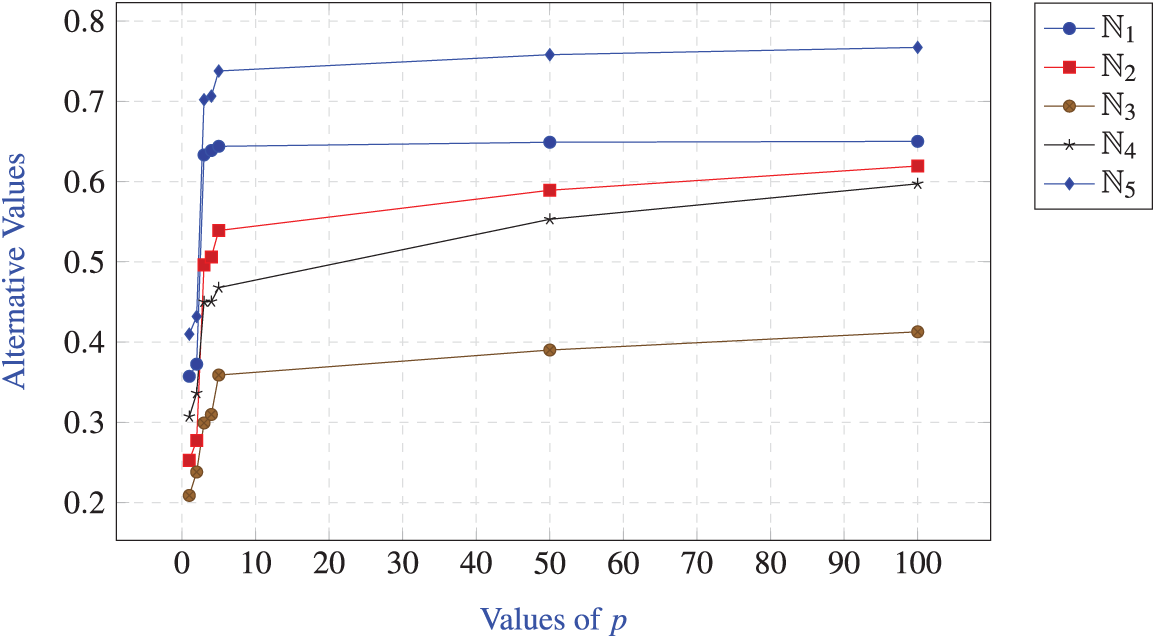

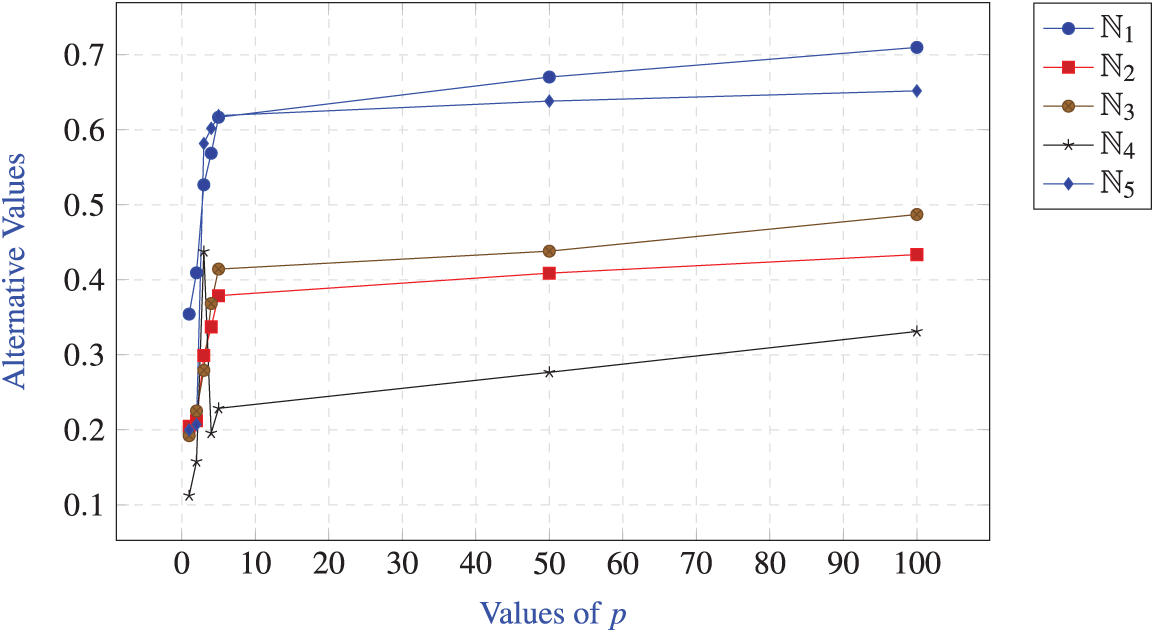

Table 18 and Fig. 1 represent the impact of parameter p on the

Figure 1: Effect of parameter p on

Table Observations: Table 18 shows that the values of all options tend to grow as p increases. The order of the alternatives is maintained regardless of the p-values, with

Graph Observations: Fig. 1 shows that

Impact of Parameter

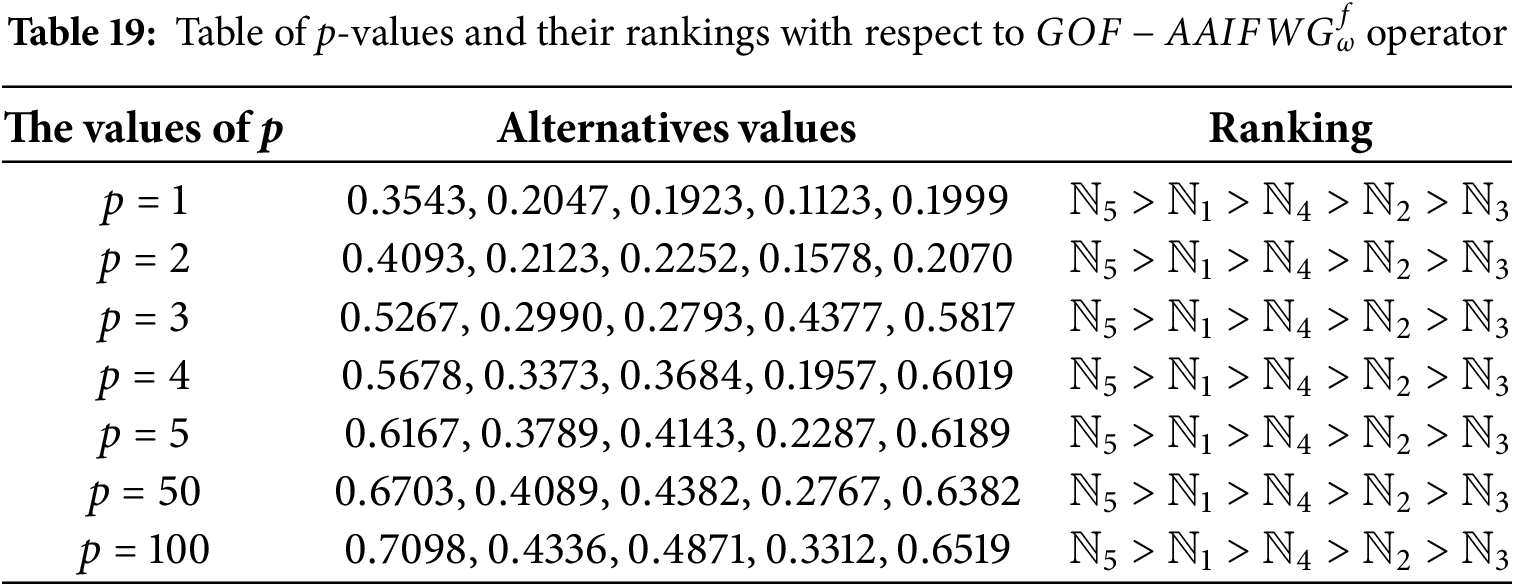

The consequence of parameter p on the

Table Observations:

When assessed using the

Increasing p causes a wider dispersion of values for each option, suggesting that greater dispersion highlights disparities in the weights of the criteria. Due to the operator’s weight distribution, although

Discussion of Graph: Fig. 2 shows the relationship between the alternative values and p and was created using the data from the tables. In the range of

Figure 2: Effect of parameter p on

10 Analysis of the Suggested Operators in Relation to Other Current Operators

The proposed GOF-based aggregation operators significantly enhance decision-making by effectively handling uncertainty, hesitation, and overlapping criteria. They offer a more flexible, accurate, and comprehensive evaluation framework, especially in complex and nonlinear MCDM environments.

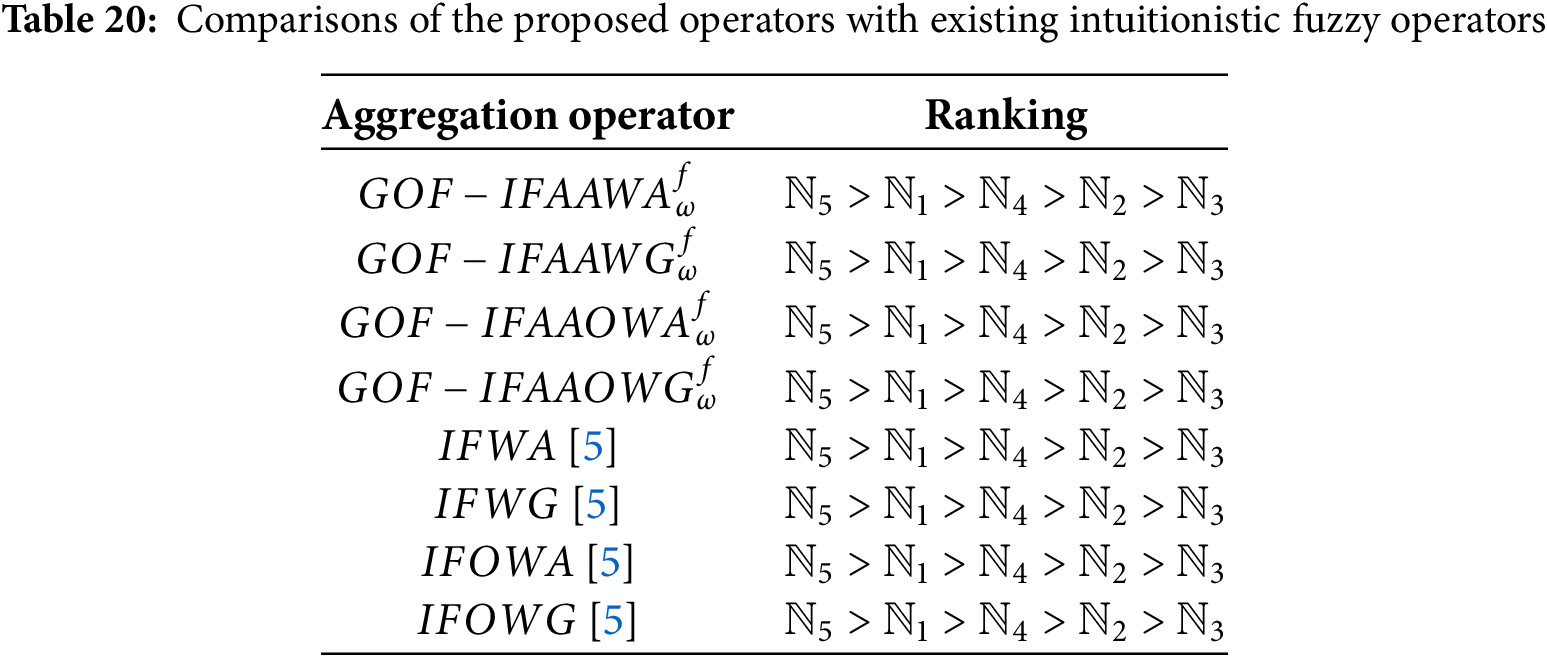

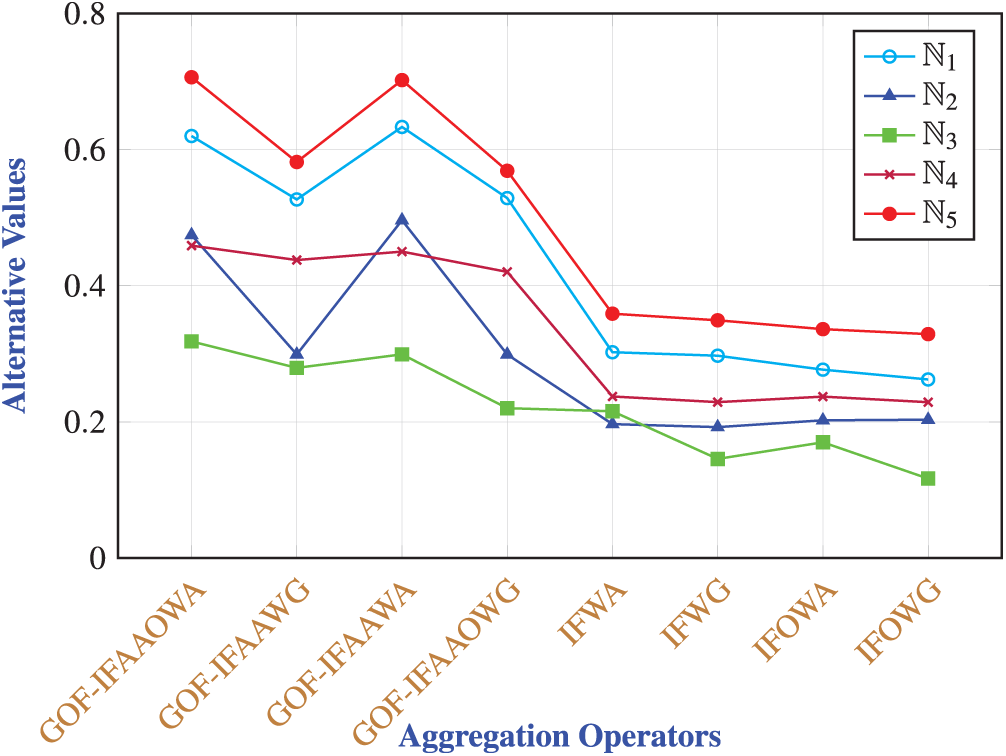

10.1 Comparisons of the Proposed Operators with Existing IF Operators

In this subsection, we compare our proposed method with the intuitionistic fuzzy weighted aggregation operator, including intuitionistic fuzzy weighted average (IFWA) [5], intuitionistic fuzzy weighted geometric (IFWG) [5], intuitionistic fuzzy ordered weighted average (IFOWA) [5] and intuitionistic fuzzy ordered weighted geometric (IFOWG) [5] operators.

Analysis of Table: Table 20 presents a comparison between the proposed Group overlap Aczel Alsina intuitionistic fuzzy (GOF-AAIF) aggregation operators and the classical IF aggregation operators introduced by Atanassov [5], showing complete consistency in the resulting rankings. All operators, both proposed (GOF-IFAAWA, GOF-IFAAWG, GOF-IFAAOWA, GOF-IFAAOWG) and existing (IFWA, IFWG, IFOWA, IFOWG) produce the same preference order:

Analysis of Graph: Fig. 3 provides a comparative plot of the performance of the proposed GOF-AAIF operators vs. the existing Intuitionistic Fuzzy Environment operators—IFWA, IFWG, IFOWA, and IFOWG—across five alternatives

Figure 3: Plot of comparisons between proposed operators and IFE operators

10.2 Comparisons of the Proposed Operators with IF Einstein Operators

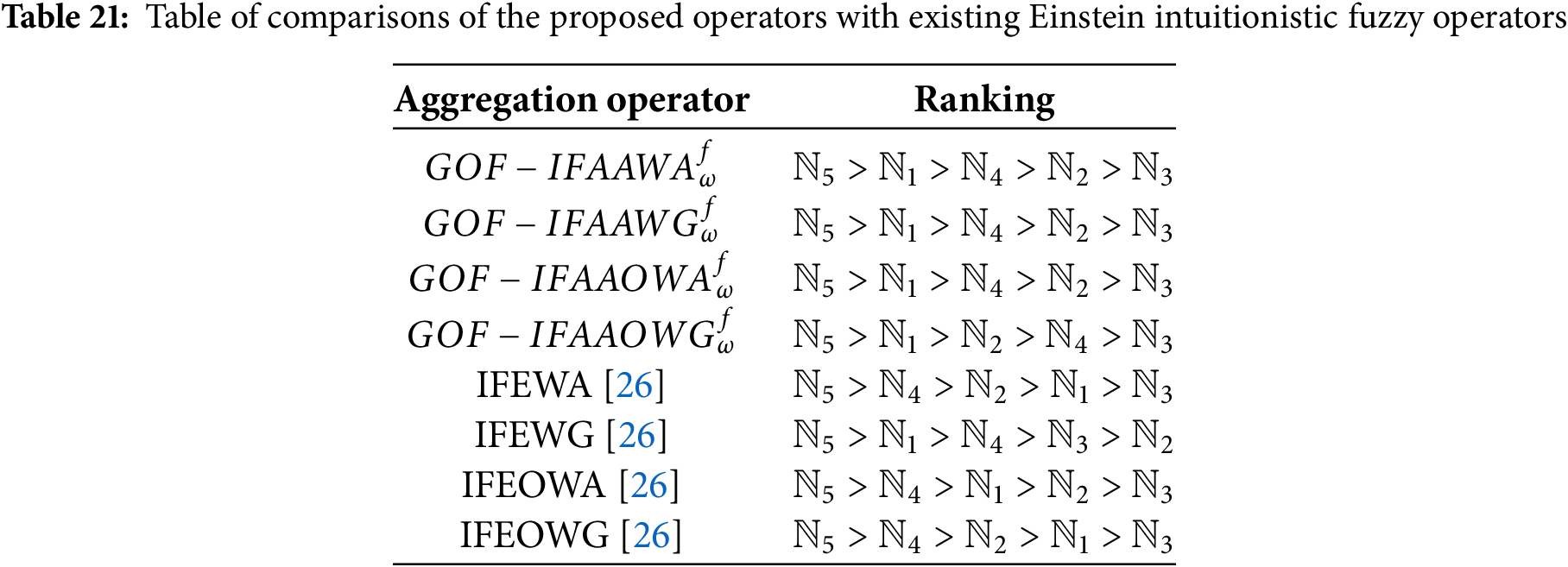

In this subsection, we compare the out proposed method with the intuitionistic fuzzy Einstein aggregation operators, including intuitionistic fuzzy Einstein weighted average (IFEWA) [26], intuitionistic fuzzy Einstein weighted geometric (IFEWG) [26], intuitionistic fuzzy ordered Einstein weighted average (IFEOWA) [26], and intuitionistic fuzzy Einstein ordered weighted geometric (IFEOWG) [26] operators.

Analysis of Table: Table 21 compares the ranking outputs of the proposed GOF-IFAA aggregation operators with the existing IFE operators developed by Wang and Liu [26]. The proposed operators—GOF-IFAAWA, GOF-IFAAWG, GOF-IFAAOWA, and GOF-IFAAOWG consistently rank

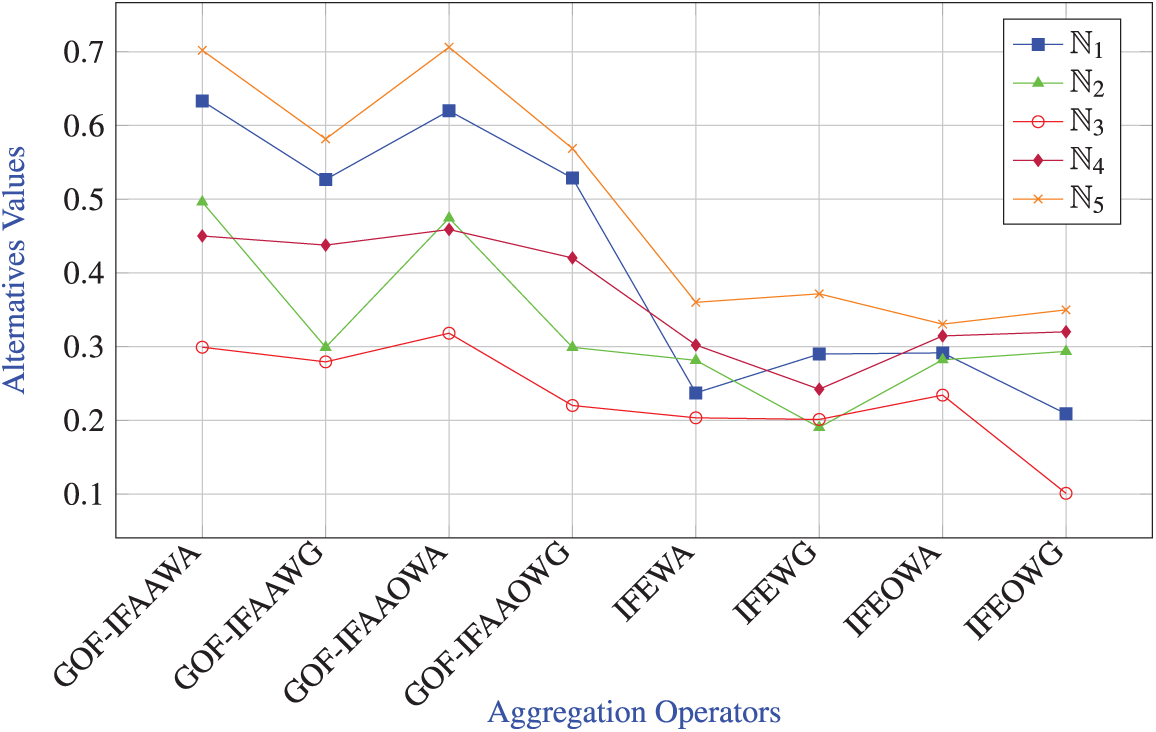

Analysis of Graph: Fig. 4 offers a graphical comparison between the proposed GOF-IFAA operators and the existing IFE operators across five alternatives (

Figure 4: Graph for comparisons of the proposed operators with existing Einstein intuitionistic fuzzy operators

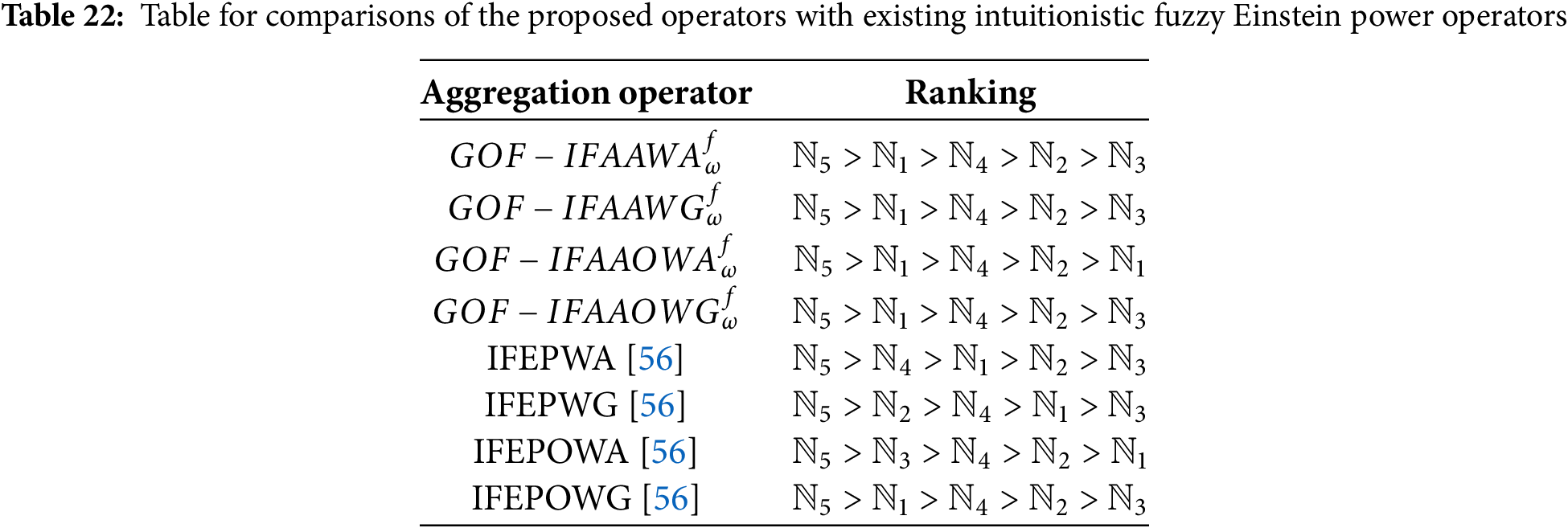

10.3 Comparisons of the Proposed Operators with IF Einstein Power Operators

In this subsection, we compare our proposed method with the intuitionistic fuzzy Enistein power aggregation operators, including intuitionistic fuzzy Enistein power weighted average (IFEPWA) [56], intuitionistic fuzzy Enistein power weighted geometric (IFEPWG) [56], intuitionistic fuzzy Enistein power ordered weighted average (IFEPOWA) [56], and intuitionistic fuzzy Enistein power ordered weighted geometric (IFEPOWG) [56] operators.

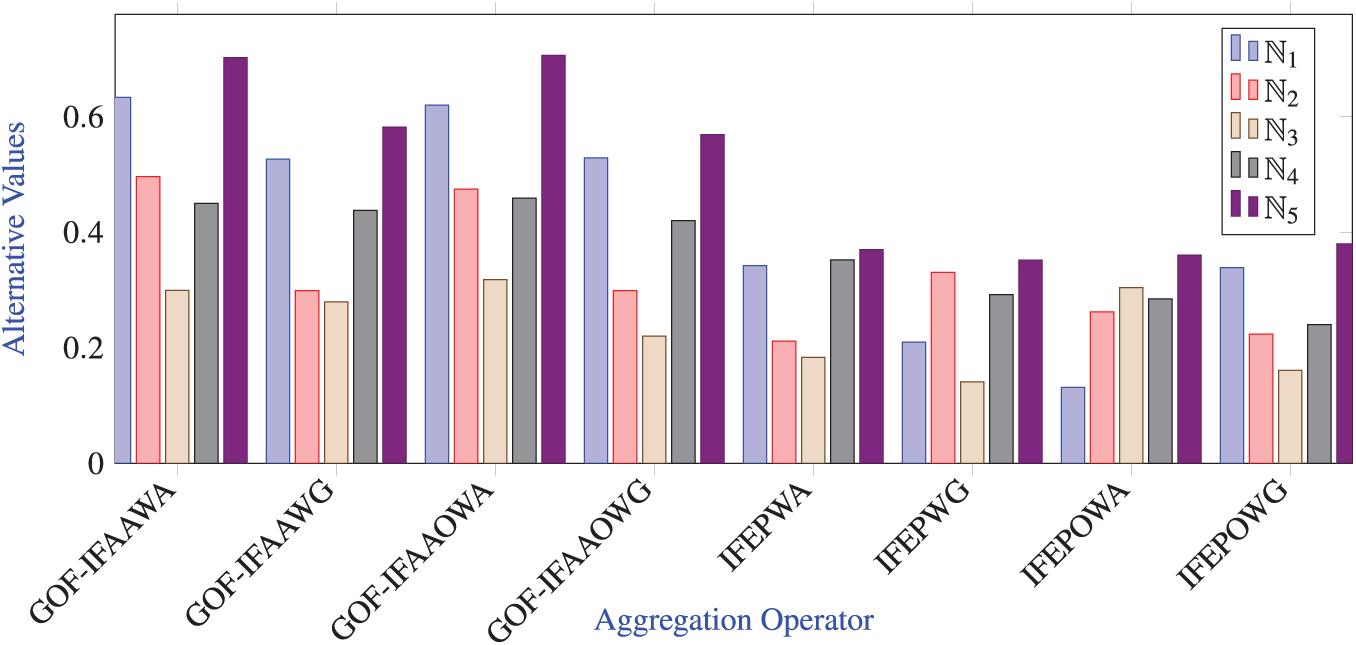

Analysis of Table: Table 22 presents a comparative ranking analysis between the proposed GOF-IFAA aggregation operators and the existing IFEP operators, revealing notable differences in decision outcomes. The proposed operators—GOF-IFAAWA GOF-IFAAWG, GOF-IFAAOWA, and GOF-IFAAOWG consistently rank

Analysis of Graph: Fig. 5 visually compares the performance of the proposed GOF-IFAA aggregation operators with the existing IFEP operators across five alternatives (

Figure 5: Graph for comparisons of the proposed operators with existing intuitionistic fuzzy Einstein power operators

10.4 Comparisons of the Proposed Operators with Other Intuitionistic Fuzzy Aczel Alsina Existing Operators

In this subsection, we compare our proposed method with the IF Aczel Alsina aggregation operator, including intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina weighted average (IFAAWA) [23], intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina weighted geometric (IFAAWG) [23], intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina ordered weighted average (IFAAOWA) [23], and intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina ordered weighted geometric (IFAAOWG) [23].

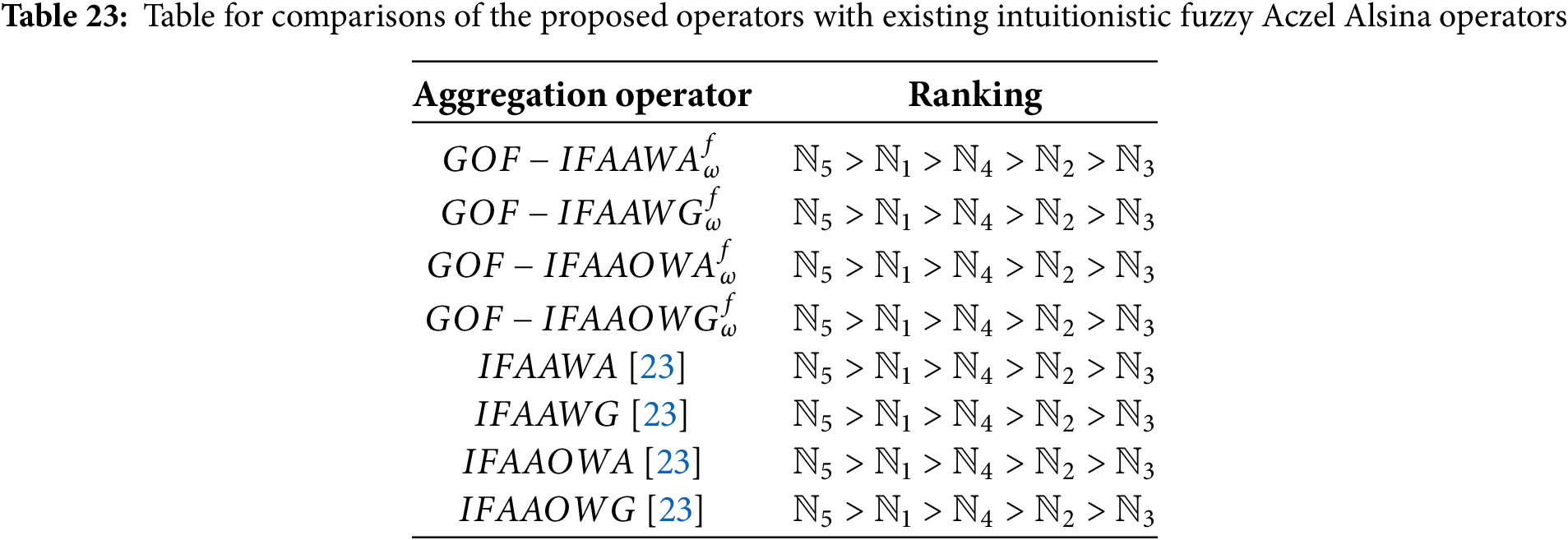

Analysis of Table: The comparative analysis presented in Table 23 demonstrates that the proposed aggregation operators GOF-IFAAWA, GOF-IFAAWG, GOF-IFAAOWA, and GOF-IFAAOWG yield identical rankings to the existing Aczel-Alsina-based intuitionistic fuzzy aggregation operators (IFAAWA, IFAAWG, IFAAOWA, IFAAOWG). Specifically, all operators rank the alternatives as

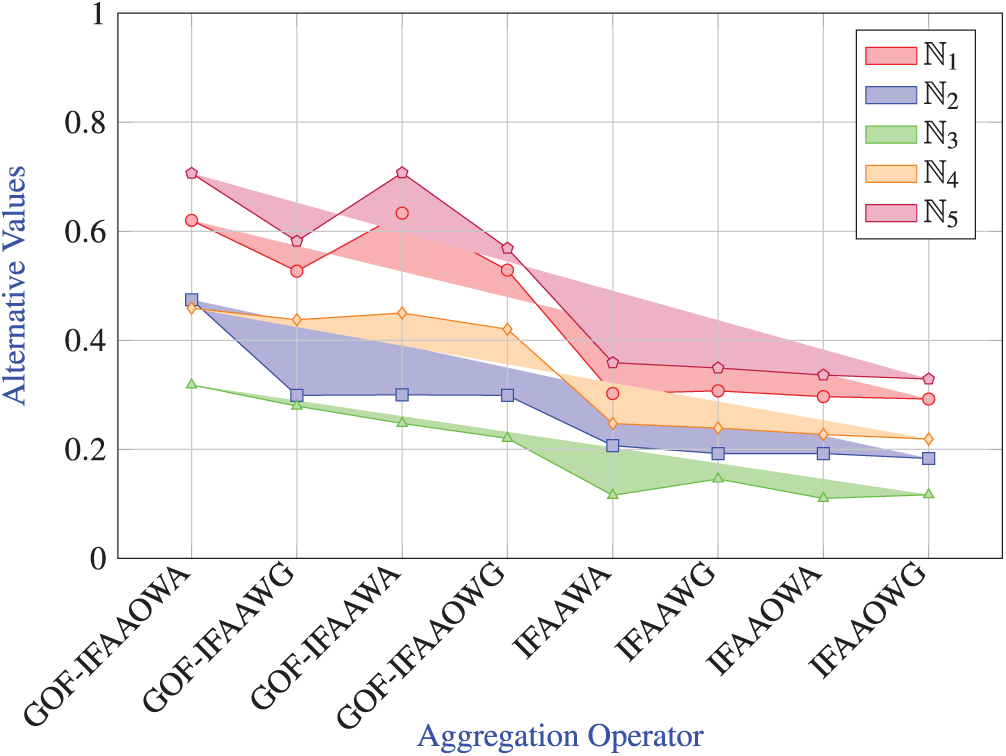

Analysis of Graph: The graphical comparison presented in this Fig. 6 illustrates the performance of various aggregation operators, both proposed (GOF-IFAA) and existing IFAA-based (IFAA) across five alternatives

Figure 6: Graph for comparisons of the proposed operators with existing intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina operators

10.5 The Comparison of Proposed Operators with IF Aczel Alsina Power Operators

In this section, we compare our proposed method with the intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina Power operators, including the intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina Power weighted average (IFAAPWA) [42], the intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina Power weighted geometric (IFAAPWG) [42], the intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina Power ordered weighted average (IFAAPOWA) [42], and the intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina Power ordered weighted geometric (IFAAOWG) [42].

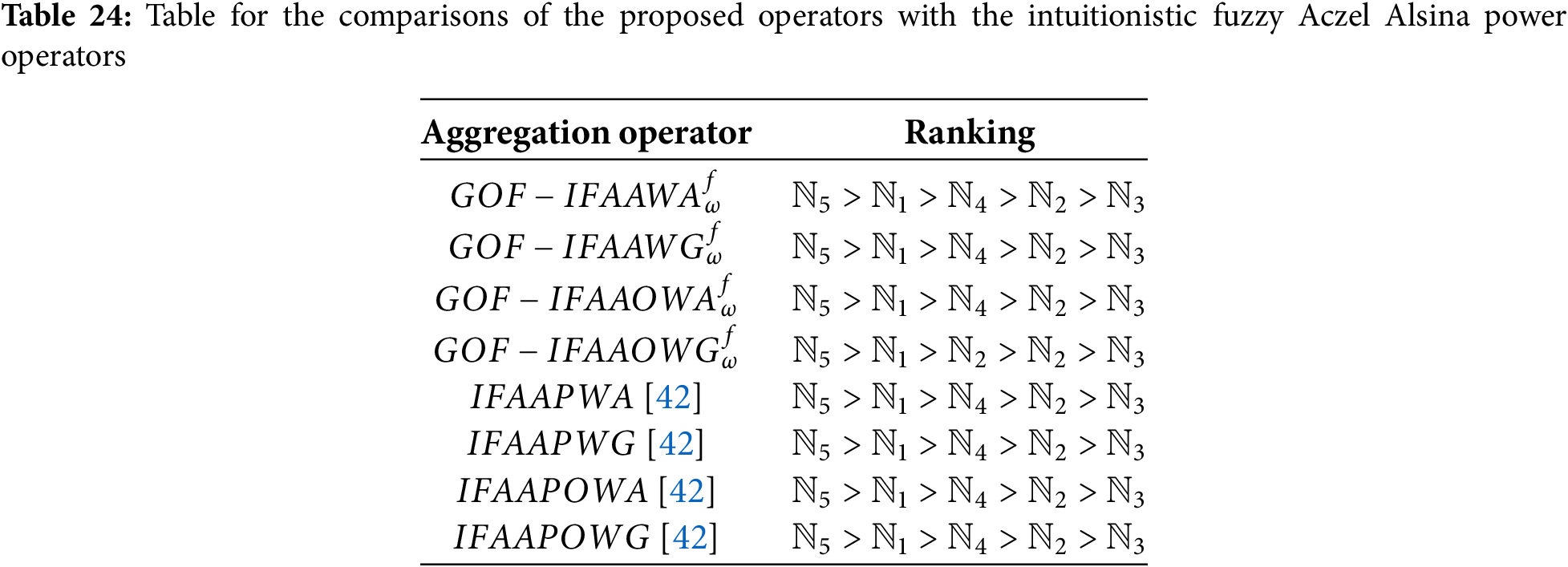

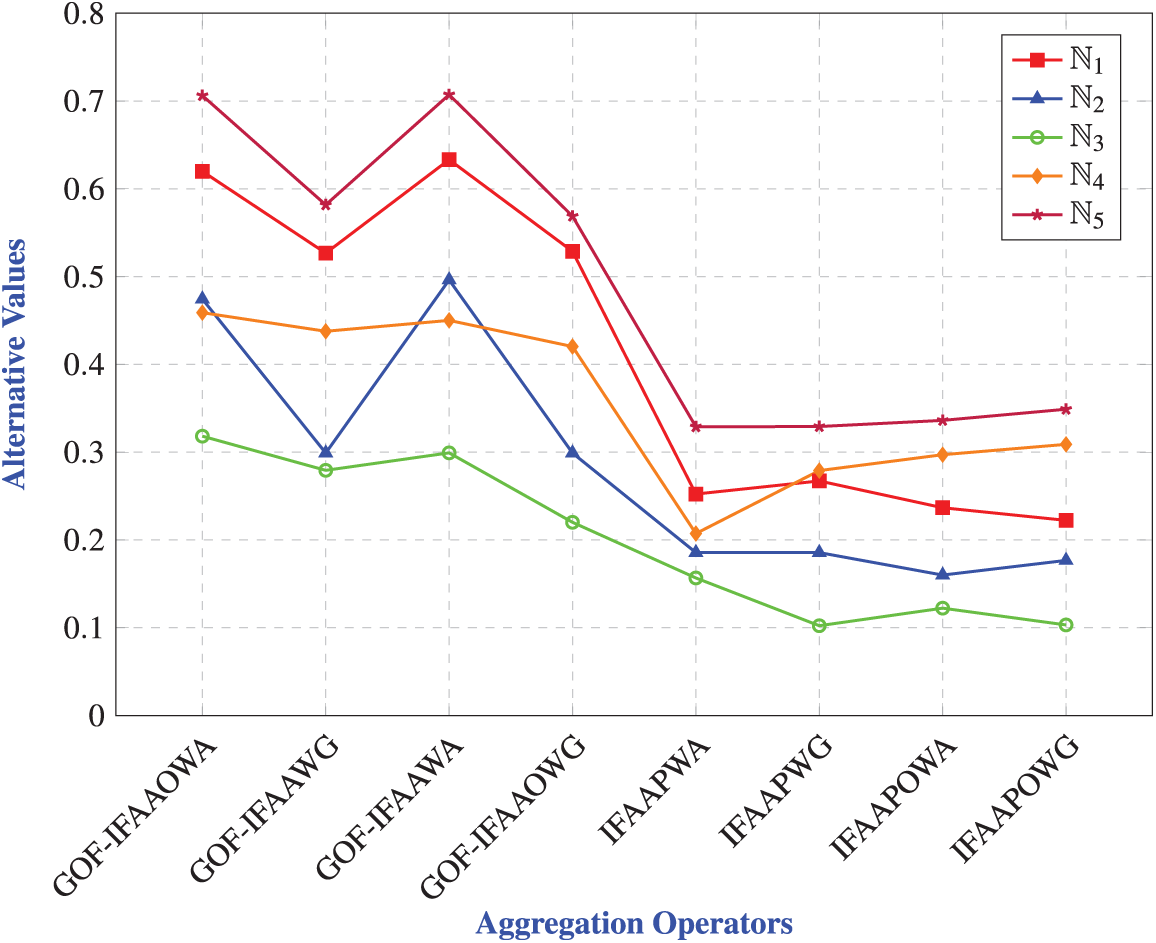

Analysis of Table: Table 24 provides a comparison between the proposed aggregation operators and the existing Intuitionistic Fuzzy Aczel-Alsina Power (IFAAP) operators. The proposed methods—

Analysis of Graph: Fig. 7 visually compares the performance of the proposed aggregation operators with the existing IFAAP operators across five alternatives. The proposed operators (

Figure 7: Plot for comparisons of the proposed operators with existing the intuitionistic fuzzy Aczel Alsina Power Operators

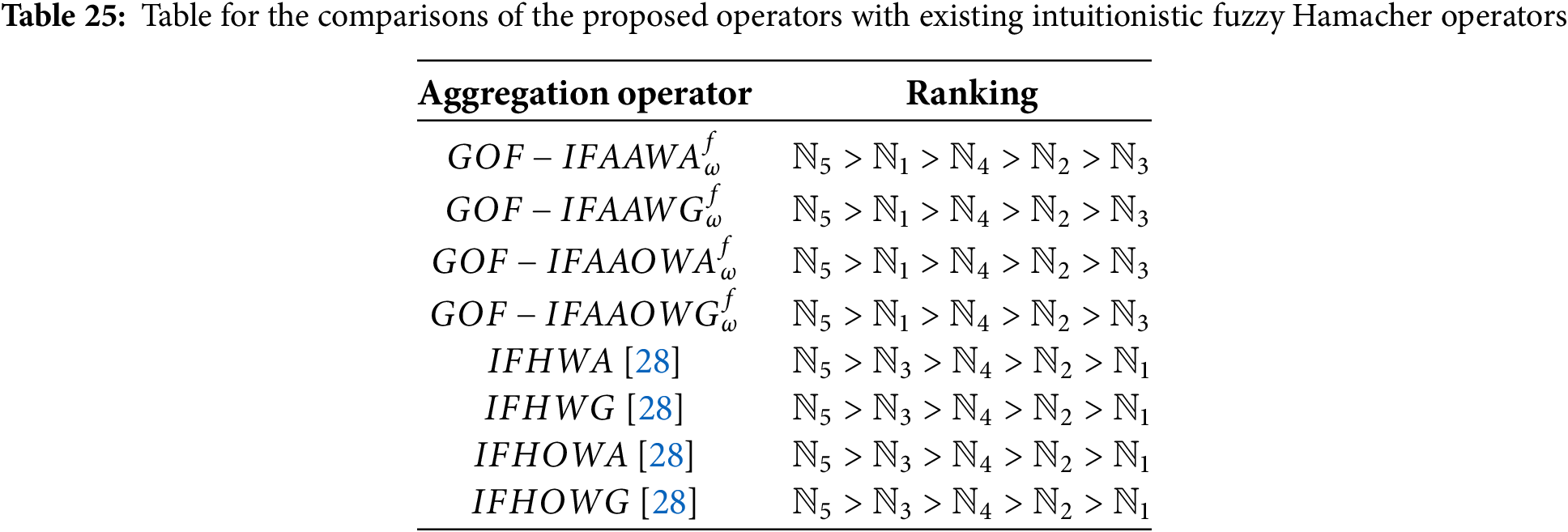

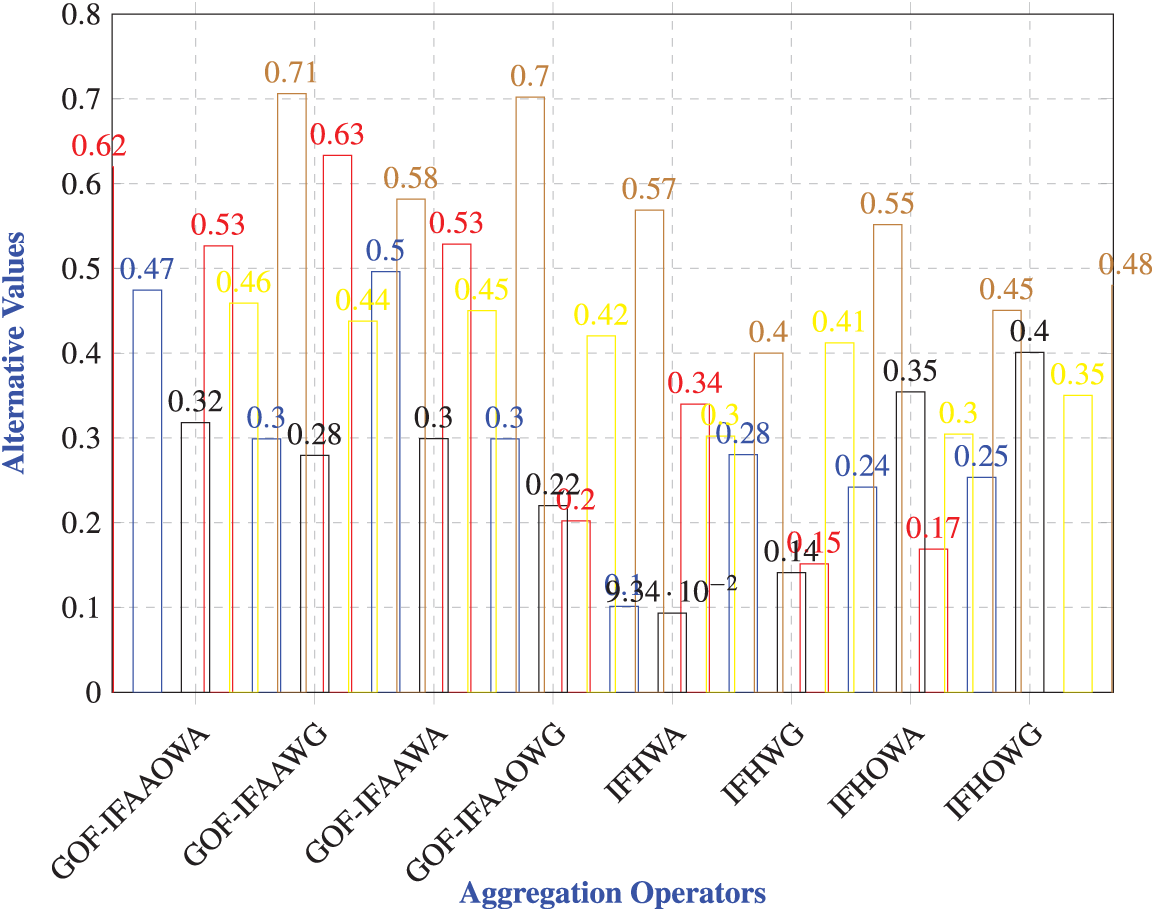

10.6 Comparison of the Proposed Operators with Existing Intuitionistic Fuzzy Hamacher Operators

We compare the proposed operators with well-known Hamacher-based intuitionistic fuzzy operators, including: intuitionistic fuzzy Hamacher weighted average [28], intuitionistic fuzzy Hamacher weighted geometric [28], and their ordered variants [28].

Analysis of Table: Table 25 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed aggregation operators against the existing HIF operators introduced by Ying (2014). The proposed operators—namely

Analysis of the Graph: Fig. 8 shows that the proposed operators consistently assign higher values to alternatives compared to existing IFH operators. Among all,

Figure 8: Graph for comparisons of the proposed operators with existing intuitionistic fuzzy Hamacher operators

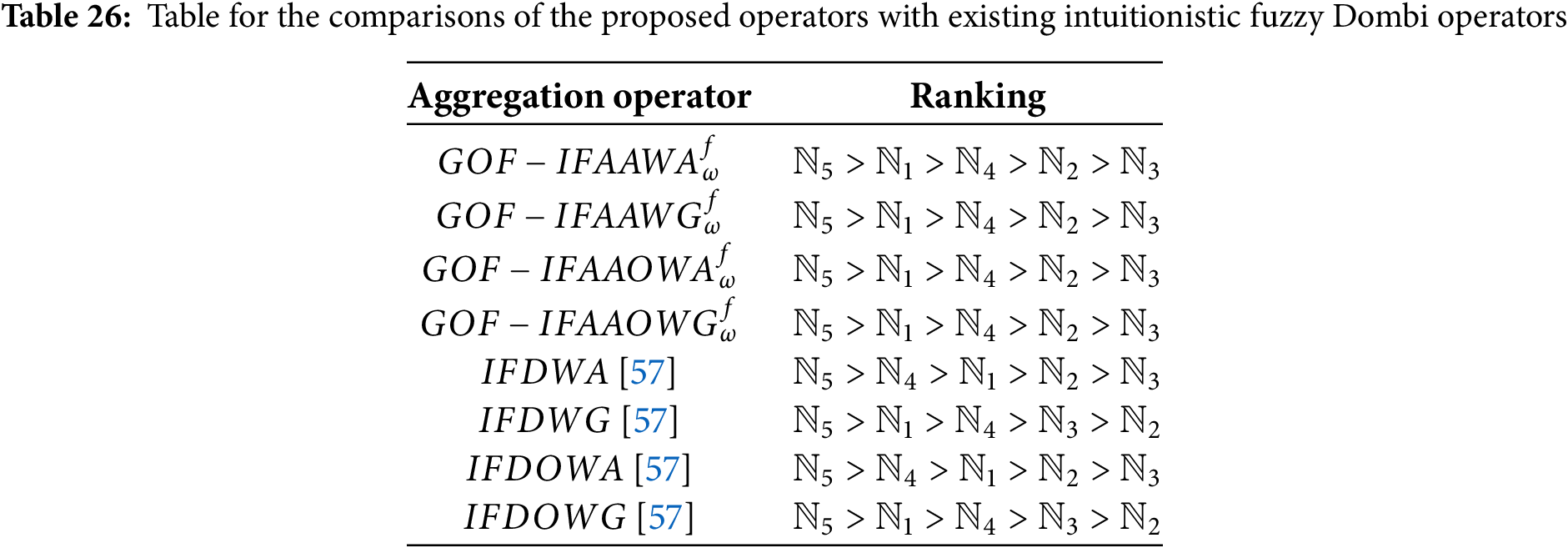

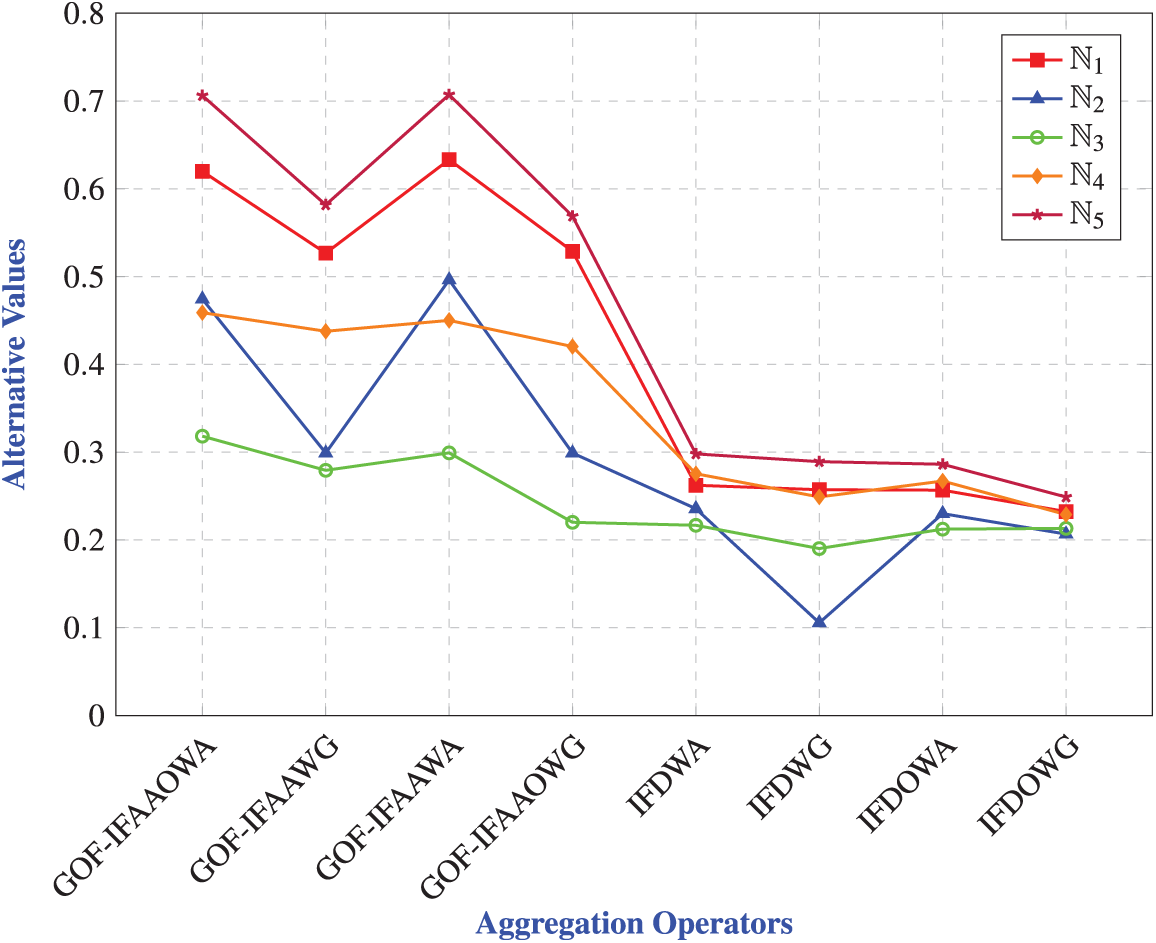

10.7 Comparison with Intuitionistic Fuzzy Dombi Operators (IFD)

The proposed method is compared with existing IFD operators, such as intuitionistic fuzzy Dombi Operators intuitionistic fuzzy Dombi weighted average (IFDWA) [57], intuitionistic fuzzy Dombi ordered weighted average (IFDOWA) [57], intuitionistic fuzzy Dombi weighted geometric (IFDWG) [57], and intuitionistic fuzzy Dombi ordered weighted geometric (IFDOWG) [57].

Analysis of Table: Table 26 presents a comparison between the proposed aggregation operators and the existing Dombi-based Intuitionistic Fuzzy (IFD) operators. The purpose of this comparison is to evaluate how different methods rank the same five alternatives, labeled as

On the other hand, the existing IFD operators show some variations in the ranking. The IFD weighted average (IFDWA) and the IFD ordered weighted average (IFDOWA) rank the alternatives as

This comparison highlights that the proposed aggregation methods are not only stable and reliable but also offer better flexibility and effectiveness in handling uncertain and complex decision-making scenarios, when compared to traditional IFD operators.

Analysis of Graph: Fig. 9 clearly shows that our proposed method provides consistent rankings across all aggregation operators. Unlike the existing methods, where each operator produces different rankings for the alternatives, our method maintains the same ranking regardless of the operator used. This consistency highlights the stability and reliability of our approach. In particular, Alternative 5 consistently performs the best under every operator, which confirms the strength of the proposed method. While

Figure 9: Plot for comparisons of the proposed operators with existing intuitionistic fuzzy Dombi operators

This study introduces novel GOF-based aggregation operators and demonstrates their effectiveness in comparison to several established methods. The proposed operators consistently outperform existing techniques by providing more reliable, accurate, and informative results across various decision-making scenarios. The following subsections provide an extended discussion of the proposed method’s performance compared to existing methods, with a focus on ranking outcomes and the stability of identifying the best alternative.

11.1 Comparison with Intuitionistic Fuzzy (IF) Operators

The proposed GOF-based operators demonstrate clear advantages over traditional Intuitionistic Fuzzy (IF) operators like IFWA, IFWG, IFOWA, and IFOWG [5]. Both approaches yield the same ranking order:

11.2 Comparison with Intuitionistic Fuzzy Einstein (IFE) Operators

When contrasted with Intuitionistic Fuzzy Einstein (IFE) operators [26], the proposed GOF-IFAA operators exhibit greater stability and reliability in ranking outcomes. While IFE operators show variations in the order of alternatives—such as IFEWA and IFEOWG placing

11.3 Comparison with Intuitionistic Fuzzy Einstein Power (IFEP) Operators

In comparison to Intuitionistic Fuzzy Einstein Power (IFEP) operators [56], the proposed GOF-IFAA operators show comparable rankings but with notable improvements in discriminative power. While IFEPWA and IFEPWG rank

11.4 Comparison with Existing IFAA Operators

The proposed GOF-IFAA operators validate their effectiveness when compared to existing Aczel-Alsina-based Intuitionistic Fuzzy operators [23]. Both sets of operators produce the same ranking order:

11.5 Comparison with Intuitionistic Fuzzy Aczel-Alsina Power (IFAAP) Operators

When matched against Intuitionistic Fuzzy Aczel-Alsina Power (IFAAP) operators [42], the proposed GOF-IFAA operators maintain consistent rankings while demonstrating superior discriminative power. The proposed operators provide clearer differentiation between alternatives, which is vital for informed decision-making. The graphical analysis confirms this advantage, with the proposed methods consistently yielding higher alternative values. This improved sensitivity allows decision-makers to better distinguish between options, leading to more informed decisions. The proposed operators also show greater adaptability to varying contexts, enhancing their reliability and stability. Overall, the proposed GOF-based aggregation operators offer a more robust and accurate approach to decision-making in intuitionistic fuzzy environments, outperforming IFAAP operators in key aspects of discriminative power and consistency.

11.6 Comparison with Intuitionistic Fuzzy Hamacher (IFH) Operators

The proposed GOF-IFAA operators outperform Intuitionistic Fuzzy Hamacher (IFH) operators [28] in both ranking consistency and alternative evaluation. While IFH operators identify the same top alternative

11.7 Comparison with Dombi Intuitionistic Fuzzy (IFD) Operators

When evaluated alongside Dombi Intuitionistic Fuzzy (IFD) operators [30], the proposed GOF-IFAA operators demonstrate superior consistency and adaptability. They maintain a uniform ranking order and show enhanced reliability in identifying the best alternative. The proposed methods also display greater flexibility in handling diverse decision-making scenarios, ensuring more stable and trustworthy results. The graphical analysis further highlights the proposed operators’ ability to assign significantly higher values to top alternatives like

The operators proposed in this paper offer distinct advantages over existing ones, like Einstein and Dombi operators. Our AA-based operators demonstrate superior flexibility and effectiveness in handling complex decision-making scenarios. Unlike Einstein operators, which are relatively inflexible and involve complicated calculations, our AA-based operators provide a more streamlined and adaptable approach. While Dombi operators are known for their flexibility, the computational procedure required for aggregating data using Dombi operators is more intricate compared to the operators developed here. This increased complexity can lead to higher computational demands and less efficient processing, especially when dealing with large datasets or intricate decision matrices. In contrast, the AA-based operators not only maintain the necessary flexibility for nuanced decision-making but also simplify the computational process, making them more efficient and practical for real-world applications. Their ability to smoothly model the intersection and union of fuzzy sets allows for a more accurate representation of uncertainty and ambiguity, which is crucial in many decision-making contexts. Therefore, the AA-based operators provide a more robust and efficient solution for the problems addressed in this study. Future research will explore the application of these operators to additional fuzzy set extensions and more sophisticated decision-making frameworks.

This study proposed a novel and effective decision-making framework that integrates AA operational rules with group and overlap functions in the IFS environment. The primary motivation was to address the limitations of traditional T-Ns and T-CNs in handling uncertainty, overlap, and hesitation—challenges commonly encountered in complex decision-making scenarios. The core contributions of this research include the development and formal definition of four innovative aggregation operators: GOF-IFAAWA, GOF-IFAAWG, GOF-IFAAOWA, and GOF-IFAAOWG. These operators were rigorously analyzed, and their theoretical properties were mathematically validated, confirming their effectiveness in fuzzy aggregation settings. To demonstrate real-world applicability, the proposed framework was used in the context of AI-Based Criminal Justice Policy Selection, successfully identifying the optimal model (

We acknowledge that applying the proposed methodology to datasets with a high number of alternatives, attributes, or experts presents computational challenges. The computational process becomes more intensive due to the multiple layers of calculations involved. However, our methodology offers advantages over Einstein or Dombi operators, as it provides more flexibility and simplicity in aggregating intuitionistic fuzzy information. To address these limitations, future research directions include parallel processing and GPU acceleration to speed up computations, dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis to minimize data loss while reducing attributes, integrating machine learning for dynamic parameter adjustment, and using sparse matrices to optimize memory usage and operation speed. Looking ahead, several avenues for future research and improvement of the proposed approach can be explored. One potential direction is the integration of other operators such as Dombi or Archimedean operators, which offer different mathematical properties that could further enhance the flexibility and applicability of the method in various decision-making contexts. For instance, Dombi operators’ ability to handle nonlinear interactions could be particularly useful in scenarios where the relationship between criteria is not strictly linear. Another promising avenue is the incorporation of machine learning techniques for parameter optimization. Machine learning algorithms could be employed to automatically adjust the parameters of the aggregation operators based on historical decision data. This would enhance the framework’s accuracy and adaptability, allowing it to better respond to changing conditions and preferences. Furthermore, the proposed framework could be extended to handle large-scale decision-making problems by integrating big data analytics. This would enable the processing and analysis of vast amounts of data, making the framework more suitable for complex and dynamic environments.

It is also noteworthy that the proposed approach could be extended to various real-life decision-making problems, such as solid waste management, electric vehicle (EV) adoption, and other sustainability and environmental issues. In solid waste management, the framework could help in selecting the most appropriate waste treatment methods by evaluating criteria such as environmental impact, cost-effectiveness, and social acceptance. For EV adoption, the framework could assist in identifying the most effective policies to promote EV use by considering factors like infrastructure availability, economic incentives, and public awareness. These applications would further demonstrate the framework’s adaptability and generalizability in addressing complex and uncertain decision-making situations.

Since the models proposed by Li and Imran are generalized forms of intuitionistic fuzzy sets, a direct comparison with our work is not feasible. However, it is possible that in future studies, the proposed method can be extended and applied within these generalized environments to enable broader comparisons and applications.

Acknowledgement: This research was supported in part by the HEC-NRPU project, under the grant No. 14566.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by “1 Decembrie 1918” University of Alba Iulia, 510009 Alba Iulia. This research was supported in part by the HEC-NRPU project, under the grant No. 14566.

Author Contributions: Ikhtesham Ullah: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, writing—original draft, visualization, writing–review and editing. Muhammad Sajjad Ali Khan: methodology, software, writing—original draft, data curation, writing—review and editing. Fawad Hussain: methodology, writing—original draft, data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing. Madad Khan: validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing, project administration. Kamran: investigation, data curation, visualization, writing—review and editing. Ioan-Lucian Popa: formal analysis, investigation, visualization, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the data produced or examined in this study are provided within this article.

Ethics Approval: There does not exist any ethical issue regarding this work.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Definition A1. For any three IFVs

1

2

3

4

Proof. We only prove the [1], [3] and [5]. The remaining are similar.

[1] let we take L.H.S, i.e.,

As we know by the definition of 1, we have

By the operational laws of IFNs, we write as:

or

which is a R.H.S

[3] let we take L.H.S, i.e.,

As we know by the definition 1, we have

then again, by the definition of 1, we have

[5] let we take L.H.S i.e

As we know by the definition of 4.1 and property 1

and by the definition of 1, we have

◼

Definition A2. Assume that

Proof. We use the mathematical induction to prove this result.

So for

so for

so for

So, it is hold for

Let the equation is true for

Now for

or

Thus, Eq. (4) is holds for

As a result of (i) and (ii), we can deduce that (1) appears to be true for any

Proof. Let

from definition 7, it is clear that

◼

Proof. Let

Let

Then, by Theorem 1 and 2, it is straight forward, and we have

then

Then

Then

Also

Then

Then

Then

Then we get

or

Proof. Similar to Property 3. ◼

Proof. Let

be the weight vector of

If

Note that (A7) also holds even if

and (A7) are transformed into the forms

Definition A3. Assume that

where

Proof. The proof is same as Theorem 4.1. ◼

Proof. The proof is same as property 1. ◼

Proof. The proof is the same as property 2. ◼

Proof. The proof is the same as property 3. ◼

Definition A4. Assume that

Proof. Same as in Theorem 1 ◼

Proof. Same as property 1 ◼

Proof. Same as property 2 ◼

Proof. The proof is similar to property 3. ◼

Definition A5. Assume that

where

Proof. The proof is the same as Theorem 4.1. ◼

Proof. The proof is the same as property 1. ◼

Proof. The proof is the same as property 2. ◼

Proof. The proof is the same as property 3. ◼

References

1. Zadeh LA. Fuzzy sets. Inf Control. 1965;8(3):338–53. doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(65)90241-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Klir GJ, Yuan B. Fuzzy sets and fuzzy logic: theory and applications. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall; 1995. p. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

3. Yang M-S, Hung W-L, Chang Chien S-J. On a similarity measure between LR type fuzzy numbers and its application to database acquisition. Int J Intell Syst. 2005;20(10):1001–16. doi:10.1002/int.20102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yang MS, Hung WL, Cheng FC. Mixed variable fuzzy clustering approach to part family and machine cell formation for GT applications. Int J Production Econ. 2006;103(1):185–98. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2005.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Atanassov KT. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Sys. 1986;20(1):87–96. doi:10.1016/S0165-0114(86)80034-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Atanassov K. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. In: Theory and applications. Heidelberg, Germany: Physica-Verlag; 1999. p. 1–137. doi:10.1007/978-3-7908-1870-3-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Atanassov K. On intuitionistic fuzzy sets theory. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2012. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-29127-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wan S-P, Dong J-Y, Chen S-M. A novel intuitionistic fuzzy best-worst method for group decision making with intuitionistic fuzzy preference relations. Inf Sci. 2024;666:120404. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Khan MB, Deaconu A, Tayyebi J, Spridon D. Diamond intuitionistic fuzzy sets and their applications. IEEE Access. 2024;12:176171–83. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3502202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yager R. Pythagorean fuzzy subsets. In: 2013 Joint IFSA World Congress and NAFIPS Annual Meeting (IFSA/NAFIPS); 2013 Jun 24–28; Edmonton, AB, Canada. p. 57–61. doi:10.1109/IFSA-NAFIPS.2013.6608375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Adak A, Kumar D, Edalatpanah SA. Some new operations on pythagorean fuzzy sets. Uncertainty Discourse Appl. 2024;1(1):11–9. doi:10.48313/uda.v1i1.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wei G, Lu M. Pythagorean fuzzy power aggregation operators in multiple attribute decision-making. Int J Intell Syst. 2018;33:169–86. doi:10.1002/int.21946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Thakur P, Paradowski B, Gandotra N, Thakur P, Saini N, Saabun W. A study and application analysis exploring pythagorean fuzzy set distance metrics in decision making. Information. 2024;15(1):28. doi:10.3390/info15010028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Garg H. A new generalized Pythagorean fuzzy information aggregation using Einstein operations and its application to decision making. Int J Intell Syst. 2016;31(9):886–920. doi:10.1002/int.21809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yager R. Generalized orthopair fuzzy sets. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2016;25(5):1222–30. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2016.2604005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Darko AP, Liang D. Some q-rung orthopair fuzzy Hamacher aggregation operators and their application to multiple attribute group decision making with modified EDAS method. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2020;87(1):103259. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2019.103259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Saha A, Majumder P, Dutta D, Debnath BK. Multi-attribute decision making using q-rung orthopair fuzzy weighted fairly aggregation operators. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2021;12(7):8149–71. doi:10.1007/s12652-020-02551-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu P, Wang P. Some q-rung orthopair fuzzy aggregation operators and their applications to multiple-attribute decision making. Int J Intell Syst. 2018;33(2):259–80. doi:10.1002/int.21927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Y, Hussain A, Mahmood T, Ali MI, Wu H, Jin Y. Decision-making based on q-rung orthopair fuzzy soft rough sets. Math Probl Eng. 2020;2020(1):6671001. doi:10.1155/2020/6671001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Klement EP, Mesiar R, Pap E. Triangular norms (Vol. 8). 1st ed. Dordrecht, Netherland: Springer; 2013. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-9540-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Beliakov G, Pradera A, Calvo T. Aggregation functions: a guide for practitioners (Vol. 221). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2007. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-73721-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Calvo T, Mayor G, Mesiar R. Aggregation operators: new trends and applications. Physica-Heidelberg; 2002. doi:10.1007/978-3-7908-1787-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Senapati T, Chen G, Yager RR. Aczel Alsina aggregation operators and their application to intuitionistic fuzzy multiple attribute decision making. Int J Intell Syst. 2022;37(2):1529–51. doi:10.1002/int.22684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Silambarasan I, Sriram S. Hamacher operations of intuitionistic fuzzy matrices. Ann Pure Appl Math. 2018;16(1):81–90. doi:10.17512/jamcm.2019.3.06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chaira T. Operations on fuzzy/intuitionistic fuzzy sets and application in decision making. In: Fuzzy set and its extension: the intuitionistic fuzzy set. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley; 2019. p. 133–70. doi:10.1002/9781119544203.ch5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang W, Liu X. Intuitionistic fuzzy information aggregation using Einstein operations. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2012;20(5):923–38. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2012.2189405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xu Z. Approaches to multiple attribute group decision making based on intuitionistic fuzzy power aggregation operators. Knowl Based Syst. 2011;24(6):749–60. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2011.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Huang J-Y, Huang JY. Intuitionistic fuzzy Hamacher aggregation operators and their application to multiple attribute decision making. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2014;27(1):505–13. doi:10.3233/IFS-131019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Son LH, Ngan RT, Ali M, Fujita H, Abdel-Basset M, Giang NL, et al. A new representation of intuitionistic fuzzy systems and their applications in critical decision making. IEEE Intell Syst. 2019;35(1):6–17. doi:10.1109/MIS.2019.2938441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Dombi J. A general class of fuzzy operators, the De Morgan class of fuzzy operators and fuzziness measures induced by fuzzy operators. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1982;8(2):149–63. doi:10.1016/0165-0114(82)90005-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu P, Liu J, Chen SM. Some intuitionistic fuzzy Dombi Bonferroni mean operators and their application to multi-attribute group decision making. J Oper Res Soc. 2018;69(1):1–24. doi:10.1057/s41274-017-0190-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen J, Ye J. Some single-valued neutrosophic Dombi weighted aggregation operators for multiple attribute decision-making. Symmetry. 2017;9(6):82. doi:10.3390/sym9060082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shi L, Ye J. Dombi aggregation operators of neutrosophic cubic sets for multiple attribute decision-making. Algorithms. 2018;11(3):29. doi:10.3390/a11030029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lu X, Ye J. Dombi aggregation operators of linguistic cubic variables for multiple attribute decision making. Information. 2018;9(8):188. doi:10.3390/info9080188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. He X. Typhoon disaster assessment based on Dombi hesitant fuzzy information aggregation operators. Nat Hazards. 2018;90(3):1–23. doi:10.1007/s11069-017-3091-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Qiyas M, Khan N, Naeem M, Abdullah S. Intuitionistic fuzzy credibility Dombi aggregation operators and their application of railway train selection in Pakistan. AIMS Math. 2023;8(3):6520–42. doi:10.3934/math.2023329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ameer M, Yousaf A. Dombi power aggregation operators with linguistic intuitionistic fuzzy set and their application in healthcare waste management. Res Square. 2024;28(1):87. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3916711/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Akram M, Dudek WA, Dar JM. Pythagorean Dombi fuzzy aggregation operators with application in multicriteria decision-making. Int J Intell Syst. 2019;34(11):3000–19. doi:10.1002/int.22183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Qin J, Liu X, Pedrycz W. Frank aggregation operators and their application to hesitant fuzzy multiple attribute decision making. Appl Soft Comput. 2016;41:428–52. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2015.12.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Xia M, Xu Z. Some issues on intuitionistic fuzzy aggregation operators based on archimedean t-conorm and t-norm. Knowl Based Syst. 2012;31:78–88. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2012.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ali W, Shaheen T, Haq IU, Toor H, Akram F, Garg H, et al. Aczel-Alsina-based aggregation operators for intuitionistic hesitant fuzzy set environment and their application to multiple attribute decision-making process. AIMS Math. 2023;8(8):18021–39. doi:10.3934/math.2023916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Garg H, Mahmood T, ur Rehman U, Nguyen GN. Multi-attribute decision-making approach based on Aczel-Alsina power aggregation operators under bipolar fuzzy information & its application to quantum computing. Alex Eng J. 2023;82(19):248–59. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2023.09.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bustince H, Fernandez J, Mesiar R, Montero J, Orduna R. Overlap functions. Nonlinear Anal: Theory, Methods Appl. 2010;72:1488–99. doi:10.1016/j.na.2009.08.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Xu Z. Group decision making based on multiple types of linguistic preference relations. Inf Sci. 2008;178(2):452–67. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2007.05.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Tapia J, Moral MJ, Martínez A, Herrera-Viedma E. A consensus model for group decision-making problems with interval fuzzy preference relations. Int J Inf Technol Decision Making. 2012;11(4):709–25. doi:10.1142/S0219622012500174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Cabrerizo F, Alonso S, Perez I, Herrera-Viedma E. On consensus measures in fuzzy group decision making, in on consensus measures in fuzzy group decision making. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2008. p. 86–97. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-88269-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Qiao J, Hu BQ. On multiplicative generators of overlap and grouping functions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2016;332(114):1–24. doi:10.1016/j.fss.2016.11.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Qiao J, Hu B. On interval additive generators of interval overlap functions and interval grouping functions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2017;323:19–55. doi:10.1016/j.fss.2017.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang X, Li M, Liu H. Overlap functions-based fuzzy mathematical morphological operators and their applications in image edge extraction. Fractal Fractional. 2023;7(6):465. doi:10.3390/fractalfract7060465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Dai S. Comparison of overlap and grouping functions. Axioms. 2022;11(8):420. doi:10.3390/axioms11080420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Sola H, Pagola M, Mesiar R, Hullermeier E, Herrera F. Grouping, overlap, and generalized bientropic functions for fuzzy modeling of pairwise comparisons. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2012;20(3):405–15. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2011.2173581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Jurio A, Sola H, Pagola M, Pradera A, Yager R. Some properties of overlap and grouping functions and their application to image thresholding. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2013;229(1):69–90. doi:10.1016/j.fss.2012.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Bedregal B, Dimuro G, Bustince H, Barrenechea E. New results on overlap and grouping functions. Inf Sci. 2013;249(2):148–70. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2013.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Ahamdani H. A method of weight update in group decision-making to accommodate the interests of all the decision makers. Int J Intell Syst Appl. 2017;9(8):1–10. doi:10.5815/ijisa.2017.08.01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Gonçalves-Coelho AM, Mourão AJF. Axiomatic design as support for decision-making in a design for manufacturing context: a case study. Int J Prod Econ. 2007;109(1–2):81–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2006.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Sharma A, Mani N, Arora R, Bhardwaj R. Power Einstein aggregation operators of intuitionistic fuzzy sets and their application in MADM. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2024. doi:10.1201/9781003497219-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Seikh MR, Mandal U. Intuitionistic fuzzy Dombi aggregation operators and their application to multiple attribute decision-making. Granular Comput. 2021;6(3):473–88. doi:10.1007/s41066-019-00209-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools