Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Evaluating Domain Randomization Techniques in DRL Agents: A Comparative Study of Normal, Randomized, and Non-Randomized Resets

Department of Software Engineering, College of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, 21959, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Abubakar Elsafi. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1749-1766. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.066449

Received 09 April 2025; Accepted 11 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Domain randomization is a widely adopted technique in deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to improve agent generalization by exposing policies to diverse environmental conditions. This paper investigates the impact of different reset strategies, normal, non-randomized, and randomized, on agent performance using the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) and Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3) algorithms within the CarRacing-v2 environment. Two experimental setups were conducted: an extended training regime with DDPG for 1000 steps per episode across 1000 episodes, and a fast execution setup comparing DDPG and TD3 for 30 episodes with 50 steps per episode under constrained computational resources. A step-based reward scaling mechanism was applied under the randomized reset condition to promote broader state exploration. Experimental results show that randomized resets significantly enhance learning efficiency and generalization, with DDPG demonstrating superior performance across all reset strategies. In particular, DDPG combined with randomized resets achieves the highest smoothed rewards (reaching approximately 15), best stability, and fastest convergence. These differences are statistically significant, as confirmed by t-tests: DDPG outperforms TD3 under randomized (t = −101.91, p < 0.0001), normal (t = −21.59, p < 0.0001), and non-randomized (t = −62.46, p < 0.0001)) reset conditions. The findings underscore the critical role of reset strategy and reward shaping in enhancing the robustness and adaptability of DRL agents in continuous control tasks, particularly in environments where computational efficiency and training stability are crucial.Keywords

Reinforcement Learning (RL) represents an evolving domain within machine learning wherein an agent acquires knowledge regarding the execution of actions through its interactions with a given environment, with the ultimate objective of maximizing the aggregated rewards [1]. In contrast to supervised learning, which depends on established datasets comprising input-output pairs, RL is characterized by a learning paradigm centered on interactions, employing a trial and error methodology, with feedback manifested as rewards or penalties contingent upon the agent’s actions [2]. This feedback mechanism is fundamental to RL and operates under the framework of the agent-environment interaction model; the agent determines its actions based on its prevailing state, while the environment reacts by transitioning to new states and issuing pertinent rewards. The principal aim within RL is to enable the agent to develop a policy that optimizes the expected return, which is delineated as the cumulative rewards accrued over a specified period [3,4].

A principal challenge in RL pertains to generalization, which encompasses the enhancement of an agent’s capacity to operate proficiently in novel or previously unencountered scenarios that were not incorporated during the training phase. The significance of generalization is amplified in practical applications that entail real-world RL agents, which must exhibit adaptability to a multitude of conditions and uncertainties. The ability to generalize effectively enables an agent that has been trained in a specific environment to adjust to variations and maintain high performance outside the confines of the training conditions [5,6].

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has emerged as a prominent area within the domain of RL, particularly in the context of managing intricate environments defined by high-dimensional state and action spaces. Through the deployment of deep neural networks, DRL methodologies, such as Deep Q-Learning (DQN) [7] and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [8], have catalyzed substantial advancements in the field of RL. Notwithstanding these developments, DRL approaches frequently grapple with challenges, including overfitting to the training environment and a constrained ability to generalize effectively to novel or unobserved situations [9,10].

Domain randomization has been suggested as a means to enhance generalization for RL [11]. This approach involves changing some features of the environment in which training is conducted to expose the agent to a diverse set of challenges. Domain randomization extends the range of experience by randomizing aspects of the environment for the given object such as texture, position, and dynamic properties, therefore ensuring the robustness of the learned policy that can be less sensitive to specific scenarios and settings [12,13]. This method is especially beneficial in making RL agents ready for deployment in real-world scenarios, where training directly in various real environments may not be feasible [14]. Domain randomization can be used as a solution for enhancing generalization in RL as it was stated by Lee et al. [15]. This method entails changing some or all of the environment’s characteristics and aspects in the training phase to cover all situations. As dynamic parameters like object textures, positions, or dynamic properties of the objects are randomly varied, domain randomization provides a broader range of training scenarios, which in turn allows the agent to learn policies that are not overly dependent on certain settings of the environment [13]. This method is especially helpful in deploying RL agents for applications where training in numerous real-world scenarios is not possible [14].

Recent advancements in RL research highlight the growing importance of continuous improvement and thorough evaluation of how well agents generalize across tasks. Researchers are now exploring techniques like structured memory and multi-task learning to help agents draw on past experiences more effectively and succeed in a wider range of tasks and environments [16]. In this context, DDPG has emerged as a model-free off-policy RL approach especially suitable for the cases where the action spaces are high-dimensional and continuous [17,18]. Expanding decision-making policy gradient techniques, DDPG incorporates a deep neural network for estimating the policy and values–functions. As an extension of the Actor-Critic model, DDPG places the balances between exploration and exploitation in continuous action space appropriately. Such experience, together with experience replay and target networks helps to stabilize the learning process and expose the model to a great variety of experiences [19,20].

Therefore, the main goal of this work is to assess the effectiveness of various domain randomization approaches on the learning, and robustness of a DDPG agent in the CarRacing-v2 environment, which is a complex and continuous control problem. Particularly, the study contrasts Normal Reset, Randomized Reset, and Non-Randomized Reset models, concerning the learning efficiency and generalization ability of the agent. The research questions of this study are aimed at identifying how the several reset approaches impact on the performance and generalization of the agent as well as how the use of domain randomization could be applied to improve RL training paradigms in complex environments.

The rest of this paper includes a literature review (Section 2), methodology (Section 3), results and discussion (Section 4), and conclusion (Section 5).

DRL has been observed as an enhanced form of the RL technique in which the conceptual architecture of the RL model is combined with the deep learning representation system [21,22]. Some of the noted methods in this context include DQN by Hester et al. [7] and proximal policy optimization (PPO) by Schulman et al. [8,23]; both of which have been observed to perform very well when applied to high dimensional approaches to state and actions essentially in video games and robotics. For instance, DQN uses a deep neural network in order to provide a direct mapping of the Q-value function where the agent is able to control large state spaces through learning a policy that best maps the states to the corresponding actions [10]. PPO reduces variance and increases the stability of policy gradient methods by bounding the change in the policy during training with an estimated clipped goal.

However, such methods have limitations especially because most DRL techniques are prone to overfitting to the training environment. It implies when an agent over-adapts to scenarios and unique states in training leading to poor performance when exposed to new scenarios that alter the state in the future [24,25]. This limitation limits the possibility of using DRL in more complex problems in the real environment, where working conditions are often unknown or varied. Liu et al. [26] explained that the generalization issue in DRL is not a theoretical problem but has real-world implications for real-world applications that require DRL such as autonomous driving and robotic manipulation [27].

Domain randomization has been suggested as one of the promising approaches to improve the generalisability of RL-based systems. It means that during the training all parameters and conditions of the environment are changed to different degrees, thus facing the agent with a great number of types of situations [14]. Domain randomization targets eliminating the over-dependence of the agent on certain conditions during training so that it adapts different policies for an array of environments.

An early and widely referenced instance of domain randomization was done by Tobin et al. [28], for robotic grasping. They showed that given a robotic arm that is trained on a simulated robot environment in which the properties of vision and the physical context are changed randomly for each trial, the policies obtained could be applied to real-world activities without any further refinements being made. In the same manner, in an autonomous driving domain, domain randomization was employed to enhance the robustness of driving policies by modifying factors such as lighting conditions, weather, and road textures during simulation-based training [29]. This is especially evident when observing the application of domain randomization and its capabilities when it comes to reducing the so-called ‘reality gap’, meaning the gap between the simulated environment in which the RL agent is trained and the actual environment in which the RL agent is to be utilized. From the work of Shakerimov et al. [30], domain randomization can improve the transferability of the policies that were learned in simulation and may help to minimize the dependency of the learning in real-world experience which is often slow and costly.

Domain randomization is one of the key steps in DRL, which involves changing the conditions of the environment during its training to improve generalization. There are several methods for domain randomization, each with different features and applications [15].

Basic Domain Randomization where parameters including object placement, textures, and lighting are altered to give the agent an experience of the different environments. Thus, the technique avoids learning specific training conditions and offers the capacity for good performance across different environments [28].

Structured Domain Randomization enhances the training process by methodically introducing a predefined range of variations into the training environments, ensuring comprehensive coverage of potential conditions. This method effectively strikes a balance between generating diverse training data and managing practical limitations, such as the availability of computational resources [31].

Sim2Real Transfer with Domain Randomization aims to mitigate the disparity between simulated training environments and real-world applications. By introducing controlled randomness in the simulation, this approach minimizes the gap between simulation and reality, thereby enhancing the transferability of learned policies to practical, real-world situations [32].

Adaptive Domain Randomization tailors the scope and intensity of randomizations in real-time, based on the agent’s performance, specifically targeting regions where the agent exhibits higher sensitivity. This adaptive approach enhances training efficiency by concentrating randomization in areas that require the most attention, thereby optimizing the learning process [30].

The critical contribution of environmental randomization along with reward design makes deep reinforcement learning (DRL) policies more robust according to recent developments. Lillicrap et al. [33] introduced DDPG as a baseline for controlling continuous systems yet Peng et al. [34,35] revealed that implementing domain randomization during training can boost policies that function between simulation and reality by presenting agents to multiple physical dynamics. Building on these principles. DRL has achieved additional sample-efficiency due to adaptive curricula integration and reward shaping. The research by Florensa et al. [36] developed automatic goal generation to function as a curriculum learning procedure which proved that tasks with increasing difficulty levels speed up learning efficiency. According to Nagpal et al., in their work [37], the dynamic adjustment of reward components leads agents to achieve convergence more efficiently under sparse reward conditions. On the other hand, Haarnoja et al. [38] provided Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) with entropy regularization which enables exploration without compromising task performance. These studies demonstrate how structured exploration incentives should work together with reward adaptability mechanisms which represent core components of contemporary DRL systems.

A key obstacle in robotics is operational resilience to environmental variations which receives dual solution through adversary-based and protocol-based approaches. Research by Pattanaik et al. [39] showed policies developed with adversarial noise training demonstrate better protection from observation/action interference and Portelas et al. [40] proved randomized reset systems help restore systems from extreme cases. This method alongside the present work advances the field by unifying environment adaptation features with performance-based reward modulation for automatic difficulty adjustment during stable training processes.

The research by Portelas et al. [40] proved automatic task generation using learning progress improves sample efficiency and Plappert et al. [41] proved policy parameter perturbation drives structured exploration. Weather conditions in Portelas’ study parallel the environment randomization method in our system while the parameter noise developed in Plappert’s research shows a comparable method for action-space exploration. The concept of performance-driven automated adaptation proven in our framework through reward scaling and reset strategies has gained validation from this research alongside other findings.

The field of policy-fitness adaptation through specific methods within time frames has increased DRL’s operational scope. The paper by Park et al. [42] presented time-independent action repetition elements that create balanced policies across changing control intervals. This share similarities with step-focused reward adjustment system for temporal credit assignment. Yoo et al. [43] adapted DDPG for industrial batch processes through sub-policies that focused on different phases which resembles the method for dealing with environment stochasticity through randomized resets. The works demonstrate the importance of adaptable time learning along with domain-specific training approaches which our proposed approach implements through time-based rewards and reset-focused domain generalization. Table 1 explains a comparative analysis of related studies.

Lastly, meta-randomization leverages meta-learning strategies to refine domain randomization processes. By using meta-information to guide how the domain should be randomized, this method enhances the agent’s capacity to generalize effectively from simulation to real-world environments, improving overall adaptability and performance [44].

2.1 Domain Randomization in Deep Reinforcement Learning

Domain randomization (DR), also known as randomized resets, is a technique to enhance the generalization of reinforcement learning (RL) agents by training them in simulated environments with varied parameters, such as initial states, environmental properties, or dynamics. This approach ensures that the agent encounters a diverse set of scenarios during training, making it robust to variations in the real world—a critical factor in sim-to-real transfer [28]. In the context of DDPG and TD3, DR can involve randomizing initial state distributions (

The entropy of the initial state distribution, formalized as

quantifies the diversity introduced by randomization, promoting exploration and robustness [28]. However, excessive randomization can increase sample complexity and slow convergence, as agents must learn to handle a broader range of scenarios, necessitating a balance in randomization intensity.

Peng et al. [35] explored dynamics randomization, a form of DR, in the context of robotic control, using a variant of DDPG called Recurrent RDPG. In their study, policies were trained in simulation with randomized dynamics for an object-pushing task with a robotic arm. The randomization enabled policies to generalize to real-world dynamics without training on physical systems, achieving reliable performance in tasks such as moving objects to desired locations from random initial configurations. The training involved 100 million samples over 8000 iterations, demonstrating the computational intensity of DR but its effectiveness in bridging the sim-to-real gap.

A study by Ajani et al. [13] evaluated DR in DRL locomotion tasks, comparing TD3 with Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) across six PyBullet environments (e.g., Ant, HalfCheetah) under different terrain conditions: Normal Terrain (NT, friction

However, SAC outperformed TD3 in 13 out of 18 train-test scenarios, suggesting that TD3’s deterministic policy may be less adaptable to certain randomization levels compared to SAC’s stochastic approach. The study highlighted that optimal DR levels vary by task, with some requiring low-dimensional randomization and others needing high-dimensional distributions.

While DR enhances generalization, it introduces trade-offs. Increased randomization can lead to higher sample complexity, as agents must learn across a wider state-action distribution, potentially slowing convergence [13]. For instance, excessive randomization of initial conditions (e.g., track color, car position) may result in a diffuse state-action distribution, making it challenging to learn a coherent policy. Ongoing research aims to optimize randomization parameters as hyperparameters to balance exploration and learning efficiency.

Recent studies have extended the application of DDPG and TD3 with DR to various domains. For example, Dankwa and Zheng [45] applied TD3 to optimize power allocation and intelligent reflecting surface orientation in wireless communication, demonstrating superior performance compared to DDPG and non-randomized setups. Similarly, Chen et al. [46] provided a theoretical framework for DR in sim-to-real transfer, modeling the simulator as a set of Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) with tunable parameters, offering bounds on the sim-to-real gap. These advancements underscore the versatility of DDPG and TD3 when combined with DR in addressing real-world challenges.

The literature highlights that DRL techniques have achieved notable progress in continuous control tasks. However, significant challenges persist in developing robust policy generalizations. Domain randomization strategies, including Normal, Randomized, and Non-Randomized Resets, offer promising avenues for enhancing agent adaptability and performance. Hence, this study seeks to fill existing gaps by conducting a comprehensive evaluation of these randomization methods. The results aim to advance the robustness and practical applicability of DRL in diverse and dynamic environments.

This section outlines the methodology followed in this paper and contains two subsections: the environment used (Section 3.1) and the DDPG algorithm with randomized resets (Section 3.2).

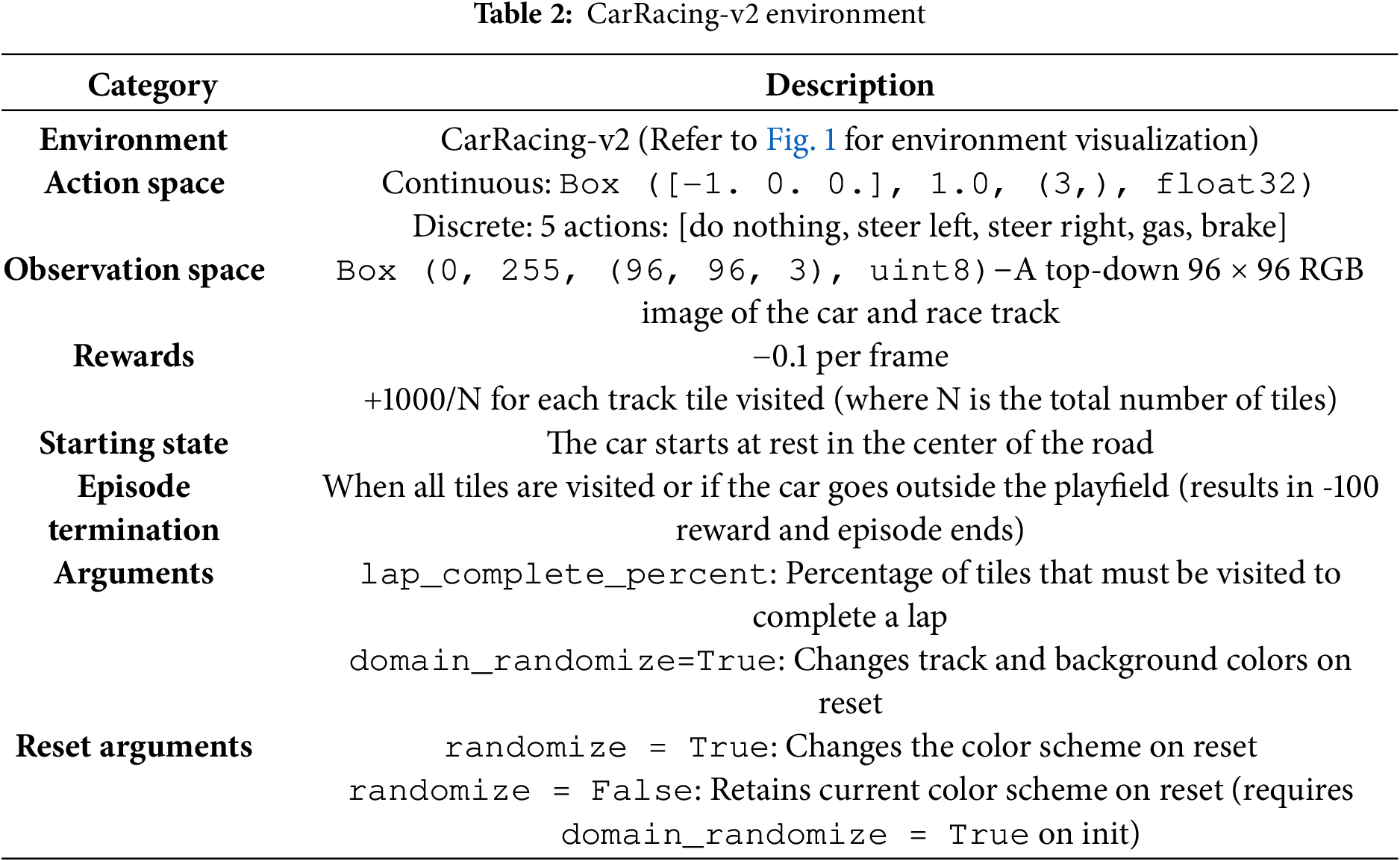

The CarRacing-v2 environment, part of the OpenAI Gym [47], serves as the simulation platform for training and evaluating our DDPG agent. This environment presents a continuous control problem where an agent must navigate a procedurally generated racetrack, using pixel input from the car’s perspective. The objective is to complete laps efficiently while minimizing collisions and staying within track boundaries. The state space is defined by a

Figure 1: CarRacing-v2 environment

The key characteristics of the environment include:

• Reward Structure: The agent is rewarded for forward movement and penalized for driving off the track.

• Termination Criteria: Episodes terminate upon completing a lap, exhausting the maximum number of timesteps, or failing to stay on the track for a specified duration.

This environment provides a challenging test for RL algorithms due to its high-dimensional state space and continuous action space.

3.2 DDPG Algorithm with Randomized Resets

DDPG merges the advantages of DQN and policy gradient methods, enabling the agent to learn a deterministic policy in high-dimensional action spaces [33]. In this work, we employed the DDPG algorithm to train an agent in the CarRacing-v2 environment under different reset strategies: normal, randomized, and non-randomized, as described in Algorithm 1. The randomized reset strategy is incorporated into the DDPG training process to enhance exploration by exposing the agent to a wide variety of initial conditions. This strategy encourages generalization and improves the robustness of the learned policy.

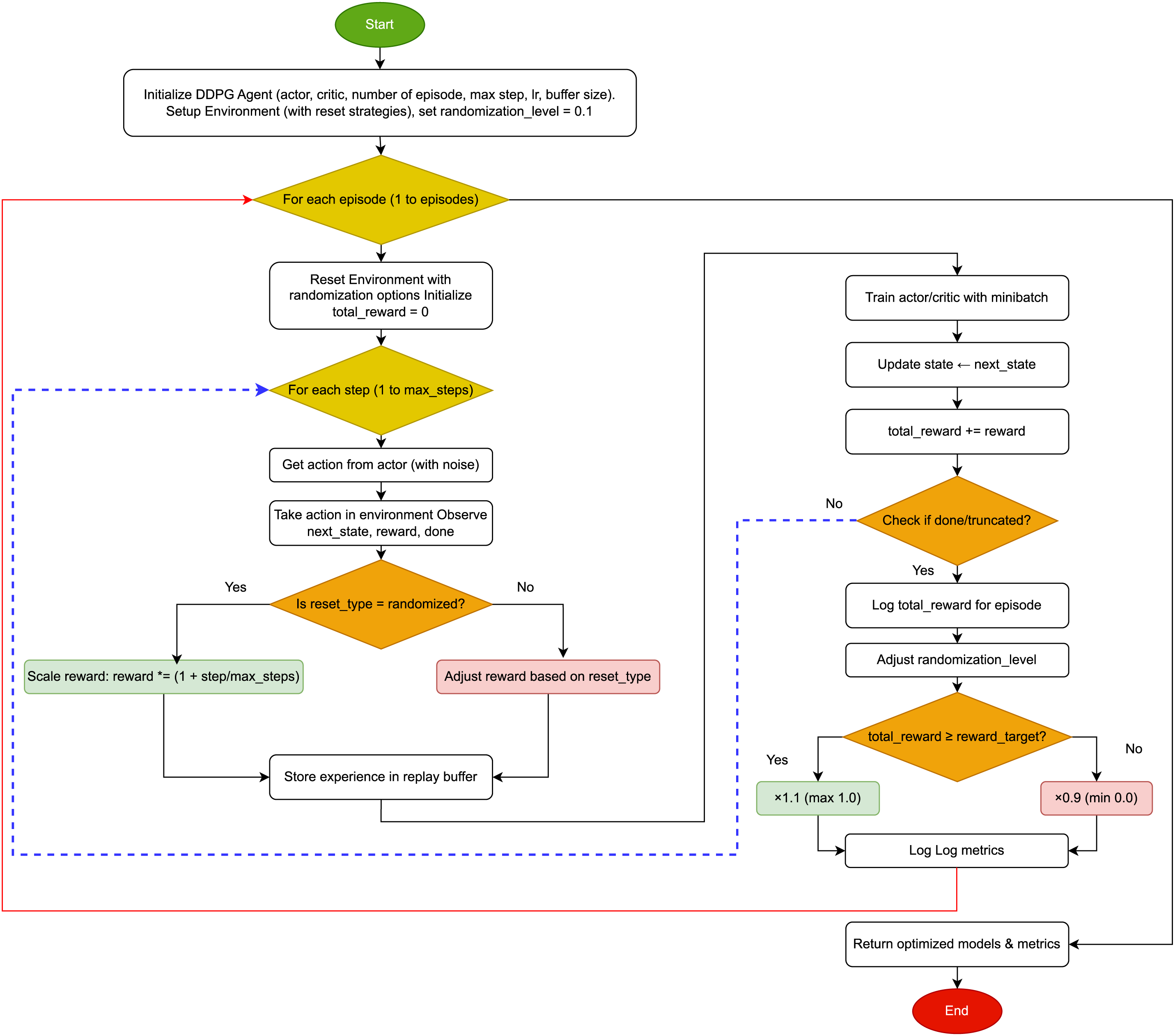

The methodology has three main stepsas shown in Fig. 2. Step 1 is initializing the environment and agent, so it includes setting up the DDPG with actor, critic, learning rate, buffer size, and the environment with different reset strategies. The initial randomization level is set to 0.1.

Figure 2: General flowchart of proposed methodology

On the other hand, step 2 is the training loop over episodes. For each episode, the environment is reset with randomization options, and total reward is initialized. Then, within each episode, there’s a loop over steps. In each step, the actor generates an action with noise, the action is executed, and the next state, reward, and done flag are observed. Depending on whether the reset type is randomized, the reward is scaled by (1 + stepmax_steps) or adjusted based on other reset types. Then, the experience is stored in the replay buffer, and the actor and critic are trained using a minibatch. The state is updated, total reward accumulated, and if done or truncated, the loop breaks. After the steps, the total reward is logged.

Step 3 is the end of training, logging completion, and returning optimized models and metrics.

The algorithm involve checking if the randomization_level changes as expected based on the reward and if the environment resets with the correct strategy. The dynamic adjustment should help the agent gradually handle more randomized environments as it meets the reward targets, promoting robustness.

The following subsection is divided into three parts. First, the key components of the DDPG algorithm are outlined, including the actor-critic architecture and experience replay. Next, the mathematical formulation is detailed. Finally, the integration of DDPG with different reset strategies is explained, highlighting randomized resets and step-based reward scaling.

3.2.1 Key Components of the DDPG Algorithm

• Actor-Critic Architecture: The DDPG algorithm relies on an actor-critic architecture. The actor network

• Target Networks: To stabilize training, DDPG uses separate target networks for both the actor and critic. The target actor network

• Experience Replay: The agent’s experiences, represented as tuples

• Reward Scaling and Reset Strategies: In our implementation, different reward scaling mechanisms were applied based on the reset strategy used in the environment. The randomized reset, described in Algorithm 1, incorporates step-based reward scaling to incentivize exploration by adjusting rewards according to the number of steps taken in each episode.

3.2.2 Mathematical Formulation

The critic network is updated by minimizing the following loss function, which measures the difference between the predicted Q-value and the target Q-value (calculated using the target networks), as originally formulated in the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm by Lillicrap et al. [33]:

Here,

The actor network is updated using the policy gradient, which aims to maximize the expected return by adjusting the policy parameters in the direction that increases the action-value function:

This gradient encourages the actor to take actions that maximize the estimated Q-value, as evaluated by the critic network.

3.2.3 DDPG Algorithm with Reset Strategies

Our study implements the DDPG algorithm under three distinct environment reset strategies, as outlined in Algorithm 1:

The specific implementation of the DDPG algorithm in our study, as outlined in Algorithm 1, involved training the agent under three different environment reset strategies:

1. Normal Reset: The environment resets to a default state at the beginning of each episode, providing consistent starting conditions but limiting exploration.

2. Randomized Reset: The environment resets to randomly selected initial conditions at the start of each episode, exposing the agent to a variety of states and enhancing generalization through step-based reward scaling.

3. Non-Randomized Reset: The environment resets to the same fixed initial state at the start of each episode, restricting the agent’s ability to learn generalizable policies.

The primary distinction lies in the degree of variability:

• The Normal Reset leverages limited randomness inherent to the environment.

• The Non-Randomized Reset eliminates this randomness entirely.

• The Randomized Reset introduces deliberate and controlled randomness beyond the default behavior.

The training configurations for these experiments, including learning rates, batch size, and other parameters, are detailed in Table 3. The performance of the agent under each reset strategy is analyzed in the following sections, highlighting the advantages of using randomized resets in continuous control tasks.

In this section, we present and analyze the results of the experiments conducted with different environment reset strategies using the DDPG algorithm. The performance of the agent under normal, randomized, and non-randomized resets is evaluated based on total rewards per episode, with a detailed comparison provided through graphical representations.

The experiments were conducted on a Windows-based machine with a standard CPU, using Python 3.8, TensorFlow 2.10, and the Gymnasium framework. Two setups were evaluated: an extended training regime with DDPG for 1000 steps per episode across 1000 episodes, and a fast execution setup comparing DDPG and TD3 for 30 episodes with a maximum of 50 steps per episode to accommodate computational constraints. The DDPG actor and critic networks used two hidden layers (256 and 128 units, ReLU activation), with learning rates of 0.0001 (actor) and 0.001 (critic), a batch size of 64, and a replay buffer size of 100,000. TD3 used a similar architecture with additional target network smoothing (tau = 0.005), delayed policy updates (every 2 steps), and exploration noise (policy noise = 0.3, noise clip = 0.7). Random seeds were fixed for reproducibility, and no hardware-specific optimizations were applied with detailed training configurations provided in Table 3.

To reduce computational overhead on a CPU-based system, we configured each training episode to terminate after 10 steps. This constraint was applied consistently across all reset strategies and did not involve modifying the internal logic of the CarRacing-v2 environment. Instead, a wrapper enforced early termination after 10 time steps, allowing us to examine agent performance in a short-horizon setting. While this setup facilitates rapid experimentation and highlights differences between reset strategies, it may limit the generalizability of the results to longer-horizon or full-episode tasks. We discuss this trade-off further in the limitations section.

To ensure experimental consistency, random seeds were fixed across all runs. This controlled for variability in environment resets, agent initialization, and stochastic exploration. Additionally, no hardware-specific optimizations or parallelization strategies were employed. All experiments were executed using a uniform software environment, including Python 3.11, TensorFlow, and the Gymnasium framework, ensuring reproducibility across reset conditions.

4.2 Performance Analysis of Reset Strategies

Table 4 shows the variation in rewards, suggesting that the reset strategy significantly impacts the agent’s learning process. The randomized reset likely introduces diverse starting conditions, enabling the agent to explore a wider range of states and thus achieve higher and more stable rewards over time. The Normal Reset provides a balanced environment, leading to moderate performance. The non-randomized reset, by contrast, may limit the agent’s exposure to varied scenarios, resulting in lower and less improving rewards. This aligns with reinforcement learning principles, where environmental diversity typically enhances learning efficiency.

Fig. 3 presents the total rewards per episode for the DDPG agent under three reset strategies: randomized reset, normal reset, and non-randomized reset, in the CarRacing-v2 environment. The results demonstrate a clear advantage of the randomized reset strategy, where the agent consistently achieves the highest total rewards, ranging from 7.2 to 7.9 over 1000 episodes. This strategy introduces variability in the starting conditions, allowing the agent to explore a broader range of scenarios, which facilitates faster learning and better generalization. In contrast, the normal reset strategy results in a moderate performance, with rewards stabilizing between 5.2 and 5.7. While this strategy provides consistent initial conditions, it limits the agent’s ability to explore diverse states, leading to slower learning progress. The non-randomized reset strategy, which consistently resets the environment to the same fixed state, exhibits the lowest performance, with rewards between 4.6 and 5.0. The lack of environmental variability hinders the agent’s capacity to explore alternative strategies, resulting in reduced adaptability and slower improvements. Overall, the figure highlights the effectiveness of the randomized reset in promoting exploration and enhancing the agent’s learning performance compared to more static reset strategies.

Figure 3: Total rewards per episode for different reset strategies in CarRacing-v2

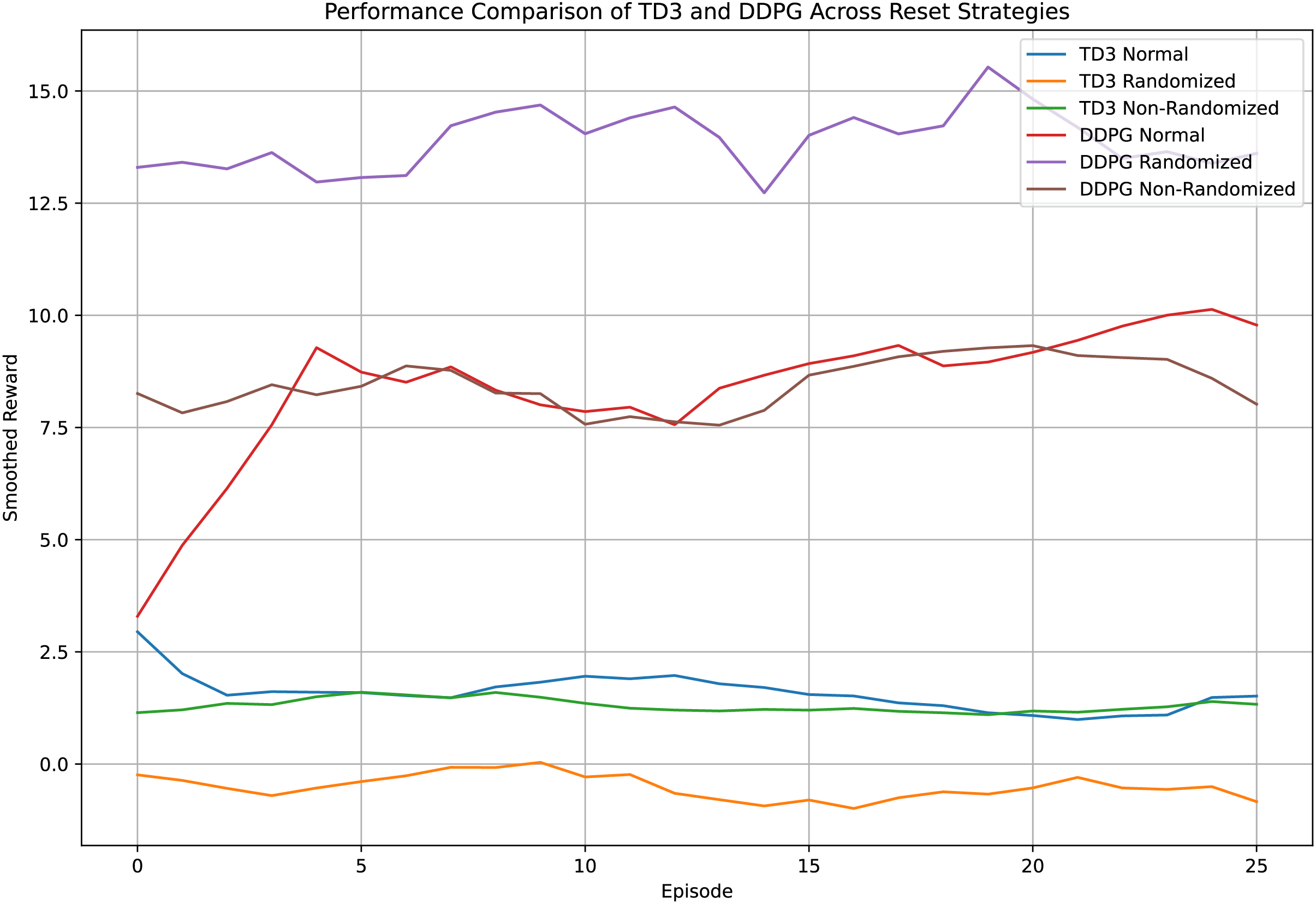

4.3 Comparison of DDPG and TD3 with Different Reset Strategies

To assess the impact of reset strategies across state-of-the-art algorithms, we evaluated DDPG and TD3 under normal, randomized, and non-randomized resets in the CarRacing-v2 environment. The fast execution setup (30 episodes, 50 steps per episode) was designed for rapid experimentation, while the extended setup (DDPG, 1000 steps per episode) allowed deeper training. Performance is visualized in total reward in Fig. 4, with rewards smoothed using a 5-point moving average to reduce noise. The plots, informed by the performance curves for DDPG (Normal, Randomized, Non-Randomized) and TD3 (Normal, Randomized, Non-Randomized), initially showed TD3 outperforming DDPG (6.8–7.2 vs. 6.0–6.5) in the fast setup, with a

Figure 4: Performance comparison of DDPG and TD3 across normal, randomized, and non-randomized reset strategies in the CarRacing-v2 environment

Table 5 presents the initial

This paper investigated the impact of different environment reset strategies, normal, non-randomized, and randomized, on reinforcement learning agent performance using the DDPG algorithm in the CarRacing-v2 environment. Results demonstrate that randomized resets significantly improve learning, achieving higher total rewards, faster convergence, and better generalization by exposing the agent to a broader range of initial states. To evaluate these strategies under different training regimes, we conducted two experiments: (1) an extended training setup using DDPG with 1000 steps per episode across 1000 episodes, and (2) a fast execution setup comparing both DDPG and TD3 over 30 episodes with 50 steps per episode to support rapid experimentation under computational constraints. In the extended setup, DDPG with randomized resets achieved a smoothed reward of approximately 15 with strong stability and convergence. This outperformed all other configurations, including TD3. In contrast, the fast setup initially showed TD3 performing slightly better than DDPG (6.8–7.2 vs. 6.0–6.5); however, re-evaluated

Despite these promising findings, limitations remain. The study was limited to a single environment and only two algorithms due to computational constraints. Advanced domain randomization methods, such as structured or adaptive resets, were not explored. Future work will conduct ablation studies on reset frequency, randomization range, and reward scaling, and validate results across diverse environments and DRL algorithms to further improve generalizability and robustness.

Acknowledgement: The author extends their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number MoE-IF-UJ-R2-22-04220773-1.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia (Project No. MoE-IF-UJ-R2-22-04220773-1).

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gosavi A. Reinforcement learning: a tutorial survey and recent advances. INFORMS J Comput. 2009;21(2):178–92. doi:10.1287/ijoc.1080.0305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhou ZH. A brief introduction to weakly supervised learning. Natl Sci Rev. 2018;5(1):44–53. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwx106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kamal MM, Abideen SZU, Al-Khasawneh M, Alabrah A, Larik RSA, Marwat MI. Optimizing secure multi-user ISAC systems with STAR-RIS: a deep reinforcement learning approach for 6G networks. IEEE Access. 2025;13:31472–84. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3542607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gottipati SK, Pathak Y, Nuttall R, Sahir, Chunduru R, Touati R, et al. Maximum reward formulation in reinforcement learning. arXiv:2010.03744. 2020. [Google Scholar]

5. Kirk R, Zhang A, Grefenstette E, Rocktäschel T. A survey of zero-shot generalisation in deep reinforcement learning. J Artif Intell Res. 2021;76:201–64. doi:10.1613/jair.1.14174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mahajan A, Zhang A. Generalization across observation shifts in reinforcement learning. arXiv:2306.04595. 2023. [Google Scholar]

7. Hester T, Vecerik M, Pietquin O, Lanctot M, Schaul T, Piot B, et al. Deep q-learning from demonstrations. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; AAAI Press; 2018. Vol. 32, p. 3223–30. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Schulman J, Wolski F, Dhariwal P, Radford A, Klimov O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv:1707.06347. 2017. [Google Scholar]

9. Nguyen T, Nguyen ND, Nahavandi S. Deep reinforcement learning for multiagent systems: a review of challenges, solutions, and applications. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2018;50(9):3826–39. doi:10.1109/tcyb.2020.2977374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mnih V, Kavukcuoglu K, Silver D, Rusu AA, Veness J, Bellemare MG, et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature. 2015;518(7540):529–33. doi:10.1038/nature14236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Mei M, Kou P, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Xue Z, Liang D. Primary frequency response of floating offshore wind turbines via deep reinforcement learning and domain randomization. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy. 2025;1–15. doi:10.1109/tste.2025.3555266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen S, Liu G, Zhou Z, Zhang K, Wang J. Robust multi-agent reinforcement learning method based on adversarial domain randomization for real-world dual-UAV cooperation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles. 2024;9(1):1615–27. doi:10.1109/tiv.2023.3307134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ajani OS, ho Hur S, Mallipeddi R. Evaluating domain randomization in deep reinforcement learning locomotion tasks. Mathematics. 2023;11(23):4744. doi:10.3390/math11234744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mehta B, Diaz M, Golemo F, Pal C, Paull L. Active domain randomization. arXiv:1904.04762. 2019. [Google Scholar]

15. Lee K, Lee K, Shin J, Lee H. A Simple randomization technique for generalization in deep reinforcement learning. arXiv:1910.05396. 2019. [Google Scholar]

16. Kelly S, Voegerl T, Banzhaf W, Gondro C. Evolving hierarchical memory-prediction machines in multi-task reinforcement learning. Genet Program Evolvable Mach. 2021;22(4):573–605. doi:10.1007/s10710-021-09418-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sumiea EH, Abdulkadir SJ, Alhussian HS, Al-Selwi SM, Alqushaibi A, Ragab MG, et al. Deep deterministic policy gradient algorithm: a systematic review. Heliyon. 2024;10(9):e30697. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3544387/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sumiea EHH, Abdulkadir SJ, Ragab MG, Al-Selwi SM, Fati SM, AlQushaibi A, et al. Enhanced deep deterministic policy gradient algorithm using grey wolf optimizer for continuous control tasks. IEEE Access. 2023;11:139771–84. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3341507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tan H. Reinforcement learning with deep deterministic policy gradient. In: 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Big Data and Algorithms (CAIBDA); IEEE; 2021. p. 82–5. doi:10.1109/CAIBDA53561.2021.00025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sumiea EH, AbdulKadir SJ, Alhussian H, Al-Selwi SM, Ragab MG, Alqushaibi A. Exploration decay policy (edp) to enhanced exploration-exploitation trade-off in ddpg for continuous action control optimization. In: 2023 IEEE 21st Student Conference on Research and Development (SCOReD). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2023. p. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

21. Yang M, Liu G, Zhou Z, Wang J. Probabilistic automata-based method for enhancing performance of deep reinforcement learning systems. IEEE/CAA J Automatic Sinica. 2024;11(11):2327–39. doi:10.1109/jas.2024.124818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Arulkumaran K, Deisenroth MP, Brundage M, Bharath AA. Deep reinforcement learning: a brief survey. IEEE Signal Proc Mag. 2017;34(6):26–38. doi:10.1109/msp.2017.2743240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Myers V, Ji C, Eysenbach B. Horizon generalization in reinforcement learning. arXiv:2501.02709. 2025. [Google Scholar]

24. Zhang C, Vinyals O, Munos R, Bengio S. A study on overfitting in deep reinforcement learning. arXiv:1804.06893. 2018. [Google Scholar]

25. Li Q, Kumar A, Kostrikov I, Levine S. Efficient deep reinforcement learning requires regulating overfitting. arXiv:2304.10466. 2023. [Google Scholar]

26. Liu R, Nageotte F, Zanne P, Mathelin M, Dresp B. Deep reinforcement learning for the control of robotic manipulation: a focussed mini-review. arXiv:2102.04148. 2021. [Google Scholar]

27. Chen L, He Y, Pan W, Yu F, Ming Z. A novel generalized meta hierarchical reinforcement learning method for autonomous vehicles. IEEE Network. 2023;37(4):230–6. doi:10.1109/mnet.005.2300020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Tobin J, Fong R, Ray A, Schneider J, Zaremba W, Abbeel P. Domain randomization for transferring deep neural networks from simulation to the real world. In: 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). Vancouver, BC, Canada: IEEE; 2017. p. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

29. Fang C, Guo B, Liu S, Ma K, Yu Z. Weather-oriented Domain Generalization of Semantic Segmentation for Autonomous Driving. In: 2022 IEEE Smartworld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Scalable Computing & Communications, Digital Twin, Privacy Computing, Metaverse, Autonomous & Trusted Vehicles (SmartWorld/UIC/ScalCom/DigitalTwin/PriComp/Meta). Haikou, China; 2022. p. 368–75. [Google Scholar]

30. Shakerimov A, Alizadeh T, Varol HA. Efficient sim-to-real transfer in reinforcement learning through domain randomization and domain adaptation. IEEE Access. 2023;11(3):136809–24. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3339568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Prakash A, Boochoon S, Brophy M, Acuna D, Cameracci E, State G, et al. Structured domain randomization: bridging the reality gap by context-aware synthetic data. In: 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). Montreal, QC, Canada: IEEE; 2019. p. 7249–55. [Google Scholar]

32. Tobin J, Biewald L, Duan R, Andrychowicz M, Handa A, Kumar V, et al. Domain randomization and generative models for robotic grasping. In: 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). Madrid, Spain: IEEE; 2018. p. 3482–9. [Google Scholar]

33. Lillicrap TP, Hunt JJ, Pritzel A, Heess N, Erez T, Tassa Y, et al. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv:1509.02971. 2015. [Google Scholar]

34. Abideen SZU, Kamal MM, Alharbi E, Malik AA, Alhalabi W, Anwar MS, et al. Computational optimization of RIS-enhanced backscatter and direct communication for 6G IoT: a DDPG-based approach with physical layer security. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;142(3):2191–210. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.061744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Peng XB, Andrychowicz M, Zaremba W, Abbeel P. Sim-to-real transfer of robotic control with dynamics randomization. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). Brisbane, QLD, Australia: IEEE; 2018. p. 3803–10. [Google Scholar]

36. Florensa C, Held D, Geng X, Abbeel P. Automatic goal generation for reinforcement learning agents. In: International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR; 2018. Vol. 80, p. 1515–28. [Google Scholar]

37. Nagpal R, Krishnan AU, Yu H. Reward engineering for object pick and place training. arXiv:2001.03792. 2020. [Google Scholar]

38. Haarnoja T, Zhou A, Abbeel P, Levine S. Soft actor-critic: off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. Stockholm, Sweden: PMLR; 2018. p. 1861–70. [Google Scholar]

39. Pattanaik A, Tang Z, Liu S, Bommannan G, Chowdhary G. Robust deep reinforcement learning with adversarial attacks. arXiv:1712.03632. 2017. [Google Scholar]

40. Portelas R, Colas C, Weng L, Hofmann K, Oudeyer PY. Automatic curriculum learning for deep rl: a short survey. arXiv:2003.04664. 2020. [Google Scholar]

41. Plappert M, Houthooft R, Dhariwal P, Sidor S, Chen RY, Chen X, et al. Parameter space noise for exploration. arXiv:1706.01905. 2017. [Google Scholar]

42. Park S, Kim J, Kim G. Time discretization-invariant safe action repetition for policy gradient methods. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:267–79. [Google Scholar]

43. Yoo H, Kim B, Kim JW, Lee JH. Reinforcement learning based optimal control of batch processes using Monte-Carlo deep deterministic policy gradient with phase segmentation. Comput Chem Eng. 2021;144(4):107133. doi:10.1016/j.compchemeng.2020.107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Volpi R, Larlus D, Rogez G. Continual adaptation of visual representations via domain randomization and meta-learning. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE; 2021. p. 4441–51. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Dankwa S, Zheng W. Twin-delayed DDPG: a deep reinforcement learning technique to model a continuous movement of an intelligent robot agent. Int J Adv Trends Comput Sci Eng. 2020;9(3):2304–12. doi:10.1145/3387168.3387199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Chen X, Wang J, Zhou Z, Rodgers M, Lee H. Understanding domain randomization for sim-to-real transfer. arXiv:2110.03239. 2021. [Google Scholar]

47. Brockman G, Cheung V, Pettersson L, Schneider J, Schulman J, Tang J, et al. Openai gym. arXiv:1606.01540. 2016. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools