Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Dynamic SDN-Based Address Hopping Model for IoT Anonymization

1 State Grid Laboratory of Power Cyber-Security Protection and Monitoring Technology, China Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd., Nanjing, 210003, China

2 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, 211189, China

3 School of Cyber Science and Engineering, Southeast University, Nanjing, 210014, China

* Corresponding Author: Bo Zhang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Computer Modeling for Future Communications and Networks)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 2545-2565. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.066822

Received 18 April 2025; Accepted 25 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

The increasing reliance on interconnected Internet of Things (IoT) devices has amplified the demand for robust anonymization strategies to protect device identities and ensure secure communication. However, traditional anonymization methods for IoT networks often rely on static identity models, making them vulnerable to inference attacks through long-term observation. Moreover, these methods tend to sacrifice data availability to protect privacy, limiting their practicality in real-world applications. To overcome these limitations, we propose a dynamic device identity anonymization framework using Moving Target Defense (MTD) principles implemented via Software-Defined Networking (SDN). In our model, the SDN controller periodically reconfigures the network addresses and routes of IoT devices using a constraint-aware backtracking algorithm that constructs new virtual topologies under connectivity and performance constraints. This address-hopping scheme introduces continuous unpredictability at the network layer dynamically changing device identifiers, routing paths, and even network topology which thwarts attacker reconnaissance while preserving normal communication. Experimental results demonstrate that our approach significantly reduces device identity exposure and scan success rates for attackers compared to static networks. Moreover, the dynamic scheme maintains high data availability and network performance. Under attack conditions it reduced average communication delay by approximately 60% vs. an unprotected network, with minimal overhead on system resources.Keywords

The emergence of integrated networks has introduced unprecedented opportunities for large-scale Internet of Things (IoT) deployment, while simultaneously posing critical challenges to device identity security and adaptive cyber defense. However, while IoT introduces intelligence, it also poses numerous security and privacy challenges. The current power equipment market lacks stringent access control mechanisms and unified technical management standards, some equipment lacks an identity authentication mechanism, which results in the exchange of sensitive information such as control commands that are easily attacked by the adversary, and then the attacker can issue malicious control commands to steal the control of the distribution network equipment terminals. The attacker can then issue malicious control commands to steal the control rights of the distribution network equipment terminals. Therefore, anonymous protection of equipment identity has become an increasingly important research area.

In the field of device anonymity protection technology, there are two main categories of methods. The first class of methods is to use the physical differences of the device itself to construct anonymity protection mechanisms, and this type of technology focuses on protecting the hardware characteristics of the device, such as the Media Access Control (MAC) address, the device serial number, etc., and prevents the device from being recognized by its physical characteristics by hiding or modifying this information through technical means. The second type of method is to use the differences in network traffic generated by the device to construct anonymity protection measures. This type of technology focuses on protecting the network behavioral patterns of the device and changes the network traffic characteristics of the device by means of encryption, proxies, obfuscation, etc., so that even if the device is active in the network, its identity information is not easy to be traced and identified.

However, these methods have the following two limitations:

(1) Staticity and predictability: Traditional methods are often based on static data models, which generalize or suppress individual attributes in a data set to reduce the risk of individuals being identified. However, these methods do not take into account the changes or dynamics of the data over time and lack the ability to adjust dynamically, making it possible for an attacker to predict the data patterns after anonymization through long-term observation and analysis.

(2) Trade-offs between data availability and privacy protection: In order to protect privacy, traditional anonymization techniques can sacrifice the detail and usefulness of the data, making it difficult to use the data for further analysis and research after desensitization.

To overcome these constraints, this thesis introduces a unique identity anonymity protection method that relies solely on the MTD technique, with a special focus on the address hopping strategy. The MTD technique improves system security by dynamically altering its configuration, making it more difficult for attackers to comprehend and exploit.

The main contributions of this paper are:

(1) In order to improve the dynamics and antiprediction of the system, this paper introduces the MTD technique, which realizes dynamic changes at the network layer through the end information dynamic hopping technique, the routing dynamic hopping technique and the topology dynamic defense technique. By dynamically changing the device addresses in the network, the risk of being attacked is effectively reduced, and the network performance is optimized. This method effectively overcomes the static nature problem of traditional methods, making it difficult for attackers to predict device identities through fixed patterns.

(2) In order to optimize the balance between data availability and privacy protection, the MTD technique protects data privacy by dynamically changing the network configuration, making it difficult for attackers to continuously track and analyze the data. This approach maintains data availability in a changing environment because it allows data to be accessed and used efficiently while maintaining privacy.

(3) In this method, effectiveness analysis, data forwarding volume analysis, and availability analysis are performed by conducting experiments in a simulated network environment constructed by the Mininet network simulation platform and the Ryu controller. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method can effectively decrease the likelihood that the host is targeted by scanning attempts, reduce the amount of data acquired by the attacker, and reduce the communication delay by approximately 60% compared to the unprotected strategy under different attack intensities, as well as reduce CPU load accordingly when the hopping frequency is reduced.

Deep learning-based device identity anonymization protection techniques focus on the problem of how to protect the identity information of a device without compromising usercy. This problem is particularly important in areas such as the IoT and smart devices, which widely collect and transmit personal data that can be misused or leaked if not protected.

Deep learning techniques, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) [1] and Residual Networks (RNN), have attained significant accomplishments in the fields of image recognition and speech recognition [2]. For example, better identity anonymization is achieved by constructing an identity decoupling network that decouples identity from other attributes using Conditional Multiscale Reconstruction loss (CMR) and identity loss. In addition, there have been studies on generating anonymized identity vectors by changing the distortion angle in the angle space to directly control the identity of anonymized faces. In addition to this, feature extraction and classification of signals emitted from devices by deep neural networks can be used to identify and protect the identity of devices [3]. Deep learning can also be used to generate adversarial samples to improve the anonymization of sensitive data such as face images to achieve better privacy protection under deep neural networks [4]. These methods not only solve the privacy leakage problem, but also promote the overall development of AI technology and play an important role in national political security, economic security, social security and cyber security.

In terms of specific implementations of device identity anonymity protection, some studies have proposed methods such as the Wearable Device Data Privacy Preserving Transform based on Distinguishing Self-Encoder (Dis AE) and the Wearable Device Data Privacy Preserving Transform based on Chunked Discrete Cosine Transform and Self-Encoder (BDCT-AE) [5]. These methods reduce the identification risk of wearable device data by adding noise to the data or changing the representation of the data to make identification more difficult.

Zhai et al. [6] proposed a scheme to effectively protect users’ location privacy by penalizing location leakage and spoofing. The basic idea is that when sending a Location-Based Service (LBS) query request, the user first constructs an anonymized zone by obtaining at least the real locations of other collaborating users, and then submits the anonymized zone to the LBS provider instead of his/her own real location, thus effectively protecting personal location privacy. In addition, compared with traditional schemes, this scheme reduces the computation latency and communication overhead of the requesting and collaborating users, while safeguarding against location leakage and location spoofing during the construction of anonymous zones, without the need for a third-party entity.

Zhang and Sun [7] proposed a smartphone authentication method based on optimized Convolutional Deep Belief Network (CDBN). The system uses two CDBN pooling layers and integrates features through GAP processing and RMS connectivity layers to reduce network parameters and shorten training time. Subsequently, a backpropagation algorithm is introduced to perform supervised learning of the model parameters and regulate the weights between the RMS connectivity layer and the output layer to determine the model’s user class. Finally, Softmax classifier is added and ACC, FRR and FAR is selected as a metric to assess the precision of the algorithm and establish the accuracy of user authentication.

The study by Hellmann et al. [8] and others reviews recent advances in the field of face anonymization, focusing on privacy protection during deep learning. Although Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) perform well in face anonymization, there is still room for improvement, such as how to avoid information leakage and absolute privacy protection. In addition, the paper explores the question of whether wearing masks can effectively protect personal privacy and proposes a benchmarking tool to assess privacy invasion. In terms of face video anonymization, the article introduces two approaches, focusing on facial region privacy and biometric-oriented privacy.

Rajasekar et al. [9] present a lightweight, privacy-preserving task offloading strategy for Internet of Vehicles (IoV) systems. First, the IoV environment is modeled as a heterogeneous graph with vehicles and base stations as nodes, connected by communication links. It employs an attention-based heterogeneous graph neural network (HetGNN) to select appropriate edge servers for offloading based on latency. To safeguard sensitive vehicular data, the model is trained using differential privacy stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD), ensuring privacy during both training and inference.

Zhou and Qian [10] have proposed various anonymity detection and privacy preservation techniques in Federated Learning (FL). These techniques include combining homomorphic encryption and differential privacy to protect client data, proposing efficient and secure aggregation methods, and a learning framework based on multi-party computation. In addition, the paper discusses the defense measures in the case of non-independent homomorphic distribution in FL to cope with the problem of uneven distribution of client data in real environments.

Lu et al. [11] proposed a direct anonymous authentication scheme that can be used to anonymize the identity of the end device through a trusted chip. This scheme is used for any service provider without the need of coercive force to guarantee the implementation and protects the user privacy before it is violated. Also the authors give a security proof of the correctness, anonymity and unforgeability of the scheme under the stochastic predicator model.

In the authentication of IoT devices, based on elliptic curve cryptography, a lightweight method for anonymous authentication of devices can be proposed [12]. This method can reduce the computation and storage overhead while ensuring security, thus adapting to resource-constrained IoT environments. Cheng et al. [13] studied the privacy protection and application of trajectory data in the context of mobile devices and location-based technologies. They proposed various techniques such as differential privacy, location coordinate transformation and cryptography based methods for protecting user’s trajectory privacy.

These literatures demonstrate a variety of different techniques and approaches to protect the anonymity of device addresses, covering a wide range of aspects from blockchain technology to trusted chips, and from Hidden Markov Models to spatial and temporal masking. Each method has its unique advantages and application scenarios, providing a rich theoretical foundation and technical support for variable anonymity protection of device addresses.

However, although several techniques and methods have been proposed for protecting device identities, there are still some challenges and limitations. For example, how to improve the anonymization effect while minimizing the impact on device performance; how to design anonymization strategies that can resist Advanced Persistent Threats (APT) and other sophisticated attacks. Therefore, based on existing research, a deep learning-based device identity anonymization protection method is proposed. The method balances the anonymization effect and efficiency, and obtains the optimal hopping strategy based on the evolutionary game strategy.

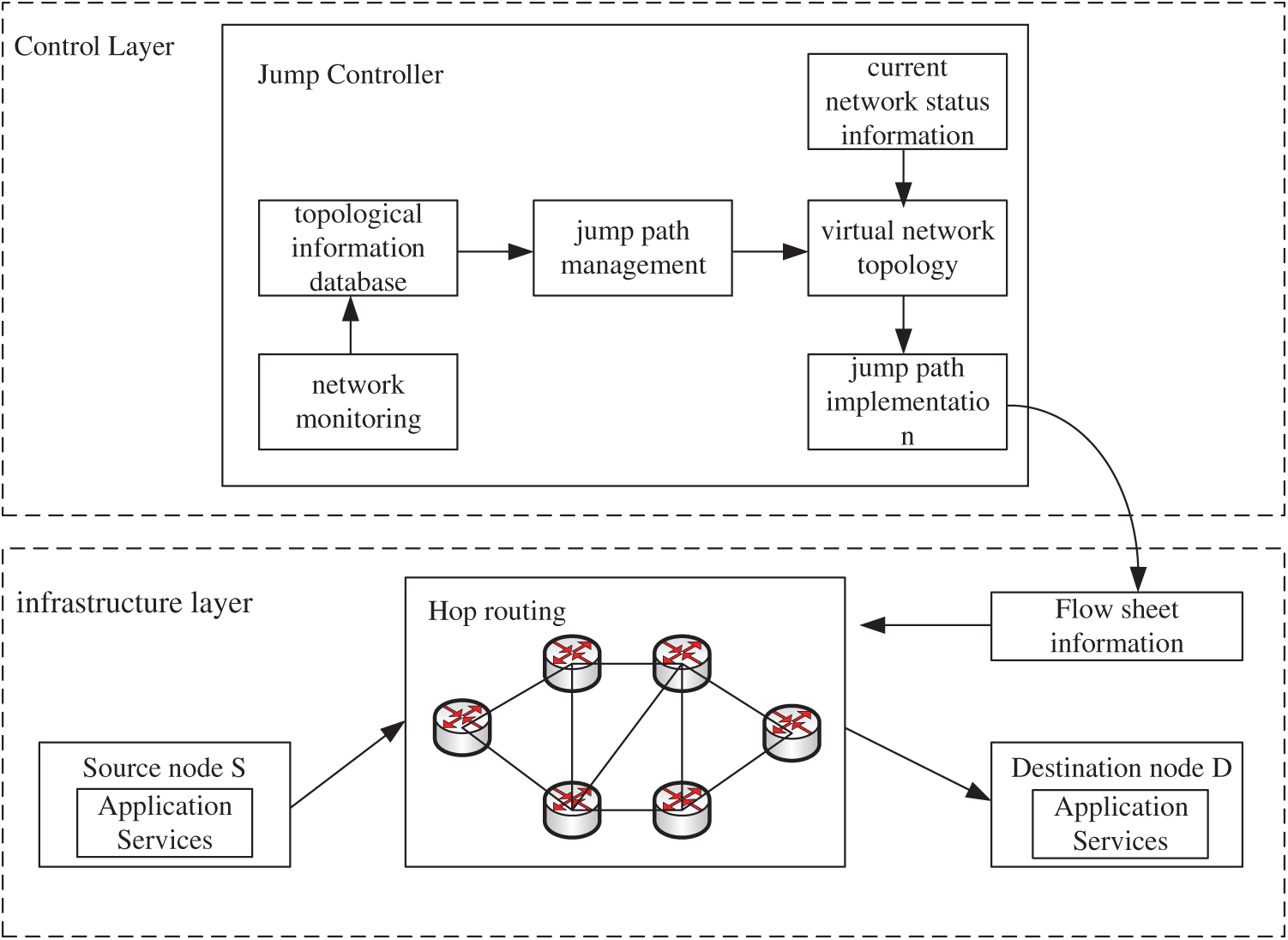

In modern network security, protecting the anonymity of device addresses is crucial. The address-hopping based device address variable anonymity protection method is effectively implemented in SDN. This approach utilizes the MTD technique to dynamically adjust the device addresses in the network to protect the anonymity of network devices and enhance network security. First, the source host sends a packet to the head switch, which decides whether to forward the packet or send the information to the controller through flow table matching. After receiving the information, the controller selects the appropriate transmission path and virtual IP to hide the real device information, and generates the corresponding flow table rules to be sent to the switches in the path. The packets are forwarded among the switches according to the flow table rules until they reach the destination host. In order to maintain anonymity, the controller will replace the virtual IP and transmission path and reissue the flow table rules after a set time interval, so that the addresses and paths in the data flow change periodically, thus realizing the anonymization of the device identity, which not only improves the anonymity and security of the network, but also strengthens the network’s dynamic adaptability and anti-attack capability. The framework diagram of the methodology is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Address hopping based anonymity protection framework for SDN networks

3.1 Moving Target Defense Approach for Address Hopping

MTD is an advanced network security strategy whose core idea is to confuse attackers by implementing continuous and dynamic changes to increase their attack cost and complexity and reduce their attack success rate. MTD is not a specific defense method, but a design guideline that can be applied to a property of the protected system to derive a variety of specific defense mechanisms.

In traditional network communication, the IP addresses and ports of nodes are fixed, which enables attackers to determine the network location of a target and then launch an attack by obtaining it in advance or analyzing it through intercepted packets. To cope with this situation, the address hopping technique has emerged as an effective proactive defense, which is particularly suitable for countering traditional man-in-the-middle attacks, and it operates independently of the attacker’s specific attributes.

Based on the concept of MTD, address hopping techniques dynamically alter the network locations of the two communicating parties, thus constantly invalidating the a priori knowledge of the attacker. Currently, the address hopping technique encompasses three primary methods of implementation: real IP address hopping, virtual IP address hopping, and port address hopping [14]. All of these methods significantly enhance the challenge for attackers in locating the target network, thereby bolstering the overall security of the system.

Real IP address hopping entails dynamically modifying the IP address of either the client or server endpoint during packet transmission, based on system settings, as a means of mitigating man-in-the-middle attacks. There are mainly the following methods to realize real IP address hopping:

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP): The use of DHCP servers to periodically change the IP address of the terminal to achieve IP address dynamics, can effectively defend against the spread of worms. This method continuously requests new IP addresses through the DHCP server to realize IP address hopping.

Address Randomization Algorithm: The IP address is dynamically changed during the communication process through the address randomization algorithm, which uses an improved DHCP server and applies a hash value and a random number generator to produce random IP addresses for hopping.

To formalize the hopping behavior, let

where

3.1.2 Virtual IP Address Hopping

Establish a mapping between virtual and real IP addresses for the communication endpoints, and change the virtual IP address while the actual IP address remains unchanged when the address is hopped. There are several ways to realize virtual IP address hopping:

Mapping of virtual IP and real IP: By setting up a mapping of virtual IP and real IP addresses for communication endpoints, only the virtual IP address can be changed when the address is hopped, with the real IP address remaining static. This method can dynamically change a device’s network location without interrupting existing network connections, making it harder for attackers to identify and launch attacks on specific devices.

Virtual IPv6 Sliding Window: Using virtual IPv6 addresses for packet transmission allows two hosts to communicate while minimizing packet loss caused by address hopping, thanks to the utilization of a sliding window mechanism. This method enables dynamic address changes while maintaining high speed data transmission.

Define a mapping function

where

By dynamically changing the address and port information of both parties during communication, an attacker is prevented from intercepting the communication data exchanged between the client and the server. There are mainly the following methods to realize port address hopping:

Dynamic Address Translation (DyNAT) Technology: By deploying the DyNAT client-side extension and configuring the DyNAT gateway on the server end, the DyNAT plug-in is responsible for processing request messages from the client and response messages into the client, and the DyNAT gateway is responsible for processing request messages arriving at the server side and response messages departing the server side [15].

Self-synchronizing HMAC Scheme: A self-synchronization mechanism based on cryptographic hashing for port address hopping communication: this approach utilizes the HMAC mechanism to generate a message authentication code (MAC), which then serves as the synchronization data for encoding and decoding port addresses. This method offers a capability for port address hopping on a per-packet basis and ensures covert message authentication within the port address hopping system [16].

Let

where

Together, these address and port mutation techniques form the mathematical backbone of a MTD system that dynamically evolves the observable network attack surface to evade static and pattern-based threats [17].

3.2 SDN-Oriented MTD Technology

SDN, being a novel network architecture, has a technical architecture that is very different from the traditional network architecture [18]. Its core idea is to separate the control logic and forwarding logic of traditional network equipment, using centralized control to control network equipment, transferring the control logic to an ordinary computer independently into a controller. The control layer controls the data forwarding layer through standard interface protocols, which improves the controllability and programmability of network equipment. The openness to programming interfaces makes control of the network more agile and reduces the overhead cost of network control.

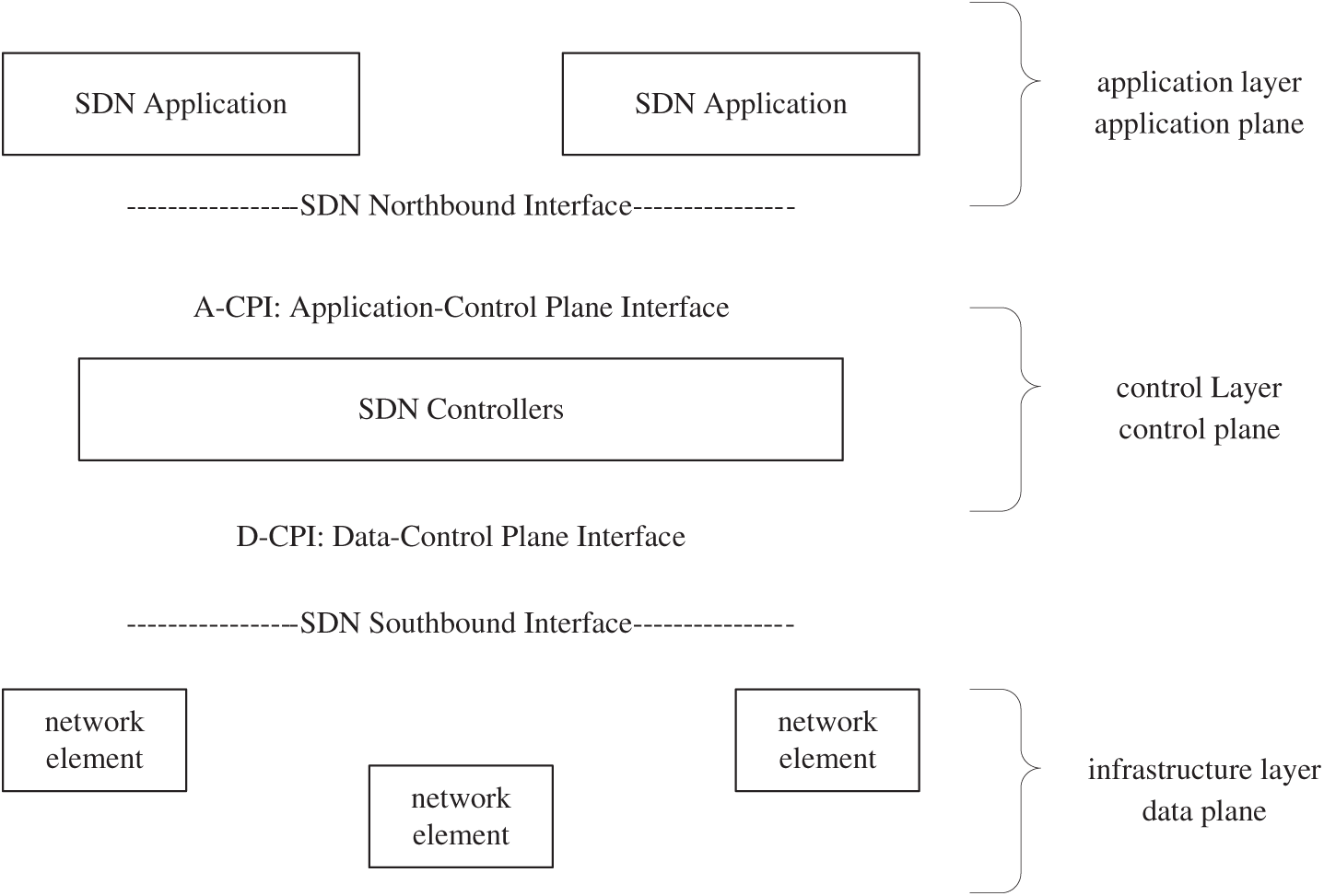

As shown in Fig. 2, the SDN architecture is typically structured into three layers: the bottom layer is the infrastructure layer, which mainly consists of network components that support SDN functionality, and functions as the data plane within the SDN architecture; the middle layer is the control layer, where the main components are controllers controlling the SDN network, and is the control plane in the SDN architecture; and the top layer is the application layer, which consists of the SDN applications and services, and is the Application plane [19].

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of network architecture for SDN

3.2.2 Combination of Address Hopping Technology and SDN Technology

The integration of Address Hopping techniques with Software Defined Networking (SDN) introduces a dynamic and flexible defense paradigm, leveraging centralized programmability and real-time control to enhance network security and anonymity. Let the SDN-controlled network be represented as a tuple

1) SDN Programmability for Address Hopping. The programmable nature of SDN allows dynamic address mapping and flow redirection. Define an address hopping controller function as:

where

2) Centralized Synchronization and Control. The controller ensures synchronization of address-hopping sequences across switches. Let the global forwarding state be

where

3) Stream-Based Address Abstraction. In SDN, all packet flows can be abstracted as high-level streams. A stream

where

4) Control and Data Plane Decoupling. The separation between the control plane and data plane allows secure policy enforcement. Denote the forwarding behavior as:

where

Together, these mechanisms make SDN an ideal platform for supporting dynamic address hopping, allowing for programmable, centralized, and synchronized reconfiguration of routing behavior that significantly complicates the attacker’s ability to perform reconnaissance or maintain persistent connections.

3.3 SDN-Based Address Hopping Model Design

First, the address hopping model collects key information about the underlying network, including network topology and node state information. This information is critical for understanding the current state of the network and potential path choices. The collected information is used to construct a global view of the network to provide data support for subsequent construction of paths. Second, the backtracking method is used to construct its corresponding virtual network topology for each possible data flow. In the process of constructing the virtual network topology, several constraints need to be considered to ensure the feasibility and efficiency of the selected paths. These constraints include reachability, transmission delay, link capacity, and non-overlap constraints [20,21].

3.3.1 Address Hopping Path Management

This module adopts a backtracking algorithm to dynamically construct a set of address hopping paths. The entire communication network is represented as an undirected graph

1) Capacity Constraint: To ensure link availability and prevent congestion, each path P must satisfy the cumulative bandwidth constraint across all constituent links:

Here,

2) Latency Constraint: The total latency of a path is proportional to its cumulative hop delay. Let

where

3) Non-overlap Constraint: To maintain path unpredictability and avoid overlap of intermediate nodes across different hopping sequences:

where

4) Objective Function for Path Selection: Each candidate path is scored based on a composite objective function that considers bandwidth, delay, and structural diversity:

where

5) Path Construction Strategy: A recursive backtracking search enumerates all feasible paths from source to destination. Each extension step checks the satisfaction of all constraints; if any constraint is violated, the current path is pruned. This results in a set of structurally diverse, resource-efficient, and unpredictable routing paths that can be selected randomly during address hopping.

3.3.2 Constructing Virtual Network Topology Based on Backtracking Method

In this section, we formalize the backtracking method used to generate a virtual network topology for address hopping. Let the network be modeled as an undirected graph

The backtracking search process initiates at node S, and recursively explores candidate paths

For a given candidate path

where:

•

•

•

If

The recursive expansion can be mathematically expressed as:

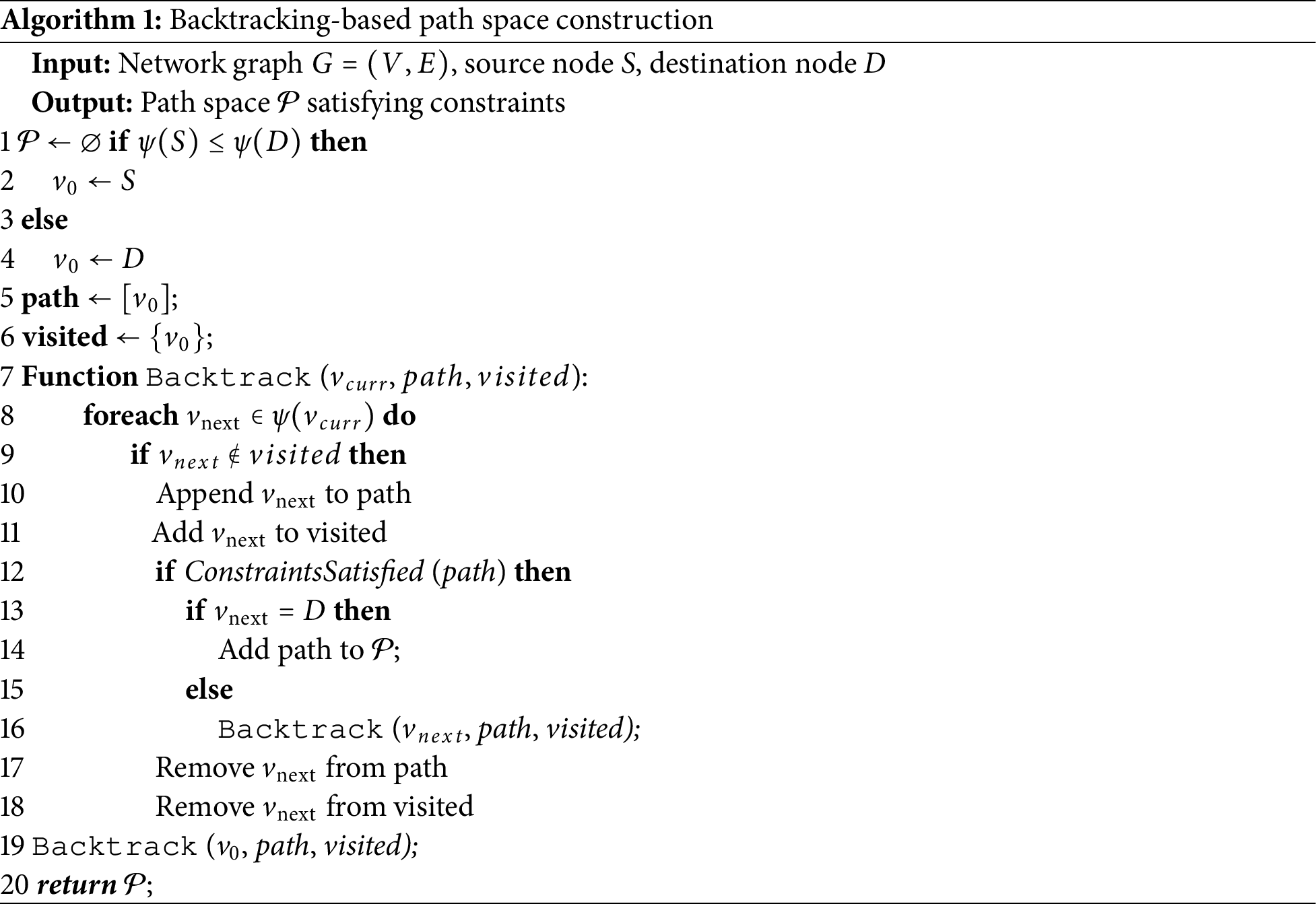

In order to efficiently explore the feasible address hopping paths under multi-dimensional constraints, we propose a structured backtracking-based path generation algorithm, as detailed in Algorithm 1. The algorithm recursively traverses the network graph in a depth-first manner, dynamically evaluating capacity, latency, and non-overlapping constraints at each step to construct qualified candidate paths.

At each recursive stage, the algorithm attempts to expand from the current node

Compared with exhaustive enumeration or greedy expansion schemes, this algorithmic design ensures that the generated paths are both valid and structurally diverse. Such diversity is critical in address hopping strategies to enhance unpredictability, resist traffic pattern inference, and avoid deterministic routing paths that may be exploited by adversaries [23].

While Mininet/Ryu provides a convenient platform for simulating SDN-controlled IoT networks, it is essential to acknowledge its inherent limitations when attempting to generalize research findings to real-world deployments. Primarily, the simulated network scale in Mininet is typically much smaller than that of actual IoT networks, and simulating very large-scale environments remains computationally expensive. Furthermore, Mininet nodes are generally homogeneous, contrasting sharply with real-world IoT networks that encompass diverse device types with varying computational capabilities, memory, and communication abilities. The simulation also defaults to idealistic channel models, failing to capture the complex interferences, fading, and multipath effects prevalent in real wireless channels. Similarly, traffic patterns in Mininet tend to be simplistic, unlike the highly complex and dynamic patterns observed in actual IoT networks. Crucially, simulated nodes often lack the resource constraints (such as limited battery life, computational power, and memory) inherent to real IoT devices. Therefore, despite the promising performance demonstrated by the experimental results in this paper within the Mininet/Ryu simulation environment, extensive further experiments and tests are imperative to thoroughly evaluate its performance and reliability under diverse real-world conditions before practical deployment. Future work should prioritize evaluation on actual IoT testbeds and actively explore approaches to mitigate these identified limitations.

3.3.3 Algorithm Complexity and Scalability Analysis

To evaluate the scalability of the proposed backtracking-based path construction algorithm, we analyze its time complexity. Let the network topology be represented as an undirected graph

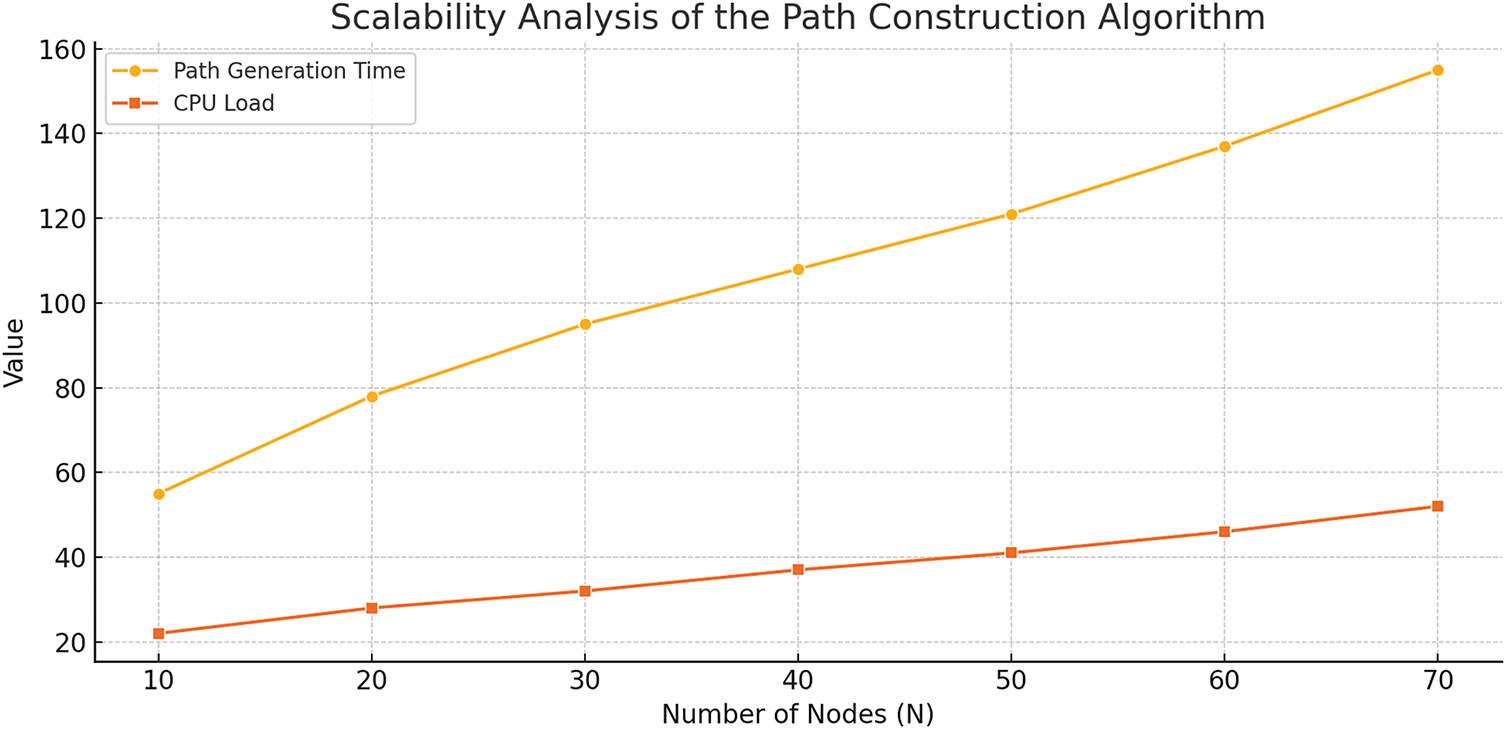

To test scalability, we constructed a topology with

To further demonstrate the scalability trend of the proposed algorithm, we extended the experiments by varying the number of nodes N from 10 to 70. The results, as shown in Fig. 3, indicate that the path generation time increases from 55 to 155 ms, and controller CPU load rises from 22% to 52%. This linear growth pattern confirms the method’s feasibility for real-time operations in mid-to-large scale IoT networks.

Figure 3: Scalability analysis of the path construction algorithm

The backtracking-based path generation algorithm was implemented as a Python module integrated into the Ryu controller and validated via simulation in Section 4.

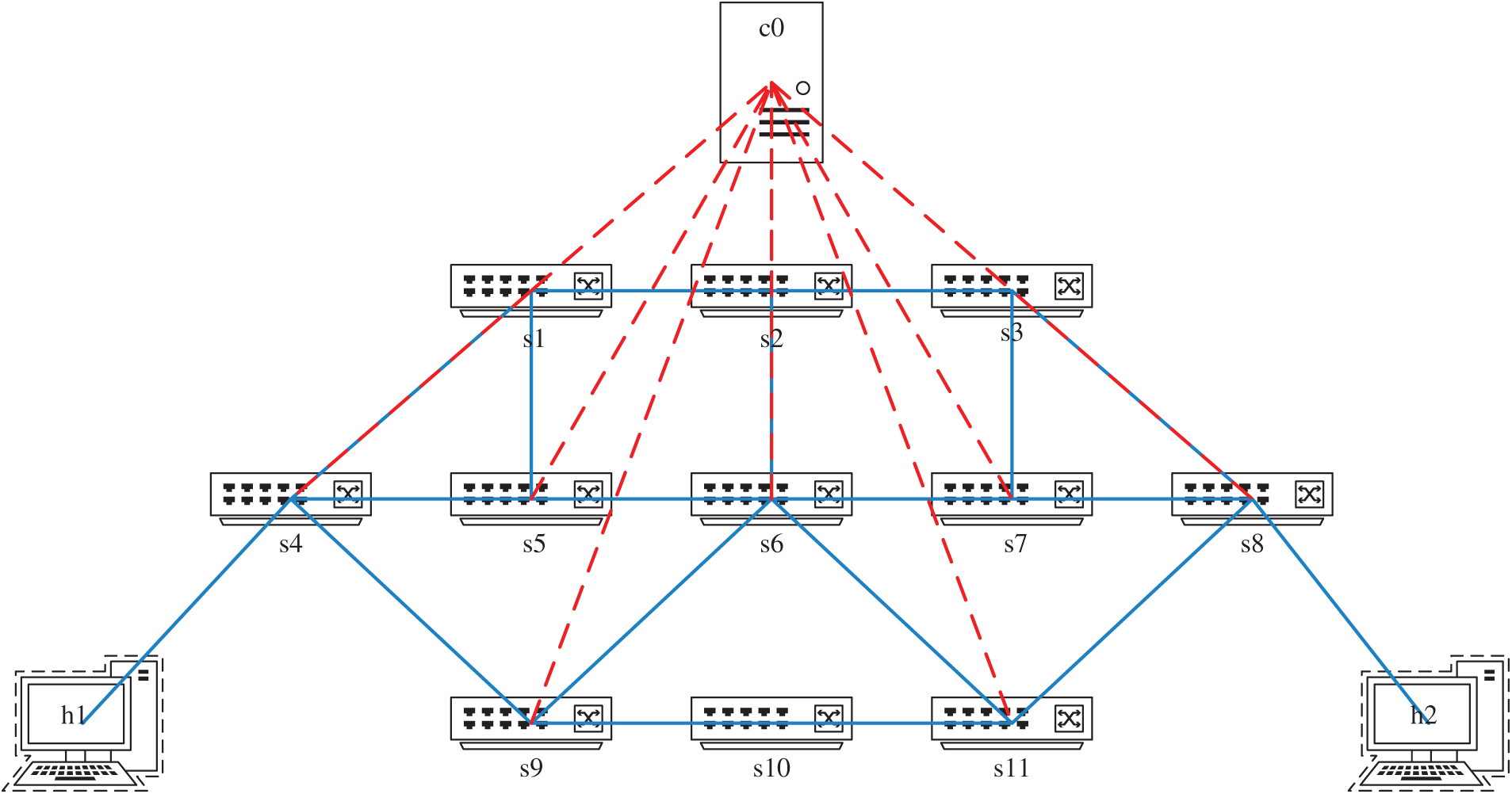

In order to confirm the protection effect of the device address variable anonymity protection method based on address hopping, this paper employs the Mininet network simulation platform and the Ryu controller to build a simulated network topology. Additionally, the miniedit visualization tool bundled with Mininet is utilized to visualize the topology, as depicted in Fig. 4, in which s1 to s11 are the Openflow1.3 protocol-supporting Openflow switches from s1 to s11 support Openflow1.3 protocol, c0 is the Ryu controller, and h1 and h2 are the communication hosts.

Figure 4: Experimental network topology diagram

4.2 Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

4.2.1 Metric Definitions and Measurement Setup

The following metrics are defined to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method:

IP Hit Rate: The percentage of real devices detected by the scanner (e.g., Nmap) during a fixed interval.

Latency: Average round-trip time (RTT) between communicating hosts, measured in milliseconds (ms) using ICMP ping tests.

Data Forwarding Volume: Total data (in MB) intercepted by an eavesdropper node using Wireshark on different paths.

CPU Load: Percentage of CPU resource consumed by the SDN controller, measured using top or htop tools.

All metrics were computed over 10 independent simulation runs, each lasting 10 min. CPU load was sampled using htop every 5 s and averaged. Latency was computed via ICMP echo with 5-ping batch tests. Eavesdropped data was logged via Wireshark with node-based filtering.

4.2.2 Simulation Topology and Baseline Configuration

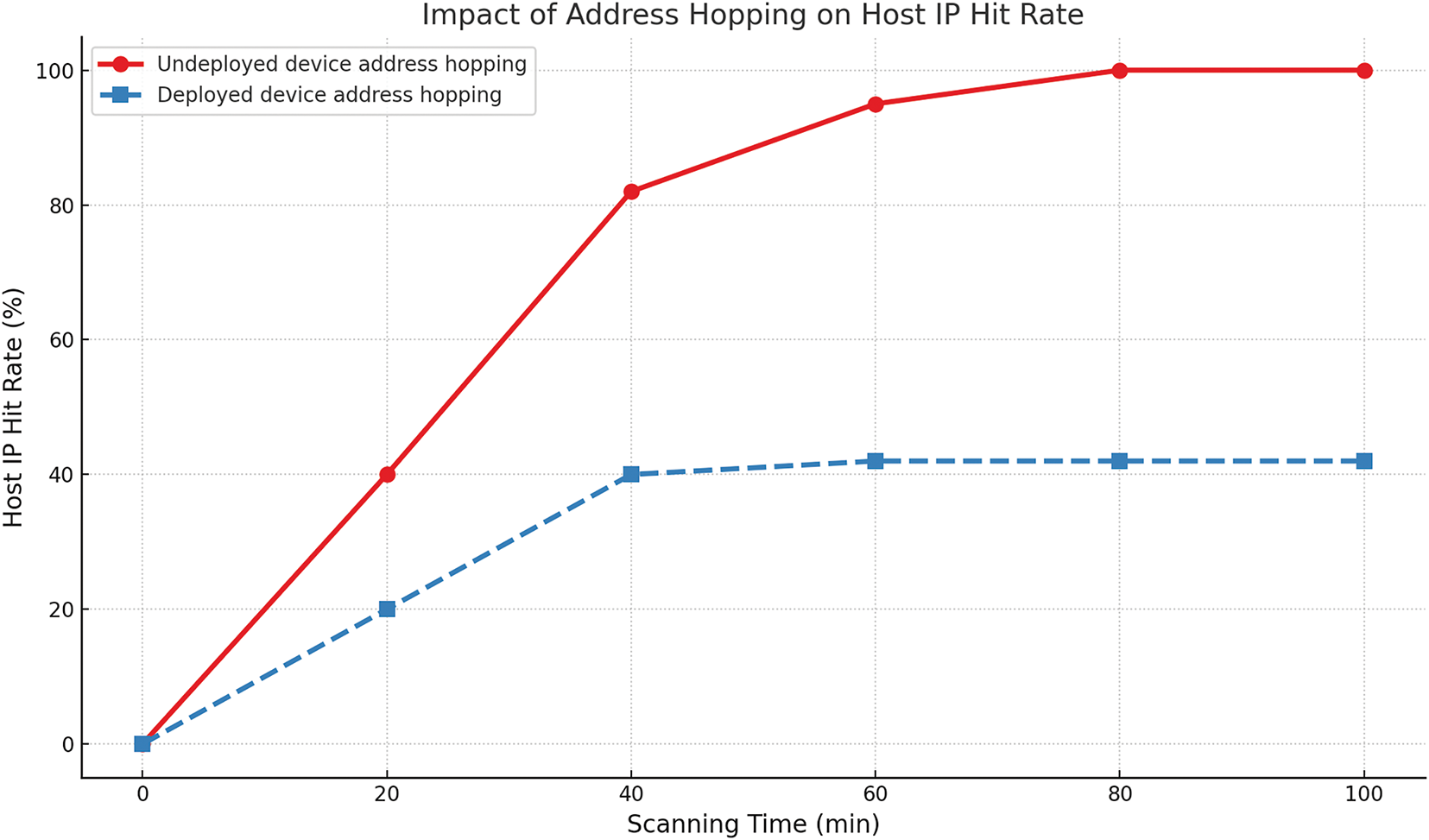

In this paper, we use Namp to perform 100 random scans of the network, take the average value after integrating the scanning results, and analyze the results to find that the hosts in the network without device address hopping are all scanned before 70 min, while only 43% of the hosts in the network using device address hopping are scanned on average. The probability of a host’s real IP being hit by the scanner decreases significantly after the use of device address hopping, demonstrating the effectiveness of the algorithm against attacks, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Comparison of host IP hit ratios with and without deploy device address hopping

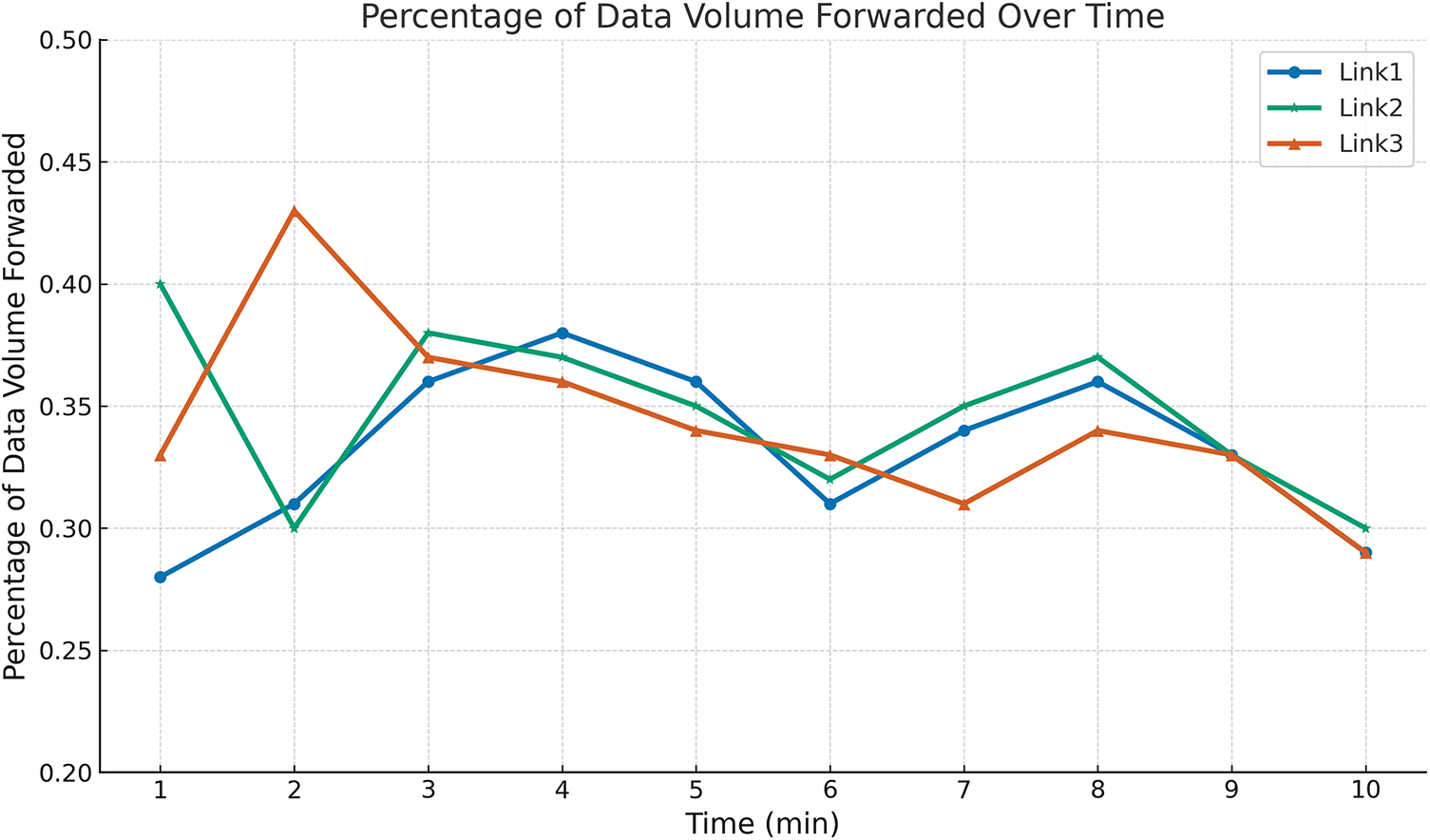

The success rate of eavesdropping attacks correlates directly with the quantity of data stolen by the attacker. In this paper, we evaluate the effectiveness of the device address hopping algorithm by comparing the amount of data that can be obtained by the attacker in the two cases of whether or not device address hopping is deployed. In the simulation environment, the link bandwidth is set to 100 Mb/s, Host1 sends packets to Host2 at a transmission rate of 10 Mb/s, and the rest of the hosts in the network provide normal communication traffic. The hopping space between Host1 and Host2 is shown in Table 1.

Using the Wireshark packet capture tool, we simulate an eavesdropping attacker to intercept packets transmitted through three different routes, and document the quantity of data transferred between Host1 and Host2 via each route every minute.

Without deploying device address hopping, data will be transmitted on the same fixed path. As shown in Fig. 6, when no device address hopping is deployed, the communication path is random, and there will be a situation where a path is selected multiple times, such as in the 4th and 5th minutes, when the data forwarding of a single path is more than 50% and if an eavesdropper places a wiretap on any node along this path, they would gain access to all session data exchanged between the communicating parties. If an attacker chooses to eavesdrop on this path, they will be able to access more than 50% of the communication data during this time.

Figure 6: Data forwarding volume without deploy device address hopping

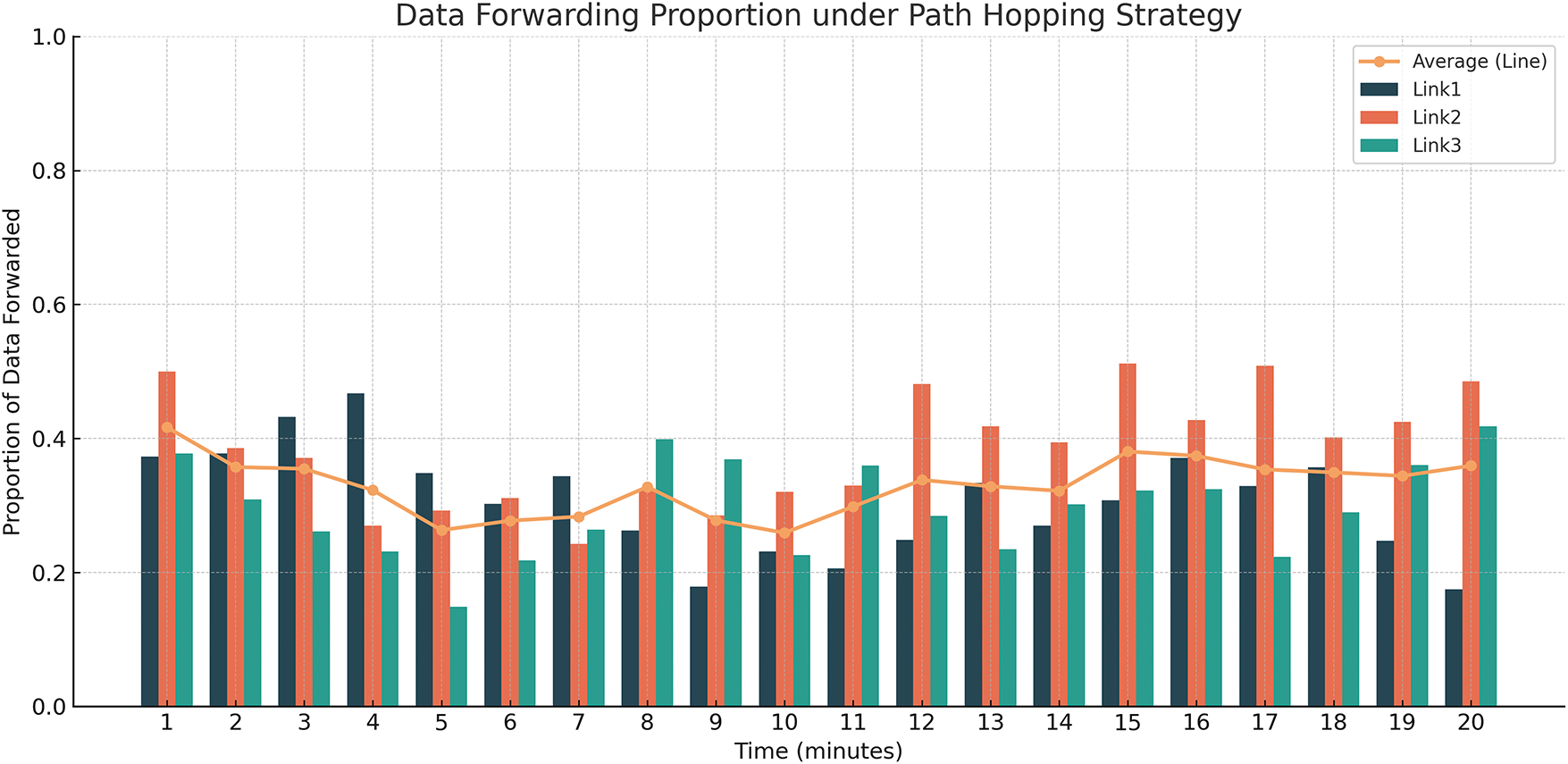

In the case of deploying device address hopping, as shown in Fig. 7, as the communication between Host1 and Host2 continues, the amount of data transfer on different paths gradually equalizes, with each path accounting for about 30% to 40% of the total data transfer. In this case, if an eavesdropper is eavesdropping at any node in the network, they can only access at most 40% of the total data volume.

Figure 7: Data forwarding volume with deploy device address hopping

4.3.1 Ablation Study on Objective Function Weights

To assess the influence of the weights

1. Equal Weights:

2. Latency Prioritized:

3. Diversity Prioritized:

4.3.2 Results and Analysis on Key Metrics

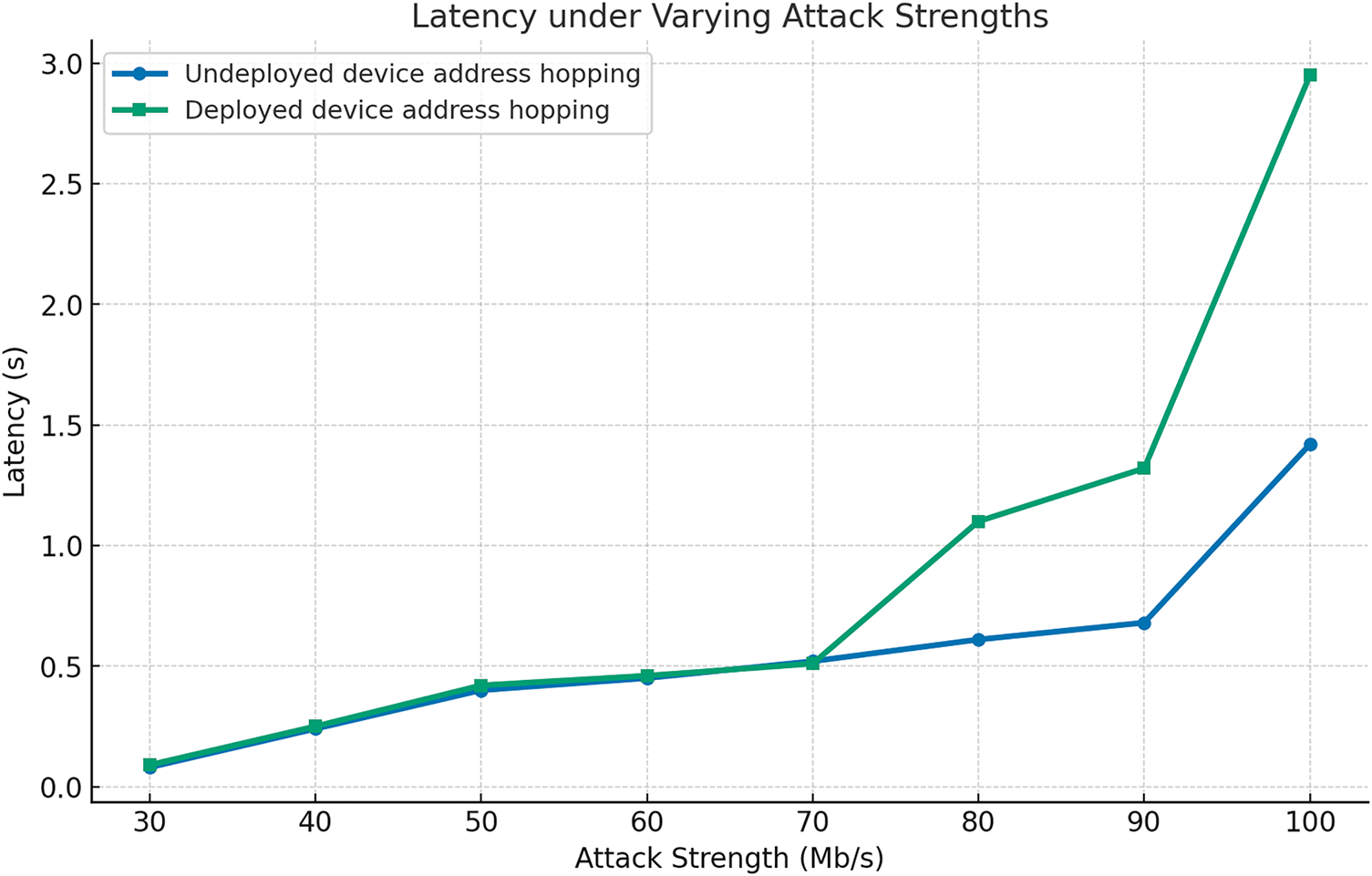

In this paper, we collect the delay data of Host1 and Host2 by performing connectivity tests on them, whether they use the device address hopping protection policy when communicating or not. This paper also compares the communication delay when the protection policy is enabled or not under different attack strengths. The specific experimental outcomes are presented in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Comparison of the latency with or without deploy device address hopping

Without the device address hopping protection policy, the communication delay between Host1 and Host2 increases exponentially with increasing attack strength. When there is a device address hopping protection policy, since the communication path is randomly selected, there is a probability close to 1/3 to select the target path. Under this mechanism, the communication delay increases with the increase of the attack strength, but the communication delay is reduced by about 60% compared to the unprotected strategy.

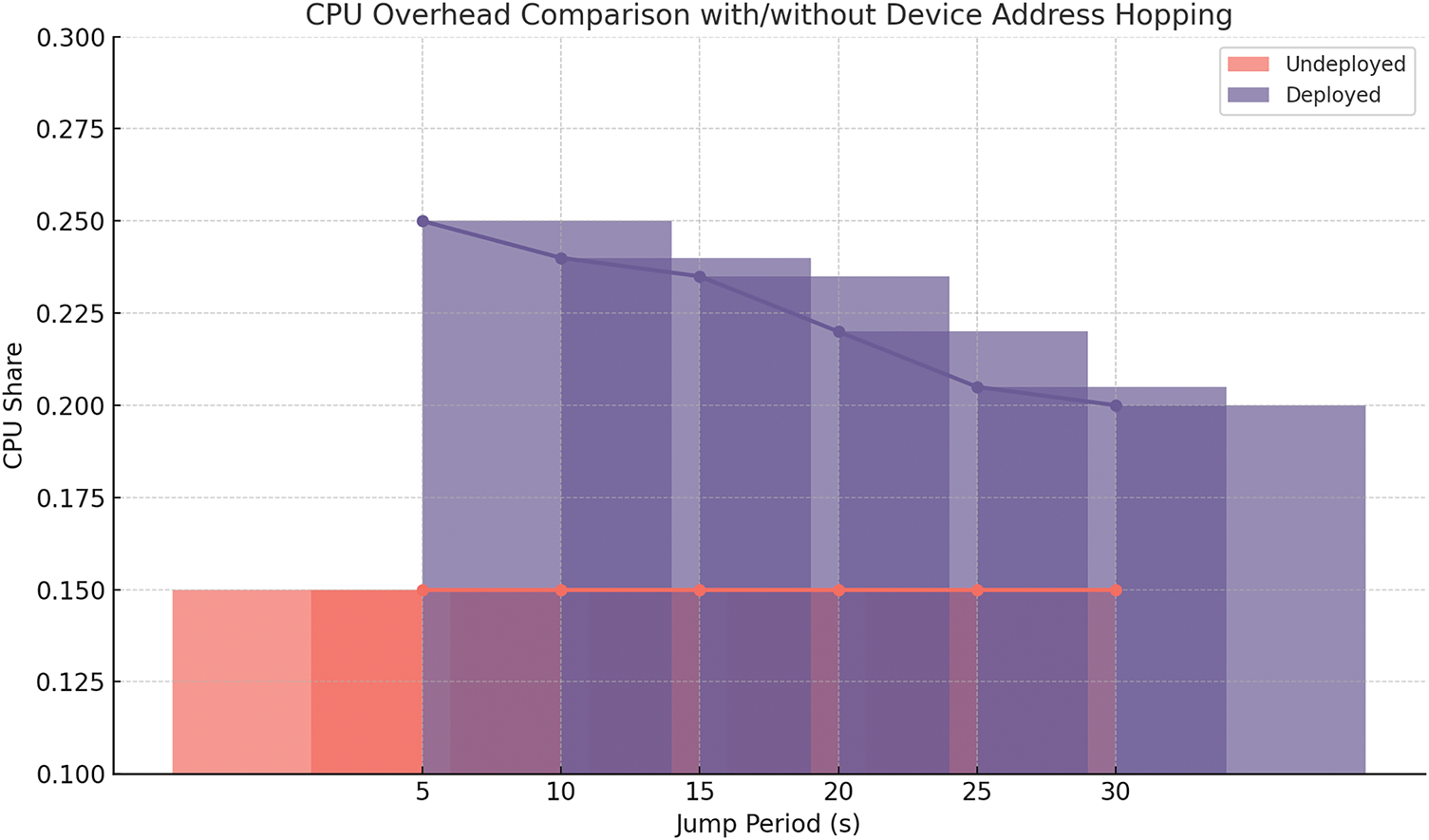

Since the end information hopping requires downstreaming the flow table and updating the true/false end information mapping table, when the hopping frequency is reduced (the hopping period becomes longer), the CPU load that needs to be occupied is also lower. The comparison of CPU load under whether or not to adopt the device hopping protection strategy is shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Comparison of the proportion of CPUs with and without deploy device address hopping

To test scalability, we constructed a topology with

To quantitatively evaluate our method’s effectiveness, we conducted comparative experiments against two representative baseline approaches: (1) Static IP Randomization, where IP addresses are randomly assigned during initialization but remain fixed thereafter, and (2) Classical SDN+MTD, which implements conventional MTD through path hopping without resource-aware optimization constraints.

As demonstrated in Table 2, our approach achieves significant performance improvements under high-intensity attack scenarios (1000+ packets/second). Specifically, the experimental results show: 27.3% reduction in average IP hit rate compared to the best-performing baseline; 60% decrease in end-to-end communication delay; Maintained comparable resource utilization.

These quantitative improvements validate the effectiveness of our multi-constraint hopping strategy in balancing security and performance. The superior metrics particularly highlight the advantage of our dynamic resource-aware optimization over static randomization and unconstrained hopping approaches.

4.5 Extended Evaluation with Anonymity Metrics

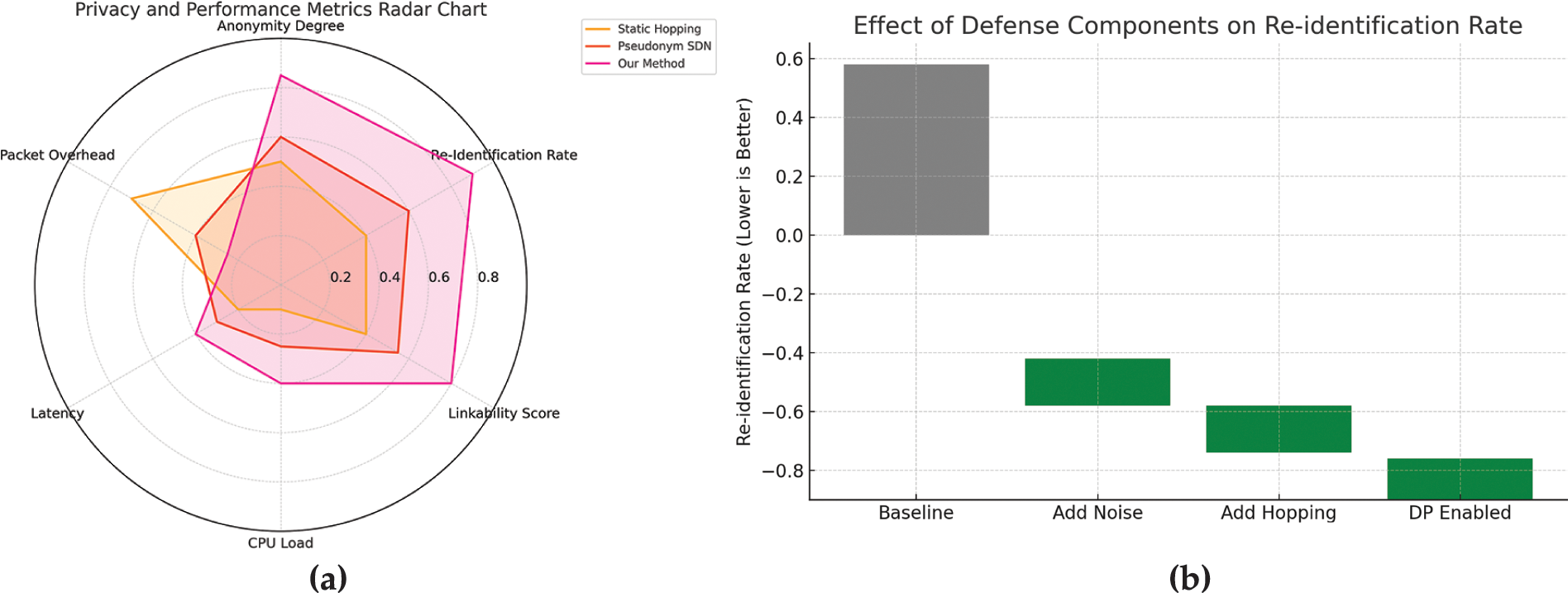

To further validate the effectiveness and practicality of our proposed anonymization mechanism, we conduct a comprehensive evaluation based on multiple privacy and system performance metrics. In addition to basic indicators like latency and CPU load, we introduce several anonymity-specific measures, including Anonymity Degree, Re-identification Rate, Linkability Score, and Entropy-based Indistinguishability. These indicators collectively provide a holistic assessment of the system’s robustness against inference attacks and privacy leakage risks.

We compare our method with two representative baselines: Static IP Hopping and Pseudonym-based SDN in Table 3. As shown in Fig. 10b, our method achieves superior anonymity without incurring excessive overhead. Specifically, it attains the highest Anonymity Degree (0.9), significantly outperforming Static Hopping (0.55) and Pseudonym SDN (0.72). The Re-identification Rate is reduced to 0.1, indicating a stronger resistance to tracking and profiling attacks. Furthermore, our method exhibits lower Linkability Score compared to others, demonstrating its effectiveness in resisting traffic pattern correlation. Importantly, despite the privacy gains, the latency and CPU load remain within acceptable bounds (0.4 and 0.35, respectively), verifying the real-time feasibility of our framework.

Figure 10: Performance and privacy evaluation of different anonymization mechanisms

To further dissect the contributions of individual defense components, we perform an ablation study by incrementally enabling each module in our framework. As illustrated in Fig. 10a, the baseline system without defense mechanisms yields a re-identification rate of 0.58. Introducing random noise reduces this rate to 0.43—a 26% improvement. Adding address hopping further lowers it to 0.32. With full activation of differential privacy mechanisms, the final re-identification rate drops to 0.18, representing a total reduction of 69% from the baseline. These results clearly indicate the additive benefit of each module and the overall strength of the defense strategy.

In summary, the proposed dynamic anonymization framework demonstrates remarkable privacy enhancement and scalability. It consistently achieves high anonymity while maintaining real-time performance, offering a promising direction for future secure communication in SDN-enabled networks.

4.6 Threat Model and Deployment Feasibility

We assume the attacker possesses various capabilities, including performing active scanning (e.g., Nmap) and traffic sniffing, deploying internal malicious nodes for man-in-the-middle attacks, and launching persistent attacks (APT) specifically targeting SDN controllers or switches. Against such threats, our address and port hopping mechanisms are designed to effectively hinder long-term traffic correlation and fingerprinting. Furthermore, the strategic use of non-overlapping paths and dynamic mapping significantly increases the uncertainty for the adversary, bolstering the system’s resilience. While implementing such a dynamic framework presents its own challenges, we have addressed them with targeted mitigation strategies. To manage synchronization overhead, a lightweight HMAC-based mechanism is applied to synchronize address states across flows. For low-power IoT devices facing resource constraints, the hopping frequency can be judiciously reduced or offloaded to more capable edge gateways. Protocol compatibility, particularly concerning TCP session consistency, is meticulously preserved through the use of NAT tables and state-aware flow rules. The robustness of the SDN controller, a critical component, is enhanced by incorporating redundant controllers and trust evaluation models, thereby mitigating potential single-point failures. Lastly, to ensure broader applicability and backward compatibility in non-SDN environments, a proxy-based address hopping gateway can be utilized for seamless legacy integration.

To empirically validate the framework’s effectiveness and assess its practical feasibility, we conducted a comprehensive series of evaluations.

4.6.1 Statistical Significance Analysis

To validate that the observed improvements are not due to random variation, we applied an unpaired two-tailed

4.6.2 Practical Deployment on Resource-Constrained Devices

We further deployed our SDN controller on a Raspberry Pi 4 (4 GB RAM) and two IoT sensor nodes emulated via low-power Linux containers. Under a 30 s hopping interval, the controller’s CPU load averaged 38.7% (

Although our framework demonstrates robust performance in simulated and small real-world tests, synchronization delay (

4.7 Impact of Hopping Frequency on Performance and Load

To assess the trade-off between security effectiveness and system overhead, we evaluated the impact of different hopping intervals (10, 30, 60 s) on key performance metrics. A higher frequency offers stronger anonymity but may increase control overhead. For this evaluation, four key metrics were measured: IP Hit Rate (representing the percentage of successful scans by an attacker), Latency (the average Round-Trip Time of communications in milliseconds), Controller CPU Load (the percentage of CPU resource consumed by the SDN controller, measured using htop), and IoT Device CPU Usage (percentage, simulated using a lightweight CPU profiler). Our findings indicate that as the hopping interval increases, the IP hit rate grows due to reduced unpredictability. Concurrently, both controller and IoT device resource consumption decrease, and latency improves, which is attributed to reduced control reconfiguration overhead. This demonstrates the inherent tunability of the proposed framework, allowing for a flexible balance between security efficacy and system efficiency.

The proposed address-hopping-based device identity anonymity protection method, which utilizes the address-hopping strategy in the MTD technology, significantly improves the defense capability and security of the network by dynamically adjusting the network topology and path strategy. First, the virtual network topology is randomly generated based on the collected node information and stored in the random network topology hopping pool. Then, CVSS is used to assess the vulnerability of the fake nodes and measure the structural stability and defense capability of the virtual network through quantitative analysis. Subsequently, the backtracking method is utilized to construct the hopping path space to ensure that the paths meet the criteria in terms of capacity, transmission delay and reachability, and at the same time, the non-overlapping constraint is set to enhance the diversity and security of the paths. Thereby, the anonymity of network devices is realized under the premise of satisfying specific constraints.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Project No. 2022YFB3104300).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Zesheng Xi and Chuan He; methodology, Zesheng Xi; software, Zesheng Xi; validation, Zesheng Xi, Chuan He and Yunfan Wang; formal analysis, Zesheng Xi; investigation, Zesheng Xi; resources, Zesheng Xi; data curation, Zesheng Xi; writing—original draft preparation, Zesheng Xi; writing—review and editing, Zesheng Xi; visualization, Zesheng Xi; supervision, Bo Zhang; project administration, Bo Zhang; funding acquisition, Bo Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used in this study were generated through simulations in a custom-built experimental network environment using the Mininet platform and Ryu controller. These datasets are not publicly available but may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Akgül İ. A pooling method developed for use in convolutional neural networks. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;141(1):751–70. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.052549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li Z, Wang P, Wang Z. Flowgananomaly: flow-based anomaly network intrusion detection with adversarial learning. Chin J Electron. 2024;33(1):58–71. doi:10.23919/cje.2022.00.173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sun GL, Xue Y, Dong Y, Wang D, Li C. An novel hybrid method for effectively classifying encrypted traffic. In: 2010 IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference GLOBECOM 2010; 2010 Dec 6–10; Miami, FL, USA: IEEE. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

4. Draper-Gil G, Lashkari AH, Mamun MSI, Ghorbani AA. Characterization of encrypted and vpn traffic using time-related. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy; 2016 Feb 19–21; Rome, Italy. p. 407–14. [Google Scholar]

5. Kim JW, Moon SM, Kang SU, Jang B. Effective privacy-preserving collection of health data from a user’s wearable device. Appl Sci. 2020;10(18):6396. doi:10.3390/app10186396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhai Z, Li X, Liu H, Lei K, Ma J, Li H. An anonymous zone construction scheme based on query range in LBS privacy protection. J Commun. 2017;38(9):125–32. [Google Scholar]

7. Zhang Y, Sun Z. Identity authentication for smart phones based on an optimized convolutional deep belief network. Laser Optoelectron Prog. 2020;57(8):081009. [Google Scholar]

8. Hellmann F, Mertes S, Benouis M, Hustinx A, Hsieh TC, Conati C, et al. Ganonymization: a GAN-based face anonymization framework for preserving emotional expressions. ACM Trans Multimed Comput Commun Appl. 2024;21(1):1–27. doi:10.1145/3641107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Rajasekar A, Vetrian V. A privacy-preserving graph neural network framework with attention mechanism for computational offloading in the Internet of Vehicles. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;143(1):225–54. doi:10.32604/cmes.2025.062642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhou Z, Qian X. Differential privacy algorithm under deep neural networks. J Electron Inform Technol. 2022;44(5):1773–81. [Google Scholar]

11. Lu B, Luktarhan N, Ding C, Zhang W. ICLSTM: encrypted traffic service identification based on inception-LSTM neural network. Symmetry. 2021;13(6):1080. doi:10.3390/sym13061080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Manjunath YSK, Zhao S, Zhang XP. Time-distributed feature learning in network traffic classification for internet of things. In: 2021 IEEE 7th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT); 2021 Jun 14–Jul 31;New Orleans, LA, USA: IEEE. p. 674–9. doi:10.1109/wf-iot51360.2021.9595307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cheng J, Wu Y, E. Y, You J, Li T, Li H, et al. MATEC: a lightweight neural network for online encry pted traffic classification. Comput Netw. 2021;199:108472. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2021.108472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hu RQ. Research on key technology of network layer mobile target defense based on SDN. Zhengzhou, China: Strategic Support Force Information Engineering University; 2022. [Google Scholar]

15. He WZ, Chen FC, Niu J, Tan JL, Huo SM, Cheng GZ. Research progress of network layer-oriented dynamic hopping technology. J Netw Inform Secur. 2017;7(6):44–55. [Google Scholar]

16. Luo YB, Wang BS, Wang XF, Zhang BF. Akeyed-hashing based self-synchronization mechanism for port address hopping communication. Front Inf Technol Electron Eng. 2017;18(5):719–28. [Google Scholar]

17. Haleplidis E. Overview of RFC7426: SDN layers and architecture terminology. In: IEEE softwareization. Los Alamitos, CA, USA: IEEE Computer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

18. Wang YH. Research and implementation of an SDN-based address hopping active defense technique [master’s thesis]. Hangzhou, China: Zhejiang University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

19. Chang SY, Park Y, Muralidharan A. Fast address hopping at the switches: Securing access for packet forwarding in SDN. In: NOMS 2016-2016 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium; 2016 Apr 25–29; Istanbul, Türkiye. p. 454–60. [Google Scholar]

20. Zheng K, Zhao X, Li X, Zhou Y. A SDN-based IP address hopping method design. In: Proceedings of the 2016 5th International Conference on Measurement, Instrumentation and Automation (ICMIA 2016); 2016 Sep 17–18; Shenzhen, China: Atlantis Press. p. 17–8. [Google Scholar]

21. Hao Z. Random routing moving target defense based on SDN. Tangshan, China: North China University of Science and Technology; 2023. [Google Scholar]

22. Jiang X, Wang Z, Dong C. A path planning algorithm based on improved RRT sampling region. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(3):4303–23. [Google Scholar]

23. Li ZY, Liu MY, Wang P, Su W, Chang T, Chen X, et al. Multi-ARCL: multimodal adaptive relay-based distributed continual learning for encrypted traffic classification. J Parallel Distrib Comput. 2025;201:105083. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2025.105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools