Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Equivalent Design Methodology for Ship-Stiffened Steel Plates under Ogival-Nosed Projectile Penetration

School of Marine Engineering, Jimei University, Xiamen, 361021, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yezhi Qin. Email: ; Qinglin Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Theoretical and Computational Modeling of Advanced Materials and Structures-II)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1883-1906. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.066844

Received 18 April 2025; Accepted 11 August 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

The penetration of ogival-nosed projectiles into ship plates represents a complex impact dynamics issue essential for analyzing structural failure mechanisms. Although stiffened plates are vital in ship construction, few studies have addressed the issue of model equivalence under penetration loading. This study employs numerical simulation to validate an experiment with an ogival-nosed projectile penetrating a Q345 steel plate. Four equivalent stiffened plate methods are proposed based on the area, flexural modulus, moment of inertia, and thickness. The results indicate that thickness equivalence (DM4) is unsuitable for penetration-loaded stiffened plates, except under low-speed, non-penetrating through impacts, and yields less accuracy than DM1/DM3. DM1, DM2, and DM3 each perform optimally with specific velocity ranges: DM1 at very low (critical) and high velocities, DM3 at low velocities, and DM2 at high speeds. Furthermore, in penetration scenarios, T-shaped stiffeners can be replaced with rectangular ones, as both exhibit similar failure behaviors and deflection trends, simplifying the design while preserving key structural characteristics. These findings provide valuable insights into the design of protective ship structures.Keywords

Penetration mechanics is a branch of applied mechanics that examines projectile–target interaction. This area holds significant importance in the military, aerospace, civil, marine, structural, and nuclear applications. Extensive experimental, theoretical, and numerical studies have been conducted on the antipenetrating performance of vessel structures in marine engineering, primarily focusing on ballistic characteristics, material constitutive behavior, and damage effects [1–5]. Model testing is often required when studying the anti-penetrating performance of vessel plates. However, researchers frequently face challenges in designing scaled models, such as the inability to produce small-sized T-stiffeners due to current manufacturing limitations. To address these structural model testing challenges effectively, equivalent modeling techniques are essential. Nevertheless, limited literature has focused on the problem of model equivalence in projectile penetration into steel plate structures.

Despite significant research achievements in the field of anti-penetration performance of ship structures and the emergence of equivalent modeling techniques as a core method for overcoming technical limitations in model testing, significant theoretical and practical gaps remain in the study of projectile penetration equivalence into steel plate structures. Current research primarily focuses on the quantitative effects of projectile nose shape on penetration efficiency, the progressive failure mechanisms of target plate structures under penetration loading, and projectile attitude evolution. Wang et al. [6] examined the penetration of ogival projectiles into the homogeneous and stiffened steel plates of a 921A large ship, summarized the failure modes of the target plates, and analyzed the effect of projectile load angle on penetration damage. Chen et al. [7] examined experimentally observed deformation and failure mechanisms, proposed a theoretical method for predicting projectile velocity, and introduced a novel approach for determining the bulging region radius based on impact data from hemisphere head projectiles. Wang et al. [8] studied impact pressure, fracture morphology, and penetration mechanisms in armor steel at different velocities, establishing correlations among these factors. Projectile nose shape plays a major role in stress distribution, energy transfer modes, and target plate damage behavior, significantly influencing anti-penetration performance, as extensively reported in the literature [9–13]. Several scholars [14–16] have investigated the effect of the projectile incident angle. Zhang et al. [17] examined multi-cabin structures with Z-shaped grillage under oblique projectile penetration and identified structurally related deflection patterns. Several researchers have proposed simplified analytical models that consider key physical phenomena and apply momentum and energy methods [18–20]. Additional studies have explored constitutive models to improve the accuracy of numerical simulations in projectile-steel plate penetration. The Johnson-Cook model has been widely adopted, and Chakraborty et al. [21,22] conducted experiments to calibrate its plasticity and failure parameters. Elek et al. [23] investigated deformable projectile penetration considering steel’s thermo-viscoplasticity using the Johnson-Cook model.

While previous research has significantly advanced the understanding of constitutive modeling for projectile penetration into steel plates—particularly through Johnson-Cook model applications, as demonstrated by Chakraborty, Elek, and others—a significant gap remains regarding equivalent design methodologies for stiffened plate structures. These marine engineering components exhibit distinct failure mechanisms under projectile impact compared to monolithic plates. This study addresses this gap by developing and evaluating equivalent design approaches for Q345 steel ship-stiffened plates subjected to ogival-nosed projectile penetration. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the numerical model calibrations, Section 3 analyzes the modeling and equivalent design methodology for stiffened plate penetration, and Section 4 provides the research conclusions.

2 Numerical Model Calibrations

High-speed projectile impact causes significant deformation of steel plate structures within extremely short timeframes, necessitating the consideration of geometric nonlinear effects in modeling. The LS-DYNA commercial software provides an effective solution for analyzing such geometric nonlinear problems under high-speed impact conditions [24]. The software automatically incorporates geometric nonlinear effects based on conservation equations by specifying material parameters, coupling conditions, and boundary conditions. To effectively address the model equivalent design problem, this study first calibrates the material model and numerical modeling. Accordingly, the combat infiltration steel plate from the experiments of Li et al. [25] serves as the calibration reference.

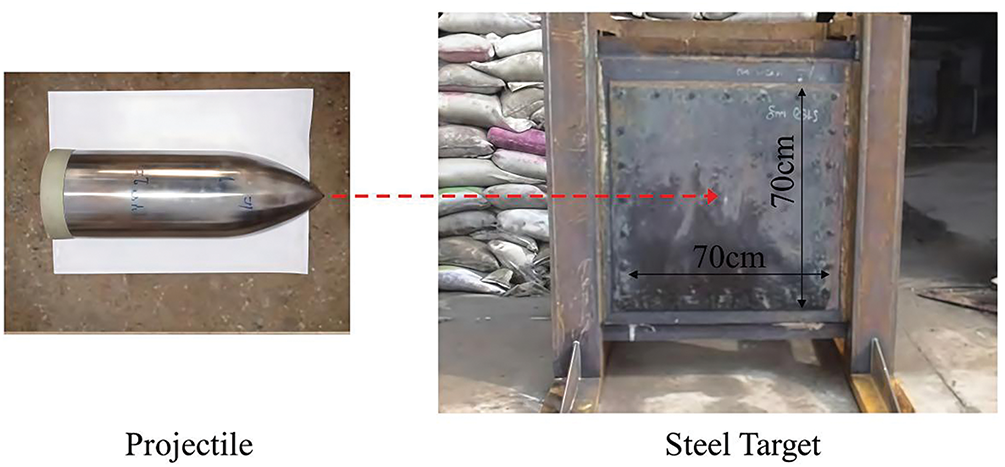

The experimental site layout, conditions, and data acquisition methods have been described in detail in the literature [25]. Fig. 1 shows the arrangement of the Q345B steel target plate and projectile. The projectile is made from 30 CrMnSi alloy structural steel, selected for its high strength and hardness, and contains an internal loading material. The ogival projectile has a diameter of 92 mm, a length of 276 mm, a shell weight of 3.21 kg, and a filler material weight of 1.45 kg, with a total mass of 4.66 kg. The Q345B steel target plate measures 1 m × 1 m with a thickness of 8 mm and features fixed support boundaries connected to the assembly frame using M24 bolts. The effective target plate area is 0.7 m × 0.7 m. The projectile was launched horizontally with an initial velocity of 208 m/s.

Figure 1: Physical model of the ogival-nosed projectile and steel target

2.2 Boundary Conditions, Mesh and Contact Conditions

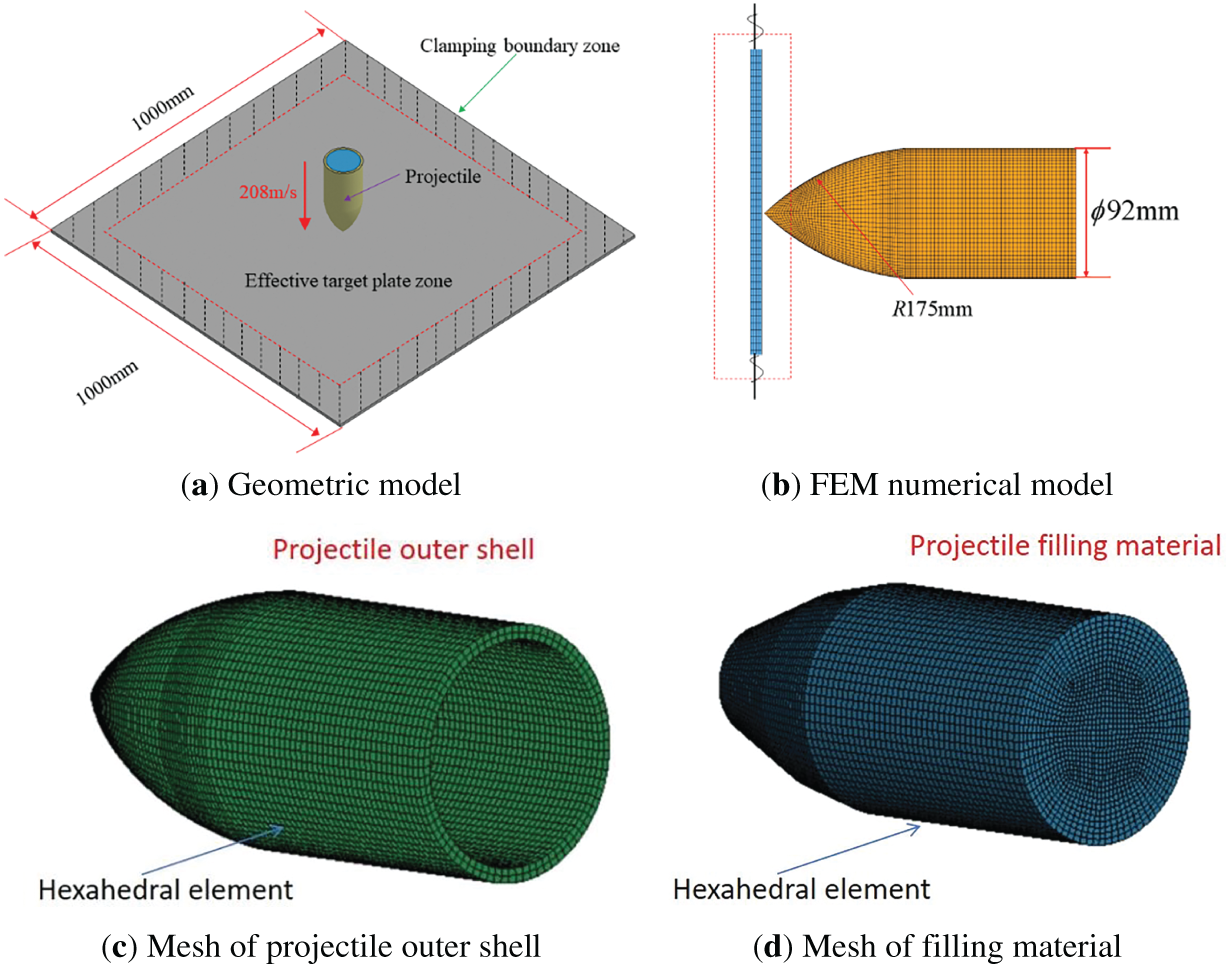

A full-scale model was developed based on the experimental dimensions to improve calculation accuracy, as shown in Fig. 2. The numerical models use eight-node solid elements, employing the Lagrange algorithm and hexahedral modeling method. The target plate is merged with a uniform hexahedral solid mapping grid using a 5 mm mesh size. The projectile body features non-uniform meshing: the cylindrical segment uses a uniform hexahedral mesh, whereas the projectile head uses a free hexahedral mesh. The filling material within the projectile also uses a uniform hexahedral mesh, as shown in Fig. 2c,d. Contact between the projectile and the target plate is simulated using the *CONTACT_ERODING_SURFACE_TO_SURFACE erosion algorithm. The boundary condition of the target plate is fixed within 30 cm of its width to replicate actual constraints. The projectile body adopts a rigid constitutive model with an initial velocity of 208 m/s.

Figure 2: The finite element method (FEM) numerical model of projectile penetrating Q345 steel target

High-strain rates are involved in both hypervelocity collision and explosion problems, and the yield stress

where

The strain-rate hardening behavior follows the relationship below.

where

The strain rate effect on materials is complex but can be simplified.

The influence of temperature on flow stress is expressed as follows:

where

The Johnson-Cook model comprehensively accounts for stress hardening, strain rate effects, and thermal softening, and represents yield stress with the following expression [26,27].

where

The failure strain incorporating damage is defined as follows:

where

The equation state of Q345 steel material uses the keyword *EOS_GRUNEISEN to define in LS-DYNA describing the pressure of the compressed, which is shown as:

where

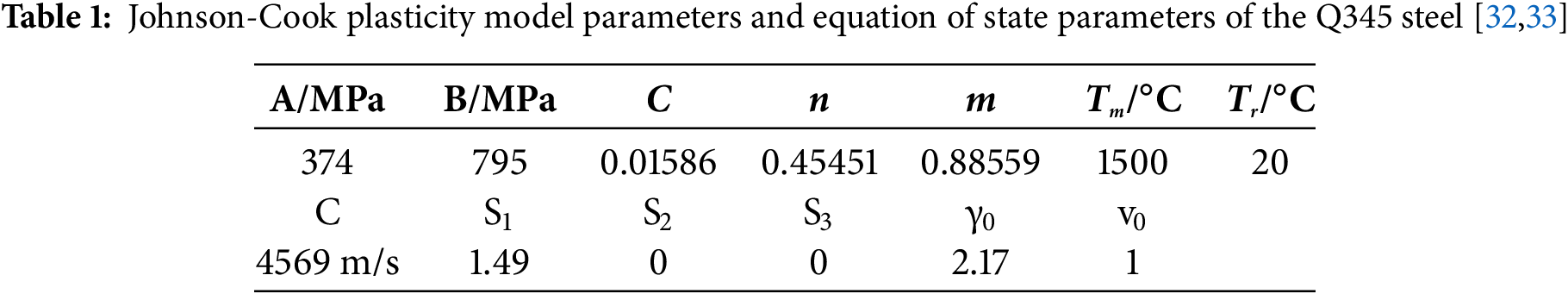

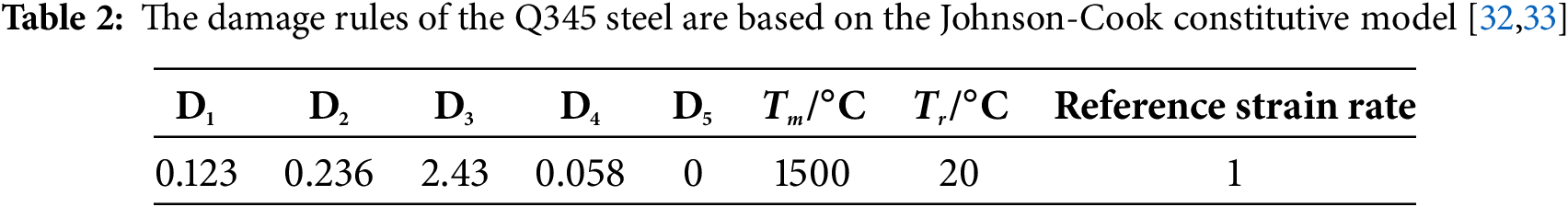

This study uses Q345 low-alloy steel as the target plate material. Q345 steel is widely used in engineering applications, including bridges, vehicles, ships, buildings, pressure vessels, and specialized equipment [28–31]. The material parameters used in the calculations are shown in Tables 1 and 2, based on data from the literature [32,33]. The 30 CrMnSi alloy used for the projectile is approximated as a rigid body.

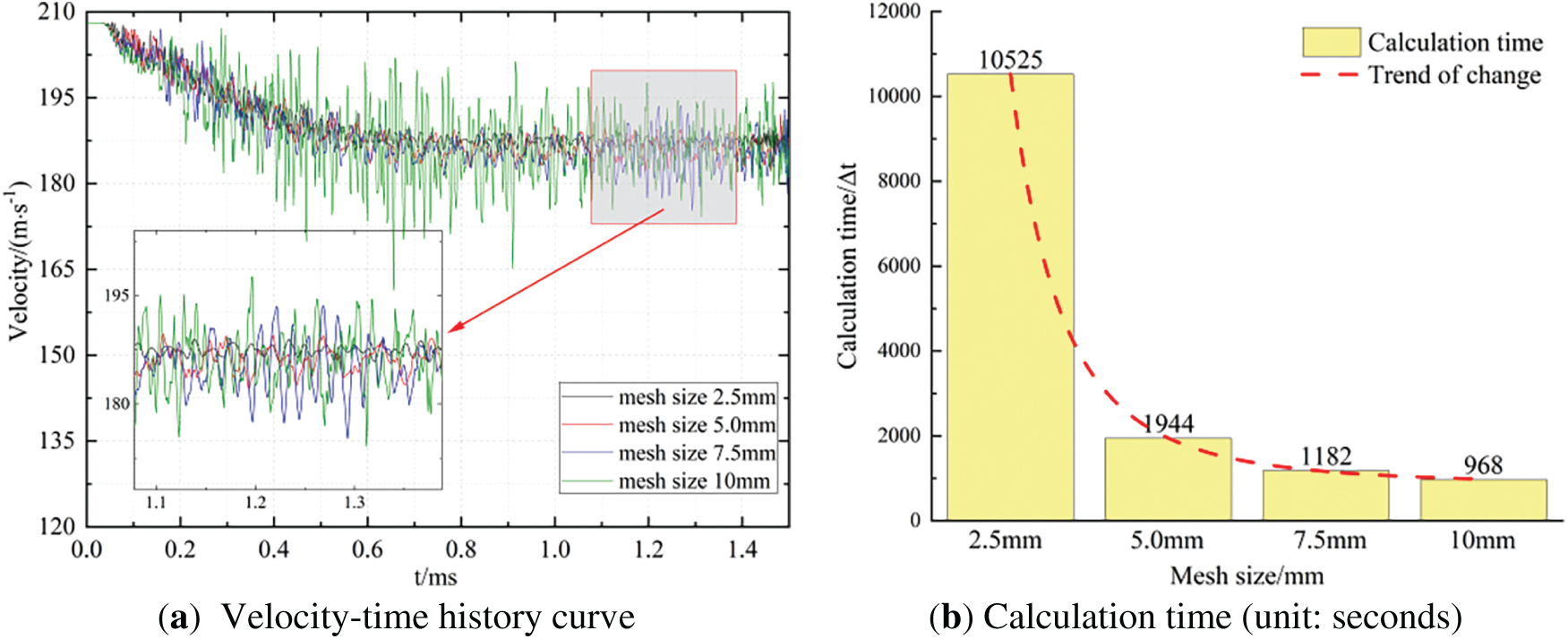

The grid dimension significantly affects the accuracy of the numerical simulation results. While smaller grid dimensions generally improve accuracy, reducing them beyond a certain threshold yields minimal variation in outcomes but greatly increases computational time and storage requirements. Therefore, selecting the optimal grid dimensions is essential for reliable calculations. Because the target plate undergoes the most significant deformation during projectile penetration, a mesh sensitivity analysis is necessary to determine the appropriate grid size for the target plate.

Target plate mesh sizes of 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 mm along the length and width, with a consistent mesh size of 2.0 mm, were selected for modeling, while maintaining the same boundary conditions and algorithms. The results of the calculation are shown in Fig. 3. Fig. 3a demonstrates that the mesh size significantly influences the projectile velocity, with smaller mesh sizes resulting in a reduced numerical oscillation amplitude. The residual velocities for mesh sizes of 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 mm were 186.51, 184.9, 184.6, and 186.9 m/s, respectively. Fig. 3b shows the computational time under different mesh conditions. When the plate mesh size was reduced from 10 to 7.5 mm, the computation time increased by 22.1%. Further reduction to 5 mm led to a 100.8% increase in computational time, while decreasing to 2.5 mm resulted in a 9.87-fold increase in computation time. These results indicate that mesh size substantially affects both computational efficiency and accuracy. The findings suggest that optimal results are achieved by selecting a mesh size that balances accuracy and computational cost rather than the finest mesh. Accordingly, a 5-mm mesh size is recommended as the reference for modeling plate structures.

Figure 3: The velocity and calculation time of the numerical model with mesh sizes 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 mm

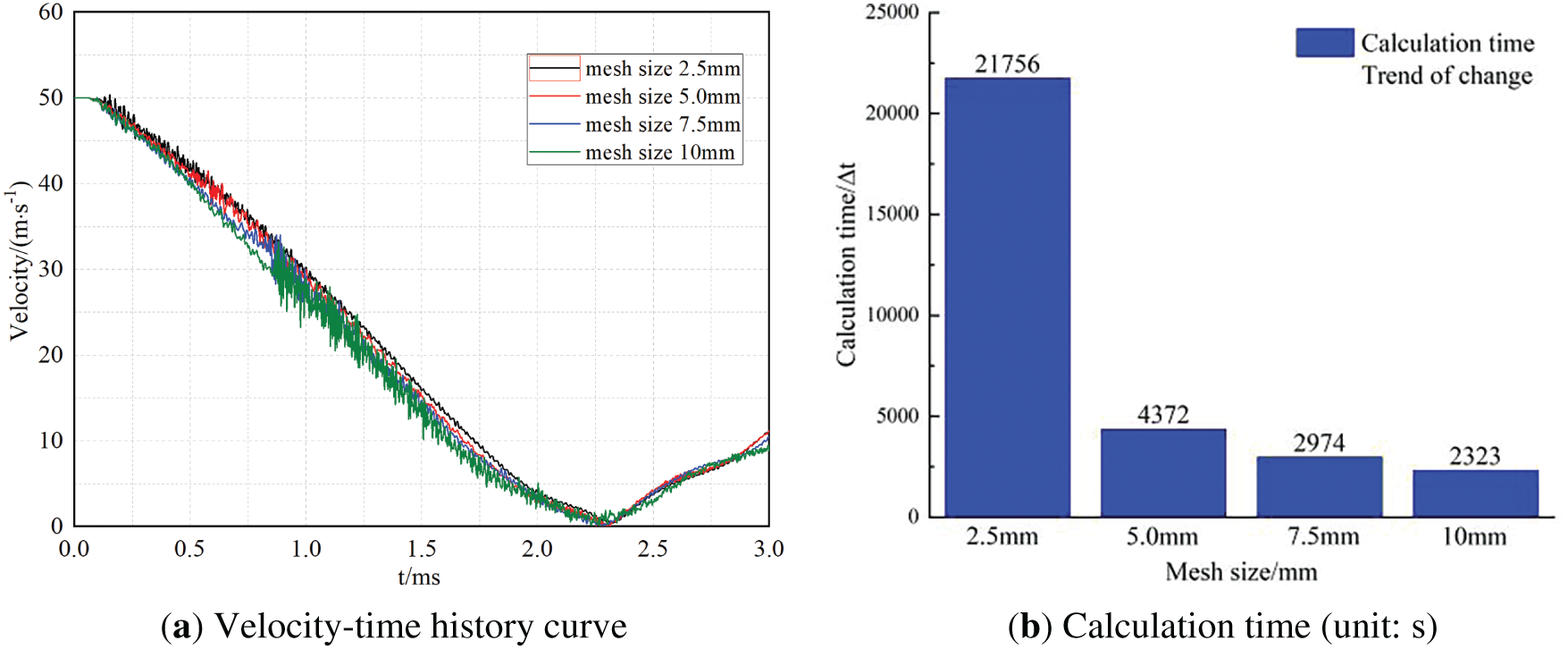

The above discussion was about the sensitivity of the mesh of the projectile under high-speed penetration conditions. Next, we will further discuss the sensitivity of the mesh of the projectile under low-speed penetration conditions. The calculation results are shown in Fig. 4. It can be seen from the calculation results that under the condition of low-speed penetration of the projectile, the calculation model converges under all four grid conditions. However, the coarser the grid, the more obvious the numerical oscillation; the finer the grid, the more stable the numerical calculation. In addition, in terms of computing time, the computing time cost increases significantly when the grid is finer. Its rule is consistent with that of the projectile under high-speed penetration conditions illustrated above.

Figure 4: The velocity and calculation time of the numerical model with mesh sizes 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 mm under the velocity of 50 m/s

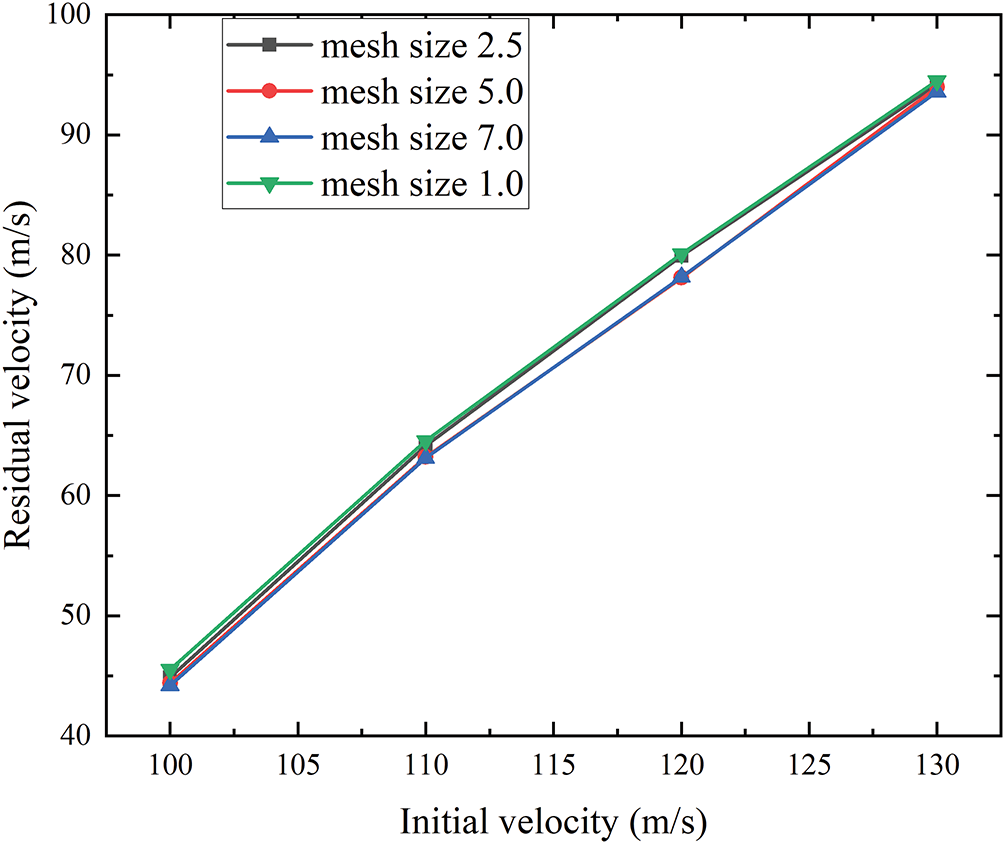

To further illustrate whether different speed affect mesh size sensitivity, additional research was conducted on the residual velocity of projectiles after penetrating steel plates under initial velocities of 100, 110, 120, and 130 m/s. The calculation results are shown in Fig. 5 below.

Figure 5: The residual velocity of projectile with initial velocity 100, 110, 120, 130 m/s at different mesh size of 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 mm

It can be seen from the calculation results that when the mesh size is coarse (10 mm) and fine (2.5 mm), the changing trends of the projectile’s residual velocity are similar. Meanwhile, when the mesh size is medium (5 and 7.5 mm), the changing trends of these two are also very close. This further verifies the aforementioned conclusion that an appropriate mesh size should be selected for calculations to achieve both precision and high computational efficiency.

2.5 Validation and Calibration of the Numerical Simulation

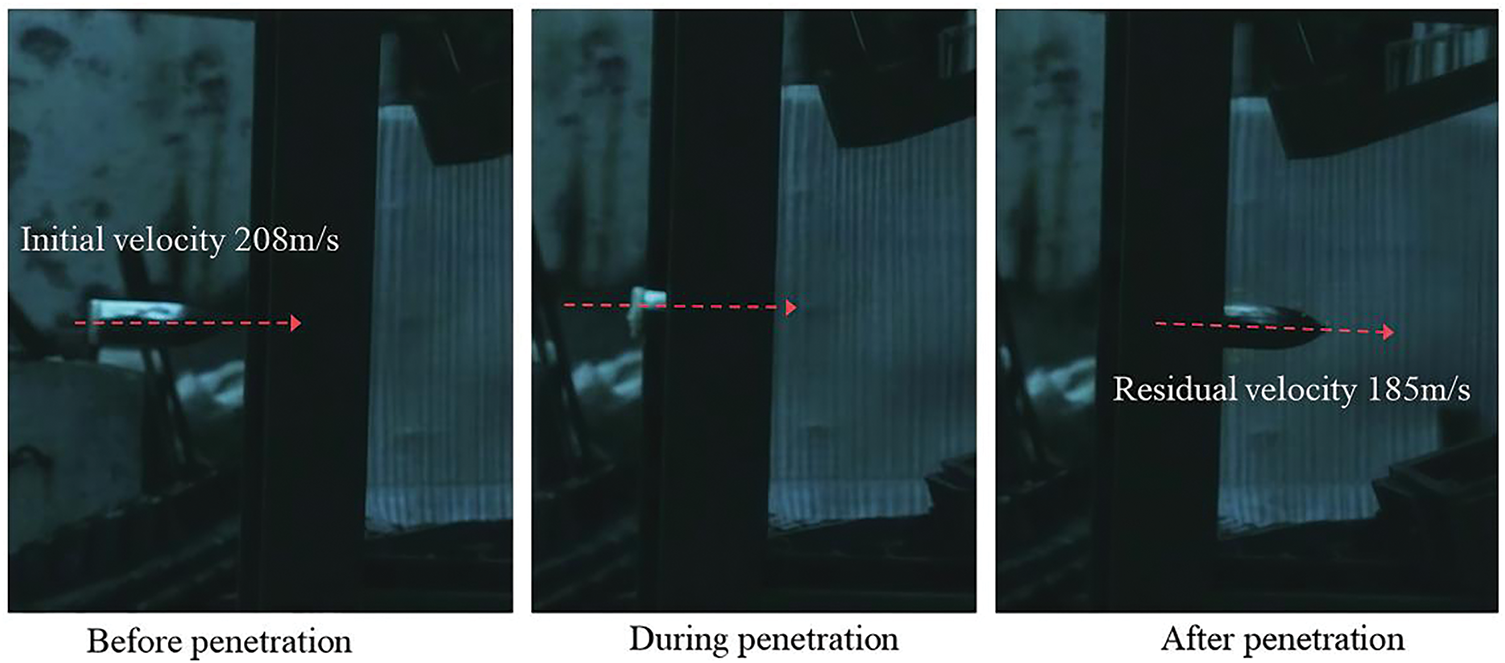

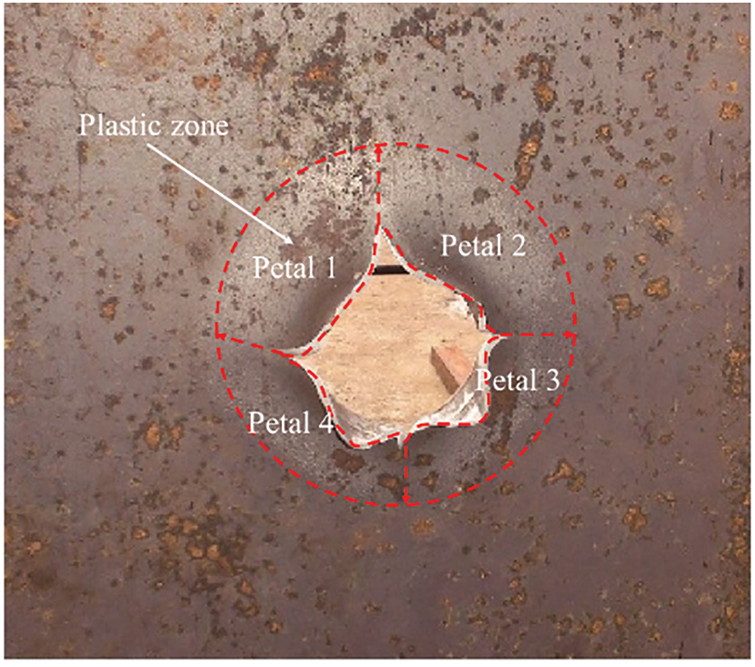

Experimental results show that the projectile maintains a perpendicular orientation both before and after penetrating the target plate [25]. Fig. 6 illustrates the dynamic process of the ogival projectile penetrating the Q345 steel target, as captured by a high-speed camera. The velocity of the projectile decreased from an initial 208 to 185 m/s. Following penetration, the steel target plate exhibited four distinct petal-shaped fractures, with four radiating cracks surrounding the fracture zone and a plastic deformation region in the central area, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 6: Schematic diagram of a process of projectile piercing target plate

Figure 7: The failure mode of Q345 steel target plate with 8 mm thickness after piercing by ogival projectile

Fig. 8 illustrates the damage pattern caused by the ogival projectile penetrating the Q345 steel target plate. The experimental and numerical results show a characteristic four-petal fracture pattern, with the projectile penetrating the steel plate at an initial velocity of 208 m/s. The crevasse diameter measured approximately 12.15 cm in both cases, with tearing observed at the petal roots and significant thinning at the petal tips. The petals exhibited a concave deformation profile, and the failure model predicted by the numerical model closely aligned with the experimental observations. The simulated residual velocities (186.51–186.9 m/s) correspond well with the experimental results (185 m/s), confirming the accuracy of the model.

Figure 8: Schematic diagram of a process of projectile piercing target plate

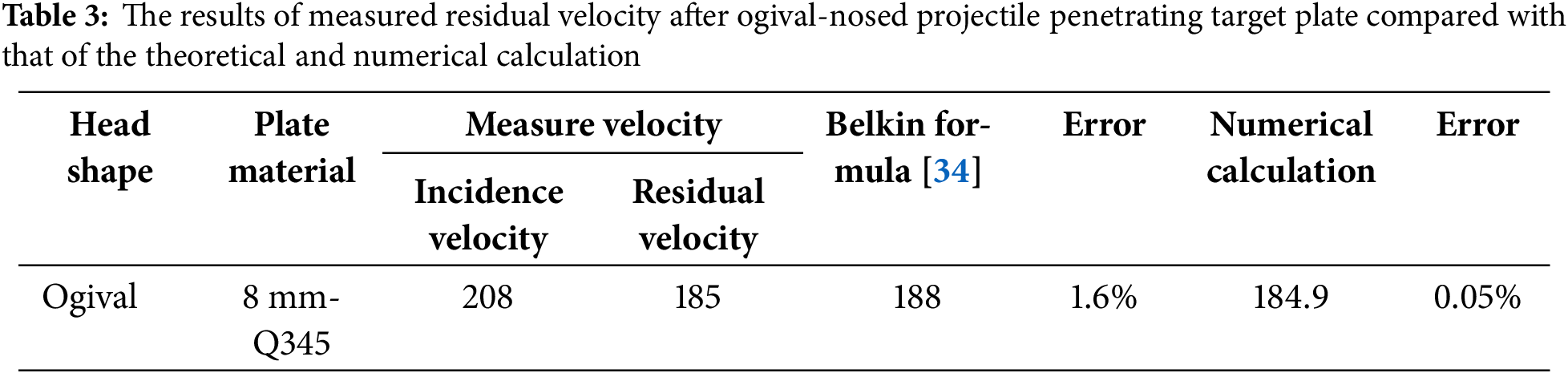

To further validate the effectiveness and accuracy of the computational model, the Belkin’s empirical formula [34] was applied to calculate the residual velocity for ogival-nosed projectile. The penetration of the Q345 target plate by a pointed projectile was analyzed using theoretical calculations, and the results were compared with experimental measurements and numerical simulations, as shown in the table.

The results in Table 3 demonstrate high consistency in projectile residual velocity across theoretical calculations, experimental data, and numerical computation. This strong correlation confirms the validity of the numerical model and calculation method, providing reliable support for subsequent numerical analyses. To further verify the validity and accuracy of the calculation results of the numerical model in this paper over a wider range, the theoretical values calculated by the Belkin empirical formula will be compared with the numerical calculation results. Based on the Belkin empirical formula, the theoretical residual velocities were calculated under the conditions of projectile initial velocities of 100, 110, 120, and 130 m/s, which are 45.60, 64.60, 80.50, and 94.70 m/s, respectively. Meanwhile, the residual velocities obtained from the numerical calculations with a mesh size of 5 mm are 44.39, 63.21, 78.12, and 93.98 m/s, respectively. The errors between the numerical calculation results and the theoretical calculation results are 2.65%, 2.10%, 2.96%, and 0.76% correspondingly. It can be seen from the calculation results that the numerical calculation results are highly consistent with the theoretical results. Additionally, it is found that as the initial velocity increases, the numerical calculation results are closer to the theoretical predicted values, with smaller errors and higher prediction accuracy.

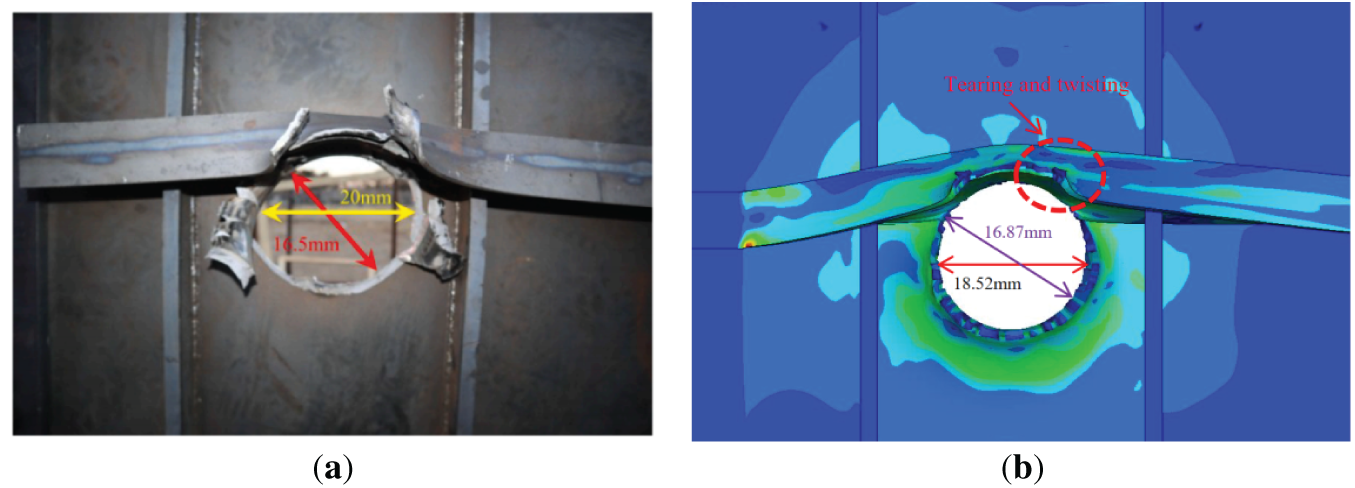

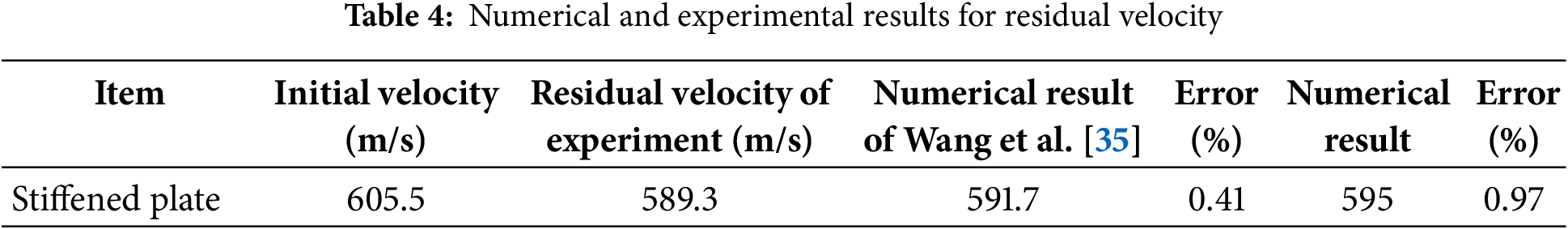

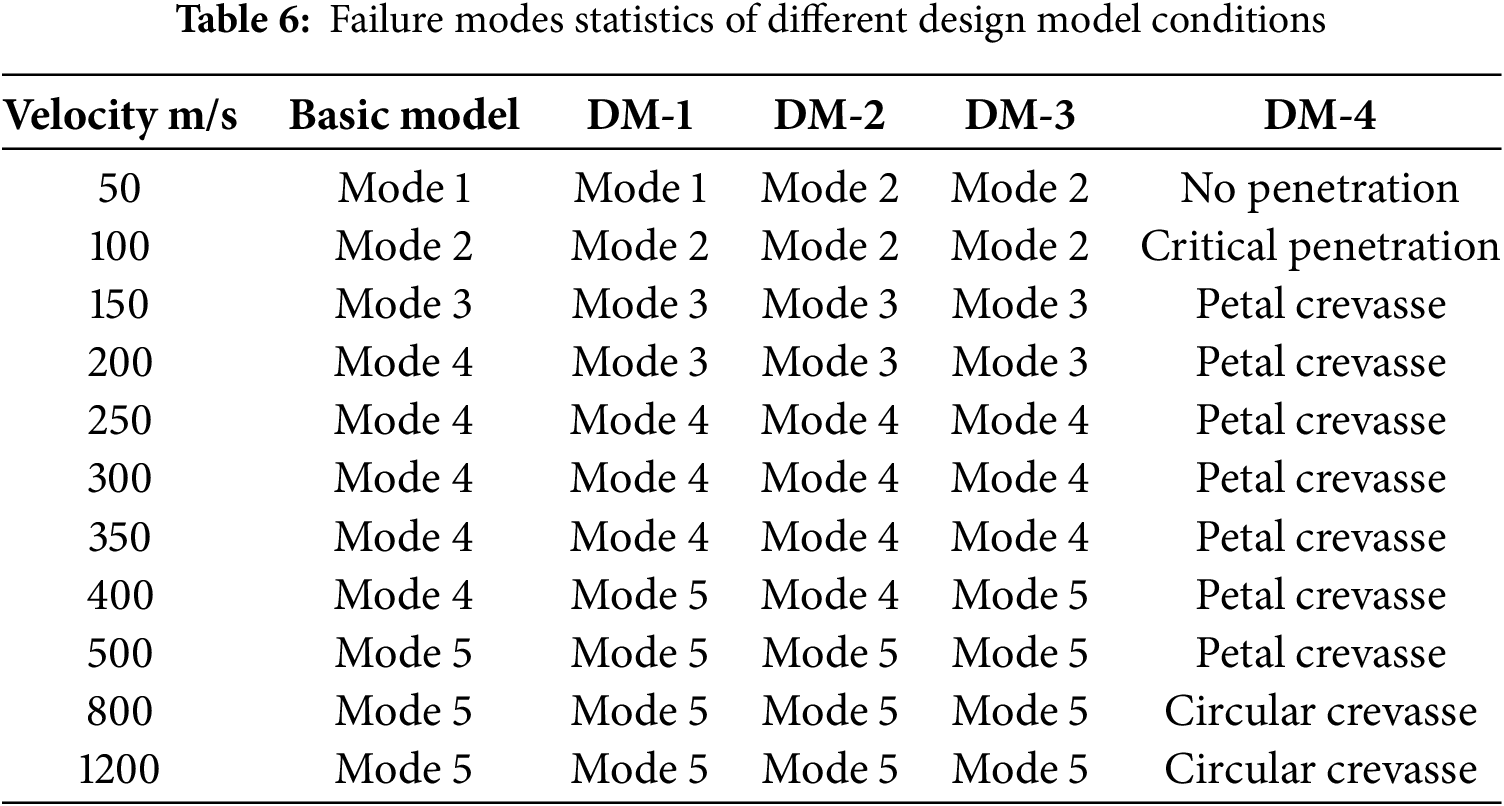

While the experimental and simulation results discussed above validate the numerical modeling method for homogeneous plates, actual ship structures typically incorporate stiffened plates, where mechanical behavior is significantly influenced by stiffener-substrate coupling effects. To validate the effectiveness of the numerical models in simulating stiffened plate penetration processes and to compare the experimental and simulation results for stiffened plate targets, particular attention was given to projectile residual velocity, target plate failure modes, and the deformation patterns of the stiffener and base plate. Experimental data from published literature [35] were used to further confirm the reliability of the numerical modeling. Comparison results are shown in Fig. 9 and Table 4.

Figure 9: The comparison between experimental and numerical result of stiffened plate suffering projectile penetration. (a) Experimental result of Wang et al. [35]; (b) Numerical result

Fig. 9 shows the strong agreement between the experimental and numerical simulation results regarding the failure modes. Both revealed characteristic failure patterns of the stiffened plate following projectile penetration: petal-shaped tears appeared in the base central area of the base plate, with the tearing direction aligned with the projectile’s impact orientation. The connection between the stiffener and base plate exhibited localized plastic deformation or tensile fracture, with fracture concentrated at the stiffener root directly beneath the impact point, consistent with stress concentration theory. Both the experimental and numerical analyses demonstrated a combined failure mode of “substrate penetration and stiffener shear fracture”, with consistent shear lip morphology and petal curling at the fracture section. For projectile residual velocity, a quantitative comparison shows a deviation of less than 5% between the simulation and experimental result, as detailed in Table 5. The overall numerical error remains within acceptable engineering limits, indicating that energy transfer and dissipation processes can be accurately modeled. Thus, both qualitative failure characteristics and quantitative velocity data confirm the numerical model’s effectiveness—it accurately reproduces the macroscopic structural failure during penetration and reliably predicts changes in projectile kinetic energy. These findings provide a solid foundation for the subsequent development and analysis of stiffened plate equivalent models.

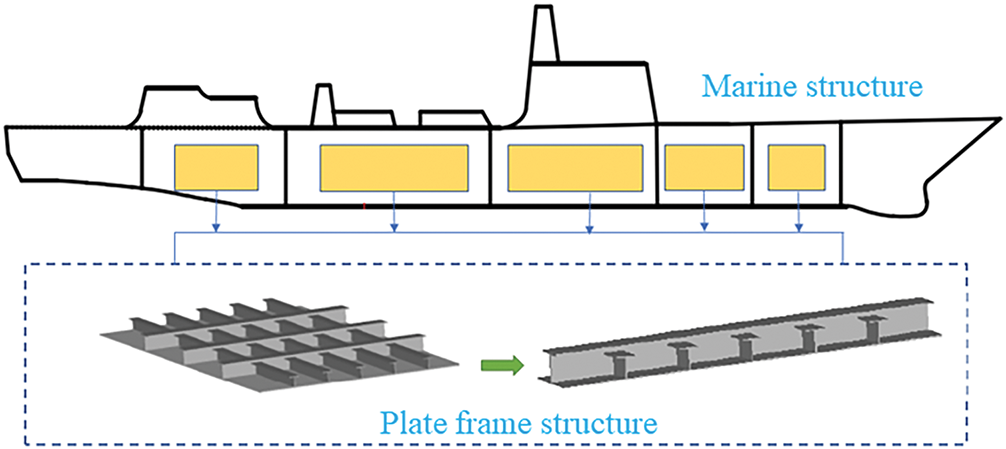

3 Modeling and Equivalent Design Methodology Analysis of the Projectile Impact the Stiffened Plate Structure

Projectile penetration into ship structures poses a complex impact dynamics challenge. Understanding the associated failure mechanisms and structural response characteristics is of strategic importance for enhancing ship defense capabilities. Research and practical evidence indicate that structural damage in a ship often initiates with localized damage progression. Consequently, local damage analysis is essential for identifying structural vulnerabilities and improving protective design and relevant studies support this point [36,37] As illustrated in Fig. 10, stiffened plate structures, which serve as fundamental components of key hull sections, play a critical role in absorbing external impact loads and maintaining structural integrity.

Figure 10: Diagram of a typical marine structure

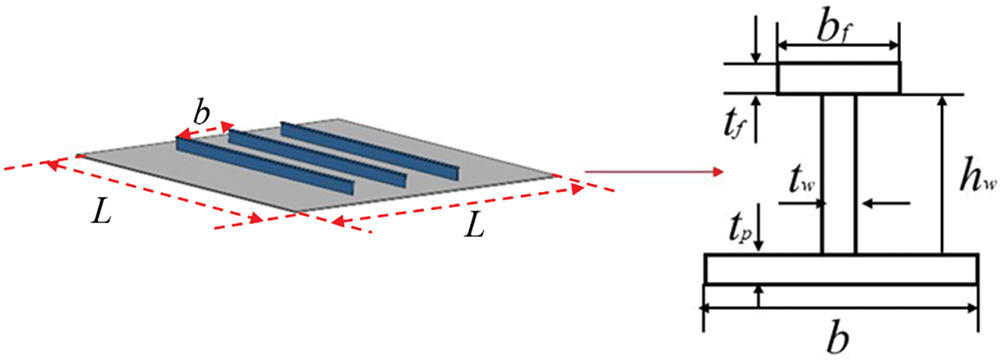

This study focuses on the failure mode of the Q345 stiffened plate structure under ogival projectile penetration. The stiffened plate structure analyzed was selected based on prior research [38]. A diagram of the typical stiffened structure is shown in Fig. 11. In Fig. 11, the symbol b is the breadth of the plate, also taken as stiffeners spacing,

Figure 11: Diagram of a typical stiffened steel structure

3.1 Equivalent Method Design of Stiffened Plate Structure

Investigating the impact performance of ship structures typically requires extensive model experiments and numerical studies, which present several challenges. For example, due to limitations in model fabrication techniques and welding considerations, T-stiffened plate structures in certain cabin areas are often simplified to equivalent treatment, replacing them with plates of uniform thickness or stiffened plates with rectangular sections. Similarly, the complexity of modeling, mesh generation, and computational demands often necessitate the use of equivalent design for ship-stiffened slab structures beyond the primary protective bulkhead when simulating and evaluating the dynamic response and protective effectiveness of the cabin bulkhead.

In the study of projectile penetration into ship-steel plates, three equivalent methods are proposed based on the area (DM-1), bending modulus (DM-2), and moment of inertia (DM-3). These methods simplify complex stiffened plate structures into more manageable models while preserving key mechanical behaviors under penetration loads. The area-based equivalent method (DM-1) operates on the principle that the cross-sectional area of the stiffener significantly plays a critical role in its load-bearing capacity. By ensuring the equivalent model has the same cross-sectional area as the original rectangular stiffener, this method aims to maintain resistance to projectile penetration. A larger cross-sectional area generally corresponds to increased resistance to deformation caused by impact; thus, equating areas helps approximate the mechanical behavior of the original structure. The bending-modulus-based equivalent method (DM-2) focuses on the resistance of the plate to bending deformation. The bending modulus or section modulus is directly related to the structural ability to withstand bending under load. During projectile impact, both the plate and stiffener experience bending deformation. Matching the bending modulus between the equivalent model and the original structure allows accurate simulation of stress distribution and deformation patterns associated with bending. The moment-of-inertia-based equivalent method (DM-3) emphasizes the structure’s resistance to rotational and torsional deformations. The moment of inertia reflects the capacity of an object to resist rotational acceleration. When subjected to projectile penetration, stiffened plates may experience complex dynamic responses involving rotation and torsion. This method maintains key resistance characteristics by equalizing the moment of inertia between the equivalent model and the original stiffener, enabling realistic simulation of the dynamic behavior during impact. Together, these equivalent methods relate the geometric and mechanical properties of original and simplified models from distinct perspectives, facilitating efficient and accurate analysis of projectile penetration into stiffened plates while maintaining constant stiffener thickness.

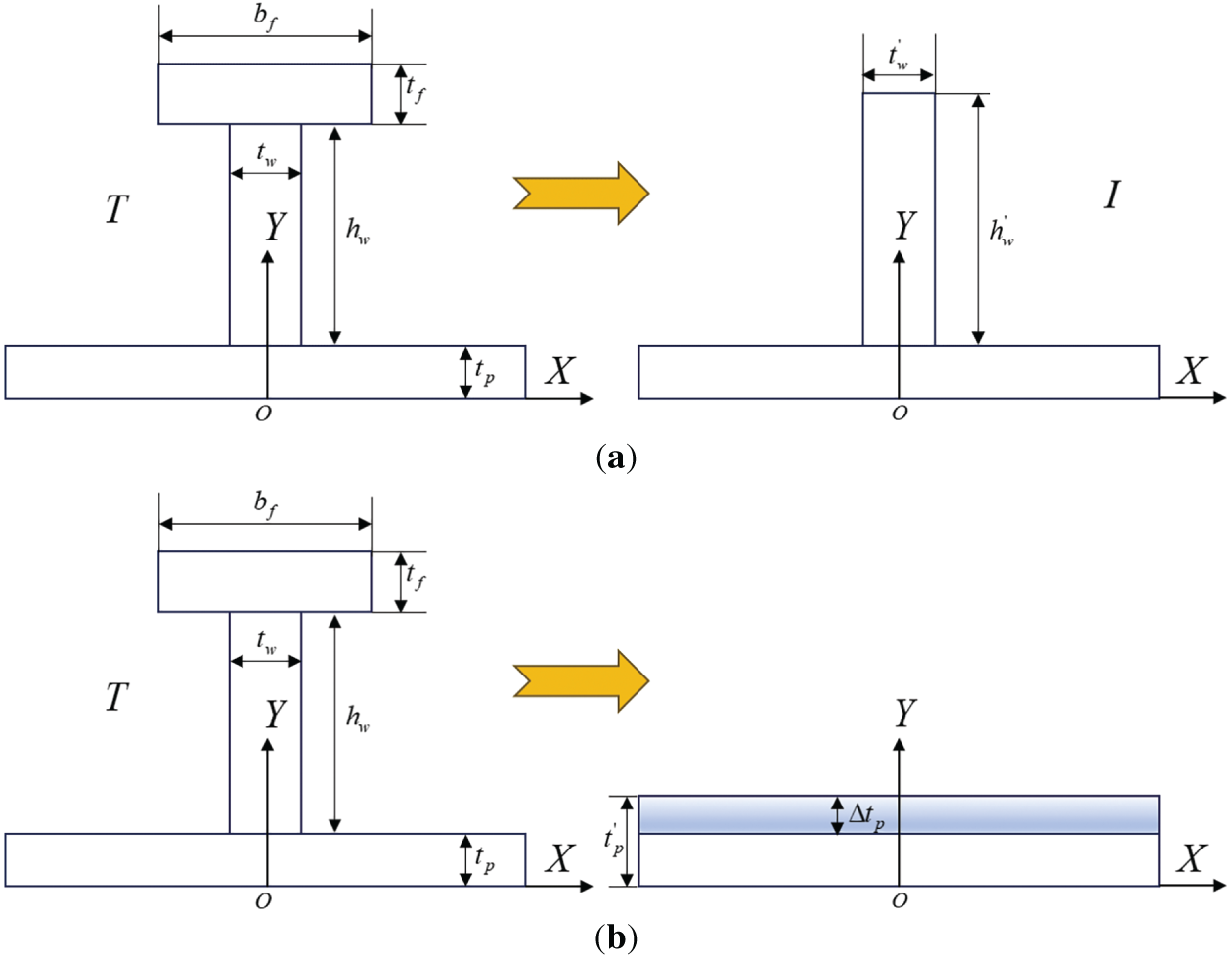

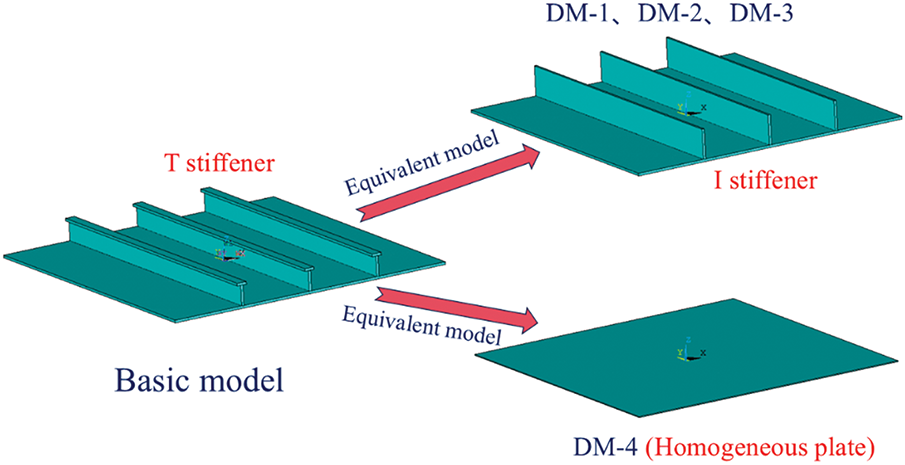

Taking the T-shaped stiffened plate structure shown in the figure as an example, the concept of equivalent design involves converting the T-shaped section stiffener into either a rectangular section stiffener, as shown in Fig. 12a, or to convert the T-shaped section stiffener into a plate of a uniform thickness, as shown in Fig. 12b, where

Figure 12: Diagram of a typical stiffened plate of marine structure

To achieve a comparable impact dynamic response between the equivalent design and the prototype structure, the cross-sectional area

1. The stiffener is retained, and the cross-sectional area and thickness of the stiffener are equal, designated as DM-1.

2. The stiffener is retained, and both the bending modulus and thickness of the stiffener are equal, designated as DM-2.

3. The stiffener is retained, and both the moment of inertia and thickness of the stiffener are equal, designated as DM-3;

4. The stiffener is not retained; the stiffener is evenly distributed across the thickness of the plate, designated as DM-4.

For the T section, the section area of the stiffener is calculated using the following formula:

The formula for calculating the moment of inertia about the X-axis is as follows:

The bending section modulus about the X-axis is given by the formula:

The basic principle of mass equivalence involves uniform distribution of the stiffener’s mass across the corresponding plate area while keeping the plate’s dimensions unchanged, effectively converting the stiffener into an increase in plate thickness. In dynamics, mass equivalence essentially reflects inertial equivalence. Assuming identical material properties and densities for both the stiffener and the plate, the equivalent additional plate thickness can be calculated using the following formula:

where

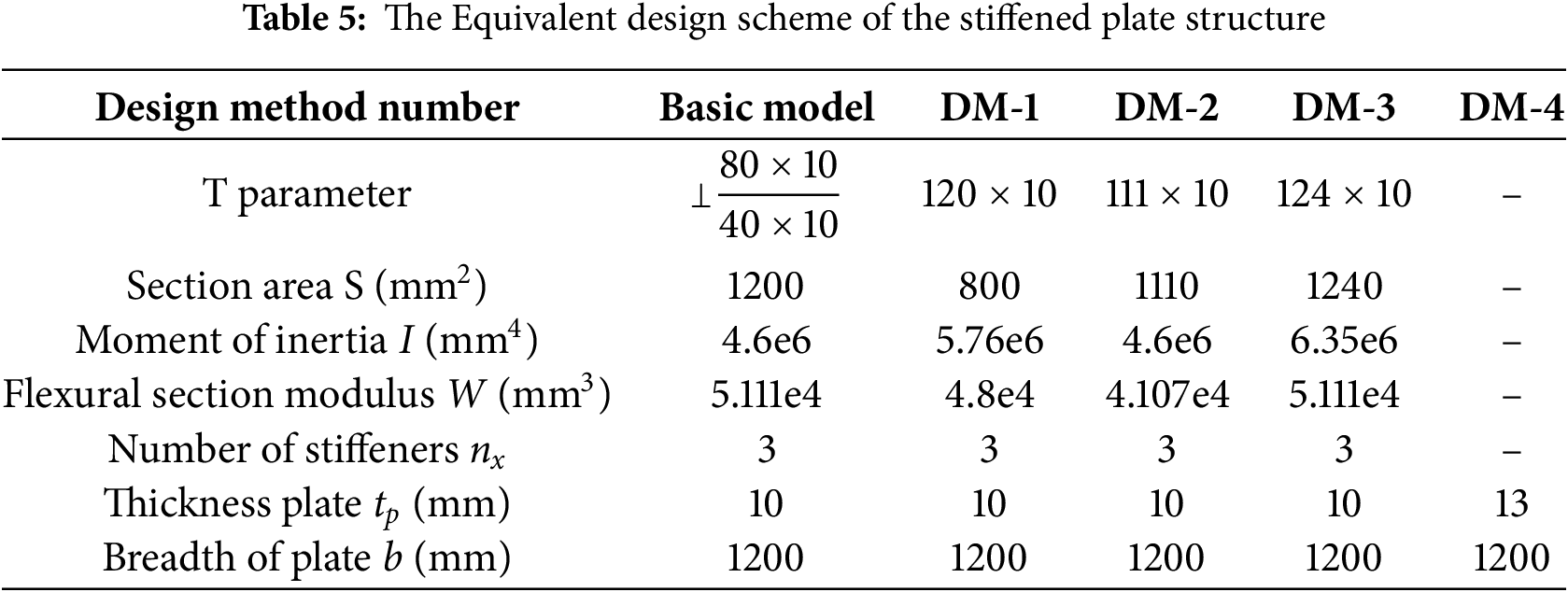

3.2.1 Numerical Analysis Equivalent Models Based on Basic T Stiffened Plate of Ship Structure

In the preliminary analysis of the stiffened plate structure, a typical example is used to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of four equivalent design schemes. Based on these schemes, rectangular stiffened plates of three different sizes, along with a homogeneous plate, were designed. The specific dimensions are provided in Table 5.

The geometric models developed based on the above design parameters are illustrated in Fig. 13:

Figure 13: Equivalent design geometry models

3.2.2 Analysis of the Velocity Properties of Projectile Penetrating Different Plate Structures under Different Equivalent Design Methods

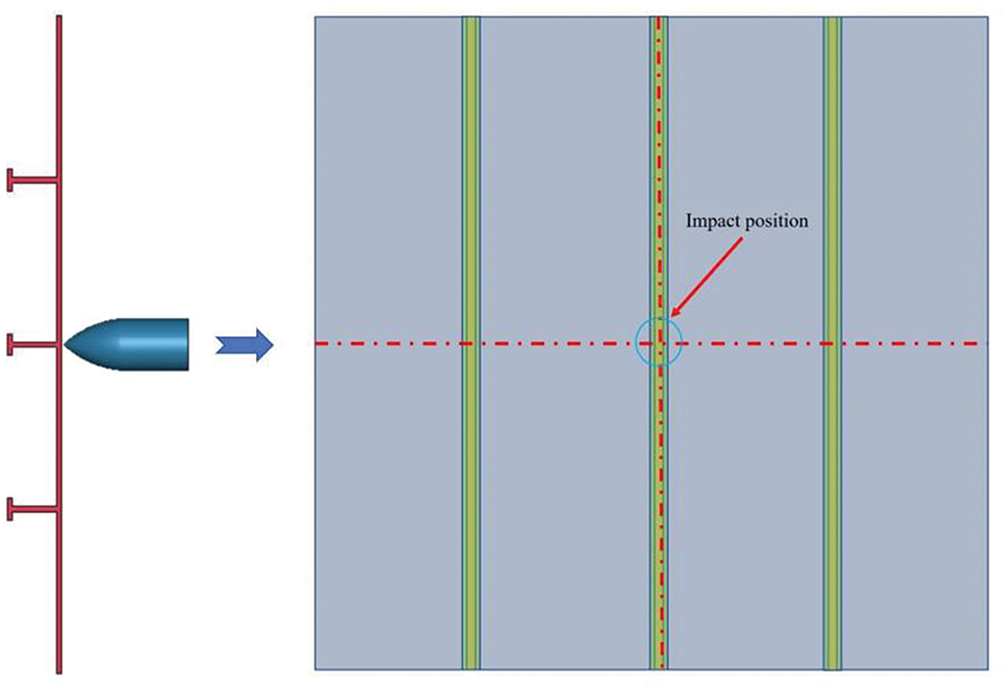

Simulation calculations were conducted to analyze the penetration behavior of the plate frame structure under various initial projectile velocities and the equivalent design method. Initially, the penetration process of the basic model was evaluated for projectile velocities ranging from 50 to 1200 m/s. The projectile’s impact position on the stiffened plate is shown in Fig. 14, and the velocity-time history curve of the projectile during penetration is presented in Fig. 15.

Figure 14: Schematic diagram of the position of the projectile impacting the stiffened plate at center of stiffener

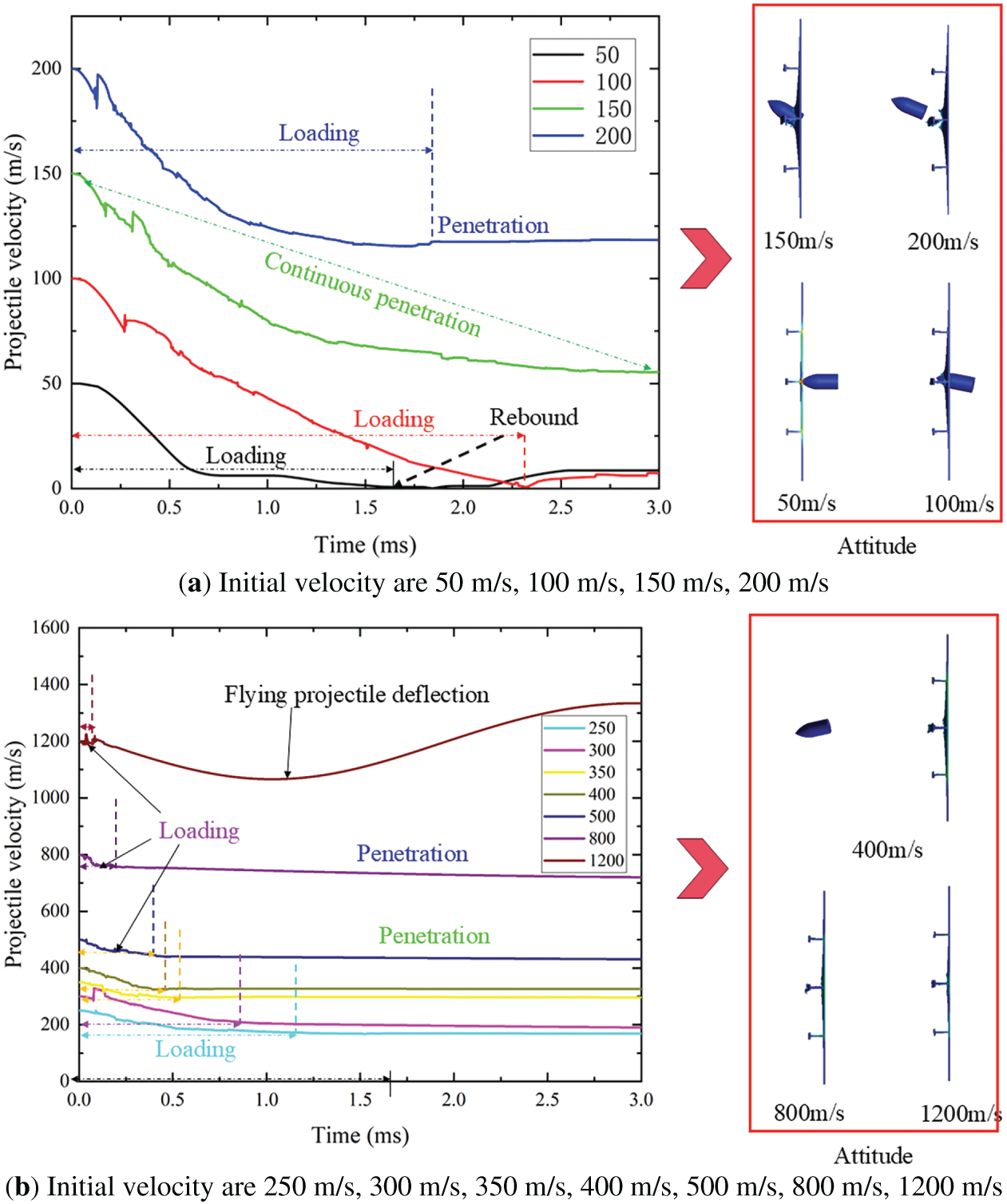

Figure 15: The velocity-history curve and final attitude of the basic model subjected to projectile penetration with different initial velocity

Analysis of Fig. 15a,b reveals that the projectile penetrates a steel plate at low velocities (below 50 m/s) in two stages during the initial loading phase. The relatively low initial kinetic energy of the projectile gradually dissipates to zero as it continuously interacts with the target plate. The directional force exerted by the plate causes the projectile to rebound at low velocity, resulting in a localized indentation in the central area of the plate without significant damage. As the initial impact velocity increases, a critical penetration velocity range emerges. Within this range, the projectile maintains contact with the target plate until its energy dissipates completely. This interaction damages the plate and deforms the T-shaped stiffener. The central area of the plate experiences both local damage and extended deformation. At higher initial impact velocities, the projectile penetrates the target plate. The T-shaped stiffened plate influences the penetration path, causing the projectile to penetrate along the welded edge between the stiffener and plate, which significantly affects its flight attitude. At moderate velocities, penetration causes substantial deformation but does not cause severe damage to the stiffened plate. Conversely, high-velocity impacts result in both penetration and damage to the stiffened plate. This analysis demonstrates how the initial velocity governs the penetration mechanism, damage patterns, and stiffener deformation, offering valuable insights for designing stiffened steel structures to resist projectile impact.

Fig. 15b shows that projectile velocities between 250 and 1200 m/s result in complete penetration of the target plate. Despite full perforation, the impact velocity significantly influences both the damage patterns of the target plate and the projectile’s flight attitude. In the 250–500 m/s range, the velocity-time curves display consistent patterns during both the penetration loading and the post-penetration flight phases. Impact velocity affects loading time in a non-linear manner: according to energy conservation, higher initial velocities correspond to shorter loading durations. Furthermore, increased velocities reduce central bulging deformation and tend to produce near-circular fractures. The velocity also has a marked effect on the projectile behavior. At particularly high velocities, the projectile experiences significant angular deflection after penetrating the plate, significantly altering its trajectory. The relationship between impact velocity, target damage, and projectile dynamics offers essential insights for optimizing armor design and predicting penetration outcomes.

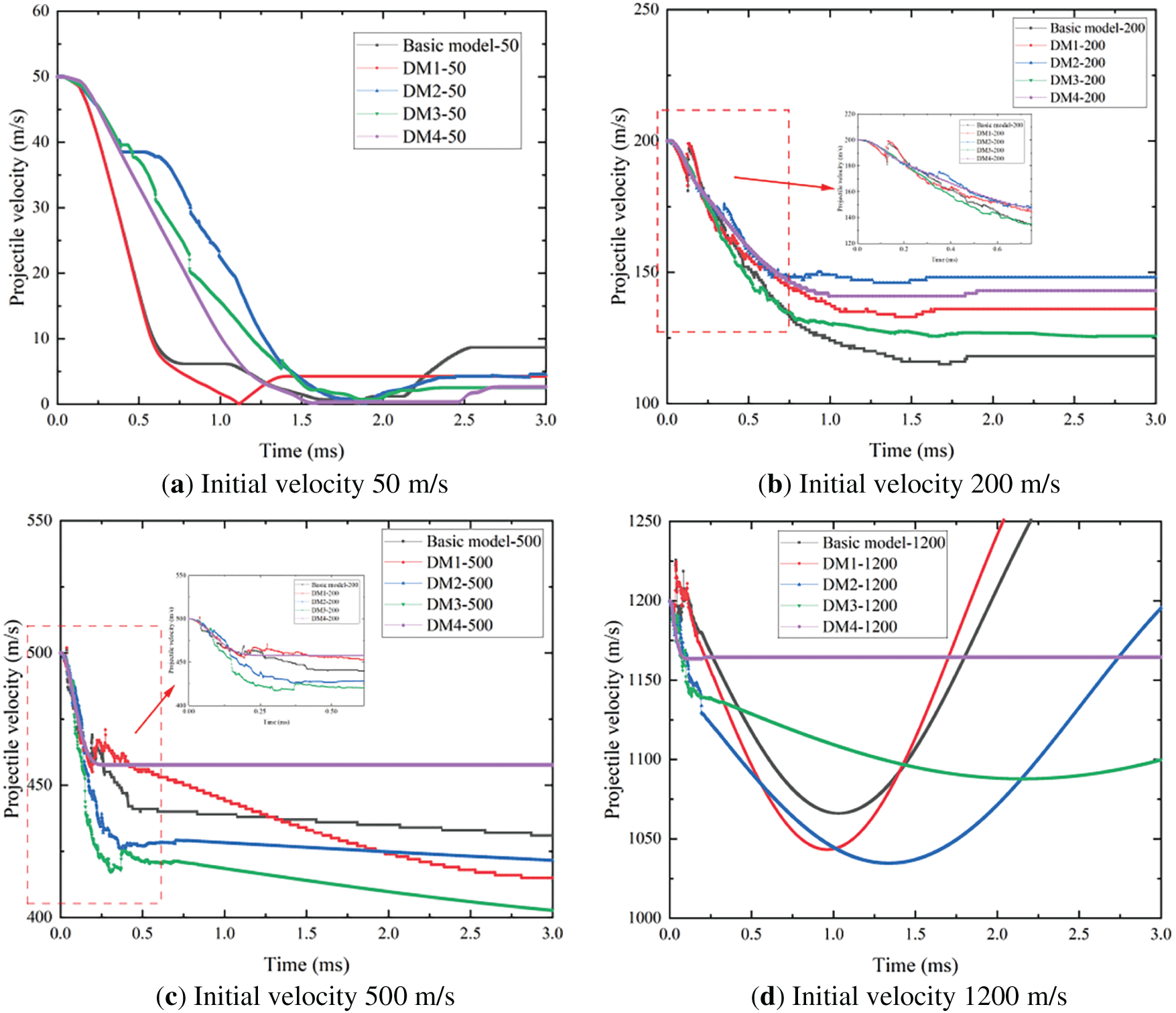

Fig. 16 compares velocity-time histories for various equivalent design models at representative impact velocities. As shown in Fig. 16a, at an impact velocity of 50 m/s, the velocity-time curves of the DM1 equivalent and basic models are substantially similar. Although a difference exists in the final rebound velocities of the projectiles, this variation is negligible relative to the initial velocity. In Fig. 16b, penetration of the target plate occurs at a projectile velocity of 200 m/s. Among the evaluated models, the DM2-equivalent model exhibits the closest velocity-time curve to the basic model, followed by the DM2-equivalent model. At 500 m/s (Fig. 16c), the velocity-time curves for projectiles penetrating various equivalent models display a similar trend, with the DM2 model showing the highest correspondence to the basic model. However, at a projectile velocity of 1200 m/s, the velocity variation pattern during penetration of the homogeneous target plate differs significantly from that of other equivalent models. After target plate penetration, all stiffened plates induce substantial deflections in projectile attitude; in extreme cases, the projectile may exhibit circular motion along a helical trajectory. These complex responses introduce uncertainty in predicting structural damage to ships, highlighting the inherently nonlinear nature of penetration problems. This analysis reveals that both impact velocity and model design critically influence penetration dynamics, emphasizing the necessity of accounting for nonlinearity in developing accurate predictive models for projectile-target interactions.The cause of this nonlinear phenomenon is the high strain rate generated by the high-speed impact of the elastic body on the steel plate, which significantly increases the yield strength of the steel plate and the elastic body material. At the same time, the thermal energy converted from plastic work causes local adiabatic temperature rise, triggering thermal softening of the material. The strengthening and softening effects compete with each other, breaking the linear relationship between stress and strain. During penetration, projectile deflection, local contact separation or the back of the target plate may also occur, leading to sudden changes in contact state and multi-point interactions, causing discontinuous changes in contact force. Therefore, the material nonlinearity of the steel plate must be taken into account in the calculation process.

Figure 16: The velocity time history comparison between different design models with projectile penetration at initial velocity 50, 200, 500 and 1200 m/s

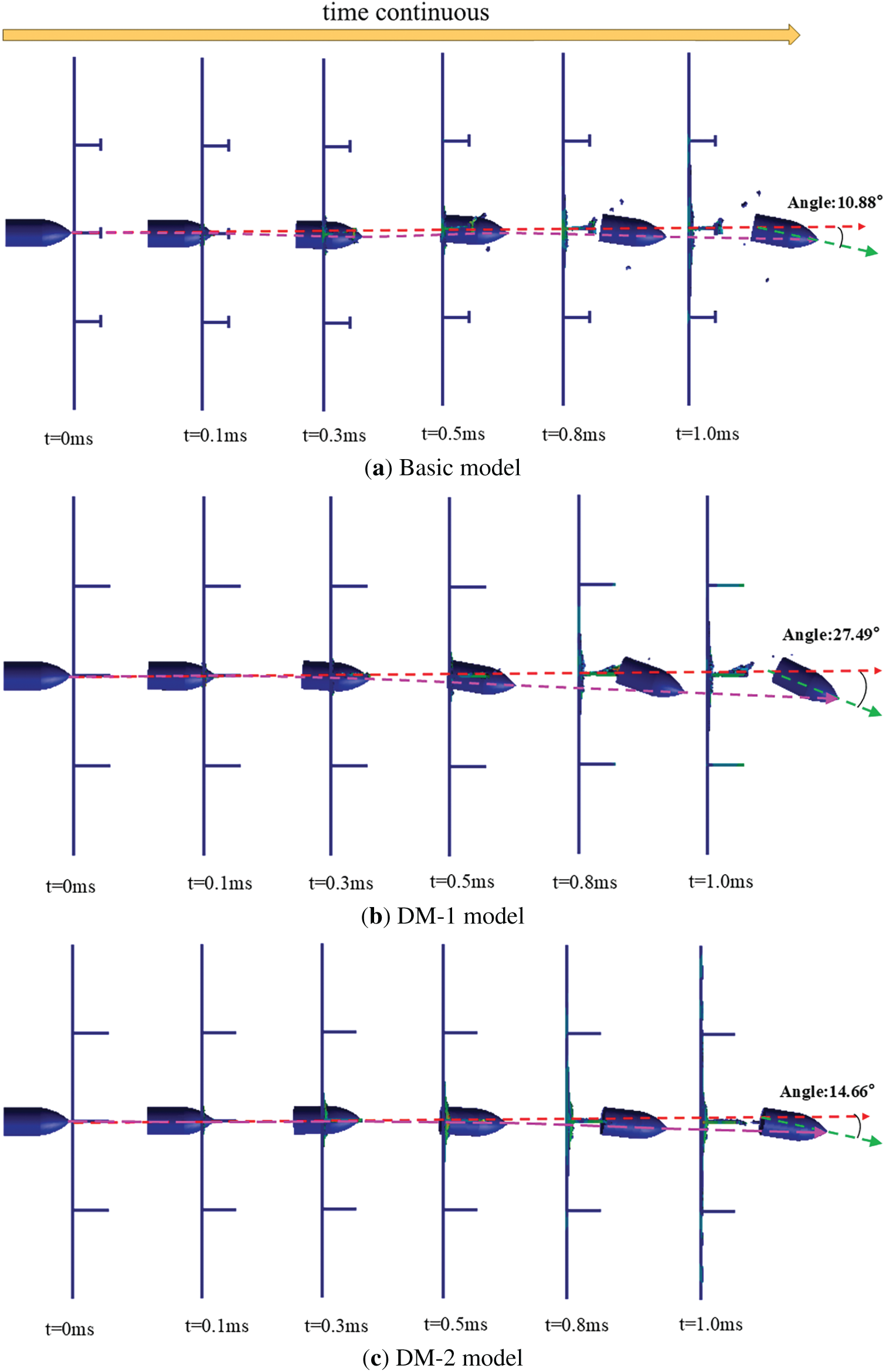

Fig. 17 depicts the allowable trajectories of projectiles with an initial velocity of 500 m/s penetrating various plates. Analysis of the projectile trajectories indicates that the path of the projectile penetrating the DM2 equivalent model closely corresponds to that of the basic model, with similar deflection angles. When the projectile penetrates equivalent target models, including DM1, DM2, DM3, and DM4 at an initial velocity of 500 m/s, the measured deflection angles at a specific moment are 10.88°, 27.49°, 14.66°, 17.94°, and 0.49°, respectively. These deflection angles indicate that the DM2-equivalent model exhibits the highest correlation with the original basic model during projectile penetration at 500 m/s, followed by the DM3-equivalent model. These results demonstrate the substantial impact of different equivalent models on projectile penetration behavior. The strong correlation between the trajectory and deflection of the DM2-DM2-equivalent model and the basic model indicates that the former effectively replicates the penetration dynamics of the latter, offering valuable insights for armor design optimization and projectile-target interaction performance prediction.

Figure 17: The projectile attitude comparison between different design models with projectile penetration at a typical initial velocity of 500 m/s

3.2.3 Comparison of Failure Modes of Plate Structure under Approximate Equivalent Conditions

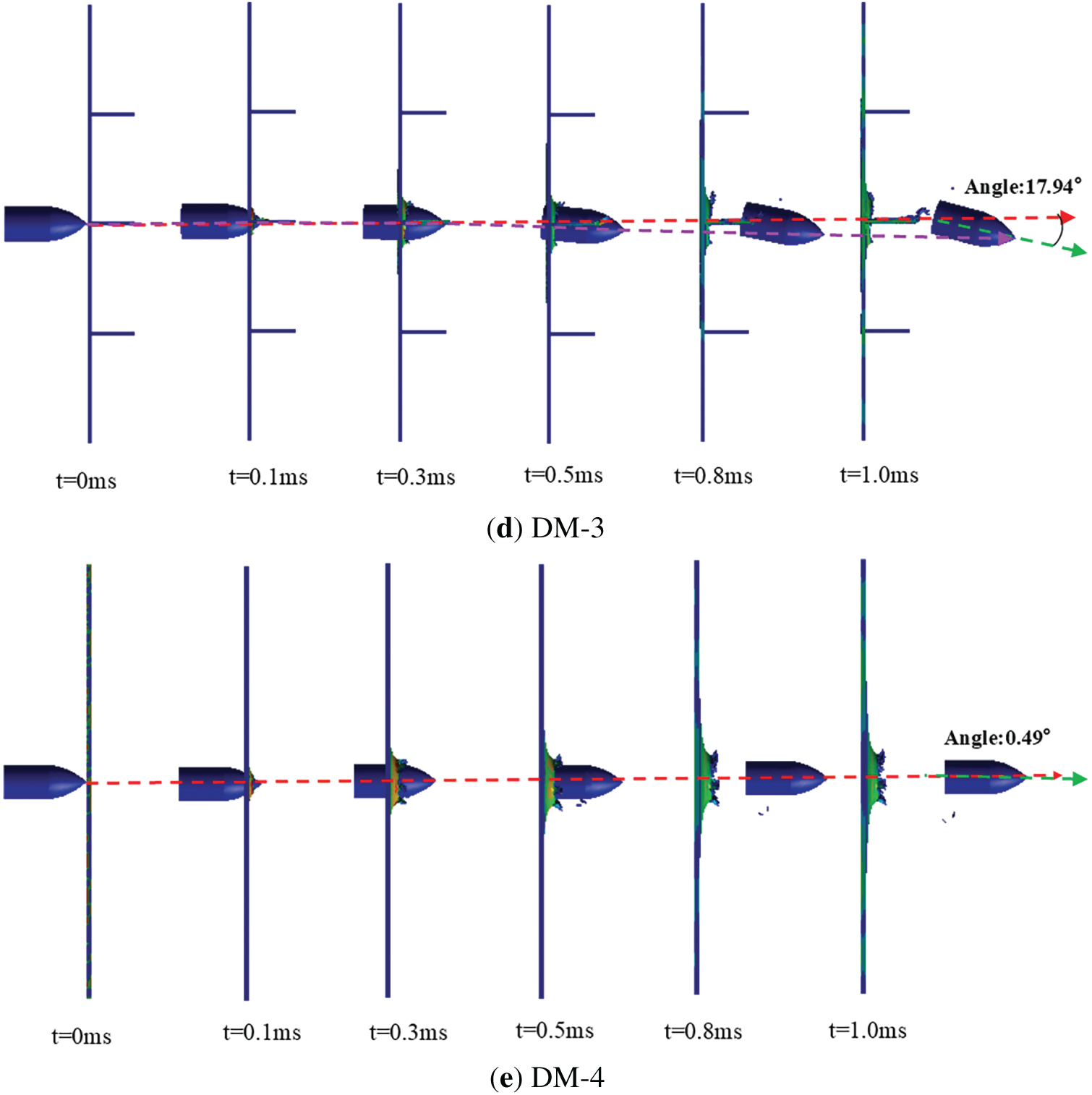

Through comprehensive numerical calculations using the basic model as the research subject, five characteristic damage modes of projectile penetration into stiffened plate structures are identified, as shown in Fig. 18. In Mode 1, projectile impact on the target plate induces only local plastic damage in the plate’s central region without complete penetration. The stiffeners remain undamaged in this scenario. Mode 2 represents a critical penetration process in which the projectile damages the target plate without penetration, whereas the stiffeners maintain their integrity. The minimal plate deformation and projectile damage in Mode 1 parallel the elastic deformation stage of materials under low-velocity impact in the Recht-Ipson classification [18], characterized by stress wave propagation without significant plastic deformation. Mode 2 exhibits plastic pits on the target plate surface, corresponding to the initial plugging failure in the Recht-Ipson classification, where the material undergoes gradual plastic flow as the projectile begins to penetrate. Mode 3 features crack formation on the steel plate without complete penetration, accompanied by local tensile tearing damage to the stiffeners without fracture. Mode 4 involves complete projectile penetration through the stiffened plate, resulting in steel plate fracture and tensile fracture with torsional deformation. Mode 5 exhibits quasi-straight shear behavior through the stiffened plate, causing fractures in both the shear sections of the plate and stiffener, resulting in approximately circular fracture patterns. These damage modes, derived from basic model numerical simulations, elucidate the complex mechanical behaviors and failure mechanisms during projectile penetration, providing crucial guidance for predicting stiffened plate structure performance under impact and optimizing their design against projectile threats.

Figure 18: Summary of typical failure modes of stiffened plate structure with projectile penetration

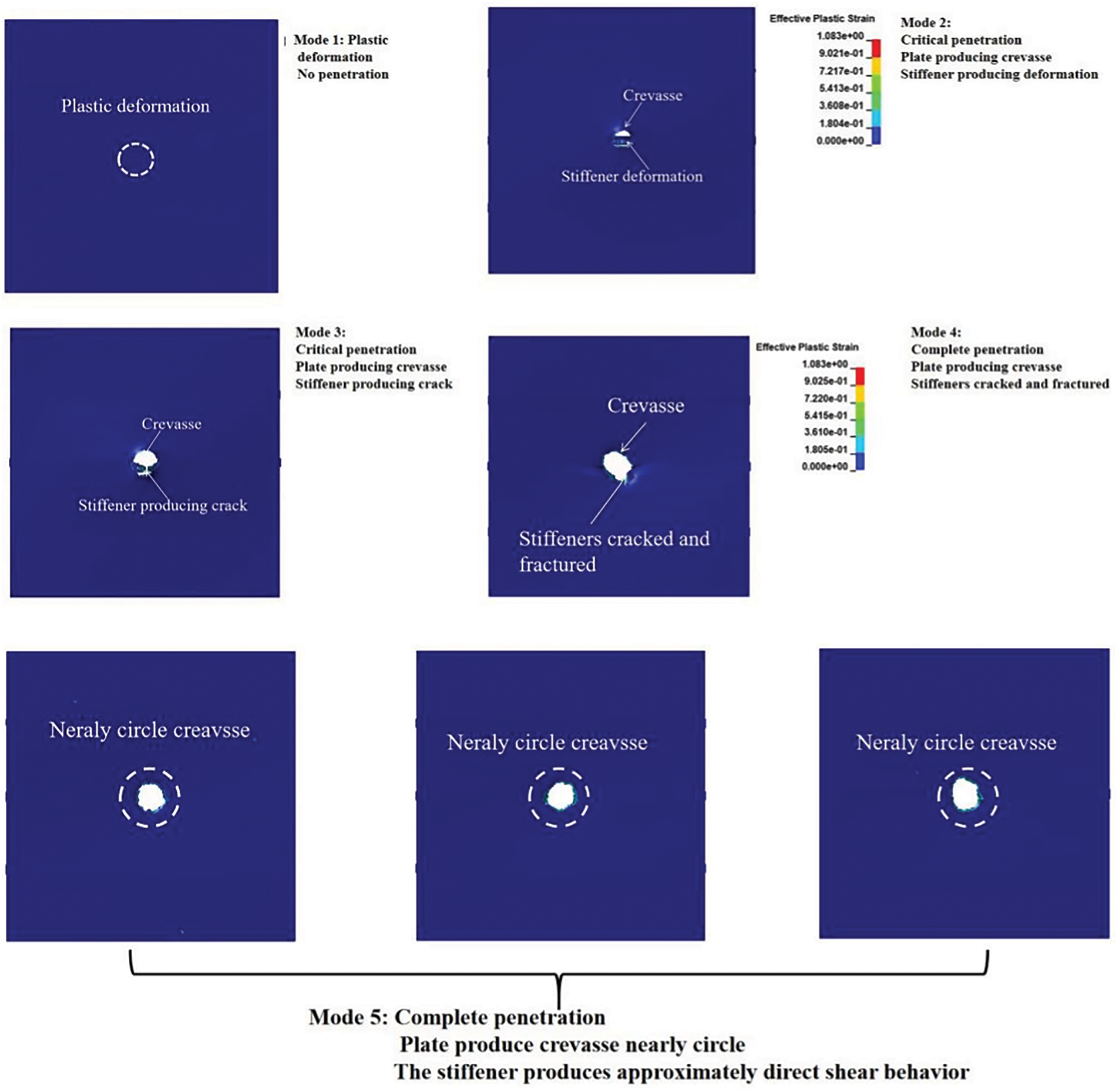

Table 6 illustrates the damage modes observed in different equivalent model designs at varying impact velocities. The damage modes of equivalent-thickness homogeneous steel plates differ significantly from those of stiffened plates, particularly at medium and low velocities. Homogeneous target plates typically exhibit petal-shaped damage patterns, whereas stiffened target plates show diverse damage patterns primarily influenced by stiffeners. These stiffeners modify the force distribution during projectile impact, resulting in distinct stress state variations. For stiffened plates with rectangular-section stiffeners, although damage mode classifications remain consistent, plate size influences damage patterns at low velocities. However, during high-velocity penetration, plate size exhibits minimal impact on the damage modes. This observation emphasizes the significance of structural geometry and impact velocity in determining the failure behavior of the stiffened plate structures. Understanding the relationships between model design, velocity, and damage modes is crucial for accurately predicting steel plate performance under projectile penetration and optimizing protective capabilities.

Each failure mode corresponds to a specific quantified energy absorption level or dissipation mechanism, such as plastic work and fracture energy, revealing the physical mechanisms underlying the damage process. In Mode 1, the projectile impact causes localized plastic damage in the central area of the target plate without complete penetration, leaving the stiffeners intact. This mode involves minimal energy absorption, primarily through limited local plastic deformation. The slight deformation and damage resemble the elastic deformation stage under low-speed impact in the Recht-Ipson classification [18], where stress waves propagate without causing extensive plastic deformation. Mode 2 represents the key penetration process, where the projectile partially penetrates the target plate while the stiffeners remain intact. Plastic pits form on the target plate surface, corresponding to the initial leak sealing failure in the Recht-Ipson classification, as the projectile begins to invade and the material undergoes plastic flow. Energy dissipation occurs primarily through plastic deformation during pit formation. Mode 3 features crack formation without complete penetration, whereas local tensile tear damage occurs without breaking stiffeners. This mode absorbs more energy than previous modes through plate plastic deformation, crack initiation and propagation, and stiffener tensile tearing. Mode 4 involves complete projectile penetration, causing plate breakage and tensile fracture with torsional deformation, resulting in maximum plastic dissipation and structural collapse. Substantial energy is consumed during penetration, including energy associated with plate and stiffener fracture, large-scale plastic and structural deformation. Mode 5 exhibits collimating shear behavior as the projectile passes through, causing simultaneous fracture of the stiffened plate and stiffener shear section with approximately circular fracture patterns. Energy absorption primarily occurs through shear work, with energy dissipation levels similar to those in Mode 4.

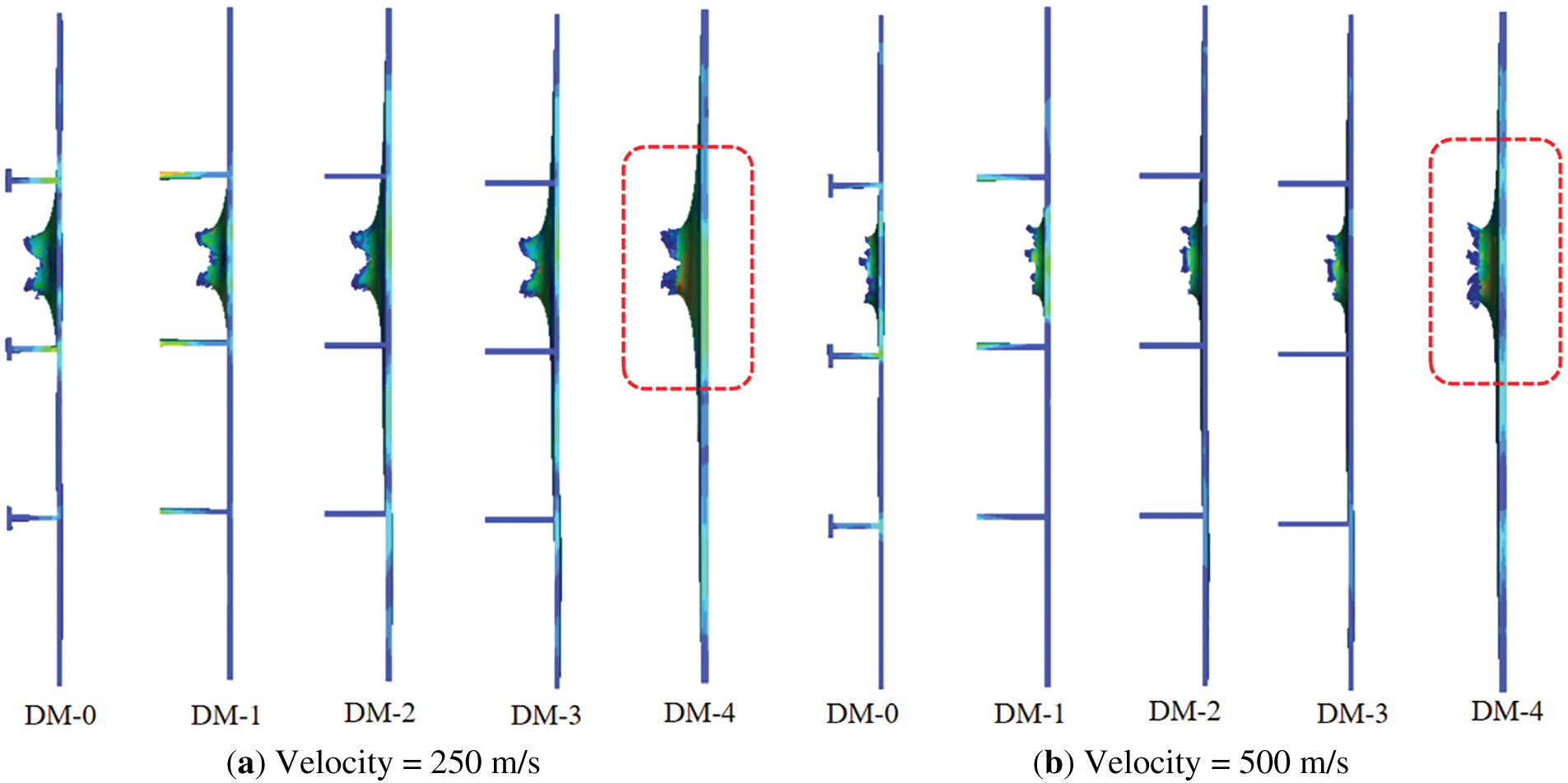

To examine the influence of penetration position, this study analyzed the equivalence between four equivalent models and the reference model velocities at 250 and 500 m/s. Fig. 19 illustrates the projectile penetration position, and Fig. 20 shows the resulting target plate failure modes. As shown in Fig. 20, the DM4 model exhibits significantly different failure modes compared to other equivalent models under both low-speed and high-speed impact conditions. Conversely, under these penetration conditions, the DM1/DM2/DM3 equivalent models display similar deformation modes without notable differences. This similarity primarily results from minimal deflection during projectile penetration when the impact point is not on the profile, preventing coupled damage to the target plate. The target plate strength remains relatively constant with reinforcing ribs bearing similar stiffness, generating comparable failure modes with strong equivalence.

Figure 19: Schematic diagram of the position of the projectile impacting the stiffened plate between two stiffeners

Figure 20: The comparison between different design models with projectile penetrating center between two stiffeners at a typical initial velocity of 205 and 500 m/s

The penetration of ship plate structures by ogival-nosed projectiles presents a complex dynamic problem. Based on experimental studies of projectile penetration through Q345 homogeneous steel plates, a numerical simulation methodology for pointed ovate projectile penetration of steel plates was established and validated. Four equivalent models were developed using the equivalent design method to investigate the equivalence of stiffened plate structures under penetration loads, followed by extensive numerical simulations. The analysis of the results yielded the following conclusions:

(1) Applicability constraints of the equivalent thickness method: Regarding the overall failure mode of the missile-plate structure and missile body flight attitude, the model (DM4) developed through the equivalent thickness method exhibits substantial deviations from the base model, except in cases where the missile body fails to penetrate the target plate. These differences manifest in both the missile body flight attitude and the target plate failure mode, indicating a lack of equivalence. Consequently, for projectile penetration of hull plate frames, the equivalent thickness method is not recommended for simulating stiffened plate penetration loads. Although DM-4 can approximately represent the overall deformation patterns in low-speed non-penetrating impact scenarios (Mode 1), its accuracy remains lower than that of DM1/DM3.

(2) Effectiveness of the velocity-dependent equivalent model: The DM1 equivalent model demonstrates damage modes that are approximately equivalent to the base model in extremely low-speed impact ranges (critical penetration range), outperforming other equivalent design models. DM1 effectively characterizes the local deformation resistance of the stiffened structure using the equivalent sectional moment of inertia. The DM3 equivalent model shows significantly higher equivalence in low-speed penetration ranges compared to other models. During this interval, as the projectile initiates plastic flow in the target plate (such as initial plug flushing in Mode 2), DM3 describes the dissipation of plastic work by coupling equivalent material yield strength parameters with stiffener spacing. The DM2 equivalent model exhibits optimal equivalence performance in high-speed penetration ranges. By matching equivalent section stiffness and fracture energy parameters, DM2 effectively captures sudden energy variations during the structural collapse. At extremely high-speed impacts (such as 1200 m/s in this study), the DM1 equivalent model demonstrates close equivalence to the base model. The quasi-linear shear behavior of the elastic body at extremely high speeds (Mode 5) predominates, and DM1 better simulates reinforced shear fracture dynamic response through an enhanced cross-sectional moment of inertia equivalence.

(3) The viability of stiffener section simplification: Considering the overall failure mode and elastic body deflection effects, conducting penetration studies using T-shaped reinforcement equivalent to rectangular section stiffeners proves feasible. Although projectile residual velocity and deflection angle affect accuracy to some extent, the target plate failure mode closely aligns with projectile deflection trends. Therefore, simplification to an equivalent rectangular cross-section stiffened plate model is appropriate when investigating T-shaped stiffened plate penetration. This simplification reduces computational complexity while maintaining consistency in key failure characteristics.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study is supported by Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2022I0019), Scientific Research Foundation for Jimei University (ZQ2024041, ZQ2024042).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yezhi Qin and Ying Wang; methodology, Yezhi Qin, Qinglin Chen and Yingqiang Cai; software, Ying Wang; validation, Yezhi Qin and Ying Wang; formal analysis, Qinglin Chen and Yingqiang Cai; investigation, Yezhi Qin; Resources, Yezhi Qin; data curation, Yezhi Qin and Yingqiang Cai; writing—original draft preparation, Yezhi Qin and Ying Wang; supervision, Yezhi Qin; project administration, Yezhi Qin, Ying Wang and Qinglin Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data are available under request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cheng YH, Wu H, Jiang PF, Fang Q. Ballistic resistance of high-strength armor steel against ogive-nosed projectile impact. Thin Walled Struct. 2023;183(3):110350. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2022.110350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li L, Zhang QC, Lu TJ. Ballistic penetration of deforming metallic plates: experimental and numerical investigation. Int J Impact Eng. 2022;170(3):104359. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2022.104359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cheon JM, Choi Y. Influence of projectile velocity on penetration into a steel plate. Int J Precis Eng Manuf. 2020;21(1):137–44. doi:10.1007/s12541-019-00079-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Shen C, Liu L, Cai X, Zhang F, Chen W, Ma Y. Investigation on the anti-penetration performance of the steel/nylon sandwich plate. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2021;28(1):128–38. doi:10.1515/secm-2021-0013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lu L, Gao C, Qi X, Zhang D, Li Q, Yan X, et al. Numerical study on the water-entry characteristics of asynchronous parallel projectiles at an oblique impact angle. Ocean Eng. 2023;271(5–6):113697. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.113697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang Y, Wang Z, Yao X, Yang N. Effect of Lode angle in predicting the behaviour of stiffened 921A steel target plates in ballistic impact by truncated ogive projectiles. Int J Impact Eng. 2024;185:104841. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2023.104841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chen CH, Zhu X, Hou HL, Tian XB, Shen XL. A new analytical model for the low-velocity perforation of thin steel plates by hemispherical-nosed projectiles. Def Technol. 2017;13(5):327–37. doi:10.1016/j.dt.2017.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang H, Li Z, Cheng X, Zhang Z, He Y. Failure mechanism of 6252-armor steel under hypervelocity impact by 93W alloy projectile. J Mater Res Technol. 2024;28(1–4):3932–42. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.12.242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kpenyigba KM, Jankowiak T, Rusinek A, Pesci R, Wang B. Effect of projectile nose shape on ballistic resistance of interstitial-free steel sheets. Int J Impact Eng. 2015;79:83–94. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2014.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Iqbal MA, Gupta G, Diwakar A, Gupta NK. Effect of projectile nose shape on the ballistic resistance of ductile targets. Eur J Mech A Solids. 2010;29(4):683–94. doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2010.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gupta NK, Iqbal MA, Sekhon GS. Effect of projectile nose shape, impact velocity and target thickness on deformation behavior of aluminum plates. Int J Solids Struct. 2007;44(10):3411–39. doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2006.09.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Arias A, Rodríguez-Martínez JA, Rusinek A. Numerical simulations of impact behaviour of thin steel plates subjected to cylindrical, conical and hemispherical non-deformable projectiles. Eng Fract Mech. 2008;75(6):1635–56. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2007.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Børvik T, Langseth M, Hopperstad OS, Malo KA. Perforation of 12 mm thick steel plates by 20 mm diameter projectiles with flat, hemispherical and conical noses. Int J Impact Eng. 2002;27(1):19–35. doi:10.1016/s0734-743x(01)00034-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Verma PN, Dhote KD. Characterising primary fragment in debris cloud formed by hypervelocity impact of spherical stainless steel projectile on thin steel plate. Int J Impact Eng. 2018;120(1161):118–25. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2018.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Senthil K, Iqbal MA, Bhargava P, Gupta NK. Experimental and numerical studies on mild steel plates against 7.62 API projectiles. Procedia Eng. 2017;173:369–74. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.12.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cui XY, Xue H, Han HY, Wang T, Huang GY. Oblique penetration of spherical tungsten alloy projectiles on high-strength steel plates. Int J Impact Eng. 2024;192:105030. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2024.105030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang X, Zhang J, Chen Z, Li Y. Investigations on deflection effect of a Z-shaped grillage subjected to an obliquely penetrating ogive-nose projectile. Thin Walled Struct. 2023;183(10):110339. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2022.110339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Recht RF, Ipson TW. Ballistic perforation dynamic. J Appl Mech. 1963;30:384–90. [Google Scholar]

19. Gupta NK, Ansari R, Gupta SK. Normal impact of ogive nosed projectiles on thin plates. Int J Impact Eng. 2001;25(7):641–60. doi:10.1016/S0734-743X(01)00003-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Forrestal MJ, Warren TL. Perforation equations for conical and ogival nose rigid projectiles into aluminum target plates. Int J Impact Eng. 2009;36(2):220–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2008.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chakraborty P, Pandouria AK, Singha MK, Tiwari V. Constitutive and impact response of AA7475-T7351 under different projectile shapes and velocities: an experimental and numerical investigation. Int J Impact Eng. 2024;194(1):105095. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2024.105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ataabadi PB, de Assunção CM, Chakraborty P, Alves M. High-velocity impact performance of AA 7475-T7351 aluminum square plates struck by steel projectiles: assessing leakage limit velocity. Int J Impact Eng. 2024;187:104913. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2024.104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Elek PM, Jaramaz SS, Micković DM, Miloradović NM. Experimental and numerical investigation of perforation of thin steel plates by deformable steel penetrators. Thin Walled Struct. 2016;102:58–67. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2016.01.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ge Y, Chen P, Wu X, Zhou Q, Fan H, Wang C, et al. Experimental and numerical study on ballistic impact behavior of explosively-welded double-layered Weldox700E targets against ogival-nosed projectiles. Int J Impact Eng. 2025;195:105134. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2024.105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li N, Wu XX, Wang HK, Zhang LP, Li JH. Experimental and theoretical research on influence of warhead’s nose shape on penetrating steel plates. Chin J Ship Res. 2024;19(3):127–33. (In Chinese). doi:10.19693/j.issn.1673-3185.03379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Johnson GR, Cook WH. A constitutive model and data for metals subjected to large strains, high strain rates and high temperatures. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Ballistics; 1983 Apr 19–21; Hague, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

27. Johnson GR, Cook WH. Fracture characteristics of three metals subjected to various strains, strain rates, temperatures and pressures. Eng Fract Mech. 1985;21(1):31–48. doi:10.1016/0013-7944(85)90052-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li Y, Jiang J, Yu Y, Wang Z, Xing Z, Zhang Q. Fire resistance of a vertical oil tank exposed to pool-fire heat radiation after high-velocity projectile impact. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2021;156(6):231–43. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2021.10.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Shi C, Zhang J, Liu F, Chen W, Song H, Zhao G, et al. Experimental study and finite element analysis on impact resistance of wind turbine steel truss foundation. Ocean Eng. 2024;302(2):117659. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhou Z, Du Z, Zhang Y, Yang G, Wang R, Liu Y, et al. Microscopic defects formation and dynamic mechanical response analysis of Q345 steel plate subjected to explosive load. Def Technol. 2024;32(4):430–42. doi:10.1016/j.dt.2023.03.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yu W, Zhao J, Shi J. Dynamic mechanical behaviour of Q345 steel at elevated temperatures: experimental study. Mater High Temp. 2010;27(4):285–93. doi:10.1179/096034010x12761931945540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li Y, Jiang J, Bian H, Yu Y, Zhang Q, Wang Z. Coupling effects of the fragment impact and adjacent pool-fire on the thermal buckling of a fixed-roof tank. Thin Walled Struct. 2019;144(2):106309. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2019.106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li W, Wang P, Feng GP, Lu YG, Yue JZ, Li HM. The deformation and failure mechanism of cylindrical shell and square plate with pre-formed holes under blast loading. Def Technol. 2021;17(4):1143–59. doi:10.1016/j.dt.2020.06.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wu HJ, Zhang QM, Chu Z, Wang KH, Gong BL, Zhou G. Study on petalling model for oblique penetration of thin metallic plates by ogive-nose projectiles. Trans Beijing Inst Technol. 2018;38(S2):41–5. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

35. Wang Y, Wang Z, Liang S, Yao X, Yang N. Experimental and numerical study on the failure modes of ship stiffened plate structure under projectile perforation. Int J Impact Eng. 2023;178:104590. doi:10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2023.104590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Han J, Li S, Zhang AM. Applications of bond-based cohesive peridynamics method (CPDM) to simulate inelastic fracture of stiffened plates in ship hull structures. Comput Struct. 2023;286(6):107108. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2023.107108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang Q, Li S, Zhang AM, Peng Y, Zhou K. A nonlocal nonlinear stiffened shell theory with stiffeners modeled as geometrically-exact beams. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2022;397(3):115150. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2022.115150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Qin Y, Wang Y, Wang Z, Yao X. Investigation on similarity laws of cabin structure for the material distortion correction under internal blast loading. Thin Walled Struct. 2022;177(7):109371. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2022.109371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools