Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Temporal Attention LSTM Network for NGAP Anomaly Detection in 5GC Boundary

School of Cyberspace Security, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, 100876, China

* Corresponding Author: Baojiang Cui. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cutting-Edge Security and Privacy Solutions for Next-Generation Intelligent Mobile Internet Technologies and Applications)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 2567-2590. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.067326

Received 30 April 2025; Accepted 07 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Service-Based Architecture (SBA) of 5G network introduces novel communication technology and advanced features, while simultaneously presenting new security requirements and challenges. Commercial 5G Core (5GC) networks are highly secure closed systems with interfaces defined through the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) specifications to fulfill communication requirements. However, the 5GC boundary, especially the access domain, faces diverse security threats due to the availability of open-source cellular software suites and Software Defined Radio (SDR) devices. Therefore, we systematically summarize security threats targeting the N2 interfaces at the 5GC boundary, which are categorized as Illegal Registration, Protocol attack, and Signaling Storm. We further construct datasets of attack and normal communication patterns based on a 5G simulated platform. In addition, we propose an anomaly detection method based on Next Generation Application Protocol (NGAP) message sequences, which extracts session temporal features at the granularity of User Equipment (UE). The method combines the Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM) and the attention mechanism can effectively mine the dynamic patterns and key anomaly time-steps in the temporal sequence. We conducted anomaly detection baseline algorithm comparison experiments, ablation experiments, and real-world simulation experiments. Experimental evaluations demonstrated that our model can accurately learn the dependencies of uplink and downlink messages for our self-constructed datasets, achieving 99.80% Accuracy and 99.85% F1 Score, which can effectively detect UE anomaly behavior.Keywords

5G networks use Service-Based Architecture (SBA), which introduces emerging technologies such as virtualization, network slicing, and edge computing, significantly changing the architecture and protocols compared to 4G networks. However, this decentralized network architecture also brings new security challenges. According to the International Mobile Telecommunications-2020 (IMT) report [1], 5G technology faces several security threats. The widespread use of Network Function Virtualization (NFV) relies on open-source and third-party software, resulting in a 5G Core (5GC) Network Function (NF) that may be at risk of functional failure or illegal control. Network slicing technology raises concerns as network slices with weaker protection capabilities become potential attack targets based on shared hardware resources, especially in the absence of effective security isolation mechanisms. In addition, Edge Computing nodes are deployed at the network edge to support different application deployments and resource sharing, which brings security risks such as privacy leakage, authentication, and authorization. The openness of network capabilities further increases the exposure of 5G networks to traditional Internet attacks.

Many research works [2–4] have been achieved on 5G security. Park et al. [5] reviewed various security threats and corresponding solutions brought by new technologies introduced in the 5G network, such as Software Defined Networking (SDN), NFV, and Edge Computing. Pacherkar et al. [6] inferred the original call flows by constructing traceability graphs to identify call flows with malicious intent. The approach focuses on analyzing Short Message Service (SMS) storm attacks, Packet Forwarding Control Protocol (PFCP) attacks, and slicing attacks. Seaver et al. [7] investigated over-privileging of OAuth policy logic in 5G networks. They found instances of excessive privileges between network slices that could lead to Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks and privacy data leaks. Although these studies have achieved significant progress in 5GC attack detection, most assume scenarios where certain NFs are maliciously controlled or illegally accessed. However, commercial 5GC systems are highly secure and closed architectures. In practice, known and unknown security risks predominantly reside in boundary networks, such as gNodeB and Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC) nodes. These boundary devices may serve as potential attack vectors due to the frequent interactions with external networks. Their exposure to untrusted environments increases vulnerabilities like unauthorized access, protocol exploitation, and data interception, highlighting the urgent need for robust security mechanisms in the 5GC boundary.

The widespread availability of open-source 4G/5G software suites [8,9] and cheap Universal Software Radio Peripheral (USRP) [10] devices has enabled attackers to execute access domain attacks, such as Fake Base Station (FBS) [11], Man-in-the-Middle Attacks (MiTM) [12] and Signal Overshadowing (SigOver) [13]. Mobile security researchers have disclosed various threats, including user tracking [14–16], message eavesdropping [17,18], SMS forgery [19,20], traffic fingerprinting [21,22], downgrade attack [23] and resource exhaustion [24]. These attacks pose serious threats to user security, privacy, and service availability. The 3GPP specification [25] divides the 5G network security architecture into several domains, including Network Access Security, Network Domain Security, User Domain Security, Application Domain Security, SBA Domain Security, and Visibility and configuration of security. The segmentation enables more targeted security challenges across different layers. In addition, the 3GPP specification [26] provides definitions for the interface between the Radio Access Network (RAN) and 5GC. Therefore, 5G security can be further enhanced by deploying appropriate security mechanisms at the boundary interfaces. For example, the N2 interface serves as a boundary interface that relays messages between the gNodeB and the Access and Mobility Management Function (AMF), which is transmitted using the Next Generation Application Protocol (NGAP).

To defend against security threats in the 5G access domain, we are dedicated to designing a systematic approach for N2 interfaces to achieve active defense by detecting anomaly behavior of NGAP sessions. However, there are some technical challenges. First, traditional Internet traffic detection methods struggle to adapt to 5G-specific protocols, leading to difficulty in identifying stealthy attacks based on message semantics. Second, the closed nature of Mobile Network Operator (MNO) networks limits access to attack samples, hindering effective monitoring of potential attack behavior and training robust models. Consequently, it becomes a challenge to construct labeled datasets and effectively identify anomalous behaviors. We investigate and synthesize three main security threats of Illegal Registration, Protocol Attack, and Signaling Storm on N2 interface. In addition, we generated an anomaly dataset, which uses EXFO [27] graphical testing tool to simulate malicious behaviors in the N2 interface. We constructed a baseline normal dataset based on OpenAirInterface [28] and UERANSIM [29] open source software to simulate user behavior.

In this paper, we propose an NGAP anomaly detection method, which covers the complete workflow of NGAP messages aggregation, temporal feature extraction, model training, and prediction with UE granularity. In addition, we propose an anomaly detection model based on Temporal Attention Long Short-Term Memory (TA-LSTM) Network. The LSTM accurately captures long-term dependencies for the NGAP messages. The attention mechanism dynamically calculates the weights of different time steps and automatically strengthens the anomaly features, such as signaling injections and anomaly intervals, to enhance the local anomaly sensitivity. The model uses contextual session temporal features, including message direction, timestamp, and procedure code. Through comparative experiments with baseline anomaly detection algorithms, our model demonstrated excellent classification performance, achieving 99.80% Accuracy, 99.69% Precision, 100% Recall, and 99.85% F1 Score to effectively detect anomaly NGAP sessions. Furthermore, we conducted ablation experiments for sequence length and feature type. The optimal TA-LSTM anomaly detection model utilized these temporal features with a sequence length of 18, validating the efficiency and robustness of our approach. Finally, we demonstrated that the balanced dataset would lead to inflated performance metrics for NGAP anomaly detection by simulating sparse anomaly sessions for real 5G networks.

In summary, our contributions are as follows:

• We summarized the security threats and anomaly behaviors in the 5G access domain. We further constructed benchmark datasets containing both normal and anomaly messages based on a 5G simulation platform, covering 6 attack scenarios and standard communication patterns.

• We designed an NGAP anomaly detection method, which extracts NGAP session sequence features at the granularity of the UE. This approach effectively captures long-term dependencies and local anomaly patterns for NGAP message sequences.

• We conducted comprehensive experiments, including baseline comparisons with anomaly detection algorithms, an ablation experiment on sequence length and feature type, and a real-world simulation experiment. The experimental results demonstrate that our NGAP anomaly detection method can effectively identify anomaly behaviors for our self-constructed datasets.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the 5G network architecture and protocols. Section 3 describes the threat model in the 5G access domain. Section 4 presents the design of the NGAP anomaly detection method. Section 5 details the construction and experimental evaluation results. Section 6 discusses related work in mobile security. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and future work.

This section first describes the 5G network architecture and details the functions of 5GC NFs. Second, we show the protocol stack and Elementary Procedures (EP) of N2 interfaces. Finally, the UE initial registration procedures are illustrated.

The 5G network architecture (as shown in the Fig. 1) is designed based on Service-Based Architecture (SBA), which is mainly composed of three functional domains: UE, Radio Access Network (RAN), and 5GC. We briefly introduce the functions of each component according to 3GPP specification [30] as follows:

Figure 1: Overview of 5G network architecture

User Equipment: UE refers to mobile user devices as defined by 3GPP. In addition to traditional smartphones, novel UE include Massive IoT sensors, Augmented Reality (AR) headsets, and Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) communication modules. The UE establishes a radio connection to RAN over the air interface, then accesses 5GC over N1 interface, and finally interacts with external data networks over N6 interface, such as the Internet or IP Multimedia Subsystems (IMS).

Radio Access Network: 5G adopts the NG-RAN architecture composed of gNodeBs. The gNodeB forwards Control Plane (CP) messages over N2 interfaces and User Plane (UP) messages over N3 interfaces. According to 3GPP specification [31], the gNodeB is designed with the separation of Distributed Unit (DU) and Centralized Unit (CU), which provides a physical foundation for NFV.

5G Core: The 5GC divides its services into different NFs based on the SAB architecture. The Access and Mobility Management Function (AMF) serves as the single entry point for UE connections. The AMF selects the appropriate Session Management Function (SMF) to manage the user sessions based on service type. The User Plane Function (UPF) routes IP data traffic between the UE and the external data network. The Authentication Server Function (AUSF) allows the AMF to authenticate UE registration. The Policy Control Function (PCF) performs dynamic resource allocation based on network slicing policies. The Unified Data Management (UDM) centralizes the management of subscription policies and authentication certificates. These NFs are connected through a standardized Service-Based Interface (SBI) and implement Application Programming Interface (API) calls based on Representational State Transfer (REST). This Request/Response and Subscribe/Notify message interaction mechanism allows NF to collaborate in a loosely coupled manner.

The N2 interface is a critical control plane interface within the 5GC boundary that connects the gNodeB and the AMF. The N2 is responsible for UE functions such as Mobility Management, Network Slicing Management, Quality of Service (QoS) Management, and Security Authentication. For example, the gNodeB completes the registration, authentication, and session establishment procedures with the AMF over N2 interface when the UE registers to 5GC. The protocol stack of N2 interface (as shown in the Fig. 2) consists of the NGAP, Stream Control Transmission Protocol (SCTP), IP, and Physical layer. The NGAP protocol handles the transmission of CP signaling, whereas the SCTP protocol ensures reliable delivery of data packets.

Figure 2: Control plane protocol stack of radio access network

According to the 3GPP specification [26], the NGAP Elementary Procedure (EP) serves as the interaction unit between the gNodeB and AMF, categorized into two classes: Class-1 (Request-Response class) and Class-2 (No-Response class). In Class-1, the initiator receives a response from the receiver indicating whether the request was successfully processed or failed. Examples of such procedures include the UE mobility procedure and the interface management procedure. Class 2 is considered to be always successful, such as the Protocol Data Unit (PDU) session management procedure and the UE context management procedure. Our goal is to perform anomaly detection for signaling on the N1 and N2 boundary interfaces. Note that signaling on the N1 interface is transparently forwarded over the N2 interface between the gNodeB and the AMF. For example, Non-Access-stratum (NAS) messages on the N1 interface are tunneled through NGAP Downlink/UplinkNASTransport messages. This mechanism requires the N2 interface to parse both NGAP metadata and encapsulated NAS semantics. Therefore, messages on the N2 interface refer to messages for both N1 and N2 interfaces in the following context.

The UE initial registration procedure [32] performs network access and resource allocation. This procedure establishes the CP connection between UE and 5GC, which completes authentication, capacity negotiation and session management initialization.

Cell Selection: The UE first performs cell search and selection by detecting the Synchronization Signal Block (SSB) to identify the physical layer parameters of available cells. Subsequently, the UE decodes System Information Block (SIB1) and completes cell selection. If the UE is in the RRC_IDLE or RRC_INACTIVE state, it will initiate the Random-Access Channel (RACH) procedure to establish an initial connection to the gNodeB with Msg1 and Msg2.

RRC Connection Setup: The UE sends the RRCSetupRequest message and waits for the RRCSetup response from gNodeB. Upon entering the RRC_CONNECTED state, the UE transmits the RRCSetupComplete message containing the NAS Registration Request which includes the Subscription Permanent Identifier (SUPI), UE Capability Information and Registration Type.

Authentication and Security: The AMF receives Registration Request message and triggers the Authentication and Key Agreement (AKA) procedure if the UE is not authenticated. The AUSF verifies UE subscription and generates an Authentication Vector (AV), enabling mutual authentication through NAS message exchanges. Subsequently, the AMF negotiates security algorithms with the UE to activate encryption/integrity protection for both AS and NAS layers, which ensures the security of the following message interactions.

PDU Session Resource Setup: The AMF updates UE mobility context, assigns Globally Unique Temporary Identifier (GUTI) to protect user privacy, and then sends PDU Session Establishment Request to SMF. The SMF selects UPF according to the policy, configuring QoS flow and Data Radio Bearer (DRB). The AMF sends Network Slicing Selection Policy (NSSP) and routing rules through UEPolicyContainer. Finally, the UE can receive paging, initiate service requests, and perform mobility management. The 5GC can perform further session management and service control based on the registration information.

As the boundary interface between the RAN and 5GC, the N2 interface handles signaling interactions for massive heterogeneous devices, exposing it to various security threats. First, the N2 interface faces security threats due to openness and protocol complexity. The extended characteristics of hundreds of Information Elements (IE) provide attackers with parameter injection vulnerabilities in the NGAP protocol. Second, the attack surface is further expanded due to the coexistence of heterogeneous devices and baseband firmware vulnerabilities of older devices. Finally, the dynamic expansion of NF in the SBA architecture may be exploited maliciously. The N2 interface covers a variety of 5G boundary attacks disclosed in existing research [33–35]. In this paper, we classify the anomaly behaviors in the N2 interface (as shown in Table 1) into the following three categories: Illegal Registration, Protocol Attack and Signaling Storm.

Illegal registration is when an attacker spoofs illegal devices to trick UE or 5GC components to establish unauthorized connections, thereby enabling them to launch attacks or engage in malicious activities.

Fake Base Station (FBS) Registration refers to attackers forging or hijacking the identity of a legitimate gNodeB to execute service hijacking. This attack causes an anomaly in Information Elements (IE) such as pLMNIdentity and RANNodeName, along with increased NG Setup Request messages. FBS Registration can be categorized as FBS attack and Commercial gNodeB Hijacking.

The FBS attack [11,36] utilizes Software Defined Radio (SDR) to forge gNodeB and trick UE registration. Specifically, the attack transmits stronger 5G New Radio (NR) signals in the target area to force triggering the cell reselection procedure. However, the attack automatically releases the UE connection due to the lack of a subscriber key. The attacker can only perform short communication disruptions or eavesdrop on messages before authentication. In addition, Commercial gNodeB Hijacking [37] involves physical attacks to obtain legitimate MNO credentials. The attacker can extract gNodeB keys in the hardware security module through reverse engineering. As a result, the malicious gNodeB can register the AMF and perform MitM attacks to hijack the communication, which can complete the full 5G AKA procedure. The attacker can manipulate messages, redirect traffic, or exhaust AMF resources, threatening user data security and degrading network performance.

3.1.2 Malicious UE Registration

Malicious UE Registration refers to an attacker who initiates a registration request to the 5GC by spoofing or hijacking the subscriber identity. This attack aims to eavesdrop on user data or disrupt network services through unauthorized registration. It involves exploiting UE registration authentication and Evolved Mobility Management (EMM) procedures. Anomaly behaviors associated include frequent connection requests from the UE, absence of security authentication, or repeated authentication failures. Malicious UE Registration can be categorized as Subscriber Forgery and Hijacking.

Subscriber Forgery Attack [38] involves forging SUPI or Subscription Concealed Identifier (SUCI), which sends fake Registration Request to AMF. Attackers can only send unprotected messages without 5G-AKA authentication. This attack may utilize SDR and programmable SIM cards to emulate UE, flooding the network with high-frequency Registration Request to exhaust AMF resources. In addition, Subscriber Hijacking Attack [20] hijacks a legitimate UE using a MiTM model. The attacker can steal the RAND, AUTN, and XRES parameters during the 5G-AKA procedure, then forge valid authentication responses to bypass security checks and complete registration. The attacker can establish unauthorized communication channels to conduct malicious activities such as eavesdropping on IMS calls or forging SMS messages.

Protocol Attack refers to attackers compromising the integrity of a message by manipulating or spoofing protocol procedures. This attack exploits design or implementation flaws in the N2 protocol stack to initiate unauthorized interactions or trigger logical vulnerabilities.

In this paper, Vulnerability Exploit refers to attackers forging message IEs to exploit parsing flaws or logical errors in protocol implementations. The attack usually targets insufficient checksums or poor fault tolerance of IE, distinguishing it from other anomaly behavior. The attack may not cause significant message changes, but it still poses threats to the 5G boundary. Vulnerability Exploit can be categorized as IE Spoofing and Malformed Message.

IE Spoofing [33,34] modifies specific IE within NAS messages to spoof 5G capability negotiations or security mechanisms. Note that the attacker crafts malicious messages that conform to 3GPP specification definitions. For example, Security Algorithm Type Spoofing configures only NULL algorithms that result in message plaintext or downgrade attacks. Security Header Type Spoofing bypasses integrity checks and injects malicious NAS messages. Reject message configuration invalid Causes that trigger code parsing exceptions. In addition, Malformed Message [39] constructs messages that violate the 3GPP specification, which exploits implementation flaws to trigger system crashes or service interruptions. For example, the attacker sets illegal parameter sets in IE to induce memory overflow or assertion failures during parsing. The attacker constructs multi-layer nested IE structures or excessively long IE lists to exhaust target device resources, leading to protocol stack crashes or process hangs.

Message Injection Attack [40,41] refers to attackers who disrupt the protocol procedures by forging, tampering, or injecting malicious messages into the N2 interface. The attack exploits vulnerabilities in network components that fail to comply with 3GPP specifications or implement flawed security mechanisms, resulting in message sequence or semantic exceptions. The attack can perform privacy leakage, DoS, and other malicious attacks. For example, the FBS attacker forges Identity Request messages during UE initial registration. The attack tricks the UE into reporting International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI), enabling attackers to track user location and launch targeted attacks. The SigOver attacker leverages signal Capture Effect to accurately overshadow subframes. The attacker injects Registration Reject or Service Reject, forcing the UE to release connections or DoS. Notably, these messages lack protection in the 3GPP specification, so they can be crafted and injected by attackers.

Signaling Storm refers to the scenario where the volume of signaling exceeds the processing capacity of the AMF, caused by malicious attacks or UE anomaly behavior. The attacker often uses this principle to launch Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) against 5GC, which triggers service downgrade or paralysis.

The attacker initiates a large number of fake Registration Request to 5GC, which simulates a massive UE attempting to register with 5GC within a short period of time. Each Registration Request triggers AMF to perform the authentication and context creation procedure, rapidly depleting CPU and memory resources. Since the AMF allocates a resource pool to temporarily store session information for each request, this may block registration procedures for legitimate users.

Anomaly Handover refers to attackers inducing UE or gNodeB to perform unexpected handover procedures. The attack typically exploits logical flaws in handover procedures to cause DoS, privacy leakage, or network resource exhaustion. For example, an FBS attacker forges stronger radio signals to repeatedly trick the UE into handover to a fake gNodeB, resulting in poor-quality communication. In addition, malicious UE forge measurement reports to actively send fake handover requests to gNodeB, forcing it to frequently execute handover and resource allocation procedures.

For defense against security threats to the N2 interface, we propose an anomaly detection method based on NGAP message sequences with the granularity of UE (as shown in Fig. 3). Specifically, we first construct fine-grained session units by SCTP session aggregation associated with UE, then extract NGAP temporal features, and finally construct a neural network model to identify UE anomaly behaviors.

Figure 3: Overview of NGAP anomaly detection framework base on TA-LSTM model

NGAP Messages Aggregation: NGAP messages are aggregated by uniquely identifying the logical SCTP session using IP and Verification Tags. Further, the RAN_UE_NGAP_ID is used to correlate NGAP messages. This constructs UE-granular message sequences, providing structured input for temporal modeling.

Temporal Features Extraction: 5G edge attacks usually manifest as temporal logic anomaly. We generate direction, timestamp, and procedureCode triple sequences. These features quantify normal patterns through spatio-temporal correlation, which provides the model with temporal inputs characterizing protocol compliance.

Detection Model Construction: We design an LSTM-based temporal attention network model that effectively mines dynamic patterns and key anomaly time-steps in the time sequence. The model incorporates the calculation of anomaly probabilities within a sliding window to realize end-to-end detection of protocol state machine violations.

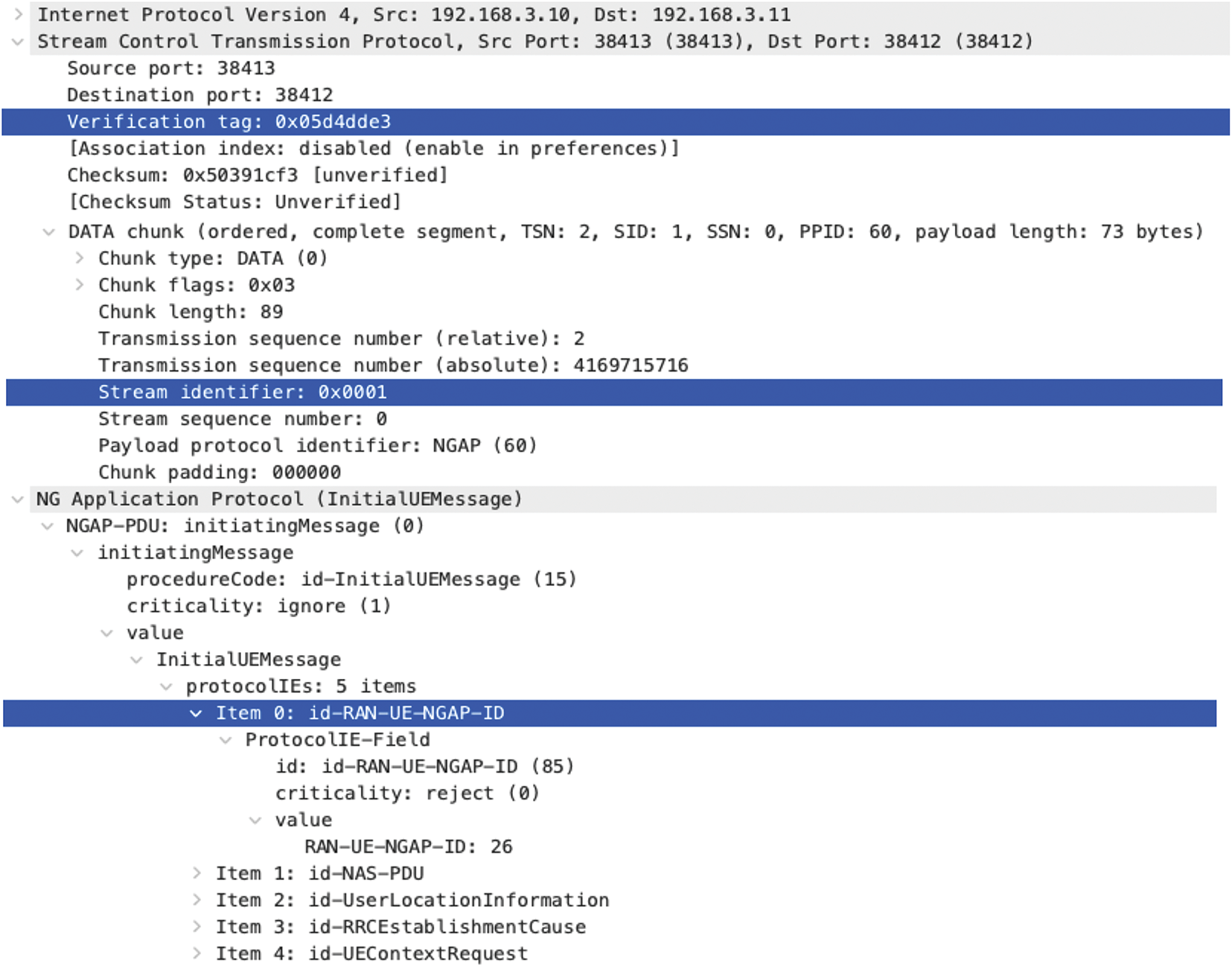

We first aggregate N2 messages into an SCTP session, and further correlate NGAP messages at the granularity of UE to extract UE context session features (as shown in Fig. 4). Specifically, SCTP is a reliable transport protocol based on IP networks. Unlike the TCP protocol, SCTP uses IP and port to uniquely identify an endpoint, while an endpoint can be defined by several IP addresses. In addition, the SCTP session is a logical channel established between two endpoints through the four-step handshake mechanism. SCTP sessions contain several flows, which is a unidirectional logical channel between endpoints and is uniquely identified by Stream Identifier. When an SCTP session is established, the endpoint generates a random Verification Tag and exchanges it during the handshake. The sender must carry the Verification Tag in the common header of each packet for checksumming. Therefore, we uniquely identify the SCTP session based on source IP (srcIP), destination IP (dstIP), and Verification Tag.

Figure 4: Example of NGAP message with signaling aggregation identifier

We further parse the NGAP message and identify types based on procedureCode. Each message type has its unique IE definition and is stored in the nested structure. The NGAP procedures can be categorized into UE-related service and Non-UE related services. Non-UE related services mainly include interface management, configuration delivery, and alarm message transmission, such as N2 gNodeB Setup. The UE-related service covers PDU session management, UE mobility management, and paging, such as delivering NAS up/downlink messages. In the UE-related service procedure, RAN_UE_NGAP_ID is used to uniquely identify the UE in the NG-RAN cell. Therefore, we correlate and aggregate UE messages based on RAN_UE_NGAP_ID to extract UE contextual session features.

The 3GPP specification [26] defines various NGAP messages, which are identified by a unique procedureCode. The NGAP messages are nested to encapsulate NAS messages between UE and 5GC, such as Registration Request, Service Request, and Authentication Response. The interaction of these messages follows strict protocol state machines, resulting in deterministic temporal patterns.

Attacks disrupt normal message interaction patterns for N2 interface. Anomalous behavior primarily manifests as deviations in signaling sequences from protocol specifications. For example, Signaling Storm generates a large number of repeated initial Registration Request within a short period of time. Protocol Vulnerability Exploit also present signaling procedure anomaly despite triggering logic error through IE. Illegal Registration may cause disorderly procedures. Consequently, these anomalies are difficult to detect by a single message, but require capturing the feature differences from the spatio-temporal correlation of the message sequence.

In traditional Internet anomaly traffic detection, the TCP/IP protocol stack uses fixed-structure packets. Anomaly detection methods can utilize standard statistical features or feature engineering to perform classification tasks. However, this paradigm is maladaptive for NGAP anomaly detection. The NGAP protocol contains more than 100 message types, each of which has different optional nested sets and IEs. To address the dynamic message interaction nature of the NGAP protocol, we heuristically select direction, timestamp, and procedureCode as temporal features to describe NGAP sessions. These feature sets imply an implicit modeling of NGAP state machines. First, we use a dynamic time sliding window to slice the session. Within the sliding windowT, the NGAP sessionS portrays the interaction pattern between UE and 5GC.

We deep-parsed the raw NAGP messages through ASN.1 format. We use direction, timestamp, and procedureCode to describe the signaling sequence between entities. Thus, each signaling consists of a triple

where the

We perform feature embedding of NGAP temporal features, which transforms the raw data into a normalized numerical form. Specifically, the direction

where the

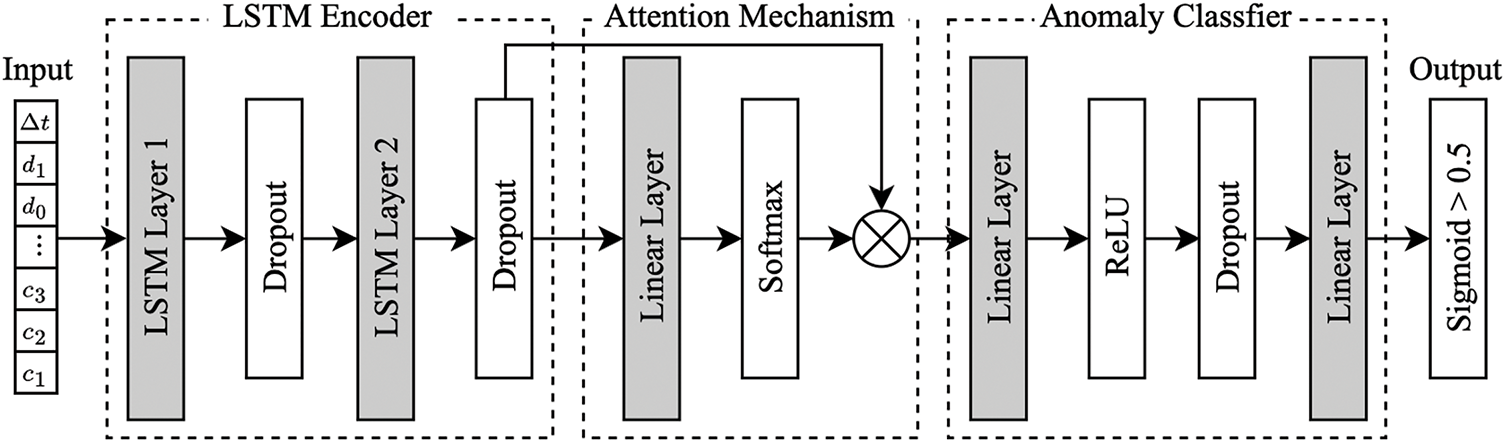

Traditional anomaly detection methods based on rule matching or statistical thresholds are difficult to effectively identify novel attacks. Especially for N2 interface attacks, the anomaly patterns are often hidden in violations of temporal logic within protocol state machines. Such scenarios require the construction of dynamic detection models capable of capturing long-term dependencies. In this paper, we propose an anomaly detection model based on Temporal Attention LSTM Network (TA-LSTM). Specifically, the LSTM captures long-term dependencies of signaling data through a gating mechanism, which is particularly suitable for dealing with complex temporal behaviors in NGAP messages. The attention mechanism enhances the model’s sensitivity to local anomaly features by dynamically assigning weights to focus on key time steps that are strongly correlated with anomalies. Specifically, the TA-LSTM model structure (as shown in Fig. 5) contains the temporal vector input, LSTM encoder, and attention layer. Ultimately, the anomaly classifier outputs the anomaly probability of the NGAP session, realizing the binary classification anomaly detection task.

Figure 5: The TA-LSTM model structure by LSTM encoder and attention mechanism

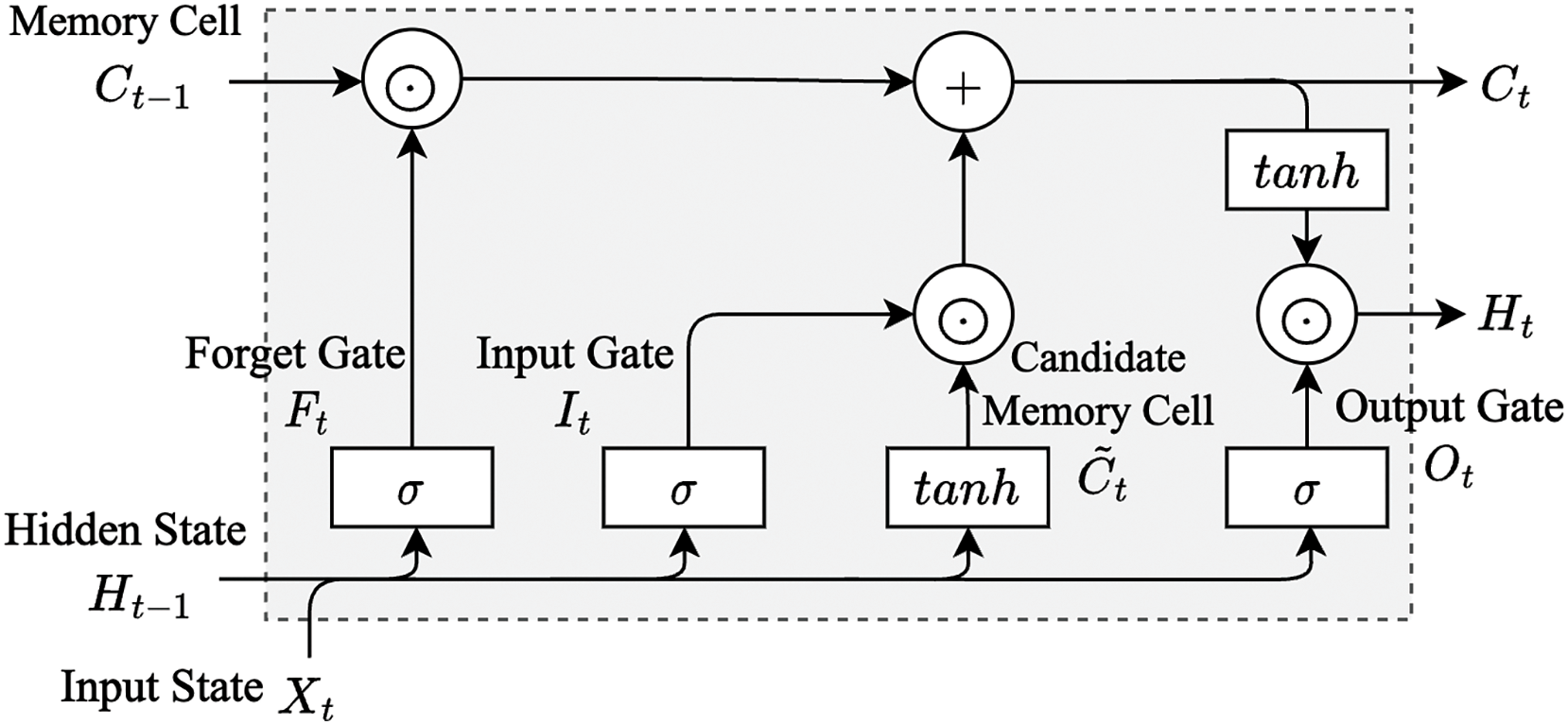

The LSTM [42] is an extension of the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), primarily designed to capture dependencies in sequential data. We designed the LSTM model for encoding NGAP message sequences. The core of LSTM is memory cells, which can selectively store, write or discard information. These memory cells (as shown in Fig. 6) are structured into three main components: Forget Gate, Input Gate, and Output Gate.

Figure 6: The architecture of long short-term memory

Assume that the LSTM model has

Forget Gate: Determine what information should be discarded. After applying the activation function

Input Gate: Determine what information should be saved to the memory cell. Candidate memory cells

Output Gate: Determine what information should be output. The Output Gate uses the

where the

The attention mechanism dynamically assigns weights to hidden states at different time steps, focuses on key information, and generates context vectors to enhance the model’s ability to capture the anomaly time steps. Given the hidden state matrix

Hidden states are mapped to scalar weights through a fully connected layer.

where

Finally, it performs a weighted aggregation of the hidden states, and the

The classification decision layer maps the context vector

where the W represents fully connected layer weight, the

We first introduce dataset construction and performance metrics. Second, we evaluate and analyze the proposed method by baseline experiments with traditional anomaly detection models. Third, we perform sequence length and feature ablation experiments. Finally, we analyze whether the balanced dataset leads to inflated performance metrics for NGAP anomaly detection.

We constructed an anomaly dataset by simulating attack behaviors of N2 interfaces, while constructing a normal dataset by simulating NGAP elementary procedures. In addition, we describe performance metrics used to evaluate the classification performance of NGAP anomaly detection.

We utilized the EAST graphical testing tool [27] to design scripts for simulating attack behaviors at the N2 interface. The EAST is an integrated test automation and traffic generation tool capable of simulating a 5G network, which is widely used for functional and load testing. The tool provides a unified and integrated environment for test case creation, execution, and result reporting. We simulated NGAP anomaly behavior for 6 attack scenarios through the EAST testbed, which performs malicious NGAP message frequency, message type, illegal IE, and etc. The attack scenarios are shown in Table 2, which contains FBS Registration, Malicious UE Registration, Vulnerability Exploit, Message Injection, Anomaly Request, and Anomaly Handover. For example, Illegal Registration and IE Vulnerability Exploit were achieved by modifying IE, such as Public Land Mobile Network (PLMN) and PDUSessionID. The NAS protocol attacks are emulated by dropping, injecting, or replaying messages in the NGAP elementary procedure. Signaling Storm was simulated by repeatedly sending specific messages. Frequent handovers were implemented by performing frequent UE Registration and De-registration. Note that due to experimental limitations, we did not simulate Advanced Persistent Attack (APA) such as multi-stage, stealth, adaptive or obfuscation attacks.

We further constructed normal datasets. We built a 5G experimental environment based on OpenAirInterface [28], which provides an open source RAN and 5GC software platform based on 3GPP specifications. We simulate user behavior using the UERANSIM [29] tool, which can be configured with hundreds of virtual UEs for high concurrent access, signaling interactions, and traffic testing. As a result, we generate 3GPP-compliant NGAP sessions in the 5G simulation platform, which contain NGAP CP elementary procedures such as UE Mobility Management Procedures, Transport of NAS Messages Procedures, UE Context Management Procedures, and PDU Session Management Procedures.

We employ Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score as evaluation metrics. These metrics are defined based on four fundamental concepts, namely True Positive (TP), False Positive (FP), True Negative (TN), and False Negative (FN), where TP denotes the number of correctly categorized positive samples, TN denotes the number of correctly categorized negative samples, FP denotes the number of incorrectly categorized negative samples, and FN denotes the number of incorrectly categorized positive samples. For binary classification tasks, the evaluation metrics are defined as follows:

Accuracy represents the proportion of correct predictions among all predictions.

Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all samples predicted as positive.

Recall quantifies the proportion of actual positive samples that are correctly identified.

F1 Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. A higher F1 Score generally indicates better classifier performance.

Due to the limitations in the scale of the 5G simulation network, the dataset is characterized by a small sample size and imbalance. Therefore, we compare it with traditional anomaly detection algorithms.

To validate the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed method, we conducted comparative experiments using Machine Learning (ML) and lightweight Deep Learning (DL) anomaly detection algorithms.

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learning method based on decision trees. By constructing several decision trees and combining their predictions, RF improves model accuracy and generalization through voting or averaging. The RF inputs 42-dimensional session statistics features, configures 100 decision trees and uses Gini coefficients as splitting criteria.

AdaBoost is an iterative boosting method that combines several weak classifiers to form a strong classifier. During each iteration, AdaBoost assigns different weights to samples based on the error rate of the previous model, gradually strengthening the focus on samples that are difficult to classify, thus improving classification accuracy. The AdaBoost inputs 42-dimensional session statistics features, setting up 50 decision tree classifiers and the SAMME.R boosting algorithm.

XGBoost is an efficient gradient boosting framework capable of parallel computation and handling large-scale datasets. It builds new trees iteratively to correct errors from previous predictions and incorporates regularization mechanisms to prevent overfitting. The XGBoost inputs 42-dimensional session statistics features and sets up 100 boosted trees with a maximum tree depth of 3.

Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is a feedforward neural network composed of several layers of neurons. Each neuron connects to others via trainable weights and biases, applying activation functions for nonlinear transformations. The MLP uses a back-propagation algorithm for weight updating and optimizes the model by minimizing a loss function. The MLP inputs NGAP temporal features with a sequence length of 18, sets 32 hidden units, batch size 100, epochs 40, and learning rate 0.005. The MLP uses the Adam optimizer and BCELoss loss function.

LSTM captures the long-term dependencies of temporal data through a gating mechanism, which can effectively model normal behavioral patterns and identify anomalies through prediction error or reconstruction bias. It combines with threshold determination or probabilistic models to achieve anomaly analysis. The LSTM inputs NGAP temporal features with a sequence length of 18 [43], sets up a single-layer LSTM and 32 hidden units, with a batch size of 32, epochs of 100, and a learning rate of 0.005. The LSTM uses the Adam optimizer and the BCELoss loss function.

The evaluation metrics for each model are derived from experiments conducted on our constructed dataset, which performs 10 experiments and uses the average values. We follow a 6:4 stratified sampling dataset to train and evaluate the machine learning models, namely RF, AdaBoost, and XGBoost. We divide the datasets according to 7:2:1 to train, validate, and test deep learning models, namely MLP, LSTM, and TA-LSTM. In addition, the TA-LSTM inputs NGAP temporal features of sequence length 18, namely direction, timestamp, and procedure code. This conclusion is analyzed in detail by Section 5.3. The TA-LSTM model inputs 63 features encoded by One hot and outputs binary classification labels thresholded at 0.5. The TA-LSTM is configured with a batch size of 32, epochs of 40, and a learning rate of 0.001, using the AdamW optimizer and the BCEWithLogitsLoss loss function.

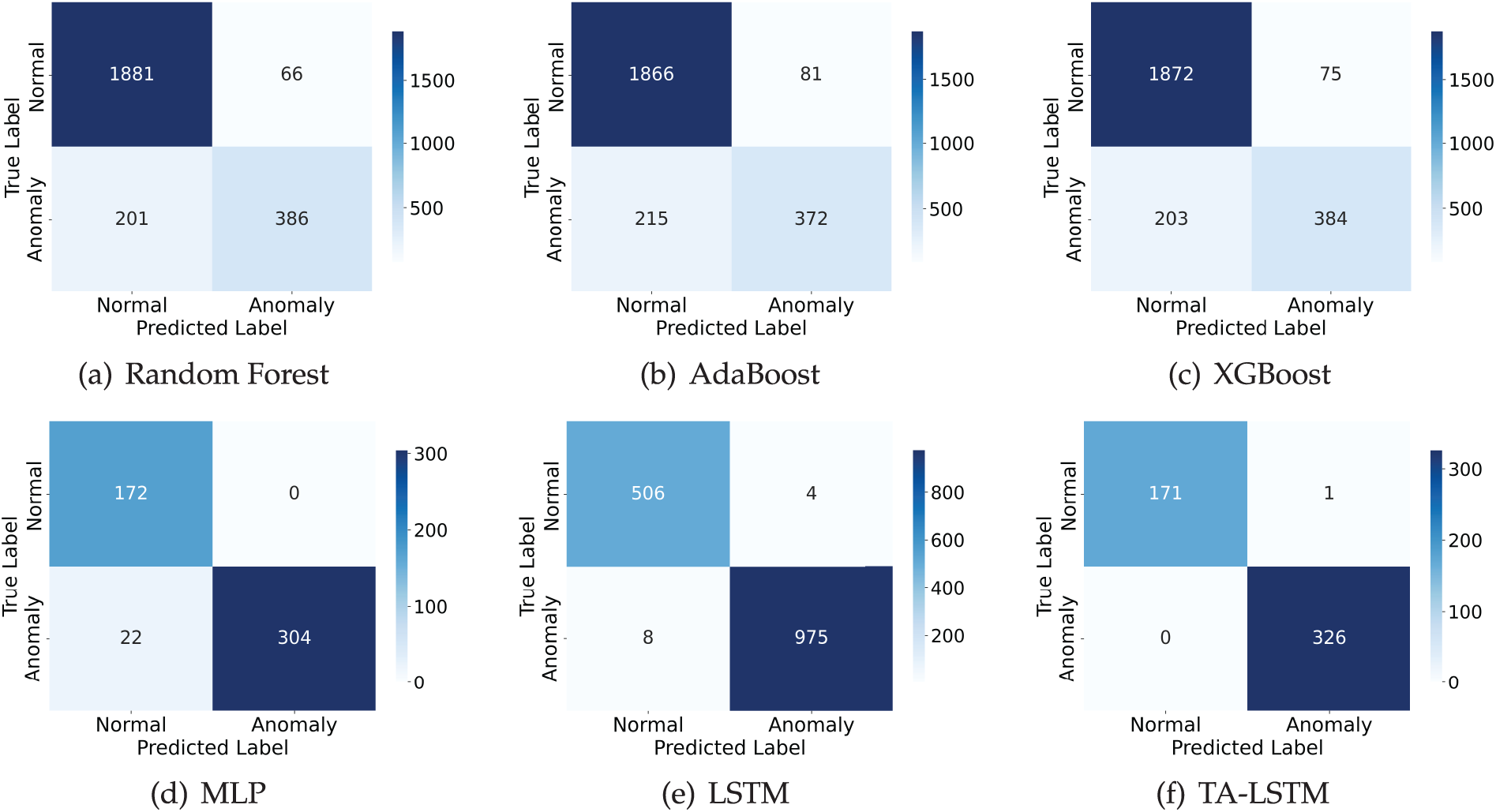

The experimental results (as shown in Fig. 7) indicated that three ML models have cross-errors on the classification task. This is primarily because NGAP anomaly behaviors were mostly reflected in signaling sequences, while session statistical features contained less valid information. The TA-LSTM classification performance was optimal among DL models, achieving 99.80% Accuracy and 99.85% F1 Score (as shown in Table 3). The MLP model showed lower metrics, mainly due to the poor adaptation to temporal data. The LSTM model structure is relatively simple and unable to effectively learn local anomaly features, with an F1 Score that is lower than the TA-LSTM 0.46%. These results suggested that sequence features can significantly enhance the differentiation between normal and anomaly behaviors, thereby greatly improving detection accuracy. Despite the relatively small dataset due to the limitation of the 5G simulation network, the TA-LSTM model still demonstrated strong classification ability, validating its effectiveness in NGAP anomaly detection tasks.

Figure 7: The heatmap of confusion matrix for baseline algorithms analysis

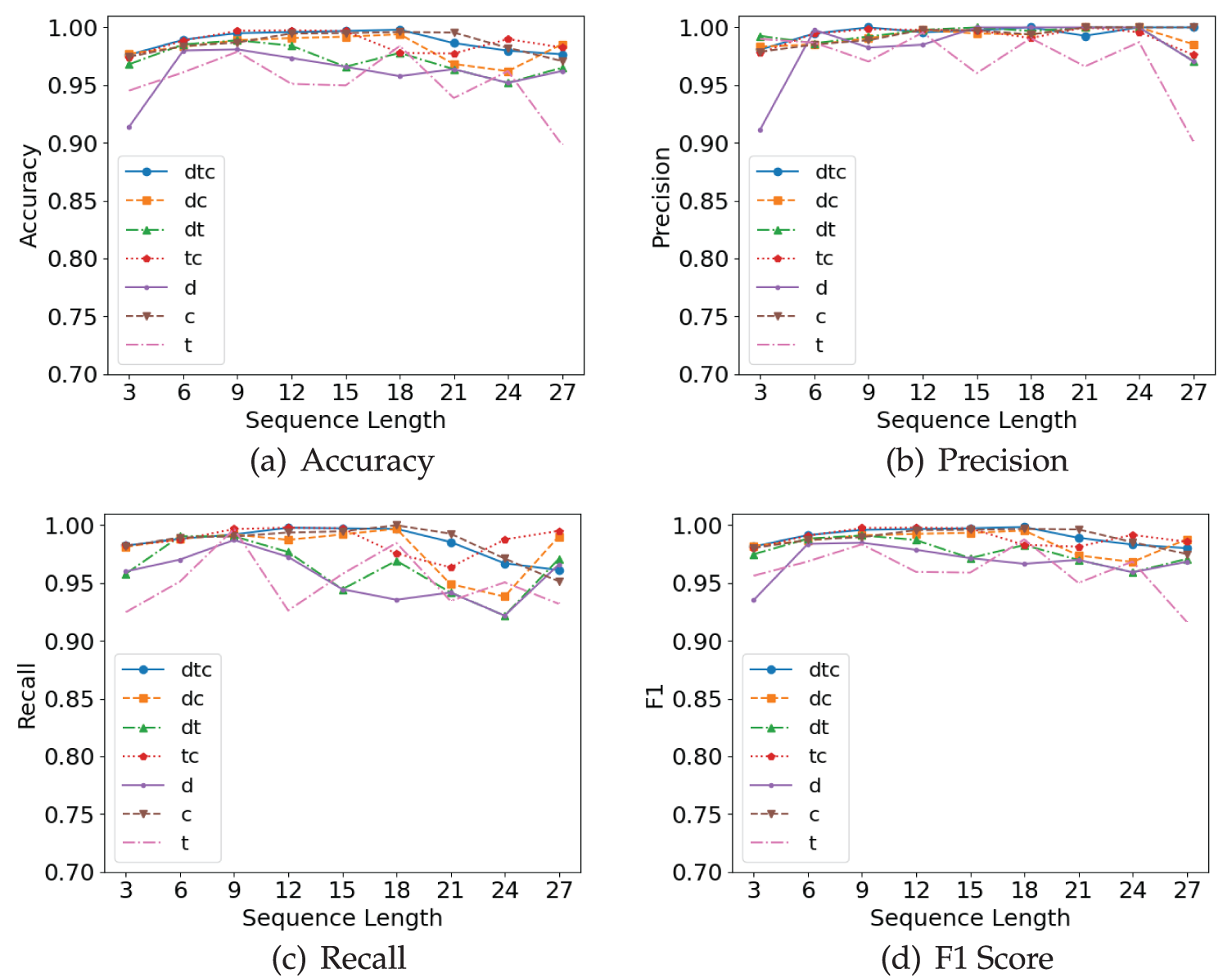

To further validate the effectiveness of our model, we performed careful ablation analysis on the TA-LSTM model. The experiment was divided into sequence length ablation and feature type ablation. Each set of experiments was configured with the same settings except for sequence length in sequence length ablation. The feature ablation experiments only input different combinations of features in each set of experiments. The TA-LSTM was configured with the same hyperparameters of batch size of 32, epochs of 40, and learning rate of 0.001.

5.3.1 Sequence Length Ablation

Our proposed method is based on the signaling sequence as temporal features to characterize UE behavior for anomaly detection. The sequence length ablation experiment investigated the impact of different sequence lengths on detection effectiveness. This experiment comprised 9 experimental groups with sequence lengths starting from 3, incrementing by a step size of 3 up to 27. The comparative analysis verified the effect patterns of the sequence length parameter on model performance.

The length ablation experimental results are illustrated in Fig. 8. The performance metrics generally showed an initial increase followed by a decline as sequence length increased. This trend can be easily explained as learning sub-sequences from the NGAP elementary procedure, while longer sequences are introduced noise due to the prevalence of short sessions in 5G networks. This necessitated the selection of an appropriate sequence length to accurately characterize UE behavior. The TA-LSTM (dtc) model had the optimal performance metrics with 99.85% F1 Score. We determined 18 to be the optimal sequence length, aligning with the definition of NGAP elementary procedures in 3GPP specifications.

Figure 8: The trend comparison of ablation experiments for sequence length and feature type

The feature ablation experiment evaluates the model performance for different feature combinations, which sets up six variants of TA-LSTM (

The TA-LSTM (

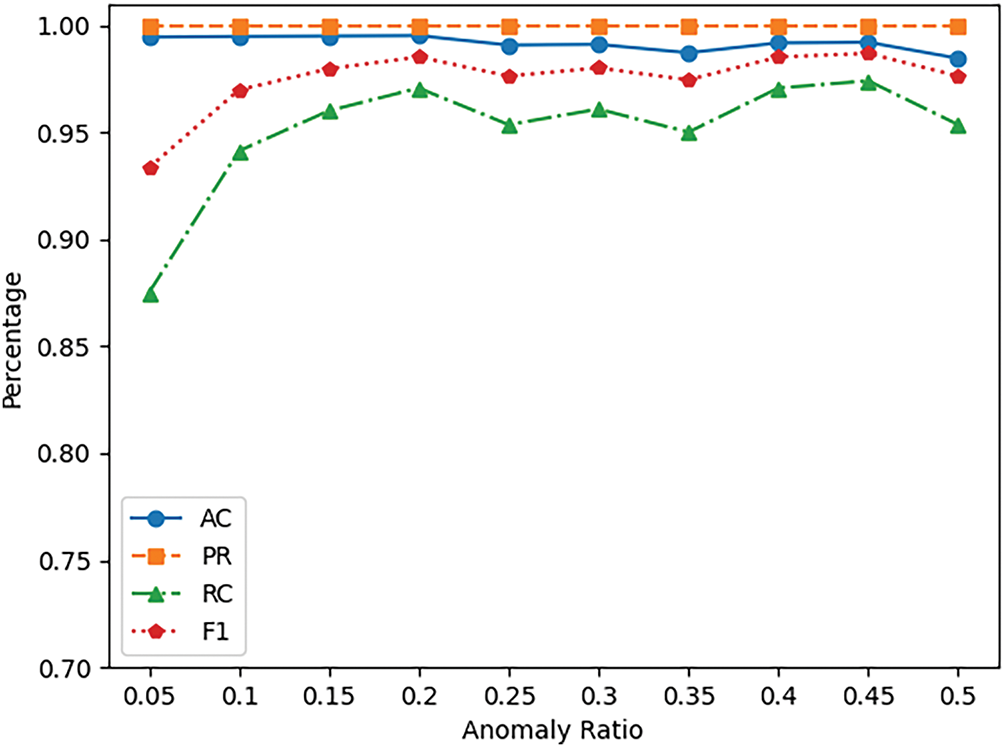

Anomaly sessions are sparse and sporadic in a real 5G network. Model evaluation methods based on balanced datasets induce inflated detection performance metrics due to distorted positive-negative sample distributions. Therefore, we designed a real-world simulation experiment to emulate sparse NGAP anomaly message distribution. We cannot obtain test datasets with real data distributions from MNO, so we employed stratified sampling from our self-constructed dataset. We configured 10 experimental groups with anomaly distribution gradients ranging from 5% to 50% at 5% increments. Each group utilized 172 normal samples and proportionally matched malicious samples excluded from model training. The experiment was evaluated using the optimal model from Section 5.3, with NGAP feature vectors of sequence length 18 as input.

Experimental results (as shown in the Fig. 9) demonstrate that the TA-LSTM model’s performance metrics exhibit an ascending trend with increasing malicious sample ratios. Specifically, the 5% anomaly group showed discrepancies of 0.36% accuracy and 6.52% F1 Score, primarily caused by a significant drop in Recall (as shown in Table 5). These findings empirically confirm that balanced datasets introduce systematic biases for NGAP anomaly detection. Notably, the limited scale of this test dataset may compromise statistical significance. Future work can improve feature engineering and detection models using large-scale MNO datasets to rigorously evaluate and validate the methodology.

Figure 9: Metrics comparison of real world simulation experiment for incremental anomaly sample ratio

We first introduced relevant anomaly signaling and NF behavior detection in 5GC, as well as describe the application of traditional machine learning in anomaly detection.

5GC anomaly detection refers to the identification of anomaly events that deviate from normal behavioral patterns. These anomalies may be caused by network attacks, failures, configuration errors, performance bottlenecks, or unexpected user behavior. Zhang et al. [44] proposed an interaction-based anomaly detection model for 5GC NFs. This model extracts multi-dimensional properties from signaling traffic and NF registration data, and employs the Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) algorithm for feature selection. The model aggregates neighboring nodes through a spatial-domain graph convolutional network by constructing a graph model of 5GC based on NF interaction relationships, thereby transforming 5GC NF anomaly detection into a graph node classification problem. Hu et al. [45] introduced an intrusion detection method based on a multi-kernel clustering algorithm, addressing the challenge of missing properties in 5GC traffic through similarity calculations. The approach improves clustering accuracy for incomplete sampled data while reducing the model’s sensitivity to traffic feature selection. Tian et al. [46] developed a network-level anomaly detection framework based on network traffic sequence modeling, utilizing a Bi-LSTM network to learn normal NF interaction logic and detect anomalies through erroneous service event predictions. Additionally, these works [47,48] accurately locate root-cause NF by reconstructing signaling trajectories from inter-NF communication data and analyzing fault instances.

6.2 Malicious Traffic Detection

Machine learning can identify malicious samples from data, which mostly use statistical features as input to detect malicious behaviors through classification or clustering. ML algorithms are widely applied in network traffic anomaly detection or intrusion detection systems, such as K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-means, and RF. Fu et al. [49] proposed a real-time malicious traffic detection model that achieves high accuracy and throughput by leveraging frequency-domain features. The model ensures bounded information loss through sequence information represented by frequency-domain features, maintaining high detection accuracy while constraining feature dimensions. Fu et al. [50] also introduced a method to detect anomaly interaction patterns by analyzing graph connectivity, sparsity and statistical features, enabling the detection of various encrypted attack traffic without requiring labeled datasets of known attacks. Anderson et al. [51] developed a supervised RF model that utilizes a unique and diverse set of network flow features to effectively identify malicious encrypted traffic. DL models such as Autoencoder, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), RNN, and Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) are applied for anomaly detection, which especially performs well when dealing with complex, high-dimensional and large-scale data. Hwang et al. [52] proposed an efficient anomaly traffic detection mechanism that examines only the first few bytes of the initial packets in each flow for early detection. The model combines CNN with an unsupervised DL architecture to automatically analyze traffic patterns and filter anomalies. Ng et al. [53] introduced an anomaly detection framework based on Vector Convolutional Deep Learning (VCDL) for fog environments, which distributes traffic processing across fog nodes to ensure system scalability.

This paper proposed an NGAP anomaly detection method. The method learns the communication pattern of UE by extracting NGAP message sequence features at the granularity of UE, which achieves anomaly behavior detection for the N2 interface. Experimental results show that the TA-LSTM model can fully utilize the dependencies of NGAP signaling sequences and has better detection performance through the baseline comparison, ablation, and real-world simulation experiments. Enhanced datasets and effective multi-classification anomaly detection are the future research.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere appreciation to our colleagues at the School of Cyberspace Security, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications for their helpful discussions and collaboration. Additionally, we acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions, which helped improve the quality of our work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Writing—original draft preparation, Shaocong Feng; writing—review and editing, Baojiang Cui; methodology and data curation, Shengjia Chang; conceptualization, Meiyi Jiang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the present study.

References

1. IMT-2020(5G) Promotion Group. 5G Security Report. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: http://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/bps/202002/P020200204353106343376.pdf. [Google Scholar]

2. Chen Y, Yao Y, Wang X, Xu D, Yue C, Liu X, et al. Bookworm game: automatic discovery of LTE vulnerabilities through documentation analysis. In: 42nd IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, SP 2021; 2021 May 24–27; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1197–214. doi:10.1109/SP40001.2021.00104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hussain SR, Echeverria M, Karim I, Chowdhury O, Bertino E. 5GReasoner: a property-directed security and privacy analysis framework for 5G cellular network protocol. In: Cavallaro L, Kinder J, Wang X, Katz J, editors. Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS 2019; 2019 Nov 11–15; London, UK: ACM; 2019. p. 669–84. doi:10.1145/3319535.3354263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wen H, Porras PA, Yegneswaran V, Gehani A, Lin Z. 5G-spector: an O-RAN compliant layer-3 cellular attack detection service. In: 31st Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, NDSS 2024; 2024 Feb 26–Mar 1; San Diego, CA, USA: The Internet Society; 2024. [Google Scholar]

5. Park JH, Rathore S, Singh SK, Salim MM, Azzaoui A, Kim TW, et al. A comprehensive survey on core technologies and services for 5G security: taxonomies, issues, and solutions. Hum-Centric Comput Inf Sci. 2021;11(3):1–22. [Google Scholar]

6. Pacherkar HS, Yan G. PROV5GC: hardening 5G core network security with attack detection and attribution based on provenance graphs. In: Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec 2024; 2024 May 27–29; Seoul, Republic of Korea: ACM; 2024. p. 254–64. [Google Scholar]

7. Thorn S, English KV, Butler KRB, Enck W. 5GAC-analyzer: identifying over-privilege between 5G core network functions. In: Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec 2024; 2024 May 27–29; Seoul, Republic of Korea: ACM. p. 66–77. [Google Scholar]

8. Software Radio Systems. srsRAN Project. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.srslte.com/. [Google Scholar]

9. Lee S. Open5GS. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://open5gs.org/. [Google Scholar]

10. Ettus Research. USRP B210. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.ettus.com/all-products/ub210-kit/. [Google Scholar]

11. Shaik A, Seifert J, Borgaonkar R, Asokan N, Niemi V. Practical attacks against privacy and availability in 4G/LTE mobile communication systems. In: 23rd Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, NDSS 2016; 2016 Feb 21–24; San Diego, CA, USA: The Internet Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

12. Rupprecht D, Kohls K, Holz T, Pöpper C. Breaking LTE on layer two. In: 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, SP 2019; 2019 May 19–23; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1121–36. doi:10.1109/SP.2019.00006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yang H, Bae S, Son M, Kim H, Kim SM, Kim Y. Hiding in plain signal: physical signal overshadowing attack on LTE. In: 28th USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 2019; 2019 Aug 14–16; Santa Clara, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2019. p. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

14. Kotuliak M, Erni S, Leu P, Röschlin M, Capkun S. LTrack: stealthy tracking of mobile phones in LTE. In: 31st USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 2022; 2022 Aug 10–12; Boston, MA, USA: USENIX Association; 2022. p. 1291–306. [Google Scholar]

15. Bitsikas E, Schnitzler T, Pöpper C, Ranganathan A. Freaky leaky SMS: extracting user locations by analyzing SMS timings. In: 32nd USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 2023; 2023 Aug 9–11; Anaheim, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2023. p. 2151–68. [Google Scholar]

16. Lakshmanan N, Budhdev N, Kang MS, Chan MC, Han J. A stealthy location identification attack exploiting carrier aggregation in cellular networks. In: Bailey MD, Greenstadt R, editors. 30th USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 2021; 2021 Aug 11–13; Virtual. USENIX Association; 2021. p. 3899–916. [Google Scholar]

17. Hoang TD, Park C, Son M, Oh T, Bae S, Ahn J, et al. LTESniffer: an open-source LTE downlink/uplink eavesdropper. In: Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec 2023; 2023 May 29–Jun 1; Guildford, UK: ACM; 2023. p. 43–8. doi:10.1145/3558482.3590196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ludant N, Robyns P, Noubir G. From 5G sniffing to harvesting leakages of privacy-preserving messengers. In: 44th IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, SP 2023; 2023 May 21–25; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 3146–61. doi:10.1109/SP46215.2023.10179353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tu G, Li C, Peng C, Li Y, Lu S. New security threats caused by IMS-based SMS service in 4G LTE networks. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2016 Oct 24–28; Vienna, Austria: ACM; 2016. p. 1118–30. doi:10.1145/2976749.2978393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yu C, Chen S, Wei Z, Wang F. Toward a truly secure telecom network: analyzing and exploiting vulnerable security configurations/implementations in commercial LTE/IMS networks. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2024;21(4):3048–64. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2023.3322267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kohls K, Rupprecht D, Holz T, Pöpper C. Lost traffic encryption: fingerprinting LTE/4G traffic on layer two. In: Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec 2019, 2019 May 15–17; Miami, FL, USA: ACM; 2019. p. 249–60. doi:10.1145/3317549.3323416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bae S, Son M, Kim D, Park C, Lee J, Son S, et al. Watching the watchers: practical video identification attack in LTE networks. In: 31st USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 2022; 2022 Aug 10–12; Boston, MA, USA: USENIX Association; 2022. p. 1307–24. [Google Scholar]

23. Karakoc B, Fürste N, Rupprecht D, Kohls K. Never let me down again: bidding-down attacks and mitigations in 5G and 4G. In: Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec 2023; 2023 May 29–Jun 1; Guildford, UK: ACM; 2023. p. 97–108. doi:10.1145/3558482.3581774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Erni S, Kotuliak M, Leu P, Roeschlin M, Capkun S. AdaptOver: adaptive overshadowing attacks in cellular networks. In: ACM MobiCom ’22: The 28th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking; 2022 Oct 17–21; Sydney, NSW, Australia: ACM; 2022. p. 743–55. doi:10.1145/3495243.3560525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. 3GPP. Security architecture and procedures for 5G System. 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP); 2023. 33.501. Version 17.8.0. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://portal.etsi.org/webapp/workprogram/Report_WorkItem.asp?WKI_ID=67701. [Google Scholar]

26. 3GPP. NG-RAN; NG Application Protocol (NGAP). 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP); 2024. 38.413. Version 18.2.0. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://portal.etsi.org/webapp/workprogram/Report_WorkItem.asp?WKI_ID=72822. [Google Scholar]

27. EXFO. 5G testing; [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.exfo.com/en/solutions/communication-service-providers/wireless/5g-testing/. [Google Scholar]

28. OpenAirInterface. 4G LTE and 5G Radio Access Network Implementation (NodeB and UE). [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://gitlab.eurecom.fr/oai/openairinterface5g/. [Google Scholar]

29. Güngör A. UERANSIM. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://github.com/aligungr/UERANSIM. [Google Scholar]

30. 3GPP. System architecture for the 5G System (5GS). 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP); 2023. 23.501. Version 17.7.0. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://portal.etsi.org/webapp/workprogram/Report_WorkItem.asp?WKI_ID=67685. [Google Scholar]

31. 3GPP. 5G; NG-RAN; Architecture description. 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP); 2018. 38.401. Version 15.2.0. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://portal.etsi.org/webapp/workprogram/Report_WorkItem.asp?WKI_ID=55189. [Google Scholar]

32. 3GPP. 5G; Non-Access-Stratum (NAS) protocol for 5G System (5GS); Stage 3. 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP); 2023. 24.501. Version 17.12.0. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://portal.etsi.org/webapp/workprogram/Report_WorkItem.asp?WKI_ID=69204. [Google Scholar]

33. Kim H, Lee J, Lee E, Kim Y. Touching the untouchables: dynamic security analysis of the LTE control plane. In: 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, SP 2019; 2019 May 19–23; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1153–68. doi:10.1109/SP.2019.00038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Park C, Bae S, Oh B, Lee J, Lee E, Yun I, et al. DoLTEst: in-depth downlink negative testing framework for LTE Devices. In: 31st USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 2022; 2022 Aug 10–12; Boston, MA, USA: USENIX Association; 2022. p. 1325–42. [Google Scholar]

35. Klischies D, Schloegel M, Scharnowski T, Bogodukhov M, Rupprecht D, Moonsamy V. Instructions unclear: undefined behaviour in cellular network specifications. In: 32nd USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 2023; 2023 Aug 9–11; Anaheim, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2023. p. 3475–92. [Google Scholar]

36. Xing J, Yoo S, Foukas X, Kim D, Reiter MK. On the criticality of integrity protection in 5G fronthaul networks. In: 33rd USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 2024; 2024 Aug 14–16; Philadelphia, PA, USA: USENIX Association; 2024. [Google Scholar]

37. Seeker. From pocket fake base station to handheld real base station. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://github.com/knownsec/KCon/tree/master/2017/. [Google Scholar]

38. sysmocom. sysmoISIM-SJA2 programmable SIM/USIM/ISIM cards. [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://sysmocom.de/products/sim/sysmousim/index.html. [Google Scholar]

39. Bennett N, Zhu W, Simon B, Kennedy R, Enck W, Traynor P, et al. RANsacked: a domain-informed approach for fuzzing LTE and 5G RAN-core interfaces. In: Luo B, Liao X, Xu J, Kirda E, Lie D, editors. Proceedings of the 2024 on ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS 2024; 2024 Oct 14–18; Salt Lake City, UT, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 2027–41. doi:10.1145/3658644.3670320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Hussain SR, Echeverria M, Chowdhury O, Li N, Bertino E. Privacy attacks to the 4G and 5G cellular paging protocols using side channel information. In: 26th Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, NDSS 2019; 2019 Feb 24-27; San Diego, CA, USA: The Internet Society; 2019. [Google Scholar]

41. Bitsikas E, Khandker S, Salous A, Ranganathan A, Jover RP, Pöpper C. UE security reloaded: developing a 5G standalone user-side security testing framework. In: Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec 2023; 2023 May 29–Jun 1; Guildford, UK: ACM; 2023. p. 121–32. doi:10.1145/3558482.3590194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Sherstinsky A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. arXiv:1808.03314. 2019. [Google Scholar]

43. Feng S, Cui B, Jian M, He W, Fu J. NGAP anomaly detection based on signaling sequences in 5GC boundary. In: The 8th International Conference on Mobile Internet Security, MobiSec 2024; 2024 Dec 17–19; Sapporo, Japan; 2024. [Google Scholar]

44. Zhang W, Ji L, Liu S, Li X, Pan F, Hu X. IBNAD: an interactive model for detecting abnormal network functions in 5G core network. J Inf Secur. 2024;9(3):94–112. [Google Scholar]

45. Hu N, Tian Z, Lu H, Du X, Guizani M. A multiple-kernel clustering based intrusion detection scheme for 5G and IoT networks. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2021;12(11):3129–44. doi:10.1007/s13042-020-01253-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zixu T, Patil R, Gurusamy M, McCloud J. ADSeq-5GCN: anomaly detection from network traffic sequences in 5G core network control plane. In: 24th IEEE International Conference on High Performance Switching and Routing, HPSR 2023; 2023 Jun 5–7; Albuquerque, NM, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 75–82. doi:10.1109/HPSR57248.2023.10147931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Vinh TQ, Quan DV, Do T, Trung LQ, Huong TT. An efficient lightweight anomaly detection for 5G core network. In: IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics, ICCE 2024; 2024 Jan 6–8; Las Vegas, NV, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICCE59016.2024.10444414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Fang J, Fu J, Sun J, Geng L, Liu Y, Ma W. STRCA: a lightweight and accurate root cause analysis system based on 5G signalling trace. In: Huang D, Si Z, Zhang C, editors. Advanced intelligent computing technology and applications. ICIC 2024. Lecture notes in computer science. Vol. 14878. Tianjin, China: Springer; 2024. p. 42–53. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-5672-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Fu C, Li Q, Shen M, Xu K. Realtime robust malicious traffic detection via frequency domain analysis. In: Kim Y, Kim J, Vigna G, Shi E, editors. CCS’21: 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2021 Nov 15–19; Virtual Event, Republic of Korea: ACM; 2021. p. 3431–46. doi:10.1145/3460120.3484585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Fu C, Li Q, Xu K. Detecting unknown encrypted malicious traffic in real time via flow interaction graph analysis. In: 30th Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, NDSS 2023; 2023 Feb 27–Mar 3; San Diego, CA, USA: The Internet Society; 2023 [Google Scholar]

51. Anderson B, McGrew DA. Identifying encrypted malware traffic with contextual flow data. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security, AISec@CCS 2016; 2016 Oct 28; Vienna, Austria: ACM; 2016. p. 35–46. doi:10.1145/2996758.2996768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hwang R, Peng M, Huang C, Lin P, Nguyen VL. An unsupervised deep learning model for early network traffic anomaly detection. IEEE Access. 2020;8:30387–99. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2973023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Amma NGB, Selvakumar S. Anomaly detection framework for Internet of things traffic using vector convolutional deep learning approach in fog environment. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2020;113(1):255–65. doi:10.1016/j.future.2020.07.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools