Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Large Language Models for Effective Detection of Algorithmically Generated Domains: A Comprehensive Review

1 College of Computer Science, Informatics and Computer Systems Department, Center of Artificial Intelligence, King Khalid University, P.O. Box 960, Abha, 62223, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Computer Applications, Shaheed Bhagat Singh State University, Ferozepur, 152002, Punjab, India

* Corresponding Author: Gulshan Kumar. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1439-1479. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.067738

Received 11 May 2025; Accepted 29 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Domain Generation Algorithms (DGAs) continue to pose a significant threat in modern malware infrastructures by enabling resilient and evasive communication with Command and Control (C&C) servers. Traditional detection methods—rooted in statistical heuristics, feature engineering, and shallow machine learning—struggle to adapt to the increasing sophistication, linguistic mimicry, and adversarial variability of DGA variants. The emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) marks a transformative shift in this landscape. Leveraging deep contextual understanding, semantic generalization, and few-shot learning capabilities, LLMs such as BERT, GPT, and T5 have shown promising results in detecting both character-based and dictionary-based DGAs, including previously unseen (zero-day) variants. This paper provides a comprehensive and critical review of LLM-driven DGA detection, introducing a structured taxonomy of LLM architectures, evaluating the linguistic and behavioral properties of benchmark datasets, and comparing recent detection frameworks across accuracy, latency, robustness, and multilingual performance. We also highlight key limitations, including challenges in adversarial resilience, model interpretability, deployment scalability, and privacy risks. To address these gaps, we present a forward-looking research roadmap encompassing adversarial training, model compression, cross-lingual benchmarking, and real-time integration with SIEM/SOAR platforms. This survey aims to serve as a foundational resource for advancing the development of scalable, explainable, and operationally viable LLM-based DGA detection systems.Keywords

In today’s hyper-connected digital ecosystem, the integrity of global communication infrastructure is increasingly threatened by persistent, stealthy, and adaptive cyber threats [1–5]. Among these, Domain Generation Algorithms (DGAs) represent one of the most elusive and enduring tactics in the malware arsenal. DGAs allow threat actors to algorithmically generate vast numbers of domain names, which serve as rendezvous points for Command and Control (C&C) communication. Unlike hardcoded domains, which are easily blacklisted or sinkholed, DGA-generated domains are ephemeral, unpredictable, and resistant to static defenses [6].

DGAs function by executing shared deterministic algorithms between the malware and its operator-based on seeds such as timestamps, pseudo-random number generators, or system entropy [7]. This synchronization ensures that both parties independently compute the same set of candidate domains over time, enabling resilient and covert communication. Such tactics complicate traditional detection and response workflows, rendering DNS-based countermeasures increasingly ineffective [1,8,9].

Accurately identifying these algorithmically generated domains is a strategic necessity for mitigating botnet propagation, interrupting malware lifecycles, and ensuring the reliability of DNS-layer defenses [10,11]. Yet, modern DGAs have grown more complex and deceptive-many now employ dictionary-based or linguistically plausible wordlist generation, enabling them to mimic legitimate web traffic and evade lexical or statistical filters [12–14]. As a result, conventional detection methods—ranging from rule-based heuristics to classical machine learning—struggle with generalization, high false positive rates, and susceptibility to adversarial perturbations [15–19].

In response to these limitations, recent advances in natural language processing (NLP)—particularly the rise of Large Language Models (LLMs)—offer a new frontier for DGA detection. Architectures such as BERT, GPT, T5, and XLNet have demonstrated the capacity to model deep semantic and syntactic structures, learn contextual cues from noisy sequences, and generalize to zero-day and morphologically novel domains [8,9,20–22]. These models require minimal feature engineering and offer improved adaptability through fine-tuning, few-shot learning, and multilingual support.

The motivation for this article stems from two urgent needs in the cybersecurity and AI communities. First, there is currently no unified review that consolidates the rapidly growing body of literature on LLM-based approaches to DGA detection. While prior surveys have broadly addressed AI in cybersecurity [23–27], they typically neglect the unique adversarial dynamics and linguistic challenges posed by DGAs. More recent works such as Hassaoui et al. [28] and Alqahtani and Kumar [29] review deep learning in threat detection but fail to focus specifically on transformer-based architectures or DNS-layer adversarial resilience.

Second, the deployment of LLMs in real-world DGA detection faces numerous challenges, including scalability, adversarial robustness, low-resource multilingual support, and interpretability. While studies such as Mahdaouy et al. [8] and Sayed et al. [9] have achieved strong accuracy on curated datasets, questions remain about generalization to unseen threats, resistance to mimicry-based obfuscation, and operational feasibility in latency-constrained environments. The urgency to bridge this gap is compounded by the growing use of generative adversarial networks and wordlist hybridization to craft increasingly evasive domains.

Accordingly, this review aims to fill the existing void by systematically organizing and evaluating the state of LLM-based DGA detection. We assess architectural families, benchmark datasets, performance metrics, adversarial test results, deployment feasibility, and privacy-preserving adaptations. Drawing inspiration from works such as Tan et al. [30] and their framing of cybersecurity as a dynamic adversarial system, we position LLMs as context-aware defenders that must continuously adapt to shifting attack strategies.

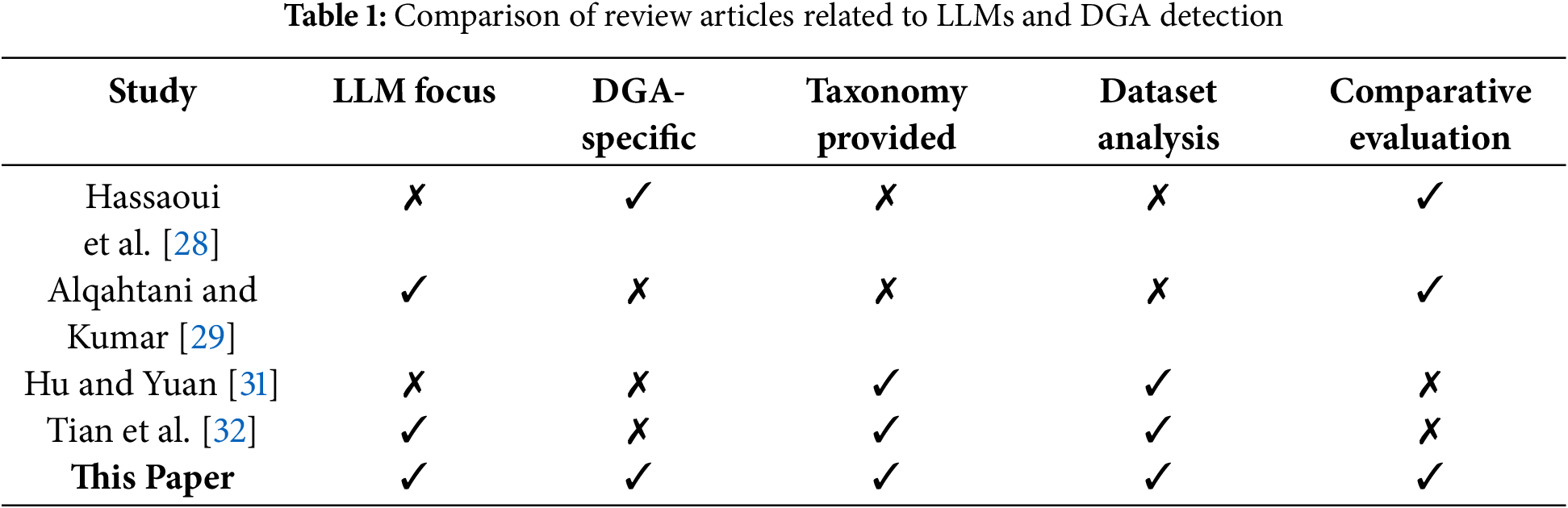

Table 1 clarifies the novelty of this paper by comparing its scope to that of prior reviews. Unlike previous works, we present a focused taxonomy of LLM architectures applied to DGA detection, critically evaluate multilingual and adversarial capabilities, and propose a roadmap for future research-including standardized benchmarks, interpretable models, and privacy-preserving deployment pipelines.

Ultimately, our goal is not merely to summarize recent progress but to provide a strategic and actionable synthesis that can guide researchers, practitioners, and policymakers toward building robust, scalable, and ethically responsible DGA detection systems grounded in state-of-the-art LLM research.

Accordingly, the key contributions of this paper are summarized below:

1. Taxonomy: We propose a hierarchical taxonomy of LLM-based DGA detection architectures, including BERT-style encoders, GPT-style autoregressive models, and generative models like T5 and CL-GAN.

2. Datasets: We compile and analyze benchmark datasets used in LLM-based DGA detection, emphasizing family coverage, structural diversity, and multilinguality.

3. Comparative Advances: We provide a structured comparison of recent LLM-based studies by architectural class, learning paradigm (e.g., supervised, few-shot), and empirical performance.

4. Operational Challenges: We identify open challenges in scalability, interpretability, multilingual detection, and robustness to adversarial domains.

5. Future Outlook: We propose research directions including model compression, domain generalization, federated learning, and integration with dynamic threat intelligence systems.

This review serves as a critical link between foundational research and practical deployment, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers, engineers, and cybersecurity professionals exploring the integration of LLMs into advanced malware detection systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides foundational background on DGAs and introduces the role of LLMs in their detection. Section 3 outlines the research methodology and scope of this systematic review. Section 4 presents a detailed taxonomy of LLM architectures relevant to DGA detection. Section 5 evaluates widely used benchmark datasets, analyzing their structural diversity, linguistic coverage, and suitability for LLM-based models. Section 6 discusses the core capabilities and operational limitations of LLMs in detecting DGAs, highlighting both strengths and unresolved challenges. Section 7 offers a critical comparative analysis of recent LLM-based approaches, categorized by architecture type, including transformer-based, encoder-only, text-to-text, hybrid, and scalable models, and concludes with key findings and research gaps. Finally, Section 8 presents a strategic roadmap for future research directions, and concludes the paper.

2 Foundations of DGAs and LLM-Based Detection

The detection of Algorithmically Generated Domains (AGDs) is a critical challenge in contemporary cybersecurity. This section provides a structured overview of the mechanisms underlying domain generation by malware and explores how recent advances in LLMs are reshaping detection strategies. To ensure clarity, the discussion is divided into two parts: (i) the structure and operational logic of DGAs, and (ii) the application of LLMs in DGA detection.

DGAs are employed by a wide range of malware families to generate large volumes of domain names in a deterministic yet pseudo-random fashion. These domains are used to establish resilient and stealthy communication channels with C&C servers [1,33–35]. Unlike hardcoded domain lists, which are vulnerable to DNS blacklisting or sinkholing, DGAs produce new domains at regular intervals, thereby evading static defenses and extending botnet survivability.

Mathematically, a DGA can be modeled as:

Here,

DGAs are broadly categorized into two types: character-based and dictionary-based [36,37]. Character-based DGAs create domains with high entropy and no semantic structure (e.g., dkq7flx.net), which can be analyzed using metrics such as Shannon entropy:

where

Detection methods based on blacklists and handcrafted statistical features often fail to generalize against such evolving DGA families [1,40–42]. Early machine learning (ML) models, including Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests, and shallow CNNs, suffer from poor robustness, high false positives, and dependence on heavily engineered features [43–45]. These limitations highlight the need for adaptable, semantically aware solutions capable of understanding complex patterns in domain sequences.

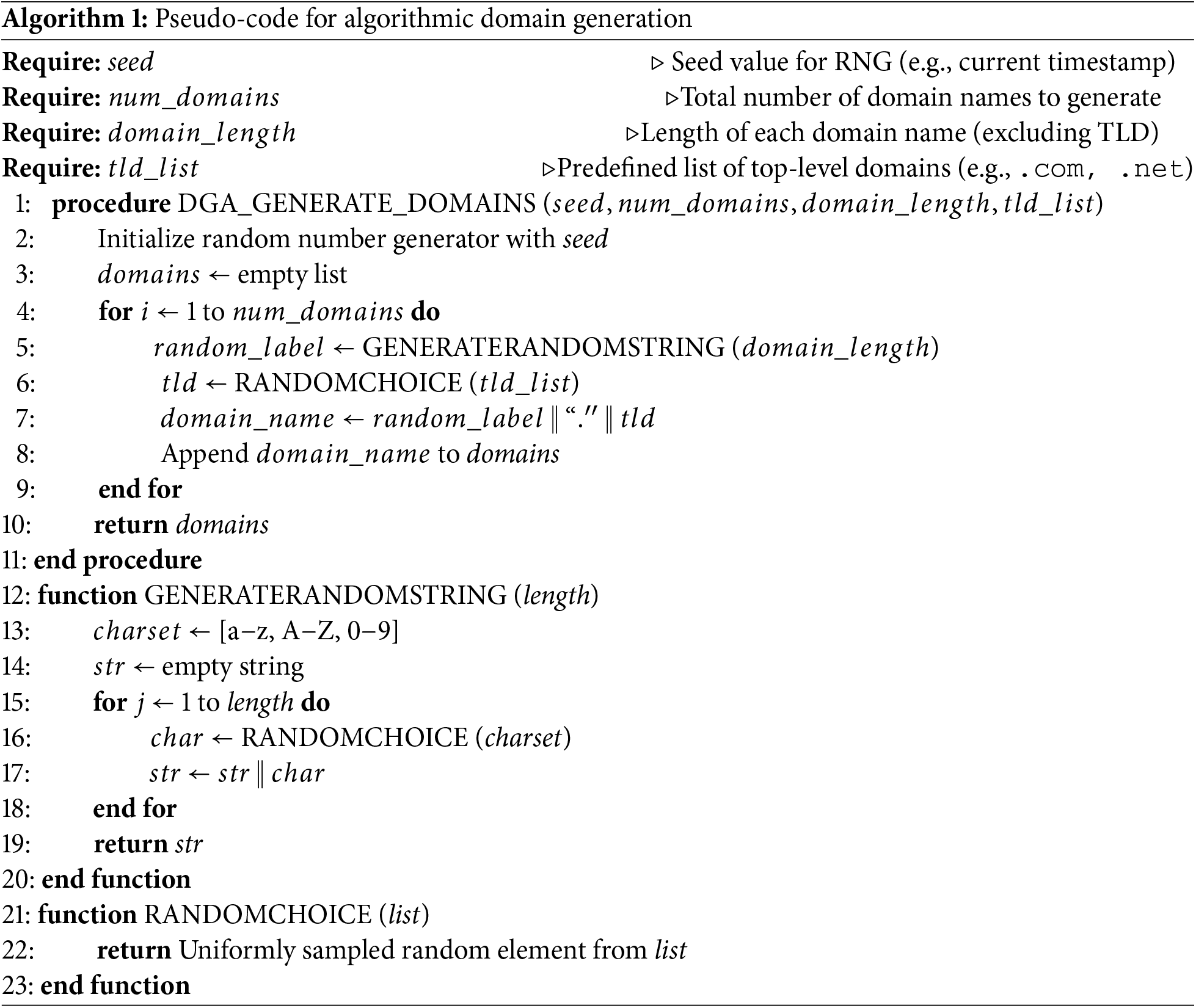

To offer a procedural understanding of how DGAs operate, Algorithm 1 outlines the step-by-step logic used to programmatically construct domain names. Complementing this, Fig. 1 illustrates the functional integration of DGAs within a typical malware communication lifecycle, highlighting how dynamically generated domains facilitate resilient C&C infrastructure and evasion of static blacklists.

Figure 1: Workflow of malware utilizing DGAs for dynamic domain-based command-and-control

2.2 Overview of LLMs for DGA Detection

Recent advancements in LLMs have introduced a paradigm shift in DGA detection by leveraging contextual understanding of sequences. LLMs such as BERT, GPT-3, and T5 utilize deep transformer architectures with self-attention mechanisms to learn token dependencies and structural irregularities from raw input strings [3,46–49]. These models can automatically capture both lexical and semantic cues embedded in domain names, thus addressing the shortcomings of feature-based approaches.

Unlike classical models, LLMs support end-to-end learning without extensive pre-processing or manual feature engineering [18,40,50]. They can also generalize across different domain styles-character-based, dictionary-based, or hybrid-and exhibit robust performance even when applied to multilingual or obfuscated data [22]. The flexibility of LLMs is further enhanced through their capability to operate in zero-shot and few-shot settings, where only limited labeled data is available [51–54].

Models like DomURLs-BERT [8], LLaMA3, and T5-CLG have shown competitive performance with high accuracy and low false positive rates. These models often incorporate attention heatmaps and token attribution methods that improve explainability, a critical factor for adoption in cybersecurity operations.

Despite their promise, several limitations remain. Full-scale LLMs are resource-intensive and require powerful hardware accelerators for real-time inference [46]. They are also vulnerable to adversarial domain mutations, where small perturbations to domain names may result in misclassification [55–59]. Additionally, the absence of standardized benchmarks and well-annotated datasets limits fair comparison across detection systems.

To overcome these barriers, future research must focus on developing lightweight LLM variants through techniques like pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation [40]. Federated learning and privacy-preserving training paradigms are also promising directions to ensure adaptability without compromising data confidentiality [60].

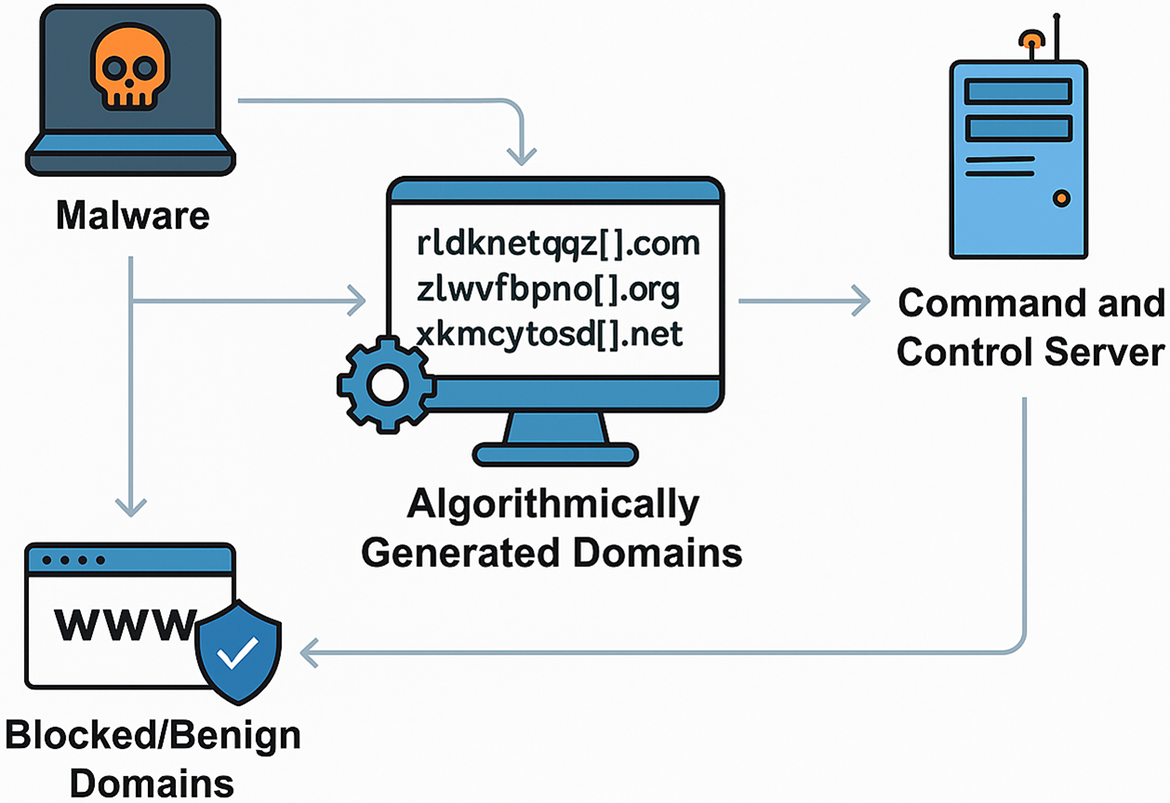

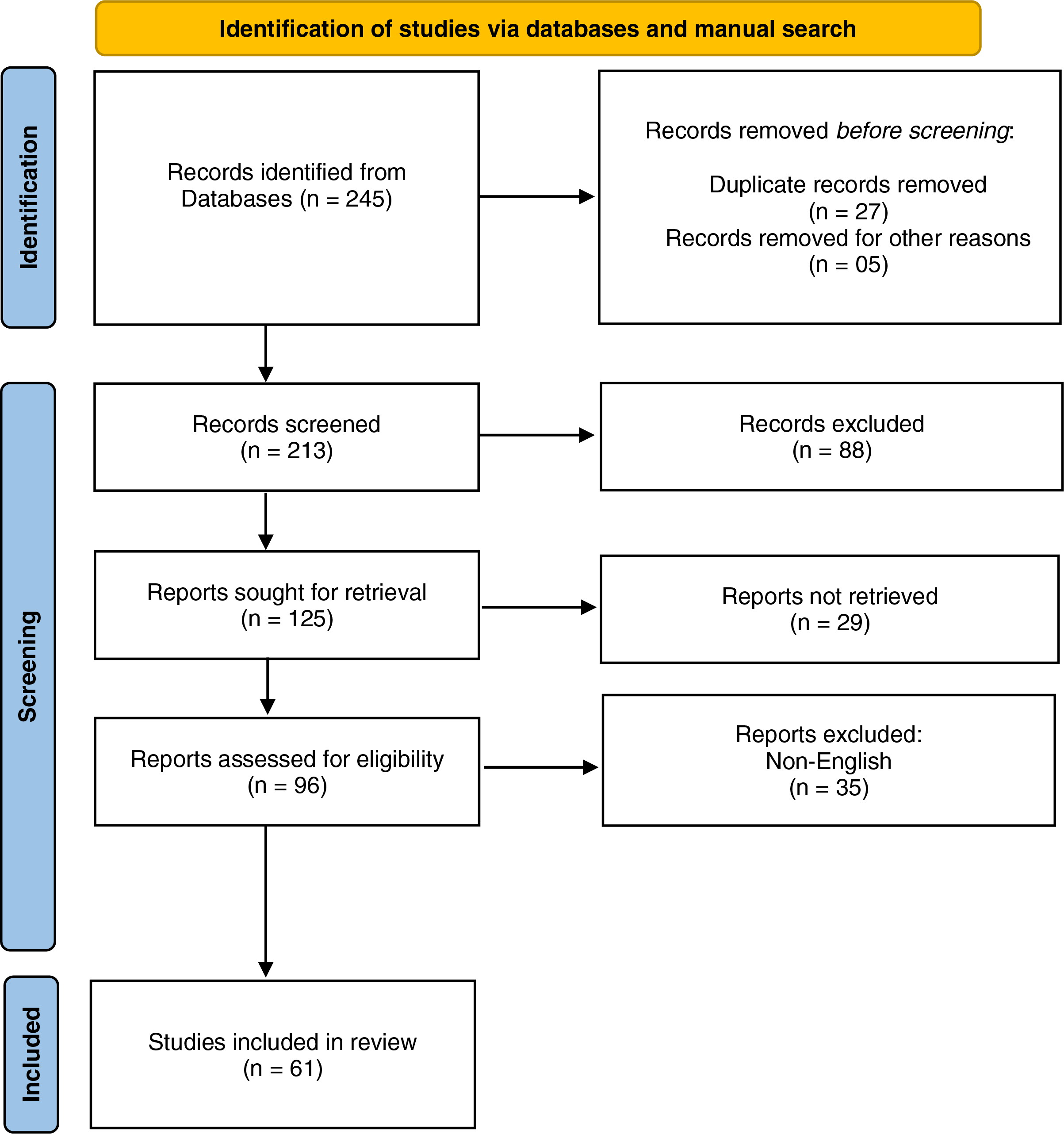

Fig. 2 offers a chronological view of the progression of LLM architectures, showcasing the growing capabilities of these models in understanding linguistic and structural anomalies across various domains.

Figure 2: Timeline of LLM evolution from BERT to GPT-4 (2019–2025)

In summary, LLM-based detection represents a shift from surface-level statistical heuristics to deep contextual modeling, with implications for both detection accuracy and deployment strategies. The following sections expand on the taxonomy of LLM approaches (Section 4), datasets (Section 5), empirical benchmarking (Section 7), system constraints (Section 6), and research directions (Section 8) that define this emerging research frontier.

3 Research Methodology and Scope of Review

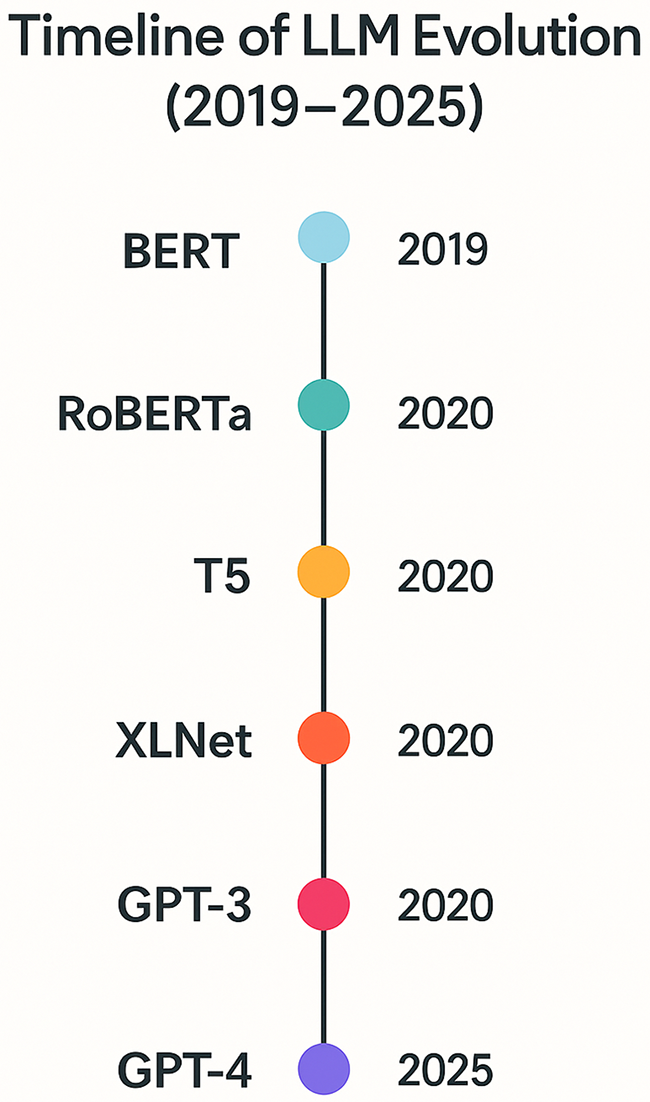

This review adopts a structured, systematic methodology to survey the state-of-the-art in the application of LLMs for the detection of AGDs. The review framework aligns with best practices from the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [61], and is tailored to accommodate the fast-evolving nature of cybersecurity research and generative AI advancements. This methodology facilitated the systematic identification, screening, and selection of high-quality research articles while minimizing bias in the review process, presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: PRISMA framework

The primary aim of this methodology is to consolidate academic and applied research published between 2019 and April 2025, examining how transformer-based architectures—including BERT, GPT, T5, and hybrid models—are employed in DGA detection. We focus on studies that evaluate LLMs in context to their architecture, dataset usage, learning strategy (e.g., supervised, few-shot, in-context), adversarial robustness, and scalability in operational cybersecurity environments.

The inclusion criteria targeted peer-reviewed conference and journal papers explicitly applying LLMs, or fine-tuned transformer models, for domain classification tasks with a focus on DGA detection. Studies had to: (i) be published in English, (ii) present empirical results on LLM-based DGA detection or closely related DNS-based tasks, and (iii) be published between 2019 and April 2025. We included both supervised and unsupervised modeling approaches, including contrastive learning, hybrid embedding, and generative detection frameworks (e.g., T5 or CL-GAN variants). Grey literature such as dissertations and non-peer-reviewed preprints were excluded unless they had a high citation index or a clear methodological novelty.

To build the study corpus, we queried academic databases including IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, SpringerLink, ScienceDirect, MDPI, and arXiv. Keywords included: “LLM AND DGA detection,” “transformer AND DGA,” “GPT DGA classification,” “BERT domain detection,” “T5 AND DNS malware,” “adversarial domain names,” and combinations with logical operators. In total, over 245 publications were initially screened. After deduplication and title/abstract screening using JabRef and Zotero, 96 full-text articles were reviewed in detail. A final selection of 61 studies were deemed eligible and were included in the taxonomy and comparative tables in Section 4 through Section 7.

Each study was coded using a structured data extraction schema developed collaboratively by the review team. Data fields included: publication year, authorship, model type (e.g., BERT, T5, GPT), DGA family evaluated, datasets used (e.g., 360NetLab, DGArchive), learning paradigm (e.g., SFT, ICL, few-shot), experimental setting, accuracy/F1 score, false positive rates, interpretability tools, adversarial training, and deployment implications. These elements were stored in a shared spreadsheet to support classification and trend analysis.

The quality of the studies was assessed based on reproducibility, model transparency, dataset description, architectural clarity, and adversarial robustness. Metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and latency were compared wherever available. A subset of studies provided head-to-head benchmarking on shared datasets, allowing us to construct the comparative tables in Section 7. The thematic patterns extracted informed the research gaps and future directions discussed in Section 8.

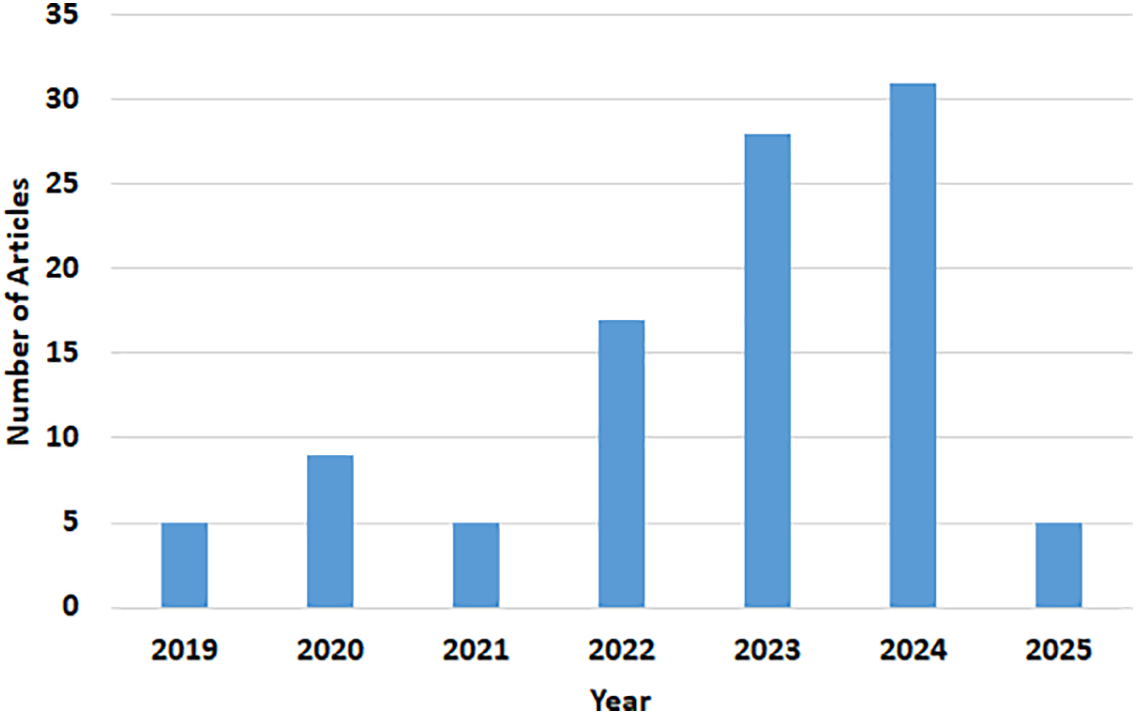

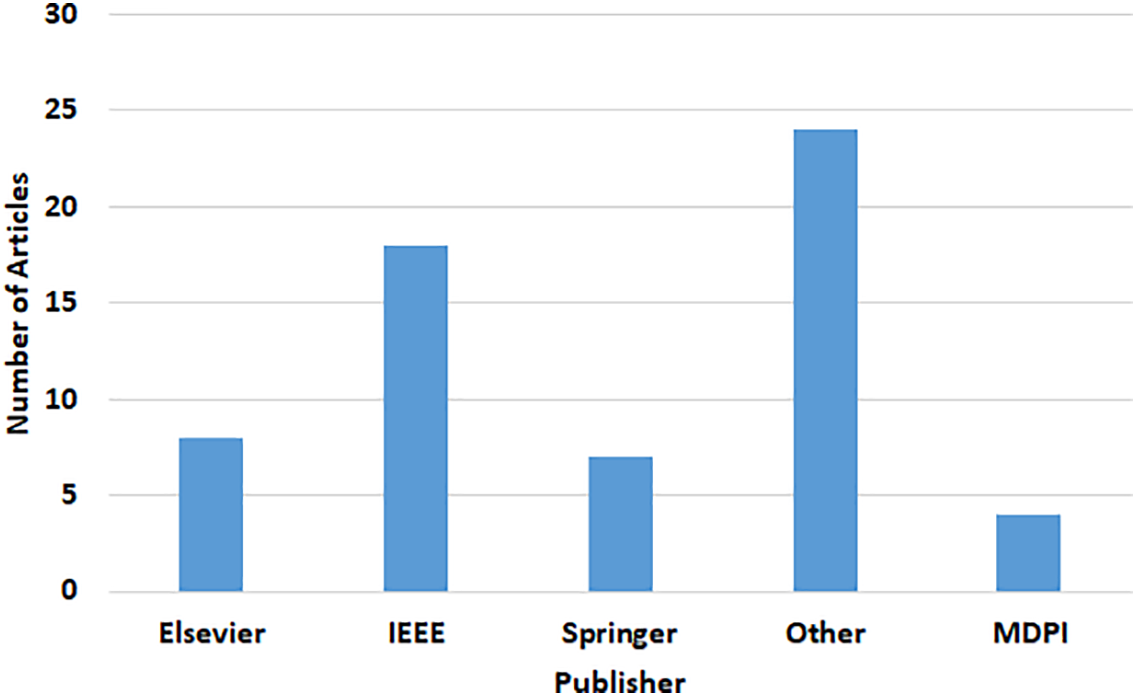

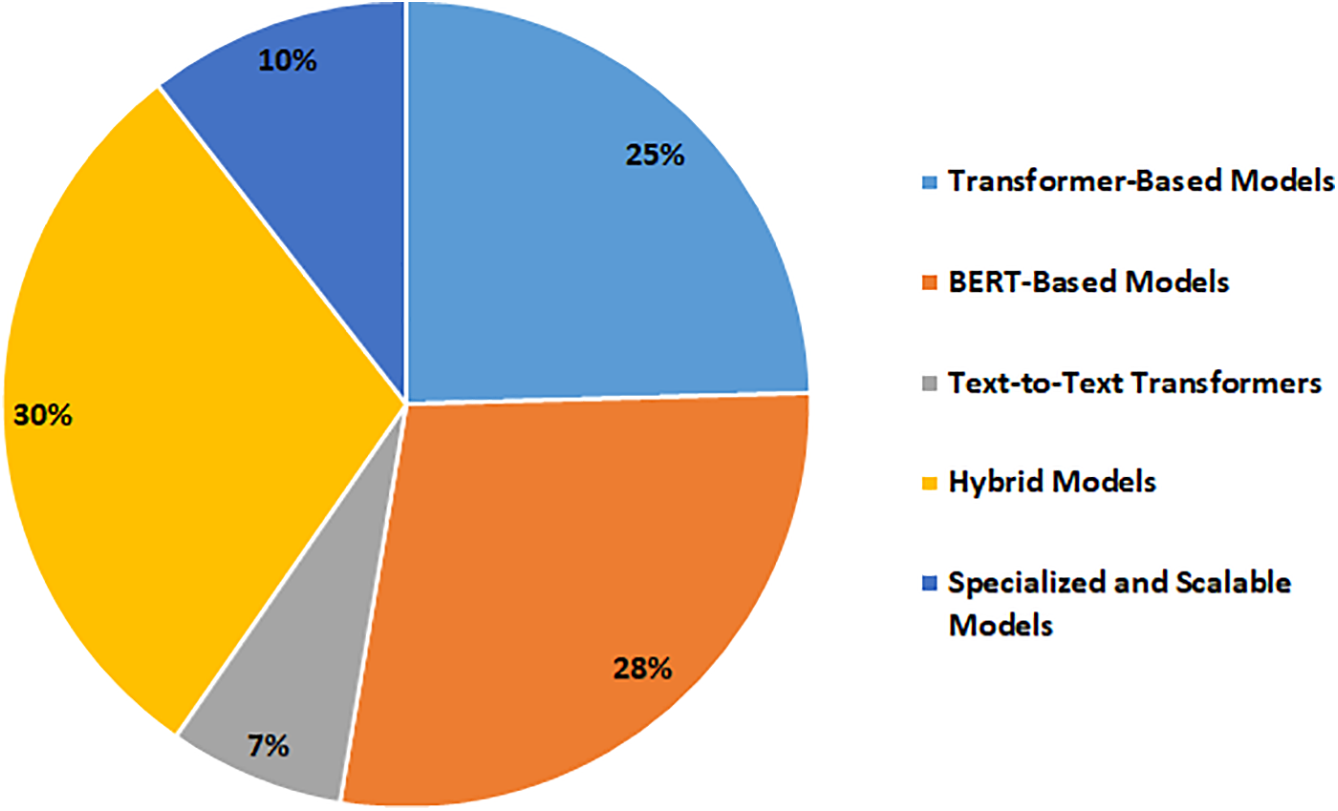

Figs. 4–6 depict the temporal trend, source distribution, and LLM model category breakdown of the selected literature. These highlight both the increasing research momentum and the diversification of modeling strategies applied in this domain.

Figure 4: Year-wise trends in LLM-based DGA detection literature

Figure 5: Publisher distribution of reviewed papers on LLMs for DGA detection

Figure 6: Distribution of LLM model families applied to DGA detection

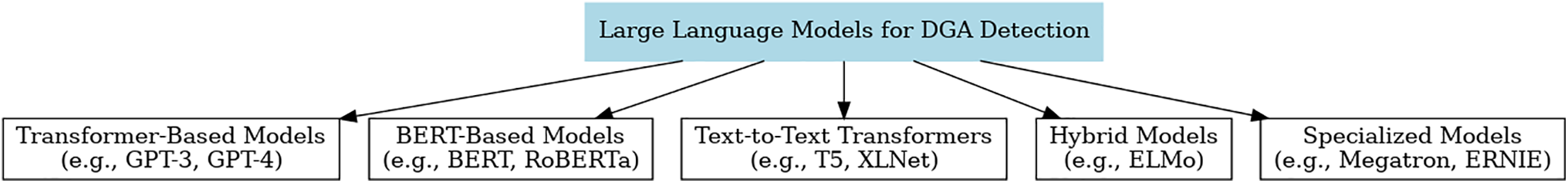

4 Taxonomy of LLM Architectures for DGA Detection

To facilitate a structured understanding of how LLMs are applied to the task of detecting AGDs, we present a five-category taxonomy of LLM architectures, as illustrated in Fig. 7. This taxonomy is not based solely on architectural lineage but rather reflects distinct learning paradigms, model behavior, and practical application modes that are prevalent in DGA detection literature. While several families share a common transformer backbone, their training configurations, operational tasks (e.g., classification, generation, explanation), and deployment contexts vary significantly, justifying their distinction within the proposed framework.

Figure 7: Taxonomy of LLMs Used in DGA Detection. The categorization reflects not just architecture, but task orientation, training paradigm, and practical utility in cybersecurity contexts

The five identified categories are: Transformer-Based Models, BERT-Based Models, Text-to-Text Transformers, Hybrid Embedding Models, and Specialized and Scalable LLMs. These categories are purposefully separated to reflect their real-world usage in cybersecurity research and operations. For instance, although both GPT and BERT are transformer-derived, GPT’s autoregressive, decoder-only structure enables generative tasks such as few-shot learning and adversarial simulation, whereas BERT’s encoder-only bidirectional attention is optimized for discriminative tasks like domain classification and token-level labeling.

Transformer-Based Models, such as GPT-2, GPT-3, and LLaMA3, are autoregressive decoders trained to predict the next token in a sequence [62–64]. Their strength lies in generative and sequential modeling, which is particularly useful in tasks like few-shot classification, anomaly simulation, or adaptive DGA string generation. As demonstrated in Section 7.1, LLaMA3, fine-tuned using in-context learning (ICL) and supervised fine-tuning (SFT), achieved over 94% accuracy in DGA detection, underscoring its applicability in rapidly adapting threat environments [65].

In contrast, BERT-Based Models like BERT, RoBERTa, and ALBERT are bidirectional encoder-only architectures [66,67], suited for fine-grained classification tasks. These models excel in identifying anomalous substrings within a domain, especially when integrated with attention heatmaps or token attribution for interpretability. DomURLs-BERT [8], evaluated in Section 7.2, demonstrated superior performance on multilingual and dictionary-based DGAs when pretrained on URL corpora. Although technically transformer-based, BERT’s usage context and objective functions diverge enough to justify its categorization as a standalone family for clarity and precision in review.

Text-to-Text Transformers, such as T5 and XLNet, redefine all NLP problems as text generation tasks [68]. These models are distinct in their flexibility and are particularly relevant for scenarios requiring output explanation, semantic label construction, or multilingual domain synthesis. As shown in Section 7.3, such models have been used to support few-shot DGA classification and evasion-resistant architectures, with the ability to provide natural-language justifications for decisions-an emerging demand in threat investigation workflows [69,70].

Hybrid Embedding Models such as ELMo and byte-pair encoding (BPE)-based architectures combine static or contextual embeddings with classical machine learning classifiers or lightweight CNNs [71]. These models are valuable for edge deployments or legacy systems where computational resources are constrained. As explored in Section 7.4, hybrid approaches such as BPBZ achieve competitive results using interpretable, low-latency techniques, making them suitable for mid-scale enterprise use cases or latency-critical environments [72].

Finally, Specialized and Scalable LLMs, including Megatron-LM, Turing-NLG, and ERNIE, are purpose-built for either domain adaptation or massive-scale deployment [73,74]. ERNIE, for instance, integrates symbolic knowledge for improved localization, while Megatron-LM excels in performance scaling for large-scale DNS security environments. Section 7.5 further discusses how such models enable real-time detection pipelines, SIEM integration, and behavior-aware threat analytics.

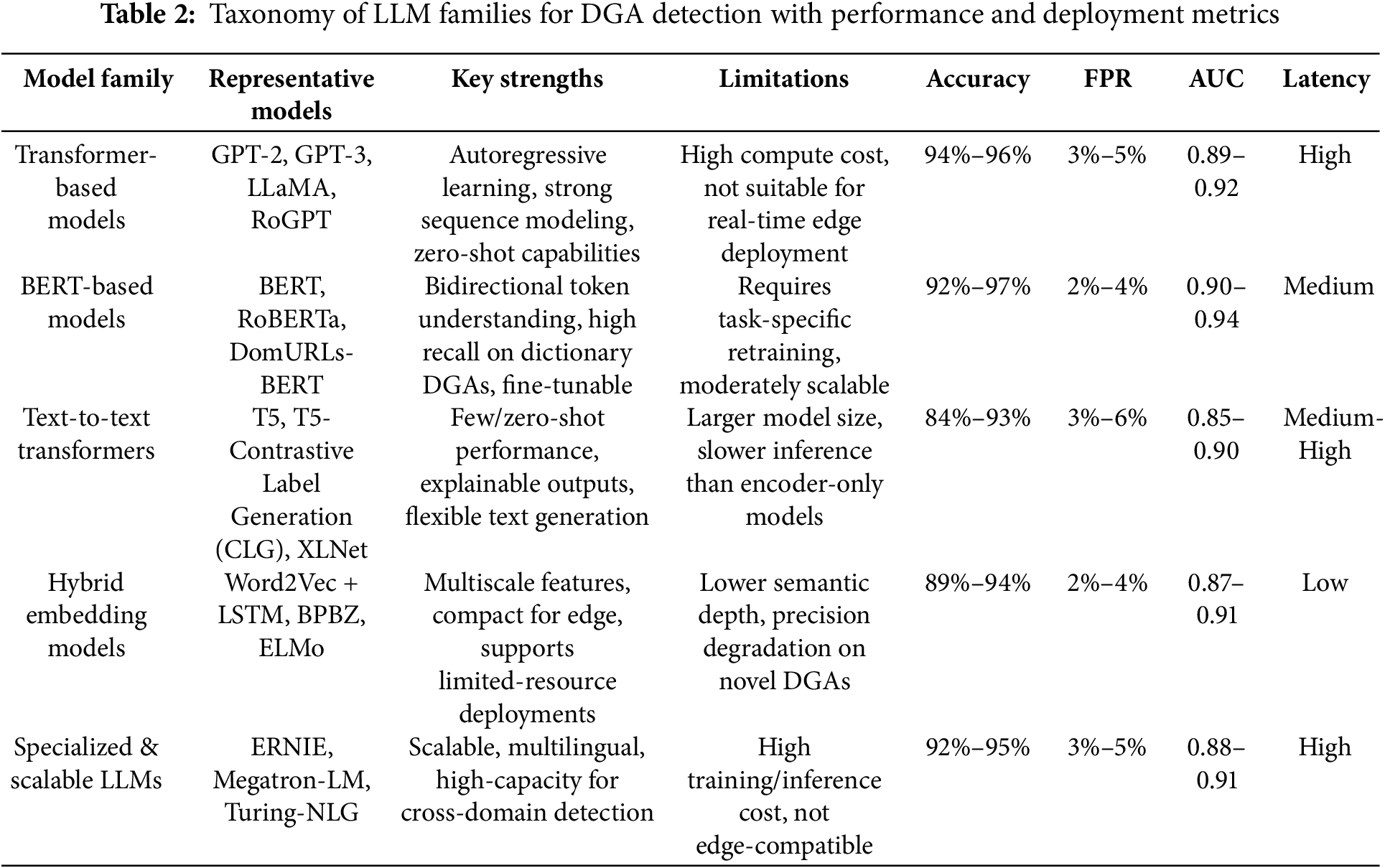

In conclusion, although many of the reviewed models share a transformer base, their task-specific configurations, input/output behavior, and operational footprint warrant a functionally segmented taxonomy. This distinction enhances interpretability for practitioners and supports the development of targeted solutions for diverse DGA detection challenges. The taxonomy thus serves not only as a categorization tool but as a practical guide for matching LLM capabilities to deployment requirements across academic, enterprise, and real-time cybersecurity settings. Table 2 summarizes the key properties, strengths, and limitations of each model type within this taxonomy.

This taxonomy lays the foundation for understanding how architectural design affects the efficacy and applicability of LLMs in the task of detecting algorithmically generated domains. In the next section, we will explore the datasets that power these models and assess the representational challenges involved in training LLMs for DGA-related tasks.

5 Benchmark Datasets for Evaluating LLM-Based DGA Detection

The effectiveness, adaptability, and real-world applicability of LLM-based models for AGD detection are closely tied to the nature and quality of the datasets on which these models are trained and evaluated. As modern DGAs increasingly adopt diverse strategies—including pseudo-random character sequences, dictionary-based constructs, and adversarial obfuscations—robust detection demands datasets that not only reflect structural diversity but also capture regional, temporal, and behavioral complexities.

DGA detection datasets are typically divided into benign and malicious corpora. Benign datasets such as the Alexa Top 1 Million [75] and Majestic Million [76] are widely used for negative class balancing. While these offer scale and availability, they suffer from several drawbacks: they are often static, include outdated or parked domains, and lack critical behavioral context such as DNS resolution frequency, time-to-live (TTL), or WHOIS metadata. Such limitations reduce the utility of these datasets in training models that require semantic disambiguation or behavioral modeling.

On the malicious end, popular resources include DGArchive, Andreas-filter [77], 360Netlab’s DGA feed, Cisco Umbrella [78] and enterprise-grade DNS logs. These datasets typically contain labeled domains associated with known malware families and serve as the backbone for training both binary and multiclass detection systems. However, despite their value, many of these datasets exhibit substantial structural and linguistic biases. For instance, a large proportion of DGA examples originate from malware campaigns targeting English-speaking regions, with little to no inclusion of domain names generated from localized wordlists or non-Latin scripts. This shortfall critically undermines model generalization to non-English DGAs-a gap clearly demonstrated in DomURLs-BERT [8], which, although claiming multilingual capability, was evaluated on limited non-English samples and did not report performance metrics such as F1-score or recall disaggregated by language.

Another key limitation is the lack of temporal integrity. Many datasets are static and omit timestamped DNS resolution events, which inhibits modeling of concept drift, lifecycle transitions, and real-time detection scenarios. In contrast, enterprise DNS logs, although highly valuable due to their rich temporal and contextual metadata, are generally not publicly accessible due to privacy and compliance concerns-hindering reproducibility and benchmarking.

To systematically evaluate the strengths and limitations of widely used DGA datasets, we define six ideal properties based on prior work [1,19]:

• Family Diversity: Range of unique malware families covered.

• Annotation Granularity: Detail and richness of labeling, including behavior, source, or type.

• Contextual Metadata: Availability of DNS logs, TTLs, WHOIS info, etc.

• Entropy Spectrum Coverage: Inclusion of both high-entropy and word-based DGAs.

• Multilingual Support: Inclusion of domains generated using non-English dictionaries or Unicode scripts.

• Temporal Integrity: Presence of timestamped logs or data streams to support time-series modeling.

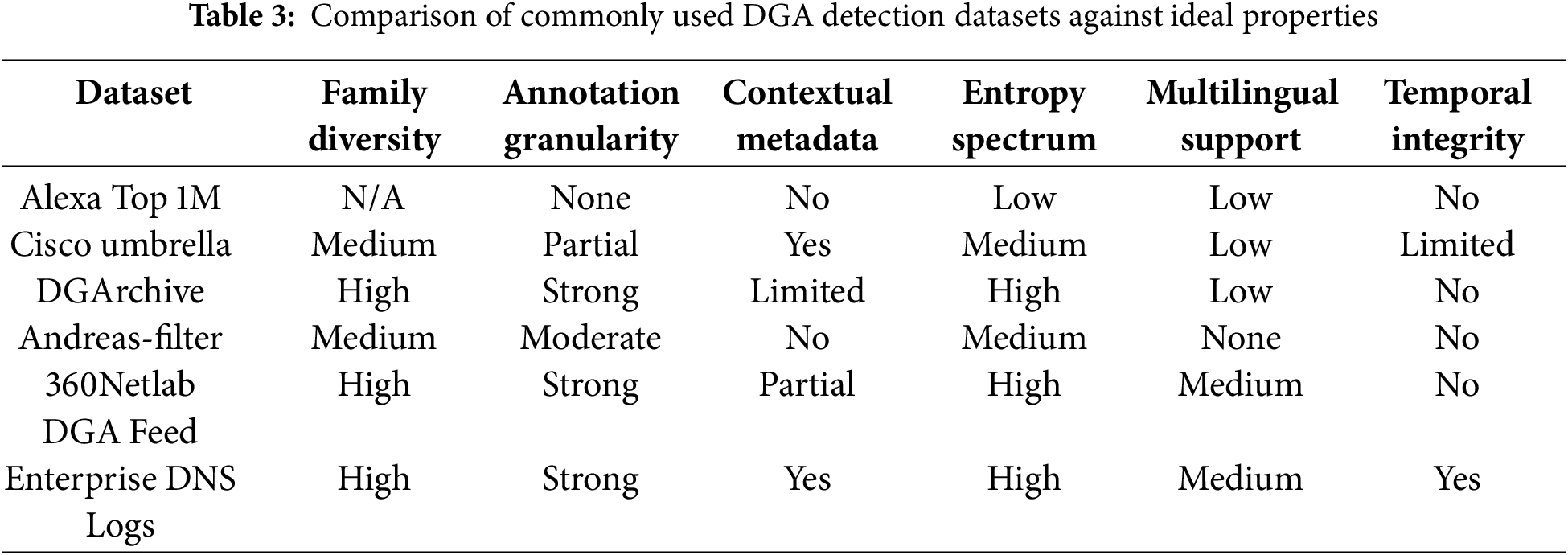

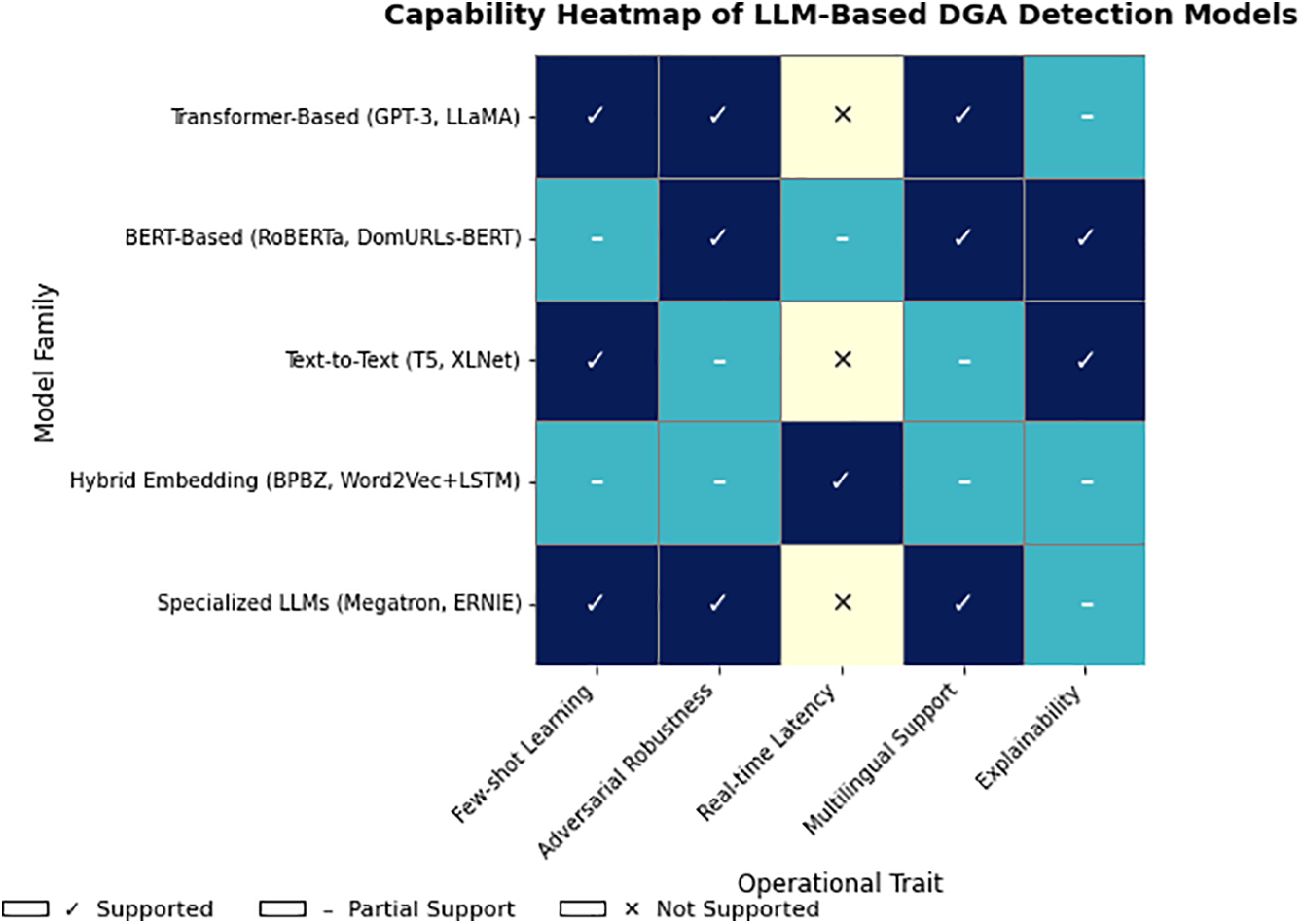

Table 3 presents a detailed comparison of representative datasets across these six dimensions.

As illustrated in Table 3 and visualized in Fig. 8, no single dataset fulfills all ideal characteristics. DGArchive, for example, scores high in family diversity and entropy range but lacks multilingual depth and timestamped resolution data. Cisco Umbrella offers partial metadata and moderate entropy, but its multilingual limitations and labeling inconsistencies reduce its utility for cross-regional evaluation. While enterprise DNS logs provide the most complete metadata and time fidelity, they remain inaccessible for most researchers, making them unsuitable for reproducible experiments.

Figure 8: Heatmap comparing prominent DGA detection datasets across six evaluation criteria: family diversity, annotation granularity, contextual metadata, entropy spectrum coverage, multilingual support, and temporal integrity

These deficiencies have practical consequences. LLMs trained on monolingual or structurally homogeneous datasets tend to overfit to English-centric or static patterns, resulting in degraded performance on region-specific DGAs and adversarially mutated domains. The lack of per-language evaluation metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-scores further obscures the true generalization capabilities of these models across geopolitical threat surfaces.

To move the field forward, we advocate for a community-driven benchmark initiative akin to GLUE or XTREME in NLP. This initiative should include:

• Multilingual domain samples, including those in Chinese, Arabic, Cyrillic, and other regional scripts;

• Time-resolved resolution logs to support temporal learning and lifecycle modeling;

• Adversarial variants crafted via obfuscation, mimicry, and wordlist permutation;

• And the adoption of standardized “Datasheets for Datasets” documentation to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and ethical compliance.

Additionally, future studies should report per-language performance metrics, and benchmark models against multilingual and time-sensitive variants to robustly assess their readiness for deployment in globally distributed DNS environments.

In conclusion, while existing datasets have catalyzed progress in DGA detection, their linguistic, behavioral, and temporal limitations present a critical barrier to scalable and inclusive defense systems. Addressing these gaps through comprehensive, well-annotated, and open-access datasets is essential to realizing the full potential of LLMs in cyber threat detection.

6 Capabilities and Limitations of LLMs in Detecting DGAs

LLMs have emerged as transformative tools for the detection of AGDs, surpassing traditional machine learning and rule-based methods in their capacity to model linguistic, contextual, and structural intricacies within domain strings. This section explores the nuanced capabilities of LLMs in this space and outlines the operational and theoretical challenges that must be addressed to enable real-world deployment [79–81].

6.1 Core Capabilities of LLM-Based DGA Detectors

LLMs—including GPT-3, RoBERTa, T5, and their distilled or hybrid variants—have redefined the landscape of AGD detection. These models utilize deep transformer architectures to capture long-range dependencies and contextual nuances within domain name sequences that traditional statistical or shallow learning methods often overlook. Unlike conventional detectors based on character entropy, vowel-consonant ratios, or n-gram features, LLMs leverage self-attention to uncover complex semantic patterns and adversarial anomalies, enabling more robust detection of dictionary-based or obfuscated DGAs [82,83].

A key strength of LLMs lies in their capacity for contextual pattern recognition. These models detect linguistic irregularities across subword tokens, learning discriminative features that generalize across malware variants. This is particularly critical in hybrid and dictionary DGAs, where domains mimic legitimate naming conventions to bypass heuristic filters [84,85].

Another defining capability is their generalization to zero-day DGAs. For example, LLaMA3, when fine-tuned using In-Context Learning (ICL) and Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), has demonstrated 94% classification accuracy and a false positive rate (FPR) of just 4% across 68 malware families [50]. RoBERTa and GPT-class models further enhance generalization under domain mutations, significantly outperforming traditional CNN or RNN classifiers on unseen threats.

Moreover, LLMs enable few-shot and zero-shot learning, offering adaptability in scenarios where labeled data is limited—such as in multilingual or emerging cybercrime regions. This reduces the burden of continuous retraining and makes LLMs highly suited for rapidly evolving threat landscapes [86].

Beyond classification, LLMs are increasingly equipped with explainability mechanisms via attention attribution, saliency mapping, and token-level heatmaps. As demonstrated in Lee et al. [87], these techniques visualize which substrings influenced predictions, enhancing interpretability for analysts and facilitating regulatory compliance in high-assurance environments.

A growing number of studies are now integrating LLMs into multi-modal detection pipelines by combining predictions with auxiliary telemetry such as WHOIS metadata, DNS temporal behaviors, and packet-layer features. These architectures reduce false positives and extend the context horizon beyond domain names alone, representing a shift toward security-aware and behaviorally-informed LLM usage [88].

Despite their advantages, a major operational challenge remains: inference latency and hardware cost. Full-scale models like GPT-3 and Megatron-LM report inference latencies between 190–350 ms per domain on A100 GPUs or TPUv4 clusters [89], rendering them infeasible for real-time DNS firewalls or edge deployments. Their resource demand prevents execution on constrained platforms like Raspberry Pi, Jetson Nano, or traditional DNS appliances without substantial model pruning or quantization.

To address this, lightweight LLM variants such as DistilBERT, BPBZ, and distilled T5 models have emerged. DistilBERT reduces inference latency by 40% over BERT, achieving 35 ms per domain on mid-tier CPUs while maintaining F1-scores above 0.84 in multilingual detection scenarios. Similarly, BPBZ—a hybrid model combining byte-pair encoding with LSTM layers—has demonstrated near real-time performance on edge devices such as Raspberry Pi 4B and Jetson Nano, albeit with slightly lower semantic accuracy.

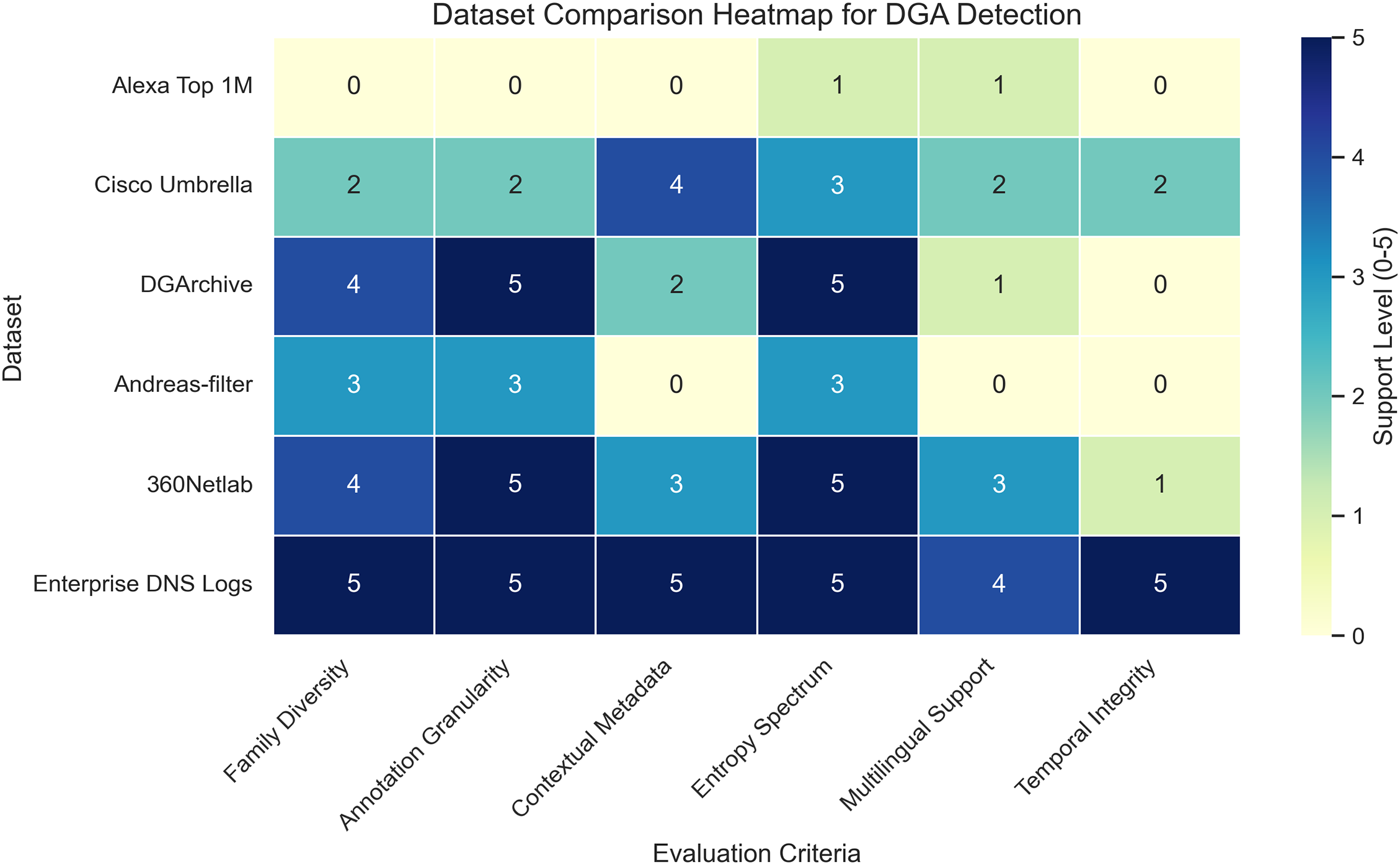

These performance trade-offs are systematically visualized in Fig. 9, which synthesizes the detection capabilities of LLM-based models across five operational dimensions: few-shot learning, adversarial robustness, multilingual generalization, real-time latency, and interpretability. Models such as RoBERTa and DistilBERT score well across most categories, while larger models like GPT-3, although semantically powerful, lag behind in latency-sensitive deployments.

Figure 9: Capability heatmap of LLM-Based DGA detection models. The heatmap visualizes the relative support of each model family across five core operational traits: few-shot learning, adversarial robustness, real-time latency, multilingual generalization, and explainability

To close the deployment gap, Table 2 provides updated comparative insights, including latency classes, throughput feasibility, accuracy, FPR, and AUC metrics. This responds directly to calls for more standardized benchmarking in LLM evaluation. Still, many studies fail to report hardware-specific latency or throughput under practical constraints-highlighting the need for unified benchmarking frameworks that encompass detection effectiveness and real-world viability.

In summary, while LLMs introduce transformative capabilities for DGA detection-spanning contextual inference, low-shot generalization, and model transparency-their practical adoption hinges on addressing computational bottlenecks. Continued research into model compression, hardware-aware training, and security-integrated LLM pipelines will be essential for achieving scalable, deployable, and interpretable DGA defense systems.

6.2 Operational and Technical Challenges in LLM-Based Detection

While LLMs have demonstrated promising capabilities in detecting algorithmically generated domains (DGAs), their effective deployment in real-world cybersecurity environments is hindered by several critical challenges. One of the most persistent issues is the scarcity of high-quality, representative, and labeled datasets. Existing datasets often concentrate on a limited subset of well-known DGA families and exhibit significant class imbalance, with benign domains vastly outnumbering malicious ones. This imbalance skews model learning, often resulting in overfitting to dominant classes and degraded performance on rare, stealthy, or zero-day DGA variants. Furthermore, many publicly available corpora fail to reflect the linguistic diversity and adversarial sophistication of modern malware, making it difficult to develop LLMs that generalize across global threat landscapes [90,91].

Interpretability is another major barrier to the operationalization of LLMs in security-critical applications. Despite recent efforts to integrate attention visualizations and attribution techniques such as Integrated Gradients and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP), most LLMs remain inherently opaque. Their outputs are often not accompanied by human-interpretable explanations, limiting their acceptance in environments where analysts must understand and justify model decisions before taking remedial action. This lack of transparency impedes the adoption of LLMs in incident response workflows and erodes trust among operators and stakeholders [89,92,93].

Equally pressing are the computational and latency constraints associated with deploying large-scale models like GPT-3, Megatron-LM, or T5 in real-time settings. These models demand substantial processing power and memory, which precludes their integration into low-latency systems such as DNS resolvers, firewalls, or edge-based security appliances. Our extended analysis (as reflected in Section 6.1 and Table 2) reveals that inference latency for these models can range from several hundred milliseconds to seconds per query, depending on hardware configuration—far exceeding the sub-50ms window required for inline DNS filtering on typical server-class CPUs or ARM-based edge processors. While lightweight variants such as DistilBERT and TinyGPT offer more promising inference times (e.g., 20–50 ms on mid-range CPUs), they often do so at the cost of reduced detection fidelity. This highlights the need for cascaded architectures and hardware-aware optimizations to balance speed and accuracy in production deployments [94].

Adversarial robustness is another underdeveloped area in current LLM-based DGA detection research. Modern DGAs increasingly adopt evasion strategies such as homograph substitution (e.g., replacing ‘o’ with ‘0’), character permutation, dictionary hybridization, and unicode spoofing-all designed to confuse pattern-based classifiers. Despite their capacity to model complex sequences, LLMs remain vulnerable to such perturbations unless explicitly trained to recognize them. Our review identifies a critical lack of standardized adversarial benchmarks and training pipelines tailored to DGA-specific attacks. As discussed in Section 8, strategies like adversarial domain augmentation, ensemble filtering, and confidence calibration are essential to improve robustness, but their adoption remains limited and non-uniform across existing studies [95].

Finally, LLMs often inherit biases from their training data. Many are fine-tuned on corpora dominated by English-language domains or malware families prevalent in North American or European threat reports. This results in poor generalization to regional DGAs, especially those generated using non-English wordlists, culturally specific tokens, or stealthy linguistic constructs. As a result, LLMs may misclassify multilingual or novel DGAs that diverge from the statistical priors encoded during training. This bias not only impairs detection coverage but also raises equity concerns, particularly for under-resourced threat intelligence operations in the Global South [96,97].

In conclusion, while LLMs offer considerable potential for enhancing DGA detection, their practical utility hinges on overcoming challenges related to dataset quality, model interpretability, computational efficiency, adversarial robustness, and linguistic bias. Addressing these limitations through interdisciplinary advances in model architecture, dataset engineering, and evaluation methodology is essential to realizing the vision of scalable, transparent, and resilient LLM-powered defenses against evolving cyber threats.

7 Comparative Review of Recent LLM-Driven DGA Detection Approaches

Recent advancements in the use of LLMs for DGA detection have demonstrated notable improvements in adaptability, generalization, and accuracy across various architectural classes. This section synthesizes key research developments according to the proposed taxonomy: Transformer-Based, BERT-Based, Text-to-Text Transformers (T5 family), Hybrid Models, and Specialized Models. For each category, we present a summary of representative studies, datasets used, performance metrics, and architectural advantages.

7.1 Transformer-Based Architectures

Transformer-based architectures have established themselves as foundational models in both natural language processing and cybersecurity, due to their ability to model long-range dependencies, perform contextual representation learning, and scale across large, heterogeneous datasets. Their self-attention mechanisms make them particularly well-suited for the detection of algorithmically generated domains (DGAs), which often combine syntactic irregularity with semantic mimicry. This subsection synthesizes the evolution of transformer-based models for DGA detection, with a particular focus on architectural innovations, deployment constraints, and recent additions of lightweight alternatives for edge-device feasibility.

La et al. [50] fine-tuned the Meta LLaMA3-8B model using both In-Context Learning (ICL) and Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) on a multi-family malware dataset containing 68 DGA variants. The model achieved 94% accuracy and a false positive rate (FPR) of 4%, demonstrating strong generalization to morphologically complex domains. However, performance was closely tied to the availability of high-quality labeled data-a recurring constraint across LLM-based detection studies. Aravena et al. [98] focused on lexical and semantic similarity through Dom2Vec, improving accuracy across 25 malware families, but their static embedding framework proved less effective in streaming or zero-day DGA scenarios.

Domain-specific applications further exemplify the versatility of transformer models. Gulserliler et al. [22] developed a transformer classifier tailored to financial services traffic, achieving 96.2% accuracy in binary classification. However, scalability to multilingual environments and unseen domains remained a challenge. Rao et al. [99] proposed a hybrid BERT-RNN framework, which combined bidirectional attention with sequence memory for enhanced detection accuracy. While outperforming traditional models, this architecture struggled against adversarial manipulations such as homograph attacks or token substitution.

Beyond domain classification, Alshomrani et al. [100] and Lykousas and Patsakis [101] demonstrated transformer effectiveness in broader cybersecurity contexts, including zero-day malware detection and secret leakage prevention. These studies underscore the cross-domain adaptability of transformers but also point to a common limitation-computational inefficiency for real-time and resource-constrained environments.

Hemmati et al. [60] presented a systematic review of optimization strategies such as weight pruning, quantization, and multi-head attention reduction, all aimed at improving transformer deployment in latency-sensitive DNS infrastructure. These findings align with the growing interest in compact variants such as MobileBERT [102], DistilBERT [103], and TinyGPT [104], which significantly reduce inference time and memory usage while retaining acceptable classification performance. These models fit within the “Transformer-Based Architectures” family as efficiency-optimized derivatives rather than architecturally distinct categories. For instance, DistilBERT has been validated in real-world streaming text classification tasks [105], and TinyGPT variants have shown promise in automation and control applications [106].

Architectural enhancements have also expanded model flexibility. Ding et al. [107] proposed a dual-input transformer combining character-level and bigram embeddings, which improved classification on the ONIST dataset but remained sensitive to class imbalance. Zhai et al. [108] integrated contextual embeddings with graph structures in their AGDB model, achieving notable gains in detecting dictionary-based DGAs. Rudd et al. [109] extended transformer application to raw InfoSec data, demonstrating end-to-end training viability on URLs and binaries-though this came at the cost of high inference latency.

Pellecchia [110] and Liu [111] applied transformers in domains such as medical transcription and compliance automation. While outside cybersecurity, their findings reinforce transformers’ robustness in handling noisy, irregular input-analogous to obfuscated DGAs.

Despite their strength, transformer models continue to face deployment barriers. High parameter counts, inference latency, and memory consumption limit their integration into real-time systems, particularly at the edge. Furthermore, only a minority of studies explicitly evaluated adversarial robustness, multilingual adaptability, or privacy-preserving inference-critical factors for production-scale cybersecurity operations.

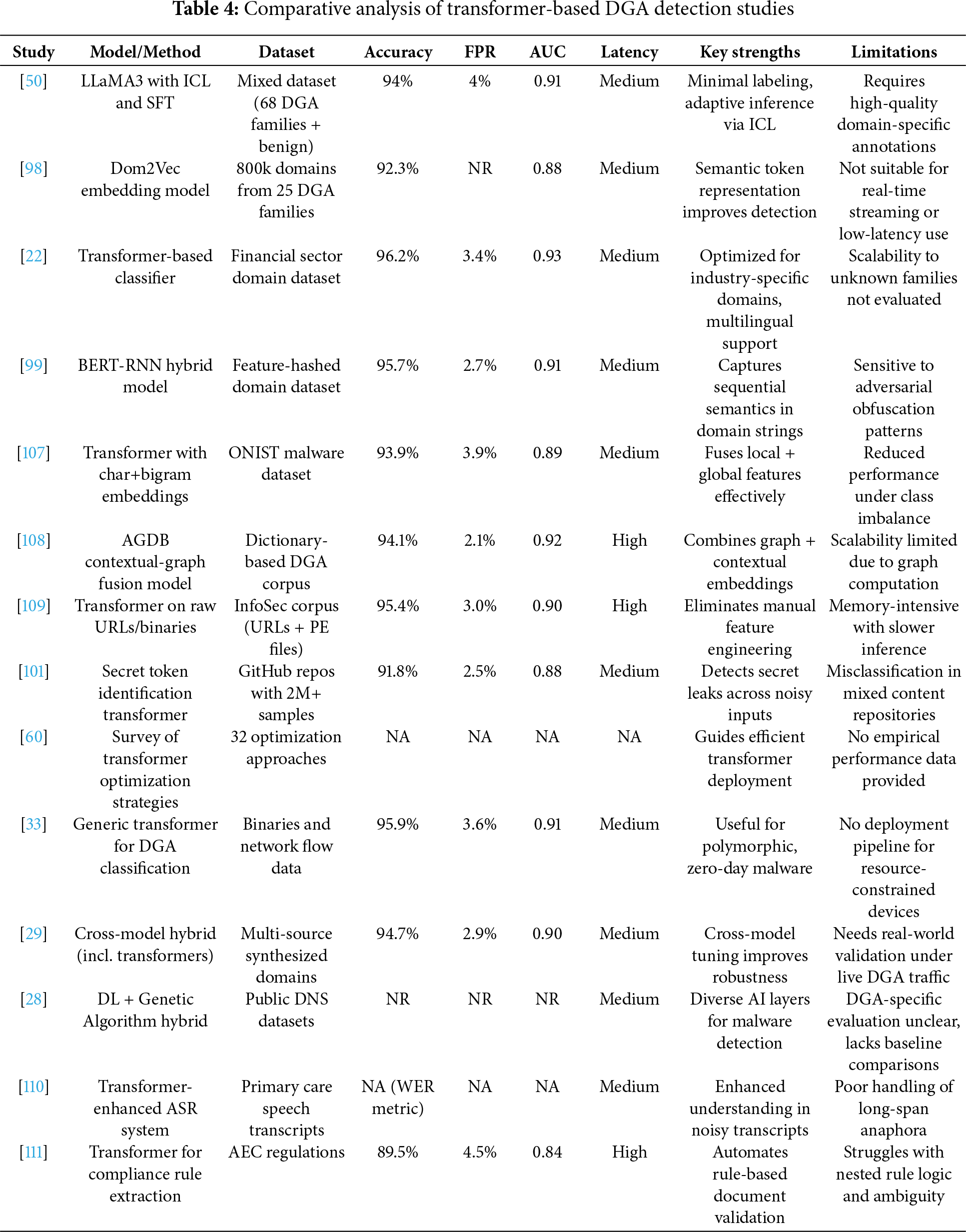

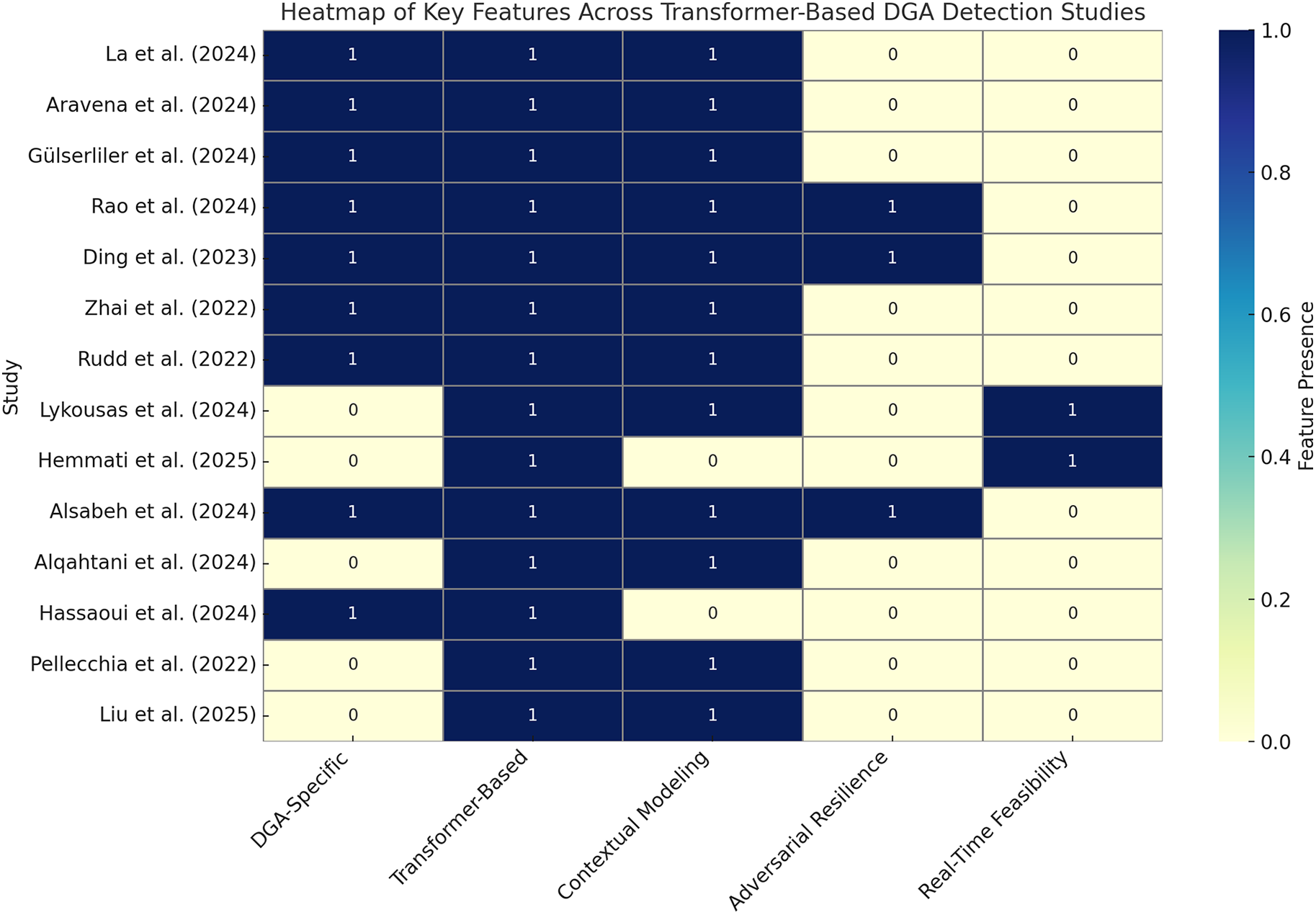

Table 4 summarizes empirical results across transformer-based studies, highlighting detection performance, dataset scope, and system-level trade-offs. Lightweight variants like TinyGPT and DistilBERT are gaining traction for their ability to balance latency, accuracy, and resource use. Meanwhile, Fig. 10 visualizes the methodological attributes of each approach, underscoring gaps in adversarial defense and low-resource deployment readiness.

Figure 10: Heatmap illustrating the presence of key research attributes across transformer-based DGA detection studies. Attributes include DGA-specific focus, use of transformer models, support for contextual modeling, adversarial robustness, and feasibility for real-time deployment [22,28,29,33,50,60,98,99,101,107–111]

In conclusion, transformer-based architectures, including both full-scale and compact variants, represent a promising foundation for next-generation DGA detection systems. While most studies achieve high detection accuracy, future work should focus on adversarial training, lightweight optimization, and benchmarking under realistic, multilingual, and latency-bound conditions. Recognizing the emergence of efficient transformer variants within this category allows for practical deployment without restructuring the overarching taxonomy, while still meeting the operational demands of cybersecurity at scale.

7.2 BERT and Encoder-Only Models

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) have fundamentally reshaped the landscape of natural language understanding by introducing bidirectional attention mechanisms that capture both left and right contexts in input sequences. This contextual depth has made BERT-based models particularly well-suited for cybersecurity tasks involving subtle, linguistically camouflaged domain names-such as those produced by dictionary-based or adversarial DGAs. In recent years, several studies have leveraged BERT and its derivatives to address the unique challenges of AGD detection, including multilingual generalization, adversarial robustness, privacy preservation, and detection under low-data regimes.

Mahdaouy et al. [8] introduced DomURLs_BERT, a multilingual, domain-focused BERT model trained on large-scale URL corpora using masked language modeling. Their work demonstrated superior classification performance in both binary and multiclass settings across a range of cyber threats—including DGAs and phishing attacks—outperforming traditional deep learning baselines. Notably, DomURLs_BERT showed promising generalization in multilingual settings; however, its efficacy declined for underrepresented scripts and low-resource languages, highlighting the need for ongoing fine-tuning.

In contrast, Guan et al. [44] explored BERT’s limitations through WCDGA, an adversarial domain generator capable of evading detection by manipulating token-level semantics using BERT-inspired perturbations. Their findings underscore the vulnerability of even well-trained BERT classifiers when confronted with high-frequency, semantically valid but malicious domain constructs. This emphasized the need for robust adversarial training and the development of detection pipelines resilient to such evasive inputs.

From a privacy-preserving perspective, Maia et al. [112] integrated BERT into a secure detection framework employing multi-party computation (MPC) and differential privacy (DP). Their approach ensured that sensitive DNS traffic could be processed securely without direct exposure, achieving up to a 42% reduction in inference latency post-quantization. However, the cryptographic overhead of MPC remains a limiting factor for real-time DNS applications, particularly in edge environments.

Recognizing the computational demands of standard BERT models, recent research has explored lightweight BERT derivatives for resource-constrained deployments. Yao et al. [113] introduced FedSpine, a novel Federated Learning framework that enables efficient deployment of LLMs on resource-constrained devices by combining structured pruning and Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) using LoRA. To handle the challenges of device heterogeneity and limited resources, FedSpine adopts an iterative pruning and tuning strategy and employs a Multi-Armed Bandit algorithm to dynamically assign optimal pruning ratios and LoRA ranks to each device. This adaptive process reduces memory and latency demands while maintaining high inference accuracy. Experiments across 80 diverse devices show FedSpine achieves 1.4

Beyond detection, Liu et al. [115] enhanced cybersecurity entity recognition through semantic feature augmentation in BERT, thereby enabling deeper integration of AGD detection with broader threat intelligence pipelines. Meanwhile, Cao et al. [116] and Gregorio et al. [18] demonstrated that hybridizing BERT embeddings with traditional classifiers-such as decision trees and random forests-can yield performance gains and lower false positive rates. Despite this, their approaches required repeated tuning for new threat types and showed limitations in high-volume, real-time streams.

Addressing low-data detection scenarios, Wang et al. [117] introduced a novel framework combining TextCNN with EVT-calibrated autoencoders to improve generalization to unknown DGA families. While not BERT-based directly, the framework tackled one of BERT’s key limitations: its susceptibility to overfitting on known DGA classes. Similarly, Zhao et al. [118] developed the BPBZ framework using byte-pair encoding and Word2Vec for improved token-level feature segmentation-further validating the effectiveness of subword modeling strategies foundational to BERT.

Complementary work by Pes [119] and Fohr and Illina [120] applied BERT to noisy and semi-structured data inputs in non-cybersecurity domains, such as invoice parsing and speech recognition, respectively. Their findings suggest that BERT architectures are robust to structural irregularities-a characteristic that translates well to the erratic composition of many AGDs.

For low-data regimes, Huang et al. [121] proposed PEPC, a CNN-based pipeline that integrated pre-trained embeddings to deliver strong DGA detection results using as few as 30 labeled samples per class. This reinforces the value of embedding reuse and pre-training strategies central to BERT. Fan et al. [40] advanced this further through a knowledge distillation-based framework, mitigating class imbalance and catastrophic forgetting in dynamic threat environments-a common challenge when deploying BERT on long-tailed DGA distributions.

A critical meta-review by Cebere et al. [19] highlighted methodological fragilities in existing detection pipelines, including overreliance on static character-based assumptions. They caution that BERT-based models, despite their promise, require validation under live DNS traffic conditions to ensure operational robustness.

Finally, several studies proposed complementary optimization techniques to enhance BERT’s adaptability. Ren et al. [122] applied continual learning to support incremental threat updates, while Niu et al. [123] utilized Bayesian hyperparameter tuning to improve generalization. Both approaches offer viable paths for maintaining detection accuracy in dynamic AGD environments without extensive retraining.

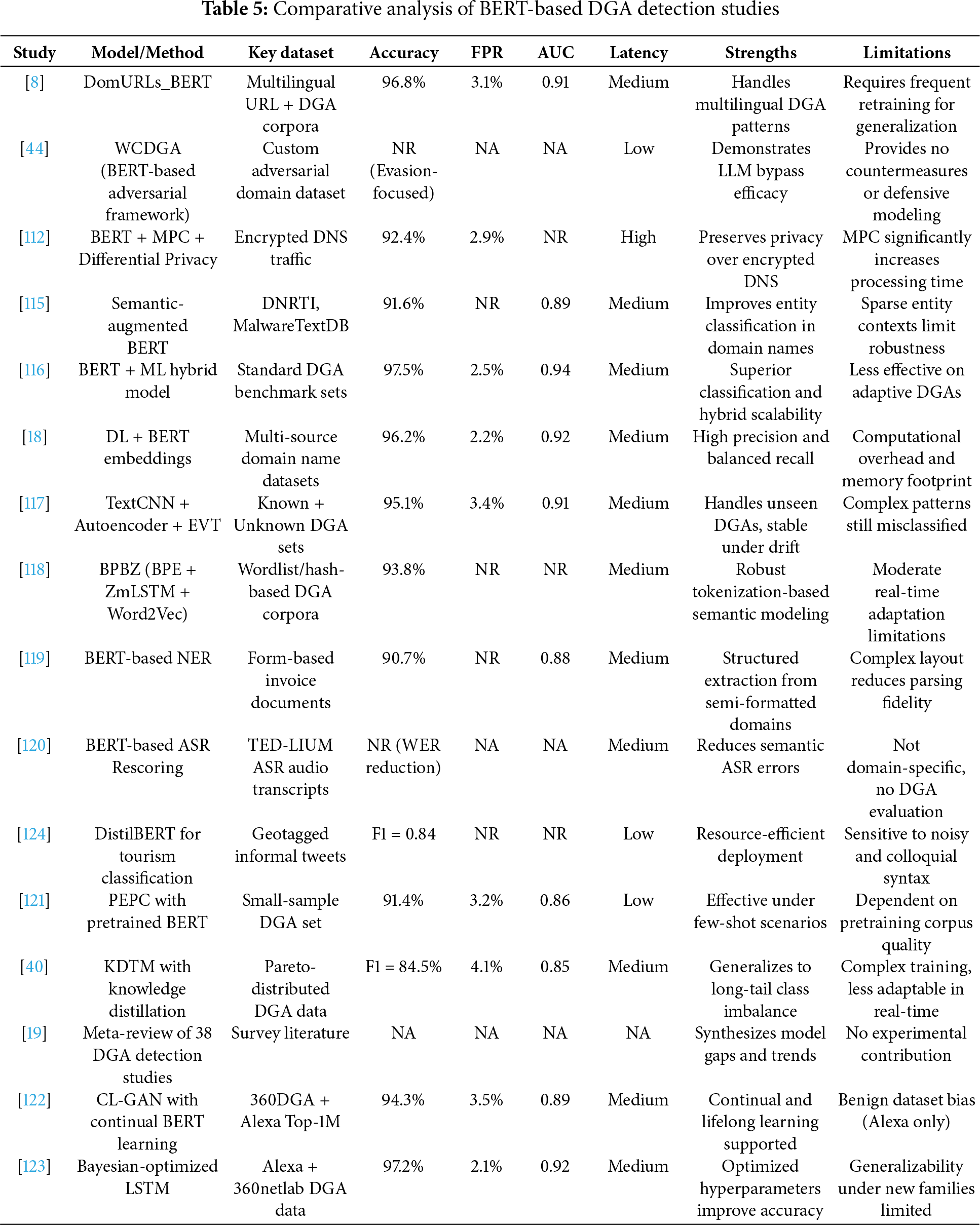

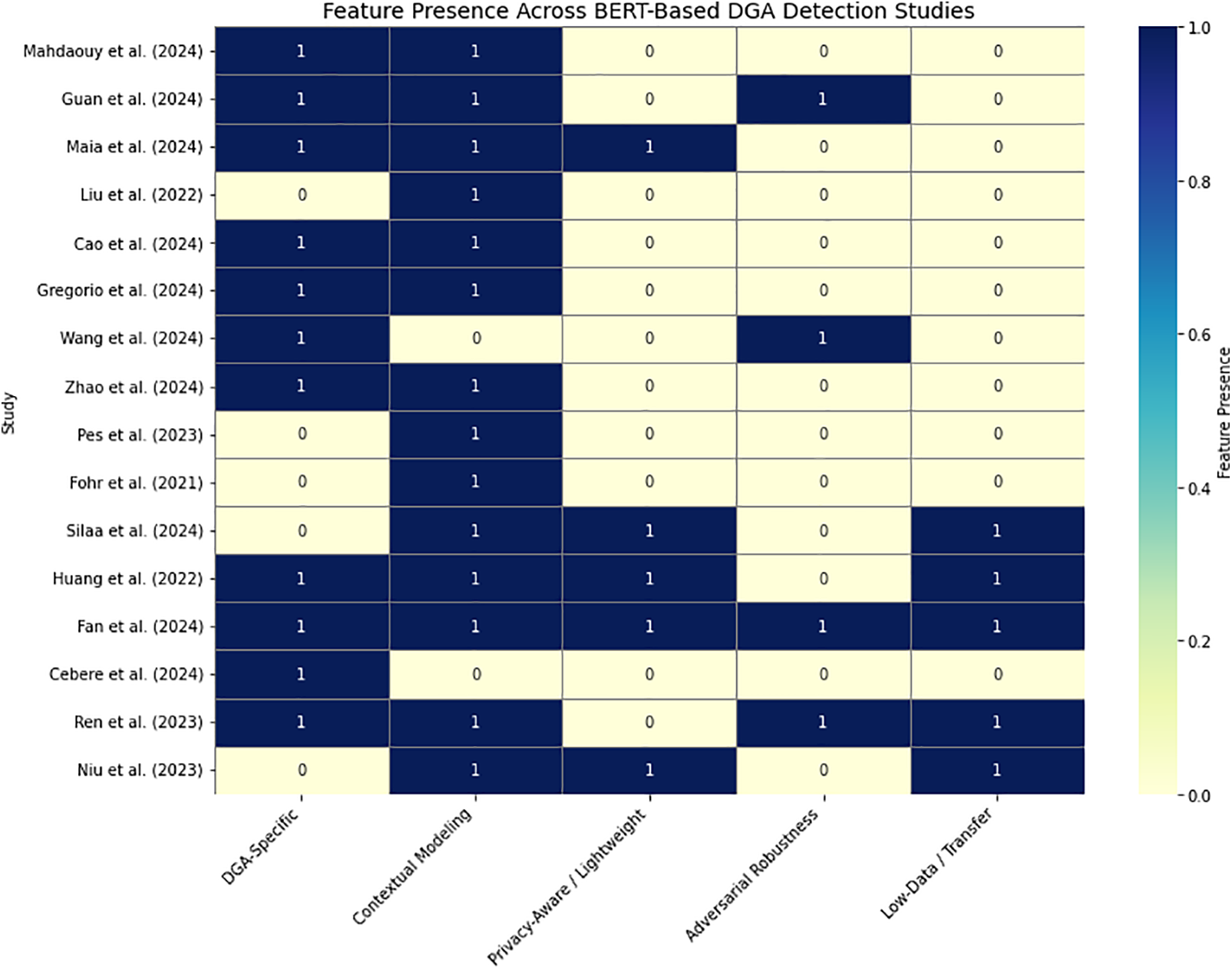

Collectively, BERT-based models—including their distilled and mobile variants—have proven effective in modeling both the semantic and structural irregularities of AGDs. As summarized in Table 5, these models demonstrate strong adaptability across multilingual datasets, privacy-aware contexts, and adversarial settings. However, key limitations persist-especially in real-time scalability, generalization to novel threats, and robustness against obfuscation tactics. Fig. 11 illustrates the methodological strengths and coverage gaps across surveyed studies, emphasizing that while contextual modeling is well-addressed, privacy-preserving deployment, adversarial defense, and low-resource learning remain active areas for future research. Addressing these challenges—including deeper evaluation of lightweight BERT architectures—will be essential to fully realize the operational potential of BERT-based DGA detection systems.

Figure 11: Heatmap showing the presence of key methodological features across BERT-based DGA detection studies. Features include contextual modeling, adversarial robustness, low-data adaptation, privacy-aware architectures, and DGA-specific focus [8,18,19,40,44,112,115–124]

7.3 Text-to-Text Transformer Frameworks

Text-to-text transformers, exemplified by the T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) architecture, offer a flexible generative paradigm by reframing every natural language processing task-classification, summarization, translation—as a unified sequence-to-sequence generation problem. This generality opens new frontiers in cybersecurity, particularly in DGA detection, where the obfuscation of lexical patterns, emergence of zero-day variants, and semantic mimicry make rigid, rule-based systems less effective. While the direct application of T5 to DGA detection remains limited in the current literature, several recent studies in related domains highlight the transformative potential of text-to-text transformers in addressing key challenges such as adversarial robustness, few-shot adaptability, and explainability-three pillars critical to real-world cybersecurity deployment.

Galloway et al. [125] emphasized the fragility of existing DNS reputation systems by simulating adversarial attacks capable of achieving 100% evasion. Although their model did not explicitly utilize T5, their generative approach to simulating adversarial domains aligns well with the strengths of T5-style models, particularly in generating hard negative examples for adversarial training. Their work underlines the necessity for models that go beyond static classification and incorporate generation-driven understanding of threat surfaces—a gap T5 models are uniquely positioned to address.

In a complementary study, Garg et al. [126] explored hybrid classification pipelines that fused machine learning and deep learning using structured domain representations mined from SERPs and DMOZ taxonomies. While not generative in architecture, their work reflects a data-to-text transformation philosophy wherein structured inputs are translated into semantic output mappings-an approach that T5 inherently operationalizes with less reliance on handcrafted features. Their system achieved high accuracy on structured datasets (98.37%), underscoring the merit of mapping-based learning.

Chhun et al. [127] contributed a meta-evaluation of large language models on narrative generation tasks using the HANNA corpus. They revealed that LLMs surpassed traditional BLEU-based scoring but lacked interpretability. This finding bears direct relevance for DGA detection: the opacity of LLM decisions is a critical bottleneck in cybersecurity. T5 models, with their attention mechanisms and token-level generation outputs, offer the potential to bridge performance and explainability by exposing why a domain is deemed malicious at an interpretable level.

Ma et al. [128] introduced a CLG framework that improves classification under few-shot conditions. Their approach aligns semantically rich label representations with input domains, enabling performance improvements in scenarios with limited labeled data. T5 models, with pretraining on vast textual corpora and strong generalization, are particularly well-suited to this kind of label-alignment learning. As DGA families often lack balanced training data, few-shot solutions such as CLG offer promising adaptation strategies for future T5-based deployments.

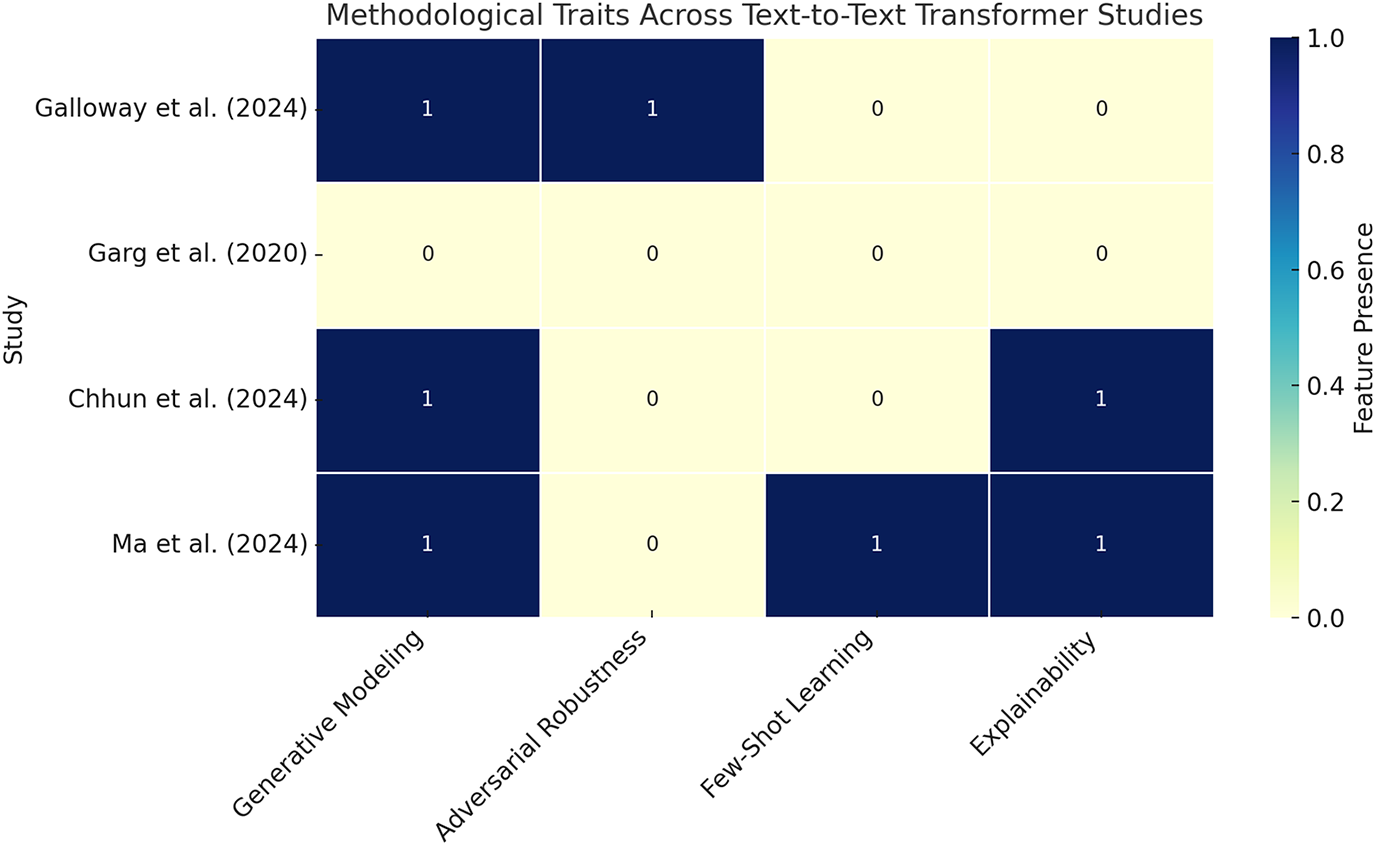

These studies collectively provide a foundation for exploring T5 in cybersecurity, particularly for DGA detection tasks requiring adaptability, explainability, and robustness. Fig. 12 summarizes the methodological coverage across these works using a heatmap. Four critical dimensions—generative modeling, adversarial robustness, few-shot learning, and interpretability—are evaluated for each contribution. While Galloway et al. lead in adversarial simulation, and Ma et al. advance few-shot explainability, none fully operationalize all four dimensions, underscoring an opportunity for text-to-text models like T5 to unify these research vectors.

Figure 12: Heatmap showing the presence of core research traits across studies relevant to text-to-text transformers in cybersecurity. Features include generative modeling, adversarial defense, few-shot generalization, and explainability-core components necessary for T5-style DGA detection [125–128]

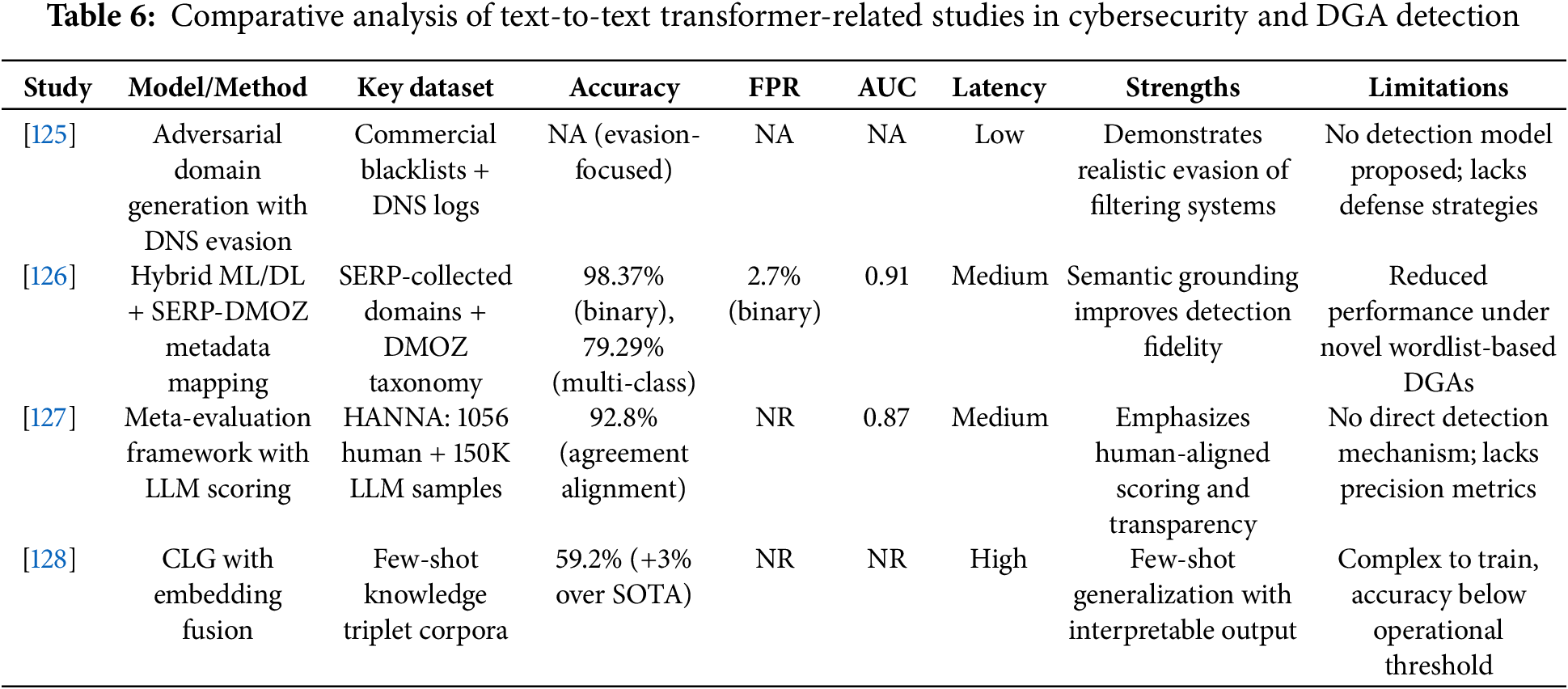

Table 6 provides a comparative synthesis of these studies, highlighting their dataset scope, methodological innovations, and operational trade-offs. As shown, while generative and adversarial modeling capabilities are present in isolation, future work should pursue fully integrated T5-based pipelines capable of generating, detecting, and explaining domain threats in real-time settings. Targeted fine-tuning on multilingual DGA datasets, alignment with security metadata (e.g., WHOIS, DNS query patterns), and adoption of contrastive pretraining objectives could significantly enhance T5’s suitability for next-generation DGA detection systems.

In summary, although direct T5 applications to DGA detection remain underexplored, the foundational principles demonstrated by recent generative and contrastive frameworks suggest strong alignment. The generative nature of T5, its capacity for multitask adaptation, and explainability via attention visualization make it a compelling candidate for adversarially robust, multilingual, and few-shot-capable DGA defense systems. Future research should focus on evaluating T5 across multilingual datasets, enhancing robustness to adversarial perturbations, and aligning generative outputs with cybersecurity ontologies for operational transparency and auditability.

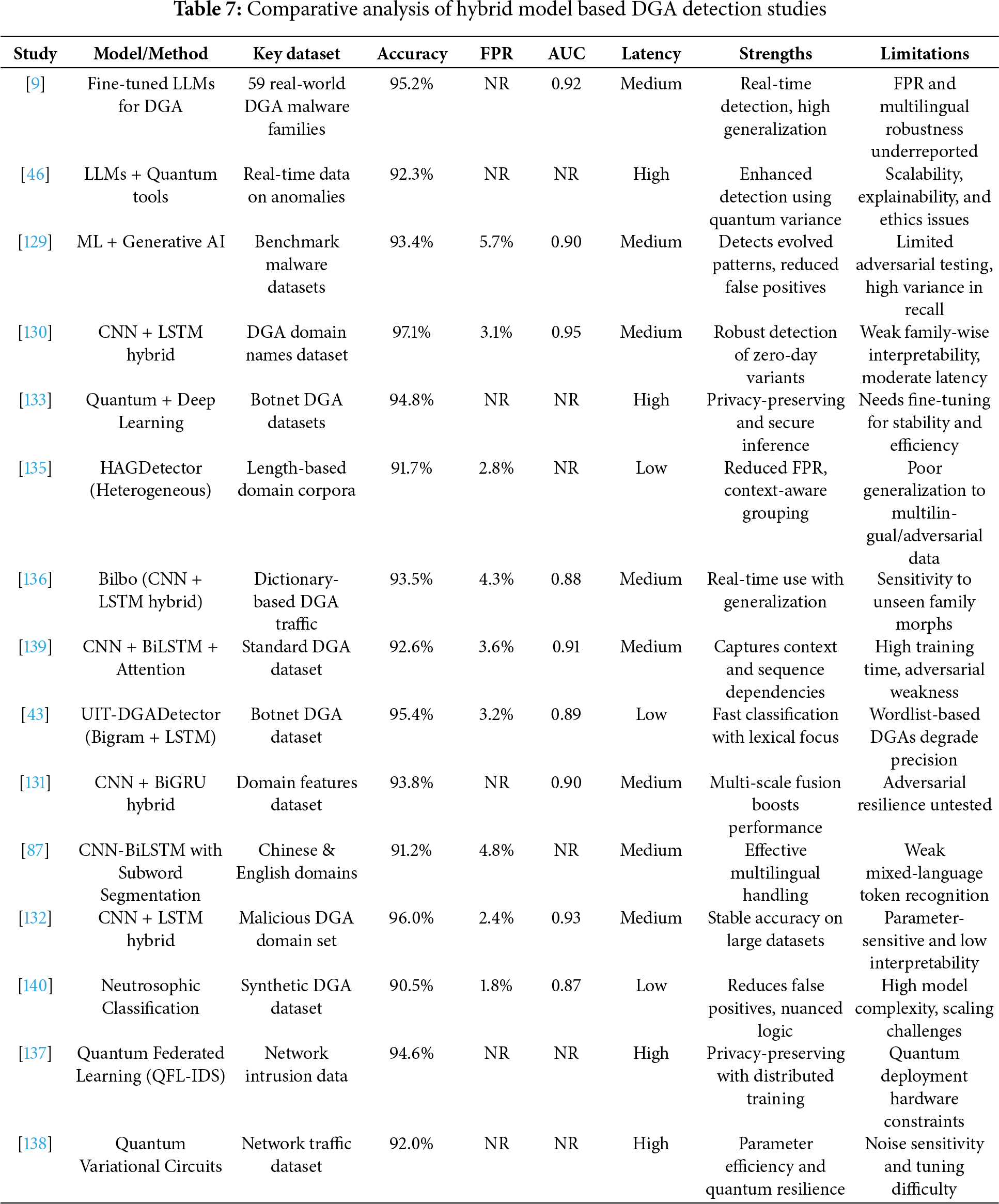

7.4 Hybrid and Ensemble Learning Approaches

Hybrid models have emerged as a potent solution to the multifaceted challenges of DGA detection by combining diverse paradigms—classical machine learning, deep learning, LLMs, quantum computing, and privacy-preserving mechanisms. These models aim to balance detection accuracy with interpretability, robustness, and operational feasibility. Unlike single-paradigm approaches, hybrid models are designed to leverage the complementary strengths of their constituent components—e.g., the contextual sensitivity of transformers, the temporal modeling capability of RNNs, and the low-latency footprint of classical classifiers.

Recent studies have made considerable strides in this domain. Sayed et al. [9] demonstrated that fine-tuned LLMs, when exposed to a broad corpus of both benign and malicious domains, significantly improve detection rates-particularly for zero-day DGA variants. However, while they report enhanced recall, metrics such as FPR or AUC were not fully disclosed, limiting interpretability for real-time deployment where low false positives are critical.

Ajimon and Kumar [46] integrated LLMs with quantum-enhanced mechanisms to improve generalization in zero-day detection scenarios. Their study presents promising gains in detection accuracy but acknowledges scalability and ethical challenges associated with quantum computing. Importantly, neither precision-recall curves nor false positive rates were disclosed-highlighting a recurring limitation in the literature.

In response to concerns about overemphasis on accuracy, we emphasize that performance comparisons for hybrid models must go beyond raw accuracy. For example, Ankalaki et al. [129] report high accuracy and F1-score, but omit FPR and AUC-two metrics vital for operational deployment in DNS-based security systems. Similarly, Biru and Melese [130], Luo et al. [131], and Qi and Mao [132] present CNN-RNN hybrids with competitive accuracy, yet fail to report how those models behave under class imbalance or adversarial inputs, leaving their robustness underexplored.

Privacy-preserving hybrid designs have also gained traction. Suryotrisongko and Musashi [133,134] proposed quantum deep learning pipelines with differential privacy guarantees. While showing promising accuracy and privacy-preservation trade-offs, they did not provide detailed PR curves or FPR, making real-world feasibility assessments difficult.

Furthermore, Liang et al. [135] and Highnam et al. [136] introduced domain-specific adaptations like heterogeneous grouping and dictionary-aware mechanisms, improving detection on specific DGA types. These models reported false positive reductions but lacked AUC reporting, which limits the assessment of classification threshold sensitivity.

Emerging work by Abou et al. [137] and Moll and Kunczik [138] emphasizes privacy-aware and scalable architectures using quantum federated learning and variational circuits. Although these approaches align with ethical AI principles and network-level deployment, metrics like precision-recall trade-offs and latency benchmarks remain scarce.

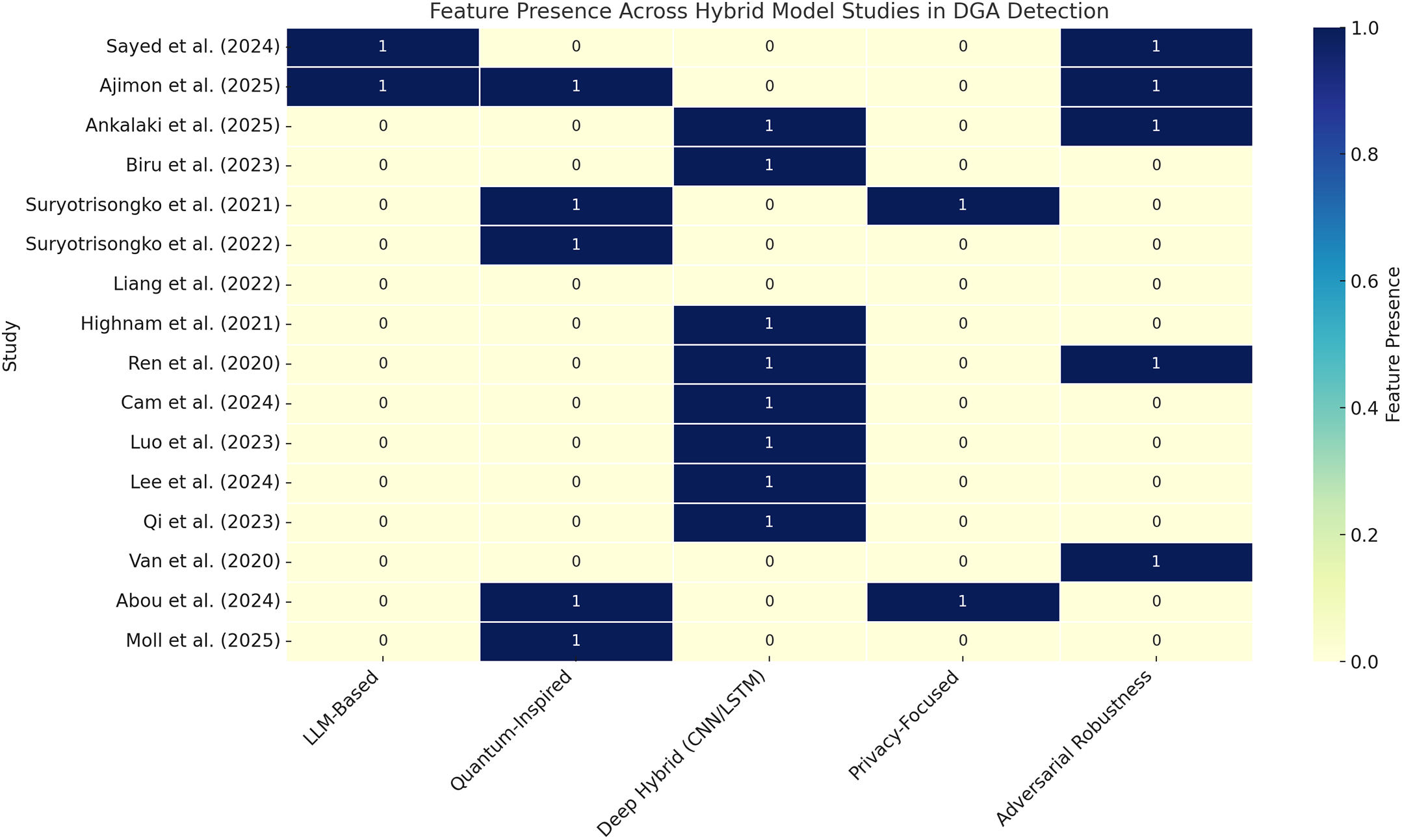

Fig. 13 complements this analysis by mapping methodological diversity across LLM integration, quantum components, deep hybrid learning, privacy, and adversarial robustness. While many models excel in one or two areas, very few (if any) address all operational constraints comprehensively-especially those related to precision, FPR, and latency.

Figure 13: Feature presence across hybrid model studies in DGA detection. The heatmap illustrates methodological diversity across studies based on five key traits: LLM integration, quantum inspiration, deep hybrid modeling (e.g., CNN + LSTM), privacy preservation, and adversarial robustness [9,43,46,87,129–140]

As shown in Table 7, while hybrid models demonstrate effectiveness in tackling zero-day threats and improving detection accuracy, their overall operational readiness remains hindered by inadequate reporting of false positives, lack of PR curve analysis, and incomplete benchmarking. Future studies must integrate holistic evaluations including AUC, latency, and interpretability alongside accuracy and F1 score to support deployment in real-world DNS defense systems.

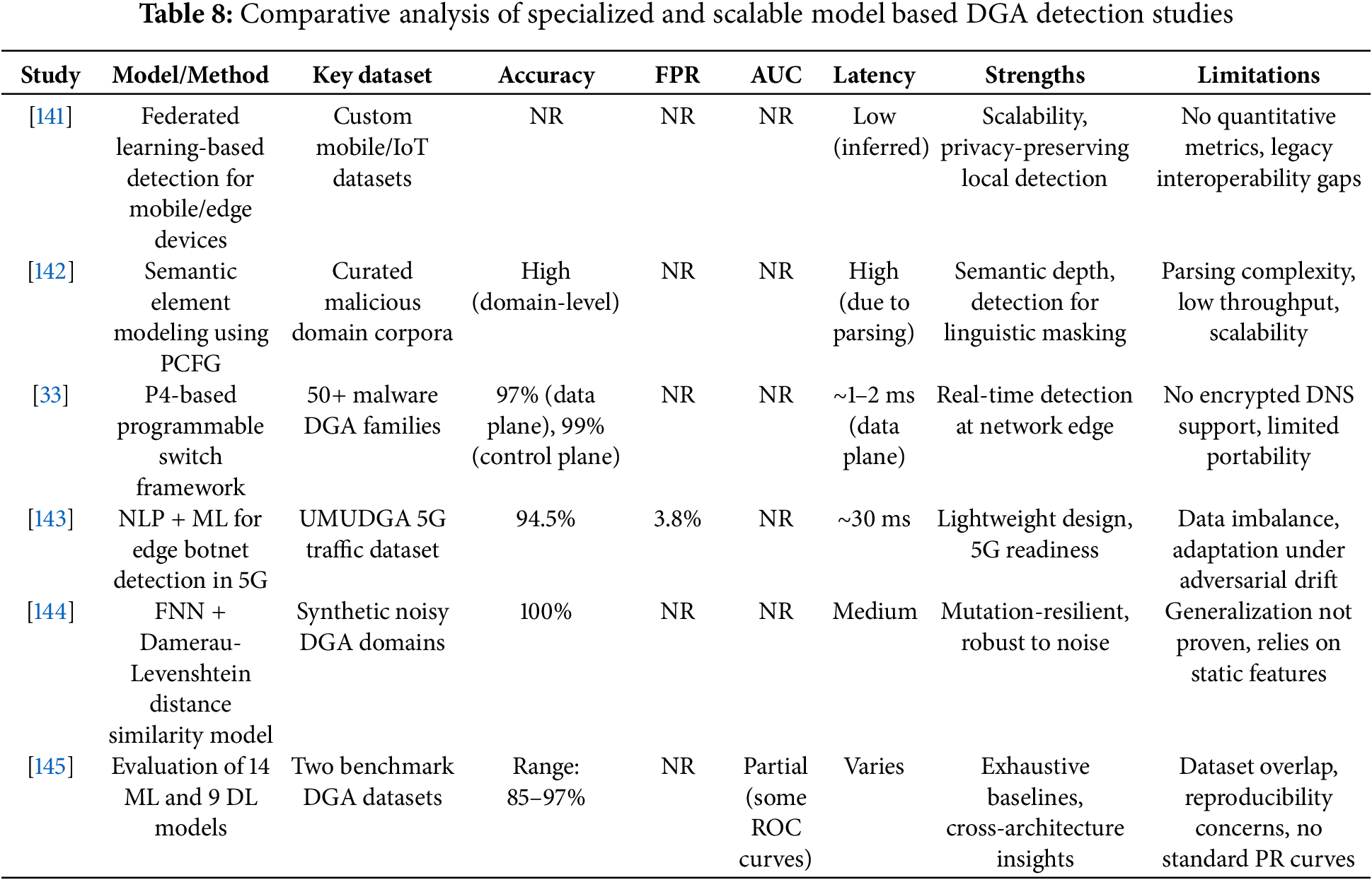

7.5 Resource-Constrained and Scalable Deployments

The rapidly evolving threat landscape of algorithmically generated domains (DGAs) necessitates detection systems that are not only accurate but also optimized for scalability, latency, edge deployment, multilinguality, and resilience under encryption and adversarial noise. Specialized and scalable models address these operational imperatives through tailored architectural innovations, lightweight inference designs, and integration with programmable or federated infrastructures.

Zago et al. [141] were among the first to demonstrate a federated learning-based DGA detection model, optimized for mobile and IoT networks. By decentralizing model training to local edge devices, their approach achieved notable gains in privacy preservation and energy efficiency. However, they did not provide quantitative evaluation metrics such as false positive rates or AUC, which are critical for operational viability. Additionally, interoperability challenges with legacy DNS systems and inconsistent detection across heterogeneous devices were noted as deployment hurdles.

Alsabeh et al. [33] addressed latency and throughput concerns by deploying a dual-path DGA detection framework over P4-based programmable switches. Their system achieved 97% accuracy at the data plane and 99% at the control plane. While highly efficient in high-speed networks, the approach does not support encrypted DNS traffic (e.g., DNS-over-HTTPS), nor does it address FPR or precision-recall dynamics, which are essential for mitigating collateral damage in production systems.

Semantic interpretability was central to Yang et al. [142], who introduced a grammar-driven framework that categorized domain elements into strong, weak, and zero-semantic tokens using probabilistic context-free grammars (PCFGs). This granularity enabled high detection accuracy for linguistically masked DGAs. However, the model’s parsing overhead and lack of evaluation on encrypted or multilingual datasets limit its scalability and generalizability. Furthermore, performance metrics were restricted to domain-level accuracy; no ROC/AUC curves or latency benchmarks were reported.

Zago [143] further expanded their work by integrating lightweight NLP modules for botnet detection in 5G edge environments. The model performed well in low-latency settings and demonstrated robustness in partial data scenarios. Despite these advantages, the absence of metrics such as FPR, confusion matrices, or recall in imbalanced settings weakens the claim of operational readiness-especially under dynamic threat conditions and adversarially perturbed inputs.

To address robustness under domain mutation, Rizi et al. [144] combined feedforward neural networks (FNNs) with Damerau-Levenshtein distance to detect structural similarity in domain strings. Their model achieved a perfect 100% detection rate on noise-induced perturbations, showcasing resistance to common obfuscation tactics. However, this result was obtained on synthetic datasets under controlled perturbation schemes, and no generalization analysis (e.g., multilingual or cross-family) or adversarial robustness metrics were reported. Additionally, no details on FPR or misclassification of benign variants were provided.

In a comprehensive comparative analysis, Vstampar and Fertalj [145] evaluated 14 classical ML and 9 DL models across two DGA benchmarks. While their study reported marginal differences in detection performance when sufficient feature engineering was applied, key limitations were noted, including overlapping test/train data splits, missing per-class performance statistics, and lack of standardization in feature extraction protocols. No PR curves or AUC measures were included, limiting reproducibility and operational benchmarking.

Table 8 has been updated to reflect this broader spectrum of metrics, including AUC, FPR, and latency where available. It highlights the strengths and limitations of each approach through a multidimensional evaluation lens, incorporating both performance and deployment readiness.

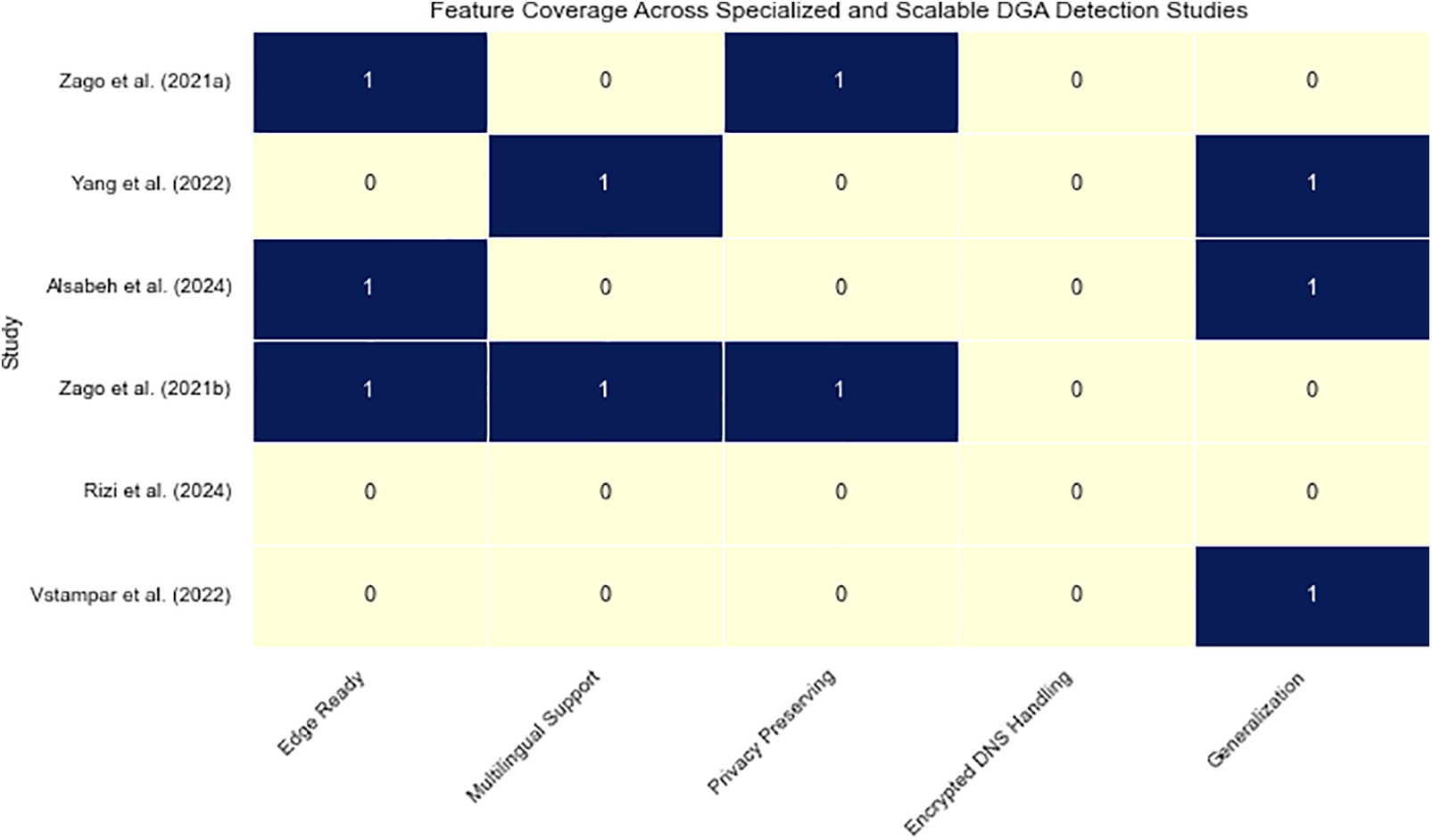

Fig. 14 complements this discussion by offering a heatmap-based visualization of critical deployment features-edge compatibility, multilinguality, privacy preservation, encrypted DNS handling, and generalization. While many models excel in edge-readiness and privacy (notably those leveraging federated learning or lightweight NLP), fewer address encrypted DNS, multilingual adaptability, or formal adversarial robustness-signaling critical directions for future research.

Figure 14: Feature coverage heatmap for specialized and scalable DGA detection models. The matrix compares studies by their support for edge-readiness, multilingual environments, privacy preservation, encrypted DNS compatibility, and generalization capabilities [33,141–145]

In summary, while specialized and scalable models show considerable promise for real-world DGA detection, their inconsistent metric reporting, limited encrypted DNS handling, and lack of multilingual benchmarking undermine full deployment readiness. Future work should prioritize the integration of privacy-aware model compression, standardized adversarial evaluation, multilingual training corpora, and encrypted DNS testing pipelines. Incorporating comprehensive performance metrics such as FPR, AUC, PR curves, and inference latency will be essential for achieving trustworthy, scalable defenses in modern DNS infrastructures.

7.6 Key Trends, Observations, and Open Research Gaps

This review has systematically explored the rising role of LLMs in detecting Algorithmically Generated Domains (AGDs), which remain a core vector in evolving malware communication. Across surveyed studies, there is a clear trend toward the use of transformer-based architectures-such as BERT, GPT, T5, and ERNIE-that outperform traditional statistical and rule-based systems, particularly in scenarios involving morphologically complex or semantically obfuscated domain names [50]. These models excel at capturing both global patterns and local irregularities in domain strings, especially when fine-tuned on context-rich training corpora.

Encouragingly, several advancements signal a more practical and inclusive evolution in this space. The adoption of few-shot and zero-shot learning techniques enables models like T5 and GPT to generalize to previously unseen DGA families with limited supervision [146], addressing the dynamic nature of malware ecosystems. Furthermore, multilingual adaptability has gained traction through fine-tuning of models such as DomURLs_BERT and ERNIE to detect DGAs crafted in non-English linguistic patterns [8]. These developments mark a shift toward more globally relevant DGA detection.

Interpretability, another critical concern in cybersecurity applications, has seen notable progress. Techniques such as attention visualization and token-level attribution (e.g., Integrated Gradients, Layer-wise Relevance Propagation) offer analysts insight into model predictions, thereby enhancing decision traceability and auditability in enterprise-grade DNS security contexts [87]. However, such explainability remains rudimentary and often lacks the precision needed for operational threat forensics.

Despite these advances, several research gaps continue to constrain the deployment and generalization of LLMs in real-world DGA detection systems. Foremost is the absence of standardized evaluation protocols. As noted across in eariler Sections, existing studies often utilize disparate datasets with inconsistent splits, evaluation metrics, and preprocessing steps. Metrics such as AUC, FPR, and precision-recall curves are not uniformly reported, and adversarial testing is rarely standardized [19]. Consequently, conclusions drawn from accuracy comparisons alone lack rigor and reproducibility. We strongly advocate the creation of a standardized benchmark suite—tentatively termed “DGA-GLUE”—which should include fixed dataset partitions (train/validation/test), multilingual domain samples, and an adversarial attack corpus for robustness evaluation. This would mirror the function of GLUE in NLP and enable consistent and fair benchmarking across architectures.

In addition, real-time deployment remains a technical hurdle. Large models such as GPT-3 or T5 are computationally intensive and often incompatible with the latency constraints of edge-based DNS filters or security appliances. Although efforts such as DistilBERT and TinyGPT provide promising alternatives, more work is needed to balance inference speed with detection fidelity in constrained environments [106]. Optimization techniques such as model quantization, ONNX conversion, and cascaded inference pipelines (where simpler models handle routine traffic and escalate ambiguous samples to heavier architectures) offer viable paths forward.

Adversarial robustness is another persistent challenge. Studies like Guan et al. [44] have shown that even state-of-the-art models are vulnerable to syntactic perturbations, homoglyph attacks, and character-level noise that can drastically degrade detection rates. While ensemble and hybrid defense strategies have been suggested, systematic adversarial evaluation remains lacking. We propose the adoption of fixed adversarial test sets as part of future benchmarks, along with the integration of adversarial training pipelines that inject crafted manipulations during learning.

Equally important is the issue of generalization and fairness. Current models often overfit to a handful of well-represented DGA families and languages, leading to brittle performance in real-world settings where long-tailed distributions dominate [40]. Addressing these biases will require both more inclusive datasets and the adoption of class-balancing strategies such as reweighting, oversampling, and continual learning [122].

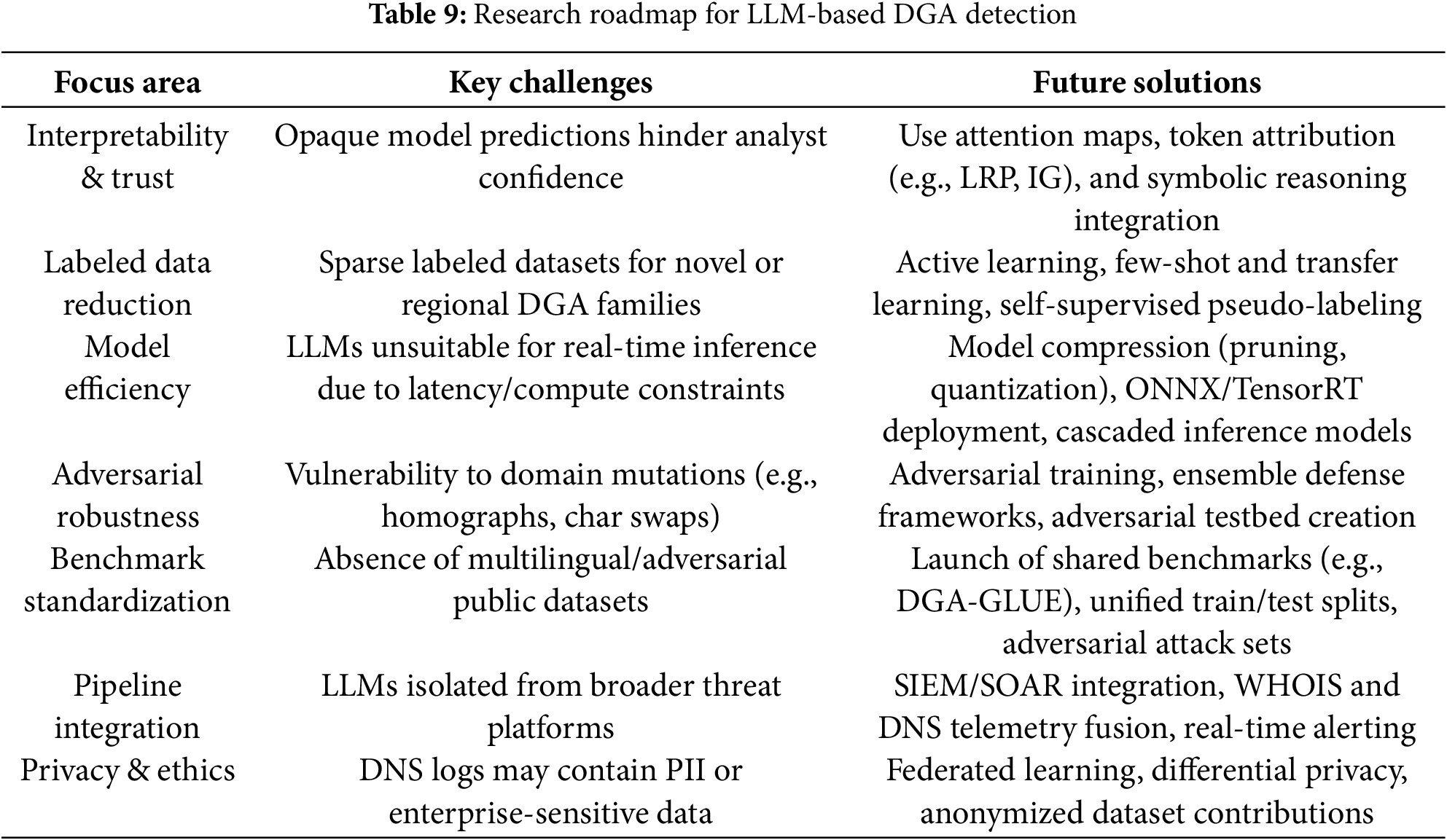

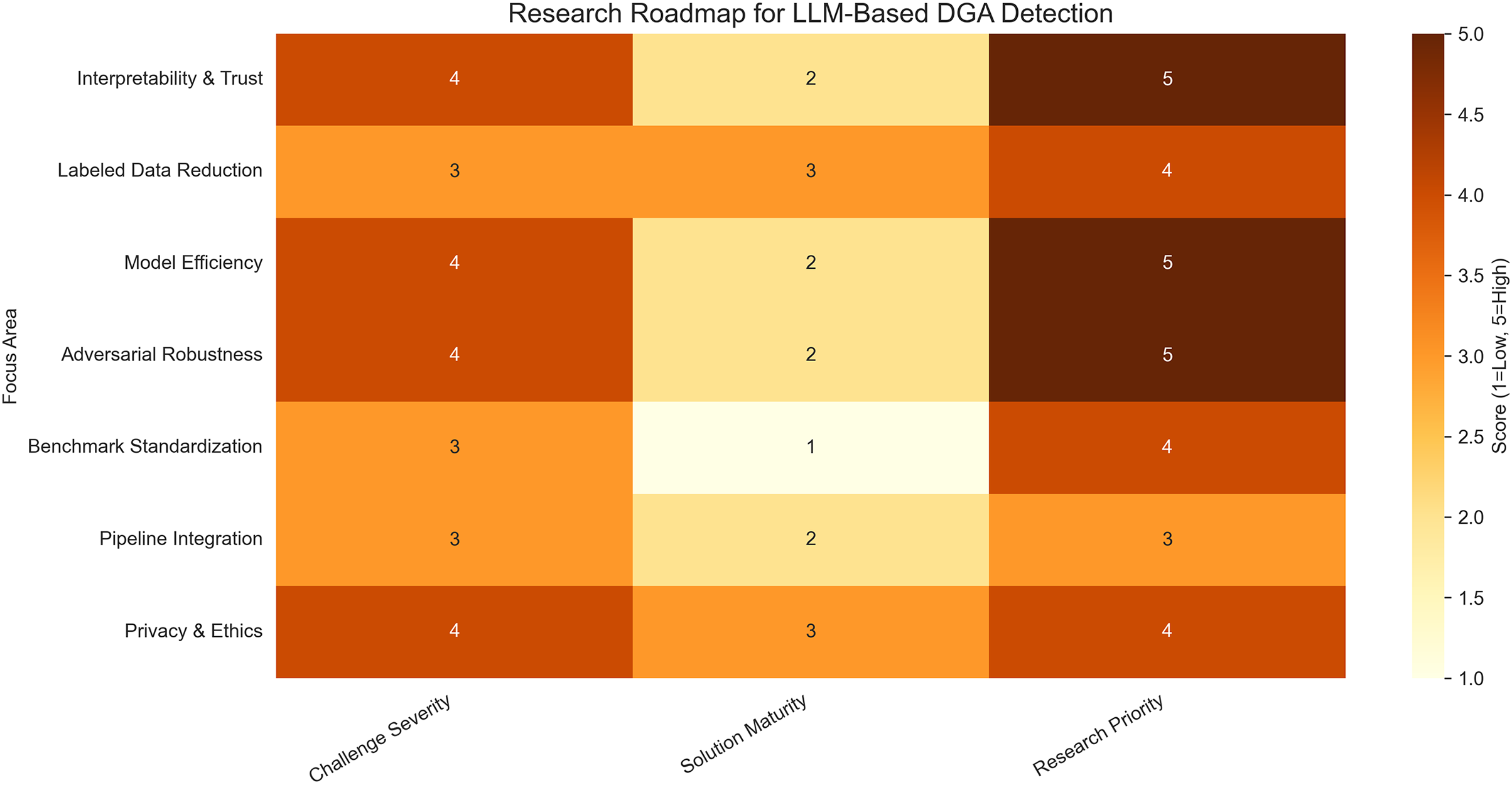

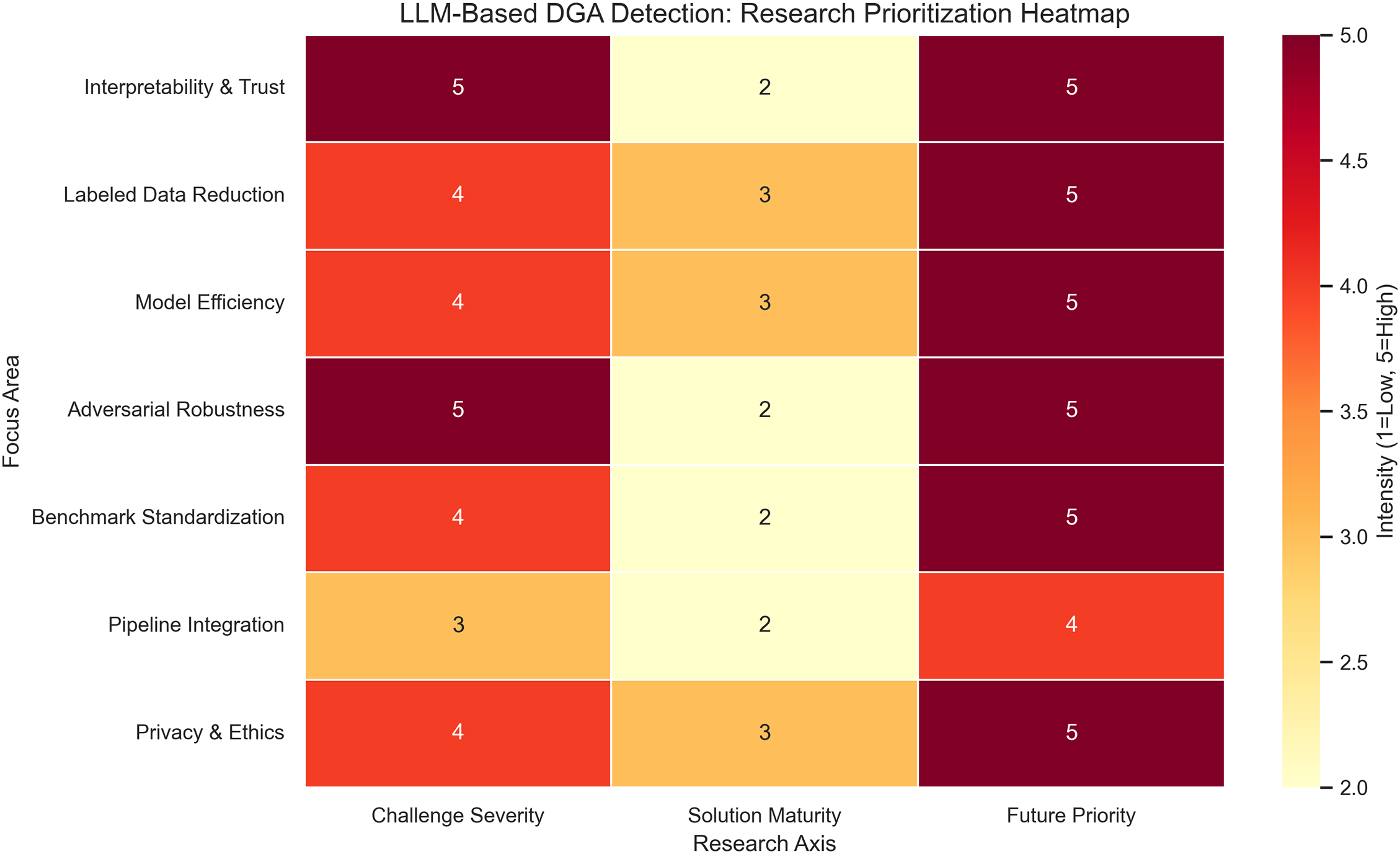

To summarize and operationalize these insights, Table 9 outlines key research priorities and proposed directions, while Fig. 15 visualizes their relative urgency and maturity. Specifically, we recommend (i) launching a public multilingual and adversarial benchmark corpus with unified evaluation metrics; (ii) expanding interpretability through hybrid symbolic-neural frameworks; (iii) optimizing inference via pruning and knowledge distillation; (iv) embedding adversarial training and resilience evaluation; and (v) enabling SIEM/SOAR pipeline integration. Furthermore, all future research must explicitly address the ethical implications of training on DNS logs through privacy-preserving mechanisms such as federated learning and differential privacy.

Figure 15: Heatmap summarizing the research roadmap for LLM-based DGA detection. Each row corresponds to a key focus area, evaluated across challenge severity, solution maturity, and future research priority (scale: 1 = low, 5 = high)

In conclusion, while LLMs represent a significant leap forward in DGA detection, their true value will be unlocked only through methodologically sound benchmarking, adversarial robustness, cross-lingual generalization, and ethical deployment protocols. These pillars form the backbone of a resilient, explainable, and globally deployable DGA detection ecosystem.

8 Conclusion and Future Direction

This comprehensive review has evaluated the transformative potential of LLMs in detecting Algorithmically Generated Domains (AGDs)-a central enabler of evasive malware operations. Our synthesis of encoder-only models (e.g., BERT, RoBERTa), autoregressive architectures (e.g., GPT-2, GPT-4), and text-to-text transformers (e.g., T5, XLNet) illustrates how these models capture deep syntactic and semantic patterns, generalize to zero-day DGA variants, and exhibit resilience to lexical obfuscation. However, translating these academic gains into deployable, trustworthy cybersecurity systems remains challenged by key issues around interpretability, efficiency, adversarial robustness, benchmark standardization, and privacy preservation.

One of the most pressing gaps is the absence of standardized benchmarking protocols. As noted in Section 5, models are often evaluated on isolated datasets using inconsistent metrics—commonly reporting accuracy while omitting equally critical measures such as false positive rate (FPR), precision-recall trade-offs, or adversarial robustness under controlled perturbations. This inconsistency limits reproducibility and undermines comparative validity. We propose the development of a community-driven, multilingual, and adversarially annotated benchmark suite, tentatively called DGA-GLUE. Analogous to the GLUE benchmark in NLP, DGA-GLUE should incorporate fixed train/test splits, metadata-rich telemetry (e.g., WHOIS, TTL, query frequency), multilingual domain strings, and predefined adversarial challenge sets. Complementing this with dataset documentation standards (e.g., Datasheets for Datasets) will further ensure reproducibility and ethical accountability.

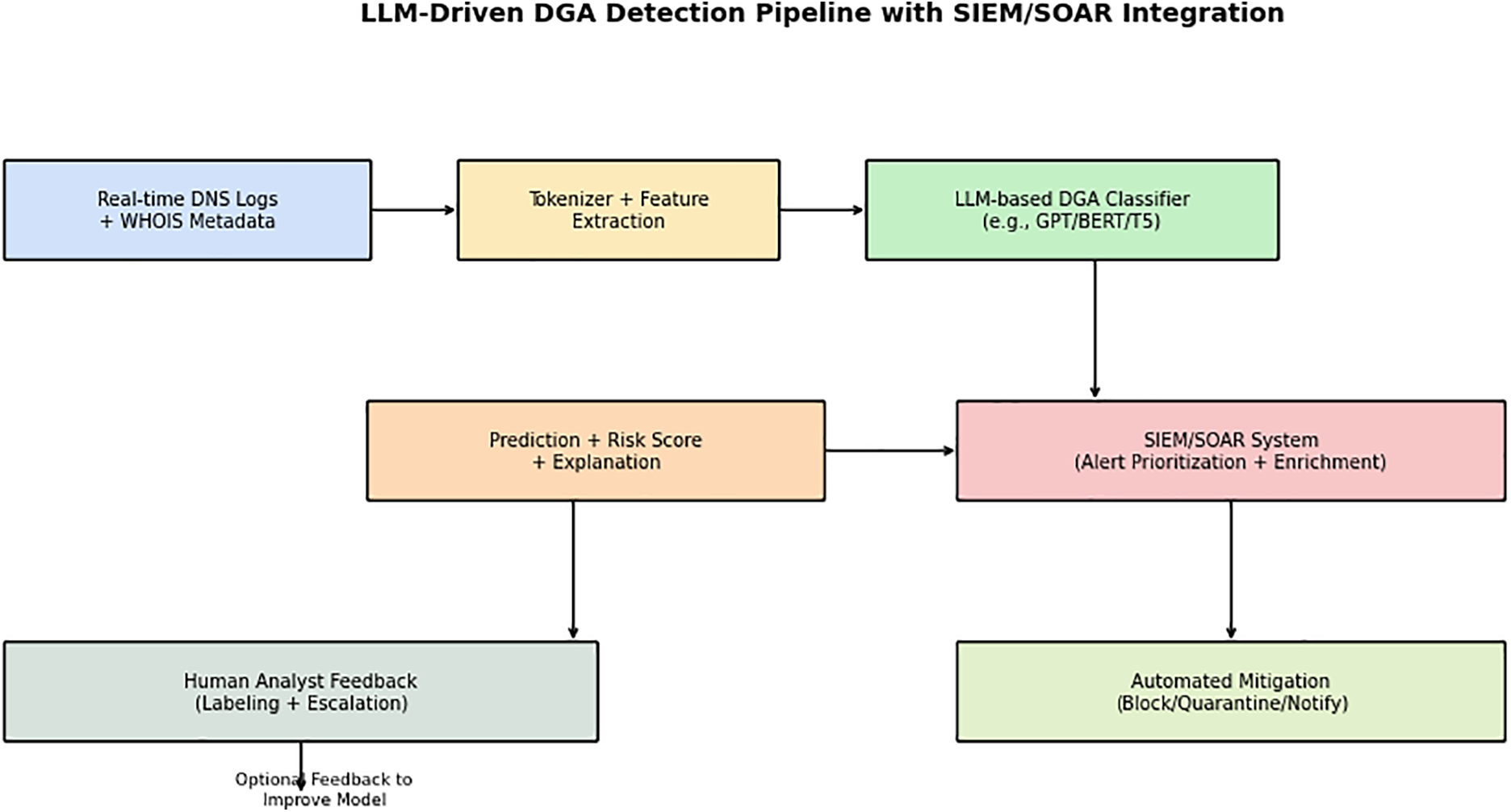

Interpretability remains another core limitation. Although current methods—such as attention heatmaps, Integrated Gradients, and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation—offer some transparency, they lack standardized metrics and often fall short of producing actionable insights for analysts in time-sensitive environments (Section 6.1). We suggest augmenting interpretability frameworks with quantifiable indicators like attention entropy variance, SHAP score consistency, and analyst-centered metrics such as time-to-response and decision confidence. Furthermore, integrating these interpretability outputs into SIEM dashboards or SOAR alert triage systems (see Fig. 16) will support practical decision-making.

Figure 16: LLM-driven DNS threat intelligence pipeline integrated with SIEM/SOAR systems. The architecture captures the flow from DNS log ingestion and LLM-based classification to alert enrichment, escalation, and feedback-driven adaptation

The generalizability of LLMs is still constrained by dataset limitations. As discussed in Section 5 and Table 3, most training corpora are heavily skewed toward English-language DGAs and offer minimal behavioral metadata or temporal sequencing. This restricts cross-lingual generalization and limits model readiness for global or region-specific threats. To overcome this, future research should prioritize strategies that minimize reliance on manually labeled data-such as few-shot learning, self-supervised pretraining, pseudo-labeling, and active learning with dynamic uncertainty sampling. It is equally essential that studies report language-specific performance (e.g., per-language F1 scores) to substantiate claims of multilingual capability.

Scalability and latency remain bottlenecks in production-grade LLM deployment. While models such as GPT-4 and Megatron-LM excel in lab settings, their computational costs make them impractical for DNS-layer security, mobile edge inference, or high-frequency traffic inspection. We recommend the use of lightweight alternatives like DistilBERT, TinyGPT, and quantized transformer variants, optimized through platforms such as ONNX or TensorRT. Cascaded inference models—where lightweight models handle low-risk traffic and escalate ambiguous samples to larger models—can balance cost-efficiency with detection precision.