Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Beyond Classical Elasticity: A Review of Strain Gradient Theories, Emphasizing Computer Modeling, Physical Interpretations, and Multifunctional Applications

SMART Lab, Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, IIT Hyderabad, Kandi, 502285, Telangana, India

* Corresponding Author: Sai Sidhardh. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1271-1334. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068141

Received 21 May 2025; Accepted 04 August 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

The increasing integration of small-scale structures in engineering, particularly in Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS), necessitates advanced modeling approaches to accurately capture their complex mechanical behavior. Classical continuum theories are inadequate at micro- and nanoscales, particularly concerning size effects, singularities, and phenomena like strain softening or phase transitions. This limitation follows from their lack of intrinsic length scale parameters, crucial for representing microstructural features. Theoretical and experimental findings emphasize the critical role of these parameters on small scales. This review thoroughly examines various strain gradient elasticity (SGE) theories commonly employed in literature to capture these size-dependent effects on the elastic response. Given the complexity arising from numerous SGE frameworks available in the literature, including first- and second-order gradient theories, we conduct a comprehensive and comparative analysis of common SGE models. This analysis highlights their unique physical interpretations and compares their effectiveness in modeling the size-dependent behavior of low-dimensional structures. A brief discussion on estimating additional material constants, such as intrinsic length scales, is also included to improve the practical relevance of SGE. Following this theoretical treatment, the review covers analytical and numerical methods for solving the associated higher-order governing differential equations. Finally, we present a detailed overview of strain gradient applications in multiscale and multiphysics response of solids. Interesting research on exploring the relevance of SGE for reduced-order modeling of complex macrostructures, a universal multiphysics coupling in low-dimensional structures without being restricted to limited material symmetries (as in the case of microstructures), is also presented here for interested readers. Finally, we briefly discuss alternative nonlocal elasticity approaches (integral and integro-differential) for incorporating size effects, and conclude with some potential areas for future research on strain gradients. This review aims to provide a clear understanding of strain gradient theories and their broad applicability beyond classical elasticity.Keywords

Low-dimensional structures, from atomically thin sheets to one-dimensional nanowires, have emerged as a cornerstone of modern science and technology, offering unprecedented opportunities to explore fundamental physics and engineer novel devices with tailored functionalities. Moreover, advances in manufacturing are enabling the production of such small-scale structures. A wide application of these small-scale structures requires the efficacy of design and simulation. Examples include micro-beams utilized in MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) as actuators [1] and sensors [2], where the beam thickness is usually of the order of microns. Further, many of these applications employ thin films for specific performance needs [3,4].

Classical continuum mechanics is based on the assumption that material behavior can be described using only the first gradient of displacement. Although effective at larger scales, this framework is inadequate for micro- and nanoscales, where size effects on elastic response become prominent. Experimental investigations using high-precision instruments, such as nanoindenters, have confirmed that classical theories cannot accurately capture the elastic response at these small scales [5,6]. Lam et al. [6] reported increased bending rigidity in experiments on epoxy micro-beams, while McFarland and Colton [7] observed similar stiffening behavior in micro-plates. At low dimensions, the structural response shows significant deviations from the predictions of classical elasticity theory. A key limitation of classical continuum theories is their inability to incorporate a material length scale that reflects the influence of microstructure. This omission makes them inadequate for problems in which the microstructure significantly affects the mechanical behavior. Both experimental and theoretical studies have shown that incorporating such length scales is essential to accurately capture the influence of microstructure on material behavior [8–12]. Further, classical continuum mechanics cannot eliminate singularities that arise from point loads, crack tips, dislocation lines, or interface discontinuities, making such problems mathematically ill-posed [13]. To address these limitations, Eringen [14,15] introduced microcontinuum field theories as an extension of classical models, tailored for materials characterized by microscale dimensions and dynamic behavior over short time scales.

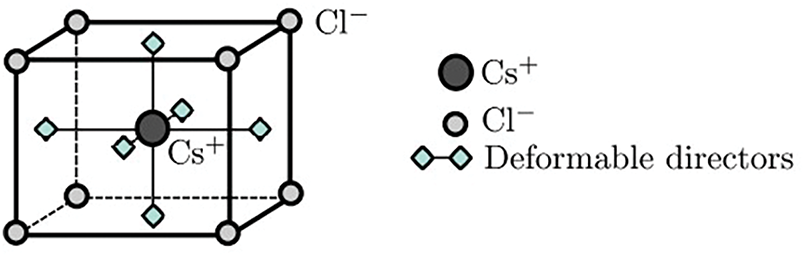

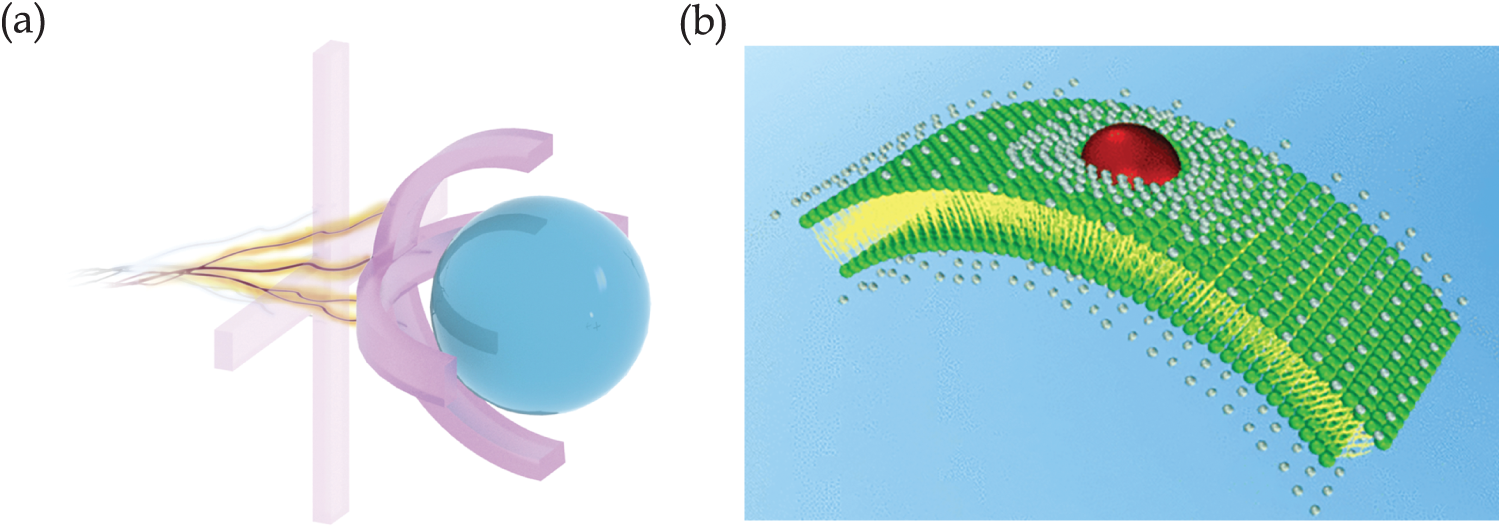

In these microcontinuum theories, materials are modeled not as a collection of point-like particles, as in classical mechanics, but as assemblies of deformable entities with inherent orientation. A conceptual example often used to illustrate this framework is the crystal lattice of cesium chloride (CsCl), as shown in Fig. 1. Unlike classical elasticity, where a material point is rigid and has only translational degrees of freedom, this approach allows the material point to have three deformable directional vectors (directors). These directors add nine new degrees of freedom collectively referred to as micro-deformations to the three translational degrees of freedom (macro-deformations) of classical theories.

Figure 1: Schematic of the Cesium Chloride lattice indicating the deformable directors associated with the microstructure [16]

This approach to modeling structural response is relevant for materials and systems with internal microstructures, such as liquid crystals with dipolar molecules, polymers, solids with defects such as microcracks or dislocations, biological fluids with deformable particles (e.g., blood platelets) and composite materials [15,17–19]. Further, various types of microcontinuum theories have evolved depending on the nature of internal constraints applied to these deformable elements. The most general form, the micromorphic theory [14,20], includes all nine degrees of freedom of the microstructure. Simplified variants include the microstretch theory, which disallows shear deformations between directors, and the micropolar theory, which treats the directors as rigid. Together, these micromorphic, microstretch, and micropolar formulations are known as 3M microcontinuum theories [15]. Note that the 3M continuum theories introduce additional degrees of freedom to capture microstructural effects, resulting in a more complex extension of classical continuum mechanics. Alternatively, modeling of micro-deformations can also be explored by employing the gradients of macro-deformation variables to reduce the number of degrees of freedom [21]. In detail, Mindlin [21] addressed the effects of size by formulating higher-grade continuum models, where the mechanical behavior of solids is described using higher order gradients of existing displacement field variables. Thus, in gradient elasticity, the strain energy function involves both the strain terms and their gradients, resulting in stresses that depend on higher-order derivatives of the displacement field. For detailed historical insights, the reader may refer to Mindlin [22].

The origins of this strain gradient elasticity approach can be traced back to Cauchy and Augustin [23], who proposed an infinite series representation of constitutive relations for isotropic materials with periodic crystal structure, and Voigt [24] further analyzed the kinematic constitutive equations of discrete lattice models, incorporating molecular displacements and rotations. In the early twentieth century, the Cosserat brothers [25] advanced a generalized continuum theory, introducing enriched kinematics in which material particles possess both translational and rotational degrees of freedom. However, these developments largely went unnoticed until the 1960s, when interest in gradient continuum theories was significantly revived. Key contributions during this period include foundational works by Toupin [26], Kröner [27], Mindlin [21,28,29], and Green and Rivlin [30]. Building upon the seminal work by Mindlin [21] in connecting micro-deformations to macro-deformation gradients, Mindlin and Tiersten [28] simplified the couple stress theory by expressing it in terms of rotation gradient tensors derived from macroscopic displacement vectors. This approach can be viewed as a reduced form of the broader framework developed by Mindlin et al. [21,31], which considers all components of the higher-order displacement gradients. Variants of this general theory have been proposed depending on the specific macro-deformation tensors used to evaluate these gradients [31]. The initial work by Mindlin included only first-order strain gradients [31], but was later expanded to include second-order gradients [29]. This allowed for the introduction of the significant effects of surface elasticity at low dimensions. In the early 1970s, Germain [32,33] developed the equilibrium relations for the first-strain gradient elasticity theory, including the effect of microstructure via additional degrees of freedom, using the method of virtual power. A second resurgence in gradient continuum theories occurred in the 1980s, driven by Eringen [9]. This formulation proposes a gradient elasticity framework via reformulation of earlier work on the integral approach to nonlocal elasticity, replacing integral-type constitutive equations with differential equations, offering a more tractable framework for these theories. However, these are fundamentally different from the Strain gradient elasticity (SGE) framework proposed by Mindlin [31].

The seminal studies reported above by Mindlin et al. [21,29,31] paved the way for numerous simplified SGE frameworks. A substantial body of literature explores analytical and numerical techniques for the solution of governing differential equations (GDEs) for a simplified SGE framework. The challenge lies in these partial differential equations (PDEs) being of higher order compared to classical elasticity. The higher-order governing differential equations arising from these strain gradient formulations have been extensively solved through exact and analytical solutions [34–37], without imposing prior assumptions on the displacement field beyond the necessary continuity conditions in the structural domain. Further, given the higher-order partial differential equations for SGE, interpolation schemes with enhanced continuity are sought in numerical formulations [38,39]. To address this, various numerical methods have been developed, including mixed formulations [40],

Strain gradient theory offers significant advantages, particularly in modeling micro- and nano-scale structures where classical elasticity falls short. Firstly, the model incorporates length scale parameters to account for the deformation of the material microstructure. This enables an accurate description of the structural response at low dimensions, where the effects of microstructure are significant. Furthermore, unlike alternate higher-order theories (3M), SGE does not introduce additional degrees of freedom [31]. Finally, the constitutive framework of the SGE remains consistent with the classical elasticity even when the material length scale tends to zero, ensuring broad applicability. Its versatility extends to static, dynamic, and stability problems, making it a powerful tool in the design and analysis of advanced materials and structures.

In particular, the presence of strain gradients was theorized to present a novel multiphysics coupling that can be leveraged to develop interesting applications at low dimensions [43]. This opens exciting avenues for micro- and nano-architected smart structures [44,45]. Among these, the coupling between the electric field and the strain gradients was first studied theoretically in crystals nearly fifty years ago [46]. Much later to these theoretical advancements, Cross and colleagues conducted experimental investigations in various dielectric materials to experimentally demonstrate this behavior [47,48]. It has been observed that non-uniform strains in a general dielectric material can induce a non-zero electric field, a phenomenon known as the flexoelectric effect. These experiments often focused on deformation of structures in bending (flexure), which generates significant strain gradients; thereby drawing the name ‘flexoelectricity’. Of significant interest is the fact that a coupling involving strain gradients is observed to be universal, without restriction to limited (non-centrosymmetric for piezoelectric) crystal structures [43]. Subsequently, extensive research has been conducted to explore the flexoelectric effect in solids, leading to advances in the design of actuators, sensors, and energy harvesting devices based on this phenomenon. Analogously to the electro-mechanical coupling above considering strain gradients, its coupling with other field variables such as the magnetic [49] and thermal field [50] variables are also noted in the literature.

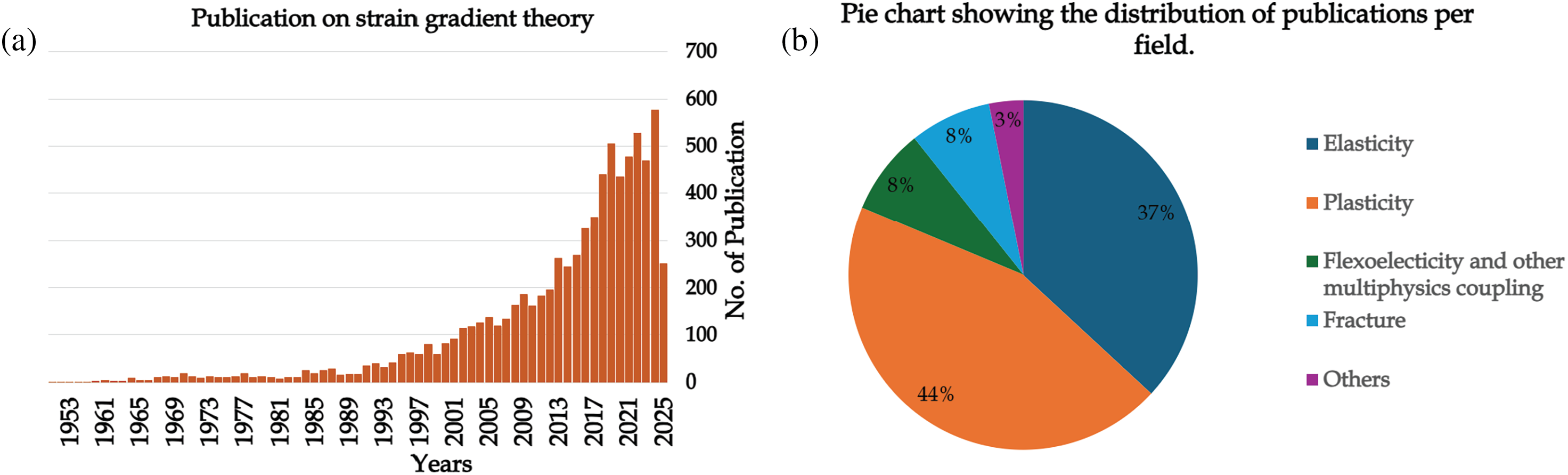

A detailed time history and a quantitative assessment of the literature produced in the general area of strain gradient theory are provided in Fig. 2. An exponential increase in the literature on SGE in the last 20 years indicates a growing interest in fundamental and applied research on strain gradients. In particular, research on strain gradients has been carried out predominantly in the domain of plasticity. Conventional plasticity theory lacks an intrinsic length scale in its constitutive laws and therefore cannot capture size-dependent effects. However, numerous plasticity phenomena exhibit clear size effects, where smaller structures show a stronger mechanical response [51–53]. For example, indentation hardness in metals and ceramics increases with decreasing indenter size, due to smaller reinforcing particles leading to higher rates of strengthening and work hardening in metals for the same volume fraction [54,55]. Although these effects may arise from different mechanisms, all require a length scale for proper interpretation. A common approach to capture such size effects is to make the yield stress a function of both the strain and the strain gradient [56–60]. In this article, we review the literature on strain gradients, highlighting their role on the elastic and multi-physics coupled response of low-dimensional structures, areas that have received less attention.

Figure 2: (a) Histogram chart showing the historical evolution of scientific publications of strain gradient theories per year starting from 1941. (b) Pie chart showing the distribution of publications per field. The data used in this figure were collected from Scopus

We begin this review article with a description of the constitutive models for SGE in Section 2. This includes a detailed derivation of the constitutive relations for strain gradient theory, including an overview of the simplified SGE models and the approaches used in the literature to estimate the corresponding material constants. This is followed by a discussion of the various analytical and numerical approaches (finite element (FE) and non-FE based) used to solve the governing differential equations for SGE in Section 3. Before proceeding to a discussion of the literature on applications of SGE and related multi-physics coupling, Section 4 discusses the physical significance of SGE. Subsequently, Sections 5 and 6 highlight the foundational and applied research on multiscale elastic and multiphysics coupling (flexo- electric, magnetic, and caloric effects) within the framework of strain gradient theories. Finally, Section 7 presents a review of alternate integral and integro-differential approaches to capture nonlocal effects beyond strain gradient elasticity. We conclude with some probable directions for future research on strain gradient elasticity.

The deformation energy density of an elastic continuum considering microstructural effects can be expressed as [15,21]:

where

Above, we introduce the additional contribution in

Another example of a higher-order deformation metric is the first gradient of the second-order strain tensor proposed by Mindlin [31]. This approach incorporates the effects of the micro-structure within the constitutive relations via gradients of the classical (second-order) strain tensor. Thereby, no additional degrees of freedom are introduced within the constitutive model following the strain gradient approach to capture microstructure effects. It is worth noting that the set of higher-order metrics can be expanded further to include contributions from the second gradient of the strain tensor, enriching the total deformation energy density described in Eq. (1).

We present here the details of a constitutive model for the first strain gradient theory. More specifically, the constitutive relations for SGE considering the first derivative of strain gradients are detailed. Later, a discussion on the alternate forms for the first strain gradient theories (either as second gradients of displacements or first gradients of the strain tensor or their components) is provided. Subsequent to this, simplified forms of the SGE proposed in literature, following from the generalized form, are introduced, and details on their relevance to different studied are provided. We follow this with brief discussions of the characterization of the additional material constants introduced via SGE.

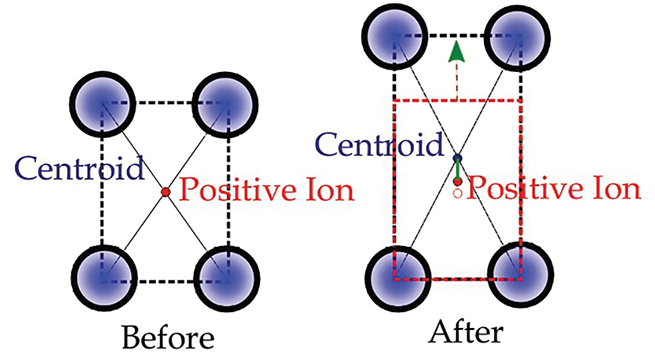

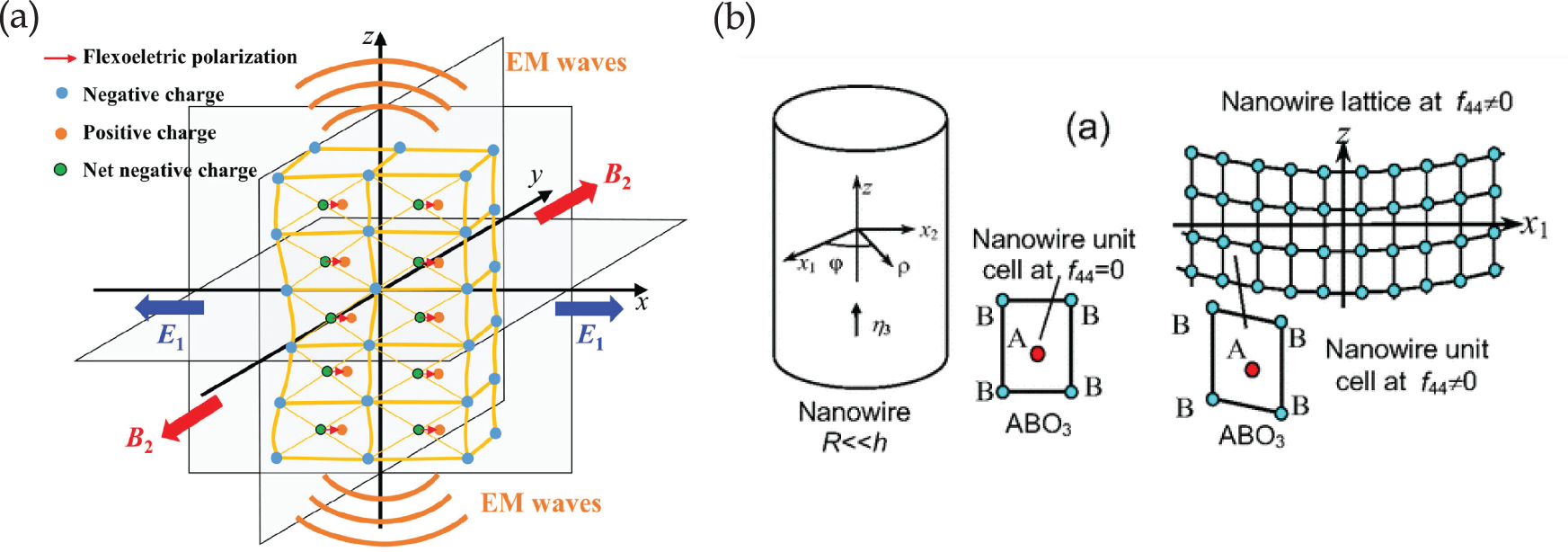

Before proceeding further, we note that an experimental observation of a non-zero polarization in centrosymmetric crystals [47,62] that cannot be explained by piezoelectric coupling. Moreover, when a strain gradient is applied across the symmetric crystal domain, the symmetry of the centrosymmetric crystal can be disrupted, resulting in net polarization upon deformation. This phenomenon is illustrated in Fig. 3. As shown, prior to deformation, the positive ion aligns with the centroid of the negative charges in the lattice, leading to zero net polarization. When a strain gradient is applied, the centroid of the negative charges shifts relative to the positive ion, and a net polarization is induced in the centrosymmetric crystal. This electro-mechanical coupling follows from the strain gradient referred to as the flexoelectric effect. This will be discussed in detail later in Section 6.

Figure 3: Net polarization induced in a centrosymmetric crystalline structure due to strain gradients [16]

2.1 First Strain Gradient Theory of Elasticity

Following Eq. (1), the deformation energy density of a homogeneous, centro-symmetric elastic continuum considering the strain gradients is given by [21,31]:

Here, the definitions of second-order tensor,

In this expression,

Alternatively, the third-order strain gradient tensor (

Further to this, Mindlin also proposed an alternative equivalent form (Form III) of strain gradients in terms of the dilatational gradient vector

where,

The material constitutive relations can be expressed directly in terms of the first gradient of strain defined in Eq. (3), or alternate forms given in Eqs. (4) and (5).

The constitutive relations for the work conjugates of the second-order strain and third-order strain gradient tensors are defined following thermodynamic considerations [66,67]. In particular, the constitutive relations for the second-order (Cauchy) stress tensor,

In the above relations,

The fourth-order material constant tensor

where

The sixth-order material constant tensor

Imposing the appropriate conditions for directional symmetries inherent in isotropic materials over

where

Considering the challenges involved in the characterization of five constants associated with the

As mentioned above, Mindlin [21] developed a comprehensive SGE theory to capture the effects of microstructure. The proposed model introduced 16 additional constitutive parameters (length scales) for isotropic materials in addition to the classical Lamé constants. Due to the complexity involved in determining these constants, the practical use of this framework is limited. To address this, Mindlin and Eshel [31] further proposed three simplified versions of the theory (given in Eq. (9)), each requiring only five internal length scale parameters/additional material constants. Despite this reduction, an experimental determination of the five parameters remains challenging. Later works by Yang et al. [65], Lam et al. [6], and others [63] proposed simplified models that further reduced the number of independent parameters, thereby enhancing the feasibility for engineering applications. A detailed discussion of the different simplified strain gradient theories available in the literature is provided in Section 2.2.

We list here a few seminal works proposing simplified models for SGE. However, we note that the below is intended to be a summary of alternate SGE constitutive models, and not an account of all the micromorphic theories and higher-order formulations in literature.

• Zhou’s Three Constant Model: Zhou et al. [63] revised the sixth-order tensor through two independent orthogonal decompositions of the strain gradient tensor, indicating that only three independent constants are necessary to evaluate the

Further, these material constants can be recast in terms of three independent material length scales

where

• Lam’s Strain Gradient Theory of Elasticity: Lam et al. [6] proposed to ignore the contribution of anti-symmetric component of the rotation gradient tensor. In particular, this constitutive model can be expressed as a simplification of the GFSGET, introduced above, by considering

We note here that the other two components of the constitutive relations in Eq. (7) remain unchanged. This theory is also referred to as Modified Strain Gradient Theory (MSGT). In addition to proposing this, Lam et al. have conducted experimental studies on epoxy polymeric beams to confirm the MSGT constitutive relations and provide a route for characterization of the length scales

• Modified Couple Stress Theory (MCST): Yang et al. [65] proposed a simplified version of Mindlin’s constitutive model considering only the contribution of couple stresses toward the deformation energy. In particular, the constitutive model for SGE proposed by Yang et al. can be realized as a simplified version of MSGT where the stretch gradient tensors (deviatoric and dilatational) do not contribute to the deformation energy density. Simply put,

• Consistent Couple Stress Theory: Hadjesfandiari and Dargush [64] noted the mathematical and physical inconsistencies caused by a symmetric assumption for couple stress. For instance, inconsistent constitutive relations are realized from an indeterminacy of the spherical component of the couple-stress tensor and the emergence of the body couple for the force-stress tensor. To address these, they proposed an alternate framework for SGE involving a couple stress conjugate to the anti-symmetric curvature tensor

The above relation may also be obtained from the GFSGET proposed above (see Eq. (12)) by ignoring the contributions of

• Indeterminate Couple Stress Model [28,74]: This theory proposes a couple stress model considering the complete curvature tensor as follows:

In this framework, the complete energy corresponding to rotation gradient tensors are considered. However, the energy contributions by the (dilatation and deviatoric) stretch gradients are ignored. In agreement with Eq. (12), it may be noted that two distinct material length constants (

• Simplified Strain Gradient Elasticity Theory (SSGET) [75,76]: This theory follows from ad hoc assumptions over the sixth-order elasticity tensor corresponding to Form II given in Eq. (7). In particular, recall that five independent constants are proposed to be necessary for the sixth-order

where

This may also be obtained from the general form of this tensor given in Eq. (9) by assuming

A brief comparison of the assumptions, advantages, and limitations of the simplified gradient theories is provided in tabular form in Table A1 of Appendix A.

2.3 Second Strain Gradient Theory of Elasticity

Mindlin [29] demonstrated that the incorporation of the third gradient of displacements into the strain energy density function can lead to the emergence of surface tension in isotropic, centro-symmetric, linearly elastic solids. This arises because of the presence of initial, homogeneous, self-equilibrating triple stresses within the constitutive relations. Around the same time, Toupin and Gazis [78] reported that within the first strain gradient theory, such effects occur only in non-centrosymmetric materials. More recently, Cordero et al. [79] revisited the role of the third gradient of the displacement vector in isotropic solids. In this study, contributions to surface tension (by the second gradient of strains) are highlighted. Further to this, the coupling between the strain tensor and their second gradients in the strain energy density is identified to present free surface effects.

In the context of Mindlin’s second strain gradient theory of elasticity, the potential energy density

where

Recall that

The additional material constants introduced in the second strain gradient theory of elasticity have been proposed to be determined from first-principles calculations and have shown good agreement with analytical solutions for simple geometries [80,81]. Using this framework, the mechanical response of the cantilever beams was investigated using Euler-Bernoulli beam displacement theory [80]. Karparvarfard et al. [82] extended these frameworks to derive the geometrically nonlinear governing differential equation of motion and associated boundary conditions for small-scale Euler–Bernoulli beams based on the SSG theory.

Theory of surface elasticity: Gurtin and Murdoch, in their seminal paper [83], introduced the concept of surface elasticity by modeling the surface as a thin elastic membrane, characterized by surface elastic constants distinct from those of the bulk material, and incorporating an intrinsic residual strain. This residual strain arises because surface atoms typically have shorter bond lengths compared to atoms within the bulk. Although at the macroscale such surface effects can often be ignored allowing bulk properties to represent the overall behavior, this is not the case for nanoscale structures. In low-dimensional nanostructures, the surface-to-volume ratio is significantly high, making the energy contribution of surface atoms non-negligible. This leads to significant surface-induced residual stresses and altered elastic properties compared to bulk material [84]. This framework rigorously incorporates surface stress and surface elastic constants, enabling the analysis of size-dependent mechanical behavior at the nanoscale. Moreover, the second strain gradient elasticity, defined in Eq. (18), can also be conceptually viewed as comprising two interacting subsystems: a bulk region that behaves as a classical Cauchy continuum and a surface that acts as a membrane-like boundary layer, both at equilibrium at local and global scales [85]. However, except for a few investigations of fluid films and rigid interfaces, such treatments are relatively rare. Instead, the Gurtin-Murdoch treatment of surface effects has been extensively employed in the literature. The effects of surface elasticity are also realized on the coupled multiphysics response, such as the electromechanical response of MEMS and NEMS [86–89].

2.4 Governing Differential Equations of Motion

In this section, we derive and discuss the governing differential equations of motion for a solid employing strain gradients to capture the effects of microstructure and micro-inertia. More specifically, the governing differential equations (GDEs) and the associated boundary conditions (BCs) for a strain gradient elastic solid are derived here following variational principles [90–92]. We provide here only the salient steps in the derivation and the physical insights drawn from the expressions encountered here. For a complete derivation, interested readers may refer to [93]. For a solid body of volume

where

By the definition of strain and strain gradients given in Eq. (3), the first variation of the potential energy can be rewritten as:

The variations

where

where

Finally, the first variation of the external work done

and

where

Now applying the variational principle (Hamilton’s stationary principle:

The variational principle also yields following boundary conditions associated with the above GDEs:

where

The above set of GDEs (or an equivalent form) is established to be well-posed with unique solutions [99]. Although this result is trivial considering the positive definiteness of the strain energy density, this observation is in contrast to the alternate (integral) theories explored for size effects in structures [100]. Thus, the solution to the above GDEs is not expected to demonstrate any paradoxical observations noted from the integral theories [101,102].

A solution of the above governing equations (including associated boundary conditions) includes the effect of the micro-structure over the elastic response of the solid. Note that the above set of governing equations is relevant to homogeneous solids such as monolithic beams, and non-homogeneous solids such as laminates or functionally graded composites [70]. In other words, the above set of governing equations employ the general form of constitutive relations for SGE given in Eq. (7). Thereby, the boundary conditions over surface and jump conditions at the edges/discontinuities are devoid of ad hoc assumptions. Furthermore, this framework can be extended to study multiphysics behavior such as the flexoelectric response of solids, allowing for electro-mechanical coupling analysis. We will discuss this aspect more in Section 6.

2.5 Estimation of Material Constants

In this section, we present some directions used in the literature for the characterization of additional material constants corresponding to the sixth-order

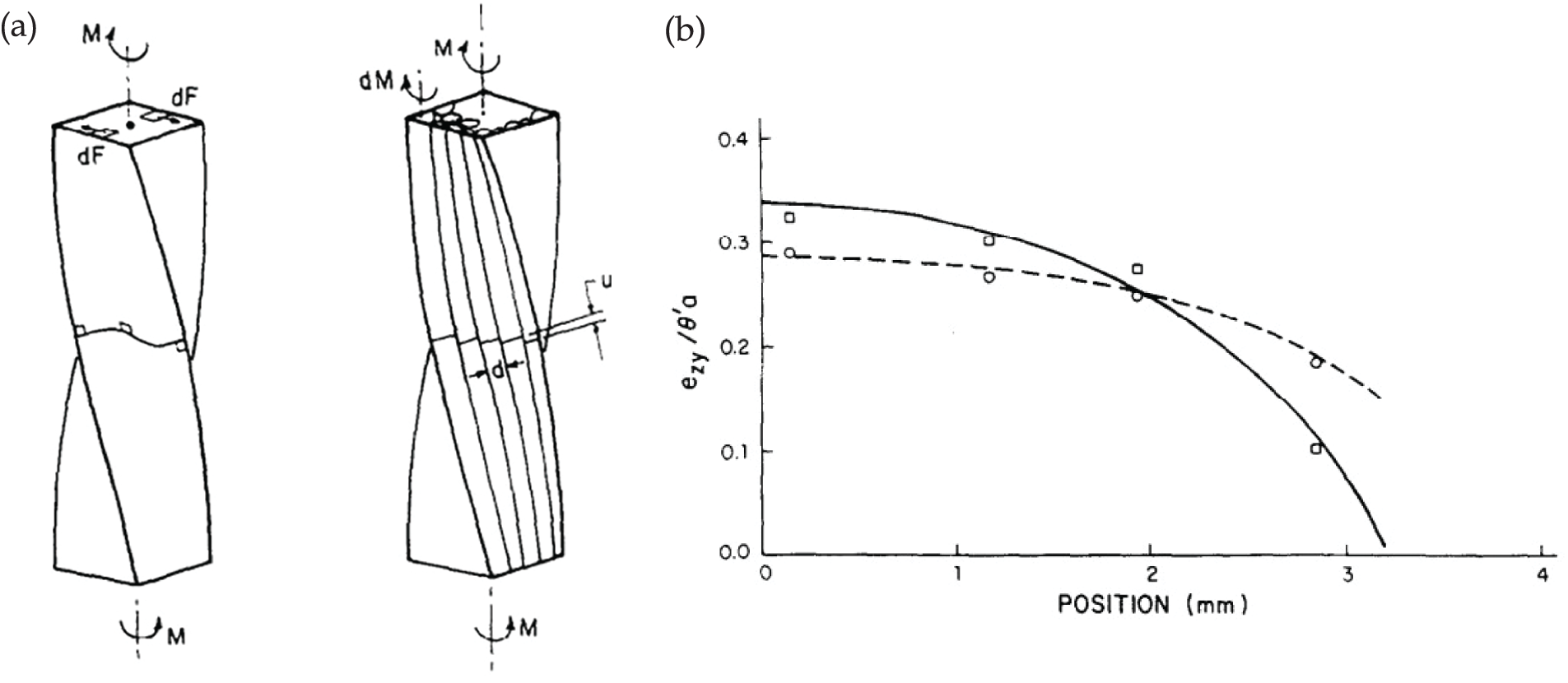

Experiments: The significance of microstructure-dependent material length scales in determining the size-dependent behavior of structures has led to numerous experimental investigations aimed at evaluating these parameters. Lakes et al. pioneered experimental investigations into the bending response of fibrous and granular materials for the estimation of the characteristic length scale corresponding to the couple stress and micro-polar theories [11,12]. These studies aimed at estimation of the material length scales for the human compact bone also present experimental evidence of microstructure effects on the structural response (either via torsion, bending or wave dispersion) as illustrated in Fig. 4. Typical values of length scales for human bone have been reported to be below 1 mm.

Figure 4: (a) Comparison of warp and strain patterns produced by torsion in a homogeneous prism modeled with classical elasticity and a fibrous human bone prism, based on the work of Park and Lakes [11]. (b) Strain distribution observed along the boundary of human bone: the solid curve corresponds to predictions from classical elasticity theory, the dashed curve represents results from Cosserat elasticity theory; Experimental data points are shown as circles for wet bone and squares for dry bone, adapted from Park and Lakes [11]

Similar effects of microstructure are reported to reduce the stress concentration around small holes [103]. Furthermore, Lakes [104] summarized observations from experimental studies on a variety of classes of materials. Metals, amorphous polymers, and particulate compounds have been reported to generally exhibit classical mechanical behavior. However, for certain cellular and fibrous materials, the characteristic lengths align with the size of the largest structural elements. Moreover, considering the example of fiber-reinforced composites, it is reported that these length scales can exceed cell size.

Later, Lam et al. [6] conducted experimental studies on bending responses of polymeric micro-beams of 10–100

Finally, a series of experimental studies on perovskites confirmed the influence of strain gradients on the elastic response of low-dimensional structures [47,105], further extending to observations and material characterization for electro-mechanical coupling through flexoelectricity.

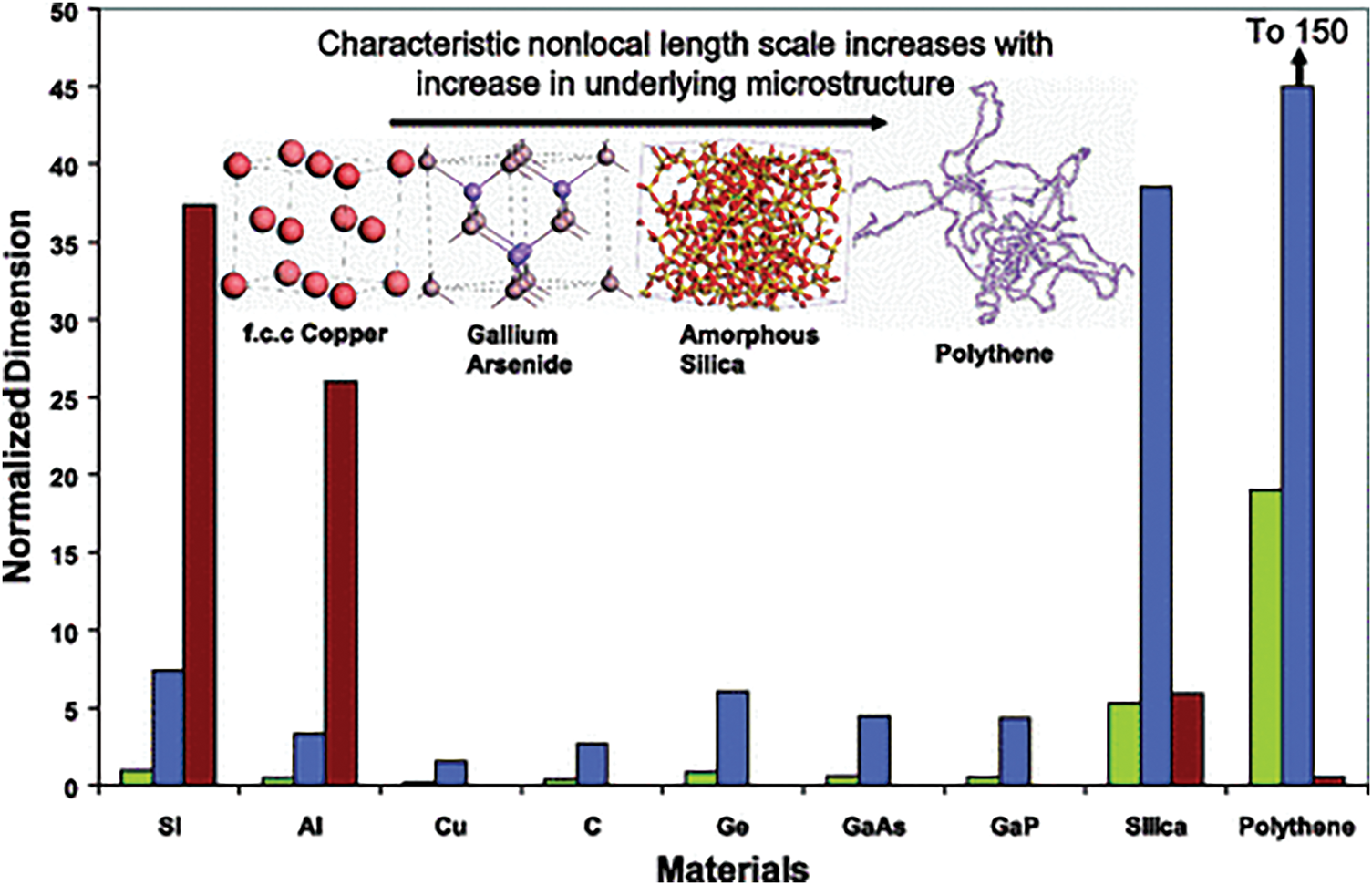

Ab-initio calculations: Marangati and Sharma [106] explored an alternate method based on molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to determine the additional constants. Using statistical mechanics techniques, they derived equations that link the strain gradient material constants to displacement within a Molecular Dynamics (MD) computational ensemble. They also compiled characteristics length scale for SGE for a range of material systems, including metals (Cu, Al), single-component semiconductors (Si, Ge, C), multi-component semiconductors (GaAs, GaP), amorphous silica, and a polymeric system (polythene). A comparison of the length scale parameters between material classes is provided in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Length scale parameters determined from the molecular dynamics and lattice dynamics studies compared for different materials [107]

This result from [107] highlights the growing significance of microstructural effects in materials, such as polymers, compared to crystalline materials. Shodja et al. [108] determined the length scales for use in SGE constitutive relations of the body-centered cubic (BCC) and face-centered cubic (FCC) metal crystals using ab initio calculations. Another route for material length characterization is via guided elastic waves that exhibit multiple modes and dispersion properties. For instance, Liu et al. [109] conducted MD simulations to investigate multi-mode guided elastic wave propagation in a 2D aluminum plate. The results of these simulations are used to calibrate the size parameters in nonlocal strain gradient theory.

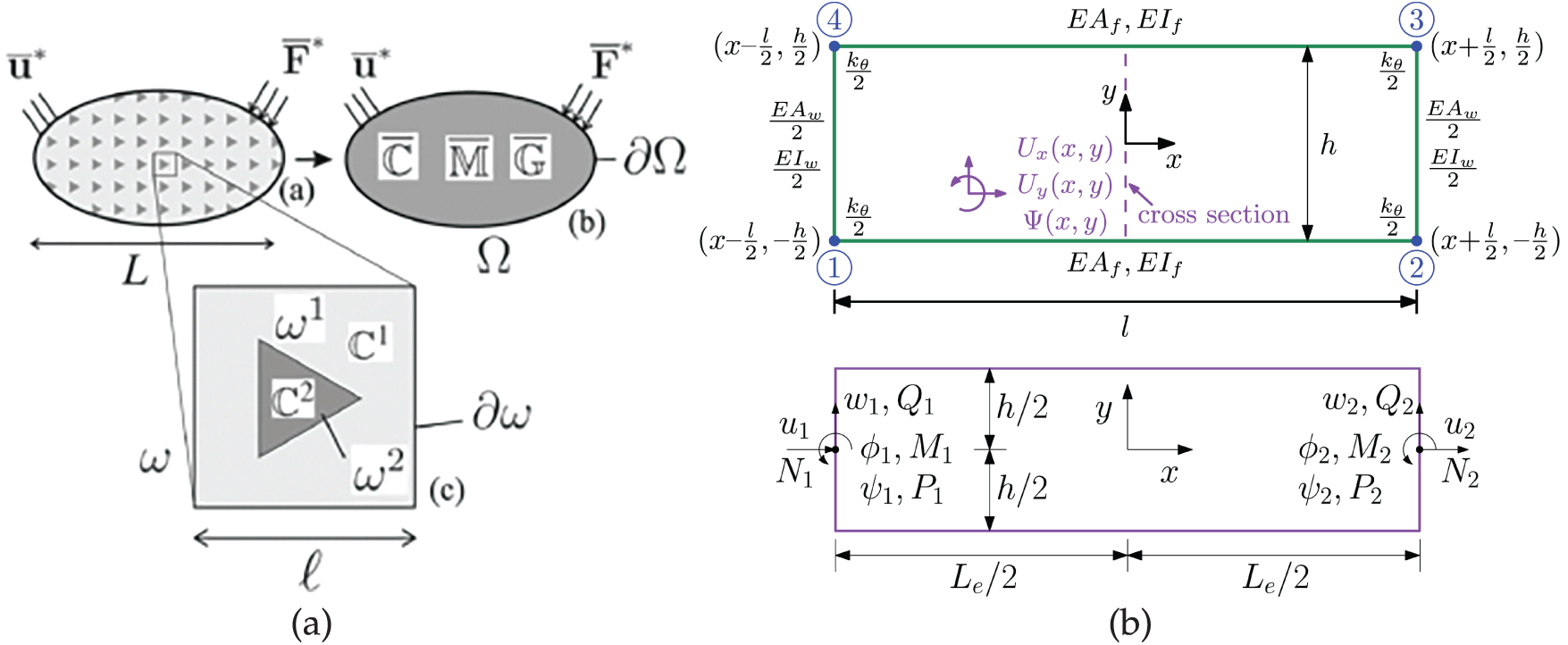

Homogenization: A common approach to determine the response of heterogeneous materials involves homogenizing the behavior of a Representative Volume Element (RVE) [110].

In particular, leveraging the recent advancements in scale-transition methods, particularly second-order homogenization, gradient theories are used at the macroscopic level to capture the response of heterogeneous materials [113–116]. These theories incorporate a length scale parameter

Figure 6: (a) Heterogeneous structure equivalent to strain-gradient homogeneous structure [111], (b) Arbitrary cross-section of the micropolar beam possessing microstructure [112]

Recently, Hu et al. [122] investigated the mechanical properties and deformation behavior of bio-inspired sandwich structures fabricated using selective laser melting. They examined various gradient lattice structures to analyze their response under compressive loading, as illustrated in Fig. 7a. Liu et al. [123] established that the nonlinear beam-like truss structure illustrated in Fig. 7b is equivalent to a nonlinear homogeneous Timoshenko beam. In particular, the nonlinear dynamics of a microscale beam is analyzed using the SGE theory and the MCST discussed in Section 2.2. Thereby, they developed and implemented an equivalent nonlinear beam model (ENBM) based on SGE for the forced vibration analysis of the nonlinear beam-like truss. Most recently, Sarhil et al. [124] scaled the curvature measurements, which are isotropic in 2D, to incorporate the size of the beam, followed by a fitting procedure to determine the characteristic length and the shear modulus associated with the micro-distortion field. The relaxed micromorphic model successfully captures the size effects consistently across both loading cases.

Figure 7: (a) Bio-inspired sandwich gradient structures [122], (b) Schematic view of nonlinear beamlike truss composed of 36 spatial repeating elements [123]

Data-driven approaches: In recent years, data-driven approaches have emerged as a powerful alternative to traditional methods for material characterization [125]. These methods have facilitated the development of machine learning (ML) techniques that enable rapid predictions based solely on existing data, eliminating the need for direct experiments or simulations [126]. For instance, Stainier et al. [127] proposed a data-driven approach to mechanics that operates without predefined models, allowing the identification of material properties and the solving of mechanical problems directly from data. Following a similar approach, Karapiperis et al. [128] introduced a data-driven framework for the mechanical analysis of generalized continua, incorporating the nonlocal effects arising from the microstructure of the material. In their study, they specifically focus on the micropolar continuum as a representative example of generalized continua. This framework is entirely parameter-free, eliminating the need to define constitutive relations or internal length scales, as these are implicitly determined from the material dataset. Additionally, it effectively captures nonlocal history-dependent behavior while explicitly ensuring thermodynamic consistency. Similar to this, Lal et al. [129] proposed a framework based on supervised ML to predict the length scale parameter for a given material. Most recently, Ulloa et al. [130] introduced generalized data-driven mechanics for micromorphic continua, motivated by the challenges of softening materials with strain localization. It has been observed that material length scale parameters vary depending on the complexity of the microstructure. Although the primary computational expense lies in generating training data from MD simulations, once trained, these models offer computationally efficient predictions of material behavior. Recently, ML has been extensively applied to predict material properties using known parameters such as microstructure or chemical composition [131]. ML models trained on output from MD simulations are increasingly being used for this purpose [132–135].

This section presents a concise overview of approaches for solving boundary value problems, including strain gradient terms within the constitutive relations (example is Eq. (26a)). We present a detailed account of the analytical and numerical methods explored in the literature for solving these equations. Before we begin, we note that Hosseini and Niiranen [136] established uniqueness of a solution for these higher-order GDEs, including SGE terms, assuming continuity and coercivity of the bilinear form (available thanks to the energy framework introduced in Eq. (1)). Although their proof is available for a 3D boundary-value problem (BVP) considering the SGE framework, these equations are similar to those developed previously in Eq. (26a)), and hence the observations can be extended. This result is significant because it provides a foundation for analytical and numerical methods, including the FE, meshfree, and IGA methods.

We discuss below some approaches employed by researches for an analytical solution of higher-order GDEs developed for SGE.

Stress Functions: The stress function approach, analogous to Airy stress functions for classical elasticity, presents significant ease for a solution of GDEs. This includes the reduction of a set of governing differential equations via the introduction of a single-scalar function. Further, in most cases, the GDEs are trivially satisfied (or reduced to biharmonic equations). Weitsman et al. [34–36] pioneered the stress function approach for solving GDEs based on a deformation energy that includes strain and strain gradient terms. More specifically, a stress function that satisfies the governing differential equation, including the SGE term, over the domain was assumed, and the boundary conditions were enforced. Following this approach, they explored the stress concentrations for spherical and cylindrical inclusions and cavities, including Form III of Mindlin’s SGE given in Eq. (5). The stress function approach employed by Eshel and Rosenfeld [137] to analytically solve the stress state around a cylindrical hole gained prominence, particularly due to their improved explanation of the extra material constants arising from SGE. Their solution to the plane stress problem of a circular cylindrical hole under uniaxial tension involved the use of modified Bessel functions of the second kind. They investigated stress concentration away from the hole, comparing their findings with predictions from couple-stress theory and classical elasticity. Further, Eshel and Rosenfeld [138] extended their methodology to solve axisymmetric exterior problems with uniform pressure applied to a circular internal boundary. This approach has also been used for analytical solutions of GDEs that involve multiphysics coupling with strain gradients to provide the stress state in flexoelectric solids [139]. Moreover, the above approach using stress functions was also extended to simplified theories of SGE, such as the SSGET provided in Eq. (16) [140].

Assumed solution forms: Recall that Mindlin introduced the foundational framework for strain gradient theory in his seminal study [21]. In addition to this, this work demonstrated the solution of the GDEs for SGE employing a simple harmonic function. Later, Savin et al. [37,141] developed an analytical model to study wave dispersion in low-dimensional structures using SGE. Their approach utilizes expressions derived using a simple harmonic function of the static and dynamic displacements for the velocities of longitudinal and transverse elastic waves in a nonlinear infinite Cosserat continuum with constrained rotation. A similar approach was adopted by Sidhardh and Ray [97] for dispersion curves of Rayleigh–Lamb waves in a micro-plate considering strain gradient elasticity. Gao et al. [142] used a method based on the harmonic traveling wave solution to solve for band gaps in periodic composite beam structures. This approach allowed them to include the effects of surface energy, transverse shear, and rotational inertia on the band gaps in the periodic structure.

In the early 2000s, Lam et al. [6] employed a power series expansion for the displacement field variable to solve the GDEs corresponding to MSGT. This analysis specifically addresses the cases of hydrostatic and uniaxial compression and dilation. More commonly, elastic field variables in the 3D structures are reduced to 1D or 2D by assuming displacement fields. We note a plethora of studies exploring analytical solutions for the SGE assuming a prescribed displacement field: Euler-Bernoulli beam displacement theory for 1D [143–145], and Kirchhoff plate displacement theory for 2D structures [146–148]. Please refer to the review article by Roudbari et al. highlighting several such studies [149].

Green’s function approach derives analytical solutions for point loads, and has significance in extending to a solution of the GDEs in case of general loads. Zhang and Sharma [150] pioneered this approach for Eshelby’s tensor of an inclusion/inhomogeneity embedded in higher-order continua. More specifically, considering the couple stresses within the constitutive relations, Green’s functions were proposed in terms of appropriate potentials for the solution of higher-order GDEs. Alternately, Gao and Ma [151] developed Green’s function for the GDEs following the SSGET provided in Eq. (16). Thereby, they provided an analytical method for solving Eshelby’s tensor in an infinite homogeneous isotropic elastic medium containing inclusions of arbitrary shapes. Sidhardh and Ray developed a similar framework for an inclusion of any arbitrary shape, under uniform eigenfields following the GFSGET in Eq. (10) [152,153]. Gourgiotis et al. [154] developed a theoretical framework by deriving Green’s functions for a concentrated force and couple in an infinite relaxed micromorphic medium. Using Fourier transform analysis and generalized functions, they obtained closed-form solutions and demonstrated that several classical continuum solutions emerge as singular limiting cases of the relaxed micromorphic model.

Fourier and Laplace transforms: The Fourier approach serves as a powerful tool for solving higher-order GDEs by transforming differential equations into algebraic equations in the frequency domain. Day et al. [155] were the first to develop an analytical solution by this approach, based on Mindlin’s strain gradient elasticity theory, to investigate bonding stresses at the interface in composite microlayers under higher-order contact conditions. Similarly, Baren and McCoy et al. [156] developed an analytical solution for a point force in an infinite medium considering the first strain gradient theory of elasticity (modified Kelvin problem). Rogula [157] developed benchmark analytical solutions for several standard problems (in 1D, 2D, and 3D, and dislocation line) employing the Fourier transform approach. Zhou et al. [158] investigated the influence of surface energy on the band structures of flexural waves in a periodic nanobeam considering Fourier series expansion according to the Bloch theory. A similar approach was used by Qian [159], considering surface energy effects, to study wave propagation in a thermo-magneto-mechanical nanobeam. Recently, Rizzi et al. [160] derived closed-form solutions for the simple shear problem across various isotropic linear-elastic micromorphic models, with a focus on the relaxed micromorphic continuum. The Cosserat model, the classical micromorphic model (except when it approaches the second gradient limit), and the microstrain model exhibit similar size effects under simple shear but show notable differences under bending [161,162]. Importantly, the relaxed micromorphic model remains well-posed and bounded, except in the limit

The transform approach is also commonly employed for the solution of Eshelby’s tensor, a fundamental problem for studies on micromechanics, dislocations, and fracture. For instance, alternative to the Fourier approach, instead employing the Laplace transform approach to convert differential equations to algebraic equations, Karlis et al. [163] developed analytical solutions for higher-order GDEs corresponding to Mindlin’s strain gradient theory of elasticity for a static response of elastic 2D and 3D strain gradient solids.

Exact solutions

An exact solution satisfies the governing differential equations and all the (natural and essential) boundary conditions of a problem precisely. This is in contrast to the analytical solutions of the GDEs, following assumptions either on the primary variables or approximations over the derived quantities. For instance, exact solutions of the GDEs provided in Eq. (26a) for the displacement vector are devoid of any assumptions, except for continuity requirements across the domain. In a continuum where these conditions are trivially satisfied, it is possible to obtain exact solutions for specific loading and boundary conditions. Instead, considering the displacement field to be Euler-Bernoulli beam displacement theory significantly simplifies the 3D GDEs to be 1D equations. However, a solution of these equations is limited by assumptions on the Euler-Bernoulli beam displacement theory. Here, we discuss the limited studies on exact solutions of GDEs corresponding to SGE. These results may serve a crucial role in providing benchmark results for the validation of analytical, numerical, and experimental studies on SGE.

In the early 1970s, Kiusalaas et al. [164] formulated an exact solution for strain gradient elasticity in pre-strained laminated materials composed of thin, rigid reinforcing sheets interspersed with thick, compliant matrix layers. However, there was a significant gap in researchers exploring exact solutions of GDEs for SGE, maybe owing to the improvements in computational models and resources. Recently, Sidhardh and Ray [93] developed the exact solution for the elastic response in micro- and nanobeams, considering the GFSGET (see Eq. (10)) for a simply-supported beam subject to sinusoidally distributed transverse load. This follows from considering a characteristic solution that satisfies the boundary conditions (both essential and natural) in a trivial manner. Later, this was extended to develop exact solutions for size-dependent elastic response in low-dimensional heterogeneous structures: laminated beams [70] and functionally graded beams [153]; with relevance to smart structures. Finally, these exact solutions were extended to multiphysics studies involving electro-mechanical coupling via flexoelectricity. In particular, exact solutions for the electrical and mechanical field variables were developed assuming independent characteristic solutions for the flexoelectric response of the nanobeams subject to combined electro-mechanical loads [92].

Clearly, limited studies are available in the literature for an analytical solution of higher-order BVPs and I-BVPs following the inclusion of strain gradients in the constitutive framework. This is owing to higher-order gradients encountered within the GDEs, increasing the difficulty in obtaining analytical solutions when compared with GDEs for classical elasticity. In the following, we present a summary of numerical approaches considered for a solution of these GDEs.

Owing to higher-order partial differential equations for SGE when compared to classical elasticity, the interpolation schemes are modified for an approximation of the primary field variables. Thereafter, numerical approaches based on mesh-based and alternate methods can be employed for a solution of these equations. A brief discussion on numerical approaches is provided below.

3.2.1 Mesh-Based Numerical Methods

First, we discuss the numerical solutions of the GDEs for SGE employing the Finite Element Method (FEM). This is in view of the popularity of FEM as a tool for the numerical solution of partial differential equation. Although the sequence of steps for developing an FE numerical solver for SGE does not differ from that of classical elasticity, there are certain fundamental differences. Firstly, considering the higher order of the GDEs, it is essential to enforce

where

Following this approach, Oden et al. [38] developed a numerical solution for 1D, 2D, and 3D problems on linear first strain gradient elasticity. Felippa used similar approximations for plane stress problems using SGE [165]. These FE solutions are established to agree well with benchmark solutions for all the cases considered. However, the higher-order requirements for interpolation increase the complexity of the FE model. For instance, the 3D FE model that employs

Alternatively, Shu et al. [168] introduced mixed-type finite elements for a numerical approximation of strain gradients. In particular, this approach employs two separate

In the above expression,

Askes et al. [171] devised a different approach referred to as staggered gradient elasticity, where it is demonstrated that

Previously, the FEA for SGE was built on elements and shape functions built for local elastic constitutive framework. Therefore, their extension to the gradient elasticity framework presented significant computational challenges. In the literature, researchers explored the development of new element types and the corresponding shape functions for structures modeled following the SGE framework. For instance, the Stress-Driven Finite Element Method (SD-FEM), formulated in a differential framework, develops nonlocal shape functions based on the Constitutive Boundary Conditions (CBC) and Constitutive Continuity Conditions (CCC). Thereafter, a systematic method to derive both the nonlocal stiffness matrix and the corresponding equivalent nodal forces for a nanobeam is presented. A key advantage of this approach is its ability to deliver the exact stress-driven solution using even a single two-noded element [175–177]. Similar approaches are also explored for the SGE framework [178].

While strain gradient plasticity problems are frequently solved analytically and verified experimentally [57], extending these solutions to general problems requires numerical methods such as FEM [179]. The difficulties listed above in using FE, the need for

3.2.2 Alternate Numerical Methods

The finite element method in its current formulation requires at least

In addition to the meshfree methods mentioned above, there exist alternate approaches for numerical approximation of strain gradients. Das and Chaudari first introduced a 2D boundary element formulation for micropolar elasticity using the reciprocal theorem [194], but it was limited to smooth surfaces. Although its use is primarily restricted to relatively small-scale problems, the Boundary Element Method (BEM) offers notable advantages over the FEM. Key benefits include precise calculation of strains and stresses, reduction of the dimensionality of 3D/2D structure (by one), and the ability to compute elastic fields for both compressible and incompressible materials. BEM has also been applied to solve two-dimensional strain gradient elastostatic problems in the context of the micropolar framework [195].

Ke et al. [196] solved the GDEs for SGE using the differential quadrature (DQ) method for an investigation of the dynamic stability based on MCST (see Section 2.2). The approximation of the

where

4 Physical Relevance of Strain Gradient Theory

As discussed in Section 1, the origins of SGE go back to enriched kinematics for material particles possessing a microstructure. In particular, unlike classical elasticity theories that treat particles as rigid, the Cosserat brothers [25] introduced enriched kinematics in which material particles possess both translational and rotational degrees of freedom. These additional degrees of freedom correspond to the deformation of the microstructure of the particle; a schematic example of the same for CsCl is shown in Fig. 3. Subsequently, a continualization of the microstructure effects introduces higher-order gradients within the constitutive relations. More specifically, a variety of higher-order continuum theories have been introduced in Section 2, each incorporating different choice of higher-order gradients into the continuum framework to capture the specific effects of the microstructure. In particular, gradient elasticity formulations have initially been proposed to better approximate the effect of discrete lattice behavior in wave propagation studies [97,201]. The effect of lattice deformations over high-frequency (low-wavelength) wave propagation is studied using micro-deformations of the directors within the lattice (see Fig. 3) [21]. Among higher-order continuum theories, the strain gradient elasticity theory successfully models size-dependent behavior in small-scale structures. It introduces three material length scale parameters, each associated with dilatation, deviatoric stretch, and symmetric rotation gradients. This theory has been used to study the static and dynamic responses of microscale Bernoulli–Euler beams [144,202,203] and Timoshenko beams [204–206]. By setting two length scale parameters corresponding to the dilatation and deviatoric terms to zero, it simplifies to the modified couple stress theory by Yang et al. [65]. This highlights the specific applicability of the strain gradient elasticity theories to capture diverse deformation mechanisms of the microstructure. In all these cases, gradients are used to enhance the representation of the complex microstructure over the structural response. This approach allows gradient to be used to regularize the solution by reducing singularities or discontinuities and smoothen the heterogeneity of the material [56,57,120,207]. In other cases, gradients are used to introduce heterogeneity, enhancing the representation of the complex microstructure over the structural response.

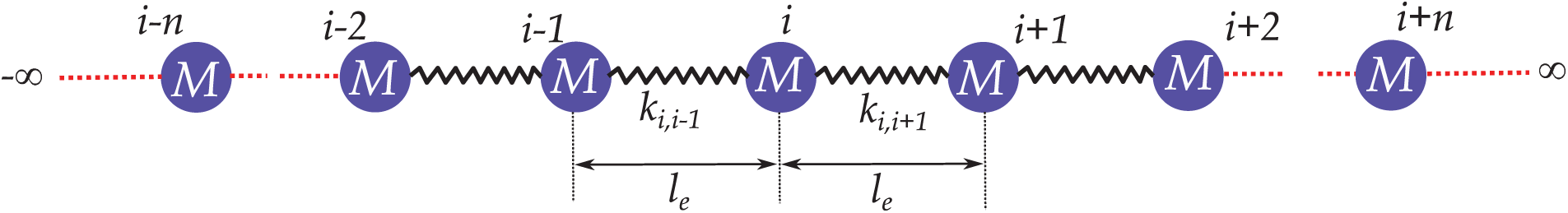

Higher-order continuum models in the literature differ in several aspects, particularly in the manner of incorporating the strain gradient terms. Some examples of the same are discussed in Section 2.2 above. Some models introduce these gradients directly, either through the energy functional or the constitutive equations, following ad hoc approaches. Other models derive higher-order terms from discrete lattice structures using homogenization techniques. This approach preserves a connection with the microstructure of the material, allowing additional material parameters to be interpreted in terms of microscale properties. In this section, we propose to demonstrate the physical significance of the SGE following both of these approaches. More specifically, we derive the SGE terms within the deformation energy following from a 1D chain of spring mass representation for an axial bar. Thereby, we demonstrate the higher-order terms corresponding to long-range interactions, beyond immediate neighbors, within this discrete structure way the foundation for strain gradient elasticity. We conclude this derivation via a continualization of the discrete structure and illustrate the higher-order terms reducing to strain gradients. Thereafter, the higher-order gradients are also connected to the specific deformation modes in a complex microstrfollows.

An infinite one-dimensional lattice of identical particles, each with mass M, is considered, arranged in a collinear manner along the

Figure 8: Schematic of a 1D chain of discrete spring mass system. The chain is considered to infinity to avoid boundary effects

Assuming small displacement gradients (

The first term in the above expression caters to the interaction of point

Here,

By assuming a small

Here, E and A represent the Young’s modulus and the cross-sectional area of the equivalent one-dimensional continuum, respectively. Thus, the constant

The above choice follows from scaling the contributions of strain and strain gradient terms towards the total deformation energy, and to maintain the dimensional consistency. Under these assumptions, the continuum limit of the discrete sum in Eq. (32)

The deformation energy density at a point

The second term in the above integral represents the deformation energy density corresponding to strain gradient elasticity. The preceding discussion highlights that incorporating strain gradients into the continuum model enables it to be weakly nonlocal across the domain. Further, the above derivation is limited to axial deformations, but can be extended to more general deformation modes as well.

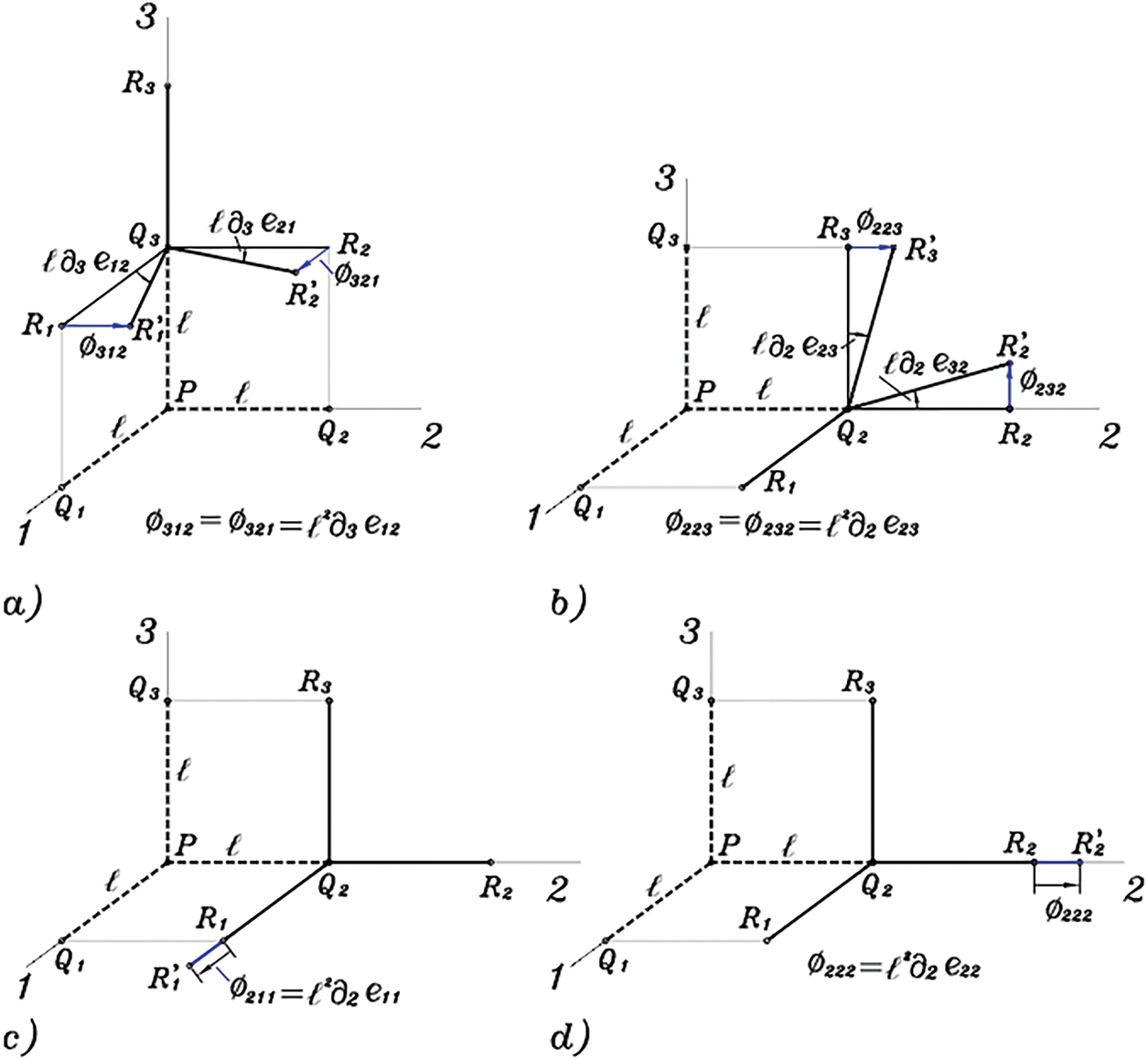

We proceed to interpret the strain gradient terms as (additional) micro-deformation variables [21,208]. This allows us to capture the deformation of the director vectors within the microstructure. In this discussion, the second-order tensor

Figure 9: A schematic illustration of the interpretation of higher-order continuum theories in terms of deformation of the microstructure. For instance, the strain gradient corresponding to: a)

5 Application for Elastic Behavior

Classical continuum theory is widely used to predict the elastic response in structural analysis and design. However, it fails to accurately predict structural behavior at the micro- and nanoscales. For instance, experimental studies on quasistatic bending of the human compact bone demonstrated a stiffening of up to a factor of two with reducing dimension, which cannot be accounted for following classical elasticity [12]. This is demonstrated to be better captured following the micropolar and couple stress (see Section 2.2) theories of elasticity. Similarly to this, Yang and Lakes repeated the tests on torsion response of the human compact bone specimen [11,12], and experimentally demonstrated the size-effects on torsional stiffness. More specifically, as the dimensions of structure decrease, the classical continuum theory tends to underestimate the structural stiffness [12,209]. To address these limitations of classical elasticity theory, higher-order elasticity theories that incorporate length scale parameters corresponding to the material microstructure have been proposed. These include Cosserat theory [25], couple stress theory [28], micromorphic theory [14], micropolar theory [210], and a family of strain gradient elasticity theories [26,29,31]. Among these, we focus here on the application of strain gradient theories for modeling the size-dependent elastic response.

Structural response: Several studies have explored gradient-based (higher-order) theories to improve the predictions of structural behavior at the micro- and nanoscales. Lam et al. [6] conducted early research in this area, observing an increase in the bending stiffness (compared to classical elasticity predictions) of epoxy microbeams as their thickness was reduced from 115 to 20

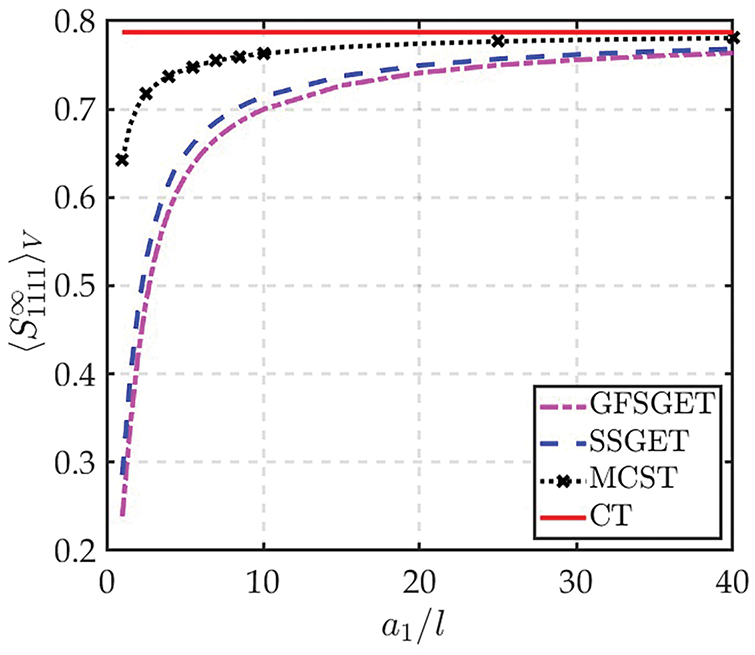

Figure 10: (a) Demonstration of size-dependent bending stiffness in an epoxy cantilever microbeam, adapted from [212]. (b) Normalized transverse deflection of a simply supported beam under a point load (aspect ratio

Recall the detailed comparison of the different higher-order strain gradient elasticity theories provided in 2.2. The simplified constitutive models differ according to the specific deformation modes they account for. For instance, the MCST proposed by [65] accounts for only the rotation gradients of the deformable directors (see Fig. 3). In contrast to this, the MSGT provided in Eq. (13) also considers the gradients of the stretch and deviatoric deformation modes of these directors within the microstructure. Finally, the GFSGET considers all the probable modes of deformation of the directors within the microstructure. This specific choice of the constitutive framework depends on the microstructure and the mechanics of its deformation. A comparison of the relative size effects realized following the GFSGET (see Eq. (11)), MSGT (Eq. (13)) and MCST over the bending response of an elastic beam is provided in Fig. 10b. Therefore, appropriate choice of the SGE theory must be chosen for modeling the structural response of low-dimensional structures composed of different material types.

Elastodynamics: The study of the propagation of elastic waves in solids is of immense theoretical and practical significance, offering valuable insights into the elastic behavior of materials and structures. Given the growing importance of micro- and nano-structures, extensive research has been conducted to analyze wave propagation in low-dimensional structures [214–218]. The effect of increasing stiffness with reducing dimensions is reflected in different forms in elastic behavior; for instance, with reference to the current context, an increase in natural frequencies with reducing microstructure dimensions [37,219]. In addition, a dispersion of elastic waves is another example of the effect of microstructure on the behavior of the material. Recall that the governing differential equation for strain gradient elasticity given in Eq. (26a). These GDEs can be further simplified using Navier’s solution. The resulting Navier’s governing equations for the first strain gradient theory of elasticity, assuming the body forces to be absent, may be expressed as [97]:

where the term

Furthermore, if the SGE effects are neglected (

where

To better illustrate the effect of SGE over wave propagation, we note that in the long-wavelength limit (wavelength>>characteristic length scale of microstructure) the phase velocities are given as:

thereby reducing to the velocities evaluated from classical elasticity. Alternatively, in the short-wavelength limit, the phase velocities of the longitudinal and transverse waves reduce as:

In the short-wavelength limit, the influence of the microstructure, captured by the SGE, is clearly significant for the elastodynamic behavior. This observation agrees with the seminal work of Mindlin [21] on elastic wave propagation, which also incorporates microstructural effects through SGE.

Building upon this, Savin et al. [37,141] explored wave dispersion in low-dimensional structures incorporating SGE. Moreover, employing the results of these studies, Savin experimentally determined the elastic constants of polycrystalline metals using ultrasonic techniques. Later, Mühlhaus et al. [201] proposed a one-dimensional Cosserat model for longitudinal wave propagation in granular media, introducing additional rotational degrees of freedom to capture grain rotations. Vardoulakis et al. [221] extended Mindlin’s theory to develop a linear gradient-elastic model with surface energy (see Section 2.3), effectively predicting Shear horizontal surface wave motions in a homogeneous half-space. Georgiadis et al. [222] further demonstrated that the couple-stress elasticity theory with microstructure enhances the accuracy of Rayleigh wave modeling, bridging classical continuum mechanics and atomistic lattice models. Incorporating SGE allowed for improved agreement with both experimental data and high-frequency predictions of discrete particle theories. Askes et al. [223] introduced four simplified versions of SGE theory, focusing on their dispersive properties, causality in accordance with Einstein’s principles, and behavior in basic boundary and initial value problems. Further, Vavva et al. [224] employed the simplified Mindlin Form-II (dipolar gradient elasticity theory) to investigate symmetric and antisymmetric wave modes in 2D stress-free gradient plates. Their study showed that variations in elastic constants highlight the influence of microstructure, which significantly affects the propagation of bulk longitudinal and shear waves by introducing both material and geometrical dispersion.

Papargyri et al. [96] highlighted that incorporating shear and rotary inertia corrections in beams and plates mimics the inclusion of micro-elastic and micro-inertia terms, contributing to wave dispersion in structural elements. Extending this perspective, Sidhardh and Ray [97] investigated the dispersion of Rayleigh–Lamb waves in micro-plates using the generalized first strain gradient elasticity theory (GFSGET). More recently, Gao et al. [142] proposed a model for elastic wave band gap analysis in periodic composite beams, accounting for surface energy, shear deformation, and rotational inertia using harmonic wave solutions—further enriching the modeling of wave propagation in gradient elastic media.

Composite homogenization: More than half a century ago, Boutin [225] studied the effects of microstructure on periodic elastic composites. In this study, higher-order terms in the form of higher-order gradients of macroscopic strain are included to introduce nonlocal effects due to the microstructure. Similar homogenization techniques have attracted renewed interest from researchers, particularly due to recent advances in manufacturing that enable the fabrication of complex microstructures. Although studies based on classical elasticity establish the influence of geometry and volume fraction of the inclusion phase on the effective properties of composites [226], several researchers [227–230] observed that the elastic properties of composites vary with the dimensions of the inclusion phase. In particular, size effects due to nonlocal interactions of low-dimensional inclusions are realized over the homogenized properties of the composite.

To address this, Eshelby’s inhomogeneity problem has been reworked within the framework of gradient elasticity theory. Recently, Sidhardh and Ray developed the modified Eshelby’s tensor for spherical, cylindrical, and elliptical inclusions considering the generalized first strain gradient elasticity theory (GFSGET in Eq. (11)) [152,153]. As expected, the Eshelby’s tensor in the SGE framework depends on the length scale of the microstructure controlling the nonlocal interactions, and varies for different simplified forms of the SGE discussed in Section 2.2. This is unlike a constant value for the Eshelby’s tensor, within the inclusion, following classical elasticity; see Fig. 11. This study and the observations therein follow from similar works by Zhang and Sharma [150] and Gao and Ma et al. [151] for Eshelby’s tensor of spherical and cylindrical inclusions within the couple stress and SSGET frameworks (discussed in Eq. (16)), respectively.

Figure 11: Volume-averaged component of the Eshelby’s tensor for different dimensions of the ellipsoidal inclusion (

Using this approach and an extension of Eshelby’s integral representation to SGE, an exact solution was derived for the problem of a spherical inhomogeneity with interphase [231]. This solution was later applied to study the scale effects on the effective material properties at low dimensions. Furthermore, within the same extended Eshelby integral framework, the problem of coated spherical inhomogeneity with surface cohesive phenomena was analyzed [232] for predicting the effective properties of the composite material. Ameen et al. [233] applied the classical and higher order method to a two-phase microstructure and compared with a rigorous full-scale numerical solution. The accuracy of classical and higher-order homogenized solutions depends only mildly on the degree of stiffness contrast. For the particle-reinforced system considered here, the error increases with increasing stiffness contrast but eventually stabilizes in the rigid-particle limit. It is noted that, higher-order periodic homogenization can effectively refine the classical solution with sufficient accuracy at low scale ratios.

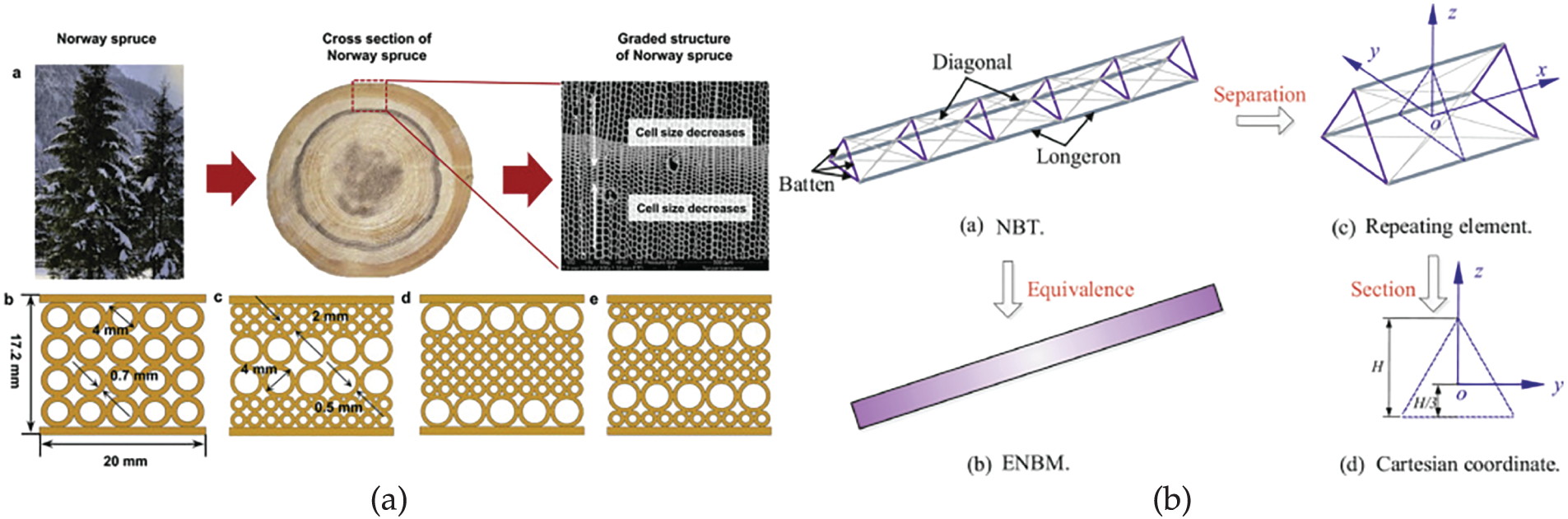

Reduced-order modeling: Modeling complex 3D structures and time-dependent problems presents high computational demands due to a large number of system of equations being involved. Among the several reduced-order models explored for improvement in the computational burden, modeling via nonlocal theories, and more specifically SGE, has attracted the research community. The nonlocal interactions presented by SGE (see Section 4) enable to capture the complex interactions within the microstructure. More specifically, the SGE allows a development of accurate reduced-order models for complex macrostructures by modeling complex interactions via nonlocal effects. For instance, modeling a beamlike lattice structure by 1D micropolar beam was carried out in [234]. Recently, Tran et al. [143] demonstrated the effectiveness of SGE theory in analyzing 2D triangular lattice structures, from the linear regime to von Kármán–type geometric nonlinearity. In addition to this, substantial computational savings were demonstrated following this approach, thanks to reduced numbers of the degrees of freedom, while still maintaining high accuracy compared to conventional 2D finite element simulations. Furthermore, Karttunen et al. [112,235] proposed a localization method to extract the response of periodic classical beam from micropolar formulations. This 1D beam model was later applied to linear bending and vibration analyses of 2D web-core sandwich panels with flexible joints, demonstrating excellent agreement with both experimental results and two-dimensional finite element beam frame simulations. Further, Nampally et al. [120] extended the formulation to a nonlinear analysis of micropolar Timoshenko beams by employing a two-scale energy method. This approach was used to derive the micropolar constitutive equations for various core topologies, including web, hexagonal, Y-frame, and corrugated cores, enabling a more comprehensive representation of their mechanical behavior. This emerging direction holds considerable promise for employing SGE in modeling complex engineering structures. For instance, an example of the lattice core structure studied using micropolar theories is illustrated in Fig. 6b.

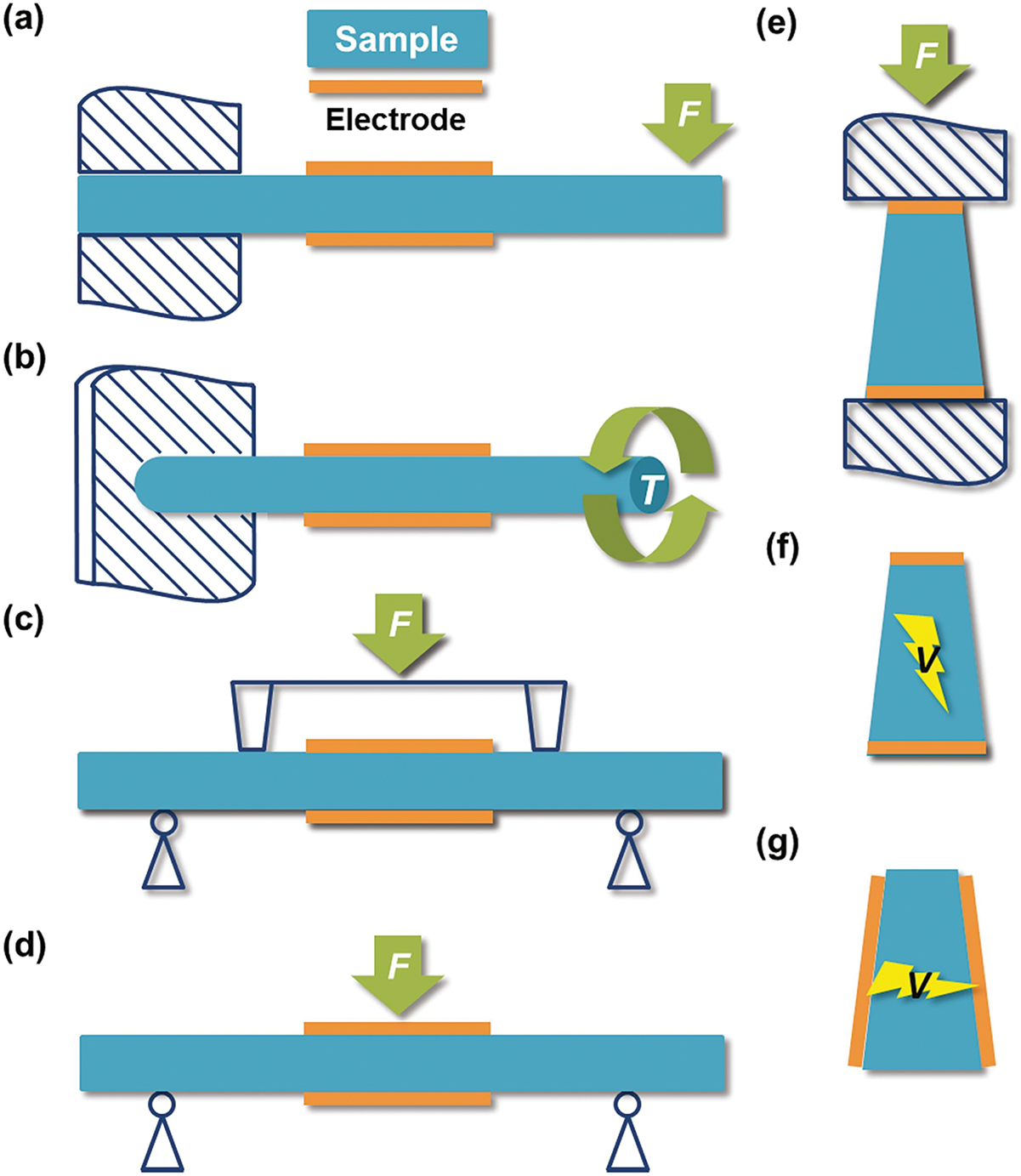

MEMS and NEMS: MEMS technology has emerged as a significant high-tech industry, following the rise of microelectronics. However, as MEMS devices scale down in size, their surface area to volume ratio increases significantly. This leads to pronounced size effects, where mechanical behavior deviates from that of macro-scale systems, and surface effects become increasingly dominant [236–238]. Therefore, various studies have explored size-effects over the dynamic behavior of MEMS and NEMS [239].

An example of the size-effects on performance of MEMS is the effect of nonlocal elastic interactions over pull-in instability; in addition to its effect on the elastic behavior. One critical challenge in designing MEMS is avoiding pull-in instability, which can cause the microbeam to collapse and lead to device failure. For instance, Xue et al. [240] investigated the size-effects in MEMS devices using a mechanism-based strain gradient approach, and noted a significant increase in mechanical strain energy (when compared to classical theory) in the digital micromirror device. Further, Hamid [241] studied the influence of vibrational amplitude on pull-in instability and natural frequency of actuated microbeams using a second-order frequency–amplitude model. Incorporating electrostatic and fringing field effects within strain gradient elasticity, the analysis showed that this theory predicts a higher pull-in voltage compared to classical and modified couple stress theories. Kahrobaiyan et al. [242] developed a FE model for Timoshenko beams based on strain gradient theory, capable of reproducing various classical and non-classical beam formulations (strain gradient Euler–Bernoulli beam element, modified couple stress Timoshenko and Euler–Bernoulli beam elements, and also classical Timoshenko and Euler–Bernoulli beam elements). This model was used to compute the static pull-in voltage of an electrostatically actuated microswitch, showing strong agreement with experimental results and outperforming classical FEM predictions. Soroush et al. [243] investigated the impact of Van der Waals forces on the stability of NEMS, considering gradient effects in nanobeams under electrostatic loading. Their findings show that stronger intermolecular forces lead to reduced pull-in deflection and voltage of the actuators. These studies underscore the necessity of advanced mathematical and computational methods for analyzing and designing MEMS and NEMS, considering the limitations of classical theories and the importance of long-range interactions at this scale.

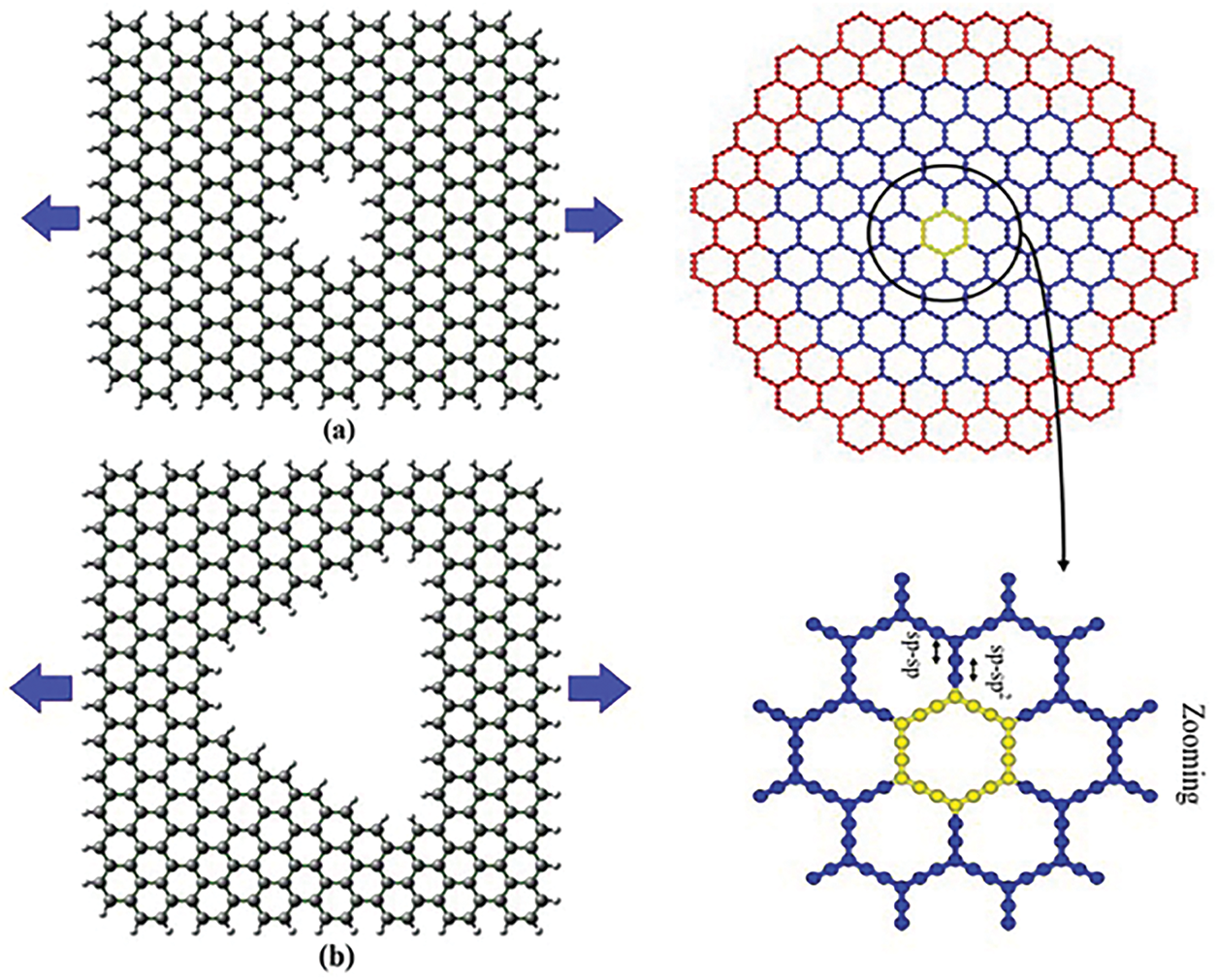

Carbon nano-structures: Since their discovery in the early 1990s [244], carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have attracted attention because of their exceptional electrical, thermal, and chemical properties [245]. However, experimental findings on elastic behavior of CNTs often vary significantly from predictions by classical theories, reflecting discrepancies due to differing test environments and methodologies [246–249]. This can be partly owed to the size-effects realized at these length scales. Therefore, several studies have focused on the elastic response of CNTs including size-effects via SGE constitutive theories, when subject to a myriad of load types and corresponding deformation modes (axial/bending, structural stability, static/dynamic) [250–254]. The improvement in predictions of the elastic response after including SGE is demonstrated via comparison with atomistic simulations. The work of Sun and Liew [255] provides a clear example of this agreement, showing that higher-order gradient theories accurately predict Single Walled NanoTubes (SWNTs) buckling as determined by atomistic simulations. In most studies, it is reported that the introduction of strain gradients within the potential energy given in Eq. (1) presents a greater stiffness of the structure with reducing dimensions (below

Figure 12: Schematic of passivated armchair graphene sheet with trapezoidal pore subjected to an axial stress [264]

6 Application for Multiphysics Coupling

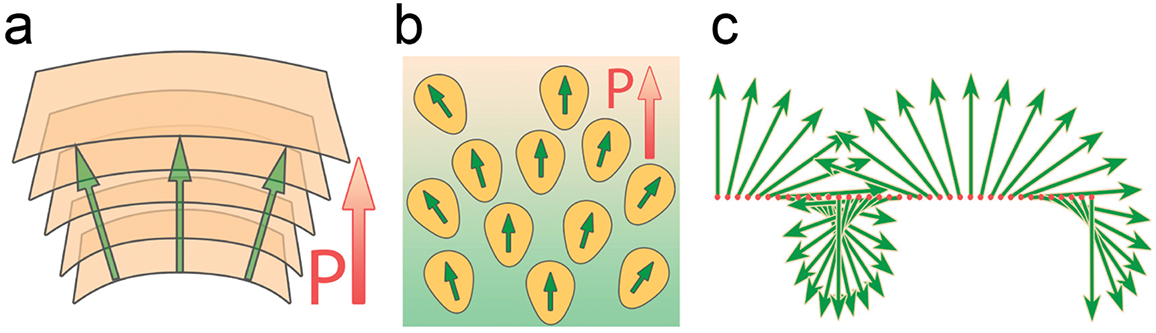

Ferroelectric materials are widely used in actuators, sensors, memory devices, electro-optics, and MEMS because of their multifunctional properties driven by interactions between internal polarization and external factors like temperature, pressure, and electric fields. Among these, piezoelectric effect, presenting a non-zero electrical polarization to applied mechanical pressure (or vice versa), is well established. This coupling of the electro-mechanical field variables is limited to the non-centrosymmetric crystalline (and semi-crystalline) materials. Surprisingly, experiments detected a non-zero polarization in ferroelectrics even in their centrosymmetric crystalline phase. More specifically, Ma and Cross [47,48,62] note a non-zero polarization upon bending of ferroelectric crystals in their centrosymmetric phase at very low dimensions. This is attributed to a loss in symmetry and a resultant polarization in the materials as a result of the strain gradients across the structure. The loss in centrosymmetry and the resulting net polarization across the crystals due to the presence of a strain gradient is called the phenomenon of flexo-electricity. The suffix flexo- follows from initial observations of non-zero polarization in centrosymmetric crystals when subject to bending (flexure). This observation is significant because it reveals that electro-mechanical coupling in smart materials is a universal property, extending beyond the limitations of non-centrosymmetric structures. Similar observations of multiphysics coupling involving strain gradients are realized over magneto-elastic and thermo-elastic field variables, and discussed briefly in the section below.

Electro-mechanical coupling: The flexoelectric effect, coupling strain-gradients and electrical polarization, was theorized long before any experimental evidence. It may be interpreted as an electro-mechanical phenomenon in which a material exhibits a non-zero electric polarization in response to a strain gradient (non-uniform mechanical deformation) as demonstrated in Fig. 3b. As seen in this figure, strain gradients (following from a non-uniform strain across the thickness due to a bending load) present an asymmetric redistribution of electrons. Thereby, a net polarization is realized in centrosymmetric material. Understanding these interactions is key for advancing nanoscale electro-mechanical coupling with relevance for energy harvesting and actuation technologies.

The constitutive relations for the flexoelectric solid can be derived from the following expression for the internal energy density in centrosymmetric solids [265]:

where