Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Fuzzy Logic-Based Robust Global Consensus in Leader-Follower Robotic Systems under Sensor and Actuator Attacks Using Hybrid Control Strategy

1 Metaverse Research Institute, School of Computer Science and Cyber Engineering, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, 510006, China

2 Department of Mathematics, College of Sciences, Northern Border University, Arar, 91431, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Lahore, Sargodha, 40100, Pakistan

4 Department of Mathematics, College of Sciences and Arts (Muhyil), King Khalid University, Muhyil, 61421, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Mathematics, College of Sciences and Humanities, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Alkharj, 11942, Saudi Arabia

6 School of Engineering Sciences, Lappeenranta-Lahti University of Technology, Lappeenranta, 53850, Finland

* Corresponding Authors: Fathia Moh. Al Samman. Email: ; Azmat Ullah Khan Niazi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Intelligent Control and Machine Learning for Renewable Energy Systems and Industries)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1971-1999. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068240

Received 23 May 2025; Accepted 11 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

This research paper tackles the complexities of achieving global fuzzy consensus in leader-follower systems in robotic systems, focusing on robust control systems against an advanced signal attack that integrates sensor and actuator disturbances within the dynamics of follower robots. Each follower robot has unknown dynamics and control inputs, which expose it to the risks of both sensor and actuator attacks. The leader robot, described by a second-order, time-varying nonlinear model, transmits its position, velocity, and acceleration information to follower robots through a wireless connection. To handle the complex setup and communication among robots in the network, we design a robust hybrid distributed adaptive control strategy combining the effect of sensor and actuator attack, which ensures asymptotic consensus, extending beyond conventional bounded consensus results. The proposed framework employs fuzzy logic systems (FLSs) as proactive controllers to estimate unknown nonlinear behaviors, while also effectively managing sensor and actuator attacks, ensuring stable consensus among all agents. To counter the impact of the combined signal attack on follower dynamics, a specialized robust control mechanism is designed, sustaining system stability and performance under adversarial conditions. The efficiency of this control strategy is demonstrated through simulations conducted across two different directed communication topologies, underscoring the protocol’s adaptability, resilience, and effectiveness in maintaining global consensus under complex attack scenarios.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Technological advancements have increasingly driven the integration of automation into various fields, revolutionizing efficiency and functionality across industries [1]. Robotics has become an important technology among these innovations, by providing imaginative options that allow for ongoing assistance with human jobs. Recent works have proposed event-triggered optimal impedance control for exoskeletons using critic neural networks [2], robust constraint-based controllers for uncertain nonlinear manipulators [3], and hierarchical adaptive coordination strategies for large-scale traffic networks [4]. High-precision simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM)-based positioning in GPS-denied environments [5] and output feedback stabilization for aperiodic sampled-data systems via looped functionals [6] further contribute to advanced control design. To enhance contour tracking, reference [7] proposed a time-varying internal model principle-based control method and a hybrid-excited vernier reluctance linear machine with Halbach Permanent Magnet (PM) arrays. Mobility on rough terrains was improved through a creeping gait strategy using fuzzy logic in wheeled robots [8], while reference [9] introduced a prescribed performance adaptive robust control for uncertain manipulators with Lyapunov-based guarantees. A prestretch-free dielectric elastomer actuator for soft robotics was developed ([10,11]) to address Lurie system stabilization using a cone complementary linearization algorithm. Robotic tracking under uncertainty was handled via a second-order sliding mode adaptive controller in [12], and Connected and Automated Vehicles were coordinated under actuation constraints using a bi-level distributed framework in [13]. Optimal consensus for delayed multiagent systems (MASs) was achieved through a delay-free deterministic policy gradient method [14], and encoder accuracy in robotic arms was improved using a hybrid deep learning-based error compensation model [15]. When coordinating a swarm, each robot must respond not only to external environmental changes but also to the movements of neighboring robots to preserve the overall formation and direction toward the target ([16,17]). The challenge, therefore, lies in developing robust control algorithms that allow swarm robots to navigate, adapt, and maintain formation cohesively while responding to unpredictable elements or situations in real-time applications [18]. With increasing indoor occupancy, occupant thermal comfort monitoring using mobile robots has emerged to overcome the inefficiencies of fixed sensors in non-uniform environments [19]. Joint LiDAR-based scene flow estimation and moving object segmentation improve autonomous driving tasks by exploiting shared geometric constraints [20]. Flexible actuators like DEA and IPMCs enable biomimetic control via FLS and barrier Lyapunov function (BLF)-based adaptive pseudo inverse schemes for constrained hysteretic systems [21]. For heavy trucks, an adaptive memory event-triggered output feedback ensures finite-time lane-keeping with roll prevention under nonlinear dynamics [22]. Microwave-based deicing struggles with Z-shaped contact wires on moving trains [23], while binocular stereo vision-based GOAL enhances robotic grasping under occlusion [24]. A sweeping-spinning gait and Bayesian optimization improve planetary rover escape from soft terrain [25]. SPL offers nano-fabrication capabilities, though limited by atomic force microscope (AFM) scanner stroke [26], and a single-step fused filament fabrication (FFF)-based method improves the rapid design and fabrication of soft pneumatic actuators [27]. Leader-follower approach, by contrast, is simpler to adopt, with a single robot designated as the leader and other robots following in a framework ([28–30]). One of the major advantages of this policy is for maintaining stability in challenging and rapidly changing critical situations [31]. To avoid complex back-stepping and coupled observer-controller designs, a neural network prescribed-time observer-based output-feedback control method is proposed for uncertain pure-feedback nonlinear systems, enabling fast and accurate estimation of states and disturbances [32]. For autonomous driving, an integrated decision-making and motion planning framework is introduced to eliminate oscillations and enhance safety in dynamic environments ([33,34]). Addressing actuator faults in heavy-lift launch vehicles, a predefined-time observer facilitates quantized attitude control with precise temporal guarantees [35]. In robotic milling, a multi-channel chatter detection method is developed to identify structural and tool-mode chatter under low-frequency vibration interferences [36]. For machining large components, mobile robot base position and cabin angle are jointly optimized using a homogeneous stiffness domain index, improving structural rigidity and machining precision [37]. Leader-follower frameworks have been recommended by a number of studies in recent years for swarm robotics formation stability [38]. In several investigations, scholars looked into the leader-follower approach in plain settings. Although these controlled situations offer valuable insights into fundamental swarm formation, they are very different from real-world situations where robots have to move around a variety of obstacles. In control systems for swarm robotics divided into two main categories: conventional control and intelligent control methods [39]. The semi-global stabilization of parabolic partial differential equations (PDEs)–ordinary differential equation (ODE) systems with input saturation is achieved via low-gain controllers under complex boundary conditions [40], while a PDE-based observer with predictor control enables output-feedback stabilization for systems with infinite delays [41]. For uncertain systems, a Padé-approximation-based optimal preview repetitive control with equivalent-input-disturbance (EID) enhances robustness [42]. Magnetic millirobots with switchable adhesion enable versatile manipulation in constrained environments [43], and force feedback bilateral teleoperation advances remote control in hazardous and medical applications [44]. A one-step FFF process simplifies soft actuator fabrication for adaptive bio-inspired robots [45]. A graph-based leader–follower strategy ensures precise tracking [46], while ship synchronization uses a stochastic observer under unknown leader velocity [47]. CB-MTE improves bot detection via multi-source fusion [48], and adaptive impedance control reduces docking collisions in unmanned vehicles [49].

Motivated by our previous discussion, we outlined contributions in a way that

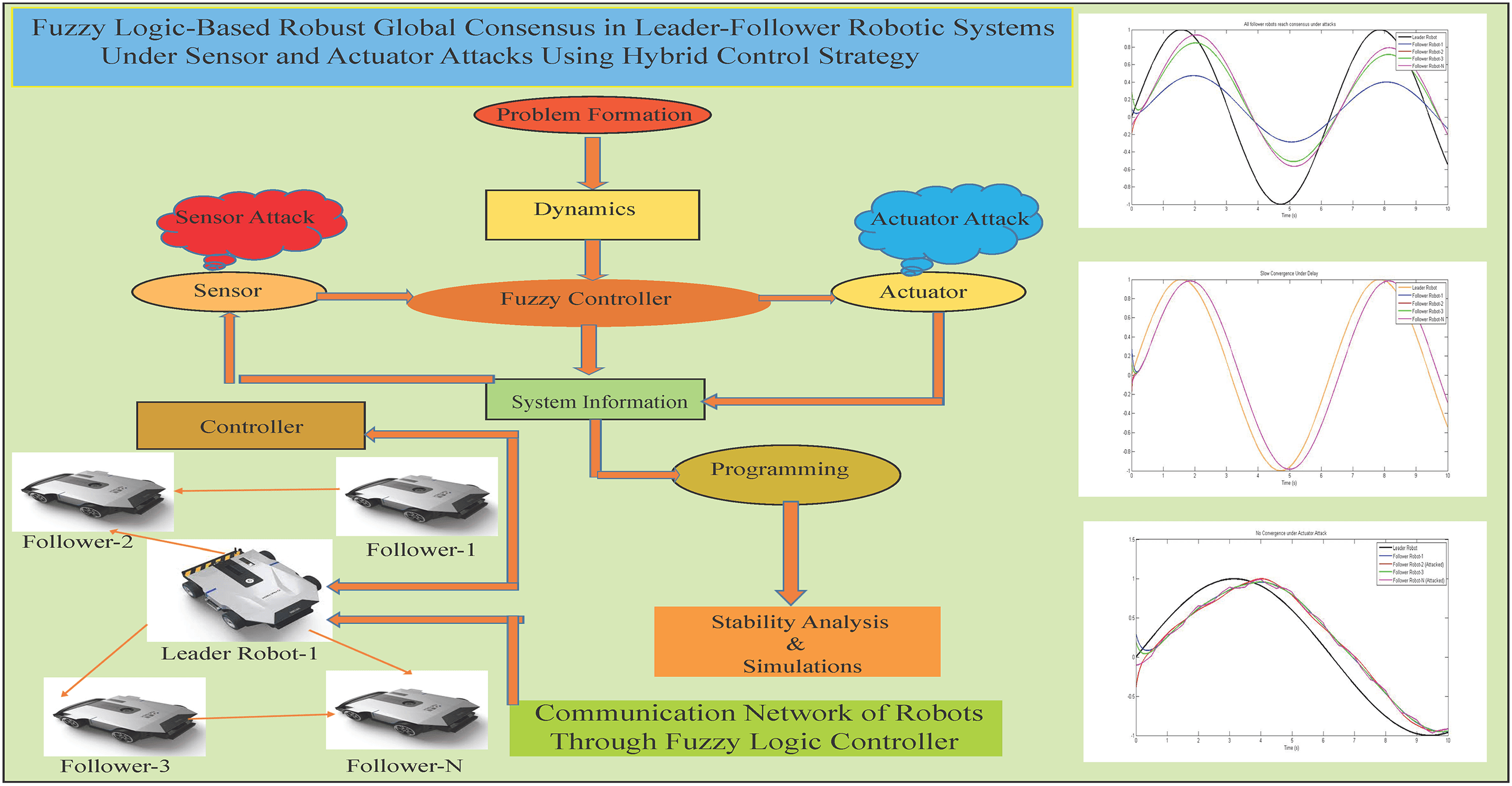

In this paper, we contribute a robust hybrid distributed adaptive control strategy for leader-follower robotic systems with both first-order and second-order dynamics, addressing simultaneous sensor and actuator faults. A specialized controller is designed to mitigate the combined effects of these attacks while ensuring system resilience. The leader robot, modeled with second-order dynamics, communicates its state information to follower robots, which approximate unknown nonlinear dynamics using fuzzy logic systems. A Lyapunov-based stability analysis is conducted to ensure the system’s asymptotic consensus. The proposed strategy is validated through simulations on two directed communication topologies, demonstrating its effectiveness and adaptability in achieving stable and robust global consensus. A comprehensive graphical representation of the proposed approach is presented in Fig. 1. The content of this article is organized as follows:

1. In Section 1, we discussed the fuzzy logic system of robots under the effect of sensor attacks and actuator attacks.

2. In Section 2, we present the graph theory for the communication of the robot system graph.

3. In Section 3, we provided a problem formation for N robots and also gave the position, velocity, and acceleration dynamics of robots, including the signal attacks.

4. Section 4 presents the influence of sensor attack and actuator attack, assumptions, and fuzzy control design framework and theorem.

5. In Section 5, we present two examples with different communication topologies under the sensor attack and actuator attack.

6. In Section 6, at the end of this paper, we wind up this paper with conclusions.

Figure 1: Graphical representation of abstract

The framework of the paper is described in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Framework of the paper

Graph Theory

Consider a network of robotic systems represented by a directed weighted graph

A directed edge

To describe the network dynamics, we define a

We consider a heterogeneous group of nonlinear robots consisting of first-order, second-order, and third-order follower robots, indexed by

where

The control input protocol is denoted by

The first-order follower robots are those that track the leader’s robot.

where

Similarly, we define the leader dynamics of robots as follows,

where consisting of its position

Now, we define the leader-follower robots tracking error for position, velocity, and acceleration such that

And we define the consensus error for position, velocity and acceleration robots.

Now we rewrite the consensus errors position, velocity, and acceleration for all follower robots in a compact matrix form. For all followers of robots, we get the vector of consensus errors. We need to express

Thus, we can rewrite the term

where

Now we define the local consensus error for the follower robots. To extend the local consensus filter error

We can write it in this form,

where

Now using (1), (2), (3), (6), (7), (8) and (9), we get result,

where

4 Influence of Actuator and Sensor Attacks on Robot Dynamics

Actuator faults in robotic systems are modeled as,

where

Similarly, the behavior of the system under sensor anomalies is described by,

where

where

This formulation captures the joint influence of actuator and sensor attacks on robotic systems, providing a foundation for analyzing and mitigating their effects through robust control strategies.

Assumption 1. Assume that each follower robot i has dynamics which is governed by a nonlinear function

where

Assumption 2. The leader’s state of robot

Assumption 3. The leader’s state of

This formulation allows for tracking errors in position, velocity, and acceleration, providing a more comprehensive approach to handling consensus errors in each state component. Fig. 3 shows the N robots model under the sensor attack and actuator attacks controlled by fuzzy logic.

Figure 3: Network communication topology with directed connected graph agents under the sensor attack and actuator attack

We design a fuzzy logic robust control protocol that addresses nonlinearities and provides robustness against sensor and actuator attacks, using adaptive techniques for optimal performance. The protocol employs fuzzy logic-based estimation, dynamic gain adjustments, and nonlinear function handling, enabling the system to adapt to disturbances while ensuring stability. To address the heterogeneity among agents with first-order, second-order, and third-order dynamics, we propose a fuzzy logic-based robust control framework that incorporates adaptive design and nonlinear estimation mechanisms. The set of follower robots is partitioned into three disjoint subsets, such that

This partitioning enables us to customize the control input

This partitioning enables us to design customized control laws for different dynamics. The control protocol for robot

Here, the second term estimates the attack signal, while

Here,

Each unknown nonlinear function

where

where

This architecture guarantees the approximation of nonlinear dynamics with bounded error. Clear mapping from robot class to control behavior. Reproducibility of the fuzzy estimator

Figure 4: Block diagram of the fuzzy logic-based robust control framework under sensor and actuator attacks

Lemma 1. [9].

where

where,

where

Theorem 1. Take the leader-following robots system defined by Eqs. (1) and (3) and by using the Assumptions (1), (2) and (3). Let

Using the consensus protocol outlined in Eqs. (14), (15) and the defined parameters Eq. (16), the system achieves the following outcomes,

This implies that each follower robot in the network can asymptotically synchronize its state with that of the leader, achieving precise tracking over time and ensuring stability within the system.

Proof. To analyze the stability of the error system defined in Eq. (10), we construct the following Lyapunov candidate function,

where

Taking the time derivative of (17), we get,

By using the Eq. (10) and simplifying the expression, we get,

Substituting

We distribute these terms such that,

Finally, combining all the terms, we obtain,

Now we take the term,

Now using the [38–40] and use the unknown function like

where

Now using the Eqs. (6)–(8), we obtain the result,

Now, we take the term second

where

where

and

where

where

By using the theorem 2 from [41], we can conclude that

Now combining the Eqs. (14), (15), (24), (25) and (26), and using in (20), we conclude that,

Now we use the Quadratic of parameter error. By using the Lyapunov function.

Now we define that,

and we define that,

Now we using the Eqs. (28)–(31).

Now solving the Eqs. (32) and (27), and we obtain the result.

where,

where we take,

Now using the Eq. (33), we use the Lemma (1),

The effectiveness of the robotic control system is demonstrated through two examples involving various directed communication topologies.

Example 1 We consider a leader robot and six follower robots under the fuzzy logic control protocol with the effect of sensor attack and actuator attack, which are shown in Fig. 3.

According to this communication strategy (Fig. 5) and we construct the adjacency matrix becomes as,

and diagonal matrix becomes,

similarly Laplacian matrix becomes,

Now we define the matrices such that,

where we take

Figure 5: Communication topology of fuzzy logic robotic system under the sensor and actuator attacks

The robot’s dynamics are described as,

For follower robots

For the leader robots,

Now we define the

And

The initial states of the robots are defined as follows,

To analyze the effects of actuator and sensor attacks on robotic systems, the following numerical values are assigned to the parameters involved:

• Actuator Parameters

– Nominal actuator state:

– Injected actuator attack signal:

– Indicator function for actuator attack:

Sensor Parameters

– Nominal sensor state:

– Injected sensor attack signal:

– Indicator function for sensor attack:

Communication Parameters

– Scalar gain for interaction:

– Adjacency matrix coefficients:

Fig. 6 shows the state error and consensus error of robots. Fig. 7 shows state curves of position and velocity of robots. Similarly, Fig. 8 shows the acceleration curve states of robots. Fig. 9 shows the sensor attack and actuator attack on the system. Fig. 10 shows the performance of the fuzzy logic controller under both attacks and the performance of the controller without the effect of both attacks.

Figure 6: The state error and consensus error of robots

Figure 7: The curves state of position and velocity of robots

Figure 8: The acceleration curve states of robots

Figure 9: The sensor attack and actuator attack on the system

Figure 10: The performance of the fuzzy logic controller under both attacks and the performance of the controller without the effect of both attacks

Example 2 In this simulation of robots, similarly, we take one leader robot and six follower robots under the sensor attack and actuator attack controlled through a fuzzy logic controller, which are shown in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Network communication topology of with directed connected graph agents under the sensor attack and actuator attack controlled through fuzzy logic controller

According to the communication topology Fig. 11, we can construct the adjacency matrix such that,

Similarly, we take here

For the leader robots,

Now we define the

And

The initial states of the robots are defined as follows,

Actuator Parameters

• Nominal actuator state:

• Injected actuator attack signal:

• Indicator function for actuator attack:

Sensor Parameters

• Nominal sensor state:

• Injected sensor attack signal:

• Indicator function for sensor attack,

Communication Parameters

• Scalar gain for interaction:

• Adjacency matrix coefficients:

Fig. 12 shows the state error and consensus error of robots. Fig. 13 represents the curve of position states and velocity states of robots. Fig. 14 shows the acceleration curve, states, and sensor attack on robots under the control system. Fig. 15 shows the actuator attacks and also shows the controller performance under both attacks. Fig. 16 shows the controller performance of robots without both attacks.

Figure 12: The state error and consensus error of robots

Figure 13: The curve of position states and velocity states of robots

Figure 14: The acceleration curve, states, and sensor attack on robots under the control system

Figure 15: The actuator attacks and also the controller performance under both attacks

Figure 16: The controller performance of robots without both attacks

Comparison with Existing Methods

Our proposed FLS control strategy substantially advances existing consensus control methods by addressing several key limitations in the current literature. Traditional consensus approaches, including classical adaptive and robust control schemes, are typically designed for systems with known or partially known dynamics and are often limited to mitigating either sensor disturbances or actuator faults in isolation. Moreover, such methods predominantly target bounded consensus rather than guaranteeing asymptotic convergence. In contrast, our approach introduces a fuzzy logic system (FLS) to estimate unknown nonlinear dynamics and combines it with a robust adaptive control mechanism that compensates for the combined impact of simultaneous sensor and actuator attacks. This comprehensive design ensures stronger resilience and performance under adversarial conditions.

A distinguishing feature of our framework lies in its cooperative multi-order consensus structure, where consensus is achieved in a hierarchical fashion: first-order consensus is enforced for position alignment, second-order consensus is established for velocity synchronization, and third-order consensus is realized for acceleration coordination. This layered control structure allows the agents to not only reach agreement on their spatial positions but also harmonize their motion profiles, leading to smoother and more realistic group behavior in robotic and vehicular networks. Furthermore, while recent fuzzy logic-based consensus strategies have made progress in handling certain classes of attacks or uncertainties, they typically focus on achieving consensus in position alone and often rely on static or bounded convergence guarantees. In contrast, our proposed method ensures asymptotic consensus across all state variables, position, velocity, and acceleration under more challenging conditions, including directed communication topologies and dynamic signal attacks. The effectiveness and generality of the proposed scheme are validated through extensive simulations, demonstrating its robustness, scalability, and adaptability in complex multi-agent environments. Unlike classical consensus protocols such as adaptive or robust controllers that typically assume bounded disturbances and known system dynamics, the proposed fuzzy logic-based hybrid distributed adaptive control framework addresses a more challenging and realistic scenario involving unknown nonlinear dynamics and simultaneous sensor-actuator attacks. Traditional methods generally focus on either robust estimation or attack mitigation in isolation, and their consensus results are often limited to bounded convergence rather than asymptotic stability. In contrast, our method employs fuzzy logic systems (FLSs) to estimate unknown nonlinearities in the dynamics of each follower robot while simultaneously incorporating a specialized robust control term to neutralize the effects of adversarial signal attacks. In addition, recent literature, such as the study, investigates global fuzzy consensus under signal attacks but does not provide a comprehensive solution that jointly addresses unknown dynamics and compound attack vectors on both sensors and actuators. Our approach extends these efforts by ensuring asymptotic consensus using a hybrid design tested across two directed communication topologies, highlighting the adaptability and resilience of the proposed control law. This integrated handling of uncertainties, attack mitigation, and dynamic topology makes our contribution distinct from and more robust than many existing baseline approaches.

In summary, this research paper addresses the complexities of achieving global fuzzy consensus in leader-follower robotic systems, with a focus on a robust control strategy that counters advanced signal attacks, integrating both sensor and actuator disturbances within the follower dynamics. Each follower robot is characterized by unknown nonlinear dynamics and uncertain control inputs, making it vulnerable to malicious interference. The leader robot, governed by a second-order, time-varying nonlinear model, transmits its position, velocity, and acceleration to the follower robots via a wireless connection, employing a fuzzy logic control strategy. To handle the intricacies of inter-robot communication and coordination in this network, we proposed a robust hybrid distributed adaptive control strategy that simultaneously addresses sensor and actuator attacks, ensuring asymptotic consensus, surpassing traditional bounded consensus outcomes. The framework leverages fuzzy logic systems (FLSs) as proactive estimators of unknown nonlinear behaviors, while effectively mitigating the influence of sensor and actuator attacks to guarantee stable consensus among all agents. A specialized robust controller is developed to counter the compounded impact of signal attacks on follower dynamics, thereby sustaining system stability and performance under adversarial conditions. The effectiveness of the proposed control strategy is validated through simulations under two distinct directed communication topologies, demonstrating its adaptability, resilience, and efficacy in ensuring global consensus in the presence of complex attack scenarios.

However, this study also presents several limitations that offer directions for future enhancement. First, the control strategy assumes complete synchronization of position, velocity, and acceleration data from the leader, which may not always be feasible under real-time network delays or packet loss. Second, the fuzzy logic system’s performance is sensitive to the choice of membership functions and rule base, which may require extensive tuning for different system configurations. Third, the attacks are assumed to be known in structure, and no real-time detection mechanism is incorporated into the current framework. Moreover, while the study considers directed communication topologies, scalability to very large and dynamically changing networks remains to be explored. Finally, the simulations are conducted in a controlled environment; real-world implementation may introduce further practical challenges such as sensor noise, terrain effects, and hardware limitations.

Future research can focus on extending the proposed control strategy to heterogeneous robotic networks and incorporating real-time attack detection mechanisms to improve system resilience. Furthermore, exploring energy-efficient communication protocols could improve scalability and practicality in large-scale robotic systems.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP.2/70/46 and authors also express their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through project number NBU-FFR-2025-1324-03.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, A. Y. Al-Rezami; Software, Fathia Moh. Al Samman; Validation, Asad Khan; Formal analysis, Mohammed M. A. Almazah; Resources, Adnan Manzor; Data curation, Waqar Ul Hassan; Writing—original draft, Waqar Ul Hassan, Azmat Ullah Khan Niazi; Writing—review & editing, Waqar Ul Hassan, Azmat Ullah Khan Niazi; Supervision, Azmat Ullah Khan Niazi; Project administration, Fathia Moh. Al Samman. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This study does not rely on any external datasets; all data are presented within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Azid SI, Raghuwaiya K, Javed A, Kumari E. Autonomous leader-follower formation of vehicular robots using the lyapunov method. Unmanned Syst. 2024;12(1):75–85. doi:10.1142/S2301385024500067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sun Y, Peng Z, Hu J, Ghosh BK. Event-triggered critic learning impedance control of lower limb exoskeleton robots in interactive environments. Neurocomputing. 2024;564:126963. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu H, Zhen S, Liu X, Zheng H, Gao L, Chen YH. Robust approximate constraint following control design for collaborative robots system and experimental validation. Robotica. 2024;42(11):3957–75. doi:10.1017/S0263574724001760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chang Y, Ren Y, Jiang H, Fu D, Cai P, Cui Z, et al. Hierarchical adaptive cross-coupled control of traffic signals and vehicle routes in large-scale road network. Comput-Aided Civil Infrastruct Eng. 2025. doi:10.1111/mice.13508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gong L, Gao B, Sun Y, Zhang W, Lin G, Zhang Z, et al. preciseSLAM: robust, real-time, LiDAR-Inertial-ultrasonic Tightly-coupled SLAM with ultraprecise positioning for plant factories. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2024;20(6):8818–27. doi:10.1109/tii.2024.3361092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang W, Liang JM, Zeng HB, Zhang XM. Novel looped functionals in designing output feedback controllers for aperiodic sampled-data control systems. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2025;22:16397–402. doi:10.1109/tase.2025.3573304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cao Y, Zhang Z. Enhanced contour tracking: a time-varying internal model principle-based approach. IEEE/ASME Trans Mechatron. 2025. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2025.3572743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Shen Y, Lu Q, Li Y. Design criterion and analysis of hybrid-excited Vernier reluctance linear machine with slot Halbach PM arrays. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2022;70(5):5074–84. doi:10.1109/tie.2022.3183278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Qi H, Ding L, Zheng M, Huang L, Gao H, Liu G, et al. Variable wheelbase control of wheeled mobile robots with worm-inspired creeping gait strategy. IEEE Trans Robot. 2024;40:3271–89. [Google Scholar]

10. Wang F, Chen K, Zhen S, Chen X, Zheng H, Wang Z. Prescribed performance adaptive robust control for robotic manipulators with fuzzy uncertainty. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2023;32(3):1318–30. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2023.3323090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yu W, Zheng W, Hua S, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Zhao J, et al. A prestretch-free dielectric elastomer with record-high energy and power density via synergistic polarization enhancement and strain stiffening. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;287:836. doi:10.1002/adfm.202425099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang W, Liang JM, Zeng HB. Sampled-data-based stability and stabilization of Lurie systems. Appl Math Comput. 2025;501:129455. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2025.129455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Baban PQ, Ahangari ME. Adaptive terminal sliding mode control of a non-holonomic wheeled mobile robot. Int J Veh Inf Commun Syst. 2024;9(4):335–56. doi:10.1504/ijvics.2024.10063703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wu J, Wang Y, Yin C. Curvilinear multilane merging and platooning with bounded control in curved road coordinates. IEEE Trans Vehicular Technol. 2021;71(2):1237–52. doi:10.1109/tvt.2021.3131751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ji L, Lin Z, Zhang C, Yang S, Li J, Li H. Data-based optimal consensus control for multiagent systems with time delays: using prioritized experience replay. IEEE Transact Syst, Man, Cybernet: Syst. 2024;54(5):3244–56. doi:10.1109/TSMC.2024.3358293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Guo J, Chai H, Li Y, Zhang Q, Wang Z, Zhang J, et al. Research on the autonomous system of the quadruped robot with a manipulator to realize leader-following, object recognition, navigation and operation. IET Cyber-Syst Robot. 2022;4(4):376–88. doi:10.1049/csy2.12069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kielczewski M, Kowalczyk W, Krysiak B. Differentially-driven robots moving in formation—leader-follower approach. Appl Sci. 2022;12(14):7273. doi:10.3390/app12147273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hameed A, Ordys A, Mozaryn J, Sibilska-Mroziewicz A. Control system design and methods for collaborative robots. Appl Sci. 2023;13(1):675. doi:10.3390/app13010675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jiang W, Zheng B, Sheng D, Li X. A compensation approach for magnetic encoder error based on improved deep belief network algorithm. Sens Actuat A: Phys. 2024;366:115003. doi:10.1016/j.sna.2023.115003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Cheng C, Deng X, Zhao X, Xiong Y, Zhang Y. Multi-occupant dynamic thermal comfort monitoring robot system. Build Environ. 2023;234:110137. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chen X, Cui J, Liu Y, Zhang X, Sun J, Ai R, et al. Joint scene flow estimation and moving object segmentation on rotational LiDAR data. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(11):17733–43. doi:10.1109/TITS.2024.3432755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang X, Liu Y, Chen X, Li Z, Su CY. Adaptive pseudoinverse control for constrained hysteretic nonlinear systems and its application on dielectric elastomer actuator. IEEE/ASME Trans Mechatron. 2023;28(4):2142–54. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2022.3231263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ding F, Zhu K, Liu J, Peng C, Wang Y, Lu J. Adaptive memory event triggered output feedback finite-time lane keeping control for autonomous heavy truck with roll prevention. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2024;32(12):6607–21. doi:10.1109/tfuzz.2024.3454344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Du G, Zhang H, Yu H, Hou P, He J, Cao S, et al. Study on automatic tracking system of microwave deicing device for railway contact wire. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2024;73:3527611. doi:10.1109/TIM.2024.3446638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li L, Cherouat A, Snoussi H, Wang T. Grasping with occlusion-aware Ally method in complex scenes. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2025;22:5944–54. doi:10.1109/TASE.2024.3434610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Guo J, Li Y, Huang B, Ding L, Gao H, Zhong M. An online optimization escape entrapment strategy for planetary rovers based on Bayesian optimization. J Field Robot. 2024;41(8):2518–29. doi:10.1002/rob.22361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu Y, Li X, Ge L, Zhang Z. Ultralarge-area stitchless scanning probe lithography and in situ characterization system using a compliant nanomanipulator. IEEE/ASME Trans Mechatron. 2023;29(2):924–35. doi:10.1109/tmech.2023.3323385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ma’shumah S, Pramartaningthyas EK. Electrital electrical conductivity control system in pakcoy plant based on fuzzy logic control. Indonesian J Elect, Electromed Eng Med Inform. 2021;3(4):133–9. doi:10.35882/ijeeemi.v3i4.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Fadillah MD, Ismail N, Mardiati R, Kusdiana A. Fuzzy logic-based control system to maintain pH in aquaponic. In: 2021 7th International Conference on Wireless and Telematics (ICWT); 2021 Aug 19–20; Bandung, Indonesia. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

30. Ullah K, Ishaq M, Tchier F, Ahmad H, Ahmad Z. Fuzzy-based maximum power point tracking (MPPT) control system for photovoltaic power generation system. Res Eng. 2023;20:101466. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sakalli A, Kumbasar T, Mendel JM. Towards systematic design of general type-2 fuzzy logic controllers: analysis, interpretation, and tuning. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2020;29(2):226–39. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2020.3016034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lv J, Ju X, Wang C. Neural network prescribed-time observer-based output-feedback control for uncertain pure-feedback nonlinear systems. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;264(5):125813. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li Z, Hu J, Leng B, Xiong L, Fu Z. An integrated of decision making and motion planning framework for enhanced oscillation-free capability. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;25(6):5718–32. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3332655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ju X, Jiang Y, Jing L, Liu P. Quantized predefined-time control for heavy-lift launch vehicles under actuator faults and rate gyro malfunctions. ISA Trans. 2023;138(2):133–50. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2023.02.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Deng K, Yang L, Lu Y, Ma S. Multitype chatter detection via multichannelinternal and external signals in robotic milling. Measurement. 2024;229(2):114417. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.114417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang Z, Gao D, Deng K, Lu Y, Ma S, Zhao J. Robot base position and spacecraft cabin angle optimization via homogeneous stiffness domain index with nonlinear stiffness characteristics. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2024;90:102793. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2024.102793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Tian G, Tan J, Li B, Duan G. Optimal fully actuated system approach-based trajectory tracking control for robot manipulators. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2024;54(12):7469–78. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2024.3467386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li S, Er MJ, Zhang J. Distributed adaptive fuzzy control for output consensus of heterogeneous stochastic nonlinear multiagent systems. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2017;26(3):1138–52. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2017.2710949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zheng S, Shi P, Wang S, Shi Y. Event triggered adaptive fuzzy consensus for interconnected switched multiagent systems. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2018;27(1):144–58. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2018.2873968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Xu X, Li B. Semi-global stabilization of parabolic PDE-ODE systems with input saturation. Automatica. 2025;171(3):111931. doi:10.1016/j.automatica.2024.111931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Xu X, Li B. PDE-based observation and predictor-based control for linear systems with distributed infinite input and output delays. Automatica. 2024;170(4):111845. doi:10.1016/j.automatica.2024.111845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lan YH, Zhao JY. Improving track performance by combining padé-approximation-based preview repetitive control and equivalent-input-disturbance. J Elect Eng Technol. 2024;19(6):3781–94. doi:10.1007/s42835-024-01830-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zhang Z, He R, Han B, Ren S, Fan J, Wang H, et al. Magnetically switchable adhesive millirobots for universal manipulation in both air and water. Adv Mater Weinheim. 2025;37(26):e2420045. doi:10.1002/adma.202420045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Tian J, Zhou Y, Yin L, AlQahtani SA, Tang M, Lu S, et al. Control structures and algorithms for force feedback bilateral teleoperation systems: a comprehensive review. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2025;142(2):973–1019. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.057261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Silva A, Fonseca D, Neto DM, Babcinschi M, Neto P. Integrated design and fabrication of pneumatic soft robot actuators in a single casting step. Cyborg and Bionic Systems. 2024;5:0137. doi:10.34133/cbsystems.0137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Xie F, Liang G, Chien YR. Robust leader-follower formation control using neural adaptive prescribed performance strategies. Mathematics. 2024;12(20):3259. doi:10.3390/math12203259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wang B, Wei X, Zhang H, Hu X. Adaptive synchronisation control for leader follower ships with disturbances and actuator attacks. Ships Offshore Struct. 2025;422:1–11. doi:10.1080/17445302.2025.2503480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Xu Y, Bao R, Zhang L, Wang J, Wang S. Embodied intelligence in RO/RO logistic terminal: autonomous intelligent transportation robot architecture. Sci China Inf Sci. 2025;68(5):1–17. doi:10.1007/s11432-024-4395-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Chen Z, Zhan G, Jiang Z, Zhang W, Rao Z, Wang H, et al. Adaptive impedance control for docking robot via Stewart parallel mechanism. ISA Trans. 2024;155:361–72. doi:10.1016/j.isatra.2024.09.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools