Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

AGV Scheduling and Bidirectional Conflict-Free Routing Problem with Battery Swapping in Automated Container Terminals

Institute of Logistics Science and Engineering, Shanghai Maritime University, No. 1550, Haigang Avenue, Pudong New Area, Shanghai, 201306, China

* Corresponding Author: Jin Zhu. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1717-1748. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068384

Received 27 May 2025; Accepted 25 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Automated guided vehicles (AGVs) are key equipment in automated container terminals (ACTs), and their operational efficiency can be impacted by conflicts and battery swapping. Additionally, AGVs have bidirectional transportation capabilities, allowing them to move in the opposite direction without turning around, which helps reduce transportation time. This paper aims at the problem of AGV scheduling and bidirectional conflict-free routing with battery swapping in automated terminals. A bi-level mixed integer programming (MIP) model is proposed, taking into account task assignment, bidirectional conflict-free routing, and battery swapping. The upper model focuses on container task assignment and AGV battery swapping planning, while the lower model ensures conflict-free movement of AGVs. A double-threshold battery swapping strategy is introduced, allowing AGVs to utilize waiting time for loading for battery swapping. An improved differential evolution variable neighborhood search (IDE-VNS) algorithm is developed to solve the bi-level MIP model, aiming to minimize the completion time of all jobs. Experimental results demonstrate that compared to the differential evolution (DE) algorithm and the genetic algorithm (GA), the IDE-VNS algorithm reduces fitness values by 44.49% and 45.22%, though it does increase computation time by 56.28% and 62.03%, respectively. Bidirectional transportation reduces the fitness value by an average of 10.97% when the container scale is small. As the container scale increases, the fitness value of bidirectional transportation gradually approaches that of unidirectional transportation. The results further show that the double-threshold battery swapping strategy enhances AGV utilization and reduces the fitness value.Keywords

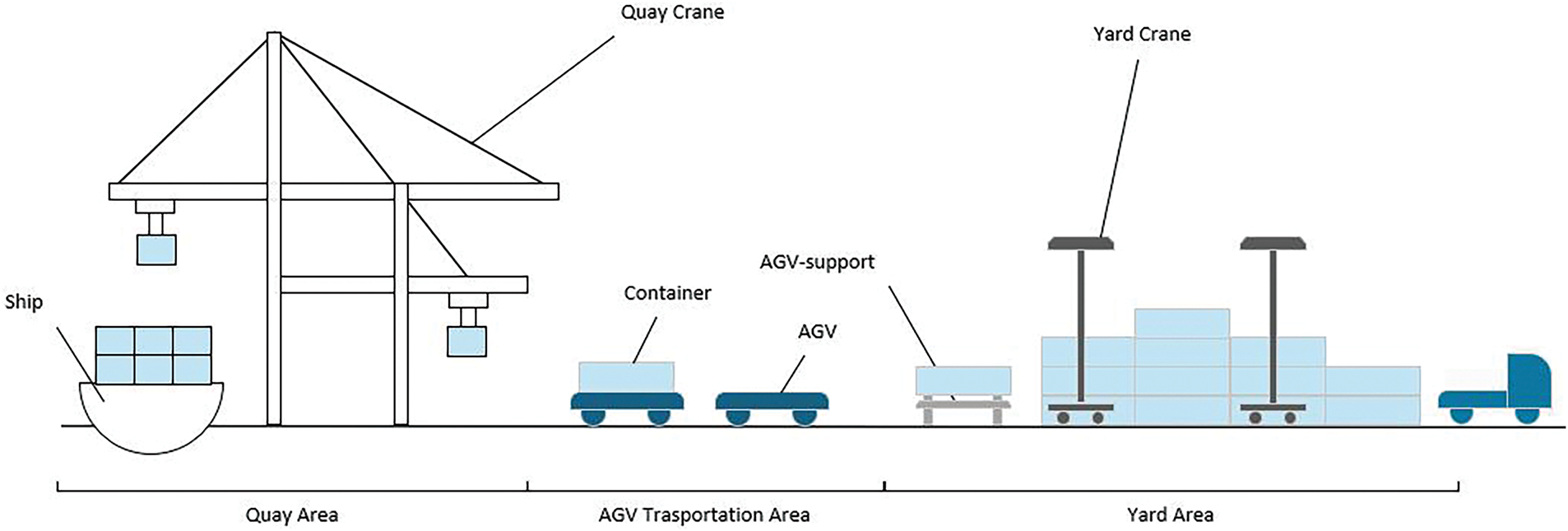

With the maturation of automated equipment technology and the update of port comprehensive management systems, traditional container terminal is gradually transformed into automated container terminal. Automated container terminals (ACT) can be divided into three core areas: terminal operation area, Automated guided vehicles (AGV) transportation area and yard operation area. AGV transportation area serves as the connecting link between these areas, and its efficiency has a significant impact on the overall operation of the automated container terminal [1]. A typical layout of an automated container terminal is shown in Fig. 1. In this layout, the quay cranes (QC) handle the loading and unloading of containers on the quay area, while the yard cranes (YC) manage these operations on the yard area. The AGV-supports are equipped on the yard side to reduce equipment waiting time [2].

Figure 1: Layout of automated container terminals

In various scenarios, the related challenges of AGV scheduling for automated materials handling systems [3] and flexible manufacturing system [4,5] have been studied. The AGV scheduling problem is complex because it involves not only task assignment but also route planning for AGVs. Multiple AGVs influence one another in the process of transportation, causing conflicts and deadlocks, which affects the scheduling of AGVs. Therefore, some studies jointly consider the scheduling problem and the conflict-free routing problem of AGVs [6–8]. But most of these studies assume that AGVs move in a single fixed direction, and this movement pattern leads to redundant paths for AGVs during transportation operations. In order to solve this problem, bidirectional transportation of AGVs has been considered and applied in AGV path planning for ACTs in a few studies [9,10]. This bidirectional transportation mode enables AGVs to move along the shortest path during transportation and improves the transportation efficiency of AGVs. However, in the recent research on AGV scheduling and conflict-free routing, there are relatively few issues considering the energy consumption and replenishment of AGVs to reduce the complexity of problem-solving. During the actual operation of ACTs, the energy replenishment of AGVs cannot be ignored. Once AGVs fall into a stranded state, it will lead to delays or even paralysis of the entire transportation operation. Therefore, it is worthy of study to take into account the two-way conflict-free transportation operation and energy replenishment of AGVs in the scheduling of AGVs at the same time.

Nowadays, AGVs in automated container terminals are driven mainly by electric power, such as Shanghai Yangshan Port Phase IV in China, the APM Terminals’ Maasvlakte II (APMT MVII) terminal in Netherlands and the middle harbor terminal at the Port of Long Beach in America all adopt electric AGVs to complete the transportation of container import and export tasks [11,12]. Therefore, the energy management of AGVs can be regarded as the battery management of AGVs. Electrically driven AGVs are mainly divided into two types: rechargeable and battery-swapping. Battery-swapping AGVs are widely used in many automated terminals due to their higher efficiency [13]. The rechargeable-type operates by setting up some charging stations in the docking area. When the AGV is idle or its battery level falls below a threshold, it heads to the charging station. During charging, the AGV cannot operate, and the charging process takes a longer time. In contrast, the battery-swapping type involves setting up a battery-swapping station in the docking area. The swapping station is responsible for storing batteries, replacing the AGV’s battery, and charging the depleted batteries. When the AGV needs to recharge, it goes to the swapping station to replace the battery with a fully charged one. The battery-swapping process allows the AGV to resume its tasks more quickly than the charging method. Thus, some studies focus on how to coordinate AGV scheduling and the battery replenishment of AGVs. For example, Yang et al. [11] study the AGV scheduling problem with limited capacity of battery swap stations with the goal of minimizing the energy consumption of AGVs. Xiao et al. [14] studied the AGV scheduling problem in the hybrid mode of battery swapping and charging and concluded that the mode can effectively reduce the costs. However, few AGV scheduling studies that consider battery management focus on the conflict-free routing issue, assuming that AGV scheduling is feasible under the condition of having sufficient spaces in the horizontal transport area.

This paper aims to solve the AGV scheduling problem in ACTs by simultaneously considering bidirectional conflict-free routing, battery swapping and the import/export container tasks. A double-threshold battery swapping strategy is proposed and an improved differential evolution variable neighborhood search (IDE-VNS) algorithm is developed to solve this problem. Specifically, the potential contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) A bi-level mixed integer programming (MIP) model is built to solve the AGV scheduling and conflict-free routing problem with battery swapping in the ACT. This model considers AGV scheduling and bidirectional conflict-free routing, battery swapping process, and import/export container tasks, thereby providing a more comprehensive analysis of the AGV scheduling problem in automated terminals.

(2) A flexible double-threshold battery swapping constraint is adopted. By setting an additional battery swapping threshold, the algorithm provides more flexible options for AGV battery swapping when this threshold is triggered. Specifically, it allows the AGV to use the waiting time for loading to perform the swap, thereby reducing the transportation delay caused by the swapping operation.

(3) The improved differential evolution-variable neighborhood search (IDE-VNS) algorithm is developed. The algorithm performs a more detailed local search within the neighborhood intervals of the solutions during the iterative process of the differential evolution algorithm to prevent the algorithm from getting trapped in local optima.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a review of related works; Section 3 defines the problem and formulates a bi-level MIP model; Section 4 discusses the proposed IDE-VNS algorithm for solving the problem; Section 5 presents and discusses the computational results; Section 6 concludes the work and proposes several directions for future research.

2.1 AGV Scheduling with Conflict-Free Routing in ACT

In an ACT system, AGV scheduling involves assigning starting and ending points to AGVs and arranging for them to complete transportation tasks between these points. Multiple AGVs influence one another in the transportation process. Some scholars endeavor to solving problems such as conflicts [15], deadlocks [16] and congestion [17] to enable AGVs to arrive at the destination nodes as swiftly as possible. Some recent works integrated the above two problems and studied the joint optimization of AGV scheduling and conflict-free path planning. Yang et al. [6] proposed a bi-level model to solve the integrated scheduling problem for handling equipment cooperation and AGV routing. Adamo et al. [7] investigated vehicle paths and speeds on different road sections to avoid conflicts, introducing a path-planning scheme that mitigates route conflicts by adjusting AGV path selection and operational speed. Zhong et al. [8] developed a mixed-integer programming model based on dynamic path planning with the goal of minimizing AGV delay time to solve the multi-AGV scheduling problem with conflict-free paths. Shen et al. [18] proposed a scheduling mode of group operation area and used a hybrid algorithm with fuzzy logic controller to simulate the behavior of AGVs, in order to minimize the maximum completion time of AGVs. Yue and Fan [19] considered the AGV scheduling and conflict-free routing problems under the delayed waiting issue in the uncertain environment during dynamic scheduling optimization, establishing a two-stage model and an integrated algorithm combining the Dijkstra and Q-learning algorithms to minimize AGV transportation costs. Gao et al. [20] established mathematical models for multi-AGV dispatching and use a contract net protocol to solve the assignment problem, while machine learning is used to the path problem. Lou et al. [21] explored a conflict resolution method based on the Yen algorithm to predict and resolve potential conflicts of AGVs, thereby achieving the scheduling and conflict-free path of AGVs. Zhong et al. [22] studied the joint scheduling problem of AGVs and YCs, considering conflict-free paths for AGVs and the capacity constraints on buffer bracket in blocks, with the goal of minimizing AGV energy consumption. Liu et al. [23] studied conflict-free scheduling of horizontal transportation and loading/unloading equipment in a U-shaped yard layout, creating a bilevel programming model to minimize AGV and truck completion and waiting times. Xu et al. [24] studied the scheduling problem of using Automated Intelligent Vehicles (AIVs) with precise and flexible mobility at automated terminals and proposed an Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search (ALNS) algorithm for real-time scheduling to quickly generate conflict-free scheduling solutions. Li et al. [25] proposed a grid-based path model to solve the conflict problem of AGV dynamic scheduling. Xiong et al. [26] proposed a fast and dynamic rolling scheduling model to efficiently and quickly perform global scheduling and realize the dynamic obstacle avoidance of AGVs. Terfasse et al. [27] suggested an integer linear programming model for collision-free path planning of AGVs in container terminals.

The above studies assume that AGVs perform transportation tasks in a single direction to reduce the occurrence of conflicts. The above articles all assume that AGVs operate in a single direction to reduce conflicts, but this leads to some paths not being the shortest. To enable AGVs to find shorter routes for transportation, some studies have applied the bidirectional characteristics of AGVs in automated container terminals [9,10]. Wang and Zeng [9] established a mixed integer programming model for the problem considering the transportation path of bidirectional multi-parallel lanes to better fit the operation status of the actual automated terminal, and solved the AGV scheduling and conflict-free routing problem on a small scale by using the branch and bound algorithm. Cao et al. [10] proposed a bi-level mixed integer programming model to minimize the completion time of all tasks for the automated terminal operation problem with comprehensive consideration of equipment collaborative, bidirectional conflict-free routing of AGV and import and export containers.

However, these above studies overlook AGV battery management when addressing AGV scheduling and conflict-free path planning. This paper incorporates energy consumption and battery swapping into the scheduling process, aligning it more closely with AGV operations in automated terminals.

2.2 AGV Scheduling with Battery Management in ACT

With the increasing application of electric AGVs in ACTs, some recent studies consider the battery management of AGVs when studying the AGV scheduling problem. Zou et al. [13] explored the two main battery management methods of automated terminals, battery charging and battery swapping, and pointed out that the battery swapping strategy was better than battery charging strategy in terms of operation time, but higher than battery charging strategy in terms of cost. Ma et al. [28] designed the layout of distributed charging stations and the progressive charging mode, and conducted simulation configuration experiments on the charging AGV of the automated wharf to prove the superiority of the proposed layout and mode. Xiang and Liu [29] developed a nested semi-open queuing network model considering the battery management and unbalanced task allocation problems of automated container terminals. Zhao et al. [30] developed two coupled models for the AGV scheduling process and battery swapping process, and solved the problem by decoupling the battery swapping demand and swapping plan as common variables. Yang et al. [31] model the integrated scheduling for battery swapping and variability of AGV speed. Li et al. [32] modeled the AGV scheduling problem with battery swapping and random tasks by establishing a two-stage model and designed a double-threshold battery swapping strategy in order to improve the utilization rate and overall operational efficiency of AGVs. Yang et al. [11] studied the solution to congestion in the case of limited capacity of AGV battery swap stations through a set partitioning method based on breadth-first and depth-first search. Li et al. [33] focused on optimizing task scheduling and battery swap times for AGVs, considering varying battery degradation states. Zhou et al. [34] took an integrated approach to optimize AGV scheduling and energy system operation and maintenance, developing a multi-objective mathematical model to minimize AGV operation time and reduce energy system maintenance costs.

However, the above studies lack the consideration of the conflict-free path of AGV. In the actual transportation of AGVs, conflicts and congestion of AGVs can have a significant impact on the scheduling process of AGVs. This paper simultaneously considers the battery management of AGVs and the bidirectional conflict-free paths, thereby better arranging the scheduling of AGVs.

Through a review of the above literature, the following insights and research gaps can be summarized:

(1) In the scheduling problem of Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs), ensuring conflict-free paths is crucial for improving AGV scheduling efficiency. Therefore, relevant research needs to address conflict resolution for AGVs. Additionally, the bidirectional transportation method is an effective way to enhance AGV transportation efficiency. However, there is still lake of studies on AGV scheduling and conflict-free path planning under bidirectional transportation.

(2) In AGV scheduling, battery swapping operations can cause delays in transportation tasks, and AGV breakdowns can lead to significant losses in container handling operations. Therefore, related research should take the AGV battery swapping process into account. However, there is still a lack of studies considering battery swapping in AGV scheduling and conflict-free path planning.

This paper focous on the above two problems and studies AGV scheduling considering bidirectional conflict-free routing, battery swapping and the import/export container tasks. And proposed a battery swapping strategy and IDE-VNS algorithm to solve this problem.

3 Problem Description and Modeling

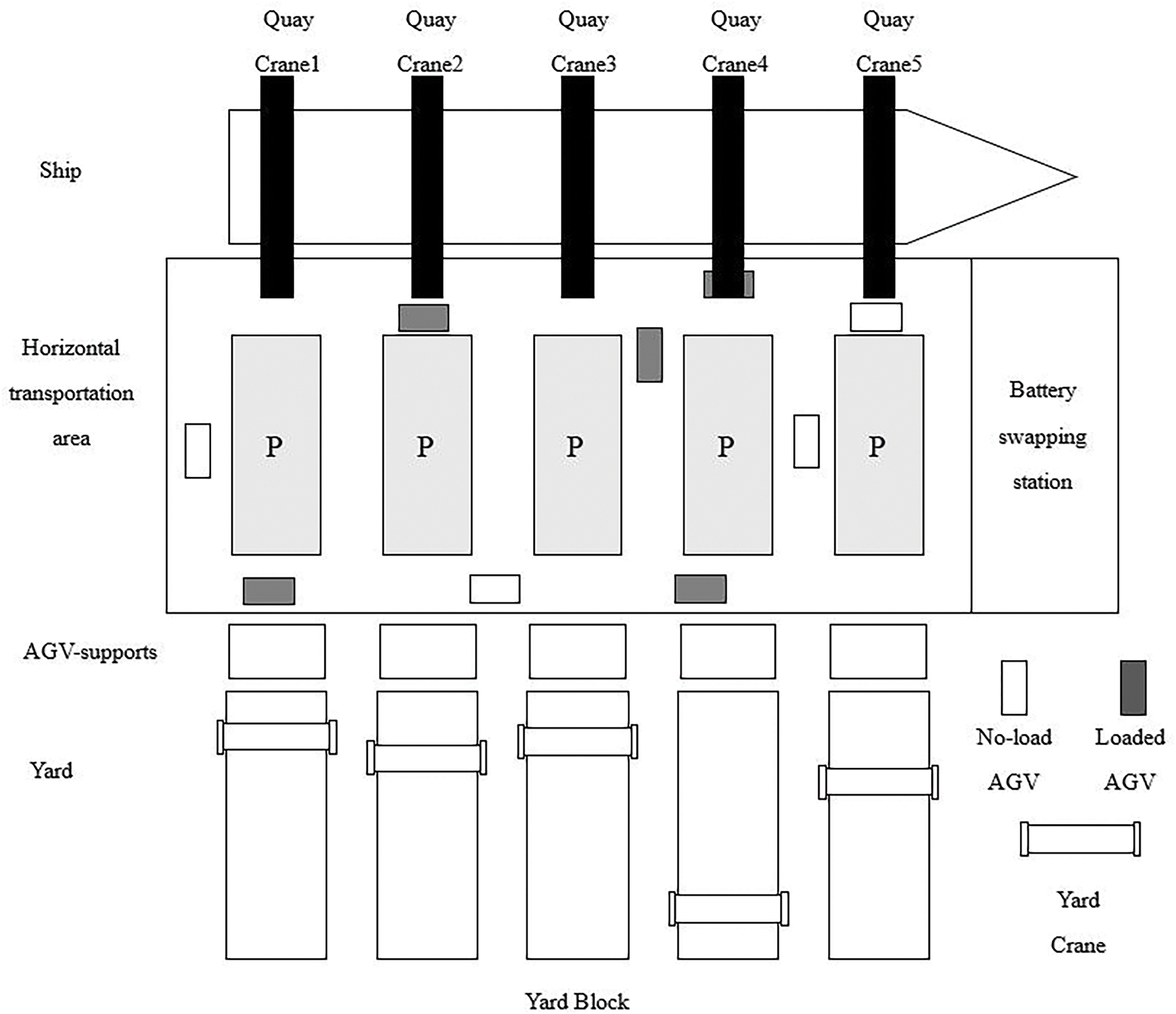

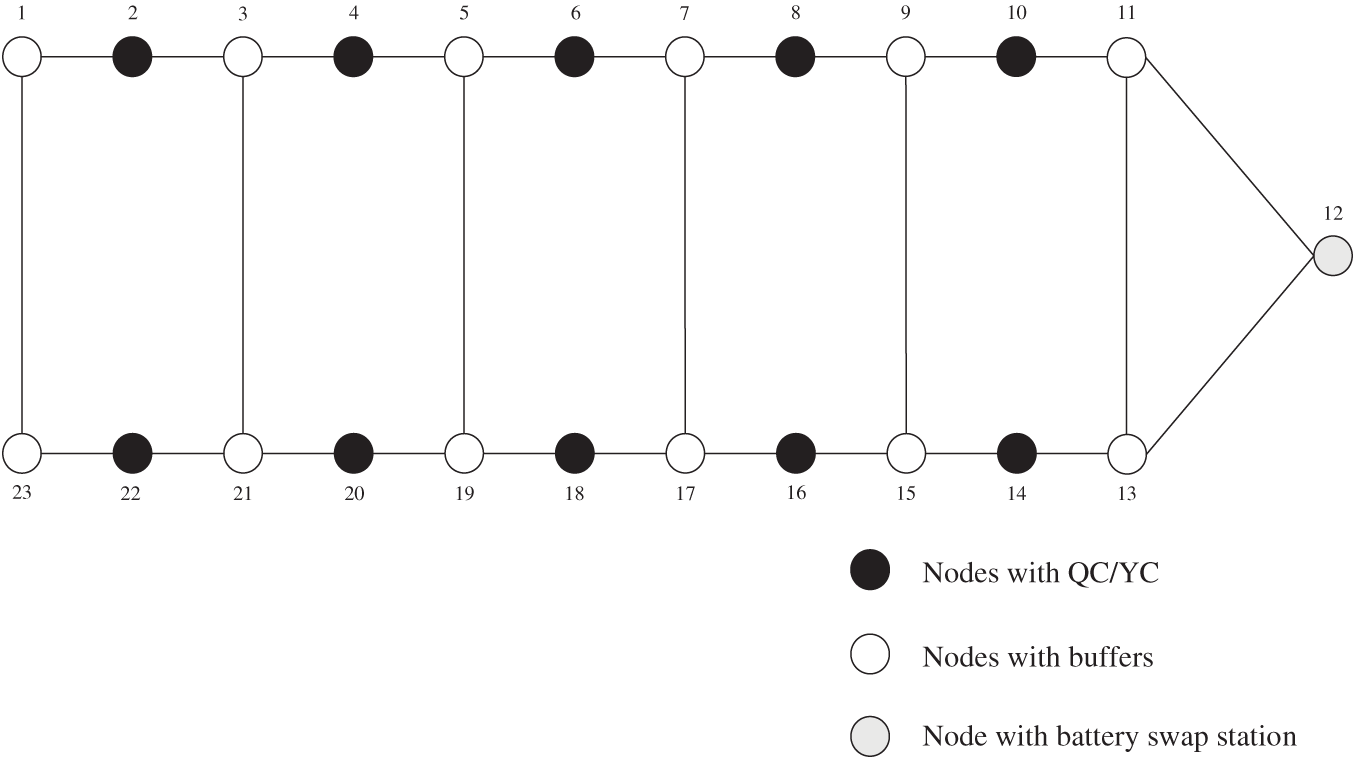

In this paper, the AGV scheduling and bidirectional conflict-free routing problem with battery swapping is addressed according the typical terminal layout commonly used in most automated terminals as shown in Fig. 2. This paper considers the operations in the horizontal transportation area of AGVs, including the interactive operations between QC, YC and AGVs, as well as the conflict-free movement and battery swapping operations of AGV equipment. Therefore, the transportation area can be simplified to the network diagram as shown in Fig. 3. In the Fig. 3, node 12 is set as the position of battery swap station, nodes {n2, n4, n6, n8, n10} are set as the position of QCs and nodes {n14, n16, n18, n20, n22} are set as the position of YCs, and the edges {(n1, n23), (n3, n21), (n5, n19), (n7, n17), (n9, n15), (n11, n13)} and their nodes are set as the buffer areas of AGVs, that is, there are a sufficient number of parking areas on these edges. For an import container task, the container is loaded onto a AGV when the AGV reaches QC operation area. Subsequently, the AGV conveys the container to YC operation area along a series of preset paths. Thereafter, the YC unloads the container from the AGV and transfers it to the yard. Export container operations can be regarded as a set of reverse operation processes. It is necessary to arrange for the AGV to go to the battery swap station to swap the battery to ensure that the AGV can maintain a normal working state when the battery capacity of the AGV meets the predetermined condition.

Figure 2: Container handling system in the ACT

Figure 3: Network of AGV transportation area

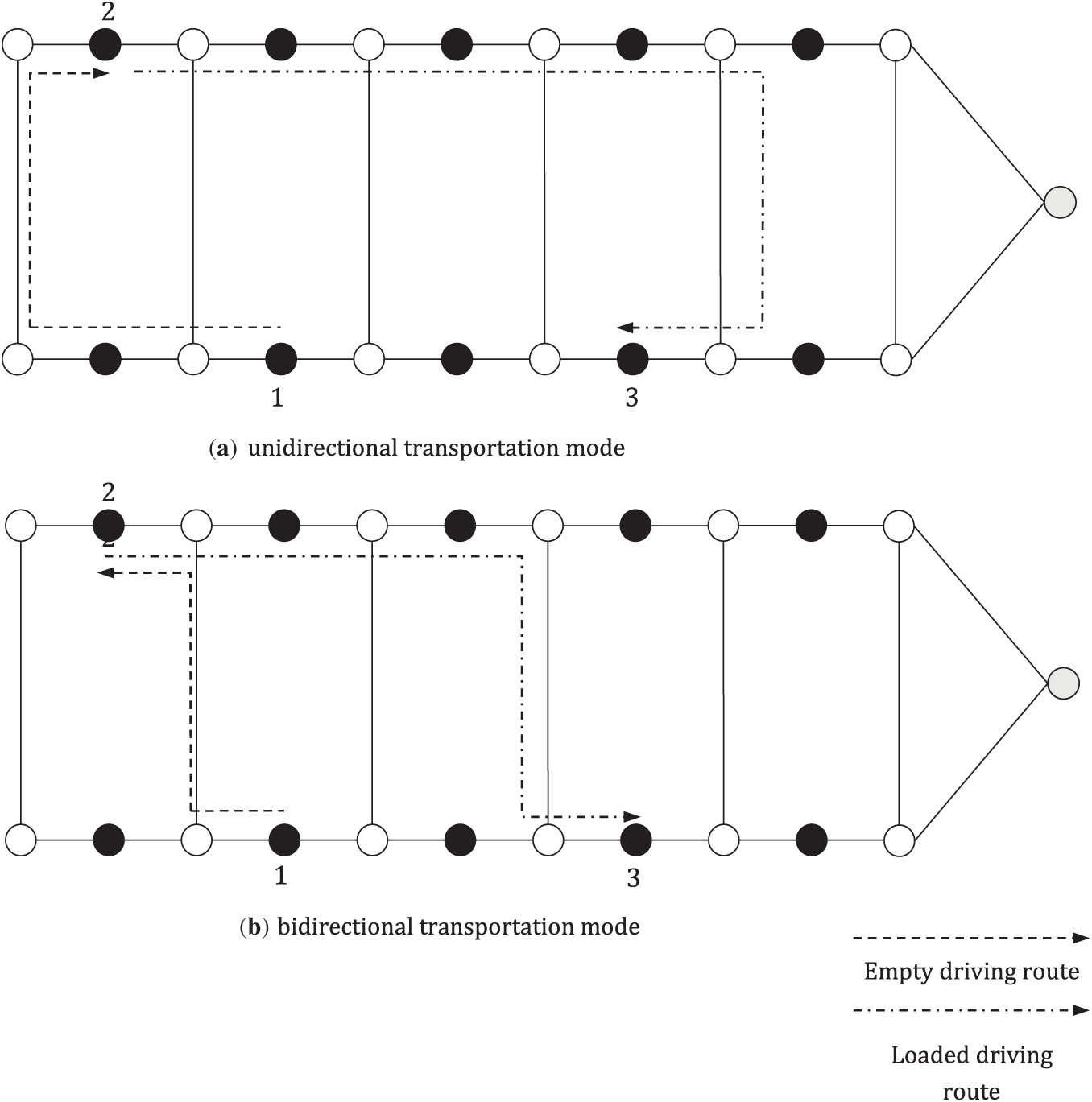

This paper considers the bidirectional transportation characteristics of AGVs. By taking advantage of this movement feature of AGVs, it enables AGVs to receive and complete two container tasks within any working cycle. For instance, when an AGV submits a container task on a YC, it can choose any YC to receive the export container task provided by it through bidirectional transportation. However, for the unidirectional transportation mode, it can only accept the task when the AGV can subsequently pass through the YC that provides the export container task. Additionally, the bidirectional transportation of the AGV offers more path options. Compared with the unidirectional transportation mode, bidirectional transportation has a shorter moving path and improve operational efficiency. As shown in Fig. 4a, the AGV follows a unidirectional movement pattern in the horizontal transport area, while Fig. 4b illustrates the bidirectional movement mode. By comparing the transport path of an AGV that picks up and transports an inbound container, we can more clearly explain the advantages of bidirectional transport. For a transport task where the AGV needs to move from point 1 to point 2 to pick up the task and then transport it to point 3, in the unidirectional transport mode, the AGV can only move in a single clockwise direction. Therefore, it needs to pass through four path nodes to reach point 2. In contrast, with bidirectional transport, the AGV can reach the loading point using only two path nodes. During the transport process, the unidirectional mode requires the AGV to travel through an additional path to reach the target node 3, while with the bidirectional mode, the AGV can choose any crossing path between the current and target nodes, achieving a shorter distance. Thus, the bidirectional transport mode offers a clear advantage in terms of distance cost compared to the unidirectional mode.

Figure 4: Unidirectional and bidirectional transportation mode of AGV transporting import containers

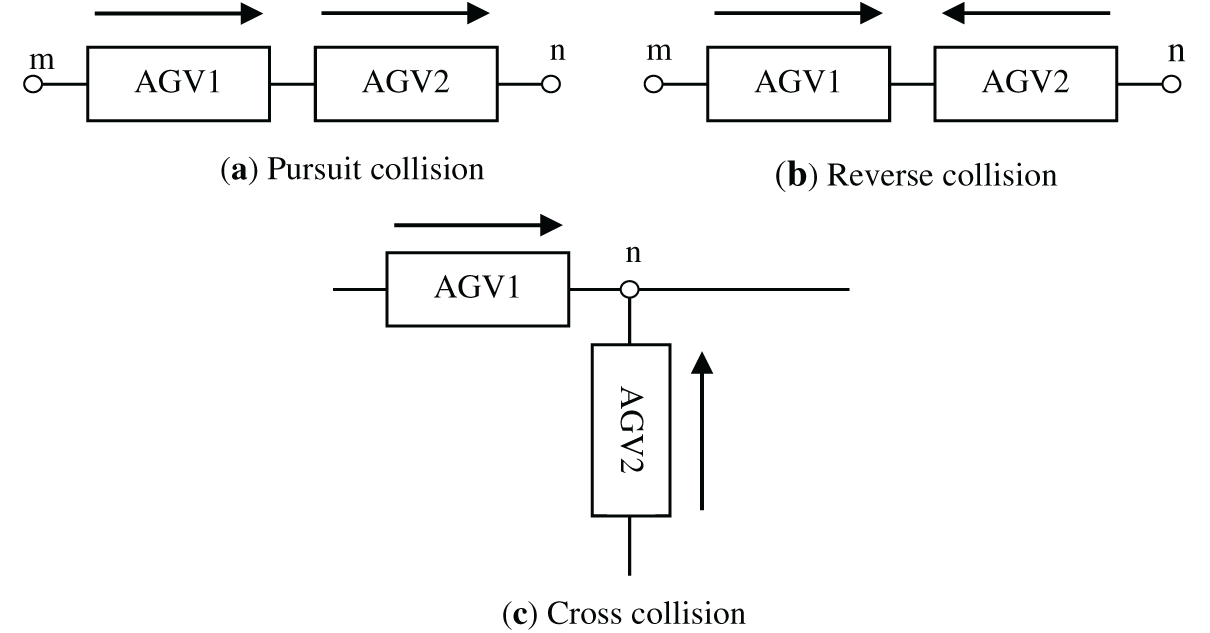

Furthermore, the conflict problem is also taken into account. As shown in Fig. 5, the common collisions included in this mode are pursuit collisions, the reverse collisions, and the cross collisions. Pursuit collisions refer to the collision that occurs when the rear vehicle of two AGVs moving in the same direction rear-ends the front vehicle in the same path segment. Reverse collisions refer to the collision that occurs when two AGVs moving in opposite directions move in the same path segment. Cross collisions refer to the collision that occurs when two AGVs move along different paths to the same node and compete for that node.

Figure 5: Types of collisions

The assumptions are as follows:

(1) The container task of QC and YC are known, consider the loading/unloading process of containers between QC/YC and AGV.

(2) Each AGV can serve any QC and YC.

(3) QCs, YCs and AGVs can only operate one container task at the same time. The next task cannot be carried out before the last task is completed.

(4) The AGVs maintain a safe distance from one another. The lane change time of the AGV is not considered.

(5) The velocities of the unloaded and loaded AGVs are known and constant.

(6) The initial charge of the AGV is full, and the power consumption per unit time of waiting for loading and unloading, loaded and unloaded transportation is known and constant.

(7) The battery swap station is equipped with sufficient available batteries.

(8) The entire operation involves both import container operations and export container operations. QC should give priority to the import container when carrying out container operation.

The problem can be characterized as follows: Given a specific quantity and starting positions of AGVs, containers are assigned to each AGV. AGVs traverse along preset paths to complete the transportation of container tasks, with these paths determined by the occupancy status of each path segment. AGVs need to go for battery swapping in time according to the battery swapping strategy during transportation. Therefore, this paper designs a bi-level MIP model, consisting of task layer and routing layer.

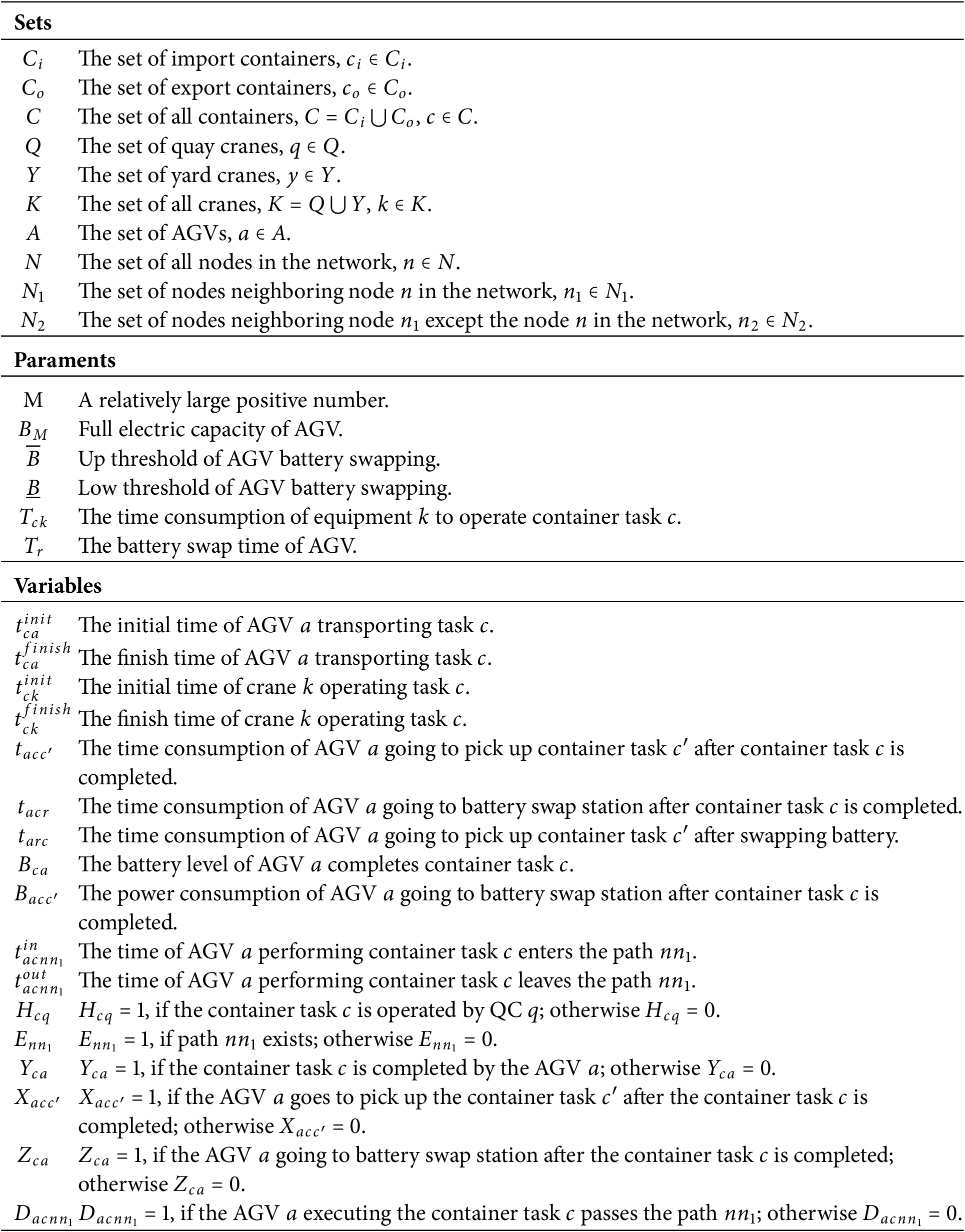

The purpose of the task layer model is to assign container tasks to AGVs and adjust the task order to minimize the completion time of all tasks while considering the battery swapping of AGVs. Thus, the task layer model of AGV can be regarded as the Parallel Machine Scheduling Problem. The model can be described as follows: (1) Denote

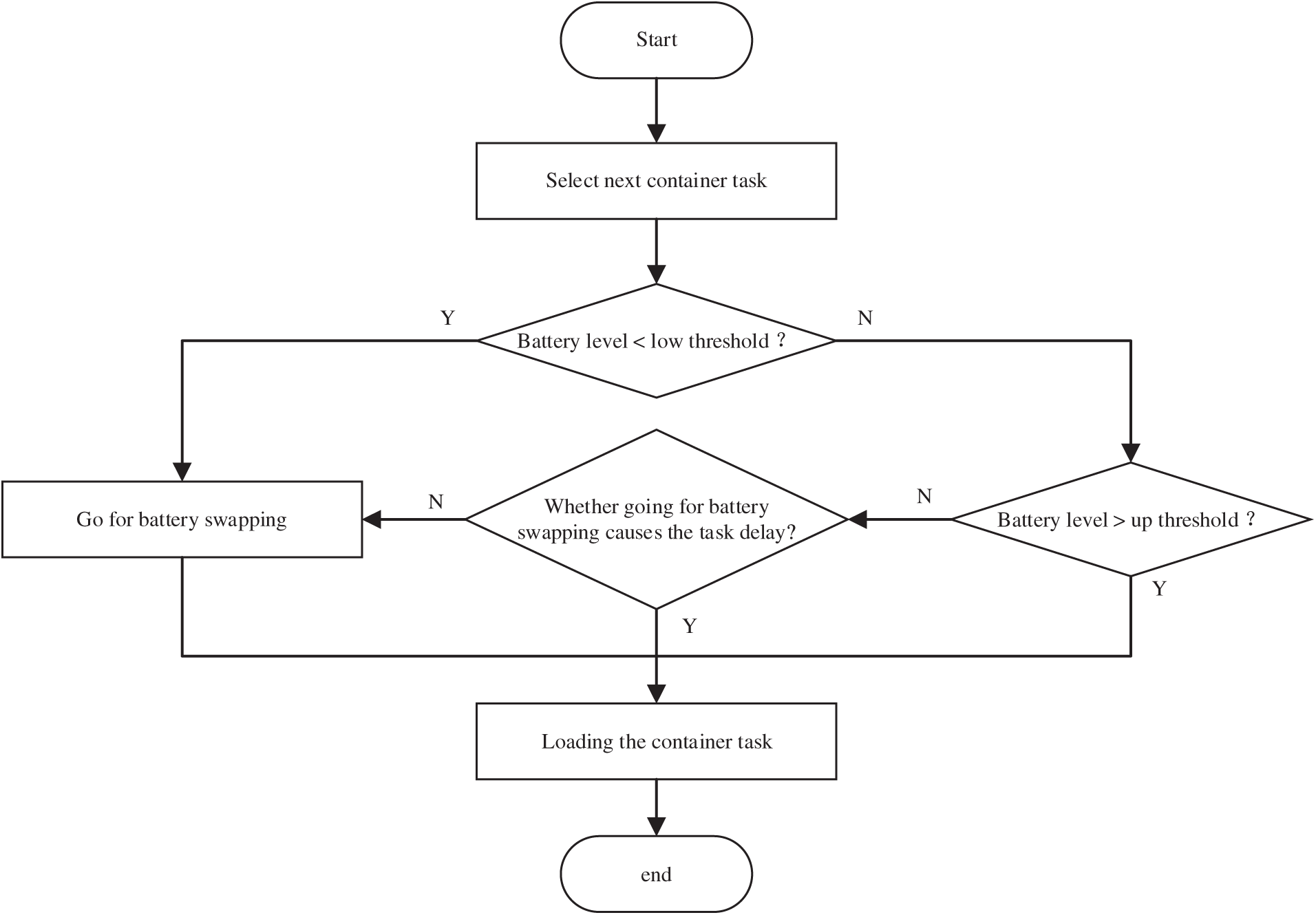

This paper designs a more flexible battery swapping strategy to optimize the battery swapping judgment of AGVs as shown in Fig. 6. The double battery swapping threshold strategy includes a criterion similar to the single fixed threshold: when the AGV’s battery level falls below this value, it must proceed immediately for battery swapping. This is defined as the low threshold. Additionally, there is a up threshold used to decide whether the AGV should continue waiting to load containers or go for battery swapping before loading. To maximize battery utilization, the low threshold is set at the minimum level that only guarantees the AGV can reach the swapping station, while the up threshold ensures the AGV can complete its current task before proceeding to swap batteries. This double-threshold battery swapping strategy can be described as follows: This strategy has two battery swapping thresholds, includes the up threshold and the low threshold. When the AGV is assigned a new task, if the battery level falls below the lower threshold, it needs to go directly for battery swapping; if the battery level is above the upper threshold, it will perform the task. When the battery level of AGV between the two thresholds, if loading the container task after the battery swapping will not cause any delay, the AGV will swap its battery first. Otherwise, the task must be performed first.

Figure 6: Diagram of battery swapping strategy

The routing layer model of AGV can be simplified to an undirected graph

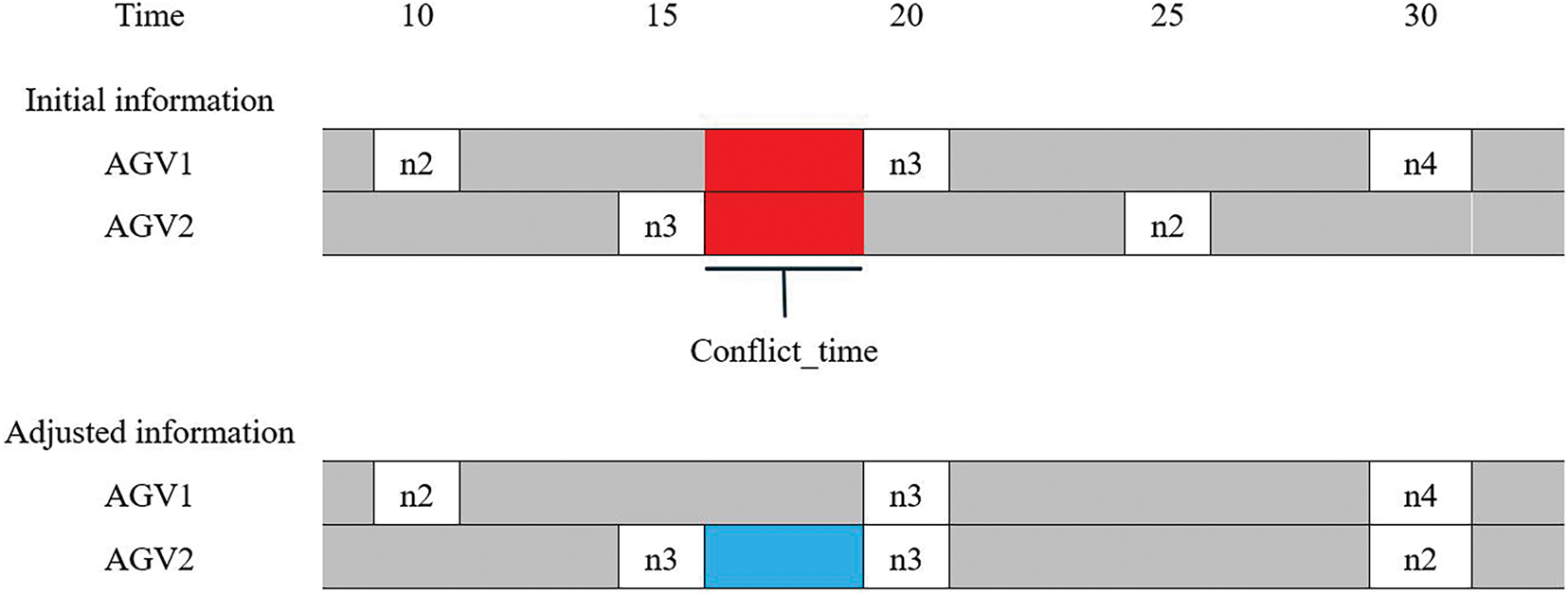

The key to ensuring the routing of AGVs without conflicts is to set the time window constraints of AGVs in the path segments, record the occupied time of AGVs entering and leaving each path segment during their movement, and then by comparing the time conflict information of AGVs in the path segments, when there is an overlap in occupied time, arrange another AGV to wait in the buffer to avoid the overlap of time. In this paper, the edges {(n1, n23), (n3, n21), (n5, n19), (n7, n17), (n9, n15), (n11, n13)} and their nodes are set as the buffer areas of AGVs, that is, there are a sufficient number of parking areas on these edges. When conflicts occur, The AGV can wait in these edges until the time conflict is resolved before continuing the current task. The specific conflict resolution method can be described as shown in Fig. 7. AGV1 and AGV2 need to pass through the edge (n2, n3) from two directions successively. AGV1 is on the edge (n2, n3) and enters the edge (n2, n3) through node 2 at 10 s and reaches node 3 at 20 s to leave the edge (n2, n3). AGV2 enters the edge (n2, n3) through node 3 at 15s and reaches node 2 at 25 s on the edge (n2, n3). It can be seen that within the time interval of 15 s–20 s, there is a conflict between AGV1 and AGV2 at the edge (n2, n3), and there is a buffer zone at node n3 where AGV2 is located. Therefore, AGV2 waits in the buffer until the occupation of the edge by AGV1 ends before entering that edge.

Figure 7: Take up the buffer waiting for solution of conflict

The model aims to minimize the container task operation time, defined as the time difference between the completion time of the last container task and the start time of the first container task, as shown in Eq. (1). Specifically, the start time of the first container task is

The constraint conditions are as follows:

Eq. (2) ensures that each container task is assigned to only one AGV. Eq. (3) guarantees that each AGV has a subsequent task while performing the current container task. Eq. (4) ensures that each AGV has a prerequisite task when performing the current container task. Eq. (5) ensures that the preceding container tasks and subsequent container tasks of each container task are different. Eq. (6) indicates that the battery capacity of each AGV is fully after battery swapping at the battery swap station. Eq. (7) ensures that the finish time of each task is not earlier than its start time. Eq. (8) ensures that when the same AGV performs two consecutive container tasks, the start of subsequent container tasks will not be earlier than the completion time of the currently executed container task. Eq. (9) ensures that each QC can carry out the task of exporting containers only after completing all the imported containers. Eq. (10) represents the time relationship in which the imported containers are moved from the QC to the AGV, transported by the AGV to the interaction area of the yard and handed over to the YC for handling. Eq. (11) represents the time relationship of the export container being moved from the YC to the AGV and then transported by the AGV to the berth interaction area and handed over to the QC for handling.

Eqs. (12) and (13) indicate the double-threshold battery swapping. Eq. (12) serves as the upper threshold constraint and Eq. (13) defines the lower threshold constraint. In Eq. (12), if current battery level

The goal of routing layer model is to minimize the transportation time of AGVs, the objective function is shown in Eq. (14):

The constraint conditions of the routing layer are as follows:

Eq. (15) illustrates the correlation between path selection and the connection matrix. Eq. (16) represents the path flow constraint of AGVs. Eq. (17) represents the time relationship between the entry and exit of an AGV transport container along a certain path section. Eq. (18) represents the time relationship between the entry and exit of an AGV transport container along two adjacent path sections. Eq. (19) ensures that two AGVs transporting different tasks maintain a safe distance when they enter the same path section successively. Eq. (20) represents the temporal relationship for two AGVs to avoid reverse collisions, while Eq. (21) represents the temporal relationship for two AGVs to avoid cross collisions.

4 Improve Differential Evolution—Variable Neighborhood Search Algorithm

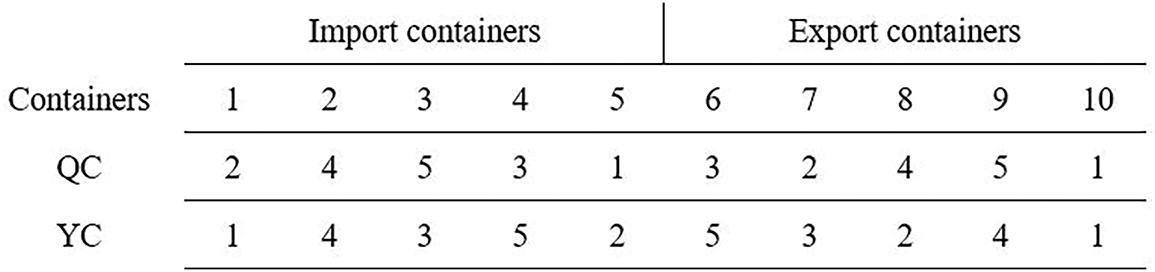

According to Assumption (1), all container tasks are operated by the identified QC and YC. Take a set of 10 container tasks as an example: containers 1–5 are import containers, and containers 6–10 are export containers. The starting and ending points of containers are randomly distributed on 5 QC and 5 YC. The information of the container tasks is shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: The information of container tasks

4.1.1 Coding and Decoding of Task Layer

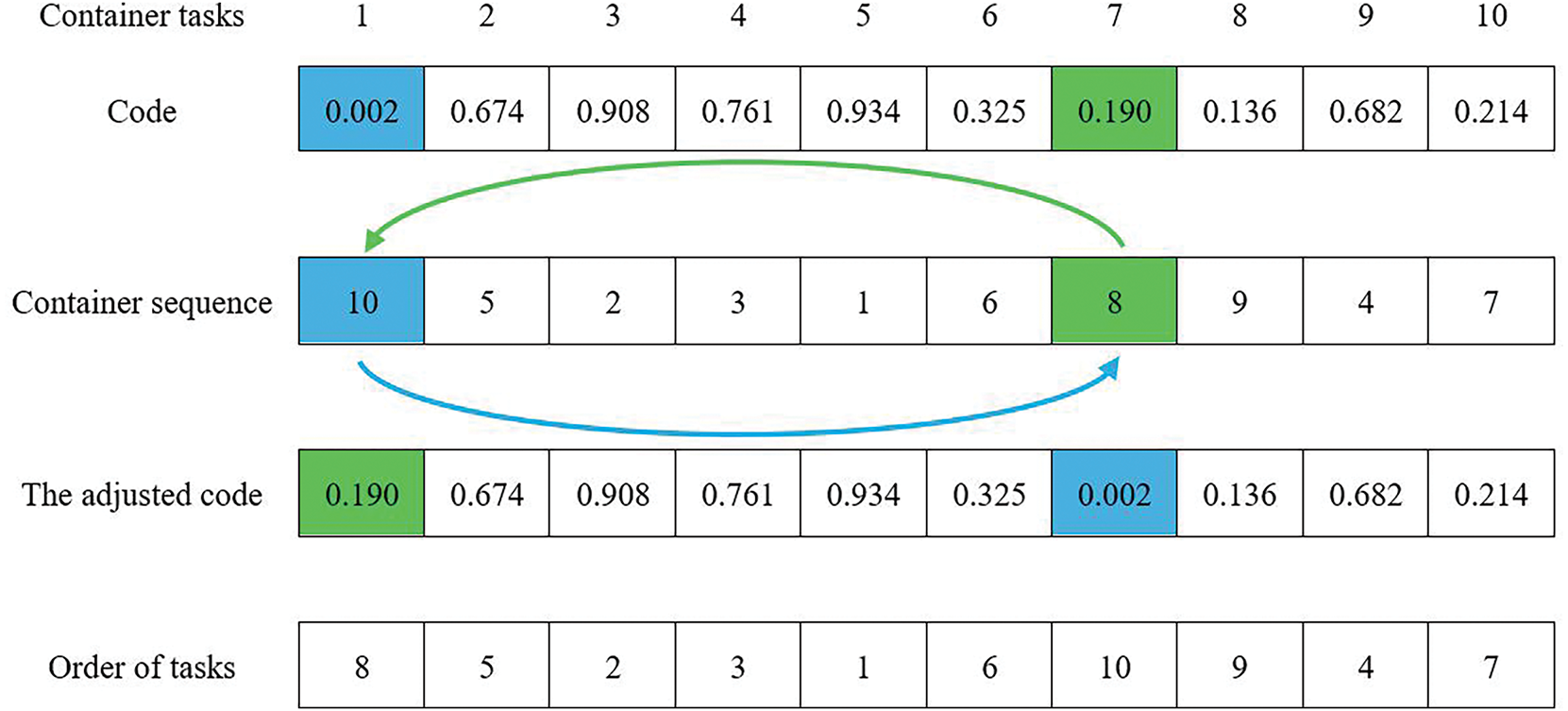

The task layer needs to solve the sequential arrangement of containers and configure appropriate AGVs for the execution of containers. Therefore, this paper designs a 2-N dimensional vector to represent the solution of the task layer model, where N is determined by the quantity of containers, and 2 signifies that the code includes the order of tasks and the assignment of AGVs. The solution to the order of tasks of task layer can be described as follows. First, generate a set of random numbers with values ranging from (0, 1) based on the number of tasks. For instance, the initial vector could be 0.002-0.674-0.908-0.761-0.934-0.325-0.190-0.136-0.682-0.214. Arrange the initial vector in descending order to obtain the initial sequence of container tasks, which is 10-5-2-3-1-6-8-9-4-7. Adjust the initial order of container tasks according to Eq. (10) so that the operation for the import containers of any QC takes priority over the export containers. The order of container Task 1 and container Task 7 needs to be swapped. Therefore, the sequence code of the swapped tasks is 0.190-0.674-0.908-0.761-0.934-0.325-0.002-0.136-0.682-0.214. And according to the adjusted vector order, it can be known that the operation sequence of the container tasks is 8-5-2-3-1-6-10-9-4-7. The process of adjusting the code and generating the task sequence is shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Encoding and decoding of task orders

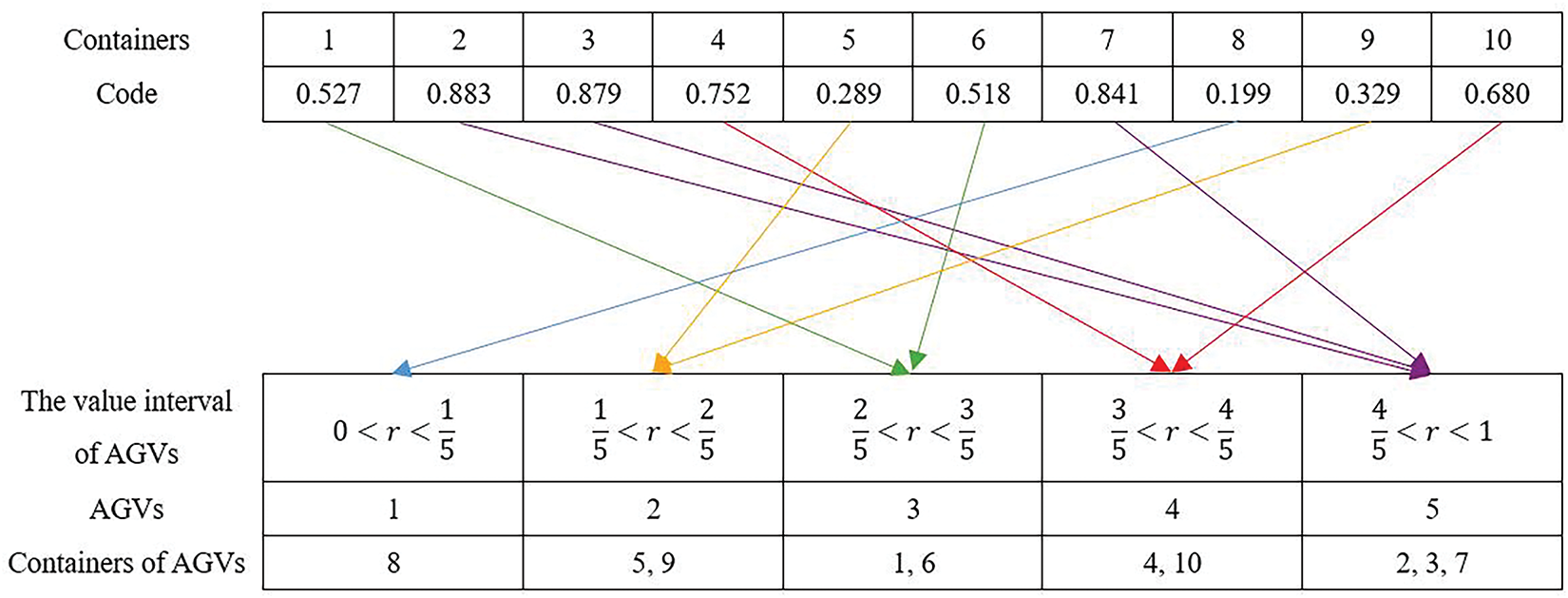

For the solution of the assignment of AGVs, the value range corresponding to each AGV is partitioned based on the quantity of AGVs, and generate a random sequence of N-dimensional values ranging from (0, 1) based on the number of containers. When the value falls within the value range of the corresponding AGV, it undertakes the transportation task, that is, when

Figure 10: Encoding and decoding of task assignments

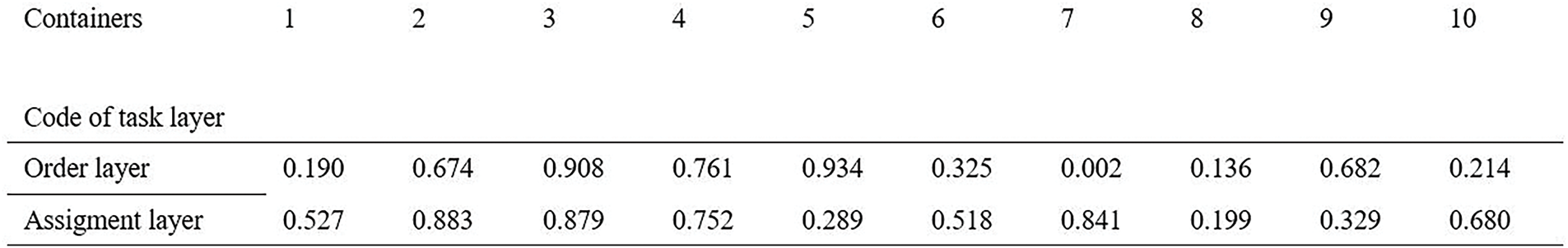

Therefore, the encoding of the task layer can be represented by the double-layer real number sequence structure as shown in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: The code of task layer

4.1.2 Coding and Decoding of Routing Layer

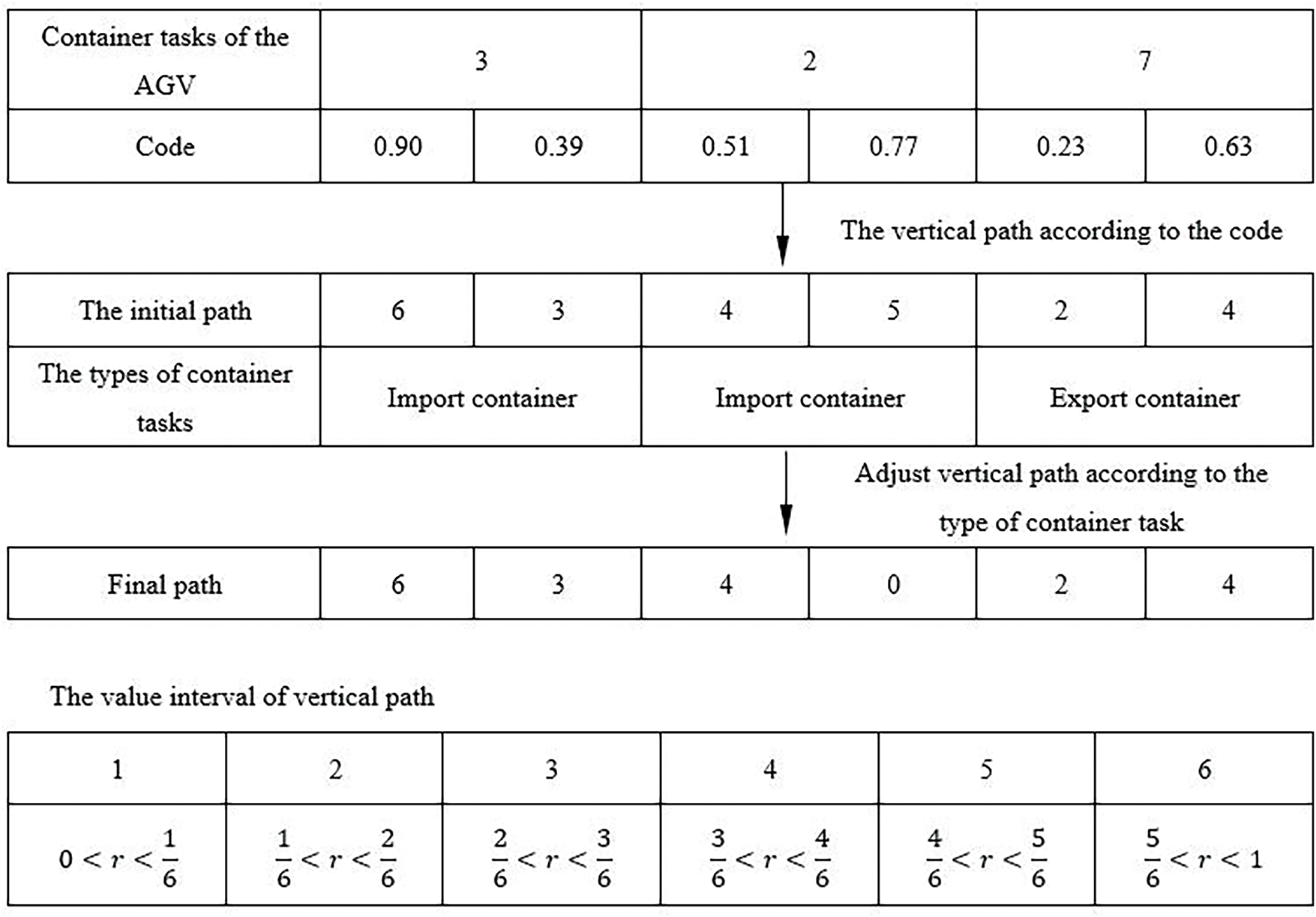

In this paper, a 2* N-dimensional real number vector is set to represent the solution of the routing layer, with N being determined by the quantity of containers. The route for an AGV to complete a container task can be determined by the starting point, the destination, and two points on the entry and exit vertical paths. Therefore, for each container task, there should be a pair of values. The first value gives the vertical path that the AGV needs to pass through during transportation, and the second value gives the vertical path that the AGV needs to enter when leaving after completing the current task. If there are no subsequent tasks, it indicates that the AGV will enter the AGV parking area from this interval after completing the task. In order to convert the real number code of AGV into the moving path of AGV, therefore, (0, 1) is divided into six value intervals to represent six selectable crossing paths. When the real number of the path selection code falls within the corresponding value interval, it indicates that the two endpoints of this path are selected as the critical path points for the AGV’s movement to form the path of the AGV.

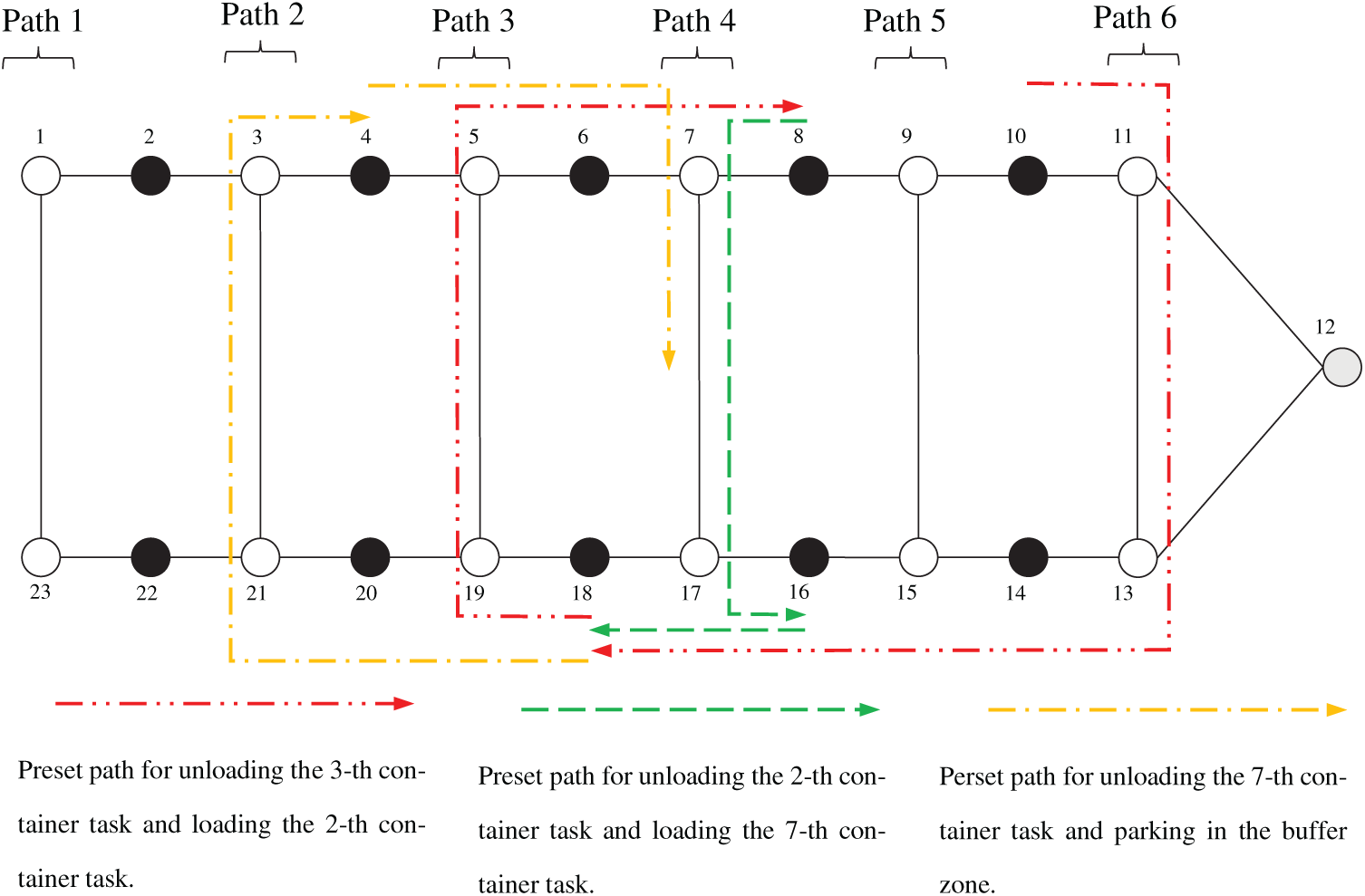

The routing layer needs to plan the movement of each AGV separately. Therefore, the path of each AGV needs to be set according to the container task sequence arranged by the task layer and the allocation of AGVs. According to the task layer, the container tasks of AGV5 are 3-2-7 in sequence. The vectors of the three tasks are obtained as 0.90-0.39-0.51-0.77-0.23-0.63, and then they are transformed into initial vertical paths, which are selected as 6-3-4-5-2-4 to represent the crossing paths passed by the AGV during its movement. When the AGV has two consecutive container tasks of different types, it does not need to go through the vertical path when traveling from the end of the current task to the beginning of the next task. Therefore, the path vector of the AGV needs to be adjusted to meet the actual movement requirements. The adjustment process is shown in Fig. 12. Since the submission node of container Task 2 and the receiving node of Task 7 are both on the yard side, the AGV only needs to move on the yard side to continue its operation tasks at the starting point of Task 7 after completing Task 2. Therefore, the second crossing path corresponding to Task 2 is selected as 0, indicating that it does not need to go through the crossing path. The final obtained adjustment path is 6-3-4-0-2-4. Therefore, the complete job task node movement of AGV5 can be represented as shown in Fig. 13: (1) after picking up the first import container on node 10 where the 5-th QC is located, the AGV drive cross the 6-th crossing path (n11, n13) and moves to the destination node 18 of the import container to submit it to the 3-rd YC, (2) then drives cross the 3-th vertical path (n5, n19) and travels to the start node 8 to load the second import container task at the 4-th QC, and then drives cross the 4-th vertical path (n7, n17) and reaches to the destination node 16 to submit task to the 4-th YC,(3) AGV drives to node 18 to pick up the export container task by the 3-thYC, and then drives cross the 2-th vertical path (n3, n21) and reaches to the destination node 4 to submit task to the 2-th QC, finally, drives to the buffer zone and waits for the next round of scheduling task.

Figure 12: Encoding and decoding of the vertical path selection

Figure 13: Preset path of AGV obtained from the decoding

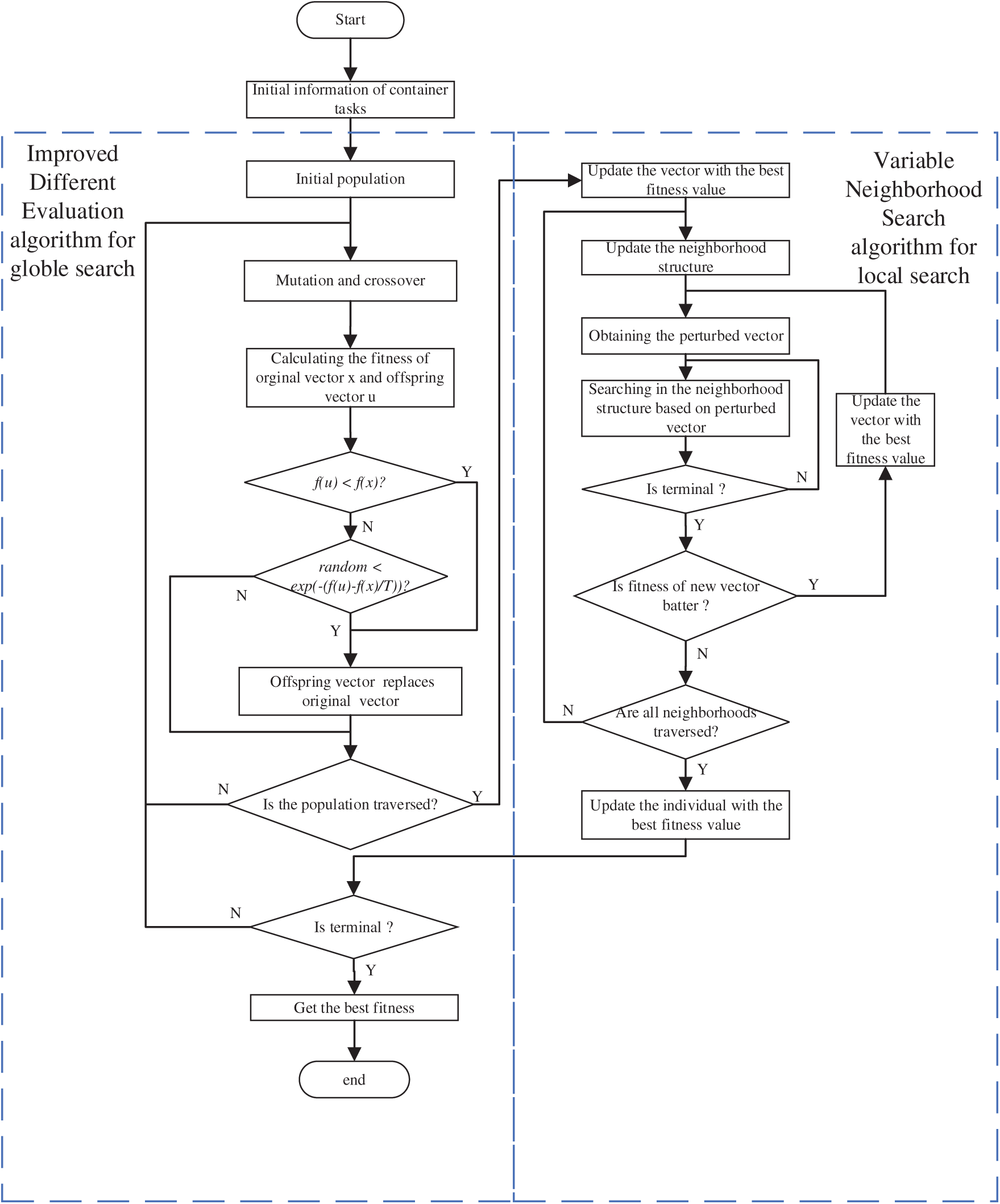

Variable neighborhood search (VNS) algorithm can effectively prevent the algorithm from being trapped in local optima and enhance the algorithm’s local search capability. In this paper, an improved differential evolution variable neighborhood search (IDE-VNS) algorithm is proposed to solve the problem as shown in Fig. 14.

Figure 14: The IDE-VNS flowchart

The differential evolution algorithm is used for global search. Firstly, a mutation operation is performed, three different vectors

where

All dimensions of each vector should be between (0, 1). If a solution outside the feasible domain emerges during the mutation process, that is,

where

Secondly, the trial vector

where

Finally, the selection operation is performed. The selection operation of the traditional DE algorithm usually adopts the one-to-one greedy idea, that is, only the fitness values of each target vector and its corresponding experimental vector are compared, and the vector with better fitness values is selected to enter the next generation. This selection method may eliminate the poor vectors that are very close to the optimal solution, resulting in a decrease in the convergence speed and search quality of the algorithm. Therefore, the solution acceptance criterion from the simulated annealing algorithm is introduced, and the vectors with poorer performance are accepted according to the probability of being affected by temperature changes. To enhance search efficiency of the algorithm, the adaptive variable temperature method is adopted. The variation of the annealing temperature T is shown in Eq. (25) as follows:

For the minimization problem, vectors with smaller fitness values are selected for the next generation; otherwise, poorer vectors are accepted according to the probability

where

The variable neighborhood search algorithm expands its search range by changing the neighborhood structure of the solution, enabling the algorithm to more easily escape the local optimum. In this paper, variable neighborhood search is performed on the optimal vectors in the current population to improve the local search ability of the differential evolution algorithm.

This paper constructs the following three neighborhood structures to generate new local solutions:

(1) Neighborhood structure N1: In the first-layer vector of the task layer, two dimensions are randomly selected. The corresponding values of the selected dimensions represent the sequence of the two container tasks, and the values corresponding to these two dimensions are swapped. Then, readjust the vector according to the adjustment method in Section 4.1 to ensure that the imported containers can be given priority for processing.

(2) Neighborhood structure N2: In the second-layer vector of the task layer, a dimension is randomly selected. The corresponding value of the selected dimension represents the AGV transporting the container task, and another AGV is then selected for the container task to complete it.

(3) Neighborhood structure N3: In the routing layer vector, a dimension is randomly selected. The value of the selected dimension represents the crossing path of the AGV when it is moving, and the crossing path is reselected to replace the current path.

Based on the above three neighborhood structures, the operation steps are as follows:

Step 1: Take the optimal solution in the contemporary population as the initial vector

Step 2: If the loop termination condition

Step 3: Random disturbance. Obtain the perturbed vector

Step 4: Local search.

(1) initialize c = 1, Take the perturbated vector

(2) Output the local optimal vector

(3) Obtain a new vector

Set

Step 5: If

In this section, a set of experiments were conducted carried out to evaluate the effectiveness of the algorithm, bidirectional transportation and battery swapping strategy. The experiments were conducted using Python 3.11.5 on a computer with Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-12600KF 3.70 GHz, 16.0 GB of RAM and Windows 11 operation system.

5.1 Parameters Setting of the Model

Experiments are conducted and parameters are set based on the automated terminal layout in Fig. 2. This layout consists of a 23-node network diagram with 5 quay cranes, 5 yard cranes and 1 battery swap station. The distance between each node is set to 64 m, the velocity of AGV is 4 m/s, the unit power consumption of the AGV when waiting for loaded and unloaded is 0.012 s−1, the unit power consumption when moving without load is 0.015 s−1, the unit power consumption when moving with load is 0.016 s−1, the battery swap time is 80 s, and the time for QC/YC to load/unload containers is 120 s.

5.2 Parameters Setting of IDE-VNS Algorithm

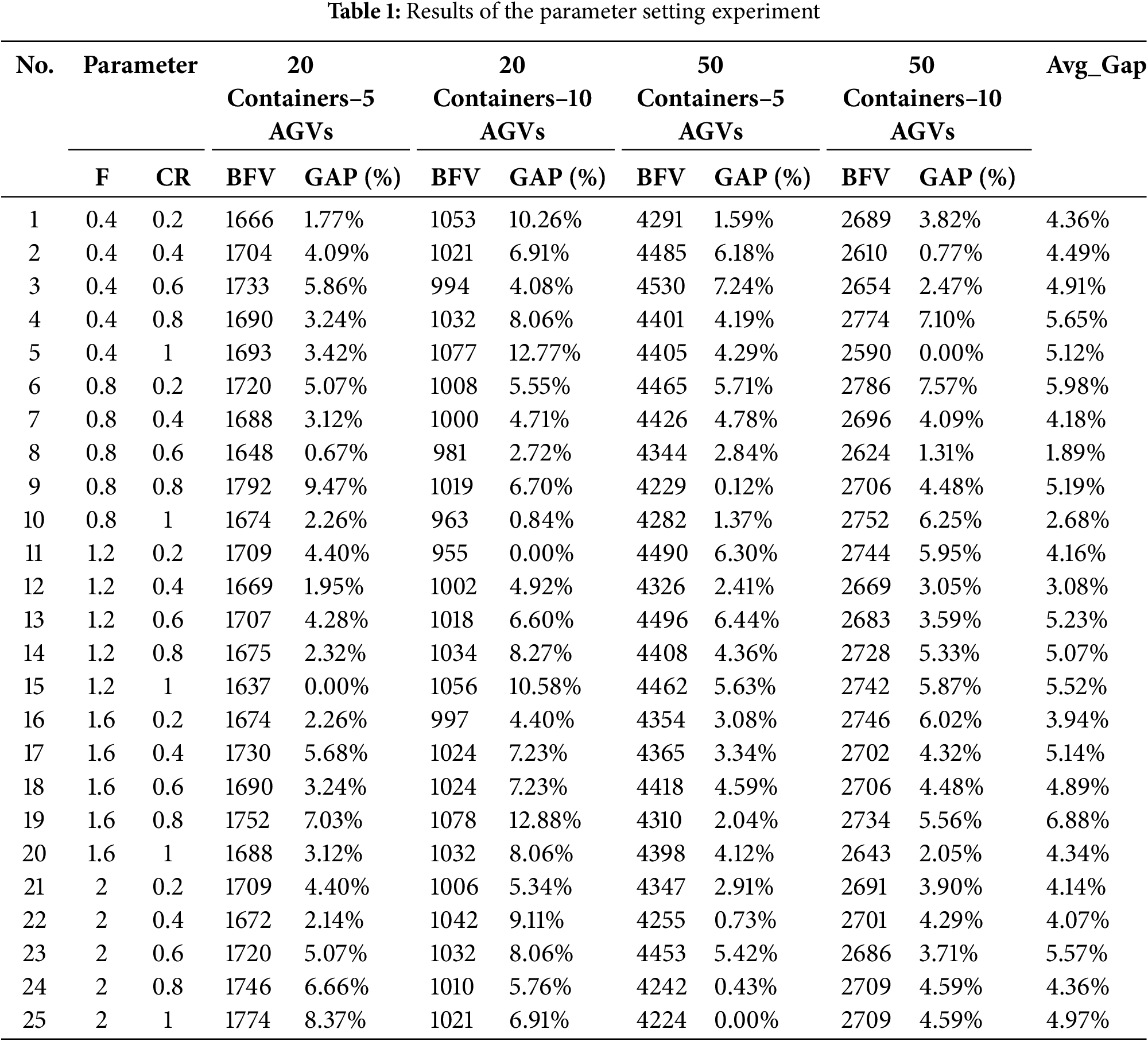

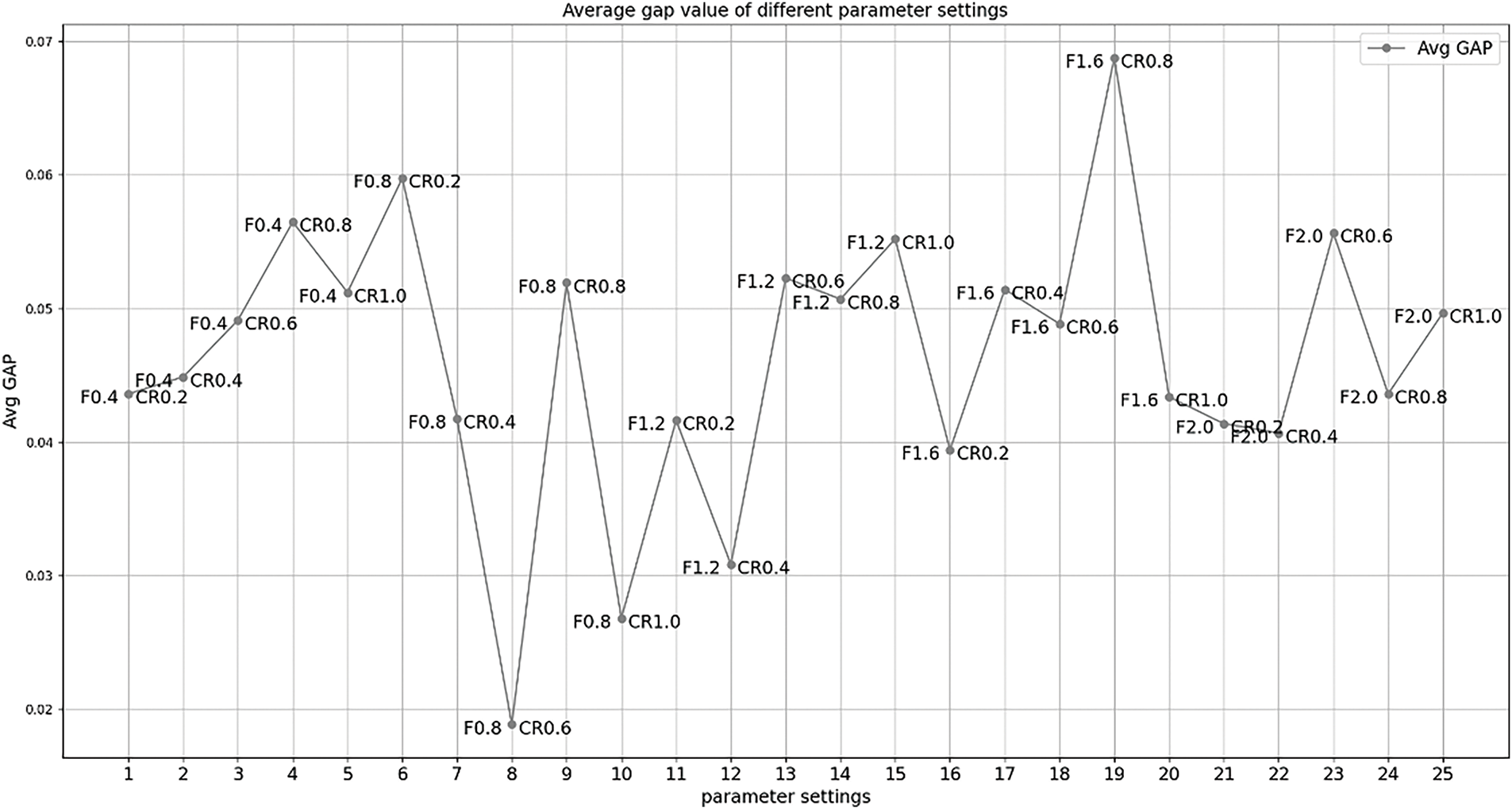

The parameters setting of the IDE-VNS algorithm will affect the accuracy and convergence speed of the solution. Therefore, in order to better utilize this algorithm to solve the problem, a parameter configuration experiment was carried out. The crossover operator F and the mutation operator CR are the key parameters that affect the global search performance. Therefore, set F

The experimental results are shown in Table 1, where BFV is the optimal fitness value obtained, and GAP represents the relative error between the problem scale and the minimum fitness value obtained. As can be seen from Fig. 15, the parameter group has the smallest average error value when (F, CR) = (0.8, 0.6). Therefore, the parament group (F, CR) = (0.8, 0.6) used in the following experiments.

Figure 15: Average gap value of different parameter settings

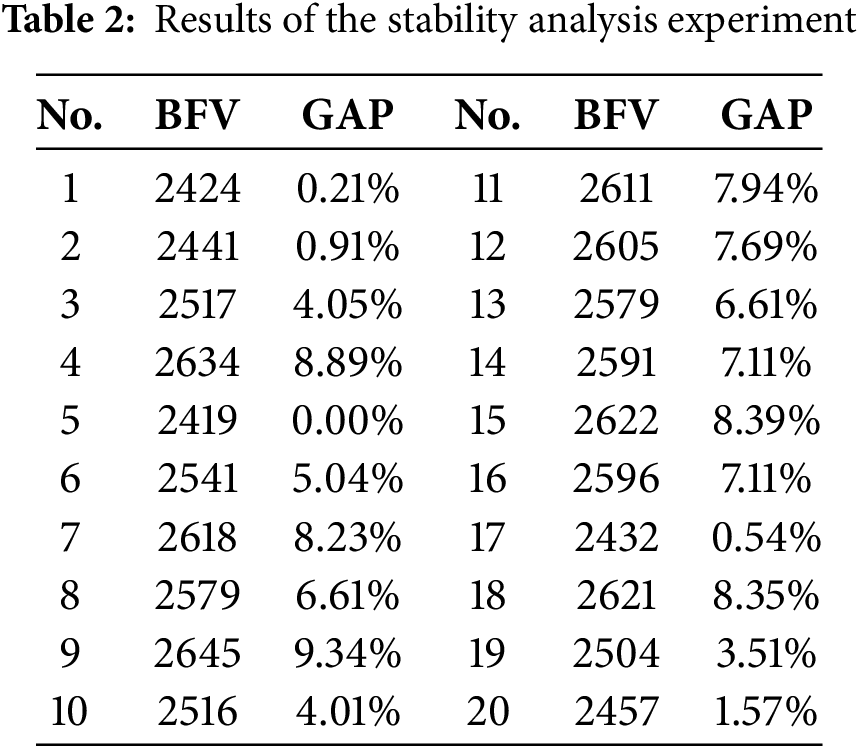

In addition, to verify the stability of the solution of the algorithm, 20 experiments were conducted on the scale of 50 containers–10 AGVs, and the results are presented in Table 2. BFV is the best fitness values of the result and GAP is the difference of BFV between the BFV under the parameter Settings and the minimum BFV.

It can be known from the 20 groups of experiments in Table 2 that the GAP between the worst solution and the best solution is 9.34%, and the average gap remains at about 5%. Therefore, the error range of the improved algorithm in solving the problem can be accepted, which shows the stability of the algorithm.

5.3 Comparative Experiments and Analysis of IDE-VNS

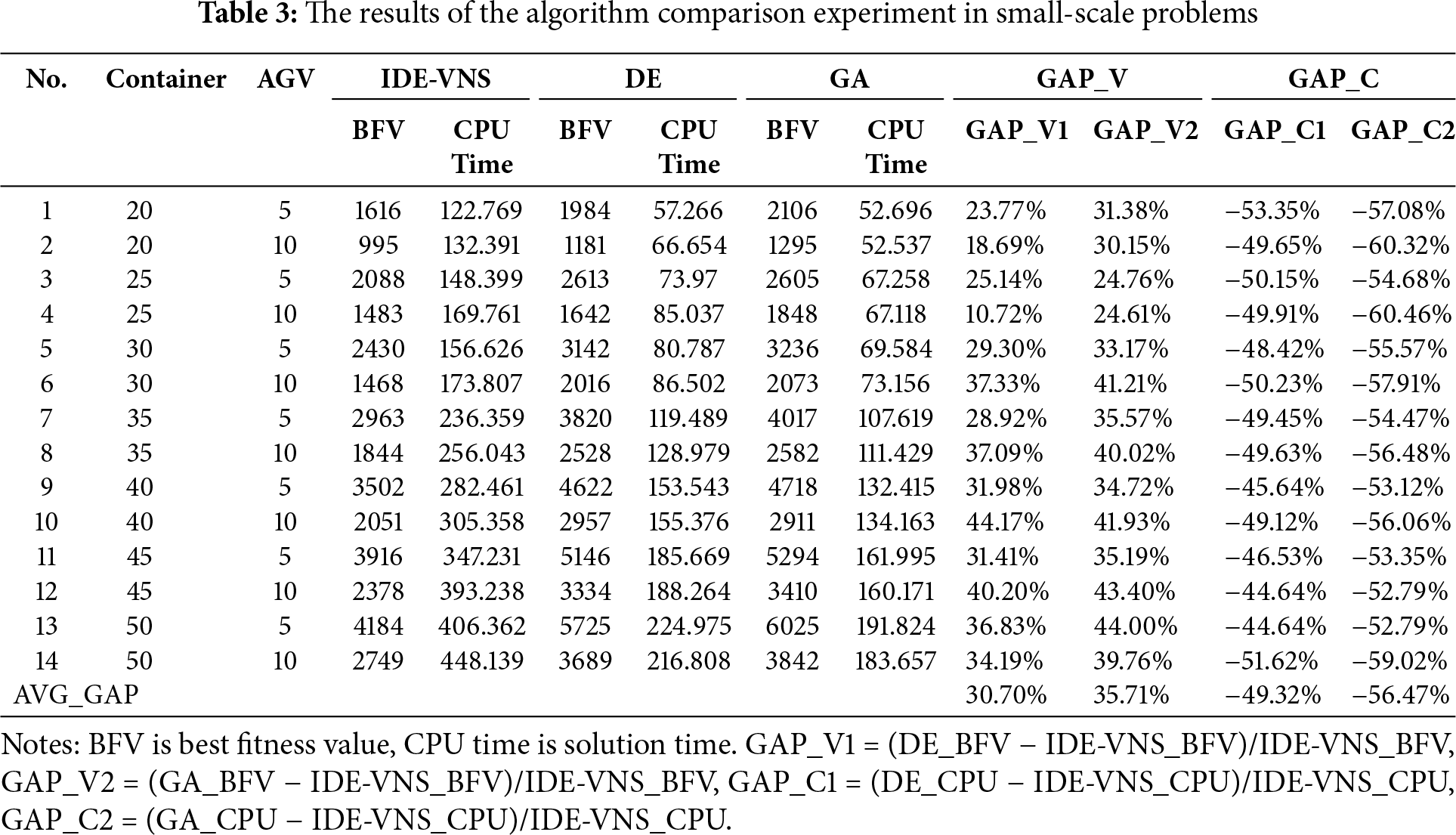

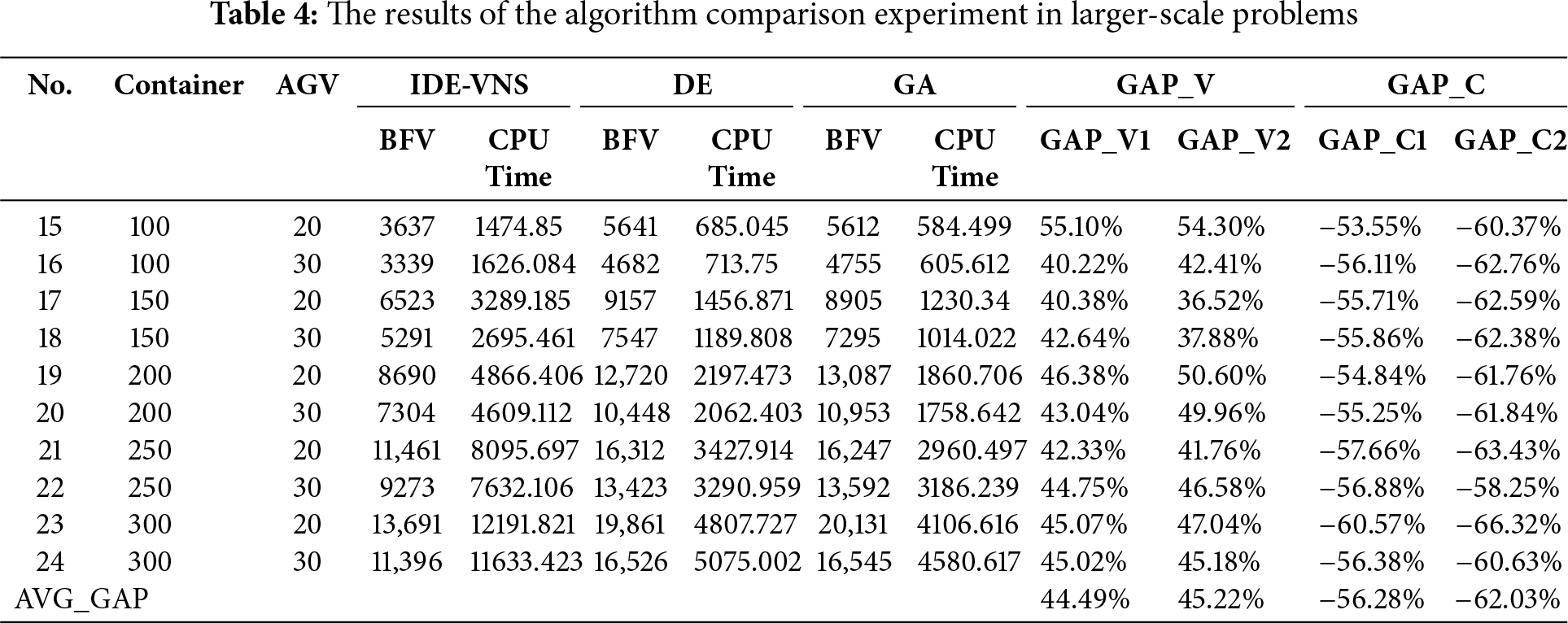

This section compares the performance between IDE-VNS, differential evolution (DE) algorithm and genetic algorithm (GA) in terms of solution accuracy, convergence speed and solution time. The above three methods adopt the same encoding and decoding for solution. The GA parameters encompass a crossover rate pc = 0.8, and a mutation rate pm = 0.01. For DE, the paraments comprise a crossover operator F = 0.7 and a mutation operator CR = 0.5. The results are presented in Tables 3 and 4. The best fitness value (BFV) and the CPU time obtained by the three algorithms are compared at a small scale and a larger scale. GAP_V is the difference of BFV between algorithms, while GAP_C is the difference of CPU time between algorithms.

Table 3 presents the results for small-scale problems, including the optimal fitness values and computation times for the three algorithms. It can be observed that the average gap (GAP-V1) between IDE-VNS and the DE algorithm is 30.70%, and the average gap (GAP-V2) between IDE-VNS and the GA algorithm is 35.71%. The IDE-VNS algorithm outperforms the DE and GA algorithms in terms of solution quality at this scale. As the number of container tasks increases, the solution quality improves. However, in terms of computation time, the IDE-VNS algorithm is slower than the other two algorithms, with an average gap (GAP_C1) of −49.32% compared to the DE algorithm, and an average gap (GAP_C2) of −56.47% compared to the GA algorithm. For the same scale of container tasks, increasing the number of AGVs can improve operational efficiency to some extent, resulting in smaller optimal fitness values.

Table 4 displays the results for large-scale problems. At this scale, the solution quality of the IDE-VNS algorithm has improved further compared to the DE and GA algorithms, and the relationship between solution quality and container number follows the trend shown in Table 3. The average gap with the DE algorithm (GAP_V1) is 44.49%, and with the GA algorithm (GAP_V2) it is 45.22%. However, the gap in computation time has also increased, with an average gap (GAP_C1) of −49.32% compared to the DE algorithm, and an average gap (GAP_C2) of −56.47% compared to the GA algorithm.

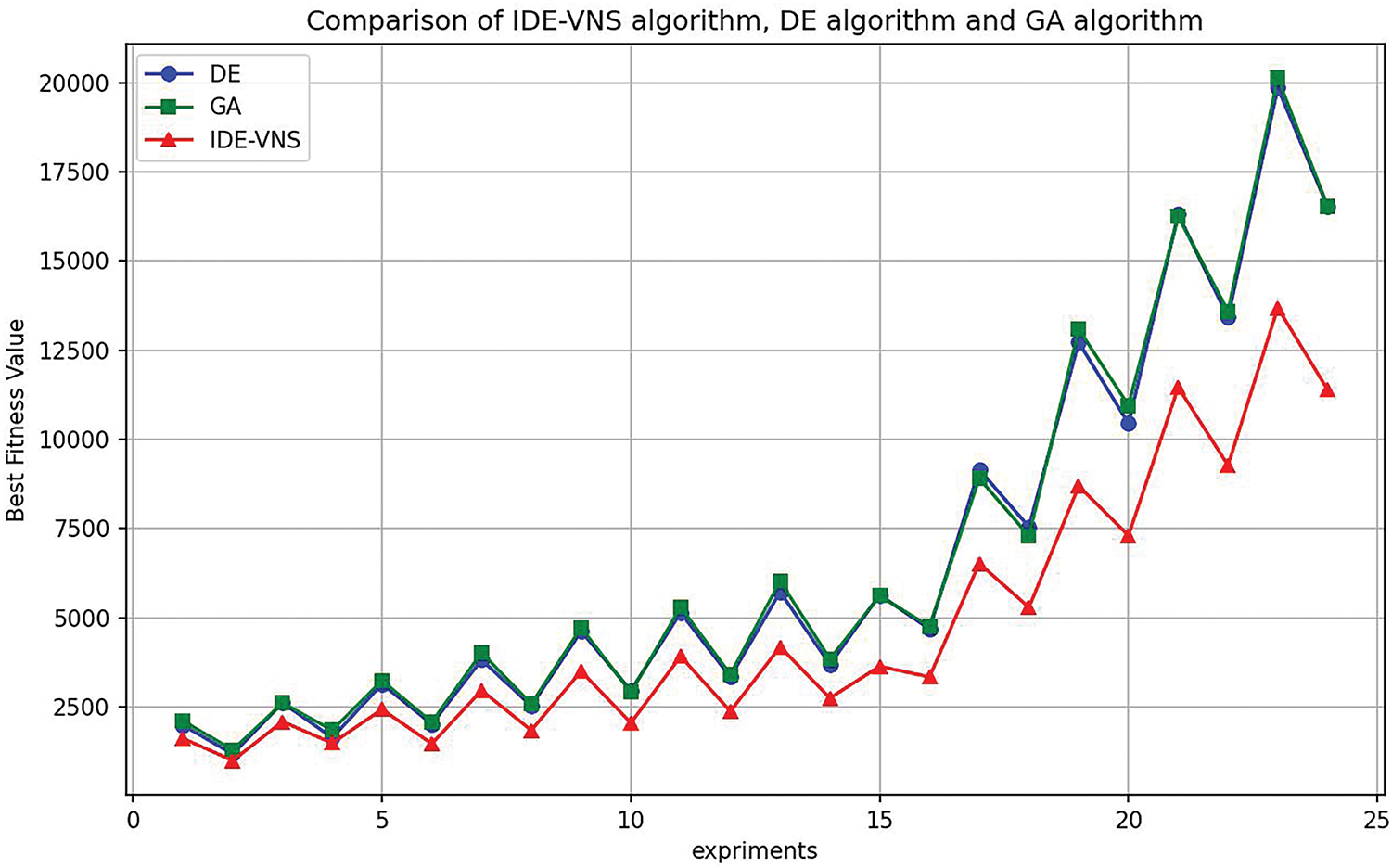

Fig. 16 illustrates the trend of the optimal values across the 24 experimental data points. From the graph, it is clearer that when the container task scale is small, the differences in solution quality between IDE-VNS, DE, and GA algorithms are minimal. However, as the container task scale increases, the solution quality gap between IDE-VNS and the other two algorithms becomes more pronounced. Furthermore, increasing the number of AGVs can enhance the operational efficiency of the automated terminal to some extent. The experimental results indicate that despite IDE-VNS sacrificing some computation speed, it significantly improves solution quality and can be applied to scheduling problems of various scales. This is due to the IDE-VNS algorithm’s use of variable neighborhood search on the optimal fitness value of each iteration, which is the main reason for the increased computation time. However, this local search strategy effectively prevents the algorithm from getting stuck in local optima, allowing for a more precise search for the global optimum.

Figure 16: Performance trends of IDE-VNS, DE and GA with 24 examples

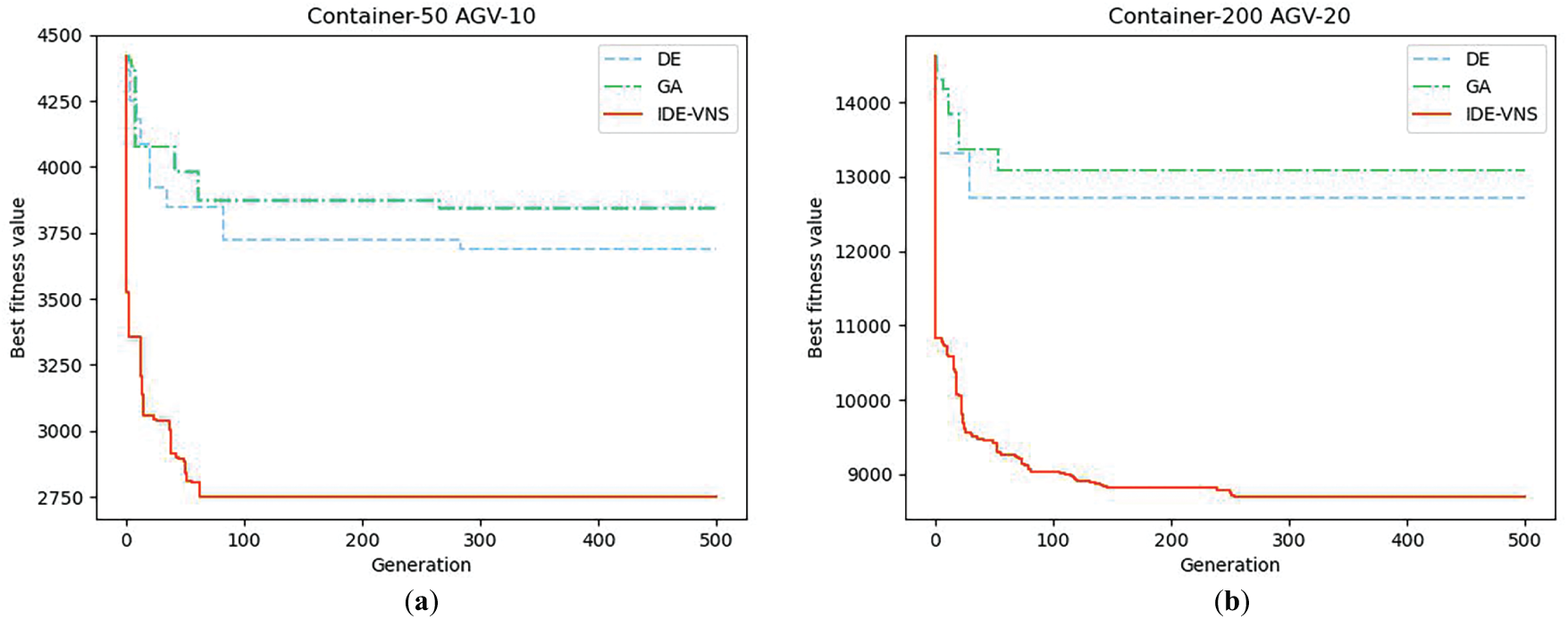

In this study, two experiments are conducted to examine the convergence capability of each algorithm. The result of the experiments as shown in Fig. 17. Under the experimental scale of 10 AGVs handling 50 containers, IDE-VNS obtains the optimal value around the 50th generation, while the convergence speeds of GA and DE are both lower than the algorithm in this paper. Under larger-scale experiments, the solution values of IDE-VNS tended to stabilize around the 150th generation, and new solution values were further found at the 250th generation, indicating that this algorithm has a certain ability to escape the local optimum. In addition, it can be seen that in terms of the ability to obtain better fitness values, IDE-VNS > DE > GA.

Figure 17: Typical convergence of IDE-VNS, DE and GA algorithm. (a) Convergence of algorithms for 10 AGVs transporting 50 containers; (b) Convergence of algorithms for 20 AGVs transporting 200 containers

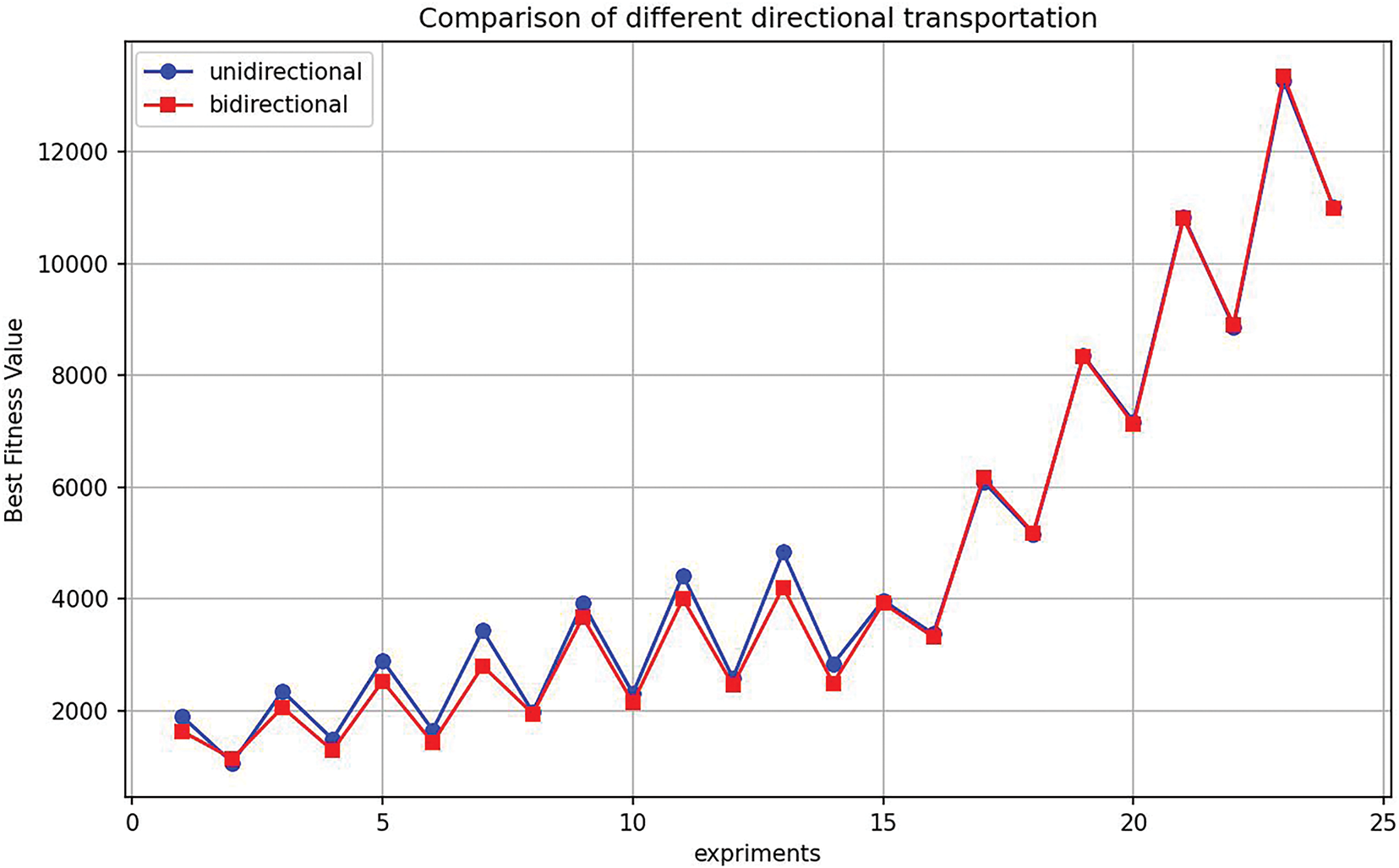

5.4 Comparative Experiments and Analysis of Unidirectional and Bidirectional Transportation

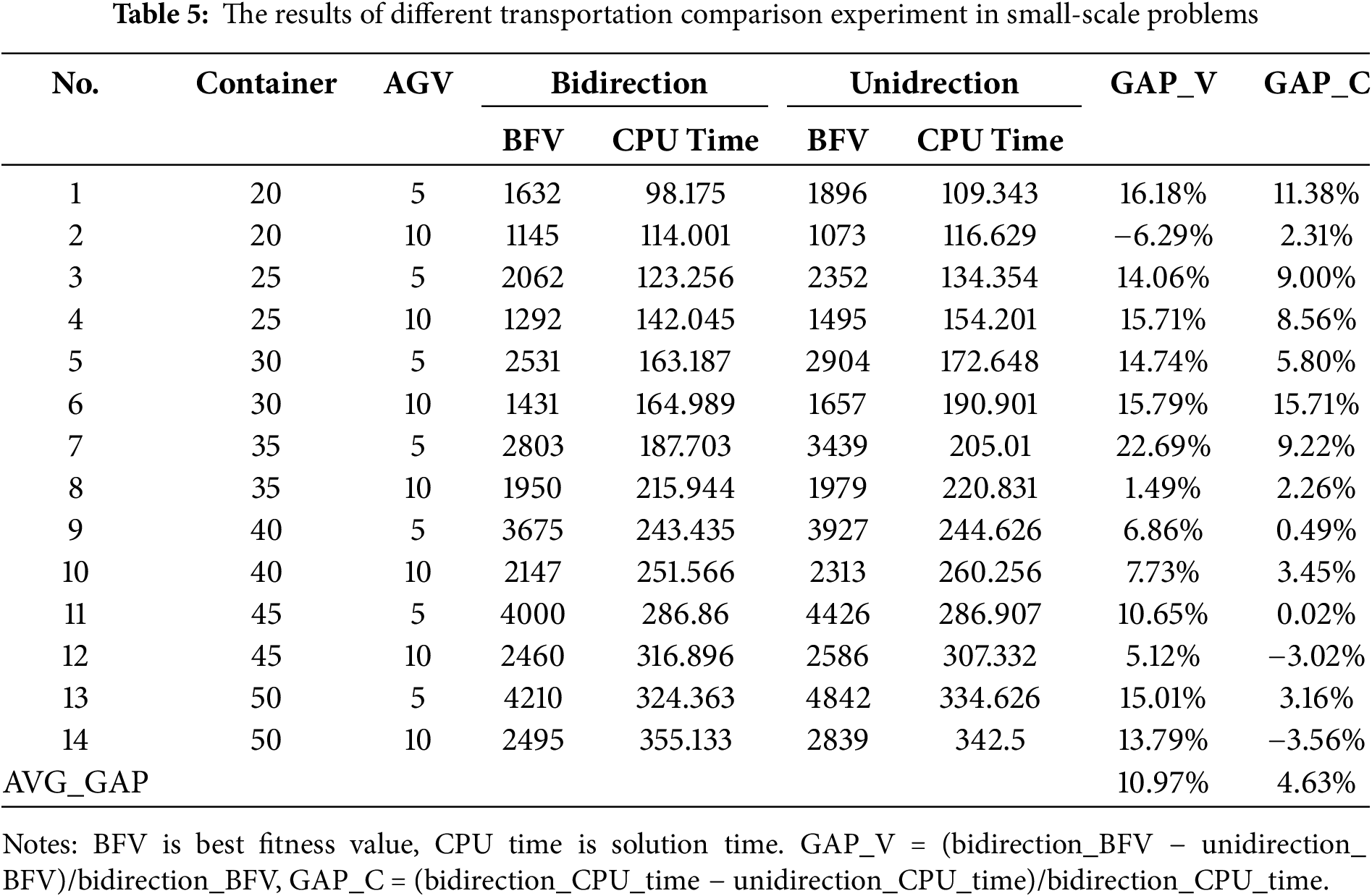

The bidirectional transportation can make the movement of AGVs more flexible and handle container tasks more flexibly. In order to verify the above characteristics, a comparative experiment between the unidirectional and bidirectional transportation was conducted. The experimental results were obtained in Tables 5 and 6. BFV is the best fitness value and CPU time is solution time, GAP_V is the difference of BFV of the bidirectional and unidirectional transportation, GAP_C is the difference of CPU time of the bidirectional and unidirectional transportation.

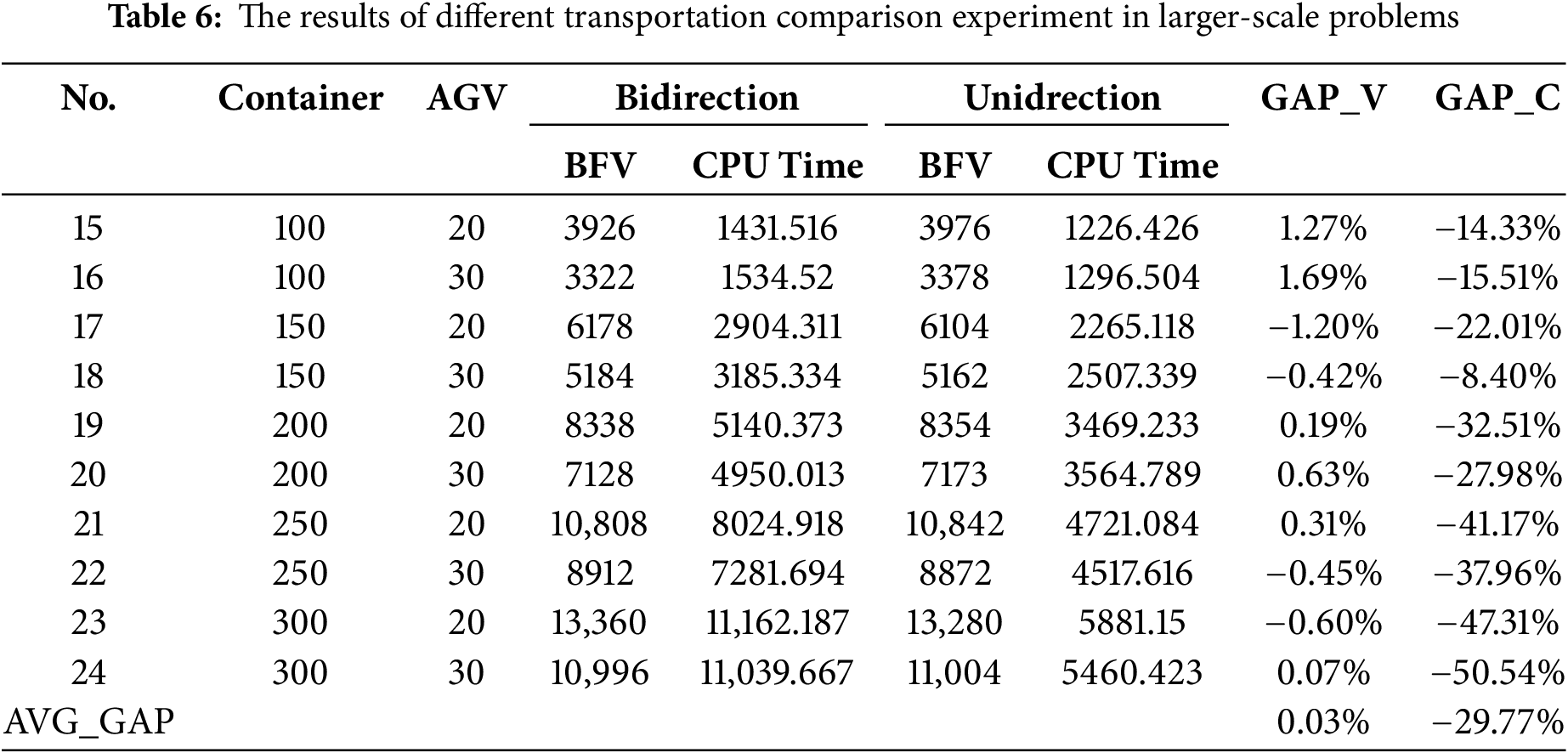

The results derived from Tables 5 and 6 are as follows: (1) When the number of AGVs is fixed, the BFV of unidirectional and bidirectional transportation gradually increase with the number of container tasks increases. (2) When the number of containers is fixed, the increase in the quantity of AGVs can reduce BFV of unidirectional and bidirectional transportation. (3) The BFV of bidirectional transportation is superior to that of unidirectional transportation in small-scale problem, and the average gap GAP_V is 10.97%, but the average gap GAP_V is 0.03% in larger-scale problem. (4) The average gap GAP_C is 4.63% in small-scale problem and −29.77% in larger-scale problem. Fig. 18 illustrates the trend of optimal values based on the above experimental data. From the figure, it is clear that when the container task scale is small, the bidirectional transportation mode performs better than the unidirectional mode, and the gap between the two modes narrows as the number of AGVs increases. Specifically, in our experiments, when the number of containers is 100 or fewer, the bidirectional transportation method demonstrates a clear advantage in BFV compared to the unidirectional approach. However, as the number of container tasks increases and the problem scale expands, bidirectional transportation gradually shows certain disadvantages, this is because, as the problem size increases, conflicts become more complex, making it difficult to find better scheduling solutions than the unidirectional mode within an efficient timeframe. Additionally, due to the increased number of conflicts, more solving time is required to resolve them, resulting in longer AGV solving times for bidirectional transportation compared to unidirectional transportation in large-scale problems. Therefore, bidirectional transportation is best suited for small to medium-sized automated container terminals, where the number of container tasks is relatively low and operational conflicts are fewer, allowing this approach to effectively enhance operational efficiency.

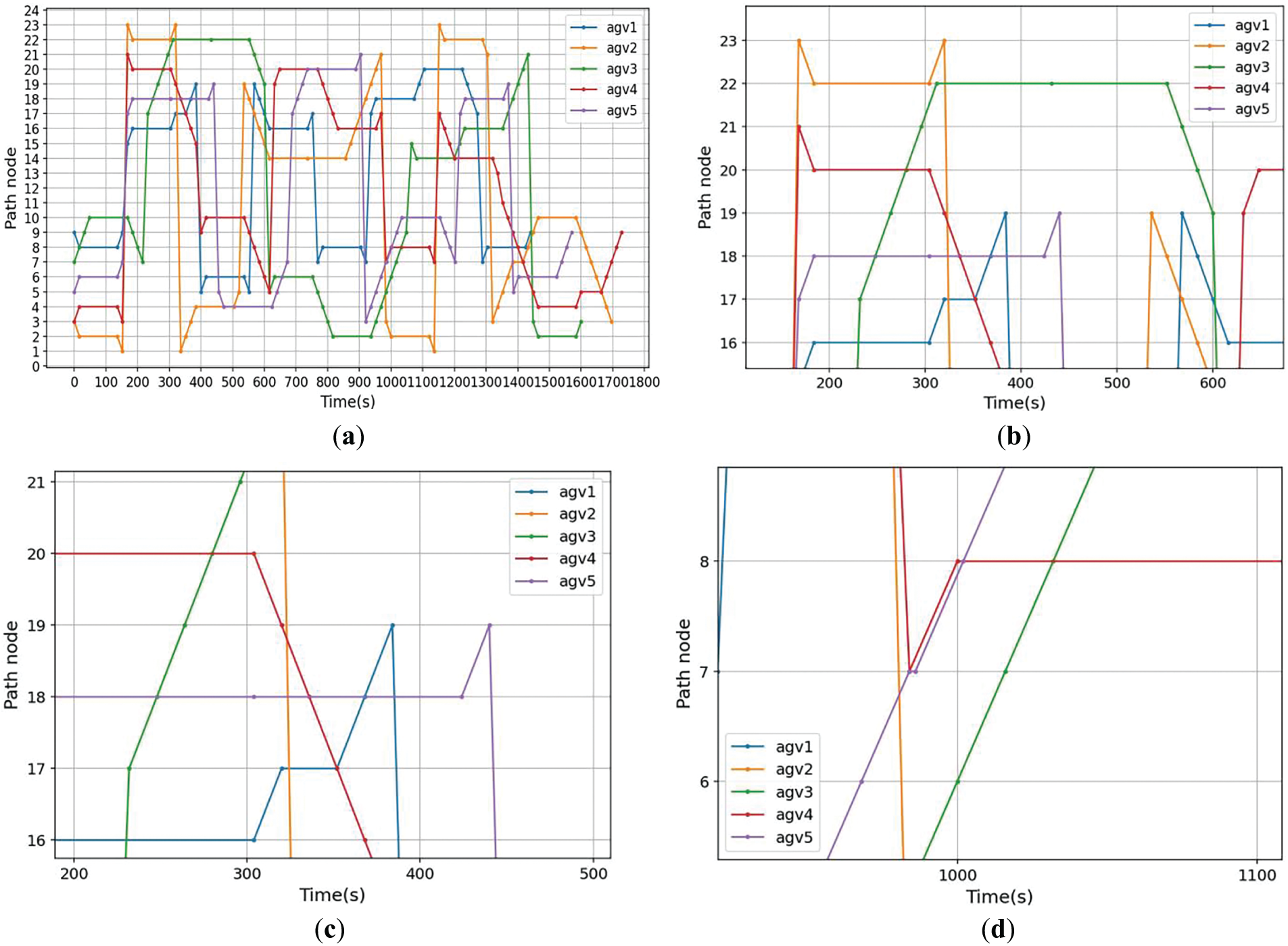

Figure 18: Performance trends of unidirectional and bidirectional transprotation

Furthermore, in order to clearly illustrate the operation process of the AGV implemented in this paper and the bidirectional conflict-free transportation, the AGV transportation routes as shown in Fig. 19 is obtained in 20 containers–5 AGVs. The Complete route as shown in Fig. 19a shows the paths of all AGVs. Fig. 19b shows in more detail the movement path of a single AGV processing task and the time relationship of interaction with the equipment. As shown in this figure, AGV3 enters node 22 from node 21 to start the container delivery operation. After YC completes the unloading operation of the above container, the new container is delivered to AGV3 and the transportation operation begins. Starting to move from node 22 back to node 21. It further demonstrates the characteristic of AGV’s free movement in the horizontal transportation area. Fig. 19c,d details the conflict-free paths of AGVs. In Fig. 19c, AGV1 needs to move from node 17 to node 18 around 330 s. However, at this time, AGV4 is entering node 18 from node 19. Since node 18 has no buffer, in order to avoid conflicts, AGV1 must wait at node 17 with a buffer until AGV4 reaches node 18 first before starting to move. Then the subsequent movement of AGV4 is from node 18 to node 17, and there is still a conflict. Therefore, AGV1 needs to continue waiting for AGV4 to move to node 17 and release the occupied paths and nodes before it can continue to move. The safe distance between AGVs is shown in Fig. 19d. When AGV4 and AGV5 reach node 7 with a buffer and both need to enter node 8, AGV5 waits in the buffer until AGV4 leaves and ensures a safe distance before restarting its movement.

Figure 19: Route results for 5 AGVs transporting 20 containers in bidirectional transportation. (a) Complete result; (b) Bidirectional transportation of AGV; (c) Avoidance of reverse collision; (d) Avoidance of pursuit collision

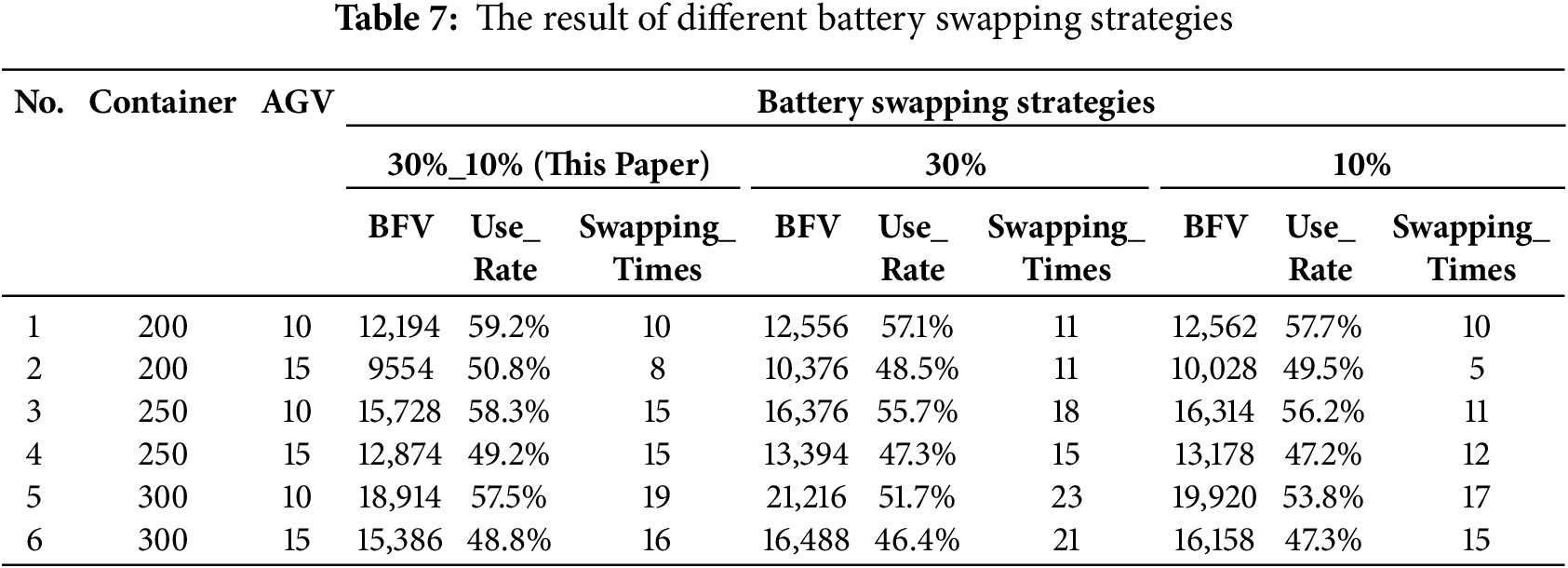

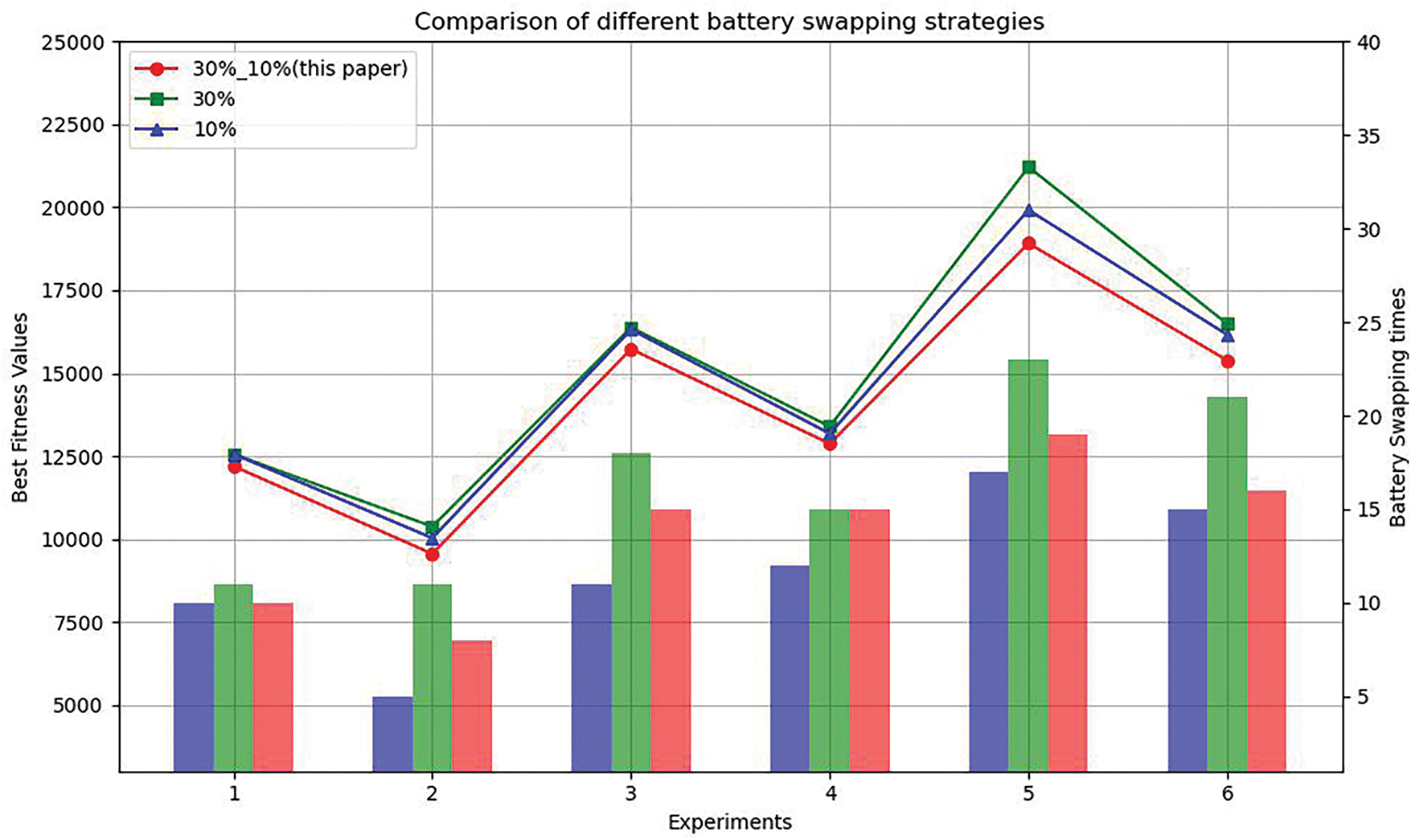

5.5 Comparison and Analysis of Different Battery Swapping Strategies

To address battery management for automated guided vehicles, this study establishes two critical thresholds: a 10% minimum safety threshold to ensure AGVs can reach the battery swapping station and a 30% operational threshold that allows AGVs to complete their current tasks before recharging. Specifically, the 10% threshold guarantees sufficient power for the return trip, while the 30% threshold balances task continuity with energy conservation.

In this section, a comparative experiment was conducted on the impact of different battery swapping strategies. This paper compares the utilization rates and maximum completion times of AGVs with 30%_10% battery swap thresholds (double-thresholds strategy), 30% battery swap thresholds, and 10% battery swap thresholds under different scales of 10 and 15 AGVs transporting 200, 250, and 300 containers. The experimental results are presented in Table 7. BFV is the best fitness values. Use_rate is the use rate of AGV, which is the sum of the operation times of each AGV divided by the sum of the differences between the start and end times of each AGV. Swapping_times is the total number of battery swaps for all AGVs during the operation process.

The findings obtained from the Table 7 are as follows: (1) With a fixed number of AGVs, the BFV and the number of battery swaps increase with the increase of task scale; (2) With a fixed number of containers, as the scale of the AGV increases, the BFV increase and the number of battery swaps decrease, but it leads to a decrease in the utilization rate of AGVs; (3) BFVs with double-threshold battery swapping outperform those with fixed-threshold battery swapping in different scale problems. The experimental results in Table 7 can be summarized in Fig. 20, which compares the BFV with the number of battery swaps. From the figure, it can be observed that the double-threshold battery swapping strategy results in fewer swaps compared to the 30% fixed swapping threshold. This is because the AGV’s swapping decision threshold is lower, allowing for more efficient use of the AGV’s battery while ensuring it does not run out of power. In contrast to the 10% fixed swapping threshold, although more swaps are required, better optimization results are achieved. This is because, during double-threshold swapping, some swap operations take advantage of waiting intervals to perform battery changes. Although this increases the number of swaps, it prevents delays in AGV operations caused by battery swapping, ultimately improving the AGV’s transportation efficiency.

Figure 20: Comparison of different battery swapping strategies

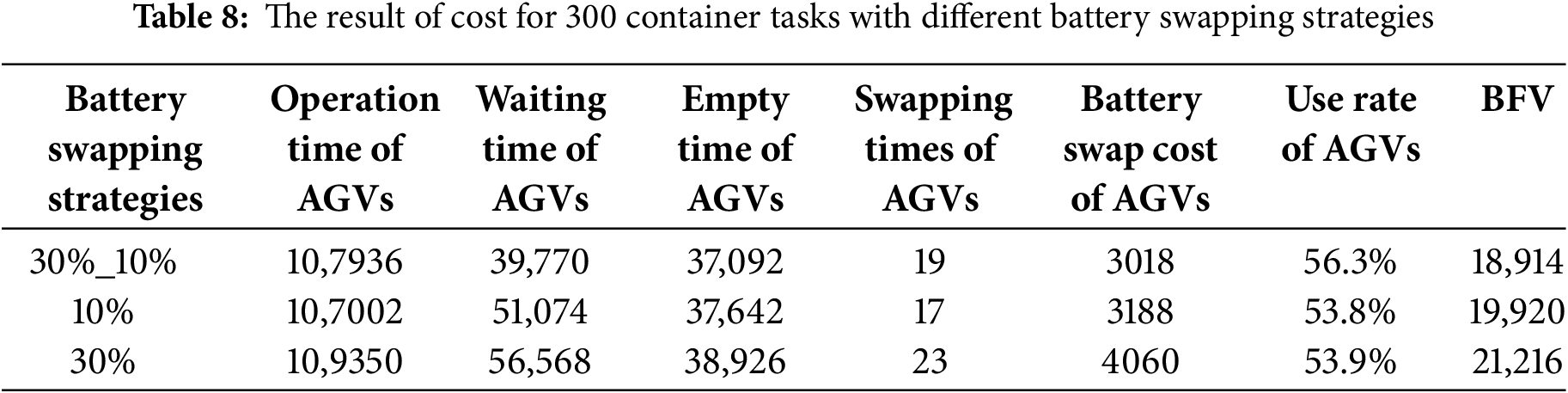

To further verify that the advantage of double-threshold battery swapping is to utilize the waiting time of AGVs, the time consumption of various states during the operation process of AGVs under 300 container tasks is listed in Table 8. The operation time of AGV refers to the time cost of the AGV transporting container task. The waiting time of AGV refers to the time cost of AGV waiting for QC/YC to complete the loading/unloading of containers. The empty time of AGV refers to the time cost of AGV moving to receive the next task. The battery swap cost of AGV refers to the time cost of moving from the current position to the battery swapping station and swapping the battery.

It can be obtained from Table 8 that the operation time of AGV under the double-threshold battery swapping strategy is very close to that of the other two battery swapping strategies, significantly reducing the waiting cost during the operation process. This is because the double-threshold battery swapping strategy can take advantage of the gap when the AGV is waiting for the QC/YC to complete the operation of the previous container task to go for battery swapping. Thereby, the idle time of the AGVs is reduced and their utilization rate is enhanced.

This paper discusses a combinatorial optimization problem in the ACT, where AGV scheduling, bidirectional conflict-free routing, battery swapping, and import/export container tasks are considered. A bi-level mixed integer programming (MIP) model is proposed, and the upper layer achieves the assignment of container tasks and the battery swapping planning of AGVs, while the lower layer ensures the movement of AGVs without conflict. A double-threshold battery swapping strategy is proposed and an improved differential evolution variable neighborhood search (IDE-VNS) algorithm is developed to solve the bi-level MIP model to minimize the completion time of all jobs. The result of the transportation mode experiment indicates that the bidirectional transportation of AGVs represents an efficient means to enhance the operational efficiency of AGVs. This is because of its more adaptable route selection and shorter driving route. Besides, the complicated routes of the bidirectional transportation have a substantial impact on AGV operations when operating at large container terminals, making it challenging to find an optimal schedule within the time limit. Therefore, the bidirectional transportation is more effectively applied to the small-scale ACT. The result of the battery swapping strategy experiment indicates that the double-threshold battery swapping strategy can reasonably arrange the battery swapping timing of AGVs, improve AGV utilization, and enhance operational efficiency. The result of the algorithm comparison experiment indicates that the IDE-VNS algorithm can better search for the optimal solution and avoid getting trapped in local optima.

Further research can be more consistent with the actual operation of ACT from the following aspects: (1) Consider the variable speed of AGVs. During the actual transportation process, the speed of AGVs is not constant. Therefore, issues such as AGV deceleration to avoid conflicts and variable speed during start and stop in the dispatching process can be further considered. (2) Further consider the collaborative operation between AGV and other equipment in the automated terminal, such as the collaboration between AGV and QC/YC. (3) Consider the impact of uncertainty problems in ACT, such as additional task arrivals, task cancellations, and AGV failures.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission for supporting this study.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62073212), Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (No. 23ZR1426600).

Author Contributions: He Huang: Methodology, software, validation, investigation, resources, writing—original draft, visualization; Jin Zhu: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data generated in this paper are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sun PZ, You J, Qiu S, Wu EQ, Xiong P, Song A, et al. AGV-based vehicle transportation in automated container terminals: a survey. IEEE T Intell Transp. 2022;24(1):341–56. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3215776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tian Y, Wang J, Chen J, Fan H. Collaborative scheduling of QCs, L-AGVs and ARMGs under mixed loading and unloading mode in automated terminals. J Shanghai Marit Univ. 2018;39(3):14–21. doi:10.13340/j.jsmu.2018.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu Q, Wang N, Li J, Ma T, Li F, Gao Z. Research on flexible job shop scheduling optimization based on segmented AGV. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;134(3):2073. doi:10.32604/cmes.2022.021433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Rahman HF, Janardhanan MN, Nielsen P. An integrated approach for line balancing and AGV scheduling towards smart assembly systems. Assembly Autom. 2020;40(2):219–34. doi:10.1108/aa-03-2019-0057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang Z, Chen J, Guo Q. Application of automated guided vehicles in smart automated warehouse systems: a survey. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2023;134(3):1529. doi:10.32604/cmes.2022.021451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang Y, Zhong M, Dessouky Y, Postolache O. An integrated scheduling method for AGV routing in automated container terminals. Comput Ind Eng. 2018;126:482–93. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2018.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Adamo T, Bektaş T, Ghiani G, Guerriero E, Manni E. Path and speed optimization for conflict-free pickup and delivery under time windows. Transport Sci. 2018;52(4):739–55. doi:10.1287/trsc.2017.0816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhong M, Yang Y, Dessouky Y, Postolache O. Multi-AGV scheduling for conflict-free path planning in automated container terminals. Comput Ind Eng. 2020;142:106371. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2020.106371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang Z, Zeng Q. A branch-and-bound approach for AGV dispatching and routing problems in automated container terminals. Comput Ind Eng. 2022;166:107968. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2022.107968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cao Y, Yang A, Liu Y, Zeng Q, Chen Q. AGV dispatching and bidirectional conflict-free routing problem in automated container terminal. Comput Ind Eng. 2023;184:109611. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2023.109611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yang X, Hu H, Jin J. Battery-powered automated guided vehicles scheduling problem in automated container terminals for minimizing energy consumption. Ocean Coast Manage. 2023;246:106873. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Farrell BR, McKie R. Designing a battery exchange building for automated guided vehicles. In: Ports 2016. Reston, VA, USA: ASCE Library. p. 71–80. doi:10.1061/9780784479919.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zou B, Xu X, De Koster R. Evaluating battery charging and swapping strategies in a robotic mobile fulfillment system. Eur J Oper Res. 2018;267(2):733–53. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2017.12.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xiao S, Huang J, Hu H, Gu Y. Automatic guided vehicle scheduling in automated container terminals based on a hybrid mode of battery swapping and charging. J Mar Sci Eng. 2024;12(2):305. doi:10.3390/jmse12020305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhou X, Zhu J. An improved bounded conflict-based search for multi-AGV pathfinding in automated container terminals. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;139(3):2705–27. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.046363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kim KH, Jeon SM, Ryu KR. Deadlock prevention for automated guided vehicles in automated container terminals. OR Spectr. 2006;28:659–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-49550-5_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xiang X, Liu C, Lee LH, Chew EP. Performance estimation and design optimization of a congested automated container terminal. IEEE T Autom Sci Eng. 2022;19(3):2437–49. doi:10.1109/tase.2021.3085329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Shen Z, Liang C, Gen M. Scheduling of AGV with group operation area in automated terminal by hybrid genetic algorithm. In: Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management; 2021 Aug 1–3; Harbin, China. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 427–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-79203-9_33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yue L, Fan H. Dynamic scheduling and path planning of automated guided vehicles in automatic container terminal. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sin. 2022;9(11):2005–19. doi:10.1109/jas.2022.105950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gao Y, Chen C-H, Chang D. A machine learning-based approach for multi-AGV dispatching at automated container terminals. J Mar Sci Eng. 2023;11(7):1407. doi:10.3390/jmse11071407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lou P, Zhong Y, Hu J, Fan C, Chen X. Digital-twin-driven AGV scheduling and routing in automated container terminals. Math-Basel. 2023;11(12):2678. doi:10.3390/math11122678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhong Z, Guo Y, Zhang J, Yang S. Energy-aware integrated scheduling for container terminals with conflict-free AGVs. J Syst Sci Syst Eng. 2023;32(4):413–43. doi:10.1007/s11518-023-5563-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu W, Zhu X, Wang L, Wang S. Multiple equipment scheduling and AGV trajectory generation in U-shaped sea-rail intermodal automated container terminal. Measurement. 2023;206:112262. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.112262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xu Z, Li J, Li H, An L, Hu J. A conflict-free dispatching method for Aivs in automated container terminals. In: Proceedings of the 2023 China Automation Congress (CAC); 2023 Nov 17–19; Chongqing, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 7707–12. doi:10.1109/cac59555.2023.10451308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li S, Fan L, Jia S. A hierarchical solution framework for dynamic and conflict-free AGV scheduling in an automated container terminal. Transport Res C-Emer. 2024;165:104724. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2024.104724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Xiong C, Wang C, Zhou S, Song X. Dynamic rolling scheduling model for multi-AGVs in automated container terminals based on spatio-temporal position information. Ocean Coast Manage. 2024;258:107349. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2024.107349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Terfasse K, Cherif G, Huguet M-J. Integer linear programming for automated guided vehicles path planning in container terminals. In: Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT); 2024 Apr 10–13; Vallette, Malta. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 940–5. doi:10.1109/codit62066.2024.10708293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ma N, Zhou C, Stephen A. Simulation model and performance evaluation of battery-powered AGV systems in automated container terminals. Simul Model Pract Th. 2021;106:102146. doi:10.1016/j.simpat.2020.102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Xiang X, Liu C. Modeling and analysis for an automated container terminal considering battery management. Comput Ind Eng. 2021;156:107258. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2021.107258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhao T, Liang C, Hu X, Wang Y. Solution of AGV scheduling and battery exchange two layer model for automated container terminal. J Dalian Univ Technol. 2021;61:623–33. doi:10.7511/dllgxb202106010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yang X, Hu H, Cheng C, Wang Y. Automated guided vehicle (AGV) scheduling in automated container terminals (ACTs) focusing on battery swapping and speed control. J Mar Sci Eng. 2023;11(10):1852. doi:10.3390/jmse11101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li L, Li Y, Liu R, Zhou Y, Pan E. A two-stage stochastic programming for AGV scheduling with random tasks and battery swapping in automated container terminals. Transport Res E-Log. 2023;174:103110. doi:10.1016/j.tre.2023.103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li Y, Li L, Liu R, Pan E. An integrated scheduling method for AGVs in an automated container terminal considering battery swapping and battery degradation. Flex Serv Manuf J. 2024;35:1–48. doi:10.1007/s10696-024-09581-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhou W, Zhang Y, Tang K, He L, Zhang C, Tian Y. Co-optimization of the operation and energy for AGVs considering battery-swapping in automated container terminals. Comput Ind Eng. 2024;195:110445. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2024.110445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools