Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Convergence of Computational Fluid Dynamics and Machine Learning in Oncology: A Review

1 School of Aerospace Engineering, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Engineering Campus, Nibong Tebal, 14300, Malaysia

2 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering & Technology, Universiti Malaysia Perlis, Arau, Perlis, 02600, Malaysia

3 Biomedical Imaging Department/Oncology and Radiotherapy Unit, Advanced Medical & Dental Institute, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Gelugor, 13200, Malaysia

4 Oncology Unit, Pantai Hospital Sungai Petani, Kedah, 08000, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: Wan Mohd Faizal. Email: ; Nurul Musfirah Mazlan. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1335-1369. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068660

Received 03 June 2025; Accepted 05 August 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Conventional oncology faces challenges such as suboptimal drug delivery, tumor heterogeneity, and therapeutic resistance, indicating a need for more personalized, and mechanistically grounded and predictive treatment strategies. This review explores the convergence of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and Machine Learning (ML) as an integrated framework to address these issues in modern cancer therapy. The paper discusses recent advancements where CFD models simulate complex tumor microenvironmental conditions, like interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) and drug perfusion, and ML enhances simulation workflows, automates image-based segmentation, and enhances predictive accuracy. The synergy between CFD and ML improves scalability and enables patient-specific treatment planning. Methodologically, it covers multi-scale modeling approaches, nanotherapeutic simulations, imaging integration, and emerging AI-driven frameworks. The paper identifies gaps in current applications, including the need for robust clinical validation, real-time model adaptability, and ethical data integration. Future directions suggest that CFD–ML hybrids could serve as digital twins for tumor evolution, offering insights for adaptive therapies. The review advocates for a computationally augmented oncology ecosystem that combines biological complexity with engineering precision for next-generation cancer care.Keywords

CFD is a transformative branch of fluid mechanics that employs numerical analysis and algorithms to simulate and analyze fluid behaviour across various environments [1]. Its applications span many fields, particularly in engineering and scientific research, where it is pivotal in optimizing designs for industries such as aerospace and automotive. By predicting fluid flow patterns, heat transfer, and chemical reactions, CFD empowers engineers to make informed decisions that enhance performance and efficiency in their designs [2,3]. The ability to visualize and manipulate fluid dynamics through simulations deepens our understanding of complex fluid interactions and accelerates the innovation cycle, allowing for rapid prototyping and testing of new concepts in a virtual setting [4,5]. In recent years, the application of CFD has expanded significantly into the clinical and medical domains, particularly oncology [6,7]. Its utilization in simulating blood flow dynamics [8] within the cardiovascular system aids in assessing conditions such as aneurysms and arterial blockages [9]. At the same time, its role in respiratory medicine enhances our understanding of airflow dynamics in diseases like asthma [10] and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [11,12]. Moreover, CFD’s capacity to optimize the design of medical devices, such as stents [13] and prosthetic implants, ensures their practical functionality within the human body, thereby minimizing potential complications [14,15]. As computational power and software sophistication evolve, the potential for CFD in personalized medicine grows, enabling tailored interventions based on individual anatomical variations and fluid behaviour.

In oncology, CFD is a powerful tool for understanding tumour microenvironments [16] and optimizing drug mechanisms [17], including nutrient delivery systems [18]. By simulating fluid flow within tumours, researchers can explore how blood perfusion impacts nutrient supply and therapeutic efficacy, ultimately leading to more effective treatment strategies tailored to individual patients [19,20]. Integrating CFD with advanced imaging techniques and genomic data further enhances our understanding of tumour behaviour, paving the way for innovative therapeutic strategies that could revolutionize cancer treatment [17]. As we explore the complexities of tumour biology, the promise of personalized medicine in oncology becomes increasingly tangible, offering hope for more targeted and efficient treatment options that align closely with patients’ specific needs. This intersection of technology and healthcare underscores the critical role of fluid mechanics in advancing cancer research and treatment, heralding a new era of precision medicine that prioritizes individualized care [21].

Furthermore, this fusion of technologies holds promise for developing predictive models that anticipate disease progression and treatment efficacy, thereby fostering a more proactive stance in cancer management rather than a reactive one [22]. As these methodologies continue to converge, the potential for personalized medicine will expand, ultimately transforming how oncological care is delivered and experienced by patients. This shift towards personalized approaches enhances the precision of treatments and empowers patients by involving them more actively in their healthcare decisions. This engagement can lead to improved adherence to treatment plans and greater control over their health outcomes, ultimately contributing to better overall satisfaction with their care [23].

Recent advances in CFD and Artificial intelligence (AI) have dramatically transformed the modeling of physiological fluid flows, particularly in the cardiovascular system. The study by Praharaj et al. [24] provides an extensive review of how CFD, paired with responsive AI techniques, is utilized to simulate pulsatile blood flow in patient-specific arterial geometries. This approach has not only allowed for the accurate reproduction of complex hemodynamic phenomena like wall shear stress (WSS), oscillatory shear index (OSI), and relative residence time (RRT), all critical markers in atherosclerosis and stenosis, but also for early detection and personalized treatment strategies in cardiovascular disease. More importantly, the integration of AI and GPU-accelerated simulation has led to a paradigm shift in CFD modeling. Neural networks, including physics-informed neural networks (PiNNs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are now trained on CFD-generated datasets to predict flow characteristics such as velocity profiles and pressure drops in real time. These predictive models drastically reduce computation time and open the door to AI-assisted diagnostics and clinical decision-making tools.

Advanced machine learning techniques and deep learning algorithms are being explored to improve the accuracy of automated segmentation, which could significantly enhance the precision and efficiency of the model generation process [25]. These techniques leverage large datasets to train models that can better distinguish between different airway structures, ultimately leading to more reliable outcomes in clinical applications. Furthermore, incorporating multi-modal imaging data and refining the training processes can also contribute to overcoming existing limitations, paving the way for more robust diagnostic tools in cancer medicine [26]. The accurate geometry model that generates fast outcomes and accurate flow in the investigated simulations will enable clinicians to make informed decisions regarding treatment plans, optimizing patient care, and improving overall health outcomes. In addition, ongoing research into AI algorithms promises to streamline these processes further, allowing for real-time analysis and feedback during patient assessments. Moreover, integrating patient-specific data into these models can enhance personalized treatment approaches, ensuring interventions are tailored to individual anatomical variations and disease presentations [27].

To further transform the analysis of cancer treatment, the integration of ML and deep learning (DL) methodologies with CFD presents a promising avenue. CFD is an advanced tool for simulating and examining cancer treatment through complex configurations, offering valuable insights into airflow dynamics, pressure variations, and possible obstructions [28]. By embedding ML and DL within CFD frameworks, we can markedly improve the precision and effectiveness of these simulations [29]. ML algorithms can be developed using comprehensive datasets encompassing patient-specific airway geometries and airflow behaviors, enabling them to forecast airway structure alterations from conditions such as sleep apnea, asthma, or surgical modifications that impact airflow dynamics. This predictive proficiency empowers clinicians to foresee potential complications and modify treatment strategies.

Moreover, deep learning, mainly through CNNs, enhances these CFD models by autonomously detecting and assimilating subtle anatomical characteristics affecting airflow [30]. This capability facilitates the generation of more intricate and precise simulations, minimizing the requirement for extensive manual intervention, thereby decreasing computational times and enabling real-time analysis during clinical evaluations. The amalgamation of ML, DL, and CFD signifies a notable progression in personalized medicine, fostering the establishment of customized treatment plans based on accurate, patient-specific airflow simulations. This strategy augments the comprehension of individual airway mechanics and improves clinical outcomes by offering more focused and effective interventions.

This review focuses on summarizing the research progress of machine learning in the field of analyzing cancer treatment via CFD analysis. This review also comprehensively summarizes the application of CFD methods in various fields of the cancer treatment system so that readers can understand the basic principles of the CFD approach and its interest and ability in solving physical problems. This article first classifies and summarizes classic CFD methods. Then, the application of ML methods in pre-processing, solving, and post-processing is summarized. Finally, we analyze the shortcomings of the current ML application and suggest further strengthening the integrated learning of machine learning and future cancer treatment. To enhance the clarity and coherence of the manuscript, AI-assisted tools (specifically ChatGPT by OpenAI) were employed solely for language refinement. These tools did not contribute to the generation of scientific content, data analysis, or interpretation.

2 Current Challenging Oncology Treatment

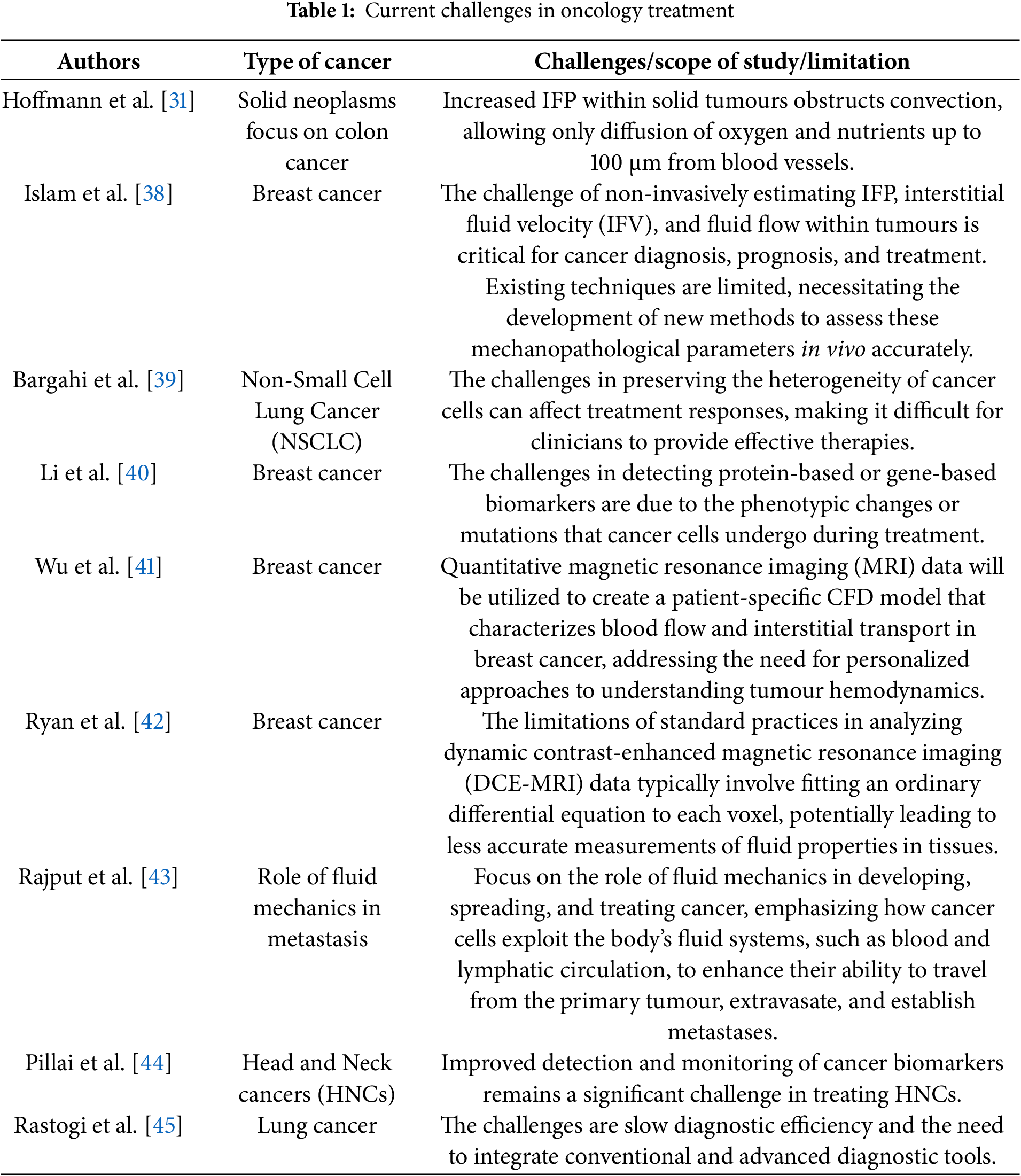

The field of oncology is continuously evolving, driven by advancements in research and technology; however, it remains fraught with significant challenges that impede effective treatment outcomes for patients. Current oncology treatments, which encompass a range of modalities, including chemotherapy [31], radiation therapy [32], immunotherapy [33], and targeted therapies [34], face a myriad of obstacles, such as drug resistance [35], treatment-related toxicities [36], and the heterogeneity of cancer types [37]. Furthermore, the complexity of cancer biology and the unique genetic and environmental factors influencing individual patients complicate the development of universally effective treatment protocols. As the incidence of cancer continues to rise globally, understanding and addressing these challenges is imperative for the advancement of therapeutic strategies, the enhancement of patient quality of life, and the improvement of survival rates. This introduction delineates the current challenges in oncology treatment, underscoring the urgent need for innovative solutions and a more personalized approach to cancer care, as summarized in Table 1.

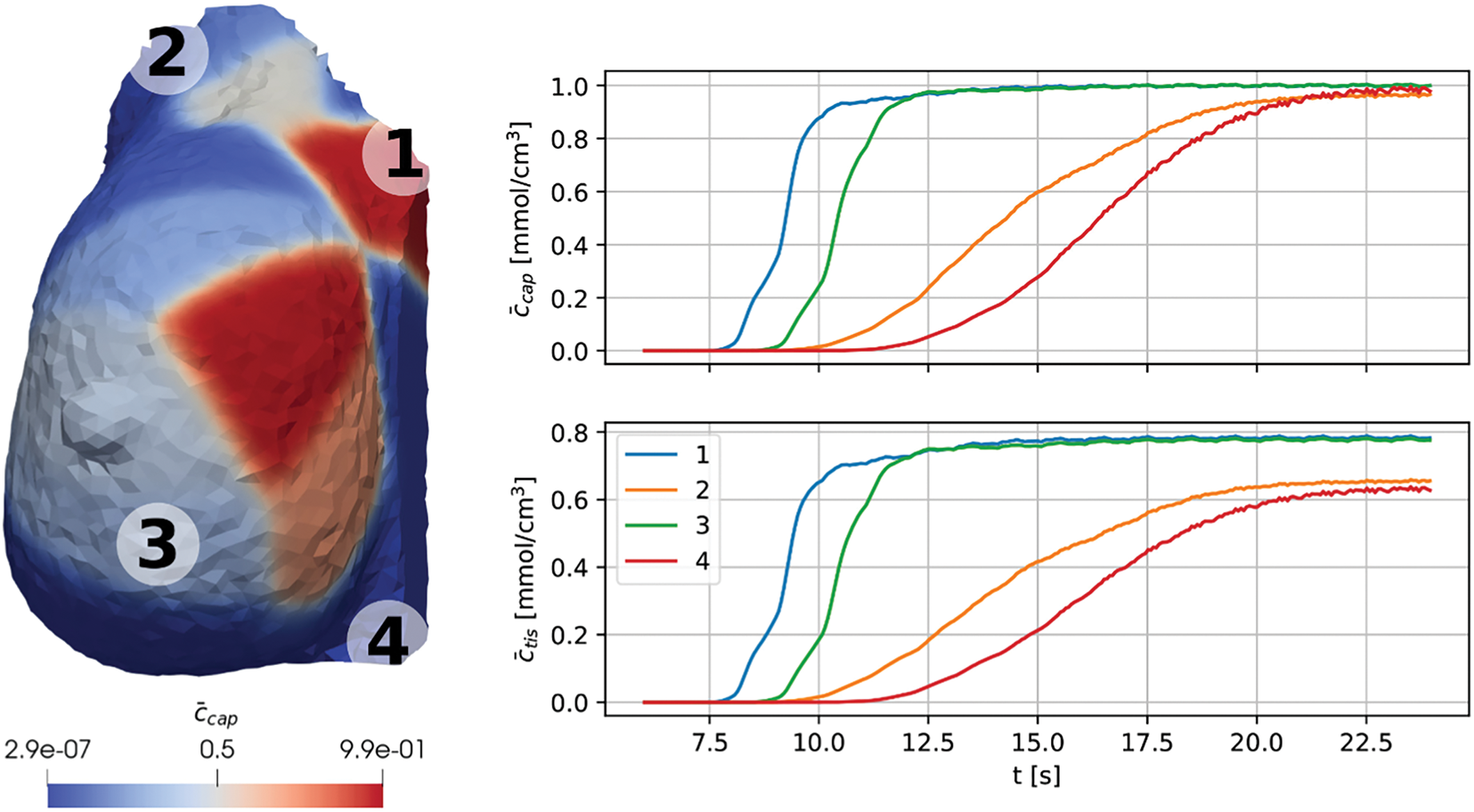

Meanwhile, Fritz et al. demonstrated a novel approach that integrates principles of CFD to simulate regional contrast agent dynamics in breast tissue, as shown in Fig. 1. Although high-resolution CFD-ML frameworks are computationally intensive, advances in reduced-order models, graphics processing unit (GPU)-accelerated computing, and real-time inference engines can alleviate the burden. Surrogate models trained on CFD datasets have demonstrated the ability to approximate flow dynamics with minimal computational delay, thus improving scalability in hospital settings. By leveraging patient-specific MRI data, the research offers a novel approach to differentiate between malignant and benign lesions, which could significantly impact diagnostic and treatment strategies in oncology. However, addressing the identified limitations and research gaps, such as expanding sample sizes and improving model accuracy, will be crucial for advancing this methodology and its application in clinical settings. This approach represents a promising step towards more personalized and precise cancer care, highlighting the importance of interdisciplinary research in oncology [46]. On the other hand, the challenges in oncology treatment are multifaceted and stem from the complex nature of cancer.

Figure 1: Fritz et al. [50] demonstrated a novel approach that integrates principles of CFD to simulate regional contrast agent dynamics in breast tissue. This method effectively distinguishes malignant from benign areas based on perfusion behavior, offering a promising tool for cancer diagnosis and treatment planning

One significant difficulty lies in the heterogeneity of tumours, which can vary significantly between patients and within the same tumour [47]. Recent pharmacological studies, such as Huang et al. [48], highlight molecular targeting strategies (e.g., CD44-Stat3 axis inhibition) to increase radiosensitivity in resistant tumors. This variability affects how cancers respond to treatments, making it difficult to predict outcomes and tailor therapies effectively. Resistance mechanisms often develop, allowing cancer cells to evade the effects of drugs that initially seemed effective. Another significant challenge is identifying and validating reliable biomarkers to guide treatment decisions and monitor disease progression, as mentioned by Zhang et al. [49]. These biomarkers are crucial for personalizing therapies, yet their discovery is often hindered by the intricate biology of cancer and the need for extensive clinical validation.

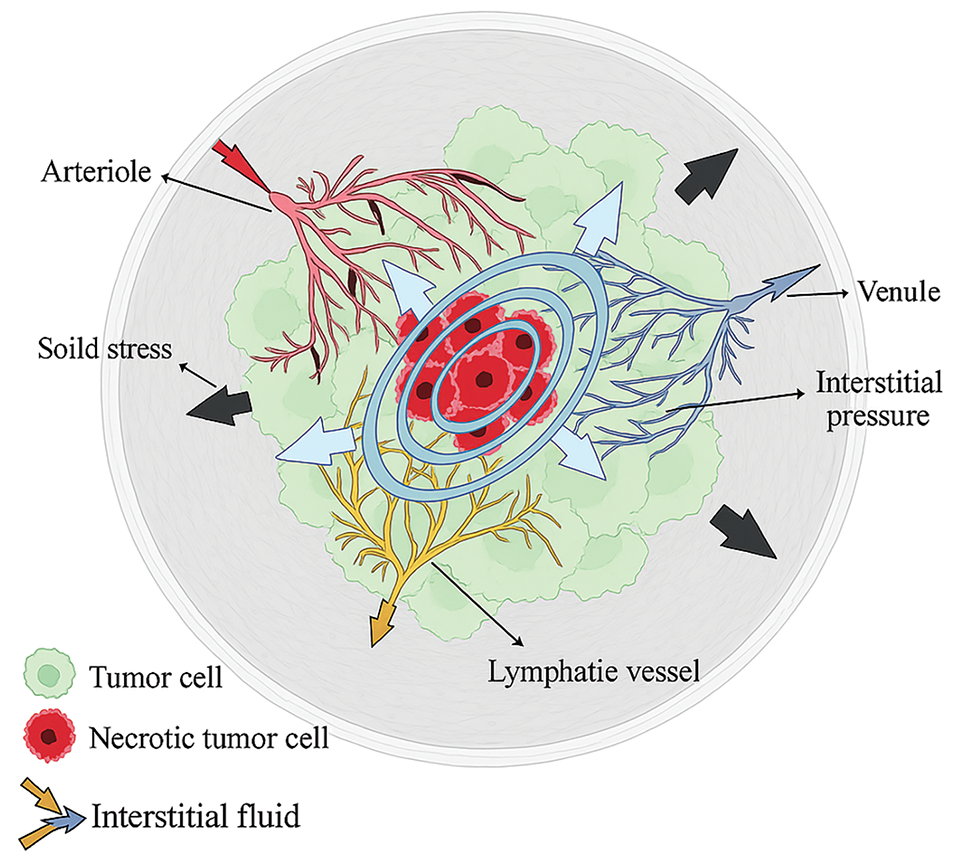

However, Rajput et al. [43] discovered that elevated IFP in tumors, caused by abnormal vasculature and lack of functional lymphatics, reduces drug delivery efficiency. Understanding fluid dynamics can help design strategies to overcome these barriers and improve drug accumulation in tumors, as shown in Fig. 2. Fluid mechanics could be integrated with existing antiangiogenic treatments (drugs that prevent new blood vessel formation) to create synergistic approaches. Such combinations may help normalize the abnormal blood vessels around tumors, thereby improving the delivery of chemotherapy drugs and reducing cancer cell spread. These integrated approaches might offer more personalized and effective treatment options, enhancing overall chances of survival. However, one of the challenges in cancer treatment is ensuring that a sufficient amount of the chemotherapeutic drugs reaches the tumor [51–53]. The study shows that by lowering IFP, the nanoparticles can accumulate in the tumor more effectively. In simpler terms, think of it as creating a clear path for a delivery truck, ensuring that it can carry more packages (or drugs) directly to the destination (the tumor) without being blocked by traffic (high fluid pressure) [54,55]. Reducing the internal pressure within the tumor microenvironment can notably improve the effectiveness of drug delivery systems. A lower intratumoral fluid pressure (IFP) fosters more favourable conditions for chemotherapeutic and immunotherapy mechanisms, offering a dual benefit in combating the tumor.

Figure 2: Rajput et al. [43] explained that the tumor growth causes a radial solid stress (black arrows), a stiffer extracellular matrix (ECM; grey fibers), higher interstitial pressure from the venule (blue arrows), and a higher rate of interstitial flow (purple, red, & yellow arrows)

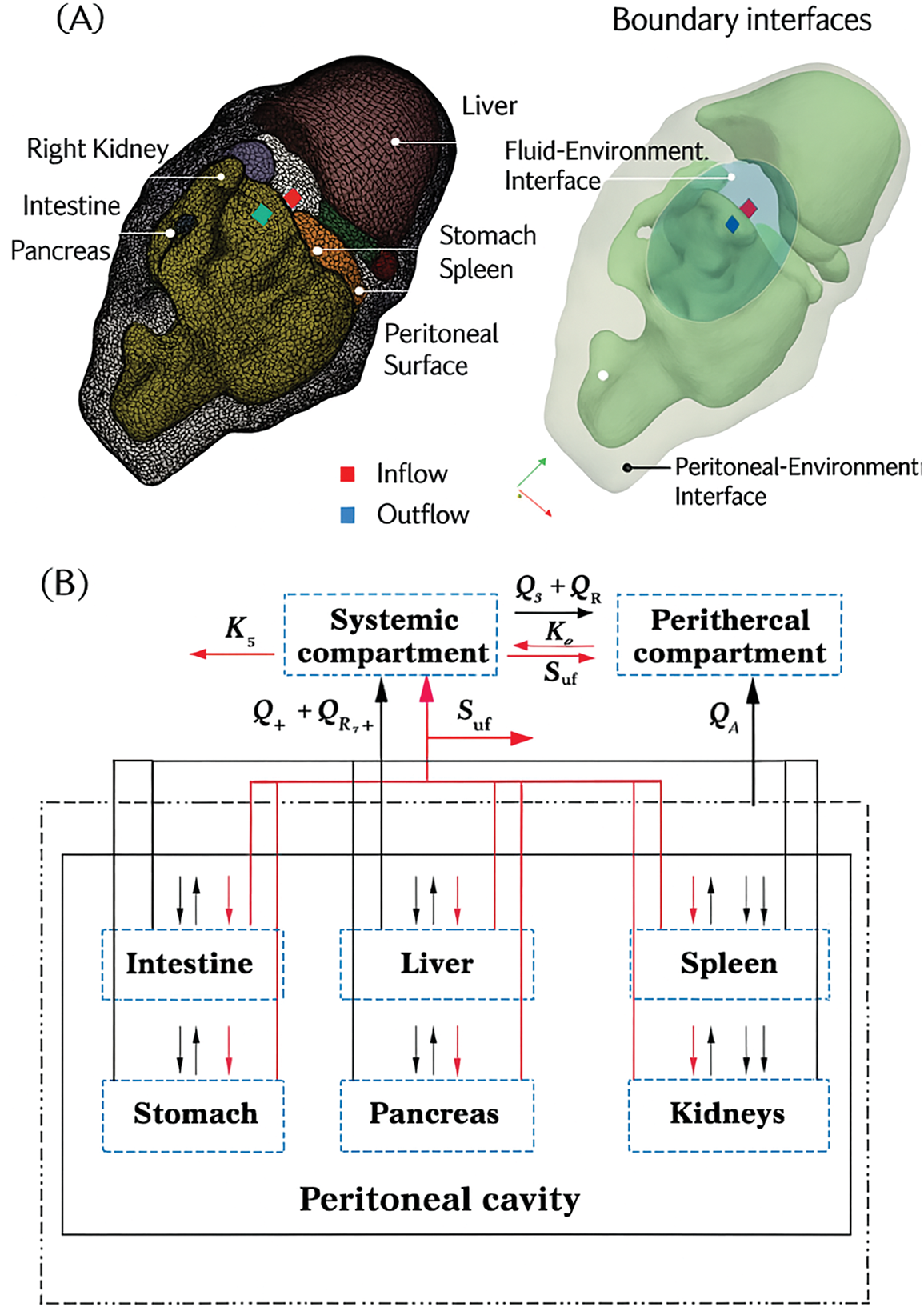

Fluid dynamics can improve oncology treatment by influencing the recruitment and detection of immune cells at metastatic sites. This knowledge helps enhance anti-metastatic immunotherapeutic strategies [56]. Fig. 3 shows the concept and design of the step-up heating protocol used in the Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) treatment simulation. Arrows and color gradients might indicate the direction of fluid flow and how heat is distributed along the flow path. The figure demonstrates the critical role of heat transfer, showing that as the fluid circulates, its temperature is modulated by both fluid motion and heat loss to the surroundings. The research also simulates the flow of chemoperfusate carrying oxaliplatin in a rat model, predicting temperature distribution, drug transport, and fluid interaction with tissues. This ensures uniform drug delivery to the tumor while avoiding overly high temperature or concentration areas. Fluid mechanics helps understand the temperature changes in the fluid as it moves from the catheter into the abdominal cavity. Since the boiling or overheating of the fluid can potentially damage healthy tissues, the study uses fluid mechanics to model the gradual change in temperature along the peritoneal cavity.

Figure 3: (A) A rat abdomen’s 3D anatomical geometry and surface mesh. Different colors indicate boundary interfaces with specific conditions. (B) The model includes abdominal organs, the peritoneal cavity, and systemic and peripheral compartments, with thermal interactions in black and chemotherapeutic interactions in red [56]

By modeling the inflow and outflow temperatures, the system can predict where hot spots might occur and help adjust the protocol to prevent overheating, providing a safer treatment approach. In this context, integrating precision medicine is a promising strategy to enhance treatment efficacy and mitigate adverse effects. By employing advanced genomic profiling techniques, healthcare providers can pinpoint specific mutations and alterations within tumours, enabling the deployment of tailored therapies that could significantly improve patient outcomes. Furthermore, immunotherapy has transformed cancer treatment paradigms, leveraging the body’s immune response to target malignancies [33]. However, the effectiveness of these therapies is often restricted to select patient populations due to variability in individual responses, highlighting the critical need for ongoing research into predictive biomarkers and the exploration of combination therapies that can more effectively address tumour heterogeneity and resistance mechanisms [57,58].

To tackle these challenges, applying CFD integrated with machine learning presents a novel approach to enhancing oncology treatment strategies [59]. By modelling the complex fluid dynamics within tumour microenvironments, researchers can gain insights into the transport phenomena that influence drug delivery and efficacy [60]. Machine learning algorithms can analyze vast datasets to identify patterns and predict outcomes, facilitating the optimization of treatment protocols tailored to individual patient profiles [61]. This synergistic approach can revolutionize cancer care, enabling a more precise understanding of tumour behaviour and treatment response. Ultimately, fostering collaboration among researchers, oncologists, and patients will be essential to navigating the complexities of cancer treatment and developing innovative strategies that promise to transform the future of oncology. In this evolving landscape, integrating advanced imaging techniques with computational modelling will further enhance our ability to visualize tumour dynamics and assess treatment effectiveness in real time [62]. By harnessing the power of AI and machine learning, clinicians can gain deeper insights into patient-specific factors that influence treatment decisions, paving the way for more personalized and effective cancer therapies. This holistic approach aims to improve patient outcomes and streamline clinical workflows, allowing healthcare professionals to focus more on patient care than administrative tasks [63,64].

Furthermore, access to cutting-edge treatments can be limited due to economic factors, healthcare disparities, and regulatory hurdles, exacerbating patient care inequalities. Finally, the emotional and psychological toll on patients and their families adds another layer of complexity to oncology treatment, highlighting the necessity for comprehensive support systems throughout the treatment journey that address the medical needs and the mental and emotional well-being of those affected. Establishing multidisciplinary care teams that include psychologists, social workers, and patient navigators can play a vital role in providing holistic support, ensuring that patients receive the necessary resources to cope with the challenges they face during their battle against cancer. The oncology landscape is marked by rapid advancements and an equally daunting set of challenges that hinder optimizing treatment outcomes for cancer patients. As the field continues to evolve, current therapeutic modalities, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapies, grapple with significant obstacles such as drug resistance, treatment-related toxicities, and the inherent heterogeneity of cancer types. The complexity of cancer biology, compounded by individual genetic and environmental factors, complicates the formulation of universally effective treatment protocols. As the global burden of cancer escalates, it becomes increasingly critical to identify and address these challenges to enhance therapeutic strategies, improve patient quality of life, and elevate survival rates. This introduction aims to elucidate the pressing challenges in oncology treatment while emphasizing the urgent need for innovative solutions and personalized approaches to cancer care.

The multifaceted nature of cancer pathophysiology continues to confound conventional treatment paradigms. Despite significant progress in therapeutic modalities, persistent limitations, including intra-tumoral heterogeneity, elevated interstitial pressures, and variable patient responses, undermine the consistency of clinical outcomes. These challenges are further exacerbated by the lack of reliable biomarkers and the physiological barriers to drug penetration, particularly in solid tumors. Collectively, these constraints underscore an urgent imperative: the integration of computational methodologies capable of capturing patient-specific complexity. This necessity is not merely technological; it is conceptual, demanding a shift from one-size-fits-all treatments to individualized, mechanistically informed strategies grounded in real-time biophysical modeling.

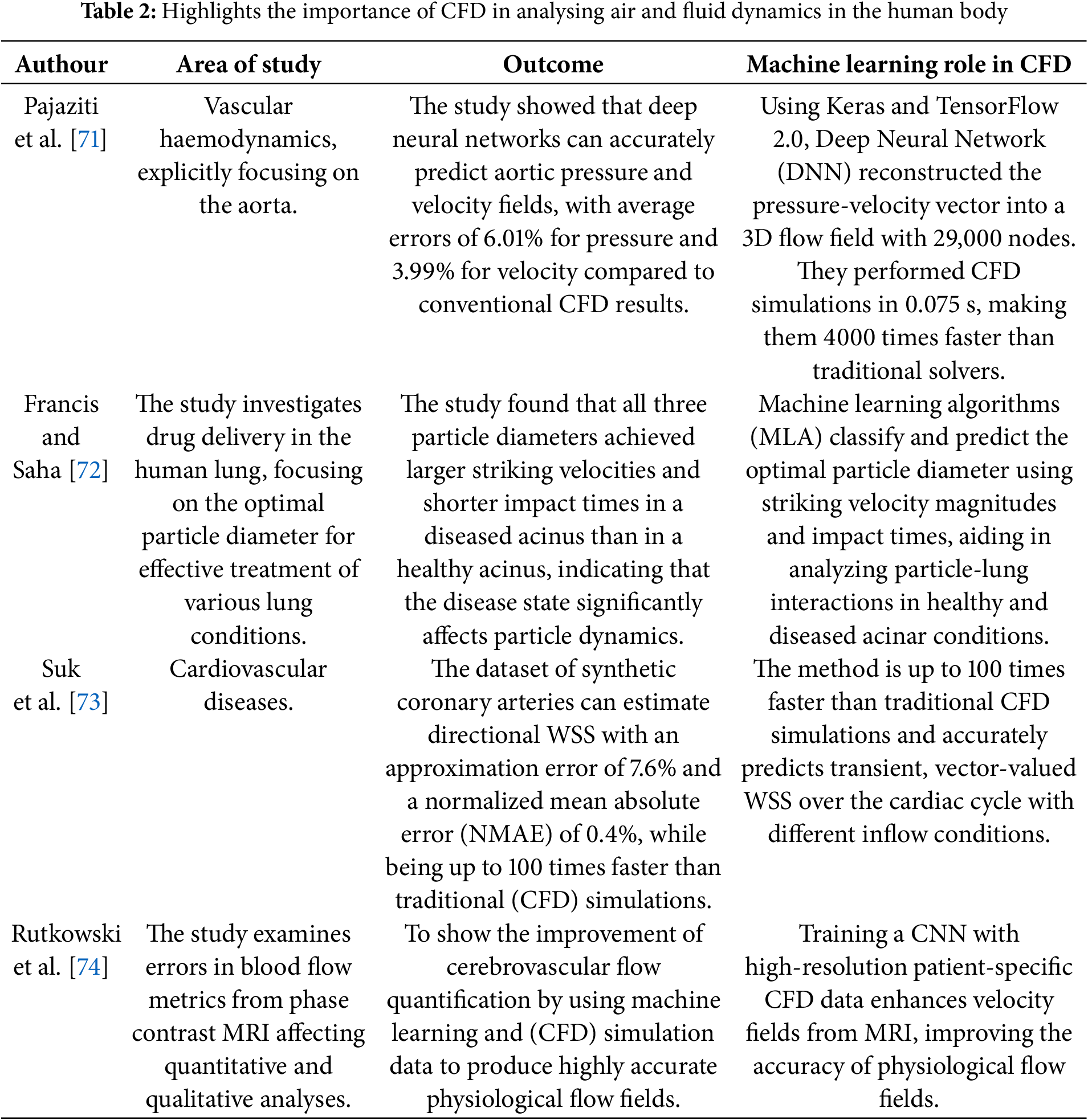

CFD is a powerful tool for simulating airflow or liquid movement in human bodies, helping clinicians visualize and analyze complex breathing patterns to understand upper airway diseases [65–68]. Traditionally, examining the upper airway has been a time-consuming and labor-intensive process that requires expert knowledge and training. To mitigate data scarcity, CFD simulations can be employed to generate synthetic datasets that mimic various physiological conditions. Combined with semi-supervised and transfer learning approaches, these datasets can improve the performance of ML models, especially when labeled clinical data is limited. However, integrated ML and CFD can analyze the upper airway faster and more accurately than ever. ML algorithms can be trained on large datasets of upper airway images and clinical data, enabling them to identify patterns and predict outcomes with high levels of accuracy. ML has shown promise in diagnosing and treating obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), a common respiratory disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep [65]. OSA affects millions of people worldwide and is associated with a range of health problems, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and stroke. CFD can simulate airflow in the upper airway during sleep, enabling clinicians to identify areas of obstruction and develop personalized treatment plans for patients with OSA. Table 2 highlights the importance of CFD in analysing air and fluid dynamics in the human body, enhancing comprehension of complex phenomena. ML has been integrated into CFD processes to speed up analysis and improve result accuracy. Yilin et al. [69] demonstrated how CFD–FSI modeling can capture complex hemodynamic alterations in stenotic arteries, providing high-fidelity data that can serve as a foundation for ML models to predict vascular risks and personalize intervention strategies. However, many of the ML-CFD models in Table 2 are trained on synthetic or single-center datasets, which may limit their generalization to rare tumor types or multi-institution scenarios. Techniques such as federated learning and domain adaptation are proposed to overcome these limitations and should be prioritized in future research. While ML accelerates simulation post-training, full-resolution 3D tumor modeling remains computationally expensive. Real-time clinical deployment will require reduced-order modeling and advanced hardware acceleration techniques. ML-integrated CFD models, as described by Zhao et al. [70], optimize experimental design and enable precise simulation of tumor environments.

An extensive review was conducted by previous research to show the importance of CFD in analyzing the respiratory system. Faizal et al. [75] described how CFD analyzes human airways using modern medical imaging to construct accurate models, optimize simulation parameters, and reveal airflow dynamics and disease processes. Integrating CFD with structure analysis, known as Fluid Structure Interaction, enhances the accuracy of biomedical simulations by combining fluid and structure analysis to mimic real phenomena in the human body [76]. CFD can also reduce cost and time efficiency, and visualizations and mathematical frameworks for respiratory investigations are highlighted. Xu et al. [77] explained an exhaustive analysis of recent numerical investigations of airflow dynamics and particle deposition in the human respiratory system, emphasizing respiratory tract models, geometric and physiological variables’ effects on airflow, and the importance of CFD in understanding these complex interactions.

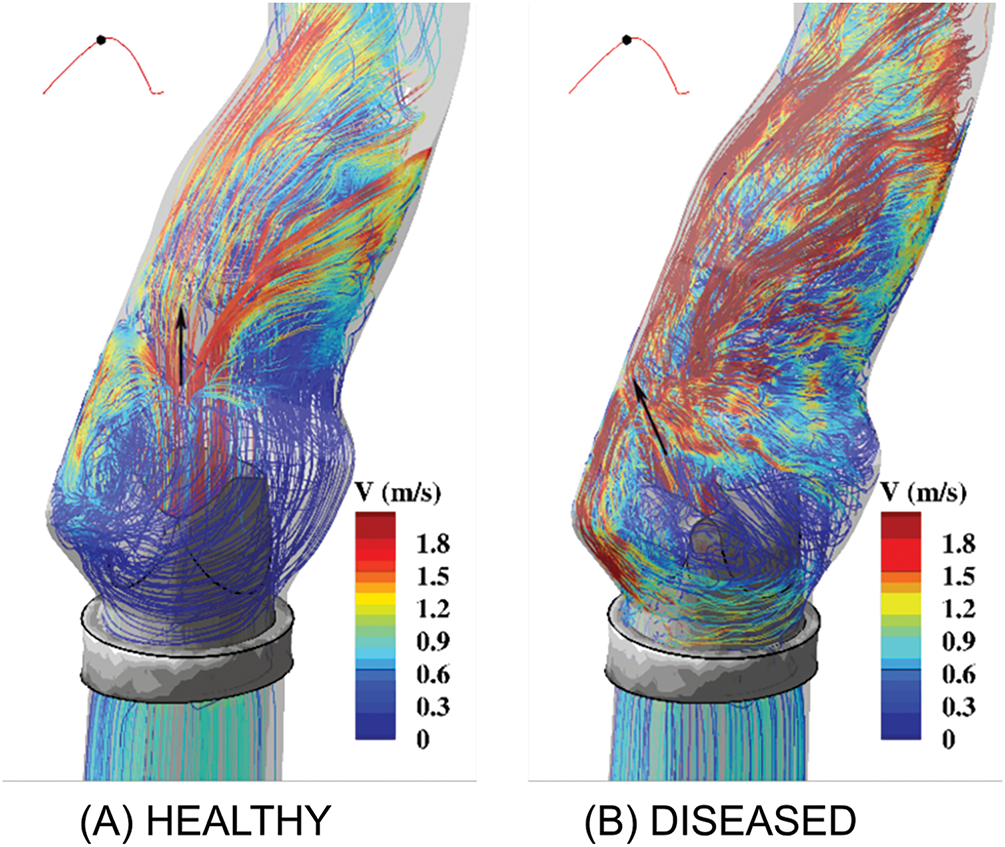

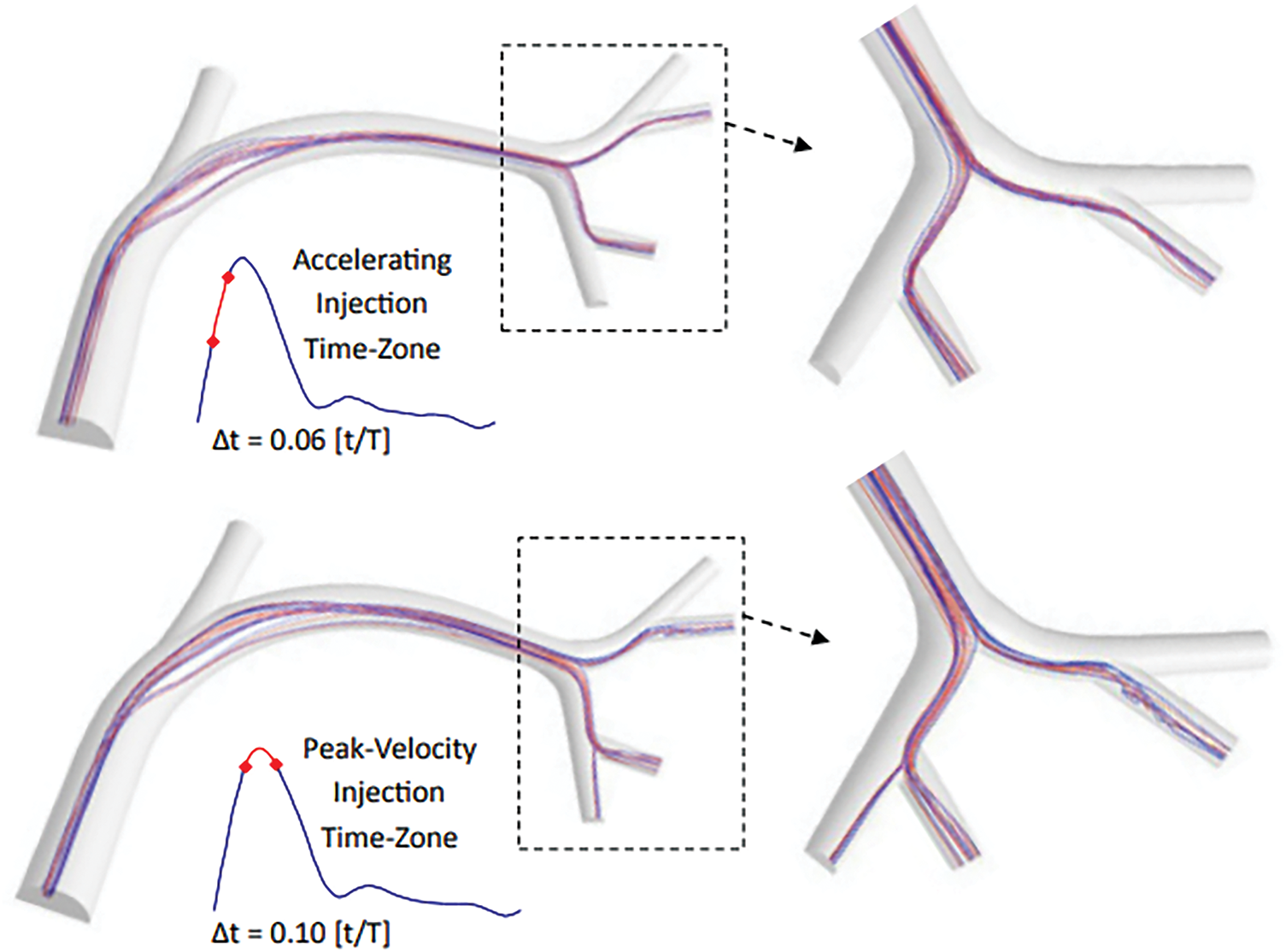

Satya Eswari et al. [78] summarized the importance of CFD in cancer treatment by emphasizing its potential to optimize drug delivery and reduce side effects, thereby improving treatment outcomes. CFD analysis can reveal how tumors interact with the body due to their unique characteristics. By modeling these interactions, CFD provides insights into cancer cell behavior and treatment response, aiding in effective treatment delivery [79,80]. Gilmanov and Sotiropoulos [81] discussed the challenges in simulating fluid-structure interactions of both native and prosthetic heart valves due to the complex anatomy of the human left heart, as shown in Fig. 4. They emphasized the need for advanced numerical methods to accurately model blood flow and valve surfaces. They also review recent advances in hemodynamics and structural dynamics in patient-specific left heart anatomies. CFD provides detailed insights into the transport and deposition of Yttrium-90 microspheres in the hepatic arterial system, crucial for optimizing liver tumor radioembolization. CFD models analyze vessel morphology and injection parameters, aiding targeted delivery to improve treatment precision and outcomes as shown in Fig. 5 [82]. Epigenomic and miRNA-regulated models, such as those proposed by Yang et al. [83], offer an opportunity for ML-enhanced stratification of tumor immune profiles. Guo et al. [84] introduced a cascade nanotherapy strategy that exploits biochemical tumor features, which can be further personalized using CFD-ML-informed drug modeling. The REANIMATE framework, combined with CFD, simulates blood flow and drug delivery in tumors to evaluate drug distribution. Comparing CFD simulations with in vivo imaging data validates model accuracy and improves predictions about drug delivery and tumor response [85]. Although REANIMATE offers high spatial resolution drug distribution modeling, it does not yet correlate its predictive output with clinical endpoints like patient survival or recurrence, which remains a vital direction for future studies.

Figure 4: Gilmanov and Sotiropoulos [81] illustrate the flow patterns at the aortic sinus under conditions involving both (A) healthy (tricuspid) and (B) diseased (bicuspid) aortic valves. The flow is visualized using streamlines, which are colour-coded by velocity magnitude. The black arrow indicates the location where the aortic jet impinges

Figure 5: The impact of various injection timings on flow dynamics and the resulting trajectories of microspheres. This model aids in visualizing and predicting these paths by simulating the intricate interactions between fluid flow and particles [82]

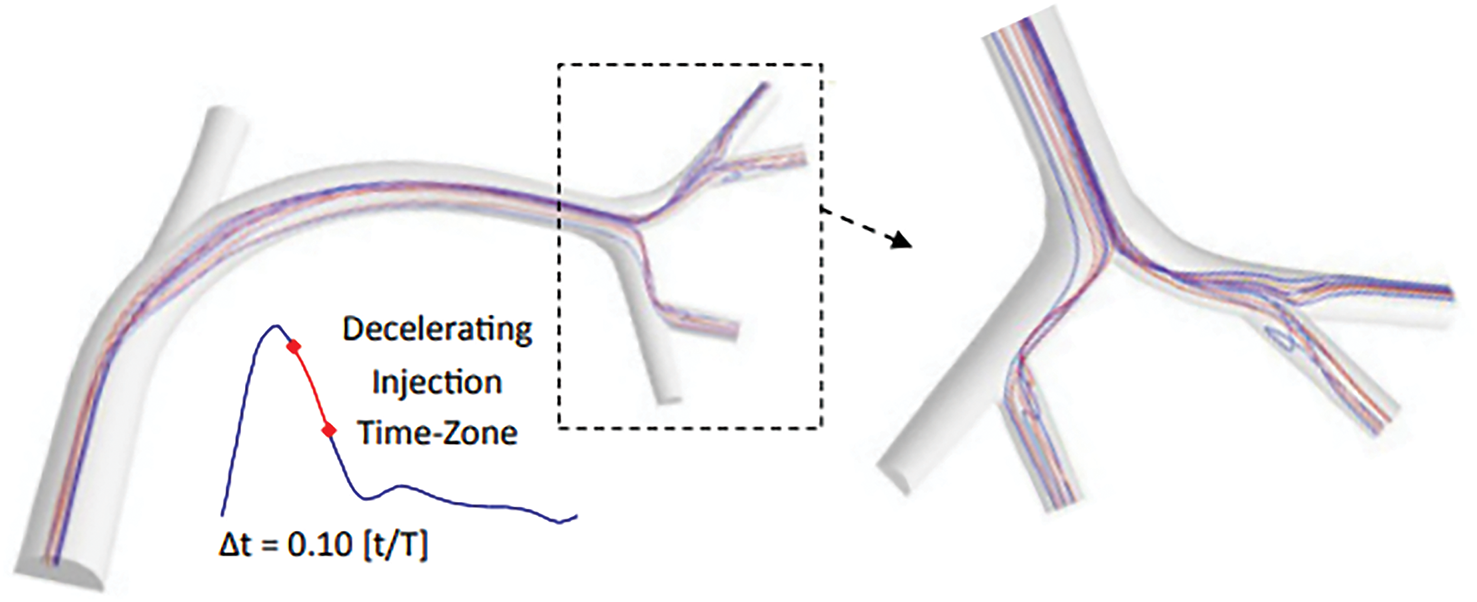

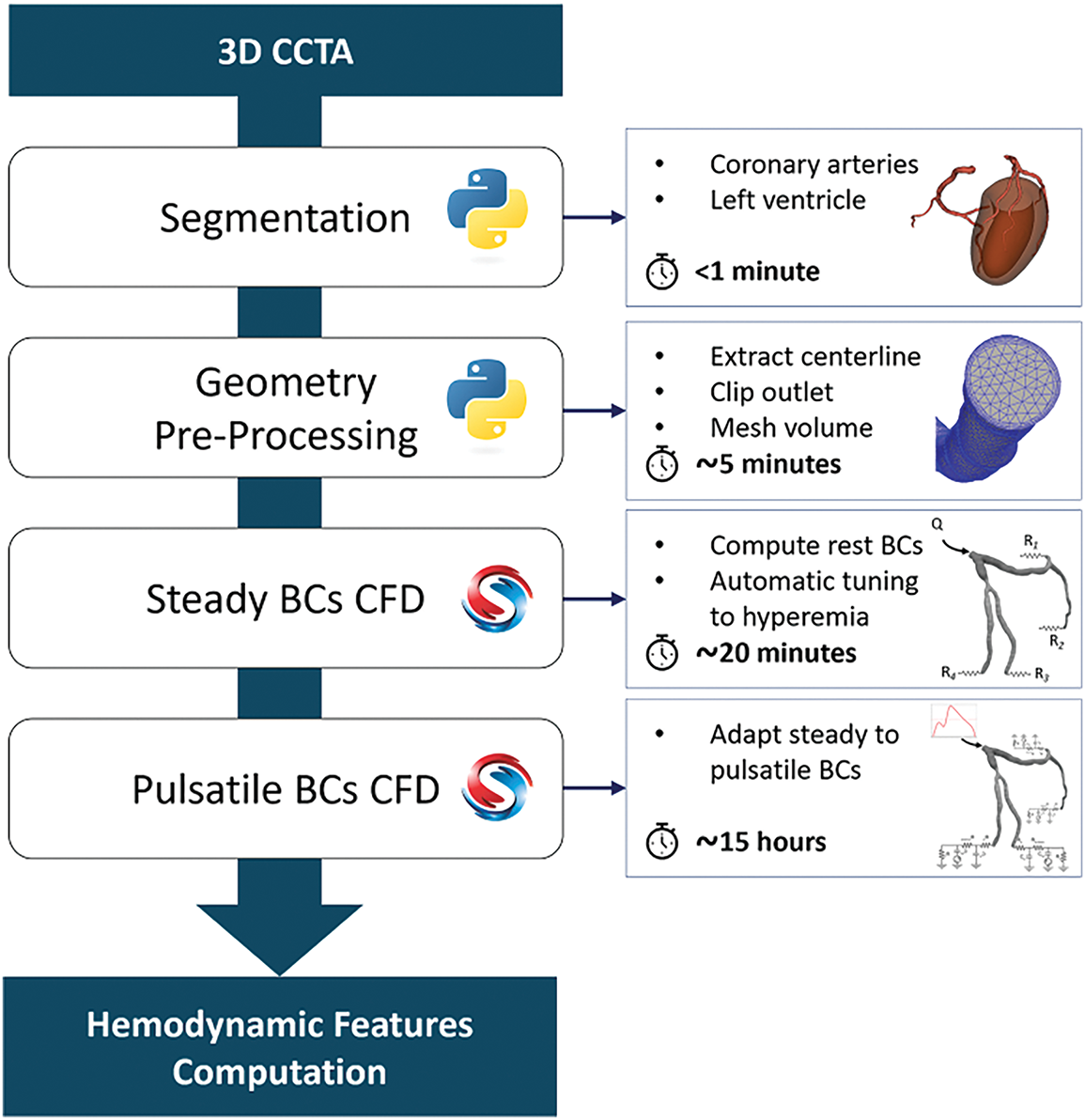

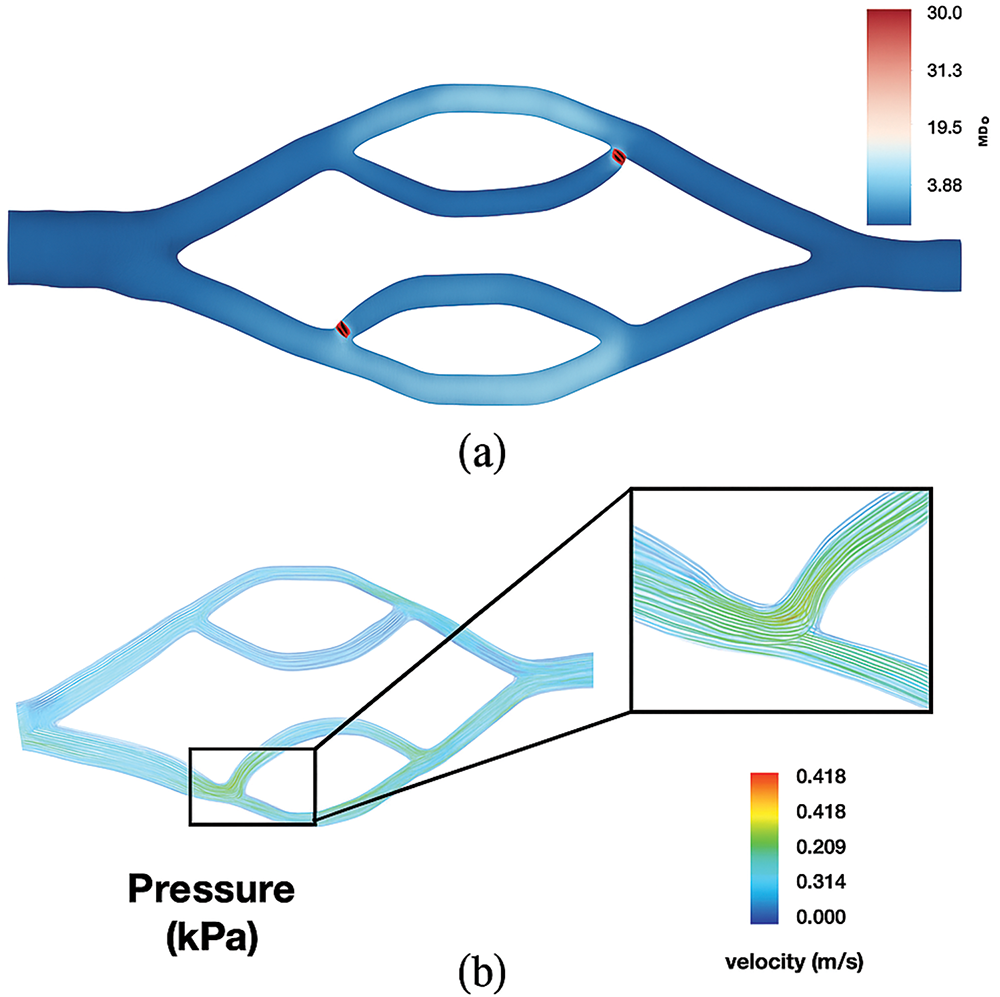

Although CFD aids in visualizing the complexity of understanding cancer treatment, integrating CFD with machine learning enhances the efficiency of CFD analysis by automating data processing and pattern recognition, speeding up simulations, and improving predictions [86]. This quick insight aids clinical decisions and treatment plans in oncology. By analyzing large datasets, machine learning algorithms uncover complex trends not visible through conventional methods, deepening our understanding of tumor microenvironments. This accelerates research and personalizes medicine by tailoring treatments to individual patient profiles and tumor characteristics, enhancing targeted therapies to improve outcomes and reduce side effects, marking a significant advancement in cancer treatment. Nannini et al. [87] addressed the fundamental issue of the cost and time-consuming nature of standard invasive Fraction Flow Reserve (FFR) measures for coronary artery disease (CAD) diagnosis, which restricts extensive clinical applicability and patient accessibility, as shown in Fig. 6. Consequently, linear regression is utilized to provide a time-efficient framework for the automated calculation of CFD and hemodynamic characterization of coronary lesions, employing stable boundary conditions for coronary flow simulations. Responsive nanoplatforms targeting the tumor microenvironment, such as those introduced by Wang et al. [88], could be integrated into CFD-ML systems for intelligent therapeutic planning.

Figure 6: Nannini et al. [87] present an automated and time-efficient system for simulating coronary blood flow in constant and pulsatile situations

As machine learning continues to refine the pre-processing stages of CFD, it also opens avenues for enhancing patient-specific modeling in oncology. By automating processes such as segmentation and meshing, machine learning can dramatically reduce the time required to prepare complex tumor geometries for simulation, enabling quicker iterations and adjustments based on real-time clinical data, as shown in Fig. 7. This efficiency accelerates research timelines and allows for more dynamic adaptation of treatment strategies as new information emerges about a patient’s unique tumor characteristics. Furthermore, integrating these advanced methodologies with insights from ongoing studies on drug delivery mechanisms within the tumor microenvironment could lead to significant breakthroughs in overcoming barriers like drug resistance and inadequate therapeutic penetration. Recent studies have used AI to speed up analysis and improve accuracy. AI involves creating systems to make decisions and solve problems, mimicking human intelligence with algorithms and computational techniques. On the other hand, ML is a subset of AI that focuses on learning from data and identifying data patterns without needing explicit programming [89] using artificial neural networks. AI and ML involve layered structures, allowing deep learning models to process vast amounts of unstructured data such as images, audio, and text [90]. Often, these models outperform traditional techniques like linear regression or clustering.

Figure 7: This flowchart shows a synergistic framework integrating CFD with ML to investigate human airways

The integration of CFD and ML in oncology represents a cutting-edge approach that enhances our understanding of tumor behavior and treatment responses. This innovative intersection not only allows for more accurate modeling of tumor microenvironments but also facilitates the development of predictive algorithms that can tailor treatment plans to individual patients, ultimately improving outcomes and reducing side effects. As research in this area continues to evolve, it is essential to explore the methodologies employed in combining CFD and ML techniques and the implications of these advancements for personalized medicine in cancer therapy. The integration of these technologies promises to revolutionize the way oncologists approach treatment, enabling the identification of optimal therapeutic strategies based on real-time data and simulations that reflect each patient’s unique tumor characteristics. This innovative approach not only enhances the precision of treatment selection but also fosters a deeper understanding of tumor biology, paving the way for novel therapeutic interventions that are both effective and patient-centered. Immune pathway modeling in tumors may leverage innovations like exosomal engineering from non-oncology contexts [91]. As a result, this paradigm shift in cancer treatment has the potential to significantly improve patient outcomes, reduce side effects, and ultimately lead to more successful long-term management of the disease.

CFD plays a significant role in cancer treatment by allowing researchers and clinicians to model and simulate the flow of fluids within tumors, which can provide insights into how drugs distribute and interact with tumor cells [92]. Drug delivery models could be enhanced by CFD–ML frameworks simulating stimuli-responsive carriers like redox-sensitive nanogels [93]. This technology helps optimize drug delivery methods, assess the impact of blood flow on tumor growth, and predict responses to therapies, ultimately leading to more personalized and effective treatment plans [94]. By harnessing the power of CFD, clinicians can tailor therapies to individual patients’ tumor characteristics, enhancing the precision of treatment and potentially increasing survival rates. These advancements improve treatment outcomes and pave the way for innovative approaches in cancer research, enabling the exploration of new therapeutic strategies and combinations that were previously difficult to evaluate [60].

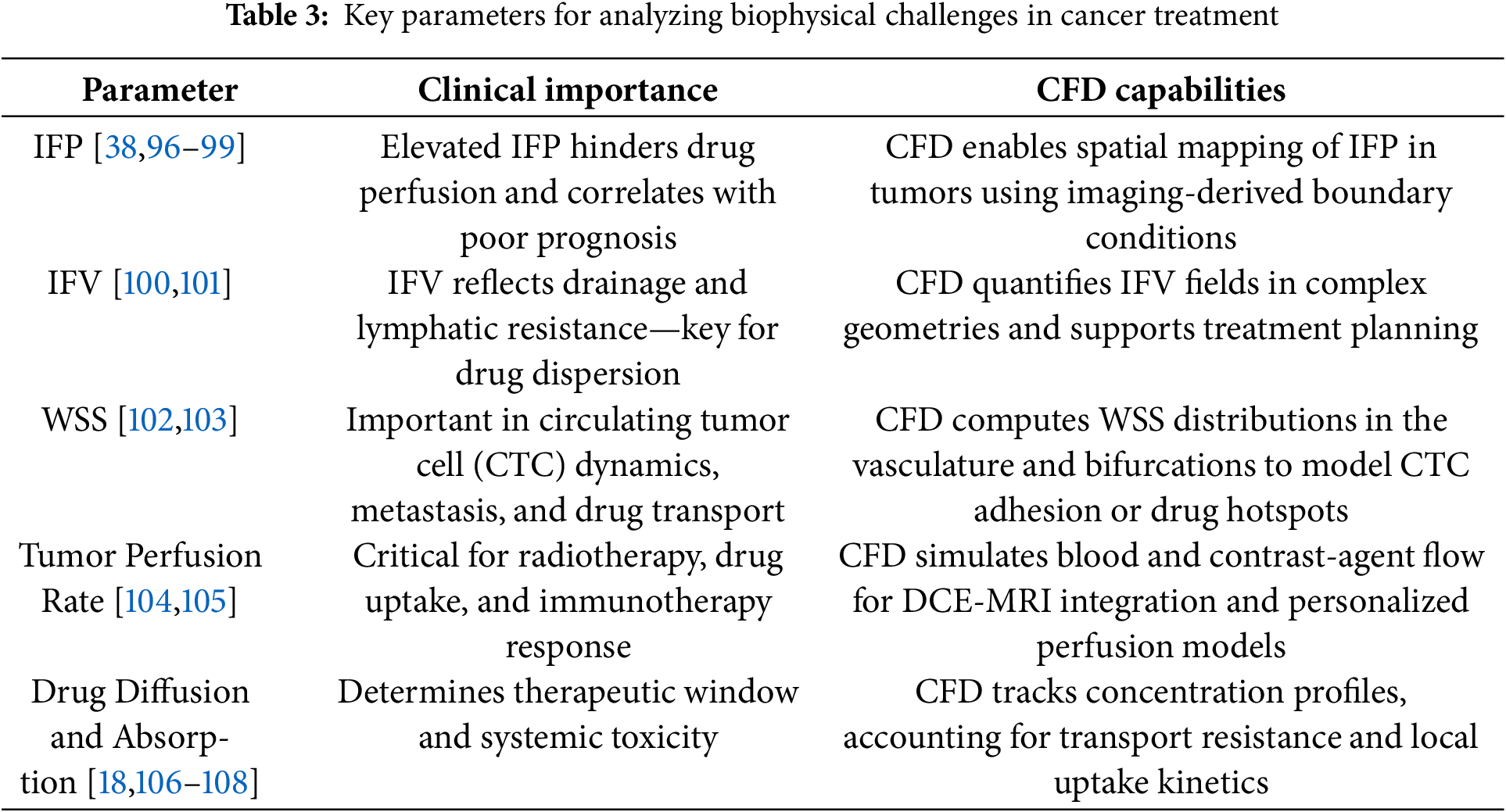

Moreover, integrating ML and CFD enhances treatment personalization and significantly accelerates new cancer therapies’ research and development cycle. Researchers can rapidly analyze vast clinical trial and simulation datasets by utilizing data-driven approaches to identify promising drug combinations or novel therapeutic targets [47]. This capability allows for a more dynamic response to emerging challenges in oncology, such as tumor heterogeneity and resistance mechanisms, which often complicate treatment efficacy. Furthermore, as these technologies evolve, there is potential for real-time monitoring and adjustment of treatment plans based on patient responses, thus fostering a proactive rather than reactive approach to cancer care [95]. Such advancements could improve patient survival rates and quality of life, marking a significant leap forward in the fight against cancer. The advancement of CFD enables precise modeling of critical biophysical parameters in cancer, such as (IFP) and velocity, wall shear stress, and drug transport dynamics, that directly influence treatment efficacy and tumor progression, as shown in Table 3. By resolving these factors in patient-specific simulations, CFD bridges a crucial gap in oncology, offering insights that traditional clinical or empirical methods cannot provide. It must be noted that the spatial resolution of imaging and assumptions such as homogeneous ECM or static vascular geometry may result in deviation from actual in vivo drug diffusion profiles, especially in regions with necrosis or abnormal vascular morphology.

The fusion of CFD with ML constitutes a methodological advancement that transcends the limits of conventional biomedical modeling. CFD provides the deterministic framework for simulating complex fluid-structure interactions within pathological anatomies, while ML offers data-driven generalization across large, heterogeneous datasets. Their confluence facilitates rapid, high-resolution insights into cancer-related biotransport phenomena, enabling not only more accurate predictions but also unprecedented scalability and automation. This hybrid paradigm accelerates hypothesis testing, informs clinical decision-making, and lays the groundwork for a truly adaptive oncology, one that responds in real time to both systemic and molecular cues.

4 Integrated CFD and ML in Oncology

Cancer remains one of the most significant global health challenges, with early detection, treatment optimization, and effective drug delivery being critical areas of focus. CFD has emerged as a powerful tool in addressing these challenges by providing insights into biological systems, optimizing therapeutic strategies, and improving drug delivery mechanisms. Web-based interventions such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy ACT demonstrate potential for ML-driven behavioral therapy optimization, enhancing holistic oncology care [109]. Multimodal ML, combining histological and genetic inputs as in He et al. [110], represents a blueprint for integrative oncology prediction tools. This response explores the role of CFD in these areas, supported by recent advancements in nanotechnology, targeted drug delivery systems, and multi-scale modeling techniques. Microfluidic biosensors, as developed by Liu et al. [111], enhance early cancer detection and can be coupled with ML classifiers to stratify patient risks more effectively. The use of CFD in cancer treatment is a promising area of research, particularly in the context of pre-processing, analysis, and post-processing for early detection, treatment optimization, and drug delivery mechanisms. CFD can simulate the complex interactions between drug delivery systems and biological environments, providing insights into the behavior of therapeutic agents within the human body, including the integration of ML with mental health platforms, which may optimize personalized delivery formats for cognitive behavioral therapy in oncology, as explored by Duan et al. [112]. Wang et al. [88] demonstrated the potential of hydrodynamic microfluidic platforms for tumor cell separation, providing valuable input for ML-based diagnostic models. ML-enhanced modeling of lateral displacement chips, such as by Zhang et al. [113], can refine CFD predictions for lab-on-chip cancer screening tools. This approach is particularly relevant in the development of targeted drug delivery systems, which aim to improve the specificity and efficacy of cancer treatments while minimizing side effects.

Early cancer detection is crucial for better patient outcomes. CFD, combined with advanced imaging techniques like nanoparticle-assisted imaging, enhances early-stage tumor detection accuracy by improving contrast and resolution in MRI, CT, and optical imaging. CFD helps detect and diagnose lung, breast, and prostate cancers through simulating fluid flow and transport phenomena. This provides valuable insights into tumor behavior, hemodynamics, and aerosol patterns, aiding in early detection and treatment monitoring. This section covers the applications and limitations of CFD-based methods in these cancers.

CFD plays a pivotal role in early cancer detection by enabling the modeling of blood flow and related phenomena, which is essential for understanding tumor behavior [114]. The application of CFD in DCE-MRI allows for the optimization of design parameters, such as inlet tube orientation and size, to achieve uniform contrast agent distribution, thereby enhancing the accuracy of tumor characterization [104]. To ensure reliable cancer detection methods, simulation accuracy is critical. Accurate models must represent real-world fluid dynamics effectively, which is facilitated by advanced software tools designed explicitly for CFD simulations. These tools allow researchers to simulate complex biological environments, including the interactions of various blood components, which is vital for understanding tumor perfusion and response to treatment [7]. Moreover, reduced-order modeling techniques can simplify these simulations while retaining essential features, making them more computationally efficient. This approach is particularly beneficial in analyzing tumor perfusion dynamics, as it allows for quicker iterations and adjustments in model parameters without sacrificing accuracy. In summary, the integration of CFD with robust software tools and advanced modeling techniques significantly enhances the capability to detect cancer early, providing a foundation for improved diagnostic methods and treatment planning. The ongoing development in this field promises to refine these techniques further, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes [105,115–117].

Concurrently, machine learning models, including Support Vector Machine (SVM) [118] and Random Forest [119], are utilized to predict prostate, lung, and breast cancer by analyzing specific attributes tailored to each cancer type, with the goal of early detection and improved patient outcomes. Additionally, the potential in CFD allows for the application of machine learning principles to develop data-driven models that optimize simulations and offer real-time analysis [65]. The integration of machine learning in both fields demonstrates the capacity for technological advancements in healthcare and engineering [120]. Pepona et al. [102] explored how CTCs interact with local hydrodynamics in blood vessels, focusing on how these forces influence CTC attachment and metastatic site preference. Fig. 8 displays the experimental and simulation results, demonstrating the effect of vessel topology and hydrodynamic forces on CTC behavior. This is important for verifying the study’s findings and has potential implications for creating diagnostic tools to detect early metastatic activity based on CTC dynamics.

Figure 8: (a) WSS distribution in the double bifurcation geometry shows higher values at the inflow and outflow points. (b) Velocity streamlines, based on experiments, highlight areas of higher flow where cells may congregate, especially at the secondary bifurcation [102]

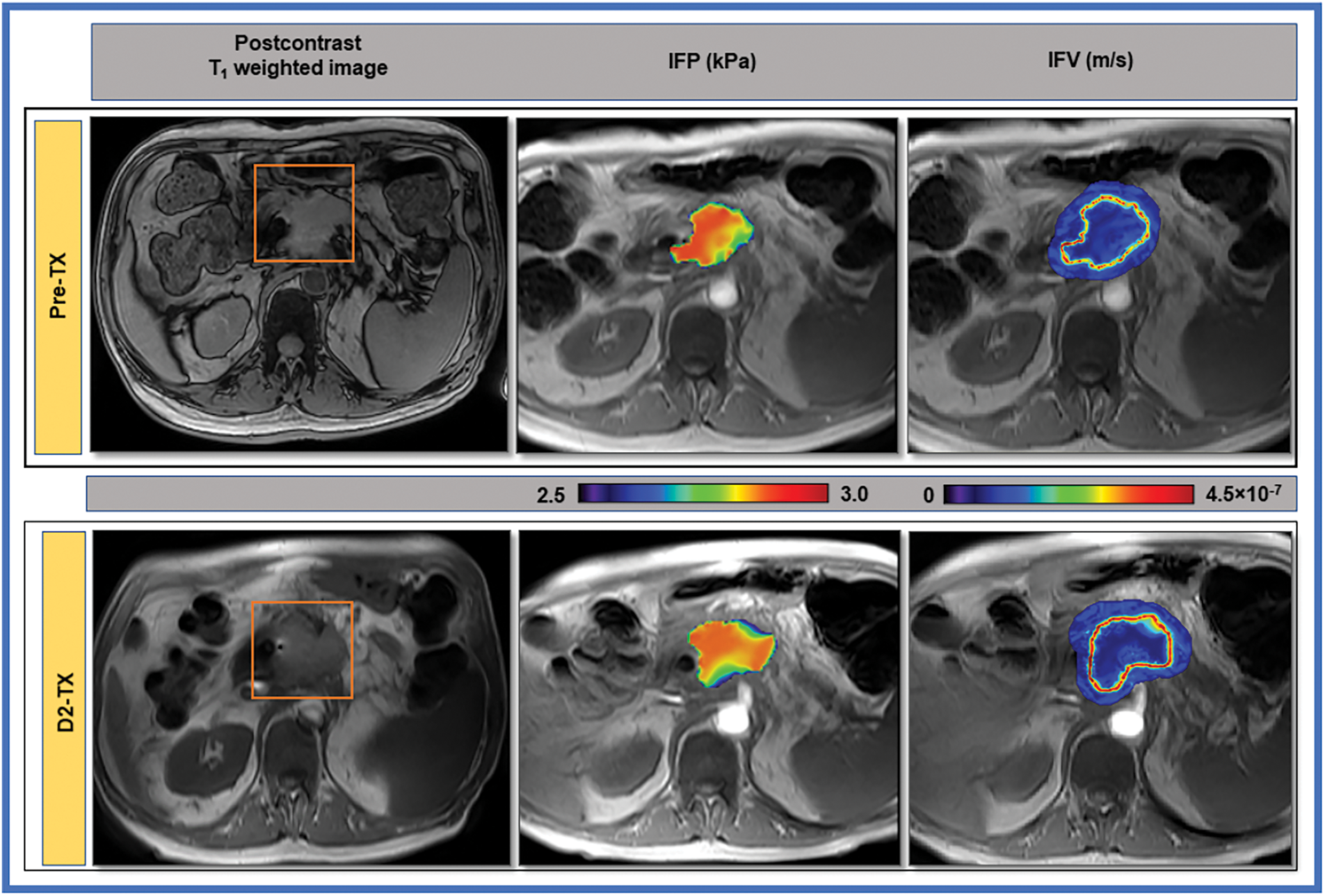

CFD is able to develop a noninvasive model for measuring IFP and velocity (IFV) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), aiming to better understand tumor microenvironments and improve early cancer detection [121]. By characterizing microvascular invasion (MVI) through specific IFP and IFV parameters, the study enhances diagnostic accuracy and offers potential for broader application in oncology [122]. This approach addresses the challenge of increased IFP in solid tumors, a significant obstacle to effective treatment [123]. However, in the case of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), a type of cancer affecting the pancreas, CFD simulated tumor IFP and IFV, aiming to monitor changes in the tumor microenvironment through DCE-MRI. By analyzing these fluid dynamics, the study seeks to identify early changes in the tumor that could indicate a response to therapy, potentially aiding in early cancer detection and treatment planning [116]. The significant correlations between tumor volume, Ktrans, IFP, and IFV suggest that these parameters could serve as imaging biomarkers for early response to therapy in PDAC patients, as shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Paudyal et al. [116] show T1-weighted post-contrast MR images of a 63-year-old male with pancreatic cancer, highlighting a marked decrease in IFP at the tumor boundary after Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT). The computational fluid model estimates and IFV maps demonstrate this change overlaid on pre-contrast images

The advancement of CFD allows for the non-invasive estimation of IFP and IFV in brain metastases from lung cancer. The goal is to predict the long-term response to stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) by identifying early biomarkers indicating treatment efficacy [99]. CFD is beneficial for estimating IFP and IFV because direct measurement is often not feasible due to the invasive nature of traditional methods, especially in surgically inaccessible tumors. The study utilizes CFD to predict the long-term response of lung cancer brain metastases to SRS by identifying early biomarkers, such as IFP and IFV, which can indicate whether a tumor will respond to treatment, allowing for timely modifications in therapy [30]. Understanding the fluid dynamics within the tumor microenvironment is crucial because the disorganized and tortuous architecture of tumor blood vessels affects fluid movement, impacting the delivery and efficacy of anti-tumor therapies [124].

CFD has emerged as a powerful tool in cancer research, offering insights into the complex interactions between fluid flow, drug transport, and tumor microenvironments. By simulating various physiological and pathological conditions, CFD provides a platform to optimize cancer treatment strategies, from drug delivery to surgical planning. Explainable AI models in oncology, like Ding et al. [125], underscore the clinical importance of interpretable ML for perioperative cognitive risks. The importance of IFP and IFV in cancer treatment is due to their role in treatment resistance. For the cancer treatment, elevated IFP and altered IFV are significant because they contribute to treatment resistance in cancer patients. High IFP can create a physical barrier that impedes the delivery of therapeutic agents to the tumor, reducing the effectiveness of treatments like chemotherapy and radiation therapy. IFP affects the distribution and penetration of drugs within the tumor. High IFP can lead to poor perfusion and limited drug access to cancer cells, making it a critical factor in the success of systemic therapies. Understanding and managing IFP can help improve drug delivery and therapeutic outcomes. The study suggests mapping IFP and IFV using non-invasive methods like DCE-MRI can provide early treatment response predictions. This predictive capability is crucial for tailoring treatment plans to individual patients, potentially leading to more effective and personalized cancer care. Cai et al. [126] proposed spatiotemporal nanodrug systems that align with CFD models of tumor perfusion for maximizing synergistic drug response. Liu et al. [127] developed a masked deep neural network for Fluid-Structure Interaction (FSI) prediction, a powerful method that can be extended to simulate tumor deformation under fluidic stress.

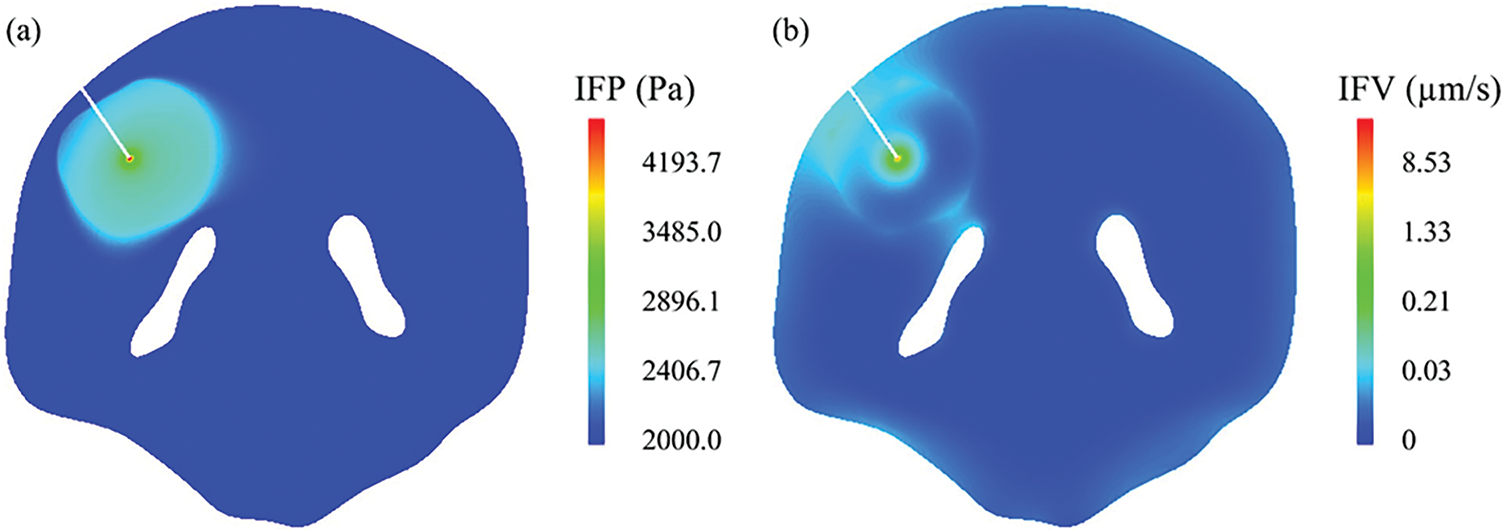

Yang and Zhan [128] discovered that the drugs are transported and distributed within brain tumours using convection-enhanced delivery (CED). CFD is employed to simulate these complex processes, allowing for accurate drug movement and effectiveness predictions, as shown in Fig. 10. By using CFD, the study creates a realistic 3-D model of brain tumours based on patient MRI images, which is crucial for capturing the actual geometry and structure of the tumour, thereby improving the accuracy of drug delivery predictions. CFD helps evaluate the impact of different tissue properties, such as hydraulic permeability, on drug delivery, enabling the optimization of delivery parameters like infusion rate and pressure, which can lead to better treatment outcomes for brain tumours.

Figure 10: The interstitial fluid flow in the brain tumour and its surrounding tissue (κ = 1.0E − 15 m2). (a) IFP, and (b) IFV [128]

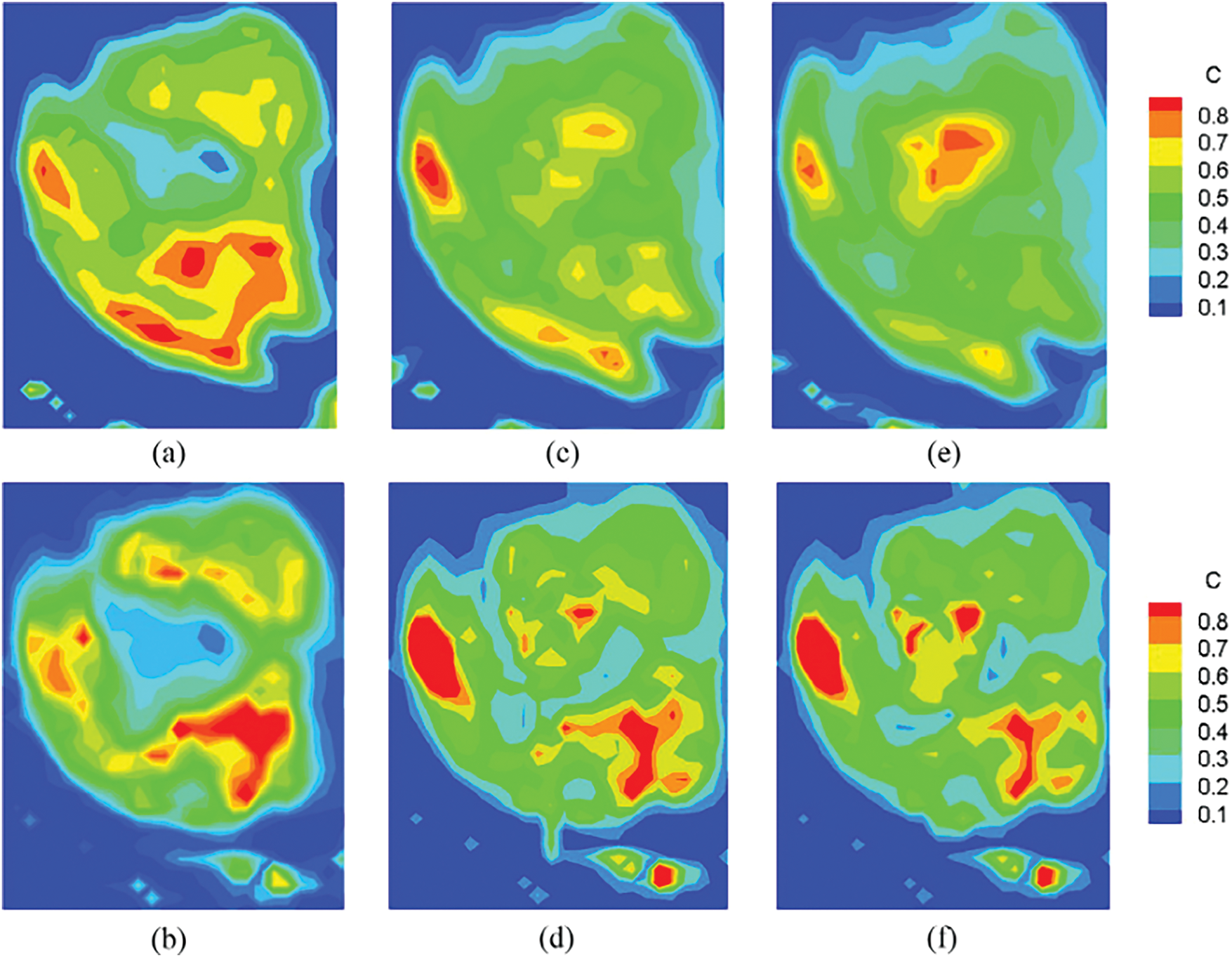

Bhandari et al. [129] showed the understanding of how drugs or contrast agents travel through human brain tumors. It develops a computational model that simulates fluid flow and drug transport inside the tumor tissue. By combining imaging data with CFD, the researchers improve the simulation’s ability to mimic real tumor environments. In simple terms, imagine using your own body’s scan to create a custom map of how medicine travels through your tumor. This process helps in understanding the behavior of drugs within tumors and guides the design of personalized treatment plans, as shown in Fig. 11. The new model is designed to overcome these limitations, offering a more nuanced view that considers various factors affecting drug delivery. For example, understanding that tumors may have high and low blood vessel density areas helps explain why some drugs work better in certain tumor regions.

Figure 11: The experimental (top row) and simulated (bottom row) tracer contour plots are the most informative and closely related to the statement. It encapsulates the entire tracer/drug transport process within the tumor, validating the computational model and thereby supporting treatment optimization and enhanced drug delivery mechanisms [129]

Furthermore, Taebi et al. [108] proposed treatment planning for Yttrium-90 (90Y) radioembolization, aiming to deliver a higher radiation dose to tumors while minimizing exposure to healthy liver tissue. Current dosimetry methods are based on simplified assumptions, leading to unreliable results, which the authors seek to address by developing a more accurate and personalized computational model. This model uses CFD simulations to predict radiation doses in different liver segments, providing a realistic and patient-specific approach. Additionally, the study highlights the importance of optimizing microsphere injection strategies to enhance delivery to the tumor, thereby improving treatment outcomes.

Preserving organ function in oral cancer treatment is crucial, as surgery often leads to severe oral dysfunction, impacting speech, mastication, and swallowing. A multidisciplinary approach, including radiotherapy and intra-arterial chemotherapy (IAC), offers an alternative [130]. IAC delivers higher concentrations of anticancer agents directly to tumor-feeding arteries compared to systemic chemotherapy, but the distribution into branches of the external carotid artery (ECA) has been inadequate. CFD can improve IAC effectiveness by examining flow distribution [131]. Advances in vascular radiological techniques have led to superselective IAC (SSIAC), further enhancing the delivery of anticancer agents. Patient-specific simulations are vital for predicting agent distribution accurately. High WSS in target arteries due to vessel geometry must be managed to prevent complications [38].

Peritoneal Metastasis (PM) occurs when cancer cells spread to the abdominal cavity lining, causing poor prognosis and complications like bowel obstructions and ascites. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy (IPC) treats cancers within the peritoneal cavity but struggles with limited drug penetration due to factors like drug dose, tumor size, and vascularization [132]. CFD can simulate drug transport within tumor tissues, helping optimize treatment strategies. CFD models use realistic tumor geometries and varying vascular properties to study drug absorption and spread. They also simulate IFP and drug concentration distributions, identifying barriers to drug penetration [133]. CFD is a cost-effective tool for testing treatment strategies without extensive experimental trials, making it valuable for improving cancer treatment protocols.

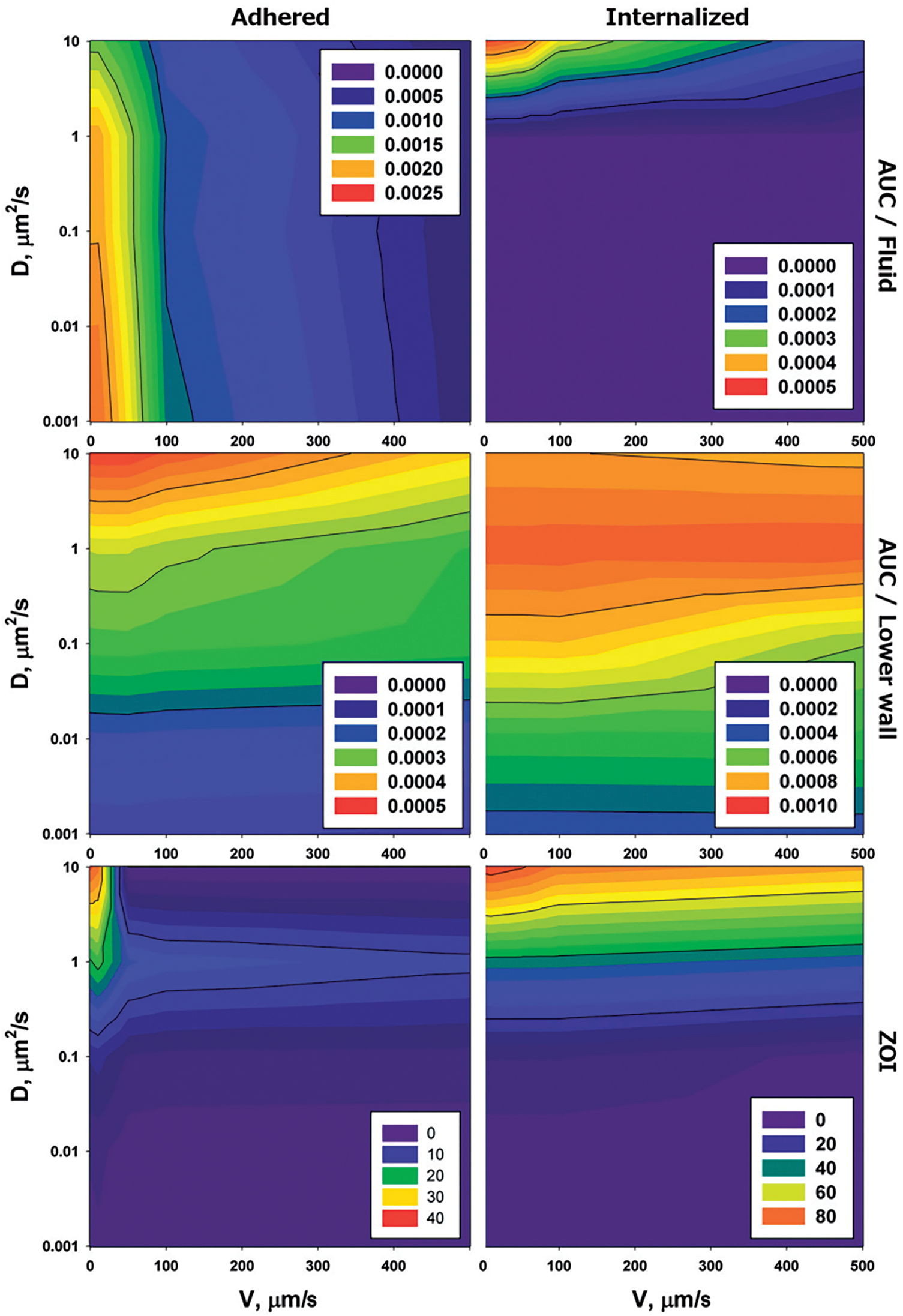

In enhancing drug delivery efficiency in oncology, CFD is crucial, particularly through targeted delivery systems and the distribution of nanoparticles [100]. By simulating fluid flow and particle dynamics, CFD allows for optimizing drug delivery mechanisms, ensuring that therapeutic agents are directed specifically to tumor sites while minimizing exposure to healthy tissues. The mathematical models developed for predicting the transport of magnetic nanoparticles in a channel are essential for understanding how these particles behave under the influence of external magnetic fields. This targeted approach improves the concentration of drugs at tumor sites and reduces the overall dosage required, thereby decreasing potential side effects, as shown in Fig. 12. Moreover, the distribution of nanoparticles is influenced by their size, shape, and surface properties, which are critical factors in achieving effective drug delivery [124]. By integrating CFD with advanced engineering tools, researchers can analyze flow patterns and optimize the design of drug delivery systems, leading to significant improvements in treatment efficacy. Overall, the application of CFD in drug delivery systems represents a substantial advancement in oncology, providing a scientific basis for developing more efficient and targeted therapies that can enhance patient outcomes while minimizing adverse effects.

Figure 12: Adhered drug vectors stick to blood vessel walls, while internalized vectors enter the tissue, and both affect the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Zone of Influence (ZOI) by determining how much drug reaches the tissue and how far it spreads [124]

Xie et al. [134] highlighted the challenges faced in nanomedicine-based cancer therapies, primarily due to limited understanding of drug delivery dynamics, such as the penetration behavior of nanoparticles in tumor tissues. The study utilizes MDA-MB-231 breast tumor spheroids and advanced imaging techniques to investigate how quasi-spherical gold nanoparticles penetrate these tissues, focusing on the extracellular pathway when intracellular pathways are blocked. A novel 3D micro-scale CFD-DEM model, integrated with a Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek (DLVO) sub-model, is employed to simulate the penetration behavior of nanoparticles, considering the extracellular matrix (ECM). The findings revealed that nanoparticles tend to remain on the spheroid surfaces, with penetration efficacy decreasing at higher concentrations due to increased collisions. This research provides a cost-effective tool for predicting nanoparticle tissue penetration, interpreting imaging data, and guiding future nanomedicine design. Alqarni et al. [119] addressed the complex problem of simulating blood flow containing magnetic nanoparticles, which is crucial for targeted drug delivery in cancer treatment. To tackle this, the research employs advanced hybrid models that integrate CFD with machine learning techniques, offering a more robust framework than conventional models. The machine learning models used include Random Forest, Extra Tree, and AdaBoost Decision Tree, optimized through the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) to enhance predictive accuracy. These models are trained on a dataset of over 17,000 rows to predict velocity, essential for understanding fluid flow dynamics in vessels with magnetic nanocarriers. The study demonstrates the effectiveness of this methodology through impressive performance metrics, such as high R-squared values and low error rates, indicating a strong fit to the data and superior predictive capabilities.

Shabbir et al. [7] focused on the challenge of delivering nanomedicine effectively within the complex microenvironments of tumors, which hinder the penetration and transport of therapeutic agents. To address this, the researchers utilize CFD to simulate the transport of nanoparticles in tumor vascular-interstitial models, allowing them to observe the impact on velocity profiles and pressure gradients. This method provides insights into optimizing nanoparticle design and delivery strategies by highlighting the significance of microenvironmental differences, such as cell pore size, in influencing therapeutic agent transport. The study’s findings emphasize the need for tailored approaches to drug delivery in different tumor types. Future research aims to incorporate immune cells into these simulations to further enhance the understanding of nanoparticle efficiency in cancer therapy.

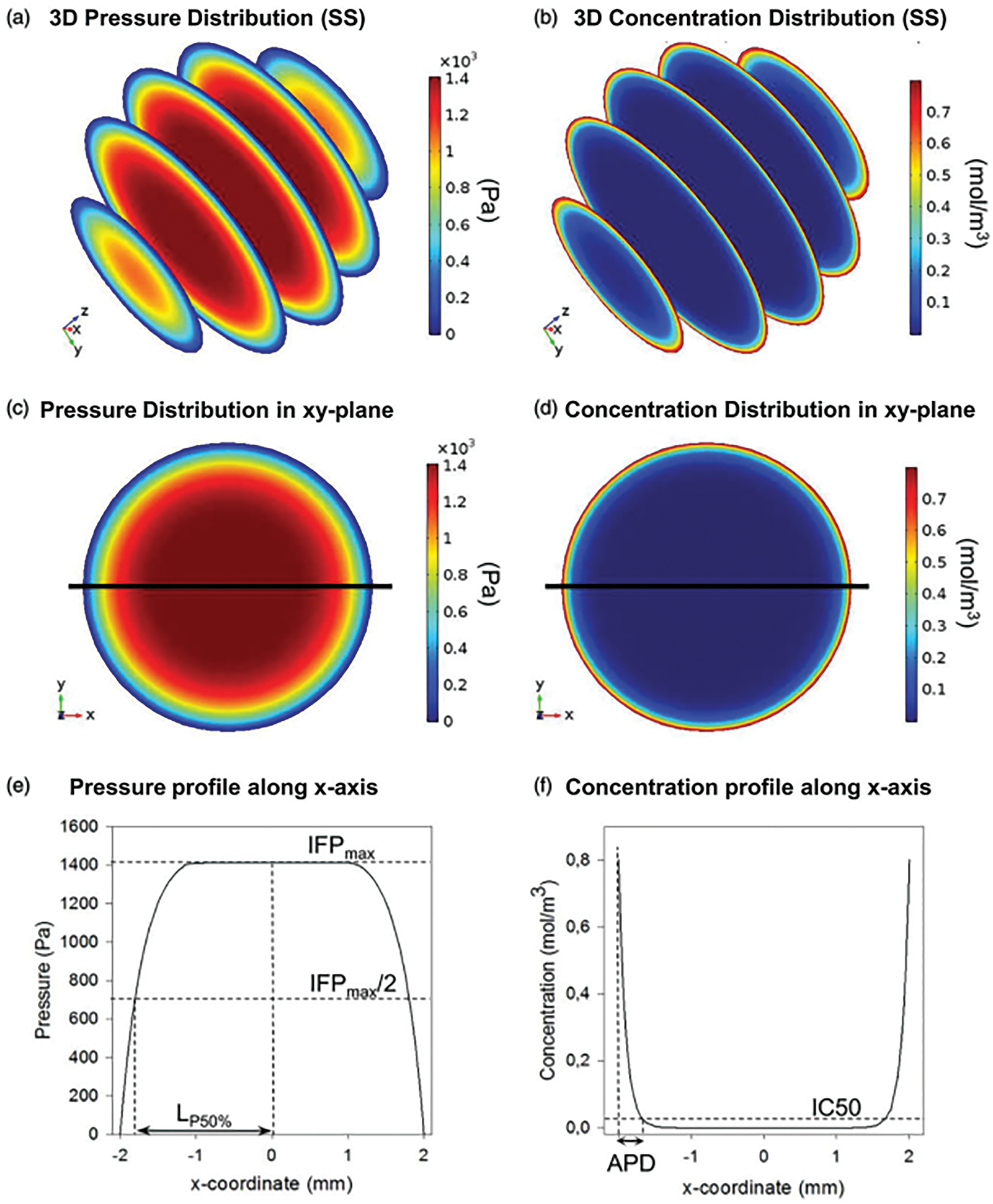

The study by Steuperaert et al. [135] addressed the issue of limited drug penetration depth in intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis, which hampers the efficacy of the treatment. Numerous researchers developed a three-dimensional CFD model to simulate drug distribution and penetration in tumor nodules. This model facilitates the examination of key parameters such as tumor size, interstitial fluid pressure, and the influence of vascular normalization therapy on drug transport, as mentioned in Fig. 13. The findings indicated that smaller tumors exhibit better drug penetration due to lower interstitial fluid pressure, and that vascular normalization can significantly enhance penetration depth. Overall, the CFD model serves as a valuable tool for comprehending and optimizing drug delivery in cancer treatment.

Figure 13: Summary of model output and variables analyzed. (a and b) 3D pressure and concentration distributions in the small spherical geometry (SS). (c and d) 2D pressure and concentration distributions in the xy-plane of the SS. (e and f) 1D pressure and concentration profiles along the x-axis in the SS [135]

Integrating CFD with ML in oncological research represents more than technological convergence, it signifies a conceptual reorientation in how cancer is understood and managed. This interdisciplinary synergy allows for modeling phenomena such as drug perfusion, tumor-induced vascular remodeling, and interstitial pressure gradients with a level of fidelity previously unattainable. ML enhances CFD workflows through intelligent automation and pattern recognition, transforming static simulations into dynamic, patient-specific tools. As a result, this integration not only enhances our grasp of tumor mechanics but also informs personalized therapeutic interventions, shifting cancer care from protocol-based practice to precision-guided engineering of treatment outcomes.

5 Prediction for the Future of CFD and ML in Oncology

As the intersection of computational fluid dynamics and machine learning evolves, it holds the potential to revolutionise oncology by enhancing predictive modelling and treatment strategies. This chapter will explore the implications of these advancements on cancer research and therapy. The integration of these technologies can lead to more personalized treatment plans, allowing for better targeting of therapies based on individual patient profiles and tumor characteristics [136]. Furthermore, the application of fluid dynamics in understanding tumor microenvironments may provide new insights into cancer progression and metastasis. Future investigations should prioritize the clinical validation of CFD-ML models through pilot studies that directly engage patient data under ethical approval. These studies are vital for evaluating the practical effectiveness of the proposed frameworks and aligning them with hospital-grade decision-making standards. These insights could facilitate the development of novel therapeutic approaches that specifically address the unique fluid-mediated processes influencing tumor behavior, thereby improving patient outcomes [43].

Additionally, machine learning algorithms can analyze vast datasets to identify patterns and correlations that may not be evident through traditional analytical methods [137]. This data-driven approach enables researchers to uncover hidden relationships between fluid dynamics and cancer biology, ultimately informing more effective interventions [138]. By leveraging these technologies, oncology can move towards a more integrated and holistic understanding of cancer treatment and management. This shift not only promises to enhance the precision of existing therapies but also encourages the exploration of innovative strategies that incorporate both biological and mechanical factors affecting tumor dynamics. As research in this area progresses, the collaboration between computational experts and oncologists will be crucial for translating these findings into clinical practice [139]. By leveraging these technologies, oncology can move towards a more integrated and holistic understanding of cancer treatment and management, including advances in oxygen-independent radiotherapy, which suggests new CFD modeling targets under hypoxic tumor conditions [140]. Immunological modeling of memory T cell dynamics, as discussed by Sun et al. [141], could benefit from CFD–ML frameworks to optimize ACT protocols. Tumor-responsive drug carriers like those discussed by Cao et al. [142] present strong potential for simulation within CFD–ML frameworks to predict therapeutic performance. This shift not only promises to enhance the precision of existing therapies but also encourages the exploration of innovative strategies that incorporate both biological and mechanical factors affecting tumor dynamics. As research in this area progresses, the collaboration between computational experts and oncologists will be crucial for translating these findings into clinical practice.

As these techniques advance, we can anticipate more robust models integrating patient-specific data, improving treatment response accuracy. This synergy between CFD and ML will not only enhance our understanding of tumor dynamics but also refine therapeutic interventions tailored to individual patient needs. Moreover, the continuous refinement of these models will likely lead to real-time monitoring of treatment efficacy, enabling oncologists to adjust therapies promptly based on patient responses. Such advancements could significantly reduce the time required for clinical decision-making, ultimately enhancing patient care and outcomes. Integrating these technologies also opens avenues for predictive analytics, allowing for identifying patients at higher risk for adverse consequences. By harnessing the power of both CFD and machine learning, researchers can develop innovative strategies to optimize treatment protocols and improve overall survival rates in oncology.

This approach not only emphasizes the importance of data quality and ethical considerations in patient management but also highlights the need for interdisciplinary collaboration among researchers, clinicians, and data scientists. As we move forward, the potential for these technologies to reshape cancer care becomes increasingly evident, paving the way for breakthroughs in personalized medicine and patient-centric treatment strategies. The collaboration between CFD and ML is expected to drive significant advancements in understanding tumor behavior and treatment personalization. By leveraging data-driven insights, we can enhance clinical decision-making, ultimately leading to more effective cancer therapies and improved patient outcomes. Furthermore, the integration of these technologies may also facilitate the discovery of new biomarkers that can predict treatment responses, thereby enabling more targeted interventions. As we continue to explore these synergies, the potential for improved therapeutic outcomes becomes more attainable, fostering a new era in oncology that prioritizes precision and efficacy. ML-driven pharmacokinetic modeling may benefit from data such as mirabegron/vibegron plasma profiling in oncology cohorts [143].

In conclusion, the convergence of computational fluid dynamics and machine learning represents a transformative shift in oncology, promising to tailor therapies more effectively to individual patient needs. As these fields continue to evolve, the integration of advanced analytics and personalized treatment strategies will be crucial in overcoming current challenges and enhancing patient care. This evolution will necessitate ongoing research into the mechanisms of tumor growth and response to therapy, ensuring that the insights gained from these technologies are translated into clinical practice effectively. Ultimately, the goal is to create a more adaptive and responsive healthcare system that prioritizes patient outcomes through precision medicine and innovative treatment paradigms. This proactive approach will improve treatment efficacy and foster a deeper understanding of cancer biology, paving the way for novel therapeutic targets and strategies. Continued collaboration among interdisciplinary teams will drive these advancements forward and ensure equitable access to cutting-edge cancer care. By fostering a culture of innovation and collaboration, we can ensure that computational fluid dynamics and machine learning breakthroughs are effectively translated into clinical applications, ultimately benefiting a broader patient population. This commitment to research and development will be vital in addressing the disparities in cancer treatment and outcomes observed globally. This commitment to research and development will be critical in addressing the disparities in cancer treatment and outcomes observed globally. As we harness these technologies, it is essential to remain vigilant about ethical considerations and equitable access to ensure that all patients benefit from advancements in oncology. This vigilance will guide the responsible implementation of these technologies, ensuring that they enhance rather than exacerbate existing inequalities in healthcare delivery. By prioritizing ethical frameworks and patient-centric approaches, the future of oncology can be shaped to provide comprehensive, effective, and accessible cancer care for all.

As oncology transitions toward a data-centric discipline, the coupling of CFD and ML emerges as a foundational pillar for future-ready cancer care. These tools, once limited to exploratory or academic applications, are now poised to support real-time clinical workflows, driven by the integration of imaging, omics, and patient-specific physiology. The next frontier lies in their convergence with ethical AI frameworks and scalable architectures that accommodate interpatient variability and intratumoral complexity. Through predictive modeling and adaptive feedback loops, this synergy will empower oncologists to anticipate disease evolution, optimize interventions dynamically, and ultimately transform treatment into a proactive, precision-guided process. Such a transformation will not only refine therapeutic efficacy but redefine the ethical and practical dimensions of personalized medicine.

6 Conclusion and Future Direction

The application of CFD in cancer treatment represents a significant paradigm shift in understanding and managing this complex disease. Traditionally, cancer treatment has relied heavily on generalized approaches such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery. However, these methods often overlook individual physiological differences, leading to inconsistent outcomes. CFD addresses this challenge by enabling personalized modeling of fluid flow, drug distribution, and thermal energy transfer within the human body, particularly cancerous tissues. CFD’s strength lies in its ability to simulate biological processes with high spatial and temporal resolution, using patient-specific anatomical and physiological data. For example, it can model how chemotherapy drugs move through blood vessels and diffuse into tumor regions, or how heat propagates during ablation therapies. It is imperative to foster sustained collaborations between CFD/ML researchers and oncology clinicians to co-design validation studies, assess model generalizability, and ensure regulatory readiness. This approach would significantly enhance the translational impact of CFD-ML applications in real-world oncology. Integrating explainable AI (XAI) techniques, such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values or Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), into CFD-ML models can greatly improve interpretability. Visualization of flow features contributing to classification decisions not only builds clinician trust but also facilitates model refinement based on expert feedback.

These simulations help predict the effectiveness of treatments before they are administered, reducing unnecessary risks and improving patient outcomes. What makes CFD a game-changer is its predictive power, non-invasive nature, and adaptability. Unlike imaging or diagnostic tests that show what has happened, CFD predicts what will happen under different treatment scenarios. This foresight allows clinicians to plan interventions more effectively, especially for complex or high-risk patients. Moreover, CFD’s versatility in integrating AI, nanotechnology, and real-time imaging opens doors to next-generation cancer treatments that are more targeted, effective, and safer.

However, key limitations remain, including the need for large-scale, high-quality clinical datasets for model validation, and the challenge of ensuring reproducibility and regulatory compliance across diverse patient populations. To fully capitalize on the capabilities of CFD in oncology, the following key directions must be prioritized. Future work should systematically benchmark various ML-CFD coupling methods (e.g., DNN, CNN, PINN) and integrate explainability tools to enhance model transparency and clinical trust. This method would reduce current fragmentation and establish standardized methodologies. These directions highlight what makes CFD uniquely capable in cancer modeling and treatment planning.

1. Integration with Patient-Specific Data: The first step forward is ensuring that CFD simulations are grounded in real patient data. Medical imaging techniques like MRI, CT scans, and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) provide detailed structural and functional information about tumors and surrounding tissues. When this data is fed into CFD models, the resulting simulations become highly accurate and tailored to each individual. This precision allows for better risk assessment and treatment customization, which no standard therapy planning method can achieve.

2. Development of Multi-Scale and Multi-Physics Models: Cancer evolves at multiple levels, from genetic mutations at the cellular level to mechanical changes at the organ level. CFD must expand to incorporate these numerous biological and physical scales within a single simulation framework. For instance, coupling fluid dynamics with tumor growth kinetics and cellular metabolism can give a more holistic view of cancer progression. This is an area where only CFD can provide the necessary integration of physical laws due to its flexibility and mathematical depth.

3. Real-Time Simulation for Clinical Application: CFD tools must offer near-real-time simulations to be useful in hospitals and clinics. This would enable oncologists to instantly visualize different treatment outcomes, such as how a drug will spread or how a thermal ablation will affect surrounding tissues. Real-time CFD tools, powered by advanced computing and AI, could become a decision-support system during surgeries or radiotherapy planning, offering insights that are impossible through any other method.

4. Predictive Modeling of Drug Delivery: One of the biggest challenges in chemotherapy and nanomedicine is ensuring that drugs reach the tumor efficiently while sparing healthy tissues. CFD can simulate drug transport mechanisms, advection, diffusion, and permeability within complex vascular networks. This predictive modeling is especially valuable in designing nanoparticle-based therapies or targeted drug carriers. Traditional tools cannot capture these microscopic flow and transport dynamics with the accuracy that CFD provides.

5. Optimization of Thermal Therapies: Treatments like radiofrequency ablation, laser therapy, and hyperthermia rely on controlled heat delivery to destroy cancerous tissue. CFD is uniquely positioned to simulate how heat moves through tissues based on their composition, blood perfusion, and geometry. This helps in planning treatment duration, intensity, and safety margins. Few others technique offers such detailed insight into thermo-fluid behavior in a living system.

In conclusion, the future of cancer therapy is increasingly dependent on the principles of personalization, precision, and predictive capability, all of which are fundamentally supported by CFD. With ongoing advancements in computational modeling, integration of high-resolution medical imaging, and enhanced interdisciplinary collaboration, CFD holds the potential to augment existing cancer treatment strategies and fundamentally transform them. Understanding the presence of cancer will no longer suffice; it will become essential to predict its progression and response to various treatment modalities accurately. In this regard, CFD is an indispensable tool in the evolution of oncological care.

Acknowledgement: AI-assisted tools were utilized to enhance the clarity and coherence of selected sections of this manuscript. Their use was strictly limited to language refinement, with no influence on the research content or interpretation of data.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia for the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme [FRGS/1/2023/TK04/USM/03/1].

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Wan Mohd Faizal and Nurul Musfirah Mazlan; methodology, Wan Mohd Faizal; validation, Shazril Imran Shaukat; formal analysis, Wan Mohd Faizal, Chu Yee Khor and Ab Hadi Mohd Haidiezul; investigation, Shazril Imran Shaukat and Ab Hadi Mohd Haidiezul; resources, Wan Mohd Faizal; data curation, Chu Yee Khor; writing—original draft preparation, Wan Mohd Faizal; writing—review and editing, Chu Yee Khor and Abdul Khadir Mohamad Syafiq; visualization, Chu Yee Khor and Abdul Khadir Mohamad Syafiq; supervision, Nurul Musfirah Mazlan; project administration, Wan Mohd Faizal and Nurul Musfirah Mazlan; funding acquisition, Nurul Musfirah Mazlan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Material: No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this research.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Eskin D. On CFD-assisted research and design in engineering. Energies. 2022;15(23):9233. doi:10.3390/en15239233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li SJ, Zhu LT, Zhang XB, Luo ZH. Recent advances in CFD simulations of multiphase flow processes with phase change. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2023;62(28):10729–86. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.3c00706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shen R, Jiao Z, Parker T, Sun Y, Wang Q. Recent application of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) in process safety and loss prevention: a review. J Loss Prev Process Ind. 2020;67(3):104252. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2020.104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Drikakis D, Frank M, Tabor G. Multiscale computational fluid dynamics. Energies. 2019;12(17):3272. doi:10.3390/en12173272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yang G, Zheng G, Li G. Computational methods and engineering applications of static/dynamic aeroelasticity based on CFD/CSD coupling solution. Sci China Technol Sci. 2012;55(9):2453–61. doi:10.1007/s11431-012-4935-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bomberna T, Maleux G, Debbaut C. Simplification strategies for a patient-specific CFD model of particle transport during liver radioembolization. Comput Biol Med. 2024;178(1):108732. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Shabbir F, Mujeeb AA, Jawed SF, Khan AH, Shakeel CS. Simulation of transvascular transport of nanoparticles in tumor microenvironments for drug delivery applications. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):1764. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-52292-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zakaria MS, Zainudin SH, Abdullah H, Yuan CS, Abd Latif MJ, Osman K. CFD simulation of non-newtonian effect on hemodynamics characteristics of blood flow through benchmark nozzle. J Adv Res Fluid Mech Thermal Sci. 2019;64(1):117–25. [Google Scholar]

9. Morris PD, Narracott A, von Tengg-Kobligk H, Silva Soto DA, Hsiao S, Lungu A, et al. Computational fluid dynamics modelling in cardiovascular medicine. Heart. 2016;102(1):18–28. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Farkas Á, Lizal F, Jedelsky J, Elcner J, Karas J, Belka M, et al. The role of the combined use of experimental and computational methods in revealing the differences between the micron-size particle deposition patterns in healthy and asthmatic subjects. J Aerosol Sci. 2020;147(4):105582. doi:10.1016/j.jaerosci.2020.105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Pan SY, Ding M, Huang J, Cai Y, Huang YZ. Airway resistance variation correlates with prognosis of critically ill COVID-19 patients: a computational fluid dynamics study. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2021;208(18):106257. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Haghnegahdar A, Zhao J, Kozak M, Williamson P, Feng Y. Development of a hybrid CFD-PBPK model to predict the transport of xenon gas around a human respiratory system to systemic regions. Heliyon. 2019;5(4):e01461. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Bouillot P, Brina O, Ouared R, Yilmaz H, Lovblad KO, Farhat M, et al. Computational fluid dynamics with stents: quantitative comparison with particle image velocimetry for three commercial off the shelf intracranial stents. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8(3):309–15. doi:10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Lee KH, Hsiao HM, Liao YC, Chiu YH, Tee YS. Development of computational models for evaluation of mechanical and hemodynamic behavior of an intravascular stent. In: ASME 2011 6th Frontiers in Biomedical Devices Conference; 2011 Sep 26–27; Irvine, CA, USA. p. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

15. Adel B, Laurent D, Ibrahima MB. Multiobjective optimization of a stent in a fluid-structure context. In: GECCO’08: Proceedings of the 10th Annual Conference Companion on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation; 2008 Jul 12–16; Atlanta, GA, USA. p. 2055–60. [Google Scholar]

16. Rieger H, Welter M. Integrative models of vascular remodeling during tumor growth. WIREs Mech Dis. 2015;7(3):113–29. doi:10.1002/wsbm.1295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lopez-Vince E, Wilhelm C, Simon-Yarza T. Vascularized tumor models for the evaluation of drug delivery systems: a paradigm shift. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2024;14(8):2216–41. doi:10.1007/s13346-024-01580-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]