Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Reliability Topology Optimization Based on Kriging-Assisted Level Set Function and Novel Dynamic Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm

School of Computer Engineering, Chengdu Technological University, Chengdu, 611730, China

* Corresponding Author: Hang Zhou. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning-Assisted Structural Integrity Assessment and Design Optimization under Uncertainty)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1907-1933. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069198

Received 17 June 2025; Accepted 31 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Structural Reliability-Based Topology Optimization (RBTO), as an efficient design methodology, serves as a crucial means to ensure the development of modern engineering structures towards high performance, long service life, and high reliability. However, in practical design processes, topology optimization must not only account for the static performance of structures but also consider the impacts of various responses and uncertainties under complex dynamic conditions, which traditional methods often struggle accommodate. Therefore, this study proposes an RBTO framework based on a Kriging-assisted level set function and a novel Dynamic Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization (DHPSO) algorithm. By leveraging the Kriging model as a surrogate, the high cost associated with repeatedly running finite element analysis processes is reduced, addressing the issue of minimizing structural compliance. Meanwhile, the DHPSO algorithm enables a better balance between the population’s developmental and exploratory capabilities, significantly accelerating convergence speed and enhancing global convergence performance. Finally, the proposed method is validated through three different structural examples, demonstrating its superior performance. Observed that the computational that, compared to the traditional Solid Isotropic Material with Penalization (SIMP) method, the proposed approach reduces the upper bound of structural compliance by approximately 30%. Additionally, the optimized results exhibit clear material interfaces without grayscale elements, and the stress concentration factor is reduced by approximately 42%. Consequently, the computational results from different examples verify the effectiveness and superiority of this study across various fields, achieving the goal of providing more precise optimization results within a shorter timeframe.Keywords

With the growing demand for lightweight design in high-end equipment fields such as aerospace and new energy vehicles, structural topology optimization technology has become a core means to achieve efficient use of materials [1]. Traditional topology optimization methods, such as Solid Isotropic Material with Penalization (SIMP) and the level set method, have produced remarkable results under deterministic conditions. However, in actual engineering applications, uncertainty in material parameters and manufacturing errors significantly affect the robustness of structural performance [2–4]. These methods exhibit clear limitations when addressing the challenges posed by material property uncertainties, thereby restricting the reliability and applicability of the optimization results. Therefore, developing new optimization strategies that can effectively account for these uncertainties is crucial for enhancing the quality and reliability of structural design [5–8].

As an important and critical essential method in structural design optimization, topology optimization can be traced back to Maxwell’s fundamental topological analysis of minimum weight frames under stress constraints in 1854, but it has only made significant progress in recent decades [9–12]. Bendsoe and Kikuchi proposed the homogenization method to solve the problems related to topology optimization of continuum structures [13–17]. Although this method has strict mathematical homogenization theory support and the optimization results have significant grid-independent characteristics, the enormous computational cost brought by its dual-scale (micro-macro) coupling analysis and the nonlinear strong coupling problem between microstructure parameters and macroscopic performance have led to this method being gradually replaced by single-scale optimization methods such as SIMP and level set optimization [18–22]. In the context of the computational complexity challenge faced by the homogenization method, Bendose and Sigmund proposed the revolutionary SIMP method. This method significantly reduces the dimensionality of the optimization model by establishing a power exponential mapping relationship between the unit pseudo-density variable and the elastic modulus, replacing the microstructure parameters with a continuous density field [23–26].

In recent years, various new topology optimization methods have been proposed. Xue et al. developed an efficient high-resolution topology optimization method based on the super-resolution convolutional neural network technology under the SIMP framework. This method achieves high computational efficiency by balancing the number of finite element analyses and the output mesh during the optimization process through a pooling strategy [27]. Hu et al. proposed a dual-scale parallel topology optimization method for structures composed of multiple lattice materials. On the premise of ensuring the connection between different lattice materials, the microstructure, structural topology and distribution of multiple lattice materials of lattice materials were optimized in parallel [28]. Because of the difficulty of load boundary identification in the density-based topology optimization framework, Fan et al. proposed a direct load boundary identification method to describe and update the design-related boundary loads, and proposed a topology optimization method suitable for structures considering design-related boundary loads [29]. Zhang et al. [30] proposed a Kriging model-assisted topology optimization method, which enables the evaluation of true constraints with a relatively small number of samples under the assistance of the Kriging model. Raponi et al. [31] presented a topology optimization method for vehicle crashworthiness and conducted an in-depth analysis of the advantages of the Kriging-assisted level set method. The research findings demonstrated that the Kriging model notable ability to reduce computational costs in topology optimization. However, while these studies employed the Kriging model as a surrogate in the constraint evaluation process to enhance efficiency, they did not investigate the potential role of efficient heuristic optimization algorithms within the optimization framework.

Some researchers have also investigated the role of heuristic algorithms in the process of topology optimization. Tao et al. developed a multiscale modeling method to predict the mechanical behavior of 3D woven composite fenders with various material and structural design parameters. They used an optimization method combining an improved Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm and a Kriging model to find the optimal combination of continuous and discrete design variables at different scales [32]. Xue et al. [33] applied a PSO-assisted optimization method to accomplish the topology optimization of the Echo State Network, thereby enhancing its adaptability, predictive capability, and stability in complex tasks. When dealing with complex multiscale structural optimization problems, traditional PSO algorithms often have difficulty balancing convergence speed and local optimization capabilities, especially when mixed variables (coexistence of continuous and discrete variables) and high-dimensional search spaces are involved. They easily fall into local optimality or cause excessive computational costs [34,35]. To this end, this paper proposes a Dynamic Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm (DHPSO), which combines the sensitivity guidance mechanism with the particle empirical evolution strategy to significantly accelerate the convergence speed while retaining the global search capability. At the same time, the paper also conducts experimental comparisons through different examples to prove that the proposed method has better performance in terms of convergence speed, structural flexibility and satisfaction of reliability constraints.

In addition, in the field of continuum topology optimization, a variety of topology optimization methods have been developed to meet different engineering needs [36]. As a relatively new technology, the level set method has attracted attention in this field due to its advantages, such as clear structure and absence of grayscale units [37–39]. However, the classical level set method still has limitations in boundary smoothness and the degree of optimization of the objective function value. How to improve the optimization efficiency while ensuring the clear and smooth boundaries of the topological model is a problem worth studying. As a commonly used strategy in optimization, the surrogate model has been adopted in the optimization of various engineering structures [40,41]. It can significantly reduce the computational cost by constructing an approximate model of the objective function or design response, while maintaining high optimization accuracy and reducing the number of finite element analyses [42–44]. Especially when dealing with complex engineering problems, it can always effectively alleviate the computational pressure caused by the problem situation’s complexity and improve the algorithm’s practicality and scalability [45,46]. By integrating the advantages of the parameterized level set method in boundary expression and the high efficiency of the Kriging model in modeling and prediction, efficient and high-quality topology optimization solutions can be achieved [47–50]. In this study, a novel Reliability-Based Topology Optimization (RBTO) framework is proposed. Traditional topology optimization techniques suffer from issues such as high computational costs, deficiencies in boundary smoothness, and limited optimization of the objective function when addressing complex optimization problems. By introducing a Kriging model-based surrogate level set strategy, it effectively approximates the highly nonlinear characteristics exhibited by structural responses, thereby enhancing the capability of topology optimization for complex geometric variations and advanced loading scenarios. An improved optimization method, named DHPSO, is also proposed to enhance the global convergence ability and speed of topology optimization, demonstrating superior performance in solving problems within a nonlinear design space. With the assistance of Kriging interpolation and high-performance optimization algorithms, the proposed topology optimization framework achieves excellent optimization capabilities for complex boundaries and irregular meshes.

The contents of other parts of this study are as follows: Section 2 introduces the various methods or principles used in the paper; Section 3 presents the reliability based topology optimization framework of Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO proposed in this paper; Section 4 applies the proposed framework method to different examples such as cantilever rectangular plate structure, hyperstatic beam structure and 3D L-beam for verification and analysis, proving the superiority of the proposed framework; Section 5 summarizes and analyzes the overall content of the article.

2 Basic Principles and Methods

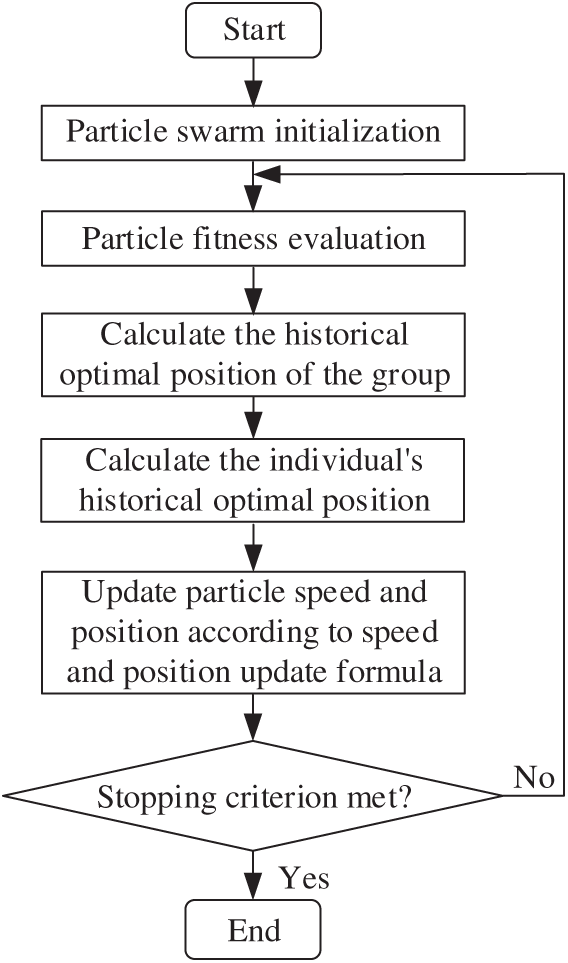

2.1 Particle Swarm Optimization

The PSO algorithm is an evolutionary computing technique developed based on the study of bird flock foraging behavior. When optimizing the proposed loss function, each optimization problem is represented by a group of elementary particles, each has a fitness function to evaluate the quality of its current position [51]. Particles can adjust according to their own fitness values and update their search direction and movement distance at a certain speed. In this way, the particle swarm explores the solution space and gradually approaches the global optimal solution. The flowchart of the PSO algorithm is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flowchart of the PSO algorithm

follows: From a mathematical point of view, the PSO algorithm can be described as follows in the continuous space coordinate system. Assuming that the size of the group is N, the position vector of each particle in the M-dimensional space is

The optimal position of the group is the sum of the optimal positions of all individuals. The speed update formula and position update formula are expressed as:

where

Although the complexity of the improved algorithm is nearly the same as that of the initial version, it significantly enhances the performance of the original algorithm and is therefore widely used. The initial version is generally referred to as the original PSO algorithm, and the modified algorithm is known as the standard PSO algorithm.

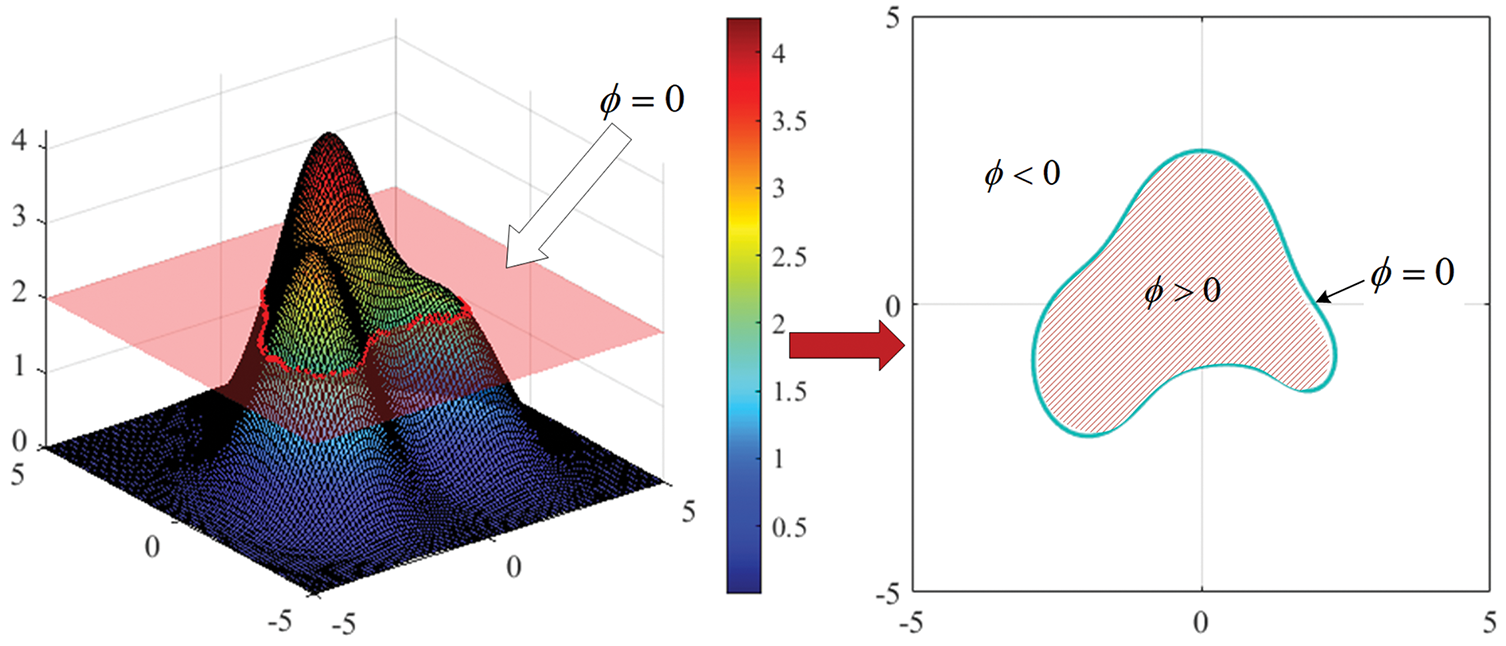

As a mathematical method, the level set method was originally developed to track moving boundaries and is now widely used in image processing, fluid mechanics, and other fields [53–55]. In the field of topology optimization, the core idea of applying the level set method to solve optimization problems is to construct an implicit level set function, which is used to determine the material distribution within the structure. The meaning of the level set function

where

Figure 2: Level set function

After determining the expression of the level set function

where v is the vector velocity field function at the i-th node. The velocity field can be decomposed into the normal velocity field and the tangential components. Only the normal velocity field affects the evolution of the structural boundary. Therefore, the Hamilton-Jacobi equation can be rewritten as:

where

In general, the basic process of structural topology optimization design using the level set method is divided into the following five steps:

(1) Construct a higher-dimensional implicit initial level set function, and use the zero-level set surface of the implicit level set function to construct the structural boundary, that is, determine the initial material distribution of the structure;

(2) Introduce a virtual time variable t, and solve the normal velocity

(3) Use the normal velocity

(4) By comparing the size relationship between the level set function

(5) When the iteration reaches convergence, the topology optimization result and the final topology configuration are output. If it does not converge, repeat steps (2)–(4).

2.3 Solid Isotropic Material with Penalization

SIMP is a milestone method in the field of structural topology optimization [56]. Its development began with the advancement of homogenization theory in the late 1980s. The early homogenization method was proposed by Bendsøe and Kikuchi (1988). The macroscopic material properties were characterized by the equivalent elastic tensor of the periodic microstructure. Topology optimization aims to achieve the optimal distribution of materials in the design domain through mathematical modeling and numerical methods to meet performance goals (such as maximizing stiffness and lightweight) and constraints (such as volume limitations and manufacturing feasibility). Among these methods, the SIMP approach explicitly links material density and elastic modulus through a penalty mechanism [57], and has gradually evolved into a core technique widely used in engineering.

The interpolation expression is as follows:

where E0 is the elastic modulus of the solid material, Emin is the minimum value to prevent singular matrices, and p ≥ 3 is the penalty factor. By adjusting the p value, the optimization result can be made to tend to a 0–1 distribution, achieving a clear material/empty area boundary. In addition, sensitivity analysis is the key to optimization iteration. Its objective function is flexibility

where xe is the unit displacement vector and Ke is the entity unit stiffness matrix. However, directly applying the original sensitivity will lead to a checkerboard pattern, that is, the density of adjacent units oscillates alternately. To this end, Sigmund proposed a sensitivity filtering technique [58], which uses a Gaussian kernel function to perform a weighted average of local sensitivities:

where N(e) is the neighborhood set of unit e, defined as all units whose distance from the center of e is less than the filter radius rmin; where rmin is the filter radius, it suppresses local gradient oscillation and improves numerical stability. To further enhance manufacturing feasibility, projection filtering (Heaviside threshold function) is introduced to binarize the continuous density field:

where

As one of the core methods of structural topology optimization, the SIMP method has demonstrated significant application value in engineering and strong compatibility with commercial software (such as ANSYS and ABAQUS) owing to its unique mathematical model and engineering adaptability. It has become the preferred method for complex structure optimization. For example, in the optimization of the Boeing 787 wing skin, the SIMP method only needs 500 iterations to converge to the million-degree-of-freedom model, and the computational efficiency is 60% greater than that of the traditional method, which fully demonstrates its high efficiency. At the same time, the sensitivity field is smoothed by combining Gaussian filtering techniques, which effectively solves the checkerboard phenomenon. For instance, in the optimization of a satellite bracket, the stress concentration factor is reduced by 42% and the fatigue life is increased threefold by adjusting the filter radius, which significantly enhances the robustness of the design results. Although SIMP has limitations such as local optimal traps and intermediate density suppression that depend on empirical parameters, it remains one of the most widely used topology optimization methods in the industry due to its balance between mathematical simplicity and engineering practicality. In the future, when combined with machine learning agent models and multi-scale homogenization theory, SIMP is expected to overcome the challenges of high-dimensional nonlinear optimization and multi-physics field coupling.

3 Kriging Surrogate Level Set-DHPSO Reliability Topology Optimization Framework

3.1 Kriging Surrogate Level Set Function Method

According to the Kriging model node level set function method used by Hamza et al. [59], on the basis of the Kriging model using a 0-order polynomial regression model, the level set value at the i-th node can be expressed as:

where n is the total number of nodes,

To decouple the Hamilton-Jacobi equation, the time quantity t is introduced to form a vector

where A is an n × n-dimensional matrix,

where

Since the matrix G is theoretically reversible, the expansion coefficient vector can be obtained by Eq. (16):

Then the level set function of the point

Substituting Eq. (18) into the Hamilton-Jacobi equation, we can obtain a control equation based on Kriging:

where

Next, the time-varying Hamilton-Jacobi partial differential equation is discretized into a set of coupled ordinary differential equations that control the dynamic interface motion, as shown in Eq. (21):

where

The approximate solution of the coupled nonlinear ordinary differential equations can be calculated as:

where ti is the i-th time step and

The coefficient

3.2 Dynamic Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm

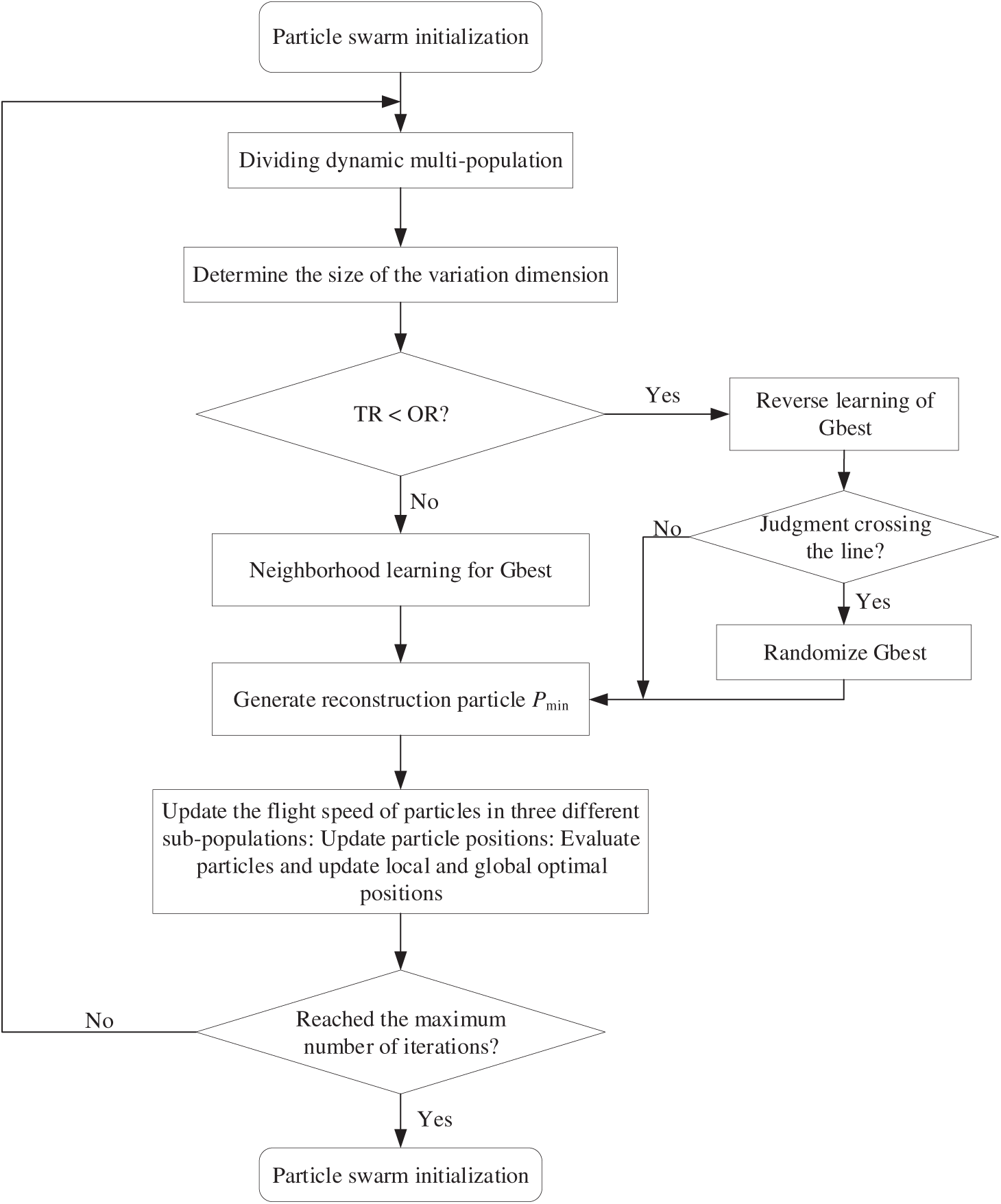

To improve the efficiency of optimization solutions, this paper proposes a DHPSO method by combining the sensitivity guided mechanism with the particle empirical evolution strategy, which significantly accelerates the convergence speed while retaining the global search capability. This method mainly includes two strategies: dynamic multi-population partitioning and probabilistic hybrid mutation selection, which are used to achieve adaptive adjustment of population structure and enhance the ability to jump out of local optimality.

3.2.1 Dynamic Multi-Population Partitioning Strategy

The PSO algorithm with multiple populations is essentially a local PSO algorithm based on a special neighborhood topology. Compared with the fixed multiple populations division, dynamic random recombination can prevent excessive restrictions on particles’ freedom and improve the efficiency of individual information exchange. Reference [60] uses the mean and standard deviation of fitness values as the metrics based on a classification approach, dividing the population into multiple levels by evaluating the positional relationships among particles. However, in the later stage of iteration, excellent populations tend to attract more individuals, leading to excessive particle aggregation and reduced information exchange between populations. Therefore, building upon this, this paper divides the sub-populations based on the median of ascending fitness value, and dynamically adjusts each generation. Particles with a smaller fitness value are defined as “top particle” while those with a larger fitness value are “bottom particle”. Then, the same number of particles is extracted from both groups to form a local PSO model, maintaining a balance across three population segments: the “close neighborhood” near the optimal solution, the “recombination domain” of the local PSO model, and the “alienation domain”.

The fitness value of particles in the “close neighborhood” is smaller, and they need to inherit the location information of the optimal solution in the population and reduce the step size for a more detailed search; while the particles in the “alienation domain” should expand the “pace”, while approaching the global extreme value, while exploring new optimal solutions around to improve mining capabilities; the “reorganization domain” as a local model will dynamically adjust the diversity of the population, absorbing individual experience and sharing global information.

3.2.2 Probabilistic Hybrid Mutation Strategy Selection

The main reason why the particle swarm algorithm converges slowly in the later stages of optimization is that it has difficulty in escaping the current local extreme value, resulting in a reduction in accuracy. Many scholars have proposed various improvement methods, such as reinitialization [61], adaptive PSO [62] and hybrid strategy [63], and have achieved positive results to varying degrees, improving the convergence speed and accuracy. However, these improvement measures lack comprehensive consideration of the fundamental reasons why the algorithm converges to the local optimum and its dynamic effects at different stages, and have certain limitations. From the perspective of mathematical theory, references [64,65] derived the following formula through rigorous derivation, which explains the “aggregation” phenomenon of PSO in the state of evolutionary stagnation:

From Eqs. (24) and (25), we can see that in the process of the algorithm, the local extreme value

Based on the above analysis, a probability-based hybrid mutation (M-P) strategy is adopted in the proposed algorithm, which combines the Opposition-based Learning (OBL) and Disturbance of Extreme (DE) value to randomly select the mutation mode with time-varying probability.

(1) Reverse learning mutation of the optimal particle. Its main idea is to calculate and evaluate Gbest and its inverse solution, and select the better value from the two as the global guide for the next generation, increasing the probability of jumping out of the local optimum. The relevant definitions are given below.

Definition 1: Reverse point. Let

Definition 2: Optimal particle reverse solution. Let

where

Using dynamic boundaries instead of fixed boundaries in the search space can not only ensure that the generated reverse solution is located in a gradually shrinking space, but also control overlearning and improve the effective mutation rate. At the same time, this paper considers the optimal characteristics of the global extreme value and uses the maximum dimension of Gbest as the dynamic boundary, without introducing the search information carried by other particles to affect its “superiority”. Of course, in the process of reverse learning, the reverse solution may fly over the dynamic boundary. Therefore, the following method is used to generate random numbers in

(2) Neighborhood learning variation of the optimal particle

Reference [65] proposed a Gaussian Mutation (GM) strategy, which uses the following formula to perturb Gbest:

where

The global extreme value perturbation strategy proposed in this paper mainly mutates

where

where

Generally speaking, in the early stages of population evolution, multi-dimensional learning can help the optimal particles to escape local optima more quickly and provide them with greater learning opportunities; in the late stages, as the global optimum approaches the true optimal solution, and retaining the advantageous information of each dimension as much as possible is conducive to improving the accuracy of the algorithm. Therefore, this paper adopts the following formula to determine the scale of the mutation dimension.

where

Combining the construction ideas and specific strategies of the above algorithms, the flowchart shown in Fig. 3 can be constructed. As can be seen from Fig. 3, the DHPSO algorithm mainly includes five parts: initialization, population division, M-P strategy, introduction of reconstruction particles, and update of speed, position and extreme value. The operations required for each part of the algorithm to iterate once are:

Figure 3: The proposed DHPSO algorithm process

(1) The complexity of initializing the population is O(N·D);

(2) The operation of dividing the dynamic subpopulation is O(1);

(3) The size of the mutation dimension in the M-P strategy decreases linearly. If the maximum size is taken for calculation, the complexity is O(D);

(4) The basic operation of generating reconstruction particles as guides is O(D);

(5) The update of the particle’s flight speed, position and extreme value is O(N·D).

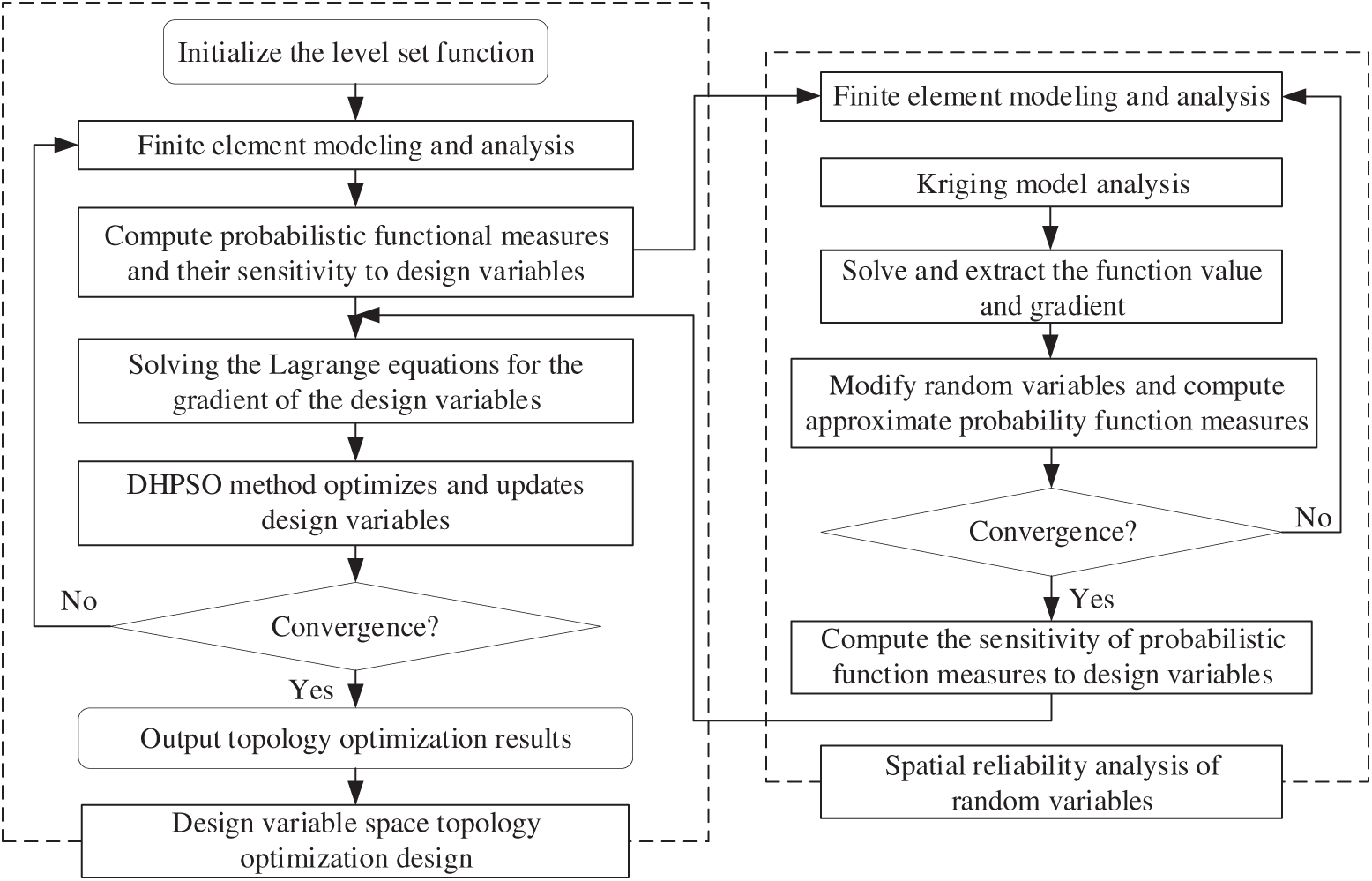

3.3 Reliability Topology Optimization Model

The reliability topology optimization is performed using the Kriging-assisted level set function method and the DHPSO algorithm mentioned above. In the reliability topology optimization design, this section uses a double-layer nested iteration method for topology optimization. The outer loop is the optimization problem of the design variable (unit density

where

Then, the Kriging-assisted level set function method performs reliability topology optimization design to minimize the structural volume under probability constraints. The optimization model is:

This section uses the two established optimization models to focus on rigid structures’ reliability topology optimization design. In the rigid structure example, the probability constraints are usually flexibility probability constraints and displacement probability constraints, and their expressions are shown in Eqs. (37) and (38), respectively:

Since the solution of the probability function metric

Figure 4: Flow chart of RBTO

The computer used in this paper is an Intel (R) Core (TM) i9-9900K CPU @ 3.60 GHz, running a 64-bit operating system. In addition, this paper solves the reliability index of the deterministic topology optimization structure through 105 Monte Carlo calculations. The population size of the optimization algorithm was set to 200, and the number of iterations was configured as 100.

4.1 Cantilever Rectangular Plate Structure

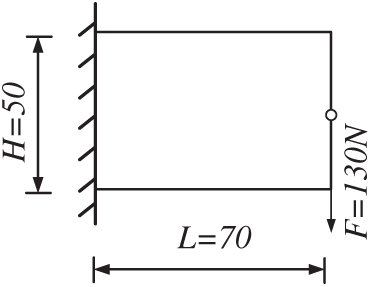

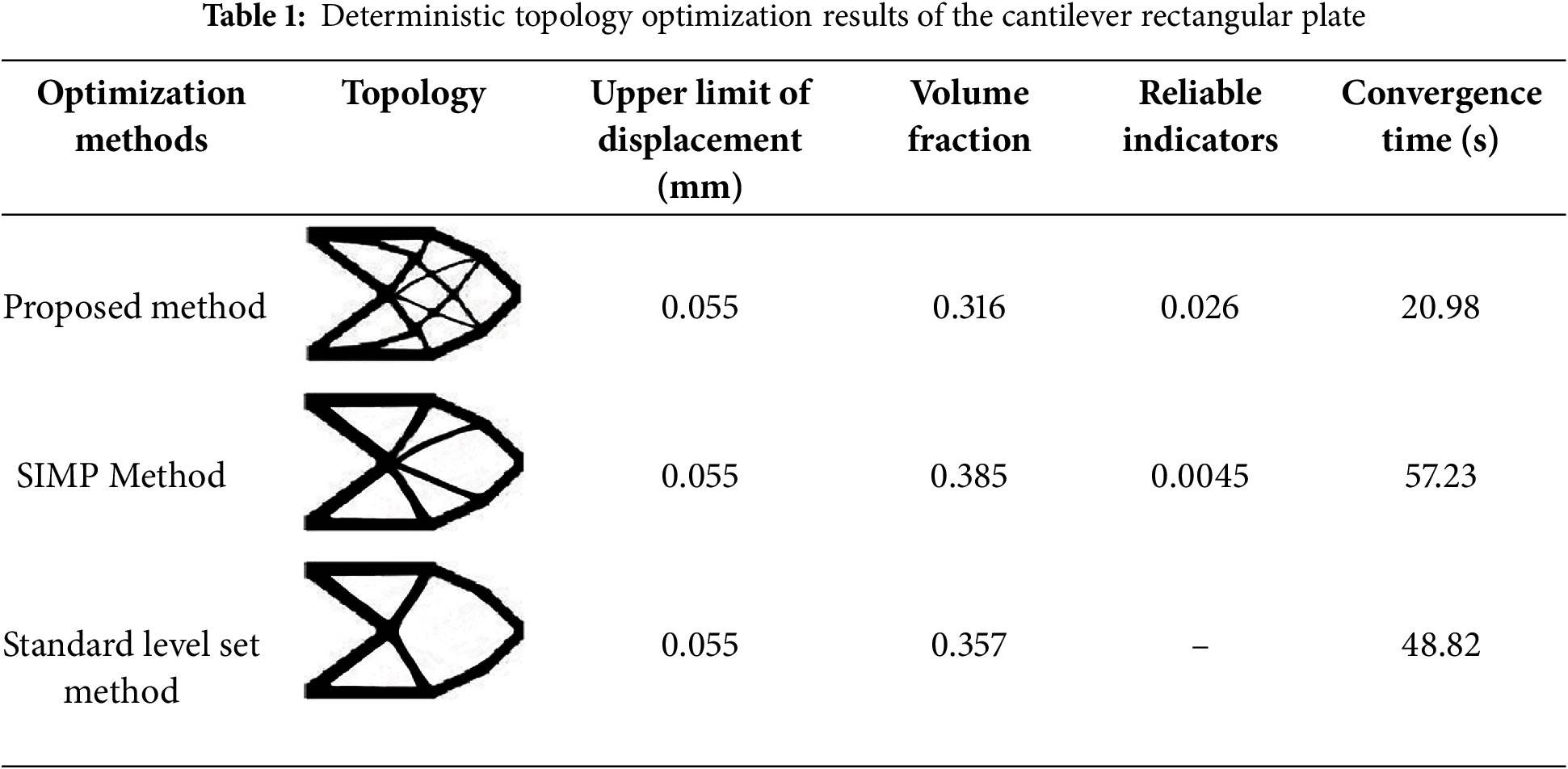

This paper uses a cantilever rectangular plate structure example for analysis and verification. Its design domain, boundary conditions and applied loads are shown in Fig. 5. The design domain is discretized into 70 × 50 units. A concentrated load of F = 130 N acts on the midpoint of the right end of the cantilever rectangular plate. The material of the selected structure is aluminum alloy, and the deterministic topology optimization model is volume minimization under displacement constraints. The upper displacement limit at the loading point is umax = 0.045 mm. The variable density method and Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO framework are used for topology optimization, respectively. The results are compared and shown in Table 1.

Figure 5: Cantilever rectangular plate structure

It can be seen from the data in Table 1 that the topological configurations and volume fractions obtained by the Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO framework and the variable density method proposed in this paper are similar to the results of the standard level set function method. The topological configuration derived from the variable density method exhibits fewer rods. In contrast, the configuration obtained using the Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO framework is characterized by the absence of gray units, smooth rod profiles, and a relatively smaller volume fraction. In addition, through the calculation of the reliability index, it is found that when the parameter uncertainty is not considered, the failure probability of the final topological configuration is close to 50%, and the structure is not reliable. In engineering, the proposed method can obtain more accurate and reliable design results within a shorter timeframe, thereby shortening the design and production cycle and reducing time-related costs.

Next, assumed that the concentrated load acting at the midpoint of the right end of the cantilever rectangular plate is subject to uncertainty and follows a normal distribution and with a mean value of 100 N. The RBTO optimization model is the volume minimization under the displacement probability constraint. The reliability topology optimization design of this example is carried out under two working conditions:

(1) The coefficient of variation is 0.1, and the target reliability index is 2.5, 3.0, and 3.5, respectively.

(2) The target reliability index is 3.2, and the coefficient of variation is 0.15, 0.2, and 0.25, respectively.

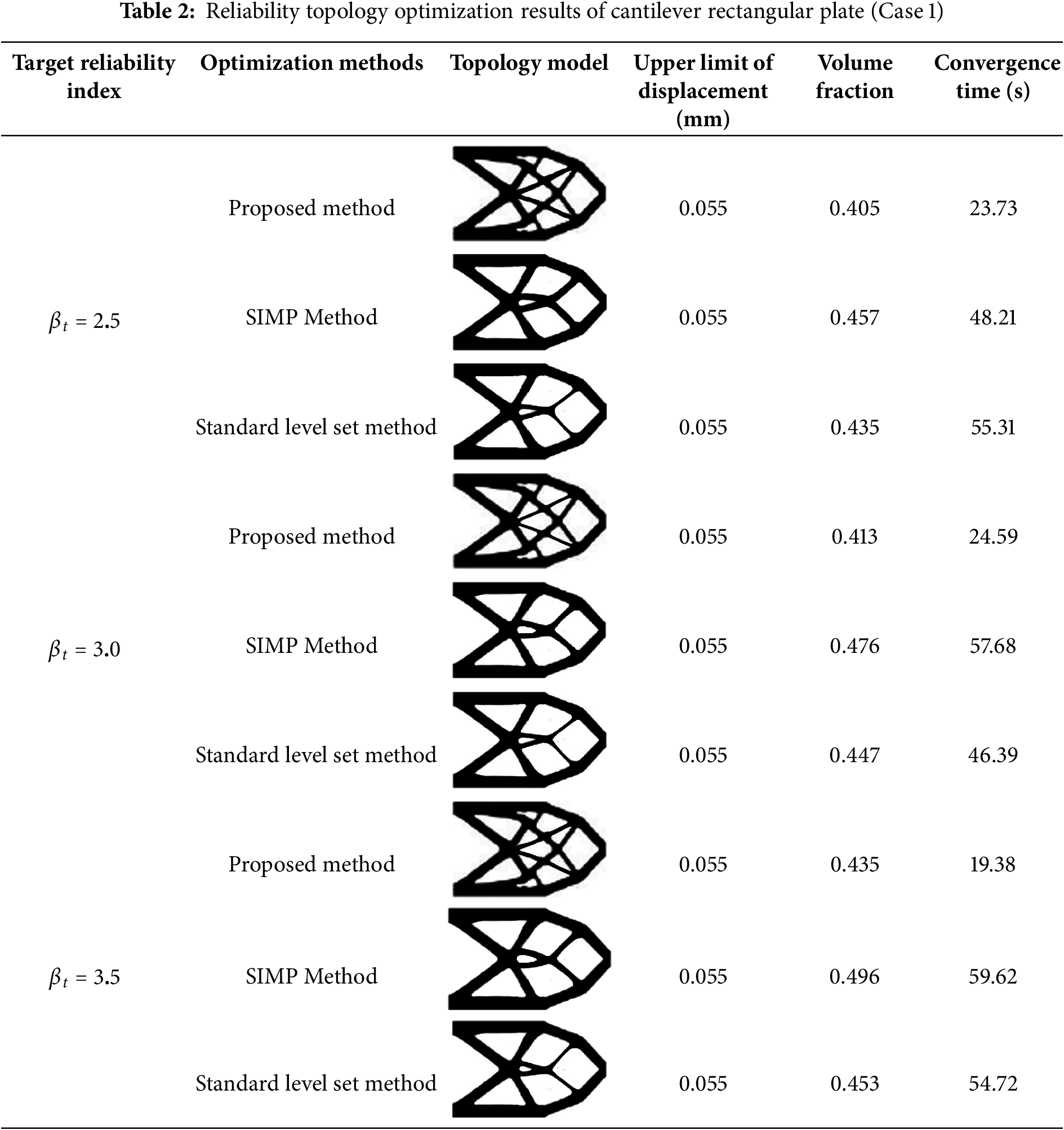

Table 2 provides the single-run optimization results achieved using the SIMP standard level set, and topology optimization methods proposed in this paper under different design conditions.

In engineering, a higher volume fraction may lead to higher material costs. A lower volume fraction, however, may lead to insufficient structure [66]. By analyzing Tables 1 and 2 together, it is evident that, after incorporating uncertainty considerations, the reliability index of the RBTO structure is substantially higher than that of the Deterministic Topology Optimization (DTO) structure. This finding confirms that reliability topology optimization yields a more reliable design. Additionally, the RBTO structure exhibits a larger volume fraction and thicker rods in the topological configuration compared to the DTO structure. In the RBTO case, the computational results from the proposed method align closely with those obtained through the level set method. As the target reliability index rises, the volume fraction of the structure progressively increases, and the rods in the topological configuration gradually thicken. This indicates a corresponding increase in the material quantity required for the structure as its uncertainty escalates. Moreover, the topological configuration generated by the Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO framework is smooth and well-defined, devoid of gray units, and exhibits lower volume fractions compared to those obtained through the variable density method. This suggests that the Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO framework for reliability topology optimization achieves a smaller objective function value and yields a superior topological configuration.

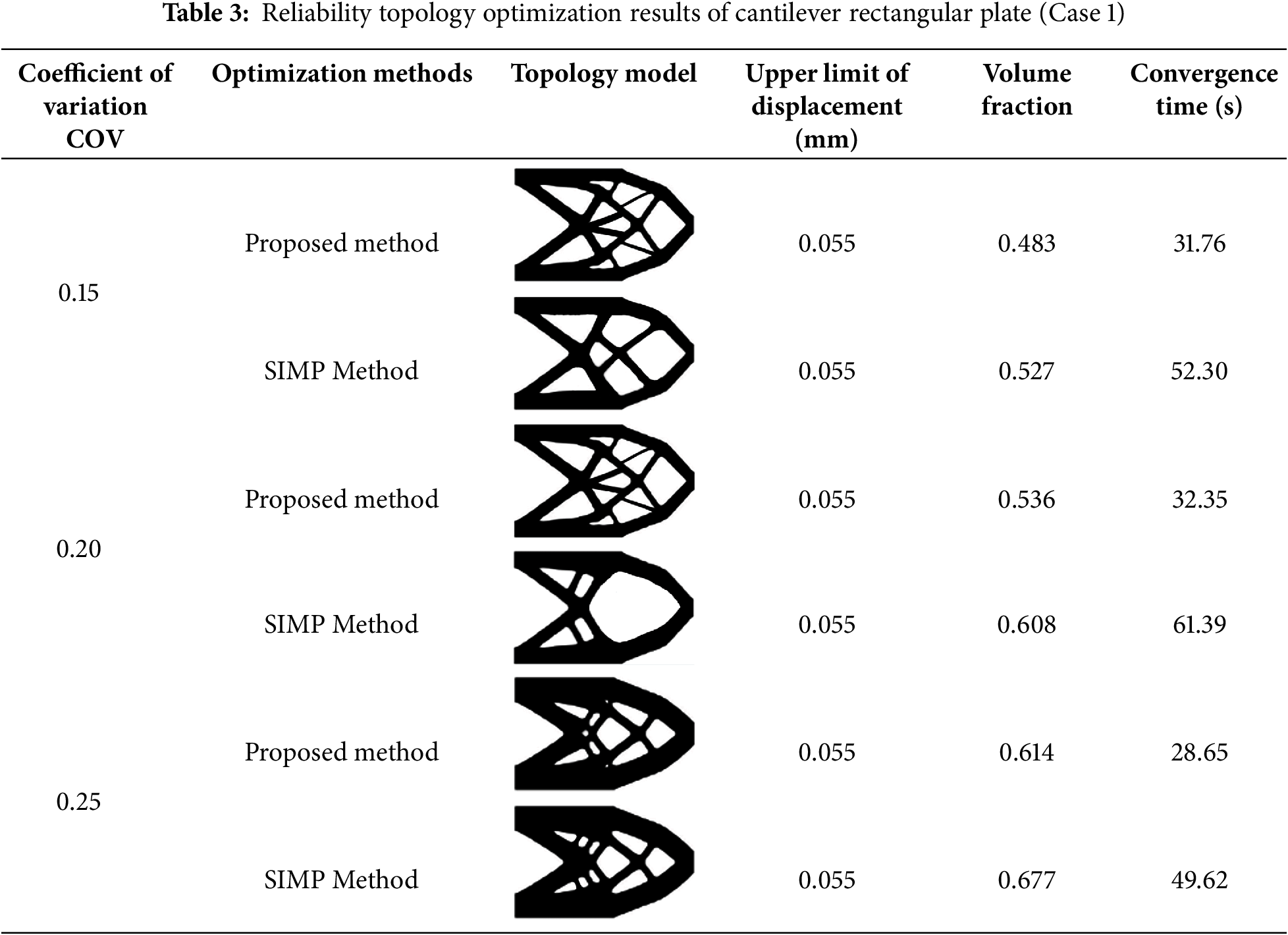

Next, the working condition 2 of the reliability topology optimization design of the cantilever rectangular plate structure is calculated, and the working conditions where the target reliability index is constant and the coefficient of variation takes different values are analyzed. The single-run computational results under various operating conditions are summarized in Table 3.

It can be seen from the data in Table 3 that when the structural variation coefficient increases, the structural volume fraction also increases, and the topological configuration rods gradually become thicker, indicating that when the uncertainty of the structure increases, the amount of material required for the structure also increases proportionally; Additionally the volume fractions obtained by the Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO framework are smaller than the volume fractions of the variable density method, which further demonstrates the advantage of the Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO framework in reliability-based topology optimization. A comparison of the computational time consumed by different optimization methods reveals that the proposed method reduces the time by approximately 42.26% compared to the original method.

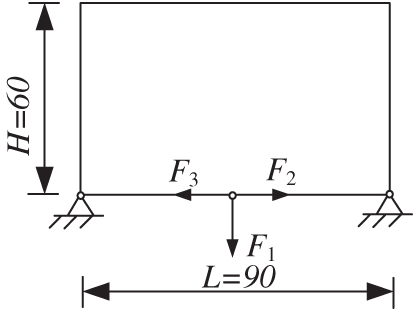

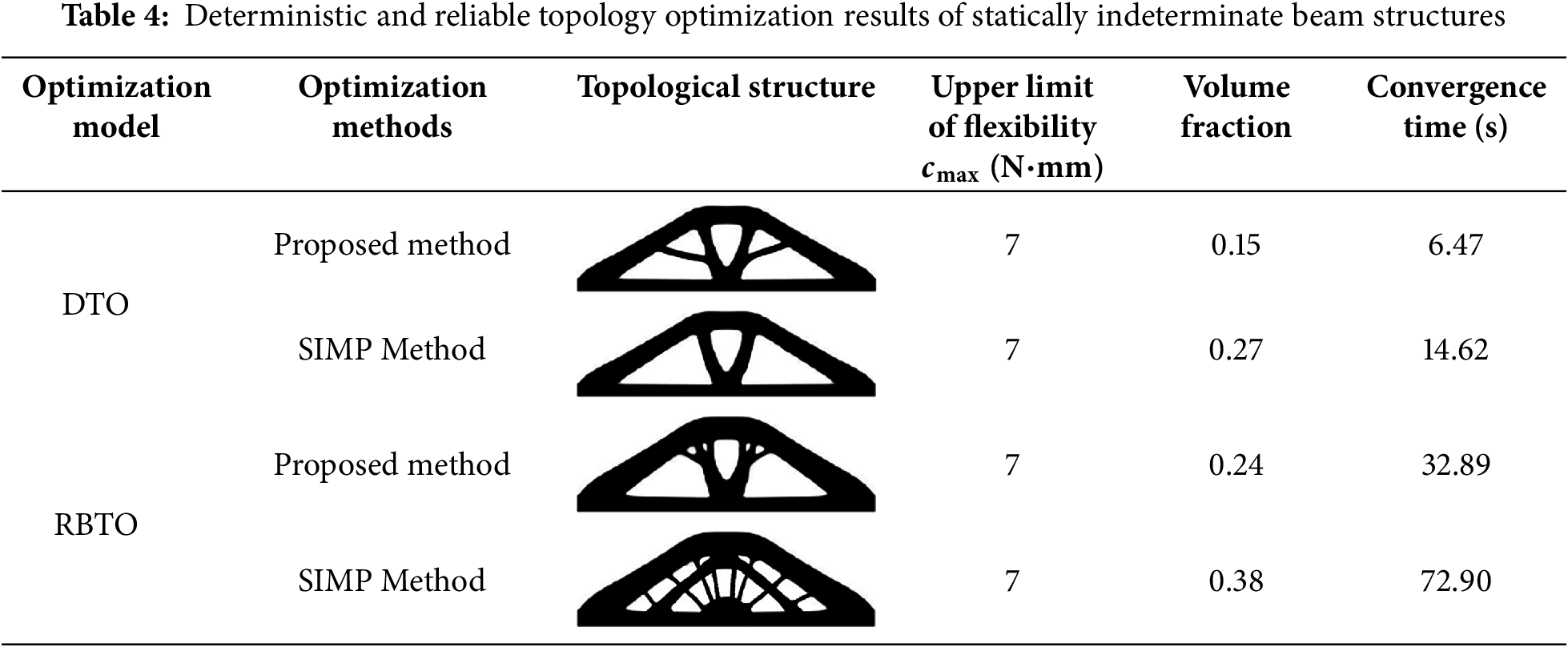

4.2 Statically Indeterminate Beam Structure

The design domain, boundary conditions and loads of the statically indeterminate beam structure are shown in Fig. 6. The design domain is discretized into 90 × 60 units. Three concentrated loads F1, F2 and F3 act vertically downward, horizontally to the right and horizontally to the left at the midpoint of the lower end of the statically indeterminate beam. The elastic modulus of the structure is E0, and the Poisson’s ratio v = 0.33. It is assumed that the three concentrated loads F1, F2 and F3 and the elastic modulus E0 are all random variables obeying independent normal distribution. The mean of the three loads is 100 N, the mean of the elastic modulus is 7.1 × 104 MPa, the coefficient of variation is 0.1, the target reliability index is 3.0, and the upper limit

Figure 6: Statistically indeterminate beam structure

It can also be seen from the data in Table 4 that compared with DTO, RBTO has a larger structural volume fraction, a more complex topological configuration, and thicker rods; the volume fractions obtained by the Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO framework are smaller than those of the variable density method, and the topological configuration has smooth boundaries and no grayscale units, indicating that the Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO framework has certain advantages in reliability topology optimization. This reduces the design cycle in the project and enhances the reliability of the final design outcomes. In addition, the proposed method reduces computation time by approximately 54.88% compared to traditional methods.

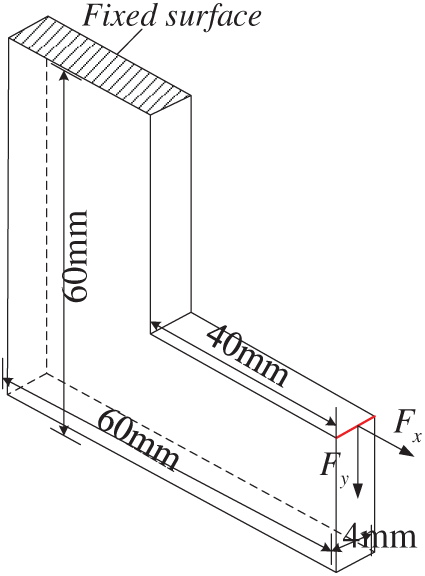

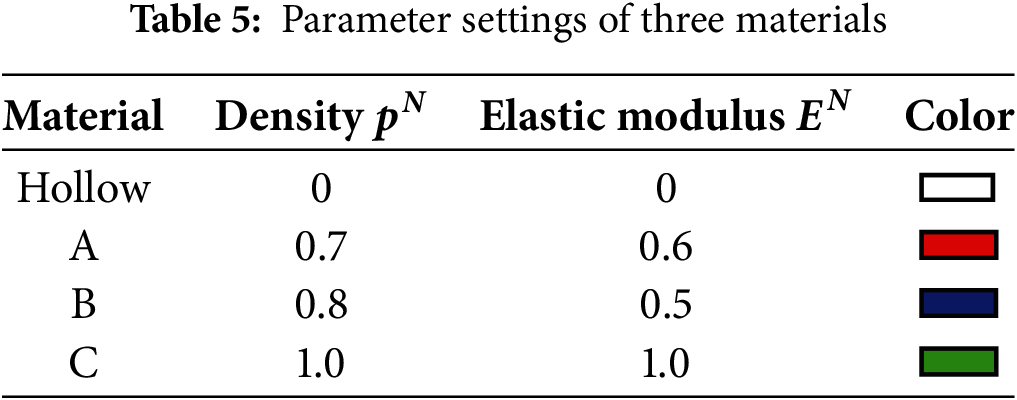

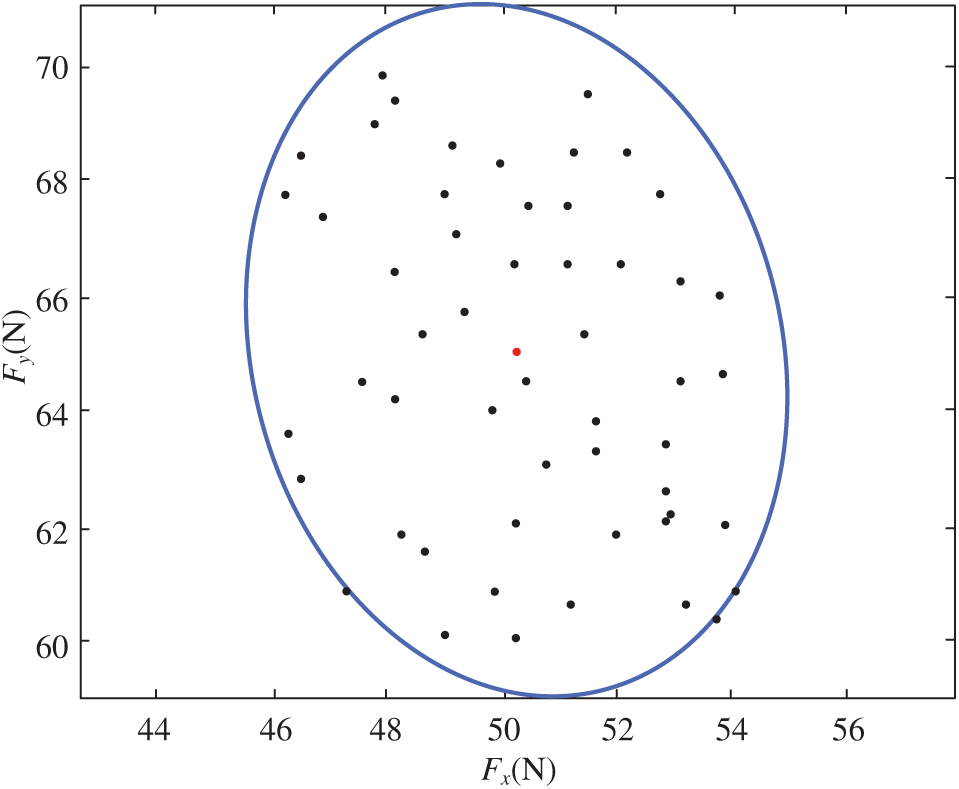

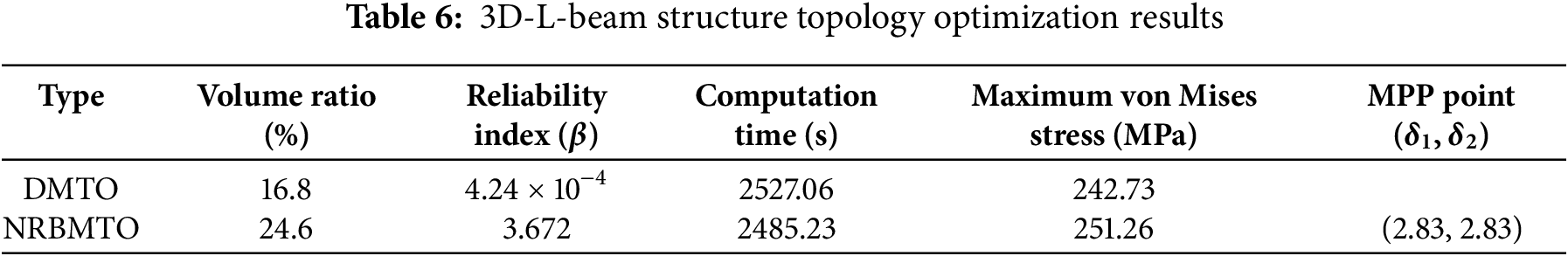

We use a 3D L-beam structure as the verification object. The design range of the structure is shown in Fig. 7. The size of the design domain is 60 mm × 60 mm × 4 mm. The upper left plane of the three-dimensional L-beam is fixedly constrained, and mechanical loads Fx and Fy are applied to the right side of the structure. The stress constraint value is set to 235 MPa. In the multi-material design, the three materials considered are normalized using the Ordered-SIMP method, and their material parameters are shown in Table 5.

Figure 7: 3D L-beam design domain

In the reliability analysis, the uncertain variable vector

Figure 8: Schematic diagram of the ellipsoid model

According to the finite sample points, the uncertain variable ellipsoid set constructed by the minimum volume closure algorithm is:

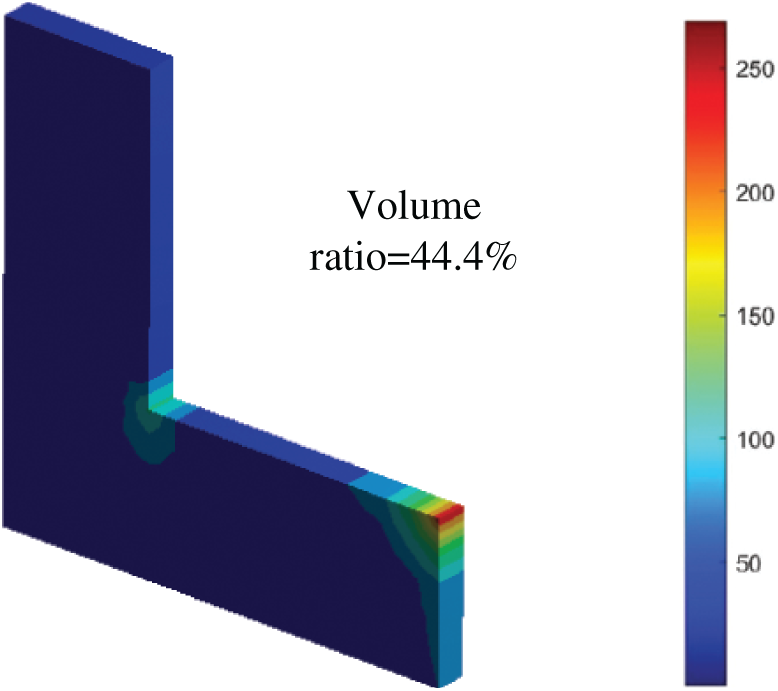

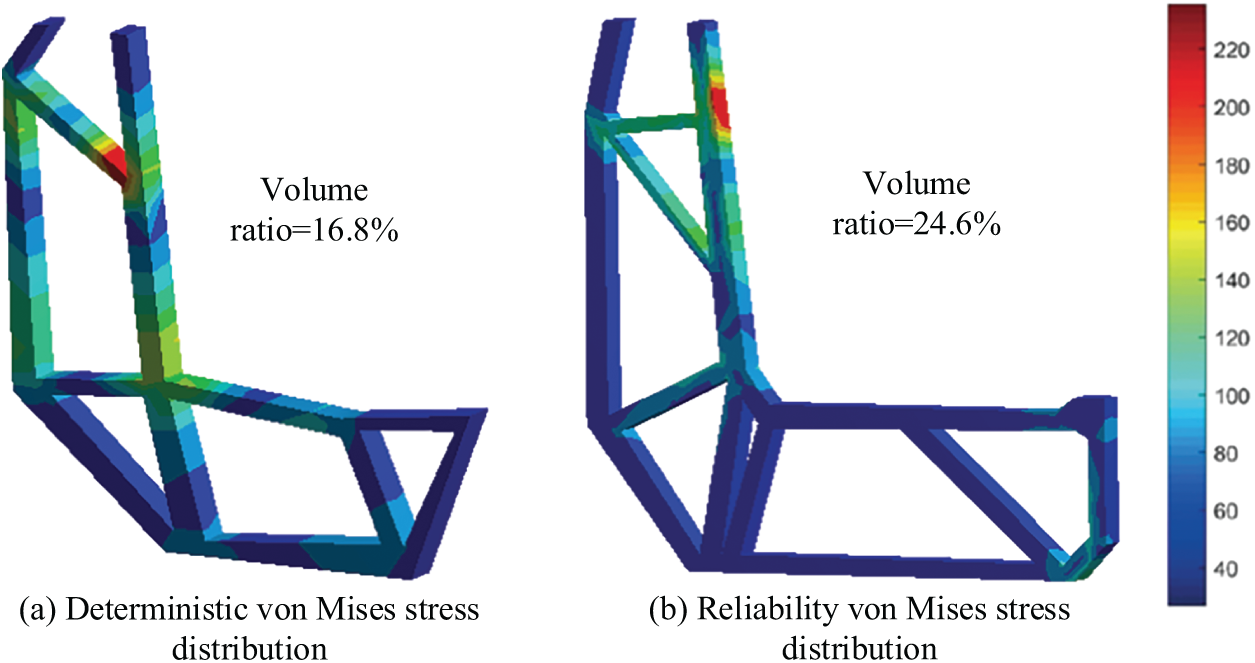

The initial von Mises stress distribution of the structure before optimization is shown in Fig. 9, and the maximum von Mises stress value is 276.22 MPa. The configurations and von Mises stress distributions of the Deterministic Multi-Material Topology Optimization (DMTO) and Non-probabilistic Reliability Based Multi-Material Topology Optimization (NRBMTO) obtained after optimization are shown in Fig. 10, and the topology optimization results are shown in Table 6.

Figure 9: Initial stress distribution of 3D L-beam

Figure 10: Multi-material topological configuration and stress distribution after 3D L-beam optimization

By observing the optimization results in Fig. 10 and Table 6, it can be seen that the structure obtained by NRBMTO has a more uniform stress distribution and a higher reliability level than the structure obtained by DMTO. However, the time consumed by these two methods is not much different. In addition, similar to the two-dimensional L-beam problem, the topological configuration obtained by NRBMTO is also significantly different from that of DMTO, such as the increase of about 5% in volume of the structure to make the structure approximately reach the target reliability index value. The increased volume of the structure is reflected in the addition of rod-shaped components mainly composed of material A in the structure, and in the increase in the proportion of high-strength materials B and C in high-stress areas.

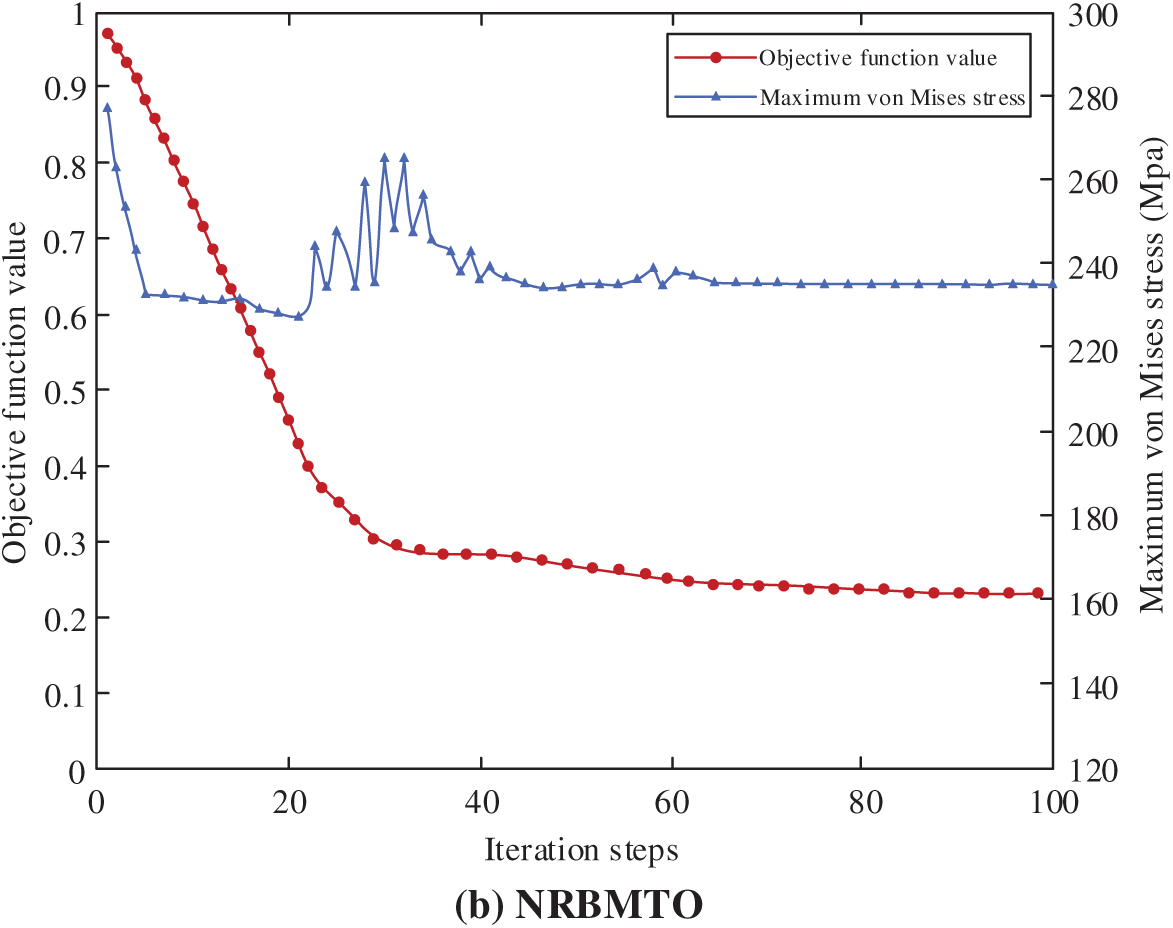

The volume fraction and maximum von Mises stress iteration curves of DMTO and NRBMTO are shown in Fig. 11. After about 50 iterations, both DMTO and NRBMTO begin to stabilize. This three-dimensional example shows that the proposed method is also well applicable and effective for three-dimensional structural problems. It has certain practical significance and application prospects for solving the uncertainty problem of multi-material structures, considering strength design requirements. It can be observed that, compared to the traditional method, the proposed approach reduces the upper bound of structural compliance by approximately 30%, and the stress concentration factor is reduced by approximately 42%. In engineering, this method can also effectively enhance the reliability of the design, while reducing the time required for the design and improving efficiency.

Figure 11: DMTO, NRBMTO objective function and maximum von Mises stress iteration curve: (a) DMTO; (b) NRBMTO

Based on the basic principles of the level set method in the field of topology optimization, this paper adopts the topology optimization method of the Kriging-assisted level set function. It combines the DHPSO that integrates particle recombination learning and probabilistic hybrid mutation strategy to propose a reliability topology optimization framework of the Kriging-assisted level set-DHPSO. The application comparison is carried out through three different structural examples such as cantilever rectangular plates, hyperstatic beams and 3D L-beams, and compared with the SIMP method and the standard level set method, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) The results of the RBTO framework proposed in this paper are comparable to those obtained using the variable density method. However, considering uncertainties, the reliability index and volume fraction of the RBTO structure are higher than those of the DTO structure. The results show that the members in the RBTO structure are thicker, demonstrating the advantages of the proposed reliability-based topology optimization framework. Additionally, in the RBTO model, as the target reliability index

(2) In the DHPSO algorithm, the sensitivity-guided mechanism utilizes gradient information of design variables to direct the movement direction of particles. Additionally, a particle experience fireworks strategy emphasizes information sharing and experiential learning among particles. The results demonstrate that, with the assistance of the two proposed strategies, the optimization design framework can more precisely approximate the optimal solution.

(3) During the optimization process, the Kriging model dynamically updates itself with newly generated sample points, enhancing its accuracy in substituting for finite element analysis. Compared to traditional FEA methods, the proposed Kriging surrogate model significantly improves computational efficiency and reduces the number of FEA iterations required. In addition, the method proposed in Case 2 reduces the time consumption by approximately 50% compared to the original SIMP method, demonstrating its effect in improving computational efficiency. By integrating with the DHPSO algorithm, the proposed Kriging model facilitates the identification of global optimal solutions, demonstrating stronger capabilities in handling influences arising from complex operating conditions and uncertain factors, thereby enhancing the applicability and reliability of the optimization design.

(4) From the computational results, it can be observed that the volume fractions obtained by the proposed framework are consistently lower than those derived from the variable density method (SIMP). Furthermore, the topological configurations exhibit smooth boundaries without grayscale elements. Therefore, the proposed framework demonstrates certain advantages over existing topology optimization methods.

Although the topology optimization method proposed in this study has demonstrated high effectiveness and applicability in engineering applications, its potential for broader utilization remains constrained by the declining accuracy of the Kriging model when addressing ultra-high-dimensional problems. Although it may be influenced by computational efficiency, by integrating physics-driven approaches with other advanced machine learning models, it is still possible to obtain solutions applicable to higher-dimensional and complex engineering problems. Therefore, subsequent research will focus on advancing machine learning techniques to develop optimization algorithms with enhanced generality. In addition, regarding the potential issue of computational resource wastage caused by the mismatch in the number of iterations between the inner and outer loops, our future research will further explore methods to optimize the algorithm structure. These may include adaptive inner-loop iteration control and outer-loop iteration acceleration strategies.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the fundings supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2025YFHZ0065).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Xiaojun Ding, Song Chen and Qijun Zhang; methodology, Hang Zhou, Xiaojun Ding, Song Chen and Qijun Zhang; software, Xiaojun Ding and Song Chen; validation, Song Chen and Qijun Zhang; formal analysis, Hang Zhou, Xiaojun Ding and Song Chen; investigation, Xiaojun Ding, Song Chen and Qijun Zhang; resources, Hang Zhou and Xiaojun Ding; writing—original draft preparation, Xiaojun Ding, Song Chen and Qijun Zhang; writing—review and editing, Hang Zhou, Xiaojun Ding, Song Chen and Qijun Zhang; visualization, Song Chen and Qijun Zhang; supervision, Hang Zhou and Xiaojun Ding; project administration, Song Chen and Qijun Zhang; funding acquisition, Hang Zhou, Xiaojun Ding and Song Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Banh TT, Kang J, Shin S, Lee D. Multi material polygonal topology optimization for functionally graded isotropic and incompressible linear elastic structures. Steel Compos Struct. 2024;51(3):261–70. [Google Scholar]

2. Zou H, Yu S, Dai X, Hou X, Wang W. Topology optimization based on combined mechanical analysis and variable density method for casting structure. Mech Adv Mater Struct. 2025;32(4):625–33. doi:10.1080/15376494.2024.2353372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Meng D, Yang S, Yang H, De Jesus AMP, Correia J, Zhu SP. Intelligent-inspired framework for fatigue reliability evaluation of offshore wind turbine support structures under hybrid uncertainty. Ocean Eng. 2024;307(4):118213. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.118213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Meng D, Yang S, He C, Wang H, Lv Z, Guo Y, et al. Multidisciplinary design optimization of engineering systems under uncertainty: a review. Int J Struct Integr. 2022;13(4):565–93. doi:10.1108/ijsi-05-2022-0076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhong C, Li G, Meng Z, Li H, Yildiz AR, Mirjalili S. Starfish optimization algorithm (SFOAa bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization compared with 100 optimizers. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;37(5):3641–83. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10694-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Meng D, Yang H, Yang S, Zhang Y, De Jesus AMP, Correia J, et al. Kriging-assisted hybrid reliability design and optimization of offshore wind turbine support structure based on a portfolio allocation strategy. Ocean Eng. 2024;295(5):116842. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.116842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yang S, Meng D, Wang H, Yang C. A novel learning function for adaptive surrogate-model-based reliability evaluation. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2024;382(2264):20220395. doi:10.1098/rsta.2022.0395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Manouchehry Nya R, Abdullah S, Singh Karam Singh S. Reliability-based fatigue life of vehicle spring under random loading. Int J Struct Integr. 2019;10(5):737–48. doi:10.1108/ijsi-03-2019-0025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Meng Z, Tian Z, Gao Y, Faes MGR, Li Q. Transient dynamic robust topology optimization methodology for continuum structure under stochastic uncertainties. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2025;442:118019. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2025.118019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xia Z, Zhao W, Wang Y, Li P, Xiao M, Gao L. Multi-material isogeometric topology optimization for thermoelastic metamaterials. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2025;245:126995. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2025.126995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang Y, Yan P, Wang X, Chen B. Energy absorption characteristic of a novel topology-optimized self-locking structure. Int J Struct Integr. 2025;16(4):793–830. doi:10.1108/ijsi-01-2025-0014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Meng Z, Lv S, Gao Y, Zhong C, An K. Data-driven reliability-based topology optimization by using the extended multi scale finite element method and neural network approach. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2025;438(8):117837. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2025.117837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ishida N, Furuta K, Kishimoto M, Hu T, Iwai H, Izui K, et al. Topology optimization for all-solid-state-batteries using homogenization method. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2024;67(9):162. doi:10.1007/s00158-024-03864-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rao X, Cheng W, Du R. Topological design of microstructured materials using energy-based homogenization theory and proportional topology optimization with the level-set method. Mater Today Commun. 2024;40(6):109511. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.109511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ozguc S, Dionne P, Thorsell M, Blennius M, Nilsson T, Pan L, et al. Experimental investigation of an additively manufactured cold plate for multi-chip module cooling generated using the homogenization approach to topology optimization. Appl Therm Eng. 2025;258(2):124741. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.124741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Müller P, Synek A, Stauß T, Steinnagel C, Ehlers T, Gembarski PC, et al. Development of a density-based topology optimization of homogenized lattice structures for individualized hip endoprostheses and validation using micro-FE. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):5719. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-56327-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Moj K, Robak G, Owsiński R. Optimization of the numerical homogenization method for cellular structures manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Procedia Struct Integr. 2024;56(C):120–30. doi:10.1016/j.prostr.2024.02.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nguyen MN, Lee D. Design of the multiphase material structures with mass, stiffness, stress, and dynamic criteria via a modified ordered SIMP topology optimization. Adv Eng Softw. 2024;189(4):103592. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2023.103592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zheng J, Zhu S, Soleymani F. A new efficient parametric level set method based on radial basis function-finite difference for structural topology optimization. Comput Struct. 2024;297(1):107364. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2024.107364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chen D, Kumar P, Kametani Y, Hasegawa Y. Multi-objective topology optimization of heat transfer surface using level-set method and adaptive mesh refinement in OpenFOAM. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2024;221(2):125099. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2023.125099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Liu C, Li S, Liu J, Bian X, Xiao Y. An advanced topology optimization technique for high-resolution designs at arbitrary scale. Eng Optim. 2025:1–27. doi:10.1080/0305215x.2024.2424368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang Q, Han H, Wang C, Liu Z. Topological control for 2D minimum compliance topology optimization using SIMP method. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2022;65(1):38. doi:10.1007/s00158-021-03124-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yarlagadda T, Zhang Z, Jiang L, Bhargava P, Usmani A. Solid isotropic material with thickness penalization—a 2.5D method for structural topology optimization. Comput Struct. 2022;270:106857. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2022.106857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Bohrer R, Kim IY. Multi-material topology optimization considering isotropic and anisotropic materials combination. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2021;64(3):1567–83. doi:10.1007/s00158-021-02941-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yang A, Wang S, Luo N, Xie X, Xiong T. Adaptive isogeometric multi-material topology optimization based on suitably graded truncated hierarchical B-spline. Compos Struct. 2022;294(2):115773. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Li H, Gao L, Li H, Li X, Tong H. Full-scale topology optimization for fiber-reinforced structures with continuous fiber paths. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2021;377:113668. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2021.113668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xue L, Liu J, Wen G, Wang H. Efficient, high-resolution topology optimization method based on convolutional neural networks. Front Mech Eng. 2021;16(1):80–96. doi:10.1007/s11465-020-0614-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hu J, Luo Y, Liu S. Two-scale concurrent topology optimization method of hierarchical structures with self-connected multiple lattice-material domains. Compos Struct. 2021;272(3):114224. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.114224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Fan B, Huang H, Hu J, Liu S. Direct load-carrying boundary identification-based topology optimization method for structures with design-dependent boundary load. Numer Meth Eng. 2025;126(6):e70010. doi:10.1002/nme.70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang J, Xiao M, Li P, Gao L. Quantile-based topology optimization under uncertainty using Kriging metamodel. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2022;393:114690. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2022.114690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Raponi E, Bujny M, Olhofer M, Aulig N, Boria S, Duddeck F. Kriging-assisted topology optimization of crash structures. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2019;348(2):730–52. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2019.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tao W, Liu Z, Zhu P, Zhu C, Chen W. Multi-scale design of three dimensional woven composite automobile fender using modified particle swarm optimization algorithm. Compos Struct. 2017;181:73–83. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.08.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xue Y, Zhang Q, Slowik A. Automatic topology optimization of echo state network based on particle swarm optimization. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;117(3):105574. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Peng J, Li Y, Kang H, Shen Y, Sun X, Chen Q. Impact of population topology on particle swarm optimization and its variants: an information propagation perspective. Swarm Evol Comput. 2022;69:100990. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2021.100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Pasandideh F, Silva TDE, Santos da Silva AA, Pignaton de Freitas E. Topology management for flying ad hoc networks based on particle swarm optimization and software-defined networking. Wirel Netw. 2022;28(1):257–72. doi:10.1007/s11276-021-02835-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Banh TT, Lee D. Efficient topology optimization for geometrically nonlinear multi-material systems under design-dependent pressure loading. Eng Comput. 2025;41(2):1155–89. doi:10.1007/s00366-024-02083-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang X, Xiao M, Luo W, Gao L, Gao J. Isogeometric topology optimization for innovative designs of the reinforced TPMS unit cells with curvy stiffeners using T-splines. Compos Struct. 2025;357:118955. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2025.118955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yang Z, Gao L, Xiao M, Luo W, Fang X, Gao J. Geometrical nonlinearity infill topology optimization for porous structures using the parametric level set method. Thin Walled Struct. 2025;210(1):113013. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2025.113013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Deng S, Wang P, Wen W, Liang J. A novel quasi-smooth tetrahedral numerical manifold method and its application in topology optimization based on parameterized level-set method. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2024;425:116948. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2024.116948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Sato H, Igarashi H. Deep learning-based surrogate model for fast multi-material topology optimization of IPM motor. COMPEL Int J Comput Math Electr Electron Eng. 2022;41(3):900–14. doi:10.1108/compel-03-2021-0086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Yang B, Wang X, Cheng C, Lee I, Hu Z. Surrogate model-based method for reliability-oriented buckling topology optimization under random field load uncertainty. Structures. 2024;63(2):106382. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Liu X, Gao L, Xiao M. An efficient multiscale topology optimization method for frequency response minimization of cellular composites. Eng Comput. 2025;41(1):267–91. doi:10.1007/s00366-024-02000-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wang J, Zhu J, Liu T, Wang Y, Zhou H, Zhang WH. Topology optimization of gradient lattice structure under harmonic load based on multiscale finite element method. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2023;66(9):202. doi:10.1007/s00158-023-03652-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Meng D, Li Y, He C, Guo J, Lv Z, Wu P. Multidisciplinary design for structural integrity using a collaborative optimization method based on adaptive surrogate modelling. Mater Des. 2021;206(2):109789. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2021.109789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Meng D, Yang S, De Jesus AMP, Fazeres-Ferradosa T, Zhu SP. A novel hybrid adaptive Kriging and water cycle algorithm for reliability-based design and optimization strategy: application in offshore wind turbine monopile. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2023;412(6):116083. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2023.116083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Seo J, Kapania RK. Topology optimization with advanced CNN using mapped physics-based data. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2023;66(1):21. doi:10.1007/s00158-022-03461-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Lu Y, Alfouneh M, Keshtegar B, Yang S, Meng D. Optimal design of cellular composite structures via topology optimization considering multisource uncertainties. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2025;68(5):89. doi:10.1007/s00158-025-04027-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Meng D, Yang S, de Jesus AMP, Zhu SP. A novel Kriging-model-assisted reliability-based multidisciplinary design optimization strategy and its application in the offshore wind turbine tower. Renew Energy. 2023;203(12):407–20. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.12.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Jia LH, Li XK, Yuan WZ, He WB, Liao ZJ. Lightweight design of front and middle shield structures based on topology optimization and Kriging model. China Mech Eng. 2022;33:2888–97. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

50. He Q, Li X, Mao W, Yang X, Wu H. Research on vehicle frame optimization methods based on the combination of size optimization and topology optimization. World Electr Veh J. 2024;15(3):107. doi:10.3390/wevj15030107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Piotrowski AP, Napiorkowski JJ, Piotrowska AE. Particle swarm optimization or differential evolution—a comparison. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;121(11):106008. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wang D, Tan D, Liu L. Particle swarm optimization algorithm: an overview. Soft Comput. 2018;22(2):387–408. doi:10.1007/s00500-016-2474-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Li Z, Wang L, Geng X. A level set reliability-based topology optimization (LS-RBTO) method considering sensitivity mapping and multi-source interval uncertainties. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2024;419(09):116587. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2023.116587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Wei P, Li Z, Li X, Wang MY. An 88-line MATLAB code for the parameterized level set method based topology optimization using radial basis functions. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2018;58(2):831–49. doi:10.1007/s00158-018-1904-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Lu C, Yuan H, Zhang N. Nanophotonic devices based on optimization algorithms. In: Intelligent nanotechnology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023. p. 71–111. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-85796-3.00004-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Nguyen MN, Hoang VN, Lee D. Topology optimization framework for thermoelastic multiphase materials under vibration and stress constraints using extended solid isotropic material penalization. Compos Struct. 2024;344(2):118316. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2024.118316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Sigmund O. Morphology-based black and white filters for topology optimization. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2007;33(4):401–24. doi:10.1007/s00158-006-0087-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Hamza K, Aly M, Hegazi H. A Kriging-interpolated level-set approach for structural topology optimization. J Mech Des. 2014;136(1):011008. doi:10.1115/1.4025706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Tong QJ, Li M, Zhao Q. An improved particle swarm optimization algorithm based on classification. Mod Electron Tech. 2019;42(19):11–4. (In Chinese). doi:10.16652/j.issn.1004-373x.2019.19.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Sabat SL, Ali L, Udgata SK. Integrated learning particle swarm optimizer for global optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2011;11(1):574–84. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2009.12.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Li M, Lu FB, Chen H. Cultural algorithm based on multi-layer belief space. Acta Electron Sin. 2015;43:888–94. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

62. Xin B, Chen J, Zhang J, Fang H, Peng ZH. Hybridizing differential evolution and particle swarm optimization to design powerful optimizers: a review and taxonomy. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Part C Appl Rev. 2012;42(5):744–67. doi:10.1109/TSMCC.2011.2160941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Clerc M, Kennedy J. The particle swarm—explosion, stability, and convergence in a multidimensional complex space. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2002;6(1):58–73. doi:10.1109/4235.985692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Hu W, Li ZS. A simpler and more effective particle swarm optimization algorithm. J Softw. 2007;18:861–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

65. Li YM, Zhang HF, Cheng L, Wang J. Particle swarm optimization based on multi-subgroup and subspace learning strategy. Comput Digit Eng. 2018;46(9):1768–72. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

66. Li VC. Large volume, high-performance applications of fibers in civil engineering. J Appl Polym Sci. 2002;83(3):660–86. doi:10.1002/app.2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools