Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Flexible Exponential Log-Logistic Distribution for Modeling Complex Failure Behaviors in Reliability and Engineering Data

1 Department of Mathematics, College of Science, Jazan University, Jazan, 45142, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Mathematical Sciences, College of Science, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, P.O. Box 84428, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

3 Higher Institute of Computer Science and Information Technology, El Shorouk Academy, Shorouk, 11837, Egypt

4 Department of Statistics, Mathematics, and Insurance, Zagazig University, Zagazig, 44519, Egypt

5 Department of Statistics, Mathematics, and Insurance, Benha University, Benha, 13511, Benha

* Corresponding Author: Ahmed Z. Afify. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Frontiers in Parametric Survival Models: Incorporating Trigonometric Baseline Distributions, Machine Learning, and Beyond)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 2029-2061. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069801

Received 01 July 2025; Accepted 04 August 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Parametric survival models are essential for analyzing time-to-event data in fields such as engineering and biomedicine. While the log-logistic distribution is popular for its simplicity and closed-form expressions, it often lacks the flexibility needed to capture complex hazard patterns. In this article, we propose a novel extension of the classical log-logistic distribution, termed the new exponential log-logistic (NExLL) distribution, designed to provide enhanced flexibility in modeling time-to-event data with complex failure behaviors. The NExLL model incorporates a new exponential generator to expand the shape adaptability of the baseline log-logistic distribution, allowing it to capture a wide range of hazard rate shapes, including increasing, decreasing, J-shaped, reversed J-shaped, modified bathtub, and unimodal forms. A key feature of the NExLL distribution is its formulation as a mixture of log-logistic densities, offering both symmetric and asymmetric patterns suitable for diverse real-world reliability scenarios. We establish several theoretical properties of the model, including closed-form expressions for its probability density function, cumulative distribution function, moments, hazard rate function, and quantiles. Parameter estimation is performed using seven classical estimation techniques, with extensive Monte Carlo simulations used to evaluate and compare their performance under various conditions. The practical utility and flexibility of the proposed model are illustrated using two real-world datasets from reliability and engineering applications, where the NExLL model demonstrates superior fit and predictive performance compared to existing log-logistic-based models. This contribution advances the toolbox of parametric survival models, offering a robust alternative for modeling complex aging and failure patterns in reliability, engineering, and other applied domains.Keywords

The quality and reliability of statistical analysis fundamentally depend on the selection of an appropriate probability distribution. In recognition of this critical requirement, considerable research efforts have been devoted to developing flexible classes of probability distributions and refining associated statistical methodologies. These advancements have found widespread application across a broad spectrum of disciplines, including insurance and actuarial science, financial risk analysis, business and economic forecasting, reliability and chemical engineering, medical and clinical research, demographic analysis, and sociological studies. The versatility of these models in capturing the complexity of real-world phenomena highlights their essential role in modern, data-driven decision-making processes.

The statistical literature has introduced several newly generated classes of univariate continuous distributions by incorporating additional shape parameters into baseline models. These extended distributions have garnered the attention of statisticians due to their flexibility and capability to model both monotonic and non-monotonic real-life data. Notable examples include the Marshall–Olkin-G [1], beta-G [2], Kumaraswamy-G [3], McDonald-G [4], Weibull-G [5], Kumaraswamy Marshal–Olkin-G [6], generalized alpha exponent power-G [7], length-biased truncated Lomax-G [8], Ramos–Louzada-G [9], Lambert-G [10], and new exponential-H (NEx-H) [11] families, among others.

The log-logistic (LL) distribution—also referred to as the Fisk distribution in economics, particularly for modeling income distributions [12–14]—is a two-parameter model defined by its scale and shape parameters. Arnold [15] extended this model by incorporating a location parameter, leading to the Pareto Type III distribution, which generalizes the LL distribution. Moreover, the LL distribution arises as a special case of two broader and more flexible families: the Burr type XII distribution [16] and the Kappa distribution [17], obtained by specifying particular values for the shape parameters within those models.

These parent distributions are especially popular in hydrological studies, where they are employed to model skewed data and extreme events, such as streamflow and precipitation. The LL distribution inherits many of these desirable characteristics while offering a more parsimonious structure, making it an appealing choice in applications where simplicity and interpretability are essential. For comprehensive discussions on the statistical properties, historical development, and wide-ranging applications of the LL distribution, refer to [18]. Recent studies have extended its applications, including detecting clinical risk shifts using LL hazard change-point models [19] and developing robust inference procedures based on minimum density power divergence estimators [20].

The LL distribution can be interpreted as the probability distribution of a random variable whose logarithm follows a logistic distribution. It is often employed as a viable alternative to the log-normal distribution, particularly due to its hazard rate function (HRF), which characteristically increases to a peak before decreasing—a feature that enhances its applicability in modeling lifetime and reliability data. To improve its flexibility and modeling capacity, numerous researchers have proposed generalized forms of the LL distribution. Among the notable extensions are the beta LL [21], the Marshall–Olkin LL [22], the McDonald LL [23], and the Zografos–Balakrishnan LL [24] distributions. Other significant contributions include the Kumaraswamy Marshall–Olkin LL [25], the extended Poisson LL [26], the odd Lomax LL [27], the alpha-power transformed LL [28], the extended LL [29], the skew LL [30], cubic transmuted LL [31], Maxwell LL [32], type–II generalized LL [33], and the recently proposed generalized Kavya–Manoharan LL distribution [34]. These developments reflect the continued interest in enhancing the LL distribution’s ability to model diverse real-world data more accurately and flexibly.

In this paper, we introduce a novel extension of the LL distribution, referred to as the new exponential log-logistic (NExLL) distribution. This model is developed within the framework of the NEx-H family of distributions [11] and is designed to provide enhanced flexibility in modeling complex real-world data. Compared to existing generalizations of the LL distribution, the NExLL model offers several advantages that motivate its development including (i) The NExLL distribution is capable of capturing a wide range of HRF shapes, including increasing, decreasing, J-shaped, reversed J-shaped, modified bathtub, and unimodal forms; (ii) It is well-suited for modeling asymmetric and skewed datasets that may not be adequately handled by traditional LL-based models; (iii) The model has potential applications across numerous fields, including survival analysis, public health, biomedical research, industrial reliability, and engineering; and (iv) Applications to two real-world datasets demonstrate that the NExLL distribution provides a superior fit compared to several well-known LL extensions. These features underscore the practical utility and theoretical contribution of the proposed distribution to the broader field of parametric survival modeling.

The final motivation of this study is to evaluate the performance of various frequentist estimation methods for the proposed NExLL distribution across different sample sizes and parameter settings. Specifically, we consider and compare the maximum likelihood estimators (MLE), least-squares estimators (LSE), weighted LS estimators (WLSE), Cramér–von Mises estimators (CRVME), Anderson–Darling estimators (ADE), right-tail AD estimators (RADE), and the maximum product of spacings estimators (MPSE). This comparative analysis aims to provide practical guidance on selecting the most suitable estimation method for the NExLL distribution, offering valuable insights for applied statisticians working with lifetime and reliability data.

While the proposed NExLL model belongs to the broader NEx-H family, it is not merely a special case of the existing NEx-H framework. The NExLL model stands out due to its complete tractability: closed-form expressions are available for all key functions, including the pro)bability density function (PDF), cumulative distribution function (CDF), moments, quantile function, and HRF. Furthermore, the model preserves the interpretability of the baseline LL parameters, while introducing a new parameter that significantly enhances shape flexibility. This structure enables the NExLL to model complex failure rate behaviors that are not easily handled by general NEx-H models. Moreover, in practical reliability and engineering applications, the NExLL model has demonstrated superior performance, as shown in our real data illustrations.

The rest of the paper is organized into seven sections. The NExLL distribution is investigated in Section 2. In Section 3, some key properties of the NExLL distribution are explored. Inference about the NExLL parameters is presented In Section 4. Section 5 provides simulation studies. In Section 6, we present two real-life data applications. Section 7 gives some conclusions.

In this section, we formally define the proposed NExLL distribution and explore its flexibility graphically. Derived from the NEx-H family [11], the NExLL distribution extends the classical LL model by incorporating an additional shape parameter, thereby enhancing its flexibility in modeling diverse data behaviors.

The CDF of the two-parameter LL model has the form

where

The NExLL distribution is constructed based on the NEx-G family, which is specified by the CDF

The corresponding PDF of the NEx-G class is expressed by

By incorporating the LL distribution (1) as the baseline model within the NEx-H family framework, the CDF of the NExLL distribution is defined as follows:

where

The PDF of the NExLL distribution takes the form

The HRF of the NExLL distribution reduces to

The quantile function (QF) of the NExLL distribution follows by inverting Eq. (5) as

where U follows the uniform (0, 1) distribution.

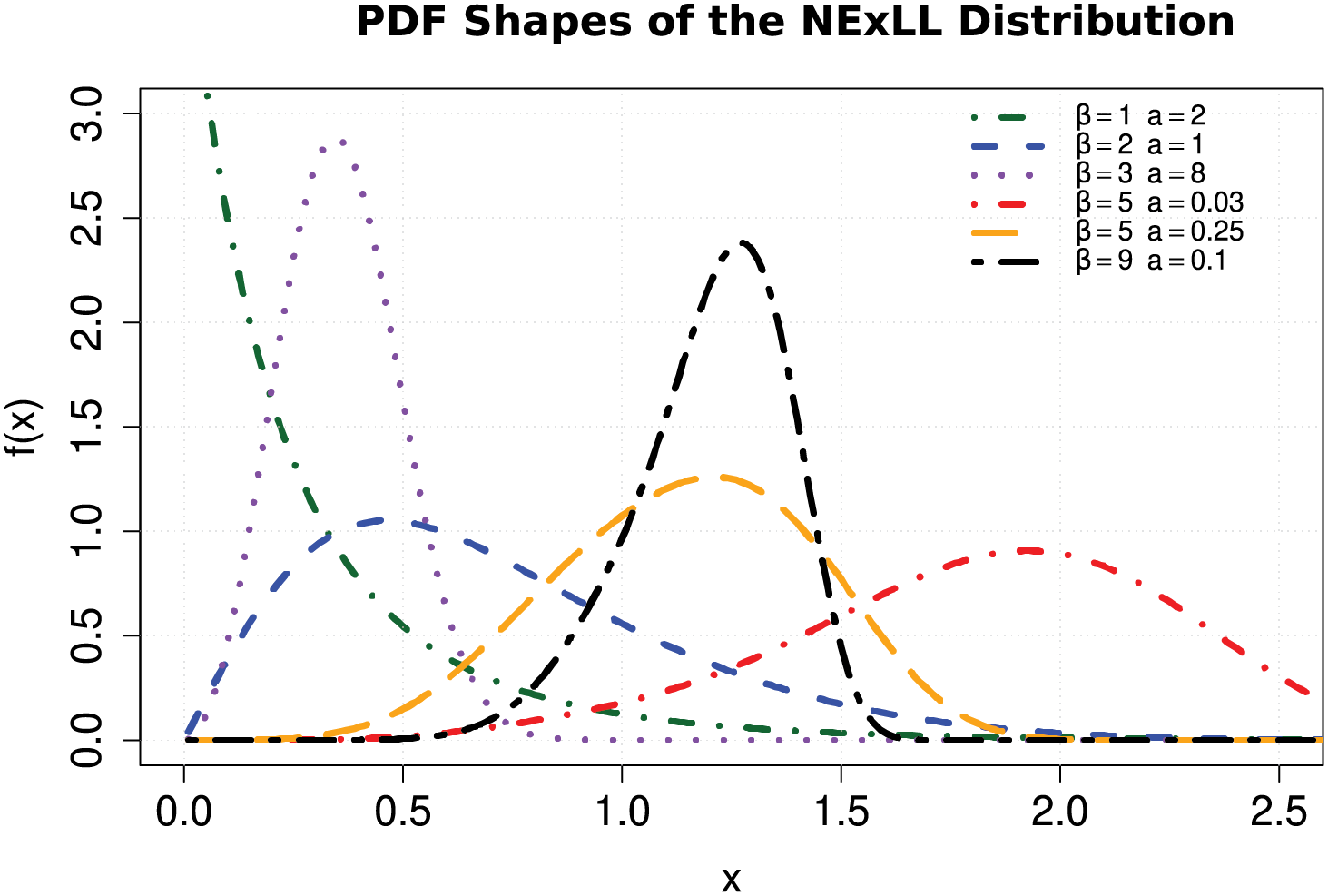

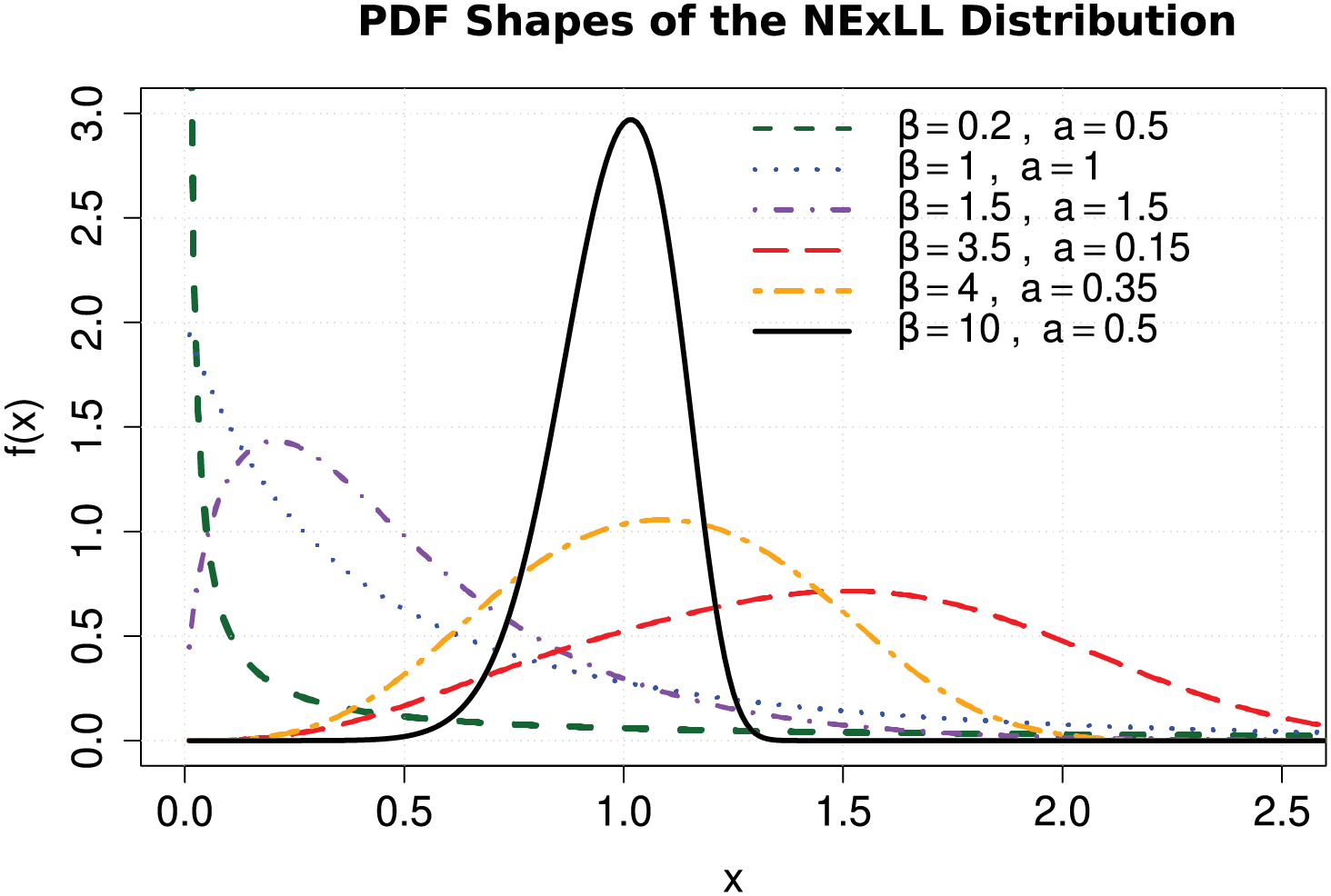

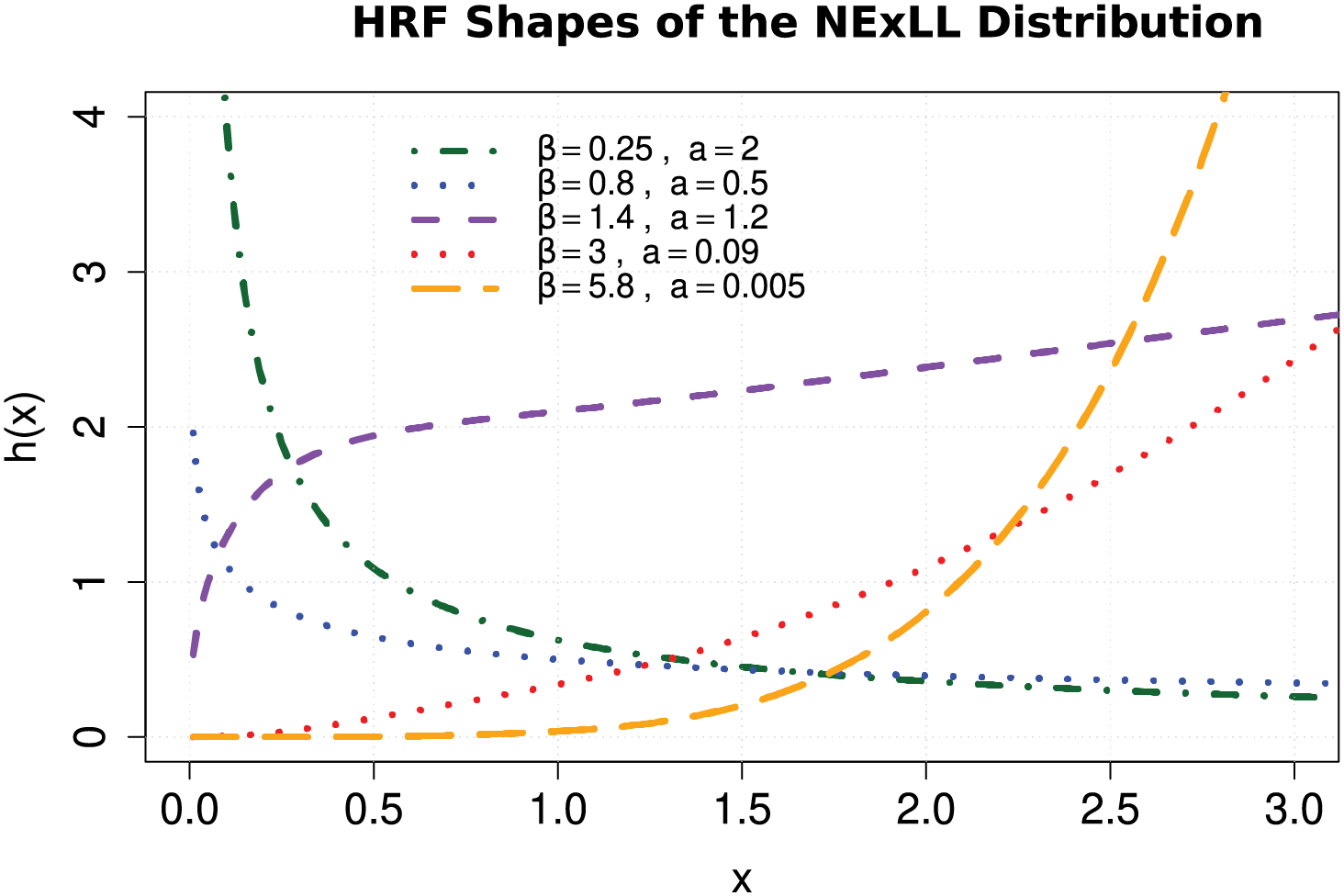

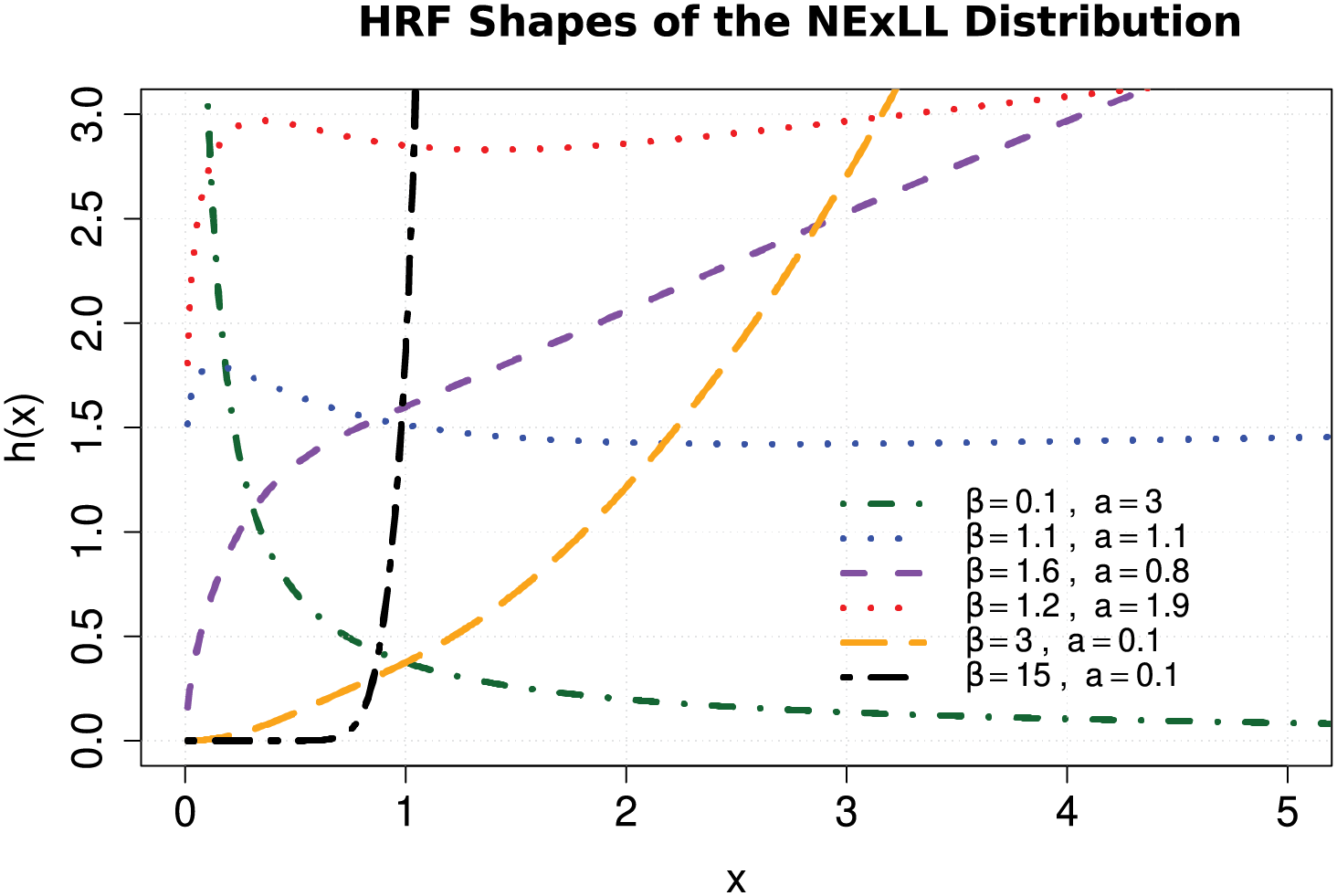

Figs. 1–4 illustrate the flexibility of the proposed NExLL distribution in modeling diverse data behaviors. Figs. 1 and 2 display various PDF shapes for different parameter settings while fixing

Figure 1: Some possible density shapes of the NExLL for various parametric values with

Figure 2: Some possible density shapes of the NExLL for various parametric values with

Figure 3: Some possible failure rate shapes of the NExLL for various parametric values with

Figure 4: Some possible failure rate shapes of the NExLL for various parametric values with

3 Properties of the NExLL Distribution

To improve interpretability, we begin by deriving a series representation of the NExLL distribution. This representation expresses the density as a weighted infinite sum of simpler exponentiated-LL (ELL) components, which facilitates theoretical development and practical computation.

A useful mixture representation of the PDF of the NEx-G class was provided in [10]. According to the NEx-G density reduces to

By substituting the PDF and CDF of the LL model into the general NEx-G formulation, we derive the expanded form of the NExLL density. This expression, although complex, captures the flexible structure of the model through a combination of LL components. After some algebra, the NExLL density takes the form:

For computational efficiency and theoretical tractability, this expression can be rewritten as a more compact infinite sum involving ELL densities, each scaled by specific weight coefficients

where

Using the linear representation, we derive the moments of the NExLL distribution by evaluating the weighted integrals of ELL components. This approach simplifies the calculation of moments by leveraging known results for the ELL distribution.

The

Hence, we have

After performing the integration, we obtain a closed-form series expression for the

The mean of X, say,

Similarly, the

The

Using Eq. (8),

Then, we obtain

where

The mean residual life of the NExLL distribution at age

where

The mean inactivity time of the NExLL distribution takes the form

The Lorenz (L) [35], Bonferroni (B), and Zenga (Z) curves are among the most important tools for measuring inequality, with notable applications in fields such as insurance, medicine, reliability, and economics.

The Lorenz (L) [35], Bonferroni (B) and Zenga (Z) curves are considered the most important inequality curves and have some applications in insurance, medicine, reliability, and economics.

The L curve is defined for the KAPLL distribution as follows:

where

The B and Z inequality curves can be determined, through their relationship with the L curve, by the following formulae [36]

The moment generating function (MGF) can also be derived using the linear representation, which leads to a nested summation form involving gamma functions. This function can be used to derive higher-order moments and cumulants.

The MGF of the NExLL model is defined by

Based on Eq. (8), we can write

The MGF of the NExLL follows, after some algebra, as

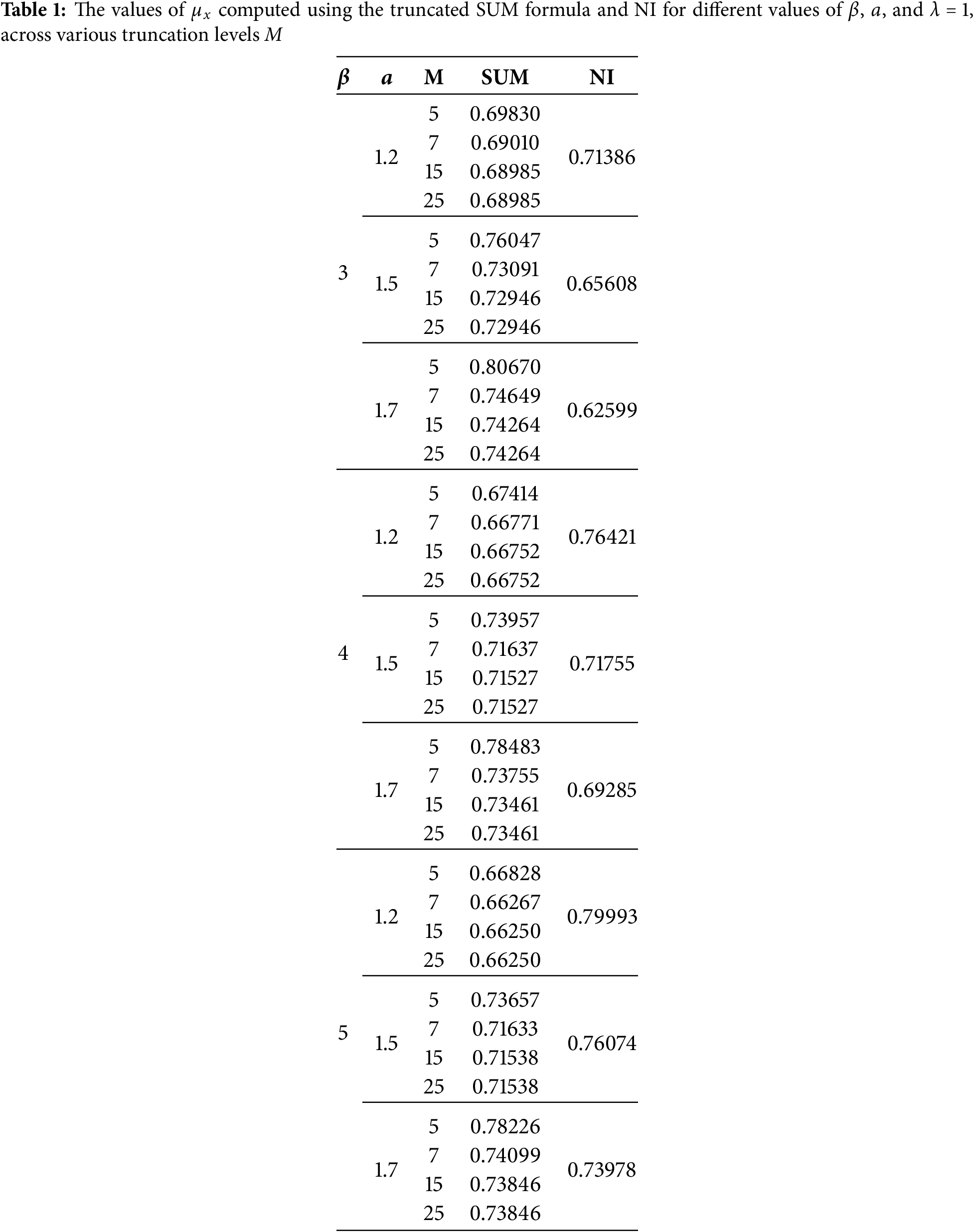

Table 1 presents the computed values of

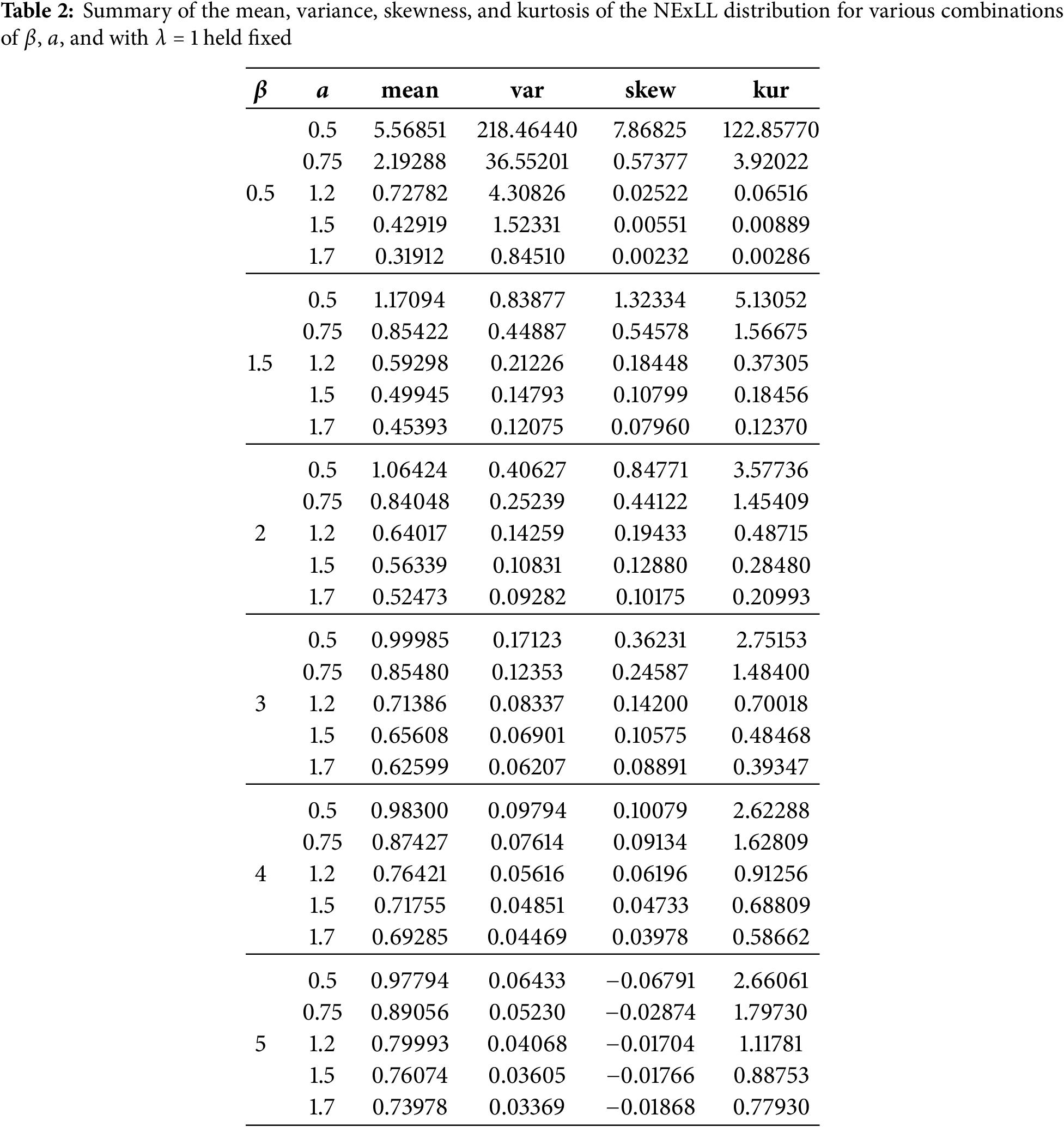

Table 2 presents key descriptive measures—mean

Measures of entropy, such as Rényi and

The Rényi entropy of a random variable X is defined by

Using Eq. (8), the Rényi entropy of the NExLL model takes the form

The

Hence, using (10), the

The order statistics of the NExLL distribution are derived from its PDF and CDF. Given the series form of the density, the order statistic distributions also naturally take the form of infinite summations over ELL components.

Let

Substituting (5) and (6) in (11), the

where

After some algebra, we obtain

The last equation can be expressed as

where

In this section, we use seven methods to estimate the NExLL parameters namely: the maximum likelihood (ML), least-squares (LS), weighted LS (WLS), maximum product of spacings (MPS), Cramér–von Mises (CRVM), Anderson–Darling (AD), and right-tail AD (RAD) methods.

Let

where

To estimate the parameters of the NExLL distribution, we derive the score functions corresponding to the log-likelihood function. These score functions, defined as the partial derivatives of the log-likelihood with respect to the parameters

and

The LSE and WLSE of the NExLL parameters

where

The LS and WLS estimators are obtained by solving the following nonlinear estimating equations:

where

Let

Using

and

Using

Note: In the above expressions,

The MPSE is an alternative approach to the MLE [37,38]. The uniform spacings of a random sample of size

where

The MPSE of the NExLL parameters are determined by solving the non-linear equations

where

The CRVM method minimizes the integrated squared difference between the theoretical and empirical CDFs. The CRVME of the NExLL parameters are obtained by minimizing the following objective function:

which also follow by solving the following estimating equations:

The AD method places more weight on the tails of the distribution. The ADE of the NExLL parameters are obtained by minimizing

where

The ADE can also be found as solutions of the following estimating equations:

The RAD method is a one-sided modification of the AD method focusing on the right tail. The RADE of the NExLL parameters

They can also be obtained from the non-linear estimating equations:

where the expressions

Each of these derivatives is given explicitly in Eqs. (13)–(15), and they are used throughout all estimating equations presented above.

In summary, the score and estimating equations for all seven estimation methods have been explicitly derived, clearly labeled, and organized for better readability. These formulations provide practitioners with the tools necessary to implement the methods and ensure reproducibility of results.

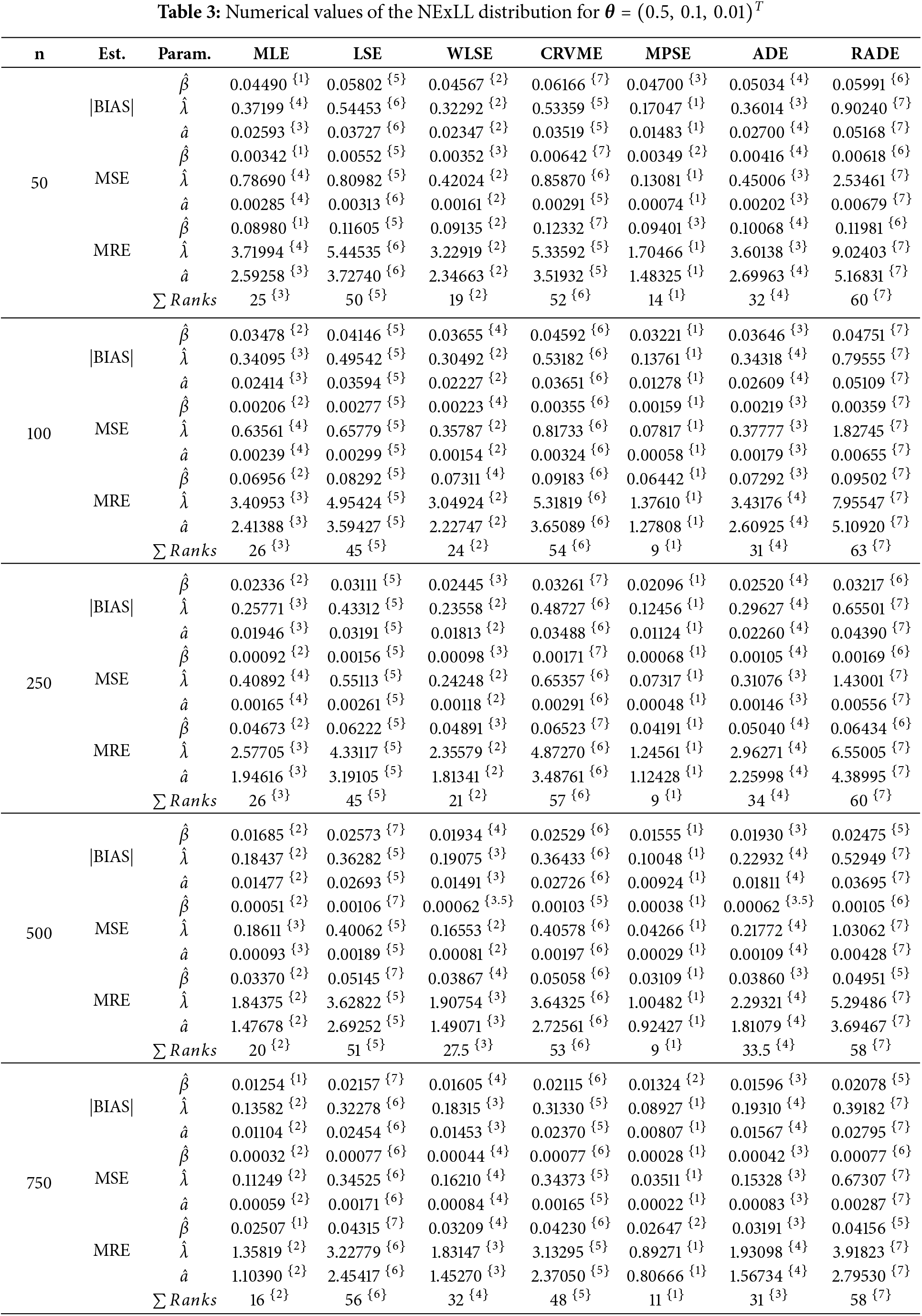

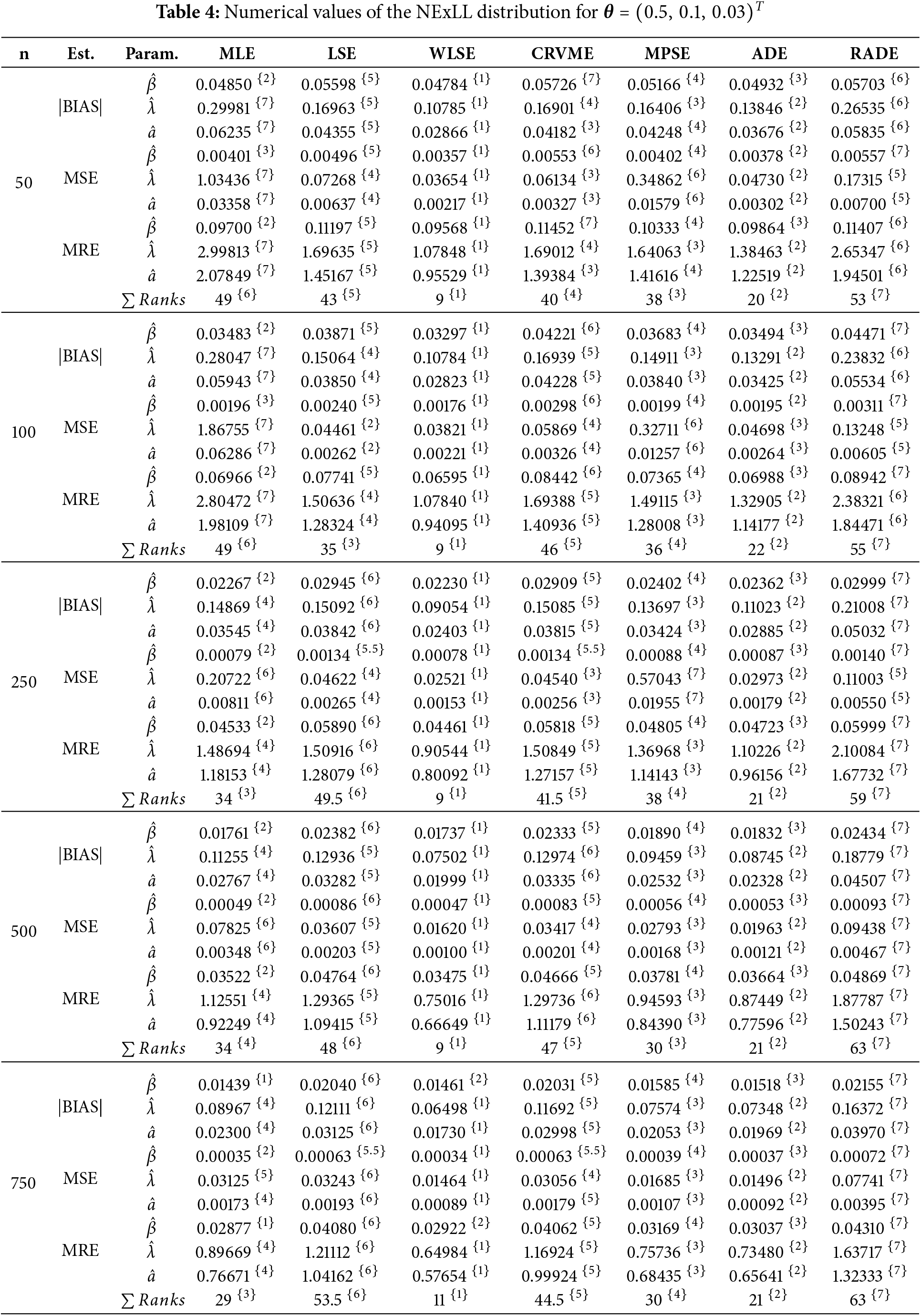

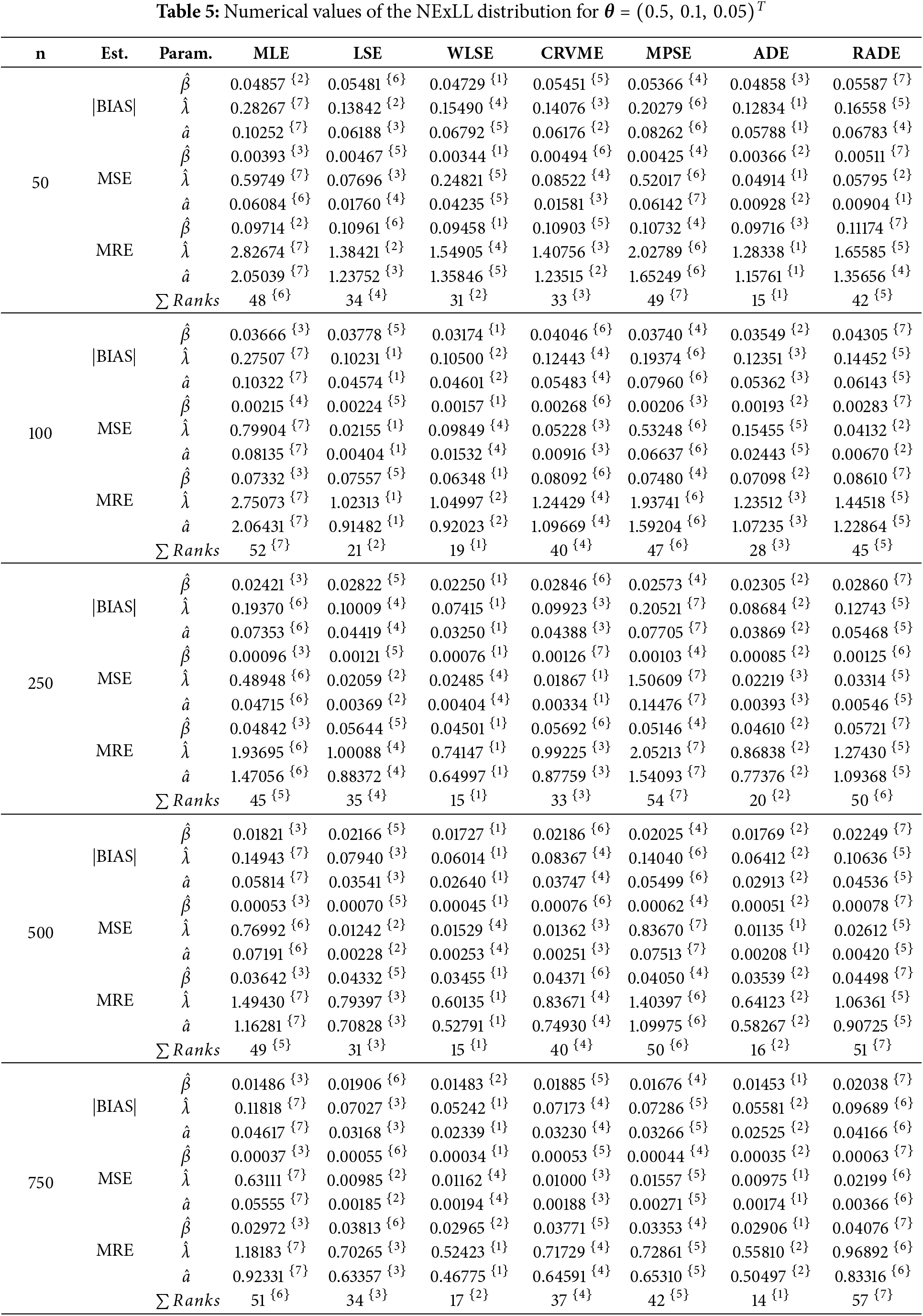

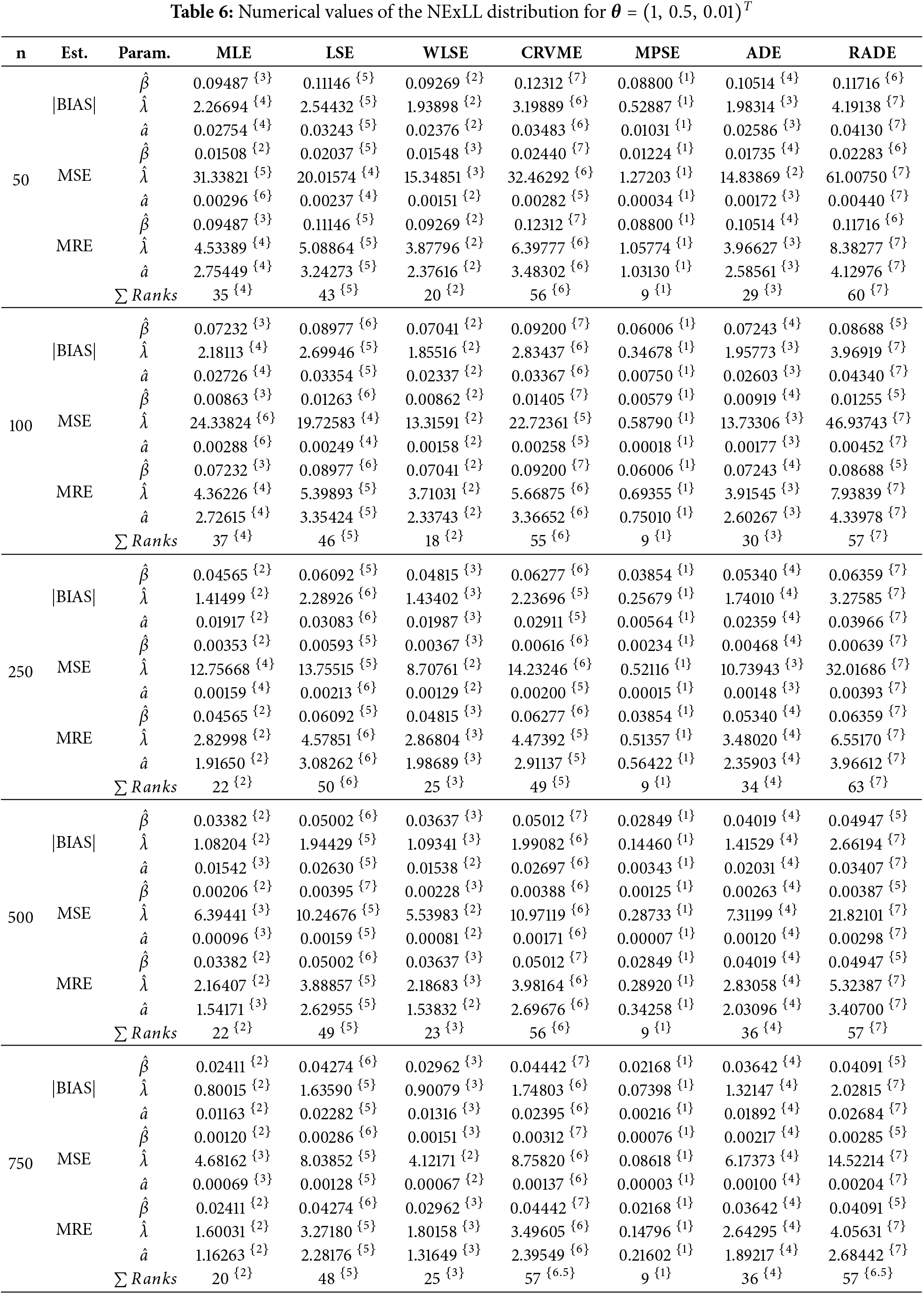

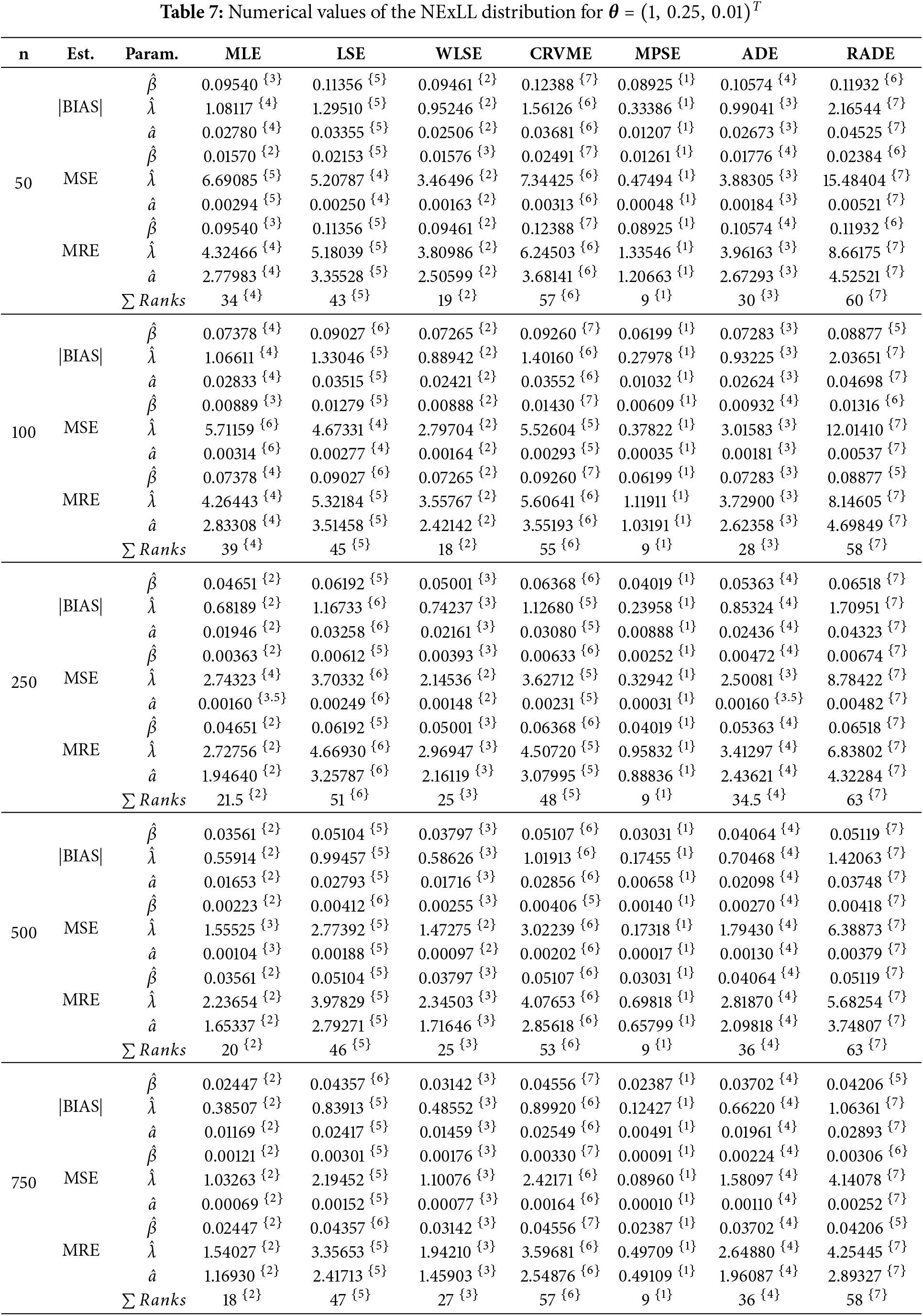

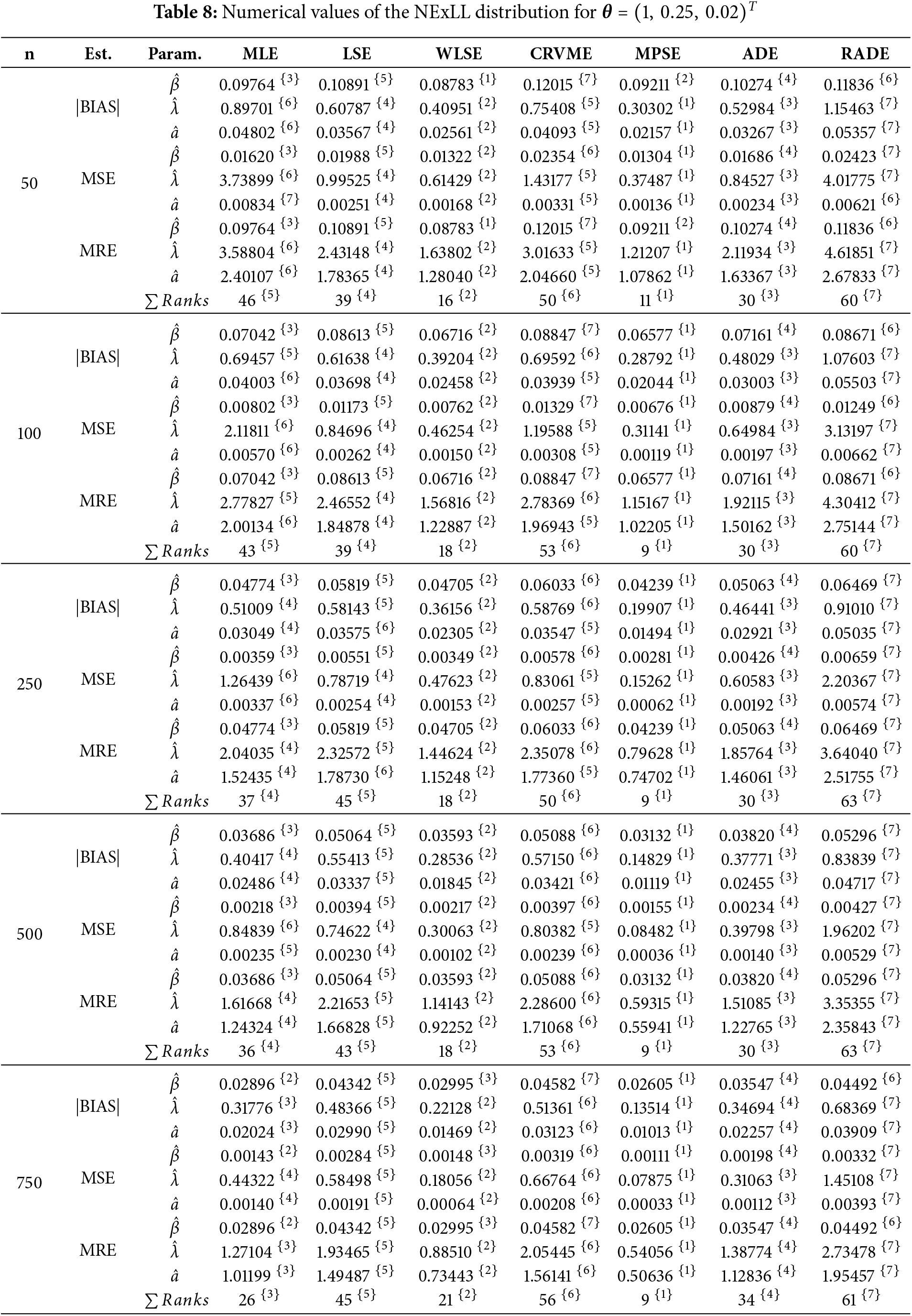

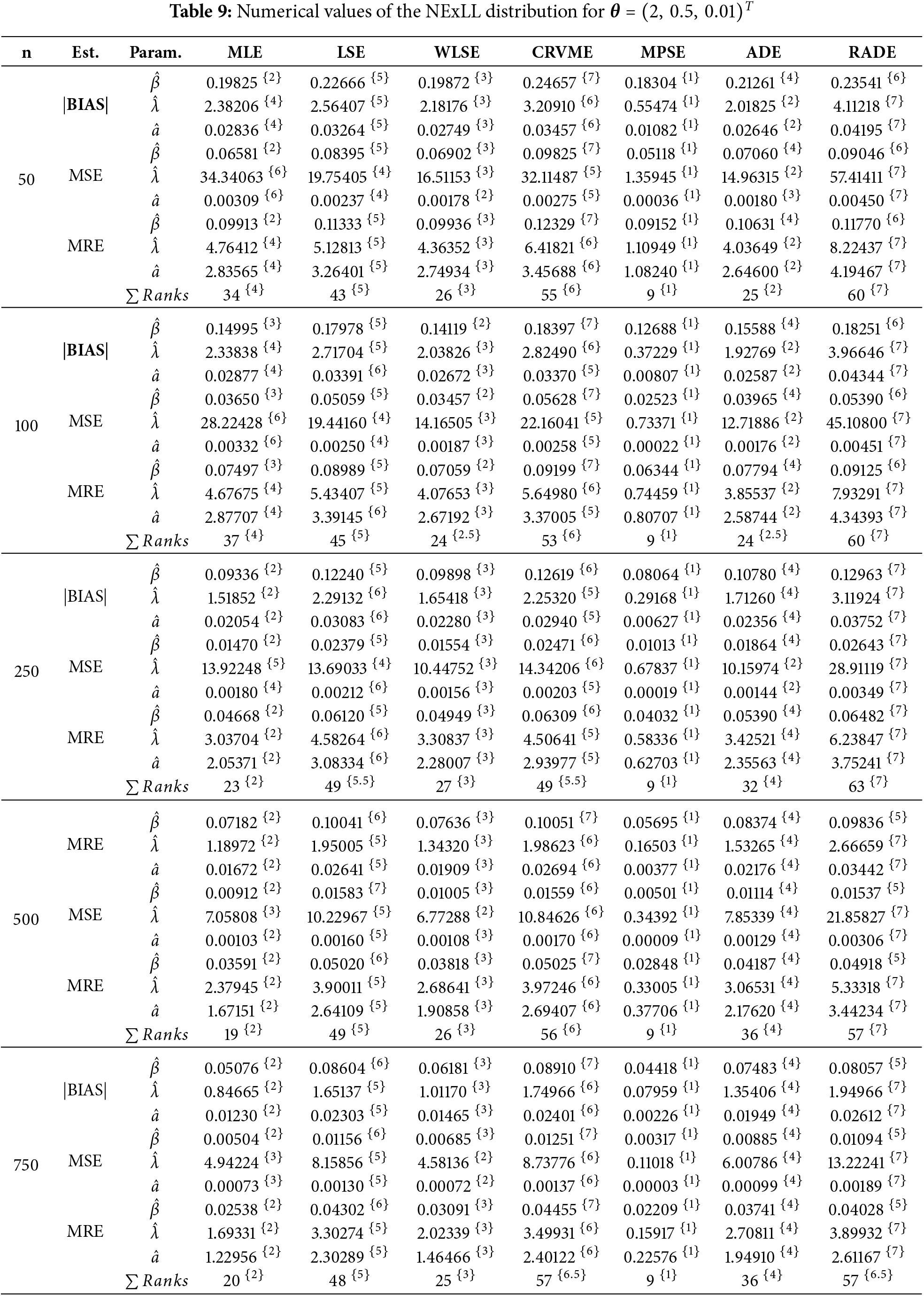

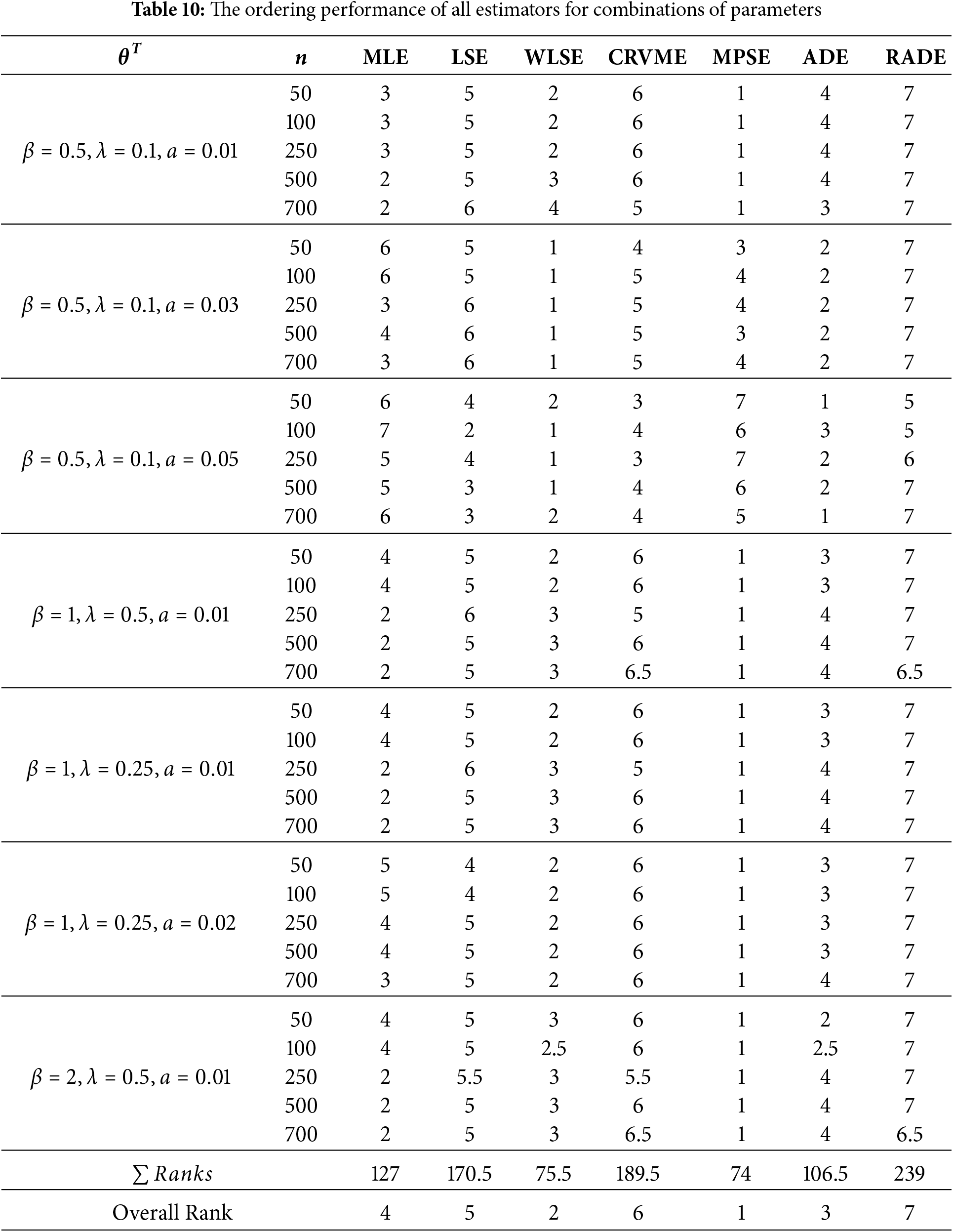

This sections gives detailed simulation results to explore the behavior and performances of the introduced estimation methods in estimating the NExLL parameters based on the following three measures namely: the mean square errors (MSE),

Several sample sizes and parameters combinations are considered, i.e.,

Tables 3–10 give the findings of simulations including the |BIAS|, MSE, and MRE for the eight estimation approaches. The results show that the values of |BIAS|, MSE and MRE decrease with the increase of

6 Real-World Data Applications

This section illustrates the importance and applicability of the NExLL distribution by fitting two real-life data applications from Reliability and engineering sciences. The first data set is addressed by [39], and it contains 40 observations of time to failure (

The second data set refers to breaking stress of carbon fibers in (Gba) for 100 observations, and it is studied by [40]. The data are: 0.39, 0.81, 0.85, 0.98, 1.08, 1.12, 1.17, 1.18, 1.22, 1.25, 1.36, 1.41, 1.47, 1.57,1.57, 1.59, 1.59, 1.61, 1.61, 1.69, 1.69, 1.71, 1.73, 1.80, 1.84, 1.84, 1.87, 1.89, 1.92, 2.0, 2.03, 2.03, 2.05, 2.12, 2.17,2.17, 2.17, 2.35, 2.38, 2.41, 2.43, 2.48, 2.48, 2.50, 2.53, 2.55, 2.55, 2.56, 2.59, 2.67, 2.73, 2.74, 2.76, 2.77, 2.79, 2.81, 2.81, 2.82, 2.83, 2.85, 2.87, 2.88, 2.93, 2.95, 2.96, 2.97, 2.97, 3.09, 3.11, 3.11, 3.15, 3.15, 3.19, 3.19, 3.22, 3.22, 3.27, 3.28, 3.31, 3.31, 3.33, 3.39, 3.39, 3.51, 3.56, 3.60, 3.65, 3.68, 3.68, 3.68, 3.70, 3.75, 4.20, 4.38, 4.42, 4.70, 4.90, 4.91, 5.08, 5.56.

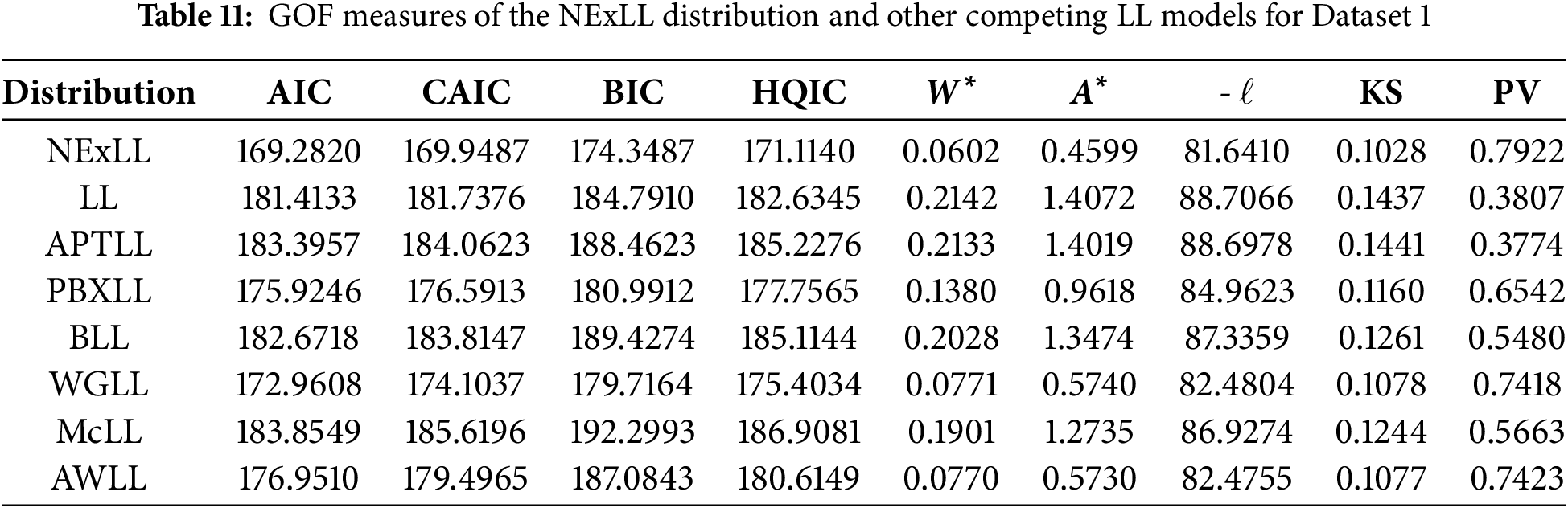

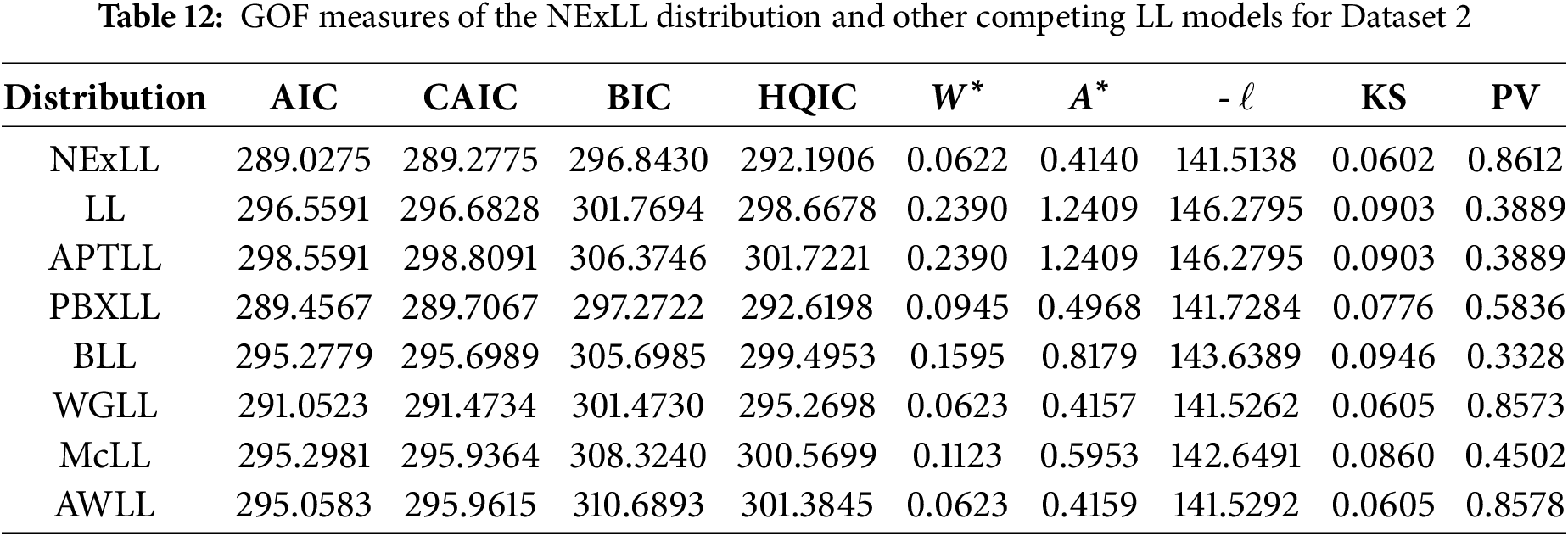

The fits of the NExLL distributions is compared with some existing LL distributions namely: the alpha power transformed LL (APTLL) [28], Poisson Burr type X LL (PBXLL) [26], beta LL (BLL) [21], Weibull generalized LL (WGLL) by [41], McDonald LL (McLL) [23], additive Weibull lL (AWLL) [42], and LL distributions.

The performance of the fitted distributions is explored using some measures including the Akaike information criterion (AIC), consistent Akaike IC (CAIC), Hannan–Quinn IC (HQIC), Bayesian IC (BIC), (

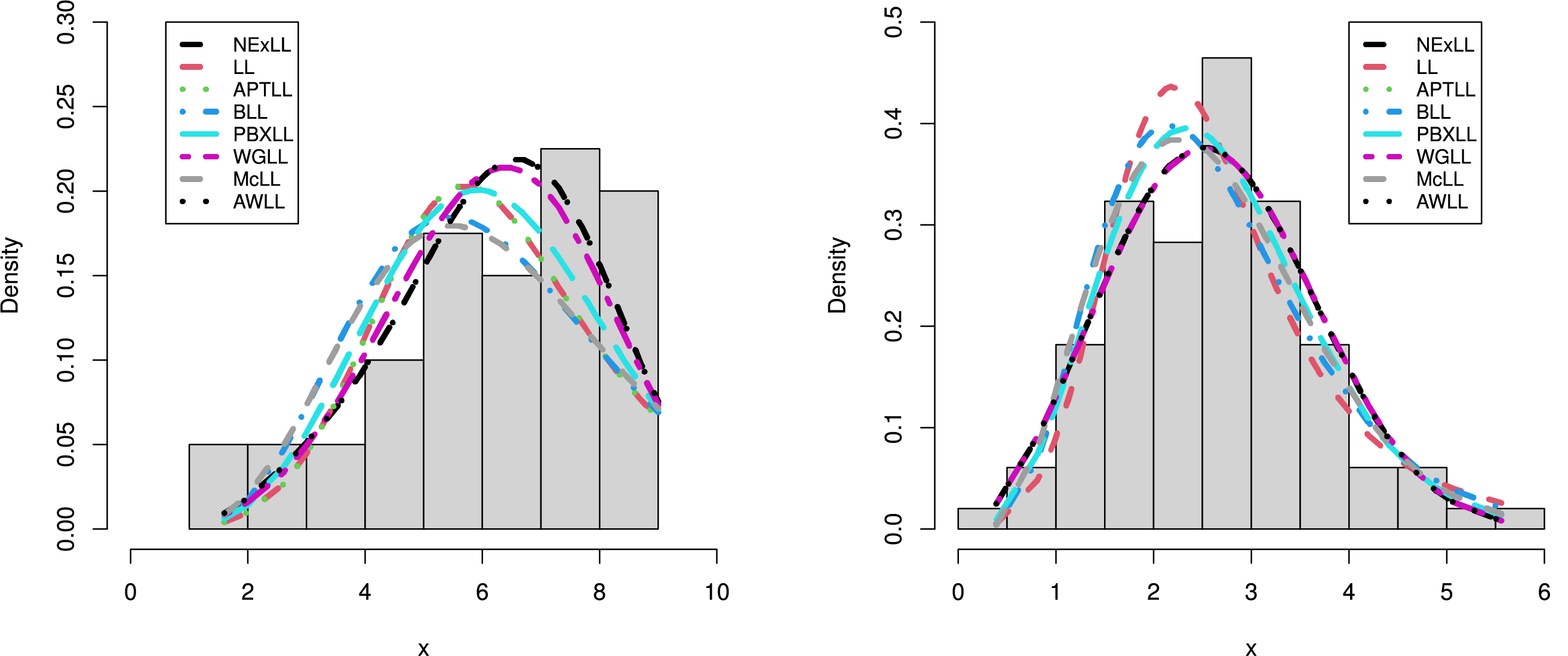

All numerical results in this section are calculated using the R software. Tables 11 and 12 present the goodness-of-fit (GOF) results for the proposed NExLL distribution alongside several competing LL-based models, applied to two real datasets. The evaluation is conducted using a comprehensive set of model selection criteria and goodness-of-fit statistics to ensure robust and meaningful comparisons.

Specifically, the model selection criteria include the AIC, CAIC, HQIC, and BIC. These criteria assess the trade-off between model fit and complexity, where lower values generally indicate better-fitting models with fewer penalties for parameter count. Additionally, the statitic

To evaluate the agreement between the empirical and theoretical distributions, we also report GOF statistics including

From Tables 11 and 12, it is evident that the NExLL distribution consistently achieves the lowest values for all considered information criteria and test statistics across both datasets. It also records the highest KS p-values, indicating no significant deviation from the empirical data. These results strongly support the superior flexibility and fitting capability of the NExLL model compared to other well-known and recently proposed LL-based distributions.

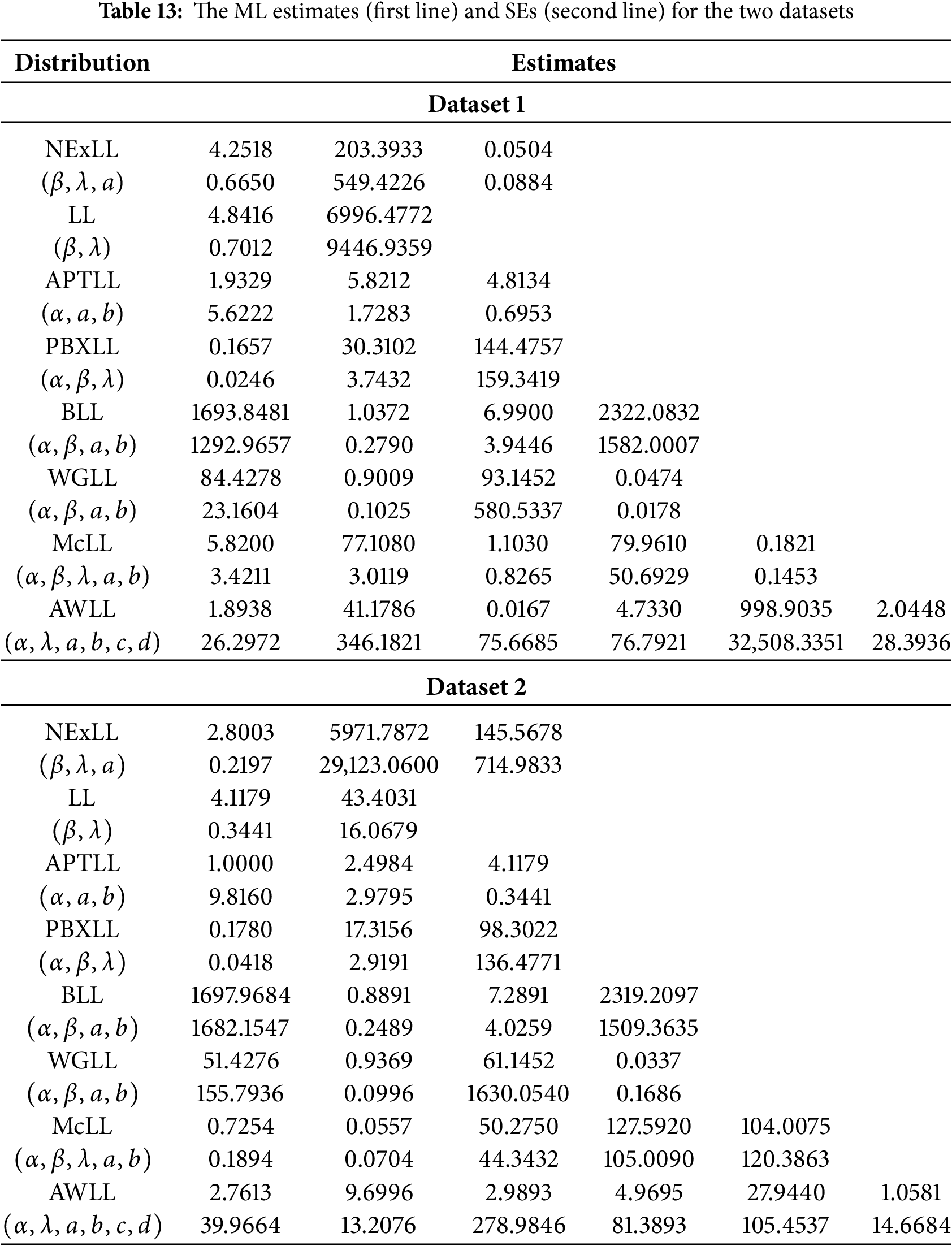

The ML estimates and standard errors (SEs) for the models’ parameters are reported in Table 13, for the two datasets. Overall, the NExLL distribution have the lowest values for goodness-of-fit criteria among all LL fitted models. Then, it could be chosen as the most adequate model for fitting the two datasets.

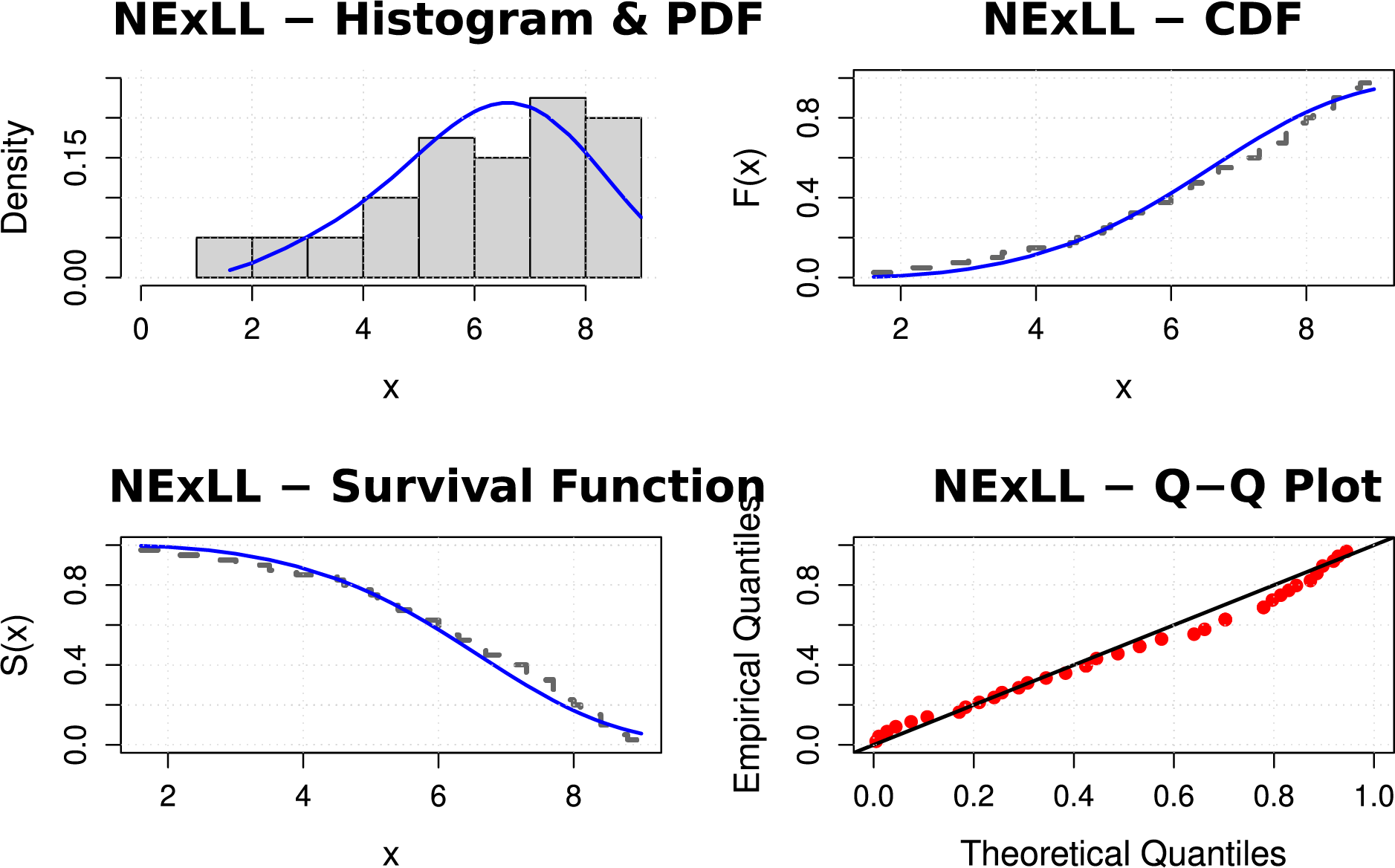

Furthermore, the visual fitting performance of the NExLL model is explored in Figs. 5 and 6. These figures show the histogram of the two data sets and the estimated PDFs, CDFs, SFs, and PP plots of the NExLL distribution. It is clear from these plots that the NExLL distribution provides the best fits to the two datasets.

Figure 5: The fitted functions of the NExLL model for first dataset

Figures 6: The fitted functions of the NExLL model for second dataset

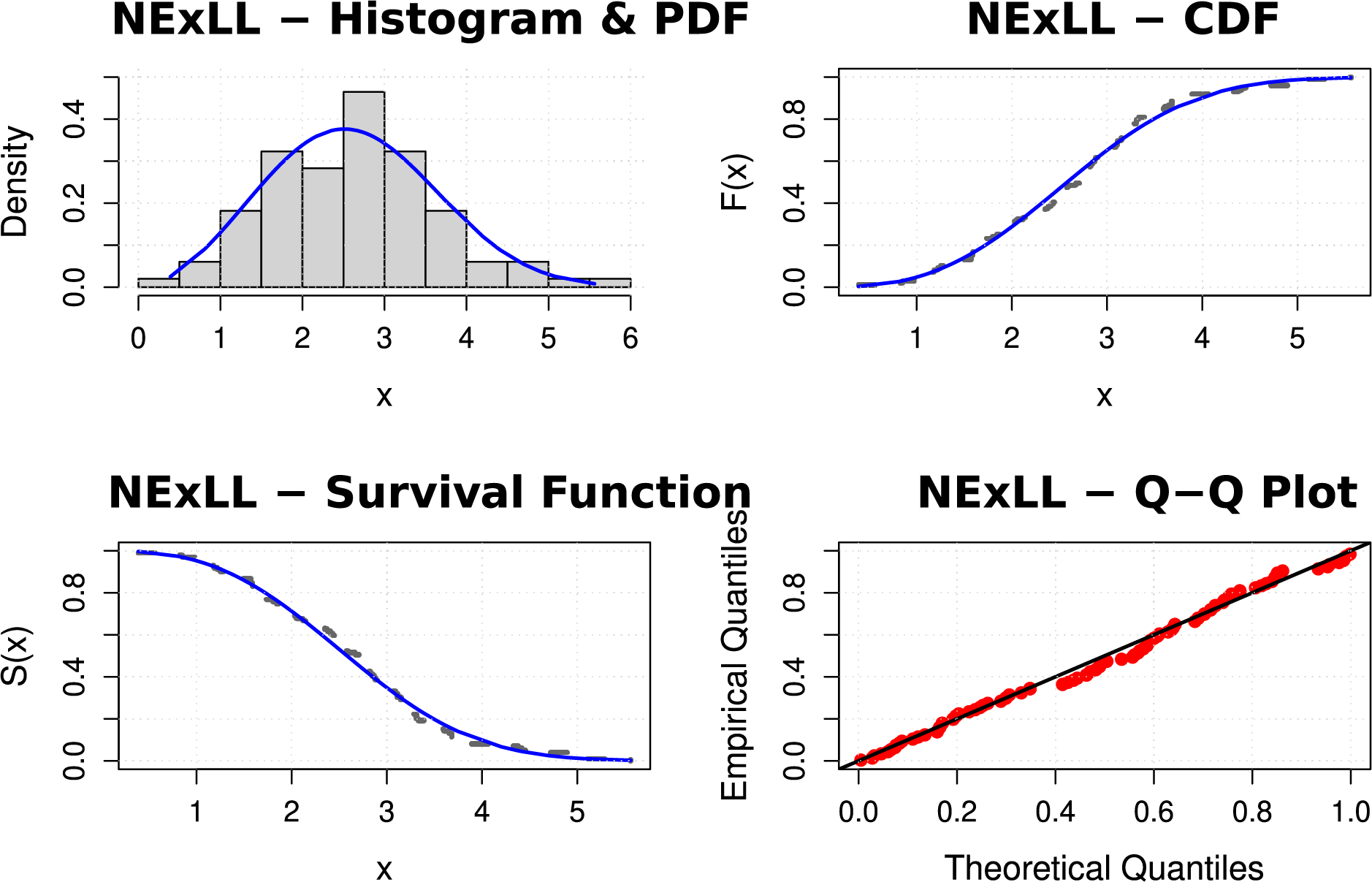

Fig. 7 displays the histogram and corresponding fitted density curves for the two real-life datasets. The left panel illustrates the fit of the proposed NExLL distribution to the first dataset, while the right panel shows the fit for the second dataset. In both cases, the NExLL model closely follows the empirical data, capturing the underlying distributional patterns effectively. The visual alignment between the histograms and the fitted curves highlights the model’s flexibility and suitability for modeling real-world lifetime data with varying shapes and characteristics.

Figure 7: The histogram and fitted densities plots for the first dataset (left panel), and for the second dataset (right panel)

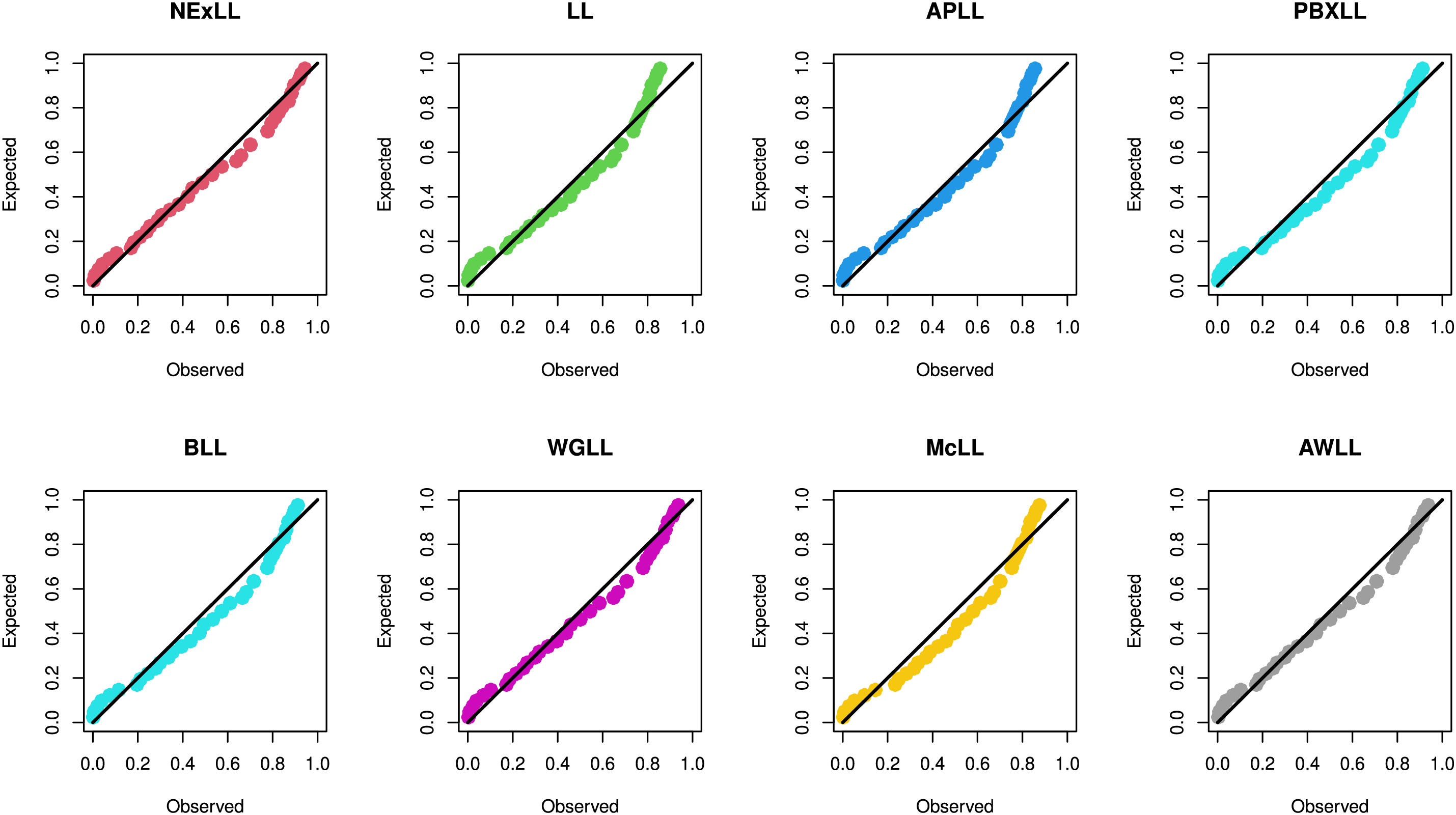

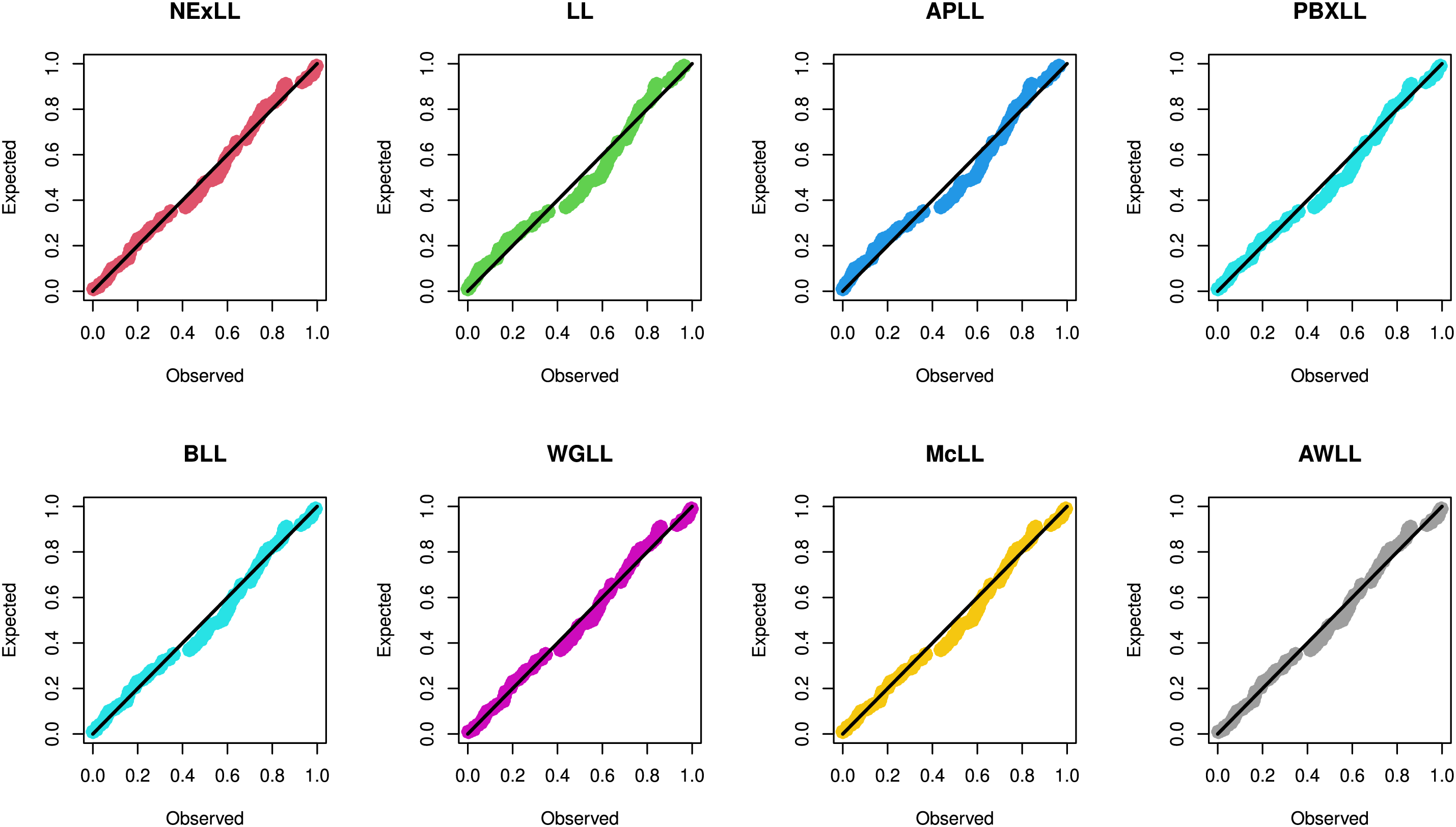

Additionally, the PP plots for the two datasets, presented in Figs. 8 and 9, confirm that the NExLL distribution provides a superior fit compared to competing distributions. The results demonstrate that the NExLL distribution consistently outperforms other LL extensions across all datasets, reinforcing its practical applicability for modeling real-world data.

Figure 8: The PP plots of the fitted models for first dataset

Figure 9: The PP plots of the fitted models for second dataset

In this study, we proposed a novel and flexible three-parameter distribution, called the NExLL distribution, as an extension of the classical log-logistic model. Unlike general NEx-H models, the NExLL distribution provides a fully closed-form, interpretable, and practically useful framework that can be directly applied to real-world survival and reliability data without requiring numerical approximation of its core functions. The proposed model exhibits remarkable flexibility, with a hazard rate function capable of capturing both monotonic and non-monotonic behaviors, and a density function that accommodates symmetric and asymmetric shapes—making it suitable for diverse survival and reliability applications. We thoroughly examined the mathematical properties of the NExLL distribution, and estimated its parameters using seven distinct estimation techniques. A comprehensive simulation study was conducted to evaluate the performance of these methods, revealing that the maximum product of spacings approach consistently yields the most efficient and accurate parameter estimates.

To demonstrate the practical utility of the model, we applied the NExLL distribution to two real-world lifetime datasets from the fields of engineering and reliability. The empirical results, supported by goodness-of-fit statistics and graphical analysis, confirm the NExLL model’s superior fitting capability over competing Log-Logistic-based models. The findings presented in this work contribute to the ongoing advancement of parametric survival modeling by offering a versatile distribution that can be further explored within broader frameworks, including the incorporation of trigonometric-based structures and machine learning-enhanced estimation strategies. As such, this study aligns with the objectives of the current special issue by pushing the boundaries of traditional parametric survival models and opening pathways for future interdisciplinary applications. Despite its promising performance, the proposed NExLL model is limited to complete and uncensored datasets, and its estimation under censoring or covariate settings remains unexplored. Future work may extend this model to handle censored data or incorporate covariates through regression frameworks for broader applicability.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R735), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Hadeel AlQadi, Fatimah M. Alghamdi, Hamada H. Hassan, Mohamed E. Mead and Ahmed Z. Afify; methodology, Hamada H. Hassan, Mohamed E. Mead and Ahmed Z. Afify; software, Ahmed Z. Afify; validation, Hadeel AlQadi, Fatimah M. Alghamdi and Mohamed E. Mead; resources, Hadeel AlQadi and Fatimah M. Alghamdi; data curation, Hamada H. Hassan and Mohamed E. Mead; writing—original draft preparation, Hadeel AlQadi and Ahmed Z. Afify; writing—review and editing, Hadeel AlQadi, Fatimah M. Alghamdi, Hamada H. Hassan, Mohamed E. Mead and Ahmed Z. Afify; visualization, Hadeel AlQadi, Fatimah M. Alghamdi, Hamada H. Hassan and Mohamed E. Mead. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: This study does not involve any human participants, animals, or identifiable personal data. The analysis is based entirely on publicly available datasets and simulated data. Therefore, ethics approval and consent to participate were not required.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Marshall AW, Olkin I. A new method for adding a parameter to a family of distributions with application to the exponential and Weibull families. Biometrika. 1997;84(3):641–52. doi:10.1093/biomet/84.3.641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Eugene N, Lee C, Famoye F. Beta-normal distribution and its applications. Commun Stat-Theory Methods. 2002;31(4):497–512. doi:10.1081/sta-120003130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cordeiro GM, de Castro M. A new family of generalized distributions. J Stat Comput Simul. 2011;81(7):883–98. doi:10.1080/00949650903530745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Alexander C, Cordeiro GM, Ortega EM, Sarabia JM. Generalized beta-generated distributions. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2012;56:1880–97. [Google Scholar]

5. Bourguignon M, Silva RB, Cordeiro GM. The Weibull-G family of probability distributions. J Data Sci. 2014;12:53–68. [Google Scholar]

6. Alizadeh M, Tahir MH, Cordeiro GM, Mansoor M, Zubair M, Hamedani G. The Kumaraswamy Marshal-Olkin family of distributions. J Egypt Math Soc. 2015;23(3):546–57. doi:10.1016/j.joems.2014.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hussain S, Rashid MS, Ul Hassan M, Ahmed R. The generalized alpha exponent power family of distributions: properties and applications. Mathematics. 2022;10(9):1421. doi:10.3390/math10091421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hassan AS, Alsadat N, Chesneau C, Shawki AW. A novel weighted family of probability distributions with applications to world natural gas, oil, and gold reserves. Electron Res Archive. 2023;31(11). doi:10.3934/mbe.2023880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Okutu JK, Frempong NK, Appiah SK, Adebanji AO. A new generated family of distributions: statistical properties and applications with real-life data. Comput Math Methods. 2023;2023(1):9325679. doi:10.1155/2023/9325679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Al Abbasi JN, Afify AZ, Alnssyan B, Shama MS. The Lambert-G family: properties, inference, and applications. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140:513–36. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.046533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jamal F, Alqawba M, Altayab Y, Iqbal T, Afify AZ. A unified exponential-H family for modeling real-life data: properties and inference. Heliyon. 2024;10(6):1–21. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27661. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Fisk PR. The graduation of income distributions. Econometrica: J Econometric Soci. 1961;29:171–85. [Google Scholar]

13. Dagum C. A model of income distribution and the conditions of existence of moments of finite order. Bulletin Intl Stat Inst. 1975;46:199–205. [Google Scholar]

14. Shoukri MM, Mian IUH, Tracy DS. Sampling properties of estimators of the log-logistic distribution with application to Canadian precipitation data. Canadian J Stat. 1988;16(3):223–36. doi:10.2307/3314729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Arnold BC. Pareto distributions. Fairland, MD, USA: International Co-Operative Publication House; 1983. [Google Scholar]

16. Burr IW. Cumulative frequency functions. Annals Math Stat. 1942;13:215–32. [Google Scholar]

17. Mielke PW, Johnson ES. Three-parameter kappa distribution maximum likelihood estimates and likelihood ratio tests. Monthly Weather Rev. 1973;101:701–9. [Google Scholar]

18. Kleiber C, Kotz S. Statistical size distributions in economics and actuarial sciences. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

19. Nadar SS, Upadhyay V, Joshi S. Detecting clinical risk shift through log-logistic hazard change-point model. Mathematics. 2025;13(9):1457. doi:10.3390/math13091457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Felipe A, Jaenada M, Miranda P, Pardo L. Robust tests for log-logistic models based on minimum density power divergence estimators. arXiv:2503.14447. 2025. [Google Scholar]

21. Lemonte AJ. The beta log-logistic distribution. Brazilian J Probability Stat. 2014;28(3):313–32. doi:10.1214/12-bjps209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gui W. Marshall–Olkin extended log-logistic distribution and its application in minification processes. Appl Math Sci. 2013;7:3947–61. doi:10.12988/ams.2013.35268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Tahir MH, Mansoor M, Zubair M, Hamedani GG. McDonald log-logistic distribution with an application to breast cancer data. J Stat Theory Appl. 2014;13:65–82. [Google Scholar]

24. Ramos MWA, Cordeiro GM, Marinho PRD, Dias CRB, Hamedani GG. The Zografos-Balakrishnan log-logistic distribution: properties and applications. J Stat Theory Appl. 2013;12:225–44. [Google Scholar]

25. Cakmakyapan S, Ozel G, Gebaly YMHE, Hamedani GG. The Kumaraswamy Marshall-Olkin log-logistic distribution with application. J Stat Theory and Appl. 2018;17:59–76. [Google Scholar]

26. Almamy JA. Extended Poisson log-logistic distribution. Int J Stat Probab. 2019;8:56–69. [Google Scholar]

27. Cordeiro GM, Afify AZ, Ortega EM, Suzuki AK, Mead ME. The odd Lomax generator of distributions: properties, estimation and applications. J Comput Appl Math. 2019;347:222–37. doi:10.1016/j.cam.2018.08.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Aldahlan MA. Alpha power transformed log-logistic distribution with application to breaking stress data. Adv Math Phy. 2020;2020(3):1–9. doi:10.1155/2020/2193787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Alfaer NM, Gemeay AM, Aljohani HM, Afify AZ. The extended log-logistic distribution: inference and actuarial applications. Mathematics. 2021;9(12):1386. doi:10.3390/math9121386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Gaire AK, Gurung YB. Skew log-logistic distribution: properties and application. Stat Transition New Ser. 2024;25:43–62. [Google Scholar]

31. Rahman MM, Darwish JA, Shahbaz SH, Hamedani G, Shahbaz MQ. A new cubic transmuted log-logistic distribution: properties, applications, and characterizations. Adv Appl Stat. 2024;91(3):335–61. doi:10.17654/0972361724018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Panitanarak U, Ishaq AI, Abiodun AA, Daud H, Suleiman AA. A new Maxwell-log logistic distribution and its applications for mortality rate data. J Nigerian Soc Phys Sci. 2025;7:1976–6. doi:10.46481/jnsps.2025.1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ahmed AD, Yassin YT, Wahhab BIA, Abdullah EKA. Comparison of some methods for estimating the parameters of the type–II generalized log logistic distribution using simulation. Iraqi Statisticians J. 2025;2:344–50. [Google Scholar]

34. Afify AZ, Abdelall YY, AlQadi H, Mahran HA. The modified log-logistic distribution: properties and inference with real-life data applications. Contemporary Math. 2025;862–902. doi:10.37256/cm.6120256273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lorenz MO. Methods of measuring the concentration of wealth. Publications Am Stat Assoc. 1905;9(70):209–19. doi:10.1080/15225437.1905.10503443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Arcagni A, Porro F. The graphical representation of the inequality. Dipartimento Di Statistica E Metodi Quantitativi Working Papers. 2014;37:419–37. [Google Scholar]

37. Cheng RCH, Amin NAK. Estimating parameters in continuous univariate distributions with a shifted origin. J Royal Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol). 1983;45(3):394–403. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1983.tb01268.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Cheng RCH, Amin NAK. Maximum product-of-spacings estimation with applications to the lognormal distribution. In: Math report. Cardiff: University of Wales Institute of Science and Technology; 1979. [Google Scholar]

39. Xu K, Xie M, Tang LC, Ho SL. Application of neural networks in forecasting engine systems reliability. Appl Soft Comput. 2003;2(4):255–68. doi:10.1016/s1568-4946(02)00059-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Nichols MD, Padgett WJ. A bootstrap control chart for Weibull percentiles. Qual Reliab Eng Intl. 2006;22(2):141–51. doi:10.1002/qre.691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Shehata W, Abdullah MM, Refaie MK. A novel four-parameter log-logistic model: mathematical properties and applications to breaking stress, survival times and leukemia data. Pakistan J Stat Oper Res. 2022;18:133–49. doi:10.18187/pjsor.v18i1.3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hemeda S. Additive Weibull log logistic distribution: properties and application. J Adv Res Appl Math Stat. 2018;3:8–15. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools