Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Towards a Real-Time Indoor Object Detection for Visually Impaired Users Using Raspberry Pi 4 and YOLOv11: A Feasibility Study

1 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer Science and Engineering, Taibah University, Madinah, 42353, Saudi Arabia

2 King Salman Center for Disability Research, Riyadh, 11614, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Computation and Technology, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Caicó, 59078-900, Brazil

* Corresponding Author: Talal H. Noor. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 3085-3111. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068393

Received 28 May 2025; Accepted 01 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

People with visual impairments face substantial navigation difficulties in residential and unfamiliar indoor spaces. Neither canes nor verbal navigation systems possess adequate features to deliver real-time spatial awareness to users. This research work represents a feasibility study for the wearable IoT-based indoor object detection assistant system architecture that employs a real-time indoor object detection approach to help visually impaired users recognize indoor objects. The system architecture includes four main layers: Wearable Internet of Things (IoT), Network, Cloud, and Indoor Object Detection Layers. The wearable hardware prototype is assembled using a Raspberry Pi 4, while the indoor object detection approach exploits YOLOv11. YOLOv11 represents the cutting edge of deep learning models optimized for both speed and accuracy in recognizing objects and powers the research prototype. In this work, we used a prototype implementation, comparative experiments, and two datasets compiled from Furniture Detection (i.e., from Roboflow Universe) and Kaggle, which comprises 3000 images evenly distributed across three object categories, including bed, sofa, and table. In the evaluation process, the Raspberry Pi is only used for a feasibility demonstration of real-time inference performance (e.g., latency and memory consumption) on embedded hardware. We also evaluated YOLOv11 by comparing its performance with other current methodologies, which involved a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) (MobileNet- Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD)) model together with the RT-DETR Vision Transformer. The experimental results show that YOLOv11 stands out by reaching an average of 99.07%, 98.51%, 97.96%, and 98.22% for the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, respectively. This feasibility study highlights the effectiveness of Raspberry Pi 4 and YOLOv11 in real-time indoor object detection, paving the way for structured user studies with visually impaired people in the future to evaluate their real-world use and impact.Keywords

Visually impaired people encounter significant challenges while navigating daily environments, safely protecting themselves from potential risks. People who lack vision find routine activities like walking through rooms and finding objects to be complex and potentially hazardous tasks. Visually impaired people constantly face the threat of bumping into obstacles such as furniture and moving people, which becomes more significant when they are in unknown surroundings. Research demonstrates that visually impaired individuals spend approximately 80 to 90 percent of their time in indoor environments because they tend to stick to familiar paths and locations [1–3]. Safe indoor mobility and navigation present serious challenges because building interiors have complex layouts, plus dynamic obstacles such as pets and appliances, and GPS signals fail inside buildings [4,5]. The challenges faced by visually impaired users point to an urgent requirement for effective assistive technologies to improve environmental awareness and independence.

Despite their crucial role for the visually impaired, traditional assistive tools contain significant deficiencies. For many decades, the long white cane has served as a main mobility tool, enabling users to perceive ground-level obstacles and terrain changes using tactile feedback. The cane functions by physical contact with obstacles and has a reach limitation of typically one meter or less, which makes it unable to detect hazards beyond this range in [6]. Using a cane for mobility demands constant attention from the user and becomes exhausting during long periods of use. A proficient guide dog provides a proven method for assisting individuals by helping them detect and navigate past obstacles and dangers. Guide dogs require extensive and costly training along with ongoing maintenance, yet remain available to just a limited number of visually impaired individuals [7]. Guide dogs are unable to provide detailed information about object identities or environmental signage. Because traditional methods have limitations, researchers now focus on developing Electronic Travel Aids (ETAs) that use technology to assist or substitute traditional canes and guide dogs [8,9]. The initial development of ETAs included devices with ultrasonic rangefinders and infrared detectors that were mounted on canes or wearable belts to detect obstacles and provide feedback through audio tones or vibrations [10]. Early electronic aids could detect obstacles from greater distances than traditional canes, but their feedback systems typically used only one sensory channel, like audio beeps, which often distracted or overwhelmed users with their sound. Numerous devices demonstrated physical bulkiness and operational unreliability under real-world conditions, which restricted their widespread acceptance [11]. The drawbacks of traditional and early electronic aids led to the development of advanced solutions integrating modern sensing technologies and machine intelligence.

The evolution of modern technology enables new breakthroughs in assistive devices for visually impaired individuals through affordable cameras and IoT connectivity combined with powerful Deep Learning (DL) algorithms [12,13]. Deep learning-based computer vision systems have recently demonstrated outstanding performance in object recognition, which allows machines to identify and sort objects in real time with precise accuracy [14]. Among the prominent computer vision systems based on DL are the Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) and Faster R-CNN [15,16]. The SSD utilizes one Deep Neural Network (DNN) to directly derive object classes and bounding boxes from images, which facilitates swift detection for real-time applications [15]. Faster R-CNN combines a Region Proposal Network (RPN) with a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to achieve precise object localization and classification, but requires more computational power [17]. The You Only Look Once (YOLO) family of models transformed real-time object detection through its end-to-end single-shot framework that accurately detects multiple objects in image frames while maintaining high frame rates [18]. Pre-trained object detection models enable compact devices to interpret visual scenes and deliver environmental information to blind users, which significantly improves their situational awareness.

We build upon these advancements to examine indoor environments where assistive technology serves an essential purpose. Visually impaired people must identify and navigate around various objects found in indoor environments such as homes, offices, and public buildings. Indoor navigation systems cannot utilize GPS references while the environment remains dynamic because elements such as chairs move and doors remain open or new obstacles emerge [4]. Our research initiative was driven by the requirement for a wearable device that detects indoor objects in real-time to help users identify common objects or obstacles and deliver immediate responses. The object detection system needs to process visual data rapidly to provide immediate warnings about potential path hazards, so users can take corrective action or change direction because of that, real-time performance is crucial. Even a brief delay of seconds can make the system either ineffective or unsafe. Users must receive intuitive feedback through audio signals, such as earpiece spoken warnings, or through haptic vibrations to promote rapid understanding and response. By utilizing IoT connectivity, the system benefits from cloud-based analysis capabilities and regular updates. The design of our proposed assistant stems from these considerations.

This work is a feasibility study for a wearable IoT-based indoor object detection assistant system architecture based on a real-time indoor object detection method to help visually impaired users understand their environment in real-time. Our prototype implementation stands out due to its combination of the advanced object detection model YOLOv11 with real-time response capabilities. The system architecture takes advantage of IoT capabilities through a Raspberry Pi 4 device and a cloud backend to support computationally intensive analyses and data storage. This work presents several main contributions, which can be summarized as follows:

• A Wearable IoT-Based Indoor Object Detection Assistant system architecture provides visually impaired individuals with navigation assistance in indoor environments through its multi-layered system architecture, enabling real-time object detection. The system architecture includes four main layers: Wearable IoT, Network, Cloud, and Indoor Object Detection Layers.

• The indoor object detection approach applies YOLOv11 to identify indoor objects such as sofas, tables, and beds to assist visually impaired people with indoor navigation.

• Using a prototype implementation, comparative experiments, and two public datasets, Roboflow Furniture Detection (i.e., 3000 labeled images in 3 classes) and Asia Furniture Video Dataset (i.e., 11 annotated video streams), the proposed indoor object detection approach is validated. The model was deployed to a Raspberry Pi 4 to evaluate the inference latency and memory consumption, showing that the research prototype is feasible for real-time detection.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the related work. Section 3 illustrates the design of the wearable IoT object detection assistant system architecture. Section 4 provides a detailed description of the indoor object detection approach that exploits the YOLOv11 model. The implementation and experimental setup are discussed in Section 5. Section 6 details the evaluation and experimental results, which assess the performance of YOLOv11 compared to CNN (MobileNet-SSD), and the RT-DETR Vision Transformer. Section 7 provides the concluding remarks and offers future research work.

In recent years, numerous studies have explored the potential of AI-driven object detection research prototypes to assist visually impaired individuals in navigating their environments. These efforts leverage advanced Deep Learning (DL) techniques, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and transformer-based models, to achieve real-time detection and classification of objects commonly encountered in daily life. This section reviews several relevant works highlighting different methodologies, their effectiveness, and the challenges faced in developing robust and efficient object detection systems for visually impaired individuals.

For instance, Kevin et al. [19] introduced an embedded prototype for detecting and classifying head-level objects using stereo vision on wearable hardware for visually impaired people. The prototype, based on YOLOv5, was assessed with a custom head-level dataset and validated through field tests, reporting a mAP@ 0.95 of 0.89, precision and recall of 98.21%, 93.75%, and user-observed obstacle-avoidance accuracy of 91% under varied lighting and ambient conditions. The technical approach in prototype implementation, dataset evaluation, and real-world testing closely parallels our methodology; however, our research emphasizes high real-time detection capabilities with the lightweight YOLOv11 model, which offers faster inference.

Brilli et al.’s [20] AIris system is a fully functional wearable vision assistant prototype that pairs a camera-mounted eyewear with natural language processing to provide real-time auditory descriptions of one’s surroundings, including object recognition (i.e., You Only Look Once (YOLO)), scene narration, text reading (i.e., Optical Character Recognition (OCR)), face detection, and money counting. YOLO model, which was tested in real-world conditions, reached 63.4% mean average precision with a response time of 150 ms. AIris establishes both practical viability and performance metrics before formalized user studies, which aligns well with our approach of architecture, deployment, and dataset-based evaluation.

The study in [21] proposes the YOLO Glass, a video-based smart object detection research prototype using the Squeeze and Attendant Block (SAB)-YOLO network for visually impaired individuals. The research prototype converts video streams into keyframes and preprocesses them with a correlation fusion-based disparity approach to enhance object detection accuracy. The SAB-YOLO network achieved a detection accuracy of 98.99%, significantly outperforming YOLOv5 and YOLOv6 by margins of 7.15% and 5.15%, respectively. The research prototype also demonstrated progress in recall of 97.15% and precision 98.77%, on the INDRA dataset. However, its reliance on computationally intensive hardware and sensitivity to environmental conditions were notable limitations, restricting broader accessibility. In contrast, our research emphasizes high real-time detection capabilities with the lightweight YOLOv11 model, which provides faster inference and reduced hardware needs while maintaining exceptional robustness to indoor environmental changes.

In [22], the authors conducted an in-depth study combining functional analysis, statistical mechanics, and DL to assess the potential of smart glasses in enhancing the mobility and independence of visually impaired individuals. Their approach involved evaluating various hardware and software components, including cameras, sensors, and CNNs, through real-life use cases and feedback tracking. The CNN-based models achieved a high accuracy of 92.56%, with a detection rate of 89.82% and a precision of 90.88%, demonstrating reliable performance in object recognition and obstacle detection. However, limitations included inconsistent durability scores (i.e., 4 to 8 out of 10) and constrained battery life ranging from 6 to 12 h, which could hinder extended use. The study highlights the importance of addressing these issues to improve adaptability and user satisfaction across diverse environments. In contrast, our research optimizes accuracy and real-time inference speed trade-offs in YOLOv11 for resource-limited wearable device deployment. Moreover, our prototype demonstrated enhanced scores in all evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, which led to both top detection performance and instant response times.

The study in [23] proposed an obstacle detection research prototype for visually impaired individuals using a modified YOLOv5 model optimized for deployment on embedded devices. The research prototype was trained on the IODR and MS COCO datasets, incorporating techniques such as model width scaling, quantization, and channel pruning to balance performance and computational efficiency. The optimized model achieved mAP of 81.02% at 67 FPS before compression and 76.41% at 89 FPS after compression, enabling real-time detection. However, the research prototype exhibited limitations in highly cluttered environments and required periodic retraining to adapt to new scenarios.

In [24], the paper proposes an object detection and recognition research prototype for visually impaired individuals using Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) and the YOLO algorithm. The research prototype processes real-time video inputs to detect and recognize objects, providing audio feedback through Google’s Text-to-Speech (GTTS) API. Their methodology involved training on the COCO dataset, which contains 91 object categories. The results demonstrated an accuracy of 90% with an inference speed of 16–18 FPS, outperforming traditional methods such as CNNs and Support Vector Machines (SVMs). However, the research prototype’s dependence on internet connectivity for GTTS processing and potential challenges in handling complex environments were identified as limitations.

In the research work [25], the authors proposed a real-time object detection research prototype for visually impaired individuals that converts the visual world into an audio world using the YOLO algorithm. The research prototype processes real-time video input from a smartphone or web camera and provides audio feedback about detected objects and their positions, allowing users to navigate independently. The methodology leverages OpenCV for image processing, TensorFlow for Machine Learning (ML) tasks, and Darknet for DL model inference. The research prototype achieved an accuracy of 85.5% on mobile devices and 89% on web applications. However, limitations include challenges in detecting objects that are too close or far from the camera and potential issues with moving objects or unstable camera conditions, impacting the detection accuracy and response time.

In the study in [26], the authors proposed a low-cost object detection research prototype incorporating SSDLite MobileNetV2 for object detection and Google Text-To-Speech (GTTS) for auditory feedback. The object detection model, trained on the MS COCO dataset (i.e., 165,000 images across 90 classes), achieved a detection accuracy of 88.89%, with a precision of 0.892 and recall of 0.89. Moreover, the “ambiance mode”, designed to describe environmental conditions (sunny, rainy, cloudy), was trained on a weather dataset (500 images across five classes), achieving a 95% accuracy after 15 epochs. The research prototype, implemented on a Raspberry Pi 4B, was lightweight and portable, but its frame rate of 2.15 FPS limited its responsiveness in real-time scenarios.

In [27], a DL-based object detection research prototype is introduced to enhance kitchen independence for visually impaired individuals. Their approach utilized transfer learning on a pre-trained MobileNet SSD model within the TensorFlow Lite framework to recognize kitchen-specific objects. The research prototype was integrated with Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) and Text-To-Speech (TTS) to provide real-time interactive guidance. Experimental evaluation using the CMU Kitchen Occlusion Dataset showed an improvement in mAP from 68% to 82%, with high detection precision for common items. However, the research prototype faced challenges with occluded and visually similar objects, highlighting the need for further object differentiation and robustness improvements.

Mukhiddinov and Cho [28] proposed a smart glass research prototype that uses DL for visually impaired individuals, focusing on low-quality image enhancement and tactile feedback. The research prototype integrated a two-branch exposure fusion network for improving image contrast by 50% and a transformer encoder-decoder for object detection capable of recognizing 133 sound categories. The device achieved an object detection accuracy of 95%, making it particularly effective in nighttime environments. Despite its advanced functionality, the research prototype faced challenges due to its reliance on client-server architecture, which introduced latency and reduced portability. This dependency on external processing limited the device’s applicability in remote or poorly connected areas, emphasizing the need for standalone solutions to enhance usability. On the other hand, our research applies the lightweight YOLOv11 model, which is optimized for providing real-time responsiveness and superior detection performance.

In the research work [29], the authors developed a wearable device research prototype that integrates Raspberry Pi, ultrasonic sensors, and CNNs for real-time object detection and distance estimation. The research prototype provides auditory and haptic feedback, enabling visually impaired individuals to navigate their surroundings with greater spatial awareness. The research prototype demonstrated an object detection accuracy of 92%, a distance estimation precision of 85%, and a fusion-based obstacle detection F1 score of 95.52%. However, the device struggled with feedback overload in cluttered environments with multiple objects, and using basic ultrasonic sensors limited its detection range and effectiveness in dynamic scenarios. Despite these limitations, the study showcased the potential of lightweight, wearable technology in addressing the needs of visually impaired users. However, our approach utilizes YOLOv11 to achieve precise real-time indoor object detection without external distance sensors, which reduces feedback overload and maintains reliable performance in changing indoor settings.

In [30], the authors developed the “SOMAVIP” framework, combining IoT devices and deep transfer learning for real-time obstacle detection and responsive navigation. The custom object detection model, trained on 60,000 annotated images of eight obstacle classes, achieved a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 97%. The research prototype used cloud computing and IoT-based sensors to provide robust and responsive obstacle detection. However, its reliance on smart city infrastructure limited its use in less-connected or rural environments.

In the study [31], the authors designed an energy-efficient smart glasses research prototype utilizing TinyissimoYOLO, a YOLO-based object detection model optimized for low-power microcontrollers. The research prototype, powered by a RISC-V processor (GAP9), achieved a processing latency of 17 ms per inference, with an energy consumption of 1.59 ms per inference. The glasses supported real-time object detection at 18 Frames Per Second (FPS), with a battery life of 9.3 h on a 154 mAh battery. Despite its high efficiency, the research prototype showed reduced accuracy compared to more significant YOLO variants, limiting its functionality in complex scenarios requiring fine-grained detection.

Our research effort advances beyond previous studies, which concentrated on particular elements of object detection research prototypes, by aiming to create an integrated solution that combines real-time detection speed with high accuracy and complete on-device functionality without requiring external connections or extensive computational resources. We employ the lightweight YOLOv11 model designed for wearable IoT environments (i.e., Raspberry Pi 4). The research prototype delivers high-performing indoor object detection through instant feedback while adapting to dynamic, cluttered environments without requiring specialized training or environmental assumptions. Our solution delivers a practical and scalable framework for real-world applications by simultaneously addressing latency issues and ensuring portability and adaptability.

3 System Architecture of the Wearable IoT-Based Indoor Object Detection Assistant

The wearable IoT-based indoor object detection assistant offers visually impaired people assistance during indoor navigation through its multi-layered system architecture, which enables real-time and efficient indoor object detection. The system architecture utilizes a structured pipeline that delivers streamlined communication while achieving quick data processing, together with dependable user feedback. The system architecture includes four primary layers, which are the Wearable IoT, Network, Cloud, and Indoor Object Detection Layers, where each layer has distinct functions that handle everything from data collection to object detection and sending notifications, as shown in Fig. 1. The system architecture uses wearable technologies alongside wireless communication and cloud computing services with advanced deep learning models to achieve precise indoor object detection and provide instant notifications, which boosts safety and independence, as well as situational awareness for visually impaired users.

Figure 1: System architecture of the wearable IoT-based indoor object detection assistant

Every architectural layer performs specific tasks while maintaining communication with the other layers. The architecture employs a simplified pipeline design to promote easy and intuitive communication. The architecture layers are as follows:

1. Wearable IoT Layer: Visual data streams requiring analysis are collected through wearable devices with cameras designed for visually impaired users in this layer. Wearable devices obtain visual records of indoor objects such as sofas and tables in the user’s environment. The wearable hardware prototype is assembled using a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (4 GB RAM) and a Pi Camera v2.1 attached to a 3D-printed smart glasses frame. The device is programmed to stream real-time video to the cloud backend over a secure Wi-Fi connection with Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT). The entire system is powered by a 10,000 mAh Li-ion battery that supports 5–6 h of use (i.e., more details about the hardware can be found in Section 5). The Pi is in charge of video capture and transmission, while the detection inference takes place in the Cloud layer and gets communicated back to the user as audio alerts through bone conduction headphones. It is worth mentioning that the Raspberry Pi is only used for a feasibility demonstration of real-time inference performance (e.g., latency and memory consumption) on embedded hardware. The Pi was not used to capture a live video scene; instead, the frames of the dataset were piped into the model to simulate real-time on a wearable setup. After visual data collection by wearable IoT devices, the system sends this information to the Network layer for additional processing. The wearable IoT layer functions as an extension of the user’s senses by gathering detailed visual data about indoor surroundings continuously.

2. Network Layer: This layer maintains connectivity between wearable IoT devices and the indoor object detection system. The network layer incorporates Wireless Access Points (WAPs) like Wi-Fi and Base Transceiver Stations (BTSs), which provide 5G network support. This system delivers captured visual streams across the Internet to cloud-based processing layers without interruptions. The transmitted data includes raw visual capture, which must be analyzed to detect and label indoor objects. A streamlined pipeline at this layer achieves efficient, high-speed communication while minimizing latency for real-time support.

3. Cloud Layer: This layer delivers both Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) and Software as a Service (SaaS) solutions to other layers, which creates a secure and scalable environment for data storage and computing resource allocation. The collected visual data, along with detection outputs and records of detected indoor objects, are stored using IaaS. SaaS is deployed to handle and run detection-related software services, including those for indoor object detection models. The cloud infrastructure ensures security and flexibility while providing high availability to enable dynamic scaling of resources according to user needs without requiring hardware management.

4. Indoor Object Detection Layer: The detection layer handles the identification, classification, annotation, and management of indoor objects found in visual data streams. The system employs a YOLOv11-based object detection model along with several essential components.

• YOLOv11-Based Object Detection: This module includes several essential components.

– Preprocessing and Analysis of Visual Data Streams: The pre-processing component standardizes incoming visual data formats while improving image quality to enable feature extraction with consistent inputs.

– Extraction of Indoor Object Features: The system analyzes preprocessed data to extract key identifying features that enable precise indoor object detection and classification.

– Classification and Annotation of Indoor Objects: YOLOv11 processes detected objects such as sofas, tables, and beds to provide bounding boxes along with labels and confidence scores, which guarantee precise object identification and mapping.

• Data Management and Storage: The role includes documenting and categorizing indoor object detection information, such as the types of objects detected and accompanying metadata like detection confidence levels and timestamps. The system records both successful object detections and empty detection instances, which maintains historical data integrity and facilitates system performance tracking.

• Indoor Object Detection Result Notifier: Delivers final detection results to users and associated services. The system provides instant notifications about indoor objects, including their types and locations, which assist visually impaired users in maintaining real-time situational awareness. The module transforms detection outputs into actionable elements by making them accessible and thus completes the system feedback loop.

To integrate these layers and enable end-to-end IoT communications, we make use of the MQTT protocol, due to its small overhead and support for real-time streaming from resource-constrained devices. The wearable IoT edge layer is responsible for capturing the frames from the camera, encoding them using a lightweight JPEG encoder, and publishing the frames to an MQTT broker over Transport Layer Security (TLS)-encrypted channels. This minimizes latency in the system and ensures the transmission of the frames is secure. The cloud layer subscribes to the MQTT topics, receives the stream of frames, and uses the YOLOv11 model that has been deployed to it for inferring on the frames. The results of inference are then sent back to the wearable device to notify the user. The cloud service stores the data on encrypted volumes, encrypted with Advanced Encryption Standard(AES)-256. This data can only be accessed by users with the right privileges set by Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) to only allow access to specific data, based on the role of the user.

4 Indoor Object Detection Approach

The process starts with receiving a live video frame from the Raspberry Pi and forwarding it to the cloud over TLS-encrypted MQTT, where YOLOv11 performs object detection, and annotated results are received by the device over MQTT in JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) format. A script onboard parses the results, and voice feedback (i.e., preloaded audio snippets) is played, announcing the detected type of furniture and its location in relation to the device. This closed-loop detection-annunciation process provides real-time feedback to users.

The indoor object detection approach in our research prototype exploits the YOLOv11 model. The object detection models in the You Only Look Once (YOLO) family use deep learning to replicate the human visual system’s instant object detection and localization abilities [32]. YOLO has developed through multiple versions, which brought new architectural features that boosted detection performance alongside accuracy and speed [33–37]. YOLOv11 represents the latest advancement by building on existing foundations and implementing major improvements to achieve optimal detection accuracy combined with real-time inference capabilities and computational efficiency.

YOLOv11 contains some improvements not found in other traditional versions of YOLO, such as YOLOv5 or YOLOv6, to optimize performance further. One of these, called Cross Stage Partial with Kernel Size 2 (C3k2) block, is used instead of larger convolutions to reduce computational cost with a series of smaller, more efficient convolutions that do not sacrifice accuracy. It also includes a lightweight transformer-based neck, as well as the Cross-Stage Partial with Parallel Spatial Attention (C2PSA) block. These additions help to improve spatial attention within the model, and especially increase performance for partially occluded or overlapping objects, as is often the case in indoor spaces. These changes help YOLOv11 to have both more reliable detection and faster convergence than YOLOv5 and YOLOv6.

YOLOv11 includes EfficientRepNet as an enhanced backbone structure that provides improved feature extraction while minimizing computational demands. The neck of the network contains a transformer-based lightweight module, which enhances contextual feature aggregation strength and dynamic label assignment during training, and enhances the model’s ability to manage ambiguous object boundaries. YOLOv11 keeps its fundamental grid-based detection system, which splits the input image into an

YOLOv11 became the primary detection model for our Wearable IoT-Based Indoor Object Detection Assistant because it meets our requirements for quick response times, precise detection accuracy, and efficient performance in resource-limited settings. The diverse indoor objects, such as sofas, tables, and beds, which vary in size and occlusion, require a detection model that maintains both fast inference and high accuracy, which YOLOv11 accomplishes.

YOLOv11 introduces three modules, including i) the Cross Stage Partial with Kernel Size 2 (C3k2) block, ii) the Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) block, and iii) the Cross-Stage Partial with Parallel Spatial Attention (C2PSA) block. The modules function separately to boost feature extraction capabilities along with multi-scale object understanding and spatial attention mechanisms.

The C3k2 block refines Cross Stage Partial (CSP) bottleneck structures by substituting larger convolutions with two smaller ones to achieve better efficiency while maintaining performance [38–41]. The C3k2 is explained in Eq. (1):

where

The SPPF block extends the model’s receptive field by pooling features from multiple regions at different image scales to capture detailed fine-grained information together with global context. Its operation is defined as Eq. (2):

Max-pooling with kernel size

YOLOv11 features a new mechanism known as the Cross-Stage Partial with Parallel Spatial Attention (C2PSA) block that enhances the spatial precision of feature maps. The module highlights essential areas that likely contain objects and focuses on smaller or partially hidden objects [38–41]. The functionality of the C2PSA block operates in the following Eq. (3):

The input feature map

YOLOv11 delivers real-time inference supported by C3k2 and SPPF blocks, along with higher detection accuracy from spatial attention mechanisms inside the C2PSA block, enabling efficient computations, which makes it fit for deployment on wearable and IoT devices with restricted resources. YOLOv11 has a modular design that allows users to easily tailor it to different indoor settings and object detection applications. YOLOv11 emerges as a promising model for helping visually impaired users achieve quick and precise recognition of objects in dynamic indoor environments through its contextually aware capabilities.

5 Implementation and Experimental Setup

The research prototype implementation of our wearable IoT-based indoor object detection assistant system architecture leveraged TensorFlow1 (v2.18). To demonstrate our research prototype performance, we have compared the performance of YOLOv11 with other state-of-the-art models, including CNN (MobileNet-SSD) and Real-Time DEtection TRansformer (RT-DETR). For the implementation of these models, we used PyTorch2 (v2.5.1) libraries (i.e., using the Ultralytics3), ensuring consistent evaluation pipelines across all models. Data augmentation was applied during training, including random flipping, rotation, jittering, and scaling. All training and evaluation were conducted on an NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPU cloud instance (i.e., 16 GB VRAM, 3584 CUDA cores), ensuring consistent benchmarking across all models.

For a real-world evaluation of the system architecture deployment, we deployed our prototype on a commercially available Raspberry Pi 4 Model B4 (4 GB RAM) and connected to Pi Camera v2.1 (i.e., 8-megapixel sensor, 1080 p, 30 fps). The Raspberry Pi connection with the wearable IoT device is illustrated in Fig. 2. The device is battery-operated with a 10,000 mAh rechargeable Li-ion battery, which allows up to 5–6 h of usage time. It uses Wi-Fi to connect to the cloud for offloaded inference. However, this is a limitation that we would like to eliminate by optimizing different YOLOv11 variants to run on the embedded platform in the future, and achieve a fully edge-based solution. This will allow the wearable device to be used in an always-on manner for indoor assistance applications and ensure that it is lightweight, mobile, and low-cost.

Figure 2: The Raspberry Pi connection with the wearable IoT device for indoor object detection assistant

For the experiments, a publicly available Roboflow Furniture Detection Dataset5 is used. It contains 3000 annotated images taken from a collection of various indoor scenes. Images contain three types of objects, and each class has 1000 images. Manual annotation of images was used to label the datasets with bounding boxes. The target objects in the photos are clearly outlined, and the labels are consistent. The images were taken under different lighting conditions, camera angles, and with the objects at different locations. The training, validation, and testing set proportions were 70%, 10%, and 20%, respectively. The dataset was uniformly distributed between all three object classes in all three subsets. A total of 2100, 300, and 600 images were used for training, validation, and testing, respectively. For image pre-processing, we have resized the images to 224

Samples of the labelled dataset are illustrated in Fig. 3, representing the bed class annotations that are used with YOLOv11 for the classification process. Fig. 4 presents the predicted bounding boxes while using the YOLOv11 model in the validation process. Moreover, Fig. 5 presents the predicted bounding boxes while using the YOLOv11 model in the validation process on video frames.

Figure 3: Annotations for a sample validation batch used with YOLOv11

Figure 4: YOLOv11 predicted bounding boxes for the same validation batch

Figure 5: YOLOv11 predicted bounding boxes on video frames

In addition to the Roboflow Furniture Detection dataset, we also used publicly available Asia Furniture Image and Video Dataset6. This dataset includes a set of 11 annotated video sequences along with the extracted static frames, which are captured in various indoor scenes. It helped us to assess YOLOv11 performance on the real-time streaming video data and simulate more realistic conditions with diverse dynamic lighting conditions, camera motions, and furniture setups. We use 8 videos from this dataset for testing, while 3 videos were held out for validation, with no overlap between the two splits to evaluate the model’s temporal stability and frame-wise inference performance under real-world video conditions.

5.2 Training Configuration and Hyperparameters

Each model was trained independently with appropriately selected loss functions and optimizers. Table 1 summarizes the hyperparameter configurations used across all three models. All input images were resized to 224

6 Evaluation and Experimental Results

This section presents a detailed evaluation of the three object detection models, including YOLOv11, CNN (MobileNet-SSD), and RT-DETR, using training, validation, and test sets. We report metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and mAP at multiple Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds. Given the real-time needs of assistive applications, inference time is also considered critical. The analysis combines per-model performance results, visualizations, and comparative insights, culminating in a deployment-oriented recommendation.

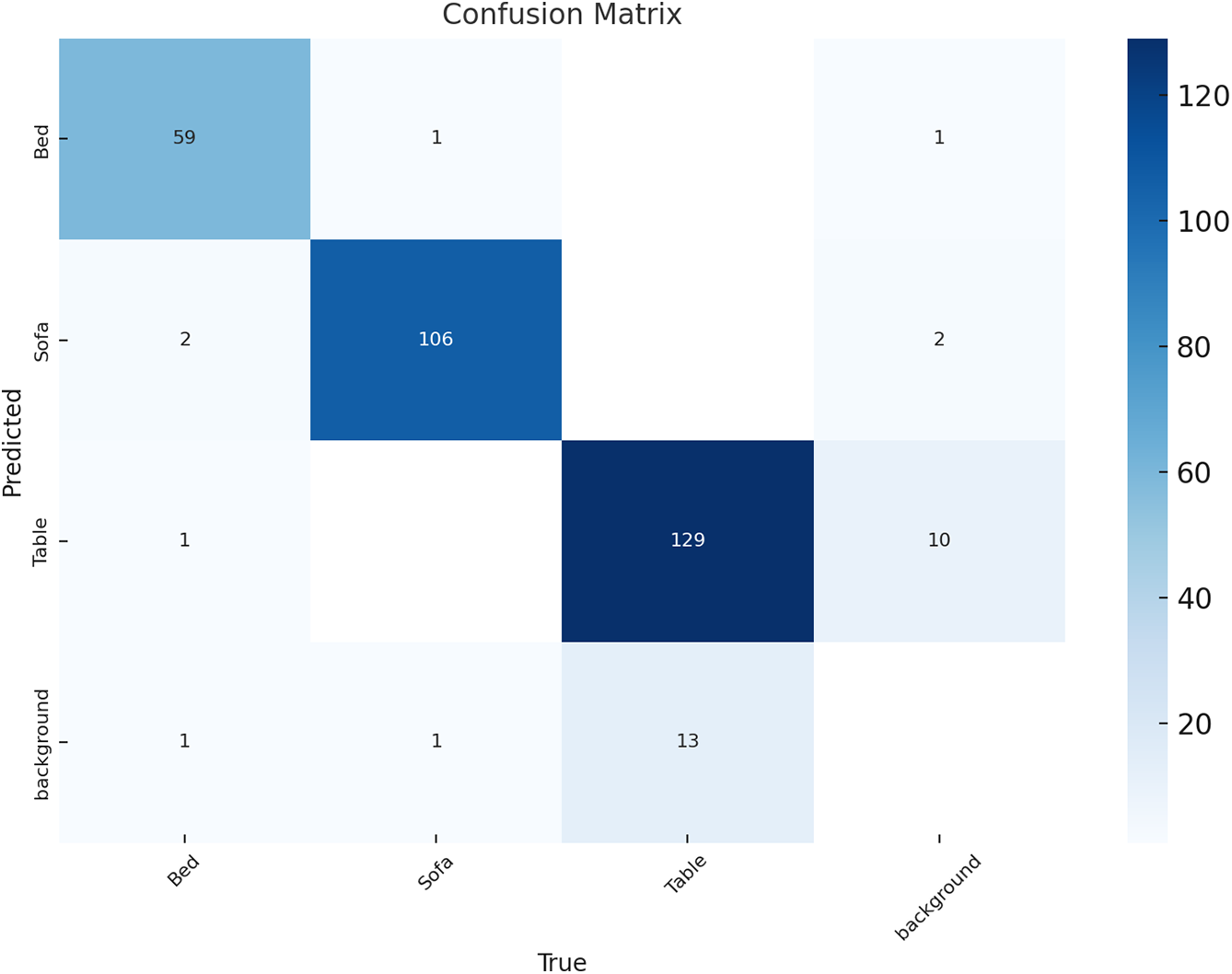

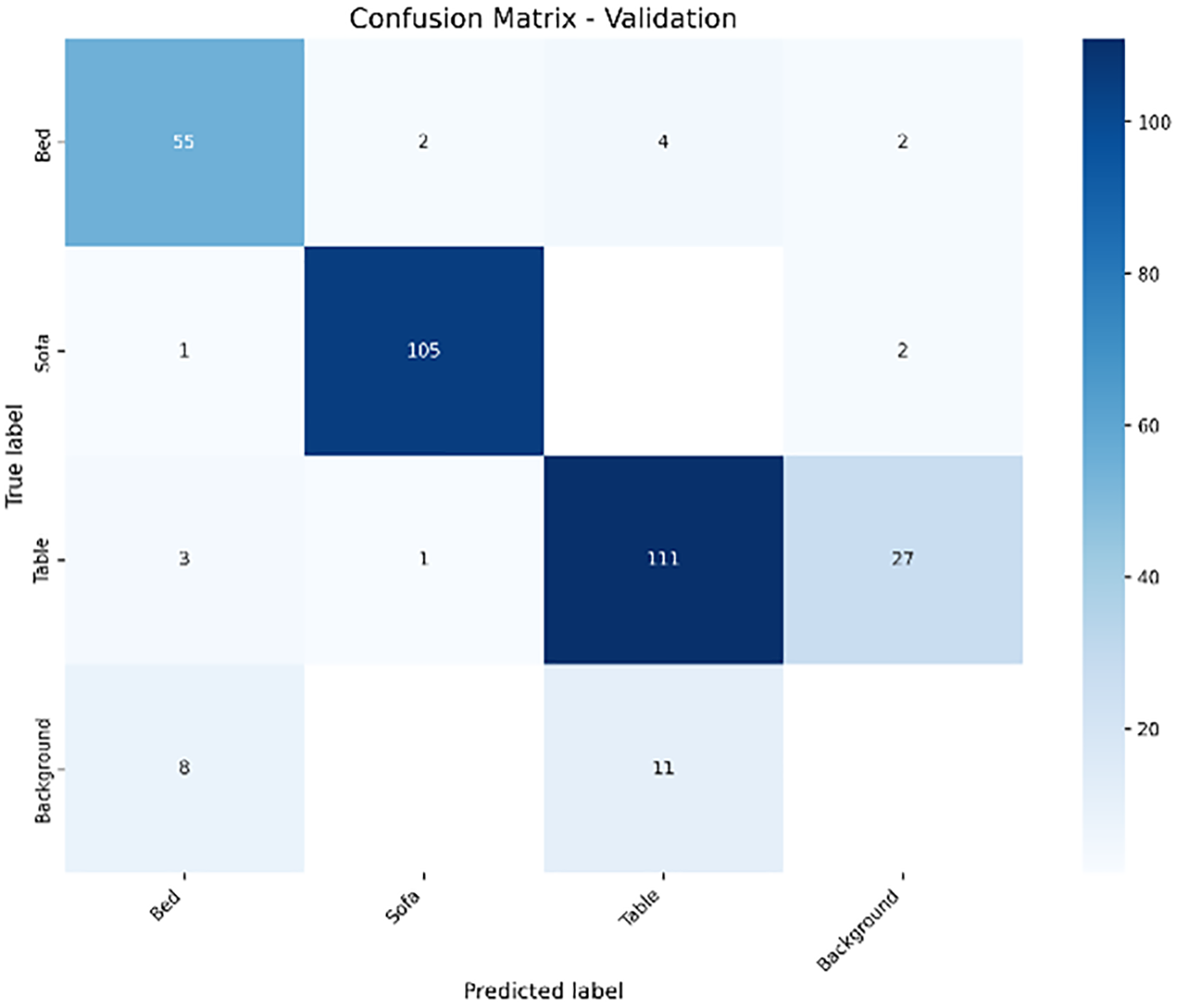

The confusion matrix in Fig. 6 reveals that YOLOv11 shows good detection capabilities for indoor objects like Bed, Sofa, and Table. High True Positive (TP) numbers were recorded for all classes, including 59 Beds, 106 Sofas, and 129 Tables, which were accurately detected. False Positive (FP) rates remain low yet existent, including 10 background samples wrongly identified as Tables and limited incorrect predictions for Beds and Sofas. The False Negative (FN) category registers 2 Sofas wrongly classified as Beds and another 2 Sofas that were mistaken for Background. The matrix demonstrates high True Negatives (TN) levels because non-target instances are correctly ignored given the sparse nature of the matrix outside its main diagonal. YOLOv11 achieves high precision and recall while experiencing minor misclassifications mainly between object classes and the background.

Figure 6: Confusion matrix for YOLOv11 model

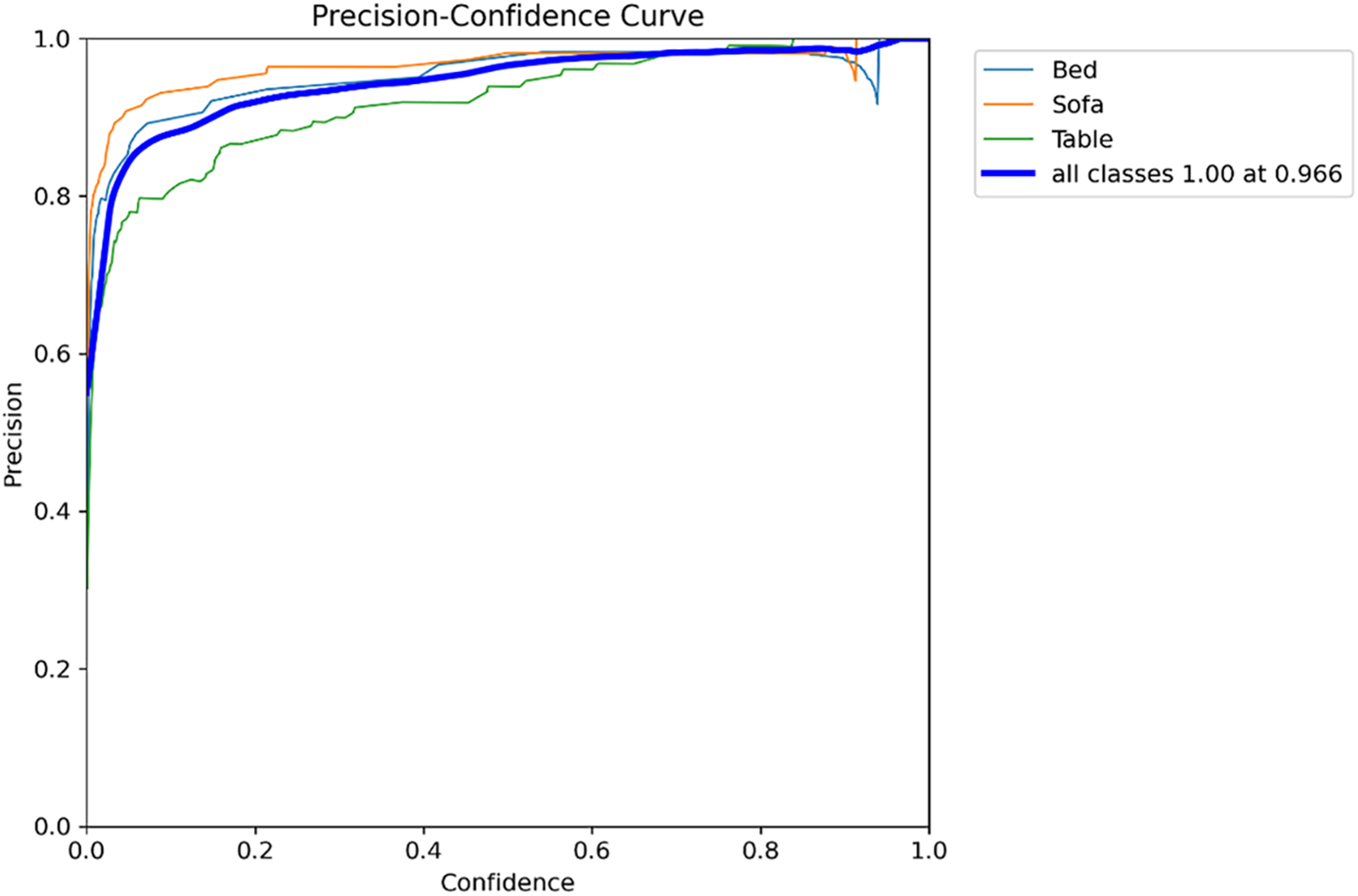

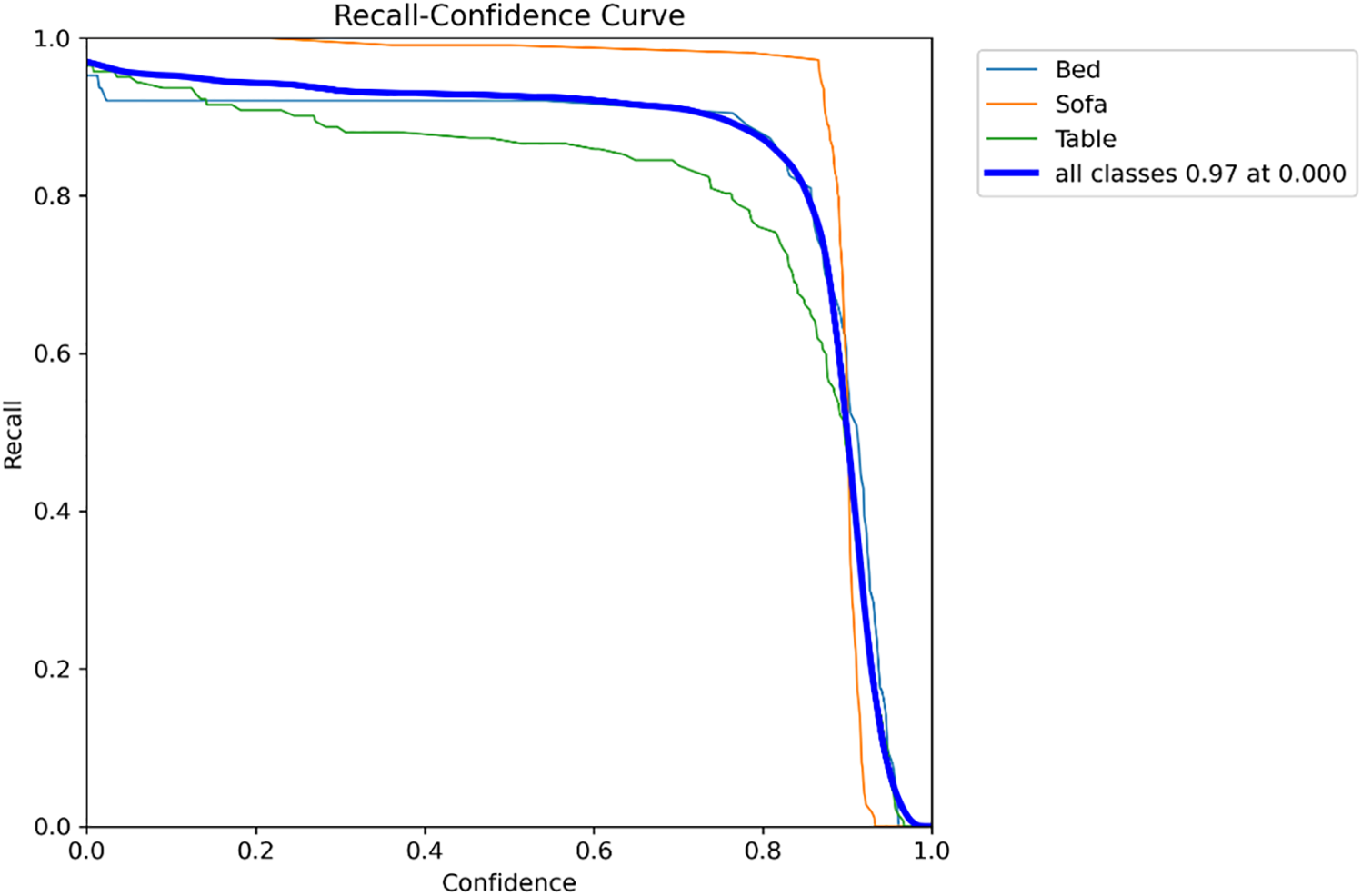

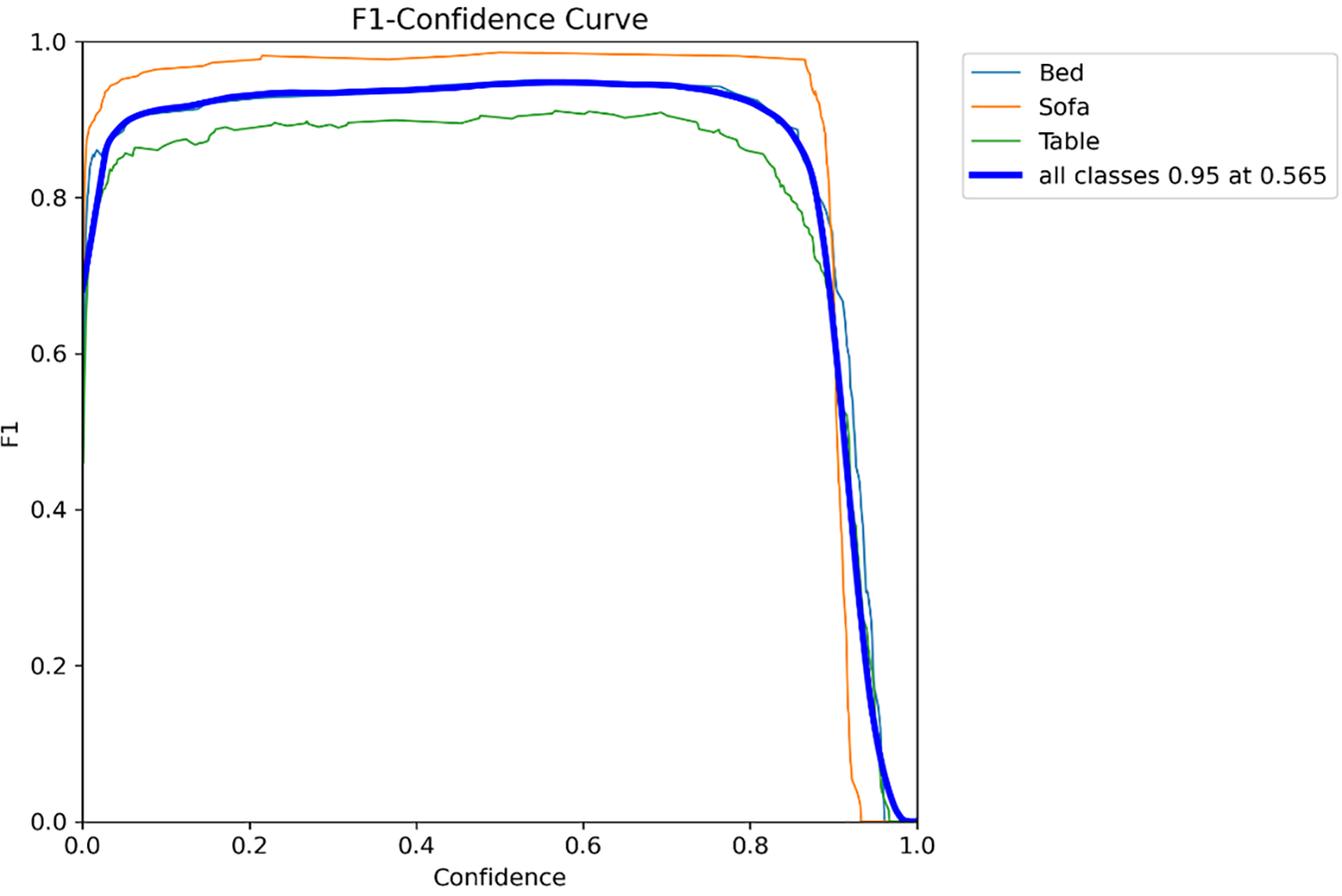

Figs. 7–9 depict the evaluation of the YOLOv11 model’s performance across Bed, Sofa, and Table classes, involving analysis through Precision-Confidence, Recall-Confidence, and F1-Confidence curves, respectively. The Precision-Confidence curve shows that the model achieves absolute precision when its confidence threshold hits 0.966, demonstrating high accuracy during its peak confidence moments. The Recall-Confidence curve demonstrates that the model sustains high recall levels of approximately 0.97 through most confidence stages but experiences a steep drop at confidence thresholds above 0.8. The F1-Confidence curve illustrates that the model reached its maximum F1-score of 0.95 when the confidence threshold was set at 0.565, which demonstrates an efficient balance between precision and recall for all classes. The findings confirm that YOLOv11 provides highly precise and dependable detection results for indoor objects when the model operates at the best confidence thresholds.

Figure 7: Precision for YOLOv11 model

Figure 8: Recall for YOLOv11 model

Figure 9: F1-score for YOLOv11 model

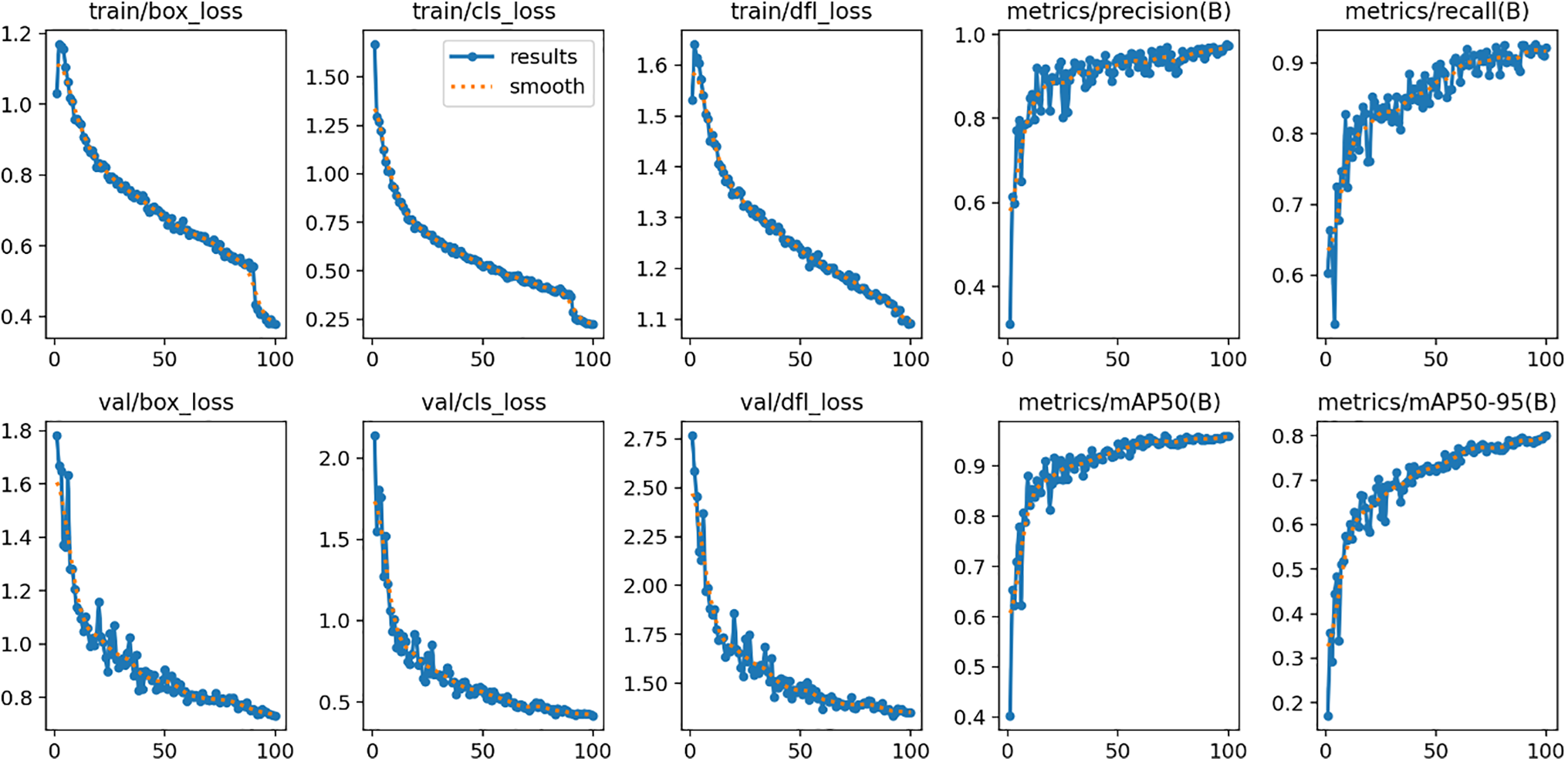

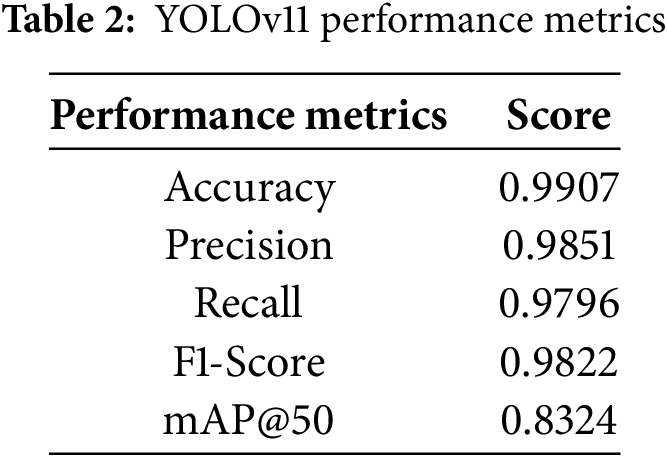

The training behavior of the YOLOv11 model remains stable and consistent throughout 100 epochs, as shown by its training and validation curves in Fig. 10. The reduction in box loss, classification loss, and Distribution Focal Loss (DFL) for both training and validation sets demonstrates successful convergence without overfitting indicators. In parallel, performance metrics steadily improve in both precision and recall, show notable growth in their values during the initial epochs, and eventually maintain high levels above 0.9. During the final stages of training, the mean Average Precision (mAP) at IoU threshold 0.5 (mAP50) reached about 0.95, while the more demanding mAP50–95 achieved approximately 0.80 through consistent improvement. The trends demonstrate that YOLOv11 mastered precise bounding box detection and classification for indoor object detection while preserving robust generalization performance between training and validation datasets. YOLOv11 overall performance metrics are detailed in Table 2.

Figure 10: YOLOv11 training and validation performance across 100 epochs

6.2 CNN (MobileNet-SSD) Evaluation

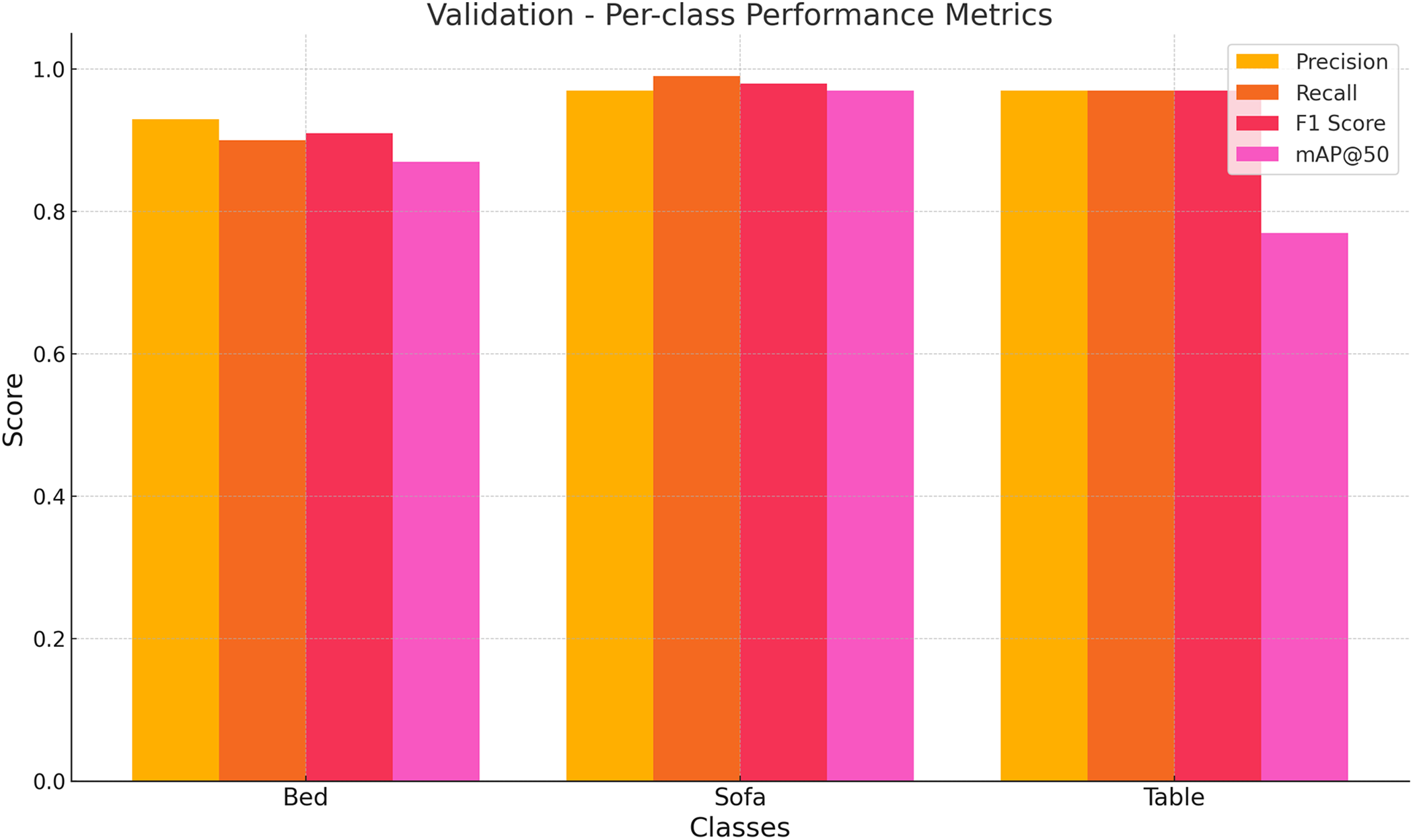

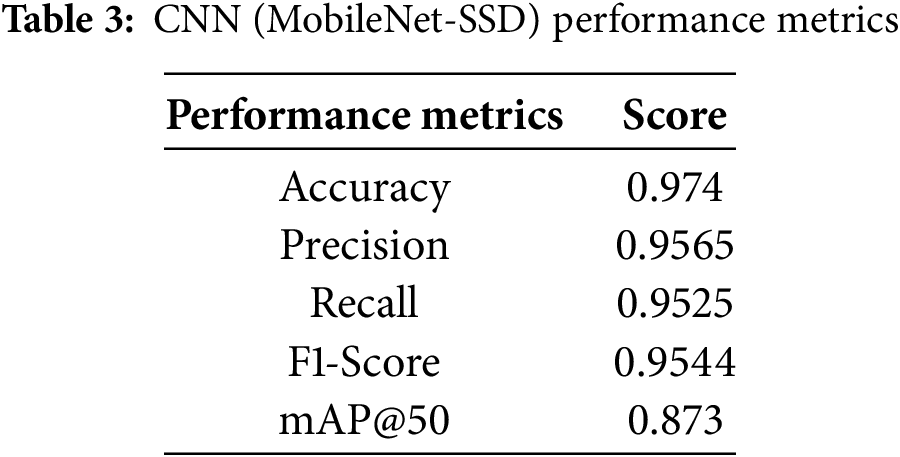

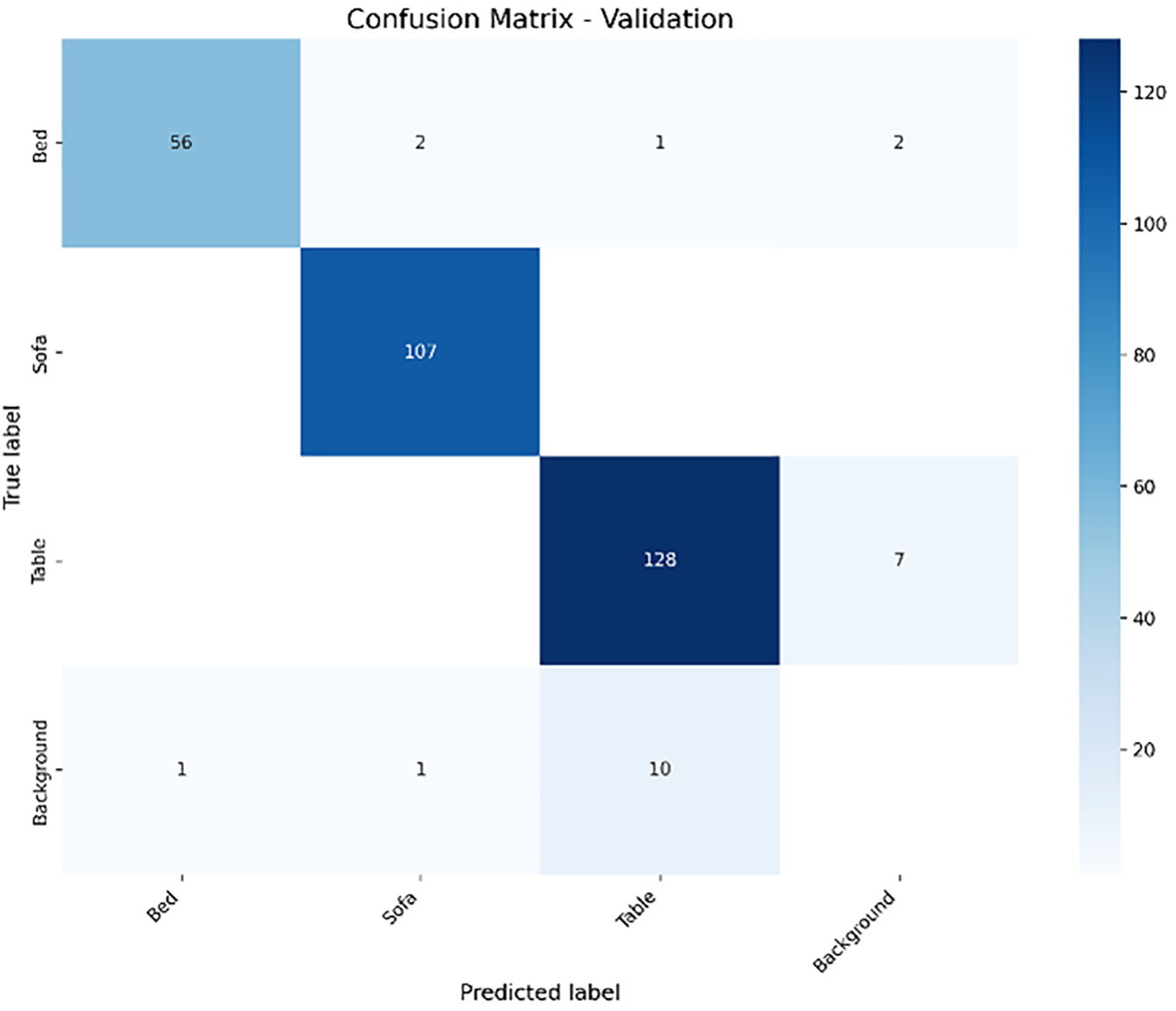

The CNN (MobileNet-SSD) evaluation results show effective classification performance across Bed, Sofa, Table, and Background classes according to the confusion matrix analysis in Fig. 11. The model achieved accurate classification of 55 Beds, 105 Sofas, and 111 Tables, which constitutes strong True Positive results. There are particularly significant FP rates for the Table class, which incorrectly labels 27 background instances as Tables. The model failed to identify the correct class in several instances, resulting in FN, such as 4 Beds incorrectly identified as Tables and 2 Beds mistaken for Background, while 2 Sofa objects were also incorrectly classified as Background. The Background class displayed classification errors with 8 samples identified as Beds and 11 samples identified as Tables. The matrix does not display TN values, but they are assumed to be high for non-target class predictions due to the general scarcity of incorrect classifications. The CNN (MobileNet-SSD) model exhibits excellent detection performance yet struggles to differentiate Tables from Background, which indicates further enhancements are necessary for processing complex environments.

Figure 11: Confusion matrix for CNN (MobileNet-SSD) model

The CNN (MobileNet-SSD) model demonstrates strong and balanced detection performance on all three classes (i.e., Bed, Sofa, and Table) in the validation set metrics as shown in Fig. 12. The Sofa class achieves peak performance levels since precision, recall, F1-score, and mAP@50 measures all reach or surpass 0.97, which shows outstanding detection and classification reliability. The Bed class maintains a precision that exceeds 0.93 with a recall near 0.90, leading to an acceptable F1-score, yet displays a mAP@50 score less than that of the Sofa class. The Table class demonstrates strong precision and recall values at around 0.96, while its mAP@50 score significantly falls to about 0.78, revealing that detection performance is strong, yet localization at stricter IoU thresholds needs enhancement. The MobileNet-SSD model demonstrates strong indoor object detection capabilities, especially for larger and less obstructed objects such as Sofas, but still faces some difficulties with accurate bounding box predictions for Tables. CNN (MobileNet-SSD) overall performance metrics are detailed in Table 3.

Figure 12: Class-wise performance metrics on the validation set for the CNN (MobileNet-SSD) model

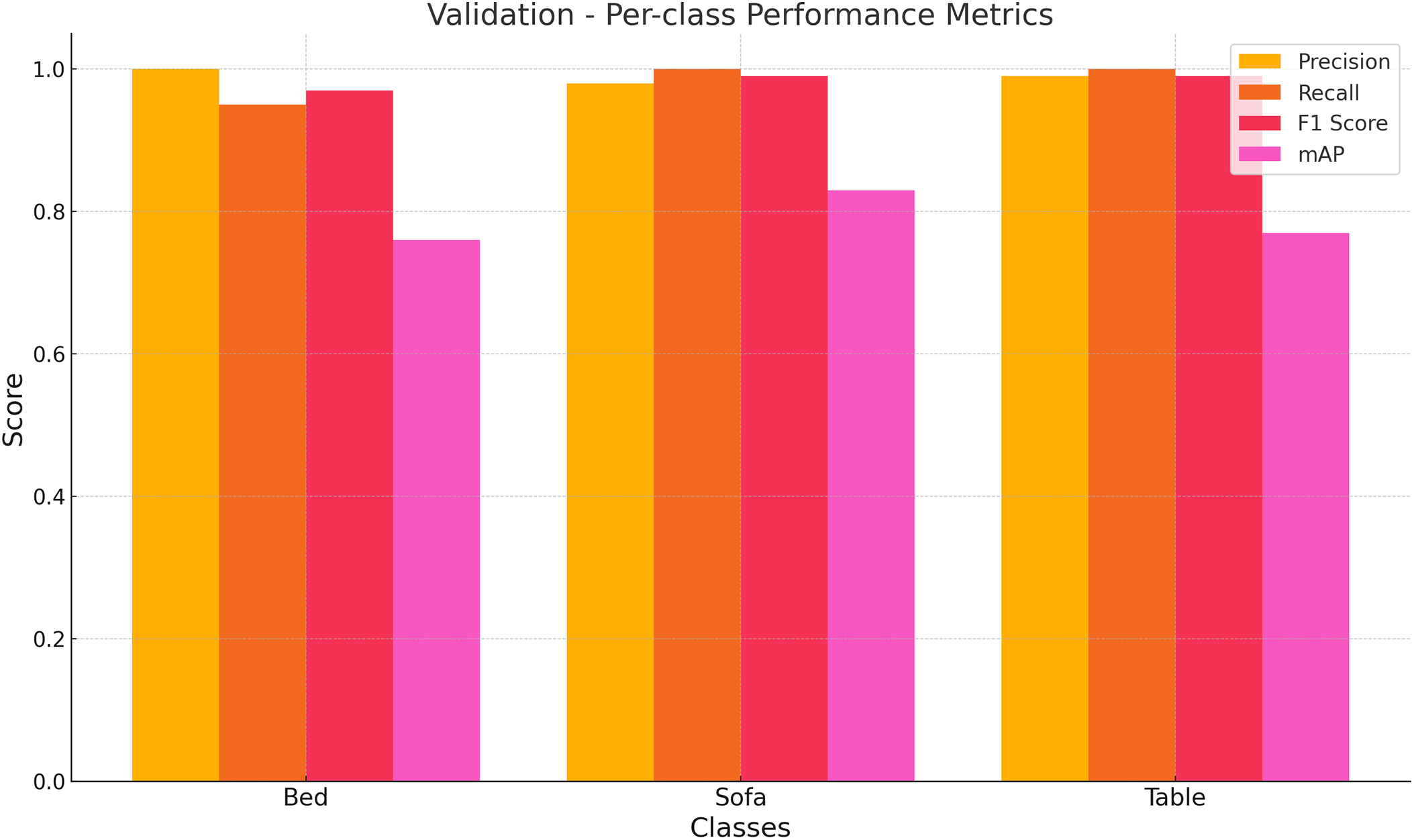

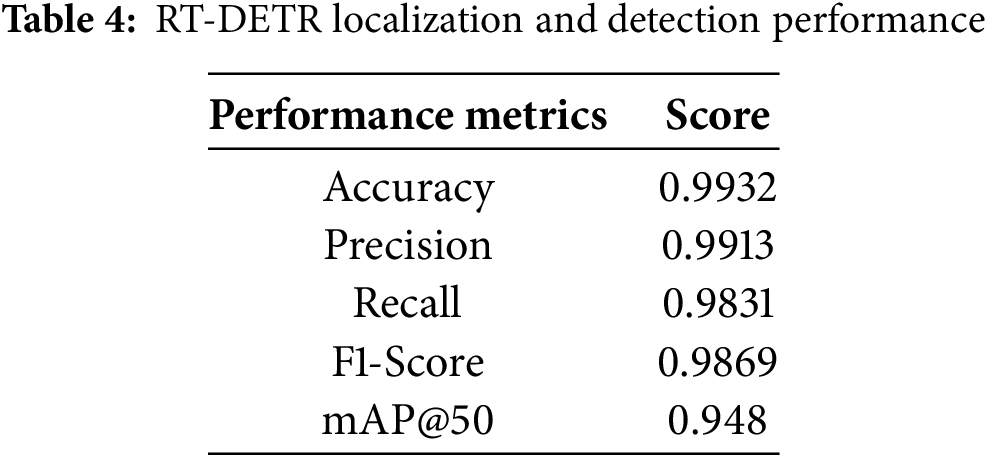

The RT-DETR model evaluation confusion matrix shows outstanding classification results for Bed, Sofa, Table, and Background categories as shown in Fig. 13. The TP rate reached impressive levels with 56 Beds and 107 Sofas correctly identified, along with 128 Tables. The FP count remains small with limited misclassifications, including 2 Beds identified as Sofas and 7 Background samples wrongly categorized as Tables. The number of FN errors remains low, as shown by 2 Bed instances that were not detected (i.e., classified as Background) and one Sofa that was incorrectly labeled as Background. The substantial presence of TN can be deduced from the model’s high accuracy and low misclassification rates despite its lack of explicit visibility. The RT-DETR model demonstrates exceptional detection performance through high precision and recall rates across all object classes, but shows minimal confusion between Tables and Background, indicating strong generalization skills in indoor object detection scenarios.

Figure 13: Confusion matrix for RT-DETR model

RT-DETR model performance metrics demonstrate exceptional detection capabilities for Bed, Sofa, and Table classes throughout validation testing as shown in Fig. 14. The Table class demonstrated high detection capabilities with precision, recall, and F1-score values nearing 1.0. The Sofa class achieved top detection performance with precision and recall values between 0.98 and 1.0, resulting in a high F1-score. The Bed class achieved precision levels near 1.0 but had slightly lower recall, resulting in a slightly diminished F1-score. The mAP scores for all classes showed strong results but fell below precision and recall metrics, notably in the Bed and Table classes, which indicates a need for improved bounding box localization accuracy at stricter IoU thresholds. RT-DETR achieves exceptional classification reliability and robustness for indoor object detection tasks and has only minor potential for improvement in precise localization performance. RT-DETR overall performance metrics are detailed in Table 4.

Figure 14: Class-wise performance metrics on the validation set for the RT-DETR model

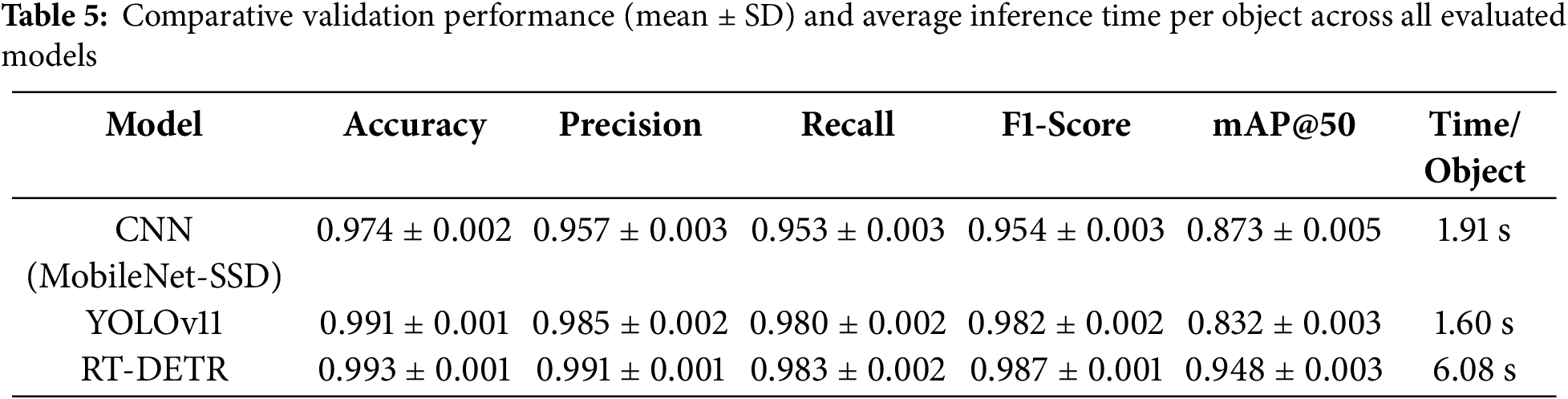

The evaluation results in Table 5 demonstrate the appropriateness of YOLOv11 as the baseline model for the Wearable IoT-Based Indoor Object Detection Assistant. RT-DETR exhibits the highest detection performance with an accuracy of 0.993

For visually impaired users who need instant feedback to navigate safely, real-time assistive applications require low latency alongside high accuracy. One-second detection delay leads to missed cues and delayed responses, which elevate safety risks. RT-DETR offers small improvements in mAP and F1-score over YOLOv11 but demands much longer inference time. YOLOv11 demonstrates swift and dependable object detection with a 1.60 s average inference time per object and maintains superior class-wise performance while running nearly three times faster than RT-DETR and faster than CNN (MobileNet-SSD). For wearable research prototypes to perform accurately, they depend on immediate response capabilities to facilitate real-time decisions.

YOLOv11 represents the best choice for real-time assistive systems like smart glasses because it meets essential requirements for speed and reliability. The model’s design maintains detection accuracy while its lightweight structure makes it ideal for implementation on devices with limited resources. The comprehensive assessment resulted in the selection of YOLOv11 as the deployment model because it provides optimal detection performance alongside efficient inference speed and practical deployability. The specific balance between detection performance and deployment feasibility enables this research prototype to effectively meet the essential needs of real-time assistive technologies for visually impaired users.

6.5 Real-Time Performance Evaluation

In order to demonstrate the practicality of the proposed system architecture for real-world wearable deployment, we conduct a series of real-time performance experiments. It is important to note that in this evaluation setup, we did not involve live camera capture, where frames are simply being read from the Asia Furniture video and processed in a real-time manner. The Raspberry Pi is used to establish a baseline for processing constraints and latency to represent a real-world deployment scenario. The metrics include not only the average inference latency, but also the Frames Per Second (FPS), Floating Point Operations (FLOPs), and memory cost on the GPU and embedded platform. In addition, we make a performance comparison with previous YOLO models (i.e., YOLOv5 and YOLOv6), and further test the performance of YOLOv11 in a video stream on the Asia Furniture Dataset to verify its robustness in complex and dynamic visual scenes.

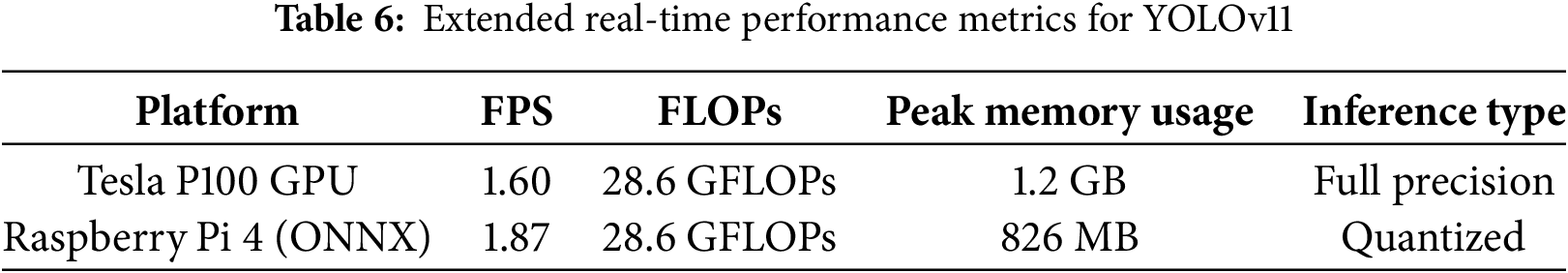

To represent the real-time performance of object detection models more accurately, we have introduced two additional metrics into our evaluation, FPS and FLOPs. YOLOv11 has a speed of 1.60 FPS on the GPU (Tesla P100), while it completes about 28.6 GFLOPs per inference at an input resolution of 640

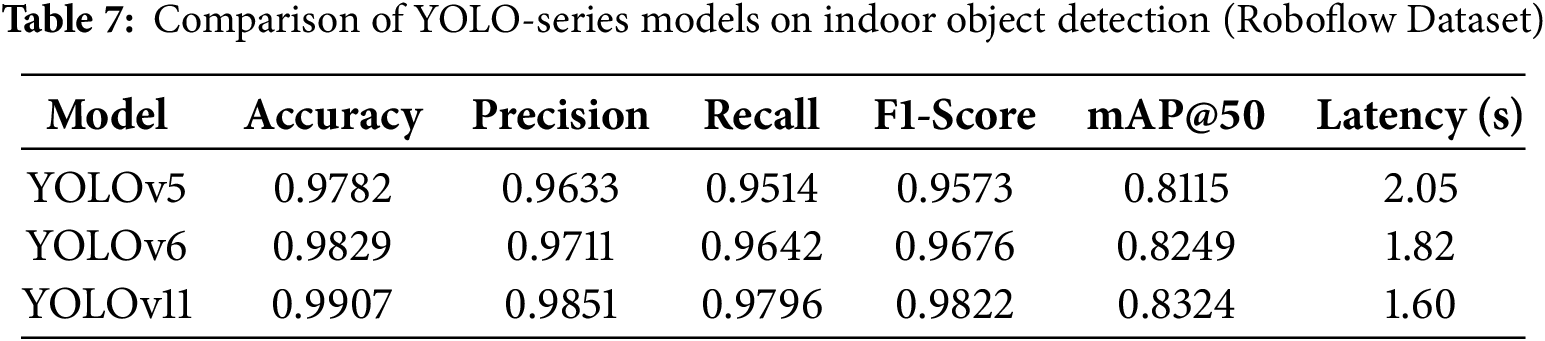

To further validate YOLOv11’s effectiveness, we compared it with previous models, YOLOv5 and YOLOv6, on the same dataset and training settings. As we can see in Table 7, YOLOv11 had a better overall detection performance and latency, further validating its effectiveness and feasibility of real-time application in assistive wearables.

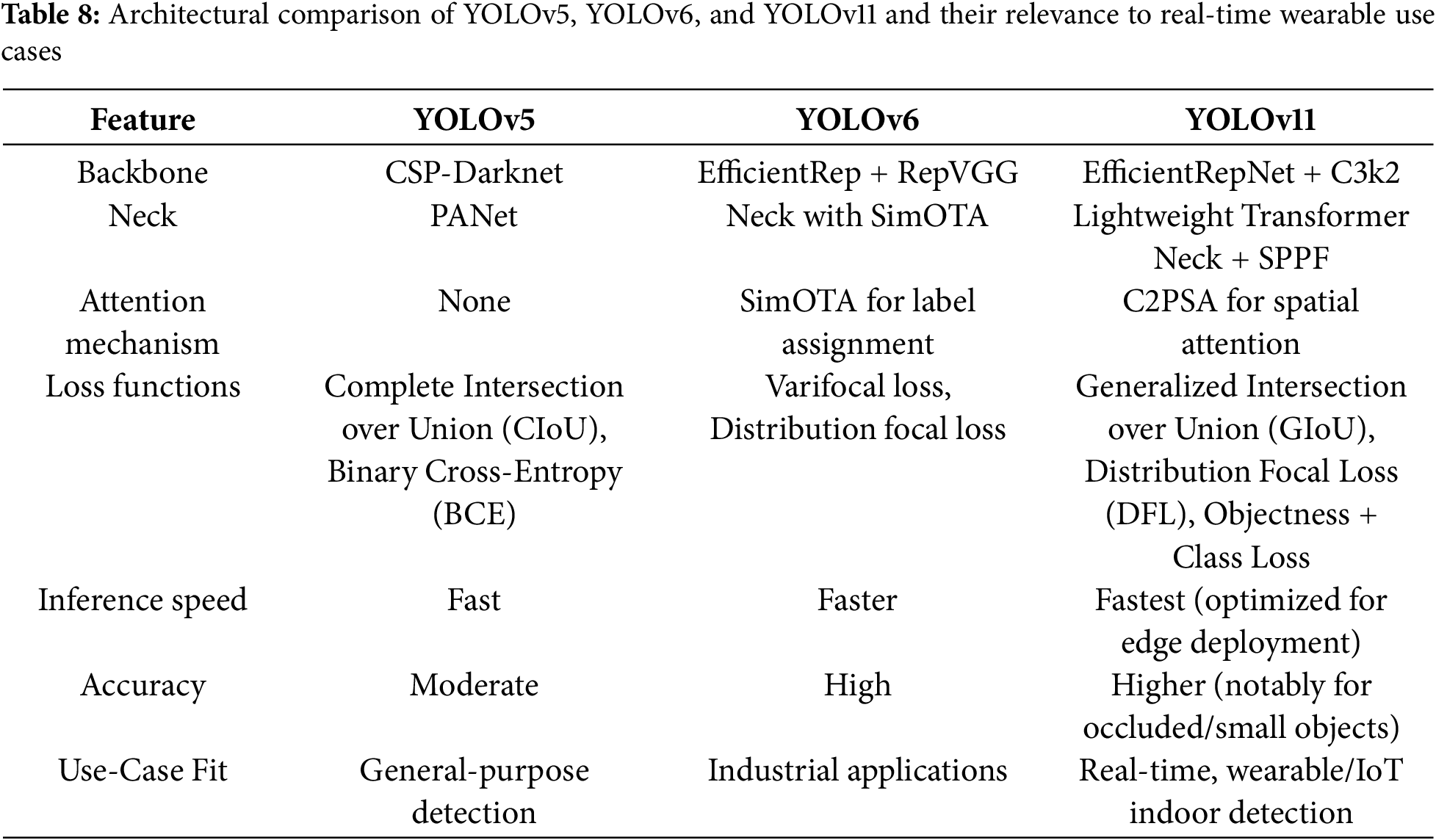

YOLOv5, YOLOv6, and YOLOv11, three models with different architectures, are compared in Table 8. The backbone and neck of YOLOv5 are CSP-Darknet and Path Aggregation Network (PANet), respectively, which are general-purpose detection components that lack advanced attention mechanisms. YOLOv6 uses more efficient components for industrial vision, such as Re-parameterizable Visual Geometry Group (RepVGG)-based EfficientRep and Simplified Optimal Transport Assignment (SimOTA) for label assignment, to improve speed and accuracy. YOLOv11 extends YOLOv6 with a lightweight transformer-based neck, the C3k2 block for reduced computation, the SPPF module for multi-scale feature representation, and the C2PSA block for improved spatial attention. It achieves high accuracy for small or occluded indoor objects while remaining lightweight for low inference latency and efficient for resource-limited wearable and IoT applications. These reasons support our decision to use YOLOv11 for real-time assistive object detection.

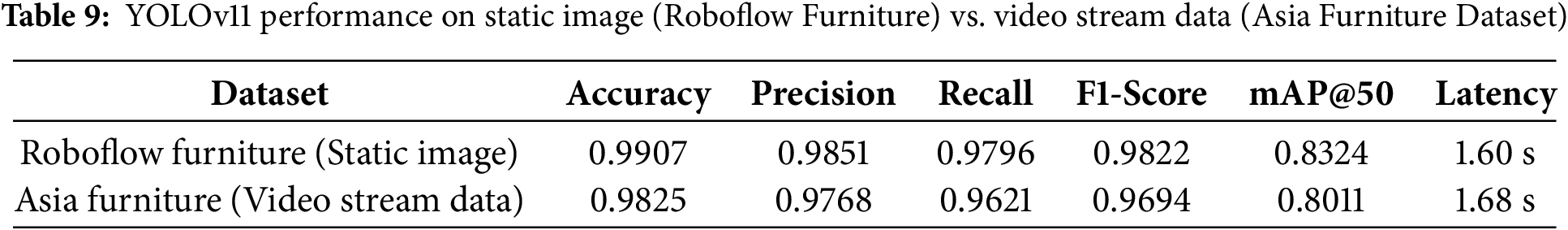

For additional validation of real-time performance, we evaluated the performance of YOLOv11 with a 30fps video stream from the Asia Furniture Image and Video Dataset. Frames were processed using OpenCV and YOLOv11 in a live inference pipeline with cloud-based deployment. The research prototype achieved an average latency of 1.68 s per frame. Evaluation results on this dataset showed slightly lower scores compared to our original experiment (i.e., image-based experiment) set, but still demonstrated strong performance in accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and mAP@50, scoring 0.9825, 0.9768, 0.9621, 0.9694, and 0.8011, respectively. These results (i.e., see Table 9) validate that YOLOv11 maintains detection robustness and real-time suitability in diverse indoor video scenarios.

These results show that YOLOv11 gives better detection accuracy and real-time inference for wearable IoT. YOLOv11 has less latency and better accuracy than YOLOv5 and YOLOv6. Its performance on real-time video streams demonstrates its practical applicability in real-world, dynamic indoor environments for assistive technology.

The paper presents a feasibility study for the wearable IoT-based indoor object detection assistant system architecture that we propose. The system architecture employs a real-time indoor object detection approach to help visually impaired users recognize indoor objects. The proposed indoor object detection approach exploits the advanced YOLOv11 object detection model, enabling our research prototype to detect indoor objects like beds, sofas, and tables with high accuracy and real-time performance. The research prototype performance was validated with two datasets compiled from Furniture Detection (i.e., from Roboflow Universe) and Kaggle, which comprises 3000 images evenly distributed across three object categories, including bed, sofa, and table. In the evaluation process, we have benchmarked YOLOv11 against CNN (MobileNet-SSD) and RT-DETR models, showing YOLOv11 provided better accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, scoring 99.07%, 98.51%, 97.96%, and 98.22%, respectively. YOLOv11 provides faster inference times, achieving 1.60 s per detected object compared with its opponents, which is essential for real-time application use. This feasibility study highlights the effectiveness of Raspberry Pi 4 and YOLOv11 in real-time indoor object detection, paving the way for structured user studies with visually impaired people in the future to evaluate their real-world use and impact.

Our future work efforts will target the improvement of real-time processing capabilities on edge computing devices to find the best compromise between detection precision and inference speed. We will further enlarge the dataset in terms of object categories, including chairs, shelves, bags, and other common movable indoor objects. We will also include smaller and occluded objects that are more prevalent in complex indoor scenes, further improving the generalization and robustness in real-world deployment. The audio feedback system for the indoor object detection result notifier requires enhancement to provide users with more detailed guidance that understands context and maintains user-friendliness. Furthermore, we will also perform structured user studies with visually impaired people in the future to evaluate their real-world use and impact. This includes assessing the system’s usability, comfort for long-term wear, clarity of audio feedback, and overall effectiveness in improving indoor navigation. Feedback from participants will inform further improvements to hardware design and feedback mechanisms to better meet the practical needs of the intended user group.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman Center for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group No. KSRG-2024-140.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the King Salman Center for Disability Research through Research Group No. KSRG-2024-140.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Ayman Noor, Hanan Almukhalfi, and Arthur Souza; methodology, Ayman Noor and Hanan Almukhalfi; software, Ayman Noor and Hanan Almukhalfi; validation, Ayman Noor and Hanan Almukhalfi; formal analysis, Ayman Noor, Hanan Almukhalfi, and Talal H. Noor; investigation, Ayman Noor and Arthur Souza; resources, Arthur Souza and Talal H. Noor; data curation, Ayman Noor and Hanan Almukhalfi; writing—original draft preparation, Ayman Noor and Hanan Almukhalfi; writing—review and editing, Arthur Souza and Talal H. Noor; visualization, Ayman Noor and Talal H. Noor; supervision, Ayman Noor; project administration, Talal H. Noor; funding acquisition, Ayman Noor and Talal H. Noor. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used for static images in this study are publicly available from the Roboflow Universe under the public project FurnitureDetection. Available from: https://universe.roboflow.com/mokhamed-nagy-u69zl/furniture-detection-qiufc (accessed 23 February 2025). Moreover, the data used for the video stream is publicly available from Kaggle. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/putdejudomthai/asia-furniture-image-and-video-dataset (accessed 01 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://www.tensorflow.org/ (accessed on 31 August 2025)

2https://pytorch.org/ (accessed on 31 August 2025)

3https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolo11/implementation (accessed on 31 August 2025)

4https://www.raspberrypi.com/products/raspberry-pi-4-model-b/ (accessed on 31 August 2025)

5https://universe.roboflow.com/mokhamed-nagy-u69zl/furniture-detection-qiufc (accessed on 31 August 2025)

6https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/putdejudomthai/asia-furniture-image-and-video-dataset (accessed on 31 August 2025)

References

1. Real S, Araujo A. Navigation systems for the blind and visually impaired: past work, challenges, and open problems. Sensors. 2019;19(15):3404. doi:10.3390/s19153404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Keryakos Y. Detection and management of stressful situations to assist blind individuals in their daily lives [Ph.D. thesis]. Besançon, France: Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté; 2024. [Google Scholar]

3. Tsai CH, Elyasi F, Ren P, Manduchi R. All the way there and back: inertial-based, phone-in-pocket indoor wayfinding and backtracking apps for blind travelers. ACM Transact Access Comput. 2024;17(4):1–35. doi:10.1145/3696005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. El-Sheimy N, Li Y. Indoor navigation: state of the art and future trends. Satellite Navigat. 2021;2(1):7. doi:10.1186/s43020-021-00041-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pešić S. Modern challenges in indoor positioning systems: AI to the rescue. In: Innovations in Indoor positioning systems (IPS). London, UK: IntechOpen; 2024. p. 65–84. doi:10.5772/intechopen.1005354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Agarwal R, Tripathi A. Current modalities for low vision rehabilitation. Cureus. 2021;13(7):e16561. doi:10.7759/cureus.16561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Rickly JM, Halpern N, Hansen M, Welsman J. Travelling with a guide dog: experiences of people with vision impairment. Sustainability. 2021;13(5):2840. doi:10.3390/su13052840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kim IJ. Recent advancements in indoor electronic travel aids for the blind or visually impaired: a comprehensive review of technologies and implementations. Univers Access Inf Soc. 2025;24(1):173–93. doi:10.1007/s10209-023-01086-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang X, Pan Z, Song Z, Zhang Y, Li W, Ding S. The aerial guide dog: a low-cognitive-load indoor electronic travel aid for visually impaired individuals. Sensors. 2024;24(1):297. doi:10.3390/s24010297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Hersh M. Wearable travel aids for blind and partially sighted people: a review with a focus on design issues. Sensors. 2022;22(14):5454. doi:10.3390/s22145454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Chavarria MA, Ortiz-Escobar LM, Bacca-Cortes B, Romero-Cano V, Villota I, Muñoz Peña JK, et al. Challenges and opportunities of the human-centered design approach: case study development of an assistive device for the navigation of persons with visual impairment. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2025;12:e70694. doi:10.2196/70694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Lavric A, Beguni C, Zadobrischi E, Căilean AM, Avătămăniţei SA. A comprehensive survey on emerging assistive technologies for visually impaired persons: lighting the path with visible light communications and artificial intelligence innovations. Sensors. 2024;24(15):4834. doi:10.3390/s24154834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Noor A, Noor TH. Federated intelligence for intrusion detection and unifying health prediction in IoHT. In: 4th International Conference on Distributed Sensing and Intelligent Systems (ICDSIS 2023). London, UK: IET; 2023. p. 556–66. [Google Scholar]

14. Abbas Q, Ibrahim ME, Jaffar MA. A comprehensive review of recent advances on deep vision systems. Artif Intell Rev. 2019;52(1):39–76. doi:10.1007/s10462-018-9633-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. Ssd: single shot multibox detector. In: Computer Vision-ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

16. Noor TH, Noor A, Alharbi AF, Faisal A, Alrashidi R, Alsaedi AS, et al. Real-time arabic sign language recognition using a hybrid deep learning model. Sensors. 2024;24(11):3683. doi:10.3390/s24113683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. El Aidouni M. SSD: Understanding single shot object detection [Internet]; 2019. [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Available from: https://manalelaidounigithubio/assets/img/pexels/SSDjpg. [Google Scholar]

18. Ali ML, Zhang Z. The YOLO framework: a comprehensive review of evolution, applications, and benchmarks in object detection. Computers. 2024;13(12):336. doi:10.3390/computers13120336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kevin M, Mario C, Ortiz L, Sutter S, Klaus S, Bladimir BC. Embedded solution to detect and classify head level objects using stereo vision for visually impaired people with audio feedback. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):17277. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-01529-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Brilli DD, Georgaras E, Tsilivaki S, Melanitis N, Nikita K. Airis: an AI-powered wearable assistive device for the visually impaired. In: 2024 10th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference for Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics BioRob; 2024 Sep 1–4; Heidelberg, Germany. p. 1236–41. [Google Scholar]

21. Sugashini T, Balakrishnan G. YOLO glass: video-based smart object detection using squeeze and attention YOLO network. Signal, Image Video Process. 2024;18(3):2105–15. doi:10.1007/s11760-023-02855-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gugulothu SS, Bhoyar DDB. Functional analysis and statistical mechanics for exploring the potential of smart glasses: an assessment of visually impaired individuals. Communicat Appl Nonlin Anal. 2024;31(2s):402–21. doi:10.52783/cana.v31.657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Atitallah AB, Said Y, Atitallah MAB, Albekairi M, Kaaniche K, Boubaker S. An effective obstacle detection system using deep learning advantages to aid blind and visually impaired navigation. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(2):102387. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2023.102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hussan M, Saidulu D, Anitha P, Manikandan A, Naresh P. Object detection and recognition in real time using deep learning for visually impaired people. Int J Elect Elect Res. 2022;10(2):80–6. [Google Scholar]

25. Vaidya S, Shah N, Shah N, Shankarmani R. Real-time object detection for visually challenged people. In: 2020 4th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS); 2020 May 13–15; Madurai, India. p. 311–6. [Google Scholar]

26. Islam RB, Akhter S, Iqbal F, Rahman MSU, Khan R. Deep learning based object detection and surrounding environment description for visually impaired people. Heliyon. 2023;9(6):e16924. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16924. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Dang B, Ma D, Li S, Dong X, Zang H, Ding R. Enhancing kitchen independence: deep learning-based object detection for visually impaired assistance. Academic J Sci Technol. 2024;9(2):180–4. doi:10.54097/hc3f1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mukhiddinov M, Cho J. Smart glass system using deep learning for the blind and visually impaired. Electronics. 2021;10(22):2756. doi:10.3390/electronics10222756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Leong X, Ramasamy RK. Obstacle detection and distance estimation for visually impaired people. IEEE Access. 2023;11:136609–29. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3338154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Khan W, Hussain A, Khan BM, Crockett K. Outdoor mobility aid for people with visual impairment: obstacle detection and responsive framework for the scene perception during the outdoor mobility of people with visual impairment. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;228(100):120464. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Moosmann J, Bonazzi P, Li Y, Bian S, Mayer P, Benini L, et al. Ultra-efficient on-device object detection on AI-integrated smart glasses with tinyissimoyolo. arXiv:2311.01057. 2023. [Google Scholar]

32. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. [Google Scholar]

33. Noor A, Almukhalfi H, Souza A, Noor TH. Harnessing YOLOv11 for enhanced detection of typical autism spectrum disorder behaviors through body movements. Diagnostics. 2025;15(14):1786. doi:10.3390/diagnostics15141786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Redmon J, Farhadi A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 7263–71. [Google Scholar]

35. Bochkovskiy A, Wang CY, Liao HYM. Yolov4: optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv:2004.10934. 2020. [Google Scholar]

36. Li C, Li L, Jiang H, Weng K, Geng Y, Li L, et al. YOLOv6: a single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv:2209.02976. 2022. [Google Scholar]

37. Noor A, Algrafi Z, Alharbi B, Noor TH, Alsaeedi A, Alluhaibi R, et al. A cloud-based ambulance detection system using YOLOv8 for minimizing ambulance response time. Appl Sci. 2024;14(6):2555. doi:10.3390/app14062555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Khanam R, Hussain M. Yolov11: an overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv:2410.17725. 2024. [Google Scholar]

39. Alkhammash EH. Multi-classification using YOLOv11 and hybrid YOLO11n-mobilenet models: a fire classes case study. Fire. 2025;8(1):17. doi:10.3390/fire8010017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li Y, Yan H, Li D, Wang H. Robust miner detection in challenging underground environments: an improved YOLOv11 approach. Appl Sci. 2024;14(24):11700. doi:10.3390/app142411700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Yan Z, Wu Y, Zhao W, Zhang S, Li X. Research on an apple recognition and yield estimation model based on the fusion of improved YOLOv11 and DeepSORT. Agriculture. 2025;15(7):765. doi:10.3390/agriculture15070765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools