Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Active Learning-Enhanced Deep Ensemble Framework for Human Activity Recognition Using Spatio-Textural Features

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Annamalai University, Annamalainagar, 608002, Tamil Nadu, India

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Gudlavalleru Engineering College, Gudlavalleru, 521356, Andhra Pradesh, India

* Corresponding Author: Lakshmi Alekhya Jandhyam. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning and Deep Learning-Based Pattern Recognition)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 3679-3714. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068941

Received 10 June 2025; Accepted 27 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) has become increasingly critical in civic surveillance, medical care monitoring, and institutional protection. Current deep learning-based approaches often suffer from excessive computational complexity, limited generalizability under varying conditions, and compromised real-time performance. To counter these, this paper introduces an Active Learning-aided Heuristic Deep Spatio-Textural Ensemble Learning (ALH-DSEL) framework. The model initially identifies keyframes from the surveillance videos with a Multi-Constraint Active Learning (MCAL) approach, with features extracted from DenseNet121. The frames are then segmented employing an optimized Fuzzy C-Means clustering algorithm with Firefly to identify areas of interest. A deep ensemble feature extractor, comprising DenseNet121, EfficientNet-B7, MobileNet, and GLCM, extracts varied spatial and textural features. Fused characteristics are enhanced through PCA and Min-Max normalization and discriminated by a maximum voting ensemble of RF, AdaBoost, and XGBoost. The experimental results show that ALH-DSEL provides higher accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, validating its superiority for real-time HAR in surveillance scenarios.Keywords

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) has attracted a lot of attention over the last few years because it plays a vital role in a broad range of applications, such as video surveillance, ambient assisted living, intelligent homes, health monitoring systems, and intelligent human-computer interaction [1–5]. It is not only helpful to improve system intelligence but also enables prompt response in dynamic and sensitive scenarios [6,7]. With the world increasingly adopting automation and intelligent technologies, the need for efficient and reliable HAR systems has grown exponentially [8,9]. Yet, identification of human activity from video streams is still a challenging problem [10,11]. Human movements are complex and vary by behavior, speed, angle, and context. Real-world videos often contain occlusion, clutter, poor lighting, and camera motion [12,13]. All of these real-world factors add substantial variability in recognition patterns, whether visual or sensor-based, so that standard recognition systems fail to function consistently across diverse situations [14,15]. The second major challenge in HAR is the effective management of massive video data [16,17]. Many video frames are redundant, increasing computational cost without improving recognition [18,19]. In real-time systems, where both speed and accuracy are necessary, it is crucial to design intelligent models that can focus on the most informative portions of the data while filtering out irrelevant or redundant features [20,21].

Additionally, the performance of HAR systems largely depends on the quality of visual features learned from video information [22]. Describing the appearance and motion properties of human activities at the same time requires combining complementary visual features [23,24]. Spatio-textural features, which relate to texture, shape, and spatial arrangement, are essential for enhancing the model’s ability to distinguish different activities [25]. Together, these features provide a more accurate description of the activity being performed. With these challenges and opportunities in mind, this study aims to build a better HAR framework that intelligently uses informative content while ensuring efficient and reliable activity prediction. The framework is designed to tackle key issues like data complexity, feature relevance, and model robustness, with a particular focus on generalization across various environmental contexts. Through this research, we strive to make a meaningful contribution to the field of HAR, addressing the growing needs of practical intelligent systems [26]. Among the numerous research studies using HAR with deep learning or machine learning models, some of the recent works are discussed as follows.

Yu et al. (2025) [27] introduced a heterogeneous federated learning architecture to address model and data heterogeneity in HAR. This architecture allowed different client models to exchange knowledge through prediction logits on a synthetic data bridge, enabling structure-agnostic learning. An information entropy loss was used to enhance the quality of the bridge, while similarity-based knowledge distillation using a relation graph facilitated effective knowledge transfer among clients. The system was tested on four benchmark HAR datasets and showed good performance in handling dual heterogeneity. However, scalability may be limited in resource-scarce environments due to synthetic data generation from high-power clients.

Topuz and Kaya (2025) [28] proposed a hybrid model called EO-LGBM-HAR for HAR, which combines the Equilibrium Optimizer (EO) with a LightGBM classifier. EO was used for efficient feature selection and hyperparameter tuning to boost performance and make training more robust. Tests on UCI-HAR and WISDM datasets showed competitive classification accuracy compared to other methods. The integration of metaheuristic optimization with a gradient-boosting platform improved learning efficiency, though the computational overhead from EO could impact performance.

Joudaki et al. (2025) [29] developed a hybrid human action recognition model combining 2D Convolutional Restricted Boltzmann Machines (2D Conv-RBM) and LSTM networks. The model learned spatial features with 2D Conv-RBM and temporal dependencies with LSTM. A smart frame selection method reduced redundancy and computational costs. It was tested on several benchmark datasets and achieved high performance. However, the model’s limitations include reliance on manually tuned hyperparameters and reduced robustness in complex occluded or cluttered scenes.

Zhan (2025) [30] designed a HAR model for single-device setups using a dual-branch spatiotemporal feature learning network. One branch used spatiotemporal convolution to learn local motion, while the other captured long-term temporal dependencies. This approach aimed to address the limitations of traditional models using data from a single sensor. Compared to common architectures on the WISDM dataset, it demonstrated superior overall performance, but its effectiveness could decrease with new device positions or sensor noise in real-world scenarios.

Zhao et al. (2025) [31] proposed CIR-DFENet, a cross-modal Human Activity Recognition (HAR) model on the basis of single wearable sensor data. The method transformed time-series signals into RGB images by adopting Markov Transition Field (MTF), Recurrence Plot (RP), and Gramian Angular Field (GAF) techniques to depict various signal features. A two-stream paradigm was then utilized: one stream utilized a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with a Global Attention Mechanism (GAM) for image inputs, while the other utilized a CNN–Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)–Self-Attention (SA) network for modeling in time. The use of residual architectures optimized training efficiency and robustness; nevertheless, the complexity of the model may require increased computational power.

Xiao and Tong (2025) [32] developed a federated contrastive learning framework with feature-based distillation (FCLFD) for HAR. The approach used a student–teacher contrastive model to transfer knowledge efficiently while maintaining user data privacy. A central server aggregated model weights from multiple mobile users with an average strategy to update the global model. Tests on distributed sensor datasets showed better performance than current federated learning methods. However, synchronized user participation might reduce real-time responsiveness in highly dynamic environments.

Jayamohan and Yuvaraj (2025) [33] created the Iv3-MGRUA model, which uses Inception v3 for spatial feature extraction and a transformed GRU with attention mechanisms. The attention module focused on key video sequence parts, improving recognition of complex actions and increasing precision and contextual understanding. Tests on HMDB51 and another dataset yielded promising results. Still, its reliance on deep architectures could pose challenges when deploying on resource-limited systems.

Li et al. (2025) [34] presented DMFT, a lightweight mid-fusion transformer network for multi-modal HAR. Using a teacher–student paradigm, the teacher learned rich spatial-temporal features from an attentive multi-modal transformer. A mid-fusion module enhanced temporal feature integration across modalities, and knowledge distillation transferred this to a lightweight student for fast inference. However, its effectiveness could be affected by dependence on synchronized modalities, especially with incomplete or noisy sensor data.

El-Assal et al. (2025) [35] introduced a spiking two-stream action recognition model based on Convolutional Spiking Neural Networks (CSNNs) trained with the unsupervised Spike Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP) rule. The model represented inputs as energy-efficient asynchronous spikes and was suitable for neuromorphic hardware implementation. By applying STDP learning to both streams, it minimized labeled data use while retaining vital spatio-temporal information. Experiments on various benchmark datasets showed promising results, though combining spatial and temporal features into one spiking stream added redundancy.

Most current HAR models face several significant limitations, primarily their reliance on entire video streams without discriminative frame analysis, leading to higher computational costs and longer processing times. Additionally, previous methods tend to use static segmentation techniques and independent deep models, which lack robustness under real-world variations such as changes in illumination, scene complexity, and motion diversity. Moreover, less focus has been placed on combining heterogeneous feature representations or improving model performance for real-time applications. To address these issues, this study proposes a novel Active Learning-aided Heuristic Segmentation-based Deep Spatio-Textural Ensemble Learning (ALH-DSEL) approach. The main contributions include: (1) a Multi-Constraint Active Learning (MCAL) algorithm for keyframe selection to reduce redundancy; (2) Fuzzy C-Means clustering (FFCM) segmentation to improve Region of Interest (ROI) extraction and class balance; (3) a deep spatio-textural feature ensemble comprising DenseNet121, EfficientNet-B7, MobileNet, and GLCM; and (4) an Ensemble-of-Ensemble (E2E) robust classifier to enhance classification accuracy. These components collectively address the shortcomings of previous research by improving accuracy, efficiency, and adaptability for real-time HAR applications. While individual components like DenseNet121, PCA, and ensemble classifiers are well-established, the innovation of this study lies in their targeted integration within a unified architecture. Specifically, we propose a Multi-Criteria Active Learning (MCAL)-based keyframe selection combined with Firefly Algorithm optimized Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) segmentation for ROI specific feature extraction. These features are then fed into a Deep Spatio-Textural Ensemble (DSTE) and an E2E classifier, which work together to enhance computational efficiency and precision across various real-time scenarios. This combination of modules has not been explored in prior HAR research literature.

This work addresses specific questions within the overarching goals, scopes, and related methodological paradigms for the HAR analytics solution. The significant contributions are outlined below:

1. To strategically combine multi-constraints active learning (MCAL), including least confidence (LC), margin sampling (MS), and entropy margin (EM) criteria, using DenseNet121 deep learning features to enhance keyframe selection.

2. To effectively utilize the Firefly Heuristic-based FFCM method for semantic human pose/posture segmentation in sequential frames, addressing the instance-level class imbalance problem while ensuring region-of-interest (ROI) specific feature learning.

3. To develop the Deep Spatio-Textural Ensemble (DSTE) feature, combining DenseNet121, EfficientNet-B7, MobileNet, and GLCM, creating a sufficiently large and diverse feature set for a highly accurate and reliable HAR analytics solution.

4. To test and evaluate the performance of Random Forest (RF), AdaBoost, and XGBoost-driven end-to-end (E2E) maximum voting ensemble (E2E-MVE) learning frameworks for high accuracy and dependability.

5. To analyze the effectiveness of MCAL keyframe selection, FFCM segmentation, DSTE ensemble feature model, and E2E-MVE ensemble learning framework when combined with PCA feature selection and Min-Max normalization.

Ultimately, the goal of this study is to develop credible responses to these questions, paving the way for a dependable and effective HAR analytics system for security cameras.

This section outlines the step-by-step implementation of the proposed paradigm in its entirety. The following stages comprise the overall suggested approach:

1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2. DenseNet121 Feature-Driven MCAL-Based Most Representative (Keyframe) Selection

3. FFCM Segmentation

4. ROI-Specific Spatio-Textural Deep Ensemble (DenseNet121, EfficientNet, MobileNet, GLCM) Feature Extraction

5. PCA Feature Selection

6. Min-Max Normalization

7. E2E Learning for HAR Prediction

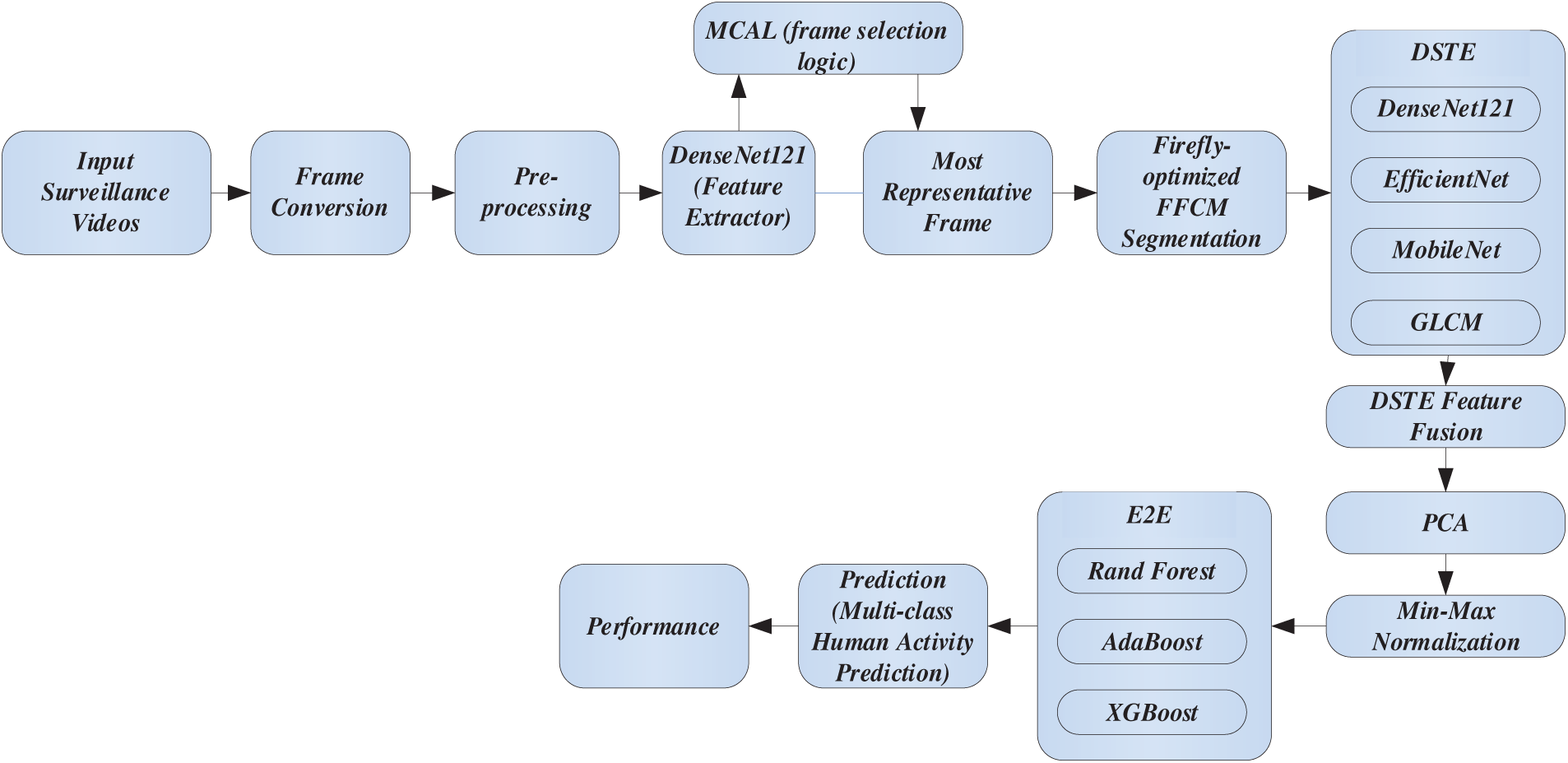

The entire pipeline of the suggested ALH-DSEL HAR analytics framework is demonstrated in Fig. 1. It depicts how the MCAL keyframe selection, Firefly-optimized FCM segmentation, deep spatio-textural ensemble learning, and the E2E classifier are interrelated, offering a thorough insight into the system’s sequential processes. In the suggested ALH-DSEL HAR analytics model, the input surveillance videos are preprocessed and converted into frames, then fed into DenseNet121 for deep feature extraction. MCAL (Margin-based Criteria Active Learning) rules choose the most representative frames, and FFCM (Firefly-optimized Fuzzy C-Means) is applied to segment them. Features are extracted using a deep spatio-textural ensemble (DSTE) that combines DenseNet121, EfficientNet, MobileNet, and GLCM. Subsequently, fusion, PCA, and normalization are applied. Final categorization is performed by an E2E (E2E classifier that includes RF, AdaBoost, and XGBoost). The proposed system consists of standard backbone modules and innovations to achieve stable person-specific posture classification. Of these, the Multilevel Cross Attention Learning (MCAL) module and the (E2E) classifier are the main innovations presented in this work. Pre-trained deep networks like DenseNet121 and EfficientNet-B7 are utilized exclusively for feature extraction. Precise pose segmentation is achieved using Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) with Firefly optimization (FFCM), and further texture-level discriminative features are obtained using GLCM. Dimensionality reduction and data distribution balancing are achieved using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Normalization, respectively.

Figure 1: Proposed ALH-DSEL HAR analytics model

The following sections offer a detailed explanation of the proposed strategy as a whole and its step-by-step implementation.

2.1 Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

A standard HAR dataset is sourced from Kaggle [36], which is derived from the UCF101 action recognition dataset, covering 13,320 video files of 101 different human activity types. The dataset involves a wide range of over 100 subjects, varying in age, body type, dress, and style of motion. Activities span various categories, including daily tasks (e.g., brushing teeth, typing), sports (e.g., biking, playing tennis, punching), and highly complex body movements (e.g., high jump, swing, skydiving). The videos were captured initially at 30 frames per second (FPS) in standard RGB color space and 320 × 240 pixels resolution. In this paper, every video was decoded into sequences of frames, which amounted to about 12,000 keyframes after initial filtering. The dataset contains ample background and lighting variation since clips were recorded both indoors and outdoors under natural and artificial lighting conditions. The angles of the camera differ for each video, where some are recorded from the side, top, or front views, providing varied spatial representation. The activity labels are fixed and uniformly distributed across the dataset. Some of these include ‘Playing Violin’, ‘Biking’, ‘Brushing Teeth’, ‘Knitting’, ‘Rock Climbing Indoor’, ‘Typing’, and many others. The varied activities and environments provided by this dataset render it most appropriate for assessing the proposed HAR model’s generalization and robustness. The dataset was separated into 80% training, 10% validation, and 10% test sets. To avoid any unfair evaluation and data leakage, no frame or data from the test set was utilized during the training or preprocessing phases, and for training and evaluation, we followed the standard UCF101 split-1 protocol as given by the official website to facilitate unbiased benchmarking and apples-to-apples comparisons with existing works. To assign each video to either the training or testing set, we used this standard partitioning. Attention was taken not to include any frame of a single video sequence in both training and testing sets to avoid data leakage of any kind. This strict distinction heightens the dependability of performance assessments and supports the model’s generalizability potential for unseen subjects and situations.

Thus, obtaining the color space input frames from each video sequence representing distinct activity types, the standard pre-processing tasks were performed. More precisely, z-score normalization, resizing, contrast adaptive histogram equalization, and intensity equalization were all carried out by the suggested method. Here, each input frame (in *.JPG format) was resized to

To retain optimal feature extraction and allied learning, this work executed pre-processing over the input frames. As stated earlier, it executed contrast adaptive equalization to normalize abrupt changes in illumination. To achieve it, Eq. (1) was applied over each video frame.

In Eq. (1),

In Eq. (4),

The normalized frames were then resized to the dimensions of

2.2 MCAL-Based Most Representative Key Frame Selection

As stated earlier, unlike major traditional vision-based HAR solutions, either the complete video sequences or frames or the randomly selected frames are passed as input to the feature extractor; the proposed method applies an active learning concept, which learns intrinsic features of each input frame to choose and retain the most representative frames. Typically, active learning methods apply two different kinds of criteria, named pool-based selection and quality-based constraints. In earlier cases (i.e., pool-based methods), the various criteria, including least confidence (LC), margin sample (MS), and entropy margin (EM) methods, are applied to retain the most representative samples. To achieve this, the active learning method first extracts features from the original input images, which are then assessed in terms of the above-stated criteria (i.e., LC, MS, and EM). In case of LC criteria-based keyframe selection, those frames having higher diversity, signifying differences and features’ uncertainty, are retained. In other words, the instance-wise feature diversity shows a high LC value and hence can be retained towards further segmentation and feature extraction tasks. Similarly, in the MS method, those frames having higher intra-sample features’ margin are considered for further segmentation tasks. Those frames having higher entropy values are retained for further segmentation and corresponding feature extraction. These active learning criteria require extracted features to identify the most representative frames. Since the proposed method applies multiple criteria together, it is referred to as the multi-constraints active learning (MCAL), especially designed to select keyframes from the input sequential frames. To apply MCAL criteria for keyframe selection, in this work, at first, DenseNet121 was applied over the input video’s frame sequences. In other words, the proposed method applied MCAL criteria over the extracted DenseNet121 features to perform the most representative frame selection. Noticeably, in this work, the DenseNet121 deep model not only serves as an input feature for the MCAL-based most representative frame selection but also functions as one of the deep feature extractors in the targeted deep ensemble feature model. All preprocessing and feature selection steps were applied only to the training set. The test set was kept out and left entirely unseen throughout all training and tuning processes. This allowed for a rigorously unbiased and leakage-free evaluation protocol.

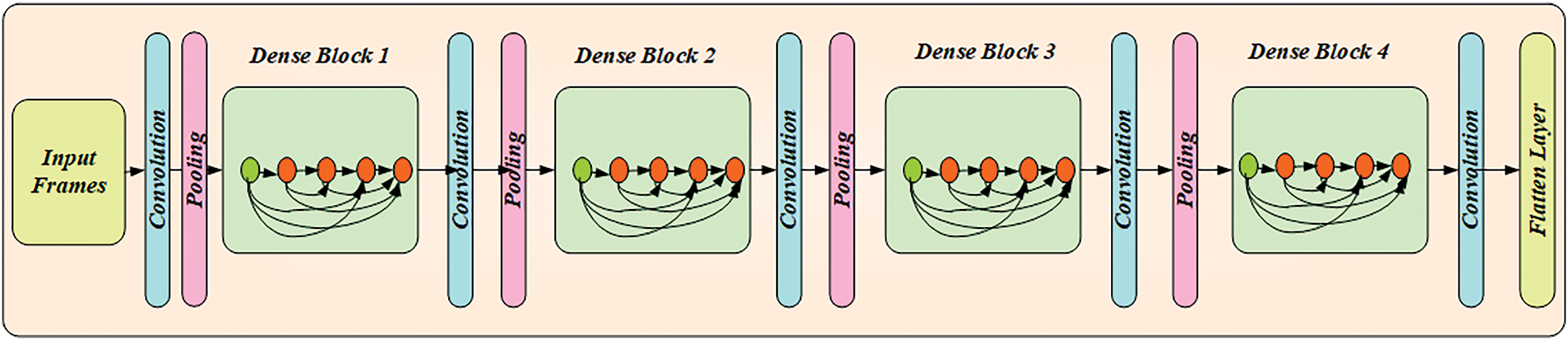

DenseNet121-Based Spatial Feature Retrieval

In this work, DenseNet121 was applied over each frame, which yielded a large set of information-rich features, primarily obtained over multiple convolutional operations. Unlike traditional CNNs, reusing features across layers makes it more information-rich and suitable for the MCAL-driven frame selection task. The deployed DenseNet121 model was designed with multiple filters to retrieve the high-dimensional spatial feature representations.

In this work, a densely connected DenseNet was designed (say, DenseNet121) in which the deep model embodied densely connected convolutional layers to extract high-dimensional residual features. The features that are extracted from each layer are directly connected to the subsequent layer. Moreover, the reduced hyperparameters make this deep model suitable for large input frames. Thus, the information-rich features produced through feature propagation and reuse over consecutive layers improved MCAL’s ability to learn and predict the most representative samples or keyframes. The proposed deep architecture uses feature maps as input for subsequent layers, retaining maximal features for analysis and prediction while preventing gradient vanishing. All feature maps from the previous layers

Thus, with the extracted features, a single tensor was obtained by merging the various inputs to

Figure 2: Architecture of the DenseNet121 deep learning model used for feature extraction

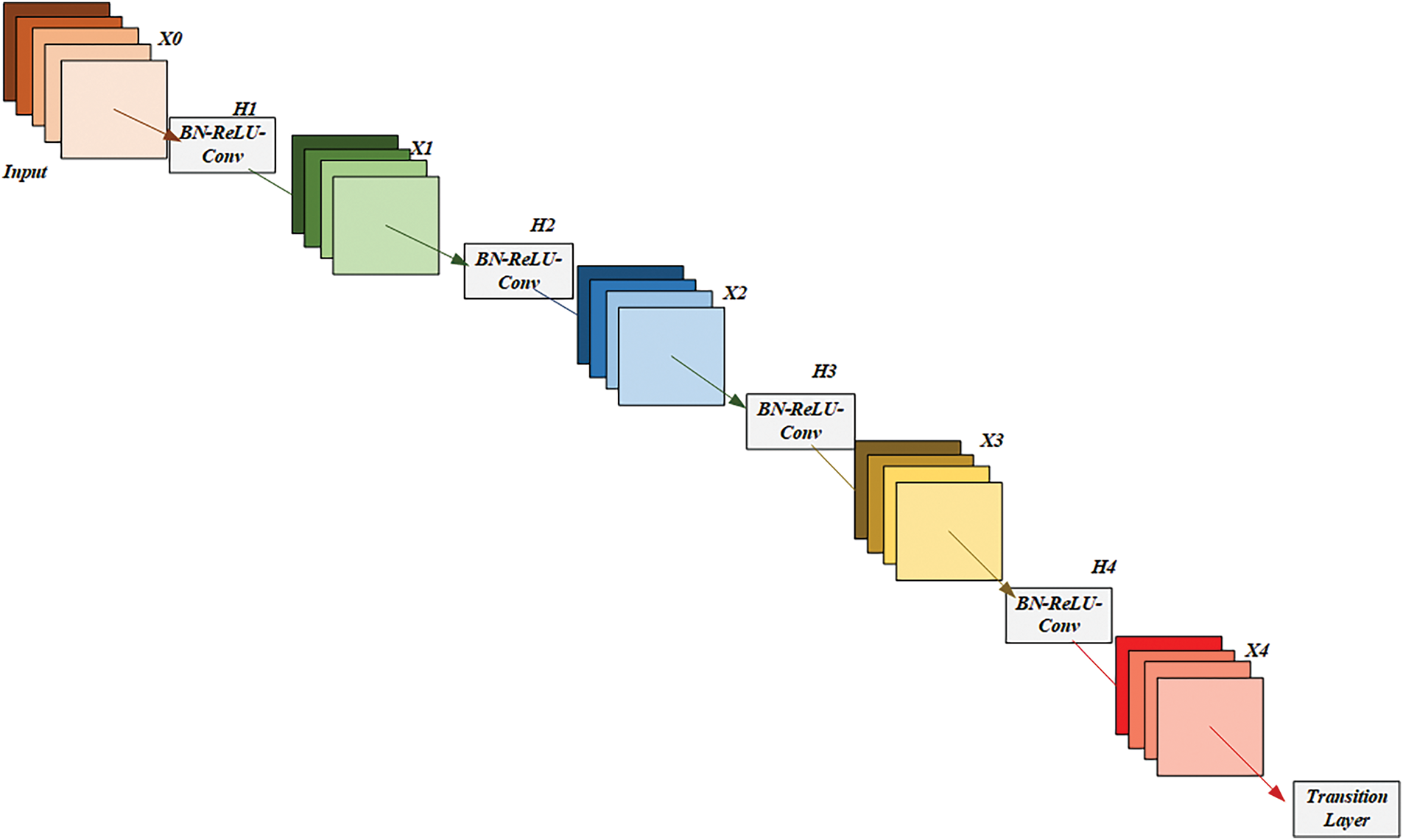

Figure 3: Illustration of the dense block and transition layer configuration in the DenseNet121 model. This highlights the use of batch normalization, clipped ReLU activation, pooling, and feature map concatenation to enable efficient learning and high-dimensional feature representation

Now, after extracting the dense features, the proposed MCAL model applies LC, MS, and EM separately, which identifies the most representative frames that are compared to select the best set of frames for further segmentation and related feature extraction and learning. A brief overview of these conditions (LC, MS, and EM) is provided below:

– Least Confidence (LC)

The video’s frames with the lowest confidence value (7) are considered vital and are retained for further processing. Mathematically, the MCAL method applies Eq. (7) to identify the ROI representative frame.

Thus, applying the above-stated criteria, the most representative frames

– Margin Sampling (MS)

With the most minor difference in likelihood between the two most probable classes (here, ROI specific or redundant/redundant), it selects the most representative frames. This method uses Eq. (8) to perform the selection of the most representative samples, where s represents the total number of retained keyframes, and their corresponding classes are given by

– Entropy Margin (EM)

In this method, the frames with the highest entropy are chosen as the most representative frames. The values of the posterior likelihood, the uncertainty estimation model, and the output are represented by

Now, once the corresponding frames were selected, the most representative frames were retained as per (10).

Once the most representative frames were selected, the selected frames were processed for ROI segmentation (i.e., person’s pose, posture, and movement pattern). Traditional segmentation models often use static thresholds like the Otsu method. However, such approaches struggle with non-linear and ambiguous ROIs (i.e., a person’s pose, posture, and movement pattern). Considering these limitations, in this work, a heuristic-driven FCM clustering is proposed. The use of a heuristic model (i.e., Firefly heuristic algorithm) can not only improve segmentation accuracy but also reduce the need for manual seed point definition. It can make overall ROI segmentation more accurate and effective for real-world applications. Once the most representative and non-redundant frames have been identified through MCAL, the subsequent imperative step is to segment out the regions of interest (ROIs) corresponding to human poses or movements. This is done through Firefly-optimized FCM segmentation, thereby improving localization accuracy before feature extraction.

2.3 Firefly Heuristic-Based Person’s Pose/Posture Segmentation

As stated earlier, considering non-linear edges and ambiguous boundary conditions, this research proposed a Firefly heuristic algorithm-based FCM clustering to detect and segment ROIs (i.e., person’s pose/posture/movement). FFCM reduces imbalance and enhances ROI-specific feature learning for HAR. This work proposes a Firefly heuristic-based FCM clustering (FFCM) method to locate and segment a person’s pose/posture and movement segmentation. In the FFCM segmentation model, the Firefly heuristic algorithm tunes the cluster’s centroid and maps instances to likely classes, enhancing clustering and segmentation.

Human Pose/Posture/Movement (Say, Gait) Detection

Moreover, by exploiting the efficacies of local spatio-textural distinctiveness, the clustering method, in contrast to the conventional threshold-based method, can enable swift and automatic person’s pose/posture/movement segmentation. FFCM improves accuracy by automatically segmenting a person’s pose or posture in each frame. This section provides a quick overview of the FCM approach before moving on to the proposed FFCM segmentation.

– Fuzzy C-Means

The input keyframe is divided into n groups of pixels by the FCM method to produce

– FFCM-Segmentation

To improve centroid value(s) for accurate segmentation, the Firefly algorithm is deployed, which minimizes inter-cluster distance to map each pixel or instance to the corresponding most probable group. In comparison with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), FA is less prone to parameter initialization sensitivity and premature convergence. These attributes make FA more appropriate for segmenting highly complex human postures and body contours, particularly under non-standard illumination and background settings. To attract nearby fireflies, it uses patterns in light behavior as a signal. The accuracy of clustering-based segmentation is increased if each pixel is represented as a firefly, as this attracts neighboring fireflies (emulating the pixels) to the same cluster.

To illustrate the ROI for additional feature extraction and learning, every pixel relevant to the subject’s attitude or posture is thus clustered in a single correlated or connected segmented region. Each firefly in the Firefly-optimized FCM clustering module encodes a candidate solution that is a collection of cluster centroids. The bounded multidimensional space is used to allow the Firefly Algorithm to explore the best clustering settings efficiently. It uses two consecutive steps: measuring the intensity differences first, then moving pixel(s) to the other to create a cluster, depicting the ROIs. Since the objective function in this case is the intensity difference, Fireflies with varying illumination intensities attract other Fireflies with correspondingly higher or lower intensities. This method groups pixels with similar patterns into clusters. Let

FFCM now initiates swarm movement, in which fireflies approach one another in proportion to the intensity of their respective illumination. Typically, the intensity of a firefly’s illumination is highly related to its attraction capabilities. The fixed attraction

As seen in (14), the attraction factor is represented by

The best Firefly position, or the pixel within the input frame, is obtained by the Firefly algorithm, which serves as the centroid for a particular pattern or cluster (depicting a person’s pose/posture or movement/gait detail). This gives it a collection of solutions in the form of an array

This work focused on increasing the efficiency of spatial clustering by taking into account the Rosenbrock function as the cost function. The Rosenbrock function was applied as a cost function. An instance’s chance of becoming the cluster’s centroid is indicated by its fitness value. Because it is thought to have less fitness, a firefly with a higher illumination intensity attracts more fireflies in the search space. Assume that there are two fireflies,

At a specific pixel location

The (17) has unit minima with

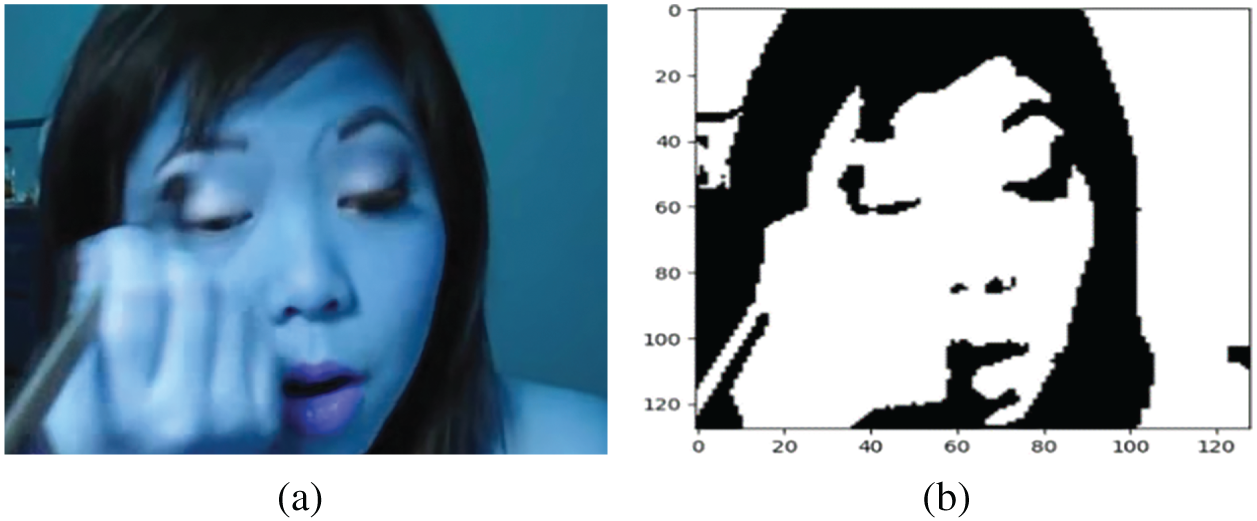

Figure 4: An illustration of the FFCM segmentation results. (a) input frame; (b) corresponding output

Fig. 4a is the original RGB input frame on which the facial posture and movement of the subject are acquired under complex background conditions, as well as varying lighting. This is the raw data before any segmentation. Fig. 4b displays the corresponding segmentation outcome achieved based on the FFCM algorithm. In this case, the concerned regions of interest (ROI), namely the subject’s face and motion-related regions, are properly isolated from the background, reflecting the potential of the segmentation technique to demarcate human posture and movements accurately. The segmented pixels in Fig. 4b are then aggregated with the original RGB image for creating ROI-specific color images, which in turn are used as input to the proposed spatio-textural deep ensemble framework to further perform discriminative feature extraction.

3 Deep Spatio-Textural Ensemble (DSTE) Feature Extraction

The suggested model utilizes multiple feature models, including spatio-textural distributions (GLCM) and deep ensembles (DenseNet121, MobileNet, EfficientNet), to ensure high accuracy and reliability. The retrieved features are horizontally concatenated to produce a composite feature vector for additional learning and prediction because the notion is a feature ensemble. The sections that follow provide a summary of these feature extraction techniques.

3.1 GLCM Spatio-Textural Features

The suggested approach took advantage of the many spatio-textural (statistical distributions) features from every input frame, such as ROI-specific color pictures. The GLCM feature extraction approach was considered for this purpose [37]. The following features were extracted by the suggested method: energy, entropy, contrast, homogeneity, correlation, mean, standard deviation, and variance.

Here is a summary of the GLCM feature extraction techniques together with allied particular feature extraction methods:

The grayscale values signifying the association between pixel pairs and from which a transpose matrix was derived, were also taken into consideration. Here, the transpose matrix, signifying the relationship between the pixels in one direction, and the grayscale data were applied to create the symmetric matrix

With the measured

3.2 Deep Ensemble Feature Extraction

The proposed method applied three distinct deep models to achieve deep ensemble feature extraction in addition to the GLCM features mentioned previously. More specifically, the ROI-specific input images were subjected to feature extraction using the DenseNet121, MobileNet, and EfficientNet deep models in this work. Here, “Deep Ensemble Feature” denotes the composite feature representation obtained through the combination of outputs from various deep learning networks, i.e., DenseNet121, EfficientNet-B7, and MobileNet, as well as spatio-textural features obtained from the use of the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM). The goal of this ensemble is to extract both high-level semantic features and low-level textural features towards reliable human activity classification. These models are discussed briefly below.

Several convolutions in the DenseNet121 were applied to the ROI-specific color space images to extract high-level information-rich features. It uses the built-in CNN (ConvNet) structure, which produces a high-dimensional feature set for feature extraction and learning when paired with several filters. In the deployed DenseNet121 network, each layer receives additional input from the preceding layers, which is then transferred to the feature map in the subsequent layer. According to standard definitions, it is a deep network with densely connected convolutional networks where features are mapped from one layer to the next (or other) layer based on their extraction. DenseNet, similar to the ResNet101 deep network, reduces the likelihood of gradient vanishing and/or gradient descent issues, thereby enhancing feature reutilization even at drastically lower hyperparameters.

The DenseNet121 uses ReLU activation to enhance non-linearity and extract more valuable features. The fully connected layers were connected to 121 convolution layers in the deployed model. The DenseNet121 network consisted of 121 convolution layers that were attached to either an output fully connected layer or a flattened layer. The production of this module was fused with the other features (i.e., GLCM, EfficientNet, and MobileNet feature vectors) at the fully connected layer to create an ensemble feature for further learning and prediction. Since the CNN structures in this case were thought to be hierarchical, the l layer received the feature maps of the l − 1 layer as input. The feed-forward network then used the output of the l layer as input to the (l + 1) layer, providing a source for the next layer transition

The combination of the feature map created over layers 0, 1…,

There was one transition layer between each of the four Dense Blocks in the DenseNet model. As previously mentioned, every Dense Block contains a convolution layer, and the transition layer includes features like batch normalization, a pooling layer, an activation function, clipped ReLU, etc. The clipped rectified linear unit (ReLU) layer was utilized, which differs significantly from typical ReLU in that all values above the clipping ceiling are set to that ceiling and all values below it are set to zero. The final extracted and retained feature

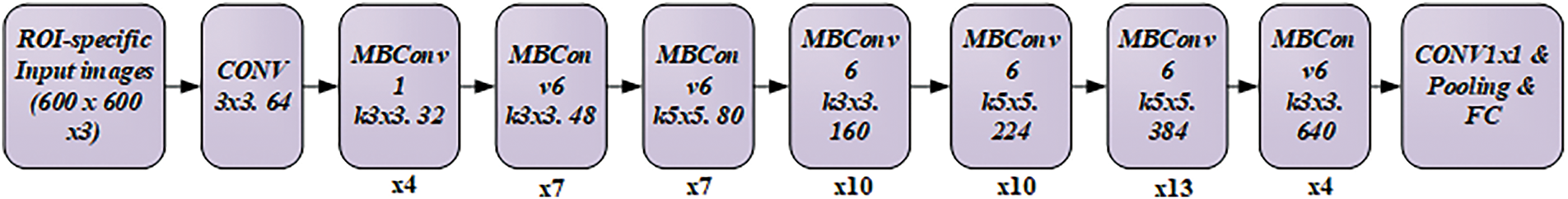

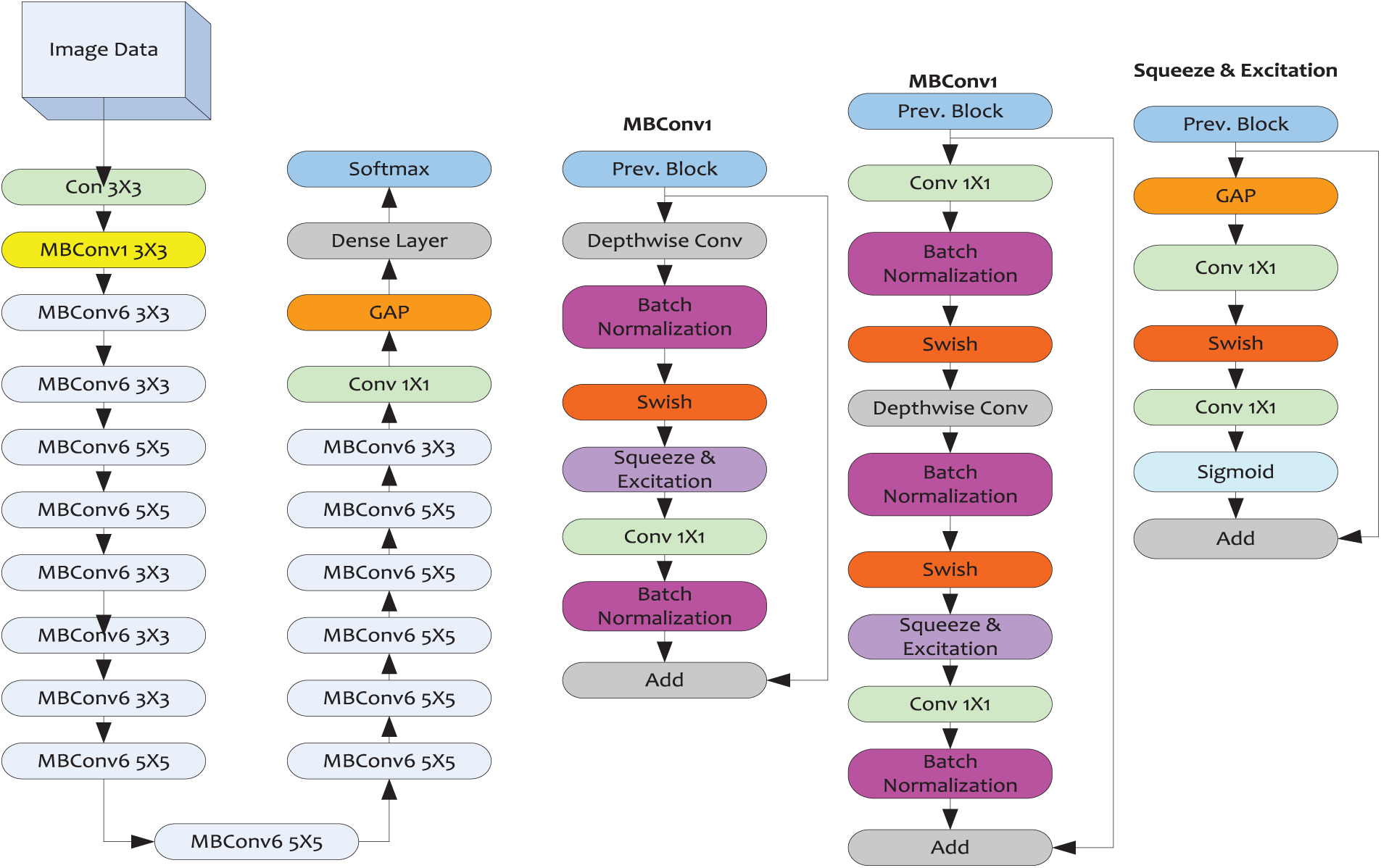

EfficientNet-B7 is an improved and evolved deep model derived from the native EfficientNet-B0. In the proposed model, the ROI-specific input images (from the input keyframes) are first resized to

Figure 5: Detailed architecture of the EfficientNet-B7 model employed for ROI-specific feature extraction

To improve ROI-specific feature learning, the EfficientNet-B7 model was added to the ensemble, as shown in Fig. 5. The model combines MBConv blocks, Swish activation, and squeeze-excitation methods to strike a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy. The architecture of the deployed MBConv module differs from the classical residual learning models. To be more precise, the MBConv module’s input and output feature (maps) are broader than those of the middle layers. As depicted in Fig. 5, the deployed MBConv module embodies a convolutional layer of kernel

As the entry matrix

The Squeeze-Excitation mechanism is used in the proposed EfficientNet-B7 deep model. The Squeeze attention module weights and evaluates each channel in the input feature map according to its importance for the current task. The subsequent mechanisms were a part of the overall feature extraction operations:

Squeeze: In this method, the input feature map of

Excitation: The excitation module utilizes a fully connected neural network to transform the squeezed map non-linearly, generating activated weights through the ReLU and sigmoid activation functions.

Scale: The deployed method applies the activated weights to weight or measure each channel in the input feature map, achieved by performing dot-multiplication.

In the deployed deep model, the ROI-specific input images and allied feature maps of the size

Figure 6: Detailed representations of the EfficientNet deep model

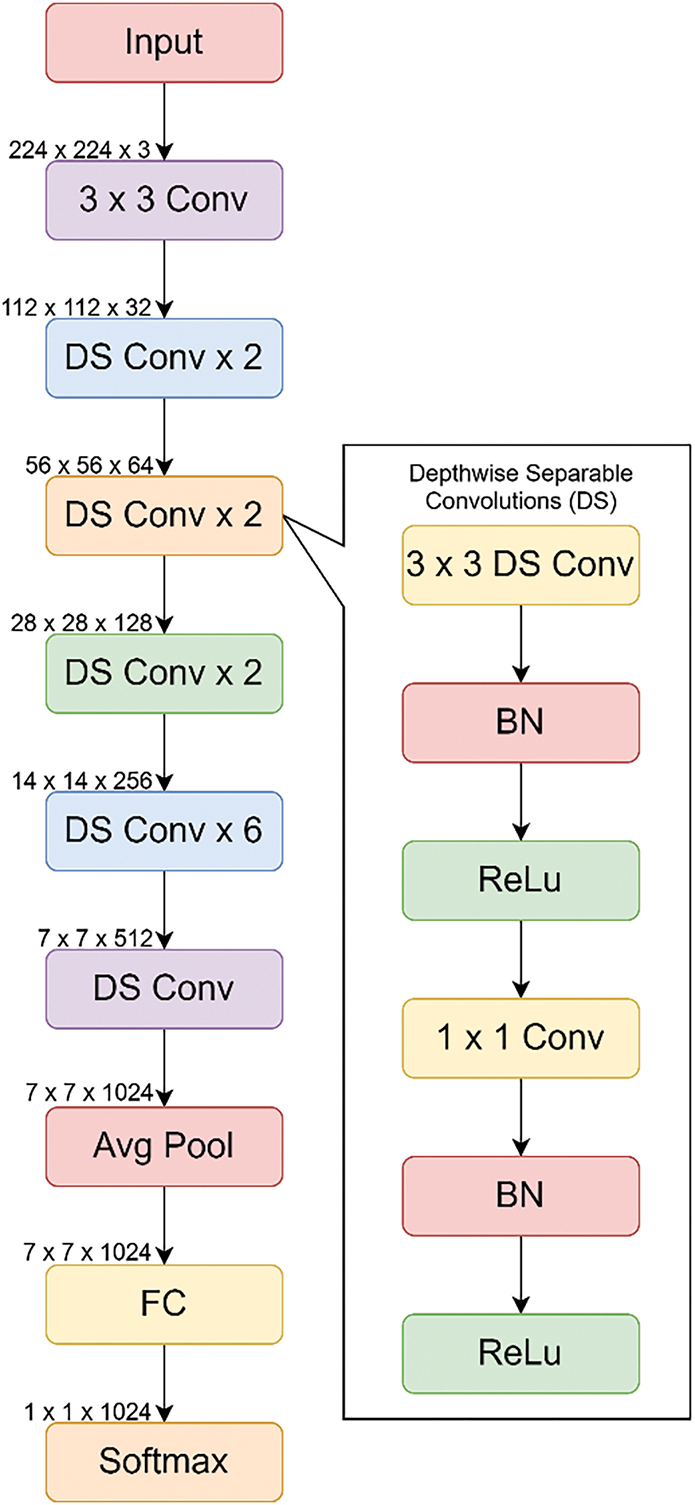

This work also used MobileNet as one of the deep feature models to extract features from ROI-specific input images, in addition to the deep models DenseNet121 and EfficientNet-B7. Fig. 7 shows the suggested structure of the MobileNet deep model. In this work, an improved MobileNet structure was designed for feature extraction. The first step was to take a pre-trained MobileNet and remove the three layers that represented the fully connected layer, the average pooling layer, and the Softmax layers. The proposed method applied or added a fully connected layer at the end to serve as input features for further fusion, learning, and prediction. The fully connected layer and batch normalization are added after the global average pooling layer in the proposed model. This was done to accelerate training even with more complex, non-linear inputs. Additionally, similar to the EfficientNet deep model, it helped to reduce local minima and convergence issues. Notably, before the fully connected layer, the proposed model also includes a dropout layer, which helps retain high-resolution or significant features and alleviates overfitting. The ReLU activation function was used between the batch normalization and dropout layers. Finally, a global average pooling (GAP) layer was applied, which produces features with fewer hyperparameters and thus enhances training. The fully connected layer takes this output as input and fuses it with other deep features to produce a deep ensemble feature.

Figure 7: Proposed MobileNet deep model used for feature extraction

It is to be noted that, unlike traditional MobileNet deep structures, in this work, depth-wise separable convolutions (DS, in Fig. 7) were taken into consideration. The lightweight MobileNet structure, depicted in Fig. 7, is also part of the ensemble to decrease computational complexity without sacrificing discriminative power. Its depth-wise separable convolutions make it ideal for deployment in Internet of Things (IoT) and edge devices.

Thus, extracting the different deep features (i.e.,

Though the DSTE stage generates a feature space of high dimension, dimensionality reduction and scaling of features are necessary to enhance the efficiency of computations and avoid overfitting. This is achieved via PCA-based compression and normalization before classification.

Under the environment of the derived composite DSTE feature, the risk of redundant data or features cannot be eliminated, which can impose additional computational costs and make learning susceptible to local minima and convergence issues. To mitigate this, the proposed method applies PCA feature selection to the retrieved composite DSTE feature (34). For each feature set, the PCA algorithm calculates the eigenvalues and principal components of the covariance matrix. The eigenvalue distance of each feature is computed relative to the principal component mean, which is fixed at 0.5. Features with a distance greater than 0.5 are eliminated, while those with a distance less than 0.5 are retained. In subsequent learning and prediction tasks, the retained features with low eigenvalue distances (less than 0.5) are used. These features are considered more important and likely to influence forecast outcomes. The final step involves applying z-score normalization to the selected features to address problems related to local minima, convergence, and over-fitting.

Any machine learning model can experience over-fitting, premature convergence, and local minima issues when trained over features with extremely high non-linearity. In this work, Min-Max normalization was carried out, mapping each data input in the range of 0 to 1 (i.e., [0, 1]), considering these likely problems. To achieve Min-Max normalization over the input features, Eq. (23) was applied in this work. The feature element in (23), when

Thus, the normalized data is passed to the proposed ensemble learning model to perform HAR analytics. The compressed and normalized feature set is then passed on to the E2E ensemble classification phase, where several learning models work together to perform final activity recognition.

3.6 Ensemble Learning Classifier for HAR Analytics

The proposed method designs a heterogeneous ensemble learning model, embodying AdaBoost, RF, and XGBoost as the base classifiers. Here, each base classifiers are trained over the normalized DSTE feature (24), which classifies the input video into the corresponding human activity class. Subsequently, it applies the maximum voting ensemble concept to make the final prediction. Being MVE or consensus-driven prediction, the reliability of the proposed model is higher than the other methods or the standalone machine learning-based HAR solutions. A brief of the base classifiers is given as follows:

One kind of adaptive boosting ensemble learning technique called AdaBoost (ADAB) can enhance feature learning, reasoning, and characterization skills recursively. To demonstrate this, corresponding prerequisite assessments and exams are given equal weight to identify learners who are weak and require additional preparation. After every computation cycle, the proposed AdaBoost approach estimates the error rate for the weak classifier. Eventually, when the weight of the accurately categorized sample increases, the weights of the samples or instances that were improperly clustered decrease. After some time, the weak learner becomes a strong learner, labelling and categorizing input features (specific to each keyframe) into the right categories. The deployed ADAB model classifies each input frame into the different categories, including biking, billiards, brushing teeth, cutting in the kitchen, knitting, mixing, punching, playing tennis, typing, writing, etc., and annotates them with a unique label.

The RF performs voting-based learning and prediction decisions by utilizing several tree-based classifiers. Every tree-based learning model assigns a unit vote to each image, signifying the class or activity it belongs to. Essentially, a certain number of trees are applied to the input images in this manner, and the image with the best score is chosen for the final prediction once the maximum voting score for each image has been estimated. A picture sample containing

In the classification procedure, twenty percent of the data were utilized as out-of-bag samples for inner cross-validation, and eighty percent of the data were used for training. Consequently, every frame is annotated with the associated most probable activity type by the suggested method.

For classification problems, a distributed gradient boosted decision tree library called Extreme Gradient Boosting Ensemble, or XGBoost, is utilized. Its functionalities include parallel tree boosting, where the prediction outputs from each decision tree approach are used as a vote to determine the final prediction for the detection and classification of breast cancer. XGBoost outperforms the conventional gradient boosting classifier in terms of efficiency because it can enhance gradient boosting over a nonlinear data space. Because of its speed and quick convergence, it can handle large input datasets. As a supervised ensemble learning, XGBoost uses a regularization function in conjunction with a generalized gradient boosting technique to produce precise classification models. Let’s say the dataset under consideration includes n examples with m features. An ensemble of decision trees

The Classification and Regression Tree (CART) space is stated by

The differential convex loss function,

A simplified objective function is obtained as (28) by using the Taylor expansion particularly with the 1st and 2nd order gradients on the basis of the loss function.

In (28),

Since a decision tree method predicts fixed values within a leaf,

In this case, the instance at the leaf

Now, substituting (30) with (29), we obtain (31) as the objective function measuring the optimal tree structure.

The precise greedy algorithm and the global and local variant approximation approach are applied to all possible splits of all the input features to determine the optimal split. The proposed method utilized the XGBoost ensemble learning method to evaluate the split candidates. Although the global algorithm requires more candidates than the local variant approximate method, it can still perform with the same level of accuracy. In this work, the distributed gradient boosting-driven XGBoost method effectively supports the exact greedy method for a single machine set, as well as the local and global variant approximation methods for all settings. However, most state-of-the-art approximations rely on direct estimations of gradient statistics. During the mth training round, we used the Dropout Meet Multiple Additive Regression Trees (DART) booster in the suggested XGBoost method to realize the model by letting

where the overshooting parameters, denoted by

In this paper, a novel and robust vision-based HAR analytics model was developed. This work aims to lower costs, improve features, and enhance model learning. To achieve this, an active learning assisted heuristic segmentation-based deep spatio-textural feature ensemble (ALH-DSEL) model for HAR analytics has been proposed. In the ALH-DSEL model, an active learning method was applied to retain the most representative frames, which could reduce redundant or less significant frames from computation, without compromising eventual analytics performance. Being a vision-based HAR solution, the UCF-101 action recognition dataset was taken into consideration. The applied dataset can be easily accessed from the Kaggle data repository. The input surveillance dataset embodied human activity patterns of the different types including: ‘Playing Violin’, ‘Biking’, ‘Billiards’, ‘Brushing Teeth’, ‘Cutting in Kitchen’, ‘Front Crawl’, ‘Head Massage’, ‘High Jump’, ‘Punching’, ‘Pulling Up’, ‘Push Ups’, ‘Knitting’, ‘Lunges’, ‘Skiing’, ‘Sky Diving’, ‘Rafting’, ‘Mixing’, ‘Punch’, ‘Table Tennis Shot’, ‘Rock climbing indoor’, ‘Skate Boarding’, ‘Rope climbing, Roping’, ‘Tennis Swing’, ‘Soccer Juggling’, ‘Soccer Penalty’, ‘Sumo Wrestling’, ‘Surfing’, ‘Typing’, ‘Swinging’, ‘Tennis Swing’, ‘Throw discuss’, ‘Trampoline Jumping’, ‘Volleyball Spiking’, ‘Waling with Dog’, ‘Writing on Board’, etc. The original videos were in *.AVI formats, which were later transformed into consecutive frame sequences. More specifically, the framing was performed at the rate of 30 frames per second. Once the frames in *.JPG format, a set of frames was obtained from each input video, representing a distinct human activity. Considering the humongous data volume and associated computational costs and delays, reducing redundant frames can be of great significance. Unlike random keyframe selection methods, which select frames arbitrarily and can compromise model performance, this work presents a novel and robust multi-constraints active learning (MCAL)-based keyframe selection model. To achieve this, the input original frames were processed for deep feature extraction using the DenseNet121 deep architecture in this work. Here, DenseNet121 was applied merely as a feature extractor, whose output was then fed as input to the MCAL module that applied margin sampling (MS), least confidence (LC), and entropy margin (EM) criteria together to select the most representative frames. In this method, the use of multiple active learning criteria helped to retain the most significant frames. The technique reduced about 80% of the computational cost by removing redundant frames. It can not only improve computational efficiency but also reduce delay to meet run-time demands. Once the set of the most representative frames from each human activity pattern was selected, FFCM segmentation was performed. Unlike traditional static threshold methods, such as Otsu methods or clustering techniques, the proposed model applies the Firefly heuristic algorithm-based FCM clustering (FFCM). To implement FFCM segmentation, the brightness coefficient

The different feature models, including

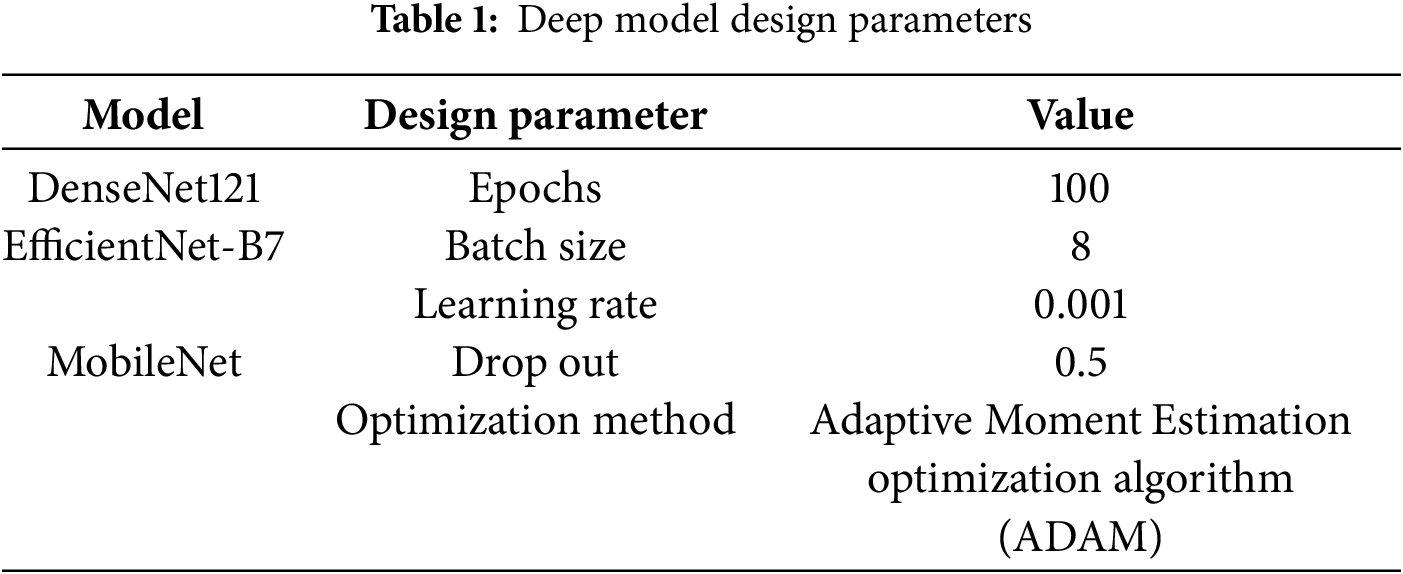

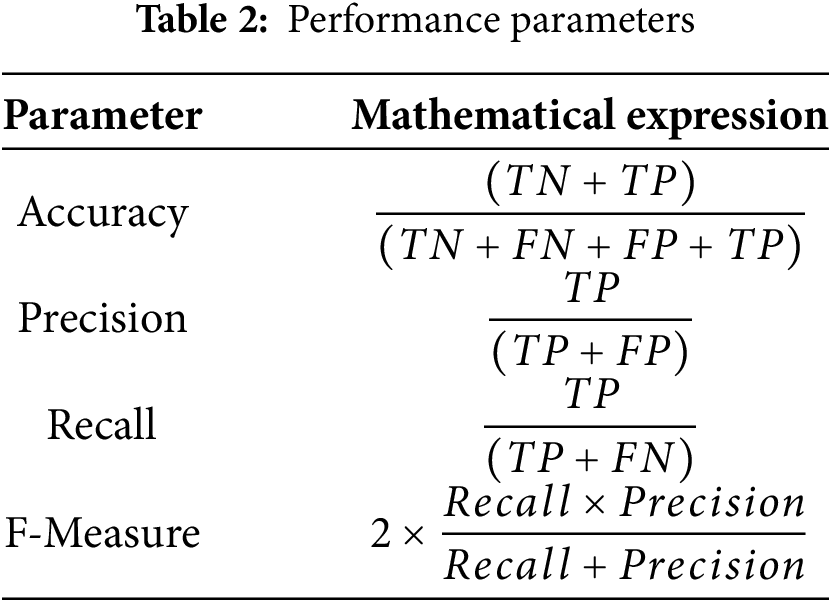

The proposed HAR analytics model was developed using the Python Notebook tool, and the simulation was conducted on the Google Colab platform. The simulation was performed using a single central processing unit equipped with 16 GB of memory and an i5 processor operating at 3.2 GHz. The performance parameters are given in Table 2.

To characterize the efficacy of the proposed method, overall performance outputs were analyzed in terms of the intra-model analysis and the inter-model analysis. In this work, different feature models and classifiers were applied to perform violent crime prediction in surveillance videos. The intra-model assessment analyzed the performance of these models and classifiers. On the contrary, in the inter-model evaluation, we compared the performance of the proposed ALH-DSEL model with other existing HAR analytics models. The detailed discussion of the overall results obtained and allied inferences is given in the subsequent section.

In this work, we applied different feature models and classifiers to assess whether the feature ensemble can achieve better performance or if E2E ensemble learning can yield higher accuracy. Additionally, the contribution was made to use FFCM segmentation; therefore, the performance was examined concerning each feature model, classifier, segmentation technique, and even keyframe selection. The simulation results obtained are discussed in this section.

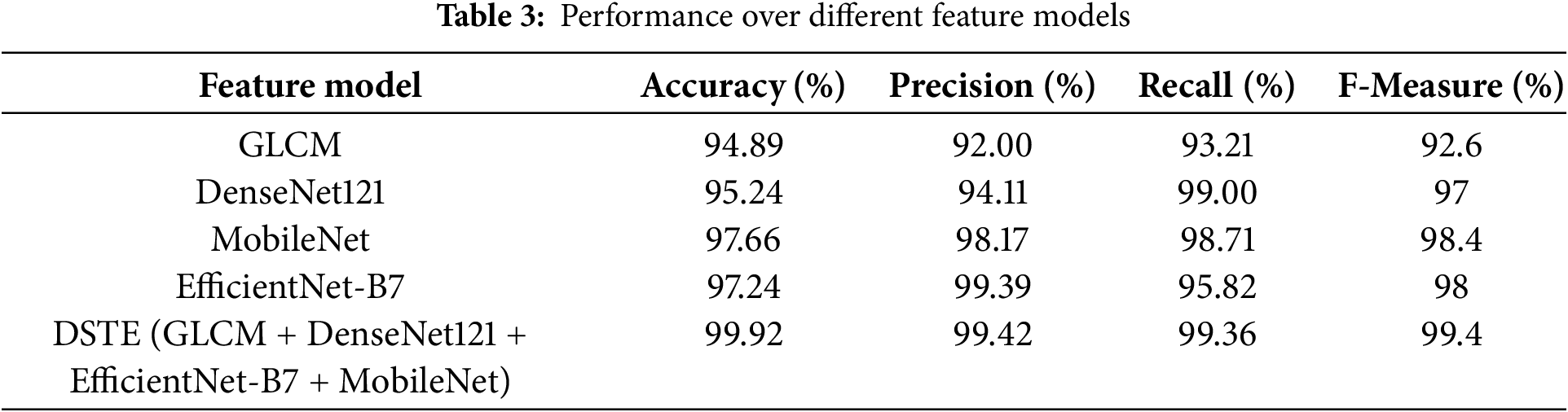

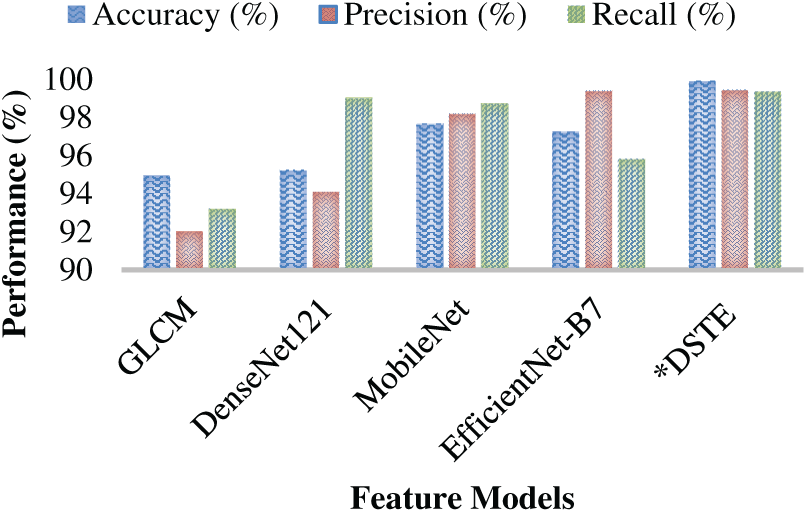

The simulation results obtained with the different feature models are depicted in Table 3. Here, the key goal is to assess whether the amalgamation of the deep ensemble features (i.e., DenseNet121, EfficientNet-B7, and MobileNet) with other spatio-textural features achieves superior performance towards HAR analytics or not. As depicted in Table 3, the GLCM feature that embodied energy, entropy, correlation, homogeneity, mean, standard deviation, and variance information could achieve the highest accuracy of 94.9%, precision of 92% and recall of 93.21%. On the other hand, the highest F-measure obtained was 92.6%. On the other hand, the DenseNet121 feature yielded accuracy, precision, recall, and F-measure of 95.24%, 94.11%, 99.00% and 97%, respectively. MobileNet achieved superior results with 97.66% accuracy, 98.17% precision, 98.71% recall, and 98.4% F-measure, while EfficientNet-B7 attained 97.24% accuracy, 99.39% precision, 95.82% recall, and 98.0% F-measure, both outperforming DenseNet121. On the other hand, their amalgamation (i.e., the feature level fusion of the GLCM, DenseNet121, MobileNet, and EfficientNet-B7) yielded HAR analytic accuracy of 99.92%, precision of 99.42%, recall of 99.36% and F-F-Measure of 99.4%, which is higher than the other feature models (Table 3, and Figs. 8 and 9). To be noted, this performance was obtained by training each of the feature models (i.e., extracted ROI specific features) over the proposed E2E ensemble classifier. The features were obtained from the proposed MCAL keyframe selection assisted FFCM segmentation specific ROI images (color images). Thus, observing overall performance, it can easily be found that the proposed DSTE feature ensemble model, due to its feature diversity and information-rich ROI representation, helped to achieve superior performance towards the targeted HAR analytics and human activity classification. Observing overall results and allied depth inferences, it can be found that though the EfficientNet-B7 model due to its squeeze and expand learning mechanism achieved superior accuracy of 97.24%, which was higher than the DenseNet121 (94.9%), MobileNet (94.24%); however, the results signify that their combination with the PCA feature selection and Min-Max normalization yields superior towards the targeted HAR analytics.

Figure 8: Accuracy, precision, and recall performance (%) over different features

Figure 9: F-Measure Performance over different feature models

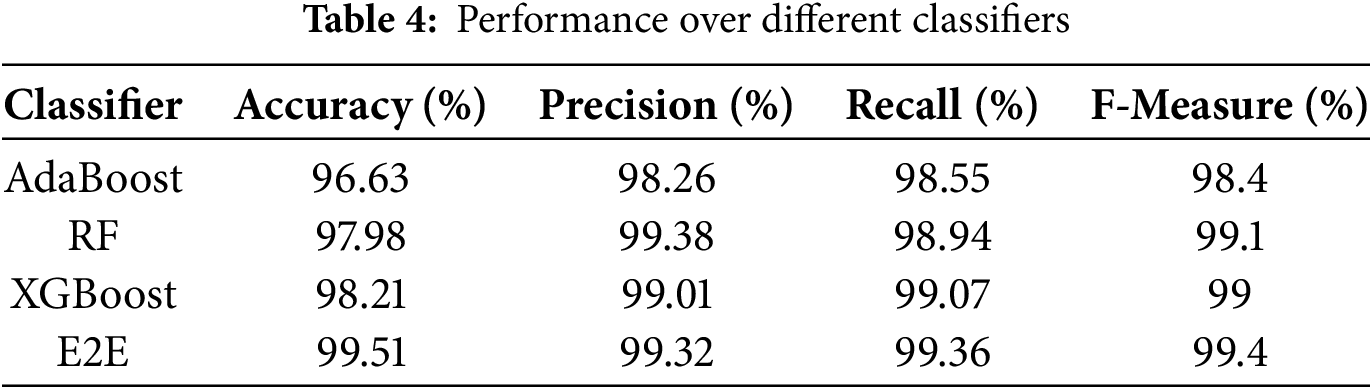

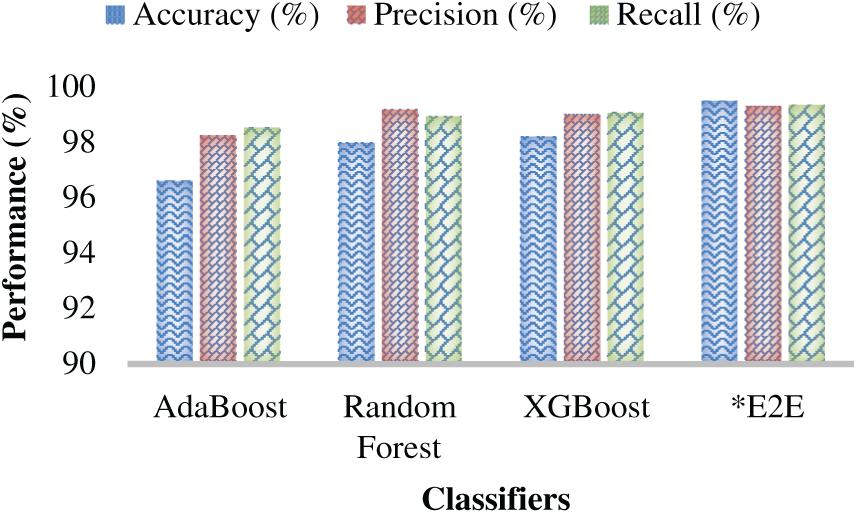

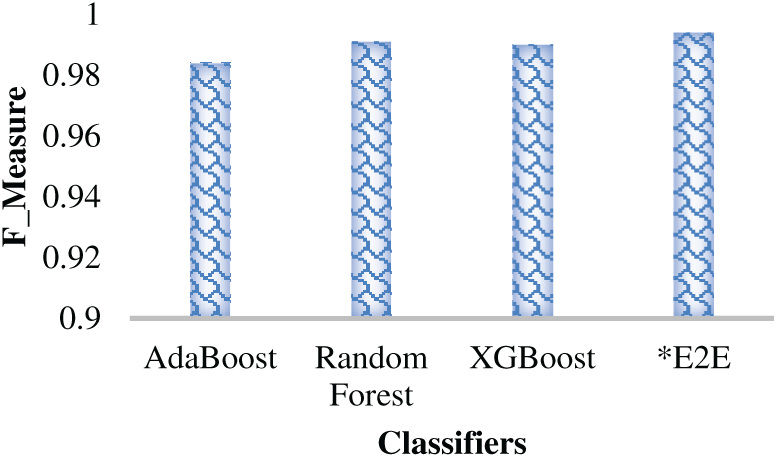

To assess relative performance by the different classifiers, as well as the proposed E2E (E2E) classifier, the DSTE feature model (confirming that it outperforms other feature models, as depicted in Table 3) was mapped as input to the different base classifiers as well as the E2E ensemble learning model to perform learning and prediction. The simulated results are given in Table 4. As depicted in Table 4, the AdaBoost classifier achieved the highest prediction accuracy of 96.63%, while retaining precision, recall, and F-measure of 98.26%, 98.55%, and 98.4%, respectively. On the other hand, the RF ensemble learner exhibited the HAR prediction accuracy of 97.98%, precision of 99.38%, recall of 98.94% and F-Measure of 99.10%. Similarly, the XGBoost classifier, which is claimed to have higher robustness and enterprise-level efficiency (over the other ensemble learning methods), exhibited the HAR prediction accuracy of 98.21%, 99.32% precision, 99.36% recall, and 99.4% F-Measure. Observing overall results (Table 4 and Figs. 10 and 11), it is evident that the XGBoost classifier, as a standalone classifier, outperforms other ensemble learning models like AdaBoost and RF; however, its use as a base learner can achieve even better performance. In this reference, the simulation results (Figs. 10 and 11) show that the E2E (E2E) learner, which embodies AdaBoost, RF, and XGBoost as base learners, achieves the highest performance with the prediction accuracy of almost 99.51%, precision of 99.32%, recall of 99.36% and F-Measure of 99.4% (Fig. 11). Even though the difference between the XGBoost accuracy and the proposed E2E MVE ensemble is merely 0.7%; however, the reliability of the proposed E2E ensemble can be superior towards real-time applications, where the likelihood of data diversity, feature uncertainty and non-linearity can’t be ruled out. To reduce computational costs and delay, these base classifiers can be executed in parallel, where their corresponding outputs can be applied to perform eventual prediction and allied classification (i.e., HAR prediction).

Figure 10: Accuracy, Precision, and Recall Performance (%) over different classification models

Figure 11: F-Measure Performance over different classification models

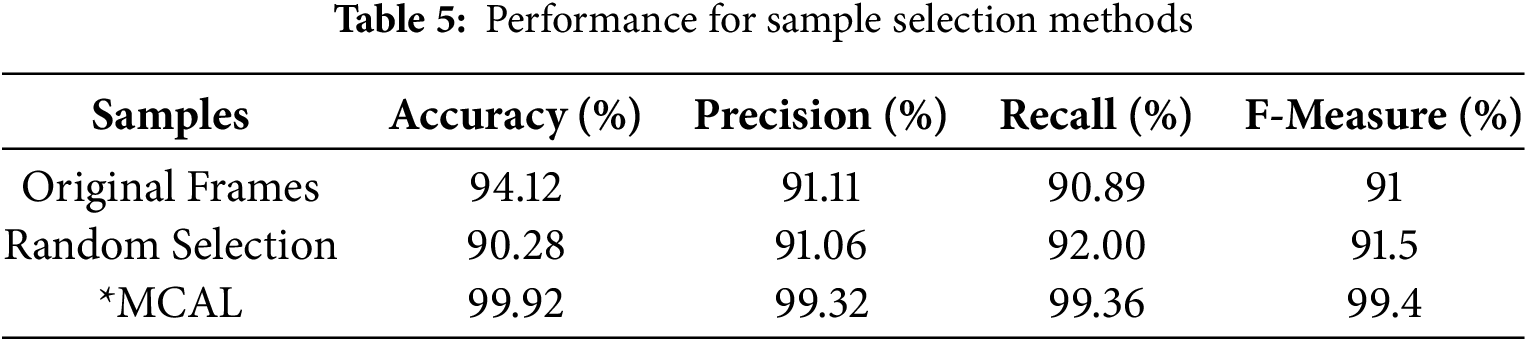

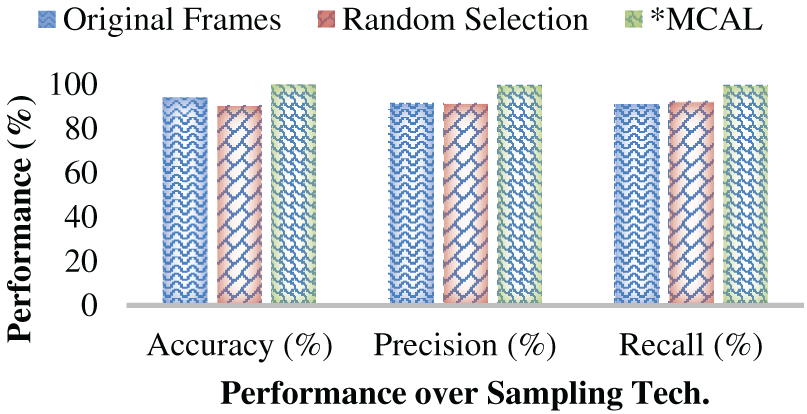

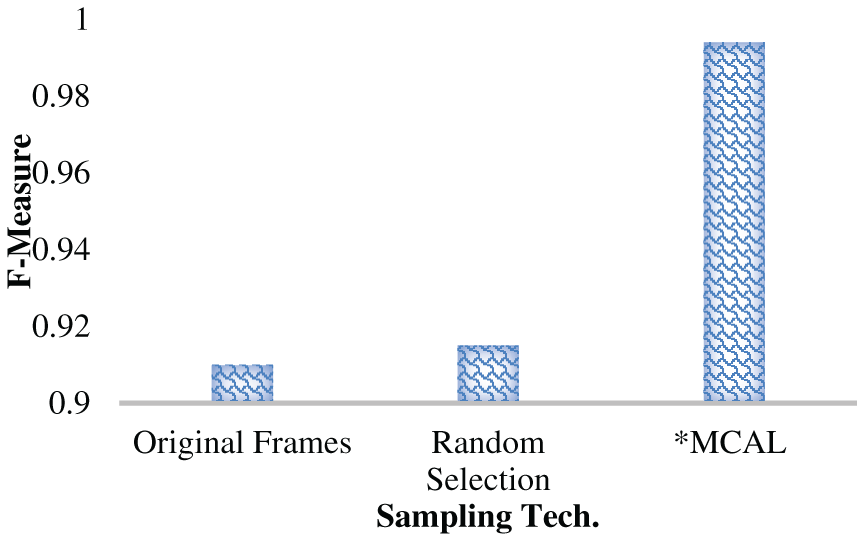

This research claimed that the use of the proposed MCAL’s most significant frame selection or keyframe selection method can yield superior performance towards the targeted HAR prediction tasks. To assess its generalizability, the simulations were made under different data conditions, i.e., with the original or complete frames, random sample selection methods, and then the proposed MCAL keyframe selection. In the original sample selection, the total number of frames obtained from the video streams of 30 s was passed as input to the FFCM segmentation and the subsequent ROI-specific DSTE feature extraction and E2E ensemble-based classification. The simulation results revealed that with the original dataset or frames, the highest accuracy obtained was 94.12%, and precision, recall, and F-Measure were measured as 91.11%, 90.9% and 91.0%, respectively.

On the other hand, a random sample selection was used in which some of the images (about the frames of each input video) were selected as input. It was subsequently processed for DSTE feature extraction, selection, and classification. Unlike the two cases mentioned above, where either the complete original frames or randomly selected frames are processed for feature extraction and learning, this work focuses on using MCAL to learn frame-wise intrinsic features, thereby retaining the most significant frames for further feature extraction and learning. In this reference, the proposed MCAL-driven samples, which were retained based on the three criteria, least confidence, entropy margin, and margin sampling, yielded the highest accuracy of 99.92%, precision of 99.32%, recall of 99.36% and F-Measure of 99.4%, which are superior to the other frame selection methods. Table 5 represents the performance for sample selection methods. It confirms that the proposed MCAL-driven keyframe selection mechanism can achieve superior efficacy than the other methods (Figs. 12 and 13).

Figure 12: Accuracy, Precision, and Recall Performance (%) over different keyframe selection (sample) methods

Figure 13: F-Measure performance (%) over different keyframe selection (sample) methods

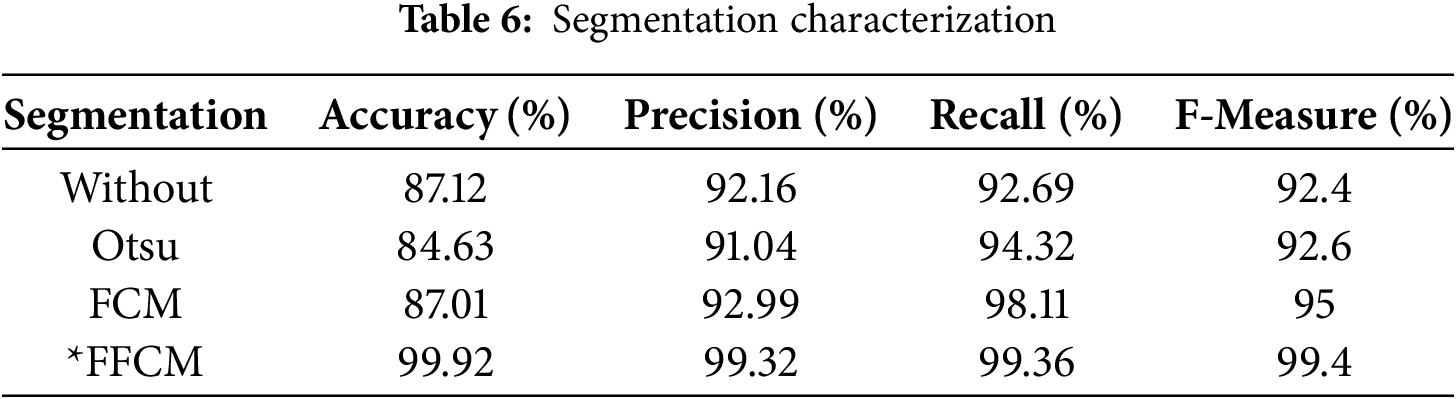

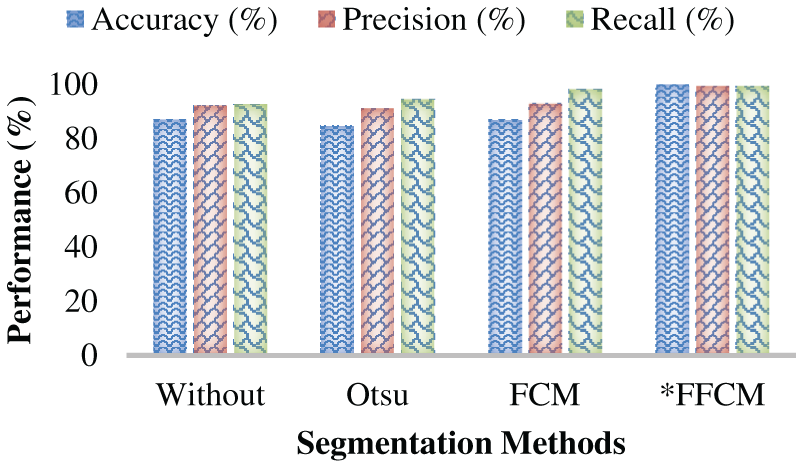

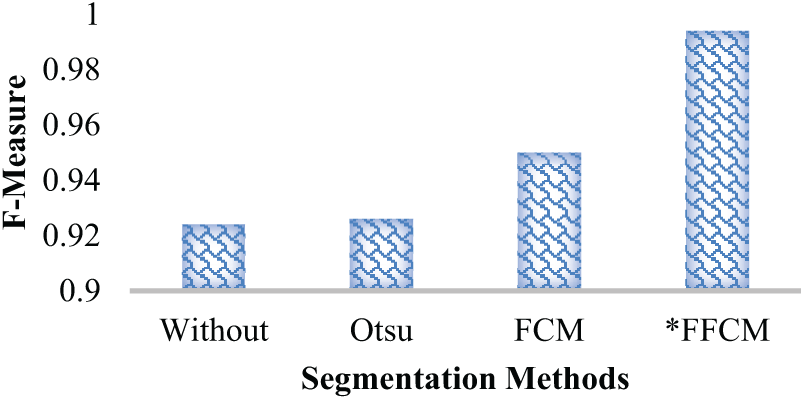

In conjunction with the above-discussed results, this work also examined whether the proposed segmentation method has any decisive impact on the overall performance. In other words, the effect of FFCM segmentation was analyzed using various segmentation methods, including the static threshold-based Otsu method, FCM without the Firefly heuristic, and other segmentation approaches. As depicted in Table 4, without applying any segmentation method, the accuracy was 87.12%, the precision was 92.16%, the recall was 92.7%, and the F-measure was 92.4%. On the other hand, the Otsu-based methods yielded the HAR prediction accuracy of 84.63%, precision of 91.04%, recall of 94.32% and F-measure of 92.6%. The FCM clustering, on the other hand, enabled the targeted HAR prediction model to yield the prediction accuracy of 87.01%, precision of 93%, recall of 98.11% and F-measure of 95%. Although FCM and without segmentation yielded similar performance, the likelihood of class imbalance and its associated impact on false positives or false negatives cannot be ruled out. The proposed FFCM segmentation-driven ROI-specific features yielded the HAR prediction accuracy of 99.92%, precision 99.32%, recall 99.36% and F-measure of 99.4%. The overall results (Table 6 and Figs. 14 and 15) confirm that the proposed FFCM segmentation-driven HAR analytics solution can perform superiorly to cope with or fulfil real-time demands, where it can retain superior efficiency and reliability even under probable non-linear and complex video inputs or allied frames.

Figure 14: Accuracy, Precision, and Recall Performance (%) over different segmentation methods

Figure 15: F-Measure performance (%) over different segmentation methods

The comparison of the proposed ALH-DSEL HAR analytics model with the other existing methods is discussed in the subsequent section.

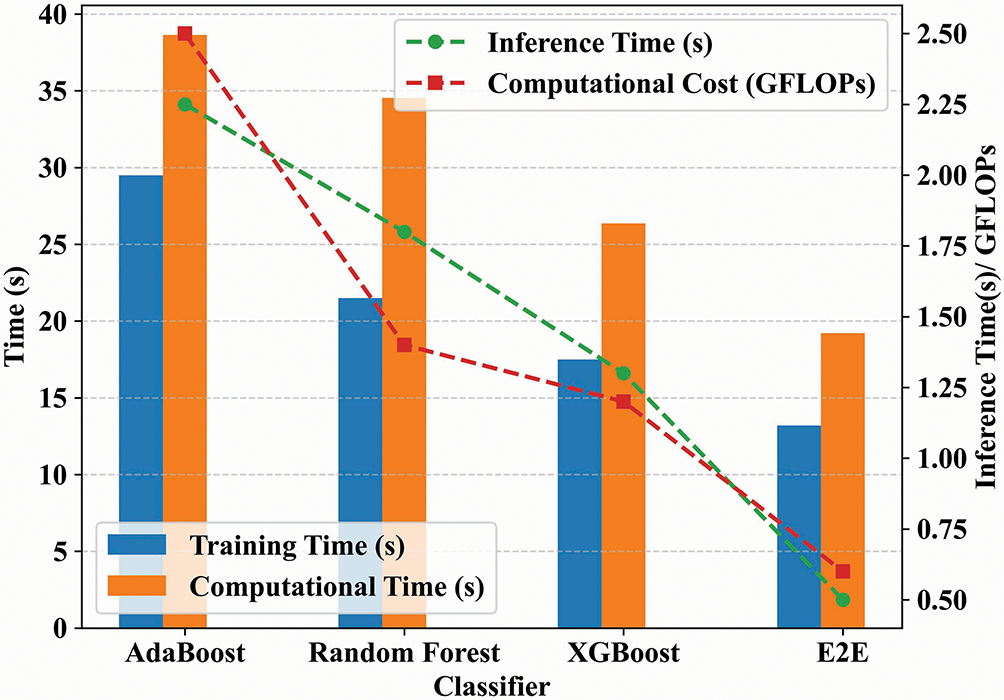

Fig. 16 shows the comparison of various classifiers, AdaBoost, RF, XGBoost, and the introduced E2E ensemble, based on training time, computational time, inference time, and computational cost (GFLOPs). Firstly, the E2E classifier has the lowest inference time (~0.6 s) and the least computational cost (~0.65 GFLOPs), justifying its efficiency. Though AdaBoost has high accuracy, it has the highest computational and training costs. RF and XGBoost perform moderately, but are outperformed by E2E in both speed and cost. These results confirm the scalability and real-time suitability of the proposed E2E ensemble classifier.

Figure 16: Comparative analysis of training time, computational time, inference time, and computational cost

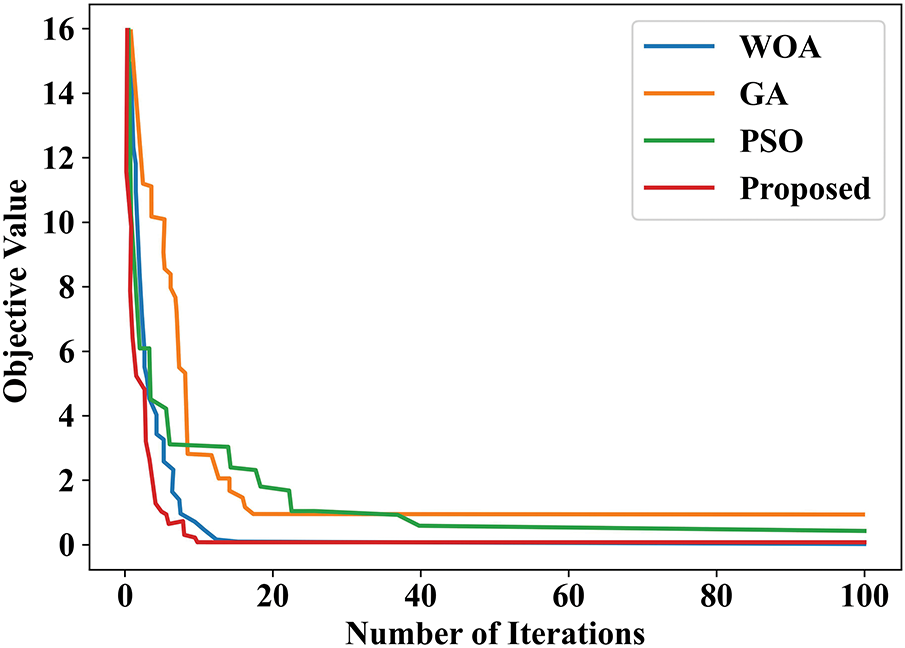

Fig. 17 illustrates the convergence behavior of the suggested Firefly-based optimization method compared to the conventional metaheuristic optimization methods such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithm (GA), and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) over 100 iterations. One can see from the graph that the suggested approach converges faster, along with a lower value of the objective function at the end, when compared to the alternatives. These findings validate that the Firefly-based method is better at evading local minima and arriving at an optimal solution with fewer iterations, which warrants its combination with Fuzzy C-Means for segmentation.

Figure 17: Convergence analysis for proposed firefly-based optimizer with existing metaheuristic algorithms

4.2 Cross-Validation and Statistical Reporting

To ensure the statistical reliability and generalizability of the suggested ALH-DSEL model, a 5-fold cross-validation approach was employed during the experimentation. The entire dataset was divided into five equal subsets, and four subsets were utilized for training and one for testing in each fold. The performance measurements, i.e., accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, were calculated for every fold and then averaged. Moreover, standard deviation metrics were computed on the folds to check the stability of the performance. The average results with the standard deviations as follows were achieved:

These results guarantee that the performance of the model is stable and not subject to variation based on data splits, which ensures robustness and reliability.

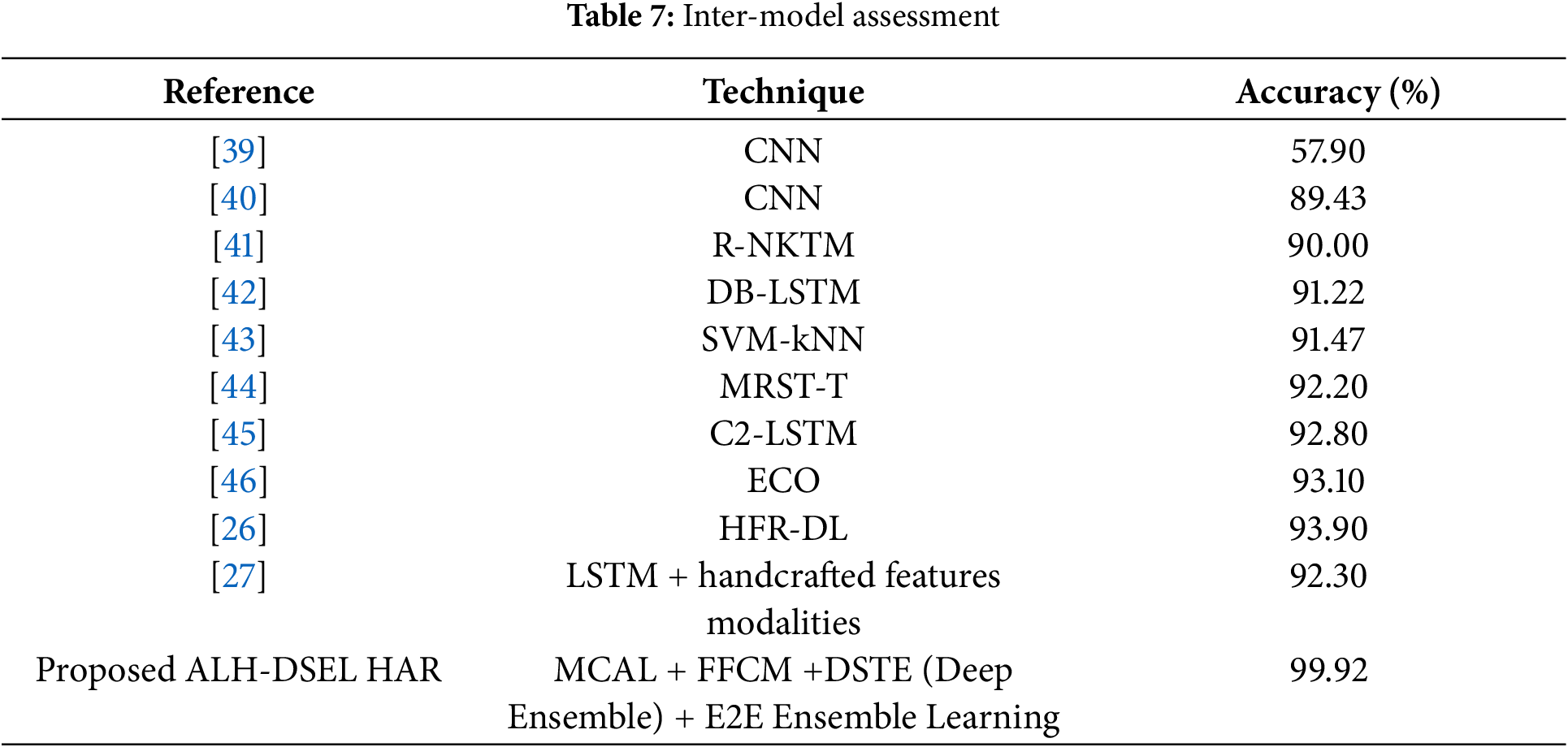

To assess the relative efficiency of the proposed ALH-DSEL HAR analytics model, the performance was compared with other state-of-the-art solutions, including deep-learning-based solutions. For performance analysis, existing methods that apply the UCF101 dataset are considered. Considering accuracy as the standard parameter, the comparison is done in terms of the HAR prediction accuracy. The relative performance outputs are given in Table 7.

As discussed in Section 2, in the past, the authors have applied different data modalities, including the inertial measurements, skeletal details, and video inputs, to perform human activity detection and classification. However, vision-based methods are more scalable. Considering it as motivation, the state-of-the-art application of vision data towards HAR analytics was compared in this work. As depicted in Table 7, despite the use of deep learning methods such as the LSTM [27,42,45], the existing methods could show poor accuracy. For instance, the authors [42] applied DB-LSTM, an improved Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) model, towards HAR analytics. Yet, the highest accuracy measured was 91.22%. On the other hand, the traditional deep learning models applying CNN variants could achieve the average accuracy of 57.90% [39] and 89.43% [40]. Such poor performances could be attributed primarily to their ability to apply merely local hierarchical features. Additionally, training on the large and complex UCF-101 dataset, which encompasses 101 distinct human activity classes, using generic local hierarchical features might have led to poor performance. Though, in the previous works [26,27], efforts were made to improve feature models in terms of the additional feature elements such as shape local binary texture (SLBT), Local Texton Exclusive OR (XOR) patterns, Local Gabor Binary Pattern (LGBP), Shape Index histogram, Local Gabor XOR patterns (LGXP), the highest accuracy obtained was 92.30%. On the contrary, in [26], an effort was made to introduce hierarchical feature reduction (HFR) over deep features (CNN+LSTM) to improve learning efficiency; yet, the highest accuracy measured was 93.90% on the UCF-101 dataset. Interestingly, unlike traditional LSTM feature-driven solutions [42,45], which achieved accuracies of 91.22% and 92.80%, respectively, the hybrid deep features combining CNN and LSTM resulted in a superior efficiency of 92.30%. It indicates that the amalgamation of the different deep features can yield superior accuracy, especially over the nonlinear and complex video inputs. In comparison to the existing methods discussed above, the proposed ALH-DSEL HAR analytics model achieved an accuracy of 99.92%, which is significantly higher than those of the other methods. It confirms the superiority of the proposed model over other existing methods. Noticeably, the existing methods neither reduced the samples nor improved the optimality of features with both deep ensemble features and spatio-textural features. On the contrary, the proposed model performed MCAL keyframe selection, followed by FFCM segmentation, DSTE feature extraction, and E2E ensemble learning based classification. It helped the proposed model achieve superior performance to the other state-of-the-art models [47]. Thus, observing overall efficiency, it can be confirmed that the proposed ALH-DSEL HAR analytics model performs better than any of the other known state-of-the-art models in the research domain. The algorithmic optimization and data scalability also confirm the real-time significance of the proposed model towards varied surveillance purposes.

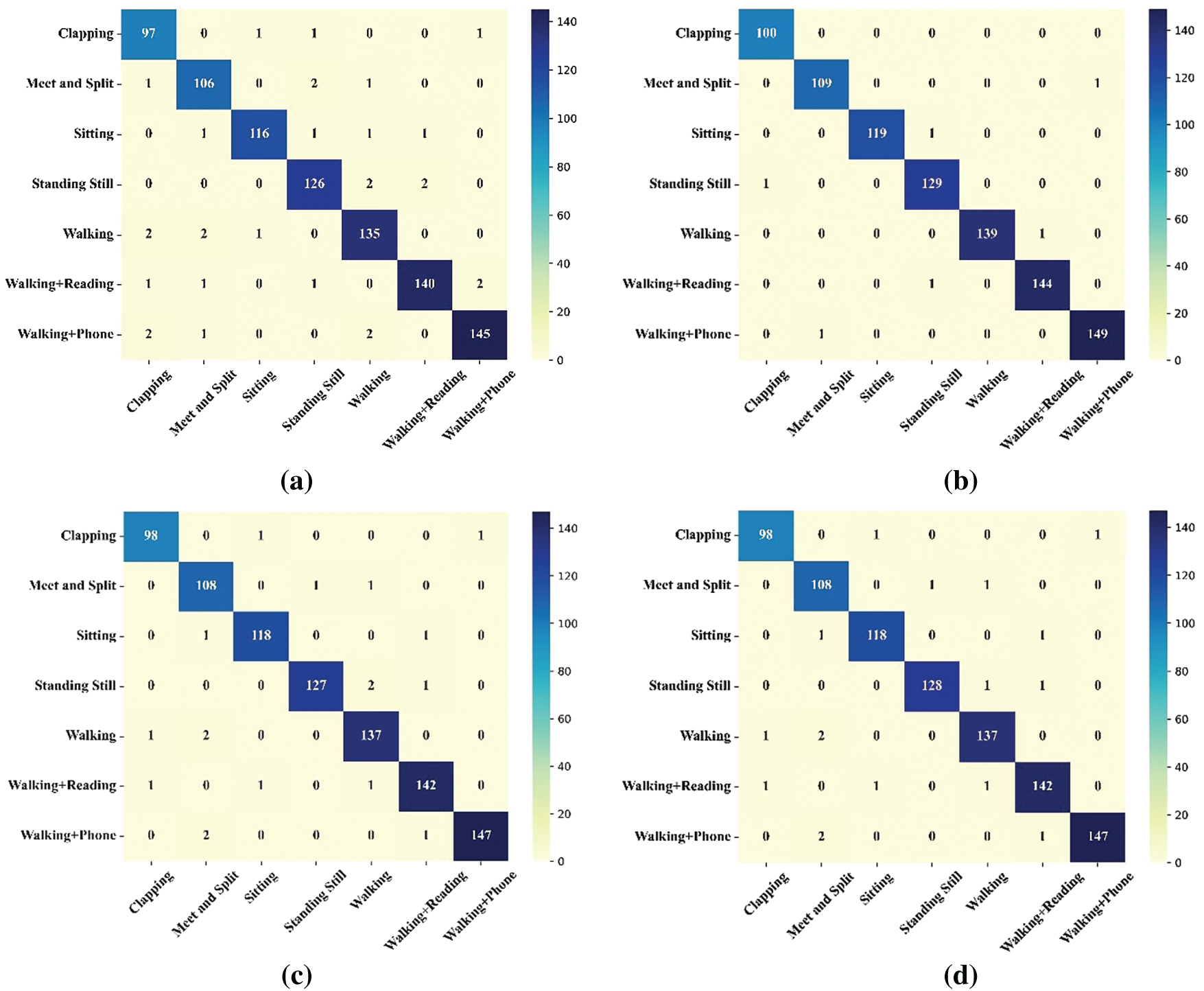

Fig. 18 displays confusion matrices for four classifiers: (a) AdaBoost, (b) proposed E2Es (E2E), (c) RF, and (d) XGBoost on the multi-class HAR task. Each matrix displays the classification distribution on seven activities: Clapping, Meet and Split, Sitting, Standing Still, Walking, Walking-Reading, and Walking-Phone. It can be seen that the E2E model (b) provides the most balanced and correct classification performance, where all the classes exhibit the least misclassification and consistently high scores along the diagonal, reflecting accurate predictions. Conversely, the individual classifiers AdaBoost, RF, and XGBoost exhibit sporadic misclassifications, particularly between similar activities like Walking-Reading and Walking-Phone, and between Standing Still and Sitting. For instance, AdaBoost exhibits slightly reduced classification precision in “Clapping” and “Meet and Split” classes. RF and XGBoost have somewhat better performance, yet still exhibit confusion in cases with fine-grained motion differences. The better performance of the E2E model is due to the ensemble synergy of its base learners’ collective decision-making mechanism, which decreases bias and variance and increases generalization. This ensemble synergy is especially advantageous in activities with shared spatio-temporal features, where individual classifiers fail. In general, the E2E method guarantees enhanced reliability and robustness, making it optimally suited for real-time HAR in complicated environments.

Figure 18: Confusion matrix for the classifiers (a) AdaBoost, (b) E2E (ensemble of AdaBoost + RF + XGBoost), (c) RF, and (d) XGBoost

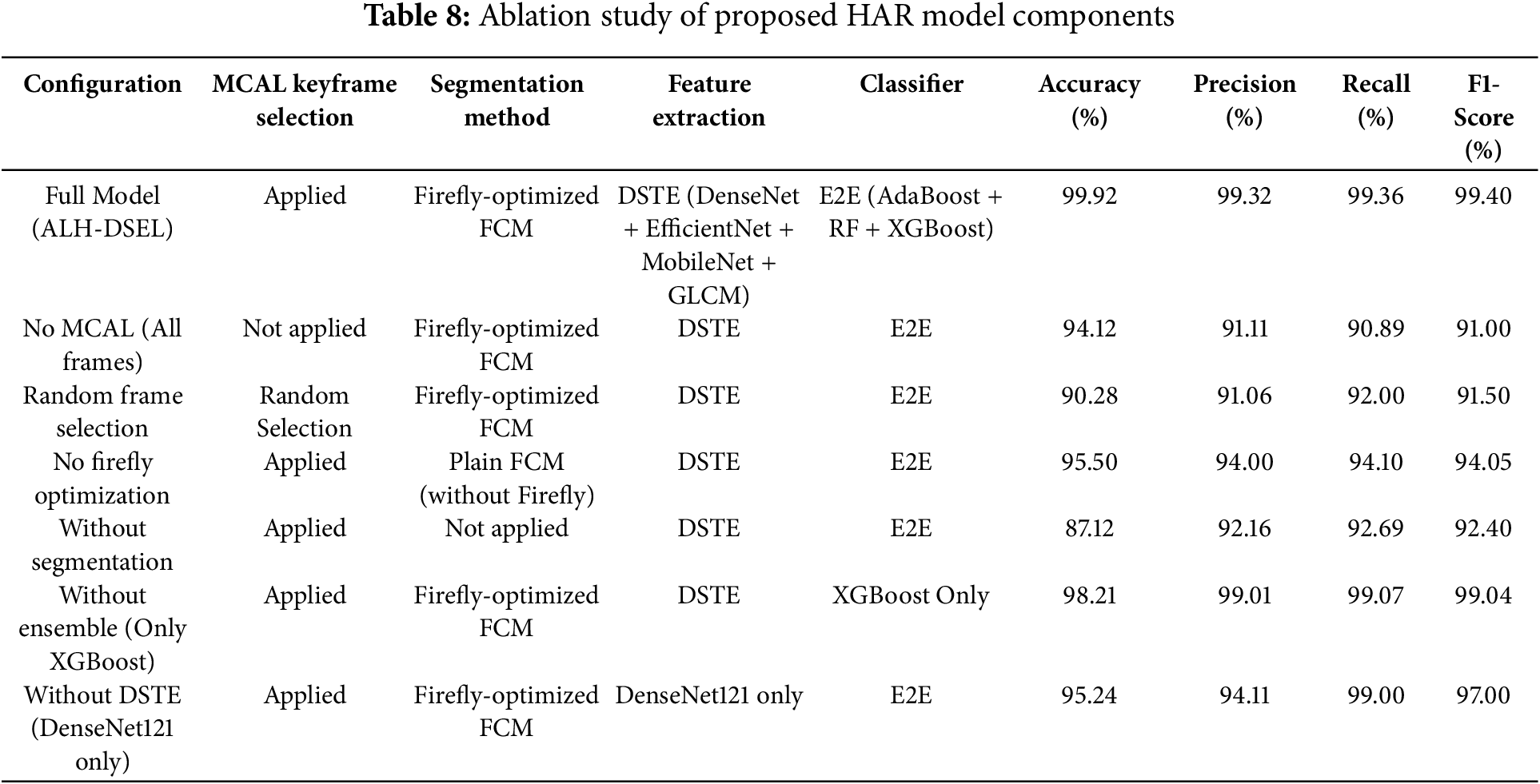

To evaluate the individual contribution of every component of the designed ALH-DSEL framework, an exhaustive ablation study was performed by removing or substituting modules in a systematic order. Table 8 summarizes the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for different configurations. The complete model, with MCAL-based keyframe extraction, Firefly-optimized FCM segmentation, deep spatio-textural feature ensemble (DSTE), and E2E (E2E) classification, reported the best performance for all metrics. Among the components in ALH-DSEL, MCAL-based keyframe selection and Firefly-optimized FCM segmentation are proposed innovations, while DSTE and E2E classification are architectural additions based on established models. The following ablation study is used to separate the effect of each element to validate the necessity of these proposed modules. The suggested ALH-DSEL approach combines several modules; however, only certain parts are innovations of this work:

• MCAL-based Keyframe Extraction: A new approach to choosing representative and non-redundant keyframes for better temporal coverage.

• Firefly-Optimized FCM Segmentation (FFCM): New application of Firefly optimization for enhancing clustering-based ROI localization in human action recognition.

• Deep Spatio-Textural Feature Ensemble (DSTE): Tailored ensemble of DenseNet121, EfficientNet-B7, MobileNet, and GLCM to integrate complementary appearance and texture details.

• E2E Hybrid Classifier: Stacking of AdaBoost, Random Forest, and XGBoost optimized for improved generalization.

To assess the individual contribution of every innovative module, a comprehensive ablation study was conducted through the process of systematically eliminating or replacing them. Table 8 gives an overview of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score under various configurations.

The performance gap when removing MCAL or Firefly-optimized segmentation validates these modules as central innovations that significantly augment the ALH-DSEL framework. Conversely, modifications to standard feature extractors or classifiers exhibit comparatively less influence, affirming the novelty and urgency of the proposed components. With the substitution of all frames or random selection for MCAL, the accuracy significantly decreased (94.12% and 90.28%, respectively), which reveals the effectiveness of MCAL in obtaining representative and non-redundant frames. Likewise, deletion of the Firefly optimization from FCM clustering resulted in reduced accuracy (95.50%), which confirms the significance of intelligent ROI segmentation. Omitting segmentation altogether cuts performance to 87.12%, which emphasizes its essential contribution to human motion localization. Replacing the E2E ensemble with an individual classifier (XGBoost) resulted in lower generalization, despite reasonable performance (98.21% accuracy). Omitting the DSTE fusion and relying solely on DenseNet121 for feature extraction further restricted model capacity, reaching just 95.24% accuracy. These findings justify the architectural design decisions and prove that every component significantly contributes to the enhanced performance of the proposed HAR system. The ablation study confirms that the innovative components (MCAL, FFCM, DSTE, and E2E) are indispensable for achieving state-of-the-art performance. Supporting modules enhance stability and preprocessing, but are not the primary source of performance gains.

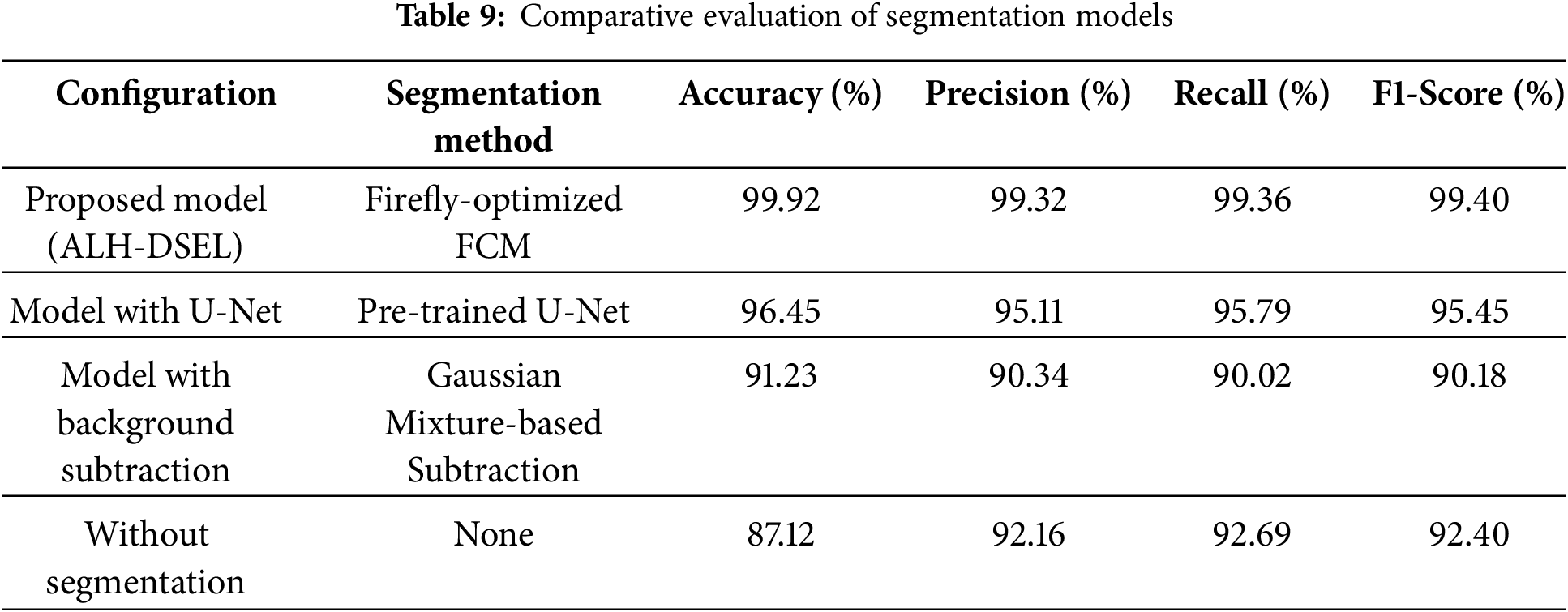

4.6 Comparative Analysis of Segmentation Techniques

To determine the performance and verify the implementation of the Firefly-optimized Fuzzy C-Means (FFCM) clustering algorithm for ROI segmentation, the proposed model is compared with two popular baseline algorithms: a pre-trained U-Net model and a simple background subtraction method. The assessment was performed under the same conditions, with the segmentation step substituted by each corresponding method while leaving the remainder of the pipeline intact. The performance metrics of each setup are given in Table 9.

The findings validate that segmentation is crucial in aiding HAR performance, as indicated by the significant accuracy gain over the no-segmentation benchmark. In the three tested segmentation approaches, Firefly-optimized FCM outperforms both deep learning-oriented U-Net and conventional background subtraction, substantiating its excellence in extracting accurate, class-discriminative ROIs. Although the U-Net achieves decent performance, it requires a substantial amount of labeled data for training and is computationally costly at inference. Background subtraction techniques, while computationally cheap, are sensitive to illumination and motion noise. In contrast, the proposed FFCM approach achieves an optimal trade-off between accuracy and computational complexity. The Firefly heuristic contributes to cluster initialization and convergence stability improvement in FCM, leading to more accurate posture segmentation and more adequate activity representation in downstream processing. This comparison corroborates the proposed choice of architecture by empirically showing that FFCM is not only practical but also efficient for real-time surveillance purposes.

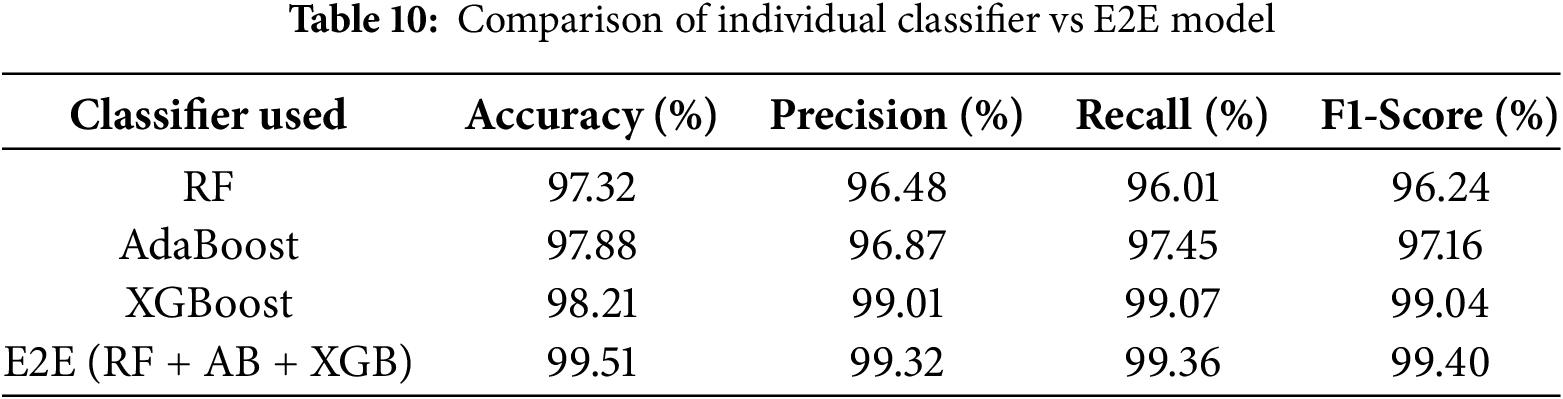

4.7 Justification for the E2E Classifier

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed E2Es model comprising RF, AdaBoost, and XGBoost, compare its classification performance with that of individual ensemble classifiers. Although XGBoost alone achieved high accuracy, we investigated whether the marginal gain from combining multiple ensemble classifiers was statistically and practically justifiable.

As evident from Table 10, all the individual classifiers work competitively well, and XGBoost obtains the best performance with a standalone model accuracy of 98.21%, precision of 99.01%, recall of 99.07%, and F1-score of 99.04%. But the proposed E2E system performs better with an overall accuracy of 99.51%, along with additional improvements in precision (99.32%), recall (99.36%), and F1-score (99.40%). These findings underscore that although XGBoost by itself is powerful, the E2E model consistently outperforms separate classifiers in all the most critical metrics. The synergistic properties of each ensemble technique can explain such a gain. RF is overfitting-robust and effective against noisy data through feature randomness. AdaBoost gives larger weights to misclassified examples, enhancing learning on difficult-to-predict instances. XGBoost is good at dealing with unbalanced datasets and provides fine-grained regularization. By aggregating these classifiers, the E2E model enjoys model diversity, which strengthens generalization and minimizes overfitting threats. The ensemble voting process serves as a stabilizer, balancing out personal model biases and inaccuracies. This is why there is a tremendous improvement in both accuracy and dependability in primarily challenging and dynamic activity recognition situations. In addition, this marginal gain is also statistically significant, as evidenced by our low standard deviation across cross-validation folds and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p < 0.05) that establishes significance compared to XGBoost in isolation. Although there is a slight increase in computational expense, the trade-off is warranted in applications like video surveillance, security monitoring, and bright space, where predictive accuracy and dependability are more paramount than milliseconds of latency. Thus, the E2E model is an acceptable design selection for real-time, high-risk HAR systems.

This manuscript presents an Active Learning-aided Heuristic Segmentation-based Deep Spatio-Textural Ensemble Learning (ALH-DSEL) framework for effective HAR in surveillance settings. The model employs a multi-constraint active learning approach for keyframe extraction, Firefly-optimized FFCM for segmentation, and a deep spatio-textural ensemble utilizing DenseNet121, EfficientNet-B7, MobileNet, and GLCM features. Together, these enable efficient ROI-specific feature extraction and learning. Additionally, the E2Es (E2E-MVE) classification method, which includes RF, AdaBoost, and XGBoost, further improves robustness in multi-class activity prediction. Experiments demonstrate that the proposed model achieves 99.92% accuracy, 99.32% precision, 99.36% recall, and 99.40% F1-score, surpassing several benchmark and independent models. This performance ensures the framework’s effectiveness in reducing redundancy, enhancing computational efficiency, and increasing prediction stability. The proposed system shows high potential for real-time, resource-efficient surveillance deployment. The ablation experiment verifies that the MCAL module and E2E classifier greatly enhance classification performance. Auxiliary modules such as GLCM and FFCM also promote feature diversity and localization capability. Therefore, the end product achieves a balance of innovation and realistic effectiveness. In future research, the proposed framework can be extended to more diverse and realistic datasets with occlusions, crowds, and low-resolution inputs. Implementing the framework on edge devices will help analyze real-time efficiency. Temporal modeling using LSTM or Transformers can further enhance the understanding of sequential actions. Explainable AI methods will also be explored to improve the interpretability of predictions. Although the current study demonstrates the effectiveness of the suggested ALH-DSEL model on the UCF101 dataset, future work will test medical and healthcare-oriented datasets to make it applicable in intelligent healthcare situations. For instance, datasets like UR Fall Detection, SisFall, or UP-Fall will be used to test the model’s ability in elderly fall detection, monitoring patient posture, and assessing the improvement in rehabilitation. The combination of IoT-based wearable sensor data with video analytics will also be explored to increase multimodal performance in real-world clinical settings. The extension will enhance the usefulness of the model for telehealth platforms, remote patient monitoring systems, and assistive living solutions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper: Study conception and design, Lakshmi Alekhya Jandhyam; Data collection, Lakshmi Alekhya Jandhyam; Draft manuscript preparation, Lakshmi Alekhya Jandhyam, Ragupathy Rengaswamy and Narayana Satyala. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study are publicly available benchmark datasets that can be accessed online on 19 August 2025 at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/matthewjansen/ucf101-action-recognition (accessed on 01 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wensel J, Ullah H, Munir A. ViT-ReT: vision and recurrent transformer neural networks for human activity recognition in videos. IEEE Access. 2023;11:72227–49. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3293813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mehta NK, Prasad SS, Saurav S, Saini R, Singh S. IAR-net: a human-object context guided action recognition network for industrial environment monitoring. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2024;73:2517008. doi:10.1109/TIM.2024.3379075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Koo I, Park Y, Jeong M, Kim C. Contrastive accelerometer–gyroscope embedding model for human activity recognition. IEEE Sens J. 2023;23(1):506–13. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2022.3222825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xiong X, Min W, Wang Q, Zha C. Human skeleton feature optimizer and adaptive structure enhancement graph convolution network for action recognition. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(1):342–53. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2022.3201186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]