Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Lightweight Residual Multi-Head Convolution with Channel Attention (ResMHCNN) for End-to-End Classification of Medical Images

1 Department of Radiology, Huzhou Wuxing People’s Hospital, Huzhou Wuxing Maternity and Child Health Hospital, Huzhou, 313000, China

2 Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, School of Engineering and Sciences, SRM University—AP, Amaravati, 522240, India

3 College of Information Engineering, Huzhou Normal University, Huzhou, 313000, China

4 Department of Instrumentation and Control Engineering, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Udupi, 576104, India

5 Department of Electronic and Information Technology, Miami College, Henan University, Kaifeng, 475004, China

6 Department of Computer Science and Mathematics, Lebanese American University, Beirut, 13-5053, Lebanon

7 Department of Computer Engineering, Inha University, Incheon, 22212, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Sudhakar Tummala. Email: ; Jungeun Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning and Deep Learning-Based Pattern Recognition)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 3585-3605. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.069731

Received 29 June 2025; Accepted 18 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Lightweight deep learning models are increasingly required in resource-constrained environments such as mobile devices and the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT). Multi-head convolution with channel attention can facilitate learning activations relevant to different kernel sizes within a multi-head convolutional layer. Therefore, this study investigates the capability of novel lightweight models incorporating residual multi-head convolution with channel attention (ResMHCNN) blocks to classify medical images. We introduced three novel lightweight deep learning models (BT-Net, LCC-Net, and BC-Net) utilizing the ResMHCNN block as their backbone. These models were cross-validated and tested on three publicly available medical image datasets: a brain tumor dataset from Figshare consisting of T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging slices of meningioma, glioma, and pituitary tumors; the LC25000 dataset, which includes microscopic images of lung and colon cancers; and the BreaKHis dataset, containing benign and malignant breast microscopic images. The lightweight models achieved accuracies of 96.9% for 3-class brain tumor classification using BT-Net, and 99.7% for 5-class lung and colon cancer classification using LCC-Net. For 2-class breast cancer classification, BC-Net achieved an accuracy of 96.7%. The parameter counts for the proposed lightweight models—LCC-Net, BC-Net, and BT-Net—are 0.528, 0.226, and 1.154 million, respectively. The presented lightweight models, featuring ResMHCNN blocks, may be effectively employed for accurate medical image classification. In the future, these models might be tested for viability in resource-constrained systems such as mobile devices and IoMT platforms.Keywords

With the advancement of state-of-the-art deep learning models, including large convolutional neural networks and vision transformer architectures, tasks such as visual recognition, segmentation, object detection, and localization have achieved a high degree of reliability across various fields, including medicine [1–3]. However, training these large models to obtain such accuracy often necessitates large amounts of data and significant computational power, typically requiring access to hardware accelerators like graphical processing units (GPUs). This poses challenges in resource-constrained environments such as mobile devices, autonomous driving, robotics, and the Internet of Things (IoT), including the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT). These environments often lack sufficient computational power, memory, and energy resources, making deploying and training large models locally tricky. Additionally, transmitting data to centralized servers for processing raises concerns about latency, bandwidth, and data privacy, particularly in sensitive applications like healthcare.

Despite these challenges, lightweight models have emerged as a promising solution [4,5]. For instance, MobileNets V1, V2, and V3 were invented using depth-wise separable convolutions, resulting in models with fewer parameters that are well suited for low-power, low-latency applications such as fine-grained classifications, embedding, segmentation, and object detection [6]. These models enable real-time processing and decision-making at the edge, reducing dependency on cloud resources. However, even these models, with over 3 million parameters, may not be suitable for highly resource-constrained environments [7]. The motivation for developing lightweight models stems from the increasing demand to deploy AI in resource-constrained environments such as mobile devices and IoMTs. These platforms often suffer from limited computational power, memory, and energy capacity, making it difficult to support large, complex deep learning models. Additionally, latency, bandwidth limitations, and data privacy concerns further hinder reliance on cloud-based processing. Nevertheless, integrating AI into IoT devices offers significant opportunities, including personalized healthcare recommendations, improved automation, and energy efficiency in diverse domains such as smart homes, agriculture, and logistics.

Another aspect is the necessity to reduce the carbon footprint during training and inference for environmental sustainability. This can be achieved by investigating energy-efficient, lightweight deep neural networks [8,9]. The training of large networks such as T5, Meena, GShard, GPT-4o, Switch Transformer, and any other large language models often generates carbon dioxide emissions that exceed those produced by several cars over their entire lifetimes [10]. Similarly, training state-of-the-art networks such as EfficientNets, ConvNeXt, Vision Transformer, and Swin Transformer models require GPUs, and between 2012 and 2018, there was a 300,000-fold increase in computing demand in deep learning [11]. Hence, there is a critical need to develop lightweight deep learning models with substantially fewer parameters that can accommodate growing computational demands while minimizing carbon emissions, yet remain efficient and accurate for their intended tasks.

Numerous studies in the literature address the development of lightweight models across various domains, including medicine, remote sensing, human activity detection, and cattle face detection [12–15]. For example, in [14], the authors introduced ResNet8 and a custom 14-layer convolutional neural network (CNN) model designed explicitly for detecting COVID-19 from chest radiographs. Another study [16] described the creation of a lightweight network that integrates recurrent neural networks and long short-term memory for human activity detection. Additionally, lightweight networks have been proposed for classifying 12 standard echocardiography views through the distillation of established CNN architectures such as VGG-16, DenseNet, and ResNet [17]. For super-resolution of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images, a multi-modal multi-head convolutional attention network was developed, capable of accommodating multiple kernel sizes [18]. In the context of weed detection within soybean plantations, a custom 5-layer CNN demonstrated superior performance with low latency and low memory requirements [19].

Furthermore, LightSeizureNet was developed utilizing dilated one-dimensional convolution and kernel-wise pruning for real-time detection of epileptic seizures based on electroencephalogram data [12]. In another recent study, a lightweight U-Net incorporating convolutional and attention blocks was proposed for automated segmentation and analysis of retinal images [20]. Although the state-of-the-art inception block [21] facilitates the use of multiple kernel sizes within a single convolutional layer, it restricts the maximum kernel size to 5 × 5, and does not explicitly emphasize specific kernel sizes. Moreover, the application of residual multi-head convolution layers with a focus on kernel sizes has yet to be explored for medical image classification to the best of our knowledge.

Cancer is the leading cause of mortality and represents a significant economic burden on healthcare systems worldwide [22]. Notably, brain tumors (particularly malignant types), along with breast cancer and lung and colon cancers, are among the most prevalent cancers that contribute substantially to global healthcare costs [22,23]. Brain tumors are typically diagnosed using T1-weighted MRI, while the other two types of cancer are identified through histopathological examination. Therefore, in this study, we present

(a) lightweight and less complex architectures comprising only a few layers (BT-Net for brain tumors, BC-Net for breast cancer, and LCC-Net for lung and colon cancer), designed for the classification of medical images that may be effectively deployed in low-resource environments. These architectures utilize a novel residual multi-head convolution with channel-wise attention (ResMHCNN) block as the backbone.

(b) The proposed lightweight models are cross-validated and tested on three distinct medical image datasets from Figshare, BreaKHis, and LC25000. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to implement the novel ResMHCNN blocks for the classification of medical images, and our findings demonstrate its efficiency.

To cross-validate and test the proposed lightweight models, we employed three publicly available medical image datasets, described below. For each dataset, 70% of the data was allocated for cross-validation, while the remaining 30% was reserved for testing.

Brain Tumor: The publicly accessible dataset from Figshare consists of 3064 two-dimensional T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI images from 233 patients diagnosed with glioma, meningioma, or pituitary tumors. The spatial resolutions of the images are either 512 × 512 or 256 × 256 pixels, which were subsequently resized to 224 × 224 pixels. Example MRI slices used in this study are shown in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes in Fig. 1. The distribution of images for each tumor type, along with the cross-validation and test sets, is provided in Table 1. Further details regarding this dataset can be found in [24,25].

Figure 1: Sample images from the Figshare dataset for Glioma, Meningioma, and Pituitary tumors in axial, sagittal, and coronal cut planes

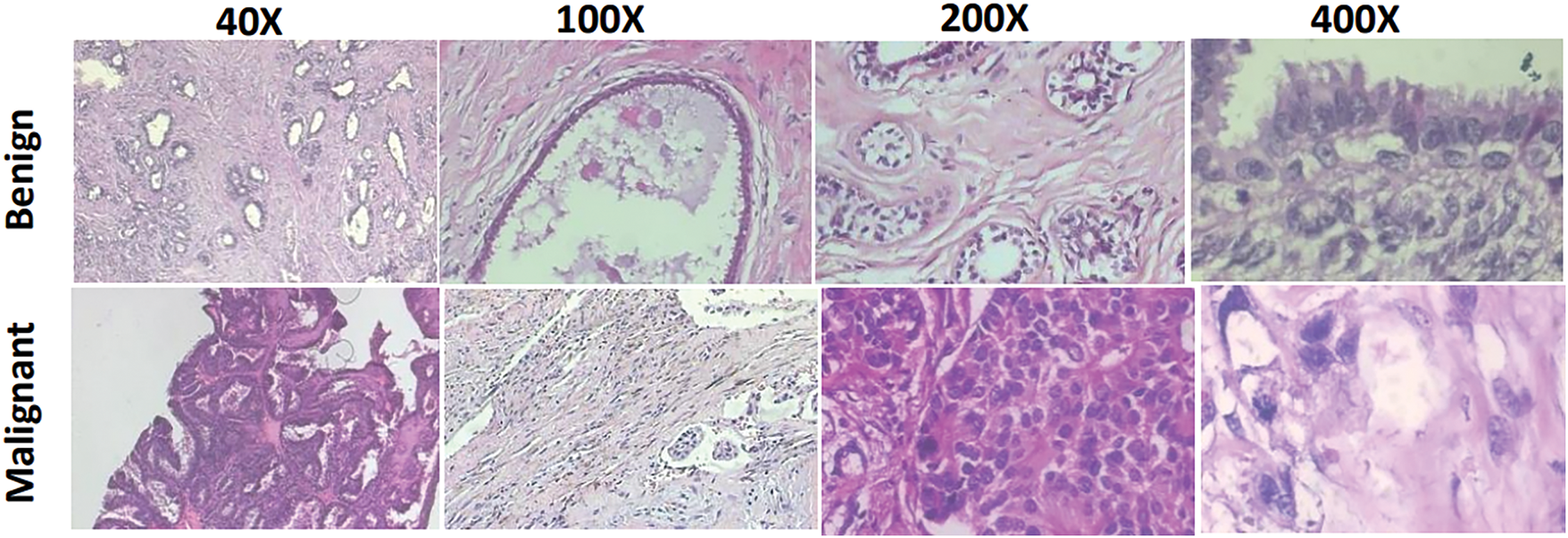

Breast Cancer: We utilized the publicly available BreaKHis dataset to classify breast tumors as benign or malignant. This dataset contains 7909 microscopic images obtained from 82 patients, representing surgical histology of breast tumors at magnification factors of 50×, 100×, 200×, and 400× [26]. The images were resized to a spatial resolution of 224 × 224 pixels. Fig. 2 shows sample images of benign and malignant tumors captured at different magnification levels. Table 1 presents the distribution of images used for cross-validation and testing, organized by tumor type and magnification factor.

Figure 2: Sample microscopic images from the BreaKHis dataset for benign and malignant at 40×, 100×, 200×, and 400× zoom factors

Lung and Colon Cancer: For the detection of lung and colon cancer, we utilized the publicly available ‘LC25000’ dataset [27]. This dataset includes three subtypes of lung cancer—adenocarcinoma, benign, and squamous cell carcinoma, as well as two subtypes of colon cancer, adenocarcinoma and benign. Each subtype initially consisted of 250 images captured using a Leica LM190 HD microscope camera. To expand the dataset, several image augmentation techniques, including horizontal and vertical flips as well as left and right rotations, were applied, increasing the number of images for each subtype to 5000. Originally captured at a spatial resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels, the images were cropped to 768 × 768 pixels before augmentation. Finally, all images were resized to 224 × 224 pixels. Example images from the LC25000 dataset, representing each lung and colon cancer subtype, are displayed in Fig. 3. Additionally, the distribution of images used for cross-validation and testing is presented in Table 1.

Figure 3: Sample microscopic images from the LC25000 dataset for (a) lung adenocarcinoma, (b) benign, and (c) squamous cell carcinoma; (d) colon adenocarcinoma, and (e) benign

Table 1 summarizes the number of images for each dataset. For brain tumors, the number of glioma images is higher than for the other two tumor types. Additionally, the number of images is consistent across each subtype for both lung and colon cancer. In contrast, for breast cancer, the number of malignant images is more than twice that of the benign microscopic images.

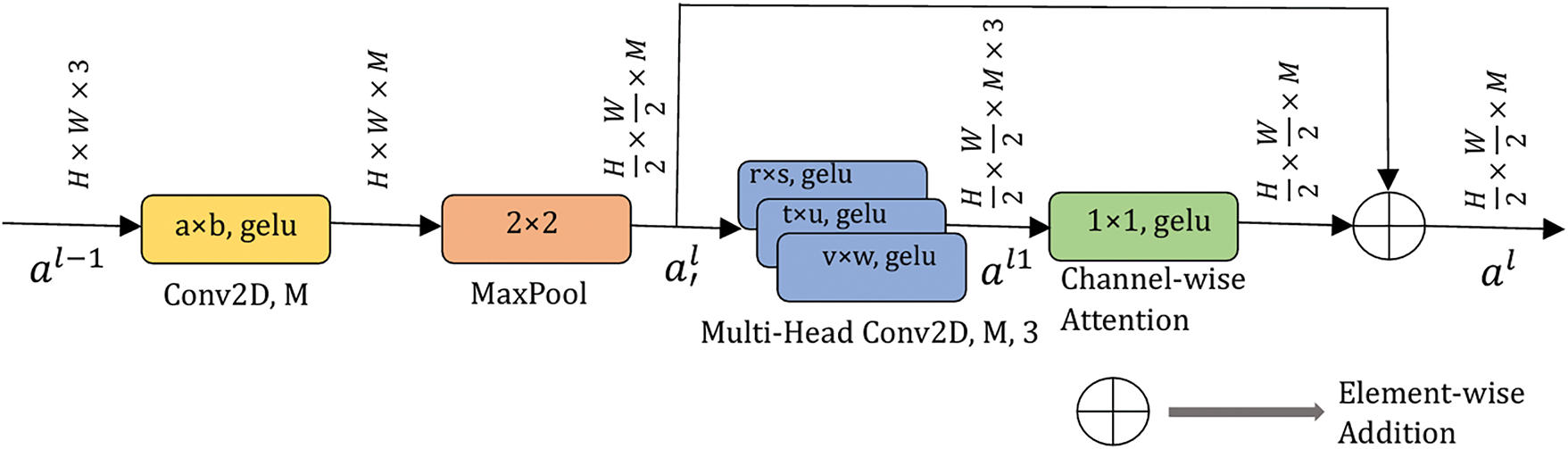

This section presents the detailed architecture of the proposed ResMHCNN block as well as the overall BT-Net, BC-Net, and LCC-Net frameworks. The first layer of the ResMHCNN block consists of a 2D convolutional layer with M filters and the flexibility to choose the kernel size (a × b), followed by a MaxPool operation with a kernel size of 2 × 2. Given an input size of

The output of the multi-head convolution layer is then passed to a channel-wise attention layer with a kernel size of 1 × 1, restoring the activation map to size

Fig. 4 illustrates the general structure of the ResMHCNN block. All convolutional layers use the Gaussian Error Linear Unit (gelu) as their activation function. Mathematically, the overall operation of the ResMHCNN block is described in Eqs. (1)–(3). Here,

Figure 4: Residual multi-head convolutional with channel attention (ResMHCNN) block. All convolution layers use gelu as the activation function. M and L are the number of filters in the corresponding convolution layers. gelu: Gaussian error linear unit. H and W represent the height and width of the input applied to the ResMHCNN block

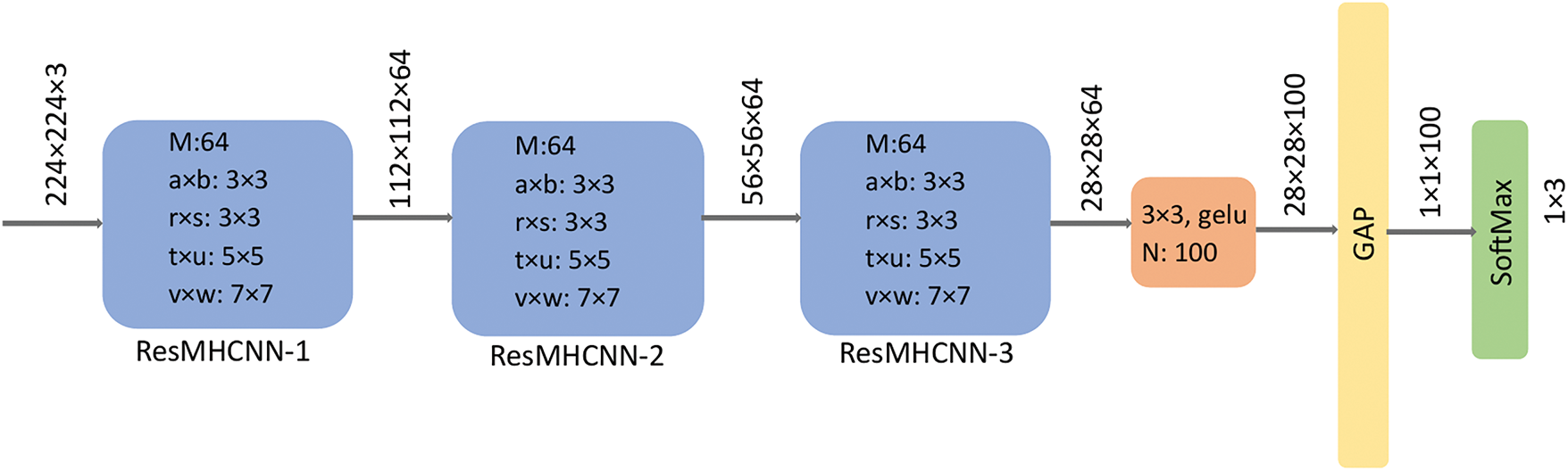

The LCC-Net architecture employs three ResMHCNN blocks, as illustrated in Fig. 5. In the first ResMHCNN block, 64 filters are used in both the initial 2D convolutional layer and the 2D convolutional layers of the multi-head. In the second and third ResMHCNN blocks, 32 filters are used in each 2D convolutional layer. The kernel size in the first convolutional layer of all three blocks is 3 × 3. Additionally, the multi-head kernel sizes in the first and second ResMHCNN blocks are 3 × 3, 5 × 5, and 7 × 7, while in the third ResMHCNN block, a kernel size of 1 × 1 is used instead of 7 × 7.

Figure 5: LCC-Net architecture for classifying lung and colon cancer into lung adenocarcinoma, benign, and squamous cell carcinoma; colon adenocarcinoma and benign. ResMHCNN: residual multi-head convolutional block with channel attention. GAP: global average pooling, gelu: Gaussian error linear unit

The output of the third ResMHCNN block is passed to a 2D convolutional layer with a kernel size of 3 × 3 and 128 filters. This is followed by a global average pooling layer and a SoftMax layer for five-class classification. The total number of parameters in the proposed LCC-Net is approximately 0.528 million, and its size is 2.02 MB.

The BT-Net architecture also employs three ResMHCNN blocks, as illustrated in Fig. 6. In each of these blocks, 64 filters are used in both the initial 2D convolutional layer and the 2D convolutional layers of the multi-head. The kernel size for the first convolutional layer in all three blocks is 3 × 3. Additionally, the multi-head kernel sizes across all ResMHCNN blocks are 3 × 3, 5 × 5, and 7 × 7.

Figure 6: BT-Net architecture for classifying brain tumors into meningioma, glioma, and pituitary tumors. ResMHCNN: residual multi-head convolutional block with channel attention. GAP: global average pooling, gelu: Gaussian error linear unit

The output of the final ResMHCNN block is passed to a 2D convolutional layer with a kernel size of 3 × 3 and 100 filters. This is followed by a global average pooling layer and a SoftMax layer for three-class classification. The total number of parameters in BT-Net is approximately 1.154 million, and its size is 4.40 MB.

The BC-Net architecture employs five ResMHCNN blocks, as illustrated in Fig. 7. In each of these blocks, 32 filters are used in both the initial 2D convolutional layer and the 2D convolutional layers of the multi-head. The kernel size for the first convolutional layer across all five blocks is 3 × 3. Furthermore, the multi-head kernel sizes in all ResMHCNN blocks are 1 × 1, 3 × 3, and 5 × 5.

Figure 7: BC-Net architecture for classification of breast cancer as malignant and benign. ResMHCNN: residual multi-head convolutional block with channel attention. GAP: global average pooling, gelu: Gaussian error linear unit

The output from the fifth ResMHCNN block is passed to a 2D convolutional layer with a kernel size of 3 × 3 and 256 filters. This output is further processed through a global average pooling layer, followed by a SoftMax layer for two-class classification. The total number of parameters in BC-Net is approximately 0.226 million, and its size is 0.86 MB.

2.6 Computational Infrastructure

We employed the Google Colab Pro cloud computing environment with an NVIDIA T4 GPU accelerator, providing approximately 50 GB of RAM. Model cross-validation and testing were implemented using the high-level Keras application programming interface with the TensorFlow backend.

We employed sparse categorical cross-entropy (SCCE, Eq. (5)) as the loss function and overall accuracy as the primary performance metric during training with N samples and during validation. In Eq. (5), the true value represents the actual class label, while softmax refers to the model output, which is a probability vector. Given the slight imbalance present in the Figshare and BreaKHis datasets, we also used a multi-class confusion matrix (CM) along with additional performance metrics such as recall, precision, F1-score, balanced accuracy (BA), area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) scores, Precision-Recall (PR) curve, and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) for model evaluation during testing.

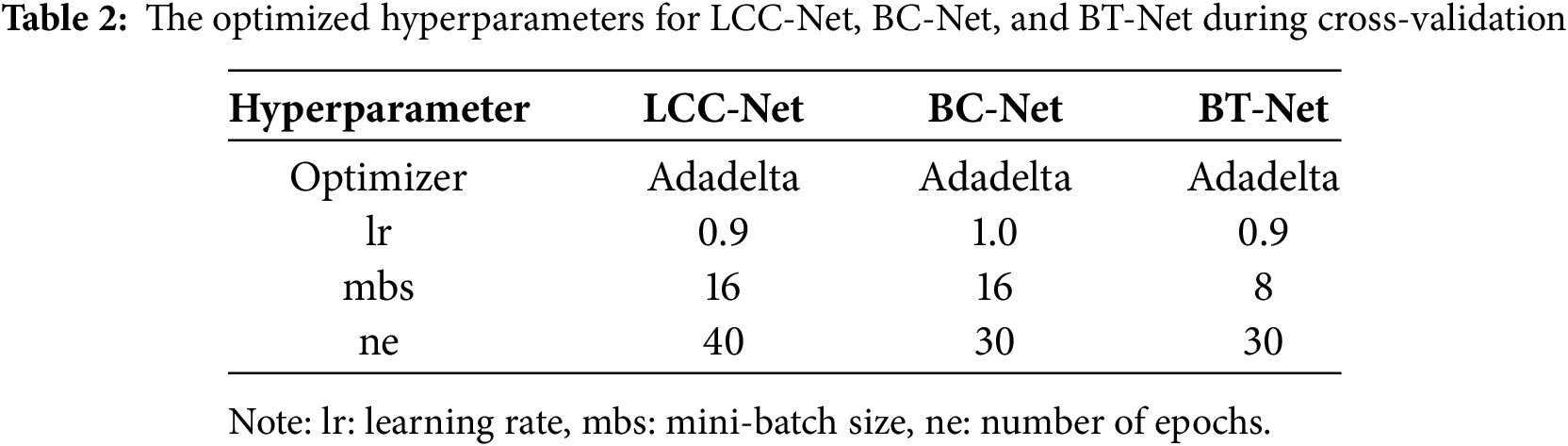

The model hyperparameters, including the optimizer (RMSprop, Adam, or Adadelta), learning rate (Adadelta: 1.0 or 0.9; RMSprop/Adam: 0.001 or 0.0001), number of epochs (30, 40, or 50), and mini-batch size (8, 16, or 32), were selected empirically. The validation set was used to ensure that the models did not overfit during training. After tuning the hyperparameters, the models were retrained by combining the training and validation sets to enhance their robustness.

The loss and performance metrics were calculated using the Python-based Scikit-learn (sklearn) toolbox. For both the three-class and five-class classification tasks, the test performance metrics were derived from the corresponding confusion matrix (CM) using a one-vs.-rest approach. For a specific class, correctly classified instances are labelled as true positives (TP), while the total number above the half-diagonal of the CM represents false positives (FP). The total count on the diagonal for classes other than the specific class is identified as true negatives (TN), and the total count below the half-diagonal of the CM corresponds to false negatives (FN).

We conducted several ablation experiments to justify the choice of the architectural designs for all three proposed networks. These include (I) reducing the number of ResMHCNN blocks to one, (II) replacing the multi-head convolution with a standard convolution block and removing the channel-wise attention layer, and (III) scheme II + removing skip connections in ResMHCNN blocks. During ablation studies, we used the same set of hyperparameters mentioned in Table 2. To evaluate whether the differences in accuracy values with and without ablation studies were statistically significant, we conducted McNemar’s test in all scenarios. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Initially, the image intensities of all three datasets were rescaled to values between 0 and 1. The BreaKHis and LC25000 microscopic images already contained three channels. Since the Figshare images were grayscale with a single channel, they were converted to three-channel images by duplicating the grayscale channel into the other two channels. The empirically selected hyperparameters for LCC-Net, BT-Net, and BC-Net during cross-validation are provided in Table 2. The Adadelta optimizer with a learning rate of 1.0 or 0.9 was found to be more suitable for all three models. Additionally, a smaller mini-batch size was used for BT-Net compared to the other two models. The training and validation loss curves for the three models are shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Training and validation loss curves for the proposed lightweight BC-Net, LCC-Net, and BT-Net models

Fig. 9 shows the CM on the test set for LCC-Net. The model achieved 100% accuracy in detecting benign lung cancer and colon adenocarcinoma. The detection accuracy was marginally higher for colon cancer than for lung cancer. Complete performance metrics in percentages on the test set are presented in Table 3. The LCC-Net demonstrated 100% recall, precision, and F1-score.

Figure 9: Confusion matrix on the test set for the LC25000 dataset using LCC-Net for classifying lung and colon cancer subtypes. aca: adenocarcinoma; scc: squamous cell carcinoma

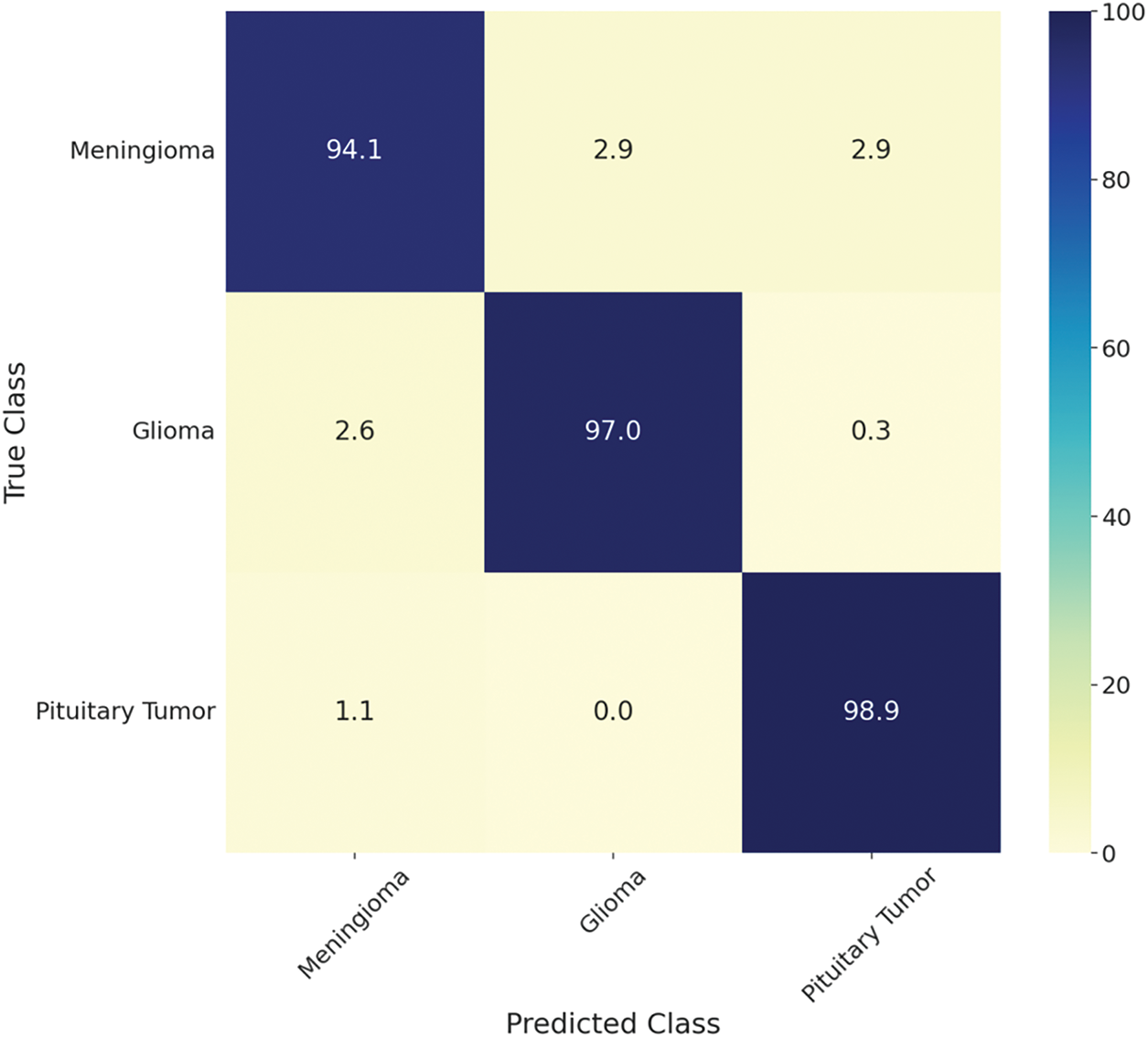

Similarly, Fig. 10 shows the CM for the three-class classification of brain tumors using BT-Net. For BT-Net, a smaller mini-batch size of 8 with 30 epochs was more suitable. The model achieved an AUC of 99.97% and an overall accuracy of 96.9%, with pituitary tumors showing the highest individual accuracy at 98.9%. Given that the Figshare dataset is slightly imbalanced, BT-Net demonstrated strong performance with an F1-score of 96.90%, BA of 96.67%, and MCC of 95.10%, as shown in Table 3.

Figure 10: Confusion matrix on the test set for Figshare using BT-Net for classifying brain tumors into meningioma, glioma, and pituitary tumors

Finally, Fig. 11 shows the CM for the two-class classification of breast cancer using BC-Net. For BC-Net, a mini-batch size of 16 and 30 epochs were used. The model achieved an AUC of 96.10% and an overall accuracy of 96.70%, with malignant tumors showing the highest individual accuracy at 97.80%. Given that the BreaKHis dataset is also slightly imbalanced, BC-Net demonstrated strong performance with an F1-score of 96.66%, BA of 96.10%, and MCC of 92.36%, as presented in Table 3.

Figure 11: Confusion matrix on the test set of the BreaKHis using BC-Net to classify breast cancer into benign and malignant

Since the Figshare and BreaKHis datasets are imbalanced, we have provided class-wise PR curves on the test set for both BC-Net and BT-Net in Fig. 12. From the curves, we can observe that the model’s performance was good irrespective of data imbalance.

Figure 12: Class-wise Precision-Recall curves are shown for BC-Net and BT-Net since they are tested on imbalanced datasets

Ablation studies indicate that reducing the number of ResMHCNN blocks or altering their internal architecture leads to a statistically significant decrease in accuracy (p < 0.05). This performance drop is consistent across all models. Since the MCC is the most conservative evaluation metric, its decline is particularly noteworthy during the ablation experiments, as MCC falls below 90% for both BT-Net and BC-Net. Similar trends are observed for all three models. The performance metrics, with and without ablation, are presented in Table 3, and for greater clarity, the corresponding bar graphs are shown in Figs. 13–15 for BC-Net, LCC-Net, and BT-Net, respectively.

Figure 13: Bar graphs showing the performance metrics during ablation studies for the BreaKHis dataset using BC-Net to classify breast cancer into benign and malignant. Ablation scheme 1: reducing the number of ResMHCNN blocks to one, Ablation scheme 2: replacing the multi-head convolution with a standard 2D convolution block and removing the channel-wise attention layer, Ablation scheme 3: scenario II + removing skip connections in ResMHCNN blocks

Figure 14: Bar graphs showing the performance metrics during ablation studies for the LC25000 dataset using LCC-Net to classify lung and colon cancer subtypes. Ablation scheme 1: reducing the number of ResMHCNN blocks to one, Ablation scheme 2: replacing the multi-head convolution with a standard 2D convolution block and removing the channel-wise attention layer, Ablation scheme 3: scheme II + removing skip connections in ResMHCNN blocks

Figure 15: Bar graphs showing the performance metrics during ablation studies for the Figshare dataset using BT-Net to classify brain tumors into meningioma, glioma, and pituitary tumors. Ablation scheme 1: reducing the number of ResMHCNN blocks to one, Ablation scheme 2: replacing the multi-head convolution with a standard 2D convolution block and removing the channel-wise attention layer, Ablation scheme 3: scheme II + removing skip connections in ResMHCNN blocks

In this study, the capability of novel lightweight models based on ResMHCNN blocks for medical image classification was evaluated across three different datasets: Figshare for brain tumors (BT-Net for three-class classification), BreaKHis for breast cancer (BC-Net for two-class classification), and LC25000 for lung and colon cancer (LCC-Net for five-class classification). The LCC-Net, with only 0.528 million parameters, demonstrated 100% accuracy in colon cancer detection and 99.7% accuracy in identifying lung cancer, performing better than several previous studies on the same dataset involving lightweight neural network models [28–30].

Interestingly, a recent study [30], developed a lightweight deep neural network based on feature fusion from MobileNetV2 and EfficientNetB3. While this approach is notable due to the use of features from state-of-the-art models, it incurs a significant parameter load because of fully connected layers. Consequently, our study restricted the number of dense layers before the final SoftMax layer to one. Furthermore, a combination of residual one-dimensional convolution and squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks was employed in [31] to build a computationally efficient architecture, in which the SE block provided channel attention similar to our channel-wise attention layer following the multi-head CNN. Although that approach achieved accuracy levels comparable to ours, it increased the parameter count by nearly forty percent.

Similarly, the BT-Net achieved an accuracy of 96.9% with only 1.154 million parameters, indicating its potential suitability for use in low-resource settings. In comparison, a lightweight CNN proposed in a recent study with 2.454 million parameters achieved a test accuracy of 96.8% for the three-class classification task [32]. However, that lightweight CNN model was relatively generic, and its parameter count is more than double that of the proposed BT-Net. Given that skip connections enable robust and stable feature learning, BT-Net may also perform well with even fewer ResMHCNN blocks, supporting experimentation with shallower networks. Nevertheless, our test accuracy of 96.9% is comparable to many previous studies employing large pre-trained and fine-tuned CNNs and vision transformer models [33–35], underscoring the effectiveness of the lightweight BT-Net architecture.

Furthermore, the lightweight BC-Net achieved a test accuracy of 96.6% with only 0.226 million parameters, performing on par with or exceeding recent studies that utilized other lightweight CNN models on the same dataset [36–39]. Notably, the study in [39] incorporated extensive preprocessing techniques, such as edge detection and contrast enhancement combined with lightweight separable convolution, resulting in an accuracy of 93.12%. Similarly, a residual dual-shuffle attention network based on the bottleneck unit of ShuffleNet, as presented in [36], attained an accuracy of 95.7% at 40× zoom factor, employing a channel attention mechanism to learn complex patterns from microscopic images. Another recent study using a lightweight generic CNN with five convolutional layers obtained an accuracy of 93% for benign-vs.-malignant classification without any preprocessing [37]. Additionally, the study in [38] developed a custom CNN with 21M parameters, almost 40 times more than BC-Net, and through extensive data augmentation, obtained an accuracy of 98.3%. Table 4 below provides details of some of the existing studies related to the classification of BT, BC, and LCC that exclusively utilized lightweight models.

Based on the ablation experiments, we could observe that by reducing the number of ResMHCNN blocks to one, the performance drop of the networks was high. Further, altering the multi-head and channel attention also decreased performance. Furthermore, skip connections are also proven to be effective in the performance of the ResMHCNN block. These performance results indicate the effectiveness of the proposed lightweight architecture for end-to-end classification.

The proposed ResMHCNN block differs significantly from traditional attention modules such as SE, convolution block attention module, or self-attention mechanisms [43–45]. While traditional attention techniques rely on global pooling and fully connected layers or softmax-based computations to explicitly model attention, ResMHCNN uses a channel-wise attention layer after a multi-head convolution setup to learn importance weights across multiple kernel-specific feature maps implicitly. This design allows it to capture diverse features using different kernel sizes in parallel, offering scale-aware representation without additional computational overhead. Furthermore, ResMHCNN integrates a residual connection to maintain efficient gradient flow, enhancing training stability and making it highly suitable for lightweight applications. Unlike parameter-heavy attention modules, ResMHCNN is convolution-based, computationally efficient, and ideal for resource-constrained environments such as IoMT or mobile platforms.

Overall, this study demonstrates the potential of the proposed ResMHCNN block, which leverages multiple kernel sizes within a single convolutional layer. Consequently, the proposed LCC-Net, BC-Net, and BT-Net may be integrated into intelligent portable hardware systems for detecting lung and colon cancer, breast cancer from microscopic images, and brain tumors from T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI slices. The proposed framework supports stable and robust feature learning by combining multiple kernel sizes within the same convolutional layer alongside skip connections. While this study demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed ResMHCNN-based lightweight architectures for medical image classification, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the evaluation was conducted on publicly available datasets focused on specific cancer types, which may not generalize to other medical imaging modalities or broader diagnostic categories. Second, although the models showed high accuracy, the datasets used may not reflect the diversity, variability, and artifacts present in real-world clinical settings. Furthermore, the models were primarily tested on retrospective data, and prospective validation in live clinical workflows is necessary to confirm their practical utility and robustness.

Hence, in future research, we aim to evaluate these lightweight models on larger, more diverse (especially for lung and colon cancer, since the LC25000 dataset involves pre-split augmentation leading to possible data leakage) and prospective datasets, and explore their effectiveness by integrating additional ResMHCNN blocks. Further, the models can be thoroughly tested on edge devices and IoMT environments. Furthermore, given their strong feature-learning capabilities, these models could serve as foundational architectures for few-shot learning methods in low-data regimes.

In this study, we proposed lightweight deep learning models utilizing a novel ResMHCNN block for medical image classification. This less complex block facilitates robust feature learning by incorporating multiple kernel sizes within a single convolutional layer. The proposed models—LCC-Net, BC-Net, and BT-Net—demonstrated very good performance in detecting lung, colon, breast, and brain tumors, achieving accuracies of 99.6%, 99.7%, 96.6%, and 96.9%, respectively. Consequently, in a future study, these models may be tested for deployment in resource-constrained environments, such as mobile devices and IoMTs. The challenges presented by IoT environments can be further addressed by optimizing these lightweight models and employing techniques such as federated learning, thereby unlocking transformative applications.

Moreover, lightweight models may contribute to reducing the carbon footprint through faster training processes, promoting environmental sustainability. Future work will focus on adapting this methodology for general image datasets and other tasks, including object detection and image segmentation. The developed framework is available at: https://github.com/sutummala/ResMHCNN (accessed on 01 August 2025).

Acknowledgement: We want to acknowledge all the sources that provided the open-access data.

Funding Statement: This work was partly supported by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP)-Innovative Human Resource Development for Local Intellectualization program grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (IITP-2025-RS-2023-00259678) and by INHA UNIVERSITY Research Grant.

Author Contributions: Sudhakar Tummala: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft. Sajjad Hussain Chauhdary: Project administration, Conceptualization, Investigation. Vikash Singh: Data curation, Resources, Investigation. Roshan Kumar and Seifedine Kadry: Software, Resources, Supervision, Project administration. Jungeun Kim: Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Figshare (Brain Tumor): brain tumor dataset. Lung and Colon Cancer: https://github.com/tampapath/lung_colon_image_set (accessed on 01 August 2025). BreaKHis: https://github.com/mrdvince/breast_cancer_detection (accessed on 01 August 2025).

Ethics Approval: This research study was conducted retrospectively using human subject data available in open access. Ethical approval was not required, as confirmed by the license attached to the open-access data.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chen X, Wang X, Zhang K, Fung KM, Thai TC, Moore K, et al. Recent advances and clinical applications of deep learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. 2022;79:102444. doi:10.1016/j.media.2022.102444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. He K, Gan C, Li Z, Rekik I, Yin Z, Ji W, et al. Transformers in medical image analysis. Intell Med. 2023;3(1):59–78. doi:10.1016/j.imed.2022.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Helaly HA, Badawy M, Haikal AY. A review of deep learning approaches in clinical and healthcare systems based on medical image analysis. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(12):36039–80. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16605-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen F, Li S, Han J, Ren F, Yang Z. Review of lightweight deep convolutional neural networks. Arch Comput Meth Eng. 2024;31(4):1915–37. doi:10.1007/s11831-023-10032-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mittal P. A comprehensive survey of deep learning-based lightweight object detection models for edge devices. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(9):242. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10877-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Howard A, Sandler M, Chen B, Wang W, Chen LC, Tan M, et al. Searching for mobileNetV3. In: Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision; 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 1314–24. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kavyashree PSP, El-Sharkawy M. Compressed MobileNet V3: a light weight variant for resource-constrained platforms. In: 2021 IEEE 11th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); 2021 Jan 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. doi:10.1109/ccwc51732.2021.9376113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Anthony LFW, Kanding B, Selvan R. Carbontracker: tracking and predicting the carbon footprint of training deep learning models. arXiv:2007.03051. 2020. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.03051v1. [Google Scholar]

9. Budennyy SA, Lazarev VD, Zakharenko NN, Korovin AN, Plosskaya OA, Dimitrov DV, et al. eco2AI: carbon emissions tracking of machine learning models as the first step towards sustainable AI. Dokl Math. 2022;106(S1):S118–28. doi:10.1134/s1064562422060230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Strubell E, Ganesh A, McCallum A. Energy and policy considerations for deep learning in NLP. arXiv:1906.02243. 2019. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.02243v1. [Google Scholar]

11. AI and compute [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://openai.com/index/ai-and-compute. [Google Scholar]

12. Qiu S, Wang W, Jiao H. LightSeizureNet: a lightweight deep learning model for real-time epileptic seizure detection. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023;27(4):1845–56. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2022.3223970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Attallah O, Aslan MF, Sabanci K. A framework for lung and colon cancer diagnosis via lightweight deep learning models and transformation methods. Diagnostics. 2022;12(12):2926. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12122926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Karakanis S, Leontidis G. Lightweight deep learning models for detecting COVID-19 from chest X-ray images. Comput Biol Med. 2021;130(5):104181. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Li Z, Lei X, Liu S. A lightweight deep learning model for cattle face recognition. Comput Electron Agric. 2022;195(1–3):106848. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2022.106848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Agarwal P, Alam M. A lightweight deep learning model for human activity recognition on edge devices. Procedia Comput Sci. 2020;167(2):2364–73. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2020.03.289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Vaseli H, Liao Z, Abdi AH, Girgis H, Behnami D, Luong C, et al. Designing lightweight deep learning models for echocardiography view classification. In: Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2019: Image-Guided Procedures, Robotic Interventions, and Modeling; 2019 Feb 16–21; San Diego, CA, USA. doi:10.1117/12.2512913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Georgescu MI, Ionescu RT, Miron AI, Savencu O, Ristea NC, Verga N, et al. Multimodal multi-head convolutional attention with various kernel sizes for medical image super-resolution. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2023 Jan 2–7; Waikoloa, HI, USA. doi:10.1109/WACV56688.2023.00223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Razfar N, True J, Bassiouny R, Venkatesh V, Kashef R. Weed detection in soybean crops using custom lightweight deep learning models. J Agric Food Res. 2022;8(3):100308. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sharma P, Ninomiya T, Omodaka K, Takahashi N, Miya T, Himori N, et al. A lightweight deep learning model for automatic segmentation and analysis of ophthalmic images. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8508. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-12486-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Szegedy C, Liu W, Jia Y, Sermanet P, Reed S, Anguelov D, et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen S, Cao Z, Prettner K, Kuhn M, Yang J, Jiao L, et al. Estimates and projections of the global economic cost of 29 cancers in 204 countries and territories from 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(4):465–72. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7826. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Patel AP, Fisher JL, Nichols E, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, Abdelalim A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of brain and other CNS cancer, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(4):376–93. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30468-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Cheng J, Huang W, Cao S, Yang R, Yang W, Yun Z, et al. Enhanced performance of brain tumor classification via tumor region augmentation and partition. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140381. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Cheng J, Yang W, Huang M, Huang W, Jiang J, Zhou Y, et al. Retrieval of brain tumors by adaptive spatial pooling and fisher vector representation. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157112. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Spanhol FA, Oliveira LS, Petitjean C, Heutte L. A dataset for breast cancer histopathological image classification. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2016;63(7):1455–62. doi:10.1109/TBME.2015.2496264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Borkowski AA, Bui MM, Thomas LB, Wilson CP, de Land LA, Mastorides SM. Lung and colon cancer histopathological image dataset. arXiv:1912.12142. 2019. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1912.12142. [Google Scholar]

28. Iqbal S, Qureshi AN, Alhussein M, Aurangzeb K, Kadry S. A novel heteromorphous convolutional neural network for automated assessment of tumors in colon and lung histopathology images. Biomimetics. 2023;8(4):370. doi:10.3390/biomimetics8040370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Singh O, Kashyap KL, Singh KK. Lung and colon cancer classification of histopathology images using convolutional neural network. SN Comput Sci. 2024;5(2):223. doi:10.1007/s42979-023-02546-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ochoa-Ornelas R, Gudiño-Ochoa A, García-Rodríguez JA. A hybrid deep learning and machine learning approach with mobile-EfficientNet and grey wolf optimizer for lung and colon cancer histopathology classification. Cancers. 2024;16(22):3791. doi:10.3390/cancers16223791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Shahadat N, Lama R, Nguyen A. Lung and colon cancer detection using a deep AI model. Cancers. 2024;16(22):3879. doi:10.3390/cancers16223879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hammad M, ElAffendi M, Ateya AA, Abd El-Latif AA. Efficient brain tumor detection with lightweight end-to-end deep learning model. Cancers. 2023;15(10):2837. doi:10.3390/cancers15102837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Tummala S, Kadry S, Ahmad Chan Bukhari S, Rauf HT. Classification of brain tumor from magnetic resonance imaging using vision transformers ensembling. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(10):7498–511. doi:10.3390/curroncol29100590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Rath A, Mishra BSP, Bagal DK. ResNet50-based Deep Learning model for accurate brain tumor detection in MRI scans. Next Res. 2025;2(1):100104. doi:10.1016/j.nexres.2024.100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Rasa SM, Islam MM, Talukder MA, Uddin MA, Khalid M, Kazi M, et al. Brain tumor classification using fine-tuned transfer learning models on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images. Digit Health. 2024;10:20552076241286140. doi:10.1177/20552076241286140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Chattopadhyay S, Dey A, Singh PK, Sarkar R. DRDA-Net: dense residual dual-shuffle attention network for breast cancer classification using histopathological images. Comput Biol Med. 2022;145(10):105437. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Elaraby A, Saad A, Elmannai H, Alabdulhafith M, Hadjouni M, Hamdi M. An approach for classification of breast cancer using lightweight deep convolution neural network. Heliyon. 2024;10(20):e38524. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Abunasser BS, Al-Hiealy MRJ, Zaqout IS, Abu-Naser SS. Convolution neural network for breast cancer detection and classification using deep learning. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2023;24(2):531–44. doi:10.31557/APJCP.2023.24.2.531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Nneji GU, Monday HN, Mgbejime GT, Pathapati VSR, Nahar S, Ukwuoma CC. Lightweight separable convolution network for breast cancer histopathological identification. Diagnostics. 2023;13(2):299. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13020299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Badža MM, Barjaktarović MČ. Classification of brain tumors from MRI images using a convolutional neural network. Appl Sci. 2020;10(6):1999. doi:10.3390/app10061999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Neena KA, Anil Kumar MN. A light weight deep learning framework for brain tumour classification from compressed MRI images. In: 2024 First International Conference on Software, Systems and Information Technology (SSITCON); 2014 Oct 18–19; Tumkur, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/SSITCON62437.2024.10796534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zeng L, Lang J. Classification of breast cancer histopathological image based on lightweight network. In: Proceedings of the CIBDA 2022; 3rd International Conference on Computer Information and Big Data Applications; 2022 Apr 22–24; Wuhan, China. [Google Scholar]

43. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 7132–41. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. Cbam: convolutional block attention module. In: Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; München, Germany. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN. Attention is all you need. arXiv:1706.03762. 2017. doi:10.48550/arxiv.1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools