Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Secure Malicious Node Detection in Decentralized Healthcare Networks Using Cloud and Edge Computing with Blockchain-Enabled Federated Learning

1 Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA

2 Department of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, College of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, 23218, Saudi Arabia

3 The Huntington National Bank, Columbus, OH 43074, USA

4 Department of Computer Sciences, Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, Northern Border University, Arar, 91431, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of AI Convergence Network, Ajou University, Suwon, 16499, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Reham Alhejaili. Email: ; Jehad Ali. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(3), 3169-3189. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.070225

Received 10 July 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Healthcare networks are transitioning from manual records to electronic health records, but this shift introduces vulnerabilities such as secure communication issues, privacy concerns, and the presence of malicious nodes. Existing machine and deep learning-based anomalies detection methods often rely on centralized training, leading to reduced accuracy and potential privacy breaches. Therefore, this study proposes a Blockchain-based-Federated Learning architecture for Malicious Node Detection (BFL-MND) model. It trains models locally within healthcare clusters, sharing only model updates instead of patient data, preserving privacy and improving accuracy. Cloud and edge computing enhance the model’s scalability, while blockchain ensures secure, tamper-proof access to health data. Using the PhysioNet dataset, the proposed model achieves an accuracy of 0.95, F1 score of 0.93, precision of 0.94, and recall of 0.96, outperforming baseline models like random forest (0.88), adaptive boosting (0.90), logistic regression (0.86), perceptron (0.83), and deep neural networks (0.92).Keywords

Electronic Health Records (EHRs) are a process for electronically storing and managing the healthcare records of patients. In recent years, modern healthcare networks have been revolutionized due to the rapid increase in technology. Due to this, the medical service provisioning has been enhanced while simultaneously minimizing the healthcare expenses for both medical healthcare units and patients [1]. Based on a report, the global medical industry is expected to grow at the rate of 8.6% from 2019 to 2026 and reach USD 35.6 billion. This shows a need for effective and reliable security frameworks to protect sensitive patient data while simultaneously preserving their privacies. However, these healthcare networks are vulnerable to various issues, such as leakage of patient privacy, security, and the presence of malicious entities [2]. In the healthcare network, the record of patients is collected from various dispersed sources such as hospitals, diagnostic centers, and IoT-enabled medical devices. The data collected from remote devices is highly vulnerable to data breaches and man-in-the-middle attacks [3]. The malicious nodes compromise the data by disseminating faulty information in the network, which ultimately compromises the accuracy and reliability of healthcare services [4,5]. This raises concerns about the privacy of patients and their sensitive medical information.

Many studies have tried to address the foregoing issues of privacy leakage and the existence of malicious nodes in the healthcare network [6]. Faisal et al. exploit the capabilities of a data generator, IoT-Flock, which aids in generating various use cases, tested for properties of both malicious and legitimate IoT devices [6]. Thereafter, an open-source framework converts traffic generated from IoT-Flock into an IoT dataset, which various machine-learning algorithms utilize to classify legitimate and malicious entities and protect healthcare units from cybersecurity attacks. Similarly, Wei et al. put forth a principal component analysis-based mechanism for detecting anomalies that ultimately fortifies the security for IoT devices [7]. Both above models are efficient for malicious entity detection and cyber-security enhancement for healthcare networks. However, these models depend on centralized and external third parties such as fog servers, clouds, and insurance companies for other operations such as patient payments, user authentication, data security, and others. This centralized structure makes these models prone to several issues such as single point of failure, network scalability, and performance bottlenecks. Hence, a decentralized Bitcoin-based mechanism for distributed authentication of network activities was put forward by Satoshi Nakamoto way back in 2008 [8]. The blockchain uses distributed ledger technology and does not require the services of any third or centralized party. Different consensus algorithms are used in blockchain networks to validate transactions and enhance trust among globally distributed entities [9]. Various cryptographic algorithms are used in the blockchain network to turn input data into fixed-sized hash values, thus improving data integrity and resistance to tempering [10,11]. The blockchain network’s digital smart contracts embed predefined business rules and conditions in them to ensure the transparent and efficient execution of agreements without interference of any centralized party [12,13].

The other blockchain-based solutions use various machine-learning and deep-learning algorithms for automatic classification of malicious and legitimate nodes in healthcare networks [6,14]. These models use random forest, logistic regression, adaptive boosting, perceptron, and deep neural networks in a centralized model training structure with malicious node detection in healthcare networks. These techniques are all done with a centralized server providing testing and training for price model classification of network entities. These techniques share sensitive, critical information of patients from different health care units with a centralized server, raising issues of privacy leakage and low classification accuracy. Therefore, it is the reason the patients are not comfortable sharing their sensitive information with the healthcare unit, as their lives can be at risk in case of a data breach [15]. On the contrary, external users also do not have the confidence in becoming part of such healthcare networks as they, too, have their critical information and sensitive records at stake within the network [16].

This study proposes an architecture of Blockchain-based Federated Learning for Malicious Node Detection (BFL-MND) in healthcare networks to solve these issues mentioned above. In the proposed BFL-MND model, the capabilities of cloud servers and edge computing are exercised to ensure network scalability and data privacy [17]. The edge servers in the proposed model are affiliated with a healthcare unit and are responsible for training the local model on features of its patients from that respective healthcare unit [18]. These edge devices bring computational power closer to data sources, such as local healthcare devices and diagnosis units, which leads to real-time data processing and low latency. The cloud server aids in the effective and reliable fusion of federated learning models. The cloud server guarantees the management of fused federated learning models across healthcare actors such as hospitals, clinics, and wearable health devices units [19]. In this manner, the BFL-MND model protects the confidentiality of patients by allowing healthcare units to locally train their models with their private data, and only sharing a secure model updates with the cloud [20]. In addition, the distributed architecture of blockchain alleviates the risk of a single point of failure, and ensures that all activities of both legitimate and malicious nodes are recorded transparently and securely without any involvement of a centralized party [21]. The key contributions of this study are presented as follows:

• A BFL-MND model is proposed for the detection of malicious nodes in decentralized healthcare networks while utilizing the capabilities of random forest, logistic regression, adaptive boosting, perceptron, and deep neural networks, which ultimately ensure patients’ privacy preservation and solves issues of the single point of failure.

• The cloud and edge computing enhance computational efficiency, real-time processing, and scalability while addressing latency and privacy challenges in healthcare systems.

• The use of blockchain is utilized to provide an immutable and auditable record of the network transactions, which ultimately enhances trust and security within the healthcare network.

Wang et al. [22], suggested many drawbacks in the existing solutions for data exchange in the healthcare environment. These include no data interoperability and unauthorized access to sensitive and important patient information. In addition, there is no mechanism to store users’ data without failing the chances of a mix-up. As a remedial solution to the above problems, Chidambaranathan et al. put forth a mechanism of utilizing blockchain and IPFS capabilities together. An effective and reliable data storage assurance, along with an assurance of information interoperability, is provided by the IPFS distributed platform. A security framework employing intrusion detection by deep learning and blockchain is proposed to guard against vulnerability from several types of cyber attacks, such as integrity attacks and replay attacks, targeted at personal medical devices. The architecture of the developed model is explained through its capabilities of a case study. All transactions among healthcare units and patients will be recorded in a blockchain digital smart contract. The proposed model will further give anonymity from denial of service, as well as from distributed denial of service, with respect to a GAN based intrusion detection mechanism. The performance of the proposed model is judged in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, F1 score, recall, algorithm complexity, time of computation, structural similarity index, mean squared error, mean absolute error, and dice coefficient. The GAN-based model achieves an accuracy of 98% which shows that it is effective in classifying legitimate network entities and intruders. However, the model faces a challenge of having poor scalability due to significant computational overhead from both GANs and blockchain. Also, the issue of practicality in implementation is not discussed in resource-constrained environments. Correspondingly, Tu et al. [23] argued that vehicles in the IoV network increase with each passing day. The data exchanged by vehicles finds its usefulness in trading data and in decision-making. Most of the existing vehicular networks depend on the central authority in processing the data and cleansing the data. In addition, these also use central servers that mostly store huge amounts of vehicular information. These centralized servers serve as intermediates between network entities to establish communication. These intermediate parties face a single point of failure, as the whole data can be lost in any internal or external attack on the centralized authority. Apart from this, the deployment and operational costs of these centralized authorities require added costs, which in the end raise network monetary overhead. In addition, when many vehicles ask a single centralized unit for data or other services, then such centralized units fail to respond adequately to all requests. Hence, this is what led to the performance bottleneck. Therefore, the study proposed a consensus algorithm based on blockchain that ensures decentralized storage of data and secures communication between mobile and dispersed vehicles. The authors also introduced an authentication protocol that handles the request process of the network in an efficient way. Only authorized nodes will be allowed to access and use the data from the authentication process. The proposed model also enables network entities to provide a mechanism of keeping immutable records, using the features of the blockchain. The data storage, data retrieval, and data trading transactions are monitored by blockchain smart contract and recorded in an immutable digital ledger; that way, all the transactions on the network are transparent, which ultimately strengthens the accountability process of the vehicular network. A strong authentication and accountability process lowers the risk of fraud and unauthorized access, resulting in affirmation of the integrity of vehicular data. The proposed blockchain-based consensus algorithm is then subjected to simulations and expected to validate the performance achieved in the entire network. The system model is analyzed in terms of authentication delay, attack detection rate, network throughput, key processing time, and packet loss rate. The proposed blockchain-based consensus algorithm effectively solves the problem of a single point of failure, performance bottlenecks, and monetary cost overhead. However, this model will not be scalable in terms of real-time data sharing in the case of large numbers of vehicles. With increasing numbers of vehicles, the blockchain network cannot handle requests, leading to a decline in performance efficiency in the entire network.

Mohammed et al. [24] similarly argued that healthcare units share and store information with different outside entities, including fog servers, clouds, and wireless sensor devices. They further provides services from different insurance companies for payments to patients, but these outside entities raise security concerns for healthcare data and applications. In addition, the blockchain-distributed protocol is still vulnerable to different cybersecurity threats, such as double-spending attacks and intrusions. Hence, Mohammed et al. proposed a pattern-proof algorithm in Industrial cyber-physical systems, where the benefits of various machine learning algorithms, such as LSTM and reinforcement learning are included to boost the speed of data processing while simultaneously securing the protection of networks against cyber-attacks. Further, the operations of reinforcement learning-based reward and feedback techniques improve the functioning of Industrial cyber-physical systems. The proposed model uses a four-layer architecture wherein all the services are provided by wireless sensors, fog, and clouds, verified by blockchain digital smart contract, which ultimately helps in the classification of known and unknown attacks on the network. The proposed model was evaluated regarding the pattern percentage, time complexity, execution delay, accuracy, and total validation time. The proposed model efficiently enhances the speed of data processing while safeguarding the network from various cybersecurity attacks and service non-repudiation.

In addition, Rathore et al. [25] identified several issues concerning AI with Blockchain in electronic health records, such as low security and integrity of data in the network and poor data management. However, it also describes how existing electronic health record units are also vulnerable to data interoperability and uncontrolled data access. Thus, the authors propose a blockchain-enabled electronic healthcare record system for ensuring data immutability and security and at the same time an effective and reliable mechanism of controlling the data. The authors investigated a range of national and international electronic healthcare record standards and a variety of requirements linked with data interoperability. In addition to this, a blockchain-enabled smart contract has also been employed to make sure that all the transactions among various network entities are monitored and any malicious entity will be identified in case of any forgery attack. The system has been evaluated against the standards of HL7 and HIPAA. The proposed blockchain-enabled EHR model is subject to a few challenges, namely, scalability, integration with legacy systems, and compliance with privacy regulations. The authors state that such problems of scalability highlighted in [24,25] have been solved in this study by providing an energy-efficient and highly scalable parallel-chain mechanism reducing message exchange by 48% approximately [26]. The authors state that the existing healthcare schemes are dependent on a centralized third party in most cases. Hence, existing healthcare units become susceptible to single points of failure, poor system integrity, and performance bottlenecks. Several solutions are proposed in different blockchain-enabled schemes to resolve the problems associated with a central authority. However, these proposed blockchain solutions require very high computation and energy resources and lack adequate scalability. The authors propose a distributed parallel-chain mechanism that is likely to address these challenges. Further, the network throughput is increased as the transactions among distributed entities are executed in a parallel manner. In place of PoW, the consensus algorithm is replaced by a leader selection process which eliminates solving a puzzle for transaction validation. In this leader selection process, an authentic and reliable validator leader is selected based on his stake and previous reputation, which ultimately helps in saving network energy resources. A security analysis is performed by the authors to evaluate the proposed model against various kinds of cybersecurity attacks, such as denial of service attacks, flash attacks, and replay attacks. In addition, the model under consideration is evaluated considering the factors of message exchange time, scalability, throughput, communication complexity, energy consumption, and block size.

The vulnerability of the proposed parallel-chain model is analyzed in a centralized stake-based leader selection, which will adversely impact rapid and intelligent decision-making in healthcare networks. An analysis of the literature review in relation to the weaknesses and strengths of existing works, as well as their main features, is listed in Table 1.

3 Federated Learning Model for Decentralized Healthcare Networks

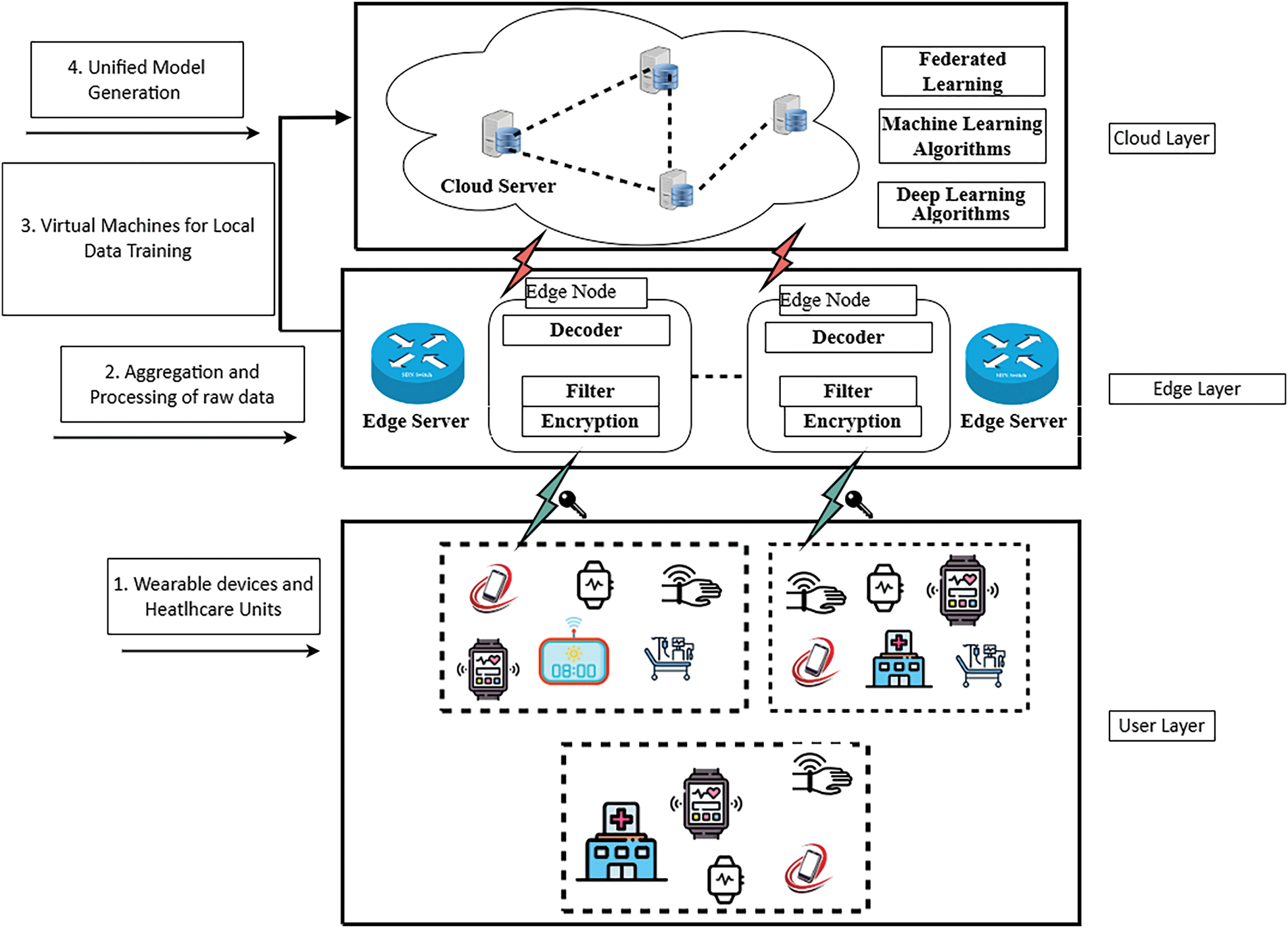

The decentralized healthcare network in the proposed BFL-MND model has various components such as IoT-enabled medical devices, edge nodes, cloud servers, and healthcare units. The wearable IoT-enabled devices are placed on the human body for continuous monitoring of health-related parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, and movement patterns. These wearable devices are resource-constrained having limited computational and storage capabilities. These wearable devices sense the data from the human body and then send it to the nearby edge node for further processing. The edge nodes receive the data and remove redundant and duplicative values, which ultimately ensures efficient and reliable data transmission and reduces network overhead. The healthcare units receive the data from edge servers and all the parameters, along with alert cases are analyzed by the healthcare unit. After the analysis of data, real-time and efficient assistance is provided to the patients, which ultimately ensures the enhancement of the healthcare provisioning process. The edge devices send the processed data to the cloud servers for further analysis and decision-making.

These healthcare networks are efficient in providing quick and reliable healthcare service provisioning. However, these networks are vulnerable to various issues such as the presence of malicious nodes that affect the healthcare service provisioning process. The malicious nodes try to overcome this by disseminating faulty information in the network. In addition, some malicious nodes restrict accurate data from reaching the healthcare unit and generate false alerts about the patient’s condition, which can cause severe danger to the patient’s life. Many studies have been proposed for the identification and removal of malicious nodes from healthcare networks [6,7]. These models are involved with centralized or third parties for various patient payments and user authentication. This causes the issues of a single point of failure, network scalability, and performance bottlenecks. In addition, many models are proposed for automated and efficient identification of malicious nodes in healthcare networks while utilizing the capabilities of machine learning and deep learning algorithms [6,14]. However, these models are vulnerable to privacy leakage issues as sensitive and critical information of patients is shared with a centralized server for testing and training the model. The trained and tested model is then utilized to classify network entities.

3.2 Blockchain-Based Model for Decentralized Healthcare Networks

This study proposes a BFL-MND model for healthcare networks to solve the issues associated with centralized structures. There is no need for any centralized or third party for user authentication, payment, and data security in the proposed model [27]. All the activities and transactions of network entities are validated by distributed blockchain miner nodes, which ultimately enhances the transparency and trust in the network [28]. First, all the network entities are registered with the consortium blockchain network by providing their credentials. When any network entity needs any data or service from the healthcare unit, then it is authenticated by the miner nodes. When any node requests the data, it broadcasts its identity records such as node ID, wallet address, block signature, and transaction hash. The miner nodes verify the identity of the requester node by comparing the record provided at the time of request with registration credentials [28]. If both records match, then the requester node is allowed to perform transactions in the network, otherwise it is broadcast as a malicious node and removed from the network.

When a requester node is authenticated, then it is allowed to share and receive data with other network entities. The communication in the proposed model is secured by asymmetric encryption [29]. In the proposed model, the cloud server utilizes the capabilities of public key infrastructure and is responsible for the generation of public and private keys for each network entity. This study also uses an effective and reliable key exchange mechanism, which ensures the secure and reliable distribution of keys to the receiver node [30]. In addition, the encryption keys in the model are periodically refreshed with a session-based key approach, which ultimately helps in maintaining continuous security. The session keys are dynamically generated for each communication round, which protects the keys against key compromise issues [31]. When any node tries to get data without authentication then the alert messages related to unauthorized access or malicious activities are encrypted using session-specific AES keys before being broadcast across the network when any node attempts to access data without authentication [32]. When an alert message is broadcasted in the healthcare network, then an area-based unique is utilized to encrypt that data. This unique is securely distributed to all entities in the specific area, which will be ultimately used for the decryption of the alert messages.

The blockchain in the proposed BFL-MND model is integrated with edge and cloud nodes for establishing a secure and reliable distributed network structure. At the edge layer, the patient data points are continuously collected by IoT-based wearable devices and sent to edge devices for further processing. All the duplicative and redundant values are removed from the data by performing lightweight operations to ensure effective and reliable communication. The encryption and decryption mechanisms in the model are performed using the following equations. The ciphertext

where

The encryption of alert messages

The session keys are updated periodically based on time to ensure network security, as shown in Eq. (4).

where

Region-specific alert messages

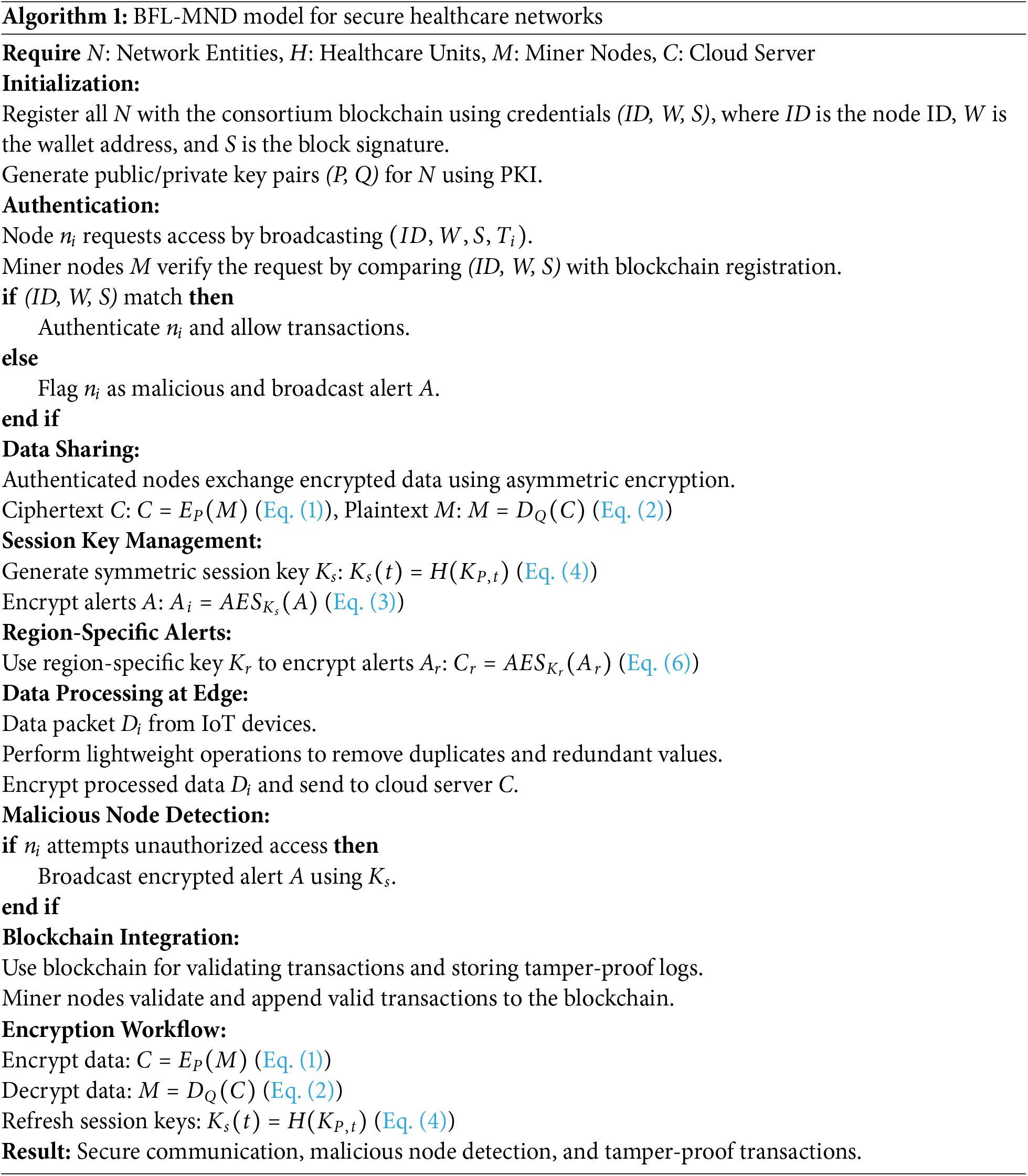

The blockchain network, along with edge and cloud servers, helps in addressing various challenges such as scalability, latency, and security [33]. In addition, the proposed model not only ensures secure and tamper-proof communication, but also provides a mechanism to efficiently detect malicious nodes in the healthcare networks [34]. The whole process of encrypted data transmission with the blockchain network is shown in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1 begins by registering all network entities (N) with the consortium blockchain network, utilizing their credentials, such as node ID (

Authenticated nodes can securely share and receive data through asymmetric encryption, using public and private keys. The ciphertext (

3.3 Federated Learning Model for Malicious Node Detection

The centralized machine learning algorithms for malicious node detection, such as random forest, logistic regression, adaptive boosting, perceptron, and deep neural networks are vulnerable to different issues, such as lower accuracy and privacy leakage [6,14]. Therefore, this study proposes a blockchain and federated learning-enabled BFL-MND model for malicious node detection in wearable devices-based healthcare networks, as shown in Fig. 1. The whole healthcare network in the proposed model is divided into various healthcare clusters, each cluster is dependent on a healthcare unit, an edge server, and multiple wearable devices. Each healthcare cluster is responsible for collecting data from wearable devices of its region and training a local model while utilizing the features of respective wearable devices. In this technique, the random forest, logistic regression, adaptive boosting, perceptron, and deep neural network classifiers are locally trained at the edge layer. When each healthcare cluster locally trains its model, then this model is sent to the respective healthcare unit of the network. The locally trained model is then collected by the respective healthcare unit. After that, each healthcare units keep a copy of the model on its server and send it to the cloud server at the cloud layer.

Figure 1: Proposed federated learning model wearable sensor network

The cloud server has large storage and computational capabilities and is responsible for the model fusion. All the local training models are collected by the cloud server, and a unified model is generated by utilizing the capabilities of the federated averaging algorithm. This algorithm helps in combining the parameters of local models based on their contribution. In this way, each parameter of the local model is weighted based on the size of the dataset that is being used for training in that specific healthcare unit. The aggregated global model is iteratively updated, as shown in Eq. (7).

where

The purpose of this aggregation process is to ensure that all the disparate, area-specific characteristics are consumed within the integrated model to improve its robustness and accuracy. Contrary to the system’s core structure, where it has centralized cloud storage, sensitive private patient information is not made available to the central cloud server since only refined parameters of models are exchanged from the health units to the cloud server. In this way, the proposed model can classify malicious and legitimate healthcare nodes effectively while keeping the patient’s privacy intact within the network. The federated averaging scheme is not only scalable but also comes without a significant computational burden. This is the ideal scheme for decentralized healthcare networks that depend heavily on distributed patient data across borders. In this way, the model improves the privacy and accuracy of healthcare networks while simultaneously ensuring the efficient use of computational resources.

In the proposed model, once the unified model is made at the cloud server then this model is shared with each healthcare unit in the network. Then these healthcare units utilize the capabilities of a unified model for the classification of legitimate and malicious nodes. In the proposed model, the actual data of patients is securely stored in the healthcare unit and only dedicatedly used for monitoring patients and providing effective and reliable healthcare service provisioning to them. As no sensitive and raw information is shared outside the healthcare cluster; therefore, the proposed BFL-MND model ensures the privacy of patients while simultaneously detecting faulty and malicious nodes in the network. In this way, the patients are confident in joining such networks for healthcare service provisioning and sharing their data with the healthcare units as there is no issue of privacy leakage. This ultimately helps in quick and intelligent decision-making in the monitoring process. In addition, external entities are also encouraged to join and rely on such networks. The computational overhead in the proposed model is reduced by dividing the whole network into three different layers.

1. User Layer: This layer comprises various IoT-enabled wearable devices and is responsible for initial data collection. Wearable sensors sense various patient parameters and healthcare units aggregate and eliminate redundant values from that data.

2. Edge Layer: This layer includes different edge servers, which are responsible for the local model training and act as intermediaries between the user and cloud layers.

3. Cloud Layer: This layer aggregates local models from the edge server and generates a unified global model. The cloud layer has large computational and storage capabilities and ensures efficient processing and training of the unified model, which is then distributed back to healthcare units for malicious node detection.

The experimental evaluation of the proposed BFL-MND model was conducted by a set of hardware as well as software resources that can be simulated for large-scale applications in the domain of health care. The environment was simulated in MATLAB R2023a and run on a workstation with Intel Core i7-12700 processor, 32 GB of RAM, and Windows 11 Pro (64-bit) OS. Blockchain components and smart contracts developed in Solidity and deployed using Remix IDE linked with Ganache for private Ethereum blockchain simulation at edge computing environments which had similar configurations to emulate distributed health units communicating with a central cloud server. The PhysioNet dataset for training and evaluation acts as the common dataset labeled physiological signals, including heart rate, ECG, body temperature, SpO2, and respiratory rate, obtained from wearable health-monitoring devices. The data were preprocessed by removing redundant or noisy entries, and normalizing the input features. The model performance was evaluated on standard metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, with stratified 10-fold cross-validation to minimize overfitting and ensure robustness. Numerical issues and errors in computation were tackled by double precision for all the floating-point operations, and feature scaling to make sure numerical stability. Encryption and deterioration during transmission in federated learning were simulated and tested on controlled packet loss probabilities and delay parameters. Potential experimental biases and errors are addressed by keeping the simulation parameters consistent for all models (centralized and federated) and randomizing the injection of malicious nodes at a fixed 10% rate across all experiments. Every simulation was repeated many times (n = 10) with different seed values, and the mean of the simulated results was reported for statistical validity. In addition, model convergence behavior, training times, and gas consumption metrics were recorded to evaluate both computational efficiency and network performance through realistic environments.

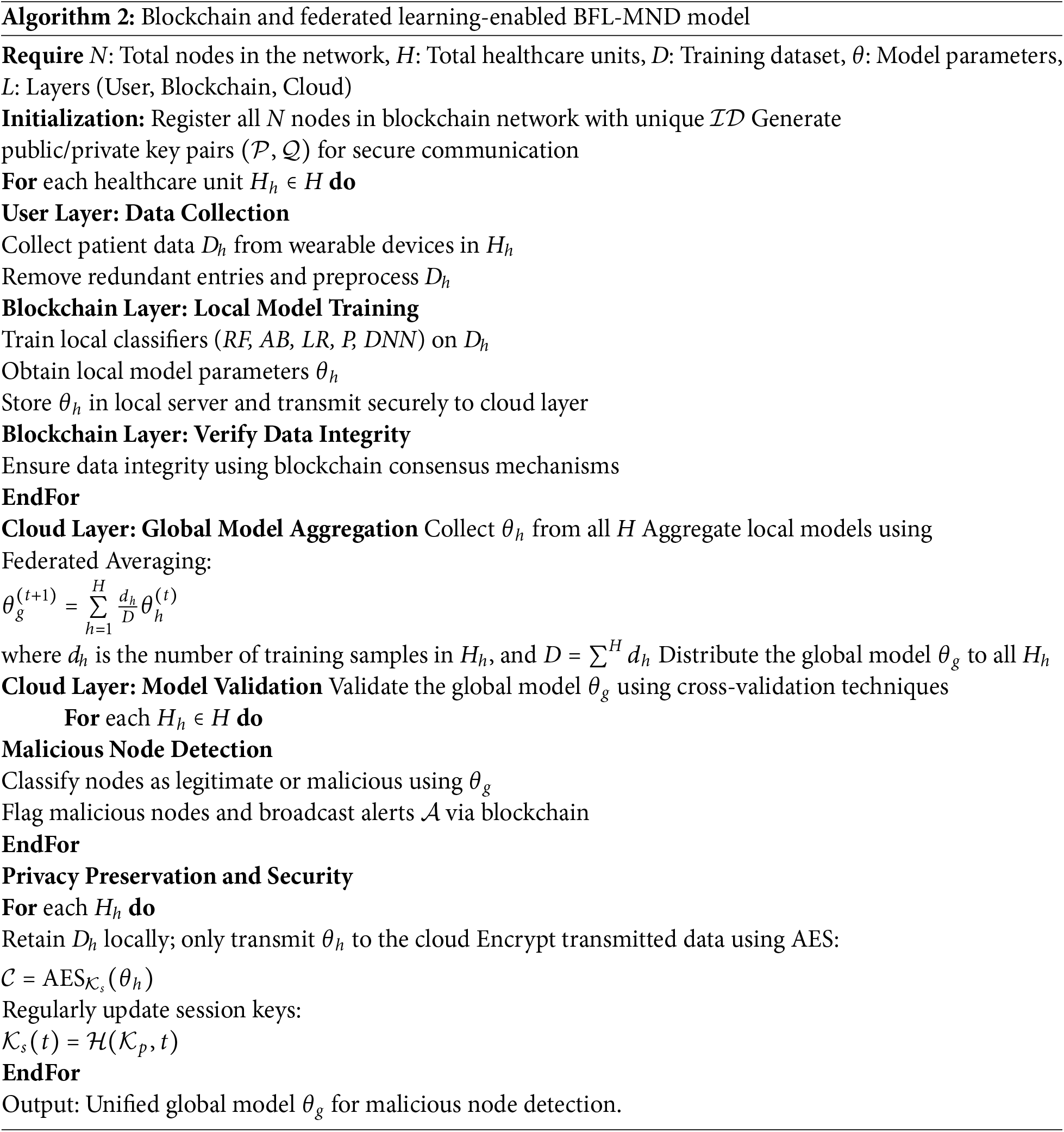

The proposed BFL-MND model uses the capabilities of blockchain-distributed structure and operates without the involvement of any centralized party. This not only solves the issue of a single point of failure, but also secures communication security while utilizing asymmetric encryption techniques. In addition, distributed federated learning is also used in the model in which a unified model is trained with an aggregation of locally trained models. This not only helps preserve the privacy of patients but also enhances the accuracy of the classification process. The whole process of federated learning technique with random forest, adaptive boosting, logistic regression, perceptron, and a deep neural is presented in Algorithm 2.

All participating nodes N in Algorithm 2 are registered in a blockchain network, each assigned a unique identifier

At the cloud layer, the algorithm aggregates the local model parameters

4 Simulation Results and Discussions

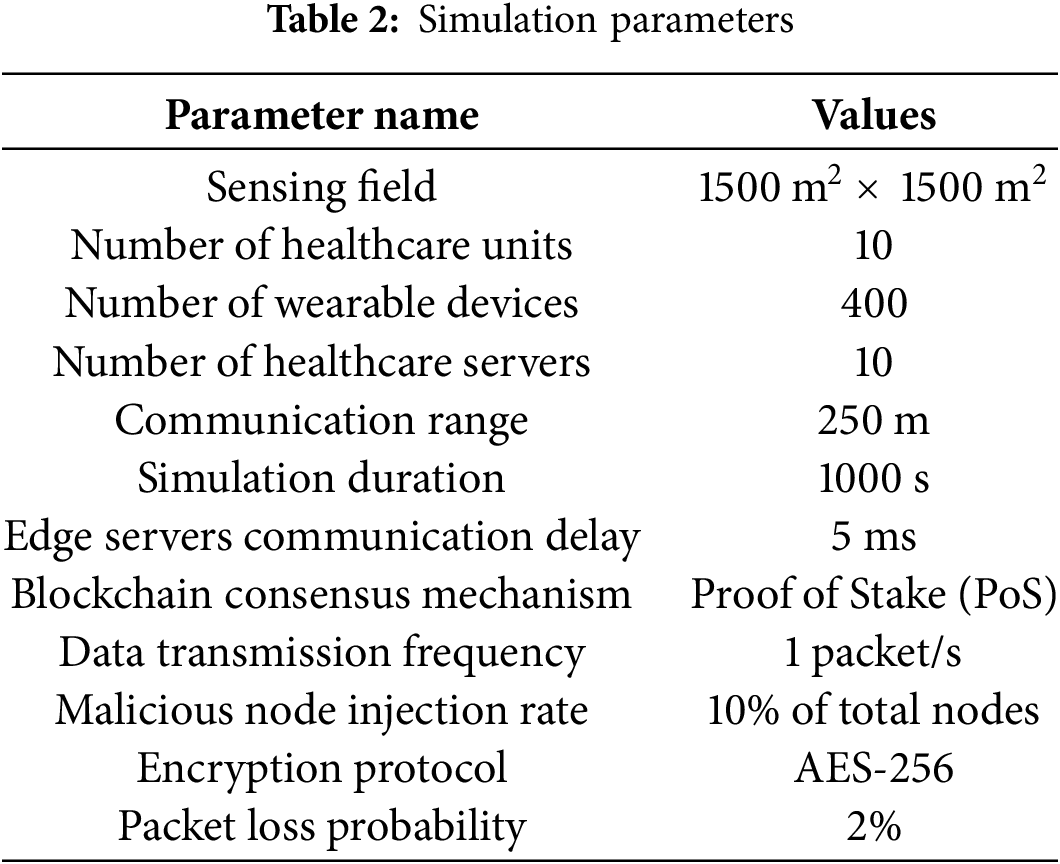

This study evaluates the performance of the proposed BFL-MND model by simulating the whole network in Matlab. The solidity language is utilized to design digital smart contracts and deploy blockchain networks. This study uses the PhysioNet dataset in the proposed model for testing and training both centralized and federated learning models [37]. The PhysioNet dataset contains sensor data from wearable devices such as; heart rate monitors, ECG sensors, activity trackers, and other health-monitoring devices. It includes features such as heart rate (in beats per minute), ECG signals, body temperature, oxygen saturation (SpO2), respiratory rate, and activity levels (walking, running, sitting). In addition, there are labeled instances of normal and abnormal behavior, with anomalies representing malicious nodes, which ultimately helps in the efficient detection of malicious nodes. This is the reason that the RealHealth dataset is suitable for the proposed malicious node detection model. This study compares the federated learning model with the centralized random forest, adaptive boosting, logistic regression, perceptron, and deep neural networks. The results from the PhysioNet dataset validate that the model can improve not only the privacy of network entities, but also the accuracy of the malicious node detection mechanism. The simulation parameters of the proposed model are given in Table 2.

This study is based on simulations, which brings extra questions around validity that can affect the credibility and generalizability of findings. The issues are classified as being under the internal or external concerns regarding validity. Internal validity depicts whether the outcome observed under simulation can really be attributed to the BFL-MND model proposed in this study, instead of other hidden or confounding factors. Although simulations create controlled environments, which assist in isolating the effects of specific components of a model, they set up an alternate environment that uses some simplifying assumptions regarding the real-world conditions. For instance, fixed communication ranges, perfectly synchronized nodes, or perfectly behaving hardware, can allow for greater variability during operations in real health setups. This study also employed a stratified 10-fold cross-validation to minimize overfitting and obtain statistical reliability to alleviate such issues. During the simulation runs, nodes acting maliciously were randomly injected, and the entire experiment was run several times while varying random seeds. Ultimately, the mean of the performance metrics of all runs-across accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score was then reported to dilute out randomness and establish robustness so that the identified performance improvements can be purely attributed to the model design and not confounded by the simulation environment. External validity assesses the extent of generalization of the simulated findings to real-life healthcare networks. Whereas the PhysioNet dataset applied in the analysis is realistic physiological data coming from wearable devices, the simulation can hardly account for the real-life complexities involved in deployments. Hospital networks, when operational, stand to face harrowing hardware breakdowns, communication failures, data discrepancies, and human factors-all too hard to properly model in an accurate feature. Added to that, the security assumptions assumed under blockchain integration and federated model sharing can weaken while verging upon adversarial conditions in the real world. This study designed the simulation based on healthcare-specific parameters, such as data transmission delays, the probabilities of packet loss, and edge-server computations to shorten this gap between simulation and hands-on deployment. Such a move was instrumental in obtaining a simulation set-up close to a real network behavior applied to reflecting real conditions for the deployment of this kind of model. However, full validation requires being implemented in a real hospital environment; such an examination will form part of the future work.

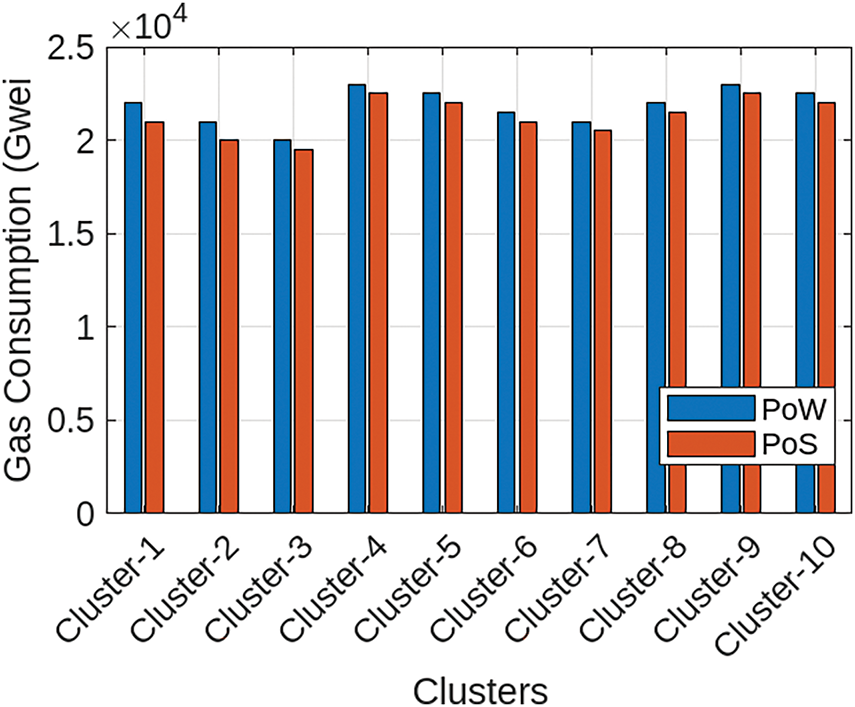

This study divided the healthcare network into various healthcare clusters. Each cluster is dependent on a healthcare unit, an edge server, and multiple wearable devices. Each healthcare cluster is responsible for collecting data from the wearable devices of its region and training a local model while utilizing the features of the respective wearable devices. In the proposed model, the Proof of Authority (PoS) consensus algorithm is used for developing consensus among the network nodes in contrast with the benchmark scheme, which uses PoW for validation of transactions and block generation. The PoS consensus algorithm is also useful for validating the transactions and adding the blocks to the blockchain. Fig. 2 shows the comparison of Proof of Work(PoW) and PoS consensus algorithms for various transactions in different healthcare clusters. It is depicted from the figure that the PoW consensus algorithm has very high blockchain gas consumption as compared to the PoS consensus algorithm, also shown in Table 3, and the reason for the high gas consumption of PoW is that PoW selects the miner nodes based on their computational and processing capabilities. Every interested node needs to solve a puzzle to be selected as a miner, which ultimately increases the computational overhead of the network. On the other hand, in PoS, there are validator nodes instead of miner nodes, which are responsible for the validation of transactions and adding new blocks in the network. The validator nodes are selected based on their stakes and previous reputation; due to which, there is a small network overhead in PoS. In addition, there is a trade-off between the security of the network and network efficiency. The PoS consensus algorithm utilises fewer network resources; however, any node that has high stakes in the network can influence the network by putting its wealth at stake. On the other hand, when a puzzle is solved by the miner node, then it is validated by other candidate miner nodes in the network and all the interested nodes have equal chances to be selected as the miner node. This study utilizes the capabilities of the PoS consensus algorithm because the healthcare network is responsible for the continuous sensing and processing of data for quick decision-making. Therefore, the primary objective is to limit the burden of sensor nodes and healthcare units, having limited resources, while simultaneously achieving network security.

Figure 2: The gas consumption of PoA and PoW

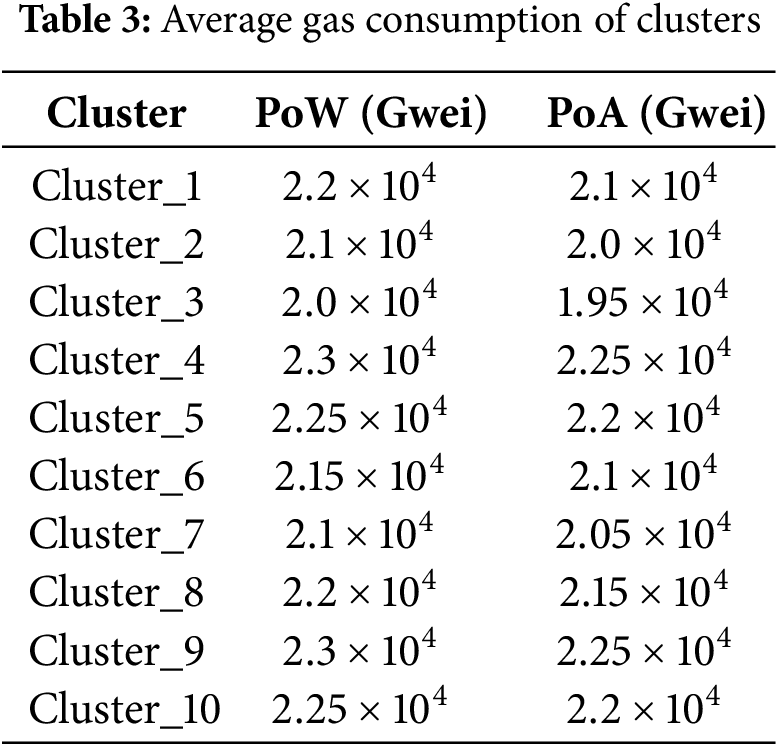

Fig. 3 shows the comparison of training times among the centralized machine learning model and the proposed BFL-MND model. It can be observed from the figure that the training time of the model is 120 s, which is around one-third of the centralized model training time (350 s). The reason for the high training time of the centralized model is that all the network data is shared with the central server for processing, which ultimately produces results in large communication overhead, storage requirements, and potential bottlenecks during the data processing. In addition, it is very time-consuming to train models with large-scale healthcare datasets. On the other hand, the proposed BFL-MND model distributes the training process across different edge servers and each edge server is responsible for training its model with local healthcare data. Due to this, there is no need to constantly transfer data, which minimizes communication delays and ensures fast and reliable local computation. It is the reason that the overall training time of the proposed model is smaller than centralized models. The proposed federated learning model is suitable for healthcare networks where data privacy and efficiency are very important. Therefore, the proposed BFL-MND with a minimal execution time is scalable and effective for quick and intelligent malicious node detection in healthcare networks.

Figure 3: Training time comparison between centralized and proposed models

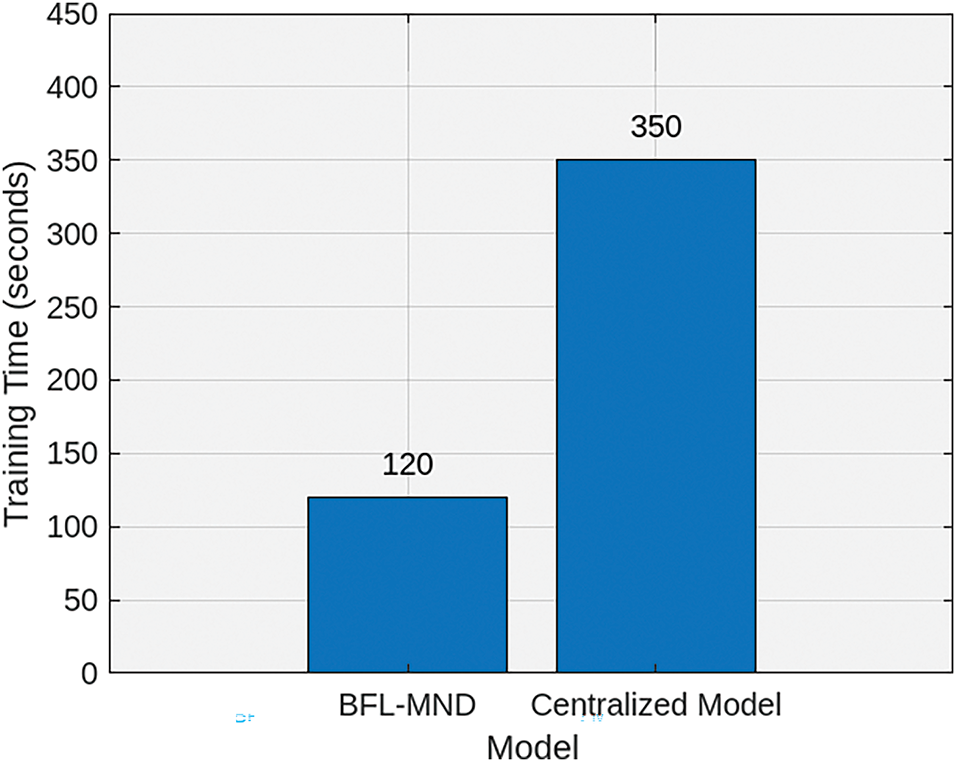

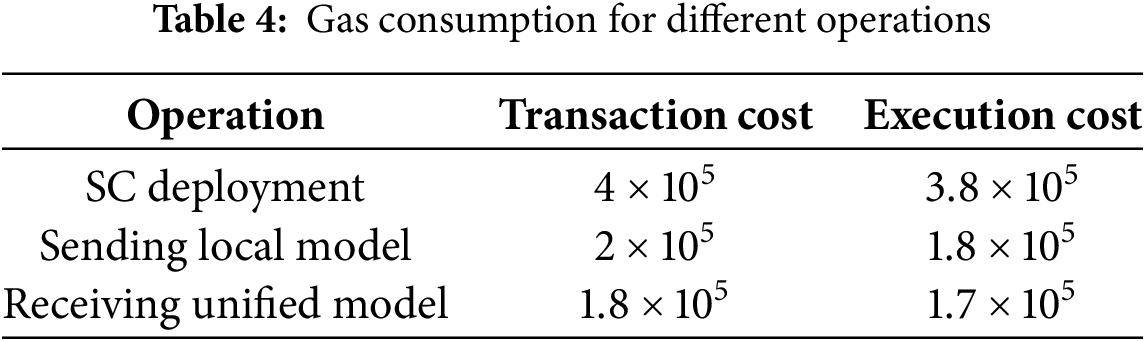

Fig. 4 shows the gas consumption of three different operations of the proposed model: smart contract deployment, sending local model, and receiving unified model. The smart contract deployment phase has the highest gas consumption as compared to the other two operations. The transaction cost of blockchain smart contract deployment is 4e5 Gwei, and its execution cost is 3.8e5 Gwei. The reason for this high gas consumption is that it requires a large amount of network resources for the deployment of a new smart contract. In addition, the sending local model phase has transaction and execution costs of 2e5 and 1.8e5 Gwei, respectively. On the other hand, the transaction and execution costs of receiving a unified model are 1.8e5 and 1.7e5 Gwei, respectively. It is clear from the figure that the sending local model cost has a higher blockchain gas consumption as compared to receiving a unified model. The reason is that there are some additional steps in sending the local model to the cloud server, such as transmitting model updates, performing data aggregation, and ensuring the secure transfer of each node’s data to the central server. This process requires more computational overhead for transaction verification. On the other hand, receiving the unified model only requires the central server to send the aggregated model to the nodes, which requires fewer network computation resources. Lastly, the transaction cost for all three operations is higher than the execution cost, as listed in Table 4. The reason is that the transaction cost includes the overhead of transmitting and verifying data across the blockchain network, which requires more resources than the local computation needed for execution.

Figure 4: Blockchain gas consumption for different model operations

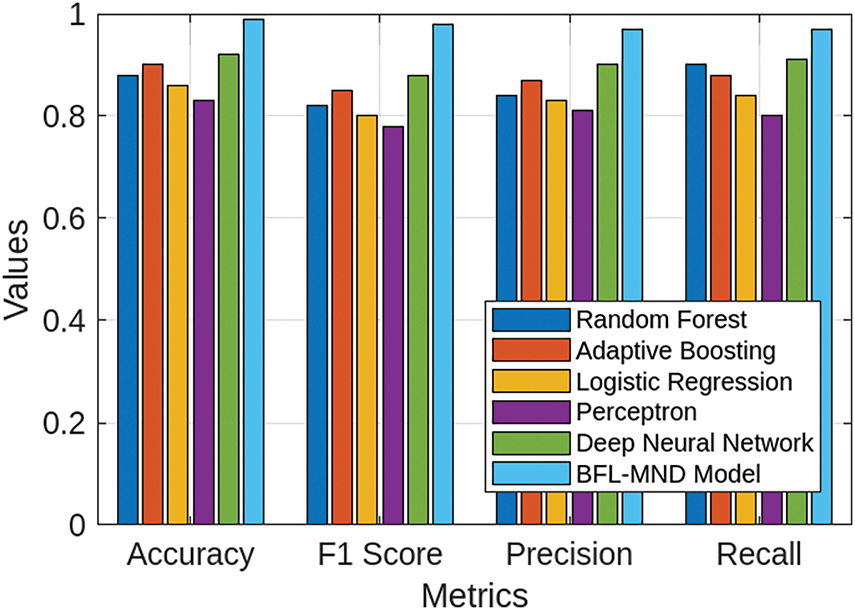

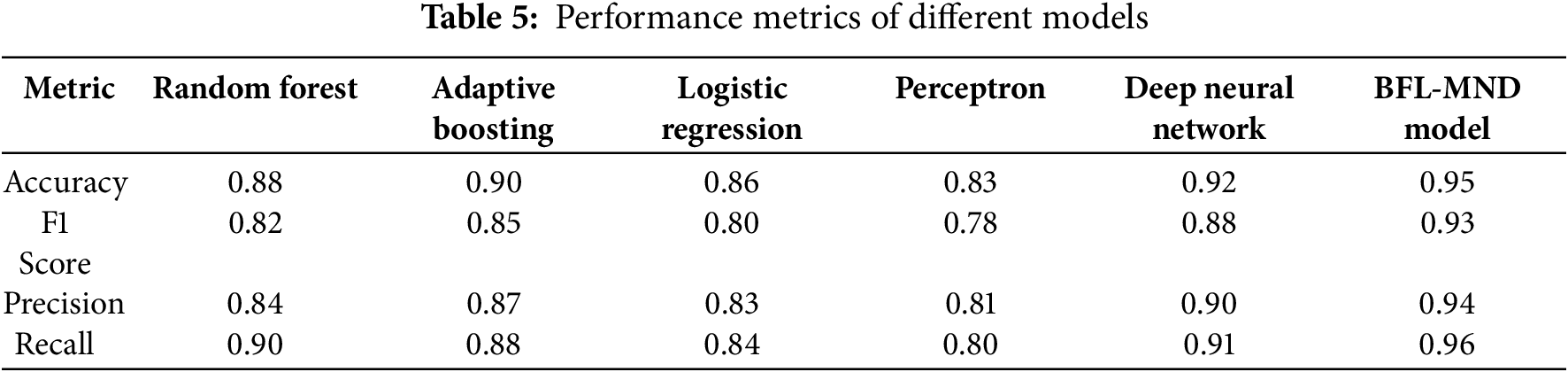

Fig. 5 shows the comparison of the performance of various centralized classification models and the proposed BFL-MND model in terms of recall, precision, F1 score, and accuracy. It can be observed from the figure that the proposed model outperforms all centralized models in each performance metric. The accuracy of the model is 0.95, which shows that the proposed model can correctly identify malicious nodes in the network. The model is trained from all the significant and rich features of different models, which helps in a small number of misclassifications as compared to random forest (0.88) and logistic regression (0.86), which struggle with complex patterns in the data. In addition, the F1-score of the model is 0.93, which shows that the model can also efficiently avoid false positives and false negatives. On the other hand, centralized models, such as random forest (0.82) and perceptron (0.78), have small F1 scores, which shows that these models are less balanced in terms of both precision and recall, as shown in Table 5. In addition to this, the precision of our proposed model is 0.94, which shows that our model can handle false positives effectively. Although random forest and logistic regression have lower precision of 0.84 and 0.83, respectively. This shows that these models frequently misclassify malicious network entities as legitimate in the network. Lastly, the recall of the proposed model is 0.96, which shows that our model can efficiently identify all the legitimate nodes in the network. On the other hand, logistic regression and perceptron have recalls of 0.84 and 0.80, which indicate that these models frequently misclassify legitimate nodes as malicious ones, which is not suitable for quick and intelligent decision-making in life-critical healthcare networks. The proposed model is better than other centralized classification models, which shows that the model is more balanced and accurate for malicious node detection in healthcare networks.

Figure 5: Comparison of centralized classification models and proposed model

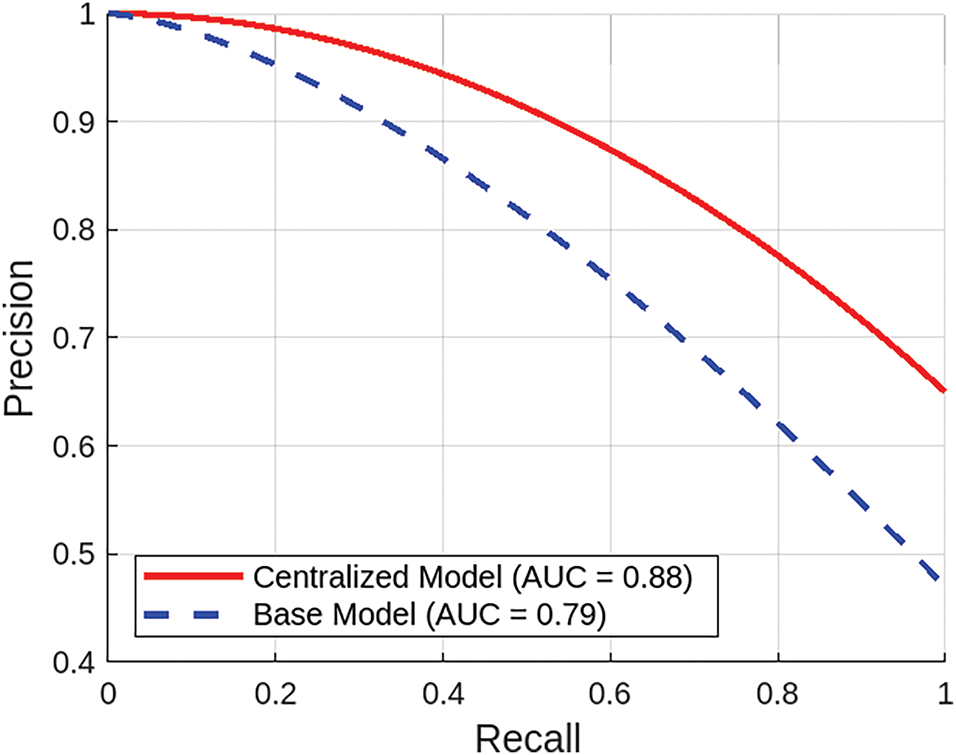

Fig. 6 compares the proposed BFL-MND Model and benchmark scheme regarding the Precision-Recall (PR) curve. It indicates that the proposed model outperforms the benchmark scheme in malicious node detection. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the proposed GNN model is 0.88, which is significantly higher than the AUC of the benchmark scheme (0.79). It shows that the GNN model has a higher precision across all recall levels, which shows that the model can effectively identify malicious nodes while minimizing false positive rates in the network.

Figure 6: Comparison of precision-recall between proposed BFL-MND model and benchmark scheme

This study proposed a blockchain and federated learning-based framework conceptualized for healthcare networks. The local models are trained inside their respective healthcare clusters, and only these trained models (rather than raw patient data) are sent to a central cloud server. Thus, patient privacy is maintained and high classification accuracy is also achieved. This enhances the soundness of the system as a combination of cloud servers. In addition, edge computing provides even better scalability for malicious node detection mechanisms. In addition, a blockchain-based distributed structure serves to secure sensitive health data from unauthorized access and thus manages the data securely in healthcare networks. The framework is evaluated against centralized classification models using the PhysioNet dataset. The results show that the malicious node detection model outperforms existing benchmark schemes in terms of accuracy of 0.95, an F1 score of 0.93, a precision of 0.94, and a recall of 0.96. Future work will implement a personalized federated learning to counter data heterogeneity and improve classification accuracy. In addition, communication protocols will be optimized for fast convergence, and edge computing will be introduced to assist in the real-time detection of malicious nodes. Furthermore, future work will also focus on extending this framework to incorporate real-time threat intelligence, multimodal healthcare data, and validation in real hospital settings to demonstrate reliability and effectiveness in real-world environments.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for funding this research under Project Number “NBU-FFR-2025-3555-07”.

Funding Statement: This work is funded by the Northern Border University, Arar, KSA, under the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-3555-07”.

Author Contributions: Raj Sonani: Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology. Reham Alhejaili: Writing—review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Pushpalika Chatterjee: Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis. Khalid Hamad Alnafisah: Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jehad Ali: Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No datasets were generated in this research.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Nowrozy R, Ahmed K, Kayes A, Wang H, McIntosh TR. Privacy preservation of electronic health records in the modern era: a systematic survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(8):1–37. doi:10.1145/3653297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Al-Nbhany WA, Zahary AT, Al-Shargabi AA. Blockchain-IoT healthcare applications and trends: a review. IEEE Access. 2024;12(3):4178–212. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3349187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Al-Khasawneh MA, Faheem M, Alarood AA, Habibullah S, Alzahrani A. A secure blockchain framework for healthcare records management systems. Healthc Technol Letters. 2024;11(6):461–70. doi:10.1049/htl2.12092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Atadoga A, Elufioye OA, Omaghomi TT, Akomolafe O, Odilibe IP, Owolabi OR, et al. Blockchain in healthcare: a comprehensive review of applications and security concerns. Int J Sci Res Arch. 2024;11(1):1605–13. doi:10.30574/ijsra.2024.11.1.0244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Halimuzzaman M, Sharma J, Bhattacharjee T, Mallik B, Rahman R, Karim MR, et al. Blockchain technology for integrating electronic records of digital healthcare system. Integ Biomed Res. 2024;8(7):1–11. [Google Scholar]

6. Hussain F, Abbas SG, Shah GA, Pires IM, Fayyaz UU, Shahzad F, et al. A framework for malicious traffic detection in IoT healthcare environment. Sensors. 2021;21(9):3025. doi:10.3390/s21093025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Lu W. Detecting malicious attacks using principal component analysis in medical cyber-physical systems. In: Artificial intelligence for cyber-physical systems hardening. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 203–15. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-16237-4_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Nakamoto S. Bitcoin: a peer-to-peer electronic cash system. 2008. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3440802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Datta S, Namasudra S. Blockchain-based smart contract model for securing healthcare transactions by using consumer electronics and mobile-edge computing. IEEE Transact Consumer Elect. 2024;70(1):4026–36. doi:10.1109/tce.2024.3357115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Al-Marridi AZ, Mohamed A, Erbad A. Optimized blockchain-based healthcare framework empowered by mixed multi-agent reinforcement learning. J Netw Comput Appl. 2024;224(8):103834. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2024.103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Pawar V, Sachdeva S. ParallelChain: a scalable healthcare framework with low-energy consumption using blockchain. Int Transact Operat Res. 2024;31(6):3621–49. doi:10.1111/itor.13278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu Y, Liu Z, Zhang Q, Su J, Cai Z, Li X. Blockchain and trusted reputation assessment-based incentive mechanism for healthcare services. Future Generat Comput Syst. 2024;154(3):59–71. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.12.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Dhingra S, Raut R, Naik K, Muduli K. Blockchain technology applications in healthcare supply chains—a review. IEEE Access. 2024;12(2):11230–57. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3348813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Khan MM, Alkhathami M. Anomaly detection in IoT-based healthcare: machine learning for enhanced security. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):5872. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-56126-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Alsamhi SH, Myrzashova R, Hawbani A, Kumar S, Srivastava S, Zhao L, et al. Federated learning meets blockchain in decentralized data sharing: healthcare use case. IEEE Int Things J. 2024;11(11):19602–15. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3367249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. El Madhoun N, Hammi B. Blockchain technology in the healthcare sector: overview and security analysis. In: 2024 IEEE 14th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); 2024 Jan 8–10; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 439–46. [Google Scholar]

17. Sharma M, Tomar A, Hazra A. Edge computing for industry 5.0: fundamental, applications, and research challenges. IEEE Int Things J. 2024;11(11):19070–93. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3359297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Qi P, Chiaro D, Guzzo A, Ianni M, Fortino G, Piccialli F. Model aggregation techniques in federated learning: a comprehensive survey. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;150(6245):272–93. doi:10.1016/j.future.2023.09.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Abid R, Rizwan M, Alabdulatif A, Alnajim A, Alamro M, Azrour M. Adaptation of federated explainable artificial intelligence for efficient and secure E-healthcare systems. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;78(3):3413–29. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.046880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chen J, Yan H, Liu Z, Zhang M, Xiong H, Yu S. When federated learning meets privacy-preserving computation. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(12):1–36. doi:10.1145/3679013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Abubaker Z, Javaid N, Almogren A, Akbar M, Zuair M, Ben-Othman J. Blockchained service provisioning and malicious node detection via federated learning in scalable Internet of Sensor Things networks. Comput Netw. 2022;204(8):108691. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2021.108691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang R, Liu H, Wang H, Yang Q, Wu D. Distributed security architecture based on blockchain for connected health: architecture, challenges, and approaches. IEEE Wirel Commun. 2019;26(6):30–6. doi:10.1109/mwc.001.1900108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Tu S, Yu H, Badshah A, Waqas M, Halim Z, Ahmad I. Secure Internet of Vehicles (IoV) with decentralized consensus blockchain mechanism. IEEE Transact Vehic Technol. 2023;72(9):11227–36. doi:10.1109/tvt.2023.3268135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mohammed MA, Lakhan A, Zebari DA, Abd Ghani MK, Marhoon HA, Abdulkareem KH, et al. Securing healthcare data in industrial cyber-physical systems using combining deep learning and blockchain technology. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;129(6):107612. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Rathore N, Kumari A, Patel M, Chudasama A, Bhalani D, Tanwar S, et al. Synergy of AI and blockchain to secure electronic healthcare records. Secur Priv. 2025;8(1):e463. doi:10.1002/spy2.463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kumar H, Kumar H, Harish, Nandanwar H, Katarya H. Enhancing security and scalability of IoMT systems using blockchain: addressing key challenges and limitations. In: 6th International Conference on Deep Learning, Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (ICDLAIR 2024). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Atlantis Press; 2025. p. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

27. Kumari D, Kumar P, Prajapat S. A blockchain assisted public auditing scheme for cloud-based digital twin healthcare services. Cluster Computing. 2024;27(3):2593–609. doi:10.1007/s10586-023-04101-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Samantray BS, Reddy KHK. Blockchain enabled secured, smart healthcare system for smart cities: a systematic review on architecture, technology, and service management. Cluster Computing. 2024;27(10):14387–415. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04661-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mutambik I, Lee J, Almuqrin A, Alharbi ZH. Identifying the barriers to acceptance of blockchain-based patient-centric data management systems in healthcare. Healthcare. 2024;12(3):345. doi:10.3390/healthcare12030345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kongsen J, Chantaradsuwan D, Koad P, Thu M, Jandaeng C. A secure blockchain-enabled remote healthcare monitoring system for home isolation. J Sens Actuator Netw. 2024;13(1):13. doi:10.3390/jsan13010013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Escorcia-Gutierrez J, Mansour RF, Leal E, Villanueva J, Jimenez-Cabas J, Soto C, et al. Privacy preserving blockchain with energy aware clustering scheme for IoT healthcare systems. Mob Netw Applicat. 2024;29(1):1–12. doi:10.1007/s11036-023-02115-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xu S, Ning J, Li X, Yuan J, Huang X, Deng RH. A privacy-preserving and redactable healthcare blockchain system. IEEE Transact Serv Comput. 2024;17(2):364–77. doi:10.1109/tsc.2024.3356595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Patel NA, Ingle PS, Patsamatla SK, Omotunde H, Ingole BS. Integration of blockchain and AI for enhancing data security in healthcare: a systematic review. Libr Prog-Libr Sci Inf Technol Comput. 2024;44:2020–9. doi:10.48165/bapas.2024.44.2.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mallick SR, Lenka RK, Tripathy PK, Rao DC, Sharma S, Ray NK. A lightweight, secure, and scalable blockchain-fog-iomt healthcare framework with ipfs data storage for healthcare 4.0. SN Comput Sci. 2024;5:198. doi:10.1007/s42979-023-02511-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Adeghe EP, Okolo CA, Ojeyinka OT. Evaluating the impact of blockchain technology in healthcare data management: a review of security, privacy, and patient outcomes. Open Access Res J Sci Technol. 2024;10(2):013–20. doi:10.53022/oarjst.2024.10.2.0044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Javed MU, Javaid N, Alrajeh N, Shafiq M, Choi JG. Mutual authentication enabled trust model for vehicular energy networks using Blockchain in Smart Healthcare Systems. Simul Model Pract Theory. 2024;136(4):103006. doi:10.1016/j.simpat.2024.103006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. PhysioNet—physionet.org [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 27]. Available from: https://physionet.org/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools