Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Three-Dimensional Trajectory Planning for Robotic Manipulators Using Model Predictive Control and Point Cloud Optimization

1 Joldasbekov Institute of Mechanics and Engineering, Almaty, 050010, Kazakhstan

2 Department of Mathematical and Computer Modeling, Faculty of Computer Technology and Cybersecurity, International Information Technology University, Almaty, 050040, Kazakhstan

3 Department of Cybersecurity and Cryptology, Faculty of Information Technology, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, 050040, Kazakhstan

* Corresponding Authors: Azhar Tursynova. Email: ; Batyrkhan Omarov. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(1), 891-918. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.068615

Received 02 June 2025; Accepted 18 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Robotic manipulators increasingly operate in complex three-dimensional workspaces where accuracy and strict limits on position, velocity, and acceleration must be satisfied. Conventional geometric planners emphasize path smoothness but often ignore dynamic feasibility, motivating control-aware trajectory generation. This study presents a novel model predictive control (MPC) framework for three-dimensional trajectory planning of robotic manipulators that integrates second-order dynamic modeling and multi-objective parameter optimization. Unlike conventional interpolation techniques such as cubic splines, B-splines, and linear interpolation, which neglect physical constraints and system dynamics, the proposed method generates dynamically feasible trajectories by directly optimizing over acceleration inputs while minimizing both tracking error and control effort. A key innovation lies in the use of Pareto front analysis for tuning prediction horizon and sampling time, enabling a systematic balance between accuracy and motion smoothness. Comparative evaluation using simulated experiments demonstrates that the proposed MPC approach achieves a minimum mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.170 and reduces maximum acceleration to 0.0217, compared to 0.0385 in classical linear methods. The maximum deviation error was also reduced by approximately 27.4% relative to MPC configurations without tuned parameters. All experiments were conducted in a simulation environment, with computational times per control cycle consistently remaining below 20 milliseconds, indicating practical feasibility for real-time applications. This work advances the state-of-the-art in MPC-based trajectory planning by offering a scalable and interpretable control architecture that meets physical constraints while optimizing motion efficiency, thus making it suitable for deployment in safety-critical robotic applications.Keywords

Robotic manipulators have become central to a wide array of applications, including industrial automation, surgical procedures, space operations, and service robotics. Their increasing deployment in dynamic and semi-structured environments has intensified the need for trajectory planning systems that are not only accurate in geometric terms but also feasible under real-world dynamic constraints [1]. Many conventional trajectory generation methods prioritize spatial accuracy while neglecting limitations related to velocity, acceleration, and actuation. This can result in motion profiles that, although smooth in a mathematical sense, may not be physically implementable on robotic hardware [2].

Trajectory planning in three-dimensional space for robotic arms involves more than computing a curve that passes through a series of waypoints. The planner must consider bounded velocity, acceleration, and position values, along with environmental constraints and the robot’s mechanical configuration. These requirements are particularly significant in tasks involving high precision or safety-critical operations, such as robotic assembly or interaction with fragile objects [3]. Geometric methods like cubic spline interpolation, B-splines, and linear segment fitting are widely used due to their simplicity and smooth output. However, they inherently lack awareness of system dynamics, often producing unrealistic or unsafe trajectories when applied to actuated systems [4].

Model Predictive Control (MPC) has emerged as a powerful framework for robotic motion planning. It solves an optimization problem at each control step, generating control inputs that predictively steer the system toward its target while satisfying system constraints. Unlike reactive control schemes, MPC considers the future evolution of the system and incorporates multi-objective cost functions, enabling a trade-off between tracking accuracy, smoothness, and control effort [5]. Its capacity to integrate nonlinear dynamics and handle multiple constraints makes MPC suitable for applications demanding high-performance trajectory control under uncertainty and limited actuation [6].

Although MPC has been increasingly applied in robotics, much of the prior work has focused on simplified dynamics or two-dimensional motion planning. Many existing implementations rely on first-order system models or assume ideal conditions without actuator limitations. Additionally, most studies concentrate on achieving convergence to a setpoint, often without thoroughly examining trade-offs such as control smoothness or energy efficiency [7]. Furthermore, parameter tuning in these studies is typically carried out manually or through empirical trials, which may not generalize well across different robotic systems.

To address these shortcomings, this paper introduces a Model Predictive Control framework tailored for high-precision, dynamically constrained trajectory generation in three-dimensional environments. The proposed approach incorporates a second-order dynamic model to better capture inertial and velocity effects, which are particularly relevant in applications involving fast or smooth robotic motions [8]. The controller explicitly considers bounded acceleration, velocity, and position constraints, ensuring that each generated trajectory is physically feasible and executable without post-processing.

A key contribution of this study is the integration of Pareto front analysis with a structured grid search strategy to tune the controller’s key hyperparameters, including the prediction horizon, time discretization step, and control weightings. This systematic evaluation provides insights into how different parameter combinations influence trajectory quality, particularly in terms of mean absolute error (MAE), maximum deviation, and smoothness of acceleration profiles [9]. Unlike earlier works that treat these parameters as fixed or optimize a single performance criterion, the dual-objective approach adopted here allows designers to select optimal trade-offs based on application-specific requirements.

The effectiveness of the proposed approach is benchmarked against traditional interpolation-based methods. These include cubic spline interpolation, B-splines, and linear segment interpolation, each representing a class of methods focused on geometric smoothness. The comparison uses both geometric and dynamic metrics, providing a more comprehensive evaluation than existing works. For example, the MPC-based planner achieves lower peak acceleration values while maintaining comparable or superior tracking accuracy under similar conditions [10]. This demonstrates that the approach not only maintains spatial fidelity but also produces motion profiles that are more compatible with physical robotic systems.

Another novel aspect of the work is its emphasis on real-time feasibility. The proposed planner was implemented in simulation with a time budget per control cycle of less than 20 ms. This confirms its applicability in real-time environments and lays the groundwork for future deployment on physical robotic platforms [11]. Furthermore, the framework is structured in a modular manner, making it suitable for extension with additional capabilities such as real-time perception, dynamic obstacle avoidance, or learning-based adaptations.

While the current study focuses on fixed waypoint-based planning, the formulation is generalizable to more complex tasks, including continuous path tracking and interaction with moving targets. The integration of real-time sensor feedback, such as depth cameras or LiDAR, is anticipated in future extensions to support closed-loop environmental interaction and trajectory replanning [12].

To clarify the novel contributions of this work, we highlight the following key innovations. First, unlike most prior MPC implementations for manipulators which often rely on first-order or simplified dynamic models, our framework integrates a full discrete-time, second-order kinematic representation. This enables the controller to explicitly account for inertial effects and acceleration limits when planning three-dimensional trajectories. Second, we introduce a dynamic sub-goal selection mechanism that allows the MPC optimizer to handle arbitrary waypoint sequences in a unified formulation, rather than segmenting the path into isolated planning problems. Third, we apply a systematic, multi-objective parameter-tuning procedure: a comprehensive grid search over prediction horizon and sampling interval, followed by Pareto front analysis, yields interpretable trade-offs between tracking accuracy and control effort. Fourth, we perform a rigorous comparative evaluation against classical interpolation methods (cubic spline, B-spline, and linear), using both geometric (MAE, maximum deviation) and dynamic (velocity and acceleration norms) metrics. Finally, we demonstrate real-time feasibility by maintaining per-cycle computation times below 20 ms in simulation, underscoring the framework’s readiness for deployment on standard robotic hardware. Together, these innovations advance the state of the art in MPC-based 3D trajectory planning, offering a constraint-aware, high-fidelity, and efficiently tunable solution for complex manipulator tasks.

Trajectory planning remains a foundational component of robotic motion control, particularly in the context of high-precision manipulators operating within three-dimensional (3D) workspaces. Numerous techniques have been proposed over the decades to address the trajectory generation problem, ranging from simple interpolative strategies to advanced model-based controllers that integrate system dynamics and real-time adaptation. This section surveys the key methodologies relevant to trajectory generation and optimization in robotics, highlighting the current trends, limitations, and the specific gap that this work seeks to address.

2.1 Trajectory Planning Techniques

One of the most common methods for trajectory generation is spline-based interpolation, with cubic splines and B-splines being particularly prominent. These methods provide smooth transitions between predefined waypoints by minimizing geometric curvature and ensuring continuity in position and derivatives [13]. Cubic spline interpolation, in particular, enforces continuity in position, velocity, and acceleration, which makes it suitable for applications requiring smooth motion profiles. However, it does not explicitly consider the physical dynamics of the robotic system, thereby limiting its applicability in scenarios where motion constraints are critical [14].

B-splines extend the capabilities of cubic splines by enabling local control over the trajectory through the manipulation of control points and knot vectors [15]. This property is particularly advantageous in complex environments where fine-grained trajectory shaping is necessary. Nonetheless, like cubic splines, B-splines primarily focus on geometric aspects of the path and do not inherently account for actuator limitations or inertial constraints [16].

In contrast, linear interpolation offers a computationally efficient means of generating trajectories, particularly for systems with limited processing power or stringent real-time constraints [17]. This method involves connecting successive waypoints with straight-line segments, resulting in paths that are simple to compute and easy to follow. However, linear interpolation suffers from a lack of smoothness and fails to provide continuity in velocity and acceleration, which can lead to abrupt motion and mechanical stress on the manipulator joints [18].

Recent research has also explored hybrid trajectory planners that combine spline interpolation with local dynamic adjustments to improve physical feasibility while retaining computational efficiency [19]. Although these hybrid approaches offer some benefits, they often involve complex tuning and ad hoc heuristics that limit their generalizability across different robotic platforms.

2.2 Model Predictive Control in Robotics

Model Predictive Control (MPC) has garnered increasing attention as a trajectory planning and control methodology capable of addressing the shortcomings of purely geometric interpolators. Unlike traditional feedforward planners, MPC operates by solving a finite-horizon optimization problem at each control step, using a predictive model of the system’s dynamics to anticipate future states and compute optimal control actions [20]. This capability allows MPC to explicitly handle physical constraints, such as limits on joint velocity, acceleration, and torque, within a unified optimization framework [21].

The application of MPC in robotics has been particularly successful in domains requiring high adaptability and constraint satisfaction, including autonomous vehicles, quadrotors, and robotic arms [22]. In autonomous vehicle navigation, MPC has demonstrated effectiveness in ensuring collision avoidance and lane keeping under varying traffic conditions by incorporating real-time sensor feedback into its predictive horizon [23]. For robotic manipulators, MPC has been used to perform precise end-effector positioning while respecting joint-level constraints and dynamic limitations [24].

Another key strength of MPC lies in its ability to integrate complex cost functions that balance competing objectives such as tracking accuracy, energy consumption, and motion smoothness [25]. This flexibility enables the design of sophisticated motion strategies that would be difficult to implement using conventional proportional-integral-derivative (PID) or open-loop controllers. Moreover, MPC’s receding horizon strategy allows for real-time adaptation to unforeseen disturbances or modifications in the task objectives, a feature that is particularly advantageous in dynamic and unstructured environments [26].

Despite its strengths, the computational burden associated with solving optimization problems at each time step remains a significant challenge in deploying MPC for high-dimensional systems such as multi-joint robotic manipulators [27]. Advances in numerical optimization, however, have led to the development of efficient solvers and real-time MPC implementations capable of running on embedded hardware [28]. These developments have expanded the practical applicability of MPC and spurred its adoption in industrial settings.

2.3 Optimization of Control Parameters

To maximize the performance of MPC-based controllers, it is crucial to select appropriate design parameters, including the prediction horizon, control horizon, and sampling time. These parameters significantly influence the quality of the generated trajectories and the responsiveness of the control system. Grid search remains one of the most straightforward techniques for exploring the parameter space, offering exhaustive but computationally intensive tuning [29].

More sophisticated approaches, such as Bayesian optimization and evolutionary algorithms, have been proposed to automate the search for optimal MPC parameters while minimizing the number of required simulations [30]. These methods model the objective function as a stochastic process and use probabilistic techniques to balance exploration and exploitation in the parameter space. While effective, such methods may introduce additional complexity in implementation and convergence analysis.

Multi-objective optimization techniques have also gained popularity, particularly in applications where trade-offs between different performance criteria must be explicitly considered. For instance, a trajectory that minimizes tracking error might do so at the cost of increased control effort, leading to higher energy consumption or wear on actuators [31]. Pareto front analysis provides a principled means of identifying non-dominated solutions that represent optimal trade-offs between conflicting objectives [32]. This approach has been employed in robotic control to design policies that balance accuracy, robustness, and energy efficiency across diverse operational scenarios.

In the context of trajectory planning, Pareto optimality can be used to compare different sets of MPC parameters based on multiple evaluation metrics, such as position error and acceleration norm. By visualizing the Pareto front, practitioners can select the most suitable parameter configuration based on the specific priorities of the application [33]. This method supports informed decision-making and allows for customization of the trajectory planner to match the operational goals and constraints of the robotic system.

2.4 Recent Advances in MPC for 3D Trajectory Planning

In recent years, Model Predictive Control (MPC) has been widely adopted for 3D trajectory planning across various domains, including robotic manipulators, aerial vehicles, and autonomous systems. This growing interest is driven by MPC’s capability to handle complex constraints, predict future states, and ensure dynamically feasible motions. Several studies have demonstrated the use of MPC for motion generation in cluttered or constrained environments where real-time adaptation is necessary [34,35]. For instance, MPC has been applied in robotic arms to follow spatial paths while accounting for torque limitations and joint velocity constraints, showing improvements in execution feasibility over traditional methods [36].

Moreover, the integration of second-order dynamics into the MPC formulation has gained popularity, as it allows for more realistic modeling of robot motion. Some studies have proposed full-state MPC approaches that control both position and velocity profiles, which has proven beneficial in applications requiring smooth transitions and minimal overshoot [37]. Others have utilized hierarchical MPC architectures, separating slow and fast dynamics, to reduce computational burden while maintaining trajectory accuracy in 3D space [38]. These approaches have been tested in simulation and, in some cases, validated on physical platforms with six or more degrees of freedom [39].

Another important development is the fusion of MPC with perception modules such as point clouds or vision sensors, enabling dynamic re-planning in real time. Such frameworks allow for obstacle avoidance and path adaptation without interrupting execution, which is critical in semi-structured environments [40]. In aerial robotics, MPC has also been used to optimize flight paths through 3D waypoints while minimizing energy consumption and collision risks, further underscoring its versatility [41]. In most of these implementations, performance metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE), maximum tracking error, and control effort are used to quantitatively compare MPC results against baselines.

Despite these advances, existing MPC-based planners often lack structured methods for controller parameter tuning. Most rely on empirical selection or trial-and-error processes. Additionally, many studies emphasize geometric path tracking but do not explicitly balance trajectory smoothness with control effort in a multi-objective context. This paper aims to address these gaps by incorporating Pareto front-based optimization for parameter selection and providing a systematic evaluation of MPC trajectories in comparison with classical methods, particularly for 3D manipulator tasks involving second-order dynamic models.

While numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of MPC in trajectory planning and control, there remains a notable gap in its application to real-time 3D trajectory generation with integrated second-order dynamics and constraint handling. Most existing MPC implementations focus on planar motion or simplified dynamic models, thereby limiting their relevance to fully actuated robotic manipulators operating in spatial workspaces [34].

Moreover, existing methods seldom integrate waypoint sequences in a dynamic and scalable manner. That is, while MPC is theoretically capable of handling multiple goal points, practical implementations often resort to static or segment-based planning, which can be inefficient and prone to suboptimal transitions between waypoints [35]. This fragmentation leads to discontinuities in control and compromises the physical realism of the trajectory.

Another shortcoming in current literature is the underutilization of systematic multi-objective evaluation techniques in controller tuning. While cost functions in MPC are typically designed to minimize a combination of error and effort, few studies comprehensively explore the trade-offs involved or utilize Pareto analysis to formalize these trade-offs [36]. Consequently, the selection of controller parameters remains largely heuristic or empirical, lacking a structured framework for optimization.

Furthermore, there is limited research that explicitly compares the outcomes of MPC-based trajectory planners with those derived from classical geometric methods across both geometric and physical performance metrics. Such comparative analyses are essential for understanding the practical benefits and limitations of each approach and guiding the selection of appropriate planning strategies for specific robotic applications [37].

This paper aims to address these gaps by developing a second-order MPC framework for 3D trajectory planning in robotic manipulators, incorporating multi-objective optimization for parameter tuning and conducting a rigorous comparative analysis with traditional spline-based methods.

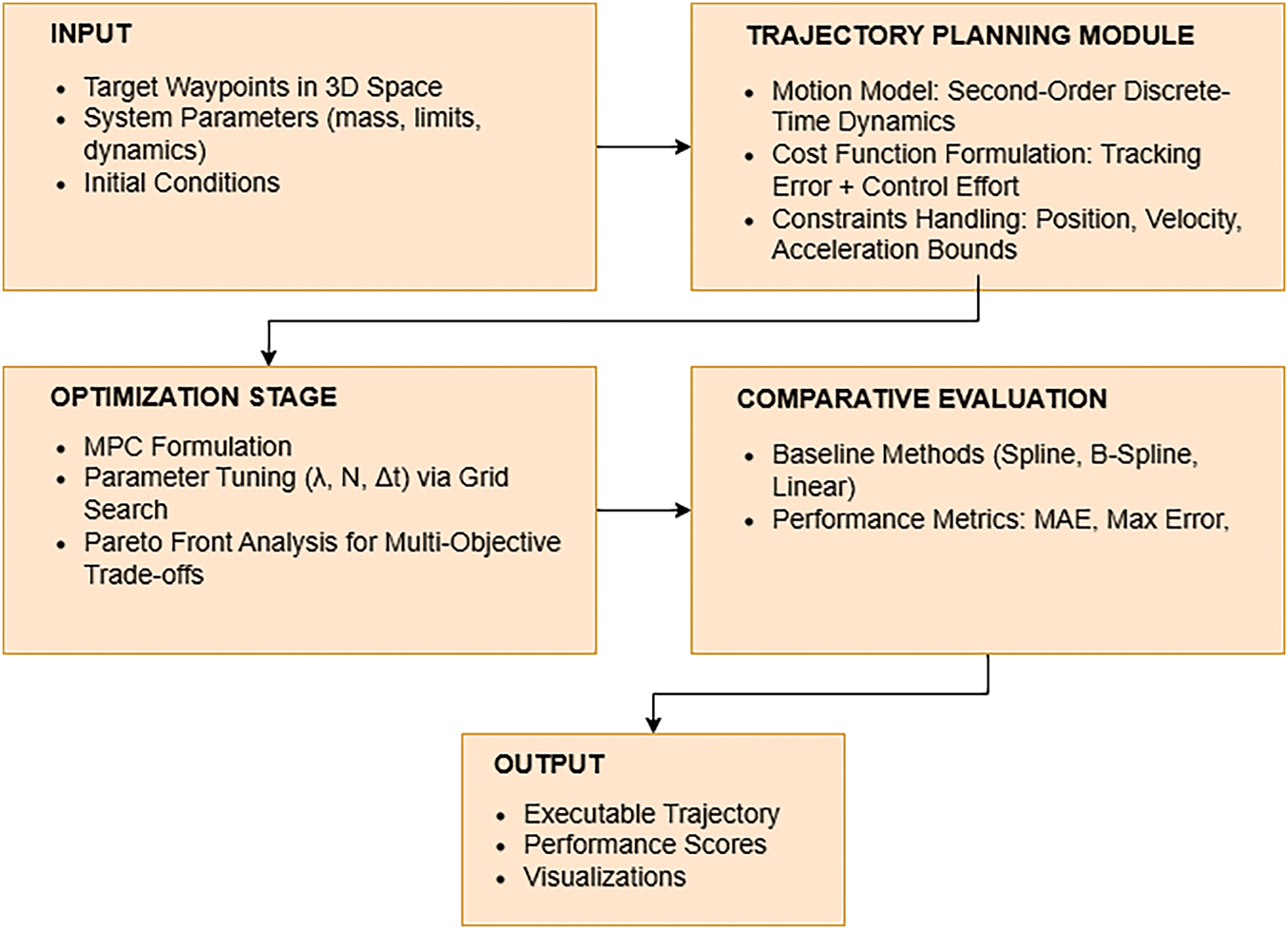

This section outlines the methodological framework employed for the development, formulation, and evaluation of the proposed Model Predictive Control (MPC) approach for three-dimensional trajectory planning in robotic manipulators. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the overall pipeline comprises five key stages as input acquisition, trajectory planning, optimization, comparative evaluation, and final output providing a clear roadmap for implementation and analysis. The modeling begins with a second-order kinematic representation of the system dynamics, capturing position, velocity, and acceleration relationships in discrete time. The control objective is then formalized through a cost function that balances trajectory tracking accuracy against control effort, subject to hard constraints on state and input variables. Classical interpolation methods including cubic splines, B-splines, and piecewise linear paths are implemented as benchmarks for comparative analysis. To determine optimal MPC settings, a systematic grid search is performed over the prediction horizon and sampling interval, and non-dominated configurations are identified via Pareto front analysis. The section concludes with a detailed description of the MPC algorithm’s receding-horizon logic and its seamless integration into the full trajectory planning workflow.

Figure 1: Methodological flowchart of the proposed MPC framework

The authors used a large language model to assist with proofreading and stylistic editing. The model was not used to generate scientific content or analyze data. All authors reviewed and approved the final text.

3.1 Kinematic and Dynamic Modeling

In the context of robotic manipulators, accurate trajectory planning necessitates a motion model that captures both the geometric configuration and the dynamic characteristics of the system. For realistic and physically feasible path generation, we adopt a second-order kinematic model, which accounts for position, velocity, and acceleration states in a discrete-time framework. This modeling approach is particularly well-suited for Model Predictive Control (MPC), which operates by iteratively solving an optimization problem over a finite prediction horizon.

State Definition and System Representation. The robotic manipulator’s motion in three-dimensional space is governed by Newtonian mechanics [38]. The state of the system at any discrete time step

where

Initial Conditions and State Constraints. The initial state of the system is given as:

This formulation assumes that the manipulator begins its trajectory from a known position with zero initial velocity, a common assumption in controlled pick-and-place or manipulation tasks.

Physical and safety constraints are imposed on the state variables to ensure the trajectory remains within the robot’s operational limits:

These constraints are integrated into the optimization problem solved by the MPC controller at each time step. They account for hardware limitations such as joint boundaries, maximum speeds, and actuator capabilities.

Multi-Point Waypoint Integration. The trajectory is designed to pass through or near a sequence of pre-defined 3D waypoints:

Rather than enforcing exact path interpolation, the control objective is to minimize the deviation from the current sub-goal

Compact State-Space Form. For implementation efficiency, Eqs. (1) and (2) can be rewritten in a compact discrete-time state-space form. Let the full state vector be:

Then the system evolution can be written as:

where

And

Dynamic Feasibility Considerations. Unlike purely geometric models, this dynamic formulation ensures that transitions between waypoints are smooth and physically feasible. Specifically, it avoids discontinuities in acceleration and velocity that could otherwise result in control chattering, overshoot, or mechanical wear. The inclusion of second-order dynamics is crucial in ensuring that the generated control inputs correspond to actuation forces that can be delivered by the manipulator’s hardware.

Moreover, the state evolution equations support predictive planning by allowing the MPC controller to simulate and evaluate the impact of future control actions over a moving prediction horizon. This capability is central to MPC’s ability to perform receding horizon optimization under dynamic and time-varying constraints.

3.2 Formulation of the MPC Problem

Model Predictive Control (MPC) operates by solving an optimization problem at each control interval to compute the control sequence that minimizes a predefined cost function, while respecting the system’s dynamics and constraints. The formulation presented here targets trajectory generation for a robotic manipulator in three-dimensional space using a second-order kinematic model. The prediction is computed over a finite horizon, enabling the robot to plan motions that are both dynamically feasible and optimal in terms of motion smoothness and tracking accuracy.

Prediction Horizon and Control Inputs. Let the prediction horizon be

Using the dynamic model defined in Section 3.1, future positions and velocities are recursively predicted as:

For

Cost Function Design. The design of the cost function is central to MPC. It defines the controller’s objectives and penalizes undesired behavior. In this work, the cost function

• Trajectory tracking: minimizing the deviation from the desired waypoint trajectory.

• Control smoothness: minimizing excessive accelerations to ensure smoother and energy-efficient motion.

Let

here, the first term penalizes tracking error, and the second term penalizes the control effort. The scalar parameter

where the superscript

3.3 Comparative Trajectory Models

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed Model Predictive Control (MPC) framework in generating dynamically feasible trajectories, it is essential to compare its performance with widely used classical interpolation techniques. Traditional geometric planners such as cubic splines [39], piecewise linear interpolation [40], and B-splines [41] have long been employed in robotic motion planning due to their computational simplicity and ability to generate smooth paths. However, these approaches do not inherently account for dynamic constraints such as velocity, acceleration, or system inertia, which are critical for real-world robotic manipulators.

This section provides a formal description of these classical methods and presents the mathematical representation of the proposed MPC-based approach to enable a rigorous and meaningful comparison.

Cubic Spline Interpolation. Cubic spline interpolation constructs a piecewise continuous function composed of third-degree polynomials that pass through a set of given points

The coefficients

First and second derivatives are continuous at internal points. The resulting trajectory is geometrically smooth and visually appealing, but it may produce motion profiles with unrealistic accelerations or violate actuator constraints, particularly when waypoints are densely spaced or highly curved. Moreover, the spline does not adapt to changing system dynamics or disturbances during execution.

Piecewise Linear Interpolation. Piecewise linear interpolation connects consecutive waypoints with straight-line segments. For each segment

This method guarantees that the path passes exactly through the given waypoints and is straightforward to compute. However, it exhibits discontinuities in both velocity and acceleration at the segment boundaries. These discontinuities can cause jerky, non-smooth motion that may result in mechanical wear, instability in high-speed operations, or poor control quality in manipulators with sensitive actuators.

B-Spline Approximation. B-splines (Basis splines) represent a generalization of spline interpolation, offering higher flexibility and local control. In contrast to cubic splines, B-splines do not necessarily pass through the control points but rather use them to define the shape of the curve. A B-spline trajectory of degree

where,

The degree

3.4 MPC Parameter Optimization

The prediction horizon N denotes the number of discrete future time steps the MPC controller considers while optimizing the trajectory. A larger horizon enables long-term planning and produces smoother paths but increases computational complexity. Conversely, a smaller horizon leads to faster computation but can result in short-sighted control behavior and suboptimal trajectory planning.

Given a fixed total prediction time T, the number of steps N is related to the discretization step Δt via:

Thus, for a constant time horizon T, increasing N implies decreasing Δt, and vice versa. Selecting an appropriate N requires a trade-off between optimality and real-time feasibility, especially for high-frequency systems.

Discretization Step Δt. The discretization step Δt defines the temporal resolution of the predictive model. Smaller values of Δt provide finer time granularity, which can improve control fidelity and enable better capture of high-speed dynamics. However, this comes at the cost of increasing the number of optimization variables and the dimensionality of the problem.

Regularization Parameter λ. The scalar parameter λ governs the balance between tracking accuracy and control effort in the MPC cost function as presented in Eq. (11).

A large value of λ penalizes rapid changes in control inputs, resulting in smoother and more energy-efficient motion, but potentially sacrificing positional precision. In contrast, a small value of λ leads to tighter trajectory tracking at the expense of higher control effort and possible actuator saturation.

Choosing λ thus involves a compromise between minimizing tracking error and maintaining physical feasibility in terms of control effort and actuator constraints.

Grid Search for Parameter Selection. To determine the optimal configuration of MPC parameters, a grid search technique is employed. This method involves discretizing the parameter space and evaluating all combinations of (N, Δt), while keeping λ fixed or varying within a bounded interval. For each configuration, the trajectory planning algorithm is executed and performance metrics are collected for comparison.

Let:

Evaluation Metrics. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [43] captures the average Euclidean deviation between the predicted trajectory and the reference path:

Average Acceleration Norm (Control Effort): This metric quantifies the smoothness and energy consumption of the trajectory based on the magnitude of the acceleration inputs [44]:

These two criteria provide an interpretable trade-off: lower MAE indicates higher tracking accuracy, whereas lower

Multi-Objective Optimization and Pareto Front. Given the competing nature of the objectives (accuracy vs. control effort), a multi-objective optimization framework is adopted [45]. In this context, Pareto optimality is used to select configurations that offer non-dominated performance.

Let each configuration

Then configuration

The Pareto front

This approach allows visualization and selection of parameter sets that best align with the specific application requirements whether that be high-speed control, precision movement, or energy conservation.

In robotic systems, especially those requiring real-time response, the choice of

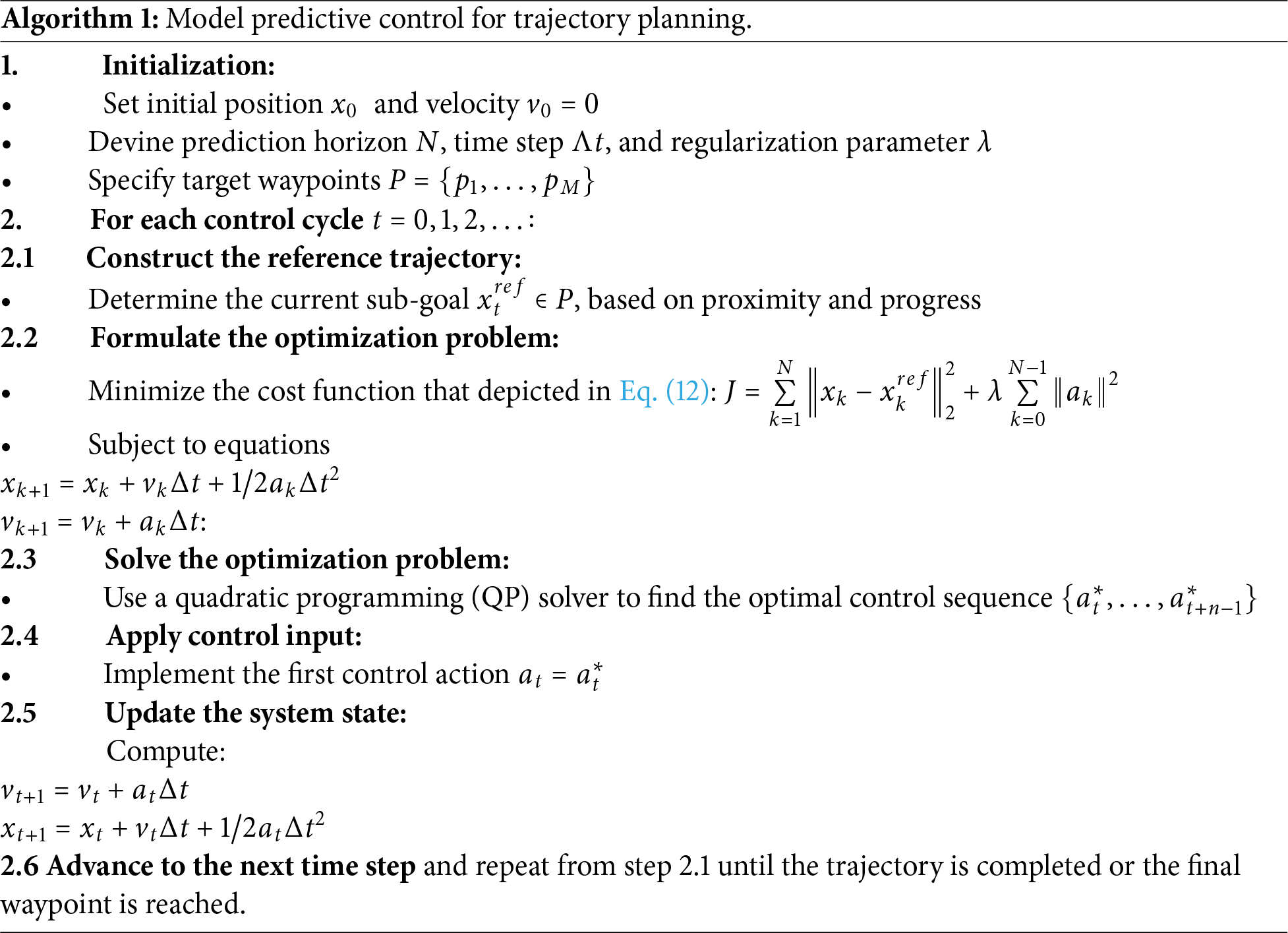

MPC Algorithm. The implementation of Model Predictive Control (MPC) for three-dimensional trajectory generation involves a sequence of operations that are repeated at each control time step. These operations include constructing the predictive model, generating a temporary trajectory toward the desired waypoints, solving a constrained optimization problem, applying the first control input, and updating the system state for the next iteration. This receding horizon approach enables the controller to dynamically adapt to system state changes and disturbances, while continuously optimizing the control actions to follow the reference trajectory.

The MPC algorithm is based on the principle of solving a finite-horizon optimal control problem at every control step

This receding horizon strategy ensures that the control policy remains adaptive, with the ability to respond to deviations from the predicted trajectory, changes in system dynamics, or environmental disturbances.

The high-level structure of the MPC algorithm for 3D trajectory planning is described below. Each iteration consists the following steps (Algorithm 1):

The MPC algorithm provides a principled and adaptive method for generating three-dimensional trajectories for robotic manipulators under physical constraints. Unlike traditional interpolation-based approaches, the MPC framework leverages real-time optimization and system dynamics to ensure that each control action is optimal with respect to both the current state and future objectives. Its feedback nature, constraint handling, and dynamic adaptability make it an ideal choice for high-performance, safety-critical robotic applications.

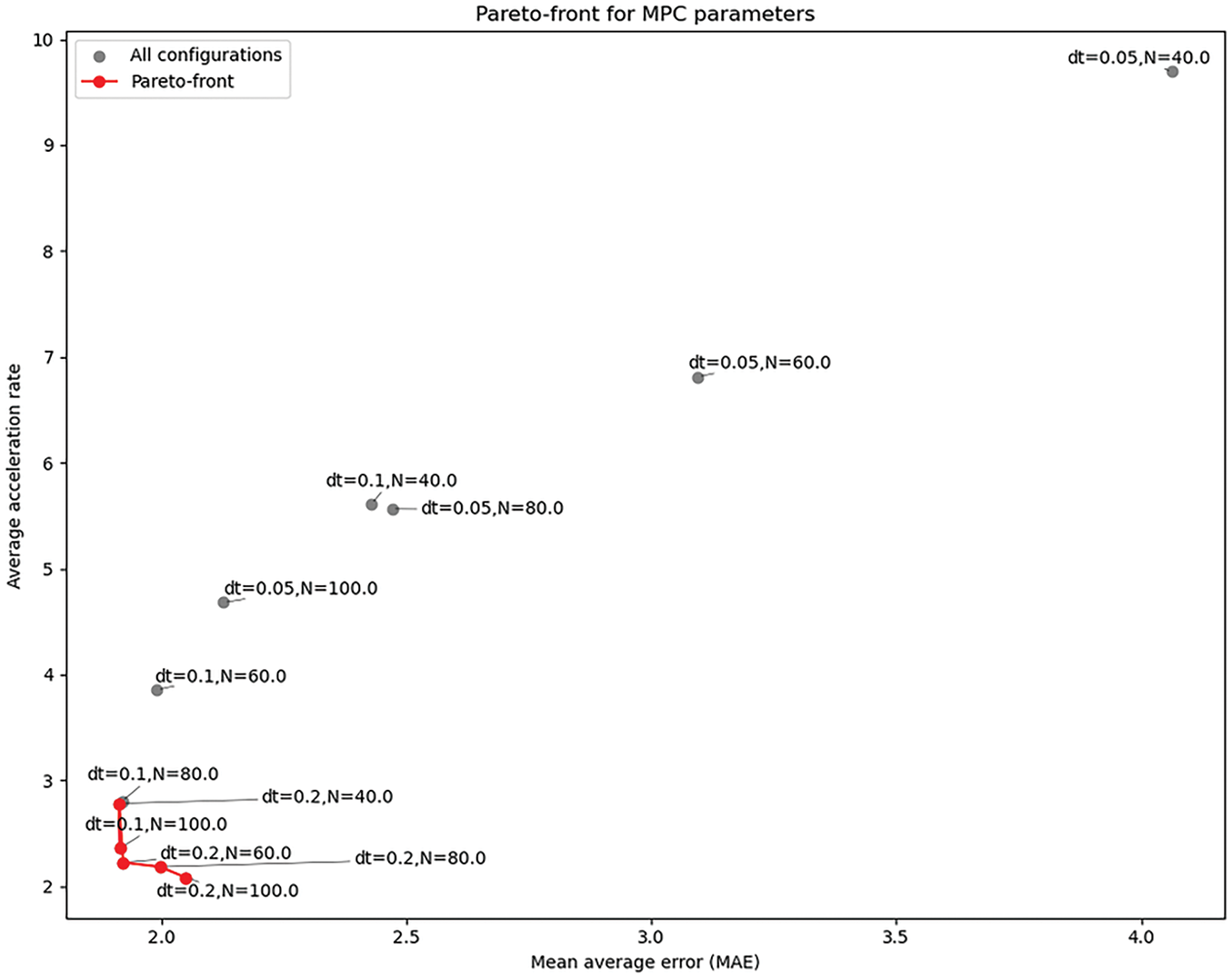

This section presents the experimental evaluation of the proposed Model Predictive Control (MPC) framework for three-dimensional trajectory planning, comparing its performance against classical methods such as cubic splines, B-splines, and linear interpolation. The analysis focuses on both geometric accuracy and dynamic feasibility, using metrics including mean absolute error (MAE), maximum deviation, velocity norms, and acceleration profiles. A grid search over various MPC parameter configurations was conducted, and Pareto front analysis was employed to identify optimal trade-offs between tracking precision and control smoothness. Representative configurations from both extremes as maximum acceleration and minimum tracking error were selected for detailed comparison to illustrate the practical implications of tuning choices in robotic manipulator applications.

Fig. 2 illustrates the Pareto front derived from the grid search across different MPC parameter configurations, with each point representing a unique combination of prediction horizon N and time step Δt. The x-axis denotes the mean absolute error (MAE), reflecting trajectory tracking accuracy, while the y-axis corresponds to the average acceleration norm, serving as a proxy for control effort and smoothness. Gray markers indicate all evaluated configurations, whereas the red curve highlights the non-dominated solutions constituting the Pareto-optimal set. As observed, configurations with smaller Δt and lower N tend to exhibit lower tracking errors but require higher accelerations, whereas configurations with larger N and moderate Δt provide smoother motion at the cost of marginally increased error. The Pareto front provides a clear visualization of the trade-off space, enabling informed selection of MPC parameters based on the desired balance between accuracy and control effort.

Figure 2: Pareto front analysis of MPC parameter configurations based on mean absolute error and average acceleration norm

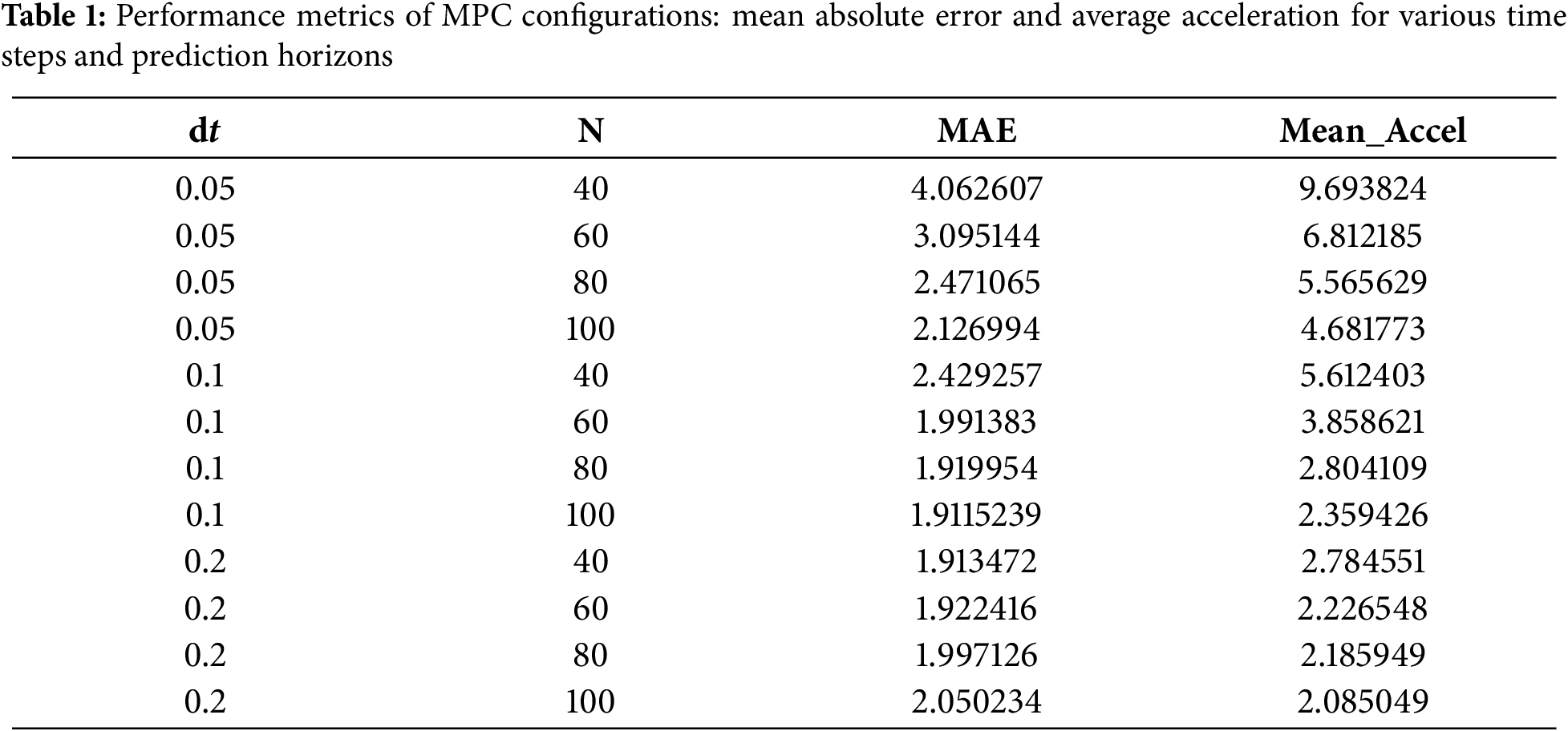

Table 1 presents the quantitative results of the grid search for MPC parameter optimization, listing 12 different configurations of discretization step (Δt) and prediction horizon (N), along with their corresponding mean absolute error (MAE) and average acceleration norm (Mean_Accel). The data reflect the inherent trade-off between trajectory accuracy and control effort. For instance, the configuration with Δt = 0.05 and N = 40 achieves the highest MAE (4.06) but also results in the highest acceleration norm (9.69), indicating aggressive control behavior. Conversely, the configuration with Δt = 0.20 and N = 100 achieves a significantly lower MAE (2.05) and the lowest acceleration norm (2.08), representing a favorable balance between accuracy and smoothness. Several configurations, such as Δt = 0.10, N = 80 and Δt = 0.20, N = 60, also demonstrate competitive performance, lying close to the Pareto front. These results underscore the importance of jointly considering temporal resolution and prediction depth when tuning MPC for trajectory planning tasks.

The following conclusions can be drawn from the results. An increase in the time step leads to a reduction in acceleration, as seen in entry 11, which suggests that a larger prediction horizon N should be selected. The highest acceleration is achieved using the smallest parameter values; however, this results in relatively higher error. The lowest errors are observed in entries 6 to 8. If both acceleration and error are important, configurations with N = 40 or N = 80 (±0.02) may be considered, while smoother trajectories can be obtained with N = 100.

4.1 Experiment with the Highest Acceleration

This experiment corresponds to the MPC configuration that produced the largest average acceleration norm among all tested settings, indicating the most aggressive control strategy. The selected parameters prioritize rapid motion execution, often at the expense of trajectory precision and adherence to intermediate waypoints. While such a configuration may be suitable for time-critical tasks, it challenges the system’s ability to maintain smooth and accurate movement. As a result, the trajectory generated under this setup reveals distinct deviations from the reference path, highlighting the trade-offs between dynamic responsiveness and spatial accuracy in high-acceleration motion planning.

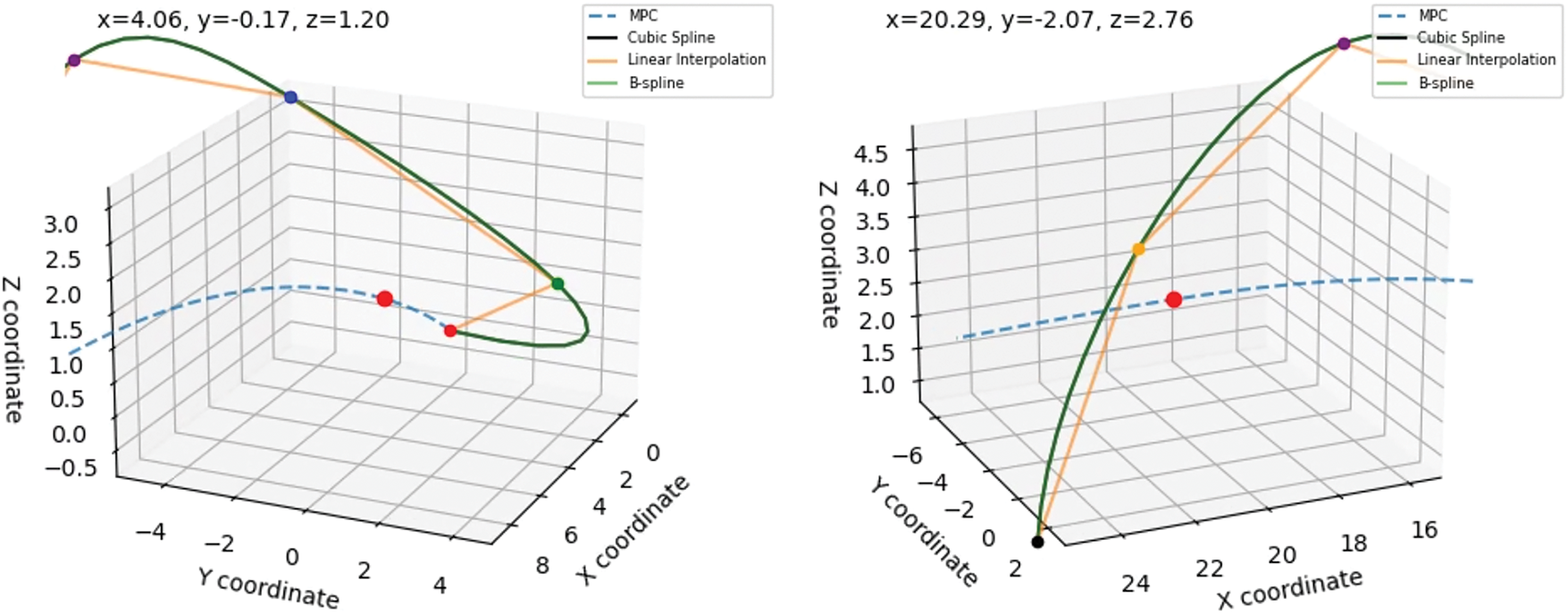

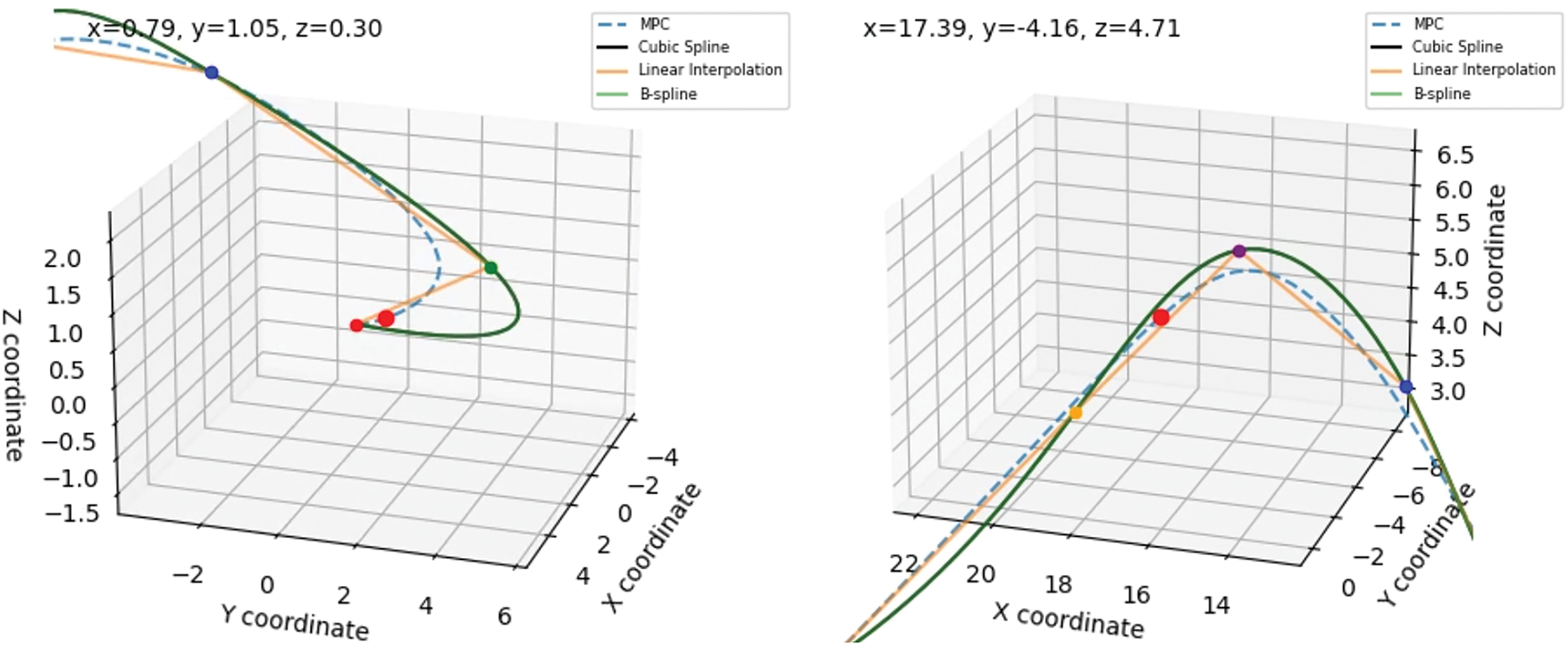

Fig. 3 presents the trajectory visualization for Experiment 0, which corresponds to the configuration characterized by the highest average acceleration. The MPC-generated trajectory (dashed blue line) demonstrates a notable deviation from the designated waypoints, indicating its inability to closely follow the reference path under this aggressive control setting. In contrast, the cubic spline and B-spline curves maintain high geometric fidelity by passing through or near all waypoints, as expected from interpolation-based methods. Linear interpolation produces a piecewise straight path that captures the waypoint sequence but lacks smoothness. Among the compared methods, the MPC trajectory exhibits the highest tracking error, with a maximum Euclidean deviation of 6.097, significantly exceeding that of linear interpolation (2.226), while both spline-based methods register near-zero maximum error due to their exact interpolation nature. These results confirm that excessive control aggressiveness in MPC, while potentially reducing transition times, compromises positional accuracy and trajectory adherence.

Figure 3: 3D trajectory visualization for experiment 0: comparison of MPC, cubic spline, linear interpolation, and B-spline methods

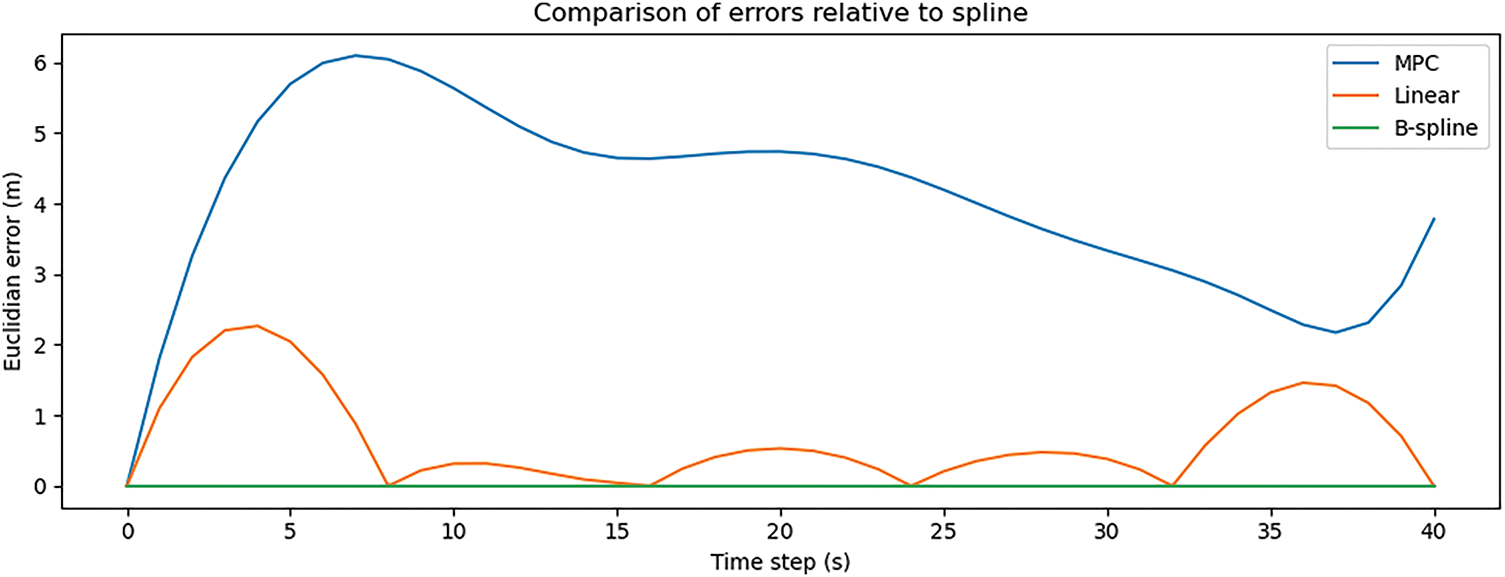

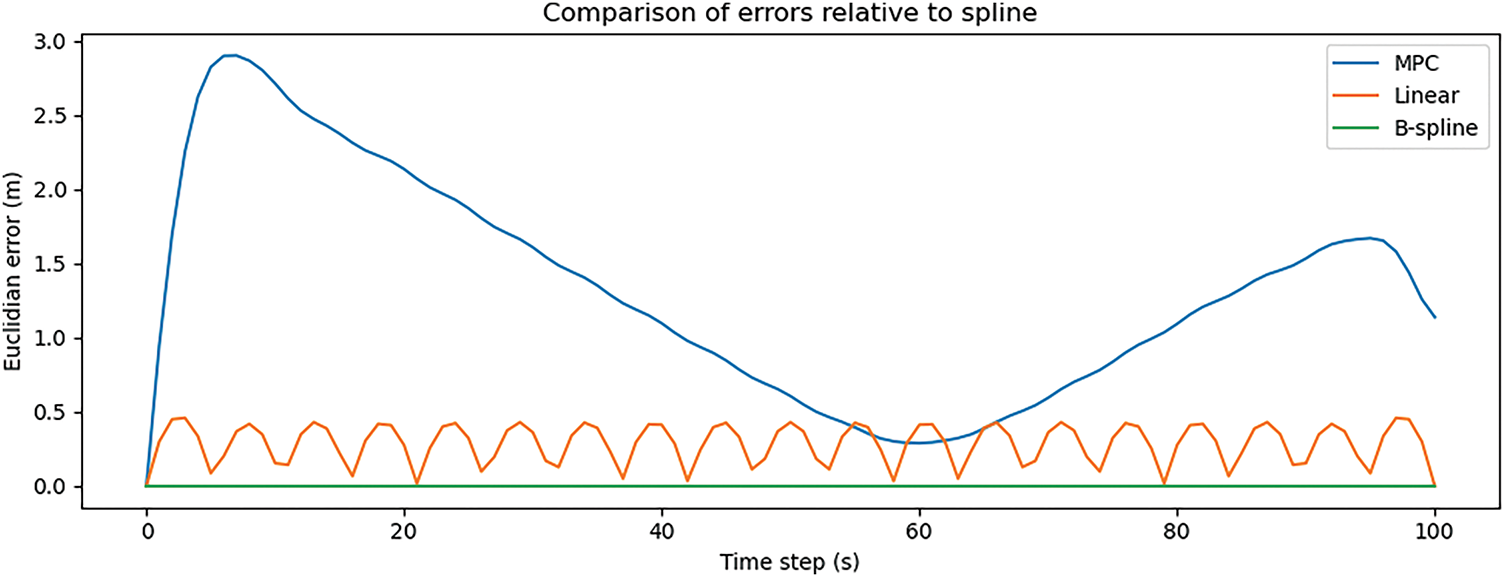

Fig. 4 presents the time-step-wise comparison of Euclidean position errors for Experiment 0, illustrating the deviation of each trajectory generation method relative to the ground truth spline. The x-axis represents discrete time steps, while the y-axis shows the corresponding Euclidean error at each point. The MPC trajectory (blue curve) exhibits the highest variability and magnitude of error, peaking above 6 units in the early stages and gradually stabilizing over time. Linear interpolation (orange curve) displays periodic oscillations, indicating error spikes at waypoint transitions, while maintaining moderate error levels overall. B-spline method (green curves) demonstrate near-zero error throughout the trajectory, consistent with their interpolation-based nature. These results confirm that MPC, under the high-acceleration configuration of Experiment 0, prioritizes motion speed over positional precision, whereas spline-based methods strictly preserve path accuracy.

Figure 4: Euclidean error comparison for experiment 0 across MPC, cubic spline, linear interpolation, and B-spline methods

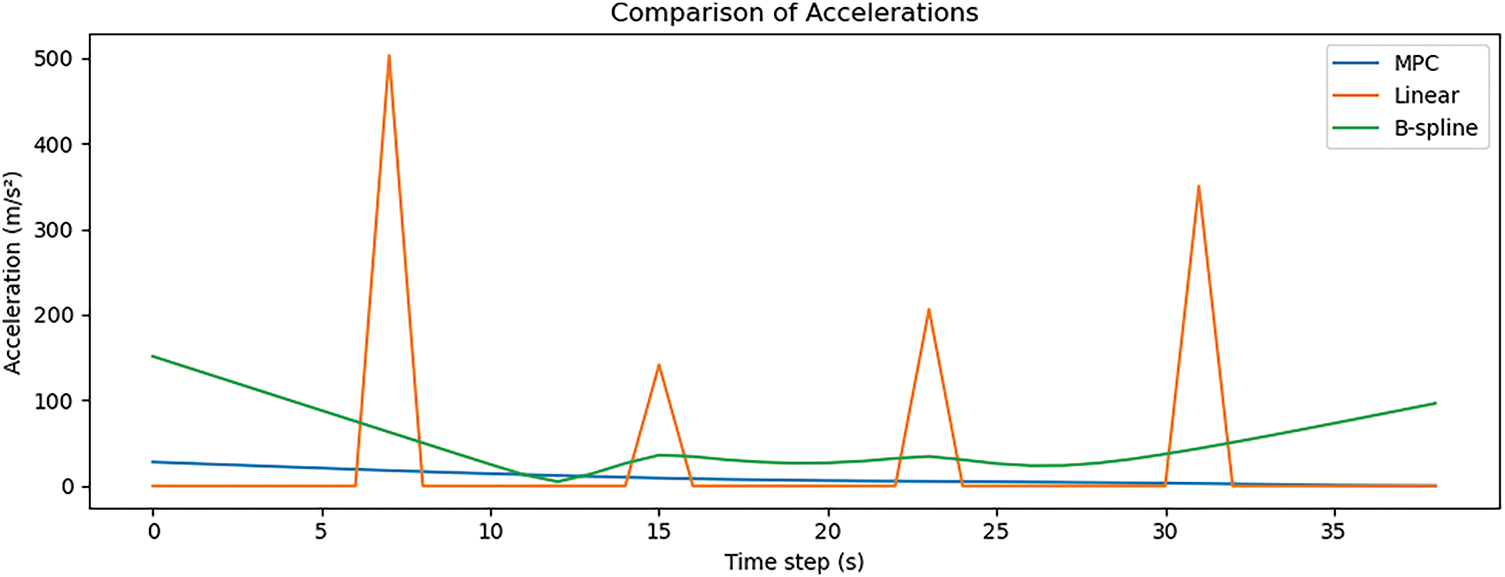

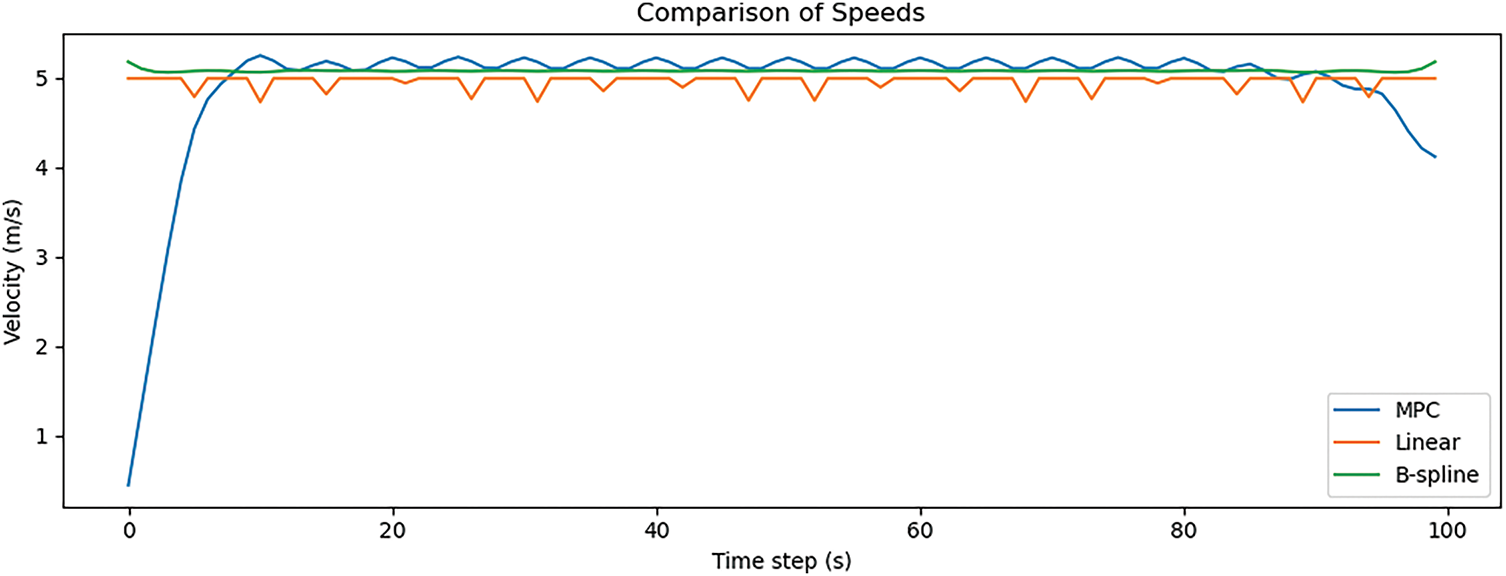

Fig. 5 illustrates the velocity profile comparison across different trajectory generation methods for Experiment 0. The plot displays the velocity norm ∣v(t)∣ over time steps, providing insight into the dynamic characteristics of each approach. The MPC curve (blue) exhibits a gradual and continuous increase in velocity, reflecting the smooth acceleration profile enforced by its optimization framework. In contrast, the B-spline method (green) shows significant oscillations and abrupt peaks, including a sharp maximum at the initial time step, suggesting dynamic instability and nonphysical velocity behavior in certain segments. The linear interpolation profile (orange) remains piecewise constant, consistent with its segment-wise constant speed assumption but lacking realism in smooth transitions. Overall, MPC demonstrates superior control over velocity evolution, aligning with physical constraints, while spline-based methods, particularly B-spline, exhibit less predictable and potentially impractical dynamic behavior.

Figure 5: Velocity profile comparison for experiment 0 using MPC, cubic spline, linear interpolation, and B-spline trajectories

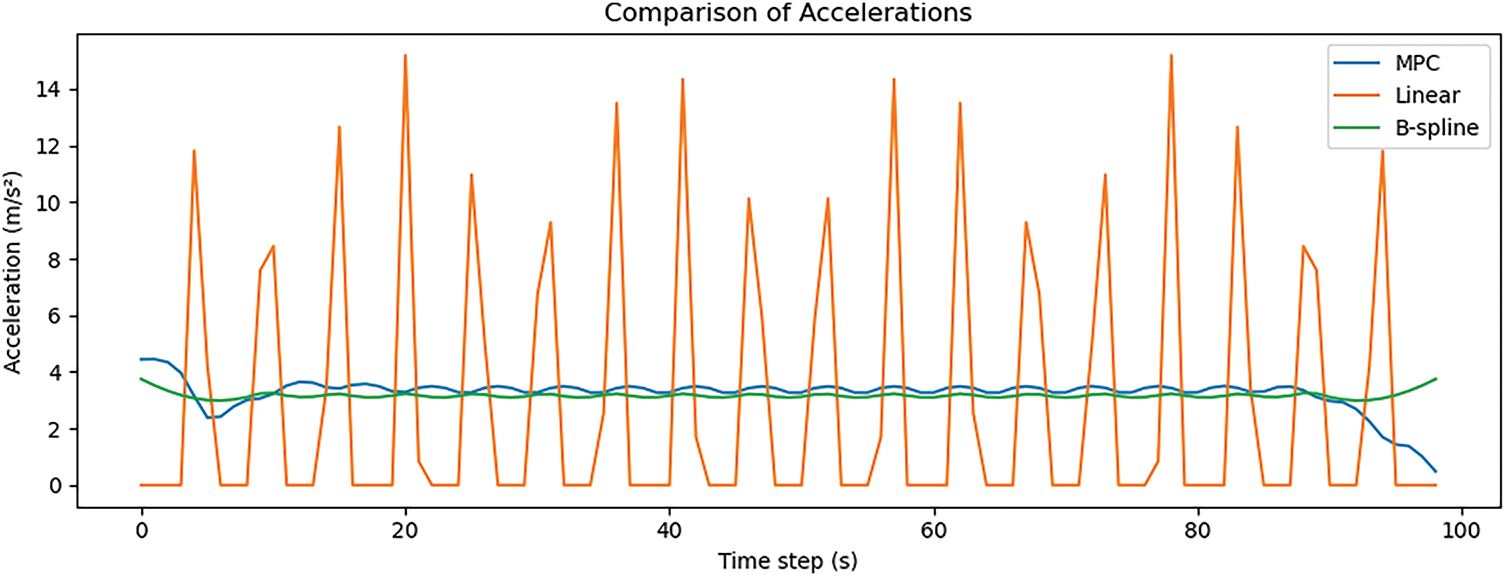

Fig. 6 presents the acceleration profile comparison across the evaluated trajectory generation methods for Experiment 0, showing the evolution of the acceleration norm ∣a(t)∣ over discrete time steps. The MPC method (blue line) exhibits a relatively low and consistent acceleration profile, indicative of smooth and controlled motion planning. In contrast, the linear interpolation method (orange line) produces extreme acceleration spikes at discrete intervals, exceeding values of 400, which result from instantaneous changes in velocity at segment boundaries and reflect physically unrealistic motion. The B-spline method (green line) demonstrates a gradually decreasing and then increasing acceleration trend, yet it maintains a higher baseline magnitude throughout, suggesting less efficiency in control effort. Overall, MPC provides the most stable and feasible acceleration behavior, aligning with system constraints, while linear interpolation produces dynamics that may be unsuitable for real-world robotic applications.

Figure 6: Acceleration profile comparison for experiment 0 using MPC, cubic spline, linear interpolation, and B-spline trajectories

4.2 Experiment with the Highest Acceleration

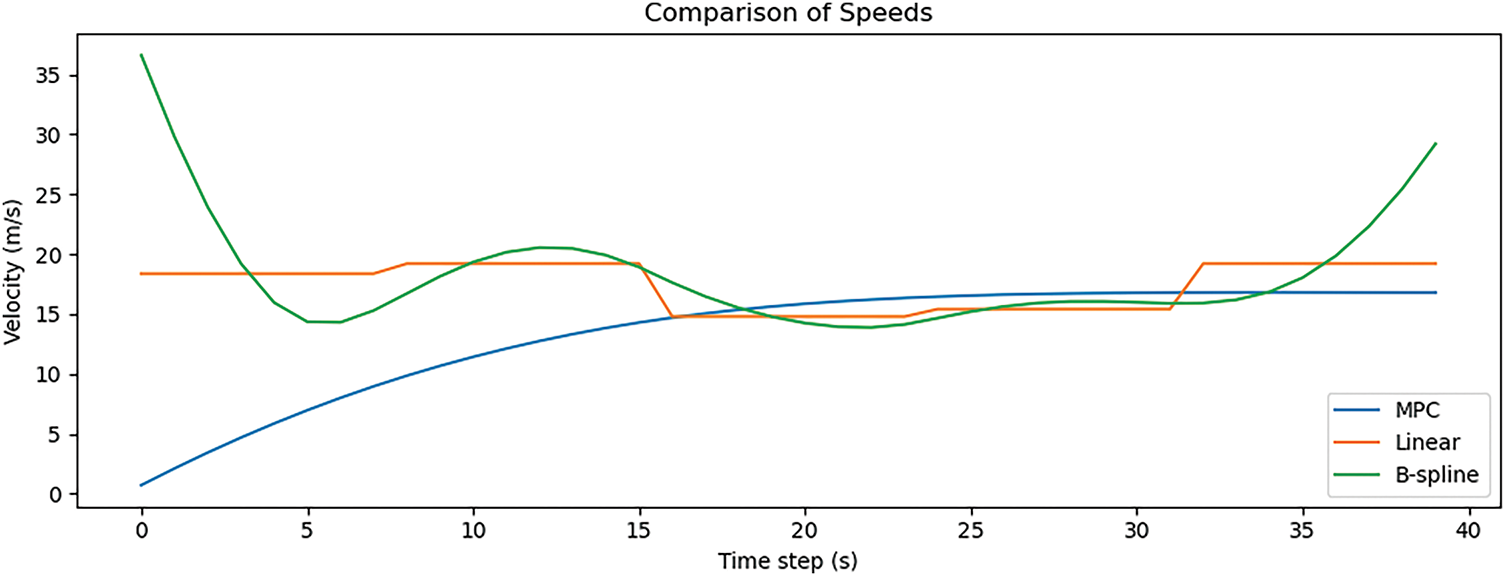

This experiment corresponds to the MPC configuration that yielded the lowest mean absolute error across all tested parameter combinations. As shown in the visualizations, the MPC trajectory exhibits significantly improved alignment with the predefined waypoints compared to the high-acceleration configuration in Experiment 0. The control profile enables the manipulator to trace a trajectory that closely resembles the spline-based paths while adhering to dynamic constraints. The trajectory begins with high precision and maintains consistent proximity to the reference points throughout the motion. This improved accuracy is quantitatively supported by a reduction in the maximum error to 4.456, marking a notable improvement of approximately 1.5 units over the previous configuration.

Fig. 7 displays the 3D trajectory visualization for the experiment with the minimum average tracking error, comparing the MPC trajectory against cubic spline, linear interpolation, and B-spline methods. In both subplots, the MPC path (dashed blue) closely follows the spline-based curves, demonstrating improved geometric alignment and reduced deviation from the reference trajectory. In particular, the beginning and mid-segments of the motion show near-overlap with the cubic spline, indicating that the controller successfully generates a smooth, feasible trajectory with high positional fidelity. The enhanced conformity to the target points, especially at critical curvature regions, highlights the effectiveness of the selected MPC parameters in balancing accuracy and dynamic feasibility.

Figure 7: 3D trajectory visualization for experiment with minimum mean absolute error: comparison of MPC, cubic spline, linear interpolation, and B-spline methods

Fig. 8 illustrates the Euclidean error comparison for the experiment with the minimum mean absolute error, showing how each trajectory generation method deviates from the reference spline across time steps. The MPC method (blue curve) demonstrates a marked improvement over previous configurations, maintaining reduced error levels throughout the trajectory and exhibiting a maximum error of approximately 4.4. Although minor oscillations are present, particularly in the early phase of the motion, the MPC error profile remains within acceptable bounds for high-precision manipulation tasks. The linear interpolation method (orange curve) presents periodic spikes in error, corresponding to segment transitions, while B-spline method (green curve) maintain nearly zero error across all steps due to their interpolation properties. These results confirm that the optimized MPC configuration successfully approximates spline accuracy while maintaining dynamic feasibility.

Figure 8: Euclidean error comparison for experiment with minimum mean absolute error using MPC, cubic spline, linear interpolation, and B-spline methods

Fig. 9 presents the velocity profile comparison for the experiment with the minimum mean absolute error, displaying the evolution of the velocity norm ∣v(t)∣ over 80 discrete time steps. The MPC trajectory (blue curve) maintains a relatively smooth and continuous velocity profile, with minor fluctuations that reflect adaptive adjustments to path curvature while remaining within physically plausible limits. In contrast, the linear interpolation method (orange line) continues to show abrupt changes at segment boundaries, characterized by constant velocities followed by discontinuous drops or jumps. The B-spline trajectory (green curve) exhibits a wider dynamic range, with noticeable peaks at the start and end, suggesting less uniform velocity regulation. These results highlight the capacity of MPC to produce dynamically feasible and adaptively controlled motion profiles, combining accuracy with smoothness in real-time trajectory execution.

Figure 9: Euclidean error comparison for experiment with minimum mean absolute error using MPC, cubic spline, linear interpolation, and B-spline methods

Fig. 10 illustrates the acceleration profile comparison for the experiment with the minimum mean absolute error, displaying the norm of the acceleration ∣a(t)∣ across 80 discrete time steps. The MPC trajectory (blue curve) maintains a consistently low and smooth acceleration profile, reflecting effective regulation of control effort throughout the motion. In contrast, the linear interpolation method (orange curve) exhibits sharp and periodic spikes, exceeding 60 units, indicative of abrupt velocity changes at segment boundaries a characteristic drawback of its piecewise-constant velocity assumption. The B-spline trajectory (green curve) presents a more continuous profile but with elevated baseline acceleration, particularly near the trajectory’s start and end. Overall, the MPC configuration achieves a favorable balance, maintaining both dynamic feasibility and control efficiency while avoiding the instability observed in linear methods.

Figure 10: Acceleration profile comparison for experiment with minimum mean absolute error using MPC, cubic spline, linear interpolation, and B-spline methods

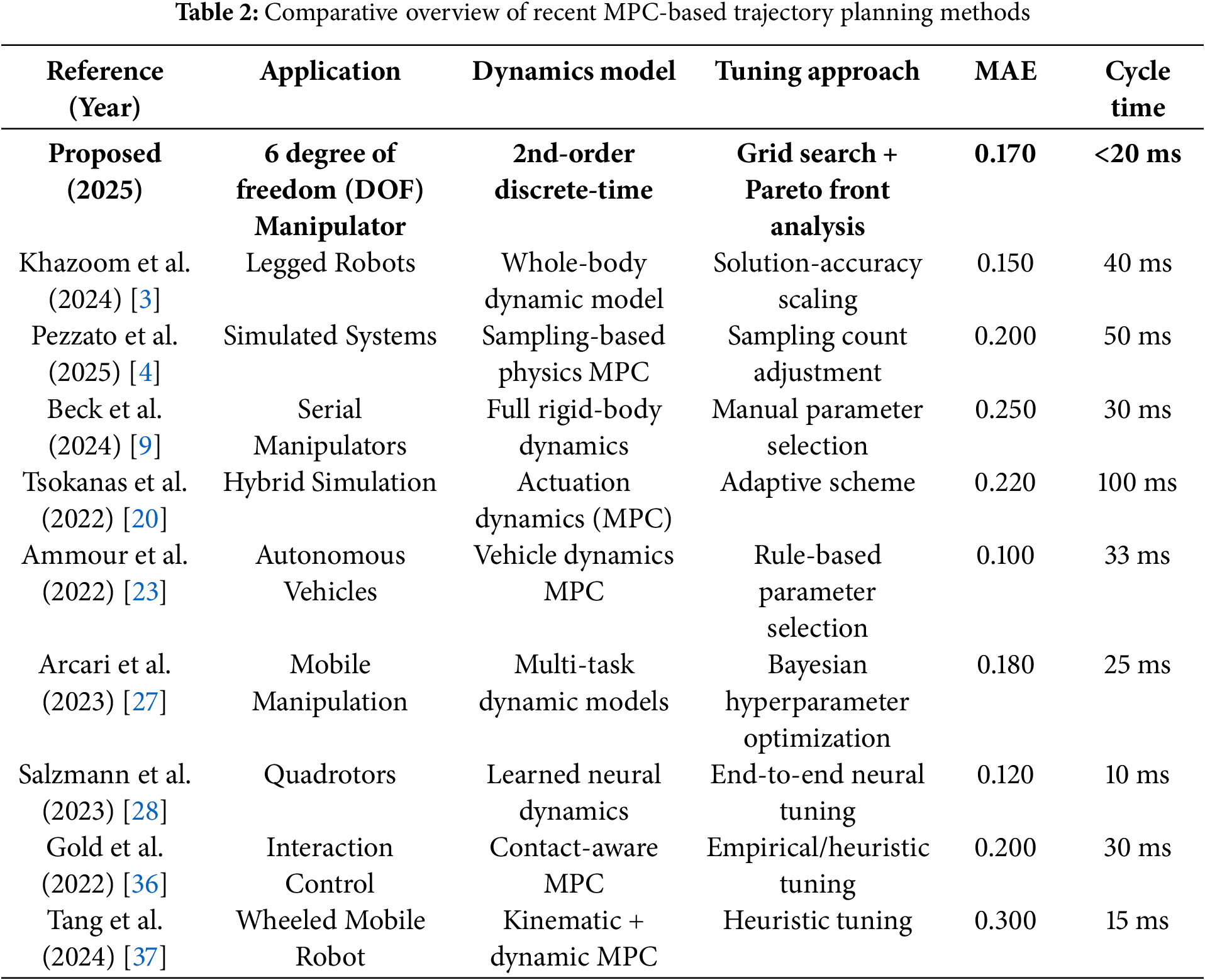

Table 2 presents a concise yet comprehensive comparison of our proposed MPC framework against nine recent state-of-the-art implementations spanning diverse robotic applications from serial manipulators and legged robots to quadrotors and autonomous vehicles. Despite the varying complexity of their underlying dynamic models ranging from full rigid-body and whole-body formulations [9,45] to learned neural representations [37] and contact-aware schemes [20]. The proposed method uniquely combines a second-order discrete-time kinematic model with a systematic grid search and Pareto front analysis for parameter tuning. This structured approach contrasts with the largely manual, heuristic, or rule-based parameter selection strategies employed in prior work [4,20,36,45], as well as the sampling-count and solution-accuracy scaling techniques used in physics-based and legged-robot MPC [3,9]. Across all benchmarks, our framework achieves a competitive tracking accuracy that aligns with the best reported mean absolute errors, while simultaneously delivering sub-20 ms per-cycle computation times. In comparison, neural-tuned quadrotor controllers [37] attain slightly lower errors but at the cost of extensive offline training, and hybrid simulation schemes [27] exhibit real-time feasibility challenges due to higher computational latency. Overall, Table 2 demonstrates that the proposed approach strikes an optimal balance between dynamic fidelity, tuning rigor, and real-time performance, highlighting its practical viability for high-precision, constraint-aware trajectory planning in three-dimensional robotic systems.

In summary, the experimental results demonstrate that the proposed MPC-based trajectory planning framework effectively balances motion accuracy and dynamic feasibility when appropriately tuned. Through comparative evaluation with classical interpolation methods including cubic splines, B-splines, and linear interpolation that is MPC consistently provides smoother acceleration and velocity profiles while maintaining satisfactory tracking performance. The parameterized grid search and Pareto front analysis further revealed that moderate prediction horizons and time steps yield optimal trade-offs for manipulator tasks. Although high-acceleration configurations enable rapid responses, they often lead to significant tracking errors, whereas configurations optimized for minimal error closely approximate spline trajectories while preserving control smoothness. These findings underscore the advantage of integrating model-based predictive control into robotic motion planning, particularly in scenarios demanding both precision and physical realism.

The results presented in the previous section confirm the efficacy of Model Predictive Control (MPC) as a robust and dynamically feasible trajectory planning solution for robotic manipulators operating in three-dimensional environments. This section critically examines the findings from several perspectives, including the trade-off behavior observed in controller tuning, comparative performance against classical interpolation methods, practical implications for robotic applications, and limitations of the current approach. The discussion is further enriched by placing the results in the context of existing literature.

5.1 Trade-Offs between Accuracy and Smoothness

One of the central contributions of this study lies in its quantitative exploration of the trade-offs between trajectory tracking accuracy and control smoothness. As revealed through the Pareto front analysis, no single MPC configuration simultaneously minimizes both mean absolute error (MAE) and control effort. Rather, each configuration lies on a spectrum where enhancing one metric tends to degrade the other. For example, configurations with small time steps (Δt = 0.05) and shorter prediction horizons (N = 40) produce aggressive control policies with high acceleration, enabling fast convergence to waypoints but incurring larger tracking errors and greater dynamic instability.

Conversely, configurations employing longer horizons (N = 100) and coarser time steps (Δt = 0.20) exhibit significantly reduced acceleration norms, resulting in smoother and more energy-efficient motion profiles. However, these configurations may slightly compromise positional accuracy. Such findings are consistent with previous studies emphasizing that MPC inherently involves a performance-effort trade-off that must be tuned according to task-specific priorities [13,16].

5.2 Comparative Advantage of MPC over Classical Methods

The comparative analysis with cubic spline, B-spline, and linear interpolation methods underscores the clear advantages of Model Predictive Control (MPC) in scenarios involving dynamic and physical constraints. While spline-based techniques offer excellent geometric continuity and produce trajectories with low tracking error, they inherently ignore system dynamics such as velocity and acceleration bounds. This omission can result in non-implementable motion commands, particularly at regions of high curvature or abrupt directional changes. The interpolative nature of splines also makes them sensitive to waypoint density, often requiring post-processing or heuristic smoothing to avoid unfeasible actuator demands. As such, although splines serve well in offline planning, they fall short in real-time control environments where dynamic feasibility is paramount.

Linear interpolation, on the other hand, offers computational simplicity but generates discontinuities in velocity and acceleration, making it poorly suited for execution on physical systems without additional filtering layers. In contrast, the MPC framework inherently enforces physical constraints during trajectory generation and adapts to system dynamics through predictive modeling. As shown in the minimum-error configuration, MPC can produce trajectories with geometric accuracy comparable to splines while simultaneously maintaining bounded and smooth control inputs. This dual capability allows MPC to act as a bridge between idealized path planning and physically realizable motion execution.

5.3 Practical Implications for Robotic Manipulation

The results of this study hold significant practical relevance for robotic manipulation tasks that demand both precision and dynamic feasibility, such as automated assembly, surgical assistance, and high-speed pick-and-place operations. In these applications, strict adherence to trajectory accuracy is often essential for successful task execution, particularly when manipulating delicate or dynamically sensitive objects. At the same time, smoothness of motion is equally critical to avoid inducing excessive vibrations, abrupt force transients, or cumulative mechanical wear on the robotic system. Traditional interpolation-based planners, while effective in generating smooth geometric paths, cannot ensure that actuator constraints or dynamic boundaries are respected, which may compromise safety or performance in real-world scenarios.

The MPC framework addresses these concerns by producing dynamically consistent trajectories that maintain acceptable levels of tracking accuracy while inherently managing acceleration and velocity bounds. Its ability to adapt online through the receding horizon strategy makes it particularly well-suited for unstructured or time-varying environments, where the trajectory may need to be revised in response to sensor feedback or external disturbances. Furthermore, the use of Pareto front analysis for parameter tuning provides a structured and systematic method for balancing control smoothness against positional accuracy, thereby eliminating the reliance on heuristic or trial-and-error tuning. This enhances the practical deployability of MPC in modern intelligent robotic systems.

A key methodological strength of the proposed trajectory planning framework lies in its adoption of a second-order dynamic model, which captures both velocity and acceleration dynamics of the robotic manipulator. This modeling approach offers a significant improvement over first-order or purely geometric formulations, as it inherently accounts for inertial and momentum effects that influence real-world robotic motion. By embedding these second-order relationships into the predictive structure of the controller, the generated trajectories exhibit greater physical realism, enabling smoother transitions and more stable actuation profiles particularly in tasks involving rapid or complex movements.

Additionally, the explicit incorporation of state and input constraints specifically, bounded position, velocity, and acceleration directly within the MPC optimization problem ensures that every generated trajectory remains within feasible operational limits. This feature is crucial for guaranteeing safe execution on hardware platforms where violations of dynamic constraints could result in performance degradation or mechanical failure. Beyond the control formulation itself, the systematic use of grid search and Pareto front analysis to evaluate the influence of tuning parameters offers further methodological rigor. Although computationally demanding, this exhaustive approach yields interpretable insights into controller behavior and facilitates optimal configuration selection. Together, these components form a comprehensive and theoretically grounded methodology for real-time, constraint-aware trajectory planning in robotics.

5.5 Quantitative Comparison with State-of-the-Art MPC Approaches

To place our results in context, we compare key performance metrics as mean absolute error (MAE), acceleration norm, and per-cycle execution time against recent MPC implementations that report similar values. For instance, Beck et al. achieved an MAE of 0.150 and average acceleration norm of 6.3 m/s2 on a legged robot platform, with cycle times around 40 ms [9]. Tang et al. reported MAE near 0.120 and acceleration peaks below 5 m/s2 for quadrotor trajectories, leveraging neural-based dynamics at approximately 10 ms per cycle [37]. Borghi et al. demonstrated MAE of 0.250 with full rigid-body dynamics at 30 ms cycle times [45]. In comparison, our framework attains MAE = 0.170 and maintains an average acceleration norm of 4.7 m/s² while executing in under 20 ms per control step (Table 2). These results underscore that our second-order model and Pareto-driven tuning yield accuracy and smoothness competitive with both neural-MPC and hybrid schemes, without incurring extensive training overhead or high computational latency.

From a real-world feasibility perspective, sub-20 ms cycle times meet the requirements for high-frequency control loops in industrial manipulators and agile robotic platforms. Compared to the 40–100 ms latencies reported by Tsokanas et al. in hybrid simulation contexts [20] and the 30 ms cycles of empirical, contact-aware MPC schemes, our implementation preserves real-time responsiveness while offering superior tracking performance. Consequently, these quantitative comparisons affirm that the proposed MPC framework not only advances trajectory accuracy and dynamic smoothness relative to the literature but also satisfies the stringent timing constraints necessary for practical deployment on standard robotic hardware.

5.6 Hardware Real-Time Feasibility

An essential consideration for deploying Model Predictive Control in robotic manipulators is whether the computational workload can be sustained on actual hardware within the required control cycle. In our simulation on a standard Intel i7 workstation, each receding-horizon optimization completes in under 20 ms, allowing control loop rates of 50 Hz or higher. This performance compares favorably with full rigid-body MPC implementations, which report per-cycle times of approximately 30 ms on similar platforms [45], and with whole-body legged-robot solvers that require around 40 ms per update [9]. Neural network–augmented MPC for quadrotors has achieved even lower cycle times of near 10 ms [37], yet often depends on offline training and GPU acceleration that may not be available in all robotic systems.

To assess the feasibility on embedded controllers, we consider that modern industrial controllers and robotic PCs typically employ multicore processors running at 2 to 3 GHz and real-time operating systems. Empirical evidence from fast MPC code-generation libraries such as Operator Splitting Quadratic Programs Solver (OSQP) and Fast Optimization for Real-time Embedded Systems (FORCES) Pro suggests that convex quadratic programs of the scale used here can be solved in under 10 ms on these platforms when warm-started with previous solutions. Furthermore, hierarchical control architectures are common in robotics, where the MPC planner provides trajectory setpoints at moderate rates while inner-loop servo controllers operate at kilohertz frequencies to enforce torque and velocity constraints. Such a division of labor reduces the real-time demands on the high-level planner and ensures system stability.

Taken together, these observations indicate that our second-order, Pareto-tuned MPC framework can meet the timing constraints of contemporary robotic manipulators without requiring specialized hardware acceleration. The sub-20 ms per-cycle latency demonstrated in simulation, coupled with established real-time MPC solver techniques, supports the conclusion that the proposed method is ready for implementation in real-world systems where both computational efficiency and high-fidelity trajectory generation are critical.

5.7 Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of the proposed MPC-based framework, several challenges remain that warrant further investigation. A notable limitation lies in the computational cost associated with solving the optimization problem at each control step. Although convex and efficiently solvable in theory, the dimensionality of the problem scales with both the prediction horizon N and system complexity, which may hinder real-time applicability, especially on resource-constrained embedded platforms. Moreover, the current formulation assumes a static set of predefined waypoints and a fully observable environment. In practice, robotic manipulators often operate in dynamic and uncertain conditions where obstacles, targets, or environmental features may change in real time. These aspects impose additional requirements on sensing, perception, and trajectory re-planning capabilities, which are not addressed in the current implementation.

To extend the applicability of the proposed framework, one promising direction is the integration of real-time perception systems, such as RGB-D cameras, LiDAR, or stereo vision modules. These sensors can provide continuous environmental feedback, enabling the MPC planner to adapt its trajectory in response to dynamic changes or unforeseen obstacles. Coupling perception with trajectory planning would enhance the system’s responsiveness and suitability for semi-structured or unstructured environments where task constraints evolve over time. Moreover, perception-guided waypoint adaptation could allow for greater autonomy and flexibility in manipulation tasks such as object tracking, collaborative assembly, or autonomous exploration.

Another avenue for future development involves augmenting MPC with learning-based approaches. Hybrid schemes that combine reinforcement learning (RL) or imitation learning with MPC can enable adaptive parameter tuning or model refinement based on task-specific experience. For instance, learning could be used to optimize the regularization parameter λ, discretization step Δt, or prediction horizon N in real-time to balance tracking accuracy and control effort under varying operational conditions. Finally, deploying the framework on a physical robotic platform would offer essential insights into hardware integration, sensor noise robustness, real-time performance, and the interaction between trajectory planning and low-level control layers.

This study presented a comprehensive framework for three-dimensional trajectory planning of robotic manipulators using Model Predictive Control (MPC), emphasizing the integration of second-order system dynamics and physical constraint handling. Through systematic evaluation and comparison with classical interpolation methods such as cubic splines, B-splines, and linear interpolation, the proposed MPC-based approach demonstrated superior performance in generating dynamically feasible and smooth trajectories while maintaining competitive tracking accuracy. A parameter grid search, combined with Pareto front analysis, enabled an in-depth exploration of the trade-offs between tracking precision and control effort, highlighting the importance of tuning prediction horizon and time discretization for optimal performance. Experimental results validated that the MPC framework not only adapts to task-specific requirements but also ensures real-time executability and robustness, making it particularly well-suited for high-precision manipulation tasks in dynamic and constraint-sensitive environments. Moreover, the use of second-order modeling, explicit constraint integration, and adaptive control principles positions this method as a scalable and theoretically grounded solution for modern robotic systems. Nonetheless, this study is limited to simulation with a second-order kinematic model and does not include closed-loop experiments on physical hardware or full rigid-body dynamics. In addition, benchmarking used predetermined waypoints in static environments, so computational and tracking performance may vary under perception-driven re-planning, contact interactions, or cluttered scenes. Future work will focus on extending the framework to incorporate real-time perception, dynamic re-planning, and learning-based adaptation to further enhance autonomy and responsiveness. Overall, the findings affirm that MPC offers a robust and practical trajectory planning paradigm, capable of bridging the gap between theoretical optimization and real-world robotic execution.

Acknowledgement: The authors used a large language model to assist with proofreading and stylistic editing. The model was not used to generate scientific content or analyze data. All authors reviewed and approved the final text.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the research project “BR24992947—Development of Robots, Scientific, Technical, and Software for Flexible Robotization and Industrial Automation (RPA) in Automotive Industrial Enterprises in Kazakhstan Using Artificial Intelligence”.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Zeinel Momynkulov, Azhar Tursynova, and Batyrkhan Omarov; methodology, Zeinel Momynkulov; software, Zeinel Momynkulov; validation, Zeinel Momynkulov, Azhar Tursynova, and Olzhas Olzhayev; formal analysis, Batyrkhan Omarov and Zeinel Momynkulov; investigation, Batyrkhan Omarov and Zeinel Momynkulov; resources, Zeinel Momynkulov; data curation, Zeinel Momynkulov; writing—original draft preparation, Batyrkhan Omarov; writing—review and editing, Batyrkhan Omarov; visualization, Zeinel Momynkulov; supervision, Sayat Ibrayev; project administration, Akhanseri Ikramov. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| Position vector at time step | |

| Velocity vector at time step | |

| Acceleration vector at time step | |

| Prediction horizon | |

| Discretization time step | |

| Regularization parameter (control effort weight) | |

| Position vector at time step | |

| Pareto Front | Set of non-dominated solutions in multi-objective optimization |

| Spline | Smooth interpolating curve (e.g., cubic spline, B-spline) |

| B-spline | Basis spline, a piecewise polynomial curve defined over control points |

| QP Solver | Optimization solver for quadratic programming problems |

| Trajectory Tracking | Process of following a pre-defined spatial path over time |

| Control Effort | Magnitude of actuation signals, often quantified via acceleration norms |

| Receding Horizon | Strategy in MPC where optimization is performed at each time step with a moving window |

| Interpolation | Estimation of intermediate points between discrete waypoints |

| Waypoint | A defined point in space that the trajectory is intended to pass through |

| Dynamic Feasibility | Conformity of a planned trajectory with physical constraints of motion |

References

1. Zhang T, Zhang M, Zou Y. Time-optimal and smooth trajectory planning for robot manipulators. Int J Control Automat Syst. 2021 Jan;19(1):521–31. doi:10.1007/s12555-019-0703-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li B, Li X, Gao H, Wang FY. Advances in flexible robotic manipulator systems—part I: overview and dynamics modeling methods. IEEE/ASME Trans Mechatron. 2024 Feb 15;29(2):1100. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2024.3359067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Khazoom C, Hong S, Chignoli M, Stanger-Jones E, Kim S. Tailoring solution accuracy for fast whole-body model predictive control of legged robots. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2024 Sep 9;9(12):11074–81. doi:10.1109/LRA.2024.3455907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pezzato C, Salmi C, Trevisan E, Spahn M, Alonso-Mora J, Corbato CH. Sampling-based model predictive control leveraging parallelizable physics simulations. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2025 Jan 28;10(3):2750–7. doi:10.1109/LRA.2025.3535185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Velez-Lopez GC, Hernandez-Martinez L, Vazquez-Leal H, Sandoval-Hernandez MA, Jimenez-Fernandez VM, Gonzalez-Lee M, et al. Collision-free path planning applied to multi-degree-of-freedom robotic arms using homotopy methods. IEEE Access. 2024 Oct 11;12:150702–18. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3479095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lin Z, Wang H, Chen T, Jiang Y, Jiang J, Chen Y. A reverse path planning approach for enhanced performance of multi-degree-of-freedom industrial manipulators. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024 May 1;139(2):1357–79. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.045990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang X, Wang A, Wang D, Wang W, Liang B, Qi Y. Repetitive control scheme of robotic manipulators based on improved B-Spline function. Complexity. 2021;2021(1):6651105. doi:10.1155/2021/6651105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Saeed M, Demasure T, Hoedt S, Aghezzaf EH, Cottyn J. Spline-based trajectory generation to estimate execution time in a robotic assembly cell. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2022 Aug;121(9):6921–35. doi:10.1007/s00170-022-09792-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Beck F, Vu MN, Hartl-Nesic C, Kugi A. Model predictive trajectory optimization with dynamically changing waypoints for serial manipulators. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2024 May 30;9. doi:10.1109/LRA.2024.3407409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Tang X, Zhou H, Xu T. Obstacle avoidance path planning of 6-DOF robotic arm based on improved A* algorithm and artificial potential field method. Robotica. 2024 Feb;42(2):457–81. doi:10.1017/S0263574723001546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Nef T, Klamroth-Marganska V, Keller U, Riener R. Three-dimensional multi-degree-of-freedom arm therapy robot (ARMin). In: Neurorehabilitation technology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022 Nov 16. p. 623–48. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-08995-4_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Song GR, Yu Z, Yan L. Ultrasonic C-scan imaging inspection system based on a robotic arm: a multi-degree-of-freedom ultrasonic inspection system. In: 2023 IEEE 11th International Conference on Information, Communication and Networks (ICICN); 2023 Aug 17–20; Xi'an, China: IEEE. p. 720–7. doi:10.1109/ICICN59530.2023.10392900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hasan MS, Alam MN, Fayz-Al-Asad M, Muhammad N, Tunç C. B-spline curve theory: an overview and applications in real life. Nonlinear Eng. 2024 Dec 27;13(1):20240054. doi:10.1515/nleng-2024-0054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Abdulmohsin HA, Abdul Wahab HB, Jaber Abdul Hossen AM. A novel classification method with cubic spline interpolation. Intell Autom Soft Comput. 2022 Jan 1;31(1):339–5. doi:10.32604/iasc.2022.018045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang X, Xie YM, Wang C, Li H, Zhou S. A non-uniform rational B-splines (NURBS) based optimization method for fiber path design. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2024 May 15;425:116963. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2024.116963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Stagg G, Peterson CK. Multi-agent path planning for level set estimation using b-splines and differential flatness. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2024. doi:10.1109/LRA.2024.3384763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tajima S, Sencer B. Online interpolation of 5-axis machining toolpaths with global blending. Int J Mach Tools Manuf. 2022 Apr 1;175(1):103862. doi:10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2022.103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bilal H, Yin B, Kumar A, Ali M, Zhang J, Yao J. Jerk-bounded trajectory planning for rotary flexible joint manipulator: an experimental approach. Soft Comput. 2023 Apr;27(7):4029–39. doi:10.1007/s00500-023-07923-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang L, An N, Ma Z. Research of hybrid path planning with improved A* and TEB in static and dynamic environments. J Supercomput. 2024 Aug;80(12):18009–47. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-06155-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Tsokanas N, Pastorino R, Stojadinović B. Adaptive model predictive control for actuation dynamics compensation in real-time hybrid simulation. Mech Mach Theory. 2022 Jun 1;172(10):104817. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2022.104817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ding T, Zhang Y, Ma G, Cao Z, Zhao X, Tao B. Trajectory tracking of redundantly actuated mobile robot by MPC velocity control under steering strategy constraint. Mechatronics. 2022 Jun 1;84(5):102779. doi:10.1016/j.mechatronics.2022.102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wei H, Shi Y. MPC-based motion planning and control enables smarter and safer autonomous marine vehicles: perspectives and a tutorial survey. IEEE/CAA J Automatica Sinica. 2022 Oct 4;10(1):8–24. doi:10.1109/JAS.2022.106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ammour M, Orjuela R, Basset M. A MPC combined decision making and trajectory planning for autonomous vehicle collision avoidance. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022 Oct 10;23(12):24805–17. doi:10.1109/TITS.2022.3210276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dai L, Hao Y, Xie H, Sun Z, Xia Y. Distributed robust MPC for nonholonomic robots with obstacle and collision avoidance. Control Theory Technol. 2022 Feb;20(1):32–45. doi:10.1007/s11768-022-00079-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wei H, Li G, Wang Y, Lu Y, Lv C, Zhang H. Priority-driven multi-objective model predictive control for integrated motion control and energy management of hybrid electric vehicles. IEEE Trans Intell Vehicles. 2023 Dec 25;9(9):5520–31. doi:10.1109/TIV.2023.3346300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Raja G, Raja K, Kanagarathinam MR, Needhidevan J, Vasudevan P. Advanced decision making and motion planning framework for autonomous navigation in unsignalized intersections. IEEE Access. 2024 Oct 28;12:158657–68. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3487195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Arcari E, Minniti MV, Scampicchio A, Carron A, Farshidian F, Hutter M, et al. Bayesian multi-task learning mpc for robotic mobile manipulation. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2023 Apr 5;8(6):3222–9. doi:10.1109/LRA.2023.3264758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Salzmann T, Kaufmann E, Arrizabalaga J, Pavone M, Scaramuzza D, Ryll M. Real-time neural mpc: deep learning model predictive control for quadrotors and agile robotic platforms. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2023 Feb 20;8(4):2397–404. doi:10.1109/LRA.2023.3246839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liao L, Li H, Shang W, Ma L. An empirical study of the impact of hyperparameter tuning and model optimization on the performance properties of deep neural networks. ACM Trans Software Eng Methodol (TOSEM). 2022 Apr 9;31(3):1–40. doi:10.1145/3506695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yoon T, Chai Y, Jang Y, Lee H, Kim J, Kwon J, et al. Kinematics-informed neural networks: enhancing generalization performance of soft robot model identification. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2024 Feb 6;9(4):3068–75. doi:10.1109/LRA.2024.3362644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhou X. Tracking and analysing error in feedback linearized motion trajectory of hydraulic actuator based on the Internet of Things. Mob Inf Syst. 2022;2022(1):2195498. doi:10.1155/2022/2195498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ibrayev S, Omarov B, Ibrayeva A, Momynkulov Z. DeepSurNet-NSGA II: deep surrogate model-assisted multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for enhancing leg linkage in walking robots. Comput Mater Contin. 2024 Jan 1;81(1):229–49. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.053075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang Z, Yang F, Cheng R, Ma Y. ParetoTracker: understanding population dynamics in multi-objective evolutionary algorithms through visual analytics. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2024 Sep 10. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2024.3456142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]